User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

Reflections on healing as a process

We physicians should not think of ourselves as ‘fixers.’

Recently, a patient excitedly told me during her session that she had been coming to see me for about 24 years. This was followed by positive remarks about where she was at the point when she first walked into my office.

Her progress has been slow but steady – and today, she finds herself at a much better place even within the context of having to deal with life’s complications. Her surprise about the longevity of this therapeutic relationship was easily and comfortably balanced by the pleasant feeling of well-being.

This interaction reminded me of a conversation I had with a friend of mine, an ophthalmologist who once asked me a related question: Why is it that people have been coming to see me for decades and I have not been able to “fix” them? Does that make me feel badly?

I clearly remember my response, which started in more of a defensive mode but ended with some self-reflection. I reminded him that, in his specialty, like many other fields of medicine, we don’t get to “fix” a lot. In fact, the majority of the conditions we deal with are chronic and lingering.

However, during the process of reminding him to look in the mirror, I was also able to articulate that many of these patients came into my office in potentially dire situations, including experiencing severe depression and suicidal thoughts, ignoring basic needs such as hygiene, feeling paralyzed with panic attacks, or having complete inability to deal with day-to-day situations.

Decades later, many of these patients, while still struggling with some ongoing issues, appeared to be alive and well – and we have wonderful interactions in our office where I get to talk to them about exciting things they’re looking forward to doing with their families or for themselves. Similar analogies can be applied to almost all medical specialties. An endocrinologist might help a patient with severe diabetes or hypothyroid disease get the illness under control but is not able to fix the problem. Clearly, patients’ quality of life improves tremendously through treatment with medications and with education about lifestyle changes, such as exercise and diet.

Even in the case of surgeons who may successfully remove the problem tissue or tumor, the patient is not in fact “fixed” and still requires ongoing medical care, psychosocial interventions, and pharmacotherapy to maintain or improve upon quality of life.

My patient’s remarks led to a similar, delightful therapeutic session reflecting on her progress and what it meant to both of us. We physicians certainly find it very frustrating that we are unable to fix things and make people feel completely better. However, it is important to reflect on the difference our contribution to the process of healing makes for our patients and the impact it has on their quality of life – which is meaningful to them, however small it may be.

, which could lead to minimal or no improvement in the pathological condition but may in fact improve patients’ outlook and willingness to carry on with dignity and satisfaction. It could do us all a lot of good to think of ourselves as healers – not fixers.

Dr. Awan, a psychiatrist, is medical director of Pennsylvania Counseling Services in Reading. He disclosed no conflicts of interest.

We physicians should not think of ourselves as ‘fixers.’

We physicians should not think of ourselves as ‘fixers.’

Recently, a patient excitedly told me during her session that she had been coming to see me for about 24 years. This was followed by positive remarks about where she was at the point when she first walked into my office.

Her progress has been slow but steady – and today, she finds herself at a much better place even within the context of having to deal with life’s complications. Her surprise about the longevity of this therapeutic relationship was easily and comfortably balanced by the pleasant feeling of well-being.

This interaction reminded me of a conversation I had with a friend of mine, an ophthalmologist who once asked me a related question: Why is it that people have been coming to see me for decades and I have not been able to “fix” them? Does that make me feel badly?

I clearly remember my response, which started in more of a defensive mode but ended with some self-reflection. I reminded him that, in his specialty, like many other fields of medicine, we don’t get to “fix” a lot. In fact, the majority of the conditions we deal with are chronic and lingering.

However, during the process of reminding him to look in the mirror, I was also able to articulate that many of these patients came into my office in potentially dire situations, including experiencing severe depression and suicidal thoughts, ignoring basic needs such as hygiene, feeling paralyzed with panic attacks, or having complete inability to deal with day-to-day situations.

Decades later, many of these patients, while still struggling with some ongoing issues, appeared to be alive and well – and we have wonderful interactions in our office where I get to talk to them about exciting things they’re looking forward to doing with their families or for themselves. Similar analogies can be applied to almost all medical specialties. An endocrinologist might help a patient with severe diabetes or hypothyroid disease get the illness under control but is not able to fix the problem. Clearly, patients’ quality of life improves tremendously through treatment with medications and with education about lifestyle changes, such as exercise and diet.

Even in the case of surgeons who may successfully remove the problem tissue or tumor, the patient is not in fact “fixed” and still requires ongoing medical care, psychosocial interventions, and pharmacotherapy to maintain or improve upon quality of life.

My patient’s remarks led to a similar, delightful therapeutic session reflecting on her progress and what it meant to both of us. We physicians certainly find it very frustrating that we are unable to fix things and make people feel completely better. However, it is important to reflect on the difference our contribution to the process of healing makes for our patients and the impact it has on their quality of life – which is meaningful to them, however small it may be.

, which could lead to minimal or no improvement in the pathological condition but may in fact improve patients’ outlook and willingness to carry on with dignity and satisfaction. It could do us all a lot of good to think of ourselves as healers – not fixers.

Dr. Awan, a psychiatrist, is medical director of Pennsylvania Counseling Services in Reading. He disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Recently, a patient excitedly told me during her session that she had been coming to see me for about 24 years. This was followed by positive remarks about where she was at the point when she first walked into my office.

Her progress has been slow but steady – and today, she finds herself at a much better place even within the context of having to deal with life’s complications. Her surprise about the longevity of this therapeutic relationship was easily and comfortably balanced by the pleasant feeling of well-being.

This interaction reminded me of a conversation I had with a friend of mine, an ophthalmologist who once asked me a related question: Why is it that people have been coming to see me for decades and I have not been able to “fix” them? Does that make me feel badly?

I clearly remember my response, which started in more of a defensive mode but ended with some self-reflection. I reminded him that, in his specialty, like many other fields of medicine, we don’t get to “fix” a lot. In fact, the majority of the conditions we deal with are chronic and lingering.

However, during the process of reminding him to look in the mirror, I was also able to articulate that many of these patients came into my office in potentially dire situations, including experiencing severe depression and suicidal thoughts, ignoring basic needs such as hygiene, feeling paralyzed with panic attacks, or having complete inability to deal with day-to-day situations.

Decades later, many of these patients, while still struggling with some ongoing issues, appeared to be alive and well – and we have wonderful interactions in our office where I get to talk to them about exciting things they’re looking forward to doing with their families or for themselves. Similar analogies can be applied to almost all medical specialties. An endocrinologist might help a patient with severe diabetes or hypothyroid disease get the illness under control but is not able to fix the problem. Clearly, patients’ quality of life improves tremendously through treatment with medications and with education about lifestyle changes, such as exercise and diet.

Even in the case of surgeons who may successfully remove the problem tissue or tumor, the patient is not in fact “fixed” and still requires ongoing medical care, psychosocial interventions, and pharmacotherapy to maintain or improve upon quality of life.

My patient’s remarks led to a similar, delightful therapeutic session reflecting on her progress and what it meant to both of us. We physicians certainly find it very frustrating that we are unable to fix things and make people feel completely better. However, it is important to reflect on the difference our contribution to the process of healing makes for our patients and the impact it has on their quality of life – which is meaningful to them, however small it may be.

, which could lead to minimal or no improvement in the pathological condition but may in fact improve patients’ outlook and willingness to carry on with dignity and satisfaction. It could do us all a lot of good to think of ourselves as healers – not fixers.

Dr. Awan, a psychiatrist, is medical director of Pennsylvania Counseling Services in Reading. He disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Moderna announces first data showing efficacy of COVID-19 vaccine booster in development

among people already vaccinated for COVID-19, according to first results released May 5.

Furthermore, data from the company’s ongoing phase 2 study show the variant-specific booster, known as mRNA-1273.351, achieved higher antibody titers against the B.1.351 variant than did a booster with the original Moderna vaccine.

