User login

ID Practitioner is an independent news source that provides infectious disease specialists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on the infectious disease specialist’s practice. Specialty focus topics include antimicrobial resistance, emerging infections, global ID, hepatitis, HIV, hospital-acquired infections, immunizations and vaccines, influenza, mycoses, pediatric infections, and STIs. Infectious Diseases News is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

sofosbuvir

ritonavir with dasabuvir

discount

support path

program

ritonavir

greedy

ledipasvir

assistance

viekira pak

vpak

advocacy

needy

protest

abbvie

paritaprevir

ombitasvir

direct-acting antivirals

dasabuvir

gilead

fake-ovir

support

v pak

oasis

harvoni

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-idp')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-medstat-latest-articles-articles-section')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-idp')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-idp')]

Updated recommendations released on COVID-19 and pediatric ALL

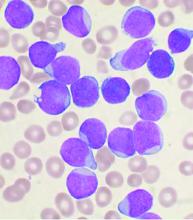

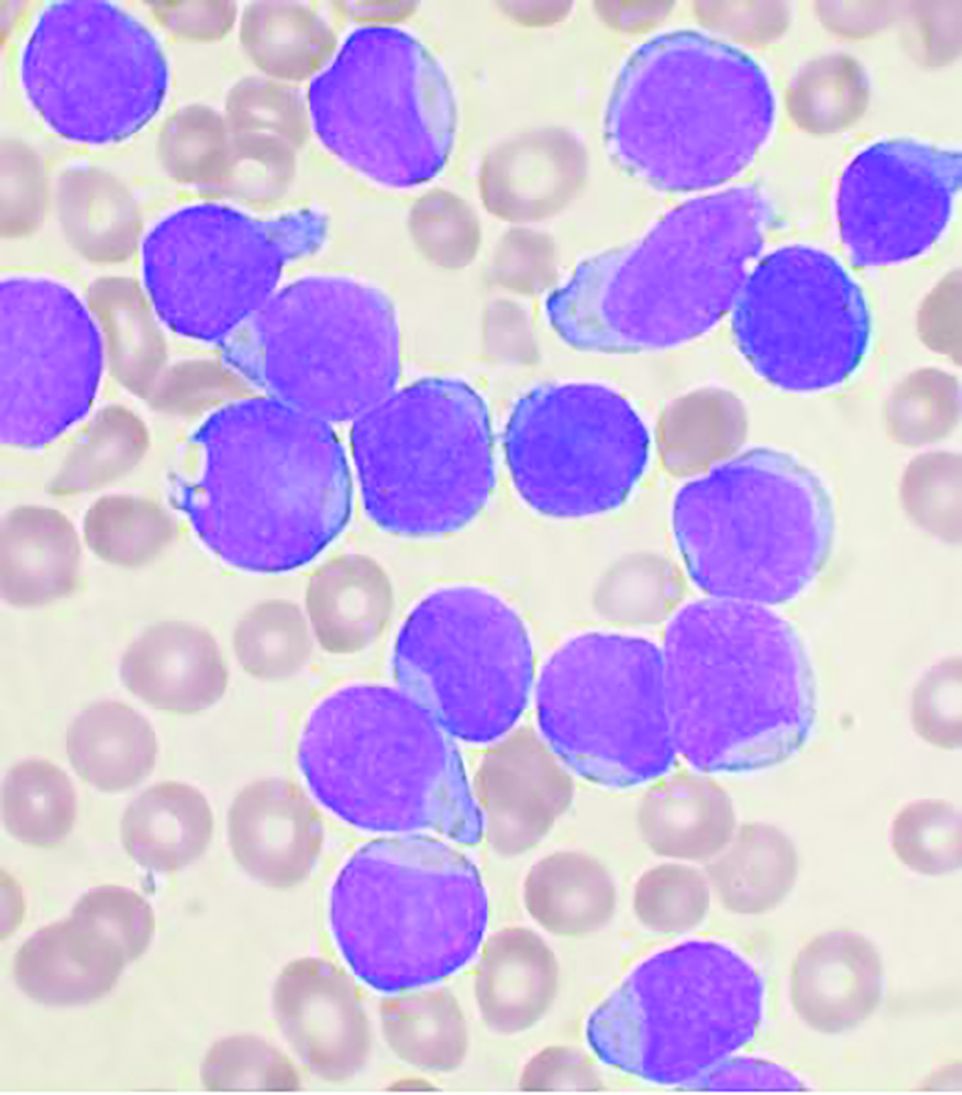

The main threat to the vast majority of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia still remains the ALL itself, according to updated recommendations released by the Leukemia Committee of the French Society for the Fight Against Cancers and Leukemias in Children and Adolescents (SFCE).

“The situation of the current COVID-19 pandemic is continuously evolving. We thus have taken the more recent knowledge into account to update the previous recommendations from the Leukemia Committee,” Jérémie Rouger-Gaudichon, MD, of Pediatric Hemato-Immuno-Oncology Unit, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire, Caen (France), and colleagues wrote on behalf of the SFCE.

The updated recommendations are based on data collected in a real-time prospective survey among the 30 SFCE centers since April 2020. As of December 2020, 127 cases of COVID-19 were reported, most of them being enrolled in the PEDONCOVID study (NCT04433871) according to the report. Of these, eight patients required hospitalization in intensive care unit and one patient with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) died from ARDS with multiorgan failure. This confirms earlier reports that SARS-CoV-2 infection can be severe in some children with cancer and/or having hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), according to the report, which was published online in Bulletin du Cancer.

Recommendations

General recommendations were provided in the report, including the following:

- Test for SARS-CoV-2 (preferably by PCR or at least by immunological tests, on nasopharyngeal swab) before starting intensive induction chemotherapy or other intensive phase of treatment, for ALL patients, with or without symptoms.

- Delay systemic treatment if possible (e.g., absence of major hyperleukocytosis) in positive patients. During later phases, if patients test positive, tests should be repeated over time until negativity, especially before the beginning of an intensive course.

- Isolate any COVID-19–negative child or adolescent to allow treatment to continue (facial mask, social distancing, barrier measures, no contact with individuals suspected of COVID-19 or COVID-19–positive), in particular for patients to be allografted.

- Limit visitation to parents and potentially siblings in patients slated for HSCT and follow all necessary sanitary procedures for those visits.

The report provides a lengthy discussion of more detailed recommendations, including the following for first-line treatment of ALL:

- For patients with high-risk ALL, an individualized decision regarding transplantation and its timing should weigh the risks of transplantation in an epidemic context of COVID-19 against the risk linked to ALL.

- Minimizing hospital visits by the use of home blood tests and partial use of telemedicine may be considered.

- A physical examination should be performed regularly to avoid any delay in the diagnosis of treatment complications or relapse and preventative measures for SARS-CoV-2 should be applied in the home.

Patients with relapsed ALL may be at more risk from the effects of COVID-19 disease, according to the others, so for ALL patients receiving second-line or more treatment the recommendations include the following:

- Testing must be performed before starting a chemotherapy block, and postponing chemotherapy in case of positive test should be discussed in accordance with each specific situation and benefits/risks ratio regarding the leukemia.

- First-relapse patients should follow the INTREALL treatment protocol as much as possible and those who reach appropriate complete remission should be considered promptly for allogeneic transplantation, despite the pandemic.

- Second relapse and refractory relapses require testing and negative results for inclusion in phase I-II trials being conducted by most if not all academic or industrial promoters.

- The indication for treatment with CAR-T cells must be weighed with the center that would perform the procedure to determine the feasibility of performing all necessary procedures including apheresis and manufacturing.

In the case of a SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosis during the treatment of ALL, discussions should occur with regard to stopping and/or postponing all chemotherapies, according to the severity of the ALL, the stage of treatment and the severity of clinical and/or radiological signs. In addition, any specific anti-COVID-19 treatment must be discussed with the infectious diseases team, according to the report.

