User login

After-hours texting and professional boundaries

Recently, I was out on a Friday night with a friend who is a resident in another program. I hadn’t seen her in a very long time because of our hectic schedules. Around 10 p.m., she received a text from her attending asking her if she had left the scripts ready for the patient who was leaving on Monday.

Much has been written about professional boundaries and bosses texting their employees. For most jobs, a boss texting after hours over nonurgent matters is completely out of line. But in the medical field, there are no limits. People say, “Oh well, it’s the physician life.” Well maybe if we had more professional boundaries, our quality of life would be better. Maybe there wouldn’t be such a huge rate of burnout.

I encourage physicians to remember to contact your resident and coworkers during business hours. If the matter is not placing patients in danger, it can wait till the next morning. Nobody wants to pick up his phone in the middle of dinner to deal with patient care–related expectations that can be addressed the next business day.

Receiving a text brings all the stress of work back in the middle of our time off in which we are trying to take care of ourselves and the rest of our lives. It adds unnecessary stress to the overall high stress level and undermines our attempt to have a social life and meet a friend. A quick Internet search shows many blogs, journals, and different websites discussing this issue, but the voices of doctors and other health care providers are strangely silent on this topic.

I consider emails a more professional way of communicating than a text. I check my email often during a 24-hour period, and when I do, I’m ready for any potential information I might receive. I do not get notifications on my phone from my work email. But like my friend, I can’t avoid texts. We should have the opportunity to use our right to disconnect.

Some may argue, “Put your phone on silent if you don’t want to deal with it.” But not only do I use my phone for my life outside of work (as a resident, I make an effort to have one), but I want to be available for my peers and juniors when they are in the hospital. I want to be a resident my coworkers can text when they have a question and appreciate my advice. That is a decision I have made about the type of resident I want to be, and I am comfortable with it. Now if they text me asking a question that can wait till business hours the following day, they are crossing boundaries.

It might seem like a gray line. Somebody – maybe residency programs or our professional organizations – should address this so we have clear guidelines to protect our off-work time. Doesn’t our culture need to change the “physician life” so that we don’t bring our work responsibilities out for dinner on a Friday night? If the issue doesn’t need to be resolved quickly, it should be a given that texting is inappropriate.

Dr. Serrano is a PGY3 psychiatry resident at the Einstein Medical Center in Philadelphia.

Recently, I was out on a Friday night with a friend who is a resident in another program. I hadn’t seen her in a very long time because of our hectic schedules. Around 10 p.m., she received a text from her attending asking her if she had left the scripts ready for the patient who was leaving on Monday.

Much has been written about professional boundaries and bosses texting their employees. For most jobs, a boss texting after hours over nonurgent matters is completely out of line. But in the medical field, there are no limits. People say, “Oh well, it’s the physician life.” Well maybe if we had more professional boundaries, our quality of life would be better. Maybe there wouldn’t be such a huge rate of burnout.

I encourage physicians to remember to contact your resident and coworkers during business hours. If the matter is not placing patients in danger, it can wait till the next morning. Nobody wants to pick up his phone in the middle of dinner to deal with patient care–related expectations that can be addressed the next business day.

Receiving a text brings all the stress of work back in the middle of our time off in which we are trying to take care of ourselves and the rest of our lives. It adds unnecessary stress to the overall high stress level and undermines our attempt to have a social life and meet a friend. A quick Internet search shows many blogs, journals, and different websites discussing this issue, but the voices of doctors and other health care providers are strangely silent on this topic.

I consider emails a more professional way of communicating than a text. I check my email often during a 24-hour period, and when I do, I’m ready for any potential information I might receive. I do not get notifications on my phone from my work email. But like my friend, I can’t avoid texts. We should have the opportunity to use our right to disconnect.

Some may argue, “Put your phone on silent if you don’t want to deal with it.” But not only do I use my phone for my life outside of work (as a resident, I make an effort to have one), but I want to be available for my peers and juniors when they are in the hospital. I want to be a resident my coworkers can text when they have a question and appreciate my advice. That is a decision I have made about the type of resident I want to be, and I am comfortable with it. Now if they text me asking a question that can wait till business hours the following day, they are crossing boundaries.

It might seem like a gray line. Somebody – maybe residency programs or our professional organizations – should address this so we have clear guidelines to protect our off-work time. Doesn’t our culture need to change the “physician life” so that we don’t bring our work responsibilities out for dinner on a Friday night? If the issue doesn’t need to be resolved quickly, it should be a given that texting is inappropriate.

Dr. Serrano is a PGY3 psychiatry resident at the Einstein Medical Center in Philadelphia.

Recently, I was out on a Friday night with a friend who is a resident in another program. I hadn’t seen her in a very long time because of our hectic schedules. Around 10 p.m., she received a text from her attending asking her if she had left the scripts ready for the patient who was leaving on Monday.

Much has been written about professional boundaries and bosses texting their employees. For most jobs, a boss texting after hours over nonurgent matters is completely out of line. But in the medical field, there are no limits. People say, “Oh well, it’s the physician life.” Well maybe if we had more professional boundaries, our quality of life would be better. Maybe there wouldn’t be such a huge rate of burnout.

I encourage physicians to remember to contact your resident and coworkers during business hours. If the matter is not placing patients in danger, it can wait till the next morning. Nobody wants to pick up his phone in the middle of dinner to deal with patient care–related expectations that can be addressed the next business day.

Receiving a text brings all the stress of work back in the middle of our time off in which we are trying to take care of ourselves and the rest of our lives. It adds unnecessary stress to the overall high stress level and undermines our attempt to have a social life and meet a friend. A quick Internet search shows many blogs, journals, and different websites discussing this issue, but the voices of doctors and other health care providers are strangely silent on this topic.

I consider emails a more professional way of communicating than a text. I check my email often during a 24-hour period, and when I do, I’m ready for any potential information I might receive. I do not get notifications on my phone from my work email. But like my friend, I can’t avoid texts. We should have the opportunity to use our right to disconnect.

Some may argue, “Put your phone on silent if you don’t want to deal with it.” But not only do I use my phone for my life outside of work (as a resident, I make an effort to have one), but I want to be available for my peers and juniors when they are in the hospital. I want to be a resident my coworkers can text when they have a question and appreciate my advice. That is a decision I have made about the type of resident I want to be, and I am comfortable with it. Now if they text me asking a question that can wait till business hours the following day, they are crossing boundaries.

It might seem like a gray line. Somebody – maybe residency programs or our professional organizations – should address this so we have clear guidelines to protect our off-work time. Doesn’t our culture need to change the “physician life” so that we don’t bring our work responsibilities out for dinner on a Friday night? If the issue doesn’t need to be resolved quickly, it should be a given that texting is inappropriate.

Dr. Serrano is a PGY3 psychiatry resident at the Einstein Medical Center in Philadelphia.

Clinical Challenges - August 2016: Benign multicystic mesothelioma

What's Your Diagnosis?

The diagnosis

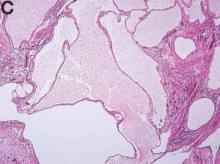

We present a case of benign multicystic mesothelioma with extensive involvement of the abdominal and pelvic cavities in a male patient. Benign multicystic mesothelioma is a rare tumor most frequently localized to the pelvic peritoneal surface. Patients are usually women of reproductive age without a history of asbestos exposure. The gross appearance is typically multiple translucent membranous cysts that are grouped together to form a mass or discontinuously studding the peritoneal surface. Microscopically, the cystic spaces are lined by mesothelial cells expressing markers such as calretinin. The major differential diagnosis is cystic lymphangioma, in which cystic spaces are lined by endothelial cells. Preoperative diagnosis by fine-needle aspiration cytology has been described in the literature. Cytology shows monomorphous cells with mesothelial features in a clean background.1 The disease course is usually indolent, but local recurrence after operative intervention is common.2,3

References

1. Devaney, K., Kragel, P.J., Devaney, E.J. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of multicystic mesothelioma. Diagn Cytopathol. 1992 Jan;8:68-72.

