User login

Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America (CCFA): Advances in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases Clinical & Research Conference

IBD specialty medical home relies on psychiatrist, insurer to succeed

In just 1 year, 34 out of about 5,000 patients seen at the inflammatory bowel disease center at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center cost more than $10 million to treat.

“Our health plan said, ‘You have to fix this,’” recalled Dr. Miguel Regueiro, codirector of the IBD center.

So, in addition to asking the insurer for ideas, Dr. Regueiro did the most cost conscious thing he could think of: He asked for ideas from his colleague, Dr. Eva Szigethy, a psychiatrist specializing in the treatment of pain and psychosocial issues faced by IBD patients.

“Nearly half of our patient population has some behavioral, stress, or mental health component that is driving their disease, [leading] to high health care utilization,” Dr. Regueiro said.

Dr. Szigethy’s work of late, both on her own and with others such as Dr. Douglas Drossman, an emeritus psychiatrist and gastroenterologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, has focused on the so-called brain-gut axis and includes the impact of narcotics on the gastrointestinal tract, the correlation between inflammation and depression, the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy in IBD, and the use of self-hypnosis to manage chronic pain.

“The vast majority of IBD patients have mood disorders, depression, reactive adjustment disorder, anxiety both [before and after] their diagnosis, and chronic pain,” Dr. Szigethy said in an interview.

In practical terms, this means patients benefit from the partnership between Dr. Regueiro, who brings a deep medical knowledge of IBD, and Dr. Szigethy, who combines her research with her psychiatric skill for asking the kinds of questions that evoke the patient’s larger story. Together, said Dr. Szigethy, they assess patients as a whole, directly accounting for the emotional complexity inherent in IBD, with an eye toward helping patients regain control of their lives, often made chaotic by the unpredictable indignities that are the hallmarks of the disease.

“Often, if we listen in the lines and between the lines, our patients tell us exactly what other factors are involved: why their disease is not getting better, why they are getting headaches, why they have such continued suffering,” Dr. Szigethy said.

“You don’t need to know the basic science to understand the stress these patients feel,” Dr. Regueiro recounted to an audience at a recent Advances in IBD meeting in Orlando, sponsored by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America.

He shared with his audience the story of 45-year-old Anne, a Crohn’s disease sufferer treated at his center. Anne is not the patient’s real name. Despite her disease being inactive, Anne was hospitalized 23 times, and given 19 CT scans and seven endoscopic procedures in one calendar year alone, qualifying her as one of the center’s top 34 “health care frequent fliers.”

Empowering patients like Anne, whose costly care Dr. Szigethy and Dr. Regueiro recognized was attributable more to her psychosocial rather than medical IBD needs, not only improves their quality of life, it saves the system money.

This is why the same health plan representatives who told Dr. Regueiro they’d like to see cost reductions have partnered with him and Dr. Szigethy to develop a specialty care medical home pilot program that combines specialty, primary, and mental health care in one location. The program officially opened in mid-January of this year.

In the mid-1990s, the UPMC Health Plan was conceived by the medical center as a “strategic move to combine the intellectual capital of the provider system with that of the payer system,” according to Sandy McAnallen, UPMC Health Plan’s senior vice president for clinical affairs and quality performance.

The result, she said in an interview, is greater flexibility when it comes to what care is provided and how it is delivered. “The physicians are setting the evidence-based pathways on the kind of care that patients need to receive, and we have the ability to be very proactive with [how we pay for that] with this kind of relationship.”

Over the course of 2 years, Dr. Regueiro and Ms. McAnallen met several times to parse data on more effective ways to address the fractured way IBD patients, particularly those with undiagnosed psychosocial concerns, were seeking and receiving treatment. The pair also honed in on ways to cut the high cost of surgeries and pharmaceuticals with the overall goal being to create a healthier IBD patient population who perceived their care to be the best possible.

To develop their specialty medical home model, Dr. Regueiro, Dr. Szigethy, Ms. McAnallen, and other key UPMC hospital system and health plan administrators, as well as other IBD specialists, met many times over the course of 2 years to plan what Ms. McAnallen calls their proof of concept.

The program is offered automatically to those covered by the UPMC Health Plan, although anyone is welcome to opt out if they choose. Participants are asked, but not required, to submit to genetic sampling for IBD research purposes, and other data also are gathered with consent at the center. Those not covered by UPMC insurance also are welcome to participate. “The center is payer-agnostic,” Ms. McAnallen said.

Dr. Regueiro and his colleagues will be the primary doctors for all patients who want to be seen at the IBD center for their chronic condition, while episodic illnesses such as colds, flus, and rashes are treated by a newly added advance practice nurse. All patients are now offered behavioral and psychosocial support, depending on the concern, either from Dr. Szigethy, a psychologist, or a social worker who was added to the team for the pilot project.

“Part of what we are defining [with this project] is when a psychiatrist is needed, and what can be done by a less expensive, but well-trained behavioral health, medically trained person like a social worker,” said Dr. Szigethy, who is also a member of the department of psychiatry.

A new patient peer group offers patients the chance to discuss their IBD-related struggles with others who can empathize directly, and a nutritionist and pharmacist both specializing in IBD needs have been added to the payroll. A 24/7 call center also has been established.

“We want patients to be in the habit of calling one place where their entire history is known,” said Ms. McAnallen. “Whether they need primary care or specialty care, we want these patients to go to the specialty medical home.”

It’s a patient-centered, rather than an institution-based model, where the referrals are controlled by the payer, “but the system is value based not volume based,” said Dr. Regueiro.

To that end, Dr. Regueiro said he hopes the center will expand its use of telemedicine to further accommodate patients, who often find it difficult to take time off from work or school, find and afford child care, and travel long distances to their doctor appointments. “Right now, some patients have to drive hours to see us, but a lot of what we do for these patients is cognitive care,” he said.

The IBD center’s additional personnel have been paid for by the health plan, in order to cover the cost of adequately serving the approximately 725 IBD patients the insurer determined were the most expensive to treat out of the more than 5,000 IBD patients, a notably high number according to Dr. Szigethy, that the center serves.

In exchange for underwriting the cost of a portion of the staff, the health plan expects Dr. Regueiro and his team to cut treatment costs for this cohort. “If we save a certain amount on patients each year, the health plan will give that back to us,” Dr. Regueiro said.

One way Ms. McAnallen said the program is projected to save is by reducing the number of times frequent fliers of UPMC’s emergency department arrive with an IBD complaint.

“The ED specializes in all acute medical issues, but for IBD we need to focus in a different way,” said Ms. McAnallen.

To wit, in her health care high-utilization heyday, Anne’s treatment typically began in the emergency department, where she arrived seeking narcotics for her condition.

“She said she hated that the people in the ED treated her like a drug addict, but she hated the pain even more,” Dr. Regueiro told his Orlando audience.

This was particularly troublesome for Anne, since Dr. Szigethy determined she was a potential sufferer of narcotic bowel syndrome.

Although at present, much of the research into this phenomenon is still bench science, Dr. Szigethy said a growing body of evidence provided in part by advanced neuroimaging techniques indicates that chronic narcotic use changes opioid receptors in some human adults from creating an analgesic effect, to a hyperanalgesic one instead, where the narcotics themselves start to create pain and exacerbate any existing bowel issues.

“In Anne’s case, she was going up and up in her opiates, but her pain was getting worse,” Dr. Szigethy said.

Dr. Szigethy obtained permission from Anne’s insurer, which happened to be UPMC Health Plan, to give her a 5-day inpatient medical hospitalization during which time Anne was weaned from her narcotics. For 6 months prior to her detoxification from the opiates, Anne learned self-hypnosis techniques from Dr. Szigethy and her colleagues, which she used to support her withdrawal from the pain medication. Anne’s self-reported favorite technique was that whenever the pain would start, she would visualize filling a balloon with it, and then letting the balloon drift away until it eventually evaporated into the air.

“I know it sounds corny, but guess what? Last year, Anne had zero hospitalizations,” Dr. Regueiro said.

According to Dr. Szigethy, Anne still has occasional pain, “But she can deal with it.”The exact savings UPMC Health Plan expects to realize by way of reimbursing the IBD center for treatment models created in response to emerging research such as that of Dr. Szigethy is still unknown. But Ms. McAnallen is optimistic the program will meet its broader targets.

