User login

Marriage of Necessity

Doctors and hospitals need each other. Healthcare reform is requiring hospitals to rely more heavily on physicians to help them meet quality, safety, and efficiency goals. But in return, doctors are demanding more financial security and a larger role in hospital leadership.

Just how far are they willing to take their mutual relationship to meet their individual needs? A new report by professional services company PwC (formerly PricewaterhouseCoopers) examines the mindsets of potential partners, including an online survey of more than 1,000 doctors and in-depth interviews with 28 healthcare executives. The results suggest plenty of opportunities for alignment, though perhaps also the need for serious pre-marriage counseling.

“From Courtship to Marriage Part II” (www.PwC.com/us/PhysicianHospitalAlignment) follows an initial report that emphasizes the element of trust that’s necessary for any doctor-hospital alignment to succeed. This time around, the sequel is focusing on more concrete steps needed to take the budding relationship to the next level and sustain it. In particular, the new report focuses on sharing power (governance), sharing resources (compensation), and sharing outcomes (guidelines).

The PwC report preempts the naysayers by acknowledging at the outset that “hospitals and physicians have been to the altar before, but many of those marriages ended in divorce.” So what’s different from the 1990s, that decade of broken marriages doomed by the irreconcilable differences over capitation?

“Number one is that back in the ’90s, there wasn’t a clear consensus in defining and determining what is quality,” says Warren Skea, a director in the PwC Health Enterprise Growth Practice. In the intervening years, he says, membership societies—SHM among them—and nonprofit organizations, such as the National Quality Forum, have helped address the need to define and measure healthcare quality. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) followed up by adopting and implementing some of those measures in programs, including hospital value-based purchasing (see “Value-Based Purchasing Raises the Stakes,” May 2011, p. 1).

Another missing component in the ’90s, Skea says, was an adequate set of tools for gauging quality. “Even if we did agree what quality was, we couldn’t go back in there and measure it in a valid way,” he explains. “We just didn’t have that capacity.”

A third lesson learned the hard way is that decision-making should involve all physicians, from primary-care doctors to specialists. That power-sharing will be critical, Skea says, as reimbursement models move away from fee-for-service, transaction-based compensation methods and toward paying for outcomes and quality. Silos of care are out, and transitioning patients across a continuum of care is definitely in.

Sound familiar? It should, and the similarity to the hospitalist job description isn’t lost on Skea. “I think hospitalists have served as a very good illustrative example of how physicians can add value to that efficiency equation, improve quality, increase [good] outcomes—all of those things,” he says. In fact, Skea says, the question now is how the quarterback role assumed by hospitalists can be translated or projected to the larger industry and other settings (e.g. outpatient clinics, home care rehabilitation, and continuing care facilities).

Accountable-care organizations (ACOs) are a hot topic in any discussion of better patient transitions and closer doctor-hospital alignments, but they’re hardly the only wedding chapels in town. The new report sketches out the corresponding amenities of a comanagement model and provider-owned plan, and Skea notes that part of the new Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation’s mandate will be to investigate other promising methods for encouraging providers to work together.

Leaders, Partners

For most doctors, according to the survey, working together means making joint decisions. More than 90% said they should be involved in “hospital governance activities such as serving on boards, being in management, and taking part in performance.”

“That didn’t surprise me at all; there’s a huge appetite for physicians to be involved in strategic governance and oversight,” Skea says. “That’s where hospitalists have been really good: taking it to that next level of strategy and leadership.”

Next to compensation, he says, governance is the biggest issue for many hospital-affiliated physicians. One wrinkle, however, is what the report’s authors heard from hospital executives. “There’s a recognition by hospital executives that they need those physicians in those governance roles,” Skea says. But the executives felt that more physicians should be trained and educated in business and financial decision-making.

Some of the training strategies, he says, are homegrown. One hospital client, for example, is providing its physicians with courses in statistical analysis, financial modeling, and change management, and referring to the educational package as “MBA in a box.” Other hospitals are steering their physicians toward outside sources of instruction. SHM’s four-day Leadership Academy (www.hospitalmedicine.org/leadership) offers another resource for hospitalists seeking more prominent roles within their institutions.

Along with a desire for more power-sharing, doctors looking to a hospital setting have clearly indicated that they expect to hold their own financially. According to the survey, 83% of doctors considering hospital employment expect to be paid as much as or more than they are currently earning.

And therein lies another potential sticking point. Based on past experience, doctors might expect that hospitals’ financial resources will still allow them to maximize their compensation. But as health reform plays out, Skea cautions, “everybody is going to have to do more with less.”

Compromise Ahead

But other survey results hint at the potential for compromise. According to the report, physicians agreed that half of their compensation should be a fixed salary, while the remaining half could be based on meeting productivity, quality, patient satisfaction, and cost-of-care goals, with the potential for performance rewards. “This shows that physicians realize the health system is changing to track and reward performance and that they can influence the quality and cost of care delivery at the institutional level,” the report states.

And as for the guidelines doctors follow while delivering healthcare, 62% of those surveyed believe nationally accepted guidelines should guide the way they practice medicine; 30% prefer local guidelines.

Skea says he was a bit surprised that nearly 1 in 3 doctors are still resistant to national guidelines, though he believes that number is on the wane. After an initial pushback, he says, doctors seem to be gravitating toward the national standards, due in part to physician societies taking active roles in the discussions.

So what should hospitalists take away from all of this? Skea says they should continue to highlight and demonstrate the value they provide in standardizing care, measuring quality, and improving efficiencies in the four walls of the hospital. “They’ve had a track record, I think they have the mindset, and they’ve had the relationship with hospital executives,” he says.

Hospitalists likely will be called upon to help educate their physician colleagues in other specialties. Because of their background and history of success, Skea says, “they could be one of the real leaders and catalysts for change within an ACO or some of these other more integrated and aligned delivery models, and then move into governance.”

With a little assistance, perhaps this marriage might work after all. TH

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer based in Seattle.

Doctors and hospitals need each other. Healthcare reform is requiring hospitals to rely more heavily on physicians to help them meet quality, safety, and efficiency goals. But in return, doctors are demanding more financial security and a larger role in hospital leadership.

Just how far are they willing to take their mutual relationship to meet their individual needs? A new report by professional services company PwC (formerly PricewaterhouseCoopers) examines the mindsets of potential partners, including an online survey of more than 1,000 doctors and in-depth interviews with 28 healthcare executives. The results suggest plenty of opportunities for alignment, though perhaps also the need for serious pre-marriage counseling.

“From Courtship to Marriage Part II” (www.PwC.com/us/PhysicianHospitalAlignment) follows an initial report that emphasizes the element of trust that’s necessary for any doctor-hospital alignment to succeed. This time around, the sequel is focusing on more concrete steps needed to take the budding relationship to the next level and sustain it. In particular, the new report focuses on sharing power (governance), sharing resources (compensation), and sharing outcomes (guidelines).

The PwC report preempts the naysayers by acknowledging at the outset that “hospitals and physicians have been to the altar before, but many of those marriages ended in divorce.” So what’s different from the 1990s, that decade of broken marriages doomed by the irreconcilable differences over capitation?

“Number one is that back in the ’90s, there wasn’t a clear consensus in defining and determining what is quality,” says Warren Skea, a director in the PwC Health Enterprise Growth Practice. In the intervening years, he says, membership societies—SHM among them—and nonprofit organizations, such as the National Quality Forum, have helped address the need to define and measure healthcare quality. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) followed up by adopting and implementing some of those measures in programs, including hospital value-based purchasing (see “Value-Based Purchasing Raises the Stakes,” May 2011, p. 1).

