User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

Powered by CHEST Physician, Clinician Reviews, MDedge Family Medicine, Internal Medicine News, and The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management.

CDC calls for masks in schools, hard-hit areas, even if vaccinated

The agency has called for masks in K-12 school settings and in areas of the United States experiencing high or substantial SARS-CoV-2 transmission, even for the fully vaccinated.

The move reverses a controversial announcement the agency made in May 2021 that fully vaccinated Americans could skip wearing a mask in most settings.

Unlike the increasing vaccination rates and decreasing case numbers reported in May, however, some regions of the United States are now reporting large jumps in COVID-19 case numbers. And the Delta variant as well as new evidence of transmission from breakthrough cases are largely driving these changes.

“Today we have new science related to the [D]elta variant that requires us to update the guidance on what you can do when you are fully vaccinated,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, MPH, said during a media briefing July 27.

New evidence has emerged on breakthrough-case transmission risk, for example. “Information on the [D]elta variant from several states and other countries indicates that in rare cases, some people infected with the [D]elta variant after vaccination may be contagious and spread virus to others,” Dr. Walensky said, adding that the viral loads appear to be about the same in vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals.

“This new science is worrisome,” she said.

Even though unvaccinated people represent the vast majority of cases of transmission, Dr. Walensky said, “we thought it was important for [vaccinated] people to understand they have the potential to transmit the virus to others.”

As a result, in addition to continuing to strongly encourage everyone to get vaccinated, the CDC recommends that fully vaccinated people wear masks in public indoor settings to help prevent the spread of the Delta variant in areas with substantial or high transmission, Dr. Walensky said. “This includes schools.”

Masks in schools

The CDC is now recommending universal indoor masking for all teachers, staff, students, and visitors to K-12 schools, regardless of vaccination status. Their goal is to optimize safety and allow children to return to full-time in-person learning in the fall.

The CDC tracks substantial and high transmission rates through the agency’s COVID Data Tracker site. Substantial transmission means between 50 and 100 cases per 100,000 people reported over 7 days and high means more than 100 cases per 100,000 people.

The B.1.617.2, or Delta, variant is believed to be responsible for COVID-19 cases increasing more than 300% nationally from June 19 to July 23, 2021.

“A prudent move”

“I think it’s a prudent move. Given the dominance of the [D]elta variant and the caseloads that we are seeing rising in many locations across the United States, including in my backyard here in San Francisco,” Joe DeRisi, PhD, copresident of the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub and professor of biochemistry and biophysics at the University of California San Francisco, said in an interview.

Dr. DeRisi said he was not surprised that vaccinated people with breakthrough infections could be capable of transmitting the virus. He added that clinical testing done by the Biohub and UCSF produced a lot of data on viral load levels, “and they cover an enormous range.”

What was unexpected to him was the rapid rise of the dominant variant. “The rise of the [D]elta strain is astonishing. It’s happened so fast,” he said.

“I know it’s difficult”

Reacting to the news, Colleen Kraft, MD, said, “One of the things that we’re learning is that if we’re going to have low vaccine uptake or we have a number of people that can’t be vaccinated yet, such as children, that we really need to go back to stopping transmission, which involves mask wearing.”

“I know that it’s very difficult and people feel like we’re sliding backward,” Dr. Kraft said during a media briefing sponsored by Emory University held shortly after the CDC announcement.

She added that the CDC updated guidance seems appropriate. “I don’t think any of us really want to be in this position or want to go back to masking but…we’re finding ourselves in the same place we were a year ago, in July 2020.

“In general we just don’t want anybody to be infected even if there’s a small chance for you to be infected and there’s a small chance for you to transmit it,” said Dr. Kraft, who’s an assistant professor in the department of pathology and associate professor in the department of medicine, division of infectious diseases at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta.

Breakthrough transmissions

“The good news is you’re still unlikely to get critically ill if you’re vaccinated. But what has changed with the [D]elta variant is instead of being 90% plus protected from getting the virus at all, you’re probably more in the 70% to 80% range,” James T. McDeavitt, MD, told this news organization.

“So we’re seeing breakthrough infections,” said Dr. McDeavitt, executive vice president and dean of clinical affairs at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. “We are starting to see [such people] are potentially infectious.” Even if a vaccinated person is individually much less likely to experience serious COVID-19 outcomes, “they can spread it to someone else who spreads it to someone else who is more vulnerable. It puts the more at-risk populations at further risk.”

It breaks down to individual and public health concerns. “I am fully vaccinated. I am very confident I am not going to end up in a hospital,” he said. “Now if I were unvaccinated, with the prevalence of the virus around the country, I’m probably in more danger than I’ve ever been in the course of the pandemic. The unvaccinated are really at risk right now.”

IDSA and AMA support mask change

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) has released a statement supporting the new CDC recommendations. “To stay ahead of the spread of the highly transmissible Delta variant, IDSA also urges that in communities with moderate transmission rates, all individuals, even those who are vaccinated, wear masks in indoor public places,” stated IDSA President Barbara D. Alexander, MD, MHS.

“IDSA also supports CDC’s guidance recommending universal indoor masking for all teachers, staff, students, and visitors to K-12 schools, regardless of vaccination status, until vaccines are authorized and widely available to all children and vaccination rates are sufficient to control transmission.”

“Mask wearing will help reduce infections, prevent serious illnesses and death, limit strain on local hospitals and stave off the development of even more troubling variants,” she added.

The American Medical Association (AMA) also released a statement supporting the CDC’s policy changes.

“According to the CDC, emerging data indicates that vaccinated individuals infected with the Delta variant have similar viral loads as those who are unvaccinated and are capable of transmission,” AMA President Gerald E. Harmon, MD said in the statement.

“However, the science remains clear, the authorized vaccines remain safe and effective in preventing severe complications from COVID-19, including hospitalization and death,” he stated. “We strongly support the updated recommendations, which call for universal masking in areas of high or substantial COVID-19 transmission and in K-12 schools, to help reduce transmission of the virus. Wearing a mask is a small but important protective measure that can help us all stay safer.”

“The highest spread of cases and [most] severe outcomes are happening in places with low vaccination rates and among unvaccinated people,” Dr. Walensky said. “With the [D]elta variant, vaccinating more Americans now is more urgent than ever.”

“This moment, and the associated suffering, illness, and death, could have been avoided with higher vaccination coverage in this country,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The agency has called for masks in K-12 school settings and in areas of the United States experiencing high or substantial SARS-CoV-2 transmission, even for the fully vaccinated.

The move reverses a controversial announcement the agency made in May 2021 that fully vaccinated Americans could skip wearing a mask in most settings.

Unlike the increasing vaccination rates and decreasing case numbers reported in May, however, some regions of the United States are now reporting large jumps in COVID-19 case numbers. And the Delta variant as well as new evidence of transmission from breakthrough cases are largely driving these changes.

“Today we have new science related to the [D]elta variant that requires us to update the guidance on what you can do when you are fully vaccinated,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, MPH, said during a media briefing July 27.

New evidence has emerged on breakthrough-case transmission risk, for example. “Information on the [D]elta variant from several states and other countries indicates that in rare cases, some people infected with the [D]elta variant after vaccination may be contagious and spread virus to others,” Dr. Walensky said, adding that the viral loads appear to be about the same in vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals.

“This new science is worrisome,” she said.

Even though unvaccinated people represent the vast majority of cases of transmission, Dr. Walensky said, “we thought it was important for [vaccinated] people to understand they have the potential to transmit the virus to others.”

As a result, in addition to continuing to strongly encourage everyone to get vaccinated, the CDC recommends that fully vaccinated people wear masks in public indoor settings to help prevent the spread of the Delta variant in areas with substantial or high transmission, Dr. Walensky said. “This includes schools.”

Masks in schools

The CDC is now recommending universal indoor masking for all teachers, staff, students, and visitors to K-12 schools, regardless of vaccination status. Their goal is to optimize safety and allow children to return to full-time in-person learning in the fall.

The CDC tracks substantial and high transmission rates through the agency’s COVID Data Tracker site. Substantial transmission means between 50 and 100 cases per 100,000 people reported over 7 days and high means more than 100 cases per 100,000 people.

The B.1.617.2, or Delta, variant is believed to be responsible for COVID-19 cases increasing more than 300% nationally from June 19 to July 23, 2021.

