User login

Solution Finder

Kenneth G. Simone, DO, FHM, grew up as the son of a revered pediatrician. As a child, he often accompanied his father on hospital rounds and house calls, developing an appreciation for the “old-fashioned” medicine his father practiced.

Already inspired to follow in his father’s footsteps, Dr. Simone became even more convinced of his calling when the physician-patient roles were reversed: His dad developed a kidney disorder that cut his career—and ultimately his life—short. “His illness and my exposure to hospitals added to my desire to pursue medicine,” Dr. Simone says. “It instilled the drive to help others, to make a difference in someone’s or some family’s life.”

He has done that by developing multiple private medical practices, building the hospitalist program at St. Joseph Hospital in Bangor, Maine, and offering consulting services to more than 100 practices.

“It has always been my nature to challenge myself and put myself in situations that take me out of my comfort zone,” says Dr. Simone, president of Hospitalist and Practice Solutions, a practice-management consultancy in Veazie, Maine. “I enjoy building things from scratch, creating, rebuilding, thinking outside the box, and networking with other healthcare professionals.”

Question: What made you decide to start Hospitalist and Practice Solutions (HPS)?

Answer: HPS was established because of the demand for my services. Initially, word spread locally and then regionally about the work I did at St. Joseph Hospital. As a natural offshoot of my growing interest in helping other programs, HPS became a national consulting firm.

Q: Why did you think this venture could provide a valuable service?

A: I believed there were more effective healthcare delivery systems with which to provide both quality and cost-effective medical care. As time went on, I gained a very unique perspective working as both a hospitalist and referring PCP in private practice. This experience, coupled with my work as an administrative director for a hospitalist program, allowed me to develop applications to help hospitalist programs on a broader basis. I realized the advice I offered to other programs consistently rendered a positive effect.

Q: Which do you find more enjoyable: building a hospitalist program from the ground up or rebuilding a struggling program?

A: I truly enjoy the challenges of both equally. Projects that involve building a program de novo appeal to my creative side. These projects enable me to work with professionals to build a customized program that meets the needs of the community.

Q: What challenges are unique to each?

A: Rebuilding an established program involves critical analysis of the current program to identify what has gone wrong, what has been successful, and what will work in the future. It calls upon one’s skills to build consensus and instill trust in the process because the stakeholders may be apprehensive to have a consultant critically review their program and hospital. In many instances, conflict management is necessary.

In both the creation and rebuilding of an HM program, it is imperative to implement strategies that guide the program to future success. Both projects also require strategic planning and the development of tools and tactics that emphasize collaboration and collegiality.

Q: Do the failing programs you help to rebuild have characteristics in common?

A: Common themes include lack of planning and consensus-building before program start-up, inadequate tools and strategies to support effective practice management, and failure to align the hospitalist practice and sponsoring hospital’s goals and vision. Another common problem is the absence of a hospitalist recruitment and retention plan, which may lead to provider turnover and program instability.

Many programs experience problems due to ineffective leadership, poor implementation and follow-through, and lack of both a short- and long-term strategic plan. Some programs are victims of their own success. The program is not properly prepared to handle the demand for its services and grow accordingly.

Q: You help programs create effective recruitment and retention plans. You also wrote a book on the subject. Why are recruitment and retention challenging for so many programs?

A: The primary contributor is that [hospitalist] supply falls significantly short of physician demand. A secondary contributor is the generational expectations of the younger physician workforce. … In addition, leaders may not prioritize recruitment and retention because they lack an appreciation for the consequences of failed efforts.

Q: What advice would you offer hospitalist program leaders about how they can improve those aspects of their programs?

A: No. 1, create an effective recruitment and retention plan and execute the plan with precision. No. 2, approach recruitment and retention with the same attention to detail as you approach patient care.

Q: You’re offering best-practice advice to help your clients develop and sustain effective programs. What advice do you find yourself giving to your clients that you wish someone gave to you early in your career?

A: From my perspective as a hospitalist administrative director, the advice I would offer is for individuals to believe in themselves and stay engaged. If you feel you have something to offer to the practice or healthcare system as a whole, share it with the appropriate parties. If you experience problems within the workplace, seek resolution in a timely manner. Stay positive and be part of the solution, not part of the problem.

Q: You have written two hospitalist books and coauthored two others. Do you have plans to write another?

A: I wouldn’t say I have immediate plans, but I am always thinking about topics and other projects that would provide value to readers. I’ve got some exciting ideas for future projects, but they are in a very early stage of development.

Q: How would you compare the feeling you get from finishing a book with the satisfaction you derive from other aspects of your career?

A: Writing a book is a highly personal accomplishment for me, while caring for patients is more of a team accomplishment that involves the patient, family, and other healthcare professionals. Typically, the completion of a book is a finite event, while caring for a patient is a long-term commitment.

Q: What is your biggest professional reward?

A: Helping people, whether they are patients in my role as physician, or other professionals—physicians, practice administrators, and hospital administrators—in my role as a practice management consultant. Whenever I reflect on my career, I tell myself how lucky I am. There are not many professions or individuals who have an opportunity to close the door behind them and have other human beings entrust them with their most intimate information. Also, there are very few individuals who are able to impact the delivery of medical care from a systems perspective. I get to do both, and for that I am most grateful.

Q: What is your biggest professional challenge?

A: Saying “no” when someone asks for help. There is nothing more rewarding for me than to help others. With that said, I try not to overextend myself, because that wouldn’t be fair to my family, colleagues, friends, or clients.

Q: What’s next for you professionally?

A: I will continue to concentrate my effort on building my hospitalist consultative practice and expanding the services I offer. In addition, I’m always tempted to explore the valley of the unknown. What excites me is venturing into new areas and to challenge myself to grow as both an individual and professional. TH

Mark Leiser is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

Kenneth G. Simone, DO, FHM, grew up as the son of a revered pediatrician. As a child, he often accompanied his father on hospital rounds and house calls, developing an appreciation for the “old-fashioned” medicine his father practiced.

Already inspired to follow in his father’s footsteps, Dr. Simone became even more convinced of his calling when the physician-patient roles were reversed: His dad developed a kidney disorder that cut his career—and ultimately his life—short. “His illness and my exposure to hospitals added to my desire to pursue medicine,” Dr. Simone says. “It instilled the drive to help others, to make a difference in someone’s or some family’s life.”

He has done that by developing multiple private medical practices, building the hospitalist program at St. Joseph Hospital in Bangor, Maine, and offering consulting services to more than 100 practices.

“It has always been my nature to challenge myself and put myself in situations that take me out of my comfort zone,” says Dr. Simone, president of Hospitalist and Practice Solutions, a practice-management consultancy in Veazie, Maine. “I enjoy building things from scratch, creating, rebuilding, thinking outside the box, and networking with other healthcare professionals.”

Question: What made you decide to start Hospitalist and Practice Solutions (HPS)?

Answer: HPS was established because of the demand for my services. Initially, word spread locally and then regionally about the work I did at St. Joseph Hospital. As a natural offshoot of my growing interest in helping other programs, HPS became a national consulting firm.

Q: Why did you think this venture could provide a valuable service?

A: I believed there were more effective healthcare delivery systems with which to provide both quality and cost-effective medical care. As time went on, I gained a very unique perspective working as both a hospitalist and referring PCP in private practice. This experience, coupled with my work as an administrative director for a hospitalist program, allowed me to develop applications to help hospitalist programs on a broader basis. I realized the advice I offered to other programs consistently rendered a positive effect.

Q: Which do you find more enjoyable: building a hospitalist program from the ground up or rebuilding a struggling program?

A: I truly enjoy the challenges of both equally. Projects that involve building a program de novo appeal to my creative side. These projects enable me to work with professionals to build a customized program that meets the needs of the community.

