User login

PTSD Rates Soar Among College Students

TOPLINE:

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) rates among college students more than doubled between 2017 and 2022, new data showed. Rates of acute stress disorder (ASD) also increased during that time.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted five waves of cross-sectional study from 2017 to 2022, involving 392,377 participants across 332 colleges and universities.

- The study utilized the Healthy Minds Study data, ensuring representativeness by applying sample weights based on institutional demographics.

- Outcome variables were diagnoses of PTSD and ASD, confirmed by healthcare practitioners, with statistical analysis assessing change in odds of estimated prevalence during 2017-2022.

TAKEAWAY:

- The prevalence of PTSD among US college students increased from 3.4% in 2017-2018 to 7.5% in 2021-2022.

- ASD diagnoses also rose from 0.2% in 2017-2018 to 0.7% in 2021-2022, with both increases remaining statistically significant after adjusting for demographic differences.

- Investigators noted that these findings underscore the need for targeted, trauma-informed intervention strategies in college settings.

IN PRACTICE:

“These trends highlight the escalating mental health challenges among college students, which is consistent with recent research reporting a surge in psychiatric diagnoses,” the authors wrote. “Factors contributing to this rise may include pandemic-related stressors (eg, loss of loved ones) and the effect of traumatic events (eg, campus shootings and racial trauma),” they added.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Yusen Zhai, PhD, University of Alabama at Birmingham. It was published online on May 30, 2024, in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The study’s reliance on self-reported data and single questions for diagnosed PTSD and ASD may have limited the accuracy of the findings. The retrospective design and the absence of longitudinal follow-up may have restricted the ability to infer causality from the observed trends.

DISCLOSURES:

No disclosures were reported. No funding information was available.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) rates among college students more than doubled between 2017 and 2022, new data showed. Rates of acute stress disorder (ASD) also increased during that time.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted five waves of cross-sectional study from 2017 to 2022, involving 392,377 participants across 332 colleges and universities.

- The study utilized the Healthy Minds Study data, ensuring representativeness by applying sample weights based on institutional demographics.

- Outcome variables were diagnoses of PTSD and ASD, confirmed by healthcare practitioners, with statistical analysis assessing change in odds of estimated prevalence during 2017-2022.

TAKEAWAY:

- The prevalence of PTSD among US college students increased from 3.4% in 2017-2018 to 7.5% in 2021-2022.

- ASD diagnoses also rose from 0.2% in 2017-2018 to 0.7% in 2021-2022, with both increases remaining statistically significant after adjusting for demographic differences.

- Investigators noted that these findings underscore the need for targeted, trauma-informed intervention strategies in college settings.

IN PRACTICE:

“These trends highlight the escalating mental health challenges among college students, which is consistent with recent research reporting a surge in psychiatric diagnoses,” the authors wrote. “Factors contributing to this rise may include pandemic-related stressors (eg, loss of loved ones) and the effect of traumatic events (eg, campus shootings and racial trauma),” they added.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Yusen Zhai, PhD, University of Alabama at Birmingham. It was published online on May 30, 2024, in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The study’s reliance on self-reported data and single questions for diagnosed PTSD and ASD may have limited the accuracy of the findings. The retrospective design and the absence of longitudinal follow-up may have restricted the ability to infer causality from the observed trends.

DISCLOSURES:

No disclosures were reported. No funding information was available.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) rates among college students more than doubled between 2017 and 2022, new data showed. Rates of acute stress disorder (ASD) also increased during that time.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted five waves of cross-sectional study from 2017 to 2022, involving 392,377 participants across 332 colleges and universities.

- The study utilized the Healthy Minds Study data, ensuring representativeness by applying sample weights based on institutional demographics.

- Outcome variables were diagnoses of PTSD and ASD, confirmed by healthcare practitioners, with statistical analysis assessing change in odds of estimated prevalence during 2017-2022.

TAKEAWAY:

- The prevalence of PTSD among US college students increased from 3.4% in 2017-2018 to 7.5% in 2021-2022.

- ASD diagnoses also rose from 0.2% in 2017-2018 to 0.7% in 2021-2022, with both increases remaining statistically significant after adjusting for demographic differences.

- Investigators noted that these findings underscore the need for targeted, trauma-informed intervention strategies in college settings.

IN PRACTICE:

“These trends highlight the escalating mental health challenges among college students, which is consistent with recent research reporting a surge in psychiatric diagnoses,” the authors wrote. “Factors contributing to this rise may include pandemic-related stressors (eg, loss of loved ones) and the effect of traumatic events (eg, campus shootings and racial trauma),” they added.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Yusen Zhai, PhD, University of Alabama at Birmingham. It was published online on May 30, 2024, in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The study’s reliance on self-reported data and single questions for diagnosed PTSD and ASD may have limited the accuracy of the findings. The retrospective design and the absence of longitudinal follow-up may have restricted the ability to infer causality from the observed trends.

DISCLOSURES:

No disclosures were reported. No funding information was available.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Early Memory Problems Linked to Increased Tau

Reports from older adults and their partners of early memory issues are associated with higher levels of tau neurofibrillary tangles in the brain, new research suggests.

The findings show that in addition to beta-amyloid, tau is implicated in cognitive decline even in the absence of overt clinical symptoms.

“Understanding the earliest signs of Alzheimer’s disease is even more important now that new disease-modifying drugs are becoming available,” study author

Rebecca E. Amariglio, PhD, clinical neuropsychologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the Massachusetts General Hospital and assistant professor in neurology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in a news release. “Our study found early suspicions of memory problems by both participants and the people who knew them well were linked to higher levels of tau tangles in the brain.”

The study was published online in Neurology.

Subjective Cognitive Decline

Beta-amyloid plaque accumulations and tau neurofibrillary tangles both underlie the clinical continuum of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Previous studies have investigated beta-amyloid burden and self- and partner-reported cognitive decline, but fewer have examined regional tau.

Subjective cognitive decline may be an early sign of AD, but self-awareness declines as individuals become increasingly symptomatic. So, a report from a partner about the participant’s level of cognitive functioning is often required in studies of mild cognitive impairment and dementia. The relevance of this model during the preclinical stage is less clear.

For the multicohort, cross-sectional study, investigators studied 675 cognitively unimpaired older adults (mean age, 72 years; 59% female), including persons with nonelevated beta-amyloid levels and those with elevated beta-amyloid levels, as determined by PET.

Participants brought a spouse, adult child, or other study partner with them to answer questions about the participant’s cognitive abilities and their ability to complete daily tasks. About 65% of participants lived with their partners and both completed the Cognitive Function Index (CFI) to assess cognitive decline, with higher scores indicating greater cognitive decline.

Covariates included age, sex, education, and cohort as well as objective cognitive performance.

The Value of Partner Reporting

Investigators found that higher tau levels were associated with greater self- and partner-reported cognitive decline (P < .001 for both).

Significant associations between self- and partner-reported CFI measures were driven by elevated beta-amyloid levels, with continuous beta-amyloid levels showing an independent effect on CFI in addition to tau.

“Our findings suggest that asking older people who have elevated Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers about subjective cognitive decline may be valuable for early detection,” Dr. Amariglio said.

Limitations include the fact that most participants were White and highly educated. Future studies should include participants from more diverse racial and ethnic groups and people with diverse levels of education, researchers noted.

“Although this study was cross-sectional, findings suggest that among older CU individuals who at risk for AD dementia, capturing self-report and study partner report of cognitive function may be valuable for understanding the relationship between early pathophysiologic progression and the emergence of functional impairment,” the authors concluded.

The study was funded in part by the National Institute on Aging, Eli Lily, and the Alzheimer’s Association, among others. Dr. Amariglio receives research funding from the National Institute on Aging. Complete study funding and other authors’ disclosures are listed in the original paper.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Reports from older adults and their partners of early memory issues are associated with higher levels of tau neurofibrillary tangles in the brain, new research suggests.

The findings show that in addition to beta-amyloid, tau is implicated in cognitive decline even in the absence of overt clinical symptoms.

“Understanding the earliest signs of Alzheimer’s disease is even more important now that new disease-modifying drugs are becoming available,” study author

Rebecca E. Amariglio, PhD, clinical neuropsychologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the Massachusetts General Hospital and assistant professor in neurology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in a news release. “Our study found early suspicions of memory problems by both participants and the people who knew them well were linked to higher levels of tau tangles in the brain.”

The study was published online in Neurology.

Subjective Cognitive Decline

Beta-amyloid plaque accumulations and tau neurofibrillary tangles both underlie the clinical continuum of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Previous studies have investigated beta-amyloid burden and self- and partner-reported cognitive decline, but fewer have examined regional tau.

Subjective cognitive decline may be an early sign of AD, but self-awareness declines as individuals become increasingly symptomatic. So, a report from a partner about the participant’s level of cognitive functioning is often required in studies of mild cognitive impairment and dementia. The relevance of this model during the preclinical stage is less clear.

