User login

Academic Pediatric Association: Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2015

More alarms mean slower response in PICU, pediatric wards

SAN ANTONIO – Alarm fatigue, the desensitization that can occur when clinicians are exposed to an excessive number of nonactionable clinical alarms, is an urgent concern for pediatric hospitalists, who are studying the phenomenon in both intensive care and ward settings, according to Dr. Christopher P. Bonafide.

This year the ECRI Institute named alarm fatigue the top health technology hazard of 2015. And a Joint Commission national patient safety goal, issued in 2014, demands that hospitals begin implementing alarm system management strategies by January 2016 to combat fatigue and other potential downstream consequences of being overwhelmed with alarms.

At the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2015 meeting, Dr. Bonafide discussed ongoing work at his institution, the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, to pinpoint how and why alarm fatigue might be occurring there.

Dr. Bonafide and his colleagues evaluated data from in-room video cameras, bedside cardiorespiratory and pulse-oximetry monitors, and text messages communicating monitor alerts to nurses. They examined whether an alert was valid (consistent with the patient’s actual physiologic state) and actionable (meriting intervention or consultation), as well as how long it took nurses to respond.

The study was conducted during day shifts. Using data from about 5,000 alarms, and 210 hours of video from both the pediatric ward and the pediatric intensive care unit, the investigators found that 76% of alarms in the PICU were valid, and 13% were actionable. In the pediatric ward, 41% of alarms were valid, and only 1% were actionable.

Exposure to more nonactionable alarms was significantly correlated with longer response times to the patient’s bedside, Dr. Bonafide and his colleagues found. Overall, it took nurses exposed to more than 80 nonactionable alarms in the previous 2-hour period more than twice as long to respond to alarms than if they’d been exposed to 29 or fewer alarms in the preceding 2 hours (P less than .01).

“We think alarm fatigue is the most likely explanation for these findings,” Dr. Bonafide said at the meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine, and the Academic Pediatric Association. He noted that a larger study was underway to look more closely at other variables, such as the patient’s acuity and the nurse’s full patient load.

In an interview, Dr. Bonafide called bedside systems such as pulse oximetry and heart rate monitoring “some of the most powerful tools we have” to detect deterioration in the hospital. But a high signal-to-noise ratio can make them “essentially useless,” he said. “They fade into the background.”

Improving alarm systems “is about making alarms less of an every-minute occurrence by improving that signal-to-noise ratio so that when that alarm buzzes, it is a good decision to interrupt what you’re doing and check on the patient to figure out what’s going on,” he said.

Some of the possible solutions to keep alarms rarer include establishing more precise heart rate and respiratory norms for pediatric patients, and adjusting the thresholds for monitoring. “We would love it if for every patient, when that alarm goes off it’s already set to a point where it’s actionable,” he said.

While Dr. Bonafide has focused on measuring and understanding alarm fatigue to date, he said he and his team are “incredibly excited to begin focusing on what we can actually do to reduce nonactionable alarms and improve outcomes for patients.”

To address this, the investigators are conducting a cluster-randomized trial evaluating a data-driven dashboard that helps physicians and nurses identify alarm hot spots, and guides them through the best ways to intervene and reduce alarms.

What’s still lacking in the hospitalist community, Dr. Bonafide said, is “consensus around what is actionable.” This will require hospitalists to meet and talk about consensus guidelines on what constitutes an actionable pulse-oximetry or heart rate alarm, when it is appropriate to intervene, and when it is absolutely necessary to intervene.

Dr. Bonafide said he plans to begin developing a protocol for this work with collaborators from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital, Stanford, Calif.

“This has the potential to really help inform decision making on thousands of patients per day across the United States,” he said.

Dr. Bonafide’s study was funded by a grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Public Health Commonwealth Universal Research Enhancement Program. His team has received funding from the National Institutes of Health, the Academic Pediatric Association, and the Society of Hospital Medicine. He declared no conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – Alarm fatigue, the desensitization that can occur when clinicians are exposed to an excessive number of nonactionable clinical alarms, is an urgent concern for pediatric hospitalists, who are studying the phenomenon in both intensive care and ward settings, according to Dr. Christopher P. Bonafide.

This year the ECRI Institute named alarm fatigue the top health technology hazard of 2015. And a Joint Commission national patient safety goal, issued in 2014, demands that hospitals begin implementing alarm system management strategies by January 2016 to combat fatigue and other potential downstream consequences of being overwhelmed with alarms.

At the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2015 meeting, Dr. Bonafide discussed ongoing work at his institution, the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, to pinpoint how and why alarm fatigue might be occurring there.

Dr. Bonafide and his colleagues evaluated data from in-room video cameras, bedside cardiorespiratory and pulse-oximetry monitors, and text messages communicating monitor alerts to nurses. They examined whether an alert was valid (consistent with the patient’s actual physiologic state) and actionable (meriting intervention or consultation), as well as how long it took nurses to respond.

The study was conducted during day shifts. Using data from about 5,000 alarms, and 210 hours of video from both the pediatric ward and the pediatric intensive care unit, the investigators found that 76% of alarms in the PICU were valid, and 13% were actionable. In the pediatric ward, 41% of alarms were valid, and only 1% were actionable.

Exposure to more nonactionable alarms was significantly correlated with longer response times to the patient’s bedside, Dr. Bonafide and his colleagues found. Overall, it took nurses exposed to more than 80 nonactionable alarms in the previous 2-hour period more than twice as long to respond to alarms than if they’d been exposed to 29 or fewer alarms in the preceding 2 hours (P less than .01).

“We think alarm fatigue is the most likely explanation for these findings,” Dr. Bonafide said at the meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine, and the Academic Pediatric Association. He noted that a larger study was underway to look more closely at other variables, such as the patient’s acuity and the nurse’s full patient load.

In an interview, Dr. Bonafide called bedside systems such as pulse oximetry and heart rate monitoring “some of the most powerful tools we have” to detect deterioration in the hospital. But a high signal-to-noise ratio can make them “essentially useless,” he said. “They fade into the background.”

Improving alarm systems “is about making alarms less of an every-minute occurrence by improving that signal-to-noise ratio so that when that alarm buzzes, it is a good decision to interrupt what you’re doing and check on the patient to figure out what’s going on,” he said.

Some of the possible solutions to keep alarms rarer include establishing more precise heart rate and respiratory norms for pediatric patients, and adjusting the thresholds for monitoring. “We would love it if for every patient, when that alarm goes off it’s already set to a point where it’s actionable,” he said.

While Dr. Bonafide has focused on measuring and understanding alarm fatigue to date, he said he and his team are “incredibly excited to begin focusing on what we can actually do to reduce nonactionable alarms and improve outcomes for patients.”

To address this, the investigators are conducting a cluster-randomized trial evaluating a data-driven dashboard that helps physicians and nurses identify alarm hot spots, and guides them through the best ways to intervene and reduce alarms.

What’s still lacking in the hospitalist community, Dr. Bonafide said, is “consensus around what is actionable.” This will require hospitalists to meet and talk about consensus guidelines on what constitutes an actionable pulse-oximetry or heart rate alarm, when it is appropriate to intervene, and when it is absolutely necessary to intervene.

Dr. Bonafide said he plans to begin developing a protocol for this work with collaborators from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital, Stanford, Calif.

“This has the potential to really help inform decision making on thousands of patients per day across the United States,” he said.

Dr. Bonafide’s study was funded by a grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Public Health Commonwealth Universal Research Enhancement Program. His team has received funding from the National Institutes of Health, the Academic Pediatric Association, and the Society of Hospital Medicine. He declared no conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – Alarm fatigue, the desensitization that can occur when clinicians are exposed to an excessive number of nonactionable clinical alarms, is an urgent concern for pediatric hospitalists, who are studying the phenomenon in both intensive care and ward settings, according to Dr. Christopher P. Bonafide.

