User login

Budesonide topped placebo for treating lymphocytic colitis

Among patients with lymphocytic colitis, 8 weeks of oral budesonide therapy was associated with significantly higher rates of clinical and histologic remission versus placebo in a multicenter, double-blind clinical trial.

Fully 79% of patients achieved clinical remission with budesonide, compared with only 42% of patients in the placebo arm (P = .01), reported Stephan Miehlke, MD, of the Center for Digestive Diseases in Hamburg, Germany, and his associates. A third group of patients received oral mesalazine therapy, which induced clinical remission in 68% of cases (P = .09). Budesonide also induced histologic remission significantly more often (68%) than did mesalazine (26%; P = .02) or placebo (21%; P = .008).

“The study population was not large, but the trial was adequately powered,” the researchers wrote. The report was published online in Gastroenterology. “These results confirm the efficacy of budesonide for the induction of remission in active lymphocytic colitis and are consistent with expert recommendations for its use as first-line therapy.”

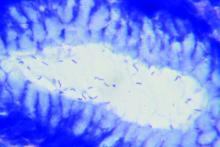

Lymphocytic colitis is a subtype of microscopic colitis that is characterized by an increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes. This condition has substantial negative effects on quality of life – the most common symptom is chronic diarrhea, and some patients also experience fecal incontinence and abdominal pain. Expert guidelines recommend first-line treatment with budesonide and second-line treatment with mesalazine, but evidence supporting either recommendation is sparse and low-quality, the investigators wrote.

For the study, they compared 8 weeks of treatment with pH-modified release oral budesonide granules (9 mg once daily), oral mesalazine granules (3 g once daily) or placebo in 57 patients (19 per arm) with histologically confirmed, newly diagnosed or relapsed lymphocytic colitis. All patients had at least a 12-week history of watery, nonbloody diarrhea, no other documented diarrheal conditions, and no recent history of antidiarrheal therapy. Nearly three-quarters were female and the mean age was 59 years. The primary endpoint was clinical remission, defined as no more than 21 stools in the 7 days before week 8, including no more than 6 watery stools.

After 8 weeks of double-blinded treatment, all clinically remitted patients stopped treatment and were followed for another 16 weeks. Those who were not in remission or who relapsed were offered 4 weeks of open-label budesonide therapy, which led to clinical remission in 88% of cases, the researchers said. “This study confirms that budesonide is effective for the induction of remission in active lymphocytic colitis,” they concluded. “Strikingly, a substantial improvement in symptoms, including a profound reduction in the number of watery stools, was seen within a median of 3 days after starting budesonide therapy.”

Serious adverse events were uncommon in all three groups, and each arm had a similar rate of adverse events considered secondary to treatment. In the budesonide group, these included one case each of weight gain, transient ischemic attack, and affective disturbance with sleep disorder. In the mesalazine group, three patients developed acute pancreatitis, increased hepatic enzymes, or dizziness. Eleven percent of budesonide recipients and 16% of mesalazine recipients stopped treatment because of adverse events. “No patient in any group had a clinically significant shift in cortisol level between baseline and week 8 that was considered related to the study drug,” the investigators said. “Other changes in laboratory parameters were not considered clinically relevant in any treatment group.”

The study was funded by Dr. Falk Pharma GmbH, Freiburg, Germany. Dr. Miehlke and two coauthors received speaker fees from Dr. Falk Pharma. Dr. Miehlke and one coauthor received consultancy fees from Tillots. One coauthor received speaker fees, has been a member of the advisory board, and has received grants from Tillots.

SOURCE: Miehlke S et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Sep 6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.042.

Among patients with lymphocytic colitis, 8 weeks of oral budesonide therapy was associated with significantly higher rates of clinical and histologic remission versus placebo in a multicenter, double-blind clinical trial.

Fully 79% of patients achieved clinical remission with budesonide, compared with only 42% of patients in the placebo arm (P = .01), reported Stephan Miehlke, MD, of the Center for Digestive Diseases in Hamburg, Germany, and his associates. A third group of patients received oral mesalazine therapy, which induced clinical remission in 68% of cases (P = .09). Budesonide also induced histologic remission significantly more often (68%) than did mesalazine (26%; P = .02) or placebo (21%; P = .008).

“The study population was not large, but the trial was adequately powered,” the researchers wrote. The report was published online in Gastroenterology. “These results confirm the efficacy of budesonide for the induction of remission in active lymphocytic colitis and are consistent with expert recommendations for its use as first-line therapy.”

Lymphocytic colitis is a subtype of microscopic colitis that is characterized by an increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes. This condition has substantial negative effects on quality of life – the most common symptom is chronic diarrhea, and some patients also experience fecal incontinence and abdominal pain. Expert guidelines recommend first-line treatment with budesonide and second-line treatment with mesalazine, but evidence supporting either recommendation is sparse and low-quality, the investigators wrote.

For the study, they compared 8 weeks of treatment with pH-modified release oral budesonide granules (9 mg once daily), oral mesalazine granules (3 g once daily) or placebo in 57 patients (19 per arm) with histologically confirmed, newly diagnosed or relapsed lymphocytic colitis. All patients had at least a 12-week history of watery, nonbloody diarrhea, no other documented diarrheal conditions, and no recent history of antidiarrheal therapy. Nearly three-quarters were female and the mean age was 59 years. The primary endpoint was clinical remission, defined as no more than 21 stools in the 7 days before week 8, including no more than 6 watery stools.

After 8 weeks of double-blinded treatment, all clinically remitted patients stopped treatment and were followed for another 16 weeks. Those who were not in remission or who relapsed were offered 4 weeks of open-label budesonide therapy, which led to clinical remission in 88% of cases, the researchers said. “This study confirms that budesonide is effective for the induction of remission in active lymphocytic colitis,” they concluded. “Strikingly, a substantial improvement in symptoms, including a profound reduction in the number of watery stools, was seen within a median of 3 days after starting budesonide therapy.”

Serious adverse events were uncommon in all three groups, and each arm had a similar rate of adverse events considered secondary to treatment. In the budesonide group, these included one case each of weight gain, transient ischemic attack, and affective disturbance with sleep disorder. In the mesalazine group, three patients developed acute pancreatitis, increased hepatic enzymes, or dizziness. Eleven percent of budesonide recipients and 16% of mesalazine recipients stopped treatment because of adverse events. “No patient in any group had a clinically significant shift in cortisol level between baseline and week 8 that was considered related to the study drug,” the investigators said. “Other changes in laboratory parameters were not considered clinically relevant in any treatment group.”

The study was funded by Dr. Falk Pharma GmbH, Freiburg, Germany. Dr. Miehlke and two coauthors received speaker fees from Dr. Falk Pharma. Dr. Miehlke and one coauthor received consultancy fees from Tillots. One coauthor received speaker fees, has been a member of the advisory board, and has received grants from Tillots.

SOURCE: Miehlke S et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Sep 6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.042.

Among patients with lymphocytic colitis, 8 weeks of oral budesonide therapy was associated with significantly higher rates of clinical and histologic remission versus placebo in a multicenter, double-blind clinical trial.

Fully 79% of patients achieved clinical remission with budesonide, compared with only 42% of patients in the placebo arm (P = .01), reported Stephan Miehlke, MD, of the Center for Digestive Diseases in Hamburg, Germany, and his associates. A third group of patients received oral mesalazine therapy, which induced clinical remission in 68% of cases (P = .09). Budesonide also induced histologic remission significantly more often (68%) than did mesalazine (26%; P = .02) or placebo (21%; P = .008).

“The study population was not large, but the trial was adequately powered,” the researchers wrote. The report was published online in Gastroenterology. “These results confirm the efficacy of budesonide for the induction of remission in active lymphocytic colitis and are consistent with expert recommendations for its use as first-line therapy.”

Lymphocytic colitis is a subtype of microscopic colitis that is characterized by an increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes. This condition has substantial negative effects on quality of life – the most common symptom is chronic diarrhea, and some patients also experience fecal incontinence and abdominal pain. Expert guidelines recommend first-line treatment with budesonide and second-line treatment with mesalazine, but evidence supporting either recommendation is sparse and low-quality, the investigators wrote.

For the study, they compared 8 weeks of treatment with pH-modified release oral budesonide granules (9 mg once daily), oral mesalazine granules (3 g once daily) or placebo in 57 patients (19 per arm) with histologically confirmed, newly diagnosed or relapsed lymphocytic colitis. All patients had at least a 12-week history of watery, nonbloody diarrhea, no other documented diarrheal conditions, and no recent history of antidiarrheal therapy. Nearly three-quarters were female and the mean age was 59 years. The primary endpoint was clinical remission, defined as no more than 21 stools in the 7 days before week 8, including no more than 6 watery stools.

