User login

Improved Prophylaxis Following Education

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), which encompasses both deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is a major cause of the morbidity and mortality of hospitalized medical patients.1 Hospitalization for an acute medical illness has been associated with an 8‐fold increase in the relative risk of VTE and is responsible for approximately a quarter of all VTE cases in the general population.2, 3

Current evidence‐based guidelines, including those from the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP), recommend prophylaxis with low‐dose unfractionated heparin (UFH) or low‐molecular‐weight heparin (LMWH) for medical patients with risk factors for VTE.4, 5 Mechanical prophylaxis methods including graduated compression stockings and intermittent pneumatic compression are recommended for those patients for whom anticoagulant therapy is contraindicated because of a high risk of bleeding.4, 5 However, several studies have shown that adherence to these guidelines is suboptimal, with many at‐risk patients receiving inadequate prophylaxis (range 32%‐87%).610

Physician‐related factors identified as potential barriers to guideline adherence include not being aware or familiar with the guidelines, not agreeing with the guidelines, or believing the guideline recommendations to be ineffective.11 More specific studies have shown that some physicians may lack basic knowledge regarding the current treatment standards for VTE and may underestimate the significance of VTE.1213 As distinct strategies, education aimed at disseminating VTE prophylaxis guidelines, as well as regular audit‐and‐feedback of physician performance, has been shown to improve rates of VTE prophylaxis in clinical practice.6, 1417 Implementation of educational programs significantly increased the level of appropriate VTE prophylaxis from 59% to 70% of patients in an Australian hospital15 and from 73% to 97% of patients in a Scottish hospital.14 Another strategy, the use of point‐of‐care electronically provided reminders with decision support, has been successful not only in increasing the rates of VTE prophylaxis, but also in decreasing the incidence of clinical VTE events.16 Although highly effective, electronic alerts with computerized decision support do not exist in many hospitals, and other methods of intervention are needed.

In this study, we evaluated adherence to the 2001 ACCP guidelines for VTE prophylaxis among medical patients in our teaching hospital. (The guidelines were updated in 2004, after our study was completed.) After determining that our baseline rates of appropriate VTE prophylaxis were suboptimal, we developed, implemented, and evaluated a multifaceted strategy to improve the rates of appropriate thromboprophylaxis among our medical inpatients.

Six categories of quality improvement strategies have been described: provider education, decision support, audit‐and‐feedback, patient education, organization change, and regulation and policy.18 The intervention we developed was a composite of 3 of these: provider education, decision support, and audit‐and‐feedback.

METHODS

Study Design and Patients

This was a before‐and‐after study designed to assess whether implementation of a VTE prophylaxis quality improvement intervention could improve the rate of appropriate thromboprophylaxis in hospitalized medical patients at the State University of New York, Downstate Medical CenterUniversity Hospital of Brooklyn, an urban university teaching hospital of approximately 400 beds. This initiative, conducted as part of a departmental quality assurance and performance improvement program, did not require institutional review board approval. After an informal survey revealed a prophylaxis rate of approximately 50%, a more formal baseline assessment of the rate of medical patients receiving VTE prophylaxis was conducted during October 2002. This assessment was a single sampling of all medical inpatients on 2 of the medical floors on a single day. The results were consistent with those of the informal survey as well as those from an international registry.19 The results from the baseline study indicated that VTE prophylaxis was underused: only 46.9% of our medical inpatients received any form of prophylaxis. The prophylaxis rate was assessed again in 2 sampling periods beginning 12 and 18 months after implementation of the intervention. Data were collected monthly and combined into 3‐month blocks. The first postintervention sample (n = 116 patient charts) was drawn from a period 12‐14 months after implementation and the second (n = 147 patient charts) from a period 18‐20 months after implementation.

On a randomly designated day in the latter half of each month during each sampling period, all charts on 2 primary medical floors were reviewed and included in the retrospective analysis. Patients who were not on the medical service were excluded from analysis. Patients, as well as their medications, were identified using a list generated from our pharmacy database. We chose this method and schedule for several reasons. First, we sought to reduce the likelihood of including a patient more than once in a monthly sample. Second, by waiting for the latter half of the month we sought to allow house staff a chance to acquire knowledge from the educational program introduced on the first day of the month. Third, we wanted to allow house staff the time to actualize new attitudes reinforced by the audit‐and‐feedback element. The house staff included approximately 4 interns and 4 residents each month plus 10‐15 attendings or hospitalists.

Data Collection

For each sampling period we conducted a medical record (paper) review, and the Division Chief of General Internal Medicine also interviewed the medical house staff and attending physicians. Data collected included risk factors for VTE, contraindications to anticoagulant prophylaxis, type of VTE prophylaxis received, and appropriateness of the prophylaxis. Prophylaxis was considered appropriate when it was given in accordance with a risk stratification scheme (Table 1) adapted from the 2001 ACCP guideline recommendations for surgical patients20 and modified for medical inpatients, similar to the risk assessment model by Caprini et al.21 Prophylaxis was also considered appropriate when no prophylaxis was given for low‐risk patients or when full anticoagulation was given for another indication (Table 1). Questionable prophylaxis was defined as UFH given every 12 hours to a high‐risk patient. All other prophylaxis was deemed inappropriate (including no prophylaxis if prophylaxis was indicated, use of enoxaparin at incorrect prophylactic doses such as 60 or 20 mg, IPC alone for a high‐risk patient with no contraindication to pharmacological prophylaxis, and the use of warfarin if no other indication for it). The risk factors for thromboembolism and contraindications to anticoagulant prophylaxis are given in Table 2. Non‐ambulatory was defined as an order for bed rest with or without bathroom privileges or was judged based on information obtained from the medical house staff and nurses about whether the patient was ambulatory or had been observed walking outside his or her room. Data on pharmacological prophylaxis were obtained from the hospital pharmacy. Information on use of mechanical prophylaxis was obtained by house staff interviews or review of the order sheet. The house officer or attending physician of each patient was interviewed retrospectively to determine the reason for admission and the risk factors for VTE present on admission. Patients were classified as having low, moderate, high, or highest risk for VTE based on their age and any major risk factors for VTE (Table 1).19 All collected data were reported to the Department of Medicine Performance Improvement Committee for independent corroboration.

| Risk category | Definition | Dosage of appropriate prophylaxis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Additional risk factorsb | Low‐dose unfractionated heparin | LMWH | |

| ||||

| Low (0‐1 risk factors) | <40 | 0‐1 factor | None | None |

| Moderate (2 risk factors) | 40‐60 | 1 factor | 5000 units q12h | 40 mg of enoxaparin or 5000 units of dalteparin |

| High (3‐4 risk factors) | >60 | 1‐2 factors or hypercoagulable state | 5000 units q8h or q12h (q8h recommended for surgical patients) | 40 mg of enoxaparin or 5000 units of dalteparin |

| Highest (5 or more factors) | >40 | Malignancy, prior VTE, or CVA | 5000 units q8h plus IPC | enoxaparin or dalteparin plus IPC |

| Risk factors for thromboembolism |

|---|

| Contraindications to anticoagulant prophylaxis |

| Age > 40 years |

| Infection |

| Inflammatory disease |

| Congestive heart failure |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| Prior venous thromboembolism |

| Cancer |

| Cerebrovascular accident |

| End‐stage renal disease |

| Hypercoagulable state |

| Atrial fibrillation |

| Recent surgery |

| Obesity |

| Non‐ambulatory |

| Active gastrointestinal bleed |

| Central nervous system bleed |

| Thrombocytopenia (platelet count <100,000/L) |

Intervention Strategies

The intervention introduced comprised 3 strategies designed to improve VTE prophylaxis: provider education, decision support, and audit‐and‐feedback.

Provider Education

On the first day of every month, an orientation was given to all incoming medicine house staff by the chief resident that included information on the scope, risk factors, and asymptomatic nature of VTE, the importance of risk stratification, the need to provide adequate prophylaxis, and recommended prophylaxis regimens. A nurse educator also provided information to the nursing staff with the expectation that they would remind physicians to prescribe prophylactic treatment if not ordered initially; however, according to the nurses and house staff, this rarely occurred. Large posters showing VTE risk factors and prophylaxis were displayed at 2 nursing stations and physician charting rooms but were not visible to patients.

Decision Support

Pocket cards containing information on VTE risk factors and prophylaxis options were handed out to the house staff at the beginning of each month. These portable decision support tools assisted physicians in the selection of prophylaxis (a more recent, revised version of the material contained in this pocket guide is available at

Audit‐and‐Feedback

Monthly audits were performed by the Division Chief of General Internal Medicine in order to evaluate the type and appropriateness of VTE prophylaxis prescribed (Table 3). During the orientation at the beginning of the month, the chief resident mentioned that an audit would take place sometime during the rotation. This random audit took place during the last 2 weeks of each month on the same day the data were requested from the pharmacy. Over 1‐2 days, physicians were interviewed either one to one or in a group, depending on the availability of house staff. All house staff and hospitalists were queried about the reasons for admission and the presence of VTE risk factors; physicians received feedback from the Division Chief on VTE risk category, prophylaxis, and appropriateness of prophylaxis treatment of their patients.

| Element | Time/effort required |

|---|---|

| |

| Orientation about VTE risk factors and the need to provide adequate prophylaxis given to all incoming house staff by the chief resident on the first day of every month | 10 min/month |

| Introduction of pocket cards containing information on VTE risk factors and prophylaxis options | 5 min/month |

| In‐hospital education of nurses by the nurse educator | 2 sessions of 1 h |

| Large posters presenting VTE risk factors and prophylaxis displayed in nursing stations and physician charting rooms | 5 min one time only |

| Monthly audits by the Division Chief of General Internal Medicine to evaluate the type and suitability of VTE prophylaxis prescribed | 2 h/month for interviews 2 h/month for record review/ data entry |

Statistical Analysis

Differences in pre‐ and post‐intervention VTE prophylaxis and appropriate VTE prophylaxis rates were analyzed using the chi‐square test for categorical variables and the one‐way analysis of variance test for continuous variables. Differences were considered significant at the 5% level (P = .05).