Q: What challenges are unique to each?

A: Rebuilding an established program involves critical analysis of the current program to identify what has gone wrong, what has been successful, and what will work in the future. It calls upon one’s skills to build consensus and instill trust in the process because the stakeholders may be apprehensive to have a consultant critically review their program and hospital. In many instances, conflict management is necessary.

In both the creation and rebuilding of an HM program, it is imperative to implement strategies that guide the program to future success. Both projects also require strategic planning and the development of tools and tactics that emphasize collaboration and collegiality.

Q: Do the failing programs you help to rebuild have characteristics in common?

A: Common themes include lack of planning and consensus-building before program start-up, inadequate tools and strategies to support effective practice management, and failure to align the hospitalist practice and sponsoring hospital’s goals and vision. Another common problem is the absence of a hospitalist recruitment and retention plan, which may lead to provider turnover and program instability.

Many programs experience problems due to ineffective leadership, poor implementation and follow-through, and lack of both a short- and long-term strategic plan. Some programs are victims of their own success. The program is not properly prepared to handle the demand for its services and grow accordingly.

Q: You help programs create effective recruitment and retention plans. You also wrote a book on the subject. Why are recruitment and retention challenging for so many programs?

A: The primary contributor is that [hospitalist] supply falls significantly short of physician demand. A secondary contributor is the generational expectations of the younger physician workforce. … In addition, leaders may not prioritize recruitment and retention because they lack an appreciation for the consequences of failed efforts.

Q: What advice would you offer hospitalist program leaders about how they can improve those aspects of their programs?

A: No. 1, create an effective recruitment and retention plan and execute the plan with precision. No. 2, approach recruitment and retention with the same attention to detail as you approach patient care.

Q: You’re offering best-practice advice to help your clients develop and sustain effective programs. What advice do you find yourself giving to your clients that you wish someone gave to you early in your career?

A: From my perspective as a hospitalist administrative director, the advice I would offer is for individuals to believe in themselves and stay engaged. If you feel you have something to offer to the practice or healthcare system as a whole, share it with the appropriate parties. If you experience problems within the workplace, seek resolution in a timely manner. Stay positive and be part of the solution, not part of the problem.

Q: You have written two hospitalist books and coauthored two others. Do you have plans to write another?

A: I wouldn’t say I have immediate plans, but I am always thinking about topics and other projects that would provide value to readers. I’ve got some exciting ideas for future projects, but they are in a very early stage of development.

Q: How would you compare the feeling you get from finishing a book with the satisfaction you derive from other aspects of your career?

A: Writing a book is a highly personal accomplishment for me, while caring for patients is more of a team accomplishment that involves the patient, family, and other healthcare professionals. Typically, the completion of a book is a finite event, while caring for a patient is a long-term commitment.

Q: What is your biggest professional reward?

A: Helping people, whether they are patients in my role as physician, or other professionals—physicians, practice administrators, and hospital administrators—in my role as a practice management consultant. Whenever I reflect on my career, I tell myself how lucky I am. There are not many professions or individuals who have an opportunity to close the door behind them and have other human beings entrust them with their most intimate information. Also, there are very few individuals who are able to impact the delivery of medical care from a systems perspective. I get to do both, and for that I am most grateful.

Q: What is your biggest professional challenge?

A: Saying “no” when someone asks for help. There is nothing more rewarding for me than to help others. With that said, I try not to overextend myself, because that wouldn’t be fair to my family, colleagues, friends, or clients.

Q: What’s next for you professionally?

A: I will continue to concentrate my effort on building my hospitalist consultative practice and expanding the services I offer. In addition, I’m always tempted to explore the valley of the unknown. What excites me is venturing into new areas and to challenge myself to grow as both an individual and professional. TH

Mark Leiser is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

Kenneth G. Simone, DO, FHM, grew up as the son of a revered pediatrician. As a child, he often accompanied his father on hospital rounds and house calls, developing an appreciation for the “old-fashioned” medicine his father practiced.

Already inspired to follow in his father’s footsteps, Dr. Simone became even more convinced of his calling when the physician-patient roles were reversed: His dad developed a kidney disorder that cut his career—and ultimately his life—short. “His illness and my exposure to hospitals added to my desire to pursue medicine,” Dr. Simone says. “It instilled the drive to help others, to make a difference in someone’s or some family’s life.”

He has done that by developing multiple private medical practices, building the hospitalist program at St. Joseph Hospital in Bangor, Maine, and offering consulting services to more than 100 practices.

“It has always been my nature to challenge myself and put myself in situations that take me out of my comfort zone,” says Dr. Simone, president of Hospitalist and Practice Solutions, a practice-management consultancy in Veazie, Maine. “I enjoy building things from scratch, creating, rebuilding, thinking outside the box, and networking with other healthcare professionals.”

Question: What made you decide to start Hospitalist and Practice Solutions (HPS)?

Answer: HPS was established because of the demand for my services. Initially, word spread locally and then regionally about the work I did at St. Joseph Hospital. As a natural offshoot of my growing interest in helping other programs, HPS became a national consulting firm.

Q: Why did you think this venture could provide a valuable service?

A: I believed there were more effective healthcare delivery systems with which to provide both quality and cost-effective medical care. As time went on, I gained a very unique perspective working as both a hospitalist and referring PCP in private practice. This experience, coupled with my work as an administrative director for a hospitalist program, allowed me to develop applications to help hospitalist programs on a broader basis. I realized the advice I offered to other programs consistently rendered a positive effect.

Q: Which do you find more enjoyable: building a hospitalist program from the ground up or rebuilding a struggling program?

A: I truly enjoy the challenges of both equally. Projects that involve building a program de novo appeal to my creative side. These projects enable me to work with professionals to build a customized program that meets the needs of the community.

Q: What challenges are unique to each?

A: Rebuilding an established program involves critical analysis of the current program to identify what has gone wrong, what has been successful, and what will work in the future. It calls upon one’s skills to build consensus and instill trust in the process because the stakeholders may be apprehensive to have a consultant critically review their program and hospital. In many instances, conflict management is necessary.

In both the creation and rebuilding of an HM program, it is imperative to implement strategies that guide the program to future success. Both projects also require strategic planning and the development of tools and tactics that emphasize collaboration and collegiality.

Q: Do the failing programs you help to rebuild have characteristics in common?

A: Common themes include lack of planning and consensus-building before program start-up, inadequate tools and strategies to support effective practice management, and failure to align the hospitalist practice and sponsoring hospital’s goals and vision. Another common problem is the absence of a hospitalist recruitment and retention plan, which may lead to provider turnover and program instability.

Many programs experience problems due to ineffective leadership, poor implementation and follow-through, and lack of both a short- and long-term strategic plan. Some programs are victims of their own success. The program is not properly prepared to handle the demand for its services and grow accordingly.

Q: You help programs create effective recruitment and retention plans. You also wrote a book on the subject. Why are recruitment and retention challenging for so many programs?

A: The primary contributor is that [hospitalist] supply falls significantly short of physician demand. A secondary contributor is the generational expectations of the younger physician workforce. … In addition, leaders may not prioritize recruitment and retention because they lack an appreciation for the consequences of failed efforts.

Q: What advice would you offer hospitalist program leaders about how they can improve those aspects of their programs?

A: No. 1, create an effective recruitment and retention plan and execute the plan with precision. No. 2, approach recruitment and retention with the same attention to detail as you approach patient care.

Q: You’re offering best-practice advice to help your clients develop and sustain effective programs. What advice do you find yourself giving to your clients that you wish someone gave to you early in your career?

A: From my perspective as a hospitalist administrative director, the advice I would offer is for individuals to believe in themselves and stay engaged. If you feel you have something to offer to the practice or healthcare system as a whole, share it with the appropriate parties. If you experience problems within the workplace, seek resolution in a timely manner. Stay positive and be part of the solution, not part of the problem.

