User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

Powered by CHEST Physician, Clinician Reviews, MDedge Family Medicine, Internal Medicine News, and The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management.

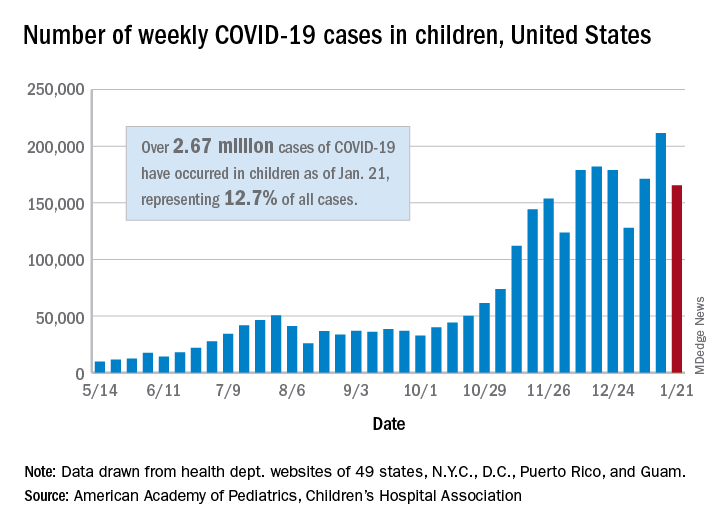

Weekly COVID-19 cases in children dropped 22%

according to new data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

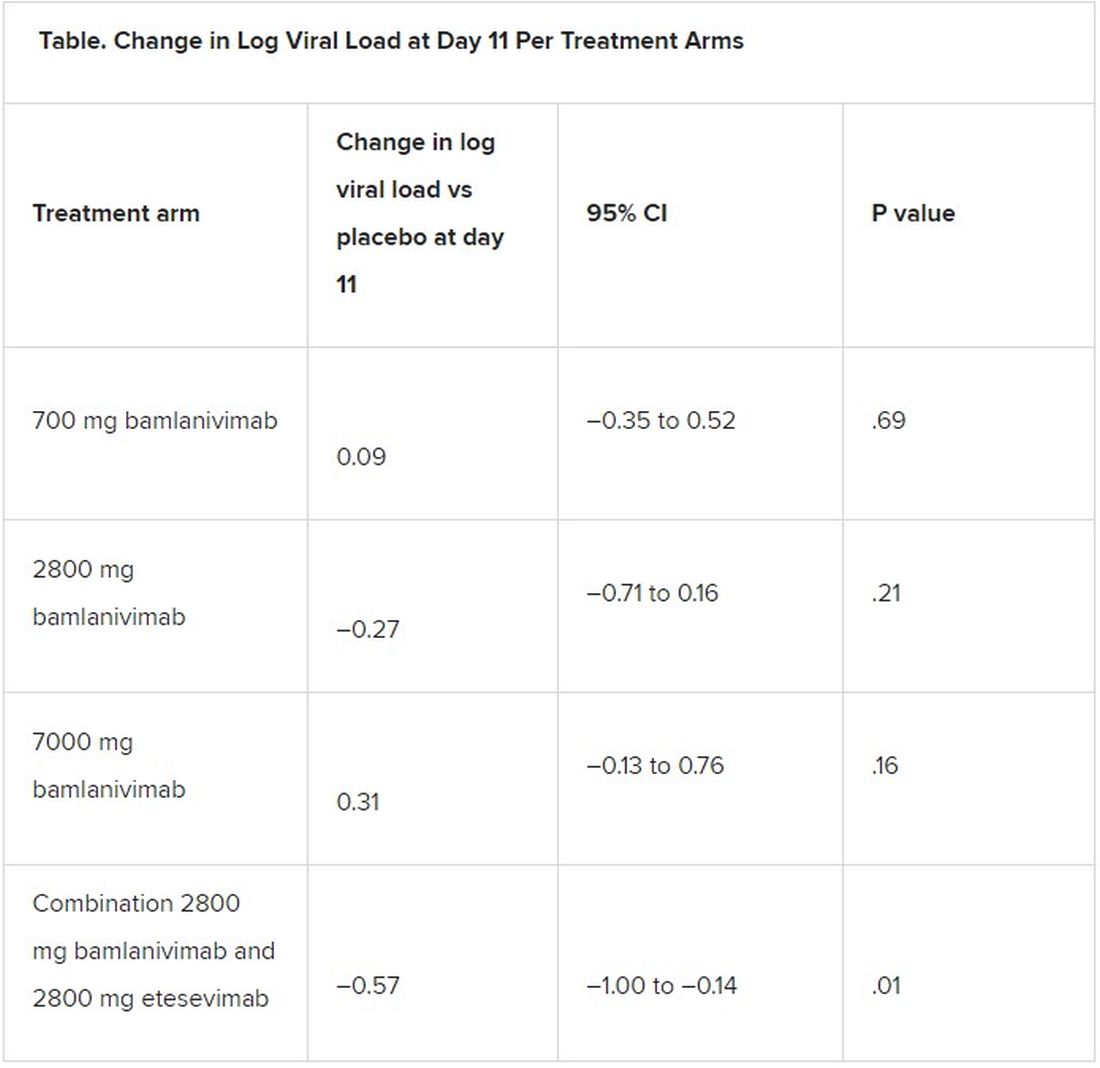

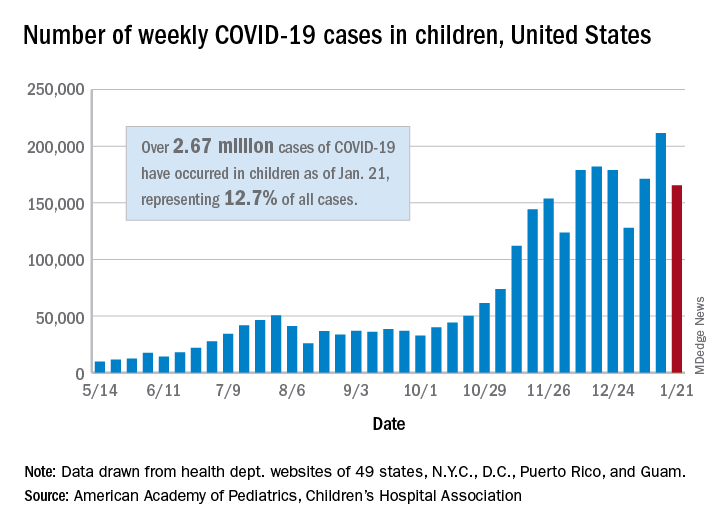

The 165,000 new cases reported during the week of Jan. 15-21 were down by almost 22% from the previous week’s 211,000, when the new-case count reached its highest point in the pandemic, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

Cumulative cases in children now stand at just over 2.67 million, and children represent 12.7% of all COVID-19 cases reported by 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam. For the week of Jan. 15-21, children made up 14.8% of all new cases, the highest proportion since late September, the AAP/CHA data show.

The cumulative rate of infection among children is up to 3,556 per 100,000 nationally, with states ranging from 943 per 100,000 in Hawaii to 8,195 in North Dakota. California has the most reported cases at 383,000, while Vermont has the fewest at 1,820, the two organizations reported.

There were 14 more deaths among children in the last week, bringing the total to 205 in the 43 states (plus New York City and Guam) reporting such data. Children represent just 0.06% of all coronavirus-related deaths, and only 0.01% of all cases in children have resulted in death, the AAP and CHA said. There are still 10 states where no children have died from COVID-19.

Although severe illness appears to be rare in children, the AAP and CHA noted, “there is an urgent need to collect more data on longer-term impacts of the pandemic on children, including ways the virus may harm the long-term physical health of infected children, as well as its emotional and mental health effects.”

according to new data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The 165,000 new cases reported during the week of Jan. 15-21 were down by almost 22% from the previous week’s 211,000, when the new-case count reached its highest point in the pandemic, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

Cumulative cases in children now stand at just over 2.67 million, and children represent 12.7% of all COVID-19 cases reported by 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam. For the week of Jan. 15-21, children made up 14.8% of all new cases, the highest proportion since late September, the AAP/CHA data show.

The cumulative rate of infection among children is up to 3,556 per 100,000 nationally, with states ranging from 943 per 100,000 in Hawaii to 8,195 in North Dakota. California has the most reported cases at 383,000, while Vermont has the fewest at 1,820, the two organizations reported.