RESULTS

Patients and Demographics

From October 2002 to August 2004 data were collected from 312 hospitalized medical patients: 49 patients in the baseline group during October 2002, and 116 and 147 at the 12‐ to 14‐month and 18‐ to 20‐month time points, respectively. Thus, approximately 40‐50 patients were randomly selected each month, representing 40% of the general medical service census. Patient demographics were similar between groups (Table 4). Overall, most patients were female (65.7%), and mean age was 61.2 years. The most common admission diagnoses were infection/sepsis (29.5%), chest pain/acute coronary syndromes/myocardial infarction (15.7%), heart failure (10.9%), and malignancy (9.6%). Overall, 7.1% (22 patients) had a contraindication to anticoagulant prophylaxis. The most common contraindication was active gastrointestinal bleeding on the current admission, which occurred in 18 of these patients.

| Baseline (n = 49) | 12 months (n = 116) | 18 months (n = 147) | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Patient demographic | ||||

| Mean age, years (SE) | 59.3 (2.6) | 63.3 (1.6) | 60.1 (1.5) | .25b |

| Men, n (%) | 20 (40.8) | 31 (26.7) | 56 (38.1) | .08 |

| Contraindications to pharmacological prophylaxis, n (%) | 7 (14.3) | 5 (4.3) | 10 (6.8) | .07 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 5 (10.2) | 5 (4.3) | 8 (5.4) | |

| CNS bleeding | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Low platelet count | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.4) | |

| Risk factor | ||||

| Mean number of risk factors (SE) | 3.1 (0.2) | 2.7 (0.1) | 3.0 (0.1) | .05b |

| Non‐ambulatoryc | 46 (93.9) | 73 (89.0) | 112 (80.0)d | .03 |

| Age > 40 years | 39 (79.6) | 101 (87.1) | 122 (83.0) | .44 |

| Cancer | 14 (28.6) | 15 (12.9) | 24 (16.3) | .05 |

| End‐stage renal disease | 13 (26.5) | 29 (25.0) | 36 (24.5) | .96 |

| Congestive heart failure | 11 (22.4) | 23 (19.8) | 28 (19.0) | .87 |

| Infection | 8 (16.3) | 24 (20.7) | 46 (31.3) | .04 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 8 (16.3) | 12 (10.3) | 15 (10.2) | .47 |

| COPD | 5 (10.2) | 9 (7.8) | 14 (9.5) | .84 |

| Sepsis | 3 (6.1) | 6 (5.2) | 21 (14.3) | .03 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 3 (6.1) | 8 (6.9) | 15 (10.2) | .52 |

| Surgery | 1 (2.0) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (1.4) | .82 |

| Previous venous thromboembolism | 0 (0.0) | 6 (5.2) | 8 (5.4) | .25 |

| Obesity (morbid) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.7) | 2 (1.4) | .66 |

| Hypercoagulable state | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

Risk Factors for VTE

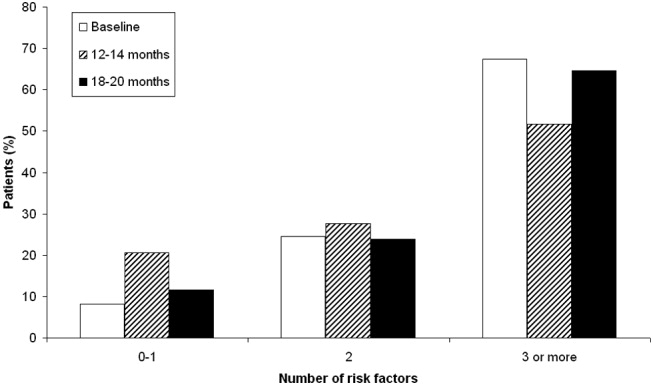

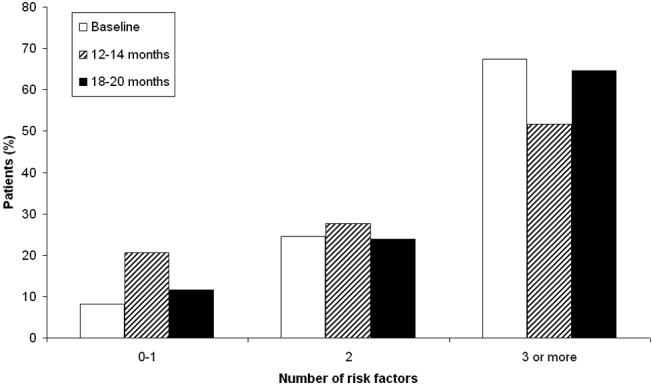

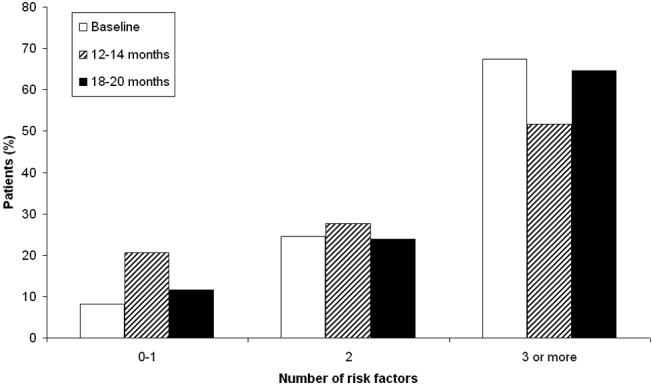

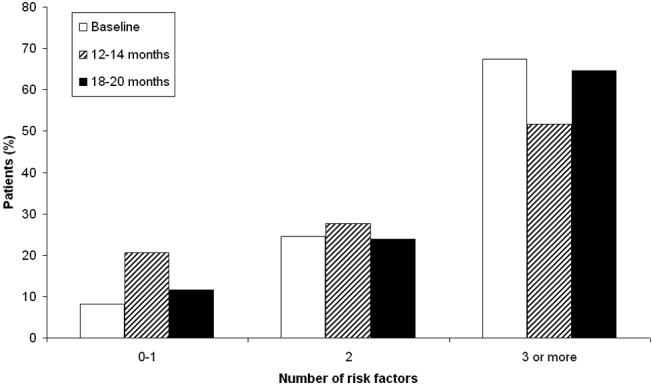

Patient risk factors for VTE in each data collection period are summarized in Table 4. Analysis of this data showed that the most prevalent risk factors for VTE in the 3 patient populations were age older than 40 years (262/312, 84.0% of the total patient population) and nonambulatory state (231/271, 85.2% of the total population). Overall, the average number of risk factors for VTE was approximately 3, with more than 60% of patients having 3 or more VTE risk factors (Fig. 1).

Prophylaxis Use

The types of VTE prophylaxis used and the proportion of patients treated appropriately are summarized for each data collection period in Tables 5 and 6, respectively. In all 3 populations, most patients received pharmacological rather than mechanical prophylaxis, most commonly UFH. At baseline, the prophylaxis decision was appropriate (in accordance with the recommendations of the ACCP guidelines) as often as it was inappropriate (42.9% of patients). The prophylaxis decision was questionable in the remaining 14.3% of patients.

| Prophylaxis type | Baseline (n = 49), n (%) | 12 months (n = 116), n (%) | P valuea | 18 months (n = 147), n (%) | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Any pharmacological | 22 (44.9) | 94 (81.0) | <.01 | 118 (80.3) | <.01 |

| Any UFH | 17 (34.7) | 61 (52.6) | .04 | 58 (39.5) | .55 |

| IV UFHb | 3 (6.1) | 5 (4.3) | 2 (1.4) | ||

| bid UFHc | 13 (26.5) | 43 (37.1) | 39 (26.5) | ||

| tid UFHc | 1 (2.0) | 10 (8.6) | 16 (10.9) | ||

| qd UFHc | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.6) | 1 (0.7) | ||

| Any LMWH | 6 (12.2) | 30 (25.9) | .05 | 59 (40.1) | <.01 |

| Mechanical prophylaxis | 1 (2.0) | 7 (6.0) | .28 | 10 (6.8) | .21 |

| Warfarin | 6 (12.2) | 20 (17.2) | .42 | 19 (12.9) | .90 |

| Baseline (n = 49), n (%) | 12 months (n = 116), n (%) | P valuea | 18 months (n = 147), n (%) | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Receiving prophylaxis | 23 (46.9) | 100 (86.2) | <.01 | 127 (86.4) | <.01 |

