User login

The Coming Windfall

In June the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued a notice proposing changes to the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS) that, if enacted, would significantly increase Medicare payments to hospitalists for many services routinely performed. Because many private health plans use the Medicare-approved RVUs for their own fee schedules, it is anticipated that hospitalists will likely see payment increases for their non-Medicare services as well.

The changes, which will take effect in January 2007 if enacted, reflect the recommendations of the Relative Value Update Committee (RUC) of the American Medical Association, along with input from SHM. At this point, however, they are only proposed changes that CMS could modify based on input from affected groups and Congress. SHM will continue to urge CMS to implement the proposed changes and we encourage all hospitalists and other interested individuals to send a letter to CMS indicating support for the proposed changes. (See “How to Show Your Support,” p. 15.) CMS is accepting comments on the rule until August 21, with the final ruling expected in November.

The suggested revisions—the largest ever proposed for services related to patient evaluation and management—are designed to improve the accuracy of payments to physicians for the services they furnish to Medicare beneficiaries. The proposed notice includes substantial increases for “evaluation and management” services (that is, time and effort that physicians spend with patients in evaluating their condition and advising and assisting them in managing their health).

The proposed notice addresses two components of physician payments under the MPFS:

- A comprehensive review of physician work RVUs; and

- A proposed change in the methodology for calculating practice expenses.

“Medicare law requires CMS to assess the accuracy of the work relative values it assigns to physician-services every five years,” says SHM CEO Larry Wellikson, MD. “SHM, on behalf of our members, participated in a coalition of internal medicine groups, led by the American College of Physicians, which provided survey data and other evidence to the RUC to show that many services were undervalued compared to other physician services and that it was essential that their work RVUs be increased.”

Consistent with the RUC’s recommendations, CMS is proposing the largest increase in the work RVUs assigned to office and hospital visits and consultations since Medicare implemented its physician fee schedule in 1992. Many of these reflect double-digit increases for codes commonly billed by hospitalists:

- The work RVU for initial hospital care (CPT code 99221) would increase by 47%;

- The work RVU for subsequent hospital care (CPT code 99232) would increase by 31%; and

- The work RVU for subsequent hospital care (CPT code 99233) would increase by 32%.

“It’s time to increase Medicare’s payment rates for physicians to spend time with their patients,” says CMS Administrator Mark McClellan, MD, PhD. “We expect that improved payments for evaluation and management services will result in better outcomes because physicians will get financial support for giving patients the help they need to manage illnesses more effectively.”

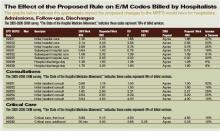

While Medicare payments to each hospitalist won’t increase by the same percentages listed in the above examples, 2007 Medicare payments for many evaluation and management services would increase significantly, assuming continuation of the current 2006 dollar conversion factor. (See “The Effect of the Proposed Rule on E/M Codes Billed by Hospitalists,” above.)

Changes in physician work RVUs affect approximately 55% of the total RVUs (the rest are determined by changes in practice expense and medical liability RVUs), so the increase in work RVUs will determine more than half of the total payments per service.

Further, by law CMS must offset the total increases in work RVUs from the five-year review with a separate budget neutrality adjustment so that 2007 expenditures are roughly equal to their 2006 level. The agency is estimating that the proposed changes to the work RVUs would cost Medicare approximately $4 billion. To achieve budget neutrality, CMS is proposing to reduce the work RVU for each service by 10%.

Overall, the proposed notice revises work RVUs for more than 400 services to better reflect the work and time required of a physician in furnishing the service, which can include not just procedures performed but also the services involved in evaluating a patient’s condition, and determining a course of treatment (known as “evaluation and management” services).

Work RVUs account for approximately $35 billion in MPFS payments, representing more than 50% of overall Medicare payments under the fee schedule. TH

SHM encourages hospitalists and others to send a letter to CMS indicating support for the proposed changes.

In June the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued a notice proposing changes to the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS) that, if enacted, would significantly increase Medicare payments to hospitalists for many services routinely performed. Because many private health plans use the Medicare-approved RVUs for their own fee schedules, it is anticipated that hospitalists will likely see payment increases for their non-Medicare services as well.

The changes, which will take effect in January 2007 if enacted, reflect the recommendations of the Relative Value Update Committee (RUC) of the American Medical Association, along with input from SHM. At this point, however, they are only proposed changes that CMS could modify based on input from affected groups and Congress. SHM will continue to urge CMS to implement the proposed changes and we encourage all hospitalists and other interested individuals to send a letter to CMS indicating support for the proposed changes. (See “How to Show Your Support,” p. 15.) CMS is accepting comments on the rule until August 21, with the final ruling expected in November.

The suggested revisions—the largest ever proposed for services related to patient evaluation and management—are designed to improve the accuracy of payments to physicians for the services they furnish to Medicare beneficiaries. The proposed notice includes substantial increases for “evaluation and management” services (that is, time and effort that physicians spend with patients in evaluating their condition and advising and assisting them in managing their health).

The proposed notice addresses two components of physician payments under the MPFS:

- A comprehensive review of physician work RVUs; and

- A proposed change in the methodology for calculating practice expenses.

“Medicare law requires CMS to assess the accuracy of the work relative values it assigns to physician-services every five years,” says SHM CEO Larry Wellikson, MD. “SHM, on behalf of our members, participated in a coalition of internal medicine groups, led by the American College of Physicians, which provided survey data and other evidence to the RUC to show that many services were undervalued compared to other physician services and that it was essential that their work RVUs be increased.”

Consistent with the RUC’s recommendations, CMS is proposing the largest increase in the work RVUs assigned to office and hospital visits and consultations since Medicare implemented its physician fee schedule in 1992. Many of these reflect double-digit increases for codes commonly billed by hospitalists:

- The work RVU for initial hospital care (CPT code 99221) would increase by 47%;

- The work RVU for subsequent hospital care (CPT code 99232) would increase by 31%; and

- The work RVU for subsequent hospital care (CPT code 99233) would increase by 32%.

“It’s time to increase Medicare’s payment rates for physicians to spend time with their patients,” says CMS Administrator Mark McClellan, MD, PhD. “We expect that improved payments for evaluation and management services will result in better outcomes because physicians will get financial support for giving patients the help they need to manage illnesses more effectively.”

While Medicare payments to each hospitalist won’t increase by the same percentages listed in the above examples, 2007 Medicare payments for many evaluation and management services would increase significantly, assuming continuation of the current 2006 dollar conversion factor. (See “The Effect of the Proposed Rule on E/M Codes Billed by Hospitalists,” above.)

Changes in physician work RVUs affect approximately 55% of the total RVUs (the rest are determined by changes in practice expense and medical liability RVUs), so the increase in work RVUs will determine more than half of the total payments per service.

Further, by law CMS must offset the total increases in work RVUs from the five-year review with a separate budget neutrality adjustment so that 2007 expenditures are roughly equal to their 2006 level. The agency is estimating that the proposed changes to the work RVUs would cost Medicare approximately $4 billion. To achieve budget neutrality, CMS is proposing to reduce the work RVU for each service by 10%.

Overall, the proposed notice revises work RVUs for more than 400 services to better reflect the work and time required of a physician in furnishing the service, which can include not just procedures performed but also the services involved in evaluating a patient’s condition, and determining a course of treatment (known as “evaluation and management” services).

Work RVUs account for approximately $35 billion in MPFS payments, representing more than 50% of overall Medicare payments under the fee schedule. TH

SHM encourages hospitalists and others to send a letter to CMS indicating support for the proposed changes.

In June the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued a notice proposing changes to the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS) that, if enacted, would significantly increase Medicare payments to hospitalists for many services routinely performed. Because many private health plans use the Medicare-approved RVUs for their own fee schedules, it is anticipated that hospitalists will likely see payment increases for their non-Medicare services as well.

