User login

Intragestational injection of methotrexate

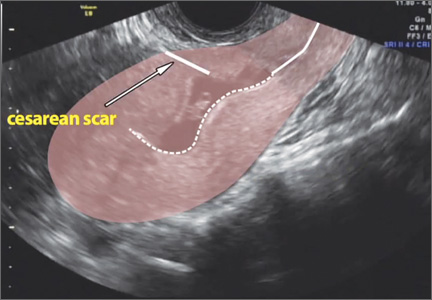

The presentation of a cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy can at times be daunting, especially without familiarity regarding its management. Women with cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy most often have no symptoms, although vaginal bleeding and abdominal pain can present. Upon visual diagnosis with transabdominal or transvaginal ultrasound, the preferred treatment method is direct injection of methotrexate into the gestational sac within the cesarean scar.

In this video, my colleagues review the indications and contraindications for direct injection of methotrexate as well as alternative treatment methods for this type of nonviable pregnancy that is increasing in frequency (given the US cesarean delivery rate). Demonstrated is the technique for methotrexate injection in the case of a 34-year-old woman (G6P0232) with ultrasound and beta−human chorionic gonadotropin confirmation of cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy.

We hope this video serves as a useful reference in your practice.

Share your thoughts on this video! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The presentation of a cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy can at times be daunting, especially without familiarity regarding its management. Women with cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy most often have no symptoms, although vaginal bleeding and abdominal pain can present. Upon visual diagnosis with transabdominal or transvaginal ultrasound, the preferred treatment method is direct injection of methotrexate into the gestational sac within the cesarean scar.

In this video, my colleagues review the indications and contraindications for direct injection of methotrexate as well as alternative treatment methods for this type of nonviable pregnancy that is increasing in frequency (given the US cesarean delivery rate). Demonstrated is the technique for methotrexate injection in the case of a 34-year-old woman (G6P0232) with ultrasound and beta−human chorionic gonadotropin confirmation of cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy.

We hope this video serves as a useful reference in your practice.

Share your thoughts on this video! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The presentation of a cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy can at times be daunting, especially without familiarity regarding its management. Women with cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy most often have no symptoms, although vaginal bleeding and abdominal pain can present. Upon visual diagnosis with transabdominal or transvaginal ultrasound, the preferred treatment method is direct injection of methotrexate into the gestational sac within the cesarean scar.

In this video, my colleagues review the indications and contraindications for direct injection of methotrexate as well as alternative treatment methods for this type of nonviable pregnancy that is increasing in frequency (given the US cesarean delivery rate). Demonstrated is the technique for methotrexate injection in the case of a 34-year-old woman (G6P0232) with ultrasound and beta−human chorionic gonadotropin confirmation of cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy.

We hope this video serves as a useful reference in your practice.

Share your thoughts on this video! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

FDA warns of anticoagulant/antidepressant mix-up

Photo courtesy of AstraZeneca

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has announced that confusion between the anticoagulant Brilinta (ticagrelor) and the antidepressant Brintellix (vortioxetine) is resulting in the wrong medication being prescribed or dispensed.

The FDA found the main reason for the confusion is the similarity of the drugs’ brand names.

None of the reports the FDA received indicate that a patient ingested the wrong medication. However, the FDA continues to receive reports of prescribing and dispensing errors.

As of June 2015, the agency has received 50 reports of name confusion between Brintellix and Brilinta. The FDA confirmed that the wrong medication was dispensed to a patient in 12 of the cases and may have been dispensed in 3 additional cases.

About the medications

Brilinta is a P2Y12 platelet inhibitor approved for use in patients with acute coronary syndrome to reduce the rate of thrombotic cardiovascular events. The drug comes in the form of a round, yellow tablet with a “90” above a “T” stamped on one side.

Brintellix is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor used to treat major depressive disorder in adults. The medication comes in the form of a tear-shaped tablet stamped with “TL” on one side of the tablet and a number that indicates the tablet strength on the other side. It varies in color depending upon the strength prescribed.

About the error reports

As of June 2015, the FDA has received 50 medication error reports describing brand name confusion with Brintellix (vortioxetine) and Brilinta (ticagrelor). In most cases, Brintellix was mistaken as Brilinta.

Some of the contributing factors to the name confusion included the following:

- Both brand names begin with the same 3 letters

- Both brand names are presented when selecting medications in a computerized physician order entry (CPOE) system

- The pharmacist was not familiar with the new medication Brintellix and so dispensed Brilinta

- The brand names look and sound similar.

Of these 50 reports, the wrong medication was actually dispensed in 12 cases and was possibly dispensed in 3 additional cases but could not be confirmed based on the case narrative information. None of the reports indicated a patient had ingested the wrong medication.

However, in one case, Brintellix was misinterpreted as Brilinta, and the pharmacist did not dispense any medication because the patient had a contraindication to antiplatelet therapy. As a result, the patient went untreated for the psychiatric indication for an unreported period.

In the 12 cases where a wrong medication was actually dispensed, the reports showed that, in 6 cases, the error occurred when prescribing the medication.

Five of these prescribing errors occurred during CPOE. Some CPOE systems auto-populate or present a drop-down menu after the first 3 letters are typed, at which point a prescriber can select the wrong medication.

In the other 6 cases, the error occurred during dispensing of the medication.

FDA recommendations

The FDA is recommending that healthcare professionals reduce the risk of name confusion when prescribing these medications by including the generic names, indications for use, correct dosage, and directions for use.

Healthcare professionals should also ensure that patients understand what their medication is used to treat and encourage patients and their caregivers to read the Medication Guides provided with their Brintellix and Brilinta prescriptions.

Healthcare professionals and patients can report name confusion and medication errors involving Brintellix and Brilinta to the FDA MedWatch Program. ![]()

Photo courtesy of AstraZeneca

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has announced that confusion between the anticoagulant Brilinta (ticagrelor) and the antidepressant Brintellix (vortioxetine) is resulting in the wrong medication being prescribed or dispensed.

The FDA found the main reason for the confusion is the similarity of the drugs’ brand names.

None of the reports the FDA received indicate that a patient ingested the wrong medication. However, the FDA continues to receive reports of prescribing and dispensing errors.

As of June 2015, the agency has received 50 reports of name confusion between Brintellix and Brilinta. The FDA confirmed that the wrong medication was dispensed to a patient in 12 of the cases and may have been dispensed in 3 additional cases.

About the medications

Brilinta is a P2Y12 platelet inhibitor approved for use in patients with acute coronary syndrome to reduce the rate of thrombotic cardiovascular events. The drug comes in the form of a round, yellow tablet with a “90” above a “T” stamped on one side.

Brintellix is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor used to treat major depressive disorder in adults. The medication comes in the form of a tear-shaped tablet stamped with “TL” on one side of the tablet and a number that indicates the tablet strength on the other side. It varies in color depending upon the strength prescribed.

About the error reports

As of June 2015, the FDA has received 50 medication error reports describing brand name confusion with Brintellix (vortioxetine) and Brilinta (ticagrelor). In most cases, Brintellix was mistaken as Brilinta.

Some of the contributing factors to the name confusion included the following:

- Both brand names begin with the same 3 letters

- Both brand names are presented when selecting medications in a computerized physician order entry (CPOE) system

- The pharmacist was not familiar with the new medication Brintellix and so dispensed Brilinta

- The brand names look and sound similar.

Of these 50 reports, the wrong medication was actually dispensed in 12 cases and was possibly dispensed in 3 additional cases but could not be confirmed based on the case narrative information. None of the reports indicated a patient had ingested the wrong medication.

However, in one case, Brintellix was misinterpreted as Brilinta, and the pharmacist did not dispense any medication because the patient had a contraindication to antiplatelet therapy. As a result, the patient went untreated for the psychiatric indication for an unreported period.

