User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

Powered by CHEST Physician, Clinician Reviews, MDedge Family Medicine, Internal Medicine News, and The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management.

Ivabradine knocks down heart rate, symptoms in POTS

The heart failure drug ivabradine (Corlanor) can provide relief from the elevated heart rate and often debilitating symptoms associated with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), a new study suggests.

Ivabradine significantly lowered standing heart rate, compared with placebo (77.9 vs. 94.2 beats/min; P < .001). The typical surge in heart rate that occurs upon standing in these patients was also blunted, compared with baseline (13.0 vs. 21.4 beats/min; P = .001).

“There are really not a lot of great options for patients with POTS and, mechanistically, ivabradine just make sense because it’s a drug that lowers heart rate very selectively and doesn’t lower blood pressure,” lead study author Pam R. Taub, MD, told this news organization.

Surprisingly, the reduction in heart rate translated into improved physical (P = .008) and social (P = .021) functioning after just 1 month of ivabradine, without any other background POTS medications or a change in nonpharmacologic therapies, she said. “What’s really nice to see is when you tackle a really significant part of the disease, which is the elevated heart rate, just how much better they feel.”

POTS patients are mostly healthy, active young women, who after some inciting event – such as viral infection, trauma, or surgery – experience an increase in heart rate of at least 30 beats/min upon standing accompanied by a range of symptoms, including dizziness, palpitations, brain fog, and fatigue.

A COVID connection?

The study enrolled patients with hyperadrenergic POTS as the predominant subtype, but another group to keep in mind that might benefit is the post-COVID POTS patient, said Dr. Taub, from the University of California, San Diego.

“We’re seeing an incredible number of patients post COVID that meet the criteria for POTS, and a lot of these patients also have COVID fatigue,” she said. “So clinically, myself and many other cardiologists who understand ivabradine have been using it off-label for the COVID patients, as long as they meet the criteria. You don’t want to use it in every COVID patient, but if someone’s predominant complaint is that their heart rate is going up when they’re standing and they’re debilitated by it, this is a drug to consider.”

Anecdotal findings in patients with long-hauler COVID need to be translated into rigorous research protocols, but mechanistically, whether it’s POTS from COVID or from another type of infection – like Lyme disease or some other viral syndrome – it should work the same, Dr. Taub said. “POTS is POTS.”

There are no first-line drugs for POTS, and current class IIb recommendations include midodrine, which increases blood pressure and can make people feel awful, and fludrocortisone, which can cause a lot of weight gain and fluid retention, she observed. Other agents that lower heart rate, like beta-blockers, also lower blood pressure and can aggravate depression and fatigue.

Ivabradine regulates heart rate by specifically blocking the Ifunny channel of the sinoatrial node. It was approved in 2015 in the United States to reduce hospitalizations in patients with systolic heart failure, and it also has a second class IIb recommendation for inappropriate sinus tachycardia.

The present study, reported in the Feb. 23 issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, is the first randomized clinical trial using ivabradine to treat POTS.

A total of 26 patients with POTS were started on ivabradine 5 mg or placebo twice daily for 1 month, then were crossed over to the other treatment for 1 month after a 1-week washout period. Six patients were started on a 2.5-mg twice-daily dose. Doses were adjusted during the study based on the patient’s heart rate response and tolerance. Patients had seven clinic visits in which norepinephrine (NE) levels were measured and head-up tilt testing conducted.

Four patients in the ivabradine arm withdrew because of adverse effects, and one withdrew during crossover.

Among the 22 patients who completed the study, exploratory analyses showed a strong trend for greater reduction in plasma NE upon standing with ivabradine (P = .056). The effect was also more profound in patients with very high baseline standing NE levels (at least 1,000 pg/mL) than in those with lower NE levels (600 to 1,000 pg/mL).

“It makes sense because that means their sympathetic nervous system is more overactive; they have a higher heart rate,” Dr. Taub said. “So it’s a potential clinical tool that people can use in their practice to determine, ‘okay, is this a patient I should be considering ivabradine on?’ ”

Although the present study had only 22 patients, “it should definitely be looked at as a step forward, both in terms of ivabradine specifically and in terms of setting the standard for the types of studies we want to see in our patients,” Satish R. Raj, MD, MSCI, University of Calgary (Alta.), said in an interview.

In a related editorial, however, Dr. Raj and coauthor Robert S. Sheldon, MD, PhD, also from the University of Calgary, point out that the standing heart rate in the placebo phase was only 94 beats/min, “suggesting that these patients may be affected only mildly by their POTS.”

Asked about the point, Dr. Taub said: “I don’t know if I agree with that.” She noted that the diagnosis of POTS was confirmed by tilt-table testing and NE levels and that patients’ symptoms vary from day to day. “The standard deviation was plus or minus 16.8, so there’s variability.”

Both Dr. Raj and Dr. Taub said they expect the results will be included in the next scientific statement for POTS, but in the meantime, it may be a struggle to get the drug covered by insurance.

“The challenge is that this is a very off-label use for this medication, and the medication’s not cheap,” Dr. Raj observed. The price for 60 tablets, which is about a 1-month supply, is $485 on GoodRx.

Another question going forward, he said, is whether ivabradine is superior to beta-blockers, which will be studied in a 20-patient crossover trial sponsored by the University of Calgary that is about to launch. The primary completion date is set for 2024.

The study was supported by a grant from Amgen. Dr. Taub has served as a consultant for Amgen, Bayer, Esperion, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi; is a shareholder in Epirium Bio; and has received research grants from the National Institutes of Health, the American Heart Association, and the Department of Homeland Security/FEMA. Dr. Raj has received a research grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and research grants from Dysautonomia International to address the pathophysiology of POTS. Dr. Sheldon has received a research grant from Dysautonomia International for a clinical trial assessing ivabradine and propranolol for the treatment of POTS.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The heart failure drug ivabradine (Corlanor) can provide relief from the elevated heart rate and often debilitating symptoms associated with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), a new study suggests.

Ivabradine significantly lowered standing heart rate, compared with placebo (77.9 vs. 94.2 beats/min; P < .001). The typical surge in heart rate that occurs upon standing in these patients was also blunted, compared with baseline (13.0 vs. 21.4 beats/min; P = .001).

“There are really not a lot of great options for patients with POTS and, mechanistically, ivabradine just make sense because it’s a drug that lowers heart rate very selectively and doesn’t lower blood pressure,” lead study author Pam R. Taub, MD, told this news organization.

Surprisingly, the reduction in heart rate translated into improved physical (P = .008) and social (P = .021) functioning after just 1 month of ivabradine, without any other background POTS medications or a change in nonpharmacologic therapies, she said. “What’s really nice to see is when you tackle a really significant part of the disease, which is the elevated heart rate, just how much better they feel.”

POTS patients are mostly healthy, active young women, who after some inciting event – such as viral infection, trauma, or surgery – experience an increase in heart rate of at least 30 beats/min upon standing accompanied by a range of symptoms, including dizziness, palpitations, brain fog, and fatigue.

A COVID connection?

The study enrolled patients with hyperadrenergic POTS as the predominant subtype, but another group to keep in mind that might benefit is the post-COVID POTS patient, said Dr. Taub, from the University of California, San Diego.

“We’re seeing an incredible number of patients post COVID that meet the criteria for POTS, and a lot of these patients also have COVID fatigue,” she said. “So clinically, myself and many other cardiologists who understand ivabradine have been using it off-label for the COVID patients, as long as they meet the criteria. You don’t want to use it in every COVID patient, but if someone’s predominant complaint is that their heart rate is going up when they’re standing and they’re debilitated by it, this is a drug to consider.”

Anecdotal findings in patients with long-hauler COVID need to be translated into rigorous research protocols, but mechanistically, whether it’s POTS from COVID or from another type of infection – like Lyme disease or some other viral syndrome – it should work the same, Dr. Taub said. “POTS is POTS.”

There are no first-line drugs for POTS, and current class IIb recommendations include midodrine, which increases blood pressure and can make people feel awful, and fludrocortisone, which can cause a lot of weight gain and fluid retention, she observed. Other agents that lower heart rate, like beta-blockers, also lower blood pressure and can aggravate depression and fatigue.