“We are encouraged by these new data, which reinforce our confidence that our booster strategy should be protective against these newly detected variants. The strong and rapid boost in titers to levels above primary vaccination also clearly demonstrates the ability of mRNA-1273 to induce immune memory,” Stéphane Bancel, chief executive officer of Moderna, said in a statement.

The phase 2 study researchers also are evaluating a multivariant booster that is a 50/50 mix of mRNA-1273.351 and mRNA-1273, the initial vaccine given Food and Drug Administration emergency use authorization, in a single vial.

Unlike the two-dose regimen with the original vaccine, the boosters are administered as a single dose immunization.

The trial participants received a booster 6-8 months after primary vaccination. Titers to the wild-type SARS-CoV-2 virus remained high and detectable in 37 out of 40 participants. However, prior to the booster, titers against the two variants of concern, B.1.351 and P.1, were lower, with about half of participants showing undetectable levels.

In contrast, 2 weeks after a booster with the original vaccine or the B.1.351 strain-specific product, pseudovirus neutralizing titers were boosted in all participants and all variants tested.

“Following [the] boost, geometric mean titers against the wild-type, B.1.351, and P.1 variants increased to levels similar to or higher than the previously reported peak titers against the ancestral (D614G) strain following primary vaccination,” the company stated.

Both mRNA-1273.351 and mRNA-1273 booster doses were generally well tolerated, the company reported. Safety and tolerability were generally comparable to those reported after the second dose of the original vaccine. Most adverse events were mild to moderate, with injection site pain most common in both groups. Participants also reported fatigue, headache, myalgia, and arthralgia.

The company plans to release data shortly on the booster efficacy at additional time points beyond 2 weeks for mRNA-1273.351, a lower-dose booster with mRNA-1272/351, as well as data on the multivariant mRNA vaccine booster.

In addition to the company’s phase 2 study, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases is conducting a separate phase 1 study of mRNA-1273.351.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

among people already vaccinated for COVID-19, according to first results released May 5.

Furthermore, data from the company’s ongoing phase 2 study show the variant-specific booster, known as mRNA-1273.351, achieved higher antibody titers against the B.1.351 variant than did a booster with the original Moderna vaccine.

“We are encouraged by these new data, which reinforce our confidence that our booster strategy should be protective against these newly detected variants. The strong and rapid boost in titers to levels above primary vaccination also clearly demonstrates the ability of mRNA-1273 to induce immune memory,” Stéphane Bancel, chief executive officer of Moderna, said in a statement.

The phase 2 study researchers also are evaluating a multivariant booster that is a 50/50 mix of mRNA-1273.351 and mRNA-1273, the initial vaccine given Food and Drug Administration emergency use authorization, in a single vial.

Unlike the two-dose regimen with the original vaccine, the boosters are administered as a single dose immunization.

The trial participants received a booster 6-8 months after primary vaccination. Titers to the wild-type SARS-CoV-2 virus remained high and detectable in 37 out of 40 participants. However, prior to the booster, titers against the two variants of concern, B.1.351 and P.1, were lower, with about half of participants showing undetectable levels.

In contrast, 2 weeks after a booster with the original vaccine or the B.1.351 strain-specific product, pseudovirus neutralizing titers were boosted in all participants and all variants tested.

“Following [the] boost, geometric mean titers against the wild-type, B.1.351, and P.1 variants increased to levels similar to or higher than the previously reported peak titers against the ancestral (D614G) strain following primary vaccination,” the company stated.

Both mRNA-1273.351 and mRNA-1273 booster doses were generally well tolerated, the company reported. Safety and tolerability were generally comparable to those reported after the second dose of the original vaccine. Most adverse events were mild to moderate, with injection site pain most common in both groups. Participants also reported fatigue, headache, myalgia, and arthralgia.

The company plans to release data shortly on the booster efficacy at additional time points beyond 2 weeks for mRNA-1273.351, a lower-dose booster with mRNA-1272/351, as well as data on the multivariant mRNA vaccine booster.

In addition to the company’s phase 2 study, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases is conducting a separate phase 1 study of mRNA-1273.351.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

among people already vaccinated for COVID-19, according to first results released May 5.

Furthermore, data from the company’s ongoing phase 2 study show the variant-specific booster, known as mRNA-1273.351, achieved higher antibody titers against the B.1.351 variant than did a booster with the original Moderna vaccine.

“We are encouraged by these new data, which reinforce our confidence that our booster strategy should be protective against these newly detected variants. The strong and rapid boost in titers to levels above primary vaccination also clearly demonstrates the ability of mRNA-1273 to induce immune memory,” Stéphane Bancel, chief executive officer of Moderna, said in a statement.

The phase 2 study researchers also are evaluating a multivariant booster that is a 50/50 mix of mRNA-1273.351 and mRNA-1273, the initial vaccine given Food and Drug Administration emergency use authorization, in a single vial.

Unlike the two-dose regimen with the original vaccine, the boosters are administered as a single dose immunization.

The trial participants received a booster 6-8 months after primary vaccination. Titers to the wild-type SARS-CoV-2 virus remained high and detectable in 37 out of 40 participants. However, prior to the booster, titers against the two variants of concern, B.1.351 and P.1, were lower, with about half of participants showing undetectable levels.

In contrast, 2 weeks after a booster with the original vaccine or the B.1.351 strain-specific product, pseudovirus neutralizing titers were boosted in all participants and all variants tested.

“Following [the] boost, geometric mean titers against the wild-type, B.1.351, and P.1 variants increased to levels similar to or higher than the previously reported peak titers against the ancestral (D614G) strain following primary vaccination,” the company stated.

Both mRNA-1273.351 and mRNA-1273 booster doses were generally well tolerated, the company reported. Safety and tolerability were generally comparable to those reported after the second dose of the original vaccine. Most adverse events were mild to moderate, with injection site pain most common in both groups. Participants also reported fatigue, headache, myalgia, and arthralgia.

The company plans to release data shortly on the booster efficacy at additional time points beyond 2 weeks for mRNA-1273.351, a lower-dose booster with mRNA-1272/351, as well as data on the multivariant mRNA vaccine booster.

In addition to the company’s phase 2 study, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases is conducting a separate phase 1 study of mRNA-1273.351.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Prioritize goals of older patients with multimorbidities, gerontologist says

said Mary Tinetti, MD, Gladys Phillips Crofoot Professor of Medicine and Public Health and chief of geriatrics at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

During a virtual presentation at the American College of Physicians annual Internal Medicine meeting, the gerontologist noted that primary care providers face a number of challenges when managing elderly patients with multimorbidity. These challenges include a lack of representative data in clinical trials, conflicting guideline recommendations, patient nonadherence, and decreased benefit from therapies due to competing conditions, she said.

“Trying to follow multiple guidelines can result in unintentional harms to these people with multiple conditions,” Dr. Tinetti said. She gave examples of the wide-ranging goals patients can have.

“Some [patients] will maximize the focus on function, regardless of how long they are likely to live,” Dr. Tinetti said. “Others will say symptom burden management is most important to them. And others will say they want to live as long as possible, and survival is most important, even if that means a reduction in their function. These individuals also vary in the care they are willing and able to receive to achieve the outcomes that matter most to them.”

For these reasons, Dr. Tinetti recommended patient priorities care, which she and her colleagues have been developing and implementing over the past 5-6 years.

“If the benefits and harms of addressing each condition in isolation is of uncertain benefit and potentially burdensome to both clinician and patient, and we know that patients vary in their health priorities ... then what else would you want to focus on in your 20-minute visit ... except each patient’s priorities?” Dr. Tinetti asked. “This is one solution to the challenge.”

What is patient priorities care?

Patient priorities care is a multidisciplinary, cyclical approach to clinical decision-making composed of three steps, Dr. Tinetti explained. First, a clinician identifies the patient’s health priorities. Second, this information is transmitted to comanaging providers, who decide which of their respective treatments are consistent with the patient’s priorities. And third, those decisions are disseminated to everyone involved in the patient’s care, both within and outside of the health care system, allowing all care providers to align with the patient’s priorities, she noted.

