User login

Top 5 list for psychiatry

Gina Henderson, my editor at Clinical Psychiatry News, recently asked me an interesting question. She wanted to know what I believe the five most important issues are for psychiatry today. My first thought was that I am the wrong person to ask – aside from what comes through on my Twitter feed and the Maryland Psychiatric Society’s listserv, I have my own areas of interest and don’t know that I’m the best measure for the pulse of today’s psychiatric issues.

I imagine that different psychiatrists would respond with different answers. If I were to guess – and I haven’t verified this – I think my co-columnist, Anne Hanson, might suggest that the single most important issue for psychiatry is new legislation related to physician-assisted suicide and how that will be applied to psychiatric patients with reportedly intractable illnesses. Steve Daviss, who also writes for our Shrink Rap News column, has had an interest in parity legislation, adequacy of insurance networks, and the application of information technology to psychiatry, and he might say those are our pressing issues. My own interest has been in involuntary treatment, its impact on patients, and if there are ways we might avoid this or do it better.

I wonder if I am missing some new breakthrough now that patients are getting genetic testing to guide their treatment with results that befuddle me.

Using the social media forums of Twitter and Facebook, I put the question out there as to what is the single most important issue for psychiatry today. Mostly, the answer I got was my own: access to care. Peter Kramer, a psychiatrist at Brown University, Providence, R.I., and author of “Ordinarily Well” tweeted that “finding disease mechanisms and finding related treatments” was important, along with access to currently available treatments. My most interesting response was from forensic psychiatrist Erik Roskes, who bluntly said on Facebook, “For someone like me, working in the trenches of our “system,” the biggest problem I see is advocates who think there is a simple solution to our problem. No offense, but asking this question is the problem, not the solution. Feel free to advocate, to be sure, but don’t be surprised when your suggested panacea does not work or is not tried, because it is too expensive and cannot compete with many other priorities that are important to advocates for other important causes.” Finally, a high school friend who works as a teaching assistant and has struggled with her own children’s issues has said the biggest problem is a lack of resources for parents of children with mental disorders.

So with a little reassurance that my ideas are not so far out of date, I’ll start my David Letterman list of what the biggest issues are for psychiatry today.

1. Access to care. No matter how wonderful our treatments are, the fact remains that they are inaccessible to many people, and those who are able to negotiate treatment often struggle to do so. This struggle to find care often comes at a time when people are depressed, psychotic, or vulnerable and often not their own best advocates. It involves bargaining with insurers, being led to believe that coverage is better than it is, and few options for the uninsured and underinsured, who often must rely on public health clinics – which often are not accepting patients or have long waits. Even those with insurance are sent a formidable list of participating providers, many of whom are dead, have relocated, are not accepting new patients, or have never been heard of by their agencies. And for the working individual who needs after-hours care, the struggle is even harder. Let’s not even talk about the number of voice mail prompts and time on hold that each call entails.

In half of all counties in this country, there are no mental health professionals at all, not just a lack of psychiatrists. So folded into the access-to-care problem, I’d like to include the fact that there are just not enough psychiatrists to see everyone who needs to be seen. As a shortage field, more than half of psychiatrists do not participate in health insurance plans, and despite long battles for parity legislation, this does little to help insured patients, who must go out of network, where they face high deductibles and low rates of reimbursement under designated “usual and customary rates,” leaving well-insured patients with very high copays, often amounting to no coverage at all, and often much to their surprise. Simply put, we need to make it easier for patients to find psychiatrists, and we need insurance to pay for psychiatric care.

2. We need to stop dichotomizing people as being mentally ill or not. The “us” versus “them” mentality and the idea that there are specific chronically mentally ill folks who are somehow different from the rest of humanity is not helpful. Yes, there are people who cycle in and out of institutions and whose symptoms are resistant to treatments, but some very sick people end up becoming very well and very successful. Sometimes they get better because of the treatment they receive, and once in a while, their improvement is tied to a spontaneous remission. Part of being human is going through rough spots where many people don’t adapt perfectly and don’t behave well during crises. The problem with reallocating resources to the sickest of the sick – those who don’t know they are ill – with a “treatment before tragedy” approach, is that it advocates forcing people who will never hurt anyone into care and pulls resources away from those whose illnesses are somehow dismissed as “the worried well,” who misuse services they don’t really need. People with less obviously severe, debilitating, and retractable illnesses can prove to be very disturbed and very tormented: a teenager who is heartbroken by a breakup and unexpectedly dies of suicide is no less deserving of care than a psychotic individual on his fourth admission. And a graduate student with no history of hospitalization or violence may well be the one to unexpectedly massacre a theater full of moviegoers. We need to offer help to those who ask for it and not suggest rationing our care to the sickest mentally ill, as though there were an obvious line in the sand. This dichotomy does not bear out clinically.

3. We need new and better treatments with fewer side effects and greater efficacy that target the truly disabling symptoms of low motivation, executive dysfunction, and deterioration of social interactions. Only with tolerable and effective treatments will we truly eradicate stigma. As long as we see that the effects of untreated or inadequately treated psychiatric symptoms lead people to frankly embarrassing behaviors, stigma will exist in a way that colorful billboards cannot counter.

4. Since our resources are precious and overextended, we need to eliminate red tape for psychiatrists (and all physicians) that does not lead to improved patient care. Maintenance of certification exams that are not relevant to what the physician sees, time spent catering to clicks on required screens of electronic health records, time spent justifying obviously needed treatment, preauthorization requests for inexpensive medications, meaningful use, clinical notes catering to insurer requirements that do not encourage better treatment, PQRS and MACRA (whatever they may be!) are diversions of physician time. They lead to burnout, job dissatisfaction, and early retirement, and they worsen the shortage of psychiatrists – all while decreasing the number of patients any individual doctor can see. At this point, we are asking our physicians to both treat their patients and to serve as government data collectors, and this is simply too much.

5. Any conversation of noncompliance by people with mental disorders moves quickly to the realm of forced care. Patients who have no insight into their illness are presumed to be unwilling to take medications, and psychiatry has become a series of 15-minute medication checks, where time can’t be devoted to understanding the patient and his hesitations to taking medications. Often, if the patient feels understood and has a sense of trust in the clinician, this noncompliance can be overcome. We need to understand our patients and work with them – and sometimes admit that our treatments just don’t work for everyone – with the hopes of making them more comfortable. Obviously, in emergency situations or when someone is violent, there may be no choice but to use force, but that needs to be a true last resort. It is a disgrace that our current system goes so quickly to talk of involuntary treatment when there are so many people in this country eager to accept voluntary care, and it is so difficult to access.

There you have it, my five bullet points of the most important issues in psychiatry. To those who contributed, both named and unnamed, thank you.

Dr. Miller is coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care,” forthcoming from Johns Hopkins University Press in fall 2016.

Gina Henderson, my editor at Clinical Psychiatry News, recently asked me an interesting question. She wanted to know what I believe the five most important issues are for psychiatry today. My first thought was that I am the wrong person to ask – aside from what comes through on my Twitter feed and the Maryland Psychiatric Society’s listserv, I have my own areas of interest and don’t know that I’m the best measure for the pulse of today’s psychiatric issues.

I imagine that different psychiatrists would respond with different answers. If I were to guess – and I haven’t verified this – I think my co-columnist, Anne Hanson, might suggest that the single most important issue for psychiatry is new legislation related to physician-assisted suicide and how that will be applied to psychiatric patients with reportedly intractable illnesses. Steve Daviss, who also writes for our Shrink Rap News column, has had an interest in parity legislation, adequacy of insurance networks, and the application of information technology to psychiatry, and he might say those are our pressing issues. My own interest has been in involuntary treatment, its impact on patients, and if there are ways we might avoid this or do it better.

I wonder if I am missing some new breakthrough now that patients are getting genetic testing to guide their treatment with results that befuddle me.

Using the social media forums of Twitter and Facebook, I put the question out there as to what is the single most important issue for psychiatry today. Mostly, the answer I got was my own: access to care. Peter Kramer, a psychiatrist at Brown University, Providence, R.I., and author of “Ordinarily Well” tweeted that “finding disease mechanisms and finding related treatments” was important, along with access to currently available treatments. My most interesting response was from forensic psychiatrist Erik Roskes, who bluntly said on Facebook, “For someone like me, working in the trenches of our “system,” the biggest problem I see is advocates who think there is a simple solution to our problem. No offense, but asking this question is the problem, not the solution. Feel free to advocate, to be sure, but don’t be surprised when your suggested panacea does not work or is not tried, because it is too expensive and cannot compete with many other priorities that are important to advocates for other important causes.” Finally, a high school friend who works as a teaching assistant and has struggled with her own children’s issues has said the biggest problem is a lack of resources for parents of children with mental disorders.

So with a little reassurance that my ideas are not so far out of date, I’ll start my David Letterman list of what the biggest issues are for psychiatry today.

1. Access to care. No matter how wonderful our treatments are, the fact remains that they are inaccessible to many people, and those who are able to negotiate treatment often struggle to do so. This struggle to find care often comes at a time when people are depressed, psychotic, or vulnerable and often not their own best advocates. It involves bargaining with insurers, being led to believe that coverage is better than it is, and few options for the uninsured and underinsured, who often must rely on public health clinics – which often are not accepting patients or have long waits. Even those with insurance are sent a formidable list of participating providers, many of whom are dead, have relocated, are not accepting new patients, or have never been heard of by their agencies. And for the working individual who needs after-hours care, the struggle is even harder. Let’s not even talk about the number of voice mail prompts and time on hold that each call entails.

In half of all counties in this country, there are no mental health professionals at all, not just a lack of psychiatrists. So folded into the access-to-care problem, I’d like to include the fact that there are just not enough psychiatrists to see everyone who needs to be seen. As a shortage field, more than half of psychiatrists do not participate in health insurance plans, and despite long battles for parity legislation, this does little to help insured patients, who must go out of network, where they face high deductibles and low rates of reimbursement under designated “usual and customary rates,” leaving well-insured patients with very high copays, often amounting to no coverage at all, and often much to their surprise. Simply put, we need to make it easier for patients to find psychiatrists, and we need insurance to pay for psychiatric care.