| Appropriate | 21 (42.9) | 79 (68.1) | <.01 | 125 (85.0) | <.01 |

| UFH | 10 (20.4) | 33 (28.4) | .28 | 45 (30.6) | .16 |

| LMWH | 5 (10.2) | 27 (23.3) | .05 | 58 (39.5) | <.01 |

| Questionable | 7 (14.3) | 28 (24.1) | .14 | 14 (9.5) | .35 |

| Inappropriate | 21 (42.9) | 9 (7.8) | <.01 | 8 (5.4) | <.01 |

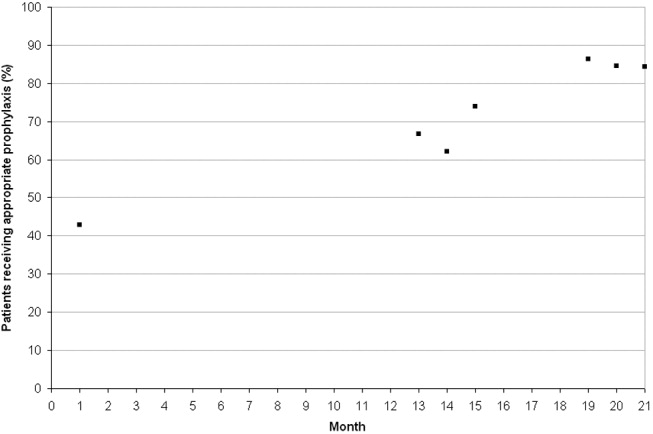

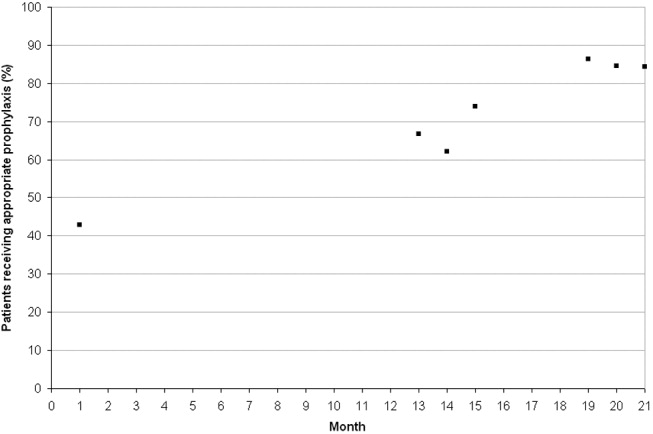

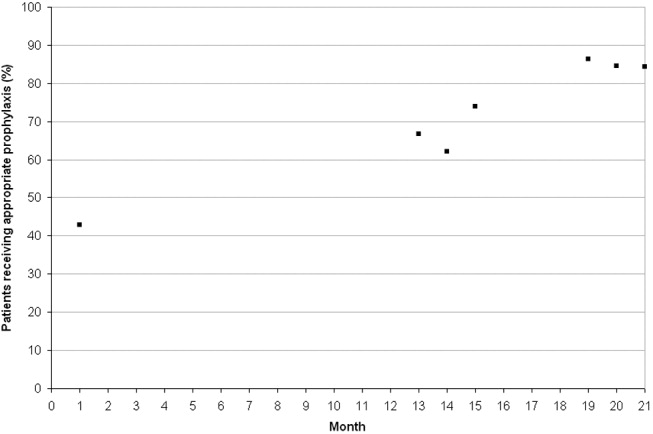

Change in Prophylaxis Use

Twelve and 18 months after implementation of the quality improvement program, we observed an increase in the use of any prophylaxis, from 46.9% at baseline to 86.2% and 86.4%, respectively (Table 5; P < .01 in both groups versus baseline). This increase was a result almost entirely of an increase in the proportion of patients receiving pharmacological prophylaxis, which significantly increased, from 44.9% to 81.0% and 80.3%, at the 12‐ and 18‐month time points, respectively (Table 5; P < .01 for both groups versus baseline). Most meaningfully, there was a significant increase in the proportion of patients for whom an appropriate prophylaxis decision was made (from 42.9% to 68.1% and 85.0%, at the 12‐ and 18‐month time points, respectively; Table 6; P < .01 for both groups versus baseline). This represented a trend toward continuing increases in the use of appropriate prophylaxis as the study progressed (Fig. 2). This change was driven mainly by a significant increase in the prescribing of LMWH, almost all of which was prescribed in accordance with the 2001 ACCP guidelines (Table 6).

DISCUSSION

In this study we evaluated the effect of an intervention that combined physician education with a decision support tool and a mechanism for audit‐and‐feedback. We have shown that implementation of such a multifaceted intervention is practical in a teaching hospital and can improve the rates of VTE prophylaxis use in medical patients. In nearly doubling the rate of appropriate prophylaxis, the effect size of our intervention was large, statistically significant, and sustained 18 months after implementation.

More than 60% of our patients had 3 or more risk factors, and more than 80% had at least 2 risk factors. The rate we observed for patients with 3 or more risk factors was 3 times higher than that reported previously.22 Despite the prevalence of high‐risk patients in our study, we observed that the preintervention rate of VTE prophylaxis among medical patients was relatively low at 47%, and only 43% of patients received prophylaxis in accordance with the ACCP guidelines. Our study findings are consistent with those of several other studies that have shown low rates of VTE prophylaxis in medical patients.6, 8, 2324 In a study of 15 hospitals in Massachusetts, only 13%‐19% of medical patients with indications and risk factors for VTE prophylaxis received any prophylaxis prior to an educational intervention.6 Similarly, a study of 368 consecutive medical patients at a Swiss hospital showed that only 22% of those at‐risk received VTE prophylaxis in accordance with the Thromboembolic Risk Factors (THRIFT) I Consensus Group recommendations.8 Results from 2 prospective patient registries also indicated low rates of VTE prophylaxis in medical patients.19, 24 In the IMPROVE registry of acutely ill medical patients, only 39% of patients hospitalized for 3 or more days received VTE prophylaxis19 and in the DVT‐FREE registry only 42% of medical patients with the inpatient diagnosis of DVT had received prophylaxis within 30 days of that diagnosis.24 In a recent retrospective study of 217 medical patients at the University of Utah hospital, just 43% of patients at high risk for VTE received any sort of prophylaxis.23

Physician education was the main intervention in several previous studies aimed at raising rates of VTE prophylaxis. Our study joins those that have also shown significant improvements after implementation of VTE prophylaxis educational initiatives.6, 14, 15, 23 In the study by Anderson et al., a significantly greater increase in the proportion of high‐risk patients receiving effective VTE prophylaxis was seen between 1986 and 1989 in hospitals that participated in a formal continuing medical education program compared with those that did not (increase: 28% versus 11%; P < .001).6 In 3 additional studies, educational interventions were shown to increase the rate of appropriate prophylaxis in at‐risk patients from 59% to 70%, from 55% to 96%, and from 43% to 72%.14, 15, 23

Other studies have cast doubt on the ability of time‐limited educational interventions to achieve a large or sustained effect.27, 28 A recent systematic review of strategies to improve the use of prophylaxis in hospitals concluded that a number of active strategies are likely to achieve optimal outcomes by combining a system for reminding clinicians to assess patients for VTE with assisting the selection of prophylaxis and providing audit‐and‐feedback.29 The large, sustained effect reported in our study might have been a result of the multifaceted and ongoing nature of the intervention, with reintroduction of the material to all incoming house staff each month. An audit from the last quarter of 2005nearly 2 years after the start of our interventionshowed that prophylaxis rates were approaching 100% (data not included in this study).

Another strategy, the use of computerized reminders to physicians, has been shown to increase the rate of VTE prophylaxis in surgical and medical/surgical patients.16, 26 Kucher et al. compared the incidence of DVT or PE in 1255 hospitalized patients whose physicians received an electronic alert of patient risk of DVT with 1251 hospitalized patients whose physicians did not receive such an alert. They found that the computer alert was associated with a significant reduction in the incidence of DVT or PE at 90 days, with a hazard ratio of 0.59 (95% confidence interval: 0.43, 0.81).16 Our study offers one practical alternative for those institutions that, like ours, do not currently have computerized order entry.

We were unable to determine if there was a specific element of the multifaceted VTE prophylaxis intervention program that contributed the most to the improvement in prophylaxis rates. Provider education was ongoing rather than just a single educational campaign. It was further supported by the pocket cards that provided support for decision making on VTE risk factors, risk categories (based on number and type of risk factor), recommended prophylaxis choices, and potential contraindications. In addition, our method of audit‐and‐feedback constructively leveraged the Hawthorne effect: aware that individual behavior was being measured, our physicians likely adjusted their practice accordingly. Taken together, it is likely that the several elements of our intervention were more powerful in combination than they would have been alone.

Although the multifaceted intervention worked well within our urban university teaching hospital, its application and outcome might be different for other types of hospitals. In our audit‐and‐feedback, for instance, review of resident physician performance was conducted by the Division Chief of General Internal Medicine, tapping into a very strong authority gradient. Hierarchical structures are likely to be different in other types of hospitals. It would therefore be valuable to examine whether the audit‐and‐feedback methodology presented in this article can be replicated in other hospital settings.

A potential limitation of this study was the use of retrospective review to determine baseline rates of VTE prophylaxis. This approach relies on medical notes being accurate and complete; such notes may not have been available for each patient. However, random reviews of both patient charts and hospital billing data for comorbidities performed after coding as a quality control step allowed for confirmation of the data or the extraction and addition of missing data. In addition, data collection was limited to a single day in the latter half of the month. It is not clear whether this sampling strategy collects data that are reflective of performance for the entire month. Our study was also limited by the absence of a control group. Without a control group, we cannot exclude the possibility that during the study factors other than the educational intervention might have contributed to the improvement in prophylaxis rates.