There were 14 more deaths among children in the last week, bringing the total to 205 in the 43 states (plus New York City and Guam) reporting such data. Children represent just 0.06% of all coronavirus-related deaths, and only 0.01% of all cases in children have resulted in death, the AAP and CHA said. There are still 10 states where no children have died from COVID-19.

Although severe illness appears to be rare in children, the AAP and CHA noted, “there is an urgent need to collect more data on longer-term impacts of the pandemic on children, including ways the virus may harm the long-term physical health of infected children, as well as its emotional and mental health effects.”

according to new data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The 165,000 new cases reported during the week of Jan. 15-21 were down by almost 22% from the previous week’s 211,000, when the new-case count reached its highest point in the pandemic, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

Cumulative cases in children now stand at just over 2.67 million, and children represent 12.7% of all COVID-19 cases reported by 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam. For the week of Jan. 15-21, children made up 14.8% of all new cases, the highest proportion since late September, the AAP/CHA data show.

The cumulative rate of infection among children is up to 3,556 per 100,000 nationally, with states ranging from 943 per 100,000 in Hawaii to 8,195 in North Dakota. California has the most reported cases at 383,000, while Vermont has the fewest at 1,820, the two organizations reported.

There were 14 more deaths among children in the last week, bringing the total to 205 in the 43 states (plus New York City and Guam) reporting such data. Children represent just 0.06% of all coronavirus-related deaths, and only 0.01% of all cases in children have resulted in death, the AAP and CHA said. There are still 10 states where no children have died from COVID-19.

Although severe illness appears to be rare in children, the AAP and CHA noted, “there is an urgent need to collect more data on longer-term impacts of the pandemic on children, including ways the virus may harm the long-term physical health of infected children, as well as its emotional and mental health effects.”

COVID-19 variants may prompt additional Moderna vaccine

As mutated strains of the coronavirus represent new threats in the pandemic, vaccine makers are racing to respond.

Moderna, whose two-dose vaccine has been authorized for use in the United States since Dec. 18, said on Jan. 25 that it is now investigating whether a third dose of the vaccine will better prevent the spread of a variant first seen in South Africa, while it also tests a new vaccine formula for the same purpose.

“Out of an abundance of caution and leveraging the flexibility of our mRNA platform, we are advancing an emerging variant booster candidate against the variant first identified in the Republic of South Africa into the clinic to determine if it will be more effective … against this and potentially future variants,” Moderna CEO Stéphane Bancel said in a statement. Pfizer and BioNTech, whose vaccine was also authorized in December, announced on Jan. 20 that their COVID-19 vaccine creates antibodies that could protect vaccine recipients from the U.K. variant B.1.1.7.

Moderna on Jan. 25 said laboratory tests have shown its COVID-19 vaccine could protect against the U.K. strain but that it is less effective – while still meeting efficacy benchmarks – against the strain identified in South Africa. Data from the study were submitted to a preprint server on Jan. 25 but have not yet been peer reviewed.

“This is not a problem yet,” Paul Offit, MD, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told CNBC.

“Prepare for it. Sequence these viruses,” he said. “Get ready just in case a variant emerges, which is resistant.”

There were at least 195 confirmed cases of patients infected with the U.K. variant, which is believed to be as much as 70% more transmissible, in the United States as of Jan. 22, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No cases from the South African variant have been confirmed in the United States. To try to prevent the variant from entering the country, President Joe Biden plans to ban travel from South Africa, except for American citizens and permanent residents.

The U.S. has reported more than 25 million total COVID-19 cases, according to data from Johns Hopkins University, marking another major milestone during the pandemic.

That means about 1 in 13 people have contracted the virus, or about 7.6% of the U.S. population.

“Twenty-five million cases is an incredible scale of tragedy,” Caitlin Rivers, an epidemiologist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, told The New York Times. She called the pandemic one of the worst public health crises in history.

After the first U.S. case was reported in January 2020, it took more than 9 months to reach 10 million cases in early November. Numbers rose during the holidays, and 10 million more cases were reported by the end of the year.

Following a major surge throughout January 2021, with a peak of more than 300,000 daily cases on some days, the U.S. reached 25 million in about 3 weeks.

Hospitalizations also peaked in early January, with more than 132,000 COVID-19 patients in hospitals across the country, according to the COVID Tracking Project. On Jan. 24, about 111,000 patients were hospitalized, which is the lowest since mid-December.

The U.S. has also reported nearly 420,000 deaths. As recently as the week starting Jan. 17, more than 4,400 deaths were reported in a single day, according to the COVID Tracking Project. Deaths are beginning to drop but still remain above 3,000 daily.

The University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation released a new projection Jan. 22 that said new cases would decline steadily in coming weeks. New COVID-19 cases had fallen about 21% in 2 weeks prior to Jan. 25, according to an analysis by The New York Times.

“We’ve been saying since summer that we thought we’d see a peak in January, and I think that, at the national level, we’re around the peak,” Christopher J.L. Murray, MD, director of the institute, told the newspaper.

At the same time, public health officials are concerned that new coronavirus variants could lead to an increase again. Dr. Murray said the variants could “totally change the story.” If the more transmissible strains spread quickly, cases and deaths will surge once more.

“We’re definitely on a downward slope, but I’m worried that the new variants will throw us a curveball in late February or March,” Ms. Rivers told the newspaper.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

As mutated strains of the coronavirus represent new threats in the pandemic, vaccine makers are racing to respond.

Moderna, whose two-dose vaccine has been authorized for use in the United States since Dec. 18, said on Jan. 25 that it is now investigating whether a third dose of the vaccine will better prevent the spread of a variant first seen in South Africa, while it also tests a new vaccine formula for the same purpose.

“Out of an abundance of caution and leveraging the flexibility of our mRNA platform, we are advancing an emerging variant booster candidate against the variant first identified in the Republic of South Africa into the clinic to determine if it will be more effective … against this and potentially future variants,” Moderna CEO Stéphane Bancel said in a statement. Pfizer and BioNTech, whose vaccine was also authorized in December, announced on Jan. 20 that their COVID-19 vaccine creates antibodies that could protect vaccine recipients from the U.K. variant B.1.1.7.

Moderna on Jan. 25 said laboratory tests have shown its COVID-19 vaccine could protect against the U.K. strain but that it is less effective – while still meeting efficacy benchmarks – against the strain identified in South Africa. Data from the study were submitted to a preprint server on Jan. 25 but have not yet been peer reviewed.

“This is not a problem yet,” Paul Offit, MD, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told CNBC.

“Prepare for it. Sequence these viruses,” he said. “Get ready just in case a variant emerges, which is resistant.”

There were at least 195 confirmed cases of patients infected with the U.K. variant, which is believed to be as much as 70% more transmissible, in the United States as of Jan. 22, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No cases from the South African variant have been confirmed in the United States. To try to prevent the variant from entering the country, President Joe Biden plans to ban travel from South Africa, except for American citizens and permanent residents.

The U.S. has reported more than 25 million total COVID-19 cases, according to data from Johns Hopkins University, marking another major milestone during the pandemic.

That means about 1 in 13 people have contracted the virus, or about 7.6% of the U.S. population.

“Twenty-five million cases is an incredible scale of tragedy,” Caitlin Rivers, an epidemiologist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, told The New York Times. She called the pandemic one of the worst public health crises in history.

After the first U.S. case was reported in January 2020, it took more than 9 months to reach 10 million cases in early November. Numbers rose during the holidays, and 10 million more cases were reported by the end of the year.

Following a major surge throughout January 2021, with a peak of more than 300,000 daily cases on some days, the U.S. reached 25 million in about 3 weeks.

Hospitalizations also peaked in early January, with more than 132,000 COVID-19 patients in hospitals across the country, according to the COVID Tracking Project. On Jan. 24, about 111,000 patients were hospitalized, which is the lowest since mid-December.

The U.S. has also reported nearly 420,000 deaths. As recently as the week starting Jan. 17, more than 4,400 deaths were reported in a single day, according to the COVID Tracking Project. Deaths are beginning to drop but still remain above 3,000 daily.

The University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation released a new projection Jan. 22 that said new cases would decline steadily in coming weeks. New COVID-19 cases had fallen about 21% in 2 weeks prior to Jan. 25, according to an analysis by The New York Times.

“We’ve been saying since summer that we thought we’d see a peak in January, and I think that, at the national level, we’re around the peak,” Christopher J.L. Murray, MD, director of the institute, told the newspaper.