The changes, which will take effect in January 2007 if enacted, reflect the recommendations of the Relative Value Update Committee (RUC) of the American Medical Association, along with input from SHM. At this point, however, they are only proposed changes that CMS could modify based on input from affected groups and Congress. SHM will continue to urge CMS to implement the proposed changes and we encourage all hospitalists and other interested individuals to send a letter to CMS indicating support for the proposed changes. (See “How to Show Your Support,” p. 15.) CMS is accepting comments on the rule until August 21, with the final ruling expected in November.

The suggested revisions—the largest ever proposed for services related to patient evaluation and management—are designed to improve the accuracy of payments to physicians for the services they furnish to Medicare beneficiaries. The proposed notice includes substantial increases for “evaluation and management” services (that is, time and effort that physicians spend with patients in evaluating their condition and advising and assisting them in managing their health).

The proposed notice addresses two components of physician payments under the MPFS:

- A comprehensive review of physician work RVUs; and

- A proposed change in the methodology for calculating practice expenses.

“Medicare law requires CMS to assess the accuracy of the work relative values it assigns to physician-services every five years,” says SHM CEO Larry Wellikson, MD. “SHM, on behalf of our members, participated in a coalition of internal medicine groups, led by the American College of Physicians, which provided survey data and other evidence to the RUC to show that many services were undervalued compared to other physician services and that it was essential that their work RVUs be increased.”

Consistent with the RUC’s recommendations, CMS is proposing the largest increase in the work RVUs assigned to office and hospital visits and consultations since Medicare implemented its physician fee schedule in 1992. Many of these reflect double-digit increases for codes commonly billed by hospitalists:

- The work RVU for initial hospital care (CPT code 99221) would increase by 47%;

- The work RVU for subsequent hospital care (CPT code 99232) would increase by 31%; and

- The work RVU for subsequent hospital care (CPT code 99233) would increase by 32%.

“It’s time to increase Medicare’s payment rates for physicians to spend time with their patients,” says CMS Administrator Mark McClellan, MD, PhD. “We expect that improved payments for evaluation and management services will result in better outcomes because physicians will get financial support for giving patients the help they need to manage illnesses more effectively.”

While Medicare payments to each hospitalist won’t increase by the same percentages listed in the above examples, 2007 Medicare payments for many evaluation and management services would increase significantly, assuming continuation of the current 2006 dollar conversion factor. (See “The Effect of the Proposed Rule on E/M Codes Billed by Hospitalists,” above.)

Changes in physician work RVUs affect approximately 55% of the total RVUs (the rest are determined by changes in practice expense and medical liability RVUs), so the increase in work RVUs will determine more than half of the total payments per service.

Further, by law CMS must offset the total increases in work RVUs from the five-year review with a separate budget neutrality adjustment so that 2007 expenditures are roughly equal to their 2006 level. The agency is estimating that the proposed changes to the work RVUs would cost Medicare approximately $4 billion. To achieve budget neutrality, CMS is proposing to reduce the work RVU for each service by 10%.

Overall, the proposed notice revises work RVUs for more than 400 services to better reflect the work and time required of a physician in furnishing the service, which can include not just procedures performed but also the services involved in evaluating a patient’s condition, and determining a course of treatment (known as “evaluation and management” services).

Work RVUs account for approximately $35 billion in MPFS payments, representing more than 50% of overall Medicare payments under the fee schedule. TH

SHM encourages hospitalists and others to send a letter to CMS indicating support for the proposed changes.

Clinical approach to patients with neuropathic pain

Lung Cancer Gender Gap

Aquatic Antagonists: Stingray Injury

ECT wipes out 30 years of memories

Woman loses 30 years of memories after electroconvulsive therapy

Richland County (SC) Circuit Court

A 55-year old woman with a history of depression underwent successful electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) after her husband and father died. Six months later she became depressed, and a new psychiatrist referred her to his partner for additional ECT treatments.

The partner administered outpatient ECT at a hospital daily for 10 days. The referring psychiatrist wrote in the patient’s chart that the patient experienced memory loss and severe cognitive problems during the initial ECT regimen but did not report this development to his partner and allegedly encouraged the patient to continue ECT.

After the second round of ECT treatments, the patient suffered brain damage and lost all her memories from the past 30 years—including the births of her children and her job skills—leaving her unable to work.

In court, the patient claimed ECT should be administered no more than three times a week, and the referring psychiatrist should have told his partner about the patient’s memory problems.

- The case was settled for $18,000

Dr. Grant’s observations

Although this case concerns ECT, the claim is based on negligence—that is, the psychiatrist did not fulfill his duty to care for the patient. The negligence claim focused on how the treatment was implemented, not whether ECT was appropriate for this woman’s depression.

ECT’s response rate ranges from 50% to 60%1 among patients who did not respond to one or more antidepressant trials. Symptomatic improvement usually is faster with ECT than with pharmacotherapy2 when ECT is administered three times per week. Mortality rates with ECT are similar to those associated with minor surgery.1

In addition to being an effective and safe treatment for depression, ECT rarely is a basis for malpractice. One study found that only 4 (0.2%) of 1,700 psychiatric malpractice claims filed between 1984 and 1990 concerned ECT’s side effects, complications, or appropriateness.3 Few patients who receive ECT file a malpractice claim because most are satisfied with the treatment; approximately 80% of ECT patients say they would consent to ECT again.4,5 In fact, one might consider withholding ECT from severely depressed patients grounds for malpractice.

Although safe and effective, ECT could present health risks that you need to discuss with patients. In particular, cognitive problems such as delirium and impaired attention and memory may result.1

Cognitive impairment risk in ect

ECT’s more severe cognitive side effects stem from:

- bilateral electrode placement

- sine wave stimulation

- suprathreshold stimulus intensity

- administration >3 times per week

- large numbers of treatments, usually >20 in an acute treatment course

- some medications, such as lithium carbonate and anticholinergics6

- pre-existing neurologic diseases such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease.1

The magnitude of retrograde amnesia often is greatest immediately after treatment. Patients are more likely to forget public information such as current events than personal information.10 The effects usually subside over time, and older memories are more likely to be recovered than more recent ones. ECT can cause permanent memory loss, particularly after bilateral electrode placement, suprathreshold stimulus intensity, sine wave stimulation, or large numbers of treatments—usually more than 20.

Ensuring adequate informed consent when delivering ECT or before referring a patient for treatment can help prevent a malpractice claim. Although specific requirements for ECT consent vary by jurisdiction, follow these general principles:1

- Provide the patient adequate information. Explain the reasons for ECT, describe the procedure including choice of stimulus electrode placement, offer alternative treatments, and explain the risks, benefits, anticipated number of treatments, relapse risk, and need for continuing treatment.

- Make sure the patient is capable of understanding and acting reasonably on this information and knows he or she can refuse treatment at any time.

- Tell the patient that a successful outcome is not guaranteed.

- Describe the likelihood and potential severity of major risks associated with ECT, including mortality, cardiovascular and CNS problems, and minor side effects such as headache, muscle aches, or nausea.

- Be sure the patient understands that consent is voluntary and can be withdrawn. The patient should know that he or she is also consenting to emergency treatment.

- Tell patients about possible behavioral restrictions—such as needing a friend or family member to monitor the patient or not being able to drive a car—that may be necessary during evaluation, treatment, and recuperation.

Although ECT might impair memory, it can improve neuropsychological domains such as global cognitive status and measures of general intelligence.11 Also, there is no evidence that ECT causes lasting problems in executive functioning, abstract reasoning, creativity, semantic memory, implicit memory, or skill acquisition or retention. Long-term negative effects on ability to learn and retain new information are unlikely.1

Avoiding an ect related malpractice claim

To reduce the possibility of a malpractice claim after ECT:

- Inform the patient about the risk of cognitive side effects as part of the informed consent process (Box).

- Assess the patient’s orientation and memory functions before and throughout ECT. In the above case, the referring psychiatrist had a duty to inform the psychiatrist administering ECT about the patient’s memory problems and recommend decreasing or discontinuing ECT.

