User login

Inpatient Ambulation

A number of observational studies have documented the association between prolonged bed rest during hospitalization with adverse short‐ and long‐term functional impairments and disability in older patients.[1, 2, 3, 4] However, the body of evidence on the benefits of early mobilization on functional outcomes in both critically ill patients and more stable patients on medical‐surgical floors remains inconclusive.[5, 6, 7, 8, 9] Despite the increased emphasis on mobilizing patients early and often in the inpatient setting, there is surprisingly little information available regarding how typically active adult patients are during their hospital stay. The few published studies that are available are limited by small samples and types of patients who were monitored.[10, 11, 12, 13, 14] Therefore, the purpose of this real‐world study was to describe the level of ambulation in a large sample of hospitalized adult patients using a validated consumer‐grade wireless accelerometer.

METHODS

This was a prospective cohort study of ambulatory patients from 3 medical‐surgical units of a community hospital from March 2014 through July 2014. The study was approved by the Kaiser Permanente Southern California Institutional Review Board. All ambulatory medical and surgical adult patients were eligible for the study except for those with isolation precautions. Patients wore an accelerometer (Tractivity; Kineteks Corp., Vancouver, BC, Canada) on the ankle from soon after admission to the unit until discharge home. The sensors were only removed for bathing and medical procedures, at which time the devices were secured to the patient's bed and reworn upon their return to the room. The nursing staff was trained to use the vendor application to register the sensor to the patient, secure the sensor to the patient's ankle, transfer the sensor data to the vendor server, review the step counts on the web application, and manually key the step count into the electronic medical records (EMRs) as part of routine nursing workflow. The staff otherwise continued with usual patient mobilization practices.

We previously validated the Tractivity device in a field study of 20 hospitalized patients using a research‐grade accelerometer, Stepwatch, as the gold standard (unpublished data). We found that the inter‐Tractivity device reliability was near perfect (intraclass correlation=0.99), and that the Tractivity step counts correlated highly with the nurses' documentation on a paper log of distance walked measured in feet (r=0.76). A small number of steps (100) were recorded over 24 hours when the device was worn by 2 bed bound patients. The 24‐hour Tractivity step count had acceptable limits of agreement with the Stepwatch (+284 [standard deviation: 314] steps; 95% limits of agreement 911‐343). In addition, for the current study, when we examined the step counts between patients who were classified by the nursing team as being able to walk 50 feet (n=320) compared to patients who were able to walk >50 feet (n=434), we found a significant difference in the median number of steps over a 24‐hour period (854 vs 1697, P0.0001).

The step count data were exported from the vendor's server, examined for irregularities, and merged with administrative and clinical data for analysis. Data extracted from the EMR system included sociodemographic (age, gender, marital status, and race/ethnicity) and clinical characteristics (LACE score [readmission risk score based on length of stay (L); acuity of the admission (A); comorbidity of the patient (measured with the Charlson comorbidity index score) (C); and emergency department use (measured as the number of visits in the six months before admission) (E),[15] Charlson Comorbidity Index, length of stay, principal discharge diagnosis, and body mass index), and nursing documentation of functional status (bed bound, sit up in bed, stand next to bed, walk 50 feet, and walk >50 feet).

Descriptive statistics and nonparametric tests (Kruskal‐Wallis and Wilcoxon signed rank) were used to analyze the non‐normally distributed step count data. Quantile regression[16] was used to determine the association between the frequency of the care team's review and documentation of steps, with median total step count adjusting for age, gender, LACE score, and medicine/surgical service line. Whereas linear regression allows one to describe how the mean of a given outcome changes with respect to some set of covariates in circumstances where data are normally distributed, quantile regression allows one to assess how a set of covariates are related to a prespecified quantile (eg, 50% percentile median) of an outcome distribution. This modeling is especially appropriate here, because step count data are not normally distributed. Because step counts can vary with a number of factors, such as age and principal admitting and discharge diagnoses, we stratified our analyses by age (65 or 65 years) and service lines (medical or surgical) due to the relatively small numbers of patients in each of the diagnostic groupings. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC); P values 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 1667 patients wore the activity sensor during their hospital stay. We included 777 patients in our analysis who had lengths of stay long enough for 24 hours of continuous monitoring, and almost half of these patients had at least 48 hours of monitoring (n=378). The demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are detailed in Table 1. The sample included mostly medical patients (77%), with a mean age of 6017 years, 57% females, and 55% nonwhites. Nearly all patients (97%) were classified as ambulatory at discharge based on the EMR data. Approximately 44% of the sensors were lost, mostly due to nursing staff forgetting to remove the devices at discharge; device failure was minimal (n=10).

| Variables | Value |

|---|---|

| |

| Sociodemographics | |

| Age | |

| 1840 years | 111 (15%) |

| 4165 years | 325 (42%) |

| 6575 years | 187 (24%) |

| 75 years | 151 (19%) |

| Females | 444 (57%) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 349 (45%) |

| Hispanics | 277 (35%) |

| African American | 101 (13%) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 37 (5%) |

| Other | 13 (2%) |

| Marital status | |

| Partnered | 435 (56%) |

| Unpartnered | 332 (43%) |

| Other/unknown | 10 (1%) |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Medical (principal discharge diagnoses) | |

| Cardiovascular | 116 (15%) |

| Respiratory | 84 (11%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 122 (16%) |

