User login

American Heart Association (AHA): Scientific Sessions 2015

New-onset AF During Hospitalization Is More Lethal in Women

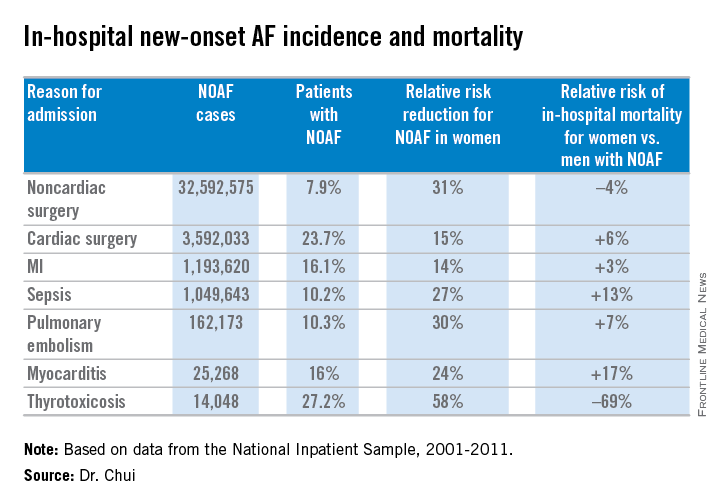

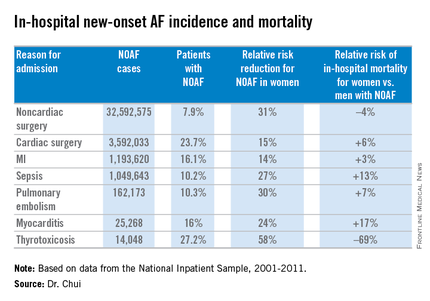

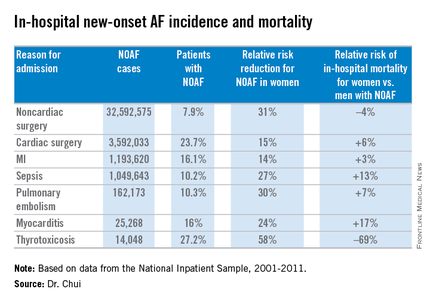

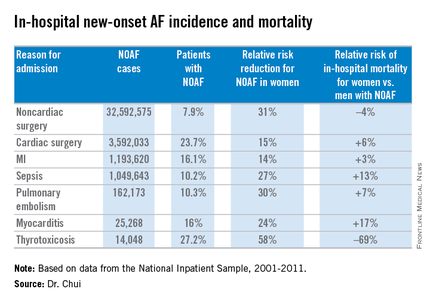

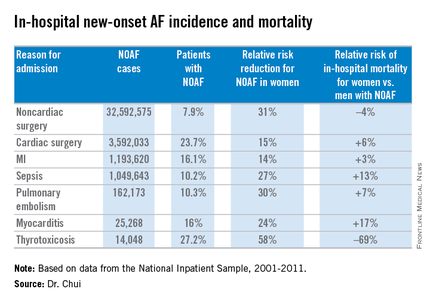

ORLANDO – Women are at lower risk than men for new-onset atrial fibrillation during hospitalization, but when it does occur it’s associated with significantly greater in-hospital mortality, according to a massive retrospective study presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Dr. Philip W. Chui analyzed 38,403,360 cases of new-onset atrial fibrillation during hospitalization (NOAF) in 2001-2011. The source was the National Inpatient Sample database. Fully 85% of all cases occurred in patients admitted for noncardiac surgery, which also was the cause of admission with the lowest incidence of NOAF. Among the patients hospitalized for sepsis, women were 27% less likely than men to develop new-onset atrial fibrillation, but when they did they were 13% more likely to die in-hospital.

In a multivariate logistic regression analysis extensively adjusted for numerous comorbid conditions and demographic factors, female gender was associated with a significantly reduced risk of NOAF across the board for all major admitting conditions known to be triggers for NOAF. The magnitude of this relative risk reduction favoring women ranged from as low as 14% for patients with an admitting diagnosis of acute MI to 58% with admission for thyrotoxicosis, reported Dr. Chui, an internal medicine resident at the University of California, Irvine.

The most provocative study finding was the significantly higher in-hospital mortality for women, compared with men with NOAF for all but two of the seven major reasons for admission studied: noncardiac surgery and thyrotoxicosis. Dr. Chui asserted that this appears to be a quality of care issue.

“The overwhelming majority of new-onset AF in-hospital occurs in postsurgical patients, who may be under the care of providers with less experience in managing AF,” he said. “Our results suggest clinicians need to be aware of the subtleties in presentation and management of female new-onset AF patients compared to their male counterparts.”

Dr. Chui reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, which was financially supported by the university’s department of internal medicine.

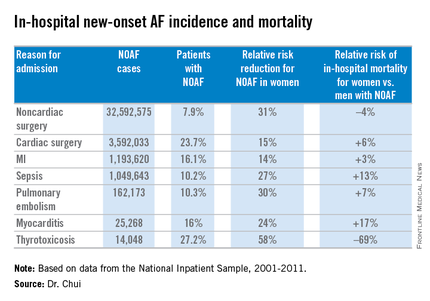

ORLANDO – Women are at lower risk than men for new-onset atrial fibrillation during hospitalization, but when it does occur it’s associated with significantly greater in-hospital mortality, according to a massive retrospective study presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Dr. Philip W. Chui analyzed 38,403,360 cases of new-onset atrial fibrillation during hospitalization (NOAF) in 2001-2011. The source was the National Inpatient Sample database. Fully 85% of all cases occurred in patients admitted for noncardiac surgery, which also was the cause of admission with the lowest incidence of NOAF. Among the patients hospitalized for sepsis, women were 27% less likely than men to develop new-onset atrial fibrillation, but when they did they were 13% more likely to die in-hospital.

In a multivariate logistic regression analysis extensively adjusted for numerous comorbid conditions and demographic factors, female gender was associated with a significantly reduced risk of NOAF across the board for all major admitting conditions known to be triggers for NOAF. The magnitude of this relative risk reduction favoring women ranged from as low as 14% for patients with an admitting diagnosis of acute MI to 58% with admission for thyrotoxicosis, reported Dr. Chui, an internal medicine resident at the University of California, Irvine.

The most provocative study finding was the significantly higher in-hospital mortality for women, compared with men with NOAF for all but two of the seven major reasons for admission studied: noncardiac surgery and thyrotoxicosis. Dr. Chui asserted that this appears to be a quality of care issue.

“The overwhelming majority of new-onset AF in-hospital occurs in postsurgical patients, who may be under the care of providers with less experience in managing AF,” he said. “Our results suggest clinicians need to be aware of the subtleties in presentation and management of female new-onset AF patients compared to their male counterparts.”

Dr. Chui reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, which was financially supported by the university’s department of internal medicine.

ORLANDO – Women are at lower risk than men for new-onset atrial fibrillation during hospitalization, but when it does occur it’s associated with significantly greater in-hospital mortality, according to a massive retrospective study presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Dr. Philip W. Chui analyzed 38,403,360 cases of new-onset atrial fibrillation during hospitalization (NOAF) in 2001-2011. The source was the National Inpatient Sample database. Fully 85% of all cases occurred in patients admitted for noncardiac surgery, which also was the cause of admission with the lowest incidence of NOAF. Among the patients hospitalized for sepsis, women were 27% less likely than men to develop new-onset atrial fibrillation, but when they did they were 13% more likely to die in-hospital.

In a multivariate logistic regression analysis extensively adjusted for numerous comorbid conditions and demographic factors, female gender was associated with a significantly reduced risk of NOAF across the board for all major admitting conditions known to be triggers for NOAF. The magnitude of this relative risk reduction favoring women ranged from as low as 14% for patients with an admitting diagnosis of acute MI to 58% with admission for thyrotoxicosis, reported Dr. Chui, an internal medicine resident at the University of California, Irvine.

The most provocative study finding was the significantly higher in-hospital mortality for women, compared with men with NOAF for all but two of the seven major reasons for admission studied: noncardiac surgery and thyrotoxicosis. Dr. Chui asserted that this appears to be a quality of care issue.

“The overwhelming majority of new-onset AF in-hospital occurs in postsurgical patients, who may be under the care of providers with less experience in managing AF,” he said. “Our results suggest clinicians need to be aware of the subtleties in presentation and management of female new-onset AF patients compared to their male counterparts.”

