User login

Psych Solutions

Kenneth Duckworth, MD, medical director at Vinfen Corporation in Boston, recalls the frustration he felt when inpatient hospital staff would release his psychiatric patients without contacting him. The lack of communication often led to gaps in his patients’ records and left him scrambling to learn more about the circumstances of the hospitalization.

Those experiences are among the reasons Dr. Duckworth, a triple-board-certified psychiatrist and medical director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), was pleased to hear The Joint Commission had released its Hospital-Based Inpatient Psychiatric Services, or HBIPS, measure set. And he’s not alone. HBIPS provides standardized measures for psychiatric services where previously none existed, and it gives hospitals the ability to use their data as a basis for national comparison.

Ann Watt, associate director, division of quality measurement and research at the Joint Commission, says although it’s still early, the measures seem to be working. “While we don’t have any actual data, we have received positive feedback,” she says. “It seems like the field has accepted them well.”

Standard of Care Guidelines

Comprised of seven main measures that the commission released in October 2008, HBIPS is the result of a determined effort by the nation’s psychiatry leaders, says Noel Mazade, PhD, executive director of the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors’ Research Institute Inc. HBIPS is available to hospitals accredited under the Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Hospitals (CAMH), says Celeste Milton, associate project director at the commission’s Department of Quality Measurement. Free-standing psychiatric hospitals and acute-care hospitals with psychiatric units can use the HBIPS measure set to help meet performance requirements under the commission’s ORYX initiative (www. jointcommission.org/AccreditationPrograms/Hospitals/ORYX/).

The Joint Commission’s final HBIPS measure set, which went into effect with Oct. 1, 2008, discharges, followed more than three years’ of field review, public comment, and pilot testing by 196 hospitals across the country. HBIPS’ seven measures address:

—Tim Lineberry, MD, medical director, Mayo Clinic Psychiatric Hospital, Rochester, Minn.

- Admission screening;

- Hours of physical restraint;

- Hours of seclusion;

- Patients discharged on multiple antipsychotic medications;

- Patients discharged on multiple antipsychotic medications with appropriate justification;

- Post-discharge plan creation; and

- Post-discharge plans transmitted to the next level of care provider.

“These are all areas that are of interest to NAMI,” Dr. Duckworth says. “We still have a long way to go, but it’s definitely a step in the right direction.”

The measure set’s effect on psychiatric hospitalists will depend on physicians’ responsibilities at the facilities where they work, Milton says. For example, a psychiatric hospitalist may be asked to screen a patient at admission for violence risk, substance abuse, psychological trauma history, and strengths, such as personal motivation and family involvement (HBIPS Measure 1). Another qualified psychiatric practitioner, such as a psychiatrist, registered nurse, physician’s assistant, or social worker, could perform the screening, she says.

The measures are intended to help unify the screening process used by psychiatric hospitalists; however, traditional hospitalists could be called on to perform a face-to-face evaluation of a patient placed in physical restraint or held in seclusion (Measures 2 and 3). As a result of the evaluation, hospitalists could be asked to write orders to discontinue or renew physical restraint or seclusion, Milton says. The feedback the Joint Commission has received shows psychiatric hospitalists are using the measures. They are most likely to be in charge of managing a patient’s medications and could play a role in documenting appropriate justification for placing a patient on more than one antipsychotic medication at discharge (Measures 4 and 5). Depending on the scope of practice, traditional hospitalists who discharge patients might be responsible for determining a final discharge diagnosis, discharge medications, and next-level-of-care recommendations (Measures 6 and 7). The provider at the next level of care could be an inpatient or outpatient clinician or entity, Milton says.

How It Works

The HBIPS data collection process is similar to other ORYX processes; however, this is the first time the Joint Commission has created a measure set for psychiatric services, says Dr. Mazade, who worked directly with the commission to develop HBIPS. Hospitals using HBIPS will submit data from patients’ medical records to their ORYX vendor. The vendor will submit performance measures to the hospital and the commission, which will provide hospitals with feedback on measure performance, Dr. Mazade says. Initially, the commission will supply acute-care and psychiatric hospitals the option of using HBIPS to meet current ORYX performance measurement requirements, although Dr. Mazade says he expects the commission will eventually mandate use of the measures.

The commission says data collection, analysis, and performance reporting is running behind schedule. Once the commission report is received, hospitals should share the message with their medical staff, Milton says. “This feedback will be useful to all staff involved in patient care to help them improve their practice,” she explains. “The purpose of an initial screening, including a trauma history, is to help the practitioner formulate an individual treatment plan based on information obtained during the initial screening.”

Tim Lineberry, MD, medical director at the Mayo Clinic Psychiatric Hospital in Rochester, Minn., says each HBIPS measure is composed of sub-elements. For example, the assessment measure includes admission screening for violence risk, substance abuse, trauma history, and patient strengths, such as motivation and family involvement. These elements create a more complete picture of the patient and might improve the initial assessment. By improving initial assessment, experts in the field hope hospital staff will be able to better identify problems, Dr. Lineberry says.

“We are all working for improvement in care,” says Dr. Lineberry, noting the Mayo Clinic was one of the pilot sites. “HBIPS is part of that effort.”

Time Is of the Essence

Many of the standards represent areas in which there is consensus among psychiatrists about the need for change, says Anand Pandya, MD, a psychiatric hospitalist and director of inpatient psychiatry at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. Many psychiatrists recognize there is a need to improve communication between inpatient psychiatric services and follow-up outpatient providers, Dr. Pandya says. However, a clear consensus has not been reached regarding the standards of tracking patients who take multiple antipsychotic medications, Dr. Pandya says.

“With the low average length of stay in inpatient psychiatric units, it is common for patients to continue a cross-taper between medications after discharge,” Dr. Pandya says. “For most antipsychotic medications, there is insufficient data to determine how fast or slow to cross-taper. I worry that these standards may send the unintentional message that these cross-tapers should be completed quickly during the course of a brief inpatient stay.”

Data suggest individuals using lithium should be tapered off the drug as slowly as possible—probably over months rather than weeks, Dr. Pandya says. “I am concerned that tracking data regarding patients on multiple antipsychotic medications may create incentives to change practice in a sub-optimal direction for some cases,” he says.

Dr. Duckworth also acknowledges patients’ length of stay is getting shorter. Psychiatric hospitalists are under a great deal of pressure to “get people patched up in too short a period of time,” he says. “They really do need more time. There is a temptation to use more than one antipsychotic medication, but people really should not be given two antipsychotic medications unless someone has performed a thoughtful assessment.”

On Board with HBIPS

While HBIPS covers areas of care important to many, the details of implementing the measure set might be challenging, Dr. Lineberry says. The requirements increase the documentation burden for physicians, nurses, and allied health professionals, such as social workers and therapists. Hospitals using electronic medical records might have to modify their records to meet the requirements. And with the new measure comes new, significant personnel costs to audit and collect the data, he says.

“For psychiatric hospitalists who are using HBIPS, it will be helpful to look at the measures from a multidisciplinary standpoint,” Dr. Lineberry says. “Approach HBIPS as a team. Look at the process and see how it works, then adapt it to fit in with your current workflow.”

As of July, more than 274 psychiatric hospitals and psychiatric units had implemented the HBIPS measures. “We don’t usually have numbers until at least six months after,” Milton says, noting the commission is eager to receive quantitative data and report back to the participating hospitals.

Milton anticipates the Joint Commission will submit the HBIPS measure set to the National Quality Forum (NQF) for consideration and endorsement. Although she anticipates the measures will receive NQF endorsement sometime this year, an exact timeline has not been established, she says. The Joint Commission will work closely with the NQF to ensure the HBIPS measure set receives endorsement, and will make necessary modifications that may be required, Milton says.

Once HBIPS receives NQF endorsement, HBIPS data will be publicly reported following the first two quarters of data collection, Milton says. Data on each hospital will be available at www.qualitycheck.org. TH

Gina Gotsill is a freelance medical writer in California. Freelance writer Chris Haliskoe contributed to this report.

