User login

Payment Reform Proposals Take Shape

Medicare’s experiment with bundling episodes of care is finding some encouraging signs of life after fee-for-service (see “A Bundle of Nerves” in the November issue of The Hospitalist). But beyond orthopedics, cardiology, and cardiovascular surgery, what diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) should be bundled, and how should such bundles be fairly divided?

Some healthcare administrators say the system might work best in areas with high device costs, such as spine surgery. SHM supports provisions in the Affordable Care Act establishing a voluntary national pilot program on bundling payments to healthcare providers, and in 2009 backed pilot programs for high-risk medical populations with COPD or congestive heart failure. Cynthia Mason, project manager with the CMS Medicare Demonstrations Group, says the latter is definitely on the list of resource-heavy conditions Medicare will be scrutinizing. “But, obviously, looking at chronic conditions is more challenging because the service is not as standardized as, say, a surgical procedure,” she adds.

That concern, in fact, is driving some of the pessimism from other healthcare experts.

“I think it’s not at all clear that there are very many conditions amenable to bundling,” says Robert Berenson, MD, a senior fellow in the Urban Institute’s Health Policy Center and vice chair of the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). “Once you get down to the cases that everybody agrees lend themselves to bundling, it may be you're dealing with too small a percentage of spending to really want to go this route."

Emerging efforts to calculate how bundled payments should be fairly divided, however, also might provide more clarity on the best bundling candidates. The experimental PROMETHEUS payment model, developed by the Newton, Conn.-based Health Care Incentives Improvement Institute, is one example. It uses what are called evidence-informed case rates, or ECRs, to assign a budget for an entire episode of care. According to the nonprofit organization, ECRs are adjusted based on the severity and complexity of each patient’s condition, and an algorithm figures out how to divide the check.

There are limits, of course, in dealing with multiple comorbidities right off the bat. Even so, Stuart Guterman, vice president of the Washington, D.C.-based Commonwealth Fund's Program on Payment and System Reform, thinks a big chunk of our healthcare system's costs could be addressed with a limited number of well-defined but high-expense categories.

Click here to listen to Dr. Berenson and Guterman further discuss Medicare payment reform.

Medicare’s experiment with bundling episodes of care is finding some encouraging signs of life after fee-for-service (see “A Bundle of Nerves” in the November issue of The Hospitalist). But beyond orthopedics, cardiology, and cardiovascular surgery, what diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) should be bundled, and how should such bundles be fairly divided?

Some healthcare administrators say the system might work best in areas with high device costs, such as spine surgery. SHM supports provisions in the Affordable Care Act establishing a voluntary national pilot program on bundling payments to healthcare providers, and in 2009 backed pilot programs for high-risk medical populations with COPD or congestive heart failure. Cynthia Mason, project manager with the CMS Medicare Demonstrations Group, says the latter is definitely on the list of resource-heavy conditions Medicare will be scrutinizing. “But, obviously, looking at chronic conditions is more challenging because the service is not as standardized as, say, a surgical procedure,” she adds.

That concern, in fact, is driving some of the pessimism from other healthcare experts.

“I think it’s not at all clear that there are very many conditions amenable to bundling,” says Robert Berenson, MD, a senior fellow in the Urban Institute’s Health Policy Center and vice chair of the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). “Once you get down to the cases that everybody agrees lend themselves to bundling, it may be you're dealing with too small a percentage of spending to really want to go this route."

Emerging efforts to calculate how bundled payments should be fairly divided, however, also might provide more clarity on the best bundling candidates. The experimental PROMETHEUS payment model, developed by the Newton, Conn.-based Health Care Incentives Improvement Institute, is one example. It uses what are called evidence-informed case rates, or ECRs, to assign a budget for an entire episode of care. According to the nonprofit organization, ECRs are adjusted based on the severity and complexity of each patient’s condition, and an algorithm figures out how to divide the check.

There are limits, of course, in dealing with multiple comorbidities right off the bat. Even so, Stuart Guterman, vice president of the Washington, D.C.-based Commonwealth Fund's Program on Payment and System Reform, thinks a big chunk of our healthcare system's costs could be addressed with a limited number of well-defined but high-expense categories.

Click here to listen to Dr. Berenson and Guterman further discuss Medicare payment reform.

Medicare’s experiment with bundling episodes of care is finding some encouraging signs of life after fee-for-service (see “A Bundle of Nerves” in the November issue of The Hospitalist). But beyond orthopedics, cardiology, and cardiovascular surgery, what diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) should be bundled, and how should such bundles be fairly divided?

Some healthcare administrators say the system might work best in areas with high device costs, such as spine surgery. SHM supports provisions in the Affordable Care Act establishing a voluntary national pilot program on bundling payments to healthcare providers, and in 2009 backed pilot programs for high-risk medical populations with COPD or congestive heart failure. Cynthia Mason, project manager with the CMS Medicare Demonstrations Group, says the latter is definitely on the list of resource-heavy conditions Medicare will be scrutinizing. “But, obviously, looking at chronic conditions is more challenging because the service is not as standardized as, say, a surgical procedure,” she adds.

That concern, in fact, is driving some of the pessimism from other healthcare experts.

“I think it’s not at all clear that there are very many conditions amenable to bundling,” says Robert Berenson, MD, a senior fellow in the Urban Institute’s Health Policy Center and vice chair of the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). “Once you get down to the cases that everybody agrees lend themselves to bundling, it may be you're dealing with too small a percentage of spending to really want to go this route."

Emerging efforts to calculate how bundled payments should be fairly divided, however, also might provide more clarity on the best bundling candidates. The experimental PROMETHEUS payment model, developed by the Newton, Conn.-based Health Care Incentives Improvement Institute, is one example. It uses what are called evidence-informed case rates, or ECRs, to assign a budget for an entire episode of care. According to the nonprofit organization, ECRs are adjusted based on the severity and complexity of each patient’s condition, and an algorithm figures out how to divide the check.

There are limits, of course, in dealing with multiple comorbidities right off the bat. Even so, Stuart Guterman, vice president of the Washington, D.C.-based Commonwealth Fund's Program on Payment and System Reform, thinks a big chunk of our healthcare system's costs could be addressed with a limited number of well-defined but high-expense categories.

Click here to listen to Dr. Berenson and Guterman further discuss Medicare payment reform.

Treatment of CML continues to progress

NEW YORK—Even with a 10-year overall survival (OS) rate of 84%-90%, researchers continue to carry out trials on emerging drugs to try and find therapies that provide a better outlook for patients.

According to Susan O’Brien, MD, of MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, who presented at the NCCN 5th Annual Congress on Hematologic Malignancies, even if a better treatment is available, it will be tough to demonstrate survival benefits.

Dr O’Brien listed standard-dose imatinib, high-dose imatinib, imatinib-based combinations, second generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) and stem cell transplant as possible frontline therapies, noting that imatinib-based combinations are only used in clinical trials and second-generation TKIs are not available commercially.

At 8 years of follow-up, data on imatinib shows a survival rate of about 84%-90%, compared to about 50% for stem cell transplant, which continues to decrease over time. Dr O’Brien believes transplant is a viable option for some patients down the line, but at this point in time for chronic stage patients, transplant is not a reasonable option when one compares these two survival curves upfront.

Most recommendations for the use of imatinib come from follow-up on the IRIS trial, Hochhaus et al 2009, said Dr O’Brien. The trial compared patients on imatinib vs interferon (IFN-α) and low-dose Ara-C, and led to the approval of imatinib for frontline therapy.

Follow-up of the IRIS trial continues to be crucial because there are not 20- or 30-year data available. Now is the 8-year data will help physicians treat current patients.

Because imatinib is such a targeted therapy, investigators thought that if patients were on imatinib long enough they would develop a mutation or something that leads to resistance, said Dr O’Brien. And as time went on, they expected to see increasingly more episodes of transformation.

“When rate of transformation came out, people were surprised.... What you see is the opposite. If you see transformation, it happens early on,” she said

This finding led to the hypothesis that in some patients there is a very small resistant clone up front. When these patients are administered imatinib , it allows the resistant clone to emerge and form resistant disease. “There are no standard techniques that will pick up this clone, so there is no reason for testing,” she added.

She also pointed out that there has not been enough follow-up to form criteria for suboptimal response. Suboptimal response at 6 months may be more like failure than suboptimal response at 12 months. Dr O’Brien noted that if the response is not technically a failure, the guidelines say imatinib can be continued. But in fact, she said, many people on the NCCN guidelines committee felt that the imatinib dose should be increased in the case of suboptimal response.

Although imatinib has revolutionized the treatment of CML, the search continues for an even better option.

To this end, investigators have conducted 2 trials comparing imatinib head-to-head with nilotinib (Larson et al, 2010 ASCO abstract) or dasatinib (Kantarjian et al, NEJM 2010) in newly diagnosed patients.

