User login

Most Important Elements of End-of-Life Care

An Australian team conducted a literature review of expected deaths in the hospital—where the majority of deaths in the developed world occur—and identified elements of end-of-life care that are important to patients and families.1 Published in the British journal Palliative Medicine, the review of nine electronic data bases and 1859 articles released between 1990 and 2014 identified eight quantitative studies that met inclusion criteria.

The authors, led by Claudia Virdun, RN, of the faculty of health at the University of Technology in Sydney, found four end-of-life domains that were most important to both patients and families:

- Effective communication and shared decision-making;

- Expert care;

- Respectful and compassionate care; and

- Trust and confidence in clinicians.

Not all patients dying in hospitals receive best evidence-based palliative care, the authors note, adding that the “challenge for healthcare services is to act on this evidence, reconfigure care systems accordingly and ensure universal access to optimal end-of-life care within hospitals.”

Reference

- Virdun C, Luckett T, Davidson PM, Phillips J. Dying in the hospital setting: A systematic review of quantitative studies identifying the elements of end-of-life care that patients and their families rank as being most important [published online ahead of print April 28, 2015]. Palliat Med.

An Australian team conducted a literature review of expected deaths in the hospital—where the majority of deaths in the developed world occur—and identified elements of end-of-life care that are important to patients and families.1 Published in the British journal Palliative Medicine, the review of nine electronic data bases and 1859 articles released between 1990 and 2014 identified eight quantitative studies that met inclusion criteria.

The authors, led by Claudia Virdun, RN, of the faculty of health at the University of Technology in Sydney, found four end-of-life domains that were most important to both patients and families:

- Effective communication and shared decision-making;

- Expert care;

- Respectful and compassionate care; and

- Trust and confidence in clinicians.

Not all patients dying in hospitals receive best evidence-based palliative care, the authors note, adding that the “challenge for healthcare services is to act on this evidence, reconfigure care systems accordingly and ensure universal access to optimal end-of-life care within hospitals.”

Reference

- Virdun C, Luckett T, Davidson PM, Phillips J. Dying in the hospital setting: A systematic review of quantitative studies identifying the elements of end-of-life care that patients and their families rank as being most important [published online ahead of print April 28, 2015]. Palliat Med.

An Australian team conducted a literature review of expected deaths in the hospital—where the majority of deaths in the developed world occur—and identified elements of end-of-life care that are important to patients and families.1 Published in the British journal Palliative Medicine, the review of nine electronic data bases and 1859 articles released between 1990 and 2014 identified eight quantitative studies that met inclusion criteria.

The authors, led by Claudia Virdun, RN, of the faculty of health at the University of Technology in Sydney, found four end-of-life domains that were most important to both patients and families:

- Effective communication and shared decision-making;

- Expert care;

- Respectful and compassionate care; and

- Trust and confidence in clinicians.

Not all patients dying in hospitals receive best evidence-based palliative care, the authors note, adding that the “challenge for healthcare services is to act on this evidence, reconfigure care systems accordingly and ensure universal access to optimal end-of-life care within hospitals.”

Reference

- Virdun C, Luckett T, Davidson PM, Phillips J. Dying in the hospital setting: A systematic review of quantitative studies identifying the elements of end-of-life care that patients and their families rank as being most important [published online ahead of print April 28, 2015]. Palliat Med.

Highest-Volume Hospitals Linked with Lower Risk for Some Procedures

An estimated 11,000 deaths could have been prevented between 2010 and 2012, if patients who went to the U.S. hospitals with the lowest patient volumes for five common procedures and conditions had gone instead to the highest-volume hospitals, according to analysis presented in U.S. News and World Report’s “Best Hospitals for Common Care.”1

For example, one small rural hospital’s relative risk for death from elective knee replacement was 24 times the national average.”1

Reference

- Sternberg S, Dougherty G. Risks are high at low-volume hospitals. May 18, 2015. U.S. News & World Report. Accessed July 2, 2015.

An estimated 11,000 deaths could have been prevented between 2010 and 2012, if patients who went to the U.S. hospitals with the lowest patient volumes for five common procedures and conditions had gone instead to the highest-volume hospitals, according to analysis presented in U.S. News and World Report’s “Best Hospitals for Common Care.”1

For example, one small rural hospital’s relative risk for death from elective knee replacement was 24 times the national average.”1

Reference

- Sternberg S, Dougherty G. Risks are high at low-volume hospitals. May 18, 2015. U.S. News & World Report. Accessed July 2, 2015.

An estimated 11,000 deaths could have been prevented between 2010 and 2012, if patients who went to the U.S. hospitals with the lowest patient volumes for five common procedures and conditions had gone instead to the highest-volume hospitals, according to analysis presented in U.S. News and World Report’s “Best Hospitals for Common Care.”1

For example, one small rural hospital’s relative risk for death from elective knee replacement was 24 times the national average.”1

Reference

- Sternberg S, Dougherty G. Risks are high at low-volume hospitals. May 18, 2015. U.S. News & World Report. Accessed July 2, 2015.

Clinical Variables Predict Debridement Failure in Septic Arthritis

Clinical question: What risk factors predict septic arthritis surgical debridement failure?

Background: Standard treatment of septic arthritis is debridement and antibiotics. Unfortunately, 23%-48% of patients fail single debridement. Data is limited on what factors correlate with treatment failure.

Study design: Retrospective, logistic regression analysis.

Setting: Billing database query of one academic medical center from 2000-2011.

Synopsis: After excluding patients with orthopedic comorbidities, multivariate logistic regression was performed on 128 patients greater than 18 years of age and treated operatively for septic arthritis, 38% of whom had failed a single debridement. Five significant independent clinical variables were identified as predictors for failure of a single surgical debridement:

- History of inflammatory arthropathy (OR, 7.3; 95% CI, 2.4 to 22.6; P<0.001);

- Involvement of a large joint (knee, shoulder, or hip; OR 7.0; 95% CI, 1.2-37.5; P=0.02);

- Synovial fluid nucleated cell count >85.0 x 109 cells/L (OR, 4.7; 95% CI, 1.8-17.7; P=0.002);

- S. aureus as an isolate (OR, 4.6; 95% CI, 1.8 to 11.9; P=0.002); and

- History of diabetes (OR, 2.6; 95% CI, 1.1 to 6.2; P=0.04).

Using these variables, a prognostic model was created with an ROC curve of 0.79.

The study’s limitations include its retrospective nature, reliance on coding and documentation, small sample size, and the fact that all patients were treated at a single center.

Bottom line: Risk factors for failing single debridement in septic arthritis include inflammatory arthropathy, large joint involvement, more than 85.0 x 109 nucleated cells, S. aureus infection, and history of diabetes.

Citation: Hunter JG, Gross JM, Dahl JD, Amsdell SL, Gorczyca JT. Risk factors for failure of a single surgical debridement in adults with acute septic arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(7):558-564.

Clinical question: What risk factors predict septic arthritis surgical debridement failure?

Background: Standard treatment of septic arthritis is debridement and antibiotics. Unfortunately, 23%-48% of patients fail single debridement. Data is limited on what factors correlate with treatment failure.

Study design: Retrospective, logistic regression analysis.

Setting: Billing database query of one academic medical center from 2000-2011.

Synopsis: After excluding patients with orthopedic comorbidities, multivariate logistic regression was performed on 128 patients greater than 18 years of age and treated operatively for septic arthritis, 38% of whom had failed a single debridement. Five significant independent clinical variables were identified as predictors for failure of a single surgical debridement:

- History of inflammatory arthropathy (OR, 7.3; 95% CI, 2.4 to 22.6; P<0.001);

- Involvement of a large joint (knee, shoulder, or hip; OR 7.0; 95% CI, 1.2-37.5; P=0.02);

- Synovial fluid nucleated cell count >85.0 x 109 cells/L (OR, 4.7; 95% CI, 1.8-17.7; P=0.002);

- S. aureus as an isolate (OR, 4.6; 95% CI, 1.8 to 11.9; P=0.002); and

- History of diabetes (OR, 2.6; 95% CI, 1.1 to 6.2; P=0.04).

