User login

Surgical palliative care – 20 years on

It was a banner year in 1998 for the moral and ethical evolution of the College. That year saw the release of its Statement of Principles of End-of-Life Care, a seminal document for the emerging framework of surgical palliative care and the first light of the work of my colleague, Peter Angelos, MD, FACS, which did much to make made ethics a less arcane element of surgical practice. These developments followed the 1997 Clinical Congress during which the College joined the then-active national debate about physician-assisted suicide.

The national debate eventually culminated with the U.S. Supreme Court’s two 1997 rulings that physician-assisted suicide is not a protected liberty interest under the Constitution. These rulings in Vacco v. Quill and Washington v. Glucksberg deferred to the states the legalization of physician-assisted suicide.

Kill the suffering, not the patient

It was ironic that the College’s attention to surgical palliative care started, literally, with a dead end. The 1997 symposium’s focus on physician-assisted suicide revealed how little there was in the surgeon’s toolbox to assist seriously ill patients and their families. At this well-attended event with a distinguished panel of surgeons and ethicists moderated by the late Thomas Krizek, MD, FACS, I heard fear of death, fear of suffering, and fear of our helplessness as practitioners in the face of our patients’ deaths. The debate was about control, not the effective response to the many species of suffering encountered in surgical practice.

Hospice care and the nascent concept of palliative care were acknowledged by both sides of the debate as beneficial but as distinctly apart from surgery. The need for improved palliative care was the one unifying idea that emerged from that day’s discussion. All sides seemed to agree that striving to mitigate suffering during the course of any serious illness would be preferable to allowing it to continue unabated until silencing it with deliberate death as a last resort. The ensuing challenge for surgeons would be the reconciliation of cure and palliation, each so much a part of surgical history, especially in the past 200 years. This would prove to be a tall order as surgeons had done such a tidy job separating these two priorities without even realizing it since the second World War. Nothing less than the soul of surgery (and medicine) would be at stake from the relentless technocratic “progress” that threatened to swallow health care and so many other aspects of our culture – a culture that perhaps has been too intoxicated by the individual “pursuit of life, liberty, and happiness” while overlooking the suffering of one’s neighbor.

Recent evidence of burnout raises the possibility that we surgeons have internalized this conflict. Because of our sacred fellowship in healing, are we now, as we were 20 years ago, in the midst of a new spiritual crisis? As the operative repertoire and our professional status become increasingly transient we will be compelled to ground our identities in something more fulfilling and enduring.

Hope in fellowship

Now, as in 1998, there is hope. Hope lies in our fellowship. The focus of palliative care as understood by surgeons has broadened considerably, encouraged by the gradual public acceptance of palliative approaches to care extending beyond hospice care and the generally favorable experiences surgeons have had with palliative care teams, some of which have been directed by surgeons. There are now dozens of surgeons currently certified in Hospice and Palliative Medicine by the American Board of Surgery who are much more skilled in palliative care than anyone practicing in 1998. The ABS’s decision (2006) to offer certification in Hospice and Palliative Medicine was, in itself, an indication of how far things had progressed since 1998.

Several challenges to contemporary surgery will benefit from the growing reservoir of palliative care expertise such as enhanced communication skill, opioid management, and burnout. The concept of shared decision making is only one example. The multidimensional understanding of suffering, a cardinal principle of palliative philosophy, could transform the current dilemma of “What do we do about opioids?” to the scientific and social research question, “What should be done with opioid receptors and countless other receptors that shape the pain experience?” And lastly, the current postgraduate educational focus on communication and burnout indicate a readiness for introspection and fellowship by surgeons, a necessary prerequisite in meeting any existential or spiritual challenge to our art.

We have come a long way in 20 years but there are still miles to go before we sleep.

Dr. Dunn was formerly the medical director of the palliative care consultation service at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hamot in Erie, Pa., and Chair of the ACS Committee on Surgical Palliative Care.

It was a banner year in 1998 for the moral and ethical evolution of the College. That year saw the release of its Statement of Principles of End-of-Life Care, a seminal document for the emerging framework of surgical palliative care and the first light of the work of my colleague, Peter Angelos, MD, FACS, which did much to make made ethics a less arcane element of surgical practice. These developments followed the 1997 Clinical Congress during which the College joined the then-active national debate about physician-assisted suicide.

The national debate eventually culminated with the U.S. Supreme Court’s two 1997 rulings that physician-assisted suicide is not a protected liberty interest under the Constitution. These rulings in Vacco v. Quill and Washington v. Glucksberg deferred to the states the legalization of physician-assisted suicide.

Kill the suffering, not the patient

It was ironic that the College’s attention to surgical palliative care started, literally, with a dead end. The 1997 symposium’s focus on physician-assisted suicide revealed how little there was in the surgeon’s toolbox to assist seriously ill patients and their families. At this well-attended event with a distinguished panel of surgeons and ethicists moderated by the late Thomas Krizek, MD, FACS, I heard fear of death, fear of suffering, and fear of our helplessness as practitioners in the face of our patients’ deaths. The debate was about control, not the effective response to the many species of suffering encountered in surgical practice.

Hospice care and the nascent concept of palliative care were acknowledged by both sides of the debate as beneficial but as distinctly apart from surgery. The need for improved palliative care was the one unifying idea that emerged from that day’s discussion. All sides seemed to agree that striving to mitigate suffering during the course of any serious illness would be preferable to allowing it to continue unabated until silencing it with deliberate death as a last resort. The ensuing challenge for surgeons would be the reconciliation of cure and palliation, each so much a part of surgical history, especially in the past 200 years. This would prove to be a tall order as surgeons had done such a tidy job separating these two priorities without even realizing it since the second World War. Nothing less than the soul of surgery (and medicine) would be at stake from the relentless technocratic “progress” that threatened to swallow health care and so many other aspects of our culture – a culture that perhaps has been too intoxicated by the individual “pursuit of life, liberty, and happiness” while overlooking the suffering of one’s neighbor.

Recent evidence of burnout raises the possibility that we surgeons have internalized this conflict. Because of our sacred fellowship in healing, are we now, as we were 20 years ago, in the midst of a new spiritual crisis? As the operative repertoire and our professional status become increasingly transient we will be compelled to ground our identities in something more fulfilling and enduring.

Hope in fellowship

Now, as in 1998, there is hope. Hope lies in our fellowship. The focus of palliative care as understood by surgeons has broadened considerably, encouraged by the gradual public acceptance of palliative approaches to care extending beyond hospice care and the generally favorable experiences surgeons have had with palliative care teams, some of which have been directed by surgeons. There are now dozens of surgeons currently certified in Hospice and Palliative Medicine by the American Board of Surgery who are much more skilled in palliative care than anyone practicing in 1998. The ABS’s decision (2006) to offer certification in Hospice and Palliative Medicine was, in itself, an indication of how far things had progressed since 1998.

Several challenges to contemporary surgery will benefit from the growing reservoir of palliative care expertise such as enhanced communication skill, opioid management, and burnout. The concept of shared decision making is only one example. The multidimensional understanding of suffering, a cardinal principle of palliative philosophy, could transform the current dilemma of “What do we do about opioids?” to the scientific and social research question, “What should be done with opioid receptors and countless other receptors that shape the pain experience?” And lastly, the current postgraduate educational focus on communication and burnout indicate a readiness for introspection and fellowship by surgeons, a necessary prerequisite in meeting any existential or spiritual challenge to our art.

We have come a long way in 20 years but there are still miles to go before we sleep.

Dr. Dunn was formerly the medical director of the palliative care consultation service at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hamot in Erie, Pa., and Chair of the ACS Committee on Surgical Palliative Care.

It was a banner year in 1998 for the moral and ethical evolution of the College. That year saw the release of its Statement of Principles of End-of-Life Care, a seminal document for the emerging framework of surgical palliative care and the first light of the work of my colleague, Peter Angelos, MD, FACS, which did much to make made ethics a less arcane element of surgical practice. These developments followed the 1997 Clinical Congress during which the College joined the then-active national debate about physician-assisted suicide.