Another missing component in the ’90s, Skea says, was an adequate set of tools for gauging quality. “Even if we did agree what quality was, we couldn’t go back in there and measure it in a valid way,” he explains. “We just didn’t have that capacity.”

A third lesson learned the hard way is that decision-making should involve all physicians, from primary-care doctors to specialists. That power-sharing will be critical, Skea says, as reimbursement models move away from fee-for-service, transaction-based compensation methods and toward paying for outcomes and quality. Silos of care are out, and transitioning patients across a continuum of care is definitely in.

Sound familiar? It should, and the similarity to the hospitalist job description isn’t lost on Skea. “I think hospitalists have served as a very good illustrative example of how physicians can add value to that efficiency equation, improve quality, increase [good] outcomes—all of those things,” he says. In fact, Skea says, the question now is how the quarterback role assumed by hospitalists can be translated or projected to the larger industry and other settings (e.g. outpatient clinics, home care rehabilitation, and continuing care facilities).

Accountable-care organizations (ACOs) are a hot topic in any discussion of better patient transitions and closer doctor-hospital alignments, but they’re hardly the only wedding chapels in town. The new report sketches out the corresponding amenities of a comanagement model and provider-owned plan, and Skea notes that part of the new Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation’s mandate will be to investigate other promising methods for encouraging providers to work together.

Leaders, Partners

For most doctors, according to the survey, working together means making joint decisions. More than 90% said they should be involved in “hospital governance activities such as serving on boards, being in management, and taking part in performance.”

“That didn’t surprise me at all; there’s a huge appetite for physicians to be involved in strategic governance and oversight,” Skea says. “That’s where hospitalists have been really good: taking it to that next level of strategy and leadership.”

Next to compensation, he says, governance is the biggest issue for many hospital-affiliated physicians. One wrinkle, however, is what the report’s authors heard from hospital executives. “There’s a recognition by hospital executives that they need those physicians in those governance roles,” Skea says. But the executives felt that more physicians should be trained and educated in business and financial decision-making.

Some of the training strategies, he says, are homegrown. One hospital client, for example, is providing its physicians with courses in statistical analysis, financial modeling, and change management, and referring to the educational package as “MBA in a box.” Other hospitals are steering their physicians toward outside sources of instruction. SHM’s four-day Leadership Academy (www.hospitalmedicine.org/leadership) offers another resource for hospitalists seeking more prominent roles within their institutions.

Along with a desire for more power-sharing, doctors looking to a hospital setting have clearly indicated that they expect to hold their own financially. According to the survey, 83% of doctors considering hospital employment expect to be paid as much as or more than they are currently earning.

And therein lies another potential sticking point. Based on past experience, doctors might expect that hospitals’ financial resources will still allow them to maximize their compensation. But as health reform plays out, Skea cautions, “everybody is going to have to do more with less.”

Compromise Ahead

But other survey results hint at the potential for compromise. According to the report, physicians agreed that half of their compensation should be a fixed salary, while the remaining half could be based on meeting productivity, quality, patient satisfaction, and cost-of-care goals, with the potential for performance rewards. “This shows that physicians realize the health system is changing to track and reward performance and that they can influence the quality and cost of care delivery at the institutional level,” the report states.

And as for the guidelines doctors follow while delivering healthcare, 62% of those surveyed believe nationally accepted guidelines should guide the way they practice medicine; 30% prefer local guidelines.

Skea says he was a bit surprised that nearly 1 in 3 doctors are still resistant to national guidelines, though he believes that number is on the wane. After an initial pushback, he says, doctors seem to be gravitating toward the national standards, due in part to physician societies taking active roles in the discussions.

So what should hospitalists take away from all of this? Skea says they should continue to highlight and demonstrate the value they provide in standardizing care, measuring quality, and improving efficiencies in the four walls of the hospital. “They’ve had a track record, I think they have the mindset, and they’ve had the relationship with hospital executives,” he says.

Hospitalists likely will be called upon to help educate their physician colleagues in other specialties. Because of their background and history of success, Skea says, “they could be one of the real leaders and catalysts for change within an ACO or some of these other more integrated and aligned delivery models, and then move into governance.”

With a little assistance, perhaps this marriage might work after all. TH

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer based in Seattle.

Doctors and hospitals need each other. Healthcare reform is requiring hospitals to rely more heavily on physicians to help them meet quality, safety, and efficiency goals. But in return, doctors are demanding more financial security and a larger role in hospital leadership.

Just how far are they willing to take their mutual relationship to meet their individual needs? A new report by professional services company PwC (formerly PricewaterhouseCoopers) examines the mindsets of potential partners, including an online survey of more than 1,000 doctors and in-depth interviews with 28 healthcare executives. The results suggest plenty of opportunities for alignment, though perhaps also the need for serious pre-marriage counseling.

“From Courtship to Marriage Part II” (www.PwC.com/us/PhysicianHospitalAlignment) follows an initial report that emphasizes the element of trust that’s necessary for any doctor-hospital alignment to succeed. This time around, the sequel is focusing on more concrete steps needed to take the budding relationship to the next level and sustain it. In particular, the new report focuses on sharing power (governance), sharing resources (compensation), and sharing outcomes (guidelines).

The PwC report preempts the naysayers by acknowledging at the outset that “hospitals and physicians have been to the altar before, but many of those marriages ended in divorce.” So what’s different from the 1990s, that decade of broken marriages doomed by the irreconcilable differences over capitation?

“Number one is that back in the ’90s, there wasn’t a clear consensus in defining and determining what is quality,” says Warren Skea, a director in the PwC Health Enterprise Growth Practice. In the intervening years, he says, membership societies—SHM among them—and nonprofit organizations, such as the National Quality Forum, have helped address the need to define and measure healthcare quality. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) followed up by adopting and implementing some of those measures in programs, including hospital value-based purchasing (see “Value-Based Purchasing Raises the Stakes,” May 2011, p. 1).

Another missing component in the ’90s, Skea says, was an adequate set of tools for gauging quality. “Even if we did agree what quality was, we couldn’t go back in there and measure it in a valid way,” he explains. “We just didn’t have that capacity.”

A third lesson learned the hard way is that decision-making should involve all physicians, from primary-care doctors to specialists. That power-sharing will be critical, Skea says, as reimbursement models move away from fee-for-service, transaction-based compensation methods and toward paying for outcomes and quality. Silos of care are out, and transitioning patients across a continuum of care is definitely in.

Sound familiar? It should, and the similarity to the hospitalist job description isn’t lost on Skea. “I think hospitalists have served as a very good illustrative example of how physicians can add value to that efficiency equation, improve quality, increase [good] outcomes—all of those things,” he says. In fact, Skea says, the question now is how the quarterback role assumed by hospitalists can be translated or projected to the larger industry and other settings (e.g. outpatient clinics, home care rehabilitation, and continuing care facilities).

Accountable-care organizations (ACOs) are a hot topic in any discussion of better patient transitions and closer doctor-hospital alignments, but they’re hardly the only wedding chapels in town. The new report sketches out the corresponding amenities of a comanagement model and provider-owned plan, and Skea notes that part of the new Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation’s mandate will be to investigate other promising methods for encouraging providers to work together.

Leaders, Partners

For most doctors, according to the survey, working together means making joint decisions. More than 90% said they should be involved in “hospital governance activities such as serving on boards, being in management, and taking part in performance.”

“That didn’t surprise me at all; there’s a huge appetite for physicians to be involved in strategic governance and oversight,” Skea says. “That’s where hospitalists have been really good: taking it to that next level of strategy and leadership.”