2. We need to stop dichotomizing people as being mentally ill or not. The “us” versus “them” mentality and the idea that there are specific chronically mentally ill folks who are somehow different from the rest of humanity is not helpful. Yes, there are people who cycle in and out of institutions and whose symptoms are resistant to treatments, but some very sick people end up becoming very well and very successful. Sometimes they get better because of the treatment they receive, and once in a while, their improvement is tied to a spontaneous remission. Part of being human is going through rough spots where many people don’t adapt perfectly and don’t behave well during crises. The problem with reallocating resources to the sickest of the sick – those who don’t know they are ill – with a “treatment before tragedy” approach, is that it advocates forcing people who will never hurt anyone into care and pulls resources away from those whose illnesses are somehow dismissed as “the worried well,” who misuse services they don’t really need. People with less obviously severe, debilitating, and retractable illnesses can prove to be very disturbed and very tormented: a teenager who is heartbroken by a breakup and unexpectedly dies of suicide is no less deserving of care than a psychotic individual on his fourth admission. And a graduate student with no history of hospitalization or violence may well be the one to unexpectedly massacre a theater full of moviegoers. We need to offer help to those who ask for it and not suggest rationing our care to the sickest mentally ill, as though there were an obvious line in the sand. This dichotomy does not bear out clinically.

3. We need new and better treatments with fewer side effects and greater efficacy that target the truly disabling symptoms of low motivation, executive dysfunction, and deterioration of social interactions. Only with tolerable and effective treatments will we truly eradicate stigma. As long as we see that the effects of untreated or inadequately treated psychiatric symptoms lead people to frankly embarrassing behaviors, stigma will exist in a way that colorful billboards cannot counter.

4. Since our resources are precious and overextended, we need to eliminate red tape for psychiatrists (and all physicians) that does not lead to improved patient care. Maintenance of certification exams that are not relevant to what the physician sees, time spent catering to clicks on required screens of electronic health records, time spent justifying obviously needed treatment, preauthorization requests for inexpensive medications, meaningful use, clinical notes catering to insurer requirements that do not encourage better treatment, PQRS and MACRA (whatever they may be!) are diversions of physician time. They lead to burnout, job dissatisfaction, and early retirement, and they worsen the shortage of psychiatrists – all while decreasing the number of patients any individual doctor can see. At this point, we are asking our physicians to both treat their patients and to serve as government data collectors, and this is simply too much.

5. Any conversation of noncompliance by people with mental disorders moves quickly to the realm of forced care. Patients who have no insight into their illness are presumed to be unwilling to take medications, and psychiatry has become a series of 15-minute medication checks, where time can’t be devoted to understanding the patient and his hesitations to taking medications. Often, if the patient feels understood and has a sense of trust in the clinician, this noncompliance can be overcome. We need to understand our patients and work with them – and sometimes admit that our treatments just don’t work for everyone – with the hopes of making them more comfortable. Obviously, in emergency situations or when someone is violent, there may be no choice but to use force, but that needs to be a true last resort. It is a disgrace that our current system goes so quickly to talk of involuntary treatment when there are so many people in this country eager to accept voluntary care, and it is so difficult to access.

There you have it, my five bullet points of the most important issues in psychiatry. To those who contributed, both named and unnamed, thank you.

Dr. Miller is coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care,” forthcoming from Johns Hopkins University Press in fall 2016.

Gina Henderson, my editor at Clinical Psychiatry News, recently asked me an interesting question. She wanted to know what I believe the five most important issues are for psychiatry today. My first thought was that I am the wrong person to ask – aside from what comes through on my Twitter feed and the Maryland Psychiatric Society’s listserv, I have my own areas of interest and don’t know that I’m the best measure for the pulse of today’s psychiatric issues.

I imagine that different psychiatrists would respond with different answers. If I were to guess – and I haven’t verified this – I think my co-columnist, Anne Hanson, might suggest that the single most important issue for psychiatry is new legislation related to physician-assisted suicide and how that will be applied to psychiatric patients with reportedly intractable illnesses. Steve Daviss, who also writes for our Shrink Rap News column, has had an interest in parity legislation, adequacy of insurance networks, and the application of information technology to psychiatry, and he might say those are our pressing issues. My own interest has been in involuntary treatment, its impact on patients, and if there are ways we might avoid this or do it better.

I wonder if I am missing some new breakthrough now that patients are getting genetic testing to guide their treatment with results that befuddle me.

Using the social media forums of Twitter and Facebook, I put the question out there as to what is the single most important issue for psychiatry today. Mostly, the answer I got was my own: access to care. Peter Kramer, a psychiatrist at Brown University, Providence, R.I., and author of “Ordinarily Well” tweeted that “finding disease mechanisms and finding related treatments” was important, along with access to currently available treatments. My most interesting response was from forensic psychiatrist Erik Roskes, who bluntly said on Facebook, “For someone like me, working in the trenches of our “system,” the biggest problem I see is advocates who think there is a simple solution to our problem. No offense, but asking this question is the problem, not the solution. Feel free to advocate, to be sure, but don’t be surprised when your suggested panacea does not work or is not tried, because it is too expensive and cannot compete with many other priorities that are important to advocates for other important causes.” Finally, a high school friend who works as a teaching assistant and has struggled with her own children’s issues has said the biggest problem is a lack of resources for parents of children with mental disorders.

So with a little reassurance that my ideas are not so far out of date, I’ll start my David Letterman list of what the biggest issues are for psychiatry today.

1. Access to care. No matter how wonderful our treatments are, the fact remains that they are inaccessible to many people, and those who are able to negotiate treatment often struggle to do so. This struggle to find care often comes at a time when people are depressed, psychotic, or vulnerable and often not their own best advocates. It involves bargaining with insurers, being led to believe that coverage is better than it is, and few options for the uninsured and underinsured, who often must rely on public health clinics – which often are not accepting patients or have long waits. Even those with insurance are sent a formidable list of participating providers, many of whom are dead, have relocated, are not accepting new patients, or have never been heard of by their agencies. And for the working individual who needs after-hours care, the struggle is even harder. Let’s not even talk about the number of voice mail prompts and time on hold that each call entails.

In half of all counties in this country, there are no mental health professionals at all, not just a lack of psychiatrists. So folded into the access-to-care problem, I’d like to include the fact that there are just not enough psychiatrists to see everyone who needs to be seen. As a shortage field, more than half of psychiatrists do not participate in health insurance plans, and despite long battles for parity legislation, this does little to help insured patients, who must go out of network, where they face high deductibles and low rates of reimbursement under designated “usual and customary rates,” leaving well-insured patients with very high copays, often amounting to no coverage at all, and often much to their surprise. Simply put, we need to make it easier for patients to find psychiatrists, and we need insurance to pay for psychiatric care.

2. We need to stop dichotomizing people as being mentally ill or not. The “us” versus “them” mentality and the idea that there are specific chronically mentally ill folks who are somehow different from the rest of humanity is not helpful. Yes, there are people who cycle in and out of institutions and whose symptoms are resistant to treatments, but some very sick people end up becoming very well and very successful. Sometimes they get better because of the treatment they receive, and once in a while, their improvement is tied to a spontaneous remission. Part of being human is going through rough spots where many people don’t adapt perfectly and don’t behave well during crises. The problem with reallocating resources to the sickest of the sick – those who don’t know they are ill – with a “treatment before tragedy” approach, is that it advocates forcing people who will never hurt anyone into care and pulls resources away from those whose illnesses are somehow dismissed as “the worried well,” who misuse services they don’t really need. People with less obviously severe, debilitating, and retractable illnesses can prove to be very disturbed and very tormented: a teenager who is heartbroken by a breakup and unexpectedly dies of suicide is no less deserving of care than a psychotic individual on his fourth admission. And a graduate student with no history of hospitalization or violence may well be the one to unexpectedly massacre a theater full of moviegoers. We need to offer help to those who ask for it and not suggest rationing our care to the sickest mentally ill, as though there were an obvious line in the sand. This dichotomy does not bear out clinically.

3. We need new and better treatments with fewer side effects and greater efficacy that target the truly disabling symptoms of low motivation, executive dysfunction, and deterioration of social interactions. Only with tolerable and effective treatments will we truly eradicate stigma. As long as we see that the effects of untreated or inadequately treated psychiatric symptoms lead people to frankly embarrassing behaviors, stigma will exist in a way that colorful billboards cannot counter.

4. Since our resources are precious and overextended, we need to eliminate red tape for psychiatrists (and all physicians) that does not lead to improved patient care. Maintenance of certification exams that are not relevant to what the physician sees, time spent catering to clicks on required screens of electronic health records, time spent justifying obviously needed treatment, preauthorization requests for inexpensive medications, meaningful use, clinical notes catering to insurer requirements that do not encourage better treatment, PQRS and MACRA (whatever they may be!) are diversions of physician time. They lead to burnout, job dissatisfaction, and early retirement, and they worsen the shortage of psychiatrists – all while decreasing the number of patients any individual doctor can see. At this point, we are asking our physicians to both treat their patients and to serve as government data collectors, and this is simply too much.

5. Any conversation of noncompliance by people with mental disorders moves quickly to the realm of forced care. Patients who have no insight into their illness are presumed to be unwilling to take medications, and psychiatry has become a series of 15-minute medication checks, where time can’t be devoted to understanding the patient and his hesitations to taking medications. Often, if the patient feels understood and has a sense of trust in the clinician, this noncompliance can be overcome. We need to understand our patients and work with them – and sometimes admit that our treatments just don’t work for everyone – with the hopes of making them more comfortable. Obviously, in emergency situations or when someone is violent, there may be no choice but to use force, but that needs to be a true last resort. It is a disgrace that our current system goes so quickly to talk of involuntary treatment when there are so many people in this country eager to accept voluntary care, and it is so difficult to access.

There you have it, my five bullet points of the most important issues in psychiatry. To those who contributed, both named and unnamed, thank you.

Dr. Miller is coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care,” forthcoming from Johns Hopkins University Press in fall 2016.

Eruptive Seborrheic Keratoses Secondary to Telaprevir-Related Dermatitis

To the Editor:

Telaprevir is a hepatitis C virus (HCV) protease inhibitor used with ribavirin and interferon for the treatment of increased viral load clearance in specific HCV genotypes. We report a case of eruptive seborrheic keratoses (SKs) secondary to telaprevir-related dermatitis.

A 65-year-old woman with a history of depression, basal cell carcinoma, and HCV presented 5 months after initiation of antiviral treatment with interferon, ribavirin, and telaprevir. Shortly after initiation of therapy, the patient developed a diffuse itch with a “pricking” sensation. The patient reported that approximately 2 months after starting treatment she developed an erythematous scaling rash that covered 75% of the body, which led to the discontinuation of telaprevir after 10 weeks of therapy; interferon and ribavirin were continued for a total of 6 months. In concert with the eczematous eruption, the patient noticed many new hyperpigmented lesions with enlargement of the few preexisting SKs. She presented to our clinic 6 weeks after the discontinuation of telaprevir for evaluation of these lesions.