“A prudent move”

“I think it’s a prudent move. Given the dominance of the [D]elta variant and the caseloads that we are seeing rising in many locations across the United States, including in my backyard here in San Francisco,” Joe DeRisi, PhD, copresident of the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub and professor of biochemistry and biophysics at the University of California San Francisco, said in an interview.

Dr. DeRisi said he was not surprised that vaccinated people with breakthrough infections could be capable of transmitting the virus. He added that clinical testing done by the Biohub and UCSF produced a lot of data on viral load levels, “and they cover an enormous range.”

What was unexpected to him was the rapid rise of the dominant variant. “The rise of the [D]elta strain is astonishing. It’s happened so fast,” he said.

“I know it’s difficult”

Reacting to the news, Colleen Kraft, MD, said, “One of the things that we’re learning is that if we’re going to have low vaccine uptake or we have a number of people that can’t be vaccinated yet, such as children, that we really need to go back to stopping transmission, which involves mask wearing.”

“I know that it’s very difficult and people feel like we’re sliding backward,” Dr. Kraft said during a media briefing sponsored by Emory University held shortly after the CDC announcement.

She added that the CDC updated guidance seems appropriate. “I don’t think any of us really want to be in this position or want to go back to masking but…we’re finding ourselves in the same place we were a year ago, in July 2020.

“In general we just don’t want anybody to be infected even if there’s a small chance for you to be infected and there’s a small chance for you to transmit it,” said Dr. Kraft, who’s an assistant professor in the department of pathology and associate professor in the department of medicine, division of infectious diseases at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta.

Breakthrough transmissions

“The good news is you’re still unlikely to get critically ill if you’re vaccinated. But what has changed with the [D]elta variant is instead of being 90% plus protected from getting the virus at all, you’re probably more in the 70% to 80% range,” James T. McDeavitt, MD, told this news organization.

“So we’re seeing breakthrough infections,” said Dr. McDeavitt, executive vice president and dean of clinical affairs at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. “We are starting to see [such people] are potentially infectious.” Even if a vaccinated person is individually much less likely to experience serious COVID-19 outcomes, “they can spread it to someone else who spreads it to someone else who is more vulnerable. It puts the more at-risk populations at further risk.”

It breaks down to individual and public health concerns. “I am fully vaccinated. I am very confident I am not going to end up in a hospital,” he said. “Now if I were unvaccinated, with the prevalence of the virus around the country, I’m probably in more danger than I’ve ever been in the course of the pandemic. The unvaccinated are really at risk right now.”

IDSA and AMA support mask change

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) has released a statement supporting the new CDC recommendations. “To stay ahead of the spread of the highly transmissible Delta variant, IDSA also urges that in communities with moderate transmission rates, all individuals, even those who are vaccinated, wear masks in indoor public places,” stated IDSA President Barbara D. Alexander, MD, MHS.

“IDSA also supports CDC’s guidance recommending universal indoor masking for all teachers, staff, students, and visitors to K-12 schools, regardless of vaccination status, until vaccines are authorized and widely available to all children and vaccination rates are sufficient to control transmission.”

“Mask wearing will help reduce infections, prevent serious illnesses and death, limit strain on local hospitals and stave off the development of even more troubling variants,” she added.

The American Medical Association (AMA) also released a statement supporting the CDC’s policy changes.

“According to the CDC, emerging data indicates that vaccinated individuals infected with the Delta variant have similar viral loads as those who are unvaccinated and are capable of transmission,” AMA President Gerald E. Harmon, MD said in the statement.

“However, the science remains clear, the authorized vaccines remain safe and effective in preventing severe complications from COVID-19, including hospitalization and death,” he stated. “We strongly support the updated recommendations, which call for universal masking in areas of high or substantial COVID-19 transmission and in K-12 schools, to help reduce transmission of the virus. Wearing a mask is a small but important protective measure that can help us all stay safer.”

“The highest spread of cases and [most] severe outcomes are happening in places with low vaccination rates and among unvaccinated people,” Dr. Walensky said. “With the [D]elta variant, vaccinating more Americans now is more urgent than ever.”

“This moment, and the associated suffering, illness, and death, could have been avoided with higher vaccination coverage in this country,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The agency has called for masks in K-12 school settings and in areas of the United States experiencing high or substantial SARS-CoV-2 transmission, even for the fully vaccinated.

The move reverses a controversial announcement the agency made in May 2021 that fully vaccinated Americans could skip wearing a mask in most settings.

Unlike the increasing vaccination rates and decreasing case numbers reported in May, however, some regions of the United States are now reporting large jumps in COVID-19 case numbers. And the Delta variant as well as new evidence of transmission from breakthrough cases are largely driving these changes.

“Today we have new science related to the [D]elta variant that requires us to update the guidance on what you can do when you are fully vaccinated,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, MPH, said during a media briefing July 27.

New evidence has emerged on breakthrough-case transmission risk, for example. “Information on the [D]elta variant from several states and other countries indicates that in rare cases, some people infected with the [D]elta variant after vaccination may be contagious and spread virus to others,” Dr. Walensky said, adding that the viral loads appear to be about the same in vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals.

“This new science is worrisome,” she said.

Even though unvaccinated people represent the vast majority of cases of transmission, Dr. Walensky said, “we thought it was important for [vaccinated] people to understand they have the potential to transmit the virus to others.”

As a result, in addition to continuing to strongly encourage everyone to get vaccinated, the CDC recommends that fully vaccinated people wear masks in public indoor settings to help prevent the spread of the Delta variant in areas with substantial or high transmission, Dr. Walensky said. “This includes schools.”

Masks in schools

The CDC is now recommending universal indoor masking for all teachers, staff, students, and visitors to K-12 schools, regardless of vaccination status. Their goal is to optimize safety and allow children to return to full-time in-person learning in the fall.

The CDC tracks substantial and high transmission rates through the agency’s COVID Data Tracker site. Substantial transmission means between 50 and 100 cases per 100,000 people reported over 7 days and high means more than 100 cases per 100,000 people.

The B.1.617.2, or Delta, variant is believed to be responsible for COVID-19 cases increasing more than 300% nationally from June 19 to July 23, 2021.

“A prudent move”

“I think it’s a prudent move. Given the dominance of the [D]elta variant and the caseloads that we are seeing rising in many locations across the United States, including in my backyard here in San Francisco,” Joe DeRisi, PhD, copresident of the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub and professor of biochemistry and biophysics at the University of California San Francisco, said in an interview.

Dr. DeRisi said he was not surprised that vaccinated people with breakthrough infections could be capable of transmitting the virus. He added that clinical testing done by the Biohub and UCSF produced a lot of data on viral load levels, “and they cover an enormous range.”

What was unexpected to him was the rapid rise of the dominant variant. “The rise of the [D]elta strain is astonishing. It’s happened so fast,” he said.

“I know it’s difficult”

Reacting to the news, Colleen Kraft, MD, said, “One of the things that we’re learning is that if we’re going to have low vaccine uptake or we have a number of people that can’t be vaccinated yet, such as children, that we really need to go back to stopping transmission, which involves mask wearing.”

“I know that it’s very difficult and people feel like we’re sliding backward,” Dr. Kraft said during a media briefing sponsored by Emory University held shortly after the CDC announcement.

She added that the CDC updated guidance seems appropriate. “I don’t think any of us really want to be in this position or want to go back to masking but…we’re finding ourselves in the same place we were a year ago, in July 2020.

“In general we just don’t want anybody to be infected even if there’s a small chance for you to be infected and there’s a small chance for you to transmit it,” said Dr. Kraft, who’s an assistant professor in the department of pathology and associate professor in the department of medicine, division of infectious diseases at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta.

Breakthrough transmissions

“The good news is you’re still unlikely to get critically ill if you’re vaccinated. But what has changed with the [D]elta variant is instead of being 90% plus protected from getting the virus at all, you’re probably more in the 70% to 80% range,” James T. McDeavitt, MD, told this news organization.

“So we’re seeing breakthrough infections,” said Dr. McDeavitt, executive vice president and dean of clinical affairs at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. “We are starting to see [such people] are potentially infectious.” Even if a vaccinated person is individually much less likely to experience serious COVID-19 outcomes, “they can spread it to someone else who spreads it to someone else who is more vulnerable. It puts the more at-risk populations at further risk.”