“Each person does that from their own expertise,” Dr. Tinetti said. “The social worker will do something different than the cardiologist, the physical therapist, the endocrinologist – but everybody is aiming at the same outcome – the patient’s priorities.”

In 2019, Dr. Tinetti led a nonrandomized clinical trial to test the feasibility of patient priorities care. The study involved 366 older adults with multimorbidity, among whom 203 received usual care, while 163 received this type of care. Patients in the latter group were twice as likely to have medications stopped, and significantly less likely to have self-management tasks added and diagnostic tests ordered.

How electronic health records can help

In an interview, Dr. Tinetti suggested that comanaging physicians communicate through electronic health records (EHRs), first to ensure that all care providers understand a patient’s goals, then to determine if recommended therapies align with those goals.

“It would be a little bit of a culture change to do that,” Dr. Tinetti said, “but the technology is there and it isn’t too terribly time consuming.”

She went on to suggest that primary care providers are typically best suited to coordinate this process; however, if a patient receives the majority of their care from a particular specialist, then that clinician may be the most suitable coordinator.

Systemic obstacles and solutions

According to Cynthia Boyd, MD, interim director of the division of geriatric medicine and gerontology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, clinicians may encounter obstacles when implementing patient priorities care.

“Our health care system doesn’t always make it easy to do this,” Dr. Boyd said. “It’s important to acknowledge this because it can be hard to do. There’s no question,” Dr. Boyd said in an interview.

Among the headwinds that clinicians may face are clinical practice guidelines, the structure of electronic health records, and quality metrics focused on specific conditions, she explained.

“There’s a lot of things that push us – in primary care and other parts of medicine – away from the approach that’s best for people with multiple chronic conditions,” Dr. Boyd said.

Dr. Tinetti said a challenge to providing this care that she expects is for clinicians, regardless of specialty, “to feel uneasy” about transitioning away from a conventional approach.

Among Dr. Tinetti’s arguments in favor of providing patient priorities care is that “it’s going to bring more joy in practice because you’re really addressing what matters to that individual while also providing good care.”

To get the most out of patient priorities care, Dr. Boyd recommended that clinicians focus on ‘the 4 M’s’: what matters most, mentation, mobility, and medications.

In an effort to address the last of these on a broad scale, Dr. Boyd is co-leading the US Deprescribing Research Network(USDeN), which aims to “improve medication use among older adults and the outcomes that are important to them,” according to the USDeN website.

To encourage deprescribing on a day-to-day level, Dr. Boyd called for strong communication between co–managing providers.

In an ideal world, there would be a better way to communicate than largely via electronic health records, she said.

“We need more than the EHR to connect us. That’s why it’s really important for primary care providers and specialists to be able to have time to actually talk to each other. This gets into how we reimburse and organize the communication and cognitive aspects of care,” Dr. Boyd noted.

Dr. Tinetti disclosed support from the John A. Hartford Foundation, the Donaghue Foundation, the National Institute on Aging, and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Dr. Boyd disclosed a relationship with UpToDate, for which she coauthored a chapter on multimorbidity.

said Mary Tinetti, MD, Gladys Phillips Crofoot Professor of Medicine and Public Health and chief of geriatrics at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

During a virtual presentation at the American College of Physicians annual Internal Medicine meeting, the gerontologist noted that primary care providers face a number of challenges when managing elderly patients with multimorbidity. These challenges include a lack of representative data in clinical trials, conflicting guideline recommendations, patient nonadherence, and decreased benefit from therapies due to competing conditions, she said.

“Trying to follow multiple guidelines can result in unintentional harms to these people with multiple conditions,” Dr. Tinetti said. She gave examples of the wide-ranging goals patients can have.

“Some [patients] will maximize the focus on function, regardless of how long they are likely to live,” Dr. Tinetti said. “Others will say symptom burden management is most important to them. And others will say they want to live as long as possible, and survival is most important, even if that means a reduction in their function. These individuals also vary in the care they are willing and able to receive to achieve the outcomes that matter most to them.”

For these reasons, Dr. Tinetti recommended patient priorities care, which she and her colleagues have been developing and implementing over the past 5-6 years.

“If the benefits and harms of addressing each condition in isolation is of uncertain benefit and potentially burdensome to both clinician and patient, and we know that patients vary in their health priorities ... then what else would you want to focus on in your 20-minute visit ... except each patient’s priorities?” Dr. Tinetti asked. “This is one solution to the challenge.”

What is patient priorities care?

Patient priorities care is a multidisciplinary, cyclical approach to clinical decision-making composed of three steps, Dr. Tinetti explained. First, a clinician identifies the patient’s health priorities. Second, this information is transmitted to comanaging providers, who decide which of their respective treatments are consistent with the patient’s priorities. And third, those decisions are disseminated to everyone involved in the patient’s care, both within and outside of the health care system, allowing all care providers to align with the patient’s priorities, she noted.

“Each person does that from their own expertise,” Dr. Tinetti said. “The social worker will do something different than the cardiologist, the physical therapist, the endocrinologist – but everybody is aiming at the same outcome – the patient’s priorities.”

In 2019, Dr. Tinetti led a nonrandomized clinical trial to test the feasibility of patient priorities care. The study involved 366 older adults with multimorbidity, among whom 203 received usual care, while 163 received this type of care. Patients in the latter group were twice as likely to have medications stopped, and significantly less likely to have self-management tasks added and diagnostic tests ordered.

How electronic health records can help

In an interview, Dr. Tinetti suggested that comanaging physicians communicate through electronic health records (EHRs), first to ensure that all care providers understand a patient’s goals, then to determine if recommended therapies align with those goals.

“It would be a little bit of a culture change to do that,” Dr. Tinetti said, “but the technology is there and it isn’t too terribly time consuming.”

She went on to suggest that primary care providers are typically best suited to coordinate this process; however, if a patient receives the majority of their care from a particular specialist, then that clinician may be the most suitable coordinator.

Systemic obstacles and solutions

According to Cynthia Boyd, MD, interim director of the division of geriatric medicine and gerontology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, clinicians may encounter obstacles when implementing patient priorities care.

“Our health care system doesn’t always make it easy to do this,” Dr. Boyd said. “It’s important to acknowledge this because it can be hard to do. There’s no question,” Dr. Boyd said in an interview.

Among the headwinds that clinicians may face are clinical practice guidelines, the structure of electronic health records, and quality metrics focused on specific conditions, she explained.

“There’s a lot of things that push us – in primary care and other parts of medicine – away from the approach that’s best for people with multiple chronic conditions,” Dr. Boyd said.

Dr. Tinetti said a challenge to providing this care that she expects is for clinicians, regardless of specialty, “to feel uneasy” about transitioning away from a conventional approach.

Among Dr. Tinetti’s arguments in favor of providing patient priorities care is that “it’s going to bring more joy in practice because you’re really addressing what matters to that individual while also providing good care.”

To get the most out of patient priorities care, Dr. Boyd recommended that clinicians focus on ‘the 4 M’s’: what matters most, mentation, mobility, and medications.

In an effort to address the last of these on a broad scale, Dr. Boyd is co-leading the US Deprescribing Research Network(USDeN), which aims to “improve medication use among older adults and the outcomes that are important to them,” according to the USDeN website.

To encourage deprescribing on a day-to-day level, Dr. Boyd called for strong communication between co–managing providers.

In an ideal world, there would be a better way to communicate than largely via electronic health records, she said.

“We need more than the EHR to connect us. That’s why it’s really important for primary care providers and specialists to be able to have time to actually talk to each other. This gets into how we reimburse and organize the communication and cognitive aspects of care,” Dr. Boyd noted.

