User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Maternal Immunization to Prevent Serious Respiratory Illness

Editor’s Note: Sadly, this is the last column in the Master Class Obstetrics series. This award-winning column has been part of Ob.Gyn. News for 20 years. The deep discussion of cutting-edge topics in obstetrics by specialists and researchers will be missed as will the leadership and curation of topics by Dr. E. Albert Reece.

Introduction: The Need for Increased Vigilance About Maternal Immunization

Viruses are becoming increasingly prevalent in our world and the consequences of viral infections are implicated in a growing number of disease states. It is well established that certain cancers are caused by viruses and it is increasingly evident that viral infections can trigger the development of chronic illness. In pregnant women, viruses such as cytomegalovirus can cause infection in utero and lead to long-term impairments for the baby.

Likewise, it appears that the virulence of viruses is increasing, whether it be the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in children or the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronaviruses in adults. Clearly, our environment is changing, with increases in population growth and urbanization, for instance, and an intensification of climate change and its effects. Viruses are part of this changing background.

Vaccines are our most powerful tool to protect people of all ages against viral threats, and fortunately, we benefit from increasing expertise in vaccinology. Since 1974, the University of Maryland School of Medicine has a Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health that has conducted research on vaccines to defend against the Zika virus, H1N1, Ebola, and SARS-CoV-2.

We’re not alone. Other vaccinology centers across the country — as well as the National Institutes of Health at the national level, through its National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases — are doing research and developing vaccines to combat viral diseases.

In this column, we are focused on viral diseases in pregnancy and the role that vaccines can play in preventing serious respiratory illness in mothers and their newborns. I have invited Laura E. Riley, MD, the Given Foundation Professor and Chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Weill Cornell Medicine, to address the importance of maternal immunization and how we can best counsel our patients and improve immunization rates.

As Dr. Riley explains, we are in a new era, and it behooves us all to be more vigilant about recommending vaccines, combating misperceptions, addressing patients’ knowledge gaps, and administering vaccines whenever possible.

Dr. Reece is the former Dean of Medicine & University Executive VP, and The Distinguished University and Endowed Professor & Director of the Center for Advanced Research Training and Innovation (CARTI) at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, as well as senior scientist at the Center for Birth Defects Research.

The alarming decline in maternal immunization rates that occurred in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic means that, now more than ever, we must fully embrace our responsibility to recommend immunizations in pregnancy and to communicate what is known about their efficacy and safety. Data show that vaccination rates drop when we do not offer vaccines in our offices, so whenever possible, we should administer them as well.