For the multicohort, cross-sectional study, investigators studied 675 cognitively unimpaired older adults (mean age, 72 years; 59% female), including persons with nonelevated beta-amyloid levels and those with elevated beta-amyloid levels, as determined by PET.

Participants brought a spouse, adult child, or other study partner with them to answer questions about the participant’s cognitive abilities and their ability to complete daily tasks. About 65% of participants lived with their partners and both completed the Cognitive Function Index (CFI) to assess cognitive decline, with higher scores indicating greater cognitive decline.

Covariates included age, sex, education, and cohort as well as objective cognitive performance.

The Value of Partner Reporting

Investigators found that higher tau levels were associated with greater self- and partner-reported cognitive decline (P < .001 for both).

Significant associations between self- and partner-reported CFI measures were driven by elevated beta-amyloid levels, with continuous beta-amyloid levels showing an independent effect on CFI in addition to tau.

“Our findings suggest that asking older people who have elevated Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers about subjective cognitive decline may be valuable for early detection,” Dr. Amariglio said.

Limitations include the fact that most participants were White and highly educated. Future studies should include participants from more diverse racial and ethnic groups and people with diverse levels of education, researchers noted.

“Although this study was cross-sectional, findings suggest that among older CU individuals who at risk for AD dementia, capturing self-report and study partner report of cognitive function may be valuable for understanding the relationship between early pathophysiologic progression and the emergence of functional impairment,” the authors concluded.

The study was funded in part by the National Institute on Aging, Eli Lily, and the Alzheimer’s Association, among others. Dr. Amariglio receives research funding from the National Institute on Aging. Complete study funding and other authors’ disclosures are listed in the original paper.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Reports from older adults and their partners of early memory issues are associated with higher levels of tau neurofibrillary tangles in the brain, new research suggests.

The findings show that in addition to beta-amyloid, tau is implicated in cognitive decline even in the absence of overt clinical symptoms.

“Understanding the earliest signs of Alzheimer’s disease is even more important now that new disease-modifying drugs are becoming available,” study author

Rebecca E. Amariglio, PhD, clinical neuropsychologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the Massachusetts General Hospital and assistant professor in neurology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in a news release. “Our study found early suspicions of memory problems by both participants and the people who knew them well were linked to higher levels of tau tangles in the brain.”

The study was published online in Neurology.

Subjective Cognitive Decline

Beta-amyloid plaque accumulations and tau neurofibrillary tangles both underlie the clinical continuum of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Previous studies have investigated beta-amyloid burden and self- and partner-reported cognitive decline, but fewer have examined regional tau.

Subjective cognitive decline may be an early sign of AD, but self-awareness declines as individuals become increasingly symptomatic. So, a report from a partner about the participant’s level of cognitive functioning is often required in studies of mild cognitive impairment and dementia. The relevance of this model during the preclinical stage is less clear.

For the multicohort, cross-sectional study, investigators studied 675 cognitively unimpaired older adults (mean age, 72 years; 59% female), including persons with nonelevated beta-amyloid levels and those with elevated beta-amyloid levels, as determined by PET.

Participants brought a spouse, adult child, or other study partner with them to answer questions about the participant’s cognitive abilities and their ability to complete daily tasks. About 65% of participants lived with their partners and both completed the Cognitive Function Index (CFI) to assess cognitive decline, with higher scores indicating greater cognitive decline.

Covariates included age, sex, education, and cohort as well as objective cognitive performance.

The Value of Partner Reporting

Investigators found that higher tau levels were associated with greater self- and partner-reported cognitive decline (P < .001 for both).

Significant associations between self- and partner-reported CFI measures were driven by elevated beta-amyloid levels, with continuous beta-amyloid levels showing an independent effect on CFI in addition to tau.

“Our findings suggest that asking older people who have elevated Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers about subjective cognitive decline may be valuable for early detection,” Dr. Amariglio said.

Limitations include the fact that most participants were White and highly educated. Future studies should include participants from more diverse racial and ethnic groups and people with diverse levels of education, researchers noted.

“Although this study was cross-sectional, findings suggest that among older CU individuals who at risk for AD dementia, capturing self-report and study partner report of cognitive function may be valuable for understanding the relationship between early pathophysiologic progression and the emergence of functional impairment,” the authors concluded.

The study was funded in part by the National Institute on Aging, Eli Lily, and the Alzheimer’s Association, among others. Dr. Amariglio receives research funding from the National Institute on Aging. Complete study funding and other authors’ disclosures are listed in the original paper.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Knowing My Limits

The records came in by fax. A patient who’d recently moved here and needed to connect with a local neurologist.

When I had time, I flipped through the records. He needed ongoing treatment for a rare neurological disease that I’d heard of, but wasn’t otherwise familiar with. It didn’t even exist in the textbooks or conferences when I was in residency. I’d never seen a case of it, just read about it here and there in journals.

I looked it up, reviewed current treatment options, monitoring, and other knowledge about it, then stared at the notes for a minute. Finally, after thinking it over, I attached a sticky note for my secretary that, if the person called, to redirect them to one of the local subspecialty neurology centers.

I have nothing against this patient, but realistically he would be better served seeing someone with time to keep up on advancements in esoteric disorders, not a general neurologist like myself.

Isn’t that why we have subspecialty centers?

Some of it is also me. There was a time in my career when keeping up on newly discovered disorders and their treatments was, well, cool. But after 25 years in practice, that changes.

It’s important to be at least somewhat aware of new developments (such as in this case) as you may encounter them, and need to know when it’s something you can handle and when to send it elsewhere.

Driving home that afternoon I thought, “I’m an old dog. I don’t want to learn new tricks.” Maybe that’s all it is. There are other neurologists my age and older who thrive on the challenge of learning about and treating new and rare disorders that were unknown when they started out. There’s nothing wrong with that.

But I’ve never pretended to be an academic or sub-sub-specialist. My patients depend on me to stay up to date on the large number of commonly seen neurological disorders, and I do my best to do that.

It ain’t easy being an old dog.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

The records came in by fax. A patient who’d recently moved here and needed to connect with a local neurologist.

When I had time, I flipped through the records. He needed ongoing treatment for a rare neurological disease that I’d heard of, but wasn’t otherwise familiar with. It didn’t even exist in the textbooks or conferences when I was in residency. I’d never seen a case of it, just read about it here and there in journals.

I looked it up, reviewed current treatment options, monitoring, and other knowledge about it, then stared at the notes for a minute. Finally, after thinking it over, I attached a sticky note for my secretary that, if the person called, to redirect them to one of the local subspecialty neurology centers.

I have nothing against this patient, but realistically he would be better served seeing someone with time to keep up on advancements in esoteric disorders, not a general neurologist like myself.

Isn’t that why we have subspecialty centers?

Some of it is also me. There was a time in my career when keeping up on newly discovered disorders and their treatments was, well, cool. But after 25 years in practice, that changes.

It’s important to be at least somewhat aware of new developments (such as in this case) as you may encounter them, and need to know when it’s something you can handle and when to send it elsewhere.

Driving home that afternoon I thought, “I’m an old dog. I don’t want to learn new tricks.” Maybe that’s all it is. There are other neurologists my age and older who thrive on the challenge of learning about and treating new and rare disorders that were unknown when they started out. There’s nothing wrong with that.

But I’ve never pretended to be an academic or sub-sub-specialist. My patients depend on me to stay up to date on the large number of commonly seen neurological disorders, and I do my best to do that.

It ain’t easy being an old dog.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

The records came in by fax. A patient who’d recently moved here and needed to connect with a local neurologist.

When I had time, I flipped through the records. He needed ongoing treatment for a rare neurological disease that I’d heard of, but wasn’t otherwise familiar with. It didn’t even exist in the textbooks or conferences when I was in residency. I’d never seen a case of it, just read about it here and there in journals.

I looked it up, reviewed current treatment options, monitoring, and other knowledge about it, then stared at the notes for a minute. Finally, after thinking it over, I attached a sticky note for my secretary that, if the person called, to redirect them to one of the local subspecialty neurology centers.

I have nothing against this patient, but realistically he would be better served seeing someone with time to keep up on advancements in esoteric disorders, not a general neurologist like myself.

Isn’t that why we have subspecialty centers?

Some of it is also me. There was a time in my career when keeping up on newly discovered disorders and their treatments was, well, cool. But after 25 years in practice, that changes.

It’s important to be at least somewhat aware of new developments (such as in this case) as you may encounter them, and need to know when it’s something you can handle and when to send it elsewhere.

Driving home that afternoon I thought, “I’m an old dog. I don’t want to learn new tricks.” Maybe that’s all it is. There are other neurologists my age and older who thrive on the challenge of learning about and treating new and rare disorders that were unknown when they started out. There’s nothing wrong with that.

But I’ve never pretended to be an academic or sub-sub-specialist. My patients depend on me to stay up to date on the large number of commonly seen neurological disorders, and I do my best to do that.

