User login

Long COVID comes in three forms: Study

, according to a new preprint study published on MedRxiv that hasn’t yet been peer-reviewed.

Long COVID has been hard to define due to its large number of symptoms, but researchers at King’s College London have identified three distinct profiles – with long-term symptoms focused on neurological, respiratory, or physical conditions. So far, they also found patterns among people infected with the original coronavirus strain, the Alpha variant, and the Delta variant.

“These data show clearly that post-COVID syndrome is not just one condition but appears to have several subtypes,” Claire Steves, PhD, one of the study authors and a senior clinical lecturer in King’s College London’s School of Life Course & Population Sciences, said in a statement.

“Understanding the root causes of these subtypes may help in finding treatment strategies,” she said. “Moreover, these data emphasize the need for long-COVID services to incorporate a personalized approach sensitive to the issues of each individual.”

The research team analyzed ZOE COVID app data for 1,459 people who have had symptoms for more than 84 days, or 12 weeks, according to their definition of long COVID or post-COVID syndrome.

They found that the largest group had a cluster of symptoms in the nervous system, such as fatigue, brain fog, and headaches. It was the most common subtype among the Alpha variant, which was dominant in winter 2020-2021, and the Delta variant, which was dominant in 2021.

The second group had respiratory symptoms, such as chest pain and severe shortness of breath, which could suggest lung damage, the researchers wrote. It was the largest cluster for the original coronavirus strain in spring 2020, when people were unvaccinated.

The third group included people who reported a diverse range of physical symptoms, including heart palpitations, muscle aches and pain, and changes to their skin and hair. This group had some of the “most severe and debilitating multi-organ symptoms,” the researchers wrote.

The researchers found that the subtypes were similar in vaccinated and unvaccinated people based on the variants investigated so far. But the data showed that the risk of long COVID was reduced by vaccination.

In addition, although the three subtypes were present in all the variants, other symptom clusters had subtle differences among the variants, such as symptoms in the stomach and intestines. The differences could be due to other things that changed during the pandemic, such as the time of year, social behaviors, and treatments, the researchers said.

“Machine learning approaches, such as clustering analysis, have made it possible to start exploring and identifying different profiles of post-COVID syndrome,” Marc Modat, PhD, who led the analysis and is a senior lecturer at King’s College London’s School of Biomedical Engineering & Imaging Sciences, said in the statement.

“This opens new avenues of research to better understand COVID-19 and to motivate clinical research that might mitigate the long-term effects of the disease,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, according to a new preprint study published on MedRxiv that hasn’t yet been peer-reviewed.

Long COVID has been hard to define due to its large number of symptoms, but researchers at King’s College London have identified three distinct profiles – with long-term symptoms focused on neurological, respiratory, or physical conditions. So far, they also found patterns among people infected with the original coronavirus strain, the Alpha variant, and the Delta variant.

“These data show clearly that post-COVID syndrome is not just one condition but appears to have several subtypes,” Claire Steves, PhD, one of the study authors and a senior clinical lecturer in King’s College London’s School of Life Course & Population Sciences, said in a statement.

“Understanding the root causes of these subtypes may help in finding treatment strategies,” she said. “Moreover, these data emphasize the need for long-COVID services to incorporate a personalized approach sensitive to the issues of each individual.”

The research team analyzed ZOE COVID app data for 1,459 people who have had symptoms for more than 84 days, or 12 weeks, according to their definition of long COVID or post-COVID syndrome.

They found that the largest group had a cluster of symptoms in the nervous system, such as fatigue, brain fog, and headaches. It was the most common subtype among the Alpha variant, which was dominant in winter 2020-2021, and the Delta variant, which was dominant in 2021.

The second group had respiratory symptoms, such as chest pain and severe shortness of breath, which could suggest lung damage, the researchers wrote. It was the largest cluster for the original coronavirus strain in spring 2020, when people were unvaccinated.

The third group included people who reported a diverse range of physical symptoms, including heart palpitations, muscle aches and pain, and changes to their skin and hair. This group had some of the “most severe and debilitating multi-organ symptoms,” the researchers wrote.

The researchers found that the subtypes were similar in vaccinated and unvaccinated people based on the variants investigated so far. But the data showed that the risk of long COVID was reduced by vaccination.

In addition, although the three subtypes were present in all the variants, other symptom clusters had subtle differences among the variants, such as symptoms in the stomach and intestines. The differences could be due to other things that changed during the pandemic, such as the time of year, social behaviors, and treatments, the researchers said.

“Machine learning approaches, such as clustering analysis, have made it possible to start exploring and identifying different profiles of post-COVID syndrome,” Marc Modat, PhD, who led the analysis and is a senior lecturer at King’s College London’s School of Biomedical Engineering & Imaging Sciences, said in the statement.

“This opens new avenues of research to better understand COVID-19 and to motivate clinical research that might mitigate the long-term effects of the disease,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, according to a new preprint study published on MedRxiv that hasn’t yet been peer-reviewed.

Long COVID has been hard to define due to its large number of symptoms, but researchers at King’s College London have identified three distinct profiles – with long-term symptoms focused on neurological, respiratory, or physical conditions. So far, they also found patterns among people infected with the original coronavirus strain, the Alpha variant, and the Delta variant.

“These data show clearly that post-COVID syndrome is not just one condition but appears to have several subtypes,” Claire Steves, PhD, one of the study authors and a senior clinical lecturer in King’s College London’s School of Life Course & Population Sciences, said in a statement.

“Understanding the root causes of these subtypes may help in finding treatment strategies,” she said. “Moreover, these data emphasize the need for long-COVID services to incorporate a personalized approach sensitive to the issues of each individual.”

The research team analyzed ZOE COVID app data for 1,459 people who have had symptoms for more than 84 days, or 12 weeks, according to their definition of long COVID or post-COVID syndrome.

They found that the largest group had a cluster of symptoms in the nervous system, such as fatigue, brain fog, and headaches. It was the most common subtype among the Alpha variant, which was dominant in winter 2020-2021, and the Delta variant, which was dominant in 2021.

The second group had respiratory symptoms, such as chest pain and severe shortness of breath, which could suggest lung damage, the researchers wrote. It was the largest cluster for the original coronavirus strain in spring 2020, when people were unvaccinated.

The third group included people who reported a diverse range of physical symptoms, including heart palpitations, muscle aches and pain, and changes to their skin and hair. This group had some of the “most severe and debilitating multi-organ symptoms,” the researchers wrote.

The researchers found that the subtypes were similar in vaccinated and unvaccinated people based on the variants investigated so far. But the data showed that the risk of long COVID was reduced by vaccination.

In addition, although the three subtypes were present in all the variants, other symptom clusters had subtle differences among the variants, such as symptoms in the stomach and intestines. The differences could be due to other things that changed during the pandemic, such as the time of year, social behaviors, and treatments, the researchers said.

“Machine learning approaches, such as clustering analysis, have made it possible to start exploring and identifying different profiles of post-COVID syndrome,” Marc Modat, PhD, who led the analysis and is a senior lecturer at King’s College London’s School of Biomedical Engineering & Imaging Sciences, said in the statement.

“This opens new avenues of research to better understand COVID-19 and to motivate clinical research that might mitigate the long-term effects of the disease,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Children and COVID: Weekly cases top 95,000, admissions continue to rise

