User login

In Case You Missed It: COVID

Long COVID’s grip will likely tighten as infections continue

COVID-19 is far from done in the United States, with more than 111,000 new cases being recorded a day in the second week of August, according to Johns Hopkins University, and 625 deaths being reported every day. , a condition that already has affected between 7.7 million and 23 million Americans, according to U.S. government estimates.

“It is evident that long COVID is real, that it already impacts a substantial number of people, and that this number may continue to grow as new infections occur,” the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) said in a research action plan released Aug. 4.

“We are heading towards a big problem on our hands,” says Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, chief of research and development at the Veterans Affairs Hospital in St. Louis. “It’s like if we are falling in a plane, hurtling towards the ground. It doesn’t matter at what speed we are falling; what matters is that we are all falling, and falling fast. It’s a real problem. We needed to bring attention to this, yesterday,” he said.

Bryan Lau, PhD, professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, and co-lead of a long COVID study there, says whether it’s 5% of the 92 million officially recorded U.S. COVID-19 cases, or 30% – on the higher end of estimates – that means anywhere between 4.5 million and 27 million Americans will have the effects of long COVID.

Other experts put the estimates even higher.

“If we conservatively assume 100 million working-age adults have been infected, that implies 10 to 33 million may have long COVID,” Alice Burns, PhD, associate director for the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured, wrote in an analysis.

And even the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says only a fraction of cases have been recorded.

That, in turn, means tens of millions of people who struggle to work, to get to school, and to take care of their families – and who will be making demands on an already stressed U.S. health care system.

The HHS said in its Aug. 4 report that long COVID could keep 1 million people a day out of work, with a loss of $50 billion in annual pay.

Dr. Lau said health workers and policymakers are woefully unprepared.

“If you have a family unit, and the mom or dad can’t work, or has trouble taking their child to activities, where does the question of support come into play? Where is there potential for food issues, or housing issues?” he asked. “I see the potential for the burden to be extremely large in that capacity.”

Dr. Lau said he has yet to see any strong estimates of how many cases of long COVID might develop. Because a person has to get COVID-19 to ultimately get long COVID, the two are linked. In other words, as COVID-19 cases rise, so will cases of long COVID, and vice versa.

Evidence from the Kaiser Family Foundation analysis suggests a significant impact on employment: Surveys showed more than half of adults with long COVID who worked before becoming infected are either out of work or working fewer hours. Conditions associated with long COVID – such as fatigue, malaise, or problems concentrating – limit people’s ability to work, even if they have jobs that allow for accommodations.

Two surveys of people with long COVID who had worked before becoming infected showed that between 22% and 27% of them were out of work after getting long COVID. In comparison, among all working-age adults in 2019, only 7% were out of work. Given the sheer number of working-age adults with long COVID, the effects on employment may be profound and are likely to involve more people over time. One study estimates that long COVID already accounts for 15% of unfilled jobs.

The most severe symptoms of long COVID include brain fog and heart complications, known to persist for weeks for months after a COVID-19 infection.

A study from the University of Norway published in Open Forum Infectious Diseases found 53% of people tested had at least one symptom of thinking problems 13 months after infection with COVID-19. According to the HHS’ latest report on long COVID, people with thinking problems, heart conditions, mobility issues, and other symptoms are going to need a considerable amount of care. Many will need lengthy periods of rehabilitation.

Dr. Al-Aly worries that long COVID has already severely affected the labor force and the job market, all while burdening the country’s health care system.

“While there are variations in how individuals respond and cope with long COVID, the unifying thread is that with the level of disability it causes, more people will be struggling to keep up with the demands of the workforce and more people will be out on disability than ever before,” he said.

Studies from Johns Hopkins and the University of Washington estimate that 5%-30% of people could get long COVID in the future. Projections beyond that are hazy.

“So far, all the studies we have done on long COVID have been reactionary. Much of the activism around long COVID has been patient led. We are seeing more and more people with lasting symptoms. We need our research to catch up,” Dr. Lau said.

Theo Vos, MD, PhD, professor of health sciences at University of Washington, Seattle, said the main reasons for the huge range of predictions are the variety of methods used, as well as differences in sample size. Also, much long COVID data is self-reported, making it difficult for epidemiologists to track.

“With self-reported data, you can’t plug people into a machine and say this is what they have or this is what they don’t have. At the population level, the only thing you can do is ask questions. There is no systematic way to define long COVID,” he said.

Dr. Vos’s most recent study, which is being peer-reviewed and revised, found that most people with long COVID have symptoms similar to those seen in other autoimmune diseases. But sometimes the immune system can overreact, causing the more severe symptoms, such as brain fog and heart problems, associated with long COVID.

One reason that researchers struggle to come up with numbers, said Dr. Al-Aly, is the rapid rise of new variants. These variants appear to sometimes cause less severe disease than previous ones, but it’s not clear whether that means different risks for long COVID.

“There’s a wide diversity in severity. Someone can have long COVID and be fully functional, while others are not functional at all. We still have a long way to go before we figure out why,” Dr. Lau said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

COVID-19 is far from done in the United States, with more than 111,000 new cases being recorded a day in the second week of August, according to Johns Hopkins University, and 625 deaths being reported every day. , a condition that already has affected between 7.7 million and 23 million Americans, according to U.S. government estimates.

“It is evident that long COVID is real, that it already impacts a substantial number of people, and that this number may continue to grow as new infections occur,” the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) said in a research action plan released Aug. 4.

“We are heading towards a big problem on our hands,” says Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, chief of research and development at the Veterans Affairs Hospital in St. Louis. “It’s like if we are falling in a plane, hurtling towards the ground. It doesn’t matter at what speed we are falling; what matters is that we are all falling, and falling fast. It’s a real problem. We needed to bring attention to this, yesterday,” he said.

Bryan Lau, PhD, professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, and co-lead of a long COVID study there, says whether it’s 5% of the 92 million officially recorded U.S. COVID-19 cases, or 30% – on the higher end of estimates – that means anywhere between 4.5 million and 27 million Americans will have the effects of long COVID.

Other experts put the estimates even higher.

“If we conservatively assume 100 million working-age adults have been infected, that implies 10 to 33 million may have long COVID,” Alice Burns, PhD, associate director for the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured, wrote in an analysis.

And even the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says only a fraction of cases have been recorded.

That, in turn, means tens of millions of people who struggle to work, to get to school, and to take care of their families – and who will be making demands on an already stressed U.S. health care system.

The HHS said in its Aug. 4 report that long COVID could keep 1 million people a day out of work, with a loss of $50 billion in annual pay.

Dr. Lau said health workers and policymakers are woefully unprepared.

“If you have a family unit, and the mom or dad can’t work, or has trouble taking their child to activities, where does the question of support come into play? Where is there potential for food issues, or housing issues?” he asked. “I see the potential for the burden to be extremely large in that capacity.”

Dr. Lau said he has yet to see any strong estimates of how many cases of long COVID might develop. Because a person has to get COVID-19 to ultimately get long COVID, the two are linked. In other words, as COVID-19 cases rise, so will cases of long COVID, and vice versa.

Evidence from the Kaiser Family Foundation analysis suggests a significant impact on employment: Surveys showed more than half of adults with long COVID who worked before becoming infected are either out of work or working fewer hours. Conditions associated with long COVID – such as fatigue, malaise, or problems concentrating – limit people’s ability to work, even if they have jobs that allow for accommodations.

Two surveys of people with long COVID who had worked before becoming infected showed that between 22% and 27% of them were out of work after getting long COVID. In comparison, among all working-age adults in 2019, only 7% were out of work. Given the sheer number of working-age adults with long COVID, the effects on employment may be profound and are likely to involve more people over time. One study estimates that long COVID already accounts for 15% of unfilled jobs.

The most severe symptoms of long COVID include brain fog and heart complications, known to persist for weeks for months after a COVID-19 infection.

A study from the University of Norway published in Open Forum Infectious Diseases found 53% of people tested had at least one symptom of thinking problems 13 months after infection with COVID-19. According to the HHS’ latest report on long COVID, people with thinking problems, heart conditions, mobility issues, and other symptoms are going to need a considerable amount of care. Many will need lengthy periods of rehabilitation.

Dr. Al-Aly worries that long COVID has already severely affected the labor force and the job market, all while burdening the country’s health care system.

“While there are variations in how individuals respond and cope with long COVID, the unifying thread is that with the level of disability it causes, more people will be struggling to keep up with the demands of the workforce and more people will be out on disability than ever before,” he said.