It ain’t easy being an old dog.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

New Era? ‘Double Selective’ Antibiotic Spares the Microbiome

A new antibiotic uses a never-before-seen mechanism to deliver a direct hit on tough-to-treat infections while leaving beneficial microbes alone. The strategy could lead to a new class of antibiotics that attack dangerous bacteria in a powerful new way, overcoming current drug resistance while sparing the gut microbiome.

“The biggest takeaway is the double-selective component,” said co-lead author Kristen A. Muñoz, PhD, who performed the research as a doctoral student at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC). “We were able to develop a drug that not only targets problematic pathogens, but because it is selective for these pathogens only, we can spare the good bacteria and preserve the integrity of the microbiome.”

The drug goes after Gram-negative bacteria — pathogens responsible for debilitating and even fatal infections like gastroenteritis, urinary tract infections, pneumonia, sepsis, and cholera. The arsenal of antibiotics against them is old, with no new classes specifically targeting these bacteria coming on the market since 1968.

Many of these bugs have become resistant to one or more antibiotics, with deadly consequences. And antibiotics against them can also wipe out beneficial gut bacteria, allowing serious secondary infections to flare up.

In a study published in Nature, the drug lolamicin knocked out or reduced 130 strains of antibiotic-resistant Gram-negative bacteria in cell cultures. It also successfully treated drug-resistant bloodstream infections and pneumonia in mice while sparing their gut microbiome.

With their microbiomes intact, the mice then fought off secondary infection with Clostridioides difficile (a leading cause of opportunistic and sometimes fatal infections in US health care facilities), while mice treated with other compounds that damaged their microbiome succumbed.

How It Works

Like a well-built medieval castle, Gram-negative bacteria are encased in two protective walls, or membranes. Dr. Muñoz and her team at UIUC set out to breach this defense by finding compounds that hinder the “Lol system,” which ferries lipoproteins between them.

From one compound they constructed lolamicin, which can stop Gram-negative pathogens — with little effect on Gram-negative beneficial bacteria and no effect on Gram-positive bacteria.

“Gram-positive bacteria do not have an outer membrane, so they do not possess the Lol system,” Dr. Muñoz said. “When we compared the sequences of the Lol system in certain Gram-negative pathogens to Gram-negative commensal [beneficial] gut bacteria, we saw that the Lol systems were pretty different.”

Tossing a monkey wrench into the Lol system may be the study’s biggest contribution to future antibiotic development, said Kim Lewis, PhD, professor of Biology and director of Antimicrobial Discovery Center at Northeastern University, Boston, who has discovered several antibiotics now in preclinical research. One, darobactin, targets Gram-negative bugs without affecting the gut microbiome. Another, teixobactin, takes down Gram-positive bacteria without causing drug resistance.

“Lolamicin hits a novel target. I would say that’s the most significant study finding,” said Dr. Lewis, who was not involved in the study. “That is rare. If you look at antibiotics introduced since 1968, they have been modifications of existing antibiotics or, rarely, new chemically but hitting the same proven targets. This one hits something properly new, and [that’s] what I found perhaps the most original and interesting.”

Kirk E. Hevener, PharmD, PhD, associate professor of Pharmaceutical Sciences at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, Tennessee, agreed. (Dr. Hevener also was not involved in the study.) “Lolamicin works by targeting a unique Gram-negative transport system. No currently approved antibacterials work in this way, meaning it potentially represents the first of a new class of antibacterials with narrow-spectrum Gram-negative activity and low gastrointestinal disturbance,” said Dr. Hevener, whose research looks at new antimicrobial drug targets.

The UIUC researchers noted that lolamicin has one drawback: Bacteria frequently developed resistance to it. But in future work, it could be tweaked, combined with other antibiotics, or used as a template for finding other Lol system attackers, they said.

“There is still a good amount of work cut out for us in terms of assessing the clinical translatability of lolamicin, but we are hopeful for the future of this drug,” Dr. Muñoz said.

Addressing a Dire Need

Bringing such a drug to market — from discovery to Food and Drug Administration approval — could take more than a decade, said Dr. Hevener. And new agents, especially for Gram-negative bugs, are sorely needed.

Not only do these bacteria shield themselves with a double membrane but they also “have more complex resistance mechanisms including special pumps that can remove antibacterial drugs from the cell before they can be effective,” Dr. Hevener said.

As a result, drug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria are making treatment of severe infections such as sepsis and pneumonia in health care settings difficult.

Bloodstream infections with drug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae have a 40% mortality rate, Dr. Lewis said. And microbiome damage caused by antibiotics is also widespread and deadly, wiping out communities of helpful, protective gut bacteria. That contributes to over half of the C. difficile infections that affect 500,000 people and kill 30,000 a year in the United States.

“Our arsenal of antibacterials that can be used to treat Gram-negative infections is dangerously low,” Dr. Hevener said. “Research will always be needed to develop new antibacterials with novel mechanisms of activity that can bypass bacterial resistance mechanisms.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A new antibiotic uses a never-before-seen mechanism to deliver a direct hit on tough-to-treat infections while leaving beneficial microbes alone. The strategy could lead to a new class of antibiotics that attack dangerous bacteria in a powerful new way, overcoming current drug resistance while sparing the gut microbiome.

“The biggest takeaway is the double-selective component,” said co-lead author Kristen A. Muñoz, PhD, who performed the research as a doctoral student at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC). “We were able to develop a drug that not only targets problematic pathogens, but because it is selective for these pathogens only, we can spare the good bacteria and preserve the integrity of the microbiome.”

The drug goes after Gram-negative bacteria — pathogens responsible for debilitating and even fatal infections like gastroenteritis, urinary tract infections, pneumonia, sepsis, and cholera. The arsenal of antibiotics against them is old, with no new classes specifically targeting these bacteria coming on the market since 1968.

Many of these bugs have become resistant to one or more antibiotics, with deadly consequences. And antibiotics against them can also wipe out beneficial gut bacteria, allowing serious secondary infections to flare up.

In a study published in Nature, the drug lolamicin knocked out or reduced 130 strains of antibiotic-resistant Gram-negative bacteria in cell cultures. It also successfully treated drug-resistant bloodstream infections and pneumonia in mice while sparing their gut microbiome.

With their microbiomes intact, the mice then fought off secondary infection with Clostridioides difficile (a leading cause of opportunistic and sometimes fatal infections in US health care facilities), while mice treated with other compounds that damaged their microbiome succumbed.

How It Works

Like a well-built medieval castle, Gram-negative bacteria are encased in two protective walls, or membranes. Dr. Muñoz and her team at UIUC set out to breach this defense by finding compounds that hinder the “Lol system,” which ferries lipoproteins between them.

From one compound they constructed lolamicin, which can stop Gram-negative pathogens — with little effect on Gram-negative beneficial bacteria and no effect on Gram-positive bacteria.

“Gram-positive bacteria do not have an outer membrane, so they do not possess the Lol system,” Dr. Muñoz said. “When we compared the sequences of the Lol system in certain Gram-negative pathogens to Gram-negative commensal [beneficial] gut bacteria, we saw that the Lol systems were pretty different.”

Tossing a monkey wrench into the Lol system may be the study’s biggest contribution to future antibiotic development, said Kim Lewis, PhD, professor of Biology and director of Antimicrobial Discovery Center at Northeastern University, Boston, who has discovered several antibiotics now in preclinical research. One, darobactin, targets Gram-negative bugs without affecting the gut microbiome. Another, teixobactin, takes down Gram-positive bacteria without causing drug resistance.

“Lolamicin hits a novel target. I would say that’s the most significant study finding,” said Dr. Lewis, who was not involved in the study. “That is rare. If you look at antibiotics introduced since 1968, they have been modifications of existing antibiotics or, rarely, new chemically but hitting the same proven targets. This one hits something properly new, and [that’s] what I found perhaps the most original and interesting.”

Kirk E. Hevener, PharmD, PhD, associate professor of Pharmaceutical Sciences at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, Tennessee, agreed. (Dr. Hevener also was not involved in the study.) “Lolamicin works by targeting a unique Gram-negative transport system. No currently approved antibacterials work in this way, meaning it potentially represents the first of a new class of antibacterials with narrow-spectrum Gram-negative activity and low gastrointestinal disturbance,” said Dr. Hevener, whose research looks at new antimicrobial drug targets.

The UIUC researchers noted that lolamicin has one drawback: Bacteria frequently developed resistance to it. But in future work, it could be tweaked, combined with other antibiotics, or used as a template for finding other Lol system attackers, they said.

“There is still a good amount of work cut out for us in terms of assessing the clinical translatability of lolamicin, but we are hopeful for the future of this drug,” Dr. Muñoz said.

Addressing a Dire Need

Bringing such a drug to market — from discovery to Food and Drug Administration approval — could take more than a decade, said Dr. Hevener. And new agents, especially for Gram-negative bugs, are sorely needed.

Not only do these bacteria shield themselves with a double membrane but they also “have more complex resistance mechanisms including special pumps that can remove antibacterial drugs from the cell before they can be effective,” Dr. Hevener said.