| Genitourinary | 31 (4%) |

| Metabolic/electrolytes | 26 (3%) |

| Septicemia | 92 (12%) |

| Nervous system | 21 (3%) |

| Cancer/malignancies | 13 (1%) |

| Other* | 103 (13%) |

| Surgical | |

| Orthopedic surgery | 60 (8%) |

| Other surgeries | 109 (14%) |

| LACE score | 9.33.5 |

| Charlson index | |

| 01 | 665 (85%) |

| 23 | 98 (13%) |

| 4+ | 14 (2%) |

| Length of stay, d | 3.983.80 |

| Body mass index | 30.27.5 |

| Functional status | |

| Preadmission level of function | |

| 1, bed bound | 3 (0.5%) |

| 2, able to sit | 6 (1%) |

| 3, stand next to bed | 3 (0.5%) |

| 4, walk 50 feet | 113 (14%) |

| 5, walk >50 feet | 651 (84%) |

| Missing | 1 (0%) |

| Current level of function | |

| 1, bed bound | 1 (0%) |

| 2, able to sit | 6 (1%) |

| 3, stand next to bed | 7 (1%) |

| 4, walk 50 feet | 320 (41%) |

| 5, walk >50 feet | 434 (56%) |

| Missing | 9 (1%) |

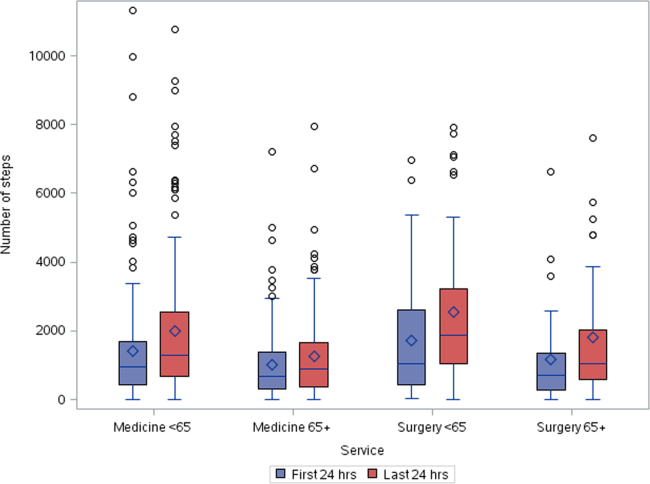

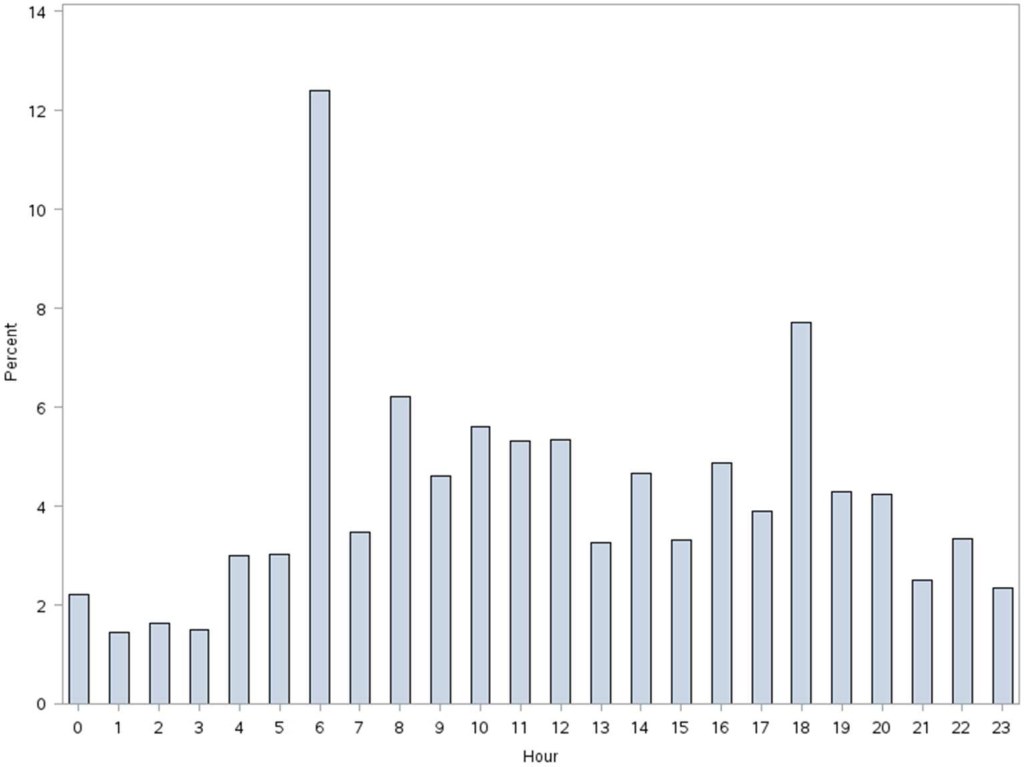

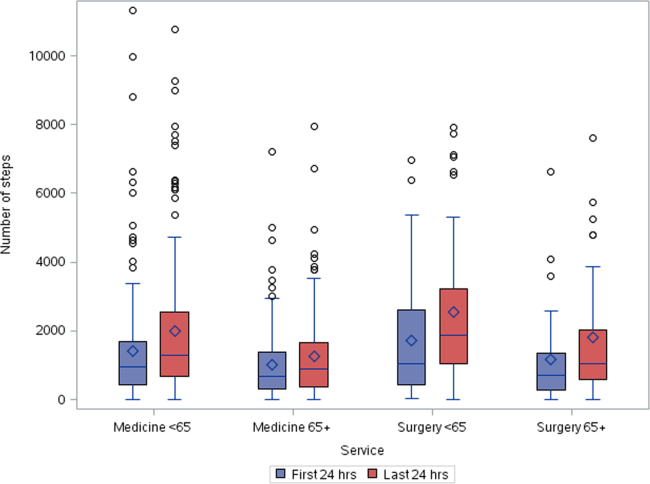

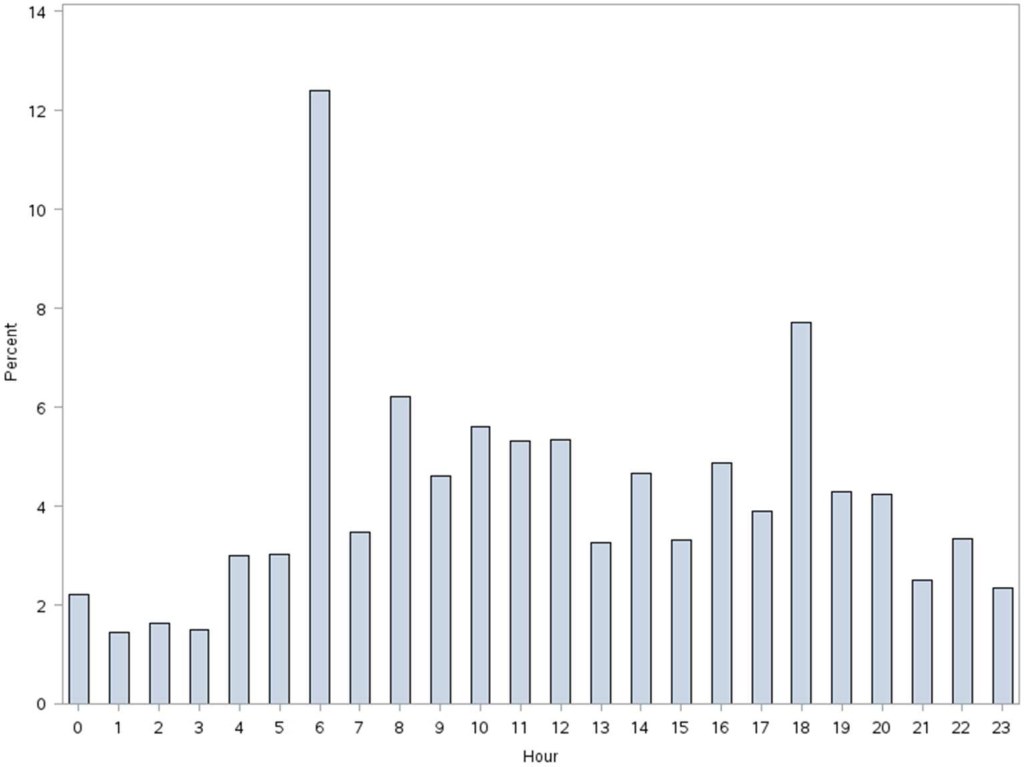

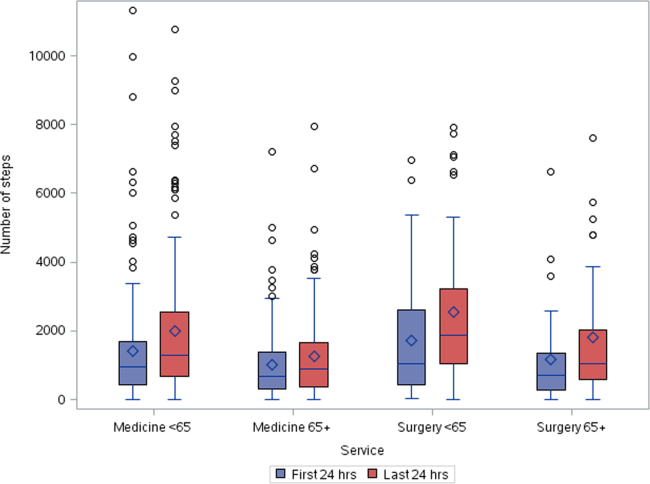

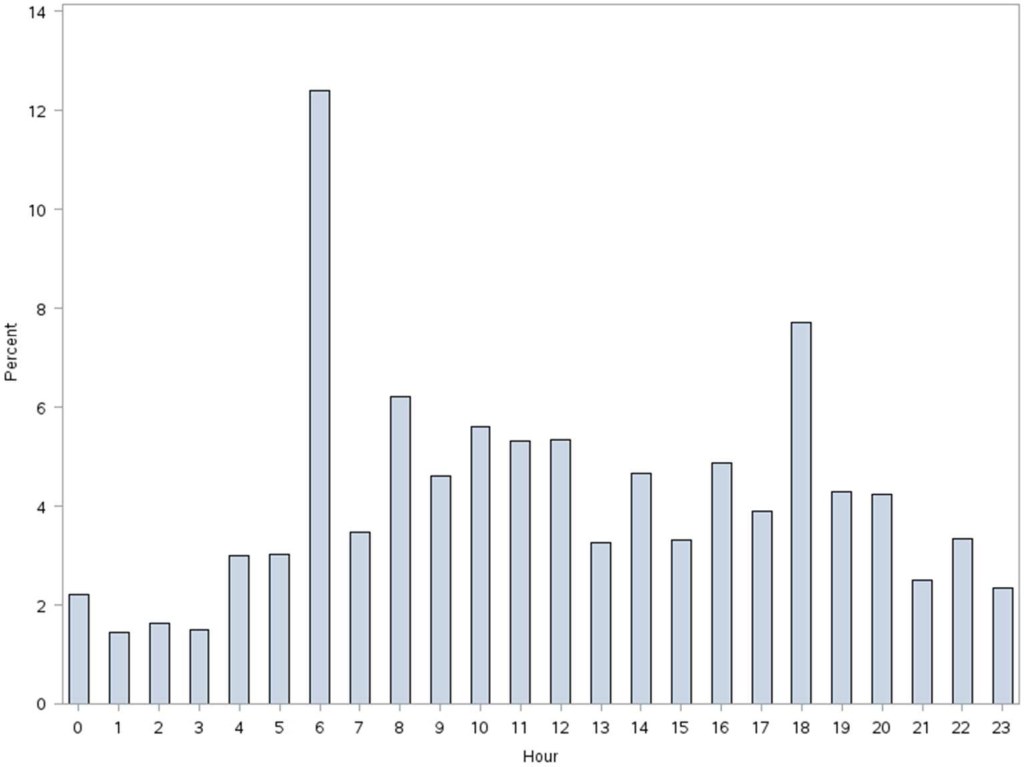

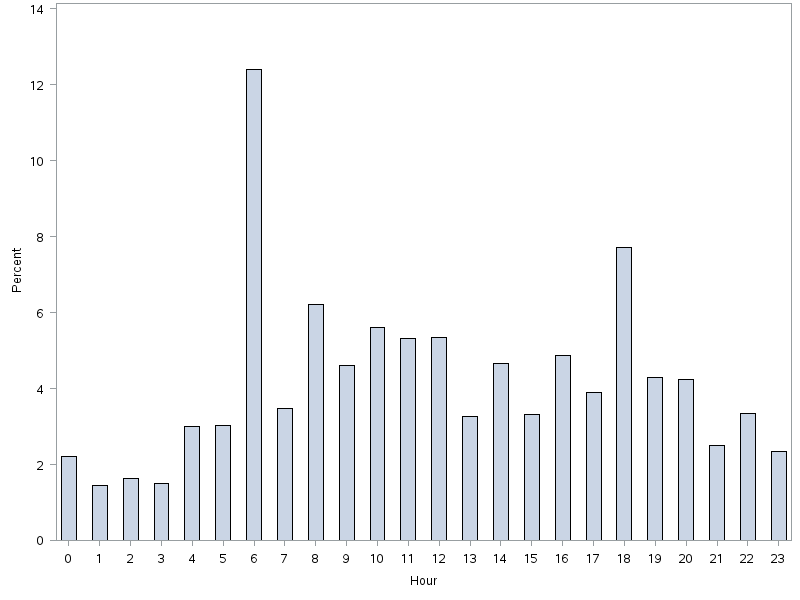

Patients accrued a median of 1158 (interquartile range: 6362238) steps over the 24 hours prior to discharge to home (Table 2). Approximately 13 (2%) patients registered zero steps in the last 24 hours; this may have been due to patients truly not accruing any steps, device failure, or the device was registered but never worn by the patient. Patients who were 65 years and older on both the medicine and surgical services accrued fewer steps compared to younger patients (962 vs 1294, P0.0001). For patients who had at least 48 hours of continuous monitoring (n=378), there was a median increase of 377 steps from the first 24 hours from admission to the unit to the final 24 hours prior to discharge (811 steps to 1188 steps, P0.0001) (Table 3 and Figure 1). The average length of stay for these patients was 5.74.9 days. Despite the longer length of stay, the level of ambulation at discharge was similar to patients with shorter stays. This is further illustrated in Figure 2 in the spaghetti plots of total steps over 4, 24‐hour monitoring increments. Ignoring the outliers, the plots suggest the following: (1) step counts tended to increase or stay about the same over the course of a hospitalization; and (2) for the medicine service line, step counts in the final 24 hours prior to discharge for patients with longer lengths of stay (72 or 96 hours) did not appear to be substantially different from patients with shorter lengths of stay. The data for the surgical patients are either too sparse or erratic to make any firm conclusions. Patients accrued steps throughout the day with the highest percentage of steps logged at approximately 6 am and 6 pm; these data are based on time stamps from the device, not the time of data transfer or documentation in the EMR (Figure 3).

| Service | Total Steps Last 24 Hours | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Median | |

| |||

| Medicine | |||

| 65 years old (n=321) | 1,972 | 1,995 | 1,284 |

| 65 years old (n=287) | 1,367 | 1,396 | 968 |

| Surgical | |||

| 65 years old (n=118) | 2,238 | 2,082 | 1,378 |

| 65 years old (n=51) | 1,485 | 1,647 | 890 |

| Total (n=777) | 1,757 | 1,818 | 1,158 |

| Service | Total Steps | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First 24 Hours | Last 24 Hours | |||||

| Mean | SD | Median | Mean | SD | Median | |

| ||||||

| Medicine | ||||||

| 65 years old (n=168) | 1,427 | 1,690 | 953 | 2,005 | 2,006 | 1,287 |

| 65 years old (n=127) | 1,004 | 1,098 | 676 | 1,260 | 1,291 | 904 |

| Surgical | ||||||

| 65 years old (n=53) | 1,722 | 1,696 | 1060 | 2,553 | 2,142 | 1,882 |

| 65 years old (n=30) | 1,184 | 1,470 | 704 | 1,829 | 1,996 | 1,053 |

| Total (n=378) | 1,307 | 1,515 | 811 | 1,817 | 1,864 | 1,188 |

More frequent documentation of step counts in the EMR (proxy for step count data retrieval and review from the vendor web site) by the care team was associated with higher total step counts after adjustments for relevant covariates (P0.001); 3 or more documentations over a 24‐hour period appears to be a minimal frequency to achieving approximately 200 steps more than the median value (Table 4).

