User login

HM11 BREAKOUT SESSIONS OVERVIEW

QUALITY

Utilizing Technology to Improve the Clinical and Operational Performance of Hospitalists

SPEAKERS: Jason Stein, MD, SFHM, associate vice chair for quality, Department of Medicine, Bryce Gartland, MD, FHM, associate director, section of hospital medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta

In an age of increasing technology, just getting technology into a hospital isn’t the answer. It’s about integrating it into practice to improve care.

At Emory, the marriage of “low-tech solutions” and patented data displays has resulted in what Drs. Stein and Gartland call an accountable-care unit (ACU). The unit-based team features geographic ownership and structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds (SIBR). Perhaps more important, the unit generates real-time data captured on monitors, allowing teams of hospitalists, nonphysician providers (NPPs), residents, interns, and social workers to “visually digest immense amounts of information in a very short time period,” Dr. Gartland said.

Dr. Stein defined an ACU as a bounded geographic inpatient area responsible for the clinical, service, and cost outcomes it produces. To help manage beds, Emory instituted a system called “e-Bed,” a McKesson system that tracks room availability. The system shows whether rooms are occupied, being cleaned, or somewhere in between. It has icons to show whether patients are elsewhere in the hospital for treatment, as well as clinical data capacities. Unit teams round together and use a portable workstation or tablet computer to input clinical data, notes, or other comments into real-time dashboards that can then show everything from VTE prophylaxis to whether a patient is at high risk for falls.

The project has been in the works for several years, and Dr. Garltand noted that any hospitalists looking to push similar initiatives at their institution need to ensure that they have buy-in from providers and a commitment to seeing the project through.

“Timing is everything,” he said. “If we tried to force this … a few years ago, it would not have worked.”

PRACTICE MANAGEMENT

Recruiting and Retaining Hospitalists: Developing a Talent Facilitation Framework

SPEAKERS: Patrick Kneeland, MD, hospitalist, Providence Regional Medical Center, Everett, Wash.; Christine Kneeland, COO, Center Partners, Fort Collins, Colo.; Niraj Sehgal, associate professor of medicine, associate chair for quality and safety, Department of Medicine, University of California at San Francisco

Lincoln Godfrey, DO, a hospitalist at Baxter Regional Medical Center in Mountain Home, Ark., was sitting and listening to strategies to lure and keep hospitalists when his hospital CEO sent him a text asking how his recruiting efforts were going with a would-be hire.

“I said I’d get back to him,” Dr. Godfrey jokes.

The C-suite’s passion is understandable, though, as the fight to hire experienced staff outside of major markets continues to stymie many HM groups. Dr. Godfrey says he can’t hire anybody without first getting them to the Ozark Mountains to learn the hospital, its people, and its community.

“There’s going to be a limited talent pool of people who will come at all,” he says. “But I don’t get anybody who doesn’t work with us for a bit first.”

Christine Kneeland—Dr. Kneeland’s mother—said HM leaders tasked with their group’s personnel duties should focus on a few main concepts:

- Think outside the bank. Some physicians look only to earn as much as they can as quickly as they can, but many seek personal and professional satisfaction.

- Engagement is instrumental. A one-day orientation program for a lifetime job doesn’t sound like enough, does it?

In the coming years, hiring managers will have to focus on “millennials”—the generation of doctors born between 1977 and 1999—which Christine Kneeland described as tech-savvy doctors interested in a blended lifestyle of work and leisure. And while some might not agree with or understand their perspective, they’d better get used to it, she said. “The millennials are here, the workplace has changed, and they are leading that change,” she added. “Just embrace it.”

QUALITY

Patient Satisfaction: Tips for Improving Your HCAHPS Scores

MODERATORS: Win Whitcomb, MD, MHM, medical director of healthcare quality, Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, Mass.; Steven Deitelzweig, MD, MMM, SFHM, system chairman, Department of Hospital Medicine, regional vice president of medical affairs, Ochsner Health System, New Orleans

Patient satisfaction scores are a big deal right now, as many HM groups tie the scores to compensation and the federal government tethers the scores and a portion of hospital payment through the value-based purchasing (VBP) program.

So how does a hospitalist improve their HCAHPS score? Here’s what the experts said:

- Personalize things. Give a business card with a picture. Sit down. Smile. Ask the patient if they understand what you’ve said, and don’t get frustrated if they don’t.

- First and last. Make good impressions when introducing yourself to the patient and when it’s time to discharge or transition them to a different facility. “When the hospitalist hands a patient off,” Dr. Whitcomb said, “it doesn’t cut it to pull out your brochure of 40 practitioners when the patient asks, ‘Who am I going to see tomorrow?’”

- Be professional. Don’t vent about workplace issues in front of patients. Dr. Deitelzweig illustrated the point with the case of an elderly patient who got out of bed to help a practitioner they heard complaining about a heavy workload. The patient fell.

- Creative use of white space. Consider using in-room white boards to help keep patients informed of a day’s care plan.

David Jaworski, MD, director of the hospitalist service at Windham Hospital in Willimantic, Conn., says honesty was a key piece of advice he gleaned from the session.

“I think one of the things people appreciate the most when they’re in the hospital is being honest about our uncertainties,” he says. “I have had more people thank me for saying, ‘I don’t know, but we will find out by doing this, this, and this.’ ”

ACADEMIC

The Role of Hospital Medicine in Adapting to the New ACGME Requirements

SPEAKER: Jeff Wiese, MD, FACP, SFHM, associate professor of medicine at Tulane University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans

The new Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) work-hour rules that take effect July 1 have received a lot of attention since they were announced last summer. The guideline that has attracted the bulk of the attention limits intern shifts to 16 hours, with upper-level residents capped at 24 consecutive hours, with four hours of administrative follow-on allowed with the caveat that strategic napping is “strongly suggested.”

“I’m all for work hours,” said Dr. Wiese, immediate past president of SHM. “It’s the right thing to do; it’s safer. But I think we have to be careful we don’t super-fragment the system or double the intensity of the system. And on both of those plates, if you don’t do it right, what you end up with is people who will be ill-prepared.”

Dr. Wiese said an easy way to question the validity of one ACGME rule is to examine the guideline that limits a first-year resident’s census to 10 patients. He wondered which scenario offers more teaching opportunities: a roster of six chest-pain cases, two pneumonia cases, and two similarly familiar or relatively safe cases, or a resident with only four cases but each one having multiple comorbidities and complex decisions?

The new rules provide hospitals and HM groups an opportunity to change their way of thinking, adds Jeffrey Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. “Every program has to change its entire way of doing business anyway, so let’s be at the table and say, ‘Well, while you’re redesigning your entire program, let’s inject patent safety and quality of care, and good pedagogy into the system,’” he says.

CLINICAL

Skin is In: Dermatological Images Every Hospitalist Should Recognize

MODERATOR: Paul Aronowitz, MD, FACP, internal medicine residency program director, California Pacific Medical Center, San Francisco

A patient comes into the ED with a blistering skin condition, but the diagnosis escapes the triage doctor on the case. The problem turns out to be bullosis diabeticorum, but the ED doc doesn’t know that yet and pushes to add a patient to the upstairs HM roster.

“The ED will usually try to admit because they’re worried [the patient has] some terrible drug eruption, but they can actually go home,” Dr. Aronowitz explained. “Hospitalists can help tell the difference.”

HM groups shouldn’t work to become amateur dermatologists, Dr. Aronowitz added. However, given that many hospitalists find themselves confronted by dermatologic cases several times a month, a rudimentary pedigree is a good idea to help sift out which cases require admission and which would take up bed space required for others.

He referred to it as knowing enough to know whether you know enough. “For sure, a hospitalist can diagnose a hypersensitivity reaction from a classic drug like Dilantin,” Dr. Aronowitz said, “and then stop the drug, because that would be one of the best things they could do.”

The session exposed hospitalists to dozens of images of skin conditions theymight come across in daily rounds, from snakebites to drug reactions to argyria.

“The idea is to help hospitalists recognize what’s serious and what’s not,” he said. “If you recognize those initial cutaneous clues, you can guide your antibiotic therapy, or whether you need antibiotics.”

