User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Hospital-acquired conditions drop 8% since 2014, saving 8,000 lives and $3 billion

From 2014 to 2016, the rate of potentially deadly hospital-acquired conditions in the United States dropped by 8% – a change that translated into 350,000 fewer such conditions, 8,000 fewer inpatient deaths, and a national savings of almost $3 billion.

The preliminary new baseline rate for hospital-acquired conditions (HACs) is 90 per 1,000 discharges – down from 98 per 1,000 discharges at the end of 2014, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s new report, “AHRQ National Scorecard on Hospital-Acquired Conditions – Updated Baseline Rates and Preliminary Results 2014-2016.”

The largest improvements occurred in central line–associated bloodstream infections (down 31% from 2014), postoperative venous thromboembolism (21% decline), adverse drug events (15% decline), and pressure ulcers (10% decline). A new category, C. difficile infections, also showed a large decline over 2014 (11%).

These numbers build on earlier successes associated with a national goal set by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to reduce HACs by 20% by 2019. They should be hailed as proof that attention to prevention strategies can save lives and money, said Seema Verma, CMS administrator.

“Today’s results show that this is a tremendous accomplishment by America’s hospitals in delivering high-quality, affordable healthcare,” Ms. Verma said in a press statement. “CMS is committed to moving the healthcare system to one that improves quality and fosters innovation while reducing administrative burden and lowering costs. This work could not be accomplished without the concerted effort of our many hospital, patient, provider, private, and federal partners – all working together to ensure the best possible care by protecting patients from harm and making care safer.”

The numbers continue to go in the right direction, the report noted. Data reported in late 2016 found a 17% decline in HACs from 2010 to 2014. This equated to 2.1 million HACs, 87,000 fewer deaths, and a savings of $19.9 billion.

Much work remains to be done to achieve the stated 2019 goal, the report noted, but the rewards are great. Reaching the 20% reduction goal would secure a total decrease in the HAC rate from 98 to 78 per 1,000 discharges. This would result in 1.78 million fewer HAC in the years from 2015-2019. That decrease would ultimately save 53,000 lives and $19.1 billion over 5 years.

From 2014 to 2016, the rate of potentially deadly hospital-acquired conditions in the United States dropped by 8% – a change that translated into 350,000 fewer such conditions, 8,000 fewer inpatient deaths, and a national savings of almost $3 billion.

The preliminary new baseline rate for hospital-acquired conditions (HACs) is 90 per 1,000 discharges – down from 98 per 1,000 discharges at the end of 2014, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s new report, “AHRQ National Scorecard on Hospital-Acquired Conditions – Updated Baseline Rates and Preliminary Results 2014-2016.”

The largest improvements occurred in central line–associated bloodstream infections (down 31% from 2014), postoperative venous thromboembolism (21% decline), adverse drug events (15% decline), and pressure ulcers (10% decline). A new category, C. difficile infections, also showed a large decline over 2014 (11%).

These numbers build on earlier successes associated with a national goal set by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to reduce HACs by 20% by 2019. They should be hailed as proof that attention to prevention strategies can save lives and money, said Seema Verma, CMS administrator.

“Today’s results show that this is a tremendous accomplishment by America’s hospitals in delivering high-quality, affordable healthcare,” Ms. Verma said in a press statement. “CMS is committed to moving the healthcare system to one that improves quality and fosters innovation while reducing administrative burden and lowering costs. This work could not be accomplished without the concerted effort of our many hospital, patient, provider, private, and federal partners – all working together to ensure the best possible care by protecting patients from harm and making care safer.”

The numbers continue to go in the right direction, the report noted. Data reported in late 2016 found a 17% decline in HACs from 2010 to 2014. This equated to 2.1 million HACs, 87,000 fewer deaths, and a savings of $19.9 billion.

Much work remains to be done to achieve the stated 2019 goal, the report noted, but the rewards are great. Reaching the 20% reduction goal would secure a total decrease in the HAC rate from 98 to 78 per 1,000 discharges. This would result in 1.78 million fewer HAC in the years from 2015-2019. That decrease would ultimately save 53,000 lives and $19.1 billion over 5 years.

From 2014 to 2016, the rate of potentially deadly hospital-acquired conditions in the United States dropped by 8% – a change that translated into 350,000 fewer such conditions, 8,000 fewer inpatient deaths, and a national savings of almost $3 billion.

The preliminary new baseline rate for hospital-acquired conditions (HACs) is 90 per 1,000 discharges – down from 98 per 1,000 discharges at the end of 2014, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s new report, “AHRQ National Scorecard on Hospital-Acquired Conditions – Updated Baseline Rates and Preliminary Results 2014-2016.”

The largest improvements occurred in central line–associated bloodstream infections (down 31% from 2014), postoperative venous thromboembolism (21% decline), adverse drug events (15% decline), and pressure ulcers (10% decline). A new category, C. difficile infections, also showed a large decline over 2014 (11%).

These numbers build on earlier successes associated with a national goal set by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to reduce HACs by 20% by 2019. They should be hailed as proof that attention to prevention strategies can save lives and money, said Seema Verma, CMS administrator.

“Today’s results show that this is a tremendous accomplishment by America’s hospitals in delivering high-quality, affordable healthcare,” Ms. Verma said in a press statement. “CMS is committed to moving the healthcare system to one that improves quality and fosters innovation while reducing administrative burden and lowering costs. This work could not be accomplished without the concerted effort of our many hospital, patient, provider, private, and federal partners – all working together to ensure the best possible care by protecting patients from harm and making care safer.”

The numbers continue to go in the right direction, the report noted. Data reported in late 2016 found a 17% decline in HACs from 2010 to 2014. This equated to 2.1 million HACs, 87,000 fewer deaths, and a savings of $19.9 billion.

Much work remains to be done to achieve the stated 2019 goal, the report noted, but the rewards are great. Reaching the 20% reduction goal would secure a total decrease in the HAC rate from 98 to 78 per 1,000 discharges. This would result in 1.78 million fewer HAC in the years from 2015-2019. That decrease would ultimately save 53,000 lives and $19.1 billion over 5 years.

CDC concerned about multidrug-resistant Shigella

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have issued follow-up recommendations for managing and reporting Shigella infections because of concerns about increasing antibiotic resistance and the possibility of treatment failures.

Isolates with no resistance to quinolone antibiotics have ciprofloxacin minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of less than 0.015 mcg/mL. However, the CDC has continued to identify isolates of Shigella that, while still within the susceptible range for the fluoroquinolone antibiotic ciprofloxacin (that is, having MIC values less than 1 mcg/mL), have MIC values for ciprofloxacin of 0.12-1.0 mcg/mL, thus appearing to harbor one or more resistance mechanisms. Furthermore, the CDC has identified an increasing number of isolates that have MIC values for azithromycin exceeding the epidemiologic cutoff value, which suggests some form of acquired resistance.

“CDC is particularly concerned about people who are at high risk for multidrug-resistant Shigella infections and are more likely to require antibiotic treatment, such as men who have sex with men, patients who are homeless, and immunocompromised patients. These patients often have more severe disease, prolonged shedding, and recurrent infections,” the recommendations stated.

More information can be found in the CDC’s Health Alert Network release.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have issued follow-up recommendations for managing and reporting Shigella infections because of concerns about increasing antibiotic resistance and the possibility of treatment failures.

Isolates with no resistance to quinolone antibiotics have ciprofloxacin minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of less than 0.015 mcg/mL. However, the CDC has continued to identify isolates of Shigella that, while still within the susceptible range for the fluoroquinolone antibiotic ciprofloxacin (that is, having MIC values less than 1 mcg/mL), have MIC values for ciprofloxacin of 0.12-1.0 mcg/mL, thus appearing to harbor one or more resistance mechanisms. Furthermore, the CDC has identified an increasing number of isolates that have MIC values for azithromycin exceeding the epidemiologic cutoff value, which suggests some form of acquired resistance.

