User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Understanding the neuroscience of narcissism

Editor’s Note: The study covered in this summary was published on ResearchSquare.com as a preprint and has not yet been peer reviewed.

Key takeaway

Why this matters

The cognitive features and phenotypic diversity of narcissism subtypes are partially unknown.

This study integrates both grandiose and vulnerable narcissism into a common framework with cognitive components connected to these traits.

Study design

This study enrolled 478 participants (397 female and 4 did not reveal their gender).

The average age of participants was 35 years (standard deviation, 14.97), with a range of 18-76 years.

A 25-item version of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI), a 40-item self-report measure of narcissism traits, was used to assess the level of authority, grandiose exhibitionism, and entitlement/exploitativeness characteristics of study participants.

The Maladaptive Covert Narcissism Scale, an expanded version of the 23-item self-report Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale, was used to assess the level of hypersensitivity, vulnerability, and entitlement of study participants.

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, a 10-item self-report scale, was used to assess the level of self-esteem of study participants.

The Young Schema Questionnaire is a 244-item measure of 19 different maladaptive schemas and was used to observe Emotional Deprivation, Vulnerability to Harm and Illness, and Entitlement schemas of study participants.

The Empathizing Quotient is a self-report measure and was used to assess the emotional intelligence of study participants.

Key results

Moderate correlation between grandiose and vulnerable narcissism and the Entitlement schema was observed.

A moderate/strong connection was observed between vulnerable narcissism and the Vulnerability to Harm and Illness schema and a moderate connection with the Emotional Deprivation schema.

No significant correlation was observed between grandiose narcissism and the Emotional Deprivation schema.

A moderate, negative correlation between vulnerable narcissism and emotional skills was observed.

A positive, weak connection between grandiose narcissism and self-esteem; and a negative, moderate connection between vulnerable narcissism and self-esteem were observed.

Gender and age were associated with empathic skills, and age was weakly/moderately connected with self-esteem and vulnerable narcissism.

Limitations

This was a cross-sectional analysis investigating a temporally specific state of personality and cognitive functioning.

The gender ratio was shifted toward women in this study.

Conclusions drawn from connections between observed components are interchangeable and cause/effect connections cannot be discerned.

Disclosures

The study was supported by the National Research, Development, and Innovation Office (Grant No. NRDI–138040) and by the Human Resource Development Operational Program – Comprehensive developments at the University of Pécs for the implementation of intelligent specialization (EFOP-3.6.1-16-2016-00004). First author Dorian Vida’s work was supported by the Collegium Talentum Programme of Hungary. None of the authors disclosed any competing interests.

This is a summary of a preprint research study, “In the mind of Narcissus: the mediating role of emotional regulation in the emergence of distorted cognitions,” written by Dorian Vida from the University of Pécs, Hungary and colleagues on ResearchSquare.com. This study has not yet been peer reviewed. The full text of the study can be found on ResearchSquare.com.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com

Editor’s Note: The study covered in this summary was published on ResearchSquare.com as a preprint and has not yet been peer reviewed.

Key takeaway

Why this matters

The cognitive features and phenotypic diversity of narcissism subtypes are partially unknown.

This study integrates both grandiose and vulnerable narcissism into a common framework with cognitive components connected to these traits.

Study design

This study enrolled 478 participants (397 female and 4 did not reveal their gender).

The average age of participants was 35 years (standard deviation, 14.97), with a range of 18-76 years.

A 25-item version of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI), a 40-item self-report measure of narcissism traits, was used to assess the level of authority, grandiose exhibitionism, and entitlement/exploitativeness characteristics of study participants.

The Maladaptive Covert Narcissism Scale, an expanded version of the 23-item self-report Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale, was used to assess the level of hypersensitivity, vulnerability, and entitlement of study participants.

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, a 10-item self-report scale, was used to assess the level of self-esteem of study participants.

The Young Schema Questionnaire is a 244-item measure of 19 different maladaptive schemas and was used to observe Emotional Deprivation, Vulnerability to Harm and Illness, and Entitlement schemas of study participants.

The Empathizing Quotient is a self-report measure and was used to assess the emotional intelligence of study participants.

Key results

Moderate correlation between grandiose and vulnerable narcissism and the Entitlement schema was observed.

A moderate/strong connection was observed between vulnerable narcissism and the Vulnerability to Harm and Illness schema and a moderate connection with the Emotional Deprivation schema.

No significant correlation was observed between grandiose narcissism and the Emotional Deprivation schema.

A moderate, negative correlation between vulnerable narcissism and emotional skills was observed.

A positive, weak connection between grandiose narcissism and self-esteem; and a negative, moderate connection between vulnerable narcissism and self-esteem were observed.

Gender and age were associated with empathic skills, and age was weakly/moderately connected with self-esteem and vulnerable narcissism.

Limitations

This was a cross-sectional analysis investigating a temporally specific state of personality and cognitive functioning.

The gender ratio was shifted toward women in this study.

Conclusions drawn from connections between observed components are interchangeable and cause/effect connections cannot be discerned.

Disclosures

The study was supported by the National Research, Development, and Innovation Office (Grant No. NRDI–138040) and by the Human Resource Development Operational Program – Comprehensive developments at the University of Pécs for the implementation of intelligent specialization (EFOP-3.6.1-16-2016-00004). First author Dorian Vida’s work was supported by the Collegium Talentum Programme of Hungary. None of the authors disclosed any competing interests.

This is a summary of a preprint research study, “In the mind of Narcissus: the mediating role of emotional regulation in the emergence of distorted cognitions,” written by Dorian Vida from the University of Pécs, Hungary and colleagues on ResearchSquare.com. This study has not yet been peer reviewed. The full text of the study can be found on ResearchSquare.com.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com

Editor’s Note: The study covered in this summary was published on ResearchSquare.com as a preprint and has not yet been peer reviewed.

Key takeaway

Why this matters

The cognitive features and phenotypic diversity of narcissism subtypes are partially unknown.

This study integrates both grandiose and vulnerable narcissism into a common framework with cognitive components connected to these traits.

Study design

This study enrolled 478 participants (397 female and 4 did not reveal their gender).

The average age of participants was 35 years (standard deviation, 14.97), with a range of 18-76 years.

A 25-item version of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI), a 40-item self-report measure of narcissism traits, was used to assess the level of authority, grandiose exhibitionism, and entitlement/exploitativeness characteristics of study participants.

The Maladaptive Covert Narcissism Scale, an expanded version of the 23-item self-report Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale, was used to assess the level of hypersensitivity, vulnerability, and entitlement of study participants.

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, a 10-item self-report scale, was used to assess the level of self-esteem of study participants.

The Young Schema Questionnaire is a 244-item measure of 19 different maladaptive schemas and was used to observe Emotional Deprivation, Vulnerability to Harm and Illness, and Entitlement schemas of study participants.

The Empathizing Quotient is a self-report measure and was used to assess the emotional intelligence of study participants.

Key results

Moderate correlation between grandiose and vulnerable narcissism and the Entitlement schema was observed.

A moderate/strong connection was observed between vulnerable narcissism and the Vulnerability to Harm and Illness schema and a moderate connection with the Emotional Deprivation schema.

No significant correlation was observed between grandiose narcissism and the Emotional Deprivation schema.

A moderate, negative correlation between vulnerable narcissism and emotional skills was observed.

A positive, weak connection between grandiose narcissism and self-esteem; and a negative, moderate connection between vulnerable narcissism and self-esteem were observed.

Gender and age were associated with empathic skills, and age was weakly/moderately connected with self-esteem and vulnerable narcissism.

Limitations

This was a cross-sectional analysis investigating a temporally specific state of personality and cognitive functioning.

The gender ratio was shifted toward women in this study.

Conclusions drawn from connections between observed components are interchangeable and cause/effect connections cannot be discerned.

Disclosures

The study was supported by the National Research, Development, and Innovation Office (Grant No. NRDI–138040) and by the Human Resource Development Operational Program – Comprehensive developments at the University of Pécs for the implementation of intelligent specialization (EFOP-3.6.1-16-2016-00004). First author Dorian Vida’s work was supported by the Collegium Talentum Programme of Hungary. None of the authors disclosed any competing interests.

This is a summary of a preprint research study, “In the mind of Narcissus: the mediating role of emotional regulation in the emergence of distorted cognitions,” written by Dorian Vida from the University of Pécs, Hungary and colleagues on ResearchSquare.com. This study has not yet been peer reviewed. The full text of the study can be found on ResearchSquare.com.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com

Hypertension heightens risk for severe COVID-19, even in the fully vaxxed

Adults with hypertension who were vaccinated for COVID-19 with at least one booster were more than twice as likely as vaccinated and boosted individuals without hypertension to be hospitalized for severe COVID-19, according to data from more than 900 individuals.