CAREER

This Disease Is Easy; It’s the Patient Who’s Difficult

Speaker: Susan Block, chair, Department of Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care at Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston

Every physician will have their “button pushed” by a patient now and then, and hospitalists are in the unfortunate position of having little or no previous relationship with most patients, according to Dr. Block, a national expert in physician-patient conflict resolution who said “interpersonal challenges are an onerous part” of the job.

“We want to make sure we provide really good care to these patients, but it can be very challenging,” she said, noting that between 10% and 30% of patients in the healthcare setting present with difficult behaviors.

Whether it’s an empowered patient, a traumatized patient, an intrusive family member, or a patient with clear psychosocial issues, Dr. Block explained that “these patients can make physicians feel lousy. … Being aware of that and trying to stop that process is one of the key issues in professionalism and competence in working with difficult patients.”

She also warned hospitalists to recognize when they become a “magnet” for difficult patients, as many times the expert in the group will become the “go-to” doc. “I don’t think anyone can take care of a large panel of these patients; it’s just too much,” she said, noting you have to negotiate some limits or you will “burn out and lose perspective.”

Many doctors are very uncomfortable with scared or crying patients, Dr. Block said, explaining these are some of her most difficult patients. “Show me a patient in the hospital who isn’t scared,” she said. “Even it they aren’t, they are scared of dying.”

Other sources of workplace discomfort include the dependent or “needy” patient, the suspicious patient, and the extremely pushy patient. Dr. Block suggested setting clear boundaries with patients; she also noted physicians should be ready and willing to identify and reflect on your own emotions so that “you have the capacity to get perspective on the problem and keep yourself from being part of the problem.

“Limit-setting is one of the most therapeutic things you can do with difficult patients,” she said. “It feels to us as a form of sadism, as though we are punishing patients. But for many patients, the most dangerous, scary, and dysfunctional thing you can do for patients is not set limits.”

CLINICAL

The Art of Clinical Problem-Solving: Mystery Cases

SPEAKER: Gupreet Dhaliwal, MD, University of California at San Francisco

Humility, patience, and practice: Those are the keys to improving one’s clinical diagnostic skills, according to Dr. Dhaliwal, an acclaimed educator and clinician at UCSF who walked a packed room through two blind cases and encouraged hospitalists to work hard at their craft.

“If you want to reach your maximum potential, you have to view it the same way we do other things, the same way a great musician rehearses and a great soccer player scrimmages,” he said. “All of us are busy, but you either have to increase the number of cases you put your mind through, or you take the cases you have and you analyze them, you seek feedback, you try to improve the process around the diagnostic.

“The message isn’t always fun, because both of those things equal more work, but there is no way to hide it because there is no field in which people get better without more work.”

Dr. Dhaliwal says hospitalists should be “humble about diagnosis.” He explained that the more experienced people become, the more we shift from analytical reasoning, “thinking hard like we did when we were students and residents,” to intuitive reasoning, which “is basically saying, ‘I recognize a pattern, this is an old friend, I’ve seen gout before.’ I think any of us can be guilty of forgetting that it has pitfalls. And there is a whole list of cognitive biases that are associated with moving fast and building patterns.”

He also believes hospitalists who dedicate themselves to clinical greatness can parlay such improvement in the quality realm. “Every one of us has used diagnosis as a core part of our identity, but in terms of getting the community or other stakeholders behind improving diagnosis or improving judgment, I think the umbrella of quality and reducing diagnostic errors is the most appealing and most logical,” he says. “I think we start to take for granted we are good at it, but I think there are ways many of us, especially if we work at it, can become great at it.”

CLINICAL

The How, When, and Why of Noninvasive Ventilation

SPEAKER: Eric Siegal, MD, SFHM, critical care fellow, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine, Madison

Dr. Siegal’s review of literature in front of a packed crowd provided a road map to Noninvasive Positive Pressure Ventilation (NPPV) usage. In the end, NPPV should be a hospitalist’s first choice for patients with hypercarbic COPD exacerbations, and likely in patients with acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema, hypoxemic respiratory failure, immunocompromised patients, and pre-intubation patients.

Dr. Siegal stressed the use of NPPV in COPD, which has been studied thoroughly and “held up to repeated scrutiny.”

“If you put people on NPPV instead of intubating them … mortality is halved, intubation rate is less than half, treatment failure is much lower, you have a third of the complications, and huge reductions in length of stay,” Dr. Siegal said.

In the absence of contraindications, he stressed, NPPV should be the first line of therapy for patients with hypercarbic COPD exacerbations. “In fact, I would argue that you really should be asking yourself, ‘Why can’t I put these patients on NPPV?’ ” he asked, “because this has really shown to be life-saving.”

Dr. Siegal also explored recent findings on NPPV in acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema patients, which surprisingly showed “no better than supplemental oxygen.” He concluded that if your patient is not hypercarbic, “there is no advantage to adding pressure support.” He also said the benefit is more robust in ACPE patients who have acute coronary syndrome.

Dr. Siegal advised hospitalists to pick the right patients, start NPPV therapy early, and if the patient doesn’t improve within one or two hours, “it’s time to move on.”

QUALITY

Utilizing Technology to Improve the Clinical and Operational Performance of Hospitalists

SPEAKERS: Jason Stein, MD, SFHM, associate vice chair for quality, Department of Medicine, Bryce Gartland, MD, FHM, associate director, section of hospital medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta

In an age of increasing technology, just getting technology into a hospital isn’t the answer. It’s about integrating it into practice to improve care.

At Emory, the marriage of “low-tech solutions” and patented data displays has resulted in what Drs. Stein and Gartland call an accountable-care unit (ACU). The unit-based team features geographic ownership and structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds (SIBR). Perhaps more important, the unit generates real-time data captured on monitors, allowing teams of hospitalists, nonphysician providers (NPPs), residents, interns, and social workers to “visually digest immense amounts of information in a very short time period,” Dr. Gartland said.

Dr. Stein defined an ACU as a bounded geographic inpatient area responsible for the clinical, service, and cost outcomes it produces. To help manage beds, Emory instituted a system called “e-Bed,” a McKesson system that tracks room availability. The system shows whether rooms are occupied, being cleaned, or somewhere in between. It has icons to show whether patients are elsewhere in the hospital for treatment, as well as clinical data capacities. Unit teams round together and use a portable workstation or tablet computer to input clinical data, notes, or other comments into real-time dashboards that can then show everything from VTE prophylaxis to whether a patient is at high risk for falls.

The project has been in the works for several years, and Dr. Garltand noted that any hospitalists looking to push similar initiatives at their institution need to ensure that they have buy-in from providers and a commitment to seeing the project through.

“Timing is everything,” he said. “If we tried to force this … a few years ago, it would not have worked.”

PRACTICE MANAGEMENT

Recruiting and Retaining Hospitalists: Developing a Talent Facilitation Framework

SPEAKERS: Patrick Kneeland, MD, hospitalist, Providence Regional Medical Center, Everett, Wash.; Christine Kneeland, COO, Center Partners, Fort Collins, Colo.; Niraj Sehgal, associate professor of medicine, associate chair for quality and safety, Department of Medicine, University of California at San Francisco

Lincoln Godfrey, DO, a hospitalist at Baxter Regional Medical Center in Mountain Home, Ark., was sitting and listening to strategies to lure and keep hospitalists when his hospital CEO sent him a text asking how his recruiting efforts were going with a would-be hire.

“I said I’d get back to him,” Dr. Godfrey jokes.

The C-suite’s passion is understandable, though, as the fight to hire experienced staff outside of major markets continues to stymie many HM groups. Dr. Godfrey says he can’t hire anybody without first getting them to the Ozark Mountains to learn the hospital, its people, and its community.

“There’s going to be a limited talent pool of people who will come at all,” he says. “But I don’t get anybody who doesn’t work with us for a bit first.”

Christine Kneeland—Dr. Kneeland’s mother—said HM leaders tasked with their group’s personnel duties should focus on a few main concepts:

- Think outside the bank. Some physicians look only to earn as much as they can as quickly as they can, but many seek personal and professional satisfaction.