In the 12 cases where a wrong medication was actually dispensed, the reports showed that, in 6 cases, the error occurred when prescribing the medication.

Five of these prescribing errors occurred during CPOE. Some CPOE systems auto-populate or present a drop-down menu after the first 3 letters are typed, at which point a prescriber can select the wrong medication.

In the other 6 cases, the error occurred during dispensing of the medication.

FDA recommendations

The FDA is recommending that healthcare professionals reduce the risk of name confusion when prescribing these medications by including the generic names, indications for use, correct dosage, and directions for use.

Healthcare professionals should also ensure that patients understand what their medication is used to treat and encourage patients and their caregivers to read the Medication Guides provided with their Brintellix and Brilinta prescriptions.

Healthcare professionals and patients can report name confusion and medication errors involving Brintellix and Brilinta to the FDA MedWatch Program. ![]()

Photo courtesy of AstraZeneca

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has announced that confusion between the anticoagulant Brilinta (ticagrelor) and the antidepressant Brintellix (vortioxetine) is resulting in the wrong medication being prescribed or dispensed.

The FDA found the main reason for the confusion is the similarity of the drugs’ brand names.

None of the reports the FDA received indicate that a patient ingested the wrong medication. However, the FDA continues to receive reports of prescribing and dispensing errors.

As of June 2015, the agency has received 50 reports of name confusion between Brintellix and Brilinta. The FDA confirmed that the wrong medication was dispensed to a patient in 12 of the cases and may have been dispensed in 3 additional cases.

About the medications

Brilinta is a P2Y12 platelet inhibitor approved for use in patients with acute coronary syndrome to reduce the rate of thrombotic cardiovascular events. The drug comes in the form of a round, yellow tablet with a “90” above a “T” stamped on one side.

Brintellix is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor used to treat major depressive disorder in adults. The medication comes in the form of a tear-shaped tablet stamped with “TL” on one side of the tablet and a number that indicates the tablet strength on the other side. It varies in color depending upon the strength prescribed.

About the error reports

As of June 2015, the FDA has received 50 medication error reports describing brand name confusion with Brintellix (vortioxetine) and Brilinta (ticagrelor). In most cases, Brintellix was mistaken as Brilinta.

Some of the contributing factors to the name confusion included the following:

- Both brand names begin with the same 3 letters

- Both brand names are presented when selecting medications in a computerized physician order entry (CPOE) system

- The pharmacist was not familiar with the new medication Brintellix and so dispensed Brilinta

- The brand names look and sound similar.

Of these 50 reports, the wrong medication was actually dispensed in 12 cases and was possibly dispensed in 3 additional cases but could not be confirmed based on the case narrative information. None of the reports indicated a patient had ingested the wrong medication.

However, in one case, Brintellix was misinterpreted as Brilinta, and the pharmacist did not dispense any medication because the patient had a contraindication to antiplatelet therapy. As a result, the patient went untreated for the psychiatric indication for an unreported period.

In the 12 cases where a wrong medication was actually dispensed, the reports showed that, in 6 cases, the error occurred when prescribing the medication.

Five of these prescribing errors occurred during CPOE. Some CPOE systems auto-populate or present a drop-down menu after the first 3 letters are typed, at which point a prescriber can select the wrong medication.

In the other 6 cases, the error occurred during dispensing of the medication.

FDA recommendations

The FDA is recommending that healthcare professionals reduce the risk of name confusion when prescribing these medications by including the generic names, indications for use, correct dosage, and directions for use.

Healthcare professionals should also ensure that patients understand what their medication is used to treat and encourage patients and their caregivers to read the Medication Guides provided with their Brintellix and Brilinta prescriptions.

Healthcare professionals and patients can report name confusion and medication errors involving Brintellix and Brilinta to the FDA MedWatch Program. ![]()

Companies ‘underinvest’ in long-term cancer research

for a clinical trial

Photo by Esther Dyson

Pharmaceutical companies “underinvest” in long-term research to develop new anticancer drugs, according to a study published in American Economic Review.

Investigators used historical data to show that companies are more likely to develop drugs for late-stage cancers than early stage cancers or cancer prevention, and this is likely because late-stage cancer drugs can be brought to market faster.

The team found that late-stage drugs extend patient survival for shorter periods so that clinical trials for these drugs get wrapped up more quickly. This, in turn, gives drug manufacturers more time to control patented drugs in the marketplace.

“There is a pattern where we get more investment in drugs that take a short time to complete and less investment in drugs that take a longer time to complete,” said study author Heidi Williams, PhD, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge.

To conduct this study, Dr Williams and her colleagues analyzed 4 decades of clinical trial data from a variety of sources, including the National Cancer Institute and the US Food and Drug Administration. The study encompassed more than 200 subcategories of cancers detected at different stages of development.

In analyzing the data, the investigators divided research and development (R&D) into 2 stages: invention (developing the basic idea for a product to the point where it is patentable) and commercialization (bringing an invented product to market).

They defined the “commercialization lag” of an R&D project as the amount of time between invention and commercialization.

The data showed that patient groups with longer commercialization lags (as proxied by longer survival times) tended to have lower levels of R&D investment than groups with shorter commercialization lags (and survival times).

The investigators also found that when surrogate endpoints (endpoints other than survival) were allowed, there were more trials and money poured into research. This supports the idea that companies are more likely to invest in drugs that will have shorter trials and take less time to develop.

Dr Williams and her colleagues used the surrogate endpoint variation to estimate improvements in cancer survival rates that would have been observed if commercialization lags were reduced. The team estimated that, among US cancer patients diagnosed in 2003, longer commercialization lags resulted in around 890,000 lost life-years.

The investigators noted that commercialization lags reduce both public and private R&D investments, but they found the commercialization lag-R&D correlation is significantly more negative for privately financed trials than publicly financed trials.

The team said that, due to either excessive discounting or the fixed patent term, private incentives decline more rapidly than public incentives, which is what gives rise to the distortion.

Based on their findings, Dr Williams and her colleagues devised 3 new policy approaches that could potentially spark the development of more drugs for early stage cancers or cancer prevention.

The first is expanded use of surrogate endpoints or more research to determine if wider use of surrogate endpoints is valid.

A second possible policy change is more public funding of R&D for anticancer drugs, since such funding is free of short-term, private-sector shareholder pressure to produce returns.

A third potential new policy would be changing the terms of drug patents, which typically run from the time of patent filing to when the drug hits the market. ![]()

for a clinical trial

Photo by Esther Dyson

Pharmaceutical companies “underinvest” in long-term research to develop new anticancer drugs, according to a study published in American Economic Review.

Investigators used historical data to show that companies are more likely to develop drugs for late-stage cancers than early stage cancers or cancer prevention, and this is likely because late-stage cancer drugs can be brought to market faster.

The team found that late-stage drugs extend patient survival for shorter periods so that clinical trials for these drugs get wrapped up more quickly. This, in turn, gives drug manufacturers more time to control patented drugs in the marketplace.

“There is a pattern where we get more investment in drugs that take a short time to complete and less investment in drugs that take a longer time to complete,” said study author Heidi Williams, PhD, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge.

To conduct this study, Dr Williams and her colleagues analyzed 4 decades of clinical trial data from a variety of sources, including the National Cancer Institute and the US Food and Drug Administration. The study encompassed more than 200 subcategories of cancers detected at different stages of development.

In analyzing the data, the investigators divided research and development (R&D) into 2 stages: invention (developing the basic idea for a product to the point where it is patentable) and commercialization (bringing an invented product to market).

They defined the “commercialization lag” of an R&D project as the amount of time between invention and commercialization.

The data showed that patient groups with longer commercialization lags (as proxied by longer survival times) tended to have lower levels of R&D investment than groups with shorter commercialization lags (and survival times).