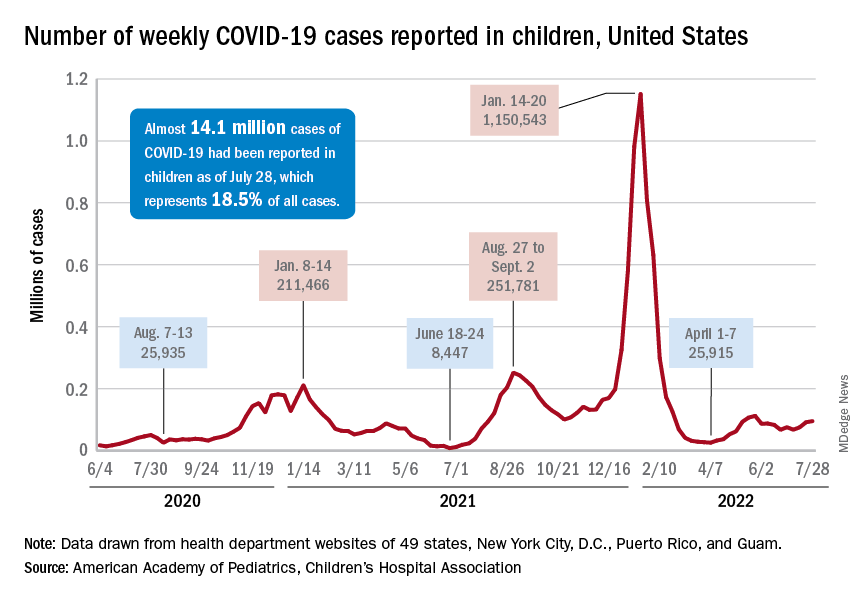

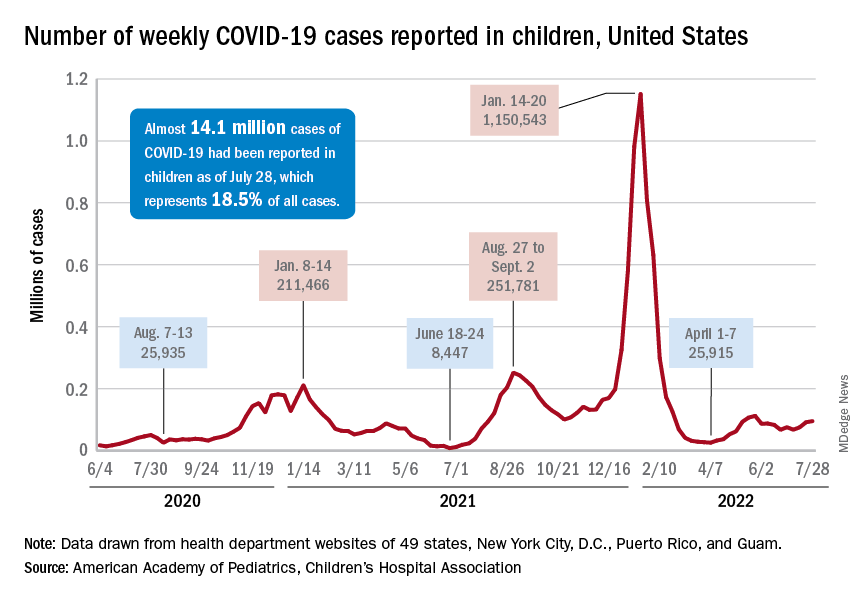

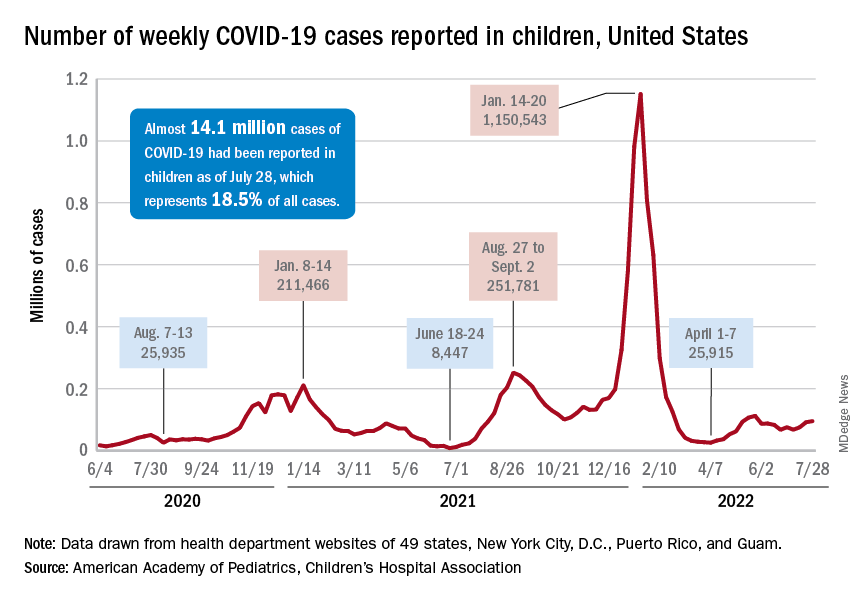

New pediatric COVID-19 cases increased for the third straight week as a substantial number of children under age 5 years started to receive their second doses of the vaccine.

Despite the 3-week trend, however, there are some positive signs. The new-case count for the latest reporting week (July 22-28) was over 95,000, but the 3.9% increase over the previous week’s 92,000 cases is much smaller than that week’s (July 15-21) corresponding jump of almost 22% over the July 8-14 total (75,000), according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

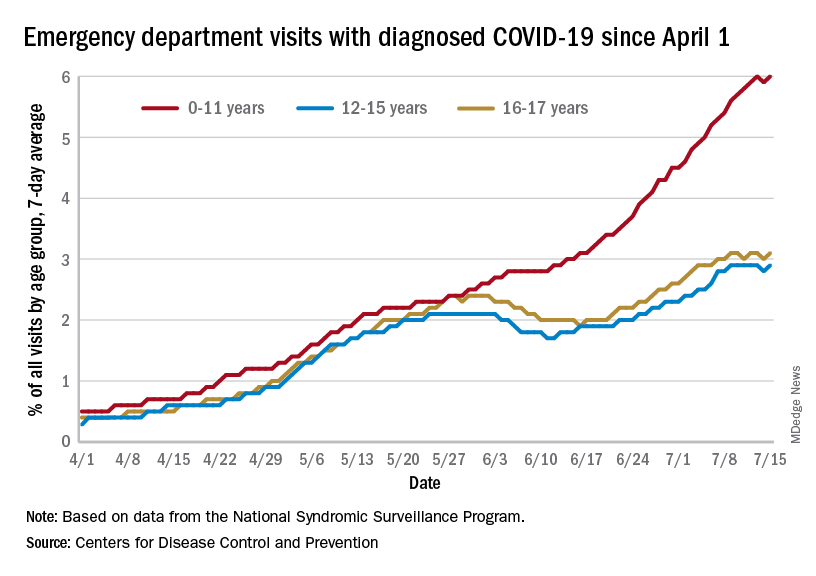

On the not-so-positive side is the trend in admissions among children aged 0-17 years, which continue to climb steadily and have nearly equaled the highest rate seen during the Delta surge in 2021. The rate on July 29 was 0.46 admissions per 100,000 population, and the highest rate over the course of the Delta surge was 0.47 per 100,000, but the all-time high from the Omicron surge – 1.25 per 100,000 in mid-January – is still a long way off, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

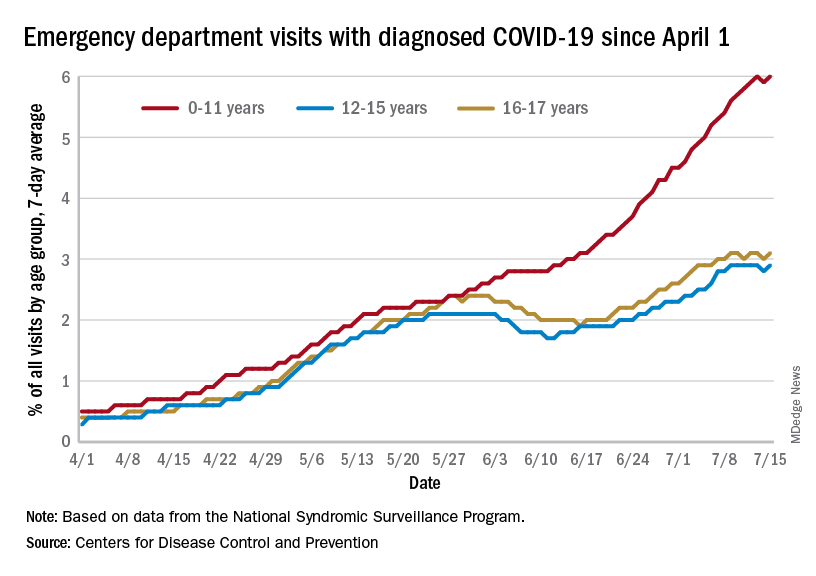

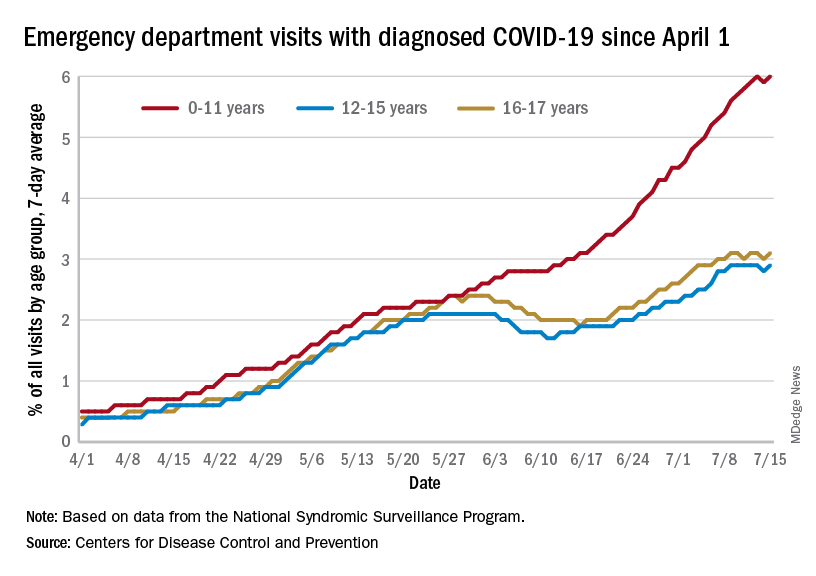

A similar situation is occurring with emergency department visits, but there is differentiation by age group. Among those aged 0-11 years, visits with diagnosed COVID made up 6.5% of all their ED visits on July 25, which was well above the high (4.0%) during the Delta surge, the CDC said.

That is not the case, however, for the older children, for whom rates are rising more slowly. Those aged 12-15 have reached 3.4% so far this summer, as have the 16- to 17-years-olds, versus Delta highs last year of around 7%, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker. As with admissions, though, current rates are well below the all-time Omicron high points, the CDC data show.