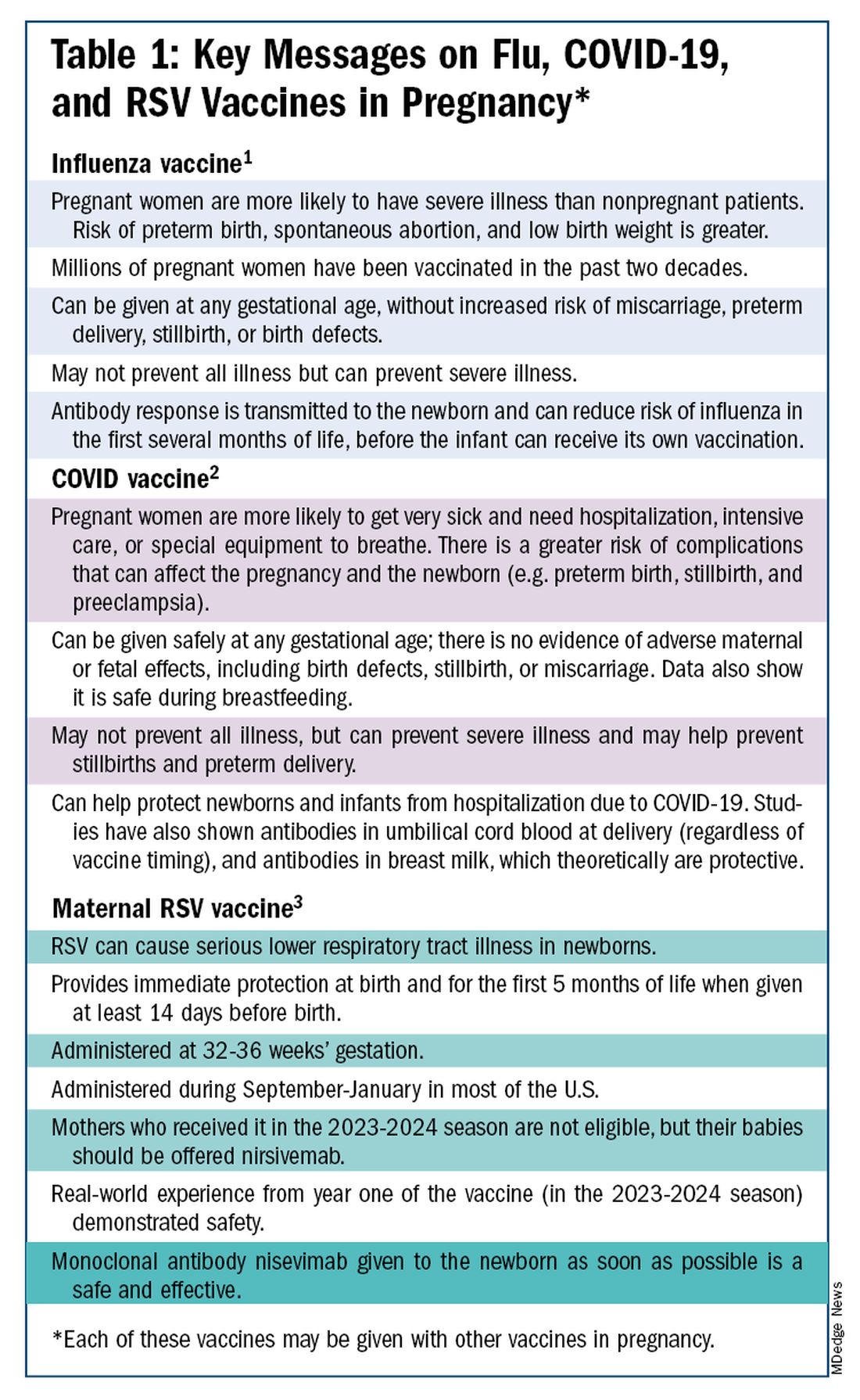

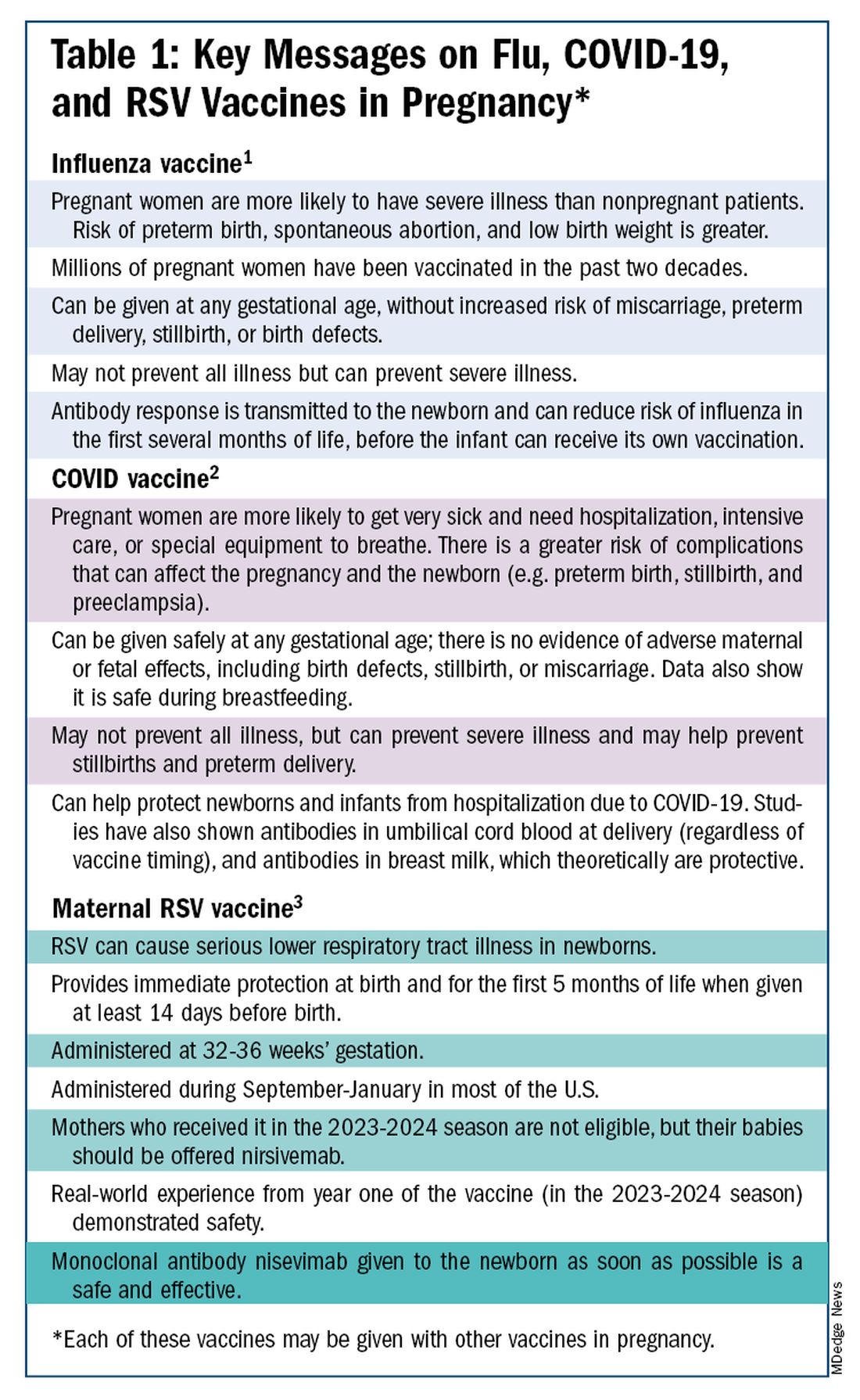

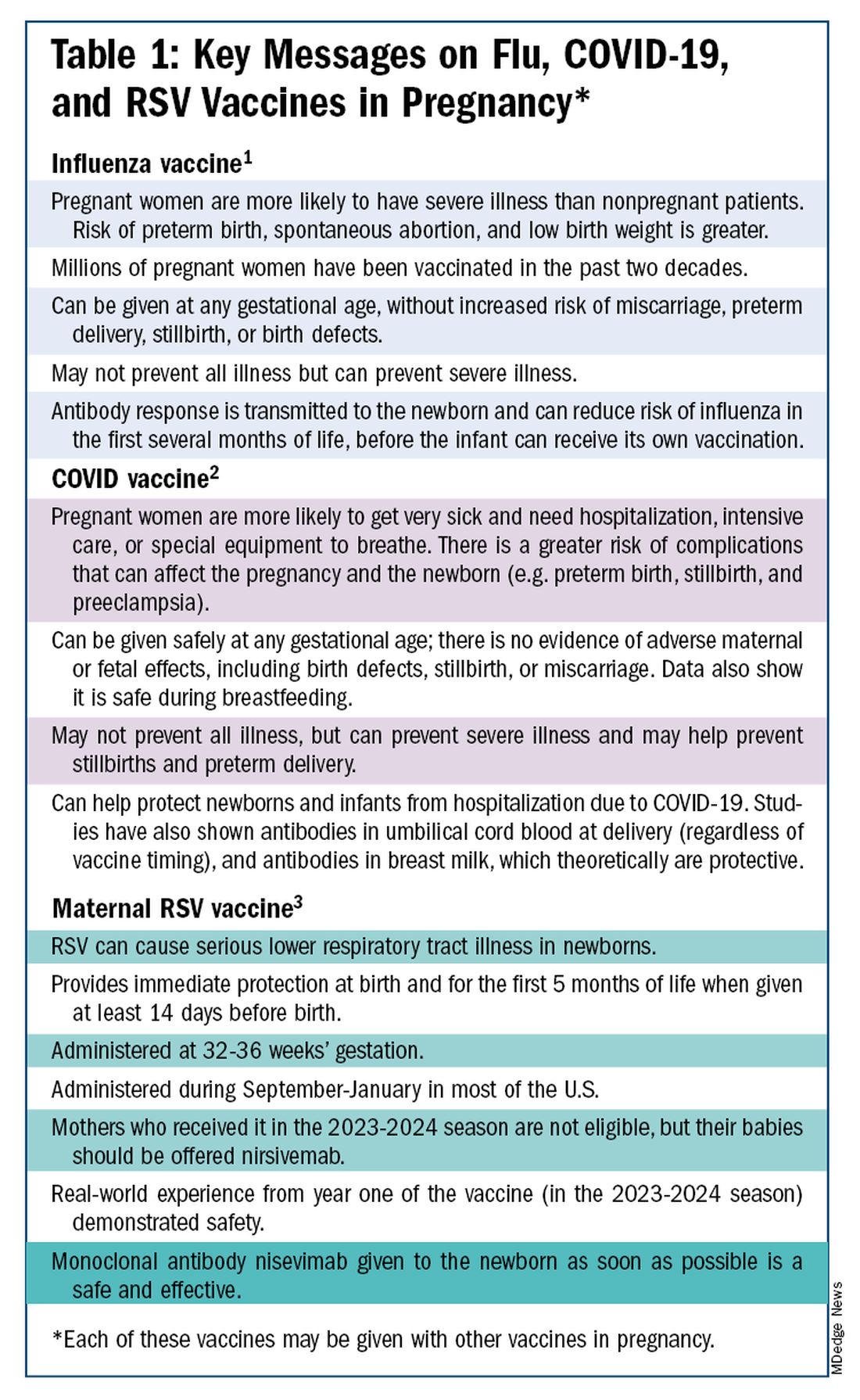

The ob.gyn. is the patient’s most trusted person in pregnancy. When patients decline or express hesitancy about vaccines, it is incumbent upon us to ask why. Oftentimes, we can identify areas in which patients lack knowledge or have misperceptions and we can successfully educate the patient or change their perspective or misunderstanding concerning the importance of vaccination for themselves and their babies. (See Table 1.) We can also successfully address concerns about safety.

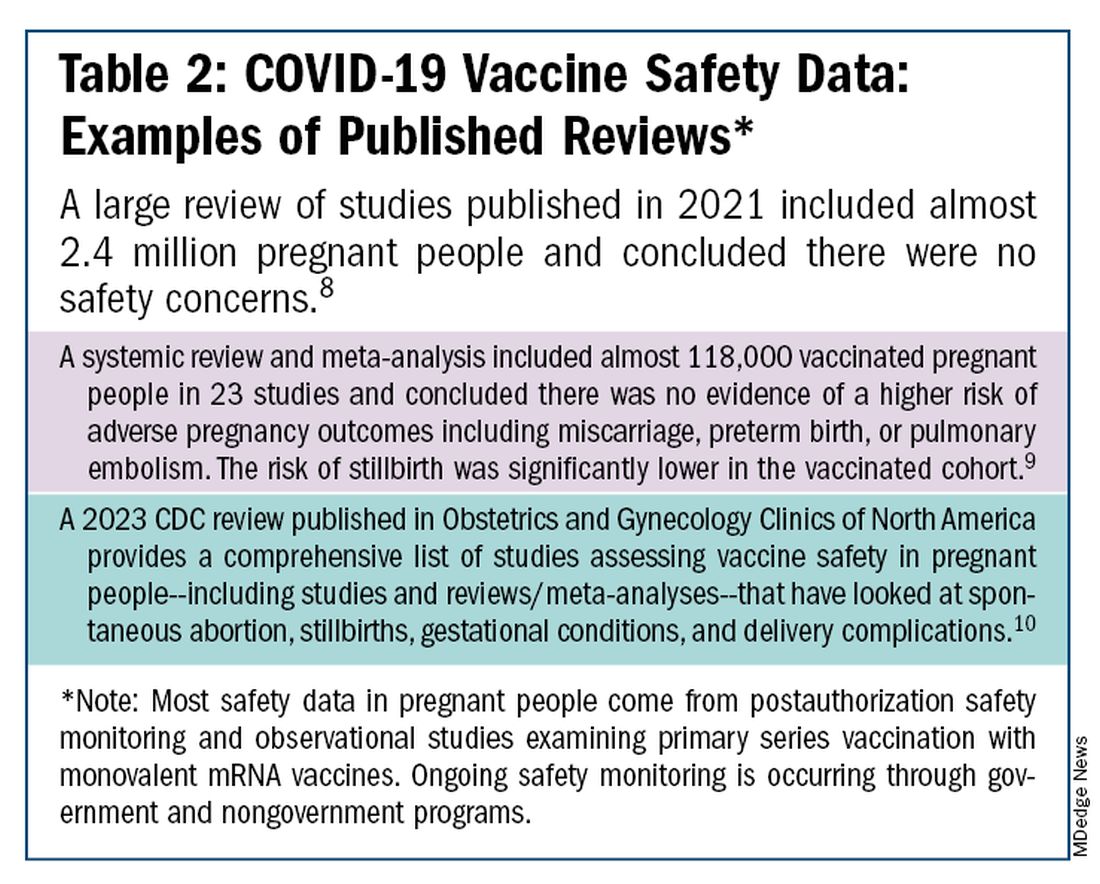

The safety of COVID-19 vaccinations in pregnancy is now backed by several years of data from multiple studies showing no increase in birth defects, preterm delivery, miscarriage, or stillbirth.

Data also show that pregnant patients are more likely than patients who are not pregnant to need hospitalization and intensive care when infected with SARS-CoV-2 and are at risk of having complications that can affect pregnancy and the newborn, including preterm birth and stillbirth. Vaccination has been shown to reduce the risk of severe illness and the risk of such adverse obstetrical outcomes, in addition to providing protection for the infant early on.

Similarly, influenza has long been more likely to be severe in pregnant patients, with an increased risk of poor obstetrical outcomes. Vaccines similarly provide “two for one protection,” protecting both mother and baby, and are, of course, backed by many years of safety and efficacy data.

With the new maternal respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine, now in its second year of availability, the goal is to protect the baby from RSV-caused serious lower respiratory tract illness. The illness has contributed to tens of thousands of annual hospitalizations and up to several hundred deaths every year in children younger than 5 years — particularly in those under age 6 months.

The RSV monoclonal antibody nirsevimab is available for the newborn as an alternative to maternal immunization but the maternal vaccine is optimal in that it will provide immediate rather than delayed protection for the newborn. The maternal vaccine is recommended during weeks 32-36 of pregnancy in mothers who were not vaccinated during last year’s RSV season. With real-world experience from year one, the available safety data are reassuring.

Counseling About Influenza and COVID-19 Vaccination

The COVID-19 pandemic took a toll on vaccination interest/receptivity broadly in pregnant and nonpregnant people. Among pregnant individuals, influenza vaccination coverage declined from 71% in the 2019-2020 influenza season to 56% in the 2021-2022 season, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Vaccine Safety Datalink.4 Coverage for the 2022-2023 and 2023-2024 influenza seasons was even worse: well under 50%.5

Fewer pregnant women have received updated COVID-19 vaccines. Only 13% of pregnant persons overall received the updated 2023-2024 COVID-19 booster vaccine (through March 30, 2024), according to the CDC.6

Maternal immunization for influenza has been recommended in the United States since 2004 (part of the recommendation that everyone over the age of 6 months receive an annual flu vaccine), and flu vaccines have been given to millions of pregnant women, but the H1N1 pandemic of 2009 reinforced its value as a priority for prenatal care. Most of the women who became severely ill from the H1N1 virus were young and healthy, without co-existing conditions known to increase risk.7

It became clearer during the H1N1 pandemic that pregnancy itself — which is associated with physiologic changes such as decreased lung capacity, increased nasal congestion and changes in the immune system – is its own significant risk factor for severe illness from the influenza virus. This increased risk applies to COVID-19 as well.