- Engagement is instrumental. A one-day orientation program for a lifetime job doesn’t sound like enough, does it?

In the coming years, hiring managers will have to focus on “millennials”—the generation of doctors born between 1977 and 1999—which Christine Kneeland described as tech-savvy doctors interested in a blended lifestyle of work and leisure. And while some might not agree with or understand their perspective, they’d better get used to it, she said. “The millennials are here, the workplace has changed, and they are leading that change,” she added. “Just embrace it.”

QUALITY

Patient Satisfaction: Tips for Improving Your HCAHPS Scores

MODERATORS: Win Whitcomb, MD, MHM, medical director of healthcare quality, Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, Mass.; Steven Deitelzweig, MD, MMM, SFHM, system chairman, Department of Hospital Medicine, regional vice president of medical affairs, Ochsner Health System, New Orleans

Patient satisfaction scores are a big deal right now, as many HM groups tie the scores to compensation and the federal government tethers the scores and a portion of hospital payment through the value-based purchasing (VBP) program.

So how does a hospitalist improve their HCAHPS score? Here’s what the experts said:

- Personalize things. Give a business card with a picture. Sit down. Smile. Ask the patient if they understand what you’ve said, and don’t get frustrated if they don’t.

- First and last. Make good impressions when introducing yourself to the patient and when it’s time to discharge or transition them to a different facility. “When the hospitalist hands a patient off,” Dr. Whitcomb said, “it doesn’t cut it to pull out your brochure of 40 practitioners when the patient asks, ‘Who am I going to see tomorrow?’”

- Be professional. Don’t vent about workplace issues in front of patients. Dr. Deitelzweig illustrated the point with the case of an elderly patient who got out of bed to help a practitioner they heard complaining about a heavy workload. The patient fell.

- Creative use of white space. Consider using in-room white boards to help keep patients informed of a day’s care plan.

David Jaworski, MD, director of the hospitalist service at Windham Hospital in Willimantic, Conn., says honesty was a key piece of advice he gleaned from the session.

“I think one of the things people appreciate the most when they’re in the hospital is being honest about our uncertainties,” he says. “I have had more people thank me for saying, ‘I don’t know, but we will find out by doing this, this, and this.’ ”

ACADEMIC

The Role of Hospital Medicine in Adapting to the New ACGME Requirements

SPEAKER: Jeff Wiese, MD, FACP, SFHM, associate professor of medicine at Tulane University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans

The new Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) work-hour rules that take effect July 1 have received a lot of attention since they were announced last summer. The guideline that has attracted the bulk of the attention limits intern shifts to 16 hours, with upper-level residents capped at 24 consecutive hours, with four hours of administrative follow-on allowed with the caveat that strategic napping is “strongly suggested.”

“I’m all for work hours,” said Dr. Wiese, immediate past president of SHM. “It’s the right thing to do; it’s safer. But I think we have to be careful we don’t super-fragment the system or double the intensity of the system. And on both of those plates, if you don’t do it right, what you end up with is people who will be ill-prepared.”

Dr. Wiese said an easy way to question the validity of one ACGME rule is to examine the guideline that limits a first-year resident’s census to 10 patients. He wondered which scenario offers more teaching opportunities: a roster of six chest-pain cases, two pneumonia cases, and two similarly familiar or relatively safe cases, or a resident with only four cases but each one having multiple comorbidities and complex decisions?

The new rules provide hospitals and HM groups an opportunity to change their way of thinking, adds Jeffrey Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. “Every program has to change its entire way of doing business anyway, so let’s be at the table and say, ‘Well, while you’re redesigning your entire program, let’s inject patent safety and quality of care, and good pedagogy into the system,’” he says.

CLINICAL

Skin is In: Dermatological Images Every Hospitalist Should Recognize

MODERATOR: Paul Aronowitz, MD, FACP, internal medicine residency program director, California Pacific Medical Center, San Francisco

A patient comes into the ED with a blistering skin condition, but the diagnosis escapes the triage doctor on the case. The problem turns out to be bullosis diabeticorum, but the ED doc doesn’t know that yet and pushes to add a patient to the upstairs HM roster.

“The ED will usually try to admit because they’re worried [the patient has] some terrible drug eruption, but they can actually go home,” Dr. Aronowitz explained. “Hospitalists can help tell the difference.”

HM groups shouldn’t work to become amateur dermatologists, Dr. Aronowitz added. However, given that many hospitalists find themselves confronted by dermatologic cases several times a month, a rudimentary pedigree is a good idea to help sift out which cases require admission and which would take up bed space required for others.

He referred to it as knowing enough to know whether you know enough. “For sure, a hospitalist can diagnose a hypersensitivity reaction from a classic drug like Dilantin,” Dr. Aronowitz said, “and then stop the drug, because that would be one of the best things they could do.”

The session exposed hospitalists to dozens of images of skin conditions theymight come across in daily rounds, from snakebites to drug reactions to argyria.

“The idea is to help hospitalists recognize what’s serious and what’s not,” he said. “If you recognize those initial cutaneous clues, you can guide your antibiotic therapy, or whether you need antibiotics.”

CAREER

This Disease Is Easy; It’s the Patient Who’s Difficult

Speaker: Susan Block, chair, Department of Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care at Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston

Every physician will have their “button pushed” by a patient now and then, and hospitalists are in the unfortunate position of having little or no previous relationship with most patients, according to Dr. Block, a national expert in physician-patient conflict resolution who said “interpersonal challenges are an onerous part” of the job.

“We want to make sure we provide really good care to these patients, but it can be very challenging,” she said, noting that between 10% and 30% of patients in the healthcare setting present with difficult behaviors.

Whether it’s an empowered patient, a traumatized patient, an intrusive family member, or a patient with clear psychosocial issues, Dr. Block explained that “these patients can make physicians feel lousy. … Being aware of that and trying to stop that process is one of the key issues in professionalism and competence in working with difficult patients.”

She also warned hospitalists to recognize when they become a “magnet” for difficult patients, as many times the expert in the group will become the “go-to” doc. “I don’t think anyone can take care of a large panel of these patients; it’s just too much,” she said, noting you have to negotiate some limits or you will “burn out and lose perspective.”

Many doctors are very uncomfortable with scared or crying patients, Dr. Block said, explaining these are some of her most difficult patients. “Show me a patient in the hospital who isn’t scared,” she said. “Even it they aren’t, they are scared of dying.”

Other sources of workplace discomfort include the dependent or “needy” patient, the suspicious patient, and the extremely pushy patient. Dr. Block suggested setting clear boundaries with patients; she also noted physicians should be ready and willing to identify and reflect on your own emotions so that “you have the capacity to get perspective on the problem and keep yourself from being part of the problem.

“Limit-setting is one of the most therapeutic things you can do with difficult patients,” she said. “It feels to us as a form of sadism, as though we are punishing patients. But for many patients, the most dangerous, scary, and dysfunctional thing you can do for patients is not set limits.”

CLINICAL

The Art of Clinical Problem-Solving: Mystery Cases

SPEAKER: Gupreet Dhaliwal, MD, University of California at San Francisco

Humility, patience, and practice: Those are the keys to improving one’s clinical diagnostic skills, according to Dr. Dhaliwal, an acclaimed educator and clinician at UCSF who walked a packed room through two blind cases and encouraged hospitalists to work hard at their craft.

“If you want to reach your maximum potential, you have to view it the same way we do other things, the same way a great musician rehearses and a great soccer player scrimmages,” he said. “All of us are busy, but you either have to increase the number of cases you put your mind through, or you take the cases you have and you analyze them, you seek feedback, you try to improve the process around the diagnostic.

“The message isn’t always fun, because both of those things equal more work, but there is no way to hide it because there is no field in which people get better without more work.”

Dr. Dhaliwal says hospitalists should be “humble about diagnosis.” He explained that the more experienced people become, the more we shift from analytical reasoning, “thinking hard like we did when we were students and residents,” to intuitive reasoning, which “is basically saying, ‘I recognize a pattern, this is an old friend, I’ve seen gout before.’ I think any of us can be guilty of forgetting that it has pitfalls. And there is a whole list of cognitive biases that are associated with moving fast and building patterns.”