Joining the ranks of the fully vaccinated

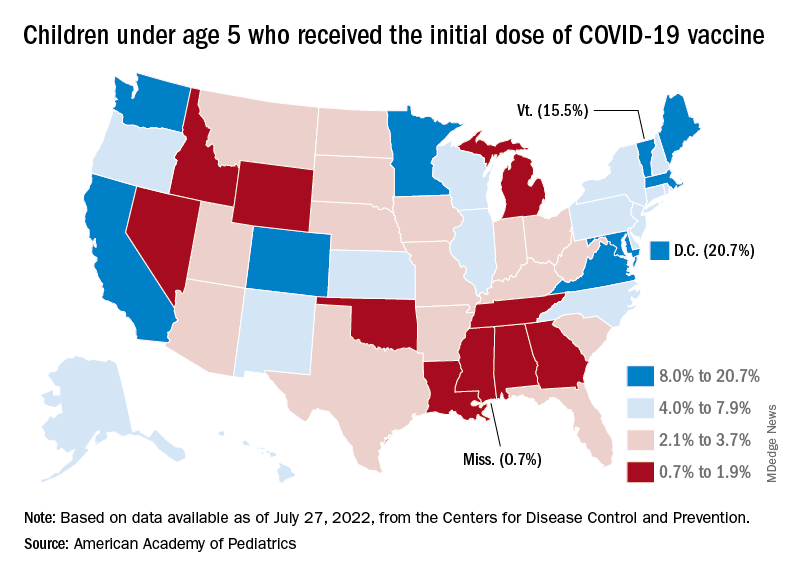

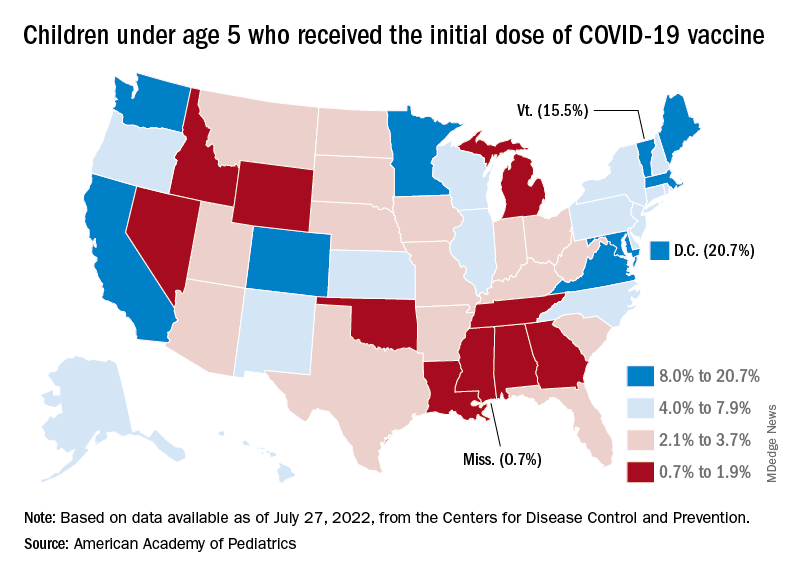

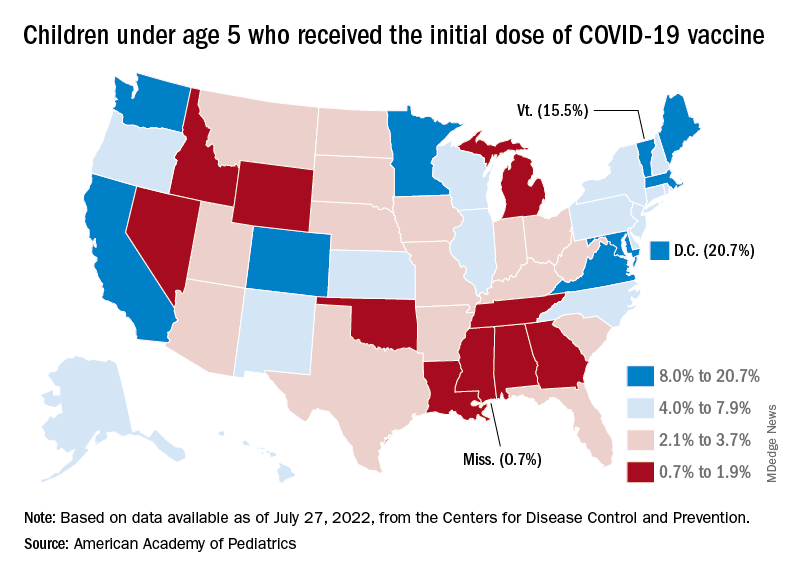

Over the last 2 weeks, the first children to receive the COVID vaccine after its approval for those under age 5 years have been coming back for their second doses. Almost 50,000, about 0.3% of all those in that age group, had done so by July 27. Just over 662,000, about 3.4% of the total under-5 population, have received at least one dose, the CDC said.

Meanwhile, analysis of “data from the first several weeks following availability of the vaccine in this age group indicate high variability across states,” the AAP said in its weekly vaccination report. In the District of Columbia, 20.7% of all children under age 5 have received an initial dose as of July 27, as have 15.5% of those in Vermont and 12.5% in Massachusetts. No other state was above 10%, but Mississippi, at 0.7%, was the only one below 1%.

The older children, obviously, have a head start, so their numbers are much higher. At the state level, Vermont has the highest initial dose rate, 69%, for those aged 5-11 years, while Alabama, Mississippi, and Wyoming, at 17%, are looking up at everyone else in the country. Among children aged 12-17 years, D.C. is the highest with 100% vaccination – Massachusetts and Rhode Island are at 98% – and Wyoming is the lowest with 40%, the AAP said.

New pediatric COVID-19 cases increased for the third straight week as a substantial number of children under age 5 years started to receive their second doses of the vaccine.

Despite the 3-week trend, however, there are some positive signs. The new-case count for the latest reporting week (July 22-28) was over 95,000, but the 3.9% increase over the previous week’s 92,000 cases is much smaller than that week’s (July 15-21) corresponding jump of almost 22% over the July 8-14 total (75,000), according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

On the not-so-positive side is the trend in admissions among children aged 0-17 years, which continue to climb steadily and have nearly equaled the highest rate seen during the Delta surge in 2021. The rate on July 29 was 0.46 admissions per 100,000 population, and the highest rate over the course of the Delta surge was 0.47 per 100,000, but the all-time high from the Omicron surge – 1.25 per 100,000 in mid-January – is still a long way off, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A similar situation is occurring with emergency department visits, but there is differentiation by age group. Among those aged 0-11 years, visits with diagnosed COVID made up 6.5% of all their ED visits on July 25, which was well above the high (4.0%) during the Delta surge, the CDC said.

That is not the case, however, for the older children, for whom rates are rising more slowly. Those aged 12-15 have reached 3.4% so far this summer, as have the 16- to 17-years-olds, versus Delta highs last year of around 7%, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker. As with admissions, though, current rates are well below the all-time Omicron high points, the CDC data show.

Joining the ranks of the fully vaccinated

Over the last 2 weeks, the first children to receive the COVID vaccine after its approval for those under age 5 years have been coming back for their second doses. Almost 50,000, about 0.3% of all those in that age group, had done so by July 27. Just over 662,000, about 3.4% of the total under-5 population, have received at least one dose, the CDC said.

Meanwhile, analysis of “data from the first several weeks following availability of the vaccine in this age group indicate high variability across states,” the AAP said in its weekly vaccination report. In the District of Columbia, 20.7% of all children under age 5 have received an initial dose as of July 27, as have 15.5% of those in Vermont and 12.5% in Massachusetts. No other state was above 10%, but Mississippi, at 0.7%, was the only one below 1%.

The older children, obviously, have a head start, so their numbers are much higher. At the state level, Vermont has the highest initial dose rate, 69%, for those aged 5-11 years, while Alabama, Mississippi, and Wyoming, at 17%, are looking up at everyone else in the country. Among children aged 12-17 years, D.C. is the highest with 100% vaccination – Massachusetts and Rhode Island are at 98% – and Wyoming is the lowest with 40%, the AAP said.

New pediatric COVID-19 cases increased for the third straight week as a substantial number of children under age 5 years started to receive their second doses of the vaccine.

Despite the 3-week trend, however, there are some positive signs. The new-case count for the latest reporting week (July 22-28) was over 95,000, but the 3.9% increase over the previous week’s 92,000 cases is much smaller than that week’s (July 15-21) corresponding jump of almost 22% over the July 8-14 total (75,000), according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

On the not-so-positive side is the trend in admissions among children aged 0-17 years, which continue to climb steadily and have nearly equaled the highest rate seen during the Delta surge in 2021. The rate on July 29 was 0.46 admissions per 100,000 population, and the highest rate over the course of the Delta surge was 0.47 per 100,000, but the all-time high from the Omicron surge – 1.25 per 100,000 in mid-January – is still a long way off, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A similar situation is occurring with emergency department visits, but there is differentiation by age group. Among those aged 0-11 years, visits with diagnosed COVID made up 6.5% of all their ED visits on July 25, which was well above the high (4.0%) during the Delta surge, the CDC said.

That is not the case, however, for the older children, for whom rates are rising more slowly. Those aged 12-15 have reached 3.4% so far this summer, as have the 16- to 17-years-olds, versus Delta highs last year of around 7%, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker. As with admissions, though, current rates are well below the all-time Omicron high points, the CDC data show.

Joining the ranks of the fully vaccinated

Over the last 2 weeks, the first children to receive the COVID vaccine after its approval for those under age 5 years have been coming back for their second doses. Almost 50,000, about 0.3% of all those in that age group, had done so by July 27. Just over 662,000, about 3.4% of the total under-5 population, have received at least one dose, the CDC said.