The investigators also found that when surrogate endpoints (endpoints other than survival) were allowed, there were more trials and money poured into research. This supports the idea that companies are more likely to invest in drugs that will have shorter trials and take less time to develop.

Dr Williams and her colleagues used the surrogate endpoint variation to estimate improvements in cancer survival rates that would have been observed if commercialization lags were reduced. The team estimated that, among US cancer patients diagnosed in 2003, longer commercialization lags resulted in around 890,000 lost life-years.

The investigators noted that commercialization lags reduce both public and private R&D investments, but they found the commercialization lag-R&D correlation is significantly more negative for privately financed trials than publicly financed trials.

The team said that, due to either excessive discounting or the fixed patent term, private incentives decline more rapidly than public incentives, which is what gives rise to the distortion.

Based on their findings, Dr Williams and her colleagues devised 3 new policy approaches that could potentially spark the development of more drugs for early stage cancers or cancer prevention.

The first is expanded use of surrogate endpoints or more research to determine if wider use of surrogate endpoints is valid.

A second possible policy change is more public funding of R&D for anticancer drugs, since such funding is free of short-term, private-sector shareholder pressure to produce returns.

A third potential new policy would be changing the terms of drug patents, which typically run from the time of patent filing to when the drug hits the market. ![]()

for a clinical trial

Photo by Esther Dyson

Pharmaceutical companies “underinvest” in long-term research to develop new anticancer drugs, according to a study published in American Economic Review.

Investigators used historical data to show that companies are more likely to develop drugs for late-stage cancers than early stage cancers or cancer prevention, and this is likely because late-stage cancer drugs can be brought to market faster.

The team found that late-stage drugs extend patient survival for shorter periods so that clinical trials for these drugs get wrapped up more quickly. This, in turn, gives drug manufacturers more time to control patented drugs in the marketplace.

“There is a pattern where we get more investment in drugs that take a short time to complete and less investment in drugs that take a longer time to complete,” said study author Heidi Williams, PhD, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge.

To conduct this study, Dr Williams and her colleagues analyzed 4 decades of clinical trial data from a variety of sources, including the National Cancer Institute and the US Food and Drug Administration. The study encompassed more than 200 subcategories of cancers detected at different stages of development.

In analyzing the data, the investigators divided research and development (R&D) into 2 stages: invention (developing the basic idea for a product to the point where it is patentable) and commercialization (bringing an invented product to market).

They defined the “commercialization lag” of an R&D project as the amount of time between invention and commercialization.

The data showed that patient groups with longer commercialization lags (as proxied by longer survival times) tended to have lower levels of R&D investment than groups with shorter commercialization lags (and survival times).

The investigators also found that when surrogate endpoints (endpoints other than survival) were allowed, there were more trials and money poured into research. This supports the idea that companies are more likely to invest in drugs that will have shorter trials and take less time to develop.

Dr Williams and her colleagues used the surrogate endpoint variation to estimate improvements in cancer survival rates that would have been observed if commercialization lags were reduced. The team estimated that, among US cancer patients diagnosed in 2003, longer commercialization lags resulted in around 890,000 lost life-years.

The investigators noted that commercialization lags reduce both public and private R&D investments, but they found the commercialization lag-R&D correlation is significantly more negative for privately financed trials than publicly financed trials.

The team said that, due to either excessive discounting or the fixed patent term, private incentives decline more rapidly than public incentives, which is what gives rise to the distortion.

Based on their findings, Dr Williams and her colleagues devised 3 new policy approaches that could potentially spark the development of more drugs for early stage cancers or cancer prevention.

The first is expanded use of surrogate endpoints or more research to determine if wider use of surrogate endpoints is valid.

A second possible policy change is more public funding of R&D for anticancer drugs, since such funding is free of short-term, private-sector shareholder pressure to produce returns.

A third potential new policy would be changing the terms of drug patents, which typically run from the time of patent filing to when the drug hits the market. ![]()

Health Canada grants drug conditional approval for MCL

Photo courtesy of

Janssen Biotech, Inc.

Health Canada has granted conditional approval for the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib (Imbruvica) to treat patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).

This approval was based on data from a phase 2 trial in which ibrutinib conferred an overall response rate of 68% in patients with relapsed/refractory MCL.

For ibrutinib to gain full approval, Health Canada must receive additional data confirming the drug provides a clinical benefit.

Ibrutinib was first approved in Canada in November 2014 for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), including those with 17p deletion, who have received at least one prior therapy, or for the frontline treatment of patients with CLL with 17p deletion. For this use, ibrutinib was issued marketing authorization without conditions.

Now, Health Canada has issued ibrutinib conditional marketing authorization for the treatment of relapsed/refractory MCL. This decision was based on data from the phase 2 PCYC-1104 trial, which was presented at ASH 2012 and published in NEJM in August 2013.

The study included 111 MCL patients who had received at least one prior therapy. The primary endpoint of the study was overall response rate according to the revised International Working Group criteria for non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The overall response rate was 68%, with a complete response rate of 21% and a partial response rate of 47%. With a median follow-up of 15.3 months, the median response duration was 17.5 months.

The estimated progression-free survival was 13.9 months, and the overall survival was not reached. The estimated rate of overall survival was 58% at 18 months.

Common nonhematologic adverse events included diarrhea (50%), fatigue (41%), nausea (31%), peripheral edema (28%), dyspnea (27%), constipation (25%), upper respiratory tract infection (23%), vomiting (23%), and decreased appetite (21%). The most common grade 3, 4, or 5 infection was pneumonia (6%).

Grade 3 and 4 hematologic adverse events included neutropenia (16%), thrombocytopenia (11%), and anemia (10%). Grade 3 bleeding events occurred in 5 patients.

Eight patients (7%) had an adverse event that led to treatment discontinuation.

Sixteen patients (14%) died during the trial, 12 due to disease progression and 4 due to an adverse event. Two patients died of pneumonia, 1 from sepsis, and 1 from a cardiac arrest that was not considered drug-related.

Ibrutinib is co-developed by Cilag GmbH International (a member of the Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies) and Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie company. Janssen Inc. markets ibrutinib as Imbruvica in Canada. ![]()

Photo courtesy of

Janssen Biotech, Inc.

Health Canada has granted conditional approval for the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib (Imbruvica) to treat patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).

This approval was based on data from a phase 2 trial in which ibrutinib conferred an overall response rate of 68% in patients with relapsed/refractory MCL.

For ibrutinib to gain full approval, Health Canada must receive additional data confirming the drug provides a clinical benefit.

Ibrutinib was first approved in Canada in November 2014 for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), including those with 17p deletion, who have received at least one prior therapy, or for the frontline treatment of patients with CLL with 17p deletion. For this use, ibrutinib was issued marketing authorization without conditions.

Now, Health Canada has issued ibrutinib conditional marketing authorization for the treatment of relapsed/refractory MCL. This decision was based on data from the phase 2 PCYC-1104 trial, which was presented at ASH 2012 and published in NEJM in August 2013.

The study included 111 MCL patients who had received at least one prior therapy. The primary endpoint of the study was overall response rate according to the revised International Working Group criteria for non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The overall response rate was 68%, with a complete response rate of 21% and a partial response rate of 47%. With a median follow-up of 15.3 months, the median response duration was 17.5 months.

The estimated progression-free survival was 13.9 months, and the overall survival was not reached. The estimated rate of overall survival was 58% at 18 months.

Common nonhematologic adverse events included diarrhea (50%), fatigue (41%), nausea (31%), peripheral edema (28%), dyspnea (27%), constipation (25%), upper respiratory tract infection (23%), vomiting (23%), and decreased appetite (21%). The most common grade 3, 4, or 5 infection was pneumonia (6%).

Grade 3 and 4 hematologic adverse events included neutropenia (16%), thrombocytopenia (11%), and anemia (10%). Grade 3 bleeding events occurred in 5 patients.