Image Source: TIM TEEBKEN/PHOTODISC

Kenneth Duckworth, MD, medical director at Vinfen Corporation in Boston, recalls the frustration he felt when inpatient hospital staff would release his psychiatric patients without contacting him. The lack of communication often led to gaps in his patients’ records and left him scrambling to learn more about the circumstances of the hospitalization.

Those experiences are among the reasons Dr. Duckworth, a triple-board-certified psychiatrist and medical director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), was pleased to hear The Joint Commission had released its Hospital-Based Inpatient Psychiatric Services, or HBIPS, measure set. And he’s not alone. HBIPS provides standardized measures for psychiatric services where previously none existed, and it gives hospitals the ability to use their data as a basis for national comparison.

Ann Watt, associate director, division of quality measurement and research at the Joint Commission, says although it’s still early, the measures seem to be working. “While we don’t have any actual data, we have received positive feedback,” she says. “It seems like the field has accepted them well.”

Standard of Care Guidelines

Comprised of seven main measures that the commission released in October 2008, HBIPS is the result of a determined effort by the nation’s psychiatry leaders, says Noel Mazade, PhD, executive director of the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors’ Research Institute Inc. HBIPS is available to hospitals accredited under the Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Hospitals (CAMH), says Celeste Milton, associate project director at the commission’s Department of Quality Measurement. Free-standing psychiatric hospitals and acute-care hospitals with psychiatric units can use the HBIPS measure set to help meet performance requirements under the commission’s ORYX initiative (www. jointcommission.org/AccreditationPrograms/Hospitals/ORYX/).

The Joint Commission’s final HBIPS measure set, which went into effect with Oct. 1, 2008, discharges, followed more than three years’ of field review, public comment, and pilot testing by 196 hospitals across the country. HBIPS’ seven measures address:

—Tim Lineberry, MD, medical director, Mayo Clinic Psychiatric Hospital, Rochester, Minn.

- Admission screening;

- Hours of physical restraint;

- Hours of seclusion;

- Patients discharged on multiple antipsychotic medications;

- Patients discharged on multiple antipsychotic medications with appropriate justification;

- Post-discharge plan creation; and

- Post-discharge plans transmitted to the next level of care provider.

“These are all areas that are of interest to NAMI,” Dr. Duckworth says. “We still have a long way to go, but it’s definitely a step in the right direction.”

The measure set’s effect on psychiatric hospitalists will depend on physicians’ responsibilities at the facilities where they work, Milton says. For example, a psychiatric hospitalist may be asked to screen a patient at admission for violence risk, substance abuse, psychological trauma history, and strengths, such as personal motivation and family involvement (HBIPS Measure 1). Another qualified psychiatric practitioner, such as a psychiatrist, registered nurse, physician’s assistant, or social worker, could perform the screening, she says.

The measures are intended to help unify the screening process used by psychiatric hospitalists; however, traditional hospitalists could be called on to perform a face-to-face evaluation of a patient placed in physical restraint or held in seclusion (Measures 2 and 3). As a result of the evaluation, hospitalists could be asked to write orders to discontinue or renew physical restraint or seclusion, Milton says. The feedback the Joint Commission has received shows psychiatric hospitalists are using the measures. They are most likely to be in charge of managing a patient’s medications and could play a role in documenting appropriate justification for placing a patient on more than one antipsychotic medication at discharge (Measures 4 and 5). Depending on the scope of practice, traditional hospitalists who discharge patients might be responsible for determining a final discharge diagnosis, discharge medications, and next-level-of-care recommendations (Measures 6 and 7). The provider at the next level of care could be an inpatient or outpatient clinician or entity, Milton says.

How It Works

The HBIPS data collection process is similar to other ORYX processes; however, this is the first time the Joint Commission has created a measure set for psychiatric services, says Dr. Mazade, who worked directly with the commission to develop HBIPS. Hospitals using HBIPS will submit data from patients’ medical records to their ORYX vendor. The vendor will submit performance measures to the hospital and the commission, which will provide hospitals with feedback on measure performance, Dr. Mazade says. Initially, the commission will supply acute-care and psychiatric hospitals the option of using HBIPS to meet current ORYX performance measurement requirements, although Dr. Mazade says he expects the commission will eventually mandate use of the measures.

The commission says data collection, analysis, and performance reporting is running behind schedule. Once the commission report is received, hospitals should share the message with their medical staff, Milton says. “This feedback will be useful to all staff involved in patient care to help them improve their practice,” she explains. “The purpose of an initial screening, including a trauma history, is to help the practitioner formulate an individual treatment plan based on information obtained during the initial screening.”

Tim Lineberry, MD, medical director at the Mayo Clinic Psychiatric Hospital in Rochester, Minn., says each HBIPS measure is composed of sub-elements. For example, the assessment measure includes admission screening for violence risk, substance abuse, trauma history, and patient strengths, such as motivation and family involvement. These elements create a more complete picture of the patient and might improve the initial assessment. By improving initial assessment, experts in the field hope hospital staff will be able to better identify problems, Dr. Lineberry says.

“We are all working for improvement in care,” says Dr. Lineberry, noting the Mayo Clinic was one of the pilot sites. “HBIPS is part of that effort.”

Time Is of the Essence

Many of the standards represent areas in which there is consensus among psychiatrists about the need for change, says Anand Pandya, MD, a psychiatric hospitalist and director of inpatient psychiatry at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. Many psychiatrists recognize there is a need to improve communication between inpatient psychiatric services and follow-up outpatient providers, Dr. Pandya says. However, a clear consensus has not been reached regarding the standards of tracking patients who take multiple antipsychotic medications, Dr. Pandya says.

“With the low average length of stay in inpatient psychiatric units, it is common for patients to continue a cross-taper between medications after discharge,” Dr. Pandya says. “For most antipsychotic medications, there is insufficient data to determine how fast or slow to cross-taper. I worry that these standards may send the unintentional message that these cross-tapers should be completed quickly during the course of a brief inpatient stay.”

Data suggest individuals using lithium should be tapered off the drug as slowly as possible—probably over months rather than weeks, Dr. Pandya says. “I am concerned that tracking data regarding patients on multiple antipsychotic medications may create incentives to change practice in a sub-optimal direction for some cases,” he says.

Dr. Duckworth also acknowledges patients’ length of stay is getting shorter. Psychiatric hospitalists are under a great deal of pressure to “get people patched up in too short a period of time,” he says. “They really do need more time. There is a temptation to use more than one antipsychotic medication, but people really should not be given two antipsychotic medications unless someone has performed a thoughtful assessment.”

On Board with HBIPS

While HBIPS covers areas of care important to many, the details of implementing the measure set might be challenging, Dr. Lineberry says. The requirements increase the documentation burden for physicians, nurses, and allied health professionals, such as social workers and therapists. Hospitals using electronic medical records might have to modify their records to meet the requirements. And with the new measure comes new, significant personnel costs to audit and collect the data, he says.

“For psychiatric hospitalists who are using HBIPS, it will be helpful to look at the measures from a multidisciplinary standpoint,” Dr. Lineberry says. “Approach HBIPS as a team. Look at the process and see how it works, then adapt it to fit in with your current workflow.”

As of July, more than 274 psychiatric hospitals and psychiatric units had implemented the HBIPS measures. “We don’t usually have numbers until at least six months after,” Milton says, noting the commission is eager to receive quantitative data and report back to the participating hospitals.

Milton anticipates the Joint Commission will submit the HBIPS measure set to the National Quality Forum (NQF) for consideration and endorsement. Although she anticipates the measures will receive NQF endorsement sometime this year, an exact timeline has not been established, she says. The Joint Commission will work closely with the NQF to ensure the HBIPS measure set receives endorsement, and will make necessary modifications that may be required, Milton says.