“We were surprised to learn that many people who were hospitalized with COVID-19 had hypertension and no other risk factors,” said Susan Cheng, MD, MPH, director of the Institute for Research on Healthy Aging in the department of cardiology at the Smidt Heart Institute, Los Angeles, and a senior author of the study. “This is concerning when you consider that almost half of American adults have high blood pressure.”

COVID-19 vaccines demonstrated ability to reduce death and some of the most severe side effects from the infection in the early stages of the pandemic. Although the Omicron surge prompted recommendations for a third mRNA vaccine dose, “a proportion of individuals who received three mRNA vaccine doses still required hospitalization for COVID-19 during the Omicron surge,” and the characteristics associated with severe illness in vaccinated and boosted patients have not been explored, Joseph Ebinger, MD, of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, and colleagues wrote.

Previous research has shown an association between high blood pressure an increased risk for developing severe COVID-19 compared to several other chronic health conditions, including kidney disease, type 2 diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and heart failure, the researchers noted.

In a study published in Hypertension, the researchers identified 912 adults who received at least three doses of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine and were later diagnosed with COVID-19 during the surge in infections from the Omicron variant between December 2021 and April 2022.

A total of 145 of the individuals were hospitalized (16%); of these, 125 (86%) had hypertension.

Patients with hypertension were the most likely to be hospitalized, with an odds ratio of 2.9. In addition to high blood pressure, factors including older age (OR, 1.3), chronic kidney disease (OR, 2.2), prior myocardial infarction or heart failure (OR, 2.2), and longer time since the last vaccination and COVID-19 infection were associated with increased risk of hospitalization in a multivariate analysis.

However, the increased risk of severe illness and hospitalization associated with high blood pressure persisted, with an OR of 2.6, in the absence of comorbid conditions such as type 2 diabetes, kidney disease, and heart failure, the researchers emphasized.

“Although the mechanism for hypertension-associated COVID-19 risk remains unclear, prior studies have identified delayed SARS-CoV-2 viral clearance and prolonged inflammatory response among hypertensive patients, which may contribute to greater disease severity,” they wrote.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the use of data from a single center and lack of information on which Omicron variants and subvariants were behind the infections, the researchers noted.

However, the results highlight the need for more research on how to reduce the risks of severe COVID-19 in vulnerable populations, and on the mechanism for a potential connection between high blood pressure and severe COVID-19, they said.

Given the high prevalence of hypertension worldwide, increased understanding of the hypertension-specific risks and identification of individual and population-level risk reduction strategies will be important to the transition of COVID-19 from pandemic to endemic, they concluded.

Omicron changes the game

“When the pandemic initially started, many conditions were seen to increase risk for more severe COVID illness, and hypertension was one of those factors – and then things changed,” lead author Dr. Ebinger said in an interview. “First, vaccines arrived on the scene and substantially reduced risk of severe COVID for everyone who received them. Second, Omicron arrived and, while more transmissible, this variant has been less likely to cause severe COVID. On the one hand, we have vaccines and boosters that we want to think of as ‘the great equalizer’ when it comes to preexisting conditions. On the other hand, we have a dominant set of SARS-CoV-2 subvariants that seem less virulent in most people.

“Taken together, we have been hoping and even assuming that we have been doing pretty well with minimizing risks. Unfortunately, our study results indicate this is not exactly the case,” he said.

“Although vaccines and boosters appear to have equalized or minimized the risks of severe COVID for some people, this has not happened for others – even in the setting of the milder Omicron variant. Of individuals who were fully vaccinated and boosted, having hypertension increased the odds of needing to be hospitalized after getting infected with Omicron by 2.6-fold, even when accounting for or in the absence of having any major chronic disease that might otherwise predispose to more severe COVID-19 illness,” Dr. Ebinger added.

“So, while the originally seen risks of having obesity or diabetes seem to have been minimized during this current era of pandemic, the risk of having hypertension has persisted. We found this both surprising and concerning, because hypertension is very common and present in over half of people over age 50.”

Surprisingly, “we found that a fair number of people, even after being fully vaccinated plus a having gotten a booster, will not only catch Omicron but get sick enough to need hospital care,” Dr. Ebinger emphasized. “Moreover, it is not just older adults with major comorbid conditions who are vulnerable. Our data show that this can happen to an adult of any age and especially if a person has only hypertension and otherwise no major chronic disease.”

The first takeaway message for clinicians at this time is to raise awareness, Dr. Ebinger stressed in the interview. “We need to raise understanding around the fact that receiving three doses of vaccine may not prevent severe COVID-19 illness in everyone, even when the circulating viral variant is presumed to be causing only mild disease in most people. Moreover, the people who are most at risk are not whom we might think they are. They are not the sickest of the sick. They include people who might not have major conditions such as heart disease or kidney disease, but they do have hypertension.”

Second, “we need more research to understand out why there is this link between hypertension and excess risk for the more severe forms of COVID-19, despite it arising from a supposedly milder variant,” said Dr. Ebinger.

“Third, we need to determine how to reduce these risks, whether through more tailored vaccine regimens or novel therapeutics or a combination approach,” he said.

Looking ahead, “the biological mechanism underpinning the association between hypertension and severe COVID-19 remains underexplored. Future work should focus on understanding the factors linking hypertension to severe COVID-19, as this may elucidate both information on how SARS-CoV-2 effects the body and potential targets for intervention,” Dr. Ebinger added.

The study was supported in part by Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, the Erika J. Glazer Family Foundation and the National Institutes of Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Adults with hypertension who were vaccinated for COVID-19 with at least one booster were more than twice as likely as vaccinated and boosted individuals without hypertension to be hospitalized for severe COVID-19, according to data from more than 900 individuals.

“We were surprised to learn that many people who were hospitalized with COVID-19 had hypertension and no other risk factors,” said Susan Cheng, MD, MPH, director of the Institute for Research on Healthy Aging in the department of cardiology at the Smidt Heart Institute, Los Angeles, and a senior author of the study. “This is concerning when you consider that almost half of American adults have high blood pressure.”

COVID-19 vaccines demonstrated ability to reduce death and some of the most severe side effects from the infection in the early stages of the pandemic. Although the Omicron surge prompted recommendations for a third mRNA vaccine dose, “a proportion of individuals who received three mRNA vaccine doses still required hospitalization for COVID-19 during the Omicron surge,” and the characteristics associated with severe illness in vaccinated and boosted patients have not been explored, Joseph Ebinger, MD, of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, and colleagues wrote.

Previous research has shown an association between high blood pressure an increased risk for developing severe COVID-19 compared to several other chronic health conditions, including kidney disease, type 2 diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and heart failure, the researchers noted.

In a study published in Hypertension, the researchers identified 912 adults who received at least three doses of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine and were later diagnosed with COVID-19 during the surge in infections from the Omicron variant between December 2021 and April 2022.

A total of 145 of the individuals were hospitalized (16%); of these, 125 (86%) had hypertension.

Patients with hypertension were the most likely to be hospitalized, with an odds ratio of 2.9. In addition to high blood pressure, factors including older age (OR, 1.3), chronic kidney disease (OR, 2.2), prior myocardial infarction or heart failure (OR, 2.2), and longer time since the last vaccination and COVID-19 infection were associated with increased risk of hospitalization in a multivariate analysis.

However, the increased risk of severe illness and hospitalization associated with high blood pressure persisted, with an OR of 2.6, in the absence of comorbid conditions such as type 2 diabetes, kidney disease, and heart failure, the researchers emphasized.

“Although the mechanism for hypertension-associated COVID-19 risk remains unclear, prior studies have identified delayed SARS-CoV-2 viral clearance and prolonged inflammatory response among hypertensive patients, which may contribute to greater disease severity,” they wrote.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the use of data from a single center and lack of information on which Omicron variants and subvariants were behind the infections, the researchers noted.

However, the results highlight the need for more research on how to reduce the risks of severe COVID-19 in vulnerable populations, and on the mechanism for a potential connection between high blood pressure and severe COVID-19, they said.

Given the high prevalence of hypertension worldwide, increased understanding of the hypertension-specific risks and identification of individual and population-level risk reduction strategies will be important to the transition of COVID-19 from pandemic to endemic, they concluded.

Omicron changes the game

“When the pandemic initially started, many conditions were seen to increase risk for more severe COVID illness, and hypertension was one of those factors – and then things changed,” lead author Dr. Ebinger said in an interview. “First, vaccines arrived on the scene and substantially reduced risk of severe COVID for everyone who received them. Second, Omicron arrived and, while more transmissible, this variant has been less likely to cause severe COVID. On the one hand, we have vaccines and boosters that we want to think of as ‘the great equalizer’ when it comes to preexisting conditions. On the other hand, we have a dominant set of SARS-CoV-2 subvariants that seem less virulent in most people.