After 8 weeks of double-blinded treatment, all clinically remitted patients stopped treatment and were followed for another 16 weeks. Those who were not in remission or who relapsed were offered 4 weeks of open-label budesonide therapy, which led to clinical remission in 88% of cases, the researchers said. “This study confirms that budesonide is effective for the induction of remission in active lymphocytic colitis,” they concluded. “Strikingly, a substantial improvement in symptoms, including a profound reduction in the number of watery stools, was seen within a median of 3 days after starting budesonide therapy.”

Serious adverse events were uncommon in all three groups, and each arm had a similar rate of adverse events considered secondary to treatment. In the budesonide group, these included one case each of weight gain, transient ischemic attack, and affective disturbance with sleep disorder. In the mesalazine group, three patients developed acute pancreatitis, increased hepatic enzymes, or dizziness. Eleven percent of budesonide recipients and 16% of mesalazine recipients stopped treatment because of adverse events. “No patient in any group had a clinically significant shift in cortisol level between baseline and week 8 that was considered related to the study drug,” the investigators said. “Other changes in laboratory parameters were not considered clinically relevant in any treatment group.”

The study was funded by Dr. Falk Pharma GmbH, Freiburg, Germany. Dr. Miehlke and two coauthors received speaker fees from Dr. Falk Pharma. Dr. Miehlke and one coauthor received consultancy fees from Tillots. One coauthor received speaker fees, has been a member of the advisory board, and has received grants from Tillots.

SOURCE: Miehlke S et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Sep 6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.042.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Budesonide significantly outperformed placebo for inducing clinical remission of lymphocytic colitis.

Major finding: Rates of clinical remission were 79% with budesonide, 42% with placebo (P = .01), and 68% with mesalazine (P = .09 vs. placebo).

Study details: Multicenter double-blind trial of 57 patients with chronic lymphocytic colitis.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Dr. Falk Pharma GmbH, Freiburg, Germany. Dr. Miehlke and two coauthors received speaker fees from Dr. Falk Pharma. Dr. Miehlke and one coauthor received consultancy fees from Tillots. One coauthor received speaker fees, has been a member of the advisory board, and has received grants from Tillots.

Source: Miehlke S et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Sep 6.

Maintaining virologic response predicted long-term survival in HBV patients with decompensated cirrhosis

according to the results of a multicenter observational study published in the December issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Survival times were “excellent” if patients survived the first 6 months of antiviral therapy and did not develop hepatocellular carcinoma, said Jeong Won Jang, MD, of the Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine in Seoul, South Korea, and his associates. Patients who developed hepatocellular carcinoma had persistent declines in survival over time, they said. Predictors of short-term mortality included a baseline Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score above 20 and multiple complications.

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is the most common cause of liver-related disease and death in Asia, and complications such as decompensated cirrhosis affect up to 40% of chronically infected persons. Five-year survival rates are as low as 14% if patients develop decompensated cirrhosis.

To explore whether virologic suppression with oral nucleoside or nucleotide analog therapy improves outcomes in these decompensated patients, the researchers studied 295 such individuals from the Epidemiology and Natural History of Liver Cirrhosis in Korea Study. At baseline, these patients did not have documented chronic hepatitis C virus infection, hepatocellular carcinoma, other cancers, autoimmune hepatitis, or alcohol use disorders. All patients initiated entecavir or lamivudine therapy immediately after their cirrhosis became decompensated. The primary outcome was transplant-free survival.

A total of 60.1% of patients survived 5 years and 45.7% survived 10 years without undergoing transplantation, for a median transplant-free survival time of 7.7 years. The 116 patients (39%) who consistently had undetectable HBV DNA levels (less than 20 IU/mL) throughout treatment had significantly longer transplant-free survival than did patients who did not maintain a virologic response (P less than .001). In addition, a maintained virologic response (MVR) was the strongest predictor of long-term transplant-free survival, the researchers said.

A significantly greater proportion of patients who received entecavir survived 10 years compared with patients who received lamivudine. However, there was no significant difference in long-term survival among patients with MVRs to either drug. “Importantly, it appears that improvement in patient survival is attained by antiviral response, not by the type of nucleos(t)ide analogue per se,” the researchers wrote.

Patients who achieved MVR also showed significant improvements in hepatic function, but “the preventive effects of MVR on the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma appeared only modest,” the investigators said. “Survival of patients without hepatocellular carcinoma who survived the first 6 months after initiation of antiviral therapy was excellent, with only a 25.3% mortality rate occurring between 6 months and 10 years.”

Based on their findings, Dr. Jang and his associates recommended aiming for an HBV DNA load less than 20 IU/mL in patients with decompensated cirrhosis to significantly improve the chances of long-term survival. Survival curves were similar regardless of whether patients had HBV DNA levels less than 10 IU/mL or between and 10 and 20 IU/mL, they noted.

Funders included Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project and the Catholic Research Coordinating Center of the Korea Health 21 R&D Project, both of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea. Dr. Jang disclosed ties to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, and Merck Sharp & Dohme. Three coinvestigators also disclosed ties to Gilead, MSD, and several other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Jang JW et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 May 18. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.04.063

according to the results of a multicenter observational study published in the December issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Survival times were “excellent” if patients survived the first 6 months of antiviral therapy and did not develop hepatocellular carcinoma, said Jeong Won Jang, MD, of the Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine in Seoul, South Korea, and his associates. Patients who developed hepatocellular carcinoma had persistent declines in survival over time, they said. Predictors of short-term mortality included a baseline Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score above 20 and multiple complications.

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is the most common cause of liver-related disease and death in Asia, and complications such as decompensated cirrhosis affect up to 40% of chronically infected persons. Five-year survival rates are as low as 14% if patients develop decompensated cirrhosis.

To explore whether virologic suppression with oral nucleoside or nucleotide analog therapy improves outcomes in these decompensated patients, the researchers studied 295 such individuals from the Epidemiology and Natural History of Liver Cirrhosis in Korea Study. At baseline, these patients did not have documented chronic hepatitis C virus infection, hepatocellular carcinoma, other cancers, autoimmune hepatitis, or alcohol use disorders. All patients initiated entecavir or lamivudine therapy immediately after their cirrhosis became decompensated. The primary outcome was transplant-free survival.

A total of 60.1% of patients survived 5 years and 45.7% survived 10 years without undergoing transplantation, for a median transplant-free survival time of 7.7 years. The 116 patients (39%) who consistently had undetectable HBV DNA levels (less than 20 IU/mL) throughout treatment had significantly longer transplant-free survival than did patients who did not maintain a virologic response (P less than .001). In addition, a maintained virologic response (MVR) was the strongest predictor of long-term transplant-free survival, the researchers said.

A significantly greater proportion of patients who received entecavir survived 10 years compared with patients who received lamivudine. However, there was no significant difference in long-term survival among patients with MVRs to either drug. “Importantly, it appears that improvement in patient survival is attained by antiviral response, not by the type of nucleos(t)ide analogue per se,” the researchers wrote.

Patients who achieved MVR also showed significant improvements in hepatic function, but “the preventive effects of MVR on the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma appeared only modest,” the investigators said. “Survival of patients without hepatocellular carcinoma who survived the first 6 months after initiation of antiviral therapy was excellent, with only a 25.3% mortality rate occurring between 6 months and 10 years.”

Based on their findings, Dr. Jang and his associates recommended aiming for an HBV DNA load less than 20 IU/mL in patients with decompensated cirrhosis to significantly improve the chances of long-term survival. Survival curves were similar regardless of whether patients had HBV DNA levels less than 10 IU/mL or between and 10 and 20 IU/mL, they noted.

Funders included Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project and the Catholic Research Coordinating Center of the Korea Health 21 R&D Project, both of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea. Dr. Jang disclosed ties to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, and Merck Sharp & Dohme. Three coinvestigators also disclosed ties to Gilead, MSD, and several other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Jang JW et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 May 18. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.04.063

according to the results of a multicenter observational study published in the December issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Survival times were “excellent” if patients survived the first 6 months of antiviral therapy and did not develop hepatocellular carcinoma, said Jeong Won Jang, MD, of the Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine in Seoul, South Korea, and his associates. Patients who developed hepatocellular carcinoma had persistent declines in survival over time, they said. Predictors of short-term mortality included a baseline Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score above 20 and multiple complications.