In this study we did not address whether an increase in VTE prophylaxis use translates to an improvement in patient outcomes, namely, a reduction in the rate of VTE. Mosen et al. showed that increasing the VTE prophylaxis rate by implementing a computerized reminder system did not decrease the rate of VTE.26 However, the baseline rate of VTE prophylaxis was already very good, and the study was only powered to detect a large difference in VTE rates. Conversely, Kucher et al. recently demonstrated a significant reduction in VTE events 90 days after initiation of a computerized alert program.16 Further studies designed to confirm the inverse relationship between rate of VTE prophylaxis and rate of clinical outcome of VTE would be helpful.

In conclusion, in a setting in which most hospitalized medically ill patients have multiple risk factors for VTE, we have shown that a practical multifaceted intervention can result in a marked increase in the proportion of medical patients receiving VTE prophylaxis, as well as in the proportion of patients receiving prophylaxis commensurate with evidence‐based guidelines.

Acknowledgements

We thank Nicholas Galeota, Director of Pharmacy at SUNY Downstate for his assistance in providing monthly patient medication lists, Helen Wiggett for providing writing support, and Dan Bridges for editorial support for this manuscript.

- .Pulmonary embolism.Lancet.2004;363:1295–1305.

- ,,,,,.Risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population‐based case‐control study.Arch Intern Med.2000;160:809–815.

- ,,, et al.Relative impact of risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population‐based study.Arch Intern Med.2002;162:1245–1248.

- ,,, et al.Prevention of venous thromboembolism: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy.Chest.2004;126:338S–400S.

- ,,, et al.,Cardiovascular Disease Educational and Research Trust, International Union of Angiology.Prevention of venous thromboembolism. International Consensus Statement. Guidelines compiled in accordance with the scientific evidence.Int Angiol.2001;20:1–37.

- ,,, et al.Changing clinical practice. Prospective study of the impact of continuing medical education and quality assurance programs on use of prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism.Arch Intern Med.1994;154:669–677.

- ,,.Missed opportunities for prevention of venous thromboembolism: an evaluation of the use of thromboprophylaxis guidelines.Chest.2001;120:1964–1971.

- ,,,.Pharmacological thromboembolic prophylaxis in a medical ward: room for improvement.J Gen Intern Med.2002;17:788–791.

- ,.Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in a South Australian teaching hospital.Ann Pharmacother.2003;37:1398–1402.

- ,,,.Use of venous thromboprophylaxis and adherence to guideline recommendations: a cross‐sectional study.Thromb J.2004;2:3–9.

- ,,, et al.Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement.JAMA.1999;282:1458–1465.

- ,.Audit of surgeon awareness of readmissions with venous thrombo‐embolism.Intern Med J.2003;33:578–580.

- ,,,A survey of physicians' knowledge and management of venous thromboembolism.Vasc Endovascular Surg.2002;36:367–375.

- ,,,.Getting a validated guideline into local practice: implementation and audit of the SIGN guideline on the prevention of deep vein thrombosis in a district general hospital.Scott Med J.1998;43:23–25.

- ,,,,.Educational campaign to improve the prevention of postoperative venous thromboembolism.J Clin Pharm Ther.1999;24:279–287.

- ,,, et al.Electronic alerts to prevent venous thromboembolism among hospitalized patients.N Engl J Med.2005;352:969–977.

- ,,.Implementation of a national guideline on prophylaxisof venous thromboembolism: a survey of acute services in Scotland.Thromboembolism Prevention Evaluation Study Group.Health Bull (Edinb).1999;57:141–147.

- ,.Evidence‐based quality improvement: the state of the science.Health Aff (Millwood).2005;24(1):138–150.

- ,,,,,.A multinational observational cohort study in acutely ill medical patients of practices in prevention of venous thromboembolism: findings of the international medical prevention registry on venous thromboembolism (IMPROVE).Blood.2003;102:321a.

- ,,, et al.Prevention of venous thromboembolism.Chest.2001;119:132S–175S.

- ,,.Effective risk stratification of surgical and nonsurgical patients for venous thromboembolic disease.Semin Hematol.2001;38(2 Suppl 5):12–19.

- ,,,,.The prevalence of risk factors for venous thromboembolism among hospital patients.Arch Intern Med.1992;152:1660–1664.

- ,,,,.Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in medically ill patients and the development of strategies to improve prophylaxis rates.Am J Hematol.2005;78:167–172.

- ,.Failure to prophylax for deep vein thrombosis: results from the DVT FREE registry.Blood.2003;102:322a.

- ,,.Improving uptake of prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism in general surgical patients using prospective audit.BMJ.1996;313:917.

- ,,, et al.The effect of a computerized reminder system on the prevention of postoperative venous thromboembolism.Chest.2004;125:1635–1641.

- ,,,,,.Comparative trial of a short workshop designed to enhance appropriate use of screening tests by family physicians.CMAJ.2002;167:1241–1246.

- ,,,.No magic bullets: a systematic review of 102 trials of interventions to improve professional practice.CMAJ.1995;153:1423–1431.

- ,,, et al.A systematic review of strategies to improve prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism in hospitals.Ann Surg.2005;241:397–415.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), which encompasses both deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is a major cause of the morbidity and mortality of hospitalized medical patients.1 Hospitalization for an acute medical illness has been associated with an 8‐fold increase in the relative risk of VTE and is responsible for approximately a quarter of all VTE cases in the general population.2, 3

Current evidence‐based guidelines, including those from the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP), recommend prophylaxis with low‐dose unfractionated heparin (UFH) or low‐molecular‐weight heparin (LMWH) for medical patients with risk factors for VTE.4, 5 Mechanical prophylaxis methods including graduated compression stockings and intermittent pneumatic compression are recommended for those patients for whom anticoagulant therapy is contraindicated because of a high risk of bleeding.4, 5 However, several studies have shown that adherence to these guidelines is suboptimal, with many at‐risk patients receiving inadequate prophylaxis (range 32%‐87%).610

Physician‐related factors identified as potential barriers to guideline adherence include not being aware or familiar with the guidelines, not agreeing with the guidelines, or believing the guideline recommendations to be ineffective.11 More specific studies have shown that some physicians may lack basic knowledge regarding the current treatment standards for VTE and may underestimate the significance of VTE.1213 As distinct strategies, education aimed at disseminating VTE prophylaxis guidelines, as well as regular audit‐and‐feedback of physician performance, has been shown to improve rates of VTE prophylaxis in clinical practice.6, 1417 Implementation of educational programs significantly increased the level of appropriate VTE prophylaxis from 59% to 70% of patients in an Australian hospital15 and from 73% to 97% of patients in a Scottish hospital.14 Another strategy, the use of point‐of‐care electronically provided reminders with decision support, has been successful not only in increasing the rates of VTE prophylaxis, but also in decreasing the incidence of clinical VTE events.16 Although highly effective, electronic alerts with computerized decision support do not exist in many hospitals, and other methods of intervention are needed.

In this study, we evaluated adherence to the 2001 ACCP guidelines for VTE prophylaxis among medical patients in our teaching hospital. (The guidelines were updated in 2004, after our study was completed.) After determining that our baseline rates of appropriate VTE prophylaxis were suboptimal, we developed, implemented, and evaluated a multifaceted strategy to improve the rates of appropriate thromboprophylaxis among our medical inpatients.

Six categories of quality improvement strategies have been described: provider education, decision support, audit‐and‐feedback, patient education, organization change, and regulation and policy.18 The intervention we developed was a composite of 3 of these: provider education, decision support, and audit‐and‐feedback.

METHODS

Study Design and Patients

This was a before‐and‐after study designed to assess whether implementation of a VTE prophylaxis quality improvement intervention could improve the rate of appropriate thromboprophylaxis in hospitalized medical patients at the State University of New York, Downstate Medical CenterUniversity Hospital of Brooklyn, an urban university teaching hospital of approximately 400 beds. This initiative, conducted as part of a departmental quality assurance and performance improvement program, did not require institutional review board approval. After an informal survey revealed a prophylaxis rate of approximately 50%, a more formal baseline assessment of the rate of medical patients receiving VTE prophylaxis was conducted during October 2002. This assessment was a single sampling of all medical inpatients on 2 of the medical floors on a single day. The results were consistent with those of the informal survey as well as those from an international registry.19 The results from the baseline study indicated that VTE prophylaxis was underused: only 46.9% of our medical inpatients received any form of prophylaxis. The prophylaxis rate was assessed again in 2 sampling periods beginning 12 and 18 months after implementation of the intervention. Data were collected monthly and combined into 3‐month blocks. The first postintervention sample (n = 116 patient charts) was drawn from a period 12‐14 months after implementation and the second (n = 147 patient charts) from a period 18‐20 months after implementation.

On a randomly designated day in the latter half of each month during each sampling period, all charts on 2 primary medical floors were reviewed and included in the retrospective analysis. Patients who were not on the medical service were excluded from analysis. Patients, as well as their medications, were identified using a list generated from our pharmacy database. We chose this method and schedule for several reasons. First, we sought to reduce the likelihood of including a patient more than once in a monthly sample. Second, by waiting for the latter half of the month we sought to allow house staff a chance to acquire knowledge from the educational program introduced on the first day of the month. Third, we wanted to allow house staff the time to actualize new attitudes reinforced by the audit‐and‐feedback element. The house staff included approximately 4 interns and 4 residents each month plus 10‐15 attendings or hospitalists.