The national debate eventually culminated with the U.S. Supreme Court’s two 1997 rulings that physician-assisted suicide is not a protected liberty interest under the Constitution. These rulings in Vacco v. Quill and Washington v. Glucksberg deferred to the states the legalization of physician-assisted suicide.

Kill the suffering, not the patient

It was ironic that the College’s attention to surgical palliative care started, literally, with a dead end. The 1997 symposium’s focus on physician-assisted suicide revealed how little there was in the surgeon’s toolbox to assist seriously ill patients and their families. At this well-attended event with a distinguished panel of surgeons and ethicists moderated by the late Thomas Krizek, MD, FACS, I heard fear of death, fear of suffering, and fear of our helplessness as practitioners in the face of our patients’ deaths. The debate was about control, not the effective response to the many species of suffering encountered in surgical practice.

Hospice care and the nascent concept of palliative care were acknowledged by both sides of the debate as beneficial but as distinctly apart from surgery. The need for improved palliative care was the one unifying idea that emerged from that day’s discussion. All sides seemed to agree that striving to mitigate suffering during the course of any serious illness would be preferable to allowing it to continue unabated until silencing it with deliberate death as a last resort. The ensuing challenge for surgeons would be the reconciliation of cure and palliation, each so much a part of surgical history, especially in the past 200 years. This would prove to be a tall order as surgeons had done such a tidy job separating these two priorities without even realizing it since the second World War. Nothing less than the soul of surgery (and medicine) would be at stake from the relentless technocratic “progress” that threatened to swallow health care and so many other aspects of our culture – a culture that perhaps has been too intoxicated by the individual “pursuit of life, liberty, and happiness” while overlooking the suffering of one’s neighbor.

Recent evidence of burnout raises the possibility that we surgeons have internalized this conflict. Because of our sacred fellowship in healing, are we now, as we were 20 years ago, in the midst of a new spiritual crisis? As the operative repertoire and our professional status become increasingly transient we will be compelled to ground our identities in something more fulfilling and enduring.

Hope in fellowship

Now, as in 1998, there is hope. Hope lies in our fellowship. The focus of palliative care as understood by surgeons has broadened considerably, encouraged by the gradual public acceptance of palliative approaches to care extending beyond hospice care and the generally favorable experiences surgeons have had with palliative care teams, some of which have been directed by surgeons. There are now dozens of surgeons currently certified in Hospice and Palliative Medicine by the American Board of Surgery who are much more skilled in palliative care than anyone practicing in 1998. The ABS’s decision (2006) to offer certification in Hospice and Palliative Medicine was, in itself, an indication of how far things had progressed since 1998.

Several challenges to contemporary surgery will benefit from the growing reservoir of palliative care expertise such as enhanced communication skill, opioid management, and burnout. The concept of shared decision making is only one example. The multidimensional understanding of suffering, a cardinal principle of palliative philosophy, could transform the current dilemma of “What do we do about opioids?” to the scientific and social research question, “What should be done with opioid receptors and countless other receptors that shape the pain experience?” And lastly, the current postgraduate educational focus on communication and burnout indicate a readiness for introspection and fellowship by surgeons, a necessary prerequisite in meeting any existential or spiritual challenge to our art.

We have come a long way in 20 years but there are still miles to go before we sleep.

Dr. Dunn was formerly the medical director of the palliative care consultation service at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hamot in Erie, Pa., and Chair of the ACS Committee on Surgical Palliative Care.

Visit ACS Central at Clinical Congress 2018 and View ACS Theatre Sessions

Make the most of your American College of Surgeons (ACS) Clinical Congress experience by visiting ACS Central in the Exhibit Hall. Open 9:00 am–4:30 pm Monday, October 22, to Wednesday, October 24, ACS Central is the place to meet with staff, learn about ACS products and programs, purchase ACS-branded items and publications, and relax during the meeting. Other select ACS programs will have a presence in the main lobby of the center, including ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC, Wi-fi and Clinical Congress App Support, Become a Member/Member Services, MyCME, SESAP® (Surgical Education and Self-Assessment Program), and Webcast Sales.

Featured areas in ACS Central include the following:

• ACS Foundation

• ACS Store

• Advocacy and Regulatory Affairs

• Education

• Manage Your Profile (receive a free professional photo)

• Member Engagement

• My Specialty and Quality Programs

• Publications and Online Resources

• Surgeon Specific Registry (SSR)

ACS Central also features the ACS Theatre. The following programs will take place during the lunch hour, so grab a bite to eat and stop by to listen.

Monday, October 22: 1:15 pm–2:15 pm

Life Skills for the Surgeon: Savings Advice for Retirement

Mark Aeder, MD, FACS, will provide advice on how to handle your debt, how to find the right financial advisor, and how to protect your family and your income?

Special Considerations for a Successful Simulation Program

Rick Feins, MD, FACS, will explain why surgical simulation is an important pathway for achieving competency in surgical resident performance and adoption of new technology by established surgeons.

Tuesday, October 23: 11:30 am–12:30 pm

Efforts to Reduce Administrative Burdens and Regulations and State Level Advocacy

Come listen to how the ACS is addressing the increasing administrative burdens and regulations that are frustrating our Fellows across the country with Vinita Ollapally, JD, ACS Manager of Regulatory Affairs.

Wednesday, October 24: 11:30 am–12:30 pm

Addressing Intimate Partner Violence in the Surgical Community: Is there a need?

ACS President Barbara Lee Bass, MD, FACS, formed an ACS Task Force earlier this year to begin to consider what the ACS should do to address and prevent intimate partner violence (IPV) within the surgical community. Dr. Bass will address the work of the task force and the resources that have been developed to address this issue.

Make the most of your American College of Surgeons (ACS) Clinical Congress experience by visiting ACS Central in the Exhibit Hall. Open 9:00 am–4:30 pm Monday, October 22, to Wednesday, October 24, ACS Central is the place to meet with staff, learn about ACS products and programs, purchase ACS-branded items and publications, and relax during the meeting. Other select ACS programs will have a presence in the main lobby of the center, including ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC, Wi-fi and Clinical Congress App Support, Become a Member/Member Services, MyCME, SESAP® (Surgical Education and Self-Assessment Program), and Webcast Sales.

Featured areas in ACS Central include the following:

• ACS Foundation

• ACS Store

• Advocacy and Regulatory Affairs

• Education

• Manage Your Profile (receive a free professional photo)

• Member Engagement

• My Specialty and Quality Programs

• Publications and Online Resources

• Surgeon Specific Registry (SSR)

ACS Central also features the ACS Theatre. The following programs will take place during the lunch hour, so grab a bite to eat and stop by to listen.

Monday, October 22: 1:15 pm–2:15 pm

Life Skills for the Surgeon: Savings Advice for Retirement

Mark Aeder, MD, FACS, will provide advice on how to handle your debt, how to find the right financial advisor, and how to protect your family and your income?

Special Considerations for a Successful Simulation Program

Rick Feins, MD, FACS, will explain why surgical simulation is an important pathway for achieving competency in surgical resident performance and adoption of new technology by established surgeons.

Tuesday, October 23: 11:30 am–12:30 pm

Efforts to Reduce Administrative Burdens and Regulations and State Level Advocacy

Come listen to how the ACS is addressing the increasing administrative burdens and regulations that are frustrating our Fellows across the country with Vinita Ollapally, JD, ACS Manager of Regulatory Affairs.

Wednesday, October 24: 11:30 am–12:30 pm

Addressing Intimate Partner Violence in the Surgical Community: Is there a need?

ACS President Barbara Lee Bass, MD, FACS, formed an ACS Task Force earlier this year to begin to consider what the ACS should do to address and prevent intimate partner violence (IPV) within the surgical community. Dr. Bass will address the work of the task force and the resources that have been developed to address this issue.

Make the most of your American College of Surgeons (ACS) Clinical Congress experience by visiting ACS Central in the Exhibit Hall. Open 9:00 am–4:30 pm Monday, October 22, to Wednesday, October 24, ACS Central is the place to meet with staff, learn about ACS products and programs, purchase ACS-branded items and publications, and relax during the meeting. Other select ACS programs will have a presence in the main lobby of the center, including ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC, Wi-fi and Clinical Congress App Support, Become a Member/Member Services, MyCME, SESAP® (Surgical Education and Self-Assessment Program), and Webcast Sales.