Studies from Johns Hopkins and the University of Washington estimate that 5%-30% of people could get long COVID in the future. Projections beyond that are hazy.

“So far, all the studies we have done on long COVID have been reactionary. Much of the activism around long COVID has been patient led. We are seeing more and more people with lasting symptoms. We need our research to catch up,” Dr. Lau said.

Theo Vos, MD, PhD, professor of health sciences at University of Washington, Seattle, said the main reasons for the huge range of predictions are the variety of methods used, as well as differences in sample size. Also, much long COVID data is self-reported, making it difficult for epidemiologists to track.

“With self-reported data, you can’t plug people into a machine and say this is what they have or this is what they don’t have. At the population level, the only thing you can do is ask questions. There is no systematic way to define long COVID,” he said.

Dr. Vos’s most recent study, which is being peer-reviewed and revised, found that most people with long COVID have symptoms similar to those seen in other autoimmune diseases. But sometimes the immune system can overreact, causing the more severe symptoms, such as brain fog and heart problems, associated with long COVID.

One reason that researchers struggle to come up with numbers, said Dr. Al-Aly, is the rapid rise of new variants. These variants appear to sometimes cause less severe disease than previous ones, but it’s not clear whether that means different risks for long COVID.

“There’s a wide diversity in severity. Someone can have long COVID and be fully functional, while others are not functional at all. We still have a long way to go before we figure out why,” Dr. Lau said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

COVID-19 is far from done in the United States, with more than 111,000 new cases being recorded a day in the second week of August, according to Johns Hopkins University, and 625 deaths being reported every day. , a condition that already has affected between 7.7 million and 23 million Americans, according to U.S. government estimates.

“It is evident that long COVID is real, that it already impacts a substantial number of people, and that this number may continue to grow as new infections occur,” the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) said in a research action plan released Aug. 4.

“We are heading towards a big problem on our hands,” says Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, chief of research and development at the Veterans Affairs Hospital in St. Louis. “It’s like if we are falling in a plane, hurtling towards the ground. It doesn’t matter at what speed we are falling; what matters is that we are all falling, and falling fast. It’s a real problem. We needed to bring attention to this, yesterday,” he said.

Bryan Lau, PhD, professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, and co-lead of a long COVID study there, says whether it’s 5% of the 92 million officially recorded U.S. COVID-19 cases, or 30% – on the higher end of estimates – that means anywhere between 4.5 million and 27 million Americans will have the effects of long COVID.

Other experts put the estimates even higher.

“If we conservatively assume 100 million working-age adults have been infected, that implies 10 to 33 million may have long COVID,” Alice Burns, PhD, associate director for the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured, wrote in an analysis.

And even the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says only a fraction of cases have been recorded.

That, in turn, means tens of millions of people who struggle to work, to get to school, and to take care of their families – and who will be making demands on an already stressed U.S. health care system.

The HHS said in its Aug. 4 report that long COVID could keep 1 million people a day out of work, with a loss of $50 billion in annual pay.

Dr. Lau said health workers and policymakers are woefully unprepared.

“If you have a family unit, and the mom or dad can’t work, or has trouble taking their child to activities, where does the question of support come into play? Where is there potential for food issues, or housing issues?” he asked. “I see the potential for the burden to be extremely large in that capacity.”

Dr. Lau said he has yet to see any strong estimates of how many cases of long COVID might develop. Because a person has to get COVID-19 to ultimately get long COVID, the two are linked. In other words, as COVID-19 cases rise, so will cases of long COVID, and vice versa.

Evidence from the Kaiser Family Foundation analysis suggests a significant impact on employment: Surveys showed more than half of adults with long COVID who worked before becoming infected are either out of work or working fewer hours. Conditions associated with long COVID – such as fatigue, malaise, or problems concentrating – limit people’s ability to work, even if they have jobs that allow for accommodations.

Two surveys of people with long COVID who had worked before becoming infected showed that between 22% and 27% of them were out of work after getting long COVID. In comparison, among all working-age adults in 2019, only 7% were out of work. Given the sheer number of working-age adults with long COVID, the effects on employment may be profound and are likely to involve more people over time. One study estimates that long COVID already accounts for 15% of unfilled jobs.

The most severe symptoms of long COVID include brain fog and heart complications, known to persist for weeks for months after a COVID-19 infection.

A study from the University of Norway published in Open Forum Infectious Diseases found 53% of people tested had at least one symptom of thinking problems 13 months after infection with COVID-19. According to the HHS’ latest report on long COVID, people with thinking problems, heart conditions, mobility issues, and other symptoms are going to need a considerable amount of care. Many will need lengthy periods of rehabilitation.

Dr. Al-Aly worries that long COVID has already severely affected the labor force and the job market, all while burdening the country’s health care system.

“While there are variations in how individuals respond and cope with long COVID, the unifying thread is that with the level of disability it causes, more people will be struggling to keep up with the demands of the workforce and more people will be out on disability than ever before,” he said.

Studies from Johns Hopkins and the University of Washington estimate that 5%-30% of people could get long COVID in the future. Projections beyond that are hazy.

“So far, all the studies we have done on long COVID have been reactionary. Much of the activism around long COVID has been patient led. We are seeing more and more people with lasting symptoms. We need our research to catch up,” Dr. Lau said.

Theo Vos, MD, PhD, professor of health sciences at University of Washington, Seattle, said the main reasons for the huge range of predictions are the variety of methods used, as well as differences in sample size. Also, much long COVID data is self-reported, making it difficult for epidemiologists to track.

“With self-reported data, you can’t plug people into a machine and say this is what they have or this is what they don’t have. At the population level, the only thing you can do is ask questions. There is no systematic way to define long COVID,” he said.

Dr. Vos’s most recent study, which is being peer-reviewed and revised, found that most people with long COVID have symptoms similar to those seen in other autoimmune diseases. But sometimes the immune system can overreact, causing the more severe symptoms, such as brain fog and heart problems, associated with long COVID.

One reason that researchers struggle to come up with numbers, said Dr. Al-Aly, is the rapid rise of new variants. These variants appear to sometimes cause less severe disease than previous ones, but it’s not clear whether that means different risks for long COVID.

“There’s a wide diversity in severity. Someone can have long COVID and be fully functional, while others are not functional at all. We still have a long way to go before we figure out why,” Dr. Lau said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Plasma biomarkers predict COVID’s neurological sequelae

SAN DIEGO – Even after recovery of an acute COVID-19 infection, some patients experience extended or even long-term symptoms that can range from mild to debilitating. Some of these symptoms are neurological: headaches, brain fog, cognitive impairment, loss of taste or smell, and even cerebrovascular complications such stroke. There are even hints that COVID-19 infection could lead to future neurodegeneration.

Those issues have prompted efforts to identify biomarkers that can help track and monitor neurological complications of COVID-19. “Throughout the course of the pandemic, it has become apparent that COVID-19 can cause various neurological symptoms. Because of this, ,” Jennifer Cooper said during a lecture at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. She presented new research suggesting that neurofilament light (NfL) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) may prove useful.

Ms. Cooper is a master’s degree student at the University of British Columbia and Canada.

Looking for sensitivity and specificity in plasma biomarkers

The researchers turned to plasma-based markers because they can reflect underlying pathology in the central nervous system. They focused on NfL, which reflects axonal damage, and GFAP, which is a marker of astrocyte activation.

The researchers analyzed data from 209 patients with COVID-19 who were admitted to the Vancouver (B.C.) General Hospital intensive care unit. Sixty-four percent were male, and the median age was 61 years. Sixty percent were ventilated, and 17% died.

The researchers determined if an individual patient’s biomarker level at hospital admission fell within a normal biomarker reference interval. A total of 53% had NfL levels outside the normal range, and 42% had GFAP levels outside the normal range. In addition, 31% of patients had both GFAP and NfL levels outside of the normal range.

Among all patients, 12% experienced ischemia, 4% hemorrhage, 2% seizures, and 10% degeneration.

At admission, NfL predicted a neurological complication with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.702. GFAP had an AUC of 0.722. In combination, they had an AUC of 0.743. At 1 week, NfL had an AUC of 0.802, GFAP an AUC of 0.733, and the combination an AUC of 0.812.

Using age-specific cutoff values, the researchers found increased risks for neurological complications at admission (NfL odds ratio [OR], 2.9; GFAP OR, 1.6; combined OR, 2.1) and at 1 week (NfL OR, not significant; GFAP OR, 4.8; combined OR, 6.6). “We can see that both NFL and GFAP have utility in detecting neurological complications. And combining both of our markers improves detection at both time points. NfL is a marker that provides more sensitivity, where in this cohort GFAP is a marker that provides a little bit more specificity,” said Ms. Cooper.