Next to compensation, he says, governance is the biggest issue for many hospital-affiliated physicians. One wrinkle, however, is what the report’s authors heard from hospital executives. “There’s a recognition by hospital executives that they need those physicians in those governance roles,” Skea says. But the executives felt that more physicians should be trained and educated in business and financial decision-making.

Some of the training strategies, he says, are homegrown. One hospital client, for example, is providing its physicians with courses in statistical analysis, financial modeling, and change management, and referring to the educational package as “MBA in a box.” Other hospitals are steering their physicians toward outside sources of instruction. SHM’s four-day Leadership Academy (www.hospitalmedicine.org/leadership) offers another resource for hospitalists seeking more prominent roles within their institutions.

Along with a desire for more power-sharing, doctors looking to a hospital setting have clearly indicated that they expect to hold their own financially. According to the survey, 83% of doctors considering hospital employment expect to be paid as much as or more than they are currently earning.

And therein lies another potential sticking point. Based on past experience, doctors might expect that hospitals’ financial resources will still allow them to maximize their compensation. But as health reform plays out, Skea cautions, “everybody is going to have to do more with less.”

Compromise Ahead

But other survey results hint at the potential for compromise. According to the report, physicians agreed that half of their compensation should be a fixed salary, while the remaining half could be based on meeting productivity, quality, patient satisfaction, and cost-of-care goals, with the potential for performance rewards. “This shows that physicians realize the health system is changing to track and reward performance and that they can influence the quality and cost of care delivery at the institutional level,” the report states.

And as for the guidelines doctors follow while delivering healthcare, 62% of those surveyed believe nationally accepted guidelines should guide the way they practice medicine; 30% prefer local guidelines.

Skea says he was a bit surprised that nearly 1 in 3 doctors are still resistant to national guidelines, though he believes that number is on the wane. After an initial pushback, he says, doctors seem to be gravitating toward the national standards, due in part to physician societies taking active roles in the discussions.

So what should hospitalists take away from all of this? Skea says they should continue to highlight and demonstrate the value they provide in standardizing care, measuring quality, and improving efficiencies in the four walls of the hospital. “They’ve had a track record, I think they have the mindset, and they’ve had the relationship with hospital executives,” he says.

Hospitalists likely will be called upon to help educate their physician colleagues in other specialties. Because of their background and history of success, Skea says, “they could be one of the real leaders and catalysts for change within an ACO or some of these other more integrated and aligned delivery models, and then move into governance.”

With a little assistance, perhaps this marriage might work after all. TH

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer based in Seattle.

Medical Industry Takes Notice of Social Media

Most companies recognize that social media have become established as viable business tools. Many leaders are using sites like Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn to connect to their customers, recruit followers, and promote their services in real time. But the opportunity to connect the dots and utilize social media in a safe and meaningful way has yet to be fully realized. Whoever gets there first has the opportunity to revolutionize and forever change the medical industry.

The Current Situation

Social media sites for the medical industry range from broad, open platforms to niche, narrowly concentrated forums. Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube are broad platforms for individuals and corporations alike to broadcast experiences and opinions large and small. CancerDoc, HealthLine, and RevolutionHealth are more narrowly targeted places for rapidly communicating and connecting to those who are sharing similar experiences, communicating information, and sharing ideas amongst patients and medical industry peers. Expert Q&A sites, such as WebMD and AskDrWiki, are popular with patients who can find credible answers to their health-related questions. Physician networks (e.g. Sermo and Ozmosis) serve as “virtual water coolers” where physicians can collaborate in real time.

But no matter what portal is being used by patient or provider, the single most beneficial aspect of social media is the collaboration enabled by the openness of vast numbers. Most are trying to get their message out, educate, inform, and simply share. The portals themselves, empowered by the strength of their members, are positioning themselves as the source of true, real-time data and insight. Many healthcare facilities use social media to crowdsource, or basically ask for input from users to help develop or improve products and services quickly and efficiently. Others are enabling real-time learning through podcasts of surgeries, which medical students can attend remotely.

In 2010 specifically, we saw a significant jump in medical companies utilizing social media tools. The Mayo Clinic has gained more than 33,000 Facebook fans in a little more than a year. The Mayo “wall” is filled with patients’ thanks, interviews, advice, industry news, and nearly 150 videos. Its presence in this space has strengthened the Mayo name as a thought leader in medical care and innovation.

Future Opportunities

While all this is important to building relationships and brands, these building blocks could be the source for more revolutionary advancements. Over time, the intimate knowledge of a contributor, a regional demographic, or an international group of sufferers could be used as proactive triggers for action. Imagine a device that collects signs of your general well-being, then the data from this blends with your Facebook postings on location, time, diet, and feeling while aggregating information from other users and facilities. When linked to your medical facility and medication status, your pharmacy, your caregiver, or your gym could generate guidance and suggestions, which are sent back to you daily. If a hazardous situation is suspected by auto-analysis of the data, then this could directly alert your doctor to provide personal, quick advice and instructions. The potential to use social media and connected, aware devices for well-being and preventative care is huge, as are the possibilities for predicting and tracking patterns in health globally.

Social media offer unique opportunities for scalable interaction and collaboration, a key reason medical and lifestyle device manufacturers have much opportunity ahead of them. By developing products that become part of the user’s daily lives (think how important your smartphone is to you now), manufacturers will find themselves building a loyal customer base that is not only using their device, but is also interacting with them and providing unparalleled insight into their habits in real time.

Nike is one company that has been quick to the punch. The NikePlus Running Monitor is an application that meshes telehealth devices with social media, monitoring and posting running information on Facebook. All of this tracking and communication serves as a great promoter of the manufacturer, as it’s advertised every time the user posts a status update.

Despite all the progress, challenges remain for medical companies when diving into social media. It remains a very new horizon for an industry that faces hurdles posed by the traditions of the medical and insurance industries. Companies who are agile and able to pivot likely will be the winners. It’s easy to imagine Google as the CDC’s biggest information source in the future, aggregating and reporting clusters of users searching for key disease symptoms through an app portal or tweeting about illnesses. Used as tools for triggers, social media can take the temperature of societal health, allowing the medical community to watch population density or pollution patterns unfold.

If device manufacturers and the medical community figure out how to harness and leverage the power of people’s desire to connect and share, they could achieve groundbreaking contributions to healthcare and the connected world as a whole in the coming years.

Tim Morton,

design director,

Product Development Technologies,

Lake Zurich, Ill.

Journal Venues for Safety and Quality-Improvement Publications

The message is clear: Conducting business as usual is no longer tenable, nor the “right thing to do” for our patients. In a recent survey of departments of medicine chairs, Staiger et al summarize: “Top-performing academic institutions have recognized that quality improvement/patient safety (QI/PS) activities, leading to improved and measurable patient outcomes, are imperative for strategic survival.”1

Long before this report, the Society of General Internal Medicine’s Academic Hospitalist Task Force provided a framework to document the scholarship for promotion in academic medical centers and to document improvement activities.2 Since then, major academic institutions have incorporated such principles to support academic promotion.

Table 1 (see p. 6) provides venues for publication to advance the science of safety and QI; each is Medline-indexed. The list is not exhaustive and is meant to serve as a starting point of reference. We have not included many other excellent clinical journals that publish QI and patient safety work. When conducting improvement studies, we encourage hospitalists to use the Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE) guidelines for publication of quality-improvement articles.3,4,5

Enjoy a new era in academic medical centers.