As a result, drug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria are making treatment of severe infections such as sepsis and pneumonia in health care settings difficult.

Bloodstream infections with drug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae have a 40% mortality rate, Dr. Lewis said. And microbiome damage caused by antibiotics is also widespread and deadly, wiping out communities of helpful, protective gut bacteria. That contributes to over half of the C. difficile infections that affect 500,000 people and kill 30,000 a year in the United States.

“Our arsenal of antibacterials that can be used to treat Gram-negative infections is dangerously low,” Dr. Hevener said. “Research will always be needed to develop new antibacterials with novel mechanisms of activity that can bypass bacterial resistance mechanisms.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A new antibiotic uses a never-before-seen mechanism to deliver a direct hit on tough-to-treat infections while leaving beneficial microbes alone. The strategy could lead to a new class of antibiotics that attack dangerous bacteria in a powerful new way, overcoming current drug resistance while sparing the gut microbiome.

“The biggest takeaway is the double-selective component,” said co-lead author Kristen A. Muñoz, PhD, who performed the research as a doctoral student at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC). “We were able to develop a drug that not only targets problematic pathogens, but because it is selective for these pathogens only, we can spare the good bacteria and preserve the integrity of the microbiome.”

The drug goes after Gram-negative bacteria — pathogens responsible for debilitating and even fatal infections like gastroenteritis, urinary tract infections, pneumonia, sepsis, and cholera. The arsenal of antibiotics against them is old, with no new classes specifically targeting these bacteria coming on the market since 1968.

Many of these bugs have become resistant to one or more antibiotics, with deadly consequences. And antibiotics against them can also wipe out beneficial gut bacteria, allowing serious secondary infections to flare up.

In a study published in Nature, the drug lolamicin knocked out or reduced 130 strains of antibiotic-resistant Gram-negative bacteria in cell cultures. It also successfully treated drug-resistant bloodstream infections and pneumonia in mice while sparing their gut microbiome.

With their microbiomes intact, the mice then fought off secondary infection with Clostridioides difficile (a leading cause of opportunistic and sometimes fatal infections in US health care facilities), while mice treated with other compounds that damaged their microbiome succumbed.

How It Works

Like a well-built medieval castle, Gram-negative bacteria are encased in two protective walls, or membranes. Dr. Muñoz and her team at UIUC set out to breach this defense by finding compounds that hinder the “Lol system,” which ferries lipoproteins between them.

From one compound they constructed lolamicin, which can stop Gram-negative pathogens — with little effect on Gram-negative beneficial bacteria and no effect on Gram-positive bacteria.

“Gram-positive bacteria do not have an outer membrane, so they do not possess the Lol system,” Dr. Muñoz said. “When we compared the sequences of the Lol system in certain Gram-negative pathogens to Gram-negative commensal [beneficial] gut bacteria, we saw that the Lol systems were pretty different.”

Tossing a monkey wrench into the Lol system may be the study’s biggest contribution to future antibiotic development, said Kim Lewis, PhD, professor of Biology and director of Antimicrobial Discovery Center at Northeastern University, Boston, who has discovered several antibiotics now in preclinical research. One, darobactin, targets Gram-negative bugs without affecting the gut microbiome. Another, teixobactin, takes down Gram-positive bacteria without causing drug resistance.

“Lolamicin hits a novel target. I would say that’s the most significant study finding,” said Dr. Lewis, who was not involved in the study. “That is rare. If you look at antibiotics introduced since 1968, they have been modifications of existing antibiotics or, rarely, new chemically but hitting the same proven targets. This one hits something properly new, and [that’s] what I found perhaps the most original and interesting.”

Kirk E. Hevener, PharmD, PhD, associate professor of Pharmaceutical Sciences at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, Tennessee, agreed. (Dr. Hevener also was not involved in the study.) “Lolamicin works by targeting a unique Gram-negative transport system. No currently approved antibacterials work in this way, meaning it potentially represents the first of a new class of antibacterials with narrow-spectrum Gram-negative activity and low gastrointestinal disturbance,” said Dr. Hevener, whose research looks at new antimicrobial drug targets.

The UIUC researchers noted that lolamicin has one drawback: Bacteria frequently developed resistance to it. But in future work, it could be tweaked, combined with other antibiotics, or used as a template for finding other Lol system attackers, they said.

“There is still a good amount of work cut out for us in terms of assessing the clinical translatability of lolamicin, but we are hopeful for the future of this drug,” Dr. Muñoz said.

Addressing a Dire Need

Bringing such a drug to market — from discovery to Food and Drug Administration approval — could take more than a decade, said Dr. Hevener. And new agents, especially for Gram-negative bugs, are sorely needed.

Not only do these bacteria shield themselves with a double membrane but they also “have more complex resistance mechanisms including special pumps that can remove antibacterial drugs from the cell before they can be effective,” Dr. Hevener said.

As a result, drug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria are making treatment of severe infections such as sepsis and pneumonia in health care settings difficult.

Bloodstream infections with drug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae have a 40% mortality rate, Dr. Lewis said. And microbiome damage caused by antibiotics is also widespread and deadly, wiping out communities of helpful, protective gut bacteria. That contributes to over half of the C. difficile infections that affect 500,000 people and kill 30,000 a year in the United States.

“Our arsenal of antibacterials that can be used to treat Gram-negative infections is dangerously low,” Dr. Hevener said. “Research will always be needed to develop new antibacterials with novel mechanisms of activity that can bypass bacterial resistance mechanisms.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Vitamin D Test Inaccuracies Persist Despite Gains in Field: CDC

Some vitamin D tests may give misleading results despite progress made in recent years to improve the quality of these assays, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Otoe Sugahara manager of the CDC Vitamin D Standardization-Certification Program (VDSCP), presented an update of her group’s work at ENDO 2024, the Endocrine Society’s annual meeting in Boston.

“Though most vitamin D tests in our program have improved, there still remain some sample-specific inaccuracies. The CDC is working with program participants to address these situations,” Ms. Sugahara said in a statement released by the Endocrine Society.

For example, some assays measure other compounds besides 25-hydroxyvitamin D, which can falsely elevate results of some blood samples, Ms. Sugahara reported. Thus, some tests may be misclassified, with results seen as sufficient from samples that should have indicated a vitamin D deficiency.

“While most vitamin D tests are effective, it is important for healthcare providers to be aware of the potential inconsistencies associated with vitamin D tests to avoid misclassification of the patients,” Ms. Sugahara and coauthors said in an abstract provided by the Endocrine Society.

Ms. Sugahara’s report provided a snapshot of the state of longstanding efforts to improve the quality of a widely performed service in US healthcare: testing vitamin D levels.

These include an international collaboration that gave rise in 2010 to a vitamin D standardization program, from which the CDC’s VDSCP certification emerged. Among the leaders of these efforts was Christopher Sempos, PhD, then with the Office of Dietary Supplements at the National Institutes of Health.

Many clinicians may not be aware of the concerns about the accuracy of vitamin D tests that led to the drive for standardization, Dr. Sempos, now retired, said in an interview. And, in his view, it’s something that busy practitioners should not have to consider.

“They have literally thousands of diseases they have to be able to recognize and diagnose,” Dr. Sempos said. “They should be able to count on the laboratory system to give them accurate and precise data.”

‘Nudging’ Toward Better Results

The CDC’s certification program gives labs and companies detailed information about the analytical accuracy and precision of their vitamin D tests.

This feedback has paid off with improved results, Andy Hoofnagle, MD, PhD, professor of laboratory medicine and pathology at the University of Washington in Seattle, told this news organization. It helps by “nudging manufacturers in the right direction,” he said.

“Some manufacturers reformulated, others recalibrated, which is a lot of effort on their part, so that when the patient get a number, it actually means the right thing,” said Dr. Hoofnagle, who is also chair of the Accuracy-Based Programs Committee of the College of American Pathologists.

“There are still many immunoassays on the market that aren’t giving the correct results, unfortunately, but the standardization certification program has really pushed the field in the right direction,” he said.

US scientists use two main types of technologies to measure vitamin D in the blood, Ms. Sugahara said. One is mass spectrometry, which separately measures 25-hydroxyvitamin D2 and D3 and sums the values. The other type, immunoassay, measures both compounds at the same time and reports one result for total 25-hydroxyvitamin D.

At the ENDO 2024 meeting, Ms. Sugahara reported generally positive trends seen in the VDSCP. For example, the program looks at specific tests’ bias, or the deviation of test results from the true value, as determined with the CDC’s reference method for vitamin D.

Average calibration bias was less than 1% for all assays in the VDSCP in 2022, Ms. Sugahara said. The average calibration bias for immunoassays was 0.86%, and for assays using mass spectrometry, it was 0.55%, Ms. Sugahara reported.

These are improved results compared with 2019 data, in which mass spectrometry–based assays had a mean bias of 1.9% and immunoassays had a mean bias of 2.4%, the CDC told this news organization in an email exchange.