Using these variables, a prognostic model was created with an ROC curve of 0.79.

The study’s limitations include its retrospective nature, reliance on coding and documentation, small sample size, and the fact that all patients were treated at a single center.

Bottom line: Risk factors for failing single debridement in septic arthritis include inflammatory arthropathy, large joint involvement, more than 85.0 x 109 nucleated cells, S. aureus infection, and history of diabetes.

Citation: Hunter JG, Gross JM, Dahl JD, Amsdell SL, Gorczyca JT. Risk factors for failure of a single surgical debridement in adults with acute septic arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(7):558-564.

Clinical question: What risk factors predict septic arthritis surgical debridement failure?

Background: Standard treatment of septic arthritis is debridement and antibiotics. Unfortunately, 23%-48% of patients fail single debridement. Data is limited on what factors correlate with treatment failure.

Study design: Retrospective, logistic regression analysis.

Setting: Billing database query of one academic medical center from 2000-2011.

Synopsis: After excluding patients with orthopedic comorbidities, multivariate logistic regression was performed on 128 patients greater than 18 years of age and treated operatively for septic arthritis, 38% of whom had failed a single debridement. Five significant independent clinical variables were identified as predictors for failure of a single surgical debridement:

- History of inflammatory arthropathy (OR, 7.3; 95% CI, 2.4 to 22.6; P<0.001);

- Involvement of a large joint (knee, shoulder, or hip; OR 7.0; 95% CI, 1.2-37.5; P=0.02);

- Synovial fluid nucleated cell count >85.0 x 109 cells/L (OR, 4.7; 95% CI, 1.8-17.7; P=0.002);

- S. aureus as an isolate (OR, 4.6; 95% CI, 1.8 to 11.9; P=0.002); and

- History of diabetes (OR, 2.6; 95% CI, 1.1 to 6.2; P=0.04).

Using these variables, a prognostic model was created with an ROC curve of 0.79.

The study’s limitations include its retrospective nature, reliance on coding and documentation, small sample size, and the fact that all patients were treated at a single center.

Bottom line: Risk factors for failing single debridement in septic arthritis include inflammatory arthropathy, large joint involvement, more than 85.0 x 109 nucleated cells, S. aureus infection, and history of diabetes.

Citation: Hunter JG, Gross JM, Dahl JD, Amsdell SL, Gorczyca JT. Risk factors for failure of a single surgical debridement in adults with acute septic arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(7):558-564.

Prednisolone or Pentoxifylline Show No Mortality Benefit in Alcoholic Hepatitis

Clinical question: Does administration of prednisolone or pentoxifylline reduce mortality in patients hospitalized with severe alcoholic hepatitis?

Background: Alcoholic hepatitis is associated with high mortality. Studies have shown unclear mortality benefit with prednisolone and pentoxifylline. Despite multiple studies and meta-analyses, controversy about the use of these medications persists.

Study Design: Multicenter, double-blind, randomized trial with 2-by-2 design.

Setting: Sixty-five hospitals across the United Kingdom.

Synopsis: Approximately 1,100 patients with a clinical diagnosis of alcoholic hepatitis were randomized to four groups: placebo + placebo; prednisolone + pentoxifylline-matched placebo; prednisolone-matched placebo + pentoxifylline; or prednisolone + pentoxifylline. Groups received 28 days of treatment. The primary endpoint was 28-day mortality. Secondary endpoints were mortality or liver transplantation at 90 days and one year.

Neither intervention showed a significant reduction in 28-day mortality. Secondary analysis with adjustments for risk showed a reduction in 28-day mortality in the prednisolone groups. There was no difference between groups for mortality or liver transplantation at 90 days or one year.

Adverse events of death, infection, and acute kidney injury were reported in 42% of patients. Infection rates were higher in the prednisolone groups; however, attributable deaths were no different between groups.

Patients in this trial were younger, with a lower incidence of encephalopathy, infection, and acute kidney injury than those seen in similar trials, which could affect the rates of mortality seen here. Also, liver biopsy was not used, so patients may have been incorrectly included.

Bottom line: No difference was found in mortality or liver transplantation at 90 days and one year for prednisolone or pentoxifylline, although subanalysis showed there may be short-term benefit with prednisolone.

Citation: Thursz MR, Richardson P, Allison M, et al. Prednisolone or pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis. New Engl J Med. 2015;372(17):1619-1628.

Clinical question: Does administration of prednisolone or pentoxifylline reduce mortality in patients hospitalized with severe alcoholic hepatitis?

Background: Alcoholic hepatitis is associated with high mortality. Studies have shown unclear mortality benefit with prednisolone and pentoxifylline. Despite multiple studies and meta-analyses, controversy about the use of these medications persists.

Study Design: Multicenter, double-blind, randomized trial with 2-by-2 design.

Setting: Sixty-five hospitals across the United Kingdom.

Synopsis: Approximately 1,100 patients with a clinical diagnosis of alcoholic hepatitis were randomized to four groups: placebo + placebo; prednisolone + pentoxifylline-matched placebo; prednisolone-matched placebo + pentoxifylline; or prednisolone + pentoxifylline. Groups received 28 days of treatment. The primary endpoint was 28-day mortality. Secondary endpoints were mortality or liver transplantation at 90 days and one year.

Neither intervention showed a significant reduction in 28-day mortality. Secondary analysis with adjustments for risk showed a reduction in 28-day mortality in the prednisolone groups. There was no difference between groups for mortality or liver transplantation at 90 days or one year.

Adverse events of death, infection, and acute kidney injury were reported in 42% of patients. Infection rates were higher in the prednisolone groups; however, attributable deaths were no different between groups.

Patients in this trial were younger, with a lower incidence of encephalopathy, infection, and acute kidney injury than those seen in similar trials, which could affect the rates of mortality seen here. Also, liver biopsy was not used, so patients may have been incorrectly included.

Bottom line: No difference was found in mortality or liver transplantation at 90 days and one year for prednisolone or pentoxifylline, although subanalysis showed there may be short-term benefit with prednisolone.

Citation: Thursz MR, Richardson P, Allison M, et al. Prednisolone or pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis. New Engl J Med. 2015;372(17):1619-1628.

Clinical question: Does administration of prednisolone or pentoxifylline reduce mortality in patients hospitalized with severe alcoholic hepatitis?

Background: Alcoholic hepatitis is associated with high mortality. Studies have shown unclear mortality benefit with prednisolone and pentoxifylline. Despite multiple studies and meta-analyses, controversy about the use of these medications persists.

Study Design: Multicenter, double-blind, randomized trial with 2-by-2 design.

Setting: Sixty-five hospitals across the United Kingdom.

Synopsis: Approximately 1,100 patients with a clinical diagnosis of alcoholic hepatitis were randomized to four groups: placebo + placebo; prednisolone + pentoxifylline-matched placebo; prednisolone-matched placebo + pentoxifylline; or prednisolone + pentoxifylline. Groups received 28 days of treatment. The primary endpoint was 28-day mortality. Secondary endpoints were mortality or liver transplantation at 90 days and one year.

Neither intervention showed a significant reduction in 28-day mortality. Secondary analysis with adjustments for risk showed a reduction in 28-day mortality in the prednisolone groups. There was no difference between groups for mortality or liver transplantation at 90 days or one year.

Adverse events of death, infection, and acute kidney injury were reported in 42% of patients. Infection rates were higher in the prednisolone groups; however, attributable deaths were no different between groups.

Patients in this trial were younger, with a lower incidence of encephalopathy, infection, and acute kidney injury than those seen in similar trials, which could affect the rates of mortality seen here. Also, liver biopsy was not used, so patients may have been incorrectly included.

Bottom line: No difference was found in mortality or liver transplantation at 90 days and one year for prednisolone or pentoxifylline, although subanalysis showed there may be short-term benefit with prednisolone.