This year the ECRI Institute named alarm fatigue the top health technology hazard of 2015. And a Joint Commission national patient safety goal, issued in 2014, demands that hospitals begin implementing alarm system management strategies by January 2016 to combat fatigue and other potential downstream consequences of being overwhelmed with alarms.

At the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2015 meeting, Dr. Bonafide discussed ongoing work at his institution, the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, to pinpoint how and why alarm fatigue might be occurring there.

Dr. Bonafide and his colleagues evaluated data from in-room video cameras, bedside cardiorespiratory and pulse-oximetry monitors, and text messages communicating monitor alerts to nurses. They examined whether an alert was valid (consistent with the patient’s actual physiologic state) and actionable (meriting intervention or consultation), as well as how long it took nurses to respond.

The study was conducted during day shifts. Using data from about 5,000 alarms, and 210 hours of video from both the pediatric ward and the pediatric intensive care unit, the investigators found that 76% of alarms in the PICU were valid, and 13% were actionable. In the pediatric ward, 41% of alarms were valid, and only 1% were actionable.

Exposure to more nonactionable alarms was significantly correlated with longer response times to the patient’s bedside, Dr. Bonafide and his colleagues found. Overall, it took nurses exposed to more than 80 nonactionable alarms in the previous 2-hour period more than twice as long to respond to alarms than if they’d been exposed to 29 or fewer alarms in the preceding 2 hours (P less than .01).

“We think alarm fatigue is the most likely explanation for these findings,” Dr. Bonafide said at the meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine, and the Academic Pediatric Association. He noted that a larger study was underway to look more closely at other variables, such as the patient’s acuity and the nurse’s full patient load.

In an interview, Dr. Bonafide called bedside systems such as pulse oximetry and heart rate monitoring “some of the most powerful tools we have” to detect deterioration in the hospital. But a high signal-to-noise ratio can make them “essentially useless,” he said. “They fade into the background.”

Improving alarm systems “is about making alarms less of an every-minute occurrence by improving that signal-to-noise ratio so that when that alarm buzzes, it is a good decision to interrupt what you’re doing and check on the patient to figure out what’s going on,” he said.

Some of the possible solutions to keep alarms rarer include establishing more precise heart rate and respiratory norms for pediatric patients, and adjusting the thresholds for monitoring. “We would love it if for every patient, when that alarm goes off it’s already set to a point where it’s actionable,” he said.

While Dr. Bonafide has focused on measuring and understanding alarm fatigue to date, he said he and his team are “incredibly excited to begin focusing on what we can actually do to reduce nonactionable alarms and improve outcomes for patients.”

To address this, the investigators are conducting a cluster-randomized trial evaluating a data-driven dashboard that helps physicians and nurses identify alarm hot spots, and guides them through the best ways to intervene and reduce alarms.

What’s still lacking in the hospitalist community, Dr. Bonafide said, is “consensus around what is actionable.” This will require hospitalists to meet and talk about consensus guidelines on what constitutes an actionable pulse-oximetry or heart rate alarm, when it is appropriate to intervene, and when it is absolutely necessary to intervene.

Dr. Bonafide said he plans to begin developing a protocol for this work with collaborators from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital, Stanford, Calif.

“This has the potential to really help inform decision making on thousands of patients per day across the United States,” he said.

Dr. Bonafide’s study was funded by a grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Public Health Commonwealth Universal Research Enhancement Program. His team has received funding from the National Institutes of Health, the Academic Pediatric Association, and the Society of Hospital Medicine. He declared no conflicts of interest.

AT PEDIATRIC HOSPITAL MEDICINE 2015

Key clinical point: Nurses’ exposure to more nonactionable pediatric alarms was found to be correlated with significantly slower response time to the patient’s bedside as their shift progressed.

Major finding: Nurses exposed to 80+ nonactionable alarms in the previous 2 hours took more than twice as long to respond to alarms as did nurses exposed to 29 or fewer alarms in the previous 2 hours (P less than .01).

Data source: 210 hours’ video and 4,962 time-stamped bedside monitor alarms on the pediatric ward and PICU at one children’s hospital; study conducted more than 120 hours in PICU and 120 hours on the ward.

Disclosures: Dr. Bonafide’s study was funded by a grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Public Health Commonwealth Universal Research Enhancement Program. His team has received funding from the National Institutes of Health, the Academic Pediatric Association, and the Society of Hospital Medicine. He declared no conflicts of interest.

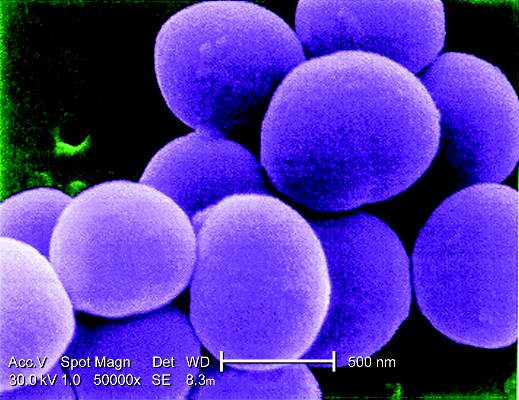

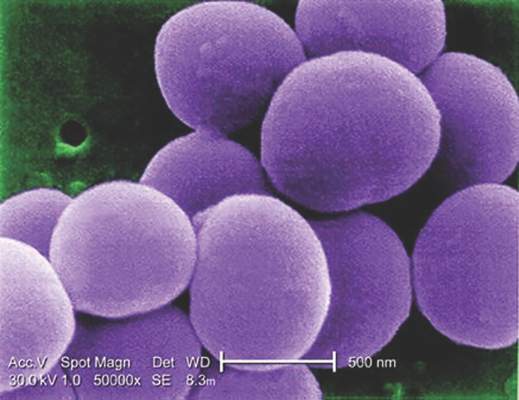

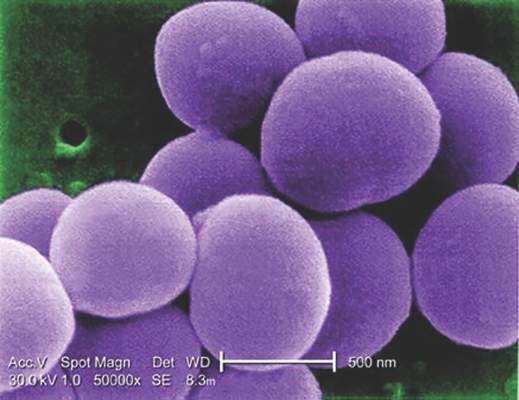

S. aureus seen in 1% of pediatric CAP cases

SAN ANTONIO – Current guidelines on community-acquired pneumonia recommend penicillin, amoxicillin, or ampicillin as first-line treatment in children with CAP.

However, a small minority will have Staphylococcus aureus infections not treatable with these antibiotics, raising some concern about how many of these cases might be missed.

At the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2015 meeting, Dr. Meghan E. Hofto of Children’s of Alabama at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, presented research from a study of 554 patients admitted to the hospital with community acquired pneumonia, including 78 patients with complicated pneumonia.

Seven patients in the cohort (1.3%) had S. aureus infections, Dr. Hofto and her colleagues found. Of those, six were recorded as having complicated pneumonia, characterized by pleural effusion or cavitation.

Six patients with S. aureus had been started on antibiotics in other health care settings prior to admission (amoxicillin n = 4, multiple agents n = 2). One patient positive for flu was first treated with oseltamavir only. However, all staph patients once admitted were started on vancomycin, which is effective against S. aureus, within 24 hours. Five were diagnosed by pleural fluid culture; one case was identified by clinical presentation, and another by sputum culture, Dr. Hofto said at the meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

The S. aureus patients were younger than the cohort as a whole (median 18 months vs. 40.5 months). Length of stay was significantly longer for these patients, compared with the rest of the cohort (median 10 vs. 2 days, P less than .01), and S. aureus patients had significantly higher incidence of anemia (P less than .01), a finding that Dr. Hofto said was striking.

