User login

Update on informed consent

Question: Which of the following statements regarding the doctrine of informed consent is best?

A. All jurisdictions now require disclosure geared toward the reasonable patient rather than the reasonable doctor.

B. Disclosures are less important and sometimes unnecessary in global clinical research protocols.

C. The trend is toward the use of simplified and personalized consent forms.

D. A and C.

Answer: C. An important development in the doctrine of informed consent deals with the typical consent form, which is lengthy (going on 14 pages in one report), largely incomprehensible, and densely legalistic. Worse, the physician may misconstrue the form as a proxy for risk disclosure, whereas in fact the duly signed form merely purports to indicate that meaningful discussion of risks, benefits, and alternatives had taken place – if indeed that has been the case.

A review of more than 500 separate informed consent forms revealed these documents have limited educational value, go mostly unread, and are frequently misunderstood by patients (Arch. Surg. 2000;135:26-33).Thus, there is much to recommend the recent move toward shorter forms that use simpler language, bigger type fonts, and even graphics to improve patient and family understanding.

For example, a novel personalized approach currently being tested offers evidence-based benefits and risks to patients undergoing elective percutaneous coronary intervention. The consent document draws on the American College of Cardiology’s National Cardiovascular Data Registry to offer individualized risk estimates, and lists the experience of the health care team and the anticipated financial costs (JAMA 2010;303:1190-1).

Such approaches are consonant with the notion of patient-centered care, which the Institute of Medicine has identified as a core attribute of high-quality health care systems.

One of the continuing controversies in informed consent is the requisite standard of disclosure.

Historically, what needed to be disclosed was judged by what was ordinarily expected of the reasonable physician in the community. However, in 1972, Canterbury v. Spence (464 F.2d 772 [D.C. Cir. 1972]) persuasively argued for replacing such a professional standard (what doctors customarily would disclose) with a patient-oriented standard, i.e., what a reasonable patient would want to know.

California quickly followed, and an increasing number of jurisdictions such as Alaska, Hawaii, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Texas, West Virginia, and Wisconsin have since embraced this patient-centered standard. However, a number of other jurisdictions, including Arkansas, Indiana, Michigan, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, and Wyoming, continue to adhere to the professional or physician-centered standard.

The momentum toward patient-centered disclosure appears to be growing, and has spread to other common-law jurisdictions abroad such as Canada and Australia. The United Kingdom was a steadfast opponent of patient-centric consent since Sidaway v. Board of Governors of the Bethlem Royal Hospital and the Maudsley Hospital ([1985] AC 871), its seminal House of Lords decision in the 1980s.

However, it finally abandoned its opposition on March 11, 2015, when its Supreme Court decided the case of a baby boy who sustained brain injury and arm paralysis at birth as a result of shoulder dystocia (Montgomery v. Lanarkshire Health Board [2015] UKSC 11).

The plaintiff alleged that being a diabetic mother, she should have been warned of the risks of shoulder dystocia and offered the alternative of a cesarean section. The obstetrician said she did not warn because the risks of a serious problem were very small. The court sided with the plaintiff, overturned Sidaway’s professional standard, and adopted the patient standard of disclosure as the new law.

What needs to be disclosed continues to plague the practitioner. The term “material risks” merely begs the question of the definition of “material.” It has been said that the crucial factor is the patient’s need.

The vexing issue surrounding the scope of risk disclosure is compounded by court decisions allowing inquiry outside the medical condition itself, such as a physician’s alcoholism or HIV status, and financial incentives amounting to a breach of fiduciary responsibility. However, courts have tended to reject requiring disclosure of practitioner experience or patient prognosis.

Novel issues continue to surface. For example, a recent Wisconsin Supreme Court case dealt with whether it was necessary for a physician to disclose the availability of a collateral test not directly linked to a patient’s diagnosis.

In Jandre v. Wis. Injured Patients & Families Comp. Fund (813 N.W.2d 627 [Wis. 2012]), a doctor diagnosed Bell’s palsy as the cause of a patient’s neurologic symptoms, because she heard no carotid bruits and the head CT scan was normal. Shortly thereafter, the patient developed a stroke. Although the doctor was found not negligent for the misdiagnosis, the plaintiff then proceeded on a lack of informed consent theory, asserting that the doctor should have advised him of the availability of a carotid ultrasound test to rule out a TIA.

In a momentous decision, the Wisconsin Supreme Court affirmed the lower court’s judgment in finding the physician liable for failing to disclose the availability of the ultrasound procedure.

Another area where informed consent is under renewed scrutiny is in research. Doctors in practice are increasingly participating as coinvestigators in industry-sponsored drug trials, and should be familiar with what is expected in the research context.

Augmented rules regarding informed consent govern all clinical research, with patient safety and free meaningful choice being paramount considerations. Federal and state regulations, implemented and monitored by institutional review boards, serve to enforce compliance and safeguard the safety of experimental subjects.

Still, as predicted nearly 50 years ago by Dr. Henry K. Beecher, “In any precise sense, statements regarding consent are meaningless unless one knows how fully the patient was informed of all risks, and if these are not known, that fact should also be made clear. A far more dependable safeguard than consent is the presence of a truly responsible investigator” (N. Engl. J. Med. 1966;274:1354-60).

Scandals in human research led by or in collaboration with U.S. investigators in foreign countries have been in the news. Global clinical trials are supposed to be carried out in compliance with the Nuremberg Code and the Declaration of Helsinki, but there may be occasional lapses or disregard for such international laws. A recent example is the trial using the antibiotic trovafloxacin, administered orally, versus FDA-approved parenteral ceftriaxone, during a meningitis outbreak in Nigeria (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:2050-3).

Finally, the politics of abortion and first amendment rights have managed to insinuate themselves into the informed consent debate. Can states mandate disclosure in the name of securing meaningful informed consent, e.g., requiring physicians to provide information that might encourage a woman to reconsider her decision to have an abortion?

In 1992, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that this passes constitutional muster, because it did not place an undue burden on the woman. However, the Fourth Circuit Appellate Court recently ruled unconstitutional a North Carolina statute called Display of Real-Time View Requirement. The statute requires physicians to display ultrasound images of the unborn child to a mother contemplating an abortion, which the court ruled violated the First Amendment’s prohibition on state-compelled speech (N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:1285-7).

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, and currently directs the St. Francis International Center for Healthcare Ethics in Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some of the articles in this series are adapted from the author’s 2006 book, “Medical Malpractice: Understanding the Law, Managing the Risk,” and his 2012 Halsbury treatise, “Medical Negligence and Professional Misconduct.” For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

Question: Which of the following statements regarding the doctrine of informed consent is best?

A. All jurisdictions now require disclosure geared toward the reasonable patient rather than the reasonable doctor.

B. Disclosures are less important and sometimes unnecessary in global clinical research protocols.

C. The trend is toward the use of simplified and personalized consent forms.

D. A and C.

Answer: C. An important development in the doctrine of informed consent deals with the typical consent form, which is lengthy (going on 14 pages in one report), largely incomprehensible, and densely legalistic. Worse, the physician may misconstrue the form as a proxy for risk disclosure, whereas in fact the duly signed form merely purports to indicate that meaningful discussion of risks, benefits, and alternatives had taken place – if indeed that has been the case.

A review of more than 500 separate informed consent forms revealed these documents have limited educational value, go mostly unread, and are frequently misunderstood by patients (Arch. Surg. 2000;135:26-33).Thus, there is much to recommend the recent move toward shorter forms that use simpler language, bigger type fonts, and even graphics to improve patient and family understanding.

For example, a novel personalized approach currently being tested offers evidence-based benefits and risks to patients undergoing elective percutaneous coronary intervention. The consent document draws on the American College of Cardiology’s National Cardiovascular Data Registry to offer individualized risk estimates, and lists the experience of the health care team and the anticipated financial costs (JAMA 2010;303:1190-1).