Will additional biomarkers help?

The researchers are continuing to follow up patients at 6 months and 18 months post diagnosis, using neuropsychiatric tests and additional biomarker analysis, as well as PET and MRI scans. The patient sample is being expanded to those in the general hospital ward and some who were not hospitalized.

During the Q&A session, Ms. Cooper was asked if the group had collected reference data from patients who were admitted to the ICU with non-COVID disease. She responded that the group has some of that data, but as the pandemic went on they had difficulty finding patients who had never been infected with COVID to serve as reliable controls. To date, they have identified 33 controls who had a respiratory condition when admitted to the ICU. “What we see is the neurological biomarker levels in COVID are slightly lower than those with another respiratory condition in the ICU. But the data has a massive spread and the significance is very small between the two groups,” said Ms. Cooper.

Unanswered questions

The study is interesting, but leaves a lot of unanswered questions, according to Wiesje van der Flier, PhD, who moderated the session where the study was presented. “There are a lot of unknowns still: Will [the biomarkers] become normal again, once the COVID is over? Also, there was an increased risk, but it was not a one-to-one correspondence, so you can also have the increased markers but not have the neurological signs or symptoms. So I thought there were lots of questions as well,” said Dr. van der Flier, professor of neurology at Amsterdam University Medical Center.

She noted that researchers at her institution in Amsterdam have observed similar relationships, and that the associations between neurological complications and plasma biomarkers over time will be an important topic of study.

The work could provide more information on neurological manifestations of long COVID, such as long-haul fatigue. “You might also think that’s some response in their brain. It would be great if we could actually capture that [using biomarkers],” said Dr. van der Flier.

Ms. Cooper and Dr. van der Flier have no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Even after recovery of an acute COVID-19 infection, some patients experience extended or even long-term symptoms that can range from mild to debilitating. Some of these symptoms are neurological: headaches, brain fog, cognitive impairment, loss of taste or smell, and even cerebrovascular complications such stroke. There are even hints that COVID-19 infection could lead to future neurodegeneration.

Those issues have prompted efforts to identify biomarkers that can help track and monitor neurological complications of COVID-19. “Throughout the course of the pandemic, it has become apparent that COVID-19 can cause various neurological symptoms. Because of this, ,” Jennifer Cooper said during a lecture at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. She presented new research suggesting that neurofilament light (NfL) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) may prove useful.

Ms. Cooper is a master’s degree student at the University of British Columbia and Canada.

Looking for sensitivity and specificity in plasma biomarkers

The researchers turned to plasma-based markers because they can reflect underlying pathology in the central nervous system. They focused on NfL, which reflects axonal damage, and GFAP, which is a marker of astrocyte activation.

The researchers analyzed data from 209 patients with COVID-19 who were admitted to the Vancouver (B.C.) General Hospital intensive care unit. Sixty-four percent were male, and the median age was 61 years. Sixty percent were ventilated, and 17% died.

The researchers determined if an individual patient’s biomarker level at hospital admission fell within a normal biomarker reference interval. A total of 53% had NfL levels outside the normal range, and 42% had GFAP levels outside the normal range. In addition, 31% of patients had both GFAP and NfL levels outside of the normal range.

Among all patients, 12% experienced ischemia, 4% hemorrhage, 2% seizures, and 10% degeneration.

At admission, NfL predicted a neurological complication with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.702. GFAP had an AUC of 0.722. In combination, they had an AUC of 0.743. At 1 week, NfL had an AUC of 0.802, GFAP an AUC of 0.733, and the combination an AUC of 0.812.

Using age-specific cutoff values, the researchers found increased risks for neurological complications at admission (NfL odds ratio [OR], 2.9; GFAP OR, 1.6; combined OR, 2.1) and at 1 week (NfL OR, not significant; GFAP OR, 4.8; combined OR, 6.6). “We can see that both NFL and GFAP have utility in detecting neurological complications. And combining both of our markers improves detection at both time points. NfL is a marker that provides more sensitivity, where in this cohort GFAP is a marker that provides a little bit more specificity,” said Ms. Cooper.

Will additional biomarkers help?

The researchers are continuing to follow up patients at 6 months and 18 months post diagnosis, using neuropsychiatric tests and additional biomarker analysis, as well as PET and MRI scans. The patient sample is being expanded to those in the general hospital ward and some who were not hospitalized.

During the Q&A session, Ms. Cooper was asked if the group had collected reference data from patients who were admitted to the ICU with non-COVID disease. She responded that the group has some of that data, but as the pandemic went on they had difficulty finding patients who had never been infected with COVID to serve as reliable controls. To date, they have identified 33 controls who had a respiratory condition when admitted to the ICU. “What we see is the neurological biomarker levels in COVID are slightly lower than those with another respiratory condition in the ICU. But the data has a massive spread and the significance is very small between the two groups,” said Ms. Cooper.

Unanswered questions

The study is interesting, but leaves a lot of unanswered questions, according to Wiesje van der Flier, PhD, who moderated the session where the study was presented. “There are a lot of unknowns still: Will [the biomarkers] become normal again, once the COVID is over? Also, there was an increased risk, but it was not a one-to-one correspondence, so you can also have the increased markers but not have the neurological signs or symptoms. So I thought there were lots of questions as well,” said Dr. van der Flier, professor of neurology at Amsterdam University Medical Center.

She noted that researchers at her institution in Amsterdam have observed similar relationships, and that the associations between neurological complications and plasma biomarkers over time will be an important topic of study.

The work could provide more information on neurological manifestations of long COVID, such as long-haul fatigue. “You might also think that’s some response in their brain. It would be great if we could actually capture that [using biomarkers],” said Dr. van der Flier.

Ms. Cooper and Dr. van der Flier have no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Even after recovery of an acute COVID-19 infection, some patients experience extended or even long-term symptoms that can range from mild to debilitating. Some of these symptoms are neurological: headaches, brain fog, cognitive impairment, loss of taste or smell, and even cerebrovascular complications such stroke. There are even hints that COVID-19 infection could lead to future neurodegeneration.

Those issues have prompted efforts to identify biomarkers that can help track and monitor neurological complications of COVID-19. “Throughout the course of the pandemic, it has become apparent that COVID-19 can cause various neurological symptoms. Because of this, ,” Jennifer Cooper said during a lecture at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. She presented new research suggesting that neurofilament light (NfL) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) may prove useful.

Ms. Cooper is a master’s degree student at the University of British Columbia and Canada.

Looking for sensitivity and specificity in plasma biomarkers

The researchers turned to plasma-based markers because they can reflect underlying pathology in the central nervous system. They focused on NfL, which reflects axonal damage, and GFAP, which is a marker of astrocyte activation.

The researchers analyzed data from 209 patients with COVID-19 who were admitted to the Vancouver (B.C.) General Hospital intensive care unit. Sixty-four percent were male, and the median age was 61 years. Sixty percent were ventilated, and 17% died.

The researchers determined if an individual patient’s biomarker level at hospital admission fell within a normal biomarker reference interval. A total of 53% had NfL levels outside the normal range, and 42% had GFAP levels outside the normal range. In addition, 31% of patients had both GFAP and NfL levels outside of the normal range.

Among all patients, 12% experienced ischemia, 4% hemorrhage, 2% seizures, and 10% degeneration.

At admission, NfL predicted a neurological complication with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.702. GFAP had an AUC of 0.722. In combination, they had an AUC of 0.743. At 1 week, NfL had an AUC of 0.802, GFAP an AUC of 0.733, and the combination an AUC of 0.812.

Using age-specific cutoff values, the researchers found increased risks for neurological complications at admission (NfL odds ratio [OR], 2.9; GFAP OR, 1.6; combined OR, 2.1) and at 1 week (NfL OR, not significant; GFAP OR, 4.8; combined OR, 6.6). “We can see that both NFL and GFAP have utility in detecting neurological complications. And combining both of our markers improves detection at both time points. NfL is a marker that provides more sensitivity, where in this cohort GFAP is a marker that provides a little bit more specificity,” said Ms. Cooper.

Will additional biomarkers help?

The researchers are continuing to follow up patients at 6 months and 18 months post diagnosis, using neuropsychiatric tests and additional biomarker analysis, as well as PET and MRI scans. The patient sample is being expanded to those in the general hospital ward and some who were not hospitalized.