“Fortunately, SARS-CoV-2 infection appears nevertheless to be mild in most children with cancer/ALL. Thus, the main threat to the vast majority of children with ALL still remains the ALL itself. Long-term data including well-matched case-control studies will tell if treatment delays/modifications due to COVID-19 have impacted the outcome if children with ALL,” the authors stated. However, “despite extremely rapid advances obtained in less than one year, our knowledge of SARS-CoV-2 and its complications is still incomplete,” they concluded, adding that the recommendations will likely need to be updated within another few months.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

The main threat to the vast majority of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia still remains the ALL itself, according to updated recommendations released by the Leukemia Committee of the French Society for the Fight Against Cancers and Leukemias in Children and Adolescents (SFCE).

“The situation of the current COVID-19 pandemic is continuously evolving. We thus have taken the more recent knowledge into account to update the previous recommendations from the Leukemia Committee,” Jérémie Rouger-Gaudichon, MD, of Pediatric Hemato-Immuno-Oncology Unit, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire, Caen (France), and colleagues wrote on behalf of the SFCE.

The updated recommendations are based on data collected in a real-time prospective survey among the 30 SFCE centers since April 2020. As of December 2020, 127 cases of COVID-19 were reported, most of them being enrolled in the PEDONCOVID study (NCT04433871) according to the report. Of these, eight patients required hospitalization in intensive care unit and one patient with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) died from ARDS with multiorgan failure. This confirms earlier reports that SARS-CoV-2 infection can be severe in some children with cancer and/or having hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), according to the report, which was published online in Bulletin du Cancer.

Recommendations

General recommendations were provided in the report, including the following:

- Test for SARS-CoV-2 (preferably by PCR or at least by immunological tests, on nasopharyngeal swab) before starting intensive induction chemotherapy or other intensive phase of treatment, for ALL patients, with or without symptoms.

- Delay systemic treatment if possible (e.g., absence of major hyperleukocytosis) in positive patients. During later phases, if patients test positive, tests should be repeated over time until negativity, especially before the beginning of an intensive course.

- Isolate any COVID-19–negative child or adolescent to allow treatment to continue (facial mask, social distancing, barrier measures, no contact with individuals suspected of COVID-19 or COVID-19–positive), in particular for patients to be allografted.

- Limit visitation to parents and potentially siblings in patients slated for HSCT and follow all necessary sanitary procedures for those visits.

The report provides a lengthy discussion of more detailed recommendations, including the following for first-line treatment of ALL:

- For patients with high-risk ALL, an individualized decision regarding transplantation and its timing should weigh the risks of transplantation in an epidemic context of COVID-19 against the risk linked to ALL.

- Minimizing hospital visits by the use of home blood tests and partial use of telemedicine may be considered.

- A physical examination should be performed regularly to avoid any delay in the diagnosis of treatment complications or relapse and preventative measures for SARS-CoV-2 should be applied in the home.

Patients with relapsed ALL may be at more risk from the effects of COVID-19 disease, according to the others, so for ALL patients receiving second-line or more treatment the recommendations include the following:

- Testing must be performed before starting a chemotherapy block, and postponing chemotherapy in case of positive test should be discussed in accordance with each specific situation and benefits/risks ratio regarding the leukemia.

- First-relapse patients should follow the INTREALL treatment protocol as much as possible and those who reach appropriate complete remission should be considered promptly for allogeneic transplantation, despite the pandemic.

- Second relapse and refractory relapses require testing and negative results for inclusion in phase I-II trials being conducted by most if not all academic or industrial promoters.

- The indication for treatment with CAR-T cells must be weighed with the center that would perform the procedure to determine the feasibility of performing all necessary procedures including apheresis and manufacturing.

In the case of a SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosis during the treatment of ALL, discussions should occur with regard to stopping and/or postponing all chemotherapies, according to the severity of the ALL, the stage of treatment and the severity of clinical and/or radiological signs. In addition, any specific anti-COVID-19 treatment must be discussed with the infectious diseases team, according to the report.

“Fortunately, SARS-CoV-2 infection appears nevertheless to be mild in most children with cancer/ALL. Thus, the main threat to the vast majority of children with ALL still remains the ALL itself. Long-term data including well-matched case-control studies will tell if treatment delays/modifications due to COVID-19 have impacted the outcome if children with ALL,” the authors stated. However, “despite extremely rapid advances obtained in less than one year, our knowledge of SARS-CoV-2 and its complications is still incomplete,” they concluded, adding that the recommendations will likely need to be updated within another few months.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

The main threat to the vast majority of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia still remains the ALL itself, according to updated recommendations released by the Leukemia Committee of the French Society for the Fight Against Cancers and Leukemias in Children and Adolescents (SFCE).

“The situation of the current COVID-19 pandemic is continuously evolving. We thus have taken the more recent knowledge into account to update the previous recommendations from the Leukemia Committee,” Jérémie Rouger-Gaudichon, MD, of Pediatric Hemato-Immuno-Oncology Unit, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire, Caen (France), and colleagues wrote on behalf of the SFCE.

The updated recommendations are based on data collected in a real-time prospective survey among the 30 SFCE centers since April 2020. As of December 2020, 127 cases of COVID-19 were reported, most of them being enrolled in the PEDONCOVID study (NCT04433871) according to the report. Of these, eight patients required hospitalization in intensive care unit and one patient with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) died from ARDS with multiorgan failure. This confirms earlier reports that SARS-CoV-2 infection can be severe in some children with cancer and/or having hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), according to the report, which was published online in Bulletin du Cancer.

Recommendations

General recommendations were provided in the report, including the following:

- Test for SARS-CoV-2 (preferably by PCR or at least by immunological tests, on nasopharyngeal swab) before starting intensive induction chemotherapy or other intensive phase of treatment, for ALL patients, with or without symptoms.

- Delay systemic treatment if possible (e.g., absence of major hyperleukocytosis) in positive patients. During later phases, if patients test positive, tests should be repeated over time until negativity, especially before the beginning of an intensive course.

- Isolate any COVID-19–negative child or adolescent to allow treatment to continue (facial mask, social distancing, barrier measures, no contact with individuals suspected of COVID-19 or COVID-19–positive), in particular for patients to be allografted.

- Limit visitation to parents and potentially siblings in patients slated for HSCT and follow all necessary sanitary procedures for those visits.

The report provides a lengthy discussion of more detailed recommendations, including the following for first-line treatment of ALL:

- For patients with high-risk ALL, an individualized decision regarding transplantation and its timing should weigh the risks of transplantation in an epidemic context of COVID-19 against the risk linked to ALL.

- Minimizing hospital visits by the use of home blood tests and partial use of telemedicine may be considered.

- A physical examination should be performed regularly to avoid any delay in the diagnosis of treatment complications or relapse and preventative measures for SARS-CoV-2 should be applied in the home.

Patients with relapsed ALL may be at more risk from the effects of COVID-19 disease, according to the others, so for ALL patients receiving second-line or more treatment the recommendations include the following:

- Testing must be performed before starting a chemotherapy block, and postponing chemotherapy in case of positive test should be discussed in accordance with each specific situation and benefits/risks ratio regarding the leukemia.

- First-relapse patients should follow the INTREALL treatment protocol as much as possible and those who reach appropriate complete remission should be considered promptly for allogeneic transplantation, despite the pandemic.

- Second relapse and refractory relapses require testing and negative results for inclusion in phase I-II trials being conducted by most if not all academic or industrial promoters.

- The indication for treatment with CAR-T cells must be weighed with the center that would perform the procedure to determine the feasibility of performing all necessary procedures including apheresis and manufacturing.

In the case of a SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosis during the treatment of ALL, discussions should occur with regard to stopping and/or postponing all chemotherapies, according to the severity of the ALL, the stage of treatment and the severity of clinical and/or radiological signs. In addition, any specific anti-COVID-19 treatment must be discussed with the infectious diseases team, according to the report.

