User login

Standardized Orders Improve Pediatric Care

For many years physicians have created and used various standardized order forms for patient hospital admissions. The increasing popularity of electronic medical records and forms has led to the use of computerized physician order entry (CPOE) as a means of reducing medication errors.13 Crowley et al.,4 Stucky,5 and Garg et al.,6 along with various committees, have recommended standardized order sets and CPOE as a strategy for reducing medication errors. However, implementation of CPOE systems is expensive and not available in most hospitals. According to a recent survey of hospitals in the US, CPOE was only available to physicians at 16% of the participating institutions.7 Until CPOE becomes widespread, standardized preprinted formatted order sets may serve as an inexpensive alternative.

There is anecdotal evidence that standardized admission order forms may improve quality of care and efficiency, and decrease provider variation.8 However, few rigorous studies exist in the pediatric research literature regarding their ability to actually improve patient care.

In 2005, our institution, a large tertiary‐care academic teaching hospital, developed a standardized preprinted pediatric admission order set (PAOS). We did so for 3 reasons. First, there was a desire to improve completeness of orders. Handwritten orders often missed important elements such as weight, allergies, vital sign parameters, activity, etc. Second, there was a need to save time and improve efficiency. Third, it was important to reduce medical errors and the number of clarification requests by decreasing the necessity to decipher physician handwriting. Our PAOS was a convenience order set as opposed to a best practices order set. In other words, our PAOS did not contain evidence‐based management guidelines or protocols for specific admission diagnoses and was created solely to improve the quality and efficiency of workflow.

Documenting improvement in patient outcomes or reduction of medical errors is ultimately needed to establish the effectiveness of a standardized order set. Secondary outcomes, howeverparticularly the perceptions of the staff who are asked to use the order setare equally important, because they may identify real‐life barriers to use that, regardless of effectiveness, could limit dissemination and uptake. With respect to perceptions, 2 groups become paramount: those who write the orders, and those who respond to them. The purpose of the current study was to examine perceived effects of the new PAOS on inpatient care among those who, in our institution, write the ordersresident physicians.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

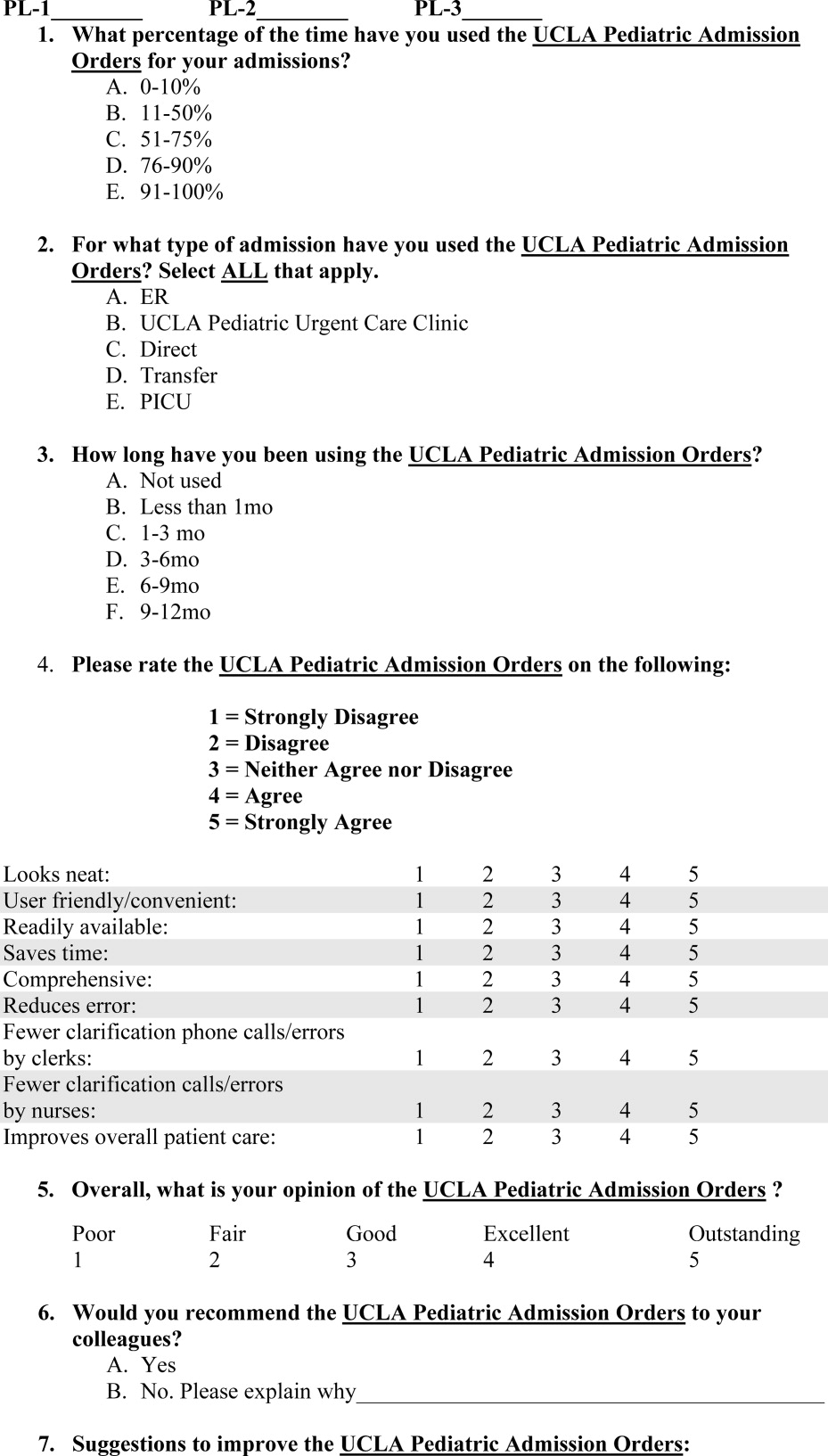

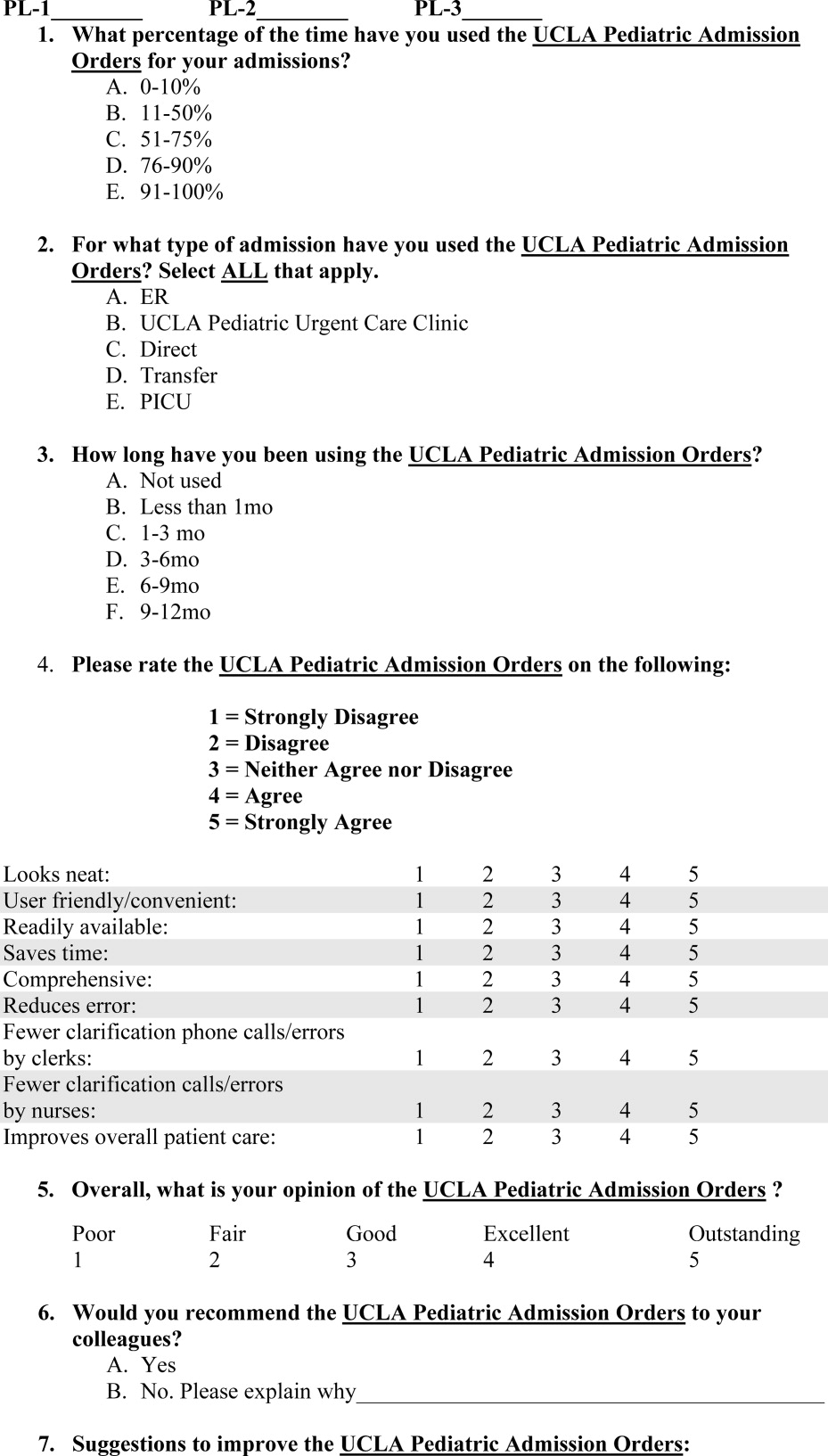

The PAOS was created in August 2005 at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Medical Center by a committee comprising pediatric hospitalists, nurses, pharmacists, residents, and clerks. The PAOS consisted mainly of check boxes (Figure 1). The PAOS was uploaded to the hospital website and made available for printing from all computers in the hospital, emergency room, and clinics.

The UCLA Hospital and Medical Center is a nonprofit, 667‐bed tertiary‐care teaching hospital in Los Angeles, California. The pediatric ward has 70 licensed beds with approximately 3,000 admissions per year. The majority of the admissions were done by the pediatric residents. Physicians were free to edit the PAOS to suit a particular patient's needs or to hand‐write orders on a blank order form.

