User login

Implementation of distress screening in an oncology setting

The recommendations of numerous groups, such as the Institute of Medicine and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, have resulted in the first regulatory standard on distress screening in oncology implemented in 2015 by the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer. This practice-changing standard promises to result in better quality cancer care, but presents unique challenges to many centers struggling to provide high-quality practical assessment and management of distress. The current paper reviews the history behind the CoC standard, identifies the most prevalent symptoms underlying distress, and discusses the importance of distress screening. We also review some commonly used instruments for assessing distress, and address barriers to implementation of screening and management.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

The recommendations of numerous groups, such as the Institute of Medicine and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, have resulted in the first regulatory standard on distress screening in oncology implemented in 2015 by the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer. This practice-changing standard promises to result in better quality cancer care, but presents unique challenges to many centers struggling to provide high-quality practical assessment and management of distress. The current paper reviews the history behind the CoC standard, identifies the most prevalent symptoms underlying distress, and discusses the importance of distress screening. We also review some commonly used instruments for assessing distress, and address barriers to implementation of screening and management.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

The recommendations of numerous groups, such as the Institute of Medicine and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, have resulted in the first regulatory standard on distress screening in oncology implemented in 2015 by the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer. This practice-changing standard promises to result in better quality cancer care, but presents unique challenges to many centers struggling to provide high-quality practical assessment and management of distress. The current paper reviews the history behind the CoC standard, identifies the most prevalent symptoms underlying distress, and discusses the importance of distress screening. We also review some commonly used instruments for assessing distress, and address barriers to implementation of screening and management.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Benchmarks are coming

We have actively avoided benchmarks in medicine since time immemorial. There is a strong argument that rote, one-size-fits-all parameters for care medicine are bad for our patients, and obviously they interfere with our flexibility in dealing with complex obscure diseases. This flexibility is critical in dermatology, where we deal with over 3,000 diseases, and there truly is more art than science involved in treating some of them.

Nonetheless, here come the benchmarks. Since we have not provided them, they have been provided for us. Look no further than United Health Care’s Optum program, or Cigna’s star ratings, both of which rank on average costs, without regard to subspecialty or intensity of disease.

Benchmarks have proven useful in industry and have improved quality there. I expect they will be most annoying to practicing physicians. There are also great variations in practice patterns we must make sure are accounted for. A pediatric dermatologist, for example, does radically fewer skin biopsies than a Mohs surgeon, and diagnoses many fewer malignancies. However, some things are inexplicable, even after opening two standard deviations, and you need to be aware they may be coming.

The Medicare data release was an eye opener for many. This information is readily available on multiple web sites in numeric and graphic display. You should look yourself and your “peers” up on the Wall Street Journal or ProPublicaweb sites. For example, it is hard to fathom how every closure can be a flap, or how every Mohs case is four stages. Or even more bizarre, how you can do Mohs and never have a second stage. It is hard to understand how most dermatologists have a certain number of skin biopsies or shave excisions per patient encounter and others ten times as many. With this in mind, I encourage all of you to look at your own ratios of procedures compared to your peers. Recall that Medicare data lag two years before publication. Areas that could be under scrutiny include:

• Number of skin biopsies per encounter.

• Number of repeat patient encounters per year.

• Number of lesion destructions per patient.

• Ratio of first to additional layers of Mohs.

• Number of Mohs procedures on trunk and extremities, compared with head and neck.

• Percentage of closures done with adjacent tissue transfers.

• Number of shave excisions per patient.

• Number of complex closures, compared with layered closures, particularly on the trunk and extremities.

• Number of diagnostic frozen sections.

• Frequency of use of special stains on pathology specimens.

We need to be actively involved in the development of these so that we are not forced into a one size fits all mold. I expect this will start with the private insurers, including Medicare advantage plans, since they have real time data analysis, and a keen desire to save money. These “benchmarks” will be a work in progress and will infuriate some of you. They are, however, more credible, and better, than the current state of affairs, where insurance companies rank you by simply averaging your costs under your tax identification number.

So heads up, benchmarks are coming your way. Review your own public data, compared with your peers and see if you are an outlier, and if so, ponder the reason why. It is not too late to take corrective action.

Dr. Coldiron is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. He is currently in private practice, but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. Reach him at [email protected].

We have actively avoided benchmarks in medicine since time immemorial. There is a strong argument that rote, one-size-fits-all parameters for care medicine are bad for our patients, and obviously they interfere with our flexibility in dealing with complex obscure diseases. This flexibility is critical in dermatology, where we deal with over 3,000 diseases, and there truly is more art than science involved in treating some of them.

Nonetheless, here come the benchmarks. Since we have not provided them, they have been provided for us. Look no further than United Health Care’s Optum program, or Cigna’s star ratings, both of which rank on average costs, without regard to subspecialty or intensity of disease.

Benchmarks have proven useful in industry and have improved quality there. I expect they will be most annoying to practicing physicians. There are also great variations in practice patterns we must make sure are accounted for. A pediatric dermatologist, for example, does radically fewer skin biopsies than a Mohs surgeon, and diagnoses many fewer malignancies. However, some things are inexplicable, even after opening two standard deviations, and you need to be aware they may be coming.

The Medicare data release was an eye opener for many. This information is readily available on multiple web sites in numeric and graphic display. You should look yourself and your “peers” up on the Wall Street Journal or ProPublicaweb sites. For example, it is hard to fathom how every closure can be a flap, or how every Mohs case is four stages. Or even more bizarre, how you can do Mohs and never have a second stage. It is hard to understand how most dermatologists have a certain number of skin biopsies or shave excisions per patient encounter and others ten times as many. With this in mind, I encourage all of you to look at your own ratios of procedures compared to your peers. Recall that Medicare data lag two years before publication. Areas that could be under scrutiny include:

• Number of skin biopsies per encounter.

• Number of repeat patient encounters per year.

• Number of lesion destructions per patient.

• Ratio of first to additional layers of Mohs.

• Number of Mohs procedures on trunk and extremities, compared with head and neck.

• Percentage of closures done with adjacent tissue transfers.

• Number of shave excisions per patient.

• Number of complex closures, compared with layered closures, particularly on the trunk and extremities.

• Number of diagnostic frozen sections.

• Frequency of use of special stains on pathology specimens.

We need to be actively involved in the development of these so that we are not forced into a one size fits all mold. I expect this will start with the private insurers, including Medicare advantage plans, since they have real time data analysis, and a keen desire to save money. These “benchmarks” will be a work in progress and will infuriate some of you. They are, however, more credible, and better, than the current state of affairs, where insurance companies rank you by simply averaging your costs under your tax identification number.

So heads up, benchmarks are coming your way. Review your own public data, compared with your peers and see if you are an outlier, and if so, ponder the reason why. It is not too late to take corrective action.

Dr. Coldiron is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. He is currently in private practice, but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. Reach him at [email protected].

We have actively avoided benchmarks in medicine since time immemorial. There is a strong argument that rote, one-size-fits-all parameters for care medicine are bad for our patients, and obviously they interfere with our flexibility in dealing with complex obscure diseases. This flexibility is critical in dermatology, where we deal with over 3,000 diseases, and there truly is more art than science involved in treating some of them.

Nonetheless, here come the benchmarks. Since we have not provided them, they have been provided for us. Look no further than United Health Care’s Optum program, or Cigna’s star ratings, both of which rank on average costs, without regard to subspecialty or intensity of disease.

Benchmarks have proven useful in industry and have improved quality there. I expect they will be most annoying to practicing physicians. There are also great variations in practice patterns we must make sure are accounted for. A pediatric dermatologist, for example, does radically fewer skin biopsies than a Mohs surgeon, and diagnoses many fewer malignancies. However, some things are inexplicable, even after opening two standard deviations, and you need to be aware they may be coming.

The Medicare data release was an eye opener for many. This information is readily available on multiple web sites in numeric and graphic display. You should look yourself and your “peers” up on the Wall Street Journal or ProPublicaweb sites. For example, it is hard to fathom how every closure can be a flap, or how every Mohs case is four stages. Or even more bizarre, how you can do Mohs and never have a second stage. It is hard to understand how most dermatologists have a certain number of skin biopsies or shave excisions per patient encounter and others ten times as many. With this in mind, I encourage all of you to look at your own ratios of procedures compared to your peers. Recall that Medicare data lag two years before publication. Areas that could be under scrutiny include:

• Number of skin biopsies per encounter.