Dr. Tinetti disclosed support from the John A. Hartford Foundation, the Donaghue Foundation, the National Institute on Aging, and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Dr. Boyd disclosed a relationship with UpToDate, for which she coauthored a chapter on multimorbidity.

said Mary Tinetti, MD, Gladys Phillips Crofoot Professor of Medicine and Public Health and chief of geriatrics at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

During a virtual presentation at the American College of Physicians annual Internal Medicine meeting, the gerontologist noted that primary care providers face a number of challenges when managing elderly patients with multimorbidity. These challenges include a lack of representative data in clinical trials, conflicting guideline recommendations, patient nonadherence, and decreased benefit from therapies due to competing conditions, she said.

“Trying to follow multiple guidelines can result in unintentional harms to these people with multiple conditions,” Dr. Tinetti said. She gave examples of the wide-ranging goals patients can have.

“Some [patients] will maximize the focus on function, regardless of how long they are likely to live,” Dr. Tinetti said. “Others will say symptom burden management is most important to them. And others will say they want to live as long as possible, and survival is most important, even if that means a reduction in their function. These individuals also vary in the care they are willing and able to receive to achieve the outcomes that matter most to them.”

For these reasons, Dr. Tinetti recommended patient priorities care, which she and her colleagues have been developing and implementing over the past 5-6 years.

“If the benefits and harms of addressing each condition in isolation is of uncertain benefit and potentially burdensome to both clinician and patient, and we know that patients vary in their health priorities ... then what else would you want to focus on in your 20-minute visit ... except each patient’s priorities?” Dr. Tinetti asked. “This is one solution to the challenge.”

What is patient priorities care?

Patient priorities care is a multidisciplinary, cyclical approach to clinical decision-making composed of three steps, Dr. Tinetti explained. First, a clinician identifies the patient’s health priorities. Second, this information is transmitted to comanaging providers, who decide which of their respective treatments are consistent with the patient’s priorities. And third, those decisions are disseminated to everyone involved in the patient’s care, both within and outside of the health care system, allowing all care providers to align with the patient’s priorities, she noted.

“Each person does that from their own expertise,” Dr. Tinetti said. “The social worker will do something different than the cardiologist, the physical therapist, the endocrinologist – but everybody is aiming at the same outcome – the patient’s priorities.”

In 2019, Dr. Tinetti led a nonrandomized clinical trial to test the feasibility of patient priorities care. The study involved 366 older adults with multimorbidity, among whom 203 received usual care, while 163 received this type of care. Patients in the latter group were twice as likely to have medications stopped, and significantly less likely to have self-management tasks added and diagnostic tests ordered.

How electronic health records can help

In an interview, Dr. Tinetti suggested that comanaging physicians communicate through electronic health records (EHRs), first to ensure that all care providers understand a patient’s goals, then to determine if recommended therapies align with those goals.

“It would be a little bit of a culture change to do that,” Dr. Tinetti said, “but the technology is there and it isn’t too terribly time consuming.”

She went on to suggest that primary care providers are typically best suited to coordinate this process; however, if a patient receives the majority of their care from a particular specialist, then that clinician may be the most suitable coordinator.

Systemic obstacles and solutions

According to Cynthia Boyd, MD, interim director of the division of geriatric medicine and gerontology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, clinicians may encounter obstacles when implementing patient priorities care.

“Our health care system doesn’t always make it easy to do this,” Dr. Boyd said. “It’s important to acknowledge this because it can be hard to do. There’s no question,” Dr. Boyd said in an interview.

Among the headwinds that clinicians may face are clinical practice guidelines, the structure of electronic health records, and quality metrics focused on specific conditions, she explained.

“There’s a lot of things that push us – in primary care and other parts of medicine – away from the approach that’s best for people with multiple chronic conditions,” Dr. Boyd said.

Dr. Tinetti said a challenge to providing this care that she expects is for clinicians, regardless of specialty, “to feel uneasy” about transitioning away from a conventional approach.

Among Dr. Tinetti’s arguments in favor of providing patient priorities care is that “it’s going to bring more joy in practice because you’re really addressing what matters to that individual while also providing good care.”

To get the most out of patient priorities care, Dr. Boyd recommended that clinicians focus on ‘the 4 M’s’: what matters most, mentation, mobility, and medications.

In an effort to address the last of these on a broad scale, Dr. Boyd is co-leading the US Deprescribing Research Network(USDeN), which aims to “improve medication use among older adults and the outcomes that are important to them,” according to the USDeN website.

To encourage deprescribing on a day-to-day level, Dr. Boyd called for strong communication between co–managing providers.

In an ideal world, there would be a better way to communicate than largely via electronic health records, she said.

“We need more than the EHR to connect us. That’s why it’s really important for primary care providers and specialists to be able to have time to actually talk to each other. This gets into how we reimburse and organize the communication and cognitive aspects of care,” Dr. Boyd noted.

Dr. Tinetti disclosed support from the John A. Hartford Foundation, the Donaghue Foundation, the National Institute on Aging, and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Dr. Boyd disclosed a relationship with UpToDate, for which she coauthored a chapter on multimorbidity.

FROM INTERNAL MEDICINE 2021

Porous pill printing and prognostic poop

Printing meds per patient

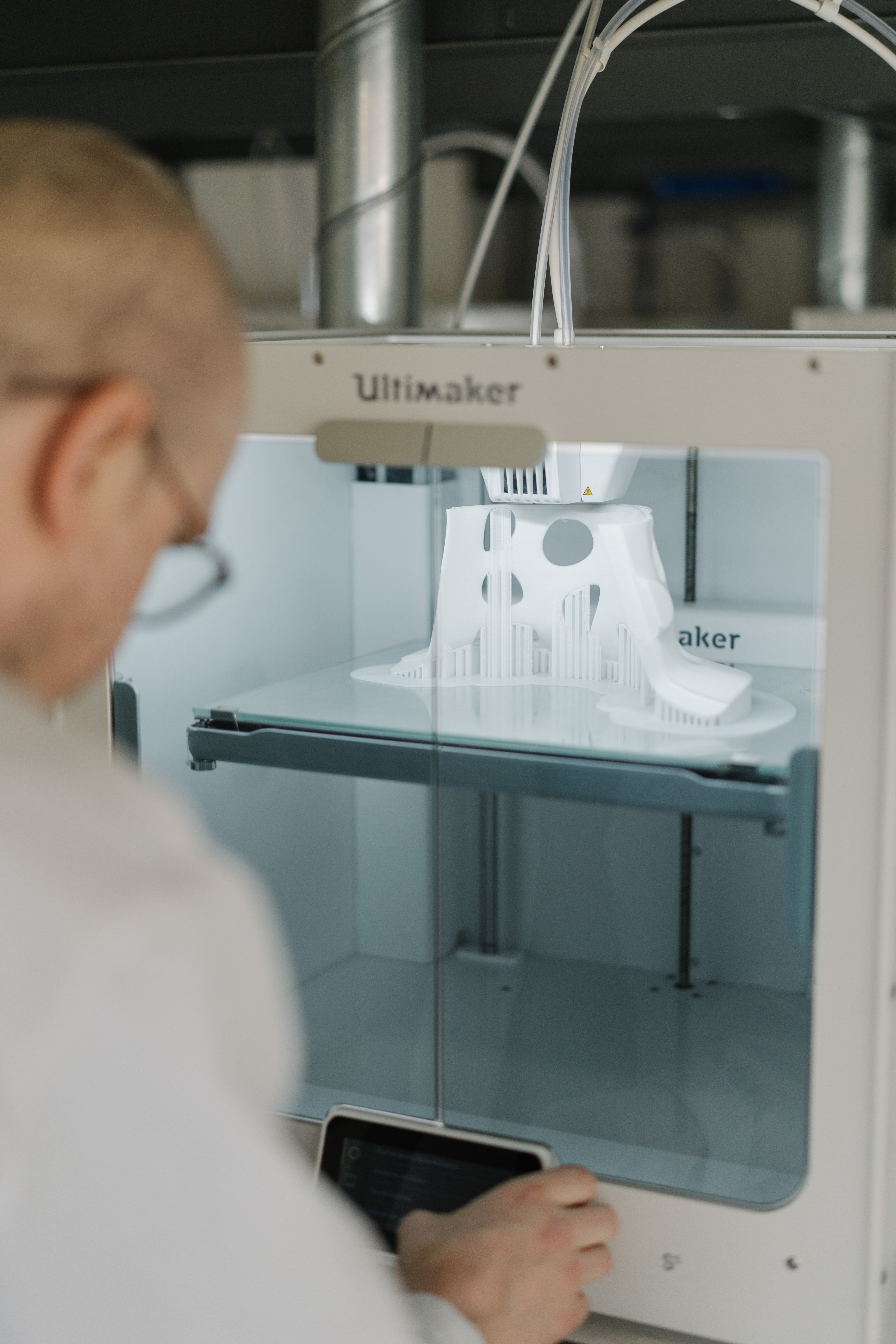

What if there was a way to get exact doses of a medication, tailored specifically for each and every patient that needed it? Well, apparently it’s as easy as getting them out of a printer.