Featured areas in ACS Central include the following:

• ACS Foundation

• ACS Store

• Advocacy and Regulatory Affairs

• Education

• Manage Your Profile (receive a free professional photo)

• Member Engagement

• My Specialty and Quality Programs

• Publications and Online Resources

• Surgeon Specific Registry (SSR)

ACS Central also features the ACS Theatre. The following programs will take place during the lunch hour, so grab a bite to eat and stop by to listen.

Monday, October 22: 1:15 pm–2:15 pm

Life Skills for the Surgeon: Savings Advice for Retirement

Mark Aeder, MD, FACS, will provide advice on how to handle your debt, how to find the right financial advisor, and how to protect your family and your income?

Special Considerations for a Successful Simulation Program

Rick Feins, MD, FACS, will explain why surgical simulation is an important pathway for achieving competency in surgical resident performance and adoption of new technology by established surgeons.

Tuesday, October 23: 11:30 am–12:30 pm

Efforts to Reduce Administrative Burdens and Regulations and State Level Advocacy

Come listen to how the ACS is addressing the increasing administrative burdens and regulations that are frustrating our Fellows across the country with Vinita Ollapally, JD, ACS Manager of Regulatory Affairs.

Wednesday, October 24: 11:30 am–12:30 pm

Addressing Intimate Partner Violence in the Surgical Community: Is there a need?

ACS President Barbara Lee Bass, MD, FACS, formed an ACS Task Force earlier this year to begin to consider what the ACS should do to address and prevent intimate partner violence (IPV) within the surgical community. Dr. Bass will address the work of the task force and the resources that have been developed to address this issue.

Second volume of Operative Standards for Cancer Surgery Manual now available

Operative Standards for Cancer Surgery, Volume 2, a collaborative manual from the American College of Surgeons (ACS) and the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology, is now available for print and electronic purchase. This second volume focuses on thyroid cancer, gastric cancer, rectal cancer, esophageal cancer, and melanoma. The goal of the manual is to recommend the steps that need to occur in the operating room, from skin incision to skin closure, that ensure the best oncological outcomes for patients. Recommendations from the first two volumes serve as an initial point of discussion as the ACS Commission on Cancer (CoC) works to revise its accreditation manual and requirements. Preliminary work is being done to incorporate a portion of the recommendations into the new CoC standards for implementation by 2020.

The recommendations in the manual are part of a shift in the way surgeons perform cancer operations to ensure the procedures are guided by the strongest available evidence, according to the leadership of the Alliance/ACS Clinical Research Program (ACS CRP) Cancer Care Standards Development Committee, which led development of both volumes.

Similar to the first volume of the manual, which covered cancer of the breast, colon, lung, and pancreas, this volume breaks down the major cancer operations for each of the five disease sites into the critical steps that teams of experts and stakeholders around the country have identified as having the most significant influence on outcomes.

“We hope that the recommendations become actively used and achieve greater legitimacy,” said Committee Chair Mathew H. G. Katz, MD, FACS.

Operative Standards for Cancer Surgery, Volume 2, is available for purchase on the Wolters Kluwer website at bit.ly/2PCHUCn. For more information, contact [email protected].

Operative Standards for Cancer Surgery, Volume 2, a collaborative manual from the American College of Surgeons (ACS) and the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology, is now available for print and electronic purchase. This second volume focuses on thyroid cancer, gastric cancer, rectal cancer, esophageal cancer, and melanoma. The goal of the manual is to recommend the steps that need to occur in the operating room, from skin incision to skin closure, that ensure the best oncological outcomes for patients. Recommendations from the first two volumes serve as an initial point of discussion as the ACS Commission on Cancer (CoC) works to revise its accreditation manual and requirements. Preliminary work is being done to incorporate a portion of the recommendations into the new CoC standards for implementation by 2020.

The recommendations in the manual are part of a shift in the way surgeons perform cancer operations to ensure the procedures are guided by the strongest available evidence, according to the leadership of the Alliance/ACS Clinical Research Program (ACS CRP) Cancer Care Standards Development Committee, which led development of both volumes.

Similar to the first volume of the manual, which covered cancer of the breast, colon, lung, and pancreas, this volume breaks down the major cancer operations for each of the five disease sites into the critical steps that teams of experts and stakeholders around the country have identified as having the most significant influence on outcomes.

“We hope that the recommendations become actively used and achieve greater legitimacy,” said Committee Chair Mathew H. G. Katz, MD, FACS.

Operative Standards for Cancer Surgery, Volume 2, is available for purchase on the Wolters Kluwer website at bit.ly/2PCHUCn. For more information, contact [email protected].

Operative Standards for Cancer Surgery, Volume 2, a collaborative manual from the American College of Surgeons (ACS) and the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology, is now available for print and electronic purchase. This second volume focuses on thyroid cancer, gastric cancer, rectal cancer, esophageal cancer, and melanoma. The goal of the manual is to recommend the steps that need to occur in the operating room, from skin incision to skin closure, that ensure the best oncological outcomes for patients. Recommendations from the first two volumes serve as an initial point of discussion as the ACS Commission on Cancer (CoC) works to revise its accreditation manual and requirements. Preliminary work is being done to incorporate a portion of the recommendations into the new CoC standards for implementation by 2020.

The recommendations in the manual are part of a shift in the way surgeons perform cancer operations to ensure the procedures are guided by the strongest available evidence, according to the leadership of the Alliance/ACS Clinical Research Program (ACS CRP) Cancer Care Standards Development Committee, which led development of both volumes.

Similar to the first volume of the manual, which covered cancer of the breast, colon, lung, and pancreas, this volume breaks down the major cancer operations for each of the five disease sites into the critical steps that teams of experts and stakeholders around the country have identified as having the most significant influence on outcomes.

“We hope that the recommendations become actively used and achieve greater legitimacy,” said Committee Chair Mathew H. G. Katz, MD, FACS.

Operative Standards for Cancer Surgery, Volume 2, is available for purchase on the Wolters Kluwer website at bit.ly/2PCHUCn. For more information, contact [email protected].

Exciting changes in the Scientific Forum this year

The Scientific Forum of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) Clinical Congress has evolved since the concept was first introduced as the Surgical Forum in 1951. This year’s Scientific Forum will build on these transformations and will offer attendees greater exposure to the surgical research conducted by the ACS community.

Background

The Surgical Forum was established in 1951 to provide a supportive venue for trainees and junior faculty to present and discuss their research. Presenting at the Forum has always been a rite of passage for aspiring academic surgeon-scientists. In 1993, the Surgical Forum was renamed to honor the program founder, Owen H. Wangensteen, MD, PhD, FACS, past-chair, department of surgery, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

As surgical science evolved, the Program Committee developed a separate Scientific Papers session for established investigators and Fellows who were not early in their career. As these two programs evolved, it became increasingly clear that there was substantial overlap. In 2014, the Surgical Forum and Scientific Papers merged into a single entity under the oversight of the existing Surgical Forum Committee.

The merged program was renamed the Scientific Forum to reflect the contributions of the Surgical Forum and the Scientific Papers, and the committee was renamed the Scientific Forum Committee. Because of the increase in scientific abstracts resulting from this merger, the committee expanded its membership to reflect the type of scientific abstracts in the broader program. The basic and translational research focus of the Surgical Forum was expanded to include clinical research in health services, education, global surgery, ethics, and other evolving areas of surgical science.

These changes have revitalized the scientific effort. The number and quality of the abstracts submitted to the Scientific Forum has grown significantly—more than 2,000 abstracts were submitted for review for Clinical Congress 2018.

The spirit of the Surgical Forum has been maintained in the new Scientific Forum, continuing with the clustering of focused areas of research to encourage discussion and collaboration among the attendees. The Program Committee continues to place great emphasis on highlighting the work of young investigators while incorporating the expertise of senior investigators into the sessions.

