User login

Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST): Annual Scientific Meeting

Low vitamin D – poor ICU outcomes

NAPLES, FLA. – Vitamin D deficiency is common in critically ill trauma patients and portends worse outcomes, a retrospective study suggests.

Among 200 trauma patients with available vitamin D levels, 26% were vitamin D deficient on ICU admission.

"These patients have a higher APACHE II score, have a longer ICU stay, and will likely be hospitalized greater than 2 weeks," Dr. Joseph Ibrahim reported at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

Long known to be essential for bone development and wound healing, recent studies have demonstrated that vitamin D deficiency is a significant predictor of 30- and 90-day all-cause mortality in critically ill patients, even after adjustment for such factors as age, Charlson/Deyo index, sepsis, and season (Crit. Care Med. 2012;40:63-72). It also has been shown to significantly predict acute kidney injury in the critically ill (Crit. Care Med. 2012;40:3170-9).

For the current analysis, vitamin D levels were drawn upon ICU admission, at 72 hours, and every 7 days until hospital discharge in 200 of 234 consecutive adult trauma patients admitted to the ICU at the Level 1 Orlando Regional Medical Center during a 4-month period. Deficiency was defined as 25-hydroxyvitamin D of 20 ng/mL or less. All patients received nutritional support using a standard protocol, but not vitamin D supplementation.

Median vitamin D ICU admission levels in the 51 vitamin D–deficient patients were significantly lower than for nondeficient patients (16 ng/mL vs. 28 ng/mL; P less than .001). Levels decreased a median of 4 ng/mL at 72 hours in both groups, but only the sufficient group returned to admission baseline levels at week 2, reported Dr. Ibrahim, a critical care surgeon with the medical center.

"This demonstrates that if we wish to obtain normal vitamin D levels in these patients, we will have to supplement them with much higher doses than what we are providing with standard enteral formulas," he said in an interview.

Patients with vitamin D deficiency spent more time than did nondeficient patients in the ICU (median 3 days vs. 2.7 days) and hospital (median 8.4 days vs. 7.1 days), but these trends did not reach statistical significance.

Significantly more deficient patients, however, remained in the hospital for at least 2 weeks (37% vs. 20%).

The investigators were unable to show a difference in mortality between the deficient and nondeficient groups (16% vs. 12%; P = .51), possibly because the study was underpowered, he said.

Deficient and sufficient patients did not differ in age (median 48 years vs. 44 years), body mass index (26.2 kg/m2 vs. 25.7 kg/m2), admission ionized calcium (1.06 mmol/L for both), or Injury Severity Score (14 vs. 13). Only APACHE II scores were significantly higher in deficient patients (20 vs. 15).

"It makes sense that with the significant difference in APACHE II score, one would expect to see a similar difference in mortality, but again we were unable to show this with this study," Dr. Ibrahim said.

Prehospital factors significantly associated with low vitamin D status were African American race, diabetes, and lack of vitamin D supplementation.

Vitamin D supplementation may be helpful in critically ill trauma patients during hospitalization, but more research is needed, Dr. Ibrahim said. The group is planning a supplementation study, looking at vitamin D dosing and frequency of testing.

"Our first goal was to demonstrate a significant incidence, which we did," he said. "It should be noted that the incidence was in a location with probably one of the highest amounts of sunshine in the country and that the findings may underestimate what one would find in other areas of the United States."

Dr. Oscar Guillamondegui, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., who proctored the poster session, said he would expect vitamin D levels to be lower in acutely sick patients requiring ICU management because production of vitamin D–binding protein, a subprotein in the albumin family of proteins involved in vitamin D transport and storage, is decreased in high stress situations to allow for the increase in acute phase protein production.

"Although the data are intriguing, as a retrospective study, it is too early to suggest that supplementation is essential," he said.

Dr. Steven Q. Simpson, FCCP, comments: This is an interesting and provocative report associating vitamin D deficiency with worse outcome among trauma patients. As noted in the article, we have currently observed only an association, not cause and effect, so it is too soon to suggest routine measurement and/or supplementation of vitamin D in this patient population. However, given the known immunomodulating effects of vitamin D, there is biological plausibility in these findings, and I suspect that a story is about to unfold.

Dr. Ibrahim and Dr. Guillamondegui reported having no financial disclosures.

If you’re interested in more about these topics, you can join a discussion on this topic within the Critical Care e-Community. Simply log in to ecommunity.chestnet.org and find the Critical Care group. If you’re not part of the Critical Care NetWork, log in to chestnet.org and add the Critical Care NetWork to your profile.

Questions? Contact [email protected].

Dr. Steven Q. Simpson, FCCP, comments: This is an interesting and provocative report associating vitamin D deficiency with worse outcome among trauma patients. As noted in the article, we have currently observed only an association, not cause and effect, so it is too soon to suggest routine measurement and/or supplementation of vitamin D in this patient population. However, given the known immunomodulating effects of vitamin D, there is biological plausibility in these findings, and I suspect that a story is about to unfold.

Dr. Steven Q. Simpson, FCCP, comments: This is an interesting and provocative report associating vitamin D deficiency with worse outcome among trauma patients. As noted in the article, we have currently observed only an association, not cause and effect, so it is too soon to suggest routine measurement and/or supplementation of vitamin D in this patient population. However, given the known immunomodulating effects of vitamin D, there is biological plausibility in these findings, and I suspect that a story is about to unfold.

Dr. Steven Q. Simpson, FCCP, comments: This is an interesting and provocative report associating vitamin D deficiency with worse outcome among trauma patients. As noted in the article, we have currently observed only an association, not cause and effect, so it is too soon to suggest routine measurement and/or supplementation of vitamin D in this patient population. However, given the known immunomodulating effects of vitamin D, there is biological plausibility in these findings, and I suspect that a story is about to unfold.

NAPLES, FLA. – Vitamin D deficiency is common in critically ill trauma patients and portends worse outcomes, a retrospective study suggests.

Among 200 trauma patients with available vitamin D levels, 26% were vitamin D deficient on ICU admission.

"These patients have a higher APACHE II score, have a longer ICU stay, and will likely be hospitalized greater than 2 weeks," Dr. Joseph Ibrahim reported at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

Long known to be essential for bone development and wound healing, recent studies have demonstrated that vitamin D deficiency is a significant predictor of 30- and 90-day all-cause mortality in critically ill patients, even after adjustment for such factors as age, Charlson/Deyo index, sepsis, and season (Crit. Care Med. 2012;40:63-72). It also has been shown to significantly predict acute kidney injury in the critically ill (Crit. Care Med. 2012;40:3170-9).

For the current analysis, vitamin D levels were drawn upon ICU admission, at 72 hours, and every 7 days until hospital discharge in 200 of 234 consecutive adult trauma patients admitted to the ICU at the Level 1 Orlando Regional Medical Center during a 4-month period. Deficiency was defined as 25-hydroxyvitamin D of 20 ng/mL or less. All patients received nutritional support using a standard protocol, but not vitamin D supplementation.

Median vitamin D ICU admission levels in the 51 vitamin D–deficient patients were significantly lower than for nondeficient patients (16 ng/mL vs. 28 ng/mL; P less than .001). Levels decreased a median of 4 ng/mL at 72 hours in both groups, but only the sufficient group returned to admission baseline levels at week 2, reported Dr. Ibrahim, a critical care surgeon with the medical center.

"This demonstrates that if we wish to obtain normal vitamin D levels in these patients, we will have to supplement them with much higher doses than what we are providing with standard enteral formulas," he said in an interview.

Patients with vitamin D deficiency spent more time than did nondeficient patients in the ICU (median 3 days vs. 2.7 days) and hospital (median 8.4 days vs. 7.1 days), but these trends did not reach statistical significance.

Significantly more deficient patients, however, remained in the hospital for at least 2 weeks (37% vs. 20%).

The investigators were unable to show a difference in mortality between the deficient and nondeficient groups (16% vs. 12%; P = .51), possibly because the study was underpowered, he said.