Ivabradine regulates heart rate by specifically blocking the Ifunny channel of the sinoatrial node. It was approved in 2015 in the United States to reduce hospitalizations in patients with systolic heart failure, and it also has a second class IIb recommendation for inappropriate sinus tachycardia.

The present study, reported in the Feb. 23 issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, is the first randomized clinical trial using ivabradine to treat POTS.

A total of 26 patients with POTS were started on ivabradine 5 mg or placebo twice daily for 1 month, then were crossed over to the other treatment for 1 month after a 1-week washout period. Six patients were started on a 2.5-mg twice-daily dose. Doses were adjusted during the study based on the patient’s heart rate response and tolerance. Patients had seven clinic visits in which norepinephrine (NE) levels were measured and head-up tilt testing conducted.

Four patients in the ivabradine arm withdrew because of adverse effects, and one withdrew during crossover.

Among the 22 patients who completed the study, exploratory analyses showed a strong trend for greater reduction in plasma NE upon standing with ivabradine (P = .056). The effect was also more profound in patients with very high baseline standing NE levels (at least 1,000 pg/mL) than in those with lower NE levels (600 to 1,000 pg/mL).

“It makes sense because that means their sympathetic nervous system is more overactive; they have a higher heart rate,” Dr. Taub said. “So it’s a potential clinical tool that people can use in their practice to determine, ‘okay, is this a patient I should be considering ivabradine on?’ ”

Although the present study had only 22 patients, “it should definitely be looked at as a step forward, both in terms of ivabradine specifically and in terms of setting the standard for the types of studies we want to see in our patients,” Satish R. Raj, MD, MSCI, University of Calgary (Alta.), said in an interview.

In a related editorial, however, Dr. Raj and coauthor Robert S. Sheldon, MD, PhD, also from the University of Calgary, point out that the standing heart rate in the placebo phase was only 94 beats/min, “suggesting that these patients may be affected only mildly by their POTS.”

Asked about the point, Dr. Taub said: “I don’t know if I agree with that.” She noted that the diagnosis of POTS was confirmed by tilt-table testing and NE levels and that patients’ symptoms vary from day to day. “The standard deviation was plus or minus 16.8, so there’s variability.”

Both Dr. Raj and Dr. Taub said they expect the results will be included in the next scientific statement for POTS, but in the meantime, it may be a struggle to get the drug covered by insurance.

“The challenge is that this is a very off-label use for this medication, and the medication’s not cheap,” Dr. Raj observed. The price for 60 tablets, which is about a 1-month supply, is $485 on GoodRx.

Another question going forward, he said, is whether ivabradine is superior to beta-blockers, which will be studied in a 20-patient crossover trial sponsored by the University of Calgary that is about to launch. The primary completion date is set for 2024.

The study was supported by a grant from Amgen. Dr. Taub has served as a consultant for Amgen, Bayer, Esperion, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi; is a shareholder in Epirium Bio; and has received research grants from the National Institutes of Health, the American Heart Association, and the Department of Homeland Security/FEMA. Dr. Raj has received a research grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and research grants from Dysautonomia International to address the pathophysiology of POTS. Dr. Sheldon has received a research grant from Dysautonomia International for a clinical trial assessing ivabradine and propranolol for the treatment of POTS.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The heart failure drug ivabradine (Corlanor) can provide relief from the elevated heart rate and often debilitating symptoms associated with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), a new study suggests.

Ivabradine significantly lowered standing heart rate, compared with placebo (77.9 vs. 94.2 beats/min; P < .001). The typical surge in heart rate that occurs upon standing in these patients was also blunted, compared with baseline (13.0 vs. 21.4 beats/min; P = .001).

“There are really not a lot of great options for patients with POTS and, mechanistically, ivabradine just make sense because it’s a drug that lowers heart rate very selectively and doesn’t lower blood pressure,” lead study author Pam R. Taub, MD, told this news organization.

Surprisingly, the reduction in heart rate translated into improved physical (P = .008) and social (P = .021) functioning after just 1 month of ivabradine, without any other background POTS medications or a change in nonpharmacologic therapies, she said. “What’s really nice to see is when you tackle a really significant part of the disease, which is the elevated heart rate, just how much better they feel.”

POTS patients are mostly healthy, active young women, who after some inciting event – such as viral infection, trauma, or surgery – experience an increase in heart rate of at least 30 beats/min upon standing accompanied by a range of symptoms, including dizziness, palpitations, brain fog, and fatigue.

A COVID connection?

The study enrolled patients with hyperadrenergic POTS as the predominant subtype, but another group to keep in mind that might benefit is the post-COVID POTS patient, said Dr. Taub, from the University of California, San Diego.

“We’re seeing an incredible number of patients post COVID that meet the criteria for POTS, and a lot of these patients also have COVID fatigue,” she said. “So clinically, myself and many other cardiologists who understand ivabradine have been using it off-label for the COVID patients, as long as they meet the criteria. You don’t want to use it in every COVID patient, but if someone’s predominant complaint is that their heart rate is going up when they’re standing and they’re debilitated by it, this is a drug to consider.”

Anecdotal findings in patients with long-hauler COVID need to be translated into rigorous research protocols, but mechanistically, whether it’s POTS from COVID or from another type of infection – like Lyme disease or some other viral syndrome – it should work the same, Dr. Taub said. “POTS is POTS.”

There are no first-line drugs for POTS, and current class IIb recommendations include midodrine, which increases blood pressure and can make people feel awful, and fludrocortisone, which can cause a lot of weight gain and fluid retention, she observed. Other agents that lower heart rate, like beta-blockers, also lower blood pressure and can aggravate depression and fatigue.

Ivabradine regulates heart rate by specifically blocking the Ifunny channel of the sinoatrial node. It was approved in 2015 in the United States to reduce hospitalizations in patients with systolic heart failure, and it also has a second class IIb recommendation for inappropriate sinus tachycardia.

The present study, reported in the Feb. 23 issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, is the first randomized clinical trial using ivabradine to treat POTS.

A total of 26 patients with POTS were started on ivabradine 5 mg or placebo twice daily for 1 month, then were crossed over to the other treatment for 1 month after a 1-week washout period. Six patients were started on a 2.5-mg twice-daily dose. Doses were adjusted during the study based on the patient’s heart rate response and tolerance. Patients had seven clinic visits in which norepinephrine (NE) levels were measured and head-up tilt testing conducted.

Four patients in the ivabradine arm withdrew because of adverse effects, and one withdrew during crossover.

Among the 22 patients who completed the study, exploratory analyses showed a strong trend for greater reduction in plasma NE upon standing with ivabradine (P = .056). The effect was also more profound in patients with very high baseline standing NE levels (at least 1,000 pg/mL) than in those with lower NE levels (600 to 1,000 pg/mL).

“It makes sense because that means their sympathetic nervous system is more overactive; they have a higher heart rate,” Dr. Taub said. “So it’s a potential clinical tool that people can use in their practice to determine, ‘okay, is this a patient I should be considering ivabradine on?’ ”

Although the present study had only 22 patients, “it should definitely be looked at as a step forward, both in terms of ivabradine specifically and in terms of setting the standard for the types of studies we want to see in our patients,” Satish R. Raj, MD, MSCI, University of Calgary (Alta.), said in an interview.

In a related editorial, however, Dr. Raj and coauthor Robert S. Sheldon, MD, PhD, also from the University of Calgary, point out that the standing heart rate in the placebo phase was only 94 beats/min, “suggesting that these patients may be affected only mildly by their POTS.”

Asked about the point, Dr. Taub said: “I don’t know if I agree with that.” She noted that the diagnosis of POTS was confirmed by tilt-table testing and NE levels and that patients’ symptoms vary from day to day. “The standard deviation was plus or minus 16.8, so there’s variability.”

Both Dr. Raj and Dr. Taub said they expect the results will be included in the next scientific statement for POTS, but in the meantime, it may be a struggle to get the drug covered by insurance.

“The challenge is that this is a very off-label use for this medication, and the medication’s not cheap,” Dr. Raj observed. The price for 60 tablets, which is about a 1-month supply, is $485 on GoodRx.