“CDC is particularly concerned about people who are at high risk for multidrug-resistant Shigella infections and are more likely to require antibiotic treatment, such as men who have sex with men, patients who are homeless, and immunocompromised patients. These patients often have more severe disease, prolonged shedding, and recurrent infections,” the recommendations stated.

More information can be found in the CDC’s Health Alert Network release.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have issued follow-up recommendations for managing and reporting Shigella infections because of concerns about increasing antibiotic resistance and the possibility of treatment failures.

Isolates with no resistance to quinolone antibiotics have ciprofloxacin minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of less than 0.015 mcg/mL. However, the CDC has continued to identify isolates of Shigella that, while still within the susceptible range for the fluoroquinolone antibiotic ciprofloxacin (that is, having MIC values less than 1 mcg/mL), have MIC values for ciprofloxacin of 0.12-1.0 mcg/mL, thus appearing to harbor one or more resistance mechanisms. Furthermore, the CDC has identified an increasing number of isolates that have MIC values for azithromycin exceeding the epidemiologic cutoff value, which suggests some form of acquired resistance.

“CDC is particularly concerned about people who are at high risk for multidrug-resistant Shigella infections and are more likely to require antibiotic treatment, such as men who have sex with men, patients who are homeless, and immunocompromised patients. These patients often have more severe disease, prolonged shedding, and recurrent infections,” the recommendations stated.

More information can be found in the CDC’s Health Alert Network release.

A U.S. model for Italian hospitals?

In the United States, family physicians (general practitioners) used to manage their patients in the hospital, either as the primary care doctor or in consultation with specialists. Only since the 1990s has a new kind of physician gained widespread acceptance: the hospitalist (“specialist of inpatient care”).1

In Italy the process has not been the same. In our health care system, primary care physicians have always transferred the responsibility of hospital care to an inpatient team. Actually, our hospital-based doctors dedicate their whole working time to inpatient care, and general practitioners are not expected to go to the hospital. The patients were (and are) admitted to one ward or another according to their main clinical problem.

Little by little, a huge number of organ specialty and subspecialty wards have filled Italian hospitals. In this context, the internal medicine specialty was unable to occupy its characteristic role, so that, a few years ago, the medical community wondered if the specialty should have continued to exist.

Anyway, as a result of hyperspecialization, we have many different specialists in inpatient care who are not specialists in global inpatient care.

Nowadays, in our country we are faced with a dramatic epidemiologic change. The Italian population is aging and the majority of patients have not only one clinical problem but multiple comorbidities. When these patients reach the emergency department, it is not easy to identify the main clinical problem and assign him/her to an organ specialty unit. And when he or she eventually arrives there, a considerable number of consultants is frequently required. The vision of organ specialists is not holistic, and they are more prone to maximizing their tools than rationalizing them. So, at present, our traditional hospital model has been generating care fragmentation, overproduction of diagnoses, overprescription of drugs, and increasing costs.

It is obvious that a new model is necessary for the future, and we look with great interest at the American hospitalist model.

We need a new hospital-based clinician who has wide-ranging competencies, and is able to define priorities and appropriateness of care when a patient requires multiple specialists’ interventions; one who is autonomous in performing basic procedures and expert in perioperative medicine; prompt to communicate with primary care doctors at the time of admission and discharge; and prepared to work in managed-care organizations.

We wonder: Are Italian hospital-based internists – the only specialists in global inpatient care – suited to this role?

We think so. However, current Italian training in internal medicine is focused mainly on scientific bases of diseases, pathophysiological, and clinical aspects. Concepts such as complexity or the management of patients with comorbidities are quite difficult to teach to medical school students and therefore often neglected. As a result, internal medicine physicians require a prolonged practical training.

Inspired by the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine published by the Society of Hospital Medicine, this year in Genoa (the birthplace of Christopher Columbus) we started a 2-year second-level University Master course, called “Hospitalist: Managing complexity in Internal Medicine inpatients” for 35 internal medicine specialists. It is the fruit of collaboration between the main association of Italian hospital-based internists (Federation of Associations of Hospital Doctors on Internal Medicine, or FADOI) and the University of Genoa’s Department of Internal Medicine, Academy of Health Management, and the Center of Simulation and Advanced Training.

In Italy, this is the first concrete initiative to train, and better define, this new type of physician expert in the management of inpatients.

According to SHM’s definition of a hospitalist, we think that the activities of this new physician should also include teaching and research related to hospital medicine. And as Dr. Steven Pantilat wrote, “patient safety, leadership, palliative care and quality improvement are the issues that pertain to all hospitalists.”2

Theoretically, the development of the hospitalist model should be easier in Italy when compared to the United States. Dr. Robert Wachter and Dr. Lee Goldman wrote in 1996 about the objections to the hospitalist model of American primary care physicians (“to preserve continuity”) and specialists (“fewer consultations, lower income”), but in Italy family doctors do not usually follow their patients in the hospital, and specialists have no incentive for in-hospital consultations.3 Moreover, patients with comorbidities, or pathologies on the border between medicine and surgery (e.g. cholecystitis, bowel obstruction, polytrauma, etc.), are already often assigned to internal medicine, and in the smallest hospitals, the internist is most of the time the only specialist doctor continually present.

Nevertheless, the Italian hospitalist model will be a challenge. We know we have to deal with organ specialists, but we strongly believe that this is the most appropriate and the most sustainable model for the future of the Italian hospitals. Our wish is not to become the “bosses” of the hospital, but to ensure global, coordinated, and respectful care to present and future patients.

Published outcomes studies demonstrate that the U.S. hospitalist model has led to consistent and pronounced cost saving with no loss in quality.4 In the United States, the hospitalist field has grown from a few hundred physicians to more than 50,000,5 making it the fastest growing physician specialty in medical history.

Why should the same not occur in Italy?

References

1. Baudendistel TE, Watcher RM. The evolution of the hospitalist movement in USA. Clin Med JRCPL. 2002;2:327-30.

2. Pantilat S. What is a Hospitalist? The Hospitalist 2006 February;2006(2).

3. Wachter RM, Goldman Lee. The emerging role of “Hospitalists” in the American Health Care System. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:514-7.

4. White HL, Glazier RH. Do hospitalist physicians improve the quality of inpatient care delivery? A systematic review of process, efficiency and outcome measures. BMC Medicine. 2011;9:58:1-22. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/9/58.

5. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 – The 20th Anniversary of the Hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1009-11.

Valerio Verdiani, MD, director of internal medicine, Grosseto, Italy. Francesco Orlandini, MD, internal medicine, health administrator, ASL4 Liguria, Chiavari (GE), Italy. Micaela La Regina, MD, internal medicine, risk management and clinical governance, ASL5 Liguria, La Spezia, Italy. Giovanni Murialdo, MD, department of internal medicine and medical specialty, University of Genoa (Italy). Andrea Fontanella, MD, director of medicine department, president of the Federation of Associations of Hospital Doctors on Internal Medicine (FADOI), Naples, Italy. Mauro Silingardi, MD, director of internal medicine, director of training and refresher of FADOI, Bologna, Italy.

In the United States, family physicians (general practitioners) used to manage their patients in the hospital, either as the primary care doctor or in consultation with specialists. Only since the 1990s has a new kind of physician gained widespread acceptance: the hospitalist (“specialist of inpatient care”).1

In Italy the process has not been the same. In our health care system, primary care physicians have always transferred the responsibility of hospital care to an inpatient team. Actually, our hospital-based doctors dedicate their whole working time to inpatient care, and general practitioners are not expected to go to the hospital. The patients were (and are) admitted to one ward or another according to their main clinical problem.

Little by little, a huge number of organ specialty and subspecialty wards have filled Italian hospitals. In this context, the internal medicine specialty was unable to occupy its characteristic role, so that, a few years ago, the medical community wondered if the specialty should have continued to exist.

