User login

Jornay PM improves classroom functioning in ADHD

SEATTLE – A novel formulation of methylphenidate could provide morning relief to pediatric patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, according to results of a pivotal phase 3 classroom trial.

In the study, delayed release/extended release methylphenidate (DR/ER MPH), when taken the night before, improved ADHD symptoms throughout a 12-hour laboratory classroom period – including in the late afternoons and early mornings.

The formulation, also known as Jornay PM, received Food and Drug Administration approval for ADHD in August for patients aged 6 and older. “For kids who have a horrendous time in the morning, getting up out of bed, and getting ready for school, they get up and they’re ready to rock and roll. [The drug] makes the mornings go better,” Ann Childress, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

In a previous phase 3 trial, DR/ER MPH proved beneficial in late afternoon and early morning symptoms in a naturalistic sample over a 3- week treatment course (J Child Adolesc Pharmacol. 2017 Aug 1;27[6]:474-82). The current work sought to show its value in a classroom setting. And in yet another earlier survey, 77% of parents rated early morning functional impairment in children with ADHD as moderate to severe (J Child Adolesc Pharmacol. 2017 Oct 1;27[8]:715-22).

“,” said Dr. Childress, president of the Center for Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine in Las Vegas.

In the current study, presented by Dr. Childress at the meeting, 117 children aged 6-12 years with ADHD and morning behavioral problems, after a 5-day washout period, were started on an evening DR/ER MPH dose of 20 mg or 40 mg. They were then seen for up to 4 more weeks, and doses optimized (maximum 100 mg/day).

Adjustments also were made in the evening dose schedule to determine an optimal dosing time, which had to range from 6:30 pm to 9:30 pm, at least 1 hour after dinner. Clinicians optimized the dose and timing to achieve maximum symptom control throughout the day (minimum 30% improvement in total symptom score from baseline), while remaining safe and well-tolerated.The participants were then randomized to maintain the current drug dose, or to switch to placebo for 1 week. The primary endpoint was the average of all post-dose SKAMP-CS (Swanson, Kotkin, Agler, M-Flynn, and Pelham combined scale) measurements, as recorded by a trained, independent observer during the 12-hour period on the last classroom day.

There was a significant improvement in the primary measure, with the treatment group averaging 14.8 on the SKAMP-CS, compared with 20.7 for the placebo group (P less than .001). The improved outcomes were steady throughout the day, failing to achieve statistical significance at 8 a.m., but achieving significance in measurements taken at 9 a.m.,10 a.m., 12 p.m., 2 pm, 4 p.m., 6 p.m., and 7 p.m.

The formulation also achieved significant difference in morning and late afternoon measurements of the Parent Rating of Evening and Morning Behavior Scale, Revised (PREMB-R AM and PREMB-R PM). The treatment group scored a mean of 0.9 on PREMB-R AM, compared with 2.7 for placebo (P less than .001), and 6.1 vs. 9.3 in the PREMB-R PM scale (P = .003).

Most treatment emergent adverse events were considered mild or moderate, and occurred in 36.9% of the treatment group and 40.7% of placebo subjects.

The study was funded by Ironshore Pharmaceuticals, which said in a press statement that it plans to launch the drug early next year. In addition to Ironshore, Dr. Childress has served on the advisory board for, consulted for, or received research support from Aevi Genomic Medicine, Akili Interactive, Alcobra, Arbor Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, Forest Laboratories, Lundbeck, KemPharm, Neos Therapeutics, Noven Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Pearson, Pfizer, Purdue Pharma, Rhodes Pharmaceuticals, Shire, Sunovion, and Tris Pharma.

SEATTLE – A novel formulation of methylphenidate could provide morning relief to pediatric patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, according to results of a pivotal phase 3 classroom trial.

In the study, delayed release/extended release methylphenidate (DR/ER MPH), when taken the night before, improved ADHD symptoms throughout a 12-hour laboratory classroom period – including in the late afternoons and early mornings.

The formulation, also known as Jornay PM, received Food and Drug Administration approval for ADHD in August for patients aged 6 and older. “For kids who have a horrendous time in the morning, getting up out of bed, and getting ready for school, they get up and they’re ready to rock and roll. [The drug] makes the mornings go better,” Ann Childress, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

In a previous phase 3 trial, DR/ER MPH proved beneficial in late afternoon and early morning symptoms in a naturalistic sample over a 3- week treatment course (J Child Adolesc Pharmacol. 2017 Aug 1;27[6]:474-82). The current work sought to show its value in a classroom setting. And in yet another earlier survey, 77% of parents rated early morning functional impairment in children with ADHD as moderate to severe (J Child Adolesc Pharmacol. 2017 Oct 1;27[8]:715-22).

“,” said Dr. Childress, president of the Center for Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine in Las Vegas.

In the current study, presented by Dr. Childress at the meeting, 117 children aged 6-12 years with ADHD and morning behavioral problems, after a 5-day washout period, were started on an evening DR/ER MPH dose of 20 mg or 40 mg. They were then seen for up to 4 more weeks, and doses optimized (maximum 100 mg/day).

Adjustments also were made in the evening dose schedule to determine an optimal dosing time, which had to range from 6:30 pm to 9:30 pm, at least 1 hour after dinner. Clinicians optimized the dose and timing to achieve maximum symptom control throughout the day (minimum 30% improvement in total symptom score from baseline), while remaining safe and well-tolerated.The participants were then randomized to maintain the current drug dose, or to switch to placebo for 1 week. The primary endpoint was the average of all post-dose SKAMP-CS (Swanson, Kotkin, Agler, M-Flynn, and Pelham combined scale) measurements, as recorded by a trained, independent observer during the 12-hour period on the last classroom day.

There was a significant improvement in the primary measure, with the treatment group averaging 14.8 on the SKAMP-CS, compared with 20.7 for the placebo group (P less than .001). The improved outcomes were steady throughout the day, failing to achieve statistical significance at 8 a.m., but achieving significance in measurements taken at 9 a.m.,10 a.m., 12 p.m., 2 pm, 4 p.m., 6 p.m., and 7 p.m.

The formulation also achieved significant difference in morning and late afternoon measurements of the Parent Rating of Evening and Morning Behavior Scale, Revised (PREMB-R AM and PREMB-R PM). The treatment group scored a mean of 0.9 on PREMB-R AM, compared with 2.7 for placebo (P less than .001), and 6.1 vs. 9.3 in the PREMB-R PM scale (P = .003).

Most treatment emergent adverse events were considered mild or moderate, and occurred in 36.9% of the treatment group and 40.7% of placebo subjects.

The study was funded by Ironshore Pharmaceuticals, which said in a press statement that it plans to launch the drug early next year. In addition to Ironshore, Dr. Childress has served on the advisory board for, consulted for, or received research support from Aevi Genomic Medicine, Akili Interactive, Alcobra, Arbor Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, Forest Laboratories, Lundbeck, KemPharm, Neos Therapeutics, Noven Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Pearson, Pfizer, Purdue Pharma, Rhodes Pharmaceuticals, Shire, Sunovion, and Tris Pharma.

SEATTLE – A novel formulation of methylphenidate could provide morning relief to pediatric patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, according to results of a pivotal phase 3 classroom trial.

In the study, delayed release/extended release methylphenidate (DR/ER MPH), when taken the night before, improved ADHD symptoms throughout a 12-hour laboratory classroom period – including in the late afternoons and early mornings.

The formulation, also known as Jornay PM, received Food and Drug Administration approval for ADHD in August for patients aged 6 and older. “For kids who have a horrendous time in the morning, getting up out of bed, and getting ready for school, they get up and they’re ready to rock and roll. [The drug] makes the mornings go better,” Ann Childress, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

In a previous phase 3 trial, DR/ER MPH proved beneficial in late afternoon and early morning symptoms in a naturalistic sample over a 3- week treatment course (J Child Adolesc Pharmacol. 2017 Aug 1;27[6]:474-82). The current work sought to show its value in a classroom setting. And in yet another earlier survey, 77% of parents rated early morning functional impairment in children with ADHD as moderate to severe (J Child Adolesc Pharmacol. 2017 Oct 1;27[8]:715-22).

“,” said Dr. Childress, president of the Center for Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine in Las Vegas.