During the Q&A session, Ms. Cooper was asked if the group had collected reference data from patients who were admitted to the ICU with non-COVID disease. She responded that the group has some of that data, but as the pandemic went on they had difficulty finding patients who had never been infected with COVID to serve as reliable controls. To date, they have identified 33 controls who had a respiratory condition when admitted to the ICU. “What we see is the neurological biomarker levels in COVID are slightly lower than those with another respiratory condition in the ICU. But the data has a massive spread and the significance is very small between the two groups,” said Ms. Cooper.

Unanswered questions

The study is interesting, but leaves a lot of unanswered questions, according to Wiesje van der Flier, PhD, who moderated the session where the study was presented. “There are a lot of unknowns still: Will [the biomarkers] become normal again, once the COVID is over? Also, there was an increased risk, but it was not a one-to-one correspondence, so you can also have the increased markers but not have the neurological signs or symptoms. So I thought there were lots of questions as well,” said Dr. van der Flier, professor of neurology at Amsterdam University Medical Center.

She noted that researchers at her institution in Amsterdam have observed similar relationships, and that the associations between neurological complications and plasma biomarkers over time will be an important topic of study.

The work could provide more information on neurological manifestations of long COVID, such as long-haul fatigue. “You might also think that’s some response in their brain. It would be great if we could actually capture that [using biomarkers],” said Dr. van der Flier.

Ms. Cooper and Dr. van der Flier have no relevant financial disclosures.

AT AAIC 2022

Guidance From the National Psoriasis Foundation COVID-19 Task Force

When COVID-19 emerged in March 2020, physicians were forced to evaluate the potential impacts of the pandemic on our patients and the conditions that we treat. For dermatologists, psoriasis came into particular focus, as many patients were being treated with biologic therapies. The initial concern was that these biologics might render our patients more susceptible to both COVID-19 infection and/or a more severe disease course.

In early 2020, the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) presented its own recommendations for treating patients with psoriatic disease during the pandemic.1 Some highlights included the following1:

• At the time, it was stipulated that patients with COVID-19 infection should stop taking a biologic.

• Psoriasis patients in high-risk groups (eg, concomitant systemic disease) should discuss with their dermatologist if their therapeutic regimen should be continued or altered.

• Patients taking oral immunosuppressive therapy may be at greater risk for COVID-19 infection, though there is no strong COVID-19–related evidence to provide specific guidelines or risk level.

In May 2020, the NPF COVID-19 Task Force was formed. This group—chaired by dermatologist Joel M. Gelfand, MD, MSCE (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), and rheumatologist Christopher T. Ritchlin, MD, MPH (Rochester, New York)—was comprised of members from both the NPF Medical Board and Scientific Advisory Committee in dermatology, rheumatology, infectious disease, and critical care. The NPF COVID-19 Task Force has been critical in keeping the dermatology community apprised of the latest scientific thinking related to COVID-19 and publishing guidance statements that are updated and amended on a regular basis as new data becomes available.2 Key recommendations most relevant to the daily care of patients with psoriatic disease included the following2:

• Patients with psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis have similar rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 outcomes as the general population based on existing data, with some exceptions.

• Therapies for psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis do not meaningfully alter the risk for acquiring SARS-CoV-2 infection or having worse COVID-19 outcomes.

• Patients should continue their biologic or oral therapies for psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis in most cases, unless they become infected with SARS-CoV-2.

• Chronic systemic steroid use for psoriatic disease in the setting of acute infection with COVID-19 may be associated with worse outcomes; however, steroids may improve outcomes for COVID-19 when initiated in hospitalized patients who require oxygen therapy.

• When local restrictions or pandemic conditions limit the ability for in-person visits, offer telemedicine to manage patients.

• Patients with psoriatic disease who do not have contraindications to vaccination should receive a messenger RNA (mRNA)–based COVID-19 vaccine and boosters, based on federal, state, and local guidance. Systemic medications for psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis are not a contraindication to the mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine.

• Patients who are to receive an mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine should continue their biologic or oral therapies for psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis in most cases.

• The use of hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, and ivermectin is not suggested for the prevention or treatment of COVID-19 disease.

These guidelines have been critical in addressing some of the most pressing issues in psoriasis patient care, particularly the susceptibility to COVID-19, the role of psoriasis therapies in initial infection and health outcomes, and issues related to the administration of vaccines in those on systemic therapies. Based on these recommendations, we have been given a solid foundation that our current standard of care can (for the most part) continue with the continued presence of COVID-19 in our society. I encourage all providers to familiarize themselves with the NPF COVID-19 Task Force guidelines and keep abreast of updates as they become available (https://www.psoriasis.org/covid-19-task-force-guidance-statements/).

- Gelfand JM, Armstrong AW, Bell S, et al. National Psoriasis Foundation COVID-19 Task Force guidance for management of psoriatic disease during the pandemic: version 1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1704-1716.

- COVID-19 Task Force guidance statements. National Psoriasis Foundation website. Updated April 28, 2022. Accessed July 12, 2022. https://www.psoriasis.org/covid-19-task-force-guidance-statements/

When COVID-19 emerged in March 2020, physicians were forced to evaluate the potential impacts of the pandemic on our patients and the conditions that we treat. For dermatologists, psoriasis came into particular focus, as many patients were being treated with biologic therapies. The initial concern was that these biologics might render our patients more susceptible to both COVID-19 infection and/or a more severe disease course.

In early 2020, the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) presented its own recommendations for treating patients with psoriatic disease during the pandemic.1 Some highlights included the following1:

• At the time, it was stipulated that patients with COVID-19 infection should stop taking a biologic.

• Psoriasis patients in high-risk groups (eg, concomitant systemic disease) should discuss with their dermatologist if their therapeutic regimen should be continued or altered.

• Patients taking oral immunosuppressive therapy may be at greater risk for COVID-19 infection, though there is no strong COVID-19–related evidence to provide specific guidelines or risk level.

In May 2020, the NPF COVID-19 Task Force was formed. This group—chaired by dermatologist Joel M. Gelfand, MD, MSCE (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), and rheumatologist Christopher T. Ritchlin, MD, MPH (Rochester, New York)—was comprised of members from both the NPF Medical Board and Scientific Advisory Committee in dermatology, rheumatology, infectious disease, and critical care. The NPF COVID-19 Task Force has been critical in keeping the dermatology community apprised of the latest scientific thinking related to COVID-19 and publishing guidance statements that are updated and amended on a regular basis as new data becomes available.2 Key recommendations most relevant to the daily care of patients with psoriatic disease included the following2:

• Patients with psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis have similar rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 outcomes as the general population based on existing data, with some exceptions.

• Therapies for psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis do not meaningfully alter the risk for acquiring SARS-CoV-2 infection or having worse COVID-19 outcomes.

• Patients should continue their biologic or oral therapies for psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis in most cases, unless they become infected with SARS-CoV-2.

• Chronic systemic steroid use for psoriatic disease in the setting of acute infection with COVID-19 may be associated with worse outcomes; however, steroids may improve outcomes for COVID-19 when initiated in hospitalized patients who require oxygen therapy.

• When local restrictions or pandemic conditions limit the ability for in-person visits, offer telemedicine to manage patients.

• Patients with psoriatic disease who do not have contraindications to vaccination should receive a messenger RNA (mRNA)–based COVID-19 vaccine and boosters, based on federal, state, and local guidance. Systemic medications for psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis are not a contraindication to the mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine.

• Patients who are to receive an mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine should continue their biologic or oral therapies for psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis in most cases.

• The use of hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, and ivermectin is not suggested for the prevention or treatment of COVID-19 disease.

These guidelines have been critical in addressing some of the most pressing issues in psoriasis patient care, particularly the susceptibility to COVID-19, the role of psoriasis therapies in initial infection and health outcomes, and issues related to the administration of vaccines in those on systemic therapies. Based on these recommendations, we have been given a solid foundation that our current standard of care can (for the most part) continue with the continued presence of COVID-19 in our society. I encourage all providers to familiarize themselves with the NPF COVID-19 Task Force guidelines and keep abreast of updates as they become available (https://www.psoriasis.org/covid-19-task-force-guidance-statements/).

When COVID-19 emerged in March 2020, physicians were forced to evaluate the potential impacts of the pandemic on our patients and the conditions that we treat. For dermatologists, psoriasis came into particular focus, as many patients were being treated with biologic therapies. The initial concern was that these biologics might render our patients more susceptible to both COVID-19 infection and/or a more severe disease course.