“We are at a point where costs are becoming out of control and the consumer can’t afford health care. You have to be in a position where you can rely on your physicians to develop evidence-based pathways for treatment of acute and chronic disease, which Eva and Miguel are doing, and to do be able to do so in a laboratory where you have the premium to support that,” Ms. McAnallen said, adding that had Dr. Regueiro approached an outside payer to help him create the medical home model, she doubted it would have come to fruition.

“Because we’re part of an integrated system, we’re all aligned with the same goals, which include improving the health status of our community and decreasing the cost of care so it’s affordable.”

Analysis of data collected on total cost and quality of care, and patient perception of care, will begin within the next 6 months, said Ms. McAnallen, who did not offer specific margins but noted that if gains are made, UPMC would look at how to apply this integrated approach to treating other chronic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis.

One central question the pilot program is expected to answer is whether it is feasible to do away with fee-for-service provider reimbursements, which Ms. McAnallen said are, in her opinion, at the crux of the current national health care crisis.

“You go to your physician, they do something, they submit a claim, they get a check. We haven’t put in a system that makes providers, whether hospitals or physicians, step back and say, ‘Let’s do this differently. I’m on a treadmill of fee for service. The more I produce, the more I get paid.’ This IBD pilot program is to really help us transform that payment structure.”

Intangible factors such as how much of a specialty medical home’s success is predicated on the verve of its leadership will also be evaluated. “If you don’t have a physician who will be the [medical home’s] champion, it will be very hard to replicate,” Ms. McAnallen said. Attracting ambitious specialists with the opportunity to create such an integrated care model could become a recruitment tool for UPMC, she added.

If the concept of a one-stop-doc-shop sounds slightly “what was old is new again,” harkening back to the days when physicians were called doctors, never “providers,” and largely were thought of as family friends who made house calls, said Dr. Szigethy, it’s because it is that model, amplified by modern means.

“We can’t go to patients’ homes because they’re even more widespread than they were back in the day of the village, but what we can do is provide care through the ancillary team members who are extraordinarily well trained, and can provide education on nutrition and medication. Whether it’s by telemedicine or face to face, patients are getting treated in an integrated way, and we’re doing it as efficaciously as possible. That is brand new.”

Dr. Regueiro said in an interview at least one other insurance company has expressed interest in learning more about the IBD center’s integrated approach, causing him to reassess the payer’s role in health care’s revolution. “There is more common ground between us than I once thought. Insurers are not the devil. They are central to improving value.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

In just 1 year, 34 out of about 5,000 patients seen at the inflammatory bowel disease center at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center cost more than $10 million to treat.

“Our health plan said, ‘You have to fix this,’” recalled Dr. Miguel Regueiro, codirector of the IBD center.

So, in addition to asking the insurer for ideas, Dr. Regueiro did the most cost conscious thing he could think of: He asked for ideas from his colleague, Dr. Eva Szigethy, a psychiatrist specializing in the treatment of pain and psychosocial issues faced by IBD patients.

“Nearly half of our patient population has some behavioral, stress, or mental health component that is driving their disease, [leading] to high health care utilization,” Dr. Regueiro said.

Dr. Szigethy’s work of late, both on her own and with others such as Dr. Douglas Drossman, an emeritus psychiatrist and gastroenterologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, has focused on the so-called brain-gut axis and includes the impact of narcotics on the gastrointestinal tract, the correlation between inflammation and depression, the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy in IBD, and the use of self-hypnosis to manage chronic pain.

“The vast majority of IBD patients have mood disorders, depression, reactive adjustment disorder, anxiety both [before and after] their diagnosis, and chronic pain,” Dr. Szigethy said in an interview.

In practical terms, this means patients benefit from the partnership between Dr. Regueiro, who brings a deep medical knowledge of IBD, and Dr. Szigethy, who combines her research with her psychiatric skill for asking the kinds of questions that evoke the patient’s larger story. Together, said Dr. Szigethy, they assess patients as a whole, directly accounting for the emotional complexity inherent in IBD, with an eye toward helping patients regain control of their lives, often made chaotic by the unpredictable indignities that are the hallmarks of the disease.

“Often, if we listen in the lines and between the lines, our patients tell us exactly what other factors are involved: why their disease is not getting better, why they are getting headaches, why they have such continued suffering,” Dr. Szigethy said.

“You don’t need to know the basic science to understand the stress these patients feel,” Dr. Regueiro recounted to an audience at a recent Advances in IBD meeting in Orlando, sponsored by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America.

He shared with his audience the story of 45-year-old Anne, a Crohn’s disease sufferer treated at his center. Anne is not the patient’s real name. Despite her disease being inactive, Anne was hospitalized 23 times, and given 19 CT scans and seven endoscopic procedures in one calendar year alone, qualifying her as one of the center’s top 34 “health care frequent fliers.”

Empowering patients like Anne, whose costly care Dr. Szigethy and Dr. Regueiro recognized was attributable more to her psychosocial rather than medical IBD needs, not only improves their quality of life, it saves the system money.

This is why the same health plan representatives who told Dr. Regueiro they’d like to see cost reductions have partnered with him and Dr. Szigethy to develop a specialty care medical home pilot program that combines specialty, primary, and mental health care in one location. The program officially opened in mid-January of this year.

In the mid-1990s, the UPMC Health Plan was conceived by the medical center as a “strategic move to combine the intellectual capital of the provider system with that of the payer system,” according to Sandy McAnallen, UPMC Health Plan’s senior vice president for clinical affairs and quality performance.

The result, she said in an interview, is greater flexibility when it comes to what care is provided and how it is delivered. “The physicians are setting the evidence-based pathways on the kind of care that patients need to receive, and we have the ability to be very proactive with [how we pay for that] with this kind of relationship.”

Over the course of 2 years, Dr. Regueiro and Ms. McAnallen met several times to parse data on more effective ways to address the fractured way IBD patients, particularly those with undiagnosed psychosocial concerns, were seeking and receiving treatment. The pair also honed in on ways to cut the high cost of surgeries and pharmaceuticals with the overall goal being to create a healthier IBD patient population who perceived their care to be the best possible.

To develop their specialty medical home model, Dr. Regueiro, Dr. Szigethy, Ms. McAnallen, and other key UPMC hospital system and health plan administrators, as well as other IBD specialists, met many times over the course of 2 years to plan what Ms. McAnallen calls their proof of concept.

The program is offered automatically to those covered by the UPMC Health Plan, although anyone is welcome to opt out if they choose. Participants are asked, but not required, to submit to genetic sampling for IBD research purposes, and other data also are gathered with consent at the center. Those not covered by UPMC insurance also are welcome to participate. “The center is payer-agnostic,” Ms. McAnallen said.

Dr. Regueiro and his colleagues will be the primary doctors for all patients who want to be seen at the IBD center for their chronic condition, while episodic illnesses such as colds, flus, and rashes are treated by a newly added advance practice nurse. All patients are now offered behavioral and psychosocial support, depending on the concern, either from Dr. Szigethy, a psychologist, or a social worker who was added to the team for the pilot project.

“Part of what we are defining [with this project] is when a psychiatrist is needed, and what can be done by a less expensive, but well-trained behavioral health, medically trained person like a social worker,” said Dr. Szigethy, who is also a member of the department of psychiatry.

A new patient peer group offers patients the chance to discuss their IBD-related struggles with others who can empathize directly, and a nutritionist and pharmacist both specializing in IBD needs have been added to the payroll. A 24/7 call center also has been established.

“We want patients to be in the habit of calling one place where their entire history is known,” said Ms. McAnallen. “Whether they need primary care or specialty care, we want these patients to go to the specialty medical home.”

It’s a patient-centered, rather than an institution-based model, where the referrals are controlled by the payer, “but the system is value based not volume based,” said Dr. Regueiro.

To that end, Dr. Regueiro said he hopes the center will expand its use of telemedicine to further accommodate patients, who often find it difficult to take time off from work or school, find and afford child care, and travel long distances to their doctor appointments. “Right now, some patients have to drive hours to see us, but a lot of what we do for these patients is cognitive care,” he said.

The IBD center’s additional personnel have been paid for by the health plan, in order to cover the cost of adequately serving the approximately 725 IBD patients the insurer determined were the most expensive to treat out of the more than 5,000 IBD patients, a notably high number according to Dr. Szigethy, that the center serves.

