User login

Identifying hyperthyroidism’s psychiatric presentations

Ms. A experienced an anxiety attack while driving home from work, with cardiac palpitations, tingling of the face, and fear of impending doom. Over the following 3 months she endured a “living hell,” consisting of basal anxiety, intermittent panic attacks, and agoraphobia, with exceptional difficulty even going to the grocery store.

A high-functioning career woman in her 30s, Ms. A also developed insomnia, depressed mood, and intrusive ego-dystonic thoughts. These symptoms emerged 10 years after a subtotal thyroidectomy for hyperthyroidism (Graves’ disease).

Hyperthyroidism’s association with psychiatric-spectrum symptoms is well-recognized (Box 1).1-4 Hyperthyroid patients are significantly more likely than controls to report feelings of isolation, impaired social functioning, anxiety, and mood disturbances5 and are more likely to be hospitalized with an affective disorder.6

Other individuals with subclinical or overt biochemical hyperthyroidism self-report above-average mood and lower-than-average anxiety.7

Ms. A’s is the first of three cases presented here to help you screen for and identify thyrotoxicosis (thyroid and nonthyroid causes of excessive thyroid hormone). Cases include:

- recurrent Graves’ disease with panic disorder and residual obsessive-compulsive disorder (Ms. A)

- undetected Graves’ hyperthyroidism in a bipolar-like mood syndrome with severe anxiety and cognitive decline (Ms. B)

- occult hyperthyroidism with occult anxiety (Mr. C).

These cases show that even when biochemical euthyroidism is restored, many formerly hyperthyroid patients with severe mood, anxiety, and/or cognitive symptoms continue to have significant residual symptoms that require ongoing psychiatric attention.6

Ms. A: Anxiety and thyrotoxicosis

Ms. A was greatly troubled by her intrusive ego-dystonic thoughts, which involved:

- violence to her beloved young children (for example, what would happen if someone started shooting her children with a gun)

- bizarre sexual ideations (for example, during dinner with an elderly woman she could not stop imagining her naked)

- paranoid ideations (for example, “Is my husband poisoning me?”).

She consulted a psychologist who told her that she suffered from an anxiety disorder and recommended psychotherapy, which was not helpful. She then sought endocrine consultation, and tests showed low-grade overt hyperthyroidism, with unmeasurably low thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) concentrations and marginally elevated total and free levothyroxine (T4). Her levothyroxine replacement dosage was reduced from 100 to 50 mcg/d, then discontinued.

Without thyroid supplementation or replacement, she became biochemically euthyroid, with TSH 1.47 mIU/L and triiodothyronine (T3) and T4 in mid-normal range. Her panic anxiety resolved and her mood and sleep normalized, but the bizarre thoughts remained. The endocrinologist referred her to a psychiatrist, who diagnosed obsessive-compulsive disorder. Ms. A was effectively treated with fluvoxamine, 125 mg/d.

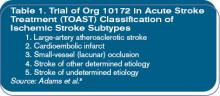

Discussion. Many patients with hyperthyroidism suffer from anxiety syndromes,8-10 including generalized anxiety disorder and social phobia (Table 1). “Nervousness” (including “feelings of apprehension and inability to concentrate”) is almost invariably present in the thyrotoxicosis of Graves’ disease.11

Hyperthyroidism-related anxiety syndromes are typically complicated by major depression and cognitive decline, such as in memory and attention.9 Thus, a pituitary-thyroid workup is an important step in the psychiatric evaluation of any patient with clinically significant anxiety (Box 2).3

The brain has among the highest expression of thyroid hormone receptors of any organ,1,2 and neurons are often more sensitive to thyroid abnormalities—including overt or subclinical hyperthyroidism and thyrotoxicosis, thyroiditis, and hypothyroidism3—than are other tissues.

Hyperthyroidism is often associated with anxiety, depression, mixed mood disorders, a hypomanic-like picture, emotional lability, mood swings, irritability/edginess, or cognitive deterioration with concentration problems. It also can manifest as psychosis or delirium.

Hyperthyroidism affects approximately 2.5% of the U.S. population (~7.5 million persons), according to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). One-half of those afflicted (1.3%) do not know they are hyperthyroid, including 0.5% with overt symptoms and 0.8% with subclinical disease.

NHANES III defined hyperthyroidism as thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) <0.1 mIU/L with total thyroxine (T4) levels either elevated (overt hyperthyroidism) or normal (subclinical hyperthyroidism). Women are at least 5 times more likely than men to be hyperthyroid.4

CNS hypersensitivity to low-grade hyperthyroidism can manifest as an anxiety disorder before other Graves’ disease stigmata emerge. Panic disorder, for example, has been reported to precede Graves’ hyperthyroidism by 4 to 5 years in some cases,12 although how frequently this occurs is not known. Therefore, re-evaluate the thyroid status of any patient with severe anxiety who is biochemically euthyroid. Check yearly, for example, if anxiety is incompletely resolved.

Table 1

Psychiatric symptoms seen with hyperthyroidism

| Anxiety |

| Apathy (more often seen in older patients) |

| Cognitive impairment |

| Delirium |

| Depression |

| Emotional lability |

| Fatigue |

| Hypomania or mania |

| Impaired concentration |

| Insomnia |

| Irritability |

| Mood swings |

| Psychomotor agitation |

| Psychosis |

Causes of hyperthyroidism

Approximately 20 causes of thyrotoxicosis and hyperthyroxinemia have been characterized (see Related resources).11,13-15 The most common causes of hyperthyroidism are Graves’ disease, toxic multinodular goiter, and toxic thyroid adenoma. Another is thyroiditis, such as from lithium or iodine excess (such as from the cardiac drug amiodarone). A TSH-secreting pituitary adenoma is a rare cause of hyperthyroidism.16

A drug-induced thyrotoxic state can be seen with excess administration of exogenous thyroid hormone. This condition usually occurs inadvertently but is sometimes intentional, as in factitious disorder or malingering.

Graves’ disease is an autoimmune disorder that occurs when antibodies (thyroid-stimulating hormone immunoglobulins) stimulate thyroid TSH receptors, increasing thyroid hormone synthesis and secretion. Graves’ disease—seen in 60% to 85% of patients with thyrotoxicosis—is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism.15

Patients most often are women of childbearing years to middle age. Exophthalmos and other eye changes are common, along with diffuse goiter. Encephalopathy can be seen in Graves’ disease and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis because the brain can become an antibody target in autoimmune disorders.

Toxic multinodular goiter consists of autonomously functioning, circumscribed thyroid nodules with an enlarged (goitrous) thyroid, that typically emerge at length from simple (nontoxic) goiter—characterized by enlarged thyroid but normal thyroid-related biochemistry. Onset is typically later in life than Graves’ disease.11,17

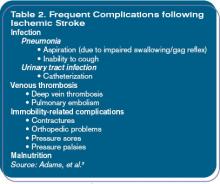

Thyrotoxicosis is often relatively mild in toxic multinodular goiter, with marginal elevations in T4 and/or T3. Unlike in Graves’ disease, ophthalmologic changes are unusual. Tachycardia and weakness are common (Table 2).

Table 2

Nonpsychiatric symptoms seen with hyperthyroidism

| Metabolic |

| Heat intolerance (cold tolerance) |

| Increased perspiration |

| Weight loss (despite good appetite) |

| Endocrinologic |

| Goiter (enlarged thyroid gland) |

| Ophthalmologic |

| Exophthalmos |

| Lid lag |

| Stare/infrequent blinking |

| Ophthalmoplegia |

| Neurologic |

| Tremor |

| Hyperreflexia |

| Motor restlessness |

| Proximal muscle weakness/myopathy |

| Cardiologic |

| Tachycardia |

| Palpitations |

| Arrhythmia |

| Worsening or precipitation of angina, heart failure |

| Sexual |

| Oligomenorrhea/amenorrhea |

| Rapid ejaculation |

| Dermatologic |

| Warm, moist skin |

| Fine hair |

| Velvety skin texture |

| Onycholysis |

| Myxedema/leg swelling |

| Ruddy or erythemic skin/facial flushing |

| Eyelash loss |

| Hair loss |

| Premature graying (Graves’ disease) |

| Pruritus |

| Gastrointestinal |

| Frequent bowel movements |

| Diarrhea |

| Nausea |

| Orthopedic |

| Osteopenia or osteoporosis |

Adenomas. Toxic thyroid adenoma is a hyperfunctioning (“toxic”) benign tumor of the thyroid follicular cell. A TSH-secreting pituitary adenoma is a rare cause of hyperthyroidism.16

Thyroid storm is a rare, life-threatening thyrotoxicosis, usually seen in medical or surgical patients. Symptoms include fever, tachycardia, hypotension, irritability and restlessness, nausea and vomiting, delirium, and possibly coma.

Psychiatrists rarely see these cases, but propranolol (40 mg initial dose), fluids, and swift transport to an emergency room or critical care unit are indicated. Antithyroid agents and glucocorticoids are the usual treatment.