“Taken together, we have been hoping and even assuming that we have been doing pretty well with minimizing risks. Unfortunately, our study results indicate this is not exactly the case,” he said.

“Although vaccines and boosters appear to have equalized or minimized the risks of severe COVID for some people, this has not happened for others – even in the setting of the milder Omicron variant. Of individuals who were fully vaccinated and boosted, having hypertension increased the odds of needing to be hospitalized after getting infected with Omicron by 2.6-fold, even when accounting for or in the absence of having any major chronic disease that might otherwise predispose to more severe COVID-19 illness,” Dr. Ebinger added.

“So, while the originally seen risks of having obesity or diabetes seem to have been minimized during this current era of pandemic, the risk of having hypertension has persisted. We found this both surprising and concerning, because hypertension is very common and present in over half of people over age 50.”

Surprisingly, “we found that a fair number of people, even after being fully vaccinated plus a having gotten a booster, will not only catch Omicron but get sick enough to need hospital care,” Dr. Ebinger emphasized. “Moreover, it is not just older adults with major comorbid conditions who are vulnerable. Our data show that this can happen to an adult of any age and especially if a person has only hypertension and otherwise no major chronic disease.”

The first takeaway message for clinicians at this time is to raise awareness, Dr. Ebinger stressed in the interview. “We need to raise understanding around the fact that receiving three doses of vaccine may not prevent severe COVID-19 illness in everyone, even when the circulating viral variant is presumed to be causing only mild disease in most people. Moreover, the people who are most at risk are not whom we might think they are. They are not the sickest of the sick. They include people who might not have major conditions such as heart disease or kidney disease, but they do have hypertension.”

Second, “we need more research to understand out why there is this link between hypertension and excess risk for the more severe forms of COVID-19, despite it arising from a supposedly milder variant,” said Dr. Ebinger.

“Third, we need to determine how to reduce these risks, whether through more tailored vaccine regimens or novel therapeutics or a combination approach,” he said.

Looking ahead, “the biological mechanism underpinning the association between hypertension and severe COVID-19 remains underexplored. Future work should focus on understanding the factors linking hypertension to severe COVID-19, as this may elucidate both information on how SARS-CoV-2 effects the body and potential targets for intervention,” Dr. Ebinger added.

The study was supported in part by Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, the Erika J. Glazer Family Foundation and the National Institutes of Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Adults with hypertension who were vaccinated for COVID-19 with at least one booster were more than twice as likely as vaccinated and boosted individuals without hypertension to be hospitalized for severe COVID-19, according to data from more than 900 individuals.

“We were surprised to learn that many people who were hospitalized with COVID-19 had hypertension and no other risk factors,” said Susan Cheng, MD, MPH, director of the Institute for Research on Healthy Aging in the department of cardiology at the Smidt Heart Institute, Los Angeles, and a senior author of the study. “This is concerning when you consider that almost half of American adults have high blood pressure.”

COVID-19 vaccines demonstrated ability to reduce death and some of the most severe side effects from the infection in the early stages of the pandemic. Although the Omicron surge prompted recommendations for a third mRNA vaccine dose, “a proportion of individuals who received three mRNA vaccine doses still required hospitalization for COVID-19 during the Omicron surge,” and the characteristics associated with severe illness in vaccinated and boosted patients have not been explored, Joseph Ebinger, MD, of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, and colleagues wrote.

Previous research has shown an association between high blood pressure an increased risk for developing severe COVID-19 compared to several other chronic health conditions, including kidney disease, type 2 diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and heart failure, the researchers noted.

In a study published in Hypertension, the researchers identified 912 adults who received at least three doses of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine and were later diagnosed with COVID-19 during the surge in infections from the Omicron variant between December 2021 and April 2022.

A total of 145 of the individuals were hospitalized (16%); of these, 125 (86%) had hypertension.

Patients with hypertension were the most likely to be hospitalized, with an odds ratio of 2.9. In addition to high blood pressure, factors including older age (OR, 1.3), chronic kidney disease (OR, 2.2), prior myocardial infarction or heart failure (OR, 2.2), and longer time since the last vaccination and COVID-19 infection were associated with increased risk of hospitalization in a multivariate analysis.

However, the increased risk of severe illness and hospitalization associated with high blood pressure persisted, with an OR of 2.6, in the absence of comorbid conditions such as type 2 diabetes, kidney disease, and heart failure, the researchers emphasized.

“Although the mechanism for hypertension-associated COVID-19 risk remains unclear, prior studies have identified delayed SARS-CoV-2 viral clearance and prolonged inflammatory response among hypertensive patients, which may contribute to greater disease severity,” they wrote.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the use of data from a single center and lack of information on which Omicron variants and subvariants were behind the infections, the researchers noted.

However, the results highlight the need for more research on how to reduce the risks of severe COVID-19 in vulnerable populations, and on the mechanism for a potential connection between high blood pressure and severe COVID-19, they said.

Given the high prevalence of hypertension worldwide, increased understanding of the hypertension-specific risks and identification of individual and population-level risk reduction strategies will be important to the transition of COVID-19 from pandemic to endemic, they concluded.

Omicron changes the game

“When the pandemic initially started, many conditions were seen to increase risk for more severe COVID illness, and hypertension was one of those factors – and then things changed,” lead author Dr. Ebinger said in an interview. “First, vaccines arrived on the scene and substantially reduced risk of severe COVID for everyone who received them. Second, Omicron arrived and, while more transmissible, this variant has been less likely to cause severe COVID. On the one hand, we have vaccines and boosters that we want to think of as ‘the great equalizer’ when it comes to preexisting conditions. On the other hand, we have a dominant set of SARS-CoV-2 subvariants that seem less virulent in most people.

“Taken together, we have been hoping and even assuming that we have been doing pretty well with minimizing risks. Unfortunately, our study results indicate this is not exactly the case,” he said.

“Although vaccines and boosters appear to have equalized or minimized the risks of severe COVID for some people, this has not happened for others – even in the setting of the milder Omicron variant. Of individuals who were fully vaccinated and boosted, having hypertension increased the odds of needing to be hospitalized after getting infected with Omicron by 2.6-fold, even when accounting for or in the absence of having any major chronic disease that might otherwise predispose to more severe COVID-19 illness,” Dr. Ebinger added.

“So, while the originally seen risks of having obesity or diabetes seem to have been minimized during this current era of pandemic, the risk of having hypertension has persisted. We found this both surprising and concerning, because hypertension is very common and present in over half of people over age 50.”

Surprisingly, “we found that a fair number of people, even after being fully vaccinated plus a having gotten a booster, will not only catch Omicron but get sick enough to need hospital care,” Dr. Ebinger emphasized. “Moreover, it is not just older adults with major comorbid conditions who are vulnerable. Our data show that this can happen to an adult of any age and especially if a person has only hypertension and otherwise no major chronic disease.”

The first takeaway message for clinicians at this time is to raise awareness, Dr. Ebinger stressed in the interview. “We need to raise understanding around the fact that receiving three doses of vaccine may not prevent severe COVID-19 illness in everyone, even when the circulating viral variant is presumed to be causing only mild disease in most people. Moreover, the people who are most at risk are not whom we might think they are. They are not the sickest of the sick. They include people who might not have major conditions such as heart disease or kidney disease, but they do have hypertension.”

Second, “we need more research to understand out why there is this link between hypertension and excess risk for the more severe forms of COVID-19, despite it arising from a supposedly milder variant,” said Dr. Ebinger.

“Third, we need to determine how to reduce these risks, whether through more tailored vaccine regimens or novel therapeutics or a combination approach,” he said.

Looking ahead, “the biological mechanism underpinning the association between hypertension and severe COVID-19 remains underexplored. Future work should focus on understanding the factors linking hypertension to severe COVID-19, as this may elucidate both information on how SARS-CoV-2 effects the body and potential targets for intervention,” Dr. Ebinger added.