Deficient and sufficient patients did not differ in age (median 48 years vs. 44 years), body mass index (26.2 kg/m2 vs. 25.7 kg/m2), admission ionized calcium (1.06 mmol/L for both), or Injury Severity Score (14 vs. 13). Only APACHE II scores were significantly higher in deficient patients (20 vs. 15).

"It makes sense that with the significant difference in APACHE II score, one would expect to see a similar difference in mortality, but again we were unable to show this with this study," Dr. Ibrahim said.

Prehospital factors significantly associated with low vitamin D status were African American race, diabetes, and lack of vitamin D supplementation.

Vitamin D supplementation may be helpful in critically ill trauma patients during hospitalization, but more research is needed, Dr. Ibrahim said. The group is planning a supplementation study, looking at vitamin D dosing and frequency of testing.

"Our first goal was to demonstrate a significant incidence, which we did," he said. "It should be noted that the incidence was in a location with probably one of the highest amounts of sunshine in the country and that the findings may underestimate what one would find in other areas of the United States."

Dr. Oscar Guillamondegui, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., who proctored the poster session, said he would expect vitamin D levels to be lower in acutely sick patients requiring ICU management because production of vitamin D–binding protein, a subprotein in the albumin family of proteins involved in vitamin D transport and storage, is decreased in high stress situations to allow for the increase in acute phase protein production.

"Although the data are intriguing, as a retrospective study, it is too early to suggest that supplementation is essential," he said.

Dr. Steven Q. Simpson, FCCP, comments: This is an interesting and provocative report associating vitamin D deficiency with worse outcome among trauma patients. As noted in the article, we have currently observed only an association, not cause and effect, so it is too soon to suggest routine measurement and/or supplementation of vitamin D in this patient population. However, given the known immunomodulating effects of vitamin D, there is biological plausibility in these findings, and I suspect that a story is about to unfold.

Dr. Ibrahim and Dr. Guillamondegui reported having no financial disclosures.

If you’re interested in more about these topics, you can join a discussion on this topic within the Critical Care e-Community. Simply log in to ecommunity.chestnet.org and find the Critical Care group. If you’re not part of the Critical Care NetWork, log in to chestnet.org and add the Critical Care NetWork to your profile.

Questions? Contact [email protected].

NAPLES, FLA. – Vitamin D deficiency is common in critically ill trauma patients and portends worse outcomes, a retrospective study suggests.

Among 200 trauma patients with available vitamin D levels, 26% were vitamin D deficient on ICU admission.

"These patients have a higher APACHE II score, have a longer ICU stay, and will likely be hospitalized greater than 2 weeks," Dr. Joseph Ibrahim reported at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

Long known to be essential for bone development and wound healing, recent studies have demonstrated that vitamin D deficiency is a significant predictor of 30- and 90-day all-cause mortality in critically ill patients, even after adjustment for such factors as age, Charlson/Deyo index, sepsis, and season (Crit. Care Med. 2012;40:63-72). It also has been shown to significantly predict acute kidney injury in the critically ill (Crit. Care Med. 2012;40:3170-9).

For the current analysis, vitamin D levels were drawn upon ICU admission, at 72 hours, and every 7 days until hospital discharge in 200 of 234 consecutive adult trauma patients admitted to the ICU at the Level 1 Orlando Regional Medical Center during a 4-month period. Deficiency was defined as 25-hydroxyvitamin D of 20 ng/mL or less. All patients received nutritional support using a standard protocol, but not vitamin D supplementation.

Median vitamin D ICU admission levels in the 51 vitamin D–deficient patients were significantly lower than for nondeficient patients (16 ng/mL vs. 28 ng/mL; P less than .001). Levels decreased a median of 4 ng/mL at 72 hours in both groups, but only the sufficient group returned to admission baseline levels at week 2, reported Dr. Ibrahim, a critical care surgeon with the medical center.

"This demonstrates that if we wish to obtain normal vitamin D levels in these patients, we will have to supplement them with much higher doses than what we are providing with standard enteral formulas," he said in an interview.

Patients with vitamin D deficiency spent more time than did nondeficient patients in the ICU (median 3 days vs. 2.7 days) and hospital (median 8.4 days vs. 7.1 days), but these trends did not reach statistical significance.

Significantly more deficient patients, however, remained in the hospital for at least 2 weeks (37% vs. 20%).

The investigators were unable to show a difference in mortality between the deficient and nondeficient groups (16% vs. 12%; P = .51), possibly because the study was underpowered, he said.

Deficient and sufficient patients did not differ in age (median 48 years vs. 44 years), body mass index (26.2 kg/m2 vs. 25.7 kg/m2), admission ionized calcium (1.06 mmol/L for both), or Injury Severity Score (14 vs. 13). Only APACHE II scores were significantly higher in deficient patients (20 vs. 15).

"It makes sense that with the significant difference in APACHE II score, one would expect to see a similar difference in mortality, but again we were unable to show this with this study," Dr. Ibrahim said.

Prehospital factors significantly associated with low vitamin D status were African American race, diabetes, and lack of vitamin D supplementation.

Vitamin D supplementation may be helpful in critically ill trauma patients during hospitalization, but more research is needed, Dr. Ibrahim said. The group is planning a supplementation study, looking at vitamin D dosing and frequency of testing.

"Our first goal was to demonstrate a significant incidence, which we did," he said. "It should be noted that the incidence was in a location with probably one of the highest amounts of sunshine in the country and that the findings may underestimate what one would find in other areas of the United States."

Dr. Oscar Guillamondegui, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., who proctored the poster session, said he would expect vitamin D levels to be lower in acutely sick patients requiring ICU management because production of vitamin D–binding protein, a subprotein in the albumin family of proteins involved in vitamin D transport and storage, is decreased in high stress situations to allow for the increase in acute phase protein production.

"Although the data are intriguing, as a retrospective study, it is too early to suggest that supplementation is essential," he said.

Dr. Steven Q. Simpson, FCCP, comments: This is an interesting and provocative report associating vitamin D deficiency with worse outcome among trauma patients. As noted in the article, we have currently observed only an association, not cause and effect, so it is too soon to suggest routine measurement and/or supplementation of vitamin D in this patient population. However, given the known immunomodulating effects of vitamin D, there is biological plausibility in these findings, and I suspect that a story is about to unfold.

Dr. Ibrahim and Dr. Guillamondegui reported having no financial disclosures.

If you’re interested in more about these topics, you can join a discussion on this topic within the Critical Care e-Community. Simply log in to ecommunity.chestnet.org and find the Critical Care group. If you’re not part of the Critical Care NetWork, log in to chestnet.org and add the Critical Care NetWork to your profile.

Questions? Contact [email protected].

Major finding: In all, 26% of patients were vitamin D deficient on ICU admission.

Data source: A retrospective study of 200 ICU trauma patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Ibrahim and Dr. Guillamondegui reported having no financial disclosures.

New takeaways from the Boston Marathon bombings

NAPLES, FLA. – Without a single life lost at area hospitals, the medical response to the Boston Marathon bombings was by all accounts remarkable. But what if police and other first-responders had tourniquets and were trained in their use?

As it was, advanced topical hemostatic agents and tourniquets were MIA in the field, forcing all but one prehospital tourniquet to be improvised, according to Massachusetts General Hospital trauma surgeon Lt. Col. David King, U. S. Army Reserve.

"It’s abundantly clear from the literature that improvised tourniquets almost never work," he said. "The fact that every soldier down range has one in his pocket and we couldn’t muster up more than one in the city of Boston is a shame and we need to rectify that."

In all, there were 66 limb injuries, with 29 patients having recognized limb exsanguination at the scene. Of the 27 tourniquets applied, 26 were improvised.

Failure to translate this important lesson from military experience meant that these homemade devices were most likely wildly ineffective and, in some cases, may have even exacerbated blood loss, he said. Surprisingly, there’s no formal protocol for tourniquet application or training paradigm in Massachusetts, such that exists in the Army’s prehospital Tactical Combat Casualty Care handbook.