Dr. Chui reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, which was financially supported by the university’s department of internal medicine.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

New-onset AF during hospitalization is more lethal in women

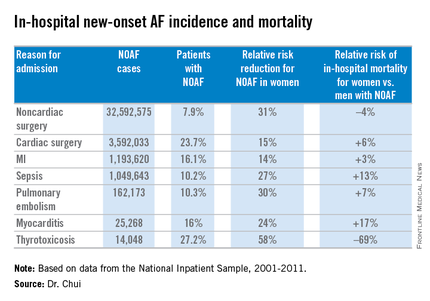

ORLANDO – Women are at lower risk than men for new-onset atrial fibrillation during hospitalization, but when it does occur it’s associated with significantly greater in-hospital mortality, according to a massive retrospective study presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Dr. Philip W. Chui analyzed 38,403,360 cases of new-onset atrial fibrillation during hospitalization (NOAF) in 2001-2011. The source was the National Inpatient Sample database. Fully 85% of all cases occurred in patients admitted for noncardiac surgery, which also was the cause of admission with the lowest incidence of NOAF. Among the patients hospitalized for sepsis, women were 27% less likely than men to develop new-onset atrial fibrillation, but when they did they were 13% more likely to die in-hospital.

In a multivariate logistic regression analysis extensively adjusted for numerous comorbid conditions and demographic factors, female gender was associated with a significantly reduced risk of NOAF across the board for all major admitting conditions known to be triggers for NOAF. The magnitude of this relative risk reduction favoring women ranged from as low as 14% for patients with an admitting diagnosis of acute MI to 58% with admission for thyrotoxicosis, reported Dr. Chui, an internal medicine resident at the University of California, Irvine.

The most provocative study finding was the significantly higher in-hospital mortality for women, compared with men with NOAF for all but two of the seven major reasons for admission studied: noncardiac surgery and thyrotoxicosis. Dr. Chui asserted that this appears to be a quality of care issue.

“The overwhelming majority of new-onset AF in-hospital occurs in postsurgical patients, who may be under the care of providers with less experience in managing AF,” he said. “Our results suggest clinicians need to be aware of the subtleties in presentation and management of female new-onset AF patients compared to their male counterparts.”

Dr. Chui reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, which was financially supported by the university’s department of internal medicine.

ORLANDO – Women are at lower risk than men for new-onset atrial fibrillation during hospitalization, but when it does occur it’s associated with significantly greater in-hospital mortality, according to a massive retrospective study presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Dr. Philip W. Chui analyzed 38,403,360 cases of new-onset atrial fibrillation during hospitalization (NOAF) in 2001-2011. The source was the National Inpatient Sample database. Fully 85% of all cases occurred in patients admitted for noncardiac surgery, which also was the cause of admission with the lowest incidence of NOAF. Among the patients hospitalized for sepsis, women were 27% less likely than men to develop new-onset atrial fibrillation, but when they did they were 13% more likely to die in-hospital.

In a multivariate logistic regression analysis extensively adjusted for numerous comorbid conditions and demographic factors, female gender was associated with a significantly reduced risk of NOAF across the board for all major admitting conditions known to be triggers for NOAF. The magnitude of this relative risk reduction favoring women ranged from as low as 14% for patients with an admitting diagnosis of acute MI to 58% with admission for thyrotoxicosis, reported Dr. Chui, an internal medicine resident at the University of California, Irvine.

The most provocative study finding was the significantly higher in-hospital mortality for women, compared with men with NOAF for all but two of the seven major reasons for admission studied: noncardiac surgery and thyrotoxicosis. Dr. Chui asserted that this appears to be a quality of care issue.

“The overwhelming majority of new-onset AF in-hospital occurs in postsurgical patients, who may be under the care of providers with less experience in managing AF,” he said. “Our results suggest clinicians need to be aware of the subtleties in presentation and management of female new-onset AF patients compared to their male counterparts.”

Dr. Chui reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, which was financially supported by the university’s department of internal medicine.

ORLANDO – Women are at lower risk than men for new-onset atrial fibrillation during hospitalization, but when it does occur it’s associated with significantly greater in-hospital mortality, according to a massive retrospective study presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Dr. Philip W. Chui analyzed 38,403,360 cases of new-onset atrial fibrillation during hospitalization (NOAF) in 2001-2011. The source was the National Inpatient Sample database. Fully 85% of all cases occurred in patients admitted for noncardiac surgery, which also was the cause of admission with the lowest incidence of NOAF. Among the patients hospitalized for sepsis, women were 27% less likely than men to develop new-onset atrial fibrillation, but when they did they were 13% more likely to die in-hospital.

In a multivariate logistic regression analysis extensively adjusted for numerous comorbid conditions and demographic factors, female gender was associated with a significantly reduced risk of NOAF across the board for all major admitting conditions known to be triggers for NOAF. The magnitude of this relative risk reduction favoring women ranged from as low as 14% for patients with an admitting diagnosis of acute MI to 58% with admission for thyrotoxicosis, reported Dr. Chui, an internal medicine resident at the University of California, Irvine.

The most provocative study finding was the significantly higher in-hospital mortality for women, compared with men with NOAF for all but two of the seven major reasons for admission studied: noncardiac surgery and thyrotoxicosis. Dr. Chui asserted that this appears to be a quality of care issue.

“The overwhelming majority of new-onset AF in-hospital occurs in postsurgical patients, who may be under the care of providers with less experience in managing AF,” he said. “Our results suggest clinicians need to be aware of the subtleties in presentation and management of female new-onset AF patients compared to their male counterparts.”

Dr. Chui reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, which was financially supported by the university’s department of internal medicine.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: New-onset atrial fibrillation has a higher associated in-hospital mortality in women than in men, suggesting a potential quality of care issue.

Major finding: Among more than 1 million patients hospitalized for sepsis, women were 27% less likely than men to develop new-onset atrial fibrillation, but when they did they were 13% more likely to die in-hospital.

Data source: This was a retrospective study of gender differences in more than 38 million cases of new-onset atrial fibrillation during hospitalization.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, which was financially supported by the University of California, Irvine, department of internal medicine.

AHA: Bariatric surgery slashes heart failure exacerbations

ORLANDO – Bariatric surgery in obese patients with heart failure was associated with a marked decrease in the subsequent rate of ED visits and hospitalizations for heart failure in a large, real-world, case-control study presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“This decline in the rate of heart failure morbidity was rapid in onset and sustained for at least 2 years after bariatric surgery,” according to Dr. Yuichi J. Shimada of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

In a separate study, however, he found that bariatric surgery for obesity in patients with atrial fibrillation didn’t produce a reduction in ED visits and hospitalizations for the arrhythmia.

The heart failure study was a case-control study of 1,664 consecutive obese patients with heart failure who underwent a single bariatric surgical procedure in California, Florida, or Nebraska. Their median age was 49 years. Women accounted for 70% of the participants. Drawing upon federal Healthcare Cost and Utility Project databases on ED visits and hospital admissions in those three states, Dr. Shimada and coinvestigators compared the group’s rates of ED visits and hospitalizations for heart failure for 2 years before and 2 years after bariatric surgery. Thus, the subjects served as their own controls.

During the reference period, which lasted from months 13-24 presurgery, the group’s combined rate of ED visits and hospital admission for heart failure exacerbation was 14.4%. The rate wasn’t significantly different during the 12 months immediately prior to surgery, at 13.3%.

The rate dropped to 8.7% during the first 12 months after bariatric surgery and remained rock solid at 8.7% during months 13-24 postsurgery. In a logistic regression analysis, this translated to a 44% reduction in the risk of ED visits or hospital admission for heart failure during the first 2 years following bariatric surgery.

These findings are consistent with previous work by other investigators showing a link between obesity and heart failure exacerbations. The new data advance the field by providing the best evidence to date of the effectiveness of substantial weight loss on heart failure morbidity, Dr. Shimada observed.

Nonbariatric surgeries such as hysterectomy or cholecysectomy in the study population had no effect on the rate of heart failure exacerbations.

Dr. Shimada’s atrial fibrillation study was structured in the same way. It included 1,056 patients with atrial fibrillation who underwent bariatric surgery for obesity in the same three states. The rate of ED visits or hospitalization for heart failure was 12.1% in months 13-24 prior to bariatric surgery, 12.6% in presurgical months 1-12, 14.2% in the first 12 months post-bariatric surgery, and 13.4% during postsurgical months 13-24. These rates weren’t statistically different.

Dr. Shimada reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding the two studies.

