User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Antibiotic stewardship in sepsis

ORLANDO – When is it rational to consider de-escalating, or even stopping, antibiotics for septic patients, and how will patients’ future health be affected by antibiotic use during critical illnesses?

According to Jennifer Hanrahan, DO, of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, locating the tipping point between optimal care for the individual patient in sepsis, and the importance of antibiotic stewardship is a balancing act. It’s a process guided by laboratory findings, by knowledge of local pathogens and patterns of antimicrobial resistance, and also by clinical judgment, she said at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

By all means, begin antibiotics for patients with sepsis, Dr. Hanrahan, also medical director of infection prevention at MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, told attendees at a pre-course at HM18. “Prompt initiation of antibiotics for sepsis is critical, and appropriate use of antibiotics decreases mortality.” However, she noted, de-escalation of antibiotics also decreases mortality.

“What is antibiotic stewardship? Most of us think of this as the microbial stewardship police calling to ask you, ‘Why are you using this antibiotic?’’ she said. “It’s really the right antibiotic, for the right diagnosis, for the appropriate duration.”

Of course, Dr. Hanrahan said, any medication is associated with potential adverse events, and antibiotics are no different. “Almost one-third of antibiotics given are either unnecessary or inappropriate,” she said.

Antimicrobial resistance is a very serious public health threat, Dr. Hanrahan affirmed. “Antibiotic use is the most important modifiable factor related to development of antibiotic resistance. With regard to multidrug resistant [MDR] gram negatives, we are running out of antibiotics” to treat these organisms, she said, noting that “Many antibiotics to treat MDRs are “astronomically expensive – and that’s a really big problem.”

It’s important to remember that, when antibiotics are prescribed, “You’re affecting the microbiome not just of that patient, but of those around them,” as resistance factors are potentially spread from one individual’s microbiome to their friends, family, and other contacts, Dr. Hanrahan said.

The later risk of sepsis has also shown to be elevated for individuals who have received high-risk antibiotics such as fluoroquinolones, third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins, beta-lactamase inhibitor formulations, vancomycin, and carbapenems – many of which are also used to treat sepsis. All of these antibiotics kill anaerobic bacteria, Dr. Hanrahan said, and “when you kill anaerobes you do a lot of bad things to people.”

Identifying the pathogens

There are already many frightening players in the antibiotic-resistant landscape. Among them are carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, increasingly common in health care settings. Unfortunately, with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), “we’ve lost the battle,” Dr. Hanrahan said.

Acinetobacter is another increasing threat, she said, as is Candida auris, which has caused large outbreaks in Europe. Because it’s resistant to azole antifungals, once C. auris comes to U.S. hospitals, “You’re going to have a really big problem,” she said. Finally, multidrug resistant and extremely drug resistant Pseudomonas species are being encountered with increasing frequency.

And, of course, Clostridium difficile infections continue to ravage older populations. “One in 11 people aged 65 or older will die from C. diff infections,” said Dr. Hanrahan.

For all of these bacteria, she said, “I can’t tell you what antibiotics to use because you have to know what the organisms are in your hospital.” A good resource for tracking local resistance patterns is the information provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, including interactive maps showing health care–associated infections, as well as HealthMap ResistanceOpen, which maps antibiotic resistance alerts across the United States. The CDC also offers training on antibiotic stewardship; Dr. Hanrahan said the several hours she spent completing the training were well spent.

After a broad-spectrum antibiotic is initiated for sepsis, Dr. Hanrahan said that the next infectious disease–related steps should focus on identifying pathogens so antimicrobial therapy can be tailored or scaled back appropriately. In many cases, this will mean obtaining blood cultures – ideally, two sets from two separate sites. It’s no longer thought necessary to separate the blood draws by 20 minutes, or to try to time the draw during a febrile episode, she said.

What is important is to make sure that you’re not treating contamination or colonization – “Treat only clinically significant infections,” Dr. Hanrahan said. A common red herring, especially among elderly individuals coming from assisted living or in patients with indwelling urinary catheters, is a positive urine culture in the absence of signs or symptoms of urinary tract infection. Think twice about whether this truly represents a source of infection, she said. “Don’t treat asymptomatic bacteriuria.”

In order to avoid “chasing contamination,” do not obtain the blood culture samples from a venipuncture site. “Contamination is twice as likely when drawing from a venipuncture site,” Dr. Hanrahan noted. “When possible you should avoid this.”

It’s also important to remember that 10% of fever in hospitalized individuals is from a noninfectious source. “Take a careful history, and do a physical exam to help distinguish infections from other causes of fever,” said Dr. Hanrahan.

Additional investigations to consider in highly immunocompromised patients might include both mycobacterial and fungal cultures, although these studies are otherwise generally low yield. And, she said, “Don’t send catheter-tip cultures – it’s pointless, and it really doesn’t add much information.”

Good clinical judgment still goes a long way toward guiding therapy. “If a patient is stable and it’s not clear whether an antibiotic is needed, consider waiting and re-evaluating later,” Dr. Hanrahan said.

Generally, duration of treatment should also be clinically based. “Stop antibiotics as soon as possible, and remove catheters as soon as possible,” Dr. Hanrahan said, adding that few infections really warrant treatment for a fixed amount of time. These include meningitis, endocarditis, tuberculosis, and many cases of osteomyelitis.

Similarly, when a patient who had been ill now looks well, feels well, and is stable or improving, there’s usually no need for repeat blood cultures, Dr. Hanrahan said. Still, a cautious balance is where most clinicians will wind up.

“I learned a long time ago that I have to do the things that let me go home and sleep at night,” she concluded.

Dr. Hanrahan reported having been a consultant for Gilead, Astellas, and Cempra.

ORLANDO – When is it rational to consider de-escalating, or even stopping, antibiotics for septic patients, and how will patients’ future health be affected by antibiotic use during critical illnesses?

According to Jennifer Hanrahan, DO, of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, locating the tipping point between optimal care for the individual patient in sepsis, and the importance of antibiotic stewardship is a balancing act. It’s a process guided by laboratory findings, by knowledge of local pathogens and patterns of antimicrobial resistance, and also by clinical judgment, she said at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

By all means, begin antibiotics for patients with sepsis, Dr. Hanrahan, also medical director of infection prevention at MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, told attendees at a pre-course at HM18. “Prompt initiation of antibiotics for sepsis is critical, and appropriate use of antibiotics decreases mortality.” However, she noted, de-escalation of antibiotics also decreases mortality.

“What is antibiotic stewardship? Most of us think of this as the microbial stewardship police calling to ask you, ‘Why are you using this antibiotic?’’ she said. “It’s really the right antibiotic, for the right diagnosis, for the appropriate duration.”

Of course, Dr. Hanrahan said, any medication is associated with potential adverse events, and antibiotics are no different. “Almost one-third of antibiotics given are either unnecessary or inappropriate,” she said.

Antimicrobial resistance is a very serious public health threat, Dr. Hanrahan affirmed. “Antibiotic use is the most important modifiable factor related to development of antibiotic resistance. With regard to multidrug resistant [MDR] gram negatives, we are running out of antibiotics” to treat these organisms, she said, noting that “Many antibiotics to treat MDRs are “astronomically expensive – and that’s a really big problem.”

It’s important to remember that, when antibiotics are prescribed, “You’re affecting the microbiome not just of that patient, but of those around them,” as resistance factors are potentially spread from one individual’s microbiome to their friends, family, and other contacts, Dr. Hanrahan said.

The later risk of sepsis has also shown to be elevated for individuals who have received high-risk antibiotics such as fluoroquinolones, third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins, beta-lactamase inhibitor formulations, vancomycin, and carbapenems – many of which are also used to treat sepsis. All of these antibiotics kill anaerobic bacteria, Dr. Hanrahan said, and “when you kill anaerobes you do a lot of bad things to people.”

Identifying the pathogens

There are already many frightening players in the antibiotic-resistant landscape. Among them are carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, increasingly common in health care settings. Unfortunately, with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), “we’ve lost the battle,” Dr. Hanrahan said.