"If you look across the paramedic medical guidelines, there is no protocol on the right, evidence-based way to put on a tourniquet or what the indications are for a tourniquet," Dr. King said at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST). "We don’t have it, and we need to" have it nationwide.

EAST is hoping to provide some guidance in this area with the development of practice management guidelines (PMG) for tourniquet use in extremity trauma. Dr. King, who heads this PMG committee, reported at the meeting that the guidelines, due out later this year, will emphasize that commercially made tourniquets should be available in the prehospital setting, improvised tourniquets rarely work and cannot be recommended; essentially all commercially made tourniquets are equieffective; and that nonmedical personnel can be trained to correctly apply a proper tourniquet.

The need for bleeding control equipment and training for the public has not gone unnoticed by other stakeholders and is the central focus of the newest statement from the Hartford Consensus, a collaborative group of trauma surgeons, law enforcement officers, and emergency responders led by the American College of Surgeons (J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2014;218:467-75).

In dissecting the medical response to the Boston bombings, much has been made of the fact that Boston is home to six Level 1 trauma centers, and that it was race day, a city holiday, 3 p.m., and low-yield devices were used. Dr. King, however, gave high praise to an unsung hero, the Boston EMS loading officer who managed most of the transport destination decisions and smartly distributed critical cases throughout the area’s hospitals.

All critical patients were evacuated within 1 hour, but some have argued this could have been accomplished more quickly were it not for a "stay-and-play" mentality in the medical tent. The after-action review suggests there probably were enough ambulances to do the job in 30 minutes, said Dr. King, who remarked that the only thing that matters in critical trauma cases is time to surgical hemorrhage control.

"This will remain a controversial issue for Boston, whether staying and playing in the medical tent was a good idea," he said. "I don’t know what the right answer is."

Credit was also given to Massachusetts General, and many of the other city hospitals, for their insistence on regular full-scale drills that allowed quick lock-down of the facility to control access and manage the surge capacity in the emergency department.

"It’s more than just a tabletop exercise," Dr. King said. "When we test the surge capacity, we actually empty the emergency room for real. Usually, it occurs between 5:00 and 7:00 or 4:30 and 7:30 in the morning, but actually doing these things was useful, because when it came time to do it for real, no one was tripping over their own feet."

ED volume on that April afternoon was reduced from 97 patients to just 39 within 1.5 hours. Nontrauma physicians, including psychiatrists, did their part by writing "barebones orders" to get patients transferred to the wards.

Staff at Massachusetts General treated 43 patients, performing nine emergent operations, six amputations, two laparotomies, and one thoracotomy, with two traumatic arrests within the first 72 hours. As with other Boston hospitals, there were no in-hospital deaths, he said.

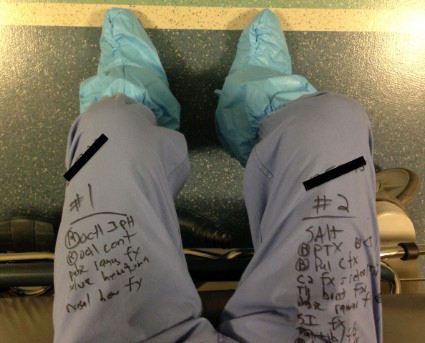

Patients arrived in such rapid succession, however, that it slowed the electronic medical record system and forced staff to use sequential record numbers, which can be dangerous. Registration couldn’t keep up and orders couldn’t be put in fast enough with 43 patients arriving in roughly 35 minutes, Dr. King explained. Workarounds were often old-school, and reminiscent of his days as a green trauma surgeon serving at Ibn Sina Hospital, Baghdad, Iraq.

"In the midst of this entire event, I turned to my nurse practitioner and asked for x, y, z information on a particular patient," he said. "She didn’t turn to her tablet or desktop computer in the operating room. She pulled out a piece of paper where she’d written all the relevant information. At the end of the event, I looked down and realized I’d done the same thing. I was keeping track of my patients on my pants with a Sharpie."

King describes this as a failure of technology and translation from the battlefield, but noted that the hospital did use the military’s practice of reviewing a critical event. Once they’d finished in the operating room and achieved hemorrhage and contamination control, the entire trauma team was reassembled. They did detailed tertiary trauma surveys and went back through every single patient to determine what additional studies they needed, what injuries had been missed.

"It was remarkable the number of things that were missed," Dr. King said. "No one was bleeding to death, but tons and tons of [small, non–life threatening] missed injuries [like ruptured ear drums], and to me this was one of the more important events that surrounded our response to the entire bombing – sitting down after the dust had settled and carefully going over every patient’s medical record."

Dr. King reported having no financial disclosures.

Lt. Col. King makes some excellent points. However, despite Dr. King's combat medicine experience, his contribution to this article reveals a gap that still exists between field medicine and hospital medicine.

The case against improvised tourniquets

There is no consensus on the definition of an "improvised" tourniquet. Homemade applications such as neckties and sticks are defined as improvised, but the Boston EMS kits (surgical tubing and Kelly clamps) also could be considered improvised. All of these methods may sound primitive since the advent of Combat-Application Tourniquets; however CATS are relatively new to the scene. Should we consider every tourniquet applied prior to their introduction to have been improvised? For the price of one CAT, we can assemble 10 tourniquet kits. And if Dr. King's initial contention was that tourniquets were in short supply, then it is a better system to deploy as many as possible. This point may be moot, however, because since the Boston bombing incident, federal grant money has allowed the purchase of CAT units in great numbers within the Metro-Boston area.

Tourniquet efficacy

"It is abundantly clear from the literature that improvised tourniquets almost never work." I feel this study had the wrong focus. Rather than ask which tourniquets have a better success rate, the study should have asked whose tourniquets have a better success rate.

Study after study has shown that successful intubation rates have little to do with the level of training of the practitioner, and everything to do with the frequency of intubation. More tubes equal more successful passes. I propose that this applies to tourniquet application as well. Field personnel who do not practice or have the opportunity to apply tourniquets frequently (which is the great majority of us) may not be applying tourniquets properly. This is why we instituted a massive tourniquet training and review program almost immediately following the 2013 bombing at the Boston Marathon.

Another point not addressed in studies is the effectiveness of nonresponder tourniquets. I would contend that an experienced practitioner with a necktie and a stick would be more successful in hemorrhage control that a civilian with a CAT, but those data have not been explored yet either.

The Loading Officer as unsung hero

All our Action Area Officers performed brilliantly (full disclosure, I was the Loading Officer). However the term Loading Officer is a misnomer. Yes, there is a Loading Officer, but there is actually a Loading Team. It consists of staff at the scene who liaise with the treatment areas and the true unsung heroes, the staff in the Operations Division or Dispatch Center. Dispatchers are in constant contact with the hospitals, scene operations, as well as continuing city service. They perform the hospital destination designations because they have a global sense of traffic, while at the scene we have only a worm's-eye view.

The stay-and-play critique

"All critical patients were evacuated within 1 hour, but some argued this could have been accomplished more quickly were it not for a 'stay-and-play' mentality." I take exception to this assertion. First, the point is contradictory. All critical patients were evacuated within 1 hour, but there was a stay-and-play mentality? Every EMT and paramedic knows that transport times translate into positive results with trauma.

Emergency personnel are taught that what matters most in trauma survival is not basic life support, advance life support, or wheelbarrow, but getting them to the ED fast. Yes, there were slowdowns in the medical tents, but most of delays came from non-EMS personnel who were not well versed in field medicine. We questioned, pleaded, and ultimately ordered some practitioners away from patients as they were attempting to perform procedures that we would never attempt on a trauma patient in the field. This is by no means a condemnation on my part. The staff we worked with was exceptional, and I witnessed true skill, heroism, and compassion. But it also demonstrated to me that a disconnect exists between field medicine and hospital medicine.

I see an opportunity here for training to better acclimate responders to working together with our hospital counterparts. We also need hospital personnel to be oriented to realities and limitations of field medicine.

Lt. Brian Pomodoro is a member of the Boston EMS.

Lt. Col. King makes some excellent points. However, despite Dr. King's combat medicine experience, his contribution to this article reveals a gap that still exists between field medicine and hospital medicine.