ORLANDO – Bariatric surgery in obese patients with heart failure was associated with a marked decrease in the subsequent rate of ED visits and hospitalizations for heart failure in a large, real-world, case-control study presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“This decline in the rate of heart failure morbidity was rapid in onset and sustained for at least 2 years after bariatric surgery,” according to Dr. Yuichi J. Shimada of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

In a separate study, however, he found that bariatric surgery for obesity in patients with atrial fibrillation didn’t produce a reduction in ED visits and hospitalizations for the arrhythmia.

The heart failure study was a case-control study of 1,664 consecutive obese patients with heart failure who underwent a single bariatric surgical procedure in California, Florida, or Nebraska. Their median age was 49 years. Women accounted for 70% of the participants. Drawing upon federal Healthcare Cost and Utility Project databases on ED visits and hospital admissions in those three states, Dr. Shimada and coinvestigators compared the group’s rates of ED visits and hospitalizations for heart failure for 2 years before and 2 years after bariatric surgery. Thus, the subjects served as their own controls.

During the reference period, which lasted from months 13-24 presurgery, the group’s combined rate of ED visits and hospital admission for heart failure exacerbation was 14.4%. The rate wasn’t significantly different during the 12 months immediately prior to surgery, at 13.3%.

The rate dropped to 8.7% during the first 12 months after bariatric surgery and remained rock solid at 8.7% during months 13-24 postsurgery. In a logistic regression analysis, this translated to a 44% reduction in the risk of ED visits or hospital admission for heart failure during the first 2 years following bariatric surgery.

These findings are consistent with previous work by other investigators showing a link between obesity and heart failure exacerbations. The new data advance the field by providing the best evidence to date of the effectiveness of substantial weight loss on heart failure morbidity, Dr. Shimada observed.

Nonbariatric surgeries such as hysterectomy or cholecysectomy in the study population had no effect on the rate of heart failure exacerbations.

Dr. Shimada’s atrial fibrillation study was structured in the same way. It included 1,056 patients with atrial fibrillation who underwent bariatric surgery for obesity in the same three states. The rate of ED visits or hospitalization for heart failure was 12.1% in months 13-24 prior to bariatric surgery, 12.6% in presurgical months 1-12, 14.2% in the first 12 months post-bariatric surgery, and 13.4% during postsurgical months 13-24. These rates weren’t statistically different.

Dr. Shimada reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding the two studies.

ORLANDO – Bariatric surgery in obese patients with heart failure was associated with a marked decrease in the subsequent rate of ED visits and hospitalizations for heart failure in a large, real-world, case-control study presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“This decline in the rate of heart failure morbidity was rapid in onset and sustained for at least 2 years after bariatric surgery,” according to Dr. Yuichi J. Shimada of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

In a separate study, however, he found that bariatric surgery for obesity in patients with atrial fibrillation didn’t produce a reduction in ED visits and hospitalizations for the arrhythmia.

The heart failure study was a case-control study of 1,664 consecutive obese patients with heart failure who underwent a single bariatric surgical procedure in California, Florida, or Nebraska. Their median age was 49 years. Women accounted for 70% of the participants. Drawing upon federal Healthcare Cost and Utility Project databases on ED visits and hospital admissions in those three states, Dr. Shimada and coinvestigators compared the group’s rates of ED visits and hospitalizations for heart failure for 2 years before and 2 years after bariatric surgery. Thus, the subjects served as their own controls.

During the reference period, which lasted from months 13-24 presurgery, the group’s combined rate of ED visits and hospital admission for heart failure exacerbation was 14.4%. The rate wasn’t significantly different during the 12 months immediately prior to surgery, at 13.3%.

The rate dropped to 8.7% during the first 12 months after bariatric surgery and remained rock solid at 8.7% during months 13-24 postsurgery. In a logistic regression analysis, this translated to a 44% reduction in the risk of ED visits or hospital admission for heart failure during the first 2 years following bariatric surgery.

These findings are consistent with previous work by other investigators showing a link between obesity and heart failure exacerbations. The new data advance the field by providing the best evidence to date of the effectiveness of substantial weight loss on heart failure morbidity, Dr. Shimada observed.

Nonbariatric surgeries such as hysterectomy or cholecysectomy in the study population had no effect on the rate of heart failure exacerbations.

Dr. Shimada’s atrial fibrillation study was structured in the same way. It included 1,056 patients with atrial fibrillation who underwent bariatric surgery for obesity in the same three states. The rate of ED visits or hospitalization for heart failure was 12.1% in months 13-24 prior to bariatric surgery, 12.6% in presurgical months 1-12, 14.2% in the first 12 months post-bariatric surgery, and 13.4% during postsurgical months 13-24. These rates weren’t statistically different.

Dr. Shimada reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding the two studies.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Bariatric surgery in obese patients with heart failure results in a dramatic reduction in ED visits and hospital admission for heart failure.

Major finding: The combined rate of ED visits and hospital admissions for heart failure dropped by 44% during the 2 years after a large group of patients with heart failure underwent bariatric surgery for obesity.

Data source: This case-control study compared the rates of ED visits and hospital admissions for worsening heart failure in 1,664 patients with heart failure during the 2 years before and 2 years after they underwent bariatric surgery for obesity.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding the study, which utilized publicly available patient data.

AHA: Poor Real-world Adherence to NOACs

ORLANDO – Adherence to the novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs) is surprisingly poor in clinical practice, Xiaoxi Yao, Ph.D., reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Her retrospective study of nearly 65,000 patients with atrial fibrillation who initiated therapy with apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or warfarin showed that during a median 1.1 years of follow-up fewer than half of all patients were treatment adherent, with adherence defined as possession of sufficient medication to cover at least 80% of days.

Adherence rates, while uniformly suboptimal, nevertheless varied considerably: lowest at 38.5% for dabigatran, followed by 40.2% for warfarin, 50.5% for rivaroxaban, and 61.9% for apixaban.

This poor adherence to NOACs in real-world clinical practice is surprising in light of the drugs’ greater convenience, with fewer drug interactions than warfarin and no need for laboratory monitoring, observed Dr. Yao of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

It’s possible, although speculative, that the NOACs’ greater convenience paradoxically contributes to the low adherence rates, since unlike warfarin, NOACs don’t require regular interactions with the health care system for INR monitoring. And then there is the hefty cost of the novel agents, she added.

The study population consisted of 3,900 patients with atrial fibrillation who initiated oral anticoagulation with apixaban (Eliquis), 10,235 who started on dabigatran (Pradaxa), 12,366 on rivaroxaban (Xarelto), and 38,190 on warfarin. The analysis utilized claims data from a large U.S. commercial insurance database.

Adherence rates were better among patients with greater stroke risk as reflected by their CHA2DS2-VASc scores. For example, at the high end of the adherence spectrum, the adherence rate for apixaban was 50% in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0-1, rising to 62% with a score of 2-3 and 64% with a score of 4 or more. The corresponding adherence rates for dabigatran were 25% in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 0-1, 40% among those with a score of 2-3, and 42% in patients with a score of 4 or higher.

Dr. Yao and coinvestigators were interested in whether lower adherence to oral anticoagulation was associated with worse outcomes. This proved to be the case with regard to stroke rate for patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or more, where a clear dose-response relationship was evident between the event rate and cumulative time off oral anticoagulation during follow-up.

Among patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 2 or 3, the stroke rate was nearly twice as high among those off oral anticoagulation for a total of 3-6 months and three times greater if off therapy for more than 6 months than in those with a total time off of less than 1 week. The stroke rate was even higher in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 4 or more who had suboptimal adherence.

An unexpected finding, she continued, was that among patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or more there was no significant relationship between cumulative time off oral anticoagulation and the risk of major bleeding unless they were off treatment for a total of 6 months or more; only then was the major bleeding risk lower than in patients whose total time off therapy was less than a week. Also, one would expect that when patients are off oral anticoagulation they should be at significantly lower risk of intracranial hemorrhage than when on-therapy, but this proved not to be the case.

For patients at substantial stroke risk as indicated by a CHA2DS2-VASc score of at least 2, this finding about off-treatment bleeding risk actually constitutes a good argument for sticking to their medication, in Dr. Yao’s view.

“Physicians and patients often fear bleeding, especially intracranial hemorrhage, but we found that for patients at higher risk for stroke there is little difference in intracranial hemorrhage risk whether you’re on or off of oral anticoagulation. So higher-risk patients should definitely adhere to their medication because of the stroke prevention benefit. However, in low-risk patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 0-1, the benefits of oral anticoagulation may not always outweigh the harm,” she said.

Dr. Yao reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her study.