Thyrotoxic symptoms from thyroid hormone therapy. Thyroid hormone has been used in psychiatric patients as an antidepressant supplement,18 with therapeutic benefit reported to range from highly valuable19 to modestly helpful or no effect.20 In some patients thyroid hormone causes thyrotoxic symptoms such as tachycardia, gross tremulousness, restlessness, anxiety, inability to sleep, and impaired concentration.

Patients newly diagnosed with hypothyroidism can be exquisitely sensitive to exogenous thyroid hormone and develop acute thyrotoxic symptoms. When this occurs, a more measured titration of thyroid dose is indicated, rather than discontinuing hormone therapy. For example, patients whose optimal maintenance levothyroxine dosage proves to be >100 mcg/d might do better by first adapting to 75 mcg/d.

Thyroid hormone replacement can increase demand on the adrenal glands of chronically hypothyroid patients. For those who develop thyrotoxic-like symptoms, a pulse of glucocorticoids—such as a single 20-mg dose of prednisone (2 to 3 times the typical daily glucocorticoid maintenance requirement)—is sometimes very helpful. Severe eye pain and periorbital edema has been reported to respond to prednisone doses of 120 mg/d.13

Serum TSH is a sensitive screen. Low (<0.1 mIU/mL) or immeasurably low (<0.05 mIU/mL) circulating TSH usually means hyperthyroidism. A TSH screen is not foolproof, however; very low TSH can be seen with low circulating thyroid hormones in central hypothyroidism or in cases of laboratory error.

The recommended routine initial screen of the pituitary-thyroid axis in psychiatric patients includes TSH, free T4, and possibly free T3.3 Suppressed TSH with high serum free T3 and/or free T4 (accompanied by high total T4 and/or T3) is diagnostic of frank biochemical hyperthyroidism. If circulating thyroid hormone concentrations are normal, hyperthyroidism is considered compensated or subclinical. Although only free thyroid hormones are active, total T4 and total T3 are of interest to grossly estimate thyroid hormone output.

When you identify a thyrotoxic state, refer the patient for an endocrinologic evaluation. Antithyroid antibodies are often positive in Graves’ disease, but anti-TSH antibodies (which can be routinely ordered) are particularly diagnostic. If thyroid dysfunction is present—especially if autoimmune-based—screening tests are indicated to rule out adrenal, gonadal, and pancreatic (glucose regulation) dysfunction.

Ms. B: Hyperthyroidism and mood

Ms. B, age 35, an energetic clerical worker and fitness devotee, developed severe insomnia. She slept no more than 1 hour per night, with irritability, verbal explosiveness, “hot flashes,” and depressed mood. “Everything pisses me off violently,” she said.

She consulted a psychiatrist and was diagnosed with major depression. Over a period of years, she was serially prescribed selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and older-generation sedating agents including trazodone and amitriptyline. She tolerated none of these because of side effects, including dysphoric hyperarousal and cognitive disruption.

“They all made me stupid,” she complained.

Zolpidem, 20 mg at night, helped temporarily as a hypnotic, but insomnia recurred within weeks. Diazepam was effective at high dosages but also dulled her cognition. The psychiatrist did not suspect a thyroid abnormality and did not perform a pituitary-thyroid laboratory evaluation.

Ms. B consulted a gynecologist, who prescribed estrogen for borderline low estradiol levels and with the hope that Ms. B’s symptoms represented early menopause. This partially ameliorated her irritability, possibly because estradiol binding of circulating T4 reduced free thyroid hormone levels.

Ms. B tried to continue working and exercising, but within 4 years her symptoms progressed to severe depression with frequent crying spells, feelings of general malaise, excessive sweating, occasional panic attacks, fatigue, sleepiness, deteriorating vision, and cognitive impairment. She struggled to read printed words and eventually took sick leave while consulting with physicians.

Finally, a routine thyroid screen before minor surgery revealed an undetectable TSH concentration. Further testing showed elevated thyroxine consistent with thyrotoxicosis. Graves’ disease was diagnosed, and euthyroidism was established with antithyroid medication.

Residual mood and anxiety symptoms persisted 1 year after euthyroidism was restored, and Ms. B sought psychiatric consultation.

Discussion. Hyperthyroidism can trigger or present as a hypomania or manic-like state, characterized by increased energy, hyperactivity, racing thoughts, hair-trigger verbal explosiveness, and decreased need for sleep.

Hypertalkativeness is common, even without pressured speech, as is irritability. Mood may be elevated, depressed, mixed, or cycling. A hyperthyroidism-related mixed syndrome of depression and hypomania can be confounding.

Mr. C: Occult hyperthyroidism

Mr. C, age 26, was apparently healthy when he was admitted into a neuroendocrine research protocol as a volunteer. His job performance was excellent, and his interactions with others were good; he was in good general health and taking no medication.

Formal psychiatric screening found no history of psychiatric disorders in Mr. C nor his family. His mental status was within normal limits. Physical exam revealed no significant abnormality. He was afebrile, normotensive, and had a resting pulse of 81 bpm.

His neurologic status was unremarkable, and laboratory screening tests showed normal CBC, liver and renal profiles, glucose, platelets and clotting times. Tests during the study, however, showed frankly elevated T4, free thyroxine (FT4), and T3 concentrations, along with undetectable TSH. Mr. C was informed of these results and referred to an endocrinologist.

Graves’ disease was diagnosed, and Mr. C received partial thyroid ablation therapy. He later reported that he had never felt better. In retrospect, he realized he had been anxious before he was treated for hyperthyroidism because he felt much more relaxed and able to concentrate after treatment.

Discussion. Subjective well-being in a patient with occult biochemical thyrotoxicosis can be misleading. Mr. C was much less anxious and able to concentrate after his return to euthyroidism.

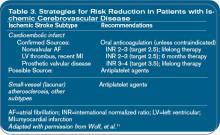

Treatment

Refer your hyperthyroid patients to an endocrinologist for further workup and, in most cases, management. Hyperthyroidism is usually easy to treat using a form of ablation (antithyroid drugs, radioactive iodine, or partial thyroidectomy).

Remain involved in the patient’s care when psychiatric symptoms are prominent, however, as they are likely to persist even after thyrotoxicosis is corrected.6 Reasonable interventions include:

- control of acute thyrotoxic symptoms such as palpitations and tremulousness with propranolol, 20 to 40 mg as needed, or a 20-mg bolus of prednisone (especially if thyroiditis is present)

- address mood cycling, depression, edginess, anxiety, lability, insomnia, and/or irritability with lithium3

- oversee smoking cessation in patients with Graves’ disease (smoking exacerbates the autoimmune pathology).

Address and correct hyperthyroidism that is artifactual (caused by overuse or secret use by a patient) or iatrogenic (related to excessive prescribed hormone dosages).

Subclinical hyperthyroidism can be transient and resolve without treatment. Lithium can be helpful when a mood disorder coexists with sub clinical hyperthyroidism. Start with 300 to 600 mg every evening with dinner. If the mood disorder is mild, even as little as 300 to 450 mg of lithium may elevate a depressed mood and remove edginess and irritability.

Lithium is antithyroid, decreases thyroid hormone output, and increases serum TSH within 24 hours of initiation, but it can provoke autoimmune hyperthyroidism in some individuals.21

- For comprehensive tables of hyperthyroidism’s causes, refer to Pearce EN. Diagnosis and management of thyrotoxicosis. BMJ 2006;332:1369-73, or Lazarus JH. Hyperthyroidism. Lancet 1997;349:339-43.

- Geracioti TD Jr. Identifying hypothyroidism’s psychiatric presentations. Current Psychiatry 2006;5(11):98-117.

- Bauer M, Heinz A, Whybrow PC. Thyroid hormones, serotonin and mood: of synergy and significance in the adult brain. Molecular Psychiatry 2002;7:140-56.

Drug brand names

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Lithium • Lithobid, others

- Levothyroxine • Synthroid, others

- Prednisone • Various brands

- Propranolol • Inderal

- Zolpidem • Ambien

Disclosures

Dr. Geracioti reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Sakurai A, Nakai A, DeGroot LJ. Expression of three forms of thyroid hormone receptor in human tissues. Mol Endocrinol 1989;3:392-9.

2. Shahrara S, Drvota V, Sylven C. Organ specific expression of thyroid hormone receptor mRNA and protein in different human tissues. Biol Pharm Bull 1999;22:1027-33.

3. Geracioti TD, Jr. How to identify hypothyroidism’s psychiatric presentations. Current Psychiatry 2006;5(11):98-117.

4. Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, Flanders WD, et al. Serum TSH, T(4), and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:489-99.

5. Bianchi GP, Zaccheroni V, Vescini F, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with thyroid disorders. Qual Life Res 2004;13:45-54.

6. Thomsen AF, Kvist TK, Andersen OK, Kessing LV. Increased risk of affective disorder following hospitalization with hyperthyroidism—a register-based study. Eur J Endocrinol 2005;152:535-43.