The CDC said the VDSCP supports laboratories and researchers from around the world, including ones based in the US, China, Australia, Japan, and Korea.

Call for Research

Vitamin D tests are widely administered despite questions about their benefit for people who do not appear likely to be deficient of it.

The Endocrine Society’s newly released practice guideline recommends against routine testing of blood vitamin D levels in the general population.

Laboratory testing has increased over the years owing to studies reporting associations between blood vitamin D [25(OH)D] levels and a variety of common disorders, including musculoskeletal, metabolic, cardiovascular, malignant, autoimmune, and infectious diseases, wrote Marie B. Demay, MD, of Harvard Medical School in Boston, and coauthors in the new guideline. It was published on June 3 in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

‘”Although a causal link between serum 25(OH)D concentrations and many disorders has not been clearly established, these associations have led to widespread supplementation with vitamin D and increased laboratory testing for 25(OH)D in the general population,” they wrote.

It’s uncertain that “any putative benefits of screening would outweigh the increased burden and cost, and whether implementation of universal 25(OH)D screening would be feasible from a societal perspective,” Dr. Demay and coauthors added.

They noted that the influential US Preventive Services Task Force also has raised doubts about widespread use of vitamin D tests.

The USPSTF has a somewhat different take from the Endocrine Society. The task force in 2021 reiterated its view that there is not enough evidence to recommend for or against widespread vitamin D testing for adults. The task force gave this test an I grade, meaning there is insufficient evidence to weigh the risks and benefits. That’s the same grade the task force gave it in 2014.

The USPSTF uses a grade of D to recommend against use of a test or service.

In an interview with this news organization, John Wong, MD, vice chair of the USPSTF, reiterated his group’s call for more research into the potential benefits and harms of vitamin D screening.

One of the challenges in addressing this issue, Dr. Wong noted, has been the variability of test results. Therefore, efforts such as the CDC’s VDSCP in improving test quality may help in eventually building up the kind of evidence base needed for the task force to offer a more definitive judgment on the tests, he said.

Wong acknowledged it must be frustrating for clinicians and patients to hear that experts don’t have the evidence needed to make a broad call about whether routine vitamin D tests are beneficial.

“We really would like to have that evidence because we recognize that it’s an important health question to help everybody in this nation stay healthy and live longer,” Dr. Wong said.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Some vitamin D tests may give misleading results despite progress made in recent years to improve the quality of these assays, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Otoe Sugahara manager of the CDC Vitamin D Standardization-Certification Program (VDSCP), presented an update of her group’s work at ENDO 2024, the Endocrine Society’s annual meeting in Boston.

“Though most vitamin D tests in our program have improved, there still remain some sample-specific inaccuracies. The CDC is working with program participants to address these situations,” Ms. Sugahara said in a statement released by the Endocrine Society.

For example, some assays measure other compounds besides 25-hydroxyvitamin D, which can falsely elevate results of some blood samples, Ms. Sugahara reported. Thus, some tests may be misclassified, with results seen as sufficient from samples that should have indicated a vitamin D deficiency.

“While most vitamin D tests are effective, it is important for healthcare providers to be aware of the potential inconsistencies associated with vitamin D tests to avoid misclassification of the patients,” Ms. Sugahara and coauthors said in an abstract provided by the Endocrine Society.

Ms. Sugahara’s report provided a snapshot of the state of longstanding efforts to improve the quality of a widely performed service in US healthcare: testing vitamin D levels.

These include an international collaboration that gave rise in 2010 to a vitamin D standardization program, from which the CDC’s VDSCP certification emerged. Among the leaders of these efforts was Christopher Sempos, PhD, then with the Office of Dietary Supplements at the National Institutes of Health.

Many clinicians may not be aware of the concerns about the accuracy of vitamin D tests that led to the drive for standardization, Dr. Sempos, now retired, said in an interview. And, in his view, it’s something that busy practitioners should not have to consider.

“They have literally thousands of diseases they have to be able to recognize and diagnose,” Dr. Sempos said. “They should be able to count on the laboratory system to give them accurate and precise data.”

‘Nudging’ Toward Better Results

The CDC’s certification program gives labs and companies detailed information about the analytical accuracy and precision of their vitamin D tests.

This feedback has paid off with improved results, Andy Hoofnagle, MD, PhD, professor of laboratory medicine and pathology at the University of Washington in Seattle, told this news organization. It helps by “nudging manufacturers in the right direction,” he said.

“Some manufacturers reformulated, others recalibrated, which is a lot of effort on their part, so that when the patient get a number, it actually means the right thing,” said Dr. Hoofnagle, who is also chair of the Accuracy-Based Programs Committee of the College of American Pathologists.

“There are still many immunoassays on the market that aren’t giving the correct results, unfortunately, but the standardization certification program has really pushed the field in the right direction,” he said.

US scientists use two main types of technologies to measure vitamin D in the blood, Ms. Sugahara said. One is mass spectrometry, which separately measures 25-hydroxyvitamin D2 and D3 and sums the values. The other type, immunoassay, measures both compounds at the same time and reports one result for total 25-hydroxyvitamin D.

At the ENDO 2024 meeting, Ms. Sugahara reported generally positive trends seen in the VDSCP. For example, the program looks at specific tests’ bias, or the deviation of test results from the true value, as determined with the CDC’s reference method for vitamin D.

Average calibration bias was less than 1% for all assays in the VDSCP in 2022, Ms. Sugahara said. The average calibration bias for immunoassays was 0.86%, and for assays using mass spectrometry, it was 0.55%, Ms. Sugahara reported.

These are improved results compared with 2019 data, in which mass spectrometry–based assays had a mean bias of 1.9% and immunoassays had a mean bias of 2.4%, the CDC told this news organization in an email exchange.

The CDC said the VDSCP supports laboratories and researchers from around the world, including ones based in the US, China, Australia, Japan, and Korea.

Call for Research

Vitamin D tests are widely administered despite questions about their benefit for people who do not appear likely to be deficient of it.

The Endocrine Society’s newly released practice guideline recommends against routine testing of blood vitamin D levels in the general population.

Laboratory testing has increased over the years owing to studies reporting associations between blood vitamin D [25(OH)D] levels and a variety of common disorders, including musculoskeletal, metabolic, cardiovascular, malignant, autoimmune, and infectious diseases, wrote Marie B. Demay, MD, of Harvard Medical School in Boston, and coauthors in the new guideline. It was published on June 3 in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

‘”Although a causal link between serum 25(OH)D concentrations and many disorders has not been clearly established, these associations have led to widespread supplementation with vitamin D and increased laboratory testing for 25(OH)D in the general population,” they wrote.

It’s uncertain that “any putative benefits of screening would outweigh the increased burden and cost, and whether implementation of universal 25(OH)D screening would be feasible from a societal perspective,” Dr. Demay and coauthors added.

They noted that the influential US Preventive Services Task Force also has raised doubts about widespread use of vitamin D tests.

The USPSTF has a somewhat different take from the Endocrine Society. The task force in 2021 reiterated its view that there is not enough evidence to recommend for or against widespread vitamin D testing for adults. The task force gave this test an I grade, meaning there is insufficient evidence to weigh the risks and benefits. That’s the same grade the task force gave it in 2014.

The USPSTF uses a grade of D to recommend against use of a test or service.

In an interview with this news organization, John Wong, MD, vice chair of the USPSTF, reiterated his group’s call for more research into the potential benefits and harms of vitamin D screening.

One of the challenges in addressing this issue, Dr. Wong noted, has been the variability of test results. Therefore, efforts such as the CDC’s VDSCP in improving test quality may help in eventually building up the kind of evidence base needed for the task force to offer a more definitive judgment on the tests, he said.

Wong acknowledged it must be frustrating for clinicians and patients to hear that experts don’t have the evidence needed to make a broad call about whether routine vitamin D tests are beneficial.

“We really would like to have that evidence because we recognize that it’s an important health question to help everybody in this nation stay healthy and live longer,” Dr. Wong said.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Some vitamin D tests may give misleading results despite progress made in recent years to improve the quality of these assays, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Otoe Sugahara manager of the CDC Vitamin D Standardization-Certification Program (VDSCP), presented an update of her group’s work at ENDO 2024, the Endocrine Society’s annual meeting in Boston.

“Though most vitamin D tests in our program have improved, there still remain some sample-specific inaccuracies. The CDC is working with program participants to address these situations,” Ms. Sugahara said in a statement released by the Endocrine Society.

For example, some assays measure other compounds besides 25-hydroxyvitamin D, which can falsely elevate results of some blood samples, Ms. Sugahara reported. Thus, some tests may be misclassified, with results seen as sufficient from samples that should have indicated a vitamin D deficiency.

“While most vitamin D tests are effective, it is important for healthcare providers to be aware of the potential inconsistencies associated with vitamin D tests to avoid misclassification of the patients,” Ms. Sugahara and coauthors said in an abstract provided by the Endocrine Society.