Another question going forward, he said, is whether ivabradine is superior to beta-blockers, which will be studied in a 20-patient crossover trial sponsored by the University of Calgary that is about to launch. The primary completion date is set for 2024.

The study was supported by a grant from Amgen. Dr. Taub has served as a consultant for Amgen, Bayer, Esperion, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi; is a shareholder in Epirium Bio; and has received research grants from the National Institutes of Health, the American Heart Association, and the Department of Homeland Security/FEMA. Dr. Raj has received a research grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and research grants from Dysautonomia International to address the pathophysiology of POTS. Dr. Sheldon has received a research grant from Dysautonomia International for a clinical trial assessing ivabradine and propranolol for the treatment of POTS.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

CDC chief lays out attack plan for COVID variants

earlier this week.

As part of JAMA’s Q&A series with JAMA editor in chief Howard Bauchner, MD, Dr. Walensky referenced the blueprint she coathored with Anthony Fauci, MD, the nation’s top infectious disease expert, and Henry T. Walke, MD, MPH, of the CDC, which was published on Feb. 17 in JAMA.

In the viewpoint article, they explain that the Department of Health & Human Services has established the SARS-CoV-2 Interagency Group to improve coordination among the CDC, the National Institutes of Health, the Food and Drug Administration, the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, the Department of Agriculture, and the Department of Defense.

Dr. Walensky said the first objective is to reinforce vigilance regarding public health mitigation strategies to decrease the amount of virus that’s circulating.

As part of that strategy, she said, the CDC strongly urges against nonessential travel.

In addition, public health leaders are working on a surveillance system to better understand the SARS-CoV-2 variants. That will take ramping up genome sequencing of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and ensuring that sampling is geographically representative.

She said the CDC is partnering with state health labs to obtain about 750 samples every week and is teaming up with commercial labs and academic centers to obtain an interim target of 6,000 samples per week.

She acknowledged the United States “is not where we need to be” with sequencing but has come a long way since January. At that time, they were sequencing 250 samples every week; they are currently sequencing thousands each week.

Data analysis is another concern: “We need to be able to understand at the basic science level what the information means,” Dr. Walensky said.

Researchers aren’t sure how the variants might affect use of convalescent plasma or monoclonal antibody treatments. It is expected that 5% of persons who are vaccinated against COVID-19 will nevertheless contract the disease. Sequencing will help answer whether such persons who have been vaccinated and who subsequently contract the virus are among those 5% or whether have been infected by a variant that evades the vaccine.

Accelerating vaccine administration globally and in the United States is essential, Dr. Walensky said.

As of Feb. 17, 56 million doses had been administered in the United States.

Top three threats

She updated the numbers on the three biggest variant threats.

Regarding B.1.1.7, which originated in the United Kingdom, she said: “So far, we’ve had over 1,200 cases in 41 states.” She noted that the variant is likely to be about 50% more transmissible and 30% to 50% more virulent.

“So far, it looks like that strain doesn’t have any real decrease in susceptibility to our vaccines,” she said.

The strain from South Africa (B.1.351) has been found in 19 cases in the United States.

The P.1. variant, which originated in Brazil, has been identified in two cases in two states.

Outlook for March and April

Dr. Bauchner asked Dr. Walensky what she envisions for March and April. He noted that public optimism is high in light of the continued reductions in COVID-19 case numbers, hospitalizations, and deaths, as well as the fact that warmer weather is coming and that more vaccinations are on the horizon.

“While I really am hopeful for what could happen in March and April,” Dr. Walensky said, “I really do know that this could go bad so fast. We saw it in November. We saw it in December.”

CDC models have projected that, by March, the more transmissible B.1.1.7 strain is likely to be the dominant strain, she reiterated.

“I worry that it will be spring, and we will all have had enough,” Dr. Walensky said. She noted that some states are already relaxing mask mandates.

“Around that time, life will look and feel a little better, and the motivation for those who might be vaccine hesitant may be diminished,” she said.

Dr. Bauchner also asked her to weigh in on whether a third vaccine, from Johnson & Johnson (J&J), may soon gain FDA emergency-use authorization – and whether its lower expected efficacy rate may result in a tiered system of vaccinations, with higher-risk populations receiving the more efficacious vaccines.

Dr. Walensky said more data are needed before that question can be answered.

“It may very well be that the data point us to the best populations in which to use this vaccine,” she said.

In phase 3 data, the J&J vaccine was shown to be 72% effective in the United States for moderate to severe disease.

Dr. Walensky said it’s important to remember that the projected efficacy for that vaccine is higher than that for the flu shot as well as many other vaccines currently in use for other diseases.

She said it also has several advantages. The vaccine has less-stringent storage requirements, requires just one dose, and protects against hospitalization and death, although it’s less efficacious in protecting against contracting the disease.

“I think many people would opt to get that one if they could get it sooner,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

earlier this week.

As part of JAMA’s Q&A series with JAMA editor in chief Howard Bauchner, MD, Dr. Walensky referenced the blueprint she coathored with Anthony Fauci, MD, the nation’s top infectious disease expert, and Henry T. Walke, MD, MPH, of the CDC, which was published on Feb. 17 in JAMA.

In the viewpoint article, they explain that the Department of Health & Human Services has established the SARS-CoV-2 Interagency Group to improve coordination among the CDC, the National Institutes of Health, the Food and Drug Administration, the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, the Department of Agriculture, and the Department of Defense.

Dr. Walensky said the first objective is to reinforce vigilance regarding public health mitigation strategies to decrease the amount of virus that’s circulating.

As part of that strategy, she said, the CDC strongly urges against nonessential travel.

In addition, public health leaders are working on a surveillance system to better understand the SARS-CoV-2 variants. That will take ramping up genome sequencing of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and ensuring that sampling is geographically representative.

She said the CDC is partnering with state health labs to obtain about 750 samples every week and is teaming up with commercial labs and academic centers to obtain an interim target of 6,000 samples per week.

She acknowledged the United States “is not where we need to be” with sequencing but has come a long way since January. At that time, they were sequencing 250 samples every week; they are currently sequencing thousands each week.

Data analysis is another concern: “We need to be able to understand at the basic science level what the information means,” Dr. Walensky said.

Researchers aren’t sure how the variants might affect use of convalescent plasma or monoclonal antibody treatments. It is expected that 5% of persons who are vaccinated against COVID-19 will nevertheless contract the disease. Sequencing will help answer whether such persons who have been vaccinated and who subsequently contract the virus are among those 5% or whether have been infected by a variant that evades the vaccine.

Accelerating vaccine administration globally and in the United States is essential, Dr. Walensky said.

As of Feb. 17, 56 million doses had been administered in the United States.

Top three threats

She updated the numbers on the three biggest variant threats.

Regarding B.1.1.7, which originated in the United Kingdom, she said: “So far, we’ve had over 1,200 cases in 41 states.” She noted that the variant is likely to be about 50% more transmissible and 30% to 50% more virulent.

“So far, it looks like that strain doesn’t have any real decrease in susceptibility to our vaccines,” she said.

The strain from South Africa (B.1.351) has been found in 19 cases in the United States.

The P.1. variant, which originated in Brazil, has been identified in two cases in two states.

Outlook for March and April

Dr. Bauchner asked Dr. Walensky what she envisions for March and April. He noted that public optimism is high in light of the continued reductions in COVID-19 case numbers, hospitalizations, and deaths, as well as the fact that warmer weather is coming and that more vaccinations are on the horizon.

“While I really am hopeful for what could happen in March and April,” Dr. Walensky said, “I really do know that this could go bad so fast. We saw it in November. We saw it in December.”

CDC models have projected that, by March, the more transmissible B.1.1.7 strain is likely to be the dominant strain, she reiterated.

“I worry that it will be spring, and we will all have had enough,” Dr. Walensky said. She noted that some states are already relaxing mask mandates.

“Around that time, life will look and feel a little better, and the motivation for those who might be vaccine hesitant may be diminished,” she said.

Dr. Bauchner also asked her to weigh in on whether a third vaccine, from Johnson & Johnson (J&J), may soon gain FDA emergency-use authorization – and whether its lower expected efficacy rate may result in a tiered system of vaccinations, with higher-risk populations receiving the more efficacious vaccines.