Measures

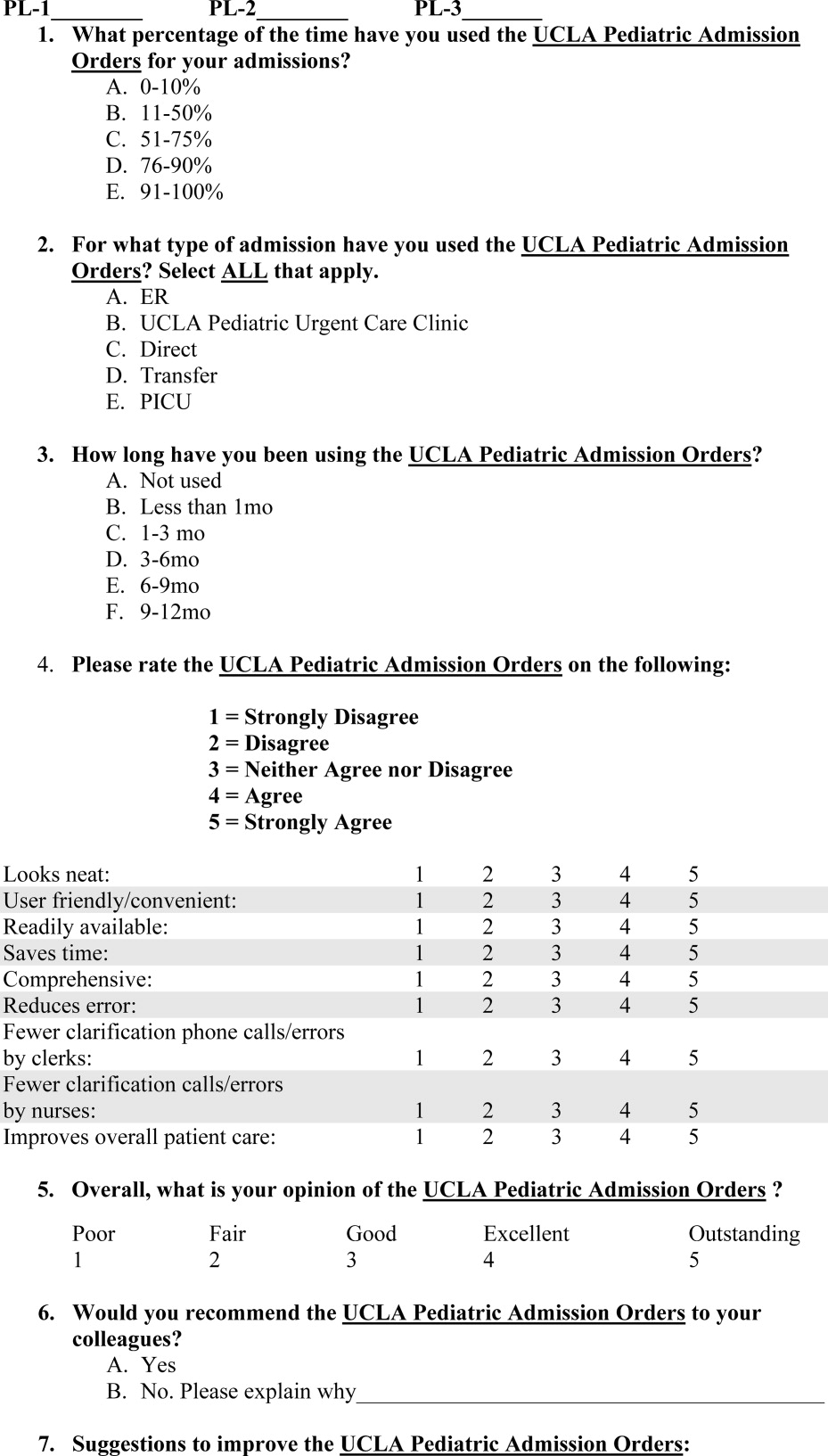

Fourteen months after the institution of the PAOS, all 97 UCLA pediatric residents (PL‐1, n = 34; PL‐2, n = 33; PL‐3, n = 30) were asked to complete a survey to anonymously evaluate the order set. All residents were US medical school graduates. Resident participation in the research project was voluntary and confidential, and residents were assured that participation would not affect their standing in the pediatric residency program. Each resident completed only 1 survey. Responses were collected October 2006 to June 2007. The residents were asked to rate the PAOS overall and with respect to 9 specific dimensions using a 5‐point Likert scale with 1 indicating strong disagreement and 5 indicating strong agreement (Figure 2).

This study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at the UCLA Medical Center.

Statistical Analysis

We used bivariate ordered logistic regression to estimate the association between overall rating and each of the 9 dimensions. Ordered logistic regression, a standard technique for ordered categorical variables, is essentially a weighted average of logistic regressions performed at each potential cut‐point of the outcome variable. For instance, potential cut‐points on our 5‐point Likert scale included strong disagreement versus any other, any disagreement versus nondisagreement, any agreement versus nonagreement, and strong agreement versus any other. We then used multivariate ordered logistic regression to examine which specific dimensions remained independently associated with the overall rating.

RESULTS

From October 2006 to June 2007, 59 residents (from a total of 97 residents; 61%) responded to the survey. Overall, 89% of respondents approved of the PAOS, 58% reported using it 90% of the time, and all said that they would recommend it to their colleagues (Table 1). Eighty‐four percent thought that the PAOS improved inpatient care, and 75% thought that medical errors were reduced. Eighty‐eight percent reported that the POAS saved time; 93% said it was convenient; and most reported less need for clarification with clerks (81%) and nurses (82%).

| Strongly Agree (%) | Agree (%) | Other (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specific dimensions | |||

| Looks neat | 63 | 32 | 5 |

| User friendly/convenient | 60 | 33 | 7 |

| Readily available | 47 | 26 | 26 |

| Saves time | 56 | 32 | 12 |

| Comprehensive | 40 | 40 | 19 |

| Reduces medical error | 40 | 35 | 25 |

| Fewer clarification phone calls/errors by clerks | 47 | 33 | 19 |

| Fewer clarification phone calls/errors by nurses | 47 | 35 | 18 |

| Improves overall patient care | 46 | 39 | 16 |

| Overall rating | 40 | 49 | 11 |

In bivariate analyses, each of the 9 dimensions was strongly associated with the overall rating (P < 0.001 for each). In multivariate analyses, however, only perceived improvement in patient care was independently associated with overall rating (OR, 3.9; P = 0.04).

We then examined whether perceived improvement in patient care itself was independently predicted by the other 8 dimensions. Residents who said that the form was comprehensive (OR, 5.6; P = 0.01), reduced medical errors (OR, 4.1; P = 0.01), or required less need for clarification with nurses (OR, 9.6; P = 0.01) were more likely to perceive that the form improved patient care than residents who did not.

DISCUSSION

A standardized admission order set is a simple, low‐cost intervention that may benefit patients by reducing medical errors and expediting high‐quality care. In general, residents rated the PAOS favorably. Just as importantly, the PAOS scored well across all specific dimensions, which suggests few perceived barriers to use among residents.

Some dimensions, however, appeared potentially more important than others. Residents who perceived an improvement in patient care tended to rate the PAOS favorably. Perceived improvement in patient care, in turn, was linked to the order set's comprehensiveness, perceived reductions in medical errors, and less need for clarification with nurses.

Even though this study did not directly query those most responsible for responding to the order set (ie, nurses, pharmacists, and clerks), the order set was created through a collaborative partnership of physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and clerks. It is reasonable to infer that resident‐perceived reduction in the need for clarification of orders with nurses and clerks might indicate a broad‐based, multidisciplinary improvement in clarity and workflow. Moreover, the fact that less need for clarification with nurses was strongly associated with resident‐perceived improvement in patient care underscores the importance of including nurses, pharmacists, and clerks in the development of these order sets.

Our experience using the standard admission orders over the past 2 years is congruent with other authors' findings. Most studies, however, have examined standardized order forms only in adult populations, and mainly for specific medical conditions. Micek et al.9 demonstrated that use of a standardized physician order set among adults with septic shock lowered 28‐day mortality and reduced hospital stay. Among stroke patients, rates of optimal treatment significantly improved after the introduction of standardized stroke orders.10 For patients with acute myocardial infarction, standardized admission orders increased early administration of aspirin and beta blockers.11, 12 With respect to cancer, implementation of a preprinted chemotherapy prescription form improved order completeness, prevented medication errors, and reduced time spent by pharmacists clarifying orders.13 Finally, standardized trauma admission orders developed in a surgical‐trauma intensive care unit reduced admission laboratory charges and improved order completeness.14 We found only a single pediatric study examining standardized order forms. Kozer et al.15 found that the use of a preprinted structured medication order form cut medication errors nearly in half in a pediatric emergency department.

Whether our results would have been similar had we implemented a series of best practices order sets rather than a single convenience order set is unclear. Although best practices order sets would have facilitated application of evidence‐based guidelines for common diagnoses, they would also have introduced potentially unwelcome logistical heterogeneity (with a separate form and protocol needed for each diagnosis) that might have reduced acceptability and uptake. In addition, there is a risk that best practices order sets would have been perceived as unduly limiting physician professional autonomy.

Our study has limitations. First, our study was performed within a single institution and may not be easily generalized. However, we believe that the basic format of the PAOS lends it to easy adaptability. Second, we did not survey residents before the order set was introduced to assess baseline perceptions. Instead, many of the questions in the survey ask about perceived improvements compared with the previous system. Conducting a formal pre‐post data collection and analysis might have yielded different results. Third, improvement in patient care was measured indirectly based on resident opinion.

In conclusion, our study suggests that our standardized admission order set prompting physicians to initiate comprehensive care is well‐liked by residents and is thought to benefit patients by reducing medical errors and expediting high‐quality care. The next step is to confirm that the resident‐perceived improvement in patient care correlates with actual improvement in patient care. If improvements can be confirmed, then PAOS adoption could be broadly recommended to pediatric hospitals. In the future, the PAOS may also help guide computerized physician order entry templates that can be further tailored to specific common diagnoses.

- ,,, et al.Effect of computerized physician order entry and a team intervention on prevention of serious medication errors.JAMA.1998;280(15):1311–1316.

- ,,.Effects of computerized physician order entry and clinical decision support systems on medication safety: a systematic review.Arch Intern Med.2003;163(12):1409–1416.

- ,,,,.The effect of computerized physician order entry on medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients.Pediatrics.2003;112(3 Pt 1):506–509.

- ,,.Medication errors in children: a descriptive summary of medication error reports submitted to the United States Pharmacopoeia.Curr Ther Res Clin Exp.2001;62:627–640.

- .Prevention of medication errors in the pediatric inpatient setting.Pediatrics.2003;112(2):431–436.

- ,,, et al.Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review.JAMA.2005;293(10):1223–1238.

- ,,,.Computerized physician order entry in U.S. hospitals: results of a 2002 survey.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2004;11(2):95–99.

- .Using standardized admit orders to improve inpatient care.Fam Pract Manag.1999;6(10):30–32.

- ,,, et al.Before‐after study of a standardized hospital order set for the management of septic shock.Crit Care Med.2006;34(11):2707–2713.

- California Acute Stroke Pilot Registry Investigators.The impact of standardized stroke orders on adherence to best practices.Neurology.2005;65(3):360–365.

- ,,,,,.Improving quality of care for acute myocardial infarction. The guidelines applied in practice (GAP) initiative.JAMA.2002;287(10):1269–1276.

- ,,,,,.Quality improvement initiative and its impact on the management of patients with acute myocardial infarction.Arch Intern Med.2000;160:3057–3061.

- ,,,,,.Effect of a cancer chemotherapy prescription form on prescription completeness.Am J Hosp Pharm.1989;46(9):1802–1806.

- ,.Standardized trauma admission orders, a pilot project.Int J Trauma Nurs.1996;2(1):13–21.

- ,,,,.Using a preprinted order sheet to reduce prescription errors in a pediatric emergency department: a randomized, controlled trial.Pediatrics.2005;116(6):1299–1302.

For many years physicians have created and used various standardized order forms for patient hospital admissions. The increasing popularity of electronic medical records and forms has led to the use of computerized physician order entry (CPOE) as a means of reducing medication errors.13 Crowley et al.,4 Stucky,5 and Garg et al.,6 along with various committees, have recommended standardized order sets and CPOE as a strategy for reducing medication errors. However, implementation of CPOE systems is expensive and not available in most hospitals. According to a recent survey of hospitals in the US, CPOE was only available to physicians at 16% of the participating institutions.7 Until CPOE becomes widespread, standardized preprinted formatted order sets may serve as an inexpensive alternative.