Once HBIPS receives NQF endorsement, HBIPS data will be publicly reported following the first two quarters of data collection, Milton says. Data on each hospital will be available at www.qualitycheck.org. TH

Gina Gotsill is a freelance medical writer in California. Freelance writer Chris Haliskoe contributed to this report.

Image Source: TIM TEEBKEN/PHOTODISC

Kenneth Duckworth, MD, medical director at Vinfen Corporation in Boston, recalls the frustration he felt when inpatient hospital staff would release his psychiatric patients without contacting him. The lack of communication often led to gaps in his patients’ records and left him scrambling to learn more about the circumstances of the hospitalization.

Those experiences are among the reasons Dr. Duckworth, a triple-board-certified psychiatrist and medical director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), was pleased to hear The Joint Commission had released its Hospital-Based Inpatient Psychiatric Services, or HBIPS, measure set. And he’s not alone. HBIPS provides standardized measures for psychiatric services where previously none existed, and it gives hospitals the ability to use their data as a basis for national comparison.

Ann Watt, associate director, division of quality measurement and research at the Joint Commission, says although it’s still early, the measures seem to be working. “While we don’t have any actual data, we have received positive feedback,” she says. “It seems like the field has accepted them well.”

Standard of Care Guidelines

Comprised of seven main measures that the commission released in October 2008, HBIPS is the result of a determined effort by the nation’s psychiatry leaders, says Noel Mazade, PhD, executive director of the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors’ Research Institute Inc. HBIPS is available to hospitals accredited under the Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Hospitals (CAMH), says Celeste Milton, associate project director at the commission’s Department of Quality Measurement. Free-standing psychiatric hospitals and acute-care hospitals with psychiatric units can use the HBIPS measure set to help meet performance requirements under the commission’s ORYX initiative (www. jointcommission.org/AccreditationPrograms/Hospitals/ORYX/).

The Joint Commission’s final HBIPS measure set, which went into effect with Oct. 1, 2008, discharges, followed more than three years’ of field review, public comment, and pilot testing by 196 hospitals across the country. HBIPS’ seven measures address:

—Tim Lineberry, MD, medical director, Mayo Clinic Psychiatric Hospital, Rochester, Minn.

- Admission screening;

- Hours of physical restraint;

- Hours of seclusion;

- Patients discharged on multiple antipsychotic medications;

- Patients discharged on multiple antipsychotic medications with appropriate justification;

- Post-discharge plan creation; and

- Post-discharge plans transmitted to the next level of care provider.

“These are all areas that are of interest to NAMI,” Dr. Duckworth says. “We still have a long way to go, but it’s definitely a step in the right direction.”

The measure set’s effect on psychiatric hospitalists will depend on physicians’ responsibilities at the facilities where they work, Milton says. For example, a psychiatric hospitalist may be asked to screen a patient at admission for violence risk, substance abuse, psychological trauma history, and strengths, such as personal motivation and family involvement (HBIPS Measure 1). Another qualified psychiatric practitioner, such as a psychiatrist, registered nurse, physician’s assistant, or social worker, could perform the screening, she says.

The measures are intended to help unify the screening process used by psychiatric hospitalists; however, traditional hospitalists could be called on to perform a face-to-face evaluation of a patient placed in physical restraint or held in seclusion (Measures 2 and 3). As a result of the evaluation, hospitalists could be asked to write orders to discontinue or renew physical restraint or seclusion, Milton says. The feedback the Joint Commission has received shows psychiatric hospitalists are using the measures. They are most likely to be in charge of managing a patient’s medications and could play a role in documenting appropriate justification for placing a patient on more than one antipsychotic medication at discharge (Measures 4 and 5). Depending on the scope of practice, traditional hospitalists who discharge patients might be responsible for determining a final discharge diagnosis, discharge medications, and next-level-of-care recommendations (Measures 6 and 7). The provider at the next level of care could be an inpatient or outpatient clinician or entity, Milton says.

How It Works

The HBIPS data collection process is similar to other ORYX processes; however, this is the first time the Joint Commission has created a measure set for psychiatric services, says Dr. Mazade, who worked directly with the commission to develop HBIPS. Hospitals using HBIPS will submit data from patients’ medical records to their ORYX vendor. The vendor will submit performance measures to the hospital and the commission, which will provide hospitals with feedback on measure performance, Dr. Mazade says. Initially, the commission will supply acute-care and psychiatric hospitals the option of using HBIPS to meet current ORYX performance measurement requirements, although Dr. Mazade says he expects the commission will eventually mandate use of the measures.

The commission says data collection, analysis, and performance reporting is running behind schedule. Once the commission report is received, hospitals should share the message with their medical staff, Milton says. “This feedback will be useful to all staff involved in patient care to help them improve their practice,” she explains. “The purpose of an initial screening, including a trauma history, is to help the practitioner formulate an individual treatment plan based on information obtained during the initial screening.”

Tim Lineberry, MD, medical director at the Mayo Clinic Psychiatric Hospital in Rochester, Minn., says each HBIPS measure is composed of sub-elements. For example, the assessment measure includes admission screening for violence risk, substance abuse, trauma history, and patient strengths, such as motivation and family involvement. These elements create a more complete picture of the patient and might improve the initial assessment. By improving initial assessment, experts in the field hope hospital staff will be able to better identify problems, Dr. Lineberry says.

“We are all working for improvement in care,” says Dr. Lineberry, noting the Mayo Clinic was one of the pilot sites. “HBIPS is part of that effort.”

Time Is of the Essence

Many of the standards represent areas in which there is consensus among psychiatrists about the need for change, says Anand Pandya, MD, a psychiatric hospitalist and director of inpatient psychiatry at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. Many psychiatrists recognize there is a need to improve communication between inpatient psychiatric services and follow-up outpatient providers, Dr. Pandya says. However, a clear consensus has not been reached regarding the standards of tracking patients who take multiple antipsychotic medications, Dr. Pandya says.

“With the low average length of stay in inpatient psychiatric units, it is common for patients to continue a cross-taper between medications after discharge,” Dr. Pandya says. “For most antipsychotic medications, there is insufficient data to determine how fast or slow to cross-taper. I worry that these standards may send the unintentional message that these cross-tapers should be completed quickly during the course of a brief inpatient stay.”

Data suggest individuals using lithium should be tapered off the drug as slowly as possible—probably over months rather than weeks, Dr. Pandya says. “I am concerned that tracking data regarding patients on multiple antipsychotic medications may create incentives to change practice in a sub-optimal direction for some cases,” he says.

Dr. Duckworth also acknowledges patients’ length of stay is getting shorter. Psychiatric hospitalists are under a great deal of pressure to “get people patched up in too short a period of time,” he says. “They really do need more time. There is a temptation to use more than one antipsychotic medication, but people really should not be given two antipsychotic medications unless someone has performed a thoughtful assessment.”

On Board with HBIPS

While HBIPS covers areas of care important to many, the details of implementing the measure set might be challenging, Dr. Lineberry says. The requirements increase the documentation burden for physicians, nurses, and allied health professionals, such as social workers and therapists. Hospitals using electronic medical records might have to modify their records to meet the requirements. And with the new measure comes new, significant personnel costs to audit and collect the data, he says.

“For psychiatric hospitalists who are using HBIPS, it will be helpful to look at the measures from a multidisciplinary standpoint,” Dr. Lineberry says. “Approach HBIPS as a team. Look at the process and see how it works, then adapt it to fit in with your current workflow.”

As of July, more than 274 psychiatric hospitals and psychiatric units had implemented the HBIPS measures. “We don’t usually have numbers until at least six months after,” Milton says, noting the commission is eager to receive quantitative data and report back to the participating hospitals.

Milton anticipates the Joint Commission will submit the HBIPS measure set to the National Quality Forum (NQF) for consideration and endorsement. Although she anticipates the measures will receive NQF endorsement sometime this year, an exact timeline has not been established, she says. The Joint Commission will work closely with the NQF to ensure the HBIPS measure set receives endorsement, and will make necessary modifications that may be required, Milton says.