The study was supported in part by Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, the Erika J. Glazer Family Foundation and the National Institutes of Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM HYPERTENSION

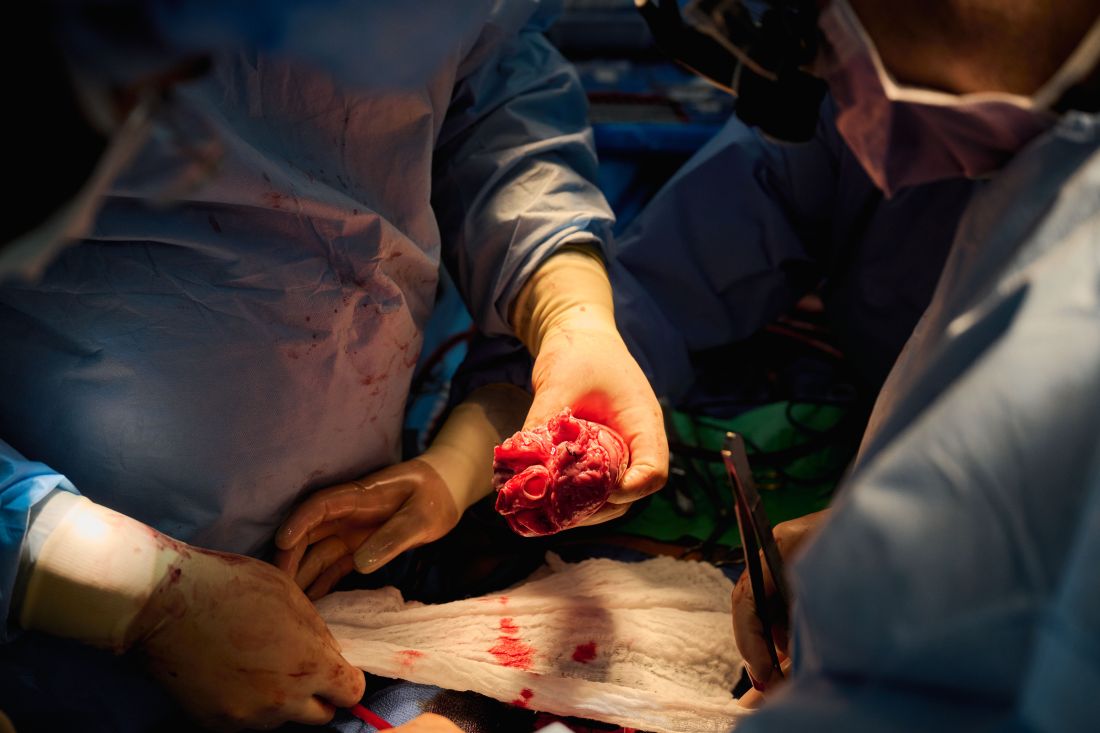

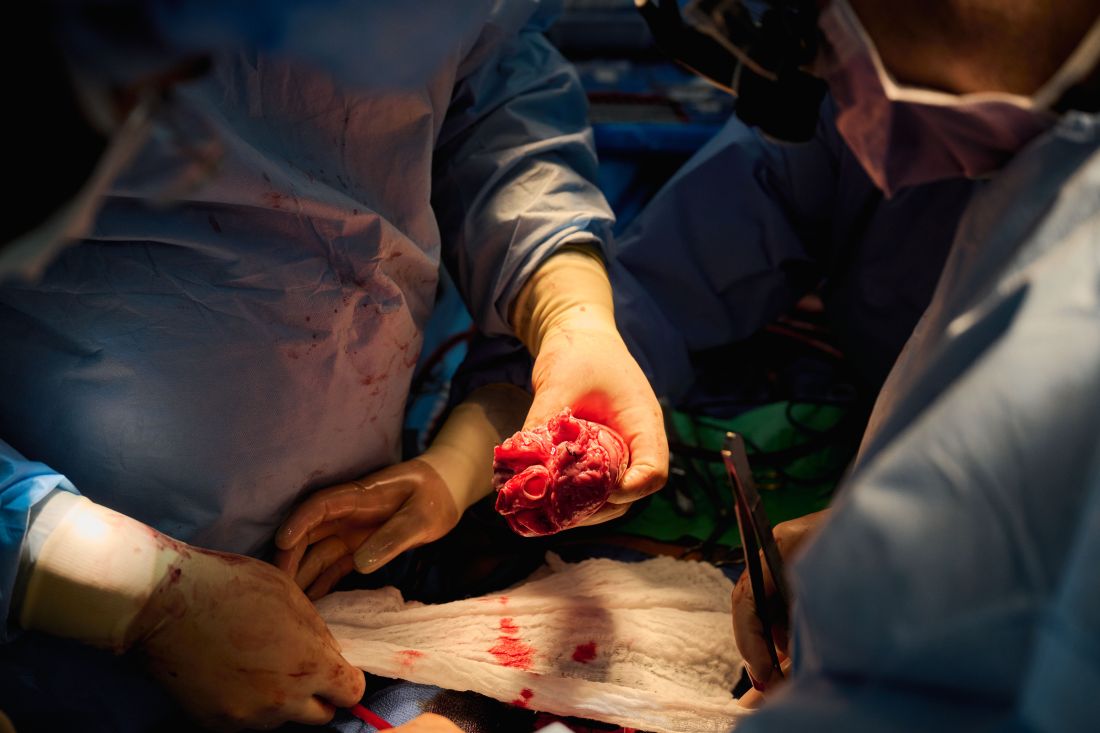

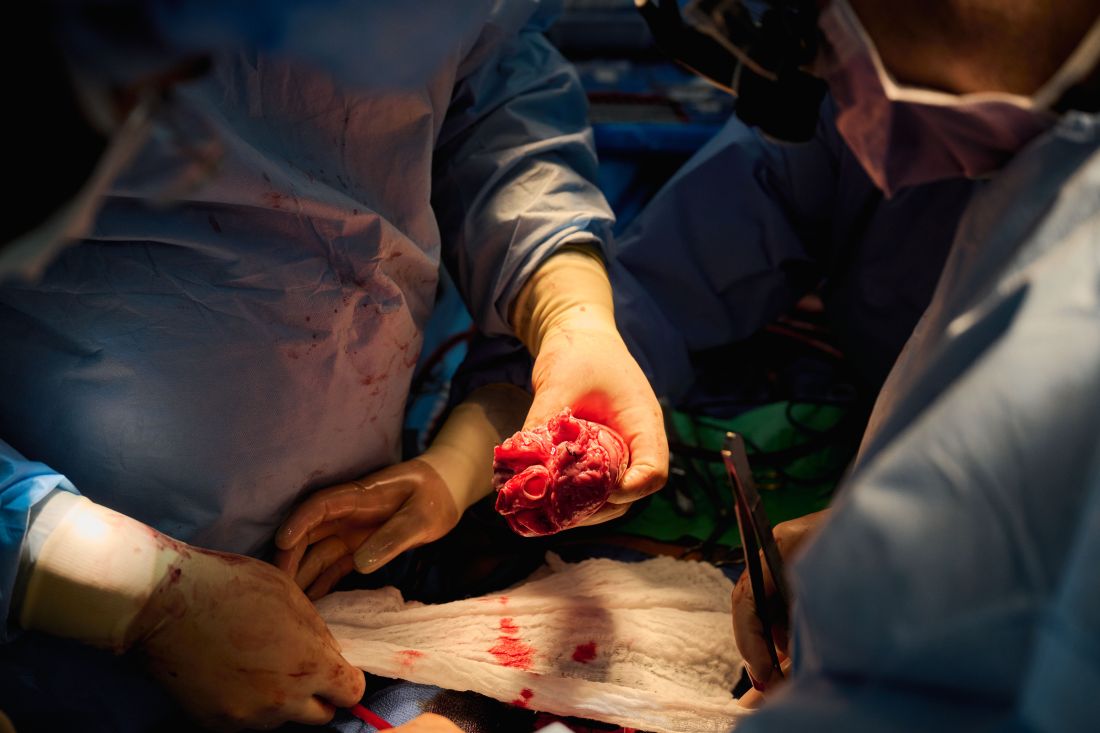

‘Case closed’: Bridging thrombolysis remains ‘gold standard’ in stroke thrombectomy

Two new noninferiority trials address the controversial question of whether thrombolytic therapy can be omitted for acute ischemic stroke in patients undergoing endovascular thrombectomy for large-vessel occlusion.

Both trials show better outcomes when standard bridging thrombolytic therapy is used before thrombectomy, with comparable safety.

The results of SWIFT-DIRECT and DIRECT-SAFE were published online June 22 in The Lancet.

“The case appears closed. Bypass intravenous thrombolysis is highly unlikely to be noninferior to standard care by a clinically acceptable margin for most patients,” writes Pooja Khatri, MD, MSc, department of neurology, University of Cincinnati, in a linked comment.

SWIFT-DIRECT

SWIFT-DIRECT enrolled 408 patients (median age 72; 51% women) with acute stroke due to large vessel occlusion admitted to stroke centers in Europe and Canada. Half were randomly allocated to thrombectomy alone and half to intravenous alteplase and thrombectomy.

Successful reperfusion was less common in patients who had thrombectomy alone (91% vs. 96%; risk difference −5.1%; 95% confidence interval, −10.2 to 0.0, P = .047).

With combination therapy, more patients achieved functional independence with a modified Rankin scale score of 0-2 at 90 days (65% vs. 57%; adjusted risk difference −7.3%; 95% CI, −16·6 to 2·1, lower limit of one-sided 95% CI, −15·1%, crossing the noninferiority margin of −12%).