At the same time, public health officials are concerned that new coronavirus variants could lead to an increase again. Dr. Murray said the variants could “totally change the story.” If the more transmissible strains spread quickly, cases and deaths will surge once more.

“We’re definitely on a downward slope, but I’m worried that the new variants will throw us a curveball in late February or March,” Ms. Rivers told the newspaper.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

As mutated strains of the coronavirus represent new threats in the pandemic, vaccine makers are racing to respond.

Moderna, whose two-dose vaccine has been authorized for use in the United States since Dec. 18, said on Jan. 25 that it is now investigating whether a third dose of the vaccine will better prevent the spread of a variant first seen in South Africa, while it also tests a new vaccine formula for the same purpose.

“Out of an abundance of caution and leveraging the flexibility of our mRNA platform, we are advancing an emerging variant booster candidate against the variant first identified in the Republic of South Africa into the clinic to determine if it will be more effective … against this and potentially future variants,” Moderna CEO Stéphane Bancel said in a statement. Pfizer and BioNTech, whose vaccine was also authorized in December, announced on Jan. 20 that their COVID-19 vaccine creates antibodies that could protect vaccine recipients from the U.K. variant B.1.1.7.

Moderna on Jan. 25 said laboratory tests have shown its COVID-19 vaccine could protect against the U.K. strain but that it is less effective – while still meeting efficacy benchmarks – against the strain identified in South Africa. Data from the study were submitted to a preprint server on Jan. 25 but have not yet been peer reviewed.

“This is not a problem yet,” Paul Offit, MD, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told CNBC.

“Prepare for it. Sequence these viruses,” he said. “Get ready just in case a variant emerges, which is resistant.”

There were at least 195 confirmed cases of patients infected with the U.K. variant, which is believed to be as much as 70% more transmissible, in the United States as of Jan. 22, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No cases from the South African variant have been confirmed in the United States. To try to prevent the variant from entering the country, President Joe Biden plans to ban travel from South Africa, except for American citizens and permanent residents.

The U.S. has reported more than 25 million total COVID-19 cases, according to data from Johns Hopkins University, marking another major milestone during the pandemic.

That means about 1 in 13 people have contracted the virus, or about 7.6% of the U.S. population.

“Twenty-five million cases is an incredible scale of tragedy,” Caitlin Rivers, an epidemiologist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, told The New York Times. She called the pandemic one of the worst public health crises in history.

After the first U.S. case was reported in January 2020, it took more than 9 months to reach 10 million cases in early November. Numbers rose during the holidays, and 10 million more cases were reported by the end of the year.

Following a major surge throughout January 2021, with a peak of more than 300,000 daily cases on some days, the U.S. reached 25 million in about 3 weeks.

Hospitalizations also peaked in early January, with more than 132,000 COVID-19 patients in hospitals across the country, according to the COVID Tracking Project. On Jan. 24, about 111,000 patients were hospitalized, which is the lowest since mid-December.

The U.S. has also reported nearly 420,000 deaths. As recently as the week starting Jan. 17, more than 4,400 deaths were reported in a single day, according to the COVID Tracking Project. Deaths are beginning to drop but still remain above 3,000 daily.

The University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation released a new projection Jan. 22 that said new cases would decline steadily in coming weeks. New COVID-19 cases had fallen about 21% in 2 weeks prior to Jan. 25, according to an analysis by The New York Times.

“We’ve been saying since summer that we thought we’d see a peak in January, and I think that, at the national level, we’re around the peak,” Christopher J.L. Murray, MD, director of the institute, told the newspaper.

At the same time, public health officials are concerned that new coronavirus variants could lead to an increase again. Dr. Murray said the variants could “totally change the story.” If the more transmissible strains spread quickly, cases and deaths will surge once more.

“We’re definitely on a downward slope, but I’m worried that the new variants will throw us a curveball in late February or March,” Ms. Rivers told the newspaper.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

More than one-third of COVID-19 infections are asymptomatic: Review

A systematic review suggests at least one-third of SARS-CoV-2 infections occur in people who never develop symptoms, providing strong evidence for the prevalence of asymptomatic infections.

The finding that nearly one in three infected people remain symptom free suggests testing should be changed, the investigators noted.

“To reduce transmission from people who are presymptomatic or asymptomatic, we need to shift our testing focus to at-home screening,” lead author Daniel Oran, AM, said in an interview. “Inexpensive rapid antigen tests, provided to millions of people for frequent use, could help us significantly reduce the spread of the virus.”

The systematic review was published online Jan. 22 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The findings come at a dire time when the official number of COVID-19 cases in the United States exceeds 25 million for the first time. Public health officials have raised concerns about more transmissible, and possibly more deadly, variants of SARS-CoV-2, while a new presidential administration tries to meet the challenge of improving vaccine distribution and acceptance rates.

The results also build on earlier findings from the same research team – Mr. Oran and senior author Eric Topol, MD – that published a review article looking at asymptomatic COVID-19 cases. Even though initial data were more limited, they likewise suggested a broader scope of testing is warranted, pointing out that asymptomatic individuals can transmit SARS-CoV-2 for up to 14 days. Dr. Topol is also editor in chief of Medscape.

In the current systematic review, the highest-quality evidence comes from large studies in England and Spain. The nationally representative evidence included serologic surveys from more than 365,000 people in England and more than 61,000 in Spain. When analyzed separately, about the same proportion of asymptomatic cases emerged: 32.4% in England and 33% in Spain.

“It was really remarkable to find that nationwide antibody testing studies in England and Spain – including hundreds of thousands of people – produced nearly identical results: About one-third of the SARS-CoV-2 infections were completely asymptomatic,” said Mr. Oran, a researcher at Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla, Calif.

The systematic review included 43 studies with PCR testing for active SARS-CoV-2 infection and another 18 with antibody results that indicated present or previous infection. The studies were published up until Nov. 17, 2020.

An appreciation for asymptomatic transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection has come a long way from initial dismissals about its importance, Dr. Topol noted via Twitter. “When Dr. @camilla_rothe reported an asymptomatic transmission a year ago, the @NEJM report was refuted and disparaged. She was later named a TIME 100 Person of the Year.”

Not symptomatic vs. never symptomatic

The term “asymptomatic” could be misleading because some people in this group do progress to develop signs of infection. This “presymptomatic” group of patients is likely a minority, the authors noted. Longitudinal studies indicate that about three-quarters of people who are asymptomatic with SARS-CoV-2 remain so.

Dr. Topol anticipated the one-third asymptomatic finding could draw some feedback about distinguishing asymptomatic from presymptomatic individuals. He tweeted, “Some will argue that there is admixture with presymptomatic cases, but review of all the data supports this estimate as being a conservative one.”

The heterogeneity of the settings, populations and other features of the studies prevented the authors from performing a meta-analysis of the findings.

Home is where the test is

Based on their findings, Mr. Oran and Dr. Topol believe “that COVID-19 control strategies must be altered, taking into account the prevalence and transmission risk of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection.” They suggested frequent use of inexpensive, rapid home tests to identify people who are asymptomatic or presymptomatic, along with programs and housing provided by the government to offer financial assistance and allow this group of people to isolate themselves.

Further research is warranted to determine if and how well vaccines for SARS-CoV-2 prevent asymptomatic infection.

Dr. Topol and Mr. Oran created a short video to highlight the findings from their systematic review.

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A systematic review suggests at least one-third of SARS-CoV-2 infections occur in people who never develop symptoms, providing strong evidence for the prevalence of asymptomatic infections.

The finding that nearly one in three infected people remain symptom free suggests testing should be changed, the investigators noted.

“To reduce transmission from people who are presymptomatic or asymptomatic, we need to shift our testing focus to at-home screening,” lead author Daniel Oran, AM, said in an interview. “Inexpensive rapid antigen tests, provided to millions of people for frequent use, could help us significantly reduce the spread of the virus.”

The systematic review was published online Jan. 22 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The findings come at a dire time when the official number of COVID-19 cases in the United States exceeds 25 million for the first time. Public health officials have raised concerns about more transmissible, and possibly more deadly, variants of SARS-CoV-2, while a new presidential administration tries to meet the challenge of improving vaccine distribution and acceptance rates.

The results also build on earlier findings from the same research team – Mr. Oran and senior author Eric Topol, MD – that published a review article looking at asymptomatic COVID-19 cases. Even though initial data were more limited, they likewise suggested a broader scope of testing is warranted, pointing out that asymptomatic individuals can transmit SARS-CoV-2 for up to 14 days. Dr. Topol is also editor in chief of Medscape.