| Service | Frequency of Documentation of Step Counts in EMR Over 24 Hours | P Value Trenda | Adjusted P Valueb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| ||||||||

| Medicine | ||||||||

| 65 years old (n=321) | MeanSD | 1,4051,414 | 2,4152,037 | 2,0101,929 | 1,9811,907 | 2,7412,876 | ||

| Median | 1,056 | 1,514 | 1284 | 1,196 | 1,702 | 0.004 | 0.003 | |

| N (%) | 83 (26%) | 109 (34%) | 71 (22%) | 25 (8%) | 33 (10%) | |||

| 65 years old (n=287) | MeanSD | 1,3481,711 | 1,1991428 | 1,290951 | 1,5291,180 | 1,8781,214 | ||

| Median | 850 | 773 | 999 | 1,278 | 1,498 | 0.07 | 0.10 | |

| N (%) | 85 (30%) | 82 (28%) | 66 (23%) | 20 (7%) | 34 (12%) | |||

| Surgical | ||||||||

| 65 years old (n=118) | MeanSD | 2,0772,001 | 1,8591,598 | 2,6182,536 | 2,3122,031 | 3,8022,979 | ||

| Median | 1,361 | 1,250 | 1,181 | 1,719 | 3,149 | 0.06 | 0.05 | |

| N (%) | 42 (35%) | 36 (31%) | 18 (15%) | 14 (12%) | 8 (7%) | |||

| 65 years old (n=51) | MeanSD | 2,0032,254 | 1,4781,603 | 1,1651,246 | 478 | 1,219469 | ||

| Median | 1,028 | 820 | 672 | 478 | 1,426 | 0.20 | 0.15 | |

| N (%) | 13 (26%) | 19 (37%) | 15 (29%) | 1 (2%) | 3 (6%) | |||

| Total (n=777) | MeanSD | 1,5441,717 | 1,7361,799 | 1,7201,699 | 1,8831720 | 2,4152,304 | ||

| Median | 1,012 | 1,116 | 1,124 | 1,314 | 1,557 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| N (%) | 223 (29%) | 246 (31%) | 170 (22%) | 60 (8%) | 78 (10%) | |||

DISCUSSION

We found that ambulatory medical‐surgical patients accrued a median of 1158 total steps in the 24 hours prior to their discharge home, which translates to walking approximately 500 meters; older patients accrued fewer steps compared to younger patients. In patients with longer length of stay, the level of ambulation at discharge was similar to patients with shorter stays, suggesting there may be an ambulation threshold (1100 steps) that patients achieve regardless of the length of stay before they are discharged home. In addition, patients whose care team reviewed and documented step counts at least 3 times over a 24‐hour period accrued significantly more steps than patients whose care team made fewer documentations.

The median step counts accrued by surgical patients in our study are similar to that found in Cook and colleagues'[14] report of patients after elective cardiac surgery using another popular consumer‐grade accelerometer. The providers in that study also had access to the data via a dashboard, but it was not clear how this information was used. Brown et al.[12] conducted the first study to objectively monitor mobility using 2 accelerometers in 45 older male veterans who had no prior mobility impairment, and found that patients spent 83% of their hospitalization lying in bed. The veterans spent about 3% of the time (43 minutes per day) standing or walking over a mean length of stay of 5 days. In a similar study with 43 older Dutch patients who had an average length of stay of 7 days, Pedersen et al.[10] found that patients spent 71% of their time lying, 21% sitting, and 4% standing or walking. Unfortunately, neither the Brown et al. nor Pedersen et al. studies were able to distinguish between standing and ambulatory activities. In a more recent study of 47 patients on medical‐surgical units at 2 hospitals that relied on time and motion observation methods, the mean duration for ambulation was 2 minutes during an 8‐hour period.[13]

We took advantage of the variability in the nursing documentation of step counts in the EMR to determine if there was a dose‐response relationship between the frequency of nursing documentation in a 24‐hour period and number of steps patients accrued. We hypothesized that if nurses make an effort to retrieve data from the vendor website and manually key in the step counts in the EMR, they are more likely to incorporate this information in their nursing care, share the information with patients and other clinicians, and therefore create a positive feedback loop for greater ambulation. Although our findings suggest a positive association between more frequent documentation and increased step counts, we cannot exclude the possibility that nurses naturally modulate the frequency with which they review and document step counts based on their overall judgment of the patients' mobility status (ie, patients who are more functionally impaired are assumed to accrue fewer steps over a shift, and therefore, nurses are less inclined to retrieve and document the information frequently). Future studies could prospectively examine what the optimal frequency for review and feedback of step counts is during a typical 8‐ or 12‐hour nursing shift for both patients and the nursing care team to promote ambulation.

A major strength of our study is the collection of objective ambulation data on a large inpatient sample by clinical staff as part of routine nursing care. This strength is balanced with several limitations. Due to the temporal pattern associated with ambulation, we were only able to analyze data for patients who had at least 24 hours of continuous monitoring. This could affect the generalizability of our findings, though we believe there is limited pragmatic value in closely tracking ambulation in patients who have such short stays. There was substantial variability in the step counts, reflecting the mix of medical versus surgical patients and their age, with very small samples available for meaningful subgroup analyses other than what we have presented. We were not able to measure other dimensions of mobility such as transfers or sitting in a chair, because the sensor is designed to only measure steps. In addition, we lost a large number of devices, mostly due to staff forgetting to remove the devices from patients' ankles at discharge. Finally, because we did not blind the nurses and patients to the step count data, the preliminary normative step counts that we present in this article may be higher than expected in patients cared for on medical‐surgical units.

In summary, we found that it is possible to measure ambulation objectively and reliably in hospitalized patients, and have provided preliminary normative step counts for a representative but heterogeneous medical‐surgical population. We also found that most patients who were discharged were ambulating at least 1100 steps over the 24 hours prior to leaving the hospital, regardless of their length of stay. This might suggest that step counts could be a useful parameter in determining readiness for hospital discharge. Our data also suggest that more frequent, objective monitoring of step counts by the nursing care team was associated with patients ambulating more. Both of these findings deserve further exploration. Future studies will need to be conducted on larger samples of medical and surgical hospitalized patients to adequately establish more refined step count norms for specific clinical populations, but especially for older patients, because this age group is at a particularly higher risk of poor functional outcomes with hospitalization. Having accurate and reliable information on ambulation is fundamental to any effort to improve ambulation in hospitalized patients. Moreover, knowing the normative range for step counts in the last 24 hours prior to discharge across specific clinical and age subgroups, could assist with discharge planning and provision of appropriate rehabilitative services in the home or community for safe transitions out of the hospital.[17]

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the patients and nurses at the Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Ontario Medical Center.

Disclosures: Funded by the Kaiser Permanente Southern California Care Improvement Research Team. Dr. Sallis contributed substantially to the study design, interpretation, and preparation of this article. Ms. Sturm and Chijioke contributed to the interpretation and preparation of this article. Dr. Kanter contributed to study design, interpretation, and preparation of this article. Mr. Huang contributed to the analysis, interpretation, and preparation of this article. Dr. Shen contributed to study design, analysis, interpretation, and preparation of this article. Dr. Nguyen had full access to the data and led the design, analysis, interpretation, and preparation of this article. Dr. Nguyen had full access to the data and will vouch for the integrity of the work as a whole, from inception to published article. The authors have no funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

- , , . Prevalence and outcomes of low mobility in hospitalized older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(8):1263–1270.

- , , , , , . Low mobility during hospitalization and functional decline in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(2):266–273.

- , , , , . The natural history of functional morbidity in hospitalized older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38(12):1296–1303.

- , , , , . Early ambulation and length of stay in older adults hospitalized for acute illness. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(21):1942–1943.

- , . Early mobilization in the intensive care unit: a systematic review. Cardiopulm Phys Ther J. 2012;23(1):5–13.

- , , . Outcomes of inpatient mobilization: a literature review. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(11–12):1486–1501.

- , , , et al. An early rehabilitation intervention to enhance recovery during hospital admission for an exacerbation of chronic respiratory disease: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2014;349:g4315.

- , , , , . Additional exercise does not change hospital or patient outcomes in older medical patients: a controlled clinical trial. Aust J Physiother. 2007;53(2):105–111.

- , , . Exercise for acutely hospitalised older medical patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD005955.

- , , , et al. Twenty‐four‐hour mobility during acute hospitalization in older medical patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(3):331–337.

- , , , , , . Mobility activity and its value as a prognostic indicator of survival in hospitalized older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(4):551–557.

- , , , . The underrecognized epidemic of low mobility during hospitalization of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(9):1660–1665.

- , , , , . Frequency and duration of nursing care related to older patient mobility. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2014;46(1):20–27.

- , , , , . Functional recovery in the elderly after major surgery: assessment of mobility recovery using wireless technology. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96(3):1057–1061.

- , , , et al. Derivation and validation of an index to predict early death or unplanned readmission after discharge from hospital to the community. CMAJ. 2010;182(6):551–557.

- , . Quantile regression: an introduction. J Econ Perspect. 2001;15(4):43–56.

- . Post‐hospital syndrome—an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):100–102.

A number of observational studies have documented the association between prolonged bed rest during hospitalization with adverse short‐ and long‐term functional impairments and disability in older patients.[1, 2, 3, 4] However, the body of evidence on the benefits of early mobilization on functional outcomes in both critically ill patients and more stable patients on medical‐surgical floors remains inconclusive.[5, 6, 7, 8, 9] Despite the increased emphasis on mobilizing patients early and often in the inpatient setting, there is surprisingly little information available regarding how typically active adult patients are during their hospital stay. The few published studies that are available are limited by small samples and types of patients who were monitored.[10, 11, 12, 13, 14] Therefore, the purpose of this real‐world study was to describe the level of ambulation in a large sample of hospitalized adult patients using a validated consumer‐grade wireless accelerometer.

METHODS

This was a prospective cohort study of ambulatory patients from 3 medical‐surgical units of a community hospital from March 2014 through July 2014. The study was approved by the Kaiser Permanente Southern California Institutional Review Board. All ambulatory medical and surgical adult patients were eligible for the study except for those with isolation precautions. Patients wore an accelerometer (Tractivity; Kineteks Corp., Vancouver, BC, Canada) on the ankle from soon after admission to the unit until discharge home. The sensors were only removed for bathing and medical procedures, at which time the devices were secured to the patient's bed and reworn upon their return to the room. The nursing staff was trained to use the vendor application to register the sensor to the patient, secure the sensor to the patient's ankle, transfer the sensor data to the vendor server, review the step counts on the web application, and manually key the step count into the electronic medical records (EMRs) as part of routine nursing workflow. The staff otherwise continued with usual patient mobilization practices.

We previously validated the Tractivity device in a field study of 20 hospitalized patients using a research‐grade accelerometer, Stepwatch, as the gold standard (unpublished data). We found that the inter‐Tractivity device reliability was near perfect (intraclass correlation=0.99), and that the Tractivity step counts correlated highly with the nurses' documentation on a paper log of distance walked measured in feet (r=0.76). A small number of steps (100) were recorded over 24 hours when the device was worn by 2 bed bound patients. The 24‐hour Tractivity step count had acceptable limits of agreement with the Stepwatch (+284 [standard deviation: 314] steps; 95% limits of agreement 911‐343). In addition, for the current study, when we examined the step counts between patients who were classified by the nursing team as being able to walk 50 feet (n=320) compared to patients who were able to walk >50 feet (n=434), we found a significant difference in the median number of steps over a 24‐hour period (854 vs 1697, P0.0001).

The step count data were exported from the vendor's server, examined for irregularities, and merged with administrative and clinical data for analysis. Data extracted from the EMR system included sociodemographic (age, gender, marital status, and race/ethnicity) and clinical characteristics (LACE score [readmission risk score based on length of stay (L); acuity of the admission (A); comorbidity of the patient (measured with the Charlson comorbidity index score) (C); and emergency department use (measured as the number of visits in the six months before admission) (E),[15] Charlson Comorbidity Index, length of stay, principal discharge diagnosis, and body mass index), and nursing documentation of functional status (bed bound, sit up in bed, stand next to bed, walk 50 feet, and walk >50 feet).

Descriptive statistics and nonparametric tests (Kruskal‐Wallis and Wilcoxon signed rank) were used to analyze the non‐normally distributed step count data. Quantile regression[16] was used to determine the association between the frequency of the care team's review and documentation of steps, with median total step count adjusting for age, gender, LACE score, and medicine/surgical service line. Whereas linear regression allows one to describe how the mean of a given outcome changes with respect to some set of covariates in circumstances where data are normally distributed, quantile regression allows one to assess how a set of covariates are related to a prespecified quantile (eg, 50% percentile median) of an outcome distribution. This modeling is especially appropriate here, because step count data are not normally distributed. Because step counts can vary with a number of factors, such as age and principal admitting and discharge diagnoses, we stratified our analyses by age (65 or 65 years) and service lines (medical or surgical) due to the relatively small numbers of patients in each of the diagnostic groupings. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC); P values 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 1667 patients wore the activity sensor during their hospital stay. We included 777 patients in our analysis who had lengths of stay long enough for 24 hours of continuous monitoring, and almost half of these patients had at least 48 hours of monitoring (n=378). The demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are detailed in Table 1. The sample included mostly medical patients (77%), with a mean age of 6017 years, 57% females, and 55% nonwhites. Nearly all patients (97%) were classified as ambulatory at discharge based on the EMR data. Approximately 44% of the sensors were lost, mostly due to nursing staff forgetting to remove the devices at discharge; device failure was minimal (n=10).

| Variables | Value |

|---|---|

| |

| Sociodemographics | |

| Age | |

| 1840 years | 111 (15%) |

| 4165 years | 325 (42%) |

| 6575 years | 187 (24%) |

| 75 years | 151 (19%) |

| Females | 444 (57%) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 349 (45%) |

| Hispanics | 277 (35%) |

| African American | 101 (13%) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 37 (5%) |

| Other | 13 (2%) |

| Marital status | |

| Partnered | 435 (56%) |

| Unpartnered | 332 (43%) |

| Other/unknown | 10 (1%) |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Medical (principal discharge diagnoses) | |

| Cardiovascular | 116 (15%) |

| Respiratory | 84 (11%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 122 (16%) |

| Genitourinary | 31 (4%) |

| Metabolic/electrolytes | 26 (3%) |

| Septicemia | 92 (12%) |

| Nervous system | 21 (3%) |

| Cancer/malignancies | 13 (1%) |

| Other* | 103 (13%) |

| Surgical | |

| Orthopedic surgery | 60 (8%) |

| Other surgeries | 109 (14%) |

| LACE score | 9.33.5 |

| Charlson index | |

| 01 | 665 (85%) |

| 23 | 98 (13%) |

| 4+ | 14 (2%) |

| Length of stay, d | 3.983.80 |

| Body mass index | 30.27.5 |

| Functional status | |

| Preadmission level of function | |

| 1, bed bound | 3 (0.5%) |

| 2, able to sit | 6 (1%) |

| 3, stand next to bed | 3 (0.5%) |

| 4, walk 50 feet | 113 (14%) |

| 5, walk >50 feet | 651 (84%) |

| Missing | 1 (0%) |

| Current level of function | |

| 1, bed bound | 1 (0%) |

| 2, able to sit | 6 (1%) |

| 3, stand next to bed | 7 (1%) |

| 4, walk 50 feet | 320 (41%) |

| 5, walk >50 feet | 434 (56%) |

| Missing | 9 (1%) |

Patients accrued a median of 1158 (interquartile range: 6362238) steps over the 24 hours prior to discharge to home (Table 2). Approximately 13 (2%) patients registered zero steps in the last 24 hours; this may have been due to patients truly not accruing any steps, device failure, or the device was registered but never worn by the patient. Patients who were 65 years and older on both the medicine and surgical services accrued fewer steps compared to younger patients (962 vs 1294, P0.0001). For patients who had at least 48 hours of continuous monitoring (n=378), there was a median increase of 377 steps from the first 24 hours from admission to the unit to the final 24 hours prior to discharge (811 steps to 1188 steps, P0.0001) (Table 3 and Figure 1). The average length of stay for these patients was 5.74.9 days. Despite the longer length of stay, the level of ambulation at discharge was similar to patients with shorter stays. This is further illustrated in Figure 2 in the spaghetti plots of total steps over 4, 24‐hour monitoring increments. Ignoring the outliers, the plots suggest the following: (1) step counts tended to increase or stay about the same over the course of a hospitalization; and (2) for the medicine service line, step counts in the final 24 hours prior to discharge for patients with longer lengths of stay (72 or 96 hours) did not appear to be substantially different from patients with shorter lengths of stay. The data for the surgical patients are either too sparse or erratic to make any firm conclusions. Patients accrued steps throughout the day with the highest percentage of steps logged at approximately 6 am and 6 pm; these data are based on time stamps from the device, not the time of data transfer or documentation in the EMR (Figure 3).

| Service | Total Steps Last 24 Hours | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Median | |

| |||

| Medicine | |||

| 65 years old (n=321) | 1,972 | 1,995 | 1,284 |

| 65 years old (n=287) | 1,367 | 1,396 | 968 |

| Surgical | |||

| 65 years old (n=118) | 2,238 | 2,082 | 1,378 |

| 65 years old (n=51) | 1,485 | 1,647 | 890 |

| Total (n=777) | 1,757 | 1,818 | 1,158 |

| Service | Total Steps | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First 24 Hours | Last 24 Hours | |||||

| Mean | SD | Median | Mean | SD | Median | |

| ||||||

| Medicine | ||||||

| 65 years old (n=168) | 1,427 | 1,690 | 953 | 2,005 | 2,006 | 1,287 |

| 65 years old (n=127) | 1,004 | 1,098 | 676 | 1,260 | 1,291 | 904 |

| Surgical | ||||||

| 65 years old (n=53) | 1,722 | 1,696 | 1060 | 2,553 | 2,142 | 1,882 |

| 65 years old (n=30) | 1,184 | 1,470 | 704 | 1,829 | 1,996 | 1,053 |

| Total (n=378) | 1,307 | 1,515 | 811 | 1,817 | 1,864 | 1,188 |

More frequent documentation of step counts in the EMR (proxy for step count data retrieval and review from the vendor web site) by the care team was associated with higher total step counts after adjustments for relevant covariates (P0.001); 3 or more documentations over a 24‐hour period appears to be a minimal frequency to achieving approximately 200 steps more than the median value (Table 4).

| Service | Frequency of Documentation of Step Counts in EMR Over 24 Hours | P Value Trenda | Adjusted P Valueb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| ||||||||

| Medicine | ||||||||

| 65 years old (n=321) | MeanSD | 1,4051,414 | 2,4152,037 | 2,0101,929 | 1,9811,907 | 2,7412,876 | ||

| Median | 1,056 | 1,514 | 1284 | 1,196 | 1,702 | 0.004 | 0.003 | |

| N (%) | 83 (26%) | 109 (34%) | 71 (22%) | 25 (8%) | 33 (10%) | |||

| 65 years old (n=287) | MeanSD | 1,3481,711 | 1,1991428 | 1,290951 | 1,5291,180 | 1,8781,214 | ||

| Median | 850 | 773 | 999 | 1,278 | 1,498 | 0.07 | 0.10 | |

| N (%) | 85 (30%) | 82 (28%) | 66 (23%) | 20 (7%) | 34 (12%) | |||

| Surgical | ||||||||

| 65 years old (n=118) | MeanSD | 2,0772,001 | 1,8591,598 | 2,6182,536 | 2,3122,031 | 3,8022,979 | ||

| Median | 1,361 | 1,250 | 1,181 | 1,719 | 3,149 | 0.06 | 0.05 | |

| N (%) | 42 (35%) | 36 (31%) | 18 (15%) | 14 (12%) | 8 (7%) | |||

| 65 years old (n=51) | MeanSD | 2,0032,254 | 1,4781,603 | 1,1651,246 | 478 | 1,219469 | ||

| Median | 1,028 | 820 | 672 | 478 | 1,426 | 0.20 | 0.15 | |

| N (%) | 13 (26%) | 19 (37%) | 15 (29%) | 1 (2%) | 3 (6%) | |||

| Total (n=777) | MeanSD | 1,5441,717 | 1,7361,799 | 1,7201,699 | 1,8831720 | 2,4152,304 | ||

| Median | 1,012 | 1,116 | 1,124 | 1,314 | 1,557 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| N (%) | 223 (29%) | 246 (31%) | 170 (22%) | 60 (8%) | 78 (10%) | |||

DISCUSSION

We found that ambulatory medical‐surgical patients accrued a median of 1158 total steps in the 24 hours prior to their discharge home, which translates to walking approximately 500 meters; older patients accrued fewer steps compared to younger patients. In patients with longer length of stay, the level of ambulation at discharge was similar to patients with shorter stays, suggesting there may be an ambulation threshold (1100 steps) that patients achieve regardless of the length of stay before they are discharged home. In addition, patients whose care team reviewed and documented step counts at least 3 times over a 24‐hour period accrued significantly more steps than patients whose care team made fewer documentations.

The median step counts accrued by surgical patients in our study are similar to that found in Cook and colleagues'[14] report of patients after elective cardiac surgery using another popular consumer‐grade accelerometer. The providers in that study also had access to the data via a dashboard, but it was not clear how this information was used. Brown et al.[12] conducted the first study to objectively monitor mobility using 2 accelerometers in 45 older male veterans who had no prior mobility impairment, and found that patients spent 83% of their hospitalization lying in bed. The veterans spent about 3% of the time (43 minutes per day) standing or walking over a mean length of stay of 5 days. In a similar study with 43 older Dutch patients who had an average length of stay of 7 days, Pedersen et al.[10] found that patients spent 71% of their time lying, 21% sitting, and 4% standing or walking. Unfortunately, neither the Brown et al. nor Pedersen et al. studies were able to distinguish between standing and ambulatory activities. In a more recent study of 47 patients on medical‐surgical units at 2 hospitals that relied on time and motion observation methods, the mean duration for ambulation was 2 minutes during an 8‐hour period.[13]

We took advantage of the variability in the nursing documentation of step counts in the EMR to determine if there was a dose‐response relationship between the frequency of nursing documentation in a 24‐hour period and number of steps patients accrued. We hypothesized that if nurses make an effort to retrieve data from the vendor website and manually key in the step counts in the EMR, they are more likely to incorporate this information in their nursing care, share the information with patients and other clinicians, and therefore create a positive feedback loop for greater ambulation. Although our findings suggest a positive association between more frequent documentation and increased step counts, we cannot exclude the possibility that nurses naturally modulate the frequency with which they review and document step counts based on their overall judgment of the patients' mobility status (ie, patients who are more functionally impaired are assumed to accrue fewer steps over a shift, and therefore, nurses are less inclined to retrieve and document the information frequently). Future studies could prospectively examine what the optimal frequency for review and feedback of step counts is during a typical 8‐ or 12‐hour nursing shift for both patients and the nursing care team to promote ambulation.

A major strength of our study is the collection of objective ambulation data on a large inpatient sample by clinical staff as part of routine nursing care. This strength is balanced with several limitations. Due to the temporal pattern associated with ambulation, we were only able to analyze data for patients who had at least 24 hours of continuous monitoring. This could affect the generalizability of our findings, though we believe there is limited pragmatic value in closely tracking ambulation in patients who have such short stays. There was substantial variability in the step counts, reflecting the mix of medical versus surgical patients and their age, with very small samples available for meaningful subgroup analyses other than what we have presented. We were not able to measure other dimensions of mobility such as transfers or sitting in a chair, because the sensor is designed to only measure steps. In addition, we lost a large number of devices, mostly due to staff forgetting to remove the devices from patients' ankles at discharge. Finally, because we did not blind the nurses and patients to the step count data, the preliminary normative step counts that we present in this article may be higher than expected in patients cared for on medical‐surgical units.

In summary, we found that it is possible to measure ambulation objectively and reliably in hospitalized patients, and have provided preliminary normative step counts for a representative but heterogeneous medical‐surgical population. We also found that most patients who were discharged were ambulating at least 1100 steps over the 24 hours prior to leaving the hospital, regardless of their length of stay. This might suggest that step counts could be a useful parameter in determining readiness for hospital discharge. Our data also suggest that more frequent, objective monitoring of step counts by the nursing care team was associated with patients ambulating more. Both of these findings deserve further exploration. Future studies will need to be conducted on larger samples of medical and surgical hospitalized patients to adequately establish more refined step count norms for specific clinical populations, but especially for older patients, because this age group is at a particularly higher risk of poor functional outcomes with hospitalization. Having accurate and reliable information on ambulation is fundamental to any effort to improve ambulation in hospitalized patients. Moreover, knowing the normative range for step counts in the last 24 hours prior to discharge across specific clinical and age subgroups, could assist with discharge planning and provision of appropriate rehabilitative services in the home or community for safe transitions out of the hospital.[17]

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the patients and nurses at the Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Ontario Medical Center.

Disclosures: Funded by the Kaiser Permanente Southern California Care Improvement Research Team. Dr. Sallis contributed substantially to the study design, interpretation, and preparation of this article. Ms. Sturm and Chijioke contributed to the interpretation and preparation of this article. Dr. Kanter contributed to study design, interpretation, and preparation of this article. Mr. Huang contributed to the analysis, interpretation, and preparation of this article. Dr. Shen contributed to study design, analysis, interpretation, and preparation of this article. Dr. Nguyen had full access to the data and led the design, analysis, interpretation, and preparation of this article. Dr. Nguyen had full access to the data and will vouch for the integrity of the work as a whole, from inception to published article. The authors have no funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

A number of observational studies have documented the association between prolonged bed rest during hospitalization with adverse short‐ and long‐term functional impairments and disability in older patients.[1, 2, 3, 4] However, the body of evidence on the benefits of early mobilization on functional outcomes in both critically ill patients and more stable patients on medical‐surgical floors remains inconclusive.[5, 6, 7, 8, 9] Despite the increased emphasis on mobilizing patients early and often in the inpatient setting, there is surprisingly little information available regarding how typically active adult patients are during their hospital stay. The few published studies that are available are limited by small samples and types of patients who were monitored.[10, 11, 12, 13, 14] Therefore, the purpose of this real‐world study was to describe the level of ambulation in a large sample of hospitalized adult patients using a validated consumer‐grade wireless accelerometer.

METHODS

This was a prospective cohort study of ambulatory patients from 3 medical‐surgical units of a community hospital from March 2014 through July 2014. The study was approved by the Kaiser Permanente Southern California Institutional Review Board. All ambulatory medical and surgical adult patients were eligible for the study except for those with isolation precautions. Patients wore an accelerometer (Tractivity; Kineteks Corp., Vancouver, BC, Canada) on the ankle from soon after admission to the unit until discharge home. The sensors were only removed for bathing and medical procedures, at which time the devices were secured to the patient's bed and reworn upon their return to the room. The nursing staff was trained to use the vendor application to register the sensor to the patient, secure the sensor to the patient's ankle, transfer the sensor data to the vendor server, review the step counts on the web application, and manually key the step count into the electronic medical records (EMRs) as part of routine nursing workflow. The staff otherwise continued with usual patient mobilization practices.

We previously validated the Tractivity device in a field study of 20 hospitalized patients using a research‐grade accelerometer, Stepwatch, as the gold standard (unpublished data). We found that the inter‐Tractivity device reliability was near perfect (intraclass correlation=0.99), and that the Tractivity step counts correlated highly with the nurses' documentation on a paper log of distance walked measured in feet (r=0.76). A small number of steps (100) were recorded over 24 hours when the device was worn by 2 bed bound patients. The 24‐hour Tractivity step count had acceptable limits of agreement with the Stepwatch (+284 [standard deviation: 314] steps; 95% limits of agreement 911‐343). In addition, for the current study, when we examined the step counts between patients who were classified by the nursing team as being able to walk 50 feet (n=320) compared to patients who were able to walk >50 feet (n=434), we found a significant difference in the median number of steps over a 24‐hour period (854 vs 1697, P0.0001).

The step count data were exported from the vendor's server, examined for irregularities, and merged with administrative and clinical data for analysis. Data extracted from the EMR system included sociodemographic (age, gender, marital status, and race/ethnicity) and clinical characteristics (LACE score [readmission risk score based on length of stay (L); acuity of the admission (A); comorbidity of the patient (measured with the Charlson comorbidity index score) (C); and emergency department use (measured as the number of visits in the six months before admission) (E),[15] Charlson Comorbidity Index, length of stay, principal discharge diagnosis, and body mass index), and nursing documentation of functional status (bed bound, sit up in bed, stand next to bed, walk 50 feet, and walk >50 feet).

Descriptive statistics and nonparametric tests (Kruskal‐Wallis and Wilcoxon signed rank) were used to analyze the non‐normally distributed step count data. Quantile regression[16] was used to determine the association between the frequency of the care team's review and documentation of steps, with median total step count adjusting for age, gender, LACE score, and medicine/surgical service line. Whereas linear regression allows one to describe how the mean of a given outcome changes with respect to some set of covariates in circumstances where data are normally distributed, quantile regression allows one to assess how a set of covariates are related to a prespecified quantile (eg, 50% percentile median) of an outcome distribution. This modeling is especially appropriate here, because step count data are not normally distributed. Because step counts can vary with a number of factors, such as age and principal admitting and discharge diagnoses, we stratified our analyses by age (65 or 65 years) and service lines (medical or surgical) due to the relatively small numbers of patients in each of the diagnostic groupings. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC); P values 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 1667 patients wore the activity sensor during their hospital stay. We included 777 patients in our analysis who had lengths of stay long enough for 24 hours of continuous monitoring, and almost half of these patients had at least 48 hours of monitoring (n=378). The demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are detailed in Table 1. The sample included mostly medical patients (77%), with a mean age of 6017 years, 57% females, and 55% nonwhites. Nearly all patients (97%) were classified as ambulatory at discharge based on the EMR data. Approximately 44% of the sensors were lost, mostly due to nursing staff forgetting to remove the devices at discharge; device failure was minimal (n=10).

| Variables | Value |

|---|---|

| |

| Sociodemographics | |

| Age | |

| 1840 years | 111 (15%) |

| 4165 years | 325 (42%) |

| 6575 years | 187 (24%) |

| 75 years | 151 (19%) |

| Females | 444 (57%) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 349 (45%) |

| Hispanics | 277 (35%) |

| African American | 101 (13%) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 37 (5%) |

| Other | 13 (2%) |

| Marital status | |

| Partnered | 435 (56%) |

| Unpartnered | 332 (43%) |

| Other/unknown | 10 (1%) |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Medical (principal discharge diagnoses) | |

| Cardiovascular | 116 (15%) |

| Respiratory | 84 (11%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 122 (16%) |

| Genitourinary | 31 (4%) |

| Metabolic/electrolytes | 26 (3%) |

| Septicemia | 92 (12%) |

| Nervous system | 21 (3%) |

| Cancer/malignancies | 13 (1%) |

| Other* | 103 (13%) |

| Surgical | |

| Orthopedic surgery | 60 (8%) |

| Other surgeries | 109 (14%) |

| LACE score | 9.33.5 |

| Charlson index | |

| 01 | 665 (85%) |

| 23 | 98 (13%) |

| 4+ | 14 (2%) |

| Length of stay, d | 3.983.80 |

| Body mass index | 30.27.5 |

| Functional status | |

| Preadmission level of function | |

| 1, bed bound | 3 (0.5%) |

| 2, able to sit | 6 (1%) |

| 3, stand next to bed | 3 (0.5%) |

| 4, walk 50 feet | 113 (14%) |

| 5, walk >50 feet | 651 (84%) |

| Missing | 1 (0%) |

| Current level of function | |

| 1, bed bound | 1 (0%) |

| 2, able to sit | 6 (1%) |

| 3, stand next to bed | 7 (1%) |

| 4, walk 50 feet | 320 (41%) |

| 5, walk >50 feet | 434 (56%) |

| Missing | 9 (1%) |

Patients accrued a median of 1158 (interquartile range: 6362238) steps over the 24 hours prior to discharge to home (Table 2). Approximately 13 (2%) patients registered zero steps in the last 24 hours; this may have been due to patients truly not accruing any steps, device failure, or the device was registered but never worn by the patient. Patients who were 65 years and older on both the medicine and surgical services accrued fewer steps compared to younger patients (962 vs 1294, P0.0001). For patients who had at least 48 hours of continuous monitoring (n=378), there was a median increase of 377 steps from the first 24 hours from admission to the unit to the final 24 hours prior to discharge (811 steps to 1188 steps, P0.0001) (Table 3 and Figure 1). The average length of stay for these patients was 5.74.9 days. Despite the longer length of stay, the level of ambulation at discharge was similar to patients with shorter stays. This is further illustrated in Figure 2 in the spaghetti plots of total steps over 4, 24‐hour monitoring increments. Ignoring the outliers, the plots suggest the following: (1) step counts tended to increase or stay about the same over the course of a hospitalization; and (2) for the medicine service line, step counts in the final 24 hours prior to discharge for patients with longer lengths of stay (72 or 96 hours) did not appear to be substantially different from patients with shorter lengths of stay. The data for the surgical patients are either too sparse or erratic to make any firm conclusions. Patients accrued steps throughout the day with the highest percentage of steps logged at approximately 6 am and 6 pm; these data are based on time stamps from the device, not the time of data transfer or documentation in the EMR (Figure 3).

| Service | Total Steps Last 24 Hours | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Median | |

| |||

| Medicine | |||

| 65 years old (n=321) | 1,972 | 1,995 | 1,284 |

| 65 years old (n=287) | 1,367 | 1,396 | 968 |

| Surgical | |||

| 65 years old (n=118) | 2,238 | 2,082 | 1,378 |

| 65 years old (n=51) | 1,485 | 1,647 | 890 |

| Total (n=777) | 1,757 | 1,818 | 1,158 |

| Service | Total Steps | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First 24 Hours | Last 24 Hours | |||||

| Mean | SD | Median | Mean | SD | Median | |

| ||||||

| Medicine | ||||||

| 65 years old (n=168) | 1,427 | 1,690 | 953 | 2,005 | 2,006 | 1,287 |

| 65 years old (n=127) | 1,004 | 1,098 | 676 | 1,260 | 1,291 | 904 |

| Surgical | ||||||

| 65 years old (n=53) | 1,722 | 1,696 | 1060 | 2,553 | 2,142 | 1,882 |

| 65 years old (n=30) | 1,184 | 1,470 | 704 | 1,829 | 1,996 | 1,053 |

| Total (n=378) | 1,307 | 1,515 | 811 | 1,817 | 1,864 | 1,188 |

More frequent documentation of step counts in the EMR (proxy for step count data retrieval and review from the vendor web site) by the care team was associated with higher total step counts after adjustments for relevant covariates (P0.001); 3 or more documentations over a 24‐hour period appears to be a minimal frequency to achieving approximately 200 steps more than the median value (Table 4).

| Service | Frequency of Documentation of Step Counts in EMR Over 24 Hours | P Value Trenda | Adjusted P Valueb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| ||||||||

| Medicine | ||||||||

| 65 years old (n=321) | MeanSD | 1,4051,414 | 2,4152,037 | 2,0101,929 | 1,9811,907 | 2,7412,876 | ||

| Median | 1,056 | 1,514 | 1284 | 1,196 | 1,702 | 0.004 | 0.003 | |

| N (%) | 83 (26%) | 109 (34%) | 71 (22%) | 25 (8%) | 33 (10%) | |||

| 65 years old (n=287) | MeanSD | 1,3481,711 | 1,1991428 | 1,290951 | 1,5291,180 | 1,8781,214 | ||

| Median | 850 | 773 | 999 | 1,278 | 1,498 | 0.07 | 0.10 | |

| N (%) | 85 (30%) | 82 (28%) | 66 (23%) | 20 (7%) | 34 (12%) | |||

| Surgical | ||||||||

| 65 years old (n=118) | MeanSD | 2,0772,001 | 1,8591,598 | 2,6182,536 | 2,3122,031 | 3,8022,979 | ||

| Median | 1,361 | 1,250 | 1,181 | 1,719 | 3,149 | 0.06 | 0.05 | |

| N (%) | 42 (35%) | 36 (31%) | 18 (15%) | 14 (12%) | 8 (7%) | |||

| 65 years old (n=51) | MeanSD | 2,0032,254 | 1,4781,603 | 1,1651,246 | 478 | 1,219469 | ||

| Median | 1,028 | 820 | 672 | 478 | 1,426 | 0.20 | 0.15 | |

| N (%) | 13 (26%) | 19 (37%) | 15 (29%) | 1 (2%) | 3 (6%) | |||

| Total (n=777) | MeanSD | 1,5441,717 | 1,7361,799 | 1,7201,699 | 1,8831720 | 2,4152,304 | ||

| Median | 1,012 | 1,116 | 1,124 | 1,314 | 1,557 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| N (%) | 223 (29%) | 246 (31%) | 170 (22%) | 60 (8%) | 78 (10%) | |||

DISCUSSION

We found that ambulatory medical‐surgical patients accrued a median of 1158 total steps in the 24 hours prior to their discharge home, which translates to walking approximately 500 meters; older patients accrued fewer steps compared to younger patients. In patients with longer length of stay, the level of ambulation at discharge was similar to patients with shorter stays, suggesting there may be an ambulation threshold (1100 steps) that patients achieve regardless of the length of stay before they are discharged home. In addition, patients whose care team reviewed and documented step counts at least 3 times over a 24‐hour period accrued significantly more steps than patients whose care team made fewer documentations.

The median step counts accrued by surgical patients in our study are similar to that found in Cook and colleagues'[14] report of patients after elective cardiac surgery using another popular consumer‐grade accelerometer. The providers in that study also had access to the data via a dashboard, but it was not clear how this information was used. Brown et al.[12] conducted the first study to objectively monitor mobility using 2 accelerometers in 45 older male veterans who had no prior mobility impairment, and found that patients spent 83% of their hospitalization lying in bed. The veterans spent about 3% of the time (43 minutes per day) standing or walking over a mean length of stay of 5 days. In a similar study with 43 older Dutch patients who had an average length of stay of 7 days, Pedersen et al.[10] found that patients spent 71% of their time lying, 21% sitting, and 4% standing or walking. Unfortunately, neither the Brown et al. nor Pedersen et al. studies were able to distinguish between standing and ambulatory activities. In a more recent study of 47 patients on medical‐surgical units at 2 hospitals that relied on time and motion observation methods, the mean duration for ambulation was 2 minutes during an 8‐hour period.[13]

We took advantage of the variability in the nursing documentation of step counts in the EMR to determine if there was a dose‐response relationship between the frequency of nursing documentation in a 24‐hour period and number of steps patients accrued. We hypothesized that if nurses make an effort to retrieve data from the vendor website and manually key in the step counts in the EMR, they are more likely to incorporate this information in their nursing care, share the information with patients and other clinicians, and therefore create a positive feedback loop for greater ambulation. Although our findings suggest a positive association between more frequent documentation and increased step counts, we cannot exclude the possibility that nurses naturally modulate the frequency with which they review and document step counts based on their overall judgment of the patients' mobility status (ie, patients who are more functionally impaired are assumed to accrue fewer steps over a shift, and therefore, nurses are less inclined to retrieve and document the information frequently). Future studies could prospectively examine what the optimal frequency for review and feedback of step counts is during a typical 8‐ or 12‐hour nursing shift for both patients and the nursing care team to promote ambulation.

A major strength of our study is the collection of objective ambulation data on a large inpatient sample by clinical staff as part of routine nursing care. This strength is balanced with several limitations. Due to the temporal pattern associated with ambulation, we were only able to analyze data for patients who had at least 24 hours of continuous monitoring. This could affect the generalizability of our findings, though we believe there is limited pragmatic value in closely tracking ambulation in patients who have such short stays. There was substantial variability in the step counts, reflecting the mix of medical versus surgical patients and their age, with very small samples available for meaningful subgroup analyses other than what we have presented. We were not able to measure other dimensions of mobility such as transfers or sitting in a chair, because the sensor is designed to only measure steps. In addition, we lost a large number of devices, mostly due to staff forgetting to remove the devices from patients' ankles at discharge. Finally, because we did not blind the nurses and patients to the step count data, the preliminary normative step counts that we present in this article may be higher than expected in patients cared for on medical‐surgical units.

In summary, we found that it is possible to measure ambulation objectively and reliably in hospitalized patients, and have provided preliminary normative step counts for a representative but heterogeneous medical‐surgical population. We also found that most patients who were discharged were ambulating at least 1100 steps over the 24 hours prior to leaving the hospital, regardless of their length of stay. This might suggest that step counts could be a useful parameter in determining readiness for hospital discharge. Our data also suggest that more frequent, objective monitoring of step counts by the nursing care team was associated with patients ambulating more. Both of these findings deserve further exploration. Future studies will need to be conducted on larger samples of medical and surgical hospitalized patients to adequately establish more refined step count norms for specific clinical populations, but especially for older patients, because this age group is at a particularly higher risk of poor functional outcomes with hospitalization. Having accurate and reliable information on ambulation is fundamental to any effort to improve ambulation in hospitalized patients. Moreover, knowing the normative range for step counts in the last 24 hours prior to discharge across specific clinical and age subgroups, could assist with discharge planning and provision of appropriate rehabilitative services in the home or community for safe transitions out of the hospital.[17]

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the patients and nurses at the Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Ontario Medical Center.

Disclosures: Funded by the Kaiser Permanente Southern California Care Improvement Research Team. Dr. Sallis contributed substantially to the study design, interpretation, and preparation of this article. Ms. Sturm and Chijioke contributed to the interpretation and preparation of this article. Dr. Kanter contributed to study design, interpretation, and preparation of this article. Mr. Huang contributed to the analysis, interpretation, and preparation of this article. Dr. Shen contributed to study design, analysis, interpretation, and preparation of this article. Dr. Nguyen had full access to the data and led the design, analysis, interpretation, and preparation of this article. Dr. Nguyen had full access to the data and will vouch for the integrity of the work as a whole, from inception to published article. The authors have no funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

- , , . Prevalence and outcomes of low mobility in hospitalized older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(8):1263–1270.

- , , , , , . Low mobility during hospitalization and functional decline in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(2):266–273.

- , , , , . The natural history of functional morbidity in hospitalized older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38(12):1296–1303.

- , , , , . Early ambulation and length of stay in older adults hospitalized for acute illness. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(21):1942–1943.

- , . Early mobilization in the intensive care unit: a systematic review. Cardiopulm Phys Ther J. 2012;23(1):5–13.

- , , . Outcomes of inpatient mobilization: a literature review. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(11–12):1486–1501.

- , , , et al. An early rehabilitation intervention to enhance recovery during hospital admission for an exacerbation of chronic respiratory disease: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2014;349:g4315.

- , , , , . Additional exercise does not change hospital or patient outcomes in older medical patients: a controlled clinical trial. Aust J Physiother. 2007;53(2):105–111.

- , , . Exercise for acutely hospitalised older medical patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD005955.

- , , , et al. Twenty‐four‐hour mobility during acute hospitalization in older medical patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(3):331–337.

- , , , , , . Mobility activity and its value as a prognostic indicator of survival in hospitalized older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(4):551–557.

- , , , . The underrecognized epidemic of low mobility during hospitalization of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(9):1660–1665.

- , , , , . Frequency and duration of nursing care related to older patient mobility. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2014;46(1):20–27.

- , , , , . Functional recovery in the elderly after major surgery: assessment of mobility recovery using wireless technology. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96(3):1057–1061.

- , , , et al. Derivation and validation of an index to predict early death or unplanned readmission after discharge from hospital to the community. CMAJ. 2010;182(6):551–557.

- , . Quantile regression: an introduction. J Econ Perspect. 2001;15(4):43–56.

- . Post‐hospital syndrome—an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):100–102.

- , , . Prevalence and outcomes of low mobility in hospitalized older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(8):1263–1270.

- , , , , , . Low mobility during hospitalization and functional decline in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(2):266–273.

- , , , , . The natural history of functional morbidity in hospitalized older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38(12):1296–1303.

- , , , , . Early ambulation and length of stay in older adults hospitalized for acute illness. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(21):1942–1943.

- , . Early mobilization in the intensive care unit: a systematic review. Cardiopulm Phys Ther J. 2012;23(1):5–13.

- , , . Outcomes of inpatient mobilization: a literature review. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(11–12):1486–1501.

- , , , et al. An early rehabilitation intervention to enhance recovery during hospital admission for an exacerbation of chronic respiratory disease: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2014;349:g4315.

- , , , , . Additional exercise does not change hospital or patient outcomes in older medical patients: a controlled clinical trial. Aust J Physiother. 2007;53(2):105–111.

- , , . Exercise for acutely hospitalised older medical patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD005955.

- , , , et al. Twenty‐four‐hour mobility during acute hospitalization in older medical patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(3):331–337.

- , , , , , . Mobility activity and its value as a prognostic indicator of survival in hospitalized older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(4):551–557.

- , , , . The underrecognized epidemic of low mobility during hospitalization of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(9):1660–1665.

- , , , , . Frequency and duration of nursing care related to older patient mobility. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2014;46(1):20–27.

- , , , , . Functional recovery in the elderly after major surgery: assessment of mobility recovery using wireless technology. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96(3):1057–1061.

- , , , et al. Derivation and validation of an index to predict early death or unplanned readmission after discharge from hospital to the community. CMAJ. 2010;182(6):551–557.

- , . Quantile regression: an introduction. J Econ Perspect. 2001;15(4):43–56.

- . Post‐hospital syndrome—an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):100–102.

Inpatients With Poor Vision

Vision impairment is an under‐recognized risk factor for adverse events among hospitalized patients.[1, 2, 3] Inpatients with poor vision are at increased risk for falls and delirium[1, 3] and have more difficulty taking medications.[4, 5] They may also be at risk for being unable to read critical health information, including consent forms and discharge instructions, or decreased quality of life such as simply ordering food from menus. However, vision is neither routinely tested nor documented for inpatients. Low‐cost ($8 and up) nonprescription reading glasses, known as readers may be a simple, high‐value intervention to improve inpatients' vision. We aimed to study initial feasibility and efficacy of screening and correcting inpatients' vision.

METHODS

From June 2012 through January 2014, research assistants (RAs) identified eligible (adults [18 years], English speaking) participants daily from electronic medical records as part of an ongoing study of general medicine inpatients measuring quality‐of‐care at the University of Chicago Medicine.[6] RAs tested visual acuity using Snellen pocket charts (participants wore corrective lenses if available). For eligible participants, readers were tested with sequential fitting (+2/+2.25/+2.75/+3.25) until vision was corrected (sufficient vision: at least 20/50 acuity in at least 1 eye).[7] Eligible participants included those with insufficient vision who were not already wearing corrective lenses and had no documented blindness or medically severe vision loss, for whom nonprescription readers would be unlikely to correct vision deficiencies such as cataracts or glaucoma. The study was approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board (IRB #9967).

Of note, although readers are typically used in populations over 40 years of age, readers were fitted for all participants to assess their utility for any hospitalized adult patient. Upon completing the vision screening and readers interventions, participants received instruction on how to access vision care and how to obtain readers (if they corrected vision) after hospital discharge.

Descriptive statistics and tests of comparison, including t tests and [2] tests, were used when appropriate. All analyses were performed using Stata version 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