He also believes hospitalists who dedicate themselves to clinical greatness can parlay such improvement in the quality realm. “Every one of us has used diagnosis as a core part of our identity, but in terms of getting the community or other stakeholders behind improving diagnosis or improving judgment, I think the umbrella of quality and reducing diagnostic errors is the most appealing and most logical,” he says. “I think we start to take for granted we are good at it, but I think there are ways many of us, especially if we work at it, can become great at it.”

CLINICAL

The How, When, and Why of Noninvasive Ventilation

SPEAKER: Eric Siegal, MD, SFHM, critical care fellow, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine, Madison

Dr. Siegal’s review of literature in front of a packed crowd provided a road map to Noninvasive Positive Pressure Ventilation (NPPV) usage. In the end, NPPV should be a hospitalist’s first choice for patients with hypercarbic COPD exacerbations, and likely in patients with acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema, hypoxemic respiratory failure, immunocompromised patients, and pre-intubation patients.

Dr. Siegal stressed the use of NPPV in COPD, which has been studied thoroughly and “held up to repeated scrutiny.”

“If you put people on NPPV instead of intubating them … mortality is halved, intubation rate is less than half, treatment failure is much lower, you have a third of the complications, and huge reductions in length of stay,” Dr. Siegal said.

In the absence of contraindications, he stressed, NPPV should be the first line of therapy for patients with hypercarbic COPD exacerbations. “In fact, I would argue that you really should be asking yourself, ‘Why can’t I put these patients on NPPV?’ ” he asked, “because this has really shown to be life-saving.”

Dr. Siegal also explored recent findings on NPPV in acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema patients, which surprisingly showed “no better than supplemental oxygen.” He concluded that if your patient is not hypercarbic, “there is no advantage to adding pressure support.” He also said the benefit is more robust in ACPE patients who have acute coronary syndrome.

Dr. Siegal advised hospitalists to pick the right patients, start NPPV therapy early, and if the patient doesn’t improve within one or two hours, “it’s time to move on.”

QUALITY

Utilizing Technology to Improve the Clinical and Operational Performance of Hospitalists

SPEAKERS: Jason Stein, MD, SFHM, associate vice chair for quality, Department of Medicine, Bryce Gartland, MD, FHM, associate director, section of hospital medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta

In an age of increasing technology, just getting technology into a hospital isn’t the answer. It’s about integrating it into practice to improve care.

At Emory, the marriage of “low-tech solutions” and patented data displays has resulted in what Drs. Stein and Gartland call an accountable-care unit (ACU). The unit-based team features geographic ownership and structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds (SIBR). Perhaps more important, the unit generates real-time data captured on monitors, allowing teams of hospitalists, nonphysician providers (NPPs), residents, interns, and social workers to “visually digest immense amounts of information in a very short time period,” Dr. Gartland said.

Dr. Stein defined an ACU as a bounded geographic inpatient area responsible for the clinical, service, and cost outcomes it produces. To help manage beds, Emory instituted a system called “e-Bed,” a McKesson system that tracks room availability. The system shows whether rooms are occupied, being cleaned, or somewhere in between. It has icons to show whether patients are elsewhere in the hospital for treatment, as well as clinical data capacities. Unit teams round together and use a portable workstation or tablet computer to input clinical data, notes, or other comments into real-time dashboards that can then show everything from VTE prophylaxis to whether a patient is at high risk for falls.

The project has been in the works for several years, and Dr. Garltand noted that any hospitalists looking to push similar initiatives at their institution need to ensure that they have buy-in from providers and a commitment to seeing the project through.

“Timing is everything,” he said. “If we tried to force this … a few years ago, it would not have worked.”

PRACTICE MANAGEMENT

Recruiting and Retaining Hospitalists: Developing a Talent Facilitation Framework

SPEAKERS: Patrick Kneeland, MD, hospitalist, Providence Regional Medical Center, Everett, Wash.; Christine Kneeland, COO, Center Partners, Fort Collins, Colo.; Niraj Sehgal, associate professor of medicine, associate chair for quality and safety, Department of Medicine, University of California at San Francisco

Lincoln Godfrey, DO, a hospitalist at Baxter Regional Medical Center in Mountain Home, Ark., was sitting and listening to strategies to lure and keep hospitalists when his hospital CEO sent him a text asking how his recruiting efforts were going with a would-be hire.

“I said I’d get back to him,” Dr. Godfrey jokes.

The C-suite’s passion is understandable, though, as the fight to hire experienced staff outside of major markets continues to stymie many HM groups. Dr. Godfrey says he can’t hire anybody without first getting them to the Ozark Mountains to learn the hospital, its people, and its community.

“There’s going to be a limited talent pool of people who will come at all,” he says. “But I don’t get anybody who doesn’t work with us for a bit first.”

Christine Kneeland—Dr. Kneeland’s mother—said HM leaders tasked with their group’s personnel duties should focus on a few main concepts:

- Think outside the bank. Some physicians look only to earn as much as they can as quickly as they can, but many seek personal and professional satisfaction.

- Engagement is instrumental. A one-day orientation program for a lifetime job doesn’t sound like enough, does it?

In the coming years, hiring managers will have to focus on “millennials”—the generation of doctors born between 1977 and 1999—which Christine Kneeland described as tech-savvy doctors interested in a blended lifestyle of work and leisure. And while some might not agree with or understand their perspective, they’d better get used to it, she said. “The millennials are here, the workplace has changed, and they are leading that change,” she added. “Just embrace it.”

QUALITY

Patient Satisfaction: Tips for Improving Your HCAHPS Scores

MODERATORS: Win Whitcomb, MD, MHM, medical director of healthcare quality, Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, Mass.; Steven Deitelzweig, MD, MMM, SFHM, system chairman, Department of Hospital Medicine, regional vice president of medical affairs, Ochsner Health System, New Orleans

Patient satisfaction scores are a big deal right now, as many HM groups tie the scores to compensation and the federal government tethers the scores and a portion of hospital payment through the value-based purchasing (VBP) program.

So how does a hospitalist improve their HCAHPS score? Here’s what the experts said:

- Personalize things. Give a business card with a picture. Sit down. Smile. Ask the patient if they understand what you’ve said, and don’t get frustrated if they don’t.

- First and last. Make good impressions when introducing yourself to the patient and when it’s time to discharge or transition them to a different facility. “When the hospitalist hands a patient off,” Dr. Whitcomb said, “it doesn’t cut it to pull out your brochure of 40 practitioners when the patient asks, ‘Who am I going to see tomorrow?’”

- Be professional. Don’t vent about workplace issues in front of patients. Dr. Deitelzweig illustrated the point with the case of an elderly patient who got out of bed to help a practitioner they heard complaining about a heavy workload. The patient fell.

- Creative use of white space. Consider using in-room white boards to help keep patients informed of a day’s care plan.

David Jaworski, MD, director of the hospitalist service at Windham Hospital in Willimantic, Conn., says honesty was a key piece of advice he gleaned from the session.

“I think one of the things people appreciate the most when they’re in the hospital is being honest about our uncertainties,” he says. “I have had more people thank me for saying, ‘I don’t know, but we will find out by doing this, this, and this.’ ”

ACADEMIC

The Role of Hospital Medicine in Adapting to the New ACGME Requirements

SPEAKER: Jeff Wiese, MD, FACP, SFHM, associate professor of medicine at Tulane University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans

The new Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) work-hour rules that take effect July 1 have received a lot of attention since they were announced last summer. The guideline that has attracted the bulk of the attention limits intern shifts to 16 hours, with upper-level residents capped at 24 consecutive hours, with four hours of administrative follow-on allowed with the caveat that strategic napping is “strongly suggested.”

“I’m all for work hours,” said Dr. Wiese, immediate past president of SHM. “It’s the right thing to do; it’s safer. But I think we have to be careful we don’t super-fragment the system or double the intensity of the system. And on both of those plates, if you don’t do it right, what you end up with is people who will be ill-prepared.”