2. Ross, M.J., Welch, W.R., Scully, R.E. Multilocular peritoneal inclusion cysts (so-called cystic mesotheliomas). Cancer. 1989 Sep;64:1336-46.

3. Weiss, S.W. Tavassoli, F.A. Multicystic mesothelioma (An analysis of pathologic findings and biologic behavior in 37 cases). Am J Surg Pathol. 1988 Oct;12:737-46.

The diagnosis

We present a case of benign multicystic mesothelioma with extensive involvement of the abdominal and pelvic cavities in a male patient. Benign multicystic mesothelioma is a rare tumor most frequently localized to the pelvic peritoneal surface. Patients are usually women of reproductive age without a history of asbestos exposure. The gross appearance is typically multiple translucent membranous cysts that are grouped together to form a mass or discontinuously studding the peritoneal surface. Microscopically, the cystic spaces are lined by mesothelial cells expressing markers such as calretinin. The major differential diagnosis is cystic lymphangioma, in which cystic spaces are lined by endothelial cells. Preoperative diagnosis by fine-needle aspiration cytology has been described in the literature. Cytology shows monomorphous cells with mesothelial features in a clean background.1 The disease course is usually indolent, but local recurrence after operative intervention is common.2,3

References

1. Devaney, K., Kragel, P.J., Devaney, E.J. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of multicystic mesothelioma. Diagn Cytopathol. 1992 Jan;8:68-72.

2. Ross, M.J., Welch, W.R., Scully, R.E. Multilocular peritoneal inclusion cysts (so-called cystic mesotheliomas). Cancer. 1989 Sep;64:1336-46.

3. Weiss, S.W. Tavassoli, F.A. Multicystic mesothelioma (An analysis of pathologic findings and biologic behavior in 37 cases). Am J Surg Pathol. 1988 Oct;12:737-46.

The diagnosis

We present a case of benign multicystic mesothelioma with extensive involvement of the abdominal and pelvic cavities in a male patient. Benign multicystic mesothelioma is a rare tumor most frequently localized to the pelvic peritoneal surface. Patients are usually women of reproductive age without a history of asbestos exposure. The gross appearance is typically multiple translucent membranous cysts that are grouped together to form a mass or discontinuously studding the peritoneal surface. Microscopically, the cystic spaces are lined by mesothelial cells expressing markers such as calretinin. The major differential diagnosis is cystic lymphangioma, in which cystic spaces are lined by endothelial cells. Preoperative diagnosis by fine-needle aspiration cytology has been described in the literature. Cytology shows monomorphous cells with mesothelial features in a clean background.1 The disease course is usually indolent, but local recurrence after operative intervention is common.2,3

References

1. Devaney, K., Kragel, P.J., Devaney, E.J. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of multicystic mesothelioma. Diagn Cytopathol. 1992 Jan;8:68-72.

2. Ross, M.J., Welch, W.R., Scully, R.E. Multilocular peritoneal inclusion cysts (so-called cystic mesotheliomas). Cancer. 1989 Sep;64:1336-46.

3. Weiss, S.W. Tavassoli, F.A. Multicystic mesothelioma (An analysis of pathologic findings and biologic behavior in 37 cases). Am J Surg Pathol. 1988 Oct;12:737-46.

What's Your Diagnosis?

What's Your Diagnosis?

What's Your Diagnosis?

BY SHAN-CHI YU, MD, CHIH-HORNG WU, MD, AND HSIN-YI HUANG, MD. Published previously in Gastroenterology (2012;143:1156, 1140).

The cystic lesions and appendix were resected under the clinical impression of pseudomyxoma peritonei.

There were multiple, thin-walled, cystic tumors containing clear fluid throughout the abdominal and pelvic cavities.

The cysts were lined by a single layer of flattened or cuboidal cells, which were positive for calretinin (Figures D) and negative for CD31 (an endothelial marker). A carcinoid tumor was incidentally found at the appendix.

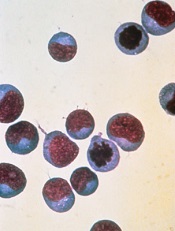

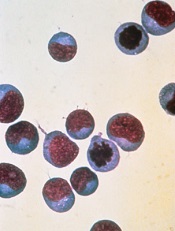

VTE risk appears to vary over time in patients with multiple myeloma

Venous thromboembolism may occur later in the disease process of multiple myeloma than has historically been reported, based on data reported by Brea Lipe, MD, of the University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, and her colleagues.

The risk for VTE appears to change over time. Patients with multiple myeloma should be assessed for VTE risk and thromboprophylaxis on an ongoing basis throughout the disease course, the researchers recommended at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

In a study originally designed to examine the adoption and utility of the International Myeloma Working Group thromboprophylaxis guidelines, the researchers used the Healthcare Enterprise Repository for Ontological Narration (HERON) database to identify case patients with multiple myeloma and a venous thromboembolism. Patients who had multiple myeloma and had not experienced a VTE were matched to the cases based on gender, age, and time of diagnosis. Patient charts were manually extracted to identify treatment history, disease history, risk factors for VTE, and guideline adherence regarding use of prophylactic anticoagulation for the matched patients at the time of diagnosis and at the time of the VTE.

There were 86 cases and 211 controls in the final cohort. The median time from diagnosis to VTE was 952 days. In accordance with the guidelines, patients with a higher risk of VTE were more likely to be on low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or warfarin versus patients with a lower risk of VTE on aspirin or no prophylaxis (P less than .001). Risk category or prophylactic medication were not associated with the rate of VTE when considering baseline risk factors. Over time, however, the risk category of case patients changed to a higher risk group and this was associated with a higher risk of VTE (P = .06).

“While we were unable to validate the IMWG recommendations for thromboprophylaxis at diagnosis, our data suggest that VTE in multiple myeloma may occur later in the disease process than has historically been reported,” the researchers concluded.

Dr. Lipe has been an adviser to Takeda.

On Twitter @maryjodales

Venous thromboembolism may occur later in the disease process of multiple myeloma than has historically been reported, based on data reported by Brea Lipe, MD, of the University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, and her colleagues.

The risk for VTE appears to change over time. Patients with multiple myeloma should be assessed for VTE risk and thromboprophylaxis on an ongoing basis throughout the disease course, the researchers recommended at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

In a study originally designed to examine the adoption and utility of the International Myeloma Working Group thromboprophylaxis guidelines, the researchers used the Healthcare Enterprise Repository for Ontological Narration (HERON) database to identify case patients with multiple myeloma and a venous thromboembolism. Patients who had multiple myeloma and had not experienced a VTE were matched to the cases based on gender, age, and time of diagnosis. Patient charts were manually extracted to identify treatment history, disease history, risk factors for VTE, and guideline adherence regarding use of prophylactic anticoagulation for the matched patients at the time of diagnosis and at the time of the VTE.

There were 86 cases and 211 controls in the final cohort. The median time from diagnosis to VTE was 952 days. In accordance with the guidelines, patients with a higher risk of VTE were more likely to be on low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or warfarin versus patients with a lower risk of VTE on aspirin or no prophylaxis (P less than .001). Risk category or prophylactic medication were not associated with the rate of VTE when considering baseline risk factors. Over time, however, the risk category of case patients changed to a higher risk group and this was associated with a higher risk of VTE (P = .06).

“While we were unable to validate the IMWG recommendations for thromboprophylaxis at diagnosis, our data suggest that VTE in multiple myeloma may occur later in the disease process than has historically been reported,” the researchers concluded.

Dr. Lipe has been an adviser to Takeda.

On Twitter @maryjodales

Venous thromboembolism may occur later in the disease process of multiple myeloma than has historically been reported, based on data reported by Brea Lipe, MD, of the University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, and her colleagues.