• Number of repeat patient encounters per year.

• Number of lesion destructions per patient.

• Ratio of first to additional layers of Mohs.

• Number of Mohs procedures on trunk and extremities, compared with head and neck.

• Percentage of closures done with adjacent tissue transfers.

• Number of shave excisions per patient.

• Number of complex closures, compared with layered closures, particularly on the trunk and extremities.

• Number of diagnostic frozen sections.

• Frequency of use of special stains on pathology specimens.

We need to be actively involved in the development of these so that we are not forced into a one size fits all mold. I expect this will start with the private insurers, including Medicare advantage plans, since they have real time data analysis, and a keen desire to save money. These “benchmarks” will be a work in progress and will infuriate some of you. They are, however, more credible, and better, than the current state of affairs, where insurance companies rank you by simply averaging your costs under your tax identification number.

So heads up, benchmarks are coming your way. Review your own public data, compared with your peers and see if you are an outlier, and if so, ponder the reason why. It is not too late to take corrective action.

Dr. Coldiron is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. He is currently in private practice, but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. Reach him at [email protected].

What Is Your Diagnosis? Herpes Zoster

The Diagnosis: Herpes Zoster

Herpes zoster is a common infection that clinically presents with moderate to intense pain in the involved dermatome (1–3 days before the outbreak1) followed by a unilateral dermatomal eruption. The most common sites of involvement include the trunk (dermatomes T3–L2) and upper face (dermatome V1).2 Herpes zoster characteristically begins as erythematous macules and papules that progress to vesicles and sometimes pustules, which subsequently crust over (7–10 days after the initial outbreak).1 Regional lymphadenopathy is present in most cases. Due to the classic presentation of herpes zoster, clinical diagnosis is the mainstay for most cases. Although it can present in any age group, herpes zoster is most commonly associated with advancing age.3

During the course of primary varicella infection, the herpes virus spreads from infected lesions to the contiguous endings of sensory nerves and travels to the dorsal root ganglion cells where it remains latent.1 It is hypothesized that cell-mediated immunity suppresses viral activity and maintains viral latency. A decline in varicella zoster virus–specific cell-mediated immunity can result in reactivation of the latent virus.1 The virus is then transported to the skin from the dorsal root ganglion via myelinated nerves, which terminate at the isthmus of hair follicles, and subsequent infection of the folliculosebaceous unit occurs.4

Laboratory tests that can assist in the diagnosis of herpes zoster, especially atypical cases, include Tzanck smear and viral culture of the vesicle fluid.1 When vesicles are not present, biopsy of the lesion followed by immunohistochemical staining and polymerase chain reaction assay can aid in the diagnosis. The differential diagnosis for our patient included pseudolymphoma, herpes simplex virus, lymphomatoid papulosis, sarcoidosis, trigeminal trophic syndrome, and Sweet syndrome.

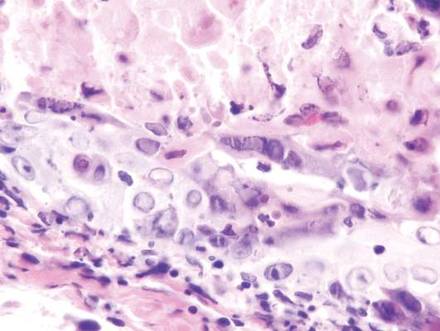

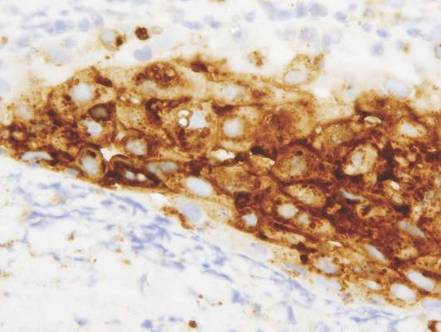

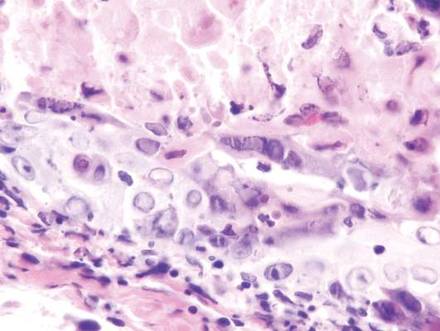

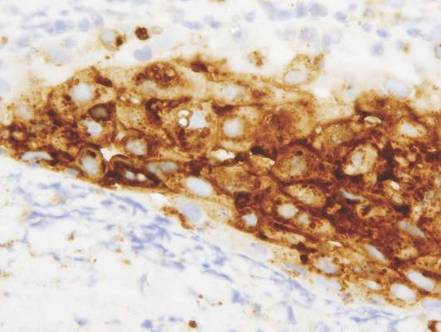

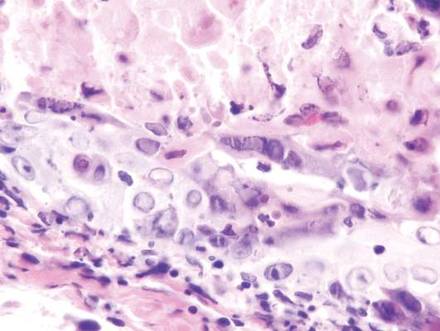

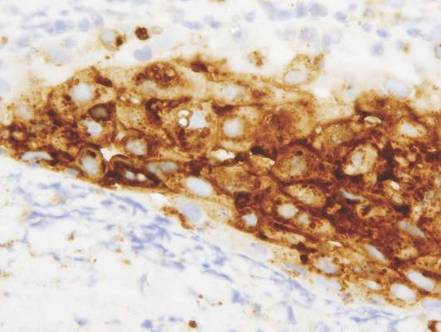

Vesicles were not present in our patient, but the dermatomal nature of the eruption and the pain she experienced made the clinical scenario suspicious for herpes zoster. A 4-mm punch biopsy of a single folliculosebaceous unit revealed herpetic, cytopathic features including prominent keratinocyte necrosis involving sebaceous, isthmic, and infundibular epithelium; ballooning of epithelial cells with steel gray nuclei; and multinucleation with nuclear molding (Figure 1). Strong nuclear and cytoplasmic staining was seen in the affected keratinocytes under anti–varicella zoster virus immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 2). Staining for herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 was negative. Within days of starting valacyclovir 1000 mg (every 8 hours for 1 week), the patient’s symptoms resolved.

|

| |

|

|

Atypical presentations of herpes zoster (eg, presentations that are not completely dermatomal) are becoming more common. Herpetic infections should always be in the differential diagnosis for cutaneous ulcerations. Misdiagnosis of herpes zoster due to atypical features is common and can delay prompt and adequate treatment.

- Rockley PF, Tyring SK. Pathophysiology and clinical manifestations of varicella zoster virus infections. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:227-232.

- Chen TM, George S, Woodruff CA, et al. Clinical manifestations of varicella-zoster virus infection. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:267-282.

- Hope-Simpson RE. The nature of herpes zoster: a long-term study and a new hypothesis. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:9-20.

- Walsh N, Boutilier R, Glasgow D, et al. Exclusive involvement of folliculosebaceous units by herpes: a reflection of early herpes zoster. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:189-194.

The Diagnosis: Herpes Zoster

Herpes zoster is a common infection that clinically presents with moderate to intense pain in the involved dermatome (1–3 days before the outbreak1) followed by a unilateral dermatomal eruption. The most common sites of involvement include the trunk (dermatomes T3–L2) and upper face (dermatome V1).2 Herpes zoster characteristically begins as erythematous macules and papules that progress to vesicles and sometimes pustules, which subsequently crust over (7–10 days after the initial outbreak).1 Regional lymphadenopathy is present in most cases. Due to the classic presentation of herpes zoster, clinical diagnosis is the mainstay for most cases. Although it can present in any age group, herpes zoster is most commonly associated with advancing age.3

During the course of primary varicella infection, the herpes virus spreads from infected lesions to the contiguous endings of sensory nerves and travels to the dorsal root ganglion cells where it remains latent.1 It is hypothesized that cell-mediated immunity suppresses viral activity and maintains viral latency. A decline in varicella zoster virus–specific cell-mediated immunity can result in reactivation of the latent virus.1 The virus is then transported to the skin from the dorsal root ganglion via myelinated nerves, which terminate at the isthmus of hair follicles, and subsequent infection of the folliculosebaceous unit occurs.4

Laboratory tests that can assist in the diagnosis of herpes zoster, especially atypical cases, include Tzanck smear and viral culture of the vesicle fluid.1 When vesicles are not present, biopsy of the lesion followed by immunohistochemical staining and polymerase chain reaction assay can aid in the diagnosis. The differential diagnosis for our patient included pseudolymphoma, herpes simplex virus, lymphomatoid papulosis, sarcoidosis, trigeminal trophic syndrome, and Sweet syndrome.

