User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

When You and Your Malpractice Insurer Disagree on Your Case

You’ve been sued for medical malpractice. If you are a physician in the United States, that is not an unlikely scenario.

An analysis by the American Medical Association shows that almost half of all physicians are sued by the time they reach 54. In some specialties, such as ob.gyn., one is almost guaranteed to be sued at some point.

But that’s what medical malpractice insurance is for, right? Your medical malpractice insurer will assign an attorney to take care of you and help you through this situation. Won’t they?

Maybe so, but the attorney and the claims representative your insurer assigns to your case may have a different idea about how to proceed than you do. Though the defense attorney assigned to you represents you, he or she gets paid by the insurance carrier.

This can create a conflict when your defense counsel and your insurance claims representative aim to take your case in a direction you don’t like.

Disagreements might include:

- Choice of expert witnesses

- Tactical decisions related to trial strategy

- Public relations considerations

- Admissions of liability

- Allocation of resources

To Settle or Not?

One of the most challenging — and common — disagreements is whether to settle the case.

Sometimes a malpractice insurer wants to settle the case against the defendant doctor’s wishes. Or the doctor wants to settle but is pushed into going to trial. In the following case, one doctor had to face the consequences of a decision he didn’t even make.

The Underlying Medical Malpractice Case

Dr. D was sued by a patient who had allegedly called Dr. D’s office six times in 2 days complaining of intermittent chest pain.

Dr. D had been swamped with patients and couldn’t squeeze this patient in for an office visit, but he did call back. The patient later claimed that during the call he told the doctor he was suffering from chest pain. The doctor recalled that the patient had complained of abdominal discomfort that began after he had exercised.

The physician wrote a prescription for an ECG at the local hospital and called to ensure that the patient could just walk in. The ECG was allegedly abnormal but was not read as representing an impending or current heart attack. Later that evening, however, the patient went to the emergency department of another hospital where it was confirmed that he had suffered a heart attack. The patient underwent cardiac catheterization and stent placement to address a blockage in his left anterior descending artery.

The patient subsequently sued Dr. D and the hospital where he had the original ECG. Dr. D contacted his medical malpractice insurance company. The insurance company assigned an attorney to represent Dr. D. Discovery in the case began.

The plaintiff’s own medical expert testified in a deposition that there was no way for the heart attack to have been prevented and that the treatment would have been the same either way. But Dr. D could not find a record of the phone calls with the patient, and he had not noted his conversation the patient in their medical records.

Dr. D held a policy for $1 million, and his state had a fund that would kick in an additional $1 million. But the plaintiffs demanded $4 million to settle.

A month before trial, the plaintiff’s attorney sent a threatening letter to Dr. D’s attorney warning him that Dr. D was underinsured and suggesting that it would be in the physician’s best interests to settle.

“I want to stress to you that it is not my desire to harm your client’s reputation or to destroy his business,” wrote the plaintiff’s attorney. “However, now is the time to avoid consequences such as these by making a good faith effort to get this case resolved.”

The letter went on to note that the defense attorney should give Dr. D a copy of the letter so that everyone would be aware of the potential consequences of an award against Dr. D in excess of his limits of insurance coverage. The plaintiff’s attorney even suggested that Dr. D should retain personal counsel.

Dr. D’s defense attorney downplayed the letter and assured him that there was no reason to worry.

Meanwhile the case inched closer to trial.

The codefendant hospital settled with the plaintiff on the night before jury selection, leaving Dr. D in the uncomfortable position of being the only defendant in the case. At this point, Dr. D decided he would like to settle, and he sent his attorney an email telling him so. But the attorney instead referred him to an insurance company claims.

Just days before the trial was to start, Dr. D repeatedly told the claims representative assigned to his claim that he did not want to go to trial but rather wanted to settle. The representative told Dr. D that he had no choice in whether the action settled.

A committee at the insurance company had decided to proceed with the trial rather than settle.

The trial proved a painful debacle for Dr. D. His attorney’s idea of showing a “gotcha” video of the allegedly permanently injured plaintiff carrying a large, heavy box backfired when the jury was shown by the plaintiff that the box actually contained ice cream cones and weighed very little.

Prior to trial, the plaintiff offered to settle for $1 million. On the first day of trial, they lowered that amount to $750,000, yet the defense attorney did not settle the case, and it proceeded to a jury verdict. The jury awarded the plaintiff over $4 million — well in excess of Dr. D’s policy limits.

The Follow-up

Dr. D was horrified, but the insurance company claims representative said the insurer would promptly offer $2 million in available insurance coverage to settle the case post verdict. This did not happen. Instead, the insurer chose to appeal the verdict against Dr. D’s wishes.

Ultimately, Dr. D was forced to hire his own lawyer. He ultimately sued the insurance company for breach of contract and bad faith.

The insurance company eventually attempted to settle with the plaintiffs’ counsel, but the plaintiff refused to accept the available insurance coverage. The insurance carrier still has not posted the entire appeal bond. The case is still pending.

Protecting Yourself

The lesson from Dr. D’s experience: Understand that the insurance company is not your friend. It’s a business looking out for its own interests.

The plaintiff’s attorney was absolutely correct in suggesting that Dr. D retain his own attorney to represent his own interests. You should hire your own lawyer when:

- You disagree with your insurer on how to proceed in a case.

- You receive a demand that exceeds your available insurance coverage or for damages that may not be covered by your policy, such as punitive damages.

- Your insurance carrier attempts to deny insurance coverage for your claim or sends you a letter stating that it is “reserving its rights” not to cover or to limit coverage for your claim.

Retaining independent counsel protects your interests, not those of your insurance company.

Independent counsel can give you a second opinion on the strengths and weaknesses of your claim, help you prepare for your deposition, and attend court dates with you to ensure that you are completely protected.

Independent counsel can challenge your insurance company’s decision to deny or limit your insurance coverage and ensure that you receive all of the benefits to which you are entitled under your insurance policy. Some policies may include an independent lawyer to be paid for by your insurance carrier in case of a conflicts.

The most important takeaway? Your medical malpractice insurance carrier is not your friend, so act accordingly in times of conflict.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

You’ve been sued for medical malpractice. If you are a physician in the United States, that is not an unlikely scenario.

An analysis by the American Medical Association shows that almost half of all physicians are sued by the time they reach 54. In some specialties, such as ob.gyn., one is almost guaranteed to be sued at some point.

But that’s what medical malpractice insurance is for, right? Your medical malpractice insurer will assign an attorney to take care of you and help you through this situation. Won’t they?

Maybe so, but the attorney and the claims representative your insurer assigns to your case may have a different idea about how to proceed than you do. Though the defense attorney assigned to you represents you, he or she gets paid by the insurance carrier.

This can create a conflict when your defense counsel and your insurance claims representative aim to take your case in a direction you don’t like.

Disagreements might include:

- Choice of expert witnesses

- Tactical decisions related to trial strategy

- Public relations considerations

- Admissions of liability

- Allocation of resources

To Settle or Not?

One of the most challenging — and common — disagreements is whether to settle the case.

Sometimes a malpractice insurer wants to settle the case against the defendant doctor’s wishes. Or the doctor wants to settle but is pushed into going to trial. In the following case, one doctor had to face the consequences of a decision he didn’t even make.

The Underlying Medical Malpractice Case

Dr. D was sued by a patient who had allegedly called Dr. D’s office six times in 2 days complaining of intermittent chest pain.

Dr. D had been swamped with patients and couldn’t squeeze this patient in for an office visit, but he did call back. The patient later claimed that during the call he told the doctor he was suffering from chest pain. The doctor recalled that the patient had complained of abdominal discomfort that began after he had exercised.

The physician wrote a prescription for an ECG at the local hospital and called to ensure that the patient could just walk in. The ECG was allegedly abnormal but was not read as representing an impending or current heart attack. Later that evening, however, the patient went to the emergency department of another hospital where it was confirmed that he had suffered a heart attack. The patient underwent cardiac catheterization and stent placement to address a blockage in his left anterior descending artery.