The risk for VTE appears to change over time. Patients with multiple myeloma should be assessed for VTE risk and thromboprophylaxis on an ongoing basis throughout the disease course, the researchers recommended at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

In a study originally designed to examine the adoption and utility of the International Myeloma Working Group thromboprophylaxis guidelines, the researchers used the Healthcare Enterprise Repository for Ontological Narration (HERON) database to identify case patients with multiple myeloma and a venous thromboembolism. Patients who had multiple myeloma and had not experienced a VTE were matched to the cases based on gender, age, and time of diagnosis. Patient charts were manually extracted to identify treatment history, disease history, risk factors for VTE, and guideline adherence regarding use of prophylactic anticoagulation for the matched patients at the time of diagnosis and at the time of the VTE.

There were 86 cases and 211 controls in the final cohort. The median time from diagnosis to VTE was 952 days. In accordance with the guidelines, patients with a higher risk of VTE were more likely to be on low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or warfarin versus patients with a lower risk of VTE on aspirin or no prophylaxis (P less than .001). Risk category or prophylactic medication were not associated with the rate of VTE when considering baseline risk factors. Over time, however, the risk category of case patients changed to a higher risk group and this was associated with a higher risk of VTE (P = .06).

“While we were unable to validate the IMWG recommendations for thromboprophylaxis at diagnosis, our data suggest that VTE in multiple myeloma may occur later in the disease process than has historically been reported,” the researchers concluded.

Dr. Lipe has been an adviser to Takeda.

On Twitter @maryjodales

FROM ASCO 16

Key clinical point: Patients with multiple myeloma should be assessed for VTE risk and thromboprophylaxis on an ongoing basis throughout the disease course.

Major finding: Over time, the risk category of case patients changed to a higher risk group and this was associated with a higher risk of VTE (P = .06).

Data source: The Healthcare Enterprise Repository for Ontological Narration (HERON) database.

Disclosures: Dr. Lipe has been an adviser to Takeda.

Venetoclax can produce short-term responses in AML

Results of a phase 2 trial suggest the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax can produce responses in patients with acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) who do not respond to or cannot tolerate chemotherapy.

However, the overall response rate in this trial was low, and responses were not durable.

All of the patients studied discontinued venetoclax, most due to disease progression.

The study was published in Cancer Discovery. It was funded by AbbVie in collaboration with Genentech/Roche.

The trial included 32 patients with AML and a median age of 71 (range, 19–84). Thirteen patients had an antecedent hematologic disorder or myeloproliferative neoplasm, and 4 had therapy-related AML with complex cytogenetics.

Twelve patients had mutations in IDH genes, and 6 had a high BCL2-sensitive protein index.

Thirty patients had received at least 1 prior therapy, and 13 had received at least 3 prior treatment regimens. Two patients were considered unfit for intensive chemotherapy and were treatment-naive at study entry.

The patients received venetoclax at 800 mg daily. All 32 patients received at least 1 dose, and 26 patients received at least 4 weeks of therapy.

Efficacy

The overall response rate was 19%. Two patients had a complete response (CR), and 4 had a CR with incomplete blood count recovery. Three of the 6 responders had an antecedent hematologic disorder.

“[E]ven among pretreated patients whose AML was refractory to intensive chemotherapy, there was evidence of exceptional sensitivity to selective BCL2 inhibition, even to the point of complete remissions,” said study author Anthony Letai, MD, PhD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts.

The median duration of therapy in responders was 144.5 days, and the median duration of CR was 48 days.

The 4 patients who had CRs with incomplete count recovery had IDH mutations. Response to the drug correlated with biomarker results, including indices of BCL2 protein expression and BH3 profiling.

“This is significant as it supports the mechanism of action of venetoclax as an on-target inhibitor of BCL2,” Dr Letai said. “Moreover, it offers the possibility of using BH3 profiling as a potential predictive biomarker for clinical use of BH3 mimetics.”

Safety and discontinuation

All of the patients discontinued therapy—29 due to progressive disease and 1 due to an adverse event (terminal ileitis). One patient withdrew consent, and 1 proceeded to allogeneic transplant after achieving stable disease.

All of the patients experienced treatment-emergent adverse events. The most common were nausea (59%), diarrhea (56%), hypokalemia (41%), vomiting (41%), fatigue (34%), headache (34%), hypomagnesemia (34%), febrile neutropenia (31%), and hypophosphatemia (31%).

Serious adverse events occurred in 84% of patients. These included febrile neutropenia (28%), pneumonia (16%), abdominal pain (6%), acute renal failure (6%), failure to thrive (6%), hypotension (6%), sepsis (6%), and urinary tract infection (6%).

Based on the results of this trial, the researchers concluded that venetoclax may be a viable treatment option for AML patients when used in combination with other therapies.

“We believe that venetoclax will soon become an equal partner to standard-of-care chemotherapy in elderly patients with AML when used in combinations with hypomethylating agents and other approaches,” said study author Marina Konopleva, MD, PhD, of MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas.

“Planned studies will test the hypothesis that venetoclax may likewise improve outcomes in younger AML patients when combined with high-dose chemotherapy.” ![]()

Results of a phase 2 trial suggest the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax can produce responses in patients with acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) who do not respond to or cannot tolerate chemotherapy.

However, the overall response rate in this trial was low, and responses were not durable.

All of the patients studied discontinued venetoclax, most due to disease progression.

The study was published in Cancer Discovery. It was funded by AbbVie in collaboration with Genentech/Roche.

The trial included 32 patients with AML and a median age of 71 (range, 19–84). Thirteen patients had an antecedent hematologic disorder or myeloproliferative neoplasm, and 4 had therapy-related AML with complex cytogenetics.

Twelve patients had mutations in IDH genes, and 6 had a high BCL2-sensitive protein index.

Thirty patients had received at least 1 prior therapy, and 13 had received at least 3 prior treatment regimens. Two patients were considered unfit for intensive chemotherapy and were treatment-naive at study entry.

The patients received venetoclax at 800 mg daily. All 32 patients received at least 1 dose, and 26 patients received at least 4 weeks of therapy.

Efficacy

The overall response rate was 19%. Two patients had a complete response (CR), and 4 had a CR with incomplete blood count recovery. Three of the 6 responders had an antecedent hematologic disorder.

“[E]ven among pretreated patients whose AML was refractory to intensive chemotherapy, there was evidence of exceptional sensitivity to selective BCL2 inhibition, even to the point of complete remissions,” said study author Anthony Letai, MD, PhD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts.

The median duration of therapy in responders was 144.5 days, and the median duration of CR was 48 days.

The 4 patients who had CRs with incomplete count recovery had IDH mutations. Response to the drug correlated with biomarker results, including indices of BCL2 protein expression and BH3 profiling.

“This is significant as it supports the mechanism of action of venetoclax as an on-target inhibitor of BCL2,” Dr Letai said. “Moreover, it offers the possibility of using BH3 profiling as a potential predictive biomarker for clinical use of BH3 mimetics.”

Safety and discontinuation

All of the patients discontinued therapy—29 due to progressive disease and 1 due to an adverse event (terminal ileitis). One patient withdrew consent, and 1 proceeded to allogeneic transplant after achieving stable disease.

All of the patients experienced treatment-emergent adverse events. The most common were nausea (59%), diarrhea (56%), hypokalemia (41%), vomiting (41%), fatigue (34%), headache (34%), hypomagnesemia (34%), febrile neutropenia (31%), and hypophosphatemia (31%).

Serious adverse events occurred in 84% of patients. These included febrile neutropenia (28%), pneumonia (16%), abdominal pain (6%), acute renal failure (6%), failure to thrive (6%), hypotension (6%), sepsis (6%), and urinary tract infection (6%).

Based on the results of this trial, the researchers concluded that venetoclax may be a viable treatment option for AML patients when used in combination with other therapies.

“We believe that venetoclax will soon become an equal partner to standard-of-care chemotherapy in elderly patients with AML when used in combinations with hypomethylating agents and other approaches,” said study author Marina Konopleva, MD, PhD, of MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas.

“Planned studies will test the hypothesis that venetoclax may likewise improve outcomes in younger AML patients when combined with high-dose chemotherapy.” ![]()

Results of a phase 2 trial suggest the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax can produce responses in patients with acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) who do not respond to or cannot tolerate chemotherapy.