ORLANDO – Adherence to the novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs) is surprisingly poor in clinical practice, Xiaoxi Yao, Ph.D., reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Her retrospective study of nearly 65,000 patients with atrial fibrillation who initiated therapy with apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or warfarin showed that during a median 1.1 years of follow-up fewer than half of all patients were treatment adherent, with adherence defined as possession of sufficient medication to cover at least 80% of days.

Adherence rates, while uniformly suboptimal, nevertheless varied considerably: lowest at 38.5% for dabigatran, followed by 40.2% for warfarin, 50.5% for rivaroxaban, and 61.9% for apixaban.

This poor adherence to NOACs in real-world clinical practice is surprising in light of the drugs’ greater convenience, with fewer drug interactions than warfarin and no need for laboratory monitoring, observed Dr. Yao of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

It’s possible, although speculative, that the NOACs’ greater convenience paradoxically contributes to the low adherence rates, since unlike warfarin, NOACs don’t require regular interactions with the health care system for INR monitoring. And then there is the hefty cost of the novel agents, she added.

The study population consisted of 3,900 patients with atrial fibrillation who initiated oral anticoagulation with apixaban (Eliquis), 10,235 who started on dabigatran (Pradaxa), 12,366 on rivaroxaban (Xarelto), and 38,190 on warfarin. The analysis utilized claims data from a large U.S. commercial insurance database.

Adherence rates were better among patients with greater stroke risk as reflected by their CHA2DS2-VASc scores. For example, at the high end of the adherence spectrum, the adherence rate for apixaban was 50% in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0-1, rising to 62% with a score of 2-3 and 64% with a score of 4 or more. The corresponding adherence rates for dabigatran were 25% in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 0-1, 40% among those with a score of 2-3, and 42% in patients with a score of 4 or higher.

Dr. Yao and coinvestigators were interested in whether lower adherence to oral anticoagulation was associated with worse outcomes. This proved to be the case with regard to stroke rate for patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or more, where a clear dose-response relationship was evident between the event rate and cumulative time off oral anticoagulation during follow-up.

Among patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 2 or 3, the stroke rate was nearly twice as high among those off oral anticoagulation for a total of 3-6 months and three times greater if off therapy for more than 6 months than in those with a total time off of less than 1 week. The stroke rate was even higher in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 4 or more who had suboptimal adherence.

An unexpected finding, she continued, was that among patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or more there was no significant relationship between cumulative time off oral anticoagulation and the risk of major bleeding unless they were off treatment for a total of 6 months or more; only then was the major bleeding risk lower than in patients whose total time off therapy was less than a week. Also, one would expect that when patients are off oral anticoagulation they should be at significantly lower risk of intracranial hemorrhage than when on-therapy, but this proved not to be the case.

For patients at substantial stroke risk as indicated by a CHA2DS2-VASc score of at least 2, this finding about off-treatment bleeding risk actually constitutes a good argument for sticking to their medication, in Dr. Yao’s view.

“Physicians and patients often fear bleeding, especially intracranial hemorrhage, but we found that for patients at higher risk for stroke there is little difference in intracranial hemorrhage risk whether you’re on or off of oral anticoagulation. So higher-risk patients should definitely adhere to their medication because of the stroke prevention benefit. However, in low-risk patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 0-1, the benefits of oral anticoagulation may not always outweigh the harm,” she said.

Dr. Yao reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her study.

ORLANDO – Adherence to the novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs) is surprisingly poor in clinical practice, Xiaoxi Yao, Ph.D., reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Her retrospective study of nearly 65,000 patients with atrial fibrillation who initiated therapy with apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or warfarin showed that during a median 1.1 years of follow-up fewer than half of all patients were treatment adherent, with adherence defined as possession of sufficient medication to cover at least 80% of days.

Adherence rates, while uniformly suboptimal, nevertheless varied considerably: lowest at 38.5% for dabigatran, followed by 40.2% for warfarin, 50.5% for rivaroxaban, and 61.9% for apixaban.

This poor adherence to NOACs in real-world clinical practice is surprising in light of the drugs’ greater convenience, with fewer drug interactions than warfarin and no need for laboratory monitoring, observed Dr. Yao of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

It’s possible, although speculative, that the NOACs’ greater convenience paradoxically contributes to the low adherence rates, since unlike warfarin, NOACs don’t require regular interactions with the health care system for INR monitoring. And then there is the hefty cost of the novel agents, she added.

The study population consisted of 3,900 patients with atrial fibrillation who initiated oral anticoagulation with apixaban (Eliquis), 10,235 who started on dabigatran (Pradaxa), 12,366 on rivaroxaban (Xarelto), and 38,190 on warfarin. The analysis utilized claims data from a large U.S. commercial insurance database.

Adherence rates were better among patients with greater stroke risk as reflected by their CHA2DS2-VASc scores. For example, at the high end of the adherence spectrum, the adherence rate for apixaban was 50% in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0-1, rising to 62% with a score of 2-3 and 64% with a score of 4 or more. The corresponding adherence rates for dabigatran were 25% in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 0-1, 40% among those with a score of 2-3, and 42% in patients with a score of 4 or higher.

Dr. Yao and coinvestigators were interested in whether lower adherence to oral anticoagulation was associated with worse outcomes. This proved to be the case with regard to stroke rate for patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or more, where a clear dose-response relationship was evident between the event rate and cumulative time off oral anticoagulation during follow-up.

Among patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 2 or 3, the stroke rate was nearly twice as high among those off oral anticoagulation for a total of 3-6 months and three times greater if off therapy for more than 6 months than in those with a total time off of less than 1 week. The stroke rate was even higher in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 4 or more who had suboptimal adherence.

An unexpected finding, she continued, was that among patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or more there was no significant relationship between cumulative time off oral anticoagulation and the risk of major bleeding unless they were off treatment for a total of 6 months or more; only then was the major bleeding risk lower than in patients whose total time off therapy was less than a week. Also, one would expect that when patients are off oral anticoagulation they should be at significantly lower risk of intracranial hemorrhage than when on-therapy, but this proved not to be the case.

For patients at substantial stroke risk as indicated by a CHA2DS2-VASc score of at least 2, this finding about off-treatment bleeding risk actually constitutes a good argument for sticking to their medication, in Dr. Yao’s view.

“Physicians and patients often fear bleeding, especially intracranial hemorrhage, but we found that for patients at higher risk for stroke there is little difference in intracranial hemorrhage risk whether you’re on or off of oral anticoagulation. So higher-risk patients should definitely adhere to their medication because of the stroke prevention benefit. However, in low-risk patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 0-1, the benefits of oral anticoagulation may not always outweigh the harm,” she said.

Dr. Yao reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her study.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

AHA: Poor real-world adherence to NOACs

ORLANDO – Adherence to the novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs) is surprisingly poor in clinical practice, Xiaoxi Yao, Ph.D., reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Her retrospective study of nearly 65,000 patients with atrial fibrillation who initiated therapy with apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or warfarin showed that during a median 1.1 years of follow-up fewer than half of all patients were treatment adherent, with adherence defined as possession of sufficient medication to cover at least 80% of days.

Adherence rates, while uniformly suboptimal, nevertheless varied considerably: lowest at 38.5% for dabigatran, followed by 40.2% for warfarin, 50.5% for rivaroxaban, and 61.9% for apixaban.

This poor adherence to NOACs in real-world clinical practice is surprising in light of the drugs’ greater convenience, with fewer drug interactions than warfarin and no need for laboratory monitoring, observed Dr. Yao of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

It’s possible, although speculative, that the NOACs’ greater convenience paradoxically contributes to the low adherence rates, since unlike warfarin, NOACs don’t require regular interactions with the health care system for INR monitoring. And then there is the hefty cost of the novel agents, she added.

The study population consisted of 3,900 patients with atrial fibrillation who initiated oral anticoagulation with apixaban (Eliquis), 10,235 who started on dabigatran (Pradaxa), 12,366 on rivaroxaban (Xarelto), and 38,190 on warfarin. The analysis utilized claims data from a large U.S. commercial insurance database.

Adherence rates were better among patients with greater stroke risk as reflected by their CHA2DS2-VASc scores. For example, at the high end of the adherence spectrum, the adherence rate for apixaban was 50% in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0-1, rising to 62% with a score of 2-3 and 64% with a score of 4 or more. The corresponding adherence rates for dabigatran were 25% in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 0-1, 40% among those with a score of 2-3, and 42% in patients with a score of 4 or higher.

Dr. Yao and coinvestigators were interested in whether lower adherence to oral anticoagulation was associated with worse outcomes. This proved to be the case with regard to stroke rate for patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or more, where a clear dose-response relationship was evident between the event rate and cumulative time off oral anticoagulation during follow-up.