As COVID-19 has become endemic, with hospitalizations and deaths not reaching the levels of previous surges — and with mask-wearing and other preventive measures having declined — patients understandably have become more complacent. Some patients are vaccine deniers, but in my practice, these patients are a much smaller group than those who believe COVID-19 “is no big deal,” especially if they have had infections recently.

This is why it’s important to actively listen to concerns and to ask patients who decline a vaccination why they are hesitant. Blanket messages about vaccine efficacy and safety are the first step, but individualized, more pointed conversations based on the patient’s personal experiences and beliefs have become increasingly important.

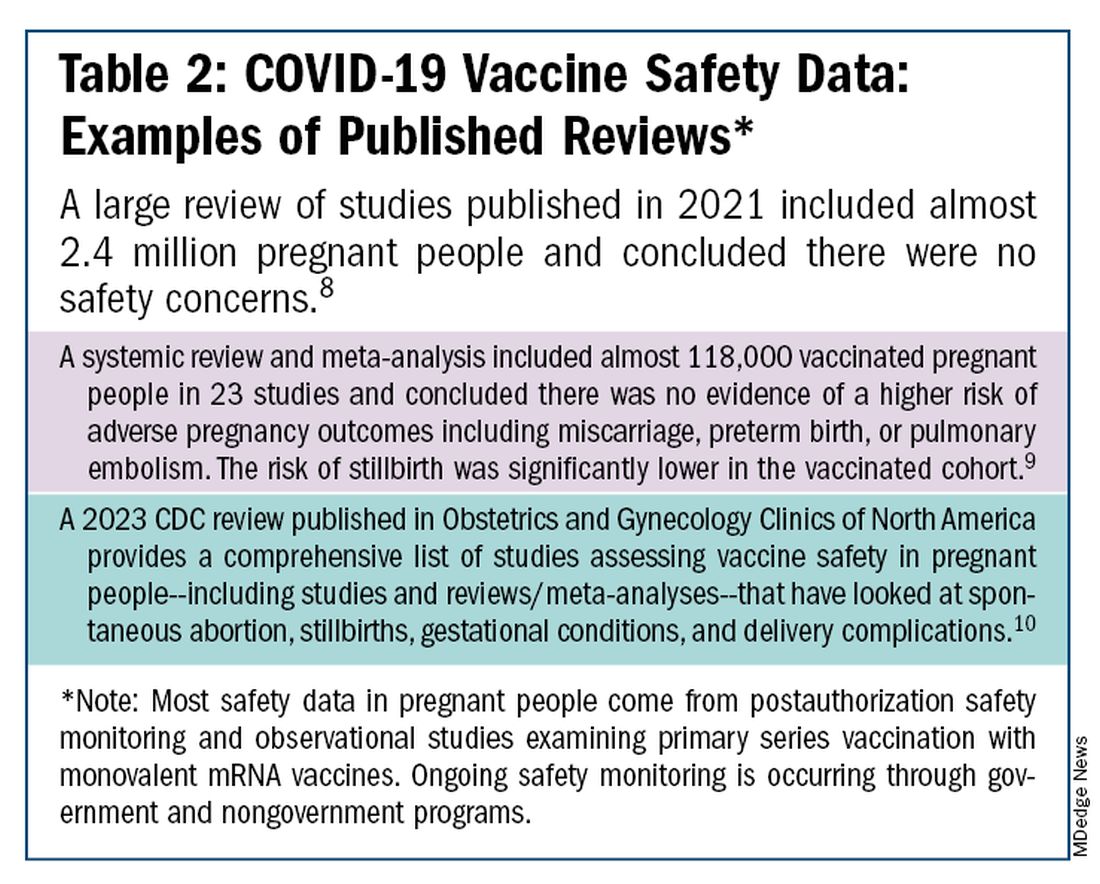

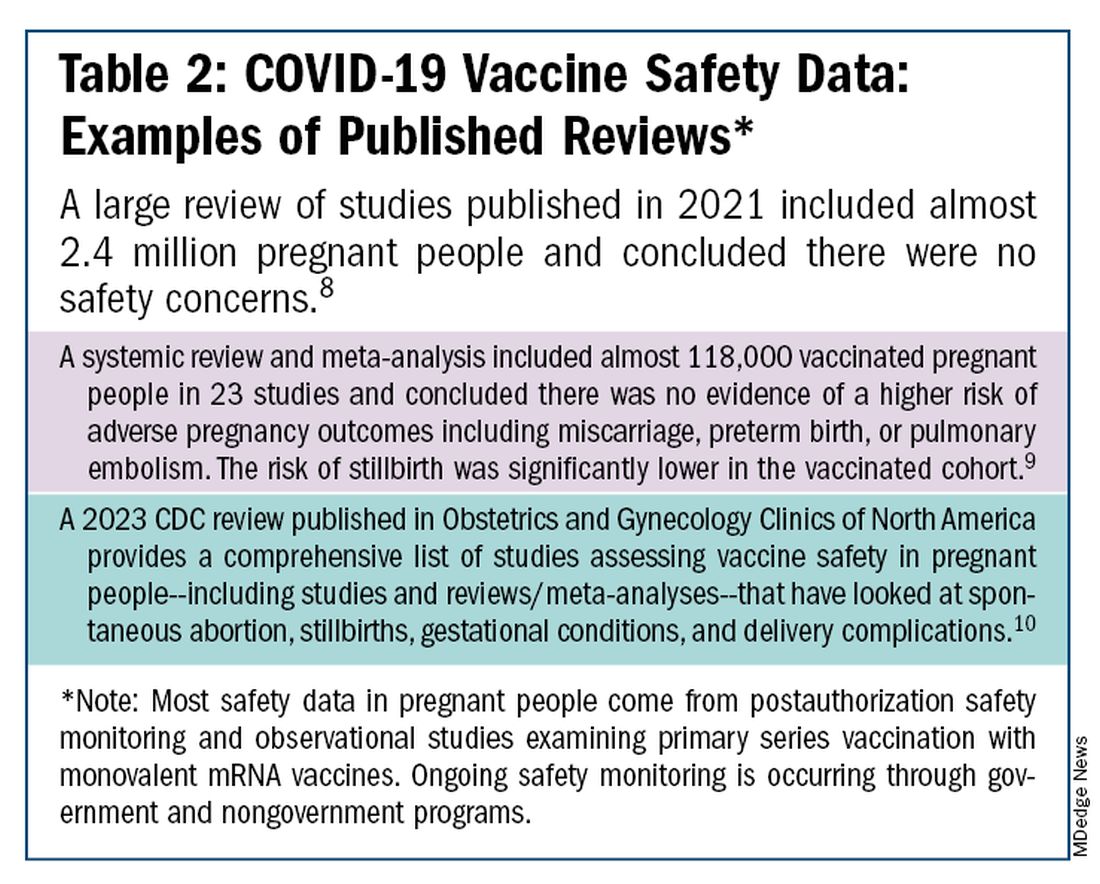

I routinely tell pregnant patients about the risks of COVID-19 and I explain that it has been difficult to predict who will develop severe illness. Sometimes more conversation is needed. For those who are still hesitant or who tell me they feel protected by a recent infection, for instance, I provide more detail on the unique risks of pregnancy — the fact that “pregnancy is different” — and that natural immunity wanes while the protection afforded by immunization is believed to last longer. Many women are also concerned about the safety of the COVID-19 vaccine, so having safety data at your fingertips is helpful. (See Table 2.)

The fact that influenza and COVID-19 vaccination protect the newborn as well as the mother is something that I find is underappreciated by many patients. Explaining that infants likely benefit from the passage of antibodies across the placenta should be part of patient counseling.

Counseling About RSV Vaccination

Importantly, for the 2024-2025 RSV season, the maternal RSV vaccine (Abrysvo, Pfizer) is recommended only for pregnant women who did not receive the vaccine during the 2023-2024 season. When more research is done and more data are obtained showing how long the immune response persists post vaccination, it may be that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) will approve the maternal RSV vaccine for use in every pregnancy.

The later timing of the vaccination recommendation — 32-36 weeks’ gestation — reflects a conservative approach taken by the FDA in response to data from one of the pivotal trials showing a numerical trend toward more preterm deliveries among vaccinated compared with unvaccinated patients. This imbalance in the original trial, which administered the vaccine during 24-36 weeks of gestation, was seen only in low-income countries with no temporal association, however.

In our experience at two Weill Cornell Medical College–associated hospitals we did not see this trend. Our cohort study of almost 3000 pregnant patients who delivered at 32 weeks’ gestation or later found no increased risk of preterm birth among the 35% of patients who received the RSV vaccine during the 2023-2024 RSV season. We also did not see any difference in preeclampsia, in contrast with original trial data that showed a signal for increased risk.11

When fewer than 2 weeks have elapsed between maternal vaccination and delivery, the monoclonal antibody nirsevimab is recommended for the newborn — ideally before the newborn leaves the hospital. Nirsevimab is also recommended for newborns of mothers who decline vaccination or were not candidates (e.g. vaccinated in a previous pregnancy), or when there is concern about the adequacy of the maternal immune response to the vaccine (e.g. in cases of immunosuppression).

While there was a limited supply of the monoclonal antibody last year, limitations are not expected this year, especially after October.

The ultimate goal is that patients choose the vaccine or the immunoglobulin, given the severity of RSV disease. Patient preferences should be considered. However, given that it takes 2 weeks after vaccination for protection to build up, I stress to patients that if they’ve vaccinated themselves, their newborn will leave the hospital with protection. If nirsevimab is relied upon, I explain, their newborn may not be protected for some period of time.

Take-home Messages

- When patients decline or are hesitant about vaccines, ask why. Listen actively, and work to correct misperceptions and knowledge gaps.

- Whenever possible, offer vaccines in your practice. Vaccination rates drop when this does not occur.

- COVID-vaccine safety is backed by many studies showing no increase in birth defects, preterm delivery, miscarriage, or stillbirth.

- Pregnant women are more likely to have severe illness from the influenza and SARS-CoV-2 viruses. Vaccines can prevent severe illness and can protect the newborn as well as the mother.

- Recommend/administer the maternal RSV vaccine at 32-36 weeks’ gestation in women who did not receive the vaccine in the 2023-2024 season. If mothers aren’t eligible their babies should be offered nirsevimab.