Data Collection

For each sampling period we conducted a medical record (paper) review, and the Division Chief of General Internal Medicine also interviewed the medical house staff and attending physicians. Data collected included risk factors for VTE, contraindications to anticoagulant prophylaxis, type of VTE prophylaxis received, and appropriateness of the prophylaxis. Prophylaxis was considered appropriate when it was given in accordance with a risk stratification scheme (Table 1) adapted from the 2001 ACCP guideline recommendations for surgical patients20 and modified for medical inpatients, similar to the risk assessment model by Caprini et al.21 Prophylaxis was also considered appropriate when no prophylaxis was given for low‐risk patients or when full anticoagulation was given for another indication (Table 1). Questionable prophylaxis was defined as UFH given every 12 hours to a high‐risk patient. All other prophylaxis was deemed inappropriate (including no prophylaxis if prophylaxis was indicated, use of enoxaparin at incorrect prophylactic doses such as 60 or 20 mg, IPC alone for a high‐risk patient with no contraindication to pharmacological prophylaxis, and the use of warfarin if no other indication for it). The risk factors for thromboembolism and contraindications to anticoagulant prophylaxis are given in Table 2. Non‐ambulatory was defined as an order for bed rest with or without bathroom privileges or was judged based on information obtained from the medical house staff and nurses about whether the patient was ambulatory or had been observed walking outside his or her room. Data on pharmacological prophylaxis were obtained from the hospital pharmacy. Information on use of mechanical prophylaxis was obtained by house staff interviews or review of the order sheet. The house officer or attending physician of each patient was interviewed retrospectively to determine the reason for admission and the risk factors for VTE present on admission. Patients were classified as having low, moderate, high, or highest risk for VTE based on their age and any major risk factors for VTE (Table 1).19 All collected data were reported to the Department of Medicine Performance Improvement Committee for independent corroboration.

| Risk category | Definition | Dosage of appropriate prophylaxis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Additional risk factorsb | Low‐dose unfractionated heparin | LMWH | |

| ||||

| Low (0‐1 risk factors) | <40 | 0‐1 factor | None | None |

| Moderate (2 risk factors) | 40‐60 | 1 factor | 5000 units q12h | 40 mg of enoxaparin or 5000 units of dalteparin |

| High (3‐4 risk factors) | >60 | 1‐2 factors or hypercoagulable state | 5000 units q8h or q12h (q8h recommended for surgical patients) | 40 mg of enoxaparin or 5000 units of dalteparin |

| Highest (5 or more factors) | >40 | Malignancy, prior VTE, or CVA | 5000 units q8h plus IPC | enoxaparin or dalteparin plus IPC |

| Risk factors for thromboembolism |

|---|

| Contraindications to anticoagulant prophylaxis |

| Age > 40 years |

| Infection |

| Inflammatory disease |

| Congestive heart failure |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| Prior venous thromboembolism |

| Cancer |

| Cerebrovascular accident |

| End‐stage renal disease |

| Hypercoagulable state |

| Atrial fibrillation |

| Recent surgery |

| Obesity |

| Non‐ambulatory |

| Active gastrointestinal bleed |

| Central nervous system bleed |

| Thrombocytopenia (platelet count <100,000/L) |

Intervention Strategies

The intervention introduced comprised 3 strategies designed to improve VTE prophylaxis: provider education, decision support, and audit‐and‐feedback.

Provider Education

On the first day of every month, an orientation was given to all incoming medicine house staff by the chief resident that included information on the scope, risk factors, and asymptomatic nature of VTE, the importance of risk stratification, the need to provide adequate prophylaxis, and recommended prophylaxis regimens. A nurse educator also provided information to the nursing staff with the expectation that they would remind physicians to prescribe prophylactic treatment if not ordered initially; however, according to the nurses and house staff, this rarely occurred. Large posters showing VTE risk factors and prophylaxis were displayed at 2 nursing stations and physician charting rooms but were not visible to patients.

Decision Support

Pocket cards containing information on VTE risk factors and prophylaxis options were handed out to the house staff at the beginning of each month. These portable decision support tools assisted physicians in the selection of prophylaxis (a more recent, revised version of the material contained in this pocket guide is available at

Audit‐and‐Feedback

Monthly audits were performed by the Division Chief of General Internal Medicine in order to evaluate the type and appropriateness of VTE prophylaxis prescribed (Table 3). During the orientation at the beginning of the month, the chief resident mentioned that an audit would take place sometime during the rotation. This random audit took place during the last 2 weeks of each month on the same day the data were requested from the pharmacy. Over 1‐2 days, physicians were interviewed either one to one or in a group, depending on the availability of house staff. All house staff and hospitalists were queried about the reasons for admission and the presence of VTE risk factors; physicians received feedback from the Division Chief on VTE risk category, prophylaxis, and appropriateness of prophylaxis treatment of their patients.

| Element | Time/effort required |

|---|---|

| |

| Orientation about VTE risk factors and the need to provide adequate prophylaxis given to all incoming house staff by the chief resident on the first day of every month | 10 min/month |

| Introduction of pocket cards containing information on VTE risk factors and prophylaxis options | 5 min/month |

| In‐hospital education of nurses by the nurse educator | 2 sessions of 1 h |

| Large posters presenting VTE risk factors and prophylaxis displayed in nursing stations and physician charting rooms | 5 min one time only |

| Monthly audits by the Division Chief of General Internal Medicine to evaluate the type and suitability of VTE prophylaxis prescribed | 2 h/month for interviews 2 h/month for record review/ data entry |

Statistical Analysis

Differences in pre‐ and post‐intervention VTE prophylaxis and appropriate VTE prophylaxis rates were analyzed using the chi‐square test for categorical variables and the one‐way analysis of variance test for continuous variables. Differences were considered significant at the 5% level (P = .05).

RESULTS

Patients and Demographics

From October 2002 to August 2004 data were collected from 312 hospitalized medical patients: 49 patients in the baseline group during October 2002, and 116 and 147 at the 12‐ to 14‐month and 18‐ to 20‐month time points, respectively. Thus, approximately 40‐50 patients were randomly selected each month, representing 40% of the general medical service census. Patient demographics were similar between groups (Table 4). Overall, most patients were female (65.7%), and mean age was 61.2 years. The most common admission diagnoses were infection/sepsis (29.5%), chest pain/acute coronary syndromes/myocardial infarction (15.7%), heart failure (10.9%), and malignancy (9.6%). Overall, 7.1% (22 patients) had a contraindication to anticoagulant prophylaxis. The most common contraindication was active gastrointestinal bleeding on the current admission, which occurred in 18 of these patients.

| Baseline (n = 49) | 12 months (n = 116) | 18 months (n = 147) | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Patient demographic | ||||

| Mean age, years (SE) | 59.3 (2.6) | 63.3 (1.6) | 60.1 (1.5) | .25b |

| Men, n (%) | 20 (40.8) | 31 (26.7) | 56 (38.1) | .08 |

| Contraindications to pharmacological prophylaxis, n (%) | 7 (14.3) | 5 (4.3) | 10 (6.8) | .07 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 5 (10.2) | 5 (4.3) | 8 (5.4) | |

| CNS bleeding | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Low platelet count | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.4) | |

| Risk factor | ||||

| Mean number of risk factors (SE) | 3.1 (0.2) | 2.7 (0.1) | 3.0 (0.1) | .05b |

| Non‐ambulatoryc | 46 (93.9) | 73 (89.0) | 112 (80.0)d | .03 |

| Age > 40 years | 39 (79.6) | 101 (87.1) | 122 (83.0) | .44 |

| Cancer | 14 (28.6) | 15 (12.9) | 24 (16.3) | .05 |

| End‐stage renal disease | 13 (26.5) | 29 (25.0) | 36 (24.5) | .96 |

| Congestive heart failure | 11 (22.4) | 23 (19.8) | 28 (19.0) | .87 |

| Infection | 8 (16.3) | 24 (20.7) | 46 (31.3) | .04 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 8 (16.3) | 12 (10.3) | 15 (10.2) | .47 |

| COPD | 5 (10.2) | 9 (7.8) | 14 (9.5) | .84 |

| Sepsis | 3 (6.1) | 6 (5.2) | 21 (14.3) | .03 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 3 (6.1) | 8 (6.9) | 15 (10.2) | .52 |

| Surgery | 1 (2.0) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (1.4) | .82 |

| Previous venous thromboembolism | 0 (0.0) | 6 (5.2) | 8 (5.4) | .25 |

| Obesity (morbid) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.7) | 2 (1.4) | .66 |

| Hypercoagulable state | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

Risk Factors for VTE

Patient risk factors for VTE in each data collection period are summarized in Table 4. Analysis of this data showed that the most prevalent risk factors for VTE in the 3 patient populations were age older than 40 years (262/312, 84.0% of the total patient population) and nonambulatory state (231/271, 85.2% of the total population). Overall, the average number of risk factors for VTE was approximately 3, with more than 60% of patients having 3 or more VTE risk factors (Fig. 1).