Vesicles were not present in our patient, but the dermatomal nature of the eruption and the pain she experienced made the clinical scenario suspicious for herpes zoster. A 4-mm punch biopsy of a single folliculosebaceous unit revealed herpetic, cytopathic features including prominent keratinocyte necrosis involving sebaceous, isthmic, and infundibular epithelium; ballooning of epithelial cells with steel gray nuclei; and multinucleation with nuclear molding (Figure 1). Strong nuclear and cytoplasmic staining was seen in the affected keratinocytes under anti–varicella zoster virus immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 2). Staining for herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 was negative. Within days of starting valacyclovir 1000 mg (every 8 hours for 1 week), the patient’s symptoms resolved.

|

| |

|

|

Atypical presentations of herpes zoster (eg, presentations that are not completely dermatomal) are becoming more common. Herpetic infections should always be in the differential diagnosis for cutaneous ulcerations. Misdiagnosis of herpes zoster due to atypical features is common and can delay prompt and adequate treatment.

The Diagnosis: Herpes Zoster

Herpes zoster is a common infection that clinically presents with moderate to intense pain in the involved dermatome (1–3 days before the outbreak1) followed by a unilateral dermatomal eruption. The most common sites of involvement include the trunk (dermatomes T3–L2) and upper face (dermatome V1).2 Herpes zoster characteristically begins as erythematous macules and papules that progress to vesicles and sometimes pustules, which subsequently crust over (7–10 days after the initial outbreak).1 Regional lymphadenopathy is present in most cases. Due to the classic presentation of herpes zoster, clinical diagnosis is the mainstay for most cases. Although it can present in any age group, herpes zoster is most commonly associated with advancing age.3

During the course of primary varicella infection, the herpes virus spreads from infected lesions to the contiguous endings of sensory nerves and travels to the dorsal root ganglion cells where it remains latent.1 It is hypothesized that cell-mediated immunity suppresses viral activity and maintains viral latency. A decline in varicella zoster virus–specific cell-mediated immunity can result in reactivation of the latent virus.1 The virus is then transported to the skin from the dorsal root ganglion via myelinated nerves, which terminate at the isthmus of hair follicles, and subsequent infection of the folliculosebaceous unit occurs.4

Laboratory tests that can assist in the diagnosis of herpes zoster, especially atypical cases, include Tzanck smear and viral culture of the vesicle fluid.1 When vesicles are not present, biopsy of the lesion followed by immunohistochemical staining and polymerase chain reaction assay can aid in the diagnosis. The differential diagnosis for our patient included pseudolymphoma, herpes simplex virus, lymphomatoid papulosis, sarcoidosis, trigeminal trophic syndrome, and Sweet syndrome.

Vesicles were not present in our patient, but the dermatomal nature of the eruption and the pain she experienced made the clinical scenario suspicious for herpes zoster. A 4-mm punch biopsy of a single folliculosebaceous unit revealed herpetic, cytopathic features including prominent keratinocyte necrosis involving sebaceous, isthmic, and infundibular epithelium; ballooning of epithelial cells with steel gray nuclei; and multinucleation with nuclear molding (Figure 1). Strong nuclear and cytoplasmic staining was seen in the affected keratinocytes under anti–varicella zoster virus immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 2). Staining for herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 was negative. Within days of starting valacyclovir 1000 mg (every 8 hours for 1 week), the patient’s symptoms resolved.

|

| |

|

|

Atypical presentations of herpes zoster (eg, presentations that are not completely dermatomal) are becoming more common. Herpetic infections should always be in the differential diagnosis for cutaneous ulcerations. Misdiagnosis of herpes zoster due to atypical features is common and can delay prompt and adequate treatment.

- Rockley PF, Tyring SK. Pathophysiology and clinical manifestations of varicella zoster virus infections. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:227-232.

- Chen TM, George S, Woodruff CA, et al. Clinical manifestations of varicella-zoster virus infection. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:267-282.

- Hope-Simpson RE. The nature of herpes zoster: a long-term study and a new hypothesis. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:9-20.

- Walsh N, Boutilier R, Glasgow D, et al. Exclusive involvement of folliculosebaceous units by herpes: a reflection of early herpes zoster. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:189-194.

- Rockley PF, Tyring SK. Pathophysiology and clinical manifestations of varicella zoster virus infections. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:227-232.

- Chen TM, George S, Woodruff CA, et al. Clinical manifestations of varicella-zoster virus infection. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:267-282.

- Hope-Simpson RE. The nature of herpes zoster: a long-term study and a new hypothesis. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:9-20.

- Walsh N, Boutilier R, Glasgow D, et al. Exclusive involvement of folliculosebaceous units by herpes: a reflection of early herpes zoster. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:189-194.

A 32-year-old woman with no remarkable medical history presented with a progressively worsening erythematous and edematous plaque on the right cheek of 8 days’ duration. She had previously been treated by her primary care physician with cephalexin for 3 days and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for 2 days, which resulted in “flattening” of the plaque, but the lesion did not resolve. She was referred to our dermatology clinic for further evaluation. She denied any trauma to the cheek or scratching of the lesion. On physical examination, a 2-cm pink, erythematous, edematous plaque with a central eschar was noted on the right cheek with crusting of the right nasal wall.

Does the Mediterranean diet reduce the risk of breast cancer?

The Mediterranean diet, characterized by an emphasis on plant foods, fish, and olive oil, is known to have cardiovascular benefits. This study by Toledo and colleagues is a secondary analysis of a large randomized trial that assessed the impact of the Mediterranean diet versus a recommended low-fat diet in patients at elevated risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD). The larger trial was stopped after 4.8 years of follow-up, when findings of early cardiovascular benefit became evident.

The 4,282 women in the trial, all of whom were white, were randomly allocated to one of the following groups:

- Mediterranean diet supplemented by EVOO. Participants were given 1 L of EVOO a week for the study duration. At baseline and quarterly thereafter, dieticians ran individual and group sessions. In individual sessions, participants completed a 14-item dietary screening questionnaire to assess adherence to the diet.

- Mediterranean diet supplemented by mixed nuts. Participants were given 30 g of mixed nuts per day (15 g walnuts, 7.5 g hazelnuts, and 7.5 g almonds). They also took part in individual and group sessions at baseline and quarterly thereafter, and completed the same screening questionnaire as the first group.

- A control group. Participants were advised to reduce dietary fat. They also underwent dietary training at the baseline visit and completed the 14-item screener. Thereafter, during the first 3 years of the trial, they received annual mailing of a leaflet explaining the low-fat diet. In 2006, however, the protocol was amended to include personalized advice and quarterly group sessions, with use of a separate 9-item dietary screener. The control group also received gifts of nonfood items as incentives.

Physical activity was not promoted in any group.

Findings of the trialAfter a median follow-up of 4.8 years, 35 confirmed cases of invasive breast cancer occurred among participants in the trial, who ranged in age from 60 to 80 years. The observed rate (per 1,000 person-years) of breast cancer was 1.1 for women following the Mediterranean diet supplemented with EVOO, 1.8 for women on the diet supplemented by mixed nuts, and 2.9 for the control group.

Women allocated to the Mediterranean diet with EVOO had a 62% reduced risk of invasive breast cancer (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.16–0.87). Women allocated to the same diet with mixed nuts had a 38% reduced risk of breast cancer, but this finding was not statistically significant.

Note that women in the control group failed to reduce their total fat intake substantially, even though they were advised to do so, although saturated fat intake remained below 10%.

Strengths and limitations of the trialAlthough the incidence of breast cancer is lower in Mediterranean countries, this is the first randomized trial to assess the impact of the Mediterranean diet on risk of this disease.

Because breast cancer was not the primary outcome, investigators were unable to verify if or when participants underwent mammography screening. However, randomization resulted in large groups of participants between whom mammographic status likely was comparable.