Ms. Sugahara’s report provided a snapshot of the state of longstanding efforts to improve the quality of a widely performed service in US healthcare: testing vitamin D levels.

These include an international collaboration that gave rise in 2010 to a vitamin D standardization program, from which the CDC’s VDSCP certification emerged. Among the leaders of these efforts was Christopher Sempos, PhD, then with the Office of Dietary Supplements at the National Institutes of Health.

Many clinicians may not be aware of the concerns about the accuracy of vitamin D tests that led to the drive for standardization, Dr. Sempos, now retired, said in an interview. And, in his view, it’s something that busy practitioners should not have to consider.

“They have literally thousands of diseases they have to be able to recognize and diagnose,” Dr. Sempos said. “They should be able to count on the laboratory system to give them accurate and precise data.”

‘Nudging’ Toward Better Results

The CDC’s certification program gives labs and companies detailed information about the analytical accuracy and precision of their vitamin D tests.

This feedback has paid off with improved results, Andy Hoofnagle, MD, PhD, professor of laboratory medicine and pathology at the University of Washington in Seattle, told this news organization. It helps by “nudging manufacturers in the right direction,” he said.

“Some manufacturers reformulated, others recalibrated, which is a lot of effort on their part, so that when the patient get a number, it actually means the right thing,” said Dr. Hoofnagle, who is also chair of the Accuracy-Based Programs Committee of the College of American Pathologists.

“There are still many immunoassays on the market that aren’t giving the correct results, unfortunately, but the standardization certification program has really pushed the field in the right direction,” he said.

US scientists use two main types of technologies to measure vitamin D in the blood, Ms. Sugahara said. One is mass spectrometry, which separately measures 25-hydroxyvitamin D2 and D3 and sums the values. The other type, immunoassay, measures both compounds at the same time and reports one result for total 25-hydroxyvitamin D.

At the ENDO 2024 meeting, Ms. Sugahara reported generally positive trends seen in the VDSCP. For example, the program looks at specific tests’ bias, or the deviation of test results from the true value, as determined with the CDC’s reference method for vitamin D.

Average calibration bias was less than 1% for all assays in the VDSCP in 2022, Ms. Sugahara said. The average calibration bias for immunoassays was 0.86%, and for assays using mass spectrometry, it was 0.55%, Ms. Sugahara reported.

These are improved results compared with 2019 data, in which mass spectrometry–based assays had a mean bias of 1.9% and immunoassays had a mean bias of 2.4%, the CDC told this news organization in an email exchange.

The CDC said the VDSCP supports laboratories and researchers from around the world, including ones based in the US, China, Australia, Japan, and Korea.

Call for Research

Vitamin D tests are widely administered despite questions about their benefit for people who do not appear likely to be deficient of it.

The Endocrine Society’s newly released practice guideline recommends against routine testing of blood vitamin D levels in the general population.

Laboratory testing has increased over the years owing to studies reporting associations between blood vitamin D [25(OH)D] levels and a variety of common disorders, including musculoskeletal, metabolic, cardiovascular, malignant, autoimmune, and infectious diseases, wrote Marie B. Demay, MD, of Harvard Medical School in Boston, and coauthors in the new guideline. It was published on June 3 in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

‘”Although a causal link between serum 25(OH)D concentrations and many disorders has not been clearly established, these associations have led to widespread supplementation with vitamin D and increased laboratory testing for 25(OH)D in the general population,” they wrote.

It’s uncertain that “any putative benefits of screening would outweigh the increased burden and cost, and whether implementation of universal 25(OH)D screening would be feasible from a societal perspective,” Dr. Demay and coauthors added.

They noted that the influential US Preventive Services Task Force also has raised doubts about widespread use of vitamin D tests.

The USPSTF has a somewhat different take from the Endocrine Society. The task force in 2021 reiterated its view that there is not enough evidence to recommend for or against widespread vitamin D testing for adults. The task force gave this test an I grade, meaning there is insufficient evidence to weigh the risks and benefits. That’s the same grade the task force gave it in 2014.

The USPSTF uses a grade of D to recommend against use of a test or service.

In an interview with this news organization, John Wong, MD, vice chair of the USPSTF, reiterated his group’s call for more research into the potential benefits and harms of vitamin D screening.

One of the challenges in addressing this issue, Dr. Wong noted, has been the variability of test results. Therefore, efforts such as the CDC’s VDSCP in improving test quality may help in eventually building up the kind of evidence base needed for the task force to offer a more definitive judgment on the tests, he said.

Wong acknowledged it must be frustrating for clinicians and patients to hear that experts don’t have the evidence needed to make a broad call about whether routine vitamin D tests are beneficial.

“We really would like to have that evidence because we recognize that it’s an important health question to help everybody in this nation stay healthy and live longer,” Dr. Wong said.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Early-Life Exposure to Pollution Linked to Psychosis, Anxiety, Depression

Early-life exposure to air and noise pollution is associated with a higher risk for psychosis, depression, and anxiety in adolescence and early adulthood, results from a longitudinal birth cohort study showed.

While air pollution was associated primarily with psychotic experiences and depression, noise pollution was more likely to be associated with anxiety in adolescence and early adulthood.

“Early-life exposure could be detrimental to mental health given the extensive brain development and epigenetic processes that occur in utero and during infancy,” the researchers, led by Joanne Newbury, PhD, of Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, England, wrote, adding that “the results of this cohort study provide novel evidence that early-life exposure to particulate matter is prospectively associated with the development of psychotic experiences and depression in youth.”

The findings were published online on May 28 in JAMA Network Open.

Large, Longitudinal Study

To learn more about how air and noise pollution may affect the brain from an early age, the investigators used data from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, an ongoing longitudinal birth cohort capturing data on new births in Southwest England from 1991 to 1992.

Investigators captured levels of air pollutants, which included nitrogen dioxide and fine particulate matter with a diameter smaller than 2.5 µm (PM2.5), in the areas where expectant mothers lived and where their children lived until age 12.

They also collected decibel levels of noise pollution in neighborhoods where expectant mothers and their children lived.

Participants were assessed for psychotic experiences, depression, and anxiety when they were 13, 18, and 24 years old.

Among the 9065 participants who had mental health data, 20% reported psychotic experiences, 11% reported depression, and 10% reported anxiety. About 60% of the participants had a family history of mental illness.

When they were age 13, 13.6% of participants reported psychotic experiences; 9.2% reported them at age 18, and 12.6% at age 24.

A lower number of participants reported feeling depressed and anxious at 13 years (5.6% for depression and 3.6% for anxiety) and 18 years (7.9% for depression and 5.7% for anxiety).

After adjusting for individual and family-level variables, including family psychiatric history, maternal social class, and neighborhood deprivation, elevated PM2.5 levels during pregnancy (P = .002) and childhood (P = .04) were associated with a significantly increased risk for psychotic experiences later in life. Pregnancy PM2.5 exposure was also associated with depression (P = .01).

Participants exposed to higher noise pollution in childhood and adolescence had an increased risk for anxiety (P = .03) as teenagers.

Vulnerability of the Developing Brain

The investigators noted that more information is needed to understand the underlying mechanisms behind these associations but noted that early-life exposure could be detrimental to mental health given “extensive brain development and epigenetic processes that occur in utero.”

They also noted that air pollution could lead to restricted fetal growth and premature birth, both of which are risk factors for psychopathology.

Martin Clift, PhD, of Swansea University in Swansea, Wales, who was not involved in the study, said that the paper highlights the need for more consideration of health consequences related to these exposures.

“As noted by the authors, this is an area that has received a lot of recent attention, yet there remains a large void of knowledge,” Dr. Clift said in a UK Science Media Centre release. “It highlights that some of the most dominant air pollutants can impact different mental health diagnoses, but that time-of-life is particularly important as to how each individual air pollutant may impact this diagnosis.”

Study limitations included limitations to generalizability of the data — the families in the study were more affluent and less diverse than the UK population overall.

The study was funded by the UK Medical Research Council, Wellcome Trust, and University of Bristol. Disclosures were noted in the original article.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Early-life exposure to air and noise pollution is associated with a higher risk for psychosis, depression, and anxiety in adolescence and early adulthood, results from a longitudinal birth cohort study showed.

While air pollution was associated primarily with psychotic experiences and depression, noise pollution was more likely to be associated with anxiety in adolescence and early adulthood.

“Early-life exposure could be detrimental to mental health given the extensive brain development and epigenetic processes that occur in utero and during infancy,” the researchers, led by Joanne Newbury, PhD, of Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, England, wrote, adding that “the results of this cohort study provide novel evidence that early-life exposure to particulate matter is prospectively associated with the development of psychotic experiences and depression in youth.”

The findings were published online on May 28 in JAMA Network Open.

Large, Longitudinal Study

To learn more about how air and noise pollution may affect the brain from an early age, the investigators used data from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, an ongoing longitudinal birth cohort capturing data on new births in Southwest England from 1991 to 1992.