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is the most common cause of liver-related disease and death in Asia, and complications such as decompensated cirrhosis affect up to 40% of chronically infected persons. Five-year survival rates are as low as 14% if patients develop decompensated cirrhosis.

To explore whether virologic suppression with oral nucleoside or nucleotide analog therapy improves outcomes in these decompensated patients, the researchers studied 295 such individuals from the Epidemiology and Natural History of Liver Cirrhosis in Korea Study. At baseline, these patients did not have documented chronic hepatitis C virus infection, hepatocellular carcinoma, other cancers, autoimmune hepatitis, or alcohol use disorders. All patients initiated entecavir or lamivudine therapy immediately after their cirrhosis became decompensated. The primary outcome was transplant-free survival.

A total of 60.1% of patients survived 5 years and 45.7% survived 10 years without undergoing transplantation, for a median transplant-free survival time of 7.7 years. The 116 patients (39%) who consistently had undetectable HBV DNA levels (less than 20 IU/mL) throughout treatment had significantly longer transplant-free survival than did patients who did not maintain a virologic response (P less than .001). In addition, a maintained virologic response (MVR) was the strongest predictor of long-term transplant-free survival, the researchers said.

A significantly greater proportion of patients who received entecavir survived 10 years compared with patients who received lamivudine. However, there was no significant difference in long-term survival among patients with MVRs to either drug. “Importantly, it appears that improvement in patient survival is attained by antiviral response, not by the type of nucleos(t)ide analogue per se,” the researchers wrote.

Patients who achieved MVR also showed significant improvements in hepatic function, but “the preventive effects of MVR on the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma appeared only modest,” the investigators said. “Survival of patients without hepatocellular carcinoma who survived the first 6 months after initiation of antiviral therapy was excellent, with only a 25.3% mortality rate occurring between 6 months and 10 years.”

Based on their findings, Dr. Jang and his associates recommended aiming for an HBV DNA load less than 20 IU/mL in patients with decompensated cirrhosis to significantly improve the chances of long-term survival. Survival curves were similar regardless of whether patients had HBV DNA levels less than 10 IU/mL or between and 10 and 20 IU/mL, they noted.

Funders included Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project and the Catholic Research Coordinating Center of the Korea Health 21 R&D Project, both of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea. Dr. Jang disclosed ties to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, and Merck Sharp & Dohme. Three coinvestigators also disclosed ties to Gilead, MSD, and several other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Jang JW et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 May 18. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.04.063

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: For patients with decompensated cirrhosis, long-term hepatitis B virus suppression was associated with significantly improved transplant-free survival.

Major finding: Lack of virologic response was associated with a more than twofold increase in hazard of long-term mortality in the multivariate analysis (HR, 2.30; 95% confidence interval, 1.60-3.29; P less than .001).

Study details: Ten-year multicenter observational study of 295 patients who began entecavir or lamivudine therapy immediately after their cirrhosis became decompensated.

Disclosures: Funders included Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project and the Catholic Research Coordinating Center of the Korea Health 21 R&D Project, both of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea. Dr. Jang disclosed ties to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, and Merck Sharp & Dohme. Three coinvestigators also disclosed ties to Gilead, MSD, and several other pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Jang JW et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 May 18. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.04.063

Norfloxacin might benefit patients with advanced cirrhosis and low ascites fluid protein levels

Six months of once-daily norfloxacin therapy did not reduce 6-month mortality among patients with Child-Pugh class C cirrhosis who had not recently received fluoroquinolone therapy.

Mortality based on the Kaplan-Meier method was 14.8% in the norfloxacin group versus 19.7% for patients receiving placebo (P = .21). “Norfloxacin, however, appear[ed] to increase survival of patients with low ascites fluid protein concentrations,” wrote Richard Moreau, MD, of Hôpital Beaujon, Paris, and his associates. The results of the multicenter, double-blind trial of 291 patients were published in the December issue of Gastroenterology.

Patients with advanced cirrhosis often develop spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and other severe bacterial infections, with potentially grave outcomes. These are often enteric gram-negative bacteria that cross the intestinal barrier, enter the systemic circulation, and travel to the site of infection.

Long-term fluoroquinolone therapy (typically with norfloxacin) might help prevent these bacterial infections, the translocation of bacterial products, systemic inflammation, and consequent end-organ dysfunction, such as acute kidney disease. However, long-term antibiotic therapy also raises the specter of multidrug resistance, which is especially concerning when it involves a crucial antibiotic class such as fluoroquinolones, the researchers noted. “[In] patients receiving prolonged fluoroquinolone therapy, the development of infections by multidrug resistant bacteria might obscure the beneficial effect of fluoroquinolones on survival,” they added.

Four previous blinded and placebo-controlled trials have investigated fluoroquinolone therapy and mortality patients with cirrhosis, but they were small, usually included mortality only as a secondary outcome, and yielded mixed results. Hence, the researchers enrolled 291 patients with advanced (Child-Pugh class C) cirrhosis from 18 clinical sites in France and randomly assigned them to receive either norfloxacin (400 mg once daily) or placebo for 6 months. Patients were evaluated monthly during treatment and then at 9 months and 12 months. The primary outcome was survival at 6 months.

In a post hoc analysis, the researchers examined cumulative death rates at 6 months after accounting for liver transplantation as a competing risk of death and including survival data for patients who developed spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Taking this approach, the estimated cumulative rate of death at 6 months was 15.5% (95% confidence interval, 10.1-21.9) in the norfloxacin group and 24.8% (95% CI, 18.1-32.1) in the placebo group, for a hazard ratio of 0.59 (95% CI, 0.35-0.99). Among patients whose ascites fluid levels were less than 15 g/L, the hazard ratio for death at 6 months was 65% lower in the norfloxacin group than in the placebo group (HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.13-0.93). Norfloxacin showed no such benefit for patients with ascites fluid protein levels above 15 g/L.

Norfloxacin therapy “could reduce the incidence of death among patients with ascitic fluid protein concentrations of less than 15 g/L but not among those with ascitic fluid protein concentration of 15 g/L or more,” the researchers concluded. “Norfloxacin may prevent some infections, especially gram-negative bacterial infections, but not the development of [spontaneous bacterial peritonitis] and other noninfectious, liver-related complications.”

The study was funded by Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique National 2008 of the French Ministry of Health. Dr. Moreau reported having no conflicts of interest. Two coinvestigators disclosed ties to Gore Norgine, Exalenz, and Conatus.

SOURCE: Moreau R et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Aug 22. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.026.

Prolonged antimicrobial use in patients with decompensated cirrhosis is an area of unclear mortality benefit and may actually increase risk in some patients given antimicrobial resistance. This randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial by Moreau et al. evaluates the mortality associated with long-term fluoroquinolone therapy in patients without indications for primary or secondary prophylaxis. Although the study had limited statistical power to detect clear benefit, the authors found that 6-month mortality was not reduced in patients with Child-Pugh class C cirrhosis who received treatment with daily oral fluoroquinolone therapy for 6 months. Subgroup analysis of individuals with ascites fluid total protein levels lower than 15 g/L showed a survival benefit at 6 months.

Determining quantifiable risk for known factors associated with liver disease mortality is a pressing issue, especially in the pretransplant setting where infectious risk is compounded post transplant with changes in gut flora, addition of potent immunosuppressants, and increased metabolic demands. Biologic measurements that correlate with increased complications and mortality, like low protein ascites, are helpful in complex clinical settings.Studying patients with advanced and decompensated liver disease in a systematic, longitudinal manner with any pharmacologic intervention is a particular challenge given the unpredictable nature of decompensation events and variable outcomes from those events. However, attempts to quantify risk and benefit even in this unpredictable patient population is worthwhile to stratify patients for interventions and minimize risk of liver-related and overall mortality – as well as peritransplant complications and posttransplant survival.

Julia J. Wattacheril, MD, MPH, is a physician- scientist and director of the Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Program in the Center for Liver Disease and Transplantation at Columbia University Irving Medical Center–New York Presbyterian Hospital, New York; an assistant professor, department of medicine, division of digestive and liver diseases at the Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons. She has no conflicts.

Prolonged antimicrobial use in patients with decompensated cirrhosis is an area of unclear mortality benefit and may actually increase risk in some patients given antimicrobial resistance. This randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial by Moreau et al. evaluates the mortality associated with long-term fluoroquinolone therapy in patients without indications for primary or secondary prophylaxis. Although the study had limited statistical power to detect clear benefit, the authors found that 6-month mortality was not reduced in patients with Child-Pugh class C cirrhosis who received treatment with daily oral fluoroquinolone therapy for 6 months. Subgroup analysis of individuals with ascites fluid total protein levels lower than 15 g/L showed a survival benefit at 6 months.