“Fortunately, SARS-CoV-2 infection appears nevertheless to be mild in most children with cancer/ALL. Thus, the main threat to the vast majority of children with ALL still remains the ALL itself. Long-term data including well-matched case-control studies will tell if treatment delays/modifications due to COVID-19 have impacted the outcome if children with ALL,” the authors stated. However, “despite extremely rapid advances obtained in less than one year, our knowledge of SARS-CoV-2 and its complications is still incomplete,” they concluded, adding that the recommendations will likely need to be updated within another few months.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

FROM BULLETIN DU CANCER

Some with long COVID see relief after vaccination

Several weeks after getting his second dose of an mRNA vaccine, Aaron Goyang thinks his long bout with COVID-19 has finally come to an end.

Mr. Goyang, who is 33 and is a radiology technician in Austin, Tex., thinks he got COVID-19 from some of the coughing, gasping patients he treated last spring.

At the time, testing was scarce, and by the time he was tested – several weeks into his illness – it came back negative. He fought off the initial symptoms but experienced relapse a week later.

Mr. Goyang says that, for the next 8 or 9 months, he was on a roller coaster with extreme shortness of breath and chest tightness that could be so severe it would send him to the emergency department. He had to use an inhaler to get through his workdays.

“Even if I was just sitting around, it would come and take me,” he says. “It almost felt like someone was bear-hugging me constantly, and I just couldn’t get in a good enough breath.”

On his best days, he would walk around his neighborhood, being careful not to overdo it. He tried running once, and it nearly sent him to the hospital.

“Very honestly, I didn’t know if I would ever be able to do it again,” he says.

But Mr. Goyang says that, several weeks after getting the Pfizer vaccine, he was able to run a mile again with no problems. “I was very thankful for that,” he says.

Mr. Goyang is not alone. Some social media groups are dedicated to patients who are living with a condition that’s been known as long COVID and that was recently termed postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). These patients are sometimes referred to as long haulers.

On social media, patients with PASC are eagerly and anxiously quizzing each other about the vaccines and their effects.

Survivor Corps, which has a public Facebook group with 159,000 members, recently took a poll to see whether there was any substance to rumors that those with long COVID were feeling better after being vaccinated.

“Out of 400 people, 36% showed an improvement in symptoms, anywhere between a mild improvement to complete resolution of symptoms,” said Diana Berrent, a long-COVID patient who founded the group. Survivor Corps has become active in patient advocacy and is a resource for researchers studying the new condition.

Ms. Berrent has become such a trusted voice during the pandemic. She interviewed Anthony Fauci, MD, head of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, last October.

“The implications are huge,” she says.

“Some of this damage is permanent damage. It’s not going to cure the scarring of your heart tissue, it’s not going to cure the irreparable damage to your lungs, but if it’s making people feel better, then that’s an indication there’s viral persistence going on,” says Ms. Berrent.

“I’ve been saying for months and months, we shouldn’t be calling this postacute anything,” she adds.

Patients report improvement

Daniel Griffin, MD, PhD, is equally excited. He’s an infectious disease specialist at Columbia University, New York. He says about one in five patients he treated for COVID-19 last year never got better. Many of them, such as Mr. Goyang, were health care workers.

“I don’t know if people actually catch this, but a lot of our coworkers are either permanently disabled or died,” Dr. Griffin says.

Health care workers were also among the first to be vaccinated. Dr. Griffin says many of his patients began reaching out to him about a week or two after being vaccinated “and saying, ‘You know, I actually feel better.’ And some of them were saying, ‘I feel all better,’ after being sick – a lot of them – for a year.”

Then he was getting calls and texts from other doctors, asking, “Hey, are you seeing this?”

The benefits of vaccination for some long-haulers came as a surprise. Dr. Griffin says that, before the vaccines came out, many of his patients were worried that getting vaccinated might overstimulate their immune systems and cause symptoms to get worse.

Indeed, a small percentage of people – about 3%-5%, based on informal polls on social media – report that they do experience worsening of symptoms after getting the shot. It’s not clear why.

Dr. Griffin estimates that between 30% and 50% of patients’ symptoms improve after they receive the mRNA vaccines. “I’m seeing this chunk of people – they tell me their brain fog has improved, their fatigue is gone, the fevers that wouldn’t resolve have now gone,” he says. “I’m seeing that personally, and I’m hearing it from my colleagues.”

Dr. Griffin says the observation has launched several studies and that there are several theories about how the vaccines might be affecting long COVID.

An immune system boost?

One possibility is that the virus continues to stimulate the immune system, which continues to fight the virus for months. If that is the case, Dr. Griffin says, the vaccine may be giving the immune system the boost it needs to finally clear the virus away.

Donna Farber, PhD, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Columbia University, has heard the stories, too.

“It is possible that the persisting virus in long COVID-19 may be at a low level – not enough to stimulate a potent immune response to clear the virus, but enough to cause symptoms. Activating the immune response therefore is therapeutic in directing viral clearance,” she says.

Dr. Farber explains that long COVID may be a bit like Lyme disease. Some patients with Lyme disease must take antibiotics for months before their symptoms disappear.

Dr. Griffin says there’s another possibility. Several studies have now shown that people with lingering COVID-19 symptoms develop autoantibodies. There’s a theory that SARS-CoV-2 may create an autoimmune condition that leads to long-term symptoms.

If that is the case, Dr. Griffin says, the vaccine may be helping the body to reset its tolerance to itself, “so maybe now you’re getting a healthy immune response.”

More studies are needed to know for sure.

Either way, the vaccines are a much-needed bit of hope for the long-COVID community, and Dr. Griffin tells his patients who are still worried that, at the very least, they’ll be protected from another SARS-CoV-2 infection.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Several weeks after getting his second dose of an mRNA vaccine, Aaron Goyang thinks his long bout with COVID-19 has finally come to an end.

Mr. Goyang, who is 33 and is a radiology technician in Austin, Tex., thinks he got COVID-19 from some of the coughing, gasping patients he treated last spring.

At the time, testing was scarce, and by the time he was tested – several weeks into his illness – it came back negative. He fought off the initial symptoms but experienced relapse a week later.

Mr. Goyang says that, for the next 8 or 9 months, he was on a roller coaster with extreme shortness of breath and chest tightness that could be so severe it would send him to the emergency department. He had to use an inhaler to get through his workdays.

“Even if I was just sitting around, it would come and take me,” he says. “It almost felt like someone was bear-hugging me constantly, and I just couldn’t get in a good enough breath.”

On his best days, he would walk around his neighborhood, being careful not to overdo it. He tried running once, and it nearly sent him to the hospital.

“Very honestly, I didn’t know if I would ever be able to do it again,” he says.

But Mr. Goyang says that, several weeks after getting the Pfizer vaccine, he was able to run a mile again with no problems. “I was very thankful for that,” he says.

Mr. Goyang is not alone. Some social media groups are dedicated to patients who are living with a condition that’s been known as long COVID and that was recently termed postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). These patients are sometimes referred to as long haulers.

On social media, patients with PASC are eagerly and anxiously quizzing each other about the vaccines and their effects.

Survivor Corps, which has a public Facebook group with 159,000 members, recently took a poll to see whether there was any substance to rumors that those with long COVID were feeling better after being vaccinated.

“Out of 400 people, 36% showed an improvement in symptoms, anywhere between a mild improvement to complete resolution of symptoms,” said Diana Berrent, a long-COVID patient who founded the group. Survivor Corps has become active in patient advocacy and is a resource for researchers studying the new condition.

Ms. Berrent has become such a trusted voice during the pandemic. She interviewed Anthony Fauci, MD, head of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, last October.

“The implications are huge,” she says.

“Some of this damage is permanent damage. It’s not going to cure the scarring of your heart tissue, it’s not going to cure the irreparable damage to your lungs, but if it’s making people feel better, then that’s an indication there’s viral persistence going on,” says Ms. Berrent.

“I’ve been saying for months and months, we shouldn’t be calling this postacute anything,” she adds.

Patients report improvement

Daniel Griffin, MD, PhD, is equally excited. He’s an infectious disease specialist at Columbia University, New York. He says about one in five patients he treated for COVID-19 last year never got better. Many of them, such as Mr. Goyang, were health care workers.

“I don’t know if people actually catch this, but a lot of our coworkers are either permanently disabled or died,” Dr. Griffin says.