Once HBIPS receives NQF endorsement, HBIPS data will be publicly reported following the first two quarters of data collection, Milton says. Data on each hospital will be available at www.qualitycheck.org. TH

Gina Gotsill is a freelance medical writer in California. Freelance writer Chris Haliskoe contributed to this report.

Image Source: TIM TEEBKEN/PHOTODISC

How do I keep my elderly patients from falling?

Case

An 85-year-old man with peripheral vascular disease, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, dementia, a history of falls, and atrial fibrillation, which was being treated with warfarin, was admitted for a left transmetatarsal amputation. On postoperative day two, the patient slipped as he was getting out of bed to use the bathroom. He hit his head on his IV pole, and a CT scan demonstrated an acute right subdural hemorrhage. He subsequently suffered eight months of delirium before passing away at a skilled nursing facility. How could this incident have been prevented?

Background

Hospitalization represents a vulnerable time for elderly people. The presence of acute illness, an unfamiliar environment, and the frequent addition of new medications predispose an elderly patient to such iatrogenic hazards of hospitalization as falls, pressure ulcers, and delirium.1 Inpatient falls are the most common type of adverse hospital event, accounting for 70% of all inpatient accidents.2 Thirty percent to 40% of inpatient falls result in injury, with 4% to 6% resulting in serious harm.2 Interestingly, 55% of falls occur in patients 60 or younger, but 60% of falls resulting in moderate to severe injury occur in those 70 and older.3

A fall is a seminal event in the life of an elderly person. Even a fall without injury can initiate a vicious circle that begins with a fear of falling and is followed by a self-restriction of mobility, which commonly results in a decline in function.4 Functional decline in the elderly has been shown to predict mortality and nursing home placement.5

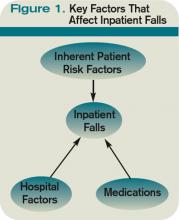

Inpatient falls are thought to occur via a complex interplay between medications, inherent patient susceptibilities, and hospital environmental hazards (see Figure 1, below).

Risk Factors

Medication prescription for the hospitalized elderly patient is perhaps the area where the hospitalist can have the greatest impact in reducing a patient’s fall risk. The most common medications thought to predispose community dwelling elders to falls are psychotropic drugs: neuroleptics, sedatives, hypnotics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines.6

Limited studies of hospitalized patients indicate similar drugs as culprits. Passaro et al demonstrated that benzodiazepines with a half-life <24 hours (e.g., lorazepam and oxazepam) were strongly associated with falls even after correcting for multiple confounders.7 Furthermore, multivariate logistic regression revealed that the use of other psychotropic drugs in addition to benzodiazepines (OR 2.3; 95% CI, 1.6–3.2) was strongly associated with an increased risk of falls. Taking more than five medications also increased a patient’s fall risk (OR 1.6; 95% CI, 1.02–2.6). Thus, the judicious prescription of medications—aimed at decreasing the number and dosage of medications an elderly patient takes—is essential to minimizing the risk for falls.

Several studies conducted in hospitalized elderly patients have repeatedly demonstrated a core group of inherent patient risk factors for falls: delirium, agitation or impaired judgment, burden of comorbidity, gait instability or lower-extremity weakness, urinary incontinence or frequency, and a history of falls.2,3,8 These risk factors are targeted as part of most inpatient fall prevention programs, as discussed below.

Several environmental hazards have been known to increase the risk of falls and injury. These include high patient-to-nurse ratio, inappropriate use of bedrails, wet floors, and lack of assistance with ambulation and toileting. The most studied of these is assistance with ambulation and toileting. Hitcho et al demonstrated that as many as 50% of falls are toileting-related.3 The study also showed that only 42% of patients who fell and used an assistive device at home had a fall in the hospital. As many as 85% of patients were not assisted with a device or person at the time of a fall.2 Unassisted falls are associated with increased injury risk (adjusted OR 1.70; 95% CI, 1.23-2.36).

Consistent with this, increased patient-to-nurse ratios are keenly associated with an increased risk of falls. Essentially, a patient whose nurse had more than five patients was 2.6 times more likely to fall than a patient whose nurse had five or fewer patients (95% CI, 1.6 to 4.1). Based on this data, hospitals have invested in low-to-the-floor beds and alarms for beds and chairs. Placing patients on a regular toileting schedule, avoiding medications that cause urinary incontinence, and attention to bowel regimens have become standard components of hospital fall prevention programs. Even though these issues have long been thought to be the purview of nurses and support staff, hospitalist involvement and awareness are crucial to ensuring that these issues are consistently addressed and enforced for every at-risk patient.

Inpatient Fall Prevention

Inpatient falls are similar to other geriatric syndromes and are multifactorial in etiology. Studies that report a decrease in the number of falls identify patients at the highest risk for falls and target multiple risk factors simultaneously.

Several inpatient fall risk assessment tools have been developed. The most widely used and validated in the acute hospital setting are the Morse Falls Scale and St. Thomas’ Risk Assessment Tool in Falling Elderly Inpatients (STRATIFY) (see Table 1, p. 24).9 Both tools incorporate the risk factors identified above—namely, the presence of cognitive or sensory deficits, environmental hazards, history of falls, lower-extremity or gait instability/weakness, and level of comorbidity to create a score. Higher scores are associated with increased fall risk. The scales have demonstrated sensitivities and specificities of 70% to 96% and 50% to 85%, respectively, depending on the population tested and the cutoff scores used.

In 2004, Healey et al published the results of one of the few successful randomized, controlled fall-prevention trials in an acute-care setting.10 Pairs of identical hospital units were randomized to intervention and control groups. The sample size was 3,386 patients, with a mean length of stay of 19 days.1 As part of the intervention group, a fall-risk assessment was performed on admission. Patients were screened for deficits in visual acuity (identify a pen, key, or watch from a distance of 2 meters), polypharmacy, orthostatic hypotension, mobility deficits, appropriate bedrail use, footwear safety, bed height, distance of patient from nursing station, loose cables, wet floors, and availability of the nurse call bell.

Interventions for patients who were identified as high fall risks included ophthalmology/optician referral for those for whom reading aides could not be procured, medication review, adjustment of bed rails, and physical therapy. Patients with a history of falls were placed close to nursing stations. Environmental hazards were removed. Patients with orthostatic hypotension were educated on slowly changing body position. Call lights were moved to within easy reach. No additional money was allocated for this study, but by performing these simple interventions, the authors were able to decrease the relative risk of falls by 29% (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.55–0.90, P=0.006). The incidence of injuries sustained as a result of falling, however, was unchanged.

Two large, prospective studies with historical controls involving 3,000 to 7,000 patients over the course of three years and incorporating similar interventions also demonstrated a decrease in the number of falls.11,12 Fonda and his colleagues were able to demonstrate a 77% reduction in the number of falls resulting in serious injuries.

Even though these studies are promising, a recent cluster-randomized, multifactorial intervention trial involving almost 4,000 patients on a dozen medical floors did not demonstrate a reduction in the incidence of falls or falls with injury.13 Several differences exist between the two randomized trials. In the latter trial, by Cumming et al, a study nurse reviewed the care plan of all of the patients on the intervention wards and made recommendations.13 Also, the study was designed so that each patient on the intervention wards received the intervention, regardless of their fall risk. Additionally, the study period was a mere three months. In the Healey trial, the nurses on the intervention units implemented targeted risk reduction for patients at high risk, and the study period was a full year.

Back to the Case

Our patient had several risk factors for falls on admission. A targeted fall risk assessment on admission would have identified him as high-risk, with a Morse score of 95 given his dementia (15 points), impaired gait status post-transmetatarsal amputation (20 points), secondary diagnoses (multiple comorbidities, 15 points) and history of falls (25 points), and presence of an IV (20 points). The STRATIFY risk assessment tool would have produced similar results.