The patient subsequently sued Dr. D and the hospital where he had the original ECG. Dr. D contacted his medical malpractice insurance company. The insurance company assigned an attorney to represent Dr. D. Discovery in the case began.

The plaintiff’s own medical expert testified in a deposition that there was no way for the heart attack to have been prevented and that the treatment would have been the same either way. But Dr. D could not find a record of the phone calls with the patient, and he had not noted his conversation the patient in their medical records.

Dr. D held a policy for $1 million, and his state had a fund that would kick in an additional $1 million. But the plaintiffs demanded $4 million to settle.

A month before trial, the plaintiff’s attorney sent a threatening letter to Dr. D’s attorney warning him that Dr. D was underinsured and suggesting that it would be in the physician’s best interests to settle.

“I want to stress to you that it is not my desire to harm your client’s reputation or to destroy his business,” wrote the plaintiff’s attorney. “However, now is the time to avoid consequences such as these by making a good faith effort to get this case resolved.”

The letter went on to note that the defense attorney should give Dr. D a copy of the letter so that everyone would be aware of the potential consequences of an award against Dr. D in excess of his limits of insurance coverage. The plaintiff’s attorney even suggested that Dr. D should retain personal counsel.

Dr. D’s defense attorney downplayed the letter and assured him that there was no reason to worry.

Meanwhile the case inched closer to trial.

The codefendant hospital settled with the plaintiff on the night before jury selection, leaving Dr. D in the uncomfortable position of being the only defendant in the case. At this point, Dr. D decided he would like to settle, and he sent his attorney an email telling him so. But the attorney instead referred him to an insurance company claims.

Just days before the trial was to start, Dr. D repeatedly told the claims representative assigned to his claim that he did not want to go to trial but rather wanted to settle. The representative told Dr. D that he had no choice in whether the action settled.

A committee at the insurance company had decided to proceed with the trial rather than settle.

The trial proved a painful debacle for Dr. D. His attorney’s idea of showing a “gotcha” video of the allegedly permanently injured plaintiff carrying a large, heavy box backfired when the jury was shown by the plaintiff that the box actually contained ice cream cones and weighed very little.

Prior to trial, the plaintiff offered to settle for $1 million. On the first day of trial, they lowered that amount to $750,000, yet the defense attorney did not settle the case, and it proceeded to a jury verdict. The jury awarded the plaintiff over $4 million — well in excess of Dr. D’s policy limits.

The Follow-up

Dr. D was horrified, but the insurance company claims representative said the insurer would promptly offer $2 million in available insurance coverage to settle the case post verdict. This did not happen. Instead, the insurer chose to appeal the verdict against Dr. D’s wishes.

Ultimately, Dr. D was forced to hire his own lawyer. He ultimately sued the insurance company for breach of contract and bad faith.

The insurance company eventually attempted to settle with the plaintiffs’ counsel, but the plaintiff refused to accept the available insurance coverage. The insurance carrier still has not posted the entire appeal bond. The case is still pending.

Protecting Yourself

The lesson from Dr. D’s experience: Understand that the insurance company is not your friend. It’s a business looking out for its own interests.

The plaintiff’s attorney was absolutely correct in suggesting that Dr. D retain his own attorney to represent his own interests. You should hire your own lawyer when:

- You disagree with your insurer on how to proceed in a case.

- You receive a demand that exceeds your available insurance coverage or for damages that may not be covered by your policy, such as punitive damages.

- Your insurance carrier attempts to deny insurance coverage for your claim or sends you a letter stating that it is “reserving its rights” not to cover or to limit coverage for your claim.

Retaining independent counsel protects your interests, not those of your insurance company.

Independent counsel can give you a second opinion on the strengths and weaknesses of your claim, help you prepare for your deposition, and attend court dates with you to ensure that you are completely protected.

Independent counsel can challenge your insurance company’s decision to deny or limit your insurance coverage and ensure that you receive all of the benefits to which you are entitled under your insurance policy. Some policies may include an independent lawyer to be paid for by your insurance carrier in case of a conflicts.

The most important takeaway? Your medical malpractice insurance carrier is not your friend, so act accordingly in times of conflict.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

You’ve been sued for medical malpractice. If you are a physician in the United States, that is not an unlikely scenario.

An analysis by the American Medical Association shows that almost half of all physicians are sued by the time they reach 54. In some specialties, such as ob.gyn., one is almost guaranteed to be sued at some point.

But that’s what medical malpractice insurance is for, right? Your medical malpractice insurer will assign an attorney to take care of you and help you through this situation. Won’t they?

Maybe so, but the attorney and the claims representative your insurer assigns to your case may have a different idea about how to proceed than you do. Though the defense attorney assigned to you represents you, he or she gets paid by the insurance carrier.

This can create a conflict when your defense counsel and your insurance claims representative aim to take your case in a direction you don’t like.

Disagreements might include:

- Choice of expert witnesses

- Tactical decisions related to trial strategy

- Public relations considerations

- Admissions of liability

- Allocation of resources

To Settle or Not?

One of the most challenging — and common — disagreements is whether to settle the case.

Sometimes a malpractice insurer wants to settle the case against the defendant doctor’s wishes. Or the doctor wants to settle but is pushed into going to trial. In the following case, one doctor had to face the consequences of a decision he didn’t even make.

The Underlying Medical Malpractice Case

Dr. D was sued by a patient who had allegedly called Dr. D’s office six times in 2 days complaining of intermittent chest pain.

Dr. D had been swamped with patients and couldn’t squeeze this patient in for an office visit, but he did call back. The patient later claimed that during the call he told the doctor he was suffering from chest pain. The doctor recalled that the patient had complained of abdominal discomfort that began after he had exercised.

The physician wrote a prescription for an ECG at the local hospital and called to ensure that the patient could just walk in. The ECG was allegedly abnormal but was not read as representing an impending or current heart attack. Later that evening, however, the patient went to the emergency department of another hospital where it was confirmed that he had suffered a heart attack. The patient underwent cardiac catheterization and stent placement to address a blockage in his left anterior descending artery.

The patient subsequently sued Dr. D and the hospital where he had the original ECG. Dr. D contacted his medical malpractice insurance company. The insurance company assigned an attorney to represent Dr. D. Discovery in the case began.

The plaintiff’s own medical expert testified in a deposition that there was no way for the heart attack to have been prevented and that the treatment would have been the same either way. But Dr. D could not find a record of the phone calls with the patient, and he had not noted his conversation the patient in their medical records.

Dr. D held a policy for $1 million, and his state had a fund that would kick in an additional $1 million. But the plaintiffs demanded $4 million to settle.

A month before trial, the plaintiff’s attorney sent a threatening letter to Dr. D’s attorney warning him that Dr. D was underinsured and suggesting that it would be in the physician’s best interests to settle.

“I want to stress to you that it is not my desire to harm your client’s reputation or to destroy his business,” wrote the plaintiff’s attorney. “However, now is the time to avoid consequences such as these by making a good faith effort to get this case resolved.”

The letter went on to note that the defense attorney should give Dr. D a copy of the letter so that everyone would be aware of the potential consequences of an award against Dr. D in excess of his limits of insurance coverage. The plaintiff’s attorney even suggested that Dr. D should retain personal counsel.

Dr. D’s defense attorney downplayed the letter and assured him that there was no reason to worry.

Meanwhile the case inched closer to trial.

The codefendant hospital settled with the plaintiff on the night before jury selection, leaving Dr. D in the uncomfortable position of being the only defendant in the case. At this point, Dr. D decided he would like to settle, and he sent his attorney an email telling him so. But the attorney instead referred him to an insurance company claims.

Just days before the trial was to start, Dr. D repeatedly told the claims representative assigned to his claim that he did not want to go to trial but rather wanted to settle. The representative told Dr. D that he had no choice in whether the action settled.

A committee at the insurance company had decided to proceed with the trial rather than settle.

The trial proved a painful debacle for Dr. D. His attorney’s idea of showing a “gotcha” video of the allegedly permanently injured plaintiff carrying a large, heavy box backfired when the jury was shown by the plaintiff that the box actually contained ice cream cones and weighed very little.