Q: You have written two hospitalist books and coauthored two others. Do you have plans to write another?

A: I wouldn’t say I have immediate plans, but I am always thinking about topics and other projects that would provide value to readers. I’ve got some exciting ideas for future projects, but they are in a very early stage of development.

Q: How would you compare the feeling you get from finishing a book with the satisfaction you derive from other aspects of your career?

A: Writing a book is a highly personal accomplishment for me, while caring for patients is more of a team accomplishment that involves the patient, family, and other healthcare professionals. Typically, the completion of a book is a finite event, while caring for a patient is a long-term commitment.

Q: What is your biggest professional reward?

A: Helping people, whether they are patients in my role as physician, or other professionals—physicians, practice administrators, and hospital administrators—in my role as a practice management consultant. Whenever I reflect on my career, I tell myself how lucky I am. There are not many professions or individuals who have an opportunity to close the door behind them and have other human beings entrust them with their most intimate information. Also, there are very few individuals who are able to impact the delivery of medical care from a systems perspective. I get to do both, and for that I am most grateful.

Q: What is your biggest professional challenge?

A: Saying “no” when someone asks for help. There is nothing more rewarding for me than to help others. With that said, I try not to overextend myself, because that wouldn’t be fair to my family, colleagues, friends, or clients.

Q: What’s next for you professionally?

A: I will continue to concentrate my effort on building my hospitalist consultative practice and expanding the services I offer. In addition, I’m always tempted to explore the valley of the unknown. What excites me is venturing into new areas and to challenge myself to grow as both an individual and professional. TH

Mark Leiser is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

Are Stress-Dose Steroids Indicated in Patients with Adrenal Insufficiency Hospitalized with Noncritical, Nonsurgical Illness?

Case

A 46-year-old woman with Addison’s disease and type II diabetes presents with one day of right leg pain, swelling, and redness. She has had mild nausea and vomiting over the past week, with an episode of diarrhea three days prior. She takes hydrocortisone 30mg in the morning and 10mg at bedtime, as well as fludrocortisone 0.2mg in the morning. She is afebrile with a pulse of 108 beats per minute. Her initial blood pressure was 74/49 mmHg, which improved to 84/45 mmHg following one liter of normal saline. She is mentating appropriately. The physical exam is significant for a large, tender area of erythema and warmth from the right ankle to mid-calf. She is admitted for cellulitis and intravenous antibiotics are initiated.

Does she require an increase in her glucocorticoid dose during her acute illness?

Overview

Adrenal insufficiency occurs in approximately 5 out of every 10,000 people and results from primary failure of the adrenal gland, or secondary impairment of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which regulates cortisol secretion.1 In developed countries, 90% of primary adrenal insufficiency (Addison’s disease) cases are due to autoimmune adrenalitis, which might occur in isolation or as part of an autoimmune polyglandular syndrome.1,2 Secondary adrenal insufficiency is most commonly the result of chronic glucocorticoid therapy, though lesions involving the hypothalamus or pituitary gland might be implicated.2,3

In a healthy individual, cortisol is secreted in a diurnal pattern from the adrenal glands under the control of corticotropin (ACTH) produced by the pituitary gland and corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) produced by the hypothalamus (see Figure 1, p. 19). In the normal state, during periods of such systemic stress as illness, trauma, burns, or surgery, cortisol production increases to a degree roughly proportional to the degree of illness (as much as sixfold).4,5 Patients with adrenal insufficiency are unable to mount an appropriate cortisol response and, therefore, are at risk for adrenal crisis—a life-threatening condition characterized by hypotension and hypovolemic shock.

Although recommendations for high-dose intravenous steroids in adrenally insufficient patients who are critically ill or undergoing surgery have been extensively discussed in the literature, there are relatively few data regarding the appropriate management of adrenal insufficiency in patients hospitalized for noncritical illness.

Several recent studies have investigated the patient characteristics, situations, and conditions most likely to provoke adrenal crisis in order to establish guidelines dictating the use of supra-physiologic steroid dosing.

Review of the Data

Studies have estimated the prevalence of adrenal crisis in patients with underlying insufficiency at 3.3 to 6.3 events per 100 patient years, with 42% of patients reporting at least one crisis.2,5,6 A recent survey of 982 patients with Addison’s disease in the United Kingdom reported an 8% annual frequency.7

A retrospective Japanese study reviewed the medical charts of 137 adult patients receiving steroid replacement for established primary or secondary adrenal insufficiency. The authors noted a significant positive association between adrenal crisis and long-term steroid replacement (>4 years), concomitant mental disorder, and sex hormone deficiency. A combination of any of these factors further increased the risk.8

A more recent survey of 444 patients ages 17-81 assessed independent risk factors for adrenal crisis in the setting of primary (N=254) or secondary (N=190) adrenal insufficiency. The incidence of crisis was higher in primary versus secondary insufficiency. In patients with primary insufficiency, concomitant, non-endocrine disorders increased the risk of adrenal crisis, whereas diabetes insipidus and female gender increased risk in patients with secondary insufficiency. This same study also investigated events leading to a crisis and found gastrointestinal infection to be the most frequent factor, followed by other infectious or febrile illnesses. Overall, infection comprised 45% of all identified triggers.6

A similar study conducted by White and Arlt evaluated 841 Addison’s patients in the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.7 Again, gastrointestinal illness was the most common provoking factor, responsible for 56% of all reported crises. Flulike illness followed at 11%, followed by infections and surgical procedures at 6% each. This study found a higher risk of crisis in patients with diabetes (type I or II), premature ovarian failure, and asthma; the presence of multiple comorbidities further increased risk.

Medications. Glucocorticoid therapy is known to suppress the HPA axis. Although it was once believed that the duration and dose of therapy correlated directly with the degree of HPA suppression, more recent studies have failed to find any definite relationship.9 Patients taking the equivalent of 5mg of prednisone per day should continue to have an intact HPA axis, as this dose mimics physiologic secretion of cortisol in a healthy individual.3

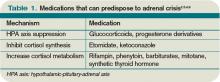

However, the dose and duration of therapy at which suppression occurs is highly variable between patients. In general, patients on 7.5mg of prednisone or more per day for at least three weeks should be considered to be suppressed.3,9 Additionally, progesterone derivatives (i.e., megestrol) have glucocorticoid activity and might suppress HPA function. Other medications that might have related effects are those that inhibit enzymes involved in cortisol synthesis; ketoconazole and etomidate are common examples. Rifampin and several classes of anti-epileptic drugs induce enzymes, which increase hepatic metabolism of cortisol (see Table 1, p. 18).

Hyperthyroidism. Thyroid hormone is involved in the metabolism of cortisol, thus an increase in T4 correlates with lower levels. Adrenal insufficiency and thyroid disease might coexist within the autoimmune polyglandular syndrome. Initiation or uptitration of thyroid replacement should be avoided if acute adrenal insufficiency is suspected, as this might provoke an adrenal crisis. Conversely, any patient with adrenal insufficiency who has uncontrolled hyperthyroidism should receive two to three times their usual glucocorticoid replacement.1,2

Pregnancy. Levels of cortisol-binding globulin increase throughout pregnancy. In women with intact adrenal function, free cortisol levels also rise during the third trimester. Therefore, glucocorticoid replacement should be increased by 50% during the last three months of pregnancy.2

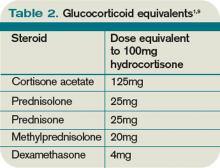

Acute illness. The cortisol response to stress is highly variable and dependent on a number of factors, including age, underlying health, and genetics. In general, most experts recommend doubling or tripling the daily replacement dose during mild to moderate illness until recovery (often referred to as the “sick-day rules”). What constitutes “recovery” is not clearly defined. When oral intake is compromised, as with vomiting or diarrhea, parenteral administration of steroids is recommended.1-5,9,10 Patients with adrenal insufficiency should be provided an emergency injection kit to use and further counseled to seek medical attention. Injection kits typically consist of 100mg of hydrocortisone or 4mg of dexamethasone, although other glucocorticoids may be used (see Table 2, above left, for conversions).