Such approaches are consonant with the notion of patient-centered care, which the Institute of Medicine has identified as a core attribute of high-quality health care systems.

One of the continuing controversies in informed consent is the requisite standard of disclosure.

Historically, what needed to be disclosed was judged by what was ordinarily expected of the reasonable physician in the community. However, in 1972, Canterbury v. Spence (464 F.2d 772 [D.C. Cir. 1972]) persuasively argued for replacing such a professional standard (what doctors customarily would disclose) with a patient-oriented standard, i.e., what a reasonable patient would want to know.

California quickly followed, and an increasing number of jurisdictions such as Alaska, Hawaii, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Texas, West Virginia, and Wisconsin have since embraced this patient-centered standard. However, a number of other jurisdictions, including Arkansas, Indiana, Michigan, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, and Wyoming, continue to adhere to the professional or physician-centered standard.

The momentum toward patient-centered disclosure appears to be growing, and has spread to other common-law jurisdictions abroad such as Canada and Australia. The United Kingdom was a steadfast opponent of patient-centric consent since Sidaway v. Board of Governors of the Bethlem Royal Hospital and the Maudsley Hospital ([1985] AC 871), its seminal House of Lords decision in the 1980s.

However, it finally abandoned its opposition on March 11, 2015, when its Supreme Court decided the case of a baby boy who sustained brain injury and arm paralysis at birth as a result of shoulder dystocia (Montgomery v. Lanarkshire Health Board [2015] UKSC 11).

The plaintiff alleged that being a diabetic mother, she should have been warned of the risks of shoulder dystocia and offered the alternative of a cesarean section. The obstetrician said she did not warn because the risks of a serious problem were very small. The court sided with the plaintiff, overturned Sidaway’s professional standard, and adopted the patient standard of disclosure as the new law.

What needs to be disclosed continues to plague the practitioner. The term “material risks” merely begs the question of the definition of “material.” It has been said that the crucial factor is the patient’s need.

The vexing issue surrounding the scope of risk disclosure is compounded by court decisions allowing inquiry outside the medical condition itself, such as a physician’s alcoholism or HIV status, and financial incentives amounting to a breach of fiduciary responsibility. However, courts have tended to reject requiring disclosure of practitioner experience or patient prognosis.

Novel issues continue to surface. For example, a recent Wisconsin Supreme Court case dealt with whether it was necessary for a physician to disclose the availability of a collateral test not directly linked to a patient’s diagnosis.

In Jandre v. Wis. Injured Patients & Families Comp. Fund (813 N.W.2d 627 [Wis. 2012]), a doctor diagnosed Bell’s palsy as the cause of a patient’s neurologic symptoms, because she heard no carotid bruits and the head CT scan was normal. Shortly thereafter, the patient developed a stroke. Although the doctor was found not negligent for the misdiagnosis, the plaintiff then proceeded on a lack of informed consent theory, asserting that the doctor should have advised him of the availability of a carotid ultrasound test to rule out a TIA.

In a momentous decision, the Wisconsin Supreme Court affirmed the lower court’s judgment in finding the physician liable for failing to disclose the availability of the ultrasound procedure.

Another area where informed consent is under renewed scrutiny is in research. Doctors in practice are increasingly participating as coinvestigators in industry-sponsored drug trials, and should be familiar with what is expected in the research context.

Augmented rules regarding informed consent govern all clinical research, with patient safety and free meaningful choice being paramount considerations. Federal and state regulations, implemented and monitored by institutional review boards, serve to enforce compliance and safeguard the safety of experimental subjects.

Still, as predicted nearly 50 years ago by Dr. Henry K. Beecher, “In any precise sense, statements regarding consent are meaningless unless one knows how fully the patient was informed of all risks, and if these are not known, that fact should also be made clear. A far more dependable safeguard than consent is the presence of a truly responsible investigator” (N. Engl. J. Med. 1966;274:1354-60).

Scandals in human research led by or in collaboration with U.S. investigators in foreign countries have been in the news. Global clinical trials are supposed to be carried out in compliance with the Nuremberg Code and the Declaration of Helsinki, but there may be occasional lapses or disregard for such international laws. A recent example is the trial using the antibiotic trovafloxacin, administered orally, versus FDA-approved parenteral ceftriaxone, during a meningitis outbreak in Nigeria (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:2050-3).

Finally, the politics of abortion and first amendment rights have managed to insinuate themselves into the informed consent debate. Can states mandate disclosure in the name of securing meaningful informed consent, e.g., requiring physicians to provide information that might encourage a woman to reconsider her decision to have an abortion?

In 1992, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that this passes constitutional muster, because it did not place an undue burden on the woman. However, the Fourth Circuit Appellate Court recently ruled unconstitutional a North Carolina statute called Display of Real-Time View Requirement. The statute requires physicians to display ultrasound images of the unborn child to a mother contemplating an abortion, which the court ruled violated the First Amendment’s prohibition on state-compelled speech (N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:1285-7).

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, and currently directs the St. Francis International Center for Healthcare Ethics in Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some of the articles in this series are adapted from the author’s 2006 book, “Medical Malpractice: Understanding the Law, Managing the Risk,” and his 2012 Halsbury treatise, “Medical Negligence and Professional Misconduct.” For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

Question: Which of the following statements regarding the doctrine of informed consent is best?

A. All jurisdictions now require disclosure geared toward the reasonable patient rather than the reasonable doctor.

B. Disclosures are less important and sometimes unnecessary in global clinical research protocols.

C. The trend is toward the use of simplified and personalized consent forms.

D. A and C.

Answer: C. An important development in the doctrine of informed consent deals with the typical consent form, which is lengthy (going on 14 pages in one report), largely incomprehensible, and densely legalistic. Worse, the physician may misconstrue the form as a proxy for risk disclosure, whereas in fact the duly signed form merely purports to indicate that meaningful discussion of risks, benefits, and alternatives had taken place – if indeed that has been the case.

A review of more than 500 separate informed consent forms revealed these documents have limited educational value, go mostly unread, and are frequently misunderstood by patients (Arch. Surg. 2000;135:26-33).Thus, there is much to recommend the recent move toward shorter forms that use simpler language, bigger type fonts, and even graphics to improve patient and family understanding.

For example, a novel personalized approach currently being tested offers evidence-based benefits and risks to patients undergoing elective percutaneous coronary intervention. The consent document draws on the American College of Cardiology’s National Cardiovascular Data Registry to offer individualized risk estimates, and lists the experience of the health care team and the anticipated financial costs (JAMA 2010;303:1190-1).

Such approaches are consonant with the notion of patient-centered care, which the Institute of Medicine has identified as a core attribute of high-quality health care systems.

One of the continuing controversies in informed consent is the requisite standard of disclosure.

Historically, what needed to be disclosed was judged by what was ordinarily expected of the reasonable physician in the community. However, in 1972, Canterbury v. Spence (464 F.2d 772 [D.C. Cir. 1972]) persuasively argued for replacing such a professional standard (what doctors customarily would disclose) with a patient-oriented standard, i.e., what a reasonable patient would want to know.

California quickly followed, and an increasing number of jurisdictions such as Alaska, Hawaii, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Texas, West Virginia, and Wisconsin have since embraced this patient-centered standard. However, a number of other jurisdictions, including Arkansas, Indiana, Michigan, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, and Wyoming, continue to adhere to the professional or physician-centered standard.

The momentum toward patient-centered disclosure appears to be growing, and has spread to other common-law jurisdictions abroad such as Canada and Australia. The United Kingdom was a steadfast opponent of patient-centric consent since Sidaway v. Board of Governors of the Bethlem Royal Hospital and the Maudsley Hospital ([1985] AC 871), its seminal House of Lords decision in the 1980s.