In the current study, presented by Dr. Childress at the meeting, 117 children aged 6-12 years with ADHD and morning behavioral problems, after a 5-day washout period, were started on an evening DR/ER MPH dose of 20 mg or 40 mg. They were then seen for up to 4 more weeks, and doses optimized (maximum 100 mg/day).

Adjustments also were made in the evening dose schedule to determine an optimal dosing time, which had to range from 6:30 pm to 9:30 pm, at least 1 hour after dinner. Clinicians optimized the dose and timing to achieve maximum symptom control throughout the day (minimum 30% improvement in total symptom score from baseline), while remaining safe and well-tolerated.The participants were then randomized to maintain the current drug dose, or to switch to placebo for 1 week. The primary endpoint was the average of all post-dose SKAMP-CS (Swanson, Kotkin, Agler, M-Flynn, and Pelham combined scale) measurements, as recorded by a trained, independent observer during the 12-hour period on the last classroom day.

There was a significant improvement in the primary measure, with the treatment group averaging 14.8 on the SKAMP-CS, compared with 20.7 for the placebo group (P less than .001). The improved outcomes were steady throughout the day, failing to achieve statistical significance at 8 a.m., but achieving significance in measurements taken at 9 a.m.,10 a.m., 12 p.m., 2 pm, 4 p.m., 6 p.m., and 7 p.m.

The formulation also achieved significant difference in morning and late afternoon measurements of the Parent Rating of Evening and Morning Behavior Scale, Revised (PREMB-R AM and PREMB-R PM). The treatment group scored a mean of 0.9 on PREMB-R AM, compared with 2.7 for placebo (P less than .001), and 6.1 vs. 9.3 in the PREMB-R PM scale (P = .003).

Most treatment emergent adverse events were considered mild or moderate, and occurred in 36.9% of the treatment group and 40.7% of placebo subjects.

The study was funded by Ironshore Pharmaceuticals, which said in a press statement that it plans to launch the drug early next year. In addition to Ironshore, Dr. Childress has served on the advisory board for, consulted for, or received research support from Aevi Genomic Medicine, Akili Interactive, Alcobra, Arbor Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, Forest Laboratories, Lundbeck, KemPharm, Neos Therapeutics, Noven Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Pearson, Pfizer, Purdue Pharma, Rhodes Pharmaceuticals, Shire, Sunovion, and Tris Pharma.

REPORTING FROM AACAP 2018

Key clinical point: Children who took the formulation experienced improved, steady outcomes throughout the day.

Major finding: The treatment group scored an average of 0.9 on the PREMB-R morning test, compared with 2.7 in the placebo group.

Study details: Randomized, controlled trial involving 117 patients.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Ironshore Pharmaceuticals, which said in a press statement that it plans to launch the drug early next year. In addition to Ironshore, Dr. Childress has served on the advisory board for, consulted for, or received research support from Aevi Genomic Medicine, Akili Interactive, Alcobra, Arbor Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, Forest Laboratories, Lundbeck, KemPharm, Neos Therapeutics, Noven Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Pearson, Pfizer, Purdue Pharma, Rhodes Pharmaceuticals, Shire, Sunovion, and Tris Pharma.

Most perpetrators in school shootings brought guns from home

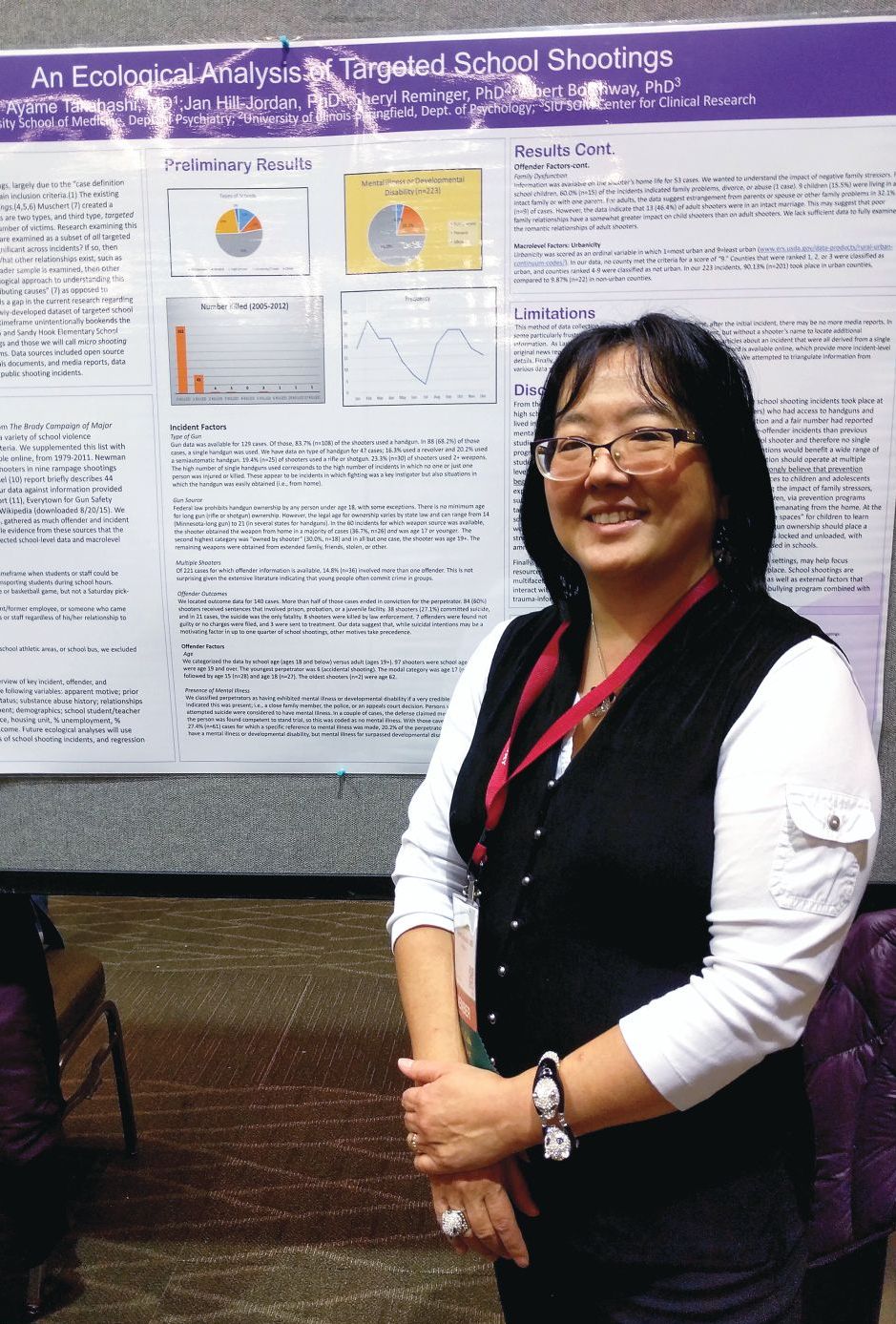

SEATTLE – A new analysis of all school shootings, including those with four or fewer victims, reinforces the need for prevention in the home by preventing guns from falling into unauthorized use.

The researchers examined 223 shootings in the United States that occurred during 2005-2012 and found that in more than a third of the 60 cases for which information was available, the perpetrator obtained the gun from the home and was aged 17 years or younger. Furthermore, evidence of mental illness in the shooter was rare.

The finding complements studies of “mass shootings,” which tend to garner headlines and more research attention, according to Ayame Takahashi, MD, who presented the findings at a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. “What we see in the news are the big rampage shootings, with multiple victims, where the target may be anyone they can get. You hear in little bits and pieces about the single-shooter incidents, which are way more common.

“We wanted to look at as many of these cases as we could find to look at the overall variables that might be behind these smaller school shootings, which are way more common,” said Dr. Takahashi, who is an assistant professor of psychiatry at Southern Illinois University Medicine, Springfield.

The researchers identified shootings using the data from the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence during 1997-2012, and supplemented it with listings found in “The Bully Society: School shootings and the crisis of bullying in America’s schools” (New York: NYU Press, 2013). Other sources included a study on rampage shootings in U.S. high school and college settings during 2002-2008; the Virginia Tech Review Panel report, a 2014 FBI report, the Everytown for Gun Safety website, and the list of school shootings on Wikipedia.

The analysis included incidents that had occurred on a school property, including school buses, at a time when students or staff would have been at risk. The offender could have been a current or former student or employee, or anyone who came onto the school property with the intent to harm students or staff.