It breaks down to individual and public health concerns. “I am fully vaccinated. I am very confident I am not going to end up in a hospital,” he said. “Now if I were unvaccinated, with the prevalence of the virus around the country, I’m probably in more danger than I’ve ever been in the course of the pandemic. The unvaccinated are really at risk right now.”

IDSA and AMA support mask change

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) has released a statement supporting the new CDC recommendations. “To stay ahead of the spread of the highly transmissible Delta variant, IDSA also urges that in communities with moderate transmission rates, all individuals, even those who are vaccinated, wear masks in indoor public places,” stated IDSA President Barbara D. Alexander, MD, MHS.

“IDSA also supports CDC’s guidance recommending universal indoor masking for all teachers, staff, students, and visitors to K-12 schools, regardless of vaccination status, until vaccines are authorized and widely available to all children and vaccination rates are sufficient to control transmission.”

“Mask wearing will help reduce infections, prevent serious illnesses and death, limit strain on local hospitals and stave off the development of even more troubling variants,” she added.

The American Medical Association (AMA) also released a statement supporting the CDC’s policy changes.

“According to the CDC, emerging data indicates that vaccinated individuals infected with the Delta variant have similar viral loads as those who are unvaccinated and are capable of transmission,” AMA President Gerald E. Harmon, MD said in the statement.

“However, the science remains clear, the authorized vaccines remain safe and effective in preventing severe complications from COVID-19, including hospitalization and death,” he stated. “We strongly support the updated recommendations, which call for universal masking in areas of high or substantial COVID-19 transmission and in K-12 schools, to help reduce transmission of the virus. Wearing a mask is a small but important protective measure that can help us all stay safer.”

“The highest spread of cases and [most] severe outcomes are happening in places with low vaccination rates and among unvaccinated people,” Dr. Walensky said. “With the [D]elta variant, vaccinating more Americans now is more urgent than ever.”

“This moment, and the associated suffering, illness, and death, could have been avoided with higher vaccination coverage in this country,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children and COVID: Vaccinations, new cases both rising

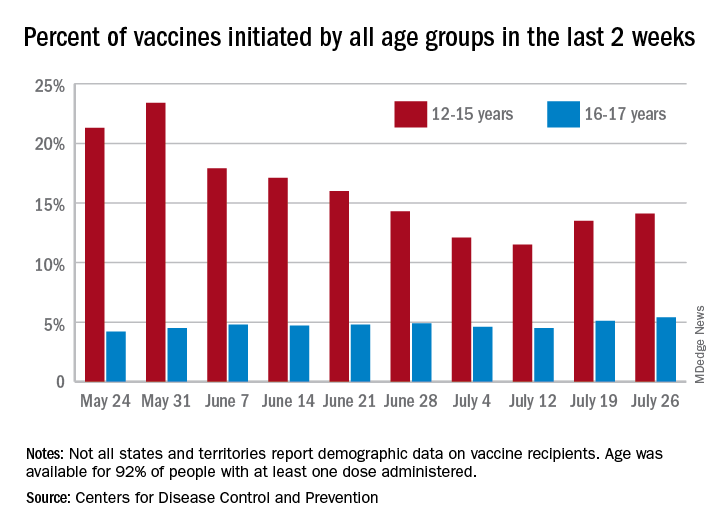

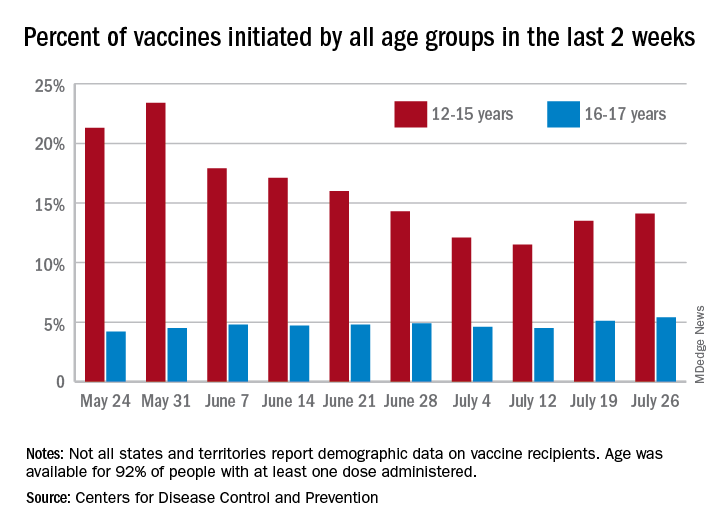

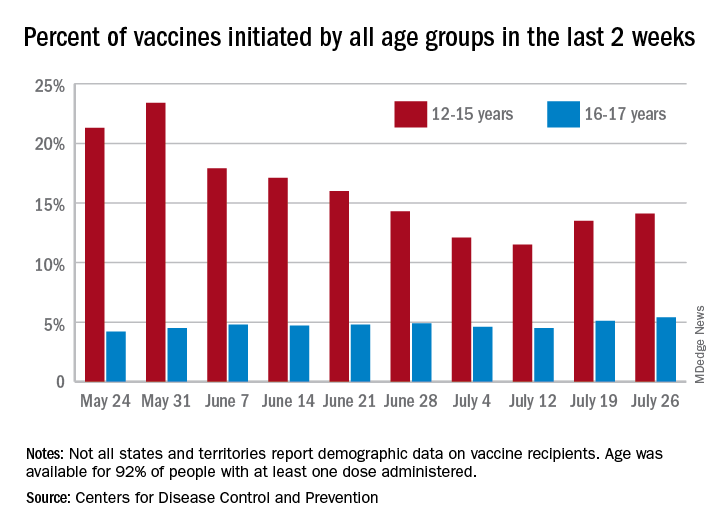

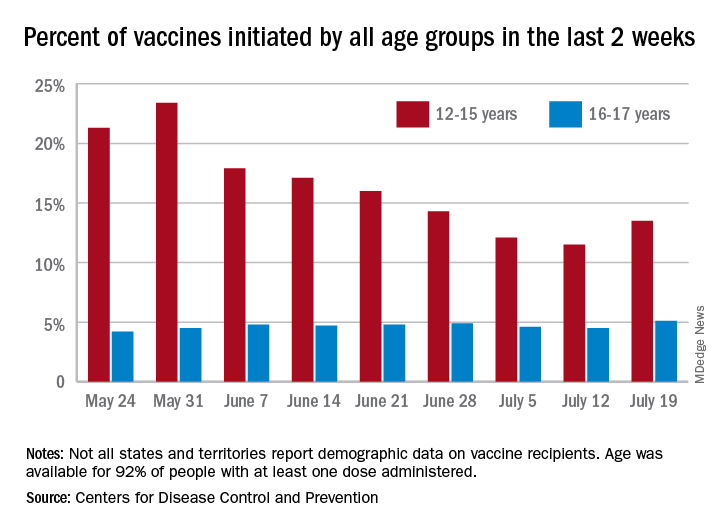

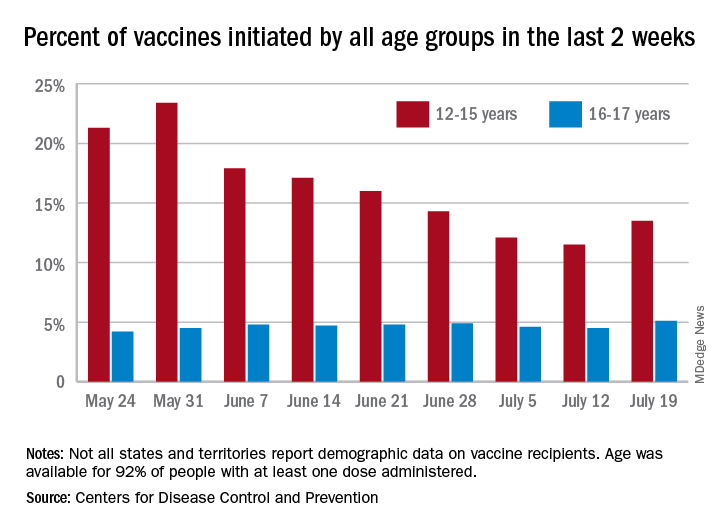

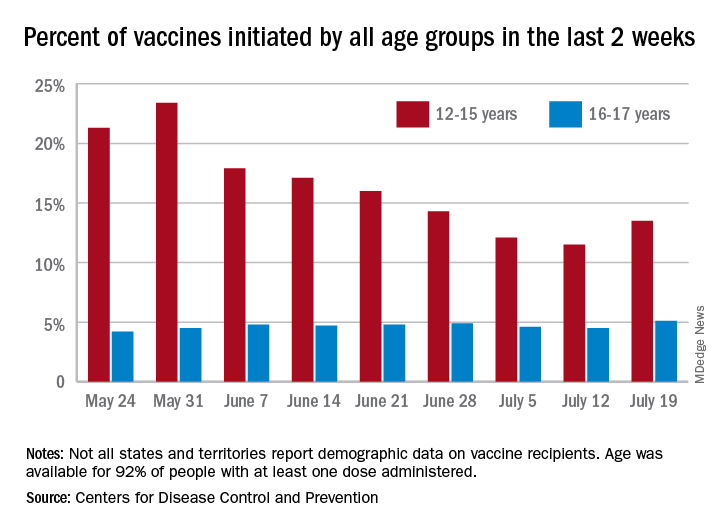

COVID-19 vaccine initiations rose in U.S. children for the second consecutive week, but new pediatric cases jumped by 64% in just 1 week, according to new data.