In the current systematic review, the highest-quality evidence comes from large studies in England and Spain. The nationally representative evidence included serologic surveys from more than 365,000 people in England and more than 61,000 in Spain. When analyzed separately, about the same proportion of asymptomatic cases emerged: 32.4% in England and 33% in Spain.

“It was really remarkable to find that nationwide antibody testing studies in England and Spain – including hundreds of thousands of people – produced nearly identical results: About one-third of the SARS-CoV-2 infections were completely asymptomatic,” said Mr. Oran, a researcher at Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla, Calif.

The systematic review included 43 studies with PCR testing for active SARS-CoV-2 infection and another 18 with antibody results that indicated present or previous infection. The studies were published up until Nov. 17, 2020.

An appreciation for asymptomatic transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection has come a long way from initial dismissals about its importance, Dr. Topol noted via Twitter. “When Dr. @camilla_rothe reported an asymptomatic transmission a year ago, the @NEJM report was refuted and disparaged. She was later named a TIME 100 Person of the Year.”

Not symptomatic vs. never symptomatic

The term “asymptomatic” could be misleading because some people in this group do progress to develop signs of infection. This “presymptomatic” group of patients is likely a minority, the authors noted. Longitudinal studies indicate that about three-quarters of people who are asymptomatic with SARS-CoV-2 remain so.

Dr. Topol anticipated the one-third asymptomatic finding could draw some feedback about distinguishing asymptomatic from presymptomatic individuals. He tweeted, “Some will argue that there is admixture with presymptomatic cases, but review of all the data supports this estimate as being a conservative one.”

The heterogeneity of the settings, populations and other features of the studies prevented the authors from performing a meta-analysis of the findings.

Home is where the test is

Based on their findings, Mr. Oran and Dr. Topol believe “that COVID-19 control strategies must be altered, taking into account the prevalence and transmission risk of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection.” They suggested frequent use of inexpensive, rapid home tests to identify people who are asymptomatic or presymptomatic, along with programs and housing provided by the government to offer financial assistance and allow this group of people to isolate themselves.

Further research is warranted to determine if and how well vaccines for SARS-CoV-2 prevent asymptomatic infection.

Dr. Topol and Mr. Oran created a short video to highlight the findings from their systematic review.

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A systematic review suggests at least one-third of SARS-CoV-2 infections occur in people who never develop symptoms, providing strong evidence for the prevalence of asymptomatic infections.

The finding that nearly one in three infected people remain symptom free suggests testing should be changed, the investigators noted.

“To reduce transmission from people who are presymptomatic or asymptomatic, we need to shift our testing focus to at-home screening,” lead author Daniel Oran, AM, said in an interview. “Inexpensive rapid antigen tests, provided to millions of people for frequent use, could help us significantly reduce the spread of the virus.”

The systematic review was published online Jan. 22 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The findings come at a dire time when the official number of COVID-19 cases in the United States exceeds 25 million for the first time. Public health officials have raised concerns about more transmissible, and possibly more deadly, variants of SARS-CoV-2, while a new presidential administration tries to meet the challenge of improving vaccine distribution and acceptance rates.

The results also build on earlier findings from the same research team – Mr. Oran and senior author Eric Topol, MD – that published a review article looking at asymptomatic COVID-19 cases. Even though initial data were more limited, they likewise suggested a broader scope of testing is warranted, pointing out that asymptomatic individuals can transmit SARS-CoV-2 for up to 14 days. Dr. Topol is also editor in chief of Medscape.

In the current systematic review, the highest-quality evidence comes from large studies in England and Spain. The nationally representative evidence included serologic surveys from more than 365,000 people in England and more than 61,000 in Spain. When analyzed separately, about the same proportion of asymptomatic cases emerged: 32.4% in England and 33% in Spain.

“It was really remarkable to find that nationwide antibody testing studies in England and Spain – including hundreds of thousands of people – produced nearly identical results: About one-third of the SARS-CoV-2 infections were completely asymptomatic,” said Mr. Oran, a researcher at Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla, Calif.

The systematic review included 43 studies with PCR testing for active SARS-CoV-2 infection and another 18 with antibody results that indicated present or previous infection. The studies were published up until Nov. 17, 2020.

An appreciation for asymptomatic transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection has come a long way from initial dismissals about its importance, Dr. Topol noted via Twitter. “When Dr. @camilla_rothe reported an asymptomatic transmission a year ago, the @NEJM report was refuted and disparaged. She was later named a TIME 100 Person of the Year.”

Not symptomatic vs. never symptomatic

The term “asymptomatic” could be misleading because some people in this group do progress to develop signs of infection. This “presymptomatic” group of patients is likely a minority, the authors noted. Longitudinal studies indicate that about three-quarters of people who are asymptomatic with SARS-CoV-2 remain so.

Dr. Topol anticipated the one-third asymptomatic finding could draw some feedback about distinguishing asymptomatic from presymptomatic individuals. He tweeted, “Some will argue that there is admixture with presymptomatic cases, but review of all the data supports this estimate as being a conservative one.”

The heterogeneity of the settings, populations and other features of the studies prevented the authors from performing a meta-analysis of the findings.

Home is where the test is

Based on their findings, Mr. Oran and Dr. Topol believe “that COVID-19 control strategies must be altered, taking into account the prevalence and transmission risk of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection.” They suggested frequent use of inexpensive, rapid home tests to identify people who are asymptomatic or presymptomatic, along with programs and housing provided by the government to offer financial assistance and allow this group of people to isolate themselves.

Further research is warranted to determine if and how well vaccines for SARS-CoV-2 prevent asymptomatic infection.

Dr. Topol and Mr. Oran created a short video to highlight the findings from their systematic review.

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Palliative care underused in pulmonary arterial hypertension

of more than 30,000 hospital admissions has found.

“Specialty palliative care services (PCS) are present in the vast majority of hospitals with more than 300 beds, and PCS use for patients who are facing serious illness with potentially life-limiting prognoses increasingly is becoming the standard of care,” wrote Vidhu Anand, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and colleagues. But despite experts recommending PCS in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), data on the use of palliative care referrals for PAH patients are limited, they added.

In a study published in Chest, the researchers used the National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample to identify 30,495 admissions with a primary diagnosis of PAH between 2001 through 2017. The primary outcome was the use of PCS in these patients.

Overall, inpatient use of PCS was 2.2%, but that figure increased from 0.5% in 2001 to 7.6% in 2017, representing a fivefold increase over the study period, with a significant increase after 2009. The reason for this notable increase remains unclear; however, “it may be related to recognition of palliative care and hospice as a medical subspecialty with board certification in 2008 or identification of palliative care by the National Priorities Partnership as one of six priority areas in 2008,” the researchers said.

Incorporating palliative care in a treatment strategy

The perception of PCS as an element of treatment plans for patients with severe lung disease, and not only as end-of-life care, has certainly increased in recent years, Sachin Gupta, MD, FCCP, said in an interview.

Dr. Gupta is a pulmonologist practicing in the San Francisco Bay area, and he did not take part in the study. He recommended early integration of PCS treating patients with PAH. “I have frequently asked PCS to aid early on during inpatient admission with PAH patients for pain management, as well as for aiding in POLST [Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment] paperwork to be completed. Increased age and comorbidities are certainly risk factors themselves for a longer hospital course and worse outcomes; in addition, in center-based PAH care there are more means available by which to give a patient with right heart failure that ‘one last shot’ – an opportunity for a longer life. I truly think it is a relationship with the patient, built from the outpatient pulmonary hypertension clinic, that allows the treating physician to have a better sense of a patient’s quality of life longitudinally, and to have the candid conversation when things begin to decline.”

Which patients receive PCS?

The study found that socioeconomic factors, and the severity of illness, are the drivers of PCS referrals. In a multivariate analysis, independent predictors of PCS use included white race, private insurance, and higher socioeconomic status. Additional independent predictors of PCS use included increased comorbidities, admission to an urban hospital, admission to a small hospital, presence of heart failure and cardiogenic shock, acute noncardiac organ failure, and use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and noninvasive mechanical ventilation, the researchers noted.

Patients who received PCS consultation were significantly more likely than those not receiving PCS to have DNR status (46.2% vs. 1.8%), longer length of hospital stay (12.9 days vs. 7.2 days), higher hospitalization costs $130,434 vs. $56,499), and higher in-hospital mortality (52.8% vs. 6.4%; P < .001 for all).