Prior to trial, the plaintiff offered to settle for $1 million. On the first day of trial, they lowered that amount to $750,000, yet the defense attorney did not settle the case, and it proceeded to a jury verdict. The jury awarded the plaintiff over $4 million — well in excess of Dr. D’s policy limits.

The Follow-up

Dr. D was horrified, but the insurance company claims representative said the insurer would promptly offer $2 million in available insurance coverage to settle the case post verdict. This did not happen. Instead, the insurer chose to appeal the verdict against Dr. D’s wishes.

Ultimately, Dr. D was forced to hire his own lawyer. He ultimately sued the insurance company for breach of contract and bad faith.

The insurance company eventually attempted to settle with the plaintiffs’ counsel, but the plaintiff refused to accept the available insurance coverage. The insurance carrier still has not posted the entire appeal bond. The case is still pending.

Protecting Yourself

The lesson from Dr. D’s experience: Understand that the insurance company is not your friend. It’s a business looking out for its own interests.

The plaintiff’s attorney was absolutely correct in suggesting that Dr. D retain his own attorney to represent his own interests. You should hire your own lawyer when:

- You disagree with your insurer on how to proceed in a case.

- You receive a demand that exceeds your available insurance coverage or for damages that may not be covered by your policy, such as punitive damages.

- Your insurance carrier attempts to deny insurance coverage for your claim or sends you a letter stating that it is “reserving its rights” not to cover or to limit coverage for your claim.

Retaining independent counsel protects your interests, not those of your insurance company.

Independent counsel can give you a second opinion on the strengths and weaknesses of your claim, help you prepare for your deposition, and attend court dates with you to ensure that you are completely protected.

Independent counsel can challenge your insurance company’s decision to deny or limit your insurance coverage and ensure that you receive all of the benefits to which you are entitled under your insurance policy. Some policies may include an independent lawyer to be paid for by your insurance carrier in case of a conflicts.

The most important takeaway? Your medical malpractice insurance carrier is not your friend, so act accordingly in times of conflict.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Reform School’ for Pharmacy Benefit Managers: How Might Legislation Help Patients?

The term “reform school” is a bit outdated. It used to refer to institutions where young offenders were sent instead of prison. Some argue that pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) should bypass reform school and go straight to prison. “PBM reform” has become a ubiquitous term, encompassing any legislative or regulatory efforts aimed at curbing PBMs’ bad behavior. When discussing PBM reform, it’s crucial to understand the various segments of the healthcare system affected by PBMs. This complexity often makes it challenging to determine what these reform packages would actually achieve and who they would benefit.

Pharmacists have long been vocal critics of PBMs, and while their issues are extremely important, it is essential to remember that the ultimate victims of PBM misconduct, in terms of access to care, are patients. At some point, we will all be patients, making this issue universally relevant. It has been quite challenging to follow federal legislation on this topic as these packages attempt to address a number of bad behaviors by PBMs affecting a variety of victims. This discussion will examine those reforms that would directly improve patient’s access to available and affordable medications.

Policy Categories of PBM Reform

There are five policy categories of PBM reform legislation overall, including three that have the greatest potential to directly address patient needs. The first is patient access to medications (utilization management, copay assistance, prior authorization, etc.), followed by delinking drug list prices from PBM income and pass-through of price concessions from the manufacturer. The remaining two categories involve transparency and pharmacy-facing reform, both of which are very important. However, this discussion will revolve around the first three categories. It should be noted that many of the legislation packages addressing the categories of patient access, delinking, and pass-through also include transparency issues, particularly as they relate to pharmacy-facing issues.

Patient Access to Medications — Step Therapy Legislation

One of the major obstacles to patient access to medications is the use of PBM utilization management tools such as step therapy (“fail first”), prior authorizations, nonmedical switching, and formulary exclusions. These tools dictate when patients can obtain necessary medications and for how long patients who are stable on their current treatments can remain on them.

While many states have enacted step therapy reforms to prevent stable patients from being whip-sawed between medications that maximize PBM profits (often labeled as “savings”), these state protections apply only to state-regulated health plans. These include fully insured health plans and those offered through the Affordable Care Act’s Health Insurance Marketplace. It also includes state employees, state corrections, and, in some cases, state labor unions. State legislation does not extend to patients covered by employer self-insured health plans, called ERISA plans for the federal law that governs employee benefit plans, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act. These ERISA plans include nearly 35 million people nationwide.

This is where the Safe Step Act (S.652/H.R.2630) becomes crucial, as it allows employees to request exceptions to harmful fail-first protocols. The bill has gained significant momentum, having been reported out of the Senate HELP Committee and discussed in House markups. The Safe Step Act would mandate that an exception to a step therapy protocol must be granted if:

- The required treatment has been ineffective

- The treatment is expected to be ineffective, and delaying effective treatment would lead to irreversible consequences

- The treatment will cause or is likely to cause an adverse reaction

- The treatment is expected to prevent the individual from performing daily activities or occupational responsibilities

- The individual is stable on their current prescription drugs

- There are other circumstances as determined by the Employee Benefits Security Administration

This legislation is vital for ensuring that patients have timely access to the medications they need without unnecessary delays or disruptions.

Patient Access to Medications — Prior Authorizations

Another significant issue affecting patient access to medications is prior authorizations (PAs). According to an American Medical Association survey, nearly one in four physicians (24%) report that a PA has led to a serious adverse event for a patient in their care. In rheumatology, PAs often result in delays in care (even for those initially approved) and a significant increase in steroid usage. In particular, PAs in Medicare Advantage (MA) plans are harmful to Medicare beneficiaries.

The Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act (H.R.8702 / S.4532) aims to reform PAs used in MA plans, making the process more efficient and transparent to improve access to care for seniors. Unfortunately, it does not cover Part D drugs and may only cover Part B drugs depending on the MA plan’s benefit package. Here are the key provisions of the act:

- Electronic PA: Implementing real-time decisions for routinely approved items and services.

- Transparency: Requiring annual publication of PA information, such as the percentage of requests approved and the average response time.

- Quality and Timeliness Standards: The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) will set standards for the quality and timeliness of PA determinations.

- Streamlining Approvals: Simplifying the approval process and reducing the time allowed for health plans to consider PA requests.

This bill passed the House in September 2022 but stalled in the Senate because of an unfavorable Congressional Budget Office score. CMS has since finalized portions of this bill via regulation, zeroing out the CBO score and increasing the chances of its passage.