Prophylaxis Use

The types of VTE prophylaxis used and the proportion of patients treated appropriately are summarized for each data collection period in Tables 5 and 6, respectively. In all 3 populations, most patients received pharmacological rather than mechanical prophylaxis, most commonly UFH. At baseline, the prophylaxis decision was appropriate (in accordance with the recommendations of the ACCP guidelines) as often as it was inappropriate (42.9% of patients). The prophylaxis decision was questionable in the remaining 14.3% of patients.

| Prophylaxis type | Baseline (n = 49), n (%) | 12 months (n = 116), n (%) | P valuea | 18 months (n = 147), n (%) | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Any pharmacological | 22 (44.9) | 94 (81.0) | <.01 | 118 (80.3) | <.01 |

| Any UFH | 17 (34.7) | 61 (52.6) | .04 | 58 (39.5) | .55 |

| IV UFHb | 3 (6.1) | 5 (4.3) | 2 (1.4) | ||

| bid UFHc | 13 (26.5) | 43 (37.1) | 39 (26.5) | ||

| tid UFHc | 1 (2.0) | 10 (8.6) | 16 (10.9) | ||

| qd UFHc | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.6) | 1 (0.7) | ||

| Any LMWH | 6 (12.2) | 30 (25.9) | .05 | 59 (40.1) | <.01 |

| Mechanical prophylaxis | 1 (2.0) | 7 (6.0) | .28 | 10 (6.8) | .21 |

| Warfarin | 6 (12.2) | 20 (17.2) | .42 | 19 (12.9) | .90 |

| Baseline (n = 49), n (%) | 12 months (n = 116), n (%) | P valuea | 18 months (n = 147), n (%) | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Receiving prophylaxis | 23 (46.9) | 100 (86.2) | <.01 | 127 (86.4) | <.01 |

| Appropriate | 21 (42.9) | 79 (68.1) | <.01 | 125 (85.0) | <.01 |

| UFH | 10 (20.4) | 33 (28.4) | .28 | 45 (30.6) | .16 |

| LMWH | 5 (10.2) | 27 (23.3) | .05 | 58 (39.5) | <.01 |

| Questionable | 7 (14.3) | 28 (24.1) | .14 | 14 (9.5) | .35 |

| Inappropriate | 21 (42.9) | 9 (7.8) | <.01 | 8 (5.4) | <.01 |

Change in Prophylaxis Use

Twelve and 18 months after implementation of the quality improvement program, we observed an increase in the use of any prophylaxis, from 46.9% at baseline to 86.2% and 86.4%, respectively (Table 5; P < .01 in both groups versus baseline). This increase was a result almost entirely of an increase in the proportion of patients receiving pharmacological prophylaxis, which significantly increased, from 44.9% to 81.0% and 80.3%, at the 12‐ and 18‐month time points, respectively (Table 5; P < .01 for both groups versus baseline). Most meaningfully, there was a significant increase in the proportion of patients for whom an appropriate prophylaxis decision was made (from 42.9% to 68.1% and 85.0%, at the 12‐ and 18‐month time points, respectively; Table 6; P < .01 for both groups versus baseline). This represented a trend toward continuing increases in the use of appropriate prophylaxis as the study progressed (Fig. 2). This change was driven mainly by a significant increase in the prescribing of LMWH, almost all of which was prescribed in accordance with the 2001 ACCP guidelines (Table 6).

DISCUSSION

In this study we evaluated the effect of an intervention that combined physician education with a decision support tool and a mechanism for audit‐and‐feedback. We have shown that implementation of such a multifaceted intervention is practical in a teaching hospital and can improve the rates of VTE prophylaxis use in medical patients. In nearly doubling the rate of appropriate prophylaxis, the effect size of our intervention was large, statistically significant, and sustained 18 months after implementation.

More than 60% of our patients had 3 or more risk factors, and more than 80% had at least 2 risk factors. The rate we observed for patients with 3 or more risk factors was 3 times higher than that reported previously.22 Despite the prevalence of high‐risk patients in our study, we observed that the preintervention rate of VTE prophylaxis among medical patients was relatively low at 47%, and only 43% of patients received prophylaxis in accordance with the ACCP guidelines. Our study findings are consistent with those of several other studies that have shown low rates of VTE prophylaxis in medical patients.6, 8, 2324 In a study of 15 hospitals in Massachusetts, only 13%‐19% of medical patients with indications and risk factors for VTE prophylaxis received any prophylaxis prior to an educational intervention.6 Similarly, a study of 368 consecutive medical patients at a Swiss hospital showed that only 22% of those at‐risk received VTE prophylaxis in accordance with the Thromboembolic Risk Factors (THRIFT) I Consensus Group recommendations.8 Results from 2 prospective patient registries also indicated low rates of VTE prophylaxis in medical patients.19, 24 In the IMPROVE registry of acutely ill medical patients, only 39% of patients hospitalized for 3 or more days received VTE prophylaxis19 and in the DVT‐FREE registry only 42% of medical patients with the inpatient diagnosis of DVT had received prophylaxis within 30 days of that diagnosis.24 In a recent retrospective study of 217 medical patients at the University of Utah hospital, just 43% of patients at high risk for VTE received any sort of prophylaxis.23

Physician education was the main intervention in several previous studies aimed at raising rates of VTE prophylaxis. Our study joins those that have also shown significant improvements after implementation of VTE prophylaxis educational initiatives.6, 14, 15, 23 In the study by Anderson et al., a significantly greater increase in the proportion of high‐risk patients receiving effective VTE prophylaxis was seen between 1986 and 1989 in hospitals that participated in a formal continuing medical education program compared with those that did not (increase: 28% versus 11%; P < .001).6 In 3 additional studies, educational interventions were shown to increase the rate of appropriate prophylaxis in at‐risk patients from 59% to 70%, from 55% to 96%, and from 43% to 72%.14, 15, 23

Other studies have cast doubt on the ability of time‐limited educational interventions to achieve a large or sustained effect.27, 28 A recent systematic review of strategies to improve the use of prophylaxis in hospitals concluded that a number of active strategies are likely to achieve optimal outcomes by combining a system for reminding clinicians to assess patients for VTE with assisting the selection of prophylaxis and providing audit‐and‐feedback.29 The large, sustained effect reported in our study might have been a result of the multifaceted and ongoing nature of the intervention, with reintroduction of the material to all incoming house staff each month. An audit from the last quarter of 2005nearly 2 years after the start of our interventionshowed that prophylaxis rates were approaching 100% (data not included in this study).

Another strategy, the use of computerized reminders to physicians, has been shown to increase the rate of VTE prophylaxis in surgical and medical/surgical patients.16, 26 Kucher et al. compared the incidence of DVT or PE in 1255 hospitalized patients whose physicians received an electronic alert of patient risk of DVT with 1251 hospitalized patients whose physicians did not receive such an alert. They found that the computer alert was associated with a significant reduction in the incidence of DVT or PE at 90 days, with a hazard ratio of 0.59 (95% confidence interval: 0.43, 0.81).16 Our study offers one practical alternative for those institutions that, like ours, do not currently have computerized order entry.

We were unable to determine if there was a specific element of the multifaceted VTE prophylaxis intervention program that contributed the most to the improvement in prophylaxis rates. Provider education was ongoing rather than just a single educational campaign. It was further supported by the pocket cards that provided support for decision making on VTE risk factors, risk categories (based on number and type of risk factor), recommended prophylaxis choices, and potential contraindications. In addition, our method of audit‐and‐feedback constructively leveraged the Hawthorne effect: aware that individual behavior was being measured, our physicians likely adjusted their practice accordingly. Taken together, it is likely that the several elements of our intervention were more powerful in combination than they would have been alone.

Although the multifaceted intervention worked well within our urban university teaching hospital, its application and outcome might be different for other types of hospitals. In our audit‐and‐feedback, for instance, review of resident physician performance was conducted by the Division Chief of General Internal Medicine, tapping into a very strong authority gradient. Hierarchical structures are likely to be different in other types of hospitals. It would therefore be valuable to examine whether the audit‐and‐feedback methodology presented in this article can be replicated in other hospital settings.

A potential limitation of this study was the use of retrospective review to determine baseline rates of VTE prophylaxis. This approach relies on medical notes being accurate and complete; such notes may not have been available for each patient. However, random reviews of both patient charts and hospital billing data for comorbidities performed after coding as a quality control step allowed for confirmation of the data or the extraction and addition of missing data. In addition, data collection was limited to a single day in the latter half of the month. It is not clear whether this sampling strategy collects data that are reflective of performance for the entire month. Our study was also limited by the absence of a control group. Without a control group, we cannot exclude the possibility that during the study factors other than the educational intervention might have contributed to the improvement in prophylaxis rates.

In this study we did not address whether an increase in VTE prophylaxis use translates to an improvement in patient outcomes, namely, a reduction in the rate of VTE. Mosen et al. showed that increasing the VTE prophylaxis rate by implementing a computerized reminder system did not decrease the rate of VTE.26 However, the baseline rate of VTE prophylaxis was already very good, and the study was only powered to detect a large difference in VTE rates. Conversely, Kucher et al. recently demonstrated a significant reduction in VTE events 90 days after initiation of a computerized alert program.16 Further studies designed to confirm the inverse relationship between rate of VTE prophylaxis and rate of clinical outcome of VTE would be helpful.

In conclusion, in a setting in which most hospitalized medically ill patients have multiple risk factors for VTE, we have shown that a practical multifaceted intervention can result in a marked increase in the proportion of medical patients receiving VTE prophylaxis, as well as in the proportion of patients receiving prophylaxis commensurate with evidence‐based guidelines.