There is anecdotal evidence that standardized admission order forms may improve quality of care and efficiency, and decrease provider variation.8 However, few rigorous studies exist in the pediatric research literature regarding their ability to actually improve patient care.

In 2005, our institution, a large tertiary‐care academic teaching hospital, developed a standardized preprinted pediatric admission order set (PAOS). We did so for 3 reasons. First, there was a desire to improve completeness of orders. Handwritten orders often missed important elements such as weight, allergies, vital sign parameters, activity, etc. Second, there was a need to save time and improve efficiency. Third, it was important to reduce medical errors and the number of clarification requests by decreasing the necessity to decipher physician handwriting. Our PAOS was a convenience order set as opposed to a best practices order set. In other words, our PAOS did not contain evidence‐based management guidelines or protocols for specific admission diagnoses and was created solely to improve the quality and efficiency of workflow.

Documenting improvement in patient outcomes or reduction of medical errors is ultimately needed to establish the effectiveness of a standardized order set. Secondary outcomes, howeverparticularly the perceptions of the staff who are asked to use the order setare equally important, because they may identify real‐life barriers to use that, regardless of effectiveness, could limit dissemination and uptake. With respect to perceptions, 2 groups become paramount: those who write the orders, and those who respond to them. The purpose of the current study was to examine perceived effects of the new PAOS on inpatient care among those who, in our institution, write the ordersresident physicians.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The PAOS was created in August 2005 at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Medical Center by a committee comprising pediatric hospitalists, nurses, pharmacists, residents, and clerks. The PAOS consisted mainly of check boxes (Figure 1). The PAOS was uploaded to the hospital website and made available for printing from all computers in the hospital, emergency room, and clinics.

The UCLA Hospital and Medical Center is a nonprofit, 667‐bed tertiary‐care teaching hospital in Los Angeles, California. The pediatric ward has 70 licensed beds with approximately 3,000 admissions per year. The majority of the admissions were done by the pediatric residents. Physicians were free to edit the PAOS to suit a particular patient's needs or to hand‐write orders on a blank order form.

Measures

Fourteen months after the institution of the PAOS, all 97 UCLA pediatric residents (PL‐1, n = 34; PL‐2, n = 33; PL‐3, n = 30) were asked to complete a survey to anonymously evaluate the order set. All residents were US medical school graduates. Resident participation in the research project was voluntary and confidential, and residents were assured that participation would not affect their standing in the pediatric residency program. Each resident completed only 1 survey. Responses were collected October 2006 to June 2007. The residents were asked to rate the PAOS overall and with respect to 9 specific dimensions using a 5‐point Likert scale with 1 indicating strong disagreement and 5 indicating strong agreement (Figure 2).

This study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at the UCLA Medical Center.

Statistical Analysis

We used bivariate ordered logistic regression to estimate the association between overall rating and each of the 9 dimensions. Ordered logistic regression, a standard technique for ordered categorical variables, is essentially a weighted average of logistic regressions performed at each potential cut‐point of the outcome variable. For instance, potential cut‐points on our 5‐point Likert scale included strong disagreement versus any other, any disagreement versus nondisagreement, any agreement versus nonagreement, and strong agreement versus any other. We then used multivariate ordered logistic regression to examine which specific dimensions remained independently associated with the overall rating.

RESULTS

From October 2006 to June 2007, 59 residents (from a total of 97 residents; 61%) responded to the survey. Overall, 89% of respondents approved of the PAOS, 58% reported using it 90% of the time, and all said that they would recommend it to their colleagues (Table 1). Eighty‐four percent thought that the PAOS improved inpatient care, and 75% thought that medical errors were reduced. Eighty‐eight percent reported that the POAS saved time; 93% said it was convenient; and most reported less need for clarification with clerks (81%) and nurses (82%).

| Strongly Agree (%) | Agree (%) | Other (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specific dimensions | |||

| Looks neat | 63 | 32 | 5 |

| User friendly/convenient | 60 | 33 | 7 |

| Readily available | 47 | 26 | 26 |

| Saves time | 56 | 32 | 12 |

| Comprehensive | 40 | 40 | 19 |

| Reduces medical error | 40 | 35 | 25 |

| Fewer clarification phone calls/errors by clerks | 47 | 33 | 19 |

| Fewer clarification phone calls/errors by nurses | 47 | 35 | 18 |

| Improves overall patient care | 46 | 39 | 16 |

| Overall rating | 40 | 49 | 11 |

In bivariate analyses, each of the 9 dimensions was strongly associated with the overall rating (P < 0.001 for each). In multivariate analyses, however, only perceived improvement in patient care was independently associated with overall rating (OR, 3.9; P = 0.04).

We then examined whether perceived improvement in patient care itself was independently predicted by the other 8 dimensions. Residents who said that the form was comprehensive (OR, 5.6; P = 0.01), reduced medical errors (OR, 4.1; P = 0.01), or required less need for clarification with nurses (OR, 9.6; P = 0.01) were more likely to perceive that the form improved patient care than residents who did not.

DISCUSSION

A standardized admission order set is a simple, low‐cost intervention that may benefit patients by reducing medical errors and expediting high‐quality care. In general, residents rated the PAOS favorably. Just as importantly, the PAOS scored well across all specific dimensions, which suggests few perceived barriers to use among residents.

Some dimensions, however, appeared potentially more important than others. Residents who perceived an improvement in patient care tended to rate the PAOS favorably. Perceived improvement in patient care, in turn, was linked to the order set's comprehensiveness, perceived reductions in medical errors, and less need for clarification with nurses.

Even though this study did not directly query those most responsible for responding to the order set (ie, nurses, pharmacists, and clerks), the order set was created through a collaborative partnership of physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and clerks. It is reasonable to infer that resident‐perceived reduction in the need for clarification of orders with nurses and clerks might indicate a broad‐based, multidisciplinary improvement in clarity and workflow. Moreover, the fact that less need for clarification with nurses was strongly associated with resident‐perceived improvement in patient care underscores the importance of including nurses, pharmacists, and clerks in the development of these order sets.

Our experience using the standard admission orders over the past 2 years is congruent with other authors' findings. Most studies, however, have examined standardized order forms only in adult populations, and mainly for specific medical conditions. Micek et al.9 demonstrated that use of a standardized physician order set among adults with septic shock lowered 28‐day mortality and reduced hospital stay. Among stroke patients, rates of optimal treatment significantly improved after the introduction of standardized stroke orders.10 For patients with acute myocardial infarction, standardized admission orders increased early administration of aspirin and beta blockers.11, 12 With respect to cancer, implementation of a preprinted chemotherapy prescription form improved order completeness, prevented medication errors, and reduced time spent by pharmacists clarifying orders.13 Finally, standardized trauma admission orders developed in a surgical‐trauma intensive care unit reduced admission laboratory charges and improved order completeness.14 We found only a single pediatric study examining standardized order forms. Kozer et al.15 found that the use of a preprinted structured medication order form cut medication errors nearly in half in a pediatric emergency department.

Whether our results would have been similar had we implemented a series of best practices order sets rather than a single convenience order set is unclear. Although best practices order sets would have facilitated application of evidence‐based guidelines for common diagnoses, they would also have introduced potentially unwelcome logistical heterogeneity (with a separate form and protocol needed for each diagnosis) that might have reduced acceptability and uptake. In addition, there is a risk that best practices order sets would have been perceived as unduly limiting physician professional autonomy.

Our study has limitations. First, our study was performed within a single institution and may not be easily generalized. However, we believe that the basic format of the PAOS lends it to easy adaptability. Second, we did not survey residents before the order set was introduced to assess baseline perceptions. Instead, many of the questions in the survey ask about perceived improvements compared with the previous system. Conducting a formal pre‐post data collection and analysis might have yielded different results. Third, improvement in patient care was measured indirectly based on resident opinion.

In conclusion, our study suggests that our standardized admission order set prompting physicians to initiate comprehensive care is well‐liked by residents and is thought to benefit patients by reducing medical errors and expediting high‐quality care. The next step is to confirm that the resident‐perceived improvement in patient care correlates with actual improvement in patient care. If improvements can be confirmed, then PAOS adoption could be broadly recommended to pediatric hospitals. In the future, the PAOS may also help guide computerized physician order entry templates that can be further tailored to specific common diagnoses.

For many years physicians have created and used various standardized order forms for patient hospital admissions. The increasing popularity of electronic medical records and forms has led to the use of computerized physician order entry (CPOE) as a means of reducing medication errors.13 Crowley et al.,4 Stucky,5 and Garg et al.,6 along with various committees, have recommended standardized order sets and CPOE as a strategy for reducing medication errors. However, implementation of CPOE systems is expensive and not available in most hospitals. According to a recent survey of hospitals in the US, CPOE was only available to physicians at 16% of the participating institutions.7 Until CPOE becomes widespread, standardized preprinted formatted order sets may serve as an inexpensive alternative.

There is anecdotal evidence that standardized admission order forms may improve quality of care and efficiency, and decrease provider variation.8 However, few rigorous studies exist in the pediatric research literature regarding their ability to actually improve patient care.

In 2005, our institution, a large tertiary‐care academic teaching hospital, developed a standardized preprinted pediatric admission order set (PAOS). We did so for 3 reasons. First, there was a desire to improve completeness of orders. Handwritten orders often missed important elements such as weight, allergies, vital sign parameters, activity, etc. Second, there was a need to save time and improve efficiency. Third, it was important to reduce medical errors and the number of clarification requests by decreasing the necessity to decipher physician handwriting. Our PAOS was a convenience order set as opposed to a best practices order set. In other words, our PAOS did not contain evidence‐based management guidelines or protocols for specific admission diagnoses and was created solely to improve the quality and efficiency of workflow.

Documenting improvement in patient outcomes or reduction of medical errors is ultimately needed to establish the effectiveness of a standardized order set. Secondary outcomes, howeverparticularly the perceptions of the staff who are asked to use the order setare equally important, because they may identify real‐life barriers to use that, regardless of effectiveness, could limit dissemination and uptake. With respect to perceptions, 2 groups become paramount: those who write the orders, and those who respond to them. The purpose of the current study was to examine perceived effects of the new PAOS on inpatient care among those who, in our institution, write the ordersresident physicians.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The PAOS was created in August 2005 at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Medical Center by a committee comprising pediatric hospitalists, nurses, pharmacists, residents, and clerks. The PAOS consisted mainly of check boxes (Figure 1). The PAOS was uploaded to the hospital website and made available for printing from all computers in the hospital, emergency room, and clinics.

The UCLA Hospital and Medical Center is a nonprofit, 667‐bed tertiary‐care teaching hospital in Los Angeles, California. The pediatric ward has 70 licensed beds with approximately 3,000 admissions per year. The majority of the admissions were done by the pediatric residents. Physicians were free to edit the PAOS to suit a particular patient's needs or to hand‐write orders on a blank order form.

Measures

Fourteen months after the institution of the PAOS, all 97 UCLA pediatric residents (PL‐1, n = 34; PL‐2, n = 33; PL‐3, n = 30) were asked to complete a survey to anonymously evaluate the order set. All residents were US medical school graduates. Resident participation in the research project was voluntary and confidential, and residents were assured that participation would not affect their standing in the pediatric residency program. Each resident completed only 1 survey. Responses were collected October 2006 to June 2007. The residents were asked to rate the PAOS overall and with respect to 9 specific dimensions using a 5‐point Likert scale with 1 indicating strong disagreement and 5 indicating strong agreement (Figure 2).

This study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at the UCLA Medical Center.