- Consider a patient’s mood state, which may influence how ECT patients rate their memory.12 Ask about symptoms of depression. Patients with cognitive complaints such as subjective memory loss are more likely than those without such problems to have depression symptoms.1

- Do not administer ECT more than 3 times per week. No evidence supports more frequent use, and daily ECT may increase cognitive problems.1 The psychiatrist in the above case was negligent in providing a treatment frequency with no scientific support or medical rationale.

- Verify that the physician is qualified to perform ECT. Hospitals must ensure ECT quality and safety and should have a written plan for providing and maintaining ECT privileges.

- Involve the family when appropriate. Family members often care for patients during outpatient ECT. Give patients and family members literature describing ECT. Allow them time to consider the procedure, then schedule an appointment to answer questions.

1. American Psychiatric Association. The practice of electroconvulsive therapy: recommendations for treatment, training, and privileging, 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2001.

2. Nobler MS, Sackeim HA, Moeller JR, et al. Quantifying the speed of symptomatic improvement with electroconvulsive therapy: comparison of alternative statistical methods. Convuls Ther 1997;13:208-21.

3. Slawson P. Psychiatric malpractice and ECT: a review of 1,700 claims. Convuls Ther 1991;7:255-61.

4. Freeman CP, Cheshire KE. Attitude studies on electroconvulsive therapy. Convuls Ther. 1986;2:31-42.

5. Pettinati HM, Tanburello TA, Ruetsch CR, et al. Patient attitudes toward electroconvulsive therapy. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1994;30:471-5.

6. Small JG, Kellams JJ, Milstein V, et al. Complications with electroconvulsive treatment combined with lithium. Biol Psychiatry 1980;15:103-12.

7. Sobin C, Sackeim HA, Prudic J, et al. Predictors of retrograde amnesia following ECT. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152:995-1001.

8. Donahue JC. Electroconvulsive therapy and memory loss: anatomy of a debate. J ECT 2000;16:133-43.

9. Sackeim HA. Memory and ECT: from polarization to reconciliation. J ECT 2000;16:87-96.

10. Lisanby SH, Maddox JH, Prudic J, et al. The effects of electroconvulsive therapy on memory of autobiographical and public events. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000;57:581-90.

11. Sackeim HA, Prudic J, Devanand DP, et al. Effects of stimulus intensity and electrode placement on the efficacy and cognitive effects of electroconvulsive therapy. N Engl J Med 1993;328:839-46.

12. Coleman EA, Sackeim HA, Prudic J, et al. Subjective memory complaints before and after electroconvulsive therapy. Biol Psychiatry 1996;39:346-56.

Woman loses 30 years of memories after electroconvulsive therapy

Richland County (SC) Circuit Court

A 55-year old woman with a history of depression underwent successful electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) after her husband and father died. Six months later she became depressed, and a new psychiatrist referred her to his partner for additional ECT treatments.

The partner administered outpatient ECT at a hospital daily for 10 days. The referring psychiatrist wrote in the patient’s chart that the patient experienced memory loss and severe cognitive problems during the initial ECT regimen but did not report this development to his partner and allegedly encouraged the patient to continue ECT.

After the second round of ECT treatments, the patient suffered brain damage and lost all her memories from the past 30 years—including the births of her children and her job skills—leaving her unable to work.

In court, the patient claimed ECT should be administered no more than three times a week, and the referring psychiatrist should have told his partner about the patient’s memory problems.

- The case was settled for $18,000

Dr. Grant’s observations

Although this case concerns ECT, the claim is based on negligence—that is, the psychiatrist did not fulfill his duty to care for the patient. The negligence claim focused on how the treatment was implemented, not whether ECT was appropriate for this woman’s depression.

ECT’s response rate ranges from 50% to 60%1 among patients who did not respond to one or more antidepressant trials. Symptomatic improvement usually is faster with ECT than with pharmacotherapy2 when ECT is administered three times per week. Mortality rates with ECT are similar to those associated with minor surgery.1

In addition to being an effective and safe treatment for depression, ECT rarely is a basis for malpractice. One study found that only 4 (0.2%) of 1,700 psychiatric malpractice claims filed between 1984 and 1990 concerned ECT’s side effects, complications, or appropriateness.3 Few patients who receive ECT file a malpractice claim because most are satisfied with the treatment; approximately 80% of ECT patients say they would consent to ECT again.4,5 In fact, one might consider withholding ECT from severely depressed patients grounds for malpractice.

Although safe and effective, ECT could present health risks that you need to discuss with patients. In particular, cognitive problems such as delirium and impaired attention and memory may result.1

Cognitive impairment risk in ect

ECT’s more severe cognitive side effects stem from:

- bilateral electrode placement

- sine wave stimulation

- suprathreshold stimulus intensity

- administration >3 times per week

- large numbers of treatments, usually >20 in an acute treatment course

- some medications, such as lithium carbonate and anticholinergics6

- pre-existing neurologic diseases such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease.1

The magnitude of retrograde amnesia often is greatest immediately after treatment. Patients are more likely to forget public information such as current events than personal information.10 The effects usually subside over time, and older memories are more likely to be recovered than more recent ones. ECT can cause permanent memory loss, particularly after bilateral electrode placement, suprathreshold stimulus intensity, sine wave stimulation, or large numbers of treatments—usually more than 20.

Ensuring adequate informed consent when delivering ECT or before referring a patient for treatment can help prevent a malpractice claim. Although specific requirements for ECT consent vary by jurisdiction, follow these general principles:1

- Provide the patient adequate information. Explain the reasons for ECT, describe the procedure including choice of stimulus electrode placement, offer alternative treatments, and explain the risks, benefits, anticipated number of treatments, relapse risk, and need for continuing treatment.

- Make sure the patient is capable of understanding and acting reasonably on this information and knows he or she can refuse treatment at any time.

- Tell the patient that a successful outcome is not guaranteed.

- Describe the likelihood and potential severity of major risks associated with ECT, including mortality, cardiovascular and CNS problems, and minor side effects such as headache, muscle aches, or nausea.

- Be sure the patient understands that consent is voluntary and can be withdrawn. The patient should know that he or she is also consenting to emergency treatment.

- Tell patients about possible behavioral restrictions—such as needing a friend or family member to monitor the patient or not being able to drive a car—that may be necessary during evaluation, treatment, and recuperation.

Although ECT might impair memory, it can improve neuropsychological domains such as global cognitive status and measures of general intelligence.11 Also, there is no evidence that ECT causes lasting problems in executive functioning, abstract reasoning, creativity, semantic memory, implicit memory, or skill acquisition or retention. Long-term negative effects on ability to learn and retain new information are unlikely.1

Avoiding an ect related malpractice claim

To reduce the possibility of a malpractice claim after ECT:

- Inform the patient about the risk of cognitive side effects as part of the informed consent process (Box).

- Assess the patient’s orientation and memory functions before and throughout ECT. In the above case, the referring psychiatrist had a duty to inform the psychiatrist administering ECT about the patient’s memory problems and recommend decreasing or discontinuing ECT.

- Consider a patient’s mood state, which may influence how ECT patients rate their memory.12 Ask about symptoms of depression. Patients with cognitive complaints such as subjective memory loss are more likely than those without such problems to have depression symptoms.1

- Do not administer ECT more than 3 times per week. No evidence supports more frequent use, and daily ECT may increase cognitive problems.1 The psychiatrist in the above case was negligent in providing a treatment frequency with no scientific support or medical rationale.

- Verify that the physician is qualified to perform ECT. Hospitals must ensure ECT quality and safety and should have a written plan for providing and maintaining ECT privileges.

- Involve the family when appropriate. Family members often care for patients during outpatient ECT. Give patients and family members literature describing ECT. Allow them time to consider the procedure, then schedule an appointment to answer questions.