the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

“After decreases in weekly reported cases over the past couple of months, in July we have seen steady increases in cases added to the cumulative total,” the AAP noted. In this latest reversal of COVID fortunes, the steady increase in new cases is in its fourth consecutive week since hitting a low of 8,447 in late June.

As of July 22, the total number of reported cases was over 4.12 million in 49 states, the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, and there have been 349 deaths in children in the 46 jurisdictions reporting age distributions of COVID-19 deaths, the AAP and CHA said in their report.

Meanwhile, over 9.3 million children received at least one dose of COVID vaccine as of July 26, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Vaccine initiation rose for the second week in a row after falling for several weeks as 301,000 children aged 12-15 years and almost 115,000 children aged 16-17 got their first dose during the week ending July 26. Children aged 12-15 represented 14.1% (up from 13.5% a week before) of all first vaccinations and 16- to 17-year-olds were 5.4% (up from 5.1%) of all vaccine initiators, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

Just over 37% of all 12- to 15-year-olds have received at least one dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine since the CDC approved its use for children under age 16 in May, and almost 28% are fully vaccinated. Use in children aged 16-17 started earlier (December 2020), and 48% of that age group have received a first dose and over 39% have completed the vaccine regimen, the CDC said.

COVID-19 vaccine initiations rose in U.S. children for the second consecutive week, but new pediatric cases jumped by 64% in just 1 week, according to new data.

the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

“After decreases in weekly reported cases over the past couple of months, in July we have seen steady increases in cases added to the cumulative total,” the AAP noted. In this latest reversal of COVID fortunes, the steady increase in new cases is in its fourth consecutive week since hitting a low of 8,447 in late June.

As of July 22, the total number of reported cases was over 4.12 million in 49 states, the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, and there have been 349 deaths in children in the 46 jurisdictions reporting age distributions of COVID-19 deaths, the AAP and CHA said in their report.

Meanwhile, over 9.3 million children received at least one dose of COVID vaccine as of July 26, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Vaccine initiation rose for the second week in a row after falling for several weeks as 301,000 children aged 12-15 years and almost 115,000 children aged 16-17 got their first dose during the week ending July 26. Children aged 12-15 represented 14.1% (up from 13.5% a week before) of all first vaccinations and 16- to 17-year-olds were 5.4% (up from 5.1%) of all vaccine initiators, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

Just over 37% of all 12- to 15-year-olds have received at least one dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine since the CDC approved its use for children under age 16 in May, and almost 28% are fully vaccinated. Use in children aged 16-17 started earlier (December 2020), and 48% of that age group have received a first dose and over 39% have completed the vaccine regimen, the CDC said.

COVID-19 vaccine initiations rose in U.S. children for the second consecutive week, but new pediatric cases jumped by 64% in just 1 week, according to new data.

the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

“After decreases in weekly reported cases over the past couple of months, in July we have seen steady increases in cases added to the cumulative total,” the AAP noted. In this latest reversal of COVID fortunes, the steady increase in new cases is in its fourth consecutive week since hitting a low of 8,447 in late June.

As of July 22, the total number of reported cases was over 4.12 million in 49 states, the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, and there have been 349 deaths in children in the 46 jurisdictions reporting age distributions of COVID-19 deaths, the AAP and CHA said in their report.

Meanwhile, over 9.3 million children received at least one dose of COVID vaccine as of July 26, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Vaccine initiation rose for the second week in a row after falling for several weeks as 301,000 children aged 12-15 years and almost 115,000 children aged 16-17 got their first dose during the week ending July 26. Children aged 12-15 represented 14.1% (up from 13.5% a week before) of all first vaccinations and 16- to 17-year-olds were 5.4% (up from 5.1%) of all vaccine initiators, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

Just over 37% of all 12- to 15-year-olds have received at least one dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine since the CDC approved its use for children under age 16 in May, and almost 28% are fully vaccinated. Use in children aged 16-17 started earlier (December 2020), and 48% of that age group have received a first dose and over 39% have completed the vaccine regimen, the CDC said.

Vaccine breakthrough cases rising with Delta: Here’s what that means

At a recent town hall meeting in Cincinnati, President Joe Biden was asked about COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths rising in response to the Delta variant.

Touting the importance of vaccination, “We have a pandemic for those who haven’t gotten a vaccination. It’s that basic, that simple,” President Biden said at the event, which was broadcast live on CNN.

“If you’re vaccinated, you’re not going to be hospitalized, not going to the ICU unit, and not going to die,” he said, adding “you’re not going to get COVID if you have these vaccinations.”

Unfortunately, it’s not so simple. Fully vaccinated people continue to be well protected against severe disease and death, even with Delta, Because of that, many experts continue to advise caution, even if fully vaccinated.

“I was disappointed,” Leana Wen, MD, MSc, an emergency physician and visiting professor of health policy and management at George Washington University’s Milken School of Public Health in Washington, told CNN in response to the president’s statement.

“I actually thought he was answering questions as if it were a month ago. He’s not really meeting the realities of what’s happening on the ground,” she said. “I think he may have led people astray.”

Vaccines still work

Recent cases support Dr. Wen’s claim. Fully vaccinated Olympic athletes, wedding guests, healthcare workers, and even White House staff have recently tested positive. So what gives?

The vast majority of these illnesses are mild, and public health officials say they are to be expected.

“The vaccines were designed to keep us out of the hospital and to keep us from dying. That was the whole purpose of the vaccine and they’re even more successful than we anticipated,” says William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease expert at Vanderbilt University in Nashville.

As good as they are, these shots aren’t perfect. Their protection differs from person to person depending on age and underlying health. People with immune function that’s weakened because of age or a health condition can still become seriously ill, and, in very rare cases, die after vaccination.

When people are infected with Delta, they carry approximately 1,000 times more virus compared with previous versions of the virus, according to a recent study. All that virus can overwhelm even the strong protection from the vaccines.

“Three months ago, breakthroughs didn’t occur nearly at this rate because there was just so much less virus exposure in the community,” said Michael Osterholm, PhD, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

Breakthroughs by the numbers

In Los Angeles County, where 69% of residents over age 12 have been fully vaccinated, COVID-19 cases are rising, and so, too, are cases that break through the protection of the vaccine.

In June, fully vaccinated people accounted for 20%, or 1 in 5, COVID cases in the county, which is the most populous in the United States. The increase mirrors Delta’s rise. The proportion of breakthrough cases is up from 11% in May, 5% in April, and 2% in March, according to the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

In the United Kingdom, which is collecting the best information on infections caused by variants, the estimated effectiveness of the vaccines to prevent an illness that causes symptoms dropped by about 10 points against Delta compared with Alpha (or B.1.1.7).

After two doses, vaccines prevent symptomatic infection about 79% of the time against Delta, according to data compiled by Public Health England. They are still highly effective at preventing hospitalization, 96% after two doses.

Out of 229,218 COVID infections in the United Kingdom between February and July 19, 28,773 — or 12.5% — were in fully vaccinated people. Of those breakthrough infections, 1,101, or 3.8%, required a visit to an emergency room, according to Public Health England. Just 474, or 2.9%, of fully vaccinated people required hospital admission, and 229, or less than 1%, died.

