User login

Studies help explain multidrug resistance in cancer

(right) and Sung Chang Lee

Photo courtesy of

The Scripps Research Institute

Scientists have discovered how the primary protein responsible for multidrug chemotherapy resistance changes shape and reacts to drugs.

They believe this information will aid the design of better molecules to inhibit or evade multidrug resistance.

The researchers noted that the proteins at work in multidrug resistance are ABC transporters. An important ABC transporter, P-glycoprotein (P-gp), catches harmful toxins in a “binding pocket” and expels them from cells.

The problem is that, in cancer patients, P-gp sometimes begins recognizing chemotherapy drugs and expelling them too. Over time, more and more cancer cells can develop multidrug resistance, eliminating all possible treatments.

“Virtually all cancer deaths can be attributed to the failure of chemotherapy,” said study author Qinghai Zhang, PhD, of The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California.

He and his colleagues theorized that scientists might be able to design more effective cancer drugs if they had a better understanding of P-gp and how it binds to molecules.

A better look at transporters

For their first study, published in Structure, the researchers looked at P-gp and MsbA, a similar transporter protein found in bacteria, under an electron microscope. This helped them solve a major problem in transporter research.

Until recently, scientists could only compare images of crystal structures made from transporter proteins. These crystallography images showed single snapshots of the transporter but didn’t show how the shape of the transporters could change.

Using electron microscopy, however, a whole range of different conformations of the structures could be visualized, essentially capturing P-gp and MsbA in action.

The research was also aided by the development of new chemical tools. The team used a solution of lipids and peptides to mimic natural conditions in the cell membrane. They used a novel chemical called beta-sheet peptide to stabilize the protein and provide enough stability for a new perspective.

Together with electron microscopy, this technique enabled the researchers to capture a series of images showing how transporter proteins change shape in response to drug and nucleotide binding. They found that transporter proteins have an open binding pocket that constantly switches to face different sides of membranes.

“The transporter goes through many steps,” Dr Zhang said. “It’s like a machine.”

A closer look at binding

In a second study, published in Acta Crystallographica Section D, the scientists investigated the drug binding sites of P-gp using higher-resolution X-ray crystallography. And they discovered how P-gp interacts with ligands.

The researchers studied crystals of the transporter bound to 4 different ligands to see how the transporters reacted. They found that when certain ligands bind to P-gp, they trigger local conformational changes in the transporter.

Binding also increased the rate of ATP hydrolysis, which provides mechanical energy and may be the first step in the process by which the binding pocket closes.

The team also discovered that ligands could bind to different areas of the transporter, leaving nearby slots open for other molecules. This suggests it may be difficult to completely halt the drug expulsion process.

Dr Zhang said the next step for this research is to develop molecules to evade P-gp binding. ![]()

(right) and Sung Chang Lee

Photo courtesy of

The Scripps Research Institute

Scientists have discovered how the primary protein responsible for multidrug chemotherapy resistance changes shape and reacts to drugs.

They believe this information will aid the design of better molecules to inhibit or evade multidrug resistance.

The researchers noted that the proteins at work in multidrug resistance are ABC transporters. An important ABC transporter, P-glycoprotein (P-gp), catches harmful toxins in a “binding pocket” and expels them from cells.

The problem is that, in cancer patients, P-gp sometimes begins recognizing chemotherapy drugs and expelling them too. Over time, more and more cancer cells can develop multidrug resistance, eliminating all possible treatments.

“Virtually all cancer deaths can be attributed to the failure of chemotherapy,” said study author Qinghai Zhang, PhD, of The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California.

He and his colleagues theorized that scientists might be able to design more effective cancer drugs if they had a better understanding of P-gp and how it binds to molecules.

A better look at transporters

For their first study, published in Structure, the researchers looked at P-gp and MsbA, a similar transporter protein found in bacteria, under an electron microscope. This helped them solve a major problem in transporter research.

Until recently, scientists could only compare images of crystal structures made from transporter proteins. These crystallography images showed single snapshots of the transporter but didn’t show how the shape of the transporters could change.

Using electron microscopy, however, a whole range of different conformations of the structures could be visualized, essentially capturing P-gp and MsbA in action.

The research was also aided by the development of new chemical tools. The team used a solution of lipids and peptides to mimic natural conditions in the cell membrane. They used a novel chemical called beta-sheet peptide to stabilize the protein and provide enough stability for a new perspective.

Together with electron microscopy, this technique enabled the researchers to capture a series of images showing how transporter proteins change shape in response to drug and nucleotide binding. They found that transporter proteins have an open binding pocket that constantly switches to face different sides of membranes.

“The transporter goes through many steps,” Dr Zhang said. “It’s like a machine.”

A closer look at binding

In a second study, published in Acta Crystallographica Section D, the scientists investigated the drug binding sites of P-gp using higher-resolution X-ray crystallography. And they discovered how P-gp interacts with ligands.

The researchers studied crystals of the transporter bound to 4 different ligands to see how the transporters reacted. They found that when certain ligands bind to P-gp, they trigger local conformational changes in the transporter.

Binding also increased the rate of ATP hydrolysis, which provides mechanical energy and may be the first step in the process by which the binding pocket closes.

The team also discovered that ligands could bind to different areas of the transporter, leaving nearby slots open for other molecules. This suggests it may be difficult to completely halt the drug expulsion process.

Dr Zhang said the next step for this research is to develop molecules to evade P-gp binding. ![]()

(right) and Sung Chang Lee

Photo courtesy of

The Scripps Research Institute

Scientists have discovered how the primary protein responsible for multidrug chemotherapy resistance changes shape and reacts to drugs.

They believe this information will aid the design of better molecules to inhibit or evade multidrug resistance.

The researchers noted that the proteins at work in multidrug resistance are ABC transporters. An important ABC transporter, P-glycoprotein (P-gp), catches harmful toxins in a “binding pocket” and expels them from cells.

The problem is that, in cancer patients, P-gp sometimes begins recognizing chemotherapy drugs and expelling them too. Over time, more and more cancer cells can develop multidrug resistance, eliminating all possible treatments.

“Virtually all cancer deaths can be attributed to the failure of chemotherapy,” said study author Qinghai Zhang, PhD, of The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California.

He and his colleagues theorized that scientists might be able to design more effective cancer drugs if they had a better understanding of P-gp and how it binds to molecules.

A better look at transporters

For their first study, published in Structure, the researchers looked at P-gp and MsbA, a similar transporter protein found in bacteria, under an electron microscope. This helped them solve a major problem in transporter research.

Until recently, scientists could only compare images of crystal structures made from transporter proteins. These crystallography images showed single snapshots of the transporter but didn’t show how the shape of the transporters could change.

Using electron microscopy, however, a whole range of different conformations of the structures could be visualized, essentially capturing P-gp and MsbA in action.

The research was also aided by the development of new chemical tools. The team used a solution of lipids and peptides to mimic natural conditions in the cell membrane. They used a novel chemical called beta-sheet peptide to stabilize the protein and provide enough stability for a new perspective.

Together with electron microscopy, this technique enabled the researchers to capture a series of images showing how transporter proteins change shape in response to drug and nucleotide binding. They found that transporter proteins have an open binding pocket that constantly switches to face different sides of membranes.

“The transporter goes through many steps,” Dr Zhang said. “It’s like a machine.”

A closer look at binding

In a second study, published in Acta Crystallographica Section D, the scientists investigated the drug binding sites of P-gp using higher-resolution X-ray crystallography. And they discovered how P-gp interacts with ligands.

The researchers studied crystals of the transporter bound to 4 different ligands to see how the transporters reacted. They found that when certain ligands bind to P-gp, they trigger local conformational changes in the transporter.

Binding also increased the rate of ATP hydrolysis, which provides mechanical energy and may be the first step in the process by which the binding pocket closes.

The team also discovered that ligands could bind to different areas of the transporter, leaving nearby slots open for other molecules. This suggests it may be difficult to completely halt the drug expulsion process.

Dr Zhang said the next step for this research is to develop molecules to evade P-gp binding. ![]()

FDA’s new app provides info on drug shortages

a Nokia smart phone

Photo by Halvard Lundgaard

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has launched the agency’s first mobile application (app) designed to speed public access to information on drug shortages.

The app provides details regarding current drug shortages, resolved shortages, and discontinued drug products.

It works just like the FDA’s drug shortages website. App users can search for a drug by its generic name or active ingredient, or they can browse by therapeutic category.

The app can also be used to report a suspected drug shortage or supply issue to the FDA.

The app is available for free download via iTunes (for Apple devices) and the Google Play store (for Android devices). It can be found by searching “FDA Drug Shortages.”

The FDA developed the app to improve access to information about drug shortages, as part of the agency’s efforts outlined in the Strategic Plan for Preventing and Mitigating Drug Shortages.

“The FDA understands that healthcare professionals and pharmacists need real-time information about drug shortages to make treatment decisions,” said Valerie Jensen, associate director of the Drug Shortage Staff in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

“The new mobile app is an innovative tool that will offer easier and faster access to important drug shortage information.” ![]()

a Nokia smart phone

Photo by Halvard Lundgaard

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has launched the agency’s first mobile application (app) designed to speed public access to information on drug shortages.

The app provides details regarding current drug shortages, resolved shortages, and discontinued drug products.

It works just like the FDA’s drug shortages website. App users can search for a drug by its generic name or active ingredient, or they can browse by therapeutic category.

The app can also be used to report a suspected drug shortage or supply issue to the FDA.

The app is available for free download via iTunes (for Apple devices) and the Google Play store (for Android devices). It can be found by searching “FDA Drug Shortages.”

The FDA developed the app to improve access to information about drug shortages, as part of the agency’s efforts outlined in the Strategic Plan for Preventing and Mitigating Drug Shortages.

“The FDA understands that healthcare professionals and pharmacists need real-time information about drug shortages to make treatment decisions,” said Valerie Jensen, associate director of the Drug Shortage Staff in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

“The new mobile app is an innovative tool that will offer easier and faster access to important drug shortage information.” ![]()

a Nokia smart phone

Photo by Halvard Lundgaard

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has launched the agency’s first mobile application (app) designed to speed public access to information on drug shortages.

The app provides details regarding current drug shortages, resolved shortages, and discontinued drug products.

It works just like the FDA’s drug shortages website. App users can search for a drug by its generic name or active ingredient, or they can browse by therapeutic category.

The app can also be used to report a suspected drug shortage or supply issue to the FDA.

The app is available for free download via iTunes (for Apple devices) and the Google Play store (for Android devices). It can be found by searching “FDA Drug Shortages.”

The FDA developed the app to improve access to information about drug shortages, as part of the agency’s efforts outlined in the Strategic Plan for Preventing and Mitigating Drug Shortages.