Anyway, as a result of hyperspecialization, we have many different specialists in inpatient care who are not specialists in global inpatient care.

Nowadays, in our country we are faced with a dramatic epidemiologic change. The Italian population is aging and the majority of patients have not only one clinical problem but multiple comorbidities. When these patients reach the emergency department, it is not easy to identify the main clinical problem and assign him/her to an organ specialty unit. And when he or she eventually arrives there, a considerable number of consultants is frequently required. The vision of organ specialists is not holistic, and they are more prone to maximizing their tools than rationalizing them. So, at present, our traditional hospital model has been generating care fragmentation, overproduction of diagnoses, overprescription of drugs, and increasing costs.

It is obvious that a new model is necessary for the future, and we look with great interest at the American hospitalist model.

We need a new hospital-based clinician who has wide-ranging competencies, and is able to define priorities and appropriateness of care when a patient requires multiple specialists’ interventions; one who is autonomous in performing basic procedures and expert in perioperative medicine; prompt to communicate with primary care doctors at the time of admission and discharge; and prepared to work in managed-care organizations.

We wonder: Are Italian hospital-based internists – the only specialists in global inpatient care – suited to this role?

We think so. However, current Italian training in internal medicine is focused mainly on scientific bases of diseases, pathophysiological, and clinical aspects. Concepts such as complexity or the management of patients with comorbidities are quite difficult to teach to medical school students and therefore often neglected. As a result, internal medicine physicians require a prolonged practical training.

Inspired by the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine published by the Society of Hospital Medicine, this year in Genoa (the birthplace of Christopher Columbus) we started a 2-year second-level University Master course, called “Hospitalist: Managing complexity in Internal Medicine inpatients” for 35 internal medicine specialists. It is the fruit of collaboration between the main association of Italian hospital-based internists (Federation of Associations of Hospital Doctors on Internal Medicine, or FADOI) and the University of Genoa’s Department of Internal Medicine, Academy of Health Management, and the Center of Simulation and Advanced Training.

In Italy, this is the first concrete initiative to train, and better define, this new type of physician expert in the management of inpatients.

According to SHM’s definition of a hospitalist, we think that the activities of this new physician should also include teaching and research related to hospital medicine. And as Dr. Steven Pantilat wrote, “patient safety, leadership, palliative care and quality improvement are the issues that pertain to all hospitalists.”2

Theoretically, the development of the hospitalist model should be easier in Italy when compared to the United States. Dr. Robert Wachter and Dr. Lee Goldman wrote in 1996 about the objections to the hospitalist model of American primary care physicians (“to preserve continuity”) and specialists (“fewer consultations, lower income”), but in Italy family doctors do not usually follow their patients in the hospital, and specialists have no incentive for in-hospital consultations.3 Moreover, patients with comorbidities, or pathologies on the border between medicine and surgery (e.g. cholecystitis, bowel obstruction, polytrauma, etc.), are already often assigned to internal medicine, and in the smallest hospitals, the internist is most of the time the only specialist doctor continually present.

Nevertheless, the Italian hospitalist model will be a challenge. We know we have to deal with organ specialists, but we strongly believe that this is the most appropriate and the most sustainable model for the future of the Italian hospitals. Our wish is not to become the “bosses” of the hospital, but to ensure global, coordinated, and respectful care to present and future patients.

Published outcomes studies demonstrate that the U.S. hospitalist model has led to consistent and pronounced cost saving with no loss in quality.4 In the United States, the hospitalist field has grown from a few hundred physicians to more than 50,000,5 making it the fastest growing physician specialty in medical history.

Why should the same not occur in Italy?

References

1. Baudendistel TE, Watcher RM. The evolution of the hospitalist movement in USA. Clin Med JRCPL. 2002;2:327-30.

2. Pantilat S. What is a Hospitalist? The Hospitalist 2006 February;2006(2).

3. Wachter RM, Goldman Lee. The emerging role of “Hospitalists” in the American Health Care System. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:514-7.

4. White HL, Glazier RH. Do hospitalist physicians improve the quality of inpatient care delivery? A systematic review of process, efficiency and outcome measures. BMC Medicine. 2011;9:58:1-22. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/9/58.

5. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 – The 20th Anniversary of the Hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1009-11.

Valerio Verdiani, MD, director of internal medicine, Grosseto, Italy. Francesco Orlandini, MD, internal medicine, health administrator, ASL4 Liguria, Chiavari (GE), Italy. Micaela La Regina, MD, internal medicine, risk management and clinical governance, ASL5 Liguria, La Spezia, Italy. Giovanni Murialdo, MD, department of internal medicine and medical specialty, University of Genoa (Italy). Andrea Fontanella, MD, director of medicine department, president of the Federation of Associations of Hospital Doctors on Internal Medicine (FADOI), Naples, Italy. Mauro Silingardi, MD, director of internal medicine, director of training and refresher of FADOI, Bologna, Italy.

In the United States, family physicians (general practitioners) used to manage their patients in the hospital, either as the primary care doctor or in consultation with specialists. Only since the 1990s has a new kind of physician gained widespread acceptance: the hospitalist (“specialist of inpatient care”).1

In Italy the process has not been the same. In our health care system, primary care physicians have always transferred the responsibility of hospital care to an inpatient team. Actually, our hospital-based doctors dedicate their whole working time to inpatient care, and general practitioners are not expected to go to the hospital. The patients were (and are) admitted to one ward or another according to their main clinical problem.

Little by little, a huge number of organ specialty and subspecialty wards have filled Italian hospitals. In this context, the internal medicine specialty was unable to occupy its characteristic role, so that, a few years ago, the medical community wondered if the specialty should have continued to exist.

Anyway, as a result of hyperspecialization, we have many different specialists in inpatient care who are not specialists in global inpatient care.

Nowadays, in our country we are faced with a dramatic epidemiologic change. The Italian population is aging and the majority of patients have not only one clinical problem but multiple comorbidities. When these patients reach the emergency department, it is not easy to identify the main clinical problem and assign him/her to an organ specialty unit. And when he or she eventually arrives there, a considerable number of consultants is frequently required. The vision of organ specialists is not holistic, and they are more prone to maximizing their tools than rationalizing them. So, at present, our traditional hospital model has been generating care fragmentation, overproduction of diagnoses, overprescription of drugs, and increasing costs.

It is obvious that a new model is necessary for the future, and we look with great interest at the American hospitalist model.

We need a new hospital-based clinician who has wide-ranging competencies, and is able to define priorities and appropriateness of care when a patient requires multiple specialists’ interventions; one who is autonomous in performing basic procedures and expert in perioperative medicine; prompt to communicate with primary care doctors at the time of admission and discharge; and prepared to work in managed-care organizations.

We wonder: Are Italian hospital-based internists – the only specialists in global inpatient care – suited to this role?

We think so. However, current Italian training in internal medicine is focused mainly on scientific bases of diseases, pathophysiological, and clinical aspects. Concepts such as complexity or the management of patients with comorbidities are quite difficult to teach to medical school students and therefore often neglected. As a result, internal medicine physicians require a prolonged practical training.

Inspired by the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine published by the Society of Hospital Medicine, this year in Genoa (the birthplace of Christopher Columbus) we started a 2-year second-level University Master course, called “Hospitalist: Managing complexity in Internal Medicine inpatients” for 35 internal medicine specialists. It is the fruit of collaboration between the main association of Italian hospital-based internists (Federation of Associations of Hospital Doctors on Internal Medicine, or FADOI) and the University of Genoa’s Department of Internal Medicine, Academy of Health Management, and the Center of Simulation and Advanced Training.

In Italy, this is the first concrete initiative to train, and better define, this new type of physician expert in the management of inpatients.