Acinetobacter is another increasing threat, she said, as is Candida auris, which has caused large outbreaks in Europe. Because it’s resistant to azole antifungals, once C. auris comes to U.S. hospitals, “You’re going to have a really big problem,” she said. Finally, multidrug resistant and extremely drug resistant Pseudomonas species are being encountered with increasing frequency.

And, of course, Clostridium difficile infections continue to ravage older populations. “One in 11 people aged 65 or older will die from C. diff infections,” said Dr. Hanrahan.

For all of these bacteria, she said, “I can’t tell you what antibiotics to use because you have to know what the organisms are in your hospital.” A good resource for tracking local resistance patterns is the information provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, including interactive maps showing health care–associated infections, as well as HealthMap ResistanceOpen, which maps antibiotic resistance alerts across the United States. The CDC also offers training on antibiotic stewardship; Dr. Hanrahan said the several hours she spent completing the training were well spent.

After a broad-spectrum antibiotic is initiated for sepsis, Dr. Hanrahan said that the next infectious disease–related steps should focus on identifying pathogens so antimicrobial therapy can be tailored or scaled back appropriately. In many cases, this will mean obtaining blood cultures – ideally, two sets from two separate sites. It’s no longer thought necessary to separate the blood draws by 20 minutes, or to try to time the draw during a febrile episode, she said.

What is important is to make sure that you’re not treating contamination or colonization – “Treat only clinically significant infections,” Dr. Hanrahan said. A common red herring, especially among elderly individuals coming from assisted living or in patients with indwelling urinary catheters, is a positive urine culture in the absence of signs or symptoms of urinary tract infection. Think twice about whether this truly represents a source of infection, she said. “Don’t treat asymptomatic bacteriuria.”

In order to avoid “chasing contamination,” do not obtain the blood culture samples from a venipuncture site. “Contamination is twice as likely when drawing from a venipuncture site,” Dr. Hanrahan noted. “When possible you should avoid this.”

It’s also important to remember that 10% of fever in hospitalized individuals is from a noninfectious source. “Take a careful history, and do a physical exam to help distinguish infections from other causes of fever,” said Dr. Hanrahan.

Additional investigations to consider in highly immunocompromised patients might include both mycobacterial and fungal cultures, although these studies are otherwise generally low yield. And, she said, “Don’t send catheter-tip cultures – it’s pointless, and it really doesn’t add much information.”

Good clinical judgment still goes a long way toward guiding therapy. “If a patient is stable and it’s not clear whether an antibiotic is needed, consider waiting and re-evaluating later,” Dr. Hanrahan said.

Generally, duration of treatment should also be clinically based. “Stop antibiotics as soon as possible, and remove catheters as soon as possible,” Dr. Hanrahan said, adding that few infections really warrant treatment for a fixed amount of time. These include meningitis, endocarditis, tuberculosis, and many cases of osteomyelitis.

Similarly, when a patient who had been ill now looks well, feels well, and is stable or improving, there’s usually no need for repeat blood cultures, Dr. Hanrahan said. Still, a cautious balance is where most clinicians will wind up.

“I learned a long time ago that I have to do the things that let me go home and sleep at night,” she concluded.

Dr. Hanrahan reported having been a consultant for Gilead, Astellas, and Cempra.

ORLANDO – When is it rational to consider de-escalating, or even stopping, antibiotics for septic patients, and how will patients’ future health be affected by antibiotic use during critical illnesses?

According to Jennifer Hanrahan, DO, of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, locating the tipping point between optimal care for the individual patient in sepsis, and the importance of antibiotic stewardship is a balancing act. It’s a process guided by laboratory findings, by knowledge of local pathogens and patterns of antimicrobial resistance, and also by clinical judgment, she said at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

By all means, begin antibiotics for patients with sepsis, Dr. Hanrahan, also medical director of infection prevention at MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, told attendees at a pre-course at HM18. “Prompt initiation of antibiotics for sepsis is critical, and appropriate use of antibiotics decreases mortality.” However, she noted, de-escalation of antibiotics also decreases mortality.

“What is antibiotic stewardship? Most of us think of this as the microbial stewardship police calling to ask you, ‘Why are you using this antibiotic?’’ she said. “It’s really the right antibiotic, for the right diagnosis, for the appropriate duration.”

Of course, Dr. Hanrahan said, any medication is associated with potential adverse events, and antibiotics are no different. “Almost one-third of antibiotics given are either unnecessary or inappropriate,” she said.

Antimicrobial resistance is a very serious public health threat, Dr. Hanrahan affirmed. “Antibiotic use is the most important modifiable factor related to development of antibiotic resistance. With regard to multidrug resistant [MDR] gram negatives, we are running out of antibiotics” to treat these organisms, she said, noting that “Many antibiotics to treat MDRs are “astronomically expensive – and that’s a really big problem.”

It’s important to remember that, when antibiotics are prescribed, “You’re affecting the microbiome not just of that patient, but of those around them,” as resistance factors are potentially spread from one individual’s microbiome to their friends, family, and other contacts, Dr. Hanrahan said.

The later risk of sepsis has also shown to be elevated for individuals who have received high-risk antibiotics such as fluoroquinolones, third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins, beta-lactamase inhibitor formulations, vancomycin, and carbapenems – many of which are also used to treat sepsis. All of these antibiotics kill anaerobic bacteria, Dr. Hanrahan said, and “when you kill anaerobes you do a lot of bad things to people.”

Identifying the pathogens

There are already many frightening players in the antibiotic-resistant landscape. Among them are carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, increasingly common in health care settings. Unfortunately, with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), “we’ve lost the battle,” Dr. Hanrahan said.

Acinetobacter is another increasing threat, she said, as is Candida auris, which has caused large outbreaks in Europe. Because it’s resistant to azole antifungals, once C. auris comes to U.S. hospitals, “You’re going to have a really big problem,” she said. Finally, multidrug resistant and extremely drug resistant Pseudomonas species are being encountered with increasing frequency.

And, of course, Clostridium difficile infections continue to ravage older populations. “One in 11 people aged 65 or older will die from C. diff infections,” said Dr. Hanrahan.

For all of these bacteria, she said, “I can’t tell you what antibiotics to use because you have to know what the organisms are in your hospital.” A good resource for tracking local resistance patterns is the information provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, including interactive maps showing health care–associated infections, as well as HealthMap ResistanceOpen, which maps antibiotic resistance alerts across the United States. The CDC also offers training on antibiotic stewardship; Dr. Hanrahan said the several hours she spent completing the training were well spent.

After a broad-spectrum antibiotic is initiated for sepsis, Dr. Hanrahan said that the next infectious disease–related steps should focus on identifying pathogens so antimicrobial therapy can be tailored or scaled back appropriately. In many cases, this will mean obtaining blood cultures – ideally, two sets from two separate sites. It’s no longer thought necessary to separate the blood draws by 20 minutes, or to try to time the draw during a febrile episode, she said.

What is important is to make sure that you’re not treating contamination or colonization – “Treat only clinically significant infections,” Dr. Hanrahan said. A common red herring, especially among elderly individuals coming from assisted living or in patients with indwelling urinary catheters, is a positive urine culture in the absence of signs or symptoms of urinary tract infection. Think twice about whether this truly represents a source of infection, she said. “Don’t treat asymptomatic bacteriuria.”

In order to avoid “chasing contamination,” do not obtain the blood culture samples from a venipuncture site. “Contamination is twice as likely when drawing from a venipuncture site,” Dr. Hanrahan noted. “When possible you should avoid this.”

It’s also important to remember that 10% of fever in hospitalized individuals is from a noninfectious source. “Take a careful history, and do a physical exam to help distinguish infections from other causes of fever,” said Dr. Hanrahan.

Additional investigations to consider in highly immunocompromised patients might include both mycobacterial and fungal cultures, although these studies are otherwise generally low yield. And, she said, “Don’t send catheter-tip cultures – it’s pointless, and it really doesn’t add much information.”

Good clinical judgment still goes a long way toward guiding therapy. “If a patient is stable and it’s not clear whether an antibiotic is needed, consider waiting and re-evaluating later,” Dr. Hanrahan said.