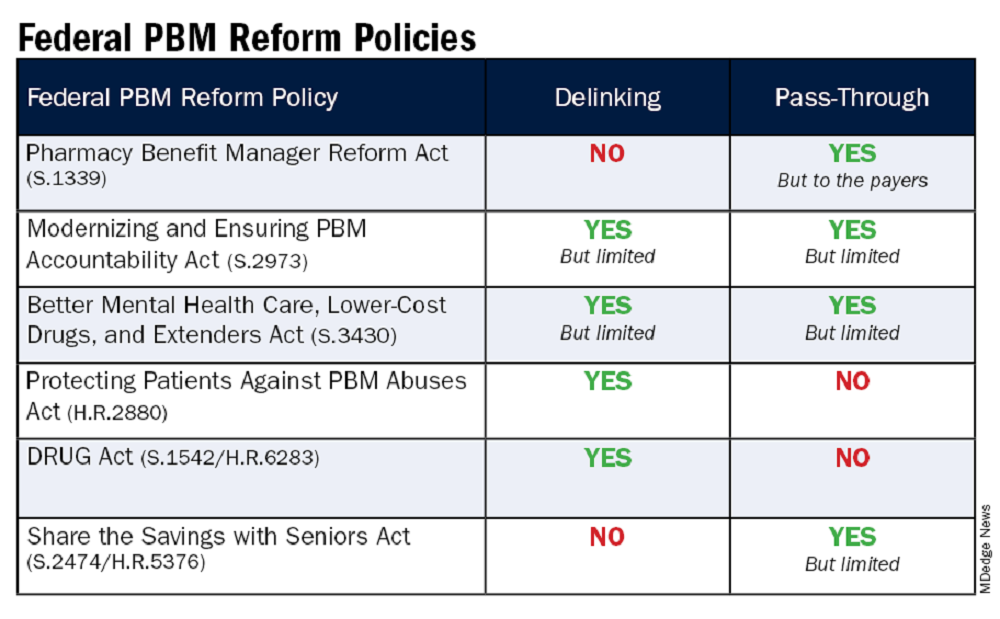

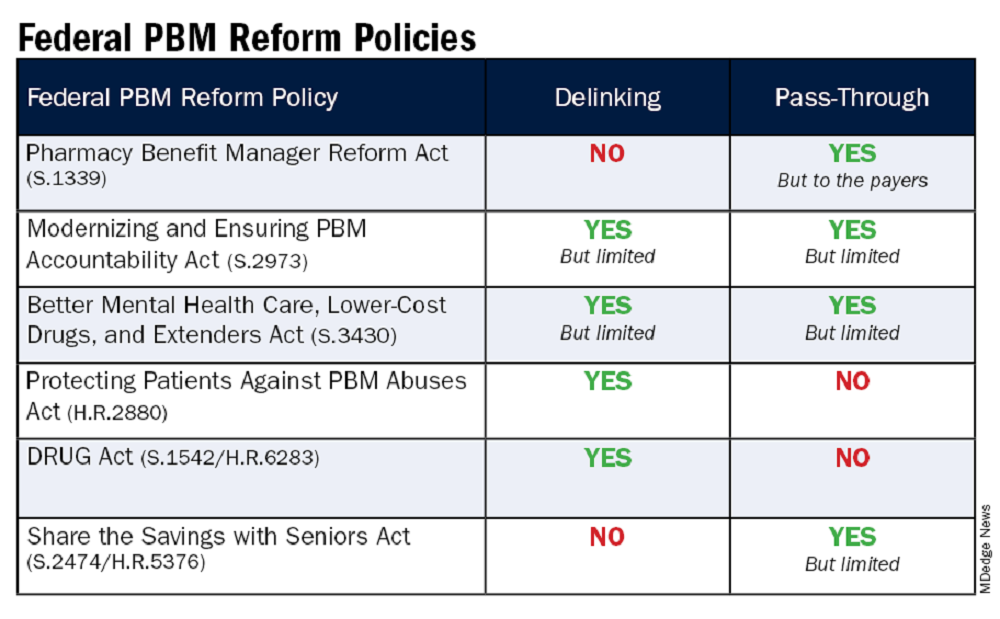

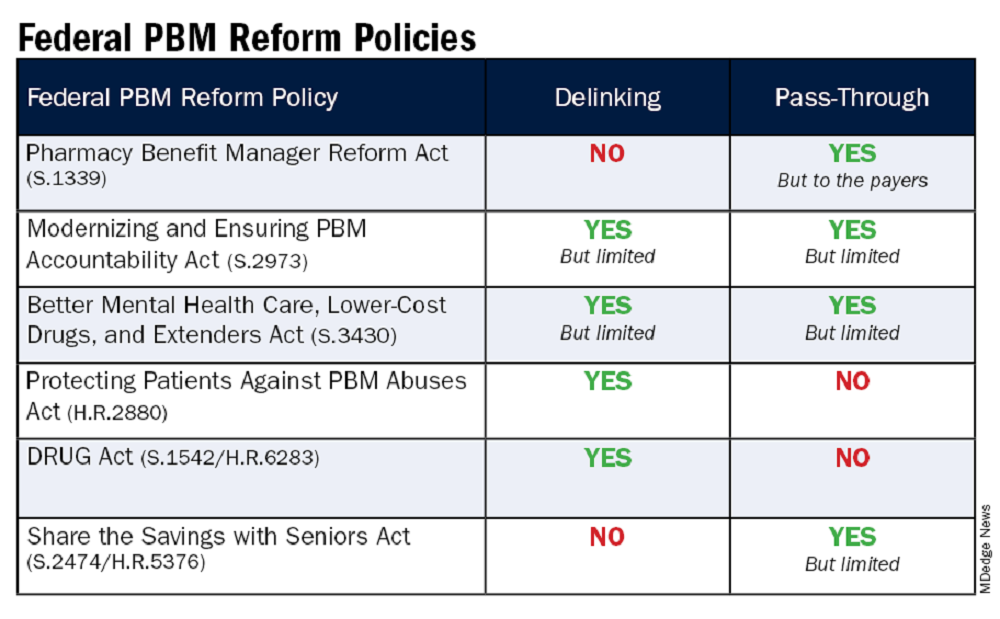

Delinking Drug Prices from PBM Income and Pass-Through of Price Concessions

Affordability is a crucial aspect of accessibility, especially when it comes to medications. Over the years, we’ve learned that PBMs often favor placing the highest list price drugs on formularies because the rebates and various fees they receive from manufacturers are based on a percentage of the list price. In other words, the higher the medication’s price, the more money the PBM makes.

This practice is evident in both commercial and government formularies, where brand-name drugs are often preferred, while lower-priced generics are either excluded or placed on higher tiers. As a result, while major PBMs benefit from these rebates and fees, patients continue to pay their cost share based on the list price of the medication.

To improve the affordability of medications, a key aspect of PBM reform should be to disincentivize PBMs from selecting higher-priced medications and/or require the pass-through of manufacturer price concessions to patients.

Several major PBM reform bills are currently being considered that address either the delinking of price concessions from the list price of the drug or some form of pass-through of these concessions. These reforms are essential to ensure that patients can access affordable medications without being burdened by inflated costs.

The legislation includes the Pharmacy Benefit Manager Reform Act (S.1339); the Modernizing & Ensuring PBM Accountability Act (S.2973); the Better Mental Health Care, Lower Cost Drugs, and Extenders Act (S.3430); the Protecting Patients Against PBM Abuses Act (H.R. 2880); the DRUG Act (S.2474 / H.R.6283); and the Share the Savings with Seniors Act (S.2474 / H.R.5376).

As with all legislation, there are limitations and compromises in each of these. However, these bills are a good first step in addressing PBM remuneration (rebates and fees) based on the list price of the drug and/or passing through to the patient the benefit of manufacturer price concessions. By focusing on key areas like utilization management, delinking drug prices from PBM income, and allowing patients to directly benefit from manufacturer price concessions, we can work toward a more equitable and efficient healthcare system. Reigning in PBM bad behavior is a challenge, but the potential benefits for patient care and access make it a crucial fight worth pursuing.

Please help in efforts to improve patients’ access to available and affordable medications by contacting your representatives in Congress to impart to them the importance of passing legislation. The CSRO’s legislative map tool can help to inform you of the latest information on these and other bills and assist you in engaging with your representatives on them.

Dr. Feldman is a rheumatologist in private practice with The Rheumatology Group in New Orleans. She is the CSRO’s vice president of Advocacy and Government Affairs and its immediate past president, as well as past chair of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines and a past member of the American College of Rheumatology insurance subcommittee. She has no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. You can reach her at [email protected].

The term “reform school” is a bit outdated. It used to refer to institutions where young offenders were sent instead of prison. Some argue that pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) should bypass reform school and go straight to prison. “PBM reform” has become a ubiquitous term, encompassing any legislative or regulatory efforts aimed at curbing PBMs’ bad behavior. When discussing PBM reform, it’s crucial to understand the various segments of the healthcare system affected by PBMs. This complexity often makes it challenging to determine what these reform packages would actually achieve and who they would benefit.

Pharmacists have long been vocal critics of PBMs, and while their issues are extremely important, it is essential to remember that the ultimate victims of PBM misconduct, in terms of access to care, are patients. At some point, we will all be patients, making this issue universally relevant. It has been quite challenging to follow federal legislation on this topic as these packages attempt to address a number of bad behaviors by PBMs affecting a variety of victims. This discussion will examine those reforms that would directly improve patient’s access to available and affordable medications.

Policy Categories of PBM Reform

There are five policy categories of PBM reform legislation overall, including three that have the greatest potential to directly address patient needs. The first is patient access to medications (utilization management, copay assistance, prior authorization, etc.), followed by delinking drug list prices from PBM income and pass-through of price concessions from the manufacturer. The remaining two categories involve transparency and pharmacy-facing reform, both of which are very important. However, this discussion will revolve around the first three categories. It should be noted that many of the legislation packages addressing the categories of patient access, delinking, and pass-through also include transparency issues, particularly as they relate to pharmacy-facing issues.