Unanswered questions

One of the biggest questions about breakthrough cases is how often people who have it may pass the virus to others.

“We know the vaccine reduces the likelihood of carrying the virus and the amount of virus you would carry,” Dr. Wen told CNN. But we don’t yet know whether a vaccinated person with a breakthrough infection may still be contagious to others.

For that reason, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that fully vaccinated people still need to be tested if they have symptoms and shouldn’t be out in public for at least 10 days after a positive test.

How should fully vaccinated people behave? That depends a lot on their underlying health and whether or not they have vulnerable people around them.

If you’re older or immunocompromised, Dr. Schaffner recommends what he calls the “belt-and-suspenders approach,” in other words, do everything you can to stay safe.

“Get vaccinated for sure, but since we can’t be absolutely certain that the vaccines are going to be optimally protective and you are particularly susceptible to serious disease, you would be well advised to adopt at least one and perhaps more of the other mitigation measures,” he said.

These include wearing a mask, social distancing, making sure your spaces are well ventilated, and not spending prolonged periods of time indoors in crowded places.

Taking young children to visit vaccinated, elderly grandparents demands extra caution, again, with Delta circulating, particularly as they go back to school and start mixing with other kids.

Dr. Schaffner recommends explaining the ground rules before the visit: Hugs around the waist. No kissing. Wearing a mask while indoors with them.

Other important unanswered questions are whether breakthrough infections can lead to prolonged symptoms, or “long covid.” Most experts think that’s less likely in vaccinated people.

And Dr. Osterholm said it will be important to see whether there’s anything unusual about the breakthrough cases happening in the community.

“I think some of us have been challenged by the number of clusters that we’ve seen,” he said. “I think that really needs to be examined more.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

At a recent town hall meeting in Cincinnati, President Joe Biden was asked about COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths rising in response to the Delta variant.

Touting the importance of vaccination, “We have a pandemic for those who haven’t gotten a vaccination. It’s that basic, that simple,” President Biden said at the event, which was broadcast live on CNN.

“If you’re vaccinated, you’re not going to be hospitalized, not going to the ICU unit, and not going to die,” he said, adding “you’re not going to get COVID if you have these vaccinations.”

Unfortunately, it’s not so simple. Fully vaccinated people continue to be well protected against severe disease and death, even with Delta, Because of that, many experts continue to advise caution, even if fully vaccinated.

“I was disappointed,” Leana Wen, MD, MSc, an emergency physician and visiting professor of health policy and management at George Washington University’s Milken School of Public Health in Washington, told CNN in response to the president’s statement.

“I actually thought he was answering questions as if it were a month ago. He’s not really meeting the realities of what’s happening on the ground,” she said. “I think he may have led people astray.”

Vaccines still work

Recent cases support Dr. Wen’s claim. Fully vaccinated Olympic athletes, wedding guests, healthcare workers, and even White House staff have recently tested positive. So what gives?

The vast majority of these illnesses are mild, and public health officials say they are to be expected.

“The vaccines were designed to keep us out of the hospital and to keep us from dying. That was the whole purpose of the vaccine and they’re even more successful than we anticipated,” says William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease expert at Vanderbilt University in Nashville.

As good as they are, these shots aren’t perfect. Their protection differs from person to person depending on age and underlying health. People with immune function that’s weakened because of age or a health condition can still become seriously ill, and, in very rare cases, die after vaccination.

When people are infected with Delta, they carry approximately 1,000 times more virus compared with previous versions of the virus, according to a recent study. All that virus can overwhelm even the strong protection from the vaccines.

“Three months ago, breakthroughs didn’t occur nearly at this rate because there was just so much less virus exposure in the community,” said Michael Osterholm, PhD, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

Breakthroughs by the numbers

In Los Angeles County, where 69% of residents over age 12 have been fully vaccinated, COVID-19 cases are rising, and so, too, are cases that break through the protection of the vaccine.

In June, fully vaccinated people accounted for 20%, or 1 in 5, COVID cases in the county, which is the most populous in the United States. The increase mirrors Delta’s rise. The proportion of breakthrough cases is up from 11% in May, 5% in April, and 2% in March, according to the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

In the United Kingdom, which is collecting the best information on infections caused by variants, the estimated effectiveness of the vaccines to prevent an illness that causes symptoms dropped by about 10 points against Delta compared with Alpha (or B.1.1.7).

After two doses, vaccines prevent symptomatic infection about 79% of the time against Delta, according to data compiled by Public Health England. They are still highly effective at preventing hospitalization, 96% after two doses.

Out of 229,218 COVID infections in the United Kingdom between February and July 19, 28,773 — or 12.5% — were in fully vaccinated people. Of those breakthrough infections, 1,101, or 3.8%, required a visit to an emergency room, according to Public Health England. Just 474, or 2.9%, of fully vaccinated people required hospital admission, and 229, or less than 1%, died.

Unanswered questions

One of the biggest questions about breakthrough cases is how often people who have it may pass the virus to others.

“We know the vaccine reduces the likelihood of carrying the virus and the amount of virus you would carry,” Dr. Wen told CNN. But we don’t yet know whether a vaccinated person with a breakthrough infection may still be contagious to others.

For that reason, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that fully vaccinated people still need to be tested if they have symptoms and shouldn’t be out in public for at least 10 days after a positive test.

How should fully vaccinated people behave? That depends a lot on their underlying health and whether or not they have vulnerable people around them.

If you’re older or immunocompromised, Dr. Schaffner recommends what he calls the “belt-and-suspenders approach,” in other words, do everything you can to stay safe.

“Get vaccinated for sure, but since we can’t be absolutely certain that the vaccines are going to be optimally protective and you are particularly susceptible to serious disease, you would be well advised to adopt at least one and perhaps more of the other mitigation measures,” he said.

These include wearing a mask, social distancing, making sure your spaces are well ventilated, and not spending prolonged periods of time indoors in crowded places.

Taking young children to visit vaccinated, elderly grandparents demands extra caution, again, with Delta circulating, particularly as they go back to school and start mixing with other kids.

Dr. Schaffner recommends explaining the ground rules before the visit: Hugs around the waist. No kissing. Wearing a mask while indoors with them.

Other important unanswered questions are whether breakthrough infections can lead to prolonged symptoms, or “long covid.” Most experts think that’s less likely in vaccinated people.

And Dr. Osterholm said it will be important to see whether there’s anything unusual about the breakthrough cases happening in the community.

“I think some of us have been challenged by the number of clusters that we’ve seen,” he said. “I think that really needs to be examined more.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

At a recent town hall meeting in Cincinnati, President Joe Biden was asked about COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths rising in response to the Delta variant.

Touting the importance of vaccination, “We have a pandemic for those who haven’t gotten a vaccination. It’s that basic, that simple,” President Biden said at the event, which was broadcast live on CNN.

“If you’re vaccinated, you’re not going to be hospitalized, not going to the ICU unit, and not going to die,” he said, adding “you’re not going to get COVID if you have these vaccinations.”

Unfortunately, it’s not so simple. Fully vaccinated people continue to be well protected against severe disease and death, even with Delta, Because of that, many experts continue to advise caution, even if fully vaccinated.

“I was disappointed,” Leana Wen, MD, MSc, an emergency physician and visiting professor of health policy and management at George Washington University’s Milken School of Public Health in Washington, told CNN in response to the president’s statement.

“I actually thought he was answering questions as if it were a month ago. He’s not really meeting the realities of what’s happening on the ground,” she said. “I think he may have led people astray.”

Vaccines still work

Recent cases support Dr. Wen’s claim. Fully vaccinated Olympic athletes, wedding guests, healthcare workers, and even White House staff have recently tested positive. So what gives?

The vast majority of these illnesses are mild, and public health officials say they are to be expected.

“The vaccines were designed to keep us out of the hospital and to keep us from dying. That was the whole purpose of the vaccine and they’re even more successful than we anticipated,” says William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease expert at Vanderbilt University in Nashville.

As good as they are, these shots aren’t perfect. Their protection differs from person to person depending on age and underlying health. People with immune function that’s weakened because of age or a health condition can still become seriously ill, and, in very rare cases, die after vaccination.

When people are infected with Delta, they carry approximately 1,000 times more virus compared with previous versions of the virus, according to a recent study. All that virus can overwhelm even the strong protection from the vaccines.