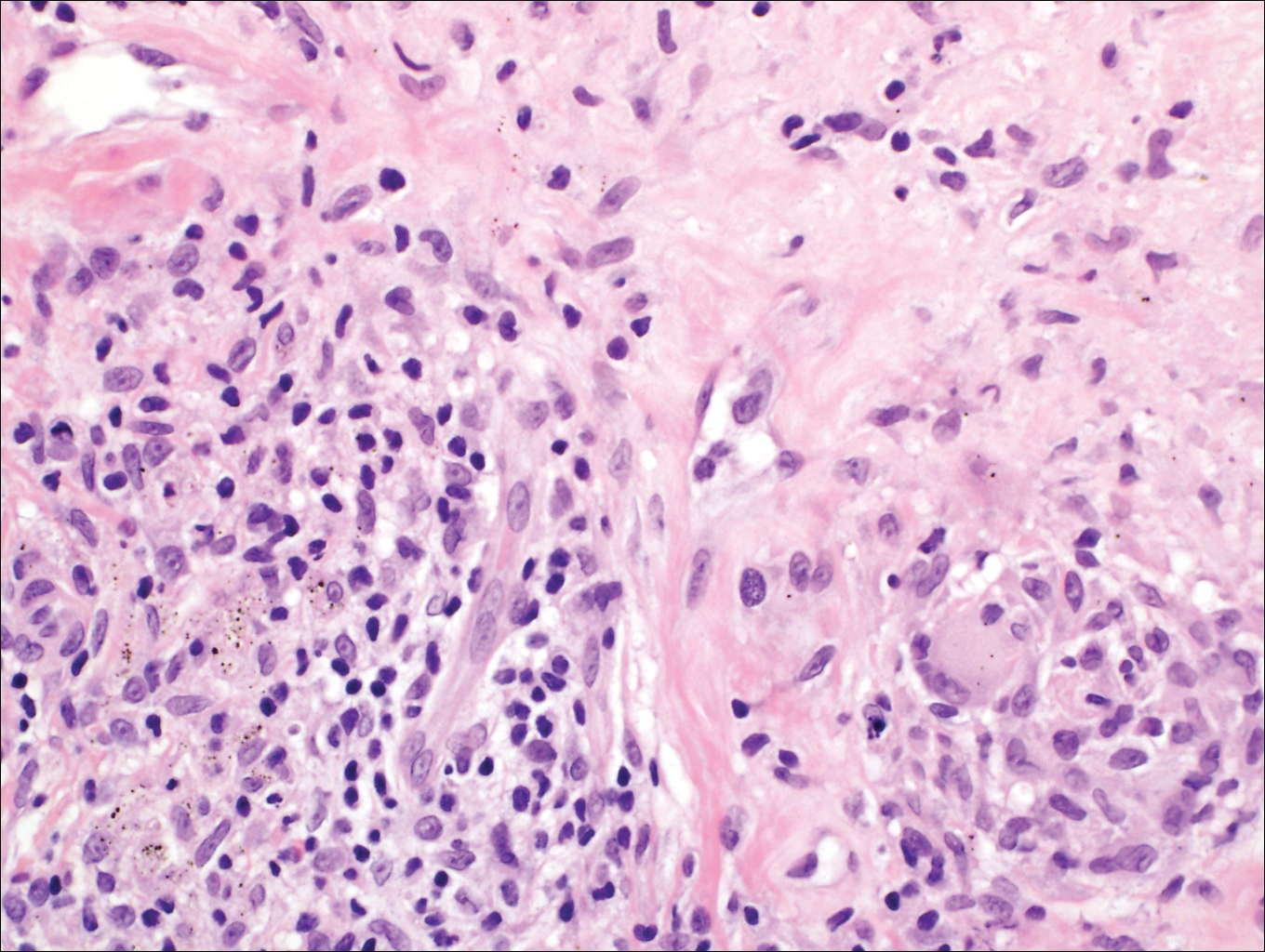

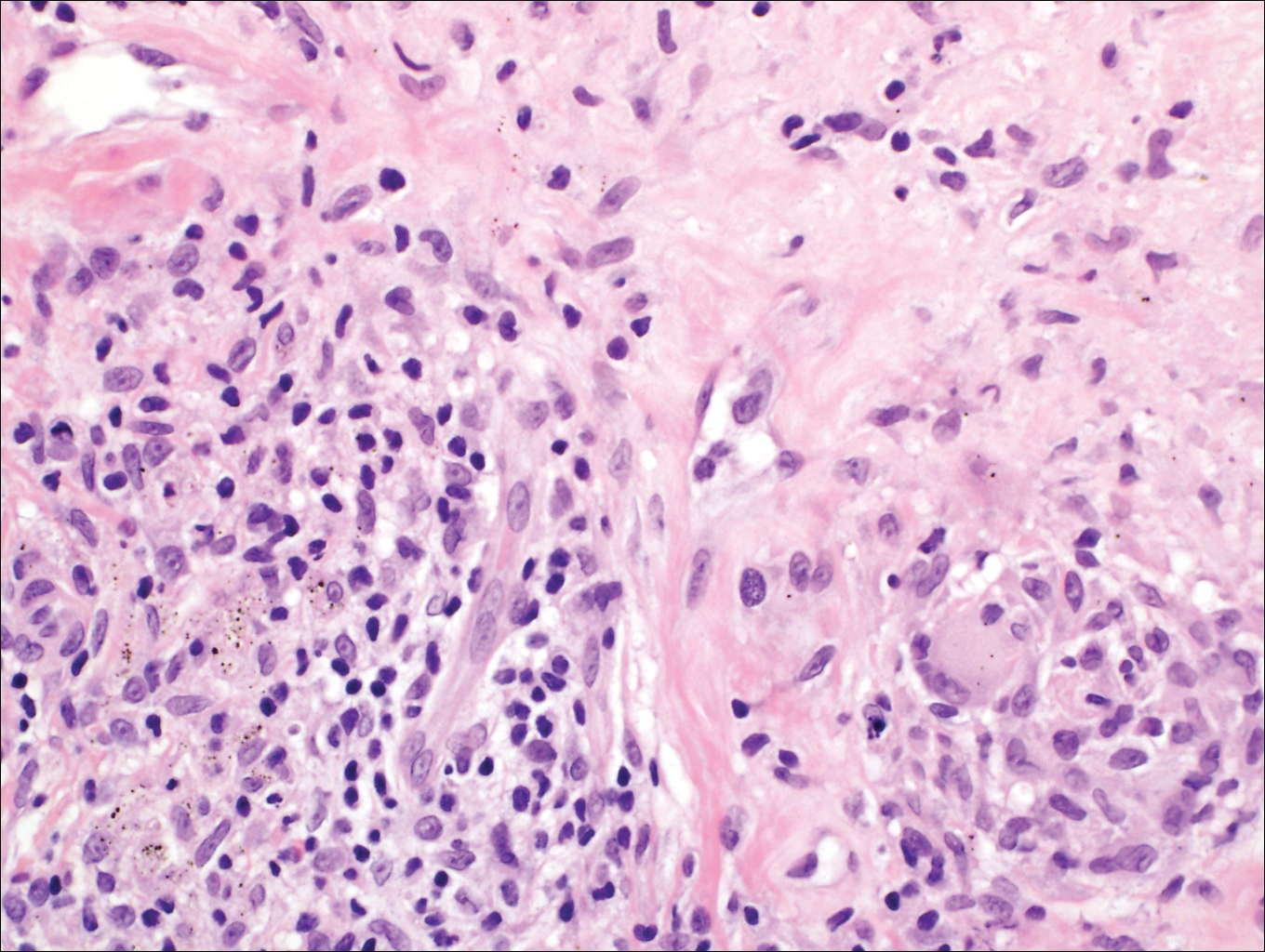

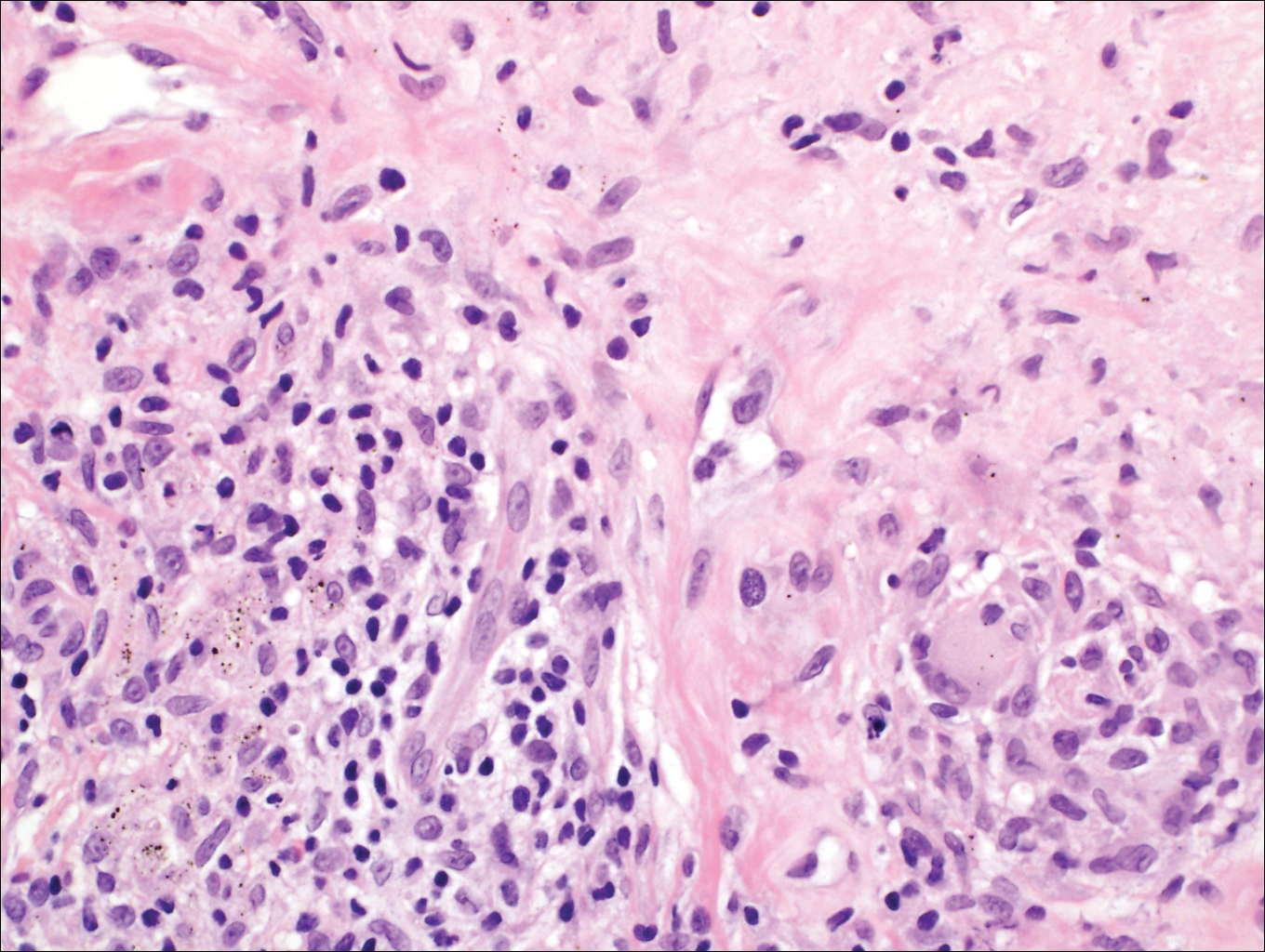

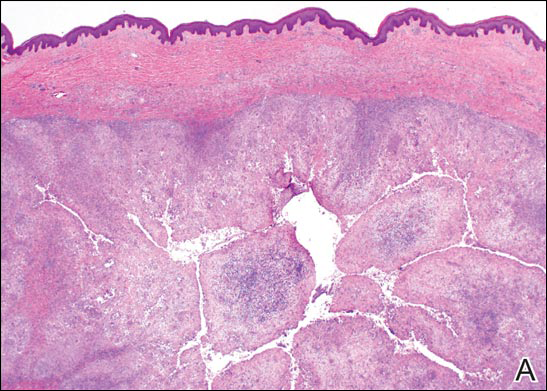

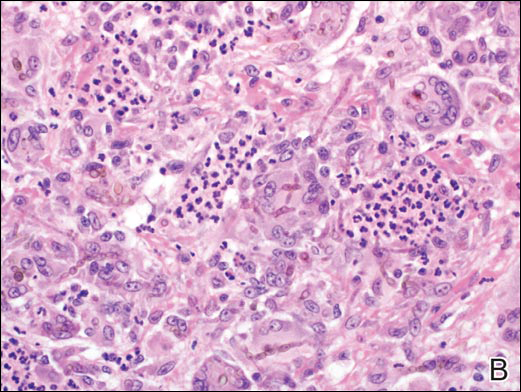

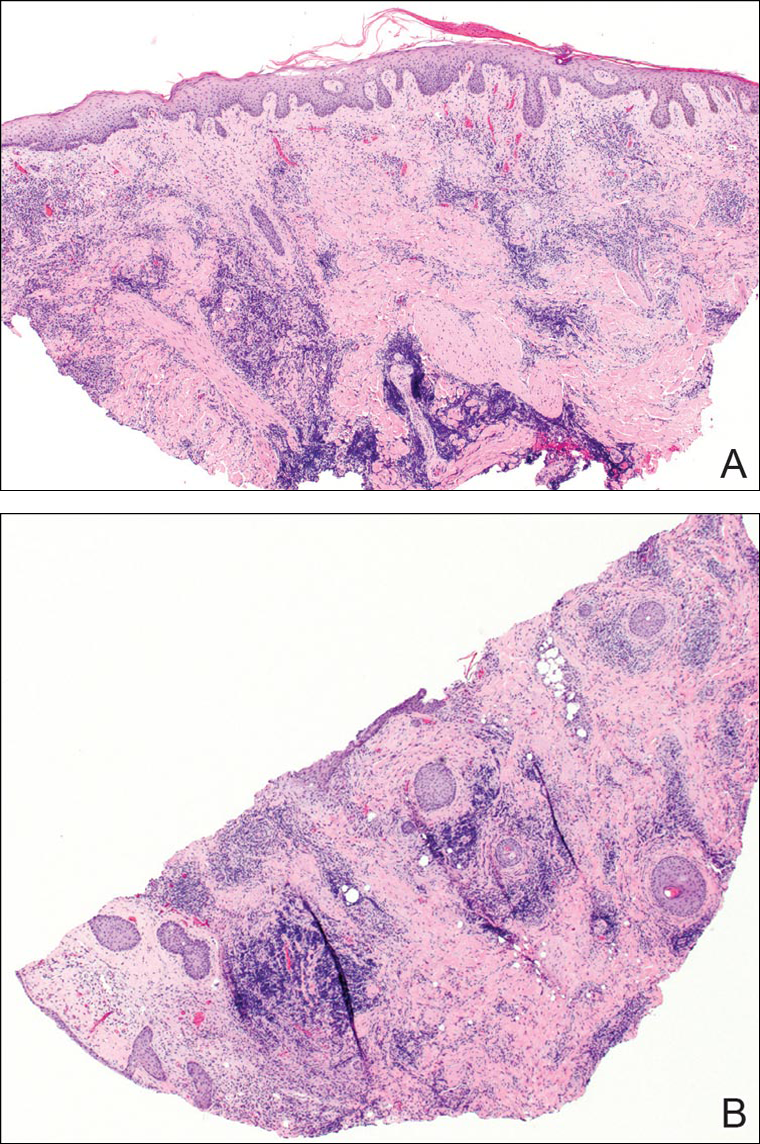

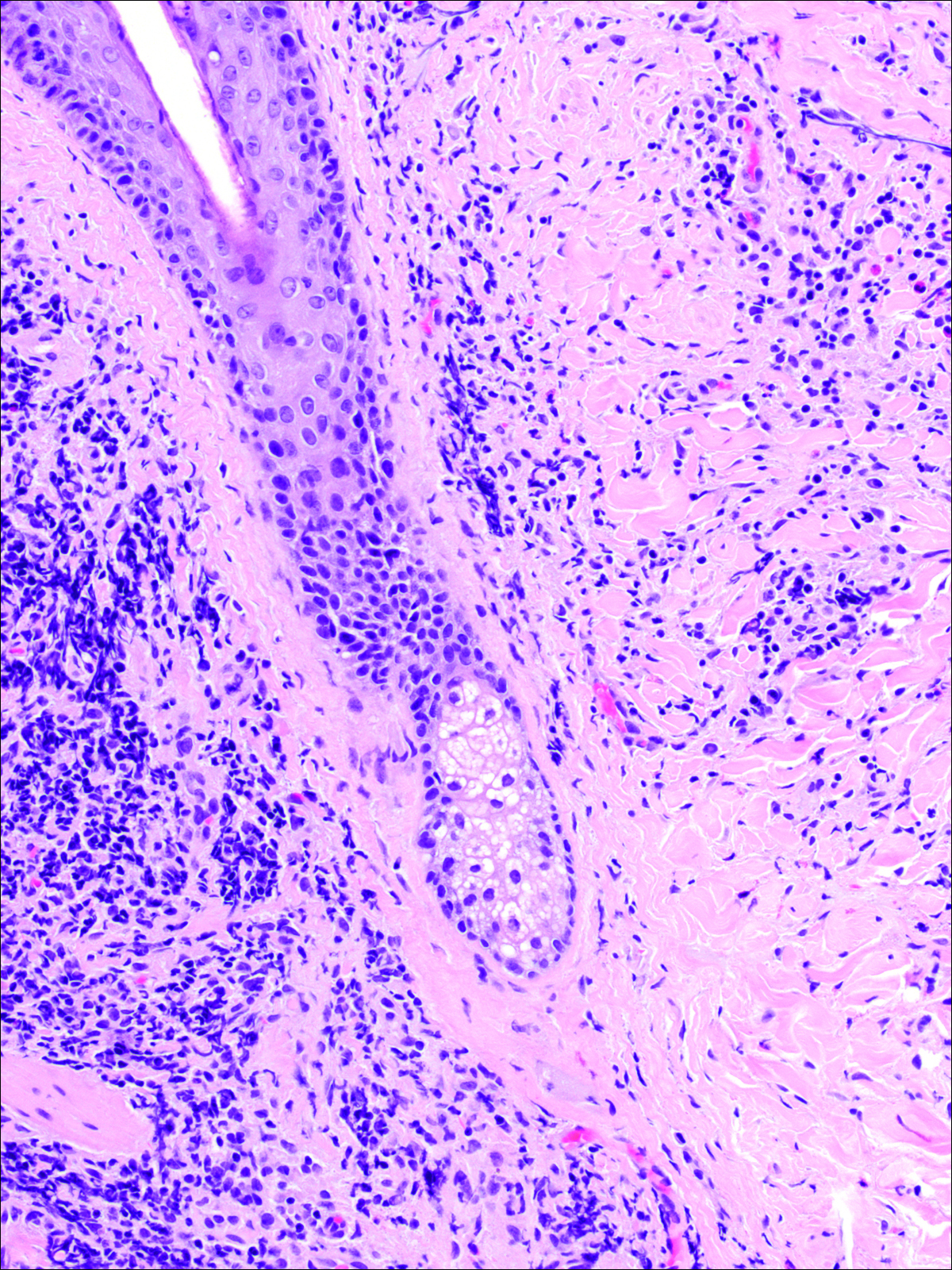

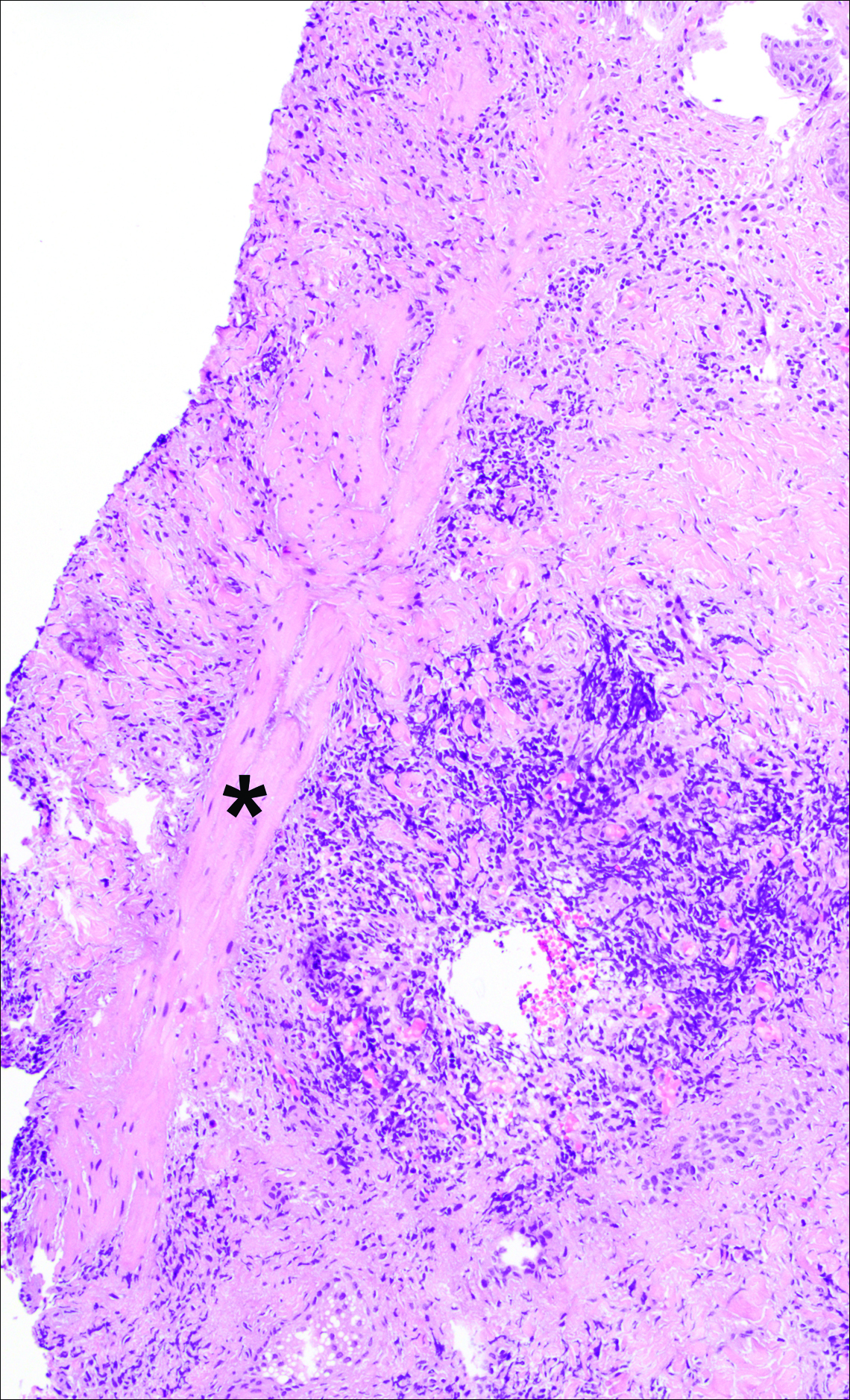

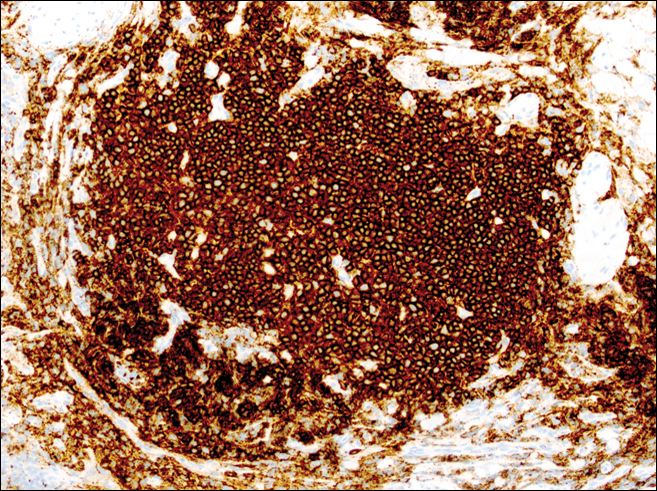

On examination, several brown, hyperpigmented, stuck-on papules and plaques were noted diffusely on the body, most prominently along the frontal hairline (Figure 1). A biopsy of the right side of the forehead showed a reticulated epidermis, horn pseudocysts, and increased basilar pigment diagnostic of an SK (Figure 2).

[[{"attributes":{},"fields":{}}]][[{"attributes":{},"fields":{}}]]

Telaprevir is an HCV protease inhibitor that is given in combination with interferon and ribavirin for increased clearance of genotype 1 HCV infection. Cutaneous reactions to telaprevir are seen in 41% to 61% of treated patients and include Stevens-Johnson syndrome, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, sarcoidosis, pityriasis rubra pilaris–like drug eruption, and most commonly telaprevir-related dermatitis.1-3 Telaprevir-related dermatitis accounts for up to 95% of cutaneous reactions and presents at a median of 15 days (interquartile range, 4–41 days) after initiation of therapy. Nearly 25% of cases occur in the first 4 days and 46% of cases occur within 4 weeks. It presents as an erythematous eczematous dermatitis commonly associated with pruritus in contrast to the common morbilliform drug eruption. Secondary xerosis, excoriation, and lichenification can be appreciated. With appropriate treatment, resolution occurs in a median of 44 days.1 Treatment of the dermatitis can allow completion of the recommended 12-week course of telaprevir and involves oral antihistamines and topical corticosteroids. Severe cases may require oral corticosteroids and discontinuation of telaprevir. If the cutaneous eruption does not resolve, discontinuation of ribavirin also may be required, as it can cause a similar cutaneous eruption.4

Eruptive SKs may be appreciated in 2 clinical circumstances: associated with an internal malignancy (Leser-Trélat sign), or secondary to an erythrodermic eruption. Flugman et al5 reported 2 cases of eruptive SKs in association with erythroderma. Their first patient developed erythroderma after initiating UVB therapy for psoriasis. The second patient developed an erythrodermic drug hypersensitivity reaction after switching to generic forms of quinidine gluconate and ranitidine. The SKs spontaneously resolved within 6 months and 10 weeks of the resolution of erythroderma, respectively.5 Most of our patient’s eruptive SKs resolved within a few months of their presentation, consistent with the time frame reported in the literature.