Within 24 hours of presentation, six out the seven staph cases had anemia, she said, while of all the 78 patients with complicated disease, 12 had anemia. Community acquired S. aureus pneumonia has been linked in other studies to severe leukopenia, Dr. Hofto noted (BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:359) and (Paediatric Respiratory Reviews 2011 Sept;12:182-9).In an interview, Dr. Hofto said the findings supported current guidance in favor of first-line penicillin, amoxicillin, or ampicillin. “Part of what we’re looking at with guideline adherence is the barriers to treating with empiric narrow spectrum antibiotics – and obviously, one of the things people are concerned about is that are we going to miss something,” she said.

“I think we can pretty confidently say that if it’s uncomplicated CAP – if there’s no pleural effusion, no necrosis, no cavitation – you can treat with narrow spectrum, and the likelihood of it being staph is slim to none.”

If within 48 hours, patients are not responding to the first-line treatment, “you should start thinking about other causes,” Dr. Hofto said, noting that her review found all staph aureus patients were started on antibiotics effective against S. aureus – mostly vancomycin and ceftriaxone – within 24 hours of presentation.

Dr. Hofto noted as a limitation of her study, which used retrospective chart reviews of more than 3,400 children hospitalized for suspected pneumonia over a 3-year period, that additional S. aureus cases could have been missed because of a lack of proper coding or microbial confirmation. Another limitation was the single-site design and the relatively small number of S. aureus cases.

Dr. Hofto said she is conducting a more in-depth chart review ensure that no further cases of S. aureus CAP were missed in her sample.

The study received no outside funding, and Dr. Hofto disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – Current guidelines on community-acquired pneumonia recommend penicillin, amoxicillin, or ampicillin as first-line treatment in children with CAP.

However, a small minority will have Staphylococcus aureus infections not treatable with these antibiotics, raising some concern about how many of these cases might be missed.

At the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2015 meeting, Dr. Meghan E. Hofto of Children’s of Alabama at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, presented research from a study of 554 patients admitted to the hospital with community acquired pneumonia, including 78 patients with complicated pneumonia.

Seven patients in the cohort (1.3%) had S. aureus infections, Dr. Hofto and her colleagues found. Of those, six were recorded as having complicated pneumonia, characterized by pleural effusion or cavitation.

Six patients with S. aureus had been started on antibiotics in other health care settings prior to admission (amoxicillin n = 4, multiple agents n = 2). One patient positive for flu was first treated with oseltamavir only. However, all staph patients once admitted were started on vancomycin, which is effective against S. aureus, within 24 hours. Five were diagnosed by pleural fluid culture; one case was identified by clinical presentation, and another by sputum culture, Dr. Hofto said at the meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

The S. aureus patients were younger than the cohort as a whole (median 18 months vs. 40.5 months). Length of stay was significantly longer for these patients, compared with the rest of the cohort (median 10 vs. 2 days, P less than .01), and S. aureus patients had significantly higher incidence of anemia (P less than .01), a finding that Dr. Hofto said was striking.

Within 24 hours of presentation, six out the seven staph cases had anemia, she said, while of all the 78 patients with complicated disease, 12 had anemia. Community acquired S. aureus pneumonia has been linked in other studies to severe leukopenia, Dr. Hofto noted (BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:359) and (Paediatric Respiratory Reviews 2011 Sept;12:182-9).In an interview, Dr. Hofto said the findings supported current guidance in favor of first-line penicillin, amoxicillin, or ampicillin. “Part of what we’re looking at with guideline adherence is the barriers to treating with empiric narrow spectrum antibiotics – and obviously, one of the things people are concerned about is that are we going to miss something,” she said.

“I think we can pretty confidently say that if it’s uncomplicated CAP – if there’s no pleural effusion, no necrosis, no cavitation – you can treat with narrow spectrum, and the likelihood of it being staph is slim to none.”

If within 48 hours, patients are not responding to the first-line treatment, “you should start thinking about other causes,” Dr. Hofto said, noting that her review found all staph aureus patients were started on antibiotics effective against S. aureus – mostly vancomycin and ceftriaxone – within 24 hours of presentation.

Dr. Hofto noted as a limitation of her study, which used retrospective chart reviews of more than 3,400 children hospitalized for suspected pneumonia over a 3-year period, that additional S. aureus cases could have been missed because of a lack of proper coding or microbial confirmation. Another limitation was the single-site design and the relatively small number of S. aureus cases.

Dr. Hofto said she is conducting a more in-depth chart review ensure that no further cases of S. aureus CAP were missed in her sample.

The study received no outside funding, and Dr. Hofto disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – Current guidelines on community-acquired pneumonia recommend penicillin, amoxicillin, or ampicillin as first-line treatment in children with CAP.

However, a small minority will have Staphylococcus aureus infections not treatable with these antibiotics, raising some concern about how many of these cases might be missed.

At the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2015 meeting, Dr. Meghan E. Hofto of Children’s of Alabama at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, presented research from a study of 554 patients admitted to the hospital with community acquired pneumonia, including 78 patients with complicated pneumonia.

Seven patients in the cohort (1.3%) had S. aureus infections, Dr. Hofto and her colleagues found. Of those, six were recorded as having complicated pneumonia, characterized by pleural effusion or cavitation.

Six patients with S. aureus had been started on antibiotics in other health care settings prior to admission (amoxicillin n = 4, multiple agents n = 2). One patient positive for flu was first treated with oseltamavir only. However, all staph patients once admitted were started on vancomycin, which is effective against S. aureus, within 24 hours. Five were diagnosed by pleural fluid culture; one case was identified by clinical presentation, and another by sputum culture, Dr. Hofto said at the meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

The S. aureus patients were younger than the cohort as a whole (median 18 months vs. 40.5 months). Length of stay was significantly longer for these patients, compared with the rest of the cohort (median 10 vs. 2 days, P less than .01), and S. aureus patients had significantly higher incidence of anemia (P less than .01), a finding that Dr. Hofto said was striking.

Within 24 hours of presentation, six out the seven staph cases had anemia, she said, while of all the 78 patients with complicated disease, 12 had anemia. Community acquired S. aureus pneumonia has been linked in other studies to severe leukopenia, Dr. Hofto noted (BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:359) and (Paediatric Respiratory Reviews 2011 Sept;12:182-9).In an interview, Dr. Hofto said the findings supported current guidance in favor of first-line penicillin, amoxicillin, or ampicillin. “Part of what we’re looking at with guideline adherence is the barriers to treating with empiric narrow spectrum antibiotics – and obviously, one of the things people are concerned about is that are we going to miss something,” she said.

“I think we can pretty confidently say that if it’s uncomplicated CAP – if there’s no pleural effusion, no necrosis, no cavitation – you can treat with narrow spectrum, and the likelihood of it being staph is slim to none.”

If within 48 hours, patients are not responding to the first-line treatment, “you should start thinking about other causes,” Dr. Hofto said, noting that her review found all staph aureus patients were started on antibiotics effective against S. aureus – mostly vancomycin and ceftriaxone – within 24 hours of presentation.

Dr. Hofto noted as a limitation of her study, which used retrospective chart reviews of more than 3,400 children hospitalized for suspected pneumonia over a 3-year period, that additional S. aureus cases could have been missed because of a lack of proper coding or microbial confirmation. Another limitation was the single-site design and the relatively small number of S. aureus cases.

Dr. Hofto said she is conducting a more in-depth chart review ensure that no further cases of S. aureus CAP were missed in her sample.

The study received no outside funding, and Dr. Hofto disclosed no conflicts of interest.

AT PEDIATRIC HOSPITAL MEDICINE 2015

Key clinical point: About 1% of children presenting to a hospital with community-acquired pneumonia had Staphylococcus aureus infections, which do not respond to recommended first-line narrow spectrum antibiotics for CAP.