Health care workers were also among the first to be vaccinated. Dr. Griffin says many of his patients began reaching out to him about a week or two after being vaccinated “and saying, ‘You know, I actually feel better.’ And some of them were saying, ‘I feel all better,’ after being sick – a lot of them – for a year.”

Then he was getting calls and texts from other doctors, asking, “Hey, are you seeing this?”

The benefits of vaccination for some long-haulers came as a surprise. Dr. Griffin says that, before the vaccines came out, many of his patients were worried that getting vaccinated might overstimulate their immune systems and cause symptoms to get worse.

Indeed, a small percentage of people – about 3%-5%, based on informal polls on social media – report that they do experience worsening of symptoms after getting the shot. It’s not clear why.

Dr. Griffin estimates that between 30% and 50% of patients’ symptoms improve after they receive the mRNA vaccines. “I’m seeing this chunk of people – they tell me their brain fog has improved, their fatigue is gone, the fevers that wouldn’t resolve have now gone,” he says. “I’m seeing that personally, and I’m hearing it from my colleagues.”

Dr. Griffin says the observation has launched several studies and that there are several theories about how the vaccines might be affecting long COVID.

An immune system boost?

One possibility is that the virus continues to stimulate the immune system, which continues to fight the virus for months. If that is the case, Dr. Griffin says, the vaccine may be giving the immune system the boost it needs to finally clear the virus away.

Donna Farber, PhD, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Columbia University, has heard the stories, too.

“It is possible that the persisting virus in long COVID-19 may be at a low level – not enough to stimulate a potent immune response to clear the virus, but enough to cause symptoms. Activating the immune response therefore is therapeutic in directing viral clearance,” she says.

Dr. Farber explains that long COVID may be a bit like Lyme disease. Some patients with Lyme disease must take antibiotics for months before their symptoms disappear.

Dr. Griffin says there’s another possibility. Several studies have now shown that people with lingering COVID-19 symptoms develop autoantibodies. There’s a theory that SARS-CoV-2 may create an autoimmune condition that leads to long-term symptoms.

If that is the case, Dr. Griffin says, the vaccine may be helping the body to reset its tolerance to itself, “so maybe now you’re getting a healthy immune response.”

More studies are needed to know for sure.

Either way, the vaccines are a much-needed bit of hope for the long-COVID community, and Dr. Griffin tells his patients who are still worried that, at the very least, they’ll be protected from another SARS-CoV-2 infection.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Several weeks after getting his second dose of an mRNA vaccine, Aaron Goyang thinks his long bout with COVID-19 has finally come to an end.

Mr. Goyang, who is 33 and is a radiology technician in Austin, Tex., thinks he got COVID-19 from some of the coughing, gasping patients he treated last spring.

At the time, testing was scarce, and by the time he was tested – several weeks into his illness – it came back negative. He fought off the initial symptoms but experienced relapse a week later.

Mr. Goyang says that, for the next 8 or 9 months, he was on a roller coaster with extreme shortness of breath and chest tightness that could be so severe it would send him to the emergency department. He had to use an inhaler to get through his workdays.

“Even if I was just sitting around, it would come and take me,” he says. “It almost felt like someone was bear-hugging me constantly, and I just couldn’t get in a good enough breath.”

On his best days, he would walk around his neighborhood, being careful not to overdo it. He tried running once, and it nearly sent him to the hospital.

“Very honestly, I didn’t know if I would ever be able to do it again,” he says.

But Mr. Goyang says that, several weeks after getting the Pfizer vaccine, he was able to run a mile again with no problems. “I was very thankful for that,” he says.

Mr. Goyang is not alone. Some social media groups are dedicated to patients who are living with a condition that’s been known as long COVID and that was recently termed postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). These patients are sometimes referred to as long haulers.

On social media, patients with PASC are eagerly and anxiously quizzing each other about the vaccines and their effects.

Survivor Corps, which has a public Facebook group with 159,000 members, recently took a poll to see whether there was any substance to rumors that those with long COVID were feeling better after being vaccinated.

“Out of 400 people, 36% showed an improvement in symptoms, anywhere between a mild improvement to complete resolution of symptoms,” said Diana Berrent, a long-COVID patient who founded the group. Survivor Corps has become active in patient advocacy and is a resource for researchers studying the new condition.

Ms. Berrent has become such a trusted voice during the pandemic. She interviewed Anthony Fauci, MD, head of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, last October.

“The implications are huge,” she says.

“Some of this damage is permanent damage. It’s not going to cure the scarring of your heart tissue, it’s not going to cure the irreparable damage to your lungs, but if it’s making people feel better, then that’s an indication there’s viral persistence going on,” says Ms. Berrent.

“I’ve been saying for months and months, we shouldn’t be calling this postacute anything,” she adds.

Patients report improvement

Daniel Griffin, MD, PhD, is equally excited. He’s an infectious disease specialist at Columbia University, New York. He says about one in five patients he treated for COVID-19 last year never got better. Many of them, such as Mr. Goyang, were health care workers.

“I don’t know if people actually catch this, but a lot of our coworkers are either permanently disabled or died,” Dr. Griffin says.

Health care workers were also among the first to be vaccinated. Dr. Griffin says many of his patients began reaching out to him about a week or two after being vaccinated “and saying, ‘You know, I actually feel better.’ And some of them were saying, ‘I feel all better,’ after being sick – a lot of them – for a year.”

Then he was getting calls and texts from other doctors, asking, “Hey, are you seeing this?”

The benefits of vaccination for some long-haulers came as a surprise. Dr. Griffin says that, before the vaccines came out, many of his patients were worried that getting vaccinated might overstimulate their immune systems and cause symptoms to get worse.

Indeed, a small percentage of people – about 3%-5%, based on informal polls on social media – report that they do experience worsening of symptoms after getting the shot. It’s not clear why.

Dr. Griffin estimates that between 30% and 50% of patients’ symptoms improve after they receive the mRNA vaccines. “I’m seeing this chunk of people – they tell me their brain fog has improved, their fatigue is gone, the fevers that wouldn’t resolve have now gone,” he says. “I’m seeing that personally, and I’m hearing it from my colleagues.”

Dr. Griffin says the observation has launched several studies and that there are several theories about how the vaccines might be affecting long COVID.

An immune system boost?

One possibility is that the virus continues to stimulate the immune system, which continues to fight the virus for months. If that is the case, Dr. Griffin says, the vaccine may be giving the immune system the boost it needs to finally clear the virus away.

Donna Farber, PhD, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Columbia University, has heard the stories, too.

“It is possible that the persisting virus in long COVID-19 may be at a low level – not enough to stimulate a potent immune response to clear the virus, but enough to cause symptoms. Activating the immune response therefore is therapeutic in directing viral clearance,” she says.

Dr. Farber explains that long COVID may be a bit like Lyme disease. Some patients with Lyme disease must take antibiotics for months before their symptoms disappear.

Dr. Griffin says there’s another possibility. Several studies have now shown that people with lingering COVID-19 symptoms develop autoantibodies. There’s a theory that SARS-CoV-2 may create an autoimmune condition that leads to long-term symptoms.

If that is the case, Dr. Griffin says, the vaccine may be helping the body to reset its tolerance to itself, “so maybe now you’re getting a healthy immune response.”

More studies are needed to know for sure.

Either way, the vaccines are a much-needed bit of hope for the long-COVID community, and Dr. Griffin tells his patients who are still worried that, at the very least, they’ll be protected from another SARS-CoV-2 infection.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

We’re all vaccinated: Can we go back to the office (unmasked) now?

Congratulations, you’ve been vaccinated!

It’s been a year like no other, and outpatient psychiatrists turned to Zoom and other telemental health platforms to provide treatment for our patients. Offices sit empty as the dust lands and the plants wilt. Perhaps a few patients are seen in person, masked and carefully distanced, after health screening and temperature checks, with surfaces sanitized between visits, all in accordance with health department regulations. But now the vaccine offers both safety and the promise of a return to a new normal, one that is certain to look different from the normal that was left behind.