Among patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 2 or 3, the stroke rate was nearly twice as high among those off oral anticoagulation for a total of 3-6 months and three times greater if off therapy for more than 6 months than in those with a total time off of less than 1 week. The stroke rate was even higher in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 4 or more who had suboptimal adherence.

An unexpected finding, she continued, was that among patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or more there was no significant relationship between cumulative time off oral anticoagulation and the risk of major bleeding unless they were off treatment for a total of 6 months or more; only then was the major bleeding risk lower than in patients whose total time off therapy was less than a week. Also, one would expect that when patients are off oral anticoagulation they should be at significantly lower risk of intracranial hemorrhage than when on-therapy, but this proved not to be the case.

For patients at substantial stroke risk as indicated by a CHA2DS2-VASc score of at least 2, this finding about off-treatment bleeding risk actually constitutes a good argument for sticking to their medication, in Dr. Yao’s view.

“Physicians and patients often fear bleeding, especially intracranial hemorrhage, but we found that for patients at higher risk for stroke there is little difference in intracranial hemorrhage risk whether you’re on or off of oral anticoagulation. So higher-risk patients should definitely adhere to their medication because of the stroke prevention benefit. However, in low-risk patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 0-1, the benefits of oral anticoagulation may not always outweigh the harm,” she said.

Dr. Yao reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her study.

ORLANDO – Adherence to the novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs) is surprisingly poor in clinical practice, Xiaoxi Yao, Ph.D., reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Her retrospective study of nearly 65,000 patients with atrial fibrillation who initiated therapy with apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or warfarin showed that during a median 1.1 years of follow-up fewer than half of all patients were treatment adherent, with adherence defined as possession of sufficient medication to cover at least 80% of days.

Adherence rates, while uniformly suboptimal, nevertheless varied considerably: lowest at 38.5% for dabigatran, followed by 40.2% for warfarin, 50.5% for rivaroxaban, and 61.9% for apixaban.

This poor adherence to NOACs in real-world clinical practice is surprising in light of the drugs’ greater convenience, with fewer drug interactions than warfarin and no need for laboratory monitoring, observed Dr. Yao of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

It’s possible, although speculative, that the NOACs’ greater convenience paradoxically contributes to the low adherence rates, since unlike warfarin, NOACs don’t require regular interactions with the health care system for INR monitoring. And then there is the hefty cost of the novel agents, she added.

The study population consisted of 3,900 patients with atrial fibrillation who initiated oral anticoagulation with apixaban (Eliquis), 10,235 who started on dabigatran (Pradaxa), 12,366 on rivaroxaban (Xarelto), and 38,190 on warfarin. The analysis utilized claims data from a large U.S. commercial insurance database.

Adherence rates were better among patients with greater stroke risk as reflected by their CHA2DS2-VASc scores. For example, at the high end of the adherence spectrum, the adherence rate for apixaban was 50% in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0-1, rising to 62% with a score of 2-3 and 64% with a score of 4 or more. The corresponding adherence rates for dabigatran were 25% in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 0-1, 40% among those with a score of 2-3, and 42% in patients with a score of 4 or higher.

Dr. Yao and coinvestigators were interested in whether lower adherence to oral anticoagulation was associated with worse outcomes. This proved to be the case with regard to stroke rate for patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or more, where a clear dose-response relationship was evident between the event rate and cumulative time off oral anticoagulation during follow-up.

Among patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 2 or 3, the stroke rate was nearly twice as high among those off oral anticoagulation for a total of 3-6 months and three times greater if off therapy for more than 6 months than in those with a total time off of less than 1 week. The stroke rate was even higher in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 4 or more who had suboptimal adherence.

An unexpected finding, she continued, was that among patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or more there was no significant relationship between cumulative time off oral anticoagulation and the risk of major bleeding unless they were off treatment for a total of 6 months or more; only then was the major bleeding risk lower than in patients whose total time off therapy was less than a week. Also, one would expect that when patients are off oral anticoagulation they should be at significantly lower risk of intracranial hemorrhage than when on-therapy, but this proved not to be the case.

For patients at substantial stroke risk as indicated by a CHA2DS2-VASc score of at least 2, this finding about off-treatment bleeding risk actually constitutes a good argument for sticking to their medication, in Dr. Yao’s view.

“Physicians and patients often fear bleeding, especially intracranial hemorrhage, but we found that for patients at higher risk for stroke there is little difference in intracranial hemorrhage risk whether you’re on or off of oral anticoagulation. So higher-risk patients should definitely adhere to their medication because of the stroke prevention benefit. However, in low-risk patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 0-1, the benefits of oral anticoagulation may not always outweigh the harm,” she said.

Dr. Yao reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her study.

ORLANDO – Adherence to the novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs) is surprisingly poor in clinical practice, Xiaoxi Yao, Ph.D., reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Her retrospective study of nearly 65,000 patients with atrial fibrillation who initiated therapy with apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or warfarin showed that during a median 1.1 years of follow-up fewer than half of all patients were treatment adherent, with adherence defined as possession of sufficient medication to cover at least 80% of days.

Adherence rates, while uniformly suboptimal, nevertheless varied considerably: lowest at 38.5% for dabigatran, followed by 40.2% for warfarin, 50.5% for rivaroxaban, and 61.9% for apixaban.

This poor adherence to NOACs in real-world clinical practice is surprising in light of the drugs’ greater convenience, with fewer drug interactions than warfarin and no need for laboratory monitoring, observed Dr. Yao of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

It’s possible, although speculative, that the NOACs’ greater convenience paradoxically contributes to the low adherence rates, since unlike warfarin, NOACs don’t require regular interactions with the health care system for INR monitoring. And then there is the hefty cost of the novel agents, she added.

The study population consisted of 3,900 patients with atrial fibrillation who initiated oral anticoagulation with apixaban (Eliquis), 10,235 who started on dabigatran (Pradaxa), 12,366 on rivaroxaban (Xarelto), and 38,190 on warfarin. The analysis utilized claims data from a large U.S. commercial insurance database.

Adherence rates were better among patients with greater stroke risk as reflected by their CHA2DS2-VASc scores. For example, at the high end of the adherence spectrum, the adherence rate for apixaban was 50% in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0-1, rising to 62% with a score of 2-3 and 64% with a score of 4 or more. The corresponding adherence rates for dabigatran were 25% in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 0-1, 40% among those with a score of 2-3, and 42% in patients with a score of 4 or higher.

Dr. Yao and coinvestigators were interested in whether lower adherence to oral anticoagulation was associated with worse outcomes. This proved to be the case with regard to stroke rate for patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or more, where a clear dose-response relationship was evident between the event rate and cumulative time off oral anticoagulation during follow-up.

Among patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 2 or 3, the stroke rate was nearly twice as high among those off oral anticoagulation for a total of 3-6 months and three times greater if off therapy for more than 6 months than in those with a total time off of less than 1 week. The stroke rate was even higher in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 4 or more who had suboptimal adherence.

An unexpected finding, she continued, was that among patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or more there was no significant relationship between cumulative time off oral anticoagulation and the risk of major bleeding unless they were off treatment for a total of 6 months or more; only then was the major bleeding risk lower than in patients whose total time off therapy was less than a week. Also, one would expect that when patients are off oral anticoagulation they should be at significantly lower risk of intracranial hemorrhage than when on-therapy, but this proved not to be the case.

For patients at substantial stroke risk as indicated by a CHA2DS2-VASc score of at least 2, this finding about off-treatment bleeding risk actually constitutes a good argument for sticking to their medication, in Dr. Yao’s view.

“Physicians and patients often fear bleeding, especially intracranial hemorrhage, but we found that for patients at higher risk for stroke there is little difference in intracranial hemorrhage risk whether you’re on or off of oral anticoagulation. So higher-risk patients should definitely adhere to their medication because of the stroke prevention benefit. However, in low-risk patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 0-1, the benefits of oral anticoagulation may not always outweigh the harm,” she said.

Dr. Yao reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her study.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Adherence to the novel oral anticoagulants by patients with atrial fibrillation is surprisingly poor outside the clinical trial setting.

Major finding: More than half of patients with atrial fibrillation who started on a novel oral anticoagulant were medication adherent less than 80% of the time.

Data source: This was a retrospective study of nearly 65,000 patients with atrial fibrillation who initiated oral anticoagulant therapy and were then followed for a median of 1.1 years.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding the study.,

Short sleep duration in hypertensives ups mortality

ORLANDO – Hypertensive persons who sleep 5 hours or less per night have a significantly higher all-cause mortality rate than those who get more shut-eye, according to an analysis from the Penn State Adult Cohort Study.