Citation: Thursz MR, Richardson P, Allison M, et al. Prednisolone or pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis. New Engl J Med. 2015;372(17):1619-1628.

Corticosteroids Show Benefit in Community-Acquired Pneumonia

Clinical question: Does corticosteroid treatment shorten systemic illness in patients admitted to the hospital for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP)?

Background: Pneumonia is the third-leading cause of death worldwide. Studies have yielded conflicting data about the benefit of adding systemic corticosteroids for treatment of CAP.

Study design: Double-blind, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: Seven tertiary care hospitals in Switzerland.

Synopsis: Seven hundred eighty-four patients hospitalized for CAP were randomized to receive either oral prednisone 50 mg daily for seven days or placebo, with the primary endpoint being time to stable vital signs. The intention-to-treat analysis found that the median time to clinical stability was 1.4 days earlier in the prednisone group (hazard ratio 1.33, 95% CI 1.15-1.50, P<0.0001) and that length of stay and IV antibiotics were reduced by one day; this effect was valid across all PSI classes and was not dependent on age. Pneumonia-associated complications in the two groups did not differ at 30 days, though the prednisone group had a higher incidence of hyperglycemia requiring insulin.

Because all study locations were in a single, fairly homogenous northern European country, care should be taken when hospitalists apply these findings to their patient population, and the risks of hyperglycemia requiring insulin should be taken into consideration.

Bottom line: Systemic steroids may reduce the time to clinical stability in patients with CAP.

Citation: Blum CA, Nigro N, Briel M, et al. Adjunct prednisone therapy for patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a multicenter, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9977):1511-1518.

Clinical question: Does corticosteroid treatment shorten systemic illness in patients admitted to the hospital for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP)?

Background: Pneumonia is the third-leading cause of death worldwide. Studies have yielded conflicting data about the benefit of adding systemic corticosteroids for treatment of CAP.

Study design: Double-blind, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: Seven tertiary care hospitals in Switzerland.

Synopsis: Seven hundred eighty-four patients hospitalized for CAP were randomized to receive either oral prednisone 50 mg daily for seven days or placebo, with the primary endpoint being time to stable vital signs. The intention-to-treat analysis found that the median time to clinical stability was 1.4 days earlier in the prednisone group (hazard ratio 1.33, 95% CI 1.15-1.50, P<0.0001) and that length of stay and IV antibiotics were reduced by one day; this effect was valid across all PSI classes and was not dependent on age. Pneumonia-associated complications in the two groups did not differ at 30 days, though the prednisone group had a higher incidence of hyperglycemia requiring insulin.

Because all study locations were in a single, fairly homogenous northern European country, care should be taken when hospitalists apply these findings to their patient population, and the risks of hyperglycemia requiring insulin should be taken into consideration.

Bottom line: Systemic steroids may reduce the time to clinical stability in patients with CAP.

Citation: Blum CA, Nigro N, Briel M, et al. Adjunct prednisone therapy for patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a multicenter, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9977):1511-1518.

Clinical question: Does corticosteroid treatment shorten systemic illness in patients admitted to the hospital for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP)?

Background: Pneumonia is the third-leading cause of death worldwide. Studies have yielded conflicting data about the benefit of adding systemic corticosteroids for treatment of CAP.

Study design: Double-blind, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: Seven tertiary care hospitals in Switzerland.

Synopsis: Seven hundred eighty-four patients hospitalized for CAP were randomized to receive either oral prednisone 50 mg daily for seven days or placebo, with the primary endpoint being time to stable vital signs. The intention-to-treat analysis found that the median time to clinical stability was 1.4 days earlier in the prednisone group (hazard ratio 1.33, 95% CI 1.15-1.50, P<0.0001) and that length of stay and IV antibiotics were reduced by one day; this effect was valid across all PSI classes and was not dependent on age. Pneumonia-associated complications in the two groups did not differ at 30 days, though the prednisone group had a higher incidence of hyperglycemia requiring insulin.

Because all study locations were in a single, fairly homogenous northern European country, care should be taken when hospitalists apply these findings to their patient population, and the risks of hyperglycemia requiring insulin should be taken into consideration.

Bottom line: Systemic steroids may reduce the time to clinical stability in patients with CAP.

Citation: Blum CA, Nigro N, Briel M, et al. Adjunct prednisone therapy for patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a multicenter, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9977):1511-1518.

Standard Discharge Communication Process Improves Verbal Handoffs between Hospitalists, PCPs

Clinical question: Can a standardized discharge communication process, coupled with an electronic health record (EHR) system, improve the proportion of completed verbal handoffs from in-hospital physicians to PCPs within 24 hours of patient discharge?

Background: Discharge from the hospital setting is known to be a transition of care fraught with patient safety risks, with more than half of discharged patients experiencing at least one error.1 Previous studies identified core elements that pediatric hospitalists and PCPs consider essential in discharge communication, which included:

- Pending laboratory or test results;

- Follow-up appointments;

- Discharge medications;

- Admission and discharge diagnoses;

- Dates of admission and discharge; and

- Suggested management plan.2

Rates of transmission and receipt of information have been found to be suboptimal after hospital discharge, and PCPs have been found to be less satisfied than hospitalists with communication.2,3 Additionally, PCPs and hospitalists have been found to have incongruent views on who should be responsible for pending labs, adverse events, or status changes, differences which can have safety implications.3 PCPs who refer to general hospitals have been found to report superior completeness of discharge communication compared to freestanding children’s hospitals, where resident physicians are generally responsible for discharge summary completion.4 Standardizing and promoting a process of verbal handoff after hospital discharge may address some of these safety concerns, although a relationship has not been established between aspects of discharge communication and associated adverse clinical outcomes.5

Study design: Quality improvement study using improvement science methods and run charts.

Setting: An urban, 598-bed, freestanding children’s hospital.

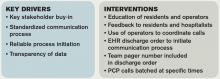

Synopsis: A 24/7 telephone operator service had been established at the investigators’ institution that was designed to facilitate communication between providers inside and outside the institution. At baseline, only 52% of hospital medicine (HM) provider discharges had a record of a discharge day call initiated to the PCP. A project team consisting of hospitalists, a chief resident, operator service administrators, and IT analysts identified system issues that led to unsuccessful communication, which facilitated identification of key drivers of improving communication and associated interventions (see Table 1).

Discharging physicians, who were usually residents, were instructed to call the operator at the time of discharge. Operators would page the PCP, and PCPs were expected to return the page within 20 minutes. Discharging physicians were expected to return the call to the operator within two to four minutes. The EHR generated a message to the operator whenever a discharge order was placed for an HM patient, leading the operator to page the discharging physician to initiate the call.

Adaptations after project initiation included:

- Reassigning primary responsibility for discharge phone calls to the daily on-call resident, if the discharging physician was not available.

- Establishing a non-changing pager number on the automated discharge notification that would always reach the appropriate team member.

- Batching discharge phone calls at times of increased resident availability to minimize hold times for PCPs and work interruptions for discharging physicians.

Weekly failure data was generated and reviewed by the improvement team, and a call record was linked to the patient’s medical record. Team-specific and overall results for HM teams were posted weekly on a run-chart. The primary outcome measure was the percentage of completed calls between PCP and HM physician within 24 hours of discharge.

Over the approximately 32-month study period, the percentage of calls initiated improved from 50% to 97% after four interventions. After one year, data was collected to assess percentage of calls completed, a number that rose from 80% in the first eight weeks to a median of 93%, which was sustained for 18 months.

Bottom line: Utilizing improvement methods and reliability science, a process of improving verbal handoffs between hospital-based physicians and PCPs within 24 hours after discharge led to a sustained improvement, to above 90%, in successful verbal handoffs.

Citation: Mussman GM, Vossmeyer MT, Brady PW, Warrick DM, Simmons JM, White CM. Improving the reliability of verbal communication between primary care physicians and pediatric hospitalists at hospital discharge [published online ahead of print May 29, 2015]. J Hosp Med. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2392.