In early 2020, the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) presented its own recommendations for treating patients with psoriatic disease during the pandemic.1 Some highlights included the following1:

• At the time, it was stipulated that patients with COVID-19 infection should stop taking a biologic.

• Psoriasis patients in high-risk groups (eg, concomitant systemic disease) should discuss with their dermatologist if their therapeutic regimen should be continued or altered.

• Patients taking oral immunosuppressive therapy may be at greater risk for COVID-19 infection, though there is no strong COVID-19–related evidence to provide specific guidelines or risk level.

In May 2020, the NPF COVID-19 Task Force was formed. This group—chaired by dermatologist Joel M. Gelfand, MD, MSCE (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), and rheumatologist Christopher T. Ritchlin, MD, MPH (Rochester, New York)—was comprised of members from both the NPF Medical Board and Scientific Advisory Committee in dermatology, rheumatology, infectious disease, and critical care. The NPF COVID-19 Task Force has been critical in keeping the dermatology community apprised of the latest scientific thinking related to COVID-19 and publishing guidance statements that are updated and amended on a regular basis as new data becomes available.2 Key recommendations most relevant to the daily care of patients with psoriatic disease included the following2:

• Patients with psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis have similar rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 outcomes as the general population based on existing data, with some exceptions.

• Therapies for psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis do not meaningfully alter the risk for acquiring SARS-CoV-2 infection or having worse COVID-19 outcomes.

• Patients should continue their biologic or oral therapies for psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis in most cases, unless they become infected with SARS-CoV-2.

• Chronic systemic steroid use for psoriatic disease in the setting of acute infection with COVID-19 may be associated with worse outcomes; however, steroids may improve outcomes for COVID-19 when initiated in hospitalized patients who require oxygen therapy.

• When local restrictions or pandemic conditions limit the ability for in-person visits, offer telemedicine to manage patients.

• Patients with psoriatic disease who do not have contraindications to vaccination should receive a messenger RNA (mRNA)–based COVID-19 vaccine and boosters, based on federal, state, and local guidance. Systemic medications for psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis are not a contraindication to the mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine.

• Patients who are to receive an mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine should continue their biologic or oral therapies for psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis in most cases.

• The use of hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, and ivermectin is not suggested for the prevention or treatment of COVID-19 disease.

These guidelines have been critical in addressing some of the most pressing issues in psoriasis patient care, particularly the susceptibility to COVID-19, the role of psoriasis therapies in initial infection and health outcomes, and issues related to the administration of vaccines in those on systemic therapies. Based on these recommendations, we have been given a solid foundation that our current standard of care can (for the most part) continue with the continued presence of COVID-19 in our society. I encourage all providers to familiarize themselves with the NPF COVID-19 Task Force guidelines and keep abreast of updates as they become available (https://www.psoriasis.org/covid-19-task-force-guidance-statements/).

- Gelfand JM, Armstrong AW, Bell S, et al. National Psoriasis Foundation COVID-19 Task Force guidance for management of psoriatic disease during the pandemic: version 1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1704-1716.

- COVID-19 Task Force guidance statements. National Psoriasis Foundation website. Updated April 28, 2022. Accessed July 12, 2022. https://www.psoriasis.org/covid-19-task-force-guidance-statements/

- Gelfand JM, Armstrong AW, Bell S, et al. National Psoriasis Foundation COVID-19 Task Force guidance for management of psoriatic disease during the pandemic: version 1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1704-1716.

- COVID-19 Task Force guidance statements. National Psoriasis Foundation website. Updated April 28, 2022. Accessed July 12, 2022. https://www.psoriasis.org/covid-19-task-force-guidance-statements/

Children and COVID: Severe illness rising as vaccination effort stalls

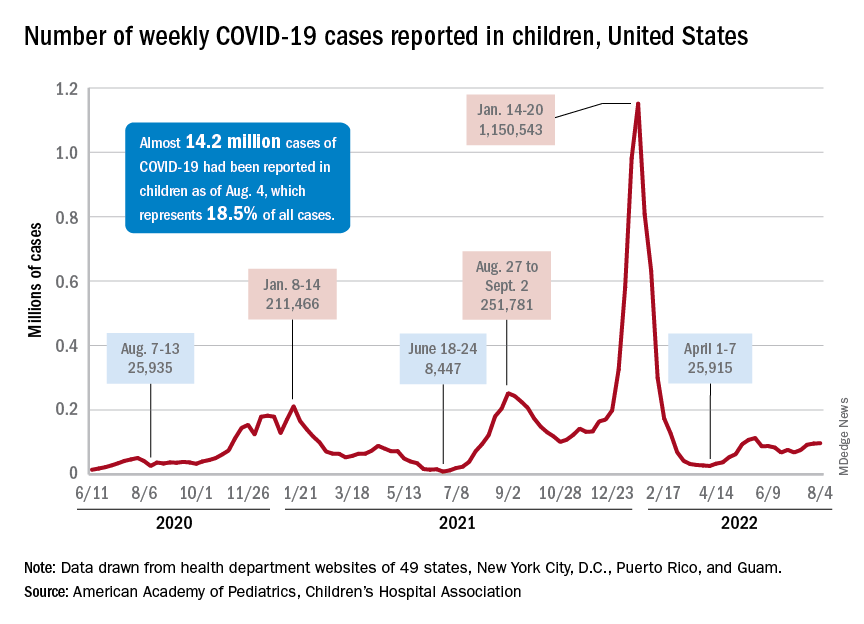

, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

After new child cases jumped by 22% during the week of July 15-21, the two successive weeks have produced increases of 3.9% (July 22-29) and 1.2% (July 30-Aug. 4). The latest weekly count from all states and territories still reporting was 96,599, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report, noting that several states have stopped reporting child cases and that others are reporting every other week.

The deceleration in new cases, however, does not apply to emergency department visits and hospital admissions. The proportion of ED visits with diagnosed COVID rose steadily throughout June and July, as 7-day averages went from 2.6% on June 1 to 6.3% on July 31 for children aged 0-11 years, from 2.1% to 3.1% for children aged 12-15, and from 2.4% to 3.5% for 16- to 17-year-olds, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The rate of new admissions with confirmed COVID, which reached 0.46 per 100,000 population for children aged 0-17 years on July 30, has more than tripled since early April, when it had fallen to 0.13 per 100,000 in the wake of the Omicron surge, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

A smaller but more detailed sample of children from the COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization Network (COVID-NET), which covers nearly 100 counties in 14 states, indicates that the increase in new admissions is occurring almost entirely among children aged 0-4 years, who had a rate of 5.6 per 100,000 for the week of July 17-23, compared with 0.8 per 100,000 for 5- to 11-year-olds and 1.5 per 100,000 for those aged 12-17, the CDC said.

Vaccine’s summer rollout gets lukewarm reception

As a group, children aged 0-4 years have not exactly flocked to the COVID-19 vaccine. As of Aug. 2 – about 6 weeks since the vaccine was authorized for children aged 6 months to 4 years – just 3.8% of those eligible had received at least one dose. Among children aged 5-11 the corresponding number on Aug. 2 was 37.4%, and for those aged 12-17 years it was 70.3%, the CDC data show.

That 3.8% of children aged less than 5 years represents almost 756,000 initial doses. That compares with over 6 million children aged 5-11 years who had received at least one dose through the first 6 weeks of their vaccination experience and over 5 million children aged 12-15, according to the COVID Data Tracker.