Investigators captured levels of air pollutants, which included nitrogen dioxide and fine particulate matter with a diameter smaller than 2.5 µm (PM2.5), in the areas where expectant mothers lived and where their children lived until age 12.

They also collected decibel levels of noise pollution in neighborhoods where expectant mothers and their children lived.

Participants were assessed for psychotic experiences, depression, and anxiety when they were 13, 18, and 24 years old.

Among the 9065 participants who had mental health data, 20% reported psychotic experiences, 11% reported depression, and 10% reported anxiety. About 60% of the participants had a family history of mental illness.

When they were age 13, 13.6% of participants reported psychotic experiences; 9.2% reported them at age 18, and 12.6% at age 24.

A lower number of participants reported feeling depressed and anxious at 13 years (5.6% for depression and 3.6% for anxiety) and 18 years (7.9% for depression and 5.7% for anxiety).

After adjusting for individual and family-level variables, including family psychiatric history, maternal social class, and neighborhood deprivation, elevated PM2.5 levels during pregnancy (P = .002) and childhood (P = .04) were associated with a significantly increased risk for psychotic experiences later in life. Pregnancy PM2.5 exposure was also associated with depression (P = .01).

Participants exposed to higher noise pollution in childhood and adolescence had an increased risk for anxiety (P = .03) as teenagers.

Vulnerability of the Developing Brain

The investigators noted that more information is needed to understand the underlying mechanisms behind these associations but noted that early-life exposure could be detrimental to mental health given “extensive brain development and epigenetic processes that occur in utero.”

They also noted that air pollution could lead to restricted fetal growth and premature birth, both of which are risk factors for psychopathology.

Martin Clift, PhD, of Swansea University in Swansea, Wales, who was not involved in the study, said that the paper highlights the need for more consideration of health consequences related to these exposures.

“As noted by the authors, this is an area that has received a lot of recent attention, yet there remains a large void of knowledge,” Dr. Clift said in a UK Science Media Centre release. “It highlights that some of the most dominant air pollutants can impact different mental health diagnoses, but that time-of-life is particularly important as to how each individual air pollutant may impact this diagnosis.”

Study limitations included limitations to generalizability of the data — the families in the study were more affluent and less diverse than the UK population overall.

The study was funded by the UK Medical Research Council, Wellcome Trust, and University of Bristol. Disclosures were noted in the original article.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Early-life exposure to air and noise pollution is associated with a higher risk for psychosis, depression, and anxiety in adolescence and early adulthood, results from a longitudinal birth cohort study showed.

While air pollution was associated primarily with psychotic experiences and depression, noise pollution was more likely to be associated with anxiety in adolescence and early adulthood.

“Early-life exposure could be detrimental to mental health given the extensive brain development and epigenetic processes that occur in utero and during infancy,” the researchers, led by Joanne Newbury, PhD, of Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, England, wrote, adding that “the results of this cohort study provide novel evidence that early-life exposure to particulate matter is prospectively associated with the development of psychotic experiences and depression in youth.”

The findings were published online on May 28 in JAMA Network Open.

Large, Longitudinal Study

To learn more about how air and noise pollution may affect the brain from an early age, the investigators used data from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, an ongoing longitudinal birth cohort capturing data on new births in Southwest England from 1991 to 1992.

Investigators captured levels of air pollutants, which included nitrogen dioxide and fine particulate matter with a diameter smaller than 2.5 µm (PM2.5), in the areas where expectant mothers lived and where their children lived until age 12.

They also collected decibel levels of noise pollution in neighborhoods where expectant mothers and their children lived.

Participants were assessed for psychotic experiences, depression, and anxiety when they were 13, 18, and 24 years old.

Among the 9065 participants who had mental health data, 20% reported psychotic experiences, 11% reported depression, and 10% reported anxiety. About 60% of the participants had a family history of mental illness.

When they were age 13, 13.6% of participants reported psychotic experiences; 9.2% reported them at age 18, and 12.6% at age 24.

A lower number of participants reported feeling depressed and anxious at 13 years (5.6% for depression and 3.6% for anxiety) and 18 years (7.9% for depression and 5.7% for anxiety).

After adjusting for individual and family-level variables, including family psychiatric history, maternal social class, and neighborhood deprivation, elevated PM2.5 levels during pregnancy (P = .002) and childhood (P = .04) were associated with a significantly increased risk for psychotic experiences later in life. Pregnancy PM2.5 exposure was also associated with depression (P = .01).

Participants exposed to higher noise pollution in childhood and adolescence had an increased risk for anxiety (P = .03) as teenagers.

Vulnerability of the Developing Brain

The investigators noted that more information is needed to understand the underlying mechanisms behind these associations but noted that early-life exposure could be detrimental to mental health given “extensive brain development and epigenetic processes that occur in utero.”

They also noted that air pollution could lead to restricted fetal growth and premature birth, both of which are risk factors for psychopathology.

Martin Clift, PhD, of Swansea University in Swansea, Wales, who was not involved in the study, said that the paper highlights the need for more consideration of health consequences related to these exposures.

“As noted by the authors, this is an area that has received a lot of recent attention, yet there remains a large void of knowledge,” Dr. Clift said in a UK Science Media Centre release. “It highlights that some of the most dominant air pollutants can impact different mental health diagnoses, but that time-of-life is particularly important as to how each individual air pollutant may impact this diagnosis.”

Study limitations included limitations to generalizability of the data — the families in the study were more affluent and less diverse than the UK population overall.

The study was funded by the UK Medical Research Council, Wellcome Trust, and University of Bristol. Disclosures were noted in the original article.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