Generally, duration of treatment should also be clinically based. “Stop antibiotics as soon as possible, and remove catheters as soon as possible,” Dr. Hanrahan said, adding that few infections really warrant treatment for a fixed amount of time. These include meningitis, endocarditis, tuberculosis, and many cases of osteomyelitis.

Similarly, when a patient who had been ill now looks well, feels well, and is stable or improving, there’s usually no need for repeat blood cultures, Dr. Hanrahan said. Still, a cautious balance is where most clinicians will wind up.

“I learned a long time ago that I have to do the things that let me go home and sleep at night,” she concluded.

Dr. Hanrahan reported having been a consultant for Gilead, Astellas, and Cempra.

REPORTING FROM HM18

Simple tool improves inpatient influenza vaccination rates

TORONTO –

“When we looked at the immunization status of children in New York City, we found that one of the vaccines most commonly missed was influenza vaccine, especially from 2011 through 2014,” one of the study authors, Anmol Goyal, MD, of SUNY Downstate Medical Center, Brooklyn, N.Y., said in an interview at the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting.

“Given this year’s epidemic of influenza and the increasing deaths, we decided to look back on interventions we had done in the past to see if any can be reimplemented to help improve the vaccination status for these children,” he said. “The national goal is 80%, but if we look at the recent trend, even though we have been able to improve vaccination status, it is still below the national goal.” For example, he said, according to New York Department of Health data, the 2012-2013 influenza vaccination rates in New York City were 65% among children 6 months to 5 years old, 47% among those 5-8 years old, and 31% among those 9-18 years old, which were well below the national goal.

In an effort to improve influenza vaccine access, lead author Stephan Kohlhoff, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the medical center, and his associates, implemented a simple vaccine screening tool to use in the inpatient setting as an opportunity to improve vaccination rates among children in New York City. It consisted of nursing staff assessing the patient’s influenza immunization status on admission and conducting source verification using the citywide immunization registry, or with vaccine cards brought by parents or guardians during admission. Influenza vaccine was administered as a standing order before discharge, unless refused by the parents or guardians. The study population comprised 602 patients between the ages of 6 months and 21 years who were admitted to the inpatient unit during 2 months of the influenza season (November and December) from 2011 to 2013.

Dr. Goyal, a second-year pediatric resident at the medical center, reported that the influenza vaccination status on admission was positive in only 31% of children in 2011, 30% in 2012, and 34% in 2013. The vaccine screening tool was implemented in 64% of admitted children in 2012 and 70% in 2013. Following implementation, the researchers observed a 5% increase in immunization rates in 2012 and an 11% increase in 2013, with an overall increase of 8% over 2 years (P less than .001). He was quick to point out that the influenza rate could have been improved by an additional 22% had 77% of patients not refused vaccination.

“Unfortunately, as our primary objective was to assess the utility of our screening tool in improving inpatient immunization status, we had very limited data points toward refusal of vaccine,” Dr. Goyal said. “Some of the reasons for refusal that were gathered during screening included preferred vaccination by their primary care provider after discharge. Or, maybe they don’t want the vaccine because they feel that the vaccine will make their kids sick. We don’t have enough data to point to any particular reason. This study provides information on acceptance rate of inpatient immunization, which may be useful for implementing additional educational initiatives to overcome potential barriers and help us reach our national goal.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

TORONTO –

“When we looked at the immunization status of children in New York City, we found that one of the vaccines most commonly missed was influenza vaccine, especially from 2011 through 2014,” one of the study authors, Anmol Goyal, MD, of SUNY Downstate Medical Center, Brooklyn, N.Y., said in an interview at the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting.

“Given this year’s epidemic of influenza and the increasing deaths, we decided to look back on interventions we had done in the past to see if any can be reimplemented to help improve the vaccination status for these children,” he said. “The national goal is 80%, but if we look at the recent trend, even though we have been able to improve vaccination status, it is still below the national goal.” For example, he said, according to New York Department of Health data, the 2012-2013 influenza vaccination rates in New York City were 65% among children 6 months to 5 years old, 47% among those 5-8 years old, and 31% among those 9-18 years old, which were well below the national goal.

In an effort to improve influenza vaccine access, lead author Stephan Kohlhoff, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the medical center, and his associates, implemented a simple vaccine screening tool to use in the inpatient setting as an opportunity to improve vaccination rates among children in New York City. It consisted of nursing staff assessing the patient’s influenza immunization status on admission and conducting source verification using the citywide immunization registry, or with vaccine cards brought by parents or guardians during admission. Influenza vaccine was administered as a standing order before discharge, unless refused by the parents or guardians. The study population comprised 602 patients between the ages of 6 months and 21 years who were admitted to the inpatient unit during 2 months of the influenza season (November and December) from 2011 to 2013.

Dr. Goyal, a second-year pediatric resident at the medical center, reported that the influenza vaccination status on admission was positive in only 31% of children in 2011, 30% in 2012, and 34% in 2013. The vaccine screening tool was implemented in 64% of admitted children in 2012 and 70% in 2013. Following implementation, the researchers observed a 5% increase in immunization rates in 2012 and an 11% increase in 2013, with an overall increase of 8% over 2 years (P less than .001). He was quick to point out that the influenza rate could have been improved by an additional 22% had 77% of patients not refused vaccination.

“Unfortunately, as our primary objective was to assess the utility of our screening tool in improving inpatient immunization status, we had very limited data points toward refusal of vaccine,” Dr. Goyal said. “Some of the reasons for refusal that were gathered during screening included preferred vaccination by their primary care provider after discharge. Or, maybe they don’t want the vaccine because they feel that the vaccine will make their kids sick. We don’t have enough data to point to any particular reason. This study provides information on acceptance rate of inpatient immunization, which may be useful for implementing additional educational initiatives to overcome potential barriers and help us reach our national goal.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

TORONTO –

“When we looked at the immunization status of children in New York City, we found that one of the vaccines most commonly missed was influenza vaccine, especially from 2011 through 2014,” one of the study authors, Anmol Goyal, MD, of SUNY Downstate Medical Center, Brooklyn, N.Y., said in an interview at the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting.

“Given this year’s epidemic of influenza and the increasing deaths, we decided to look back on interventions we had done in the past to see if any can be reimplemented to help improve the vaccination status for these children,” he said. “The national goal is 80%, but if we look at the recent trend, even though we have been able to improve vaccination status, it is still below the national goal.” For example, he said, according to New York Department of Health data, the 2012-2013 influenza vaccination rates in New York City were 65% among children 6 months to 5 years old, 47% among those 5-8 years old, and 31% among those 9-18 years old, which were well below the national goal.

In an effort to improve influenza vaccine access, lead author Stephan Kohlhoff, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the medical center, and his associates, implemented a simple vaccine screening tool to use in the inpatient setting as an opportunity to improve vaccination rates among children in New York City. It consisted of nursing staff assessing the patient’s influenza immunization status on admission and conducting source verification using the citywide immunization registry, or with vaccine cards brought by parents or guardians during admission. Influenza vaccine was administered as a standing order before discharge, unless refused by the parents or guardians. The study population comprised 602 patients between the ages of 6 months and 21 years who were admitted to the inpatient unit during 2 months of the influenza season (November and December) from 2011 to 2013.

Dr. Goyal, a second-year pediatric resident at the medical center, reported that the influenza vaccination status on admission was positive in only 31% of children in 2011, 30% in 2012, and 34% in 2013. The vaccine screening tool was implemented in 64% of admitted children in 2012 and 70% in 2013. Following implementation, the researchers observed a 5% increase in immunization rates in 2012 and an 11% increase in 2013, with an overall increase of 8% over 2 years (P less than .001). He was quick to point out that the influenza rate could have been improved by an additional 22% had 77% of patients not refused vaccination.