Dr. Wiese said an easy way to question the validity of one ACGME rule is to examine the guideline that limits a first-year resident’s census to 10 patients. He wondered which scenario offers more teaching opportunities: a roster of six chest-pain cases, two pneumonia cases, and two similarly familiar or relatively safe cases, or a resident with only four cases but each one having multiple comorbidities and complex decisions?

The new rules provide hospitals and HM groups an opportunity to change their way of thinking, adds Jeffrey Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. “Every program has to change its entire way of doing business anyway, so let’s be at the table and say, ‘Well, while you’re redesigning your entire program, let’s inject patent safety and quality of care, and good pedagogy into the system,’” he says.

CLINICAL

Skin is In: Dermatological Images Every Hospitalist Should Recognize

MODERATOR: Paul Aronowitz, MD, FACP, internal medicine residency program director, California Pacific Medical Center, San Francisco

A patient comes into the ED with a blistering skin condition, but the diagnosis escapes the triage doctor on the case. The problem turns out to be bullosis diabeticorum, but the ED doc doesn’t know that yet and pushes to add a patient to the upstairs HM roster.

“The ED will usually try to admit because they’re worried [the patient has] some terrible drug eruption, but they can actually go home,” Dr. Aronowitz explained. “Hospitalists can help tell the difference.”

HM groups shouldn’t work to become amateur dermatologists, Dr. Aronowitz added. However, given that many hospitalists find themselves confronted by dermatologic cases several times a month, a rudimentary pedigree is a good idea to help sift out which cases require admission and which would take up bed space required for others.

He referred to it as knowing enough to know whether you know enough. “For sure, a hospitalist can diagnose a hypersensitivity reaction from a classic drug like Dilantin,” Dr. Aronowitz said, “and then stop the drug, because that would be one of the best things they could do.”

The session exposed hospitalists to dozens of images of skin conditions theymight come across in daily rounds, from snakebites to drug reactions to argyria.

“The idea is to help hospitalists recognize what’s serious and what’s not,” he said. “If you recognize those initial cutaneous clues, you can guide your antibiotic therapy, or whether you need antibiotics.”

CAREER

This Disease Is Easy; It’s the Patient Who’s Difficult

Speaker: Susan Block, chair, Department of Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care at Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston

Every physician will have their “button pushed” by a patient now and then, and hospitalists are in the unfortunate position of having little or no previous relationship with most patients, according to Dr. Block, a national expert in physician-patient conflict resolution who said “interpersonal challenges are an onerous part” of the job.

“We want to make sure we provide really good care to these patients, but it can be very challenging,” she said, noting that between 10% and 30% of patients in the healthcare setting present with difficult behaviors.

Whether it’s an empowered patient, a traumatized patient, an intrusive family member, or a patient with clear psychosocial issues, Dr. Block explained that “these patients can make physicians feel lousy. … Being aware of that and trying to stop that process is one of the key issues in professionalism and competence in working with difficult patients.”

She also warned hospitalists to recognize when they become a “magnet” for difficult patients, as many times the expert in the group will become the “go-to” doc. “I don’t think anyone can take care of a large panel of these patients; it’s just too much,” she said, noting you have to negotiate some limits or you will “burn out and lose perspective.”

Many doctors are very uncomfortable with scared or crying patients, Dr. Block said, explaining these are some of her most difficult patients. “Show me a patient in the hospital who isn’t scared,” she said. “Even it they aren’t, they are scared of dying.”

Other sources of workplace discomfort include the dependent or “needy” patient, the suspicious patient, and the extremely pushy patient. Dr. Block suggested setting clear boundaries with patients; she also noted physicians should be ready and willing to identify and reflect on your own emotions so that “you have the capacity to get perspective on the problem and keep yourself from being part of the problem.

“Limit-setting is one of the most therapeutic things you can do with difficult patients,” she said. “It feels to us as a form of sadism, as though we are punishing patients. But for many patients, the most dangerous, scary, and dysfunctional thing you can do for patients is not set limits.”

CLINICAL

The Art of Clinical Problem-Solving: Mystery Cases

SPEAKER: Gupreet Dhaliwal, MD, University of California at San Francisco

Humility, patience, and practice: Those are the keys to improving one’s clinical diagnostic skills, according to Dr. Dhaliwal, an acclaimed educator and clinician at UCSF who walked a packed room through two blind cases and encouraged hospitalists to work hard at their craft.

“If you want to reach your maximum potential, you have to view it the same way we do other things, the same way a great musician rehearses and a great soccer player scrimmages,” he said. “All of us are busy, but you either have to increase the number of cases you put your mind through, or you take the cases you have and you analyze them, you seek feedback, you try to improve the process around the diagnostic.

“The message isn’t always fun, because both of those things equal more work, but there is no way to hide it because there is no field in which people get better without more work.”

Dr. Dhaliwal says hospitalists should be “humble about diagnosis.” He explained that the more experienced people become, the more we shift from analytical reasoning, “thinking hard like we did when we were students and residents,” to intuitive reasoning, which “is basically saying, ‘I recognize a pattern, this is an old friend, I’ve seen gout before.’ I think any of us can be guilty of forgetting that it has pitfalls. And there is a whole list of cognitive biases that are associated with moving fast and building patterns.”

He also believes hospitalists who dedicate themselves to clinical greatness can parlay such improvement in the quality realm. “Every one of us has used diagnosis as a core part of our identity, but in terms of getting the community or other stakeholders behind improving diagnosis or improving judgment, I think the umbrella of quality and reducing diagnostic errors is the most appealing and most logical,” he says. “I think we start to take for granted we are good at it, but I think there are ways many of us, especially if we work at it, can become great at it.”

CLINICAL

The How, When, and Why of Noninvasive Ventilation

SPEAKER: Eric Siegal, MD, SFHM, critical care fellow, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine, Madison

Dr. Siegal’s review of literature in front of a packed crowd provided a road map to Noninvasive Positive Pressure Ventilation (NPPV) usage. In the end, NPPV should be a hospitalist’s first choice for patients with hypercarbic COPD exacerbations, and likely in patients with acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema, hypoxemic respiratory failure, immunocompromised patients, and pre-intubation patients.

Dr. Siegal stressed the use of NPPV in COPD, which has been studied thoroughly and “held up to repeated scrutiny.”

“If you put people on NPPV instead of intubating them … mortality is halved, intubation rate is less than half, treatment failure is much lower, you have a third of the complications, and huge reductions in length of stay,” Dr. Siegal said.

In the absence of contraindications, he stressed, NPPV should be the first line of therapy for patients with hypercarbic COPD exacerbations. “In fact, I would argue that you really should be asking yourself, ‘Why can’t I put these patients on NPPV?’ ” he asked, “because this has really shown to be life-saving.”

Dr. Siegal also explored recent findings on NPPV in acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema patients, which surprisingly showed “no better than supplemental oxygen.” He concluded that if your patient is not hypercarbic, “there is no advantage to adding pressure support.” He also said the benefit is more robust in ACPE patients who have acute coronary syndrome.

Dr. Siegal advised hospitalists to pick the right patients, start NPPV therapy early, and if the patient doesn’t improve within one or two hours, “it’s time to move on.”

HM11 Special Report: Pediatric Perils

Pediatric hospitalists demonstrated their leadership and ownership of clinical hospital medicine on this year’s pediatric track at HM11.

Joel Tieder, MD, MPH, advocated for a balanced and risk-based approach to apparent life-threatening events (ALTEs). Although the differential for this observer-defined symptom remains broad, a link to perhaps the most worrisome outcome, sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), has not been borne out in the medical literature. Testing seldom offers conclusive answers, Dr. Tieder said in his review.

Thus, a risk-based approach to guide work-up is prudent. Young age and a history of recurrent events are two factors that could signify risk for worrisome underlying pathology, to include infection and nonaccidental trauma. Dr. Tieder has worked with SHM to organize and lead an expert panel that hopes to release a white paper on this topic in the future.