7. Grabe HJ, Volzke H, Ludermann J, et al. Mental and physical complaints in thyroid disorders in the general population. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2005;112:286-93.

8. Kathol RG, Delahunt JW. The relationship of anxiety and depression to symptoms of hyperthyroidism using operational criteria. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1986;8:23-8.

9. Trzepacz PT, McCue M, Klein I, et al. A psychiatric and neuropsychological study of patients with untreated Graves’ disease. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1988;10:49-55.

10. Bunevicius R, Velickiene D, Prange AJ, Jr. Mood and anxiety disorders in women with treated hyperthyroidism and ophthalmopathy caused by Graves’ disease. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2005;27:133-9.

11. Larson PR, Davies TF, Hay ID. The thyroid gland. In: Wilson JD, Forster DW, Kronenberg HM, Larsen PR eds. Williams textbook of endocrinology. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders;1998:389-515.

12. Matsubayashi S, Tamai H, Matsumoto Y, et al. Graves’ disease after the onset of panic disorder. Psychother Psychosom 1996;65(5):277-80.

13. Lazarus JH. Hyperthyroidism. Lancet 1997;349:339-43.

14. Pearce EN. Diagnosis and management of thyrotoxicosis. BMJ 2006;332:1369-73.

15. Utiger RD. The thyroid: physiology, thyrotoxicosis, hypothyroidism, and the painful thyroid. In: Felig P, Frohman LA, eds. Endocrinology and metabolism, 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2001:261-347.

16. Beckers A, Abs R, Mahler C, et al. Thyrotropin-secreting pituitary adenomas: report of seven cases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1991;72:477-83.

17. Kinder BK, Burrow GN. The thyroid: nodules and neoplasiaIn: Felig P, Frohman LA eds. Endocrinology and metabolism, 4th ed New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2001:349-383.

18. Prange AJ, Jr, Wilson IC, Rabon AM, Lipton MA. Enhancement of imipramine antidepressant activity by thyroid hormone. Am J Psychiatry 1969;126:457-69.

19. Geracioti TD, Jr, Loosen PT, Gold PW, Kling MA. Cortisol, thyroid hormone, and mood in atypical depression: a longitudinal case study. Biol Psychiatry 1992;31:515-9.

20. Geracioti TD, Kling MA, Post R, Gold PW. Antithyroid antibody-linked symptoms in borderline personality disorder. Endocrine 2003;21:153-8.

21. Bocchetta A, Mossa P, Velluzzi F, et al. Ten-year follow-up of thyroid function in lithium patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2001;21:594-8.

Ms. A experienced an anxiety attack while driving home from work, with cardiac palpitations, tingling of the face, and fear of impending doom. Over the following 3 months she endured a “living hell,” consisting of basal anxiety, intermittent panic attacks, and agoraphobia, with exceptional difficulty even going to the grocery store.

A high-functioning career woman in her 30s, Ms. A also developed insomnia, depressed mood, and intrusive ego-dystonic thoughts. These symptoms emerged 10 years after a subtotal thyroidectomy for hyperthyroidism (Graves’ disease).

Hyperthyroidism’s association with psychiatric-spectrum symptoms is well-recognized (Box 1).1-4 Hyperthyroid patients are significantly more likely than controls to report feelings of isolation, impaired social functioning, anxiety, and mood disturbances5 and are more likely to be hospitalized with an affective disorder.6

Other individuals with subclinical or overt biochemical hyperthyroidism self-report above-average mood and lower-than-average anxiety.7

Ms. A’s is the first of three cases presented here to help you screen for and identify thyrotoxicosis (thyroid and nonthyroid causes of excessive thyroid hormone). Cases include:

- recurrent Graves’ disease with panic disorder and residual obsessive-compulsive disorder (Ms. A)

- undetected Graves’ hyperthyroidism in a bipolar-like mood syndrome with severe anxiety and cognitive decline (Ms. B)

- occult hyperthyroidism with occult anxiety (Mr. C).

These cases show that even when biochemical euthyroidism is restored, many formerly hyperthyroid patients with severe mood, anxiety, and/or cognitive symptoms continue to have significant residual symptoms that require ongoing psychiatric attention.6

Ms. A: Anxiety and thyrotoxicosis

Ms. A was greatly troubled by her intrusive ego-dystonic thoughts, which involved:

- violence to her beloved young children (for example, what would happen if someone started shooting her children with a gun)

- bizarre sexual ideations (for example, during dinner with an elderly woman she could not stop imagining her naked)

- paranoid ideations (for example, “Is my husband poisoning me?”).

She consulted a psychologist who told her that she suffered from an anxiety disorder and recommended psychotherapy, which was not helpful. She then sought endocrine consultation, and tests showed low-grade overt hyperthyroidism, with unmeasurably low thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) concentrations and marginally elevated total and free levothyroxine (T4). Her levothyroxine replacement dosage was reduced from 100 to 50 mcg/d, then discontinued.

Without thyroid supplementation or replacement, she became biochemically euthyroid, with TSH 1.47 mIU/L and triiodothyronine (T3) and T4 in mid-normal range. Her panic anxiety resolved and her mood and sleep normalized, but the bizarre thoughts remained. The endocrinologist referred her to a psychiatrist, who diagnosed obsessive-compulsive disorder. Ms. A was effectively treated with fluvoxamine, 125 mg/d.

Discussion. Many patients with hyperthyroidism suffer from anxiety syndromes,8-10 including generalized anxiety disorder and social phobia (Table 1). “Nervousness” (including “feelings of apprehension and inability to concentrate”) is almost invariably present in the thyrotoxicosis of Graves’ disease.11

Hyperthyroidism-related anxiety syndromes are typically complicated by major depression and cognitive decline, such as in memory and attention.9 Thus, a pituitary-thyroid workup is an important step in the psychiatric evaluation of any patient with clinically significant anxiety (Box 2).3

The brain has among the highest expression of thyroid hormone receptors of any organ,1,2 and neurons are often more sensitive to thyroid abnormalities—including overt or subclinical hyperthyroidism and thyrotoxicosis, thyroiditis, and hypothyroidism3—than are other tissues.

Hyperthyroidism is often associated with anxiety, depression, mixed mood disorders, a hypomanic-like picture, emotional lability, mood swings, irritability/edginess, or cognitive deterioration with concentration problems. It also can manifest as psychosis or delirium.

Hyperthyroidism affects approximately 2.5% of the U.S. population (~7.5 million persons), according to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). One-half of those afflicted (1.3%) do not know they are hyperthyroid, including 0.5% with overt symptoms and 0.8% with subclinical disease.

NHANES III defined hyperthyroidism as thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) <0.1 mIU/L with total thyroxine (T4) levels either elevated (overt hyperthyroidism) or normal (subclinical hyperthyroidism). Women are at least 5 times more likely than men to be hyperthyroid.4

CNS hypersensitivity to low-grade hyperthyroidism can manifest as an anxiety disorder before other Graves’ disease stigmata emerge. Panic disorder, for example, has been reported to precede Graves’ hyperthyroidism by 4 to 5 years in some cases,12 although how frequently this occurs is not known. Therefore, re-evaluate the thyroid status of any patient with severe anxiety who is biochemically euthyroid. Check yearly, for example, if anxiety is incompletely resolved.

Table 1

Psychiatric symptoms seen with hyperthyroidism

| Anxiety |

| Apathy (more often seen in older patients) |

| Cognitive impairment |

| Delirium |

| Depression |

| Emotional lability |

| Fatigue |

| Hypomania or mania |

| Impaired concentration |

| Insomnia |

| Irritability |

| Mood swings |

| Psychomotor agitation |

| Psychosis |

Causes of hyperthyroidism

Approximately 20 causes of thyrotoxicosis and hyperthyroxinemia have been characterized (see Related resources).11,13-15 The most common causes of hyperthyroidism are Graves’ disease, toxic multinodular goiter, and toxic thyroid adenoma. Another is thyroiditis, such as from lithium or iodine excess (such as from the cardiac drug amiodarone). A TSH-secreting pituitary adenoma is a rare cause of hyperthyroidism.16

A drug-induced thyrotoxic state can be seen with excess administration of exogenous thyroid hormone. This condition usually occurs inadvertently but is sometimes intentional, as in factitious disorder or malingering.

Graves’ disease is an autoimmune disorder that occurs when antibodies (thyroid-stimulating hormone immunoglobulins) stimulate thyroid TSH receptors, increasing thyroid hormone synthesis and secretion. Graves’ disease—seen in 60% to 85% of patients with thyrotoxicosis—is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism.15

Patients most often are women of childbearing years to middle age. Exophthalmos and other eye changes are common, along with diffuse goiter. Encephalopathy can be seen in Graves’ disease and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis because the brain can become an antibody target in autoimmune disorders.