The sample included 223 shootings. In 60 cases, the researchers found information about how guns were obtained, and in 37% of those cases, the source was the offender’s home and the offender was 17 years old or younger. In 30% of the cases, the shooter owned the gun, but in almost all these cases, the shooter was aged 19 years or older.

Sixty-one cases had information available about the presence or absence of mental illness in the offender. In 20% of these cases, the shooter was determined to have a mental illness or, rarely, a developmental disability.

The results suggest that mental illness might be rare among school shooters, and therefore, call into question efforts to limit gun ownership among people with mental illness. “It may be barking up the wrong tree,” Dr. Takahashi said.

Instead, she advocates more messaging of gun safety in the home, to prevent unauthorized use. Psychiatrists can help by discussing these issues with patients, but she also called for more community involvement and education about the issue.

“The people who come to you, they’re kind of in your court already. so that the message gets out there beyond the folks that we see in our offices,” she said.

Dr. Takahashi has no relevant disclosures.

SEATTLE – A new analysis of all school shootings, including those with four or fewer victims, reinforces the need for prevention in the home by preventing guns from falling into unauthorized use.

The researchers examined 223 shootings in the United States that occurred during 2005-2012 and found that in more than a third of the 60 cases for which information was available, the perpetrator obtained the gun from the home and was aged 17 years or younger. Furthermore, evidence of mental illness in the shooter was rare.

The finding complements studies of “mass shootings,” which tend to garner headlines and more research attention, according to Ayame Takahashi, MD, who presented the findings at a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. “What we see in the news are the big rampage shootings, with multiple victims, where the target may be anyone they can get. You hear in little bits and pieces about the single-shooter incidents, which are way more common.

“We wanted to look at as many of these cases as we could find to look at the overall variables that might be behind these smaller school shootings, which are way more common,” said Dr. Takahashi, who is an assistant professor of psychiatry at Southern Illinois University Medicine, Springfield.

The researchers identified shootings using the data from the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence during 1997-2012, and supplemented it with listings found in “The Bully Society: School shootings and the crisis of bullying in America’s schools” (New York: NYU Press, 2013). Other sources included a study on rampage shootings in U.S. high school and college settings during 2002-2008; the Virginia Tech Review Panel report, a 2014 FBI report, the Everytown for Gun Safety website, and the list of school shootings on Wikipedia.

The analysis included incidents that had occurred on a school property, including school buses, at a time when students or staff would have been at risk. The offender could have been a current or former student or employee, or anyone who came onto the school property with the intent to harm students or staff.

The sample included 223 shootings. In 60 cases, the researchers found information about how guns were obtained, and in 37% of those cases, the source was the offender’s home and the offender was 17 years old or younger. In 30% of the cases, the shooter owned the gun, but in almost all these cases, the shooter was aged 19 years or older.

Sixty-one cases had information available about the presence or absence of mental illness in the offender. In 20% of these cases, the shooter was determined to have a mental illness or, rarely, a developmental disability.

The results suggest that mental illness might be rare among school shooters, and therefore, call into question efforts to limit gun ownership among people with mental illness. “It may be barking up the wrong tree,” Dr. Takahashi said.

Instead, she advocates more messaging of gun safety in the home, to prevent unauthorized use. Psychiatrists can help by discussing these issues with patients, but she also called for more community involvement and education about the issue.

“The people who come to you, they’re kind of in your court already. so that the message gets out there beyond the folks that we see in our offices,” she said.

Dr. Takahashi has no relevant disclosures.

SEATTLE – A new analysis of all school shootings, including those with four or fewer victims, reinforces the need for prevention in the home by preventing guns from falling into unauthorized use.

The researchers examined 223 shootings in the United States that occurred during 2005-2012 and found that in more than a third of the 60 cases for which information was available, the perpetrator obtained the gun from the home and was aged 17 years or younger. Furthermore, evidence of mental illness in the shooter was rare.

The finding complements studies of “mass shootings,” which tend to garner headlines and more research attention, according to Ayame Takahashi, MD, who presented the findings at a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. “What we see in the news are the big rampage shootings, with multiple victims, where the target may be anyone they can get. You hear in little bits and pieces about the single-shooter incidents, which are way more common.

“We wanted to look at as many of these cases as we could find to look at the overall variables that might be behind these smaller school shootings, which are way more common,” said Dr. Takahashi, who is an assistant professor of psychiatry at Southern Illinois University Medicine, Springfield.

The researchers identified shootings using the data from the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence during 1997-2012, and supplemented it with listings found in “The Bully Society: School shootings and the crisis of bullying in America’s schools” (New York: NYU Press, 2013). Other sources included a study on rampage shootings in U.S. high school and college settings during 2002-2008; the Virginia Tech Review Panel report, a 2014 FBI report, the Everytown for Gun Safety website, and the list of school shootings on Wikipedia.

The analysis included incidents that had occurred on a school property, including school buses, at a time when students or staff would have been at risk. The offender could have been a current or former student or employee, or anyone who came onto the school property with the intent to harm students or staff.

The sample included 223 shootings. In 60 cases, the researchers found information about how guns were obtained, and in 37% of those cases, the source was the offender’s home and the offender was 17 years old or younger. In 30% of the cases, the shooter owned the gun, but in almost all these cases, the shooter was aged 19 years or older.

Sixty-one cases had information available about the presence or absence of mental illness in the offender. In 20% of these cases, the shooter was determined to have a mental illness or, rarely, a developmental disability.

The results suggest that mental illness might be rare among school shooters, and therefore, call into question efforts to limit gun ownership among people with mental illness. “It may be barking up the wrong tree,” Dr. Takahashi said.

Instead, she advocates more messaging of gun safety in the home, to prevent unauthorized use. Psychiatrists can help by discussing these issues with patients, but she also called for more community involvement and education about the issue.

“The people who come to you, they’re kind of in your court already. so that the message gets out there beyond the folks that we see in our offices,” she said.

Dr. Takahashi has no relevant disclosures.

REPORTING FROM AACAP 2018

Key clinical point: Psychiatrists can help by discussing gun safety with patients.

Major finding: About 20% of school shooters had a confirmed mental illness or developmental disability.

Study details: Analysis of 223 school shootings in the United States between 2005 and 2012.

Disclosures: Dr. Takahashi had no relevant disclosures.

DBT can help traumatized, suicidal youth manage emotions

SEATTLE – Children who are suicidal and victims of trauma, especially those with PTSD, pose an especially difficult challenge for psychiatrists. Trauma, suicidality, and self-harm often present together, and they might heighten the risk of treatment.

“It becomes a dilemma to know in what order to treat those symptoms, because sometimes it feels like one will not get better without treating the other,” said Michele Berk, PhD. “But there’s also some question around when it’s safe to do exposure-based treatments – which are the key ingredient to resolving PTSD symptoms,” Dr. Berk said during a session focused on trauma and suicidality in youth at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

Dialectical behavior therapy, or DBT, is an option. DBT was developed by Marsha M. Linehan, PhD, to treat chronic suicidality comorbid with borderline personality disorder. In addition to PTSD, newer work has shown DBT as efficacious for treating substance use disorders, depression, and eating disorders.

DBT is based on the idea that self-harm occurs, at least in some cases, because the patient is predisposed to experiencing heightened emotional reactions. When the patient is exposed to an invalidating environment, such as when a parent or caregiver tells them to “just get over it; you’re overreacting,” this can lead patients to question their emotions. Most importantly, patients never learn effective strategies to that manage their emotions, according to Dr. Berk, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford (Calif.) University.

In addition, Dr. Berk said, traumatized youth sometimes present with the most extreme form of invalidation, in which the patient’s entire being is violated through physical violence.

“So you have people who have these really intense negative emotions but don’t know how to help themselves manage them, and that is where DBT believes suicidal and self-harm behavior comes in,” Dr. Berk said. “We know that self-harm, though not suicidal self-injury, does in fact reduce emotion.”

DBT aims to counter suicidality by assisting the patient to build a life worth living. It encompasses five modes, including skills training, individual psychotherapy, in-the-moment coaching, case management, and a DBT consultation team to support the therapist.

The program prioritizes life-threatening behaviors in stage I and saving any exposure or PTSD therapy for stage II, which might begin up to 12 months later.