Determining quantifiable risk for known factors associated with liver disease mortality is a pressing issue, especially in the pretransplant setting where infectious risk is compounded post transplant with changes in gut flora, addition of potent immunosuppressants, and increased metabolic demands. Biologic measurements that correlate with increased complications and mortality, like low protein ascites, are helpful in complex clinical settings.Studying patients with advanced and decompensated liver disease in a systematic, longitudinal manner with any pharmacologic intervention is a particular challenge given the unpredictable nature of decompensation events and variable outcomes from those events. However, attempts to quantify risk and benefit even in this unpredictable patient population is worthwhile to stratify patients for interventions and minimize risk of liver-related and overall mortality – as well as peritransplant complications and posttransplant survival.

Julia J. Wattacheril, MD, MPH, is a physician- scientist and director of the Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Program in the Center for Liver Disease and Transplantation at Columbia University Irving Medical Center–New York Presbyterian Hospital, New York; an assistant professor, department of medicine, division of digestive and liver diseases at the Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons. She has no conflicts.

Prolonged antimicrobial use in patients with decompensated cirrhosis is an area of unclear mortality benefit and may actually increase risk in some patients given antimicrobial resistance. This randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial by Moreau et al. evaluates the mortality associated with long-term fluoroquinolone therapy in patients without indications for primary or secondary prophylaxis. Although the study had limited statistical power to detect clear benefit, the authors found that 6-month mortality was not reduced in patients with Child-Pugh class C cirrhosis who received treatment with daily oral fluoroquinolone therapy for 6 months. Subgroup analysis of individuals with ascites fluid total protein levels lower than 15 g/L showed a survival benefit at 6 months.

Determining quantifiable risk for known factors associated with liver disease mortality is a pressing issue, especially in the pretransplant setting where infectious risk is compounded post transplant with changes in gut flora, addition of potent immunosuppressants, and increased metabolic demands. Biologic measurements that correlate with increased complications and mortality, like low protein ascites, are helpful in complex clinical settings.Studying patients with advanced and decompensated liver disease in a systematic, longitudinal manner with any pharmacologic intervention is a particular challenge given the unpredictable nature of decompensation events and variable outcomes from those events. However, attempts to quantify risk and benefit even in this unpredictable patient population is worthwhile to stratify patients for interventions and minimize risk of liver-related and overall mortality – as well as peritransplant complications and posttransplant survival.

Julia J. Wattacheril, MD, MPH, is a physician- scientist and director of the Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Program in the Center for Liver Disease and Transplantation at Columbia University Irving Medical Center–New York Presbyterian Hospital, New York; an assistant professor, department of medicine, division of digestive and liver diseases at the Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons. She has no conflicts.

Six months of once-daily norfloxacin therapy did not reduce 6-month mortality among patients with Child-Pugh class C cirrhosis who had not recently received fluoroquinolone therapy.

Mortality based on the Kaplan-Meier method was 14.8% in the norfloxacin group versus 19.7% for patients receiving placebo (P = .21). “Norfloxacin, however, appear[ed] to increase survival of patients with low ascites fluid protein concentrations,” wrote Richard Moreau, MD, of Hôpital Beaujon, Paris, and his associates. The results of the multicenter, double-blind trial of 291 patients were published in the December issue of Gastroenterology.

Patients with advanced cirrhosis often develop spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and other severe bacterial infections, with potentially grave outcomes. These are often enteric gram-negative bacteria that cross the intestinal barrier, enter the systemic circulation, and travel to the site of infection.

Long-term fluoroquinolone therapy (typically with norfloxacin) might help prevent these bacterial infections, the translocation of bacterial products, systemic inflammation, and consequent end-organ dysfunction, such as acute kidney disease. However, long-term antibiotic therapy also raises the specter of multidrug resistance, which is especially concerning when it involves a crucial antibiotic class such as fluoroquinolones, the researchers noted. “[In] patients receiving prolonged fluoroquinolone therapy, the development of infections by multidrug resistant bacteria might obscure the beneficial effect of fluoroquinolones on survival,” they added.

Four previous blinded and placebo-controlled trials have investigated fluoroquinolone therapy and mortality patients with cirrhosis, but they were small, usually included mortality only as a secondary outcome, and yielded mixed results. Hence, the researchers enrolled 291 patients with advanced (Child-Pugh class C) cirrhosis from 18 clinical sites in France and randomly assigned them to receive either norfloxacin (400 mg once daily) or placebo for 6 months. Patients were evaluated monthly during treatment and then at 9 months and 12 months. The primary outcome was survival at 6 months.

In a post hoc analysis, the researchers examined cumulative death rates at 6 months after accounting for liver transplantation as a competing risk of death and including survival data for patients who developed spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Taking this approach, the estimated cumulative rate of death at 6 months was 15.5% (95% confidence interval, 10.1-21.9) in the norfloxacin group and 24.8% (95% CI, 18.1-32.1) in the placebo group, for a hazard ratio of 0.59 (95% CI, 0.35-0.99). Among patients whose ascites fluid levels were less than 15 g/L, the hazard ratio for death at 6 months was 65% lower in the norfloxacin group than in the placebo group (HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.13-0.93). Norfloxacin showed no such benefit for patients with ascites fluid protein levels above 15 g/L.

Norfloxacin therapy “could reduce the incidence of death among patients with ascitic fluid protein concentrations of less than 15 g/L but not among those with ascitic fluid protein concentration of 15 g/L or more,” the researchers concluded. “Norfloxacin may prevent some infections, especially gram-negative bacterial infections, but not the development of [spontaneous bacterial peritonitis] and other noninfectious, liver-related complications.”

The study was funded by Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique National 2008 of the French Ministry of Health. Dr. Moreau reported having no conflicts of interest. Two coinvestigators disclosed ties to Gore Norgine, Exalenz, and Conatus.

SOURCE: Moreau R et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Aug 22. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.026.

Six months of once-daily norfloxacin therapy did not reduce 6-month mortality among patients with Child-Pugh class C cirrhosis who had not recently received fluoroquinolone therapy.

Mortality based on the Kaplan-Meier method was 14.8% in the norfloxacin group versus 19.7% for patients receiving placebo (P = .21). “Norfloxacin, however, appear[ed] to increase survival of patients with low ascites fluid protein concentrations,” wrote Richard Moreau, MD, of Hôpital Beaujon, Paris, and his associates. The results of the multicenter, double-blind trial of 291 patients were published in the December issue of Gastroenterology.

Patients with advanced cirrhosis often develop spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and other severe bacterial infections, with potentially grave outcomes. These are often enteric gram-negative bacteria that cross the intestinal barrier, enter the systemic circulation, and travel to the site of infection.

Long-term fluoroquinolone therapy (typically with norfloxacin) might help prevent these bacterial infections, the translocation of bacterial products, systemic inflammation, and consequent end-organ dysfunction, such as acute kidney disease. However, long-term antibiotic therapy also raises the specter of multidrug resistance, which is especially concerning when it involves a crucial antibiotic class such as fluoroquinolones, the researchers noted. “[In] patients receiving prolonged fluoroquinolone therapy, the development of infections by multidrug resistant bacteria might obscure the beneficial effect of fluoroquinolones on survival,” they added.

Four previous blinded and placebo-controlled trials have investigated fluoroquinolone therapy and mortality patients with cirrhosis, but they were small, usually included mortality only as a secondary outcome, and yielded mixed results. Hence, the researchers enrolled 291 patients with advanced (Child-Pugh class C) cirrhosis from 18 clinical sites in France and randomly assigned them to receive either norfloxacin (400 mg once daily) or placebo for 6 months. Patients were evaluated monthly during treatment and then at 9 months and 12 months. The primary outcome was survival at 6 months.

In a post hoc analysis, the researchers examined cumulative death rates at 6 months after accounting for liver transplantation as a competing risk of death and including survival data for patients who developed spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Taking this approach, the estimated cumulative rate of death at 6 months was 15.5% (95% confidence interval, 10.1-21.9) in the norfloxacin group and 24.8% (95% CI, 18.1-32.1) in the placebo group, for a hazard ratio of 0.59 (95% CI, 0.35-0.99). Among patients whose ascites fluid levels were less than 15 g/L, the hazard ratio for death at 6 months was 65% lower in the norfloxacin group than in the placebo group (HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.13-0.93). Norfloxacin showed no such benefit for patients with ascites fluid protein levels above 15 g/L.