Clinical Shorts

MAJORITY OF NONOBSTRUCTING ASYMPTOMATIC RENAL STONES REMAIN ASYMPTOMATIC OVER TIME

Retrospective trial of active surveillance of asymptomatic nonobstructing renal calculi demonstrated that 28% of stones became symptomatic, with 17% requiring surgical intervention and 2% causing asymptomatic hydronephrosis over three years.

Citation: Dropkin BM, Moses RA, Sharma D, Pais VM Jr. The natural history of nonobstructing asymptomatic renal stones managed with active surveillance. J Urol. 2015;193(4):1265-1269.

CPR USE IS HIGH, YET OUTCOMES ARE POOR IN HEMODIALYSIS PATIENTS

In a national cohort of hemodialysis patients, receipt of in-hospital CPR was significantly higher (6.3% vs. 0.3%) than the general population, but post-discharge survival was substantially shorter (33 vs. five months).

Citation: Wong SY, Kreuter W, Curtis JR, Hall YN, O’Hare AM. Trends in in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation and survival in adults receiving maintenance dialysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(6):1028-1035. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0406.

ULTRASOUND GUIDANCE INCREASES RATE OF SUCCESSFUL FIRST ATTEMPT RADIAL ARTERY CANNULATION

Randomized controlled trial of 749 anesthesia trainees showed that ultrasound guidance increased rate of first attempt radial artery cannulation by 14% when compared to Doppler and palpation (95% CI 5-22%).

Citation: Ueda K, Bayman EO, Johnson C, Odum NJ, Lee JJ. A randomised controlled trial of radial artery cannulation guided by Doppler vs palpation vs ultrasound [published online ahead of print April 8, 2015]. Anaesthesia. doi: 10.1111/anae.13062.

NO DIFFERENCE BETWEEN EPIDURAL STEROID INJECTIONS AND GABAPENTIN FOR TREATMENT OF LUMBOSACRAL RADICULAR PAIN

Multicenter, randomized study found no difference in lumbosacral radicular pain at one and three months in patients treated with epidural steroid injection versus gabapentin.

Citation: Cohen SP, Hanling S, Bicket MC, et al. Epidural steroid injections compared with gabapentin for lumbosacral radicular pain: multicenter randomized double blind comparative efficacy study. BMJ. 2015;350:h1748 doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1748.

References

- Smith K. Effective communication with primary care providers. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2014;61(4):671-679.

- Coghlin DT, Leyenaar JK, Shen M, et al. Pediatric discharge content: a multisite assessment of physician preferences and experiences. Hosp Pediatr. 2014;4(1):9-15.

- Ruth JL, Geskey JM, Shaffer ML, Bramley HP, Paul IM. Evaluating communication between pediatric primary care physicians and hospitalists. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2011;50(10):923-928.

- Leyenaar JK, Bergert L, Mallory LA, et al. Pediatric primary care providers’ perspectives regarding hospital discharge communication: a mixed methods analysis. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15(1):61-68.

- Bell CM, Schnipper JL, Auerbach AD, et al. Association of communication between hospital-based physicians and primary care providers with patient outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(3):381-386.

Clinical question: Can a standardized discharge communication process, coupled with an electronic health record (EHR) system, improve the proportion of completed verbal handoffs from in-hospital physicians to PCPs within 24 hours of patient discharge?

Background: Discharge from the hospital setting is known to be a transition of care fraught with patient safety risks, with more than half of discharged patients experiencing at least one error.1 Previous studies identified core elements that pediatric hospitalists and PCPs consider essential in discharge communication, which included:

- Pending laboratory or test results;

- Follow-up appointments;

- Discharge medications;

- Admission and discharge diagnoses;

- Dates of admission and discharge; and

- Suggested management plan.2

Rates of transmission and receipt of information have been found to be suboptimal after hospital discharge, and PCPs have been found to be less satisfied than hospitalists with communication.2,3 Additionally, PCPs and hospitalists have been found to have incongruent views on who should be responsible for pending labs, adverse events, or status changes, differences which can have safety implications.3 PCPs who refer to general hospitals have been found to report superior completeness of discharge communication compared to freestanding children’s hospitals, where resident physicians are generally responsible for discharge summary completion.4 Standardizing and promoting a process of verbal handoff after hospital discharge may address some of these safety concerns, although a relationship has not been established between aspects of discharge communication and associated adverse clinical outcomes.5

Study design: Quality improvement study using improvement science methods and run charts.

Setting: An urban, 598-bed, freestanding children’s hospital.

Synopsis: A 24/7 telephone operator service had been established at the investigators’ institution that was designed to facilitate communication between providers inside and outside the institution. At baseline, only 52% of hospital medicine (HM) provider discharges had a record of a discharge day call initiated to the PCP. A project team consisting of hospitalists, a chief resident, operator service administrators, and IT analysts identified system issues that led to unsuccessful communication, which facilitated identification of key drivers of improving communication and associated interventions (see Table 1).

Discharging physicians, who were usually residents, were instructed to call the operator at the time of discharge. Operators would page the PCP, and PCPs were expected to return the page within 20 minutes. Discharging physicians were expected to return the call to the operator within two to four minutes. The EHR generated a message to the operator whenever a discharge order was placed for an HM patient, leading the operator to page the discharging physician to initiate the call.

Adaptations after project initiation included:

- Reassigning primary responsibility for discharge phone calls to the daily on-call resident, if the discharging physician was not available.

- Establishing a non-changing pager number on the automated discharge notification that would always reach the appropriate team member.

- Batching discharge phone calls at times of increased resident availability to minimize hold times for PCPs and work interruptions for discharging physicians.

Weekly failure data was generated and reviewed by the improvement team, and a call record was linked to the patient’s medical record. Team-specific and overall results for HM teams were posted weekly on a run-chart. The primary outcome measure was the percentage of completed calls between PCP and HM physician within 24 hours of discharge.

Over the approximately 32-month study period, the percentage of calls initiated improved from 50% to 97% after four interventions. After one year, data was collected to assess percentage of calls completed, a number that rose from 80% in the first eight weeks to a median of 93%, which was sustained for 18 months.

Bottom line: Utilizing improvement methods and reliability science, a process of improving verbal handoffs between hospital-based physicians and PCPs within 24 hours after discharge led to a sustained improvement, to above 90%, in successful verbal handoffs.

Citation: Mussman GM, Vossmeyer MT, Brady PW, Warrick DM, Simmons JM, White CM. Improving the reliability of verbal communication between primary care physicians and pediatric hospitalists at hospital discharge [published online ahead of print May 29, 2015]. J Hosp Med. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2392.

Clinical Shorts

MAJORITY OF NONOBSTRUCTING ASYMPTOMATIC RENAL STONES REMAIN ASYMPTOMATIC OVER TIME

Retrospective trial of active surveillance of asymptomatic nonobstructing renal calculi demonstrated that 28% of stones became symptomatic, with 17% requiring surgical intervention and 2% causing asymptomatic hydronephrosis over three years.

Citation: Dropkin BM, Moses RA, Sharma D, Pais VM Jr. The natural history of nonobstructing asymptomatic renal stones managed with active surveillance. J Urol. 2015;193(4):1265-1269.

CPR USE IS HIGH, YET OUTCOMES ARE POOR IN HEMODIALYSIS PATIENTS

In a national cohort of hemodialysis patients, receipt of in-hospital CPR was significantly higher (6.3% vs. 0.3%) than the general population, but post-discharge survival was substantially shorter (33 vs. five months).

Citation: Wong SY, Kreuter W, Curtis JR, Hall YN, O’Hare AM. Trends in in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation and survival in adults receiving maintenance dialysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(6):1028-1035. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0406.