Meanwhile, analysis of “data from the first several weeks following availability of the vaccine in this age group indicate high variability across states,” the AAP said in its weekly vaccination report. In the District of Columbia, 20.7% of all children under age 5 have received an initial dose as of July 27, as have 15.5% of those in Vermont and 12.5% in Massachusetts. No other state was above 10%, but Mississippi, at 0.7%, was the only one below 1%.

The older children, obviously, have a head start, so their numbers are much higher. At the state level, Vermont has the highest initial dose rate, 69%, for those aged 5-11 years, while Alabama, Mississippi, and Wyoming, at 17%, are looking up at everyone else in the country. Among children aged 12-17 years, D.C. is the highest with 100% vaccination – Massachusetts and Rhode Island are at 98% – and Wyoming is the lowest with 40%, the AAP said.

Ongoing debate whether COVID links to new diabetes in kids

compared with the pre-pandemic rate, in new research.

This contrasts with findings from a U.S. study and a German study, but this is “not the final word” about this possible association, lead author Rayzel Shulman, MD, admits, since the study may have been underpowered.

The population-based, cross-sectional study was published recently as a research letter in JAMA Open.

The researchers found a nonsignificant increase in the monthly rate of new diabetes during the first 18 months of the COVID-19 pandemic, compared with the 3 prior years (relative risk 1.09, 95% confidence interval).

New study contrasts with previous reports

This differs from a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in which COVID-19 infection was associated with a significant increase in new onset of diabetes in children during March 2020 through June 2021, “although some experts have criticized the study methods and conclusion validity,” Dr. Shulman and colleagues write.

Another study, from Germany, reported a significant 1.15-fold increase in type 1 diabetes in children during the pandemic, they note.

The current study may have been underpowered and too small to show a significant association between COVID-19 and new diabetes, the researchers acknowledge.

And the 1.30 upper limit of the confidence interval shows that it “cannot rule out a possible 1.3-fold increase” in relative risk of a diagnosis of diabetes related to COVID, Dr. Shulman explained to this news organization.

It will be important to see how the rates have changed since September 2021 (the end of the current study), added Dr. Shulman, an adjunct scientist at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) and a physician and scientist at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto.

The current study did find a decreased (delayed) rate of diagnosis of new diabetes during the first months of the pandemic when there were lockdowns, followed by a “catch-up” increase in rates later on, as has been reported earlier.

“Our study is definitely not the final word on this,” Dr. Shulman summarized in a statement from ICES. “However, our findings call into question whether a direct association between COVID-19 and new-onset diabetes in children exists.”

COVID-diabetes link?

The researchers analyzed health administrative data from January 2017 to September 2021.

They identified 2,700,178 children and youth in Ontario who were under age 18 in 2021, who had a mean age of 9.2, and about half were girls.

Between November 2020 and April 2021, an estimated 3.3% of children in Ontario had a SARS-COV-2 infection.

New diagnoses of diabetes in this age group are mostly type 1 diabetes, based on previous studies.

The rate of incident diabetes was 15%-32% lower during the first 3 months of the pandemic, March-May 2020 (1.67-2.34 cases per 100,000), compared with the pre-pandemic monthly rate during 2017, 2018, and 2019 (2.54-2.59 cases per 100,000).

The rate of incident diabetes was 33%-50% higher during February to July 2021 (3.48-4.18 cases per 100,000), compared with the pre-pandemic rate.

The pre-pandemic and pandemic monthly rates of incident diabetes were similar during the other months.

The group concludes: “The lack of both an observable increase in overall diabetes incidence among children during the 18-month pandemic restrictions [in this Ontario study] and a plausible biological mechanism call into question an association between COVID-19 and new-onset diabetes.”

More research is needed. “Given the variability in monthly [relative risks], additional population-based, longer-term data are needed to examine the direct and indirect effects of COVID-19 and diabetes risk among children,” the authors write.

This study was supported by ICES (which is funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health) and by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Shulman reported receiving fees from Dexcom outside the submitted work, and she and three other authors reported receiving grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research outside the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

compared with the pre-pandemic rate, in new research.

This contrasts with findings from a U.S. study and a German study, but this is “not the final word” about this possible association, lead author Rayzel Shulman, MD, admits, since the study may have been underpowered.

The population-based, cross-sectional study was published recently as a research letter in JAMA Open.

The researchers found a nonsignificant increase in the monthly rate of new diabetes during the first 18 months of the COVID-19 pandemic, compared with the 3 prior years (relative risk 1.09, 95% confidence interval).

New study contrasts with previous reports

This differs from a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in which COVID-19 infection was associated with a significant increase in new onset of diabetes in children during March 2020 through June 2021, “although some experts have criticized the study methods and conclusion validity,” Dr. Shulman and colleagues write.

Another study, from Germany, reported a significant 1.15-fold increase in type 1 diabetes in children during the pandemic, they note.

The current study may have been underpowered and too small to show a significant association between COVID-19 and new diabetes, the researchers acknowledge.

And the 1.30 upper limit of the confidence interval shows that it “cannot rule out a possible 1.3-fold increase” in relative risk of a diagnosis of diabetes related to COVID, Dr. Shulman explained to this news organization.

It will be important to see how the rates have changed since September 2021 (the end of the current study), added Dr. Shulman, an adjunct scientist at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) and a physician and scientist at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto.

The current study did find a decreased (delayed) rate of diagnosis of new diabetes during the first months of the pandemic when there were lockdowns, followed by a “catch-up” increase in rates later on, as has been reported earlier.

“Our study is definitely not the final word on this,” Dr. Shulman summarized in a statement from ICES. “However, our findings call into question whether a direct association between COVID-19 and new-onset diabetes in children exists.”

COVID-diabetes link?

The researchers analyzed health administrative data from January 2017 to September 2021.

They identified 2,700,178 children and youth in Ontario who were under age 18 in 2021, who had a mean age of 9.2, and about half were girls.

Between November 2020 and April 2021, an estimated 3.3% of children in Ontario had a SARS-COV-2 infection.

New diagnoses of diabetes in this age group are mostly type 1 diabetes, based on previous studies.

The rate of incident diabetes was 15%-32% lower during the first 3 months of the pandemic, March-May 2020 (1.67-2.34 cases per 100,000), compared with the pre-pandemic monthly rate during 2017, 2018, and 2019 (2.54-2.59 cases per 100,000).

The rate of incident diabetes was 33%-50% higher during February to July 2021 (3.48-4.18 cases per 100,000), compared with the pre-pandemic rate.

The pre-pandemic and pandemic monthly rates of incident diabetes were similar during the other months.

The group concludes: “The lack of both an observable increase in overall diabetes incidence among children during the 18-month pandemic restrictions [in this Ontario study] and a plausible biological mechanism call into question an association between COVID-19 and new-onset diabetes.”

More research is needed. “Given the variability in monthly [relative risks], additional population-based, longer-term data are needed to examine the direct and indirect effects of COVID-19 and diabetes risk among children,” the authors write.

This study was supported by ICES (which is funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health) and by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Shulman reported receiving fees from Dexcom outside the submitted work, and she and three other authors reported receiving grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research outside the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

compared with the pre-pandemic rate, in new research.

This contrasts with findings from a U.S. study and a German study, but this is “not the final word” about this possible association, lead author Rayzel Shulman, MD, admits, since the study may have been underpowered.

The population-based, cross-sectional study was published recently as a research letter in JAMA Open.

The researchers found a nonsignificant increase in the monthly rate of new diabetes during the first 18 months of the COVID-19 pandemic, compared with the 3 prior years (relative risk 1.09, 95% confidence interval).

New study contrasts with previous reports

This differs from a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in which COVID-19 infection was associated with a significant increase in new onset of diabetes in children during March 2020 through June 2021, “although some experts have criticized the study methods and conclusion validity,” Dr. Shulman and colleagues write.

Another study, from Germany, reported a significant 1.15-fold increase in type 1 diabetes in children during the pandemic, they note.

The current study may have been underpowered and too small to show a significant association between COVID-19 and new diabetes, the researchers acknowledge.

And the 1.30 upper limit of the confidence interval shows that it “cannot rule out a possible 1.3-fold increase” in relative risk of a diagnosis of diabetes related to COVID, Dr. Shulman explained to this news organization.

It will be important to see how the rates have changed since September 2021 (the end of the current study), added Dr. Shulman, an adjunct scientist at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) and a physician and scientist at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto.

The current study did find a decreased (delayed) rate of diagnosis of new diabetes during the first months of the pandemic when there were lockdowns, followed by a “catch-up” increase in rates later on, as has been reported earlier.

“Our study is definitely not the final word on this,” Dr. Shulman summarized in a statement from ICES. “However, our findings call into question whether a direct association between COVID-19 and new-onset diabetes in children exists.”

COVID-diabetes link?

The researchers analyzed health administrative data from January 2017 to September 2021.

They identified 2,700,178 children and youth in Ontario who were under age 18 in 2021, who had a mean age of 9.2, and about half were girls.

Between November 2020 and April 2021, an estimated 3.3% of children in Ontario had a SARS-COV-2 infection.

New diagnoses of diabetes in this age group are mostly type 1 diabetes, based on previous studies.

The rate of incident diabetes was 15%-32% lower during the first 3 months of the pandemic, March-May 2020 (1.67-2.34 cases per 100,000), compared with the pre-pandemic monthly rate during 2017, 2018, and 2019 (2.54-2.59 cases per 100,000).