Eight patients (7%) had an adverse event that led to treatment discontinuation.

Sixteen patients (14%) died during the trial, 12 due to disease progression and 4 due to an adverse event. Two patients died of pneumonia, 1 from sepsis, and 1 from a cardiac arrest that was not considered drug-related.

Ibrutinib is co-developed by Cilag GmbH International (a member of the Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies) and Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie company. Janssen Inc. markets ibrutinib as Imbruvica in Canada. ![]()

Photo courtesy of

Janssen Biotech, Inc.

Health Canada has granted conditional approval for the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib (Imbruvica) to treat patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).

This approval was based on data from a phase 2 trial in which ibrutinib conferred an overall response rate of 68% in patients with relapsed/refractory MCL.

For ibrutinib to gain full approval, Health Canada must receive additional data confirming the drug provides a clinical benefit.

Ibrutinib was first approved in Canada in November 2014 for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), including those with 17p deletion, who have received at least one prior therapy, or for the frontline treatment of patients with CLL with 17p deletion. For this use, ibrutinib was issued marketing authorization without conditions.

Now, Health Canada has issued ibrutinib conditional marketing authorization for the treatment of relapsed/refractory MCL. This decision was based on data from the phase 2 PCYC-1104 trial, which was presented at ASH 2012 and published in NEJM in August 2013.

The study included 111 MCL patients who had received at least one prior therapy. The primary endpoint of the study was overall response rate according to the revised International Working Group criteria for non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The overall response rate was 68%, with a complete response rate of 21% and a partial response rate of 47%. With a median follow-up of 15.3 months, the median response duration was 17.5 months.

The estimated progression-free survival was 13.9 months, and the overall survival was not reached. The estimated rate of overall survival was 58% at 18 months.

Common nonhematologic adverse events included diarrhea (50%), fatigue (41%), nausea (31%), peripheral edema (28%), dyspnea (27%), constipation (25%), upper respiratory tract infection (23%), vomiting (23%), and decreased appetite (21%). The most common grade 3, 4, or 5 infection was pneumonia (6%).

Grade 3 and 4 hematologic adverse events included neutropenia (16%), thrombocytopenia (11%), and anemia (10%). Grade 3 bleeding events occurred in 5 patients.

Eight patients (7%) had an adverse event that led to treatment discontinuation.

Sixteen patients (14%) died during the trial, 12 due to disease progression and 4 due to an adverse event. Two patients died of pneumonia, 1 from sepsis, and 1 from a cardiac arrest that was not considered drug-related.

Ibrutinib is co-developed by Cilag GmbH International (a member of the Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies) and Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie company. Janssen Inc. markets ibrutinib as Imbruvica in Canada. ![]()

Is menopausal hormone therapy safe when your patient carries a BRCA mutation?

Case: Disabling vasomotor symptoms in a BRCA1 mutation carrier

Christine is a 39-year-old mother of 2 who underwent risk-reducing, minimally invasive bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with hysterectomy 4 months ago for a BRCA1 mutation (with benign findings on pathology). Eighteen months before that surgery, she had risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy with reconstruction (implants) and was advised by her surgeon that she no longer needs breast imaging.

Today she reports disabling hot flashes, insomnia, vaginal dryness, and painful sex. Her previous ObGyn, who performed the hysterectomy, was unwilling to prescribe hormone therapy (HT) due to safety concerns. Christine tried venlafaxine at 37 to 75 mg but noted little relief of her vasomotor symptoms.

In discussing her symptoms with you during this initial visit, Christine, a practicing accountant, also reveals that she does not feel as intellectually “sharp” as she did before her gynecologic surgery.

What can you offer for relief of her symptoms?

More BRCA mutation carriers are being identified and choosing to undergo risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy and bilateral mastectomy. Accordingly, clinicians are likely to face more questions about the use of systemic HT in this population. Because mutation carriers may worry about the safety of HT, given their BRCA status, some may delay or avoid salpingo-oophorectomy—a surgery that not only reduces the risk of ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal cancer by 80% but also decreases the risk of breast cancer by 48%.1

Surgically menopausal women in their 30s or 40s who are not treated with HT appear to have an elevated risk for dementia and Parkinsonism.2 In addition, vasomotor symptoms are often more severe, and the risks for osteoporosis and, likely, cardiovascular disease are elevated in women with early menopause who are not treated with HT. For these reasons, systemic HT is recommended for women with early menopause, and generally should be continued at least until the normal age of menopause unless specific contraindications are present.3

Because Christine not only has had risk-reducing gynecologic surgery but also risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy, her current risk for breast cancer is very low whether or not she uses HT. Because she does not have a uterus, her symptoms can effectively and safely be treated with systemic estrogen-only therapy.

Among clinicians with special expertise in the management of BRCA mutation carriers, the use of systemic HT would be considered appropriate—and not controversial—in this setting.4

Angelina Jolie details her surgeries

In March 2015, 39-year-old Oscar-winning actress and filmmaker Angelina Jolie Pitt published an opinion piece in the New York Times detailing her recent laparoscopic salpingo-oophorectomy and initiation of HT.5 Ms. Jolie Pitt, who carries the BRCA1 mutation, lost her mother, grandmother, and aunt to hereditary breast/ovarian cancer. Two years earlier, Ms. Jolie Pitt made news by describing her decision to move ahead with risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy.

Following her risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy, she initiated systemic HT using transdermal estradiol and off-label use of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for endometrial protection.

Her courageous decision to publicly describe her surgery and subsequent initiation of systemic HT will likely encourage women with ominous family histories to seek out genetic counseling and testing. Her decision to “go public” regarding surgery should help mutation carriers without a history of cancer (known in the BRCA community as “previvors”) who have completed their families to move forward with risk-reducing gynecologic surgery and, when appropriate, use of systemic HT.6

The outlook for previvors with intact breasts

Three studies address the risk of breast cancer with use of systemic HT among previvors with intact breasts. A 2005 study followed a cohort of BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers with intact breasts, 155 of whom had undergone risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy, for a mean of 3.6 years. Of these women, 60% and 7%, respectively, of those who had and had not undergone salpingo-oophorectomy used HT. The authors noted that bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy reduced the risk of breast cancer by some 60%, whether or not women used HT.7

A 2008 case-control study focused on 472 menopausal BRCA1 carriers, half of whom had been diagnosed with breast cancer (cases); the other half had not received this diagnosis (controls). A 43% reduction in the risk of breast cancer was associated with prior use of HT.8

A 2011 presentation described a cohort study in which 1,299 BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers with intact breasts who had undergone salpingo-oophorectomy were followed for a mean of 5.4 years postoperatively. In this population, use of HT was not associated with an increased risk of breast cancer. Among women with BRCA1 mutations, use of systemic HT was associated with a reduced risk of breast cancer.9

Viewed in aggregate, these studies reassure us that short-term use of systemic HT does not increase breast cancer risk in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and intact breasts.

Dr. Simon

Nevertheless, I think it is important to point out that a properly powered study to assess actual risk in this setting is not available in the literature.

When a patient refuses HT

Dr. Pinkerton

Some BRCA mutation carriers may refuse HT despite reassurance that it is safe. Nonhormonal therapies are not as effective at relieving severe menopausal symptoms. Almost all selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) can be offered, although only low-dose paroxetine salt is approved for treatment of postmenopausal hot flashes.10,11 Gabapentin also has shown efficacy in relieving hot flashes.

For genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM; formerly known as vulvovaginal atrophy), lubricants and moisturizers may provide some benefit, but they don’t improve the vaginal superficial cells and, therefore, are not as effective as hormonal options. There is now a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) approved to treat GSM—ospemifene. However, in clinical trials, ospemifene has been shown to increase hot flashes, so it would not be a good option for our patient.12

Case: Continued

Christine follows up 3 months after initiating estrogen therapy (oral estradiol 2 mg daily). She reports significant improvement in her hot flashes, with improved sleep and fewer sleep disruptions. In addition, she feels that her “mental sharpness” has returned.

Dr. Pinkerton

What if this patient had an intact uterus? Then she would not be a candidate for estrogen-only therapy because she would need continued endometrial protection. Options then would include low-dose continuous or cyclic progestogen therapy, often starting with micronized progesterone, as the E3N Study suggested it has a less negative effect on the uterus.13 Or she could use a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system off label, as Ms. Jolie Pitt elected to do.

Another option would be combining estrogen with a SERM. The only estrogen/SERM combination currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is conjugated estrogen/bazedoxefine, which showed no increase in breast tenderness, breast density, or bleeding rates, compared with placebo, in multiple trials up to 5 years in duration.14

Case: Resolved

Christine says she would like to continue HT, although she still experiences dryness and discomfort when sexually active with her husband, despite use of a vaginal lubricant. A pelvic examination is consistent with early changes of GSM.15

You discuss GSM with Christine and suggest that she consider 1 of 2 strategies:

- Switch from daily use of oral estradiol to the 3-month systemic 0.1-mg estradiol ring (Femring), which would address both her vasomotor symptoms and her GSM.

- Continue oral estradiol and add low-dose vaginal estrogen (cream, tablets, or Estring 2 mg).

Christine chooses Option 2. When she returns 6 months later for her well-woman visit, she reports that all of her menopausal symptoms have resolved, and a pelvic examination no longer reveals changes of GSM.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Finch AP, Lubinski J, Moller P, et al. Impact of oophorectomy on cancer incidence and mortality in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15):1547–1553.

2. Rocca WA, Bower JH, Maraganore DM, et al. Increased risk of cognitive impairment or dementia in women who underwent oophorectomy before menopause. Neurology. 2007;69(11):1074–1083.

3. North American Menopause Society. The 2012 hormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2012;19(3):257–271.

4. Finch AP, Evans G, Narod SA. BRCA carriers, prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy and menopause: clinical management considerations and recommendations. Womens Health (Lond Engl). 2012;8(5):543–555.

5. Pitt AJ. Angelina Jolie Pitt: Diary of a Surgery. New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/24/opinion/angelina-jolie-pitt-diary-of-a-surgery.html. Published March 24, 2015. Accessed July 9, 2015.

6. Holman L, Brandt A, Daniels M, et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy and prophylactic mastectomy among BRCA mutation “previvors.” Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127(1 suppl):S17.

7. Rebbeck TR, Friebel T, Wagner T, et al; PROSE Study Group. Effect of short-term hormone replacement therapy on breast cancer risk reduction after bilateral prophylactic oophorectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: the PROSE Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(31):7804–7810.

8. Eisen A, Lubinski J, Gronwald J, et al; Hereditary Breast Cancer Clinical Study Group. Hormone therapy and the risk of breast cancer in BRCA1 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(19):1361–1367.

9. Domchek SM, Mitchell G, Lindeman GJ, et al. Challenges to the development of new agents for molecularly defined patient subsets: lessons from BRCA1/2-associated breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(32):4224–4226.

10. Krause MS, Nakajima ST. Hormonal and nonhormonal treatment of vasomotor symptoms. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015;42(1):163–179.

11. Simon JA, Portman DJ, Kaunitz AM, et al. Low-dose paroxetine 7.5 mg for menopausal vasomotor symptoms: two randomized controlled trials. Menopause. 2013;20(10):1027–1030.

12. Bachmann GA, Komi JO; Ospemifene Study Group. Ospemifene effectively treats vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: results from a pivotal phase 3 study. Menopause. 2010;17(3):480–486.

13. Fournier A, Fabre A, Mesrine S, Boutron-Ruault MC, Berrino F, Clavel-Chapelon F. Use of different postmenopausal hormone therapies and risk of histology- and hormone receptor–defined invasive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(8):1260–1268.

14. Pinkerton JV, Pickar JH, Racketa J, Mirkin S. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for menopausal symptom treatment and osteoporosis prevention. Climacteric. 2012;15(5):411–418.

15. Rahn DD, Carberry C, Sanses TV, et al; Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group. Vaginal estrogen for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(6):1147–1156.

Angelina Jolie, previvors, systemic HT, nonhormonal therapy, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, SSRIs, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, SNRIs, paroxetine salt, gabapentin, genitourinary syndrome of menopause, GSM, vaginal lubricants, vaginal moisturizers, selective estrogen receptor modulator, SERM, ospemifene, estrogen therapy, oral estradiol, endometrial protection, progestogen therapy, micronized progesterone,

Case: Disabling vasomotor symptoms in a BRCA1 mutation carrier

Christine is a 39-year-old mother of 2 who underwent risk-reducing, minimally invasive bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with hysterectomy 4 months ago for a BRCA1 mutation (with benign findings on pathology). Eighteen months before that surgery, she had risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy with reconstruction (implants) and was advised by her surgeon that she no longer needs breast imaging.

Today she reports disabling hot flashes, insomnia, vaginal dryness, and painful sex. Her previous ObGyn, who performed the hysterectomy, was unwilling to prescribe hormone therapy (HT) due to safety concerns. Christine tried venlafaxine at 37 to 75 mg but noted little relief of her vasomotor symptoms.

In discussing her symptoms with you during this initial visit, Christine, a practicing accountant, also reveals that she does not feel as intellectually “sharp” as she did before her gynecologic surgery.

What can you offer for relief of her symptoms?

More BRCA mutation carriers are being identified and choosing to undergo risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy and bilateral mastectomy. Accordingly, clinicians are likely to face more questions about the use of systemic HT in this population. Because mutation carriers may worry about the safety of HT, given their BRCA status, some may delay or avoid salpingo-oophorectomy—a surgery that not only reduces the risk of ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal cancer by 80% but also decreases the risk of breast cancer by 48%.1

Surgically menopausal women in their 30s or 40s who are not treated with HT appear to have an elevated risk for dementia and Parkinsonism.2 In addition, vasomotor symptoms are often more severe, and the risks for osteoporosis and, likely, cardiovascular disease are elevated in women with early menopause who are not treated with HT. For these reasons, systemic HT is recommended for women with early menopause, and generally should be continued at least until the normal age of menopause unless specific contraindications are present.3

Because Christine not only has had risk-reducing gynecologic surgery but also risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy, her current risk for breast cancer is very low whether or not she uses HT. Because she does not have a uterus, her symptoms can effectively and safely be treated with systemic estrogen-only therapy.

Among clinicians with special expertise in the management of BRCA mutation carriers, the use of systemic HT would be considered appropriate—and not controversial—in this setting.4

Angelina Jolie details her surgeries

In March 2015, 39-year-old Oscar-winning actress and filmmaker Angelina Jolie Pitt published an opinion piece in the New York Times detailing her recent laparoscopic salpingo-oophorectomy and initiation of HT.5 Ms. Jolie Pitt, who carries the BRCA1 mutation, lost her mother, grandmother, and aunt to hereditary breast/ovarian cancer. Two years earlier, Ms. Jolie Pitt made news by describing her decision to move ahead with risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy.

Following her risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy, she initiated systemic HT using transdermal estradiol and off-label use of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for endometrial protection.