According to SHM’s definition of a hospitalist, we think that the activities of this new physician should also include teaching and research related to hospital medicine. And as Dr. Steven Pantilat wrote, “patient safety, leadership, palliative care and quality improvement are the issues that pertain to all hospitalists.”2

Theoretically, the development of the hospitalist model should be easier in Italy when compared to the United States. Dr. Robert Wachter and Dr. Lee Goldman wrote in 1996 about the objections to the hospitalist model of American primary care physicians (“to preserve continuity”) and specialists (“fewer consultations, lower income”), but in Italy family doctors do not usually follow their patients in the hospital, and specialists have no incentive for in-hospital consultations.3 Moreover, patients with comorbidities, or pathologies on the border between medicine and surgery (e.g. cholecystitis, bowel obstruction, polytrauma, etc.), are already often assigned to internal medicine, and in the smallest hospitals, the internist is most of the time the only specialist doctor continually present.

Nevertheless, the Italian hospitalist model will be a challenge. We know we have to deal with organ specialists, but we strongly believe that this is the most appropriate and the most sustainable model for the future of the Italian hospitals. Our wish is not to become the “bosses” of the hospital, but to ensure global, coordinated, and respectful care to present and future patients.

Published outcomes studies demonstrate that the U.S. hospitalist model has led to consistent and pronounced cost saving with no loss in quality.4 In the United States, the hospitalist field has grown from a few hundred physicians to more than 50,000,5 making it the fastest growing physician specialty in medical history.

Why should the same not occur in Italy?

References

1. Baudendistel TE, Watcher RM. The evolution of the hospitalist movement in USA. Clin Med JRCPL. 2002;2:327-30.

2. Pantilat S. What is a Hospitalist? The Hospitalist 2006 February;2006(2).

3. Wachter RM, Goldman Lee. The emerging role of “Hospitalists” in the American Health Care System. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:514-7.

4. White HL, Glazier RH. Do hospitalist physicians improve the quality of inpatient care delivery? A systematic review of process, efficiency and outcome measures. BMC Medicine. 2011;9:58:1-22. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/9/58.

5. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 – The 20th Anniversary of the Hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1009-11.

Valerio Verdiani, MD, director of internal medicine, Grosseto, Italy. Francesco Orlandini, MD, internal medicine, health administrator, ASL4 Liguria, Chiavari (GE), Italy. Micaela La Regina, MD, internal medicine, risk management and clinical governance, ASL5 Liguria, La Spezia, Italy. Giovanni Murialdo, MD, department of internal medicine and medical specialty, University of Genoa (Italy). Andrea Fontanella, MD, director of medicine department, president of the Federation of Associations of Hospital Doctors on Internal Medicine (FADOI), Naples, Italy. Mauro Silingardi, MD, director of internal medicine, director of training and refresher of FADOI, Bologna, Italy.

A clinical pathway to standardize use of maintenance IV fluids

Clinical question

Can an evidence-based clinical pathway improve adherence to recent recommendations to use isotonic solutions for maintenance intravenous fluids in hospitalized children?

Background

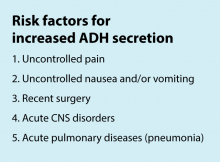

The traditional teaching regarding composition of maintenance intravenous fluids (IVF) in children has been based on the Holliday-Segar method.1 Since its publication in Pediatrics in 1957, concerns have been raised regarding the risk of iatrogenic hyponatremia caused by giving hypotonic fluids determined by this method,2 especially in patients with an elevated risk of increased antidiuretic hormone (ADH) secretion.3 Multiple recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have confirmed that isotonic IVF reduces the risk of hyponatremia in hospitalized children.4

Study design

Interrupted time series analysis before and after pathway implementation.

Setting

370-bed tertiary care free-standing children’s hospital.

Synopsis

A multidisciplinary team was assembled, comprising physicians and nurses in hospital medicine, general pediatrics, emergency medicine, and nephrology. After a systematic review of the recent literature, a clinical algorithm and web-based training module were developed. Faculty in general pediatrics, hospital medicine, and emergency medicine were required to complete the module, while medical and surgical residents were encouraged but not required to complete the module. A maintenance IVF order set was created and embedded into all order sets previously containing IVF orders and was also available in stand-alone form.

Inclusion criteria (“pathway eligible”) included being euvolemic and requiring IVF. Exclusion criteria included fluid status derangements, critical illness, severe serum sodium abnormalities (serum sodium ≥150 mEq/L or ≤130 mEq/L) use of TPN or ketogenic diet. In the order set, IVF composition was determined based on risk factors for increased ADH secretion. Inclusion of potassium in IVF was also determined by the pathway.

Over the 1-year study period, 11,602 pathway-eligible encounters in 10,287 patients were reviewed. Use of isotonic maintenance IVF increased significantly from 9.3% to 50.6%, while use of hypotonic fluids decreased from 94.2% to 56.6%. Use of potassium-containing IVF increased from 52.9% to 75.3%. Dysnatremia continued to occur due to hypotonic IVF use.

Bottom line

A combined clinical pathway and training module to standardize the composition of IVF is feasible, and results in increased use of isotonic and potassium-containing fluids.

Citation

Rooholamini S, Clifton H, Haaland W, et al. Outcomes of a clinical pathway to standardize use of maintenance intravenous fluids. Hosp Pediatr. 2017 Dec;7(12):703-9.

Dr. Chang is a pediatric hospitalist at Baystate Children’s Hospital in Springfield, Mass., and is the pediatric editor of The Hospitalist.

References

1. Holliday MA et al. The maintenance need for water in parenteral fluid therapy. Pediatrics 1957;19:823-32.

2. Friedman JN et al. Comparison of isotonic and hypotonic intravenous maintenance fluids: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:445-51.

3. Fuchs J et al. Current Issues in Intravenous Fluid Use in Hospitalized Children. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2017;12:284-9.

4. McNab S et al. Isotonic versus hypotonic solutions for maintenance intravenous fluid administration in children. Cochrane Database. Syst Rev 2014:CD009457.

Clinical question

Can an evidence-based clinical pathway improve adherence to recent recommendations to use isotonic solutions for maintenance intravenous fluids in hospitalized children?

Background

The traditional teaching regarding composition of maintenance intravenous fluids (IVF) in children has been based on the Holliday-Segar method.1 Since its publication in Pediatrics in 1957, concerns have been raised regarding the risk of iatrogenic hyponatremia caused by giving hypotonic fluids determined by this method,2 especially in patients with an elevated risk of increased antidiuretic hormone (ADH) secretion.3 Multiple recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have confirmed that isotonic IVF reduces the risk of hyponatremia in hospitalized children.4

Study design

Interrupted time series analysis before and after pathway implementation.

Setting

370-bed tertiary care free-standing children’s hospital.

Synopsis

A multidisciplinary team was assembled, comprising physicians and nurses in hospital medicine, general pediatrics, emergency medicine, and nephrology. After a systematic review of the recent literature, a clinical algorithm and web-based training module were developed. Faculty in general pediatrics, hospital medicine, and emergency medicine were required to complete the module, while medical and surgical residents were encouraged but not required to complete the module. A maintenance IVF order set was created and embedded into all order sets previously containing IVF orders and was also available in stand-alone form.

Inclusion criteria (“pathway eligible”) included being euvolemic and requiring IVF. Exclusion criteria included fluid status derangements, critical illness, severe serum sodium abnormalities (serum sodium ≥150 mEq/L or ≤130 mEq/L) use of TPN or ketogenic diet. In the order set, IVF composition was determined based on risk factors for increased ADH secretion. Inclusion of potassium in IVF was also determined by the pathway.

Over the 1-year study period, 11,602 pathway-eligible encounters in 10,287 patients were reviewed. Use of isotonic maintenance IVF increased significantly from 9.3% to 50.6%, while use of hypotonic fluids decreased from 94.2% to 56.6%. Use of potassium-containing IVF increased from 52.9% to 75.3%. Dysnatremia continued to occur due to hypotonic IVF use.