Dr. Riley is the Given Foundation Professor and Chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Weill Cornell Medicine and the obstetrician and gynecologist-in-chief at New York Presbyterian Hospital. She disclosed that she has provided one-time consultations to Pfizer (Abrysvo RSV vaccine) and GSK (cytomegalovirus vaccine), and is providing consultant education on CMV for Moderna. She is chair of ACOG’s task force on immunization and emerging infectious diseases, serves on the medical advisory board for MAVEN, and serves as an editor or editorial board member for several medical publications.

References

1. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 741: Maternal Immunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(6):e214-e217.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 Vaccination for People Who are Pregnant or Breastfeeding. https://www.cdc.gov/covid/vaccines/pregnant-or-breastfeeding.html.

3. ACOG Practice Advisory on Maternal Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccination, September 2023. (Updated August 2024).4. Irving S et al. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023;10(Suppl 2):ofad500.1002.

5. Flu Vaccination Dashboard, CDC, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

6. Weekly COVID-19 Vaccination Dashboard, CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/covidvaxview/weekly-dashboard/index.html

7. Louie JK et al. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:27-35. 8. Ciapponi A et al. Vaccine. 2021;39(40):5891-908.

9. Prasad S et al. Nature Communications. 2022;13:2414. 10. Fleming-Dutra KE et al. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2023;50(2):279-97. 11. Mouen S et al. JAMA Network Open 2024;7(7):e2419268.

Editor’s Note: Sadly, this is the last column in the Master Class Obstetrics series. This award-winning column has been part of Ob.Gyn. News for 20 years. The deep discussion of cutting-edge topics in obstetrics by specialists and researchers will be missed as will the leadership and curation of topics by Dr. E. Albert Reece.

Introduction: The Need for Increased Vigilance About Maternal Immunization

Viruses are becoming increasingly prevalent in our world and the consequences of viral infections are implicated in a growing number of disease states. It is well established that certain cancers are caused by viruses and it is increasingly evident that viral infections can trigger the development of chronic illness. In pregnant women, viruses such as cytomegalovirus can cause infection in utero and lead to long-term impairments for the baby.

Likewise, it appears that the virulence of viruses is increasing, whether it be the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in children or the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronaviruses in adults. Clearly, our environment is changing, with increases in population growth and urbanization, for instance, and an intensification of climate change and its effects. Viruses are part of this changing background.

Vaccines are our most powerful tool to protect people of all ages against viral threats, and fortunately, we benefit from increasing expertise in vaccinology. Since 1974, the University of Maryland School of Medicine has a Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health that has conducted research on vaccines to defend against the Zika virus, H1N1, Ebola, and SARS-CoV-2.

We’re not alone. Other vaccinology centers across the country — as well as the National Institutes of Health at the national level, through its National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases — are doing research and developing vaccines to combat viral diseases.

In this column, we are focused on viral diseases in pregnancy and the role that vaccines can play in preventing serious respiratory illness in mothers and their newborns. I have invited Laura E. Riley, MD, the Given Foundation Professor and Chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Weill Cornell Medicine, to address the importance of maternal immunization and how we can best counsel our patients and improve immunization rates.

As Dr. Riley explains, we are in a new era, and it behooves us all to be more vigilant about recommending vaccines, combating misperceptions, addressing patients’ knowledge gaps, and administering vaccines whenever possible.

Dr. Reece is the former Dean of Medicine & University Executive VP, and The Distinguished University and Endowed Professor & Director of the Center for Advanced Research Training and Innovation (CARTI) at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, as well as senior scientist at the Center for Birth Defects Research.

The alarming decline in maternal immunization rates that occurred in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic means that, now more than ever, we must fully embrace our responsibility to recommend immunizations in pregnancy and to communicate what is known about their efficacy and safety. Data show that vaccination rates drop when we do not offer vaccines in our offices, so whenever possible, we should administer them as well.

The ob.gyn. is the patient’s most trusted person in pregnancy. When patients decline or express hesitancy about vaccines, it is incumbent upon us to ask why. Oftentimes, we can identify areas in which patients lack knowledge or have misperceptions and we can successfully educate the patient or change their perspective or misunderstanding concerning the importance of vaccination for themselves and their babies. (See Table 1.) We can also successfully address concerns about safety.

The safety of COVID-19 vaccinations in pregnancy is now backed by several years of data from multiple studies showing no increase in birth defects, preterm delivery, miscarriage, or stillbirth.

Data also show that pregnant patients are more likely than patients who are not pregnant to need hospitalization and intensive care when infected with SARS-CoV-2 and are at risk of having complications that can affect pregnancy and the newborn, including preterm birth and stillbirth. Vaccination has been shown to reduce the risk of severe illness and the risk of such adverse obstetrical outcomes, in addition to providing protection for the infant early on.

Similarly, influenza has long been more likely to be severe in pregnant patients, with an increased risk of poor obstetrical outcomes. Vaccines similarly provide “two for one protection,” protecting both mother and baby, and are, of course, backed by many years of safety and efficacy data.

With the new maternal respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine, now in its second year of availability, the goal is to protect the baby from RSV-caused serious lower respiratory tract illness. The illness has contributed to tens of thousands of annual hospitalizations and up to several hundred deaths every year in children younger than 5 years — particularly in those under age 6 months.

The RSV monoclonal antibody nirsevimab is available for the newborn as an alternative to maternal immunization but the maternal vaccine is optimal in that it will provide immediate rather than delayed protection for the newborn. The maternal vaccine is recommended during weeks 32-36 of pregnancy in mothers who were not vaccinated during last year’s RSV season. With real-world experience from year one, the available safety data are reassuring.

Counseling About Influenza and COVID-19 Vaccination

The COVID-19 pandemic took a toll on vaccination interest/receptivity broadly in pregnant and nonpregnant people. Among pregnant individuals, influenza vaccination coverage declined from 71% in the 2019-2020 influenza season to 56% in the 2021-2022 season, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Vaccine Safety Datalink.4 Coverage for the 2022-2023 and 2023-2024 influenza seasons was even worse: well under 50%.5

Fewer pregnant women have received updated COVID-19 vaccines. Only 13% of pregnant persons overall received the updated 2023-2024 COVID-19 booster vaccine (through March 30, 2024), according to the CDC.6

Maternal immunization for influenza has been recommended in the United States since 2004 (part of the recommendation that everyone over the age of 6 months receive an annual flu vaccine), and flu vaccines have been given to millions of pregnant women, but the H1N1 pandemic of 2009 reinforced its value as a priority for prenatal care. Most of the women who became severely ill from the H1N1 virus were young and healthy, without co-existing conditions known to increase risk.7

It became clearer during the H1N1 pandemic that pregnancy itself — which is associated with physiologic changes such as decreased lung capacity, increased nasal congestion and changes in the immune system – is its own significant risk factor for severe illness from the influenza virus. This increased risk applies to COVID-19 as well.

As COVID-19 has become endemic, with hospitalizations and deaths not reaching the levels of previous surges — and with mask-wearing and other preventive measures having declined — patients understandably have become more complacent. Some patients are vaccine deniers, but in my practice, these patients are a much smaller group than those who believe COVID-19 “is no big deal,” especially if they have had infections recently.

This is why it’s important to actively listen to concerns and to ask patients who decline a vaccination why they are hesitant. Blanket messages about vaccine efficacy and safety are the first step, but individualized, more pointed conversations based on the patient’s personal experiences and beliefs have become increasingly important.

I routinely tell pregnant patients about the risks of COVID-19 and I explain that it has been difficult to predict who will develop severe illness. Sometimes more conversation is needed. For those who are still hesitant or who tell me they feel protected by a recent infection, for instance, I provide more detail on the unique risks of pregnancy — the fact that “pregnancy is different” — and that natural immunity wanes while the protection afforded by immunization is believed to last longer. Many women are also concerned about the safety of the COVID-19 vaccine, so having safety data at your fingertips is helpful. (See Table 2.)

The fact that influenza and COVID-19 vaccination protect the newborn as well as the mother is something that I find is underappreciated by many patients. Explaining that infants likely benefit from the passage of antibodies across the placenta should be part of patient counseling.

Counseling About RSV Vaccination

Importantly, for the 2024-2025 RSV season, the maternal RSV vaccine (Abrysvo, Pfizer) is recommended only for pregnant women who did not receive the vaccine during the 2023-2024 season. When more research is done and more data are obtained showing how long the immune response persists post vaccination, it may be that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) will approve the maternal RSV vaccine for use in every pregnancy.

The later timing of the vaccination recommendation — 32-36 weeks’ gestation — reflects a conservative approach taken by the FDA in response to data from one of the pivotal trials showing a numerical trend toward more preterm deliveries among vaccinated compared with unvaccinated patients. This imbalance in the original trial, which administered the vaccine during 24-36 weeks of gestation, was seen only in low-income countries with no temporal association, however.

In our experience at two Weill Cornell Medical College–associated hospitals we did not see this trend. Our cohort study of almost 3000 pregnant patients who delivered at 32 weeks’ gestation or later found no increased risk of preterm birth among the 35% of patients who received the RSV vaccine during the 2023-2024 RSV season. We also did not see any difference in preeclampsia, in contrast with original trial data that showed a signal for increased risk.11

When fewer than 2 weeks have elapsed between maternal vaccination and delivery, the monoclonal antibody nirsevimab is recommended for the newborn — ideally before the newborn leaves the hospital. Nirsevimab is also recommended for newborns of mothers who decline vaccination or were not candidates (e.g. vaccinated in a previous pregnancy), or when there is concern about the adequacy of the maternal immune response to the vaccine (e.g. in cases of immunosuppression).

While there was a limited supply of the monoclonal antibody last year, limitations are not expected this year, especially after October.

The ultimate goal is that patients choose the vaccine or the immunoglobulin, given the severity of RSV disease. Patient preferences should be considered. However, given that it takes 2 weeks after vaccination for protection to build up, I stress to patients that if they’ve vaccinated themselves, their newborn will leave the hospital with protection. If nirsevimab is relied upon, I explain, their newborn may not be protected for some period of time.