Frequent toileting assistance, early mobilization, medication review, and environmental modification might have prevented his fall (see Table 2, pg. 24).

Bottom Line

Focused assessment of patients on admission can identify those at risk for falls. Multifactorial inpatient fall-prevention strategies have been shown to reduce the rate of falls in inpatients without increasing costs. TH

Dr. Ölveczky is a geriatric nocturnist in the hospital medicine program, division of medicine, at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

References

- Fernandez HM, Callahan KE, Likourezos A, Leipzig RM. House staff member awareness of older inpatients’ risks for hazards of hospitalization. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(4):390-396.

- Krauss MJ, Evanoff B, Hitcho E, et al. A case control study of patient, medication, and care-related risk factors for inpatient falls. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(2):116-122.

- Hitcho EB, Krauss MJ, Birge S, et al. Characteristics and circumstances of falls in a hospital setting: a prospective analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(7):732-739.

- Tinetti ME. Clinical practice. Preventing falls in elderly persons. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(1):42-49.

- Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Salive ME, Wallace RB. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(9):556-561.

- Leipzig RM, Cumming RG, Tinetti ME. Drugs and falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis: I. Psychotropic drugs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(1):30-39.

- Passaro A, Volpato S, Romagnoni F, Manzoli N, Zuliani G, Fellin R. Benzodiazepines with different half-life and falling in a hospitalized population: The GIFA study. Gruppo Italiano di Farmacovigilanza nell'Anziano. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(12):1222-1229.

- Oliver D, Daly F, Martin FC, McMurdo ME. Risk factors and risk assessment tools for falls in hospital in-patients: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2004;33(2):122-130.

- Scott V, Votova K, Scanlan A, Close J. Multifactorial and functional mobility assessment tools for fall risk among older adults in community, home-support, long-term and acute care settings. Age Ageing. 2007;36(2):130-139.

- Healey F, Monro A, Cockram A, Adams V, Heseltine D. Using targeted risk factor reduction to prevent falls in older in-patients: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2004;33(4):390-395.

- Fonda D, Cook J, Sandler V, Bailey M. Sustained reduction in serious fall-related injuries in older people in hospital. Med J Aust. 2006;184(8):379-382.

- Von Renteln-Kruse W, Krause T. Incidence of in-hospital falls in geriatric patients before and after the introduction of an interdisciplinary team-based fall-prevention intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(12):2068-2074.

- Cumming RG, Sherrington C, Lord SR, et al. Cluster randomised trial of a targeted multifactorial intervention to prevent falls among older people in hospital. BMJ. 2008;336(7647):758-760.

- Oliver D, Britton M, Seed P, Martin FC, Hopper AH. Development and evaluation of evidence based risk assessment tool (STRATIFY) to predict which elderly inpatients will fall: case-control and cohort studies. BMJ. 1997;315(7115):1049-1053.

Case

An 85-year-old man with peripheral vascular disease, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, dementia, a history of falls, and atrial fibrillation, which was being treated with warfarin, was admitted for a left transmetatarsal amputation. On postoperative day two, the patient slipped as he was getting out of bed to use the bathroom. He hit his head on his IV pole, and a CT scan demonstrated an acute right subdural hemorrhage. He subsequently suffered eight months of delirium before passing away at a skilled nursing facility. How could this incident have been prevented?

Background

Hospitalization represents a vulnerable time for elderly people. The presence of acute illness, an unfamiliar environment, and the frequent addition of new medications predispose an elderly patient to such iatrogenic hazards of hospitalization as falls, pressure ulcers, and delirium.1 Inpatient falls are the most common type of adverse hospital event, accounting for 70% of all inpatient accidents.2 Thirty percent to 40% of inpatient falls result in injury, with 4% to 6% resulting in serious harm.2 Interestingly, 55% of falls occur in patients 60 or younger, but 60% of falls resulting in moderate to severe injury occur in those 70 and older.3

A fall is a seminal event in the life of an elderly person. Even a fall without injury can initiate a vicious circle that begins with a fear of falling and is followed by a self-restriction of mobility, which commonly results in a decline in function.4 Functional decline in the elderly has been shown to predict mortality and nursing home placement.5

Inpatient falls are thought to occur via a complex interplay between medications, inherent patient susceptibilities, and hospital environmental hazards (see Figure 1, below).

Risk Factors

Medication prescription for the hospitalized elderly patient is perhaps the area where the hospitalist can have the greatest impact in reducing a patient’s fall risk. The most common medications thought to predispose community dwelling elders to falls are psychotropic drugs: neuroleptics, sedatives, hypnotics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines.6

Limited studies of hospitalized patients indicate similar drugs as culprits. Passaro et al demonstrated that benzodiazepines with a half-life <24 hours (e.g., lorazepam and oxazepam) were strongly associated with falls even after correcting for multiple confounders.7 Furthermore, multivariate logistic regression revealed that the use of other psychotropic drugs in addition to benzodiazepines (OR 2.3; 95% CI, 1.6–3.2) was strongly associated with an increased risk of falls. Taking more than five medications also increased a patient’s fall risk (OR 1.6; 95% CI, 1.02–2.6). Thus, the judicious prescription of medications—aimed at decreasing the number and dosage of medications an elderly patient takes—is essential to minimizing the risk for falls.

Several studies conducted in hospitalized elderly patients have repeatedly demonstrated a core group of inherent patient risk factors for falls: delirium, agitation or impaired judgment, burden of comorbidity, gait instability or lower-extremity weakness, urinary incontinence or frequency, and a history of falls.2,3,8 These risk factors are targeted as part of most inpatient fall prevention programs, as discussed below.

Several environmental hazards have been known to increase the risk of falls and injury. These include high patient-to-nurse ratio, inappropriate use of bedrails, wet floors, and lack of assistance with ambulation and toileting. The most studied of these is assistance with ambulation and toileting. Hitcho et al demonstrated that as many as 50% of falls are toileting-related.3 The study also showed that only 42% of patients who fell and used an assistive device at home had a fall in the hospital. As many as 85% of patients were not assisted with a device or person at the time of a fall.2 Unassisted falls are associated with increased injury risk (adjusted OR 1.70; 95% CI, 1.23-2.36).

Consistent with this, increased patient-to-nurse ratios are keenly associated with an increased risk of falls. Essentially, a patient whose nurse had more than five patients was 2.6 times more likely to fall than a patient whose nurse had five or fewer patients (95% CI, 1.6 to 4.1). Based on this data, hospitals have invested in low-to-the-floor beds and alarms for beds and chairs. Placing patients on a regular toileting schedule, avoiding medications that cause urinary incontinence, and attention to bowel regimens have become standard components of hospital fall prevention programs. Even though these issues have long been thought to be the purview of nurses and support staff, hospitalist involvement and awareness are crucial to ensuring that these issues are consistently addressed and enforced for every at-risk patient.

Inpatient Fall Prevention

Inpatient falls are similar to other geriatric syndromes and are multifactorial in etiology. Studies that report a decrease in the number of falls identify patients at the highest risk for falls and target multiple risk factors simultaneously.

Several inpatient fall risk assessment tools have been developed. The most widely used and validated in the acute hospital setting are the Morse Falls Scale and St. Thomas’ Risk Assessment Tool in Falling Elderly Inpatients (STRATIFY) (see Table 1, p. 24).9 Both tools incorporate the risk factors identified above—namely, the presence of cognitive or sensory deficits, environmental hazards, history of falls, lower-extremity or gait instability/weakness, and level of comorbidity to create a score. Higher scores are associated with increased fall risk. The scales have demonstrated sensitivities and specificities of 70% to 96% and 50% to 85%, respectively, depending on the population tested and the cutoff scores used.