Patient Access to Medications — Step Therapy Legislation

One of the major obstacles to patient access to medications is the use of PBM utilization management tools such as step therapy (“fail first”), prior authorizations, nonmedical switching, and formulary exclusions. These tools dictate when patients can obtain necessary medications and for how long patients who are stable on their current treatments can remain on them.

While many states have enacted step therapy reforms to prevent stable patients from being whip-sawed between medications that maximize PBM profits (often labeled as “savings”), these state protections apply only to state-regulated health plans. These include fully insured health plans and those offered through the Affordable Care Act’s Health Insurance Marketplace. It also includes state employees, state corrections, and, in some cases, state labor unions. State legislation does not extend to patients covered by employer self-insured health plans, called ERISA plans for the federal law that governs employee benefit plans, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act. These ERISA plans include nearly 35 million people nationwide.

This is where the Safe Step Act (S.652/H.R.2630) becomes crucial, as it allows employees to request exceptions to harmful fail-first protocols. The bill has gained significant momentum, having been reported out of the Senate HELP Committee and discussed in House markups. The Safe Step Act would mandate that an exception to a step therapy protocol must be granted if:

- The required treatment has been ineffective

- The treatment is expected to be ineffective, and delaying effective treatment would lead to irreversible consequences

- The treatment will cause or is likely to cause an adverse reaction

- The treatment is expected to prevent the individual from performing daily activities or occupational responsibilities

- The individual is stable on their current prescription drugs

- There are other circumstances as determined by the Employee Benefits Security Administration

This legislation is vital for ensuring that patients have timely access to the medications they need without unnecessary delays or disruptions.

Patient Access to Medications — Prior Authorizations

Another significant issue affecting patient access to medications is prior authorizations (PAs). According to an American Medical Association survey, nearly one in four physicians (24%) report that a PA has led to a serious adverse event for a patient in their care. In rheumatology, PAs often result in delays in care (even for those initially approved) and a significant increase in steroid usage. In particular, PAs in Medicare Advantage (MA) plans are harmful to Medicare beneficiaries.

The Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act (H.R.8702 / S.4532) aims to reform PAs used in MA plans, making the process more efficient and transparent to improve access to care for seniors. Unfortunately, it does not cover Part D drugs and may only cover Part B drugs depending on the MA plan’s benefit package. Here are the key provisions of the act:

- Electronic PA: Implementing real-time decisions for routinely approved items and services.

- Transparency: Requiring annual publication of PA information, such as the percentage of requests approved and the average response time.

- Quality and Timeliness Standards: The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) will set standards for the quality and timeliness of PA determinations.

- Streamlining Approvals: Simplifying the approval process and reducing the time allowed for health plans to consider PA requests.

This bill passed the House in September 2022 but stalled in the Senate because of an unfavorable Congressional Budget Office score. CMS has since finalized portions of this bill via regulation, zeroing out the CBO score and increasing the chances of its passage.

Delinking Drug Prices from PBM Income and Pass-Through of Price Concessions

Affordability is a crucial aspect of accessibility, especially when it comes to medications. Over the years, we’ve learned that PBMs often favor placing the highest list price drugs on formularies because the rebates and various fees they receive from manufacturers are based on a percentage of the list price. In other words, the higher the medication’s price, the more money the PBM makes.

This practice is evident in both commercial and government formularies, where brand-name drugs are often preferred, while lower-priced generics are either excluded or placed on higher tiers. As a result, while major PBMs benefit from these rebates and fees, patients continue to pay their cost share based on the list price of the medication.

To improve the affordability of medications, a key aspect of PBM reform should be to disincentivize PBMs from selecting higher-priced medications and/or require the pass-through of manufacturer price concessions to patients.

Several major PBM reform bills are currently being considered that address either the delinking of price concessions from the list price of the drug or some form of pass-through of these concessions. These reforms are essential to ensure that patients can access affordable medications without being burdened by inflated costs.

The legislation includes the Pharmacy Benefit Manager Reform Act (S.1339); the Modernizing & Ensuring PBM Accountability Act (S.2973); the Better Mental Health Care, Lower Cost Drugs, and Extenders Act (S.3430); the Protecting Patients Against PBM Abuses Act (H.R. 2880); the DRUG Act (S.2474 / H.R.6283); and the Share the Savings with Seniors Act (S.2474 / H.R.5376).

As with all legislation, there are limitations and compromises in each of these. However, these bills are a good first step in addressing PBM remuneration (rebates and fees) based on the list price of the drug and/or passing through to the patient the benefit of manufacturer price concessions. By focusing on key areas like utilization management, delinking drug prices from PBM income, and allowing patients to directly benefit from manufacturer price concessions, we can work toward a more equitable and efficient healthcare system. Reigning in PBM bad behavior is a challenge, but the potential benefits for patient care and access make it a crucial fight worth pursuing.

Please help in efforts to improve patients’ access to available and affordable medications by contacting your representatives in Congress to impart to them the importance of passing legislation. The CSRO’s legislative map tool can help to inform you of the latest information on these and other bills and assist you in engaging with your representatives on them.

Dr. Feldman is a rheumatologist in private practice with The Rheumatology Group in New Orleans. She is the CSRO’s vice president of Advocacy and Government Affairs and its immediate past president, as well as past chair of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines and a past member of the American College of Rheumatology insurance subcommittee. She has no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. You can reach her at [email protected].

The term “reform school” is a bit outdated. It used to refer to institutions where young offenders were sent instead of prison. Some argue that pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) should bypass reform school and go straight to prison. “PBM reform” has become a ubiquitous term, encompassing any legislative or regulatory efforts aimed at curbing PBMs’ bad behavior. When discussing PBM reform, it’s crucial to understand the various segments of the healthcare system affected by PBMs. This complexity often makes it challenging to determine what these reform packages would actually achieve and who they would benefit.

Pharmacists have long been vocal critics of PBMs, and while their issues are extremely important, it is essential to remember that the ultimate victims of PBM misconduct, in terms of access to care, are patients. At some point, we will all be patients, making this issue universally relevant. It has been quite challenging to follow federal legislation on this topic as these packages attempt to address a number of bad behaviors by PBMs affecting a variety of victims. This discussion will examine those reforms that would directly improve patient’s access to available and affordable medications.

Policy Categories of PBM Reform

There are five policy categories of PBM reform legislation overall, including three that have the greatest potential to directly address patient needs. The first is patient access to medications (utilization management, copay assistance, prior authorization, etc.), followed by delinking drug list prices from PBM income and pass-through of price concessions from the manufacturer. The remaining two categories involve transparency and pharmacy-facing reform, both of which are very important. However, this discussion will revolve around the first three categories. It should be noted that many of the legislation packages addressing the categories of patient access, delinking, and pass-through also include transparency issues, particularly as they relate to pharmacy-facing issues.

Patient Access to Medications — Step Therapy Legislation

One of the major obstacles to patient access to medications is the use of PBM utilization management tools such as step therapy (“fail first”), prior authorizations, nonmedical switching, and formulary exclusions. These tools dictate when patients can obtain necessary medications and for how long patients who are stable on their current treatments can remain on them.

While many states have enacted step therapy reforms to prevent stable patients from being whip-sawed between medications that maximize PBM profits (often labeled as “savings”), these state protections apply only to state-regulated health plans. These include fully insured health plans and those offered through the Affordable Care Act’s Health Insurance Marketplace. It also includes state employees, state corrections, and, in some cases, state labor unions. State legislation does not extend to patients covered by employer self-insured health plans, called ERISA plans for the federal law that governs employee benefit plans, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act. These ERISA plans include nearly 35 million people nationwide.