“Unfortunately, as our primary objective was to assess the utility of our screening tool in improving inpatient immunization status, we had very limited data points toward refusal of vaccine,” Dr. Goyal said. “Some of the reasons for refusal that were gathered during screening included preferred vaccination by their primary care provider after discharge. Or, maybe they don’t want the vaccine because they feel that the vaccine will make their kids sick. We don’t have enough data to point to any particular reason. This study provides information on acceptance rate of inpatient immunization, which may be useful for implementing additional educational initiatives to overcome potential barriers and help us reach our national goal.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

AT PAS 18

Key clinical point: The inpatient setting can be used to successfully improve influenza vaccine rates.

Major finding: Following implementation of a simple inpatient vaccine screening tool, a 5% increase in immunization rates occurred in 2012 and an 11% increase occurred in 2013.

Study details: A review of 602 patients between the ages of 6 months and 21 years who were admitted to the inpatient unit during 2 months of the influenza season (November and December) from 2011 to 2013.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Teaching hospitals order more lab testing for certain conditions

Clinical question: Is there a difference in the ordering of laboratory tests between teaching and nonteaching hospitals?

Background: There is a general impression that trainees at teaching hospitals order more unnecessary laboratory testing, compared with those at nonteaching hospitals, but there are not enough data to support this generalization. In addition, there may be factors at teaching hospitals that influence these results.

Study design: Cross-sectional study.

Setting: Teaching and nonteaching hospitals.

Synopsis: Investigators used the Texas Inpatient Public Use Data file to examine hospital discharges from both teaching and nonteaching hospitals with a discharge diagnosis of cellulitis or pneumonia. There were a greater number of laboratory tests ordered at teaching hospitals, compared with nonteaching hospitals. For pneumonia, there were an additional 3.6 tests ordered per day, and for cellulitis, there were an additional 2.6 tests ordered per day. This finding was statistically significant, even when adjusted for illness severity, length of stay, and patient demographics.

This study did not account for confounding diagnoses that may have influenced ordering or the prescribing habits of different practitioner groups (such as residents, attending physicians, or advanced practice providers).

Bottom line: There is an increase in laboratory test orders in teaching versus nonteaching hospitals for pneumonia and cellulitis.

Citation: Valencia V et al. A comparison of laboratory testing in teaching vs nonteaching hospitals for 2 common medical conditions. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Jan 1;178(1):39-47.

Dr. Shaffie is a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Clinical question: Is there a difference in the ordering of laboratory tests between teaching and nonteaching hospitals?

Background: There is a general impression that trainees at teaching hospitals order more unnecessary laboratory testing, compared with those at nonteaching hospitals, but there are not enough data to support this generalization. In addition, there may be factors at teaching hospitals that influence these results.

Study design: Cross-sectional study.

Setting: Teaching and nonteaching hospitals.

Synopsis: Investigators used the Texas Inpatient Public Use Data file to examine hospital discharges from both teaching and nonteaching hospitals with a discharge diagnosis of cellulitis or pneumonia. There were a greater number of laboratory tests ordered at teaching hospitals, compared with nonteaching hospitals. For pneumonia, there were an additional 3.6 tests ordered per day, and for cellulitis, there were an additional 2.6 tests ordered per day. This finding was statistically significant, even when adjusted for illness severity, length of stay, and patient demographics.

This study did not account for confounding diagnoses that may have influenced ordering or the prescribing habits of different practitioner groups (such as residents, attending physicians, or advanced practice providers).

Bottom line: There is an increase in laboratory test orders in teaching versus nonteaching hospitals for pneumonia and cellulitis.

Citation: Valencia V et al. A comparison of laboratory testing in teaching vs nonteaching hospitals for 2 common medical conditions. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Jan 1;178(1):39-47.

Dr. Shaffie is a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Clinical question: Is there a difference in the ordering of laboratory tests between teaching and nonteaching hospitals?

Background: There is a general impression that trainees at teaching hospitals order more unnecessary laboratory testing, compared with those at nonteaching hospitals, but there are not enough data to support this generalization. In addition, there may be factors at teaching hospitals that influence these results.

Study design: Cross-sectional study.

Setting: Teaching and nonteaching hospitals.

Synopsis: Investigators used the Texas Inpatient Public Use Data file to examine hospital discharges from both teaching and nonteaching hospitals with a discharge diagnosis of cellulitis or pneumonia. There were a greater number of laboratory tests ordered at teaching hospitals, compared with nonteaching hospitals. For pneumonia, there were an additional 3.6 tests ordered per day, and for cellulitis, there were an additional 2.6 tests ordered per day. This finding was statistically significant, even when adjusted for illness severity, length of stay, and patient demographics.

This study did not account for confounding diagnoses that may have influenced ordering or the prescribing habits of different practitioner groups (such as residents, attending physicians, or advanced practice providers).

Bottom line: There is an increase in laboratory test orders in teaching versus nonteaching hospitals for pneumonia and cellulitis.

Citation: Valencia V et al. A comparison of laboratory testing in teaching vs nonteaching hospitals for 2 common medical conditions. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Jan 1;178(1):39-47.

Dr. Shaffie is a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Kawasaki disease: New info to enhance our index of suspicion

Most U.S. mainland pediatric practitioners will see only one or two cases of Kawasaki disease (KD) in their careers, but no one wants to miss even one case.

Making the diagnosis as early as possible is important to reduce the chance of sequelae, particularly the coronary artery aneurysms that will eventually lead to 5% of overall acute coronary syndromes in adults. And because there is no “KD test,” or sometimes incomplete KD. And there are some new data that complicate this. Despite the recently updated 2017 guideline,1 most cases end up being confirmed and managed by regional “experts.” But nearly all of the approximately 6,000 KD cases/year in U.S. children younger than 5 years old start out with one or more primary care, urgent care, or ED visits.

This means that every clinician in the trenches not only needs a high index of suspicion but also needs to be at least a partial expert, too. What raises our index of suspicion? Classic data tell us we need 5 consecutive days of fever plus four or five other principal clinical findings for a KD diagnosis. The principal findings are:

1. Eyes: Bilateral bulbar nonexudative conjunctival injection.

2. Mouth: Erythema of oral/pharyngeal mucosa or cracked lips or strawberry tongue or oral mucositis.

3. Rash.

4. Hands or feet findings: Swelling/erythema or later periungual desquamation.

5. Cervical adenopathy greater than 1.4 cm, usually unilateral.

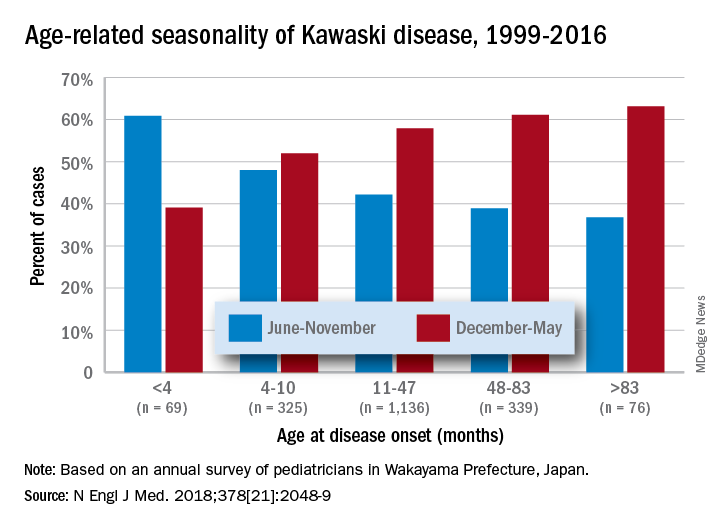

Other factors that have classically increased suspicion are winter/early spring presentation in North America, male gender (1.5:1 ratio to females), and Asian (particularly Japanese) ancestry. The importance of genetics was initially based on epidemiology (Japan/Asian risk) but lately has been further associated with six gene polymorphisms. However, molecular genetic testing is not currently a practical tool.

Clinical scenarios that also should raise suspicion include less-than-6-month-old infants with prolonged fever/irritability (may be the only clinical manifestations of KD) and children over 4 years old who more often may have incomplete KD. Both groups have higher prevalence of coronary artery abnormalities. Other high suspicion scenarios include prolonged fever with unexplained/culture-negative shock, or antibiotic treatment failure for cervical adenitis or retro/parapharyngeal phlegmon. Consultation with or referral to a regional KD expert may be needed.