Toxic multinodular goiter consists of autonomously functioning, circumscribed thyroid nodules with an enlarged (goitrous) thyroid, that typically emerge at length from simple (nontoxic) goiter—characterized by enlarged thyroid but normal thyroid-related biochemistry. Onset is typically later in life than Graves’ disease.11,17

Thyrotoxicosis is often relatively mild in toxic multinodular goiter, with marginal elevations in T4 and/or T3. Unlike in Graves’ disease, ophthalmologic changes are unusual. Tachycardia and weakness are common (Table 2).

Table 2

Nonpsychiatric symptoms seen with hyperthyroidism

| Metabolic |

| Heat intolerance (cold tolerance) |

| Increased perspiration |

| Weight loss (despite good appetite) |

| Endocrinologic |

| Goiter (enlarged thyroid gland) |

| Ophthalmologic |

| Exophthalmos |

| Lid lag |

| Stare/infrequent blinking |

| Ophthalmoplegia |

| Neurologic |

| Tremor |

| Hyperreflexia |

| Motor restlessness |

| Proximal muscle weakness/myopathy |

| Cardiologic |

| Tachycardia |

| Palpitations |

| Arrhythmia |

| Worsening or precipitation of angina, heart failure |

| Sexual |

| Oligomenorrhea/amenorrhea |

| Rapid ejaculation |

| Dermatologic |

| Warm, moist skin |

| Fine hair |

| Velvety skin texture |

| Onycholysis |

| Myxedema/leg swelling |

| Ruddy or erythemic skin/facial flushing |

| Eyelash loss |

| Hair loss |

| Premature graying (Graves’ disease) |

| Pruritus |

| Gastrointestinal |

| Frequent bowel movements |

| Diarrhea |

| Nausea |

| Orthopedic |

| Osteopenia or osteoporosis |

Adenomas. Toxic thyroid adenoma is a hyperfunctioning (“toxic”) benign tumor of the thyroid follicular cell. A TSH-secreting pituitary adenoma is a rare cause of hyperthyroidism.16

Thyroid storm is a rare, life-threatening thyrotoxicosis, usually seen in medical or surgical patients. Symptoms include fever, tachycardia, hypotension, irritability and restlessness, nausea and vomiting, delirium, and possibly coma.

Psychiatrists rarely see these cases, but propranolol (40 mg initial dose), fluids, and swift transport to an emergency room or critical care unit are indicated. Antithyroid agents and glucocorticoids are the usual treatment.

Thyrotoxic symptoms from thyroid hormone therapy. Thyroid hormone has been used in psychiatric patients as an antidepressant supplement,18 with therapeutic benefit reported to range from highly valuable19 to modestly helpful or no effect.20 In some patients thyroid hormone causes thyrotoxic symptoms such as tachycardia, gross tremulousness, restlessness, anxiety, inability to sleep, and impaired concentration.

Patients newly diagnosed with hypothyroidism can be exquisitely sensitive to exogenous thyroid hormone and develop acute thyrotoxic symptoms. When this occurs, a more measured titration of thyroid dose is indicated, rather than discontinuing hormone therapy. For example, patients whose optimal maintenance levothyroxine dosage proves to be >100 mcg/d might do better by first adapting to 75 mcg/d.

Thyroid hormone replacement can increase demand on the adrenal glands of chronically hypothyroid patients. For those who develop thyrotoxic-like symptoms, a pulse of glucocorticoids—such as a single 20-mg dose of prednisone (2 to 3 times the typical daily glucocorticoid maintenance requirement)—is sometimes very helpful. Severe eye pain and periorbital edema has been reported to respond to prednisone doses of 120 mg/d.13

Serum TSH is a sensitive screen. Low (<0.1 mIU/mL) or immeasurably low (<0.05 mIU/mL) circulating TSH usually means hyperthyroidism. A TSH screen is not foolproof, however; very low TSH can be seen with low circulating thyroid hormones in central hypothyroidism or in cases of laboratory error.

The recommended routine initial screen of the pituitary-thyroid axis in psychiatric patients includes TSH, free T4, and possibly free T3.3 Suppressed TSH with high serum free T3 and/or free T4 (accompanied by high total T4 and/or T3) is diagnostic of frank biochemical hyperthyroidism. If circulating thyroid hormone concentrations are normal, hyperthyroidism is considered compensated or subclinical. Although only free thyroid hormones are active, total T4 and total T3 are of interest to grossly estimate thyroid hormone output.

When you identify a thyrotoxic state, refer the patient for an endocrinologic evaluation. Antithyroid antibodies are often positive in Graves’ disease, but anti-TSH antibodies (which can be routinely ordered) are particularly diagnostic. If thyroid dysfunction is present—especially if autoimmune-based—screening tests are indicated to rule out adrenal, gonadal, and pancreatic (glucose regulation) dysfunction.

Ms. B: Hyperthyroidism and mood

Ms. B, age 35, an energetic clerical worker and fitness devotee, developed severe insomnia. She slept no more than 1 hour per night, with irritability, verbal explosiveness, “hot flashes,” and depressed mood. “Everything pisses me off violently,” she said.

She consulted a psychiatrist and was diagnosed with major depression. Over a period of years, she was serially prescribed selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and older-generation sedating agents including trazodone and amitriptyline. She tolerated none of these because of side effects, including dysphoric hyperarousal and cognitive disruption.

“They all made me stupid,” she complained.

Zolpidem, 20 mg at night, helped temporarily as a hypnotic, but insomnia recurred within weeks. Diazepam was effective at high dosages but also dulled her cognition. The psychiatrist did not suspect a thyroid abnormality and did not perform a pituitary-thyroid laboratory evaluation.

Ms. B consulted a gynecologist, who prescribed estrogen for borderline low estradiol levels and with the hope that Ms. B’s symptoms represented early menopause. This partially ameliorated her irritability, possibly because estradiol binding of circulating T4 reduced free thyroid hormone levels.

Ms. B tried to continue working and exercising, but within 4 years her symptoms progressed to severe depression with frequent crying spells, feelings of general malaise, excessive sweating, occasional panic attacks, fatigue, sleepiness, deteriorating vision, and cognitive impairment. She struggled to read printed words and eventually took sick leave while consulting with physicians.

Finally, a routine thyroid screen before minor surgery revealed an undetectable TSH concentration. Further testing showed elevated thyroxine consistent with thyrotoxicosis. Graves’ disease was diagnosed, and euthyroidism was established with antithyroid medication.

Residual mood and anxiety symptoms persisted 1 year after euthyroidism was restored, and Ms. B sought psychiatric consultation.

Discussion. Hyperthyroidism can trigger or present as a hypomania or manic-like state, characterized by increased energy, hyperactivity, racing thoughts, hair-trigger verbal explosiveness, and decreased need for sleep.

Hypertalkativeness is common, even without pressured speech, as is irritability. Mood may be elevated, depressed, mixed, or cycling. A hyperthyroidism-related mixed syndrome of depression and hypomania can be confounding.

Mr. C: Occult hyperthyroidism

Mr. C, age 26, was apparently healthy when he was admitted into a neuroendocrine research protocol as a volunteer. His job performance was excellent, and his interactions with others were good; he was in good general health and taking no medication.

Formal psychiatric screening found no history of psychiatric disorders in Mr. C nor his family. His mental status was within normal limits. Physical exam revealed no significant abnormality. He was afebrile, normotensive, and had a resting pulse of 81 bpm.

His neurologic status was unremarkable, and laboratory screening tests showed normal CBC, liver and renal profiles, glucose, platelets and clotting times. Tests during the study, however, showed frankly elevated T4, free thyroxine (FT4), and T3 concentrations, along with undetectable TSH. Mr. C was informed of these results and referred to an endocrinologist.

Graves’ disease was diagnosed, and Mr. C received partial thyroid ablation therapy. He later reported that he had never felt better. In retrospect, he realized he had been anxious before he was treated for hyperthyroidism because he felt much more relaxed and able to concentrate after treatment.

Discussion. Subjective well-being in a patient with occult biochemical thyrotoxicosis can be misleading. Mr. C was much less anxious and able to concentrate after his return to euthyroidism.

Treatment

Refer your hyperthyroid patients to an endocrinologist for further workup and, in most cases, management. Hyperthyroidism is usually easy to treat using a form of ablation (antithyroid drugs, radioactive iodine, or partial thyroidectomy).

Remain involved in the patient’s care when psychiatric symptoms are prominent, however, as they are likely to persist even after thyrotoxicosis is corrected.6 Reasonable interventions include:

- control of acute thyrotoxic symptoms such as palpitations and tremulousness with propranolol, 20 to 40 mg as needed, or a 20-mg bolus of prednisone (especially if thyroiditis is present)

- address mood cycling, depression, edginess, anxiety, lability, insomnia, and/or irritability with lithium3

- oversee smoking cessation in patients with Graves’ disease (smoking exacerbates the autoimmune pathology).

Address and correct hyperthyroidism that is artifactual (caused by overuse or secret use by a patient) or iatrogenic (related to excessive prescribed hormone dosages).

Subclinical hyperthyroidism can be transient and resolve without treatment. Lithium can be helpful when a mood disorder coexists with sub clinical hyperthyroidism. Start with 300 to 600 mg every evening with dinner. If the mood disorder is mild, even as little as 300 to 450 mg of lithium may elevate a depressed mood and remove edginess and irritability.