This is where the Safe Step Act (S.652/H.R.2630) becomes crucial, as it allows employees to request exceptions to harmful fail-first protocols. The bill has gained significant momentum, having been reported out of the Senate HELP Committee and discussed in House markups. The Safe Step Act would mandate that an exception to a step therapy protocol must be granted if:

- The required treatment has been ineffective

- The treatment is expected to be ineffective, and delaying effective treatment would lead to irreversible consequences

- The treatment will cause or is likely to cause an adverse reaction

- The treatment is expected to prevent the individual from performing daily activities or occupational responsibilities

- The individual is stable on their current prescription drugs

- There are other circumstances as determined by the Employee Benefits Security Administration

This legislation is vital for ensuring that patients have timely access to the medications they need without unnecessary delays or disruptions.

Patient Access to Medications — Prior Authorizations

Another significant issue affecting patient access to medications is prior authorizations (PAs). According to an American Medical Association survey, nearly one in four physicians (24%) report that a PA has led to a serious adverse event for a patient in their care. In rheumatology, PAs often result in delays in care (even for those initially approved) and a significant increase in steroid usage. In particular, PAs in Medicare Advantage (MA) plans are harmful to Medicare beneficiaries.

The Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act (H.R.8702 / S.4532) aims to reform PAs used in MA plans, making the process more efficient and transparent to improve access to care for seniors. Unfortunately, it does not cover Part D drugs and may only cover Part B drugs depending on the MA plan’s benefit package. Here are the key provisions of the act:

- Electronic PA: Implementing real-time decisions for routinely approved items and services.

- Transparency: Requiring annual publication of PA information, such as the percentage of requests approved and the average response time.

- Quality and Timeliness Standards: The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) will set standards for the quality and timeliness of PA determinations.

- Streamlining Approvals: Simplifying the approval process and reducing the time allowed for health plans to consider PA requests.

This bill passed the House in September 2022 but stalled in the Senate because of an unfavorable Congressional Budget Office score. CMS has since finalized portions of this bill via regulation, zeroing out the CBO score and increasing the chances of its passage.

Delinking Drug Prices from PBM Income and Pass-Through of Price Concessions

Affordability is a crucial aspect of accessibility, especially when it comes to medications. Over the years, we’ve learned that PBMs often favor placing the highest list price drugs on formularies because the rebates and various fees they receive from manufacturers are based on a percentage of the list price. In other words, the higher the medication’s price, the more money the PBM makes.

This practice is evident in both commercial and government formularies, where brand-name drugs are often preferred, while lower-priced generics are either excluded or placed on higher tiers. As a result, while major PBMs benefit from these rebates and fees, patients continue to pay their cost share based on the list price of the medication.

To improve the affordability of medications, a key aspect of PBM reform should be to disincentivize PBMs from selecting higher-priced medications and/or require the pass-through of manufacturer price concessions to patients.

Several major PBM reform bills are currently being considered that address either the delinking of price concessions from the list price of the drug or some form of pass-through of these concessions. These reforms are essential to ensure that patients can access affordable medications without being burdened by inflated costs.

The legislation includes the Pharmacy Benefit Manager Reform Act (S.1339); the Modernizing & Ensuring PBM Accountability Act (S.2973); the Better Mental Health Care, Lower Cost Drugs, and Extenders Act (S.3430); the Protecting Patients Against PBM Abuses Act (H.R. 2880); the DRUG Act (S.2474 / H.R.6283); and the Share the Savings with Seniors Act (S.2474 / H.R.5376).

As with all legislation, there are limitations and compromises in each of these. However, these bills are a good first step in addressing PBM remuneration (rebates and fees) based on the list price of the drug and/or passing through to the patient the benefit of manufacturer price concessions. By focusing on key areas like utilization management, delinking drug prices from PBM income, and allowing patients to directly benefit from manufacturer price concessions, we can work toward a more equitable and efficient healthcare system. Reigning in PBM bad behavior is a challenge, but the potential benefits for patient care and access make it a crucial fight worth pursuing.

Please help in efforts to improve patients’ access to available and affordable medications by contacting your representatives in Congress to impart to them the importance of passing legislation. The CSRO’s legislative map tool can help to inform you of the latest information on these and other bills and assist you in engaging with your representatives on them.

Dr. Feldman is a rheumatologist in private practice with The Rheumatology Group in New Orleans. She is the CSRO’s vice president of Advocacy and Government Affairs and its immediate past president, as well as past chair of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines and a past member of the American College of Rheumatology insurance subcommittee. She has no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. You can reach her at [email protected].

AI-Powered Clinical Documentation Tool Reduces EHR Time for Clinicians

TOPLINE:

An artificial intelligence (AI)-powered clinical documentation tool helped reduce time spent on electronic health records (EHR) at home for almost 48% physicians, and nearly 45% reported less weekly time spent on EHR tasks outside of normal work hours.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers recruited 112 clinicians from family medicine, internal medicine, and general pediatrics in North Carolina and Georgia.

- Patients were divided into an intervention group (n = 85) and control group (n = 55), with the intervention group receiving a 1-hour training program on a commercially available AI tool.

- A seven-question survey was administered to participants before and 5 weeks after the intervention to evaluate their experience.

TAKEAWAY:

- The researchers found 47.1% of clinicians in the intervention group reported spending less time on the EHR at home compared with 14.5% in the control group (P < .001); 44.7% reported decreased weekly time on the EHR outside normal work hours compared with 20% in the control group (P = .003).

- The study revealed 43.5% of physicians who used the AI instrument reported spending less time on documentation after visits compared with 18.2% in the control group (P = .002).

- Further, 44.7% reported less frustration when using the EHR compared with 14.5% in the control group (P < .001).

IN PRACTICE:

“Approximately half of clinicians using the AI-powered clinical documentation tool based on interest reported a positive outcome, potentially reducing burnout. However, a significant subset did not find time-saving benefits or improved EHR experience,” the authors of the study wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Tsai-Ling Liu, PhD, Center for Health System Sciences, Atrium Health in Charlotte, North Carolina. It was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The researchers reported potential selection and recall bias in both groups. Additional research is needed to find areas of improvement and assess the effects on clinician groups and health systems, they said.

DISCLOSURES:

Andrew McWilliams, MD, MPH, reported receiving grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research Quality, the National Institutes of Health, and the Duke Endowment unrelated to this work. Ajay Dharod, MD, reported his role as an electronic health record consultant for the Association of American Medical College CORE program. Jeffrey Cleveland, MD, disclosed his participation on the Executive Client Council, a noncompensated advisory group, for Nuance/Microsoft.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

An artificial intelligence (AI)-powered clinical documentation tool helped reduce time spent on electronic health records (EHR) at home for almost 48% physicians, and nearly 45% reported less weekly time spent on EHR tasks outside of normal work hours.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers recruited 112 clinicians from family medicine, internal medicine, and general pediatrics in North Carolina and Georgia.

- Patients were divided into an intervention group (n = 85) and control group (n = 55), with the intervention group receiving a 1-hour training program on a commercially available AI tool.

- A seven-question survey was administered to participants before and 5 weeks after the intervention to evaluate their experience.

TAKEAWAY:

- The researchers found 47.1% of clinicians in the intervention group reported spending less time on the EHR at home compared with 14.5% in the control group (P < .001); 44.7% reported decreased weekly time on the EHR outside normal work hours compared with 20% in the control group (P = .003).

- The study revealed 43.5% of physicians who used the AI instrument reported spending less time on documentation after visits compared with 18.2% in the control group (P = .002).

- Further, 44.7% reported less frustration when using the EHR compared with 14.5% in the control group (P < .001).

IN PRACTICE:

“Approximately half of clinicians using the AI-powered clinical documentation tool based on interest reported a positive outcome, potentially reducing burnout. However, a significant subset did not find time-saving benefits or improved EHR experience,” the authors of the study wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Tsai-Ling Liu, PhD, Center for Health System Sciences, Atrium Health in Charlotte, North Carolina. It was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The researchers reported potential selection and recall bias in both groups. Additional research is needed to find areas of improvement and assess the effects on clinician groups and health systems, they said.