Some patients refuse PCS and others are not offered PCS. Dr. Gupta noted that it should be no surprise that not all patients are comfortable with the idea of a PCS referral. “Fear, misunderstanding, and cultural beliefs may be individually or together at the root of resistance to PCS. Their reluctance may be due to a ‘false narrative’ of the purpose of palliative care. The conception of PCS being for end-of-life care may be the result of personal experiences or experience with loved ones. Occasionally, a patient equates PCS with access to narcotics (‘knock me out’), which they may or may not want. I try to reassure patients that there will be no coercion for anything they do not want, and at the end of the day, the medical team is the main driver of their care, not the palliative service.”

Actively drug-abusing PAH patients are a particular challenge, said Dr. Gupta. These patients often refuse palliative care referral both as inpatients and outpatients. “Such patients are an enigma for many PAH-treating physicians as they may survive to discharge, despite a terrible prognosis predicted by their testing.”

In addition, patients in whom organ transplantation is being pursued may not receive timely PCS, he said. “It can be an absolute challenge to bring such patients to the finish line (transplantation), and the timing of PCS referral is often deferred. Arguably, for better or worse, such patients refuse, or more often are not offered, PCS as inpatients while there is still a chance organ transplantation is a viable option for them.”

The use of PCS in less than 10% of PAH admissions is similar to previous studies showing low use of PCS for patients with acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and COPD, the researchers noted. However, “Given the high morbidity and mortality associated with PAH even after hospitalization, hospital admissions without PCS use represent a missed opportunity,” the investigators wrote.

Early warning on the need for PCS

Increasing PCS referrals for PAH patients requires clinicians to be proactive, Dr. Gupta stressed. “Pulmonologists, especially those managing pulmonary hypertension outpatients without the aid of a PAH center, should remain vigilant at all routine visits to calculate a patient’s risk score (i.e. REVEAL 2.0 risk calculator) to stratify their risk of 1-year mortality. Based on this assessment, shared decision making can help guide next steps including early outpatient PCS involvement for those at high risk. I also calculate a patient’s risk score, based on the data I have, when PAH patients are admitted to the hospital. Occasionally, a patient who I initially think is moderate risk turns out to be high risk when I calculate their risk score. In such high-risk patients, PCS consultation should certainly be considered early on.”

The study findings were limited by several factors including the possible coding errors associated with use of discharge diagnosis, lack of data on medication and the cause of PAH, and lack of information on the reasons for PCS referrals, the researchers noted. However, the results “addressed an important knowledge gap highlighting the national use of PCS in PAH,” they said. Further research is needed to address disparities and the integration of PCS into PAH care protocols, they added.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The study received no outside funding; one coauthor disclosed support from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Clinical and Translational Science.

of more than 30,000 hospital admissions has found.

“Specialty palliative care services (PCS) are present in the vast majority of hospitals with more than 300 beds, and PCS use for patients who are facing serious illness with potentially life-limiting prognoses increasingly is becoming the standard of care,” wrote Vidhu Anand, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and colleagues. But despite experts recommending PCS in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), data on the use of palliative care referrals for PAH patients are limited, they added.

In a study published in Chest, the researchers used the National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample to identify 30,495 admissions with a primary diagnosis of PAH between 2001 through 2017. The primary outcome was the use of PCS in these patients.

Overall, inpatient use of PCS was 2.2%, but that figure increased from 0.5% in 2001 to 7.6% in 2017, representing a fivefold increase over the study period, with a significant increase after 2009. The reason for this notable increase remains unclear; however, “it may be related to recognition of palliative care and hospice as a medical subspecialty with board certification in 2008 or identification of palliative care by the National Priorities Partnership as one of six priority areas in 2008,” the researchers said.

Incorporating palliative care in a treatment strategy

The perception of PCS as an element of treatment plans for patients with severe lung disease, and not only as end-of-life care, has certainly increased in recent years, Sachin Gupta, MD, FCCP, said in an interview.

Dr. Gupta is a pulmonologist practicing in the San Francisco Bay area, and he did not take part in the study. He recommended early integration of PCS treating patients with PAH. “I have frequently asked PCS to aid early on during inpatient admission with PAH patients for pain management, as well as for aiding in POLST [Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment] paperwork to be completed. Increased age and comorbidities are certainly risk factors themselves for a longer hospital course and worse outcomes; in addition, in center-based PAH care there are more means available by which to give a patient with right heart failure that ‘one last shot’ – an opportunity for a longer life. I truly think it is a relationship with the patient, built from the outpatient pulmonary hypertension clinic, that allows the treating physician to have a better sense of a patient’s quality of life longitudinally, and to have the candid conversation when things begin to decline.”

Which patients receive PCS?

The study found that socioeconomic factors, and the severity of illness, are the drivers of PCS referrals. In a multivariate analysis, independent predictors of PCS use included white race, private insurance, and higher socioeconomic status. Additional independent predictors of PCS use included increased comorbidities, admission to an urban hospital, admission to a small hospital, presence of heart failure and cardiogenic shock, acute noncardiac organ failure, and use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and noninvasive mechanical ventilation, the researchers noted.

Patients who received PCS consultation were significantly more likely than those not receiving PCS to have DNR status (46.2% vs. 1.8%), longer length of hospital stay (12.9 days vs. 7.2 days), higher hospitalization costs $130,434 vs. $56,499), and higher in-hospital mortality (52.8% vs. 6.4%; P < .001 for all).

Some patients refuse PCS and others are not offered PCS. Dr. Gupta noted that it should be no surprise that not all patients are comfortable with the idea of a PCS referral. “Fear, misunderstanding, and cultural beliefs may be individually or together at the root of resistance to PCS. Their reluctance may be due to a ‘false narrative’ of the purpose of palliative care. The conception of PCS being for end-of-life care may be the result of personal experiences or experience with loved ones. Occasionally, a patient equates PCS with access to narcotics (‘knock me out’), which they may or may not want. I try to reassure patients that there will be no coercion for anything they do not want, and at the end of the day, the medical team is the main driver of their care, not the palliative service.”

Actively drug-abusing PAH patients are a particular challenge, said Dr. Gupta. These patients often refuse palliative care referral both as inpatients and outpatients. “Such patients are an enigma for many PAH-treating physicians as they may survive to discharge, despite a terrible prognosis predicted by their testing.”

In addition, patients in whom organ transplantation is being pursued may not receive timely PCS, he said. “It can be an absolute challenge to bring such patients to the finish line (transplantation), and the timing of PCS referral is often deferred. Arguably, for better or worse, such patients refuse, or more often are not offered, PCS as inpatients while there is still a chance organ transplantation is a viable option for them.”

The use of PCS in less than 10% of PAH admissions is similar to previous studies showing low use of PCS for patients with acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and COPD, the researchers noted. However, “Given the high morbidity and mortality associated with PAH even after hospitalization, hospital admissions without PCS use represent a missed opportunity,” the investigators wrote.

Early warning on the need for PCS

Increasing PCS referrals for PAH patients requires clinicians to be proactive, Dr. Gupta stressed. “Pulmonologists, especially those managing pulmonary hypertension outpatients without the aid of a PAH center, should remain vigilant at all routine visits to calculate a patient’s risk score (i.e. REVEAL 2.0 risk calculator) to stratify their risk of 1-year mortality. Based on this assessment, shared decision making can help guide next steps including early outpatient PCS involvement for those at high risk. I also calculate a patient’s risk score, based on the data I have, when PAH patients are admitted to the hospital. Occasionally, a patient who I initially think is moderate risk turns out to be high risk when I calculate their risk score. In such high-risk patients, PCS consultation should certainly be considered early on.”

The study findings were limited by several factors including the possible coding errors associated with use of discharge diagnosis, lack of data on medication and the cause of PAH, and lack of information on the reasons for PCS referrals, the researchers noted. However, the results “addressed an important knowledge gap highlighting the national use of PCS in PAH,” they said. Further research is needed to address disparities and the integration of PCS into PAH care protocols, they added.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The study received no outside funding; one coauthor disclosed support from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Clinical and Translational Science.

of more than 30,000 hospital admissions has found.