Also in stage I, after life-threatening behaviors have been resolved, the therapist addresses symptoms or factors that potentially interfere with further therapy. That’s important, because patients usually have comorbid symptoms and might be acutely distressed. “DBT has developed a clear hierarchy of how to target those things so that the sessions don’t get chaotic or off track,” Dr. Berk said.

Trauma symptoms might be tackled in stage I if they’re directly linked to suicidality or interfere with treatment, through reluctance to share information or because they might lead to dissociation during a session. After that, the program addresses quality of life, since its goal is to help patients create lives they deem worth living.

The skills training component of DBT includes mindfulness to help ground patients in the present moment. It also fosters skills that can be used to address trauma, including distress tolerance. Distress tolerance incorporates actions such as distraction and self-soothing. Emotional regulation seeks to help patients alter their emotions when possible. Interpersonal relationship skills help the patients ask for what they want and how to say “no” effectively.

Exposure therapy does not begin until patients have gone at least 2 months without any self-harming behavior, and it is interrupted if the patients exhibit self-harming behavior after it starts.

DBT remains a subject of continuing research. One avenue would be to more directly integrate exposure therapy with DBT in adolescents, but a protocol has not yet been developed. Prolonged exposure is typically used in adult PTSD patients, but trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy more often is the choice for adolescents.

Whatever the choice, involvement of caring adults would be key. “In adolescents, there’s a need to involve parents and caregivers in whatever the trauma treatment is going to be,” Dr. Berk said.

Dr. Berk disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SEATTLE – Children who are suicidal and victims of trauma, especially those with PTSD, pose an especially difficult challenge for psychiatrists. Trauma, suicidality, and self-harm often present together, and they might heighten the risk of treatment.

“It becomes a dilemma to know in what order to treat those symptoms, because sometimes it feels like one will not get better without treating the other,” said Michele Berk, PhD. “But there’s also some question around when it’s safe to do exposure-based treatments – which are the key ingredient to resolving PTSD symptoms,” Dr. Berk said during a session focused on trauma and suicidality in youth at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

Dialectical behavior therapy, or DBT, is an option. DBT was developed by Marsha M. Linehan, PhD, to treat chronic suicidality comorbid with borderline personality disorder. In addition to PTSD, newer work has shown DBT as efficacious for treating substance use disorders, depression, and eating disorders.

DBT is based on the idea that self-harm occurs, at least in some cases, because the patient is predisposed to experiencing heightened emotional reactions. When the patient is exposed to an invalidating environment, such as when a parent or caregiver tells them to “just get over it; you’re overreacting,” this can lead patients to question their emotions. Most importantly, patients never learn effective strategies to that manage their emotions, according to Dr. Berk, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford (Calif.) University.

In addition, Dr. Berk said, traumatized youth sometimes present with the most extreme form of invalidation, in which the patient’s entire being is violated through physical violence.

“So you have people who have these really intense negative emotions but don’t know how to help themselves manage them, and that is where DBT believes suicidal and self-harm behavior comes in,” Dr. Berk said. “We know that self-harm, though not suicidal self-injury, does in fact reduce emotion.”

DBT aims to counter suicidality by assisting the patient to build a life worth living. It encompasses five modes, including skills training, individual psychotherapy, in-the-moment coaching, case management, and a DBT consultation team to support the therapist.

The program prioritizes life-threatening behaviors in stage I and saving any exposure or PTSD therapy for stage II, which might begin up to 12 months later.

Also in stage I, after life-threatening behaviors have been resolved, the therapist addresses symptoms or factors that potentially interfere with further therapy. That’s important, because patients usually have comorbid symptoms and might be acutely distressed. “DBT has developed a clear hierarchy of how to target those things so that the sessions don’t get chaotic or off track,” Dr. Berk said.

Trauma symptoms might be tackled in stage I if they’re directly linked to suicidality or interfere with treatment, through reluctance to share information or because they might lead to dissociation during a session. After that, the program addresses quality of life, since its goal is to help patients create lives they deem worth living.

The skills training component of DBT includes mindfulness to help ground patients in the present moment. It also fosters skills that can be used to address trauma, including distress tolerance. Distress tolerance incorporates actions such as distraction and self-soothing. Emotional regulation seeks to help patients alter their emotions when possible. Interpersonal relationship skills help the patients ask for what they want and how to say “no” effectively.

Exposure therapy does not begin until patients have gone at least 2 months without any self-harming behavior, and it is interrupted if the patients exhibit self-harming behavior after it starts.

DBT remains a subject of continuing research. One avenue would be to more directly integrate exposure therapy with DBT in adolescents, but a protocol has not yet been developed. Prolonged exposure is typically used in adult PTSD patients, but trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy more often is the choice for adolescents.

Whatever the choice, involvement of caring adults would be key. “In adolescents, there’s a need to involve parents and caregivers in whatever the trauma treatment is going to be,” Dr. Berk said.

Dr. Berk disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SEATTLE – Children who are suicidal and victims of trauma, especially those with PTSD, pose an especially difficult challenge for psychiatrists. Trauma, suicidality, and self-harm often present together, and they might heighten the risk of treatment.

“It becomes a dilemma to know in what order to treat those symptoms, because sometimes it feels like one will not get better without treating the other,” said Michele Berk, PhD. “But there’s also some question around when it’s safe to do exposure-based treatments – which are the key ingredient to resolving PTSD symptoms,” Dr. Berk said during a session focused on trauma and suicidality in youth at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

Dialectical behavior therapy, or DBT, is an option. DBT was developed by Marsha M. Linehan, PhD, to treat chronic suicidality comorbid with borderline personality disorder. In addition to PTSD, newer work has shown DBT as efficacious for treating substance use disorders, depression, and eating disorders.

DBT is based on the idea that self-harm occurs, at least in some cases, because the patient is predisposed to experiencing heightened emotional reactions. When the patient is exposed to an invalidating environment, such as when a parent or caregiver tells them to “just get over it; you’re overreacting,” this can lead patients to question their emotions. Most importantly, patients never learn effective strategies to that manage their emotions, according to Dr. Berk, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford (Calif.) University.

In addition, Dr. Berk said, traumatized youth sometimes present with the most extreme form of invalidation, in which the patient’s entire being is violated through physical violence.

“So you have people who have these really intense negative emotions but don’t know how to help themselves manage them, and that is where DBT believes suicidal and self-harm behavior comes in,” Dr. Berk said. “We know that self-harm, though not suicidal self-injury, does in fact reduce emotion.”

DBT aims to counter suicidality by assisting the patient to build a life worth living. It encompasses five modes, including skills training, individual psychotherapy, in-the-moment coaching, case management, and a DBT consultation team to support the therapist.

The program prioritizes life-threatening behaviors in stage I and saving any exposure or PTSD therapy for stage II, which might begin up to 12 months later.

Also in stage I, after life-threatening behaviors have been resolved, the therapist addresses symptoms or factors that potentially interfere with further therapy. That’s important, because patients usually have comorbid symptoms and might be acutely distressed. “DBT has developed a clear hierarchy of how to target those things so that the sessions don’t get chaotic or off track,” Dr. Berk said.

Trauma symptoms might be tackled in stage I if they’re directly linked to suicidality or interfere with treatment, through reluctance to share information or because they might lead to dissociation during a session. After that, the program addresses quality of life, since its goal is to help patients create lives they deem worth living.

The skills training component of DBT includes mindfulness to help ground patients in the present moment. It also fosters skills that can be used to address trauma, including distress tolerance. Distress tolerance incorporates actions such as distraction and self-soothing. Emotional regulation seeks to help patients alter their emotions when possible. Interpersonal relationship skills help the patients ask for what they want and how to say “no” effectively.

Exposure therapy does not begin until patients have gone at least 2 months without any self-harming behavior, and it is interrupted if the patients exhibit self-harming behavior after it starts.

DBT remains a subject of continuing research. One avenue would be to more directly integrate exposure therapy with DBT in adolescents, but a protocol has not yet been developed. Prolonged exposure is typically used in adult PTSD patients, but trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy more often is the choice for adolescents.

Whatever the choice, involvement of caring adults would be key. “In adolescents, there’s a need to involve parents and caregivers in whatever the trauma treatment is going to be,” Dr. Berk said.