“Despite a very liberal noninferiority margin and strict inclusion and exclusion criteria aimed at studying a population most likely to benefit from thrombectomy alone, point estimates directionally favored intravenous thrombolysis plus thrombectomy,” Urs Fischer, MD, cochair of the Stroke Center, University Hospital Basel, Switzerland, told this news organization.

“Furthermore, we could demonstrate that overall reperfusion rates were extremely high and yet significantly better in patients receiving intravenous thrombolysis plus thrombectomy than in patients treated with thrombectomy alone, a finding which has not been shown before,” Dr. Fischer said.

There was no significant difference in the risk of symptomatic intracranial bleeding (3% with combination therapy and 2% with thrombectomy alone).

Based on the results, in patients suitable for thrombolysis, skipping it before thrombectomy “is not justified,” the study team concludes.

DIRECT-SAFE

DIRECT-SAFE enrolled 295 patients (median age 69; 43% women) with stroke and large vessel occlusion from Australia, New Zealand, China, and Vietnam, with half undergoing direct thrombectomy and half bridging therapy first.

Functional independence (modified Rankin Scale 0-2 or return to baseline at 90 days) was more common in the bridging group (61% vs. 55%).

Safety outcomes were similar between groups. Symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage occurred in 2 (1%) patients in the direct group and 1 (1%) patient in the bridging group. There were 22 (15%) deaths in the direct group and 24 in the bridging group.

“There has been concern across the world regarding cost of treatment, together with fears of increasing bleeding risk or clot migration with intravenous thrombolytic,” lead investigator Peter Mitchell, MBBS, director, NeuroIntervention Service, The Royal Melbourne Hospital, Parkville, Victoria, Australia, told this news organization.

“We showed that patients in the bridging treatment arm had better outcomes across the entire study, especially in Asian region patients” and therefore remains “the gold standard,” Dr. Mitchell said.

To date, six published trials have addressed this question of endovascular therapy alone or with thrombolysis – SKIP, DIRECT-MT, MR CLEAN NO IV, SWIFT-DIRECT, and DIRECT-SAFE.

Dr. Fischer said the SWIFT-DIRECT study group plans to perform an individual participant data meta-analysis known as Improving Reperfusion Strategies in Ischemic Stroke (IRIS) of all six trials to see whether there are subgroups of patients in whom thrombectomy alone is as effective as thrombolysis plus thrombectomy.

Subgroups of interest, he said, include patients with early ischemic signs on imaging, those at increased risk for hemorrhagic complications, and patients with a high clot burden.

SWIFT-DIRECT was funding by Medtronic and University Hospital Bern. DIRECT-SAFE was funded by Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and Stryker USA. A complete list of author disclosures is available with the original articles.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two new noninferiority trials address the controversial question of whether thrombolytic therapy can be omitted for acute ischemic stroke in patients undergoing endovascular thrombectomy for large-vessel occlusion.

Both trials show better outcomes when standard bridging thrombolytic therapy is used before thrombectomy, with comparable safety.

The results of SWIFT-DIRECT and DIRECT-SAFE were published online June 22 in The Lancet.

“The case appears closed. Bypass intravenous thrombolysis is highly unlikely to be noninferior to standard care by a clinically acceptable margin for most patients,” writes Pooja Khatri, MD, MSc, department of neurology, University of Cincinnati, in a linked comment.

SWIFT-DIRECT

SWIFT-DIRECT enrolled 408 patients (median age 72; 51% women) with acute stroke due to large vessel occlusion admitted to stroke centers in Europe and Canada. Half were randomly allocated to thrombectomy alone and half to intravenous alteplase and thrombectomy.

Successful reperfusion was less common in patients who had thrombectomy alone (91% vs. 96%; risk difference −5.1%; 95% confidence interval, −10.2 to 0.0, P = .047).

With combination therapy, more patients achieved functional independence with a modified Rankin scale score of 0-2 at 90 days (65% vs. 57%; adjusted risk difference −7.3%; 95% CI, −16·6 to 2·1, lower limit of one-sided 95% CI, −15·1%, crossing the noninferiority margin of −12%).

“Despite a very liberal noninferiority margin and strict inclusion and exclusion criteria aimed at studying a population most likely to benefit from thrombectomy alone, point estimates directionally favored intravenous thrombolysis plus thrombectomy,” Urs Fischer, MD, cochair of the Stroke Center, University Hospital Basel, Switzerland, told this news organization.

“Furthermore, we could demonstrate that overall reperfusion rates were extremely high and yet significantly better in patients receiving intravenous thrombolysis plus thrombectomy than in patients treated with thrombectomy alone, a finding which has not been shown before,” Dr. Fischer said.

There was no significant difference in the risk of symptomatic intracranial bleeding (3% with combination therapy and 2% with thrombectomy alone).

Based on the results, in patients suitable for thrombolysis, skipping it before thrombectomy “is not justified,” the study team concludes.

DIRECT-SAFE

DIRECT-SAFE enrolled 295 patients (median age 69; 43% women) with stroke and large vessel occlusion from Australia, New Zealand, China, and Vietnam, with half undergoing direct thrombectomy and half bridging therapy first.

Functional independence (modified Rankin Scale 0-2 or return to baseline at 90 days) was more common in the bridging group (61% vs. 55%).

Safety outcomes were similar between groups. Symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage occurred in 2 (1%) patients in the direct group and 1 (1%) patient in the bridging group. There were 22 (15%) deaths in the direct group and 24 in the bridging group.

“There has been concern across the world regarding cost of treatment, together with fears of increasing bleeding risk or clot migration with intravenous thrombolytic,” lead investigator Peter Mitchell, MBBS, director, NeuroIntervention Service, The Royal Melbourne Hospital, Parkville, Victoria, Australia, told this news organization.

“We showed that patients in the bridging treatment arm had better outcomes across the entire study, especially in Asian region patients” and therefore remains “the gold standard,” Dr. Mitchell said.

To date, six published trials have addressed this question of endovascular therapy alone or with thrombolysis – SKIP, DIRECT-MT, MR CLEAN NO IV, SWIFT-DIRECT, and DIRECT-SAFE.

Dr. Fischer said the SWIFT-DIRECT study group plans to perform an individual participant data meta-analysis known as Improving Reperfusion Strategies in Ischemic Stroke (IRIS) of all six trials to see whether there are subgroups of patients in whom thrombectomy alone is as effective as thrombolysis plus thrombectomy.

Subgroups of interest, he said, include patients with early ischemic signs on imaging, those at increased risk for hemorrhagic complications, and patients with a high clot burden.

SWIFT-DIRECT was funding by Medtronic and University Hospital Bern. DIRECT-SAFE was funded by Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and Stryker USA. A complete list of author disclosures is available with the original articles.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two new noninferiority trials address the controversial question of whether thrombolytic therapy can be omitted for acute ischemic stroke in patients undergoing endovascular thrombectomy for large-vessel occlusion.

Both trials show better outcomes when standard bridging thrombolytic therapy is used before thrombectomy, with comparable safety.

The results of SWIFT-DIRECT and DIRECT-SAFE were published online June 22 in The Lancet.

“The case appears closed. Bypass intravenous thrombolysis is highly unlikely to be noninferior to standard care by a clinically acceptable margin for most patients,” writes Pooja Khatri, MD, MSc, department of neurology, University of Cincinnati, in a linked comment.

SWIFT-DIRECT

SWIFT-DIRECT enrolled 408 patients (median age 72; 51% women) with acute stroke due to large vessel occlusion admitted to stroke centers in Europe and Canada. Half were randomly allocated to thrombectomy alone and half to intravenous alteplase and thrombectomy.

Successful reperfusion was less common in patients who had thrombectomy alone (91% vs. 96%; risk difference −5.1%; 95% confidence interval, −10.2 to 0.0, P = .047).

With combination therapy, more patients achieved functional independence with a modified Rankin scale score of 0-2 at 90 days (65% vs. 57%; adjusted risk difference −7.3%; 95% CI, −16·6 to 2·1, lower limit of one-sided 95% CI, −15·1%, crossing the noninferiority margin of −12%).

“Despite a very liberal noninferiority margin and strict inclusion and exclusion criteria aimed at studying a population most likely to benefit from thrombectomy alone, point estimates directionally favored intravenous thrombolysis plus thrombectomy,” Urs Fischer, MD, cochair of the Stroke Center, University Hospital Basel, Switzerland, told this news organization.

“Furthermore, we could demonstrate that overall reperfusion rates were extremely high and yet significantly better in patients receiving intravenous thrombolysis plus thrombectomy than in patients treated with thrombectomy alone, a finding which has not been shown before,” Dr. Fischer said.

There was no significant difference in the risk of symptomatic intracranial bleeding (3% with combination therapy and 2% with thrombectomy alone).