The rate of incident diabetes was 33%-50% higher during February to July 2021 (3.48-4.18 cases per 100,000), compared with the pre-pandemic rate.

The pre-pandemic and pandemic monthly rates of incident diabetes were similar during the other months.

The group concludes: “The lack of both an observable increase in overall diabetes incidence among children during the 18-month pandemic restrictions [in this Ontario study] and a plausible biological mechanism call into question an association between COVID-19 and new-onset diabetes.”

More research is needed. “Given the variability in monthly [relative risks], additional population-based, longer-term data are needed to examine the direct and indirect effects of COVID-19 and diabetes risk among children,” the authors write.

This study was supported by ICES (which is funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health) and by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Shulman reported receiving fees from Dexcom outside the submitted work, and she and three other authors reported receiving grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research outside the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA OPEN

Evusheld for COVID-19: Lifesaving and free, but still few takers

Evusheld (AstraZeneca), a medication used to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients at high risk, has problems: Namely, that supplies of the potentially lifesaving drug outweigh demand.

At least 7 million people who are immunocompromised could benefit from it, as could many others who are undergoing cancer treatment, have received a transplant, or who are allergic to the COVID-19 vaccines. The medication has laboratory-produced antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and helps the body protect itself. It can slash the chances of becoming infected by 77%, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

And it’s free to eligible patients (although there may be an out-of-pocket administrative fee in some cases).

To meet demand, the Biden administration secured 1.7 million doses of the medicine, which was granted emergency use authorization by the FDA in December 2021. As of July 25, however, 793,348 doses have been ordered by the administration sites, and only 398,181 doses have been reported as used, a spokesperson for the Department of Health & Human Services tells this news organization.

Each week, a certain amount of doses from the 1.7 million dose stockpile is made available to state and territorial health departments. States have not been asking for their full allotment, the spokesperson said July 28.

Now, HHS and AstraZeneca have taken a number of steps to increase awareness of the medication and access to it.

- On July 27, HHS announced that individual providers and smaller sites of care that don’t currently receive Evusheld through the federal distribution process via the HHS Health Partner Order Portal can now order up to three patient courses of the medicine. These can be

- Health care providers can use the HHS’s COVID-19 Therapeutics Locator to find Evusheld in their area.

- AstraZeneca has launched a new website with educational materials and says it is working closely with patient and professional groups to inform patients and health care providers.

- A direct-to-consumer ad launched on June 22 and will run in the United States online and on TV (Yahoo, Fox, CBS Sports, MSN, ESPN) and be amplified on social and digital channels through year’s end, an AstraZeneca spokesperson said in an interview.

- AstraZeneca set up a toll-free number for providers: 1-833-EVUSHLD.

Evusheld includes two monoclonal antibodies, tixagevimab and cilgavimab. The medication is given as two consecutive intramuscular injections during a single visit to a doctor’s office, infusion center, or other health care facility. The antibodies bind to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and prevent the virus from getting into human cells and infecting them. It’s authorized for use in children and adults aged 12 years and older who weigh at least 88 pounds.

Studies have found that the medication decreases the risk of getting COVID-19 for up to 6 months after it is given. The FDA recommends repeat dosing every 6 months with the doses of 300 mg of each monoclonal antibody. In clinical trials, Evusheld reduced the incidence of COVID-19 symptomatic illness by 77%, compared with placebo.

Physicians monitor patients for an hour after administering Evusheld for allergic reactions. Other possible side effects include cardiac events, but they are not common.

Doctors and patients weigh in

Physicians – and patients – from the United States to the United Kingdom and beyond are questioning why the medication is underused while lauding the recent efforts to expand access and increase awareness.

The U.S. federal government may have underestimated the amount of communication needed to increase awareness of the medication and its applications, said infectious disease specialist William Schaffner, MD, professor of preventive medicine at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tenn.

“HHS hasn’t made a major educational effort to promote it,” he said in an interview.

Many physicians who need to know about it, such as transplant doctors and rheumatologists, are outside the typical public health communications loop, he said.

Eric Topol, MD, director of the Scripps Research Transational Institute and editor-in-chief of Medscape, has taken to social media to bemoan the lack of awareness.

Another infectious disease expert agrees. “In my experience, the awareness of Evusheld is low amongst many patients as well as many providers,” said Amesh Adalja, MD, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Baltimore.

“Initially, there were scarce supplies of the drug, and certain hospital systems tiered eligibility based on degrees of immunosuppression, and only the most immunosuppressed were proactively approached for treatment.”

“Also, many community hospitals never initially ordered Evusheld – they may have been crowded out by academic centers who treat many more immunosuppressed patients and may not currently see it as a priority,” Dr. Adalja said in an interview. “As such, many immunosuppressed patients would have to seek treatment at academic medical centers, where the drug is more likely to be available.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Evusheld (AstraZeneca), a medication used to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients at high risk, has problems: Namely, that supplies of the potentially lifesaving drug outweigh demand.

At least 7 million people who are immunocompromised could benefit from it, as could many others who are undergoing cancer treatment, have received a transplant, or who are allergic to the COVID-19 vaccines. The medication has laboratory-produced antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and helps the body protect itself. It can slash the chances of becoming infected by 77%, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

And it’s free to eligible patients (although there may be an out-of-pocket administrative fee in some cases).

To meet demand, the Biden administration secured 1.7 million doses of the medicine, which was granted emergency use authorization by the FDA in December 2021. As of July 25, however, 793,348 doses have been ordered by the administration sites, and only 398,181 doses have been reported as used, a spokesperson for the Department of Health & Human Services tells this news organization.

Each week, a certain amount of doses from the 1.7 million dose stockpile is made available to state and territorial health departments. States have not been asking for their full allotment, the spokesperson said July 28.

Now, HHS and AstraZeneca have taken a number of steps to increase awareness of the medication and access to it.

- On July 27, HHS announced that individual providers and smaller sites of care that don’t currently receive Evusheld through the federal distribution process via the HHS Health Partner Order Portal can now order up to three patient courses of the medicine. These can be

- Health care providers can use the HHS’s COVID-19 Therapeutics Locator to find Evusheld in their area.

- AstraZeneca has launched a new website with educational materials and says it is working closely with patient and professional groups to inform patients and health care providers.

- A direct-to-consumer ad launched on June 22 and will run in the United States online and on TV (Yahoo, Fox, CBS Sports, MSN, ESPN) and be amplified on social and digital channels through year’s end, an AstraZeneca spokesperson said in an interview.

- AstraZeneca set up a toll-free number for providers: 1-833-EVUSHLD.

Evusheld includes two monoclonal antibodies, tixagevimab and cilgavimab. The medication is given as two consecutive intramuscular injections during a single visit to a doctor’s office, infusion center, or other health care facility. The antibodies bind to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and prevent the virus from getting into human cells and infecting them. It’s authorized for use in children and adults aged 12 years and older who weigh at least 88 pounds.

Studies have found that the medication decreases the risk of getting COVID-19 for up to 6 months after it is given. The FDA recommends repeat dosing every 6 months with the doses of 300 mg of each monoclonal antibody. In clinical trials, Evusheld reduced the incidence of COVID-19 symptomatic illness by 77%, compared with placebo.

Physicians monitor patients for an hour after administering Evusheld for allergic reactions. Other possible side effects include cardiac events, but they are not common.

Doctors and patients weigh in

Physicians – and patients – from the United States to the United Kingdom and beyond are questioning why the medication is underused while lauding the recent efforts to expand access and increase awareness.

The U.S. federal government may have underestimated the amount of communication needed to increase awareness of the medication and its applications, said infectious disease specialist William Schaffner, MD, professor of preventive medicine at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tenn.

“HHS hasn’t made a major educational effort to promote it,” he said in an interview.

Many physicians who need to know about it, such as transplant doctors and rheumatologists, are outside the typical public health communications loop, he said.

Eric Topol, MD, director of the Scripps Research Transational Institute and editor-in-chief of Medscape, has taken to social media to bemoan the lack of awareness.

Another infectious disease expert agrees. “In my experience, the awareness of Evusheld is low amongst many patients as well as many providers,” said Amesh Adalja, MD, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Baltimore.

“Initially, there were scarce supplies of the drug, and certain hospital systems tiered eligibility based on degrees of immunosuppression, and only the most immunosuppressed were proactively approached for treatment.”

“Also, many community hospitals never initially ordered Evusheld – they may have been crowded out by academic centers who treat many more immunosuppressed patients and may not currently see it as a priority,” Dr. Adalja said in an interview. “As such, many immunosuppressed patients would have to seek treatment at academic medical centers, where the drug is more likely to be available.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Evusheld (AstraZeneca), a medication used to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients at high risk, has problems: Namely, that supplies of the potentially lifesaving drug outweigh demand.

At least 7 million people who are immunocompromised could benefit from it, as could many others who are undergoing cancer treatment, have received a transplant, or who are allergic to the COVID-19 vaccines. The medication has laboratory-produced antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and helps the body protect itself. It can slash the chances of becoming infected by 77%, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

And it’s free to eligible patients (although there may be an out-of-pocket administrative fee in some cases).

To meet demand, the Biden administration secured 1.7 million doses of the medicine, which was granted emergency use authorization by the FDA in December 2021. As of July 25, however, 793,348 doses have been ordered by the administration sites, and only 398,181 doses have been reported as used, a spokesperson for the Department of Health & Human Services tells this news organization.