Dr. Walensky said more data are needed before that question can be answered.

“It may very well be that the data point us to the best populations in which to use this vaccine,” she said.

In phase 3 data, the J&J vaccine was shown to be 72% effective in the United States for moderate to severe disease.

Dr. Walensky said it’s important to remember that the projected efficacy for that vaccine is higher than that for the flu shot as well as many other vaccines currently in use for other diseases.

She said it also has several advantages. The vaccine has less-stringent storage requirements, requires just one dose, and protects against hospitalization and death, although it’s less efficacious in protecting against contracting the disease.

“I think many people would opt to get that one if they could get it sooner,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

earlier this week.

As part of JAMA’s Q&A series with JAMA editor in chief Howard Bauchner, MD, Dr. Walensky referenced the blueprint she coathored with Anthony Fauci, MD, the nation’s top infectious disease expert, and Henry T. Walke, MD, MPH, of the CDC, which was published on Feb. 17 in JAMA.

In the viewpoint article, they explain that the Department of Health & Human Services has established the SARS-CoV-2 Interagency Group to improve coordination among the CDC, the National Institutes of Health, the Food and Drug Administration, the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, the Department of Agriculture, and the Department of Defense.

Dr. Walensky said the first objective is to reinforce vigilance regarding public health mitigation strategies to decrease the amount of virus that’s circulating.

As part of that strategy, she said, the CDC strongly urges against nonessential travel.

In addition, public health leaders are working on a surveillance system to better understand the SARS-CoV-2 variants. That will take ramping up genome sequencing of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and ensuring that sampling is geographically representative.

She said the CDC is partnering with state health labs to obtain about 750 samples every week and is teaming up with commercial labs and academic centers to obtain an interim target of 6,000 samples per week.

She acknowledged the United States “is not where we need to be” with sequencing but has come a long way since January. At that time, they were sequencing 250 samples every week; they are currently sequencing thousands each week.

Data analysis is another concern: “We need to be able to understand at the basic science level what the information means,” Dr. Walensky said.

Researchers aren’t sure how the variants might affect use of convalescent plasma or monoclonal antibody treatments. It is expected that 5% of persons who are vaccinated against COVID-19 will nevertheless contract the disease. Sequencing will help answer whether such persons who have been vaccinated and who subsequently contract the virus are among those 5% or whether have been infected by a variant that evades the vaccine.

Accelerating vaccine administration globally and in the United States is essential, Dr. Walensky said.

As of Feb. 17, 56 million doses had been administered in the United States.

Top three threats

She updated the numbers on the three biggest variant threats.

Regarding B.1.1.7, which originated in the United Kingdom, she said: “So far, we’ve had over 1,200 cases in 41 states.” She noted that the variant is likely to be about 50% more transmissible and 30% to 50% more virulent.

“So far, it looks like that strain doesn’t have any real decrease in susceptibility to our vaccines,” she said.

The strain from South Africa (B.1.351) has been found in 19 cases in the United States.

The P.1. variant, which originated in Brazil, has been identified in two cases in two states.

Outlook for March and April

Dr. Bauchner asked Dr. Walensky what she envisions for March and April. He noted that public optimism is high in light of the continued reductions in COVID-19 case numbers, hospitalizations, and deaths, as well as the fact that warmer weather is coming and that more vaccinations are on the horizon.

“While I really am hopeful for what could happen in March and April,” Dr. Walensky said, “I really do know that this could go bad so fast. We saw it in November. We saw it in December.”

CDC models have projected that, by March, the more transmissible B.1.1.7 strain is likely to be the dominant strain, she reiterated.

“I worry that it will be spring, and we will all have had enough,” Dr. Walensky said. She noted that some states are already relaxing mask mandates.

“Around that time, life will look and feel a little better, and the motivation for those who might be vaccine hesitant may be diminished,” she said.

Dr. Bauchner also asked her to weigh in on whether a third vaccine, from Johnson & Johnson (J&J), may soon gain FDA emergency-use authorization – and whether its lower expected efficacy rate may result in a tiered system of vaccinations, with higher-risk populations receiving the more efficacious vaccines.

Dr. Walensky said more data are needed before that question can be answered.

“It may very well be that the data point us to the best populations in which to use this vaccine,” she said.

In phase 3 data, the J&J vaccine was shown to be 72% effective in the United States for moderate to severe disease.

Dr. Walensky said it’s important to remember that the projected efficacy for that vaccine is higher than that for the flu shot as well as many other vaccines currently in use for other diseases.

She said it also has several advantages. The vaccine has less-stringent storage requirements, requires just one dose, and protects against hospitalization and death, although it’s less efficacious in protecting against contracting the disease.

“I think many people would opt to get that one if they could get it sooner,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

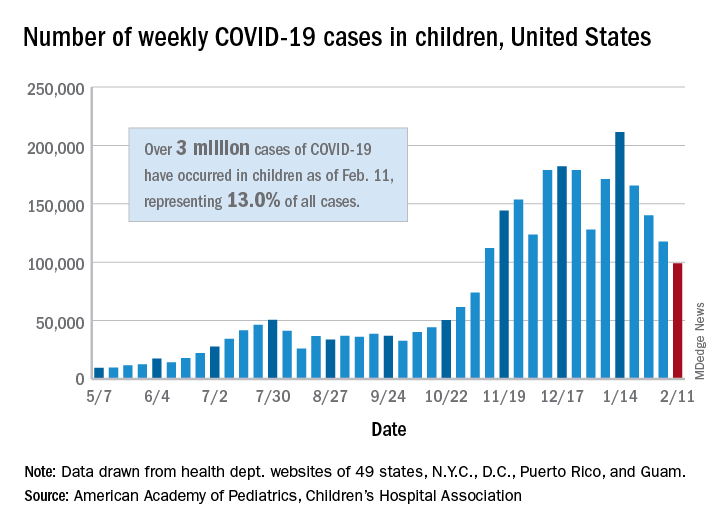

New child COVID-19 cases decline as total passes 3 million

New COVID-19 cases in children continue to drop each week, but the total number of cases has now surpassed 3 million since the start of the pandemic, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

It was still enough, though, to bring the total to 3.03 million children infected with SARS-CoV-19 in the United States, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly report.

The nation also hit a couple of other ignominious milestones. The cumulative rate of COVID-19 infection now stands at 4,030 per 100,000, so 4% of all children have been infected. Also, children represented 16.9% of all new cases for the week, which equals the highest proportion seen throughout the pandemic, based on data from health departments in 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

There have been 241 COVID-19–related deaths in children so far, with 14 reported during the week of Feb. 5-11. Kansas just recorded its first pediatric death, which leaves 10 states that have had no fatalities. Texas, with 39 deaths, has had more than any other state, among the 43 that are reporting mortality by age, the AAP/CHA report showed.

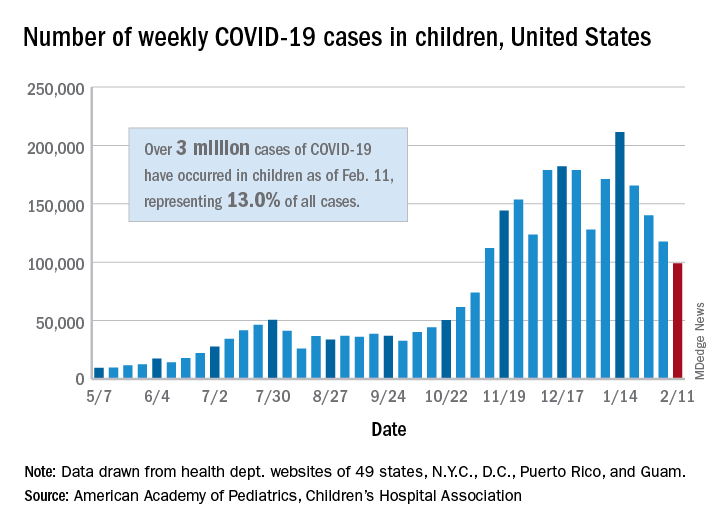

New COVID-19 cases in children continue to drop each week, but the total number of cases has now surpassed 3 million since the start of the pandemic, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

It was still enough, though, to bring the total to 3.03 million children infected with SARS-CoV-19 in the United States, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly report.