Statistical Analysis

We used bivariate ordered logistic regression to estimate the association between overall rating and each of the 9 dimensions. Ordered logistic regression, a standard technique for ordered categorical variables, is essentially a weighted average of logistic regressions performed at each potential cut‐point of the outcome variable. For instance, potential cut‐points on our 5‐point Likert scale included strong disagreement versus any other, any disagreement versus nondisagreement, any agreement versus nonagreement, and strong agreement versus any other. We then used multivariate ordered logistic regression to examine which specific dimensions remained independently associated with the overall rating.

RESULTS

From October 2006 to June 2007, 59 residents (from a total of 97 residents; 61%) responded to the survey. Overall, 89% of respondents approved of the PAOS, 58% reported using it 90% of the time, and all said that they would recommend it to their colleagues (Table 1). Eighty‐four percent thought that the PAOS improved inpatient care, and 75% thought that medical errors were reduced. Eighty‐eight percent reported that the POAS saved time; 93% said it was convenient; and most reported less need for clarification with clerks (81%) and nurses (82%).

| Strongly Agree (%) | Agree (%) | Other (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specific dimensions | |||

| Looks neat | 63 | 32 | 5 |

| User friendly/convenient | 60 | 33 | 7 |

| Readily available | 47 | 26 | 26 |

| Saves time | 56 | 32 | 12 |

| Comprehensive | 40 | 40 | 19 |

| Reduces medical error | 40 | 35 | 25 |

| Fewer clarification phone calls/errors by clerks | 47 | 33 | 19 |

| Fewer clarification phone calls/errors by nurses | 47 | 35 | 18 |

| Improves overall patient care | 46 | 39 | 16 |

| Overall rating | 40 | 49 | 11 |

In bivariate analyses, each of the 9 dimensions was strongly associated with the overall rating (P < 0.001 for each). In multivariate analyses, however, only perceived improvement in patient care was independently associated with overall rating (OR, 3.9; P = 0.04).

We then examined whether perceived improvement in patient care itself was independently predicted by the other 8 dimensions. Residents who said that the form was comprehensive (OR, 5.6; P = 0.01), reduced medical errors (OR, 4.1; P = 0.01), or required less need for clarification with nurses (OR, 9.6; P = 0.01) were more likely to perceive that the form improved patient care than residents who did not.

DISCUSSION

A standardized admission order set is a simple, low‐cost intervention that may benefit patients by reducing medical errors and expediting high‐quality care. In general, residents rated the PAOS favorably. Just as importantly, the PAOS scored well across all specific dimensions, which suggests few perceived barriers to use among residents.

Some dimensions, however, appeared potentially more important than others. Residents who perceived an improvement in patient care tended to rate the PAOS favorably. Perceived improvement in patient care, in turn, was linked to the order set's comprehensiveness, perceived reductions in medical errors, and less need for clarification with nurses.

Even though this study did not directly query those most responsible for responding to the order set (ie, nurses, pharmacists, and clerks), the order set was created through a collaborative partnership of physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and clerks. It is reasonable to infer that resident‐perceived reduction in the need for clarification of orders with nurses and clerks might indicate a broad‐based, multidisciplinary improvement in clarity and workflow. Moreover, the fact that less need for clarification with nurses was strongly associated with resident‐perceived improvement in patient care underscores the importance of including nurses, pharmacists, and clerks in the development of these order sets.

Our experience using the standard admission orders over the past 2 years is congruent with other authors' findings. Most studies, however, have examined standardized order forms only in adult populations, and mainly for specific medical conditions. Micek et al.9 demonstrated that use of a standardized physician order set among adults with septic shock lowered 28‐day mortality and reduced hospital stay. Among stroke patients, rates of optimal treatment significantly improved after the introduction of standardized stroke orders.10 For patients with acute myocardial infarction, standardized admission orders increased early administration of aspirin and beta blockers.11, 12 With respect to cancer, implementation of a preprinted chemotherapy prescription form improved order completeness, prevented medication errors, and reduced time spent by pharmacists clarifying orders.13 Finally, standardized trauma admission orders developed in a surgical‐trauma intensive care unit reduced admission laboratory charges and improved order completeness.14 We found only a single pediatric study examining standardized order forms. Kozer et al.15 found that the use of a preprinted structured medication order form cut medication errors nearly in half in a pediatric emergency department.

Whether our results would have been similar had we implemented a series of best practices order sets rather than a single convenience order set is unclear. Although best practices order sets would have facilitated application of evidence‐based guidelines for common diagnoses, they would also have introduced potentially unwelcome logistical heterogeneity (with a separate form and protocol needed for each diagnosis) that might have reduced acceptability and uptake. In addition, there is a risk that best practices order sets would have been perceived as unduly limiting physician professional autonomy.

Our study has limitations. First, our study was performed within a single institution and may not be easily generalized. However, we believe that the basic format of the PAOS lends it to easy adaptability. Second, we did not survey residents before the order set was introduced to assess baseline perceptions. Instead, many of the questions in the survey ask about perceived improvements compared with the previous system. Conducting a formal pre‐post data collection and analysis might have yielded different results. Third, improvement in patient care was measured indirectly based on resident opinion.

In conclusion, our study suggests that our standardized admission order set prompting physicians to initiate comprehensive care is well‐liked by residents and is thought to benefit patients by reducing medical errors and expediting high‐quality care. The next step is to confirm that the resident‐perceived improvement in patient care correlates with actual improvement in patient care. If improvements can be confirmed, then PAOS adoption could be broadly recommended to pediatric hospitals. In the future, the PAOS may also help guide computerized physician order entry templates that can be further tailored to specific common diagnoses.

- ,,, et al.Effect of computerized physician order entry and a team intervention on prevention of serious medication errors.JAMA.1998;280(15):1311–1316.

- ,,.Effects of computerized physician order entry and clinical decision support systems on medication safety: a systematic review.Arch Intern Med.2003;163(12):1409–1416.

- ,,,,.The effect of computerized physician order entry on medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients.Pediatrics.2003;112(3 Pt 1):506–509.

- ,,.Medication errors in children: a descriptive summary of medication error reports submitted to the United States Pharmacopoeia.Curr Ther Res Clin Exp.2001;62:627–640.

- .Prevention of medication errors in the pediatric inpatient setting.Pediatrics.2003;112(2):431–436.

- ,,, et al.Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review.JAMA.2005;293(10):1223–1238.

- ,,,.Computerized physician order entry in U.S. hospitals: results of a 2002 survey.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2004;11(2):95–99.

- .Using standardized admit orders to improve inpatient care.Fam Pract Manag.1999;6(10):30–32.

- ,,, et al.Before‐after study of a standardized hospital order set for the management of septic shock.Crit Care Med.2006;34(11):2707–2713.

- California Acute Stroke Pilot Registry Investigators.The impact of standardized stroke orders on adherence to best practices.Neurology.2005;65(3):360–365.

- ,,,,,.Improving quality of care for acute myocardial infarction. The guidelines applied in practice (GAP) initiative.JAMA.2002;287(10):1269–1276.

- ,,,,,.Quality improvement initiative and its impact on the management of patients with acute myocardial infarction.Arch Intern Med.2000;160:3057–3061.

- ,,,,,.Effect of a cancer chemotherapy prescription form on prescription completeness.Am J Hosp Pharm.1989;46(9):1802–1806.

- ,.Standardized trauma admission orders, a pilot project.Int J Trauma Nurs.1996;2(1):13–21.

- ,,,,.Using a preprinted order sheet to reduce prescription errors in a pediatric emergency department: a randomized, controlled trial.Pediatrics.2005;116(6):1299–1302.

- ,,, et al.Effect of computerized physician order entry and a team intervention on prevention of serious medication errors.JAMA.1998;280(15):1311–1316.

- ,,.Effects of computerized physician order entry and clinical decision support systems on medication safety: a systematic review.Arch Intern Med.2003;163(12):1409–1416.

- ,,,,.The effect of computerized physician order entry on medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients.Pediatrics.2003;112(3 Pt 1):506–509.

- ,,.Medication errors in children: a descriptive summary of medication error reports submitted to the United States Pharmacopoeia.Curr Ther Res Clin Exp.2001;62:627–640.

- .Prevention of medication errors in the pediatric inpatient setting.Pediatrics.2003;112(2):431–436.

- ,,, et al.Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review.JAMA.2005;293(10):1223–1238.

- ,,,.Computerized physician order entry in U.S. hospitals: results of a 2002 survey.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2004;11(2):95–99.

- .Using standardized admit orders to improve inpatient care.Fam Pract Manag.1999;6(10):30–32.

- ,,, et al.Before‐after study of a standardized hospital order set for the management of septic shock.Crit Care Med.2006;34(11):2707–2713.

- California Acute Stroke Pilot Registry Investigators.The impact of standardized stroke orders on adherence to best practices.Neurology.2005;65(3):360–365.

- ,,,,,.Improving quality of care for acute myocardial infarction. The guidelines applied in practice (GAP) initiative.JAMA.2002;287(10):1269–1276.

- ,,,,,.Quality improvement initiative and its impact on the management of patients with acute myocardial infarction.Arch Intern Med.2000;160:3057–3061.

- ,,,,,.Effect of a cancer chemotherapy prescription form on prescription completeness.Am J Hosp Pharm.1989;46(9):1802–1806.

- ,.Standardized trauma admission orders, a pilot project.Int J Trauma Nurs.1996;2(1):13–21.

- ,,,,.Using a preprinted order sheet to reduce prescription errors in a pediatric emergency department: a randomized, controlled trial.Pediatrics.2005;116(6):1299–1302.

Copyright © 2009 Society of Hospital Medicine

A change of heart

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through presentation of an actual patient's case in an approach typical of morning report. Similar to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant.