Dr. Berk disclosed no conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM AACAP 2018

OV-101 shows promise for Angelman syndrome

SEATTLE – A novel extrasynaptic gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)–receptor agonist called OV-101 was safe and well-tolerated in adult and adolescent Angelman syndrome patients in a 12-week phase 2 trial. In a secondary analysis, the treatment appeared to improve sleep.

Angelman syndrome is associated with a microdeletion on chromosome 15 encompassing the ubiquitin protein ligase E3a (UBE3A) gene. The resulting loss of expression of the UBE3A protein leads to increases in the uptake of GABA and reduces levels of extrasynaptic GABA. Patients with Angelman syndrome typically have motor dysfunction, often extreme: “These kids are very excitable, very active, and they have lots of trouble with sleep,” said Alex Kolevzon, MD, professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, in an interview.

Dr. Kolevzon presented the results at a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

The study was conducted at 12 sites in the United States and 1 in Israel. Ovid Pharmaceuticals plans to apply to the Food and Drug Administration later this year for approval. There is no existing drug for Angelman syndrome, and the study provided good safety reassurance. “There were some side effects, but for the most part we considered them mild, and only four (out of 88 subjects) discontinued because of side effects,” said Dr. Kolevzon.

The researchers used actigraphy to gain a more objective measure of sleep in the study participants. They randomized 88 patients with Angelman syndrome (aged 13-49 years) to receive placebo in the morning and 15 mg of OV-101 at night, 10 mg OVID-101 in the morning and 15 mg OVID-101 at night, or placebo both in the morning and at night.

Pyrexia occurred in 24% of the group who received the active drug only at night, 3% of the group given the twice-daily dose, and 7% of the placebo group. Seizures occurred in 7% of the once-daily group and 10% of the twice-daily group; seizures were not noted in the placebo group.

The main efficacy outcome measure was the Clinical Global Impressions-9 (CGI-9) scale. The once-daily group had a significant benefit in the sleep domain at 12 weeks, compared with placebo (difference, –0.77; P = .0141), but the twice-daily group had only a trend toward improvement in sleep (difference, –0.45; P = .1407).

Both active therapy groups had significant improvement in CGI-9 measures after 12 weeks of treatment compared to placebo – the twice-daily group (P = .0206, Fisher’s Exact Test) and the once-daily group (P = .0006, mixed model repeated measures analysis).

The actigraphy analysis, conducted in the 45% of patients who could tolerate its use, found that, compared to placebo, the once-daily dosing group experienced an 25.7 minute improvement in latency to sleep onset (P = .0147), as well an approximately 50 minute reduction in sleep time during the day, and a 3.65% improvement in sleep efficiency.

OV-101 has the potential to treat other conditions as well. “Obviously there are a lot of neurodevelopmental disorders where you see dysregulation between the GABAergic and glutamergic systems. This is a drug that has a unique effect on the GABAergic system. It’s already being studied in Fragile X syndrome, where we see this same kind of dysregulation and excess excitation,” said Dr. Kolevzon.

Dr. Kolevzon is a consultant for several drug companies including Ovid Therapeutics.

SOURCE: AACAP 2018. New Research Poster 3.1.

SEATTLE – A novel extrasynaptic gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)–receptor agonist called OV-101 was safe and well-tolerated in adult and adolescent Angelman syndrome patients in a 12-week phase 2 trial. In a secondary analysis, the treatment appeared to improve sleep.

Angelman syndrome is associated with a microdeletion on chromosome 15 encompassing the ubiquitin protein ligase E3a (UBE3A) gene. The resulting loss of expression of the UBE3A protein leads to increases in the uptake of GABA and reduces levels of extrasynaptic GABA. Patients with Angelman syndrome typically have motor dysfunction, often extreme: “These kids are very excitable, very active, and they have lots of trouble with sleep,” said Alex Kolevzon, MD, professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, in an interview.

Dr. Kolevzon presented the results at a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

The study was conducted at 12 sites in the United States and 1 in Israel. Ovid Pharmaceuticals plans to apply to the Food and Drug Administration later this year for approval. There is no existing drug for Angelman syndrome, and the study provided good safety reassurance. “There were some side effects, but for the most part we considered them mild, and only four (out of 88 subjects) discontinued because of side effects,” said Dr. Kolevzon.

The researchers used actigraphy to gain a more objective measure of sleep in the study participants. They randomized 88 patients with Angelman syndrome (aged 13-49 years) to receive placebo in the morning and 15 mg of OV-101 at night, 10 mg OVID-101 in the morning and 15 mg OVID-101 at night, or placebo both in the morning and at night.

Pyrexia occurred in 24% of the group who received the active drug only at night, 3% of the group given the twice-daily dose, and 7% of the placebo group. Seizures occurred in 7% of the once-daily group and 10% of the twice-daily group; seizures were not noted in the placebo group.

The main efficacy outcome measure was the Clinical Global Impressions-9 (CGI-9) scale. The once-daily group had a significant benefit in the sleep domain at 12 weeks, compared with placebo (difference, –0.77; P = .0141), but the twice-daily group had only a trend toward improvement in sleep (difference, –0.45; P = .1407).

Both active therapy groups had significant improvement in CGI-9 measures after 12 weeks of treatment compared to placebo – the twice-daily group (P = .0206, Fisher’s Exact Test) and the once-daily group (P = .0006, mixed model repeated measures analysis).

The actigraphy analysis, conducted in the 45% of patients who could tolerate its use, found that, compared to placebo, the once-daily dosing group experienced an 25.7 minute improvement in latency to sleep onset (P = .0147), as well an approximately 50 minute reduction in sleep time during the day, and a 3.65% improvement in sleep efficiency.

OV-101 has the potential to treat other conditions as well. “Obviously there are a lot of neurodevelopmental disorders where you see dysregulation between the GABAergic and glutamergic systems. This is a drug that has a unique effect on the GABAergic system. It’s already being studied in Fragile X syndrome, where we see this same kind of dysregulation and excess excitation,” said Dr. Kolevzon.

Dr. Kolevzon is a consultant for several drug companies including Ovid Therapeutics.

SOURCE: AACAP 2018. New Research Poster 3.1.

SEATTLE – A novel extrasynaptic gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)–receptor agonist called OV-101 was safe and well-tolerated in adult and adolescent Angelman syndrome patients in a 12-week phase 2 trial. In a secondary analysis, the treatment appeared to improve sleep.

Angelman syndrome is associated with a microdeletion on chromosome 15 encompassing the ubiquitin protein ligase E3a (UBE3A) gene. The resulting loss of expression of the UBE3A protein leads to increases in the uptake of GABA and reduces levels of extrasynaptic GABA. Patients with Angelman syndrome typically have motor dysfunction, often extreme: “These kids are very excitable, very active, and they have lots of trouble with sleep,” said Alex Kolevzon, MD, professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, in an interview.

Dr. Kolevzon presented the results at a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

The study was conducted at 12 sites in the United States and 1 in Israel. Ovid Pharmaceuticals plans to apply to the Food and Drug Administration later this year for approval. There is no existing drug for Angelman syndrome, and the study provided good safety reassurance. “There were some side effects, but for the most part we considered them mild, and only four (out of 88 subjects) discontinued because of side effects,” said Dr. Kolevzon.

The researchers used actigraphy to gain a more objective measure of sleep in the study participants. They randomized 88 patients with Angelman syndrome (aged 13-49 years) to receive placebo in the morning and 15 mg of OV-101 at night, 10 mg OVID-101 in the morning and 15 mg OVID-101 at night, or placebo both in the morning and at night.

Pyrexia occurred in 24% of the group who received the active drug only at night, 3% of the group given the twice-daily dose, and 7% of the placebo group. Seizures occurred in 7% of the once-daily group and 10% of the twice-daily group; seizures were not noted in the placebo group.

The main efficacy outcome measure was the Clinical Global Impressions-9 (CGI-9) scale. The once-daily group had a significant benefit in the sleep domain at 12 weeks, compared with placebo (difference, –0.77; P = .0141), but the twice-daily group had only a trend toward improvement in sleep (difference, –0.45; P = .1407).

Both active therapy groups had significant improvement in CGI-9 measures after 12 weeks of treatment compared to placebo – the twice-daily group (P = .0206, Fisher’s Exact Test) and the once-daily group (P = .0006, mixed model repeated measures analysis).