“The FDA understands that healthcare professionals and pharmacists need real-time information about drug shortages to make treatment decisions,” said Valerie Jensen, associate director of the Drug Shortage Staff in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

“The new mobile app is an innovative tool that will offer easier and faster access to important drug shortage information.” ![]()

Navigating Venous Access

Reliable venous access is fundamental for the safe and effective care of hospitalized patients. Venous access devices (VADs) are conduits for this purpose, providing delivery of intravenous medications, accurate measurement of central venous pressure, or administration of life‐saving blood products. Despite this important role, VADs are also often the source of hospital‐acquired complications. Although inpatient providers must balance the relative risks of VADs against their benefits, the evidence supporting such decisions is often limited. Advances in technology, scattered research, and growing availability of novel devices has only further fragmented provider knowledge in the field of vascular access.[1]

It is not surprising, then, that survey‐based studies of hospitalists reveal important knowledge gaps with regard to practices associated with VADs.[2] In this narrative review, we seek to bridge this gap by providing a concise and pragmatic overview of the fundamentals of venous access. We focus specifically on parameters that influence decisions regarding VAD placement in hospitalized patients, providing key takeaways for practicing hospitalists.

METHODS

To compile this review, we systematically searched Medline (via Ovid) for several keywords, including: peripheral intravenous catheters, ultrasound‐guided peripheral catheter, intraosseous, midline, peripherally inserted central catheter, central venous catheters, and vascular access device complications. We concentrated on full‐length articles in English only; no date restrictions were placed on the search. We reviewed guidelines and consensus statements (eg, from the Center for Disease Control [CDC] or Choosing Wisely criteria) as appropriate. Additional studies of interest were identified through content experts (M.P., C.M.R.) and bibliographies of included studies.

SCIENTIFIC PRINCIPLES UNDERPINNING VENOUS ACCESS

It is useful to begin by reviewing VAD‐related nomenclature and physiology. In the simplest sense, a VAD consists of a hub (providing access to various connectors), a hollow tube divided into 1 or many sections (lumens), and a tip that may terminate within a central or peripheral blood vessel. VADs are classified as central venous catheters (eg, centrally inserted central catheters [CICCs] or peripherally inserted central catheters [PICCs]) or peripheral intravenous catheters (eg, midlines or peripheral intravenous catheters) based on site of entry and location of the catheter tip. Therefore, VADs entering via proximal or distal veins of the arm are often referred to as peripheral lines, as their site of entry and tip both reside within peripheral veins. Conversely, the term central line is often used when VADs enter or terminate in a central vein (eg, subclavian vein insertion with the catheter tip in the lower superior vena cava).

Attention to a host of clinical and theoretical parameters is important when choosing a device for venous access. Some such parameters are summarized in Table 1.

| Parameter | Major Considerations |

|---|---|

| |

| Desired flow rate | Smaller diameter veins susceptible to damage with high flow rates. |

| Short, large‐bore catheters facilitate rapid infusion. | |

| Nature of infusion | pH, viscosity, and temperature may damage vessels. |

| Vesicants and irritants should always be administered into larger, central veins. | |

| Desired duration of vascular access, or dwell time | Vessel thrombosis or phlebitis increase over time with catheter in place. |

| Intermittent infusions increase complications in central catheters; often tunneled catheters are recommended. | |

| Urgency of placement | Access to large caliber vessels is often needed in emergencies. |

| Critically ill or hemodynamically unstable patients may require urgent access for invasive monitoring or rapid infusions. | |

| Patients with trauma often require large volumes of blood products and reliable access to central veins. | |

| Number of device lumens | VADs may have single or multiple lumens. |

| Multilumen allows for multiple functions (eg, infusion of multiple agents, measurement of central venous pressures, blood draws). | |

| Device gauge | In general, use of a smaller‐gauge catheter is preferred to prevent complications. |

| However, larger catheter diameter may be needed for specific clinical needs (eg, blood transfusion). | |

| Device coating | VADs may have antithrombotic or anti‐infective coatings. |

| These devices may be of value in patients at high risk of complications. | |

| Such devices, however, may be more costly than their counterparts. | |

| Self‐care compatibility | VADs that can be cared for by patients are ideal for outpatient care. |

| Conversely, VADs such as peripheral catheters, are highly prone to dislodgement and should be reserved for supervised settings only. | |

VENOUS ACCESS DEVICES

We will organize our discussion of VADs based on whether they terminate in peripheral or central vessels. These anatomical considerations are relevant as they determine physical characteristics, compatibility with particular infusates, dwell time, and risk of complications associated with each VAD discussed in Table 2.

| Complications | Major Considerations |

|---|---|

| |

| Infection | VADs breach the integrity of skin and permit skin pathogens to enter the blood stream (extraluminal infection). |

| Inadequate antisepsis of the VAD hub, including poor hand hygiene, failure to "scrub the hub," and multiple manipulations may also increase the risk of VAD‐related infection (endoluminal infection). | |

| Infections may be local (eg, exit‐site infections) or may spread hematogenously (eg, CLABSI). | |

| Type of VAD, duration of therapy, and host characteristics interact to influence infection risk. | |

| VADs with antiseptic coatings (eg, chlorhexidine) or antibiotic coatings (eg, minocycline) may reduce risk of infection in high‐risk patients. | |

| Antiseptic‐impregnated dressings may reduce risk of extraluminal infection. | |

| Venous thrombosis | VADs predispose to venous stasis and thrombosis. |

| Duration of VAD use, type and care of the VAD, and patient characteristics affect risk of thromboembolism. | |

| VAD tip position is a key determinant of venous thrombosis; central VADs that do not terminate at the cavo‐atrial junction should be repositioned to reduce the risk of thrombosis. | |

| Antithrombotic coated or eluting devices may reduce risk of thrombosis, though definitive data are lacking. | |

| Phlebitis | Inflammation caused by damage to tunica media.[18] |

| 3 types of phlebitis: | |

| Chemical: due to irritation of media from the infusate. | |

| Mechanical: VAD physically damages the vessel. | |

| Infective: bacteria invade vein and inflame vessel wall. | |

| Phlebitis may be limited by close attention to infusate compatibility with peripheral veins, appropriate dilution, and prompt removal of catheters that show signs of inflammation. | |

| Phlebitis may be prevented in PICCs by ensuring at least a 2:1 vein:catheter ratio. | |

| Extravasation | Extravasation (also called infiltration) is defined as leakage of infusate from intravascular to extravascular space. |

| Extravasation of vesicants/emrritants is particularly worrisome. | |

| May result in severe tissue injury, blistering, and tissue necrosis.[11] | |

| VADs should be checked frequently for adequate flushing and position prior to each infusion to minimize risk. | |

| Any VAD with redness, swelling, and tenderness at the entry site or problems with flushing should not be used without further examination and review of position. | |