At 12 months, nilotinib 300 mg and 400 mg twice a day produced a greater percentage of major molecular responses (MMR) than imatinib 400 mg once a day (44%, 43% vs 22%, respectively). More patients on either dose of nilotinib experienced complete cytogenetic response (CCyR) than with imatinib at 12 months (80%, 78% vs 65%, respectively) and overall response (85%, 82% vs 74%, respectively).

Dasatinib also proved to be more effective than imatinib. More patients randomized to 100mg of dasatinib once a day experienced CCyr by 12 months than patients randomized to 400mg of imatinib once a day (83% vs 72%) as frontline treatment. Percentages of confirmed CCyR were 77% for desatinib and 66% for imatinib. Also, 1.9% of patients receiving dasatinib progressed to accelerated phase or blast phase, compared to 3.5% of patients receiving imatinib.

Dasatinib and nilotonib both result in lower rates of anemia and neutropenia than imatinib. Imatinib therapy still has the lowest occurrence of thrombocytopenia.

With all these new developments and less than 10 years of data to go on, Dr O’Brien brought up some issues physicians should consider when choosing frontline therapy for CML, including the relevance of short-term endpoints, the difficulty of assessing survival differences among developing therapies, the cost of drugs, and the spectrum of toxicities. ![]()

NEW YORK—Even with a 10-year overall survival (OS) rate of 84%-90%, researchers continue to carry out trials on emerging drugs to try and find therapies that provide a better outlook for patients.

According to Susan O’Brien, MD, of MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, who presented at the NCCN 5th Annual Congress on Hematologic Malignancies, even if a better treatment is available, it will be tough to demonstrate survival benefits.

Dr O’Brien listed standard-dose imatinib, high-dose imatinib, imatinib-based combinations, second generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) and stem cell transplant as possible frontline therapies, noting that imatinib-based combinations are only used in clinical trials and second-generation TKIs are not available commercially.

At 8 years of follow-up, data on imatinib shows a survival rate of about 84%-90%, compared to about 50% for stem cell transplant, which continues to decrease over time. Dr O’Brien believes transplant is a viable option for some patients down the line, but at this point in time for chronic stage patients, transplant is not a reasonable option when one compares these two survival curves upfront.

Most recommendations for the use of imatinib come from follow-up on the IRIS trial, Hochhaus et al 2009, said Dr O’Brien. The trial compared patients on imatinib vs interferon (IFN-α) and low-dose Ara-C, and led to the approval of imatinib for frontline therapy.

Follow-up of the IRIS trial continues to be crucial because there are not 20- or 30-year data available. Now is the 8-year data will help physicians treat current patients.

Because imatinib is such a targeted therapy, investigators thought that if patients were on imatinib long enough they would develop a mutation or something that leads to resistance, said Dr O’Brien. And as time went on, they expected to see increasingly more episodes of transformation.

“When rate of transformation came out, people were surprised.... What you see is the opposite. If you see transformation, it happens early on,” she said

This finding led to the hypothesis that in some patients there is a very small resistant clone up front. When these patients are administered imatinib , it allows the resistant clone to emerge and form resistant disease. “There are no standard techniques that will pick up this clone, so there is no reason for testing,” she added.

She also pointed out that there has not been enough follow-up to form criteria for suboptimal response. Suboptimal response at 6 months may be more like failure than suboptimal response at 12 months. Dr O’Brien noted that if the response is not technically a failure, the guidelines say imatinib can be continued. But in fact, she said, many people on the NCCN guidelines committee felt that the imatinib dose should be increased in the case of suboptimal response.

Although imatinib has revolutionized the treatment of CML, the search continues for an even better option.

To this end, investigators have conducted 2 trials comparing imatinib head-to-head with nilotinib (Larson et al, 2010 ASCO abstract) or dasatinib (Kantarjian et al, NEJM 2010) in newly diagnosed patients.

At 12 months, nilotinib 300 mg and 400 mg twice a day produced a greater percentage of major molecular responses (MMR) than imatinib 400 mg once a day (44%, 43% vs 22%, respectively). More patients on either dose of nilotinib experienced complete cytogenetic response (CCyR) than with imatinib at 12 months (80%, 78% vs 65%, respectively) and overall response (85%, 82% vs 74%, respectively).

Dasatinib also proved to be more effective than imatinib. More patients randomized to 100mg of dasatinib once a day experienced CCyr by 12 months than patients randomized to 400mg of imatinib once a day (83% vs 72%) as frontline treatment. Percentages of confirmed CCyR were 77% for desatinib and 66% for imatinib. Also, 1.9% of patients receiving dasatinib progressed to accelerated phase or blast phase, compared to 3.5% of patients receiving imatinib.

Dasatinib and nilotonib both result in lower rates of anemia and neutropenia than imatinib. Imatinib therapy still has the lowest occurrence of thrombocytopenia.

With all these new developments and less than 10 years of data to go on, Dr O’Brien brought up some issues physicians should consider when choosing frontline therapy for CML, including the relevance of short-term endpoints, the difficulty of assessing survival differences among developing therapies, the cost of drugs, and the spectrum of toxicities. ![]()

NEW YORK—Even with a 10-year overall survival (OS) rate of 84%-90%, researchers continue to carry out trials on emerging drugs to try and find therapies that provide a better outlook for patients.

According to Susan O’Brien, MD, of MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, who presented at the NCCN 5th Annual Congress on Hematologic Malignancies, even if a better treatment is available, it will be tough to demonstrate survival benefits.

Dr O’Brien listed standard-dose imatinib, high-dose imatinib, imatinib-based combinations, second generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) and stem cell transplant as possible frontline therapies, noting that imatinib-based combinations are only used in clinical trials and second-generation TKIs are not available commercially.

At 8 years of follow-up, data on imatinib shows a survival rate of about 84%-90%, compared to about 50% for stem cell transplant, which continues to decrease over time. Dr O’Brien believes transplant is a viable option for some patients down the line, but at this point in time for chronic stage patients, transplant is not a reasonable option when one compares these two survival curves upfront.

Most recommendations for the use of imatinib come from follow-up on the IRIS trial, Hochhaus et al 2009, said Dr O’Brien. The trial compared patients on imatinib vs interferon (IFN-α) and low-dose Ara-C, and led to the approval of imatinib for frontline therapy.

Follow-up of the IRIS trial continues to be crucial because there are not 20- or 30-year data available. Now is the 8-year data will help physicians treat current patients.

Because imatinib is such a targeted therapy, investigators thought that if patients were on imatinib long enough they would develop a mutation or something that leads to resistance, said Dr O’Brien. And as time went on, they expected to see increasingly more episodes of transformation.

“When rate of transformation came out, people were surprised.... What you see is the opposite. If you see transformation, it happens early on,” she said

This finding led to the hypothesis that in some patients there is a very small resistant clone up front. When these patients are administered imatinib , it allows the resistant clone to emerge and form resistant disease. “There are no standard techniques that will pick up this clone, so there is no reason for testing,” she added.

She also pointed out that there has not been enough follow-up to form criteria for suboptimal response. Suboptimal response at 6 months may be more like failure than suboptimal response at 12 months. Dr O’Brien noted that if the response is not technically a failure, the guidelines say imatinib can be continued. But in fact, she said, many people on the NCCN guidelines committee felt that the imatinib dose should be increased in the case of suboptimal response.

Although imatinib has revolutionized the treatment of CML, the search continues for an even better option.

To this end, investigators have conducted 2 trials comparing imatinib head-to-head with nilotinib (Larson et al, 2010 ASCO abstract) or dasatinib (Kantarjian et al, NEJM 2010) in newly diagnosed patients.

At 12 months, nilotinib 300 mg and 400 mg twice a day produced a greater percentage of major molecular responses (MMR) than imatinib 400 mg once a day (44%, 43% vs 22%, respectively). More patients on either dose of nilotinib experienced complete cytogenetic response (CCyR) than with imatinib at 12 months (80%, 78% vs 65%, respectively) and overall response (85%, 82% vs 74%, respectively).

Dasatinib also proved to be more effective than imatinib. More patients randomized to 100mg of dasatinib once a day experienced CCyr by 12 months than patients randomized to 400mg of imatinib once a day (83% vs 72%) as frontline treatment. Percentages of confirmed CCyR were 77% for desatinib and 66% for imatinib. Also, 1.9% of patients receiving dasatinib progressed to accelerated phase or blast phase, compared to 3.5% of patients receiving imatinib.

Dasatinib and nilotonib both result in lower rates of anemia and neutropenia than imatinib. Imatinib therapy still has the lowest occurrence of thrombocytopenia.

