User login

Anxiety before Mohs surgery can be easily managed

ORLANDO – Assessment, education, and a judicious dose of medication can make a big difference to patients who are feeling anxious about undergoing Mohs surgery.

No studies or guidelines lay out a step-by-step management plan for anxious patients. But a little bit of common sense and empathy go a long way in easing the feeling, according to presenters at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

“We don’t have an algorithm for reducing anxiety,” said Dr. Joseph Sobanko of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “But we do have a lot of studies showing that better psychosocial health is related to better surgical outcomes.”

The lack of definitive guidance means that anxious patients might be identified and assessed by gut instinct, he continued. “Those of you who see patients probably have a gestalt technique of identifying the anxious ones. I would suggest this might not be the best way.”

Instead of guessing, he recommends assessing all patients with a validated screening tool, and dealing with anxiety proactively.

Assessing anxiety

Although anxiety assessment may not be part of a typical Mohs surgery intake, it probably should be, Dr. Sobanko said. There are a number of excellent, well-validated tools, and none of them require expertise in psychology to administer.

The Beck Anxiety Inventory is a 21-question index that takes about 10 minutes to complete. It assesses subjective, somatic, and panic-related symptoms of anxiety, and has been validated in a variety of clinical settings. It focuses quite a bit on strong physical symptoms, however, which Dr. Sobanko feels “may not be as relevant for our patients.”

The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory consists of 40 questions and takes about 15 minutes to complete. “I like it because it not only assesses how they generally feel, but how they feel at the moment,” he said. “We think it’s good and we do use it, but it takes a while to complete.”

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale is short, with only 14 questions, and takes only about 5 minutes to complete. “It’s validated for hospital patients, but we are often working with patients who are less sick than that,” Dr. Sobanko said.

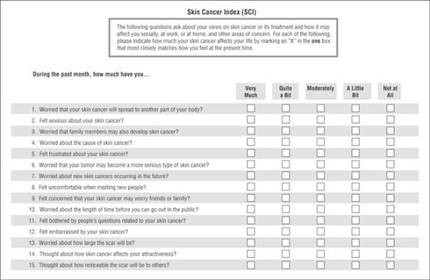

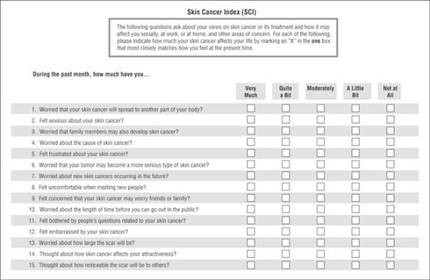

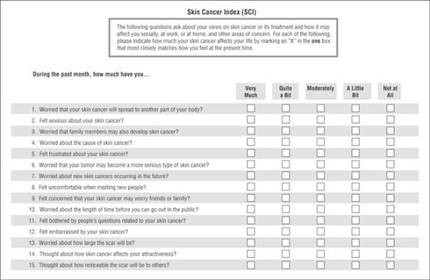

The Skin Cancer Index is his go-to anxiety screen for Mohs patients. It includes 15 questions that “really get to the heart of things that matter to our patients: emotional, social, and appearance issues,” he noted. Created in 2006, it was validated in a large cohort of Mohs surgery patients (Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2006;8[5]:314-318). The questions probe patients’ feelings about the seriousness of their skin cancer, its long-term health effect, and the impact the lesion – and its treatment – will have on appearance.

Tackling anxiety

Dr. Sobanko described his own, soon-to-be-published study of 104 Mohs surgery patients, who were randomized to receive a presurgical phone call to discuss anxiety, or the usual presurgical consultation. It was easy to implement the call, he said, noting that 70% were reached on the first try, and the interaction only took about 7 minutes.

Anxiety was common, with 43% reporting being anxious about the procedure. A frequent worry (25%) was whether their skin cancer would threaten their health over the long term. But both groups reported about the same reduction in anxiety after their discussion with the provider, whether it occurred over the phone or in person. After surgery, they expressed similar levels of satisfaction with the experience.

Clearly, the most effective method of dealing with patient anxiety has yet to be identified, Dr. Sobanko noted. Others are being explored, including music and educational videos.

In 2013, he and colleagues published a small study showing that music significantly reduced anxiety during Mohs surgery (Dermatol Surg. 2013 Feb;39[2]:298-305). It randomized 100 patients to surgery without music, or to listening to a playlist they had selected for themselves. Anxiety was measured using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory and on a visual analog scale. Subjects in the music group experienced statistically significantly lower scores on both measures, Dr. Sobanko said.

A study presented at the meeting found that a preoperative education video helped as well. Dr. Sidney Smith of the Georgia Skin and Cancer Clinic, Savannah, examined the benefit of a 9-minute video created by the American College of Mohs Surgery. The video interviews patients about their experiences, describes the surgery and overall cure rates, and touches on reconstruction and follow-up.

The study comprised 200 patients; 100 saw the movie, and then completed a 24 question survey about their perception of the procedure. Almost all (94%) of those who viewed it said the video answered their questions; 85% said it relieved their fear about undergoing the surgery.

Treating anxiety

Anxiolytics can be easily employed to help ease day-of-surgery anxiety, Dr. Jerry Brewer said at the meeting. Generally speaking, the medications are safe, well-tolerated, and very effective.

“One thing we should remember, however, is that anxiolytics do not affect pain. They have no effect on pain receptors, although they may affect a patient’s memory of pain. For people who are anxious, though, this can be a really great help,” said Dr. Brewer of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

He favors the short-acting benzodiazepines, particularly midazolam. It has a peak concentration of 17-55 minutes, so it’s particularly well suited for shorter cases. It also has a very rapid metabolization profile, with an elimination half life of 3-7 hours.

Since midazolam has twice the affinity for the benzodiazepine receptors as does diazepam, it can be effective in relatively small doses – usually about 0.25 mg/kg. The dose should be reduced by half for elderly patients and for those with renal or hepatic failure. In those patients, the elimination half-life can be increased up to 13 hours.

The typical dose for both adults and children is 10-20 mg. “We should remember that patients who take narcotics and those who take a benzodiazepine as a sleep aide may be quite tolerant and need a higher dose,” Dr. Brewer said.

Diazepam has a peak concentration of about 2 hours, but a much longer elimination half-life – up to 48 hours in a healthy adult and up to 80 hours in an elderly person. “It’s important that patients know they’re going to have this drug in their system for a couple days. This should be part of the consenting process,” Dr. Brewer pointed out.

Lorazepam has a peak concentration of about 2 hours as well, but a shorter half-life of 12-18 hours. That can be prolonged by 75% in patients with renal problems.

With the right clinical supervision, these medications are very safe, he said. “We treat about 800 patients per year with these and have data on about 12,000. Of those, we have had very few problems. Two have fallen out of bed. One patient wrote and said he was discharged too early, as he was very tired. One person fell and hit his head in the bathroom. One was sedated enough to need a sternal rub to improve responsiveness. And one gentleman enjoyed the medication so much that when the nurse left the room for a moment he grabbed the rest of the dose and drank it.”

Safe discharge is crucial when using anxiolytics, he added. “They absolutely cannot drive themselves home and they cannot go back to work. We make sure there is a reliable person to stay with the patient for at least 4 hours after discharge.”

Dr. Brewer does not discharge any patient until that person displays a zero rating on the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS) sedation scale. “That means he is awake, alert, and calmly interacting with you.”

Neither Dr. Sobanko nor Dr. Brewer had any financial declarations.

ORLANDO – Assessment, education, and a judicious dose of medication can make a big difference to patients who are feeling anxious about undergoing Mohs surgery.

No studies or guidelines lay out a step-by-step management plan for anxious patients. But a little bit of common sense and empathy go a long way in easing the feeling, according to presenters at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

“We don’t have an algorithm for reducing anxiety,” said Dr. Joseph Sobanko of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “But we do have a lot of studies showing that better psychosocial health is related to better surgical outcomes.”

The lack of definitive guidance means that anxious patients might be identified and assessed by gut instinct, he continued. “Those of you who see patients probably have a gestalt technique of identifying the anxious ones. I would suggest this might not be the best way.”

Instead of guessing, he recommends assessing all patients with a validated screening tool, and dealing with anxiety proactively.