Major finding: In a cohort of 554 children admitted with CAP, 7 had S. aureus infections, 6 classed as complicated. All received vancomycin within 24 hours of admission; anemia incidence was significantly higher in S. aureus patients than for the rest of the cohort.

Data source: Retrospective cohort study of more than 3,400 children.

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding, and Dr. Hofto disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Mood disorders affect length of stay, complication risk in pediatric pneumonia

SAN ANTONIO – Pediatric pneumonia patients were found to have a significantly longer length of hospital stay and a higher rate of complications when they also had mood or anxiety disorders, in a study of nearly 35,000 hospitalizations.

Children with chronic complex illnesses have been shown to have longer hospital stays when they also have mood or anxiety disorders; less is known, however, about how these disorders affect children hospitalized for more common conditions, according to Dr. Stephanie Doupnik.

At the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2015 meeting, Dr. Doupnik of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia presented research aimed at understanding the effect of mood and anxiety disorders on complications and length of stay in pediatric pneumonia patients.

Dr. Doupnik and her colleagues used the 2012 Kids’ Inpatient Database to identify 34,795 hospitalizations nationwide for pneumonia among children and adolescents aged 5-20. Of those 13 and older (28% of the cohort), a mood or anxiety diagnosis was recorded at discharge for 9.3%, and in school-age children, for 1.1%. Those diagnoses included major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder. (Some studies have looked at attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and those outcomes, but children with ADHD were not part of the current study.)

Pneumonia complications such as respiratory failure, sepsis, and suppuration were seen in 10.7% of the younger children, and 18.7% of those 13 and older.

The researchers found that the odds of experiencing any complication were significantly higher in children with mood and anxiety disorders, regardless of age. The older children saw an odds ratio of 1.8 (95% confidence interval, 1.3-2.0) and the younger children, 1.6 (95% CI, 13-2.0 ) (P less than 0.001 for both). Length of stay also was prolonged among the patients with mood and anxiety disorders by 11% in the younger children and by 13% in the adolescents and young adults.

Dr. Doupnik and her colleagues suspected that an increased rate of complications might explain the differences in length of stay. But they found, in analyzing records for adolescents without complications, that length of stay was still longer (6.8 vs. 5.4 days) for those with mood disorders. Among adolescents with complications, length of stay was still slightly higher in the mood disorder group (4.4 vs. 3.7 days ). These differences were statistically significant.

No statistically significant interaction was seen between complications and a mood or anxiety disorder diagnosis at discharge. “If complications were accounting for that prolonged length of stay, we would have expected differences between those groups,” Dr. Doupnik said at the meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

“It appears that complications do not account for the increase in length of stay among patients with mood and anxiety disorders,” she said.

Dr. Doupnik noted as a limitation of her study a lack of granularity in the data “that would allow us to identify other factors that might be contributing to this association.”

Dr. Doupnik said in an interview that she came to the study having noted that many patients with mental health disorders had more trouble during their hospitalizations. Although this phenomenon has been studied among children with chronic complex illnesses, such as sickle cell disease, diabetes, and cystic fibrosis, “there was a gap in the literature around general pediatric conditions” such as pneumonia, she said.

One potential reason for the association between mental health disorders and length of stay might be delays in presentation to the hospital, Dr. Doupnik said. Also, “there’s the possibility that patients interact differently with staff and providers in the hospital. If they can’t cope as well with the things that need to happen during a hospitalization, that could prolong their length of stay or increase risk of complications.”

Because absolute length of stay differences seen in the study were not very great, it was unlikely that the mood and anxiety disorders developed in the hospital, she noted, adding that the discharge diagnoses likely reflected preexisting diagnoses.

Dr. Doupnik is now planning a prospective cohort study among children admitted to her institution for pneumonia, hoping to help clarify some of the lingering questions surrounding the associations seen in this study.

She disclosed no outside funding or conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – Pediatric pneumonia patients were found to have a significantly longer length of hospital stay and a higher rate of complications when they also had mood or anxiety disorders, in a study of nearly 35,000 hospitalizations.

Children with chronic complex illnesses have been shown to have longer hospital stays when they also have mood or anxiety disorders; less is known, however, about how these disorders affect children hospitalized for more common conditions, according to Dr. Stephanie Doupnik.

At the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2015 meeting, Dr. Doupnik of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia presented research aimed at understanding the effect of mood and anxiety disorders on complications and length of stay in pediatric pneumonia patients.

Dr. Doupnik and her colleagues used the 2012 Kids’ Inpatient Database to identify 34,795 hospitalizations nationwide for pneumonia among children and adolescents aged 5-20. Of those 13 and older (28% of the cohort), a mood or anxiety diagnosis was recorded at discharge for 9.3%, and in school-age children, for 1.1%. Those diagnoses included major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder. (Some studies have looked at attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and those outcomes, but children with ADHD were not part of the current study.)

Pneumonia complications such as respiratory failure, sepsis, and suppuration were seen in 10.7% of the younger children, and 18.7% of those 13 and older.

The researchers found that the odds of experiencing any complication were significantly higher in children with mood and anxiety disorders, regardless of age. The older children saw an odds ratio of 1.8 (95% confidence interval, 1.3-2.0) and the younger children, 1.6 (95% CI, 13-2.0 ) (P less than 0.001 for both). Length of stay also was prolonged among the patients with mood and anxiety disorders by 11% in the younger children and by 13% in the adolescents and young adults.

Dr. Doupnik and her colleagues suspected that an increased rate of complications might explain the differences in length of stay. But they found, in analyzing records for adolescents without complications, that length of stay was still longer (6.8 vs. 5.4 days) for those with mood disorders. Among adolescents with complications, length of stay was still slightly higher in the mood disorder group (4.4 vs. 3.7 days ). These differences were statistically significant.

No statistically significant interaction was seen between complications and a mood or anxiety disorder diagnosis at discharge. “If complications were accounting for that prolonged length of stay, we would have expected differences between those groups,” Dr. Doupnik said at the meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

“It appears that complications do not account for the increase in length of stay among patients with mood and anxiety disorders,” she said.

Dr. Doupnik noted as a limitation of her study a lack of granularity in the data “that would allow us to identify other factors that might be contributing to this association.”

Dr. Doupnik said in an interview that she came to the study having noted that many patients with mental health disorders had more trouble during their hospitalizations. Although this phenomenon has been studied among children with chronic complex illnesses, such as sickle cell disease, diabetes, and cystic fibrosis, “there was a gap in the literature around general pediatric conditions” such as pneumonia, she said.

One potential reason for the association between mental health disorders and length of stay might be delays in presentation to the hospital, Dr. Doupnik said. Also, “there’s the possibility that patients interact differently with staff and providers in the hospital. If they can’t cope as well with the things that need to happen during a hospitalization, that could prolong their length of stay or increase risk of complications.”

Because absolute length of stay differences seen in the study were not very great, it was unlikely that the mood and anxiety disorders developed in the hospital, she noted, adding that the discharge diagnoses likely reflected preexisting diagnoses.

Dr. Doupnik is now planning a prospective cohort study among children admitted to her institution for pneumonia, hoping to help clarify some of the lingering questions surrounding the associations seen in this study.

She disclosed no outside funding or conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – Pediatric pneumonia patients were found to have a significantly longer length of hospital stay and a higher rate of complications when they also had mood or anxiety disorders, in a study of nearly 35,000 hospitalizations.

Children with chronic complex illnesses have been shown to have longer hospital stays when they also have mood or anxiety disorders; less is known, however, about how these disorders affect children hospitalized for more common conditions, according to Dr. Stephanie Doupnik.

At the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2015 meeting, Dr. Doupnik of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia presented research aimed at understanding the effect of mood and anxiety disorders on complications and length of stay in pediatric pneumonia patients.