The lack of ethnic diversity represents another limitation.

Toledo and colleagues describe differences between olive oils in general and EVOO, including biologic mechanisms that might result in breast cancer prophylaxis.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICEGiven the known cardiovascular benefits, it is reasonable to suggest to our menopausal patients that a Mediterranean diet with EVOO may reduce their risk of breast cancer.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The Mediterranean diet, characterized by an emphasis on plant foods, fish, and olive oil, is known to have cardiovascular benefits. This study by Toledo and colleagues is a secondary analysis of a large randomized trial that assessed the impact of the Mediterranean diet versus a recommended low-fat diet in patients at elevated risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD). The larger trial was stopped after 4.8 years of follow-up, when findings of early cardiovascular benefit became evident.

The 4,282 women in the trial, all of whom were white, were randomly allocated to one of the following groups:

- Mediterranean diet supplemented by EVOO. Participants were given 1 L of EVOO a week for the study duration. At baseline and quarterly thereafter, dieticians ran individual and group sessions. In individual sessions, participants completed a 14-item dietary screening questionnaire to assess adherence to the diet.

- Mediterranean diet supplemented by mixed nuts. Participants were given 30 g of mixed nuts per day (15 g walnuts, 7.5 g hazelnuts, and 7.5 g almonds). They also took part in individual and group sessions at baseline and quarterly thereafter, and completed the same screening questionnaire as the first group.

- A control group. Participants were advised to reduce dietary fat. They also underwent dietary training at the baseline visit and completed the 14-item screener. Thereafter, during the first 3 years of the trial, they received annual mailing of a leaflet explaining the low-fat diet. In 2006, however, the protocol was amended to include personalized advice and quarterly group sessions, with use of a separate 9-item dietary screener. The control group also received gifts of nonfood items as incentives.

Physical activity was not promoted in any group.

Findings of the trialAfter a median follow-up of 4.8 years, 35 confirmed cases of invasive breast cancer occurred among participants in the trial, who ranged in age from 60 to 80 years. The observed rate (per 1,000 person-years) of breast cancer was 1.1 for women following the Mediterranean diet supplemented with EVOO, 1.8 for women on the diet supplemented by mixed nuts, and 2.9 for the control group.

Women allocated to the Mediterranean diet with EVOO had a 62% reduced risk of invasive breast cancer (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.16–0.87). Women allocated to the same diet with mixed nuts had a 38% reduced risk of breast cancer, but this finding was not statistically significant.

Note that women in the control group failed to reduce their total fat intake substantially, even though they were advised to do so, although saturated fat intake remained below 10%.

Strengths and limitations of the trialAlthough the incidence of breast cancer is lower in Mediterranean countries, this is the first randomized trial to assess the impact of the Mediterranean diet on risk of this disease.

Because breast cancer was not the primary outcome, investigators were unable to verify if or when participants underwent mammography screening. However, randomization resulted in large groups of participants between whom mammographic status likely was comparable.

The lack of ethnic diversity represents another limitation.

Toledo and colleagues describe differences between olive oils in general and EVOO, including biologic mechanisms that might result in breast cancer prophylaxis.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICEGiven the known cardiovascular benefits, it is reasonable to suggest to our menopausal patients that a Mediterranean diet with EVOO may reduce their risk of breast cancer.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The Mediterranean diet, characterized by an emphasis on plant foods, fish, and olive oil, is known to have cardiovascular benefits. This study by Toledo and colleagues is a secondary analysis of a large randomized trial that assessed the impact of the Mediterranean diet versus a recommended low-fat diet in patients at elevated risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD). The larger trial was stopped after 4.8 years of follow-up, when findings of early cardiovascular benefit became evident.

The 4,282 women in the trial, all of whom were white, were randomly allocated to one of the following groups:

- Mediterranean diet supplemented by EVOO. Participants were given 1 L of EVOO a week for the study duration. At baseline and quarterly thereafter, dieticians ran individual and group sessions. In individual sessions, participants completed a 14-item dietary screening questionnaire to assess adherence to the diet.

- Mediterranean diet supplemented by mixed nuts. Participants were given 30 g of mixed nuts per day (15 g walnuts, 7.5 g hazelnuts, and 7.5 g almonds). They also took part in individual and group sessions at baseline and quarterly thereafter, and completed the same screening questionnaire as the first group.

- A control group. Participants were advised to reduce dietary fat. They also underwent dietary training at the baseline visit and completed the 14-item screener. Thereafter, during the first 3 years of the trial, they received annual mailing of a leaflet explaining the low-fat diet. In 2006, however, the protocol was amended to include personalized advice and quarterly group sessions, with use of a separate 9-item dietary screener. The control group also received gifts of nonfood items as incentives.

Physical activity was not promoted in any group.

Findings of the trialAfter a median follow-up of 4.8 years, 35 confirmed cases of invasive breast cancer occurred among participants in the trial, who ranged in age from 60 to 80 years. The observed rate (per 1,000 person-years) of breast cancer was 1.1 for women following the Mediterranean diet supplemented with EVOO, 1.8 for women on the diet supplemented by mixed nuts, and 2.9 for the control group.

Women allocated to the Mediterranean diet with EVOO had a 62% reduced risk of invasive breast cancer (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.16–0.87). Women allocated to the same diet with mixed nuts had a 38% reduced risk of breast cancer, but this finding was not statistically significant.

Note that women in the control group failed to reduce their total fat intake substantially, even though they were advised to do so, although saturated fat intake remained below 10%.

Strengths and limitations of the trialAlthough the incidence of breast cancer is lower in Mediterranean countries, this is the first randomized trial to assess the impact of the Mediterranean diet on risk of this disease.

Because breast cancer was not the primary outcome, investigators were unable to verify if or when participants underwent mammography screening. However, randomization resulted in large groups of participants between whom mammographic status likely was comparable.

The lack of ethnic diversity represents another limitation.

Toledo and colleagues describe differences between olive oils in general and EVOO, including biologic mechanisms that might result in breast cancer prophylaxis.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICEGiven the known cardiovascular benefits, it is reasonable to suggest to our menopausal patients that a Mediterranean diet with EVOO may reduce their risk of breast cancer.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Pregnancy did not increase Hodgkin lymphoma relapse rate

Women who become pregnant while in remission from Hodgkin lymphoma were not at increased risk for cancer relapse, according to an analysis of data from Swedish health care registries combined with medical records.

Of 449 women who were diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma between 1992 and 2009, 144 (32%) became pregnant during follow-up, which started 6 months after diagnosis, when the disease was assumed to be in remission. Only one of these women experienced a pregnancy-associated relapse, which was defined as a relapse occurring during pregnancy or within 5 years of delivery. Of the women who did not become pregnant, 46 had a relapse.

The effect of pregnancy on relapse has been a concern of patients and clinicians, but “our findings suggest that the risk of pregnancy-associated relapse does not need to be taken into account in family planning for women whose Hodgkin lymphoma is in remission,” said Caroline E. Weibull of Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, and her associates.

The researchers used the nationwide “Swedish Cancer Register” to identify all cases of Hodgkin lymphoma (reporting is mandatory) and merged this data with clinical information from other registries and medical records.

The pregnancy rates were similar among women who had limited- and advanced-stage disease and among women with and without B symptoms at diagnosis – a finding that negates consideration of a so-called “healthy mother effect” in protecting against relapse, they wrote (J Clin Onc. 2015 Dec. 14 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.63.3446]).

The researchers also found that the absolute risk for relapse was highest in the first 2-3 years after diagnosis, which suggests that women should be advised, “if possible, to wait 2 years after cessation of treatment before becoming pregnant.” Additionally, the relapse rate more than doubled in women aged 30 years or older at diagnosis, compared with women aged 18-24 years at diagnosis – a finding consistent with previous research, they noted.

Women in the study were aged 18-40 at diagnosis. Follow-up ended on the date of relapse, the date of death, or at the end of 2010, whichever came first.

Women who become pregnant while in remission from Hodgkin lymphoma were not at increased risk for cancer relapse, according to an analysis of data from Swedish health care registries combined with medical records.

Of 449 women who were diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma between 1992 and 2009, 144 (32%) became pregnant during follow-up, which started 6 months after diagnosis, when the disease was assumed to be in remission. Only one of these women experienced a pregnancy-associated relapse, which was defined as a relapse occurring during pregnancy or within 5 years of delivery. Of the women who did not become pregnant, 46 had a relapse.