Assessing anxiety

Although anxiety assessment may not be part of a typical Mohs surgery intake, it probably should be, Dr. Sobanko said. There are a number of excellent, well-validated tools, and none of them require expertise in psychology to administer.

The Beck Anxiety Inventory is a 21-question index that takes about 10 minutes to complete. It assesses subjective, somatic, and panic-related symptoms of anxiety, and has been validated in a variety of clinical settings. It focuses quite a bit on strong physical symptoms, however, which Dr. Sobanko feels “may not be as relevant for our patients.”

The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory consists of 40 questions and takes about 15 minutes to complete. “I like it because it not only assesses how they generally feel, but how they feel at the moment,” he said. “We think it’s good and we do use it, but it takes a while to complete.”

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale is short, with only 14 questions, and takes only about 5 minutes to complete. “It’s validated for hospital patients, but we are often working with patients who are less sick than that,” Dr. Sobanko said.

The Skin Cancer Index is his go-to anxiety screen for Mohs patients. It includes 15 questions that “really get to the heart of things that matter to our patients: emotional, social, and appearance issues,” he noted. Created in 2006, it was validated in a large cohort of Mohs surgery patients (Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2006;8[5]:314-318). The questions probe patients’ feelings about the seriousness of their skin cancer, its long-term health effect, and the impact the lesion – and its treatment – will have on appearance.

Tackling anxiety

Dr. Sobanko described his own, soon-to-be-published study of 104 Mohs surgery patients, who were randomized to receive a presurgical phone call to discuss anxiety, or the usual presurgical consultation. It was easy to implement the call, he said, noting that 70% were reached on the first try, and the interaction only took about 7 minutes.

Anxiety was common, with 43% reporting being anxious about the procedure. A frequent worry (25%) was whether their skin cancer would threaten their health over the long term. But both groups reported about the same reduction in anxiety after their discussion with the provider, whether it occurred over the phone or in person. After surgery, they expressed similar levels of satisfaction with the experience.

Clearly, the most effective method of dealing with patient anxiety has yet to be identified, Dr. Sobanko noted. Others are being explored, including music and educational videos.

In 2013, he and colleagues published a small study showing that music significantly reduced anxiety during Mohs surgery (Dermatol Surg. 2013 Feb;39[2]:298-305). It randomized 100 patients to surgery without music, or to listening to a playlist they had selected for themselves. Anxiety was measured using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory and on a visual analog scale. Subjects in the music group experienced statistically significantly lower scores on both measures, Dr. Sobanko said.

A study presented at the meeting found that a preoperative education video helped as well. Dr. Sidney Smith of the Georgia Skin and Cancer Clinic, Savannah, examined the benefit of a 9-minute video created by the American College of Mohs Surgery. The video interviews patients about their experiences, describes the surgery and overall cure rates, and touches on reconstruction and follow-up.

The study comprised 200 patients; 100 saw the movie, and then completed a 24 question survey about their perception of the procedure. Almost all (94%) of those who viewed it said the video answered their questions; 85% said it relieved their fear about undergoing the surgery.

Treating anxiety

Anxiolytics can be easily employed to help ease day-of-surgery anxiety, Dr. Jerry Brewer said at the meeting. Generally speaking, the medications are safe, well-tolerated, and very effective.

“One thing we should remember, however, is that anxiolytics do not affect pain. They have no effect on pain receptors, although they may affect a patient’s memory of pain. For people who are anxious, though, this can be a really great help,” said Dr. Brewer of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

He favors the short-acting benzodiazepines, particularly midazolam. It has a peak concentration of 17-55 minutes, so it’s particularly well suited for shorter cases. It also has a very rapid metabolization profile, with an elimination half life of 3-7 hours.

Since midazolam has twice the affinity for the benzodiazepine receptors as does diazepam, it can be effective in relatively small doses – usually about 0.25 mg/kg. The dose should be reduced by half for elderly patients and for those with renal or hepatic failure. In those patients, the elimination half-life can be increased up to 13 hours.

The typical dose for both adults and children is 10-20 mg. “We should remember that patients who take narcotics and those who take a benzodiazepine as a sleep aide may be quite tolerant and need a higher dose,” Dr. Brewer said.

Diazepam has a peak concentration of about 2 hours, but a much longer elimination half-life – up to 48 hours in a healthy adult and up to 80 hours in an elderly person. “It’s important that patients know they’re going to have this drug in their system for a couple days. This should be part of the consenting process,” Dr. Brewer pointed out.

Lorazepam has a peak concentration of about 2 hours as well, but a shorter half-life of 12-18 hours. That can be prolonged by 75% in patients with renal problems.

With the right clinical supervision, these medications are very safe, he said. “We treat about 800 patients per year with these and have data on about 12,000. Of those, we have had very few problems. Two have fallen out of bed. One patient wrote and said he was discharged too early, as he was very tired. One person fell and hit his head in the bathroom. One was sedated enough to need a sternal rub to improve responsiveness. And one gentleman enjoyed the medication so much that when the nurse left the room for a moment he grabbed the rest of the dose and drank it.”

Safe discharge is crucial when using anxiolytics, he added. “They absolutely cannot drive themselves home and they cannot go back to work. We make sure there is a reliable person to stay with the patient for at least 4 hours after discharge.”

Dr. Brewer does not discharge any patient until that person displays a zero rating on the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS) sedation scale. “That means he is awake, alert, and calmly interacting with you.”

Neither Dr. Sobanko nor Dr. Brewer had any financial declarations.

ORLANDO – Assessment, education, and a judicious dose of medication can make a big difference to patients who are feeling anxious about undergoing Mohs surgery.

No studies or guidelines lay out a step-by-step management plan for anxious patients. But a little bit of common sense and empathy go a long way in easing the feeling, according to presenters at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

“We don’t have an algorithm for reducing anxiety,” said Dr. Joseph Sobanko of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “But we do have a lot of studies showing that better psychosocial health is related to better surgical outcomes.”

The lack of definitive guidance means that anxious patients might be identified and assessed by gut instinct, he continued. “Those of you who see patients probably have a gestalt technique of identifying the anxious ones. I would suggest this might not be the best way.”

Instead of guessing, he recommends assessing all patients with a validated screening tool, and dealing with anxiety proactively.

Assessing anxiety

Although anxiety assessment may not be part of a typical Mohs surgery intake, it probably should be, Dr. Sobanko said. There are a number of excellent, well-validated tools, and none of them require expertise in psychology to administer.

The Beck Anxiety Inventory is a 21-question index that takes about 10 minutes to complete. It assesses subjective, somatic, and panic-related symptoms of anxiety, and has been validated in a variety of clinical settings. It focuses quite a bit on strong physical symptoms, however, which Dr. Sobanko feels “may not be as relevant for our patients.”

The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory consists of 40 questions and takes about 15 minutes to complete. “I like it because it not only assesses how they generally feel, but how they feel at the moment,” he said. “We think it’s good and we do use it, but it takes a while to complete.”

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale is short, with only 14 questions, and takes only about 5 minutes to complete. “It’s validated for hospital patients, but we are often working with patients who are less sick than that,” Dr. Sobanko said.

The Skin Cancer Index is his go-to anxiety screen for Mohs patients. It includes 15 questions that “really get to the heart of things that matter to our patients: emotional, social, and appearance issues,” he noted. Created in 2006, it was validated in a large cohort of Mohs surgery patients (Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2006;8[5]:314-318). The questions probe patients’ feelings about the seriousness of their skin cancer, its long-term health effect, and the impact the lesion – and its treatment – will have on appearance.

Tackling anxiety

Dr. Sobanko described his own, soon-to-be-published study of 104 Mohs surgery patients, who were randomized to receive a presurgical phone call to discuss anxiety, or the usual presurgical consultation. It was easy to implement the call, he said, noting that 70% were reached on the first try, and the interaction only took about 7 minutes.

Anxiety was common, with 43% reporting being anxious about the procedure. A frequent worry (25%) was whether their skin cancer would threaten their health over the long term. But both groups reported about the same reduction in anxiety after their discussion with the provider, whether it occurred over the phone or in person. After surgery, they expressed similar levels of satisfaction with the experience.

Clearly, the most effective method of dealing with patient anxiety has yet to be identified, Dr. Sobanko noted. Others are being explored, including music and educational videos.