The case against improvised tourniquets

There is no consensus on the definition of an "improvised" tourniquet. Homemade applications such as neckties and sticks are defined as improvised, but the Boston EMS kits (surgical tubing and Kelly clamps) also could be considered improvised. All of these methods may sound primitive since the advent of Combat-Application Tourniquets; however CATS are relatively new to the scene. Should we consider every tourniquet applied prior to their introduction to have been improvised? For the price of one CAT, we can assemble 10 tourniquet kits. And if Dr. King's initial contention was that tourniquets were in short supply, then it is a better system to deploy as many as possible. This point may be moot, however, because since the Boston bombing incident, federal grant money has allowed the purchase of CAT units in great numbers within the Metro-Boston area.

Tourniquet efficacy

"It is abundantly clear from the literature that improvised tourniquets almost never work." I feel this study had the wrong focus. Rather than ask which tourniquets have a better success rate, the study should have asked whose tourniquets have a better success rate.

Study after study has shown that successful intubation rates have little to do with the level of training of the practitioner, and everything to do with the frequency of intubation. More tubes equal more successful passes. I propose that this applies to tourniquet application as well. Field personnel who do not practice or have the opportunity to apply tourniquets frequently (which is the great majority of us) may not be applying tourniquets properly. This is why we instituted a massive tourniquet training and review program almost immediately following the 2013 bombing at the Boston Marathon.

Another point not addressed in studies is the effectiveness of nonresponder tourniquets. I would contend that an experienced practitioner with a necktie and a stick would be more successful in hemorrhage control that a civilian with a CAT, but those data have not been explored yet either.

The Loading Officer as unsung hero

All our Action Area Officers performed brilliantly (full disclosure, I was the Loading Officer). However the term Loading Officer is a misnomer. Yes, there is a Loading Officer, but there is actually a Loading Team. It consists of staff at the scene who liaise with the treatment areas and the true unsung heroes, the staff in the Operations Division or Dispatch Center. Dispatchers are in constant contact with the hospitals, scene operations, as well as continuing city service. They perform the hospital destination designations because they have a global sense of traffic, while at the scene we have only a worm's-eye view.

The stay-and-play critique

"All critical patients were evacuated within 1 hour, but some argued this could have been accomplished more quickly were it not for a 'stay-and-play' mentality." I take exception to this assertion. First, the point is contradictory. All critical patients were evacuated within 1 hour, but there was a stay-and-play mentality? Every EMT and paramedic knows that transport times translate into positive results with trauma.

Emergency personnel are taught that what matters most in trauma survival is not basic life support, advance life support, or wheelbarrow, but getting them to the ED fast. Yes, there were slowdowns in the medical tents, but most of delays came from non-EMS personnel who were not well versed in field medicine. We questioned, pleaded, and ultimately ordered some practitioners away from patients as they were attempting to perform procedures that we would never attempt on a trauma patient in the field. This is by no means a condemnation on my part. The staff we worked with was exceptional, and I witnessed true skill, heroism, and compassion. But it also demonstrated to me that a disconnect exists between field medicine and hospital medicine.

I see an opportunity here for training to better acclimate responders to working together with our hospital counterparts. We also need hospital personnel to be oriented to realities and limitations of field medicine.

Lt. Brian Pomodoro is a member of the Boston EMS.

Lt. Col. King makes some excellent points. However, despite Dr. King's combat medicine experience, his contribution to this article reveals a gap that still exists between field medicine and hospital medicine.

The case against improvised tourniquets

There is no consensus on the definition of an "improvised" tourniquet. Homemade applications such as neckties and sticks are defined as improvised, but the Boston EMS kits (surgical tubing and Kelly clamps) also could be considered improvised. All of these methods may sound primitive since the advent of Combat-Application Tourniquets; however CATS are relatively new to the scene. Should we consider every tourniquet applied prior to their introduction to have been improvised? For the price of one CAT, we can assemble 10 tourniquet kits. And if Dr. King's initial contention was that tourniquets were in short supply, then it is a better system to deploy as many as possible. This point may be moot, however, because since the Boston bombing incident, federal grant money has allowed the purchase of CAT units in great numbers within the Metro-Boston area.

Tourniquet efficacy

"It is abundantly clear from the literature that improvised tourniquets almost never work." I feel this study had the wrong focus. Rather than ask which tourniquets have a better success rate, the study should have asked whose tourniquets have a better success rate.

Study after study has shown that successful intubation rates have little to do with the level of training of the practitioner, and everything to do with the frequency of intubation. More tubes equal more successful passes. I propose that this applies to tourniquet application as well. Field personnel who do not practice or have the opportunity to apply tourniquets frequently (which is the great majority of us) may not be applying tourniquets properly. This is why we instituted a massive tourniquet training and review program almost immediately following the 2013 bombing at the Boston Marathon.

Another point not addressed in studies is the effectiveness of nonresponder tourniquets. I would contend that an experienced practitioner with a necktie and a stick would be more successful in hemorrhage control that a civilian with a CAT, but those data have not been explored yet either.

The Loading Officer as unsung hero

All our Action Area Officers performed brilliantly (full disclosure, I was the Loading Officer). However the term Loading Officer is a misnomer. Yes, there is a Loading Officer, but there is actually a Loading Team. It consists of staff at the scene who liaise with the treatment areas and the true unsung heroes, the staff in the Operations Division or Dispatch Center. Dispatchers are in constant contact with the hospitals, scene operations, as well as continuing city service. They perform the hospital destination designations because they have a global sense of traffic, while at the scene we have only a worm's-eye view.

The stay-and-play critique

"All critical patients were evacuated within 1 hour, but some argued this could have been accomplished more quickly were it not for a 'stay-and-play' mentality." I take exception to this assertion. First, the point is contradictory. All critical patients were evacuated within 1 hour, but there was a stay-and-play mentality? Every EMT and paramedic knows that transport times translate into positive results with trauma.

Emergency personnel are taught that what matters most in trauma survival is not basic life support, advance life support, or wheelbarrow, but getting them to the ED fast. Yes, there were slowdowns in the medical tents, but most of delays came from non-EMS personnel who were not well versed in field medicine. We questioned, pleaded, and ultimately ordered some practitioners away from patients as they were attempting to perform procedures that we would never attempt on a trauma patient in the field. This is by no means a condemnation on my part. The staff we worked with was exceptional, and I witnessed true skill, heroism, and compassion. But it also demonstrated to me that a disconnect exists between field medicine and hospital medicine.

I see an opportunity here for training to better acclimate responders to working together with our hospital counterparts. We also need hospital personnel to be oriented to realities and limitations of field medicine.

Lt. Brian Pomodoro is a member of the Boston EMS.

NAPLES, FLA. – Without a single life lost at area hospitals, the medical response to the Boston Marathon bombings was by all accounts remarkable. But what if police and other first-responders had tourniquets and were trained in their use?

As it was, advanced topical hemostatic agents and tourniquets were MIA in the field, forcing all but one prehospital tourniquet to be improvised, according to Massachusetts General Hospital trauma surgeon Lt. Col. David King, U. S. Army Reserve.

"It’s abundantly clear from the literature that improvised tourniquets almost never work," he said. "The fact that every soldier down range has one in his pocket and we couldn’t muster up more than one in the city of Boston is a shame and we need to rectify that."

In all, there were 66 limb injuries, with 29 patients having recognized limb exsanguination at the scene. Of the 27 tourniquets applied, 26 were improvised.

Failure to translate this important lesson from military experience meant that these homemade devices were most likely wildly ineffective and, in some cases, may have even exacerbated blood loss, he said. Surprisingly, there’s no formal protocol for tourniquet application or training paradigm in Massachusetts, such that exists in the Army’s prehospital Tactical Combat Casualty Care handbook.

"If you look across the paramedic medical guidelines, there is no protocol on the right, evidence-based way to put on a tourniquet or what the indications are for a tourniquet," Dr. King said at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST). "We don’t have it, and we need to" have it nationwide.