ULTRASOUND GUIDANCE INCREASES RATE OF SUCCESSFUL FIRST ATTEMPT RADIAL ARTERY CANNULATION

Randomized controlled trial of 749 anesthesia trainees showed that ultrasound guidance increased rate of first attempt radial artery cannulation by 14% when compared to Doppler and palpation (95% CI 5-22%).

Citation: Ueda K, Bayman EO, Johnson C, Odum NJ, Lee JJ. A randomised controlled trial of radial artery cannulation guided by Doppler vs palpation vs ultrasound [published online ahead of print April 8, 2015]. Anaesthesia. doi: 10.1111/anae.13062.

NO DIFFERENCE BETWEEN EPIDURAL STEROID INJECTIONS AND GABAPENTIN FOR TREATMENT OF LUMBOSACRAL RADICULAR PAIN

Multicenter, randomized study found no difference in lumbosacral radicular pain at one and three months in patients treated with epidural steroid injection versus gabapentin.

Citation: Cohen SP, Hanling S, Bicket MC, et al. Epidural steroid injections compared with gabapentin for lumbosacral radicular pain: multicenter randomized double blind comparative efficacy study. BMJ. 2015;350:h1748 doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1748.

References

- Smith K. Effective communication with primary care providers. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2014;61(4):671-679.

- Coghlin DT, Leyenaar JK, Shen M, et al. Pediatric discharge content: a multisite assessment of physician preferences and experiences. Hosp Pediatr. 2014;4(1):9-15.

- Ruth JL, Geskey JM, Shaffer ML, Bramley HP, Paul IM. Evaluating communication between pediatric primary care physicians and hospitalists. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2011;50(10):923-928.

- Leyenaar JK, Bergert L, Mallory LA, et al. Pediatric primary care providers’ perspectives regarding hospital discharge communication: a mixed methods analysis. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15(1):61-68.

- Bell CM, Schnipper JL, Auerbach AD, et al. Association of communication between hospital-based physicians and primary care providers with patient outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(3):381-386.

Clinical question: Can a standardized discharge communication process, coupled with an electronic health record (EHR) system, improve the proportion of completed verbal handoffs from in-hospital physicians to PCPs within 24 hours of patient discharge?

Background: Discharge from the hospital setting is known to be a transition of care fraught with patient safety risks, with more than half of discharged patients experiencing at least one error.1 Previous studies identified core elements that pediatric hospitalists and PCPs consider essential in discharge communication, which included:

- Pending laboratory or test results;

- Follow-up appointments;

- Discharge medications;

- Admission and discharge diagnoses;

- Dates of admission and discharge; and

- Suggested management plan.2

Rates of transmission and receipt of information have been found to be suboptimal after hospital discharge, and PCPs have been found to be less satisfied than hospitalists with communication.2,3 Additionally, PCPs and hospitalists have been found to have incongruent views on who should be responsible for pending labs, adverse events, or status changes, differences which can have safety implications.3 PCPs who refer to general hospitals have been found to report superior completeness of discharge communication compared to freestanding children’s hospitals, where resident physicians are generally responsible for discharge summary completion.4 Standardizing and promoting a process of verbal handoff after hospital discharge may address some of these safety concerns, although a relationship has not been established between aspects of discharge communication and associated adverse clinical outcomes.5

Study design: Quality improvement study using improvement science methods and run charts.

Setting: An urban, 598-bed, freestanding children’s hospital.

Synopsis: A 24/7 telephone operator service had been established at the investigators’ institution that was designed to facilitate communication between providers inside and outside the institution. At baseline, only 52% of hospital medicine (HM) provider discharges had a record of a discharge day call initiated to the PCP. A project team consisting of hospitalists, a chief resident, operator service administrators, and IT analysts identified system issues that led to unsuccessful communication, which facilitated identification of key drivers of improving communication and associated interventions (see Table 1).

Discharging physicians, who were usually residents, were instructed to call the operator at the time of discharge. Operators would page the PCP, and PCPs were expected to return the page within 20 minutes. Discharging physicians were expected to return the call to the operator within two to four minutes. The EHR generated a message to the operator whenever a discharge order was placed for an HM patient, leading the operator to page the discharging physician to initiate the call.

Adaptations after project initiation included:

- Reassigning primary responsibility for discharge phone calls to the daily on-call resident, if the discharging physician was not available.

- Establishing a non-changing pager number on the automated discharge notification that would always reach the appropriate team member.

- Batching discharge phone calls at times of increased resident availability to minimize hold times for PCPs and work interruptions for discharging physicians.

Weekly failure data was generated and reviewed by the improvement team, and a call record was linked to the patient’s medical record. Team-specific and overall results for HM teams were posted weekly on a run-chart. The primary outcome measure was the percentage of completed calls between PCP and HM physician within 24 hours of discharge.

Over the approximately 32-month study period, the percentage of calls initiated improved from 50% to 97% after four interventions. After one year, data was collected to assess percentage of calls completed, a number that rose from 80% in the first eight weeks to a median of 93%, which was sustained for 18 months.

Bottom line: Utilizing improvement methods and reliability science, a process of improving verbal handoffs between hospital-based physicians and PCPs within 24 hours after discharge led to a sustained improvement, to above 90%, in successful verbal handoffs.

Citation: Mussman GM, Vossmeyer MT, Brady PW, Warrick DM, Simmons JM, White CM. Improving the reliability of verbal communication between primary care physicians and pediatric hospitalists at hospital discharge [published online ahead of print May 29, 2015]. J Hosp Med. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2392.

Clinical Shorts

MAJORITY OF NONOBSTRUCTING ASYMPTOMATIC RENAL STONES REMAIN ASYMPTOMATIC OVER TIME

Retrospective trial of active surveillance of asymptomatic nonobstructing renal calculi demonstrated that 28% of stones became symptomatic, with 17% requiring surgical intervention and 2% causing asymptomatic hydronephrosis over three years.

Citation: Dropkin BM, Moses RA, Sharma D, Pais VM Jr. The natural history of nonobstructing asymptomatic renal stones managed with active surveillance. J Urol. 2015;193(4):1265-1269.

CPR USE IS HIGH, YET OUTCOMES ARE POOR IN HEMODIALYSIS PATIENTS

In a national cohort of hemodialysis patients, receipt of in-hospital CPR was significantly higher (6.3% vs. 0.3%) than the general population, but post-discharge survival was substantially shorter (33 vs. five months).

Citation: Wong SY, Kreuter W, Curtis JR, Hall YN, O’Hare AM. Trends in in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation and survival in adults receiving maintenance dialysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(6):1028-1035. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0406.

ULTRASOUND GUIDANCE INCREASES RATE OF SUCCESSFUL FIRST ATTEMPT RADIAL ARTERY CANNULATION

Randomized controlled trial of 749 anesthesia trainees showed that ultrasound guidance increased rate of first attempt radial artery cannulation by 14% when compared to Doppler and palpation (95% CI 5-22%).

Citation: Ueda K, Bayman EO, Johnson C, Odum NJ, Lee JJ. A randomised controlled trial of radial artery cannulation guided by Doppler vs palpation vs ultrasound [published online ahead of print April 8, 2015]. Anaesthesia. doi: 10.1111/anae.13062.

NO DIFFERENCE BETWEEN EPIDURAL STEROID INJECTIONS AND GABAPENTIN FOR TREATMENT OF LUMBOSACRAL RADICULAR PAIN

Multicenter, randomized study found no difference in lumbosacral radicular pain at one and three months in patients treated with epidural steroid injection versus gabapentin.

Citation: Cohen SP, Hanling S, Bicket MC, et al. Epidural steroid injections compared with gabapentin for lumbosacral radicular pain: multicenter randomized double blind comparative efficacy study. BMJ. 2015;350:h1748 doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1748.

References

- Smith K. Effective communication with primary care providers. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2014;61(4):671-679.

- Coghlin DT, Leyenaar JK, Shen M, et al. Pediatric discharge content: a multisite assessment of physician preferences and experiences. Hosp Pediatr. 2014;4(1):9-15.