In 2004, Healey et al published the results of one of the few successful randomized, controlled fall-prevention trials in an acute-care setting.10 Pairs of identical hospital units were randomized to intervention and control groups. The sample size was 3,386 patients, with a mean length of stay of 19 days.1 As part of the intervention group, a fall-risk assessment was performed on admission. Patients were screened for deficits in visual acuity (identify a pen, key, or watch from a distance of 2 meters), polypharmacy, orthostatic hypotension, mobility deficits, appropriate bedrail use, footwear safety, bed height, distance of patient from nursing station, loose cables, wet floors, and availability of the nurse call bell.

Interventions for patients who were identified as high fall risks included ophthalmology/optician referral for those for whom reading aides could not be procured, medication review, adjustment of bed rails, and physical therapy. Patients with a history of falls were placed close to nursing stations. Environmental hazards were removed. Patients with orthostatic hypotension were educated on slowly changing body position. Call lights were moved to within easy reach. No additional money was allocated for this study, but by performing these simple interventions, the authors were able to decrease the relative risk of falls by 29% (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.55–0.90, P=0.006). The incidence of injuries sustained as a result of falling, however, was unchanged.

Two large, prospective studies with historical controls involving 3,000 to 7,000 patients over the course of three years and incorporating similar interventions also demonstrated a decrease in the number of falls.11,12 Fonda and his colleagues were able to demonstrate a 77% reduction in the number of falls resulting in serious injuries.

Even though these studies are promising, a recent cluster-randomized, multifactorial intervention trial involving almost 4,000 patients on a dozen medical floors did not demonstrate a reduction in the incidence of falls or falls with injury.13 Several differences exist between the two randomized trials. In the latter trial, by Cumming et al, a study nurse reviewed the care plan of all of the patients on the intervention wards and made recommendations.13 Also, the study was designed so that each patient on the intervention wards received the intervention, regardless of their fall risk. Additionally, the study period was a mere three months. In the Healey trial, the nurses on the intervention units implemented targeted risk reduction for patients at high risk, and the study period was a full year.

Back to the Case

Our patient had several risk factors for falls on admission. A targeted fall risk assessment on admission would have identified him as high-risk, with a Morse score of 95 given his dementia (15 points), impaired gait status post-transmetatarsal amputation (20 points), secondary diagnoses (multiple comorbidities, 15 points) and history of falls (25 points), and presence of an IV (20 points). The STRATIFY risk assessment tool would have produced similar results.

Frequent toileting assistance, early mobilization, medication review, and environmental modification might have prevented his fall (see Table 2, pg. 24).

Bottom Line

Focused assessment of patients on admission can identify those at risk for falls. Multifactorial inpatient fall-prevention strategies have been shown to reduce the rate of falls in inpatients without increasing costs. TH

Dr. Ölveczky is a geriatric nocturnist in the hospital medicine program, division of medicine, at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

References

- Fernandez HM, Callahan KE, Likourezos A, Leipzig RM. House staff member awareness of older inpatients’ risks for hazards of hospitalization. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(4):390-396.

- Krauss MJ, Evanoff B, Hitcho E, et al. A case control study of patient, medication, and care-related risk factors for inpatient falls. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(2):116-122.

- Hitcho EB, Krauss MJ, Birge S, et al. Characteristics and circumstances of falls in a hospital setting: a prospective analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(7):732-739.

- Tinetti ME. Clinical practice. Preventing falls in elderly persons. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(1):42-49.

- Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Salive ME, Wallace RB. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(9):556-561.

- Leipzig RM, Cumming RG, Tinetti ME. Drugs and falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis: I. Psychotropic drugs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(1):30-39.

- Passaro A, Volpato S, Romagnoni F, Manzoli N, Zuliani G, Fellin R. Benzodiazepines with different half-life and falling in a hospitalized population: The GIFA study. Gruppo Italiano di Farmacovigilanza nell'Anziano. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(12):1222-1229.

- Oliver D, Daly F, Martin FC, McMurdo ME. Risk factors and risk assessment tools for falls in hospital in-patients: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2004;33(2):122-130.

- Scott V, Votova K, Scanlan A, Close J. Multifactorial and functional mobility assessment tools for fall risk among older adults in community, home-support, long-term and acute care settings. Age Ageing. 2007;36(2):130-139.

- Healey F, Monro A, Cockram A, Adams V, Heseltine D. Using targeted risk factor reduction to prevent falls in older in-patients: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2004;33(4):390-395.

- Fonda D, Cook J, Sandler V, Bailey M. Sustained reduction in serious fall-related injuries in older people in hospital. Med J Aust. 2006;184(8):379-382.

- Von Renteln-Kruse W, Krause T. Incidence of in-hospital falls in geriatric patients before and after the introduction of an interdisciplinary team-based fall-prevention intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(12):2068-2074.

- Cumming RG, Sherrington C, Lord SR, et al. Cluster randomised trial of a targeted multifactorial intervention to prevent falls among older people in hospital. BMJ. 2008;336(7647):758-760.

- Oliver D, Britton M, Seed P, Martin FC, Hopper AH. Development and evaluation of evidence based risk assessment tool (STRATIFY) to predict which elderly inpatients will fall: case-control and cohort studies. BMJ. 1997;315(7115):1049-1053.

Case

An 85-year-old man with peripheral vascular disease, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, dementia, a history of falls, and atrial fibrillation, which was being treated with warfarin, was admitted for a left transmetatarsal amputation. On postoperative day two, the patient slipped as he was getting out of bed to use the bathroom. He hit his head on his IV pole, and a CT scan demonstrated an acute right subdural hemorrhage. He subsequently suffered eight months of delirium before passing away at a skilled nursing facility. How could this incident have been prevented?

Background

Hospitalization represents a vulnerable time for elderly people. The presence of acute illness, an unfamiliar environment, and the frequent addition of new medications predispose an elderly patient to such iatrogenic hazards of hospitalization as falls, pressure ulcers, and delirium.1 Inpatient falls are the most common type of adverse hospital event, accounting for 70% of all inpatient accidents.2 Thirty percent to 40% of inpatient falls result in injury, with 4% to 6% resulting in serious harm.2 Interestingly, 55% of falls occur in patients 60 or younger, but 60% of falls resulting in moderate to severe injury occur in those 70 and older.3

A fall is a seminal event in the life of an elderly person. Even a fall without injury can initiate a vicious circle that begins with a fear of falling and is followed by a self-restriction of mobility, which commonly results in a decline in function.4 Functional decline in the elderly has been shown to predict mortality and nursing home placement.5

Inpatient falls are thought to occur via a complex interplay between medications, inherent patient susceptibilities, and hospital environmental hazards (see Figure 1, below).

Risk Factors

Medication prescription for the hospitalized elderly patient is perhaps the area where the hospitalist can have the greatest impact in reducing a patient’s fall risk. The most common medications thought to predispose community dwelling elders to falls are psychotropic drugs: neuroleptics, sedatives, hypnotics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines.6

Limited studies of hospitalized patients indicate similar drugs as culprits. Passaro et al demonstrated that benzodiazepines with a half-life <24 hours (e.g., lorazepam and oxazepam) were strongly associated with falls even after correcting for multiple confounders.7 Furthermore, multivariate logistic regression revealed that the use of other psychotropic drugs in addition to benzodiazepines (OR 2.3; 95% CI, 1.6–3.2) was strongly associated with an increased risk of falls. Taking more than five medications also increased a patient’s fall risk (OR 1.6; 95% CI, 1.02–2.6). Thus, the judicious prescription of medications—aimed at decreasing the number and dosage of medications an elderly patient takes—is essential to minimizing the risk for falls.

Several studies conducted in hospitalized elderly patients have repeatedly demonstrated a core group of inherent patient risk factors for falls: delirium, agitation or impaired judgment, burden of comorbidity, gait instability or lower-extremity weakness, urinary incontinence or frequency, and a history of falls.2,3,8 These risk factors are targeted as part of most inpatient fall prevention programs, as discussed below.