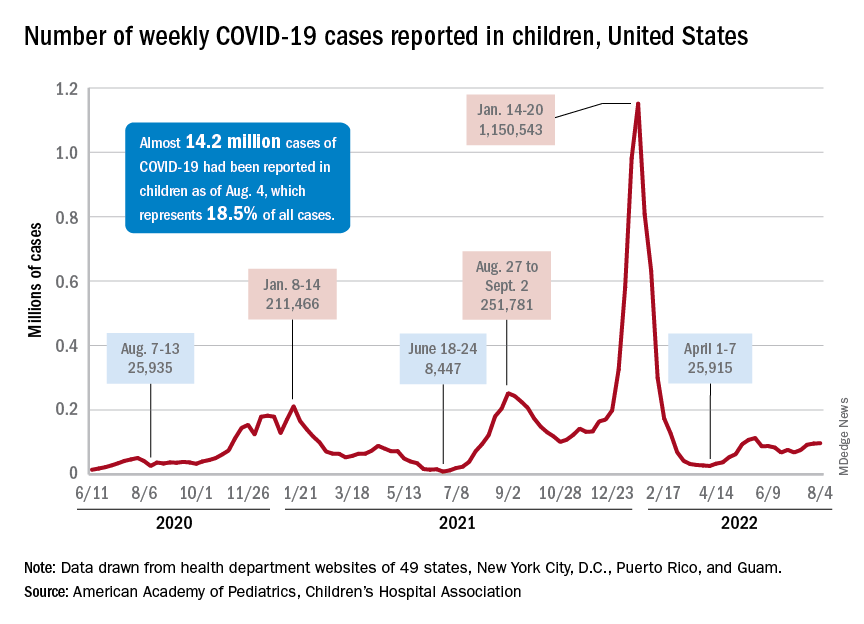

, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

After new child cases jumped by 22% during the week of July 15-21, the two successive weeks have produced increases of 3.9% (July 22-29) and 1.2% (July 30-Aug. 4). The latest weekly count from all states and territories still reporting was 96,599, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report, noting that several states have stopped reporting child cases and that others are reporting every other week.

The deceleration in new cases, however, does not apply to emergency department visits and hospital admissions. The proportion of ED visits with diagnosed COVID rose steadily throughout June and July, as 7-day averages went from 2.6% on June 1 to 6.3% on July 31 for children aged 0-11 years, from 2.1% to 3.1% for children aged 12-15, and from 2.4% to 3.5% for 16- to 17-year-olds, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The rate of new admissions with confirmed COVID, which reached 0.46 per 100,000 population for children aged 0-17 years on July 30, has more than tripled since early April, when it had fallen to 0.13 per 100,000 in the wake of the Omicron surge, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

A smaller but more detailed sample of children from the COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization Network (COVID-NET), which covers nearly 100 counties in 14 states, indicates that the increase in new admissions is occurring almost entirely among children aged 0-4 years, who had a rate of 5.6 per 100,000 for the week of July 17-23, compared with 0.8 per 100,000 for 5- to 11-year-olds and 1.5 per 100,000 for those aged 12-17, the CDC said.

Vaccine’s summer rollout gets lukewarm reception

As a group, children aged 0-4 years have not exactly flocked to the COVID-19 vaccine. As of Aug. 2 – about 6 weeks since the vaccine was authorized for children aged 6 months to 4 years – just 3.8% of those eligible had received at least one dose. Among children aged 5-11 the corresponding number on Aug. 2 was 37.4%, and for those aged 12-17 years it was 70.3%, the CDC data show.

That 3.8% of children aged less than 5 years represents almost 756,000 initial doses. That compares with over 6 million children aged 5-11 years who had received at least one dose through the first 6 weeks of their vaccination experience and over 5 million children aged 12-15, according to the COVID Data Tracker.

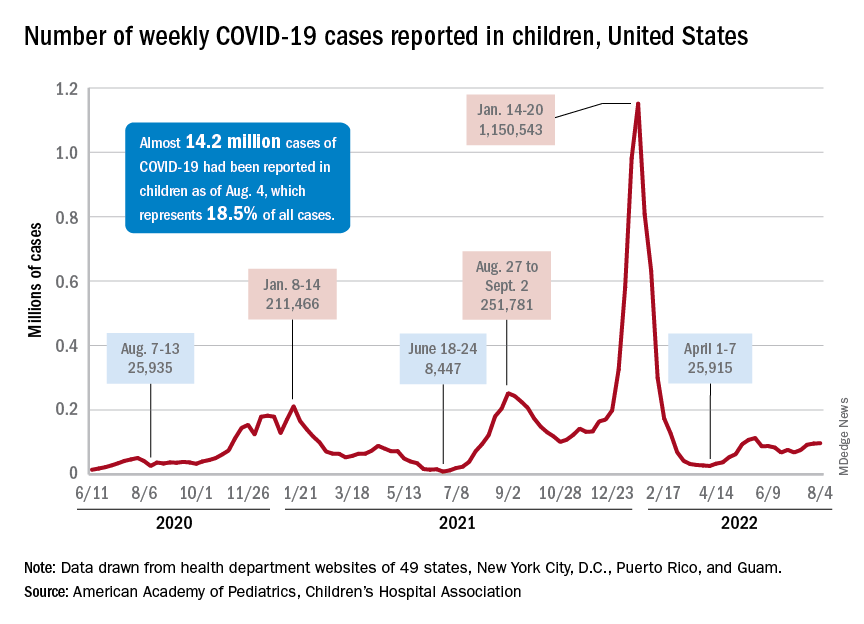

, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

After new child cases jumped by 22% during the week of July 15-21, the two successive weeks have produced increases of 3.9% (July 22-29) and 1.2% (July 30-Aug. 4). The latest weekly count from all states and territories still reporting was 96,599, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report, noting that several states have stopped reporting child cases and that others are reporting every other week.

The deceleration in new cases, however, does not apply to emergency department visits and hospital admissions. The proportion of ED visits with diagnosed COVID rose steadily throughout June and July, as 7-day averages went from 2.6% on June 1 to 6.3% on July 31 for children aged 0-11 years, from 2.1% to 3.1% for children aged 12-15, and from 2.4% to 3.5% for 16- to 17-year-olds, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The rate of new admissions with confirmed COVID, which reached 0.46 per 100,000 population for children aged 0-17 years on July 30, has more than tripled since early April, when it had fallen to 0.13 per 100,000 in the wake of the Omicron surge, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

A smaller but more detailed sample of children from the COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization Network (COVID-NET), which covers nearly 100 counties in 14 states, indicates that the increase in new admissions is occurring almost entirely among children aged 0-4 years, who had a rate of 5.6 per 100,000 for the week of July 17-23, compared with 0.8 per 100,000 for 5- to 11-year-olds and 1.5 per 100,000 for those aged 12-17, the CDC said.

Vaccine’s summer rollout gets lukewarm reception

As a group, children aged 0-4 years have not exactly flocked to the COVID-19 vaccine. As of Aug. 2 – about 6 weeks since the vaccine was authorized for children aged 6 months to 4 years – just 3.8% of those eligible had received at least one dose. Among children aged 5-11 the corresponding number on Aug. 2 was 37.4%, and for those aged 12-17 years it was 70.3%, the CDC data show.

That 3.8% of children aged less than 5 years represents almost 756,000 initial doses. That compares with over 6 million children aged 5-11 years who had received at least one dose through the first 6 weeks of their vaccination experience and over 5 million children aged 12-15, according to the COVID Data Tracker.

Updates on treatment/prevention of VTE in cancer patients

Updated clinical practice guidelines for the treatment and prevention of venous thromboembolism for patients with cancer, including those with cancer and COVID-19, have been released by the International Initiative on Thrombosis and Cancer (ITAC), an academic working group of VTE experts.

“Because patients with cancer have a baseline increased risk of VTE, compared with patients without cancer, the combination of both COVID-19 and cancer – and its effect on VTE risk and treatment – is of concern,” said the authors, led by Dominique Farge, MD, PhD, Nord Universite de Paris.

they added.

The new guidelines were published online in The Lancet Oncology.

“Cancer-associated VTE remains an important clinical problem, associated with increased morbidity and mortality,” Dr. Farge and colleagues observed.

“The ITAC guidelines’ companion free web-based mobile application will assist the practicing clinician with decision making at various levels to provide optimal care of patients with cancer to treat and prevent VTE,” they emphasized. More information is available at itaccme.com.

Cancer patients with COVID

The new section of the guidelines notes that the treatment and prevention of VTE for cancer patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 remain the same as for patients without COVID.

Whether or not cancer patients with COVID-19 are hospitalized, have been discharged, or are ambulatory, they should be assessed for the risk of VTE, as should any other patient. For cancer patients with COVID-19 who are hospitalized, pharmacologic prophylaxis should be given at the same dose and anticoagulant type as for hospitalized cancer patients who do not have COVID-19.

Following discharge, VTE prophylaxis is not advised for cancer patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, and routine primary pharmacologic prophylaxis of VTE for ambulatory patients with COVID-19 is also not recommended, the authors noted.

Initial treatment of established VTE

Initial treatment of established VTE for up to 10 days of anticoagulation should include low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) when creatinine clearance is at least 30 mL/min.

“A regimen of LMWH, taken once per day, is recommended unless a twice-per-day regimen is required because of patients’ characteristics,” the authors noted. These characteristics include a high risk of bleeding, moderate renal failure, and the need for technical intervention, including surgery.