Fuzzy KD math

Current guidelines list an exception to the 5-day fever requirement in that only 4 days of fever are needed with four or more principal clinical features, particularly when hand and feet findings exist. Some call this the “4X4 exception.” Then there is a sub-caveat: “Experienced clinicians who have treated many patients with KD may establish the diagnosis with 3 days of fever in rare cases.”1

Incomplete KD

This is another exception, which seems to be a more frequent diagnosis in the past decade. Incomplete KD requires the 5 days of fever duration plus an elevated C-reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rate. But one needs only two or three of the five principal clinical KD criteria plus three or more of six other laboratory findings (anemia, low albumin, leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, pyuria, or elevated alanine aminotransferase). Incomplete KD can be confirmed by an abnormal echocardiogram – usually not until after 7 days of KD symptoms.1

New KD nuances

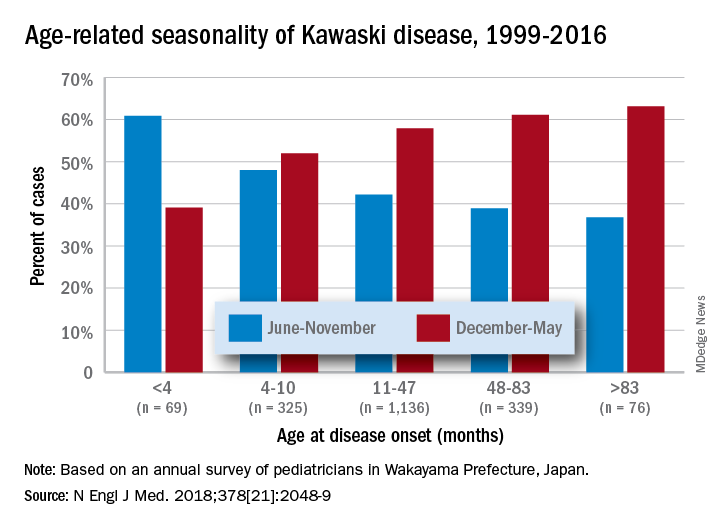

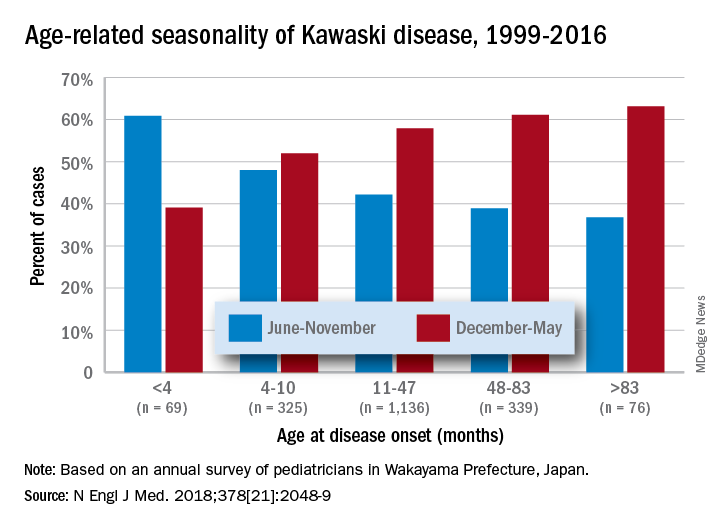

In a recent report on 20 years of data from Japan (n = 1,945 KD cases), more granularity on age, seasonal epidemiology, and outcome were seen.2 There was an inverse correlation of male predominance to age, i.e. as age groups got older, there was a gradual shift to female predominance by 7 years of age. The winter/spring predominance (60% of overall cases) did not hold true in younger age groups where summer/fall was the peak season (65% of cases).

With the goal of not missing any KD and diagnosing as early as possible to limit sequelae, we all need to be relative experts and keep alert for clinical scenarios that warrant our raising our index of suspicion. But now the seasonality trends appear blurred in the youngest cases and the male predominance is blurred in the oldest cases. And remember that fever and irritability for longer than 7 days in young infants may be the only clue to KD.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Mo. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Circulation. 2017 Mar 29. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000484

2. N Engl J Med. 2018 May 24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1804312.

Most U.S. mainland pediatric practitioners will see only one or two cases of Kawasaki disease (KD) in their careers, but no one wants to miss even one case.

Making the diagnosis as early as possible is important to reduce the chance of sequelae, particularly the coronary artery aneurysms that will eventually lead to 5% of overall acute coronary syndromes in adults. And because there is no “KD test,” or sometimes incomplete KD. And there are some new data that complicate this. Despite the recently updated 2017 guideline,1 most cases end up being confirmed and managed by regional “experts.” But nearly all of the approximately 6,000 KD cases/year in U.S. children younger than 5 years old start out with one or more primary care, urgent care, or ED visits.

This means that every clinician in the trenches not only needs a high index of suspicion but also needs to be at least a partial expert, too. What raises our index of suspicion? Classic data tell us we need 5 consecutive days of fever plus four or five other principal clinical findings for a KD diagnosis. The principal findings are:

1. Eyes: Bilateral bulbar nonexudative conjunctival injection.

2. Mouth: Erythema of oral/pharyngeal mucosa or cracked lips or strawberry tongue or oral mucositis.

3. Rash.

4. Hands or feet findings: Swelling/erythema or later periungual desquamation.

5. Cervical adenopathy greater than 1.4 cm, usually unilateral.

Other factors that have classically increased suspicion are winter/early spring presentation in North America, male gender (1.5:1 ratio to females), and Asian (particularly Japanese) ancestry. The importance of genetics was initially based on epidemiology (Japan/Asian risk) but lately has been further associated with six gene polymorphisms. However, molecular genetic testing is not currently a practical tool.

Clinical scenarios that also should raise suspicion include less-than-6-month-old infants with prolonged fever/irritability (may be the only clinical manifestations of KD) and children over 4 years old who more often may have incomplete KD. Both groups have higher prevalence of coronary artery abnormalities. Other high suspicion scenarios include prolonged fever with unexplained/culture-negative shock, or antibiotic treatment failure for cervical adenitis or retro/parapharyngeal phlegmon. Consultation with or referral to a regional KD expert may be needed.

Fuzzy KD math

Current guidelines list an exception to the 5-day fever requirement in that only 4 days of fever are needed with four or more principal clinical features, particularly when hand and feet findings exist. Some call this the “4X4 exception.” Then there is a sub-caveat: “Experienced clinicians who have treated many patients with KD may establish the diagnosis with 3 days of fever in rare cases.”1

Incomplete KD

This is another exception, which seems to be a more frequent diagnosis in the past decade. Incomplete KD requires the 5 days of fever duration plus an elevated C-reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rate. But one needs only two or three of the five principal clinical KD criteria plus three or more of six other laboratory findings (anemia, low albumin, leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, pyuria, or elevated alanine aminotransferase). Incomplete KD can be confirmed by an abnormal echocardiogram – usually not until after 7 days of KD symptoms.1

New KD nuances

In a recent report on 20 years of data from Japan (n = 1,945 KD cases), more granularity on age, seasonal epidemiology, and outcome were seen.2 There was an inverse correlation of male predominance to age, i.e. as age groups got older, there was a gradual shift to female predominance by 7 years of age. The winter/spring predominance (60% of overall cases) did not hold true in younger age groups where summer/fall was the peak season (65% of cases).

With the goal of not missing any KD and diagnosing as early as possible to limit sequelae, we all need to be relative experts and keep alert for clinical scenarios that warrant our raising our index of suspicion. But now the seasonality trends appear blurred in the youngest cases and the male predominance is blurred in the oldest cases. And remember that fever and irritability for longer than 7 days in young infants may be the only clue to KD.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Mo. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Circulation. 2017 Mar 29. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000484

2. N Engl J Med. 2018 May 24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1804312.

Most U.S. mainland pediatric practitioners will see only one or two cases of Kawasaki disease (KD) in their careers, but no one wants to miss even one case.