EAST is hoping to provide some guidance in this area with the development of practice management guidelines (PMG) for tourniquet use in extremity trauma. Dr. King, who heads this PMG committee, reported at the meeting that the guidelines, due out later this year, will emphasize that commercially made tourniquets should be available in the prehospital setting, improvised tourniquets rarely work and cannot be recommended; essentially all commercially made tourniquets are equieffective; and that nonmedical personnel can be trained to correctly apply a proper tourniquet.

The need for bleeding control equipment and training for the public has not gone unnoticed by other stakeholders and is the central focus of the newest statement from the Hartford Consensus, a collaborative group of trauma surgeons, law enforcement officers, and emergency responders led by the American College of Surgeons (J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2014;218:467-75).

In dissecting the medical response to the Boston bombings, much has been made of the fact that Boston is home to six Level 1 trauma centers, and that it was race day, a city holiday, 3 p.m., and low-yield devices were used. Dr. King, however, gave high praise to an unsung hero, the Boston EMS loading officer who managed most of the transport destination decisions and smartly distributed critical cases throughout the area’s hospitals.

All critical patients were evacuated within 1 hour, but some have argued this could have been accomplished more quickly were it not for a "stay-and-play" mentality in the medical tent. The after-action review suggests there probably were enough ambulances to do the job in 30 minutes, said Dr. King, who remarked that the only thing that matters in critical trauma cases is time to surgical hemorrhage control.

"This will remain a controversial issue for Boston, whether staying and playing in the medical tent was a good idea," he said. "I don’t know what the right answer is."

Credit was also given to Massachusetts General, and many of the other city hospitals, for their insistence on regular full-scale drills that allowed quick lock-down of the facility to control access and manage the surge capacity in the emergency department.

"It’s more than just a tabletop exercise," Dr. King said. "When we test the surge capacity, we actually empty the emergency room for real. Usually, it occurs between 5:00 and 7:00 or 4:30 and 7:30 in the morning, but actually doing these things was useful, because when it came time to do it for real, no one was tripping over their own feet."

ED volume on that April afternoon was reduced from 97 patients to just 39 within 1.5 hours. Nontrauma physicians, including psychiatrists, did their part by writing "barebones orders" to get patients transferred to the wards.

Staff at Massachusetts General treated 43 patients, performing nine emergent operations, six amputations, two laparotomies, and one thoracotomy, with two traumatic arrests within the first 72 hours. As with other Boston hospitals, there were no in-hospital deaths, he said.

Patients arrived in such rapid succession, however, that it slowed the electronic medical record system and forced staff to use sequential record numbers, which can be dangerous. Registration couldn’t keep up and orders couldn’t be put in fast enough with 43 patients arriving in roughly 35 minutes, Dr. King explained. Workarounds were often old-school, and reminiscent of his days as a green trauma surgeon serving at Ibn Sina Hospital, Baghdad, Iraq.

"In the midst of this entire event, I turned to my nurse practitioner and asked for x, y, z information on a particular patient," he said. "She didn’t turn to her tablet or desktop computer in the operating room. She pulled out a piece of paper where she’d written all the relevant information. At the end of the event, I looked down and realized I’d done the same thing. I was keeping track of my patients on my pants with a Sharpie."

King describes this as a failure of technology and translation from the battlefield, but noted that the hospital did use the military’s practice of reviewing a critical event. Once they’d finished in the operating room and achieved hemorrhage and contamination control, the entire trauma team was reassembled. They did detailed tertiary trauma surveys and went back through every single patient to determine what additional studies they needed, what injuries had been missed.

"It was remarkable the number of things that were missed," Dr. King said. "No one was bleeding to death, but tons and tons of [small, non–life threatening] missed injuries [like ruptured ear drums], and to me this was one of the more important events that surrounded our response to the entire bombing – sitting down after the dust had settled and carefully going over every patient’s medical record."

Dr. King reported having no financial disclosures.

NAPLES, FLA. – Without a single life lost at area hospitals, the medical response to the Boston Marathon bombings was by all accounts remarkable. But what if police and other first-responders had tourniquets and were trained in their use?

As it was, advanced topical hemostatic agents and tourniquets were MIA in the field, forcing all but one prehospital tourniquet to be improvised, according to Massachusetts General Hospital trauma surgeon Lt. Col. David King, U. S. Army Reserve.

"It’s abundantly clear from the literature that improvised tourniquets almost never work," he said. "The fact that every soldier down range has one in his pocket and we couldn’t muster up more than one in the city of Boston is a shame and we need to rectify that."

In all, there were 66 limb injuries, with 29 patients having recognized limb exsanguination at the scene. Of the 27 tourniquets applied, 26 were improvised.

Failure to translate this important lesson from military experience meant that these homemade devices were most likely wildly ineffective and, in some cases, may have even exacerbated blood loss, he said. Surprisingly, there’s no formal protocol for tourniquet application or training paradigm in Massachusetts, such that exists in the Army’s prehospital Tactical Combat Casualty Care handbook.

"If you look across the paramedic medical guidelines, there is no protocol on the right, evidence-based way to put on a tourniquet or what the indications are for a tourniquet," Dr. King said at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST). "We don’t have it, and we need to" have it nationwide.

EAST is hoping to provide some guidance in this area with the development of practice management guidelines (PMG) for tourniquet use in extremity trauma. Dr. King, who heads this PMG committee, reported at the meeting that the guidelines, due out later this year, will emphasize that commercially made tourniquets should be available in the prehospital setting, improvised tourniquets rarely work and cannot be recommended; essentially all commercially made tourniquets are equieffective; and that nonmedical personnel can be trained to correctly apply a proper tourniquet.

The need for bleeding control equipment and training for the public has not gone unnoticed by other stakeholders and is the central focus of the newest statement from the Hartford Consensus, a collaborative group of trauma surgeons, law enforcement officers, and emergency responders led by the American College of Surgeons (J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2014;218:467-75).

In dissecting the medical response to the Boston bombings, much has been made of the fact that Boston is home to six Level 1 trauma centers, and that it was race day, a city holiday, 3 p.m., and low-yield devices were used. Dr. King, however, gave high praise to an unsung hero, the Boston EMS loading officer who managed most of the transport destination decisions and smartly distributed critical cases throughout the area’s hospitals.

All critical patients were evacuated within 1 hour, but some have argued this could have been accomplished more quickly were it not for a "stay-and-play" mentality in the medical tent. The after-action review suggests there probably were enough ambulances to do the job in 30 minutes, said Dr. King, who remarked that the only thing that matters in critical trauma cases is time to surgical hemorrhage control.

"This will remain a controversial issue for Boston, whether staying and playing in the medical tent was a good idea," he said. "I don’t know what the right answer is."

Credit was also given to Massachusetts General, and many of the other city hospitals, for their insistence on regular full-scale drills that allowed quick lock-down of the facility to control access and manage the surge capacity in the emergency department.

"It’s more than just a tabletop exercise," Dr. King said. "When we test the surge capacity, we actually empty the emergency room for real. Usually, it occurs between 5:00 and 7:00 or 4:30 and 7:30 in the morning, but actually doing these things was useful, because when it came time to do it for real, no one was tripping over their own feet."

ED volume on that April afternoon was reduced from 97 patients to just 39 within 1.5 hours. Nontrauma physicians, including psychiatrists, did their part by writing "barebones orders" to get patients transferred to the wards.

Staff at Massachusetts General treated 43 patients, performing nine emergent operations, six amputations, two laparotomies, and one thoracotomy, with two traumatic arrests within the first 72 hours. As with other Boston hospitals, there were no in-hospital deaths, he said.

Patients arrived in such rapid succession, however, that it slowed the electronic medical record system and forced staff to use sequential record numbers, which can be dangerous. Registration couldn’t keep up and orders couldn’t be put in fast enough with 43 patients arriving in roughly 35 minutes, Dr. King explained. Workarounds were often old-school, and reminiscent of his days as a green trauma surgeon serving at Ibn Sina Hospital, Baghdad, Iraq.