Dr. Doupnik and her colleagues used the 2012 Kids’ Inpatient Database to identify 34,795 hospitalizations nationwide for pneumonia among children and adolescents aged 5-20. Of those 13 and older (28% of the cohort), a mood or anxiety diagnosis was recorded at discharge for 9.3%, and in school-age children, for 1.1%. Those diagnoses included major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder. (Some studies have looked at attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and those outcomes, but children with ADHD were not part of the current study.)

Pneumonia complications such as respiratory failure, sepsis, and suppuration were seen in 10.7% of the younger children, and 18.7% of those 13 and older.

The researchers found that the odds of experiencing any complication were significantly higher in children with mood and anxiety disorders, regardless of age. The older children saw an odds ratio of 1.8 (95% confidence interval, 1.3-2.0) and the younger children, 1.6 (95% CI, 13-2.0 ) (P less than 0.001 for both). Length of stay also was prolonged among the patients with mood and anxiety disorders by 11% in the younger children and by 13% in the adolescents and young adults.

Dr. Doupnik and her colleagues suspected that an increased rate of complications might explain the differences in length of stay. But they found, in analyzing records for adolescents without complications, that length of stay was still longer (6.8 vs. 5.4 days) for those with mood disorders. Among adolescents with complications, length of stay was still slightly higher in the mood disorder group (4.4 vs. 3.7 days ). These differences were statistically significant.

No statistically significant interaction was seen between complications and a mood or anxiety disorder diagnosis at discharge. “If complications were accounting for that prolonged length of stay, we would have expected differences between those groups,” Dr. Doupnik said at the meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

“It appears that complications do not account for the increase in length of stay among patients with mood and anxiety disorders,” she said.

Dr. Doupnik noted as a limitation of her study a lack of granularity in the data “that would allow us to identify other factors that might be contributing to this association.”

Dr. Doupnik said in an interview that she came to the study having noted that many patients with mental health disorders had more trouble during their hospitalizations. Although this phenomenon has been studied among children with chronic complex illnesses, such as sickle cell disease, diabetes, and cystic fibrosis, “there was a gap in the literature around general pediatric conditions” such as pneumonia, she said.

One potential reason for the association between mental health disorders and length of stay might be delays in presentation to the hospital, Dr. Doupnik said. Also, “there’s the possibility that patients interact differently with staff and providers in the hospital. If they can’t cope as well with the things that need to happen during a hospitalization, that could prolong their length of stay or increase risk of complications.”

Because absolute length of stay differences seen in the study were not very great, it was unlikely that the mood and anxiety disorders developed in the hospital, she noted, adding that the discharge diagnoses likely reflected preexisting diagnoses.

Dr. Doupnik is now planning a prospective cohort study among children admitted to her institution for pneumonia, hoping to help clarify some of the lingering questions surrounding the associations seen in this study.

She disclosed no outside funding or conflicts of interest.

AT PEDIATRIC HOSPITAL MEDICINE 2015

Key clinical point: Pediatric pneumonia patients have a significantly longer length of hospital stay and a higher rate of complications when they also have mood or anxiety disorders.

Major finding: Length of stay was 13% longer among adolescents with mood disorders, compared with those without, and the odds ratio for complications was 1.8 (95% CI, 1.3-2.0; P less than 0.001), compared with those without.

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of records from nearly 35,000 pediatric hospitalizations in a national database.

Disclosures: Dr. Doupnik disclosed no outside funding or conflicts of interest.

Continuous albuterol is safe intermediate-care option in community hospitals

SAN ANTONIO – More community hospitals are offering continuous albuterol to pediatric patients as an intermediate-care service, a level of care that’s higher than usual for the pediatric ward, but not as high as in pediatric intensive care units, according to Dr. Michelle Hofmann.

A 2014 study established that continuous albuterol can be initiated safely in the nonintensive pediatric care setting, but not all hospitals have followed suit (Pediatrics 2014;134[4]:e976-82).

At the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2015 meeting, Dr. Hofmann, a pediatric hospitalist with the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and the Riverton (Utah) Hospital, presented findings from a study she conducted to determine whether initiating continuous albuterol outside the PICU was worthwhile, safe, and feasible in her own community hospital. She found that it was.

“When we looked at the patients we were transferring to the PICU, nothing else was happening to them – all they were getting was continuous albuterol once they got there,” Dr. Hofmann said at the conference. “And we thought, ‘we [hospitalists] are on site 24/7. How do we capitalize on our resource?”

Dr. Hofmann and her colleagues first conducted a 1-year pilot study of pediatric asthma admissions (n = 76) at Primary Children’s Hospital in Salt Lake City, which like Riverton is part of the Intermountain Healthcare network. There, children were treated with continuous albuterol in the PICU only. Dr. Hofmann and her colleagues found that most children required no additional resources beyond continuous albuterol once they were admitted to the PICU from either the floor or the emergency department.

Moreover, patients classified as severe who got started on continuous albuterol in the ED and went right to the PICU did better than those who got admitted to the floor, were given intermittent albuterol, deteriorated, and then were transferred to intensive care, Dr. Hofmann said. This indicated that best practice was not occurring, even at the children’s hospital.

Dr. Hofmann and her colleagues then developed a protocol for her community hospital in which children presenting with asthma could be started on continuous albuterol in the emergency department or on the ward. She set up a pilot study to evaluate its safety and feasibility.

Of 74 asthma admissions over the 1-year pilot period, 22% of patients (n = 16) received continuous albuterol on the floor. Most of these (75%) received all their care on the floor (mean length of stay 30 hours), while those who deteriorated were transferred to the PICU; four additional cases were transferred directly from the ED to the PICU. In only two cases transferred from the community to children’s hospital did patients require care beyond continuous albuterol.

Dr. Hofmann noted that while more community hospitals are administering continuous albuterol outside the PICU, it was important to consider the benefits or drawbacks on a case-by-case basis.

A community hospital has the advantage of “not dealing with all the different layers of physicians involved in care” in a children’s hospital, Dr. Hofmann said in an interview. “Our costs are lower, in part due to shorter length of stay, but also we have a different cost structure. It’s a small self-contained unit, and our facilities are closer to home for many families.”

However, she said, the continuous albuterol intermediate-care protocol may not suit all community hospitals. “There are significant differences in personnel, facilities, and diagnostic and treatment capabilities from hospital to hospital; there’s no set criteria that will apply at every institution for intermediate care,” Dr. Hofmann said. The feasibility of appropriate staffing and continuous monitoring capabilities and the cost-benefit of achieving these in a lower-volume program are important considerations.

Hospitals should consider “what your baseline transfer rate is, and the kinds of patients you’re already seeing. Are you really going to be able to improve it that much, to provide the extra infrastructure and work to develop this process? Will you capture that many more patients?”

Offering intermediate-care services such as continuous albuterol, which can be billed at a higher level of care, is one way to help make community hospitals’ pediatric programs more sustainable. “We tend to operate in the red,” Dr. Hofmann said, because “pediatrics is not a high revenue earner for a facility. Moving to these intermediate-level care options and figuring out what is safe and what we can keep in the community hospital is really important to us – this is just one example of ways we could do that.”

Dr. Hofmann noted as a limitation of her study the low patient volume and the fact that some asthma patients may have been transferred from the community hospital’s ED to the children’s hospital year over year, and these were only captured during the pilot study, though it may be that ED transfer rates are decreasing as well as a result of the protocol.

The meeting was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine, and the Academic Pediatric Association. Dr. Hofmann reported no outside funding for her study or conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – More community hospitals are offering continuous albuterol to pediatric patients as an intermediate-care service, a level of care that’s higher than usual for the pediatric ward, but not as high as in pediatric intensive care units, according to Dr. Michelle Hofmann.

A 2014 study established that continuous albuterol can be initiated safely in the nonintensive pediatric care setting, but not all hospitals have followed suit (Pediatrics 2014;134[4]:e976-82).