Norfloxacin therapy “could reduce the incidence of death among patients with ascitic fluid protein concentrations of less than 15 g/L but not among those with ascitic fluid protein concentration of 15 g/L or more,” the researchers concluded. “Norfloxacin may prevent some infections, especially gram-negative bacterial infections, but not the development of [spontaneous bacterial peritonitis] and other noninfectious, liver-related complications.”

The study was funded by Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique National 2008 of the French Ministry of Health. Dr. Moreau reported having no conflicts of interest. Two coinvestigators disclosed ties to Gore Norgine, Exalenz, and Conatus.

SOURCE: Moreau R et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Aug 22. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.026.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Six months of once-daily norfloxacin therapy did not reduce 6-month mortality among patients with Child-Pugh class C cirrhosis who had not recently received fluoroquinolone therapy, but norfloxacin did appear to benefit a subgroup of patients with low ascites fluid protein levels.

Major finding: Mortality based on the Kaplan-Meier method was 14.8% in the norfloxacin group versus 19.7% for patients receiving placebo (P = .21). Among patients whose ascites fluid levels were less than 15 g/L, the hazard ratio for death at 6 months was 65% lower in the norfloxacin group than in the placebo group (HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.13-0.93).

Study details: Multicenter double-blind trial of 291 patients with Child-Pugh class C cirrhosis who had not received recent fluoroquinolone therapy.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique National 2008 of the French Ministry of Health. Dr. Moreau reported having no conflicts of interest. Two coinvestigators disclosed ties to Gore Norgine, Exalenz, and Conatus.

Source: Moreau R et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Aug 22. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.026.

Crohn’s disease tied to anal canal high-risk HPV infection

Crohn’s disease was significantly associated with anal canal high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in a prospective, single-center study of patients undergoing colonoscopy for various indications.

High-risk HPV and HPV strain 16 were detected in 30% of patients with Crohn’s disease and 18% of patients without Crohn’s disease (P = .005), said Lucine Vuitton, MD, of University Hospital of Besançon (France) and her associates. “Increasing our knowledge of HPV infection of anal tissues could help physicians identify populations at risk and promote prophylaxis with vaccination and adequate screening,” the investigators wrote in the November issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Most anal cancers are squamous cell carcinomas, for which infection with high-risk HPV (especially high-risk HPV16) is a driving risk factor. Case studies and literature reviews have linked Crohn’s disease to increased rates of anal canal cancers, but population-based data were lacking, the researchers wrote. Therefore, they prospectively analyzed anal tissue samples from 467 consecutive patients undergoing colonoscopy at a tertiary care center in France. Median age was 54 years (interquartile range, 18-86 years), and 52% of patients were women. No patient had detectable macroscopic neoplastic lesions at the anal margin at baseline.

The researchers used the QIAamp DNA Blood minikit (Qiagen) for DNA extraction and the INNO-LiPA HPV Genotyping Extra kit (Fujirebio Diagnostics) for HPV DNA detection and genotyping. These methods identified HPV DNA in anal tissue samples from 34% of the patients and high-risk HPV DNA in 18% of patients. The most prevalent genotype was HPV16 (detected in 7% of samples), followed by HPV51, HPV52, and HPV39.

A total of 112 patients were receiving at least one immunosuppressive treatment for inflammatory bowel disease or another condition. Seventy patients had Crohn’s disease, and 29 patients had ulcerative colitis. The prevalence of anal canal high-risk HPV and HPV16 infection in patients with ulcerative colitis was similar to that seen in those without inflammatory bowel disease. However, patients with Crohn’s disease were more likely to have anal canal high-risk HPV infection (30%) and HPV16 infection (14%), compared with patients without Crohn’s disease (18% and 7%, respectively). Additionally, among 22 patients with Crohn’s disease and perianal involvement, 11 had HPV DNA in the anal canal versus 30% of other patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

Women were more likely to have anal canal high-risk HPV (23%) infection than were men (13%; P = .004). In a multivariable analysis of self-reported data and medical data, significant risk factors for high-risk HPV infection included female sex, a history of sexually transmitted infections, having more than 10 sexual partners over the life course, having at least one sexual partner during the past year, current smoking, and immunosuppressive therapy. The multivariable analysis also linked Crohn’s disease with anal canal high-risk HPV16 infection (odds ratio, 3.8), but the association did not reach statistical significance (95% confidence interval, 0.9-16.9).

Most patients with Crohn’s disease were on immunosuppressive therapy, “which markedly affected statistical power,” the researchers commented. Nonetheless, their findings support HPV vaccination for patients with Crohn’s disease, as well as efforts to target high-risk patients who could benefit from anal cancer screening, they said.

The work was funded by the APICHU research grant from Besançon (France) University Hospital and by the Région de Franche-Comté. Dr. Vuitton disclosed ties to AbbVie, Ferring, MSD, Hospira, Janssen, and Takeda. Three coinvestigators disclosed relationships with AbbVie, MSD, Hospira, Mayoli, and Roche.

SOURCE: Vuitton L et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.03.008.

Crohn’s disease was significantly associated with anal canal high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in a prospective, single-center study of patients undergoing colonoscopy for various indications.

High-risk HPV and HPV strain 16 were detected in 30% of patients with Crohn’s disease and 18% of patients without Crohn’s disease (P = .005), said Lucine Vuitton, MD, of University Hospital of Besançon (France) and her associates. “Increasing our knowledge of HPV infection of anal tissues could help physicians identify populations at risk and promote prophylaxis with vaccination and adequate screening,” the investigators wrote in the November issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Most anal cancers are squamous cell carcinomas, for which infection with high-risk HPV (especially high-risk HPV16) is a driving risk factor. Case studies and literature reviews have linked Crohn’s disease to increased rates of anal canal cancers, but population-based data were lacking, the researchers wrote. Therefore, they prospectively analyzed anal tissue samples from 467 consecutive patients undergoing colonoscopy at a tertiary care center in France. Median age was 54 years (interquartile range, 18-86 years), and 52% of patients were women. No patient had detectable macroscopic neoplastic lesions at the anal margin at baseline.

The researchers used the QIAamp DNA Blood minikit (Qiagen) for DNA extraction and the INNO-LiPA HPV Genotyping Extra kit (Fujirebio Diagnostics) for HPV DNA detection and genotyping. These methods identified HPV DNA in anal tissue samples from 34% of the patients and high-risk HPV DNA in 18% of patients. The most prevalent genotype was HPV16 (detected in 7% of samples), followed by HPV51, HPV52, and HPV39.

A total of 112 patients were receiving at least one immunosuppressive treatment for inflammatory bowel disease or another condition. Seventy patients had Crohn’s disease, and 29 patients had ulcerative colitis. The prevalence of anal canal high-risk HPV and HPV16 infection in patients with ulcerative colitis was similar to that seen in those without inflammatory bowel disease. However, patients with Crohn’s disease were more likely to have anal canal high-risk HPV infection (30%) and HPV16 infection (14%), compared with patients without Crohn’s disease (18% and 7%, respectively). Additionally, among 22 patients with Crohn’s disease and perianal involvement, 11 had HPV DNA in the anal canal versus 30% of other patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

Women were more likely to have anal canal high-risk HPV (23%) infection than were men (13%; P = .004). In a multivariable analysis of self-reported data and medical data, significant risk factors for high-risk HPV infection included female sex, a history of sexually transmitted infections, having more than 10 sexual partners over the life course, having at least one sexual partner during the past year, current smoking, and immunosuppressive therapy. The multivariable analysis also linked Crohn’s disease with anal canal high-risk HPV16 infection (odds ratio, 3.8), but the association did not reach statistical significance (95% confidence interval, 0.9-16.9).

Most patients with Crohn’s disease were on immunosuppressive therapy, “which markedly affected statistical power,” the researchers commented. Nonetheless, their findings support HPV vaccination for patients with Crohn’s disease, as well as efforts to target high-risk patients who could benefit from anal cancer screening, they said.

The work was funded by the APICHU research grant from Besançon (France) University Hospital and by the Région de Franche-Comté. Dr. Vuitton disclosed ties to AbbVie, Ferring, MSD, Hospira, Janssen, and Takeda. Three coinvestigators disclosed relationships with AbbVie, MSD, Hospira, Mayoli, and Roche.

SOURCE: Vuitton L et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.03.008.