“Three months ago, breakthroughs didn’t occur nearly at this rate because there was just so much less virus exposure in the community,” said Michael Osterholm, PhD, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

Breakthroughs by the numbers

In Los Angeles County, where 69% of residents over age 12 have been fully vaccinated, COVID-19 cases are rising, and so, too, are cases that break through the protection of the vaccine.

In June, fully vaccinated people accounted for 20%, or 1 in 5, COVID cases in the county, which is the most populous in the United States. The increase mirrors Delta’s rise. The proportion of breakthrough cases is up from 11% in May, 5% in April, and 2% in March, according to the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

In the United Kingdom, which is collecting the best information on infections caused by variants, the estimated effectiveness of the vaccines to prevent an illness that causes symptoms dropped by about 10 points against Delta compared with Alpha (or B.1.1.7).

After two doses, vaccines prevent symptomatic infection about 79% of the time against Delta, according to data compiled by Public Health England. They are still highly effective at preventing hospitalization, 96% after two doses.

Out of 229,218 COVID infections in the United Kingdom between February and July 19, 28,773 — or 12.5% — were in fully vaccinated people. Of those breakthrough infections, 1,101, or 3.8%, required a visit to an emergency room, according to Public Health England. Just 474, or 2.9%, of fully vaccinated people required hospital admission, and 229, or less than 1%, died.

Unanswered questions

One of the biggest questions about breakthrough cases is how often people who have it may pass the virus to others.

“We know the vaccine reduces the likelihood of carrying the virus and the amount of virus you would carry,” Dr. Wen told CNN. But we don’t yet know whether a vaccinated person with a breakthrough infection may still be contagious to others.

For that reason, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that fully vaccinated people still need to be tested if they have symptoms and shouldn’t be out in public for at least 10 days after a positive test.

How should fully vaccinated people behave? That depends a lot on their underlying health and whether or not they have vulnerable people around them.

If you’re older or immunocompromised, Dr. Schaffner recommends what he calls the “belt-and-suspenders approach,” in other words, do everything you can to stay safe.

“Get vaccinated for sure, but since we can’t be absolutely certain that the vaccines are going to be optimally protective and you are particularly susceptible to serious disease, you would be well advised to adopt at least one and perhaps more of the other mitigation measures,” he said.

These include wearing a mask, social distancing, making sure your spaces are well ventilated, and not spending prolonged periods of time indoors in crowded places.

Taking young children to visit vaccinated, elderly grandparents demands extra caution, again, with Delta circulating, particularly as they go back to school and start mixing with other kids.

Dr. Schaffner recommends explaining the ground rules before the visit: Hugs around the waist. No kissing. Wearing a mask while indoors with them.

Other important unanswered questions are whether breakthrough infections can lead to prolonged symptoms, or “long covid.” Most experts think that’s less likely in vaccinated people.

And Dr. Osterholm said it will be important to see whether there’s anything unusual about the breakthrough cases happening in the community.

“I think some of us have been challenged by the number of clusters that we’ve seen,” he said. “I think that really needs to be examined more.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

CDC panel updates info on rare side effect after J&J vaccine

Despite recent reports of Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) after the Johnson & Johnson vaccine,

The company also presented new data suggesting that the shots generate strong immune responses against circulating variants and that antibodies generated by the vaccine stay elevated for at least 8 months.

Members of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) did not vote, but discussed and affirmed their support for recent decisions by the Food and Drug Administration and CDC to update patient information about the very low risk of GBS that appears to be associated with the vaccine, but to continue offering the vaccine to people in the United States.

The Johnson & Johnson shot has been a minor player in the U.S. vaccination campaign, accounting for less than 4% of all vaccine doses given in this country. Still, the single-dose inoculation, which doesn’t require ultra-cold storage, has been important for reaching people in rural areas, through mobile clinics, at colleges and primary care offices, and in vulnerable populations – those who are incarcerated or homeless.

The FDA says it has received reports of 100 cases of GBS after the Johnson & Johnson vaccine in its Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System database through the end of June. The cases are still under investigation.

To date, more than 12 million doses of the vaccine have been administered, making the rate of GBS 8.1 cases for every million doses administered.

Although it is still extremely rare, that’s above the expected background rate of GBS of 1.6 cases for every million people, said Grace Lee, MD, a Stanford, Calif., pediatrician who chairs the ACIP’s Vaccine Safety Technical Work Group.

So far, most GBS cases (61%) have been among men. The midpoint age of the cases was 57 years. The average time to onset was 14 days, and 98% of cases occurred within 42 days of the shot. Facial paralysis has been associated with an estimated 30%-50% of cases. One person, who had heart failure, high blood pressure, and diabetes, has died.

Still, the benefits of the vaccine far outweigh its risks. For every million doses given to people over age 50, the vaccine prevents nearly 7,500 COVID-19 hospitalizations and nearly 100 deaths in women, and more than 13,000 COVID-19 hospitalizations and more than 2,400 deaths in men.

Rates of GBS after the mRNA vaccines made by Pfizer and Moderna were around 1 case for every 1 million doses given, which is not above the rate that would be expected without vaccination.

The link to the Johnson & Johnson vaccine prompted the FDA to add a warning to the vaccine’s patient safety information on July 12.

Also in July, the European Medicines Agency recommended a similar warning for the product information of the AstraZeneca vaccine Vaxzevria, which relies on similar technology.

Good against variants

Johnson & Johnson also presented new information showing its vaccine maintained high levels of neutralizing antibodies against four of the so-called “variants of concern” – Alpha, Gamma, Beta, and Delta. The protection generated by the vaccine lasted for at least 8 months after the shot, the company said.

“We’re still learning about the duration of protection and the breadth of coverage against this evolving variant landscape for each of the authorized vaccines,” said Mathai Mammen, MD, PhD, global head of research and development at Janssen, the company that makes the vaccine for J&J.

The company also said that its vaccine generated very strong T-cell responses. T cells destroy infected cells and, along with antibodies, are an important part of the body’s immune response.

Antibody levels and T-cell responses are markers for immunity. Measuring these levels isn’t the same as proving that shots can fend off an infection.

It’s still unclear exactly which component of the immune response is most important for fighting off COVID-19.

Dr. Mammen said the companies are still gathering that clinical data, and would present it soon.

“We will have a better view of the clinical efficacy in the coming weeks,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Despite recent reports of Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) after the Johnson & Johnson vaccine,

The company also presented new data suggesting that the shots generate strong immune responses against circulating variants and that antibodies generated by the vaccine stay elevated for at least 8 months.

Members of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) did not vote, but discussed and affirmed their support for recent decisions by the Food and Drug Administration and CDC to update patient information about the very low risk of GBS that appears to be associated with the vaccine, but to continue offering the vaccine to people in the United States.

The Johnson & Johnson shot has been a minor player in the U.S. vaccination campaign, accounting for less than 4% of all vaccine doses given in this country. Still, the single-dose inoculation, which doesn’t require ultra-cold storage, has been important for reaching people in rural areas, through mobile clinics, at colleges and primary care offices, and in vulnerable populations – those who are incarcerated or homeless.

The FDA says it has received reports of 100 cases of GBS after the Johnson & Johnson vaccine in its Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System database through the end of June. The cases are still under investigation.

To date, more than 12 million doses of the vaccine have been administered, making the rate of GBS 8.1 cases for every million doses administered.

Although it is still extremely rare, that’s above the expected background rate of GBS of 1.6 cases for every million people, said Grace Lee, MD, a Stanford, Calif., pediatrician who chairs the ACIP’s Vaccine Safety Technical Work Group.

So far, most GBS cases (61%) have been among men. The midpoint age of the cases was 57 years. The average time to onset was 14 days, and 98% of cases occurred within 42 days of the shot. Facial paralysis has been associated with an estimated 30%-50% of cases. One person, who had heart failure, high blood pressure, and diabetes, has died.

Still, the benefits of the vaccine far outweigh its risks. For every million doses given to people over age 50, the vaccine prevents nearly 7,500 COVID-19 hospitalizations and nearly 100 deaths in women, and more than 13,000 COVID-19 hospitalizations and more than 2,400 deaths in men.

Rates of GBS after the mRNA vaccines made by Pfizer and Moderna were around 1 case for every 1 million doses given, which is not above the rate that would be expected without vaccination.