Woman loses 30 years of memories after electroconvulsive therapy

Richland County (SC) Circuit Court

A 55-year old woman with a history of depression underwent successful electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) after her husband and father died. Six months later she became depressed, and a new psychiatrist referred her to his partner for additional ECT treatments.

The partner administered outpatient ECT at a hospital daily for 10 days. The referring psychiatrist wrote in the patient’s chart that the patient experienced memory loss and severe cognitive problems during the initial ECT regimen but did not report this development to his partner and allegedly encouraged the patient to continue ECT.

After the second round of ECT treatments, the patient suffered brain damage and lost all her memories from the past 30 years—including the births of her children and her job skills—leaving her unable to work.

In court, the patient claimed ECT should be administered no more than three times a week, and the referring psychiatrist should have told his partner about the patient’s memory problems.

- The case was settled for $18,000

Dr. Grant’s observations

Although this case concerns ECT, the claim is based on negligence—that is, the psychiatrist did not fulfill his duty to care for the patient. The negligence claim focused on how the treatment was implemented, not whether ECT was appropriate for this woman’s depression.

ECT’s response rate ranges from 50% to 60%1 among patients who did not respond to one or more antidepressant trials. Symptomatic improvement usually is faster with ECT than with pharmacotherapy2 when ECT is administered three times per week. Mortality rates with ECT are similar to those associated with minor surgery.1

In addition to being an effective and safe treatment for depression, ECT rarely is a basis for malpractice. One study found that only 4 (0.2%) of 1,700 psychiatric malpractice claims filed between 1984 and 1990 concerned ECT’s side effects, complications, or appropriateness.3 Few patients who receive ECT file a malpractice claim because most are satisfied with the treatment; approximately 80% of ECT patients say they would consent to ECT again.4,5 In fact, one might consider withholding ECT from severely depressed patients grounds for malpractice.

Although safe and effective, ECT could present health risks that you need to discuss with patients. In particular, cognitive problems such as delirium and impaired attention and memory may result.1

Cognitive impairment risk in ect

ECT’s more severe cognitive side effects stem from:

- bilateral electrode placement

- sine wave stimulation

- suprathreshold stimulus intensity

- administration >3 times per week

- large numbers of treatments, usually >20 in an acute treatment course

- some medications, such as lithium carbonate and anticholinergics6

- pre-existing neurologic diseases such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease.1

The magnitude of retrograde amnesia often is greatest immediately after treatment. Patients are more likely to forget public information such as current events than personal information.10 The effects usually subside over time, and older memories are more likely to be recovered than more recent ones. ECT can cause permanent memory loss, particularly after bilateral electrode placement, suprathreshold stimulus intensity, sine wave stimulation, or large numbers of treatments—usually more than 20.

Ensuring adequate informed consent when delivering ECT or before referring a patient for treatment can help prevent a malpractice claim. Although specific requirements for ECT consent vary by jurisdiction, follow these general principles:1

- Provide the patient adequate information. Explain the reasons for ECT, describe the procedure including choice of stimulus electrode placement, offer alternative treatments, and explain the risks, benefits, anticipated number of treatments, relapse risk, and need for continuing treatment.

- Make sure the patient is capable of understanding and acting reasonably on this information and knows he or she can refuse treatment at any time.

- Tell the patient that a successful outcome is not guaranteed.

- Describe the likelihood and potential severity of major risks associated with ECT, including mortality, cardiovascular and CNS problems, and minor side effects such as headache, muscle aches, or nausea.

- Be sure the patient understands that consent is voluntary and can be withdrawn. The patient should know that he or she is also consenting to emergency treatment.

- Tell patients about possible behavioral restrictions—such as needing a friend or family member to monitor the patient or not being able to drive a car—that may be necessary during evaluation, treatment, and recuperation.

Although ECT might impair memory, it can improve neuropsychological domains such as global cognitive status and measures of general intelligence.11 Also, there is no evidence that ECT causes lasting problems in executive functioning, abstract reasoning, creativity, semantic memory, implicit memory, or skill acquisition or retention. Long-term negative effects on ability to learn and retain new information are unlikely.1

Avoiding an ect related malpractice claim

To reduce the possibility of a malpractice claim after ECT:

- Inform the patient about the risk of cognitive side effects as part of the informed consent process (Box).

- Assess the patient’s orientation and memory functions before and throughout ECT. In the above case, the referring psychiatrist had a duty to inform the psychiatrist administering ECT about the patient’s memory problems and recommend decreasing or discontinuing ECT.

- Consider a patient’s mood state, which may influence how ECT patients rate their memory.12 Ask about symptoms of depression. Patients with cognitive complaints such as subjective memory loss are more likely than those without such problems to have depression symptoms.1

- Do not administer ECT more than 3 times per week. No evidence supports more frequent use, and daily ECT may increase cognitive problems.1 The psychiatrist in the above case was negligent in providing a treatment frequency with no scientific support or medical rationale.

- Verify that the physician is qualified to perform ECT. Hospitals must ensure ECT quality and safety and should have a written plan for providing and maintaining ECT privileges.

- Involve the family when appropriate. Family members often care for patients during outpatient ECT. Give patients and family members literature describing ECT. Allow them time to consider the procedure, then schedule an appointment to answer questions.

1. American Psychiatric Association. The practice of electroconvulsive therapy: recommendations for treatment, training, and privileging, 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2001.

2. Nobler MS, Sackeim HA, Moeller JR, et al. Quantifying the speed of symptomatic improvement with electroconvulsive therapy: comparison of alternative statistical methods. Convuls Ther 1997;13:208-21.

3. Slawson P. Psychiatric malpractice and ECT: a review of 1,700 claims. Convuls Ther 1991;7:255-61.

4. Freeman CP, Cheshire KE. Attitude studies on electroconvulsive therapy. Convuls Ther. 1986;2:31-42.

5. Pettinati HM, Tanburello TA, Ruetsch CR, et al. Patient attitudes toward electroconvulsive therapy. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1994;30:471-5.

6. Small JG, Kellams JJ, Milstein V, et al. Complications with electroconvulsive treatment combined with lithium. Biol Psychiatry 1980;15:103-12.

7. Sobin C, Sackeim HA, Prudic J, et al. Predictors of retrograde amnesia following ECT. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152:995-1001.

8. Donahue JC. Electroconvulsive therapy and memory loss: anatomy of a debate. J ECT 2000;16:133-43.

9. Sackeim HA. Memory and ECT: from polarization to reconciliation. J ECT 2000;16:87-96.

10. Lisanby SH, Maddox JH, Prudic J, et al. The effects of electroconvulsive therapy on memory of autobiographical and public events. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000;57:581-90.

11. Sackeim HA, Prudic J, Devanand DP, et al. Effects of stimulus intensity and electrode placement on the efficacy and cognitive effects of electroconvulsive therapy. N Engl J Med 1993;328:839-46.

12. Coleman EA, Sackeim HA, Prudic J, et al. Subjective memory complaints before and after electroconvulsive therapy. Biol Psychiatry 1996;39:346-56.

1. American Psychiatric Association. The practice of electroconvulsive therapy: recommendations for treatment, training, and privileging, 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2001.

2. Nobler MS, Sackeim HA, Moeller JR, et al. Quantifying the speed of symptomatic improvement with electroconvulsive therapy: comparison of alternative statistical methods. Convuls Ther 1997;13:208-21.

3. Slawson P. Psychiatric malpractice and ECT: a review of 1,700 claims. Convuls Ther 1991;7:255-61.

4. Freeman CP, Cheshire KE. Attitude studies on electroconvulsive therapy. Convuls Ther. 1986;2:31-42.

5. Pettinati HM, Tanburello TA, Ruetsch CR, et al. Patient attitudes toward electroconvulsive therapy. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1994;30:471-5.

6. Small JG, Kellams JJ, Milstein V, et al. Complications with electroconvulsive treatment combined with lithium. Biol Psychiatry 1980;15:103-12.