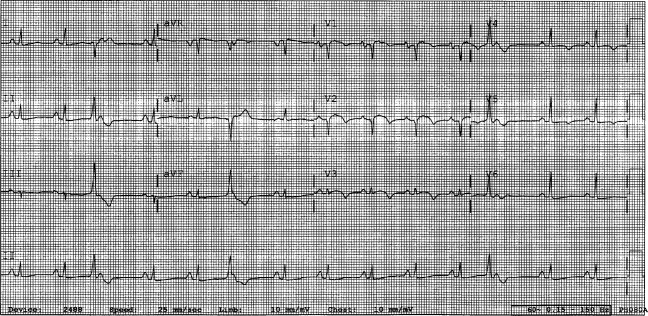

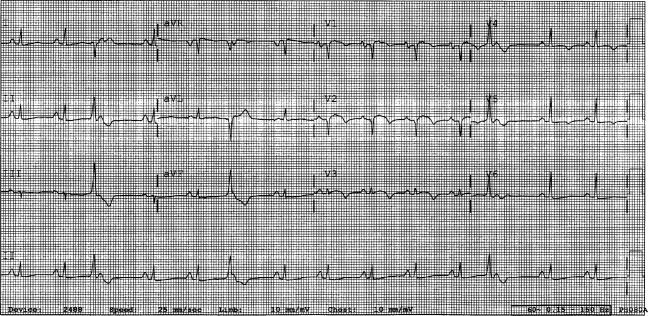

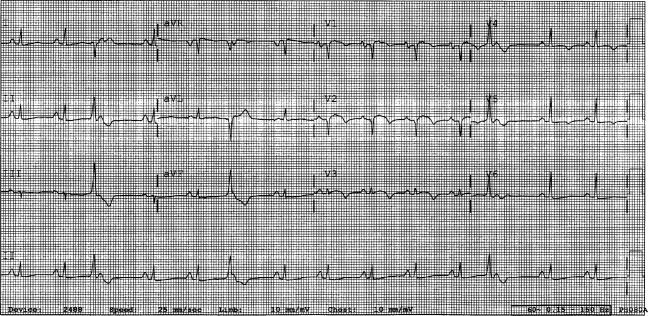

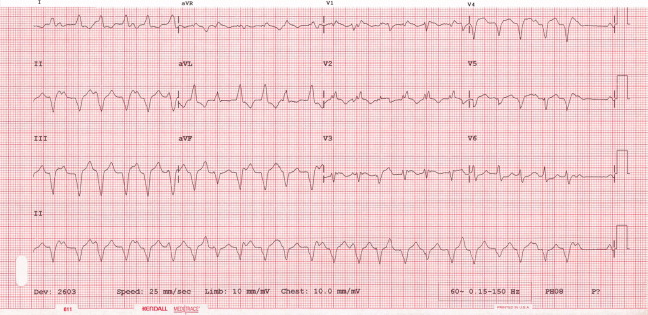

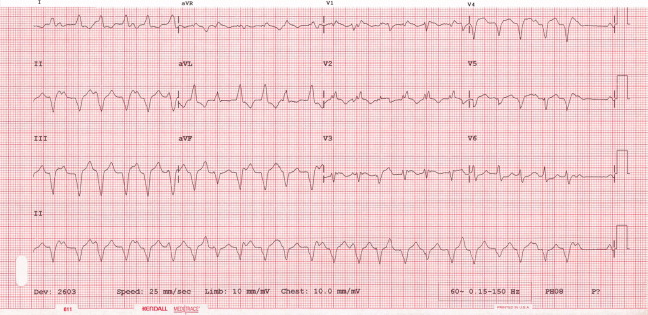

A 29‐year‐old man developed palpitations and dyspnea while loading boxes into a truck. In the emergency department, telemetry demonstrated a wide‐complex tachycardia at a rate of 204 beats per minute. The patient spontaneously cardioverted to sinus rhythm (Figure 1) before direct current cardioversion was performed.

Wide‐complex tachycardia is usually explained by a supraventricular tachycardia with aberrant ventricular conduction or a ventricular tachycardia. Although algorithms exist to guide the clinician in parsing out those etiologies, often the knowledge of underlying structural cardiac disease is most informative. In patients with a history of myocardial infarction, greater than 95% of wide‐complex tachycardia is ventricular tachycardia. The ventricular ectopy, T‐wave inversion or flattening, and poor R‐wave progression are suggestive of a cardiomyopathy, either acute or chronic. A pressing concern, especially with the Q waves and concave ST morphology in V1 and V2, would be coronary ischemia. His age makes this less likely, but an aberrant coronary circulation or drug use could account for it.

Over the past 2 years, the patient had several episodes of sustained palpitations, which terminated after several minutes. Previously, the patient exercised frequently including playing rugby in college. However, over the past year he experienced difficulty climbing stairs due to shortness of breath, which he attributed to deconditioning and smoking. He had no significant medical history, was not taking any medications, nor did he use recreational stimulants. He drank alcohol occasionally. He had no risk factors for the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Both of the patient's parents were alive and well. There was no family history of sudden cardiac death.

The duration of symptoms suggests that this is a chronic cardiomyopathy rather than acute myocarditis or acute ischemia, acknowledging that either one could be superimposed. The absence of family history lowers the likelihood of heritable causes of arrhythmia that may accompany a structurally normal (eg, long QT syndrome) or abnormal (eg, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy) heart, although penetrance can be variable. What might account for a cardiomyopathy in a young person? Most cases are probably idiopathic, but etiologies that diverge from the usual suspects of coronary artery disease, hypertension, and valvular disease, which affect an older population, include antecedent viral myocarditis, substance abuse, HIV, or infiltrative disorders such as sarcoidosis.

The patient's pulse was 92 beats per minute and regular and the blood pressure was 96/52 mm Hg. The jugular venous pressure was elevated with prominent v‐waves, the point of maximal impulse was diffuse, there were no extra heart sounds or murmurs, and an enlarged liver was detected. An echocardiogram demonstrated left ventricular dysfunction with an ejection fraction of 30%, severe enlargement of the right atrium and right ventricle, and moderate tricuspid regurgitation. Cardiac catheterization revealed normal coronary arteries without evidence of pulmonary hypertension or intracardiac shunt.

The physical examination and echocardiographic findings of right‐sided failure are unusual given the absence of pulmonary hypertension or intracardiac shunt, and could prompt repeat of the hemodynamic measurements and/or investigations for pulmonary disease that may account for right‐sided pressure overload (in addition to that caused by left ventricular failure). An alternative explanation would be a cardiomyopathic process that preferentially involves the right side of the heart, such as arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (ARVD), but that would not satisfactorily explain the significant decline in left ventricular function. An acute right ventricular infarction could cause his acute symptoms and his examination and echocardiographic findings, but not the underlying chronic illness. It is common to see patients with long‐standing biventricular failure who present with prominent signs of right‐sided failure (elevated neck veins, hepatomegaly, and edema) but limited or no signs of left‐sided failure (rales) to match their degree of volume overload or dyspnea.

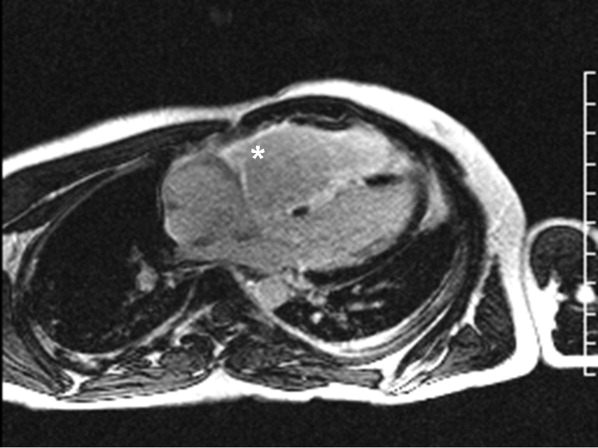

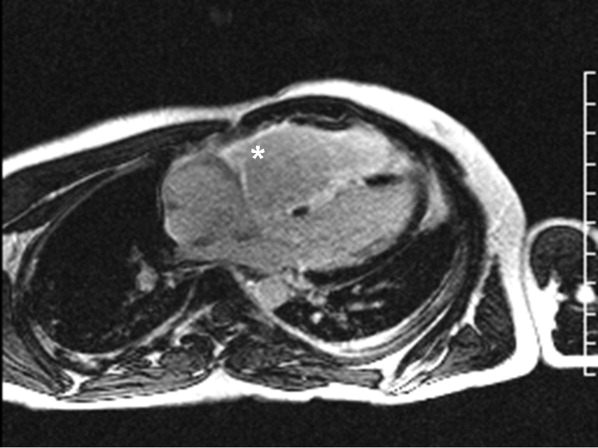

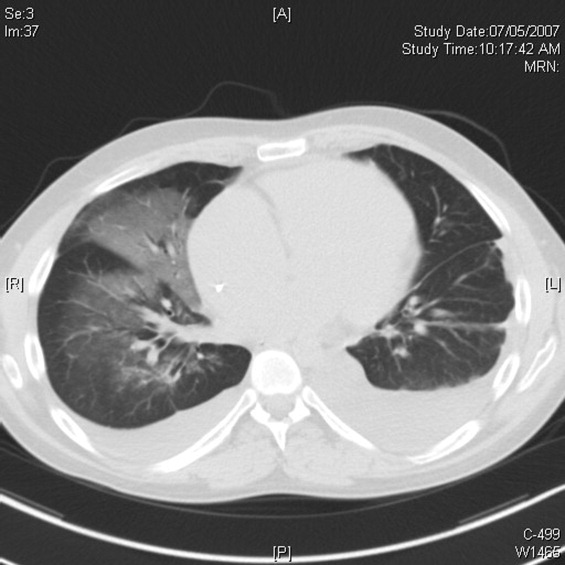

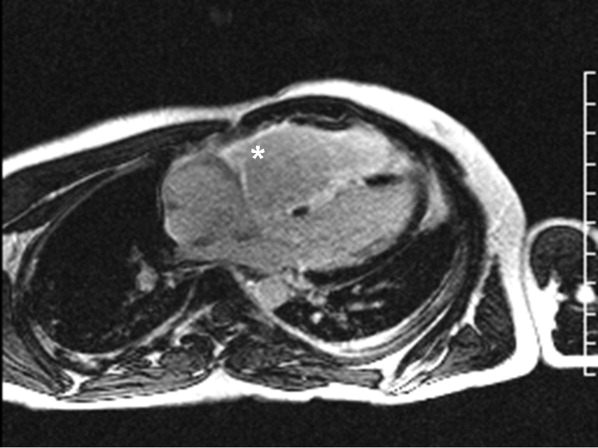

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a dilated right ventricle with extensive hyperenhancement, a right ventricular ejection fraction of 9%, and moderate left ventricular dysfunction (Figure 2). Electrophysiology testing induced both nonsustained polymorphic and monomorphic ventricular tachycardia. Late potentials were detected on a signal‐averaged electrocardiogram. A single‐chamber cardioverter defibrillator was implanted and the patient was discharged on carvedilol, lisinopril, and spironolactone. An HIV‐1 antibody was negative and a thyroid‐stimulating hormone concentration was within normal limits.

Assuming that accurate evaluation of the pulmonary circulation has been undertaken to exclude pulmonary hypertension, the enlarged and hyperenhanced right ventricle on MRI suggests a process that preferentially infiltrates the right ventricular myocardium, and may secondarily affect the left ventricle either by further infiltration or as a consequence of altered mechanics from the highly dysfunctional right ventricle. ARVD affects the right ventricle, but it is possible that another infiltrative cardiomyopathy, such as sarcoid or an antecedent viral infection, could be restricted in its distribution. Late‐potentials identified on signal average electrocardiograms indicate areas of abnormal conduction that may serve as substrate for reentrant ventricular arrhythmias. They are, however, nonspecific, as they are seen in a variety of myocardial diseases.

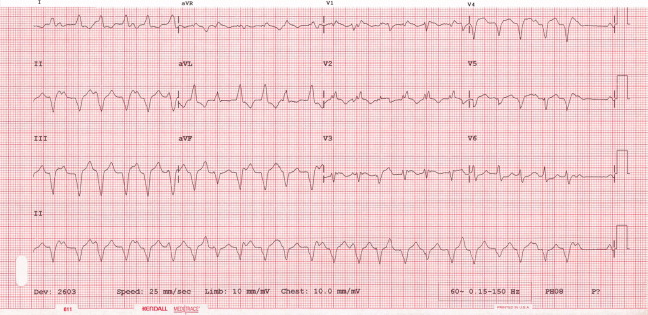

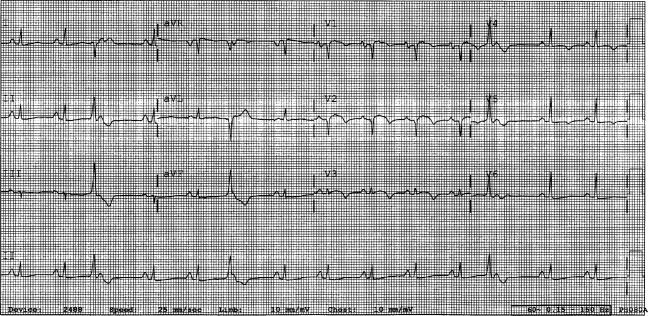

The patient continued to have progressive dyspnea and was readmitted after receiving an appropriate implantable cardioverter defibrillator shock for ventricular tachycardia. Recurrent slow ventricular tachycardia (Figure 3) was treated with supplemental beta‐blockade and amiodarone (10 g total). Repeat echocardiography demonstrated severe left ventricular dysfunction with an ejection fraction of less than 15%. There were no recurrences of ventricular arrhythmias and the patient was discharged and referred for cardiac transplant evaluation for ARVD.