With all these new developments and less than 10 years of data to go on, Dr O’Brien brought up some issues physicians should consider when choosing frontline therapy for CML, including the relevance of short-term endpoints, the difficulty of assessing survival differences among developing therapies, the cost of drugs, and the spectrum of toxicities. ![]()

Pending Tests at Discharge

The period following discharge is a vulnerable time for patientsthe prevalence of medical errors related to this transition is high and has important patient safety and medico‐legal ramifications.13 Factors contributing to this vulnerability include complexity of hospitalized patients, shorter lengths of stay, and increased discontinuity of care. Hospitalists have recognized this threat to patient safety and have worked toward improving information exchange between inpatient and outpatient providers at hospital discharge.46 Nonetheless, the evidence suggests that more work is necessary. A recent study found that discharge summaries are often incomplete, and do not contain important information requiring follow‐up, such as pending tests.7 Additionally, a review by Kripalani et al. characterizing information deficits at hospital discharge found few interventions which specifically improve communication of pending tests at hospital discharge.8

In a prior study we determined that 41% of patients left the hospital before all laboratory and radiology test results were finalized. Of these results, 9.4% were potentially actionable and could have altered management. Physicians were aware of only 38% of post‐discharge test results.9 This awareness gap is a consequence of several factors including the lack of systems to track and alert providers of test results finalized post discharge. Also, it is unclear who is responsible for pending tests at discharge, since these tests are ordered by the inpatient physicians but often reported in the time period between hospital discharge and the patient's first follow‐up appointment with the primary care physician (PCP). Because responsibility is not explicitly made in the final communication between physicians at discharge, such test results may not be reviewed in a timely manner, potentially resulting in delays in treatment, a need for readmission, or other unfavorable outcomes.