7. Sobin C, Sackeim HA, Prudic J, et al. Predictors of retrograde amnesia following ECT. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152:995-1001.

8. Donahue JC. Electroconvulsive therapy and memory loss: anatomy of a debate. J ECT 2000;16:133-43.

9. Sackeim HA. Memory and ECT: from polarization to reconciliation. J ECT 2000;16:87-96.

10. Lisanby SH, Maddox JH, Prudic J, et al. The effects of electroconvulsive therapy on memory of autobiographical and public events. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000;57:581-90.

11. Sackeim HA, Prudic J, Devanand DP, et al. Effects of stimulus intensity and electrode placement on the efficacy and cognitive effects of electroconvulsive therapy. N Engl J Med 1993;328:839-46.

12. Coleman EA, Sackeim HA, Prudic J, et al. Subjective memory complaints before and after electroconvulsive therapy. Biol Psychiatry 1996;39:346-56.

Locum Terrans

Dr. Mann looked out the reinforced window at the acutely curving horizon. He saw a vista of lifeless craters under a harsh gray sky. Robotic equipment excavated along the sides of the craters for rare minerals. For about the thousandth time he asked himself what he was doing on this god-forsaken asteroid. He looked down at his scheduling terminal. Three patients were listed on his roster for the day: two burns and a fracture. They were all basic humanoids—what a bore.

When Hugh Mann was hired as a locum, he was excited. He had trained in humanoid medicine as well as xeno-geno-biology. He was in the top half of his class at the University of Ganymede—no easy accomplishment in a galaxy of overachieving life forms. His minority status as a native Terran had helped him get into school, but his sheer determination and long hours had made him successful.

He had served during the Great Rigellian War, followed by 10 solar standard years of private practice on Ios-3. Now he was getting fed up with the assortment of life forms he was treating. Dealing with the usual high platinum levels, impacted crillobars, and tentacular torsion had grown old. Even the few human patients who were grateful for a physician of their own species wasn’t enough to keep him satisfied.

When the invitation to work for Pro Lo—interstellar Locums—arrived on his screen, he was ready for adventure. An asteroid mine in the outer ring of Nebulon sounded exotic. He knew the choice locations went to those doctors who had worked with the company for years, but it was worth the risk. Or so he had thought. The mine colony was dull. There was no nightlife, not even any vaguely humanoid females for recreation. Two more weeks and his three-month tour of duty would be over. It had been at best unexciting, but he had made some serious dinars. Maybe the next assignment would be more interesting.

His self-pity was interrupted by his greatest source of annoyance. It was the pathetic excuse for a robot assistant with which he had been saddled. Some perverse designer had come up with the Old Chap 7. Perhaps the basic model had been a fairly functional assistant—175 years ago. This one had been modified to resemble an old Earth-style English butler, down to the bowler, umbrella (like it ever rained on this rock) and “Cheerio!” vernacular. He shook his head in dismay. The robot looked at him and printed out “Stiff upper lip old bean.” Dr. Mann just groaned. Worse than its pseudo-British façade, the robotic unit was severely out of date. The data banks were loaded with the Annals of Interstellar Medicine for the past 500 years, but nothing for the past three decades. That might be interesting for an archivist, but he had never seen any value in studying history. He’d taken to calling the robot Jeeves.

Dr. Mann looked out the window again at the star-filled sky. Suddenly there was a great flash of light at the horizon line. Alarms started to blare. A message came across the screen. A small asteroid had hit an Imperial transport vehicle. An emergency docking at mine base Nebulon was requested.

The mine’s director, an obstreperous Vegan named Weezul, barged into Dr. Mann’s clinic space, nervously rubbing his furry tentacles.

“Get ready for action,” he bellowed. “We have a VILF coming.”

A very important life form? This was what Dr. Mann had been waiting for. Then the bad news: The vessel had been transporting the Rigellian ambassador. This was bad news on multiple fronts. Dr. Mann had never treated a Rigellian, though he’d seen a lot of them incinerated during the war. They were allies—at least for now.

Dr. Mann called Jeeves over, and they reviewed what information there was about these enormous creatures. The Rigellian races evolved in a low gravity environment and were huge—often 24 meters or longer. They were aquatic and had two lower limbs and four upper. They had a circulatory system with a carbon monoxide-based metabolism and some strange religious beliefs about modern medicine.

The damaged ship’s lifeboat landed with two passengers—the captain and the Rigellian ambassador himself—as well as an entourage of support, translator, and protocol robots. Talk about extreme VILFs!

The captain’s injury seemed minor. An Iogan, his thick outer cortex had been lacerated. Iogans tend to have an unpleasant personality, and the captain was no exception. His rigid mouth worked to form Lingua words Dr. Mann could understand: “Don’t worry about me you fool, see to the ambassador.” Good advice, coming from a creature that looked like a giant lima bean.

The ambassador lay floating in a large, rapidly improvised tub of clear oil, supporting its large body in the higher artificial gravity of the asteroid. It would take hours to decrease the radial spin of the mine to diminish the gravitational pull to more tolerable levels. The left lower appendage was out of alignment. Donning a somewhat snug space suit, Dr. Mann climbed into the tub. With great difficulty he manipulated the injured limb. To his credit, the ambassador never winced. Dr. Mann had no way to image the limb with its tough cartilage. It would not fit into the mine’s limited scanner facility, and the portable unit would not function in liquid. Using an elastic waterproof wrap he managed to put the limb back into alignment. He hoped it would be sufficient.

Dr. Mann wanted to give the ambassador something for pain. The protocol robot came forward. “Rigellians will accept no medicine that is not derived from their home world.” Dr. Mann never liked to have a patient of any life form in pain, but if the ambassador could stand it, so could he.

Dr. Mann climbed out of the tank and checked on the captain. Jeeves had finished the dressing and had administered Iogian pain medication from stock. “I hope you are not allergic,” Dr. Mann quipped to the captain, who glared in response.

It looked like the emergency was over. Dr. Mann was pleased with himself.

Suddenly, though, things got ugly. It started with the captain. His normally green skin became spotted with blue wheals. It looked like an allergic reaction to the pain medication. Dr. Mann had Jeeves administer Moruvian pineal extract. It usually did the trick on these sentient legumes.

Dr. Mann thought he’d better check the ambassador. When he walked over to the tank something seemed wrong. The injured limb had grown to twice its normal size, and the ambassador seemed to be struggling to respire. A grim realization hit Dr. Mann: A clot had formed in the limb and embolized to the ambassador’s breathing apparatus.

Dr. Mann ran to Jeeves and accessed the medical data banks. There was nothing about the Rigellian coagulation cascade. Jeeves’ bank had only a few vague references to Rigellian physiology. The species refusal to use medication only made things worse. If he did not act quickly his patient might die. And Dr. Mann did not want to be responsible for a resumption of interstellar conflict.

He stared at Jeeves. He had never seen a robot look nervous before, but the Old Chap 7 was showing some odd behavior, taking off his hat and spinning his umbrella. Dr. Mann tried to concentrate. He had Jeeves pull up everything he had on the treatment of embolism. The modern treatment was to inject clot-eating bacteria, modified to the specie. This was out of the question; the nearest xeno-genome lab was two days from the asteroid.

He looked further back in the medical journals. Before bacteria lysis it was Q-beam radiation, and before that mini-robots with lasers. He had no Q-beam facility and rigging up mini-robots with lasers would take at least two days.

Jeeves poked him with his umbrella. What was wrong with the crazy robot? Dr. Mann had gone all the way back to the 20th century looking for an option. Then it hit him. He had read about something called an IVC filter. Perhaps he could fashion something to block the ambassador’s oversize vessel—but what? Jeeves poked him again.