Adolfo Peña, MD,

hospitalist,

Saint Joseph Hospital,

London, Ky.;

Benjamin Taylor, MD, MPH,

chief quality officer,

University Hospital,

The University of Alabama at Birmingham,

SGIM Academic Hospitalist Task Force member;

Pat Patrician, RN, PhD,

senior scholar,

Birmingham VA Quality Scholars Program;

Carlos A. Estrada, MD, MS,

senior scholar,

Birmingham VA Quality Scholars Program

References

- Staiger TO, Wong EY, Schleyer AM, Martin DP, Levinson W, Bremner WJ. The role of quality improvement and patient safety in academic promotion: results of a survey of chairs of departments of internal medicine in North America. Am J Med. 2011;124:277-280.

- Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM) Academic Hospitalist Task Force. Quality Portfolio. SGIM website. Available at: www.sgim.org/index.cfm?pageId=844. Accessed May 3, 2011.

- Davidoff D, Batalden P, Stevens D, Ogrinc D, Mooney S. Publication guidelines for quality improvement in health care: evolution of the SQUIRE project. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17 Suppl 1:i3-i9.

- Ogrinc G, Mooney S, Estrada C, et al. The SQUIRE (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence) guidelines for quality improvement reporting: explanation and elaboration. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17 Suppl 1:i13-i32.

- Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE) guidelines for publication of quality improvement articles. SQUIRE website. Available at: http://squire-statement.org. Accessed May 3, 2011.

Most companies recognize that social media have become established as viable business tools. Many leaders are using sites like Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn to connect to their customers, recruit followers, and promote their services in real time. But the opportunity to connect the dots and utilize social media in a safe and meaningful way has yet to be fully realized. Whoever gets there first has the opportunity to revolutionize and forever change the medical industry.

The Current Situation

Social media sites for the medical industry range from broad, open platforms to niche, narrowly concentrated forums. Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube are broad platforms for individuals and corporations alike to broadcast experiences and opinions large and small. CancerDoc, HealthLine, and RevolutionHealth are more narrowly targeted places for rapidly communicating and connecting to those who are sharing similar experiences, communicating information, and sharing ideas amongst patients and medical industry peers. Expert Q&A sites, such as WebMD and AskDrWiki, are popular with patients who can find credible answers to their health-related questions. Physician networks (e.g. Sermo and Ozmosis) serve as “virtual water coolers” where physicians can collaborate in real time.

But no matter what portal is being used by patient or provider, the single most beneficial aspect of social media is the collaboration enabled by the openness of vast numbers. Most are trying to get their message out, educate, inform, and simply share. The portals themselves, empowered by the strength of their members, are positioning themselves as the source of true, real-time data and insight. Many healthcare facilities use social media to crowdsource, or basically ask for input from users to help develop or improve products and services quickly and efficiently. Others are enabling real-time learning through podcasts of surgeries, which medical students can attend remotely.

In 2010 specifically, we saw a significant jump in medical companies utilizing social media tools. The Mayo Clinic has gained more than 33,000 Facebook fans in a little more than a year. The Mayo “wall” is filled with patients’ thanks, interviews, advice, industry news, and nearly 150 videos. Its presence in this space has strengthened the Mayo name as a thought leader in medical care and innovation.

Future Opportunities

While all this is important to building relationships and brands, these building blocks could be the source for more revolutionary advancements. Over time, the intimate knowledge of a contributor, a regional demographic, or an international group of sufferers could be used as proactive triggers for action. Imagine a device that collects signs of your general well-being, then the data from this blends with your Facebook postings on location, time, diet, and feeling while aggregating information from other users and facilities. When linked to your medical facility and medication status, your pharmacy, your caregiver, or your gym could generate guidance and suggestions, which are sent back to you daily. If a hazardous situation is suspected by auto-analysis of the data, then this could directly alert your doctor to provide personal, quick advice and instructions. The potential to use social media and connected, aware devices for well-being and preventative care is huge, as are the possibilities for predicting and tracking patterns in health globally.

Social media offer unique opportunities for scalable interaction and collaboration, a key reason medical and lifestyle device manufacturers have much opportunity ahead of them. By developing products that become part of the user’s daily lives (think how important your smartphone is to you now), manufacturers will find themselves building a loyal customer base that is not only using their device, but is also interacting with them and providing unparalleled insight into their habits in real time.

Nike is one company that has been quick to the punch. The NikePlus Running Monitor is an application that meshes telehealth devices with social media, monitoring and posting running information on Facebook. All of this tracking and communication serves as a great promoter of the manufacturer, as it’s advertised every time the user posts a status update.

Despite all the progress, challenges remain for medical companies when diving into social media. It remains a very new horizon for an industry that faces hurdles posed by the traditions of the medical and insurance industries. Companies who are agile and able to pivot likely will be the winners. It’s easy to imagine Google as the CDC’s biggest information source in the future, aggregating and reporting clusters of users searching for key disease symptoms through an app portal or tweeting about illnesses. Used as tools for triggers, social media can take the temperature of societal health, allowing the medical community to watch population density or pollution patterns unfold.

If device manufacturers and the medical community figure out how to harness and leverage the power of people’s desire to connect and share, they could achieve groundbreaking contributions to healthcare and the connected world as a whole in the coming years.

Tim Morton,

design director,

Product Development Technologies,

Lake Zurich, Ill.

Journal Venues for Safety and Quality-Improvement Publications

The message is clear: Conducting business as usual is no longer tenable, nor the “right thing to do” for our patients. In a recent survey of departments of medicine chairs, Staiger et al summarize: “Top-performing academic institutions have recognized that quality improvement/patient safety (QI/PS) activities, leading to improved and measurable patient outcomes, are imperative for strategic survival.”1

Long before this report, the Society of General Internal Medicine’s Academic Hospitalist Task Force provided a framework to document the scholarship for promotion in academic medical centers and to document improvement activities.2 Since then, major academic institutions have incorporated such principles to support academic promotion.

Table 1 (see p. 6) provides venues for publication to advance the science of safety and QI; each is Medline-indexed. The list is not exhaustive and is meant to serve as a starting point of reference. We have not included many other excellent clinical journals that publish QI and patient safety work. When conducting improvement studies, we encourage hospitalists to use the Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE) guidelines for publication of quality-improvement articles.3,4,5

Enjoy a new era in academic medical centers.

Adolfo Peña, MD,

hospitalist,

Saint Joseph Hospital,

London, Ky.;

Benjamin Taylor, MD, MPH,

chief quality officer,

University Hospital,

The University of Alabama at Birmingham,

SGIM Academic Hospitalist Task Force member;

Pat Patrician, RN, PhD,

senior scholar,

Birmingham VA Quality Scholars Program;

Carlos A. Estrada, MD, MS,

senior scholar,

Birmingham VA Quality Scholars Program

References

- Staiger TO, Wong EY, Schleyer AM, Martin DP, Levinson W, Bremner WJ. The role of quality improvement and patient safety in academic promotion: results of a survey of chairs of departments of internal medicine in North America. Am J Med. 2011;124:277-280.

- Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM) Academic Hospitalist Task Force. Quality Portfolio. SGIM website. Available at: www.sgim.org/index.cfm?pageId=844. Accessed May 3, 2011.

- Davidoff D, Batalden P, Stevens D, Ogrinc D, Mooney S. Publication guidelines for quality improvement in health care: evolution of the SQUIRE project. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17 Suppl 1:i3-i9.

- Ogrinc G, Mooney S, Estrada C, et al. The SQUIRE (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence) guidelines for quality improvement reporting: explanation and elaboration. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17 Suppl 1:i13-i32.

- Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE) guidelines for publication of quality improvement articles. SQUIRE website. Available at: http://squire-statement.org. Accessed May 3, 2011.

Most companies recognize that social media have become established as viable business tools. Many leaders are using sites like Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn to connect to their customers, recruit followers, and promote their services in real time. But the opportunity to connect the dots and utilize social media in a safe and meaningful way has yet to be fully realized. Whoever gets there first has the opportunity to revolutionize and forever change the medical industry.

The Current Situation

Social media sites for the medical industry range from broad, open platforms to niche, narrowly concentrated forums. Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube are broad platforms for individuals and corporations alike to broadcast experiences and opinions large and small. CancerDoc, HealthLine, and RevolutionHealth are more narrowly targeted places for rapidly communicating and connecting to those who are sharing similar experiences, communicating information, and sharing ideas amongst patients and medical industry peers. Expert Q&A sites, such as WebMD and AskDrWiki, are popular with patients who can find credible answers to their health-related questions. Physician networks (e.g. Sermo and Ozmosis) serve as “virtual water coolers” where physicians can collaborate in real time.

But no matter what portal is being used by patient or provider, the single most beneficial aspect of social media is the collaboration enabled by the openness of vast numbers. Most are trying to get their message out, educate, inform, and simply share. The portals themselves, empowered by the strength of their members, are positioning themselves as the source of true, real-time data and insight. Many healthcare facilities use social media to crowdsource, or basically ask for input from users to help develop or improve products and services quickly and efficiently. Others are enabling real-time learning through podcasts of surgeries, which medical students can attend remotely.

In 2010 specifically, we saw a significant jump in medical companies utilizing social media tools. The Mayo Clinic has gained more than 33,000 Facebook fans in a little more than a year. The Mayo “wall” is filled with patients’ thanks, interviews, advice, industry news, and nearly 150 videos. Its presence in this space has strengthened the Mayo name as a thought leader in medical care and innovation.

Future Opportunities

While all this is important to building relationships and brands, these building blocks could be the source for more revolutionary advancements. Over time, the intimate knowledge of a contributor, a regional demographic, or an international group of sufferers could be used as proactive triggers for action. Imagine a device that collects signs of your general well-being, then the data from this blends with your Facebook postings on location, time, diet, and feeling while aggregating information from other users and facilities. When linked to your medical facility and medication status, your pharmacy, your caregiver, or your gym could generate guidance and suggestions, which are sent back to you daily. If a hazardous situation is suspected by auto-analysis of the data, then this could directly alert your doctor to provide personal, quick advice and instructions. The potential to use social media and connected, aware devices for well-being and preventative care is huge, as are the possibilities for predicting and tracking patterns in health globally.

Social media offer unique opportunities for scalable interaction and collaboration, a key reason medical and lifestyle device manufacturers have much opportunity ahead of them. By developing products that become part of the user’s daily lives (think how important your smartphone is to you now), manufacturers will find themselves building a loyal customer base that is not only using their device, but is also interacting with them and providing unparalleled insight into their habits in real time.

Nike is one company that has been quick to the punch. The NikePlus Running Monitor is an application that meshes telehealth devices with social media, monitoring and posting running information on Facebook. All of this tracking and communication serves as a great promoter of the manufacturer, as it’s advertised every time the user posts a status update.

Despite all the progress, challenges remain for medical companies when diving into social media. It remains a very new horizon for an industry that faces hurdles posed by the traditions of the medical and insurance industries. Companies who are agile and able to pivot likely will be the winners. It’s easy to imagine Google as the CDC’s biggest information source in the future, aggregating and reporting clusters of users searching for key disease symptoms through an app portal or tweeting about illnesses. Used as tools for triggers, social media can take the temperature of societal health, allowing the medical community to watch population density or pollution patterns unfold.

If device manufacturers and the medical community figure out how to harness and leverage the power of people’s desire to connect and share, they could achieve groundbreaking contributions to healthcare and the connected world as a whole in the coming years.

Tim Morton,

design director,

Product Development Technologies,

Lake Zurich, Ill.

Journal Venues for Safety and Quality-Improvement Publications

The message is clear: Conducting business as usual is no longer tenable, nor the “right thing to do” for our patients. In a recent survey of departments of medicine chairs, Staiger et al summarize: “Top-performing academic institutions have recognized that quality improvement/patient safety (QI/PS) activities, leading to improved and measurable patient outcomes, are imperative for strategic survival.”1

Long before this report, the Society of General Internal Medicine’s Academic Hospitalist Task Force provided a framework to document the scholarship for promotion in academic medical centers and to document improvement activities.2 Since then, major academic institutions have incorporated such principles to support academic promotion.

Table 1 (see p. 6) provides venues for publication to advance the science of safety and QI; each is Medline-indexed. The list is not exhaustive and is meant to serve as a starting point of reference. We have not included many other excellent clinical journals that publish QI and patient safety work. When conducting improvement studies, we encourage hospitalists to use the Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE) guidelines for publication of quality-improvement articles.3,4,5

Enjoy a new era in academic medical centers.

Adolfo Peña, MD,

hospitalist,

Saint Joseph Hospital,

London, Ky.;

Benjamin Taylor, MD, MPH,

chief quality officer,

University Hospital,

The University of Alabama at Birmingham,

SGIM Academic Hospitalist Task Force member;

Pat Patrician, RN, PhD,

senior scholar,

Birmingham VA Quality Scholars Program;

Carlos A. Estrada, MD, MS,

senior scholar,

Birmingham VA Quality Scholars Program

References

- Staiger TO, Wong EY, Schleyer AM, Martin DP, Levinson W, Bremner WJ. The role of quality improvement and patient safety in academic promotion: results of a survey of chairs of departments of internal medicine in North America. Am J Med. 2011;124:277-280.

- Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM) Academic Hospitalist Task Force. Quality Portfolio. SGIM website. Available at: www.sgim.org/index.cfm?pageId=844. Accessed May 3, 2011.

- Davidoff D, Batalden P, Stevens D, Ogrinc D, Mooney S. Publication guidelines for quality improvement in health care: evolution of the SQUIRE project. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17 Suppl 1:i3-i9.

- Ogrinc G, Mooney S, Estrada C, et al. The SQUIRE (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence) guidelines for quality improvement reporting: explanation and elaboration. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17 Suppl 1:i13-i32.

- Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE) guidelines for publication of quality improvement articles. SQUIRE website. Available at: http://squire-statement.org. Accessed May 3, 2011.

Virtual Mentorship

With more than 250 hospitals adopting them in the last three years, SHM’s mentored implementation programs make a compelling case for the need to address care transitions, improve the management of diabetes, and prevent VTEs in hospitalized patients. And early results from the sites show that the mentored implementation model, with its combination of a best-practices toolkit and individualized support from national experts, can make a real difference.

“Quality improvement (QI) is the niche of hospital medicine; our mentored implementation programs have achieved both the goals of improving care in a clinical area nationwide as well as creating quality improvement leaders within our ranks,” says Kendall M. Rogers, MD, CPE, FACP, SFHM, associate professor of medicine and hospital medicine section chief at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center’s Department of Internal Medicine.

That’s the reasoning behind SHM’s new eQUIPS program. In essence, eQUIPS (Electronic Quality Improvement Programs) is SHM’s proven mentored implementation program, but without the mentor. Participants can access the same educational tools and resources, the same data center for tracking performance, and participate in the same online collaborative available to mentored implementation sites.