Her courageous decision to publicly describe her surgery and subsequent initiation of systemic HT will likely encourage women with ominous family histories to seek out genetic counseling and testing. Her decision to “go public” regarding surgery should help mutation carriers without a history of cancer (known in the BRCA community as “previvors”) who have completed their families to move forward with risk-reducing gynecologic surgery and, when appropriate, use of systemic HT.6

The outlook for previvors with intact breasts

Three studies address the risk of breast cancer with use of systemic HT among previvors with intact breasts. A 2005 study followed a cohort of BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers with intact breasts, 155 of whom had undergone risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy, for a mean of 3.6 years. Of these women, 60% and 7%, respectively, of those who had and had not undergone salpingo-oophorectomy used HT. The authors noted that bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy reduced the risk of breast cancer by some 60%, whether or not women used HT.7

A 2008 case-control study focused on 472 menopausal BRCA1 carriers, half of whom had been diagnosed with breast cancer (cases); the other half had not received this diagnosis (controls). A 43% reduction in the risk of breast cancer was associated with prior use of HT.8

A 2011 presentation described a cohort study in which 1,299 BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers with intact breasts who had undergone salpingo-oophorectomy were followed for a mean of 5.4 years postoperatively. In this population, use of HT was not associated with an increased risk of breast cancer. Among women with BRCA1 mutations, use of systemic HT was associated with a reduced risk of breast cancer.9

Viewed in aggregate, these studies reassure us that short-term use of systemic HT does not increase breast cancer risk in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and intact breasts.

Dr. Simon

Nevertheless, I think it is important to point out that a properly powered study to assess actual risk in this setting is not available in the literature.

When a patient refuses HT

Dr. Pinkerton

Some BRCA mutation carriers may refuse HT despite reassurance that it is safe. Nonhormonal therapies are not as effective at relieving severe menopausal symptoms. Almost all selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) can be offered, although only low-dose paroxetine salt is approved for treatment of postmenopausal hot flashes.10,11 Gabapentin also has shown efficacy in relieving hot flashes.

For genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM; formerly known as vulvovaginal atrophy), lubricants and moisturizers may provide some benefit, but they don’t improve the vaginal superficial cells and, therefore, are not as effective as hormonal options. There is now a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) approved to treat GSM—ospemifene. However, in clinical trials, ospemifene has been shown to increase hot flashes, so it would not be a good option for our patient.12

Case: Continued

Christine follows up 3 months after initiating estrogen therapy (oral estradiol 2 mg daily). She reports significant improvement in her hot flashes, with improved sleep and fewer sleep disruptions. In addition, she feels that her “mental sharpness” has returned.

Dr. Pinkerton

What if this patient had an intact uterus? Then she would not be a candidate for estrogen-only therapy because she would need continued endometrial protection. Options then would include low-dose continuous or cyclic progestogen therapy, often starting with micronized progesterone, as the E3N Study suggested it has a less negative effect on the uterus.13 Or she could use a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system off label, as Ms. Jolie Pitt elected to do.

Another option would be combining estrogen with a SERM. The only estrogen/SERM combination currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is conjugated estrogen/bazedoxefine, which showed no increase in breast tenderness, breast density, or bleeding rates, compared with placebo, in multiple trials up to 5 years in duration.14

Case: Resolved

Christine says she would like to continue HT, although she still experiences dryness and discomfort when sexually active with her husband, despite use of a vaginal lubricant. A pelvic examination is consistent with early changes of GSM.15

You discuss GSM with Christine and suggest that she consider 1 of 2 strategies:

- Switch from daily use of oral estradiol to the 3-month systemic 0.1-mg estradiol ring (Femring), which would address both her vasomotor symptoms and her GSM.

- Continue oral estradiol and add low-dose vaginal estrogen (cream, tablets, or Estring 2 mg).

Christine chooses Option 2. When she returns 6 months later for her well-woman visit, she reports that all of her menopausal symptoms have resolved, and a pelvic examination no longer reveals changes of GSM.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Case: Disabling vasomotor symptoms in a BRCA1 mutation carrier

Christine is a 39-year-old mother of 2 who underwent risk-reducing, minimally invasive bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with hysterectomy 4 months ago for a BRCA1 mutation (with benign findings on pathology). Eighteen months before that surgery, she had risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy with reconstruction (implants) and was advised by her surgeon that she no longer needs breast imaging.

Today she reports disabling hot flashes, insomnia, vaginal dryness, and painful sex. Her previous ObGyn, who performed the hysterectomy, was unwilling to prescribe hormone therapy (HT) due to safety concerns. Christine tried venlafaxine at 37 to 75 mg but noted little relief of her vasomotor symptoms.

In discussing her symptoms with you during this initial visit, Christine, a practicing accountant, also reveals that she does not feel as intellectually “sharp” as she did before her gynecologic surgery.

What can you offer for relief of her symptoms?

More BRCA mutation carriers are being identified and choosing to undergo risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy and bilateral mastectomy. Accordingly, clinicians are likely to face more questions about the use of systemic HT in this population. Because mutation carriers may worry about the safety of HT, given their BRCA status, some may delay or avoid salpingo-oophorectomy—a surgery that not only reduces the risk of ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal cancer by 80% but also decreases the risk of breast cancer by 48%.1

Surgically menopausal women in their 30s or 40s who are not treated with HT appear to have an elevated risk for dementia and Parkinsonism.2 In addition, vasomotor symptoms are often more severe, and the risks for osteoporosis and, likely, cardiovascular disease are elevated in women with early menopause who are not treated with HT. For these reasons, systemic HT is recommended for women with early menopause, and generally should be continued at least until the normal age of menopause unless specific contraindications are present.3

Because Christine not only has had risk-reducing gynecologic surgery but also risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy, her current risk for breast cancer is very low whether or not she uses HT. Because she does not have a uterus, her symptoms can effectively and safely be treated with systemic estrogen-only therapy.

Among clinicians with special expertise in the management of BRCA mutation carriers, the use of systemic HT would be considered appropriate—and not controversial—in this setting.4

Angelina Jolie details her surgeries

In March 2015, 39-year-old Oscar-winning actress and filmmaker Angelina Jolie Pitt published an opinion piece in the New York Times detailing her recent laparoscopic salpingo-oophorectomy and initiation of HT.5 Ms. Jolie Pitt, who carries the BRCA1 mutation, lost her mother, grandmother, and aunt to hereditary breast/ovarian cancer. Two years earlier, Ms. Jolie Pitt made news by describing her decision to move ahead with risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy.

Following her risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy, she initiated systemic HT using transdermal estradiol and off-label use of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for endometrial protection.

Her courageous decision to publicly describe her surgery and subsequent initiation of systemic HT will likely encourage women with ominous family histories to seek out genetic counseling and testing. Her decision to “go public” regarding surgery should help mutation carriers without a history of cancer (known in the BRCA community as “previvors”) who have completed their families to move forward with risk-reducing gynecologic surgery and, when appropriate, use of systemic HT.6

The outlook for previvors with intact breasts

Three studies address the risk of breast cancer with use of systemic HT among previvors with intact breasts. A 2005 study followed a cohort of BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers with intact breasts, 155 of whom had undergone risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy, for a mean of 3.6 years. Of these women, 60% and 7%, respectively, of those who had and had not undergone salpingo-oophorectomy used HT. The authors noted that bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy reduced the risk of breast cancer by some 60%, whether or not women used HT.7

A 2008 case-control study focused on 472 menopausal BRCA1 carriers, half of whom had been diagnosed with breast cancer (cases); the other half had not received this diagnosis (controls). A 43% reduction in the risk of breast cancer was associated with prior use of HT.8

A 2011 presentation described a cohort study in which 1,299 BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers with intact breasts who had undergone salpingo-oophorectomy were followed for a mean of 5.4 years postoperatively. In this population, use of HT was not associated with an increased risk of breast cancer. Among women with BRCA1 mutations, use of systemic HT was associated with a reduced risk of breast cancer.9

Viewed in aggregate, these studies reassure us that short-term use of systemic HT does not increase breast cancer risk in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and intact breasts.