"In the midst of this entire event, I turned to my nurse practitioner and asked for x, y, z information on a particular patient," he said. "She didn’t turn to her tablet or desktop computer in the operating room. She pulled out a piece of paper where she’d written all the relevant information. At the end of the event, I looked down and realized I’d done the same thing. I was keeping track of my patients on my pants with a Sharpie."

King describes this as a failure of technology and translation from the battlefield, but noted that the hospital did use the military’s practice of reviewing a critical event. Once they’d finished in the operating room and achieved hemorrhage and contamination control, the entire trauma team was reassembled. They did detailed tertiary trauma surveys and went back through every single patient to determine what additional studies they needed, what injuries had been missed.

"It was remarkable the number of things that were missed," Dr. King said. "No one was bleeding to death, but tons and tons of [small, non–life threatening] missed injuries [like ruptured ear drums], and to me this was one of the more important events that surrounded our response to the entire bombing – sitting down after the dust had settled and carefully going over every patient’s medical record."

Dr. King reported having no financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM EAST SCIENTIFIC ASSEMBLY 2014

Sizzle magnets: a worrisome buzz in the emergency department

NAPLES, FLA. – They sizzle, they buzz, they vibrate. And they’re sending some children to the emergency department.

"One of the newest things we’re seeing a fair amount of are magnets, those sizzle magnets," reported Karen Macauley, DHA, R.N., trauma program director, All Children’s Hospital, St. Petersburg, Fla., and secretary of the Society of Trauma Nurses.

So-called "sizzle" magnets make a sound when they connect and are being sold as novelty toys, jewelry, and even for purported health benefits. One website specializing in gifts for the visually impaired notes that the magnetic field of these hematite magnets is "so strong," they’ll stay put if placed on the front and back of hands or ear lobes.

That strong magnetic force, however, can create havoc if children ingest magnets of any kind, Dr. Macauley said at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

"If the magnets stay in a string, they’re probably okay; but if they swallow one and wait a little while and swallow another, you can start to imagine what happens as it starts to pass through," she said. "One magnet stays, another comes in another part of the bowel, and they sizzle together. Now all of a sudden you have magnets that aren’t moving and cause a lot of necrosis. They’re actually very dangerous, and we don’t think too much about how dangerous they can be."

Between 2009 and 2011, an estimated 1,700 emergency department visits occurred because of magnet ingestion, with more than 70% of those cases involving children between age 4 and 12 years, according to researchers at the U.S. Public Interest Research Group, which highlighted magnets in its most recent annual toy safety survey.

Dr. Macauley also cautioned that button-size batteries, now in everything from remote controls to Grandma’s singing greeting card and hearing aid, are also a concern because they can cause burns or erode through tissue if ingested or put into body orifices.

"These batteries are everywhere, and kids do crazy stuff with them," she said.

The National Capital Poison Center, which operates a 24-hour National Battery Ingestion Hotline (202-625-3333)* for swallowed battery cases, estimates 3,500 Americans of all ages swallow miniature disc or button batteries each year.

The problem has been recognized for some time, but what few parents or providers realize is how quickly burns can occur, Dr. Macauley said.

She described a case involving a 6-year-old girl who picked up a small battery off the playground and amazed her friends by making it disappear in her ear. The child complained of severe pain overnight and presented to the emergency department in the morning, where surgery to remove the battery revealed third-degree burns to the ear canal and 65% perforation of the eardrum.

"It seemed like it should have been nothing; it was in there maybe 12 hours, but she had very severe injuries to her ear," Dr. Macauley said. "She’s been in the operating room probably a total of six different times trying to get that repaired, has a fair amount of hearing loss that stays, and ended up at a specialist hospital, out of network, to get a graft put in that ear."

Greeting card makers such as Hallmark have taken steps to secure button batteries, such as enclosing them underneath metal caps or in modules in which the cap is secured with screws. And the card makers warn consumers to properly dispose of old batteries after they’ve been replaced.

Dr. Macauley reported having no financial disclosures.

Correction, 3/5/2014: An earlier version of this article misstated the phone number for the Battery Ingestion hotline.

NAPLES, FLA. – They sizzle, they buzz, they vibrate. And they’re sending some children to the emergency department.

"One of the newest things we’re seeing a fair amount of are magnets, those sizzle magnets," reported Karen Macauley, DHA, R.N., trauma program director, All Children’s Hospital, St. Petersburg, Fla., and secretary of the Society of Trauma Nurses.

So-called "sizzle" magnets make a sound when they connect and are being sold as novelty toys, jewelry, and even for purported health benefits. One website specializing in gifts for the visually impaired notes that the magnetic field of these hematite magnets is "so strong," they’ll stay put if placed on the front and back of hands or ear lobes.

That strong magnetic force, however, can create havoc if children ingest magnets of any kind, Dr. Macauley said at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

"If the magnets stay in a string, they’re probably okay; but if they swallow one and wait a little while and swallow another, you can start to imagine what happens as it starts to pass through," she said. "One magnet stays, another comes in another part of the bowel, and they sizzle together. Now all of a sudden you have magnets that aren’t moving and cause a lot of necrosis. They’re actually very dangerous, and we don’t think too much about how dangerous they can be."

Between 2009 and 2011, an estimated 1,700 emergency department visits occurred because of magnet ingestion, with more than 70% of those cases involving children between age 4 and 12 years, according to researchers at the U.S. Public Interest Research Group, which highlighted magnets in its most recent annual toy safety survey.

Dr. Macauley also cautioned that button-size batteries, now in everything from remote controls to Grandma’s singing greeting card and hearing aid, are also a concern because they can cause burns or erode through tissue if ingested or put into body orifices.

"These batteries are everywhere, and kids do crazy stuff with them," she said.

The National Capital Poison Center, which operates a 24-hour National Battery Ingestion Hotline (202-625-3333)* for swallowed battery cases, estimates 3,500 Americans of all ages swallow miniature disc or button batteries each year.

The problem has been recognized for some time, but what few parents or providers realize is how quickly burns can occur, Dr. Macauley said.

She described a case involving a 6-year-old girl who picked up a small battery off the playground and amazed her friends by making it disappear in her ear. The child complained of severe pain overnight and presented to the emergency department in the morning, where surgery to remove the battery revealed third-degree burns to the ear canal and 65% perforation of the eardrum.

"It seemed like it should have been nothing; it was in there maybe 12 hours, but she had very severe injuries to her ear," Dr. Macauley said. "She’s been in the operating room probably a total of six different times trying to get that repaired, has a fair amount of hearing loss that stays, and ended up at a specialist hospital, out of network, to get a graft put in that ear."

Greeting card makers such as Hallmark have taken steps to secure button batteries, such as enclosing them underneath metal caps or in modules in which the cap is secured with screws. And the card makers warn consumers to properly dispose of old batteries after they’ve been replaced.

Dr. Macauley reported having no financial disclosures.

Correction, 3/5/2014: An earlier version of this article misstated the phone number for the Battery Ingestion hotline.

NAPLES, FLA. – They sizzle, they buzz, they vibrate. And they’re sending some children to the emergency department.

"One of the newest things we’re seeing a fair amount of are magnets, those sizzle magnets," reported Karen Macauley, DHA, R.N., trauma program director, All Children’s Hospital, St. Petersburg, Fla., and secretary of the Society of Trauma Nurses.

So-called "sizzle" magnets make a sound when they connect and are being sold as novelty toys, jewelry, and even for purported health benefits. One website specializing in gifts for the visually impaired notes that the magnetic field of these hematite magnets is "so strong," they’ll stay put if placed on the front and back of hands or ear lobes.

That strong magnetic force, however, can create havoc if children ingest magnets of any kind, Dr. Macauley said at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

"If the magnets stay in a string, they’re probably okay; but if they swallow one and wait a little while and swallow another, you can start to imagine what happens as it starts to pass through," she said. "One magnet stays, another comes in another part of the bowel, and they sizzle together. Now all of a sudden you have magnets that aren’t moving and cause a lot of necrosis. They’re actually very dangerous, and we don’t think too much about how dangerous they can be."