Based on the results, in patients suitable for thrombolysis, skipping it before thrombectomy “is not justified,” the study team concludes.

DIRECT-SAFE

DIRECT-SAFE enrolled 295 patients (median age 69; 43% women) with stroke and large vessel occlusion from Australia, New Zealand, China, and Vietnam, with half undergoing direct thrombectomy and half bridging therapy first.

Functional independence (modified Rankin Scale 0-2 or return to baseline at 90 days) was more common in the bridging group (61% vs. 55%).

Safety outcomes were similar between groups. Symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage occurred in 2 (1%) patients in the direct group and 1 (1%) patient in the bridging group. There were 22 (15%) deaths in the direct group and 24 in the bridging group.

“There has been concern across the world regarding cost of treatment, together with fears of increasing bleeding risk or clot migration with intravenous thrombolytic,” lead investigator Peter Mitchell, MBBS, director, NeuroIntervention Service, The Royal Melbourne Hospital, Parkville, Victoria, Australia, told this news organization.

“We showed that patients in the bridging treatment arm had better outcomes across the entire study, especially in Asian region patients” and therefore remains “the gold standard,” Dr. Mitchell said.

To date, six published trials have addressed this question of endovascular therapy alone or with thrombolysis – SKIP, DIRECT-MT, MR CLEAN NO IV, SWIFT-DIRECT, and DIRECT-SAFE.

Dr. Fischer said the SWIFT-DIRECT study group plans to perform an individual participant data meta-analysis known as Improving Reperfusion Strategies in Ischemic Stroke (IRIS) of all six trials to see whether there are subgroups of patients in whom thrombectomy alone is as effective as thrombolysis plus thrombectomy.

Subgroups of interest, he said, include patients with early ischemic signs on imaging, those at increased risk for hemorrhagic complications, and patients with a high clot burden.

SWIFT-DIRECT was funding by Medtronic and University Hospital Bern. DIRECT-SAFE was funded by Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and Stryker USA. A complete list of author disclosures is available with the original articles.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE LANCET

Body-brain neuroinflammation loop may cause chronic ME/CFS, long COVID symptoms

ME/CFS has been established as resulting from infections, environmental exposures, stressors, and surgery. Similarities have been drawn during the COVID-19 pandemic between ME/CFS and a large subgroup of patients with post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection – also known as post-COVID conditions, or long COVID – who continue to have viral fatigue and other lingering symptoms after their infection resolves.

What has been less clearly understood, the researchers said, is the reason behind why ME/CFS and other postviral fatigue tends to be chronic and can sometime develop into a lifelong condition.

“These diseases are very closely related, and it is clear the biological basis of long COVID is unequivocally connected to the original COVID infection – so there should no longer be any debate and doubt about the fact that postviral fatigue syndromes like ME/CFS are biologically based and involve much disturbed physiology,” Warren Tate, MSc, PhD, emeritus professor in the department of biochemistry at the University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand, stated in a press release.

Their hypothesis, set forth in a study published in Frontiers of Neurology, proposes that the systemic immune/inflammatory response that occurs after an infection or stressful event does not revolve, which results in a “fluctuating chronic neuroinflammation that sustains and controls the complex neurological symptoms of ME/CFS and long COVID and facilitates frequent more serious relapses in response to life stress, as evidenced from a comprehensive disruption to the cellular molecular biology and body’s physiological pathways.”

Dr. Tate and colleagues said that it is still unclear how the neuroinflammation occurs, why it’s persistent in ME/CFS, and how it causes symptoms associated with ME/CFS. In their hypothesis, “abnormal signaling or transport of molecules/cells occurs through one or both of neurovascular pathways and/or a dysfunctional blood brain barrier,” they said, noting “the normally separate and contained brain/CNS compartment in the healthy person becomes more porous.” The neurological symptoms associated with ME/CFS occur due to strong signals sent because of persistent “inflammatory signals or immune cells/molecules migrating into the brain,” they explained.

This results in a continuous loop where the central nervous system sends signals back to the body through the hypothalamus/paraventricular nucleus and the brain stem. “The resulting symptoms and the neurologically driven ‘sickness response’ for the ME/CFS patient would persist, preventing healing and a return to the preinfectious/stress-related state,” Dr. Tate and colleagues said.

Lingering inflammation may be the culprit

Commenting on the study, Achillefs Ntranos, MD, a board-certified neurologist in private practice in Scarsdale, N.Y., who was not involved with the research, said previous studies have shown that long COVID is linked to chronic activation of microglia in the brain, which has also been seen to activate in patients with ME/CFS.

“The hypothesis that lingering inflammation in the brain is the culprit behind the neurological symptoms of long COVID and ME/CFS is valid,” he said. “If these cells remain activated in the brain, they can cause a state of increased and lingering inflammation, which can interfere with the function of neurons, thus producing neurological symptoms. Since the neurological symptoms are similar between these entities, the mechanisms that produce them might also be similar.”

While the exact cause of ME/CFS is still unclear, it is often tied to the aftereffects of a flu-like illness, Dr. Ntranos said. “This has led researchers to propose that it arises after a viral infection, with many different types of viruses being associated with it. Other ways researchers think ME/CFS is being brought on after a viral illness is via changes in the immune system, such as chronic production of cytokines, neuroinflammation, and disruption of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, which regulates the body’s response to stress,” he explained.

While a newer condition, long COVID is not all that different from ME/CFS, Dr. Ntranos noted, sharing the catalyst of a viral infection and core neurological symptoms such as fatigue, postexertional malaise, a “brain fog” that makes thinking or concentrating difficult, sleep problems, and lightheadedness, but there are differences that set it apart from ME/CFS.

“Long COVID is unique in having additional symptoms that are specific to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, such as respiratory and cardiovascular symptoms and loss of smell and taste. However most central nervous system effects are the same between these two entities,” he said.

Dr. Ntranos said long COVID’s neurological symptoms are similar to that of multiple sclerosis (MS), such as “brain fog” and postexertional malaise. “Since MS only affects the brain and spinal cord, there are no symptoms from other organ systems, such as the lungs, heart, or digestive system, contrary to long COVID. Furthermore, MS rarely affects smell and taste, making these symptoms unique to COVID,” he said.

However, he pointed out that brain fog and fatigue symptoms on their own can be nonspecific and attributed to many different conditions, such as obstructive sleep apnea, migraines, depression, anxiety, thyroid problems, vitamin deficiencies, dehydration, sleep disorders, and side effects of medications.

“More research needs to be done to understand how these cells are being activated, how they interfere with neuronal function, and why they remain in that state in some people, who then go on to develop fatigue and brain fog,” he said.

This study was funded by the Healthcare Otago Charitable Trust, the Associated New Zealand Myalgic Encephalomyelitis Society, and donations from families of patients with ME/CFS. The authors and Dr. Ntranos report no relevant financial disclosures.

ME/CFS has been established as resulting from infections, environmental exposures, stressors, and surgery. Similarities have been drawn during the COVID-19 pandemic between ME/CFS and a large subgroup of patients with post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection – also known as post-COVID conditions, or long COVID – who continue to have viral fatigue and other lingering symptoms after their infection resolves.

What has been less clearly understood, the researchers said, is the reason behind why ME/CFS and other postviral fatigue tends to be chronic and can sometime develop into a lifelong condition.

“These diseases are very closely related, and it is clear the biological basis of long COVID is unequivocally connected to the original COVID infection – so there should no longer be any debate and doubt about the fact that postviral fatigue syndromes like ME/CFS are biologically based and involve much disturbed physiology,” Warren Tate, MSc, PhD, emeritus professor in the department of biochemistry at the University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand, stated in a press release.

Their hypothesis, set forth in a study published in Frontiers of Neurology, proposes that the systemic immune/inflammatory response that occurs after an infection or stressful event does not revolve, which results in a “fluctuating chronic neuroinflammation that sustains and controls the complex neurological symptoms of ME/CFS and long COVID and facilitates frequent more serious relapses in response to life stress, as evidenced from a comprehensive disruption to the cellular molecular biology and body’s physiological pathways.”

Dr. Tate and colleagues said that it is still unclear how the neuroinflammation occurs, why it’s persistent in ME/CFS, and how it causes symptoms associated with ME/CFS. In their hypothesis, “abnormal signaling or transport of molecules/cells occurs through one or both of neurovascular pathways and/or a dysfunctional blood brain barrier,” they said, noting “the normally separate and contained brain/CNS compartment in the healthy person becomes more porous.” The neurological symptoms associated with ME/CFS occur due to strong signals sent because of persistent “inflammatory signals or immune cells/molecules migrating into the brain,” they explained.