“SHM’s eQUIPS program takes the collective knowledge from the programs and offers it as a self-guided program that includes robust data collection and display programs,” Dr. Rogers says. “It will allow hospital quality-improvement teams more time to focus on driving change through the effective use of data, rather than spending their time trying to get the data.”

eQUIPS empowers hospitalists to move forward on valuable QI programs at their own pace, at any time. Hospitalists begin with the confidence that an entire community of likeminded physicians is supporting them, sharing their information, challenges, and successes.

Now, hospitalists can bring best practices to their hospitals and show their directors and executive leadership that they are on the cutting edge of addressing some of the most pervasive challenges in today’s hospitals.

Although they share a similar approach, each of eQUIPS’ three programs tackles the individual challenges of care transitions, VTE, and glycemic control separately. Hospitals can subscribe to any combination of the three topics.

Because eQUIPS is meant for year-after-year use and designed so that its utility grows along with its user base, access to eQUIPS is based on a yearly subscription model. The first year of access to eQUIPS is $2,500, which includes a one-time technology start-up fee. Each following year’s subscription is $1,500.

Hospitalists can apply for eQUIPS at www.hospitalmedicine.org/equips.

Educational Resources Get eQUIPS Users Started

Regardless of how far a hospital has advanced its programs, the educational materials that come with the subscription take hospitalists through the best in evidence-based medicine to address care transitions, VTE, and glycemic control, essentially forming a toolkit of relevant journal articles, presentations, step-by-step implementation guides, clinical tools, program files submitted by participants, and on-demand educational webinars facilitated by content experts.

Analysis and Reporting

Most experts agree that tracking and reporting results are the linchpins of QI programs. eQUIPS makes it easier with secure online tools for recording, benchmarking, process management, and tracking milestones.

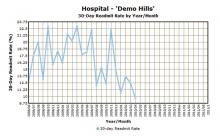

Plus, eQUIPS enables hospitalists to compare their programs to others across the country. By uploading performance data to the secure eQUIPS data center for performance tracking, hospitals can analyze and compare outcomes from their programs to other eQUIPS sites and national norms (see Figure 1).

And hospitalists can assure their hospitals’ legal staffs that SHM has taken steps to ensure HIPAA compliance through third-party reviews. eQUIPS subscribers log into the site through a secured-password authentication similar to those of other online public health and financial institutions. In addition, SHM’s QI programs have earned the Patient Safety Organization (PSO) designation from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), which makes it easier for hospitals to share performance data with SHM.

Real-Time Collaboration

Every hospital faces unique challenges, but they also have much in common when it comes to implementing new programs. As eQUIPS subscribers join, they can share their QI experiences and ask others for feedback in finding solutions.

The eQUIPS community website feature serves as a central, on-demand repository for sharing documents and educational materials, while the online workspace enables hospitalists to collaborate in real time by posting documents and editing them with other participating eQUIPS sites.

eQUIPS also brings collaboration right to users’ inboxes. Access to QI listservs has been a productive way for hospitalists to connect and benefit from the collective experience of the group; it’s a key component of the eQUIPS programs.

For Rogers, eQUIPS and its collaborative tools are a logistical extension of SHM’s successful QI track record. TH

Brendon Shank is assistant vice president of communications for SHM.

With more than 250 hospitals adopting them in the last three years, SHM’s mentored implementation programs make a compelling case for the need to address care transitions, improve the management of diabetes, and prevent VTEs in hospitalized patients. And early results from the sites show that the mentored implementation model, with its combination of a best-practices toolkit and individualized support from national experts, can make a real difference.

“Quality improvement (QI) is the niche of hospital medicine; our mentored implementation programs have achieved both the goals of improving care in a clinical area nationwide as well as creating quality improvement leaders within our ranks,” says Kendall M. Rogers, MD, CPE, FACP, SFHM, associate professor of medicine and hospital medicine section chief at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center’s Department of Internal Medicine.

That’s the reasoning behind SHM’s new eQUIPS program. In essence, eQUIPS (Electronic Quality Improvement Programs) is SHM’s proven mentored implementation program, but without the mentor. Participants can access the same educational tools and resources, the same data center for tracking performance, and participate in the same online collaborative available to mentored implementation sites.

“SHM’s eQUIPS program takes the collective knowledge from the programs and offers it as a self-guided program that includes robust data collection and display programs,” Dr. Rogers says. “It will allow hospital quality-improvement teams more time to focus on driving change through the effective use of data, rather than spending their time trying to get the data.”

eQUIPS empowers hospitalists to move forward on valuable QI programs at their own pace, at any time. Hospitalists begin with the confidence that an entire community of likeminded physicians is supporting them, sharing their information, challenges, and successes.

Now, hospitalists can bring best practices to their hospitals and show their directors and executive leadership that they are on the cutting edge of addressing some of the most pervasive challenges in today’s hospitals.

Although they share a similar approach, each of eQUIPS’ three programs tackles the individual challenges of care transitions, VTE, and glycemic control separately. Hospitals can subscribe to any combination of the three topics.

Because eQUIPS is meant for year-after-year use and designed so that its utility grows along with its user base, access to eQUIPS is based on a yearly subscription model. The first year of access to eQUIPS is $2,500, which includes a one-time technology start-up fee. Each following year’s subscription is $1,500.

Hospitalists can apply for eQUIPS at www.hospitalmedicine.org/equips.

Educational Resources Get eQUIPS Users Started

Regardless of how far a hospital has advanced its programs, the educational materials that come with the subscription take hospitalists through the best in evidence-based medicine to address care transitions, VTE, and glycemic control, essentially forming a toolkit of relevant journal articles, presentations, step-by-step implementation guides, clinical tools, program files submitted by participants, and on-demand educational webinars facilitated by content experts.

Analysis and Reporting

Most experts agree that tracking and reporting results are the linchpins of QI programs. eQUIPS makes it easier with secure online tools for recording, benchmarking, process management, and tracking milestones.

Plus, eQUIPS enables hospitalists to compare their programs to others across the country. By uploading performance data to the secure eQUIPS data center for performance tracking, hospitals can analyze and compare outcomes from their programs to other eQUIPS sites and national norms (see Figure 1).

And hospitalists can assure their hospitals’ legal staffs that SHM has taken steps to ensure HIPAA compliance through third-party reviews. eQUIPS subscribers log into the site through a secured-password authentication similar to those of other online public health and financial institutions. In addition, SHM’s QI programs have earned the Patient Safety Organization (PSO) designation from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), which makes it easier for hospitals to share performance data with SHM.

Real-Time Collaboration

Every hospital faces unique challenges, but they also have much in common when it comes to implementing new programs. As eQUIPS subscribers join, they can share their QI experiences and ask others for feedback in finding solutions.

The eQUIPS community website feature serves as a central, on-demand repository for sharing documents and educational materials, while the online workspace enables hospitalists to collaborate in real time by posting documents and editing them with other participating eQUIPS sites.

eQUIPS also brings collaboration right to users’ inboxes. Access to QI listservs has been a productive way for hospitalists to connect and benefit from the collective experience of the group; it’s a key component of the eQUIPS programs.

For Rogers, eQUIPS and its collaborative tools are a logistical extension of SHM’s successful QI track record. TH

Brendon Shank is assistant vice president of communications for SHM.

With more than 250 hospitals adopting them in the last three years, SHM’s mentored implementation programs make a compelling case for the need to address care transitions, improve the management of diabetes, and prevent VTEs in hospitalized patients. And early results from the sites show that the mentored implementation model, with its combination of a best-practices toolkit and individualized support from national experts, can make a real difference.