The actigraphy analysis, conducted in the 45% of patients who could tolerate its use, found that, compared to placebo, the once-daily dosing group experienced an 25.7 minute improvement in latency to sleep onset (P = .0147), as well an approximately 50 minute reduction in sleep time during the day, and a 3.65% improvement in sleep efficiency.

OV-101 has the potential to treat other conditions as well. “Obviously there are a lot of neurodevelopmental disorders where you see dysregulation between the GABAergic and glutamergic systems. This is a drug that has a unique effect on the GABAergic system. It’s already being studied in Fragile X syndrome, where we see this same kind of dysregulation and excess excitation,” said Dr. Kolevzon.

Dr. Kolevzon is a consultant for several drug companies including Ovid Therapeutics.

SOURCE: AACAP 2018. New Research Poster 3.1.

REPORTING FROM AACAP 2018

Key clinical point: A new drug may improve sleep outcomes in Angelman Syndrome.

Major finding: Patients who received a single daily dose of OV-101 scored better than study participants given placebo on the Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement scale.

Study details: Randomized, controlled phase 2 trial (n = 88).

Disclosures: The study was funded by Ovid Therapeutics. Dr. Kolevzon is a consultant for Ovid Therapeutics and several other drug companies.

Source: AACAP 2018 New Research Poster 3.1. .

Mindfulness training for parents boosted mental health measures

SEATTLE – Mindfulness exercises can ease stress for low-income parents and improve mental health measures in their children, results of a small pilot study presented at the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry indicate.

The researchers credit the location of the mindfulness intervention, an early childhood developmental center, and the focus on the child rather than the parent for the success of the program. The intervention is designed to help the child, and that is the major message to the parent. “Every parent will do things to help their child, even though not every parent will do things to help themselves,” said Matthew G. Biel, MD, of Georgetown University, Washington, who presented the study at a poster session.

Mindfulness has gained traction among adults and children, but its application to parenting is new, he said. The study was open label and included 33 caregivers of children aged 0-5 years (85% female, 82% African American, 85% with household income less than $50,000/year). All subjects participated in a weekly mindfulness session lasting 60-90 minutes, which was led by an experienced instructor who had strong cultural knowledge of the local community. Sessions were conducted in a circle and included mindfulness practices and parent sharing of experiences. Focal points for mindfulness practices included breathing, body awareness, mindful movement, thoughts, emotions, and mindful listening and speaking.

The intervention was associated with statistically significant improvements in a range of measures, including sleep disturbance (effect size, 0.50; P = .005), parenting stress (ES, 0.33; P = .012), mindful discipline (ES, 0.21; P = .043), parental support (ES, 0.44; P = .007), child autonomy (ES, 032; P = .033), positive affect in parents (ES, 0.28; P = .046) and negative affect in parents (ES, 0.49; P = .028), and overall parental mental health (ES, 0.55; P = .020). “Across the board we’re seeing a positive impact,” said Dr. Biel.

The researchers are now implementing the program in another school and planning an intervention study with a waiting list control.

Satyani McPherson, a coauthor of the study and a mindfulness expert who has been teaching since the 1980s, explained that mindfulness really needs to be experienced to be understood. “You can talk about this all day, and no one gets it until they experience it. As soon as people have their mindfulness practice, they come out of it and they say, ‘Aaah, I feel so much better,’ ” she said in an interview.

The key to success lies in repetition and practice, and parents who did their mindfulness “homework” between sessions saw more benefit in the pilot study, said Ms. McPherson. The good news is that mindfulness can be incorporated into all sorts of daily activities, whether it’s showering, eating, or being stopped at a red light. It can even be used as a sort of time-out for patients. “Go into the restroom, lock the door, and observe your breath for one minute, or just one breath or three breaths. It helps you to ground yourself,” said Ms. McPherson.

Ms McPherson is an employee of Minds Incorporated. Dr. Biel receives research support from the Bainum Family Foundation, Chan-Zuckerberg Initiative, DC Health, Marriott Foundation, and self-funds his research.

SOURCE: AACAP 2018. Abstract 1.40.

SEATTLE – Mindfulness exercises can ease stress for low-income parents and improve mental health measures in their children, results of a small pilot study presented at the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry indicate.

The researchers credit the location of the mindfulness intervention, an early childhood developmental center, and the focus on the child rather than the parent for the success of the program. The intervention is designed to help the child, and that is the major message to the parent. “Every parent will do things to help their child, even though not every parent will do things to help themselves,” said Matthew G. Biel, MD, of Georgetown University, Washington, who presented the study at a poster session.

Mindfulness has gained traction among adults and children, but its application to parenting is new, he said. The study was open label and included 33 caregivers of children aged 0-5 years (85% female, 82% African American, 85% with household income less than $50,000/year). All subjects participated in a weekly mindfulness session lasting 60-90 minutes, which was led by an experienced instructor who had strong cultural knowledge of the local community. Sessions were conducted in a circle and included mindfulness practices and parent sharing of experiences. Focal points for mindfulness practices included breathing, body awareness, mindful movement, thoughts, emotions, and mindful listening and speaking.

The intervention was associated with statistically significant improvements in a range of measures, including sleep disturbance (effect size, 0.50; P = .005), parenting stress (ES, 0.33; P = .012), mindful discipline (ES, 0.21; P = .043), parental support (ES, 0.44; P = .007), child autonomy (ES, 032; P = .033), positive affect in parents (ES, 0.28; P = .046) and negative affect in parents (ES, 0.49; P = .028), and overall parental mental health (ES, 0.55; P = .020). “Across the board we’re seeing a positive impact,” said Dr. Biel.

The researchers are now implementing the program in another school and planning an intervention study with a waiting list control.

Satyani McPherson, a coauthor of the study and a mindfulness expert who has been teaching since the 1980s, explained that mindfulness really needs to be experienced to be understood. “You can talk about this all day, and no one gets it until they experience it. As soon as people have their mindfulness practice, they come out of it and they say, ‘Aaah, I feel so much better,’ ” she said in an interview.

The key to success lies in repetition and practice, and parents who did their mindfulness “homework” between sessions saw more benefit in the pilot study, said Ms. McPherson. The good news is that mindfulness can be incorporated into all sorts of daily activities, whether it’s showering, eating, or being stopped at a red light. It can even be used as a sort of time-out for patients. “Go into the restroom, lock the door, and observe your breath for one minute, or just one breath or three breaths. It helps you to ground yourself,” said Ms. McPherson.

Ms McPherson is an employee of Minds Incorporated. Dr. Biel receives research support from the Bainum Family Foundation, Chan-Zuckerberg Initiative, DC Health, Marriott Foundation, and self-funds his research.

SOURCE: AACAP 2018. Abstract 1.40.

SEATTLE – Mindfulness exercises can ease stress for low-income parents and improve mental health measures in their children, results of a small pilot study presented at the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry indicate.

The researchers credit the location of the mindfulness intervention, an early childhood developmental center, and the focus on the child rather than the parent for the success of the program. The intervention is designed to help the child, and that is the major message to the parent. “Every parent will do things to help their child, even though not every parent will do things to help themselves,” said Matthew G. Biel, MD, of Georgetown University, Washington, who presented the study at a poster session.

Mindfulness has gained traction among adults and children, but its application to parenting is new, he said. The study was open label and included 33 caregivers of children aged 0-5 years (85% female, 82% African American, 85% with household income less than $50,000/year). All subjects participated in a weekly mindfulness session lasting 60-90 minutes, which was led by an experienced instructor who had strong cultural knowledge of the local community. Sessions were conducted in a circle and included mindfulness practices and parent sharing of experiences. Focal points for mindfulness practices included breathing, body awareness, mindful movement, thoughts, emotions, and mindful listening and speaking.

The intervention was associated with statistically significant improvements in a range of measures, including sleep disturbance (effect size, 0.50; P = .005), parenting stress (ES, 0.33; P = .012), mindful discipline (ES, 0.21; P = .043), parental support (ES, 0.44; P = .007), child autonomy (ES, 032; P = .033), positive affect in parents (ES, 0.28; P = .046) and negative affect in parents (ES, 0.49; P = .028), and overall parental mental health (ES, 0.55; P = .020). “Across the board we’re seeing a positive impact,” said Dr. Biel.

The researchers are now implementing the program in another school and planning an intervention study with a waiting list control.