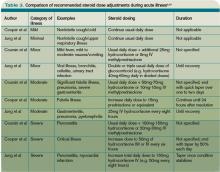

Limited data are available to support guidelines for glucocorticoid adjustment during acute, non-critical illness. Published guidelines vary both in illness categorization and category-specific recommendations (see Table 3, below).

Coursin and Wood devised a set of guidelines based on a literature review and consultation with experts, categorizing medical illness as minor, moderate, severe, and critical (see Table 3).3 For noncritical illness, they recommended continuation of standard replacement therapy with an additional, once-daily dose, which varied according to illness severity.

Cooper and Stewart conducted a similar review, basing their guidelines on a categorization of mild, moderate, severe/critical, or septic shock. These guidelines recommended a total daily dose of glucocorticoid supplementation, rather than an addition of a single dose to current therapy. They also stated that the least severe category of illness (defined as mild) did not require any change to a patient’s regular therapy.4

Jung et al classified illness as minimal, minor, moderate, severe, and critical.9 Under these guidelines, supplemental therapy was not advised for minimal (nonfebrile) illness. Moderate illness, including cellulitis, warranted a doubling or tripling of the outpatient dose until recovery, which was consistent with prior expert recommendation. More severe illness warranted intravenous administration of steroids.

Back to the Case

The patient had a mild case of cellulitis, classified by most experts as moderate illness, which responded well to vancomycin. Her outpatient glucocorticoid dose was doubled on admission and administered orally for the duration of her hospitalization, as she had no further episodes of vomiting or diarrhea.

Review of the patient’s records from prior hospitalizations and ambulatory visits revealed that her systolic blood pressure typically ran in the 80 mmHg to 100 mmHg range. Following initial volume resuscitation, her systolic blood pressure remained in the 90-100 mmHg range.

She was discharged home in stable condition, with instructions to complete a course of oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, resume her baseline dose of hydrocortisone the day after discharge, and follow up with her PCP for further monitoring and adjustment of her adrenal replacement therapy.

Bottom Line

For adults with adrenal insufficiency hospitalized with noncritical, nonsurgical illness, the expert recommendation is to double or triple the usual outpatient dose of glucocorticoid; however, data to support this is limited, and each patient should be assessed carefully and monitored to determine the optimal dose adjustment. TH

Dr. Shaw is a resident in the Department of Medicine at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle. Dr. Best is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine, University of Washington School of Medicine.

References

- Arlt W. The approach to the adult with newly diagnosed adrenal insufficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(4):1059-1067.

- Arlt W, Allolio B. Adrenal insufficiency. Lancet. 2003; 361:1881-1893.

- Coursin DB, Wood KE. Corticosteroid supplementation for adrenal insufficiency. JAMA. 2002;287:236-240.

- Cooper MS, Stewart PM. Corticosteroid insufficiency in acutely ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:727-734.

- Hahner S, Allolio B. Therapeutic management of adrenal insufficiency. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;23:167-179.

- Hahner S, Loeffler M, Bleicken B, et al. Epidemiology of adrenal crisis in chronic adrenal insufficiency: the need for new prevention strategies. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;162:597:602.

- White K, Arlt W. Adrenal crisis in treated Addison’s disease: a predictable but under-managed event. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;162:115-120.

- Omori K, Nomura K, Shimizu S, Omori N, Takano K. Risk factors for adrenal crises in patients with adrenal insufficiency. Endocr J. 2003;50:745-752.

- Jung C, Inder WJ. Management of adrenal insufficiency during the stress of medical illness and surgery. Med J Aust. 2008;188:409-413.

- Crown A, Lightman S. Why is the management of glucocorticoid deficiency still controversial: a review of the literature. Clin Endocrinol. 2005;63:483-492.

Case

A 46-year-old woman with Addison’s disease and type II diabetes presents with one day of right leg pain, swelling, and redness. She has had mild nausea and vomiting over the past week, with an episode of diarrhea three days prior. She takes hydrocortisone 30mg in the morning and 10mg at bedtime, as well as fludrocortisone 0.2mg in the morning. She is afebrile with a pulse of 108 beats per minute. Her initial blood pressure was 74/49 mmHg, which improved to 84/45 mmHg following one liter of normal saline. She is mentating appropriately. The physical exam is significant for a large, tender area of erythema and warmth from the right ankle to mid-calf. She is admitted for cellulitis and intravenous antibiotics are initiated.

Does she require an increase in her glucocorticoid dose during her acute illness?

Overview

Adrenal insufficiency occurs in approximately 5 out of every 10,000 people and results from primary failure of the adrenal gland, or secondary impairment of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which regulates cortisol secretion.1 In developed countries, 90% of primary adrenal insufficiency (Addison’s disease) cases are due to autoimmune adrenalitis, which might occur in isolation or as part of an autoimmune polyglandular syndrome.1,2 Secondary adrenal insufficiency is most commonly the result of chronic glucocorticoid therapy, though lesions involving the hypothalamus or pituitary gland might be implicated.2,3

In a healthy individual, cortisol is secreted in a diurnal pattern from the adrenal glands under the control of corticotropin (ACTH) produced by the pituitary gland and corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) produced by the hypothalamus (see Figure 1, p. 19). In the normal state, during periods of such systemic stress as illness, trauma, burns, or surgery, cortisol production increases to a degree roughly proportional to the degree of illness (as much as sixfold).4,5 Patients with adrenal insufficiency are unable to mount an appropriate cortisol response and, therefore, are at risk for adrenal crisis—a life-threatening condition characterized by hypotension and hypovolemic shock.

Although recommendations for high-dose intravenous steroids in adrenally insufficient patients who are critically ill or undergoing surgery have been extensively discussed in the literature, there are relatively few data regarding the appropriate management of adrenal insufficiency in patients hospitalized for noncritical illness.

Several recent studies have investigated the patient characteristics, situations, and conditions most likely to provoke adrenal crisis in order to establish guidelines dictating the use of supra-physiologic steroid dosing.

Review of the Data

Studies have estimated the prevalence of adrenal crisis in patients with underlying insufficiency at 3.3 to 6.3 events per 100 patient years, with 42% of patients reporting at least one crisis.2,5,6 A recent survey of 982 patients with Addison’s disease in the United Kingdom reported an 8% annual frequency.7

A retrospective Japanese study reviewed the medical charts of 137 adult patients receiving steroid replacement for established primary or secondary adrenal insufficiency. The authors noted a significant positive association between adrenal crisis and long-term steroid replacement (>4 years), concomitant mental disorder, and sex hormone deficiency. A combination of any of these factors further increased the risk.8

A more recent survey of 444 patients ages 17-81 assessed independent risk factors for adrenal crisis in the setting of primary (N=254) or secondary (N=190) adrenal insufficiency. The incidence of crisis was higher in primary versus secondary insufficiency. In patients with primary insufficiency, concomitant, non-endocrine disorders increased the risk of adrenal crisis, whereas diabetes insipidus and female gender increased risk in patients with secondary insufficiency. This same study also investigated events leading to a crisis and found gastrointestinal infection to be the most frequent factor, followed by other infectious or febrile illnesses. Overall, infection comprised 45% of all identified triggers.6

A similar study conducted by White and Arlt evaluated 841 Addison’s patients in the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.7 Again, gastrointestinal illness was the most common provoking factor, responsible for 56% of all reported crises. Flulike illness followed at 11%, followed by infections and surgical procedures at 6% each. This study found a higher risk of crisis in patients with diabetes (type I or II), premature ovarian failure, and asthma; the presence of multiple comorbidities further increased risk.