- Ruth JL, Geskey JM, Shaffer ML, Bramley HP, Paul IM. Evaluating communication between pediatric primary care physicians and hospitalists. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2011;50(10):923-928.

- Leyenaar JK, Bergert L, Mallory LA, et al. Pediatric primary care providers’ perspectives regarding hospital discharge communication: a mixed methods analysis. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15(1):61-68.

- Bell CM, Schnipper JL, Auerbach AD, et al. Association of communication between hospital-based physicians and primary care providers with patient outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(3):381-386.

Nomogram Predicts Post-Operative Readmission

Clinical question: Can a nomogram accurately predict a patient’s risk of post-operative 30-day readmission?

Background: Medicare and Medicaid have implemented penalties for hospitals with high readmission rates. While this does not yet apply to post-operative readmissions, there is concern that it soon will. Algorithms for predicting readmission have been developed for medical patients; however, to date, no such tool has been developed for post-operative patients.

Study design: Retrospective review and prospective validation of a predictive nomogram.

Setting: Single academic hospital.

Synopsis: Using the American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) and hospital billing data, a retrospective analysis of 2,799 patients who had elective surgery between 2006 and 2011 was performed in order to develop a predictive nomogram for post-operative readmissions. Pre-operative, operative, and post-operative variables associated with readmission were evaluated, and the following variables were found to be independently associated with readmission:

- Bleeding disorder;

- Prolonged procedure length;

- In-hospital complications;

- Dependent functional status; and/or

- Higher care at discharge.

Using a linear regression model, a nomogram was developed that was prospectively validated in 255 patients from a single center. The nomogram accurately predicted the risk of post-operative readmission (C statistic=0.756) in the prospective analysis.

The nomogram has limited generalizability given the fact that it included patients from a single institution; it would benefit from external validation before widespread use.

Bottom line: The use of this predictive nomogram could aid in identifying patients at high risk of readmission.

Citation: Tevis SE, Weber SM, Kent KC, Kennedy GD. Nomogram to predict postoperative readmission in patients who undergo general surgery. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(6):505-510. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.4043.

Clinical question: Can a nomogram accurately predict a patient’s risk of post-operative 30-day readmission?

Background: Medicare and Medicaid have implemented penalties for hospitals with high readmission rates. While this does not yet apply to post-operative readmissions, there is concern that it soon will. Algorithms for predicting readmission have been developed for medical patients; however, to date, no such tool has been developed for post-operative patients.

Study design: Retrospective review and prospective validation of a predictive nomogram.

Setting: Single academic hospital.

Synopsis: Using the American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) and hospital billing data, a retrospective analysis of 2,799 patients who had elective surgery between 2006 and 2011 was performed in order to develop a predictive nomogram for post-operative readmissions. Pre-operative, operative, and post-operative variables associated with readmission were evaluated, and the following variables were found to be independently associated with readmission:

- Bleeding disorder;

- Prolonged procedure length;

- In-hospital complications;

- Dependent functional status; and/or

- Higher care at discharge.

Using a linear regression model, a nomogram was developed that was prospectively validated in 255 patients from a single center. The nomogram accurately predicted the risk of post-operative readmission (C statistic=0.756) in the prospective analysis.

The nomogram has limited generalizability given the fact that it included patients from a single institution; it would benefit from external validation before widespread use.

Bottom line: The use of this predictive nomogram could aid in identifying patients at high risk of readmission.

Citation: Tevis SE, Weber SM, Kent KC, Kennedy GD. Nomogram to predict postoperative readmission in patients who undergo general surgery. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(6):505-510. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.4043.

Clinical question: Can a nomogram accurately predict a patient’s risk of post-operative 30-day readmission?

Background: Medicare and Medicaid have implemented penalties for hospitals with high readmission rates. While this does not yet apply to post-operative readmissions, there is concern that it soon will. Algorithms for predicting readmission have been developed for medical patients; however, to date, no such tool has been developed for post-operative patients.

Study design: Retrospective review and prospective validation of a predictive nomogram.

Setting: Single academic hospital.

Synopsis: Using the American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) and hospital billing data, a retrospective analysis of 2,799 patients who had elective surgery between 2006 and 2011 was performed in order to develop a predictive nomogram for post-operative readmissions. Pre-operative, operative, and post-operative variables associated with readmission were evaluated, and the following variables were found to be independently associated with readmission:

- Bleeding disorder;

- Prolonged procedure length;

- In-hospital complications;

- Dependent functional status; and/or

- Higher care at discharge.

Using a linear regression model, a nomogram was developed that was prospectively validated in 255 patients from a single center. The nomogram accurately predicted the risk of post-operative readmission (C statistic=0.756) in the prospective analysis.

The nomogram has limited generalizability given the fact that it included patients from a single institution; it would benefit from external validation before widespread use.

Bottom line: The use of this predictive nomogram could aid in identifying patients at high risk of readmission.

Citation: Tevis SE, Weber SM, Kent KC, Kennedy GD. Nomogram to predict postoperative readmission in patients who undergo general surgery. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(6):505-510. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.4043.

The Hospitalist Earns Pair of 2015 Awards for Publication Excellence for Health and Medical Writing

The Hospitalist has been honored with two 2015 Awards of Excellence in the Health and Medical Writing category from the Awards for Publication Excellence (APEX).

The annual awards, presented to corporate and nonprofit publications, received 1,851 total entries, including nearly 400 entries to the writing category. Only 16 Awards of Excellence were presented.

Freelance medical writer Bryn Nelson, PhD, was honored for his eight-page special report on ObamaCare.

Freelance writer Gretchen Henkel was honored for her cover story, “Deaf Hospitalist Focuses on Teaching, Co-Management, Patient-Centered Care,” which explores the inspiring and enlightening careers of hospitalists with hearing impairments.

Published by Wiley Inc., The Hospitalist is the official newsmagazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine. The Hospitalist has garnered nine APEX Awards in the past seven years, receiving the APEX Grand Award for Magazines, Journals, and Tabloids last year, as well as attaining finalist status for “Best Healthcare Business Publication” from Medical Marketing and Media in 2009.

“We have long known that The Hospitalist provides hospitalists with some of the most compelling and informative content in hospital medicine,” SHM President Bob Harrington, MD, SFHM, wrote in an email. “It is great to have that content recognized by APEX this year, as it has been in the past. We know that APEX judges received nearly 2,000 entries this year, so we are thrilled to see our newsmagazine rise to the top again."

“This year’s recognition is especially valuable, as The Hospitalist is now distributed to more than 32,000 hospitalists and other leaders in healthcare.”

Physician Editor Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSCR, SFHM, also commends The Hospitalist, emphasizing the importance of these awards.

“These awards exemplify how well written the content is for The Hospitalist,” she said. “This is a huge honor for the publication, as well as for all hospitalists, for which the publication is intended. I am personally honored to be the physician editor of such an exemplary publication!”

The Hospitalist has been honored with two 2015 Awards of Excellence in the Health and Medical Writing category from the Awards for Publication Excellence (APEX).

The annual awards, presented to corporate and nonprofit publications, received 1,851 total entries, including nearly 400 entries to the writing category. Only 16 Awards of Excellence were presented.

Freelance medical writer Bryn Nelson, PhD, was honored for his eight-page special report on ObamaCare.

Freelance writer Gretchen Henkel was honored for her cover story, “Deaf Hospitalist Focuses on Teaching, Co-Management, Patient-Centered Care,” which explores the inspiring and enlightening careers of hospitalists with hearing impairments.

Published by Wiley Inc., The Hospitalist is the official newsmagazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine. The Hospitalist has garnered nine APEX Awards in the past seven years, receiving the APEX Grand Award for Magazines, Journals, and Tabloids last year, as well as attaining finalist status for “Best Healthcare Business Publication” from Medical Marketing and Media in 2009.