Changes at Clinical Congress 2017

Quick Shots and e-Posters were introduced at Clinical Congress 2017 in San Diego, CA. Quick Shots are three-minute oral abstract presentations, which were incorporated into the Scientific Forum sessions. This addition, which allowed for more presenters in a session, was met with a positive reception.

The poster sessions were restructured to an electronic format. The e-Posters were placed in a central, dedicated location among the Scientific Forum sessions rather than the Exhibit Hall. The modern e-Poster sessions brought greater visibility to the poster presentations and energized the format. In the e-Poster room, special sessions were scheduled to highlight the exceptional research efforts of the surgical trainees through the Excellence in Research Awards and the Posters of Exceptional Merit. In addition, the Scientific Forum is dedicated to a senior surgeon-scientist who has demonstrated a career-long commitment to training surgeon-scientists and the academic mission.

To further promote and support surgical research, the Scientific Forum Committee partnered with the Journal of the American College of Surgeons (JACS) to solicit the highest-rated abstracts for publication in JACS. In the first year, the top 5 percent of abstracts in the clinical sciences were solicited for manuscript submissions. More than half of those authors submitted a manuscript for review. All accepted manuscripts will be electronically published concurrently with the ACS Clinical Congress 2018 to provide greater visibility to the high-quality research being generated by the ACS community.

Clinical trials session added in 2018

The Scientific Forum Committee strongly believes the Clinical Congress is the premier venue to present practice-changing research. New for 2018, a call for late-breaking clinical trials abstracts was issued, and the committee selected six clinical trials that have the potential to change practice and improve patient care. This new clinical trials session will be presented at Clinical Congress 2018 Monday, October 22, at 9:45 am.

The ACS Clinical Congress is the largest surgical meeting in the U.S. The vision of the Scientific Forum Committee is for leaders of surgical trials to view the Clinical Congress as the premier venue to present their results. These exciting and transformative changes to the Scientific Forum will bring greater exposure to the leading-edge research in clinical care, while continuing to support and encourage young surgeon-scientists—the future of the study and practice of surgery—in their work. ♦

Note

The authors of this article are part of the Owen H. Wangensteen Scientific Forum Committee—Mary T. Hawn, MD, FACS; Edith Tzeng, MD, FACS; and Valerie W. Rusch, MD, FACS, are members, and M. Jane Burns, MJHL; Richard V. King, PhD; and Ajit K. Sachdeva, MD, FACS, FRCSC, are ACS staff.

Dr. Hawn is professor of surgery and chair, department of surgery, Stanford University, CA. She is Chair, ACS Scientific Forum Committee.

Dr. Tzeng is professor of surgery, University of Pittsburgh, and chief, vascular surgery, Veterans Affairs Pittsburgh Healthcare System, University Drive Campus, PA. She is Vice-Chair, ACS Scientific Forum Committee.

Dr. Rusch is vice-chair, clinical research, department of surgery; Miner Family Chair in Intrathoracic Cancers; attending surgeon, thoracic service, department of surgery, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center; and professor of surgery, Weill Cornell Medical College. She is a consultant for the ACS Program Committee.

Ms. Burns is Senior Manager, Clinical Congress Program, ACS Division of Education, Chicago.

Mr. King is Assistant Director, Clinical Congress Program and Skills Courses, ACS Division of Education.

Dr. Sachdeva is Director, ACS Division of Education.

The Scientific Forum of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) Clinical Congress has evolved since the concept was first introduced as the Surgical Forum in 1951. This year’s Scientific Forum will build on these transformations and will offer attendees greater exposure to the surgical research conducted by the ACS community.

Background

The Surgical Forum was established in 1951 to provide a supportive venue for trainees and junior faculty to present and discuss their research. Presenting at the Forum has always been a rite of passage for aspiring academic surgeon-scientists. In 1993, the Surgical Forum was renamed to honor the program founder, Owen H. Wangensteen, MD, PhD, FACS, past-chair, department of surgery, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

As surgical science evolved, the Program Committee developed a separate Scientific Papers session for established investigators and Fellows who were not early in their career. As these two programs evolved, it became increasingly clear that there was substantial overlap. In 2014, the Surgical Forum and Scientific Papers merged into a single entity under the oversight of the existing Surgical Forum Committee.

The merged program was renamed the Scientific Forum to reflect the contributions of the Surgical Forum and the Scientific Papers, and the committee was renamed the Scientific Forum Committee. Because of the increase in scientific abstracts resulting from this merger, the committee expanded its membership to reflect the type of scientific abstracts in the broader program. The basic and translational research focus of the Surgical Forum was expanded to include clinical research in health services, education, global surgery, ethics, and other evolving areas of surgical science.

These changes have revitalized the scientific effort. The number and quality of the abstracts submitted to the Scientific Forum has grown significantly—more than 2,000 abstracts were submitted for review for Clinical Congress 2018.

The spirit of the Surgical Forum has been maintained in the new Scientific Forum, continuing with the clustering of focused areas of research to encourage discussion and collaboration among the attendees. The Program Committee continues to place great emphasis on highlighting the work of young investigators while incorporating the expertise of senior investigators into the sessions.

Changes at Clinical Congress 2017

Quick Shots and e-Posters were introduced at Clinical Congress 2017 in San Diego, CA. Quick Shots are three-minute oral abstract presentations, which were incorporated into the Scientific Forum sessions. This addition, which allowed for more presenters in a session, was met with a positive reception.

The poster sessions were restructured to an electronic format. The e-Posters were placed in a central, dedicated location among the Scientific Forum sessions rather than the Exhibit Hall. The modern e-Poster sessions brought greater visibility to the poster presentations and energized the format. In the e-Poster room, special sessions were scheduled to highlight the exceptional research efforts of the surgical trainees through the Excellence in Research Awards and the Posters of Exceptional Merit. In addition, the Scientific Forum is dedicated to a senior surgeon-scientist who has demonstrated a career-long commitment to training surgeon-scientists and the academic mission.

To further promote and support surgical research, the Scientific Forum Committee partnered with the Journal of the American College of Surgeons (JACS) to solicit the highest-rated abstracts for publication in JACS. In the first year, the top 5 percent of abstracts in the clinical sciences were solicited for manuscript submissions. More than half of those authors submitted a manuscript for review. All accepted manuscripts will be electronically published concurrently with the ACS Clinical Congress 2018 to provide greater visibility to the high-quality research being generated by the ACS community.

Clinical trials session added in 2018

The Scientific Forum Committee strongly believes the Clinical Congress is the premier venue to present practice-changing research. New for 2018, a call for late-breaking clinical trials abstracts was issued, and the committee selected six clinical trials that have the potential to change practice and improve patient care. This new clinical trials session will be presented at Clinical Congress 2018 Monday, October 22, at 9:45 am.

The ACS Clinical Congress is the largest surgical meeting in the U.S. The vision of the Scientific Forum Committee is for leaders of surgical trials to view the Clinical Congress as the premier venue to present their results. These exciting and transformative changes to the Scientific Forum will bring greater exposure to the leading-edge research in clinical care, while continuing to support and encourage young surgeon-scientists—the future of the study and practice of surgery—in their work. ♦

Note

The authors of this article are part of the Owen H. Wangensteen Scientific Forum Committee—Mary T. Hawn, MD, FACS; Edith Tzeng, MD, FACS; and Valerie W. Rusch, MD, FACS, are members, and M. Jane Burns, MJHL; Richard V. King, PhD; and Ajit K. Sachdeva, MD, FACS, FRCSC, are ACS staff.

Dr. Hawn is professor of surgery and chair, department of surgery, Stanford University, CA. She is Chair, ACS Scientific Forum Committee.

Dr. Tzeng is professor of surgery, University of Pittsburgh, and chief, vascular surgery, Veterans Affairs Pittsburgh Healthcare System, University Drive Campus, PA. She is Vice-Chair, ACS Scientific Forum Committee.

Dr. Rusch is vice-chair, clinical research, department of surgery; Miner Family Chair in Intrathoracic Cancers; attending surgeon, thoracic service, department of surgery, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center; and professor of surgery, Weill Cornell Medical College. She is a consultant for the ACS Program Committee.