Dr. Simon

Nevertheless, I think it is important to point out that a properly powered study to assess actual risk in this setting is not available in the literature.

When a patient refuses HT

Dr. Pinkerton

Some BRCA mutation carriers may refuse HT despite reassurance that it is safe. Nonhormonal therapies are not as effective at relieving severe menopausal symptoms. Almost all selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) can be offered, although only low-dose paroxetine salt is approved for treatment of postmenopausal hot flashes.10,11 Gabapentin also has shown efficacy in relieving hot flashes.

For genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM; formerly known as vulvovaginal atrophy), lubricants and moisturizers may provide some benefit, but they don’t improve the vaginal superficial cells and, therefore, are not as effective as hormonal options. There is now a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) approved to treat GSM—ospemifene. However, in clinical trials, ospemifene has been shown to increase hot flashes, so it would not be a good option for our patient.12

Case: Continued

Christine follows up 3 months after initiating estrogen therapy (oral estradiol 2 mg daily). She reports significant improvement in her hot flashes, with improved sleep and fewer sleep disruptions. In addition, she feels that her “mental sharpness” has returned.

Dr. Pinkerton

What if this patient had an intact uterus? Then she would not be a candidate for estrogen-only therapy because she would need continued endometrial protection. Options then would include low-dose continuous or cyclic progestogen therapy, often starting with micronized progesterone, as the E3N Study suggested it has a less negative effect on the uterus.13 Or she could use a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system off label, as Ms. Jolie Pitt elected to do.

Another option would be combining estrogen with a SERM. The only estrogen/SERM combination currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is conjugated estrogen/bazedoxefine, which showed no increase in breast tenderness, breast density, or bleeding rates, compared with placebo, in multiple trials up to 5 years in duration.14

Case: Resolved

Christine says she would like to continue HT, although she still experiences dryness and discomfort when sexually active with her husband, despite use of a vaginal lubricant. A pelvic examination is consistent with early changes of GSM.15

You discuss GSM with Christine and suggest that she consider 1 of 2 strategies:

- Switch from daily use of oral estradiol to the 3-month systemic 0.1-mg estradiol ring (Femring), which would address both her vasomotor symptoms and her GSM.

- Continue oral estradiol and add low-dose vaginal estrogen (cream, tablets, or Estring 2 mg).

Christine chooses Option 2. When she returns 6 months later for her well-woman visit, she reports that all of her menopausal symptoms have resolved, and a pelvic examination no longer reveals changes of GSM.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Finch AP, Lubinski J, Moller P, et al. Impact of oophorectomy on cancer incidence and mortality in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15):1547–1553.

2. Rocca WA, Bower JH, Maraganore DM, et al. Increased risk of cognitive impairment or dementia in women who underwent oophorectomy before menopause. Neurology. 2007;69(11):1074–1083.

3. North American Menopause Society. The 2012 hormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2012;19(3):257–271.

4. Finch AP, Evans G, Narod SA. BRCA carriers, prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy and menopause: clinical management considerations and recommendations. Womens Health (Lond Engl). 2012;8(5):543–555.

5. Pitt AJ. Angelina Jolie Pitt: Diary of a Surgery. New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/24/opinion/angelina-jolie-pitt-diary-of-a-surgery.html. Published March 24, 2015. Accessed July 9, 2015.

6. Holman L, Brandt A, Daniels M, et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy and prophylactic mastectomy among BRCA mutation “previvors.” Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127(1 suppl):S17.

7. Rebbeck TR, Friebel T, Wagner T, et al; PROSE Study Group. Effect of short-term hormone replacement therapy on breast cancer risk reduction after bilateral prophylactic oophorectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: the PROSE Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(31):7804–7810.

8. Eisen A, Lubinski J, Gronwald J, et al; Hereditary Breast Cancer Clinical Study Group. Hormone therapy and the risk of breast cancer in BRCA1 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(19):1361–1367.

9. Domchek SM, Mitchell G, Lindeman GJ, et al. Challenges to the development of new agents for molecularly defined patient subsets: lessons from BRCA1/2-associated breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(32):4224–4226.

10. Krause MS, Nakajima ST. Hormonal and nonhormonal treatment of vasomotor symptoms. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015;42(1):163–179.

11. Simon JA, Portman DJ, Kaunitz AM, et al. Low-dose paroxetine 7.5 mg for menopausal vasomotor symptoms: two randomized controlled trials. Menopause. 2013;20(10):1027–1030.

12. Bachmann GA, Komi JO; Ospemifene Study Group. Ospemifene effectively treats vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: results from a pivotal phase 3 study. Menopause. 2010;17(3):480–486.

13. Fournier A, Fabre A, Mesrine S, Boutron-Ruault MC, Berrino F, Clavel-Chapelon F. Use of different postmenopausal hormone therapies and risk of histology- and hormone receptor–defined invasive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(8):1260–1268.

14. Pinkerton JV, Pickar JH, Racketa J, Mirkin S. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for menopausal symptom treatment and osteoporosis prevention. Climacteric. 2012;15(5):411–418.

15. Rahn DD, Carberry C, Sanses TV, et al; Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group. Vaginal estrogen for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(6):1147–1156.

1. Finch AP, Lubinski J, Moller P, et al. Impact of oophorectomy on cancer incidence and mortality in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15):1547–1553.

2. Rocca WA, Bower JH, Maraganore DM, et al. Increased risk of cognitive impairment or dementia in women who underwent oophorectomy before menopause. Neurology. 2007;69(11):1074–1083.

3. North American Menopause Society. The 2012 hormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2012;19(3):257–271.

4. Finch AP, Evans G, Narod SA. BRCA carriers, prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy and menopause: clinical management considerations and recommendations. Womens Health (Lond Engl). 2012;8(5):543–555.

5. Pitt AJ. Angelina Jolie Pitt: Diary of a Surgery. New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/24/opinion/angelina-jolie-pitt-diary-of-a-surgery.html. Published March 24, 2015. Accessed July 9, 2015.

6. Holman L, Brandt A, Daniels M, et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy and prophylactic mastectomy among BRCA mutation “previvors.” Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127(1 suppl):S17.

7. Rebbeck TR, Friebel T, Wagner T, et al; PROSE Study Group. Effect of short-term hormone replacement therapy on breast cancer risk reduction after bilateral prophylactic oophorectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: the PROSE Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(31):7804–7810.

8. Eisen A, Lubinski J, Gronwald J, et al; Hereditary Breast Cancer Clinical Study Group. Hormone therapy and the risk of breast cancer in BRCA1 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(19):1361–1367.

9. Domchek SM, Mitchell G, Lindeman GJ, et al. Challenges to the development of new agents for molecularly defined patient subsets: lessons from BRCA1/2-associated breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(32):4224–4226.

10. Krause MS, Nakajima ST. Hormonal and nonhormonal treatment of vasomotor symptoms. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015;42(1):163–179.

11. Simon JA, Portman DJ, Kaunitz AM, et al. Low-dose paroxetine 7.5 mg for menopausal vasomotor symptoms: two randomized controlled trials. Menopause. 2013;20(10):1027–1030.

12. Bachmann GA, Komi JO; Ospemifene Study Group. Ospemifene effectively treats vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: results from a pivotal phase 3 study. Menopause. 2010;17(3):480–486.

13. Fournier A, Fabre A, Mesrine S, Boutron-Ruault MC, Berrino F, Clavel-Chapelon F. Use of different postmenopausal hormone therapies and risk of histology- and hormone receptor–defined invasive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(8):1260–1268.

14. Pinkerton JV, Pickar JH, Racketa J, Mirkin S. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for menopausal symptom treatment and osteoporosis prevention. Climacteric. 2012;15(5):411–418.

15. Rahn DD, Carberry C, Sanses TV, et al; Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group. Vaginal estrogen for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(6):1147–1156.