This results in a continuous loop where the central nervous system sends signals back to the body through the hypothalamus/paraventricular nucleus and the brain stem. “The resulting symptoms and the neurologically driven ‘sickness response’ for the ME/CFS patient would persist, preventing healing and a return to the preinfectious/stress-related state,” Dr. Tate and colleagues said.

Lingering inflammation may be the culprit

Commenting on the study, Achillefs Ntranos, MD, a board-certified neurologist in private practice in Scarsdale, N.Y., who was not involved with the research, said previous studies have shown that long COVID is linked to chronic activation of microglia in the brain, which has also been seen to activate in patients with ME/CFS.

“The hypothesis that lingering inflammation in the brain is the culprit behind the neurological symptoms of long COVID and ME/CFS is valid,” he said. “If these cells remain activated in the brain, they can cause a state of increased and lingering inflammation, which can interfere with the function of neurons, thus producing neurological symptoms. Since the neurological symptoms are similar between these entities, the mechanisms that produce them might also be similar.”

While the exact cause of ME/CFS is still unclear, it is often tied to the aftereffects of a flu-like illness, Dr. Ntranos said. “This has led researchers to propose that it arises after a viral infection, with many different types of viruses being associated with it. Other ways researchers think ME/CFS is being brought on after a viral illness is via changes in the immune system, such as chronic production of cytokines, neuroinflammation, and disruption of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, which regulates the body’s response to stress,” he explained.

While a newer condition, long COVID is not all that different from ME/CFS, Dr. Ntranos noted, sharing the catalyst of a viral infection and core neurological symptoms such as fatigue, postexertional malaise, a “brain fog” that makes thinking or concentrating difficult, sleep problems, and lightheadedness, but there are differences that set it apart from ME/CFS.

“Long COVID is unique in having additional symptoms that are specific to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, such as respiratory and cardiovascular symptoms and loss of smell and taste. However most central nervous system effects are the same between these two entities,” he said.

Dr. Ntranos said long COVID’s neurological symptoms are similar to that of multiple sclerosis (MS), such as “brain fog” and postexertional malaise. “Since MS only affects the brain and spinal cord, there are no symptoms from other organ systems, such as the lungs, heart, or digestive system, contrary to long COVID. Furthermore, MS rarely affects smell and taste, making these symptoms unique to COVID,” he said.

However, he pointed out that brain fog and fatigue symptoms on their own can be nonspecific and attributed to many different conditions, such as obstructive sleep apnea, migraines, depression, anxiety, thyroid problems, vitamin deficiencies, dehydration, sleep disorders, and side effects of medications.

“More research needs to be done to understand how these cells are being activated, how they interfere with neuronal function, and why they remain in that state in some people, who then go on to develop fatigue and brain fog,” he said.

This study was funded by the Healthcare Otago Charitable Trust, the Associated New Zealand Myalgic Encephalomyelitis Society, and donations from families of patients with ME/CFS. The authors and Dr. Ntranos report no relevant financial disclosures.

ME/CFS has been established as resulting from infections, environmental exposures, stressors, and surgery. Similarities have been drawn during the COVID-19 pandemic between ME/CFS and a large subgroup of patients with post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection – also known as post-COVID conditions, or long COVID – who continue to have viral fatigue and other lingering symptoms after their infection resolves.

What has been less clearly understood, the researchers said, is the reason behind why ME/CFS and other postviral fatigue tends to be chronic and can sometime develop into a lifelong condition.

“These diseases are very closely related, and it is clear the biological basis of long COVID is unequivocally connected to the original COVID infection – so there should no longer be any debate and doubt about the fact that postviral fatigue syndromes like ME/CFS are biologically based and involve much disturbed physiology,” Warren Tate, MSc, PhD, emeritus professor in the department of biochemistry at the University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand, stated in a press release.

Their hypothesis, set forth in a study published in Frontiers of Neurology, proposes that the systemic immune/inflammatory response that occurs after an infection or stressful event does not revolve, which results in a “fluctuating chronic neuroinflammation that sustains and controls the complex neurological symptoms of ME/CFS and long COVID and facilitates frequent more serious relapses in response to life stress, as evidenced from a comprehensive disruption to the cellular molecular biology and body’s physiological pathways.”

Dr. Tate and colleagues said that it is still unclear how the neuroinflammation occurs, why it’s persistent in ME/CFS, and how it causes symptoms associated with ME/CFS. In their hypothesis, “abnormal signaling or transport of molecules/cells occurs through one or both of neurovascular pathways and/or a dysfunctional blood brain barrier,” they said, noting “the normally separate and contained brain/CNS compartment in the healthy person becomes more porous.” The neurological symptoms associated with ME/CFS occur due to strong signals sent because of persistent “inflammatory signals or immune cells/molecules migrating into the brain,” they explained.

This results in a continuous loop where the central nervous system sends signals back to the body through the hypothalamus/paraventricular nucleus and the brain stem. “The resulting symptoms and the neurologically driven ‘sickness response’ for the ME/CFS patient would persist, preventing healing and a return to the preinfectious/stress-related state,” Dr. Tate and colleagues said.

Lingering inflammation may be the culprit

Commenting on the study, Achillefs Ntranos, MD, a board-certified neurologist in private practice in Scarsdale, N.Y., who was not involved with the research, said previous studies have shown that long COVID is linked to chronic activation of microglia in the brain, which has also been seen to activate in patients with ME/CFS.

“The hypothesis that lingering inflammation in the brain is the culprit behind the neurological symptoms of long COVID and ME/CFS is valid,” he said. “If these cells remain activated in the brain, they can cause a state of increased and lingering inflammation, which can interfere with the function of neurons, thus producing neurological symptoms. Since the neurological symptoms are similar between these entities, the mechanisms that produce them might also be similar.”

While the exact cause of ME/CFS is still unclear, it is often tied to the aftereffects of a flu-like illness, Dr. Ntranos said. “This has led researchers to propose that it arises after a viral infection, with many different types of viruses being associated with it. Other ways researchers think ME/CFS is being brought on after a viral illness is via changes in the immune system, such as chronic production of cytokines, neuroinflammation, and disruption of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, which regulates the body’s response to stress,” he explained.

While a newer condition, long COVID is not all that different from ME/CFS, Dr. Ntranos noted, sharing the catalyst of a viral infection and core neurological symptoms such as fatigue, postexertional malaise, a “brain fog” that makes thinking or concentrating difficult, sleep problems, and lightheadedness, but there are differences that set it apart from ME/CFS.

“Long COVID is unique in having additional symptoms that are specific to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, such as respiratory and cardiovascular symptoms and loss of smell and taste. However most central nervous system effects are the same between these two entities,” he said.

Dr. Ntranos said long COVID’s neurological symptoms are similar to that of multiple sclerosis (MS), such as “brain fog” and postexertional malaise. “Since MS only affects the brain and spinal cord, there are no symptoms from other organ systems, such as the lungs, heart, or digestive system, contrary to long COVID. Furthermore, MS rarely affects smell and taste, making these symptoms unique to COVID,” he said.

However, he pointed out that brain fog and fatigue symptoms on their own can be nonspecific and attributed to many different conditions, such as obstructive sleep apnea, migraines, depression, anxiety, thyroid problems, vitamin deficiencies, dehydration, sleep disorders, and side effects of medications.

“More research needs to be done to understand how these cells are being activated, how they interfere with neuronal function, and why they remain in that state in some people, who then go on to develop fatigue and brain fog,” he said.

This study was funded by the Healthcare Otago Charitable Trust, the Associated New Zealand Myalgic Encephalomyelitis Society, and donations from families of patients with ME/CFS. The authors and Dr. Ntranos report no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM FRONTIERS IN NEUROLOGY

Cross-training across the map

There was a recent post on Sermo about medical office staff cross-training. It talked about the importance of the scheduler being able to cover for the medical assistant (to an extent), a billing person being able to room patients, and so on.

Here, in my little three-person office, the only thing my staff can’t do is see patients.

Actually, more than 2 years out since the pandemic changed everyone’s lives, we’ve settled into a very different cross-training routine. I’m the only one at my office. My medical assistant works from home, far north of me, and so does my scheduler, who is across town.

So, at the office, I handle it all. I check people in, copy insurance cards, collect copays, see patients, and make follow-ups.

At this time, I’ve not only gotten used to it, but really don’t mind it.

We don’t worry about freeway traffic. My staff starts at the exact time each day, and so I don’t worry about one of them being an hour late, trapped behind a rush-hour pile-up on the 101. Staying at home with a sick kid isn’t an issue either, anymore. If my secretary has to make her young daughter lunch, or run her over to a birthday party, I don’t even notice it. If there are any problems, she knows how to reach me. Same with my medical assistant.

Nobody worries about what to throw together for dinner if they get home late.

It saves money on rent, and money and time on transportation.