Between 2009 and 2011, an estimated 1,700 emergency department visits occurred because of magnet ingestion, with more than 70% of those cases involving children between age 4 and 12 years, according to researchers at the U.S. Public Interest Research Group, which highlighted magnets in its most recent annual toy safety survey.

Dr. Macauley also cautioned that button-size batteries, now in everything from remote controls to Grandma’s singing greeting card and hearing aid, are also a concern because they can cause burns or erode through tissue if ingested or put into body orifices.

"These batteries are everywhere, and kids do crazy stuff with them," she said.

The National Capital Poison Center, which operates a 24-hour National Battery Ingestion Hotline (202-625-3333)* for swallowed battery cases, estimates 3,500 Americans of all ages swallow miniature disc or button batteries each year.

The problem has been recognized for some time, but what few parents or providers realize is how quickly burns can occur, Dr. Macauley said.

She described a case involving a 6-year-old girl who picked up a small battery off the playground and amazed her friends by making it disappear in her ear. The child complained of severe pain overnight and presented to the emergency department in the morning, where surgery to remove the battery revealed third-degree burns to the ear canal and 65% perforation of the eardrum.

"It seemed like it should have been nothing; it was in there maybe 12 hours, but she had very severe injuries to her ear," Dr. Macauley said. "She’s been in the operating room probably a total of six different times trying to get that repaired, has a fair amount of hearing loss that stays, and ended up at a specialist hospital, out of network, to get a graft put in that ear."

Greeting card makers such as Hallmark have taken steps to secure button batteries, such as enclosing them underneath metal caps or in modules in which the cap is secured with screws. And the card makers warn consumers to properly dispose of old batteries after they’ve been replaced.

Dr. Macauley reported having no financial disclosures.

Correction, 3/5/2014: An earlier version of this article misstated the phone number for the Battery Ingestion hotline.

AT EAST 2014

Multiple gut operations tip scale against laparoscopic gall bladder surgery

NAPLES, FLA. – Only fewer prior abdominal surgeries predicted successful laparoscopic gall bladder surgery after percutaneous cholecystostomy tube placement in a review of 245 patients.

Notably, the degree of illness at the time of percutaneous cholecystostomy tube (PCT) placement did not seem to influence the rate of laparoscopy, Dr. Mohammad Khasawneh reported at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

"Our data suggest that having three or more prior abdominal operations seemed to reliably lean toward conversion to an open cholecystectomy," he said in an interview.

Many patients with high operative morbidity and mortality risk developing cholecystitis and are treated with PCT drainage. Cholecystectomy after PCT placement is the definitive treatment for cholecystitis among patients whose risk profile improves, but it is unclear which patients will be able to have a laparoscopic cholecystectomy, explained Dr. Khasawneh, with the department of surgery at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

The investigators reviewed 245 patients who had a PCT placed at the clinic from 2009 to 2011. Their median age was 71 years, and two-thirds were male. Of these, 43 patients died, 131 were not surgical candidates, and 71 went on to interval cholecystectomy in a median of 55 days (range, 42-75 days).

Laparoscopy was planned for 63 patients (89%) and successfully completed in 50 (79%), with 13 converted to open surgery. Eight cases were originally planned for open surgery.

The high mortality rate after PCT placement (17.5%) was due to the presence of comorbid conditions, according to Dr. Khasawneh.

Index admission comorbidities among cholecystectomy and non-cholecystectomy patients were prior abdominal surgeries (44% vs. 55%, respectively), mechanical ventilation (8% vs. 16%), steroid use (8.5% vs. 15%), anticoagulation use (28% vs. 32%), vasopressor use (10% both), and dysrhythmia (23% vs. 27%).

Interval cholecystectomy patients had a significantly lower overall Charlson Comorbidity Index (5 vs. 6; P = .005) and spent significantly less time in the intensive care unit (3 vs. 7 days; P less than .01) and hospital (6 vs. 9 days; P less than .01), he reported.

In multivariable regression analysis, comorbidity index and number of prior abdominal operations significantly predicted interval cholecystectomy, whereas age (odds ratio, 1.1; P = .39), presence of stones (OR, 1.7; P = .11), and mechanical ventilation at the time of PCT drainage (OR, 0.55; P = .12) did not.

Only the number of prior abdominal operations significantly predicted laparoscopic cholecystectomy (OR, 0.52; P = .02), Dr. Khasawneh reported.

"Patients who are medically cleared for cholecystectomy should have an attempt at laparoscopic cholecystectomy unless they have multiple prior operations," the authors concluded.

Dr. Khasawneh and his coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

NAPLES, FLA. – Only fewer prior abdominal surgeries predicted successful laparoscopic gall bladder surgery after percutaneous cholecystostomy tube placement in a review of 245 patients.

Notably, the degree of illness at the time of percutaneous cholecystostomy tube (PCT) placement did not seem to influence the rate of laparoscopy, Dr. Mohammad Khasawneh reported at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

"Our data suggest that having three or more prior abdominal operations seemed to reliably lean toward conversion to an open cholecystectomy," he said in an interview.

Many patients with high operative morbidity and mortality risk developing cholecystitis and are treated with PCT drainage. Cholecystectomy after PCT placement is the definitive treatment for cholecystitis among patients whose risk profile improves, but it is unclear which patients will be able to have a laparoscopic cholecystectomy, explained Dr. Khasawneh, with the department of surgery at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

The investigators reviewed 245 patients who had a PCT placed at the clinic from 2009 to 2011. Their median age was 71 years, and two-thirds were male. Of these, 43 patients died, 131 were not surgical candidates, and 71 went on to interval cholecystectomy in a median of 55 days (range, 42-75 days).

Laparoscopy was planned for 63 patients (89%) and successfully completed in 50 (79%), with 13 converted to open surgery. Eight cases were originally planned for open surgery.

The high mortality rate after PCT placement (17.5%) was due to the presence of comorbid conditions, according to Dr. Khasawneh.

Index admission comorbidities among cholecystectomy and non-cholecystectomy patients were prior abdominal surgeries (44% vs. 55%, respectively), mechanical ventilation (8% vs. 16%), steroid use (8.5% vs. 15%), anticoagulation use (28% vs. 32%), vasopressor use (10% both), and dysrhythmia (23% vs. 27%).

Interval cholecystectomy patients had a significantly lower overall Charlson Comorbidity Index (5 vs. 6; P = .005) and spent significantly less time in the intensive care unit (3 vs. 7 days; P less than .01) and hospital (6 vs. 9 days; P less than .01), he reported.

In multivariable regression analysis, comorbidity index and number of prior abdominal operations significantly predicted interval cholecystectomy, whereas age (odds ratio, 1.1; P = .39), presence of stones (OR, 1.7; P = .11), and mechanical ventilation at the time of PCT drainage (OR, 0.55; P = .12) did not.

Only the number of prior abdominal operations significantly predicted laparoscopic cholecystectomy (OR, 0.52; P = .02), Dr. Khasawneh reported.

"Patients who are medically cleared for cholecystectomy should have an attempt at laparoscopic cholecystectomy unless they have multiple prior operations," the authors concluded.

Dr. Khasawneh and his coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

NAPLES, FLA. – Only fewer prior abdominal surgeries predicted successful laparoscopic gall bladder surgery after percutaneous cholecystostomy tube placement in a review of 245 patients.

Notably, the degree of illness at the time of percutaneous cholecystostomy tube (PCT) placement did not seem to influence the rate of laparoscopy, Dr. Mohammad Khasawneh reported at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

"Our data suggest that having three or more prior abdominal operations seemed to reliably lean toward conversion to an open cholecystectomy," he said in an interview.

Many patients with high operative morbidity and mortality risk developing cholecystitis and are treated with PCT drainage. Cholecystectomy after PCT placement is the definitive treatment for cholecystitis among patients whose risk profile improves, but it is unclear which patients will be able to have a laparoscopic cholecystectomy, explained Dr. Khasawneh, with the department of surgery at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

The investigators reviewed 245 patients who had a PCT placed at the clinic from 2009 to 2011. Their median age was 71 years, and two-thirds were male. Of these, 43 patients died, 131 were not surgical candidates, and 71 went on to interval cholecystectomy in a median of 55 days (range, 42-75 days).