However, the overall response rate in this trial was low, and responses were not durable.

All of the patients studied discontinued venetoclax, most due to disease progression.

The study was published in Cancer Discovery. It was funded by AbbVie in collaboration with Genentech/Roche.

The trial included 32 patients with AML and a median age of 71 (range, 19–84). Thirteen patients had an antecedent hematologic disorder or myeloproliferative neoplasm, and 4 had therapy-related AML with complex cytogenetics.

Twelve patients had mutations in IDH genes, and 6 had a high BCL2-sensitive protein index.

Thirty patients had received at least 1 prior therapy, and 13 had received at least 3 prior treatment regimens. Two patients were considered unfit for intensive chemotherapy and were treatment-naive at study entry.

The patients received venetoclax at 800 mg daily. All 32 patients received at least 1 dose, and 26 patients received at least 4 weeks of therapy.

Efficacy

The overall response rate was 19%. Two patients had a complete response (CR), and 4 had a CR with incomplete blood count recovery. Three of the 6 responders had an antecedent hematologic disorder.

“[E]ven among pretreated patients whose AML was refractory to intensive chemotherapy, there was evidence of exceptional sensitivity to selective BCL2 inhibition, even to the point of complete remissions,” said study author Anthony Letai, MD, PhD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts.

The median duration of therapy in responders was 144.5 days, and the median duration of CR was 48 days.

The 4 patients who had CRs with incomplete count recovery had IDH mutations. Response to the drug correlated with biomarker results, including indices of BCL2 protein expression and BH3 profiling.

“This is significant as it supports the mechanism of action of venetoclax as an on-target inhibitor of BCL2,” Dr Letai said. “Moreover, it offers the possibility of using BH3 profiling as a potential predictive biomarker for clinical use of BH3 mimetics.”

Safety and discontinuation

All of the patients discontinued therapy—29 due to progressive disease and 1 due to an adverse event (terminal ileitis). One patient withdrew consent, and 1 proceeded to allogeneic transplant after achieving stable disease.

All of the patients experienced treatment-emergent adverse events. The most common were nausea (59%), diarrhea (56%), hypokalemia (41%), vomiting (41%), fatigue (34%), headache (34%), hypomagnesemia (34%), febrile neutropenia (31%), and hypophosphatemia (31%).

Serious adverse events occurred in 84% of patients. These included febrile neutropenia (28%), pneumonia (16%), abdominal pain (6%), acute renal failure (6%), failure to thrive (6%), hypotension (6%), sepsis (6%), and urinary tract infection (6%).

Based on the results of this trial, the researchers concluded that venetoclax may be a viable treatment option for AML patients when used in combination with other therapies.

“We believe that venetoclax will soon become an equal partner to standard-of-care chemotherapy in elderly patients with AML when used in combinations with hypomethylating agents and other approaches,” said study author Marina Konopleva, MD, PhD, of MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas.

“Planned studies will test the hypothesis that venetoclax may likewise improve outcomes in younger AML patients when combined with high-dose chemotherapy.” ![]()

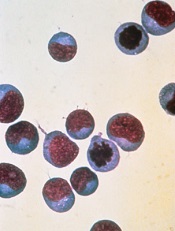

Protein promotes hematopoietic regeneration

Photo by Chad McNeeley

The protein angiogenin (ANG) plays a significant role in the regulation of hematopoiesis, according to a group of researchers.

The team discovered that ANG suppresses the proliferation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) while promoting the proliferation of myeloid progenitor cells.

They also showed that treatment with recombinant ANG protein improved survival in irradiated mice and enhanced the regenerative capabilities of HSPCs.

The researchers believe these findings have significant implications for hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) and bone marrow injury.

The team reported the findings in Cell.

“We knew that ANG was involved in promoting cell growth, so it was not unexpected to find that ANG stimulates proliferation of myeloid progenitor cells,” said study author Guo-fu Hu, PhD, of Tufts Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts.

“But it was surprising to find that ANG also suppresses growth of stem cells and that it accomplishes these divergent promotion or suppression functions through RNA processing events specific to individual cell types.”

The researchers discovered that, in HSPCs, ANG induces processing of tiRNA, which suppresses global protein synthesis. And in myeloid progenitor cells, ANG induces processing of rRNA, which enhances protein synthesis.

The team also tested ANG’s ability to prevent and mitigate radiation-induced bone marrow failure. They found that treating mice with recombinant ANG protein, either before or after lethal irradiation, increased survival, improved bone marrow cellularity, and enhanced peripheral blood content.

Finally, the researchers assessed the effects of ANG in the context of HSCT in mice. They found that treating mouse long-term HSCs with ANG ex vivo resulted in a “dramatic” increase in multi-lineage reconstitution over 24 weeks after HSCT.

Upon secondary transplant, enhanced regeneration occurred over 16 weeks, and mice had elevated peripheral blood counts at 1 year post-HSCT, without any signs of leukemia.

The researchers observed similar results in experiments with human cells. They transplanted CD34+ cord blood cells—cultured in the presence or absence of ANG—into mice. Treatment with ANG resulted in enhanced multi-lineage regeneration and enhanced reconstitution upon secondary transplant.

“Proper blood cell production is dependent on functioning hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells that are destroyed during conditioning procedures for transplantation or following bone marrow injury,” said study author Kevin A. Goncalves, of Tufts Medical Center.

“Our study demonstrates that ANG regulates critical functions of both clinically relevant cell types.” ![]()

Photo by Chad McNeeley

The protein angiogenin (ANG) plays a significant role in the regulation of hematopoiesis, according to a group of researchers.

The team discovered that ANG suppresses the proliferation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) while promoting the proliferation of myeloid progenitor cells.

They also showed that treatment with recombinant ANG protein improved survival in irradiated mice and enhanced the regenerative capabilities of HSPCs.

The researchers believe these findings have significant implications for hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) and bone marrow injury.

The team reported the findings in Cell.

“We knew that ANG was involved in promoting cell growth, so it was not unexpected to find that ANG stimulates proliferation of myeloid progenitor cells,” said study author Guo-fu Hu, PhD, of Tufts Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts.

“But it was surprising to find that ANG also suppresses growth of stem cells and that it accomplishes these divergent promotion or suppression functions through RNA processing events specific to individual cell types.”

The researchers discovered that, in HSPCs, ANG induces processing of tiRNA, which suppresses global protein synthesis. And in myeloid progenitor cells, ANG induces processing of rRNA, which enhances protein synthesis.

The team also tested ANG’s ability to prevent and mitigate radiation-induced bone marrow failure. They found that treating mice with recombinant ANG protein, either before or after lethal irradiation, increased survival, improved bone marrow cellularity, and enhanced peripheral blood content.

Finally, the researchers assessed the effects of ANG in the context of HSCT in mice. They found that treating mouse long-term HSCs with ANG ex vivo resulted in a “dramatic” increase in multi-lineage reconstitution over 24 weeks after HSCT.

Upon secondary transplant, enhanced regeneration occurred over 16 weeks, and mice had elevated peripheral blood counts at 1 year post-HSCT, without any signs of leukemia.

The researchers observed similar results in experiments with human cells. They transplanted CD34+ cord blood cells—cultured in the presence or absence of ANG—into mice. Treatment with ANG resulted in enhanced multi-lineage regeneration and enhanced reconstitution upon secondary transplant.

“Proper blood cell production is dependent on functioning hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells that are destroyed during conditioning procedures for transplantation or following bone marrow injury,” said study author Kevin A. Goncalves, of Tufts Medical Center.

“Our study demonstrates that ANG regulates critical functions of both clinically relevant cell types.” ![]()

Photo by Chad McNeeley

The protein angiogenin (ANG) plays a significant role in the regulation of hematopoiesis, according to a group of researchers.

The team discovered that ANG suppresses the proliferation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) while promoting the proliferation of myeloid progenitor cells.

They also showed that treatment with recombinant ANG protein improved survival in irradiated mice and enhanced the regenerative capabilities of HSPCs.

The researchers believe these findings have significant implications for hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) and bone marrow injury.