Telaprevir-related dermatitis presumably served as the inciting factor for the development of SKs in our patient, as the lesions improved after discontinuation of telaprevir despite continued therapy with ribavirin. As noted by Flugman et al,5 SKs may be seen in erythroderma due to diverse etiologies such as psoriasis, pityriasis rubra pilaris, or allergic contact dermatitis. We hypothesize that the eruption immunologically releases cytokines and/or growth factors that stimulate the production of the SKs. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 mutations have been associated with SKs.6 An erythrodermic milieu may incite such mutations in genetically predisposed patients.

We present a case of eruptive SKs related to telaprevir therapy. Our report expands the clinical scenarios in which the clinician can observe eruptive SKs. Although further research is necessary to ascertain the pathogenesis of these lesions, patients may be reassured that most lesions will spontaneously resolve.

- Roujeau J, Mockenhaupt M, Tahan S, et al. Telaprevir-related dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:152-158.

- Stalling S, Vu J, English J. Telaprevir-induced pityriasis rubra pilaris-like drug eruption. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1215-1217.

- Hinds B, Sonnier G, Waldman M. Cutaneous sarcoidosis triggered by immunotherapy for chronic hepatitis C: a case report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:AB47.

- Lawitz E. Diagnosis and management of telaprevir-associated rash. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;7:469-471.

- Flugman SL, McClain SA, Clark RA. Transient eruptive seborrheic keratoses associated with erythrodermic psoriasis and erythrodermic drug eruption: report of two cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45(6 suppl):S212-S214.

- Hafner C, Hartman A, van Oers JM, et al. FGFR3 mutations in seborrheic keratoses are already present in flat lesions and associated with age and localization. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:895-903.

To the Editor:

Telaprevir is a hepatitis C virus (HCV) protease inhibitor used with ribavirin and interferon for the treatment of increased viral load clearance in specific HCV genotypes. We report a case of eruptive seborrheic keratoses (SKs) secondary to telaprevir-related dermatitis.

A 65-year-old woman with a history of depression, basal cell carcinoma, and HCV presented 5 months after initiation of antiviral treatment with interferon, ribavirin, and telaprevir. Shortly after initiation of therapy, the patient developed a diffuse itch with a “pricking” sensation. The patient reported that approximately 2 months after starting treatment she developed an erythematous scaling rash that covered 75% of the body, which led to the discontinuation of telaprevir after 10 weeks of therapy; interferon and ribavirin were continued for a total of 6 months. In concert with the eczematous eruption, the patient noticed many new hyperpigmented lesions with enlargement of the few preexisting SKs. She presented to our clinic 6 weeks after the discontinuation of telaprevir for evaluation of these lesions.