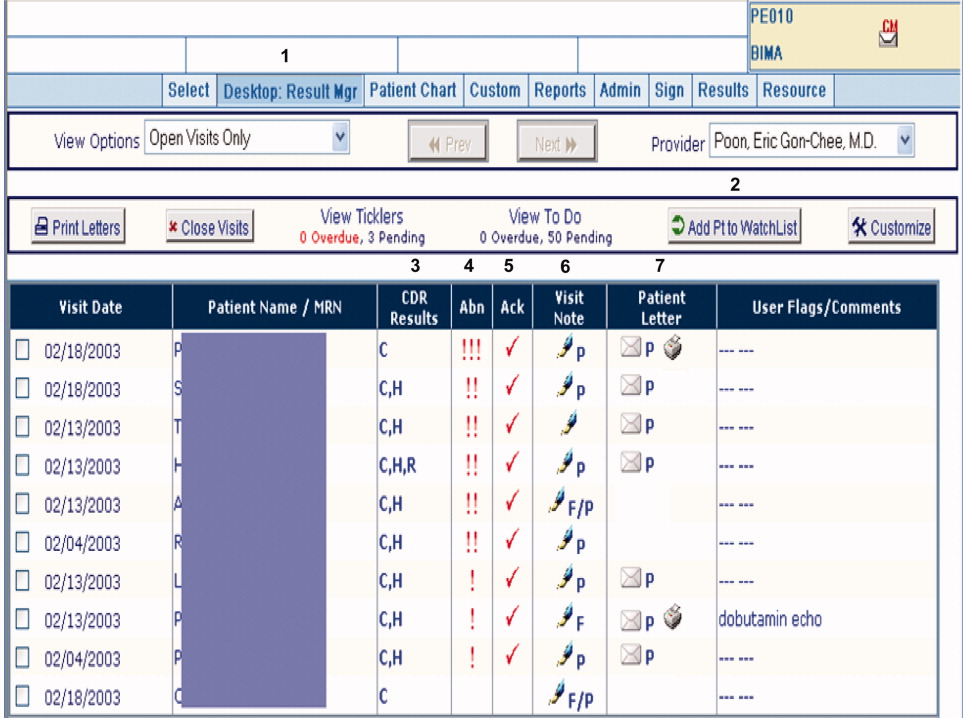

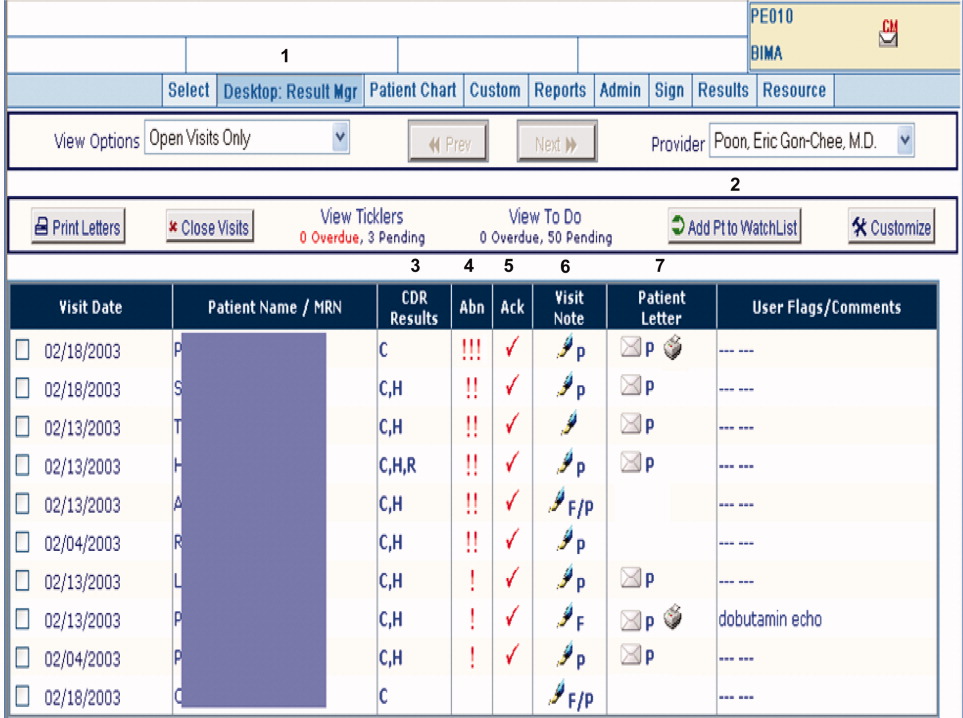

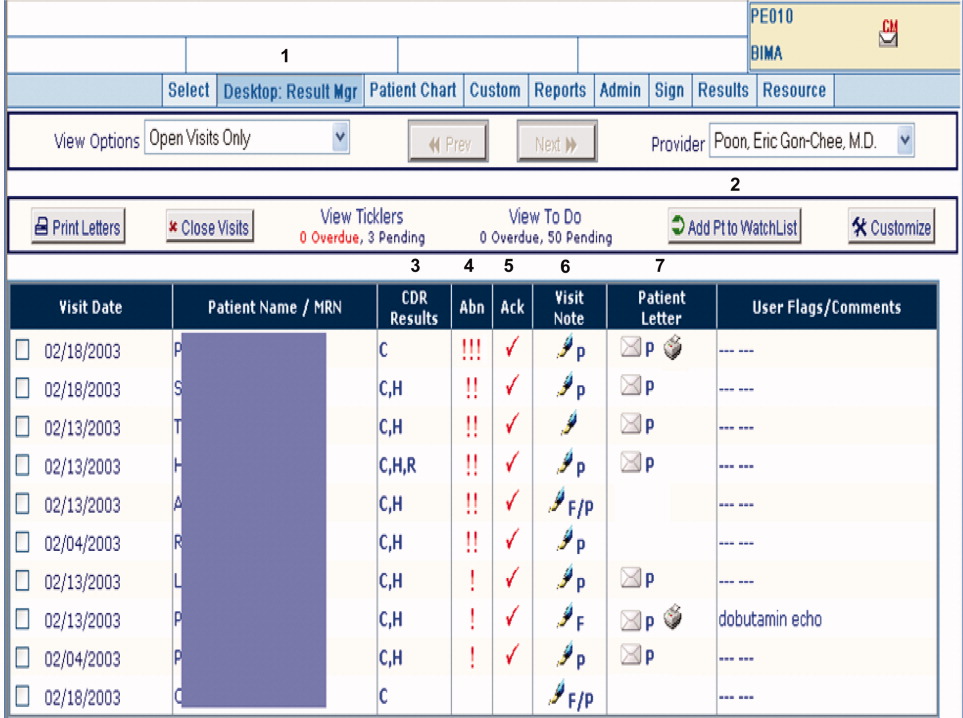

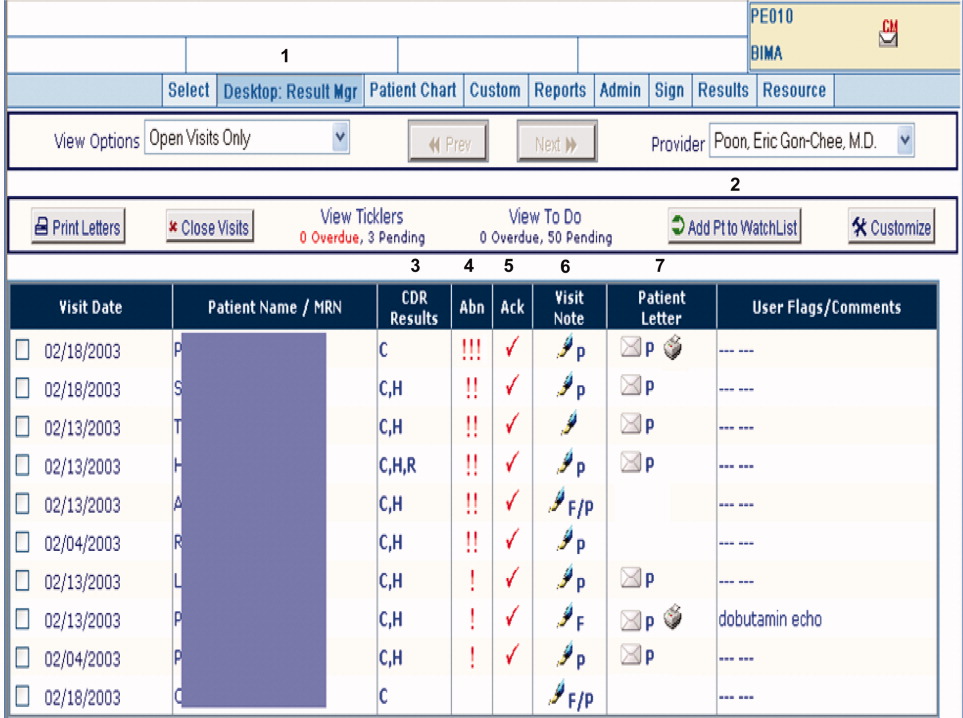

Even in integrated health systems with advanced electronic health records, missed test results which result in treatment delays remain prevalent.10, 11 Test result management applications aid clinicians in reviewing and acting upon results as they become available and such systems may provide solutions to this problem. At Partners Healthcare in Boston, the Results Manager (RM) application was developed to help clinicians in the ambulatory setting safely, reliably, and efficiently review and act upon test results. The application enables clinicians to prioritize test results, utilize guidelines, and generate letters to patients. This system also prompts physicians to set reminders for future testing.12 In a 2.5‐year study evaluating the impact of this intervention, PCPs at 26 adult primary care practices were able to expedite communication of outpatient laboratory and imaging test results to patients with the help of RM. Patients of physicians who participated in the project reported greater satisfaction with test result communication and with information provided about their condition than did a control group of similar patients.13 RM has not yet been studied in the inpatient setting or at care transitions. We describe an attempt at modifying the Partners RM application to help inpatient physicians manage pending tests at hospital discharge.

Methods

Study Setting and Participants

We piloted our application at 2 major academic medical centers (hospitals A and B) associated with Partners Healthcare, an integrated regional health delivery network in eastern Massachusetts, from October 2004 to March 2005. Both centers use the longitudinal medical record (LMR), the electronic medical record (EMR), for nearly all ambulatory practices. The LMR is an internally developed full‐featured EMR, including a repository of laboratory and radiology reports, discharge summaries, ambulatory care notes, medication lists, problem lists, coded allergies, and other patient data. Both centers also have their own inpatient results viewing and order entry systems which provide clinicians caring for patients in the hospital the ability to review results and write orders. Although possible, clinicians caring for patients in the inpatient setting do not routinely access LMR to view test results. Inpatient physician use of the LMR is generally limited to review of the outpatient record, medication lists, and ambulatory notes at admission.

At hospital A, the hospitalist attending physician is typically responsible for all communication to outpatient physicians at discharge, as well as for follow‐up on all test results that return after discharge. Hospital B has 2 types of hospitalist services. One is staffed only by hospitalist and nonhospitalist attending physicians. Nonhospitalist attending physicians were excluded because they care for their own patients in the inpatient and ambulatory setting and typically use RM to manage test results. The other hospitalist service at hospital B is a teaching service consisting of an attending physician, resident, and interns. For this service, the resident is responsible for communication at discharge and follow‐up on all pending tests. For purposes of this study inpatient physicians refers to those physicians responsible for communication with PCPs and follow‐up on pending tests. All inpatient physicians were eligible to participate during the study period.

Test Result Management Application

RM was originally developed by Partners Healthcare to improve timely review and appropriate management of test results in the ambulatory setting. RM was developed for and vetted by primarily ambulatory physicians. The application is browser‐based, provider‐centric, and embedded in the LMR to help ambulatory clinicians review and act upon test results in a safe, reliable, and efficient manner. Although RM has access to all inpatient and outpatient data in the Partners Clinical Data Repository (CDR), given the volume of inpatient tests ordered, hospital‐based results are suppressed by default to limit inundating ambulatory clinicians' queues. Therefore, users of RM only receive results of laboratory and radiology tests ordered in the ambulatory setting. They can track these tests for specific patients for a designated period of time by placing the patient on a watch list. Finally, RM incorporates extensive decision support features to classify the degree of abnormality for each result, presents guidelines to help clinicians manage abnormal results, allows clinicians to generate result letters to patients using predefined, context‐sensitive templates, and prompts physicians to set reminders for future testing. Because RM was developed from the ambulatory perspective, there was limited input from hospitalist physicians with regard to inpatient workflow in the original design of the module.12 See Figure 1 for a screen shot of RM and a description of its features.

figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

For purposes of this pilot, we modified RM to allow results of tests ordered in the inpatient setting to be available for viewing (Hospitalist Results Manager, HRM). This feature was turned on only for inpatient physicians as previously defined. Inpatient tests, including pending tests at discharge, continued to be suppressed from PCP's RM queue (however, any physician could access a patient's test result(s) directly from the Partners CDR). Inpatient physicians could track laboratory and radiology results finalized after discharge by keeping discharged patients on their HRM watch list for a designated period of time. The finalized results would become available for review in their HRM queue and abnormal results were displayed prominently at the top of this queue. Inpatient physicians were trained to use HRM in a series of meetings and demonstrations. Although HRM could be accessed from inpatient clinical workstations, it was not part of the inpatient clinical information system.

Surveys

Study surveys were developed and refined through an iterative process and pilot tested among inpatient physicians at both centers for clarity. We surveyed inpatient physicians five months after HRM implementation. Inpatient physicians were asked how often they used HRM, what barriers they faced (respondents asked to quantify agreement to statements on a 5‐point Likert scale), and which elements of an ideal system they would prefer. Finally, we solicited comments regarding perceived obstacles and suggestions for improvement. Because HRM was targeted to inpatient physicians, and because RM has been evaluated from the ambulatory perspective in a prior study,13 PCPs were not surveyed. See Supporting Information Appendix for the survey instrument used in the study.

Results

A total of 35 inpatient physicians participated in the pilot. Among 649 patients discharged during the study period, there were 1075 tests pending of which 555 were subsequently flagged as abnormal in HRM. Study surveys were sent to the 35 inpatient physician participants and 29 were completed, including partial responses (83% survey response rate). The 35 inpatient physician participants had the following characteristics: 22 were male, 13 were female; 21 were trainees and 14 were nontrainees/faculty. All 21 trainees were PGY2s. Nontrainees and faculty varied in experience level (PGY 15: 5, PGY 610: 7, PGY 1120: 1, PGY 21+: 1). Of 29 survey respondents, 7 were from hospital A and 22 were from hospital B; 19 were trainees and 10 were nontrainees/faculty. Of the 6 nonrespondents, 2 were from hospital A and 4 were from hospital B; 2 were trainees and 4 were nontrainees/faculty.

Table 1 shows the results of our survey of inpatient physicians regarding usage of HRM. Of 29 survey respondents, 14 (48%) reported never using HRM. Thirteen (45%) reported using HRM 1 to 2 times per week. None of the respondents used it more than 4 times per week. The frequency of usage was similar for hospitals A and B. Table 2 details barriers to using HRM. Twenty‐three inpatient physicians (79%) reported barriers. Seventeen (59%) thought that results in their HRM queue were not clinically relevant, 16 (55%) felt that HRM did not fit into their daily workflow, 14 (48%) had limited time to use HRM, and 12 (41%) noted that too many results in their HRM queue were on other physician's patients. Seven (24%) reported operational issues and 3 (10%) reported technical issues prohibiting use of HRM. With regard to preferred elements of an ideal results manager system, 21 (72%) inpatient physician respondents wanted to receive notification of abnormal and clinician‐designated pending test results. Four (14%) wanted to receive only abnormal results and 1 (3%) wanted to receive all results. Twenty‐seven (93%) physicians agreed that an ideally designed computerized test result management application would be valuable for managing pending tests at discharge.