I have been vaccinated and many of my patients have also been vaccinated. I began to wonder if it was safe to start seeing patients in person; could I see fully vaccinated patients, unmasked and without temperature checks and sanitizing? I started asking this question in February, and the response I got then was that it was too soon to tell; we did not have any data on whether vaccinated people could transmit the novel coronavirus. Two vaccinated people might be at risk of transmitting the virus and then infecting others, and the question of whether the vaccines would protect against illness caused by variants remained. Preliminary data out of Israel indicated that the vaccine did reduce transmission, but no one was saying that it was fine to see patients without masks, and video-conferencing remained the safest option.

On Monday, March 8, 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released long-awaited interim public health guidelines for fully vaccinated people. The guidelines allowed for two vaccinated people to be in a room together unmasked, and for a fully-vaccinated person to be in a room unmasked with an unvaccinated person who did not have risk factors for becoming severely ill with COVID. Was this the green light that psychiatrists were waiting for? Was there new data about transmission, or was this part of the CDC’s effort to make vaccines more desirable?

Michael Chang, MD, is a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. We spoke 2 days after the CDC interim guidelines were released. Dr. Chang was optimistic.

“, including data about variants and about transmission. At some point, however, the risk is low enough, and we should probably start thinking about going back to in-person visits,” Dr. Chang said. He said he personally would feel safe meeting unmasked with a vaccinated patient, but noted that his institution still requires doctors to wear masks. “Most vaccinations reduce transmission of illness,” Dr. Chang said, “but SARS-CoV-2 continues to surprise us in many ways.”

Katelyn Jetelina, PhD, MPH, an epidemiologist at the University of Texas School of Public Health in Dallas, distributes a newsletter, “Your Local Epidemiologist,” where she discusses data pertaining to the pandemic. In her newsletter dated March 14, 2021, Dr. Jetelina wrote, “There are now 7 sub-studies/press releases that confirm a 50-95% reduced transmission after vaccination. This is a big range, which is typical for such drastically different scientific studies. Variability is likely due to different sample sizes, locations, vaccines, genetics, cultures, etc. It will be a while until we know the ‘true’ percentage for each vaccine.”

Leslie Walker, MD, is a fully vaccinated psychiatrist in private practice in Shaker Heights, Ohio. She has recently started seeing fully vaccinated patients in person.

“So far it’s only 1 or 2 patients a day. I’m leaving it up to the patient. If they prefer masks, we stay masked. I may reverse course, depending on what information comes out.” She went on to note, “There are benefits to being able to see someone’s full facial expressions and whether they match someone’s words and body language, so the benefit of “unmasking” extends beyond comfort and convenience and must be balanced against the theoretical risk of COVID exposure in the room.”

While the CDC has now said it is safe to meet, the state health departments also have guidelines for medical practices, and everyone is still worried about vulnerable people in their households and potential spread to the community at large.

In Maryland, where I work, Aliya Jones, MD, MBA, is the head of the Behavioral Health Administration (BHA) for the Maryland Department of Health. “It remains risky to not wear masks, however, the risk is low when both individuals are vaccinated,” Dr. Jones wrote. “BHA is not recommending that providers see clients without both parties wearing a mask. All of our general practice recommendations for infection control are unchanged. People should be screened before entering clinical practices and persons who are symptomatic, whether vaccinated or not, should not be seen face-to-face, except in cases of an emergency, in which case additional precautions should be taken.”

So is it safe for a fully-vaccinated psychiatrist to have a session with a fully-vaccinated patient sitting 8 feet apart without masks? I’m left with the idea that it is for those two people, but when it comes to unvaccinated people in their households, we want more certainty than we currently have. The messaging remains unclear. The CDC’s interim guidelines offer hope for a future, but the science is still catching up, and to feel safe enough, we may want to wait a little longer for more definitive data – or herd immunity – before we reveal our smiles.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

Congratulations, you’ve been vaccinated!

It’s been a year like no other, and outpatient psychiatrists turned to Zoom and other telemental health platforms to provide treatment for our patients. Offices sit empty as the dust lands and the plants wilt. Perhaps a few patients are seen in person, masked and carefully distanced, after health screening and temperature checks, with surfaces sanitized between visits, all in accordance with health department regulations. But now the vaccine offers both safety and the promise of a return to a new normal, one that is certain to look different from the normal that was left behind.

I have been vaccinated and many of my patients have also been vaccinated. I began to wonder if it was safe to start seeing patients in person; could I see fully vaccinated patients, unmasked and without temperature checks and sanitizing? I started asking this question in February, and the response I got then was that it was too soon to tell; we did not have any data on whether vaccinated people could transmit the novel coronavirus. Two vaccinated people might be at risk of transmitting the virus and then infecting others, and the question of whether the vaccines would protect against illness caused by variants remained. Preliminary data out of Israel indicated that the vaccine did reduce transmission, but no one was saying that it was fine to see patients without masks, and video-conferencing remained the safest option.

On Monday, March 8, 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released long-awaited interim public health guidelines for fully vaccinated people. The guidelines allowed for two vaccinated people to be in a room together unmasked, and for a fully-vaccinated person to be in a room unmasked with an unvaccinated person who did not have risk factors for becoming severely ill with COVID. Was this the green light that psychiatrists were waiting for? Was there new data about transmission, or was this part of the CDC’s effort to make vaccines more desirable?

Michael Chang, MD, is a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. We spoke 2 days after the CDC interim guidelines were released. Dr. Chang was optimistic.

“, including data about variants and about transmission. At some point, however, the risk is low enough, and we should probably start thinking about going back to in-person visits,” Dr. Chang said. He said he personally would feel safe meeting unmasked with a vaccinated patient, but noted that his institution still requires doctors to wear masks. “Most vaccinations reduce transmission of illness,” Dr. Chang said, “but SARS-CoV-2 continues to surprise us in many ways.”

Katelyn Jetelina, PhD, MPH, an epidemiologist at the University of Texas School of Public Health in Dallas, distributes a newsletter, “Your Local Epidemiologist,” where she discusses data pertaining to the pandemic. In her newsletter dated March 14, 2021, Dr. Jetelina wrote, “There are now 7 sub-studies/press releases that confirm a 50-95% reduced transmission after vaccination. This is a big range, which is typical for such drastically different scientific studies. Variability is likely due to different sample sizes, locations, vaccines, genetics, cultures, etc. It will be a while until we know the ‘true’ percentage for each vaccine.”

Leslie Walker, MD, is a fully vaccinated psychiatrist in private practice in Shaker Heights, Ohio. She has recently started seeing fully vaccinated patients in person.

“So far it’s only 1 or 2 patients a day. I’m leaving it up to the patient. If they prefer masks, we stay masked. I may reverse course, depending on what information comes out.” She went on to note, “There are benefits to being able to see someone’s full facial expressions and whether they match someone’s words and body language, so the benefit of “unmasking” extends beyond comfort and convenience and must be balanced against the theoretical risk of COVID exposure in the room.”

While the CDC has now said it is safe to meet, the state health departments also have guidelines for medical practices, and everyone is still worried about vulnerable people in their households and potential spread to the community at large.

In Maryland, where I work, Aliya Jones, MD, MBA, is the head of the Behavioral Health Administration (BHA) for the Maryland Department of Health. “It remains risky to not wear masks, however, the risk is low when both individuals are vaccinated,” Dr. Jones wrote. “BHA is not recommending that providers see clients without both parties wearing a mask. All of our general practice recommendations for infection control are unchanged. People should be screened before entering clinical practices and persons who are symptomatic, whether vaccinated or not, should not be seen face-to-face, except in cases of an emergency, in which case additional precautions should be taken.”

So is it safe for a fully-vaccinated psychiatrist to have a session with a fully-vaccinated patient sitting 8 feet apart without masks? I’m left with the idea that it is for those two people, but when it comes to unvaccinated people in their households, we want more certainty than we currently have. The messaging remains unclear. The CDC’s interim guidelines offer hope for a future, but the science is still catching up, and to feel safe enough, we may want to wait a little longer for more definitive data – or herd immunity – before we reveal our smiles.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

Congratulations, you’ve been vaccinated!