The nation also hit a couple of other ignominious milestones. The cumulative rate of COVID-19 infection now stands at 4,030 per 100,000, so 4% of all children have been infected. Also, children represented 16.9% of all new cases for the week, which equals the highest proportion seen throughout the pandemic, based on data from health departments in 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

There have been 241 COVID-19–related deaths in children so far, with 14 reported during the week of Feb. 5-11. Kansas just recorded its first pediatric death, which leaves 10 states that have had no fatalities. Texas, with 39 deaths, has had more than any other state, among the 43 that are reporting mortality by age, the AAP/CHA report showed.

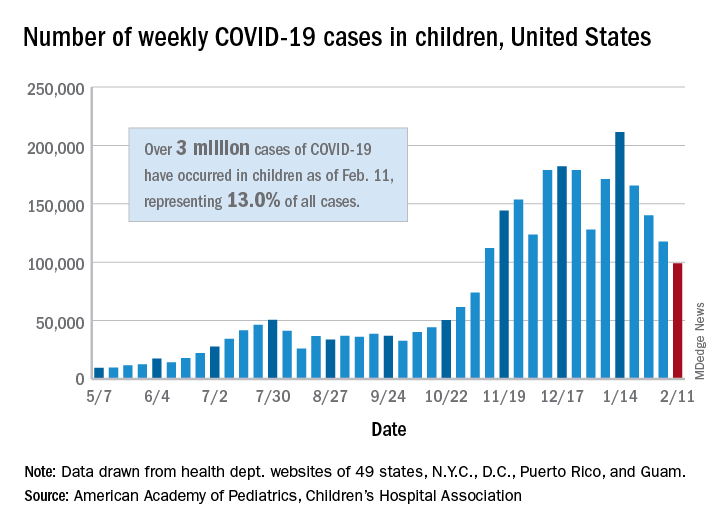

New COVID-19 cases in children continue to drop each week, but the total number of cases has now surpassed 3 million since the start of the pandemic, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

It was still enough, though, to bring the total to 3.03 million children infected with SARS-CoV-19 in the United States, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly report.

The nation also hit a couple of other ignominious milestones. The cumulative rate of COVID-19 infection now stands at 4,030 per 100,000, so 4% of all children have been infected. Also, children represented 16.9% of all new cases for the week, which equals the highest proportion seen throughout the pandemic, based on data from health departments in 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

There have been 241 COVID-19–related deaths in children so far, with 14 reported during the week of Feb. 5-11. Kansas just recorded its first pediatric death, which leaves 10 states that have had no fatalities. Texas, with 39 deaths, has had more than any other state, among the 43 that are reporting mortality by age, the AAP/CHA report showed.

Outcomes have improved for PAH in connective tissue disease

Survival rates for patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with connective tissue diseases have improved significantly in recent years, and there is growing evidence that treatments for idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension can also benefit this group.

In an article published online Feb. 3, 2021, in Arthritis & Rheumatology, researchers report the outcomes of a meta-analysis to explore the effect of more modern pulmonary arterial hypertension treatments on patients with conditions such as systemic sclerosis.

First author Dinesh Khanna, MBBS, MSc, of the division of rheumatology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, said in an interview that connective tissue disease–associated pulmonary arterial hypertension (CTD-PAH) was a leading cause of death, but earlier clinical trials had found poor outcomes in patients with CTD, compared with those with idiopathic PAH.

“Recent clinical trial data show that aggressive, up-front PAH treatments have better outcomes in those with CTD-PAH, and we wanted to explore these observations carefully in a systematic review and meta-analysis,” Dr. Khanna said.

The analysis included 11 randomized, controlled trials, involving 4,329 patients with PAH (1,267 with CTD), and 19 registries with a total of 9,739 patients with PAH, including 4,008 with CTD. Trials were required to report long-term clinical outcomes with a median enrollment time of greater than 6 months, and outcomes measured between 3-6 months after the patients started treatment.

Patients with CTDs had an older mean age and a lower 6-minute walk distance than did those with idiopathic PAH.

Five randomized, controlled trials – involving 3,172 patients, 941 of whom had a CTD – found that additional PAH treatment was associated with a 36% reduction in the risk of morbidity or mortality events, compared with controls both in the overall PAH group and in those with CTD.

Additional therapy was also associated with a 34.6-meter increase in 6-minute walk distance in the general PAH population, and a 20.4-meter increase in those with CTD.

The authors commented that the smaller improvement in 6-minute walk distance among patients with CTD may be influenced by comorbidities such as musculoskeletal involvement that would be independent of their cardiopulmonary function.

Differential patient survival among PAH etiologies

“Our meta-analysis of RCTs demonstrated that patients with CTD-PAH derive a clinically significant benefit from currently available PAH therapies which, in many patients, comprised the addition of a drug targeting a second or third pathway involved in the pathophysiology of PAH,” the authors wrote.

When researchers analyzed data from nine registries that included a wide range of PAH etiologies, they found the overall survival rates were lower among patients with CTD, compared with the overall population. The analysis also suggested that patients with systemic sclerosis and PAH had lower survival rates than did those with systemic lupus erythematosus.

Dr. Khanna said this may relate to different pathophysiology of PAH in patients with CTDs, but could also be a reflection of other differences, such as older age and the involvement of other comorbidities, including lung fibrosis and heart involvement.

Data across all 19 registries also showed that survival rates among those with CTD were higher in registries where more than 50% of the registry study period was during or after 2010, compared with registries where 50% or more of the study period was before 2010.

The authors suggested the differences in survival rates may relate to increased screening for PAH, particularly among people with CTDs. They noted that increased screening leads to earlier diagnosis, which could introduce a lead-time bias such that later registries would have younger participants with less severe disease. However, their analysis found that the later registries had older patients but also with less severe disease, and they suggested that it wasn’t possible to determine if lead-time bias was playing a role in their results.

Improvements in treatment options could also account for differences in survival over time, although the authors commented that only six registries in the study included patients from 2015 or later, when currently available treatments came into use and early combination therapy was used more.

“These data also support the 2018 World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension recommendations to initiate up-front combination pulmonary arterial hypertension therapy in majority of cases with CTD-PAH,” Dr. Khanna said.

‘Still have to be aggressive at identifying the high-risk patients’

Commenting on the findings, Virginia Steen, MD, of the division of rheumatology at Georgetown University, Washington, said clinicians were finally seeing some significant changes over time in scleroderma-associated PAH.

“Although some of it may be just early diagnosis, I think that the combination of early diagnosis and more aggressive treatment with combination medication is definitely making a difference,” Dr. Steen said in an interview. “The bottom line is that we as rheumatologists still have to be aggressive at identifying the high-risk patients, making an early diagnosis, and working with our pulmonary hypertension colleagues and aggressively treating these patients so we can make a long-term difference.”

The authors of an accompanying editorial said the meta-analysis’ findings showed the positive impact of early combination therapy and early diagnosis through proactive screening.

“It is notable because the present analysis again confirms that outcomes are worse in CTD-PAH than in idiopathic or familial forms of PAH, the impact of treatments should no longer be regarded as insignificant,” the editorial’s authors wrote. “This is a practice changing observation, especially now that many of the drugs are available in generic formulations and so the cost of modern PAH treatment has fallen at the same time as its true value is convincingly demonstrated.”

They also argued there was strong evidence for the value of combination therapies, both for PAH-targeted drugs used in combination and concurrent use of immunosuppression and drugs specifically for PAH in some patients with CTD-PAH.

However, they pointed out that not all treatments for idiopathic PAH were suitable for patients with CTDs, highlighting the example of anticoagulation that can improve survival in the first but worsen it in the second.

The study was funded by Actelion. Six authors declared funding and grants from the pharmaceutical sector, including the study sponsor, and three authors were employees of Actelion.

Survival rates for patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with connective tissue diseases have improved significantly in recent years, and there is growing evidence that treatments for idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension can also benefit this group.