Crohn’s disease was significantly associated with anal canal high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in a prospective, single-center study of patients undergoing colonoscopy for various indications.

High-risk HPV and HPV strain 16 were detected in 30% of patients with Crohn’s disease and 18% of patients without Crohn’s disease (P = .005), said Lucine Vuitton, MD, of University Hospital of Besançon (France) and her associates. “Increasing our knowledge of HPV infection of anal tissues could help physicians identify populations at risk and promote prophylaxis with vaccination and adequate screening,” the investigators wrote in the November issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Most anal cancers are squamous cell carcinomas, for which infection with high-risk HPV (especially high-risk HPV16) is a driving risk factor. Case studies and literature reviews have linked Crohn’s disease to increased rates of anal canal cancers, but population-based data were lacking, the researchers wrote. Therefore, they prospectively analyzed anal tissue samples from 467 consecutive patients undergoing colonoscopy at a tertiary care center in France. Median age was 54 years (interquartile range, 18-86 years), and 52% of patients were women. No patient had detectable macroscopic neoplastic lesions at the anal margin at baseline.

The researchers used the QIAamp DNA Blood minikit (Qiagen) for DNA extraction and the INNO-LiPA HPV Genotyping Extra kit (Fujirebio Diagnostics) for HPV DNA detection and genotyping. These methods identified HPV DNA in anal tissue samples from 34% of the patients and high-risk HPV DNA in 18% of patients. The most prevalent genotype was HPV16 (detected in 7% of samples), followed by HPV51, HPV52, and HPV39.

A total of 112 patients were receiving at least one immunosuppressive treatment for inflammatory bowel disease or another condition. Seventy patients had Crohn’s disease, and 29 patients had ulcerative colitis. The prevalence of anal canal high-risk HPV and HPV16 infection in patients with ulcerative colitis was similar to that seen in those without inflammatory bowel disease. However, patients with Crohn’s disease were more likely to have anal canal high-risk HPV infection (30%) and HPV16 infection (14%), compared with patients without Crohn’s disease (18% and 7%, respectively). Additionally, among 22 patients with Crohn’s disease and perianal involvement, 11 had HPV DNA in the anal canal versus 30% of other patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

Women were more likely to have anal canal high-risk HPV (23%) infection than were men (13%; P = .004). In a multivariable analysis of self-reported data and medical data, significant risk factors for high-risk HPV infection included female sex, a history of sexually transmitted infections, having more than 10 sexual partners over the life course, having at least one sexual partner during the past year, current smoking, and immunosuppressive therapy. The multivariable analysis also linked Crohn’s disease with anal canal high-risk HPV16 infection (odds ratio, 3.8), but the association did not reach statistical significance (95% confidence interval, 0.9-16.9).

Most patients with Crohn’s disease were on immunosuppressive therapy, “which markedly affected statistical power,” the researchers commented. Nonetheless, their findings support HPV vaccination for patients with Crohn’s disease, as well as efforts to target high-risk patients who could benefit from anal cancer screening, they said.

The work was funded by the APICHU research grant from Besançon (France) University Hospital and by the Région de Franche-Comté. Dr. Vuitton disclosed ties to AbbVie, Ferring, MSD, Hospira, Janssen, and Takeda. Three coinvestigators disclosed relationships with AbbVie, MSD, Hospira, Mayoli, and Roche.

SOURCE: Vuitton L et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.03.008.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Crohn’s disease was associated with high-risk human papillomavirus infection.

Major finding: High-risk HPV and HPV16 were detected in 30% of patients with Crohn’s disease versus 18% of those without Crohn’s disease (P = .005).

Study details: Analyses of anal tissue samples from 467 consecutive patients, including 70 with Crohn’s disease.

Disclosures: The work was funded by the APICHU research grant from Besançon (France) University Hospital and by the Région de Franche-Comté. Dr. Vuitton disclosed ties to AbbVie, Ferring, MSD, Hospira, Janssen, and Takeda. Three coinvestigators disclosed relationships with AbbVie, MSD, Hospira, Mayoli, and Roche.

Source: Vuitton L et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.03.008.

H. pylori antibiotic resistance reaches ‘alarming levels’

Over the past decade, Helicobacter pylori strains have reached “alarming levels” of antimicrobial resistance worldwide, investigators reported in the November issue of Gastroenterology.

In a large meta-analysis spanning 2007-2017, H. pylori isolates showed a 15% or higher pooled prevalence of primary and secondary resistance to clarithromycin, metronidazole, and levofloxacin in almost all World Health Organization (WHO) regions. “Local surveillance networks are required to select appropriate eradication regimens for each region,” concluded Alessia Savoldi, MD, of the University of Tübingen (Germany) and her associates.

Typically, the threshold of antimicrobial resistance for choosing empiric regimens is 15%, Dr. Savoldi and her associates noted. Their systematic review and meta-analysis included 178 studies comprising 66,142 isolates from 65 countries. They defined H. pylori infection as a positive histology, serology, stool antigen, urea breath test, or rapid urease test. They excluded studies of fewer than 50 isolates, studies that only reported resistance as a percentage with no denominator, studies that failed to specify time frames or clustered data over more than 3 years, and data reported in guidelines, conference presentations, or letters without formal publication.

The prevalence of primary clarithromycin resistance exceeded 15% in the WHO European Region (18%; 95% confidence interval, 16%-20%), the Eastern Mediterranean Region (33%), and the Western Pacific Region (34%) and reached 10% in the Americas and the South East Asia region. Furthermore, primary resistance to metronidazole exceeded 15% in all WHO regions, ranging from 56% in the Eastern Mediterranean Region to 23% in the Americas. Resistance to levofloxacin was at least 15% in all WHO regions except the European region (11%).

In most regions, H. pylori also accrued substantially more antimicrobial resistance over time, the investigators said. Clarithromycin resistance rose from 13% during 2006 through 2008 to 21% during 2012 through 2016 (P less than .001). Levofloxacin resistance in the Western Pacific region increased from 12% to 31% during the same two time periods (P less than .001). Several other WHO regions showed less significant trends toward increasing resistance. Multidrug resistance also rose. Resistance to both clarithromycin and metronidazole increased markedly in all WHO areas with available data, reaching 14% in the Eastern Mediterranean and Western Pacific regions and 23% in the European region.

Secondary analyses linked resistance with dramatic increases in the odds of treatment failure. For example, clarithromycin resistance conferred a sevenfold increase in the odds of treatment failure for regimens containing clarithromycin (odds ratio, 7.0; 95% CI, 5.2 to 9.3; P less than .001). Corresponding ORs were 8.2 for levofloxacin resistance, 2.5 for metronidazole resistance, and 9.4 for dual clarithromycin-metronidazole resistance.

The investigators acknowledged several limitations. Of publications in this meta-analysis, 85% represented single-center studies with limited sample sizes, they wrote. Studies often excluded demographic and endoscopic details. Furthermore, only three studies provided prevalence data for the WHO Africa Region and these only provided overall estimates without stratifying by resistance type.

The German Center for Infection Research, Clinical Research Unit, and the WHO Priority List Pathogens project helped fund the work. One coinvestigator disclosed ties to RedHill Biopharma, BioGaia, and Takeda related to novel H. pylori therapies.

SOURCE: Savoldi A et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Nov. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.007.

The first-line treatment of individuals with Helicobacter pylori infection using clarithromycin-based triple therapies or, if penicillin allergic, bismuth-based quadruple therapies is generally effective. However, reports of declining therapeutic efficacy have led to published guidelines to recommend confirmation of H. pylori eradication after completing a course of antibiotics. It is believed that increasing antibiotic use in agriculture and medicine around the globe have contributed to the increasing H. pylori antibiotic resistance and declining efficacy of standard H. pylori regimens.

Indeed, most H. pylori guidelines recommend antibiotic sensitivity testing after failing two courses of treatment; however, performing such testing successfully may require sending fresh gastric biopsy samples to an in-house H. pylori culture lab within 1 hour, which is generally not available to most clinicians. Clearly, the gap in knowledge of local antibiotic resistance could be addressed by having a readily accessible culture facility and the testing should be reimbursed by health insurance.

Single-center experiences with antibiotic sensitivity–guided salvage therapy in the United States, however, registered a lower efficacy rate of approximately 50%, which indicates that other host factors (such as gastric acidity pH less than 5.5 or body mass index greater than 30 kg/m2) may affect the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the antibiotics against H. pylori.