Ms. Burns is Senior Manager, Clinical Congress Program, ACS Division of Education, Chicago.

Mr. King is Assistant Director, Clinical Congress Program and Skills Courses, ACS Division of Education.

Dr. Sachdeva is Director, ACS Division of Education.

The Scientific Forum of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) Clinical Congress has evolved since the concept was first introduced as the Surgical Forum in 1951. This year’s Scientific Forum will build on these transformations and will offer attendees greater exposure to the surgical research conducted by the ACS community.

Background

The Surgical Forum was established in 1951 to provide a supportive venue for trainees and junior faculty to present and discuss their research. Presenting at the Forum has always been a rite of passage for aspiring academic surgeon-scientists. In 1993, the Surgical Forum was renamed to honor the program founder, Owen H. Wangensteen, MD, PhD, FACS, past-chair, department of surgery, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

As surgical science evolved, the Program Committee developed a separate Scientific Papers session for established investigators and Fellows who were not early in their career. As these two programs evolved, it became increasingly clear that there was substantial overlap. In 2014, the Surgical Forum and Scientific Papers merged into a single entity under the oversight of the existing Surgical Forum Committee.

The merged program was renamed the Scientific Forum to reflect the contributions of the Surgical Forum and the Scientific Papers, and the committee was renamed the Scientific Forum Committee. Because of the increase in scientific abstracts resulting from this merger, the committee expanded its membership to reflect the type of scientific abstracts in the broader program. The basic and translational research focus of the Surgical Forum was expanded to include clinical research in health services, education, global surgery, ethics, and other evolving areas of surgical science.

These changes have revitalized the scientific effort. The number and quality of the abstracts submitted to the Scientific Forum has grown significantly—more than 2,000 abstracts were submitted for review for Clinical Congress 2018.

The spirit of the Surgical Forum has been maintained in the new Scientific Forum, continuing with the clustering of focused areas of research to encourage discussion and collaboration among the attendees. The Program Committee continues to place great emphasis on highlighting the work of young investigators while incorporating the expertise of senior investigators into the sessions.

Changes at Clinical Congress 2017

Quick Shots and e-Posters were introduced at Clinical Congress 2017 in San Diego, CA. Quick Shots are three-minute oral abstract presentations, which were incorporated into the Scientific Forum sessions. This addition, which allowed for more presenters in a session, was met with a positive reception.

The poster sessions were restructured to an electronic format. The e-Posters were placed in a central, dedicated location among the Scientific Forum sessions rather than the Exhibit Hall. The modern e-Poster sessions brought greater visibility to the poster presentations and energized the format. In the e-Poster room, special sessions were scheduled to highlight the exceptional research efforts of the surgical trainees through the Excellence in Research Awards and the Posters of Exceptional Merit. In addition, the Scientific Forum is dedicated to a senior surgeon-scientist who has demonstrated a career-long commitment to training surgeon-scientists and the academic mission.

To further promote and support surgical research, the Scientific Forum Committee partnered with the Journal of the American College of Surgeons (JACS) to solicit the highest-rated abstracts for publication in JACS. In the first year, the top 5 percent of abstracts in the clinical sciences were solicited for manuscript submissions. More than half of those authors submitted a manuscript for review. All accepted manuscripts will be electronically published concurrently with the ACS Clinical Congress 2018 to provide greater visibility to the high-quality research being generated by the ACS community.

Clinical trials session added in 2018

The Scientific Forum Committee strongly believes the Clinical Congress is the premier venue to present practice-changing research. New for 2018, a call for late-breaking clinical trials abstracts was issued, and the committee selected six clinical trials that have the potential to change practice and improve patient care. This new clinical trials session will be presented at Clinical Congress 2018 Monday, October 22, at 9:45 am.

The ACS Clinical Congress is the largest surgical meeting in the U.S. The vision of the Scientific Forum Committee is for leaders of surgical trials to view the Clinical Congress as the premier venue to present their results. These exciting and transformative changes to the Scientific Forum will bring greater exposure to the leading-edge research in clinical care, while continuing to support and encourage young surgeon-scientists—the future of the study and practice of surgery—in their work. ♦

Note

The authors of this article are part of the Owen H. Wangensteen Scientific Forum Committee—Mary T. Hawn, MD, FACS; Edith Tzeng, MD, FACS; and Valerie W. Rusch, MD, FACS, are members, and M. Jane Burns, MJHL; Richard V. King, PhD; and Ajit K. Sachdeva, MD, FACS, FRCSC, are ACS staff.

Dr. Hawn is professor of surgery and chair, department of surgery, Stanford University, CA. She is Chair, ACS Scientific Forum Committee.

Dr. Tzeng is professor of surgery, University of Pittsburgh, and chief, vascular surgery, Veterans Affairs Pittsburgh Healthcare System, University Drive Campus, PA. She is Vice-Chair, ACS Scientific Forum Committee.

Dr. Rusch is vice-chair, clinical research, department of surgery; Miner Family Chair in Intrathoracic Cancers; attending surgeon, thoracic service, department of surgery, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center; and professor of surgery, Weill Cornell Medical College. She is a consultant for the ACS Program Committee.

Ms. Burns is Senior Manager, Clinical Congress Program, ACS Division of Education, Chicago.

Mr. King is Assistant Director, Clinical Congress Program and Skills Courses, ACS Division of Education.

Dr. Sachdeva is Director, ACS Division of Education.

Obesity paradox extends to PE patients

SAN ANTONIO – compared with those who are not obese, according to results of a retrospective analysis covering 13 years and nearly 2 million PE discharges.

The obese patients in the analysis had a lower mortality risk, despite receiving more thrombolytics and mechanical intubation, said investigator Zubair Khan, MD, an internal medicine resident at the University of Toledo (Ohio) Medical Center.

“Surprisingly, the mortality of PE was significantly less in obese patients,” Dr. Khan said in a podium presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians. “When we initiated the study, we did not expect this result.”

The association between obesity and lower mortality, sometimes called the “obesity paradox,” has been observed in studies of other chronic health conditions including stable heart failure, coronary artery disease, unstable angina, MI, and also in some PE studies, Dr. Khan said.

The study by Dr. Khan and his colleagues, based on the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database, included adults with a primary discharge diagnosis of PE between 2002 and 2014. They included 1,959,018 PE discharges, of which 312,770 (16%) had an underlying obesity diagnosis.

Obese PE patients had more risk factors and more severe disease but had an overall mortality of 2.2%, compared with 3.7% in PE patients without obesity (P less than .001), Dr. Khan reported.

Hypertension was significantly more prevalent in the obese PE patients (65% vs. 50.5%; P less than .001), as was chronic lung disease and chronic liver disease, he noted in his presentation.

Obese patients more often received thrombolytics (3.6% vs. 1.9%; P less than .001) and mechanical ventilation (5.8% vs. 4%; P less than .001), and more frequently had cardiogenic shock (0.65% vs. 0.45%; P less than .001), he said.

The obese PE patients were more often female, black, and younger than 65 years of age, it was reported.

Notably, the prevalence of obesity in PE patients more than doubled over the course of the study period, from 10.2% in 2002 to 22.6% in 2014, Dr. Khan added.

The paradoxically lower mortality in obese patients might be explained by increased levels of endocannabinoids, which have shown protective effects in rat and mouse studies, Dr. Khan told attendees at the meeting.

“I think it’s a rich area for more and further research, especially in basic science,” Dr. Khan said.

Dr. Khan and his coauthors disclosed that they had no relationships relevant to the study.

SOURCE: Khan Z et al. CHEST. 2018 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.08.919.

SAN ANTONIO – compared with those who are not obese, according to results of a retrospective analysis covering 13 years and nearly 2 million PE discharges.

The obese patients in the analysis had a lower mortality risk, despite receiving more thrombolytics and mechanical intubation, said investigator Zubair Khan, MD, an internal medicine resident at the University of Toledo (Ohio) Medical Center.

“Surprisingly, the mortality of PE was significantly less in obese patients,” Dr. Khan said in a podium presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians. “When we initiated the study, we did not expect this result.”