However, it finally abandoned its opposition on March 11, 2015, when its Supreme Court decided the case of a baby boy who sustained brain injury and arm paralysis at birth as a result of shoulder dystocia (Montgomery v. Lanarkshire Health Board [2015] UKSC 11).

The plaintiff alleged that being a diabetic mother, she should have been warned of the risks of shoulder dystocia and offered the alternative of a cesarean section. The obstetrician said she did not warn because the risks of a serious problem were very small. The court sided with the plaintiff, overturned Sidaway’s professional standard, and adopted the patient standard of disclosure as the new law.

What needs to be disclosed continues to plague the practitioner. The term “material risks” merely begs the question of the definition of “material.” It has been said that the crucial factor is the patient’s need.

The vexing issue surrounding the scope of risk disclosure is compounded by court decisions allowing inquiry outside the medical condition itself, such as a physician’s alcoholism or HIV status, and financial incentives amounting to a breach of fiduciary responsibility. However, courts have tended to reject requiring disclosure of practitioner experience or patient prognosis.

Novel issues continue to surface. For example, a recent Wisconsin Supreme Court case dealt with whether it was necessary for a physician to disclose the availability of a collateral test not directly linked to a patient’s diagnosis.

In Jandre v. Wis. Injured Patients & Families Comp. Fund (813 N.W.2d 627 [Wis. 2012]), a doctor diagnosed Bell’s palsy as the cause of a patient’s neurologic symptoms, because she heard no carotid bruits and the head CT scan was normal. Shortly thereafter, the patient developed a stroke. Although the doctor was found not negligent for the misdiagnosis, the plaintiff then proceeded on a lack of informed consent theory, asserting that the doctor should have advised him of the availability of a carotid ultrasound test to rule out a TIA.

In a momentous decision, the Wisconsin Supreme Court affirmed the lower court’s judgment in finding the physician liable for failing to disclose the availability of the ultrasound procedure.

Another area where informed consent is under renewed scrutiny is in research. Doctors in practice are increasingly participating as coinvestigators in industry-sponsored drug trials, and should be familiar with what is expected in the research context.

Augmented rules regarding informed consent govern all clinical research, with patient safety and free meaningful choice being paramount considerations. Federal and state regulations, implemented and monitored by institutional review boards, serve to enforce compliance and safeguard the safety of experimental subjects.

Still, as predicted nearly 50 years ago by Dr. Henry K. Beecher, “In any precise sense, statements regarding consent are meaningless unless one knows how fully the patient was informed of all risks, and if these are not known, that fact should also be made clear. A far more dependable safeguard than consent is the presence of a truly responsible investigator” (N. Engl. J. Med. 1966;274:1354-60).

Scandals in human research led by or in collaboration with U.S. investigators in foreign countries have been in the news. Global clinical trials are supposed to be carried out in compliance with the Nuremberg Code and the Declaration of Helsinki, but there may be occasional lapses or disregard for such international laws. A recent example is the trial using the antibiotic trovafloxacin, administered orally, versus FDA-approved parenteral ceftriaxone, during a meningitis outbreak in Nigeria (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:2050-3).

Finally, the politics of abortion and first amendment rights have managed to insinuate themselves into the informed consent debate. Can states mandate disclosure in the name of securing meaningful informed consent, e.g., requiring physicians to provide information that might encourage a woman to reconsider her decision to have an abortion?

In 1992, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that this passes constitutional muster, because it did not place an undue burden on the woman. However, the Fourth Circuit Appellate Court recently ruled unconstitutional a North Carolina statute called Display of Real-Time View Requirement. The statute requires physicians to display ultrasound images of the unborn child to a mother contemplating an abortion, which the court ruled violated the First Amendment’s prohibition on state-compelled speech (N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:1285-7).

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, and currently directs the St. Francis International Center for Healthcare Ethics in Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some of the articles in this series are adapted from the author’s 2006 book, “Medical Malpractice: Understanding the Law, Managing the Risk,” and his 2012 Halsbury treatise, “Medical Negligence and Professional Misconduct.” For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

Witch hunts and hidden agendas

Witch hunt: An intensive effort to discover and expose disloyalty, subversion, dishonesty or the like, usually based on slight, doubtful or irrelevant evidence, and to punish accordingly. - Merriam-Webster Dictionary

Over the years, several excellent vascular surgeons have either lost their jobs or been pressured to resign for reasons that are unclear – although in some instances a few particular cases with bad outcomes have been cited as a reason.

Vascular Surgery is a difficult specialty. If one takes on challenging cases that need treatment – patients with large complex AAAs, extensive foot gangrene, or high-risk symptomatic carotid disease, an occasional poor outcome can be expected even if everything the vascular surgeon does is correct. One, two, or three bad outcomes per year in a busy vascular practice are inevitable, and should not be a reason for a vascular surgeon’s termination. Something more must be involved. Likely it is a hidden agenda.

That something can best be summarized by the term “medical politics.” This term may sound benign. In fact, medical politics are anything but benign. In the case of vascular surgeons, they are often subject to the governance and direction of administrators or senior surgical leaders who have little understanding of the risks of complex vascular surgery, and are interested only in the money generated by vascular admissions and procedures. Quantity and dollars trumps quality most times in the eyes of these administrative leaders.

Moreover, these leaders are not immune from the frailties of bias and jealousy which motivate much of human behavior. Throughout my career I have seen many instances when such administrative leaders resented a vascular surgeon because he or she used many hospital resources for a large practice, was successful academically, but behaved “too independently” from the larger department or its leader. It was one reason, vascular surgery needed to be its own independent specialty rather than a part of general surgery.

In the case of the vascular surgeons facing termination for reasons that they cannot understand, there is usually an administrative superior who is involved. Perhaps the vascular surgeon has questioned the authority or judgment of the superior on the grounds that they do not understand a particular vascular surgery issue. The resulting anger of the superior prompts him to want to eliminate the vascular surgeon who is under his administrative control. The witch hunt begins and may be inflamed by other unjustified motives such as jealousy or other hidden agendas which may never be known.

Once the witch hunt has begun, if the vascular surgeon has one or a few cases with bad outcomes, they make him or her vulnerable to the unjustified attack leading to termination by those who do not understand the nature of vascular surgery. Other factors, e.g., a disgruntled or jealous competitor in vascular surgery, can exacerbate the situation and accelerate the termination. The few bad-outcome cases, however, are the excuse or smoking gun which is used as the reason for termination. What goes unrecognized is the fact that every competent vascular surgeon who treats sick patients has such cases which can be used if uninformed enemies wish to focus on them.

How can a vascular surgeon protect him or herself from such witch hunts? First, they must be aware that the nature of vascular surgery and its requirement for treating challenging patients makes them vulnerable if one or another superior dislikes them or is “out to get them.” Second, if one is dealing with a case likely to have a bad outcome, it should be discussed beforehand with superiors, and it is wise to get help from a colleague who can share responsibility if things go poorly.

Third, try not to make enemies of important administrative leaders by challenging their authority or judgment.

Share successes with them, rather than taking all the glory. It will help to neutralize their jealousy. If possible, be humble. Make as many friends in other specialties as possible. They can sometimes diffuse the intensity of a witch hunt. And lastly be aware that any vascular surgeon, particularly a good one, can be the subject of a damaging witch hunt in the imperfect world in which we function.

Dr. Veith is professor of surgery at New York University Medical Center and the Cleveland Clinic and an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

The ideas and opinions expressed in Vascsular Specialist do not necessarily reflect those of the Society or publisher.