“We have long known that The Hospitalist provides hospitalists with some of the most compelling and informative content in hospital medicine,” SHM President Bob Harrington, MD, SFHM, wrote in an email. “It is great to have that content recognized by APEX this year, as it has been in the past. We know that APEX judges received nearly 2,000 entries this year, so we are thrilled to see our newsmagazine rise to the top again."

“This year’s recognition is especially valuable, as The Hospitalist is now distributed to more than 32,000 hospitalists and other leaders in healthcare.”

Physician Editor Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSCR, SFHM, also commends The Hospitalist, emphasizing the importance of these awards.

“These awards exemplify how well written the content is for The Hospitalist,” she said. “This is a huge honor for the publication, as well as for all hospitalists, for which the publication is intended. I am personally honored to be the physician editor of such an exemplary publication!”

The Hospitalist has been honored with two 2015 Awards of Excellence in the Health and Medical Writing category from the Awards for Publication Excellence (APEX).

The annual awards, presented to corporate and nonprofit publications, received 1,851 total entries, including nearly 400 entries to the writing category. Only 16 Awards of Excellence were presented.

Freelance medical writer Bryn Nelson, PhD, was honored for his eight-page special report on ObamaCare.

Freelance writer Gretchen Henkel was honored for her cover story, “Deaf Hospitalist Focuses on Teaching, Co-Management, Patient-Centered Care,” which explores the inspiring and enlightening careers of hospitalists with hearing impairments.

Published by Wiley Inc., The Hospitalist is the official newsmagazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine. The Hospitalist has garnered nine APEX Awards in the past seven years, receiving the APEX Grand Award for Magazines, Journals, and Tabloids last year, as well as attaining finalist status for “Best Healthcare Business Publication” from Medical Marketing and Media in 2009.

“We have long known that The Hospitalist provides hospitalists with some of the most compelling and informative content in hospital medicine,” SHM President Bob Harrington, MD, SFHM, wrote in an email. “It is great to have that content recognized by APEX this year, as it has been in the past. We know that APEX judges received nearly 2,000 entries this year, so we are thrilled to see our newsmagazine rise to the top again."

“This year’s recognition is especially valuable, as The Hospitalist is now distributed to more than 32,000 hospitalists and other leaders in healthcare.”

Physician Editor Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSCR, SFHM, also commends The Hospitalist, emphasizing the importance of these awards.

“These awards exemplify how well written the content is for The Hospitalist,” she said. “This is a huge honor for the publication, as well as for all hospitalists, for which the publication is intended. I am personally honored to be the physician editor of such an exemplary publication!”

Medical Professionalism: Its Evolution and What It Means to Hospitalists

Professionalism is an overused word in the medical industry. What exactly is meant by professionalism, and what should it mean to hospitalists? Wikipedia notes that a professional is one who earns a living from a specified activity that has standards of education and training that prepare members of the profession with the knowledge and skills necessary to perform the role required. In addition, professionals are subject to strict codes of conduct enshrining rigorous ethical and moral obligations.

Physicians are the consummate professionals; over centuries, we have been afforded the reputation of being one of the “highest-ranking” professionals within societies, along with divinity and law. We are held to very high standards, both in and out of the workplace, including arduous and rigorous standards of education and training. We are in one of the only professions that take the Hippocratic Oath at graduation. This oath requires us to swear to uphold specific ethical standards. Being a professional means we always act within our professional standards and advocate for our patients in all circumstances.1

Threats to Professionalism?

Over the past several decades, concern has been growing about a widespread decline in professionalism among physicians, a decline that extends beyond a single generation. There are many purported reasons for this erosion of professionalism; we need to first understand the threats to professionalism in order to guard against its erosion in ourselves and in the next generation of physicians.1

One major issue is that we do not have a common understanding of the nature of professionalism; the definition is both overused and misused. We often refer to professionalism by what it isn’t, rather than understanding what it is. For example, there are scores of definitions for “unprofessional” conduct in the medical industry, many of which refer to physician behaviors. These include actions that intimidate, berate, or bully others, regardless of the rationale or intent, and encompass any form of physical or psychological harm. The actions of the “disruptive physician” are often thought of as synonymous with unprofessional behavior. But professionalism is so much more than the absence of disruptive behavior. So part of the erosion of professionalism is an oversimplification of what it isn’t, rather than what it is.

Another issue with upholding professionalism over time is that many physicians forget their professional standards, because there are few “booster sessions” to remind us of why we practice medicine. Once we enter the workforce, we are confronted with so many obstacles to delivering good care to patients that we often feel overwhelmed or incapable of removing the real barriers to good care, and therefore incapable of fulfilling our mission. There are no regular “revivals” or checkpoints to refresh our memory of what we went into medicine to accomplish.

Although our ultimate goal is to take good care of patients, another threat to professionalism is that doing this often requires physicians to operate outside their “trained” knowledge and skill sets. It requires us to act on behalf of patients as an advocate in all aspects of their life, not just as a “diagnoser” or “prescriber.” As a result, maintaining the ideals of professionalism has become ever more complex, because the social determinants of health have a major impact on patient well-being and health, including access to food, housing, and transportation. Many times, diagnosing and prescribing have little impact on the patient’s outcome; these social determinants of disease take sole precedence. A patient’s education, income, and home environment have a much greater impact in determining their health outcomes than does access to prescription medications. This means that advocating for patient health and well-being extends far beyond the walls of a hospital or emergency room, a role in which most hospitalists are incapable and/or uncomfortable.1

Another major catalyst in the erosion of professionalism is the complex issue of money and income. Many physicians, including hospitalists, are “judged” by their relative value units, an indicator of the quantity and complexity of patients seen. Services not “billable” are generally delegated to others, or they go undone. Such services include communicating tirelessly with all the stakeholders in the patients’ care, including family members, primary care physicians, other physician specialists, and other disciplines. Untoward behaviors, such as “upcoding,” selecting funded patients for care, creating patient streams for highly lucrative services, and under-resourcing care provisions that “lose money”—regardless of the value to the patient—are inadvertently incentivized on individual and system levels to enhance revenue. Many hospitalists are strapped with student loans early in their careers, requiring them to earn enough to pay back these loans in a timely fashion. These perverse incentives can and often do confound our ability to act solely on behalf of our patients.2

How Do We Overcome These Threats?

The first step in reviving professionalism is to define it by what it is, not by what it isn’t. Professionalism is not the absence of bad behavior. Professionalism is the “commitment to carrying out professional responsibilities and an adherence to ethical principles.”3 Professionalism is the pursuit of the tenets of the Hippocratic Oath. As a litmus test, read and reread the oath, and honestly reflect upon your practice.

Another step is to continuously work in multidisciplinary teams, a skill that comes naturally to most hospitalists. In order to fulfill the oath, you should not work as a social worker, but you should advocate for your patients’ social work needs. You need a plethora of other disciplines to help you fulfill your role as a patient advocate. Know and respect the roles that your team members are playing, all of which are invaluable to you and your patients.

An additional step in helping you fulfill your role as a professional is to get the education and skills you need to function effectively within the complex systems in which we currently work. You should incorporate business and management education into your continuing medical education so that you can help patients traverse a system that is complex. You should know and understand the general concepts of value-based payment, insurance exchanges, federal-state-private insurances, and the basic tenets of health systems. You should know how to recognize and reduce waste and unnecessary variation in the system, and know how to measure and improve upon processes.

In the words of Emanuel Ezekiel, MD, PhD, “Learning clinical medicine is necessary for making patient well-being the physician’s primary obligation. But it is not sufficient. To promote professionalism and all that it entails (reducing errors; ensuring safe, consistent, high-quality, and convenient care; removing unnecessary services; and improving the efficiency in the delivery of services), physicians must develop better management skills … Becoming better managers will make physicians better medical professionals”.2

For those entering medical school, nine core competencies can predict success in medical school and later in practice; we should all commit to excellence in these, which go beyond clinical knowledge:

- ethical responsibility to self and others;

- reliability and dependability;

- service orientation;

- social skills;

- capacity for improvement;

- resilience and adaptability;

- cultural competence;

- oral communication; and

- teamwork.