“Specialty palliative care services (PCS) are present in the vast majority of hospitals with more than 300 beds, and PCS use for patients who are facing serious illness with potentially life-limiting prognoses increasingly is becoming the standard of care,” wrote Vidhu Anand, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and colleagues. But despite experts recommending PCS in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), data on the use of palliative care referrals for PAH patients are limited, they added.

In a study published in Chest, the researchers used the National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample to identify 30,495 admissions with a primary diagnosis of PAH between 2001 through 2017. The primary outcome was the use of PCS in these patients.

Overall, inpatient use of PCS was 2.2%, but that figure increased from 0.5% in 2001 to 7.6% in 2017, representing a fivefold increase over the study period, with a significant increase after 2009. The reason for this notable increase remains unclear; however, “it may be related to recognition of palliative care and hospice as a medical subspecialty with board certification in 2008 or identification of palliative care by the National Priorities Partnership as one of six priority areas in 2008,” the researchers said.

Incorporating palliative care in a treatment strategy

The perception of PCS as an element of treatment plans for patients with severe lung disease, and not only as end-of-life care, has certainly increased in recent years, Sachin Gupta, MD, FCCP, said in an interview.

Dr. Gupta is a pulmonologist practicing in the San Francisco Bay area, and he did not take part in the study. He recommended early integration of PCS treating patients with PAH. “I have frequently asked PCS to aid early on during inpatient admission with PAH patients for pain management, as well as for aiding in POLST [Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment] paperwork to be completed. Increased age and comorbidities are certainly risk factors themselves for a longer hospital course and worse outcomes; in addition, in center-based PAH care there are more means available by which to give a patient with right heart failure that ‘one last shot’ – an opportunity for a longer life. I truly think it is a relationship with the patient, built from the outpatient pulmonary hypertension clinic, that allows the treating physician to have a better sense of a patient’s quality of life longitudinally, and to have the candid conversation when things begin to decline.”

Which patients receive PCS?

The study found that socioeconomic factors, and the severity of illness, are the drivers of PCS referrals. In a multivariate analysis, independent predictors of PCS use included white race, private insurance, and higher socioeconomic status. Additional independent predictors of PCS use included increased comorbidities, admission to an urban hospital, admission to a small hospital, presence of heart failure and cardiogenic shock, acute noncardiac organ failure, and use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and noninvasive mechanical ventilation, the researchers noted.

Patients who received PCS consultation were significantly more likely than those not receiving PCS to have DNR status (46.2% vs. 1.8%), longer length of hospital stay (12.9 days vs. 7.2 days), higher hospitalization costs $130,434 vs. $56,499), and higher in-hospital mortality (52.8% vs. 6.4%; P < .001 for all).

Some patients refuse PCS and others are not offered PCS. Dr. Gupta noted that it should be no surprise that not all patients are comfortable with the idea of a PCS referral. “Fear, misunderstanding, and cultural beliefs may be individually or together at the root of resistance to PCS. Their reluctance may be due to a ‘false narrative’ of the purpose of palliative care. The conception of PCS being for end-of-life care may be the result of personal experiences or experience with loved ones. Occasionally, a patient equates PCS with access to narcotics (‘knock me out’), which they may or may not want. I try to reassure patients that there will be no coercion for anything they do not want, and at the end of the day, the medical team is the main driver of their care, not the palliative service.”

Actively drug-abusing PAH patients are a particular challenge, said Dr. Gupta. These patients often refuse palliative care referral both as inpatients and outpatients. “Such patients are an enigma for many PAH-treating physicians as they may survive to discharge, despite a terrible prognosis predicted by their testing.”

In addition, patients in whom organ transplantation is being pursued may not receive timely PCS, he said. “It can be an absolute challenge to bring such patients to the finish line (transplantation), and the timing of PCS referral is often deferred. Arguably, for better or worse, such patients refuse, or more often are not offered, PCS as inpatients while there is still a chance organ transplantation is a viable option for them.”

The use of PCS in less than 10% of PAH admissions is similar to previous studies showing low use of PCS for patients with acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and COPD, the researchers noted. However, “Given the high morbidity and mortality associated with PAH even after hospitalization, hospital admissions without PCS use represent a missed opportunity,” the investigators wrote.

Early warning on the need for PCS

Increasing PCS referrals for PAH patients requires clinicians to be proactive, Dr. Gupta stressed. “Pulmonologists, especially those managing pulmonary hypertension outpatients without the aid of a PAH center, should remain vigilant at all routine visits to calculate a patient’s risk score (i.e. REVEAL 2.0 risk calculator) to stratify their risk of 1-year mortality. Based on this assessment, shared decision making can help guide next steps including early outpatient PCS involvement for those at high risk. I also calculate a patient’s risk score, based on the data I have, when PAH patients are admitted to the hospital. Occasionally, a patient who I initially think is moderate risk turns out to be high risk when I calculate their risk score. In such high-risk patients, PCS consultation should certainly be considered early on.”

The study findings were limited by several factors including the possible coding errors associated with use of discharge diagnosis, lack of data on medication and the cause of PAH, and lack of information on the reasons for PCS referrals, the researchers noted. However, the results “addressed an important knowledge gap highlighting the national use of PCS in PAH,” they said. Further research is needed to address disparities and the integration of PCS into PAH care protocols, they added.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The study received no outside funding; one coauthor disclosed support from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Clinical and Translational Science.

FROM CHEST

Vaccines may not be as effective against variants

The current COVID-19 vaccines may not be as effective against new coronavirus variants, but they should be powerful enough to still be beneficial, Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said during a news briefing on Jan. 21.

Both vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna have such high efficacy rates that it creates a “cushion effect,” he said, meaning that new variants will likely only diminish vaccine efficacy slightly.

“Bottom line: We’re paying very close attention to it,” he said. “There are alternative plans if we ever have to modify the vaccine.”

The U.S. has reported 144 cases of the B.1.1.7 variant, which was first identified in the United Kingdom, according to the latest update from the CDC. So far, no cases of the variant strain identified in South Africa have been reported in the U.S., but Dr. Fauci said public health officials are looking for it.

“We’re following very carefully the one in South Africa, which is a little bit more concerning, but nonetheless not something that we don’t think we can handle,” he said.

Despite challenges with vaccine distribution and administration, the U.S. “can and should” vaccinate 70% to 85% of adults by the end of the summer, Dr. Fauci told CNN. If that happens, people could begin to return to some sense of normalcy by the fall, he added.

“When you put ... the pedal to the floor, you can get it done,” he said.

If the U.S. administered one million shots per day, it would take until the end of 2021 to fully vaccine 75% of adults, according to a CNN analysis. Dr. Fauci said he believes the U.S. can give more than one million shots per day. An updated tally from the CDC showed that 1.6 million shots were given in the past 24 hours, which was the largest single-day increase yet reported.

“I’d like it to be a lot more,” Dr. Fauci told CNN. “If we can do better than that, which I personally think we likely will, then great.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The current COVID-19 vaccines may not be as effective against new coronavirus variants, but they should be powerful enough to still be beneficial, Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said during a news briefing on Jan. 21.

Both vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna have such high efficacy rates that it creates a “cushion effect,” he said, meaning that new variants will likely only diminish vaccine efficacy slightly.

“Bottom line: We’re paying very close attention to it,” he said. “There are alternative plans if we ever have to modify the vaccine.”

The U.S. has reported 144 cases of the B.1.1.7 variant, which was first identified in the United Kingdom, according to the latest update from the CDC. So far, no cases of the variant strain identified in South Africa have been reported in the U.S., but Dr. Fauci said public health officials are looking for it.

“We’re following very carefully the one in South Africa, which is a little bit more concerning, but nonetheless not something that we don’t think we can handle,” he said.

Despite challenges with vaccine distribution and administration, the U.S. “can and should” vaccinate 70% to 85% of adults by the end of the summer, Dr. Fauci told CNN. If that happens, people could begin to return to some sense of normalcy by the fall, he added.

“When you put ... the pedal to the floor, you can get it done,” he said.

If the U.S. administered one million shots per day, it would take until the end of 2021 to fully vaccine 75% of adults, according to a CNN analysis. Dr. Fauci said he believes the U.S. can give more than one million shots per day. An updated tally from the CDC showed that 1.6 million shots were given in the past 24 hours, which was the largest single-day increase yet reported.

“I’d like it to be a lot more,” Dr. Fauci told CNN. “If we can do better than that, which I personally think we likely will, then great.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The current COVID-19 vaccines may not be as effective against new coronavirus variants, but they should be powerful enough to still be beneficial, Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said during a news briefing on Jan. 21.