Take-home Messages

- When patients decline or are hesitant about vaccines, ask why. Listen actively, and work to correct misperceptions and knowledge gaps.

- Whenever possible, offer vaccines in your practice. Vaccination rates drop when this does not occur.

- COVID-vaccine safety is backed by many studies showing no increase in birth defects, preterm delivery, miscarriage, or stillbirth.

- Pregnant women are more likely to have severe illness from the influenza and SARS-CoV-2 viruses. Vaccines can prevent severe illness and can protect the newborn as well as the mother.

- Recommend/administer the maternal RSV vaccine at 32-36 weeks’ gestation in women who did not receive the vaccine in the 2023-2024 season. If mothers aren’t eligible their babies should be offered nirsevimab.

Dr. Riley is the Given Foundation Professor and Chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Weill Cornell Medicine and the obstetrician and gynecologist-in-chief at New York Presbyterian Hospital. She disclosed that she has provided one-time consultations to Pfizer (Abrysvo RSV vaccine) and GSK (cytomegalovirus vaccine), and is providing consultant education on CMV for Moderna. She is chair of ACOG’s task force on immunization and emerging infectious diseases, serves on the medical advisory board for MAVEN, and serves as an editor or editorial board member for several medical publications.

References

1. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 741: Maternal Immunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(6):e214-e217.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 Vaccination for People Who are Pregnant or Breastfeeding. https://www.cdc.gov/covid/vaccines/pregnant-or-breastfeeding.html.

3. ACOG Practice Advisory on Maternal Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccination, September 2023. (Updated August 2024).4. Irving S et al. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023;10(Suppl 2):ofad500.1002.

5. Flu Vaccination Dashboard, CDC, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

6. Weekly COVID-19 Vaccination Dashboard, CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/covidvaxview/weekly-dashboard/index.html

7. Louie JK et al. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:27-35. 8. Ciapponi A et al. Vaccine. 2021;39(40):5891-908.

9. Prasad S et al. Nature Communications. 2022;13:2414. 10. Fleming-Dutra KE et al. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2023;50(2):279-97. 11. Mouen S et al. JAMA Network Open 2024;7(7):e2419268.

Editor’s Note: Sadly, this is the last column in the Master Class Obstetrics series. This award-winning column has been part of Ob.Gyn. News for 20 years. The deep discussion of cutting-edge topics in obstetrics by specialists and researchers will be missed as will the leadership and curation of topics by Dr. E. Albert Reece.

Introduction: The Need for Increased Vigilance About Maternal Immunization

Viruses are becoming increasingly prevalent in our world and the consequences of viral infections are implicated in a growing number of disease states. It is well established that certain cancers are caused by viruses and it is increasingly evident that viral infections can trigger the development of chronic illness. In pregnant women, viruses such as cytomegalovirus can cause infection in utero and lead to long-term impairments for the baby.

Likewise, it appears that the virulence of viruses is increasing, whether it be the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in children or the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronaviruses in adults. Clearly, our environment is changing, with increases in population growth and urbanization, for instance, and an intensification of climate change and its effects. Viruses are part of this changing background.

Vaccines are our most powerful tool to protect people of all ages against viral threats, and fortunately, we benefit from increasing expertise in vaccinology. Since 1974, the University of Maryland School of Medicine has a Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health that has conducted research on vaccines to defend against the Zika virus, H1N1, Ebola, and SARS-CoV-2.

We’re not alone. Other vaccinology centers across the country — as well as the National Institutes of Health at the national level, through its National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases — are doing research and developing vaccines to combat viral diseases.

In this column, we are focused on viral diseases in pregnancy and the role that vaccines can play in preventing serious respiratory illness in mothers and their newborns. I have invited Laura E. Riley, MD, the Given Foundation Professor and Chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Weill Cornell Medicine, to address the importance of maternal immunization and how we can best counsel our patients and improve immunization rates.

As Dr. Riley explains, we are in a new era, and it behooves us all to be more vigilant about recommending vaccines, combating misperceptions, addressing patients’ knowledge gaps, and administering vaccines whenever possible.

Dr. Reece is the former Dean of Medicine & University Executive VP, and The Distinguished University and Endowed Professor & Director of the Center for Advanced Research Training and Innovation (CARTI) at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, as well as senior scientist at the Center for Birth Defects Research.

The alarming decline in maternal immunization rates that occurred in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic means that, now more than ever, we must fully embrace our responsibility to recommend immunizations in pregnancy and to communicate what is known about their efficacy and safety. Data show that vaccination rates drop when we do not offer vaccines in our offices, so whenever possible, we should administer them as well.

The ob.gyn. is the patient’s most trusted person in pregnancy. When patients decline or express hesitancy about vaccines, it is incumbent upon us to ask why. Oftentimes, we can identify areas in which patients lack knowledge or have misperceptions and we can successfully educate the patient or change their perspective or misunderstanding concerning the importance of vaccination for themselves and their babies. (See Table 1.) We can also successfully address concerns about safety.

The safety of COVID-19 vaccinations in pregnancy is now backed by several years of data from multiple studies showing no increase in birth defects, preterm delivery, miscarriage, or stillbirth.

Data also show that pregnant patients are more likely than patients who are not pregnant to need hospitalization and intensive care when infected with SARS-CoV-2 and are at risk of having complications that can affect pregnancy and the newborn, including preterm birth and stillbirth. Vaccination has been shown to reduce the risk of severe illness and the risk of such adverse obstetrical outcomes, in addition to providing protection for the infant early on.

Similarly, influenza has long been more likely to be severe in pregnant patients, with an increased risk of poor obstetrical outcomes. Vaccines similarly provide “two for one protection,” protecting both mother and baby, and are, of course, backed by many years of safety and efficacy data.

With the new maternal respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine, now in its second year of availability, the goal is to protect the baby from RSV-caused serious lower respiratory tract illness. The illness has contributed to tens of thousands of annual hospitalizations and up to several hundred deaths every year in children younger than 5 years — particularly in those under age 6 months.

The RSV monoclonal antibody nirsevimab is available for the newborn as an alternative to maternal immunization but the maternal vaccine is optimal in that it will provide immediate rather than delayed protection for the newborn. The maternal vaccine is recommended during weeks 32-36 of pregnancy in mothers who were not vaccinated during last year’s RSV season. With real-world experience from year one, the available safety data are reassuring.

Counseling About Influenza and COVID-19 Vaccination

The COVID-19 pandemic took a toll on vaccination interest/receptivity broadly in pregnant and nonpregnant people. Among pregnant individuals, influenza vaccination coverage declined from 71% in the 2019-2020 influenza season to 56% in the 2021-2022 season, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Vaccine Safety Datalink.4 Coverage for the 2022-2023 and 2023-2024 influenza seasons was even worse: well under 50%.5

Fewer pregnant women have received updated COVID-19 vaccines. Only 13% of pregnant persons overall received the updated 2023-2024 COVID-19 booster vaccine (through March 30, 2024), according to the CDC.6

Maternal immunization for influenza has been recommended in the United States since 2004 (part of the recommendation that everyone over the age of 6 months receive an annual flu vaccine), and flu vaccines have been given to millions of pregnant women, but the H1N1 pandemic of 2009 reinforced its value as a priority for prenatal care. Most of the women who became severely ill from the H1N1 virus were young and healthy, without co-existing conditions known to increase risk.7

It became clearer during the H1N1 pandemic that pregnancy itself — which is associated with physiologic changes such as decreased lung capacity, increased nasal congestion and changes in the immune system – is its own significant risk factor for severe illness from the influenza virus. This increased risk applies to COVID-19 as well.

As COVID-19 has become endemic, with hospitalizations and deaths not reaching the levels of previous surges — and with mask-wearing and other preventive measures having declined — patients understandably have become more complacent. Some patients are vaccine deniers, but in my practice, these patients are a much smaller group than those who believe COVID-19 “is no big deal,” especially if they have had infections recently.

This is why it’s important to actively listen to concerns and to ask patients who decline a vaccination why they are hesitant. Blanket messages about vaccine efficacy and safety are the first step, but individualized, more pointed conversations based on the patient’s personal experiences and beliefs have become increasingly important.

I routinely tell pregnant patients about the risks of COVID-19 and I explain that it has been difficult to predict who will develop severe illness. Sometimes more conversation is needed. For those who are still hesitant or who tell me they feel protected by a recent infection, for instance, I provide more detail on the unique risks of pregnancy — the fact that “pregnancy is different” — and that natural immunity wanes while the protection afforded by immunization is believed to last longer. Many women are also concerned about the safety of the COVID-19 vaccine, so having safety data at your fingertips is helpful. (See Table 2.)

The fact that influenza and COVID-19 vaccination protect the newborn as well as the mother is something that I find is underappreciated by many patients. Explaining that infants likely benefit from the passage of antibodies across the placenta should be part of patient counseling.

Counseling About RSV Vaccination

Importantly, for the 2024-2025 RSV season, the maternal RSV vaccine (Abrysvo, Pfizer) is recommended only for pregnant women who did not receive the vaccine during the 2023-2024 season. When more research is done and more data are obtained showing how long the immune response persists post vaccination, it may be that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) will approve the maternal RSV vaccine for use in every pregnancy.

The later timing of the vaccination recommendation — 32-36 weeks’ gestation — reflects a conservative approach taken by the FDA in response to data from one of the pivotal trials showing a numerical trend toward more preterm deliveries among vaccinated compared with unvaccinated patients. This imbalance in the original trial, which administered the vaccine during 24-36 weeks of gestation, was seen only in low-income countries with no temporal association, however.

In our experience at two Weill Cornell Medical College–associated hospitals we did not see this trend. Our cohort study of almost 3000 pregnant patients who delivered at 32 weeks’ gestation or later found no increased risk of preterm birth among the 35% of patients who received the RSV vaccine during the 2023-2024 RSV season. We also did not see any difference in preeclampsia, in contrast with original trial data that showed a signal for increased risk.11

When fewer than 2 weeks have elapsed between maternal vaccination and delivery, the monoclonal antibody nirsevimab is recommended for the newborn — ideally before the newborn leaves the hospital. Nirsevimab is also recommended for newborns of mothers who decline vaccination or were not candidates (e.g. vaccinated in a previous pregnancy), or when there is concern about the adequacy of the maternal immune response to the vaccine (e.g. in cases of immunosuppression).