Gas prices, at least for driving to and from work for them, don’t have to be factored into the wage equations. I’d guess it’s about 1,000 gallons of gas a year saved. On a national scale that’s nothing, but to my staff right now that’s $3,000-$4,000 more in their pockets at the end of the year. Not to mention it’s two more cars off the road.

Granted, this doesn’t change what I’m doing. Seeing patients in person is a key part of being a doctor. Some things can be handled equally well over the phone or Zoom, but many can’t. It’s what I signed up for, and I really don’t mind it. Seeing patients is still what I enjoy.

My staff is a lot happier with this arrangement, and I don’t mind it either. I always, by nature, kept a reasonably paced schedule. Trying to shoehorn patients in has never been my way, so I have time to run a credit card or scan insurance information.

When one of my staff goes out of town, the other covers her calls and relays messages to me. Yes, it’s extra work, but no more so than if they were here in person. Probably less.

I’m sure many physicians wouldn’t agree with my office model, but it suits me fine. Cross-training and all.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

There was a recent post on Sermo about medical office staff cross-training. It talked about the importance of the scheduler being able to cover for the medical assistant (to an extent), a billing person being able to room patients, and so on.

Here, in my little three-person office, the only thing my staff can’t do is see patients.

Actually, more than 2 years out since the pandemic changed everyone’s lives, we’ve settled into a very different cross-training routine. I’m the only one at my office. My medical assistant works from home, far north of me, and so does my scheduler, who is across town.

So, at the office, I handle it all. I check people in, copy insurance cards, collect copays, see patients, and make follow-ups.

At this time, I’ve not only gotten used to it, but really don’t mind it.

We don’t worry about freeway traffic. My staff starts at the exact time each day, and so I don’t worry about one of them being an hour late, trapped behind a rush-hour pile-up on the 101. Staying at home with a sick kid isn’t an issue either, anymore. If my secretary has to make her young daughter lunch, or run her over to a birthday party, I don’t even notice it. If there are any problems, she knows how to reach me. Same with my medical assistant.

Nobody worries about what to throw together for dinner if they get home late.

It saves money on rent, and money and time on transportation.

Gas prices, at least for driving to and from work for them, don’t have to be factored into the wage equations. I’d guess it’s about 1,000 gallons of gas a year saved. On a national scale that’s nothing, but to my staff right now that’s $3,000-$4,000 more in their pockets at the end of the year. Not to mention it’s two more cars off the road.

Granted, this doesn’t change what I’m doing. Seeing patients in person is a key part of being a doctor. Some things can be handled equally well over the phone or Zoom, but many can’t. It’s what I signed up for, and I really don’t mind it. Seeing patients is still what I enjoy.

My staff is a lot happier with this arrangement, and I don’t mind it either. I always, by nature, kept a reasonably paced schedule. Trying to shoehorn patients in has never been my way, so I have time to run a credit card or scan insurance information.

When one of my staff goes out of town, the other covers her calls and relays messages to me. Yes, it’s extra work, but no more so than if they were here in person. Probably less.

I’m sure many physicians wouldn’t agree with my office model, but it suits me fine. Cross-training and all.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

There was a recent post on Sermo about medical office staff cross-training. It talked about the importance of the scheduler being able to cover for the medical assistant (to an extent), a billing person being able to room patients, and so on.

Here, in my little three-person office, the only thing my staff can’t do is see patients.

Actually, more than 2 years out since the pandemic changed everyone’s lives, we’ve settled into a very different cross-training routine. I’m the only one at my office. My medical assistant works from home, far north of me, and so does my scheduler, who is across town.

So, at the office, I handle it all. I check people in, copy insurance cards, collect copays, see patients, and make follow-ups.

At this time, I’ve not only gotten used to it, but really don’t mind it.

We don’t worry about freeway traffic. My staff starts at the exact time each day, and so I don’t worry about one of them being an hour late, trapped behind a rush-hour pile-up on the 101. Staying at home with a sick kid isn’t an issue either, anymore. If my secretary has to make her young daughter lunch, or run her over to a birthday party, I don’t even notice it. If there are any problems, she knows how to reach me. Same with my medical assistant.

Nobody worries about what to throw together for dinner if they get home late.

It saves money on rent, and money and time on transportation.

Gas prices, at least for driving to and from work for them, don’t have to be factored into the wage equations. I’d guess it’s about 1,000 gallons of gas a year saved. On a national scale that’s nothing, but to my staff right now that’s $3,000-$4,000 more in their pockets at the end of the year. Not to mention it’s two more cars off the road.

Granted, this doesn’t change what I’m doing. Seeing patients in person is a key part of being a doctor. Some things can be handled equally well over the phone or Zoom, but many can’t. It’s what I signed up for, and I really don’t mind it. Seeing patients is still what I enjoy.

My staff is a lot happier with this arrangement, and I don’t mind it either. I always, by nature, kept a reasonably paced schedule. Trying to shoehorn patients in has never been my way, so I have time to run a credit card or scan insurance information.

When one of my staff goes out of town, the other covers her calls and relays messages to me. Yes, it’s extra work, but no more so than if they were here in person. Probably less.

I’m sure many physicians wouldn’t agree with my office model, but it suits me fine. Cross-training and all.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Neuroscientist alleges irregularities in Alzheimer’s research

A U.S. neuroscientist claims that some of the studies of the experimental agent, simufilam (Cassava Sciences), a drug that targets amyloid beta (Abeta) in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), are flawed, and, as a result, has taken his concerns to the National Institutes of Health.

Matthew Schrag, MD, PhD, department of neurology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., uncovered what he calls inconsistencies in major studies examining the drug.

to support the hypothesis that buildup of amyloid in the brain causes AD. The NIH has funded research into Abeta as a potential cause of AD to the tune of millions of dollars for years.

“This hypothesis has been the central dominant thinking of the field,” Dr. Schrag told this news organization. “A lot of the therapies that have been developed and tested clinically over the last decade focused on the amyloid hypothesis in one formulation or another. So, it’s an important component of the way we think about Alzheimer’s disease,” he added.

In an in-depth article published in Science and written by investigative reporter Charles Piller, Dr. Schrag said he became involved after a colleague suggested he work with an attorney investigating simufilam. The lawyer paid Dr. Schrag $18,000 to investigate the research behind the agent. Cassava Sciences denies any misconduct, according to the article.

Dr. Schrag ran many AD studies through sophisticated imaging software. The effort revealed multiple Western blot images – which scientists use to detect the presence and amount of proteins in a sample – that appeared to be altered.

High stakes

Dr. Schrag found “apparently altered or duplicated images in dozens of journal articles,” the Science article states.

“A lot is at stake in terms of getting this right and it’s also important to acknowledge the limitations of what we can do. We were working with what’s published, what’s publicly available, and I think that it raises quite a lot of red flags, but we’ve also not reviewed the original material because it’s simply not available to us,” Dr. Schrag said in an interview.

However, he added that despite these limitations he believes “there’s enough here that it’s important for regulatory bodies to take a closer look at it to make sure that the data is right.”

Science reports that it launched its own independent review, asking several neuroscience experts to also review the research. They agreed with Dr. Schrag’s overall conclusions that something was amiss.

Many of the studies questioned in the whistleblower report involve Sylvain Lesné, PhD, who runs The Lesné Laboratory at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and is an associate professor of neuroscience. His colleague Karen Ashe, MD, PhD, a professor of neurology at the same institution, was also mentioned in the whistleblower report. She was coauthor of a 2006 report in Nature that identified an Abeta subtype as a potential culprit behind AD.

This news organization reached out to Dr. Lesné and Dr. Ashe for comment, but has not received a response.

However, an email from a University of Minnesota spokesperson said the institution is “aware that questions have arisen regarding certain images used in peer-reviewed research publications authored by University faculty Dr. Ashe and Dr. Lesné. The University will follow its processes to review the questions any claims have raised. At this time, we have no further information to provide.”

A matter of trust

Dr. Schrag noted the “important trust relationship between patients, physicians and scientists. When we’re exploring diseases that we don’t have good treatments for.” He added that when patients agree to participate in trials and accept the associated risks, “we owe them a very high degree of integrity regarding the foundational data.”

Dr. Schrag also pointed out that there are limited resources to study these diseases. “There is some potential for that to be misdirected. It’s important for us to pay attention to data integrity issues, to make sure that we’re investing in the right places.”

The term “fraud” does not appear in Dr. Schrag’s whistleblower report, nor does he claim misconduct in the report. However, his work has spurred some independent, ongoing investigation into the claims by several journals that published the works in question, including Nature and Science Signaling.

Dr. Schrag said that if his findings are validated through an investigation he would like to see the scientific record corrected.

“Ultimately, I’d like to see a new set of hypotheses given a chance to look at this disease from a new perspective,” he added.