| Frequency | Number of Inpatient Physicians Using HRM, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Hospital A | Hospital B | |

| |||

| Never | 14 (48) | 3 (43) | 11 (50) |

| 12 times per week | 13 (45) | 3 (43) | 10 (45.5) |

| 34 times per week | 2 (7) | 1 (14) | 1 (4.5) |

| 57 times per week | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| >7 times per week | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Barrier | Overall, n (%) | Hospital A, n (%) | Hospital B, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Forgot to use HRM | 23 (79) | 7 (100) | 16 (73) |

| Results not clinically relevant | 17 (59) | 7 (100) | 10 (45) |

| Did not fit daily workflow | 16 (55) | 7 (100) | 9 (41) |

| Too little time to use HRM | 14 (48) | 6 (86) | 8 (46) |

| Results on others' patients | 12 (41) | 6 (86) | 6 (27) |

| HRM was difficult to use | 7 (24) | 2 (29) | 5 (23) |

| Had technical difficulties | 3 (10) | 0 (0) | 3 (14) |

Table 3 provides comments from inpatient physician respondents regarding obstacles prohibiting use of HRM and suggestions for future systems.

|

| Suggestions |

| Would be more useful if accessible from (the inpatient clinical information system). |

| Email notification (would have been useful). |

| At time of discharge, if there is a way to find pending labs at discharge, this would be of great utility. |

| Linking responsibility for follow‐up to test ordering (would have been useful). |

| Smarter system for filtering results so less important results are filtered out (is desirable). |

| Can the system be tied into PCP's email somehow? |

| Obstacles |

| Blood cultures, abnormal films can be difficult and time‐consuming to look up. |

| A big problem is results that automatically trigger even though they're not clinically relevant. |

| Keeping a record of patients that left with tests pending (is often difficult to do). |

| Addressing pending results is very time consuming. |

Discussion

We describe a pilot implementation of a computerized application for the management of pending tests at hospital discharge. From responses to post‐implementation surveys, we were able to identify multiple factors prohibiting successful implementation of the application. These observations may help inform future interventions and evaluations.

Almost half of inpatient physicians reported never using HRM despite training and reminders. The feedback provided by physicians in our study suggested that HRM was not ideally designed from an inpatient physician perspective. We discovered several barriers to its use: (1) HRM overburdened physicians with clinically irrelevant test results, suggesting that more robust filtering of abnormal but low importance test results may be required (eg, a borderline electrolyte abnormality or low but stable hematocrit); (2) HRM did not integrate well into inpatient workflowthe system was not integrated into the inpatient results viewing and computerized physician order entry (CPOE) applications, and therefore required an extra step to access; (3) there was no mechanism of alerting inpatient physicians that finalized test results were available for viewing in their HRM queues (eg, by email or by an alert in the inpatient computer system); (4) because responsibility for these results was unclear, most inpatient physicians had no formal method of managing them, and for many, using HRM represented an additional task; and finally (5) several physicians commented on finding results in their HRM queue that belonged to other physician's patients, implying that the hospital databases were inaccurate in identifying the discharging physician or that rotation schedules, and therefore patient responsibility, had changed in the intervening period. Table 4 summarizes the advantages and respective limitations of features of HRM available to inpatient physicians.

| Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|

| |

| Creates a physician‐managed queue of pending test results by patient | Does not provide alert or push notification when new results available for patients |

| Filters test results by severity with most critical results appearing at the top of the queue | Severity filter set for outpatients; not restrictive enough for post‐discharge period, resulting in excessive alerting |

| Independent, voluntary acknowledgement of results by user | Active acknowledgment not required; no audit trail, feedback, or escalation if result not acknowledged |

| Embedded within LMR (the ambulatory EMR) | LMR not routinely used by many inpatient physicians |

| Offers patient communication tools (eg, pre‐populated patient results letter) | Tools not optimized for post‐discharge test result communication by inpatient physicians (eg, a tool for PCP result notification and acknowledgment) |

In the literature, there is little information regarding optimal features of a test result management system for transitions from the inpatient to ambulatory care setting. Prior studies outline important functions for results management systems developed for noninpatient sites of care, including the ambulatory and emergency room setting.12, 14, 15 These include a method of prioritizing by degree of abnormality, the ability to reliably and efficiently act upon results, and an automated alerting system for abnormal results. Findings from our study provide insight in defining core functions for result management systems which focus on transitions from the inpatient to ambulatory care setting. These functions include tight integration with applications used by inpatient physicians, clear assignment of responsibility for test results finalized after hospital discharge (as well as a mechanism to reassign responsibility), automated alerts to responsible providers of test results finalized post‐discharge, and ways to automatically filter test results to avoid over‐burdening physicians with clinically irrelevant results.

Almost all surveyed inpatient physicians agreed that an ideally designed electronic post‐discharge results management system would be valuable. For such systems to be successfully adopted, we offer several principles to help guide future work. These include: (1) clarifying responsibility at the time a test is ordered and again at discharge, (2) understanding workflow and communication patterns among inpatient and outpatient clinicians, and (3) integrating technological solutions into existing systems to minimize workflow disruptions. For example, if the primary responsibility for post‐discharge result follow‐up lies with the ordering physician, the system should be integrated within the EMR most often used by inpatient physicians and become part of inpatient physician workflow. If the system depends on administrative databases to identify the responsible providers, these must be accurate. Alternatively, in organizations with computerized provider order entry, responsibility for the result could be assigned when the test is ordered and confirmed at discharge (ie, the results management system would be integrated into the discharge order such that pending tests are reviewed at the time of discharge). The discharging physician should have the ability to assign responsibility for each pending test and select preferred mode(s) of notification once its result is finalized (eg, e‐mail, alphanumeric page, etc.). The system should have the ability to generate an automatic notification to the inpatient and PCP (and perhaps other designated providers involved in the patient's inpatient care), but it should not burden busy clinicians with unnecessary alerts and warnings. Finally, the rules by which results are prioritized must be robust enough to filter out less urgent results, and should be modified to reflect the severity of illness of recently discharged patients. In essence, in consideration of the time constraints of busy clinicians, an ideal results management system should achieve automated notification of test results while minimizing the risk of alert fatigue from the potentially large volume of alerts generated.

Our study has several important limitations. First, although our survey response rate was high, the sample size of actual participants was small. Second, because the study was conducted in 2 similar, tertiary care academic centers, it may not generalize to other settings (we note that hospital B included a nonteaching service similar to those in nonacademic medical centers). This may be particularly true in assessing the importance of specific barriers to use of results management systems, which may vary at different institutions. Third, the representation of survey respondents were skeweda majority of the responses were from trainees (all post‐graduate level [PGY] level 2) and from hospital B. Fourth, we did not actively monitor physician interaction with the test result management application, and therefore, we depended heavily on physician recollection of use of the system when responding to surveys. Finally, we did not convene focus groups of key individuals with regard to the factors facilitating or prohibiting adoption of the system. Use of semi‐structured, key informant interviews (ie, focus groups) before and after implementation of an electronic results management application, have been shown to be effective in evaluating potential barriers and facilitators of adoption.16 Focus groups of and/or interviews with inpatient and PCPs, physician extenders, and housestaff could have been useful to better characterize the potential barriers and facilitators of adoption noted by survey respondents in our study.

In summary, we offer several lessons from our attempt to implement a system to manage pending tests at hospital discharge. The success of implementing future systems to address this patient safety concern will rely on accurately assigning responsibility for these test results, integrating the system within clinical information systems commonly used by the inpatient physician, addressing workflow issues and time constraints, maximizing appropriateness of alerting, and minimizing alert fatigue.

- ,,,,.The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital.Ann Intern Med.2003;138(3):161–167.

- ,,,.Medical errors related to discontinuity of care from an inpatient to an outpatient setting.J Gen Intern Med.2003;18(8):646–651.

- .Key legal principles for hospitalists.Am J Med.2001;111(9B):5S–9S.

- ,,.Passing the clinical baton: 6 principles to guide the hospitalist.Am J Med.2001;111(9B):36S–39S.

- ,.Lost in transition: challenges and opportunities for improving the quality of transitional care.Ann Intern Med.2004;141(7):533–536.

- ,,,.Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists.J Hosp Med.2007;2(5):314–323.

- ,,, et al.Adequacy of hospital discharge summaries in documenting tests with pending results and outpatient follow‐up providers.J Gen Intern Med.2009;24(9):1002–1006.

- ,,,,,.Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital‐based and primary care physicians: Implications for patient safety and continuity of care.JAMA.2007;297(8):831–841.

- ,,, et al.Patient safety concerns arising from test results that return after hospital discharge.Ann Intern Med.2005;143(2):121–128.

- ,,.The continuing problem of missed test results in an integrated health system with an advanced electronic medical record.Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf.2007;33(8):485–492.

- ,.The frequency of missed test results and associated treatment delays in a highly computerized health system.BMC Fam Pract.2007;8:32.

- ,,,,.Design and implementation of a comprehensive outpatient results manager.J Biomed Inform.2003;36(1–2):80–91.

- ,,, et al.Impact of an automated test results management system on patients' satisfaction about test result communication.Arch Intern Med.2007;167(20):2233–2239.