Satyani McPherson, a coauthor of the study and a mindfulness expert who has been teaching since the 1980s, explained that mindfulness really needs to be experienced to be understood. “You can talk about this all day, and no one gets it until they experience it. As soon as people have their mindfulness practice, they come out of it and they say, ‘Aaah, I feel so much better,’ ” she said in an interview.

The key to success lies in repetition and practice, and parents who did their mindfulness “homework” between sessions saw more benefit in the pilot study, said Ms. McPherson. The good news is that mindfulness can be incorporated into all sorts of daily activities, whether it’s showering, eating, or being stopped at a red light. It can even be used as a sort of time-out for patients. “Go into the restroom, lock the door, and observe your breath for one minute, or just one breath or three breaths. It helps you to ground yourself,” said Ms. McPherson.

Ms McPherson is an employee of Minds Incorporated. Dr. Biel receives research support from the Bainum Family Foundation, Chan-Zuckerberg Initiative, DC Health, Marriott Foundation, and self-funds his research.

SOURCE: AACAP 2018. Abstract 1.40.

REPORTING FROM AACAP 2018

Key clinical point: Weekly mindfulness improved measures of parenting and parent mental health.

Major finding: Eight measures showed significant improvement with mindfulness training.

Study details: Prospective, open-label study of 33 caregivers.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Marriot Foundation. Dr. Biel receives research funding from various foundations. Ms. McPherson is an employee of Minds Incorporated and was compensated for teaching the mindfulness courses in the study.

Source: AACAP 2018. Abstract 1.40.

Movement disorders in children warrant screening evaluations

SEATTLE – Movement disorders should be a factor in screening children receiving pharmacotherapy, Jagan K. Chilakamarri, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

“I started seeing a very, very complex group of pediatric patients in my office,” said Dr. Chilakamarri, medical director at the Atlanta Psychiatric Institute, and codirector of the Movement Disorders Program at Emory University, Atlanta. “I decided I needed to coordinate with a neurologist and sort out what was happening.”

Dr. Chilakamarri suspects that the advent of new drug therapies and polytherapy is leading to a range of movement effects, especially in young patients prescribed multiple agents.

Many psychiatrists may not be comfortable with screening or diagnosing movement disorders, preferring instead to refer a patient to a neurologist. That’s understandable, but the neurologist may not have the psychotropic drug history in mind when assessing a patient. If a drug or drug combination is responsible for a movement disorder, it befits the psychiatrist to address it, he said.

“I want psychiatrists to be more familiar with how to do a basic movement disorder assessment, and how to understand these movements in the context of the patient, whether they’re drug induced or related to their own disorder, or something comorbid that we are not able to understand – how to measure them, how to understand them, and when to send them to the appropriate referral so that these patients are being well addressed. Some may not be addressed by a neurologist; maybe the patient should go to an endocrinologist because of a thyroid problem,” said Dr. Chilakamarri.

The best way to gain that understanding and familiarity, aside from reviewing the potential side effects of psychotropic medications, is to partner with a neurologist who can impart a better understanding of how movement disorders present.

“Whenever we see these odd or strange movements, we basically see if we can send the patient to a neurologist. I have no problem with that, but what I’m trying to say is, if we can be a little bit more aware, a little bit more understanding of these things, we can reduce some of those events,” said Dr. Chilakamarri.

He disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Commonly occurring movement disorders in children, AACAP 2018.

SEATTLE – Movement disorders should be a factor in screening children receiving pharmacotherapy, Jagan K. Chilakamarri, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

“I started seeing a very, very complex group of pediatric patients in my office,” said Dr. Chilakamarri, medical director at the Atlanta Psychiatric Institute, and codirector of the Movement Disorders Program at Emory University, Atlanta. “I decided I needed to coordinate with a neurologist and sort out what was happening.”

Dr. Chilakamarri suspects that the advent of new drug therapies and polytherapy is leading to a range of movement effects, especially in young patients prescribed multiple agents.

Many psychiatrists may not be comfortable with screening or diagnosing movement disorders, preferring instead to refer a patient to a neurologist. That’s understandable, but the neurologist may not have the psychotropic drug history in mind when assessing a patient. If a drug or drug combination is responsible for a movement disorder, it befits the psychiatrist to address it, he said.

“I want psychiatrists to be more familiar with how to do a basic movement disorder assessment, and how to understand these movements in the context of the patient, whether they’re drug induced or related to their own disorder, or something comorbid that we are not able to understand – how to measure them, how to understand them, and when to send them to the appropriate referral so that these patients are being well addressed. Some may not be addressed by a neurologist; maybe the patient should go to an endocrinologist because of a thyroid problem,” said Dr. Chilakamarri.

The best way to gain that understanding and familiarity, aside from reviewing the potential side effects of psychotropic medications, is to partner with a neurologist who can impart a better understanding of how movement disorders present.

“Whenever we see these odd or strange movements, we basically see if we can send the patient to a neurologist. I have no problem with that, but what I’m trying to say is, if we can be a little bit more aware, a little bit more understanding of these things, we can reduce some of those events,” said Dr. Chilakamarri.

He disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Commonly occurring movement disorders in children, AACAP 2018.

SEATTLE – Movement disorders should be a factor in screening children receiving pharmacotherapy, Jagan K. Chilakamarri, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

“I started seeing a very, very complex group of pediatric patients in my office,” said Dr. Chilakamarri, medical director at the Atlanta Psychiatric Institute, and codirector of the Movement Disorders Program at Emory University, Atlanta. “I decided I needed to coordinate with a neurologist and sort out what was happening.”

Dr. Chilakamarri suspects that the advent of new drug therapies and polytherapy is leading to a range of movement effects, especially in young patients prescribed multiple agents.

Many psychiatrists may not be comfortable with screening or diagnosing movement disorders, preferring instead to refer a patient to a neurologist. That’s understandable, but the neurologist may not have the psychotropic drug history in mind when assessing a patient. If a drug or drug combination is responsible for a movement disorder, it befits the psychiatrist to address it, he said.

“I want psychiatrists to be more familiar with how to do a basic movement disorder assessment, and how to understand these movements in the context of the patient, whether they’re drug induced or related to their own disorder, or something comorbid that we are not able to understand – how to measure them, how to understand them, and when to send them to the appropriate referral so that these patients are being well addressed. Some may not be addressed by a neurologist; maybe the patient should go to an endocrinologist because of a thyroid problem,” said Dr. Chilakamarri.

The best way to gain that understanding and familiarity, aside from reviewing the potential side effects of psychotropic medications, is to partner with a neurologist who can impart a better understanding of how movement disorders present.

“Whenever we see these odd or strange movements, we basically see if we can send the patient to a neurologist. I have no problem with that, but what I’m trying to say is, if we can be a little bit more aware, a little bit more understanding of these things, we can reduce some of those events,” said Dr. Chilakamarri.

He disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Commonly occurring movement disorders in children, AACAP 2018.

REPORTING FROM AACAP 2018

Talk to adolescents about sexual assault

SEATTLE – Recent events have highlighted the issue of sexual assault in adolescents. But the onus still is on psychiatrists and other clinicians to ask patients whether they’ve ever been a victim of sexual assault or other kinds of trauma, according to an expert.

“It turns out that these experiences are common for kids, and they’re very correlated with the development of all kinds of psychiatric disorders. And if we ask, they will tell us. If we don’t ask they probably won’t,” said Lucy Berliner, director of the Harborview Center for Sexual Assault and Traumatic Stress, who discussed the epidemiology of sexual trauma in adolescents at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

A common misconception is that victims of sexual assault have endured multiple, chronic traumas. A more common scenario, however, is a single incident, much like the one described by Christine Blasey Ford, PhD, in her testimony before Congress, and clinicians should be more on the lookout for such cases. “I think those young people get a little bit lost,” Ms. Berliner said at the meeting.

Unlike the incident described by Dr. Ford, coercion often was not physical. Fifty-two percent of the time, the adolescents experienced abuse by authority figures, such as an assault by a teacher or coach, or even someone who used social advantage such as being older or more popular. In 17% of the cases, the victim was drugged or unconscious. Physical restraint was reported in 20% of cases. Weapons were involved only 7% of the time.

Twenty-eight percent of the adolescents were victims of a teenager, compared with 54% who attributed the assault to an adult. Overall, 72% of the subjects presented at an emergency department rather than a counseling clinic, which suggests that screening in medical environments also is a key factor in identifying and responding to people who have been assaulted.