Peripheral Venous Access

Short Peripheral Intravenous Catheter

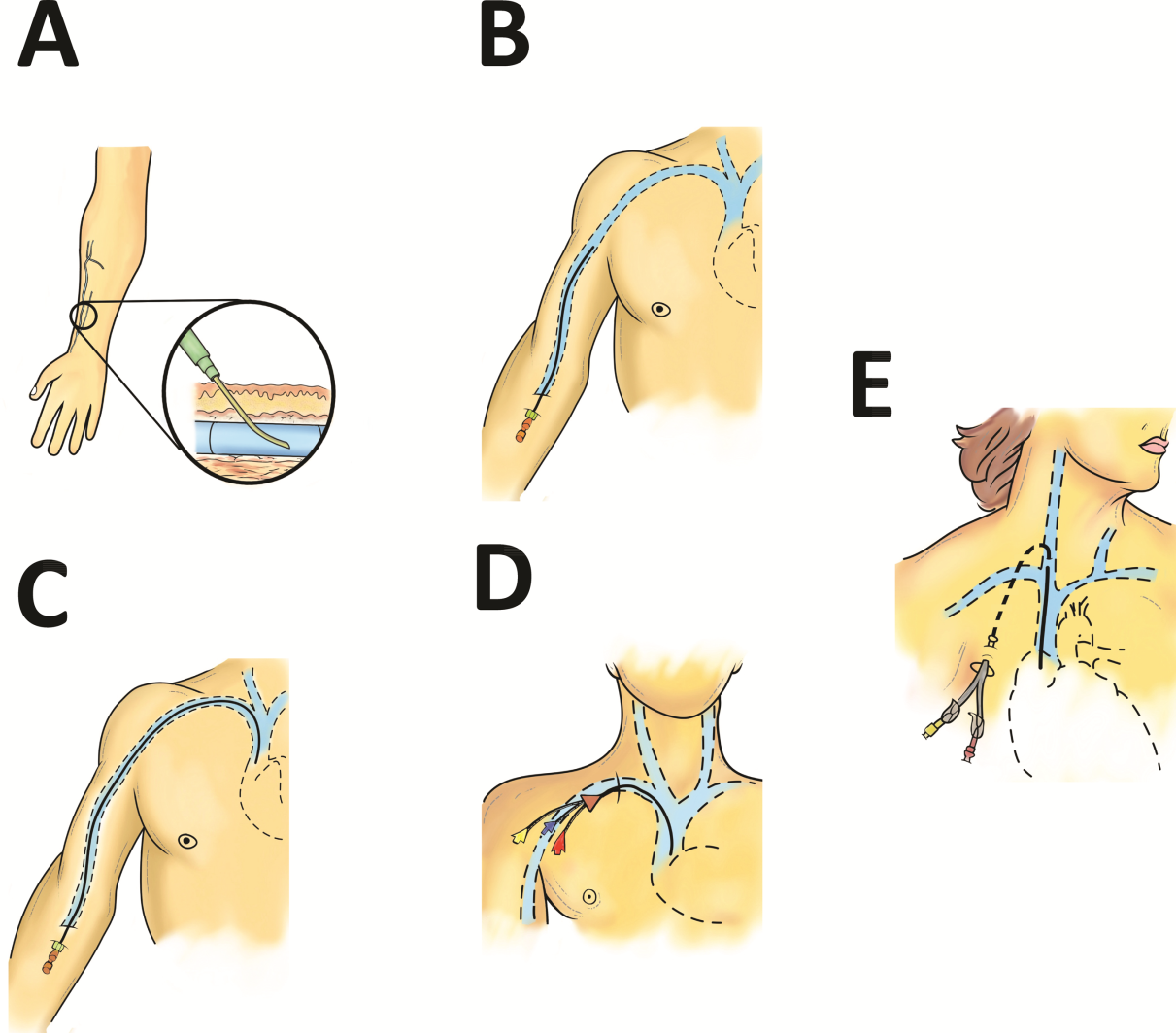

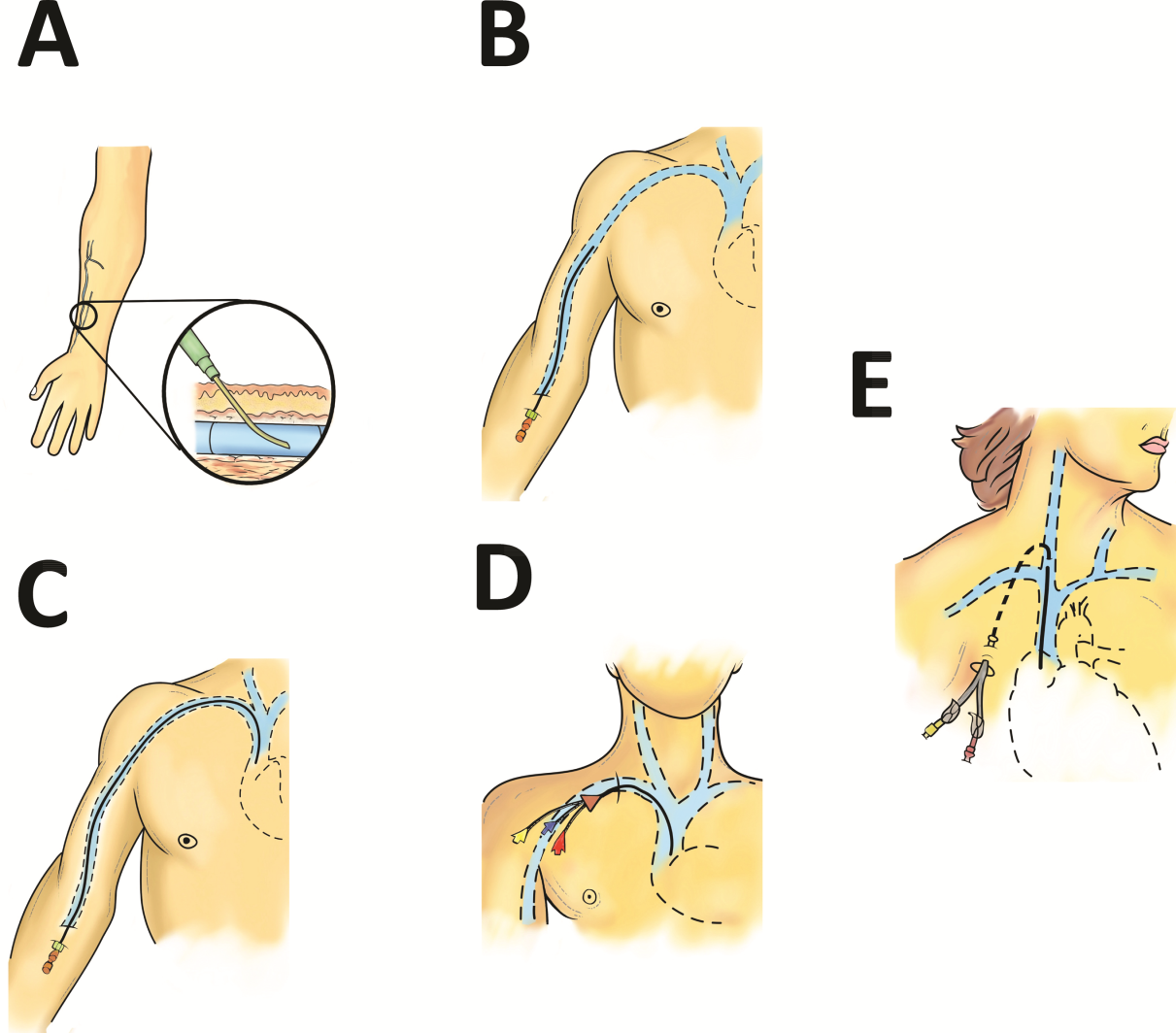

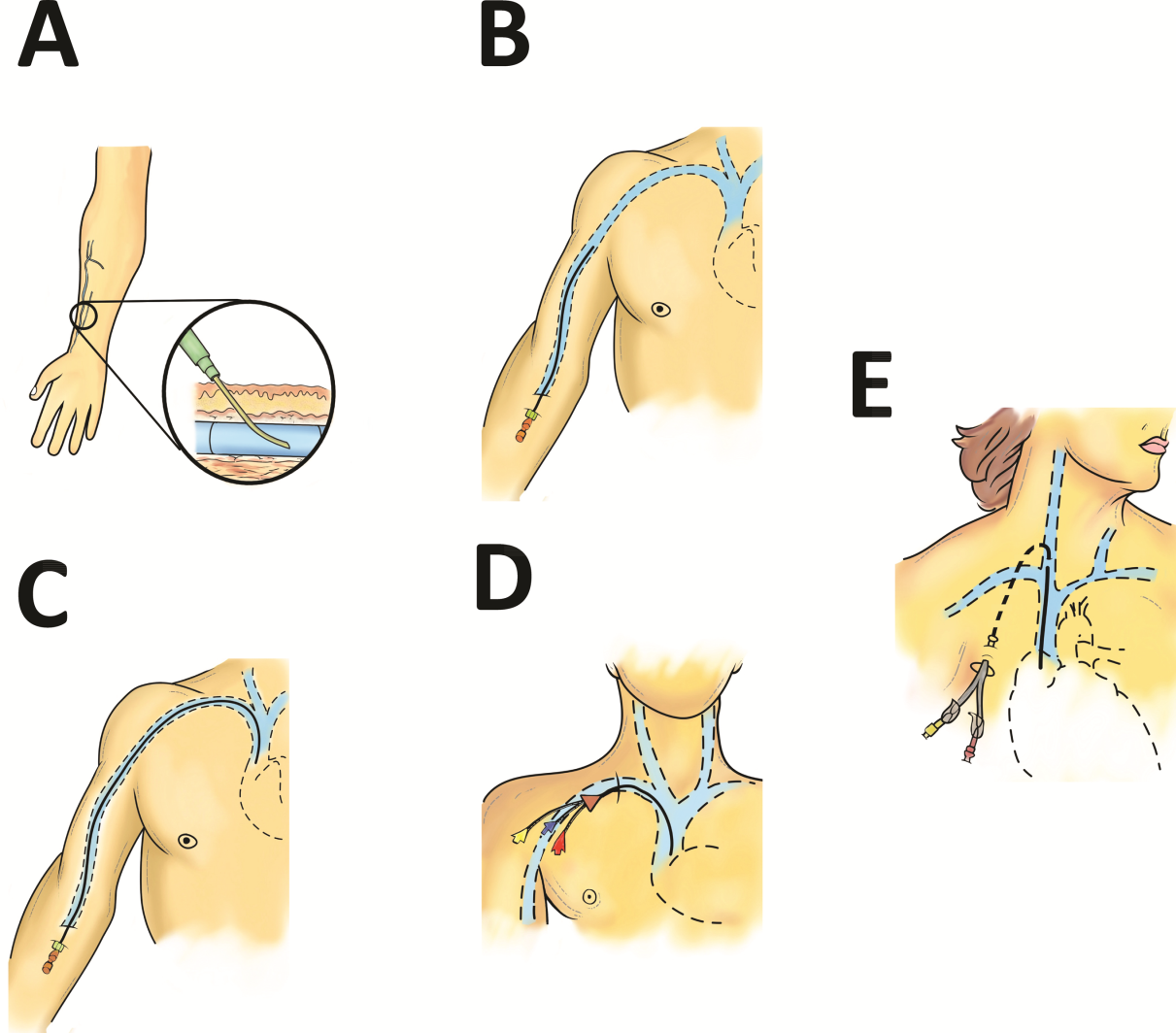

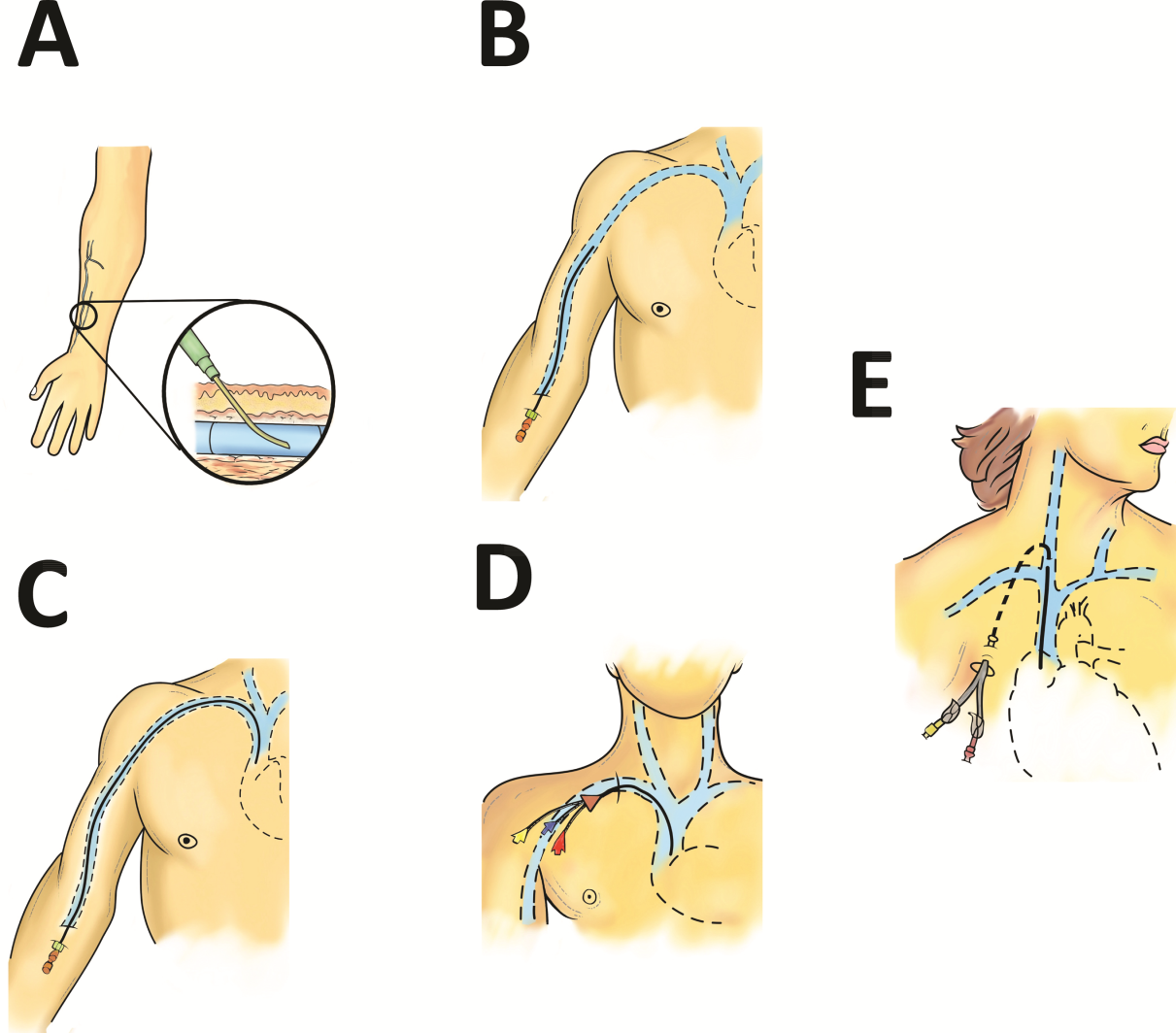

Approximately 200 million peripheral intravenous catheters (PIVs) are placed annually in the United States, making them the most common intravenous catheter.[3] PIVs are short devices, 3 to 6 cm in length, that enter and terminate in peripheral veins (Figure 1A). Placement is recommended in forearm veins rather than those of the hand, wrist, or upper arm, as forearm sites are less prone to occlusion, accidental removal, and phlebitis.[4] Additionally, placement in hand veins impedes activities of daily living (eg, hand washing) and is not preferred by patients.[5] PIV size ranges from 24 gauge (smallest) to 14 gauge (largest); larger catheters are often reserved for fluid resuscitation or blood transfusion as they accommodate greater flow and limit hemolysis. To decrease risk of phlebitis and thrombosis, the shortest catheter and smallest diameter should be used. However, unless adequately secured, smaller diameter catheters are also associated with greater rates of accidental removal.[4, 5]

By definition, PIVs are short‐term devices. The CDC currently recommends removal and replacement of these devices no more frequently than every 72 to 96 hours in adults. However, a recent randomized controlled trial found that replacing PIVs when clinically indicated (eg, device failure, phlebitis) rather than on a routine schedule added 30 hours to their lifespan without an increase in complications.[6] A systematic review by the Cochrane Collaboration echoes these findings.[3] These data have thus been incorporated into recommendations from the Infusion Nurses Society (INS) and the National Health Service in the United Kingdom.[5, 7] In hospitalized patients, this approach is relevant, as it preserves venous access sites, maximizes device dwell, and limits additional PIV insertions. In turn, these differences may reduce the need for invasive VADs such as PICCs. Furthermore, the projected 5‐year savings from implementation of clinically indicated PIV removal policies is US$300 million and 1 million health‐worker hours in the United States alone.[4]

PIVs offer many advantages. First, they are minimally invasive and require little training to insert. Second, they can be used for diverse indications in patients requiring short‐term (1 week) venous access. Third, PIVs do not require imaging to ensure correct placement; palpation of superficial veins is sufficient. Fourth, PIVs exhibit a risk of bloodstream infection that is about 40‐fold lower than more invasive, longer‐dwelling VADs[8] (0.06 bacteremia per 1000 catheter‐days).