The effect of pregnancy on relapse has been a concern of patients and clinicians, but “our findings suggest that the risk of pregnancy-associated relapse does not need to be taken into account in family planning for women whose Hodgkin lymphoma is in remission,” said Caroline E. Weibull of Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, and her associates.

The researchers used the nationwide “Swedish Cancer Register” to identify all cases of Hodgkin lymphoma (reporting is mandatory) and merged this data with clinical information from other registries and medical records.

The pregnancy rates were similar among women who had limited- and advanced-stage disease and among women with and without B symptoms at diagnosis – a finding that negates consideration of a so-called “healthy mother effect” in protecting against relapse, they wrote (J Clin Onc. 2015 Dec. 14 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.63.3446]).

The researchers also found that the absolute risk for relapse was highest in the first 2-3 years after diagnosis, which suggests that women should be advised, “if possible, to wait 2 years after cessation of treatment before becoming pregnant.” Additionally, the relapse rate more than doubled in women aged 30 years or older at diagnosis, compared with women aged 18-24 years at diagnosis – a finding consistent with previous research, they noted.

Women in the study were aged 18-40 at diagnosis. Follow-up ended on the date of relapse, the date of death, or at the end of 2010, whichever came first.

Women who become pregnant while in remission from Hodgkin lymphoma were not at increased risk for cancer relapse, according to an analysis of data from Swedish health care registries combined with medical records.

Of 449 women who were diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma between 1992 and 2009, 144 (32%) became pregnant during follow-up, which started 6 months after diagnosis, when the disease was assumed to be in remission. Only one of these women experienced a pregnancy-associated relapse, which was defined as a relapse occurring during pregnancy or within 5 years of delivery. Of the women who did not become pregnant, 46 had a relapse.

The effect of pregnancy on relapse has been a concern of patients and clinicians, but “our findings suggest that the risk of pregnancy-associated relapse does not need to be taken into account in family planning for women whose Hodgkin lymphoma is in remission,” said Caroline E. Weibull of Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, and her associates.

The researchers used the nationwide “Swedish Cancer Register” to identify all cases of Hodgkin lymphoma (reporting is mandatory) and merged this data with clinical information from other registries and medical records.

The pregnancy rates were similar among women who had limited- and advanced-stage disease and among women with and without B symptoms at diagnosis – a finding that negates consideration of a so-called “healthy mother effect” in protecting against relapse, they wrote (J Clin Onc. 2015 Dec. 14 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.63.3446]).

The researchers also found that the absolute risk for relapse was highest in the first 2-3 years after diagnosis, which suggests that women should be advised, “if possible, to wait 2 years after cessation of treatment before becoming pregnant.” Additionally, the relapse rate more than doubled in women aged 30 years or older at diagnosis, compared with women aged 18-24 years at diagnosis – a finding consistent with previous research, they noted.

Women in the study were aged 18-40 at diagnosis. Follow-up ended on the date of relapse, the date of death, or at the end of 2010, whichever came first.

FROM JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Pregnancy did not increase the risk of relapse of Hodgkin lymphoma in a population-based study.

Major finding: Of 144 women who became pregnant 6 months or longer after diagnosis of Hodgkin lymphoma, 1 experienced a pregnancy-associated relapse.

Data source: Population-based study utilizing Swedish health care registries and medical records, in which 449 women with Hodgkin lymphoma diagnoses, and 47 relapses, were identified.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Swedish Cancer Society, the Strategic Research Program in Epidemiology at Karolinska Institutet, the Swedish Society for Medicine, and the Swedish Society for Medical Research.

Minimal residual disease predicts outcome of allogeneic HCT in acute myeloid leukemia

Patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) who are in remission but with minimal residual disease (MRD) detectable by multiparameter flow cytometry have outcomes similar to those of patients with morphologically detectable disease, and both groups have significantly worse outcomes than patients in MRD-negative remission.

“Is it time to move toward an MRD-based definition of CR [complete remission]? We believe so,” wrote Dr. Daisuke Araki of the University of Washington, Seattle, and colleagues. The researchers suggest that decision algorithms based on “the classic morphologic remission definition are not ideal. Our data support treatment algorithms that use MRD-based (i.e., patients in MRD-negative CR [versus] all other patients), rather than morphology-based disease assessments” (J Clin Oncol. 2015 Dec 12 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.63.3826]).

Three-year overall survival estimates for patients with active AML, patients in MRD-positive remission, and patients in MRD-negative remission were 23% (12%-35%), 26% (17%-37%), and 73% (66%-78%), respectively. Progression-free survival estimates showed a similar delineation between patients with morphologically detectable AML and MRD-positive remission compared with MRD-negative remission: 13% (5%-23%) for active AML, 12% (5%-21%) for MRD-positive remission, and 67% (61%-73%) for MRD-negative remission.

The retrospective analysis included 359 patients with AML treated with myeloablative hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center from 2006 to 2014. In total, 311 patients (87%) had morphologically determined CR (less than 5% bone marrow blasts). Of these, 76 patients (24%) had MRD by multiparameter flow cytometry (MRD-positive remission) and 235 (76%) had no flow cytometric evidence of MRD (MRD-negative remission). In the pre-HCT assessment, 48 patients (13%) had 5% or more bone marrow blasts and were classified as having active AML.

Even patients with the lowest detectable amount of MRD had significantly worse outcomes than did patients with no MRD. Among the patients with evidence of leukemia (those in MRD-positive remission and with classified active AML), researchers found no statistically significant differences in outcomes based on MRD levels (less than 0.5%, 0.5%-5%, and greater than 5% abnormal blasts). Sensitivity analysis with different cut points yielded similar findings.

However, in line with previous findings, the data show that a small but significant subset of patients with active leukemia at the time of HCT can achieve long-term disease control with myeloablative conditioning.

No significant associations were found between disease status and non-relapse mortality.

The investigators caution that the results do not necessarily demonstrate that HCT outcomes for patients in MRD-positive remission and those with active disease are identical, because the preparative regimens, in general, were different for the two groups.

Dr. Araki reported having no disclosures. Several of his coauthors reported ties to industry.

For patients in complete remission, with a risk profile that suggests HCT to cure acute myeloid leukemia, MRD should not be ignored. The inexpensive, relatively easy-to-assess analysis provides a sensitive and patient-specific risk indicator, adding information beyond cytogenetic risk class and underlying genetic abnormalities. The results from Araki et al. prompt new clinical studies and, perhaps, a new transplantation strategy. Patients in MRD-positive remission could be combined with patients with active disease in trials aimed primarily at reducing the risk of post-transplant relapse.

In acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), MRD refines individual risk assessment and is crucial to decision making regarding HCT. Its role in AML is similarly growing in importance.

HCT is a powerful therapy commonly prescribed for younger patients in CR with intermediate- and high-risk characteristics, but has significant downsides in terms of economic costs, acute and chronic toxicities, and above all, risk of transplant-related mortality, which averages just below 10%. Use of MRD may profoundly influence the treatment approach for AML by permitting a better definition of CR and risk class, and favoring better risk-adapted treatment strategies oriented to spared the risk of treatment-related mortality and transplant-related morbidity.

One additional note concerns the potential bias in positive results for successful late transplantation in MRD-negative patients (after 6-12 months from CR). Some of these patients may have been cured by prior chemotherapy, particularly if a patient tests negative for MRD soon after achieving CR and prior to HCT. New trials should address this bias by using predefined MRD time points from CR to HCT.

Dr. Renato Bassan is an oncologist at UOC Ematologia, Ospedale dell’Angelo, Mestre-Venezia, Italy. These remarks were part of an editorial accompanying a report in the Journal of Clinical Oncology (2015 Dec 12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.8907). Dr. Bassan reported ties to Mundipharma, ARIAD, Roche, and Amgen.

For patients in complete remission, with a risk profile that suggests HCT to cure acute myeloid leukemia, MRD should not be ignored. The inexpensive, relatively easy-to-assess analysis provides a sensitive and patient-specific risk indicator, adding information beyond cytogenetic risk class and underlying genetic abnormalities. The results from Araki et al. prompt new clinical studies and, perhaps, a new transplantation strategy. Patients in MRD-positive remission could be combined with patients with active disease in trials aimed primarily at reducing the risk of post-transplant relapse.

In acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), MRD refines individual risk assessment and is crucial to decision making regarding HCT. Its role in AML is similarly growing in importance.

HCT is a powerful therapy commonly prescribed for younger patients in CR with intermediate- and high-risk characteristics, but has significant downsides in terms of economic costs, acute and chronic toxicities, and above all, risk of transplant-related mortality, which averages just below 10%. Use of MRD may profoundly influence the treatment approach for AML by permitting a better definition of CR and risk class, and favoring better risk-adapted treatment strategies oriented to spared the risk of treatment-related mortality and transplant-related morbidity.

One additional note concerns the potential bias in positive results for successful late transplantation in MRD-negative patients (after 6-12 months from CR). Some of these patients may have been cured by prior chemotherapy, particularly if a patient tests negative for MRD soon after achieving CR and prior to HCT. New trials should address this bias by using predefined MRD time points from CR to HCT.

Dr. Renato Bassan is an oncologist at UOC Ematologia, Ospedale dell’Angelo, Mestre-Venezia, Italy. These remarks were part of an editorial accompanying a report in the Journal of Clinical Oncology (2015 Dec 12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.8907). Dr. Bassan reported ties to Mundipharma, ARIAD, Roche, and Amgen.

For patients in complete remission, with a risk profile that suggests HCT to cure acute myeloid leukemia, MRD should not be ignored. The inexpensive, relatively easy-to-assess analysis provides a sensitive and patient-specific risk indicator, adding information beyond cytogenetic risk class and underlying genetic abnormalities. The results from Araki et al. prompt new clinical studies and, perhaps, a new transplantation strategy. Patients in MRD-positive remission could be combined with patients with active disease in trials aimed primarily at reducing the risk of post-transplant relapse.

In acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), MRD refines individual risk assessment and is crucial to decision making regarding HCT. Its role in AML is similarly growing in importance.

HCT is a powerful therapy commonly prescribed for younger patients in CR with intermediate- and high-risk characteristics, but has significant downsides in terms of economic costs, acute and chronic toxicities, and above all, risk of transplant-related mortality, which averages just below 10%. Use of MRD may profoundly influence the treatment approach for AML by permitting a better definition of CR and risk class, and favoring better risk-adapted treatment strategies oriented to spared the risk of treatment-related mortality and transplant-related morbidity.

One additional note concerns the potential bias in positive results for successful late transplantation in MRD-negative patients (after 6-12 months from CR). Some of these patients may have been cured by prior chemotherapy, particularly if a patient tests negative for MRD soon after achieving CR and prior to HCT. New trials should address this bias by using predefined MRD time points from CR to HCT.

Dr. Renato Bassan is an oncologist at UOC Ematologia, Ospedale dell’Angelo, Mestre-Venezia, Italy. These remarks were part of an editorial accompanying a report in the Journal of Clinical Oncology (2015 Dec 12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.8907). Dr. Bassan reported ties to Mundipharma, ARIAD, Roche, and Amgen.

Patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) who are in remission but with minimal residual disease (MRD) detectable by multiparameter flow cytometry have outcomes similar to those of patients with morphologically detectable disease, and both groups have significantly worse outcomes than patients in MRD-negative remission.

“Is it time to move toward an MRD-based definition of CR [complete remission]? We believe so,” wrote Dr. Daisuke Araki of the University of Washington, Seattle, and colleagues. The researchers suggest that decision algorithms based on “the classic morphologic remission definition are not ideal. Our data support treatment algorithms that use MRD-based (i.e., patients in MRD-negative CR [versus] all other patients), rather than morphology-based disease assessments” (J Clin Oncol. 2015 Dec 12 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.63.3826]).

Three-year overall survival estimates for patients with active AML, patients in MRD-positive remission, and patients in MRD-negative remission were 23% (12%-35%), 26% (17%-37%), and 73% (66%-78%), respectively. Progression-free survival estimates showed a similar delineation between patients with morphologically detectable AML and MRD-positive remission compared with MRD-negative remission: 13% (5%-23%) for active AML, 12% (5%-21%) for MRD-positive remission, and 67% (61%-73%) for MRD-negative remission.

The retrospective analysis included 359 patients with AML treated with myeloablative hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center from 2006 to 2014. In total, 311 patients (87%) had morphologically determined CR (less than 5% bone marrow blasts). Of these, 76 patients (24%) had MRD by multiparameter flow cytometry (MRD-positive remission) and 235 (76%) had no flow cytometric evidence of MRD (MRD-negative remission). In the pre-HCT assessment, 48 patients (13%) had 5% or more bone marrow blasts and were classified as having active AML.

Even patients with the lowest detectable amount of MRD had significantly worse outcomes than did patients with no MRD. Among the patients with evidence of leukemia (those in MRD-positive remission and with classified active AML), researchers found no statistically significant differences in outcomes based on MRD levels (less than 0.5%, 0.5%-5%, and greater than 5% abnormal blasts). Sensitivity analysis with different cut points yielded similar findings.

However, in line with previous findings, the data show that a small but significant subset of patients with active leukemia at the time of HCT can achieve long-term disease control with myeloablative conditioning.

No significant associations were found between disease status and non-relapse mortality.

The investigators caution that the results do not necessarily demonstrate that HCT outcomes for patients in MRD-positive remission and those with active disease are identical, because the preparative regimens, in general, were different for the two groups.

Dr. Araki reported having no disclosures. Several of his coauthors reported ties to industry.

Patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) who are in remission but with minimal residual disease (MRD) detectable by multiparameter flow cytometry have outcomes similar to those of patients with morphologically detectable disease, and both groups have significantly worse outcomes than patients in MRD-negative remission.

“Is it time to move toward an MRD-based definition of CR [complete remission]? We believe so,” wrote Dr. Daisuke Araki of the University of Washington, Seattle, and colleagues. The researchers suggest that decision algorithms based on “the classic morphologic remission definition are not ideal. Our data support treatment algorithms that use MRD-based (i.e., patients in MRD-negative CR [versus] all other patients), rather than morphology-based disease assessments” (J Clin Oncol. 2015 Dec 12 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.63.3826]).

Three-year overall survival estimates for patients with active AML, patients in MRD-positive remission, and patients in MRD-negative remission were 23% (12%-35%), 26% (17%-37%), and 73% (66%-78%), respectively. Progression-free survival estimates showed a similar delineation between patients with morphologically detectable AML and MRD-positive remission compared with MRD-negative remission: 13% (5%-23%) for active AML, 12% (5%-21%) for MRD-positive remission, and 67% (61%-73%) for MRD-negative remission.

The retrospective analysis included 359 patients with AML treated with myeloablative hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center from 2006 to 2014. In total, 311 patients (87%) had morphologically determined CR (less than 5% bone marrow blasts). Of these, 76 patients (24%) had MRD by multiparameter flow cytometry (MRD-positive remission) and 235 (76%) had no flow cytometric evidence of MRD (MRD-negative remission). In the pre-HCT assessment, 48 patients (13%) had 5% or more bone marrow blasts and were classified as having active AML.

Even patients with the lowest detectable amount of MRD had significantly worse outcomes than did patients with no MRD. Among the patients with evidence of leukemia (those in MRD-positive remission and with classified active AML), researchers found no statistically significant differences in outcomes based on MRD levels (less than 0.5%, 0.5%-5%, and greater than 5% abnormal blasts). Sensitivity analysis with different cut points yielded similar findings.

However, in line with previous findings, the data show that a small but significant subset of patients with active leukemia at the time of HCT can achieve long-term disease control with myeloablative conditioning.

No significant associations were found between disease status and non-relapse mortality.

The investigators caution that the results do not necessarily demonstrate that HCT outcomes for patients in MRD-positive remission and those with active disease are identical, because the preparative regimens, in general, were different for the two groups.

Dr. Araki reported having no disclosures. Several of his coauthors reported ties to industry.

Key clinical point: Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) outcomes for patients in minimal residual disease (MRD)–positive remission were similar to outcomes of patients with morphologically detectable acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and significantly worse than outcomes of patients in MRD-negative remission.

Major finding: Three-year overall survival estimates for patients with active AML, patients in MRD-positive remission, and patients in MRD-negative remission were 23% (12%-35%), 26% (17%-37%), and 73% (66%-78%), respectively.