It’s been a year like no other, and outpatient psychiatrists turned to Zoom and other telemental health platforms to provide treatment for our patients. Offices sit empty as the dust lands and the plants wilt. Perhaps a few patients are seen in person, masked and carefully distanced, after health screening and temperature checks, with surfaces sanitized between visits, all in accordance with health department regulations. But now the vaccine offers both safety and the promise of a return to a new normal, one that is certain to look different from the normal that was left behind.

I have been vaccinated and many of my patients have also been vaccinated. I began to wonder if it was safe to start seeing patients in person; could I see fully vaccinated patients, unmasked and without temperature checks and sanitizing? I started asking this question in February, and the response I got then was that it was too soon to tell; we did not have any data on whether vaccinated people could transmit the novel coronavirus. Two vaccinated people might be at risk of transmitting the virus and then infecting others, and the question of whether the vaccines would protect against illness caused by variants remained. Preliminary data out of Israel indicated that the vaccine did reduce transmission, but no one was saying that it was fine to see patients without masks, and video-conferencing remained the safest option.

On Monday, March 8, 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released long-awaited interim public health guidelines for fully vaccinated people. The guidelines allowed for two vaccinated people to be in a room together unmasked, and for a fully-vaccinated person to be in a room unmasked with an unvaccinated person who did not have risk factors for becoming severely ill with COVID. Was this the green light that psychiatrists were waiting for? Was there new data about transmission, or was this part of the CDC’s effort to make vaccines more desirable?

Michael Chang, MD, is a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. We spoke 2 days after the CDC interim guidelines were released. Dr. Chang was optimistic.

“, including data about variants and about transmission. At some point, however, the risk is low enough, and we should probably start thinking about going back to in-person visits,” Dr. Chang said. He said he personally would feel safe meeting unmasked with a vaccinated patient, but noted that his institution still requires doctors to wear masks. “Most vaccinations reduce transmission of illness,” Dr. Chang said, “but SARS-CoV-2 continues to surprise us in many ways.”

Katelyn Jetelina, PhD, MPH, an epidemiologist at the University of Texas School of Public Health in Dallas, distributes a newsletter, “Your Local Epidemiologist,” where she discusses data pertaining to the pandemic. In her newsletter dated March 14, 2021, Dr. Jetelina wrote, “There are now 7 sub-studies/press releases that confirm a 50-95% reduced transmission after vaccination. This is a big range, which is typical for such drastically different scientific studies. Variability is likely due to different sample sizes, locations, vaccines, genetics, cultures, etc. It will be a while until we know the ‘true’ percentage for each vaccine.”

Leslie Walker, MD, is a fully vaccinated psychiatrist in private practice in Shaker Heights, Ohio. She has recently started seeing fully vaccinated patients in person.

“So far it’s only 1 or 2 patients a day. I’m leaving it up to the patient. If they prefer masks, we stay masked. I may reverse course, depending on what information comes out.” She went on to note, “There are benefits to being able to see someone’s full facial expressions and whether they match someone’s words and body language, so the benefit of “unmasking” extends beyond comfort and convenience and must be balanced against the theoretical risk of COVID exposure in the room.”

While the CDC has now said it is safe to meet, the state health departments also have guidelines for medical practices, and everyone is still worried about vulnerable people in their households and potential spread to the community at large.

In Maryland, where I work, Aliya Jones, MD, MBA, is the head of the Behavioral Health Administration (BHA) for the Maryland Department of Health. “It remains risky to not wear masks, however, the risk is low when both individuals are vaccinated,” Dr. Jones wrote. “BHA is not recommending that providers see clients without both parties wearing a mask. All of our general practice recommendations for infection control are unchanged. People should be screened before entering clinical practices and persons who are symptomatic, whether vaccinated or not, should not be seen face-to-face, except in cases of an emergency, in which case additional precautions should be taken.”

So is it safe for a fully-vaccinated psychiatrist to have a session with a fully-vaccinated patient sitting 8 feet apart without masks? I’m left with the idea that it is for those two people, but when it comes to unvaccinated people in their households, we want more certainty than we currently have. The messaging remains unclear. The CDC’s interim guidelines offer hope for a future, but the science is still catching up, and to feel safe enough, we may want to wait a little longer for more definitive data – or herd immunity – before we reveal our smiles.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

Decline in child COVID-19 cases picks up after 2-week slowdown

, according to data gathered by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

From Feb. 19 to March 4, the drop in new cases averaged just 5% each week, compared with 13.3% per week over the 5-week period from Jan. 15 to Feb. 18. For the week of March 5-11, a total of 52,695 COVID-19 cases were reported in children, down from 63,562 the previous week and the lowest number since late October, based on data from 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

In those jurisdictions, 3.28 million children have been infected with SARS-CoV-2, representing 13.2% of all cases since the beginning of the pandemic. The cumulative rate of COVID-19 has now risen to 4,364 cases per 100,000 children nationally, with state rates ranging from 1,062 per 100,000 in Hawaii to 8,692 per 100,000 in North Dakota, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

Hospitalization data are more limited – 24 states and New York City – but continue to show that serious illness is much less common in younger individuals: Children represent just 1.9% of all hospitalizations, and only 0.8% of the children who have been infected were hospitalized. Neither rate has changed since early February, the AAP and CHA said.

The number of deaths in children, however, rose from 253 to 266, the largest 1-week increase since early February in the 43 states (along with New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam) that are tracking mortality data by age, the AAP and CHA reported.

Among those 46 jurisdictions, there are 10 (9 states and the District of Columbia) that have not yet reported a COVID-19–related child death, while Texas has almost twice as many deaths, 47, as the next state, Arizona, which has 24. Meanwhile, California’s total of 452,000 cases is almost 2½ times higher than the 183,000 recorded by Illinois, according to the report.

, according to data gathered by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

From Feb. 19 to March 4, the drop in new cases averaged just 5% each week, compared with 13.3% per week over the 5-week period from Jan. 15 to Feb. 18. For the week of March 5-11, a total of 52,695 COVID-19 cases were reported in children, down from 63,562 the previous week and the lowest number since late October, based on data from 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

In those jurisdictions, 3.28 million children have been infected with SARS-CoV-2, representing 13.2% of all cases since the beginning of the pandemic. The cumulative rate of COVID-19 has now risen to 4,364 cases per 100,000 children nationally, with state rates ranging from 1,062 per 100,000 in Hawaii to 8,692 per 100,000 in North Dakota, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

Hospitalization data are more limited – 24 states and New York City – but continue to show that serious illness is much less common in younger individuals: Children represent just 1.9% of all hospitalizations, and only 0.8% of the children who have been infected were hospitalized. Neither rate has changed since early February, the AAP and CHA said.

The number of deaths in children, however, rose from 253 to 266, the largest 1-week increase since early February in the 43 states (along with New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam) that are tracking mortality data by age, the AAP and CHA reported.

Among those 46 jurisdictions, there are 10 (9 states and the District of Columbia) that have not yet reported a COVID-19–related child death, while Texas has almost twice as many deaths, 47, as the next state, Arizona, which has 24. Meanwhile, California’s total of 452,000 cases is almost 2½ times higher than the 183,000 recorded by Illinois, according to the report.

, according to data gathered by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

From Feb. 19 to March 4, the drop in new cases averaged just 5% each week, compared with 13.3% per week over the 5-week period from Jan. 15 to Feb. 18. For the week of March 5-11, a total of 52,695 COVID-19 cases were reported in children, down from 63,562 the previous week and the lowest number since late October, based on data from 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

In those jurisdictions, 3.28 million children have been infected with SARS-CoV-2, representing 13.2% of all cases since the beginning of the pandemic. The cumulative rate of COVID-19 has now risen to 4,364 cases per 100,000 children nationally, with state rates ranging from 1,062 per 100,000 in Hawaii to 8,692 per 100,000 in North Dakota, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

Hospitalization data are more limited – 24 states and New York City – but continue to show that serious illness is much less common in younger individuals: Children represent just 1.9% of all hospitalizations, and only 0.8% of the children who have been infected were hospitalized. Neither rate has changed since early February, the AAP and CHA said.