This degree of left ventricular dysfunction is unlikely to be accounted for by altered mechanics and interactions from a failing right ventricle alone and frames this as a biventricular cardiomyopathy, which has an extensive differential diagnosis and requires information from the general medical evaluation.

On routine laboratory testing 6 months later, a serum aspartate aminotransferase of 79 units/L and a serum alanine aminotransferase of 118 units/L were found. Bilirubin, albumin, and alkaline phosphatase were normal. The transaminase levels had been normal on initial evaluation. The patient reported that 2 paternal uncles had end‐stage nonalcoholic cirrhosis. Transjugular liver biopsy was consistent with mild lobular hepatitis with mild portal fibrosis with a few lobular collections of mononuclear cells. There was no evidence of iron overload. The hepatic venogram and transhepatic pressure gradient (2 mm Hg) were normal.

The elevated transaminase levels could be due to amiodarone‐associated hepatotoxicity, hepatic congestion, or a primary liver disease. It is important to consider combined cardiohepatic syndromes such as hemochromatosis, sarcoidosis, or amyloidosis. The relatively normal liver histology and normal hepatic hemodynamics do not suggest a significant primary intrinsic liver disease. The 2 uncles with cirrhosis could suggest a heritable liver disease, although cirrhosis in multiple family members is frequently accounted for by shared habits such as alcohol consumption or excessive caloric intake. Liver disorders with a genetic component, such as hemochromatosis, Wilson's disease, and alpha‐1‐antitrypsin deficiency are mostly autosomal recessive, which would make this pattern of transmission unusual. Furthermore, aside from hemochromatosis, these genetic hepatic disorders have few cardiac manifestations. Right‐sided congestion and amiodarone appear to be the most likely explanations of his liver abnormalities.

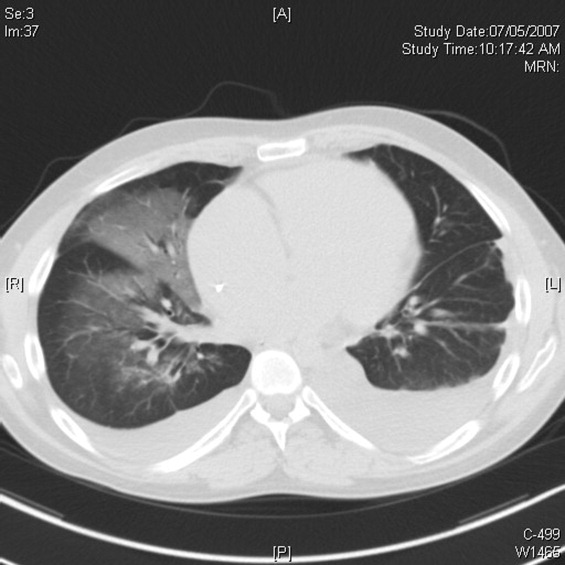

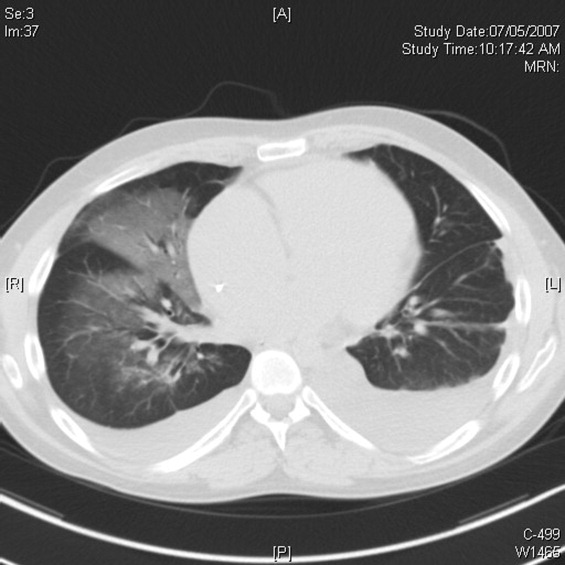

Pulmonary function testing revealed normal lung volumes without obstruction, but the diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide was substantially reduced. Computed tomography of the chest identified scattered ground‐glass opacities as well as small nodules with an upper lobe distribution (Figure 4). Although not reported on the initial interpretation, review of a chest x‐ray taken 6 months previously also demonstrated small nodules in the upper lobe distribution. Bronchoscopic examination was normal. Bronchioalveolar lavage fluid stains and cultures for bacteria, mycobacteria, Pneumocystis, and fungus were negative. Transbronchial biopsies of the right middle lobe had no evidence of infection, malignancy, or granulomatous inflammation. The patient continued to have progressive New York Heart Association Class IV heart failure symptoms. Repeat right heart catheterization was notable for a cardiac index of 1.4 L/minute/m2. The mean pulmonary artery pressure was 20 mm Hg. An intraaortic balloon pump was placed for refractory cardiogenic shock.

The reduced diffusion capacity and ground‐glass opacities suggest an interstitial process, which may have been missed on transbronchial biopsy because of sampling error. His pulmonary disease is likely another manifestation of his infiltrative cardiac disease. The constellation of cardiac, pulmonary, and hepatic involvement in the context of progressive dyspnea over 2 years is suggestive of sarcoidosis although the absence of hilar lymphadenopathy and 2 biopsy specimens without granulomas argue against the diagnosis, and the effects of amiodarone on the latter 2 organs cannot be ignored. On the limited menu of pharmacologic treatments that may treat this severe and progressive cardiomyopathy are steroids, which makes a diligent search for a steroid‐responsive syndrome important. Therefore, despite the negative studies, sarcoidosis must be investigated to the fullest extent with either an endomyocardial biopsy or surgical lung biopsy.

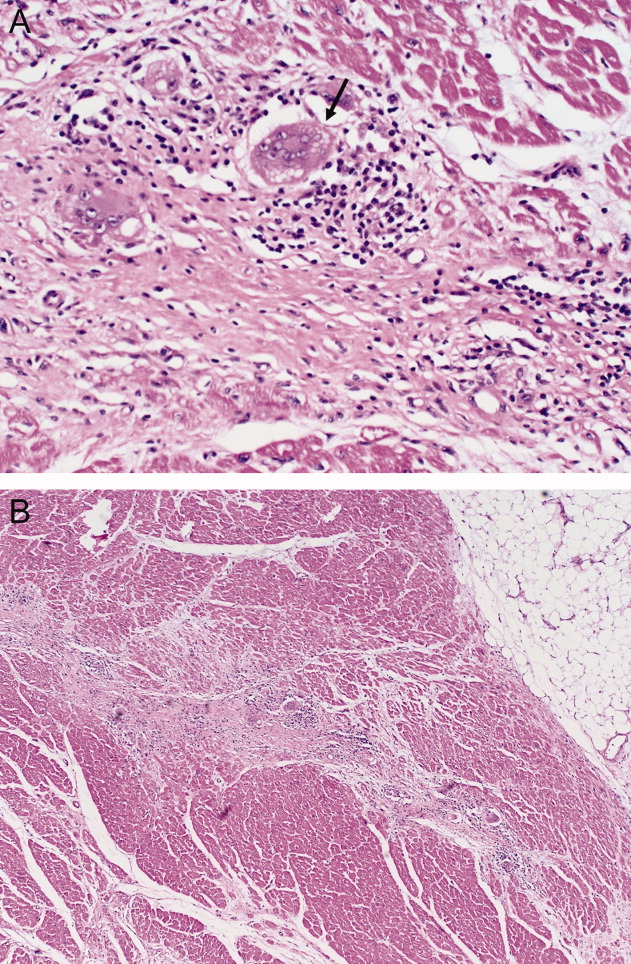

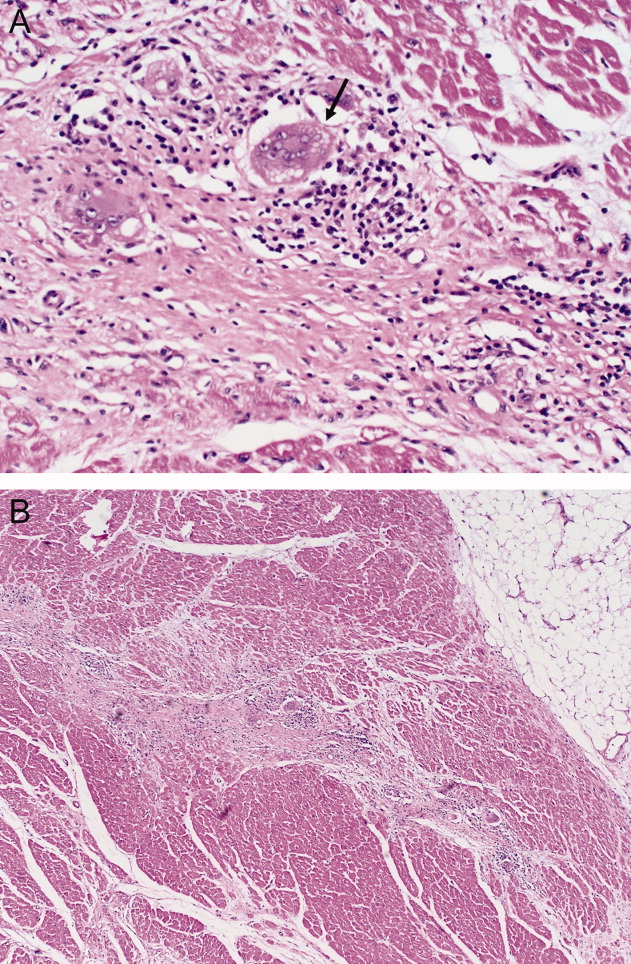

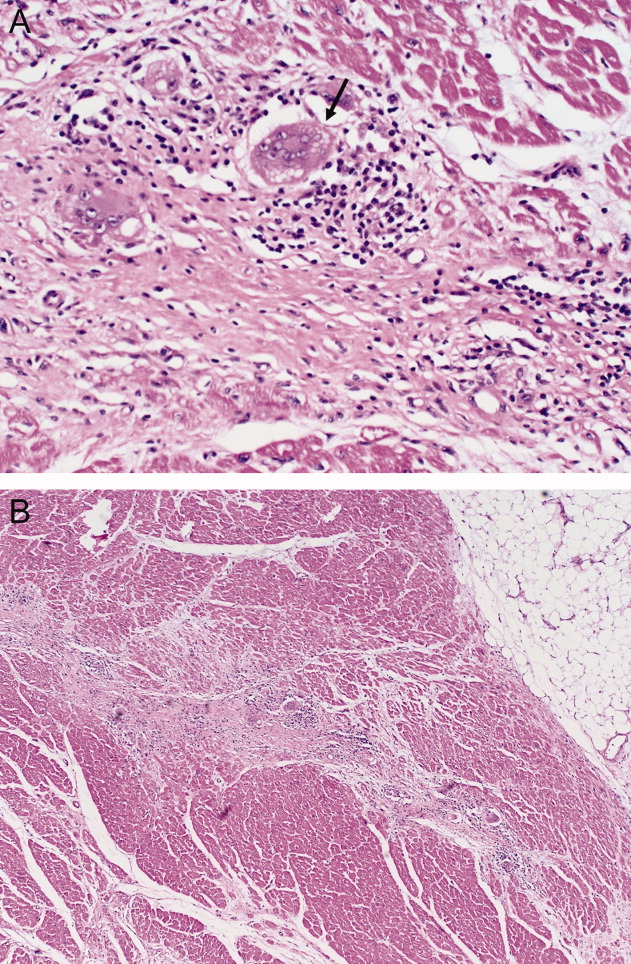

The patient underwent cardiac transplantation. The native heart was found to have right ventricular thinning, which was most notable at the right ventricular outflow tract. Microscopic examination revealed extensive fibrosis and granulomatous inflammation (Figure 5) with scarring typical of cardiac sarcoidosis. Six months after cardiac transplantation, the patient is doing well on prednisone, tacrolimus, and mycophenolate mofetil. Follow‐up chest x‐rays show resolution of the pulmonary nodules.