If a twice-a-day regimen is required, only enoxaparin at a dose of 1 mg/kg twice daily can be used, the authors cautioned.

For patients with a low risk of gastrointestinal or genitourinary bleeding, rivaroxaban (Xarelto) or apixaban (Eliquis) can be given in the first 10 days, as well as edoxaban (Lixiana). The latter should be started after at least 5 days of parenteral anticoagulation, provided creatinine clearance is at least 30 mL/min.

“Unfractionated heparin as well as fondaparinux (GlaxoSmithKline) can be also used for the initial treatment of established VTE when LMWH or direct oral anticoagulants are contraindicated,” Dr. Farge and colleagues wrote.

Thrombolysis can be considered on a case-by-case basis, although physicians must pay attention to specific contraindications, especially bleeding risk.

“In the initial treatment of VTE, inferior vena cava filters might be considered when anticoagulant treatment is contraindicated or, in the case of pulmonary embolism, when recurrence occurs under optimal anticoagulation,” the authors noted.

Maintenance VTE treatment

For maintenance therapy, which the authors define as early maintenance for up to 6 months and long-term maintenance beyond 6 months, they point out that LMWHs are preferred over vitamin K antagonists for the treatment of VTE when the creatinine clearance is again at least 30 mL/min.

Any of the direct oral anticoagulants (DOAs) – edoxaban, rivaroxaban, or apixaban – is also recommended for the same patients, provided there is no risk of inducing a strong drug-drug interaction or GI absorption is impaired.

However, the DOAs should be used with caution for patients with GI malignancies, especially upper GI cancers, because data show there is an increased risk of GI bleeding with both edoxaban and rivaroxaban.

“LMWH or direct oral anticoagulants should be used for a minimum of 6 months to treat established VTE in patients with cancer,” the authors wrote.

“After 6 months, termination or continuation of anticoagulation (LMWH, direct oral anticoagulants, or vitamin K antagonists) should be based on individual evaluation of the benefit-risk ratio,” they added.

Treatment of VTE recurrence

The guideline authors explain that three options can be considered in the event of VTE recurrence. These include an increase in the LMWH dose by 20%-25%, or a switch to a DOA, or, if patients are taking a DOA, a switch to an LMWH. If the patient is taking a vitamin K antagonist, it can be switched to either an LMWH or a DOA.

For treatment of catheter-related thrombosis, anticoagulant treatment is recommended for a minimum of 3 months and as long as the central venous catheter is in place. In this setting, the LMWHs are recommended.

The central venous catheter can be kept in place if it is functional, well positioned, and is not infected, provided there is good resolution of symptoms under close surveillance while anticoagulants are being administered.

In surgically treated patients, the LMWH, given once a day, to patients with a serum creatinine concentration of at least 30 mL/min can be used to prevent VTE. Alternatively, VTE can be prevented by the use low-dose unfractionated heparin, given three times a day.

“Pharmacological prophylaxis should be started 2-12 h preoperatively and continued for at least 7–10 days,” Dr. Farge and colleagues advised. In this setting, there is insufficient evidence to support the use of fondaparinux or a DOA as an alternative to an LMWH for the prophylaxis of postoperative VTE. “Use of the highest prophylactic dose of LMWH to prevent postoperative VTE in patients with cancer is recommended,” the authors advised.

Furthermore, extended prophylaxis of at least 4 weeks with LMWH is advised to prevent postoperative VTE after major abdominal or pelvic surgery. Mechanical methods are not recommended except when pharmacologic methods are contraindicated. Inferior vena cava filters are also not recommended for routine prophylaxis.

Patients with reduced mobility

For medically treated hospitalized patients with cancer whose mobility is reduced, the authors recommend prophylaxis with either an LMWH or fondaparinux, provided their creatinine clearance is at least 30 mL/min. These patients can also be treated with unfractionated heparin, they add.

In contrast, DOAs are not recommended – at least not routinely – in this setting, the authors cautioned. Primary pharmacologic prophylaxis of VTE with either LMWH or DOAs – either rivaroxaban or apixaban – is indicated in ambulatory patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer who are receiving systemic anticancer therapy, provided they are at low risk of bleeding.

However, primary pharmacologic prophylaxis with LMWH is not recommended outside of a clinical trial for patients with locally advanced or metastatic lung cancer who are undergoing systemic anticancer therapy, even for patients who are at low risk of bleeding.

For ambulatory patients who are receiving systemic anticancer therapy and who are at intermediate risk of VTE, primary prophylaxis with rivaroxaban or apixaban is recommended for those with myeloma who are receiving immunomodulatory therapy plus steroids or other systemic therapies.

In this setting, oral anticoagulants should consist of a vitamin K antagonist, given at low or therapeutic doses, or apixaban, given at prophylactic doses. Alternatively, LMWH, given at prophylactic doses, or low-dose aspirin, given at a dose of 100 mg/day, can be used.

Catheter-related thrombosis

Use of anticoagulation for routine prophylaxis of catheter-related thrombosis is not recommended. Catheters should be inserted on the right side in the jugular vein, and the distal extremity of the central catheter should be located at the junction of the superior vena cava and the right atrium. “In patients requiring central venous catheters, we suggest the use of implanted ports over peripheral inserted central catheter lines,” the authors noted.

The authors described a number of unique situations regarding the treatment of VTE. These situations include patients with a brain tumor, for whom treatment of established VTE should favor either LMWH or a DOA. The authors also recommended the use of LMWH or unfractionated heparin, started postoperatively, for the prevention of VTE for patients undergoing neurosurgery.

In contrast, pharmacologic prophylaxis of VTE in medically treated patients with a brain tumor who are not undergoing neurosurgery is not recommended. “In the presence of severe renal failure...we suggest using unfractionated heparin followed by early vitamin K antagonists (possibly from day 1) or LMWH adjusted to anti-Xa concentration of the treatment of established VTE,” Dr. Farge and colleagues wrote.

Anticoagulant treatment is also recommended for a minimum of 3 months for children with symptomatic catheter-related thrombosis and as long as the central venous catheter is in place. For children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia who are undergoing induction chemotherapy, LMWH is also recommended as thromboprophylaxis.

For children who require a central venous catheter, the authors suggested that physicians use implanted ports over peripherally inserted central lines.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Updated clinical practice guidelines for the treatment and prevention of venous thromboembolism for patients with cancer, including those with cancer and COVID-19, have been released by the International Initiative on Thrombosis and Cancer (ITAC), an academic working group of VTE experts.

“Because patients with cancer have a baseline increased risk of VTE, compared with patients without cancer, the combination of both COVID-19 and cancer – and its effect on VTE risk and treatment – is of concern,” said the authors, led by Dominique Farge, MD, PhD, Nord Universite de Paris.

they added.

The new guidelines were published online in The Lancet Oncology.

“Cancer-associated VTE remains an important clinical problem, associated with increased morbidity and mortality,” Dr. Farge and colleagues observed.

“The ITAC guidelines’ companion free web-based mobile application will assist the practicing clinician with decision making at various levels to provide optimal care of patients with cancer to treat and prevent VTE,” they emphasized. More information is available at itaccme.com.

Cancer patients with COVID

The new section of the guidelines notes that the treatment and prevention of VTE for cancer patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 remain the same as for patients without COVID.

Whether or not cancer patients with COVID-19 are hospitalized, have been discharged, or are ambulatory, they should be assessed for the risk of VTE, as should any other patient. For cancer patients with COVID-19 who are hospitalized, pharmacologic prophylaxis should be given at the same dose and anticoagulant type as for hospitalized cancer patients who do not have COVID-19.

Following discharge, VTE prophylaxis is not advised for cancer patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, and routine primary pharmacologic prophylaxis of VTE for ambulatory patients with COVID-19 is also not recommended, the authors noted.

Initial treatment of established VTE

Initial treatment of established VTE for up to 10 days of anticoagulation should include low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) when creatinine clearance is at least 30 mL/min.

“A regimen of LMWH, taken once per day, is recommended unless a twice-per-day regimen is required because of patients’ characteristics,” the authors noted. These characteristics include a high risk of bleeding, moderate renal failure, and the need for technical intervention, including surgery.

If a twice-a-day regimen is required, only enoxaparin at a dose of 1 mg/kg twice daily can be used, the authors cautioned.

For patients with a low risk of gastrointestinal or genitourinary bleeding, rivaroxaban (Xarelto) or apixaban (Eliquis) can be given in the first 10 days, as well as edoxaban (Lixiana). The latter should be started after at least 5 days of parenteral anticoagulation, provided creatinine clearance is at least 30 mL/min.