Lithium is antithyroid, decreases thyroid hormone output, and increases serum TSH within 24 hours of initiation, but it can provoke autoimmune hyperthyroidism in some individuals.21

- For comprehensive tables of hyperthyroidism’s causes, refer to Pearce EN. Diagnosis and management of thyrotoxicosis. BMJ 2006;332:1369-73, or Lazarus JH. Hyperthyroidism. Lancet 1997;349:339-43.

- Geracioti TD Jr. Identifying hypothyroidism’s psychiatric presentations. Current Psychiatry 2006;5(11):98-117.

- Bauer M, Heinz A, Whybrow PC. Thyroid hormones, serotonin and mood: of synergy and significance in the adult brain. Molecular Psychiatry 2002;7:140-56.

Drug brand names

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Lithium • Lithobid, others

- Levothyroxine • Synthroid, others

- Prednisone • Various brands

- Propranolol • Inderal

- Zolpidem • Ambien

Disclosures

Dr. Geracioti reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Ms. A experienced an anxiety attack while driving home from work, with cardiac palpitations, tingling of the face, and fear of impending doom. Over the following 3 months she endured a “living hell,” consisting of basal anxiety, intermittent panic attacks, and agoraphobia, with exceptional difficulty even going to the grocery store.

A high-functioning career woman in her 30s, Ms. A also developed insomnia, depressed mood, and intrusive ego-dystonic thoughts. These symptoms emerged 10 years after a subtotal thyroidectomy for hyperthyroidism (Graves’ disease).

Hyperthyroidism’s association with psychiatric-spectrum symptoms is well-recognized (Box 1).1-4 Hyperthyroid patients are significantly more likely than controls to report feelings of isolation, impaired social functioning, anxiety, and mood disturbances5 and are more likely to be hospitalized with an affective disorder.6

Other individuals with subclinical or overt biochemical hyperthyroidism self-report above-average mood and lower-than-average anxiety.7

Ms. A’s is the first of three cases presented here to help you screen for and identify thyrotoxicosis (thyroid and nonthyroid causes of excessive thyroid hormone). Cases include:

- recurrent Graves’ disease with panic disorder and residual obsessive-compulsive disorder (Ms. A)

- undetected Graves’ hyperthyroidism in a bipolar-like mood syndrome with severe anxiety and cognitive decline (Ms. B)

- occult hyperthyroidism with occult anxiety (Mr. C).

These cases show that even when biochemical euthyroidism is restored, many formerly hyperthyroid patients with severe mood, anxiety, and/or cognitive symptoms continue to have significant residual symptoms that require ongoing psychiatric attention.6

Ms. A: Anxiety and thyrotoxicosis

Ms. A was greatly troubled by her intrusive ego-dystonic thoughts, which involved:

- violence to her beloved young children (for example, what would happen if someone started shooting her children with a gun)

- bizarre sexual ideations (for example, during dinner with an elderly woman she could not stop imagining her naked)

- paranoid ideations (for example, “Is my husband poisoning me?”).

She consulted a psychologist who told her that she suffered from an anxiety disorder and recommended psychotherapy, which was not helpful. She then sought endocrine consultation, and tests showed low-grade overt hyperthyroidism, with unmeasurably low thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) concentrations and marginally elevated total and free levothyroxine (T4). Her levothyroxine replacement dosage was reduced from 100 to 50 mcg/d, then discontinued.

Without thyroid supplementation or replacement, she became biochemically euthyroid, with TSH 1.47 mIU/L and triiodothyronine (T3) and T4 in mid-normal range. Her panic anxiety resolved and her mood and sleep normalized, but the bizarre thoughts remained. The endocrinologist referred her to a psychiatrist, who diagnosed obsessive-compulsive disorder. Ms. A was effectively treated with fluvoxamine, 125 mg/d.

Discussion. Many patients with hyperthyroidism suffer from anxiety syndromes,8-10 including generalized anxiety disorder and social phobia (Table 1). “Nervousness” (including “feelings of apprehension and inability to concentrate”) is almost invariably present in the thyrotoxicosis of Graves’ disease.11

Hyperthyroidism-related anxiety syndromes are typically complicated by major depression and cognitive decline, such as in memory and attention.9 Thus, a pituitary-thyroid workup is an important step in the psychiatric evaluation of any patient with clinically significant anxiety (Box 2).3

The brain has among the highest expression of thyroid hormone receptors of any organ,1,2 and neurons are often more sensitive to thyroid abnormalities—including overt or subclinical hyperthyroidism and thyrotoxicosis, thyroiditis, and hypothyroidism3—than are other tissues.

Hyperthyroidism is often associated with anxiety, depression, mixed mood disorders, a hypomanic-like picture, emotional lability, mood swings, irritability/edginess, or cognitive deterioration with concentration problems. It also can manifest as psychosis or delirium.

Hyperthyroidism affects approximately 2.5% of the U.S. population (~7.5 million persons), according to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). One-half of those afflicted (1.3%) do not know they are hyperthyroid, including 0.5% with overt symptoms and 0.8% with subclinical disease.

NHANES III defined hyperthyroidism as thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) <0.1 mIU/L with total thyroxine (T4) levels either elevated (overt hyperthyroidism) or normal (subclinical hyperthyroidism). Women are at least 5 times more likely than men to be hyperthyroid.4

CNS hypersensitivity to low-grade hyperthyroidism can manifest as an anxiety disorder before other Graves’ disease stigmata emerge. Panic disorder, for example, has been reported to precede Graves’ hyperthyroidism by 4 to 5 years in some cases,12 although how frequently this occurs is not known. Therefore, re-evaluate the thyroid status of any patient with severe anxiety who is biochemically euthyroid. Check yearly, for example, if anxiety is incompletely resolved.

Table 1

Psychiatric symptoms seen with hyperthyroidism

| Anxiety |

| Apathy (more often seen in older patients) |

| Cognitive impairment |

| Delirium |

| Depression |

| Emotional lability |

| Fatigue |

| Hypomania or mania |

| Impaired concentration |

| Insomnia |

| Irritability |

| Mood swings |

| Psychomotor agitation |

| Psychosis |

Causes of hyperthyroidism

Approximately 20 causes of thyrotoxicosis and hyperthyroxinemia have been characterized (see Related resources).11,13-15 The most common causes of hyperthyroidism are Graves’ disease, toxic multinodular goiter, and toxic thyroid adenoma. Another is thyroiditis, such as from lithium or iodine excess (such as from the cardiac drug amiodarone). A TSH-secreting pituitary adenoma is a rare cause of hyperthyroidism.16

A drug-induced thyrotoxic state can be seen with excess administration of exogenous thyroid hormone. This condition usually occurs inadvertently but is sometimes intentional, as in factitious disorder or malingering.

Graves’ disease is an autoimmune disorder that occurs when antibodies (thyroid-stimulating hormone immunoglobulins) stimulate thyroid TSH receptors, increasing thyroid hormone synthesis and secretion. Graves’ disease—seen in 60% to 85% of patients with thyrotoxicosis—is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism.15

Patients most often are women of childbearing years to middle age. Exophthalmos and other eye changes are common, along with diffuse goiter. Encephalopathy can be seen in Graves’ disease and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis because the brain can become an antibody target in autoimmune disorders.

Toxic multinodular goiter consists of autonomously functioning, circumscribed thyroid nodules with an enlarged (goitrous) thyroid, that typically emerge at length from simple (nontoxic) goiter—characterized by enlarged thyroid but normal thyroid-related biochemistry. Onset is typically later in life than Graves’ disease.11,17

Thyrotoxicosis is often relatively mild in toxic multinodular goiter, with marginal elevations in T4 and/or T3. Unlike in Graves’ disease, ophthalmologic changes are unusual. Tachycardia and weakness are common (Table 2).

Table 2

Nonpsychiatric symptoms seen with hyperthyroidism

| Metabolic |

| Heat intolerance (cold tolerance) |

| Increased perspiration |

| Weight loss (despite good appetite) |

| Endocrinologic |

| Goiter (enlarged thyroid gland) |

| Ophthalmologic |

| Exophthalmos |

| Lid lag |

| Stare/infrequent blinking |

| Ophthalmoplegia |

| Neurologic |

| Tremor |

| Hyperreflexia |

| Motor restlessness |

| Proximal muscle weakness/myopathy |

| Cardiologic |

| Tachycardia |

| Palpitations |

| Arrhythmia |

| Worsening or precipitation of angina, heart failure |

| Sexual |

| Oligomenorrhea/amenorrhea |

| Rapid ejaculation |

| Dermatologic |

| Warm, moist skin |

| Fine hair |

| Velvety skin texture |

| Onycholysis |

| Myxedema/leg swelling |

| Ruddy or erythemic skin/facial flushing |

| Eyelash loss |

| Hair loss |

| Premature graying (Graves’ disease) |

| Pruritus |

| Gastrointestinal |

| Frequent bowel movements |

| Diarrhea |

| Nausea |

| Orthopedic |

| Osteopenia or osteoporosis |

Adenomas. Toxic thyroid adenoma is a hyperfunctioning (“toxic”) benign tumor of the thyroid follicular cell. A TSH-secreting pituitary adenoma is a rare cause of hyperthyroidism.16

Thyroid storm is a rare, life-threatening thyrotoxicosis, usually seen in medical or surgical patients. Symptoms include fever, tachycardia, hypotension, irritability and restlessness, nausea and vomiting, delirium, and possibly coma.