Each week, a certain amount of doses from the 1.7 million dose stockpile is made available to state and territorial health departments. States have not been asking for their full allotment, the spokesperson said July 28.

Now, HHS and AstraZeneca have taken a number of steps to increase awareness of the medication and access to it.

- On July 27, HHS announced that individual providers and smaller sites of care that don’t currently receive Evusheld through the federal distribution process via the HHS Health Partner Order Portal can now order up to three patient courses of the medicine. These can be

- Health care providers can use the HHS’s COVID-19 Therapeutics Locator to find Evusheld in their area.

- AstraZeneca has launched a new website with educational materials and says it is working closely with patient and professional groups to inform patients and health care providers.

- A direct-to-consumer ad launched on June 22 and will run in the United States online and on TV (Yahoo, Fox, CBS Sports, MSN, ESPN) and be amplified on social and digital channels through year’s end, an AstraZeneca spokesperson said in an interview.

- AstraZeneca set up a toll-free number for providers: 1-833-EVUSHLD.

Evusheld includes two monoclonal antibodies, tixagevimab and cilgavimab. The medication is given as two consecutive intramuscular injections during a single visit to a doctor’s office, infusion center, or other health care facility. The antibodies bind to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and prevent the virus from getting into human cells and infecting them. It’s authorized for use in children and adults aged 12 years and older who weigh at least 88 pounds.

Studies have found that the medication decreases the risk of getting COVID-19 for up to 6 months after it is given. The FDA recommends repeat dosing every 6 months with the doses of 300 mg of each monoclonal antibody. In clinical trials, Evusheld reduced the incidence of COVID-19 symptomatic illness by 77%, compared with placebo.

Physicians monitor patients for an hour after administering Evusheld for allergic reactions. Other possible side effects include cardiac events, but they are not common.

Doctors and patients weigh in

Physicians – and patients – from the United States to the United Kingdom and beyond are questioning why the medication is underused while lauding the recent efforts to expand access and increase awareness.

The U.S. federal government may have underestimated the amount of communication needed to increase awareness of the medication and its applications, said infectious disease specialist William Schaffner, MD, professor of preventive medicine at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tenn.

“HHS hasn’t made a major educational effort to promote it,” he said in an interview.

Many physicians who need to know about it, such as transplant doctors and rheumatologists, are outside the typical public health communications loop, he said.

Eric Topol, MD, director of the Scripps Research Transational Institute and editor-in-chief of Medscape, has taken to social media to bemoan the lack of awareness.

Another infectious disease expert agrees. “In my experience, the awareness of Evusheld is low amongst many patients as well as many providers,” said Amesh Adalja, MD, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Baltimore.

“Initially, there were scarce supplies of the drug, and certain hospital systems tiered eligibility based on degrees of immunosuppression, and only the most immunosuppressed were proactively approached for treatment.”

“Also, many community hospitals never initially ordered Evusheld – they may have been crowded out by academic centers who treat many more immunosuppressed patients and may not currently see it as a priority,” Dr. Adalja said in an interview. “As such, many immunosuppressed patients would have to seek treatment at academic medical centers, where the drug is more likely to be available.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Striking’ disparities in CVD deaths persist across COVID waves

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality rose significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic and persists more than 2 years on and, once again, Blacks and African Americans have been disproportionately affected, an analysis of death certificates shows.

The findings “suggest that the pandemic may reverse years or decades of work aimed at reducing gaps in cardiovascular outcomes,” Sadeer G. Al-Kindi, MD, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, said in an interview.

Although the disparities are in line with previous research, he said, “what was surprising is the persistence of excess cardiovascular mortality approximately 2 years after the pandemic started, even during a period of low COVID-19 mortality.”

“This suggests that the pandemic resulted in a disruption of health care access and, along with disparities in COVID-19 infection and its complications, he said, “may have a long-lasting effect on health care disparities, especially among vulnerable populations.”

The study was published online in Mayo Clinic Proceedings with lead author Scott E. Janus, MD, also of Case Western Reserve University.

Impact consistently greater for Blacks

Dr. Al-Kindi and colleagues used 3,598,352 U.S. death files to investigate trends in deaths caused specifically by CVD as well as its subtypes myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure (HF) in 2018 and 2019 (prepandemic) and the pandemic years 2020 and 2021. Baseline demographics showed a higher percentage of older, female, and Black individuals among the CVD subtypes of interest.

Overall, there was an excess CVD mortality of 6.7% during the pandemic, compared with prepandemic years, including a 2.5% rise in MI deaths and an 8.5% rise in stroke deaths. HF mortality remained relatively steady, rising only 0.1%.

Subgroup analyses revealed “striking differences” in excess mortality between Blacks and Whites, the authors noted. Blacks had an overall excess mortality of 13.8% versus 5.1% for Whites, compared with the prepandemic years. The differences were consistent across subtypes: MI (9.6% vs. 1.0%); stroke (14.5% vs. 6.9%); and HF (5.1% vs. –1.2%; P value for all < .001).

When the investigators looked at deaths on a yearly basis with 2018 as the baseline, they found CVD deaths increased by 1.5% in 2019, 15.8% in 2020, and 13.5% in 2021 among Black Americans, compared with 0.5%, 5.1%, and 5.7%, respectively, among White Americans.

Excess deaths from MI rose by 9.5% in 2020 and by 6.7% in 2021 among Blacks but fell by 1.2% in 2020 and by 1.0% in 2021 among Whites.

Disparities in excess HF mortality were similar, rising 9.1% and 4.1% in 2020 and 2021 among Blacks, while dipping 0.1% and 0.8% in 2020 and 2021 among Whites.

The “most striking difference” was in excess stroke mortality, which doubled among Blacks compared with whites in 2020 (14.9% vs. 6.7%) and in 2021 (17.5% vs. 8.1%), according to the authors.

Awareness urged

Although the disparities were expected, “there is clear value in documenting and quantifying the magnitude of these disparities,” Amil M. Shah, MD, MPH, of Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, said in an interview.

In addition to being observational, the main limitation of the study, he noted, is the quality and resolution of the death certificate data, which may limit the accuracy of the cause of death ascertainment and classification of race or ethnicity. “However, I think these potential inaccuracies are unlikely to materially impact the overall study findings.”

Dr. Shah, who was not involved in the study, said he would like to see additional research into the diversity and heterogeneity in risk among Black communities. “Understanding the environmental, social, and health care factors – both harmful and protective – that influence risk for CVD morbidity and mortality among Black individuals and communities offers the promise to provide actionable insights to mitigate these disparities.”

“Intervention studies testing approaches to mitigate disparities based on race/ethnicity” are also needed, he added. These may be at the policy, community, health system, or individual level, and community involvement in phases will be essential.”

Meanwhile, both Dr. Al-Kindi and Dr. Shah urged clinicians to be aware of the disparities and the need to improve access to care and address social determinants of health in vulnerable populations.

These disparities “are driven by structural factors, and are reinforced by individual behaviors. In this context, implicit bias training is important to help clinicians recognize and mitigate bias in their own practice,” Dr. Shah said. “Supporting diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts, and advocating for anti-racist policies and practices in their health systems” can also help.

Dr. Al-Kindi and Dr. Shah disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality rose significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic and persists more than 2 years on and, once again, Blacks and African Americans have been disproportionately affected, an analysis of death certificates shows.

The findings “suggest that the pandemic may reverse years or decades of work aimed at reducing gaps in cardiovascular outcomes,” Sadeer G. Al-Kindi, MD, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, said in an interview.

Although the disparities are in line with previous research, he said, “what was surprising is the persistence of excess cardiovascular mortality approximately 2 years after the pandemic started, even during a period of low COVID-19 mortality.”

“This suggests that the pandemic resulted in a disruption of health care access and, along with disparities in COVID-19 infection and its complications, he said, “may have a long-lasting effect on health care disparities, especially among vulnerable populations.”

The study was published online in Mayo Clinic Proceedings with lead author Scott E. Janus, MD, also of Case Western Reserve University.

Impact consistently greater for Blacks

Dr. Al-Kindi and colleagues used 3,598,352 U.S. death files to investigate trends in deaths caused specifically by CVD as well as its subtypes myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure (HF) in 2018 and 2019 (prepandemic) and the pandemic years 2020 and 2021. Baseline demographics showed a higher percentage of older, female, and Black individuals among the CVD subtypes of interest.

Overall, there was an excess CVD mortality of 6.7% during the pandemic, compared with prepandemic years, including a 2.5% rise in MI deaths and an 8.5% rise in stroke deaths. HF mortality remained relatively steady, rising only 0.1%.

Subgroup analyses revealed “striking differences” in excess mortality between Blacks and Whites, the authors noted. Blacks had an overall excess mortality of 13.8% versus 5.1% for Whites, compared with the prepandemic years. The differences were consistent across subtypes: MI (9.6% vs. 1.0%); stroke (14.5% vs. 6.9%); and HF (5.1% vs. –1.2%; P value for all < .001).

When the investigators looked at deaths on a yearly basis with 2018 as the baseline, they found CVD deaths increased by 1.5% in 2019, 15.8% in 2020, and 13.5% in 2021 among Black Americans, compared with 0.5%, 5.1%, and 5.7%, respectively, among White Americans.