Bottom line

A combined clinical pathway and training module to standardize the composition of IVF is feasible, and results in increased use of isotonic and potassium-containing fluids.

Citation

Rooholamini S, Clifton H, Haaland W, et al. Outcomes of a clinical pathway to standardize use of maintenance intravenous fluids. Hosp Pediatr. 2017 Dec;7(12):703-9.

Dr. Chang is a pediatric hospitalist at Baystate Children’s Hospital in Springfield, Mass., and is the pediatric editor of The Hospitalist.

References

1. Holliday MA et al. The maintenance need for water in parenteral fluid therapy. Pediatrics 1957;19:823-32.

2. Friedman JN et al. Comparison of isotonic and hypotonic intravenous maintenance fluids: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:445-51.

3. Fuchs J et al. Current Issues in Intravenous Fluid Use in Hospitalized Children. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2017;12:284-9.

4. McNab S et al. Isotonic versus hypotonic solutions for maintenance intravenous fluid administration in children. Cochrane Database. Syst Rev 2014:CD009457.

Clinical question

Can an evidence-based clinical pathway improve adherence to recent recommendations to use isotonic solutions for maintenance intravenous fluids in hospitalized children?

Background

The traditional teaching regarding composition of maintenance intravenous fluids (IVF) in children has been based on the Holliday-Segar method.1 Since its publication in Pediatrics in 1957, concerns have been raised regarding the risk of iatrogenic hyponatremia caused by giving hypotonic fluids determined by this method,2 especially in patients with an elevated risk of increased antidiuretic hormone (ADH) secretion.3 Multiple recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have confirmed that isotonic IVF reduces the risk of hyponatremia in hospitalized children.4

Study design

Interrupted time series analysis before and after pathway implementation.

Setting

370-bed tertiary care free-standing children’s hospital.

Synopsis

A multidisciplinary team was assembled, comprising physicians and nurses in hospital medicine, general pediatrics, emergency medicine, and nephrology. After a systematic review of the recent literature, a clinical algorithm and web-based training module were developed. Faculty in general pediatrics, hospital medicine, and emergency medicine were required to complete the module, while medical and surgical residents were encouraged but not required to complete the module. A maintenance IVF order set was created and embedded into all order sets previously containing IVF orders and was also available in stand-alone form.

Inclusion criteria (“pathway eligible”) included being euvolemic and requiring IVF. Exclusion criteria included fluid status derangements, critical illness, severe serum sodium abnormalities (serum sodium ≥150 mEq/L or ≤130 mEq/L) use of TPN or ketogenic diet. In the order set, IVF composition was determined based on risk factors for increased ADH secretion. Inclusion of potassium in IVF was also determined by the pathway.

Over the 1-year study period, 11,602 pathway-eligible encounters in 10,287 patients were reviewed. Use of isotonic maintenance IVF increased significantly from 9.3% to 50.6%, while use of hypotonic fluids decreased from 94.2% to 56.6%. Use of potassium-containing IVF increased from 52.9% to 75.3%. Dysnatremia continued to occur due to hypotonic IVF use.

Bottom line

A combined clinical pathway and training module to standardize the composition of IVF is feasible, and results in increased use of isotonic and potassium-containing fluids.

Citation

Rooholamini S, Clifton H, Haaland W, et al. Outcomes of a clinical pathway to standardize use of maintenance intravenous fluids. Hosp Pediatr. 2017 Dec;7(12):703-9.

Dr. Chang is a pediatric hospitalist at Baystate Children’s Hospital in Springfield, Mass., and is the pediatric editor of The Hospitalist.

References

1. Holliday MA et al. The maintenance need for water in parenteral fluid therapy. Pediatrics 1957;19:823-32.

2. Friedman JN et al. Comparison of isotonic and hypotonic intravenous maintenance fluids: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:445-51.

3. Fuchs J et al. Current Issues in Intravenous Fluid Use in Hospitalized Children. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2017;12:284-9.

4. McNab S et al. Isotonic versus hypotonic solutions for maintenance intravenous fluid administration in children. Cochrane Database. Syst Rev 2014:CD009457.

Concerns in the Management of Chronic Heart Failure - Staying on the Path to Optimal Medical Therapy

Trio of blood biomarkers elevated in children with LRTIs

TORONTO – While C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, and proadrenomedullin are associated with development of severe clinical outcomes in children with lower respiratory tract infections, proadrenomedullin is most strongly associated with disease severity, preliminary results from a prospective cohort study showed.

“Despite the fact that pneumonia guidelines call the site of care decision the most important decision in the management of pediatric pneumonia, no validated risk stratification tools exist for pediatric lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI),” lead study author Todd A. Florin, MD, said at the annual Pediatric Academic Societies meeting. “Biomarkers offer an objective means of classifying disease severity and clinical outcomes.”

PCT is a precursor of calcitonin secreted by the thyroid, lung, and intestine in response to bacterial infections. It also has been shown to be associated with adverse outcomes and mortality in adults, with results generally suggesting that it is a stronger predictor of severity than CRP. “There is limited data on the association of CRP or PCT with severe outcomes in children with LRTIs,” Dr. Florin noted. “One recent U.S. study of 532 children did demonstrate an association of elevated PCT with ICU admission, chest drainage, and hospital length of stay in children with [community-acquired pneumonia] CAP.”

ProADM, meanwhile, is a vasodilatory peptide with antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory functions synthesized during severe infections. It has a half-life of several hours and has been shown to be associated with disease severity in adults with LRTI. Recent studies have shown that it has improved prognostication over WBC, CRP, and PCT. “In two small studies of children with pneumonia, proADM levels were significantly elevated in children with complicated pneumonia, compared to those with uncomplicated pneumonia,” Dr. Florin said. “Although all three of these markers demonstrate promise in predicting severe outcomes in adults with LRTIs, very few studies have examined their association with disease severity in pediatric disease. Therefore, the aim of the current analysis was to determine the association between blood biomarkers and disease severity in children who present to the ED with lower respiratory tract infections.”

In a study known as Catalyzing Ambulatory Research in Pneumonia Etiology and Diagnostic Innovations in Emergency Medicine (CARPE DIEM), he and his associates performed a prospective cohort analysis of children with suspected CAP who were admitted to the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital ED between July 2012 and December 2017. They limited the analysis to children aged 3 months to 18 years with signs and symptoms of an LRTI, and all eligible patients were required to have a chest radiograph ordered for suspicion of CAP. They excluded children hospitalized within 14 days prior to the index ED visit, immunodeficient or immunosuppressed children, those with a history of aspiration or aspiration pneumonia, and those who weighed less than 5 kg because of blood drawing maximums. Biomarkers were measured only in children with focal findings on chest x-ray in the ED. The primary outcome was disease severity: mild (defined as discharged home), moderate (defined as hospitalized, but not severe) and severe (defined as having an ICU length of stay of greater than 48 hours, chest drainage, severe sepsis, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation, intubation, vasoactive infusions, or death). Biomarkers were obtained at the time of presentation to the ED, prior to the occurrence of clinical outcomes.

Over a period of 4.5 years, the researchers enrolled 1,142 patients. Of these, 478 had focal findings on chest x-ray and blood obtained. The median age of these 478 children was 4.4 years, 52% were male, and 82% had all three biomarkers performed. Specifically, 456 had CRP and PCT performed, while 358 had proADM performed. “Not every child had every marker performed due to challenges in obtaining sufficient blood for all three biomarkers in some children,” Dr. Florin explained.

Preliminary data that Dr. Florin presented at PAS found that the median CRP, PCT, and proADM did not differ by gender, race, ethnicity, or insurance status. “In addition, there were not significant differences in the distribution of disease severity by biomarker performed, with approximately 27% of patients being classified as mild, 66% as moderate, and 7% as severe,” he said.