While there was a limited supply of the monoclonal antibody last year, limitations are not expected this year, especially after October.

The ultimate goal is that patients choose the vaccine or the immunoglobulin, given the severity of RSV disease. Patient preferences should be considered. However, given that it takes 2 weeks after vaccination for protection to build up, I stress to patients that if they’ve vaccinated themselves, their newborn will leave the hospital with protection. If nirsevimab is relied upon, I explain, their newborn may not be protected for some period of time.

Take-home Messages

- When patients decline or are hesitant about vaccines, ask why. Listen actively, and work to correct misperceptions and knowledge gaps.

- Whenever possible, offer vaccines in your practice. Vaccination rates drop when this does not occur.

- COVID-vaccine safety is backed by many studies showing no increase in birth defects, preterm delivery, miscarriage, or stillbirth.

- Pregnant women are more likely to have severe illness from the influenza and SARS-CoV-2 viruses. Vaccines can prevent severe illness and can protect the newborn as well as the mother.

- Recommend/administer the maternal RSV vaccine at 32-36 weeks’ gestation in women who did not receive the vaccine in the 2023-2024 season. If mothers aren’t eligible their babies should be offered nirsevimab.

Dr. Riley is the Given Foundation Professor and Chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Weill Cornell Medicine and the obstetrician and gynecologist-in-chief at New York Presbyterian Hospital. She disclosed that she has provided one-time consultations to Pfizer (Abrysvo RSV vaccine) and GSK (cytomegalovirus vaccine), and is providing consultant education on CMV for Moderna. She is chair of ACOG’s task force on immunization and emerging infectious diseases, serves on the medical advisory board for MAVEN, and serves as an editor or editorial board member for several medical publications.

References

1. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 741: Maternal Immunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(6):e214-e217.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 Vaccination for People Who are Pregnant or Breastfeeding. https://www.cdc.gov/covid/vaccines/pregnant-or-breastfeeding.html.

3. ACOG Practice Advisory on Maternal Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccination, September 2023. (Updated August 2024).4. Irving S et al. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023;10(Suppl 2):ofad500.1002.

5. Flu Vaccination Dashboard, CDC, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

6. Weekly COVID-19 Vaccination Dashboard, CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/covidvaxview/weekly-dashboard/index.html

7. Louie JK et al. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:27-35. 8. Ciapponi A et al. Vaccine. 2021;39(40):5891-908.

9. Prasad S et al. Nature Communications. 2022;13:2414. 10. Fleming-Dutra KE et al. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2023;50(2):279-97. 11. Mouen S et al. JAMA Network Open 2024;7(7):e2419268.

Lawsuit Targets Publishers: Is Peer Review Flawed?

The peer-review process, which is used by scientific journals to validate legitimate research, is now under legal scrutiny. The US District Court for the Southern District of New York will soon rule on whether scientific publishers have compromised this system for profit. In mid-September, University of California, Los Angeles neuroscientist Lucina Uddin filed a class action lawsuit against six leading academic publishers — Elsevier, Wolters Kluwer, Wiley, Sage Publications, Taylor & Francis, and Springer Nature — accusing them of violating antitrust laws and obstructing academic research.

The lawsuit targets several long-standing practices in scientific publishing, including the lack of compensation for peer reviewers, restrictions that require submitting to only one journal at a time, and bans on sharing manuscripts under review. Uddin’s complaint argues that these practices contribute to inefficiencies in the review process, thus delaying the publication of critical discoveries, which could hinder research, clinical advancements, and the development of new medical treatments.

The suit also noted that these publishers generated $10 billion in revenue in 2023 in peer-reviewed journals. However, the complaint seemingly overlooks the widespread practice of preprint repositories, where many manuscripts are shared while awaiting peer review.

Flawed Reviews

A growing number of studies have highlighted subpar or unethical behaviors among reviewers, who are supposed to adhere to the highest standards of methodological rigor, both in conducting research and reviewing work for journals. One recent study published in Scientometrics in August examined 263 reviews from 37 journals across various disciplines and found alarming patterns of duplication. Many of the reviews contained identical or highly similar language. Some reviewers were found to be suggesting that the authors expand their bibliographies to include the reviewers’ own work, thus inflating their citation counts.

As María Ángeles Oviedo-García from the University of Seville in Spain, pointed out: “The analysis of 263 review reports shows a pattern of vague, repetitive statements — often identical or very similar — along with coercive citations, ultimately resulting in misleading reviews.”

Experts in research integrity and ethics argue that while issues persist, the integrity of scientific research is improving. Increasing research and public disclosure reflect a heightened awareness of problems long overlooked.

Speaking to this news organization, Fanelli, who has been studying scientific misconduct for about 20 years, noted that while his early work left him disillusioned, further research has replaced his cynicism with what he describes as healthy skepticism and a more optimistic outlook. Fanelli also collaborates with the Luxembourg Agency for Research Integrity and the Advisory Committee on Research Ethics and Bioethics at the Italian National Research Council (CNR), where he helped develop the first research integrity guidelines.

Lack of Awareness

A recurring challenge is the difficulty in distinguishing between honest mistakes and intentional misconduct. “This is why greater investment in education is essential,” said Daniel Pizzolato, European Network of Research Ethics Committees, Bonn, Germany, and the Centre for Biomedical Ethics and Law, KU Leuven in Belgium.

While Pizzolato acknowledged that institutions such as the CNR in Italy provide a positive example, awareness of research integrity is generally still lacking across much of Europe, and there are few offices dedicated to promoting research integrity. However, he pointed to promising developments in other countries. “In France and Denmark, researchers are required to be familiar with integrity norms because codes of conduct have legal standing. Some major international funding bodies like the European Molecular Biology Organization are making participation in research integrity courses a condition for receiving grants.”

Pizzolato remains optimistic. “There is a growing willingness to move past this impasse,” he said.

A recent study published in The Journal of Clinical Epidemiology reveals troubling gaps in how retracted biomedical articles are flagged and cited. Led by Caitlin Bakkera, Department of Epidemiology, Maastricht University, Maastricht, the Netherlands, the research sought to determine whether articles retracted because of errors or fraud were properly flagged across various databases.

The results were concerning: Less than 5% of retracted articles had consistent retraction notices across all databases that hosted them, and less than 50% of citations referenced the retraction. None of the 414 retraction notices analyzed met best-practice guidelines for completeness. Bakkera and colleagues warned that these shortcomings threaten the integrity of public health research.

Fanelli’s Perspective

Despite the concerns, Fanelli remains calm. “Science is based on debate and a perspective called organized skepticism, which helps reveal the truth,” he explained. “While there is often excessive skepticism today, the overall quality of clinical trials is improving.

“It’s important to remember that reliable results take time and shouldn’t depend on the outcome of a single study. It’s essential to consider the broader context, the history of the research field, and potential conflicts of interest, both financial and otherwise. Biomedical research requires constant updates,” he concluded.

This story was translated from Univadis Italy using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The peer-review process, which is used by scientific journals to validate legitimate research, is now under legal scrutiny. The US District Court for the Southern District of New York will soon rule on whether scientific publishers have compromised this system for profit. In mid-September, University of California, Los Angeles neuroscientist Lucina Uddin filed a class action lawsuit against six leading academic publishers — Elsevier, Wolters Kluwer, Wiley, Sage Publications, Taylor & Francis, and Springer Nature — accusing them of violating antitrust laws and obstructing academic research.

The lawsuit targets several long-standing practices in scientific publishing, including the lack of compensation for peer reviewers, restrictions that require submitting to only one journal at a time, and bans on sharing manuscripts under review. Uddin’s complaint argues that these practices contribute to inefficiencies in the review process, thus delaying the publication of critical discoveries, which could hinder research, clinical advancements, and the development of new medical treatments.

The suit also noted that these publishers generated $10 billion in revenue in 2023 in peer-reviewed journals. However, the complaint seemingly overlooks the widespread practice of preprint repositories, where many manuscripts are shared while awaiting peer review.

Flawed Reviews

A growing number of studies have highlighted subpar or unethical behaviors among reviewers, who are supposed to adhere to the highest standards of methodological rigor, both in conducting research and reviewing work for journals. One recent study published in Scientometrics in August examined 263 reviews from 37 journals across various disciplines and found alarming patterns of duplication. Many of the reviews contained identical or highly similar language. Some reviewers were found to be suggesting that the authors expand their bibliographies to include the reviewers’ own work, thus inflating their citation counts.

As María Ángeles Oviedo-García from the University of Seville in Spain, pointed out: “The analysis of 263 review reports shows a pattern of vague, repetitive statements — often identical or very similar — along with coercive citations, ultimately resulting in misleading reviews.”

Experts in research integrity and ethics argue that while issues persist, the integrity of scientific research is improving. Increasing research and public disclosure reflect a heightened awareness of problems long overlooked.

Speaking to this news organization, Fanelli, who has been studying scientific misconduct for about 20 years, noted that while his early work left him disillusioned, further research has replaced his cynicism with what he describes as healthy skepticism and a more optimistic outlook. Fanelli also collaborates with the Luxembourg Agency for Research Integrity and the Advisory Committee on Research Ethics and Bioethics at the Italian National Research Council (CNR), where he helped develop the first research integrity guidelines.

Lack of Awareness

A recurring challenge is the difficulty in distinguishing between honest mistakes and intentional misconduct. “This is why greater investment in education is essential,” said Daniel Pizzolato, European Network of Research Ethics Committees, Bonn, Germany, and the Centre for Biomedical Ethics and Law, KU Leuven in Belgium.

While Pizzolato acknowledged that institutions such as the CNR in Italy provide a positive example, awareness of research integrity is generally still lacking across much of Europe, and there are few offices dedicated to promoting research integrity. However, he pointed to promising developments in other countries. “In France and Denmark, researchers are required to be familiar with integrity norms because codes of conduct have legal standing. Some major international funding bodies like the European Molecular Biology Organization are making participation in research integrity courses a condition for receiving grants.”

Pizzolato remains optimistic. “There is a growing willingness to move past this impasse,” he said.