Angelina Jolie, previvors, systemic HT, nonhormonal therapy, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, SSRIs, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, SNRIs, paroxetine salt, gabapentin, genitourinary syndrome of menopause, GSM, vaginal lubricants, vaginal moisturizers, selective estrogen receptor modulator, SERM, ospemifene, estrogen therapy, oral estradiol, endometrial protection, progestogen therapy, micronized progesterone,

Angelina Jolie, previvors, systemic HT, nonhormonal therapy, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, SSRIs, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, SNRIs, paroxetine salt, gabapentin, genitourinary syndrome of menopause, GSM, vaginal lubricants, vaginal moisturizers, selective estrogen receptor modulator, SERM, ospemifene, estrogen therapy, oral estradiol, endometrial protection, progestogen therapy, micronized progesterone,

In This Article

- Angelina Jolie describes her surgeries

- Hormone therapy for previvors with intact breasts?

- When a patient refuses hormone therapy

ICD-10-CM documentation and coding for GYN procedures

In 2 months, the new coding set will become the only accepted format for diagnostic coding on medical claims. By now, most clinicians and their staffs should have begun the training process, including the examination of current documentation patterns, to ensure that the more specific International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes can be reported.

In 2014, I informed you about the more general changes that are to come in the format and ideas for preparation.1 But now it is time to get down to the nitty-gritty (or granularity, if you prefer) of this coding format to ensure correct coding every time for your gynecology services. A separate article will appear in the September 2015 issue of OBG Management to describe diagnostic coding for obstetric care.

No wheel reinvention necessary

Many of the guidelines for ICD-9-CM will transfer over to ICD-10-CM, so it will not be necessary to reinvent the wheel—but there are important changes that will affect both your documentation and payers’ requirements for the highest level of specificity. There also will be some instructions in the tabular section of ICD-10-CM that will let you know whether a combination of codes can or cannot be reported together (called “excludes” notes). In the beginning, this process may require additional communication between practice staff and clinicians.

However, if your practice has prepared a teaching document that outlines currently used codes and compares them with ICD-10-CM code choices and provides comments in regard to issues such as code combinations, conversion to the new system should be almost seamless.

Remember, the documentation of the clinician drives the selection of the code. The less information provided, the less specificity—and the result may be increased denials due to medical necessity for procedures and treatments.

Most reported codes will begin with “N”

Although the format of the codes will change under ICD-10-CM, diagnostic reporting will remain the same for most of the gynecologic conditions reported, and clinicians should be aware that the codes they will be reporting mainly will come from those that begin with “N.” One advantage: None of these codes require a 7th character or utilize the “x” placeholder code. In fact, the majority of codes from this chapter will have a one-to-one counterpart in the ICD-9-CM codes. A few exceptions are outlined below.

In addition to the core of “N” codes, a handful of codes will come from other chapters to capture reasons for a gynecologic encounter or surgery. For instance, “Z” codes will be reported for encounters for reasons other than illness and include codes for contraceptive and procreative management, general counseling, history of diseases, preventive gynecologic examinations, and screening scenarios, to name just a few. “R” codes will be used most often for general signs and symptoms, such as abdominal pain or nausea and vomiting.

Your documentation will need to change in some important areas

When you see a patient for an injury to the urinary or pelvic organs that is not a complication of a procedure, or for a complication of a genitourinary prosthetic device, implant, or graft, you will need to document whether this is an initial or subsequent encounter or a sequela. This information is added as a 7th alpha character (a = initial, d = subsequent, s = sequela).

ICD-10-CM defines an initial encounter as the time period in which the patient is actively being treated. A subsequent encounter would be reported after the patient’s active treatment, while she is receiving routine care during the healing or recovery phase. For instance, you would report the encounter as subsequent when the patient is seen after her surgery for an injury to the ovary due to an automobile accident, but you would report an initial encounter for all visits through the surgical date of service when a patient presents with symptoms of mesh erosion requiring surgery. Sequela refers to a condition that developed as a result of another condition. For instance, if the patient’s intrauterine device (IUD) becomes embedded in the ostium due to an undetected uterine fibroid, that is a sequela.

The requirement to indicate laterality also will affect documentation, but this concept is limited to a few codes that might be reported by ObGyns. A designation of the right versus left organ will be required for reported cases of primary, secondary, borderline, or benign tumors of the breast, ovary, fallopian tube, broad ligament, and round ligament, as well as cancer in situ of the breast. However, the terms “bilateral” and “unilateral” are applied only to codes that describe hernias, acquired absence of the ovaries, and injuries to the ovaries and fallopian tubes that are not due to a surgical complication.

Unspecified codes still play a role

Unspecified ICD-10-CM codes still come into play when the clinician does not have enough information to assign a more specific code—that is, when, by the end of an encounter, no further information is available to assign a more specific diagnosis. For example, if a patient has signs of a fibroid upon examination, only the unspecified code can be reported until the clinician can discover whether it is intramural, submucosal, or subserosal. However, it would be equally incorrect to assign an unspecified code to an encounter once the nature of the fibroid has been determined.

Take note of these differences in coding

Here is a list of important new gynecologic coding requirements, which are presented in alphabetical order.

Amenorrhea, oligomenorrhea (N91.0–N91.5) and dysmenorrhea (N94.4–N94.5) will require documentation to indicate whether the condition is primary or secondary. Although an unspecified code is available, once treatment is begun the cause should be known and documented.

Artificial insemination problems will have a section:

- N98.0 Infection associated with artificial insemination

- N98.1 Hyperstimulation of ovaries

- N98.2 Complications of attempted introduction of fertilized ovum following in vitro fertilization

- N98.3 Complications of attempted introduction of embryo in embryo transfer

- N98.8 Other complications associated with artificial fertilization

- N98.9 Complication associated with artificial fertilization, unspecified.

Breast cancer codes will require documentation of which breast and what part of the breast is affected.

Contraceptive management highlights:

- Injectable contraceptives will have new codes for the initial prescription (Z30.013) and subsequent surveillance (Z30.42)

- IUD encounter for the prescription will have a new code (Z30.014), which is reported when the IUD is not being inserted on the same day

- Subdermal contraceptive implant surveillance will no longer have a specific code but will be included in the “other” contraceptive code Z30.49.

Conversion of a laparoscopic procedure to an open procedure will not have a code.

Cystocele, unspecified, will have code N81.10.

Dysplasia of vagina will be expanded into 3 codes based on mild, moderate, or unspecified: N89.0–N89.3.

Female genitourinary cancer codes:

- Documentation of right or left organs and which part of the uterus is affected will be required

- Cancer in situ of cervix will be expanded by site on the cervix: D06.0–D06.7

- Cancer in situ of the endometrium will have a specific code: D07.0.

Genuine stress urinary incontinence will only be referred to as stress incontinence (male or female). The code is now located in the urinary section of Chapter N: N39.3.

Genitourinary complications due to procedures and surgery will be organized in 1 section: N99

- Some conditions have more than 1 code based on cause:

- N99.2 Stricture of vagina due to surgical complication

- N89.5 Stricture of vagina not due to surgical complication

- N99.4 Pelvic adhesions due to surgical complication

- N73.6 Pelvic adhesions not due to surgical complication - Other codes will differentiate between intraoperative or postprocedure complications and whether the surgery is on the genitourinary system or a different surgery:

- N99.61 Intraoperative hemorrhage and hematoma of a genitourinary system organ or structure complicating a genitourinary system procedure

- N99.62 Intraoperative hemorrhage and hematoma of a genitourinary system organ or structure complicating other procedure

- N99.820 Postprocedural hemorrhage and hematoma of a genitourinary system organ or structure following a genitourinary system procedure

- N99.821 Postprocedural hemorrhage and hematoma of a genitourinary system organ or structure following other procedure.