On examination, several brown, hyperpigmented, stuck-on papules and plaques were noted diffusely on the body, most prominently along the frontal hairline (Figure 1). A biopsy of the right side of the forehead showed a reticulated epidermis, horn pseudocysts, and increased basilar pigment diagnostic of an SK (Figure 2).

[[{"attributes":{},"fields":{}}]][[{"attributes":{},"fields":{}}]]

Telaprevir is an HCV protease inhibitor that is given in combination with interferon and ribavirin for increased clearance of genotype 1 HCV infection. Cutaneous reactions to telaprevir are seen in 41% to 61% of treated patients and include Stevens-Johnson syndrome, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, sarcoidosis, pityriasis rubra pilaris–like drug eruption, and most commonly telaprevir-related dermatitis.1-3 Telaprevir-related dermatitis accounts for up to 95% of cutaneous reactions and presents at a median of 15 days (interquartile range, 4–41 days) after initiation of therapy. Nearly 25% of cases occur in the first 4 days and 46% of cases occur within 4 weeks. It presents as an erythematous eczematous dermatitis commonly associated with pruritus in contrast to the common morbilliform drug eruption. Secondary xerosis, excoriation, and lichenification can be appreciated. With appropriate treatment, resolution occurs in a median of 44 days.1 Treatment of the dermatitis can allow completion of the recommended 12-week course of telaprevir and involves oral antihistamines and topical corticosteroids. Severe cases may require oral corticosteroids and discontinuation of telaprevir. If the cutaneous eruption does not resolve, discontinuation of ribavirin also may be required, as it can cause a similar cutaneous eruption.4

Eruptive SKs may be appreciated in 2 clinical circumstances: associated with an internal malignancy (Leser-Trélat sign), or secondary to an erythrodermic eruption. Flugman et al5 reported 2 cases of eruptive SKs in association with erythroderma. Their first patient developed erythroderma after initiating UVB therapy for psoriasis. The second patient developed an erythrodermic drug hypersensitivity reaction after switching to generic forms of quinidine gluconate and ranitidine. The SKs spontaneously resolved within 6 months and 10 weeks of the resolution of erythroderma, respectively.5 Most of our patient’s eruptive SKs resolved within a few months of their presentation, consistent with the time frame reported in the literature.