COMMENTARY

Cardiomyopathy in a young person is a relatively uncommon clinical event that prompts consideration of a broad differential diagnosis that is notably different from the most common etiologies of cardiomyopathy in older adults. This case highlights the challenges of arriving at a diagnosis in the absence of a gold standard, and the greater challenges of modifying initial diagnostic impressions as new clinical data become available.

After encountering ventricular tachycardia and right ventricular dysfunction in a young patient, the clinicians arrived at the diagnosis of ARVD. This rare and progressive disorder is associated with up to 20% of ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death in the young,1, 2 but can be challenging to diagnose. Despite common referrals for cardiac MRI to exclude ARVD, cardiac MRI is not the gold standard for diagnosis and is the most common method of misdiagnosis of ARVD.3 A diagnosis of ARVD requires the presence of 2 major, 1 major and 2 minor, or 4 minor International Task Force criteria (Table 1).4, 5 While the diagnostic criteria provide standardization across populations (eg, in clinical studies), additional considerations are needed in the management of individual patients. Scoring systems serve as a tool, but the final diagnosis requires balancing such criteria with competing hypotheses. This dilemma is familiar to clinicians considering other less common conditions such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (World Neurology Foundation), rheumatic fever (Jones criteria), or systemic lupus erythematosus (American College of Rheumatology). This patient's cardiac MRI findings, precordial T‐wave inversions, frequent ventricular ectopy, and late potentials on a signal‐averaged electrocardiogram fulfilled the International Task Force criteria for a diagnosis of ARVD. Discordant information included the right bundle branch pattern of the ventricular tachycardia, which suggested left ventricular origin, as opposed to the more common left bundle branch pattern observed in ARVD, and the absence of a family history. In addition, in U.S. populations only 25% of cases present with heart failure and fewer than 5% develop biventricular failure.6 Nonetheless, this patient's imaging evidence of right ventricular structural abnormalities and dysfunction and electrocardiographic abnormalities coupled with the absence of obvious systemic disease made ARVD the logical working diagnosis.

| Major | Minor | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| I. Global and/or regional dysfunction and structural alterations | Severe dilation and reduction of right ventricular ejection fraction, localized right ventricular aneurysms | Mild right ventricular dilatation and/or reduced ejection fraction |

| II. Endomyocardial biopsy | Fibrofatty replacement of myocardium | |

| III. Repolarization abnormalities | T‐wave inversion in leads V1‐V3 or beyond | |

| IV. Depolarization/conduction abnormalities | Epsilon waves or localized QRS prolongation (>110 msec) in leads V1‐V3 | Late potentials on signal‐averaged electrocardiogram |

| V. Arrhythmias | Left bundle branch block‐type ventricular tachycardia (sustained and nonsustained) or frequent ventricular extra systoles (>1,000/24 hours) | |

| VI. Family history | Familial disease confirmed at necropsy or surgery | Familial history of premature sudden death (35 years old) or clinical diagnosis based on present criteria |

When more widespread manifestations developed, namely hepatic and pulmonary abnormalities, each was investigated with imaging and biopsy. Once a multisystem illness became apparent, the discussant reframed the patient's illness to include other diagnostic possibilities. In practice it is difficult to reverse a working diagnosis despite contradictory evidence because of the common pitfall of anchoring bias. Tversky and Kahneman7 were the first to describe the cognitive processes behind probability assessment and decision making in time‐sensitive situations. Under these conditions, decision makers tend to focus on the first symptom, striking feature, or diagnosis and anchor subsequent probabilities to that initial presentation. Once a decision or diagnosis has been reached, clinicians tend to interpret subsequent findings in the context of the original diagnosis rather than reevaluating their initial impression. In the setting of a known diagnosis of ARVD, 3 separate diagnoses (ARVD, amiodarone‐associated lung injury, and amiodarone‐induced hepatic dysfunction) were considered by the treating physicians. The initial diagnosis of ARVD followed by the sequential rather than simultaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis made arriving at the revised diagnosis even more challenging.

Cardiac sarcoidosis is a mimic of ARVD and should be considered when evaluating a patient for right ventricular dysplasia.8, 9 The differential diagnosis of ARVD includes idiopathic ventricular tachycardia, myocarditis, idiopathic cardiomyopathy, and sarcoidosis. Cardiac sarcoidosis can present as ventricular ectopy, sustained ventricular arrhythmias, asymptomatic ventricular dysfunction, heart failure, or sudden death.10 Although 25% of patients with sarcoidosis have evidence of cardiac involvement at autopsy, only 5% have clinical manifestations.11 Those patients with clinical evidence of cardiac sarcoidosis have a wide range of clinical findings (Table 2). While the patient's cardiomyopathy was advanced, it is possible that earlier administration of corticosteroid therapy may have arrested his progressive biventricular failure. As clinicians, we should always remember to force ourselves to broaden our differential diagnosis when new findings become available, especially those that point to a systemicrather than an organ‐specificdisorder. In this case, while the original diagnostic findings were accurate and strongly suggested ARVD, a change of heart was needed to arrive at the ultimate diagnosis.

| Clinical Manifestation | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|

| Atrioventricular block | 40 |

| Bundle branch block | 40 |

| Supraventricular tachycardia | 20 |

| Ventricular arrhythmias | 25 |

| Heart failure | 25 |

| Sudden cardiac death | 35 |

KEY POINTS FOR HOSPITALISTS

-

Cardiomyopathy in a young person requires consideration of a broad differential diagnosis that is notably different from the most common etiologies of cardiomyopathy in the elderly.

-

Anchoring bias is a common pitfall in clinical decision making. When new or contradictory findings are uncovered, clinicians should reevaluate their initial impression to ensure it remains the most likely diagnosis.

-

Cardiac sarcoidosis is a mimic of ARVD and should be considered when evaluating a patient for right ventricular cardiomyopathy. The differential diagnosis of ARVD includes idiopathic ventricular tachycardia, right ventricular outflow tract tachycardia, myocarditis, idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy, and sarcoidosis.

- ,,, et al.Right ventricular dysplasia: a report of 24 adult cases.Circulation.1982;65:384–398.

- ,,,,.Right ventricular cardiomyopathy and sudden death in young people.N Engl J Med.1988;318:129–133.

- ,,, et al.Misdiagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy.J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol.2004;15:300–306.

- ,,, et al.Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Task Force of the Working Group Myocardial and Pericardial Disease of the European Society of Cardiology and the Scientific Council on Cardiomyopathies of the International Society and Federation of Cardiology.Br Heart J.1994;71:215–218.

- ,,, et al.Predictors of appropriate implantable defibrillator therapies in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia.Heart Rhythm.2005;2:1188–1194.

- ,,, et al.Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia: a United States experience.Circulation.2005;112:3823–3832.

- ,.Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases.Science.1974;185:1124–1131.

- ,,.Unusual presentation of cardiac sarcoidosis.Congest Heart Fail.2007;13:116–118.

- ,,, et al.Cardiac sarcoidosis mimicking right ventricular dysplasia.Circ J.2003;67:169–171.

- ,,,,.Refractory ventricular tachycardia secondary to cardiac sarcoid: electrophysiologic characteristics, mapping, and ablation.Heart Rhythm.2006;3:924–929.

- ,.Sarcoid heart disease: clinical course and treatment.Int J Cardiol.2004;97:173–182.

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through presentation of an actual patient's case in an approach typical of morning report. Similar to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant.

A 29‐year‐old man developed palpitations and dyspnea while loading boxes into a truck. In the emergency department, telemetry demonstrated a wide‐complex tachycardia at a rate of 204 beats per minute. The patient spontaneously cardioverted to sinus rhythm (Figure 1) before direct current cardioversion was performed.

Wide‐complex tachycardia is usually explained by a supraventricular tachycardia with aberrant ventricular conduction or a ventricular tachycardia. Although algorithms exist to guide the clinician in parsing out those etiologies, often the knowledge of underlying structural cardiac disease is most informative. In patients with a history of myocardial infarction, greater than 95% of wide‐complex tachycardia is ventricular tachycardia. The ventricular ectopy, T‐wave inversion or flattening, and poor R‐wave progression are suggestive of a cardiomyopathy, either acute or chronic. A pressing concern, especially with the Q waves and concave ST morphology in V1 and V2, would be coronary ischemia. His age makes this less likely, but an aberrant coronary circulation or drug use could account for it.

Over the past 2 years, the patient had several episodes of sustained palpitations, which terminated after several minutes. Previously, the patient exercised frequently including playing rugby in college. However, over the past year he experienced difficulty climbing stairs due to shortness of breath, which he attributed to deconditioning and smoking. He had no significant medical history, was not taking any medications, nor did he use recreational stimulants. He drank alcohol occasionally. He had no risk factors for the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Both of the patient's parents were alive and well. There was no family history of sudden cardiac death.

The duration of symptoms suggests that this is a chronic cardiomyopathy rather than acute myocarditis or acute ischemia, acknowledging that either one could be superimposed. The absence of family history lowers the likelihood of heritable causes of arrhythmia that may accompany a structurally normal (eg, long QT syndrome) or abnormal (eg, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy) heart, although penetrance can be variable. What might account for a cardiomyopathy in a young person? Most cases are probably idiopathic, but etiologies that diverge from the usual suspects of coronary artery disease, hypertension, and valvular disease, which affect an older population, include antecedent viral myocarditis, substance abuse, HIV, or infiltrative disorders such as sarcoidosis.

The patient's pulse was 92 beats per minute and regular and the blood pressure was 96/52 mm Hg. The jugular venous pressure was elevated with prominent v‐waves, the point of maximal impulse was diffuse, there were no extra heart sounds or murmurs, and an enlarged liver was detected. An echocardiogram demonstrated left ventricular dysfunction with an ejection fraction of 30%, severe enlargement of the right atrium and right ventricle, and moderate tricuspid regurgitation. Cardiac catheterization revealed normal coronary arteries without evidence of pulmonary hypertension or intracardiac shunt.

The physical examination and echocardiographic findings of right‐sided failure are unusual given the absence of pulmonary hypertension or intracardiac shunt, and could prompt repeat of the hemodynamic measurements and/or investigations for pulmonary disease that may account for right‐sided pressure overload (in addition to that caused by left ventricular failure). An alternative explanation would be a cardiomyopathic process that preferentially involves the right side of the heart, such as arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (ARVD), but that would not satisfactorily explain the significant decline in left ventricular function. An acute right ventricular infarction could cause his acute symptoms and his examination and echocardiographic findings, but not the underlying chronic illness. It is common to see patients with long‐standing biventricular failure who present with prominent signs of right‐sided failure (elevated neck veins, hepatomegaly, and edema) but limited or no signs of left‐sided failure (rales) to match their degree of volume overload or dyspnea.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a dilated right ventricle with extensive hyperenhancement, a right ventricular ejection fraction of 9%, and moderate left ventricular dysfunction (Figure 2). Electrophysiology testing induced both nonsustained polymorphic and monomorphic ventricular tachycardia. Late potentials were detected on a signal‐averaged electrocardiogram. A single‐chamber cardioverter defibrillator was implanted and the patient was discharged on carvedilol, lisinopril, and spironolactone. An HIV‐1 antibody was negative and a thyroid‐stimulating hormone concentration was within normal limits.