“We found that the odds of all-cause mortality associated with hypertension increased in a dose-response manner as a function of the degree of objective short sleep duration, even after adjusting for a multitude of factors,” Julio Fernandez-Mendoza, Ph.D., reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The Penn State Adult Cohort consists of a random, general population sample of 1,741 men and women who enrolled in the study back in the 1990s, at a mean age of 48.7 years. As part of their comprehensive evaluation they were studied in the overnight sleep laboratory. The cohort has been followed for 15.5 years, during which 20% of subjects died.

As expected, hypertension was associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality in the Penn State Adult Cohort. But Dr. Fernandez-Mendoza and coinvestigators further dissected this association by incorporating the subjects’ objective sleep lab data, something that hadn’t been done in other studies. They found that while as a group the roughly 35% of study participants with hypertension had an adjusted 2.54-fold increased risk of all-cause mortality, compared with normotensive subjects, those who slept 6 or more hours at night – placing them at or above the 50th percentile for sleep duration – had a 1.75-fold increased risk, which just barely reached statistical significance.

In contrast, those who slept 5-6 hours per night were at 2.36-fold increased risk of all-cause mortality, while hypertensives in the bottom quartile for sleep duration with 5 hours or less of sleep had an even more robust 4.04-fold increased risk. All risk figures were determined in a multivariate logistic regression analysis extensively adjusted for age, gender, race, diabetes, obesity, smoking, depression, insomnia, sleep apnea, and history of heart disease or stroke.

This finding of an inverse association between sleep duration and all-cause mortality was consistent with the investigators’ study hypothesis that short sleep duration in hypertensive patients may be a marker of the severity of autonomic dysfunction. After all, it is known that the autonomic nervous system not only controls cardiovascular function, it also regulates sleep, explained Dr. Fernandez-Mendoza, a behavioral psychologist at Pennsylvania State University in Hershey.

Other possible explanations for the findings are that short sleep duration in hypertensive patients might be genetically driven or behaviorally induced, but he considers these less plausible.

In an interview, Dr. Fernandez-Mendoza said he and his coinvestigators have found the same relationship between short sleep duration and increased all-cause mortality in Penn State Adult Cohort members with diabetes or dyslipidemia, although he didn’t present those data at the AHA meeting.

If indeed short sleep duration is a marker of autonomic dysfunction, it would have important clinical implications: “Objective sleep duration may allow for refinement of estimates of mortality risk. I predict that someday cardiovascular risk calculators will incorporate sleep duration,” he said.

The Penn State Adult Cohort findings bring a measure of clarity to what has been a somewhat cloudy area, Dr. Fernandez-Mendoza said. Most prior epidemiologic studies of sleep’s impact on health have relied upon self-reported sleep duration, which is considerably less reliable than objectively measured sleep lab data. And many studies have looked at sleep duration as an isolated variable in relation to morbidity and mortality risk. This, he said, has contributed to public misunderstanding.

“We have people coming into the sleep lab thinking, ‘If I don’t get 7 hours of sleep I’m going to die,’ ” according to the sleep scientist. “But the paradigm we’ve developed, tied to what we know about autonomic control, is that the cardiovascular system and the sleep system are connected to each other. It doesn’t mean that short sleep kills you, it’s that the combination of the traditional cardiometabolic risk factors and short sleep increases risk of morbidity and mortality.”

Dr. Fernandez-Mendoza’s study was funded by an AHA Scientist Development Grant. He reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – Hypertensive persons who sleep 5 hours or less per night have a significantly higher all-cause mortality rate than those who get more shut-eye, according to an analysis from the Penn State Adult Cohort Study.

“We found that the odds of all-cause mortality associated with hypertension increased in a dose-response manner as a function of the degree of objective short sleep duration, even after adjusting for a multitude of factors,” Julio Fernandez-Mendoza, Ph.D., reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The Penn State Adult Cohort consists of a random, general population sample of 1,741 men and women who enrolled in the study back in the 1990s, at a mean age of 48.7 years. As part of their comprehensive evaluation they were studied in the overnight sleep laboratory. The cohort has been followed for 15.5 years, during which 20% of subjects died.

As expected, hypertension was associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality in the Penn State Adult Cohort. But Dr. Fernandez-Mendoza and coinvestigators further dissected this association by incorporating the subjects’ objective sleep lab data, something that hadn’t been done in other studies. They found that while as a group the roughly 35% of study participants with hypertension had an adjusted 2.54-fold increased risk of all-cause mortality, compared with normotensive subjects, those who slept 6 or more hours at night – placing them at or above the 50th percentile for sleep duration – had a 1.75-fold increased risk, which just barely reached statistical significance.

In contrast, those who slept 5-6 hours per night were at 2.36-fold increased risk of all-cause mortality, while hypertensives in the bottom quartile for sleep duration with 5 hours or less of sleep had an even more robust 4.04-fold increased risk. All risk figures were determined in a multivariate logistic regression analysis extensively adjusted for age, gender, race, diabetes, obesity, smoking, depression, insomnia, sleep apnea, and history of heart disease or stroke.

This finding of an inverse association between sleep duration and all-cause mortality was consistent with the investigators’ study hypothesis that short sleep duration in hypertensive patients may be a marker of the severity of autonomic dysfunction. After all, it is known that the autonomic nervous system not only controls cardiovascular function, it also regulates sleep, explained Dr. Fernandez-Mendoza, a behavioral psychologist at Pennsylvania State University in Hershey.

Other possible explanations for the findings are that short sleep duration in hypertensive patients might be genetically driven or behaviorally induced, but he considers these less plausible.

In an interview, Dr. Fernandez-Mendoza said he and his coinvestigators have found the same relationship between short sleep duration and increased all-cause mortality in Penn State Adult Cohort members with diabetes or dyslipidemia, although he didn’t present those data at the AHA meeting.

If indeed short sleep duration is a marker of autonomic dysfunction, it would have important clinical implications: “Objective sleep duration may allow for refinement of estimates of mortality risk. I predict that someday cardiovascular risk calculators will incorporate sleep duration,” he said.

The Penn State Adult Cohort findings bring a measure of clarity to what has been a somewhat cloudy area, Dr. Fernandez-Mendoza said. Most prior epidemiologic studies of sleep’s impact on health have relied upon self-reported sleep duration, which is considerably less reliable than objectively measured sleep lab data. And many studies have looked at sleep duration as an isolated variable in relation to morbidity and mortality risk. This, he said, has contributed to public misunderstanding.

“We have people coming into the sleep lab thinking, ‘If I don’t get 7 hours of sleep I’m going to die,’ ” according to the sleep scientist. “But the paradigm we’ve developed, tied to what we know about autonomic control, is that the cardiovascular system and the sleep system are connected to each other. It doesn’t mean that short sleep kills you, it’s that the combination of the traditional cardiometabolic risk factors and short sleep increases risk of morbidity and mortality.”

Dr. Fernandez-Mendoza’s study was funded by an AHA Scientist Development Grant. He reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – Hypertensive persons who sleep 5 hours or less per night have a significantly higher all-cause mortality rate than those who get more shut-eye, according to an analysis from the Penn State Adult Cohort Study.

“We found that the odds of all-cause mortality associated with hypertension increased in a dose-response manner as a function of the degree of objective short sleep duration, even after adjusting for a multitude of factors,” Julio Fernandez-Mendoza, Ph.D., reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The Penn State Adult Cohort consists of a random, general population sample of 1,741 men and women who enrolled in the study back in the 1990s, at a mean age of 48.7 years. As part of their comprehensive evaluation they were studied in the overnight sleep laboratory. The cohort has been followed for 15.5 years, during which 20% of subjects died.

As expected, hypertension was associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality in the Penn State Adult Cohort. But Dr. Fernandez-Mendoza and coinvestigators further dissected this association by incorporating the subjects’ objective sleep lab data, something that hadn’t been done in other studies. They found that while as a group the roughly 35% of study participants with hypertension had an adjusted 2.54-fold increased risk of all-cause mortality, compared with normotensive subjects, those who slept 6 or more hours at night – placing them at or above the 50th percentile for sleep duration – had a 1.75-fold increased risk, which just barely reached statistical significance.

In contrast, those who slept 5-6 hours per night were at 2.36-fold increased risk of all-cause mortality, while hypertensives in the bottom quartile for sleep duration with 5 hours or less of sleep had an even more robust 4.04-fold increased risk. All risk figures were determined in a multivariate logistic regression analysis extensively adjusted for age, gender, race, diabetes, obesity, smoking, depression, insomnia, sleep apnea, and history of heart disease or stroke.