Lastly, a critical step in preventing the erosion of professionalism in medicine is self-regulation. External regulation comes to those who refuse or are unwilling to regulate themselves. Professionalism is a set of skills that can be taught, learned, and modeled. As a new specialty, we all own the success or failure of the reputation of hospitalists as consummate professionals.1

Professionalism is an overused word in the medical industry. What exactly is meant by professionalism, and what should it mean to hospitalists? Wikipedia notes that a professional is one who earns a living from a specified activity that has standards of education and training that prepare members of the profession with the knowledge and skills necessary to perform the role required. In addition, professionals are subject to strict codes of conduct enshrining rigorous ethical and moral obligations.

Physicians are the consummate professionals; over centuries, we have been afforded the reputation of being one of the “highest-ranking” professionals within societies, along with divinity and law. We are held to very high standards, both in and out of the workplace, including arduous and rigorous standards of education and training. We are in one of the only professions that take the Hippocratic Oath at graduation. This oath requires us to swear to uphold specific ethical standards. Being a professional means we always act within our professional standards and advocate for our patients in all circumstances.1

Threats to Professionalism?

Over the past several decades, concern has been growing about a widespread decline in professionalism among physicians, a decline that extends beyond a single generation. There are many purported reasons for this erosion of professionalism; we need to first understand the threats to professionalism in order to guard against its erosion in ourselves and in the next generation of physicians.1

One major issue is that we do not have a common understanding of the nature of professionalism; the definition is both overused and misused. We often refer to professionalism by what it isn’t, rather than understanding what it is. For example, there are scores of definitions for “unprofessional” conduct in the medical industry, many of which refer to physician behaviors. These include actions that intimidate, berate, or bully others, regardless of the rationale or intent, and encompass any form of physical or psychological harm. The actions of the “disruptive physician” are often thought of as synonymous with unprofessional behavior. But professionalism is so much more than the absence of disruptive behavior. So part of the erosion of professionalism is an oversimplification of what it isn’t, rather than what it is.

Another issue with upholding professionalism over time is that many physicians forget their professional standards, because there are few “booster sessions” to remind us of why we practice medicine. Once we enter the workforce, we are confronted with so many obstacles to delivering good care to patients that we often feel overwhelmed or incapable of removing the real barriers to good care, and therefore incapable of fulfilling our mission. There are no regular “revivals” or checkpoints to refresh our memory of what we went into medicine to accomplish.

Although our ultimate goal is to take good care of patients, another threat to professionalism is that doing this often requires physicians to operate outside their “trained” knowledge and skill sets. It requires us to act on behalf of patients as an advocate in all aspects of their life, not just as a “diagnoser” or “prescriber.” As a result, maintaining the ideals of professionalism has become ever more complex, because the social determinants of health have a major impact on patient well-being and health, including access to food, housing, and transportation. Many times, diagnosing and prescribing have little impact on the patient’s outcome; these social determinants of disease take sole precedence. A patient’s education, income, and home environment have a much greater impact in determining their health outcomes than does access to prescription medications. This means that advocating for patient health and well-being extends far beyond the walls of a hospital or emergency room, a role in which most hospitalists are incapable and/or uncomfortable.1

Another major catalyst in the erosion of professionalism is the complex issue of money and income. Many physicians, including hospitalists, are “judged” by their relative value units, an indicator of the quantity and complexity of patients seen. Services not “billable” are generally delegated to others, or they go undone. Such services include communicating tirelessly with all the stakeholders in the patients’ care, including family members, primary care physicians, other physician specialists, and other disciplines. Untoward behaviors, such as “upcoding,” selecting funded patients for care, creating patient streams for highly lucrative services, and under-resourcing care provisions that “lose money”—regardless of the value to the patient—are inadvertently incentivized on individual and system levels to enhance revenue. Many hospitalists are strapped with student loans early in their careers, requiring them to earn enough to pay back these loans in a timely fashion. These perverse incentives can and often do confound our ability to act solely on behalf of our patients.2

How Do We Overcome These Threats?

The first step in reviving professionalism is to define it by what it is, not by what it isn’t. Professionalism is not the absence of bad behavior. Professionalism is the “commitment to carrying out professional responsibilities and an adherence to ethical principles.”3 Professionalism is the pursuit of the tenets of the Hippocratic Oath. As a litmus test, read and reread the oath, and honestly reflect upon your practice.

Another step is to continuously work in multidisciplinary teams, a skill that comes naturally to most hospitalists. In order to fulfill the oath, you should not work as a social worker, but you should advocate for your patients’ social work needs. You need a plethora of other disciplines to help you fulfill your role as a patient advocate. Know and respect the roles that your team members are playing, all of which are invaluable to you and your patients.

An additional step in helping you fulfill your role as a professional is to get the education and skills you need to function effectively within the complex systems in which we currently work. You should incorporate business and management education into your continuing medical education so that you can help patients traverse a system that is complex. You should know and understand the general concepts of value-based payment, insurance exchanges, federal-state-private insurances, and the basic tenets of health systems. You should know how to recognize and reduce waste and unnecessary variation in the system, and know how to measure and improve upon processes.

In the words of Emanuel Ezekiel, MD, PhD, “Learning clinical medicine is necessary for making patient well-being the physician’s primary obligation. But it is not sufficient. To promote professionalism and all that it entails (reducing errors; ensuring safe, consistent, high-quality, and convenient care; removing unnecessary services; and improving the efficiency in the delivery of services), physicians must develop better management skills … Becoming better managers will make physicians better medical professionals”.2

For those entering medical school, nine core competencies can predict success in medical school and later in practice; we should all commit to excellence in these, which go beyond clinical knowledge:

- ethical responsibility to self and others;

- reliability and dependability;

- service orientation;

- social skills;

- capacity for improvement;

- resilience and adaptability;

- cultural competence;

- oral communication; and

- teamwork.

Lastly, a critical step in preventing the erosion of professionalism in medicine is self-regulation. External regulation comes to those who refuse or are unwilling to regulate themselves. Professionalism is a set of skills that can be taught, learned, and modeled. As a new specialty, we all own the success or failure of the reputation of hospitalists as consummate professionals.1

Professionalism is an overused word in the medical industry. What exactly is meant by professionalism, and what should it mean to hospitalists? Wikipedia notes that a professional is one who earns a living from a specified activity that has standards of education and training that prepare members of the profession with the knowledge and skills necessary to perform the role required. In addition, professionals are subject to strict codes of conduct enshrining rigorous ethical and moral obligations.

Physicians are the consummate professionals; over centuries, we have been afforded the reputation of being one of the “highest-ranking” professionals within societies, along with divinity and law. We are held to very high standards, both in and out of the workplace, including arduous and rigorous standards of education and training. We are in one of the only professions that take the Hippocratic Oath at graduation. This oath requires us to swear to uphold specific ethical standards. Being a professional means we always act within our professional standards and advocate for our patients in all circumstances.1

Threats to Professionalism?

Over the past several decades, concern has been growing about a widespread decline in professionalism among physicians, a decline that extends beyond a single generation. There are many purported reasons for this erosion of professionalism; we need to first understand the threats to professionalism in order to guard against its erosion in ourselves and in the next generation of physicians.1

One major issue is that we do not have a common understanding of the nature of professionalism; the definition is both overused and misused. We often refer to professionalism by what it isn’t, rather than understanding what it is. For example, there are scores of definitions for “unprofessional” conduct in the medical industry, many of which refer to physician behaviors. These include actions that intimidate, berate, or bully others, regardless of the rationale or intent, and encompass any form of physical or psychological harm. The actions of the “disruptive physician” are often thought of as synonymous with unprofessional behavior. But professionalism is so much more than the absence of disruptive behavior. So part of the erosion of professionalism is an oversimplification of what it isn’t, rather than what it is.