In exchange for underwriting the cost of a portion of the staff, the health plan expects Dr. Regueiro and his team to cut treatment costs for this cohort. “If we save a certain amount on patients each year, the health plan will give that back to us,” Dr. Regueiro said.

One way Ms. McAnallen said the program is projected to save is by reducing the number of times frequent fliers of UPMC’s emergency department arrive with an IBD complaint.

“The ED specializes in all acute medical issues, but for IBD we need to focus in a different way,” said Ms. McAnallen.

To wit, in her health care high-utilization heyday, Anne’s treatment typically began in the emergency department, where she arrived seeking narcotics for her condition.

“She said she hated that the people in the ED treated her like a drug addict, but she hated the pain even more,” Dr. Regueiro told his Orlando audience.

This was particularly troublesome for Anne, since Dr. Szigethy determined she was a potential sufferer of narcotic bowel syndrome.

Although at present, much of the research into this phenomenon is still bench science, Dr. Szigethy said a growing body of evidence provided in part by advanced neuroimaging techniques indicates that chronic narcotic use changes opioid receptors in some human adults from creating an analgesic effect, to a hyperanalgesic one instead, where the narcotics themselves start to create pain and exacerbate any existing bowel issues.

“In Anne’s case, she was going up and up in her opiates, but her pain was getting worse,” Dr. Szigethy said.

Dr. Szigethy obtained permission from Anne’s insurer, which happened to be UPMC Health Plan, to give her a 5-day inpatient medical hospitalization during which time Anne was weaned from her narcotics. For 6 months prior to her detoxification from the opiates, Anne learned self-hypnosis techniques from Dr. Szigethy and her colleagues, which she used to support her withdrawal from the pain medication. Anne’s self-reported favorite technique was that whenever the pain would start, she would visualize filling a balloon with it, and then letting the balloon drift away until it eventually evaporated into the air.

“I know it sounds corny, but guess what? Last year, Anne had zero hospitalizations,” Dr. Regueiro said.

According to Dr. Szigethy, Anne still has occasional pain, “But she can deal with it.”The exact savings UPMC Health Plan expects to realize by way of reimbursing the IBD center for treatment models created in response to emerging research such as that of Dr. Szigethy is still unknown. But Ms. McAnallen is optimistic the program will meet its broader targets.

“We are at a point where costs are becoming out of control and the consumer can’t afford health care. You have to be in a position where you can rely on your physicians to develop evidence-based pathways for treatment of acute and chronic disease, which Eva and Miguel are doing, and to do be able to do so in a laboratory where you have the premium to support that,” Ms. McAnallen said, adding that had Dr. Regueiro approached an outside payer to help him create the medical home model, she doubted it would have come to fruition.

“Because we’re part of an integrated system, we’re all aligned with the same goals, which include improving the health status of our community and decreasing the cost of care so it’s affordable.”

Analysis of data collected on total cost and quality of care, and patient perception of care, will begin within the next 6 months, said Ms. McAnallen, who did not offer specific margins but noted that if gains are made, UPMC would look at how to apply this integrated approach to treating other chronic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis.

One central question the pilot program is expected to answer is whether it is feasible to do away with fee-for-service provider reimbursements, which Ms. McAnallen said are, in her opinion, at the crux of the current national health care crisis.

“You go to your physician, they do something, they submit a claim, they get a check. We haven’t put in a system that makes providers, whether hospitals or physicians, step back and say, ‘Let’s do this differently. I’m on a treadmill of fee for service. The more I produce, the more I get paid.’ This IBD pilot program is to really help us transform that payment structure.”

Intangible factors such as how much of a specialty medical home’s success is predicated on the verve of its leadership will also be evaluated. “If you don’t have a physician who will be the [medical home’s] champion, it will be very hard to replicate,” Ms. McAnallen said. Attracting ambitious specialists with the opportunity to create such an integrated care model could become a recruitment tool for UPMC, she added.

If the concept of a one-stop-doc-shop sounds slightly “what was old is new again,” harkening back to the days when physicians were called doctors, never “providers,” and largely were thought of as family friends who made house calls, said Dr. Szigethy, it’s because it is that model, amplified by modern means.

“We can’t go to patients’ homes because they’re even more widespread than they were back in the day of the village, but what we can do is provide care through the ancillary team members who are extraordinarily well trained, and can provide education on nutrition and medication. Whether it’s by telemedicine or face to face, patients are getting treated in an integrated way, and we’re doing it as efficaciously as possible. That is brand new.”

Dr. Regueiro said in an interview at least one other insurance company has expressed interest in learning more about the IBD center’s integrated approach, causing him to reassess the payer’s role in health care’s revolution. “There is more common ground between us than I once thought. Insurers are not the devil. They are central to improving value.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

In just 1 year, 34 out of about 5,000 patients seen at the inflammatory bowel disease center at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center cost more than $10 million to treat.

“Our health plan said, ‘You have to fix this,’” recalled Dr. Miguel Regueiro, codirector of the IBD center.

So, in addition to asking the insurer for ideas, Dr. Regueiro did the most cost conscious thing he could think of: He asked for ideas from his colleague, Dr. Eva Szigethy, a psychiatrist specializing in the treatment of pain and psychosocial issues faced by IBD patients.

“Nearly half of our patient population has some behavioral, stress, or mental health component that is driving their disease, [leading] to high health care utilization,” Dr. Regueiro said.

Dr. Szigethy’s work of late, both on her own and with others such as Dr. Douglas Drossman, an emeritus psychiatrist and gastroenterologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, has focused on the so-called brain-gut axis and includes the impact of narcotics on the gastrointestinal tract, the correlation between inflammation and depression, the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy in IBD, and the use of self-hypnosis to manage chronic pain.

“The vast majority of IBD patients have mood disorders, depression, reactive adjustment disorder, anxiety both [before and after] their diagnosis, and chronic pain,” Dr. Szigethy said in an interview.

In practical terms, this means patients benefit from the partnership between Dr. Regueiro, who brings a deep medical knowledge of IBD, and Dr. Szigethy, who combines her research with her psychiatric skill for asking the kinds of questions that evoke the patient’s larger story. Together, said Dr. Szigethy, they assess patients as a whole, directly accounting for the emotional complexity inherent in IBD, with an eye toward helping patients regain control of their lives, often made chaotic by the unpredictable indignities that are the hallmarks of the disease.

“Often, if we listen in the lines and between the lines, our patients tell us exactly what other factors are involved: why their disease is not getting better, why they are getting headaches, why they have such continued suffering,” Dr. Szigethy said.

“You don’t need to know the basic science to understand the stress these patients feel,” Dr. Regueiro recounted to an audience at a recent Advances in IBD meeting in Orlando, sponsored by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America.

He shared with his audience the story of 45-year-old Anne, a Crohn’s disease sufferer treated at his center. Anne is not the patient’s real name. Despite her disease being inactive, Anne was hospitalized 23 times, and given 19 CT scans and seven endoscopic procedures in one calendar year alone, qualifying her as one of the center’s top 34 “health care frequent fliers.”

Empowering patients like Anne, whose costly care Dr. Szigethy and Dr. Regueiro recognized was attributable more to her psychosocial rather than medical IBD needs, not only improves their quality of life, it saves the system money.

This is why the same health plan representatives who told Dr. Regueiro they’d like to see cost reductions have partnered with him and Dr. Szigethy to develop a specialty care medical home pilot program that combines specialty, primary, and mental health care in one location. The program officially opened in mid-January of this year.

In the mid-1990s, the UPMC Health Plan was conceived by the medical center as a “strategic move to combine the intellectual capital of the provider system with that of the payer system,” according to Sandy McAnallen, UPMC Health Plan’s senior vice president for clinical affairs and quality performance.

The result, she said in an interview, is greater flexibility when it comes to what care is provided and how it is delivered. “The physicians are setting the evidence-based pathways on the kind of care that patients need to receive, and we have the ability to be very proactive with [how we pay for that] with this kind of relationship.”