In order to better study the effects of these host factors relative to the effect of antibiotic resistance on therapeutic efficacy, it is critical that we practice precision medicine by determining the antibiotic sensitivity of the H. pylori strain prior to initiating the antibiotic treatment. It may be possible to achieve more than 90% therapeutic efficacy given known antibiotic sensitivities of the bacteria and optimized host factors to lower the MIC. In addition, with the increasing awareness of the importance of gut microbiota in health and disease, clinicians should strive to narrow the antibiotic coverage that will be possible if antibiotic sensitivity is known (for example, use high-dose amoxicillin and proton-pump inhibitor dual therapy).

John Y. Kao, MD, AGAF, is the current chair of the AGA Institute Council Esophageal, Gastric and Duodenal Disorders Section, a physician investigator in the University of Michigan Center for Gastrointestinal Research, and an associate professor in the department of medicine in the division of gastroenterology & hepatology and an associate program director of the GI Fellowship Program at Michigan Medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He has no conflicts.

The first-line treatment of individuals with Helicobacter pylori infection using clarithromycin-based triple therapies or, if penicillin allergic, bismuth-based quadruple therapies is generally effective. However, reports of declining therapeutic efficacy have led to published guidelines to recommend confirmation of H. pylori eradication after completing a course of antibiotics. It is believed that increasing antibiotic use in agriculture and medicine around the globe have contributed to the increasing H. pylori antibiotic resistance and declining efficacy of standard H. pylori regimens.

Indeed, most H. pylori guidelines recommend antibiotic sensitivity testing after failing two courses of treatment; however, performing such testing successfully may require sending fresh gastric biopsy samples to an in-house H. pylori culture lab within 1 hour, which is generally not available to most clinicians. Clearly, the gap in knowledge of local antibiotic resistance could be addressed by having a readily accessible culture facility and the testing should be reimbursed by health insurance.

Single-center experiences with antibiotic sensitivity–guided salvage therapy in the United States, however, registered a lower efficacy rate of approximately 50%, which indicates that other host factors (such as gastric acidity pH less than 5.5 or body mass index greater than 30 kg/m2) may affect the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the antibiotics against H. pylori.

In order to better study the effects of these host factors relative to the effect of antibiotic resistance on therapeutic efficacy, it is critical that we practice precision medicine by determining the antibiotic sensitivity of the H. pylori strain prior to initiating the antibiotic treatment. It may be possible to achieve more than 90% therapeutic efficacy given known antibiotic sensitivities of the bacteria and optimized host factors to lower the MIC. In addition, with the increasing awareness of the importance of gut microbiota in health and disease, clinicians should strive to narrow the antibiotic coverage that will be possible if antibiotic sensitivity is known (for example, use high-dose amoxicillin and proton-pump inhibitor dual therapy).

John Y. Kao, MD, AGAF, is the current chair of the AGA Institute Council Esophageal, Gastric and Duodenal Disorders Section, a physician investigator in the University of Michigan Center for Gastrointestinal Research, and an associate professor in the department of medicine in the division of gastroenterology & hepatology and an associate program director of the GI Fellowship Program at Michigan Medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He has no conflicts.

The first-line treatment of individuals with Helicobacter pylori infection using clarithromycin-based triple therapies or, if penicillin allergic, bismuth-based quadruple therapies is generally effective. However, reports of declining therapeutic efficacy have led to published guidelines to recommend confirmation of H. pylori eradication after completing a course of antibiotics. It is believed that increasing antibiotic use in agriculture and medicine around the globe have contributed to the increasing H. pylori antibiotic resistance and declining efficacy of standard H. pylori regimens.

Indeed, most H. pylori guidelines recommend antibiotic sensitivity testing after failing two courses of treatment; however, performing such testing successfully may require sending fresh gastric biopsy samples to an in-house H. pylori culture lab within 1 hour, which is generally not available to most clinicians. Clearly, the gap in knowledge of local antibiotic resistance could be addressed by having a readily accessible culture facility and the testing should be reimbursed by health insurance.

Single-center experiences with antibiotic sensitivity–guided salvage therapy in the United States, however, registered a lower efficacy rate of approximately 50%, which indicates that other host factors (such as gastric acidity pH less than 5.5 or body mass index greater than 30 kg/m2) may affect the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the antibiotics against H. pylori.

In order to better study the effects of these host factors relative to the effect of antibiotic resistance on therapeutic efficacy, it is critical that we practice precision medicine by determining the antibiotic sensitivity of the H. pylori strain prior to initiating the antibiotic treatment. It may be possible to achieve more than 90% therapeutic efficacy given known antibiotic sensitivities of the bacteria and optimized host factors to lower the MIC. In addition, with the increasing awareness of the importance of gut microbiota in health and disease, clinicians should strive to narrow the antibiotic coverage that will be possible if antibiotic sensitivity is known (for example, use high-dose amoxicillin and proton-pump inhibitor dual therapy).

John Y. Kao, MD, AGAF, is the current chair of the AGA Institute Council Esophageal, Gastric and Duodenal Disorders Section, a physician investigator in the University of Michigan Center for Gastrointestinal Research, and an associate professor in the department of medicine in the division of gastroenterology & hepatology and an associate program director of the GI Fellowship Program at Michigan Medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He has no conflicts.

Over the past decade, Helicobacter pylori strains have reached “alarming levels” of antimicrobial resistance worldwide, investigators reported in the November issue of Gastroenterology.

In a large meta-analysis spanning 2007-2017, H. pylori isolates showed a 15% or higher pooled prevalence of primary and secondary resistance to clarithromycin, metronidazole, and levofloxacin in almost all World Health Organization (WHO) regions. “Local surveillance networks are required to select appropriate eradication regimens for each region,” concluded Alessia Savoldi, MD, of the University of Tübingen (Germany) and her associates.

Typically, the threshold of antimicrobial resistance for choosing empiric regimens is 15%, Dr. Savoldi and her associates noted. Their systematic review and meta-analysis included 178 studies comprising 66,142 isolates from 65 countries. They defined H. pylori infection as a positive histology, serology, stool antigen, urea breath test, or rapid urease test. They excluded studies of fewer than 50 isolates, studies that only reported resistance as a percentage with no denominator, studies that failed to specify time frames or clustered data over more than 3 years, and data reported in guidelines, conference presentations, or letters without formal publication.

The prevalence of primary clarithromycin resistance exceeded 15% in the WHO European Region (18%; 95% confidence interval, 16%-20%), the Eastern Mediterranean Region (33%), and the Western Pacific Region (34%) and reached 10% in the Americas and the South East Asia region. Furthermore, primary resistance to metronidazole exceeded 15% in all WHO regions, ranging from 56% in the Eastern Mediterranean Region to 23% in the Americas. Resistance to levofloxacin was at least 15% in all WHO regions except the European region (11%).

In most regions, H. pylori also accrued substantially more antimicrobial resistance over time, the investigators said. Clarithromycin resistance rose from 13% during 2006 through 2008 to 21% during 2012 through 2016 (P less than .001). Levofloxacin resistance in the Western Pacific region increased from 12% to 31% during the same two time periods (P less than .001). Several other WHO regions showed less significant trends toward increasing resistance. Multidrug resistance also rose. Resistance to both clarithromycin and metronidazole increased markedly in all WHO areas with available data, reaching 14% in the Eastern Mediterranean and Western Pacific regions and 23% in the European region.

Secondary analyses linked resistance with dramatic increases in the odds of treatment failure. For example, clarithromycin resistance conferred a sevenfold increase in the odds of treatment failure for regimens containing clarithromycin (odds ratio, 7.0; 95% CI, 5.2 to 9.3; P less than .001). Corresponding ORs were 8.2 for levofloxacin resistance, 2.5 for metronidazole resistance, and 9.4 for dual clarithromycin-metronidazole resistance.

The investigators acknowledged several limitations. Of publications in this meta-analysis, 85% represented single-center studies with limited sample sizes, they wrote. Studies often excluded demographic and endoscopic details. Furthermore, only three studies provided prevalence data for the WHO Africa Region and these only provided overall estimates without stratifying by resistance type.

The German Center for Infection Research, Clinical Research Unit, and the WHO Priority List Pathogens project helped fund the work. One coinvestigator disclosed ties to RedHill Biopharma, BioGaia, and Takeda related to novel H. pylori therapies.

SOURCE: Savoldi A et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Nov. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.007.

Over the past decade, Helicobacter pylori strains have reached “alarming levels” of antimicrobial resistance worldwide, investigators reported in the November issue of Gastroenterology.