Laparoscopy was planned for 63 patients (89%) and successfully completed in 50 (79%), with 13 converted to open surgery. Eight cases were originally planned for open surgery.

The high mortality rate after PCT placement (17.5%) was due to the presence of comorbid conditions, according to Dr. Khasawneh.

Index admission comorbidities among cholecystectomy and non-cholecystectomy patients were prior abdominal surgeries (44% vs. 55%, respectively), mechanical ventilation (8% vs. 16%), steroid use (8.5% vs. 15%), anticoagulation use (28% vs. 32%), vasopressor use (10% both), and dysrhythmia (23% vs. 27%).

Interval cholecystectomy patients had a significantly lower overall Charlson Comorbidity Index (5 vs. 6; P = .005) and spent significantly less time in the intensive care unit (3 vs. 7 days; P less than .01) and hospital (6 vs. 9 days; P less than .01), he reported.

In multivariable regression analysis, comorbidity index and number of prior abdominal operations significantly predicted interval cholecystectomy, whereas age (odds ratio, 1.1; P = .39), presence of stones (OR, 1.7; P = .11), and mechanical ventilation at the time of PCT drainage (OR, 0.55; P = .12) did not.

Only the number of prior abdominal operations significantly predicted laparoscopic cholecystectomy (OR, 0.52; P = .02), Dr. Khasawneh reported.

"Patients who are medically cleared for cholecystectomy should have an attempt at laparoscopic cholecystectomy unless they have multiple prior operations," the authors concluded.

Dr. Khasawneh and his coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE EAST SCIENTIFIC ASSEMBLY

Major finding: Fewer prior abdominal operations significantly predict successful laparoscopic cholecystectomy (OR, 0.52; P = .02).

Data source: A retrospective study of 245 patients with a percutaneous cholecystostomy tube.

Disclosures: Dr. Khasawneh and his coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

Advanced clinical providers proving their mettle

NAPLES, FLA. – Complication rates are similar for advanced clinical practitioners and resident physicians performing key routine procedures in the ICU or trauma setting, a retrospective study found.

Advanced clinical practitioners (ACPs) performed 555 procedures with 11 complications (2%), while resident physicians (RPs) performed 1,020 procedures with 20 complications (2%).

Procedures consisted of arterial lines, central venous lines, bronchoalveolar lavage, thoracotomy tubes, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG), and tracheostomies, Massanu Sirleaf, a board-certified acute care nurse practitioner, said at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

No differences were observed between the ACP and RP groups in mean ICU length of stay (3.7 days vs. 3.9 days) or hospital stay (13.3 days vs. 12.2 days).

Mortality rates were also similar for ACPs and RPs (9.7% vs. 11%; P = .07), despite significantly higher age (mean 54.5 years vs. 49.9 years; P less than .05) and APACHE III scores for the ACP group (mean 47.7 vs. 40.8; P less than .05).

"Our results demonstrate that ACPs have become a very important part of our health care team and substantiate the safety of ACPs in performing surgical procedures in critically ill patients," Ms. Sirleaf said.

Restrictions in resident work hours have imposed workload challenges on trauma centers, leading some to recruit nurse practitioners and physician assistants to care for critically ill patients in the ICU and to perform invasive procedures previously done exclusively by physicians, she observed. Very few studies, however, have addressed ACPs’ procedural competence and complication rates.

The retrospective study included all procedures performed from January to December 2011 in the trauma and surgical ICUs at the F.H. "Sammy" Ross Jr. Trauma Center, Carolinas Medical Center in Charlotte, N.C. Eight ACPs performed invasive procedures for surgical critical care patients under attending supervision, while three postgraduate year two (PGY2) surgical and emergency residents performed procedures for trauma patients.

Invited discussant Dr. Jeffrey Claridge, director of trauma, critical care, and burns at MetroHealth Medical Center in Cleveland, agreed with the study’s conclusion that complications were similar between ACPs and RPs, but went on to say that 2% is extremely low and that "something is missing or oversimplified."

In particular, he pressed Ms. Sirleaf on where the procedures were performed, the level of supervision provided to ACPs, and how extensive the review of complications was other than procedural notes. For example, did the authors look at whether chest tubes fell out within 24 hours because they were inappropriately secured, PEG or tracheostomy sites that got infected, or breaks occurred in sterile technique.

"Determining a more comprehensive complication panel would give more power to detect differences and, truthfully, more credibility to the paper," Dr. Claridge said.

Ms. Sirleaf replied that in addition to reviewing postprocedural notes, radiologists looked for complications 24 hours after chest tube placement and patients with a tracheostomy were followed for complications for 7 days by the attending.

Urgency of the procedure was not evaluated since the procedures were elective and most were performed at the bedside.

"For the ACPs with a level of competency, just like interns at the beginning, they assisted the attending and as they got better, the majority of the procedure was performed by the ACP at the bedside with the attending scrubbed in," she said.

At the time of the study, three ACPs had 1 year of experience, with up to 7 years’ experience in the remaining ACPs. Senior ACPs provided training along with the attendings, and both ACPs and RPs underwent quarterly simulation lab training on procedures. To maintain competency, Carolinas Medical Center also requires ACPs perform a set number of each type of procedure on a yearly basis and have these procedures witnessed and signed off on by an attending, said Ms. Sirleaf, now with Sharp Memorial Hospital, San Diego.

Ms. Sirleaf and her coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

NAPLES, FLA. – Complication rates are similar for advanced clinical practitioners and resident physicians performing key routine procedures in the ICU or trauma setting, a retrospective study found.

Advanced clinical practitioners (ACPs) performed 555 procedures with 11 complications (2%), while resident physicians (RPs) performed 1,020 procedures with 20 complications (2%).

Procedures consisted of arterial lines, central venous lines, bronchoalveolar lavage, thoracotomy tubes, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG), and tracheostomies, Massanu Sirleaf, a board-certified acute care nurse practitioner, said at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

No differences were observed between the ACP and RP groups in mean ICU length of stay (3.7 days vs. 3.9 days) or hospital stay (13.3 days vs. 12.2 days).

Mortality rates were also similar for ACPs and RPs (9.7% vs. 11%; P = .07), despite significantly higher age (mean 54.5 years vs. 49.9 years; P less than .05) and APACHE III scores for the ACP group (mean 47.7 vs. 40.8; P less than .05).

"Our results demonstrate that ACPs have become a very important part of our health care team and substantiate the safety of ACPs in performing surgical procedures in critically ill patients," Ms. Sirleaf said.

Restrictions in resident work hours have imposed workload challenges on trauma centers, leading some to recruit nurse practitioners and physician assistants to care for critically ill patients in the ICU and to perform invasive procedures previously done exclusively by physicians, she observed. Very few studies, however, have addressed ACPs’ procedural competence and complication rates.

The retrospective study included all procedures performed from January to December 2011 in the trauma and surgical ICUs at the F.H. "Sammy" Ross Jr. Trauma Center, Carolinas Medical Center in Charlotte, N.C. Eight ACPs performed invasive procedures for surgical critical care patients under attending supervision, while three postgraduate year two (PGY2) surgical and emergency residents performed procedures for trauma patients.

Invited discussant Dr. Jeffrey Claridge, director of trauma, critical care, and burns at MetroHealth Medical Center in Cleveland, agreed with the study’s conclusion that complications were similar between ACPs and RPs, but went on to say that 2% is extremely low and that "something is missing or oversimplified."

In particular, he pressed Ms. Sirleaf on where the procedures were performed, the level of supervision provided to ACPs, and how extensive the review of complications was other than procedural notes. For example, did the authors look at whether chest tubes fell out within 24 hours because they were inappropriately secured, PEG or tracheostomy sites that got infected, or breaks occurred in sterile technique.

"Determining a more comprehensive complication panel would give more power to detect differences and, truthfully, more credibility to the paper," Dr. Claridge said.