Over the course of 2 years, Dr. Regueiro and Ms. McAnallen met several times to parse data on more effective ways to address the fractured way IBD patients, particularly those with undiagnosed psychosocial concerns, were seeking and receiving treatment. The pair also honed in on ways to cut the high cost of surgeries and pharmaceuticals with the overall goal being to create a healthier IBD patient population who perceived their care to be the best possible.

To develop their specialty medical home model, Dr. Regueiro, Dr. Szigethy, Ms. McAnallen, and other key UPMC hospital system and health plan administrators, as well as other IBD specialists, met many times over the course of 2 years to plan what Ms. McAnallen calls their proof of concept.

The program is offered automatically to those covered by the UPMC Health Plan, although anyone is welcome to opt out if they choose. Participants are asked, but not required, to submit to genetic sampling for IBD research purposes, and other data also are gathered with consent at the center. Those not covered by UPMC insurance also are welcome to participate. “The center is payer-agnostic,” Ms. McAnallen said.

Dr. Regueiro and his colleagues will be the primary doctors for all patients who want to be seen at the IBD center for their chronic condition, while episodic illnesses such as colds, flus, and rashes are treated by a newly added advance practice nurse. All patients are now offered behavioral and psychosocial support, depending on the concern, either from Dr. Szigethy, a psychologist, or a social worker who was added to the team for the pilot project.

“Part of what we are defining [with this project] is when a psychiatrist is needed, and what can be done by a less expensive, but well-trained behavioral health, medically trained person like a social worker,” said Dr. Szigethy, who is also a member of the department of psychiatry.

A new patient peer group offers patients the chance to discuss their IBD-related struggles with others who can empathize directly, and a nutritionist and pharmacist both specializing in IBD needs have been added to the payroll. A 24/7 call center also has been established.

“We want patients to be in the habit of calling one place where their entire history is known,” said Ms. McAnallen. “Whether they need primary care or specialty care, we want these patients to go to the specialty medical home.”

It’s a patient-centered, rather than an institution-based model, where the referrals are controlled by the payer, “but the system is value based not volume based,” said Dr. Regueiro.

To that end, Dr. Regueiro said he hopes the center will expand its use of telemedicine to further accommodate patients, who often find it difficult to take time off from work or school, find and afford child care, and travel long distances to their doctor appointments. “Right now, some patients have to drive hours to see us, but a lot of what we do for these patients is cognitive care,” he said.

The IBD center’s additional personnel have been paid for by the health plan, in order to cover the cost of adequately serving the approximately 725 IBD patients the insurer determined were the most expensive to treat out of the more than 5,000 IBD patients, a notably high number according to Dr. Szigethy, that the center serves.

In exchange for underwriting the cost of a portion of the staff, the health plan expects Dr. Regueiro and his team to cut treatment costs for this cohort. “If we save a certain amount on patients each year, the health plan will give that back to us,” Dr. Regueiro said.

One way Ms. McAnallen said the program is projected to save is by reducing the number of times frequent fliers of UPMC’s emergency department arrive with an IBD complaint.

“The ED specializes in all acute medical issues, but for IBD we need to focus in a different way,” said Ms. McAnallen.

To wit, in her health care high-utilization heyday, Anne’s treatment typically began in the emergency department, where she arrived seeking narcotics for her condition.

“She said she hated that the people in the ED treated her like a drug addict, but she hated the pain even more,” Dr. Regueiro told his Orlando audience.

This was particularly troublesome for Anne, since Dr. Szigethy determined she was a potential sufferer of narcotic bowel syndrome.

Although at present, much of the research into this phenomenon is still bench science, Dr. Szigethy said a growing body of evidence provided in part by advanced neuroimaging techniques indicates that chronic narcotic use changes opioid receptors in some human adults from creating an analgesic effect, to a hyperanalgesic one instead, where the narcotics themselves start to create pain and exacerbate any existing bowel issues.

“In Anne’s case, she was going up and up in her opiates, but her pain was getting worse,” Dr. Szigethy said.

Dr. Szigethy obtained permission from Anne’s insurer, which happened to be UPMC Health Plan, to give her a 5-day inpatient medical hospitalization during which time Anne was weaned from her narcotics. For 6 months prior to her detoxification from the opiates, Anne learned self-hypnosis techniques from Dr. Szigethy and her colleagues, which she used to support her withdrawal from the pain medication. Anne’s self-reported favorite technique was that whenever the pain would start, she would visualize filling a balloon with it, and then letting the balloon drift away until it eventually evaporated into the air.

“I know it sounds corny, but guess what? Last year, Anne had zero hospitalizations,” Dr. Regueiro said.

According to Dr. Szigethy, Anne still has occasional pain, “But she can deal with it.”The exact savings UPMC Health Plan expects to realize by way of reimbursing the IBD center for treatment models created in response to emerging research such as that of Dr. Szigethy is still unknown. But Ms. McAnallen is optimistic the program will meet its broader targets.

“We are at a point where costs are becoming out of control and the consumer can’t afford health care. You have to be in a position where you can rely on your physicians to develop evidence-based pathways for treatment of acute and chronic disease, which Eva and Miguel are doing, and to do be able to do so in a laboratory where you have the premium to support that,” Ms. McAnallen said, adding that had Dr. Regueiro approached an outside payer to help him create the medical home model, she doubted it would have come to fruition.

“Because we’re part of an integrated system, we’re all aligned with the same goals, which include improving the health status of our community and decreasing the cost of care so it’s affordable.”

Analysis of data collected on total cost and quality of care, and patient perception of care, will begin within the next 6 months, said Ms. McAnallen, who did not offer specific margins but noted that if gains are made, UPMC would look at how to apply this integrated approach to treating other chronic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis.

One central question the pilot program is expected to answer is whether it is feasible to do away with fee-for-service provider reimbursements, which Ms. McAnallen said are, in her opinion, at the crux of the current national health care crisis.

“You go to your physician, they do something, they submit a claim, they get a check. We haven’t put in a system that makes providers, whether hospitals or physicians, step back and say, ‘Let’s do this differently. I’m on a treadmill of fee for service. The more I produce, the more I get paid.’ This IBD pilot program is to really help us transform that payment structure.”

Intangible factors such as how much of a specialty medical home’s success is predicated on the verve of its leadership will also be evaluated. “If you don’t have a physician who will be the [medical home’s] champion, it will be very hard to replicate,” Ms. McAnallen said. Attracting ambitious specialists with the opportunity to create such an integrated care model could become a recruitment tool for UPMC, she added.

If the concept of a one-stop-doc-shop sounds slightly “what was old is new again,” harkening back to the days when physicians were called doctors, never “providers,” and largely were thought of as family friends who made house calls, said Dr. Szigethy, it’s because it is that model, amplified by modern means.

“We can’t go to patients’ homes because they’re even more widespread than they were back in the day of the village, but what we can do is provide care through the ancillary team members who are extraordinarily well trained, and can provide education on nutrition and medication. Whether it’s by telemedicine or face to face, patients are getting treated in an integrated way, and we’re doing it as efficaciously as possible. That is brand new.”

Dr. Regueiro said in an interview at least one other insurance company has expressed interest in learning more about the IBD center’s integrated approach, causing him to reassess the payer’s role in health care’s revolution. “There is more common ground between us than I once thought. Insurers are not the devil. They are central to improving value.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Sample size, patient selection keys to successful small studies

ORLANDO – Studies with small patient populations but large effect sizes are the backbone of an independent investigator’s success. Rigorous patient selection doesn’t hurt, either.

“We often hide behind the words ‘pilot and feasibility’ to justify what was not a very good study,” Dr. Joshua Korzenik, director of Harvard Medical School’s Crohn’s and Colitis Center, Boston, said at a conference on inflammatory bowel diseases sponsored by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America. “The term can indicate something was not statistically significant, and that can be legitimate, but ‘pilot’ should not be a substitute for not sizing the study appropriately.”

Sample size consideration is important with respect to data analysis and endpoints, said Dr. Korzenik, but disciplined selection criteria strictly applied sweetens the odds for a study’s impact. Cultivating a cohort that is the “most homogeneous, cleanest, and clearest ... will give you the best insight.” Consider choosing patients according to disease subtype, bio- and genetic markers, a history of at least 3 consecutive months of disease, and a history of certain medication failures.

Steer clear of the assumption that just because you already treat a certain number of patients, you will be able to recruit them. “Some patients won’t want to commit to a study,” warned Dr. Korzenik. “You need to think more carefully.”