Several environmental hazards have been known to increase the risk of falls and injury. These include high patient-to-nurse ratio, inappropriate use of bedrails, wet floors, and lack of assistance with ambulation and toileting. The most studied of these is assistance with ambulation and toileting. Hitcho et al demonstrated that as many as 50% of falls are toileting-related.3 The study also showed that only 42% of patients who fell and used an assistive device at home had a fall in the hospital. As many as 85% of patients were not assisted with a device or person at the time of a fall.2 Unassisted falls are associated with increased injury risk (adjusted OR 1.70; 95% CI, 1.23-2.36).

Consistent with this, increased patient-to-nurse ratios are keenly associated with an increased risk of falls. Essentially, a patient whose nurse had more than five patients was 2.6 times more likely to fall than a patient whose nurse had five or fewer patients (95% CI, 1.6 to 4.1). Based on this data, hospitals have invested in low-to-the-floor beds and alarms for beds and chairs. Placing patients on a regular toileting schedule, avoiding medications that cause urinary incontinence, and attention to bowel regimens have become standard components of hospital fall prevention programs. Even though these issues have long been thought to be the purview of nurses and support staff, hospitalist involvement and awareness are crucial to ensuring that these issues are consistently addressed and enforced for every at-risk patient.

Inpatient Fall Prevention

Inpatient falls are similar to other geriatric syndromes and are multifactorial in etiology. Studies that report a decrease in the number of falls identify patients at the highest risk for falls and target multiple risk factors simultaneously.

Several inpatient fall risk assessment tools have been developed. The most widely used and validated in the acute hospital setting are the Morse Falls Scale and St. Thomas’ Risk Assessment Tool in Falling Elderly Inpatients (STRATIFY) (see Table 1, p. 24).9 Both tools incorporate the risk factors identified above—namely, the presence of cognitive or sensory deficits, environmental hazards, history of falls, lower-extremity or gait instability/weakness, and level of comorbidity to create a score. Higher scores are associated with increased fall risk. The scales have demonstrated sensitivities and specificities of 70% to 96% and 50% to 85%, respectively, depending on the population tested and the cutoff scores used.

In 2004, Healey et al published the results of one of the few successful randomized, controlled fall-prevention trials in an acute-care setting.10 Pairs of identical hospital units were randomized to intervention and control groups. The sample size was 3,386 patients, with a mean length of stay of 19 days.1 As part of the intervention group, a fall-risk assessment was performed on admission. Patients were screened for deficits in visual acuity (identify a pen, key, or watch from a distance of 2 meters), polypharmacy, orthostatic hypotension, mobility deficits, appropriate bedrail use, footwear safety, bed height, distance of patient from nursing station, loose cables, wet floors, and availability of the nurse call bell.

Interventions for patients who were identified as high fall risks included ophthalmology/optician referral for those for whom reading aides could not be procured, medication review, adjustment of bed rails, and physical therapy. Patients with a history of falls were placed close to nursing stations. Environmental hazards were removed. Patients with orthostatic hypotension were educated on slowly changing body position. Call lights were moved to within easy reach. No additional money was allocated for this study, but by performing these simple interventions, the authors were able to decrease the relative risk of falls by 29% (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.55–0.90, P=0.006). The incidence of injuries sustained as a result of falling, however, was unchanged.

Two large, prospective studies with historical controls involving 3,000 to 7,000 patients over the course of three years and incorporating similar interventions also demonstrated a decrease in the number of falls.11,12 Fonda and his colleagues were able to demonstrate a 77% reduction in the number of falls resulting in serious injuries.

Even though these studies are promising, a recent cluster-randomized, multifactorial intervention trial involving almost 4,000 patients on a dozen medical floors did not demonstrate a reduction in the incidence of falls or falls with injury.13 Several differences exist between the two randomized trials. In the latter trial, by Cumming et al, a study nurse reviewed the care plan of all of the patients on the intervention wards and made recommendations.13 Also, the study was designed so that each patient on the intervention wards received the intervention, regardless of their fall risk. Additionally, the study period was a mere three months. In the Healey trial, the nurses on the intervention units implemented targeted risk reduction for patients at high risk, and the study period was a full year.

Back to the Case

Our patient had several risk factors for falls on admission. A targeted fall risk assessment on admission would have identified him as high-risk, with a Morse score of 95 given his dementia (15 points), impaired gait status post-transmetatarsal amputation (20 points), secondary diagnoses (multiple comorbidities, 15 points) and history of falls (25 points), and presence of an IV (20 points). The STRATIFY risk assessment tool would have produced similar results.

Frequent toileting assistance, early mobilization, medication review, and environmental modification might have prevented his fall (see Table 2, pg. 24).

Bottom Line

Focused assessment of patients on admission can identify those at risk for falls. Multifactorial inpatient fall-prevention strategies have been shown to reduce the rate of falls in inpatients without increasing costs. TH

Dr. Ölveczky is a geriatric nocturnist in the hospital medicine program, division of medicine, at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

References

- Fernandez HM, Callahan KE, Likourezos A, Leipzig RM. House staff member awareness of older inpatients’ risks for hazards of hospitalization. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(4):390-396.

- Krauss MJ, Evanoff B, Hitcho E, et al. A case control study of patient, medication, and care-related risk factors for inpatient falls. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(2):116-122.

- Hitcho EB, Krauss MJ, Birge S, et al. Characteristics and circumstances of falls in a hospital setting: a prospective analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(7):732-739.

- Tinetti ME. Clinical practice. Preventing falls in elderly persons. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(1):42-49.

- Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Salive ME, Wallace RB. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(9):556-561.

- Leipzig RM, Cumming RG, Tinetti ME. Drugs and falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis: I. Psychotropic drugs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(1):30-39.

- Passaro A, Volpato S, Romagnoni F, Manzoli N, Zuliani G, Fellin R. Benzodiazepines with different half-life and falling in a hospitalized population: The GIFA study. Gruppo Italiano di Farmacovigilanza nell'Anziano. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(12):1222-1229.

- Oliver D, Daly F, Martin FC, McMurdo ME. Risk factors and risk assessment tools for falls in hospital in-patients: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2004;33(2):122-130.

- Scott V, Votova K, Scanlan A, Close J. Multifactorial and functional mobility assessment tools for fall risk among older adults in community, home-support, long-term and acute care settings. Age Ageing. 2007;36(2):130-139.

- Healey F, Monro A, Cockram A, Adams V, Heseltine D. Using targeted risk factor reduction to prevent falls in older in-patients: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2004;33(4):390-395.

- Fonda D, Cook J, Sandler V, Bailey M. Sustained reduction in serious fall-related injuries in older people in hospital. Med J Aust. 2006;184(8):379-382.

- Von Renteln-Kruse W, Krause T. Incidence of in-hospital falls in geriatric patients before and after the introduction of an interdisciplinary team-based fall-prevention intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(12):2068-2074.

- Cumming RG, Sherrington C, Lord SR, et al. Cluster randomised trial of a targeted multifactorial intervention to prevent falls among older people in hospital. BMJ. 2008;336(7647):758-760.

- Oliver D, Britton M, Seed P, Martin FC, Hopper AH. Development and evaluation of evidence based risk assessment tool (STRATIFY) to predict which elderly inpatients will fall: case-control and cohort studies. BMJ. 1997;315(7115):1049-1053.

Job Hunter’s Checklist

Apart from the part-time job that provided pocket money while you were in high school or during your undergraduate years, physicians generally have little experience in the job-hunting arena. A physician’s career path requires much skill at applying for such educational endeavors as medical school and residency training, but applying for a “real” job can be a strange concept for most.

Not lost in the equation is the fact that the application process doesn’t begin until most physicians are in their late 20s. While many of our non-physician friends are on their second or third jobs, graduating residents looking to launch their careers often struggle with the transition to the world of HM. In order to help navigate these waters, we have put together a yearlong guide to help make the transition from third-year resident to hospitalist a little smoother.