The team reported the findings in Cell.

“We knew that ANG was involved in promoting cell growth, so it was not unexpected to find that ANG stimulates proliferation of myeloid progenitor cells,” said study author Guo-fu Hu, PhD, of Tufts Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts.

“But it was surprising to find that ANG also suppresses growth of stem cells and that it accomplishes these divergent promotion or suppression functions through RNA processing events specific to individual cell types.”

The researchers discovered that, in HSPCs, ANG induces processing of tiRNA, which suppresses global protein synthesis. And in myeloid progenitor cells, ANG induces processing of rRNA, which enhances protein synthesis.

The team also tested ANG’s ability to prevent and mitigate radiation-induced bone marrow failure. They found that treating mice with recombinant ANG protein, either before or after lethal irradiation, increased survival, improved bone marrow cellularity, and enhanced peripheral blood content.

Finally, the researchers assessed the effects of ANG in the context of HSCT in mice. They found that treating mouse long-term HSCs with ANG ex vivo resulted in a “dramatic” increase in multi-lineage reconstitution over 24 weeks after HSCT.

Upon secondary transplant, enhanced regeneration occurred over 16 weeks, and mice had elevated peripheral blood counts at 1 year post-HSCT, without any signs of leukemia.

The researchers observed similar results in experiments with human cells. They transplanted CD34+ cord blood cells—cultured in the presence or absence of ANG—into mice. Treatment with ANG resulted in enhanced multi-lineage regeneration and enhanced reconstitution upon secondary transplant.

“Proper blood cell production is dependent on functioning hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells that are destroyed during conditioning procedures for transplantation or following bone marrow injury,” said study author Kevin A. Goncalves, of Tufts Medical Center.

“Our study demonstrates that ANG regulates critical functions of both clinically relevant cell types.” ![]()

HM Turns 20: A Look at the Evolution of Hospital Medicine

Editor's Note: Listen to Dr. Goldman, Dr. Wachter, Dr. Gandhi, Dr. Bessler, Dr. Gorman, and Dr. Merlino share more of their views on hospital medicine.

When Lee Goldman, MD, became chair of medicine at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) in January 1995, the construct of the medical service wasn’t all that different from when he had left as a resident 20 years earlier.

“It was still largely one month a year attending,” he recalls. “A couple of people did two months, I think. Some physicians still took care of their own patients even though there were teaching attending.”

Sure, it was an antiquated way to manage inpatient care, but since it had worked well enough for decades, who was going to change it?

“I got the idea that we could do better than that,” Dr. Goldman says.

He was right.

Dr. Goldman lured a young physician over from San Francisco General Hospital. The guy was a rising star of sorts. Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, had helped run the International AIDS Conference, held in the City by the Bay in 1990. He joined the faculty at San Francisco General that year and two years later became UCSF’s residency program director.

Then, Dr. Goldman asked Dr. Wachter to take on a new role as chief of the medical center at UCSF Medical Center. The charge was simple: “Come up with a new and innovative model by which fewer, selected faculty each spent multiple months as inpatient attendings and teachers.”

The model Dr. Wachter settled on—internal medicine physicians who practice solely in the hospital—wasn’t entirely novel. He recalled an American College of Physicians (ACP) presentation at 7 a.m. on a Sunday in 1995, the sort of session most conventioneers choose sleep over. Also, some doctors nationwide, in Minnesota and Arizona, for instance, were hospital-based as healthcare maintenance organizations (HMOs) struggled to make care more efficient and less costly to provide.

But those efforts were few and far between. And they were nearly all in the community setting. No one had tried to staff inpatient services with committed generalists in an academic setting.

Until Dr. Wachter and Dr. Goldman.

On Aug. 15, 1996, their article, “The Emerging Role of ‘Hospitalists’ in the American Health Care System,” was published in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM).

A burgeoning specialty was given a name.

Its practitioners were called “hospitalists.”

And the rest, as they say, is history.

The Early Days

The idea of hospital-based physicians seems obvious in the rubric of medical history. There are now an estimated 44,000 hospitalists nationwide. The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) bills itself as the fastest-growing specialty in healthcare.

But it wasn’t always this way.

The novelty of hospital-based practitioners taking over care for some or all inpatient admissions wasn’t immediately embraced as a positive paradigm shift. Just ask Rob Bessler, MD, chief executive officer of Sound Physicians of Tacoma, Wash., among the largest hospitalist management groups (HMGs) in the country, with more than 2,200 hospitalists, ED physicians, intensivists, and post-acute-care physicians.

When the NEJM piece bestowing a name on hospitalists was published, Dr. Bessler was just finishing medical school at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine in Cleveland. He started out in private practice and immediately saw issues in how hospitalized patients were treated.

“As an ED physician, nobody wanted to admit my patients as they were too busy in their office. I felt that those docs that were practicing in the hospital were using evidence that was 15 years old from when they finished their training,” he says. “I raised my hand to the hospital CEO to do things differently.”

Pushback against a new model came from multiple stakeholders. For every Dr. Bessler who was interested in a new way of doing things, there were physicians worried about turf battles.

“Doctors in practice around the county were afraid that these hospitalists would become mandatory,” says Dr. Goldman, who now is Dean of the Faculties of Health Sciences and Medicine, and chief executive at Columbia University Medical Center in New York City. “Some states actually had medical societies that passed resolutions saying they couldn’t become mandatory.”

In the early days, there were more critics than advocates. Critical-care doctors were one group that was, at best, ambivalent about the new model.

“The biggest brush fire in the early days was with critical care, which kind of surprised me,” Dr. Wachter says. “But ICU doctors had spent a huge amount of energy in the prior 20 years establishing their role. When hospitalists came out and often began to manage ICU cases—usually collaboratively with intensivists and partly filling a massive national shortage in intensivists—the leaders of the critical-care field felt like we were encroaching on their turf.”

Perhaps the biggest concerns to hospital medicine in the beginning came from the residents at UCSF. Initially, residents worried—some aloud—that hospitalists would become too controlling and “take away their delegated and graduated autonomy,” Dr. Goldman recalls.

At a meeting with the medical residents, “some actually said this could be awful and maybe they shouldn’t have come here,” he says, “maybe they should tell the internship applicants this would be a bad place to come because they wouldn’t have much autonomy, and I still remember asking a specific question to them. ‘Imagine your mother is admitted to the medical service at the teaching hospital back home where you live. What’s the first question you would ask?’

“And someone raised their hand and said, ‘Who’s the doctor?’

“And I said, ‘You mean who’s the intern?’

“They said, ‘No.’

“I said, ‘Or who’s the ward resident?’

“They said, ‘No.’

“And then, ‘Who is the attending?’

“And they said, ‘Yes.’

“So I said, ‘We have to have a good answer to that question when Mom gets admitted. Now that we’ve figured out how to get Mom the best care, let’s figure out how to make this the best possible teaching service.’”

Dr. Wachter and Dr. Goldman also prepared for some fears that didn’t pan out. One was the clout of specialists who might oppose the new model.

Some “specialists worried that if hospitalists were more knowledgeable than once-a-month-a-year attendings, and knew more about what was going on, they would be less likely to consult a specialist,” Dr. Goldman explains, adding he and Dr. Wachter thought that would be an unintended consequence of HM. “If there was a reduction in requested consults, that expertise would somehow be lost.”

Dr. Wachter and other early leaders also worried that patients, used to continuity of care with their primary-care doctors, would not take well to hospitalists. Would patients revolt against the idea of a new doctor seeing them every day?

“Yes, there were patients who felt that they wanted to see their regular doctor in the hospital. But for every one of them, there was another one or two that said this actually worked better,” Dr. Wachter says.

Community Views

Of course, the early success and adoption of the model in academic settings didn’t necessarily translate to community settings. Former SHM President Mary Jo Gorman, MD, MBA, MHM, who had just completed her MBA at Washington University in St. Louis when the NEJM article was published, wrote a business plan for her degree on implementing a hospitalist-style program at her institution, SSM DePaul Health Center, also in St. Louis.