Psychiatrists rarely see these cases, but propranolol (40 mg initial dose), fluids, and swift transport to an emergency room or critical care unit are indicated. Antithyroid agents and glucocorticoids are the usual treatment.

Thyrotoxic symptoms from thyroid hormone therapy. Thyroid hormone has been used in psychiatric patients as an antidepressant supplement,18 with therapeutic benefit reported to range from highly valuable19 to modestly helpful or no effect.20 In some patients thyroid hormone causes thyrotoxic symptoms such as tachycardia, gross tremulousness, restlessness, anxiety, inability to sleep, and impaired concentration.

Patients newly diagnosed with hypothyroidism can be exquisitely sensitive to exogenous thyroid hormone and develop acute thyrotoxic symptoms. When this occurs, a more measured titration of thyroid dose is indicated, rather than discontinuing hormone therapy. For example, patients whose optimal maintenance levothyroxine dosage proves to be >100 mcg/d might do better by first adapting to 75 mcg/d.

Thyroid hormone replacement can increase demand on the adrenal glands of chronically hypothyroid patients. For those who develop thyrotoxic-like symptoms, a pulse of glucocorticoids—such as a single 20-mg dose of prednisone (2 to 3 times the typical daily glucocorticoid maintenance requirement)—is sometimes very helpful. Severe eye pain and periorbital edema has been reported to respond to prednisone doses of 120 mg/d.13

Serum TSH is a sensitive screen. Low (<0.1 mIU/mL) or immeasurably low (<0.05 mIU/mL) circulating TSH usually means hyperthyroidism. A TSH screen is not foolproof, however; very low TSH can be seen with low circulating thyroid hormones in central hypothyroidism or in cases of laboratory error.

The recommended routine initial screen of the pituitary-thyroid axis in psychiatric patients includes TSH, free T4, and possibly free T3.3 Suppressed TSH with high serum free T3 and/or free T4 (accompanied by high total T4 and/or T3) is diagnostic of frank biochemical hyperthyroidism. If circulating thyroid hormone concentrations are normal, hyperthyroidism is considered compensated or subclinical. Although only free thyroid hormones are active, total T4 and total T3 are of interest to grossly estimate thyroid hormone output.

When you identify a thyrotoxic state, refer the patient for an endocrinologic evaluation. Antithyroid antibodies are often positive in Graves’ disease, but anti-TSH antibodies (which can be routinely ordered) are particularly diagnostic. If thyroid dysfunction is present—especially if autoimmune-based—screening tests are indicated to rule out adrenal, gonadal, and pancreatic (glucose regulation) dysfunction.

Ms. B: Hyperthyroidism and mood

Ms. B, age 35, an energetic clerical worker and fitness devotee, developed severe insomnia. She slept no more than 1 hour per night, with irritability, verbal explosiveness, “hot flashes,” and depressed mood. “Everything pisses me off violently,” she said.

She consulted a psychiatrist and was diagnosed with major depression. Over a period of years, she was serially prescribed selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and older-generation sedating agents including trazodone and amitriptyline. She tolerated none of these because of side effects, including dysphoric hyperarousal and cognitive disruption.

“They all made me stupid,” she complained.

Zolpidem, 20 mg at night, helped temporarily as a hypnotic, but insomnia recurred within weeks. Diazepam was effective at high dosages but also dulled her cognition. The psychiatrist did not suspect a thyroid abnormality and did not perform a pituitary-thyroid laboratory evaluation.

Ms. B consulted a gynecologist, who prescribed estrogen for borderline low estradiol levels and with the hope that Ms. B’s symptoms represented early menopause. This partially ameliorated her irritability, possibly because estradiol binding of circulating T4 reduced free thyroid hormone levels.

Ms. B tried to continue working and exercising, but within 4 years her symptoms progressed to severe depression with frequent crying spells, feelings of general malaise, excessive sweating, occasional panic attacks, fatigue, sleepiness, deteriorating vision, and cognitive impairment. She struggled to read printed words and eventually took sick leave while consulting with physicians.

Finally, a routine thyroid screen before minor surgery revealed an undetectable TSH concentration. Further testing showed elevated thyroxine consistent with thyrotoxicosis. Graves’ disease was diagnosed, and euthyroidism was established with antithyroid medication.

Residual mood and anxiety symptoms persisted 1 year after euthyroidism was restored, and Ms. B sought psychiatric consultation.

Discussion. Hyperthyroidism can trigger or present as a hypomania or manic-like state, characterized by increased energy, hyperactivity, racing thoughts, hair-trigger verbal explosiveness, and decreased need for sleep.

Hypertalkativeness is common, even without pressured speech, as is irritability. Mood may be elevated, depressed, mixed, or cycling. A hyperthyroidism-related mixed syndrome of depression and hypomania can be confounding.

Mr. C: Occult hyperthyroidism

Mr. C, age 26, was apparently healthy when he was admitted into a neuroendocrine research protocol as a volunteer. His job performance was excellent, and his interactions with others were good; he was in good general health and taking no medication.

Formal psychiatric screening found no history of psychiatric disorders in Mr. C nor his family. His mental status was within normal limits. Physical exam revealed no significant abnormality. He was afebrile, normotensive, and had a resting pulse of 81 bpm.

His neurologic status was unremarkable, and laboratory screening tests showed normal CBC, liver and renal profiles, glucose, platelets and clotting times. Tests during the study, however, showed frankly elevated T4, free thyroxine (FT4), and T3 concentrations, along with undetectable TSH. Mr. C was informed of these results and referred to an endocrinologist.

Graves’ disease was diagnosed, and Mr. C received partial thyroid ablation therapy. He later reported that he had never felt better. In retrospect, he realized he had been anxious before he was treated for hyperthyroidism because he felt much more relaxed and able to concentrate after treatment.

Discussion. Subjective well-being in a patient with occult biochemical thyrotoxicosis can be misleading. Mr. C was much less anxious and able to concentrate after his return to euthyroidism.

Treatment

Refer your hyperthyroid patients to an endocrinologist for further workup and, in most cases, management. Hyperthyroidism is usually easy to treat using a form of ablation (antithyroid drugs, radioactive iodine, or partial thyroidectomy).

Remain involved in the patient’s care when psychiatric symptoms are prominent, however, as they are likely to persist even after thyrotoxicosis is corrected.6 Reasonable interventions include:

- control of acute thyrotoxic symptoms such as palpitations and tremulousness with propranolol, 20 to 40 mg as needed, or a 20-mg bolus of prednisone (especially if thyroiditis is present)

- address mood cycling, depression, edginess, anxiety, lability, insomnia, and/or irritability with lithium3

- oversee smoking cessation in patients with Graves’ disease (smoking exacerbates the autoimmune pathology).

Address and correct hyperthyroidism that is artifactual (caused by overuse or secret use by a patient) or iatrogenic (related to excessive prescribed hormone dosages).

Subclinical hyperthyroidism can be transient and resolve without treatment. Lithium can be helpful when a mood disorder coexists with sub clinical hyperthyroidism. Start with 300 to 600 mg every evening with dinner. If the mood disorder is mild, even as little as 300 to 450 mg of lithium may elevate a depressed mood and remove edginess and irritability.

Lithium is antithyroid, decreases thyroid hormone output, and increases serum TSH within 24 hours of initiation, but it can provoke autoimmune hyperthyroidism in some individuals.21

- For comprehensive tables of hyperthyroidism’s causes, refer to Pearce EN. Diagnosis and management of thyrotoxicosis. BMJ 2006;332:1369-73, or Lazarus JH. Hyperthyroidism. Lancet 1997;349:339-43.

- Geracioti TD Jr. Identifying hypothyroidism’s psychiatric presentations. Current Psychiatry 2006;5(11):98-117.

- Bauer M, Heinz A, Whybrow PC. Thyroid hormones, serotonin and mood: of synergy and significance in the adult brain. Molecular Psychiatry 2002;7:140-56.

Drug brand names

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Lithium • Lithobid, others

- Levothyroxine • Synthroid, others

- Prednisone • Various brands

- Propranolol • Inderal

- Zolpidem • Ambien

Disclosures

Dr. Geracioti reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Sakurai A, Nakai A, DeGroot LJ. Expression of three forms of thyroid hormone receptor in human tissues. Mol Endocrinol 1989;3:392-9.