John Pope, MD, Kris Rehm, MD, and Brian Alverson, MD, collectively presented an update on the top articles of the year relevant to pediatric HM.

Highlights included:

- The potential utility of the Pediatric Early Warning Score in identifying clinical deterioration;

- A reduction in symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome given Lactobacillus GG;

- The positive impact of an antimicrobial stewardship program on vancomycin usage;

- The utility of the clinical examination in deciding whether a lumbar puncture is warranted to evaluate for bacterial meningitis in patients presenting with complex febrile seizures; and

- The adequacy of short-term IV antibiotic therapy in young infants with UTIs.

Dr. Alverson provided an update on the development of clinical practice guidelines for community-acquired pneumonia in children, highlighting his participation on a committee cosponsored by the Pediatric Infectious Disease Society and the Infectious Disease Society of America. Laboratory and radiographic data rarely clarify the diagnosis of clinical pneumonia and are not as useful in the outpatient setting but may be justified to look for complications in children who are hospitalized, he reported.

Other take-home points:

- Antimicrobial therapy in uncomplicated pneumonia should primarily target pneumococcus;

- Ampicillin and amoxicillin penetrate lung tissue well, and in high dosages can overcome most pneumococcal resistance; and

- Management of mycoplasma in children remains controversial and requires further investigation.

- The final guidelines are expected to be published sometime toward the end of the year.

Dr. Shen is pediatric editor of The Hospitalist.

Pediatric hospitalists demonstrated their leadership and ownership of clinical hospital medicine on this year’s pediatric track at HM11.

Joel Tieder, MD, MPH, advocated for a balanced and risk-based approach to apparent life-threatening events (ALTEs). Although the differential for this observer-defined symptom remains broad, a link to perhaps the most worrisome outcome, sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), has not been borne out in the medical literature. Testing seldom offers conclusive answers, Dr. Tieder said in his review.

Thus, a risk-based approach to guide work-up is prudent. Young age and a history of recurrent events are two factors that could signify risk for worrisome underlying pathology, to include infection and nonaccidental trauma. Dr. Tieder has worked with SHM to organize and lead an expert panel that hopes to release a white paper on this topic in the future.

John Pope, MD, Kris Rehm, MD, and Brian Alverson, MD, collectively presented an update on the top articles of the year relevant to pediatric HM.

Highlights included:

- The potential utility of the Pediatric Early Warning Score in identifying clinical deterioration;

- A reduction in symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome given Lactobacillus GG;

- The positive impact of an antimicrobial stewardship program on vancomycin usage;

- The utility of the clinical examination in deciding whether a lumbar puncture is warranted to evaluate for bacterial meningitis in patients presenting with complex febrile seizures; and

- The adequacy of short-term IV antibiotic therapy in young infants with UTIs.

Dr. Alverson provided an update on the development of clinical practice guidelines for community-acquired pneumonia in children, highlighting his participation on a committee cosponsored by the Pediatric Infectious Disease Society and the Infectious Disease Society of America. Laboratory and radiographic data rarely clarify the diagnosis of clinical pneumonia and are not as useful in the outpatient setting but may be justified to look for complications in children who are hospitalized, he reported.

Other take-home points:

- Antimicrobial therapy in uncomplicated pneumonia should primarily target pneumococcus;

- Ampicillin and amoxicillin penetrate lung tissue well, and in high dosages can overcome most pneumococcal resistance; and

- Management of mycoplasma in children remains controversial and requires further investigation.

- The final guidelines are expected to be published sometime toward the end of the year.

Dr. Shen is pediatric editor of The Hospitalist.

Pediatric hospitalists demonstrated their leadership and ownership of clinical hospital medicine on this year’s pediatric track at HM11.

Joel Tieder, MD, MPH, advocated for a balanced and risk-based approach to apparent life-threatening events (ALTEs). Although the differential for this observer-defined symptom remains broad, a link to perhaps the most worrisome outcome, sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), has not been borne out in the medical literature. Testing seldom offers conclusive answers, Dr. Tieder said in his review.

Thus, a risk-based approach to guide work-up is prudent. Young age and a history of recurrent events are two factors that could signify risk for worrisome underlying pathology, to include infection and nonaccidental trauma. Dr. Tieder has worked with SHM to organize and lead an expert panel that hopes to release a white paper on this topic in the future.

John Pope, MD, Kris Rehm, MD, and Brian Alverson, MD, collectively presented an update on the top articles of the year relevant to pediatric HM.

Highlights included:

- The potential utility of the Pediatric Early Warning Score in identifying clinical deterioration;

- A reduction in symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome given Lactobacillus GG;

- The positive impact of an antimicrobial stewardship program on vancomycin usage;

- The utility of the clinical examination in deciding whether a lumbar puncture is warranted to evaluate for bacterial meningitis in patients presenting with complex febrile seizures; and

- The adequacy of short-term IV antibiotic therapy in young infants with UTIs.

Dr. Alverson provided an update on the development of clinical practice guidelines for community-acquired pneumonia in children, highlighting his participation on a committee cosponsored by the Pediatric Infectious Disease Society and the Infectious Disease Society of America. Laboratory and radiographic data rarely clarify the diagnosis of clinical pneumonia and are not as useful in the outpatient setting but may be justified to look for complications in children who are hospitalized, he reported.

Other take-home points:

- Antimicrobial therapy in uncomplicated pneumonia should primarily target pneumococcus;

- Ampicillin and amoxicillin penetrate lung tissue well, and in high dosages can overcome most pneumococcal resistance; and

- Management of mycoplasma in children remains controversial and requires further investigation.

- The final guidelines are expected to be published sometime toward the end of the year.

Dr. Shen is pediatric editor of The Hospitalist.

Something for Everyone

GRAPEVINE, Texas—Femi Adewunmi, MD, MBA, SFHM, might land a new job as a multisite medical director because of it. Amaka Nweke, MD, might have gained an idea for a new committee for her hospital from it. And Randa Perkins, MD, is going to lead one long brown-bag lunch thanks to it.

Everyone gets something different out of SHM’s annual meeting, a four-day bazaar of CME, plenary sessions, and breakout sessions akin to one-hour crash courses that follow clinical, academic, practice management, pediatric, and quality tracks.

The Hospitalist sat down with three attendees to break down what each took home from HM11.

New Year, New Job?

A veteran of multiple annual meetings, Dr. Adewunmi usually splits his time between breakout sessions and networking. But this year, the former medical director of the hospitalist service at Johnston Medical Center in Smithfield, N.C., says he’s looking to step up from a single-site leadership position to a regional head. So the mission was more about networking than note-taking.

“It’s been invaluable for me at this point,” Dr. Adewunmi says, “as I navigate and decide what the next steps should be in terms of my career progression.”

Of course, that progression meant using his time-management skills to hold discussions with potential employers.

“I was in and out,” he says, noting he’s been doing locum tenens work for several months as he weighs his next move. “Sometimes, if you want to have the time to meet one-on-one [at the exhibitor hall]without the crowd and the distractions, it’s probably easier and better to go in between sessions.”

Dr. Adewunmi, a newly seated member of Team Hospitalist, says he met with eight to 10 of the largest HM firms during the meeting. He leveraged contacts he’s built over the years, and also used relationships with SHM staff to make introductions. He thinks employers appreciate the annual meeting for the same reason.

“It’s one spot where rather than trying to fly in 10 or 20 candidates every month or every few weeks, you can just come in one spot and interview several people … or put your feelers out,” he says. “It works both ways.”

Dr. Adewunmi can’t be sure his networking will be successful. He plans to keep working locums with one potential employer so both sides can get to know each other. But even if nothing pans out, between the clinical sessions he attended and the relationships he either built or strengthened, he says he’s glad he came again to the annual meeting.

“This, for me, has always been the best resource in terms of place you could come to one stop and get a little bit of everything,” he adds. “It’s like a buffet.”