Making the diagnosis as early as possible is important to reduce the chance of sequelae, particularly the coronary artery aneurysms that will eventually lead to 5% of overall acute coronary syndromes in adults. And because there is no “KD test,” or sometimes incomplete KD. And there are some new data that complicate this. Despite the recently updated 2017 guideline,1 most cases end up being confirmed and managed by regional “experts.” But nearly all of the approximately 6,000 KD cases/year in U.S. children younger than 5 years old start out with one or more primary care, urgent care, or ED visits.

This means that every clinician in the trenches not only needs a high index of suspicion but also needs to be at least a partial expert, too. What raises our index of suspicion? Classic data tell us we need 5 consecutive days of fever plus four or five other principal clinical findings for a KD diagnosis. The principal findings are:

1. Eyes: Bilateral bulbar nonexudative conjunctival injection.

2. Mouth: Erythema of oral/pharyngeal mucosa or cracked lips or strawberry tongue or oral mucositis.

3. Rash.

4. Hands or feet findings: Swelling/erythema or later periungual desquamation.

5. Cervical adenopathy greater than 1.4 cm, usually unilateral.

Other factors that have classically increased suspicion are winter/early spring presentation in North America, male gender (1.5:1 ratio to females), and Asian (particularly Japanese) ancestry. The importance of genetics was initially based on epidemiology (Japan/Asian risk) but lately has been further associated with six gene polymorphisms. However, molecular genetic testing is not currently a practical tool.

Clinical scenarios that also should raise suspicion include less-than-6-month-old infants with prolonged fever/irritability (may be the only clinical manifestations of KD) and children over 4 years old who more often may have incomplete KD. Both groups have higher prevalence of coronary artery abnormalities. Other high suspicion scenarios include prolonged fever with unexplained/culture-negative shock, or antibiotic treatment failure for cervical adenitis or retro/parapharyngeal phlegmon. Consultation with or referral to a regional KD expert may be needed.

Fuzzy KD math

Current guidelines list an exception to the 5-day fever requirement in that only 4 days of fever are needed with four or more principal clinical features, particularly when hand and feet findings exist. Some call this the “4X4 exception.” Then there is a sub-caveat: “Experienced clinicians who have treated many patients with KD may establish the diagnosis with 3 days of fever in rare cases.”1

Incomplete KD

This is another exception, which seems to be a more frequent diagnosis in the past decade. Incomplete KD requires the 5 days of fever duration plus an elevated C-reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rate. But one needs only two or three of the five principal clinical KD criteria plus three or more of six other laboratory findings (anemia, low albumin, leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, pyuria, or elevated alanine aminotransferase). Incomplete KD can be confirmed by an abnormal echocardiogram – usually not until after 7 days of KD symptoms.1

New KD nuances

In a recent report on 20 years of data from Japan (n = 1,945 KD cases), more granularity on age, seasonal epidemiology, and outcome were seen.2 There was an inverse correlation of male predominance to age, i.e. as age groups got older, there was a gradual shift to female predominance by 7 years of age. The winter/spring predominance (60% of overall cases) did not hold true in younger age groups where summer/fall was the peak season (65% of cases).

With the goal of not missing any KD and diagnosing as early as possible to limit sequelae, we all need to be relative experts and keep alert for clinical scenarios that warrant our raising our index of suspicion. But now the seasonality trends appear blurred in the youngest cases and the male predominance is blurred in the oldest cases. And remember that fever and irritability for longer than 7 days in young infants may be the only clue to KD.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Mo. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Circulation. 2017 Mar 29. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000484

2. N Engl J Med. 2018 May 24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1804312.

Simple bedside tool effectively detected sepsis in the ED

SAN DIEGO – The product of compared with the quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment prompt, a small, single-center study showed.

“We know a lot about the pathophysiology of sepsis, but we don’t have great ways of identifying septic patients at an early stage,” lead study author David Lynch, MD, said in an interview at an international conference of the American Thoracic Society.

He noted that screening tools such as the quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment and Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome criteria have a sensitivity of about 70% in detecting sepsis. “Over the last 10-15 years we’ve been able to find ways of improving outcomes in patients whom we confirm are septic with early antibiotics and fluids,” said Dr. Lynch, a second-year resident in the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine within the department of medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “We know that in sepsis, systemic vascular resistance is decreased and cardiac output is increased. We tried to come up with a way of estimating cardiac output at the bedside by multiplying heart rate with pulse pressure, with the pulse pressure being the surrogate for stroke volume, which you can measure easily.”

In a cross-sectional, observational study, Dr. Lynch, senior author Thomas Bice, MD, and their associates reviewed the records of 116 patients who were admitted directly to the University of North Carolina’s medical ICU (MICU) from the UNC ED between Jan. 5, 2016, and June 30, 2017. The primary outcome of interest was culture-positive sepsis, and the primary exposure was the product of pulse pressure and heart rate. Patients were determined to be positive for sepsis if an infection was suspected (such as if blood cultures were drawn and antibiotics were started), the admitting physician suspected sepsis, and cultures were subsequently positive.

The average age of all patients was 53 years, 51% were female, the mortality rate was 12%, and the median length of stay was 4 days. A total of 25 of the 116 patients (22%) were positive for sepsis. The researchers observed that the pulse pressure multiplied by the heart rate was significantly higher in the culture-positive sepsis group, compared with controls (6,710 vs. 3,741, respectively; P less than .001).

Dr. Lynch and his associates found that, as a continuous variable, pulse pressure multiplied by the heart rate accurately classified 90% of sepsis cases (area under the receiver operator curve, 0.96; P less than .001). When using 5,000 as a cutoff, pulse pressure multiplied by the heart rate had a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 89% in detecting culture-positive sepsis. “We were surprised by how high the sensitivity was,” Dr. Lynch said. “The question is, will this translate to a larger cohort? And, would this be transferable to all patients in the ED, as opposed to the sicker patients who are going to the MICU?”

He and his associates plan to confirm the study’s results in a broader population of patients. “We don’t yet understand at what point in time this would be most applicable,” he added. “We looked at the first set of vitals when they came into the ED. We’d like to know if that applies to the second, third and fourth set of vitals, and whether it would be most useful to have an average of those.”

The study was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Lynch reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The product of compared with the quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment prompt, a small, single-center study showed.

“We know a lot about the pathophysiology of sepsis, but we don’t have great ways of identifying septic patients at an early stage,” lead study author David Lynch, MD, said in an interview at an international conference of the American Thoracic Society.

He noted that screening tools such as the quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment and Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome criteria have a sensitivity of about 70% in detecting sepsis. “Over the last 10-15 years we’ve been able to find ways of improving outcomes in patients whom we confirm are septic with early antibiotics and fluids,” said Dr. Lynch, a second-year resident in the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine within the department of medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “We know that in sepsis, systemic vascular resistance is decreased and cardiac output is increased. We tried to come up with a way of estimating cardiac output at the bedside by multiplying heart rate with pulse pressure, with the pulse pressure being the surrogate for stroke volume, which you can measure easily.”

In a cross-sectional, observational study, Dr. Lynch, senior author Thomas Bice, MD, and their associates reviewed the records of 116 patients who were admitted directly to the University of North Carolina’s medical ICU (MICU) from the UNC ED between Jan. 5, 2016, and June 30, 2017. The primary outcome of interest was culture-positive sepsis, and the primary exposure was the product of pulse pressure and heart rate. Patients were determined to be positive for sepsis if an infection was suspected (such as if blood cultures were drawn and antibiotics were started), the admitting physician suspected sepsis, and cultures were subsequently positive.

The average age of all patients was 53 years, 51% were female, the mortality rate was 12%, and the median length of stay was 4 days. A total of 25 of the 116 patients (22%) were positive for sepsis. The researchers observed that the pulse pressure multiplied by the heart rate was significantly higher in the culture-positive sepsis group, compared with controls (6,710 vs. 3,741, respectively; P less than .001).

Dr. Lynch and his associates found that, as a continuous variable, pulse pressure multiplied by the heart rate accurately classified 90% of sepsis cases (area under the receiver operator curve, 0.96; P less than .001). When using 5,000 as a cutoff, pulse pressure multiplied by the heart rate had a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 89% in detecting culture-positive sepsis. “We were surprised by how high the sensitivity was,” Dr. Lynch said. “The question is, will this translate to a larger cohort? And, would this be transferable to all patients in the ED, as opposed to the sicker patients who are going to the MICU?”