Researchers from the University of East Anglia in England may have found a new method to do just that.

Currently, medicine is “manufactured in ‘one-size-fits-all’ fashion,” said Dr. Sheng Qi, the research lead. But no patient is exactly the same, so why shouldn’t their medications be just as unique? Research on pharmaceutical 3D printing has been developing over the past 5 years, with the most common method requiring the drug to be put into “spaghetti-like filaments” before printing.

Dr. Qi and his team developed a process that bypasses the filaments, allowing them to 3D-print pills with varied porous structures that can regulate the rate of release of the drug into the body. This could be revolutionary for elderly patients and patients with complicated conditions – who often take many different drugs – to ensure more accurate doses that provide maximum benefits and minimal adverse effects.

Just as a custom-tailored suit perfectly fits the body for which it was made, the ability to tailor medication could have the same effect on a patient’s health. The only difference is what’s coming through the printer would be pills, not fabric.

It’s hip to be Pfizered

COVID-19 vaccination levels are rising, but we’ve heard a rumor that some people are still a bit reticent to participate. So how can physicians get more people to come in for a shot?

Make sure that they’re giving patients the right vaccine, for one thing. And by “right” vaccine, we mean, of course, the cool vaccine. Yes, the Internet has decided that the Pfizer vaccine is cooler than the others, according to the Atlantic.

There is, it seems, such a thing as “Pfizer superiority complex,” the article noted, while adding that, “on TikTok, hundreds of videos use a soundtrack of a woman explaining – slowly, voice full of disdain, like the rudest preschool teacher on Earth – ‘Only hot people get the Pfizer vaccine.’ ” A reporter from Slate was welcomed “to the ruling class” after sharing her upcoming Pfizer vaccination.

For the ultimate test of coolness, we surveyed the LOTME staff about the COVID-19 vaccines they had received. The results? Two Pfizers (coincidentally, the only two who knew what the hell TikTok is), one Moderna, one Johnson & Johnson, and one Godbold’s Vegetable Balsam (coincidentally, the same one who told us to get off his lawn).

And yes, we are checking on that last one.

Allergies stink!

A baby’s first bowel movement might mean more than just being the first of many diaper changes.

That particular bowel movement, called meconium, is a mixture of materials that have gone into a baby’s mouth late in the pregnancy, such as skin cells and amniotic fluid. Sounds lovely, right? The contents also include certain biochemicals and gut bacteria, and a lack of these can show an increased risk of allergies, eczema, and asthma.

Studies show that certain gut bacteria actually teach the immune system to accept compounds that are not harmful. Since allergies and other conditions are caused by a person’s immune system telling them harmless compounds are bad, it makes sense that lacking gut bacteria might show potential for developing such conditions.

Charisse Petersen, a researcher at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, told NewScientist that parents could help decrease the development of allergies by not giving their children antibiotics that aren’t necessary and by letting kids play outside more.

Tom Marrs of King’s College London even noted that having a dog in the house is linked to a lower risk of allergies, so it might be time to get that puppy that the kids have been begging you for all through the pandemic.

Indiana Jones and the outhouse of parasites

Some archaeological finds are more impressive than others. Sometimes you find evidence of some long-lost civilization, sometimes you find a 200-year-old outhouse. That was the case with an outhouse buried near Dartmouth College that belonged to Mill Olcott, a wealthy businessman and politician who was a graduate of the college, and his family.

Now, that’s not particularly medically interesting, but the contents of the outhouse were very well preserved. That treasure trove included some fecal samples, and that’s where the story gets good, since they were preserved enough to be analyzed for parasites. Now, researchers know that parasites were very common in urban areas back in those days, when medicinal knowledge and sanitation were still deep in the dark ages, but whether or not people who lived in rural areas, wealthy or not, had them as well was a mystery.

Of course, 200-year-old poop is 200-year-old poop, so, in a task we wouldn’t envy anyone, the samples were rehydrated and run through several sieves to isolate the ancient goodies within. When all was said and done, both tapeworm and whipworm eggs were found, a surprise considering parasitic preference for warmer environments – not something northern New England is known for. But don’t forget, parasites can be your friend, too.

We will probably never know just which member of the Olcott household the poop belonged to, but the researchers noted that it was almost certain the entire house was infected. They added that, without proper infrastructure, even wealth was unable to protect people from disease. Hmm, we can’t think of any relevance that has in today’s world. Nope, absolutely none, since our health infrastructure is literally without flaw.

Printing meds per patient

What if there was a way to get exact doses of a medication, tailored specifically for each and every patient that needed it? Well, apparently it’s as easy as getting them out of a printer.

Researchers from the University of East Anglia in England may have found a new method to do just that.

Currently, medicine is “manufactured in ‘one-size-fits-all’ fashion,” said Dr. Sheng Qi, the research lead. But no patient is exactly the same, so why shouldn’t their medications be just as unique? Research on pharmaceutical 3D printing has been developing over the past 5 years, with the most common method requiring the drug to be put into “spaghetti-like filaments” before printing.

Dr. Qi and his team developed a process that bypasses the filaments, allowing them to 3D-print pills with varied porous structures that can regulate the rate of release of the drug into the body. This could be revolutionary for elderly patients and patients with complicated conditions – who often take many different drugs – to ensure more accurate doses that provide maximum benefits and minimal adverse effects.

Just as a custom-tailored suit perfectly fits the body for which it was made, the ability to tailor medication could have the same effect on a patient’s health. The only difference is what’s coming through the printer would be pills, not fabric.

It’s hip to be Pfizered

COVID-19 vaccination levels are rising, but we’ve heard a rumor that some people are still a bit reticent to participate. So how can physicians get more people to come in for a shot?

Make sure that they’re giving patients the right vaccine, for one thing. And by “right” vaccine, we mean, of course, the cool vaccine. Yes, the Internet has decided that the Pfizer vaccine is cooler than the others, according to the Atlantic.

There is, it seems, such a thing as “Pfizer superiority complex,” the article noted, while adding that, “on TikTok, hundreds of videos use a soundtrack of a woman explaining – slowly, voice full of disdain, like the rudest preschool teacher on Earth – ‘Only hot people get the Pfizer vaccine.’ ” A reporter from Slate was welcomed “to the ruling class” after sharing her upcoming Pfizer vaccination.

For the ultimate test of coolness, we surveyed the LOTME staff about the COVID-19 vaccines they had received. The results? Two Pfizers (coincidentally, the only two who knew what the hell TikTok is), one Moderna, one Johnson & Johnson, and one Godbold’s Vegetable Balsam (coincidentally, the same one who told us to get off his lawn).

And yes, we are checking on that last one.

Allergies stink!

A baby’s first bowel movement might mean more than just being the first of many diaper changes.

That particular bowel movement, called meconium, is a mixture of materials that have gone into a baby’s mouth late in the pregnancy, such as skin cells and amniotic fluid. Sounds lovely, right? The contents also include certain biochemicals and gut bacteria, and a lack of these can show an increased risk of allergies, eczema, and asthma.