- ,,,,,.“I wish I had seen this test result earlier!”: dissatisfaction with test result management systems in primary care.Arch Intern Med.2004;164(20):2223–2228.

- ,,.Potential impact of a computerized system to report late‐arriving laboratory results in the emergency department.Pediatr Emerg Care.2000;16(5):313–315.

- ,,, et al.Electronic results management in pediatric ambulatory care: Qualitative assessment.Pediatrics.2009;123Suppl 2:S85–S91.

The period following discharge is a vulnerable time for patientsthe prevalence of medical errors related to this transition is high and has important patient safety and medico‐legal ramifications.13 Factors contributing to this vulnerability include complexity of hospitalized patients, shorter lengths of stay, and increased discontinuity of care. Hospitalists have recognized this threat to patient safety and have worked toward improving information exchange between inpatient and outpatient providers at hospital discharge.46 Nonetheless, the evidence suggests that more work is necessary. A recent study found that discharge summaries are often incomplete, and do not contain important information requiring follow‐up, such as pending tests.7 Additionally, a review by Kripalani et al. characterizing information deficits at hospital discharge found few interventions which specifically improve communication of pending tests at hospital discharge.8

In a prior study we determined that 41% of patients left the hospital before all laboratory and radiology test results were finalized. Of these results, 9.4% were potentially actionable and could have altered management. Physicians were aware of only 38% of post‐discharge test results.9 This awareness gap is a consequence of several factors including the lack of systems to track and alert providers of test results finalized post discharge. Also, it is unclear who is responsible for pending tests at discharge, since these tests are ordered by the inpatient physicians but often reported in the time period between hospital discharge and the patient's first follow‐up appointment with the primary care physician (PCP). Because responsibility is not explicitly made in the final communication between physicians at discharge, such test results may not be reviewed in a timely manner, potentially resulting in delays in treatment, a need for readmission, or other unfavorable outcomes.

Even in integrated health systems with advanced electronic health records, missed test results which result in treatment delays remain prevalent.10, 11 Test result management applications aid clinicians in reviewing and acting upon results as they become available and such systems may provide solutions to this problem. At Partners Healthcare in Boston, the Results Manager (RM) application was developed to help clinicians in the ambulatory setting safely, reliably, and efficiently review and act upon test results. The application enables clinicians to prioritize test results, utilize guidelines, and generate letters to patients. This system also prompts physicians to set reminders for future testing.12 In a 2.5‐year study evaluating the impact of this intervention, PCPs at 26 adult primary care practices were able to expedite communication of outpatient laboratory and imaging test results to patients with the help of RM. Patients of physicians who participated in the project reported greater satisfaction with test result communication and with information provided about their condition than did a control group of similar patients.13 RM has not yet been studied in the inpatient setting or at care transitions. We describe an attempt at modifying the Partners RM application to help inpatient physicians manage pending tests at hospital discharge.

Methods

Study Setting and Participants

We piloted our application at 2 major academic medical centers (hospitals A and B) associated with Partners Healthcare, an integrated regional health delivery network in eastern Massachusetts, from October 2004 to March 2005. Both centers use the longitudinal medical record (LMR), the electronic medical record (EMR), for nearly all ambulatory practices. The LMR is an internally developed full‐featured EMR, including a repository of laboratory and radiology reports, discharge summaries, ambulatory care notes, medication lists, problem lists, coded allergies, and other patient data. Both centers also have their own inpatient results viewing and order entry systems which provide clinicians caring for patients in the hospital the ability to review results and write orders. Although possible, clinicians caring for patients in the inpatient setting do not routinely access LMR to view test results. Inpatient physician use of the LMR is generally limited to review of the outpatient record, medication lists, and ambulatory notes at admission.

At hospital A, the hospitalist attending physician is typically responsible for all communication to outpatient physicians at discharge, as well as for follow‐up on all test results that return after discharge. Hospital B has 2 types of hospitalist services. One is staffed only by hospitalist and nonhospitalist attending physicians. Nonhospitalist attending physicians were excluded because they care for their own patients in the inpatient and ambulatory setting and typically use RM to manage test results. The other hospitalist service at hospital B is a teaching service consisting of an attending physician, resident, and interns. For this service, the resident is responsible for communication at discharge and follow‐up on all pending tests. For purposes of this study inpatient physicians refers to those physicians responsible for communication with PCPs and follow‐up on pending tests. All inpatient physicians were eligible to participate during the study period.

Test Result Management Application

RM was originally developed by Partners Healthcare to improve timely review and appropriate management of test results in the ambulatory setting. RM was developed for and vetted by primarily ambulatory physicians. The application is browser‐based, provider‐centric, and embedded in the LMR to help ambulatory clinicians review and act upon test results in a safe, reliable, and efficient manner. Although RM has access to all inpatient and outpatient data in the Partners Clinical Data Repository (CDR), given the volume of inpatient tests ordered, hospital‐based results are suppressed by default to limit inundating ambulatory clinicians' queues. Therefore, users of RM only receive results of laboratory and radiology tests ordered in the ambulatory setting. They can track these tests for specific patients for a designated period of time by placing the patient on a watch list. Finally, RM incorporates extensive decision support features to classify the degree of abnormality for each result, presents guidelines to help clinicians manage abnormal results, allows clinicians to generate result letters to patients using predefined, context‐sensitive templates, and prompts physicians to set reminders for future testing. Because RM was developed from the ambulatory perspective, there was limited input from hospitalist physicians with regard to inpatient workflow in the original design of the module.12 See Figure 1 for a screen shot of RM and a description of its features.

figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

For purposes of this pilot, we modified RM to allow results of tests ordered in the inpatient setting to be available for viewing (Hospitalist Results Manager, HRM). This feature was turned on only for inpatient physicians as previously defined. Inpatient tests, including pending tests at discharge, continued to be suppressed from PCP's RM queue (however, any physician could access a patient's test result(s) directly from the Partners CDR). Inpatient physicians could track laboratory and radiology results finalized after discharge by keeping discharged patients on their HRM watch list for a designated period of time. The finalized results would become available for review in their HRM queue and abnormal results were displayed prominently at the top of this queue. Inpatient physicians were trained to use HRM in a series of meetings and demonstrations. Although HRM could be accessed from inpatient clinical workstations, it was not part of the inpatient clinical information system.

Surveys

Study surveys were developed and refined through an iterative process and pilot tested among inpatient physicians at both centers for clarity. We surveyed inpatient physicians five months after HRM implementation. Inpatient physicians were asked how often they used HRM, what barriers they faced (respondents asked to quantify agreement to statements on a 5‐point Likert scale), and which elements of an ideal system they would prefer. Finally, we solicited comments regarding perceived obstacles and suggestions for improvement. Because HRM was targeted to inpatient physicians, and because RM has been evaluated from the ambulatory perspective in a prior study,13 PCPs were not surveyed. See Supporting Information Appendix for the survey instrument used in the study.

Results

A total of 35 inpatient physicians participated in the pilot. Among 649 patients discharged during the study period, there were 1075 tests pending of which 555 were subsequently flagged as abnormal in HRM. Study surveys were sent to the 35 inpatient physician participants and 29 were completed, including partial responses (83% survey response rate). The 35 inpatient physician participants had the following characteristics: 22 were male, 13 were female; 21 were trainees and 14 were nontrainees/faculty. All 21 trainees were PGY2s. Nontrainees and faculty varied in experience level (PGY 15: 5, PGY 610: 7, PGY 1120: 1, PGY 21+: 1). Of 29 survey respondents, 7 were from hospital A and 22 were from hospital B; 19 were trainees and 10 were nontrainees/faculty. Of the 6 nonrespondents, 2 were from hospital A and 4 were from hospital B; 2 were trainees and 4 were nontrainees/faculty.