2. Shahrara S, Drvota V, Sylven C. Organ specific expression of thyroid hormone receptor mRNA and protein in different human tissues. Biol Pharm Bull 1999;22:1027-33.

3. Geracioti TD, Jr. How to identify hypothyroidism’s psychiatric presentations. Current Psychiatry 2006;5(11):98-117.

4. Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, Flanders WD, et al. Serum TSH, T(4), and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:489-99.

5. Bianchi GP, Zaccheroni V, Vescini F, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with thyroid disorders. Qual Life Res 2004;13:45-54.

6. Thomsen AF, Kvist TK, Andersen OK, Kessing LV. Increased risk of affective disorder following hospitalization with hyperthyroidism—a register-based study. Eur J Endocrinol 2005;152:535-43.

7. Grabe HJ, Volzke H, Ludermann J, et al. Mental and physical complaints in thyroid disorders in the general population. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2005;112:286-93.

8. Kathol RG, Delahunt JW. The relationship of anxiety and depression to symptoms of hyperthyroidism using operational criteria. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1986;8:23-8.

9. Trzepacz PT, McCue M, Klein I, et al. A psychiatric and neuropsychological study of patients with untreated Graves’ disease. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1988;10:49-55.

10. Bunevicius R, Velickiene D, Prange AJ, Jr. Mood and anxiety disorders in women with treated hyperthyroidism and ophthalmopathy caused by Graves’ disease. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2005;27:133-9.

11. Larson PR, Davies TF, Hay ID. The thyroid gland. In: Wilson JD, Forster DW, Kronenberg HM, Larsen PR eds. Williams textbook of endocrinology. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders;1998:389-515.

12. Matsubayashi S, Tamai H, Matsumoto Y, et al. Graves’ disease after the onset of panic disorder. Psychother Psychosom 1996;65(5):277-80.

13. Lazarus JH. Hyperthyroidism. Lancet 1997;349:339-43.

14. Pearce EN. Diagnosis and management of thyrotoxicosis. BMJ 2006;332:1369-73.

15. Utiger RD. The thyroid: physiology, thyrotoxicosis, hypothyroidism, and the painful thyroid. In: Felig P, Frohman LA, eds. Endocrinology and metabolism, 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2001:261-347.

16. Beckers A, Abs R, Mahler C, et al. Thyrotropin-secreting pituitary adenomas: report of seven cases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1991;72:477-83.

17. Kinder BK, Burrow GN. The thyroid: nodules and neoplasiaIn: Felig P, Frohman LA eds. Endocrinology and metabolism, 4th ed New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2001:349-383.

18. Prange AJ, Jr, Wilson IC, Rabon AM, Lipton MA. Enhancement of imipramine antidepressant activity by thyroid hormone. Am J Psychiatry 1969;126:457-69.

19. Geracioti TD, Jr, Loosen PT, Gold PW, Kling MA. Cortisol, thyroid hormone, and mood in atypical depression: a longitudinal case study. Biol Psychiatry 1992;31:515-9.

20. Geracioti TD, Kling MA, Post R, Gold PW. Antithyroid antibody-linked symptoms in borderline personality disorder. Endocrine 2003;21:153-8.

21. Bocchetta A, Mossa P, Velluzzi F, et al. Ten-year follow-up of thyroid function in lithium patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2001;21:594-8.

1. Sakurai A, Nakai A, DeGroot LJ. Expression of three forms of thyroid hormone receptor in human tissues. Mol Endocrinol 1989;3:392-9.

2. Shahrara S, Drvota V, Sylven C. Organ specific expression of thyroid hormone receptor mRNA and protein in different human tissues. Biol Pharm Bull 1999;22:1027-33.

3. Geracioti TD, Jr. How to identify hypothyroidism’s psychiatric presentations. Current Psychiatry 2006;5(11):98-117.

4. Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, Flanders WD, et al. Serum TSH, T(4), and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:489-99.

5. Bianchi GP, Zaccheroni V, Vescini F, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with thyroid disorders. Qual Life Res 2004;13:45-54.

6. Thomsen AF, Kvist TK, Andersen OK, Kessing LV. Increased risk of affective disorder following hospitalization with hyperthyroidism—a register-based study. Eur J Endocrinol 2005;152:535-43.

7. Grabe HJ, Volzke H, Ludermann J, et al. Mental and physical complaints in thyroid disorders in the general population. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2005;112:286-93.

8. Kathol RG, Delahunt JW. The relationship of anxiety and depression to symptoms of hyperthyroidism using operational criteria. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1986;8:23-8.

9. Trzepacz PT, McCue M, Klein I, et al. A psychiatric and neuropsychological study of patients with untreated Graves’ disease. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1988;10:49-55.

10. Bunevicius R, Velickiene D, Prange AJ, Jr. Mood and anxiety disorders in women with treated hyperthyroidism and ophthalmopathy caused by Graves’ disease. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2005;27:133-9.

11. Larson PR, Davies TF, Hay ID. The thyroid gland. In: Wilson JD, Forster DW, Kronenberg HM, Larsen PR eds. Williams textbook of endocrinology. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders;1998:389-515.

12. Matsubayashi S, Tamai H, Matsumoto Y, et al. Graves’ disease after the onset of panic disorder. Psychother Psychosom 1996;65(5):277-80.

13. Lazarus JH. Hyperthyroidism. Lancet 1997;349:339-43.

14. Pearce EN. Diagnosis and management of thyrotoxicosis. BMJ 2006;332:1369-73.

15. Utiger RD. The thyroid: physiology, thyrotoxicosis, hypothyroidism, and the painful thyroid. In: Felig P, Frohman LA, eds. Endocrinology and metabolism, 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2001:261-347.

16. Beckers A, Abs R, Mahler C, et al. Thyrotropin-secreting pituitary adenomas: report of seven cases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1991;72:477-83.

17. Kinder BK, Burrow GN. The thyroid: nodules and neoplasiaIn: Felig P, Frohman LA eds. Endocrinology and metabolism, 4th ed New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2001:349-383.

18. Prange AJ, Jr, Wilson IC, Rabon AM, Lipton MA. Enhancement of imipramine antidepressant activity by thyroid hormone. Am J Psychiatry 1969;126:457-69.

19. Geracioti TD, Jr, Loosen PT, Gold PW, Kling MA. Cortisol, thyroid hormone, and mood in atypical depression: a longitudinal case study. Biol Psychiatry 1992;31:515-9.

20. Geracioti TD, Kling MA, Post R, Gold PW. Antithyroid antibody-linked symptoms in borderline personality disorder. Endocrine 2003;21:153-8.

21. Bocchetta A, Mossa P, Velluzzi F, et al. Ten-year follow-up of thyroid function in lithium patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2001;21:594-8.

Hospitalist Horoscopes

The Prescriptionist

Birthdate: January 1-February 21

Symbol: Rx

There is a disease for every drug. If it’s new, you’re on it. You’re on the pharmacy and therapeutics committee, and when you get journals you read the ads first. You’ve never met a drug rep you didn’t like. You are willing to experiment on yourself if need be; you would have made a great hippie. You like to hang with double Helixes, but you also like to hang heparin, fentanyl, ephedrine, and anything else that will fit in a bag of D5W.

The Statistician

Birthdate: February 22-April 19 (+/-two days)

Symbol: 1A

Evidence-based medicine is your mantra. You will do nothing without a double-blind, randomized multicenter control study. You are a therapeutic nihilist. You read Sherlock Holmes as a child. As you are reading this, you are wondering why you were assigned this month and how they know that this horoscope is correct. What was the control group? Is it a horoscopic placebo effect? You will submit an article to a major journal and have it rejected because your sample size was too small.

The Sentinel

Birthdate: April 20-May 20

Symbol: The Guardsman

You are always alert, but somehow bad things still happen to your patients. Delirious octogenarians fall out of bed and fracture their femurs; mistaken medications are administered, leading to adverse consequences. You admitted a diabetic patient for a below-the-knee amputation. The surgeon did a wonderful job and took off the left leg—too bad it was the wrong patient. The patient who was due for the amputation had an inadvertent orchiectomy. You cannot stop using abbreviations. A JCAHO survey is in your future; perhaps it is a good time for a vacation.

Hirudis

Birthdate: May 21-June 20

Symbol: The Leach

You love to order tests: CAT scans. PET Scans. Ultrasounds and Dopplers. You want contrast? That’s no problem! We’ll just Mucomyst and bicarb the patient. You especially love phlebotomy. Every patient gets full lab every day. You would not want to miss a drop in hemoglobin, even if you caused it with excessive phlebotomy. If the patient is a tough stick, you’ll give it a try. You once found a vein on a particularly cicatricial heroin addict and you are still talking about it. You love Bela Lugosi movies.

The Chairman

Birthdate: June 21-July 20

Symbol: The Gavel

You love committees. Face it—there is not one you don’t want to be on. You like to know what’s going on and want to be involved. You don’t want someone to surprise you. You prefer to run the meeting and talk more than anyone else. As you read this, you think it could have been written more concisely, and you advise the formation of an ad hoc committee for wordsmithing, after which it will be sent to the communications committee, then on to exec. SHM has a place for you.