All study subjects were offered counseling, but the uptake was low: The median was 2 sessions.

“My guess is that in the beginning, a lot of people say, ‘I just want to put it behind me, or I want to try to figure it out myself,’ and it only comes around later, in mental health settings, where these kids are in there for some type of psychiatric disorder. And unless we ask, we’re not going to find out (about a previous assault), and we won’t be able to give them the help that would help them with this psychiatric disorder,” said Ms. Berliner, also a clinical associate professor at the University of Washington School of Social Work in Seattle.

Clinicians might not ask about these experiences, she said, because of fears of triggering raw emotions. But such fears are unfounded, she stated. “We need to get over ourselves,” Ms. Berliner said. “If we don’t create the opportunity, why would they tell us? And if they don’t want to tell us, they won’t. But you can’t traumatize a kid by talking about something that’s already actually happened to them.”

That point can even extend to the legal system. Also during the session, Emily Petersen, senior deputy prosecuting attorney in the Special Assault Unit in King County, Washington, emphasized that, in her experience, young people who are victims of sexual and other forms of assault are resilient – and they will not be traumatized by speaking with a prosecutor or to police about their experiences.

But the legal system cannot provide healing, she and Ms. Berliner noted. That must come from the victim’s support system. “These experiences don’t have to define victims of sexual assault as long as the adults in their lives are responding appropriately to them,” Ms. Petersen said.

Ms. Berliner and Ms. Petersen disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SEATTLE – Recent events have highlighted the issue of sexual assault in adolescents. But the onus still is on psychiatrists and other clinicians to ask patients whether they’ve ever been a victim of sexual assault or other kinds of trauma, according to an expert.

“It turns out that these experiences are common for kids, and they’re very correlated with the development of all kinds of psychiatric disorders. And if we ask, they will tell us. If we don’t ask they probably won’t,” said Lucy Berliner, director of the Harborview Center for Sexual Assault and Traumatic Stress, who discussed the epidemiology of sexual trauma in adolescents at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

A common misconception is that victims of sexual assault have endured multiple, chronic traumas. A more common scenario, however, is a single incident, much like the one described by Christine Blasey Ford, PhD, in her testimony before Congress, and clinicians should be more on the lookout for such cases. “I think those young people get a little bit lost,” Ms. Berliner said at the meeting.

Unlike the incident described by Dr. Ford, coercion often was not physical. Fifty-two percent of the time, the adolescents experienced abuse by authority figures, such as an assault by a teacher or coach, or even someone who used social advantage such as being older or more popular. In 17% of the cases, the victim was drugged or unconscious. Physical restraint was reported in 20% of cases. Weapons were involved only 7% of the time.

Twenty-eight percent of the adolescents were victims of a teenager, compared with 54% who attributed the assault to an adult. Overall, 72% of the subjects presented at an emergency department rather than a counseling clinic, which suggests that screening in medical environments also is a key factor in identifying and responding to people who have been assaulted.

All study subjects were offered counseling, but the uptake was low: The median was 2 sessions.

“My guess is that in the beginning, a lot of people say, ‘I just want to put it behind me, or I want to try to figure it out myself,’ and it only comes around later, in mental health settings, where these kids are in there for some type of psychiatric disorder. And unless we ask, we’re not going to find out (about a previous assault), and we won’t be able to give them the help that would help them with this psychiatric disorder,” said Ms. Berliner, also a clinical associate professor at the University of Washington School of Social Work in Seattle.

Clinicians might not ask about these experiences, she said, because of fears of triggering raw emotions. But such fears are unfounded, she stated. “We need to get over ourselves,” Ms. Berliner said. “If we don’t create the opportunity, why would they tell us? And if they don’t want to tell us, they won’t. But you can’t traumatize a kid by talking about something that’s already actually happened to them.”

That point can even extend to the legal system. Also during the session, Emily Petersen, senior deputy prosecuting attorney in the Special Assault Unit in King County, Washington, emphasized that, in her experience, young people who are victims of sexual and other forms of assault are resilient – and they will not be traumatized by speaking with a prosecutor or to police about their experiences.

But the legal system cannot provide healing, she and Ms. Berliner noted. That must come from the victim’s support system. “These experiences don’t have to define victims of sexual assault as long as the adults in their lives are responding appropriately to them,” Ms. Petersen said.

Ms. Berliner and Ms. Petersen disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SEATTLE – Recent events have highlighted the issue of sexual assault in adolescents. But the onus still is on psychiatrists and other clinicians to ask patients whether they’ve ever been a victim of sexual assault or other kinds of trauma, according to an expert.

“It turns out that these experiences are common for kids, and they’re very correlated with the development of all kinds of psychiatric disorders. And if we ask, they will tell us. If we don’t ask they probably won’t,” said Lucy Berliner, director of the Harborview Center for Sexual Assault and Traumatic Stress, who discussed the epidemiology of sexual trauma in adolescents at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

A common misconception is that victims of sexual assault have endured multiple, chronic traumas. A more common scenario, however, is a single incident, much like the one described by Christine Blasey Ford, PhD, in her testimony before Congress, and clinicians should be more on the lookout for such cases. “I think those young people get a little bit lost,” Ms. Berliner said at the meeting.

Unlike the incident described by Dr. Ford, coercion often was not physical. Fifty-two percent of the time, the adolescents experienced abuse by authority figures, such as an assault by a teacher or coach, or even someone who used social advantage such as being older or more popular. In 17% of the cases, the victim was drugged or unconscious. Physical restraint was reported in 20% of cases. Weapons were involved only 7% of the time.

Twenty-eight percent of the adolescents were victims of a teenager, compared with 54% who attributed the assault to an adult. Overall, 72% of the subjects presented at an emergency department rather than a counseling clinic, which suggests that screening in medical environments also is a key factor in identifying and responding to people who have been assaulted.

All study subjects were offered counseling, but the uptake was low: The median was 2 sessions.

“My guess is that in the beginning, a lot of people say, ‘I just want to put it behind me, or I want to try to figure it out myself,’ and it only comes around later, in mental health settings, where these kids are in there for some type of psychiatric disorder. And unless we ask, we’re not going to find out (about a previous assault), and we won’t be able to give them the help that would help them with this psychiatric disorder,” said Ms. Berliner, also a clinical associate professor at the University of Washington School of Social Work in Seattle.

Clinicians might not ask about these experiences, she said, because of fears of triggering raw emotions. But such fears are unfounded, she stated. “We need to get over ourselves,” Ms. Berliner said. “If we don’t create the opportunity, why would they tell us? And if they don’t want to tell us, they won’t. But you can’t traumatize a kid by talking about something that’s already actually happened to them.”

That point can even extend to the legal system. Also during the session, Emily Petersen, senior deputy prosecuting attorney in the Special Assault Unit in King County, Washington, emphasized that, in her experience, young people who are victims of sexual and other forms of assault are resilient – and they will not be traumatized by speaking with a prosecutor or to police about their experiences.

But the legal system cannot provide healing, she and Ms. Berliner noted. That must come from the victim’s support system. “These experiences don’t have to define victims of sexual assault as long as the adults in their lives are responding appropriately to them,” Ms. Petersen said.

Ms. Berliner and Ms. Petersen disclosed no conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM AACAP 2018

Collaborative approach for suicidal youth helps providers, too

SEATTLE – When it comes to treating children and adolescents who have experienced trauma and present suicidality, it is not just the patients who need support. Clinicians also experience grave anxiety when dealing with a traumatized child exhibiting suicidal behavior. The Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicide (CAMS) framework can help clinicians or health care workers manage the care of these challenging patients.

CAMS is well established in adults with suicidal behavior, but it is unproven in youth and adolescents. The key is to its success in younger patients will be whether the program is developmentally appropriate, according to Molly C. Adrian, PhD, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Adrian discussed CAMS and its potential applications at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

The CAMS approach emphasizes cooperation between the therapist and patient. “Adolescents are seeking autonomy and independence, and so it’s a good fit philosophically that you would partner alongside the teen as opposed to starting in a more adversarial sort of way – not that we as therapists ever do that. But it can be more tense when suicide is on the table and you feel unprepared,” Dr. Adrian said.

Seattle Children’s Hospital is persuaded enough to make CAMS part of its standard of care, Dr. Adrian said.