Medications. Glucocorticoid therapy is known to suppress the HPA axis. Although it was once believed that the duration and dose of therapy correlated directly with the degree of HPA suppression, more recent studies have failed to find any definite relationship.9 Patients taking the equivalent of 5mg of prednisone per day should continue to have an intact HPA axis, as this dose mimics physiologic secretion of cortisol in a healthy individual.3

However, the dose and duration of therapy at which suppression occurs is highly variable between patients. In general, patients on 7.5mg of prednisone or more per day for at least three weeks should be considered to be suppressed.3,9 Additionally, progesterone derivatives (i.e., megestrol) have glucocorticoid activity and might suppress HPA function. Other medications that might have related effects are those that inhibit enzymes involved in cortisol synthesis; ketoconazole and etomidate are common examples. Rifampin and several classes of anti-epileptic drugs induce enzymes, which increase hepatic metabolism of cortisol (see Table 1, p. 18).

Hyperthyroidism. Thyroid hormone is involved in the metabolism of cortisol, thus an increase in T4 correlates with lower levels. Adrenal insufficiency and thyroid disease might coexist within the autoimmune polyglandular syndrome. Initiation or uptitration of thyroid replacement should be avoided if acute adrenal insufficiency is suspected, as this might provoke an adrenal crisis. Conversely, any patient with adrenal insufficiency who has uncontrolled hyperthyroidism should receive two to three times their usual glucocorticoid replacement.1,2

Pregnancy. Levels of cortisol-binding globulin increase throughout pregnancy. In women with intact adrenal function, free cortisol levels also rise during the third trimester. Therefore, glucocorticoid replacement should be increased by 50% during the last three months of pregnancy.2

Acute illness. The cortisol response to stress is highly variable and dependent on a number of factors, including age, underlying health, and genetics. In general, most experts recommend doubling or tripling the daily replacement dose during mild to moderate illness until recovery (often referred to as the “sick-day rules”). What constitutes “recovery” is not clearly defined. When oral intake is compromised, as with vomiting or diarrhea, parenteral administration of steroids is recommended.1-5,9,10 Patients with adrenal insufficiency should be provided an emergency injection kit to use and further counseled to seek medical attention. Injection kits typically consist of 100mg of hydrocortisone or 4mg of dexamethasone, although other glucocorticoids may be used (see Table 2, above left, for conversions).

Limited data are available to support guidelines for glucocorticoid adjustment during acute, non-critical illness. Published guidelines vary both in illness categorization and category-specific recommendations (see Table 3, below).

Coursin and Wood devised a set of guidelines based on a literature review and consultation with experts, categorizing medical illness as minor, moderate, severe, and critical (see Table 3).3 For noncritical illness, they recommended continuation of standard replacement therapy with an additional, once-daily dose, which varied according to illness severity.

Cooper and Stewart conducted a similar review, basing their guidelines on a categorization of mild, moderate, severe/critical, or septic shock. These guidelines recommended a total daily dose of glucocorticoid supplementation, rather than an addition of a single dose to current therapy. They also stated that the least severe category of illness (defined as mild) did not require any change to a patient’s regular therapy.4

Jung et al classified illness as minimal, minor, moderate, severe, and critical.9 Under these guidelines, supplemental therapy was not advised for minimal (nonfebrile) illness. Moderate illness, including cellulitis, warranted a doubling or tripling of the outpatient dose until recovery, which was consistent with prior expert recommendation. More severe illness warranted intravenous administration of steroids.

Back to the Case

The patient had a mild case of cellulitis, classified by most experts as moderate illness, which responded well to vancomycin. Her outpatient glucocorticoid dose was doubled on admission and administered orally for the duration of her hospitalization, as she had no further episodes of vomiting or diarrhea.

Review of the patient’s records from prior hospitalizations and ambulatory visits revealed that her systolic blood pressure typically ran in the 80 mmHg to 100 mmHg range. Following initial volume resuscitation, her systolic blood pressure remained in the 90-100 mmHg range.

She was discharged home in stable condition, with instructions to complete a course of oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, resume her baseline dose of hydrocortisone the day after discharge, and follow up with her PCP for further monitoring and adjustment of her adrenal replacement therapy.

Bottom Line

For adults with adrenal insufficiency hospitalized with noncritical, nonsurgical illness, the expert recommendation is to double or triple the usual outpatient dose of glucocorticoid; however, data to support this is limited, and each patient should be assessed carefully and monitored to determine the optimal dose adjustment. TH

Dr. Shaw is a resident in the Department of Medicine at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle. Dr. Best is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine, University of Washington School of Medicine.

References

- Arlt W. The approach to the adult with newly diagnosed adrenal insufficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(4):1059-1067.

- Arlt W, Allolio B. Adrenal insufficiency. Lancet. 2003; 361:1881-1893.

- Coursin DB, Wood KE. Corticosteroid supplementation for adrenal insufficiency. JAMA. 2002;287:236-240.

- Cooper MS, Stewart PM. Corticosteroid insufficiency in acutely ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:727-734.

- Hahner S, Allolio B. Therapeutic management of adrenal insufficiency. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;23:167-179.

- Hahner S, Loeffler M, Bleicken B, et al. Epidemiology of adrenal crisis in chronic adrenal insufficiency: the need for new prevention strategies. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;162:597:602.

- White K, Arlt W. Adrenal crisis in treated Addison’s disease: a predictable but under-managed event. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;162:115-120.

- Omori K, Nomura K, Shimizu S, Omori N, Takano K. Risk factors for adrenal crises in patients with adrenal insufficiency. Endocr J. 2003;50:745-752.

- Jung C, Inder WJ. Management of adrenal insufficiency during the stress of medical illness and surgery. Med J Aust. 2008;188:409-413.

- Crown A, Lightman S. Why is the management of glucocorticoid deficiency still controversial: a review of the literature. Clin Endocrinol. 2005;63:483-492.

Case

A 46-year-old woman with Addison’s disease and type II diabetes presents with one day of right leg pain, swelling, and redness. She has had mild nausea and vomiting over the past week, with an episode of diarrhea three days prior. She takes hydrocortisone 30mg in the morning and 10mg at bedtime, as well as fludrocortisone 0.2mg in the morning. She is afebrile with a pulse of 108 beats per minute. Her initial blood pressure was 74/49 mmHg, which improved to 84/45 mmHg following one liter of normal saline. She is mentating appropriately. The physical exam is significant for a large, tender area of erythema and warmth from the right ankle to mid-calf. She is admitted for cellulitis and intravenous antibiotics are initiated.

Does she require an increase in her glucocorticoid dose during her acute illness?

Overview

Adrenal insufficiency occurs in approximately 5 out of every 10,000 people and results from primary failure of the adrenal gland, or secondary impairment of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which regulates cortisol secretion.1 In developed countries, 90% of primary adrenal insufficiency (Addison’s disease) cases are due to autoimmune adrenalitis, which might occur in isolation or as part of an autoimmune polyglandular syndrome.1,2 Secondary adrenal insufficiency is most commonly the result of chronic glucocorticoid therapy, though lesions involving the hypothalamus or pituitary gland might be implicated.2,3

In a healthy individual, cortisol is secreted in a diurnal pattern from the adrenal glands under the control of corticotropin (ACTH) produced by the pituitary gland and corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) produced by the hypothalamus (see Figure 1, p. 19). In the normal state, during periods of such systemic stress as illness, trauma, burns, or surgery, cortisol production increases to a degree roughly proportional to the degree of illness (as much as sixfold).4,5 Patients with adrenal insufficiency are unable to mount an appropriate cortisol response and, therefore, are at risk for adrenal crisis—a life-threatening condition characterized by hypotension and hypovolemic shock.