DISCLOSURES:

Andrew McWilliams, MD, MPH, reported receiving grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research Quality, the National Institutes of Health, and the Duke Endowment unrelated to this work. Ajay Dharod, MD, reported his role as an electronic health record consultant for the Association of American Medical College CORE program. Jeffrey Cleveland, MD, disclosed his participation on the Executive Client Council, a noncompensated advisory group, for Nuance/Microsoft.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

An artificial intelligence (AI)-powered clinical documentation tool helped reduce time spent on electronic health records (EHR) at home for almost 48% physicians, and nearly 45% reported less weekly time spent on EHR tasks outside of normal work hours.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers recruited 112 clinicians from family medicine, internal medicine, and general pediatrics in North Carolina and Georgia.

- Patients were divided into an intervention group (n = 85) and control group (n = 55), with the intervention group receiving a 1-hour training program on a commercially available AI tool.

- A seven-question survey was administered to participants before and 5 weeks after the intervention to evaluate their experience.

TAKEAWAY:

- The researchers found 47.1% of clinicians in the intervention group reported spending less time on the EHR at home compared with 14.5% in the control group (P < .001); 44.7% reported decreased weekly time on the EHR outside normal work hours compared with 20% in the control group (P = .003).

- The study revealed 43.5% of physicians who used the AI instrument reported spending less time on documentation after visits compared with 18.2% in the control group (P = .002).

- Further, 44.7% reported less frustration when using the EHR compared with 14.5% in the control group (P < .001).

IN PRACTICE:

“Approximately half of clinicians using the AI-powered clinical documentation tool based on interest reported a positive outcome, potentially reducing burnout. However, a significant subset did not find time-saving benefits or improved EHR experience,” the authors of the study wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Tsai-Ling Liu, PhD, Center for Health System Sciences, Atrium Health in Charlotte, North Carolina. It was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The researchers reported potential selection and recall bias in both groups. Additional research is needed to find areas of improvement and assess the effects on clinician groups and health systems, they said.

DISCLOSURES:

Andrew McWilliams, MD, MPH, reported receiving grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research Quality, the National Institutes of Health, and the Duke Endowment unrelated to this work. Ajay Dharod, MD, reported his role as an electronic health record consultant for the Association of American Medical College CORE program. Jeffrey Cleveland, MD, disclosed his participation on the Executive Client Council, a noncompensated advisory group, for Nuance/Microsoft.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Study Reports Safety Data in Children on JAK Inhibitors

TOPLINE:

which also found that acne was the most common skin-related AE in children, and serious AEs were less common.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers analyzed 399,649 AEs in 133,216 adult patients and 2883 AEs in 955 pediatric patients (age, < 18 years) from November 2011 to February 2023 using the US Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System and the Canada Vigilance Adverse Reaction Online Database.

- AEs were categorized on the basis of the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities system organ class.

- Five JAK inhibitors approved for use in children were included in the study: Baricitinib, upadacitinib, abrocitinib, ruxolitinib, and tofacitinib.

TAKEAWAY:

- The most frequently reported AEs in children were blood and lymphatic system disorders, including neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia (24%); viral, fungal, and bacterial infections, such as pneumonia and sepsis (17.2%); constitutional symptoms and administrative concerns, including pyrexia and fatigue (15.7%); gastrointestinal disorders, such as vomiting and abdominal pain (13.6%); and respiratory disorders, such as cough and respiratory distress (5.3%).

- In adults, the most common AEs were viral, fungal, and bacterial infections (16.8%); constitutional symptoms and administrative concerns (13.5%); musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders (7.04%); and gastrointestinal (5.8%) and nervous system (5%) disorders.

- Acne (30.6%), atopic dermatitis (22.2%), and psoriasis (16.7%) were the most common skin and subcutaneous tissue AEs reported in children. Skin and subcutaneous AEs were more common with upadacitinib (21.1%), abrocitinib (9.1%), and tofacitinib (6.3%) in children.

- Serious AEs included in the boxed warning for JAK inhibitors — serious infection, mortality, malignancy, cardiovascular events, and thrombosis — were similar for baricitinib in children (4 of 49 patients, 8.2%) and adults (325 of 3707, 8.8%). For other JAK inhibitors, absolute numbers of these AEs in children were small and rates were lower in children than in adults.

IN PRACTICE:

“This information can support customized treatment and minimize the potential for undesired or intolerable AEs,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Sahithi Talasila, BS, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, and was published online in Pediatric Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Pharmacovigilance registries did not fully capture the complete range of AEs because of potential reporting bias or recall bias. Additionally, events lacking sufficient objective evidence were underreported, while common AEs associated with JAK inhibitor therapy were overreported.

DISCLOSURES:

No specific funding sources for the study were reported. One author reported being a consultant, one reported serving as a principal investigator in clinical trials, and another reported serving on data and safety monitoring boards of various pharmaceutical companies.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

which also found that acne was the most common skin-related AE in children, and serious AEs were less common.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers analyzed 399,649 AEs in 133,216 adult patients and 2883 AEs in 955 pediatric patients (age, < 18 years) from November 2011 to February 2023 using the US Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System and the Canada Vigilance Adverse Reaction Online Database.

- AEs were categorized on the basis of the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities system organ class.

- Five JAK inhibitors approved for use in children were included in the study: Baricitinib, upadacitinib, abrocitinib, ruxolitinib, and tofacitinib.

TAKEAWAY:

- The most frequently reported AEs in children were blood and lymphatic system disorders, including neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia (24%); viral, fungal, and bacterial infections, such as pneumonia and sepsis (17.2%); constitutional symptoms and administrative concerns, including pyrexia and fatigue (15.7%); gastrointestinal disorders, such as vomiting and abdominal pain (13.6%); and respiratory disorders, such as cough and respiratory distress (5.3%).

- In adults, the most common AEs were viral, fungal, and bacterial infections (16.8%); constitutional symptoms and administrative concerns (13.5%); musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders (7.04%); and gastrointestinal (5.8%) and nervous system (5%) disorders.

- Acne (30.6%), atopic dermatitis (22.2%), and psoriasis (16.7%) were the most common skin and subcutaneous tissue AEs reported in children. Skin and subcutaneous AEs were more common with upadacitinib (21.1%), abrocitinib (9.1%), and tofacitinib (6.3%) in children.

- Serious AEs included in the boxed warning for JAK inhibitors — serious infection, mortality, malignancy, cardiovascular events, and thrombosis — were similar for baricitinib in children (4 of 49 patients, 8.2%) and adults (325 of 3707, 8.8%). For other JAK inhibitors, absolute numbers of these AEs in children were small and rates were lower in children than in adults.

IN PRACTICE:

“This information can support customized treatment and minimize the potential for undesired or intolerable AEs,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Sahithi Talasila, BS, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, and was published online in Pediatric Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Pharmacovigilance registries did not fully capture the complete range of AEs because of potential reporting bias or recall bias. Additionally, events lacking sufficient objective evidence were underreported, while common AEs associated with JAK inhibitor therapy were overreported.

DISCLOSURES:

No specific funding sources for the study were reported. One author reported being a consultant, one reported serving as a principal investigator in clinical trials, and another reported serving on data and safety monitoring boards of various pharmaceutical companies.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

which also found that acne was the most common skin-related AE in children, and serious AEs were less common.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers analyzed 399,649 AEs in 133,216 adult patients and 2883 AEs in 955 pediatric patients (age, < 18 years) from November 2011 to February 2023 using the US Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System and the Canada Vigilance Adverse Reaction Online Database.

- AEs were categorized on the basis of the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities system organ class.

- Five JAK inhibitors approved for use in children were included in the study: Baricitinib, upadacitinib, abrocitinib, ruxolitinib, and tofacitinib.

TAKEAWAY:

- The most frequently reported AEs in children were blood and lymphatic system disorders, including neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia (24%); viral, fungal, and bacterial infections, such as pneumonia and sepsis (17.2%); constitutional symptoms and administrative concerns, including pyrexia and fatigue (15.7%); gastrointestinal disorders, such as vomiting and abdominal pain (13.6%); and respiratory disorders, such as cough and respiratory distress (5.3%).

- In adults, the most common AEs were viral, fungal, and bacterial infections (16.8%); constitutional symptoms and administrative concerns (13.5%); musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders (7.04%); and gastrointestinal (5.8%) and nervous system (5%) disorders.