And don’t forget the “tremendous” impact of standard deviation on sample size. Dr. Korzenik recommended the “usual” power of .8 with a P value less than .05 for early phase studies.

For the neophyte independent investigator, sweating over what to write in his or her hypothesis, and struggling against temptation to justify sample size by stretching how small the placebo response will be vs. how great the efficacy rate is only to find actual results are not nearly what was predicted, can be devastating. “Then you’ve shot yourself in the foot,” said Dr. Korzenik.

One problem is that few, if any, previous data exist for these kinds of studies. And preclinical data “tends not to be helpful at all,” Dr. Korzenik opined.

Even in trials for anti–tumor necrosis factor drugs, what Dr. Korzenik argued are the most revolutionary treatments to yet impact the field, the question of placebo effect on sample size was tricky. “For the most part, anti-TNFs are about 20% better than placebo for inducing remission. That’s a pretty high bar to set, and most investigator-sponsored studies set the bar even higher, making it very difficult.”

If, for example, an investigator hopes to achieve a 50% reduction in calprotectin, and so sets a “modest” rate of 20% for placebo and 35% for the test drug, that means the investigator must recruit 136 patients per arm. “Yikes!”

But estimating at 15% vs. 40% for the drug, with 47 in each arm, may push the benefit of the study drug “too much.” Using a placebo effect size of 10% vs. 50% for the drug, with 17 patients per arm, the investigator runs the risk of overestimating what’s possible. “You might need to look for another endpoint, or some other set of collaborators,” Dr. Korzenik said.

Open-label studies can be useful for helping with sample size, particularly if the study is to evaluate a novel approach to treatment, but things can still go wobbly. “Open-label trials have limitations we don’t fully understand,” Dr. Korzenik said.

To wit, open-label trials on the use of the helminth Trichuris suis to treat Crohn’s disease showed robust response remission rates, but a successive, placebo-controlled trial did not achieve these results. For independent investigators conducting a placebo-controlled trial using a comparator for the control group, Dr. Korzenik suggested ways to keep the placebo response lower. These included, among other strategies, recruiting patients with higher disease activity and keeping trials as short as possible. “When you do longer studies, the placebo response remission rates go up. Keep that in mind.”

And, don’t forget: Not all small studies with impact need focus on pharmaceuticals. Possibilities Dr. Korzenik suggested include alternative interventions such as marijuana, curcumin, and aloe vera. “These things have been done, but deserve further study,” he said, adding that nutritional interventions are “undervalued, and although difficult to study, are very important.”

The role of depression, fatigue, and other psychosocial impacts of inflammatory bowel disease are also worthy of study, as are the utility of telemedicine and social media for helping patients, he said.

Because investigators will want to protect their resources – namely, the goodwill of the patients they painstakingly recruited – Dr. Korzenik advised using telemedicine to interact with study participants whenever possible, and to consider using smartphone apps to record symptom data. “Remember that repeated evaluations become an enormous burden on the patient.”

Dr. Korzenik urged young investigators not to be intimidated, and to see their inexperience as liberation from having preconceived notions of what the correct approaches are to studying IBD. Still, finding a mentor “who can help shape your ideas and help develop techniques,” can be confidence building.

“You don’t necessarily need to have a final piece of work that can stand on its own,” Dr. Korzenik concluded. “You’re learning how to do a clinical trial and get your career moving forward.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

ORLANDO – Studies with small patient populations but large effect sizes are the backbone of an independent investigator’s success. Rigorous patient selection doesn’t hurt, either.

“We often hide behind the words ‘pilot and feasibility’ to justify what was not a very good study,” Dr. Joshua Korzenik, director of Harvard Medical School’s Crohn’s and Colitis Center, Boston, said at a conference on inflammatory bowel diseases sponsored by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America. “The term can indicate something was not statistically significant, and that can be legitimate, but ‘pilot’ should not be a substitute for not sizing the study appropriately.”

Sample size consideration is important with respect to data analysis and endpoints, said Dr. Korzenik, but disciplined selection criteria strictly applied sweetens the odds for a study’s impact. Cultivating a cohort that is the “most homogeneous, cleanest, and clearest ... will give you the best insight.” Consider choosing patients according to disease subtype, bio- and genetic markers, a history of at least 3 consecutive months of disease, and a history of certain medication failures.

Steer clear of the assumption that just because you already treat a certain number of patients, you will be able to recruit them. “Some patients won’t want to commit to a study,” warned Dr. Korzenik. “You need to think more carefully.”

And don’t forget the “tremendous” impact of standard deviation on sample size. Dr. Korzenik recommended the “usual” power of .8 with a P value less than .05 for early phase studies.

For the neophyte independent investigator, sweating over what to write in his or her hypothesis, and struggling against temptation to justify sample size by stretching how small the placebo response will be vs. how great the efficacy rate is only to find actual results are not nearly what was predicted, can be devastating. “Then you’ve shot yourself in the foot,” said Dr. Korzenik.

One problem is that few, if any, previous data exist for these kinds of studies. And preclinical data “tends not to be helpful at all,” Dr. Korzenik opined.

Even in trials for anti–tumor necrosis factor drugs, what Dr. Korzenik argued are the most revolutionary treatments to yet impact the field, the question of placebo effect on sample size was tricky. “For the most part, anti-TNFs are about 20% better than placebo for inducing remission. That’s a pretty high bar to set, and most investigator-sponsored studies set the bar even higher, making it very difficult.”

If, for example, an investigator hopes to achieve a 50% reduction in calprotectin, and so sets a “modest” rate of 20% for placebo and 35% for the test drug, that means the investigator must recruit 136 patients per arm. “Yikes!”

But estimating at 15% vs. 40% for the drug, with 47 in each arm, may push the benefit of the study drug “too much.” Using a placebo effect size of 10% vs. 50% for the drug, with 17 patients per arm, the investigator runs the risk of overestimating what’s possible. “You might need to look for another endpoint, or some other set of collaborators,” Dr. Korzenik said.

Open-label studies can be useful for helping with sample size, particularly if the study is to evaluate a novel approach to treatment, but things can still go wobbly. “Open-label trials have limitations we don’t fully understand,” Dr. Korzenik said.

To wit, open-label trials on the use of the helminth Trichuris suis to treat Crohn’s disease showed robust response remission rates, but a successive, placebo-controlled trial did not achieve these results. For independent investigators conducting a placebo-controlled trial using a comparator for the control group, Dr. Korzenik suggested ways to keep the placebo response lower. These included, among other strategies, recruiting patients with higher disease activity and keeping trials as short as possible. “When you do longer studies, the placebo response remission rates go up. Keep that in mind.”

And, don’t forget: Not all small studies with impact need focus on pharmaceuticals. Possibilities Dr. Korzenik suggested include alternative interventions such as marijuana, curcumin, and aloe vera. “These things have been done, but deserve further study,” he said, adding that nutritional interventions are “undervalued, and although difficult to study, are very important.”

The role of depression, fatigue, and other psychosocial impacts of inflammatory bowel disease are also worthy of study, as are the utility of telemedicine and social media for helping patients, he said.

Because investigators will want to protect their resources – namely, the goodwill of the patients they painstakingly recruited – Dr. Korzenik advised using telemedicine to interact with study participants whenever possible, and to consider using smartphone apps to record symptom data. “Remember that repeated evaluations become an enormous burden on the patient.”

Dr. Korzenik urged young investigators not to be intimidated, and to see their inexperience as liberation from having preconceived notions of what the correct approaches are to studying IBD. Still, finding a mentor “who can help shape your ideas and help develop techniques,” can be confidence building.

“You don’t necessarily need to have a final piece of work that can stand on its own,” Dr. Korzenik concluded. “You’re learning how to do a clinical trial and get your career moving forward.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

ORLANDO – Studies with small patient populations but large effect sizes are the backbone of an independent investigator’s success. Rigorous patient selection doesn’t hurt, either.

“We often hide behind the words ‘pilot and feasibility’ to justify what was not a very good study,” Dr. Joshua Korzenik, director of Harvard Medical School’s Crohn’s and Colitis Center, Boston, said at a conference on inflammatory bowel diseases sponsored by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America. “The term can indicate something was not statistically significant, and that can be legitimate, but ‘pilot’ should not be a substitute for not sizing the study appropriately.”