In a large meta-analysis spanning 2007-2017, H. pylori isolates showed a 15% or higher pooled prevalence of primary and secondary resistance to clarithromycin, metronidazole, and levofloxacin in almost all World Health Organization (WHO) regions. “Local surveillance networks are required to select appropriate eradication regimens for each region,” concluded Alessia Savoldi, MD, of the University of Tübingen (Germany) and her associates.

Typically, the threshold of antimicrobial resistance for choosing empiric regimens is 15%, Dr. Savoldi and her associates noted. Their systematic review and meta-analysis included 178 studies comprising 66,142 isolates from 65 countries. They defined H. pylori infection as a positive histology, serology, stool antigen, urea breath test, or rapid urease test. They excluded studies of fewer than 50 isolates, studies that only reported resistance as a percentage with no denominator, studies that failed to specify time frames or clustered data over more than 3 years, and data reported in guidelines, conference presentations, or letters without formal publication.

The prevalence of primary clarithromycin resistance exceeded 15% in the WHO European Region (18%; 95% confidence interval, 16%-20%), the Eastern Mediterranean Region (33%), and the Western Pacific Region (34%) and reached 10% in the Americas and the South East Asia region. Furthermore, primary resistance to metronidazole exceeded 15% in all WHO regions, ranging from 56% in the Eastern Mediterranean Region to 23% in the Americas. Resistance to levofloxacin was at least 15% in all WHO regions except the European region (11%).

In most regions, H. pylori also accrued substantially more antimicrobial resistance over time, the investigators said. Clarithromycin resistance rose from 13% during 2006 through 2008 to 21% during 2012 through 2016 (P less than .001). Levofloxacin resistance in the Western Pacific region increased from 12% to 31% during the same two time periods (P less than .001). Several other WHO regions showed less significant trends toward increasing resistance. Multidrug resistance also rose. Resistance to both clarithromycin and metronidazole increased markedly in all WHO areas with available data, reaching 14% in the Eastern Mediterranean and Western Pacific regions and 23% in the European region.

Secondary analyses linked resistance with dramatic increases in the odds of treatment failure. For example, clarithromycin resistance conferred a sevenfold increase in the odds of treatment failure for regimens containing clarithromycin (odds ratio, 7.0; 95% CI, 5.2 to 9.3; P less than .001). Corresponding ORs were 8.2 for levofloxacin resistance, 2.5 for metronidazole resistance, and 9.4 for dual clarithromycin-metronidazole resistance.

The investigators acknowledged several limitations. Of publications in this meta-analysis, 85% represented single-center studies with limited sample sizes, they wrote. Studies often excluded demographic and endoscopic details. Furthermore, only three studies provided prevalence data for the WHO Africa Region and these only provided overall estimates without stratifying by resistance type.

The German Center for Infection Research, Clinical Research Unit, and the WHO Priority List Pathogens project helped fund the work. One coinvestigator disclosed ties to RedHill Biopharma, BioGaia, and Takeda related to novel H. pylori therapies.

SOURCE: Savoldi A et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Nov. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.007.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Helicobacter pylori now shows significant levels of antibiotic resistance worldwide, complicating choices of empiric therapy.

Major finding: Primary and secondary resistance to clarithromycin, metronidazole, and levofloxacin was 15% or more in all WHO regions except for primary clarithromycin resistance in the Americas (10%) and South East Asia (10%) and primary levofloxacin resistance in Europe (11%).

Study details: Meta-analysis of 178 studies comprising 66,142 isolates from 65 countries.

Disclosures: The German Center for Infection Research, Clinical Research Unit, and the WHO Priority List Pathogens project helped fund the work. One coinvestigator disclosed ties to RedHill Biopharma, BioGaia, and Takeda related to novel H. pylori therapies.

Source: Savoldi A et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Nov. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.007

Thiopurines linked to zoster in IBD patients

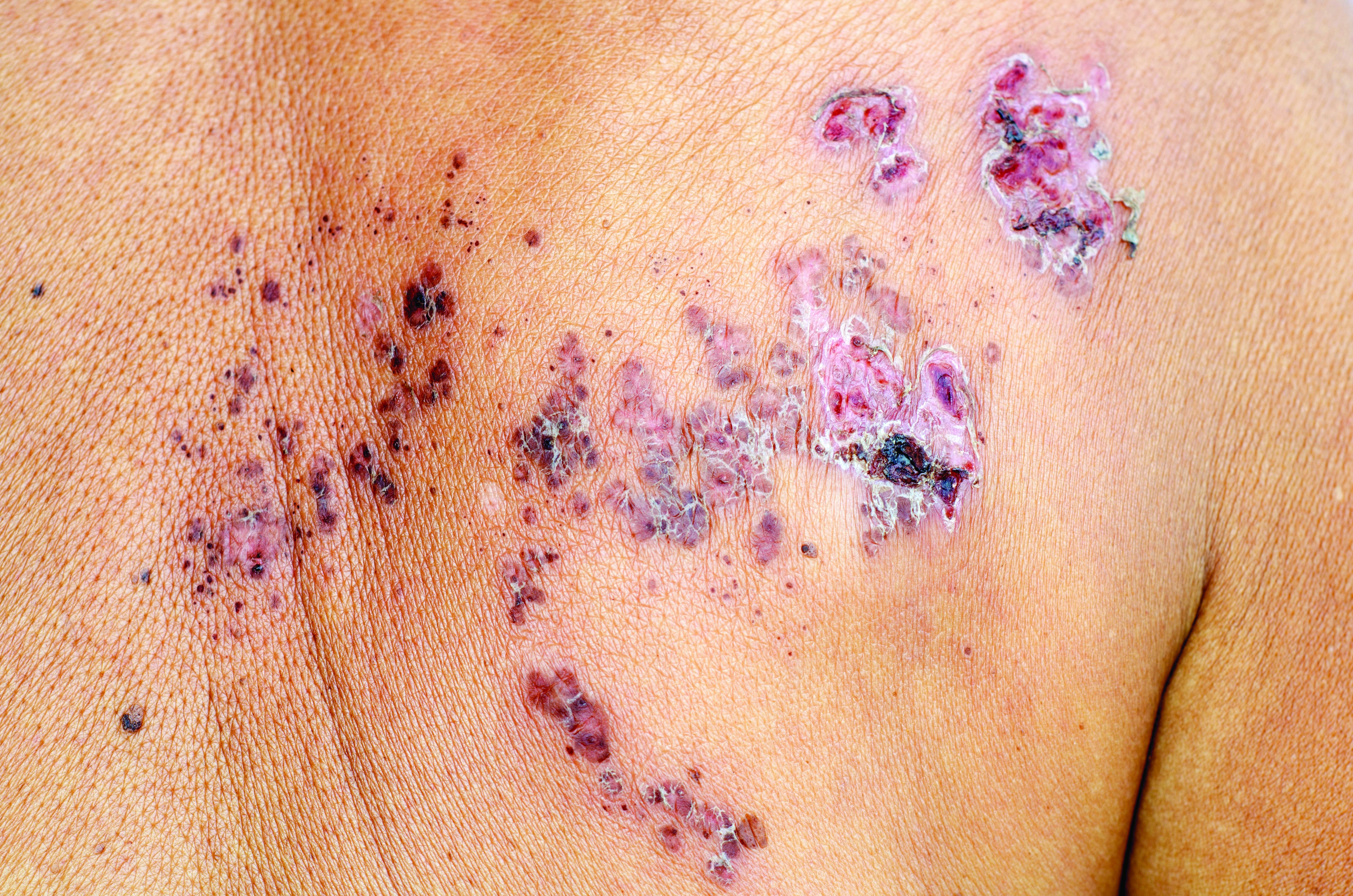

For patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), thiopurine exposure was associated with a significantly increased risk of herpes zoster, compared with 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) monotherapy, according to the results of two large retrospective cohort studies.

In the multivariable analysis, thiopurine monotherapy was linked to about a 47% increase in the risk of herpes zoster, compared with 5-ASA monotherapy (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.47; 95% confidence interval, 1.31-1.65; P less than .001). Combination therapy with thiopurines and tumor necrosis factor antagonists conferred about a 65% increase in zoster risk (aHR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.22-2.23; P = .001). However, tumor necrosis factor–antagonist monotherapy did not appear to significantly increase the risk of zoster when compared with 5-ASA monotherapy, reported Nabeel Khan, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and his associates.

“Compared to [patients without] IBD, ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) each were associated with significantly increased risk of herpes zoster infection,” the researchers wrote online in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “With the approval of a new and potentially safer vaccine for herpes zoster, the effects of immunization of patients with IBD should be investigated.”