At the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2015 meeting, Dr. Hofmann, a pediatric hospitalist with the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and the Riverton (Utah) Hospital, presented findings from a study she conducted to determine whether initiating continuous albuterol outside the PICU was worthwhile, safe, and feasible in her own community hospital. She found that it was.

“When we looked at the patients we were transferring to the PICU, nothing else was happening to them – all they were getting was continuous albuterol once they got there,” Dr. Hofmann said at the conference. “And we thought, ‘we [hospitalists] are on site 24/7. How do we capitalize on our resource?”

Dr. Hofmann and her colleagues first conducted a 1-year pilot study of pediatric asthma admissions (n = 76) at Primary Children’s Hospital in Salt Lake City, which like Riverton is part of the Intermountain Healthcare network. There, children were treated with continuous albuterol in the PICU only. Dr. Hofmann and her colleagues found that most children required no additional resources beyond continuous albuterol once they were admitted to the PICU from either the floor or the emergency department.

Moreover, patients classified as severe who got started on continuous albuterol in the ED and went right to the PICU did better than those who got admitted to the floor, were given intermittent albuterol, deteriorated, and then were transferred to intensive care, Dr. Hofmann said. This indicated that best practice was not occurring, even at the children’s hospital.

Dr. Hofmann and her colleagues then developed a protocol for her community hospital in which children presenting with asthma could be started on continuous albuterol in the emergency department or on the ward. She set up a pilot study to evaluate its safety and feasibility.

Of 74 asthma admissions over the 1-year pilot period, 22% of patients (n = 16) received continuous albuterol on the floor. Most of these (75%) received all their care on the floor (mean length of stay 30 hours), while those who deteriorated were transferred to the PICU; four additional cases were transferred directly from the ED to the PICU. In only two cases transferred from the community to children’s hospital did patients require care beyond continuous albuterol.

Dr. Hofmann noted that while more community hospitals are administering continuous albuterol outside the PICU, it was important to consider the benefits or drawbacks on a case-by-case basis.

A community hospital has the advantage of “not dealing with all the different layers of physicians involved in care” in a children’s hospital, Dr. Hofmann said in an interview. “Our costs are lower, in part due to shorter length of stay, but also we have a different cost structure. It’s a small self-contained unit, and our facilities are closer to home for many families.”

However, she said, the continuous albuterol intermediate-care protocol may not suit all community hospitals. “There are significant differences in personnel, facilities, and diagnostic and treatment capabilities from hospital to hospital; there’s no set criteria that will apply at every institution for intermediate care,” Dr. Hofmann said. The feasibility of appropriate staffing and continuous monitoring capabilities and the cost-benefit of achieving these in a lower-volume program are important considerations.

Hospitals should consider “what your baseline transfer rate is, and the kinds of patients you’re already seeing. Are you really going to be able to improve it that much, to provide the extra infrastructure and work to develop this process? Will you capture that many more patients?”

Offering intermediate-care services such as continuous albuterol, which can be billed at a higher level of care, is one way to help make community hospitals’ pediatric programs more sustainable. “We tend to operate in the red,” Dr. Hofmann said, because “pediatrics is not a high revenue earner for a facility. Moving to these intermediate-level care options and figuring out what is safe and what we can keep in the community hospital is really important to us – this is just one example of ways we could do that.”

Dr. Hofmann noted as a limitation of her study the low patient volume and the fact that some asthma patients may have been transferred from the community hospital’s ED to the children’s hospital year over year, and these were only captured during the pilot study, though it may be that ED transfer rates are decreasing as well as a result of the protocol.

The meeting was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine, and the Academic Pediatric Association. Dr. Hofmann reported no outside funding for her study or conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – More community hospitals are offering continuous albuterol to pediatric patients as an intermediate-care service, a level of care that’s higher than usual for the pediatric ward, but not as high as in pediatric intensive care units, according to Dr. Michelle Hofmann.

A 2014 study established that continuous albuterol can be initiated safely in the nonintensive pediatric care setting, but not all hospitals have followed suit (Pediatrics 2014;134[4]:e976-82).

At the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2015 meeting, Dr. Hofmann, a pediatric hospitalist with the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and the Riverton (Utah) Hospital, presented findings from a study she conducted to determine whether initiating continuous albuterol outside the PICU was worthwhile, safe, and feasible in her own community hospital. She found that it was.

“When we looked at the patients we were transferring to the PICU, nothing else was happening to them – all they were getting was continuous albuterol once they got there,” Dr. Hofmann said at the conference. “And we thought, ‘we [hospitalists] are on site 24/7. How do we capitalize on our resource?”

Dr. Hofmann and her colleagues first conducted a 1-year pilot study of pediatric asthma admissions (n = 76) at Primary Children’s Hospital in Salt Lake City, which like Riverton is part of the Intermountain Healthcare network. There, children were treated with continuous albuterol in the PICU only. Dr. Hofmann and her colleagues found that most children required no additional resources beyond continuous albuterol once they were admitted to the PICU from either the floor or the emergency department.

Moreover, patients classified as severe who got started on continuous albuterol in the ED and went right to the PICU did better than those who got admitted to the floor, were given intermittent albuterol, deteriorated, and then were transferred to intensive care, Dr. Hofmann said. This indicated that best practice was not occurring, even at the children’s hospital.

Dr. Hofmann and her colleagues then developed a protocol for her community hospital in which children presenting with asthma could be started on continuous albuterol in the emergency department or on the ward. She set up a pilot study to evaluate its safety and feasibility.

Of 74 asthma admissions over the 1-year pilot period, 22% of patients (n = 16) received continuous albuterol on the floor. Most of these (75%) received all their care on the floor (mean length of stay 30 hours), while those who deteriorated were transferred to the PICU; four additional cases were transferred directly from the ED to the PICU. In only two cases transferred from the community to children’s hospital did patients require care beyond continuous albuterol.

Dr. Hofmann noted that while more community hospitals are administering continuous albuterol outside the PICU, it was important to consider the benefits or drawbacks on a case-by-case basis.

A community hospital has the advantage of “not dealing with all the different layers of physicians involved in care” in a children’s hospital, Dr. Hofmann said in an interview. “Our costs are lower, in part due to shorter length of stay, but also we have a different cost structure. It’s a small self-contained unit, and our facilities are closer to home for many families.”

However, she said, the continuous albuterol intermediate-care protocol may not suit all community hospitals. “There are significant differences in personnel, facilities, and diagnostic and treatment capabilities from hospital to hospital; there’s no set criteria that will apply at every institution for intermediate care,” Dr. Hofmann said. The feasibility of appropriate staffing and continuous monitoring capabilities and the cost-benefit of achieving these in a lower-volume program are important considerations.

Hospitals should consider “what your baseline transfer rate is, and the kinds of patients you’re already seeing. Are you really going to be able to improve it that much, to provide the extra infrastructure and work to develop this process? Will you capture that many more patients?”

Offering intermediate-care services such as continuous albuterol, which can be billed at a higher level of care, is one way to help make community hospitals’ pediatric programs more sustainable. “We tend to operate in the red,” Dr. Hofmann said, because “pediatrics is not a high revenue earner for a facility. Moving to these intermediate-level care options and figuring out what is safe and what we can keep in the community hospital is really important to us – this is just one example of ways we could do that.”

Dr. Hofmann noted as a limitation of her study the low patient volume and the fact that some asthma patients may have been transferred from the community hospital’s ED to the children’s hospital year over year, and these were only captured during the pilot study, though it may be that ED transfer rates are decreasing as well as a result of the protocol.

The meeting was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine, and the Academic Pediatric Association. Dr. Hofmann reported no outside funding for her study or conflicts of interest.

AT PEDIATRIC HOSPITAL MEDICINE 2015

Key clinical point:With proper protocols, community hospitals can safely offer continuous albuterol in pediatric wards instead of mandating transfer to PICUs.