Acknowledgements

We thank Nicholas Galeota, Director of Pharmacy at SUNY Downstate for his assistance in providing monthly patient medication lists, Helen Wiggett for providing writing support, and Dan Bridges for editorial support for this manuscript.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), which encompasses both deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is a major cause of the morbidity and mortality of hospitalized medical patients.1 Hospitalization for an acute medical illness has been associated with an 8‐fold increase in the relative risk of VTE and is responsible for approximately a quarter of all VTE cases in the general population.2, 3

Current evidence‐based guidelines, including those from the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP), recommend prophylaxis with low‐dose unfractionated heparin (UFH) or low‐molecular‐weight heparin (LMWH) for medical patients with risk factors for VTE.4, 5 Mechanical prophylaxis methods including graduated compression stockings and intermittent pneumatic compression are recommended for those patients for whom anticoagulant therapy is contraindicated because of a high risk of bleeding.4, 5 However, several studies have shown that adherence to these guidelines is suboptimal, with many at‐risk patients receiving inadequate prophylaxis (range 32%‐87%).610

Physician‐related factors identified as potential barriers to guideline adherence include not being aware or familiar with the guidelines, not agreeing with the guidelines, or believing the guideline recommendations to be ineffective.11 More specific studies have shown that some physicians may lack basic knowledge regarding the current treatment standards for VTE and may underestimate the significance of VTE.1213 As distinct strategies, education aimed at disseminating VTE prophylaxis guidelines, as well as regular audit‐and‐feedback of physician performance, has been shown to improve rates of VTE prophylaxis in clinical practice.6, 1417 Implementation of educational programs significantly increased the level of appropriate VTE prophylaxis from 59% to 70% of patients in an Australian hospital15 and from 73% to 97% of patients in a Scottish hospital.14 Another strategy, the use of point‐of‐care electronically provided reminders with decision support, has been successful not only in increasing the rates of VTE prophylaxis, but also in decreasing the incidence of clinical VTE events.16 Although highly effective, electronic alerts with computerized decision support do not exist in many hospitals, and other methods of intervention are needed.

In this study, we evaluated adherence to the 2001 ACCP guidelines for VTE prophylaxis among medical patients in our teaching hospital. (The guidelines were updated in 2004, after our study was completed.) After determining that our baseline rates of appropriate VTE prophylaxis were suboptimal, we developed, implemented, and evaluated a multifaceted strategy to improve the rates of appropriate thromboprophylaxis among our medical inpatients.

Six categories of quality improvement strategies have been described: provider education, decision support, audit‐and‐feedback, patient education, organization change, and regulation and policy.18 The intervention we developed was a composite of 3 of these: provider education, decision support, and audit‐and‐feedback.

METHODS

Study Design and Patients

This was a before‐and‐after study designed to assess whether implementation of a VTE prophylaxis quality improvement intervention could improve the rate of appropriate thromboprophylaxis in hospitalized medical patients at the State University of New York, Downstate Medical CenterUniversity Hospital of Brooklyn, an urban university teaching hospital of approximately 400 beds. This initiative, conducted as part of a departmental quality assurance and performance improvement program, did not require institutional review board approval. After an informal survey revealed a prophylaxis rate of approximately 50%, a more formal baseline assessment of the rate of medical patients receiving VTE prophylaxis was conducted during October 2002. This assessment was a single sampling of all medical inpatients on 2 of the medical floors on a single day. The results were consistent with those of the informal survey as well as those from an international registry.19 The results from the baseline study indicated that VTE prophylaxis was underused: only 46.9% of our medical inpatients received any form of prophylaxis. The prophylaxis rate was assessed again in 2 sampling periods beginning 12 and 18 months after implementation of the intervention. Data were collected monthly and combined into 3‐month blocks. The first postintervention sample (n = 116 patient charts) was drawn from a period 12‐14 months after implementation and the second (n = 147 patient charts) from a period 18‐20 months after implementation.

On a randomly designated day in the latter half of each month during each sampling period, all charts on 2 primary medical floors were reviewed and included in the retrospective analysis. Patients who were not on the medical service were excluded from analysis. Patients, as well as their medications, were identified using a list generated from our pharmacy database. We chose this method and schedule for several reasons. First, we sought to reduce the likelihood of including a patient more than once in a monthly sample. Second, by waiting for the latter half of the month we sought to allow house staff a chance to acquire knowledge from the educational program introduced on the first day of the month. Third, we wanted to allow house staff the time to actualize new attitudes reinforced by the audit‐and‐feedback element. The house staff included approximately 4 interns and 4 residents each month plus 10‐15 attendings or hospitalists.

Data Collection

For each sampling period we conducted a medical record (paper) review, and the Division Chief of General Internal Medicine also interviewed the medical house staff and attending physicians. Data collected included risk factors for VTE, contraindications to anticoagulant prophylaxis, type of VTE prophylaxis received, and appropriateness of the prophylaxis. Prophylaxis was considered appropriate when it was given in accordance with a risk stratification scheme (Table 1) adapted from the 2001 ACCP guideline recommendations for surgical patients20 and modified for medical inpatients, similar to the risk assessment model by Caprini et al.21 Prophylaxis was also considered appropriate when no prophylaxis was given for low‐risk patients or when full anticoagulation was given for another indication (Table 1). Questionable prophylaxis was defined as UFH given every 12 hours to a high‐risk patient. All other prophylaxis was deemed inappropriate (including no prophylaxis if prophylaxis was indicated, use of enoxaparin at incorrect prophylactic doses such as 60 or 20 mg, IPC alone for a high‐risk patient with no contraindication to pharmacological prophylaxis, and the use of warfarin if no other indication for it). The risk factors for thromboembolism and contraindications to anticoagulant prophylaxis are given in Table 2. Non‐ambulatory was defined as an order for bed rest with or without bathroom privileges or was judged based on information obtained from the medical house staff and nurses about whether the patient was ambulatory or had been observed walking outside his or her room. Data on pharmacological prophylaxis were obtained from the hospital pharmacy. Information on use of mechanical prophylaxis was obtained by house staff interviews or review of the order sheet. The house officer or attending physician of each patient was interviewed retrospectively to determine the reason for admission and the risk factors for VTE present on admission. Patients were classified as having low, moderate, high, or highest risk for VTE based on their age and any major risk factors for VTE (Table 1).19 All collected data were reported to the Department of Medicine Performance Improvement Committee for independent corroboration.

| Risk category | Definition | Dosage of appropriate prophylaxis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Additional risk factorsb | Low‐dose unfractionated heparin | LMWH | |

| ||||

| Low (0‐1 risk factors) | <40 | 0‐1 factor | None | None |

| Moderate (2 risk factors) | 40‐60 | 1 factor | 5000 units q12h | 40 mg of enoxaparin or 5000 units of dalteparin |

| High (3‐4 risk factors) | >60 | 1‐2 factors or hypercoagulable state | 5000 units q8h or q12h (q8h recommended for surgical patients) | 40 mg of enoxaparin or 5000 units of dalteparin |

| Highest (5 or more factors) | >40 | Malignancy, prior VTE, or CVA | 5000 units q8h plus IPC | enoxaparin or dalteparin plus IPC |

| Risk factors for thromboembolism |

|---|

| Contraindications to anticoagulant prophylaxis |

| Age > 40 years |

| Infection |

| Inflammatory disease |

| Congestive heart failure |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| Prior venous thromboembolism |

| Cancer |

| Cerebrovascular accident |

| End‐stage renal disease |

| Hypercoagulable state |

| Atrial fibrillation |

| Recent surgery |

| Obesity |

| Non‐ambulatory |

| Active gastrointestinal bleed |

| Central nervous system bleed |

| Thrombocytopenia (platelet count <100,000/L) |

Intervention Strategies

The intervention introduced comprised 3 strategies designed to improve VTE prophylaxis: provider education, decision support, and audit‐and‐feedback.

Provider Education

On the first day of every month, an orientation was given to all incoming medicine house staff by the chief resident that included information on the scope, risk factors, and asymptomatic nature of VTE, the importance of risk stratification, the need to provide adequate prophylaxis, and recommended prophylaxis regimens. A nurse educator also provided information to the nursing staff with the expectation that they would remind physicians to prescribe prophylactic treatment if not ordered initially; however, according to the nurses and house staff, this rarely occurred. Large posters showing VTE risk factors and prophylaxis were displayed at 2 nursing stations and physician charting rooms but were not visible to patients.