Meet and Greet, Over and Over

Dr. Nweke, assistant site director for Hospitalists Management Group at Kenosha Medical Center in Wisconsin, wasn’t going to let her first meeting overwhelm her. She laid out her agenda early, planning to attend as many practice management and leadership classes as she could. When she arrived, she sat through talks including “Understanding Your Hospital’s Key Financial Drivers,” “Hiding in Plain Sight,” and “Introduction to QI Methodology.”

But it was a session on basic tips to improve patient-satisfaction scores that gave her the most feedback.

“There are a lot of things you kind of instinctively know just as a human being as opposed to being a physician,” Dr. Nweke says. “It’s only polite that you shake the hand of the person you’re meeting and you smile at them, as opposed to being a grouch. But it’s interesting to hear what questions are asked in the patient surveys. While I was there, I actually sat thinking from a patient’s perspective: ‘What would I be looking for in my hospital?’ ”

Dr. Nweke admittedly felt a bit frustrated with some sessions, as she’d hoped to extract more advanced tips. However, she had no complaints about the networking opportunities. Everywhere she turned, she says, she had the chance to discuss ideas with new faces.

“I’ve randomly met people, introduced myself to people, and talked about different challenges,” she says. “For someone like me, it’s really very important because I’m at the bottom of the totem pole, so to speak, as far as leadership.”

One bit of practical advice Dr. Nweke learned from meeting someone was the idea of a medical records committee. One of her new contacts chairs such a committee, which prompted Dr. Nweke to check in with her hospital while the annual meeting was happening. Turns out, her hospital doesn’t have a similar committee. Yet.

“Maybe this might be something I could throw out there and say, ‘How about we do this or that?’ ” Dr. Nweke adds, “whatever it might be, little things that I could do to improve and add some value and worth to my program, and our relationship with the hospital.”

A Kid in a Candy Store

If Dr. Perkins ever becomes president of the society, HM11 will be why. A self-proclaimed lame-duck chief resident at Tallahassee Memorial’s Family Medicine Residency Program in Florida, she’d already signed her first contract as a hospitalist and starts the job in August. Yet she didn’t know about SHM or the annual meeting until shortly before it started, when a community physician mentioned it to her.

So she booked a room at a nearby hotel (the 1,551-room Gaylord Texan Resort and Convention Center having filled up early) and spent the last of her CME money on HM11. She had trouble picking out any specific tips she wanted to take home to her new practice, Tallahassee Memorial HealthCare Hospitalists Group, as she had so many.

She sat in a recruitment session just to have things to tell her new boss. She took feverish notes during a presentation on best practices in the ICU because she’ll be spending a lot of time there. And during a meet-and-greet pairing residents with potential mentors, she befriended Daniel Dressler, MD, MSc, SFHM, an SHM board member, HM11’s course director, and academic hospitalist heavyweight at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta.

“It’s kind of like when you start any adventure, you don’t have everything laid out in a guidebook,” Dr. Perkins says. “You just kind of have to put your feet out there and start moving and hope to God that things fall into your lap sometimes. This conference kind of did. This is kind of my guidebook, this is my compass, this is what I can look to when I’m trying to figure out how to make my own path in the specialty.”

Dr. Perkins adds that the fraternal feel of HM11 makes her feel like she chose the right specialty. Given all of the research talk, she might even start pushing her 12-member hospitalist group to begin more projects that could “help our community.”

“All the educational opportunities that were at the conference pulled me into it and then, all of a sudden, all these resources are laid out in front of me,” she adds. “I’m literally a kid in a candy store with access to data and information and guides. It’s great.” TH

GRAPEVINE, Texas—Femi Adewunmi, MD, MBA, SFHM, might land a new job as a multisite medical director because of it. Amaka Nweke, MD, might have gained an idea for a new committee for her hospital from it. And Randa Perkins, MD, is going to lead one long brown-bag lunch thanks to it.

Everyone gets something different out of SHM’s annual meeting, a four-day bazaar of CME, plenary sessions, and breakout sessions akin to one-hour crash courses that follow clinical, academic, practice management, pediatric, and quality tracks.

The Hospitalist sat down with three attendees to break down what each took home from HM11.

New Year, New Job?

A veteran of multiple annual meetings, Dr. Adewunmi usually splits his time between breakout sessions and networking. But this year, the former medical director of the hospitalist service at Johnston Medical Center in Smithfield, N.C., says he’s looking to step up from a single-site leadership position to a regional head. So the mission was more about networking than note-taking.

“It’s been invaluable for me at this point,” Dr. Adewunmi says, “as I navigate and decide what the next steps should be in terms of my career progression.”

Of course, that progression meant using his time-management skills to hold discussions with potential employers.

“I was in and out,” he says, noting he’s been doing locum tenens work for several months as he weighs his next move. “Sometimes, if you want to have the time to meet one-on-one [at the exhibitor hall]without the crowd and the distractions, it’s probably easier and better to go in between sessions.”

Dr. Adewunmi, a newly seated member of Team Hospitalist, says he met with eight to 10 of the largest HM firms during the meeting. He leveraged contacts he’s built over the years, and also used relationships with SHM staff to make introductions. He thinks employers appreciate the annual meeting for the same reason.

“It’s one spot where rather than trying to fly in 10 or 20 candidates every month or every few weeks, you can just come in one spot and interview several people … or put your feelers out,” he says. “It works both ways.”

Dr. Adewunmi can’t be sure his networking will be successful. He plans to keep working locums with one potential employer so both sides can get to know each other. But even if nothing pans out, between the clinical sessions he attended and the relationships he either built or strengthened, he says he’s glad he came again to the annual meeting.

“This, for me, has always been the best resource in terms of place you could come to one stop and get a little bit of everything,” he adds. “It’s like a buffet.”

Meet and Greet, Over and Over

Dr. Nweke, assistant site director for Hospitalists Management Group at Kenosha Medical Center in Wisconsin, wasn’t going to let her first meeting overwhelm her. She laid out her agenda early, planning to attend as many practice management and leadership classes as she could. When she arrived, she sat through talks including “Understanding Your Hospital’s Key Financial Drivers,” “Hiding in Plain Sight,” and “Introduction to QI Methodology.”

But it was a session on basic tips to improve patient-satisfaction scores that gave her the most feedback.

“There are a lot of things you kind of instinctively know just as a human being as opposed to being a physician,” Dr. Nweke says. “It’s only polite that you shake the hand of the person you’re meeting and you smile at them, as opposed to being a grouch. But it’s interesting to hear what questions are asked in the patient surveys. While I was there, I actually sat thinking from a patient’s perspective: ‘What would I be looking for in my hospital?’ ”

Dr. Nweke admittedly felt a bit frustrated with some sessions, as she’d hoped to extract more advanced tips. However, she had no complaints about the networking opportunities. Everywhere she turned, she says, she had the chance to discuss ideas with new faces.

“I’ve randomly met people, introduced myself to people, and talked about different challenges,” she says. “For someone like me, it’s really very important because I’m at the bottom of the totem pole, so to speak, as far as leadership.”

One bit of practical advice Dr. Nweke learned from meeting someone was the idea of a medical records committee. One of her new contacts chairs such a committee, which prompted Dr. Nweke to check in with her hospital while the annual meeting was happening. Turns out, her hospital doesn’t have a similar committee. Yet.

“Maybe this might be something I could throw out there and say, ‘How about we do this or that?’ ” Dr. Nweke adds, “whatever it might be, little things that I could do to improve and add some value and worth to my program, and our relationship with the hospital.”

A Kid in a Candy Store

If Dr. Perkins ever becomes president of the society, HM11 will be why. A self-proclaimed lame-duck chief resident at Tallahassee Memorial’s Family Medicine Residency Program in Florida, she’d already signed her first contract as a hospitalist and starts the job in August. Yet she didn’t know about SHM or the annual meeting until shortly before it started, when a community physician mentioned it to her.

So she booked a room at a nearby hotel (the 1,551-room Gaylord Texan Resort and Convention Center having filled up early) and spent the last of her CME money on HM11. She had trouble picking out any specific tips she wanted to take home to her new practice, Tallahassee Memorial HealthCare Hospitalists Group, as she had so many.