“Quality improvement (QI) is the niche of hospital medicine; our mentored implementation programs have achieved both the goals of improving care in a clinical area nationwide as well as creating quality improvement leaders within our ranks,” says Kendall M. Rogers, MD, CPE, FACP, SFHM, associate professor of medicine and hospital medicine section chief at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center’s Department of Internal Medicine.

That’s the reasoning behind SHM’s new eQUIPS program. In essence, eQUIPS (Electronic Quality Improvement Programs) is SHM’s proven mentored implementation program, but without the mentor. Participants can access the same educational tools and resources, the same data center for tracking performance, and participate in the same online collaborative available to mentored implementation sites.

“SHM’s eQUIPS program takes the collective knowledge from the programs and offers it as a self-guided program that includes robust data collection and display programs,” Dr. Rogers says. “It will allow hospital quality-improvement teams more time to focus on driving change through the effective use of data, rather than spending their time trying to get the data.”

eQUIPS empowers hospitalists to move forward on valuable QI programs at their own pace, at any time. Hospitalists begin with the confidence that an entire community of likeminded physicians is supporting them, sharing their information, challenges, and successes.

Now, hospitalists can bring best practices to their hospitals and show their directors and executive leadership that they are on the cutting edge of addressing some of the most pervasive challenges in today’s hospitals.

Although they share a similar approach, each of eQUIPS’ three programs tackles the individual challenges of care transitions, VTE, and glycemic control separately. Hospitals can subscribe to any combination of the three topics.

Because eQUIPS is meant for year-after-year use and designed so that its utility grows along with its user base, access to eQUIPS is based on a yearly subscription model. The first year of access to eQUIPS is $2,500, which includes a one-time technology start-up fee. Each following year’s subscription is $1,500.

Hospitalists can apply for eQUIPS at www.hospitalmedicine.org/equips.

Educational Resources Get eQUIPS Users Started

Regardless of how far a hospital has advanced its programs, the educational materials that come with the subscription take hospitalists through the best in evidence-based medicine to address care transitions, VTE, and glycemic control, essentially forming a toolkit of relevant journal articles, presentations, step-by-step implementation guides, clinical tools, program files submitted by participants, and on-demand educational webinars facilitated by content experts.

Analysis and Reporting

Most experts agree that tracking and reporting results are the linchpins of QI programs. eQUIPS makes it easier with secure online tools for recording, benchmarking, process management, and tracking milestones.

Plus, eQUIPS enables hospitalists to compare their programs to others across the country. By uploading performance data to the secure eQUIPS data center for performance tracking, hospitals can analyze and compare outcomes from their programs to other eQUIPS sites and national norms (see Figure 1).

And hospitalists can assure their hospitals’ legal staffs that SHM has taken steps to ensure HIPAA compliance through third-party reviews. eQUIPS subscribers log into the site through a secured-password authentication similar to those of other online public health and financial institutions. In addition, SHM’s QI programs have earned the Patient Safety Organization (PSO) designation from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), which makes it easier for hospitals to share performance data with SHM.

Real-Time Collaboration

Every hospital faces unique challenges, but they also have much in common when it comes to implementing new programs. As eQUIPS subscribers join, they can share their QI experiences and ask others for feedback in finding solutions.

The eQUIPS community website feature serves as a central, on-demand repository for sharing documents and educational materials, while the online workspace enables hospitalists to collaborate in real time by posting documents and editing them with other participating eQUIPS sites.

eQUIPS also brings collaboration right to users’ inboxes. Access to QI listservs has been a productive way for hospitalists to connect and benefit from the collective experience of the group; it’s a key component of the eQUIPS programs.

For Rogers, eQUIPS and its collaborative tools are a logistical extension of SHM’s successful QI track record. TH

Brendon Shank is assistant vice president of communications for SHM.

POLICY CORNER: SHM Pledges Support to Patient-Safety Initiative

On April 12, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Kathleen Sebelius joined the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) administrator Donald Berwick, MD, in announcing a major patient-safety initiative bringing together hospitals, clinicians, consumers, employers, federal and state governments, and many more groups around two common goals: reducing harm caused to patients in hospitals and reducing hospital readmissions.

SHM was one of the first physician groups to sign on to the Pledge of Support, which aims to reduce hospital-acquired conditions by 40% and decrease preventable readmissions within 30 days of discharge by 20%, both by the end of 2013.

The pledge includes specific expectations for each of the different healthcare entities signing on. By signing, SHM agrees on behalf of hospitalists that they will work together to redesign activities within the hospital to reduce harm, learn from experiences and share best practices, and engage with patients and families to implement practices that foster more patient-centered care that improves safety, communication, and care coordination.

HHS is committing a total of $1 billion from the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) to support hospitals and other providers in their efforts to reach these goals. Of the funding, $500 million will come through the Community-Based Care Transitions Program (CCTP) created in the ACA to help community-based organizations partnering with eligible hospitals to improve transitions between settings of care. The other $500 million will come from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) to test different models of improving patient care, patient engagement, and collaboration in order to reduce hospital-acquired conditions and improve care transitions nationwide.

The partnership takes the best ideas from the public and private sectors and accelerates their spread to achieve a safer, higher-quality healthcare system for all Americans. It aligns Dr. Berwick’s triple aim (improve care, improve people’s health, and reduce the overall cost of healthcare) with SHM’s efforts to improve quality and patient safety through innovation and collaboration.

SHM’s Project BOOST (www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost) is listed in the solicitation for applications for the CCTP, and SHM’s VTE resource room is among the resources posted on the partnership website.

For more information on the initiative, visit www.healthcare.gov. TH

On April 12, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Kathleen Sebelius joined the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) administrator Donald Berwick, MD, in announcing a major patient-safety initiative bringing together hospitals, clinicians, consumers, employers, federal and state governments, and many more groups around two common goals: reducing harm caused to patients in hospitals and reducing hospital readmissions.

SHM was one of the first physician groups to sign on to the Pledge of Support, which aims to reduce hospital-acquired conditions by 40% and decrease preventable readmissions within 30 days of discharge by 20%, both by the end of 2013.

The pledge includes specific expectations for each of the different healthcare entities signing on. By signing, SHM agrees on behalf of hospitalists that they will work together to redesign activities within the hospital to reduce harm, learn from experiences and share best practices, and engage with patients and families to implement practices that foster more patient-centered care that improves safety, communication, and care coordination.

HHS is committing a total of $1 billion from the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) to support hospitals and other providers in their efforts to reach these goals. Of the funding, $500 million will come through the Community-Based Care Transitions Program (CCTP) created in the ACA to help community-based organizations partnering with eligible hospitals to improve transitions between settings of care. The other $500 million will come from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) to test different models of improving patient care, patient engagement, and collaboration in order to reduce hospital-acquired conditions and improve care transitions nationwide.

The partnership takes the best ideas from the public and private sectors and accelerates their spread to achieve a safer, higher-quality healthcare system for all Americans. It aligns Dr. Berwick’s triple aim (improve care, improve people’s health, and reduce the overall cost of healthcare) with SHM’s efforts to improve quality and patient safety through innovation and collaboration.

SHM’s Project BOOST (www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost) is listed in the solicitation for applications for the CCTP, and SHM’s VTE resource room is among the resources posted on the partnership website.

For more information on the initiative, visit www.healthcare.gov. TH

On April 12, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Kathleen Sebelius joined the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) administrator Donald Berwick, MD, in announcing a major patient-safety initiative bringing together hospitals, clinicians, consumers, employers, federal and state governments, and many more groups around two common goals: reducing harm caused to patients in hospitals and reducing hospital readmissions.