She didn’t use the terms “hospital medicine” or “hospitalist.” They didn’t exist yet.

She was writing about what she was witnessing in her hospital: primary-care physicians (PCPs) who no longer wanted to visit hospitals because there simply wasn’t enough to do and make the trip worthwhile. In addition, she saw many of those same doctors no longer wanting to pick up ED calls.

So she pitched a model (same as Dr. Wachter was doing on the West Coast) of having someone in the hospital dedicated to inpatients as their sole responsibility. A “vocal minority” rebelled.

“It was a battlefield,” she recounts. “No other way to describe it. There were multiple hospital committees that reviewed it. There were letters of protest to the hospitals.”

Two major complaints emerged early on, Dr. Gorman says. Number one was the notion that hospitalists were enablers, allowing PCPs to shirk their long-established duty of shepherding their patients’ care through the walls of their local hospital. Number two, ironically, was the opposite: PCPs who didn’t want to cede control of their patients also moonlit taking ED calls that could generate patients for their own practice.

“It didn’t shock me at the time because I had already made major changes in our intensive-care unit at the hospital, which were unpopular,” Dr. Gorman says, adding all of the changes were good for patients and produced “fabulous” results. “But it was new. And it was different. And people don’t like to change the status quo.”

Perfect Timing

The seeds of hospitalist practice were planted before the NEJM article published. But the NEJM audience was nationwide, even beyond American borders. And the playing field was set up particularly well, says James Merlino, MD, president and chief medical officer of Press Ganey’s strategic consulting division. In 1996, the AIDS crisis was full-blown and a particular burden in inpatient wards.

“It was before we really had any of these amazing drugs that have turned HIV/AIDS into a quiet disease as opposed to a killer,” Dr. Merlino says. “At least 50% of the patients on the floors that we were rotating through [then] had patients, unfortunately, who were succumbing to AIDS.”

Dr. Merlino says he’s proud of the specialists who rotated through the hospital rooms of AIDS patients. But so many disparate doctors with no “quarterback” to manage the process holistically meant consistency in treatment was generally lacking.

“The role of the hospitalist often is to take recommendations from a lot of different specialties and come up with the best plan for the patient,” says Tejal Gandhi, MD, MPH, CPPS, president and CEO of the National Patient Safety Foundation. “They’re the true patient advocate who is getting the cardiologist’s opinion, the rheumatologist’s opinion, and the surgeon’s opinion, and they come up with the best plan for the patient.”

Dr. Merlino has an even blunter viewpoint: “I reflect back on that and think today about what the hospitalist model brings to us; it is an amazing transformation on how the hospitalist model really delivers.”

That type of optimism permeated nascent hospitalist groups. But it was time to start proving the anecdotal stories. Nearly two years to the day after the Wachter/Goldman paper published, a team led by Herbert Diamond, MD, published “The Effect of Full-Time Faculty Hospitalists on the Efficiency of Care at a Community Teaching Hospital” in the Annals of Internal Medicine.1 It was among the first reports to show evidence that hospitalists improved care.

Results published in that article showed median length of stay (LOS) decreased to 5.01 days from 6.01 days (P<0.001). It showed median cost of care decreased to $3,552 from $4,139 (P<0.001), and the 14-day readmission rate decreased to 4.64 readmissions per 100 admissions from 9.9 per 100 (P<0.001). In the comparison groups, LOS decreased, but both cost of care and readmission rates increased.

The research was so early on that the paper’s background section noted that “hospitalists are increasingly being used for inpatient care.”

“What we found, of course, was that they were providing an excellent service. They were well-trained, and you could get hospital people instead of having family-practice people managing the patients,” says nurse practitioner Robert Donaldson, NPC, clinical director of emergency medicine at Ellenville Regional Hospital in upstate New York and a veteran of working alongside hospitalists since the specialty arrived in the late 1990s. “We were getting better throughput times, better receipt of patients from our emergency rooms, and, I think, better outcomes as well.”

Growth Spurt

The refrain was familiar across the country as HM spread from health system to health system. Early results were looking good. The model was taking hold in more hospitals, both academic and community. Initial research studies supported the premise that the model improved efficiency without compromising quality or patient experience.

“My feeling at the time was this was a good idea,” Dr. Wachter says. “The trend toward our system being pushed to deliver better, more efficient care was going to be enduring, and the old model of the primary-care doc being your hospital doc … couldn’t possibly achieve the goal of producing the highest value.”

Dr. Wachter and other early leaders pushed the field to become involved in systems-improvement work. This turned out to be prophetic in December 1999, when patient safety zoomed to the national forefront with the publication of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report “To Err Is Human.” Its conclusions, by now, are well-known. It showed between 44,000 and 98,000 people a year die from preventable medical errors, the equivalent of a jumbo jet a day crashing.

The impact was profound, and safety initiatives became a focal point of hospitals. The federal Agency for Health Care Policy and Research was renamed the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (ARHQ) to indicate the change in focus.

“When the IOM report came out, it gave us a focus and a language that we didn’t have before,” says Dr. Wachter, who served as president of SHM’s Board of Directors and to this day lectures at SHM annual meetings. “But I think the general sensibility that hospitalists are about improving quality and safety and patients’ experience and efficiency—I think that was baked in from the start.”

Two years later, IOM followed up its safety push with “Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century.” The sequel study laid out focus areas and guidelines to start reducing the spate of medical mistakes that “To Err Is Human” lay bare.

Hospitalists were seen as people to lead the charge for safety because they were already taking care of patients, already focused on reducing LOS and improving care delivery—and never to be underestimated, they were omnipresent, Dr. Gandhi says of her experience with hospitalists around 2000 at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“At least where I was, hospitalists truly were leaders in the quality and safety space, and it was just a really good fit for the kind of mindset and personality of a hospitalist because they’re very much … integrators of care across hospitals,” she says. “They interface with so many different areas of the hospital and then try to make all of that work better.”

Revenue Rules the Day

Dr. Gorman saw a different playing field in community hospitals where she worked. She was named chief medical officer for IPC Healthcare, Inc., in North Hollywood, Calif., in 2003 amid the push for quality and safety. And while the specialty’s early adoption of those initiatives clearly was a major reason for the exponential growth of hospitalists, Dr. Gorman doesn’t want people to forget that the cost of care was what motivated community facilities.

“This has all been an economic move,” she says. “People sort of forget that, I think. It was discovered by some of the HMOs on the West Coast, and it was really not the HMOs, it was the medical groups that were taking risks—economic risks for their group of patients—that figured out if they sent … primary-care people to the hospital and they assigned them on a rotation of a week at a time, that they can bring down the LOS in the hospital.

“That meant more money in their own pockets because the medical group was taking the risk.”

Once hospitalists set up practice in a hospital, C-suite administrators quickly saw them gaining patient share and began realizing that they could be partners.

“They woke up one day, and just like that, they pay attention to how many cases the orthopedist does,” she says. “[They said], ‘Oh, Dr. Smith did 10 cases last week, he did 10 cases this week, then he did no cases or he did two cases. … They started to come to the hospitalists and say, ‘Look, you’re controlling X% of my patients a day. We’re having a length of stay problem; we’re having an early-discharge problem.’ Whatever it was, they were looking for partners to try to solve these issues.”

And when hospitalists grew in number again as the model continued to take hold and blossom as an effective care-delivery method, hospitalists again were turned to as partners.

“Once you get to that point, that you’re seeing enough patients and you’re enough of a movement,” Dr. Gorman says, “you get asked to be on the pharmacy committee and this committee, and chairman of the medical staff, and all those sort of things, and those evolve over time.”

Tech Effect

In the last 20 years, HM and technology have drastically changed the hospital landscape. But was HM pushed along by generational advances in computing power, smart devices in the shape of phones and tablets, and the software that powered those machines? Or was technology spurred on by having people it could serve directly in the hospital, as opposed to the traditionally fragmented system that preceded HM?

“Bob [Wachter] and others used to joke that the only people that actually understand the computer system are the hospitalists,” Dr. Goldman notes.