This finding of an inverse association between sleep duration and all-cause mortality was consistent with the investigators’ study hypothesis that short sleep duration in hypertensive patients may be a marker of the severity of autonomic dysfunction. After all, it is known that the autonomic nervous system not only controls cardiovascular function, it also regulates sleep, explained Dr. Fernandez-Mendoza, a behavioral psychologist at Pennsylvania State University in Hershey.

Other possible explanations for the findings are that short sleep duration in hypertensive patients might be genetically driven or behaviorally induced, but he considers these less plausible.

In an interview, Dr. Fernandez-Mendoza said he and his coinvestigators have found the same relationship between short sleep duration and increased all-cause mortality in Penn State Adult Cohort members with diabetes or dyslipidemia, although he didn’t present those data at the AHA meeting.

If indeed short sleep duration is a marker of autonomic dysfunction, it would have important clinical implications: “Objective sleep duration may allow for refinement of estimates of mortality risk. I predict that someday cardiovascular risk calculators will incorporate sleep duration,” he said.

The Penn State Adult Cohort findings bring a measure of clarity to what has been a somewhat cloudy area, Dr. Fernandez-Mendoza said. Most prior epidemiologic studies of sleep’s impact on health have relied upon self-reported sleep duration, which is considerably less reliable than objectively measured sleep lab data. And many studies have looked at sleep duration as an isolated variable in relation to morbidity and mortality risk. This, he said, has contributed to public misunderstanding.

“We have people coming into the sleep lab thinking, ‘If I don’t get 7 hours of sleep I’m going to die,’ ” according to the sleep scientist. “But the paradigm we’ve developed, tied to what we know about autonomic control, is that the cardiovascular system and the sleep system are connected to each other. It doesn’t mean that short sleep kills you, it’s that the combination of the traditional cardiometabolic risk factors and short sleep increases risk of morbidity and mortality.”

Dr. Fernandez-Mendoza’s study was funded by an AHA Scientist Development Grant. He reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: The shorter a hypertensive patient’s objectively measured sleep duration, the greater the all-cause mortality risk, compared with normotensives.

Major finding: Hypertensive persons with 5 hours of sleep or less were at 4.04-fold increased risk of all-cause mortality, compared with normotensives. Those with a sleep duration of 5-6 hours were at 2.36-fold increased risk, while hypertensives with a sleep duration of 6 hours or more were at 1.75-fold increased risk.

Data source: This study involved 1,741 participants in the Penn State Adult Cohort followed prospectively for 15.5 years.

Disclosures: The presenter’s study was funded by an AHA Scientist Development Grant. He reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Moderate, Intensive Exercise Cut Triglycerides Equally in NAFLD

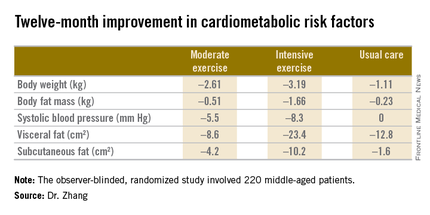

ORLANDO – Moderate aerobic exercise and a more intensive regimen proved equally effective in reducing intrahepatic triglyceride content in centrally obese patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a 12-month randomized, controlled trial.

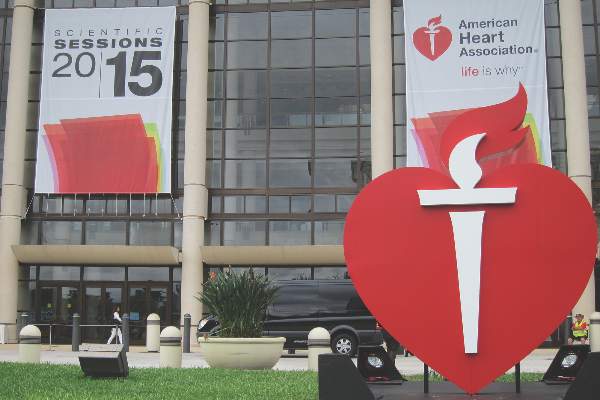

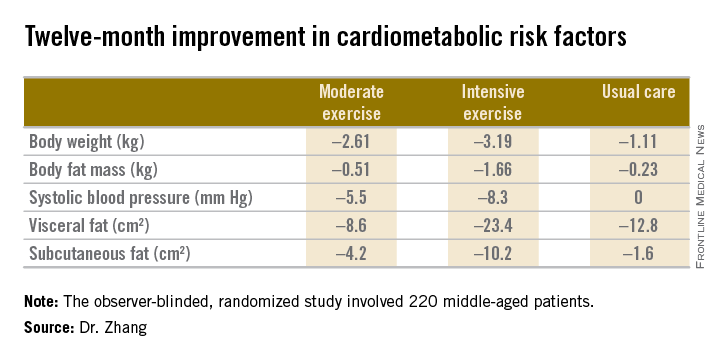

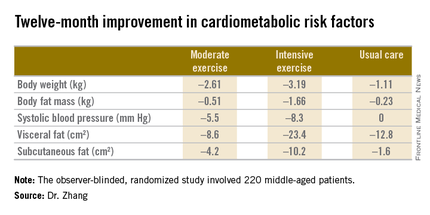

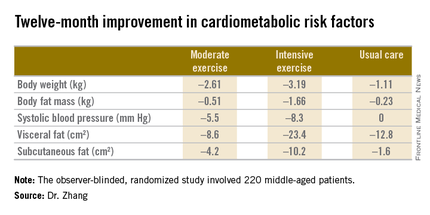

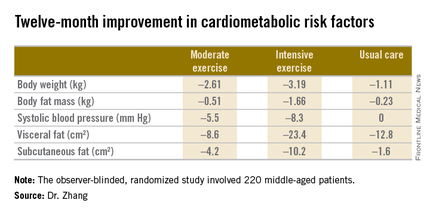

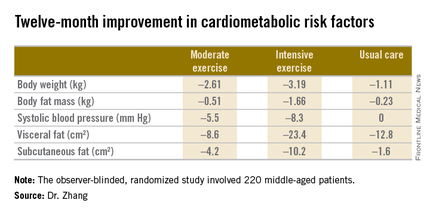

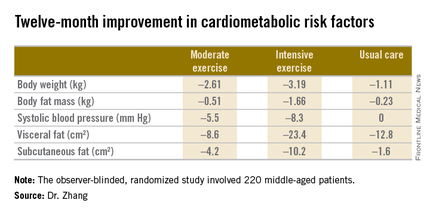

However, the more intensive exercise program had the edge in terms of favorable impact on metabolic risk factors. While both exercise prescriptions reduced body weight and blood pressure to a similar extent over the course of 12 months, the intensive-exercise group showed bigger reductions in body fat mass, visceral fat, and subcutaneous fat (see graphic), Dr. Hui-Jie Zhang of Xiamen (China) University said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The observer-blinded study included 220 middle-age Chinese patients with central obesity and confirmed nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), a common risk factor for cardiovascular disease. They were randomized to three groups: a moderate exercise program that consisted of brisk walking for 150 minutes per week for 12 months; an intensive exercise regimen involving 30 minutes of treadmill running at 65%-80% of maximum oxygen consumption 5 days per week for 6 months, followed by 6 months of brisk walking on the same schedule as the moderate exercise group; or a usual-care control group that received lifestyle counseling.

The primary endpoint was change in intrahepatic triglyceride content as measured by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy at 12 months. It was reduced from baseline by 6.45% in the intensive exercise group and similarly by 6.19% with moderate exercise, both significantly greater effects than the 2.85% decrease in the control group.

Dr. Zhang reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding this study.

ORLANDO – Moderate aerobic exercise and a more intensive regimen proved equally effective in reducing intrahepatic triglyceride content in centrally obese patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a 12-month randomized, controlled trial.

However, the more intensive exercise program had the edge in terms of favorable impact on metabolic risk factors. While both exercise prescriptions reduced body weight and blood pressure to a similar extent over the course of 12 months, the intensive-exercise group showed bigger reductions in body fat mass, visceral fat, and subcutaneous fat (see graphic), Dr. Hui-Jie Zhang of Xiamen (China) University said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The observer-blinded study included 220 middle-age Chinese patients with central obesity and confirmed nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), a common risk factor for cardiovascular disease. They were randomized to three groups: a moderate exercise program that consisted of brisk walking for 150 minutes per week for 12 months; an intensive exercise regimen involving 30 minutes of treadmill running at 65%-80% of maximum oxygen consumption 5 days per week for 6 months, followed by 6 months of brisk walking on the same schedule as the moderate exercise group; or a usual-care control group that received lifestyle counseling.