In an article published online Feb. 3, 2021, in Arthritis & Rheumatology, researchers report the outcomes of a meta-analysis to explore the effect of more modern pulmonary arterial hypertension treatments on patients with conditions such as systemic sclerosis.

First author Dinesh Khanna, MBBS, MSc, of the division of rheumatology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, said in an interview that connective tissue disease–associated pulmonary arterial hypertension (CTD-PAH) was a leading cause of death, but earlier clinical trials had found poor outcomes in patients with CTD, compared with those with idiopathic PAH.

“Recent clinical trial data show that aggressive, up-front PAH treatments have better outcomes in those with CTD-PAH, and we wanted to explore these observations carefully in a systematic review and meta-analysis,” Dr. Khanna said.

The analysis included 11 randomized, controlled trials, involving 4,329 patients with PAH (1,267 with CTD), and 19 registries with a total of 9,739 patients with PAH, including 4,008 with CTD. Trials were required to report long-term clinical outcomes with a median enrollment time of greater than 6 months, and outcomes measured between 3-6 months after the patients started treatment.

Patients with CTDs had an older mean age and a lower 6-minute walk distance than did those with idiopathic PAH.

Five randomized, controlled trials – involving 3,172 patients, 941 of whom had a CTD – found that additional PAH treatment was associated with a 36% reduction in the risk of morbidity or mortality events, compared with controls both in the overall PAH group and in those with CTD.

Additional therapy was also associated with a 34.6-meter increase in 6-minute walk distance in the general PAH population, and a 20.4-meter increase in those with CTD.

The authors commented that the smaller improvement in 6-minute walk distance among patients with CTD may be influenced by comorbidities such as musculoskeletal involvement that would be independent of their cardiopulmonary function.

Differential patient survival among PAH etiologies

“Our meta-analysis of RCTs demonstrated that patients with CTD-PAH derive a clinically significant benefit from currently available PAH therapies which, in many patients, comprised the addition of a drug targeting a second or third pathway involved in the pathophysiology of PAH,” the authors wrote.

When researchers analyzed data from nine registries that included a wide range of PAH etiologies, they found the overall survival rates were lower among patients with CTD, compared with the overall population. The analysis also suggested that patients with systemic sclerosis and PAH had lower survival rates than did those with systemic lupus erythematosus.

Dr. Khanna said this may relate to different pathophysiology of PAH in patients with CTDs, but could also be a reflection of other differences, such as older age and the involvement of other comorbidities, including lung fibrosis and heart involvement.

Data across all 19 registries also showed that survival rates among those with CTD were higher in registries where more than 50% of the registry study period was during or after 2010, compared with registries where 50% or more of the study period was before 2010.

The authors suggested the differences in survival rates may relate to increased screening for PAH, particularly among people with CTDs. They noted that increased screening leads to earlier diagnosis, which could introduce a lead-time bias such that later registries would have younger participants with less severe disease. However, their analysis found that the later registries had older patients but also with less severe disease, and they suggested that it wasn’t possible to determine if lead-time bias was playing a role in their results.

Improvements in treatment options could also account for differences in survival over time, although the authors commented that only six registries in the study included patients from 2015 or later, when currently available treatments came into use and early combination therapy was used more.

“These data also support the 2018 World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension recommendations to initiate up-front combination pulmonary arterial hypertension therapy in majority of cases with CTD-PAH,” Dr. Khanna said.

‘Still have to be aggressive at identifying the high-risk patients’

Commenting on the findings, Virginia Steen, MD, of the division of rheumatology at Georgetown University, Washington, said clinicians were finally seeing some significant changes over time in scleroderma-associated PAH.

“Although some of it may be just early diagnosis, I think that the combination of early diagnosis and more aggressive treatment with combination medication is definitely making a difference,” Dr. Steen said in an interview. “The bottom line is that we as rheumatologists still have to be aggressive at identifying the high-risk patients, making an early diagnosis, and working with our pulmonary hypertension colleagues and aggressively treating these patients so we can make a long-term difference.”

The authors of an accompanying editorial said the meta-analysis’ findings showed the positive impact of early combination therapy and early diagnosis through proactive screening.

“It is notable because the present analysis again confirms that outcomes are worse in CTD-PAH than in idiopathic or familial forms of PAH, the impact of treatments should no longer be regarded as insignificant,” the editorial’s authors wrote. “This is a practice changing observation, especially now that many of the drugs are available in generic formulations and so the cost of modern PAH treatment has fallen at the same time as its true value is convincingly demonstrated.”

They also argued there was strong evidence for the value of combination therapies, both for PAH-targeted drugs used in combination and concurrent use of immunosuppression and drugs specifically for PAH in some patients with CTD-PAH.

However, they pointed out that not all treatments for idiopathic PAH were suitable for patients with CTDs, highlighting the example of anticoagulation that can improve survival in the first but worsen it in the second.

The study was funded by Actelion. Six authors declared funding and grants from the pharmaceutical sector, including the study sponsor, and three authors were employees of Actelion.

Survival rates for patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with connective tissue diseases have improved significantly in recent years, and there is growing evidence that treatments for idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension can also benefit this group.

In an article published online Feb. 3, 2021, in Arthritis & Rheumatology, researchers report the outcomes of a meta-analysis to explore the effect of more modern pulmonary arterial hypertension treatments on patients with conditions such as systemic sclerosis.

First author Dinesh Khanna, MBBS, MSc, of the division of rheumatology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, said in an interview that connective tissue disease–associated pulmonary arterial hypertension (CTD-PAH) was a leading cause of death, but earlier clinical trials had found poor outcomes in patients with CTD, compared with those with idiopathic PAH.

“Recent clinical trial data show that aggressive, up-front PAH treatments have better outcomes in those with CTD-PAH, and we wanted to explore these observations carefully in a systematic review and meta-analysis,” Dr. Khanna said.

The analysis included 11 randomized, controlled trials, involving 4,329 patients with PAH (1,267 with CTD), and 19 registries with a total of 9,739 patients with PAH, including 4,008 with CTD. Trials were required to report long-term clinical outcomes with a median enrollment time of greater than 6 months, and outcomes measured between 3-6 months after the patients started treatment.

Patients with CTDs had an older mean age and a lower 6-minute walk distance than did those with idiopathic PAH.

Five randomized, controlled trials – involving 3,172 patients, 941 of whom had a CTD – found that additional PAH treatment was associated with a 36% reduction in the risk of morbidity or mortality events, compared with controls both in the overall PAH group and in those with CTD.

Additional therapy was also associated with a 34.6-meter increase in 6-minute walk distance in the general PAH population, and a 20.4-meter increase in those with CTD.

The authors commented that the smaller improvement in 6-minute walk distance among patients with CTD may be influenced by comorbidities such as musculoskeletal involvement that would be independent of their cardiopulmonary function.

Differential patient survival among PAH etiologies

“Our meta-analysis of RCTs demonstrated that patients with CTD-PAH derive a clinically significant benefit from currently available PAH therapies which, in many patients, comprised the addition of a drug targeting a second or third pathway involved in the pathophysiology of PAH,” the authors wrote.

When researchers analyzed data from nine registries that included a wide range of PAH etiologies, they found the overall survival rates were lower among patients with CTD, compared with the overall population. The analysis also suggested that patients with systemic sclerosis and PAH had lower survival rates than did those with systemic lupus erythematosus.

Dr. Khanna said this may relate to different pathophysiology of PAH in patients with CTDs, but could also be a reflection of other differences, such as older age and the involvement of other comorbidities, including lung fibrosis and heart involvement.

Data across all 19 registries also showed that survival rates among those with CTD were higher in registries where more than 50% of the registry study period was during or after 2010, compared with registries where 50% or more of the study period was before 2010.

The authors suggested the differences in survival rates may relate to increased screening for PAH, particularly among people with CTDs. They noted that increased screening leads to earlier diagnosis, which could introduce a lead-time bias such that later registries would have younger participants with less severe disease. However, their analysis found that the later registries had older patients but also with less severe disease, and they suggested that it wasn’t possible to determine if lead-time bias was playing a role in their results.

Improvements in treatment options could also account for differences in survival over time, although the authors commented that only six registries in the study included patients from 2015 or later, when currently available treatments came into use and early combination therapy was used more.