In 2013, he and colleagues published a small study showing that music significantly reduced anxiety during Mohs surgery (Dermatol Surg. 2013 Feb;39[2]:298-305). It randomized 100 patients to surgery without music, or to listening to a playlist they had selected for themselves. Anxiety was measured using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory and on a visual analog scale. Subjects in the music group experienced statistically significantly lower scores on both measures, Dr. Sobanko said.

A study presented at the meeting found that a preoperative education video helped as well. Dr. Sidney Smith of the Georgia Skin and Cancer Clinic, Savannah, examined the benefit of a 9-minute video created by the American College of Mohs Surgery. The video interviews patients about their experiences, describes the surgery and overall cure rates, and touches on reconstruction and follow-up.

The study comprised 200 patients; 100 saw the movie, and then completed a 24 question survey about their perception of the procedure. Almost all (94%) of those who viewed it said the video answered their questions; 85% said it relieved their fear about undergoing the surgery.

Treating anxiety

Anxiolytics can be easily employed to help ease day-of-surgery anxiety, Dr. Jerry Brewer said at the meeting. Generally speaking, the medications are safe, well-tolerated, and very effective.

“One thing we should remember, however, is that anxiolytics do not affect pain. They have no effect on pain receptors, although they may affect a patient’s memory of pain. For people who are anxious, though, this can be a really great help,” said Dr. Brewer of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

He favors the short-acting benzodiazepines, particularly midazolam. It has a peak concentration of 17-55 minutes, so it’s particularly well suited for shorter cases. It also has a very rapid metabolization profile, with an elimination half life of 3-7 hours.

Since midazolam has twice the affinity for the benzodiazepine receptors as does diazepam, it can be effective in relatively small doses – usually about 0.25 mg/kg. The dose should be reduced by half for elderly patients and for those with renal or hepatic failure. In those patients, the elimination half-life can be increased up to 13 hours.

The typical dose for both adults and children is 10-20 mg. “We should remember that patients who take narcotics and those who take a benzodiazepine as a sleep aide may be quite tolerant and need a higher dose,” Dr. Brewer said.

Diazepam has a peak concentration of about 2 hours, but a much longer elimination half-life – up to 48 hours in a healthy adult and up to 80 hours in an elderly person. “It’s important that patients know they’re going to have this drug in their system for a couple days. This should be part of the consenting process,” Dr. Brewer pointed out.

Lorazepam has a peak concentration of about 2 hours as well, but a shorter half-life of 12-18 hours. That can be prolonged by 75% in patients with renal problems.

With the right clinical supervision, these medications are very safe, he said. “We treat about 800 patients per year with these and have data on about 12,000. Of those, we have had very few problems. Two have fallen out of bed. One patient wrote and said he was discharged too early, as he was very tired. One person fell and hit his head in the bathroom. One was sedated enough to need a sternal rub to improve responsiveness. And one gentleman enjoyed the medication so much that when the nurse left the room for a moment he grabbed the rest of the dose and drank it.”

Safe discharge is crucial when using anxiolytics, he added. “They absolutely cannot drive themselves home and they cannot go back to work. We make sure there is a reliable person to stay with the patient for at least 4 hours after discharge.”

Dr. Brewer does not discharge any patient until that person displays a zero rating on the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS) sedation scale. “That means he is awake, alert, and calmly interacting with you.”

Neither Dr. Sobanko nor Dr. Brewer had any financial declarations.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ACMS ANNUAL MEETING

Gene expression test predicts melanoma metastasis

ORLANDO – A commercially available melanoma gene expression test had a negative predictive value of 98% for metastasis, but also correctly identified patients at very high risk of disease spread.

In a retrospective study, the DecisionDx-Melanoma test, which examines 28 risk genes, showed that patients stratified as high risk with the test were 22 times more likely to develop metastatic disease than were those stratified as low risk, Dr. Bradley Greenhaw said at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery. The test classifies patients with stage I and stage II melanoma as having a low risk (class 1) or a high risk (class 2) of metastasis within 5 years.

“Our mean follow-up time is less than half of the 5-year risk this test is able to predict,” said Dr. Greenhaw, a Mohs surgeon in Tupelo, Miss. “So if the test is performing as it’s supposed to, there would be even more events – you would see this gap widen even more as time passes. Seeing this with our limited follow-up period is pretty significant.”

The test also added valuable prognostic information to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging method, he said. “For example, based on AJCC staging alone, we would expect to see a 5-year metastatic rate of 5%-10% for stage I melanomas. We saw less than a 1% rate. That is a pretty significant negative predictive value.”

The genes in the panel were selected from those examined in eight different genetic risk studies of cutaneous melanomas. The panel divides tumors into the high- and low-risk groups. A validation study published last year concluded that the 5-year disease-free survival rates were 97% for class 1 tumors and 31% for class 2 tumors (Clin Cancer Res 2015;21[1];175-83).

In the retrospective study, Dr. Greenhaw and his associates examined the test’s accuracy in a cohort of 256 patients treated at his center. The mean follow-up time was 23 months, although some patients have completed 5 years of follow-up.

Of the tumor blocks analyzed, 214 were class 1 and 42 were class 2. He noted significant differences between the class 1 and class 2 tumors, including mean patient age (66 years vs. 74 years, respectively), mean Breslow’s depth (0.7 mm vs. 2.3 mm), mitotic rate (0.8 vs. 3.3), and ulceration (4% vs. 41%).

Over the mean 2-year follow-up time, three class 1 tumors and 10 class 2 tumors metastasized (1.4% vs. 23.8%). The test’s negative predictive value was 98%; class 2 tumors were 22 times more likely to metastasize. “About 77% of metastatic tumors were correctly identified as high risk by this test,” Dr. Greenhaw said in an interview. “For comparison, more than 80% were correctly identified in the validation study, so our study was in line with it.”

The test showed a link between metastatic risk and ulceration at presentation. Of the class 1 tumors, 4% were ulcerated, compared to 41% of class 2 tumors; class 2 tumors were 16 times more likely to be ulcerated. Among the ulcerated lesions, metastasis occurred in 11% of class 1 and 41% of class 2 tumors.

Dr. Greenhaw also compared the gene test’s characterization of tumors to the AJCC staging.

Of the 214 class 1 tumors, 94% were stage IA or IB. Among these, there was no metastasis. Of the class 2 tumors, 17% were stage IA and 26% were stage IB. Interestingly, Dr. Greenhaw said, despite the high-risk genetic signature, none of these tumors metastasized. “This could have been because although the gene expression showed them to be associated with a high risk of metastases, the tumors were completely excised prior to the metastatic event, or because our follow-up is still relatively short,” he noted.

In the class 1 group, 4% of the tumors were stage IIA and 2% were stage IIB. Of these 13 tumors, two metastasized. “This 15% metastatic rate is a lower rate than we would predict by the AJCC staging,” Dr. Greenhaw said.

In the class 2 groups, 24% were stage IIA, 26% were stage IIB, and 7% were stage IIC. Of these 24 tumors, 10 metastasized. “This is a higher rate than the AJCC staging would predict, and it occurred rather quickly, with our abbreviated follow-up period,” Dr. Greenhaw noted.

Based on these findings, Dr. Greenhaw suggested a clinical management algorithm:

• All patients with invasive melanoma should be offered the gene expression profiling.

• Those with class 1 tumors have a high chance of cure and a low risk of metastasis. They can be reasonably managed with clinical skin and nodal exams every 6 months for 2 years, and then annually.

• Those with class 2 tumors have a much higher risk of metastatic disease. They should receive clinical skin and nodal exams every 3 months for 2 years, then every 6-12 months for 5 years. After that, a yearly exam should suffice.

Tests like this are an important advance in managing melanoma, Dr. Greenhaw said. “I think this is where the future of melanoma prognosis is. The keys are found in the genes and DNA of these tumors. These tests are being used in other types of cancer and I think it’s where we need to go in our field as well.”

Dr. Greenhaw has no financial disclosures to report.

ORLANDO – A commercially available melanoma gene expression test had a negative predictive value of 98% for metastasis, but also correctly identified patients at very high risk of disease spread.

In a retrospective study, the DecisionDx-Melanoma test, which examines 28 risk genes, showed that patients stratified as high risk with the test were 22 times more likely to develop metastatic disease than were those stratified as low risk, Dr. Bradley Greenhaw said at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery. The test classifies patients with stage I and stage II melanoma as having a low risk (class 1) or a high risk (class 2) of metastasis within 5 years.

“Our mean follow-up time is less than half of the 5-year risk this test is able to predict,” said Dr. Greenhaw, a Mohs surgeon in Tupelo, Miss. “So if the test is performing as it’s supposed to, there would be even more events – you would see this gap widen even more as time passes. Seeing this with our limited follow-up period is pretty significant.”

The test also added valuable prognostic information to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging method, he said. “For example, based on AJCC staging alone, we would expect to see a 5-year metastatic rate of 5%-10% for stage I melanomas. We saw less than a 1% rate. That is a pretty significant negative predictive value.”

The genes in the panel were selected from those examined in eight different genetic risk studies of cutaneous melanomas. The panel divides tumors into the high- and low-risk groups. A validation study published last year concluded that the 5-year disease-free survival rates were 97% for class 1 tumors and 31% for class 2 tumors (Clin Cancer Res 2015;21[1];175-83).

In the retrospective study, Dr. Greenhaw and his associates examined the test’s accuracy in a cohort of 256 patients treated at his center. The mean follow-up time was 23 months, although some patients have completed 5 years of follow-up.

Of the tumor blocks analyzed, 214 were class 1 and 42 were class 2. He noted significant differences between the class 1 and class 2 tumors, including mean patient age (66 years vs. 74 years, respectively), mean Breslow’s depth (0.7 mm vs. 2.3 mm), mitotic rate (0.8 vs. 3.3), and ulceration (4% vs. 41%).

Over the mean 2-year follow-up time, three class 1 tumors and 10 class 2 tumors metastasized (1.4% vs. 23.8%). The test’s negative predictive value was 98%; class 2 tumors were 22 times more likely to metastasize. “About 77% of metastatic tumors were correctly identified as high risk by this test,” Dr. Greenhaw said in an interview. “For comparison, more than 80% were correctly identified in the validation study, so our study was in line with it.”

The test showed a link between metastatic risk and ulceration at presentation. Of the class 1 tumors, 4% were ulcerated, compared to 41% of class 2 tumors; class 2 tumors were 16 times more likely to be ulcerated. Among the ulcerated lesions, metastasis occurred in 11% of class 1 and 41% of class 2 tumors.

Dr. Greenhaw also compared the gene test’s characterization of tumors to the AJCC staging.

Of the 214 class 1 tumors, 94% were stage IA or IB. Among these, there was no metastasis. Of the class 2 tumors, 17% were stage IA and 26% were stage IB. Interestingly, Dr. Greenhaw said, despite the high-risk genetic signature, none of these tumors metastasized. “This could have been because although the gene expression showed them to be associated with a high risk of metastases, the tumors were completely excised prior to the metastatic event, or because our follow-up is still relatively short,” he noted.

In the class 1 group, 4% of the tumors were stage IIA and 2% were stage IIB. Of these 13 tumors, two metastasized. “This 15% metastatic rate is a lower rate than we would predict by the AJCC staging,” Dr. Greenhaw said.

In the class 2 groups, 24% were stage IIA, 26% were stage IIB, and 7% were stage IIC. Of these 24 tumors, 10 metastasized. “This is a higher rate than the AJCC staging would predict, and it occurred rather quickly, with our abbreviated follow-up period,” Dr. Greenhaw noted.

Based on these findings, Dr. Greenhaw suggested a clinical management algorithm:

• All patients with invasive melanoma should be offered the gene expression profiling.

• Those with class 1 tumors have a high chance of cure and a low risk of metastasis. They can be reasonably managed with clinical skin and nodal exams every 6 months for 2 years, and then annually.

• Those with class 2 tumors have a much higher risk of metastatic disease. They should receive clinical skin and nodal exams every 3 months for 2 years, then every 6-12 months for 5 years. After that, a yearly exam should suffice.

Tests like this are an important advance in managing melanoma, Dr. Greenhaw said. “I think this is where the future of melanoma prognosis is. The keys are found in the genes and DNA of these tumors. These tests are being used in other types of cancer and I think it’s where we need to go in our field as well.”

Dr. Greenhaw has no financial disclosures to report.

ORLANDO – A commercially available melanoma gene expression test had a negative predictive value of 98% for metastasis, but also correctly identified patients at very high risk of disease spread.

In a retrospective study, the DecisionDx-Melanoma test, which examines 28 risk genes, showed that patients stratified as high risk with the test were 22 times more likely to develop metastatic disease than were those stratified as low risk, Dr. Bradley Greenhaw said at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery. The test classifies patients with stage I and stage II melanoma as having a low risk (class 1) or a high risk (class 2) of metastasis within 5 years.

“Our mean follow-up time is less than half of the 5-year risk this test is able to predict,” said Dr. Greenhaw, a Mohs surgeon in Tupelo, Miss. “So if the test is performing as it’s supposed to, there would be even more events – you would see this gap widen even more as time passes. Seeing this with our limited follow-up period is pretty significant.”

The test also added valuable prognostic information to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging method, he said. “For example, based on AJCC staging alone, we would expect to see a 5-year metastatic rate of 5%-10% for stage I melanomas. We saw less than a 1% rate. That is a pretty significant negative predictive value.”

The genes in the panel were selected from those examined in eight different genetic risk studies of cutaneous melanomas. The panel divides tumors into the high- and low-risk groups. A validation study published last year concluded that the 5-year disease-free survival rates were 97% for class 1 tumors and 31% for class 2 tumors (Clin Cancer Res 2015;21[1];175-83).

In the retrospective study, Dr. Greenhaw and his associates examined the test’s accuracy in a cohort of 256 patients treated at his center. The mean follow-up time was 23 months, although some patients have completed 5 years of follow-up.

Of the tumor blocks analyzed, 214 were class 1 and 42 were class 2. He noted significant differences between the class 1 and class 2 tumors, including mean patient age (66 years vs. 74 years, respectively), mean Breslow’s depth (0.7 mm vs. 2.3 mm), mitotic rate (0.8 vs. 3.3), and ulceration (4% vs. 41%).

Over the mean 2-year follow-up time, three class 1 tumors and 10 class 2 tumors metastasized (1.4% vs. 23.8%). The test’s negative predictive value was 98%; class 2 tumors were 22 times more likely to metastasize. “About 77% of metastatic tumors were correctly identified as high risk by this test,” Dr. Greenhaw said in an interview. “For comparison, more than 80% were correctly identified in the validation study, so our study was in line with it.”

The test showed a link between metastatic risk and ulceration at presentation. Of the class 1 tumors, 4% were ulcerated, compared to 41% of class 2 tumors; class 2 tumors were 16 times more likely to be ulcerated. Among the ulcerated lesions, metastasis occurred in 11% of class 1 and 41% of class 2 tumors.

Dr. Greenhaw also compared the gene test’s characterization of tumors to the AJCC staging.

Of the 214 class 1 tumors, 94% were stage IA or IB. Among these, there was no metastasis. Of the class 2 tumors, 17% were stage IA and 26% were stage IB. Interestingly, Dr. Greenhaw said, despite the high-risk genetic signature, none of these tumors metastasized. “This could have been because although the gene expression showed them to be associated with a high risk of metastases, the tumors were completely excised prior to the metastatic event, or because our follow-up is still relatively short,” he noted.

In the class 1 group, 4% of the tumors were stage IIA and 2% were stage IIB. Of these 13 tumors, two metastasized. “This 15% metastatic rate is a lower rate than we would predict by the AJCC staging,” Dr. Greenhaw said.

In the class 2 groups, 24% were stage IIA, 26% were stage IIB, and 7% were stage IIC. Of these 24 tumors, 10 metastasized. “This is a higher rate than the AJCC staging would predict, and it occurred rather quickly, with our abbreviated follow-up period,” Dr. Greenhaw noted.

Based on these findings, Dr. Greenhaw suggested a clinical management algorithm:

• All patients with invasive melanoma should be offered the gene expression profiling.

• Those with class 1 tumors have a high chance of cure and a low risk of metastasis. They can be reasonably managed with clinical skin and nodal exams every 6 months for 2 years, and then annually.

• Those with class 2 tumors have a much higher risk of metastatic disease. They should receive clinical skin and nodal exams every 3 months for 2 years, then every 6-12 months for 5 years. After that, a yearly exam should suffice.

Tests like this are an important advance in managing melanoma, Dr. Greenhaw said. “I think this is where the future of melanoma prognosis is. The keys are found in the genes and DNA of these tumors. These tests are being used in other types of cancer and I think it’s where we need to go in our field as well.”

Dr. Greenhaw has no financial disclosures to report.

AT THE ACMS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: A commercially available gene expression test can help predict metastasis in early melanoma cases.

Major finding: The test had a 98% negative predictive value.

Data source: A retrospective study that evaluated the gene expression test in 256 patients with melanoma.

Disclosures: Dr. Greenhaw has no financial interest in the test.

Ibuprofen plus acetaminophen works well for postop Mohs pain

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ACMS ANNUAL MEETING

ORLANDO – An alternating schedule of ibuprofen and acetaminophen every 3 hours is an excellent method of managing postoperative pain associated with Mohs surgery, especially if the initial dose is taken at the start of the procedure.

By starting with ibuprofen, the regimen capitalizes on the drug’s anti-inflammatory component to reduce overall postoperative analgesic requirement, Dr. Bryan Carroll said at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

“This combination has even been shown to be superior to narcotics, both alone and in combination,” said Dr. Carroll, director of dermatologic surgery at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk. “This finding has been reinforced in the Mohs literature,” he added, citing a study that found the combination of acetaminophen and ibuprofen was more effective than acetaminophen alone or acetaminophen with codeine in controlling pain after Mohs surgery and reconstruction (Dermatol Surg. 2011 Jul;37[7]:1007-13).

Alternately layering the analgesics allows both to build to a maximum concentration in the blood without any nadirs where pain can get a foothold, an important concept in pain management, Dr. Carroll said.

And having two medications on board allows simultaneous targeting of different portions of the pain signaling pathway, he added. Ibuprofen works at the points of transduction and transmission, while acetaminophen works at the points of transmission and perception.

Dr. Carroll’s regimen starts at the time of surgery, when patients receive 400 mg ibuprofen. Three hours later, they receive 1 gram of acetaminophen; this dose should be adjusted for patients older than 60 years, who should not get more than 3 grams in 24 hours, and for those with liver failure, who should be limited to 2 grams over 24 hours.

This alternating dose is repeated every 3 hours. By the time of discharge, most patients have had at least two doses. This schedule is usually sufficient for patients at moderate to high risk of uncontrolled pain, who can then manage their discomfort with either drug the next day, he said.

Patients at higher risk of uncontrolled pain can use the regimen for the first day, and then titrate off according to their comfort. Some of these patients, however, may benefit from oxycodone, with the addition of laxative and an antiemetic, he noted.

The layering technique provides consistent postoperative pain relief that’s effective for most patients – even those who undergo substantial reconstruction, Dr. Carroll said in an interview. “This schedule is sufficient for all of our procedures, including larger reconstructions such as forehead flaps and cervicofacial rotation flaps. But additional interventions are indicated for patients with a high risk of uncontrolled pain. It’s the patient, not the procedure, which determines need for escalation.”

Teasing out those patients who may need more assertive pain management should be done in a preoperative assessment, Dr. Carroll said. A patient’s expectations of pain and history of chronic pain are some of the biggest factors in predicting a patient who will have uncontrolled pain.

“The experience of pain in Mohs surgery has limited studies,” he said. “Only a handful of investigations have looked at predictors that could help us plan. But of these, two things do stand out: a patient’s expectation of pain and a patient’s history of chronic pain.”

Surprisingly, he said, studies have determined that even a modestly elevated expectation of pain is enough to tip patients into a high-risk category. “If a patient predicted that his pain would be a 4 on a 1-10 scale, that was correlated with a lack of pain control during the operative experience. Maybe we’d expect this correlation if the expectation was an 8 or a 10, but a 4 was surprising. If a patient has even that amount of concern, I start thinking about additional interventions I can provide to maximize comfort.”

A patient’s past experience with pain is also a very large factor in how that person will experience postoperative pain. “Chronic pain does correlate with uncontrolled pain during surgery. I always ask about it. And this talk also helps drive your conversation about what you will be doing to keep them comfortable.”

That chat should include an explanation of how chronic and acute pain differ, Dr. Carroll said. “Chronic and acute pain involve different pathways and need different interventions. If the patient expresses fear, saying something like, ‘Tylenol is like water to me,’ believe him. It is like water for chronic pain. But you can also tell that patient that chronic pain is different from acute pain, and that acetaminophen will be a part of successfully managing it.”

Dr. Carroll had no financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ACMS ANNUAL MEETING

ORLANDO – An alternating schedule of ibuprofen and acetaminophen every 3 hours is an excellent method of managing postoperative pain associated with Mohs surgery, especially if the initial dose is taken at the start of the procedure.

By starting with ibuprofen, the regimen capitalizes on the drug’s anti-inflammatory component to reduce overall postoperative analgesic requirement, Dr. Bryan Carroll said at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

“This combination has even been shown to be superior to narcotics, both alone and in combination,” said Dr. Carroll, director of dermatologic surgery at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk. “This finding has been reinforced in the Mohs literature,” he added, citing a study that found the combination of acetaminophen and ibuprofen was more effective than acetaminophen alone or acetaminophen with codeine in controlling pain after Mohs surgery and reconstruction (Dermatol Surg. 2011 Jul;37[7]:1007-13).

Alternately layering the analgesics allows both to build to a maximum concentration in the blood without any nadirs where pain can get a foothold, an important concept in pain management, Dr. Carroll said.

And having two medications on board allows simultaneous targeting of different portions of the pain signaling pathway, he added. Ibuprofen works at the points of transduction and transmission, while acetaminophen works at the points of transmission and perception.

Dr. Carroll’s regimen starts at the time of surgery, when patients receive 400 mg ibuprofen. Three hours later, they receive 1 gram of acetaminophen; this dose should be adjusted for patients older than 60 years, who should not get more than 3 grams in 24 hours, and for those with liver failure, who should be limited to 2 grams over 24 hours.

This alternating dose is repeated every 3 hours. By the time of discharge, most patients have had at least two doses. This schedule is usually sufficient for patients at moderate to high risk of uncontrolled pain, who can then manage their discomfort with either drug the next day, he said.

Patients at higher risk of uncontrolled pain can use the regimen for the first day, and then titrate off according to their comfort. Some of these patients, however, may benefit from oxycodone, with the addition of laxative and an antiemetic, he noted.

The layering technique provides consistent postoperative pain relief that’s effective for most patients – even those who undergo substantial reconstruction, Dr. Carroll said in an interview. “This schedule is sufficient for all of our procedures, including larger reconstructions such as forehead flaps and cervicofacial rotation flaps. But additional interventions are indicated for patients with a high risk of uncontrolled pain. It’s the patient, not the procedure, which determines need for escalation.”

Teasing out those patients who may need more assertive pain management should be done in a preoperative assessment, Dr. Carroll said. A patient’s expectations of pain and history of chronic pain are some of the biggest factors in predicting a patient who will have uncontrolled pain.

“The experience of pain in Mohs surgery has limited studies,” he said. “Only a handful of investigations have looked at predictors that could help us plan. But of these, two things do stand out: a patient’s expectation of pain and a patient’s history of chronic pain.”

Surprisingly, he said, studies have determined that even a modestly elevated expectation of pain is enough to tip patients into a high-risk category. “If a patient predicted that his pain would be a 4 on a 1-10 scale, that was correlated with a lack of pain control during the operative experience. Maybe we’d expect this correlation if the expectation was an 8 or a 10, but a 4 was surprising. If a patient has even that amount of concern, I start thinking about additional interventions I can provide to maximize comfort.”

A patient’s past experience with pain is also a very large factor in how that person will experience postoperative pain. “Chronic pain does correlate with uncontrolled pain during surgery. I always ask about it. And this talk also helps drive your conversation about what you will be doing to keep them comfortable.”

That chat should include an explanation of how chronic and acute pain differ, Dr. Carroll said. “Chronic and acute pain involve different pathways and need different interventions. If the patient expresses fear, saying something like, ‘Tylenol is like water to me,’ believe him. It is like water for chronic pain. But you can also tell that patient that chronic pain is different from acute pain, and that acetaminophen will be a part of successfully managing it.”

Dr. Carroll had no financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ACMS ANNUAL MEETING

ORLANDO – An alternating schedule of ibuprofen and acetaminophen every 3 hours is an excellent method of managing postoperative pain associated with Mohs surgery, especially if the initial dose is taken at the start of the procedure.

By starting with ibuprofen, the regimen capitalizes on the drug’s anti-inflammatory component to reduce overall postoperative analgesic requirement, Dr. Bryan Carroll said at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

“This combination has even been shown to be superior to narcotics, both alone and in combination,” said Dr. Carroll, director of dermatologic surgery at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk. “This finding has been reinforced in the Mohs literature,” he added, citing a study that found the combination of acetaminophen and ibuprofen was more effective than acetaminophen alone or acetaminophen with codeine in controlling pain after Mohs surgery and reconstruction (Dermatol Surg. 2011 Jul;37[7]:1007-13).

Alternately layering the analgesics allows both to build to a maximum concentration in the blood without any nadirs where pain can get a foothold, an important concept in pain management, Dr. Carroll said.

And having two medications on board allows simultaneous targeting of different portions of the pain signaling pathway, he added. Ibuprofen works at the points of transduction and transmission, while acetaminophen works at the points of transmission and perception.

Dr. Carroll’s regimen starts at the time of surgery, when patients receive 400 mg ibuprofen. Three hours later, they receive 1 gram of acetaminophen; this dose should be adjusted for patients older than 60 years, who should not get more than 3 grams in 24 hours, and for those with liver failure, who should be limited to 2 grams over 24 hours.

This alternating dose is repeated every 3 hours. By the time of discharge, most patients have had at least two doses. This schedule is usually sufficient for patients at moderate to high risk of uncontrolled pain, who can then manage their discomfort with either drug the next day, he said.

Patients at higher risk of uncontrolled pain can use the regimen for the first day, and then titrate off according to their comfort. Some of these patients, however, may benefit from oxycodone, with the addition of laxative and an antiemetic, he noted.

The layering technique provides consistent postoperative pain relief that’s effective for most patients – even those who undergo substantial reconstruction, Dr. Carroll said in an interview. “This schedule is sufficient for all of our procedures, including larger reconstructions such as forehead flaps and cervicofacial rotation flaps. But additional interventions are indicated for patients with a high risk of uncontrolled pain. It’s the patient, not the procedure, which determines need for escalation.”

Teasing out those patients who may need more assertive pain management should be done in a preoperative assessment, Dr. Carroll said. A patient’s expectations of pain and history of chronic pain are some of the biggest factors in predicting a patient who will have uncontrolled pain.

“The experience of pain in Mohs surgery has limited studies,” he said. “Only a handful of investigations have looked at predictors that could help us plan. But of these, two things do stand out: a patient’s expectation of pain and a patient’s history of chronic pain.”

Surprisingly, he said, studies have determined that even a modestly elevated expectation of pain is enough to tip patients into a high-risk category. “If a patient predicted that his pain would be a 4 on a 1-10 scale, that was correlated with a lack of pain control during the operative experience. Maybe we’d expect this correlation if the expectation was an 8 or a 10, but a 4 was surprising. If a patient has even that amount of concern, I start thinking about additional interventions I can provide to maximize comfort.”

A patient’s past experience with pain is also a very large factor in how that person will experience postoperative pain. “Chronic pain does correlate with uncontrolled pain during surgery. I always ask about it. And this talk also helps drive your conversation about what you will be doing to keep them comfortable.”

That chat should include an explanation of how chronic and acute pain differ, Dr. Carroll said. “Chronic and acute pain involve different pathways and need different interventions. If the patient expresses fear, saying something like, ‘Tylenol is like water to me,’ believe him. It is like water for chronic pain. But you can also tell that patient that chronic pain is different from acute pain, and that acetaminophen will be a part of successfully managing it.”

Dr. Carroll had no financial disclosures.

Sentinel node biopsies may be useful in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

ORLANDO – Sentinel node biopsies may be a useful staging tool for patients with cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck.

These patients – especially those with compromised immune systems – appear to be at sufficiently high risk of metastasis to justify the procedure, Dr. Jonathan Lopez said at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

“We found that sentinel lymph node biopsy in our clinic had a 91% negative predictive value for local recurrence, nodal recurrence, and disease-specific death. It provides valuable prognostic information for patients at increased risk of nodal metastasis,” said Dr. Lopez, a dermatology resident at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

He and his associates conducted a chart review of 24 patients treated at the Mayo Clinic from 2000 to 2014 for a cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the head or neck. Of these, 11 patients were immunosuppressed. Five had undergone a kidney transplant and three a lung transplant. One patient had Hodgkin’s lymphoma, one had cutaneous lymphocytic leukemia, and one, metastatic urothelial carcinoma.

Before sentinel node biopsy, eight patients had a wide local excision; 12 were treated with Mohs micrographic surgery only; and four had a Mohs procedure followed by resection for better margins.

The biopsies identified two patients with nodal disease, but failed to identify a third who had it, Dr. Lopez said.

Patient No. 1 had a primary SCC on the nasal tip that was stage 2, according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system, and 2b according to the Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) system. He had undergone a prior double lung transplant and his lymph node dissection showed no nodal metastasis. He declined radiotherapy and died within 2 months of the biopsy, of unclear causes that were not related to his skin cancer.

Patient No. 2 had a primary lesion on the right cheek, and a history of kidney transplant. His cancer was stage 2 by the AJCC system and 2b by the BWH system. His lymph node dissection of the right parotid and neck was negative. At last follow-up of 3.5 years, he was cancer free. However, Dr. Lopez noted, the patient died at 4 years’ follow-up of unknown causes.

The final patient had a primary lesion on the right conchal bowl. It was a stage 2 cancer by the AJCC system and 2a by the BWH system. His sentinel node biopsy was negative. However, the otolaryngologist who performed the biopsy also took seven superficial parotid nodes and one of those was positive. This patient had no recurrence at the last visit, 1.5 years after the biopsy.

The sentinel node biopsies were negative in the 21 other patients. Of these, 14 had no evidence of recurrence at a mean of 3 years’ follow-up after the sentinel lymph node biopsy. Two developed local recurrence and two others, both of whom had a history of multiple squamous cell carcinomas, developed nodal spread and died of metastatic disease. Three have died of causes unrelated to their cancer.

Dr. Lopez had no financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – Sentinel node biopsies may be a useful staging tool for patients with cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck.

These patients – especially those with compromised immune systems – appear to be at sufficiently high risk of metastasis to justify the procedure, Dr. Jonathan Lopez said at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

“We found that sentinel lymph node biopsy in our clinic had a 91% negative predictive value for local recurrence, nodal recurrence, and disease-specific death. It provides valuable prognostic information for patients at increased risk of nodal metastasis,” said Dr. Lopez, a dermatology resident at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

He and his associates conducted a chart review of 24 patients treated at the Mayo Clinic from 2000 to 2014 for a cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the head or neck. Of these, 11 patients were immunosuppressed. Five had undergone a kidney transplant and three a lung transplant. One patient had Hodgkin’s lymphoma, one had cutaneous lymphocytic leukemia, and one, metastatic urothelial carcinoma.

Before sentinel node biopsy, eight patients had a wide local excision; 12 were treated with Mohs micrographic surgery only; and four had a Mohs procedure followed by resection for better margins.

The biopsies identified two patients with nodal disease, but failed to identify a third who had it, Dr. Lopez said.

Patient No. 1 had a primary SCC on the nasal tip that was stage 2, according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system, and 2b according to the Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) system. He had undergone a prior double lung transplant and his lymph node dissection showed no nodal metastasis. He declined radiotherapy and died within 2 months of the biopsy, of unclear causes that were not related to his skin cancer.

Patient No. 2 had a primary lesion on the right cheek, and a history of kidney transplant. His cancer was stage 2 by the AJCC system and 2b by the BWH system. His lymph node dissection of the right parotid and neck was negative. At last follow-up of 3.5 years, he was cancer free. However, Dr. Lopez noted, the patient died at 4 years’ follow-up of unknown causes.