“Chicken or the egg, right?” adds Dr. Merlino of Press Ganey. “Technology is an enabler that helps providers deliver better care. I think healthcare quality in general has been helped by both.

“It doesn’t just help make hospitalists work better. It makes nursing better. It makes surgeons better. It makes pharmacy better.”

Dr. Bessler of Sound Physicians notes that advances in technology have come with their hurdles as well. Take the oft-maligned world of electronic medical records (EMRs).

“EMRs are great for data, but they’re not workflow solutions,” Dr. Bessler says. “They don’t tell you what do next.”

So Sound Physicians created its own technology platform, dubbed Sound Connect, that interacts with in-place EMRs at hospitals across the country. The in-house system takes the functional documentation of EMRs and overlays productivity protocols, Dr. Bessler says.

“It allows us to run a standard workflow and drive reproducible results and put meaningful data in the hands of the docs on a daily basis in the way that an EMR is just not set up to do,” he adds. Technology will continue “to be instrumental, of course, but I think the key thing is interoperability, which plenty has been written on, so we’re not unique in that. The more the public demands and the clinicians demand … the better patient care will be. I think the concept of EMR companies not being easy to work with has to end.”

Kendall Rogers, MD, CPE, SFHM, chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center in Albuquerque and chair of SHM’s Information Technology Committee, believes that hospitalists have to take ownership of health information technology (HIT) in their own buildings.

He and other SHM officials have pushed hospitalists for the past few years to formalize their HIT duties by seeing if they would qualify to take the exam for board certification in medical informatics, which was created in 2013 by the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS). Between certification of that skill set and working more with technology vendors and others to improve HIT, Dr. Rogers sees HM being able to help reform much of the current technology woes in just a few years.

“To me, this is the new frontier,” Dr. Wachter says. “If our defining mantra as a field is, ‘How do we make care better for patients, and how do we create a better system?’ … well, I don’t see how you say that without really owning the issue of informatics.”

Teamwork: An HM Tradition

Hospitalists are often referred to as the quarterbacks of the hospital. But even the best QB needs a good team to succeed. For HMGs, that roster increasingly includes nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs).

Recent State of Hospital Medicine surveys showed that 83% of hospitalist groups are utilizing NPs and PAs, and SHM earlier this year added Tracy Cardin, ACNP-BC, SFHM, as its first non-physician voting board member.

Dr. Donaldson believes that integrating hospitalists and non-physician providers (NPPs) allows both sets of practitioners to “work at the top of their license.”

“Any time when nurse practitioners and other providers get together, there is always this challenge of professions,” he says. “You’re doing this or you’re doing that, and once you get people who understand what the capabilities are past the title name and what you can do, it’s just amazing.”

Dr. Donaldson sees SHM’s acceptance of NPs and PAs as a good sign for HM.

“The day is upon us where we need to strongly consider nurse practitioners and physician assistants as equal in the field,” he says. “We’re going to find a much better continuity of care for all our patients at various institutions with hospital medicine and … a nurse practitioner who is at the top of their license.”

The Post-Acute Space

Aside from NPs and PAs, another extension of HM has been the gravitation in recent years of hospitalists into post-acute-care settings, including skilled-nursing facilities (SNFs), long-term care facilities, post-discharge clinics, and patient-centered homes.

Dr. Bessler says that as HMGs continued to focus on improving quality and lowering costs, they had little choice but to get involved in activities outside the hospital.

“We got into post-acute medicines because there was an abyss in quality,” he says. “We were accountable to send patients out, and there was nobody to send them to. Or the quality of the facilities was terrible, or the docs or clinicians weren’t going to see those patients regularly. That’s how we got into solving post-acute.”

Dr. Gorman, formerly the chief executive of St. Louis–based Advanced ICU Care, which provides intensivists to community hospitals using telemedicine, agrees that for hospitalists to exert even more control over quality of care, they have to team with people outside the hospital.

“If we can’t build what I think of as a pyramid of care with one doctor and many, many other people supporting a broad group of patients, I don’t think we’re going to be able to find the scale to take care of the aging population that’s coming at us,” she says.

Caring for patients once they are discharged means including home nurses, pharmacists, physical therapists, dietitians, hired caregivers, and others in the process, Dr. Gorman says. But that doesn’t mean overburdening the wrong people with the wrong tasks. The same way no one would think to allow a social worker to prescribe medication is the same way that a hospitalist shouldn’t be the one checking up on a patient to make sure there is food in that person’s fridge.

And while the hospitalist can work in concert with others and run many things from the hospital, maybe hospital-based physicians aren’t always the best physicians for the task.

“There are certain things that only the doctor can do, of course, but there are a lot more things that somebody else can do,” Dr. Gorman says, adding, “some of the times, you’re going to need the physician, it’s going to be escalated to a medication change, but sometimes maybe you need to escalate to a dietary visit or you need to escalate to three physical therapy visits.

“The nitty-gritty of taking care of people outside of the hospital is so complex and problematic, and most of the solutions are not really medical, but you need the medical part of the dynamic. So rather [than a hospitalist running cases], it’s a super-talented social worker, nurse, or physical therapist. I don’t know, but somebody who can make sure that all of that works and it’s a process that can be leveraged.”

Whoever it is, the gravitation beyond the walls of the hospital has been tied to a growing sea change in how healthcare will compensate providers. Medicare has been migrating from fee-for-service to payments based on the totality of care for decades. The names change, of course. In the early 1980s, it was an “inpatient prospective payment system.”

Five years ago, it was accountable care organizations and value-based purchasing that SHM glommed on to as programs to be embraced as heralding the future.

Now it’s the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement initiative (BCPI), introduced by the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) back in 2011 and now compiling its first data sets for the next frontier of payments for episodic care.

BCPI was mandated by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2009, which included a provision that the government establish a five-year pilot program by 2013 that bundled payments for inpatient care, according to the American Hospital Association. BCPI now has more than 650 participating organizations, not including thousands of physicians who then partner with those groups, over four models. The initiative covers 48 defined episodes of care, both medical and surgical, that could begin three days prior to admission and stretch 30, 60, or 90 days post-discharge.

“The reason this is so special is that it is one of the few CMS programs that allows providers to be in the driver’s seat,” says Kerry Weiner, MD, chief medical officer of acute and post-acute services at TeamHealth-IPC. “They have the opportunity to be accountable and to actually be the designers of reengineering care. The other programs that you just mentioned, like value-based purchasing, largely originate from health systems or the federal government and dictate the principles and the metrics that as a provider you’re going to be evaluated upon.

“The bundled model [BCPI] gives us the flexibility, scale, and brackets of risk that we want to accept and thereby gives us a lot more control over what physicians and physician groups can manage successfully.”

A Score of Success

Twenty years of unbridled growth is great in any business. Put in perspective, the first iPhone, which redefined personal communication, is just nine years old, and already, stock analysts question whether Apple can grow any bigger or if it’s plateaued.

To be sure, the field of HM and its leaders have accomplished more than even Dr. Wachter and Dr. Goldman envisioned 20 summers ago. Much of it may seem so easily established by now, but when pioneering hospitalists John Nelson, MD, MHM, and Winthrop Whitcomb, MD, MHM, founded the National Association of Inpatient Physicians (NAIP) a year after the NEJM paper, they promoted and held a special session at UCSF’s first “Management of the Hospitalized Patient” conference in April 1997.

By 2003, the term “hospitalist” had become ubiquitous enough that NAIP was renamed the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Again, progress followed quickly.

By 2007, SHM had launched Project BOOST (Better Outcomes by Optimizing Safe Transitions), an award-winning mentored-implementation program to reduce LOS, adverse events, and unnecessary 30-day readmissions. Other mentored-implementation programs followed. The Glycemic Control Mentored Implementation (GCMI) program focuses on preventing hypoglycemia, while the Venous Thromboembolism Prevention Collaborative (VTE PC) seeks to give practical assistance on how to reduce blood clots via a VTE prevention program.