SHM was one of the first physician groups to sign on to the Pledge of Support, which aims to reduce hospital-acquired conditions by 40% and decrease preventable readmissions within 30 days of discharge by 20%, both by the end of 2013.

The pledge includes specific expectations for each of the different healthcare entities signing on. By signing, SHM agrees on behalf of hospitalists that they will work together to redesign activities within the hospital to reduce harm, learn from experiences and share best practices, and engage with patients and families to implement practices that foster more patient-centered care that improves safety, communication, and care coordination.

HHS is committing a total of $1 billion from the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) to support hospitals and other providers in their efforts to reach these goals. Of the funding, $500 million will come through the Community-Based Care Transitions Program (CCTP) created in the ACA to help community-based organizations partnering with eligible hospitals to improve transitions between settings of care. The other $500 million will come from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) to test different models of improving patient care, patient engagement, and collaboration in order to reduce hospital-acquired conditions and improve care transitions nationwide.

The partnership takes the best ideas from the public and private sectors and accelerates their spread to achieve a safer, higher-quality healthcare system for all Americans. It aligns Dr. Berwick’s triple aim (improve care, improve people’s health, and reduce the overall cost of healthcare) with SHM’s efforts to improve quality and patient safety through innovation and collaboration.

SHM’s Project BOOST (www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost) is listed in the solicitation for applications for the CCTP, and SHM’s VTE resource room is among the resources posted on the partnership website.

For more information on the initiative, visit www.healthcare.gov. TH

Hospitalists on the Move: June 2011

Robert Harrington Jr., MD, SFHM, and Erin Stucky Fisher, MD, MHM, have been elected to SHM’s board of directors. Dr. Harrington, chief medical officer for Locum Leaders, serves as chair of SHM’s Family Medicine Task Force and board liaison to the IT Core Committee. Dr. Fisher, professor of clinical pediatrics at the University of California at San Diego, is actively involved with quality initiatives for the American Academy of Pediatrics, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, and the National Association of Children’s Hospitals.

Jasen W. Gundersen, MD, MBA, CPE, SFHM, has been appointed chief medical officer for TeamHealth Hospital Medicine.

IPC: The Hospitalist Company Inc. has appointed Kerry Weiner, MD, to the newly created position of chief clinical officer. Dr. Weiner will lead the clinical functions of the company and continue the development of hospitalist leaders throughout IPC.

Steven Pantilat, MD, FACP, SFHM, has received a 2011 James Irvine Foundation Leadership Award. Dr. Pantilat, one of five recipients, is professor of clinical medicine, the Alan M. Kates and John M. Burnard Endowed Chair in Palliative Care, and director of the Palliative Care Leadership Center at UCSF. Now in its sixth year, the award celebrates extraordinary leaders who are applying innovative and effective solutions to significant state issues. Dr. Pantilat, a past SHM president, will receive $125,000 in organizational support.

Hospitalist Patrick O’Neil, DO, has been named Lake Regional Health System’s 2011 Physician of the Year. The 116-bed health system serves 1,300 employees in the Land of the Ozarks, Mo., area.

Hospitalist Wiley Robinson, MD, has been named president-elect of the Tennessee Medical Association and will head the organization for 2012-2013. An internal-medicine specialist, Dr. Robinson is cofounder and president of Inpatient Physicians of the Mid-South, a Memphis-based hospitalist group.

The Association of Specialty Professors announced Robert M. Wachter, MD, MHM, will receive the 2011 ASP Eric G. Neilson, MD, Distinguished Professor Award. Dr. Wachter is professor of medicine and the Marc and Lynne Benioff Endowed Chair in Hospital Medicine at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) School of Medicine, and a past president of SHM. The Neilson Award is presented annually to a leader who has shaped the internal-medicine landscape and promotes the work of leaders who bring about change for specialty medicine. TH

Robert Harrington Jr., MD, SFHM, and Erin Stucky Fisher, MD, MHM, have been elected to SHM’s board of directors. Dr. Harrington, chief medical officer for Locum Leaders, serves as chair of SHM’s Family Medicine Task Force and board liaison to the IT Core Committee. Dr. Fisher, professor of clinical pediatrics at the University of California at San Diego, is actively involved with quality initiatives for the American Academy of Pediatrics, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, and the National Association of Children’s Hospitals.

Jasen W. Gundersen, MD, MBA, CPE, SFHM, has been appointed chief medical officer for TeamHealth Hospital Medicine.

IPC: The Hospitalist Company Inc. has appointed Kerry Weiner, MD, to the newly created position of chief clinical officer. Dr. Weiner will lead the clinical functions of the company and continue the development of hospitalist leaders throughout IPC.

Steven Pantilat, MD, FACP, SFHM, has received a 2011 James Irvine Foundation Leadership Award. Dr. Pantilat, one of five recipients, is professor of clinical medicine, the Alan M. Kates and John M. Burnard Endowed Chair in Palliative Care, and director of the Palliative Care Leadership Center at UCSF. Now in its sixth year, the award celebrates extraordinary leaders who are applying innovative and effective solutions to significant state issues. Dr. Pantilat, a past SHM president, will receive $125,000 in organizational support.

Hospitalist Patrick O’Neil, DO, has been named Lake Regional Health System’s 2011 Physician of the Year. The 116-bed health system serves 1,300 employees in the Land of the Ozarks, Mo., area.

Hospitalist Wiley Robinson, MD, has been named president-elect of the Tennessee Medical Association and will head the organization for 2012-2013. An internal-medicine specialist, Dr. Robinson is cofounder and president of Inpatient Physicians of the Mid-South, a Memphis-based hospitalist group.

The Association of Specialty Professors announced Robert M. Wachter, MD, MHM, will receive the 2011 ASP Eric G. Neilson, MD, Distinguished Professor Award. Dr. Wachter is professor of medicine and the Marc and Lynne Benioff Endowed Chair in Hospital Medicine at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) School of Medicine, and a past president of SHM. The Neilson Award is presented annually to a leader who has shaped the internal-medicine landscape and promotes the work of leaders who bring about change for specialty medicine. TH

Robert Harrington Jr., MD, SFHM, and Erin Stucky Fisher, MD, MHM, have been elected to SHM’s board of directors. Dr. Harrington, chief medical officer for Locum Leaders, serves as chair of SHM’s Family Medicine Task Force and board liaison to the IT Core Committee. Dr. Fisher, professor of clinical pediatrics at the University of California at San Diego, is actively involved with quality initiatives for the American Academy of Pediatrics, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, and the National Association of Children’s Hospitals.

Jasen W. Gundersen, MD, MBA, CPE, SFHM, has been appointed chief medical officer for TeamHealth Hospital Medicine.

IPC: The Hospitalist Company Inc. has appointed Kerry Weiner, MD, to the newly created position of chief clinical officer. Dr. Weiner will lead the clinical functions of the company and continue the development of hospitalist leaders throughout IPC.

Steven Pantilat, MD, FACP, SFHM, has received a 2011 James Irvine Foundation Leadership Award. Dr. Pantilat, one of five recipients, is professor of clinical medicine, the Alan M. Kates and John M. Burnard Endowed Chair in Palliative Care, and director of the Palliative Care Leadership Center at UCSF. Now in its sixth year, the award celebrates extraordinary leaders who are applying innovative and effective solutions to significant state issues. Dr. Pantilat, a past SHM president, will receive $125,000 in organizational support.

Hospitalist Patrick O’Neil, DO, has been named Lake Regional Health System’s 2011 Physician of the Year. The 116-bed health system serves 1,300 employees in the Land of the Ozarks, Mo., area.