Studies show that certain gut bacteria actually teach the immune system to accept compounds that are not harmful. Since allergies and other conditions are caused by a person’s immune system telling them harmless compounds are bad, it makes sense that lacking gut bacteria might show potential for developing such conditions.

Charisse Petersen, a researcher at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, told NewScientist that parents could help decrease the development of allergies by not giving their children antibiotics that aren’t necessary and by letting kids play outside more.

Tom Marrs of King’s College London even noted that having a dog in the house is linked to a lower risk of allergies, so it might be time to get that puppy that the kids have been begging you for all through the pandemic.

Indiana Jones and the outhouse of parasites

Some archaeological finds are more impressive than others. Sometimes you find evidence of some long-lost civilization, sometimes you find a 200-year-old outhouse. That was the case with an outhouse buried near Dartmouth College that belonged to Mill Olcott, a wealthy businessman and politician who was a graduate of the college, and his family.

Now, that’s not particularly medically interesting, but the contents of the outhouse were very well preserved. That treasure trove included some fecal samples, and that’s where the story gets good, since they were preserved enough to be analyzed for parasites. Now, researchers know that parasites were very common in urban areas back in those days, when medicinal knowledge and sanitation were still deep in the dark ages, but whether or not people who lived in rural areas, wealthy or not, had them as well was a mystery.

Of course, 200-year-old poop is 200-year-old poop, so, in a task we wouldn’t envy anyone, the samples were rehydrated and run through several sieves to isolate the ancient goodies within. When all was said and done, both tapeworm and whipworm eggs were found, a surprise considering parasitic preference for warmer environments – not something northern New England is known for. But don’t forget, parasites can be your friend, too.

We will probably never know just which member of the Olcott household the poop belonged to, but the researchers noted that it was almost certain the entire house was infected. They added that, without proper infrastructure, even wealth was unable to protect people from disease. Hmm, we can’t think of any relevance that has in today’s world. Nope, absolutely none, since our health infrastructure is literally without flaw.

Printing meds per patient

What if there was a way to get exact doses of a medication, tailored specifically for each and every patient that needed it? Well, apparently it’s as easy as getting them out of a printer.

Researchers from the University of East Anglia in England may have found a new method to do just that.

Currently, medicine is “manufactured in ‘one-size-fits-all’ fashion,” said Dr. Sheng Qi, the research lead. But no patient is exactly the same, so why shouldn’t their medications be just as unique? Research on pharmaceutical 3D printing has been developing over the past 5 years, with the most common method requiring the drug to be put into “spaghetti-like filaments” before printing.

Dr. Qi and his team developed a process that bypasses the filaments, allowing them to 3D-print pills with varied porous structures that can regulate the rate of release of the drug into the body. This could be revolutionary for elderly patients and patients with complicated conditions – who often take many different drugs – to ensure more accurate doses that provide maximum benefits and minimal adverse effects.

Just as a custom-tailored suit perfectly fits the body for which it was made, the ability to tailor medication could have the same effect on a patient’s health. The only difference is what’s coming through the printer would be pills, not fabric.

It’s hip to be Pfizered

COVID-19 vaccination levels are rising, but we’ve heard a rumor that some people are still a bit reticent to participate. So how can physicians get more people to come in for a shot?

Make sure that they’re giving patients the right vaccine, for one thing. And by “right” vaccine, we mean, of course, the cool vaccine. Yes, the Internet has decided that the Pfizer vaccine is cooler than the others, according to the Atlantic.

There is, it seems, such a thing as “Pfizer superiority complex,” the article noted, while adding that, “on TikTok, hundreds of videos use a soundtrack of a woman explaining – slowly, voice full of disdain, like the rudest preschool teacher on Earth – ‘Only hot people get the Pfizer vaccine.’ ” A reporter from Slate was welcomed “to the ruling class” after sharing her upcoming Pfizer vaccination.

For the ultimate test of coolness, we surveyed the LOTME staff about the COVID-19 vaccines they had received. The results? Two Pfizers (coincidentally, the only two who knew what the hell TikTok is), one Moderna, one Johnson & Johnson, and one Godbold’s Vegetable Balsam (coincidentally, the same one who told us to get off his lawn).

And yes, we are checking on that last one.

Allergies stink!

A baby’s first bowel movement might mean more than just being the first of many diaper changes.

That particular bowel movement, called meconium, is a mixture of materials that have gone into a baby’s mouth late in the pregnancy, such as skin cells and amniotic fluid. Sounds lovely, right? The contents also include certain biochemicals and gut bacteria, and a lack of these can show an increased risk of allergies, eczema, and asthma.

Studies show that certain gut bacteria actually teach the immune system to accept compounds that are not harmful. Since allergies and other conditions are caused by a person’s immune system telling them harmless compounds are bad, it makes sense that lacking gut bacteria might show potential for developing such conditions.

Charisse Petersen, a researcher at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, told NewScientist that parents could help decrease the development of allergies by not giving their children antibiotics that aren’t necessary and by letting kids play outside more.

Tom Marrs of King’s College London even noted that having a dog in the house is linked to a lower risk of allergies, so it might be time to get that puppy that the kids have been begging you for all through the pandemic.

Indiana Jones and the outhouse of parasites

Some archaeological finds are more impressive than others. Sometimes you find evidence of some long-lost civilization, sometimes you find a 200-year-old outhouse. That was the case with an outhouse buried near Dartmouth College that belonged to Mill Olcott, a wealthy businessman and politician who was a graduate of the college, and his family.

Now, that’s not particularly medically interesting, but the contents of the outhouse were very well preserved. That treasure trove included some fecal samples, and that’s where the story gets good, since they were preserved enough to be analyzed for parasites. Now, researchers know that parasites were very common in urban areas back in those days, when medicinal knowledge and sanitation were still deep in the dark ages, but whether or not people who lived in rural areas, wealthy or not, had them as well was a mystery.

Of course, 200-year-old poop is 200-year-old poop, so, in a task we wouldn’t envy anyone, the samples were rehydrated and run through several sieves to isolate the ancient goodies within. When all was said and done, both tapeworm and whipworm eggs were found, a surprise considering parasitic preference for warmer environments – not something northern New England is known for. But don’t forget, parasites can be your friend, too.

We will probably never know just which member of the Olcott household the poop belonged to, but the researchers noted that it was almost certain the entire house was infected. They added that, without proper infrastructure, even wealth was unable to protect people from disease. Hmm, we can’t think of any relevance that has in today’s world. Nope, absolutely none, since our health infrastructure is literally without flaw.

COVID-19 coaching program provides ‘psychological PPE’ for HCPs

A novel program that coaches healthcare workers effectively bolsters wellness and resilience in the face of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Investigators found the program they developed successfully reduced the severity of mental health threats in healthcare workers.

The pandemic has been “an enormous threat to the resilience of healthcare workers,” said program leader Benjamin Rosen, MD, assistant professor, department of psychiatry, University of Toronto, and staff psychiatrist at Sinai Health in Toronto.

“Working at a hospital this year, you’re not only worried about battling COVID, but you’re also enduring uncertainty and fear and moral distress, which has contributed to unprecedented levels of burnout,” Dr. Rosen added.

The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, held virtually this year.

‘Psychological PPE’

Building on previous experience supporting colleagues through the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in Toronto, Dr. Rosen’s team designed and implemented an initiative to support colleagues’ wellness and resilience early in the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Resilience Coaching for Healthcare Workers program is designed to support psychological well-being during times of chronic stress and help healthcare workers “keep their heads in the game so that they can sustain the focus and the rigor that they need to do their work,” Dr. Rosen said during a press briefing.

Participating coaches are mental health clinicians with training in psychological first aid, resilience, and psychotherapy to provide peer support to units and teams working on the front line. The program provides a kind of “psychological PPE” to complement other protective measures, Dr. Rosen explained.