Dr. Mann grabbed the umbrella from the robot and was about to snap it in two when an idea hit him. He pulled the fabric from the metal skeleton, ran to the radiation sterilizer, and sanitized the remains of the umbrella. One hour later it was inserted in the ambassador’s main vessel, ready to catch any further errant clot. Hopefully he’d live until a cruiser with a well-stocked sickbay arrived

Dr. Mann stared at Jeeves. Perhaps he had been wrong about his robot assistant. It had helped save the ambassador. Then Dr. Mann checked the captain, noticing for the first time how ancient the being looked. The captain had worsened acutely, its breathing labored, a sick wheezing sound coming past the rigid fiber that made up the upper part of its mouth.

Dr. Mann grabbed an intubation tube. The captain needed to be on a ventilator. Luckily Dr. Mann had had experience with this type of geriatric vegetable-like creature. He tried three times unsuccessfully, but managed on the fourth to slide the tube pass the rigid maxilla.

Dr. Mann sat on the floor. He was exhausted by the efforts of the day, especially the stressful intubation. Jeeves rolled over to him, and placed his bowler on Dr. Mann’s head. With a sly robotic wink his print out read, “Stiff upper lip, old bean” TH

Jamie Newman, MD, FACP, is the physician editor of The Hospitalist, consultant, Hospital Internal Medicine, and assistant professor of internal medicine and medical history, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.

Dr. Mann looked out the reinforced window at the acutely curving horizon. He saw a vista of lifeless craters under a harsh gray sky. Robotic equipment excavated along the sides of the craters for rare minerals. For about the thousandth time he asked himself what he was doing on this god-forsaken asteroid. He looked down at his scheduling terminal. Three patients were listed on his roster for the day: two burns and a fracture. They were all basic humanoids—what a bore.

When Hugh Mann was hired as a locum, he was excited. He had trained in humanoid medicine as well as xeno-geno-biology. He was in the top half of his class at the University of Ganymede—no easy accomplishment in a galaxy of overachieving life forms. His minority status as a native Terran had helped him get into school, but his sheer determination and long hours had made him successful.

He had served during the Great Rigellian War, followed by 10 solar standard years of private practice on Ios-3. Now he was getting fed up with the assortment of life forms he was treating. Dealing with the usual high platinum levels, impacted crillobars, and tentacular torsion had grown old. Even the few human patients who were grateful for a physician of their own species wasn’t enough to keep him satisfied.

When the invitation to work for Pro Lo—interstellar Locums—arrived on his screen, he was ready for adventure. An asteroid mine in the outer ring of Nebulon sounded exotic. He knew the choice locations went to those doctors who had worked with the company for years, but it was worth the risk. Or so he had thought. The mine colony was dull. There was no nightlife, not even any vaguely humanoid females for recreation. Two more weeks and his three-month tour of duty would be over. It had been at best unexciting, but he had made some serious dinars. Maybe the next assignment would be more interesting.

His self-pity was interrupted by his greatest source of annoyance. It was the pathetic excuse for a robot assistant with which he had been saddled. Some perverse designer had come up with the Old Chap 7. Perhaps the basic model had been a fairly functional assistant—175 years ago. This one had been modified to resemble an old Earth-style English butler, down to the bowler, umbrella (like it ever rained on this rock) and “Cheerio!” vernacular. He shook his head in dismay. The robot looked at him and printed out “Stiff upper lip old bean.” Dr. Mann just groaned. Worse than its pseudo-British façade, the robotic unit was severely out of date. The data banks were loaded with the Annals of Interstellar Medicine for the past 500 years, but nothing for the past three decades. That might be interesting for an archivist, but he had never seen any value in studying history. He’d taken to calling the robot Jeeves.

Dr. Mann looked out the window again at the star-filled sky. Suddenly there was a great flash of light at the horizon line. Alarms started to blare. A message came across the screen. A small asteroid had hit an Imperial transport vehicle. An emergency docking at mine base Nebulon was requested.

The mine’s director, an obstreperous Vegan named Weezul, barged into Dr. Mann’s clinic space, nervously rubbing his furry tentacles.

“Get ready for action,” he bellowed. “We have a VILF coming.”

A very important life form? This was what Dr. Mann had been waiting for. Then the bad news: The vessel had been transporting the Rigellian ambassador. This was bad news on multiple fronts. Dr. Mann had never treated a Rigellian, though he’d seen a lot of them incinerated during the war. They were allies—at least for now.

Dr. Mann called Jeeves over, and they reviewed what information there was about these enormous creatures. The Rigellian races evolved in a low gravity environment and were huge—often 24 meters or longer. They were aquatic and had two lower limbs and four upper. They had a circulatory system with a carbon monoxide-based metabolism and some strange religious beliefs about modern medicine.

The damaged ship’s lifeboat landed with two passengers—the captain and the Rigellian ambassador himself—as well as an entourage of support, translator, and protocol robots. Talk about extreme VILFs!

The captain’s injury seemed minor. An Iogan, his thick outer cortex had been lacerated. Iogans tend to have an unpleasant personality, and the captain was no exception. His rigid mouth worked to form Lingua words Dr. Mann could understand: “Don’t worry about me you fool, see to the ambassador.” Good advice, coming from a creature that looked like a giant lima bean.

The ambassador lay floating in a large, rapidly improvised tub of clear oil, supporting its large body in the higher artificial gravity of the asteroid. It would take hours to decrease the radial spin of the mine to diminish the gravitational pull to more tolerable levels. The left lower appendage was out of alignment. Donning a somewhat snug space suit, Dr. Mann climbed into the tub. With great difficulty he manipulated the injured limb. To his credit, the ambassador never winced. Dr. Mann had no way to image the limb with its tough cartilage. It would not fit into the mine’s limited scanner facility, and the portable unit would not function in liquid. Using an elastic waterproof wrap he managed to put the limb back into alignment. He hoped it would be sufficient.

Dr. Mann wanted to give the ambassador something for pain. The protocol robot came forward. “Rigellians will accept no medicine that is not derived from their home world.” Dr. Mann never liked to have a patient of any life form in pain, but if the ambassador could stand it, so could he.

Dr. Mann climbed out of the tank and checked on the captain. Jeeves had finished the dressing and had administered Iogian pain medication from stock. “I hope you are not allergic,” Dr. Mann quipped to the captain, who glared in response.

It looked like the emergency was over. Dr. Mann was pleased with himself.

Suddenly, though, things got ugly. It started with the captain. His normally green skin became spotted with blue wheals. It looked like an allergic reaction to the pain medication. Dr. Mann had Jeeves administer Moruvian pineal extract. It usually did the trick on these sentient legumes.

Dr. Mann thought he’d better check the ambassador. When he walked over to the tank something seemed wrong. The injured limb had grown to twice its normal size, and the ambassador seemed to be struggling to respire. A grim realization hit Dr. Mann: A clot had formed in the limb and embolized to the ambassador’s breathing apparatus.

Dr. Mann ran to Jeeves and accessed the medical data banks. There was nothing about the Rigellian coagulation cascade. Jeeves’ bank had only a few vague references to Rigellian physiology. The species refusal to use medication only made things worse. If he did not act quickly his patient might die. And Dr. Mann did not want to be responsible for a resumption of interstellar conflict.

He stared at Jeeves. He had never seen a robot look nervous before, but the Old Chap 7 was showing some odd behavior, taking off his hat and spinning his umbrella. Dr. Mann tried to concentrate. He had Jeeves pull up everything he had on the treatment of embolism. The modern treatment was to inject clot-eating bacteria, modified to the specie. This was out of the question; the nearest xeno-genome lab was two days from the asteroid.

He looked further back in the medical journals. Before bacteria lysis it was Q-beam radiation, and before that mini-robots with lasers. He had no Q-beam facility and rigging up mini-robots with lasers would take at least two days.

Jeeves poked him with his umbrella. What was wrong with the crazy robot? Dr. Mann had gone all the way back to the 20th century looking for an option. Then it hit him. He had read about something called an IVC filter. Perhaps he could fashion something to block the ambassador’s oversize vessel—but what? Jeeves poked him again.