Major finding: Of 74 pediatric asthma admissions over a 12-month period, 22% of patients (n = 16) received continuous albuterol on the floor, with 75% receiving all their care on the floor. Most cases transferred to PICUs received no further care beyond continuous albuterol.

Data source: A single-site study at a community hospital, with comparison data also collected from a network-associated children’s hospital.

Disclosures: Dr. Hofmann had no relevant financial disclosures.

Blood Cultures Contribute Little to Uncomplicated SSTI Treatment

SAN ANTONIO – Despite mounting evidence that blood cultures don’t contribute to the care of immunocompetent children admitted to the hospital with uncomplicated skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs), they continue to be performed routinely in some hospitals, according to a study presented at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2015 meeting.

Current practice guidelines recommend against routine use of blood cultures in uncomplicated SSTIs (Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):e10-52).

A 2013 study of children admitted for uncomplicated SSTIs (n = 482) found no positive blood cultures in the cohort, and cultures were also associated with a significantly longer length of stay. More than half of those children, however, had received antibiotics before their blood cultures, leaving open the possibility that some negative results were the result of treatment with antibiotics (Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):454-9).

Dr. Claudette Gonzalez and her colleagues at Nicklaus Children’s Hospital, Miami, presented findings from a study that used a cohort of otherwise healthy infants and children (n = 176) admitted from the emergency department with uncomplicated SSTIs.

Dr. Gonzalez and her associates sought to strengthen the evidence against routine use of cultures by excluding children who had received antibiotics within 2 weeks of presenting to the hospital.Dr. Gonzalez noted that, despite guidelines, blood cultures remained a routine part of the workup at her hospital, with 66% of the study sample receiving cultures (n = 116). Of febrile patients, 80% received cultures; of nonfebrile patients, 59% received cultures. Patients who had a blood culture drawn were significantly more likely to have had fever (P < .01). They also were more likely to have higher white blood cell and C-reactive protein (CRP) counts (P > .05 for both), but despite this, the rate of positive blood cultures was still less than 1%.

Of the 116 blood cultures drawn, 5 grew contaminants and only 1 was a true positive, for methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA).

The study, unlike most previous studies, enrolled patients younger than 1 year of age (n = 28), but Dr. Gonzalez said that “we don’t have a big enough sample to really make conclusions about that age group.” Also in contrast to some previous studies, Dr. Gonzalez and her associates did not find a statistically significant difference in length of stay between the patients who had received cultures and those that did not (mean 3.62 vs. 3.4 days, P > .05).The one patient in the study with true bacteremia was a 1.4-year-old child presenting with no fever, cellulitis of hands and feet, no lymphangitis, and a white blood count of 8.5 × 103/L and a CRP of less than 0.5 mg/dL. “The WBC count was within normal range and the CRP was not elevated, so you wouldn’t have necessarily picked this kid out to say he needs a blood culture,” Dr. Gonzalez said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Still, she said, the study strengthens the evidence base against use of blood cultures in this population. “For children 1 year and older I think it’s very clear,” she said. The investigators are now proceeding with an implementation study to determine whether guidance against routine blood cultures should be put into practice at their institution.

Although the initial study revealed that 66% of children with uncomplicated SSTIs were receiving cultures, preliminary unpublished results show “it’s now at about 44%,” she said, following education of residents, fellows, and ED clinicians.

In addition to communicating with the ED to reduce use of blood cultures in this population, Dr. Gonzalez said, “we’re getting guidelines plugged into our order set in the [electronic medical record], so that’s a second reminder not to draw blood cultures. And we’re measuring to see if our rates improve further.”

Dr. Gonzalez received no outside funding for her study and disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – Despite mounting evidence that blood cultures don’t contribute to the care of immunocompetent children admitted to the hospital with uncomplicated skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs), they continue to be performed routinely in some hospitals, according to a study presented at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2015 meeting.

Current practice guidelines recommend against routine use of blood cultures in uncomplicated SSTIs (Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):e10-52).

A 2013 study of children admitted for uncomplicated SSTIs (n = 482) found no positive blood cultures in the cohort, and cultures were also associated with a significantly longer length of stay. More than half of those children, however, had received antibiotics before their blood cultures, leaving open the possibility that some negative results were the result of treatment with antibiotics (Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):454-9).

Dr. Claudette Gonzalez and her colleagues at Nicklaus Children’s Hospital, Miami, presented findings from a study that used a cohort of otherwise healthy infants and children (n = 176) admitted from the emergency department with uncomplicated SSTIs.

Dr. Gonzalez and her associates sought to strengthen the evidence against routine use of cultures by excluding children who had received antibiotics within 2 weeks of presenting to the hospital.Dr. Gonzalez noted that, despite guidelines, blood cultures remained a routine part of the workup at her hospital, with 66% of the study sample receiving cultures (n = 116). Of febrile patients, 80% received cultures; of nonfebrile patients, 59% received cultures. Patients who had a blood culture drawn were significantly more likely to have had fever (P < .01). They also were more likely to have higher white blood cell and C-reactive protein (CRP) counts (P > .05 for both), but despite this, the rate of positive blood cultures was still less than 1%.

Of the 116 blood cultures drawn, 5 grew contaminants and only 1 was a true positive, for methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA).

The study, unlike most previous studies, enrolled patients younger than 1 year of age (n = 28), but Dr. Gonzalez said that “we don’t have a big enough sample to really make conclusions about that age group.” Also in contrast to some previous studies, Dr. Gonzalez and her associates did not find a statistically significant difference in length of stay between the patients who had received cultures and those that did not (mean 3.62 vs. 3.4 days, P > .05).The one patient in the study with true bacteremia was a 1.4-year-old child presenting with no fever, cellulitis of hands and feet, no lymphangitis, and a white blood count of 8.5 × 103/L and a CRP of less than 0.5 mg/dL. “The WBC count was within normal range and the CRP was not elevated, so you wouldn’t have necessarily picked this kid out to say he needs a blood culture,” Dr. Gonzalez said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Still, she said, the study strengthens the evidence base against use of blood cultures in this population. “For children 1 year and older I think it’s very clear,” she said. The investigators are now proceeding with an implementation study to determine whether guidance against routine blood cultures should be put into practice at their institution.

Although the initial study revealed that 66% of children with uncomplicated SSTIs were receiving cultures, preliminary unpublished results show “it’s now at about 44%,” she said, following education of residents, fellows, and ED clinicians.

In addition to communicating with the ED to reduce use of blood cultures in this population, Dr. Gonzalez said, “we’re getting guidelines plugged into our order set in the [electronic medical record], so that’s a second reminder not to draw blood cultures. And we’re measuring to see if our rates improve further.”

Dr. Gonzalez received no outside funding for her study and disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – Despite mounting evidence that blood cultures don’t contribute to the care of immunocompetent children admitted to the hospital with uncomplicated skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs), they continue to be performed routinely in some hospitals, according to a study presented at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2015 meeting.

Current practice guidelines recommend against routine use of blood cultures in uncomplicated SSTIs (Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):e10-52).

A 2013 study of children admitted for uncomplicated SSTIs (n = 482) found no positive blood cultures in the cohort, and cultures were also associated with a significantly longer length of stay. More than half of those children, however, had received antibiotics before their blood cultures, leaving open the possibility that some negative results were the result of treatment with antibiotics (Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):454-9).

Dr. Claudette Gonzalez and her colleagues at Nicklaus Children’s Hospital, Miami, presented findings from a study that used a cohort of otherwise healthy infants and children (n = 176) admitted from the emergency department with uncomplicated SSTIs.