There are currently 15 coaches working with 17 units and clinical teams at Sinai Health, which encompasses Mount Sinai Hospital and Bridgepoint Active Health, both in Toronto. Most coaches provide support to groups of up to 15 people either virtually or in person. More than 5,300 staff members have received coaching support since the program’s launch in April 2020.

Mary Preisman, MD, consultation liaison psychiatrist at Mount Sinai Hospital, who is involved with the program, said it’s important to note that coaches are not in clinical relationships with healthcare providers, but rather are applying diverse psychotherapeutic tools to deliver collegial support. When clinical support is requested, coaches facilitate connection with other psychiatrists.

‘An excellent model’

Preliminary analysis of qualitative data, which includes interviews with coaches and providers, suggests that coaching is successful in mitigating the severity of mental health threats that healthcare workers face.

“The feedback so far is that coaching has really helped to strengthen team cohesiveness and resilience, which has been really encouraging for us,” Dr. Rosen said.

For example, some participants said the coaching improved relationships with their colleagues, decreased loneliness, and increased the sense of support from their employer.

Others commented on the value of regularly scheduled coaching “huddles” that are embedded within the work environment.

Dr. Rosen said the program is funded by academic grants through the end of next year, which is key given that Toronto is currently in the middle of a third wave of the pandemic.

“ There have been studies that show, even years after a pandemic or an epidemic has ended, the psychological consequences of anxiety and distress persist,” Dr. Rosen said.

Briefing moderator Jeffrey Borenstein, MD, president and CEO, Brain & Behavior Research Foundation and editor-in-chief, Psychiatric News, said the Toronto team has developed “an excellent model that could be used around the world to support the well-being of healthcare workers who are on the front lines of a pandemic.”

This research had no commercial funding. Dr. Rosen, Dr. Preisman, and Dr. Borenstein have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A novel program that coaches healthcare workers effectively bolsters wellness and resilience in the face of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Investigators found the program they developed successfully reduced the severity of mental health threats in healthcare workers.

The pandemic has been “an enormous threat to the resilience of healthcare workers,” said program leader Benjamin Rosen, MD, assistant professor, department of psychiatry, University of Toronto, and staff psychiatrist at Sinai Health in Toronto.

“Working at a hospital this year, you’re not only worried about battling COVID, but you’re also enduring uncertainty and fear and moral distress, which has contributed to unprecedented levels of burnout,” Dr. Rosen added.

The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, held virtually this year.

‘Psychological PPE’

Building on previous experience supporting colleagues through the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in Toronto, Dr. Rosen’s team designed and implemented an initiative to support colleagues’ wellness and resilience early in the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Resilience Coaching for Healthcare Workers program is designed to support psychological well-being during times of chronic stress and help healthcare workers “keep their heads in the game so that they can sustain the focus and the rigor that they need to do their work,” Dr. Rosen said during a press briefing.

Participating coaches are mental health clinicians with training in psychological first aid, resilience, and psychotherapy to provide peer support to units and teams working on the front line. The program provides a kind of “psychological PPE” to complement other protective measures, Dr. Rosen explained.

There are currently 15 coaches working with 17 units and clinical teams at Sinai Health, which encompasses Mount Sinai Hospital and Bridgepoint Active Health, both in Toronto. Most coaches provide support to groups of up to 15 people either virtually or in person. More than 5,300 staff members have received coaching support since the program’s launch in April 2020.

Mary Preisman, MD, consultation liaison psychiatrist at Mount Sinai Hospital, who is involved with the program, said it’s important to note that coaches are not in clinical relationships with healthcare providers, but rather are applying diverse psychotherapeutic tools to deliver collegial support. When clinical support is requested, coaches facilitate connection with other psychiatrists.

‘An excellent model’

Preliminary analysis of qualitative data, which includes interviews with coaches and providers, suggests that coaching is successful in mitigating the severity of mental health threats that healthcare workers face.

“The feedback so far is that coaching has really helped to strengthen team cohesiveness and resilience, which has been really encouraging for us,” Dr. Rosen said.

For example, some participants said the coaching improved relationships with their colleagues, decreased loneliness, and increased the sense of support from their employer.

Others commented on the value of regularly scheduled coaching “huddles” that are embedded within the work environment.

Dr. Rosen said the program is funded by academic grants through the end of next year, which is key given that Toronto is currently in the middle of a third wave of the pandemic.

“ There have been studies that show, even years after a pandemic or an epidemic has ended, the psychological consequences of anxiety and distress persist,” Dr. Rosen said.

Briefing moderator Jeffrey Borenstein, MD, president and CEO, Brain & Behavior Research Foundation and editor-in-chief, Psychiatric News, said the Toronto team has developed “an excellent model that could be used around the world to support the well-being of healthcare workers who are on the front lines of a pandemic.”

This research had no commercial funding. Dr. Rosen, Dr. Preisman, and Dr. Borenstein have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A novel program that coaches healthcare workers effectively bolsters wellness and resilience in the face of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Investigators found the program they developed successfully reduced the severity of mental health threats in healthcare workers.

The pandemic has been “an enormous threat to the resilience of healthcare workers,” said program leader Benjamin Rosen, MD, assistant professor, department of psychiatry, University of Toronto, and staff psychiatrist at Sinai Health in Toronto.

“Working at a hospital this year, you’re not only worried about battling COVID, but you’re also enduring uncertainty and fear and moral distress, which has contributed to unprecedented levels of burnout,” Dr. Rosen added.

The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, held virtually this year.

‘Psychological PPE’

Building on previous experience supporting colleagues through the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in Toronto, Dr. Rosen’s team designed and implemented an initiative to support colleagues’ wellness and resilience early in the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Resilience Coaching for Healthcare Workers program is designed to support psychological well-being during times of chronic stress and help healthcare workers “keep their heads in the game so that they can sustain the focus and the rigor that they need to do their work,” Dr. Rosen said during a press briefing.

Participating coaches are mental health clinicians with training in psychological first aid, resilience, and psychotherapy to provide peer support to units and teams working on the front line. The program provides a kind of “psychological PPE” to complement other protective measures, Dr. Rosen explained.

There are currently 15 coaches working with 17 units and clinical teams at Sinai Health, which encompasses Mount Sinai Hospital and Bridgepoint Active Health, both in Toronto. Most coaches provide support to groups of up to 15 people either virtually or in person. More than 5,300 staff members have received coaching support since the program’s launch in April 2020.

Mary Preisman, MD, consultation liaison psychiatrist at Mount Sinai Hospital, who is involved with the program, said it’s important to note that coaches are not in clinical relationships with healthcare providers, but rather are applying diverse psychotherapeutic tools to deliver collegial support. When clinical support is requested, coaches facilitate connection with other psychiatrists.

‘An excellent model’

Preliminary analysis of qualitative data, which includes interviews with coaches and providers, suggests that coaching is successful in mitigating the severity of mental health threats that healthcare workers face.

“The feedback so far is that coaching has really helped to strengthen team cohesiveness and resilience, which has been really encouraging for us,” Dr. Rosen said.

For example, some participants said the coaching improved relationships with their colleagues, decreased loneliness, and increased the sense of support from their employer.

Others commented on the value of regularly scheduled coaching “huddles” that are embedded within the work environment.

Dr. Rosen said the program is funded by academic grants through the end of next year, which is key given that Toronto is currently in the middle of a third wave of the pandemic.

“ There have been studies that show, even years after a pandemic or an epidemic has ended, the psychological consequences of anxiety and distress persist,” Dr. Rosen said.

Briefing moderator Jeffrey Borenstein, MD, president and CEO, Brain & Behavior Research Foundation and editor-in-chief, Psychiatric News, said the Toronto team has developed “an excellent model that could be used around the world to support the well-being of healthcare workers who are on the front lines of a pandemic.”