Table 1 shows the results of our survey of inpatient physicians regarding usage of HRM. Of 29 survey respondents, 14 (48%) reported never using HRM. Thirteen (45%) reported using HRM 1 to 2 times per week. None of the respondents used it more than 4 times per week. The frequency of usage was similar for hospitals A and B. Table 2 details barriers to using HRM. Twenty‐three inpatient physicians (79%) reported barriers. Seventeen (59%) thought that results in their HRM queue were not clinically relevant, 16 (55%) felt that HRM did not fit into their daily workflow, 14 (48%) had limited time to use HRM, and 12 (41%) noted that too many results in their HRM queue were on other physician's patients. Seven (24%) reported operational issues and 3 (10%) reported technical issues prohibiting use of HRM. With regard to preferred elements of an ideal results manager system, 21 (72%) inpatient physician respondents wanted to receive notification of abnormal and clinician‐designated pending test results. Four (14%) wanted to receive only abnormal results and 1 (3%) wanted to receive all results. Twenty‐seven (93%) physicians agreed that an ideally designed computerized test result management application would be valuable for managing pending tests at discharge.

| Frequency | Number of Inpatient Physicians Using HRM, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Hospital A | Hospital B | |

| |||

| Never | 14 (48) | 3 (43) | 11 (50) |

| 12 times per week | 13 (45) | 3 (43) | 10 (45.5) |

| 34 times per week | 2 (7) | 1 (14) | 1 (4.5) |

| 57 times per week | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| >7 times per week | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Barrier | Overall, n (%) | Hospital A, n (%) | Hospital B, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Forgot to use HRM | 23 (79) | 7 (100) | 16 (73) |

| Results not clinically relevant | 17 (59) | 7 (100) | 10 (45) |

| Did not fit daily workflow | 16 (55) | 7 (100) | 9 (41) |

| Too little time to use HRM | 14 (48) | 6 (86) | 8 (46) |

| Results on others' patients | 12 (41) | 6 (86) | 6 (27) |

| HRM was difficult to use | 7 (24) | 2 (29) | 5 (23) |

| Had technical difficulties | 3 (10) | 0 (0) | 3 (14) |

Table 3 provides comments from inpatient physician respondents regarding obstacles prohibiting use of HRM and suggestions for future systems.

|

| Suggestions |

| Would be more useful if accessible from (the inpatient clinical information system). |

| Email notification (would have been useful). |

| At time of discharge, if there is a way to find pending labs at discharge, this would be of great utility. |

| Linking responsibility for follow‐up to test ordering (would have been useful). |

| Smarter system for filtering results so less important results are filtered out (is desirable). |

| Can the system be tied into PCP's email somehow? |

| Obstacles |

| Blood cultures, abnormal films can be difficult and time‐consuming to look up. |

| A big problem is results that automatically trigger even though they're not clinically relevant. |

| Keeping a record of patients that left with tests pending (is often difficult to do). |

| Addressing pending results is very time consuming. |

Discussion

We describe a pilot implementation of a computerized application for the management of pending tests at hospital discharge. From responses to post‐implementation surveys, we were able to identify multiple factors prohibiting successful implementation of the application. These observations may help inform future interventions and evaluations.

Almost half of inpatient physicians reported never using HRM despite training and reminders. The feedback provided by physicians in our study suggested that HRM was not ideally designed from an inpatient physician perspective. We discovered several barriers to its use: (1) HRM overburdened physicians with clinically irrelevant test results, suggesting that more robust filtering of abnormal but low importance test results may be required (eg, a borderline electrolyte abnormality or low but stable hematocrit); (2) HRM did not integrate well into inpatient workflowthe system was not integrated into the inpatient results viewing and computerized physician order entry (CPOE) applications, and therefore required an extra step to access; (3) there was no mechanism of alerting inpatient physicians that finalized test results were available for viewing in their HRM queues (eg, by email or by an alert in the inpatient computer system); (4) because responsibility for these results was unclear, most inpatient physicians had no formal method of managing them, and for many, using HRM represented an additional task; and finally (5) several physicians commented on finding results in their HRM queue that belonged to other physician's patients, implying that the hospital databases were inaccurate in identifying the discharging physician or that rotation schedules, and therefore patient responsibility, had changed in the intervening period. Table 4 summarizes the advantages and respective limitations of features of HRM available to inpatient physicians.

| Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|

| |

| Creates a physician‐managed queue of pending test results by patient | Does not provide alert or push notification when new results available for patients |

| Filters test results by severity with most critical results appearing at the top of the queue | Severity filter set for outpatients; not restrictive enough for post‐discharge period, resulting in excessive alerting |

| Independent, voluntary acknowledgement of results by user | Active acknowledgment not required; no audit trail, feedback, or escalation if result not acknowledged |

| Embedded within LMR (the ambulatory EMR) | LMR not routinely used by many inpatient physicians |

| Offers patient communication tools (eg, pre‐populated patient results letter) | Tools not optimized for post‐discharge test result communication by inpatient physicians (eg, a tool for PCP result notification and acknowledgment) |

In the literature, there is little information regarding optimal features of a test result management system for transitions from the inpatient to ambulatory care setting. Prior studies outline important functions for results management systems developed for noninpatient sites of care, including the ambulatory and emergency room setting.12, 14, 15 These include a method of prioritizing by degree of abnormality, the ability to reliably and efficiently act upon results, and an automated alerting system for abnormal results. Findings from our study provide insight in defining core functions for result management systems which focus on transitions from the inpatient to ambulatory care setting. These functions include tight integration with applications used by inpatient physicians, clear assignment of responsibility for test results finalized after hospital discharge (as well as a mechanism to reassign responsibility), automated alerts to responsible providers of test results finalized post‐discharge, and ways to automatically filter test results to avoid over‐burdening physicians with clinically irrelevant results.

Almost all surveyed inpatient physicians agreed that an ideally designed electronic post‐discharge results management system would be valuable. For such systems to be successfully adopted, we offer several principles to help guide future work. These include: (1) clarifying responsibility at the time a test is ordered and again at discharge, (2) understanding workflow and communication patterns among inpatient and outpatient clinicians, and (3) integrating technological solutions into existing systems to minimize workflow disruptions. For example, if the primary responsibility for post‐discharge result follow‐up lies with the ordering physician, the system should be integrated within the EMR most often used by inpatient physicians and become part of inpatient physician workflow. If the system depends on administrative databases to identify the responsible providers, these must be accurate. Alternatively, in organizations with computerized provider order entry, responsibility for the result could be assigned when the test is ordered and confirmed at discharge (ie, the results management system would be integrated into the discharge order such that pending tests are reviewed at the time of discharge). The discharging physician should have the ability to assign responsibility for each pending test and select preferred mode(s) of notification once its result is finalized (eg, e‐mail, alphanumeric page, etc.). The system should have the ability to generate an automatic notification to the inpatient and PCP (and perhaps other designated providers involved in the patient's inpatient care), but it should not burden busy clinicians with unnecessary alerts and warnings. Finally, the rules by which results are prioritized must be robust enough to filter out less urgent results, and should be modified to reflect the severity of illness of recently discharged patients. In essence, in consideration of the time constraints of busy clinicians, an ideal results management system should achieve automated notification of test results while minimizing the risk of alert fatigue from the potentially large volume of alerts generated.

Our study has several important limitations. First, although our survey response rate was high, the sample size of actual participants was small. Second, because the study was conducted in 2 similar, tertiary care academic centers, it may not generalize to other settings (we note that hospital B included a nonteaching service similar to those in nonacademic medical centers). This may be particularly true in assessing the importance of specific barriers to use of results management systems, which may vary at different institutions. Third, the representation of survey respondents were skeweda majority of the responses were from trainees (all post‐graduate level [PGY] level 2) and from hospital B. Fourth, we did not actively monitor physician interaction with the test result management application, and therefore, we depended heavily on physician recollection of use of the system when responding to surveys. Finally, we did not convene focus groups of key individuals with regard to the factors facilitating or prohibiting adoption of the system. Use of semi‐structured, key informant interviews (ie, focus groups) before and after implementation of an electronic results management application, have been shown to be effective in evaluating potential barriers and facilitators of adoption.16 Focus groups of and/or interviews with inpatient and PCPs, physician extenders, and housestaff could have been useful to better characterize the potential barriers and facilitators of adoption noted by survey respondents in our study.

In summary, we offer several lessons from our attempt to implement a system to manage pending tests at hospital discharge. The success of implementing future systems to address this patient safety concern will rely on accurately assigning responsibility for these test results, integrating the system within clinical information systems commonly used by the inpatient physician, addressing workflow issues and time constraints, maximizing appropriateness of alerting, and minimizing alert fatigue.

The period following discharge is a vulnerable time for patientsthe prevalence of medical errors related to this transition is high and has important patient safety and medico‐legal ramifications.13 Factors contributing to this vulnerability include complexity of hospitalized patients, shorter lengths of stay, and increased discontinuity of care. Hospitalists have recognized this threat to patient safety and have worked toward improving information exchange between inpatient and outpatient providers at hospital discharge.46 Nonetheless, the evidence suggests that more work is necessary. A recent study found that discharge summaries are often incomplete, and do not contain important information requiring follow‐up, such as pending tests.7 Additionally, a review by Kripalani et al. characterizing information deficits at hospital discharge found few interventions which specifically improve communication of pending tests at hospital discharge.8

In a prior study we determined that 41% of patients left the hospital before all laboratory and radiology test results were finalized. Of these results, 9.4% were potentially actionable and could have altered management. Physicians were aware of only 38% of post‐discharge test results.9 This awareness gap is a consequence of several factors including the lack of systems to track and alert providers of test results finalized post discharge. Also, it is unclear who is responsible for pending tests at discharge, since these tests are ordered by the inpatient physicians but often reported in the time period between hospital discharge and the patient's first follow‐up appointment with the primary care physician (PCP). Because responsibility is not explicitly made in the final communication between physicians at discharge, such test results may not be reviewed in a timely manner, potentially resulting in delays in treatment, a need for readmission, or other unfavorable outcomes.