He and his associates plan to confirm the study’s results in a broader population of patients. “We don’t yet understand at what point in time this would be most applicable,” he added. “We looked at the first set of vitals when they came into the ED. We’d like to know if that applies to the second, third and fourth set of vitals, and whether it would be most useful to have an average of those.”

The study was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Lynch reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The product of compared with the quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment prompt, a small, single-center study showed.

“We know a lot about the pathophysiology of sepsis, but we don’t have great ways of identifying septic patients at an early stage,” lead study author David Lynch, MD, said in an interview at an international conference of the American Thoracic Society.

He noted that screening tools such as the quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment and Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome criteria have a sensitivity of about 70% in detecting sepsis. “Over the last 10-15 years we’ve been able to find ways of improving outcomes in patients whom we confirm are septic with early antibiotics and fluids,” said Dr. Lynch, a second-year resident in the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine within the department of medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “We know that in sepsis, systemic vascular resistance is decreased and cardiac output is increased. We tried to come up with a way of estimating cardiac output at the bedside by multiplying heart rate with pulse pressure, with the pulse pressure being the surrogate for stroke volume, which you can measure easily.”

In a cross-sectional, observational study, Dr. Lynch, senior author Thomas Bice, MD, and their associates reviewed the records of 116 patients who were admitted directly to the University of North Carolina’s medical ICU (MICU) from the UNC ED between Jan. 5, 2016, and June 30, 2017. The primary outcome of interest was culture-positive sepsis, and the primary exposure was the product of pulse pressure and heart rate. Patients were determined to be positive for sepsis if an infection was suspected (such as if blood cultures were drawn and antibiotics were started), the admitting physician suspected sepsis, and cultures were subsequently positive.

The average age of all patients was 53 years, 51% were female, the mortality rate was 12%, and the median length of stay was 4 days. A total of 25 of the 116 patients (22%) were positive for sepsis. The researchers observed that the pulse pressure multiplied by the heart rate was significantly higher in the culture-positive sepsis group, compared with controls (6,710 vs. 3,741, respectively; P less than .001).

Dr. Lynch and his associates found that, as a continuous variable, pulse pressure multiplied by the heart rate accurately classified 90% of sepsis cases (area under the receiver operator curve, 0.96; P less than .001). When using 5,000 as a cutoff, pulse pressure multiplied by the heart rate had a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 89% in detecting culture-positive sepsis. “We were surprised by how high the sensitivity was,” Dr. Lynch said. “The question is, will this translate to a larger cohort? And, would this be transferable to all patients in the ED, as opposed to the sicker patients who are going to the MICU?”

He and his associates plan to confirm the study’s results in a broader population of patients. “We don’t yet understand at what point in time this would be most applicable,” he added. “We looked at the first set of vitals when they came into the ED. We’d like to know if that applies to the second, third and fourth set of vitals, and whether it would be most useful to have an average of those.”

The study was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Lynch reported having no financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM ATS 2018

Key clinical point: A simple calculation of pulse pressure multiplied by heart rate at ED triage could lead to earlier implementation of lifesaving interventions in septic patients.

Major finding: When using 5,000 as a cutoff, pulse pressure multiplied by heart rate had a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 89% in detecting culture-positive sepsis.

Study details: A cross-sectional, observational study of 116 medical ICU patients who were admitted directly from an ED.

Disclosures: The study was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Lynch reported having no financial disclosures.

Delays in lactate measurement ups mortality risk in sepsis patients

For patients with , findings of a retrospective study show.

Those patients had a longer time to administration of IV fluids (IVF) and antibiotics, researchers reported in the journal Chest®.

In previous studies, delayed antibiotics in patients with sepsis has been associated with increased mortality, wrote Xuan Han, MD, department of medicine, University of Chicago, and coauthors. “Systematic early lactate measurements when a patient presents with sepsis may thus be useful in prompting earlier, potentially life-saving interventions,” they noted.

The retrospective study comprised 5,762 adults admitted to the University of Chicago from November 2008 to January 2016. These patients met criteria for severe sepsis, as outlined in the Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock Early Management Bundle (SEP-1), a quality measure introduced by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in 2015. The SEP-1 mandates interventions including lactate draws and antibiotics for patients identified as having severe sepsis via clinical and laboratory evaluation, the authors noted.

They found that 60% of these patients had serum lactate measurements drawn within the time window specified in SEP-1. But timelines varied significantly by setting, at just 32% in patients who first met the criteria on the wards, compared with 55% in the ICU, and 79% in the emergency department.

In-hospital mortality was highest in patients with delayed lactate measurements, at 29%, compared with 27% for those with lactates taken within the specified time window, and 23% for patients without lactate samples (P less than .01), the researchers reported.

For patients with initial lactates greater than 2.0 mmol/L, the increase in odds of death was 2% for each hour of delay, while no such increase was noted in patients with initial lactates lower than that threshold.

The increased odds of death in patients with higher initial lactates was significant (odds ratio, 1.02; 95% confidence interval, 1.0003-1.05; P = .04); however, the association was no longer significant when adjusted for time to IVF and antibiotics (P = .51). Based on that observation, the difference in mortality may be due to earlier interventions among patients treated in the specified time frame.

“Patients with lactates drawn within the SEP-1 window received both IV antibiotics and fluids sooner than their counterparts who had lactates drawn outside of the window,” Dr. Han and coauthors explained.

These findings complement prior studies suggesting the benefit of interventions in patients with lactate levels above 2.0 mmol/L, and, conversely, highlight the fact that many patients who meet the severe sepsis criteria nevertheless have normal lactates.

“Although elements of the SEP-1 bundle are useful in managing sepsis, the measure may also lead to an increase in lactate measurements and subsequently excessive utilization of resources on patients who may not benefit,” the researchers wrote.

They reported disclosures related to Philips Healthcare, Laerdal Medical, and Quant HC, among other entities.

SOURCE: Han X et al. Chest. 2018 May 24. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.03.025.

For patients with , findings of a retrospective study show.

Those patients had a longer time to administration of IV fluids (IVF) and antibiotics, researchers reported in the journal Chest®.

In previous studies, delayed antibiotics in patients with sepsis has been associated with increased mortality, wrote Xuan Han, MD, department of medicine, University of Chicago, and coauthors. “Systematic early lactate measurements when a patient presents with sepsis may thus be useful in prompting earlier, potentially life-saving interventions,” they noted.

The retrospective study comprised 5,762 adults admitted to the University of Chicago from November 2008 to January 2016. These patients met criteria for severe sepsis, as outlined in the Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock Early Management Bundle (SEP-1), a quality measure introduced by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in 2015. The SEP-1 mandates interventions including lactate draws and antibiotics for patients identified as having severe sepsis via clinical and laboratory evaluation, the authors noted.

They found that 60% of these patients had serum lactate measurements drawn within the time window specified in SEP-1. But timelines varied significantly by setting, at just 32% in patients who first met the criteria on the wards, compared with 55% in the ICU, and 79% in the emergency department.

In-hospital mortality was highest in patients with delayed lactate measurements, at 29%, compared with 27% for those with lactates taken within the specified time window, and 23% for patients without lactate samples (P less than .01), the researchers reported.

For patients with initial lactates greater than 2.0 mmol/L, the increase in odds of death was 2% for each hour of delay, while no such increase was noted in patients with initial lactates lower than that threshold.

The increased odds of death in patients with higher initial lactates was significant (odds ratio, 1.02; 95% confidence interval, 1.0003-1.05; P = .04); however, the association was no longer significant when adjusted for time to IVF and antibiotics (P = .51). Based on that observation, the difference in mortality may be due to earlier interventions among patients treated in the specified time frame.

“Patients with lactates drawn within the SEP-1 window received both IV antibiotics and fluids sooner than their counterparts who had lactates drawn outside of the window,” Dr. Han and coauthors explained.