Witch hunt: An intensive effort to discover and expose disloyalty, subversion, dishonesty or the like, usually based on slight, doubtful or irrelevant evidence, and to punish accordingly. - Merriam-Webster Dictionary

Over the years, several excellent vascular surgeons have either lost their jobs or been pressured to resign for reasons that are unclear – although in some instances a few particular cases with bad outcomes have been cited as a reason.

Vascular Surgery is a difficult specialty. If one takes on challenging cases that need treatment – patients with large complex AAAs, extensive foot gangrene, or high-risk symptomatic carotid disease, an occasional poor outcome can be expected even if everything the vascular surgeon does is correct. One, two, or three bad outcomes per year in a busy vascular practice are inevitable, and should not be a reason for a vascular surgeon’s termination. Something more must be involved. Likely it is a hidden agenda.

That something can best be summarized by the term “medical politics.” This term may sound benign. In fact, medical politics are anything but benign. In the case of vascular surgeons, they are often subject to the governance and direction of administrators or senior surgical leaders who have little understanding of the risks of complex vascular surgery, and are interested only in the money generated by vascular admissions and procedures. Quantity and dollars trumps quality most times in the eyes of these administrative leaders.

Moreover, these leaders are not immune from the frailties of bias and jealousy which motivate much of human behavior. Throughout my career I have seen many instances when such administrative leaders resented a vascular surgeon because he or she used many hospital resources for a large practice, was successful academically, but behaved “too independently” from the larger department or its leader. It was one reason, vascular surgery needed to be its own independent specialty rather than a part of general surgery.

In the case of the vascular surgeons facing termination for reasons that they cannot understand, there is usually an administrative superior who is involved. Perhaps the vascular surgeon has questioned the authority or judgment of the superior on the grounds that they do not understand a particular vascular surgery issue. The resulting anger of the superior prompts him to want to eliminate the vascular surgeon who is under his administrative control. The witch hunt begins and may be inflamed by other unjustified motives such as jealousy or other hidden agendas which may never be known.

Once the witch hunt has begun, if the vascular surgeon has one or a few cases with bad outcomes, they make him or her vulnerable to the unjustified attack leading to termination by those who do not understand the nature of vascular surgery. Other factors, e.g., a disgruntled or jealous competitor in vascular surgery, can exacerbate the situation and accelerate the termination. The few bad-outcome cases, however, are the excuse or smoking gun which is used as the reason for termination. What goes unrecognized is the fact that every competent vascular surgeon who treats sick patients has such cases which can be used if uninformed enemies wish to focus on them.

How can a vascular surgeon protect him or herself from such witch hunts? First, they must be aware that the nature of vascular surgery and its requirement for treating challenging patients makes them vulnerable if one or another superior dislikes them or is “out to get them.” Second, if one is dealing with a case likely to have a bad outcome, it should be discussed beforehand with superiors, and it is wise to get help from a colleague who can share responsibility if things go poorly.

Third, try not to make enemies of important administrative leaders by challenging their authority or judgment.

Share successes with them, rather than taking all the glory. It will help to neutralize their jealousy. If possible, be humble. Make as many friends in other specialties as possible. They can sometimes diffuse the intensity of a witch hunt. And lastly be aware that any vascular surgeon, particularly a good one, can be the subject of a damaging witch hunt in the imperfect world in which we function.

Dr. Veith is professor of surgery at New York University Medical Center and the Cleveland Clinic and an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

The ideas and opinions expressed in Vascsular Specialist do not necessarily reflect those of the Society or publisher.

Witch hunt: An intensive effort to discover and expose disloyalty, subversion, dishonesty or the like, usually based on slight, doubtful or irrelevant evidence, and to punish accordingly. - Merriam-Webster Dictionary

Over the years, several excellent vascular surgeons have either lost their jobs or been pressured to resign for reasons that are unclear – although in some instances a few particular cases with bad outcomes have been cited as a reason.

Vascular Surgery is a difficult specialty. If one takes on challenging cases that need treatment – patients with large complex AAAs, extensive foot gangrene, or high-risk symptomatic carotid disease, an occasional poor outcome can be expected even if everything the vascular surgeon does is correct. One, two, or three bad outcomes per year in a busy vascular practice are inevitable, and should not be a reason for a vascular surgeon’s termination. Something more must be involved. Likely it is a hidden agenda.

That something can best be summarized by the term “medical politics.” This term may sound benign. In fact, medical politics are anything but benign. In the case of vascular surgeons, they are often subject to the governance and direction of administrators or senior surgical leaders who have little understanding of the risks of complex vascular surgery, and are interested only in the money generated by vascular admissions and procedures. Quantity and dollars trumps quality most times in the eyes of these administrative leaders.

Moreover, these leaders are not immune from the frailties of bias and jealousy which motivate much of human behavior. Throughout my career I have seen many instances when such administrative leaders resented a vascular surgeon because he or she used many hospital resources for a large practice, was successful academically, but behaved “too independently” from the larger department or its leader. It was one reason, vascular surgery needed to be its own independent specialty rather than a part of general surgery.

In the case of the vascular surgeons facing termination for reasons that they cannot understand, there is usually an administrative superior who is involved. Perhaps the vascular surgeon has questioned the authority or judgment of the superior on the grounds that they do not understand a particular vascular surgery issue. The resulting anger of the superior prompts him to want to eliminate the vascular surgeon who is under his administrative control. The witch hunt begins and may be inflamed by other unjustified motives such as jealousy or other hidden agendas which may never be known.

Once the witch hunt has begun, if the vascular surgeon has one or a few cases with bad outcomes, they make him or her vulnerable to the unjustified attack leading to termination by those who do not understand the nature of vascular surgery. Other factors, e.g., a disgruntled or jealous competitor in vascular surgery, can exacerbate the situation and accelerate the termination. The few bad-outcome cases, however, are the excuse or smoking gun which is used as the reason for termination. What goes unrecognized is the fact that every competent vascular surgeon who treats sick patients has such cases which can be used if uninformed enemies wish to focus on them.

How can a vascular surgeon protect him or herself from such witch hunts? First, they must be aware that the nature of vascular surgery and its requirement for treating challenging patients makes them vulnerable if one or another superior dislikes them or is “out to get them.” Second, if one is dealing with a case likely to have a bad outcome, it should be discussed beforehand with superiors, and it is wise to get help from a colleague who can share responsibility if things go poorly.

Third, try not to make enemies of important administrative leaders by challenging their authority or judgment.

Share successes with them, rather than taking all the glory. It will help to neutralize their jealousy. If possible, be humble. Make as many friends in other specialties as possible. They can sometimes diffuse the intensity of a witch hunt. And lastly be aware that any vascular surgeon, particularly a good one, can be the subject of a damaging witch hunt in the imperfect world in which we function.

Dr. Veith is professor of surgery at New York University Medical Center and the Cleveland Clinic and an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

The ideas and opinions expressed in Vascsular Specialist do not necessarily reflect those of the Society or publisher.