In 2012, SHM earned the 2011 John M. Eisenberg Patient Safety and Quality Award for Innovation in Patient Safety and Quality at the National Level, thanks to its mentored-implementation programs. SHM was the first professional society to earn the award, bestowed by the National Quality Forum (NQF) and The Joint Commission.

And earlier this year, CMS announced that by this time next year hospitalists would be assigned their own specialty designation code. SHM’s Public Policy Committee lobbied for the move for more than two years.

Dr. Merlino says it’s not just accomplishments that have set the field apart in its first 20 years. It’s the people.

Take Modern Healthcare’s list of the 50 Most Influential Physician Executives and Leaders of 2016. Third on the list is pediatric hospitalist Patrick Conway, MD, MSc, MHM, deputy administrator for innovation and quality and CMS’s chief medical officer. One spot behind him is Dr. Wachter, who in addition to being an architect of the HM movement was the first hospitalist to serve as chair of the Board of Directors of the American Board of Internal Medicine, which provides certification for the majority of working hospitalists.

Rounding out HM’s presence on the list is Vivek Murthy, MD, MBA, a Boston hospitalist and the current U.S. Surgeon General.

“It does demonstrate the emergence of their leadership,” Dr. Merlino says. “I don’t think yet they’re viewed as being the leaders, but I would add to that I don’t think they have yet the respect they deserve for the work they’re doing. When people who have worked with them can understand the value that they bring to clinical care, they clearly view hospitalists as being critical leaders.”

The Future

So what now? For all the talk of SHM’s success, HM’s positive impacts, and the specialty’s rocket growth trajectory, the work isn’t done, industry leaders say.

Hospitalists are not just working toward a more valuable delivery of care, they’re also increasingly viewed as leaders of projects all around the hospital because, well, they are always there, according to Dr. Gandhi.

“Hospitalists really are a leader in the hospital around quality and safety issues because they are there on the wards all the time,” she says. “They really have an interest in being the physician champions around various initiatives, so [in my hospital tenures] I partnered with many of my hospitalist colleagues on ways to improve care, such as test-result management, medication reconciliation, and similar efforts. We often would establish multidisciplinary committees to work on things, and almost always there was a hospitalist who was chairing or co-chairing or participating very actively in that group.”

Dr. Gandhi, who was finishing her second year of residency at Duke Medical Center in Raleigh, N.C., when the NEJM paper was published, sees the acuity of patients getting worse in the coming years as America rapidly ages. Baby boomers will start turning 80 in the next decade, and longer life spans translate to increasing medical problems that will often require hospitalization.

And while hospitalists have already moved into post-acute-care settings, Dr. Bessler says that will become an even bigger focus in the next 20 years of the specialty.

“It’s not generally been the psyche of the hospitalist in the past to feel accountable beyond the walls of the hospital,” he says. “But between episodic care [and] bundled payments … you can’t just wash your hands of it. You have to understand your next site-of-care decision. You need to make sure care happens at the right location.”

At a time of once-in-a-generation reform to healthcare in this country, the leaders of HM can’t afford to rest on their laurels, says Dr. Goldman. Three years ago, he wrote a paper for the Journal of Hospital Medicine titled “An Intellectual Agenda for Hospitalists.” In short, Dr. Goldman would like to see hospitalists move more into advancing science themselves rather than implementing the scientific discoveries of others. He cautions anyone against taking that as criticism of the field.

“If hospitalists are going to be the people who implement what other people have found, they run the risk of being the ones who make sure everybody gets perioperative beta-blockers even if they don’t really work,” he says. “If you want to take it to the illogical extreme, you could have people who were experts in how most efficiently to do bloodletting.

“The future for hospitalists, if they’re going to get to the next level—I think they can and will—is that they have to be in the discovery zone as well as the implementation zone.”

Dr. Wachter says it’s about staying ahead of the curve. For 20 years, the field has been on the cutting edge of how hospitals treat patients. To grow even more, it will be crucial to keep that focus.

Hospitalists need to continue to take C-suite positions at hospitals and policy roles at think tanks and governmental agencies. They need to continue to master technology, clinical care, and the ever-growing importance of where those two intersect.

Most of all, the field can’t get lazy. Otherwise, the “better mousetrap” of HM might one day be replaced by the next group of physicians willing to work harder to implement their great idea.

“If we continue to be the vanguard of innovation, the vanguard of making the system work better than it ever has before,” Dr. Wachter says, “the field that creates new models of care, that integrates technology in new ways, and that has this can-do attitude and optimism, then the sky is the limit.” TH

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Diamond HS, Goldberg E, Janosky JE. The effect of full-time faculty hospitalists on the efficiency of care at a community teaching hospital. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129(3):197-203.

Editor's Note: Listen to Dr. Goldman, Dr. Wachter, Dr. Gandhi, Dr. Bessler, Dr. Gorman, and Dr. Merlino share more of their views on hospital medicine.

When Lee Goldman, MD, became chair of medicine at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) in January 1995, the construct of the medical service wasn’t all that different from when he had left as a resident 20 years earlier.

“It was still largely one month a year attending,” he recalls. “A couple of people did two months, I think. Some physicians still took care of their own patients even though there were teaching attending.”

Sure, it was an antiquated way to manage inpatient care, but since it had worked well enough for decades, who was going to change it?

“I got the idea that we could do better than that,” Dr. Goldman says.

He was right.

Dr. Goldman lured a young physician over from San Francisco General Hospital. The guy was a rising star of sorts. Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, had helped run the International AIDS Conference, held in the City by the Bay in 1990. He joined the faculty at San Francisco General that year and two years later became UCSF’s residency program director.

Then, Dr. Goldman asked Dr. Wachter to take on a new role as chief of the medical center at UCSF Medical Center. The charge was simple: “Come up with a new and innovative model by which fewer, selected faculty each spent multiple months as inpatient attendings and teachers.”

The model Dr. Wachter settled on—internal medicine physicians who practice solely in the hospital—wasn’t entirely novel. He recalled an American College of Physicians (ACP) presentation at 7 a.m. on a Sunday in 1995, the sort of session most conventioneers choose sleep over. Also, some doctors nationwide, in Minnesota and Arizona, for instance, were hospital-based as healthcare maintenance organizations (HMOs) struggled to make care more efficient and less costly to provide.

But those efforts were few and far between. And they were nearly all in the community setting. No one had tried to staff inpatient services with committed generalists in an academic setting.

Until Dr. Wachter and Dr. Goldman.

On Aug. 15, 1996, their article, “The Emerging Role of ‘Hospitalists’ in the American Health Care System,” was published in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM).

A burgeoning specialty was given a name.

Its practitioners were called “hospitalists.”

And the rest, as they say, is history.

The Early Days

The idea of hospital-based physicians seems obvious in the rubric of medical history. There are now an estimated 44,000 hospitalists nationwide. The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) bills itself as the fastest-growing specialty in healthcare.

But it wasn’t always this way.

The novelty of hospital-based practitioners taking over care for some or all inpatient admissions wasn’t immediately embraced as a positive paradigm shift. Just ask Rob Bessler, MD, chief executive officer of Sound Physicians of Tacoma, Wash., among the largest hospitalist management groups (HMGs) in the country, with more than 2,200 hospitalists, ED physicians, intensivists, and post-acute-care physicians.

When the NEJM piece bestowing a name on hospitalists was published, Dr. Bessler was just finishing medical school at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine in Cleveland. He started out in private practice and immediately saw issues in how hospitalized patients were treated.

“As an ED physician, nobody wanted to admit my patients as they were too busy in their office. I felt that those docs that were practicing in the hospital were using evidence that was 15 years old from when they finished their training,” he says. “I raised my hand to the hospital CEO to do things differently.”

Pushback against a new model came from multiple stakeholders. For every Dr. Bessler who was interested in a new way of doing things, there were physicians worried about turf battles.

“Doctors in practice around the county were afraid that these hospitalists would become mandatory,” says Dr. Goldman, who now is Dean of the Faculties of Health Sciences and Medicine, and chief executive at Columbia University Medical Center in New York City. “Some states actually had medical societies that passed resolutions saying they couldn’t become mandatory.”