The link to the Johnson & Johnson vaccine prompted the FDA to add a warning to the vaccine’s patient safety information on July 12.

Also in July, the European Medicines Agency recommended a similar warning for the product information of the AstraZeneca vaccine Vaxzevria, which relies on similar technology.

Good against variants

Johnson & Johnson also presented new information showing its vaccine maintained high levels of neutralizing antibodies against four of the so-called “variants of concern” – Alpha, Gamma, Beta, and Delta. The protection generated by the vaccine lasted for at least 8 months after the shot, the company said.

“We’re still learning about the duration of protection and the breadth of coverage against this evolving variant landscape for each of the authorized vaccines,” said Mathai Mammen, MD, PhD, global head of research and development at Janssen, the company that makes the vaccine for J&J.

The company also said that its vaccine generated very strong T-cell responses. T cells destroy infected cells and, along with antibodies, are an important part of the body’s immune response.

Antibody levels and T-cell responses are markers for immunity. Measuring these levels isn’t the same as proving that shots can fend off an infection.

It’s still unclear exactly which component of the immune response is most important for fighting off COVID-19.

Dr. Mammen said the companies are still gathering that clinical data, and would present it soon.

“We will have a better view of the clinical efficacy in the coming weeks,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Despite recent reports of Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) after the Johnson & Johnson vaccine,

The company also presented new data suggesting that the shots generate strong immune responses against circulating variants and that antibodies generated by the vaccine stay elevated for at least 8 months.

Members of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) did not vote, but discussed and affirmed their support for recent decisions by the Food and Drug Administration and CDC to update patient information about the very low risk of GBS that appears to be associated with the vaccine, but to continue offering the vaccine to people in the United States.

The Johnson & Johnson shot has been a minor player in the U.S. vaccination campaign, accounting for less than 4% of all vaccine doses given in this country. Still, the single-dose inoculation, which doesn’t require ultra-cold storage, has been important for reaching people in rural areas, through mobile clinics, at colleges and primary care offices, and in vulnerable populations – those who are incarcerated or homeless.

The FDA says it has received reports of 100 cases of GBS after the Johnson & Johnson vaccine in its Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System database through the end of June. The cases are still under investigation.

To date, more than 12 million doses of the vaccine have been administered, making the rate of GBS 8.1 cases for every million doses administered.

Although it is still extremely rare, that’s above the expected background rate of GBS of 1.6 cases for every million people, said Grace Lee, MD, a Stanford, Calif., pediatrician who chairs the ACIP’s Vaccine Safety Technical Work Group.

So far, most GBS cases (61%) have been among men. The midpoint age of the cases was 57 years. The average time to onset was 14 days, and 98% of cases occurred within 42 days of the shot. Facial paralysis has been associated with an estimated 30%-50% of cases. One person, who had heart failure, high blood pressure, and diabetes, has died.

Still, the benefits of the vaccine far outweigh its risks. For every million doses given to people over age 50, the vaccine prevents nearly 7,500 COVID-19 hospitalizations and nearly 100 deaths in women, and more than 13,000 COVID-19 hospitalizations and more than 2,400 deaths in men.

Rates of GBS after the mRNA vaccines made by Pfizer and Moderna were around 1 case for every 1 million doses given, which is not above the rate that would be expected without vaccination.

The link to the Johnson & Johnson vaccine prompted the FDA to add a warning to the vaccine’s patient safety information on July 12.

Also in July, the European Medicines Agency recommended a similar warning for the product information of the AstraZeneca vaccine Vaxzevria, which relies on similar technology.

Good against variants

Johnson & Johnson also presented new information showing its vaccine maintained high levels of neutralizing antibodies against four of the so-called “variants of concern” – Alpha, Gamma, Beta, and Delta. The protection generated by the vaccine lasted for at least 8 months after the shot, the company said.

“We’re still learning about the duration of protection and the breadth of coverage against this evolving variant landscape for each of the authorized vaccines,” said Mathai Mammen, MD, PhD, global head of research and development at Janssen, the company that makes the vaccine for J&J.

The company also said that its vaccine generated very strong T-cell responses. T cells destroy infected cells and, along with antibodies, are an important part of the body’s immune response.

Antibody levels and T-cell responses are markers for immunity. Measuring these levels isn’t the same as proving that shots can fend off an infection.

It’s still unclear exactly which component of the immune response is most important for fighting off COVID-19.

Dr. Mammen said the companies are still gathering that clinical data, and would present it soon.

“We will have a better view of the clinical efficacy in the coming weeks,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Necessary or not, COVID booster shots are probably on the horizon

The drug maker Pfizer recently announced that vaccinated people are likely to need a booster shot to be effectively protected against new variants of COVID-19 and that the company would apply for Food and Drug Administration emergency use authorization for the shot. Top government health officials immediately and emphatically announced that the booster isn’t needed right now – and held firm to that position even after Pfizer’s top scientist made his case and shared preliminary data with them on July 12.

This has led to confusion. Is the protection that has allowed them to see loved ones and go out to dinner fading?

Ultimately, the question of whether a booster is needed is unlikely to determine the FDA’s decision. If recent history is predictive, booster shots will be here before long. That’s because of the outdated, 60-year-old basic standard the FDA uses to authorize medicines for sale: Is a new drug “safe and effective?”

The FDA, using that standard, will very likely have to authorize Pfizer’s booster for emergency use, as it did the company’s prior COVID shot. The booster is likely to be safe – hundreds of millions have taken the earlier shots – and Pfizer reported that it dramatically increases a vaccinated person’s antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. From that perspective, it may also be considered very effective.

But does that kind of efficacy matter? Is a higher level of antibodies needed to protect vaccinated Americans? Though antibody levels may wane some over time, the current vaccines deliver perfectly good immunity so far.

What if a booster is safe and effective in one sense but simply not needed – at least for now?

Reliance on the simple “safe and effective” standard – which certainly sounds reasonable – is a relic of a time when there were far fewer and simpler medicines available to treat diseases and before pharmaceutical manufacturing became one of the world’s biggest businesses.

The FDA’s 1938 landmark legislation focused primarily on safety after more than 100 Americans died from a raspberry-flavored liquid form of an early antibiotic because one of its ingredients was used as antifreeze. The 1962 Kefauver-Harris Amendments to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act set out more specific requirements for drug approval: Companies must scientifically prove a drug’s effectiveness through “adequate and well-controlled studies.”

In today’s pharmaceutical universe, a simple “safe and effective” determination is not always an adequate bar, and it can be manipulated to sell drugs of questionable value. There’s also big money involved: Pfizer is already projecting $26 billion in COVID revenue in 2021.

The United States’ continued use of this standard to let drugs into the market has led to the approval of expensive, not necessarily very effective drugs. In 2014, for example, the FDA approved a toenail fungus drug that can cost up to $1,500 a month and that studies showed cured fewer than 10% of patients after a year of treatment. That’s more effective than doing nothing but less effective and more costly than a number of other treatments for this bothersome malady.

It has also led to a plethora of high-priced drugs to treat diseases like cancers, multiple sclerosis and type 2 diabetes that are all more effective than a placebo but have often not been tested very much against one another to determine which are most effective.

In today’s complex world, clarification is needed to determine just what kind of effectiveness the FDA should demand. And should that be the job of the FDA alone?

For example, should drugmakers prove a drug is significantly more effective than products already on the market? Or demonstrate cost-effectiveness – the health value of a product relative to its price – a metric used by Britain’s health system? And in which cases is effectiveness against a surrogate marker – like an antibody level – a good enough stand-in for whether a drug will have a significant impact on a patient’s health?

In most industrialized countries, broad access to the national market is a two-step process, said Aaron Kesselheim, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, who studies drug development, marketing and law and recently served on an FDA advisory committee. The first part certifies that a drug is sufficiently safe and effective. That is immediately followed by an independent health technology assessment to see where it fits in the treatment armamentarium, including, in some countries, whether it is useful enough to be sold at all at the stated price. But there’s no such automatic process in the United States.

When Pfizer applies for authorization, the FDA may well clear a booster for the U.S. market. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, likely with advice from National Institutes of Health experts, will then have to decide whether to recommend it and for whom. This judgment call usually determines whether insurers will cover it. Pfizer is likely to profit handsomely from a government authorization, and the company will gain some revenue even if only the worried well, who can pay out of pocket, decide to get the shot.