Familial hypercholesterolemia: Clues to catching it early

› When one member of a family has early heart disease, screen the entire family for familial hypercholesterolemia (FH). A

› Consider all patients with FH as being at high risk for coronary heart disease, regardless of their Framingham Risk Score. C

› Treat FH patients with statins early to avoid cardiovascular events. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) poses a “silent” threat to patients with the condition, putting them at great risk of a coronary event. This genetic disorder, in which one or more mutations cause extremely high low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels, goes undiagnosed in approximately 80% of patients who have it.1 As a result, men with FH have a >50% risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) by age 50 and women with FH have a 30% risk of CHD by age 60.2 Patients with FH face a much higher risk of dying from a coronary event than those in the general population.3 For example, women between the ages of 20 and 39 who have this disorder are 125 times more likely to die of a coronary event than those who don’t.3

Unfortunately, FH can be difficult to diagnose. Some patients have physical findings, but these features can be subtle and easily missed. Typically, however, FH is diagnosed based on a patient’s cholesterol level and family history. By implementing screening and early treatment for FH, you may be able to initiate treatment that can temper the development of atherosclerosis and possibly extend a patient’s life.4

Two forms of the disorder, although one is more common

There are 2 types of FH:

Heterozygous FH (HeFH) occurs in about 1 in 300 to 500 people, which makes it more common than Down syndrome.5 More than a half a million people in the United States have HeFH.6

Homozygous FH (HoFH) is more serious than HeFH, and less common, affecting one in 1 million people. Homozygous carriers suffer from CHD much earlier than those with HeFH; some die within the first few years of life.7

Regardless of whether an affected individual inherited FH from one or both parents, more than one thousand mutations are known to cause inadequate clearance of LDL from the bloodstream.8 One of the most common mutations is a defective LDL receptor gene. Other abnormalities are known to occur with the proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) and apolipoprotein B genes.9

Start with screening

Suspect FH in patients who have a family history of premature heart disease. Also consider the patient’s ethnic background. The prevalence of FH is as high as one in 100 among certain groups, including French Canadians, Christian Lebanese, and 3 populations in South Africa (Ashkenazi Jews, Dutch Afrikaners, and Asian Indians).10

When there is high suspicion of FH based on a patient’s family history or ethnicity, additional screening is warranted for any patient older than age 2.11 If a patient’s family history is incomplete (eg, adoption, single-parent family), a lower threshold for screening is appropriate.

Lipid screening includes measuring serum total, LDL, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in either fasting or non-fasting samples. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) offers gender-specific recommendations for lipid disorder screening in the general population. For men, universal screening is recommended starting at age 35, and screening for those at increased risk of CHD should start at age 20.12

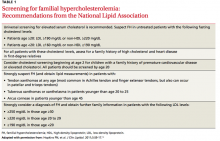

For women, the USPSTF recommends lipid screening only for those over age 20 who are at increased risk for CHD; such screening is strongly recommended for high-risk women ages 45 and older. In light of the serious consequences associated with FH, the National Lipid Association recommends lipid screening for all adults starting at age 20 (TABLE 1).13

What about kids? The recommendations for lipid screening in children and adolescents are mixed. Both the USPSTF and the American Academy of Family Physicians indicate that there is insufficient evidence to screen for lipid disorders in asymptomatic children and adolescents.14,15 However, in a set of recommendations based on expert opinion, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) suggests universal screening for younger patients with a non-fasting lipid profile once between ages 9 to 11 and again between ages 17 to 21.16 The American Academy of Pediatrics has adopted the NHLBI recommendations.17

Physical exam findings that suggest familial hypercholesterolemia

Tendon xanthomas (A), a thickening of the soft tissue as a result of infiltration by lipid-rich cells, most commonly occur at the Achilles and metacarpal tendons, but also can be seen at the patellar and triceps tendons.

Tuberous xanthomas or xanthelasmas (B) are waxy-appearing growths that appear to be pasted on the skin in areas around the face, commonly the eyelids.

Arcus corneae (C) is an opaque ring around the outer edge of the cornea.

Use validated criteria to make the diagnosis

Include FH in your differential diagnosis when evaluating patients with very high LDL levels. However, rule out possible secondary causes of elevated LDL before rendering a conclusion. Hypothyroidism, nephrotic syndrome, diabetes, and liver disease are among the most common secondary causes of high LDL cholesterol.13

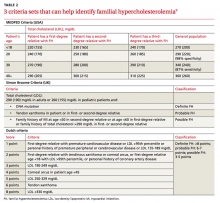

Several validated criteria sets can be used to establish an FH diagnosis. No single criteria set is more valid or more widely adopted around the world. All 3 of the most commonly used criteria sets take into account family history and a patient’s LDL level, and 2 of the 3 factor in physical findings (TABLE 2).9

Physical exam findings that suggest FH can be subtle (FIGURE). Tendon xanthomas are a thickening of the soft tissue as a result of infiltration by lipid-rich cells. They most commonly occur at the Achilles and metacarpal tendons, but can also be seen at the patellar and triceps tendons. Xanthomas may not be readily visible, so it’s important to run your fingers over these areas to detect nodularity or thickening. While the presence of a tendon xanthoma makes FH highly likely, they are present in less than half of patients with FH.17

Tuberous xanthomas or xanthelasmas are waxy-appearing growths that may look yellow or orange and appear to be pasted on the skin in areas around the face, commonly the eyelids. The presence of xanthelasmas in a patient younger than age 25 suggests FH.

Finally, arcus corneae is an opaque ring around the outer edge of the cornea. When this is seen in patients younger than age 45, it’s suggestive of FH.13 If you note tendon xanthomas, xanthelasmas, or arcus corneae while examining any of your patients, be sure to order an LDL level if it hasn’t already been done.

Is genetic testing necessary?

The only way to make a definitive diagnosis of FH is to find a mutation in a gene known to affect LDL metabolism. However, because genetic testing is expensive—and because more than one thousand different genetic defects can contribute to FH—it’s not practical to test every patient. Furthermore, since an estimated 20% of the mutations that contribute to FH have not yet been clearly delineated, a “normal” result on a genetic test might be misleading.5 Therefore, the diagnosis of FH usually is a clinical one. After clinically diagnosing a patient with FH, it’s imperative to screen first-degree family members by measuring their LDL cholesterol levels.

Lifestyle changes, statins can ward off CHD

Lifestyle modifications (ie, improved diet and exercise) and statins are the treatments of choice for patients with FH. Before starting pharmacotherapy, patients should undergo 3 months of lifestyle modification to assess how well this approach improves their lipid levels, assuming the patient doesn’t have additional risk factors such as hypertension or tobacco use, in which case he or she might require immediate pharmacotherapy. Statins can be initiated simultaneously with lifestyle choices in patients with an LDL >190 mg/dL.18

Lifestyle modification. Although FH is a genetic problem, patients should be encouraged to make healthy choices regarding diet and exercise. While the best choices may not get FH patients to their LDL goal, better choices may mean that patients can take fewer medications, or lower doses of them. Healthy lifestyle choices can also have other positive effects on cardiovascular risk (eg, lowering blood pressure).

Patients can’t be expected to navigate their food choices alone, and several visits with a dietician will likely be needed. It’s important to emphasize the family influence on diet and get the entire family involved with making healthy food choices.

In addition to addressing diet and exercise, be sure to encourage patients to abstain from tobacco and manage stress as part of their overall effort to reduce the likelihood of a cardiovascular event.

Statins. Early treatment of FH with statins can delay initial coronary events and prolong life.19 In a 12.5-year study of 2146 patients with FH, approximately 80% of patients treated with statins survived without experiencing CHD, compared to slightly less than 40% of those who were not treated with statins.19 Patients treated with statins had a 76% reduction in risk of CHD compared to those who didn’t receive statins.19 Even low doses of statins started early have been shown to help avoid myocardial infarction in adults with FH.20

The goal of treatment for FH is to reduced LDL levels by 50%.21 In pediatric patients, treating to an LDL level of 130 mg/dL is an alternative goal.21 Because it’s challenging to achieve this goal with improved diet and exercise alone, treatment with a statin is often necessary.22

Statins can be used in children as young as age 8, or even earlier in homozygous FH.6 While a physician might be hesitant to start a chronic medication in a young patient, research shows that earlier intervention results in additional years of life.23 To date, no significant adverse effects of statins in pediatric patients have been identified, and statins have not been shown to impair growth.24,25 Young female patients should be counseled about the adverse effects statins can have on a fetus if the patient becomes pregnant while taking the medication.