Although recommendations for high-dose intravenous steroids in adrenally insufficient patients who are critically ill or undergoing surgery have been extensively discussed in the literature, there are relatively few data regarding the appropriate management of adrenal insufficiency in patients hospitalized for noncritical illness.

Several recent studies have investigated the patient characteristics, situations, and conditions most likely to provoke adrenal crisis in order to establish guidelines dictating the use of supra-physiologic steroid dosing.

Review of the Data

Studies have estimated the prevalence of adrenal crisis in patients with underlying insufficiency at 3.3 to 6.3 events per 100 patient years, with 42% of patients reporting at least one crisis.2,5,6 A recent survey of 982 patients with Addison’s disease in the United Kingdom reported an 8% annual frequency.7

A retrospective Japanese study reviewed the medical charts of 137 adult patients receiving steroid replacement for established primary or secondary adrenal insufficiency. The authors noted a significant positive association between adrenal crisis and long-term steroid replacement (>4 years), concomitant mental disorder, and sex hormone deficiency. A combination of any of these factors further increased the risk.8

A more recent survey of 444 patients ages 17-81 assessed independent risk factors for adrenal crisis in the setting of primary (N=254) or secondary (N=190) adrenal insufficiency. The incidence of crisis was higher in primary versus secondary insufficiency. In patients with primary insufficiency, concomitant, non-endocrine disorders increased the risk of adrenal crisis, whereas diabetes insipidus and female gender increased risk in patients with secondary insufficiency. This same study also investigated events leading to a crisis and found gastrointestinal infection to be the most frequent factor, followed by other infectious or febrile illnesses. Overall, infection comprised 45% of all identified triggers.6

A similar study conducted by White and Arlt evaluated 841 Addison’s patients in the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.7 Again, gastrointestinal illness was the most common provoking factor, responsible for 56% of all reported crises. Flulike illness followed at 11%, followed by infections and surgical procedures at 6% each. This study found a higher risk of crisis in patients with diabetes (type I or II), premature ovarian failure, and asthma; the presence of multiple comorbidities further increased risk.

Medications. Glucocorticoid therapy is known to suppress the HPA axis. Although it was once believed that the duration and dose of therapy correlated directly with the degree of HPA suppression, more recent studies have failed to find any definite relationship.9 Patients taking the equivalent of 5mg of prednisone per day should continue to have an intact HPA axis, as this dose mimics physiologic secretion of cortisol in a healthy individual.3

However, the dose and duration of therapy at which suppression occurs is highly variable between patients. In general, patients on 7.5mg of prednisone or more per day for at least three weeks should be considered to be suppressed.3,9 Additionally, progesterone derivatives (i.e., megestrol) have glucocorticoid activity and might suppress HPA function. Other medications that might have related effects are those that inhibit enzymes involved in cortisol synthesis; ketoconazole and etomidate are common examples. Rifampin and several classes of anti-epileptic drugs induce enzymes, which increase hepatic metabolism of cortisol (see Table 1, p. 18).

Hyperthyroidism. Thyroid hormone is involved in the metabolism of cortisol, thus an increase in T4 correlates with lower levels. Adrenal insufficiency and thyroid disease might coexist within the autoimmune polyglandular syndrome. Initiation or uptitration of thyroid replacement should be avoided if acute adrenal insufficiency is suspected, as this might provoke an adrenal crisis. Conversely, any patient with adrenal insufficiency who has uncontrolled hyperthyroidism should receive two to three times their usual glucocorticoid replacement.1,2

Pregnancy. Levels of cortisol-binding globulin increase throughout pregnancy. In women with intact adrenal function, free cortisol levels also rise during the third trimester. Therefore, glucocorticoid replacement should be increased by 50% during the last three months of pregnancy.2

Acute illness. The cortisol response to stress is highly variable and dependent on a number of factors, including age, underlying health, and genetics. In general, most experts recommend doubling or tripling the daily replacement dose during mild to moderate illness until recovery (often referred to as the “sick-day rules”). What constitutes “recovery” is not clearly defined. When oral intake is compromised, as with vomiting or diarrhea, parenteral administration of steroids is recommended.1-5,9,10 Patients with adrenal insufficiency should be provided an emergency injection kit to use and further counseled to seek medical attention. Injection kits typically consist of 100mg of hydrocortisone or 4mg of dexamethasone, although other glucocorticoids may be used (see Table 2, above left, for conversions).

Limited data are available to support guidelines for glucocorticoid adjustment during acute, non-critical illness. Published guidelines vary both in illness categorization and category-specific recommendations (see Table 3, below).

Coursin and Wood devised a set of guidelines based on a literature review and consultation with experts, categorizing medical illness as minor, moderate, severe, and critical (see Table 3).3 For noncritical illness, they recommended continuation of standard replacement therapy with an additional, once-daily dose, which varied according to illness severity.

Cooper and Stewart conducted a similar review, basing their guidelines on a categorization of mild, moderate, severe/critical, or septic shock. These guidelines recommended a total daily dose of glucocorticoid supplementation, rather than an addition of a single dose to current therapy. They also stated that the least severe category of illness (defined as mild) did not require any change to a patient’s regular therapy.4

Jung et al classified illness as minimal, minor, moderate, severe, and critical.9 Under these guidelines, supplemental therapy was not advised for minimal (nonfebrile) illness. Moderate illness, including cellulitis, warranted a doubling or tripling of the outpatient dose until recovery, which was consistent with prior expert recommendation. More severe illness warranted intravenous administration of steroids.

Back to the Case

The patient had a mild case of cellulitis, classified by most experts as moderate illness, which responded well to vancomycin. Her outpatient glucocorticoid dose was doubled on admission and administered orally for the duration of her hospitalization, as she had no further episodes of vomiting or diarrhea.

Review of the patient’s records from prior hospitalizations and ambulatory visits revealed that her systolic blood pressure typically ran in the 80 mmHg to 100 mmHg range. Following initial volume resuscitation, her systolic blood pressure remained in the 90-100 mmHg range.

She was discharged home in stable condition, with instructions to complete a course of oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, resume her baseline dose of hydrocortisone the day after discharge, and follow up with her PCP for further monitoring and adjustment of her adrenal replacement therapy.

Bottom Line

For adults with adrenal insufficiency hospitalized with noncritical, nonsurgical illness, the expert recommendation is to double or triple the usual outpatient dose of glucocorticoid; however, data to support this is limited, and each patient should be assessed carefully and monitored to determine the optimal dose adjustment. TH

Dr. Shaw is a resident in the Department of Medicine at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle. Dr. Best is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine, University of Washington School of Medicine.

References

- Arlt W. The approach to the adult with newly diagnosed adrenal insufficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(4):1059-1067.

- Arlt W, Allolio B. Adrenal insufficiency. Lancet. 2003; 361:1881-1893.

- Coursin DB, Wood KE. Corticosteroid supplementation for adrenal insufficiency. JAMA. 2002;287:236-240.

- Cooper MS, Stewart PM. Corticosteroid insufficiency in acutely ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:727-734.

- Hahner S, Allolio B. Therapeutic management of adrenal insufficiency. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;23:167-179.

- Hahner S, Loeffler M, Bleicken B, et al. Epidemiology of adrenal crisis in chronic adrenal insufficiency: the need for new prevention strategies. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;162:597:602.

- White K, Arlt W. Adrenal crisis in treated Addison’s disease: a predictable but under-managed event. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;162:115-120.