Even in integrated health systems with advanced electronic health records, missed test results which result in treatment delays remain prevalent.10, 11 Test result management applications aid clinicians in reviewing and acting upon results as they become available and such systems may provide solutions to this problem. At Partners Healthcare in Boston, the Results Manager (RM) application was developed to help clinicians in the ambulatory setting safely, reliably, and efficiently review and act upon test results. The application enables clinicians to prioritize test results, utilize guidelines, and generate letters to patients. This system also prompts physicians to set reminders for future testing.12 In a 2.5‐year study evaluating the impact of this intervention, PCPs at 26 adult primary care practices were able to expedite communication of outpatient laboratory and imaging test results to patients with the help of RM. Patients of physicians who participated in the project reported greater satisfaction with test result communication and with information provided about their condition than did a control group of similar patients.13 RM has not yet been studied in the inpatient setting or at care transitions. We describe an attempt at modifying the Partners RM application to help inpatient physicians manage pending tests at hospital discharge.

Methods

Study Setting and Participants

We piloted our application at 2 major academic medical centers (hospitals A and B) associated with Partners Healthcare, an integrated regional health delivery network in eastern Massachusetts, from October 2004 to March 2005. Both centers use the longitudinal medical record (LMR), the electronic medical record (EMR), for nearly all ambulatory practices. The LMR is an internally developed full‐featured EMR, including a repository of laboratory and radiology reports, discharge summaries, ambulatory care notes, medication lists, problem lists, coded allergies, and other patient data. Both centers also have their own inpatient results viewing and order entry systems which provide clinicians caring for patients in the hospital the ability to review results and write orders. Although possible, clinicians caring for patients in the inpatient setting do not routinely access LMR to view test results. Inpatient physician use of the LMR is generally limited to review of the outpatient record, medication lists, and ambulatory notes at admission.

At hospital A, the hospitalist attending physician is typically responsible for all communication to outpatient physicians at discharge, as well as for follow‐up on all test results that return after discharge. Hospital B has 2 types of hospitalist services. One is staffed only by hospitalist and nonhospitalist attending physicians. Nonhospitalist attending physicians were excluded because they care for their own patients in the inpatient and ambulatory setting and typically use RM to manage test results. The other hospitalist service at hospital B is a teaching service consisting of an attending physician, resident, and interns. For this service, the resident is responsible for communication at discharge and follow‐up on all pending tests. For purposes of this study inpatient physicians refers to those physicians responsible for communication with PCPs and follow‐up on pending tests. All inpatient physicians were eligible to participate during the study period.

Test Result Management Application

RM was originally developed by Partners Healthcare to improve timely review and appropriate management of test results in the ambulatory setting. RM was developed for and vetted by primarily ambulatory physicians. The application is browser‐based, provider‐centric, and embedded in the LMR to help ambulatory clinicians review and act upon test results in a safe, reliable, and efficient manner. Although RM has access to all inpatient and outpatient data in the Partners Clinical Data Repository (CDR), given the volume of inpatient tests ordered, hospital‐based results are suppressed by default to limit inundating ambulatory clinicians' queues. Therefore, users of RM only receive results of laboratory and radiology tests ordered in the ambulatory setting. They can track these tests for specific patients for a designated period of time by placing the patient on a watch list. Finally, RM incorporates extensive decision support features to classify the degree of abnormality for each result, presents guidelines to help clinicians manage abnormal results, allows clinicians to generate result letters to patients using predefined, context‐sensitive templates, and prompts physicians to set reminders for future testing. Because RM was developed from the ambulatory perspective, there was limited input from hospitalist physicians with regard to inpatient workflow in the original design of the module.12 See Figure 1 for a screen shot of RM and a description of its features.

figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

For purposes of this pilot, we modified RM to allow results of tests ordered in the inpatient setting to be available for viewing (Hospitalist Results Manager, HRM). This feature was turned on only for inpatient physicians as previously defined. Inpatient tests, including pending tests at discharge, continued to be suppressed from PCP's RM queue (however, any physician could access a patient's test result(s) directly from the Partners CDR). Inpatient physicians could track laboratory and radiology results finalized after discharge by keeping discharged patients on their HRM watch list for a designated period of time. The finalized results would become available for review in their HRM queue and abnormal results were displayed prominently at the top of this queue. Inpatient physicians were trained to use HRM in a series of meetings and demonstrations. Although HRM could be accessed from inpatient clinical workstations, it was not part of the inpatient clinical information system.

Surveys

Study surveys were developed and refined through an iterative process and pilot tested among inpatient physicians at both centers for clarity. We surveyed inpatient physicians five months after HRM implementation. Inpatient physicians were asked how often they used HRM, what barriers they faced (respondents asked to quantify agreement to statements on a 5‐point Likert scale), and which elements of an ideal system they would prefer. Finally, we solicited comments regarding perceived obstacles and suggestions for improvement. Because HRM was targeted to inpatient physicians, and because RM has been evaluated from the ambulatory perspective in a prior study,13 PCPs were not surveyed. See Supporting Information Appendix for the survey instrument used in the study.

Results

A total of 35 inpatient physicians participated in the pilot. Among 649 patients discharged during the study period, there were 1075 tests pending of which 555 were subsequently flagged as abnormal in HRM. Study surveys were sent to the 35 inpatient physician participants and 29 were completed, including partial responses (83% survey response rate). The 35 inpatient physician participants had the following characteristics: 22 were male, 13 were female; 21 were trainees and 14 were nontrainees/faculty. All 21 trainees were PGY2s. Nontrainees and faculty varied in experience level (PGY 15: 5, PGY 610: 7, PGY 1120: 1, PGY 21+: 1). Of 29 survey respondents, 7 were from hospital A and 22 were from hospital B; 19 were trainees and 10 were nontrainees/faculty. Of the 6 nonrespondents, 2 were from hospital A and 4 were from hospital B; 2 were trainees and 4 were nontrainees/faculty.

Table 1 shows the results of our survey of inpatient physicians regarding usage of HRM. Of 29 survey respondents, 14 (48%) reported never using HRM. Thirteen (45%) reported using HRM 1 to 2 times per week. None of the respondents used it more than 4 times per week. The frequency of usage was similar for hospitals A and B. Table 2 details barriers to using HRM. Twenty‐three inpatient physicians (79%) reported barriers. Seventeen (59%) thought that results in their HRM queue were not clinically relevant, 16 (55%) felt that HRM did not fit into their daily workflow, 14 (48%) had limited time to use HRM, and 12 (41%) noted that too many results in their HRM queue were on other physician's patients. Seven (24%) reported operational issues and 3 (10%) reported technical issues prohibiting use of HRM. With regard to preferred elements of an ideal results manager system, 21 (72%) inpatient physician respondents wanted to receive notification of abnormal and clinician‐designated pending test results. Four (14%) wanted to receive only abnormal results and 1 (3%) wanted to receive all results. Twenty‐seven (93%) physicians agreed that an ideally designed computerized test result management application would be valuable for managing pending tests at discharge.

| Frequency | Number of Inpatient Physicians Using HRM, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Hospital A | Hospital B | |

| |||

| Never | 14 (48) | 3 (43) | 11 (50) |

| 12 times per week | 13 (45) | 3 (43) | 10 (45.5) |

| 34 times per week | 2 (7) | 1 (14) | 1 (4.5) |

| 57 times per week | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| >7 times per week | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Barrier | Overall, n (%) | Hospital A, n (%) | Hospital B, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Forgot to use HRM | 23 (79) | 7 (100) | 16 (73) |

| Results not clinically relevant | 17 (59) | 7 (100) | 10 (45) |

| Did not fit daily workflow | 16 (55) | 7 (100) | 9 (41) |

| Too little time to use HRM | 14 (48) | 6 (86) | 8 (46) |

| Results on others' patients | 12 (41) | 6 (86) | 6 (27) |

| HRM was difficult to use | 7 (24) | 2 (29) | 5 (23) |

| Had technical difficulties | 3 (10) | 0 (0) | 3 (14) |

Table 3 provides comments from inpatient physician respondents regarding obstacles prohibiting use of HRM and suggestions for future systems.

|

| Suggestions |

| Would be more useful if accessible from (the inpatient clinical information system). |

| Email notification (would have been useful). |

| At time of discharge, if there is a way to find pending labs at discharge, this would be of great utility. |

| Linking responsibility for follow‐up to test ordering (would have been useful). |

| Smarter system for filtering results so less important results are filtered out (is desirable). |

| Can the system be tied into PCP's email somehow? |

| Obstacles |

| Blood cultures, abnormal films can be difficult and time‐consuming to look up. |

| A big problem is results that automatically trigger even though they're not clinically relevant. |

| Keeping a record of patients that left with tests pending (is often difficult to do). |

| Addressing pending results is very time consuming. |

Discussion