Navigating the waters of statin treatment

Musculoskeletal symptoms are the most common adverse effect reported by patients taking statins. A thorough assessment of a patient’s muscle complaints is necessary to avoid prematurely concluding that he or she cannot tolerate statins.

A study in which “statin-intolerant” patients were re-challenged found that more than 90% of patients could tolerate statins through the course of the one-year study and that it was likely that the patients’ initial muscle complaints were not due to statin use.23 (To read more about potential adverse events of statins, see “Statin adverse effects: Sorting out the evidence,” J Fam Pract. 2014;63:497-506.).

If LDL levels in a patient with HeFH remain at or above 160 mg/dL, intensifying treatment by adding another lipid-lowering medication might be warranted.22 For patients with HoFH, in whom the condition is more quickly life-threatening, there are additional choices, including LDL apheresis and medications such as mipomersen and lomitapide. Both of these medications can cause hepatotoxicity, and are available only through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy program, which means they can only be prescribed by certified physicians. PCSK9 inhibitors are in the pipeline and may one day help patients with HoFH by addressing one of the genetic causes of this disorder.

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard Safeer, MD, 6704 Curtis Court, Glen Burnie, MD 21060; [email protected]

1. Datta BN, McDowell IF, Rees A. Integrating provision of specialist lipid services with cascade testing for familial hypercholesterolaemia. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2010;21:366-371.

2. DeMott K, Nherera L, Shaw EJ, et al. Clinical Guidelines and Evidence Review for Familial Hypercholesterolaemia: The Identification and Management of Adults and Children with Familial Hypercholesterolaemia. 2008. London, UK: National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care and Royal College of General Practitioners.

3. Mortality in treated heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia: implications for clinical management. Scientific Steering Committee on behalf of the Simon Broome Register Group. Atherosclerosis. 1999;142:105-112.

4. Kavey RE, Allada V, Daniels SR, et al. American Heart Association Expert Panel on Population and Prevention Science; American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Cardiovascular risk reduction in high-risk pediatric patients. Circulation. 2006;114:2710-2738.

5. Rees A. Familial hypercholesterolaemia: underdiagnosed and undertreated. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2583-2584.

6. Goldberg AC, Hopkins PN, Toth PP, et al. Familial hypercholesterolemia: screening, diagnosis and management of pediatric and adult patients. Clinical guidance from the National Lipid Association Expert Panel on Familial Hypercholesterolemia. J Clin Lipidol. 2011;5:S1-8.

7. Moriarty PM. LDL-apheresis therapy. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2006;8:282-288.

8. Goldstein JL, Brown MS. The LDL receptor locus and the genetics of familial hypercholesterolemia. Annu Rev Genet. 1979;13:259-289.

9. Fahed AC, Nemer GM. Familial hypercholesterolemia: the lipids or the genes? Nutr Metab (Lond). 2011;8:23.

10. Goldstein J, Hobbs H, Brown M. Familial hypercholesterolemia. In: Scriver C, Baudet A, Sly W, et al, eds. The Metabolic Basis of Inherited Disease. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2001: 2863-2913.

11. Kwiterovich, PO. Clinical and laboratory assessment of cardiovascular risk in children: Guidelines for screening, evaluation and treatment. J Clin Lipidol. 2008;2:248-266.

12. US Preventive Services Task Force. Lipid disorders in adults (cholesterol, dyslipidemia): Screening. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Topic/recommendation-summary/lipid-disorders-in-adults-cholesterol-dyslipidemia-screening. Accessed July 6, 2015.

13. Hopkins PN, Toth PP, Ballantyne CM, et al; National Lipid Association Expert Panel on Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Familial hypercholesterolemias: prevalence, genetics, diagnosis and screening recommendations from the National Lipid Association Expert Panel on Familial Hypercholesterolemia. J Clin Lipidol. 2011;5:S9-17.

14. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for lipid disorders in children: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Pediatrics. 2007;120;e215-219.

15. American Academy of Family Physicians. Summary of recommendations for clinical preventive services. American Academy of Family Physicians Web site. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/patient_care/clinical_recommendations/cps-recommendations.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2015.

16. Expert Panel on Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health and Risk Reduction in Children and Adolescents; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents: summary report. Pediatrics. 2011;128:S213-56.

17. American Academy of Pediatrics. 2014 Recommendations for Pediatric Preventive Health Care. American Academy of Pediatrics Web site. Available at: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/133/3/568.full.pdf+html. Accessed May 2, 2015.

18. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2889-2934.

19. Nordestgaard BG, Chapman MJ, Humphries SE, et al; European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Familial hypercholesterolaemia is underdiagnosed and undertreated in the general population: guidance for clinicians to prevent coronary heart disease: consensus statement of the European Atherosclerosis Society. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:3478-3490a.

20. Versmissen J, Oosterveer DM, Yazdanpanah M, et al. Efficacy of statins in familial hypercholesterolaemia: a long term cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:a2423.

21. Daniels SR, Gidding SS, de Ferranti SD; National Lipid Association Expert Panel on Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Pediatric aspects of familial hypercholesterolemias: recommendations from the National Lipid Association Expert Panel on Familial Hypercholesterolemia. J Clin Lipidol. 2011;5:S30-37.

22. Robinson JG, Goldberg AC; National Lipid Association Expert Panel on Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Treatment of adults with familial hypercholesterolemia and evidence for treatment: recommendations from the National Lipid Association Expert Panel on Familial Hypercholesterolemia. J Clin Lipidol. 2011;5:S18-29.

23. Zhang H, Plutzky J, Skentzos S, et al. Discontinuation of statins in routine care settings: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:526-534.

24. Eiland LS, Luttrell PK. Use of statins for dyslipidemia in the pediatric population. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2010;15:160-172.

25. O’Gorman CS, Higgins MF, O’Neill MB. Systematic review and metaanalysis of statins for heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia in children: evaluation of cholesterol changes and side effects. Pediatr Cardiol. 2009;30:482-489.

› When one member of a family has early heart disease, screen the entire family for familial hypercholesterolemia (FH). A

› Consider all patients with FH as being at high risk for coronary heart disease, regardless of their Framingham Risk Score. C

› Treat FH patients with statins early to avoid cardiovascular events. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) poses a “silent” threat to patients with the condition, putting them at great risk of a coronary event. This genetic disorder, in which one or more mutations cause extremely high low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels, goes undiagnosed in approximately 80% of patients who have it.1 As a result, men with FH have a >50% risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) by age 50 and women with FH have a 30% risk of CHD by age 60.2 Patients with FH face a much higher risk of dying from a coronary event than those in the general population.3 For example, women between the ages of 20 and 39 who have this disorder are 125 times more likely to die of a coronary event than those who don’t.3

Unfortunately, FH can be difficult to diagnose. Some patients have physical findings, but these features can be subtle and easily missed. Typically, however, FH is diagnosed based on a patient’s cholesterol level and family history. By implementing screening and early treatment for FH, you may be able to initiate treatment that can temper the development of atherosclerosis and possibly extend a patient’s life.4

Two forms of the disorder, although one is more common

There are 2 types of FH:

Heterozygous FH (HeFH) occurs in about 1 in 300 to 500 people, which makes it more common than Down syndrome.5 More than a half a million people in the United States have HeFH.6

Homozygous FH (HoFH) is more serious than HeFH, and less common, affecting one in 1 million people. Homozygous carriers suffer from CHD much earlier than those with HeFH; some die within the first few years of life.7

Regardless of whether an affected individual inherited FH from one or both parents, more than one thousand mutations are known to cause inadequate clearance of LDL from the bloodstream.8 One of the most common mutations is a defective LDL receptor gene. Other abnormalities are known to occur with the proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) and apolipoprotein B genes.9

Start with screening

Suspect FH in patients who have a family history of premature heart disease. Also consider the patient’s ethnic background. The prevalence of FH is as high as one in 100 among certain groups, including French Canadians, Christian Lebanese, and 3 populations in South Africa (Ashkenazi Jews, Dutch Afrikaners, and Asian Indians).10

When there is high suspicion of FH based on a patient’s family history or ethnicity, additional screening is warranted for any patient older than age 2.11 If a patient’s family history is incomplete (eg, adoption, single-parent family), a lower threshold for screening is appropriate.