Sample size consideration is important with respect to data analysis and endpoints, said Dr. Korzenik, but disciplined selection criteria strictly applied sweetens the odds for a study’s impact. Cultivating a cohort that is the “most homogeneous, cleanest, and clearest ... will give you the best insight.” Consider choosing patients according to disease subtype, bio- and genetic markers, a history of at least 3 consecutive months of disease, and a history of certain medication failures.

Steer clear of the assumption that just because you already treat a certain number of patients, you will be able to recruit them. “Some patients won’t want to commit to a study,” warned Dr. Korzenik. “You need to think more carefully.”

And don’t forget the “tremendous” impact of standard deviation on sample size. Dr. Korzenik recommended the “usual” power of .8 with a P value less than .05 for early phase studies.

For the neophyte independent investigator, sweating over what to write in his or her hypothesis, and struggling against temptation to justify sample size by stretching how small the placebo response will be vs. how great the efficacy rate is only to find actual results are not nearly what was predicted, can be devastating. “Then you’ve shot yourself in the foot,” said Dr. Korzenik.

One problem is that few, if any, previous data exist for these kinds of studies. And preclinical data “tends not to be helpful at all,” Dr. Korzenik opined.

Even in trials for anti–tumor necrosis factor drugs, what Dr. Korzenik argued are the most revolutionary treatments to yet impact the field, the question of placebo effect on sample size was tricky. “For the most part, anti-TNFs are about 20% better than placebo for inducing remission. That’s a pretty high bar to set, and most investigator-sponsored studies set the bar even higher, making it very difficult.”

If, for example, an investigator hopes to achieve a 50% reduction in calprotectin, and so sets a “modest” rate of 20% for placebo and 35% for the test drug, that means the investigator must recruit 136 patients per arm. “Yikes!”

But estimating at 15% vs. 40% for the drug, with 47 in each arm, may push the benefit of the study drug “too much.” Using a placebo effect size of 10% vs. 50% for the drug, with 17 patients per arm, the investigator runs the risk of overestimating what’s possible. “You might need to look for another endpoint, or some other set of collaborators,” Dr. Korzenik said.

Open-label studies can be useful for helping with sample size, particularly if the study is to evaluate a novel approach to treatment, but things can still go wobbly. “Open-label trials have limitations we don’t fully understand,” Dr. Korzenik said.

To wit, open-label trials on the use of the helminth Trichuris suis to treat Crohn’s disease showed robust response remission rates, but a successive, placebo-controlled trial did not achieve these results. For independent investigators conducting a placebo-controlled trial using a comparator for the control group, Dr. Korzenik suggested ways to keep the placebo response lower. These included, among other strategies, recruiting patients with higher disease activity and keeping trials as short as possible. “When you do longer studies, the placebo response remission rates go up. Keep that in mind.”

And, don’t forget: Not all small studies with impact need focus on pharmaceuticals. Possibilities Dr. Korzenik suggested include alternative interventions such as marijuana, curcumin, and aloe vera. “These things have been done, but deserve further study,” he said, adding that nutritional interventions are “undervalued, and although difficult to study, are very important.”

The role of depression, fatigue, and other psychosocial impacts of inflammatory bowel disease are also worthy of study, as are the utility of telemedicine and social media for helping patients, he said.

Because investigators will want to protect their resources – namely, the goodwill of the patients they painstakingly recruited – Dr. Korzenik advised using telemedicine to interact with study participants whenever possible, and to consider using smartphone apps to record symptom data. “Remember that repeated evaluations become an enormous burden on the patient.”

Dr. Korzenik urged young investigators not to be intimidated, and to see their inexperience as liberation from having preconceived notions of what the correct approaches are to studying IBD. Still, finding a mentor “who can help shape your ideas and help develop techniques,” can be confidence building.

“You don’t necessarily need to have a final piece of work that can stand on its own,” Dr. Korzenik concluded. “You’re learning how to do a clinical trial and get your career moving forward.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM 2014 ADVANCES IN IBD

Rx for specialists: Know how ACA affects patients’ ability to pay for meds

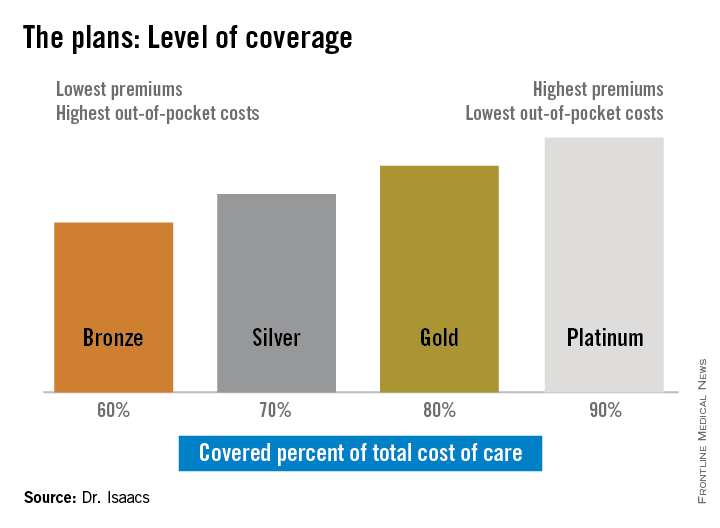

ORLANDO – Despite recent, significant shifts in health care coverage thanks to the Affordable Care Act, many specialists are unaware of how patients pay for pricey prescriptions such as biologics.

One reason is that clinicians just haven’t been paying enough attention, according to Dr. Kim L. Isaacs, codirector of the multidiscipline treatment and research center for inflammatory bowel disease at the University of North Carolina.

“It gets complicated because we’re taking care of patients, so it’s hard to think about the financial end of things as well, and it lands on the patient’s lap,” Dr. Isaacs said in an interview after her presentation, “Navigating the Affordable Care Act,” at a conference on inflammatory bowel diseases sponsored by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America.

But not knowing how and if chronically ill patients can afford to pay for their medications can impact their compliance, and even their disease states.

Dr. Isaacs compared the histories of two patients. The first one purchased through the ACA’s health insurance marketplace provision, and regardless of her preexisting condition, she was able to receive and afford treatment for her Crohn’s disease for the first time in a decade. The second patient purchased ACA-sanctioned insurance but it still wasn’t enough to cover the costs of her care.

“She told me she had thought the Silver Plan would work for her, but that she still couldn’t afford her medications, and I was thinking, ‘What’s a Silver Plan?’ ” Dr. Isaacs said. “I didn’t have a clue.”

The discrepancy between the patients’ plans prompted Dr. Isaacs to investigate whether what she was prescribing was practical under her patients’ various levels of coverage. She discovered that under the ACA, the individual mandate requiring all Americans to purchase some form of health insurance means many have turned to a variety of state- and federally-sponsored health insurance marketplaces that offer coverage plans ranging from Bronze to Platinum.

“If you ask [most specialists] what the Gold Plan is, most of them won’t have heard of it, they don’t know,” she said.

But she said that physicians need to be aware of whether the drugs they are prescribing are on the formulary used by their patients’ respective plans since the different insurance providers that back the various plans often don’t cover the same medications.

In addition, the so-called “donut hole,” the annually adjusted gap in prescription drug coverage for Medicare patients, is not scheduled to close until 2020. While the gap exists, Medicare patients have a set amount of annual drug coverage after which the patient shares a substantial portion of the cost until the following year when the process begins again.

“For our IBD patients, this is very important because for some of our more expensive drugs, there may be a period of time [annually] when the drugs are not covered,” Dr. Isaacs said.

The same could be true for other specialties such as oncology, rheumatology, and neurology, where disease states require high-cost specialty drugs; however, some patient advocacy groups will assist patients in paying for their treatment, she said.

Patients who purchase their health plans through the government-sponsored insurance marketplaces are usually eligible for subsidies, depending on their income and where they fall in relation to the federally set poverty level, said Dr. Isaacs.

Another important, basic point, she added, is that providers need to ensure that they are on their patients’ chosen plans. “If you’re not, then you need to be sure there is someone else who is on the plan who can take care of your patient.”