To make any recommendation on a booster, government experts say they need more data. They could, for example, as Anthony S. Fauci, MD, has suggested, eventually green-light the additional vaccine shot only for a small group of patients at high risk for a deadly infection, such as the very old or transplant recipients who take immunosuppressant drugs, as some other countries have done.

But until the United States refines the FDA’s “safe and effective” standard or adds a second layer of vetting, when new products hit the market and manufacturers promote them, Americans will be left to decipher whose version of effective and necessary matters to them.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

The drug maker Pfizer recently announced that vaccinated people are likely to need a booster shot to be effectively protected against new variants of COVID-19 and that the company would apply for Food and Drug Administration emergency use authorization for the shot. Top government health officials immediately and emphatically announced that the booster isn’t needed right now – and held firm to that position even after Pfizer’s top scientist made his case and shared preliminary data with them on July 12.

This has led to confusion. Is the protection that has allowed them to see loved ones and go out to dinner fading?

Ultimately, the question of whether a booster is needed is unlikely to determine the FDA’s decision. If recent history is predictive, booster shots will be here before long. That’s because of the outdated, 60-year-old basic standard the FDA uses to authorize medicines for sale: Is a new drug “safe and effective?”

The FDA, using that standard, will very likely have to authorize Pfizer’s booster for emergency use, as it did the company’s prior COVID shot. The booster is likely to be safe – hundreds of millions have taken the earlier shots – and Pfizer reported that it dramatically increases a vaccinated person’s antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. From that perspective, it may also be considered very effective.

But does that kind of efficacy matter? Is a higher level of antibodies needed to protect vaccinated Americans? Though antibody levels may wane some over time, the current vaccines deliver perfectly good immunity so far.

What if a booster is safe and effective in one sense but simply not needed – at least for now?

Reliance on the simple “safe and effective” standard – which certainly sounds reasonable – is a relic of a time when there were far fewer and simpler medicines available to treat diseases and before pharmaceutical manufacturing became one of the world’s biggest businesses.

The FDA’s 1938 landmark legislation focused primarily on safety after more than 100 Americans died from a raspberry-flavored liquid form of an early antibiotic because one of its ingredients was used as antifreeze. The 1962 Kefauver-Harris Amendments to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act set out more specific requirements for drug approval: Companies must scientifically prove a drug’s effectiveness through “adequate and well-controlled studies.”

In today’s pharmaceutical universe, a simple “safe and effective” determination is not always an adequate bar, and it can be manipulated to sell drugs of questionable value. There’s also big money involved: Pfizer is already projecting $26 billion in COVID revenue in 2021.

The United States’ continued use of this standard to let drugs into the market has led to the approval of expensive, not necessarily very effective drugs. In 2014, for example, the FDA approved a toenail fungus drug that can cost up to $1,500 a month and that studies showed cured fewer than 10% of patients after a year of treatment. That’s more effective than doing nothing but less effective and more costly than a number of other treatments for this bothersome malady.

It has also led to a plethora of high-priced drugs to treat diseases like cancers, multiple sclerosis and type 2 diabetes that are all more effective than a placebo but have often not been tested very much against one another to determine which are most effective.

In today’s complex world, clarification is needed to determine just what kind of effectiveness the FDA should demand. And should that be the job of the FDA alone?

For example, should drugmakers prove a drug is significantly more effective than products already on the market? Or demonstrate cost-effectiveness – the health value of a product relative to its price – a metric used by Britain’s health system? And in which cases is effectiveness against a surrogate marker – like an antibody level – a good enough stand-in for whether a drug will have a significant impact on a patient’s health?

In most industrialized countries, broad access to the national market is a two-step process, said Aaron Kesselheim, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, who studies drug development, marketing and law and recently served on an FDA advisory committee. The first part certifies that a drug is sufficiently safe and effective. That is immediately followed by an independent health technology assessment to see where it fits in the treatment armamentarium, including, in some countries, whether it is useful enough to be sold at all at the stated price. But there’s no such automatic process in the United States.

When Pfizer applies for authorization, the FDA may well clear a booster for the U.S. market. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, likely with advice from National Institutes of Health experts, will then have to decide whether to recommend it and for whom. This judgment call usually determines whether insurers will cover it. Pfizer is likely to profit handsomely from a government authorization, and the company will gain some revenue even if only the worried well, who can pay out of pocket, decide to get the shot.

To make any recommendation on a booster, government experts say they need more data. They could, for example, as Anthony S. Fauci, MD, has suggested, eventually green-light the additional vaccine shot only for a small group of patients at high risk for a deadly infection, such as the very old or transplant recipients who take immunosuppressant drugs, as some other countries have done.

But until the United States refines the FDA’s “safe and effective” standard or adds a second layer of vetting, when new products hit the market and manufacturers promote them, Americans will be left to decipher whose version of effective and necessary matters to them.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

The drug maker Pfizer recently announced that vaccinated people are likely to need a booster shot to be effectively protected against new variants of COVID-19 and that the company would apply for Food and Drug Administration emergency use authorization for the shot. Top government health officials immediately and emphatically announced that the booster isn’t needed right now – and held firm to that position even after Pfizer’s top scientist made his case and shared preliminary data with them on July 12.

This has led to confusion. Is the protection that has allowed them to see loved ones and go out to dinner fading?

Ultimately, the question of whether a booster is needed is unlikely to determine the FDA’s decision. If recent history is predictive, booster shots will be here before long. That’s because of the outdated, 60-year-old basic standard the FDA uses to authorize medicines for sale: Is a new drug “safe and effective?”

The FDA, using that standard, will very likely have to authorize Pfizer’s booster for emergency use, as it did the company’s prior COVID shot. The booster is likely to be safe – hundreds of millions have taken the earlier shots – and Pfizer reported that it dramatically increases a vaccinated person’s antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. From that perspective, it may also be considered very effective.

But does that kind of efficacy matter? Is a higher level of antibodies needed to protect vaccinated Americans? Though antibody levels may wane some over time, the current vaccines deliver perfectly good immunity so far.

What if a booster is safe and effective in one sense but simply not needed – at least for now?

Reliance on the simple “safe and effective” standard – which certainly sounds reasonable – is a relic of a time when there were far fewer and simpler medicines available to treat diseases and before pharmaceutical manufacturing became one of the world’s biggest businesses.

The FDA’s 1938 landmark legislation focused primarily on safety after more than 100 Americans died from a raspberry-flavored liquid form of an early antibiotic because one of its ingredients was used as antifreeze. The 1962 Kefauver-Harris Amendments to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act set out more specific requirements for drug approval: Companies must scientifically prove a drug’s effectiveness through “adequate and well-controlled studies.”

In today’s pharmaceutical universe, a simple “safe and effective” determination is not always an adequate bar, and it can be manipulated to sell drugs of questionable value. There’s also big money involved: Pfizer is already projecting $26 billion in COVID revenue in 2021.

The United States’ continued use of this standard to let drugs into the market has led to the approval of expensive, not necessarily very effective drugs. In 2014, for example, the FDA approved a toenail fungus drug that can cost up to $1,500 a month and that studies showed cured fewer than 10% of patients after a year of treatment. That’s more effective than doing nothing but less effective and more costly than a number of other treatments for this bothersome malady.

It has also led to a plethora of high-priced drugs to treat diseases like cancers, multiple sclerosis and type 2 diabetes that are all more effective than a placebo but have often not been tested very much against one another to determine which are most effective.

In today’s complex world, clarification is needed to determine just what kind of effectiveness the FDA should demand. And should that be the job of the FDA alone?

For example, should drugmakers prove a drug is significantly more effective than products already on the market? Or demonstrate cost-effectiveness – the health value of a product relative to its price – a metric used by Britain’s health system? And in which cases is effectiveness against a surrogate marker – like an antibody level – a good enough stand-in for whether a drug will have a significant impact on a patient’s health?

In most industrialized countries, broad access to the national market is a two-step process, said Aaron Kesselheim, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, who studies drug development, marketing and law and recently served on an FDA advisory committee. The first part certifies that a drug is sufficiently safe and effective. That is immediately followed by an independent health technology assessment to see where it fits in the treatment armamentarium, including, in some countries, whether it is useful enough to be sold at all at the stated price. But there’s no such automatic process in the United States.