Dr. Gonzalez and her associates sought to strengthen the evidence against routine use of cultures by excluding children who had received antibiotics within 2 weeks of presenting to the hospital.Dr. Gonzalez noted that, despite guidelines, blood cultures remained a routine part of the workup at her hospital, with 66% of the study sample receiving cultures (n = 116). Of febrile patients, 80% received cultures; of nonfebrile patients, 59% received cultures. Patients who had a blood culture drawn were significantly more likely to have had fever (P < .01). They also were more likely to have higher white blood cell and C-reactive protein (CRP) counts (P > .05 for both), but despite this, the rate of positive blood cultures was still less than 1%.

Of the 116 blood cultures drawn, 5 grew contaminants and only 1 was a true positive, for methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA).

The study, unlike most previous studies, enrolled patients younger than 1 year of age (n = 28), but Dr. Gonzalez said that “we don’t have a big enough sample to really make conclusions about that age group.” Also in contrast to some previous studies, Dr. Gonzalez and her associates did not find a statistically significant difference in length of stay between the patients who had received cultures and those that did not (mean 3.62 vs. 3.4 days, P > .05).The one patient in the study with true bacteremia was a 1.4-year-old child presenting with no fever, cellulitis of hands and feet, no lymphangitis, and a white blood count of 8.5 × 103/L and a CRP of less than 0.5 mg/dL. “The WBC count was within normal range and the CRP was not elevated, so you wouldn’t have necessarily picked this kid out to say he needs a blood culture,” Dr. Gonzalez said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Still, she said, the study strengthens the evidence base against use of blood cultures in this population. “For children 1 year and older I think it’s very clear,” she said. The investigators are now proceeding with an implementation study to determine whether guidance against routine blood cultures should be put into practice at their institution.

Although the initial study revealed that 66% of children with uncomplicated SSTIs were receiving cultures, preliminary unpublished results show “it’s now at about 44%,” she said, following education of residents, fellows, and ED clinicians.

In addition to communicating with the ED to reduce use of blood cultures in this population, Dr. Gonzalez said, “we’re getting guidelines plugged into our order set in the [electronic medical record], so that’s a second reminder not to draw blood cultures. And we’re measuring to see if our rates improve further.”

Dr. Gonzalez received no outside funding for her study and disclosed no conflicts of interest.

AT PEDIATRIC HOSPITAL MEDICINE 2015

Blood cultures contribute little to uncomplicated SSTI treatment

SAN ANTONIO – Despite mounting evidence that blood cultures don’t contribute to the care of immunocompetent children admitted to the hospital with uncomplicated skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs), they continue to be performed routinely in some hospitals, according to a study presented at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2015 meeting.

Current practice guidelines recommend against routine use of blood cultures in uncomplicated SSTIs (Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):e10-52).

A 2013 study of children admitted for uncomplicated SSTIs (n = 482) found no positive blood cultures in the cohort, and cultures were also associated with a significantly longer length of stay. More than half of those children, however, had received antibiotics before their blood cultures, leaving open the possibility that some negative results were the result of treatment with antibiotics (Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):454-9).

Dr. Claudette Gonzalez and her colleagues at Nicklaus Children’s Hospital, Miami, presented findings from a study that used a cohort of otherwise healthy infants and children (n = 176) admitted from the emergency department with uncomplicated SSTIs.

Dr. Gonzalez and her associates sought to strengthen the evidence against routine use of cultures by excluding children who had received antibiotics within 2 weeks of presenting to the hospital.Dr. Gonzalez noted that, despite guidelines, blood cultures remained a routine part of the workup at her hospital, with 66% of the study sample receiving cultures (n = 116). Of febrile patients, 80% received cultures; of nonfebrile patients, 59% received cultures. Patients who had a blood culture drawn were significantly more likely to have had fever (P < .01). They also were more likely to have higher white blood cell and C-reactive protein (CRP) counts (P > .05 for both), but despite this, the rate of positive blood cultures was still less than 1%.

Of the 116 blood cultures drawn, 5 grew contaminants and only 1 was a true positive, for methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA).

The study, unlike most previous studies, enrolled patients younger than 1 year of age (n = 28), but Dr. Gonzalez said that “we don’t have a big enough sample to really make conclusions about that age group.” Also in contrast to some previous studies, Dr. Gonzalez and her associates did not find a statistically significant difference in length of stay between the patients who had received cultures and those that did not (mean 3.62 vs. 3.4 days, P > .05).The one patient in the study with true bacteremia was a 1.4-year-old child presenting with no fever, cellulitis of hands and feet, no lymphangitis, and a white blood count of 8.5 × 103/L and a CRP of less than 0.5 mg/dL. “The WBC count was within normal range and the CRP was not elevated, so you wouldn’t have necessarily picked this kid out to say he needs a blood culture,” Dr. Gonzalez said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Still, she said, the study strengthens the evidence base against use of blood cultures in this population. “For children 1 year and older I think it’s very clear,” she said. The investigators are now proceeding with an implementation study to determine whether guidance against routine blood cultures should be put into practice at their institution.

Although the initial study revealed that 66% of children with uncomplicated SSTIs were receiving cultures, preliminary unpublished results show “it’s now at about 44%,” she said, following education of residents, fellows, and ED clinicians.

In addition to communicating with the ED to reduce use of blood cultures in this population, Dr. Gonzalez said, “we’re getting guidelines plugged into our order set in the [electronic medical record], so that’s a second reminder not to draw blood cultures. And we’re measuring to see if our rates improve further.”

Dr. Gonzalez received no outside funding for her study and disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – Despite mounting evidence that blood cultures don’t contribute to the care of immunocompetent children admitted to the hospital with uncomplicated skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs), they continue to be performed routinely in some hospitals, according to a study presented at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2015 meeting.

Current practice guidelines recommend against routine use of blood cultures in uncomplicated SSTIs (Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):e10-52).

A 2013 study of children admitted for uncomplicated SSTIs (n = 482) found no positive blood cultures in the cohort, and cultures were also associated with a significantly longer length of stay. More than half of those children, however, had received antibiotics before their blood cultures, leaving open the possibility that some negative results were the result of treatment with antibiotics (Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):454-9).

Dr. Claudette Gonzalez and her colleagues at Nicklaus Children’s Hospital, Miami, presented findings from a study that used a cohort of otherwise healthy infants and children (n = 176) admitted from the emergency department with uncomplicated SSTIs.

Dr. Gonzalez and her associates sought to strengthen the evidence against routine use of cultures by excluding children who had received antibiotics within 2 weeks of presenting to the hospital.Dr. Gonzalez noted that, despite guidelines, blood cultures remained a routine part of the workup at her hospital, with 66% of the study sample receiving cultures (n = 116). Of febrile patients, 80% received cultures; of nonfebrile patients, 59% received cultures. Patients who had a blood culture drawn were significantly more likely to have had fever (P < .01). They also were more likely to have higher white blood cell and C-reactive protein (CRP) counts (P > .05 for both), but despite this, the rate of positive blood cultures was still less than 1%.

Of the 116 blood cultures drawn, 5 grew contaminants and only 1 was a true positive, for methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA).

The study, unlike most previous studies, enrolled patients younger than 1 year of age (n = 28), but Dr. Gonzalez said that “we don’t have a big enough sample to really make conclusions about that age group.” Also in contrast to some previous studies, Dr. Gonzalez and her associates did not find a statistically significant difference in length of stay between the patients who had received cultures and those that did not (mean 3.62 vs. 3.4 days, P > .05).The one patient in the study with true bacteremia was a 1.4-year-old child presenting with no fever, cellulitis of hands and feet, no lymphangitis, and a white blood count of 8.5 × 103/L and a CRP of less than 0.5 mg/dL. “The WBC count was within normal range and the CRP was not elevated, so you wouldn’t have necessarily picked this kid out to say he needs a blood culture,” Dr. Gonzalez said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Still, she said, the study strengthens the evidence base against use of blood cultures in this population. “For children 1 year and older I think it’s very clear,” she said. The investigators are now proceeding with an implementation study to determine whether guidance against routine blood cultures should be put into practice at their institution.