Dr. Isaacs reported she has affiliations with AbbVie, Janssen, Millennium, Takeda, UCB, and others.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

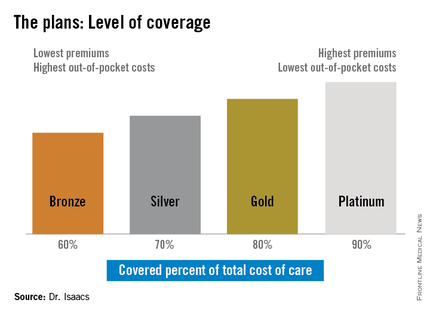

ORLANDO – Despite recent, significant shifts in health care coverage thanks to the Affordable Care Act, many specialists are unaware of how patients pay for pricey prescriptions such as biologics.

One reason is that clinicians just haven’t been paying enough attention, according to Dr. Kim L. Isaacs, codirector of the multidiscipline treatment and research center for inflammatory bowel disease at the University of North Carolina.

“It gets complicated because we’re taking care of patients, so it’s hard to think about the financial end of things as well, and it lands on the patient’s lap,” Dr. Isaacs said in an interview after her presentation, “Navigating the Affordable Care Act,” at a conference on inflammatory bowel diseases sponsored by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America.

But not knowing how and if chronically ill patients can afford to pay for their medications can impact their compliance, and even their disease states.

Dr. Isaacs compared the histories of two patients. The first one purchased through the ACA’s health insurance marketplace provision, and regardless of her preexisting condition, she was able to receive and afford treatment for her Crohn’s disease for the first time in a decade. The second patient purchased ACA-sanctioned insurance but it still wasn’t enough to cover the costs of her care.

“She told me she had thought the Silver Plan would work for her, but that she still couldn’t afford her medications, and I was thinking, ‘What’s a Silver Plan?’ ” Dr. Isaacs said. “I didn’t have a clue.”

The discrepancy between the patients’ plans prompted Dr. Isaacs to investigate whether what she was prescribing was practical under her patients’ various levels of coverage. She discovered that under the ACA, the individual mandate requiring all Americans to purchase some form of health insurance means many have turned to a variety of state- and federally-sponsored health insurance marketplaces that offer coverage plans ranging from Bronze to Platinum.

“If you ask [most specialists] what the Gold Plan is, most of them won’t have heard of it, they don’t know,” she said.

But she said that physicians need to be aware of whether the drugs they are prescribing are on the formulary used by their patients’ respective plans since the different insurance providers that back the various plans often don’t cover the same medications.

In addition, the so-called “donut hole,” the annually adjusted gap in prescription drug coverage for Medicare patients, is not scheduled to close until 2020. While the gap exists, Medicare patients have a set amount of annual drug coverage after which the patient shares a substantial portion of the cost until the following year when the process begins again.

“For our IBD patients, this is very important because for some of our more expensive drugs, there may be a period of time [annually] when the drugs are not covered,” Dr. Isaacs said.

The same could be true for other specialties such as oncology, rheumatology, and neurology, where disease states require high-cost specialty drugs; however, some patient advocacy groups will assist patients in paying for their treatment, she said.

Patients who purchase their health plans through the government-sponsored insurance marketplaces are usually eligible for subsidies, depending on their income and where they fall in relation to the federally set poverty level, said Dr. Isaacs.

Another important, basic point, she added, is that providers need to ensure that they are on their patients’ chosen plans. “If you’re not, then you need to be sure there is someone else who is on the plan who can take care of your patient.”

Dr. Isaacs reported she has affiliations with AbbVie, Janssen, Millennium, Takeda, UCB, and others.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

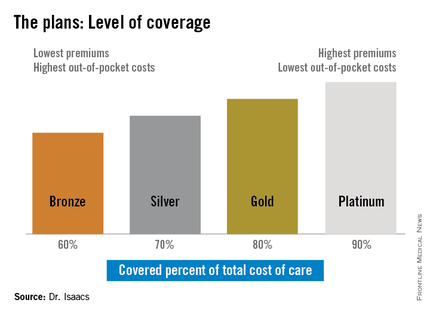

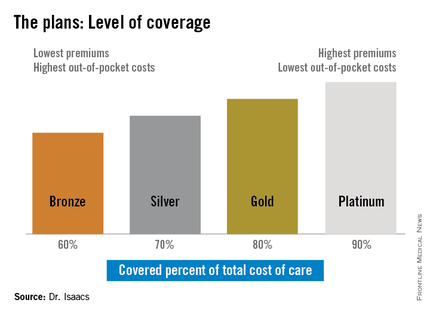

ORLANDO – Despite recent, significant shifts in health care coverage thanks to the Affordable Care Act, many specialists are unaware of how patients pay for pricey prescriptions such as biologics.

One reason is that clinicians just haven’t been paying enough attention, according to Dr. Kim L. Isaacs, codirector of the multidiscipline treatment and research center for inflammatory bowel disease at the University of North Carolina.

“It gets complicated because we’re taking care of patients, so it’s hard to think about the financial end of things as well, and it lands on the patient’s lap,” Dr. Isaacs said in an interview after her presentation, “Navigating the Affordable Care Act,” at a conference on inflammatory bowel diseases sponsored by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America.

But not knowing how and if chronically ill patients can afford to pay for their medications can impact their compliance, and even their disease states.

Dr. Isaacs compared the histories of two patients. The first one purchased through the ACA’s health insurance marketplace provision, and regardless of her preexisting condition, she was able to receive and afford treatment for her Crohn’s disease for the first time in a decade. The second patient purchased ACA-sanctioned insurance but it still wasn’t enough to cover the costs of her care.

“She told me she had thought the Silver Plan would work for her, but that she still couldn’t afford her medications, and I was thinking, ‘What’s a Silver Plan?’ ” Dr. Isaacs said. “I didn’t have a clue.”

The discrepancy between the patients’ plans prompted Dr. Isaacs to investigate whether what she was prescribing was practical under her patients’ various levels of coverage. She discovered that under the ACA, the individual mandate requiring all Americans to purchase some form of health insurance means many have turned to a variety of state- and federally-sponsored health insurance marketplaces that offer coverage plans ranging from Bronze to Platinum.

“If you ask [most specialists] what the Gold Plan is, most of them won’t have heard of it, they don’t know,” she said.

But she said that physicians need to be aware of whether the drugs they are prescribing are on the formulary used by their patients’ respective plans since the different insurance providers that back the various plans often don’t cover the same medications.

In addition, the so-called “donut hole,” the annually adjusted gap in prescription drug coverage for Medicare patients, is not scheduled to close until 2020. While the gap exists, Medicare patients have a set amount of annual drug coverage after which the patient shares a substantial portion of the cost until the following year when the process begins again.

“For our IBD patients, this is very important because for some of our more expensive drugs, there may be a period of time [annually] when the drugs are not covered,” Dr. Isaacs said.

The same could be true for other specialties such as oncology, rheumatology, and neurology, where disease states require high-cost specialty drugs; however, some patient advocacy groups will assist patients in paying for their treatment, she said.

Patients who purchase their health plans through the government-sponsored insurance marketplaces are usually eligible for subsidies, depending on their income and where they fall in relation to the federally set poverty level, said Dr. Isaacs.

Another important, basic point, she added, is that providers need to ensure that they are on their patients’ chosen plans. “If you’re not, then you need to be sure there is someone else who is on the plan who can take care of your patient.”

Dr. Isaacs reported she has affiliations with AbbVie, Janssen, Millennium, Takeda, UCB, and others.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM 2014 ADVANCES IN IBD

Faster clearance of vedolizumab associated with less mucosal healing in UC

ORLANDO – Ulcerative colitis sufferers with higher vedolizumab trough scores at 6 weeks in the GEMINI-1 study were found to have higher rates of mucosal healing, a post hoc, population pharmacokinetics analysis has shown.

The findings’ significance, however, is still a matter of debate, according to Maria Rosario, Ph.D., a director at Takeda Pharmaceuticals, and the data’s presenter at this year’s annual Advances in Inflammatory Bowel Disease meeting sponsored by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America.

“We have established a relationship between higher endoscopic scores and faster clearance, but we need to be careful how we interpret the data,” she concluded in her presentation, citing a lack of an established causal relationship between the two.

Results from the GEMINI-1 study lead to the Food and Drug Administration’s 2013 indication of vedolizumab, a disease-modifying monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of refractory ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease.