A recent study published in The Journal of Clinical Epidemiology reveals troubling gaps in how retracted biomedical articles are flagged and cited. Led by Caitlin Bakkera, Department of Epidemiology, Maastricht University, Maastricht, the Netherlands, the research sought to determine whether articles retracted because of errors or fraud were properly flagged across various databases.

The results were concerning: Less than 5% of retracted articles had consistent retraction notices across all databases that hosted them, and less than 50% of citations referenced the retraction. None of the 414 retraction notices analyzed met best-practice guidelines for completeness. Bakkera and colleagues warned that these shortcomings threaten the integrity of public health research.

Fanelli’s Perspective

Despite the concerns, Fanelli remains calm. “Science is based on debate and a perspective called organized skepticism, which helps reveal the truth,” he explained. “While there is often excessive skepticism today, the overall quality of clinical trials is improving.

“It’s important to remember that reliable results take time and shouldn’t depend on the outcome of a single study. It’s essential to consider the broader context, the history of the research field, and potential conflicts of interest, both financial and otherwise. Biomedical research requires constant updates,” he concluded.

This story was translated from Univadis Italy using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The peer-review process, which is used by scientific journals to validate legitimate research, is now under legal scrutiny. The US District Court for the Southern District of New York will soon rule on whether scientific publishers have compromised this system for profit. In mid-September, University of California, Los Angeles neuroscientist Lucina Uddin filed a class action lawsuit against six leading academic publishers — Elsevier, Wolters Kluwer, Wiley, Sage Publications, Taylor & Francis, and Springer Nature — accusing them of violating antitrust laws and obstructing academic research.

The lawsuit targets several long-standing practices in scientific publishing, including the lack of compensation for peer reviewers, restrictions that require submitting to only one journal at a time, and bans on sharing manuscripts under review. Uddin’s complaint argues that these practices contribute to inefficiencies in the review process, thus delaying the publication of critical discoveries, which could hinder research, clinical advancements, and the development of new medical treatments.

The suit also noted that these publishers generated $10 billion in revenue in 2023 in peer-reviewed journals. However, the complaint seemingly overlooks the widespread practice of preprint repositories, where many manuscripts are shared while awaiting peer review.

Flawed Reviews

A growing number of studies have highlighted subpar or unethical behaviors among reviewers, who are supposed to adhere to the highest standards of methodological rigor, both in conducting research and reviewing work for journals. One recent study published in Scientometrics in August examined 263 reviews from 37 journals across various disciplines and found alarming patterns of duplication. Many of the reviews contained identical or highly similar language. Some reviewers were found to be suggesting that the authors expand their bibliographies to include the reviewers’ own work, thus inflating their citation counts.

As María Ángeles Oviedo-García from the University of Seville in Spain, pointed out: “The analysis of 263 review reports shows a pattern of vague, repetitive statements — often identical or very similar — along with coercive citations, ultimately resulting in misleading reviews.”

Experts in research integrity and ethics argue that while issues persist, the integrity of scientific research is improving. Increasing research and public disclosure reflect a heightened awareness of problems long overlooked.

Speaking to this news organization, Fanelli, who has been studying scientific misconduct for about 20 years, noted that while his early work left him disillusioned, further research has replaced his cynicism with what he describes as healthy skepticism and a more optimistic outlook. Fanelli also collaborates with the Luxembourg Agency for Research Integrity and the Advisory Committee on Research Ethics and Bioethics at the Italian National Research Council (CNR), where he helped develop the first research integrity guidelines.

Lack of Awareness

A recurring challenge is the difficulty in distinguishing between honest mistakes and intentional misconduct. “This is why greater investment in education is essential,” said Daniel Pizzolato, European Network of Research Ethics Committees, Bonn, Germany, and the Centre for Biomedical Ethics and Law, KU Leuven in Belgium.

While Pizzolato acknowledged that institutions such as the CNR in Italy provide a positive example, awareness of research integrity is generally still lacking across much of Europe, and there are few offices dedicated to promoting research integrity. However, he pointed to promising developments in other countries. “In France and Denmark, researchers are required to be familiar with integrity norms because codes of conduct have legal standing. Some major international funding bodies like the European Molecular Biology Organization are making participation in research integrity courses a condition for receiving grants.”

Pizzolato remains optimistic. “There is a growing willingness to move past this impasse,” he said.

A recent study published in The Journal of Clinical Epidemiology reveals troubling gaps in how retracted biomedical articles are flagged and cited. Led by Caitlin Bakkera, Department of Epidemiology, Maastricht University, Maastricht, the Netherlands, the research sought to determine whether articles retracted because of errors or fraud were properly flagged across various databases.

The results were concerning: Less than 5% of retracted articles had consistent retraction notices across all databases that hosted them, and less than 50% of citations referenced the retraction. None of the 414 retraction notices analyzed met best-practice guidelines for completeness. Bakkera and colleagues warned that these shortcomings threaten the integrity of public health research.

Fanelli’s Perspective

Despite the concerns, Fanelli remains calm. “Science is based on debate and a perspective called organized skepticism, which helps reveal the truth,” he explained. “While there is often excessive skepticism today, the overall quality of clinical trials is improving.

“It’s important to remember that reliable results take time and shouldn’t depend on the outcome of a single study. It’s essential to consider the broader context, the history of the research field, and potential conflicts of interest, both financial and otherwise. Biomedical research requires constant updates,” he concluded.

This story was translated from Univadis Italy using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Is Metformin An Unexpected Ally Against Long COVID?

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Previous studies have shown that metformin use before and during SARS-CoV-2 infection reduces severe COVID-19 and postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 (PASC), also referred to as long COVID, in adults.

- A retrospective cohort analysis was conducted to evaluate the association between metformin use before and during SARS-CoV-2 infection and the subsequent incidence of PASC.

- Researchers used data from the National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C) and National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network (PCORnet) electronic health record (EHR) databases to identify adults (age, ≥ 21 years) with T2D prescribed a diabetes medication within the past 12 months.

- Participants were categorized into those using metformin (metformin group) and those using other noninsulin diabetes medications such as sulfonylureas, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, or thiazolidinediones (the comparator group); those who used glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists or sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors were excluded.

- The primary outcome was the incidence of PASC or death within 180 days after SARS-CoV-2 infection, defined using International Classification of Diseases U09.9 diagnosis code and/or computable phenotype defined by a predicted probability of > 75% for PASC using a machine learning model trained on patients diagnosed using U09.9 (PASC computable phenotype).

TAKEAWAY:

- Researchers identified 51,385 and 37,947 participants from the N3C and PCORnet datasets, respectively.

- Metformin use was associated with a 21% lower risk for death or PASC using the U09.9 diagnosis code (P < .001) and a 15% lower risk using the PASC computable phenotype (P < .001) in the N3C dataset than non-metformin use.

- In the PCORnet dataset, the risk for death or PASC was 13% lower using the U09.9 diagnosis code (P = .08) with metformin use vs non-metformin use, whereas the risk did not differ significantly between the groups when using the PASC computable phenotype (P = .58).

- The incidence of PASC using the U09.9 diagnosis code for the metformin and comparator groups was similar between the two datasets (1.6% and 2.0% in N3C and 2.2 and 2.6% in PCORnet, respectively).

- However, when using the computable phenotype, the incidence rates of PASC for the metformin and comparator groups were 4.8% and 5.2% in N3C and 25.2% and 24.2% in PCORnet, respectively.

IN PRACTICE:

“The incidence of PASC was lower when defined by [International Classification of Diseases] code, compared with a computable phenotype in both databases,” the authors wrote. “This may reflect the challenges of clinical care for adults needing chronic medication management and the likelihood of those adults receiving a formal PASC diagnosis.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Steven G. Johnson, PhD, Institute for Health Informatics, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. It was published online in Diabetes Care.

LIMITATIONS:

The use of EHR data had several limitations, including the inability to examine a dose-dependent relationship and the lack of information on whether medications were taken before, during, or after the acute infection. The outcome definition involved the need for a medical encounter and, thus, may not capture data on all patients experiencing symptoms of PASC. The analysis focused on the prevalent use of chronic medications, limiting the assessment of initiating metformin in those diagnosed with COVID-19.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health Agreement as part of the RECOVER research program. One author reported receiving salary support from the Center for Pharmacoepidemiology and owning stock options in various pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical companies. Another author reported receiving grant support and consulting contracts, being involved in expert witness engagement, and owning stock options in various pharmaceutical, biopharmaceutical, diabetes management, and medical device companies.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Previous studies have shown that metformin use before and during SARS-CoV-2 infection reduces severe COVID-19 and postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 (PASC), also referred to as long COVID, in adults.

- A retrospective cohort analysis was conducted to evaluate the association between metformin use before and during SARS-CoV-2 infection and the subsequent incidence of PASC.

- Researchers used data from the National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C) and National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network (PCORnet) electronic health record (EHR) databases to identify adults (age, ≥ 21 years) with T2D prescribed a diabetes medication within the past 12 months.

- Participants were categorized into those using metformin (metformin group) and those using other noninsulin diabetes medications such as sulfonylureas, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, or thiazolidinediones (the comparator group); those who used glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists or sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors were excluded.

- The primary outcome was the incidence of PASC or death within 180 days after SARS-CoV-2 infection, defined using International Classification of Diseases U09.9 diagnosis code and/or computable phenotype defined by a predicted probability of > 75% for PASC using a machine learning model trained on patients diagnosed using U09.9 (PASC computable phenotype).

TAKEAWAY:

- Researchers identified 51,385 and 37,947 participants from the N3C and PCORnet datasets, respectively.

- Metformin use was associated with a 21% lower risk for death or PASC using the U09.9 diagnosis code (P < .001) and a 15% lower risk using the PASC computable phenotype (P < .001) in the N3C dataset than non-metformin use.

- In the PCORnet dataset, the risk for death or PASC was 13% lower using the U09.9 diagnosis code (P = .08) with metformin use vs non-metformin use, whereas the risk did not differ significantly between the groups when using the PASC computable phenotype (P = .58).