Data sources: A retrospective analysis of 359 patients with AML treated with myeloablative HCT at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center from 2006 to 2014.

Disclosures: Dr. Araki reported having no disclosures. Several of his coauthors reported ties to industry.

Early infection-related hospitalization portends poor breast cancer prognosis

SAN ANTONIO – Hospitalization for an infection within the first year following diagnosis of primary nonmetastatic breast cancer is a red flag for increased risk of subsequent development of distant metastases or breast cancer–related death, Judith S. Brand, Ph.D., reported at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

This increased risk for future adverse breast cancer outcomes was statistically significant and clinically meaningful for women hospitalized for respiratory tract or skin infections or sepsis. Those are the patients for whom particularly close monitoring for recurrence of breast cancer is warranted in the next 5 years, said Dr. Brand of the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm.

In contrast, hospitalization for a gastrointestinal or urinary tract infection didn’t achieve significance as an independent predictor of increased risk of adverse breast cancer outcomes.

Dr. Brand presented a prospective population-based study of 8,338 women diagnosed with stage I-III breast cancer in the Stockholm area during 2001-2008. During a median 4.9 years of follow-up after diagnosis, 720 women had an infection-related hospitalization, with the great majority of these events occurring during the first year.

The incidence of hospitalization for sepsis among breast cancer patients in their first year post diagnosis was 14-fold greater than in the general Swedish female population matched for age and year. Respiratory infections resulting in hospitalization were fourfold more frequent than in the general population, skin infections were eightfold more common, and GI infections were twice as common.

Infection-related hospitalizations had a strong and independent association with breast cancer mortality during follow-up, as seen in a multivariate analysis adjusted for age at diagnosis, comorbid conditions, infectious disease history, type of breast cancer therapy, and tumor characteristics including size, grade, hormone receptor status, and lymph node involvement.

Moreover, the risk of developing distant metastases was 50%-78% greater in breast cancer patients hospitalized for respiratory infection, sepsis, or skin infection, compared with breast cancer patients who didn’t have an infection-related hospitalization.

“We think the sepsis results are the most interesting findings,” Dr. Brand said in an interview. “Sepsis could be an expression of an immunosuppressed state. And sepsis itself can induce immunosuppression for a long time, which could trigger tumor growth. Animal studies have shown that in postseptic mice, tumor grows faster.”

Infection-related hospitalizations didn’t increase the future risk of locoregional recurrences.

Independent predictors of infection-related hospitalization included older age, comorbidities, markers indicative of greater tumor aggressiveness, and treatment with chemotherapy or axillary radiotherapy.

“This shows that the risk of infection-related hospitalizations is not only due to immunosuppression caused by chemotherapy, but that the characteristics of the tumor itself play a role, as do patient characteristics. This is the first epidemiologic study to show with very extensive data that all three elements contribute to the risk,” Dr. Brand said.

SAN ANTONIO – Hospitalization for an infection within the first year following diagnosis of primary nonmetastatic breast cancer is a red flag for increased risk of subsequent development of distant metastases or breast cancer–related death, Judith S. Brand, Ph.D., reported at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

This increased risk for future adverse breast cancer outcomes was statistically significant and clinically meaningful for women hospitalized for respiratory tract or skin infections or sepsis. Those are the patients for whom particularly close monitoring for recurrence of breast cancer is warranted in the next 5 years, said Dr. Brand of the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm.

In contrast, hospitalization for a gastrointestinal or urinary tract infection didn’t achieve significance as an independent predictor of increased risk of adverse breast cancer outcomes.

Dr. Brand presented a prospective population-based study of 8,338 women diagnosed with stage I-III breast cancer in the Stockholm area during 2001-2008. During a median 4.9 years of follow-up after diagnosis, 720 women had an infection-related hospitalization, with the great majority of these events occurring during the first year.

The incidence of hospitalization for sepsis among breast cancer patients in their first year post diagnosis was 14-fold greater than in the general Swedish female population matched for age and year. Respiratory infections resulting in hospitalization were fourfold more frequent than in the general population, skin infections were eightfold more common, and GI infections were twice as common.

Infection-related hospitalizations had a strong and independent association with breast cancer mortality during follow-up, as seen in a multivariate analysis adjusted for age at diagnosis, comorbid conditions, infectious disease history, type of breast cancer therapy, and tumor characteristics including size, grade, hormone receptor status, and lymph node involvement.

Moreover, the risk of developing distant metastases was 50%-78% greater in breast cancer patients hospitalized for respiratory infection, sepsis, or skin infection, compared with breast cancer patients who didn’t have an infection-related hospitalization.

“We think the sepsis results are the most interesting findings,” Dr. Brand said in an interview. “Sepsis could be an expression of an immunosuppressed state. And sepsis itself can induce immunosuppression for a long time, which could trigger tumor growth. Animal studies have shown that in postseptic mice, tumor grows faster.”

Infection-related hospitalizations didn’t increase the future risk of locoregional recurrences.

Independent predictors of infection-related hospitalization included older age, comorbidities, markers indicative of greater tumor aggressiveness, and treatment with chemotherapy or axillary radiotherapy.

“This shows that the risk of infection-related hospitalizations is not only due to immunosuppression caused by chemotherapy, but that the characteristics of the tumor itself play a role, as do patient characteristics. This is the first epidemiologic study to show with very extensive data that all three elements contribute to the risk,” Dr. Brand said.

SAN ANTONIO – Hospitalization for an infection within the first year following diagnosis of primary nonmetastatic breast cancer is a red flag for increased risk of subsequent development of distant metastases or breast cancer–related death, Judith S. Brand, Ph.D., reported at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

This increased risk for future adverse breast cancer outcomes was statistically significant and clinically meaningful for women hospitalized for respiratory tract or skin infections or sepsis. Those are the patients for whom particularly close monitoring for recurrence of breast cancer is warranted in the next 5 years, said Dr. Brand of the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm.

In contrast, hospitalization for a gastrointestinal or urinary tract infection didn’t achieve significance as an independent predictor of increased risk of adverse breast cancer outcomes.

Dr. Brand presented a prospective population-based study of 8,338 women diagnosed with stage I-III breast cancer in the Stockholm area during 2001-2008. During a median 4.9 years of follow-up after diagnosis, 720 women had an infection-related hospitalization, with the great majority of these events occurring during the first year.

The incidence of hospitalization for sepsis among breast cancer patients in their first year post diagnosis was 14-fold greater than in the general Swedish female population matched for age and year. Respiratory infections resulting in hospitalization were fourfold more frequent than in the general population, skin infections were eightfold more common, and GI infections were twice as common.

Infection-related hospitalizations had a strong and independent association with breast cancer mortality during follow-up, as seen in a multivariate analysis adjusted for age at diagnosis, comorbid conditions, infectious disease history, type of breast cancer therapy, and tumor characteristics including size, grade, hormone receptor status, and lymph node involvement.

Moreover, the risk of developing distant metastases was 50%-78% greater in breast cancer patients hospitalized for respiratory infection, sepsis, or skin infection, compared with breast cancer patients who didn’t have an infection-related hospitalization.

“We think the sepsis results are the most interesting findings,” Dr. Brand said in an interview. “Sepsis could be an expression of an immunosuppressed state. And sepsis itself can induce immunosuppression for a long time, which could trigger tumor growth. Animal studies have shown that in postseptic mice, tumor grows faster.”

Infection-related hospitalizations didn’t increase the future risk of locoregional recurrences.

Independent predictors of infection-related hospitalization included older age, comorbidities, markers indicative of greater tumor aggressiveness, and treatment with chemotherapy or axillary radiotherapy.

“This shows that the risk of infection-related hospitalizations is not only due to immunosuppression caused by chemotherapy, but that the characteristics of the tumor itself play a role, as do patient characteristics. This is the first epidemiologic study to show with very extensive data that all three elements contribute to the risk,” Dr. Brand said.

AT SABCS 2015

Key clinical point: Particularly close monitoring for adverse breast cancer outcomes is warranted for women with an infection-related hospitalization during the first year after breast cancer diagnosis.

Major finding: Women hospitalized for sepsis or a respiratory or skin infection during the first year after being diagnosed with stage I-III breast cancer were up to 4.8 times more likely to subsequently die of breast cancer than those without an infection-related hospitalization.

Data source: This was a prospective observational study of 8,338 Stockholm-area breast cancer patients followed for a median of 4.9 years post diagnosis.