“These data also support the 2018 World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension recommendations to initiate up-front combination pulmonary arterial hypertension therapy in majority of cases with CTD-PAH,” Dr. Khanna said.

‘Still have to be aggressive at identifying the high-risk patients’

Commenting on the findings, Virginia Steen, MD, of the division of rheumatology at Georgetown University, Washington, said clinicians were finally seeing some significant changes over time in scleroderma-associated PAH.

“Although some of it may be just early diagnosis, I think that the combination of early diagnosis and more aggressive treatment with combination medication is definitely making a difference,” Dr. Steen said in an interview. “The bottom line is that we as rheumatologists still have to be aggressive at identifying the high-risk patients, making an early diagnosis, and working with our pulmonary hypertension colleagues and aggressively treating these patients so we can make a long-term difference.”

The authors of an accompanying editorial said the meta-analysis’ findings showed the positive impact of early combination therapy and early diagnosis through proactive screening.

“It is notable because the present analysis again confirms that outcomes are worse in CTD-PAH than in idiopathic or familial forms of PAH, the impact of treatments should no longer be regarded as insignificant,” the editorial’s authors wrote. “This is a practice changing observation, especially now that many of the drugs are available in generic formulations and so the cost of modern PAH treatment has fallen at the same time as its true value is convincingly demonstrated.”

They also argued there was strong evidence for the value of combination therapies, both for PAH-targeted drugs used in combination and concurrent use of immunosuppression and drugs specifically for PAH in some patients with CTD-PAH.

However, they pointed out that not all treatments for idiopathic PAH were suitable for patients with CTDs, highlighting the example of anticoagulation that can improve survival in the first but worsen it in the second.

The study was funded by Actelion. Six authors declared funding and grants from the pharmaceutical sector, including the study sponsor, and three authors were employees of Actelion.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

Tocilizumab may improve lung function in early systemic sclerosis

Treatment with tocilizumab (Actemra) could stabilize or improve lung function in people with early interstitial lung disease associated with systemic sclerosis (SSc-ILD), a new study has found.

A paper published online Feb. 3 in Arthritis & Rheumatology presents the results of a post hoc analysis of data from a phase 3, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial of subcutaneous tocilizumab in patients with SSc and progressive skin disease, which included high-resolution chest CT to assess lung involvement and fibrosis.

Tocilizumab is a monoclonal antibody that targets interleukin-6 and is currently approved for the treatment of immune-mediated diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, giant cell arteritis, cytokine release syndrome, and systemic and polyarticular course juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

Two previous studies of tocilizumab in patients with early, diffuse cutaneous SSc had also found that the treatment was associated with preservation of lung function but did not characterize that effect using radiography.

Of the 210 participants in the trial, called focuSSced, 136 were found to have interstitial lung disease at baseline and were randomized to 162 mg tocilizumab weekly or placebo for 48 weeks.

At baseline, around three-quarters of those with interstitial lung disease had moderate to severe lung involvement, defined as ground glass opacities, honeycombing, and fibrotic reticulation across at least 20% of the whole lung.

Those in the tocilizumab group showed a 0.1% mean decline in forced vital capacity (FVC) over the 48-week study, while those in the placebo group had a mean decline of 6.3%.

When stratified by severity of lung involvement, those with mild lung disease group treated with tocilizumab had a 4.1% decline in FVC, compared with a 10% decline in the placebo group; those with moderate disease in the treatment group had an 0.7% mean increase in FVC, compared with a 5.7% decrease in the placebo group, and those with severe lung involvement in the treatment arm had a 2.1% increase in FVC, compared with a 6.7% decrease in the placebo arm.

Those treated with tocilizumab also showed a statistically significant 1.8% improvement in the amount of lung involvement, which was largely seen in those with more extensive lung involvement at baseline. Those with more than 20% of the lung affected had a significant 4.9% reduction in lung area affected, while those in the placebo arm showed a significant increase in fibrosis.

First author David Roofeh, MD, of the University of Michigan Scleroderma Program, and colleagues wrote that most patients with SSc will develop interstitial lung disease – particularly those with early, diffuse cutaneous SSc and elevated markers such as C-reactive protein.

“Patients with these high-risk features, especially those with disease in the initial phase of development, represent an important target for early intervention as ILD is largely irreversible in SSc,” the authors wrote.

Findings from a specific patient population may not be generalizable

Commenting on the findings, Lorinda Chung, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview that the study demonstrated that tocilizumab could prevent radiographic progression of ILD in early diffuse SSc patients with mild to severe lung disease and evidence of active skin disease, as well as elevated inflammatory markers.

“This was a very specific patient population who was studied in the focuSSced clinical trial, and this paper only evaluated a subset of these patients,” Dr. Chung said. “The results may not be generalizable to all SSc-ILD patients and further studies are needed.”

The authors suggested that the patients with progressive skin disease and elevated acute phase reactants may represent a group in the immunoinflammatory phase of the disease rather than the advanced fibrotic stage, and that this might be a “window of therapeutic opportunity to preserve lung function.”

Dr. Chung noted that the radiographic improvement induced by tocilizumab treatment was greatest in those with the most radiographic disease at baseline.

“This may reflect tocilizumab’s impact on decreasing inflammation, but we are not provided the data on the effects of tocilizumab on the individual components of the QILD [quantitative ILD: summation of ground glass opacities, honeycombing, and fibrotic reticulation],” she said.

The study’s authors also made a point about the utility of screening patients with high-resolution chest CT to detect early signs of ILD.

“Our data demonstrate the value of obtaining HRCT at the time of diagnosis: PFTs [pulmonary function tests] are not sensitive enough to accurately assess the presence of ILD and delays in treatment initiation may lead to irreversible disease,” they wrote.

Describing the results as ‘hypothesis-generating’ owing to the post hoc nature of the analysis, the authors said that FVC was an indirect measure of the flow-resistive properties of the lung, and that other aspects of SSc – such as hide-bound chest thickness – could cause thoracic restriction.

Two authors were funded by the National Institutes of Health. Six authors declared grants, funding, and other support from the pharmaceutical sector, including Roche, which sponsored the original focuSSced trial.

Treatment with tocilizumab (Actemra) could stabilize or improve lung function in people with early interstitial lung disease associated with systemic sclerosis (SSc-ILD), a new study has found.

A paper published online Feb. 3 in Arthritis & Rheumatology presents the results of a post hoc analysis of data from a phase 3, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial of subcutaneous tocilizumab in patients with SSc and progressive skin disease, which included high-resolution chest CT to assess lung involvement and fibrosis.

Tocilizumab is a monoclonal antibody that targets interleukin-6 and is currently approved for the treatment of immune-mediated diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, giant cell arteritis, cytokine release syndrome, and systemic and polyarticular course juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

Two previous studies of tocilizumab in patients with early, diffuse cutaneous SSc had also found that the treatment was associated with preservation of lung function but did not characterize that effect using radiography.

Of the 210 participants in the trial, called focuSSced, 136 were found to have interstitial lung disease at baseline and were randomized to 162 mg tocilizumab weekly or placebo for 48 weeks.

At baseline, around three-quarters of those with interstitial lung disease had moderate to severe lung involvement, defined as ground glass opacities, honeycombing, and fibrotic reticulation across at least 20% of the whole lung.

Those in the tocilizumab group showed a 0.1% mean decline in forced vital capacity (FVC) over the 48-week study, while those in the placebo group had a mean decline of 6.3%.

When stratified by severity of lung involvement, those with mild lung disease group treated with tocilizumab had a 4.1% decline in FVC, compared with a 10% decline in the placebo group; those with moderate disease in the treatment group had an 0.7% mean increase in FVC, compared with a 5.7% decrease in the placebo group, and those with severe lung involvement in the treatment arm had a 2.1% increase in FVC, compared with a 6.7% decrease in the placebo arm.

Those treated with tocilizumab also showed a statistically significant 1.8% improvement in the amount of lung involvement, which was largely seen in those with more extensive lung involvement at baseline. Those with more than 20% of the lung affected had a significant 4.9% reduction in lung area affected, while those in the placebo arm showed a significant increase in fibrosis.