The association between obesity and lower mortality, sometimes called the “obesity paradox,” has been observed in studies of other chronic health conditions including stable heart failure, coronary artery disease, unstable angina, MI, and also in some PE studies, Dr. Khan said.

The study by Dr. Khan and his colleagues, based on the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database, included adults with a primary discharge diagnosis of PE between 2002 and 2014. They included 1,959,018 PE discharges, of which 312,770 (16%) had an underlying obesity diagnosis.

Obese PE patients had more risk factors and more severe disease but had an overall mortality of 2.2%, compared with 3.7% in PE patients without obesity (P less than .001), Dr. Khan reported.

Hypertension was significantly more prevalent in the obese PE patients (65% vs. 50.5%; P less than .001), as was chronic lung disease and chronic liver disease, he noted in his presentation.

Obese patients more often received thrombolytics (3.6% vs. 1.9%; P less than .001) and mechanical ventilation (5.8% vs. 4%; P less than .001), and more frequently had cardiogenic shock (0.65% vs. 0.45%; P less than .001), he said.

The obese PE patients were more often female, black, and younger than 65 years of age, it was reported.

Notably, the prevalence of obesity in PE patients more than doubled over the course of the study period, from 10.2% in 2002 to 22.6% in 2014, Dr. Khan added.

The paradoxically lower mortality in obese patients might be explained by increased levels of endocannabinoids, which have shown protective effects in rat and mouse studies, Dr. Khan told attendees at the meeting.

“I think it’s a rich area for more and further research, especially in basic science,” Dr. Khan said.

Dr. Khan and his coauthors disclosed that they had no relationships relevant to the study.

SOURCE: Khan Z et al. CHEST. 2018 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.08.919.

SAN ANTONIO – compared with those who are not obese, according to results of a retrospective analysis covering 13 years and nearly 2 million PE discharges.

The obese patients in the analysis had a lower mortality risk, despite receiving more thrombolytics and mechanical intubation, said investigator Zubair Khan, MD, an internal medicine resident at the University of Toledo (Ohio) Medical Center.

“Surprisingly, the mortality of PE was significantly less in obese patients,” Dr. Khan said in a podium presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians. “When we initiated the study, we did not expect this result.”

The association between obesity and lower mortality, sometimes called the “obesity paradox,” has been observed in studies of other chronic health conditions including stable heart failure, coronary artery disease, unstable angina, MI, and also in some PE studies, Dr. Khan said.

The study by Dr. Khan and his colleagues, based on the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database, included adults with a primary discharge diagnosis of PE between 2002 and 2014. They included 1,959,018 PE discharges, of which 312,770 (16%) had an underlying obesity diagnosis.

Obese PE patients had more risk factors and more severe disease but had an overall mortality of 2.2%, compared with 3.7% in PE patients without obesity (P less than .001), Dr. Khan reported.

Hypertension was significantly more prevalent in the obese PE patients (65% vs. 50.5%; P less than .001), as was chronic lung disease and chronic liver disease, he noted in his presentation.

Obese patients more often received thrombolytics (3.6% vs. 1.9%; P less than .001) and mechanical ventilation (5.8% vs. 4%; P less than .001), and more frequently had cardiogenic shock (0.65% vs. 0.45%; P less than .001), he said.

The obese PE patients were more often female, black, and younger than 65 years of age, it was reported.

Notably, the prevalence of obesity in PE patients more than doubled over the course of the study period, from 10.2% in 2002 to 22.6% in 2014, Dr. Khan added.

The paradoxically lower mortality in obese patients might be explained by increased levels of endocannabinoids, which have shown protective effects in rat and mouse studies, Dr. Khan told attendees at the meeting.

“I think it’s a rich area for more and further research, especially in basic science,” Dr. Khan said.

Dr. Khan and his coauthors disclosed that they had no relationships relevant to the study.

SOURCE: Khan Z et al. CHEST. 2018 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.08.919.

REPORTING FROM CHEST 2018

Key clinical point: The obesity paradox observed in other chronic conditions held true in this study of patients with pulmonary embolism (PE).

Major finding: Obese PE patients had more risk factors and more severe disease, but an overall mortality of 2.2% vs 3.7% in nonobese PE patients.

Study details: Retrospective analysis of the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database including almost 2 million individuals with a primary discharge diagnosis of PE.

Disclosures: Study authors had no disclosures.

Source: Khan Z et al. CHEST. 2018 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.08.919.

Planning for ventilator-dependent patients during natural disasters

SAN ANTONIO – For patients with neuromuscular disorders, the stress and danger from natural disasters such Hurricane Harvey are best avoided by leaving the area as soon as possible, according to Venessa A. Holland, MD, FCCP, of Houston Methodist Hospital.

While none of Dr. Holland’s patients died during this catastrophic hurricane, there were considerable challenges, particularly for those trapped by the many trillion gallons of water fell on Texas and Louisiana in August 2017. Houston was flooded, and hospitals and other medical facilities were hit hard. The vulnerability of ventilator-dependent and incapacitated patients was of particular concern.

In one case, a ventilator-dependent patient trapped by flood waters at home became diaphoretic and hypotensive. The patient was treated with electrolyte-replacement sports drink administered via percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube, Dr. Holland told attendees at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Dr. Holland spoke in a video interview about how neuromuscular disorder patients fared during Hurricane Harvey and her recommendations for the next natural disaster.

Dr. Holland disclosed that she previously served as a consultant to Hill-Rom.

SAN ANTONIO – For patients with neuromuscular disorders, the stress and danger from natural disasters such Hurricane Harvey are best avoided by leaving the area as soon as possible, according to Venessa A. Holland, MD, FCCP, of Houston Methodist Hospital.

While none of Dr. Holland’s patients died during this catastrophic hurricane, there were considerable challenges, particularly for those trapped by the many trillion gallons of water fell on Texas and Louisiana in August 2017. Houston was flooded, and hospitals and other medical facilities were hit hard. The vulnerability of ventilator-dependent and incapacitated patients was of particular concern.

In one case, a ventilator-dependent patient trapped by flood waters at home became diaphoretic and hypotensive. The patient was treated with electrolyte-replacement sports drink administered via percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube, Dr. Holland told attendees at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Dr. Holland spoke in a video interview about how neuromuscular disorder patients fared during Hurricane Harvey and her recommendations for the next natural disaster.

Dr. Holland disclosed that she previously served as a consultant to Hill-Rom.

SAN ANTONIO – For patients with neuromuscular disorders, the stress and danger from natural disasters such Hurricane Harvey are best avoided by leaving the area as soon as possible, according to Venessa A. Holland, MD, FCCP, of Houston Methodist Hospital.

While none of Dr. Holland’s patients died during this catastrophic hurricane, there were considerable challenges, particularly for those trapped by the many trillion gallons of water fell on Texas and Louisiana in August 2017. Houston was flooded, and hospitals and other medical facilities were hit hard. The vulnerability of ventilator-dependent and incapacitated patients was of particular concern.

In one case, a ventilator-dependent patient trapped by flood waters at home became diaphoretic and hypotensive. The patient was treated with electrolyte-replacement sports drink administered via percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube, Dr. Holland told attendees at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Dr. Holland spoke in a video interview about how neuromuscular disorder patients fared during Hurricane Harvey and her recommendations for the next natural disaster.

Dr. Holland disclosed that she previously served as a consultant to Hill-Rom.

REPORTING FROM CHEST 2018

Latest clinical trials advance COPD management

SAN ANTONIO – Recent studies have shown that the use of a long-acting beta2-agonist/long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LABA/LAMA) combination is superior to LAMA alone in endpoints including exacerbation, Nicola A. Hanania, MD, FCCP, said in a panel discussion session at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Other recent evidence has shown that the use of LABA/LAMA has cardiovascular benefits in hyperinflated patients with COPD, according to Dr. Hanania, director of the Airways Clinical Research Center at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

Meanwhile, emerging data in patients with advanced COPD have demonstrated the benefits of single-inhaler triple therapy with inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)/LABA/LAMA versus LABA/LAMA or ICS/LABA combinations, Dr. Hanania said in an interview.