The number of deaths in children, however, rose from 253 to 266, the largest 1-week increase since early February in the 43 states (along with New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam) that are tracking mortality data by age, the AAP and CHA reported.

Among those 46 jurisdictions, there are 10 (9 states and the District of Columbia) that have not yet reported a COVID-19–related child death, while Texas has almost twice as many deaths, 47, as the next state, Arizona, which has 24. Meanwhile, California’s total of 452,000 cases is almost 2½ times higher than the 183,000 recorded by Illinois, according to the report.

First pill for COVID-19 could be ready by year’s end

New pills to treat patients with COVID-19 are currently in midstage clinical trials and, if successful, could be ready by the end of the year.

Only one treatment – remdesivir (Veklury) – has been fully approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for patients in the hospital and it must be administered intravenously.

Hopes for a day when patients with COVID-19 can take a pill to rid their bodies of the virus got a boost when early trial results were presented at a medical conference.

Interim phase 2 results for the oral experimental COVID-19 drug molnupiravir, designed to do for patients with COVID-19 what oseltamivir (Tamiflu) can do for patients with the flu, were presented at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections 2021 Annual Meeting, as reported by this news organization.

In the small study, the pill significantly reduced infectious virus in patients who were symptomatic and had tested positive for COVID-19 during the previous 4 days but were not hospitalized.

After 5 days of treatment, no participants who received molnupiravir had detectable virus, whereas 24% who received placebo did.

Two other oral agents are being developed by RedHill Biopharma: one for severe COVID-19 infection for hospitalized patients and one for patients at home with mild infection.

The first, opaganib (Yeliva), proceeded to a phase 2/3 global trial for hospitalized patients after the company announced top-line safety and efficacy data in December. In phase 2, the drug was shown to be safe in patients requiring oxygen and effectively reduced the need for oxygen by the end of the treatment period.

A key feature is that it is both an antiviral and an anti-inflammatory, Gilead Raday, RedHill’s chief operating officer, said in an interview. Data are expected midyear on its performance in 464 patients. The drug is being tested on top of remdesivir or in addition to dexamethasone.

The second, upamostat (RHB-107), is currently undergoing a phase 2/3 trial in the United States and is being investigated for use in nonhospitalized COVID-19 patients.

“I would expect data to be available in the second half of this year,” Mr. Raday said.

Upamostat is a novel serine protease inhibitor expected to be effective against emerging variants because it targets human cell factors involved in viral entry, according to the company.

Other drugs are being investigated in trials that are in earlier stages.

Urgent need for oral agents

Infectious disease specialists are watching the move toward a COVID-19 pill enthusiastically.

“We badly need an oral treatment option for COVID,” said Sarah Doernberg, MD, an infectious disease specialist from the University of California, San Francisco.

“It’s a real gap in our armamentarium for COVID in outpatient treatment, which is where most who contract COVID-19 will seek care,” she said in an interview.

Although some studies have shown the benefit of monoclonal antibodies for prevention and early treatment, there are major logistical issues because all the current options require IV administration, she explained.

“If we had a pill to treat early COVID, especially in high-risk patients, it would fill a gap,” she said, noting that a pill could help people get better faster and prevent hospital stays.

Studies of molnupiravir suggest that it decreases viral shedding in the first few days after COVID infection, Dr. Doernberg reported.

There is excitement around the drug, but it will be important to see whether the results translate into fewer people requiring hospital admission and whether people feel better faster.

“I want to see the clinical data,” Dr. Doernberg said.

She will also be watching for the upamostat and opaganib results in the coming weeks.

“If these drugs are successful, I think it’s possible we could use them – maybe under an emergency use authorization – this year,” she said.

Once antiviral pills are a viable option for COVID-19 treatment, questions will arise about their use, she said.

One question is whether patients who are getting remdesivir in the hospital and are ready to leave after 5 days should continue treatment with antiviral pills at home.

Another is whether the pills – if they are shown to be effective – will be helpful for COVID post exposure. That use would be important for people who do not have COVID-19 but who are in close contact with someone who does, such as a member of their household.

“We have that model,” Dr. Doernberg said. “We know that oseltamivir can be used for postexposure prophylaxis and can help to prevent development of clinical disease.”

But she cautioned that a challenge with COVID is that people are contagious very early. A pill would need to come with the ability to test for COVID-19 early and get patients linked to care immediately.

“Those are not small challenges,” she said.

Vaccines alone won’t end the COVID threat

Treatments are part of the “belt-and-suspenders” approach, along with vaccines to combat COVID-19, Dr. Doernberg said.

“We’re not going to eradicate COVID,” she said. “We’re still going to need treatments for people who either don’t respond to the vaccine or haven’t gotten the vaccine or developed disease despite the vaccine.”

Oral formulations are desperately needed, agreed Kenneth Johnson, PhD, professor of molecular biosciences at the University of Texas at Austin.

Right now, remdesivir treatments involve patients being hooked up to an IV for 30-120 minutes each day for 5 days. And the cost of a 5-day course of remdesivir ranges from $2340 to $3120 in the United States.

“We’re hoping we can come up with something that is a little bit easier to administer, and without as many concerns for toxic side effects,” he said.

Dr. Johnson’s team at UT-Austin recently made a key discovery about the way remdesivir stops the replication of viral RNA.

The understanding of where the virus starts to replicate in the infection chain of events and how and where it reacts with remdesivir might lead to the development of better, more concentrated pill forms of antivirals in the future, with fewer toxicities, he said.

The team used a lab dish to recreate the step-by-step process that occurs when a patient who is infected with SARS-CoV-2 receives remdesivir.

The discovery was published online in Molecular Cell in January and will be printed in the April issue of the journal.

The discovery won’t lead to an effective COVID-19 pill for our current crisis, but will be important for the next generation of drugs needed to deal with future coronaviruses, Dr. Johnson explained.

And there will be other coronaviruses, he said, noting that this one is the third in 20 years to jump from animals to humans. “It’s just a matter of time,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New pills to treat patients with COVID-19 are currently in midstage clinical trials and, if successful, could be ready by the end of the year.

Only one treatment – remdesivir (Veklury) – has been fully approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for patients in the hospital and it must be administered intravenously.

Hopes for a day when patients with COVID-19 can take a pill to rid their bodies of the virus got a boost when early trial results were presented at a medical conference.

Interim phase 2 results for the oral experimental COVID-19 drug molnupiravir, designed to do for patients with COVID-19 what oseltamivir (Tamiflu) can do for patients with the flu, were presented at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections 2021 Annual Meeting, as reported by this news organization.

In the small study, the pill significantly reduced infectious virus in patients who were symptomatic and had tested positive for COVID-19 during the previous 4 days but were not hospitalized.

After 5 days of treatment, no participants who received molnupiravir had detectable virus, whereas 24% who received placebo did.

Two other oral agents are being developed by RedHill Biopharma: one for severe COVID-19 infection for hospitalized patients and one for patients at home with mild infection.

The first, opaganib (Yeliva), proceeded to a phase 2/3 global trial for hospitalized patients after the company announced top-line safety and efficacy data in December. In phase 2, the drug was shown to be safe in patients requiring oxygen and effectively reduced the need for oxygen by the end of the treatment period.

A key feature is that it is both an antiviral and an anti-inflammatory, Gilead Raday, RedHill’s chief operating officer, said in an interview. Data are expected midyear on its performance in 464 patients. The drug is being tested on top of remdesivir or in addition to dexamethasone.

The second, upamostat (RHB-107), is currently undergoing a phase 2/3 trial in the United States and is being investigated for use in nonhospitalized COVID-19 patients.

“I would expect data to be available in the second half of this year,” Mr. Raday said.

Upamostat is a novel serine protease inhibitor expected to be effective against emerging variants because it targets human cell factors involved in viral entry, according to the company.

Other drugs are being investigated in trials that are in earlier stages.