She sat in a recruitment session just to have things to tell her new boss. She took feverish notes during a presentation on best practices in the ICU because she’ll be spending a lot of time there. And during a meet-and-greet pairing residents with potential mentors, she befriended Daniel Dressler, MD, MSc, SFHM, an SHM board member, HM11’s course director, and academic hospitalist heavyweight at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta.

“It’s kind of like when you start any adventure, you don’t have everything laid out in a guidebook,” Dr. Perkins says. “You just kind of have to put your feet out there and start moving and hope to God that things fall into your lap sometimes. This conference kind of did. This is kind of my guidebook, this is my compass, this is what I can look to when I’m trying to figure out how to make my own path in the specialty.”

Dr. Perkins adds that the fraternal feel of HM11 makes her feel like she chose the right specialty. Given all of the research talk, she might even start pushing her 12-member hospitalist group to begin more projects that could “help our community.”

“All the educational opportunities that were at the conference pulled me into it and then, all of a sudden, all these resources are laid out in front of me,” she adds. “I’m literally a kid in a candy store with access to data and information and guides. It’s great.” TH

GRAPEVINE, Texas—Femi Adewunmi, MD, MBA, SFHM, might land a new job as a multisite medical director because of it. Amaka Nweke, MD, might have gained an idea for a new committee for her hospital from it. And Randa Perkins, MD, is going to lead one long brown-bag lunch thanks to it.

Everyone gets something different out of SHM’s annual meeting, a four-day bazaar of CME, plenary sessions, and breakout sessions akin to one-hour crash courses that follow clinical, academic, practice management, pediatric, and quality tracks.

The Hospitalist sat down with three attendees to break down what each took home from HM11.

New Year, New Job?

A veteran of multiple annual meetings, Dr. Adewunmi usually splits his time between breakout sessions and networking. But this year, the former medical director of the hospitalist service at Johnston Medical Center in Smithfield, N.C., says he’s looking to step up from a single-site leadership position to a regional head. So the mission was more about networking than note-taking.

“It’s been invaluable for me at this point,” Dr. Adewunmi says, “as I navigate and decide what the next steps should be in terms of my career progression.”

Of course, that progression meant using his time-management skills to hold discussions with potential employers.

“I was in and out,” he says, noting he’s been doing locum tenens work for several months as he weighs his next move. “Sometimes, if you want to have the time to meet one-on-one [at the exhibitor hall]without the crowd and the distractions, it’s probably easier and better to go in between sessions.”

Dr. Adewunmi, a newly seated member of Team Hospitalist, says he met with eight to 10 of the largest HM firms during the meeting. He leveraged contacts he’s built over the years, and also used relationships with SHM staff to make introductions. He thinks employers appreciate the annual meeting for the same reason.

“It’s one spot where rather than trying to fly in 10 or 20 candidates every month or every few weeks, you can just come in one spot and interview several people … or put your feelers out,” he says. “It works both ways.”

Dr. Adewunmi can’t be sure his networking will be successful. He plans to keep working locums with one potential employer so both sides can get to know each other. But even if nothing pans out, between the clinical sessions he attended and the relationships he either built or strengthened, he says he’s glad he came again to the annual meeting.

“This, for me, has always been the best resource in terms of place you could come to one stop and get a little bit of everything,” he adds. “It’s like a buffet.”

Meet and Greet, Over and Over

Dr. Nweke, assistant site director for Hospitalists Management Group at Kenosha Medical Center in Wisconsin, wasn’t going to let her first meeting overwhelm her. She laid out her agenda early, planning to attend as many practice management and leadership classes as she could. When she arrived, she sat through talks including “Understanding Your Hospital’s Key Financial Drivers,” “Hiding in Plain Sight,” and “Introduction to QI Methodology.”

But it was a session on basic tips to improve patient-satisfaction scores that gave her the most feedback.

“There are a lot of things you kind of instinctively know just as a human being as opposed to being a physician,” Dr. Nweke says. “It’s only polite that you shake the hand of the person you’re meeting and you smile at them, as opposed to being a grouch. But it’s interesting to hear what questions are asked in the patient surveys. While I was there, I actually sat thinking from a patient’s perspective: ‘What would I be looking for in my hospital?’ ”

Dr. Nweke admittedly felt a bit frustrated with some sessions, as she’d hoped to extract more advanced tips. However, she had no complaints about the networking opportunities. Everywhere she turned, she says, she had the chance to discuss ideas with new faces.

“I’ve randomly met people, introduced myself to people, and talked about different challenges,” she says. “For someone like me, it’s really very important because I’m at the bottom of the totem pole, so to speak, as far as leadership.”

One bit of practical advice Dr. Nweke learned from meeting someone was the idea of a medical records committee. One of her new contacts chairs such a committee, which prompted Dr. Nweke to check in with her hospital while the annual meeting was happening. Turns out, her hospital doesn’t have a similar committee. Yet.

“Maybe this might be something I could throw out there and say, ‘How about we do this or that?’ ” Dr. Nweke adds, “whatever it might be, little things that I could do to improve and add some value and worth to my program, and our relationship with the hospital.”

A Kid in a Candy Store

If Dr. Perkins ever becomes president of the society, HM11 will be why. A self-proclaimed lame-duck chief resident at Tallahassee Memorial’s Family Medicine Residency Program in Florida, she’d already signed her first contract as a hospitalist and starts the job in August. Yet she didn’t know about SHM or the annual meeting until shortly before it started, when a community physician mentioned it to her.

So she booked a room at a nearby hotel (the 1,551-room Gaylord Texan Resort and Convention Center having filled up early) and spent the last of her CME money on HM11. She had trouble picking out any specific tips she wanted to take home to her new practice, Tallahassee Memorial HealthCare Hospitalists Group, as she had so many.

She sat in a recruitment session just to have things to tell her new boss. She took feverish notes during a presentation on best practices in the ICU because she’ll be spending a lot of time there. And during a meet-and-greet pairing residents with potential mentors, she befriended Daniel Dressler, MD, MSc, SFHM, an SHM board member, HM11’s course director, and academic hospitalist heavyweight at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta.

“It’s kind of like when you start any adventure, you don’t have everything laid out in a guidebook,” Dr. Perkins says. “You just kind of have to put your feet out there and start moving and hope to God that things fall into your lap sometimes. This conference kind of did. This is kind of my guidebook, this is my compass, this is what I can look to when I’m trying to figure out how to make my own path in the specialty.”

Dr. Perkins adds that the fraternal feel of HM11 makes her feel like she chose the right specialty. Given all of the research talk, she might even start pushing her 12-member hospitalist group to begin more projects that could “help our community.”

“All the educational opportunities that were at the conference pulled me into it and then, all of a sudden, all these resources are laid out in front of me,” she adds. “I’m literally a kid in a candy store with access to data and information and guides. It’s great.” TH

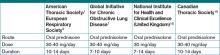

What Corticosteroid is Most Appropriate for treating Acute Exacerbations of CoPD?

Case

A 66-year-old Caucasian female with moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (FEV1 55% predicted), obesity, hypertension, and Type 2 diabetes mellitus on insulin therapy presents to the ED with four days of increased cough productive of yellow sputum and progressive shortness of breath. Her physical exam is notable for an oxygen saturation of 87% on room air, along with diffuse expiratory wheezing with use of accessory muscles; her chest X-ray is unchanged from previous. The patient is given oxygen, nebulized bronchodilators, and one dose of IV methylprednisolone. Her symptoms do not improve significantly, and she is admitted for further management. What regimen of corticosteroids is most appropriate to treat her acute exacerbation of COPD?

Overview

COPD is the fourth-leading cause of death in the United States and continues to increase in prevalence.1 Acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) contribute significantly to this high mortality rate, which approaches 40% at one year in those patients requiring mechanical support.1 An exacerbation of COPD has been defined as an acute change in a patient’s baseline dyspnea, cough, and/or sputum beyond day-to-day variability sufficient to warrant a change in therapy.2 Exacerbations commonly occur in COPD patients and often necessitate hospital admission. In fact, COPD consistently is one of the 10 most common reasons for hospitalization, with billions of dollars in associated healthcare costs.3