July-September

The first step in landing a job is to find a mentor who can assist you through the entire process. Choose your mentor wisely; an experienced hospitalist can provide valuable feedback during your job search. If your goal is employment with a private hospitalist group, find a hospitalist with private-practice experience.

Choose your senior-year electives carefully. Consider focusing on areas of weakness or areas that are pertinent to HM (e.g., infectious disease, cardiology, neurology, critical-care medicine). Think about an outside elective in HM.

If you haven’t done so already, now is the time to create a curriculum vitae, also known as a CV, and a cover letter. The CV is a vital document. It might be the key element in determining whether you are worthy of an interview. Work on this document early, as you will need time for edits, updates, and mentor review. The cover letter should clearly describe the type of position you want and confidently state why you would be an asset to a particular hospitalist program. Edit your words carefully; spelling errors or typos in documents can be costly.

Once the Labor Day holiday has passed, you should start requesting letters of recommendation. Think hard about who you want before asking for a letter of recommendation, as these typically carry a lot of weight in the interview selection process. Although program directors, chiefs of medicine, and hospitalists can be good choices, it is important to choose people who know you well, as they tend to generate a more personal and powerful letter. Because letter-writers often are busy people, it is appropriate to give a deadline for when you need the letter.

October-December

Actively start the job search and apply for desired positions. This is the time of year when HM jobs are heavily advertised and programs are looking to fill positions. Hospitalists are in high demand throughout the country. Some great places to find job openings are:

- SHM’s Career Center (www.hospitalmedicine.org/careers);

- Classified ad sections in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, general medicine journals, and HM news magazines like The Hospitalist (see “SHM Career Center,” p. 35); and

- Hospitals and HM groups of interest, even if they are not advertising; contact them personally.

Begin the interview process by researching the hospital and HM group in advance. Prepare appropriate interview questions. When you interview, try to meet with as many people as possible to get a feel for what the job entails. Talk to the everyday hospitalists and try to gauge how satisfied they are in their jobs.

Bring extra copies of your updated CV and look sharp. Shine your shoes. Is it time to replace the suit you used to apply for residency?

Send a thank-you note or e-mail to the person(s) you interviewed with. If possible, do this within three days of your visit. It’s an important step in the process, yet this simple task often is overlooked. Remain in contact with the HM programs you are most interested in. Think about a follow-up visit or phone call to address any unanswered questions.

January-March

Hopefully you will have one or more offers by now. This is the time to negotiate a contract and accept an offer. Review the contract carefully and don’t hesitate to ask for clarification of unclear points. Some applicants prefer to have a lawyer review the contract prior to signing (see “The Art of Negotiation,” December 2008, p. 20).

Register for your board examination. Most specialties, including internal medicine, family medicine, and pediatrics, as well as board exams for osteopathic medicine, have registration deadlines in February. Given the significant cost of applying for these exams, it pays not to be tardy, as late fees can set you back hundreds of dollars.

Apply for state medical licensure. This process varies by state, but it can take several months to complete, especially if you are applying in a state other than where you trained. For example, California recommends starting the application process six to nine months in advance. International medical graduates who require a work visa need to ensure their paperwork is processed in a timely manner.

Each hospital is different, but applications for hospital credentialing generally means filling out a mountain of paperwork. Most hospitals will perform a thorough background check, so don’t be surprised if fingerprinting is required. The hospital or hospitalist group usually helps new hires navigate through this process, which can take several weeks or even months.

April-June

Moving to a different city or state can be exciting—and stressful. Start talking to hospitalists at the facility where you will be working to get a feel for the city and recommendations for places to live. Revisit the location to become more familiar with the surroundings. Some hospitals are very helpful; some provide new hires with a real estate agent. Moving expenses often are covered as a condition of employment, but it depends on your contract.

Consider taking a vacation to either further explore relocation options or to simply relax. If you have followed the recommendations outlined in the previous months, you should have time to unwind as your residency comes to an end. Some future hospitalists like to use this time to intensify board review; others cringe at the thought.

Transitioning from resident to hospitalist is no easy task, and it shouldn’t be taken lightly. It’s not a one-month process, either, so planning is essential. Although it might seem to be a daunting journey, it’s very rewarding in the long run. TH

Dr. Grant is a hospitalist at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor. Dr. Warren-Marzola is a hospitalist at St. Luke’s Hospital in Toledo, Ohio. Both are members of SHM’s Young Physicians Committee.

Apart from the part-time job that provided pocket money while you were in high school or during your undergraduate years, physicians generally have little experience in the job-hunting arena. A physician’s career path requires much skill at applying for such educational endeavors as medical school and residency training, but applying for a “real” job can be a strange concept for most.

Not lost in the equation is the fact that the application process doesn’t begin until most physicians are in their late 20s. While many of our non-physician friends are on their second or third jobs, graduating residents looking to launch their careers often struggle with the transition to the world of HM. In order to help navigate these waters, we have put together a yearlong guide to help make the transition from third-year resident to hospitalist a little smoother.

July-September

The first step in landing a job is to find a mentor who can assist you through the entire process. Choose your mentor wisely; an experienced hospitalist can provide valuable feedback during your job search. If your goal is employment with a private hospitalist group, find a hospitalist with private-practice experience.

Choose your senior-year electives carefully. Consider focusing on areas of weakness or areas that are pertinent to HM (e.g., infectious disease, cardiology, neurology, critical-care medicine). Think about an outside elective in HM.

If you haven’t done so already, now is the time to create a curriculum vitae, also known as a CV, and a cover letter. The CV is a vital document. It might be the key element in determining whether you are worthy of an interview. Work on this document early, as you will need time for edits, updates, and mentor review. The cover letter should clearly describe the type of position you want and confidently state why you would be an asset to a particular hospitalist program. Edit your words carefully; spelling errors or typos in documents can be costly.

Once the Labor Day holiday has passed, you should start requesting letters of recommendation. Think hard about who you want before asking for a letter of recommendation, as these typically carry a lot of weight in the interview selection process. Although program directors, chiefs of medicine, and hospitalists can be good choices, it is important to choose people who know you well, as they tend to generate a more personal and powerful letter. Because letter-writers often are busy people, it is appropriate to give a deadline for when you need the letter.

October-December

Actively start the job search and apply for desired positions. This is the time of year when HM jobs are heavily advertised and programs are looking to fill positions. Hospitalists are in high demand throughout the country. Some great places to find job openings are:

- SHM’s Career Center (www.hospitalmedicine.org/careers);

- Classified ad sections in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, general medicine journals, and HM news magazines like The Hospitalist (see “SHM Career Center,” p. 35); and

- Hospitals and HM groups of interest, even if they are not advertising; contact them personally.

Begin the interview process by researching the hospital and HM group in advance. Prepare appropriate interview questions. When you interview, try to meet with as many people as possible to get a feel for what the job entails. Talk to the everyday hospitalists and try to gauge how satisfied they are in their jobs.

Bring extra copies of your updated CV and look sharp. Shine your shoes. Is it time to replace the suit you used to apply for residency?

Send a thank-you note or e-mail to the person(s) you interviewed with. If possible, do this within three days of your visit. It’s an important step in the process, yet this simple task often is overlooked. Remain in contact with the HM programs you are most interested in. Think about a follow-up visit or phone call to address any unanswered questions.

January-March

Hopefully you will have one or more offers by now. This is the time to negotiate a contract and accept an offer. Review the contract carefully and don’t hesitate to ask for clarification of unclear points. Some applicants prefer to have a lawyer review the contract prior to signing (see “The Art of Negotiation,” December 2008, p. 20).

Register for your board examination. Most specialties, including internal medicine, family medicine, and pediatrics, as well as board exams for osteopathic medicine, have registration deadlines in February. Given the significant cost of applying for these exams, it pays not to be tardy, as late fees can set you back hundreds of dollars.