Both vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna have such high efficacy rates that it creates a “cushion effect,” he said, meaning that new variants will likely only diminish vaccine efficacy slightly.

“Bottom line: We’re paying very close attention to it,” he said. “There are alternative plans if we ever have to modify the vaccine.”

The U.S. has reported 144 cases of the B.1.1.7 variant, which was first identified in the United Kingdom, according to the latest update from the CDC. So far, no cases of the variant strain identified in South Africa have been reported in the U.S., but Dr. Fauci said public health officials are looking for it.

“We’re following very carefully the one in South Africa, which is a little bit more concerning, but nonetheless not something that we don’t think we can handle,” he said.

Despite challenges with vaccine distribution and administration, the U.S. “can and should” vaccinate 70% to 85% of adults by the end of the summer, Dr. Fauci told CNN. If that happens, people could begin to return to some sense of normalcy by the fall, he added.

“When you put ... the pedal to the floor, you can get it done,” he said.

If the U.S. administered one million shots per day, it would take until the end of 2021 to fully vaccine 75% of adults, according to a CNN analysis. Dr. Fauci said he believes the U.S. can give more than one million shots per day. An updated tally from the CDC showed that 1.6 million shots were given in the past 24 hours, which was the largest single-day increase yet reported.

“I’d like it to be a lot more,” Dr. Fauci told CNN. “If we can do better than that, which I personally think we likely will, then great.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

ColCORONA: Colchicine reduces complications in outpatient COVID-19

The oral, anti-inflammatory drug colchicine can prevent complications and hospitalizations in nonhospitalized patients newly diagnosed with COVID-19, according to a press release from the ColCORONA trial investigators.

After 1 month of therapy, there was a 21% risk reduction in the primary composite endpoint of death or hospitalizations that missed statistical significance, compared with placebo among 4,488 outpatients enrolled in the global, phase 3 trial.

After excluding 329 patients without a confirmatory polymerase chain reaction test, however, the use of colchicine was reported to significantly reduce hospitalizations by 25%, the need for mechanical ventilation by 50%, and deaths by 44%.

“We believe that this is a medical breakthrough. There’s no approved therapy to prevent complications of COVID-19 in outpatients, to prevent them from reaching the hospital,” lead investigator Jean-Claude Tardif, MD, from the Montreal Heart Institute, said in an interview.

“I know that several countries will be reviewing the data very rapidly and that Greece approved it today,” he said. “So this is providing hope for patients.”

Having been burned by hydroxychloroquine and other treatments brought forth without peer review, the response to the announcement was tempered by a desire for more details.

Asked for comment, Steven E. Nissen, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation, was cautious. “The press release about the trial is vague and lacks details such as hazard ratios, confidence intervals, and P values,” he said in an interview.

“It is impossible to evaluate the results of this trial without these details. It is also uncertain how rigorously data were collected,” he added. “We’ll need to see the manuscript to adequately interpret the results.”

The evidence in the press release is hard to interpret, but early intervention with anti-inflammatory therapy has considerable biologic appeal in COVID, said Paul Ridker, MD, MPH, who led the pivotal CANTOS trial of the anti-inflammatory drug canakinumab in the post-MI setting, and is also chair of the ACTIV-4B trial currently investigating anticoagulants and antithrombotics in outpatient COVID-19.

“Colchicine is both inexpensive and generally well tolerated, and the apparent benefits so far reported are substantial,” Dr. Ridker, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said in an interview. “We are eager to see the full data as rapidly as possible.”

The commonly used gout and rheumatic disease agent costs about 26 cents in Canada and between $4 and $6 in the United States. As previously reported, it reduced the time to clinical deterioration and hospital stay but not mortality in the 105-patient Greek Study in the Effects of Colchicine in COVID-19 Complications Prevention (GRECCO-19) study.

Dr. Tardif said he’s looking forward to having the data in the public domain and that they acted swiftly because the evidence was “clinically persuasive” and “the health system is congested now.”

“We received the results Friday, Jan. 22 at 5 p.m., an hour later we were in meetings with our data safety monitoring board [DSMB], 2 hours later we issued a press release, and a day later we’re submitting a full manuscript to a major scientific journal, so I don’t know if anyone has done this at this speed,” he said. “So we are actually very proud of what we did.”

ColCORONA was designed to enroll 6,000 outpatients, at least 40 years of age, who were diagnosed with COVID-19 infection within the previous 24 hours, and had a least one high-risk criterion, including age at least 70 years, body mass index of at least 30 kg/m2, diabetes mellitus, uncontrolled hypertension, known respiratory disease, heart failure or coronary disease, fever of at least 38.4° C within the last 48 hours, dyspnea at presentation, bicytopenia, pancytopenia, or the combination of high neutrophil count and low lymphocyte count.

Participants were randomly assigned to receive either placebo or colchicine 0.5 mg twice daily for 3 days and then once daily for another 27 days.

The number needed to prevent one COVID-19 complication is about 60 patients, Dr. Tardif said.

Colchicine was well tolerated and resulted in fewer serious adverse events than with placebo, he said. Diarrhea occurred more often with colchicine, but there was no increase in pneumonia. Caution should be used, however, in treating patients with severe renal disease.

Dr. Tardif said he would not prescribe colchicine to an 18-year-old COVID outpatient who doesn’t have any concomitant diseases, but would for those meeting the study protocol.

“As long as a patient appears to me to be at risk of a complication, I would prescribe it, without a doubt,” he said. “I can tell you that when we held the meeting with the DSMB Friday evening, I actually put each member on the spot and asked them: ‘If it were you – not even treating a patient, but if you had COVID today, would you take it based on the data you’ve seen?’ and all of the DSMB members said they would.

“So we’ll have that debate in the public domain when the paper is out, but I believe most physicians will use it to treat their patients.”

The trial was coordinated by the Montreal Heart Institute and funded by the government of Quebec; the U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Montreal philanthropist Sophie Desmarais; and the COVID-19 Therapeutics Accelerator launched by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Wellcome, and Mastercard. CGI, Dacima, and Pharmascience of Montreal were also collaborators.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The oral, anti-inflammatory drug colchicine can prevent complications and hospitalizations in nonhospitalized patients newly diagnosed with COVID-19, according to a press release from the ColCORONA trial investigators.

After 1 month of therapy, there was a 21% risk reduction in the primary composite endpoint of death or hospitalizations that missed statistical significance, compared with placebo among 4,488 outpatients enrolled in the global, phase 3 trial.

After excluding 329 patients without a confirmatory polymerase chain reaction test, however, the use of colchicine was reported to significantly reduce hospitalizations by 25%, the need for mechanical ventilation by 50%, and deaths by 44%.

“We believe that this is a medical breakthrough. There’s no approved therapy to prevent complications of COVID-19 in outpatients, to prevent them from reaching the hospital,” lead investigator Jean-Claude Tardif, MD, from the Montreal Heart Institute, said in an interview.

“I know that several countries will be reviewing the data very rapidly and that Greece approved it today,” he said. “So this is providing hope for patients.”

Having been burned by hydroxychloroquine and other treatments brought forth without peer review, the response to the announcement was tempered by a desire for more details.

Asked for comment, Steven E. Nissen, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation, was cautious. “The press release about the trial is vague and lacks details such as hazard ratios, confidence intervals, and P values,” he said in an interview.

“It is impossible to evaluate the results of this trial without these details. It is also uncertain how rigorously data were collected,” he added. “We’ll need to see the manuscript to adequately interpret the results.”

The evidence in the press release is hard to interpret, but early intervention with anti-inflammatory therapy has considerable biologic appeal in COVID, said Paul Ridker, MD, MPH, who led the pivotal CANTOS trial of the anti-inflammatory drug canakinumab in the post-MI setting, and is also chair of the ACTIV-4B trial currently investigating anticoagulants and antithrombotics in outpatient COVID-19.

“Colchicine is both inexpensive and generally well tolerated, and the apparent benefits so far reported are substantial,” Dr. Ridker, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said in an interview. “We are eager to see the full data as rapidly as possible.”

The commonly used gout and rheumatic disease agent costs about 26 cents in Canada and between $4 and $6 in the United States. As previously reported, it reduced the time to clinical deterioration and hospital stay but not mortality in the 105-patient Greek Study in the Effects of Colchicine in COVID-19 Complications Prevention (GRECCO-19) study.