Decision Support

Pocket cards containing information on VTE risk factors and prophylaxis options were handed out to the house staff at the beginning of each month. These portable decision support tools assisted physicians in the selection of prophylaxis (a more recent, revised version of the material contained in this pocket guide is available at

Audit‐and‐Feedback

Monthly audits were performed by the Division Chief of General Internal Medicine in order to evaluate the type and appropriateness of VTE prophylaxis prescribed (Table 3). During the orientation at the beginning of the month, the chief resident mentioned that an audit would take place sometime during the rotation. This random audit took place during the last 2 weeks of each month on the same day the data were requested from the pharmacy. Over 1‐2 days, physicians were interviewed either one to one or in a group, depending on the availability of house staff. All house staff and hospitalists were queried about the reasons for admission and the presence of VTE risk factors; physicians received feedback from the Division Chief on VTE risk category, prophylaxis, and appropriateness of prophylaxis treatment of their patients.

| Element | Time/effort required |

|---|---|

| |

| Orientation about VTE risk factors and the need to provide adequate prophylaxis given to all incoming house staff by the chief resident on the first day of every month | 10 min/month |

| Introduction of pocket cards containing information on VTE risk factors and prophylaxis options | 5 min/month |

| In‐hospital education of nurses by the nurse educator | 2 sessions of 1 h |

| Large posters presenting VTE risk factors and prophylaxis displayed in nursing stations and physician charting rooms | 5 min one time only |

| Monthly audits by the Division Chief of General Internal Medicine to evaluate the type and suitability of VTE prophylaxis prescribed | 2 h/month for interviews 2 h/month for record review/ data entry |

Statistical Analysis

Differences in pre‐ and post‐intervention VTE prophylaxis and appropriate VTE prophylaxis rates were analyzed using the chi‐square test for categorical variables and the one‐way analysis of variance test for continuous variables. Differences were considered significant at the 5% level (P = .05).

RESULTS

Patients and Demographics

From October 2002 to August 2004 data were collected from 312 hospitalized medical patients: 49 patients in the baseline group during October 2002, and 116 and 147 at the 12‐ to 14‐month and 18‐ to 20‐month time points, respectively. Thus, approximately 40‐50 patients were randomly selected each month, representing 40% of the general medical service census. Patient demographics were similar between groups (Table 4). Overall, most patients were female (65.7%), and mean age was 61.2 years. The most common admission diagnoses were infection/sepsis (29.5%), chest pain/acute coronary syndromes/myocardial infarction (15.7%), heart failure (10.9%), and malignancy (9.6%). Overall, 7.1% (22 patients) had a contraindication to anticoagulant prophylaxis. The most common contraindication was active gastrointestinal bleeding on the current admission, which occurred in 18 of these patients.

| Baseline (n = 49) | 12 months (n = 116) | 18 months (n = 147) | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Patient demographic | ||||

| Mean age, years (SE) | 59.3 (2.6) | 63.3 (1.6) | 60.1 (1.5) | .25b |

| Men, n (%) | 20 (40.8) | 31 (26.7) | 56 (38.1) | .08 |

| Contraindications to pharmacological prophylaxis, n (%) | 7 (14.3) | 5 (4.3) | 10 (6.8) | .07 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 5 (10.2) | 5 (4.3) | 8 (5.4) | |

| CNS bleeding | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Low platelet count | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.4) | |

| Risk factor | ||||

| Mean number of risk factors (SE) | 3.1 (0.2) | 2.7 (0.1) | 3.0 (0.1) | .05b |

| Non‐ambulatoryc | 46 (93.9) | 73 (89.0) | 112 (80.0)d | .03 |

| Age > 40 years | 39 (79.6) | 101 (87.1) | 122 (83.0) | .44 |

| Cancer | 14 (28.6) | 15 (12.9) | 24 (16.3) | .05 |

| End‐stage renal disease | 13 (26.5) | 29 (25.0) | 36 (24.5) | .96 |

| Congestive heart failure | 11 (22.4) | 23 (19.8) | 28 (19.0) | .87 |

| Infection | 8 (16.3) | 24 (20.7) | 46 (31.3) | .04 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 8 (16.3) | 12 (10.3) | 15 (10.2) | .47 |

| COPD | 5 (10.2) | 9 (7.8) | 14 (9.5) | .84 |

| Sepsis | 3 (6.1) | 6 (5.2) | 21 (14.3) | .03 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 3 (6.1) | 8 (6.9) | 15 (10.2) | .52 |

| Surgery | 1 (2.0) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (1.4) | .82 |

| Previous venous thromboembolism | 0 (0.0) | 6 (5.2) | 8 (5.4) | .25 |

| Obesity (morbid) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.7) | 2 (1.4) | .66 |

| Hypercoagulable state | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

Risk Factors for VTE

Patient risk factors for VTE in each data collection period are summarized in Table 4. Analysis of this data showed that the most prevalent risk factors for VTE in the 3 patient populations were age older than 40 years (262/312, 84.0% of the total patient population) and nonambulatory state (231/271, 85.2% of the total population). Overall, the average number of risk factors for VTE was approximately 3, with more than 60% of patients having 3 or more VTE risk factors (Fig. 1).

Prophylaxis Use

The types of VTE prophylaxis used and the proportion of patients treated appropriately are summarized for each data collection period in Tables 5 and 6, respectively. In all 3 populations, most patients received pharmacological rather than mechanical prophylaxis, most commonly UFH. At baseline, the prophylaxis decision was appropriate (in accordance with the recommendations of the ACCP guidelines) as often as it was inappropriate (42.9% of patients). The prophylaxis decision was questionable in the remaining 14.3% of patients.

| Prophylaxis type | Baseline (n = 49), n (%) | 12 months (n = 116), n (%) | P valuea | 18 months (n = 147), n (%) | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Any pharmacological | 22 (44.9) | 94 (81.0) | <.01 | 118 (80.3) | <.01 |

| Any UFH | 17 (34.7) | 61 (52.6) | .04 | 58 (39.5) | .55 |

| IV UFHb | 3 (6.1) | 5 (4.3) | 2 (1.4) | ||

| bid UFHc | 13 (26.5) | 43 (37.1) | 39 (26.5) | ||

| tid UFHc | 1 (2.0) | 10 (8.6) | 16 (10.9) | ||

| qd UFHc | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.6) | 1 (0.7) | ||

| Any LMWH | 6 (12.2) | 30 (25.9) | .05 | 59 (40.1) | <.01 |

| Mechanical prophylaxis | 1 (2.0) | 7 (6.0) | .28 | 10 (6.8) | .21 |

| Warfarin | 6 (12.2) | 20 (17.2) | .42 | 19 (12.9) | .90 |

| Baseline (n = 49), n (%) | 12 months (n = 116), n (%) | P valuea | 18 months (n = 147), n (%) | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Receiving prophylaxis | 23 (46.9) | 100 (86.2) | <.01 | 127 (86.4) | <.01 |

| Appropriate | 21 (42.9) | 79 (68.1) | <.01 | 125 (85.0) | <.01 |

| UFH | 10 (20.4) | 33 (28.4) | .28 | 45 (30.6) | .16 |

| LMWH | 5 (10.2) | 27 (23.3) | .05 | 58 (39.5) | <.01 |

| Questionable | 7 (14.3) | 28 (24.1) | .14 | 14 (9.5) | .35 |

| Inappropriate | 21 (42.9) | 9 (7.8) | <.01 | 8 (5.4) | <.01 |

Change in Prophylaxis Use

Twelve and 18 months after implementation of the quality improvement program, we observed an increase in the use of any prophylaxis, from 46.9% at baseline to 86.2% and 86.4%, respectively (Table 5; P < .01 in both groups versus baseline). This increase was a result almost entirely of an increase in the proportion of patients receiving pharmacological prophylaxis, which significantly increased, from 44.9% to 81.0% and 80.3%, at the 12‐ and 18‐month time points, respectively (Table 5; P < .01 for both groups versus baseline). Most meaningfully, there was a significant increase in the proportion of patients for whom an appropriate prophylaxis decision was made (from 42.9% to 68.1% and 85.0%, at the 12‐ and 18‐month time points, respectively; Table 6; P < .01 for both groups versus baseline). This represented a trend toward continuing increases in the use of appropriate prophylaxis as the study progressed (Fig. 2). This change was driven mainly by a significant increase in the prescribing of LMWH, almost all of which was prescribed in accordance with the 2001 ACCP guidelines (Table 6).

DISCUSSION

In this study we evaluated the effect of an intervention that combined physician education with a decision support tool and a mechanism for audit‐and‐feedback. We have shown that implementation of such a multifaceted intervention is practical in a teaching hospital and can improve the rates of VTE prophylaxis use in medical patients. In nearly doubling the rate of appropriate prophylaxis, the effect size of our intervention was large, statistically significant, and sustained 18 months after implementation.

More than 60% of our patients had 3 or more risk factors, and more than 80% had at least 2 risk factors. The rate we observed for patients with 3 or more risk factors was 3 times higher than that reported previously.22 Despite the prevalence of high‐risk patients in our study, we observed that the preintervention rate of VTE prophylaxis among medical patients was relatively low at 47%, and only 43% of patients received prophylaxis in accordance with the ACCP guidelines. Our study findings are consistent with those of several other studies that have shown low rates of VTE prophylaxis in medical patients.6, 8, 2324 In a study of 15 hospitals in Massachusetts, only 13%‐19% of medical patients with indications and risk factors for VTE prophylaxis received any prophylaxis prior to an educational intervention.6 Similarly, a study of 368 consecutive medical patients at a Swiss hospital showed that only 22% of those at‐risk received VTE prophylaxis in accordance with the Thromboembolic Risk Factors (THRIFT) I Consensus Group recommendations.8 Results from 2 prospective patient registries also indicated low rates of VTE prophylaxis in medical patients.19, 24 In the IMPROVE registry of acutely ill medical patients, only 39% of patients hospitalized for 3 or more days received VTE prophylaxis19 and in the DVT‐FREE registry only 42% of medical patients with the inpatient diagnosis of DVT had received prophylaxis within 30 days of that diagnosis.24 In a recent retrospective study of 217 medical patients at the University of Utah hospital, just 43% of patients at high risk for VTE received any sort of prophylaxis.23