Despite these advantages, PIVs also have important drawbacks. First, a quarter of all PIVs fail through occlusion or accidental dislodgement.[4] Infiltration, extravasation, and hematoma formation are important adverse events that may occur in such cases. Second, thrombophlebitis (pain and redness at the insertion site) is frequent, and may require device removal, especially in patients with catheters 20 guage.[9] Third, despite their relative safety, PIVs can cause localized or hematogenous infection. Septic thrombophlebitis (superficial thrombosis and bloodstream infection) and catheter‐related bloodstream infection, though rare, have been reported with PIVs and may lead to serious complications.[8, 10] In fact, some suggest that the overall burden of bloodstream infection risk posed by PIVs may be similar to that of CICCs given the substantially greater number of devices used and greater number of device days.[8]

PIVs and other peripheral VADs are not suitable for infusion of vesicants or irritants, which require larger, central veins for delivery. Vesicants (drugs that cause blistering on infusion) include chemotherapeutic agents (eg, dactinomycin, paclitaxel) and commonly used nonchemotherapeutical agents (eg, diazepam, piperacillin, vancomycin, esmolol, or total parenteral nutrition [TPN]).[11] Irritants (phlebitogenic drugs) cause short‐term inflammation and pain, and thus should not be peripherally infused for prolonged durations. Common irritants in the hospital setting include acyclovir, dobutamine, penicillin, and potassium chloride.

Of note, about one‐quarter of PIV insertions fail owing to difficult intravenous access.[12] Ultrasound‐guided peripheral intravenous (USGPIV) catheter placement is emerging as a technique to provide peripheral access for such patients to avoid placement of central venous access devices. Novel, longer devices (>8 cm) with built‐in guide wires have been developed to increase placement success of USGPIVs. These new designs provide easier access into deeper arm veins (brachial or basilic) not otherwise accessible by short PIVs. Although studies comparing the efficacy of USGPIV devices to other VADs are limited, a recent systematic review showed that time to successful cannulation was shorter, and fewer attempts were required to place USGPIVs compared to PIVs.[13] A recent study in France found that USGPIVs met the infusion needs of patients with difficult veins with minimal increase in complications.[14] Despite these encouraging data, future studies are needed to better evaluate this technology.

Midline Catheter

A midline is a VAD that is between 7.5 to 25 cm in length and is typically inserted into veins above the antecubital fossa. The catheter tip resides in a peripheral upper arm vein, often the basilic or cephalic vein, terminating just short of the subclavian vein (Figure 1B). Midline‐like devices were first developed in the 1950s and were initially used as an alternative to PIVs because they were thought to allow longer dwell times.[15] However, because they were originally constructed with a fairly rigid material, infiltration, mechanical phlebitis, and inflammation were common and tempered enthusiasm for their use.[15, 16] Newer midline devices obviate many of these problems and are inserted by ultrasound guidance and modified Seldinger technique.[17] Despite these advances, data regarding comparative efficacy are limited.

Midlines offer longer dwell times than standard PIVs owing to termination in the larger diameter basilic and brachial veins of the arm. Additionally, owing to their length, midlines are less prone to dislodgement. As they are inserted with greater antisepsis than PIVs and better secured to the skin, they are more durable than PIVs.[5, 9, 18] Current INS standards recommend use of midlines for 1 to 4 weeks.[5] Because they terminate in a peripheral vein, medications and infusions compatible with midlines are identical to those that are infused through a PIV. Thus, TPN, vesicants or irritants, or drugs that feature a pH 5 or pH >9, or >500 mOsm should not be infused through a midline.[15] New evidence suggests that diluted solutions of vancomycin (usually pH 5) may be safe to infuse for short durations (6 days) through a midline, and that concentration rather than pH may be more important in this regard.[19] Although it is possible that the use of midlines may extend to agents typically not deemed peripheral access compatible, limited evidence exists to support such a strategy at this time.

Midlines offer several advantages. First, because blood flow is greater in the more proximal veins of the arm, midlines can accommodate infusions at rates of 100 to 150 mL/min compared to 20 to 40 mL/min in smaller peripheral veins. Higher flow rates offer greater hemodilution (dilution of the infusion with blood), decreasing the likelihood of phlebitis and infiltration.[20] Second, midlines do not require x‐ray verification of tip placement; thus, their use is often favored in resource‐depleted settings such as skilled nursing facilities. Third, midlines offer longer dwell times than peripheral intravenous catheters and can thus serve as bridge devices for short‐term intravenous antibiotics or peripheral‐compatible infusions in an outpatient setting. Available evidence suggests that midlines are associated with low rates of bloodstream infection (0.30.8 per 1000 catheter‐days).[17] The most frequent complications include phlebitis (4.2%) and occlusion (3.3%).[20] Given these favorable statistics, midlines may offer a good alternative to PIVs in select patients who require peripheral infusions of intermediate duration.

Intraosseous Vascular Access

Intraosseous (IO) devices access the vascular system by piercing cortical bone. These devices provide access to the intramedullary cavity and venous plexi of long bones such as the tibia, femur, or humerus. Several insertion devices are now commercially available and have enhanced the ease and safety of IO placement. Using these newer devices, IO access may be obtained in 1 to 2 minutes with minimal training. By comparison, a central venous catheter often requires 10 to 15 minutes to insert with substantial training efforts for providers.[21, 22, 23]

IO devices thus offer several advantages. First, given the rapidity with which they can be inserted, they are often preferred in emergency settings (eg, trauma). Second, these devices are versatile and can accommodate both central and peripheral infusates.[24] Third, a recent meta‐analysis found that IOs have a low complication rate of 0.8%, with extravasation of infusate through the cortical entry site being the most common adverse event.[21] Of note, this study also reported zero local or distal infectious complications, a finding that may relate to the shorter dwell of these devices.[21] Some animal studies suggest that fat embolism from bone may occur at high rates with IO VADs.[25] However, death or significant morbidity from fat emboli in humans following IO access has not been described. Whether such emboli occur or are clinically significant in the context of IO devices remains unclear at this time.[21]

Central Venous Access Devices

Central venous access devices (CVADs) share in common tip termination in the cavo‐atrial junction, either in the lower portion of the superior vena cava or in the upper portion of the right atrium. CVADs can be safely used for irritant or vesicant medications as well as for blood withdrawal, blood exchange procedures (eg, dialysis), and hemodynamic monitoring. Traditionally, these devices are 15 to 25 cm in length and are directly inserted in the deep veins of the supra‐ or infraclavicular area, including the internal jugular, brachiocephalic, subclavian, or axillary veins. PICCs are unique CVADs in that they enter through peripheral veins but terminate in the proximity of the cavoatrial junction. Regarding nomenclature, CICC will be used to denote devices that enter directly into veins of the neck or chest, whereas PICC will be used for devices that are inserted peripherally but terminate centrally.

Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter

PICCs are inserted into peripheral veins of the upper arm (eg, brachial, basilica, or cephalic vein) and advanced such that the tip resides at the cavoatrial junction (Figure 1C). PICCs offer prolonged dwell times and are thus indicated when patients require venous access for weeks or months.[26] Additionally, they can accommodate a variety of infusates and are safer to insert than CICCs, given placement in peripheral veins of the arm rather than central veins of the chest/neck. Thus, insertion complications such as pneumothorax, hemothorax, or significant bleeding are rare with PICCs. In fact, a recent study reported that PICC insertion by hospitalists was associated with low rates of insertion or infectious complications.[27]

However, like CICCs, PICCs are associated with central lineassociated bloodstream infection (CLABSI), a serious complication known to prolong length of hospital stay, increase costs, and carry a 12% to 25% associated mortality.[28, 29] In the United States alone, over 250,000 CLASBI cases occur per year drawing considerable attention from the CDC and Joint Commission, who now mandate reporting and nonpayment for hospital‐acquired CLABSI.[30, 31, 32] A recent systematic review and meta‐analysis found that PICCs are associated with a substantial risk of CLABSI in hospitalized patients.[33] Importantly, no difference in CLABSI rates between PICCs and CICCs in hospitalized patients was evident in this meta‐analysis. Therefore, current guidelines specifically recommend against use of PICCs over CICCs as a strategy to reduce CLABSI.[34] Additionally, PICCs are associated with 2.5‐fold greater risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) compared to CICCs; thus, they should be used with caution in patients with cancer or those with underlying hypercoagulable states.

Of particular import to hospitalists is the fact that PICC placement is contraindicated in patients with stage IIIB or greater chronic kidney disease (CKD). In such patients, sequelae of PICC use, such as phlebitis or central vein stenosis, can be devastating in patients with CKD.[35] In a recent study, prior PICC placement was the strongest predictor of subsequent arteriovenous graft failure.[36] For this reason, Choosing Wisely recommendations call for avoidance of PICCs in such patients.[37]

Centrally Inserted Central Catheter

CICCs are CVADs placed by puncture and cannulation of the internal jugular, subclavian, brachiocephalic, or femoral veins (Figure 1D) and compose the vast majority of VADs placed in ICU settings.[38, 39] Central termination of CICCs allows for a variety of infusions, including irritants, vesicants, and vasopressors, as well as blood withdrawal and hemodynamic monitoring. CICCs are typically used for 7 to 14 days, but may remain for longer durations if they remain complication free and clinically necessary.[40] A key advantage of CICCs is that they can be placed in emergent settings to facilitate quick access for rapid infusion or hemodynamic monitoring. In particular, CICCs are inserted in the femoral vein and may be useful in emergency settings. However, owing to risk of infection and inability to monitor central pressures, these femoral devices should be replaced with a proper CICC or PICC when possible. Importantly, although CICCs are almost exclusively used in intensive or emergency care, PICCs may also be considered in such settings.[41, 42] CICCs usually have multiple lumens and often serve several simultaneous functions such as both infusions and hemodynamic monitoring.

Despite their benefits, CICCs have several disadvantages. First, insertion requires an experienced clinician and has historically been a task limited to physicians. However, this is changing rapidly (especially in Europe and Australia) where specially trained nurses are assuming responsibility for CICC placement.[43] Second, these devices are historically more likely to be associated with CLABSI, with estimates of infection rates varying between 2 and 5 infections per 1000 catheter‐days.[44] Third, CICCs pose a significant DVT risk, with rates around 22 DVTs per 1000 catheter‐days.[45] However, compared to PICCs, the DVT risk appears lower, and CICC use may be preferable in patients at high risk of DVT, such as critically ill or cancer populations.[46] An important note to prevent CICC insertion complications relates to use of ultrasound, a practice that has been associated with decreased accidental arterial puncture and hematoma formation. The role of ultrasound guidance with PICCs as well as implications for thrombotic and infectious events remains less characterized at this point.[47]

Tunneled Central Venous Access Devices

Tunneled devices (either CICCs or PICCs) are characterized by the fact that the insertion site on the skin and site of ultimate venipuncture are physically separated (Figure 1E). Tunneling limits bacterial entry from the extraluminal aspect of the CVAD to the bloodstream. For example, internal jugular veins are often ideal sites of puncture but inappropriate sites for catheter placement, as providing care to this area is challenging and may increase risk of infection.[34] Tunneling to the infraclavicular area provides a better option, as it provides an exit site that can be adequately cared for. Importantly, any CVAD (PICCs or CICCs) can be tunneled. Additionally, tunneled CICCs may be used in patients with chronic or impending renal failure where PICCs are contraindicated because entry into dialysis‐relevant vessels is to be avoided.[48] Such devices also allow regular blood sampling in patients who require frequent testing but have limited peripheral access, such as those with hematological malignancies. Additionally, tunneled catheters are more comfortable for patients and viewed as being more socially acceptable than nontunneled devices. However, the more invasive and permanent nature of these devices often requires deliberation prior to insertion.

Of note, tunneled devices and ports may be used as long‐term (>3 months to years) VADs. As our focus in this review is short‐term devices, we will not expand the discussion of these devices as they are almost always used for prolonged durations.[7]

OPERATIONALIZING THE DATA: AN ALGORITHMIC APPROACH TO VENOUS ACCESS

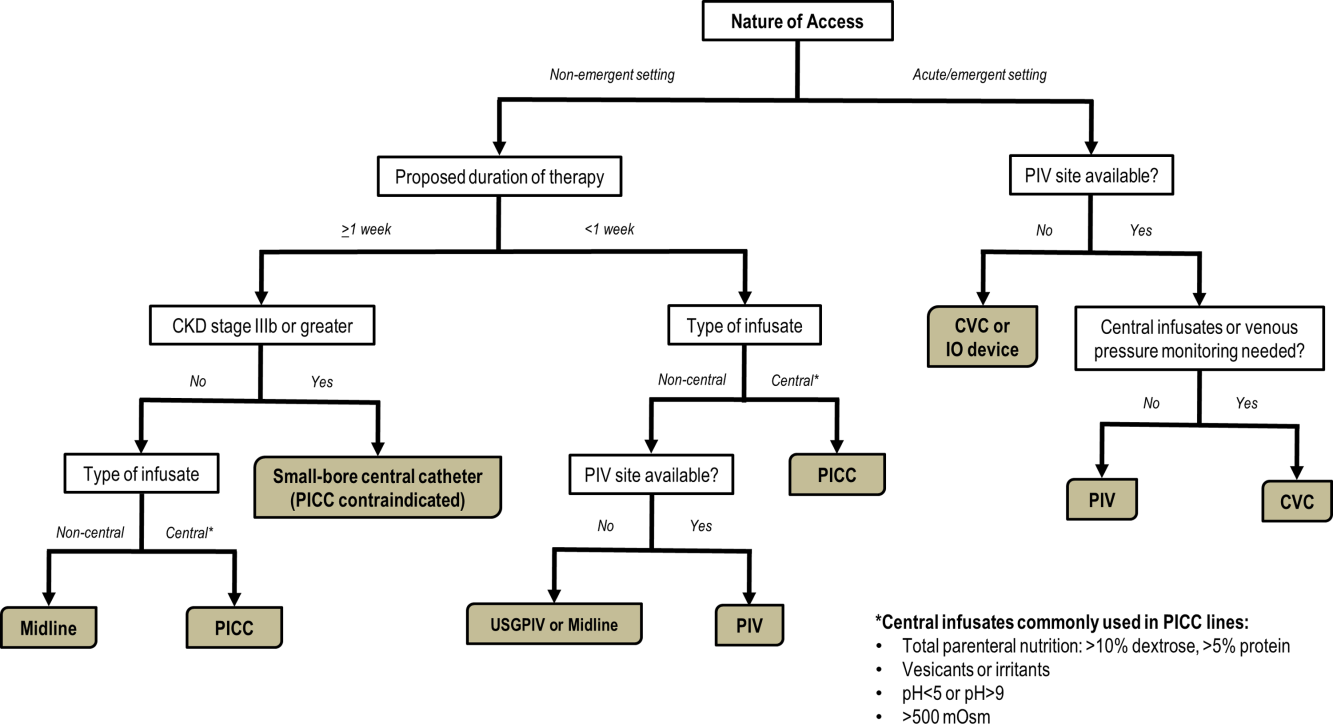

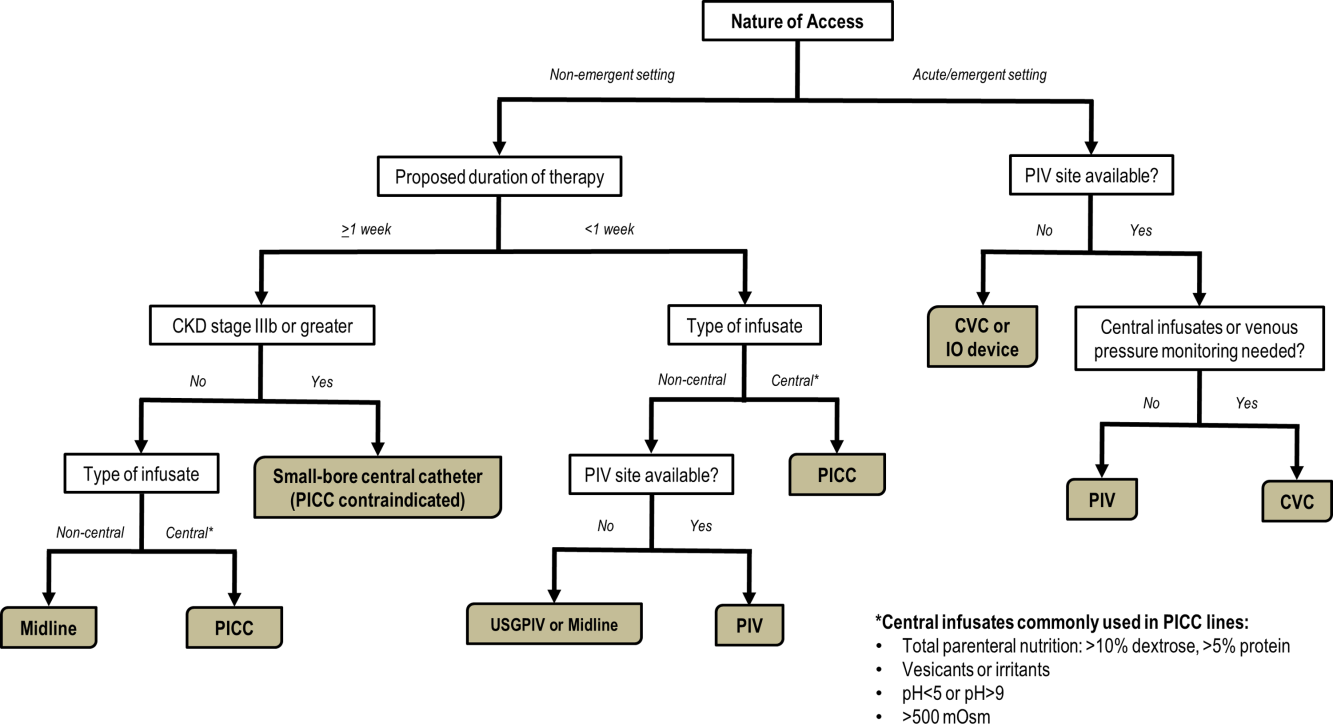

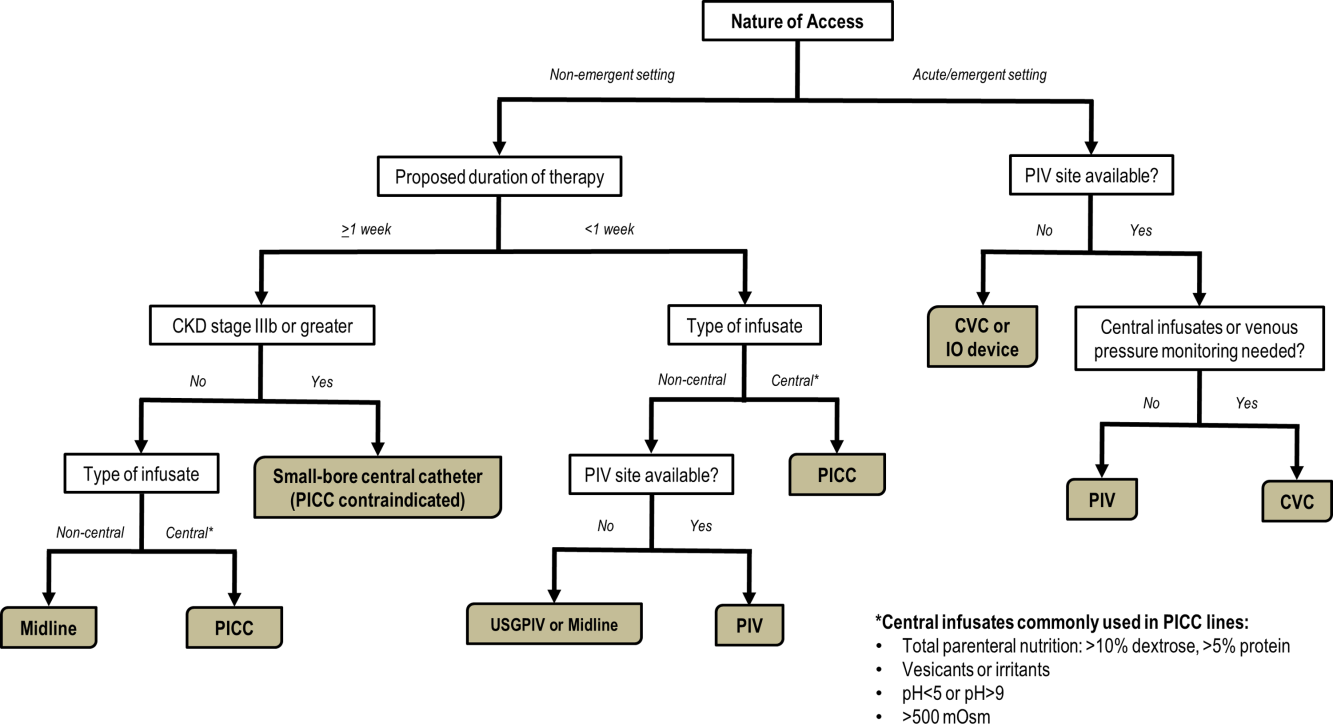

Hospitalists should consider approaching venous access using an algorithm based on a number of parameters. For example, a critically ill patient who requires vasopressor support and hemodynamic monitoring will need a CICC or a PICC. Given the potential greater risk of thromboses from PICCs, a CICC is preferable for critically ill patients provided an experienced inserter is available. Conversely, patients who require short‐term (710 days) venous access for infusion of nonirritant or nonvesicant therapy often only require a PIV. In patients with poor or difficult venous access, USGPIVs or midlines may be ideal and preferred over short PIVs. Finally, patients who require longer‐term or home‐based treatment may benefit from early placement of a midline or a PICC, depending again on the nature of the infusion, duration of treatment, and available venous access sites.

An algorithmic approach considering these parameters is suggested in Figure 2, and a brief overview of the devices and their considerations is shown in Table 3.

| Vascular Access Device | Central/Peripheral | Anatomical Location of Placement | Desired Duration of Placement | Common Uses | BSI Risk (Per 1,000 Catheter‐Days) | Thrombosis Risk | Important Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Small peripheral IV | Peripheral | Peripheral veins, usually forearm | 710 days | Fluid resuscitation, most medications, blood products | 0.06[8] | Virtually no risk | Consider necessity of PIV daily and remove unnecessary devices |

| Midline | Peripheral | Inserted around antecubital fossa, reside within basilic or cephalic vein of the arm | 24 weeks | Long‐term medications excluding TPN, vesicants, corrosives | 0.30.8[17] | Insufficient data | Can be used as bridge devices for patients to complete short‐term antibiotics/emnfusions as an outpatient |

| Peripherally inserted central catheter | Central | Inserted into peripheral arm vein and advanced to larger veins (eg, internal jugular or subclavian) to the CAJ | >1 week, 3 months | Large variety of infusates, including TPN, vesicants, corrosives | 2.4[44] | 6.30% | Contraindicated in patients with CKD stage IIIb or higher |

| Centrally inserted central catheters | Central | Inserted above (internal jugular vein, brachiocephalic vein, subclavian vein), or below the clavicle (axillary vein) | >1 week, 3 months | Same infusate variety as PICC, measurement of central venous pressures, common in trauma/emergent settings | 2.3[44] | 1.30% | Given lower rates of DVT than PICC, preferred in ICU and hypercoagulable environments |

| Tunneled CICCs | Central | Placed percutaneously in any large vein in the arm, chest, neck or groin | >3 months to years | Central infusates, as in any CVAD; used for patients with CKD stage IIIb or greater when a PICC is indicated | Insufficient data | Insufficient data | May be superior when insertion site and puncture site are not congruent and may increase risk of infection |

CONCLUSIONS

With strides in technology and progress in medicine, hospitalists have access to an array of options for venous access. However, every VAD has limitations that can be easily overlooked in a perfunctory decision‐making process. The data presented in this review thus provide a first step to improving safety in this evolving science. Studies that further determine appropriateness of VADs in hospitalized settings are necessary. Only through such progressive scientific enquiry will complication‐free venous access be realized.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- , . The need for comparative data in vascular access: the rationale and design of the PICC registry. J Vasc Access. 2013; 18(4): 219–224.

- , , , et al. Hospitalist experiences, practice, opinions, and knowledge regarding peripherally inserted central catheters: a Michigan survey. J Hosp Med. 2013; 8(6): 309–314.

- , , , . Clinically‐indicated replacement versus routine replacement of peripheral venous catheters. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013; 4: CD007798.

- , , , et al. Cost‐effectiveness analysis of clinically indicated versus routine replacement of peripheral intravenous catheters. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2014; 12(1): 51–58.

- Infusion Nurses Society. Infusion Nursing Standards of Practice. Norwood, MA; Infusion Nurses Society; 2011.

- , , , et al. Routine versus clinically indicated replacement of peripheral intravenous catheters: a randomised controlled equivalence trial. Lancet. 2012; 380(9847): 1066–1074.

- , , , et al. epic3: national evidence‐based guidelines for preventing healthcare‐associated infections in NHS hospitals in England. J Hosp Infect. 2014; 86(suppl 1): S1–S70.

- . Short peripheral intravenous catheters and infections. J Infus Nurs. 2012; 35(4): 230–240.

- , , , et al. Phlebitis risk varies by peripheral venous catheter site and increases after 96 hours: a large multi‐centre prospective study. J Adv Nurs. 2014; 70(11): 2539–2549.

- , . Intravenous catheter complications in the hand and forearm. J Trauma. 2004; 56(1): 123–127.

- , , , . Vesicant extravasation part I: Mechanisms, pathogenesis, and nursing care to reduce risk. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006; 33(6): 1134–1141.

- , . Variables influencing intravenous catheter insertion difficulty and failure: an analysis of 339 intravenous catheter insertions. Heart Lung. 2005; 34(5): 345–359.

- , , . Ultrasound‐guided peripheral venous access: a systematic review of randomized‐controlled trials. Eur J Emerg Med. 2014; 21(1): 18–23.

- , , , et al. Difficult peripheral venous access: clinical evaluation of a catheter inserted with the Seldinger method under ultrasound guidance. J Crit Care. 2014; 29(5): 823–827.

- . Choosing the right intravenous catheter. Home Healthc Nurse. 2007; 25(8): 523–531; quiz 532–523.

- Adverse reactions associated with midline catheters—United States, 1992–1995. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1996; 45(5): 101–103.

- , , . The risk of midline catheterization in hospitalized patients. A prospective study. Ann Intern Med. 1995; 123(11): 841–844.

- . Midline catheters: indications, complications and maintenance. Nurs Stand. 2007; 22(11): 48–57; quiz 58.

- , . Safe administration of vancomycin through a novel midline catheter: a randomized, prospective clinical trial. J Vasc Access. 2014; 15(4): 251–256.

- . Midline catheters: the middle ground of intravenous therapy administration. J Infus Nurs. 2004; 27(5): 313–321.

- . Vascular access in resuscitation: is there a role for the intraosseous route? Anesthesiology. 2014; 120(4): 1015–1031.

- , , , et al. A new system for sternal intraosseous infusion in adults. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2000; 4(2): 173–177.

- , , , , , . Comparison of two intraosseous access devices in adult patients under resuscitation in the emergency department: a prospective, randomized study. Resuscitation. 2010; 81(8): 994–999.

- , , , , . Comparison study of intraosseous, central intravenous, and peripheral intravenous infusions of emergency drugs. Am J Dis Child. 1990; 144(1): 112–117.

- , , , , . The safety of intraosseous infusions: risks of fat and bone marrow emboli to the lungs. Ann Emerg Med. 1989; 18(10): 1062–1067.

- , , , , . ESPEN guidelines on parenteral nutrition: central venous catheters (access, care, diagnosis and therapy of complications). Clin Nutr. 2009; 28(4): 365–377.

- , . Peripherally inserted central catheter use in the hospitalized patient: is there a role for the hospitalist? J Hosp Med. 2009; 4(6): E1–E4.

- Vital signs: central line‐associated blood stream infections—United States, 2001, 2008, and 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011; 60(8): 243–248.

- , , , . Hospital costs of central line‐associated bloodstream infections and cost‐effectiveness of closed vs. open infusion containers. The case of Intensive Care Units in Italy. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2010; 8: 8.

- , , . The risk of bloodstream infection in adults with different intravascular devices: a systematic review of 200 published prospective studies. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006; 81(9): 1159–1171.

- The Joint Commission. Preventing Central Line‐Associated Bloodstream Infections: A Global Challenge, a Global Perspective. Oak Brook, IL: Joint Commission Resources; 2012.

- , , , et al. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter‐related infections. Am J Infect Control. 2011; 39(4 suppl 1): S1–S34.

- , , , , . The risk of bloodstream infection associated with peripherally inserted central catheters compared with central venous catheters in adults: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013; 34(9): 908–918.

- Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, Infectious Diseases Society of America, American Hospital Association, Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology, The Joint Commission. Compendium of Strategies to Prevent Healthcare‐Associated Infections in Acute Care Hospitals: 2014 Updates. Available at: http://www.shea‐online.org. Accessed August 1, 2014.

- , , , , . Guidelines for venous access in patients with chronic kidney disease. A Position Statement from the American Society of Diagnostic and Interventional Nephrology, Clinical Practice Committee and the Association for Vascular Access. Semin Dial. 2008; 21(2): 186–191.

- , , , et al. Association between prior peripherally inserted central catheters and lack of functioning arteriovenous fistulas: a case‐control study in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012; 60(4): 601–608.

- , , , et al. Critical and honest conversations: the evidence behind the “Choosing Wisely” campaign recommendations by the American Society of Nephrology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012; 7(10): 1664–1672.

- , , , et al. Do physicians know which of their patients have central venous catheters? A multi‐center observational study. Ann Intern Med. 2014; 161(8): 562–567.

- , , , et al. Hospital‐wide survey of the use of central venous catheters. J Hosp Infect. 2011; 77(4): 304–308.

- , , , , , . Peripherally inserted central catheter‐related deep vein thrombosis: contemporary patterns and predictors. J Thromb Haemost. 2014; 12(6): 847–854.

- , , , . An in vitro study comparing a peripherally inserted central catheter to a conventional central venous catheter: no difference in static and dynamic pressure transmission. BMC Anesthesiol. 2010; 10: 18.

- , , , et al. Clinical experience with power‐injectable PICCs in intensive care patients. Crit Care. 2012; 16(1): R21.

- , , , et al. Nurse‐led central venous catheter insertion‐procedural characteristics and outcomes of three intensive care based catheter placement services. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012; 49(2): 162–168.

- , , , et al. Peripherally inserted central venous catheters in the acute care setting: a safe alternative to high‐risk short‐term central venous catheters. Am J Infect Control. 2010; 38(2): 149–153.

- , , , et al. Which central venous catheters have the highest rate of catheter‐associated deep venous thrombosis: a prospective analysis of 2,128 catheter days in the surgical intensive care unit. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013; 74(2): 454–460; discussion 461–452.

- , , , et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism associated with peripherally inserted central catheters: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet. 2013; 382(9889): 311–325.

- , , , , . Ultrasound guidance versus anatomical landmarks for subclavian or femoral vein catheterization. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015; 1: CD011447.

- , , , et al. Tunneled jugular small‐bore central catheters as an alternative to peripherally inserted central catheters for intermediate‐term venous access in patients with hemodialysis and chronic renal insufficiency. Radiology. 1999; 213(1): 303–306.

Reliable venous access is fundamental for the safe and effective care of hospitalized patients. Venous access devices (VADs) are conduits for this purpose, providing delivery of intravenous medications, accurate measurement of central venous pressure, or administration of life‐saving blood products. Despite this important role, VADs are also often the source of hospital‐acquired complications. Although inpatient providers must balance the relative risks of VADs against their benefits, the evidence supporting such decisions is often limited. Advances in technology, scattered research, and growing availability of novel devices has only further fragmented provider knowledge in the field of vascular access.[1]

It is not surprising, then, that survey‐based studies of hospitalists reveal important knowledge gaps with regard to practices associated with VADs.[2] In this narrative review, we seek to bridge this gap by providing a concise and pragmatic overview of the fundamentals of venous access. We focus specifically on parameters that influence decisions regarding VAD placement in hospitalized patients, providing key takeaways for practicing hospitalists.

METHODS

To compile this review, we systematically searched Medline (via Ovid) for several keywords, including: peripheral intravenous catheters, ultrasound‐guided peripheral catheter, intraosseous, midline, peripherally inserted central catheter, central venous catheters, and vascular access device complications. We concentrated on full‐length articles in English only; no date restrictions were placed on the search. We reviewed guidelines and consensus statements (eg, from the Center for Disease Control [CDC] or Choosing Wisely criteria) as appropriate. Additional studies of interest were identified through content experts (M.P., C.M.R.) and bibliographies of included studies.

SCIENTIFIC PRINCIPLES UNDERPINNING VENOUS ACCESS

It is useful to begin by reviewing VAD‐related nomenclature and physiology. In the simplest sense, a VAD consists of a hub (providing access to various connectors), a hollow tube divided into 1 or many sections (lumens), and a tip that may terminate within a central or peripheral blood vessel. VADs are classified as central venous catheters (eg, centrally inserted central catheters [CICCs] or peripherally inserted central catheters [PICCs]) or peripheral intravenous catheters (eg, midlines or peripheral intravenous catheters) based on site of entry and location of the catheter tip. Therefore, VADs entering via proximal or distal veins of the arm are often referred to as peripheral lines, as their site of entry and tip both reside within peripheral veins. Conversely, the term central line is often used when VADs enter or terminate in a central vein (eg, subclavian vein insertion with the catheter tip in the lower superior vena cava).

Attention to a host of clinical and theoretical parameters is important when choosing a device for venous access. Some such parameters are summarized in Table 1.

| Parameter | Major Considerations |

|---|---|

| |

| Desired flow rate | Smaller diameter veins susceptible to damage with high flow rates. |

| Short, large‐bore catheters facilitate rapid infusion. | |

| Nature of infusion | pH, viscosity, and temperature may damage vessels. |

| Vesicants and irritants should always be administered into larger, central veins. | |

| Desired duration of vascular access, or dwell time | Vessel thrombosis or phlebitis increase over time with catheter in place. |

| Intermittent infusions increase complications in central catheters; often tunneled catheters are recommended. | |

| Urgency of placement | Access to large caliber vessels is often needed in emergencies. |

| Critically ill or hemodynamically unstable patients may require urgent access for invasive monitoring or rapid infusions. | |

| Patients with trauma often require large volumes of blood products and reliable access to central veins. | |

| Number of device lumens | VADs may have single or multiple lumens. |

| Multilumen allows for multiple functions (eg, infusion of multiple agents, measurement of central venous pressures, blood draws). | |

| Device gauge | In general, use of a smaller‐gauge catheter is preferred to prevent complications. |

| However, larger catheter diameter may be needed for specific clinical needs (eg, blood transfusion). | |

| Device coating | VADs may have antithrombotic or anti‐infective coatings. |

| These devices may be of value in patients at high risk of complications. | |

| Such devices, however, may be more costly than their counterparts. | |

| Self‐care compatibility | VADs that can be cared for by patients are ideal for outpatient care. |

| Conversely, VADs such as peripheral catheters, are highly prone to dislodgement and should be reserved for supervised settings only. | |

VENOUS ACCESS DEVICES

We will organize our discussion of VADs based on whether they terminate in peripheral or central vessels. These anatomical considerations are relevant as they determine physical characteristics, compatibility with particular infusates, dwell time, and risk of complications associated with each VAD discussed in Table 2.

| Complications | Major Considerations |

|---|---|

| |

| Infection | VADs breach the integrity of skin and permit skin pathogens to enter the blood stream (extraluminal infection). |

| Inadequate antisepsis of the VAD hub, including poor hand hygiene, failure to "scrub the hub," and multiple manipulations may also increase the risk of VAD‐related infection (endoluminal infection). | |

| Infections may be local (eg, exit‐site infections) or may spread hematogenously (eg, CLABSI). | |

| Type of VAD, duration of therapy, and host characteristics interact to influence infection risk. | |

| VADs with antiseptic coatings (eg, chlorhexidine) or antibiotic coatings (eg, minocycline) may reduce risk of infection in high‐risk patients. | |

| Antiseptic‐impregnated dressings may reduce risk of extraluminal infection. | |

| Venous thrombosis | VADs predispose to venous stasis and thrombosis. |

| Duration of VAD use, type and care of the VAD, and patient characteristics affect risk of thromboembolism. | |

| VAD tip position is a key determinant of venous thrombosis; central VADs that do not terminate at the cavo‐atrial junction should be repositioned to reduce the risk of thrombosis. | |

| Antithrombotic coated or eluting devices may reduce risk of thrombosis, though definitive data are lacking. | |

| Phlebitis | Inflammation caused by damage to tunica media.[18] |

| 3 types of phlebitis: | |

| Chemical: due to irritation of media from the infusate. | |

| Mechanical: VAD physically damages the vessel. | |

| Infective: bacteria invade vein and inflame vessel wall. | |

| Phlebitis may be limited by close attention to infusate compatibility with peripheral veins, appropriate dilution, and prompt removal of catheters that show signs of inflammation. | |

| Phlebitis may be prevented in PICCs by ensuring at least a 2:1 vein:catheter ratio. | |

| Extravasation | Extravasation (also called infiltration) is defined as leakage of infusate from intravascular to extravascular space. |

| Extravasation of vesicants/emrritants is particularly worrisome. | |

| May result in severe tissue injury, blistering, and tissue necrosis.[11] | |

| VADs should be checked frequently for adequate flushing and position prior to each infusion to minimize risk. | |

| Any VAD with redness, swelling, and tenderness at the entry site or problems with flushing should not be used without further examination and review of position. | |

Peripheral Venous Access

Short Peripheral Intravenous Catheter

Approximately 200 million peripheral intravenous catheters (PIVs) are placed annually in the United States, making them the most common intravenous catheter.[3] PIVs are short devices, 3 to 6 cm in length, that enter and terminate in peripheral veins (Figure 1A). Placement is recommended in forearm veins rather than those of the hand, wrist, or upper arm, as forearm sites are less prone to occlusion, accidental removal, and phlebitis.[4] Additionally, placement in hand veins impedes activities of daily living (eg, hand washing) and is not preferred by patients.[5] PIV size ranges from 24 gauge (smallest) to 14 gauge (largest); larger catheters are often reserved for fluid resuscitation or blood transfusion as they accommodate greater flow and limit hemolysis. To decrease risk of phlebitis and thrombosis, the shortest catheter and smallest diameter should be used. However, unless adequately secured, smaller diameter catheters are also associated with greater rates of accidental removal.[4, 5]

By definition, PIVs are short‐term devices. The CDC currently recommends removal and replacement of these devices no more frequently than every 72 to 96 hours in adults. However, a recent randomized controlled trial found that replacing PIVs when clinically indicated (eg, device failure, phlebitis) rather than on a routine schedule added 30 hours to their lifespan without an increase in complications.[6] A systematic review by the Cochrane Collaboration echoes these findings.[3] These data have thus been incorporated into recommendations from the Infusion Nurses Society (INS) and the National Health Service in the United Kingdom.[5, 7] In hospitalized patients, this approach is relevant, as it preserves venous access sites, maximizes device dwell, and limits additional PIV insertions. In turn, these differences may reduce the need for invasive VADs such as PICCs. Furthermore, the projected 5‐year savings from implementation of clinically indicated PIV removal policies is US$300 million and 1 million health‐worker hours in the United States alone.[4]

PIVs offer many advantages. First, they are minimally invasive and require little training to insert. Second, they can be used for diverse indications in patients requiring short‐term (1 week) venous access. Third, PIVs do not require imaging to ensure correct placement; palpation of superficial veins is sufficient. Fourth, PIVs exhibit a risk of bloodstream infection that is about 40‐fold lower than more invasive, longer‐dwelling VADs[8] (0.06 bacteremia per 1000 catheter‐days).

Despite these advantages, PIVs also have important drawbacks. First, a quarter of all PIVs fail through occlusion or accidental dislodgement.[4] Infiltration, extravasation, and hematoma formation are important adverse events that may occur in such cases. Second, thrombophlebitis (pain and redness at the insertion site) is frequent, and may require device removal, especially in patients with catheters 20 guage.[9] Third, despite their relative safety, PIVs can cause localized or hematogenous infection. Septic thrombophlebitis (superficial thrombosis and bloodstream infection) and catheter‐related bloodstream infection, though rare, have been reported with PIVs and may lead to serious complications.[8, 10] In fact, some suggest that the overall burden of bloodstream infection risk posed by PIVs may be similar to that of CICCs given the substantially greater number of devices used and greater number of device days.[8]

PIVs and other peripheral VADs are not suitable for infusion of vesicants or irritants, which require larger, central veins for delivery. Vesicants (drugs that cause blistering on infusion) include chemotherapeutic agents (eg, dactinomycin, paclitaxel) and commonly used nonchemotherapeutical agents (eg, diazepam, piperacillin, vancomycin, esmolol, or total parenteral nutrition [TPN]).[11] Irritants (phlebitogenic drugs) cause short‐term inflammation and pain, and thus should not be peripherally infused for prolonged durations. Common irritants in the hospital setting include acyclovir, dobutamine, penicillin, and potassium chloride.

Of note, about one‐quarter of PIV insertions fail owing to difficult intravenous access.[12] Ultrasound‐guided peripheral intravenous (USGPIV) catheter placement is emerging as a technique to provide peripheral access for such patients to avoid placement of central venous access devices. Novel, longer devices (>8 cm) with built‐in guide wires have been developed to increase placement success of USGPIVs. These new designs provide easier access into deeper arm veins (brachial or basilic) not otherwise accessible by short PIVs. Although studies comparing the efficacy of USGPIV devices to other VADs are limited, a recent systematic review showed that time to successful cannulation was shorter, and fewer attempts were required to place USGPIVs compared to PIVs.[13] A recent study in France found that USGPIVs met the infusion needs of patients with difficult veins with minimal increase in complications.[14] Despite these encouraging data, future studies are needed to better evaluate this technology.

Midline Catheter

A midline is a VAD that is between 7.5 to 25 cm in length and is typically inserted into veins above the antecubital fossa. The catheter tip resides in a peripheral upper arm vein, often the basilic or cephalic vein, terminating just short of the subclavian vein (Figure 1B). Midline‐like devices were first developed in the 1950s and were initially used as an alternative to PIVs because they were thought to allow longer dwell times.[15] However, because they were originally constructed with a fairly rigid material, infiltration, mechanical phlebitis, and inflammation were common and tempered enthusiasm for their use.[15, 16] Newer midline devices obviate many of these problems and are inserted by ultrasound guidance and modified Seldinger technique.[17] Despite these advances, data regarding comparative efficacy are limited.

Midlines offer longer dwell times than standard PIVs owing to termination in the larger diameter basilic and brachial veins of the arm. Additionally, owing to their length, midlines are less prone to dislodgement. As they are inserted with greater antisepsis than PIVs and better secured to the skin, they are more durable than PIVs.[5, 9, 18] Current INS standards recommend use of midlines for 1 to 4 weeks.[5] Because they terminate in a peripheral vein, medications and infusions compatible with midlines are identical to those that are infused through a PIV. Thus, TPN, vesicants or irritants, or drugs that feature a pH 5 or pH >9, or >500 mOsm should not be infused through a midline.[15] New evidence suggests that diluted solutions of vancomycin (usually pH 5) may be safe to infuse for short durations (6 days) through a midline, and that concentration rather than pH may be more important in this regard.[19] Although it is possible that the use of midlines may extend to agents typically not deemed peripheral access compatible, limited evidence exists to support such a strategy at this time.

Midlines offer several advantages. First, because blood flow is greater in the more proximal veins of the arm, midlines can accommodate infusions at rates of 100 to 150 mL/min compared to 20 to 40 mL/min in smaller peripheral veins. Higher flow rates offer greater hemodilution (dilution of the infusion with blood), decreasing the likelihood of phlebitis and infiltration.[20] Second, midlines do not require x‐ray verification of tip placement; thus, their use is often favored in resource‐depleted settings such as skilled nursing facilities. Third, midlines offer longer dwell times than peripheral intravenous catheters and can thus serve as bridge devices for short‐term intravenous antibiotics or peripheral‐compatible infusions in an outpatient setting. Available evidence suggests that midlines are associated with low rates of bloodstream infection (0.30.8 per 1000 catheter‐days).[17] The most frequent complications include phlebitis (4.2%) and occlusion (3.3%).[20] Given these favorable statistics, midlines may offer a good alternative to PIVs in select patients who require peripheral infusions of intermediate duration.

Intraosseous Vascular Access

Intraosseous (IO) devices access the vascular system by piercing cortical bone. These devices provide access to the intramedullary cavity and venous plexi of long bones such as the tibia, femur, or humerus. Several insertion devices are now commercially available and have enhanced the ease and safety of IO placement. Using these newer devices, IO access may be obtained in 1 to 2 minutes with minimal training. By comparison, a central venous catheter often requires 10 to 15 minutes to insert with substantial training efforts for providers.[21, 22, 23]

IO devices thus offer several advantages. First, given the rapidity with which they can be inserted, they are often preferred in emergency settings (eg, trauma). Second, these devices are versatile and can accommodate both central and peripheral infusates.[24] Third, a recent meta‐analysis found that IOs have a low complication rate of 0.8%, with extravasation of infusate through the cortical entry site being the most common adverse event.[21] Of note, this study also reported zero local or distal infectious complications, a finding that may relate to the shorter dwell of these devices.[21] Some animal studies suggest that fat embolism from bone may occur at high rates with IO VADs.[25] However, death or significant morbidity from fat emboli in humans following IO access has not been described. Whether such emboli occur or are clinically significant in the context of IO devices remains unclear at this time.[21]

Central Venous Access Devices

Central venous access devices (CVADs) share in common tip termination in the cavo‐atrial junction, either in the lower portion of the superior vena cava or in the upper portion of the right atrium. CVADs can be safely used for irritant or vesicant medications as well as for blood withdrawal, blood exchange procedures (eg, dialysis), and hemodynamic monitoring. Traditionally, these devices are 15 to 25 cm in length and are directly inserted in the deep veins of the supra‐ or infraclavicular area, including the internal jugular, brachiocephalic, subclavian, or axillary veins. PICCs are unique CVADs in that they enter through peripheral veins but terminate in the proximity of the cavoatrial junction. Regarding nomenclature, CICC will be used to denote devices that enter directly into veins of the neck or chest, whereas PICC will be used for devices that are inserted peripherally but terminate centrally.

Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter

PICCs are inserted into peripheral veins of the upper arm (eg, brachial, basilica, or cephalic vein) and advanced such that the tip resides at the cavoatrial junction (Figure 1C). PICCs offer prolonged dwell times and are thus indicated when patients require venous access for weeks or months.[26] Additionally, they can accommodate a variety of infusates and are safer to insert than CICCs, given placement in peripheral veins of the arm rather than central veins of the chest/neck. Thus, insertion complications such as pneumothorax, hemothorax, or significant bleeding are rare with PICCs. In fact, a recent study reported that PICC insertion by hospitalists was associated with low rates of insertion or infectious complications.[27]

However, like CICCs, PICCs are associated with central lineassociated bloodstream infection (CLABSI), a serious complication known to prolong length of hospital stay, increase costs, and carry a 12% to 25% associated mortality.[28, 29] In the United States alone, over 250,000 CLASBI cases occur per year drawing considerable attention from the CDC and Joint Commission, who now mandate reporting and nonpayment for hospital‐acquired CLABSI.[30, 31, 32] A recent systematic review and meta‐analysis found that PICCs are associated with a substantial risk of CLABSI in hospitalized patients.[33] Importantly, no difference in CLABSI rates between PICCs and CICCs in hospitalized patients was evident in this meta‐analysis. Therefore, current guidelines specifically recommend against use of PICCs over CICCs as a strategy to reduce CLABSI.[34] Additionally, PICCs are associated with 2.5‐fold greater risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) compared to CICCs; thus, they should be used with caution in patients with cancer or those with underlying hypercoagulable states.

Of particular import to hospitalists is the fact that PICC placement is contraindicated in patients with stage IIIB or greater chronic kidney disease (CKD). In such patients, sequelae of PICC use, such as phlebitis or central vein stenosis, can be devastating in patients with CKD.[35] In a recent study, prior PICC placement was the strongest predictor of subsequent arteriovenous graft failure.[36] For this reason, Choosing Wisely recommendations call for avoidance of PICCs in such patients.[37]

Centrally Inserted Central Catheter

CICCs are CVADs placed by puncture and cannulation of the internal jugular, subclavian, brachiocephalic, or femoral veins (Figure 1D) and compose the vast majority of VADs placed in ICU settings.[38, 39] Central termination of CICCs allows for a variety of infusions, including irritants, vesicants, and vasopressors, as well as blood withdrawal and hemodynamic monitoring. CICCs are typically used for 7 to 14 days, but may remain for longer durations if they remain complication free and clinically necessary.[40] A key advantage of CICCs is that they can be placed in emergent settings to facilitate quick access for rapid infusion or hemodynamic monitoring. In particular, CICCs are inserted in the femoral vein and may be useful in emergency settings. However, owing to risk of infection and inability to monitor central pressures, these femoral devices should be replaced with a proper CICC or PICC when possible. Importantly, although CICCs are almost exclusively used in intensive or emergency care, PICCs may also be considered in such settings.[41, 42] CICCs usually have multiple lumens and often serve several simultaneous functions such as both infusions and hemodynamic monitoring.

Despite their benefits, CICCs have several disadvantages. First, insertion requires an experienced clinician and has historically been a task limited to physicians. However, this is changing rapidly (especially in Europe and Australia) where specially trained nurses are assuming responsibility for CICC placement.[43] Second, these devices are historically more likely to be associated with CLABSI, with estimates of infection rates varying between 2 and 5 infections per 1000 catheter‐days.[44] Third, CICCs pose a significant DVT risk, with rates around 22 DVTs per 1000 catheter‐days.[45] However, compared to PICCs, the DVT risk appears lower, and CICC use may be preferable in patients at high risk of DVT, such as critically ill or cancer populations.[46] An important note to prevent CICC insertion complications relates to use of ultrasound, a practice that has been associated with decreased accidental arterial puncture and hematoma formation. The role of ultrasound guidance with PICCs as well as implications for thrombotic and infectious events remains less characterized at this point.[47]

Tunneled Central Venous Access Devices

Tunneled devices (either CICCs or PICCs) are characterized by the fact that the insertion site on the skin and site of ultimate venipuncture are physically separated (Figure 1E). Tunneling limits bacterial entry from the extraluminal aspect of the CVAD to the bloodstream. For example, internal jugular veins are often ideal sites of puncture but inappropriate sites for catheter placement, as providing care to this area is challenging and may increase risk of infection.[34] Tunneling to the infraclavicular area provides a better option, as it provides an exit site that can be adequately cared for. Importantly, any CVAD (PICCs or CICCs) can be tunneled. Additionally, tunneled CICCs may be used in patients with chronic or impending renal failure where PICCs are contraindicated because entry into dialysis‐relevant vessels is to be avoided.[48] Such devices also allow regular blood sampling in patients who require frequent testing but have limited peripheral access, such as those with hematological malignancies. Additionally, tunneled catheters are more comfortable for patients and viewed as being more socially acceptable than nontunneled devices. However, the more invasive and permanent nature of these devices often requires deliberation prior to insertion.

Of note, tunneled devices and ports may be used as long‐term (>3 months to years) VADs. As our focus in this review is short‐term devices, we will not expand the discussion of these devices as they are almost always used for prolonged durations.[7]

OPERATIONALIZING THE DATA: AN ALGORITHMIC APPROACH TO VENOUS ACCESS

Hospitalists should consider approaching venous access using an algorithm based on a number of parameters. For example, a critically ill patient who requires vasopressor support and hemodynamic monitoring will need a CICC or a PICC. Given the potential greater risk of thromboses from PICCs, a CICC is preferable for critically ill patients provided an experienced inserter is available. Conversely, patients who require short‐term (710 days) venous access for infusion of nonirritant or nonvesicant therapy often only require a PIV. In patients with poor or difficult venous access, USGPIVs or midlines may be ideal and preferred over short PIVs. Finally, patients who require longer‐term or home‐based treatment may benefit from early placement of a midline or a PICC, depending again on the nature of the infusion, duration of treatment, and available venous access sites.

An algorithmic approach considering these parameters is suggested in Figure 2, and a brief overview of the devices and their considerations is shown in Table 3.

| Vascular Access Device | Central/Peripheral | Anatomical Location of Placement | Desired Duration of Placement | Common Uses | BSI Risk (Per 1,000 Catheter‐Days) | Thrombosis Risk | Important Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Small peripheral IV | Peripheral | Peripheral veins, usually forearm | 710 days | Fluid resuscitation, most medications, blood products | 0.06[8] | Virtually no risk | Consider necessity of PIV daily and remove unnecessary devices |

| Midline | Peripheral | Inserted around antecubital fossa, reside within basilic or cephalic vein of the arm | 24 weeks | Long‐term medications excluding TPN, vesicants, corrosives | 0.30.8[17] | Insufficient data | Can be used as bridge devices for patients to complete short‐term antibiotics/emnfusions as an outpatient |

| Peripherally inserted central catheter | Central | Inserted into peripheral arm vein and advanced to larger veins (eg, internal jugular or subclavian) to the CAJ | >1 week, 3 months | Large variety of infusates, including TPN, vesicants, corrosives | 2.4[44] | 6.30% | Contraindicated in patients with CKD stage IIIb or higher |