Telaprevir-related dermatitis presumably served as the inciting factor for the development of SKs in our patient, as the lesions improved after discontinuation of telaprevir despite continued therapy with ribavirin. As noted by Flugman et al,5 SKs may be seen in erythroderma due to diverse etiologies such as psoriasis, pityriasis rubra pilaris, or allergic contact dermatitis. We hypothesize that the eruption immunologically releases cytokines and/or growth factors that stimulate the production of the SKs. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 mutations have been associated with SKs.6 An erythrodermic milieu may incite such mutations in genetically predisposed patients.

We present a case of eruptive SKs related to telaprevir therapy. Our report expands the clinical scenarios in which the clinician can observe eruptive SKs. Although further research is necessary to ascertain the pathogenesis of these lesions, patients may be reassured that most lesions will spontaneously resolve.

To the Editor:

Telaprevir is a hepatitis C virus (HCV) protease inhibitor used with ribavirin and interferon for the treatment of increased viral load clearance in specific HCV genotypes. We report a case of eruptive seborrheic keratoses (SKs) secondary to telaprevir-related dermatitis.

A 65-year-old woman with a history of depression, basal cell carcinoma, and HCV presented 5 months after initiation of antiviral treatment with interferon, ribavirin, and telaprevir. Shortly after initiation of therapy, the patient developed a diffuse itch with a “pricking” sensation. The patient reported that approximately 2 months after starting treatment she developed an erythematous scaling rash that covered 75% of the body, which led to the discontinuation of telaprevir after 10 weeks of therapy; interferon and ribavirin were continued for a total of 6 months. In concert with the eczematous eruption, the patient noticed many new hyperpigmented lesions with enlargement of the few preexisting SKs. She presented to our clinic 6 weeks after the discontinuation of telaprevir for evaluation of these lesions.

On examination, several brown, hyperpigmented, stuck-on papules and plaques were noted diffusely on the body, most prominently along the frontal hairline (Figure 1). A biopsy of the right side of the forehead showed a reticulated epidermis, horn pseudocysts, and increased basilar pigment diagnostic of an SK (Figure 2).

[[{"attributes":{},"fields":{}}]][[{"attributes":{},"fields":{}}]]

Telaprevir is an HCV protease inhibitor that is given in combination with interferon and ribavirin for increased clearance of genotype 1 HCV infection. Cutaneous reactions to telaprevir are seen in 41% to 61% of treated patients and include Stevens-Johnson syndrome, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, sarcoidosis, pityriasis rubra pilaris–like drug eruption, and most commonly telaprevir-related dermatitis.1-3 Telaprevir-related dermatitis accounts for up to 95% of cutaneous reactions and presents at a median of 15 days (interquartile range, 4–41 days) after initiation of therapy. Nearly 25% of cases occur in the first 4 days and 46% of cases occur within 4 weeks. It presents as an erythematous eczematous dermatitis commonly associated with pruritus in contrast to the common morbilliform drug eruption. Secondary xerosis, excoriation, and lichenification can be appreciated. With appropriate treatment, resolution occurs in a median of 44 days.1 Treatment of the dermatitis can allow completion of the recommended 12-week course of telaprevir and involves oral antihistamines and topical corticosteroids. Severe cases may require oral corticosteroids and discontinuation of telaprevir. If the cutaneous eruption does not resolve, discontinuation of ribavirin also may be required, as it can cause a similar cutaneous eruption.4

Eruptive SKs may be appreciated in 2 clinical circumstances: associated with an internal malignancy (Leser-Trélat sign), or secondary to an erythrodermic eruption. Flugman et al5 reported 2 cases of eruptive SKs in association with erythroderma. Their first patient developed erythroderma after initiating UVB therapy for psoriasis. The second patient developed an erythrodermic drug hypersensitivity reaction after switching to generic forms of quinidine gluconate and ranitidine. The SKs spontaneously resolved within 6 months and 10 weeks of the resolution of erythroderma, respectively.5 Most of our patient’s eruptive SKs resolved within a few months of their presentation, consistent with the time frame reported in the literature.

Telaprevir-related dermatitis presumably served as the inciting factor for the development of SKs in our patient, as the lesions improved after discontinuation of telaprevir despite continued therapy with ribavirin. As noted by Flugman et al,5 SKs may be seen in erythroderma due to diverse etiologies such as psoriasis, pityriasis rubra pilaris, or allergic contact dermatitis. We hypothesize that the eruption immunologically releases cytokines and/or growth factors that stimulate the production of the SKs. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 mutations have been associated with SKs.6 An erythrodermic milieu may incite such mutations in genetically predisposed patients.

We present a case of eruptive SKs related to telaprevir therapy. Our report expands the clinical scenarios in which the clinician can observe eruptive SKs. Although further research is necessary to ascertain the pathogenesis of these lesions, patients may be reassured that most lesions will spontaneously resolve.

- Roujeau J, Mockenhaupt M, Tahan S, et al. Telaprevir-related dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:152-158.

- Stalling S, Vu J, English J. Telaprevir-induced pityriasis rubra pilaris-like drug eruption. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1215-1217.

- Hinds B, Sonnier G, Waldman M. Cutaneous sarcoidosis triggered by immunotherapy for chronic hepatitis C: a case report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:AB47.

- Lawitz E. Diagnosis and management of telaprevir-associated rash. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;7:469-471.

- Flugman SL, McClain SA, Clark RA. Transient eruptive seborrheic keratoses associated with erythrodermic psoriasis and erythrodermic drug eruption: report of two cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45(6 suppl):S212-S214.

- Hafner C, Hartman A, van Oers JM, et al. FGFR3 mutations in seborrheic keratoses are already present in flat lesions and associated with age and localization. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:895-903.

- Roujeau J, Mockenhaupt M, Tahan S, et al. Telaprevir-related dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:152-158.

- Stalling S, Vu J, English J. Telaprevir-induced pityriasis rubra pilaris-like drug eruption. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1215-1217.

- Hinds B, Sonnier G, Waldman M. Cutaneous sarcoidosis triggered by immunotherapy for chronic hepatitis C: a case report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:AB47.

- Lawitz E. Diagnosis and management of telaprevir-associated rash. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;7:469-471.

- Flugman SL, McClain SA, Clark RA. Transient eruptive seborrheic keratoses associated with erythrodermic psoriasis and erythrodermic drug eruption: report of two cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45(6 suppl):S212-S214.

- Hafner C, Hartman A, van Oers JM, et al. FGFR3 mutations in seborrheic keratoses are already present in flat lesions and associated with age and localization. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:895-903.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous reactions presenting as eczematous dermatitis are common (41%–61%) during telaprevir treatment.

- Telaprevir-related dermatitis can lead to eruptive seborrheic keratoses that may spontaneously resolve.

Family, culture, and cultural identity key to improving assessment and treatment

Editor’s Note: This is the third installment of Curbside Consult, written by two Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry (GAP) committees – the Committee on Family Psychiatry and the Committee on Cultural Psychiatry.

Erica is a 19-year-old woman from an ethnically mixed background. Her father is an African American retired U.S. military officer who met her mother while he was stationed in Japan, where her mother was born and raised. Erica lived in Japan until she was 8, when the family moved to Seattle, and her father began a new career in a large company.

At age 10, she began to have episodes during which she felt her heart racing, was short of breath, and was diaphoretic. These episodes often took place when the family went out to large public spaces, like a shopping mall, and she would be separated from her parents. They increased in frequency until she was taken to a pediatrician and saw a counselor. Her panic symptoms gradually disappeared during high school, but since starting college and moving away from home, she has felt lost in her environment, and feels as though no one understands her background and upbringing. For example, she abruptly left the first college party she attended, feeling that “everybody had met everybody already and nobody noticed me; maybe they don’t like the way I look.” She has had a return of panic episodes that are now more frequent, coming on without warning, and they have begun to wake her from sleep.

Discussion

Incorporating a family and culture lens to the case can improve assessment and treatment planning. Given the brevity of the case description, many of our recommendations focus on obtaining additional information. It is also important to rule out any medical conditions that could be causing her symptoms. Finally, since great heterogeneity exists within every culture, the clinician should investigate the meanings associated with specific cultural backgrounds for each person to avoid stereotyping that would interfere with an accurate assessment and treatment plan.

Possible cultural conflicts

Although the identified patient in this case is the young woman, the number of culture- and family-related stresses experienced by each member of her family cannot be overstated. The family is truly multicultural, in every sense of the word. Many Americans associate the word “culture” with the influence of race, ethnicity, and country of origin, but the term encompasses many other aspects of the family’s background as well, including the father’s immersion in military culture as an officer of color, the culture of American ex-pats in Japan and of Japanese immigrants to the West Coast of the United States, multiracial children’s adaptations to Japanese and state schools, and U.S. corporate culture. Every member of the family has therefore had to adapt to many cultural transitions. All of these moves require new relationships with the dominant culture and immediate community, which increases stresses within the family as well as between the family and the broader society in which they live. Conflict between the parents increases vigilance and anxiety in children, and since Erica does not have siblings, the likelihood of being caught in a conflict between both parent would be high.

One adaptation that the family has undergone involves negotiating variations in “individualism” – a cultural ideology that prizes the role and desires of the individual over that of the group – and “collectivism” – in which the values and expectations of the social group are prioritized. Each society (for example, urban Japan) and social group (for example, the U.S. military) is characterized by a combination of individualistic and collectivistic traits, though a certain cultural flavor tends to predominate.

If Erica’s mother’s family of origin in Japan was very traditionally collectivistic, she may have experienced a difficult cultural shift when she moved to the United States, which tends to value more individualistic self-presentation. This conflict may have affected Erica’s development, particularly if it were an area of difficulty during her mother’s adaptation to her move or a potential sore spot in the father’s relationship with his wife. It would be good to explore to what extent the mother embraced her move to her new home in Seattle, and whether she also tried to keep her culture of origin alive in the family, while she negotiated her acculturation to U.S. society. In a cosmopolitan city like Seattle with a growing Asian population, this may be easier than in past years, but still might require a great deal of effort. The mother’s adaptation seems an important topic for further assessment, including discovering whether she found work in the United States, if she created new social networks, or whether she remained isolated with her husband and her daughter.

As to the father, if he grew up in a U.S. community that relied on a direct communication style that valued individual assertion as a component of identity and self-esteem, he may have seen his wife’s approach to communication as too reserved, private, or other-directed, especially if her English proficiency or his Japanese fluency was limited. These conflicts may have affected Erica’s sense of self but must be evaluated directly rather than assumed; each parent’s fluency and communication style are fruitful questions to explore. It is possible that conflicts in this area may have interfered with Erica’s incorporation of either parent as a role model for her as a young woman in contemporary U.S. society, threatening her sense of self and leading to anxiety symptoms.