Lipid screening includes measuring serum total, LDL, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in either fasting or non-fasting samples. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) offers gender-specific recommendations for lipid disorder screening in the general population. For men, universal screening is recommended starting at age 35, and screening for those at increased risk of CHD should start at age 20.12

For women, the USPSTF recommends lipid screening only for those over age 20 who are at increased risk for CHD; such screening is strongly recommended for high-risk women ages 45 and older. In light of the serious consequences associated with FH, the National Lipid Association recommends lipid screening for all adults starting at age 20 (TABLE 1).13

What about kids? The recommendations for lipid screening in children and adolescents are mixed. Both the USPSTF and the American Academy of Family Physicians indicate that there is insufficient evidence to screen for lipid disorders in asymptomatic children and adolescents.14,15 However, in a set of recommendations based on expert opinion, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) suggests universal screening for younger patients with a non-fasting lipid profile once between ages 9 to 11 and again between ages 17 to 21.16 The American Academy of Pediatrics has adopted the NHLBI recommendations.17

Physical exam findings that suggest familial hypercholesterolemia

Tendon xanthomas (A), a thickening of the soft tissue as a result of infiltration by lipid-rich cells, most commonly occur at the Achilles and metacarpal tendons, but also can be seen at the patellar and triceps tendons.

Tuberous xanthomas or xanthelasmas (B) are waxy-appearing growths that appear to be pasted on the skin in areas around the face, commonly the eyelids.

Arcus corneae (C) is an opaque ring around the outer edge of the cornea.

Use validated criteria to make the diagnosis

Include FH in your differential diagnosis when evaluating patients with very high LDL levels. However, rule out possible secondary causes of elevated LDL before rendering a conclusion. Hypothyroidism, nephrotic syndrome, diabetes, and liver disease are among the most common secondary causes of high LDL cholesterol.13

Several validated criteria sets can be used to establish an FH diagnosis. No single criteria set is more valid or more widely adopted around the world. All 3 of the most commonly used criteria sets take into account family history and a patient’s LDL level, and 2 of the 3 factor in physical findings (TABLE 2).9

Physical exam findings that suggest FH can be subtle (FIGURE). Tendon xanthomas are a thickening of the soft tissue as a result of infiltration by lipid-rich cells. They most commonly occur at the Achilles and metacarpal tendons, but can also be seen at the patellar and triceps tendons. Xanthomas may not be readily visible, so it’s important to run your fingers over these areas to detect nodularity or thickening. While the presence of a tendon xanthoma makes FH highly likely, they are present in less than half of patients with FH.17

Tuberous xanthomas or xanthelasmas are waxy-appearing growths that may look yellow or orange and appear to be pasted on the skin in areas around the face, commonly the eyelids. The presence of xanthelasmas in a patient younger than age 25 suggests FH.

Finally, arcus corneae is an opaque ring around the outer edge of the cornea. When this is seen in patients younger than age 45, it’s suggestive of FH.13 If you note tendon xanthomas, xanthelasmas, or arcus corneae while examining any of your patients, be sure to order an LDL level if it hasn’t already been done.

Is genetic testing necessary?

The only way to make a definitive diagnosis of FH is to find a mutation in a gene known to affect LDL metabolism. However, because genetic testing is expensive—and because more than one thousand different genetic defects can contribute to FH—it’s not practical to test every patient. Furthermore, since an estimated 20% of the mutations that contribute to FH have not yet been clearly delineated, a “normal” result on a genetic test might be misleading.5 Therefore, the diagnosis of FH usually is a clinical one. After clinically diagnosing a patient with FH, it’s imperative to screen first-degree family members by measuring their LDL cholesterol levels.

Lifestyle changes, statins can ward off CHD

Lifestyle modifications (ie, improved diet and exercise) and statins are the treatments of choice for patients with FH. Before starting pharmacotherapy, patients should undergo 3 months of lifestyle modification to assess how well this approach improves their lipid levels, assuming the patient doesn’t have additional risk factors such as hypertension or tobacco use, in which case he or she might require immediate pharmacotherapy. Statins can be initiated simultaneously with lifestyle choices in patients with an LDL >190 mg/dL.18

Lifestyle modification. Although FH is a genetic problem, patients should be encouraged to make healthy choices regarding diet and exercise. While the best choices may not get FH patients to their LDL goal, better choices may mean that patients can take fewer medications, or lower doses of them. Healthy lifestyle choices can also have other positive effects on cardiovascular risk (eg, lowering blood pressure).

Patients can’t be expected to navigate their food choices alone, and several visits with a dietician will likely be needed. It’s important to emphasize the family influence on diet and get the entire family involved with making healthy food choices.

In addition to addressing diet and exercise, be sure to encourage patients to abstain from tobacco and manage stress as part of their overall effort to reduce the likelihood of a cardiovascular event.

Statins. Early treatment of FH with statins can delay initial coronary events and prolong life.19 In a 12.5-year study of 2146 patients with FH, approximately 80% of patients treated with statins survived without experiencing CHD, compared to slightly less than 40% of those who were not treated with statins.19 Patients treated with statins had a 76% reduction in risk of CHD compared to those who didn’t receive statins.19 Even low doses of statins started early have been shown to help avoid myocardial infarction in adults with FH.20

The goal of treatment for FH is to reduced LDL levels by 50%.21 In pediatric patients, treating to an LDL level of 130 mg/dL is an alternative goal.21 Because it’s challenging to achieve this goal with improved diet and exercise alone, treatment with a statin is often necessary.22

Statins can be used in children as young as age 8, or even earlier in homozygous FH.6 While a physician might be hesitant to start a chronic medication in a young patient, research shows that earlier intervention results in additional years of life.23 To date, no significant adverse effects of statins in pediatric patients have been identified, and statins have not been shown to impair growth.24,25 Young female patients should be counseled about the adverse effects statins can have on a fetus if the patient becomes pregnant while taking the medication.

Navigating the waters of statin treatment

Musculoskeletal symptoms are the most common adverse effect reported by patients taking statins. A thorough assessment of a patient’s muscle complaints is necessary to avoid prematurely concluding that he or she cannot tolerate statins.

A study in which “statin-intolerant” patients were re-challenged found that more than 90% of patients could tolerate statins through the course of the one-year study and that it was likely that the patients’ initial muscle complaints were not due to statin use.23 (To read more about potential adverse events of statins, see “Statin adverse effects: Sorting out the evidence,” J Fam Pract. 2014;63:497-506.).

If LDL levels in a patient with HeFH remain at or above 160 mg/dL, intensifying treatment by adding another lipid-lowering medication might be warranted.22 For patients with HoFH, in whom the condition is more quickly life-threatening, there are additional choices, including LDL apheresis and medications such as mipomersen and lomitapide. Both of these medications can cause hepatotoxicity, and are available only through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy program, which means they can only be prescribed by certified physicians. PCSK9 inhibitors are in the pipeline and may one day help patients with HoFH by addressing one of the genetic causes of this disorder.