The median CRP was 2.4 ng/mL in those with mild disease, 2.5 ng/mL in those with moderate disease, and 6.25 ng/mL in those with severe disease, with the difference between the two subclasses of nonsevere disease and moderate disease and severe disease reaching statistical significance (P = .002). The median PCT was 0.16 ng/mL in those with mild disease, 0.26 ng/mL in those with moderate disease, and 0.49 ng/mL in those with severe disease, with the difference between the two subclasses of nonsevere disease and moderate disease and severe disease reaching statistical significance (P = .047). Meanwhile, the median proADM was 0.53 ng/mL in those with mild disease, 0.59 ng/mL in those with moderate disease, and 0.81 ng/mL in those with severe disease, with the difference between the two subclasses of nonsevere disease and moderate disease and severe disease also reaching statistical significance (P less than .0001).

Next, the researchers performed logistic regression of each biomarker individually and in combination. They found that and had the best ability to discriminate those developing severe vs. nonsevere disease (area under the receiving operating curve of 0.72, vs. 0.67 and 0.60, respectively). When CRP and PCT markers were combined with proADM, they were no longer associated with severe disease, while a strong association with proADM remained significant.

Dr. Florin acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that requiring collection of blood samples may have resulted in an enrollment bias toward patients receiving phlebotomy or IV line placement in the ED. “In addition, the children in the moderate-severity group are likely more heterogeneous than the other two severity groups,” he said. “Finally, given that this is a single-center study, we had a relatively small number of outcomes for some of the individual severity measures, which may have limited power and precision.”

He concluded his presentation by saying that he is “cautiously optimistic” about the study results. “As is the case in many biomarker studies, I do not anticipate that any single biomarker will be the magic bullet for predicting disease severity in pediatric CAP,” Dr. Florin said. “It will likely be a combination of clinical factors and several biomarkers that will achieve optimal prognostic ability. That said, our results suggest that similar to adult studies, proADM appears to have the strongest association with severe disease, compared with CRP and PCT. Combinations of biomarkers did not perform better than proADM alone. With the advent of rapid point-of-care diagnostics, these markers may have a role in management and site-of-care decisions for children with LRTI.”

The study received funding support from the Gerber Foundation, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Dr. Florin reported having no financial disclosures.

TORONTO – While C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, and proadrenomedullin are associated with development of severe clinical outcomes in children with lower respiratory tract infections, proadrenomedullin is most strongly associated with disease severity, preliminary results from a prospective cohort study showed.

“Despite the fact that pneumonia guidelines call the site of care decision the most important decision in the management of pediatric pneumonia, no validated risk stratification tools exist for pediatric lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI),” lead study author Todd A. Florin, MD, said at the annual Pediatric Academic Societies meeting. “Biomarkers offer an objective means of classifying disease severity and clinical outcomes.”

PCT is a precursor of calcitonin secreted by the thyroid, lung, and intestine in response to bacterial infections. It also has been shown to be associated with adverse outcomes and mortality in adults, with results generally suggesting that it is a stronger predictor of severity than CRP. “There is limited data on the association of CRP or PCT with severe outcomes in children with LRTIs,” Dr. Florin noted. “One recent U.S. study of 532 children did demonstrate an association of elevated PCT with ICU admission, chest drainage, and hospital length of stay in children with [community-acquired pneumonia] CAP.”

ProADM, meanwhile, is a vasodilatory peptide with antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory functions synthesized during severe infections. It has a half-life of several hours and has been shown to be associated with disease severity in adults with LRTI. Recent studies have shown that it has improved prognostication over WBC, CRP, and PCT. “In two small studies of children with pneumonia, proADM levels were significantly elevated in children with complicated pneumonia, compared to those with uncomplicated pneumonia,” Dr. Florin said. “Although all three of these markers demonstrate promise in predicting severe outcomes in adults with LRTIs, very few studies have examined their association with disease severity in pediatric disease. Therefore, the aim of the current analysis was to determine the association between blood biomarkers and disease severity in children who present to the ED with lower respiratory tract infections.”

In a study known as Catalyzing Ambulatory Research in Pneumonia Etiology and Diagnostic Innovations in Emergency Medicine (CARPE DIEM), he and his associates performed a prospective cohort analysis of children with suspected CAP who were admitted to the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital ED between July 2012 and December 2017. They limited the analysis to children aged 3 months to 18 years with signs and symptoms of an LRTI, and all eligible patients were required to have a chest radiograph ordered for suspicion of CAP. They excluded children hospitalized within 14 days prior to the index ED visit, immunodeficient or immunosuppressed children, those with a history of aspiration or aspiration pneumonia, and those who weighed less than 5 kg because of blood drawing maximums. Biomarkers were measured only in children with focal findings on chest x-ray in the ED. The primary outcome was disease severity: mild (defined as discharged home), moderate (defined as hospitalized, but not severe) and severe (defined as having an ICU length of stay of greater than 48 hours, chest drainage, severe sepsis, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation, intubation, vasoactive infusions, or death). Biomarkers were obtained at the time of presentation to the ED, prior to the occurrence of clinical outcomes.

Over a period of 4.5 years, the researchers enrolled 1,142 patients. Of these, 478 had focal findings on chest x-ray and blood obtained. The median age of these 478 children was 4.4 years, 52% were male, and 82% had all three biomarkers performed. Specifically, 456 had CRP and PCT performed, while 358 had proADM performed. “Not every child had every marker performed due to challenges in obtaining sufficient blood for all three biomarkers in some children,” Dr. Florin explained.

Preliminary data that Dr. Florin presented at PAS found that the median CRP, PCT, and proADM did not differ by gender, race, ethnicity, or insurance status. “In addition, there were not significant differences in the distribution of disease severity by biomarker performed, with approximately 27% of patients being classified as mild, 66% as moderate, and 7% as severe,” he said.

The median CRP was 2.4 ng/mL in those with mild disease, 2.5 ng/mL in those with moderate disease, and 6.25 ng/mL in those with severe disease, with the difference between the two subclasses of nonsevere disease and moderate disease and severe disease reaching statistical significance (P = .002). The median PCT was 0.16 ng/mL in those with mild disease, 0.26 ng/mL in those with moderate disease, and 0.49 ng/mL in those with severe disease, with the difference between the two subclasses of nonsevere disease and moderate disease and severe disease reaching statistical significance (P = .047). Meanwhile, the median proADM was 0.53 ng/mL in those with mild disease, 0.59 ng/mL in those with moderate disease, and 0.81 ng/mL in those with severe disease, with the difference between the two subclasses of nonsevere disease and moderate disease and severe disease also reaching statistical significance (P less than .0001).

Next, the researchers performed logistic regression of each biomarker individually and in combination. They found that and had the best ability to discriminate those developing severe vs. nonsevere disease (area under the receiving operating curve of 0.72, vs. 0.67 and 0.60, respectively). When CRP and PCT markers were combined with proADM, they were no longer associated with severe disease, while a strong association with proADM remained significant.

Dr. Florin acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that requiring collection of blood samples may have resulted in an enrollment bias toward patients receiving phlebotomy or IV line placement in the ED. “In addition, the children in the moderate-severity group are likely more heterogeneous than the other two severity groups,” he said. “Finally, given that this is a single-center study, we had a relatively small number of outcomes for some of the individual severity measures, which may have limited power and precision.”

He concluded his presentation by saying that he is “cautiously optimistic” about the study results. “As is the case in many biomarker studies, I do not anticipate that any single biomarker will be the magic bullet for predicting disease severity in pediatric CAP,” Dr. Florin said. “It will likely be a combination of clinical factors and several biomarkers that will achieve optimal prognostic ability. That said, our results suggest that similar to adult studies, proADM appears to have the strongest association with severe disease, compared with CRP and PCT. Combinations of biomarkers did not perform better than proADM alone. With the advent of rapid point-of-care diagnostics, these markers may have a role in management and site-of-care decisions for children with LRTI.”