Excess deaths from MI rose by 9.5% in 2020 and by 6.7% in 2021 among Blacks but fell by 1.2% in 2020 and by 1.0% in 2021 among Whites.

Disparities in excess HF mortality were similar, rising 9.1% and 4.1% in 2020 and 2021 among Blacks, while dipping 0.1% and 0.8% in 2020 and 2021 among Whites.

The “most striking difference” was in excess stroke mortality, which doubled among Blacks compared with whites in 2020 (14.9% vs. 6.7%) and in 2021 (17.5% vs. 8.1%), according to the authors.

Awareness urged

Although the disparities were expected, “there is clear value in documenting and quantifying the magnitude of these disparities,” Amil M. Shah, MD, MPH, of Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, said in an interview.

In addition to being observational, the main limitation of the study, he noted, is the quality and resolution of the death certificate data, which may limit the accuracy of the cause of death ascertainment and classification of race or ethnicity. “However, I think these potential inaccuracies are unlikely to materially impact the overall study findings.”

Dr. Shah, who was not involved in the study, said he would like to see additional research into the diversity and heterogeneity in risk among Black communities. “Understanding the environmental, social, and health care factors – both harmful and protective – that influence risk for CVD morbidity and mortality among Black individuals and communities offers the promise to provide actionable insights to mitigate these disparities.”

“Intervention studies testing approaches to mitigate disparities based on race/ethnicity” are also needed, he added. These may be at the policy, community, health system, or individual level, and community involvement in phases will be essential.”

Meanwhile, both Dr. Al-Kindi and Dr. Shah urged clinicians to be aware of the disparities and the need to improve access to care and address social determinants of health in vulnerable populations.

These disparities “are driven by structural factors, and are reinforced by individual behaviors. In this context, implicit bias training is important to help clinicians recognize and mitigate bias in their own practice,” Dr. Shah said. “Supporting diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts, and advocating for anti-racist policies and practices in their health systems” can also help.

Dr. Al-Kindi and Dr. Shah disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality rose significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic and persists more than 2 years on and, once again, Blacks and African Americans have been disproportionately affected, an analysis of death certificates shows.

The findings “suggest that the pandemic may reverse years or decades of work aimed at reducing gaps in cardiovascular outcomes,” Sadeer G. Al-Kindi, MD, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, said in an interview.

Although the disparities are in line with previous research, he said, “what was surprising is the persistence of excess cardiovascular mortality approximately 2 years after the pandemic started, even during a period of low COVID-19 mortality.”

“This suggests that the pandemic resulted in a disruption of health care access and, along with disparities in COVID-19 infection and its complications, he said, “may have a long-lasting effect on health care disparities, especially among vulnerable populations.”

The study was published online in Mayo Clinic Proceedings with lead author Scott E. Janus, MD, also of Case Western Reserve University.

Impact consistently greater for Blacks

Dr. Al-Kindi and colleagues used 3,598,352 U.S. death files to investigate trends in deaths caused specifically by CVD as well as its subtypes myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure (HF) in 2018 and 2019 (prepandemic) and the pandemic years 2020 and 2021. Baseline demographics showed a higher percentage of older, female, and Black individuals among the CVD subtypes of interest.

Overall, there was an excess CVD mortality of 6.7% during the pandemic, compared with prepandemic years, including a 2.5% rise in MI deaths and an 8.5% rise in stroke deaths. HF mortality remained relatively steady, rising only 0.1%.

Subgroup analyses revealed “striking differences” in excess mortality between Blacks and Whites, the authors noted. Blacks had an overall excess mortality of 13.8% versus 5.1% for Whites, compared with the prepandemic years. The differences were consistent across subtypes: MI (9.6% vs. 1.0%); stroke (14.5% vs. 6.9%); and HF (5.1% vs. –1.2%; P value for all < .001).

When the investigators looked at deaths on a yearly basis with 2018 as the baseline, they found CVD deaths increased by 1.5% in 2019, 15.8% in 2020, and 13.5% in 2021 among Black Americans, compared with 0.5%, 5.1%, and 5.7%, respectively, among White Americans.

Excess deaths from MI rose by 9.5% in 2020 and by 6.7% in 2021 among Blacks but fell by 1.2% in 2020 and by 1.0% in 2021 among Whites.

Disparities in excess HF mortality were similar, rising 9.1% and 4.1% in 2020 and 2021 among Blacks, while dipping 0.1% and 0.8% in 2020 and 2021 among Whites.

The “most striking difference” was in excess stroke mortality, which doubled among Blacks compared with whites in 2020 (14.9% vs. 6.7%) and in 2021 (17.5% vs. 8.1%), according to the authors.

Awareness urged

Although the disparities were expected, “there is clear value in documenting and quantifying the magnitude of these disparities,” Amil M. Shah, MD, MPH, of Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, said in an interview.

In addition to being observational, the main limitation of the study, he noted, is the quality and resolution of the death certificate data, which may limit the accuracy of the cause of death ascertainment and classification of race or ethnicity. “However, I think these potential inaccuracies are unlikely to materially impact the overall study findings.”

Dr. Shah, who was not involved in the study, said he would like to see additional research into the diversity and heterogeneity in risk among Black communities. “Understanding the environmental, social, and health care factors – both harmful and protective – that influence risk for CVD morbidity and mortality among Black individuals and communities offers the promise to provide actionable insights to mitigate these disparities.”

“Intervention studies testing approaches to mitigate disparities based on race/ethnicity” are also needed, he added. These may be at the policy, community, health system, or individual level, and community involvement in phases will be essential.”

Meanwhile, both Dr. Al-Kindi and Dr. Shah urged clinicians to be aware of the disparities and the need to improve access to care and address social determinants of health in vulnerable populations.

These disparities “are driven by structural factors, and are reinforced by individual behaviors. In this context, implicit bias training is important to help clinicians recognize and mitigate bias in their own practice,” Dr. Shah said. “Supporting diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts, and advocating for anti-racist policies and practices in their health systems” can also help.

Dr. Al-Kindi and Dr. Shah disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM MAYO CLINIC PROCEEDINGS

More evidence that COVID-19 started in Wuhan marketplace

The original spread of the virus was a one-two punch, the studies found. Twice, the virus jumped from animals to humans. Virus genetics and outbreak modeling in one study revealed two strains released a few weeks apart in November and December 2019.

“Now I realize it sounds like I just said that a once-in-a-generation event happened twice in short succession, and pandemics are indeed rare,” Joel O. Wertheim, PhD, said at a briefing sponsored by the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

A unique storm of factors had to be present for the outbreak to blow up into a pandemic: Animals carrying a virus that could spread to humans, close human contact with these animals, and a city large enough for the infection to take off before it could be contained are examples.

Unluckily for us humans, this coronavirus – SARS-CoV-2 – is a “generalist virus” capable of infecting many animals, including humans.

“Once all the conditions are in place ... the barriers to spillover have been lowered,” said Dr. Wertheim, a researcher in genetic and molecular networks at the University of California, San Diego. In fact, beyond the two strains of the virus that took hold, there were likely up to two dozen more times where people got the virus but did not spread it far and wide, and it died out.

Overall, the odds were against the virus – 78% of the time, the “introduction” to humans was likely to go extinct, the study showed.

The research revealed the COVID-19 pandemic started small.

“Our model shows that there were likely only a few dozen infections, and only several hospitalizations due to COVID-19, by early December,” said Jonathan Pekar, a graduate student working with Dr. Wertheim.

In Wuhan in late 2019, Mr. Pekar said, there was not a single positive coronavirus sample from thousands of samples from healthy blood donors tested between September and December. Likewise, not one blood sample from patients hospitalized with flu-like illness from October to December 2019 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

Mapping the outbreak

A second study published in the journal Science mapped out the earliest COVID-19 cases. This effort showed a tight cluster around the wholesale seafood market inside Wuhan, a city of 11 million residents.

When researchers tried other scenarios – modeling outbreaks in other parts of the city – the pattern did not hold. Again, the Wuhan market appeared to be ground zero for the start of the pandemic.

Michael Worobey, PhD, and colleagues used data from Chinese scientists and the World Health Organization for the study.

“There was this extraordinary pattern where the highest density of cases was both extremely near to and very centered on this market,” said Dr. Worobey, head of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Arizona, Tucson.

The highest density of cases, in a city of 8,000 square kilometers, was a “very, very small area of about a third of a kilometer square,” he said.

The outbreak pattern showed the Wuhan market “smack dab in the middle.”

So if it started with infected workers at the market, how did it spread from there? It’s likely the virus got into the community as the vendors at the market went to local shops, infecting people in those stores. Then local community members not linked to the market started getting the virus, Dr. Worobey said.

The investigators also identified which stalls in the market were most likely involved, a sort of internal clustering. “That clustering is very, very specifically in the parts of the market where ... they were selling wildlife, including, for example, raccoon dogs and other animals that we know are susceptible to infection with SARS-CoV-2,” said Kristian Andersen, PhD, director of infectious disease genomics at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, Calif.

What remains unknown is which animal or animals carried the virus, although the raccoon dog – an animal similar to a fox that is native to parts of Asia – remains central to most theories. In addition, many of the farms supplying animals to the market have since been closed, making it challenging for researchers to figure out exactly where infected animals came from.

“We don’t know necessarily, but raccoon dogs were sold at this market all the way up to the beginning of the pandemic,” Dr. Andersen said.