Dr. Tardif said he’s looking forward to having the data in the public domain and that they acted swiftly because the evidence was “clinically persuasive” and “the health system is congested now.”

“We received the results Friday, Jan. 22 at 5 p.m., an hour later we were in meetings with our data safety monitoring board [DSMB], 2 hours later we issued a press release, and a day later we’re submitting a full manuscript to a major scientific journal, so I don’t know if anyone has done this at this speed,” he said. “So we are actually very proud of what we did.”

ColCORONA was designed to enroll 6,000 outpatients, at least 40 years of age, who were diagnosed with COVID-19 infection within the previous 24 hours, and had a least one high-risk criterion, including age at least 70 years, body mass index of at least 30 kg/m2, diabetes mellitus, uncontrolled hypertension, known respiratory disease, heart failure or coronary disease, fever of at least 38.4° C within the last 48 hours, dyspnea at presentation, bicytopenia, pancytopenia, or the combination of high neutrophil count and low lymphocyte count.

Participants were randomly assigned to receive either placebo or colchicine 0.5 mg twice daily for 3 days and then once daily for another 27 days.

The number needed to prevent one COVID-19 complication is about 60 patients, Dr. Tardif said.

Colchicine was well tolerated and resulted in fewer serious adverse events than with placebo, he said. Diarrhea occurred more often with colchicine, but there was no increase in pneumonia. Caution should be used, however, in treating patients with severe renal disease.

Dr. Tardif said he would not prescribe colchicine to an 18-year-old COVID outpatient who doesn’t have any concomitant diseases, but would for those meeting the study protocol.

“As long as a patient appears to me to be at risk of a complication, I would prescribe it, without a doubt,” he said. “I can tell you that when we held the meeting with the DSMB Friday evening, I actually put each member on the spot and asked them: ‘If it were you – not even treating a patient, but if you had COVID today, would you take it based on the data you’ve seen?’ and all of the DSMB members said they would.

“So we’ll have that debate in the public domain when the paper is out, but I believe most physicians will use it to treat their patients.”

The trial was coordinated by the Montreal Heart Institute and funded by the government of Quebec; the U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Montreal philanthropist Sophie Desmarais; and the COVID-19 Therapeutics Accelerator launched by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Wellcome, and Mastercard. CGI, Dacima, and Pharmascience of Montreal were also collaborators.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The oral, anti-inflammatory drug colchicine can prevent complications and hospitalizations in nonhospitalized patients newly diagnosed with COVID-19, according to a press release from the ColCORONA trial investigators.

After 1 month of therapy, there was a 21% risk reduction in the primary composite endpoint of death or hospitalizations that missed statistical significance, compared with placebo among 4,488 outpatients enrolled in the global, phase 3 trial.

After excluding 329 patients without a confirmatory polymerase chain reaction test, however, the use of colchicine was reported to significantly reduce hospitalizations by 25%, the need for mechanical ventilation by 50%, and deaths by 44%.

“We believe that this is a medical breakthrough. There’s no approved therapy to prevent complications of COVID-19 in outpatients, to prevent them from reaching the hospital,” lead investigator Jean-Claude Tardif, MD, from the Montreal Heart Institute, said in an interview.

“I know that several countries will be reviewing the data very rapidly and that Greece approved it today,” he said. “So this is providing hope for patients.”

Having been burned by hydroxychloroquine and other treatments brought forth without peer review, the response to the announcement was tempered by a desire for more details.

Asked for comment, Steven E. Nissen, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation, was cautious. “The press release about the trial is vague and lacks details such as hazard ratios, confidence intervals, and P values,” he said in an interview.

“It is impossible to evaluate the results of this trial without these details. It is also uncertain how rigorously data were collected,” he added. “We’ll need to see the manuscript to adequately interpret the results.”

The evidence in the press release is hard to interpret, but early intervention with anti-inflammatory therapy has considerable biologic appeal in COVID, said Paul Ridker, MD, MPH, who led the pivotal CANTOS trial of the anti-inflammatory drug canakinumab in the post-MI setting, and is also chair of the ACTIV-4B trial currently investigating anticoagulants and antithrombotics in outpatient COVID-19.

“Colchicine is both inexpensive and generally well tolerated, and the apparent benefits so far reported are substantial,” Dr. Ridker, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said in an interview. “We are eager to see the full data as rapidly as possible.”

The commonly used gout and rheumatic disease agent costs about 26 cents in Canada and between $4 and $6 in the United States. As previously reported, it reduced the time to clinical deterioration and hospital stay but not mortality in the 105-patient Greek Study in the Effects of Colchicine in COVID-19 Complications Prevention (GRECCO-19) study.

Dr. Tardif said he’s looking forward to having the data in the public domain and that they acted swiftly because the evidence was “clinically persuasive” and “the health system is congested now.”

“We received the results Friday, Jan. 22 at 5 p.m., an hour later we were in meetings with our data safety monitoring board [DSMB], 2 hours later we issued a press release, and a day later we’re submitting a full manuscript to a major scientific journal, so I don’t know if anyone has done this at this speed,” he said. “So we are actually very proud of what we did.”

ColCORONA was designed to enroll 6,000 outpatients, at least 40 years of age, who were diagnosed with COVID-19 infection within the previous 24 hours, and had a least one high-risk criterion, including age at least 70 years, body mass index of at least 30 kg/m2, diabetes mellitus, uncontrolled hypertension, known respiratory disease, heart failure or coronary disease, fever of at least 38.4° C within the last 48 hours, dyspnea at presentation, bicytopenia, pancytopenia, or the combination of high neutrophil count and low lymphocyte count.

Participants were randomly assigned to receive either placebo or colchicine 0.5 mg twice daily for 3 days and then once daily for another 27 days.

The number needed to prevent one COVID-19 complication is about 60 patients, Dr. Tardif said.

Colchicine was well tolerated and resulted in fewer serious adverse events than with placebo, he said. Diarrhea occurred more often with colchicine, but there was no increase in pneumonia. Caution should be used, however, in treating patients with severe renal disease.

Dr. Tardif said he would not prescribe colchicine to an 18-year-old COVID outpatient who doesn’t have any concomitant diseases, but would for those meeting the study protocol.

“As long as a patient appears to me to be at risk of a complication, I would prescribe it, without a doubt,” he said. “I can tell you that when we held the meeting with the DSMB Friday evening, I actually put each member on the spot and asked them: ‘If it were you – not even treating a patient, but if you had COVID today, would you take it based on the data you’ve seen?’ and all of the DSMB members said they would.

“So we’ll have that debate in the public domain when the paper is out, but I believe most physicians will use it to treat their patients.”

The trial was coordinated by the Montreal Heart Institute and funded by the government of Quebec; the U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Montreal philanthropist Sophie Desmarais; and the COVID-19 Therapeutics Accelerator launched by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Wellcome, and Mastercard. CGI, Dacima, and Pharmascience of Montreal were also collaborators.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Full-dose anticoagulation reduces need for life support in COVID-19

Full-dose anticoagulation was superior to low, prophylactic doses in reducing the need for vital organ support such as ventilation in moderately ill patients hospitalized for COVID-19, according to a report released Jan. 22 by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

“This is a major advance for patients hospitalized with COVID. Full dose of anticoagulation in these non-ICU patients improved outcomes and there’s a trend toward a reduction in mortality,” Judith Hochman, MD, director of the Cardiovascular Clinical Research Center at NYU Langone Medical Center, New York, said in an interview.

“We have treatments that are improving outcomes but not as many that reduce mortality, so we’re hopeful when the full dataset comes in that will be confirmed,” she said.

The observation of increased rates of blood clots and inflammation among COVID-19 patients, which can lead to complications such as lung failure, heart attack, and stroke, has given rise to various anticoagulant treatment protocols and a need for randomized data on routinely administering increased doses of anticoagulation to hospitalized patients.

Today’s top-line findings come from three linked clinical trials – REMAP-CAP, ACTIV-4, and ATTACC – examining the safety and efficacy of full-dose anticoagulation to treat moderately ill or critically ill adults hospitalized with COVID-19 compared with a lower dose typically used to prevent blood clots in hospitalized patients.

In December 2020, all three trials paused enrollment of the critically ill subgroup after results showed that full-dose anticoagulation started in the intensive care unit (ICU) was not beneficial and may have been harmful in some patients.

Moderately ill patients with COVID-19, defined as those who did not require ICU care or organ support, made up 80% of participants at enrollment in the three trials, Dr. Hochman said.