The past year also has brought news that ICS de-escalation is possible in patients with moderate COPD with no exacerbation risk, though it may not be possible in patients with high baseline blood eosinophils, he added.

Recent developments have not all been about drug therapy. The Zephyr endobronchial valve improved outcomes in patients with little to no collateral ventilation in target lobes, Dr. Hanania said. However, the therapy comes with a potential risk of pneumothorax, so patients need to be monitored in the hospital.

Dr. Hanania provided disclosures related to Roche (Genentech), AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, and Sanofi/Regeneron, as well as institutional research grant support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the American Lung Association.

SAN ANTONIO – Recent studies have shown that the use of a long-acting beta2-agonist/long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LABA/LAMA) combination is superior to LAMA alone in endpoints including exacerbation, Nicola A. Hanania, MD, FCCP, said in a panel discussion session at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Other recent evidence has shown that the use of LABA/LAMA has cardiovascular benefits in hyperinflated patients with COPD, according to Dr. Hanania, director of the Airways Clinical Research Center at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

Meanwhile, emerging data in patients with advanced COPD have demonstrated the benefits of single-inhaler triple therapy with inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)/LABA/LAMA versus LABA/LAMA or ICS/LABA combinations, Dr. Hanania said in an interview.

The past year also has brought news that ICS de-escalation is possible in patients with moderate COPD with no exacerbation risk, though it may not be possible in patients with high baseline blood eosinophils, he added.

Recent developments have not all been about drug therapy. The Zephyr endobronchial valve improved outcomes in patients with little to no collateral ventilation in target lobes, Dr. Hanania said. However, the therapy comes with a potential risk of pneumothorax, so patients need to be monitored in the hospital.

Dr. Hanania provided disclosures related to Roche (Genentech), AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, and Sanofi/Regeneron, as well as institutional research grant support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the American Lung Association.

SAN ANTONIO – Recent studies have shown that the use of a long-acting beta2-agonist/long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LABA/LAMA) combination is superior to LAMA alone in endpoints including exacerbation, Nicola A. Hanania, MD, FCCP, said in a panel discussion session at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Other recent evidence has shown that the use of LABA/LAMA has cardiovascular benefits in hyperinflated patients with COPD, according to Dr. Hanania, director of the Airways Clinical Research Center at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

Meanwhile, emerging data in patients with advanced COPD have demonstrated the benefits of single-inhaler triple therapy with inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)/LABA/LAMA versus LABA/LAMA or ICS/LABA combinations, Dr. Hanania said in an interview.

The past year also has brought news that ICS de-escalation is possible in patients with moderate COPD with no exacerbation risk, though it may not be possible in patients with high baseline blood eosinophils, he added.

Recent developments have not all been about drug therapy. The Zephyr endobronchial valve improved outcomes in patients with little to no collateral ventilation in target lobes, Dr. Hanania said. However, the therapy comes with a potential risk of pneumothorax, so patients need to be monitored in the hospital.

Dr. Hanania provided disclosures related to Roche (Genentech), AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, and Sanofi/Regeneron, as well as institutional research grant support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the American Lung Association.

REPORTING FROM CHEST 2018

COPD and Asthma Supplement

COPD and Asthma Update

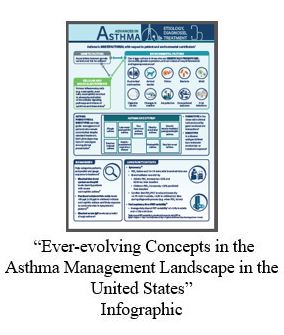

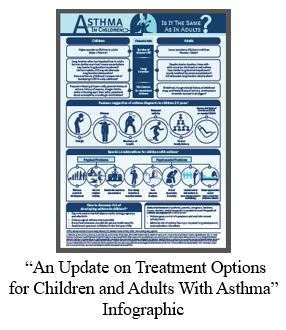

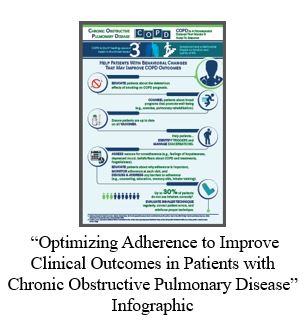

"COPD and Asthma Update" is a clinical aid for PCPs to further understand and manage patients with COPD or asthma. Click here to read the supplement, then click the buttons below for supplementary materials to each chapter.

Supplementary Materials:

Supplemental Materials are joint copyright © 2018 Frontline Medical Communications and Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

COPD and Asthma Update

"COPD and Asthma Update" is a clinical aid for PCPs to further understand and manage patients with COPD or asthma. Click here to read the supplement, then click the buttons below for supplementary materials to each chapter.

Supplementary Materials:

Supplemental Materials are joint copyright © 2018 Frontline Medical Communications and Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

COPD and Asthma Update

"COPD and Asthma Update" is a clinical aid for PCPs to further understand and manage patients with COPD or asthma. Click here to read the supplement, then click the buttons below for supplementary materials to each chapter.

Supplementary Materials:

Supplemental Materials are joint copyright © 2018 Frontline Medical Communications and Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Upper Extremity Injuries in Soccer

ABSTRACT

Upper limb injuries in soccer represent only a marginal portion of injuries, however this is mainly true for outfield players. Goalkeepers are reported to have up to 5 times more upper extremity injuries, many of them requiring substantial time-loss for treatment and rehabilitation. The most common upper extremity injury locations are the shoulder/clavicle followed by the hand/finger/thumb, elbow, wrist, forearm, and upper arm. The mechanism of injury, presentation, physical examination, and imaging features all play a significant role in reaching the correct diagnosis. Taking to consideration the position the player plays and his demands will also enable tailoring the optimal treatment plan that allows timely and safe return to play. This article discusses common upper extremity injuries observed in soccer players, focusing on proper diagnosis and optimal management.

Continue to: Upper limb injuries in association with soccer...

Upper limb injuries in association with soccer have been reported to represent only 3% of all time-loss injuries in professional soccer players1. However, they are considered an increasing problem in recent years2-4 and have been reported in high proportions in children under the age of 15 years.5 Some of the reasons for the increase in upper extremity injuries may be explained by modern soccer tactics that have been characterized by high speed, pressing, and marking.2 Furthermore, upper extremity injuries may still be underestimated in soccer, mainly because outfield players are sometimes able to train and play even when they suffer from an upper extremity injury.

Unsurprisingly, upper extremity injuries are reported to be up to 5 times more common in goalkeepers than in outfield players,1,2 reaching a high rate of up to 18% of all injuries among professional goalkeepers. The usage of upper extremities to stop the ball and repeated reaching to the ball and landing on the ground with changing upper extremity positions are some of the contributors to the increased upper extremity injury risk in goalkeepers.

Following 57 male professional European soccer teams from 16 countries between the years 2001 and 2011, Ekstrand and colleagues1 showed that 90% of upper extremity injuries are traumatic, and only 10% are related to overuse. They also reported that the most common upper extremity injury location is the shoulder/clavicle (56%), followed by the hand/finger/thumb (24%), elbow (10%), wrist (5%), forearm (4%), and upper arm (1%). Specifically, the 6 most common injuries are acromioclavicular joint (ACJ) sprain (13%), shoulder dislocation (12%), hand metacarpal fracture (8%), shoulder rotator cuff tendinopathy (6%), hand phalanx fracture (6%), and shoulder ACJ dislocation (5%).

This article will discuss common upper extremity injuries observed in soccer players, focusing on proper diagnosis and optimal management.

Continue to: THE SHOULDER...

THE SHOULDER

The majority of upper extremity injuries in professional soccer players are shoulder injuries.1,2,4 Almost a third of these injuries (28%) are considered severe, preventing participation in training and matches for 28 days or more.6Ekstrand and colleagues1 reported that shoulder dislocation represents the most severe upper extremity injury with a mean of 41 days of absence from soccer. When considering the position of the player, they further demonstrated that absence from full training and matches is twice as long for goalkeepers as for outfield players, which reflects the importance of shoulder function for goalkeepers.