This research had no commercial funding. Dr. Rosen, Dr. Preisman, and Dr. Borenstein have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Parental attitudes to kids’ sexual orientation: Unexpected findings

For gay and lesbian individuals, consistency in parents’ attitudes toward their child’s sexual orientation, even when they are negative, is an important factor in positive mental health outcomes, new research shows.

Study investigator Matthew Verdun, MS, a licensed marriage and family therapist and doctoral student at the Chicago School of Professional Psychology at Los Angeles, California, found that gays and lesbians whose parents were not supportive of their sexual orientation could still have good outcomes.

The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, which was held as a virtual live event.

High rates of mental illness

Research shows that members of the gay and lesbian community experience higher rates of mental illness and substance use disorders and that psychological well-being declines during periods close to when sexual orientation is disclosed.

Mr. Verdun referred to a theory in the literature of homosexual identity formation that describes how individuals go through six stages: confusion, comparison, tolerance, acceptance, pride, and synthesis.

Research shows a U-shaped relationship between subjective reports of well-being at these six stages. The lowest rates occur during the identity comparison and identity tolerance stages.

“Those stages roughly correspond with the time when people would disclose their sexual orientation to parents and family members. The time when a person discloses is probably one of the most anxious times in their life; it’s also where their rate of well-being is the lowest,” said Mr. Verdun.

Mr. Verdun said he “wanted to know what happens when a parent is supportive or rejecting at that moment, but also what happens over time.”

To determine whether parental support affects depression, anxiety, or substance abuse in members of the gay and lesbian community, Mr. Verdun studied 175 individuals who self-identified as gay or lesbian (77 males and 98 females) and were recruited via social media. Most (70.3%) were of White race or ethnicity.

Participants completed surveys asking about their parents’ initial and current level of support regarding their sexual orientation. They also completed the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), the seven-item General Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7), and the 20-item Drug Abuse Screening Tool (DAST-20).

The investigators categorized participants into one of three groups on the basis of parental support:

- Consistently positive.

- Negative to positive.

- Consistently negative.

A fourth group, positive to negative, was excluded from the analysis because it was too small.

Mr. Verdun was unable analyze results for substance abuse. “The DAST-20 results violated the assumption of homogeneity of variances, which meant the analysis could result in error,” he explained.

Analyses for the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 showed that the consistently positive group had the lowest symptom scores.

“People whose parents were accepting had the lowest scores for anxiety and depression,” said Mr. Verdun.

For both the PHQ and GAD, the findings were significant (P < .05) for the consistently positive and the consistently negative groups in comparison with the negative to positive group.

The difference between the consistently positive and the consistently negative groups was not statistically significant.

Surprise finding

Previous research has shown that current levels of parental support relate to better mental health, so Mr. Verdun initially thought children whose parents were consistently supportive or those whose parents became supportive over time would have the best mental health outcomes.

“But, interestingly, what I found was that people whose parents vacillated between being accepting and rejecting over time actually had significantly more mental health symptoms at the time of the assessment than people whose parents were consistently accepting or consistently rejecting,” he said.

Although the study provided evidence of better outcomes for those with consistently unsupportive parents, Mr. Verdun believes some hypotheses are worthy of further research.

One is that people with unsupportive parents receive support elsewhere and could, for example, turn to peers, teachers, or other community members, including faith leaders, and that symptoms of mental illness may improve with such support, said Mr. Verdun.

These individuals may also develop ways to “buffer their mental health symptoms,” possibly by cultivating meaningful relationships “where they’re seen as a complete and total person, not just in terms of their sexual orientation,” he said.

Gay and lesbian individuals may also benefit from “healing activities,” which might include engagement and involvement in their community, such as performing volunteer work and learning about the history of their community, said Mr. Verdun.

Mental health providers can play a role in creating a positive environment by referring patients to support groups, to centers that cater to gays and lesbians, to faith communities, or by encouraging recreational activities, said Mr. Verdun.

Clinicians can also help gay and lesbian patients determine how and when to safely disclose their sexual orientation, he said.

The study did not include bisexual or transsexual individuals because processes of identifying sexual orientation differ for those persons, said Mr. Verdun.

“I would like to conduct future research that includes bisexual, trans people, and intersectional groups within the LGBTQIA [lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual] community,” he said.

Important research

Commenting on the study, Jeffrey Borenstein, MD, president and CEO of the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation and editor-in-chief of Psychiatric News, said the work is “extremely important and that it has the potential to lead to clinical guidance.”

The finding that levels of depression and anxiety were lower in children whose parents were accepting of their sexual orientation is not surprising, said Dr. Borenstein. “It’s common sense, but it’s always good to have such a finding demonstrate it,” he said.

Parents who understand this relationship may be better able to help their child who is depressed or anxious, he added.

Dr. Borenstein agreed that further research is needed regarding the finding of benefits from consistent parenting, even when that parenting involves rejection.

Such research might uncover “what types of other supports these individuals have that allow for lower levels of depression and anxiety,” he said.

“For this population, the risk of mental health issues is higher, and the risk of suicide is higher, so anything we can do to provide support and improved treatment is extremely important,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For gay and lesbian individuals, consistency in parents’ attitudes toward their child’s sexual orientation, even when they are negative, is an important factor in positive mental health outcomes, new research shows.

Study investigator Matthew Verdun, MS, a licensed marriage and family therapist and doctoral student at the Chicago School of Professional Psychology at Los Angeles, California, found that gays and lesbians whose parents were not supportive of their sexual orientation could still have good outcomes.

The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, which was held as a virtual live event.

High rates of mental illness

Research shows that members of the gay and lesbian community experience higher rates of mental illness and substance use disorders and that psychological well-being declines during periods close to when sexual orientation is disclosed.

Mr. Verdun referred to a theory in the literature of homosexual identity formation that describes how individuals go through six stages: confusion, comparison, tolerance, acceptance, pride, and synthesis.

Research shows a U-shaped relationship between subjective reports of well-being at these six stages. The lowest rates occur during the identity comparison and identity tolerance stages.

“Those stages roughly correspond with the time when people would disclose their sexual orientation to parents and family members. The time when a person discloses is probably one of the most anxious times in their life; it’s also where their rate of well-being is the lowest,” said Mr. Verdun.

Mr. Verdun said he “wanted to know what happens when a parent is supportive or rejecting at that moment, but also what happens over time.”

To determine whether parental support affects depression, anxiety, or substance abuse in members of the gay and lesbian community, Mr. Verdun studied 175 individuals who self-identified as gay or lesbian (77 males and 98 females) and were recruited via social media. Most (70.3%) were of White race or ethnicity.

Participants completed surveys asking about their parents’ initial and current level of support regarding their sexual orientation. They also completed the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), the seven-item General Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7), and the 20-item Drug Abuse Screening Tool (DAST-20).

The investigators categorized participants into one of three groups on the basis of parental support:

- Consistently positive.

- Negative to positive.

- Consistently negative.

A fourth group, positive to negative, was excluded from the analysis because it was too small.

Mr. Verdun was unable analyze results for substance abuse. “The DAST-20 results violated the assumption of homogeneity of variances, which meant the analysis could result in error,” he explained.

Analyses for the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 showed that the consistently positive group had the lowest symptom scores.

“People whose parents were accepting had the lowest scores for anxiety and depression,” said Mr. Verdun.

For both the PHQ and GAD, the findings were significant (P < .05) for the consistently positive and the consistently negative groups in comparison with the negative to positive group.

The difference between the consistently positive and the consistently negative groups was not statistically significant.

Surprise finding

Previous research has shown that current levels of parental support relate to better mental health, so Mr. Verdun initially thought children whose parents were consistently supportive or those whose parents became supportive over time would have the best mental health outcomes.

“But, interestingly, what I found was that people whose parents vacillated between being accepting and rejecting over time actually had significantly more mental health symptoms at the time of the assessment than people whose parents were consistently accepting or consistently rejecting,” he said.

Although the study provided evidence of better outcomes for those with consistently unsupportive parents, Mr. Verdun believes some hypotheses are worthy of further research.