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard Safeer, MD, 6704 Curtis Court, Glen Burnie, MD 21060; [email protected]

› When one member of a family has early heart disease, screen the entire family for familial hypercholesterolemia (FH). A

› Consider all patients with FH as being at high risk for coronary heart disease, regardless of their Framingham Risk Score. C

› Treat FH patients with statins early to avoid cardiovascular events. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) poses a “silent” threat to patients with the condition, putting them at great risk of a coronary event. This genetic disorder, in which one or more mutations cause extremely high low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels, goes undiagnosed in approximately 80% of patients who have it.1 As a result, men with FH have a >50% risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) by age 50 and women with FH have a 30% risk of CHD by age 60.2 Patients with FH face a much higher risk of dying from a coronary event than those in the general population.3 For example, women between the ages of 20 and 39 who have this disorder are 125 times more likely to die of a coronary event than those who don’t.3

Unfortunately, FH can be difficult to diagnose. Some patients have physical findings, but these features can be subtle and easily missed. Typically, however, FH is diagnosed based on a patient’s cholesterol level and family history. By implementing screening and early treatment for FH, you may be able to initiate treatment that can temper the development of atherosclerosis and possibly extend a patient’s life.4

Two forms of the disorder, although one is more common

There are 2 types of FH:

Heterozygous FH (HeFH) occurs in about 1 in 300 to 500 people, which makes it more common than Down syndrome.5 More than a half a million people in the United States have HeFH.6

Homozygous FH (HoFH) is more serious than HeFH, and less common, affecting one in 1 million people. Homozygous carriers suffer from CHD much earlier than those with HeFH; some die within the first few years of life.7

Regardless of whether an affected individual inherited FH from one or both parents, more than one thousand mutations are known to cause inadequate clearance of LDL from the bloodstream.8 One of the most common mutations is a defective LDL receptor gene. Other abnormalities are known to occur with the proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) and apolipoprotein B genes.9

Start with screening

Suspect FH in patients who have a family history of premature heart disease. Also consider the patient’s ethnic background. The prevalence of FH is as high as one in 100 among certain groups, including French Canadians, Christian Lebanese, and 3 populations in South Africa (Ashkenazi Jews, Dutch Afrikaners, and Asian Indians).10

When there is high suspicion of FH based on a patient’s family history or ethnicity, additional screening is warranted for any patient older than age 2.11 If a patient’s family history is incomplete (eg, adoption, single-parent family), a lower threshold for screening is appropriate.

Lipid screening includes measuring serum total, LDL, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in either fasting or non-fasting samples. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) offers gender-specific recommendations for lipid disorder screening in the general population. For men, universal screening is recommended starting at age 35, and screening for those at increased risk of CHD should start at age 20.12

For women, the USPSTF recommends lipid screening only for those over age 20 who are at increased risk for CHD; such screening is strongly recommended for high-risk women ages 45 and older. In light of the serious consequences associated with FH, the National Lipid Association recommends lipid screening for all adults starting at age 20 (TABLE 1).13

What about kids? The recommendations for lipid screening in children and adolescents are mixed. Both the USPSTF and the American Academy of Family Physicians indicate that there is insufficient evidence to screen for lipid disorders in asymptomatic children and adolescents.14,15 However, in a set of recommendations based on expert opinion, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) suggests universal screening for younger patients with a non-fasting lipid profile once between ages 9 to 11 and again between ages 17 to 21.16 The American Academy of Pediatrics has adopted the NHLBI recommendations.17

Physical exam findings that suggest familial hypercholesterolemia

Tendon xanthomas (A), a thickening of the soft tissue as a result of infiltration by lipid-rich cells, most commonly occur at the Achilles and metacarpal tendons, but also can be seen at the patellar and triceps tendons.

Tuberous xanthomas or xanthelasmas (B) are waxy-appearing growths that appear to be pasted on the skin in areas around the face, commonly the eyelids.

Arcus corneae (C) is an opaque ring around the outer edge of the cornea.

Use validated criteria to make the diagnosis

Include FH in your differential diagnosis when evaluating patients with very high LDL levels. However, rule out possible secondary causes of elevated LDL before rendering a conclusion. Hypothyroidism, nephrotic syndrome, diabetes, and liver disease are among the most common secondary causes of high LDL cholesterol.13

Several validated criteria sets can be used to establish an FH diagnosis. No single criteria set is more valid or more widely adopted around the world. All 3 of the most commonly used criteria sets take into account family history and a patient’s LDL level, and 2 of the 3 factor in physical findings (TABLE 2).9

Physical exam findings that suggest FH can be subtle (FIGURE). Tendon xanthomas are a thickening of the soft tissue as a result of infiltration by lipid-rich cells. They most commonly occur at the Achilles and metacarpal tendons, but can also be seen at the patellar and triceps tendons. Xanthomas may not be readily visible, so it’s important to run your fingers over these areas to detect nodularity or thickening. While the presence of a tendon xanthoma makes FH highly likely, they are present in less than half of patients with FH.17

Tuberous xanthomas or xanthelasmas are waxy-appearing growths that may look yellow or orange and appear to be pasted on the skin in areas around the face, commonly the eyelids. The presence of xanthelasmas in a patient younger than age 25 suggests FH.

Finally, arcus corneae is an opaque ring around the outer edge of the cornea. When this is seen in patients younger than age 45, it’s suggestive of FH.13 If you note tendon xanthomas, xanthelasmas, or arcus corneae while examining any of your patients, be sure to order an LDL level if it hasn’t already been done.

Is genetic testing necessary?

The only way to make a definitive diagnosis of FH is to find a mutation in a gene known to affect LDL metabolism. However, because genetic testing is expensive—and because more than one thousand different genetic defects can contribute to FH—it’s not practical to test every patient. Furthermore, since an estimated 20% of the mutations that contribute to FH have not yet been clearly delineated, a “normal” result on a genetic test might be misleading.5 Therefore, the diagnosis of FH usually is a clinical one. After clinically diagnosing a patient with FH, it’s imperative to screen first-degree family members by measuring their LDL cholesterol levels.

Lifestyle changes, statins can ward off CHD

Lifestyle modifications (ie, improved diet and exercise) and statins are the treatments of choice for patients with FH. Before starting pharmacotherapy, patients should undergo 3 months of lifestyle modification to assess how well this approach improves their lipid levels, assuming the patient doesn’t have additional risk factors such as hypertension or tobacco use, in which case he or she might require immediate pharmacotherapy. Statins can be initiated simultaneously with lifestyle choices in patients with an LDL >190 mg/dL.18

Lifestyle modification. Although FH is a genetic problem, patients should be encouraged to make healthy choices regarding diet and exercise. While the best choices may not get FH patients to their LDL goal, better choices may mean that patients can take fewer medications, or lower doses of them. Healthy lifestyle choices can also have other positive effects on cardiovascular risk (eg, lowering blood pressure).

Patients can’t be expected to navigate their food choices alone, and several visits with a dietician will likely be needed. It’s important to emphasize the family influence on diet and get the entire family involved with making healthy food choices.

In addition to addressing diet and exercise, be sure to encourage patients to abstain from tobacco and manage stress as part of their overall effort to reduce the likelihood of a cardiovascular event.

Statins. Early treatment of FH with statins can delay initial coronary events and prolong life.19 In a 12.5-year study of 2146 patients with FH, approximately 80% of patients treated with statins survived without experiencing CHD, compared to slightly less than 40% of those who were not treated with statins.19 Patients treated with statins had a 76% reduction in risk of CHD compared to those who didn’t receive statins.19 Even low doses of statins started early have been shown to help avoid myocardial infarction in adults with FH.20

The goal of treatment for FH is to reduced LDL levels by 50%.21 In pediatric patients, treating to an LDL level of 130 mg/dL is an alternative goal.21 Because it’s challenging to achieve this goal with improved diet and exercise alone, treatment with a statin is often necessary.22