In terms of the mechanism of shoulder instability injuries in soccer players, more than half (56%) of these injuries occur with a high-energy mechanism in the recognized position of combined humeral abduction and external rotation against a force of external rotation and horizontal extension.3 However, almost a quarter (24%) occur with a mechanism of varied upper extremity position and low-energy trauma, and 20% of injuries are either a low energy injury with little or no contact or gradual onset. These unique characteristics of shoulder instability injuries in soccer players should be accounted for during training and may imply that current training programs are suboptimal for the prevention of upper extremity injuries and shoulder injuries. Ejnisman and colleagues2 reported on the development of a Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) 11+ shoulder injury prevention program for soccer goalkeepers as one of the ways to promote training programs that address the risk of shoulder injuries.

Reporting on the management of severe shoulder injuries requiring surgery in 25 professional soccer players in England, between 2007 and 2011, Hart and Funk3 found that the majority of subjects (88%) reported a dislocation as a feature of their presentation. Twenty-one (84%) subjects were diagnosed with labral injuries, of which 7 had an associated Hill-Sachs lesion. Two (8%) subjects were diagnosed with rotator cuff tears requiring repair, and 2 (8%) subjects had a combination of rotator cuff and labral injury repair. All patients underwent arthroscopic repair, except for 5 who had a Latarjet coracoid transfer. Post-surgery, all players were able to return to unrestricted participation in soccer at a mean of 11.4 weeks, with no significant difference between goalkeepers and outfield players and no recurrences at a mean of 91 weeks’ follow-up.

Up to one-third of shoulder instability injuries in soccer players are reported to be recurrences,1,3 which emphasizes the need to carefully assess soccer players before clearing them to return to play. These data raise the controversy over the treatment of first time shoulder dislocators and may support early surgical intervention.7-9 In terms of the preferred surgical intervention in these cases, Balg and Boileau10 suggested a simple scoring system based on factors derived from a preoperative questionnaire, physical examination, and anteroposterior radiographs to help distinguish between patients who will benefit from an arthroscopic anterior stabilization using suture anchors and those who will require a bony procedure (open or arthroscopic). Cerciello and colleagues11 reported excellent results for bony stabilization (modified Latarjet) in a population of 26 soccer players (28 shoulders) affected by chronic anterior instability. Only 1 player did not return to soccer, and 18 players (20 shoulders, 71%) returned to the same level. One re-dislocation was noted in a goalkeeper 74 months after surgery.

An injury to the ACJ has been previously reported to be the most prevalent type of shoulder injury in contact sports.12In soccer, injury to the ACJ is responsible for 18% of upper extremity injuries, and the majority (72%) are sprains.1Interestingly, but unsurprisingly, implications of such an injury differ significantly between goalkeepers and outfield players with up to 3 times longer required absence periods for goalkeepers vs outfield players sustaining the same injury.

ACJ injury is commonly the result of a direct fall on the shoulder with the arm adducted or extended. Six grades of ACJ injuries have been described and distinguished by the injured anatomical structure (acromioclavicular ligaments and coracoclavicular ligaments) and the direction and magnitude of clavicular dislocation.13,14 Presentation will usually include anterior shoulder pain, a noticeable swelling or change in morphology of the lateral end of the clavicle (mainly in dislocation types), and sharp pain provoked by palpation of the ACJ. Radiographic imaging will confirm the diagnosis and help with identifying the specific grade/type of injury.

Decision making and management of acute ACJ injury should be based on the type/grade of injury. Nonoperative treatment is recommended for types I and II, and most athletes have a successful outcome with a full return to play.12Types IV, V, and VI are treated early with operative intervention, mostly due to the morbidity associated with prolonged dislocation of the joint and subsequent soft tissue damage.12 Treatment of type III injury remains controversial. Pereira-Graterol and colleagues15 reported the effectiveness of clavicular hook plate (DePuy Synthes) in the surgical stabilization of grade III ACJ dislocation in 11 professional soccer players. At a mean follow-up of 4 years, they showed excellent functional results with full shoulder range of motion at 5 weeks and latest return to soccer at 6 months. The hook plate was removed after 16 weeks in 10 patients in whom no apparent complication was observed.

Continue to: THE ELBOW...

THE ELBOW

Ekstrand and colleagues1 reported that 10% of all upper extremity injuries in professional soccer players are elbow injuries, of which only 19% are considered severe injuries that require more than 28 days of absence from playing soccer. The most common elbow injuries in their cohort were elbow medial collateral ligament (MCL) sprain and olecranon bursitis.

Elbow MCL is the primary constraint of the elbow joint to valgus stress, and MCL sprain occurs when the elbow is subjected to a valgus, or laterally directed force, which distracts the medial side of the elbow, exceeding the tensile properties of the MCL.16 A thorough physical examination that includes valgus stress tests through the arc of elbow flexion and extension to elicit a possible subjective feeling of apprehension, instability, or localized pain is essential for optimal evaluation and treatment.16,17 Imaging studies (X-ray and stress X-rays, dynamic ultrasound, computed tomography [CT], magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], and MR arthrography) have a role in further establishing the diagnosis and identifying possible additional associated injuries.16 The treatment plan should be specifically tailored to the individual athlete, depending on his demands and the degree of MCL injury. In soccer, which is a non-throwing shoulder sport, nonoperative treatment should be the preferred initial treatment in most cases. Ekstrand and colleagues1 showed that this injury requires a mean of 4 days of absence from soccer for outfield players and a mean of 21 days of absence from soccer for goalkeepers, thereby indicating more severe sprains and cautious return to soccer in goalkeepers. Athletes who fail nonoperative treatment are candidates for MCL reconstruction.16

The olecranon bursa is a synovium-lined sac that facilitates gliding between the olecranon and overlying skin. Olecranon bursitis is characterized by accumulation of fluid in the bursa with or without inflammation. The fluid can be serous, sanguineous, or purulent depending on the etiology.18 In soccer, traumatic etiology is common, but infection secondary to cuts or scratches of the skin around the elbow or previous therapeutic injections around the elbow should always be ruled out. Local pain, swelling, warmth, and redness are usually the presenting symptoms. Aseptic olecranon bursitis may be managed non-surgically with ‘‘benign neglect’’ and avoidance of pressure to the area, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, needle aspiration, corticosteroid injection, compression dressings, and/or padded splinting; whereas acute septic bursitis requires needle aspiration for diagnosis, appropriate oral or intravenous antibiotics directed toward the offending organism, and, when clinically indicated, surgical evacuation/excision of the bursa.18 When treating this condition with cortisone injection, possible complications, such as skin atrophy, secondary infection, and chronic local pain, have been reported and should be considered.19

Severe elbow injuries in professional athletes in general,20-22 and soccer players specifically, are elbow subluxations/dislocations and elbow fracture. The mechanism of injury is usually contact injury with an opponent player or a fall on the palm with the arm extended. Posterolateral is the most common type of elbow dislocation. Elbow dislocations are further classified into simple (no associated fractures) and complex (associated with fractures) categories.22 Simple dislocations are usually treated with early mobilization after closed reduction; it is associated with a low risk for re-dislocation and with generally good results. The complex type of elbow fracture dislocation is more difficult to treat, has higher complication and re-dislocation rates, and requires operative treatment in most cases compared with simple dislocation.22 The “terrible triad” of the elbow (posterior elbow dislocation, radial head fracture, and coronoid fracture) represents a specific complex elbow dislocation scenario that is difficult to manage because of conflicting aims of ensuring elbow stability while maintaining early range of motion.22

Isolated fracture around the elbow should be treated based on known principles of fracture management: mechanism of injury, fracture patterns, fracture displacement, intra-articular involvement, soft tissue condition, and associated injuries.

Continue to: THE WRIST...

THE WRIST

Ekstrand and colleagues1 reported that 5% of all upper extremity injuries in their cohort of professional soccer players are wrist injuries, of which, only 2% are considered severe injuries that require >28 days of absence from playing soccer. The more common wrist injuries in soccer, which is considered a high-impact sport, are fractures (distal radius, scaphoid, capitate), and less reported injuries are dislocations (lunate, perilunate) and ligamentous injuries or tears (scapholunate ligament).23