These findings complement prior studies suggesting the benefit of interventions in patients with lactate levels above 2.0 mmol/L, and, conversely, highlight the fact that many patients who meet the severe sepsis criteria nevertheless have normal lactates.

“Although elements of the SEP-1 bundle are useful in managing sepsis, the measure may also lead to an increase in lactate measurements and subsequently excessive utilization of resources on patients who may not benefit,” the researchers wrote.

They reported disclosures related to Philips Healthcare, Laerdal Medical, and Quant HC, among other entities.

SOURCE: Han X et al. Chest. 2018 May 24. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.03.025.

For patients with , findings of a retrospective study show.

Those patients had a longer time to administration of IV fluids (IVF) and antibiotics, researchers reported in the journal Chest®.

In previous studies, delayed antibiotics in patients with sepsis has been associated with increased mortality, wrote Xuan Han, MD, department of medicine, University of Chicago, and coauthors. “Systematic early lactate measurements when a patient presents with sepsis may thus be useful in prompting earlier, potentially life-saving interventions,” they noted.

The retrospective study comprised 5,762 adults admitted to the University of Chicago from November 2008 to January 2016. These patients met criteria for severe sepsis, as outlined in the Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock Early Management Bundle (SEP-1), a quality measure introduced by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in 2015. The SEP-1 mandates interventions including lactate draws and antibiotics for patients identified as having severe sepsis via clinical and laboratory evaluation, the authors noted.

They found that 60% of these patients had serum lactate measurements drawn within the time window specified in SEP-1. But timelines varied significantly by setting, at just 32% in patients who first met the criteria on the wards, compared with 55% in the ICU, and 79% in the emergency department.

In-hospital mortality was highest in patients with delayed lactate measurements, at 29%, compared with 27% for those with lactates taken within the specified time window, and 23% for patients without lactate samples (P less than .01), the researchers reported.

For patients with initial lactates greater than 2.0 mmol/L, the increase in odds of death was 2% for each hour of delay, while no such increase was noted in patients with initial lactates lower than that threshold.

The increased odds of death in patients with higher initial lactates was significant (odds ratio, 1.02; 95% confidence interval, 1.0003-1.05; P = .04); however, the association was no longer significant when adjusted for time to IVF and antibiotics (P = .51). Based on that observation, the difference in mortality may be due to earlier interventions among patients treated in the specified time frame.

“Patients with lactates drawn within the SEP-1 window received both IV antibiotics and fluids sooner than their counterparts who had lactates drawn outside of the window,” Dr. Han and coauthors explained.

These findings complement prior studies suggesting the benefit of interventions in patients with lactate levels above 2.0 mmol/L, and, conversely, highlight the fact that many patients who meet the severe sepsis criteria nevertheless have normal lactates.

“Although elements of the SEP-1 bundle are useful in managing sepsis, the measure may also lead to an increase in lactate measurements and subsequently excessive utilization of resources on patients who may not benefit,” the researchers wrote.

They reported disclosures related to Philips Healthcare, Laerdal Medical, and Quant HC, among other entities.

SOURCE: Han X et al. Chest. 2018 May 24. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.03.025.

FROM CHEST

Key clinical point: Sepsis patients who have timely lactate measurements have lower mortality risk.

Major finding: Odds of death increased with each hour of delay (odds ratio, 1.02).

Study details: Retrospective study of 5,762 admissions meeting Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock Early Management Bundle (SEP-1) criteria for severe sepsis.

Disclosures: The study authors reported disclosures related to Philips Healthcare, Laerdal Medical, and Quant HC, among other entities.

Source: Han X et al. Chest. 2018 May 24. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.03.025.

Skip the catheter-directed thrombolytics

Background: Nearly half of all patients with proximal deep vein thrombosis (DVT) will develop postthrombotic syndrome at 2 years. Small trials have shown that the combination of catheter-directed delivery of thrombolytics, along with active mechanical clot removal, may prevent the postthrombotic syndrome.

Study design: Randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: Fifty-six clinical centers throughout the United States.

Synopsis: A total of 692 patients with symptomatic proximal DVT were randomized to receive either pharmacomechanical thrombolysis followed by anticoagulation or solely anticoagulation consistent with published guidelines. The primary outcome measured was the development of postthrombotic syndrome between 6 and 24 months. Over the 24 months that these patients were followed, 157 of 336 patients (47%) in the pharmacomechanical thrombolysis group and 171 of 355 patients (48%) in the control group developed postthrombotic syndrome (risk ratio, 0.96; 95% confidence interval, 0.82-1.11; P = .56). This result was consistent across predetermined subgroups.

Importantly, major bleeding within 10 days was more frequent in the pharmacomechanical thrombolysis group occurring in 6 of 336 patients (1.7%) versus 1 of 335 patients (0.3%) in the control group (P = .049). There was no significant difference in either recurrent venous thromboembolism at 24 months (12% in treatment group vs. 8% in control; P = .09) or deaths.

Of the 80 patients that did not present for follow-up postthrombotic syndrome assessments, two-thirds were in the control group, potentially leading to an underestimation of the effect of the intervention.

Bottom line: Pharmacomechanical catheter-directed thrombolysis does not reduce postthrombotic syndrome in proximal DVT and leads to an increased risk of major bleeding.

Citation: Vedantham S et al. Pharmacomechanical catheter-directed thrombolysis for deep-vein thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2017 Dec 7;377(23):2240-52.

Dr. Scaletta is a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Background: Nearly half of all patients with proximal deep vein thrombosis (DVT) will develop postthrombotic syndrome at 2 years. Small trials have shown that the combination of catheter-directed delivery of thrombolytics, along with active mechanical clot removal, may prevent the postthrombotic syndrome.

Study design: Randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: Fifty-six clinical centers throughout the United States.

Synopsis: A total of 692 patients with symptomatic proximal DVT were randomized to receive either pharmacomechanical thrombolysis followed by anticoagulation or solely anticoagulation consistent with published guidelines. The primary outcome measured was the development of postthrombotic syndrome between 6 and 24 months. Over the 24 months that these patients were followed, 157 of 336 patients (47%) in the pharmacomechanical thrombolysis group and 171 of 355 patients (48%) in the control group developed postthrombotic syndrome (risk ratio, 0.96; 95% confidence interval, 0.82-1.11; P = .56). This result was consistent across predetermined subgroups.

Importantly, major bleeding within 10 days was more frequent in the pharmacomechanical thrombolysis group occurring in 6 of 336 patients (1.7%) versus 1 of 335 patients (0.3%) in the control group (P = .049). There was no significant difference in either recurrent venous thromboembolism at 24 months (12% in treatment group vs. 8% in control; P = .09) or deaths.

Of the 80 patients that did not present for follow-up postthrombotic syndrome assessments, two-thirds were in the control group, potentially leading to an underestimation of the effect of the intervention.

Bottom line: Pharmacomechanical catheter-directed thrombolysis does not reduce postthrombotic syndrome in proximal DVT and leads to an increased risk of major bleeding.

Citation: Vedantham S et al. Pharmacomechanical catheter-directed thrombolysis for deep-vein thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2017 Dec 7;377(23):2240-52.

Dr. Scaletta is a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Background: Nearly half of all patients with proximal deep vein thrombosis (DVT) will develop postthrombotic syndrome at 2 years. Small trials have shown that the combination of catheter-directed delivery of thrombolytics, along with active mechanical clot removal, may prevent the postthrombotic syndrome.

Study design: Randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: Fifty-six clinical centers throughout the United States.

Synopsis: A total of 692 patients with symptomatic proximal DVT were randomized to receive either pharmacomechanical thrombolysis followed by anticoagulation or solely anticoagulation consistent with published guidelines. The primary outcome measured was the development of postthrombotic syndrome between 6 and 24 months. Over the 24 months that these patients were followed, 157 of 336 patients (47%) in the pharmacomechanical thrombolysis group and 171 of 355 patients (48%) in the control group developed postthrombotic syndrome (risk ratio, 0.96; 95% confidence interval, 0.82-1.11; P = .56). This result was consistent across predetermined subgroups.