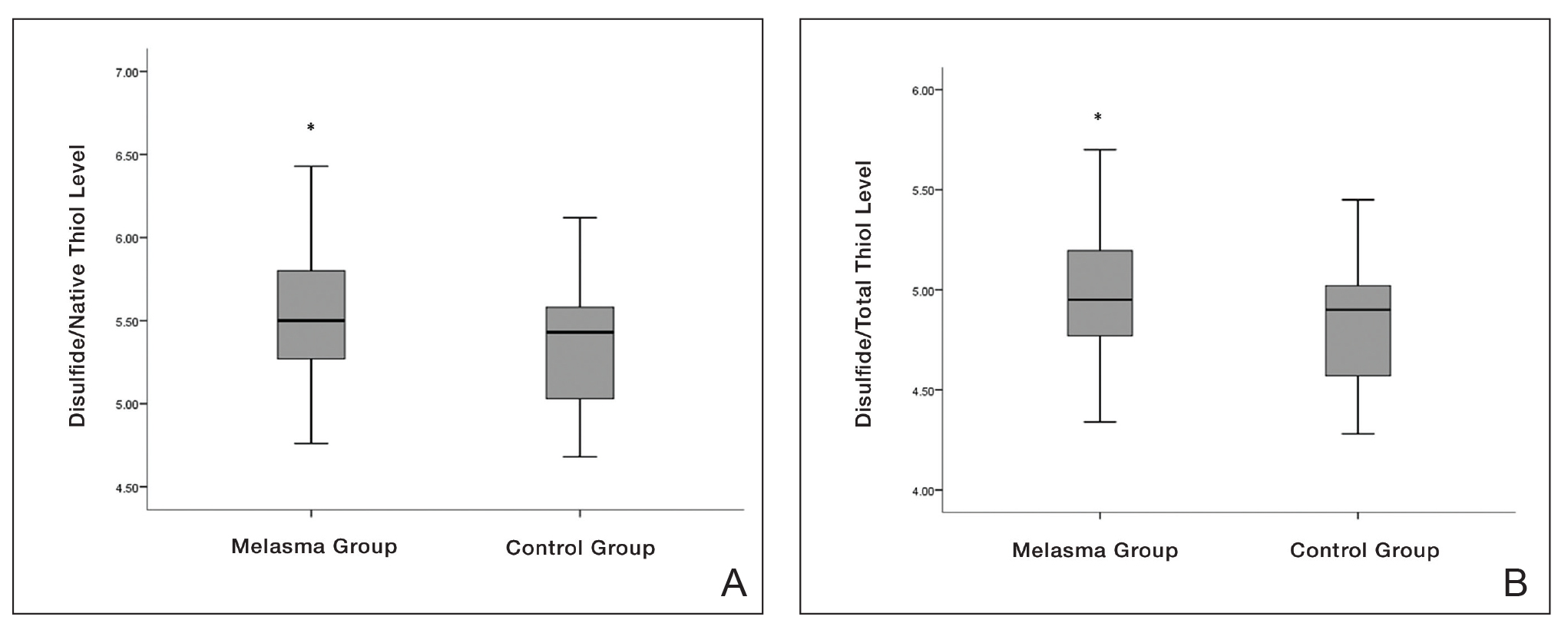

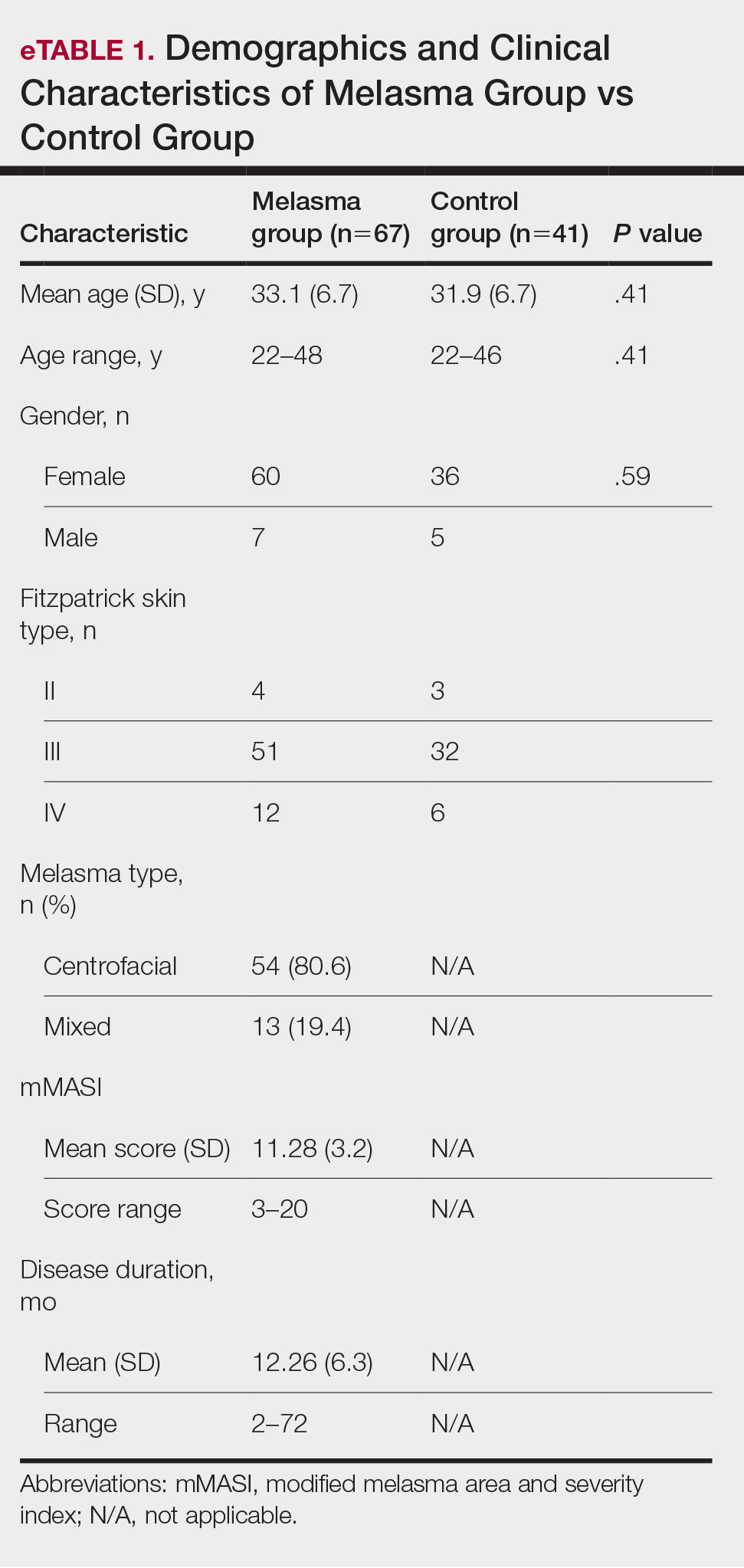

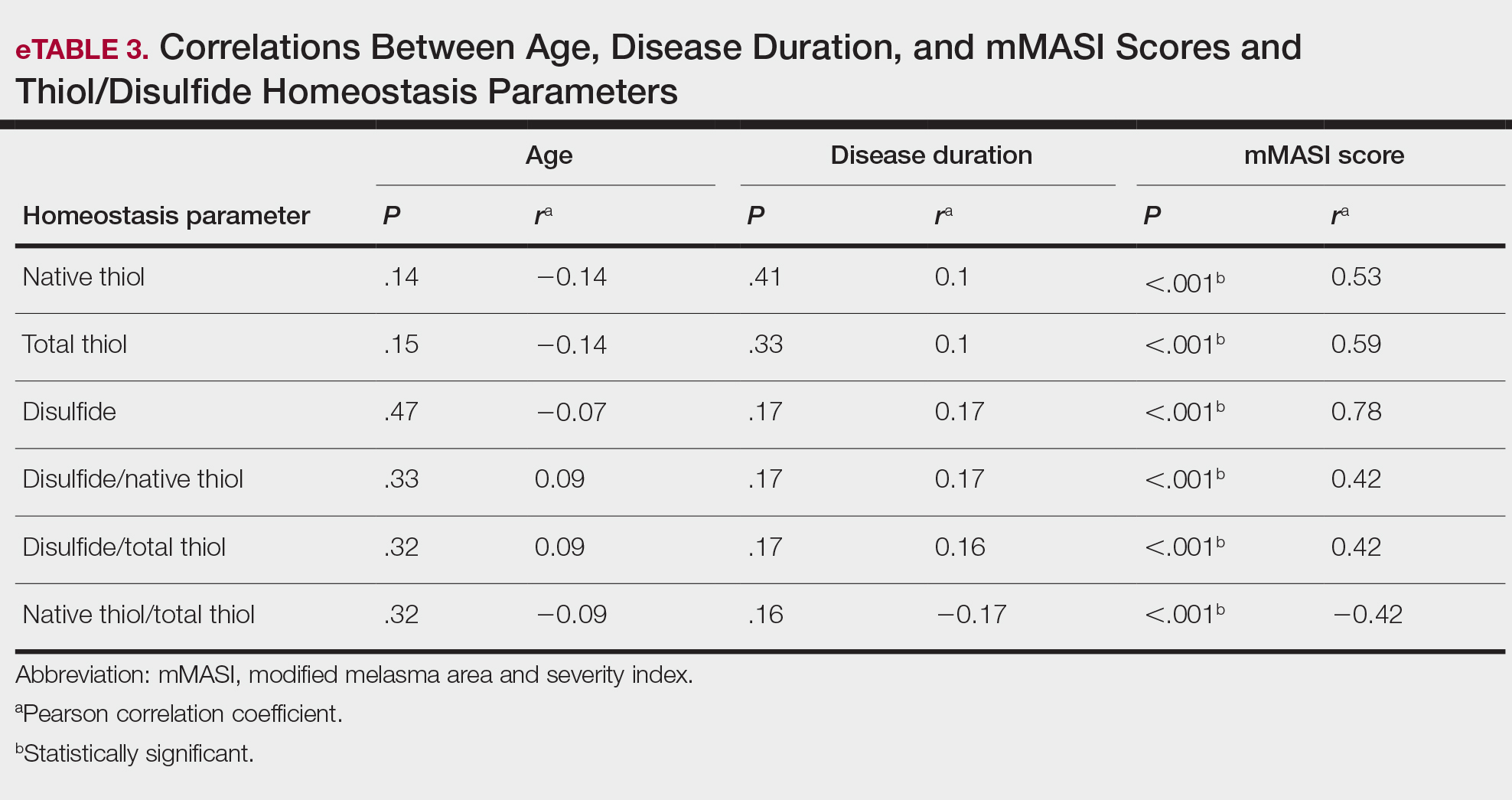

Oxidative Stress in Patients With Melasma: An Evaluation of the Correlation of the Thiol/Disulfide Homeostasis Parameters and Modified MASI Score

Melasma is an acquired hyperpigmentation disorder characterized by irregular brown macules and patches that usually appear on sun-exposed areas of the skin. The term melasma originates from the Greek word melas meaning black.1 Facial melasma is divided into 2 groups according to its clinical distribution: centrofacial lesions are located in the center of the face (eg, the glabellar, frontal, nasal, zygomatic, upper lip, chin areas), and peripheral lesions manifest on the frontotemporal, preauricular, and mandibular regions.1,2 There is debate on the categorization of zygomatic (or malar) melasma; some researchers argue it should be categorized independent of other areas, while others include malar melasma in the centrofacial group because of its frequent association with the centrofacial type, especially with glabellar lesions.2 Mandibular melasma is rare and occurs mostly in postmenopausal women after intense sun exposure.1,2 Although the etiopathogenesis of the disease is not clearly known, increased melanogenesis, extracellular matrix alterations, inflammation, and angiogenesis are assumed to play a role.3 Various risk factors such as genetic predisposition, UV radiation (UVR) exposure, pregnancy, thyroid dysfunction, and exogenous hormones (eg, oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy) have been identified; phototoxic drugs, anticonvulsants, and some cosmetics also have been implicated.4,5 Exposure to UVR is thought to be the main triggering environmental factor by inducing both melanin production and oxidative stress.5 However, it also has been shown that visible light can induce hyperpigmentation in darker skin types.6