- The incidence of PASC using the U09.9 diagnosis code for the metformin and comparator groups was similar between the two datasets (1.6% and 2.0% in N3C and 2.2 and 2.6% in PCORnet, respectively).

- However, when using the computable phenotype, the incidence rates of PASC for the metformin and comparator groups were 4.8% and 5.2% in N3C and 25.2% and 24.2% in PCORnet, respectively.

IN PRACTICE:

“The incidence of PASC was lower when defined by [International Classification of Diseases] code, compared with a computable phenotype in both databases,” the authors wrote. “This may reflect the challenges of clinical care for adults needing chronic medication management and the likelihood of those adults receiving a formal PASC diagnosis.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Steven G. Johnson, PhD, Institute for Health Informatics, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. It was published online in Diabetes Care.

LIMITATIONS:

The use of EHR data had several limitations, including the inability to examine a dose-dependent relationship and the lack of information on whether medications were taken before, during, or after the acute infection. The outcome definition involved the need for a medical encounter and, thus, may not capture data on all patients experiencing symptoms of PASC. The analysis focused on the prevalent use of chronic medications, limiting the assessment of initiating metformin in those diagnosed with COVID-19.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health Agreement as part of the RECOVER research program. One author reported receiving salary support from the Center for Pharmacoepidemiology and owning stock options in various pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical companies. Another author reported receiving grant support and consulting contracts, being involved in expert witness engagement, and owning stock options in various pharmaceutical, biopharmaceutical, diabetes management, and medical device companies.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Previous studies have shown that metformin use before and during SARS-CoV-2 infection reduces severe COVID-19 and postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 (PASC), also referred to as long COVID, in adults.

- A retrospective cohort analysis was conducted to evaluate the association between metformin use before and during SARS-CoV-2 infection and the subsequent incidence of PASC.

- Researchers used data from the National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C) and National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network (PCORnet) electronic health record (EHR) databases to identify adults (age, ≥ 21 years) with T2D prescribed a diabetes medication within the past 12 months.

- Participants were categorized into those using metformin (metformin group) and those using other noninsulin diabetes medications such as sulfonylureas, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, or thiazolidinediones (the comparator group); those who used glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists or sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors were excluded.

- The primary outcome was the incidence of PASC or death within 180 days after SARS-CoV-2 infection, defined using International Classification of Diseases U09.9 diagnosis code and/or computable phenotype defined by a predicted probability of > 75% for PASC using a machine learning model trained on patients diagnosed using U09.9 (PASC computable phenotype).

TAKEAWAY:

- Researchers identified 51,385 and 37,947 participants from the N3C and PCORnet datasets, respectively.

- Metformin use was associated with a 21% lower risk for death or PASC using the U09.9 diagnosis code (P < .001) and a 15% lower risk using the PASC computable phenotype (P < .001) in the N3C dataset than non-metformin use.

- In the PCORnet dataset, the risk for death or PASC was 13% lower using the U09.9 diagnosis code (P = .08) with metformin use vs non-metformin use, whereas the risk did not differ significantly between the groups when using the PASC computable phenotype (P = .58).

- The incidence of PASC using the U09.9 diagnosis code for the metformin and comparator groups was similar between the two datasets (1.6% and 2.0% in N3C and 2.2 and 2.6% in PCORnet, respectively).

- However, when using the computable phenotype, the incidence rates of PASC for the metformin and comparator groups were 4.8% and 5.2% in N3C and 25.2% and 24.2% in PCORnet, respectively.

IN PRACTICE:

“The incidence of PASC was lower when defined by [International Classification of Diseases] code, compared with a computable phenotype in both databases,” the authors wrote. “This may reflect the challenges of clinical care for adults needing chronic medication management and the likelihood of those adults receiving a formal PASC diagnosis.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Steven G. Johnson, PhD, Institute for Health Informatics, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. It was published online in Diabetes Care.

LIMITATIONS:

The use of EHR data had several limitations, including the inability to examine a dose-dependent relationship and the lack of information on whether medications were taken before, during, or after the acute infection. The outcome definition involved the need for a medical encounter and, thus, may not capture data on all patients experiencing symptoms of PASC. The analysis focused on the prevalent use of chronic medications, limiting the assessment of initiating metformin in those diagnosed with COVID-19.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health Agreement as part of the RECOVER research program. One author reported receiving salary support from the Center for Pharmacoepidemiology and owning stock options in various pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical companies. Another author reported receiving grant support and consulting contracts, being involved in expert witness engagement, and owning stock options in various pharmaceutical, biopharmaceutical, diabetes management, and medical device companies.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Why Residents Are Joining Unions in Droves

Before the 350 residents finalized their union contract at the University of Vermont (UVM) Medical Center, Burlington, in 2022, Jesse Mostoller, DO, now a third-year pathology resident, recalls hearing about another resident at the hospital who resorted to moonlighting as an Uber driver to make ends meet.

“In Vermont, rent and childcare are expensive,” said Dr. Mostoller, adding that, thanks to union bargaining, first-year residents at UVM are now paid $71,000 per year instead of $61,000. In addition, residents now receive $1800 per year for food (up from $200-$300 annually) and a $1800 annual fund to help pay for board exams that can be carried over for 2 years. “When we were negotiating, the biggest item on our list of demands was to help alleviate the financial pressure residents have been facing for years.”

The UVM residents’ collective bargaining also includes a cap on working hours so that residents don’t work 80 hours a week, paid parental leave, affordable housing, and funds for education and wellness.

These are some of the most common challenges that are faced by residents all over the country, said A. Taylor Walker, MD, MPH, family medicine chief physician at Tufts University School of Medicine/Cambridge Health Alliance in Boston, Massachusetts, and national president of the Committee of Interns and Residents (CIR), which is part of the Service Employees International Union.

For these reasons, residents at Montefiore Medical Center, Stanford Health Care, George Washington University, and the University of Pennsylvania have recently voted to unionize, according to Dr. Walker.

And while there are several small local unions that have picked up residents at local hospitals, CIR is the largest union of physicians in the United States, with a total of 33,000 residents and fellows across the country (15% of the staff at more than 60 hospitals nationwide).

“We’ve doubled in size in the last 4 years,” said Dr. Walker. “The reason is that we’re in a national reckoning on the corporatization of American medicine and the way in which graduate medical education is rooted in a cycle of exploitation that doesn’t center on the health, well-being, or safety of our doctors and ultimately negatively affects our patients.”

Here’s what residents are fighting for — right now.

Adequate Parental Leave

Christopher Domanski, MD, a first-year resident in psychiatry at California Pacific Medical Center (CPMC) in San Francisco, is also a new dad to a 5-month-old son and is currently in the sixth week of parental leave. One goal of CPMC’s union, started a year and a half ago, is to expand parental leave to 8 weeks.

“I started as a resident here in mid-June, but the fight with CPMC leaders has been going on for a year and a half,” Dr. Domanski said. “It can feel very frustrating because many times there’s no budge in the conversations we want to have.”

Contract negotiations here continue to be slow — and arduous.

“It goes back and forth,” said Dr. Domanski, who makes about $75,000 a year. “Sometimes they listen to our proposals, but they deny the vast majority or make a paltry increase in salary or time off. It goes like this: We’ll have a negotiation; we’ll talk about it, and then they say, ‘we’re not comfortable doing this’ and it stalls again.”

If a resident hasn’t started a family yet, access to fertility benefits and reproductive healthcare is paramount because most residents are in their 20s and 30s, Dr. Walker said.

“Our reproductive futures are really hindered by what care we have access to and what care is covered,” she added. “We don’t make enough money to pay for reproductive care out of pocket.”

Fair Pay

In Boston, the residents at Mass General Brigham certified their union in June 2023, but they still don’t have a contract.

“When I applied for a residency in September 2023, I spoke to the folks here, and I was basically under the impression that we would have a contract by the time I matched,” said Madison Masters, MD, a resident in internal medicine. “We are not there.”

This timeline isn’t unusual — the 1400 Penn Medicine residents who unionized in 2023 only recently secured a tentative union contract at the end of September, and at Stanford, the process to ratify their first contract took 13 months.

Still, the salary issue remains frustrating as resident compensation doesn’t line up with the cost of living or the amount of work residents do, said Dr. Masters, who says starting salaries at Mass General Brigham are $78,500 plus a $10,000 stipend for housing.

“There’s been a long tradition of underpaying residents — we’re treated like trainees, but we’re also a primary labor force,” Dr. Masters said, adding that nurse practitioners and physician assistants are paid almost twice as much as residents — some make $120,000 per year or more, while the salary range for residents nationwide is $49,000-$65,000 per year.

“Every time we discuss the contract and talk about a financial package, they offer a 1.5% raise for the next 3 years while we had asked for closer to 8%,” Dr. Masters said. “Then, when they come back for the next bargaining session, they go up a quarter of a percent each time. Recently, they said we will need to go to a mediator to try and resolve this.”

Adequate Healthcare

The biggest — and perhaps the most shocking — ask is for robust health insurance coverage.

“At my hospital, they’re telling us to get Amazon One Medical for health insurance,” Dr. Masters said. “They’re saying it’s hard for anyone to get primary care coverage here.”

Inadequate health insurance is a big issue, as burnout among residents and fellows remains a problem. At UVM, a $10,000 annual wellness stipend has helped address some of these issues. Even so, union members at UVM are planning to return to the table within 18 months to continue their collective bargaining.

The ability to access mental health services anywhere you want is also critical for residents, Dr. Walker said.

“If you can only go to a therapist at your own institution, there is a hesitation to utilize that specialist if that’s even offered,” Dr. Walker said. “Do you want to go to therapy with a colleague? Probably not.”

Ultimately, the residents we spoke to are committed to fighting for their workplace rights — no matter how time-consuming or difficult this has been.

“No administration wants us to have to have a union, but it’s necessary,” Dr. Mostoller said. “As an individual, you don’t have leverage to get a seat at the table, but now we have a seat at the table. We have a wonderful contract, but we’re going to keep fighting to make it even better.”

Paving the way for future residents is a key motivator, too.

“There’s this idea of leaving the campsite cleaner than you found it,” Dr. Mostoller told this news organization. “It’s the same thing here — we’re trying to fix this so that the next generation of residents won’t have to.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.