The study received funding support from the Gerber Foundation, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Dr. Florin reported having no financial disclosures.

TORONTO – While C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, and proadrenomedullin are associated with development of severe clinical outcomes in children with lower respiratory tract infections, proadrenomedullin is most strongly associated with disease severity, preliminary results from a prospective cohort study showed.

“Despite the fact that pneumonia guidelines call the site of care decision the most important decision in the management of pediatric pneumonia, no validated risk stratification tools exist for pediatric lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI),” lead study author Todd A. Florin, MD, said at the annual Pediatric Academic Societies meeting. “Biomarkers offer an objective means of classifying disease severity and clinical outcomes.”

PCT is a precursor of calcitonin secreted by the thyroid, lung, and intestine in response to bacterial infections. It also has been shown to be associated with adverse outcomes and mortality in adults, with results generally suggesting that it is a stronger predictor of severity than CRP. “There is limited data on the association of CRP or PCT with severe outcomes in children with LRTIs,” Dr. Florin noted. “One recent U.S. study of 532 children did demonstrate an association of elevated PCT with ICU admission, chest drainage, and hospital length of stay in children with [community-acquired pneumonia] CAP.”

ProADM, meanwhile, is a vasodilatory peptide with antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory functions synthesized during severe infections. It has a half-life of several hours and has been shown to be associated with disease severity in adults with LRTI. Recent studies have shown that it has improved prognostication over WBC, CRP, and PCT. “In two small studies of children with pneumonia, proADM levels were significantly elevated in children with complicated pneumonia, compared to those with uncomplicated pneumonia,” Dr. Florin said. “Although all three of these markers demonstrate promise in predicting severe outcomes in adults with LRTIs, very few studies have examined their association with disease severity in pediatric disease. Therefore, the aim of the current analysis was to determine the association between blood biomarkers and disease severity in children who present to the ED with lower respiratory tract infections.”

In a study known as Catalyzing Ambulatory Research in Pneumonia Etiology and Diagnostic Innovations in Emergency Medicine (CARPE DIEM), he and his associates performed a prospective cohort analysis of children with suspected CAP who were admitted to the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital ED between July 2012 and December 2017. They limited the analysis to children aged 3 months to 18 years with signs and symptoms of an LRTI, and all eligible patients were required to have a chest radiograph ordered for suspicion of CAP. They excluded children hospitalized within 14 days prior to the index ED visit, immunodeficient or immunosuppressed children, those with a history of aspiration or aspiration pneumonia, and those who weighed less than 5 kg because of blood drawing maximums. Biomarkers were measured only in children with focal findings on chest x-ray in the ED. The primary outcome was disease severity: mild (defined as discharged home), moderate (defined as hospitalized, but not severe) and severe (defined as having an ICU length of stay of greater than 48 hours, chest drainage, severe sepsis, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation, intubation, vasoactive infusions, or death). Biomarkers were obtained at the time of presentation to the ED, prior to the occurrence of clinical outcomes.

Over a period of 4.5 years, the researchers enrolled 1,142 patients. Of these, 478 had focal findings on chest x-ray and blood obtained. The median age of these 478 children was 4.4 years, 52% were male, and 82% had all three biomarkers performed. Specifically, 456 had CRP and PCT performed, while 358 had proADM performed. “Not every child had every marker performed due to challenges in obtaining sufficient blood for all three biomarkers in some children,” Dr. Florin explained.

Preliminary data that Dr. Florin presented at PAS found that the median CRP, PCT, and proADM did not differ by gender, race, ethnicity, or insurance status. “In addition, there were not significant differences in the distribution of disease severity by biomarker performed, with approximately 27% of patients being classified as mild, 66% as moderate, and 7% as severe,” he said.

The median CRP was 2.4 ng/mL in those with mild disease, 2.5 ng/mL in those with moderate disease, and 6.25 ng/mL in those with severe disease, with the difference between the two subclasses of nonsevere disease and moderate disease and severe disease reaching statistical significance (P = .002). The median PCT was 0.16 ng/mL in those with mild disease, 0.26 ng/mL in those with moderate disease, and 0.49 ng/mL in those with severe disease, with the difference between the two subclasses of nonsevere disease and moderate disease and severe disease reaching statistical significance (P = .047). Meanwhile, the median proADM was 0.53 ng/mL in those with mild disease, 0.59 ng/mL in those with moderate disease, and 0.81 ng/mL in those with severe disease, with the difference between the two subclasses of nonsevere disease and moderate disease and severe disease also reaching statistical significance (P less than .0001).

Next, the researchers performed logistic regression of each biomarker individually and in combination. They found that and had the best ability to discriminate those developing severe vs. nonsevere disease (area under the receiving operating curve of 0.72, vs. 0.67 and 0.60, respectively). When CRP and PCT markers were combined with proADM, they were no longer associated with severe disease, while a strong association with proADM remained significant.

Dr. Florin acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that requiring collection of blood samples may have resulted in an enrollment bias toward patients receiving phlebotomy or IV line placement in the ED. “In addition, the children in the moderate-severity group are likely more heterogeneous than the other two severity groups,” he said. “Finally, given that this is a single-center study, we had a relatively small number of outcomes for some of the individual severity measures, which may have limited power and precision.”

He concluded his presentation by saying that he is “cautiously optimistic” about the study results. “As is the case in many biomarker studies, I do not anticipate that any single biomarker will be the magic bullet for predicting disease severity in pediatric CAP,” Dr. Florin said. “It will likely be a combination of clinical factors and several biomarkers that will achieve optimal prognostic ability. That said, our results suggest that similar to adult studies, proADM appears to have the strongest association with severe disease, compared with CRP and PCT. Combinations of biomarkers did not perform better than proADM alone. With the advent of rapid point-of-care diagnostics, these markers may have a role in management and site-of-care decisions for children with LRTI.”

The study received funding support from the Gerber Foundation, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Dr. Florin reported having no financial disclosures.

AT PAS 18

Key clinical point: Blood biomarkers such as C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin (PCT), and proadrenomedullin (proADM) may have a role in management and site-of-care decisions for children with LRTIs.

Major finding: The proADM alone was associated with the largest odds for severe disease (OR 13.1), compared with CRP alone (OR 1.6) and PCT alone (OR 1.4).

Study details: Preliminary results from prospective cohort analysis of 478 children with suspected community-acquired pneumonia who were admitted to the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital ED.

Disclosures: The study received funding support from the Gerber Foundation, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Dr. Florin reported having no financial disclosures.

Neonatal deaths lower in high-volume hospitals

AUSTIN, TEX. – A first look at the timing of neonatal deaths showed an association with weekend deliveries in one Texas county. However, birth weight and ethnicity attenuated the association, according to a recent study. Higher hospital volumes were associated with lower risk of neonatal deaths.

The retrospective, population-based cohort study, presented during the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, used data from birth certificates and infant death certificates in the state of Texas. The investigators, said Elizabeth Restrepo, PhD, chose to examine data from Tarrant County, Tex., which has historically had persistently high infant mortality rates; in 2013, she said, the infant mortality rate in that county was 7.11/1,000 births – the highest in the state for that year.

The first question Dr. Restrepo and her colleagues at Texas Women’s University, Denton, wanted to answer was whether there was an association between the risk of neonatal mortality and the day of the week of the birth. For this and the study’s other research questions, she and her colleagues looked at 2012 data, matching 32,140 birth certificate records with 92 infant death certificates.

The investigators found an independent association between the risk of neonatal death and whether the birth happened on a weekday (Monday at 7:00 a.m. through Friday at 6:59 p.m.), or on a weekend (Friday at 7:00 p.m. through Monday at 6:59 a.m.). However, once birth weight and ethnicity were controlled in the statistical analysis, the association was not statistically significant despite an odds ratio of 1.44 (95% confidence interval, 0.911-2.27; P = .119).