Urgent need for oral agents

Infectious disease specialists are watching the move toward a COVID-19 pill enthusiastically.

“We badly need an oral treatment option for COVID,” said Sarah Doernberg, MD, an infectious disease specialist from the University of California, San Francisco.

“It’s a real gap in our armamentarium for COVID in outpatient treatment, which is where most who contract COVID-19 will seek care,” she said in an interview.

Although some studies have shown the benefit of monoclonal antibodies for prevention and early treatment, there are major logistical issues because all the current options require IV administration, she explained.

“If we had a pill to treat early COVID, especially in high-risk patients, it would fill a gap,” she said, noting that a pill could help people get better faster and prevent hospital stays.

Studies of molnupiravir suggest that it decreases viral shedding in the first few days after COVID infection, Dr. Doernberg reported.

There is excitement around the drug, but it will be important to see whether the results translate into fewer people requiring hospital admission and whether people feel better faster.

“I want to see the clinical data,” Dr. Doernberg said.

She will also be watching for the upamostat and opaganib results in the coming weeks.

“If these drugs are successful, I think it’s possible we could use them – maybe under an emergency use authorization – this year,” she said.

Once antiviral pills are a viable option for COVID-19 treatment, questions will arise about their use, she said.

One question is whether patients who are getting remdesivir in the hospital and are ready to leave after 5 days should continue treatment with antiviral pills at home.

Another is whether the pills – if they are shown to be effective – will be helpful for COVID post exposure. That use would be important for people who do not have COVID-19 but who are in close contact with someone who does, such as a member of their household.

“We have that model,” Dr. Doernberg said. “We know that oseltamivir can be used for postexposure prophylaxis and can help to prevent development of clinical disease.”

But she cautioned that a challenge with COVID is that people are contagious very early. A pill would need to come with the ability to test for COVID-19 early and get patients linked to care immediately.

“Those are not small challenges,” she said.

Vaccines alone won’t end the COVID threat

Treatments are part of the “belt-and-suspenders” approach, along with vaccines to combat COVID-19, Dr. Doernberg said.

“We’re not going to eradicate COVID,” she said. “We’re still going to need treatments for people who either don’t respond to the vaccine or haven’t gotten the vaccine or developed disease despite the vaccine.”

Oral formulations are desperately needed, agreed Kenneth Johnson, PhD, professor of molecular biosciences at the University of Texas at Austin.

Right now, remdesivir treatments involve patients being hooked up to an IV for 30-120 minutes each day for 5 days. And the cost of a 5-day course of remdesivir ranges from $2340 to $3120 in the United States.

“We’re hoping we can come up with something that is a little bit easier to administer, and without as many concerns for toxic side effects,” he said.

Dr. Johnson’s team at UT-Austin recently made a key discovery about the way remdesivir stops the replication of viral RNA.

The understanding of where the virus starts to replicate in the infection chain of events and how and where it reacts with remdesivir might lead to the development of better, more concentrated pill forms of antivirals in the future, with fewer toxicities, he said.

The team used a lab dish to recreate the step-by-step process that occurs when a patient who is infected with SARS-CoV-2 receives remdesivir.

The discovery was published online in Molecular Cell in January and will be printed in the April issue of the journal.

The discovery won’t lead to an effective COVID-19 pill for our current crisis, but will be important for the next generation of drugs needed to deal with future coronaviruses, Dr. Johnson explained.

And there will be other coronaviruses, he said, noting that this one is the third in 20 years to jump from animals to humans. “It’s just a matter of time,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New pills to treat patients with COVID-19 are currently in midstage clinical trials and, if successful, could be ready by the end of the year.

Only one treatment – remdesivir (Veklury) – has been fully approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for patients in the hospital and it must be administered intravenously.

Hopes for a day when patients with COVID-19 can take a pill to rid their bodies of the virus got a boost when early trial results were presented at a medical conference.

Interim phase 2 results for the oral experimental COVID-19 drug molnupiravir, designed to do for patients with COVID-19 what oseltamivir (Tamiflu) can do for patients with the flu, were presented at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections 2021 Annual Meeting, as reported by this news organization.

In the small study, the pill significantly reduced infectious virus in patients who were symptomatic and had tested positive for COVID-19 during the previous 4 days but were not hospitalized.

After 5 days of treatment, no participants who received molnupiravir had detectable virus, whereas 24% who received placebo did.

Two other oral agents are being developed by RedHill Biopharma: one for severe COVID-19 infection for hospitalized patients and one for patients at home with mild infection.

The first, opaganib (Yeliva), proceeded to a phase 2/3 global trial for hospitalized patients after the company announced top-line safety and efficacy data in December. In phase 2, the drug was shown to be safe in patients requiring oxygen and effectively reduced the need for oxygen by the end of the treatment period.

A key feature is that it is both an antiviral and an anti-inflammatory, Gilead Raday, RedHill’s chief operating officer, said in an interview. Data are expected midyear on its performance in 464 patients. The drug is being tested on top of remdesivir or in addition to dexamethasone.

The second, upamostat (RHB-107), is currently undergoing a phase 2/3 trial in the United States and is being investigated for use in nonhospitalized COVID-19 patients.

“I would expect data to be available in the second half of this year,” Mr. Raday said.

Upamostat is a novel serine protease inhibitor expected to be effective against emerging variants because it targets human cell factors involved in viral entry, according to the company.

Other drugs are being investigated in trials that are in earlier stages.

Urgent need for oral agents

Infectious disease specialists are watching the move toward a COVID-19 pill enthusiastically.

“We badly need an oral treatment option for COVID,” said Sarah Doernberg, MD, an infectious disease specialist from the University of California, San Francisco.

“It’s a real gap in our armamentarium for COVID in outpatient treatment, which is where most who contract COVID-19 will seek care,” she said in an interview.

Although some studies have shown the benefit of monoclonal antibodies for prevention and early treatment, there are major logistical issues because all the current options require IV administration, she explained.

“If we had a pill to treat early COVID, especially in high-risk patients, it would fill a gap,” she said, noting that a pill could help people get better faster and prevent hospital stays.

Studies of molnupiravir suggest that it decreases viral shedding in the first few days after COVID infection, Dr. Doernberg reported.

There is excitement around the drug, but it will be important to see whether the results translate into fewer people requiring hospital admission and whether people feel better faster.

“I want to see the clinical data,” Dr. Doernberg said.

She will also be watching for the upamostat and opaganib results in the coming weeks.

“If these drugs are successful, I think it’s possible we could use them – maybe under an emergency use authorization – this year,” she said.

Once antiviral pills are a viable option for COVID-19 treatment, questions will arise about their use, she said.

One question is whether patients who are getting remdesivir in the hospital and are ready to leave after 5 days should continue treatment with antiviral pills at home.

Another is whether the pills – if they are shown to be effective – will be helpful for COVID post exposure. That use would be important for people who do not have COVID-19 but who are in close contact with someone who does, such as a member of their household.

“We have that model,” Dr. Doernberg said. “We know that oseltamivir can be used for postexposure prophylaxis and can help to prevent development of clinical disease.”

But she cautioned that a challenge with COVID is that people are contagious very early. A pill would need to come with the ability to test for COVID-19 early and get patients linked to care immediately.

“Those are not small challenges,” she said.

Vaccines alone won’t end the COVID threat

Treatments are part of the “belt-and-suspenders” approach, along with vaccines to combat COVID-19, Dr. Doernberg said.

“We’re not going to eradicate COVID,” she said. “We’re still going to need treatments for people who either don’t respond to the vaccine or haven’t gotten the vaccine or developed disease despite the vaccine.”

Oral formulations are desperately needed, agreed Kenneth Johnson, PhD, professor of molecular biosciences at the University of Texas at Austin.

Right now, remdesivir treatments involve patients being hooked up to an IV for 30-120 minutes each day for 5 days. And the cost of a 5-day course of remdesivir ranges from $2340 to $3120 in the United States.

“We’re hoping we can come up with something that is a little bit easier to administer, and without as many concerns for toxic side effects,” he said.