Dr. Mann grabbed the umbrella from the robot and was about to snap it in two when an idea hit him. He pulled the fabric from the metal skeleton, ran to the radiation sterilizer, and sanitized the remains of the umbrella. One hour later it was inserted in the ambassador’s main vessel, ready to catch any further errant clot. Hopefully he’d live until a cruiser with a well-stocked sickbay arrived

Dr. Mann stared at Jeeves. Perhaps he had been wrong about his robot assistant. It had helped save the ambassador. Then Dr. Mann checked the captain, noticing for the first time how ancient the being looked. The captain had worsened acutely, its breathing labored, a sick wheezing sound coming past the rigid fiber that made up the upper part of its mouth.

Dr. Mann grabbed an intubation tube. The captain needed to be on a ventilator. Luckily Dr. Mann had had experience with this type of geriatric vegetable-like creature. He tried three times unsuccessfully, but managed on the fourth to slide the tube pass the rigid maxilla.

Dr. Mann sat on the floor. He was exhausted by the efforts of the day, especially the stressful intubation. Jeeves rolled over to him, and placed his bowler on Dr. Mann’s head. With a sly robotic wink his print out read, “Stiff upper lip, old bean” TH

Jamie Newman, MD, FACP, is the physician editor of The Hospitalist, consultant, Hospital Internal Medicine, and assistant professor of internal medicine and medical history, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.

Dr. Mann looked out the reinforced window at the acutely curving horizon. He saw a vista of lifeless craters under a harsh gray sky. Robotic equipment excavated along the sides of the craters for rare minerals. For about the thousandth time he asked himself what he was doing on this god-forsaken asteroid. He looked down at his scheduling terminal. Three patients were listed on his roster for the day: two burns and a fracture. They were all basic humanoids—what a bore.

When Hugh Mann was hired as a locum, he was excited. He had trained in humanoid medicine as well as xeno-geno-biology. He was in the top half of his class at the University of Ganymede—no easy accomplishment in a galaxy of overachieving life forms. His minority status as a native Terran had helped him get into school, but his sheer determination and long hours had made him successful.

He had served during the Great Rigellian War, followed by 10 solar standard years of private practice on Ios-3. Now he was getting fed up with the assortment of life forms he was treating. Dealing with the usual high platinum levels, impacted crillobars, and tentacular torsion had grown old. Even the few human patients who were grateful for a physician of their own species wasn’t enough to keep him satisfied.

When the invitation to work for Pro Lo—interstellar Locums—arrived on his screen, he was ready for adventure. An asteroid mine in the outer ring of Nebulon sounded exotic. He knew the choice locations went to those doctors who had worked with the company for years, but it was worth the risk. Or so he had thought. The mine colony was dull. There was no nightlife, not even any vaguely humanoid females for recreation. Two more weeks and his three-month tour of duty would be over. It had been at best unexciting, but he had made some serious dinars. Maybe the next assignment would be more interesting.

His self-pity was interrupted by his greatest source of annoyance. It was the pathetic excuse for a robot assistant with which he had been saddled. Some perverse designer had come up with the Old Chap 7. Perhaps the basic model had been a fairly functional assistant—175 years ago. This one had been modified to resemble an old Earth-style English butler, down to the bowler, umbrella (like it ever rained on this rock) and “Cheerio!” vernacular. He shook his head in dismay. The robot looked at him and printed out “Stiff upper lip old bean.” Dr. Mann just groaned. Worse than its pseudo-British façade, the robotic unit was severely out of date. The data banks were loaded with the Annals of Interstellar Medicine for the past 500 years, but nothing for the past three decades. That might be interesting for an archivist, but he had never seen any value in studying history. He’d taken to calling the robot Jeeves.

Dr. Mann looked out the window again at the star-filled sky. Suddenly there was a great flash of light at the horizon line. Alarms started to blare. A message came across the screen. A small asteroid had hit an Imperial transport vehicle. An emergency docking at mine base Nebulon was requested.

The mine’s director, an obstreperous Vegan named Weezul, barged into Dr. Mann’s clinic space, nervously rubbing his furry tentacles.

“Get ready for action,” he bellowed. “We have a VILF coming.”

A very important life form? This was what Dr. Mann had been waiting for. Then the bad news: The vessel had been transporting the Rigellian ambassador. This was bad news on multiple fronts. Dr. Mann had never treated a Rigellian, though he’d seen a lot of them incinerated during the war. They were allies—at least for now.

Dr. Mann called Jeeves over, and they reviewed what information there was about these enormous creatures. The Rigellian races evolved in a low gravity environment and were huge—often 24 meters or longer. They were aquatic and had two lower limbs and four upper. They had a circulatory system with a carbon monoxide-based metabolism and some strange religious beliefs about modern medicine.

The damaged ship’s lifeboat landed with two passengers—the captain and the Rigellian ambassador himself—as well as an entourage of support, translator, and protocol robots. Talk about extreme VILFs!

The captain’s injury seemed minor. An Iogan, his thick outer cortex had been lacerated. Iogans tend to have an unpleasant personality, and the captain was no exception. His rigid mouth worked to form Lingua words Dr. Mann could understand: “Don’t worry about me you fool, see to the ambassador.” Good advice, coming from a creature that looked like a giant lima bean.

The ambassador lay floating in a large, rapidly improvised tub of clear oil, supporting its large body in the higher artificial gravity of the asteroid. It would take hours to decrease the radial spin of the mine to diminish the gravitational pull to more tolerable levels. The left lower appendage was out of alignment. Donning a somewhat snug space suit, Dr. Mann climbed into the tub. With great difficulty he manipulated the injured limb. To his credit, the ambassador never winced. Dr. Mann had no way to image the limb with its tough cartilage. It would not fit into the mine’s limited scanner facility, and the portable unit would not function in liquid. Using an elastic waterproof wrap he managed to put the limb back into alignment. He hoped it would be sufficient.

Dr. Mann wanted to give the ambassador something for pain. The protocol robot came forward. “Rigellians will accept no medicine that is not derived from their home world.” Dr. Mann never liked to have a patient of any life form in pain, but if the ambassador could stand it, so could he.

Dr. Mann climbed out of the tank and checked on the captain. Jeeves had finished the dressing and had administered Iogian pain medication from stock. “I hope you are not allergic,” Dr. Mann quipped to the captain, who glared in response.

It looked like the emergency was over. Dr. Mann was pleased with himself.

Suddenly, though, things got ugly. It started with the captain. His normally green skin became spotted with blue wheals. It looked like an allergic reaction to the pain medication. Dr. Mann had Jeeves administer Moruvian pineal extract. It usually did the trick on these sentient legumes.

Dr. Mann thought he’d better check the ambassador. When he walked over to the tank something seemed wrong. The injured limb had grown to twice its normal size, and the ambassador seemed to be struggling to respire. A grim realization hit Dr. Mann: A clot had formed in the limb and embolized to the ambassador’s breathing apparatus.

Dr. Mann ran to Jeeves and accessed the medical data banks. There was nothing about the Rigellian coagulation cascade. Jeeves’ bank had only a few vague references to Rigellian physiology. The species refusal to use medication only made things worse. If he did not act quickly his patient might die. And Dr. Mann did not want to be responsible for a resumption of interstellar conflict.

He stared at Jeeves. He had never seen a robot look nervous before, but the Old Chap 7 was showing some odd behavior, taking off his hat and spinning his umbrella. Dr. Mann tried to concentrate. He had Jeeves pull up everything he had on the treatment of embolism. The modern treatment was to inject clot-eating bacteria, modified to the specie. This was out of the question; the nearest xeno-genome lab was two days from the asteroid.

He looked further back in the medical journals. Before bacteria lysis it was Q-beam radiation, and before that mini-robots with lasers. He had no Q-beam facility and rigging up mini-robots with lasers would take at least two days.