“Births in the 12 hospitals studied appear to have been organized to take place more frequently on the working weekday rather than weekend days,” wrote Dr. Restrepo and her colleagues in the poster accompanying the presentation. Although the study wasn’t designed to answer this particular question, Dr. Restrepo said in discussion during the poster session that planned deliveries, such as inductions and cesarean deliveries, are likely to happen during the week, while the case mix is wider on weekends. Patient characteristics, as well as staffing patterns, may come into play.

The researchers also asked whether birth volume at a given institution increases the odds of neonatal death on weekends. Here, they found a significant inverse relationship between hospital birth volume and neonatal deaths (r = –0.021; P less than .001). With each additional increase of 1% in the weekday birth rate, the odds of neonatal death dropped by approximately 7.4%.

Examining the Tarrant County data further, Dr. Restrepo and her colleagues found that the hospitals with higher birth volumes had a more even distribution of births across the days of the week, with resulting lower concentrations of births during the week (r = –.394; P less than .001).

To classify infant deaths, the investigators included only ICD-10 diagnoses classified as P-codes to capture deaths occurring in the first 28 days after birth, but excluding congenital problems that are incompatible with life or that usually cause early death.

The researchers reported that they had no conflicts of interest; the study was funded by a research enhancement program award from the Texas Women’s University Office of Research and Sponsored Programs.

SOURCE: Restrepo E et al. ACOG 2018, Abstract 22R.

AUSTIN, TEX. – A first look at the timing of neonatal deaths showed an association with weekend deliveries in one Texas county. However, birth weight and ethnicity attenuated the association, according to a recent study. Higher hospital volumes were associated with lower risk of neonatal deaths.

The retrospective, population-based cohort study, presented during the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, used data from birth certificates and infant death certificates in the state of Texas. The investigators, said Elizabeth Restrepo, PhD, chose to examine data from Tarrant County, Tex., which has historically had persistently high infant mortality rates; in 2013, she said, the infant mortality rate in that county was 7.11/1,000 births – the highest in the state for that year.

The first question Dr. Restrepo and her colleagues at Texas Women’s University, Denton, wanted to answer was whether there was an association between the risk of neonatal mortality and the day of the week of the birth. For this and the study’s other research questions, she and her colleagues looked at 2012 data, matching 32,140 birth certificate records with 92 infant death certificates.

The investigators found an independent association between the risk of neonatal death and whether the birth happened on a weekday (Monday at 7:00 a.m. through Friday at 6:59 p.m.), or on a weekend (Friday at 7:00 p.m. through Monday at 6:59 a.m.). However, once birth weight and ethnicity were controlled in the statistical analysis, the association was not statistically significant despite an odds ratio of 1.44 (95% confidence interval, 0.911-2.27; P = .119).

“Births in the 12 hospitals studied appear to have been organized to take place more frequently on the working weekday rather than weekend days,” wrote Dr. Restrepo and her colleagues in the poster accompanying the presentation. Although the study wasn’t designed to answer this particular question, Dr. Restrepo said in discussion during the poster session that planned deliveries, such as inductions and cesarean deliveries, are likely to happen during the week, while the case mix is wider on weekends. Patient characteristics, as well as staffing patterns, may come into play.

The researchers also asked whether birth volume at a given institution increases the odds of neonatal death on weekends. Here, they found a significant inverse relationship between hospital birth volume and neonatal deaths (r = –0.021; P less than .001). With each additional increase of 1% in the weekday birth rate, the odds of neonatal death dropped by approximately 7.4%.

Examining the Tarrant County data further, Dr. Restrepo and her colleagues found that the hospitals with higher birth volumes had a more even distribution of births across the days of the week, with resulting lower concentrations of births during the week (r = –.394; P less than .001).

To classify infant deaths, the investigators included only ICD-10 diagnoses classified as P-codes to capture deaths occurring in the first 28 days after birth, but excluding congenital problems that are incompatible with life or that usually cause early death.

The researchers reported that they had no conflicts of interest; the study was funded by a research enhancement program award from the Texas Women’s University Office of Research and Sponsored Programs.

SOURCE: Restrepo E et al. ACOG 2018, Abstract 22R.

AUSTIN, TEX. – A first look at the timing of neonatal deaths showed an association with weekend deliveries in one Texas county. However, birth weight and ethnicity attenuated the association, according to a recent study. Higher hospital volumes were associated with lower risk of neonatal deaths.

The retrospective, population-based cohort study, presented during the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, used data from birth certificates and infant death certificates in the state of Texas. The investigators, said Elizabeth Restrepo, PhD, chose to examine data from Tarrant County, Tex., which has historically had persistently high infant mortality rates; in 2013, she said, the infant mortality rate in that county was 7.11/1,000 births – the highest in the state for that year.

The first question Dr. Restrepo and her colleagues at Texas Women’s University, Denton, wanted to answer was whether there was an association between the risk of neonatal mortality and the day of the week of the birth. For this and the study’s other research questions, she and her colleagues looked at 2012 data, matching 32,140 birth certificate records with 92 infant death certificates.

The investigators found an independent association between the risk of neonatal death and whether the birth happened on a weekday (Monday at 7:00 a.m. through Friday at 6:59 p.m.), or on a weekend (Friday at 7:00 p.m. through Monday at 6:59 a.m.). However, once birth weight and ethnicity were controlled in the statistical analysis, the association was not statistically significant despite an odds ratio of 1.44 (95% confidence interval, 0.911-2.27; P = .119).

“Births in the 12 hospitals studied appear to have been organized to take place more frequently on the working weekday rather than weekend days,” wrote Dr. Restrepo and her colleagues in the poster accompanying the presentation. Although the study wasn’t designed to answer this particular question, Dr. Restrepo said in discussion during the poster session that planned deliveries, such as inductions and cesarean deliveries, are likely to happen during the week, while the case mix is wider on weekends. Patient characteristics, as well as staffing patterns, may come into play.

The researchers also asked whether birth volume at a given institution increases the odds of neonatal death on weekends. Here, they found a significant inverse relationship between hospital birth volume and neonatal deaths (r = –0.021; P less than .001). With each additional increase of 1% in the weekday birth rate, the odds of neonatal death dropped by approximately 7.4%.

Examining the Tarrant County data further, Dr. Restrepo and her colleagues found that the hospitals with higher birth volumes had a more even distribution of births across the days of the week, with resulting lower concentrations of births during the week (r = –.394; P less than .001).

To classify infant deaths, the investigators included only ICD-10 diagnoses classified as P-codes to capture deaths occurring in the first 28 days after birth, but excluding congenital problems that are incompatible with life or that usually cause early death.

The researchers reported that they had no conflicts of interest; the study was funded by a research enhancement program award from the Texas Women’s University Office of Research and Sponsored Programs.

SOURCE: Restrepo E et al. ACOG 2018, Abstract 22R.

REPORTING FROM ACOG 2018

Key clinical point: Neonatal deaths were lower in hospitals with higher delivery volumes.

Major finding: Higher weekday birth volumes were associated with lower risk of neonatal death (P = .002).

Study details: Retrospective cohort study of 92 neonatal deaths in a single Texas county in 2012.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Texas Women’s University. The authors reported that they had no relevant disclosures.

Source: Restrepo E et al. ACOG 2018, Abstract 22R.

Rethinking preop testing

ORLANDO – Michael Rothberg, MD, a nocturnist who works at Presbyterian Rust Medical Center in Albuquerque, often is torn when asked to routinely perform preoperative tests, such as ECGs, on patients.

On the one hand, Dr. Rothberg knows that for many patients there is almost certainly no benefit to some of the tests. On the other hand, surgeons expect the tests to be performed – so, for the sake of collegiality, patients often have tests ordered that hospitalists suspect are unnecessary.