Another area of potential stress for the family involves the experience of discrimination tied to racism or other forms of prejudice. Each family member is vulnerable in this area in his/her own right, given the potential mismatches between their racial/ethnic background and the sometimes intolerant views of dominant social groupings in their societies of origin or their societies of migration. Erica may be most vulnerable in this regard, in light of her dual minority background. The clinician should assess to what extent either or both families of origin may be unhappy about the marriage and biracial child and the possible resulting impact on Erica’s sense of herself. Does she feel more attracted to one aspect of her background? In terms of Erica’s developing identity, it is important to understand whether the family maintains one culture as the family of heritage or works toward developing a multicultural identity. If neither parent can completely identify with Erica, they must work with her to find a way to mesh both cultures. If they do not, she may feel that she has to choose her presentation to the world as African American, Japanese, multiracial, or “post racial.” This may complicate her sense of connection to one or both parents. To some extent this may be affected by which parent she most takes after physically or to which side of the extended family she feels closer. The clinician should consider all these issues in conducting a culturally competent assessment and family-based intervention.

Development context of Erica’s symptom course

Since Erica was asymptomatic during the first 2 years after the move to the United States, it may be possible to assume that early adaptation went reasonably well. The onset of symptoms at age 10 may stem from numerous causes. Biologically, she may have been in prepuberty, which can increase emotional reactivity. Psychologically, this is typically the point at which children become more self-conscious and peer pressure ratchets up, so her possible lack of instinctive understanding of U.S. cultural norms, or her biracial makeup, may have become more salient, either in the form of an intrapsychic racial identity conflict or as an object of interpersonal bullying. It would be helpful to understand these details so as to attend to them in psychotherapy.

If she had begun middle school, academic pressure may have increased. However, her clinicians also should consider the possibility that one or both of her parents may have become stressed by the multiple cultural adaptations required by the move, or that the marriage had become strained, and that she responded to parental stress with increased anxiety. These are possibilities that need to be explored during the assessment.

Her ability to deal with her difficulties and finish high school speaks to her and her family’s resilience. To plan future treatment, it would be useful to explore what aspect of her treatment at age 10 was most helpful (medication, therapy, or both). Ideally, it would be helpful to understand the cultural elements of the relationship between the patient and the pediatrician and counselor. However, given her history, it is no surprise that when she is asked once more to navigate a new culture of college, this time without parental support, that her symptoms reoccur. If she is far from home, in a college where racial tensions are high or where there is not a large multiracial population, or if her parents are having trouble with empty nesting, this would make things more difficult. Her own cultural identity may have been challenged by an environment where she felt “no one understands her background and upbringing,” where “nobody noticed me,” and where “maybe they don’t like the way I look.”

How should clinicians explore these issues?

Erica’s clinicians should seek to understand how she herself defines her background, identity, and upbringing to help her examine possible conflictual issues that are causing distress. The DSM-5 Cultural Formulation Interview is a useful tool for achieving this goal, including its supplementary modules such as the one on Cultural Identity. As part of this assessment, her clinician could ask questions like: How does she see herself and how do other people see her in terms of her identity? How does she present herself? Is she being harassed on campus? Are any of these issues causes of her anxiety? Direct assessment of these topics is necessary to avoid initial impressions that might be affected by the clinician’s own identity, values, and biases. Her clinician should also be conversant in the stresses of the college environment, both at the intrapsychic and interpersonal levels.

While the usual treatments for anxiety, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and medications if necessary, may well be part of her clinical care, helping her understand her own personal cultural identity, how to negotiate the stresses of living on her college campus, and increasing both family and community supports are critical to her well-being and mental health.

While it is true that few people could exactly share Erica’s life experience, there are many pan-nationals and expats who would very much relate to her feelings. Erica faces many of the challenges of those in a group called “third culture kids,” a term coined in the 1950s by social scientists to describe the experience of children raised by Americans working in other countries. The expatriate lifestyle they described as an “interstitial culture” – different from but including elements of both the home culture and the host culture – often is specific to the work group (for example, military, business) that the adults were engaged in. For these children, the question of cultural identity, and “where is home,” is a complex one. For them, unlike their parents, the United States is not home but a foreign land. But their host country is not exactly home, either. Patients like Erica may benefit from reading “Third Culture Kids: The Experience of Growing Up Among Worlds,” by David C. Pollock and Ruth E. Van Reken, and clinicians would likely benefit as well.

Finally, Erica’s therapist could encourage her to find connections in the international student community; there are usually groups on campus for them, and they would understand a multicultural experience. Her therapist also should meet with, or speak with, her parents to see whether there are stresses at home, and could encourage them to support her by frequent visits or calls. When Erica finds a place where she feels at home, we believe her anxiety will decrease.

Key take-home points

1. Ask about, do not assume, the person’s own understanding of his/her background and identity to obtain more specific and precise information so as to guard against stereotyping that could lead to erroneous assessments.

2. Understand the heterogeneity of culture and the complexity of cultural identity.

3. Ask about the family. Who is in the family, both nuclear and extended? Draw a simple genogram. Envision and implement assessment beyond just the individual patient.

4. Assess the impact of culture change on cultural identity and family dynamics.

5. Use the DSM-5 Cultural Formulation Interview to help guide the cultural assessment.

Contributors

Ellen M. Berman, MD – University of Pennsylvania, Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia

Roberto Lewis-Fernández, MD – Columbia University and New York State Psychiatric Institute

Francis G. Lu, MD – University of California, Davis

The contributors have revised selected patient details to shield the identities of the patients/cases and to comply with HIPAA requirements. This column is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical advice. The opinions expressed are those of the contributors and do not represent those of the organizations they are employed by or those affiliated with GAP.

Resources

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5). (Arlington, Va.: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2013).

Lewis-Fernández, R., et al. (eds.) DSM-5 Handbook on the Cultural Formulation Interview (Arlington, Va.: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2016).

Lim, R. (ed.). Clinical Manual of Cultural Psychiatry, 2nd edition (Arlington, Va.: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2015).

Pollock, D. and Van Reken, R. Third Culture Kids: The Experience of Growing Up Among Worlds (London: Nicholas Breasley Publishing, 2009).

Curbside Consult is inspired by the DSM-5’s emphasis on developing a cultural formulation of patients’ illnesses, and addressing family dynamics and resilience in promoting care that fosters prevention and recovery. We request that you submit cases to [email protected] in which your understanding and treatment are affected by challenging cultural and family issues. We will then write back with our best answers about how one might proceed in such a case. Your case and our response will be published in Clinical Psychiatry News. Please limit your case description to 250 words and include the following details:

1. Patient’s presenting problem or reason for the visit.

2. Patient’s age and gender.

3. Indicators of the patient’s identity – self-identified race/ethnicity, culture, religion/spirituality, socioeconomic status, education, among other variables.

4. Patient’s living situation, family composition, and genogram information (if available).

5. Patient’s geographic location (rural, suburban, urban) and occupation.

6. Patient’s and family’s degree of participation in their identified culture.

7. Questions of the individual submitting the case, including concerns about the role of the family and culture in the case, diagnosis, and treatment planning.

8. Please follow local ethical requirements, disguise the case to protect confidentiality and attend to HIPAA requirements, so that patients or family members reading the article would not recognize themselves.

Additional information might be requested, and editing of the case, questions, and commentary might be needed prior to final publication.

Editor’s Note: This is the third installment of Curbside Consult, written by two Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry (GAP) committees – the Committee on Family Psychiatry and the Committee on Cultural Psychiatry.

Erica is a 19-year-old woman from an ethnically mixed background. Her father is an African American retired U.S. military officer who met her mother while he was stationed in Japan, where her mother was born and raised. Erica lived in Japan until she was 8, when the family moved to Seattle, and her father began a new career in a large company.

At age 10, she began to have episodes during which she felt her heart racing, was short of breath, and was diaphoretic. These episodes often took place when the family went out to large public spaces, like a shopping mall, and she would be separated from her parents. They increased in frequency until she was taken to a pediatrician and saw a counselor. Her panic symptoms gradually disappeared during high school, but since starting college and moving away from home, she has felt lost in her environment, and feels as though no one understands her background and upbringing. For example, she abruptly left the first college party she attended, feeling that “everybody had met everybody already and nobody noticed me; maybe they don’t like the way I look.” She has had a return of panic episodes that are now more frequent, coming on without warning, and they have begun to wake her from sleep.

Discussion

Incorporating a family and culture lens to the case can improve assessment and treatment planning. Given the brevity of the case description, many of our recommendations focus on obtaining additional information. It is also important to rule out any medical conditions that could be causing her symptoms. Finally, since great heterogeneity exists within every culture, the clinician should investigate the meanings associated with specific cultural backgrounds for each person to avoid stereotyping that would interfere with an accurate assessment and treatment plan.

Possible cultural conflicts

Although the identified patient in this case is the young woman, the number of culture- and family-related stresses experienced by each member of her family cannot be overstated. The family is truly multicultural, in every sense of the word. Many Americans associate the word “culture” with the influence of race, ethnicity, and country of origin, but the term encompasses many other aspects of the family’s background as well, including the father’s immersion in military culture as an officer of color, the culture of American ex-pats in Japan and of Japanese immigrants to the West Coast of the United States, multiracial children’s adaptations to Japanese and state schools, and U.S. corporate culture. Every member of the family has therefore had to adapt to many cultural transitions. All of these moves require new relationships with the dominant culture and immediate community, which increases stresses within the family as well as between the family and the broader society in which they live. Conflict between the parents increases vigilance and anxiety in children, and since Erica does not have siblings, the likelihood of being caught in a conflict between both parent would be high.

One adaptation that the family has undergone involves negotiating variations in “individualism” – a cultural ideology that prizes the role and desires of the individual over that of the group – and “collectivism” – in which the values and expectations of the social group are prioritized. Each society (for example, urban Japan) and social group (for example, the U.S. military) is characterized by a combination of individualistic and collectivistic traits, though a certain cultural flavor tends to predominate.