Not ruling out other theories

People who believe SARS-CoV-2 was released from a laboratory in China at first included Dr. Worobey himself. “I’ve in the past been much more open to the lab leak idea,” he said. “And published that in a letter in Science” in November 2021.

The letter was “much more influential than I thought it would be in ways that I think it turned out to be quite damaging,” he said. As more evidence emerged since then, Dr. Worobey said he came around to the Wuhan market source theory.

Dr. Andersen agreed he was more open to the lab-leak theory at first. “I was quite convinced of the lab leak myself until we dove into this very carefully and looked at it much closer,” he said. Newer evidence convinced him “that actually, the data points to this particular market.”

“Have we disproved the lab-leak theory? No,” Dr. Anderson said. “Will we ever be able to? No.” But the Wuhan market origin scenario is more plausible. “I would say these two papers combined present the strongest evidence of that to date.”

Identifying the source of the outbreak that led to the COVID-19 pandemic is based in science, Dr. Andersen said. “What we’re trying to understand is the origin of the pandemic. We’re not trying to place blame.”

Future directions

“With pandemics being pandemics, they affect all of us,” Dr. Andersen said. “We can’t prevent these kinds of events that led to the COVID-19 pandemic. But what we can hope to do is to prevent outbreaks from becoming pandemics.”

Rapid reporting of data and cooperation are needed going forward, Dr. Andersen said. Very strong surveillance systems, including wastewater surveillance, could help monitor for SARS-CoV-2, and other pathogens of potential concern in the future as well.

It should be standard practice for medical professionals to be on alert for unusual respiratory infections too, the researchers said.

“It’s a bloody lucky thing that the doctors at the Shinwa hospital were so on the ball, that they noticed that these cases were something unusual at the end of December,” Dr. Worobey said. “It didn’t have to work out that way.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The original spread of the virus was a one-two punch, the studies found. Twice, the virus jumped from animals to humans. Virus genetics and outbreak modeling in one study revealed two strains released a few weeks apart in November and December 2019.

“Now I realize it sounds like I just said that a once-in-a-generation event happened twice in short succession, and pandemics are indeed rare,” Joel O. Wertheim, PhD, said at a briefing sponsored by the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

A unique storm of factors had to be present for the outbreak to blow up into a pandemic: Animals carrying a virus that could spread to humans, close human contact with these animals, and a city large enough for the infection to take off before it could be contained are examples.

Unluckily for us humans, this coronavirus – SARS-CoV-2 – is a “generalist virus” capable of infecting many animals, including humans.

“Once all the conditions are in place ... the barriers to spillover have been lowered,” said Dr. Wertheim, a researcher in genetic and molecular networks at the University of California, San Diego. In fact, beyond the two strains of the virus that took hold, there were likely up to two dozen more times where people got the virus but did not spread it far and wide, and it died out.

Overall, the odds were against the virus – 78% of the time, the “introduction” to humans was likely to go extinct, the study showed.

The research revealed the COVID-19 pandemic started small.

“Our model shows that there were likely only a few dozen infections, and only several hospitalizations due to COVID-19, by early December,” said Jonathan Pekar, a graduate student working with Dr. Wertheim.

In Wuhan in late 2019, Mr. Pekar said, there was not a single positive coronavirus sample from thousands of samples from healthy blood donors tested between September and December. Likewise, not one blood sample from patients hospitalized with flu-like illness from October to December 2019 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

Mapping the outbreak

A second study published in the journal Science mapped out the earliest COVID-19 cases. This effort showed a tight cluster around the wholesale seafood market inside Wuhan, a city of 11 million residents.

When researchers tried other scenarios – modeling outbreaks in other parts of the city – the pattern did not hold. Again, the Wuhan market appeared to be ground zero for the start of the pandemic.

Michael Worobey, PhD, and colleagues used data from Chinese scientists and the World Health Organization for the study.

“There was this extraordinary pattern where the highest density of cases was both extremely near to and very centered on this market,” said Dr. Worobey, head of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Arizona, Tucson.

The highest density of cases, in a city of 8,000 square kilometers, was a “very, very small area of about a third of a kilometer square,” he said.

The outbreak pattern showed the Wuhan market “smack dab in the middle.”

So if it started with infected workers at the market, how did it spread from there? It’s likely the virus got into the community as the vendors at the market went to local shops, infecting people in those stores. Then local community members not linked to the market started getting the virus, Dr. Worobey said.

The investigators also identified which stalls in the market were most likely involved, a sort of internal clustering. “That clustering is very, very specifically in the parts of the market where ... they were selling wildlife, including, for example, raccoon dogs and other animals that we know are susceptible to infection with SARS-CoV-2,” said Kristian Andersen, PhD, director of infectious disease genomics at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, Calif.

What remains unknown is which animal or animals carried the virus, although the raccoon dog – an animal similar to a fox that is native to parts of Asia – remains central to most theories. In addition, many of the farms supplying animals to the market have since been closed, making it challenging for researchers to figure out exactly where infected animals came from.

“We don’t know necessarily, but raccoon dogs were sold at this market all the way up to the beginning of the pandemic,” Dr. Andersen said.

Not ruling out other theories

People who believe SARS-CoV-2 was released from a laboratory in China at first included Dr. Worobey himself. “I’ve in the past been much more open to the lab leak idea,” he said. “And published that in a letter in Science” in November 2021.

The letter was “much more influential than I thought it would be in ways that I think it turned out to be quite damaging,” he said. As more evidence emerged since then, Dr. Worobey said he came around to the Wuhan market source theory.

Dr. Andersen agreed he was more open to the lab-leak theory at first. “I was quite convinced of the lab leak myself until we dove into this very carefully and looked at it much closer,” he said. Newer evidence convinced him “that actually, the data points to this particular market.”

“Have we disproved the lab-leak theory? No,” Dr. Anderson said. “Will we ever be able to? No.” But the Wuhan market origin scenario is more plausible. “I would say these two papers combined present the strongest evidence of that to date.”

Identifying the source of the outbreak that led to the COVID-19 pandemic is based in science, Dr. Andersen said. “What we’re trying to understand is the origin of the pandemic. We’re not trying to place blame.”

Future directions

“With pandemics being pandemics, they affect all of us,” Dr. Andersen said. “We can’t prevent these kinds of events that led to the COVID-19 pandemic. But what we can hope to do is to prevent outbreaks from becoming pandemics.”

Rapid reporting of data and cooperation are needed going forward, Dr. Andersen said. Very strong surveillance systems, including wastewater surveillance, could help monitor for SARS-CoV-2, and other pathogens of potential concern in the future as well.

It should be standard practice for medical professionals to be on alert for unusual respiratory infections too, the researchers said.

“It’s a bloody lucky thing that the doctors at the Shinwa hospital were so on the ball, that they noticed that these cases were something unusual at the end of December,” Dr. Worobey said. “It didn’t have to work out that way.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The original spread of the virus was a one-two punch, the studies found. Twice, the virus jumped from animals to humans. Virus genetics and outbreak modeling in one study revealed two strains released a few weeks apart in November and December 2019.

“Now I realize it sounds like I just said that a once-in-a-generation event happened twice in short succession, and pandemics are indeed rare,” Joel O. Wertheim, PhD, said at a briefing sponsored by the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

A unique storm of factors had to be present for the outbreak to blow up into a pandemic: Animals carrying a virus that could spread to humans, close human contact with these animals, and a city large enough for the infection to take off before it could be contained are examples.

Unluckily for us humans, this coronavirus – SARS-CoV-2 – is a “generalist virus” capable of infecting many animals, including humans.

“Once all the conditions are in place ... the barriers to spillover have been lowered,” said Dr. Wertheim, a researcher in genetic and molecular networks at the University of California, San Diego. In fact, beyond the two strains of the virus that took hold, there were likely up to two dozen more times where people got the virus but did not spread it far and wide, and it died out.

Overall, the odds were against the virus – 78% of the time, the “introduction” to humans was likely to go extinct, the study showed.

The research revealed the COVID-19 pandemic started small.

“Our model shows that there were likely only a few dozen infections, and only several hospitalizations due to COVID-19, by early December,” said Jonathan Pekar, a graduate student working with Dr. Wertheim.

In Wuhan in late 2019, Mr. Pekar said, there was not a single positive coronavirus sample from thousands of samples from healthy blood donors tested between September and December. Likewise, not one blood sample from patients hospitalized with flu-like illness from October to December 2019 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

Mapping the outbreak

A second study published in the journal Science mapped out the earliest COVID-19 cases. This effort showed a tight cluster around the wholesale seafood market inside Wuhan, a city of 11 million residents.

When researchers tried other scenarios – modeling outbreaks in other parts of the city – the pattern did not hold. Again, the Wuhan market appeared to be ground zero for the start of the pandemic.

Michael Worobey, PhD, and colleagues used data from Chinese scientists and the World Health Organization for the study.

“There was this extraordinary pattern where the highest density of cases was both extremely near to and very centered on this market,” said Dr. Worobey, head of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Arizona, Tucson.

The highest density of cases, in a city of 8,000 square kilometers, was a “very, very small area of about a third of a kilometer square,” he said.

The outbreak pattern showed the Wuhan market “smack dab in the middle.”

So if it started with infected workers at the market, how did it spread from there? It’s likely the virus got into the community as the vendors at the market went to local shops, infecting people in those stores. Then local community members not linked to the market started getting the virus, Dr. Worobey said.