Jeeves poked him with his umbrella. What was wrong with the crazy robot? Dr. Mann had gone all the way back to the 20th century looking for an option. Then it hit him. He had read about something called an IVC filter. Perhaps he could fashion something to block the ambassador’s oversize vessel—but what? Jeeves poked him again.

Dr. Mann grabbed the umbrella from the robot and was about to snap it in two when an idea hit him. He pulled the fabric from the metal skeleton, ran to the radiation sterilizer, and sanitized the remains of the umbrella. One hour later it was inserted in the ambassador’s main vessel, ready to catch any further errant clot. Hopefully he’d live until a cruiser with a well-stocked sickbay arrived

Dr. Mann stared at Jeeves. Perhaps he had been wrong about his robot assistant. It had helped save the ambassador. Then Dr. Mann checked the captain, noticing for the first time how ancient the being looked. The captain had worsened acutely, its breathing labored, a sick wheezing sound coming past the rigid fiber that made up the upper part of its mouth.

Dr. Mann grabbed an intubation tube. The captain needed to be on a ventilator. Luckily Dr. Mann had had experience with this type of geriatric vegetable-like creature. He tried three times unsuccessfully, but managed on the fourth to slide the tube pass the rigid maxilla.

Dr. Mann sat on the floor. He was exhausted by the efforts of the day, especially the stressful intubation. Jeeves rolled over to him, and placed his bowler on Dr. Mann’s head. With a sly robotic wink his print out read, “Stiff upper lip, old bean” TH

Jamie Newman, MD, FACP, is the physician editor of The Hospitalist, consultant, Hospital Internal Medicine, and assistant professor of internal medicine and medical history, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.

Production-Based Compensation for Hospitalists Overlooked Too Often?

Should hospitalists, or doctors in general, be compensated based on their production? This question has received increased attention in the last few years. A major criticism of production-based compensation is that it is essentially a system that pays doctors for doing more, not for doing better. There is a growing interest in shifting at least some of physician (and hospital) compensation to a system based on the quality of care delivered.

At this point it isn’t entirely clear how all of this will play out in the coming years. What is clear is that for the time being the financial health of our practices is very dependent on our production (as well as other factors such as financial support from a hospital). So until Medicare and other payers change their system of physician reimbursement, I think it can be a good idea in many practices for at least some of a hospitalist’s income to be based on production because that helps connect him/her to the economic health of the practice.

In my May 2006 column (p. 50) I suggested that you consider production-based compensation because it can allow you and your partners to take more control of decisions about how hard you want to work and when you want to add additional doctors to your group. Most production-based compensation formulas allow doctors in the same group to work different amounts, such as working a different number of days on the schedule, and carrying different patient loads. In contrast, groups in which the hospitalists have a fixed salary (or one with a very small production-based component) usually require the doctors to work the same number of days on the schedule, and try to ensure all doctors have similar daily patient load.

When I discuss this idea with hospitalists around the country they often express concern that it would be too risky to go on a production-based salary system. They say things like, “I can’t go on production because I can’t control how many patients are referred to our practice.”

While it’s true that we have little control over patient volume from one day to the next, we have significant control over volume for any lengthy interval such as a year. If you provide good service to referring doctors and usually accept referrals graciously you will have a much higher volume than if you regularly resist referrals.

And I’ll bet that the majority of the other doctors at your hospital can’t precisely control their patient volume, but their compensation is based entirely on individual production. This is true of many emergency department and radiology practices, and some medical subspecialty groups. Why should hospitalist practice be different?

Another misconception about production-based compensation is that it is synonymous with foregoing any financial support from your hospital or other sponsoring institution. It isn’t. You can still pay individual doctors on productivity and include financial support from the hospital. For example, if the doctors are paid $55 for every wRVU generated, then $40 of that might come from professional fee collections, and $15 from the hospital (employer).

Others fear that a salary based on production will cause doctors to work at unreasonably high workloads, leading to poor patient care or patient satisfaction, or less efficient use of hospital resources (e.g., keep patients in the hospital longer). This is a potential risk, but not a common problem in my experience. There can also be concern that compensation based on productivity will cause the doctors within a group to compete with one another for patients (and income), leading to stress within the group. This is an uncommon problem, and—if it occurs within your group—it probably means that there are too many doctors in your practice (or that you should market the practice to attract more patients) rather than proving that productivity-based compensation is a bad idea.

But an explanation that clarifies objections to productivity-based compensation certainly isn’t enough of a reason to support it. You need to be convinced of some of its benefits. Hospitalists who aren’t used to being paid based in part or in whole on production tend to see it as a very stressful—or even oppressive—way to be paid. But I hope to convince you it is actually liberating.

In the absence of a production component, many groups try hard to ensure that every doctor works the same amount. For example, a group that pays a fixed annual salary to all doctors typically encourages or insists that each doctor must work almost the same amount. But when paid on production, each doctor in the group can, within reasonable boundaries, decide how much he or she wants to work. Of course all of the group’s work must be taken care of, but in nearly every group some doctors are probably willing to work a little more and others a little less than the average workload for the group.

Nearly 15 years ago, before I married and had children, I got hooked on the idea of learning to fly airplanes. Wow, did I enjoy it. But it is pretty time consuming to get a pilot’s license, to say nothing of the expense. There were a number of days that I was to be the admitting doctor for our practice, but great weather and an available plane and instructor would lure me away. On a number of occasions at 4 or 5 p.m. I called my partner who had gone home for the day and said, “Chuck, would you be willing to cover admissions so I can go flying?” He usually said “sure,” at which point I’d tell him that there were already two patients waiting in the ED.

This system made both of us happy. After nine months I was a licensed pilot and for that year my partner had a much higher income than I did. We both got what we wanted, and paying ourselves on production is what made this possible. If we were in a group with a fixed salary I can’t imagine he would have been willing to help me out so often (if ever), and I would have been limited to taking flying lessons only on my days off. Or I would have needed to pay my partner back by making up the evenings he covered for me.

My point in telling this story is that so many people think of paying hospitalists based entirely, or in part, on production is just a way to get them to maintain unreasonably high work loads. But I think it simply liberates the doctor to decide for himself what the right workload is, while owning the economic consequences of that choice. It allowed me the opportunity to work less.

A few hospitalists paid on production might choose badly and choose to work at an unreasonable (or unsafe) pace, but nearly all will make reasonable decisions. And members of a group can periodically adjust their workload up or down according to their need at the time; there is no requirement to work at the same load year after year. In fact, my partners and I in Florida didn’t even keep track of precisely how often each of us was on call over the year because there wasn’t any reason it needed to be the same for each person. (We did make some effort to distribute call evenly, but didn’t worry when it never worked out just right because each doctor could take more or less call and see a corresponding change in income).

I realize that there is no perfect compensation system, and one based on production can have shortcomings. But I think too many hospitalists assume the only reasonable system is one such as a fixed annual salary, or an hourly rate, or some method that intentionally avoids paying for productivity. You should think about how liberating productivity compensation can be. Basing a significant portion (say 40% or more—or even 100%) on productivity might be a good idea for you.

And there is nothing about productivity-based compensation that interferes with also providing financial reward for good quality of care. I’m a fan of both. If payers increasingly use quality of care as the basis for physician reimbursement in the future, individual physician compensation formulas should be based more on quality than production. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is a co-founder and past-president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Should hospitalists, or doctors in general, be compensated based on their production? This question has received increased attention in the last few years. A major criticism of production-based compensation is that it is essentially a system that pays doctors for doing more, not for doing better. There is a growing interest in shifting at least some of physician (and hospital) compensation to a system based on the quality of care delivered.

At this point it isn’t entirely clear how all of this will play out in the coming years. What is clear is that for the time being the financial health of our practices is very dependent on our production (as well as other factors such as financial support from a hospital). So until Medicare and other payers change their system of physician reimbursement, I think it can be a good idea in many practices for at least some of a hospitalist’s income to be based on production because that helps connect him/her to the economic health of the practice.