Nimbus

Birthdate: July 21–August 20 and August 22–September 20

Symbol: The Black Cloud

When you have been on hospital duty, nobody wants to take over the service from you. You always have the most patients. When you are on nights, you have 27 admissions when other people don’t get any. Your patients always get chest pain as you are about to roll over the pager, and it’s guaranteed not to be gas. Your post-op patients get to the floor very late, and they always have ileus, urinary retention, and delirium. You are paged constantly, even on your day off. The computer system just crashed; you must be on call. Your patients love you because you are always there.

The Dumpster

Birthdate: August 21

Symbol: The Garbage Can

You never mind leaving some work for your colleagues; you would not want them to be bored. You are going on vacation and need to leave early to pack, you have a headache and are home sick, or your dog has the flu, can somebody cover? Your discharge summaries are sketchy; you like to have residents so that they can do your paperwork for you. You are on good terms with Inertias and always seem to be changing call nights with Nimbuses.

The Geneticist

Birthdate: September 21-October 20

Symbol: The Double Helix

Face it—you’re twisted, dude. You like things to align nicely; your clothing always matches your shoes. You love consanguinity and the interesting diseases that develop. Nobody knows what you are talking about at parties. You hear hoofbeats (it’s not a horse). Bad news: They just discovered that Linus Pauling was right. DNA is a triple helix.

Inertia

Birthdate: October 21–November 19

Symbol: The Snail

You think the world is changing too fast. You were right about HMOs and still think LBJ made a mistake when he signed Medicare into law. When you are on a committee, you always find something that needs a rewrite. You always want a second review.

If it was good enough for you, it’s good enough for those who follow you. You still write notes by hand and are damned if you’ll learn how to operate a computer.

You are a natural bureaucrat. You love to block Chairmen from getting anything done.

The Techie

Birthdate: November 20 at 6 a.m.-December 31 at 11:59p.m.

Symbol: The Palm Pilot

You are first to embrace a new technology. If it’s embedded, you’ll root it out. You get your news from a podcast, and you have a Blackberry and a Blueberry. You don’t understand how anyone could not like having an electronic health record. Your entire medical school education is saved on a memory card, though you are not sure where it is. Your secret shame: Your vintage VCR still has a blinking red light. You get along well with Chairmen as long as they move your technology request through the committees. You would like to see all Inertias implode. TH

Jamie Newman, MD, FACP, is the physician editor of The Hospitalist, consultant, Hospital Internal Medicine, and assistant professor of internal medicine and medical history, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.

The Prescriptionist

Birthdate: January 1-February 21

Symbol: Rx

There is a disease for every drug. If it’s new, you’re on it. You’re on the pharmacy and therapeutics committee, and when you get journals you read the ads first. You’ve never met a drug rep you didn’t like. You are willing to experiment on yourself if need be; you would have made a great hippie. You like to hang with double Helixes, but you also like to hang heparin, fentanyl, ephedrine, and anything else that will fit in a bag of D5W.

The Statistician

Birthdate: February 22-April 19 (+/-two days)

Symbol: 1A

Evidence-based medicine is your mantra. You will do nothing without a double-blind, randomized multicenter control study. You are a therapeutic nihilist. You read Sherlock Holmes as a child. As you are reading this, you are wondering why you were assigned this month and how they know that this horoscope is correct. What was the control group? Is it a horoscopic placebo effect? You will submit an article to a major journal and have it rejected because your sample size was too small.

The Sentinel

Birthdate: April 20-May 20

Symbol: The Guardsman

You are always alert, but somehow bad things still happen to your patients. Delirious octogenarians fall out of bed and fracture their femurs; mistaken medications are administered, leading to adverse consequences. You admitted a diabetic patient for a below-the-knee amputation. The surgeon did a wonderful job and took off the left leg—too bad it was the wrong patient. The patient who was due for the amputation had an inadvertent orchiectomy. You cannot stop using abbreviations. A JCAHO survey is in your future; perhaps it is a good time for a vacation.

Hirudis

Birthdate: May 21-June 20

Symbol: The Leach

You love to order tests: CAT scans. PET Scans. Ultrasounds and Dopplers. You want contrast? That’s no problem! We’ll just Mucomyst and bicarb the patient. You especially love phlebotomy. Every patient gets full lab every day. You would not want to miss a drop in hemoglobin, even if you caused it with excessive phlebotomy. If the patient is a tough stick, you’ll give it a try. You once found a vein on a particularly cicatricial heroin addict and you are still talking about it. You love Bela Lugosi movies.

The Chairman

Birthdate: June 21-July 20

Symbol: The Gavel

You love committees. Face it—there is not one you don’t want to be on. You like to know what’s going on and want to be involved. You don’t want someone to surprise you. You prefer to run the meeting and talk more than anyone else. As you read this, you think it could have been written more concisely, and you advise the formation of an ad hoc committee for wordsmithing, after which it will be sent to the communications committee, then on to exec. SHM has a place for you.

Nimbus

Birthdate: July 21–August 20 and August 22–September 20

Symbol: The Black Cloud

When you have been on hospital duty, nobody wants to take over the service from you. You always have the most patients. When you are on nights, you have 27 admissions when other people don’t get any. Your patients always get chest pain as you are about to roll over the pager, and it’s guaranteed not to be gas. Your post-op patients get to the floor very late, and they always have ileus, urinary retention, and delirium. You are paged constantly, even on your day off. The computer system just crashed; you must be on call. Your patients love you because you are always there.

The Dumpster

Birthdate: August 21

Symbol: The Garbage Can

You never mind leaving some work for your colleagues; you would not want them to be bored. You are going on vacation and need to leave early to pack, you have a headache and are home sick, or your dog has the flu, can somebody cover? Your discharge summaries are sketchy; you like to have residents so that they can do your paperwork for you. You are on good terms with Inertias and always seem to be changing call nights with Nimbuses.

The Geneticist

Birthdate: September 21-October 20

Symbol: The Double Helix

Face it—you’re twisted, dude. You like things to align nicely; your clothing always matches your shoes. You love consanguinity and the interesting diseases that develop. Nobody knows what you are talking about at parties. You hear hoofbeats (it’s not a horse). Bad news: They just discovered that Linus Pauling was right. DNA is a triple helix.

Inertia

Birthdate: October 21–November 19

Symbol: The Snail

You think the world is changing too fast. You were right about HMOs and still think LBJ made a mistake when he signed Medicare into law. When you are on a committee, you always find something that needs a rewrite. You always want a second review.

If it was good enough for you, it’s good enough for those who follow you. You still write notes by hand and are damned if you’ll learn how to operate a computer.

You are a natural bureaucrat. You love to block Chairmen from getting anything done.

The Techie

Birthdate: November 20 at 6 a.m.-December 31 at 11:59p.m.

Symbol: The Palm Pilot

You are first to embrace a new technology. If it’s embedded, you’ll root it out. You get your news from a podcast, and you have a Blackberry and a Blueberry. You don’t understand how anyone could not like having an electronic health record. Your entire medical school education is saved on a memory card, though you are not sure where it is. Your secret shame: Your vintage VCR still has a blinking red light. You get along well with Chairmen as long as they move your technology request through the committees. You would like to see all Inertias implode. TH

Jamie Newman, MD, FACP, is the physician editor of The Hospitalist, consultant, Hospital Internal Medicine, and assistant professor of internal medicine and medical history, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.

The Prescriptionist

Birthdate: January 1-February 21

Symbol: Rx

There is a disease for every drug. If it’s new, you’re on it. You’re on the pharmacy and therapeutics committee, and when you get journals you read the ads first. You’ve never met a drug rep you didn’t like. You are willing to experiment on yourself if need be; you would have made a great hippie. You like to hang with double Helixes, but you also like to hang heparin, fentanyl, ephedrine, and anything else that will fit in a bag of D5W.

The Statistician

Birthdate: February 22-April 19 (+/-two days)

Symbol: 1A

Evidence-based medicine is your mantra. You will do nothing without a double-blind, randomized multicenter control study. You are a therapeutic nihilist. You read Sherlock Holmes as a child. As you are reading this, you are wondering why you were assigned this month and how they know that this horoscope is correct. What was the control group? Is it a horoscopic placebo effect? You will submit an article to a major journal and have it rejected because your sample size was too small.

The Sentinel

Birthdate: April 20-May 20

Symbol: The Guardsman

You are always alert, but somehow bad things still happen to your patients. Delirious octogenarians fall out of bed and fracture their femurs; mistaken medications are administered, leading to adverse consequences. You admitted a diabetic patient for a below-the-knee amputation. The surgeon did a wonderful job and took off the left leg—too bad it was the wrong patient. The patient who was due for the amputation had an inadvertent orchiectomy. You cannot stop using abbreviations. A JCAHO survey is in your future; perhaps it is a good time for a vacation.

Hirudis

Birthdate: May 21-June 20

Symbol: The Leach