The final patient had a primary lesion on the right conchal bowl. It was a stage 2 cancer by the AJCC system and 2a by the BWH system. His sentinel node biopsy was negative. However, the otolaryngologist who performed the biopsy also took seven superficial parotid nodes and one of those was positive. This patient had no recurrence at the last visit, 1.5 years after the biopsy.

The sentinel node biopsies were negative in the 21 other patients. Of these, 14 had no evidence of recurrence at a mean of 3 years’ follow-up after the sentinel lymph node biopsy. Two developed local recurrence and two others, both of whom had a history of multiple squamous cell carcinomas, developed nodal spread and died of metastatic disease. Three have died of causes unrelated to their cancer.

Dr. Lopez had no financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – Sentinel node biopsies may be a useful staging tool for patients with cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck.

These patients – especially those with compromised immune systems – appear to be at sufficiently high risk of metastasis to justify the procedure, Dr. Jonathan Lopez said at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

“We found that sentinel lymph node biopsy in our clinic had a 91% negative predictive value for local recurrence, nodal recurrence, and disease-specific death. It provides valuable prognostic information for patients at increased risk of nodal metastasis,” said Dr. Lopez, a dermatology resident at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

He and his associates conducted a chart review of 24 patients treated at the Mayo Clinic from 2000 to 2014 for a cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the head or neck. Of these, 11 patients were immunosuppressed. Five had undergone a kidney transplant and three a lung transplant. One patient had Hodgkin’s lymphoma, one had cutaneous lymphocytic leukemia, and one, metastatic urothelial carcinoma.

Before sentinel node biopsy, eight patients had a wide local excision; 12 were treated with Mohs micrographic surgery only; and four had a Mohs procedure followed by resection for better margins.

The biopsies identified two patients with nodal disease, but failed to identify a third who had it, Dr. Lopez said.

Patient No. 1 had a primary SCC on the nasal tip that was stage 2, according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system, and 2b according to the Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) system. He had undergone a prior double lung transplant and his lymph node dissection showed no nodal metastasis. He declined radiotherapy and died within 2 months of the biopsy, of unclear causes that were not related to his skin cancer.

Patient No. 2 had a primary lesion on the right cheek, and a history of kidney transplant. His cancer was stage 2 by the AJCC system and 2b by the BWH system. His lymph node dissection of the right parotid and neck was negative. At last follow-up of 3.5 years, he was cancer free. However, Dr. Lopez noted, the patient died at 4 years’ follow-up of unknown causes.

The final patient had a primary lesion on the right conchal bowl. It was a stage 2 cancer by the AJCC system and 2a by the BWH system. His sentinel node biopsy was negative. However, the otolaryngologist who performed the biopsy also took seven superficial parotid nodes and one of those was positive. This patient had no recurrence at the last visit, 1.5 years after the biopsy.

The sentinel node biopsies were negative in the 21 other patients. Of these, 14 had no evidence of recurrence at a mean of 3 years’ follow-up after the sentinel lymph node biopsy. Two developed local recurrence and two others, both of whom had a history of multiple squamous cell carcinomas, developed nodal spread and died of metastatic disease. Three have died of causes unrelated to their cancer.

Dr. Lopez had no financial disclosures.

AT THE ACMS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Sentinel node biopsies identified nodal spread in some patients with cutaneous SCC of the head and neck

Major finding: The procedure had a 91% negative predictive value for nodal spread and disease-specific death.

Data source: The retrospective chart review comprised of 24 patients, treated at the Mayo Clinic for cutaneous SCC of the head and neck from 2000 to 2014.

Disclosures: Dr. Lopez had no financial disclosures.

Matrilin-2 protein distinguished BCCs from benign tumors in study

ORLANDO – Matrilin-2 – a matrix protein found in peritumoral stroma – reliably distinguished invasive basal cell carcinoma from the often difficult-to-distinguish basaloid follicular hamartoma (BFH), in a study that evaluated the protein as a marker in this setting.

The protein marked 41 of 42 cancers and none of the hamartomas, Dr. Renato Goreshi reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery. The one cancer it failed to identify was a superficial basal cell tumor – a finding that makes sense, since dermal fibroblasts appear to secrete matrilin-2 as a response to invasive skin tumors, said Dr. Goreshi of the Roger Williams Cancer Center, Providence, R.I.

Mohs surgery typically employs hematoxylin and eosin staining to delineate tumor boundary. But, Dr. Goreshi said, that stain doesn’t always reliably differentiate adnexal tumors from basal cell carcinomas. “Basaloid follicular hamartoma can be particularly difficult to distinguish from basal cell carcinoma,” he said.

BFH typically presents as individual or linearly arranged, small skin-colored to brown papules or plaques, or as multiple lesions in a generalized distribution on the face, scalp, and occasionally, the trunk (Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010 Aug;134[8]:1215-9). These are often stable for many years. The differential diagnosis includes basal cell carcinoma and trichoepithelioma.

BFH sometimes occurs near a BCC, although there are no data on how often this happens.

Dr. Goreshi cited a 2007 case report of a young woman that illustrates this problem. The patient presented with a basal cell carcinoma on the side of her nose. The adjacent BFH was unrecognized, however. She underwent a multiple-stage Mohs that was unnecessarily extended because tumor margins included sections of the BFH.

“The lesion was interpreted as malignancy by both the Mohs surgeon and the dermatopathologist, but was later determined to have been a hamartoma. This highlights the importance of finding an effective marker,” Dr. Goreshi said.

He and his fellowship director, Dr. Satori Iwamoto, chief of Mohs micrographic surgery at Roger Williams, looked for a reliable way to differentiate these tumors, capitalizing on the invasive nature of BCC. The peritumoral stroma plays a role in tumor growth and invasion. It involves fibroblasts, inflammatory and endothelial cells, and extracellular matrix proteins. Matrilin-2, which is involved in the formation of filamentous networks, was a promising candidate and the initial investigations looked good, said Dr. Goreshi said.

Their confirmatory study comprised 42 BCC and seven BFH sections that were obtained during Mohs surgery. All were stained for matrilin-2 and scored for location and intensity of staining by two reviewers. The investigators also conducted flow cytometry to determine the source of the protein.

The BCC set consisted of 11 morpheaform/infiltrative BCCs, 25 nodular BCCs, and 6 superficial BCCs. With the exception of one superficial lesion, all of these stained positive for matrilin-2 in the peritumoral stroma. None of the BFH sections stained positive for the protein, however. Flow cytometry determined that the protein was coming from dermal fibroblasts in the stroma.

This is actually a key point, Dr. Goreshi noted. “Matrilin-2 is not acting as a conventional tumor marker would, but as a marker of invasion.”

This was again played out in the variation of staining intensity in the tumor subtypes. It was most intense around the infiltrative subtypes. There was also adnexal staining, but it was significantly less than what was seen in the peritumoral stroma. There was virtually no staining in or around the hamartoma.

Staining was not as intense around the superficial BCC subtypes. In fact, it was not significantly different from what was seen in the adnexal structures. Again, however, there was no staining in or around the hamartoma.

“Now we are looking at the staining patterns of other lesions, including melanoma and squamous cell carcinoma, and trying to figure out why the dermal fibroblasts are secreting matrilin-2,” Dr. Goreshi said.

The study was the winner of the 2016 Theodore Tromovitch Award, presented for original research conducted by a fellow-in-training during his or her year of training.

Neither Dr. Goreshi nor Dr. Iwamoto had any relevant financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – Matrilin-2 – a matrix protein found in peritumoral stroma – reliably distinguished invasive basal cell carcinoma from the often difficult-to-distinguish basaloid follicular hamartoma (BFH), in a study that evaluated the protein as a marker in this setting.

The protein marked 41 of 42 cancers and none of the hamartomas, Dr. Renato Goreshi reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery. The one cancer it failed to identify was a superficial basal cell tumor – a finding that makes sense, since dermal fibroblasts appear to secrete matrilin-2 as a response to invasive skin tumors, said Dr. Goreshi of the Roger Williams Cancer Center, Providence, R.I.

Mohs surgery typically employs hematoxylin and eosin staining to delineate tumor boundary. But, Dr. Goreshi said, that stain doesn’t always reliably differentiate adnexal tumors from basal cell carcinomas. “Basaloid follicular hamartoma can be particularly difficult to distinguish from basal cell carcinoma,” he said.

BFH typically presents as individual or linearly arranged, small skin-colored to brown papules or plaques, or as multiple lesions in a generalized distribution on the face, scalp, and occasionally, the trunk (Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010 Aug;134[8]:1215-9). These are often stable for many years. The differential diagnosis includes basal cell carcinoma and trichoepithelioma.

BFH sometimes occurs near a BCC, although there are no data on how often this happens.

Dr. Goreshi cited a 2007 case report of a young woman that illustrates this problem. The patient presented with a basal cell carcinoma on the side of her nose. The adjacent BFH was unrecognized, however. She underwent a multiple-stage Mohs that was unnecessarily extended because tumor margins included sections of the BFH.

“The lesion was interpreted as malignancy by both the Mohs surgeon and the dermatopathologist, but was later determined to have been a hamartoma. This highlights the importance of finding an effective marker,” Dr. Goreshi said.

He and his fellowship director, Dr. Satori Iwamoto, chief of Mohs micrographic surgery at Roger Williams, looked for a reliable way to differentiate these tumors, capitalizing on the invasive nature of BCC. The peritumoral stroma plays a role in tumor growth and invasion. It involves fibroblasts, inflammatory and endothelial cells, and extracellular matrix proteins. Matrilin-2, which is involved in the formation of filamentous networks, was a promising candidate and the initial investigations looked good, said Dr. Goreshi said.

Their confirmatory study comprised 42 BCC and seven BFH sections that were obtained during Mohs surgery. All were stained for matrilin-2 and scored for location and intensity of staining by two reviewers. The investigators also conducted flow cytometry to determine the source of the protein.

The BCC set consisted of 11 morpheaform/infiltrative BCCs, 25 nodular BCCs, and 6 superficial BCCs. With the exception of one superficial lesion, all of these stained positive for matrilin-2 in the peritumoral stroma. None of the BFH sections stained positive for the protein, however. Flow cytometry determined that the protein was coming from dermal fibroblasts in the stroma.

This is actually a key point, Dr. Goreshi noted. “Matrilin-2 is not acting as a conventional tumor marker would, but as a marker of invasion.”

This was again played out in the variation of staining intensity in the tumor subtypes. It was most intense around the infiltrative subtypes. There was also adnexal staining, but it was significantly less than what was seen in the peritumoral stroma. There was virtually no staining in or around the hamartoma.

Staining was not as intense around the superficial BCC subtypes. In fact, it was not significantly different from what was seen in the adnexal structures. Again, however, there was no staining in or around the hamartoma.

“Now we are looking at the staining patterns of other lesions, including melanoma and squamous cell carcinoma, and trying to figure out why the dermal fibroblasts are secreting matrilin-2,” Dr. Goreshi said.

The study was the winner of the 2016 Theodore Tromovitch Award, presented for original research conducted by a fellow-in-training during his or her year of training.

Neither Dr. Goreshi nor Dr. Iwamoto had any relevant financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – Matrilin-2 – a matrix protein found in peritumoral stroma – reliably distinguished invasive basal cell carcinoma from the often difficult-to-distinguish basaloid follicular hamartoma (BFH), in a study that evaluated the protein as a marker in this setting.

The protein marked 41 of 42 cancers and none of the hamartomas, Dr. Renato Goreshi reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery. The one cancer it failed to identify was a superficial basal cell tumor – a finding that makes sense, since dermal fibroblasts appear to secrete matrilin-2 as a response to invasive skin tumors, said Dr. Goreshi of the Roger Williams Cancer Center, Providence, R.I.

Mohs surgery typically employs hematoxylin and eosin staining to delineate tumor boundary. But, Dr. Goreshi said, that stain doesn’t always reliably differentiate adnexal tumors from basal cell carcinomas. “Basaloid follicular hamartoma can be particularly difficult to distinguish from basal cell carcinoma,” he said.

BFH typically presents as individual or linearly arranged, small skin-colored to brown papules or plaques, or as multiple lesions in a generalized distribution on the face, scalp, and occasionally, the trunk (Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010 Aug;134[8]:1215-9). These are often stable for many years. The differential diagnosis includes basal cell carcinoma and trichoepithelioma.

BFH sometimes occurs near a BCC, although there are no data on how often this happens.

Dr. Goreshi cited a 2007 case report of a young woman that illustrates this problem. The patient presented with a basal cell carcinoma on the side of her nose. The adjacent BFH was unrecognized, however. She underwent a multiple-stage Mohs that was unnecessarily extended because tumor margins included sections of the BFH.

“The lesion was interpreted as malignancy by both the Mohs surgeon and the dermatopathologist, but was later determined to have been a hamartoma. This highlights the importance of finding an effective marker,” Dr. Goreshi said.

He and his fellowship director, Dr. Satori Iwamoto, chief of Mohs micrographic surgery at Roger Williams, looked for a reliable way to differentiate these tumors, capitalizing on the invasive nature of BCC. The peritumoral stroma plays a role in tumor growth and invasion. It involves fibroblasts, inflammatory and endothelial cells, and extracellular matrix proteins. Matrilin-2, which is involved in the formation of filamentous networks, was a promising candidate and the initial investigations looked good, said Dr. Goreshi said.

Their confirmatory study comprised 42 BCC and seven BFH sections that were obtained during Mohs surgery. All were stained for matrilin-2 and scored for location and intensity of staining by two reviewers. The investigators also conducted flow cytometry to determine the source of the protein.

The BCC set consisted of 11 morpheaform/infiltrative BCCs, 25 nodular BCCs, and 6 superficial BCCs. With the exception of one superficial lesion, all of these stained positive for matrilin-2 in the peritumoral stroma. None of the BFH sections stained positive for the protein, however. Flow cytometry determined that the protein was coming from dermal fibroblasts in the stroma.

This is actually a key point, Dr. Goreshi noted. “Matrilin-2 is not acting as a conventional tumor marker would, but as a marker of invasion.”

This was again played out in the variation of staining intensity in the tumor subtypes. It was most intense around the infiltrative subtypes. There was also adnexal staining, but it was significantly less than what was seen in the peritumoral stroma. There was virtually no staining in or around the hamartoma.

Staining was not as intense around the superficial BCC subtypes. In fact, it was not significantly different from what was seen in the adnexal structures. Again, however, there was no staining in or around the hamartoma.

“Now we are looking at the staining patterns of other lesions, including melanoma and squamous cell carcinoma, and trying to figure out why the dermal fibroblasts are secreting matrilin-2,” Dr. Goreshi said.

The study was the winner of the 2016 Theodore Tromovitch Award, presented for original research conducted by a fellow-in-training during his or her year of training.

Neither Dr. Goreshi nor Dr. Iwamoto had any relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE ACMS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Matrilin-2 is the first marker of tumor invasion to be used in skin cancers.

Major finding: The protein bound to 41 of 42 BCCs, and to none of the hamartoma lesions studied, reliably distinguishing the two.

Data source: 42 frozen section BCCs and seven basaloid follicular hamartomas.

Disclosures: Neither Dr. Goreshi nor Dr. Iwamoto had any relevant financial disclosures.

Mohs surgeons, dermatopathologists nearly always agree on frozen section analysis

ORLANDO – Mohs fellowship–trained surgeons are highly skilled at reading frozen section slides obtained during surgery, agreeing with the dermatopathologist’s assessment more than 99% of the time, according to a review of more than 4,000 cases.

Among 4,145 slides in five datasets, only 28 were discordant. The concordance of surgeons’ and dermatopathologists’ assessments was quite consistent, ranging from 95%-of 99.7%.

“There is absolutely no detriment to our interpretation of these frozen section slides,” Dr. James Highsmith said at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery. “These numbers give credence as to why we have these good cure rates. We can say with 99% accuracy that yes, we are removing these tumors from our patients.”

Dr. Highsmith, a Mohs surgeon in Birmingham, Ala., reviewed 10 years of his own data (1,720 cases), as well as four published cohorts comprising another 2,425 cases. All of the studies examined the concordance of frozen section assessments between fellowship-trained Mohs surgeons and the dermatopathologists working with them. All of the series reported concordance, discordance, sensitivity, and specificity.