- Omori K, Nomura K, Shimizu S, Omori N, Takano K. Risk factors for adrenal crises in patients with adrenal insufficiency. Endocr J. 2003;50:745-752.

- Jung C, Inder WJ. Management of adrenal insufficiency during the stress of medical illness and surgery. Med J Aust. 2008;188:409-413.

- Crown A, Lightman S. Why is the management of glucocorticoid deficiency still controversial: a review of the literature. Clin Endocrinol. 2005;63:483-492.

Career Development

Although the term “hospitalist” was coined in 1996 in a New England Journal of Medicine article, the field of HM grew organically from pressure to optimize hospital economics and improve efficiency in economically pressed healthcare markets.1

Scholarship in HM has also grown and now includes regular publications of investigations exploring optimization of efficiency and quality, many with an emphasis on patient safety. In this way, HM is a unique field, with tools for approaching problems that aren’t commonly used in other branches of medicine.

In parallel to the emergence of HM as a field distinct from general internal medicine (IM), the HM fellowship is similar but distinct. Such fellowships serve multiple purposes.

HM fellowships can add clinical expertise and scholarship skills for a career in HM. While early HM research focused on proving the value of the hospitalist model, the field has expanded greatly for those interested in an academic career. The molding of a safer, more efficient hospital of the future depends on the creativity and scholarship of HM leaders. Further, experts suggest that with its unique emphasis on quality, safety, and efficiency, the field will be a key player in healthcare reform.2 Its strength lies in traditional clinical research, as well as further adoption of lessons from other fields including industry, ethnography, and public health.3 As such, fellowships to train future leaders and researchers is essential.

SHM’s website (www.hospitalmedicine.org/fellowships) lists dozens of IM hospitalist fellowships, as well as programs in family practice, pediatrics, and psychiatry. These programs last from one to three years, accept from one to six fellows per year, and exist in locations throughout the U.S. and Canada.

An excellent description of the nature and scope of pediatric HM fellowships was published last year in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.4 Descriptions of IM and HM fellowships also have been published.3,5

Hospitalist fellowships, like IM fellowships, aren’t credentialed by a governing body. In contrast to subspecialty fellowships, no separate specialty board exam is required for admittance to the field after completion of fellowship. HM positions do not require training after residency, and HM job opportunities continue to outpace the available workforce. This is the basis for the most important question confronting anyone considering such a fellowship: How is a fellowship of benefit to a career as a hospitalist?

Program Types

Ranji and colleagues wrote that the “goal of hospital medicine fellowship training is to produce clinicians who are trained explicitly in studying and optimizing medical care of the hospitalized patient and in disseminating that knowledge for the advancement of patient care.”3 A review of information available for the different programs reveals two distinct approaches to this goal, with much overlap but distinct emphases:

Clinical programs usually last one year with a majority of time spent filling clinical responsibilities. In addition to providing focused exposure to HM with an emphasis on the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine as outlined by SHM, such a program generally expands a trainee’s clinical scope. Additional training in palliative care, the management of neurologic emergencies, and comanagement of surgical patients are likely to be a part of clinical practice but often are underemphasized during residency. Research expectations vary, but most clinical programs allot some time for quality-improvement (QI) projects.

Clinical fellowships also afford more leadership training than most jobs would offer in the period immediately following residency. It also offers the possibility of refining clinical skills and developing a clinical niche.

Academic programs last two years and are characterized by two to four months of clinical responsibility per year. They offer a formal teaching curriculum and provide dedicated training in research, health policy, or health economics.3 Research training varies from program to program. Most include basic biostatistics and research-method coursework at a minimum; others offer the option to pursue a graduate degree in clinical research or public health.

Academic programs also offer dedicated research mentorship.

Other Considerations

The value of an HM fellowship lies in career development. The decision to commit to a relatively low-paying fellowship can be a difficult one, especially given the debt burden most graduating residents bear and the abundance of high-paying HM jobs. It also is important for those interested in a career as an academic hospitalist to consider not only HM fellowships, but other programs as well, such as the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program (rwjcsp.unc.edu/about/index.html).

While all of the fellowship programs aren’t geared specifically toward the hospitalist, they often incorporate faculty with expertise that would benefit a future academic hospitalist. Of course, the best fit for an individual depends on their particular interests and needs.

Fellowship in HM can offer training in clinical skills, clinical research, teaching, and quality and patient safety. Anyone interested in an HM career should consider a fellowship an opportunity for career development in a young specialty entrenched in revolutionizing the care of hospitalized patients. Academic HM fellowships hold the promise of empowering tomorrow’s academic leaders with the tools to continue to move the field forward. TH

Dr. Mann is a fellow in the division of hospital medicine, Department of Medicine, at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City. Dr. Markoff is associate division chief and fellowship director in the division of hospital medicine, Department of Medicine, at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City.

References

- Wachter RM. Reflections: the hospitalist movement a decade later. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(4):248-252.

- Wachter RM. Keynote presentation. SHM national meeting. National Harbor, Md.: May 2010.

- Ranji SR, Rosenman DJ, Amin AN, Kripalani S. Hospital medicine fellowships: works in progress. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):72.e1-e7.

- Freed GL, Dunham KM, Research advisory committee of the American Board of Pediatrics. Characteristics of pediatric hospital medicine fellowships and training programs. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:157-163.

- Arora V, Fang MC, Kripalani S, Amin AN. Preparing for “diastole”: advanced training opportunities for academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(6):368-377.

Although the term “hospitalist” was coined in 1996 in a New England Journal of Medicine article, the field of HM grew organically from pressure to optimize hospital economics and improve efficiency in economically pressed healthcare markets.1

Scholarship in HM has also grown and now includes regular publications of investigations exploring optimization of efficiency and quality, many with an emphasis on patient safety. In this way, HM is a unique field, with tools for approaching problems that aren’t commonly used in other branches of medicine.

In parallel to the emergence of HM as a field distinct from general internal medicine (IM), the HM fellowship is similar but distinct. Such fellowships serve multiple purposes.

HM fellowships can add clinical expertise and scholarship skills for a career in HM. While early HM research focused on proving the value of the hospitalist model, the field has expanded greatly for those interested in an academic career. The molding of a safer, more efficient hospital of the future depends on the creativity and scholarship of HM leaders. Further, experts suggest that with its unique emphasis on quality, safety, and efficiency, the field will be a key player in healthcare reform.2 Its strength lies in traditional clinical research, as well as further adoption of lessons from other fields including industry, ethnography, and public health.3 As such, fellowships to train future leaders and researchers is essential.

SHM’s website (www.hospitalmedicine.org/fellowships) lists dozens of IM hospitalist fellowships, as well as programs in family practice, pediatrics, and psychiatry. These programs last from one to three years, accept from one to six fellows per year, and exist in locations throughout the U.S. and Canada.

An excellent description of the nature and scope of pediatric HM fellowships was published last year in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.4 Descriptions of IM and HM fellowships also have been published.3,5

Hospitalist fellowships, like IM fellowships, aren’t credentialed by a governing body. In contrast to subspecialty fellowships, no separate specialty board exam is required for admittance to the field after completion of fellowship. HM positions do not require training after residency, and HM job opportunities continue to outpace the available workforce. This is the basis for the most important question confronting anyone considering such a fellowship: How is a fellowship of benefit to a career as a hospitalist?

Program Types

Ranji and colleagues wrote that the “goal of hospital medicine fellowship training is to produce clinicians who are trained explicitly in studying and optimizing medical care of the hospitalized patient and in disseminating that knowledge for the advancement of patient care.”3 A review of information available for the different programs reveals two distinct approaches to this goal, with much overlap but distinct emphases:

Clinical programs usually last one year with a majority of time spent filling clinical responsibilities. In addition to providing focused exposure to HM with an emphasis on the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine as outlined by SHM, such a program generally expands a trainee’s clinical scope. Additional training in palliative care, the management of neurologic emergencies, and comanagement of surgical patients are likely to be a part of clinical practice but often are underemphasized during residency. Research expectations vary, but most clinical programs allot some time for quality-improvement (QI) projects.