- Acne (30.6%), atopic dermatitis (22.2%), and psoriasis (16.7%) were the most common skin and subcutaneous tissue AEs reported in children. Skin and subcutaneous AEs were more common with upadacitinib (21.1%), abrocitinib (9.1%), and tofacitinib (6.3%) in children.

- Serious AEs included in the boxed warning for JAK inhibitors — serious infection, mortality, malignancy, cardiovascular events, and thrombosis — were similar for baricitinib in children (4 of 49 patients, 8.2%) and adults (325 of 3707, 8.8%). For other JAK inhibitors, absolute numbers of these AEs in children were small and rates were lower in children than in adults.

IN PRACTICE:

“This information can support customized treatment and minimize the potential for undesired or intolerable AEs,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Sahithi Talasila, BS, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, and was published online in Pediatric Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Pharmacovigilance registries did not fully capture the complete range of AEs because of potential reporting bias or recall bias. Additionally, events lacking sufficient objective evidence were underreported, while common AEs associated with JAK inhibitor therapy were overreported.

DISCLOSURES:

No specific funding sources for the study were reported. One author reported being a consultant, one reported serving as a principal investigator in clinical trials, and another reported serving on data and safety monitoring boards of various pharmaceutical companies.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Oropouche Virus

The pediatrician’s first patient of the day was a 15-year-old boy complaining of fever, chills, and profound arthralgias. His exam, including a careful assessment of his joints, yielded no clues, and the pediatrician was ready to diagnose this as a routine viral illness. An additional bit of history provided by the patient’s mother prompted the pediatrician to pause and reconsider.

“A week ago, we returned from a visit to Cuba,” the mother reported. “Could this be Oropouche virus infection?”

Oropouche virus disease is an arboviral disease caused by the Oropouche virus (OROV). It is transmitted to humans through midge or mosquito bites. Although largely unknown to most United States clinicians until recently, this vector-borne virus is not new. The first human Oropouche virus infection was identified in Trinidad and Tobago in 1955 and since then, there have been intermittent outbreaks in the Amazon region. In recent months, though, the epidemiology of Oropouche virus infections has changed. Infections are being identified in new geographic areas, including Cuba. According to the Pan American Health Organization, 506 cases of Oropouche virus infection have been identified in Cuba since May 27, 2024.

Two deaths from Oropouche virus infection have been reported in previously healthy people. Evolving data suggests adverse outcomes associated with vertical transmission during pregnancy. One fetal death and child with congenital anomalies have been reported in Brazil. Additional fetal deaths, miscarriages, and congenital anomalies are under investigation.

Travel-associated cases have been reported in the United States. As of September 10, 2024, 52 Oropouche virus disease cases had been reported from five states in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed that the first 31 of these cases were travelers returning from Cuba. The CDC issued a health advisory on August 16, 2024: Increased Oropouche Virus Activity and Associated Risk to Travelers.

The pediatrician quickly reviewed the signs and symptoms of Oropouche virus infection. Disease typically presents as an abrupt onset of fever, severe headache, chills, myalgia, and arthralgia 3 to 10 days after the bite of infected mosquito. Some patients develop a maculopapular rash that starts on the trunk and spreads to the extremities. Meningitis and encephalitis develop in less than 1 in 20 people. The symptoms of Oropouche virus infection overlap with those of other arboviruses such as dengue, chikungunya, and Zika viruses. The disease can also mimic malaria or rickettsial infection. Approximately 60% of people with Oropouche virus infection experience a recurrence of symptoms within days to weeks of the initial resolution of symptoms.

Testing for Oropouche virus infection is available through the CDC’s Arbovirus Diagnostic Laboratory. In people who are acutely ill, reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction testing can be used to identify the virus in serum and cerebrospinal fluid. Serologic testing is also available for people who have been symptomatic for at least 6 days.

The pediatrician contacted his local health department to discuss the possibility of Oropouche virus infection. After reviewing the case definition, public health authorities recommended laboratory testing for Oropouche virus, dengue, and Zika virus.

Back in the exam room, the pediatrician provided anticipatory guidance to the patient and his mother. There are no antiviral medications to treat Oropouche virus infection, so the pediatrician recommended supportive care, including acetaminophen for fever and pain. He also advised avoiding aspirin or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) until dengue could be ruled out to reduce the risk of bleeding. After confirming that no one else in the home was sick with similar symptoms, he counseled about prevention strategies.

To date, transmission of Oropouche virus in the United States has not been documented, but vectors potentially capable of transmitting the virus are present in some areas of the United States. When people who are infected with Oropouche are bitten, they can spread the virus through their blood to biting midges or mosquitoes. The insects can then spread the virus to other people. To reduce to potential for local transmission, people who are sick with suspected Oropouche virus infection are advised to avoid biting-midge and mosquito bites for the first week of their illness. Any person who has recently traveled to an area where Oropouche virus transmission is occurring should also avoid insect bites for 3 weeks after returning home to account for the potential incubation period of the virus. This includes wearing an EPA-registered insect repellent.

A suspect case is a patient who has been in an area with documented or suspected OROV circulation* within 2 weeks of initial symptom onset (as patients may experience recurrent symptoms) and the following:

- Abrupt onset of reported fever, headache, and one or more of the following: myalgia, arthralgia, photophobia, retro-orbital/eye pain, or signs and symptoms of neuroinvasive disease (eg, stiff neck, altered mental status, seizures, limb weakness, or cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis).

- Tested negative for other possible diseases, in particular dengue.†

- Absence of a more likely clinical explanation.

*If concern exists for local transmission in a nonendemic area, consider if the patient shared an exposure location with a person with confirmed OROV infection, lives in an area where travel-related cases have been identified, or has known vector exposure (eg, mosquitoes or biting midges).

†If strong suspicion of OROV disease exists based on the patient’s clinical features and history of travel to an area with virus circulation, do not wait on negative testing before sending specimens to CDC.

Adapted from: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Response to Oropouche Virus Disease Cases in U.S. States and Territories in the Americas. Available at: https.//www.cdc.gov/oropouche/media/pdfs/2024/09/response-to-oropouche-virus-disease.pdf

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She is a member of the AAP’s Committee on Infectious Diseases and one of the lead authors of the AAP’s Recommendations for Prevention and Control of Influenza in Children, 2022-2023. The opinions expressed in this article are her own. Dr. Bryant discloses that she has served as an investigator on clinical trials funded by Pfizer, Enanta and Gilead. Email her at [email protected]. (Also [email protected])

The pediatrician’s first patient of the day was a 15-year-old boy complaining of fever, chills, and profound arthralgias. His exam, including a careful assessment of his joints, yielded no clues, and the pediatrician was ready to diagnose this as a routine viral illness. An additional bit of history provided by the patient’s mother prompted the pediatrician to pause and reconsider.

“A week ago, we returned from a visit to Cuba,” the mother reported. “Could this be Oropouche virus infection?”

Oropouche virus disease is an arboviral disease caused by the Oropouche virus (OROV). It is transmitted to humans through midge or mosquito bites. Although largely unknown to most United States clinicians until recently, this vector-borne virus is not new. The first human Oropouche virus infection was identified in Trinidad and Tobago in 1955 and since then, there have been intermittent outbreaks in the Amazon region. In recent months, though, the epidemiology of Oropouche virus infections has changed. Infections are being identified in new geographic areas, including Cuba. According to the Pan American Health Organization, 506 cases of Oropouche virus infection have been identified in Cuba since May 27, 2024.

Two deaths from Oropouche virus infection have been reported in previously healthy people. Evolving data suggests adverse outcomes associated with vertical transmission during pregnancy. One fetal death and child with congenital anomalies have been reported in Brazil. Additional fetal deaths, miscarriages, and congenital anomalies are under investigation.

Travel-associated cases have been reported in the United States. As of September 10, 2024, 52 Oropouche virus disease cases had been reported from five states in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed that the first 31 of these cases were travelers returning from Cuba. The CDC issued a health advisory on August 16, 2024: Increased Oropouche Virus Activity and Associated Risk to Travelers.