“Unfractionated heparin as well as fondaparinux (GlaxoSmithKline) can be also used for the initial treatment of established VTE when LMWH or direct oral anticoagulants are contraindicated,” Dr. Farge and colleagues wrote.

Thrombolysis can be considered on a case-by-case basis, although physicians must pay attention to specific contraindications, especially bleeding risk.

“In the initial treatment of VTE, inferior vena cava filters might be considered when anticoagulant treatment is contraindicated or, in the case of pulmonary embolism, when recurrence occurs under optimal anticoagulation,” the authors noted.

Maintenance VTE treatment

For maintenance therapy, which the authors define as early maintenance for up to 6 months and long-term maintenance beyond 6 months, they point out that LMWHs are preferred over vitamin K antagonists for the treatment of VTE when the creatinine clearance is again at least 30 mL/min.

Any of the direct oral anticoagulants (DOAs) – edoxaban, rivaroxaban, or apixaban – is also recommended for the same patients, provided there is no risk of inducing a strong drug-drug interaction or GI absorption is impaired.

However, the DOAs should be used with caution for patients with GI malignancies, especially upper GI cancers, because data show there is an increased risk of GI bleeding with both edoxaban and rivaroxaban.

“LMWH or direct oral anticoagulants should be used for a minimum of 6 months to treat established VTE in patients with cancer,” the authors wrote.

“After 6 months, termination or continuation of anticoagulation (LMWH, direct oral anticoagulants, or vitamin K antagonists) should be based on individual evaluation of the benefit-risk ratio,” they added.

Treatment of VTE recurrence

The guideline authors explain that three options can be considered in the event of VTE recurrence. These include an increase in the LMWH dose by 20%-25%, or a switch to a DOA, or, if patients are taking a DOA, a switch to an LMWH. If the patient is taking a vitamin K antagonist, it can be switched to either an LMWH or a DOA.

For treatment of catheter-related thrombosis, anticoagulant treatment is recommended for a minimum of 3 months and as long as the central venous catheter is in place. In this setting, the LMWHs are recommended.

The central venous catheter can be kept in place if it is functional, well positioned, and is not infected, provided there is good resolution of symptoms under close surveillance while anticoagulants are being administered.

In surgically treated patients, the LMWH, given once a day, to patients with a serum creatinine concentration of at least 30 mL/min can be used to prevent VTE. Alternatively, VTE can be prevented by the use low-dose unfractionated heparin, given three times a day.

“Pharmacological prophylaxis should be started 2-12 h preoperatively and continued for at least 7–10 days,” Dr. Farge and colleagues advised. In this setting, there is insufficient evidence to support the use of fondaparinux or a DOA as an alternative to an LMWH for the prophylaxis of postoperative VTE. “Use of the highest prophylactic dose of LMWH to prevent postoperative VTE in patients with cancer is recommended,” the authors advised.

Furthermore, extended prophylaxis of at least 4 weeks with LMWH is advised to prevent postoperative VTE after major abdominal or pelvic surgery. Mechanical methods are not recommended except when pharmacologic methods are contraindicated. Inferior vena cava filters are also not recommended for routine prophylaxis.

Patients with reduced mobility

For medically treated hospitalized patients with cancer whose mobility is reduced, the authors recommend prophylaxis with either an LMWH or fondaparinux, provided their creatinine clearance is at least 30 mL/min. These patients can also be treated with unfractionated heparin, they add.

In contrast, DOAs are not recommended – at least not routinely – in this setting, the authors cautioned. Primary pharmacologic prophylaxis of VTE with either LMWH or DOAs – either rivaroxaban or apixaban – is indicated in ambulatory patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer who are receiving systemic anticancer therapy, provided they are at low risk of bleeding.

However, primary pharmacologic prophylaxis with LMWH is not recommended outside of a clinical trial for patients with locally advanced or metastatic lung cancer who are undergoing systemic anticancer therapy, even for patients who are at low risk of bleeding.

For ambulatory patients who are receiving systemic anticancer therapy and who are at intermediate risk of VTE, primary prophylaxis with rivaroxaban or apixaban is recommended for those with myeloma who are receiving immunomodulatory therapy plus steroids or other systemic therapies.

In this setting, oral anticoagulants should consist of a vitamin K antagonist, given at low or therapeutic doses, or apixaban, given at prophylactic doses. Alternatively, LMWH, given at prophylactic doses, or low-dose aspirin, given at a dose of 100 mg/day, can be used.

Catheter-related thrombosis

Use of anticoagulation for routine prophylaxis of catheter-related thrombosis is not recommended. Catheters should be inserted on the right side in the jugular vein, and the distal extremity of the central catheter should be located at the junction of the superior vena cava and the right atrium. “In patients requiring central venous catheters, we suggest the use of implanted ports over peripheral inserted central catheter lines,” the authors noted.

The authors described a number of unique situations regarding the treatment of VTE. These situations include patients with a brain tumor, for whom treatment of established VTE should favor either LMWH or a DOA. The authors also recommended the use of LMWH or unfractionated heparin, started postoperatively, for the prevention of VTE for patients undergoing neurosurgery.

In contrast, pharmacologic prophylaxis of VTE in medically treated patients with a brain tumor who are not undergoing neurosurgery is not recommended. “In the presence of severe renal failure...we suggest using unfractionated heparin followed by early vitamin K antagonists (possibly from day 1) or LMWH adjusted to anti-Xa concentration of the treatment of established VTE,” Dr. Farge and colleagues wrote.

Anticoagulant treatment is also recommended for a minimum of 3 months for children with symptomatic catheter-related thrombosis and as long as the central venous catheter is in place. For children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia who are undergoing induction chemotherapy, LMWH is also recommended as thromboprophylaxis.

For children who require a central venous catheter, the authors suggested that physicians use implanted ports over peripherally inserted central lines.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Updated clinical practice guidelines for the treatment and prevention of venous thromboembolism for patients with cancer, including those with cancer and COVID-19, have been released by the International Initiative on Thrombosis and Cancer (ITAC), an academic working group of VTE experts.

“Because patients with cancer have a baseline increased risk of VTE, compared with patients without cancer, the combination of both COVID-19 and cancer – and its effect on VTE risk and treatment – is of concern,” said the authors, led by Dominique Farge, MD, PhD, Nord Universite de Paris.

they added.

The new guidelines were published online in The Lancet Oncology.

“Cancer-associated VTE remains an important clinical problem, associated with increased morbidity and mortality,” Dr. Farge and colleagues observed.

“The ITAC guidelines’ companion free web-based mobile application will assist the practicing clinician with decision making at various levels to provide optimal care of patients with cancer to treat and prevent VTE,” they emphasized. More information is available at itaccme.com.

Cancer patients with COVID

The new section of the guidelines notes that the treatment and prevention of VTE for cancer patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 remain the same as for patients without COVID.

Whether or not cancer patients with COVID-19 are hospitalized, have been discharged, or are ambulatory, they should be assessed for the risk of VTE, as should any other patient. For cancer patients with COVID-19 who are hospitalized, pharmacologic prophylaxis should be given at the same dose and anticoagulant type as for hospitalized cancer patients who do not have COVID-19.

Following discharge, VTE prophylaxis is not advised for cancer patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, and routine primary pharmacologic prophylaxis of VTE for ambulatory patients with COVID-19 is also not recommended, the authors noted.

Initial treatment of established VTE

Initial treatment of established VTE for up to 10 days of anticoagulation should include low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) when creatinine clearance is at least 30 mL/min.

“A regimen of LMWH, taken once per day, is recommended unless a twice-per-day regimen is required because of patients’ characteristics,” the authors noted. These characteristics include a high risk of bleeding, moderate renal failure, and the need for technical intervention, including surgery.

If a twice-a-day regimen is required, only enoxaparin at a dose of 1 mg/kg twice daily can be used, the authors cautioned.

For patients with a low risk of gastrointestinal or genitourinary bleeding, rivaroxaban (Xarelto) or apixaban (Eliquis) can be given in the first 10 days, as well as edoxaban (Lixiana). The latter should be started after at least 5 days of parenteral anticoagulation, provided creatinine clearance is at least 30 mL/min.

“Unfractionated heparin as well as fondaparinux (GlaxoSmithKline) can be also used for the initial treatment of established VTE when LMWH or direct oral anticoagulants are contraindicated,” Dr. Farge and colleagues wrote.