If Erica’s mother’s family of origin in Japan was very traditionally collectivistic, she may have experienced a difficult cultural shift when she moved to the United States, which tends to value more individualistic self-presentation. This conflict may have affected Erica’s development, particularly if it were an area of difficulty during her mother’s adaptation to her move or a potential sore spot in the father’s relationship with his wife. It would be good to explore to what extent the mother embraced her move to her new home in Seattle, and whether she also tried to keep her culture of origin alive in the family, while she negotiated her acculturation to U.S. society. In a cosmopolitan city like Seattle with a growing Asian population, this may be easier than in past years, but still might require a great deal of effort. The mother’s adaptation seems an important topic for further assessment, including discovering whether she found work in the United States, if she created new social networks, or whether she remained isolated with her husband and her daughter.

As to the father, if he grew up in a U.S. community that relied on a direct communication style that valued individual assertion as a component of identity and self-esteem, he may have seen his wife’s approach to communication as too reserved, private, or other-directed, especially if her English proficiency or his Japanese fluency was limited. These conflicts may have affected Erica’s sense of self but must be evaluated directly rather than assumed; each parent’s fluency and communication style are fruitful questions to explore. It is possible that conflicts in this area may have interfered with Erica’s incorporation of either parent as a role model for her as a young woman in contemporary U.S. society, threatening her sense of self and leading to anxiety symptoms.

Another area of potential stress for the family involves the experience of discrimination tied to racism or other forms of prejudice. Each family member is vulnerable in this area in his/her own right, given the potential mismatches between their racial/ethnic background and the sometimes intolerant views of dominant social groupings in their societies of origin or their societies of migration. Erica may be most vulnerable in this regard, in light of her dual minority background. The clinician should assess to what extent either or both families of origin may be unhappy about the marriage and biracial child and the possible resulting impact on Erica’s sense of herself. Does she feel more attracted to one aspect of her background? In terms of Erica’s developing identity, it is important to understand whether the family maintains one culture as the family of heritage or works toward developing a multicultural identity. If neither parent can completely identify with Erica, they must work with her to find a way to mesh both cultures. If they do not, she may feel that she has to choose her presentation to the world as African American, Japanese, multiracial, or “post racial.” This may complicate her sense of connection to one or both parents. To some extent this may be affected by which parent she most takes after physically or to which side of the extended family she feels closer. The clinician should consider all these issues in conducting a culturally competent assessment and family-based intervention.

Development context of Erica’s symptom course

Since Erica was asymptomatic during the first 2 years after the move to the United States, it may be possible to assume that early adaptation went reasonably well. The onset of symptoms at age 10 may stem from numerous causes. Biologically, she may have been in prepuberty, which can increase emotional reactivity. Psychologically, this is typically the point at which children become more self-conscious and peer pressure ratchets up, so her possible lack of instinctive understanding of U.S. cultural norms, or her biracial makeup, may have become more salient, either in the form of an intrapsychic racial identity conflict or as an object of interpersonal bullying. It would be helpful to understand these details so as to attend to them in psychotherapy.

If she had begun middle school, academic pressure may have increased. However, her clinicians also should consider the possibility that one or both of her parents may have become stressed by the multiple cultural adaptations required by the move, or that the marriage had become strained, and that she responded to parental stress with increased anxiety. These are possibilities that need to be explored during the assessment.

Her ability to deal with her difficulties and finish high school speaks to her and her family’s resilience. To plan future treatment, it would be useful to explore what aspect of her treatment at age 10 was most helpful (medication, therapy, or both). Ideally, it would be helpful to understand the cultural elements of the relationship between the patient and the pediatrician and counselor. However, given her history, it is no surprise that when she is asked once more to navigate a new culture of college, this time without parental support, that her symptoms reoccur. If she is far from home, in a college where racial tensions are high or where there is not a large multiracial population, or if her parents are having trouble with empty nesting, this would make things more difficult. Her own cultural identity may have been challenged by an environment where she felt “no one understands her background and upbringing,” where “nobody noticed me,” and where “maybe they don’t like the way I look.”

How should clinicians explore these issues?

Erica’s clinicians should seek to understand how she herself defines her background, identity, and upbringing to help her examine possible conflictual issues that are causing distress. The DSM-5 Cultural Formulation Interview is a useful tool for achieving this goal, including its supplementary modules such as the one on Cultural Identity. As part of this assessment, her clinician could ask questions like: How does she see herself and how do other people see her in terms of her identity? How does she present herself? Is she being harassed on campus? Are any of these issues causes of her anxiety? Direct assessment of these topics is necessary to avoid initial impressions that might be affected by the clinician’s own identity, values, and biases. Her clinician should also be conversant in the stresses of the college environment, both at the intrapsychic and interpersonal levels.

While the usual treatments for anxiety, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and medications if necessary, may well be part of her clinical care, helping her understand her own personal cultural identity, how to negotiate the stresses of living on her college campus, and increasing both family and community supports are critical to her well-being and mental health.

While it is true that few people could exactly share Erica’s life experience, there are many pan-nationals and expats who would very much relate to her feelings. Erica faces many of the challenges of those in a group called “third culture kids,” a term coined in the 1950s by social scientists to describe the experience of children raised by Americans working in other countries. The expatriate lifestyle they described as an “interstitial culture” – different from but including elements of both the home culture and the host culture – often is specific to the work group (for example, military, business) that the adults were engaged in. For these children, the question of cultural identity, and “where is home,” is a complex one. For them, unlike their parents, the United States is not home but a foreign land. But their host country is not exactly home, either. Patients like Erica may benefit from reading “Third Culture Kids: The Experience of Growing Up Among Worlds,” by David C. Pollock and Ruth E. Van Reken, and clinicians would likely benefit as well.

Finally, Erica’s therapist could encourage her to find connections in the international student community; there are usually groups on campus for them, and they would understand a multicultural experience. Her therapist also should meet with, or speak with, her parents to see whether there are stresses at home, and could encourage them to support her by frequent visits or calls. When Erica finds a place where she feels at home, we believe her anxiety will decrease.

Key take-home points

1. Ask about, do not assume, the person’s own understanding of his/her background and identity to obtain more specific and precise information so as to guard against stereotyping that could lead to erroneous assessments.

2. Understand the heterogeneity of culture and the complexity of cultural identity.

3. Ask about the family. Who is in the family, both nuclear and extended? Draw a simple genogram. Envision and implement assessment beyond just the individual patient.

4. Assess the impact of culture change on cultural identity and family dynamics.

5. Use the DSM-5 Cultural Formulation Interview to help guide the cultural assessment.

Contributors

Ellen M. Berman, MD – University of Pennsylvania, Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia

Roberto Lewis-Fernández, MD – Columbia University and New York State Psychiatric Institute

Francis G. Lu, MD – University of California, Davis

The contributors have revised selected patient details to shield the identities of the patients/cases and to comply with HIPAA requirements. This column is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical advice. The opinions expressed are those of the contributors and do not represent those of the organizations they are employed by or those affiliated with GAP.

Resources

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5). (Arlington, Va.: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2013).

Lewis-Fernández, R., et al. (eds.) DSM-5 Handbook on the Cultural Formulation Interview (Arlington, Va.: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2016).

Lim, R. (ed.). Clinical Manual of Cultural Psychiatry, 2nd edition (Arlington, Va.: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2015).

Pollock, D. and Van Reken, R. Third Culture Kids: The Experience of Growing Up Among Worlds (London: Nicholas Breasley Publishing, 2009).

Curbside Consult is inspired by the DSM-5’s emphasis on developing a cultural formulation of patients’ illnesses, and addressing family dynamics and resilience in promoting care that fosters prevention and recovery. We request that you submit cases to [email protected] in which your understanding and treatment are affected by challenging cultural and family issues. We will then write back with our best answers about how one might proceed in such a case. Your case and our response will be published in Clinical Psychiatry News. Please limit your case description to 250 words and include the following details:

1. Patient’s presenting problem or reason for the visit.

2. Patient’s age and gender.

3. Indicators of the patient’s identity – self-identified race/ethnicity, culture, religion/spirituality, socioeconomic status, education, among other variables.

4. Patient’s living situation, family composition, and genogram information (if available).

5. Patient’s geographic location (rural, suburban, urban) and occupation.

6. Patient’s and family’s degree of participation in their identified culture.

7. Questions of the individual submitting the case, including concerns about the role of the family and culture in the case, diagnosis, and treatment planning.

8. Please follow local ethical requirements, disguise the case to protect confidentiality and attend to HIPAA requirements, so that patients or family members reading the article would not recognize themselves.

Additional information might be requested, and editing of the case, questions, and commentary might be needed prior to final publication.

Editor’s Note: This is the third installment of Curbside Consult, written by two Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry (GAP) committees – the Committee on Family Psychiatry and the Committee on Cultural Psychiatry.

Erica is a 19-year-old woman from an ethnically mixed background. Her father is an African American retired U.S. military officer who met her mother while he was stationed in Japan, where her mother was born and raised. Erica lived in Japan until she was 8, when the family moved to Seattle, and her father began a new career in a large company.

At age 10, she began to have episodes during which she felt her heart racing, was short of breath, and was diaphoretic. These episodes often took place when the family went out to large public spaces, like a shopping mall, and she would be separated from her parents. They increased in frequency until she was taken to a pediatrician and saw a counselor. Her panic symptoms gradually disappeared during high school, but since starting college and moving away from home, she has felt lost in her environment, and feels as though no one understands her background and upbringing. For example, she abruptly left the first college party she attended, feeling that “everybody had met everybody already and nobody noticed me; maybe they don’t like the way I look.” She has had a return of panic episodes that are now more frequent, coming on without warning, and they have begun to wake her from sleep.

Discussion

Incorporating a family and culture lens to the case can improve assessment and treatment planning. Given the brevity of the case description, many of our recommendations focus on obtaining additional information. It is also important to rule out any medical conditions that could be causing her symptoms. Finally, since great heterogeneity exists within every culture, the clinician should investigate the meanings associated with specific cultural backgrounds for each person to avoid stereotyping that would interfere with an accurate assessment and treatment plan.

Possible cultural conflicts

Although the identified patient in this case is the young woman, the number of culture- and family-related stresses experienced by each member of her family cannot be overstated. The family is truly multicultural, in every sense of the word. Many Americans associate the word “culture” with the influence of race, ethnicity, and country of origin, but the term encompasses many other aspects of the family’s background as well, including the father’s immersion in military culture as an officer of color, the culture of American ex-pats in Japan and of Japanese immigrants to the West Coast of the United States, multiracial children’s adaptations to Japanese and state schools, and U.S. corporate culture. Every member of the family has therefore had to adapt to many cultural transitions. All of these moves require new relationships with the dominant culture and immediate community, which increases stresses within the family as well as between the family and the broader society in which they live. Conflict between the parents increases vigilance and anxiety in children, and since Erica does not have siblings, the likelihood of being caught in a conflict between both parent would be high.