Disclosures: The study presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding this university-funded study.

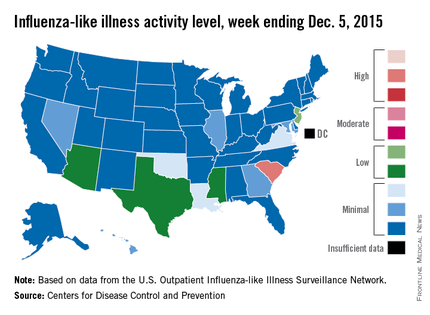

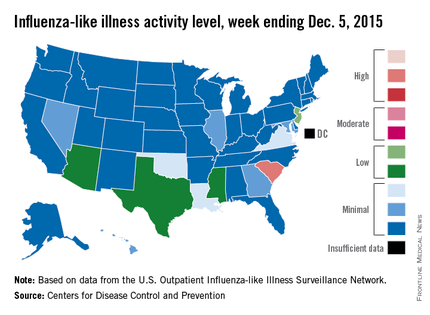

Flu activity at ‘high’ level in South Carolina

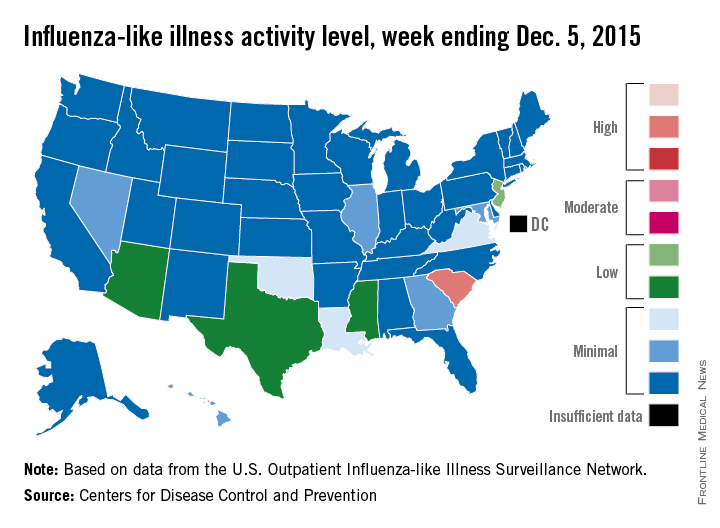

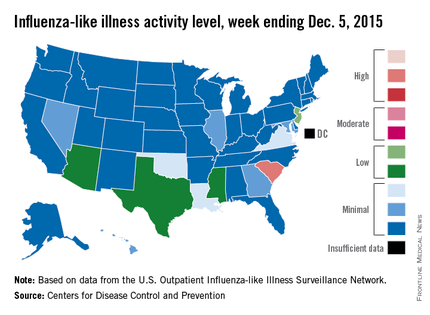

South Carolina officially became the first state to reach a “high” level of influenza activity during the 2015-2016 flu season, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported Dec. 11.

Activity of influenza-like illness (ILI) in the state was at level 9 on a scale of 1-10 for the week ending Dec. 5, 2015. For the country as a whole, however, activity was down a bit, with 13 states at level 2 or higher, compared with 20 states the week before. Among those with reduced ILI activity was Oklahoma, which went from level 6 for the week ending Nov. 28 to level 3 for the week ending Dec. 5, according to the CDC report.

For the week, 1.8% of patient visits reported to the U.S. Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network were for ILI, which is below the national baseline of 2.1%. This measure peaked at almost 6% during last year’s flu season, with that high coming at the end of Dec. 2014. The pattern was similar for the 2013-2014 season, with a peak of about 4.5% during the same week at the end of December, the report showed.

There was one influenza-related pediatric death for the week ending Dec. 5, bringing the total to three that have been reported for the season, the CDC said.

South Carolina officially became the first state to reach a “high” level of influenza activity during the 2015-2016 flu season, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported Dec. 11.

Activity of influenza-like illness (ILI) in the state was at level 9 on a scale of 1-10 for the week ending Dec. 5, 2015. For the country as a whole, however, activity was down a bit, with 13 states at level 2 or higher, compared with 20 states the week before. Among those with reduced ILI activity was Oklahoma, which went from level 6 for the week ending Nov. 28 to level 3 for the week ending Dec. 5, according to the CDC report.

For the week, 1.8% of patient visits reported to the U.S. Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network were for ILI, which is below the national baseline of 2.1%. This measure peaked at almost 6% during last year’s flu season, with that high coming at the end of Dec. 2014. The pattern was similar for the 2013-2014 season, with a peak of about 4.5% during the same week at the end of December, the report showed.

There was one influenza-related pediatric death for the week ending Dec. 5, bringing the total to three that have been reported for the season, the CDC said.

South Carolina officially became the first state to reach a “high” level of influenza activity during the 2015-2016 flu season, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported Dec. 11.

Activity of influenza-like illness (ILI) in the state was at level 9 on a scale of 1-10 for the week ending Dec. 5, 2015. For the country as a whole, however, activity was down a bit, with 13 states at level 2 or higher, compared with 20 states the week before. Among those with reduced ILI activity was Oklahoma, which went from level 6 for the week ending Nov. 28 to level 3 for the week ending Dec. 5, according to the CDC report.

For the week, 1.8% of patient visits reported to the U.S. Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network were for ILI, which is below the national baseline of 2.1%. This measure peaked at almost 6% during last year’s flu season, with that high coming at the end of Dec. 2014. The pattern was similar for the 2013-2014 season, with a peak of about 4.5% during the same week at the end of December, the report showed.

There was one influenza-related pediatric death for the week ending Dec. 5, bringing the total to three that have been reported for the season, the CDC said.

David Henry's JCSO podcast, December 2015

In his December podcast for The Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology, Dr David Henry takes a look at filgrastim-sndz, the first biosimilar to be approved in United States. He also highlights two Original Reports that focus on cancer patients from racially diverse or underserved communities – one study looks at the patients’ enrollment in clinical trials; the other, at racial disparities in breast cancer diagnosis – as well as articles on the implementation of distress screening in an oncology setting and on oncology nurses’ perceptions of and practices and perceived barriers in regard to sexual health assessment and counseling among patients with cancer. The podcast rounds off with a discussion about a new era of combination therapy in cancer.

In his December podcast for The Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology, Dr David Henry takes a look at filgrastim-sndz, the first biosimilar to be approved in United States. He also highlights two Original Reports that focus on cancer patients from racially diverse or underserved communities – one study looks at the patients’ enrollment in clinical trials; the other, at racial disparities in breast cancer diagnosis – as well as articles on the implementation of distress screening in an oncology setting and on oncology nurses’ perceptions of and practices and perceived barriers in regard to sexual health assessment and counseling among patients with cancer. The podcast rounds off with a discussion about a new era of combination therapy in cancer.

In his December podcast for The Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology, Dr David Henry takes a look at filgrastim-sndz, the first biosimilar to be approved in United States. He also highlights two Original Reports that focus on cancer patients from racially diverse or underserved communities – one study looks at the patients’ enrollment in clinical trials; the other, at racial disparities in breast cancer diagnosis – as well as articles on the implementation of distress screening in an oncology setting and on oncology nurses’ perceptions of and practices and perceived barriers in regard to sexual health assessment and counseling among patients with cancer. The podcast rounds off with a discussion about a new era of combination therapy in cancer.

Oncology 2015: new therapies and new transitions toward value-based cancer care

The past year has been an exciting one for new oncology and hematology drug approvals and the continued evolution of our oncology delivery system toward high quality and value. In all, at press time in mid-November, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had approved or granted expanded indications for 24 drugs, compared with 19 in the 2 preceding years. Of those 24 approvals, 7 were accelerated and 6 were expanded approvals, and 3 alone were for the immunotherapeutic drug, nivolumab – 2 for non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and 1 for metastatic melanoma.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

The past year has been an exciting one for new oncology and hematology drug approvals and the continued evolution of our oncology delivery system toward high quality and value. In all, at press time in mid-November, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had approved or granted expanded indications for 24 drugs, compared with 19 in the 2 preceding years. Of those 24 approvals, 7 were accelerated and 6 were expanded approvals, and 3 alone were for the immunotherapeutic drug, nivolumab – 2 for non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and 1 for metastatic melanoma.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.