First author David Roofeh, MD, of the University of Michigan Scleroderma Program, and colleagues wrote that most patients with SSc will develop interstitial lung disease – particularly those with early, diffuse cutaneous SSc and elevated markers such as C-reactive protein.

“Patients with these high-risk features, especially those with disease in the initial phase of development, represent an important target for early intervention as ILD is largely irreversible in SSc,” the authors wrote.

Findings from a specific patient population may not be generalizable

Commenting on the findings, Lorinda Chung, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview that the study demonstrated that tocilizumab could prevent radiographic progression of ILD in early diffuse SSc patients with mild to severe lung disease and evidence of active skin disease, as well as elevated inflammatory markers.

“This was a very specific patient population who was studied in the focuSSced clinical trial, and this paper only evaluated a subset of these patients,” Dr. Chung said. “The results may not be generalizable to all SSc-ILD patients and further studies are needed.”

The authors suggested that the patients with progressive skin disease and elevated acute phase reactants may represent a group in the immunoinflammatory phase of the disease rather than the advanced fibrotic stage, and that this might be a “window of therapeutic opportunity to preserve lung function.”

Dr. Chung noted that the radiographic improvement induced by tocilizumab treatment was greatest in those with the most radiographic disease at baseline.

“This may reflect tocilizumab’s impact on decreasing inflammation, but we are not provided the data on the effects of tocilizumab on the individual components of the QILD [quantitative ILD: summation of ground glass opacities, honeycombing, and fibrotic reticulation],” she said.

The study’s authors also made a point about the utility of screening patients with high-resolution chest CT to detect early signs of ILD.

“Our data demonstrate the value of obtaining HRCT at the time of diagnosis: PFTs [pulmonary function tests] are not sensitive enough to accurately assess the presence of ILD and delays in treatment initiation may lead to irreversible disease,” they wrote.

Describing the results as ‘hypothesis-generating’ owing to the post hoc nature of the analysis, the authors said that FVC was an indirect measure of the flow-resistive properties of the lung, and that other aspects of SSc – such as hide-bound chest thickness – could cause thoracic restriction.

Two authors were funded by the National Institutes of Health. Six authors declared grants, funding, and other support from the pharmaceutical sector, including Roche, which sponsored the original focuSSced trial.

Treatment with tocilizumab (Actemra) could stabilize or improve lung function in people with early interstitial lung disease associated with systemic sclerosis (SSc-ILD), a new study has found.

A paper published online Feb. 3 in Arthritis & Rheumatology presents the results of a post hoc analysis of data from a phase 3, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial of subcutaneous tocilizumab in patients with SSc and progressive skin disease, which included high-resolution chest CT to assess lung involvement and fibrosis.

Tocilizumab is a monoclonal antibody that targets interleukin-6 and is currently approved for the treatment of immune-mediated diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, giant cell arteritis, cytokine release syndrome, and systemic and polyarticular course juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

Two previous studies of tocilizumab in patients with early, diffuse cutaneous SSc had also found that the treatment was associated with preservation of lung function but did not characterize that effect using radiography.

Of the 210 participants in the trial, called focuSSced, 136 were found to have interstitial lung disease at baseline and were randomized to 162 mg tocilizumab weekly or placebo for 48 weeks.

At baseline, around three-quarters of those with interstitial lung disease had moderate to severe lung involvement, defined as ground glass opacities, honeycombing, and fibrotic reticulation across at least 20% of the whole lung.

Those in the tocilizumab group showed a 0.1% mean decline in forced vital capacity (FVC) over the 48-week study, while those in the placebo group had a mean decline of 6.3%.

When stratified by severity of lung involvement, those with mild lung disease group treated with tocilizumab had a 4.1% decline in FVC, compared with a 10% decline in the placebo group; those with moderate disease in the treatment group had an 0.7% mean increase in FVC, compared with a 5.7% decrease in the placebo group, and those with severe lung involvement in the treatment arm had a 2.1% increase in FVC, compared with a 6.7% decrease in the placebo arm.

Those treated with tocilizumab also showed a statistically significant 1.8% improvement in the amount of lung involvement, which was largely seen in those with more extensive lung involvement at baseline. Those with more than 20% of the lung affected had a significant 4.9% reduction in lung area affected, while those in the placebo arm showed a significant increase in fibrosis.

First author David Roofeh, MD, of the University of Michigan Scleroderma Program, and colleagues wrote that most patients with SSc will develop interstitial lung disease – particularly those with early, diffuse cutaneous SSc and elevated markers such as C-reactive protein.

“Patients with these high-risk features, especially those with disease in the initial phase of development, represent an important target for early intervention as ILD is largely irreversible in SSc,” the authors wrote.

Findings from a specific patient population may not be generalizable

Commenting on the findings, Lorinda Chung, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview that the study demonstrated that tocilizumab could prevent radiographic progression of ILD in early diffuse SSc patients with mild to severe lung disease and evidence of active skin disease, as well as elevated inflammatory markers.

“This was a very specific patient population who was studied in the focuSSced clinical trial, and this paper only evaluated a subset of these patients,” Dr. Chung said. “The results may not be generalizable to all SSc-ILD patients and further studies are needed.”

The authors suggested that the patients with progressive skin disease and elevated acute phase reactants may represent a group in the immunoinflammatory phase of the disease rather than the advanced fibrotic stage, and that this might be a “window of therapeutic opportunity to preserve lung function.”

Dr. Chung noted that the radiographic improvement induced by tocilizumab treatment was greatest in those with the most radiographic disease at baseline.

“This may reflect tocilizumab’s impact on decreasing inflammation, but we are not provided the data on the effects of tocilizumab on the individual components of the QILD [quantitative ILD: summation of ground glass opacities, honeycombing, and fibrotic reticulation],” she said.

The study’s authors also made a point about the utility of screening patients with high-resolution chest CT to detect early signs of ILD.

“Our data demonstrate the value of obtaining HRCT at the time of diagnosis: PFTs [pulmonary function tests] are not sensitive enough to accurately assess the presence of ILD and delays in treatment initiation may lead to irreversible disease,” they wrote.

Describing the results as ‘hypothesis-generating’ owing to the post hoc nature of the analysis, the authors said that FVC was an indirect measure of the flow-resistive properties of the lung, and that other aspects of SSc – such as hide-bound chest thickness – could cause thoracic restriction.

Two authors were funded by the National Institutes of Health. Six authors declared grants, funding, and other support from the pharmaceutical sector, including Roche, which sponsored the original focuSSced trial.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

What to do if an employee tests positive for COVID-19

An increasingly common question I’m receiving is:

As always, it depends, but here is some general advice: The specifics will vary depending on state/local laws, or your particular situation.

First, you need to determine the level of exposure, and whether it requires action. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, actionable exposure occurs 2 days prior to the onset of illness, and lasts 10 days after onset.

If action is required, you’ll need to determine who needs to quarantine and who needs to be tested. Vaccinated employees who have been exposed to suspected or confirmed COVID-19 are not required to quarantine or be tested if they are fully vaccinated and have remained asymptomatic since the exposure. Those employees should, however, follow all the usual precautions (masks, social distancing, handwashing, etc.) with increased diligence. Remind them that no vaccine is 100% effective, and suggest they self-monitor for symptoms (fever, cough, shortness of breath, etc.)

All other exposed employees should be tested. A negative test means an individual was not infected at the time the sample was collected, but that does not mean an individual will not get sick later. Some providers are retesting on days 5 and 7 post exposure.

Some experts advise that you monitor exposed employees (vaccinated or not) yourself, with daily temperature readings and inquiries regarding symptoms, and perhaps a daily pulse oximetry check, for 14 days following exposure. Document these screenings in writing. Anyone testing positive or developing a fever or other symptoms should, of course, be sent home and seek medical treatment as necessary.

Employees who develop symptoms or test positive for COVID-19 should remain out of work until all CDC “return-to-work” criteria are met. At this writing, the basic criteria include:

- At least 10 days pass after symptoms first appeared

- At least 24 hours pass after last fever without the use of fever-reducing medications

- Cough, shortness of breath, and any other symptoms improve