In the phase III study, two cohorts of UC patients were either double-blinded to vedolizumab 300 mg or placebo; or, to open-label vedolizumab 300 mg at weeks 0 and 2 during induction.

At week 6, responders to the medication in each cohort were re-randomized to either placebo or the study drug every 4 or 8 weeks during maintenance, up to week 52. Induction placebo patients and week 6 nonresponders continued their respective regimens.

For the post hoc analysis, serum levels of the drug in both cohorts were determined at weeks 6 and 46 according to each person’s Mayo Clinic endoscopic subscore at weeks 6 and 52. Trough concentration levels were divided into quartiles at weeks 6 and 46, as were the associated rates of mucosal healing at weeks 6 and 52. Dr. Rosario and her colleagues then used population pharmacokinetic modeling to estimate individual clearance values.

Patients who had higher levels of drug serum concentrations at week 6 were also found to have more mucosal healing. In the 55 patients who had an endoscopic subscore of 0, median trough concentrations were 34.5 mcg/mL; 30.4 mcg/mL in the 223 patients with subscores of 1; 24.0 mcg/mL in the 224 patients with a subscore of 2; and 19.6 mcg/mL in the 188 patients who had a subscore of 3.

Dr. Rosario also noted that in median week 6, trough concentrations in patients with the highest subscores lagged behind the overall week 6 median GEMINI-1 results, which were 25.6 mcg/mL.

Because this study did not measure fecal levels of the drug, these preliminary findings should encourage further investigation, said Dr. Rosario, who said the role of disease severity would be key to more precise interpretation of the data. Dr. Rosario is a director at Takeda Pharmaceuticals, manufacturer of Entyvio, the brand name for vedolizumab.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

ORLANDO – Ulcerative colitis sufferers with higher vedolizumab trough scores at 6 weeks in the GEMINI-1 study were found to have higher rates of mucosal healing, a post hoc, population pharmacokinetics analysis has shown.

The findings’ significance, however, is still a matter of debate, according to Maria Rosario, Ph.D., a director at Takeda Pharmaceuticals, and the data’s presenter at this year’s annual Advances in Inflammatory Bowel Disease meeting sponsored by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America.

“We have established a relationship between higher endoscopic scores and faster clearance, but we need to be careful how we interpret the data,” she concluded in her presentation, citing a lack of an established causal relationship between the two.

Results from the GEMINI-1 study lead to the Food and Drug Administration’s 2013 indication of vedolizumab, a disease-modifying monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of refractory ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease.

In the phase III study, two cohorts of UC patients were either double-blinded to vedolizumab 300 mg or placebo; or, to open-label vedolizumab 300 mg at weeks 0 and 2 during induction.

At week 6, responders to the medication in each cohort were re-randomized to either placebo or the study drug every 4 or 8 weeks during maintenance, up to week 52. Induction placebo patients and week 6 nonresponders continued their respective regimens.

For the post hoc analysis, serum levels of the drug in both cohorts were determined at weeks 6 and 46 according to each person’s Mayo Clinic endoscopic subscore at weeks 6 and 52. Trough concentration levels were divided into quartiles at weeks 6 and 46, as were the associated rates of mucosal healing at weeks 6 and 52. Dr. Rosario and her colleagues then used population pharmacokinetic modeling to estimate individual clearance values.

Patients who had higher levels of drug serum concentrations at week 6 were also found to have more mucosal healing. In the 55 patients who had an endoscopic subscore of 0, median trough concentrations were 34.5 mcg/mL; 30.4 mcg/mL in the 223 patients with subscores of 1; 24.0 mcg/mL in the 224 patients with a subscore of 2; and 19.6 mcg/mL in the 188 patients who had a subscore of 3.

Dr. Rosario also noted that in median week 6, trough concentrations in patients with the highest subscores lagged behind the overall week 6 median GEMINI-1 results, which were 25.6 mcg/mL.

Because this study did not measure fecal levels of the drug, these preliminary findings should encourage further investigation, said Dr. Rosario, who said the role of disease severity would be key to more precise interpretation of the data. Dr. Rosario is a director at Takeda Pharmaceuticals, manufacturer of Entyvio, the brand name for vedolizumab.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

ORLANDO – Ulcerative colitis sufferers with higher vedolizumab trough scores at 6 weeks in the GEMINI-1 study were found to have higher rates of mucosal healing, a post hoc, population pharmacokinetics analysis has shown.

The findings’ significance, however, is still a matter of debate, according to Maria Rosario, Ph.D., a director at Takeda Pharmaceuticals, and the data’s presenter at this year’s annual Advances in Inflammatory Bowel Disease meeting sponsored by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America.

“We have established a relationship between higher endoscopic scores and faster clearance, but we need to be careful how we interpret the data,” she concluded in her presentation, citing a lack of an established causal relationship between the two.

Results from the GEMINI-1 study lead to the Food and Drug Administration’s 2013 indication of vedolizumab, a disease-modifying monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of refractory ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease.

In the phase III study, two cohorts of UC patients were either double-blinded to vedolizumab 300 mg or placebo; or, to open-label vedolizumab 300 mg at weeks 0 and 2 during induction.

At week 6, responders to the medication in each cohort were re-randomized to either placebo or the study drug every 4 or 8 weeks during maintenance, up to week 52. Induction placebo patients and week 6 nonresponders continued their respective regimens.

For the post hoc analysis, serum levels of the drug in both cohorts were determined at weeks 6 and 46 according to each person’s Mayo Clinic endoscopic subscore at weeks 6 and 52. Trough concentration levels were divided into quartiles at weeks 6 and 46, as were the associated rates of mucosal healing at weeks 6 and 52. Dr. Rosario and her colleagues then used population pharmacokinetic modeling to estimate individual clearance values.

Patients who had higher levels of drug serum concentrations at week 6 were also found to have more mucosal healing. In the 55 patients who had an endoscopic subscore of 0, median trough concentrations were 34.5 mcg/mL; 30.4 mcg/mL in the 223 patients with subscores of 1; 24.0 mcg/mL in the 224 patients with a subscore of 2; and 19.6 mcg/mL in the 188 patients who had a subscore of 3.

Dr. Rosario also noted that in median week 6, trough concentrations in patients with the highest subscores lagged behind the overall week 6 median GEMINI-1 results, which were 25.6 mcg/mL.

Because this study did not measure fecal levels of the drug, these preliminary findings should encourage further investigation, said Dr. Rosario, who said the role of disease severity would be key to more precise interpretation of the data. Dr. Rosario is a director at Takeda Pharmaceuticals, manufacturer of Entyvio, the brand name for vedolizumab.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

AT ADVANCES IN IBD 2014

Key clinical point: Patients with higher endoscopic subscores may be clearing vedolizumab faster than are those who show more mucosal healing.

Major finding: At 6 weeks, patients with higher trough concentrations of vedolizumab had lower endoscopic subscores.

Data source: Post hoc analysis of 693 ulcerative colitis patients from phase III, randomized GEMINI-1 study of vedolizumab’s efficacy in UC.

Disclosures: Dr. Rosario is a director at Takeda Pharmaceuticals, manufacturer of Entyvio, the brand name for vedolizumab.

Immunosuppression not tied to subsequent cancer in IBD with cancer history

ORLANDO – Immunosuppressive therapies were not associated with subsequent cancers in patients with inflammatory bowel disease who also had a history of cancer, a retrospective analysis showed.

In a review of 185 patient records from three sites chosen according to whether the person had both a history of cancer and a confirmed diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), patients had at least one follow-up visit after their respective cancer diagnosis.

There were three study arms: 65 patients who’d been treated for their IBD with anti–TNF-alpha immunosuppression, 46 patients who’d received antimetabolite immunosuppressive treatment, and 74 controls who’d not been exposed to immunosuppression. The primary outcome was the development of incident cancer, whether new or recurrent, as calculated from the date of the initial cancer diagnosis to the date of the recurrent or new malignancy or to the date of the patient’s last clinical visit.

Nearly a third of all patients developed incident cancer during the follow-up period, but there were not any statistically significant differences in incident rates between groups, Dr. Jordan Axelrad reported at a conference on inflammatory bowel diseases, sponsored by the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America.