Clinical fellowships also afford more leadership training than most jobs would offer in the period immediately following residency. It also offers the possibility of refining clinical skills and developing a clinical niche.

Academic programs last two years and are characterized by two to four months of clinical responsibility per year. They offer a formal teaching curriculum and provide dedicated training in research, health policy, or health economics.3 Research training varies from program to program. Most include basic biostatistics and research-method coursework at a minimum; others offer the option to pursue a graduate degree in clinical research or public health.

Academic programs also offer dedicated research mentorship.

Other Considerations

The value of an HM fellowship lies in career development. The decision to commit to a relatively low-paying fellowship can be a difficult one, especially given the debt burden most graduating residents bear and the abundance of high-paying HM jobs. It also is important for those interested in a career as an academic hospitalist to consider not only HM fellowships, but other programs as well, such as the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program (rwjcsp.unc.edu/about/index.html).

While all of the fellowship programs aren’t geared specifically toward the hospitalist, they often incorporate faculty with expertise that would benefit a future academic hospitalist. Of course, the best fit for an individual depends on their particular interests and needs.

Fellowship in HM can offer training in clinical skills, clinical research, teaching, and quality and patient safety. Anyone interested in an HM career should consider a fellowship an opportunity for career development in a young specialty entrenched in revolutionizing the care of hospitalized patients. Academic HM fellowships hold the promise of empowering tomorrow’s academic leaders with the tools to continue to move the field forward. TH

Dr. Mann is a fellow in the division of hospital medicine, Department of Medicine, at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City. Dr. Markoff is associate division chief and fellowship director in the division of hospital medicine, Department of Medicine, at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City.

References

- Wachter RM. Reflections: the hospitalist movement a decade later. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(4):248-252.

- Wachter RM. Keynote presentation. SHM national meeting. National Harbor, Md.: May 2010.

- Ranji SR, Rosenman DJ, Amin AN, Kripalani S. Hospital medicine fellowships: works in progress. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):72.e1-e7.

- Freed GL, Dunham KM, Research advisory committee of the American Board of Pediatrics. Characteristics of pediatric hospital medicine fellowships and training programs. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:157-163.

- Arora V, Fang MC, Kripalani S, Amin AN. Preparing for “diastole”: advanced training opportunities for academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(6):368-377.

Although the term “hospitalist” was coined in 1996 in a New England Journal of Medicine article, the field of HM grew organically from pressure to optimize hospital economics and improve efficiency in economically pressed healthcare markets.1

Scholarship in HM has also grown and now includes regular publications of investigations exploring optimization of efficiency and quality, many with an emphasis on patient safety. In this way, HM is a unique field, with tools for approaching problems that aren’t commonly used in other branches of medicine.

In parallel to the emergence of HM as a field distinct from general internal medicine (IM), the HM fellowship is similar but distinct. Such fellowships serve multiple purposes.

HM fellowships can add clinical expertise and scholarship skills for a career in HM. While early HM research focused on proving the value of the hospitalist model, the field has expanded greatly for those interested in an academic career. The molding of a safer, more efficient hospital of the future depends on the creativity and scholarship of HM leaders. Further, experts suggest that with its unique emphasis on quality, safety, and efficiency, the field will be a key player in healthcare reform.2 Its strength lies in traditional clinical research, as well as further adoption of lessons from other fields including industry, ethnography, and public health.3 As such, fellowships to train future leaders and researchers is essential.

SHM’s website (www.hospitalmedicine.org/fellowships) lists dozens of IM hospitalist fellowships, as well as programs in family practice, pediatrics, and psychiatry. These programs last from one to three years, accept from one to six fellows per year, and exist in locations throughout the U.S. and Canada.

An excellent description of the nature and scope of pediatric HM fellowships was published last year in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.4 Descriptions of IM and HM fellowships also have been published.3,5

Hospitalist fellowships, like IM fellowships, aren’t credentialed by a governing body. In contrast to subspecialty fellowships, no separate specialty board exam is required for admittance to the field after completion of fellowship. HM positions do not require training after residency, and HM job opportunities continue to outpace the available workforce. This is the basis for the most important question confronting anyone considering such a fellowship: How is a fellowship of benefit to a career as a hospitalist?

Program Types

Ranji and colleagues wrote that the “goal of hospital medicine fellowship training is to produce clinicians who are trained explicitly in studying and optimizing medical care of the hospitalized patient and in disseminating that knowledge for the advancement of patient care.”3 A review of information available for the different programs reveals two distinct approaches to this goal, with much overlap but distinct emphases:

Clinical programs usually last one year with a majority of time spent filling clinical responsibilities. In addition to providing focused exposure to HM with an emphasis on the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine as outlined by SHM, such a program generally expands a trainee’s clinical scope. Additional training in palliative care, the management of neurologic emergencies, and comanagement of surgical patients are likely to be a part of clinical practice but often are underemphasized during residency. Research expectations vary, but most clinical programs allot some time for quality-improvement (QI) projects.

Clinical fellowships also afford more leadership training than most jobs would offer in the period immediately following residency. It also offers the possibility of refining clinical skills and developing a clinical niche.

Academic programs last two years and are characterized by two to four months of clinical responsibility per year. They offer a formal teaching curriculum and provide dedicated training in research, health policy, or health economics.3 Research training varies from program to program. Most include basic biostatistics and research-method coursework at a minimum; others offer the option to pursue a graduate degree in clinical research or public health.

Academic programs also offer dedicated research mentorship.

Other Considerations

The value of an HM fellowship lies in career development. The decision to commit to a relatively low-paying fellowship can be a difficult one, especially given the debt burden most graduating residents bear and the abundance of high-paying HM jobs. It also is important for those interested in a career as an academic hospitalist to consider not only HM fellowships, but other programs as well, such as the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program (rwjcsp.unc.edu/about/index.html).

While all of the fellowship programs aren’t geared specifically toward the hospitalist, they often incorporate faculty with expertise that would benefit a future academic hospitalist. Of course, the best fit for an individual depends on their particular interests and needs.

Fellowship in HM can offer training in clinical skills, clinical research, teaching, and quality and patient safety. Anyone interested in an HM career should consider a fellowship an opportunity for career development in a young specialty entrenched in revolutionizing the care of hospitalized patients. Academic HM fellowships hold the promise of empowering tomorrow’s academic leaders with the tools to continue to move the field forward. TH

Dr. Mann is a fellow in the division of hospital medicine, Department of Medicine, at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City. Dr. Markoff is associate division chief and fellowship director in the division of hospital medicine, Department of Medicine, at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City.

References

- Wachter RM. Reflections: the hospitalist movement a decade later. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(4):248-252.

- Wachter RM. Keynote presentation. SHM national meeting. National Harbor, Md.: May 2010.

- Ranji SR, Rosenman DJ, Amin AN, Kripalani S. Hospital medicine fellowships: works in progress. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):72.e1-e7.

- Freed GL, Dunham KM, Research advisory committee of the American Board of Pediatrics. Characteristics of pediatric hospital medicine fellowships and training programs. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:157-163.

- Arora V, Fang MC, Kripalani S, Amin AN. Preparing for “diastole”: advanced training opportunities for academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(6):368-377.

Sound Advice

Recent media reports about the dangers surrounding unused prescription medications, including abuse by teens and medications finding their way into the water supply, have prompted an increase in inquiries to healthcare providers about disposing of unused medication. These issues are complicated when controlled substances are involved.