The primary endpoint was change in intrahepatic triglyceride content as measured by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy at 12 months. It was reduced from baseline by 6.45% in the intensive exercise group and similarly by 6.19% with moderate exercise, both significantly greater effects than the 2.85% decrease in the control group.

Dr. Zhang reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding this study.

ORLANDO – Moderate aerobic exercise and a more intensive regimen proved equally effective in reducing intrahepatic triglyceride content in centrally obese patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a 12-month randomized, controlled trial.

However, the more intensive exercise program had the edge in terms of favorable impact on metabolic risk factors. While both exercise prescriptions reduced body weight and blood pressure to a similar extent over the course of 12 months, the intensive-exercise group showed bigger reductions in body fat mass, visceral fat, and subcutaneous fat (see graphic), Dr. Hui-Jie Zhang of Xiamen (China) University said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The observer-blinded study included 220 middle-age Chinese patients with central obesity and confirmed nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), a common risk factor for cardiovascular disease. They were randomized to three groups: a moderate exercise program that consisted of brisk walking for 150 minutes per week for 12 months; an intensive exercise regimen involving 30 minutes of treadmill running at 65%-80% of maximum oxygen consumption 5 days per week for 6 months, followed by 6 months of brisk walking on the same schedule as the moderate exercise group; or a usual-care control group that received lifestyle counseling.

The primary endpoint was change in intrahepatic triglyceride content as measured by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy at 12 months. It was reduced from baseline by 6.45% in the intensive exercise group and similarly by 6.19% with moderate exercise, both significantly greater effects than the 2.85% decrease in the control group.

Dr. Zhang reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding this study.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Moderate, intensive exercise cut triglycerides equally in NAFLD

ORLANDO – Moderate aerobic exercise and a more intensive regimen proved equally effective in reducing intrahepatic triglyceride content in centrally obese patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a 12-month randomized, controlled trial.

However, the more intensive exercise program had the edge in terms of favorable impact on metabolic risk factors. While both exercise prescriptions reduced body weight and blood pressure to a similar extent over the course of 12 months, the intensive-exercise group showed bigger reductions in body fat mass, visceral fat, and subcutaneous fat (see graphic), Dr. Hui-Jie Zhang of Xiamen (China) University said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The observer-blinded study included 220 middle-age Chinese patients with central obesity and confirmed nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), a common risk factor for cardiovascular disease. They were randomized to three groups: a moderate exercise program that consisted of brisk walking for 150 minutes per week for 12 months; an intensive exercise regimen involving 30 minutes of treadmill running at 65%-80% of maximum oxygen consumption 5 days per week for 6 months, followed by 6 months of brisk walking on the same schedule as the moderate exercise group; or a usual-care control group that received lifestyle counseling.

The primary endpoint was change in intrahepatic triglyceride content as measured by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy at 12 months. It was reduced from baseline by 6.45% in the intensive exercise group and similarly by 6.19% with moderate exercise, both significantly greater effects than the 2.85% decrease in the control group.

Dr. Zhang reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding this study.

ORLANDO – Moderate aerobic exercise and a more intensive regimen proved equally effective in reducing intrahepatic triglyceride content in centrally obese patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a 12-month randomized, controlled trial.

However, the more intensive exercise program had the edge in terms of favorable impact on metabolic risk factors. While both exercise prescriptions reduced body weight and blood pressure to a similar extent over the course of 12 months, the intensive-exercise group showed bigger reductions in body fat mass, visceral fat, and subcutaneous fat (see graphic), Dr. Hui-Jie Zhang of Xiamen (China) University said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The observer-blinded study included 220 middle-age Chinese patients with central obesity and confirmed nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), a common risk factor for cardiovascular disease. They were randomized to three groups: a moderate exercise program that consisted of brisk walking for 150 minutes per week for 12 months; an intensive exercise regimen involving 30 minutes of treadmill running at 65%-80% of maximum oxygen consumption 5 days per week for 6 months, followed by 6 months of brisk walking on the same schedule as the moderate exercise group; or a usual-care control group that received lifestyle counseling.

The primary endpoint was change in intrahepatic triglyceride content as measured by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy at 12 months. It was reduced from baseline by 6.45% in the intensive exercise group and similarly by 6.19% with moderate exercise, both significantly greater effects than the 2.85% decrease in the control group.

Dr. Zhang reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding this study.

ORLANDO – Moderate aerobic exercise and a more intensive regimen proved equally effective in reducing intrahepatic triglyceride content in centrally obese patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a 12-month randomized, controlled trial.

However, the more intensive exercise program had the edge in terms of favorable impact on metabolic risk factors. While both exercise prescriptions reduced body weight and blood pressure to a similar extent over the course of 12 months, the intensive-exercise group showed bigger reductions in body fat mass, visceral fat, and subcutaneous fat (see graphic), Dr. Hui-Jie Zhang of Xiamen (China) University said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The observer-blinded study included 220 middle-age Chinese patients with central obesity and confirmed nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), a common risk factor for cardiovascular disease. They were randomized to three groups: a moderate exercise program that consisted of brisk walking for 150 minutes per week for 12 months; an intensive exercise regimen involving 30 minutes of treadmill running at 65%-80% of maximum oxygen consumption 5 days per week for 6 months, followed by 6 months of brisk walking on the same schedule as the moderate exercise group; or a usual-care control group that received lifestyle counseling.

The primary endpoint was change in intrahepatic triglyceride content as measured by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy at 12 months. It was reduced from baseline by 6.45% in the intensive exercise group and similarly by 6.19% with moderate exercise, both significantly greater effects than the 2.85% decrease in the control group.

Dr. Zhang reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding this study.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Moderate and intensive aerobic exercise, done regularly, are equally effective in reducing the intrahepatic triglyceride level in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Major finding: Intrahepatic triglyceride concentration in patients with NAFLD was reduced by a mean of 6.19% after 12 months on a moderate exercise program and 6.45% with a more intensive exercise regimen, compared with 2.85% in usual-care controls.

Data source: A 12-month, observer-blinded randomized trial in which 220 middle-age Chinese patients with NAFLD and central obesity were randomized to a program of moderate aerobic exercise, a more intensive regimen, or a usual-care control group.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding this study.

Subtly elevated maternal glucose linked to increased risk of tetralogy of Fallot

ORLANDO – Subclinical elevated maternal blood glucose levels during the second trimester are strongly associated with increased risk of tetralogy of Fallot, Dr. James R. Priest reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

It’s well established that maternal type 2 diabetes and gestational diabetes are strong maternal risk factors for structural congenital heart disease in their offspring. But the women in this study didn’t meet criteria for those diagnoses. They were asymptomatic, and their elevations in blood glucose in random nonfasting measurements obtained in the second trimester were below the 200 mg/dL threshold.

Thus, this study provides the first evidence that maternal blood glucose as a continuous variable is associated with increased risk of specific congenital heart defects in offspring, according to Dr. Priest, a pediatric cardiologist at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Of note, in this study of nondiabetic women, an elevated blood glucose was not associated with increased risk of d-transposition of the great arteries (dTGA), which, like tetralogy of Fallot, has been associated with maternal diabetes.

Dr. Priest presented an observational study of 277 pregnant, nondiabetic women, of whom 55 gave birth to a baby with tetralogy of Fallot, 42 had a baby with dTGA, and 180 gave birth to a baby without congenital heart disease or other malformations. Random nonfasting blood glucose and serum insulin levels were obtained from all subjects during weeks 15-18 of pregnancy.

The median maternal blood glucose level was 91.5 mg/dL in controls, similar at 90 mg/dL in the mothers of infants with dTGA, and significantly increased at 97 mg/dL in the mothers of offspring with tetralogy of Fallot. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for maternal age and ethnicity, elevated nonfasting second-trimester maternal glucose was associated with a 7.54-fold increased risk of having an infant with tetralogy of Fallot.

Maternal serum insulin level wasn’t associated with the risk of congenital heart disease.

Dr. Priest emphasized that while this study breaks new ground, the findings must be considered preliminary.

“Maternal blood glucose levels are influenced by diet, exercise, beta-cell function, and insulin resistance. Thus, blood glucose levels may simply be a marker of risk conferred by another physiologic process. The question remains whether elevated blood glucose or a variety of correlated but independent traits is behind the observed association,” he noted.

He plans to answer this key question by studying the relationship between these physiologic traits and blood glucose levels earlier in pregnancy.

This study was funded by the Stanford Cardiovascular Institute and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Priest reported having no financial conflicts of interest.