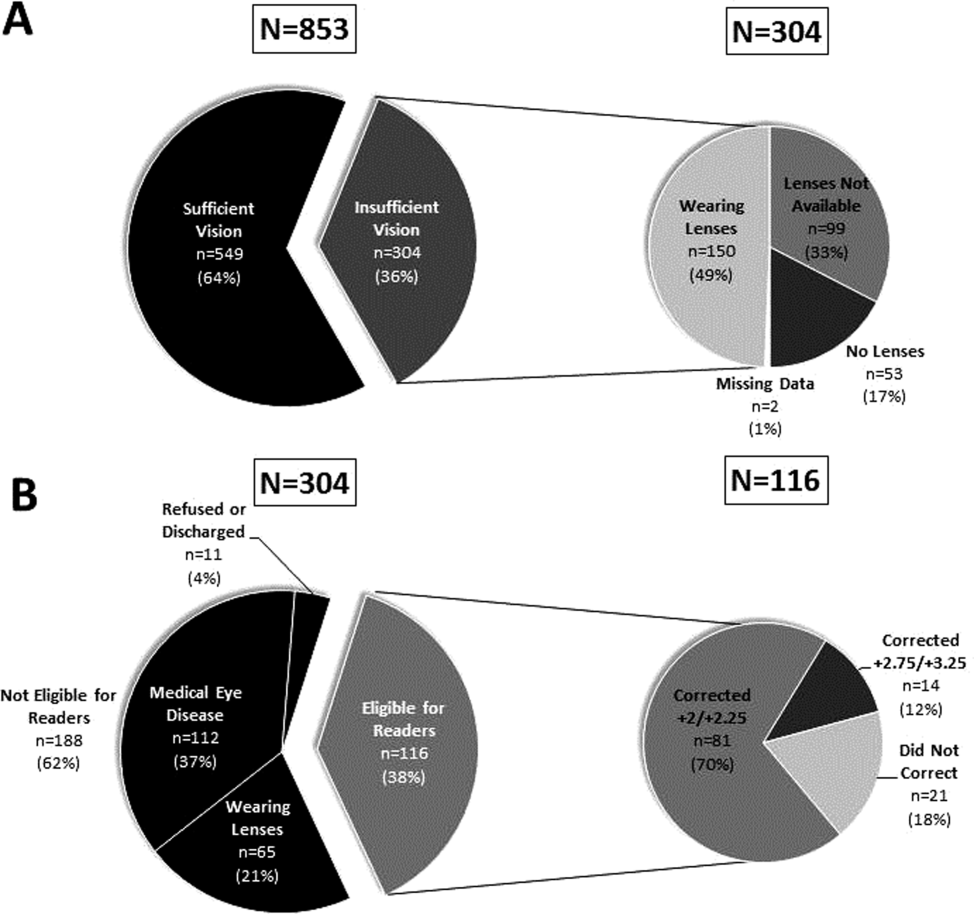

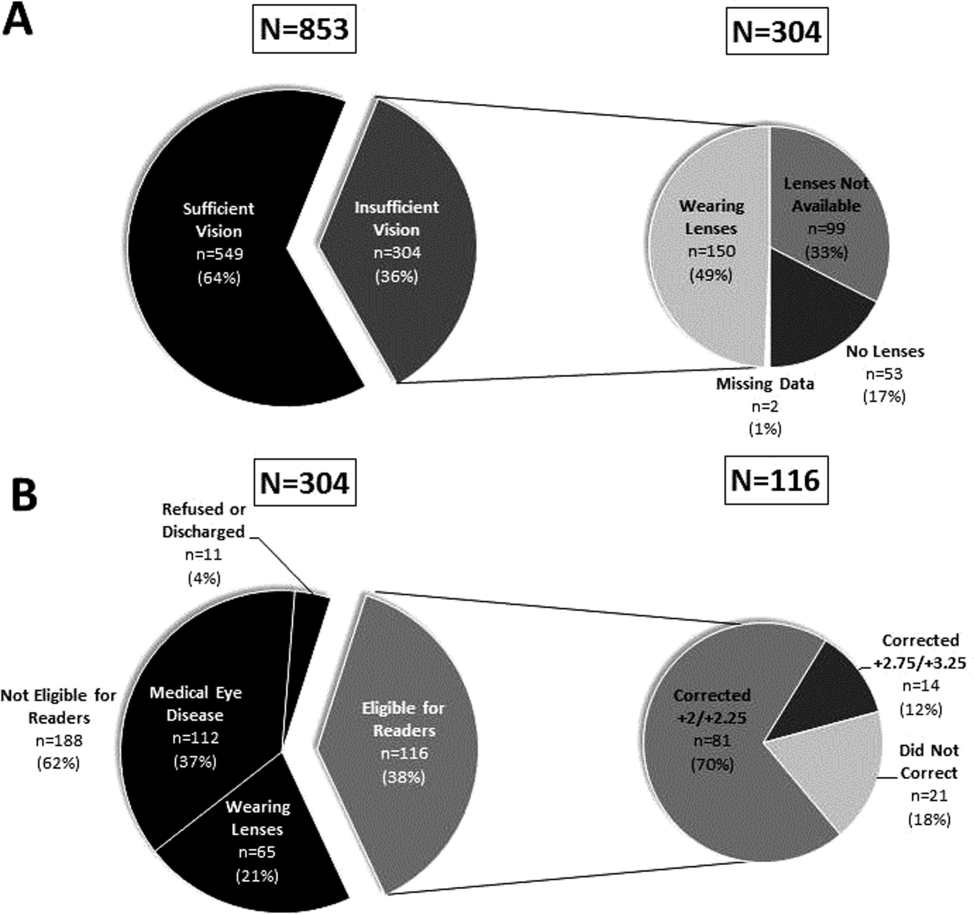

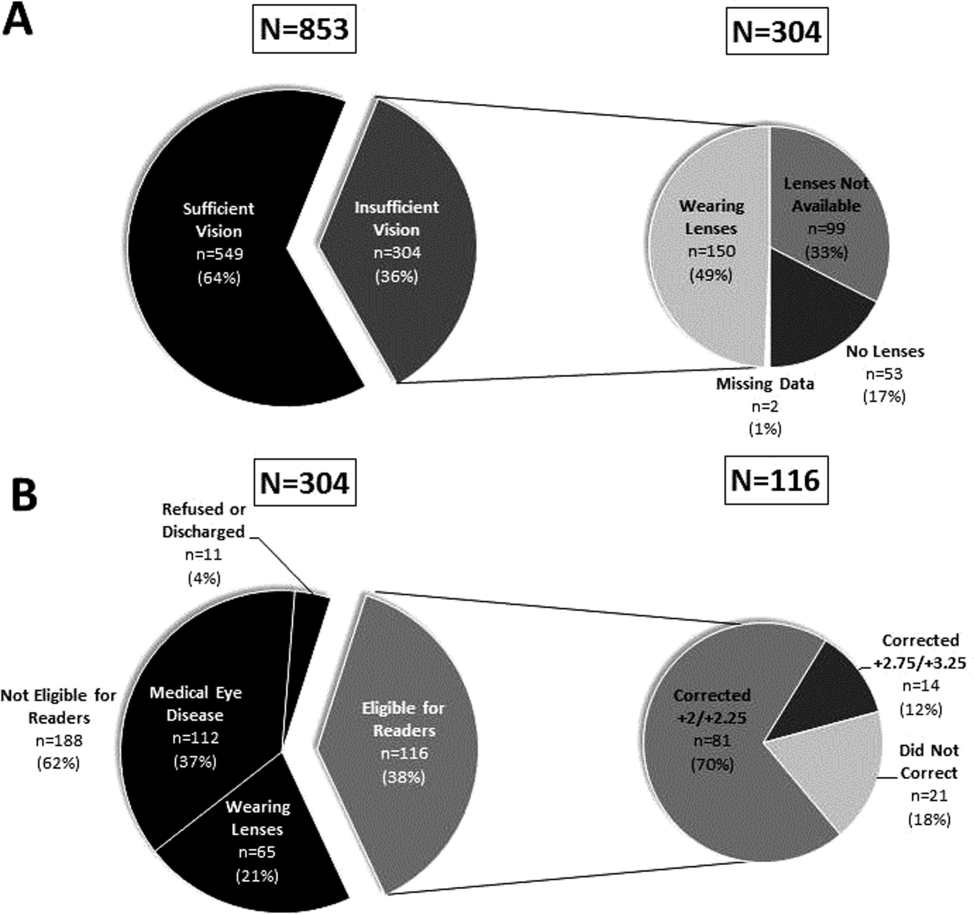

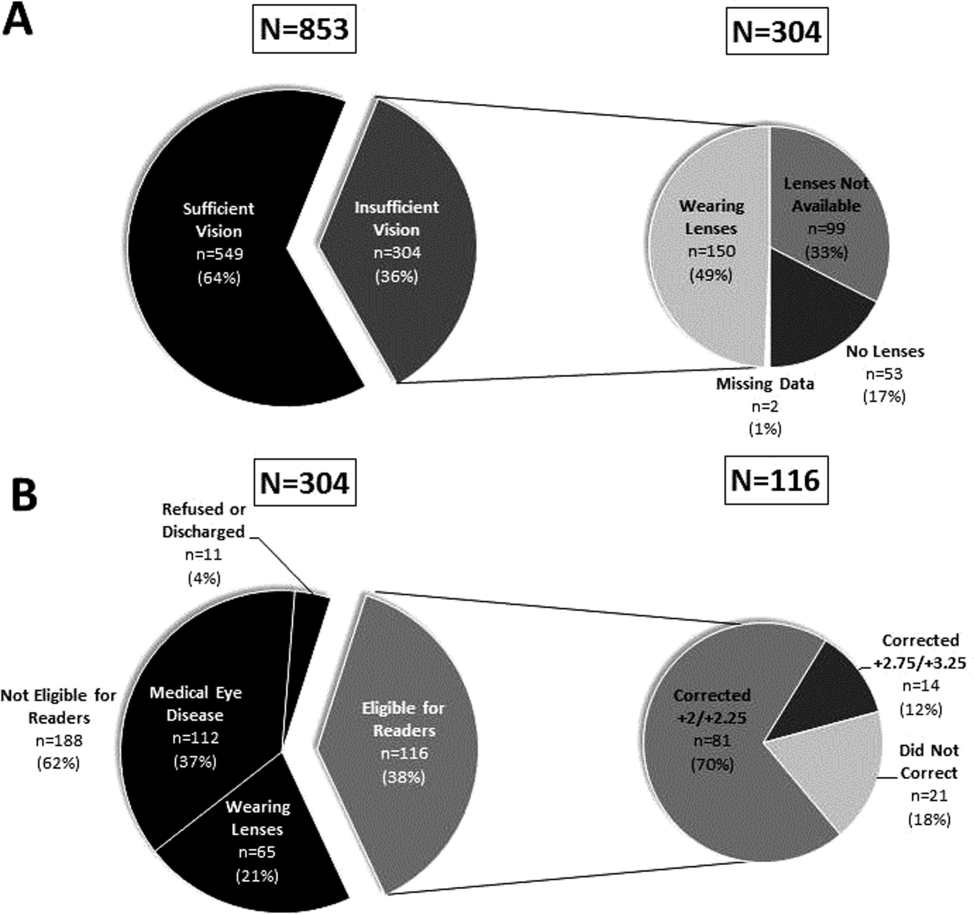

Over 800 participants' vision was screened (n=853); the majority were female (56%, 480/853), African American (76%, 650/853), with a mean age of 53.4 years (standard deviation 18.7), consistent with our study site's demographics. Over one‐third (36%, 304/853) of participants had insufficient vision. Older (65 years) participants (56%, 136/244) were more likely to have insufficient vision than younger participants (28%, 168/608; P0.001).

Participants with insufficient vision were wearing their own corrective lenses during the testing (150/304, 49%), did not use corrective lenses (53/304, 17%), or were without available corrective lenses (99/304, 33%) (Figure 1A).

One‐hundred sixteen of 304 participants approached for the readers intervention were eligible (112 reported medical eye disease, 65 were wearing lenses, and 11 refused or were discharged before intervention implementation).

Nonprescription readers corrected the majority of eligible participants' vision (82%, 95/116). Most participants' (81/116, 70%) vision was corrected using the 2 lowest calibration readers (+2/+2.25); another 14 participants' (12%) vision was corrected with higher‐strength lenses (+2.75/+3.25) (Figure 1B)

DISCUSSION

We found that over one‐third of the inpatients we examined have poor vision. Furthermore, among an easily identified subgroup of inpatients with poor vision, low‐cost readers successfully corrected most participants' vision. Although preventive health is not commonly considered an inpatient issue, hospitalists and other clinicians working in the inpatient setting can play an important role in identifying opportunities to provide high‐value care related to patients' vision.

Several important ethical, safety, and cost considerations related to these findings exist. Hospitalized patients commonly sign written informed consent; therefore, due diligence to ensure patients' ability to read and understand the forms is imperative. Further, inpatient delirium is common, particularly among older patients.[8] Existing or new onset delirium occurs in up to 24% to 35% of elderly inpatients.[8] Vision is an important risk factor for multifactorial inpatient delirium, and early vision correction has been shown to improve delirium rates, as part of a multicomponent intervention.[9] Hospital‐related patient costs per delirium episode have been estimated at $16,303 to $64,421.[10] The cost of a multicomponent intervention was $6341 per case of delirium prevented,[9] whereas only 1 potentially critical component, the cost of readers ($8+), would pale in comparison.[1] Vision screening takes approximately 2.25 minutes plus 2 to 6 minutes for the readers' assessment, with little training and high fidelity. Therefore, this easily implemented, potentially cost saving, intervention targeting inpatients with poor vision may improve patient safety and quality of life in the hospital and even after discharge.

Limitations of the study include considerations of generalizability, as participants were from a single, urban, academic medical center. Additionally, long‐term benefits of the readers intervention were not assessed in this study. Finally, RAs provided the assessments; therefore, further work is required to determine costs of efficient large‐scale clinical implementation through nurse‐led programs.

Despite these study limitations, the surprisingly high prevalence of poor vision among inpatients is a call to action for hospitalists. Future work should investigate the impact and cost of vision correction on hospital outcomes such as patient satisfaction, reduced rehospitalizations, and decreased delirium.[11]

Acknowledgements

The authors thank several individuals for their assistance with this project. Andrea Flores, MA, Senior Programmer, helped with programming and data support. Kristin Constantine, BA, Project Manager, helped with developing and implementing the database for this project. Edward Kim, BA, Project Manager, helped with management of the database and data collection. The authors also thank Ainoa Coltri and the Hospitalist Project research assistants for assistance with data collection, Frank Zadravecz, MPH, for assistance with the creation of figures, and Nicole Twu, MS, for assistance with the project. The authors thank other students who helped to collect data for this project, including Allison Louis, Victoria Moreira, and Esther Schoenfeld.

Disclosures: Dr. Press is supported by a career development award from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NIH K23HL118151). A pilot award from The Center on the Demography and Economics of Aging (CoA, National Institute of Aging P30 AG012857) supported this project. Dr. Matthiesen and Ms. Ranadive received support from the Summer Research Program funded by the National Institutes on Aging Short‐Term Aging‐Related Research Program (T35AG029795). Dr. Matthiesen also received funding from the Calvin Fentress Fellowship Program. Dr. Hariprasad reports being a consultant or participating on a speaker's bureau for Alcon, Allergan, Regeneron, Genentech, Optos, OD‐OS, Bayer, Clearside Biomedical, and Ocular Therapeutix. Dr. Meltzer received funding from the National Institutes on Aging Short‐Term Aging‐Related Research Program (T35AG029795), and from the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research through the Hospital Medicine and Economics Center for Education and Research in Therapeutics (U18 HS016967‐01), and from the National Institute of Aging through a Midcareer Career Development Award (K24 AG031326‐01), from the National Cancer Institute (KM1 CA156717), and from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (2UL1TR000430‐06). Dr. Arora received funding from the National Institutes on Aging Short‐Term Aging‐Related Research Program (T35AG029795) and National Institutes on Aging (K23AG033763).

- , , , . Risk factors and risk assessment tools for falls in hospital in‐patients: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2004;33(2):122–130.

- , , , , . More than meets the eye: relationship between low health literacy and poor vision in hospitalized patients. J Health Commun. 2013;18(suppl 1):197–204.

- , , , , , . Risk factors for delirium at discharge: development and validation of a predictive model. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(13):1406–1413.

- , , , et al. Misuse of respiratory inhalers in hospitalized patients with asthma or COPD. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(6):635–642.

- , , . Can elderly people take their medicine? Patient Educ Couns. 2005;59(2):186–191.

- , , , et al. Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):866–874.

- . Prospective evaluation of visual acuity assessment: a comparison of Snellen versus ETDRS charts in clinical practice (An AOS Thesis). Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2009;107:311–324.

- , , , et al. Delirium. The occurrence and persistence of symptoms among elderly hospitalized patients. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152(2):334–340.

- , , , et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(9):669–676.

- , , , , . One‐year health care costs associated with delirium in the elderly population. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(1):27–32.

- , , , et al. A low‐vision rehabilitation program for patients with mild cognitive deficits. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(7):912–919.

Vision impairment is an under‐recognized risk factor for adverse events among hospitalized patients.[1, 2, 3] Inpatients with poor vision are at increased risk for falls and delirium[1, 3] and have more difficulty taking medications.[4, 5] They may also be at risk for being unable to read critical health information, including consent forms and discharge instructions, or decreased quality of life such as simply ordering food from menus. However, vision is neither routinely tested nor documented for inpatients. Low‐cost ($8 and up) nonprescription reading glasses, known as readers may be a simple, high‐value intervention to improve inpatients' vision. We aimed to study initial feasibility and efficacy of screening and correcting inpatients' vision.

METHODS

From June 2012 through January 2014, research assistants (RAs) identified eligible (adults [18 years], English speaking) participants daily from electronic medical records as part of an ongoing study of general medicine inpatients measuring quality‐of‐care at the University of Chicago Medicine.[6] RAs tested visual acuity using Snellen pocket charts (participants wore corrective lenses if available). For eligible participants, readers were tested with sequential fitting (+2/+2.25/+2.75/+3.25) until vision was corrected (sufficient vision: at least 20/50 acuity in at least 1 eye).[7] Eligible participants included those with insufficient vision who were not already wearing corrective lenses and had no documented blindness or medically severe vision loss, for whom nonprescription readers would be unlikely to correct vision deficiencies such as cataracts or glaucoma. The study was approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board (IRB #9967).

Of note, although readers are typically used in populations over 40 years of age, readers were fitted for all participants to assess their utility for any hospitalized adult patient. Upon completing the vision screening and readers interventions, participants received instruction on how to access vision care and how to obtain readers (if they corrected vision) after hospital discharge.

Descriptive statistics and tests of comparison, including t tests and [2] tests, were used when appropriate. All analyses were performed using Stata version 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Over 800 participants' vision was screened (n=853); the majority were female (56%, 480/853), African American (76%, 650/853), with a mean age of 53.4 years (standard deviation 18.7), consistent with our study site's demographics. Over one‐third (36%, 304/853) of participants had insufficient vision. Older (65 years) participants (56%, 136/244) were more likely to have insufficient vision than younger participants (28%, 168/608; P0.001).

Participants with insufficient vision were wearing their own corrective lenses during the testing (150/304, 49%), did not use corrective lenses (53/304, 17%), or were without available corrective lenses (99/304, 33%) (Figure 1A).

One‐hundred sixteen of 304 participants approached for the readers intervention were eligible (112 reported medical eye disease, 65 were wearing lenses, and 11 refused or were discharged before intervention implementation).