Assuming that accurate evaluation of the pulmonary circulation has been undertaken to exclude pulmonary hypertension, the enlarged and hyperenhanced right ventricle on MRI suggests a process that preferentially infiltrates the right ventricular myocardium, and may secondarily affect the left ventricle either by further infiltration or as a consequence of altered mechanics from the highly dysfunctional right ventricle. ARVD affects the right ventricle, but it is possible that another infiltrative cardiomyopathy, such as sarcoid or an antecedent viral infection, could be restricted in its distribution. Late‐potentials identified on signal average electrocardiograms indicate areas of abnormal conduction that may serve as substrate for reentrant ventricular arrhythmias. They are, however, nonspecific, as they are seen in a variety of myocardial diseases.

The patient continued to have progressive dyspnea and was readmitted after receiving an appropriate implantable cardioverter defibrillator shock for ventricular tachycardia. Recurrent slow ventricular tachycardia (Figure 3) was treated with supplemental beta‐blockade and amiodarone (10 g total). Repeat echocardiography demonstrated severe left ventricular dysfunction with an ejection fraction of less than 15%. There were no recurrences of ventricular arrhythmias and the patient was discharged and referred for cardiac transplant evaluation for ARVD.

This degree of left ventricular dysfunction is unlikely to be accounted for by altered mechanics and interactions from a failing right ventricle alone and frames this as a biventricular cardiomyopathy, which has an extensive differential diagnosis and requires information from the general medical evaluation.

On routine laboratory testing 6 months later, a serum aspartate aminotransferase of 79 units/L and a serum alanine aminotransferase of 118 units/L were found. Bilirubin, albumin, and alkaline phosphatase were normal. The transaminase levels had been normal on initial evaluation. The patient reported that 2 paternal uncles had end‐stage nonalcoholic cirrhosis. Transjugular liver biopsy was consistent with mild lobular hepatitis with mild portal fibrosis with a few lobular collections of mononuclear cells. There was no evidence of iron overload. The hepatic venogram and transhepatic pressure gradient (2 mm Hg) were normal.

The elevated transaminase levels could be due to amiodarone‐associated hepatotoxicity, hepatic congestion, or a primary liver disease. It is important to consider combined cardiohepatic syndromes such as hemochromatosis, sarcoidosis, or amyloidosis. The relatively normal liver histology and normal hepatic hemodynamics do not suggest a significant primary intrinsic liver disease. The 2 uncles with cirrhosis could suggest a heritable liver disease, although cirrhosis in multiple family members is frequently accounted for by shared habits such as alcohol consumption or excessive caloric intake. Liver disorders with a genetic component, such as hemochromatosis, Wilson's disease, and alpha‐1‐antitrypsin deficiency are mostly autosomal recessive, which would make this pattern of transmission unusual. Furthermore, aside from hemochromatosis, these genetic hepatic disorders have few cardiac manifestations. Right‐sided congestion and amiodarone appear to be the most likely explanations of his liver abnormalities.

Pulmonary function testing revealed normal lung volumes without obstruction, but the diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide was substantially reduced. Computed tomography of the chest identified scattered ground‐glass opacities as well as small nodules with an upper lobe distribution (Figure 4). Although not reported on the initial interpretation, review of a chest x‐ray taken 6 months previously also demonstrated small nodules in the upper lobe distribution. Bronchoscopic examination was normal. Bronchioalveolar lavage fluid stains and cultures for bacteria, mycobacteria, Pneumocystis, and fungus were negative. Transbronchial biopsies of the right middle lobe had no evidence of infection, malignancy, or granulomatous inflammation. The patient continued to have progressive New York Heart Association Class IV heart failure symptoms. Repeat right heart catheterization was notable for a cardiac index of 1.4 L/minute/m2. The mean pulmonary artery pressure was 20 mm Hg. An intraaortic balloon pump was placed for refractory cardiogenic shock.

The reduced diffusion capacity and ground‐glass opacities suggest an interstitial process, which may have been missed on transbronchial biopsy because of sampling error. His pulmonary disease is likely another manifestation of his infiltrative cardiac disease. The constellation of cardiac, pulmonary, and hepatic involvement in the context of progressive dyspnea over 2 years is suggestive of sarcoidosis although the absence of hilar lymphadenopathy and 2 biopsy specimens without granulomas argue against the diagnosis, and the effects of amiodarone on the latter 2 organs cannot be ignored. On the limited menu of pharmacologic treatments that may treat this severe and progressive cardiomyopathy are steroids, which makes a diligent search for a steroid‐responsive syndrome important. Therefore, despite the negative studies, sarcoidosis must be investigated to the fullest extent with either an endomyocardial biopsy or surgical lung biopsy.

The patient underwent cardiac transplantation. The native heart was found to have right ventricular thinning, which was most notable at the right ventricular outflow tract. Microscopic examination revealed extensive fibrosis and granulomatous inflammation (Figure 5) with scarring typical of cardiac sarcoidosis. Six months after cardiac transplantation, the patient is doing well on prednisone, tacrolimus, and mycophenolate mofetil. Follow‐up chest x‐rays show resolution of the pulmonary nodules.

COMMENTARY

Cardiomyopathy in a young person is a relatively uncommon clinical event that prompts consideration of a broad differential diagnosis that is notably different from the most common etiologies of cardiomyopathy in older adults. This case highlights the challenges of arriving at a diagnosis in the absence of a gold standard, and the greater challenges of modifying initial diagnostic impressions as new clinical data become available.

After encountering ventricular tachycardia and right ventricular dysfunction in a young patient, the clinicians arrived at the diagnosis of ARVD. This rare and progressive disorder is associated with up to 20% of ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death in the young,1, 2 but can be challenging to diagnose. Despite common referrals for cardiac MRI to exclude ARVD, cardiac MRI is not the gold standard for diagnosis and is the most common method of misdiagnosis of ARVD.3 A diagnosis of ARVD requires the presence of 2 major, 1 major and 2 minor, or 4 minor International Task Force criteria (Table 1).4, 5 While the diagnostic criteria provide standardization across populations (eg, in clinical studies), additional considerations are needed in the management of individual patients. Scoring systems serve as a tool, but the final diagnosis requires balancing such criteria with competing hypotheses. This dilemma is familiar to clinicians considering other less common conditions such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (World Neurology Foundation), rheumatic fever (Jones criteria), or systemic lupus erythematosus (American College of Rheumatology). This patient's cardiac MRI findings, precordial T‐wave inversions, frequent ventricular ectopy, and late potentials on a signal‐averaged electrocardiogram fulfilled the International Task Force criteria for a diagnosis of ARVD. Discordant information included the right bundle branch pattern of the ventricular tachycardia, which suggested left ventricular origin, as opposed to the more common left bundle branch pattern observed in ARVD, and the absence of a family history. In addition, in U.S. populations only 25% of cases present with heart failure and fewer than 5% develop biventricular failure.6 Nonetheless, this patient's imaging evidence of right ventricular structural abnormalities and dysfunction and electrocardiographic abnormalities coupled with the absence of obvious systemic disease made ARVD the logical working diagnosis.

| Major | Minor | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| I. Global and/or regional dysfunction and structural alterations | Severe dilation and reduction of right ventricular ejection fraction, localized right ventricular aneurysms | Mild right ventricular dilatation and/or reduced ejection fraction |

| II. Endomyocardial biopsy | Fibrofatty replacement of myocardium | |

| III. Repolarization abnormalities | T‐wave inversion in leads V1‐V3 or beyond | |

| IV. Depolarization/conduction abnormalities | Epsilon waves or localized QRS prolongation (>110 msec) in leads V1‐V3 | Late potentials on signal‐averaged electrocardiogram |

| V. Arrhythmias | Left bundle branch block‐type ventricular tachycardia (sustained and nonsustained) or frequent ventricular extra systoles (>1,000/24 hours) | |

| VI. Family history | Familial disease confirmed at necropsy or surgery | Familial history of premature sudden death (35 years old) or clinical diagnosis based on present criteria |

When more widespread manifestations developed, namely hepatic and pulmonary abnormalities, each was investigated with imaging and biopsy. Once a multisystem illness became apparent, the discussant reframed the patient's illness to include other diagnostic possibilities. In practice it is difficult to reverse a working diagnosis despite contradictory evidence because of the common pitfall of anchoring bias. Tversky and Kahneman7 were the first to describe the cognitive processes behind probability assessment and decision making in time‐sensitive situations. Under these conditions, decision makers tend to focus on the first symptom, striking feature, or diagnosis and anchor subsequent probabilities to that initial presentation. Once a decision or diagnosis has been reached, clinicians tend to interpret subsequent findings in the context of the original diagnosis rather than reevaluating their initial impression. In the setting of a known diagnosis of ARVD, 3 separate diagnoses (ARVD, amiodarone‐associated lung injury, and amiodarone‐induced hepatic dysfunction) were considered by the treating physicians. The initial diagnosis of ARVD followed by the sequential rather than simultaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis made arriving at the revised diagnosis even more challenging.

Cardiac sarcoidosis is a mimic of ARVD and should be considered when evaluating a patient for right ventricular dysplasia.8, 9 The differential diagnosis of ARVD includes idiopathic ventricular tachycardia, myocarditis, idiopathic cardiomyopathy, and sarcoidosis. Cardiac sarcoidosis can present as ventricular ectopy, sustained ventricular arrhythmias, asymptomatic ventricular dysfunction, heart failure, or sudden death.10 Although 25% of patients with sarcoidosis have evidence of cardiac involvement at autopsy, only 5% have clinical manifestations.11 Those patients with clinical evidence of cardiac sarcoidosis have a wide range of clinical findings (Table 2). While the patient's cardiomyopathy was advanced, it is possible that earlier administration of corticosteroid therapy may have arrested his progressive biventricular failure. As clinicians, we should always remember to force ourselves to broaden our differential diagnosis when new findings become available, especially those that point to a systemicrather than an organ‐specificdisorder. In this case, while the original diagnostic findings were accurate and strongly suggested ARVD, a change of heart was needed to arrive at the ultimate diagnosis.

| Clinical Manifestation | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|

| Atrioventricular block | 40 |

| Bundle branch block | 40 |

| Supraventricular tachycardia | 20 |

| Ventricular arrhythmias | 25 |

| Heart failure | 25 |

| Sudden cardiac death | 35 |

KEY POINTS FOR HOSPITALISTS

-

Cardiomyopathy in a young person requires consideration of a broad differential diagnosis that is notably different from the most common etiologies of cardiomyopathy in the elderly.

-

Anchoring bias is a common pitfall in clinical decision making. When new or contradictory findings are uncovered, clinicians should reevaluate their initial impression to ensure it remains the most likely diagnosis.

-

Cardiac sarcoidosis is a mimic of ARVD and should be considered when evaluating a patient for right ventricular cardiomyopathy. The differential diagnosis of ARVD includes idiopathic ventricular tachycardia, right ventricular outflow tract tachycardia, myocarditis, idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy, and sarcoidosis.

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through presentation of an actual patient's case in an approach typical of morning report. Similar to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant.