User login

For everything there is a season

2020 SoHM Survey ready to launch

Wow, the last 2 years have just flown by! I can’t believe it’s already time to launch the Society of Hospital Medicine State of Hospital Medicine survey again! Right now is the season for you to roll up your sleeves and get to work helping SHM develop the nation’s definitive resource on the current state of hospital medicine practice.

I’m really excited about this year’s survey. SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee has redesigned it to eliminate some out-of-date or little-used questions and to add a few new, more relevant questions. Even more exciting, we have a new survey platform that should massively improve your experience of submitting data for the survey and also make the back-end data tabulation and analysis much quicker and more accurate. Multisite groups will now have two options for submitting data – a redesigned, more user-friendly Excel tool, or a new pathway to submit data in the reporting platform by replicating responses.

In addition, our new survey platform should help us produce the final report a little more quickly and improve its usability.

New-for-2020 survey topics will include:

- Expanded information on nurse practitioner/physician assistant roles

- Diversity in hospital medicine physician leadership

- Specific questions for hospital medicine groups (HMGs) serving children that will better capture unique attributes of these hospital medicine practices

Why participate?

I can’t emphasize enough that each and every survey submission matters a lot. The State of Hospital Medicine report claims to be the authoritative resource for information about the specialty of hospital medicine. But the report can’t fulfill this claim if the underlying data is skimpy because people were too busy, couldn’t be bothered to participate, or if participation is not broadly representative of the amazing diversity of hospital medicine practices out there.

Your participation will help ensure that you are contributing to a robust hospital medicine database, and that your own group’s information is represented in the survey results. By doing so you will be helping to ensure hospital medicine’s place as perhaps the crucial specialty for U.S. health care in the coming decade.

In addition, participants will receive free access to the survey results, so there’s a direct benefit to you and your HMG as well.

How can you participate?

Here’s what you need to know:

1. The survey opens on Jan.6, 2020, and closes on Feb. 14, 2020.

2. You can find general information about the survey at this link: https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/, and register to participate by using this link: https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/sohm-survey/.

3. To participate, you’ll want to collect the following general types of information for your hospital medicine group:

- Basic group descriptive information (for example, types of patients seen, number of hospitals covered, teaching status, etc.)

- Scope of clinical services

- Nurse practitioners and physician assistants in the HMG

- Full-time equivalent (FTE) information

- Information about the physician leader(s)

- Staffing/scheduling arrangements, including backup plans, paid time off, unfilled positions, predominant scheduling pattern, night coverage arrangements, dedicated admitters, unit-based assignments, etc.

- Compensation model (but not specific amounts)

- Value of employee benefits and CME

- Total work relative value units generated by the HMG, and number of times the following CPT codes were billed: 99221, 99222, 99223, 99231, 99232, 99233, 99238, 99239

- Information about financial support provided to the HMG

- Specific questions for academic HMGs, including financial support for nonclinical work, and allocation of FTEs

- Specific questions for HMGs serving children, including the hospital settings served, proportion of part-time staff, FTE definition, and information about board certification in pediatric hospital medicine

I’m hoping that all of you will join me in working to make the 2020 State of Hospital Medicine survey and report the best one yet!

Ms. Flores is a partner at Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants in La Quinta, Calif. She serves on SHM’s Practice Analysis and Annual Meeting Committees, and helps to coordinate SHM’s biannual State of Hospital Medicine survey.

2020 SoHM Survey ready to launch

2020 SoHM Survey ready to launch

Wow, the last 2 years have just flown by! I can’t believe it’s already time to launch the Society of Hospital Medicine State of Hospital Medicine survey again! Right now is the season for you to roll up your sleeves and get to work helping SHM develop the nation’s definitive resource on the current state of hospital medicine practice.

I’m really excited about this year’s survey. SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee has redesigned it to eliminate some out-of-date or little-used questions and to add a few new, more relevant questions. Even more exciting, we have a new survey platform that should massively improve your experience of submitting data for the survey and also make the back-end data tabulation and analysis much quicker and more accurate. Multisite groups will now have two options for submitting data – a redesigned, more user-friendly Excel tool, or a new pathway to submit data in the reporting platform by replicating responses.

In addition, our new survey platform should help us produce the final report a little more quickly and improve its usability.

New-for-2020 survey topics will include:

- Expanded information on nurse practitioner/physician assistant roles

- Diversity in hospital medicine physician leadership

- Specific questions for hospital medicine groups (HMGs) serving children that will better capture unique attributes of these hospital medicine practices

Why participate?

I can’t emphasize enough that each and every survey submission matters a lot. The State of Hospital Medicine report claims to be the authoritative resource for information about the specialty of hospital medicine. But the report can’t fulfill this claim if the underlying data is skimpy because people were too busy, couldn’t be bothered to participate, or if participation is not broadly representative of the amazing diversity of hospital medicine practices out there.

Your participation will help ensure that you are contributing to a robust hospital medicine database, and that your own group’s information is represented in the survey results. By doing so you will be helping to ensure hospital medicine’s place as perhaps the crucial specialty for U.S. health care in the coming decade.

In addition, participants will receive free access to the survey results, so there’s a direct benefit to you and your HMG as well.

How can you participate?

Here’s what you need to know:

1. The survey opens on Jan.6, 2020, and closes on Feb. 14, 2020.

2. You can find general information about the survey at this link: https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/, and register to participate by using this link: https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/sohm-survey/.

3. To participate, you’ll want to collect the following general types of information for your hospital medicine group:

- Basic group descriptive information (for example, types of patients seen, number of hospitals covered, teaching status, etc.)

- Scope of clinical services

- Nurse practitioners and physician assistants in the HMG

- Full-time equivalent (FTE) information

- Information about the physician leader(s)

- Staffing/scheduling arrangements, including backup plans, paid time off, unfilled positions, predominant scheduling pattern, night coverage arrangements, dedicated admitters, unit-based assignments, etc.

- Compensation model (but not specific amounts)

- Value of employee benefits and CME

- Total work relative value units generated by the HMG, and number of times the following CPT codes were billed: 99221, 99222, 99223, 99231, 99232, 99233, 99238, 99239

- Information about financial support provided to the HMG

- Specific questions for academic HMGs, including financial support for nonclinical work, and allocation of FTEs

- Specific questions for HMGs serving children, including the hospital settings served, proportion of part-time staff, FTE definition, and information about board certification in pediatric hospital medicine

I’m hoping that all of you will join me in working to make the 2020 State of Hospital Medicine survey and report the best one yet!

Ms. Flores is a partner at Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants in La Quinta, Calif. She serves on SHM’s Practice Analysis and Annual Meeting Committees, and helps to coordinate SHM’s biannual State of Hospital Medicine survey.

Wow, the last 2 years have just flown by! I can’t believe it’s already time to launch the Society of Hospital Medicine State of Hospital Medicine survey again! Right now is the season for you to roll up your sleeves and get to work helping SHM develop the nation’s definitive resource on the current state of hospital medicine practice.

I’m really excited about this year’s survey. SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee has redesigned it to eliminate some out-of-date or little-used questions and to add a few new, more relevant questions. Even more exciting, we have a new survey platform that should massively improve your experience of submitting data for the survey and also make the back-end data tabulation and analysis much quicker and more accurate. Multisite groups will now have two options for submitting data – a redesigned, more user-friendly Excel tool, or a new pathway to submit data in the reporting platform by replicating responses.

In addition, our new survey platform should help us produce the final report a little more quickly and improve its usability.

New-for-2020 survey topics will include:

- Expanded information on nurse practitioner/physician assistant roles

- Diversity in hospital medicine physician leadership

- Specific questions for hospital medicine groups (HMGs) serving children that will better capture unique attributes of these hospital medicine practices

Why participate?

I can’t emphasize enough that each and every survey submission matters a lot. The State of Hospital Medicine report claims to be the authoritative resource for information about the specialty of hospital medicine. But the report can’t fulfill this claim if the underlying data is skimpy because people were too busy, couldn’t be bothered to participate, or if participation is not broadly representative of the amazing diversity of hospital medicine practices out there.

Your participation will help ensure that you are contributing to a robust hospital medicine database, and that your own group’s information is represented in the survey results. By doing so you will be helping to ensure hospital medicine’s place as perhaps the crucial specialty for U.S. health care in the coming decade.

In addition, participants will receive free access to the survey results, so there’s a direct benefit to you and your HMG as well.

How can you participate?

Here’s what you need to know:

1. The survey opens on Jan.6, 2020, and closes on Feb. 14, 2020.

2. You can find general information about the survey at this link: https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/, and register to participate by using this link: https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/sohm-survey/.

3. To participate, you’ll want to collect the following general types of information for your hospital medicine group:

- Basic group descriptive information (for example, types of patients seen, number of hospitals covered, teaching status, etc.)

- Scope of clinical services

- Nurse practitioners and physician assistants in the HMG

- Full-time equivalent (FTE) information

- Information about the physician leader(s)

- Staffing/scheduling arrangements, including backup plans, paid time off, unfilled positions, predominant scheduling pattern, night coverage arrangements, dedicated admitters, unit-based assignments, etc.

- Compensation model (but not specific amounts)

- Value of employee benefits and CME

- Total work relative value units generated by the HMG, and number of times the following CPT codes were billed: 99221, 99222, 99223, 99231, 99232, 99233, 99238, 99239

- Information about financial support provided to the HMG

- Specific questions for academic HMGs, including financial support for nonclinical work, and allocation of FTEs

- Specific questions for HMGs serving children, including the hospital settings served, proportion of part-time staff, FTE definition, and information about board certification in pediatric hospital medicine

I’m hoping that all of you will join me in working to make the 2020 State of Hospital Medicine survey and report the best one yet!

Ms. Flores is a partner at Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants in La Quinta, Calif. She serves on SHM’s Practice Analysis and Annual Meeting Committees, and helps to coordinate SHM’s biannual State of Hospital Medicine survey.

Treatment of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction is a work in progress

LOS ANGELES – When it comes to the optimal treatment of patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and diabetes, cardiologists like Mark T. Kearney, MB ChB, MD, remain stumped.

“Over the years, the diagnosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction has been notoriously difficult [to treat], controversial, and ultimately involves aggressive catheterization of the heart to assess diastolic dysfunction, complex echocardiography, and invasive tests,” Dr. Kearney said at the World Congress on Insulin Resistance, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Disease. “These patients have an ejection fraction of over 50% and classic signs and symptoms of heart failure. Studies of beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and angiotensin II receptor blockers have been unsuccessful in this group of patients. We’re at the beginning of a journey in understanding this disorder, and it’s important, because more and more patients present to us with signs and symptoms of heart failure with an ejection fraction greater than 50%.”

In a recent analysis of 1,797 patients with chronic heart failure, Dr. Kearney, British Heart Foundation Professor of Cardiovascular and Diabetes Research at the Leeds (England) Institute of Cardiovascular and Metabolic Medicine, and colleagues examined whether beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors were associated with differential effects on mortality in patients with and without diabetes (Diabetes Care. 2018;41:136-42). Mean follow-up was 4 years.

For the ACE inhibitor component of the trial, the researchers correlated the dose of ramipril to outcomes and found that each milligram increase of ramipril reduced the risk of death by about 3%. “In the nondiabetic patients who did not receive an ACE inhibitor, mortality was about 60% – worse than most cancers,” Dr. Kearney said. “In patients with diabetes, there was a similar pattern. If you didn’t get an ACE inhibitor, mortality was 70%. So, if you get patients on an optimal dose of an ACE inhibitor, you improve their mortality substantially, whether they have diabetes or not.”

The beta-blocker component of the trial yielded similar results. “Among patients who did not receive a beta-blocker, the mortality was about 70% at 5 years – really terrible,” he said. “Every milligram of bisoprolol was associated with a reduction in mortality of about 9%. So, if a patient gets on an optimal dose of a beta-blocker and they have diabetes, it’s associated with prolongation of life over a year.”

Dr. Kearney said that patients often do not want to take an increased dose of a beta-blocker because of concerns about side effects, such as tiredness. “They ask me what the side effects of an increased dose would be. My answer is: ‘It will make you live longer.’ Usually, they’ll respond by agreeing to have a little bit more of the beta-blocker. The message here is, if you have a patient with ejection fraction heart failure and diabetes, get them on the optimal dose of a beta-blocker, even at the expense of an ACE inhibitor.”

In 2016, the European Society of Cardiology introduced guidelines for physicians to make a diagnosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. The guidelines mandate that a diagnosis requires signs and symptoms of heart failure, elevated levels of natriuretic peptide, and echocardiographic abnormalities of cardiac structure and/or function in the presence of a left ventricular ejection fraction of 50% or more (Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18[8]:891-975).

“Signs and symptoms of heart failure, elevated BNP [brain natriuretic peptide], and echocardiography allow us to make a diagnosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction,” Dr. Kearney, who is also dean of the Leeds University School of Medicine. “But we don’t know the outcome of these patients, we don’t know how to treat them, and we don’t know the impact on hospitalizations.”

In a large, unpublished cohort study conducted at Leeds, Dr. Kearney and colleagues evaluated how many patients met criteria for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction or heart failure with preserved ejection fraction after undergoing a BNP measurement. Ultimately, 959 patients met criteria. After assessment, 23% had no heart failure, 44% had heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, and 33% had heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. They found that patients with preserved ejection fraction were older (mean age, 84 years); were more likely to be female; and had less ischemia, less diabetes, and more hypertension. In addition, patients with preserved ejection fraction had significantly better survival than patients with reduced ejection fraction over 5 years follow-up.

“What was really interesting were the findings related to hospitalization,” he said. “All 959 patients accounted for 20,517 days in the hospital over 5 years, which is the equivalent of 1 patient occupying a hospital bed for 56 years. This disorder [heart failure with preserved ejection fraction], despite having a lower mortality than heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, leads to a significant burden on health care systems.”

Among patients with preserved ejection fraction, 82% were hospitalized for a noncardiovascular cause, 6.9% because of heart failure, and 11% were caused by other cardiovascular causes. Most of the hospital admissions were because of chest infections, falls, and other frailty-linked causes. “This link between systemic frailty and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction warrants further investigation,” Dr. Kearney said. “This is a major burden on patient hospital care.”

When the researchers examined outcomes in patients with and without diabetes, those with diabetes were younger, more likely to be male, and have a higher body mass index. They found that, in the presence of diabetes, mortality was increased in heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. “So, even at the age of 81 or 82, diabetes changes the pathophysiology of mortality in what was previously believed to be a benign disease,” he said.

In a subset analysis of patients with and without diabetes who were not taking a beta-blocker, there did not seem to be increased sympathetic activation in the patients with diabetes and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, nor a difference in heart rate between the nondiabetic patients and patients with diabetes. However, among patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, those with diabetes had an increased heart rate.

“Is heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in diabetes benign? I think the answer is no,” Dr. Kearney said. “It increases hospitalization and is a major burden on health care systems. What should we do? We deal with comorbidity and fall risk. It’s good old-fashioned doctoring, really. We address frailty and respiratory tract infections, but the key thing here is that we need more research.”

Dr. Kearney reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – When it comes to the optimal treatment of patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and diabetes, cardiologists like Mark T. Kearney, MB ChB, MD, remain stumped.

“Over the years, the diagnosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction has been notoriously difficult [to treat], controversial, and ultimately involves aggressive catheterization of the heart to assess diastolic dysfunction, complex echocardiography, and invasive tests,” Dr. Kearney said at the World Congress on Insulin Resistance, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Disease. “These patients have an ejection fraction of over 50% and classic signs and symptoms of heart failure. Studies of beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and angiotensin II receptor blockers have been unsuccessful in this group of patients. We’re at the beginning of a journey in understanding this disorder, and it’s important, because more and more patients present to us with signs and symptoms of heart failure with an ejection fraction greater than 50%.”

In a recent analysis of 1,797 patients with chronic heart failure, Dr. Kearney, British Heart Foundation Professor of Cardiovascular and Diabetes Research at the Leeds (England) Institute of Cardiovascular and Metabolic Medicine, and colleagues examined whether beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors were associated with differential effects on mortality in patients with and without diabetes (Diabetes Care. 2018;41:136-42). Mean follow-up was 4 years.

For the ACE inhibitor component of the trial, the researchers correlated the dose of ramipril to outcomes and found that each milligram increase of ramipril reduced the risk of death by about 3%. “In the nondiabetic patients who did not receive an ACE inhibitor, mortality was about 60% – worse than most cancers,” Dr. Kearney said. “In patients with diabetes, there was a similar pattern. If you didn’t get an ACE inhibitor, mortality was 70%. So, if you get patients on an optimal dose of an ACE inhibitor, you improve their mortality substantially, whether they have diabetes or not.”

The beta-blocker component of the trial yielded similar results. “Among patients who did not receive a beta-blocker, the mortality was about 70% at 5 years – really terrible,” he said. “Every milligram of bisoprolol was associated with a reduction in mortality of about 9%. So, if a patient gets on an optimal dose of a beta-blocker and they have diabetes, it’s associated with prolongation of life over a year.”

Dr. Kearney said that patients often do not want to take an increased dose of a beta-blocker because of concerns about side effects, such as tiredness. “They ask me what the side effects of an increased dose would be. My answer is: ‘It will make you live longer.’ Usually, they’ll respond by agreeing to have a little bit more of the beta-blocker. The message here is, if you have a patient with ejection fraction heart failure and diabetes, get them on the optimal dose of a beta-blocker, even at the expense of an ACE inhibitor.”

In 2016, the European Society of Cardiology introduced guidelines for physicians to make a diagnosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. The guidelines mandate that a diagnosis requires signs and symptoms of heart failure, elevated levels of natriuretic peptide, and echocardiographic abnormalities of cardiac structure and/or function in the presence of a left ventricular ejection fraction of 50% or more (Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18[8]:891-975).

“Signs and symptoms of heart failure, elevated BNP [brain natriuretic peptide], and echocardiography allow us to make a diagnosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction,” Dr. Kearney, who is also dean of the Leeds University School of Medicine. “But we don’t know the outcome of these patients, we don’t know how to treat them, and we don’t know the impact on hospitalizations.”

In a large, unpublished cohort study conducted at Leeds, Dr. Kearney and colleagues evaluated how many patients met criteria for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction or heart failure with preserved ejection fraction after undergoing a BNP measurement. Ultimately, 959 patients met criteria. After assessment, 23% had no heart failure, 44% had heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, and 33% had heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. They found that patients with preserved ejection fraction were older (mean age, 84 years); were more likely to be female; and had less ischemia, less diabetes, and more hypertension. In addition, patients with preserved ejection fraction had significantly better survival than patients with reduced ejection fraction over 5 years follow-up.

“What was really interesting were the findings related to hospitalization,” he said. “All 959 patients accounted for 20,517 days in the hospital over 5 years, which is the equivalent of 1 patient occupying a hospital bed for 56 years. This disorder [heart failure with preserved ejection fraction], despite having a lower mortality than heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, leads to a significant burden on health care systems.”

Among patients with preserved ejection fraction, 82% were hospitalized for a noncardiovascular cause, 6.9% because of heart failure, and 11% were caused by other cardiovascular causes. Most of the hospital admissions were because of chest infections, falls, and other frailty-linked causes. “This link between systemic frailty and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction warrants further investigation,” Dr. Kearney said. “This is a major burden on patient hospital care.”

When the researchers examined outcomes in patients with and without diabetes, those with diabetes were younger, more likely to be male, and have a higher body mass index. They found that, in the presence of diabetes, mortality was increased in heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. “So, even at the age of 81 or 82, diabetes changes the pathophysiology of mortality in what was previously believed to be a benign disease,” he said.

In a subset analysis of patients with and without diabetes who were not taking a beta-blocker, there did not seem to be increased sympathetic activation in the patients with diabetes and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, nor a difference in heart rate between the nondiabetic patients and patients with diabetes. However, among patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, those with diabetes had an increased heart rate.

“Is heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in diabetes benign? I think the answer is no,” Dr. Kearney said. “It increases hospitalization and is a major burden on health care systems. What should we do? We deal with comorbidity and fall risk. It’s good old-fashioned doctoring, really. We address frailty and respiratory tract infections, but the key thing here is that we need more research.”

Dr. Kearney reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – When it comes to the optimal treatment of patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and diabetes, cardiologists like Mark T. Kearney, MB ChB, MD, remain stumped.

“Over the years, the diagnosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction has been notoriously difficult [to treat], controversial, and ultimately involves aggressive catheterization of the heart to assess diastolic dysfunction, complex echocardiography, and invasive tests,” Dr. Kearney said at the World Congress on Insulin Resistance, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Disease. “These patients have an ejection fraction of over 50% and classic signs and symptoms of heart failure. Studies of beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and angiotensin II receptor blockers have been unsuccessful in this group of patients. We’re at the beginning of a journey in understanding this disorder, and it’s important, because more and more patients present to us with signs and symptoms of heart failure with an ejection fraction greater than 50%.”

In a recent analysis of 1,797 patients with chronic heart failure, Dr. Kearney, British Heart Foundation Professor of Cardiovascular and Diabetes Research at the Leeds (England) Institute of Cardiovascular and Metabolic Medicine, and colleagues examined whether beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors were associated with differential effects on mortality in patients with and without diabetes (Diabetes Care. 2018;41:136-42). Mean follow-up was 4 years.

For the ACE inhibitor component of the trial, the researchers correlated the dose of ramipril to outcomes and found that each milligram increase of ramipril reduced the risk of death by about 3%. “In the nondiabetic patients who did not receive an ACE inhibitor, mortality was about 60% – worse than most cancers,” Dr. Kearney said. “In patients with diabetes, there was a similar pattern. If you didn’t get an ACE inhibitor, mortality was 70%. So, if you get patients on an optimal dose of an ACE inhibitor, you improve their mortality substantially, whether they have diabetes or not.”

The beta-blocker component of the trial yielded similar results. “Among patients who did not receive a beta-blocker, the mortality was about 70% at 5 years – really terrible,” he said. “Every milligram of bisoprolol was associated with a reduction in mortality of about 9%. So, if a patient gets on an optimal dose of a beta-blocker and they have diabetes, it’s associated with prolongation of life over a year.”

Dr. Kearney said that patients often do not want to take an increased dose of a beta-blocker because of concerns about side effects, such as tiredness. “They ask me what the side effects of an increased dose would be. My answer is: ‘It will make you live longer.’ Usually, they’ll respond by agreeing to have a little bit more of the beta-blocker. The message here is, if you have a patient with ejection fraction heart failure and diabetes, get them on the optimal dose of a beta-blocker, even at the expense of an ACE inhibitor.”

In 2016, the European Society of Cardiology introduced guidelines for physicians to make a diagnosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. The guidelines mandate that a diagnosis requires signs and symptoms of heart failure, elevated levels of natriuretic peptide, and echocardiographic abnormalities of cardiac structure and/or function in the presence of a left ventricular ejection fraction of 50% or more (Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18[8]:891-975).

“Signs and symptoms of heart failure, elevated BNP [brain natriuretic peptide], and echocardiography allow us to make a diagnosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction,” Dr. Kearney, who is also dean of the Leeds University School of Medicine. “But we don’t know the outcome of these patients, we don’t know how to treat them, and we don’t know the impact on hospitalizations.”

In a large, unpublished cohort study conducted at Leeds, Dr. Kearney and colleagues evaluated how many patients met criteria for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction or heart failure with preserved ejection fraction after undergoing a BNP measurement. Ultimately, 959 patients met criteria. After assessment, 23% had no heart failure, 44% had heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, and 33% had heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. They found that patients with preserved ejection fraction were older (mean age, 84 years); were more likely to be female; and had less ischemia, less diabetes, and more hypertension. In addition, patients with preserved ejection fraction had significantly better survival than patients with reduced ejection fraction over 5 years follow-up.

“What was really interesting were the findings related to hospitalization,” he said. “All 959 patients accounted for 20,517 days in the hospital over 5 years, which is the equivalent of 1 patient occupying a hospital bed for 56 years. This disorder [heart failure with preserved ejection fraction], despite having a lower mortality than heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, leads to a significant burden on health care systems.”

Among patients with preserved ejection fraction, 82% were hospitalized for a noncardiovascular cause, 6.9% because of heart failure, and 11% were caused by other cardiovascular causes. Most of the hospital admissions were because of chest infections, falls, and other frailty-linked causes. “This link between systemic frailty and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction warrants further investigation,” Dr. Kearney said. “This is a major burden on patient hospital care.”

When the researchers examined outcomes in patients with and without diabetes, those with diabetes were younger, more likely to be male, and have a higher body mass index. They found that, in the presence of diabetes, mortality was increased in heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. “So, even at the age of 81 or 82, diabetes changes the pathophysiology of mortality in what was previously believed to be a benign disease,” he said.

In a subset analysis of patients with and without diabetes who were not taking a beta-blocker, there did not seem to be increased sympathetic activation in the patients with diabetes and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, nor a difference in heart rate between the nondiabetic patients and patients with diabetes. However, among patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, those with diabetes had an increased heart rate.

“Is heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in diabetes benign? I think the answer is no,” Dr. Kearney said. “It increases hospitalization and is a major burden on health care systems. What should we do? We deal with comorbidity and fall risk. It’s good old-fashioned doctoring, really. We address frailty and respiratory tract infections, but the key thing here is that we need more research.”

Dr. Kearney reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM WCIRDC 2019

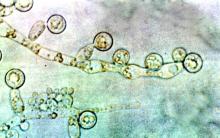

ID consult for Candida bloodstream infections can reduce mortality risk

findings from a large retrospective study suggest.

Mortality attributable to Candida bloodstream infection ranges between 15% and 47%, and delay in initiation of appropriate treatment has been associated with increased mortality. Previous small studies showed that ID consultation has conferred benefits to patients with Candida bloodstream infections. Carlos Mejia-Chew, MD, and colleagues from Washington University, St. Louis, sought to explore this further by performing a retrospective, single-center cohort study of 1,691 patients aged 18 years or older with Candida bloodstream infection from 2002 to 2015. They analyzed demographics, comorbidities, predisposing factors, all-cause mortality, antifungal use, central-line removal, and ophthalmological and echocardiographic evaluation in order to compare 90-day all-cause mortality between individuals with and without an ID consultation.

They found that those patients who received an ID consult for a Candida bloodstream infection had a significantly lower 90-day mortality rate than did those who did not (29% vs. 51%).

With a model using inverse weighting by the propensity score, they found that ID consultation was associated with a hazard ratio of 0.81 for mortality (95% confidence interval, 0.73-0.91; P less than .0001). In the ID consultation group, the median duration of antifungal therapy was significantly longer (18 vs. 14 days; P less than .0001); central-line removal was significantly more common (76% vs. 59%; P less than .0001); echocardiography use was more frequent (57% vs. 33%; P less than .0001); and ophthalmological examinations were performed more often (53% vs. 17%; P less than .0001). Importantly, fewer patients in the ID consultation group were untreated (2% vs. 14%; P less than .0001).

In an accompanying commentary, Katrien Lagrou, MD, and Eric Van Wijngaerden, MD, of the department of microbiology, immunology and transplantation, University Hospitals Leuven (Belgium) stated: “We think that the high proportion of patients (14%) with a Candida bloodstream infection who did not receive any antifungal treatment and did not have an infectious disease consultation is a particularly alarming finding. ... Ninety-day mortality in these untreated patients was high (67%).”

“We believe every hospital should have an expert management strategy addressing all individual cases of candidaemia. The need for such expert management should be incorporated in all future candidaemia management guidelines,” they concluded.

The study was funded by the Astellas Global Development Pharma, the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Several of the authors had financial connections to Astellas Global Development or other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Lagrou and Dr. Van Wijngaerden both reported receiving personal fees and nonfinancial support from a number of pharmaceutical companies, but all outside the scope of the study.

SOURCE: Mejia-Chew C et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19:1336-44.

findings from a large retrospective study suggest.

Mortality attributable to Candida bloodstream infection ranges between 15% and 47%, and delay in initiation of appropriate treatment has been associated with increased mortality. Previous small studies showed that ID consultation has conferred benefits to patients with Candida bloodstream infections. Carlos Mejia-Chew, MD, and colleagues from Washington University, St. Louis, sought to explore this further by performing a retrospective, single-center cohort study of 1,691 patients aged 18 years or older with Candida bloodstream infection from 2002 to 2015. They analyzed demographics, comorbidities, predisposing factors, all-cause mortality, antifungal use, central-line removal, and ophthalmological and echocardiographic evaluation in order to compare 90-day all-cause mortality between individuals with and without an ID consultation.

They found that those patients who received an ID consult for a Candida bloodstream infection had a significantly lower 90-day mortality rate than did those who did not (29% vs. 51%).

With a model using inverse weighting by the propensity score, they found that ID consultation was associated with a hazard ratio of 0.81 for mortality (95% confidence interval, 0.73-0.91; P less than .0001). In the ID consultation group, the median duration of antifungal therapy was significantly longer (18 vs. 14 days; P less than .0001); central-line removal was significantly more common (76% vs. 59%; P less than .0001); echocardiography use was more frequent (57% vs. 33%; P less than .0001); and ophthalmological examinations were performed more often (53% vs. 17%; P less than .0001). Importantly, fewer patients in the ID consultation group were untreated (2% vs. 14%; P less than .0001).

In an accompanying commentary, Katrien Lagrou, MD, and Eric Van Wijngaerden, MD, of the department of microbiology, immunology and transplantation, University Hospitals Leuven (Belgium) stated: “We think that the high proportion of patients (14%) with a Candida bloodstream infection who did not receive any antifungal treatment and did not have an infectious disease consultation is a particularly alarming finding. ... Ninety-day mortality in these untreated patients was high (67%).”

“We believe every hospital should have an expert management strategy addressing all individual cases of candidaemia. The need for such expert management should be incorporated in all future candidaemia management guidelines,” they concluded.

The study was funded by the Astellas Global Development Pharma, the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Several of the authors had financial connections to Astellas Global Development or other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Lagrou and Dr. Van Wijngaerden both reported receiving personal fees and nonfinancial support from a number of pharmaceutical companies, but all outside the scope of the study.

SOURCE: Mejia-Chew C et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19:1336-44.

findings from a large retrospective study suggest.

Mortality attributable to Candida bloodstream infection ranges between 15% and 47%, and delay in initiation of appropriate treatment has been associated with increased mortality. Previous small studies showed that ID consultation has conferred benefits to patients with Candida bloodstream infections. Carlos Mejia-Chew, MD, and colleagues from Washington University, St. Louis, sought to explore this further by performing a retrospective, single-center cohort study of 1,691 patients aged 18 years or older with Candida bloodstream infection from 2002 to 2015. They analyzed demographics, comorbidities, predisposing factors, all-cause mortality, antifungal use, central-line removal, and ophthalmological and echocardiographic evaluation in order to compare 90-day all-cause mortality between individuals with and without an ID consultation.

They found that those patients who received an ID consult for a Candida bloodstream infection had a significantly lower 90-day mortality rate than did those who did not (29% vs. 51%).

With a model using inverse weighting by the propensity score, they found that ID consultation was associated with a hazard ratio of 0.81 for mortality (95% confidence interval, 0.73-0.91; P less than .0001). In the ID consultation group, the median duration of antifungal therapy was significantly longer (18 vs. 14 days; P less than .0001); central-line removal was significantly more common (76% vs. 59%; P less than .0001); echocardiography use was more frequent (57% vs. 33%; P less than .0001); and ophthalmological examinations were performed more often (53% vs. 17%; P less than .0001). Importantly, fewer patients in the ID consultation group were untreated (2% vs. 14%; P less than .0001).

In an accompanying commentary, Katrien Lagrou, MD, and Eric Van Wijngaerden, MD, of the department of microbiology, immunology and transplantation, University Hospitals Leuven (Belgium) stated: “We think that the high proportion of patients (14%) with a Candida bloodstream infection who did not receive any antifungal treatment and did not have an infectious disease consultation is a particularly alarming finding. ... Ninety-day mortality in these untreated patients was high (67%).”

“We believe every hospital should have an expert management strategy addressing all individual cases of candidaemia. The need for such expert management should be incorporated in all future candidaemia management guidelines,” they concluded.

The study was funded by the Astellas Global Development Pharma, the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Several of the authors had financial connections to Astellas Global Development or other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Lagrou and Dr. Van Wijngaerden both reported receiving personal fees and nonfinancial support from a number of pharmaceutical companies, but all outside the scope of the study.

SOURCE: Mejia-Chew C et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19:1336-44.

FROM LANCET: INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Accelerating the careers of future hospitalists

Grant program provides funding, research support

When it comes to what future hospitalists should be doing to accelerate their careers, is there such a thing as a “no-brainer” opportunity? Aram Namavar, MD, MS, thinks so.

Dr. Namavar is a first-year internal medicine resident at UC San Diego pursuing a career as an academic hospitalist. He is passionate about building interdisciplinary platforms for patient care enhancement and serving disadvantaged and underserved communities.

Membership in the Society of Hospital Medicine is free for medical students and offers a diverse array of resources specifically curated for the ever-expanding needs of the specialty and its aspiring leaders. An active member of SHM since 2015, Dr. Namavar has looked to the organization for leading career-enhancing opportunities and resources in hospital medicine to help him achieve his altruistic career goals.

For Dr. Namavar, a few of these professional development–focused opportunities include becoming an active member of the Physicians-in-Training Committee, a founding member of the Resident and Student Special Interest Group, and a recipient of the Student Hospitalist Scholar Grant.

“I applied for the Student Hospitalist Scholar Grant to have a dedicated summer of learning quality improvement through being in meetings with hospital medicine leaders and leading my research initiatives alongside my team,” Dr. Namavar said. He described the experience as pivotal to his growth within hospital medicine and as a medical student.

The key component to SHM’s Student Hospitalist Scholar Grant opportunity is the ability for first- and second-year medical students to work alongside leading hospital medicine professionals in scholarly projects to help interested students gain perspective on working within the specialty.

“As a young, interested trainee in hospital medicine, working with a mentor who is established in the field allows one to learn what steps to take in the future to become a leader,” he said. “[It allowed me to] gain insight into leadership style and develop a strong network for the future.”

In addition to the program’s mentorship benefits, grant recipients also receive complimentary registration to SHM’s Annual Conference with the added perks of funding and research support, accommodation expenses, and acceptance into SHM’s RIV Poster Competition.

“I attended the SHM Annual Conference previously,” Dr. Namavar said. “However, as a grant recipient, you have the chance to connect with faculty who will come to your poster presentation and want to learn about your project. This platform allows you to meet individuals from across the nation and connect with those interested in helping trainees thrive within hospital medicine.”

With the grant funding, Dr. Namavar completed his project, “Evaluation of Decisional Conflict as a Simple Tool to Assess Risk of Readmission.” He described this endeavor as a multidimensional project that took on a holistic view of patient-centered readmissions. “We evaluated patient conflict in posthospitalization resources as a marker of readmission, social determinants of health, and health literacy as risk factors for hospital readmission.”

Described by Dr. Namavar as a “no-brainer” opportunity, SHM’s Student Hospitalist Scholar Grant “offers some of the best benefits overall – funding for your project, automatic acceptance at the Annual Conference, the chance to have your work highlighted in blog posts, networking opportunities with faculty across the nation, and travel reimbursement for the conference.”

Building your networks or establishing your professional career path does not stop at individual networking events or scholarship programs, Dr. Namavar said. It’s about piecing together the building blocks to set yourself up for success.

“My long-term involvement in SHM through working on a committee, leading a special interest group, attending annual meetings, and receiving the grant from SHM has helped me to build new, long-lasting connections in the field,” he said. “Because of this, I plan to continue to serve within SHM in multiple capacities throughout my career in hospital medicine.”

Are you a first- or second-year medical student interested in taking the next step in your hospital medicine career? Apply to SHM’s Student Hospitalist Scholar Grant program through late January 2020 at hospitalmedicine.org/scholargrant.

Ms. Cowan is a marketing communications specialist at the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Grant program provides funding, research support

Grant program provides funding, research support

When it comes to what future hospitalists should be doing to accelerate their careers, is there such a thing as a “no-brainer” opportunity? Aram Namavar, MD, MS, thinks so.

Dr. Namavar is a first-year internal medicine resident at UC San Diego pursuing a career as an academic hospitalist. He is passionate about building interdisciplinary platforms for patient care enhancement and serving disadvantaged and underserved communities.

Membership in the Society of Hospital Medicine is free for medical students and offers a diverse array of resources specifically curated for the ever-expanding needs of the specialty and its aspiring leaders. An active member of SHM since 2015, Dr. Namavar has looked to the organization for leading career-enhancing opportunities and resources in hospital medicine to help him achieve his altruistic career goals.

For Dr. Namavar, a few of these professional development–focused opportunities include becoming an active member of the Physicians-in-Training Committee, a founding member of the Resident and Student Special Interest Group, and a recipient of the Student Hospitalist Scholar Grant.

“I applied for the Student Hospitalist Scholar Grant to have a dedicated summer of learning quality improvement through being in meetings with hospital medicine leaders and leading my research initiatives alongside my team,” Dr. Namavar said. He described the experience as pivotal to his growth within hospital medicine and as a medical student.

The key component to SHM’s Student Hospitalist Scholar Grant opportunity is the ability for first- and second-year medical students to work alongside leading hospital medicine professionals in scholarly projects to help interested students gain perspective on working within the specialty.

“As a young, interested trainee in hospital medicine, working with a mentor who is established in the field allows one to learn what steps to take in the future to become a leader,” he said. “[It allowed me to] gain insight into leadership style and develop a strong network for the future.”

In addition to the program’s mentorship benefits, grant recipients also receive complimentary registration to SHM’s Annual Conference with the added perks of funding and research support, accommodation expenses, and acceptance into SHM’s RIV Poster Competition.

“I attended the SHM Annual Conference previously,” Dr. Namavar said. “However, as a grant recipient, you have the chance to connect with faculty who will come to your poster presentation and want to learn about your project. This platform allows you to meet individuals from across the nation and connect with those interested in helping trainees thrive within hospital medicine.”

With the grant funding, Dr. Namavar completed his project, “Evaluation of Decisional Conflict as a Simple Tool to Assess Risk of Readmission.” He described this endeavor as a multidimensional project that took on a holistic view of patient-centered readmissions. “We evaluated patient conflict in posthospitalization resources as a marker of readmission, social determinants of health, and health literacy as risk factors for hospital readmission.”

Described by Dr. Namavar as a “no-brainer” opportunity, SHM’s Student Hospitalist Scholar Grant “offers some of the best benefits overall – funding for your project, automatic acceptance at the Annual Conference, the chance to have your work highlighted in blog posts, networking opportunities with faculty across the nation, and travel reimbursement for the conference.”

Building your networks or establishing your professional career path does not stop at individual networking events or scholarship programs, Dr. Namavar said. It’s about piecing together the building blocks to set yourself up for success.

“My long-term involvement in SHM through working on a committee, leading a special interest group, attending annual meetings, and receiving the grant from SHM has helped me to build new, long-lasting connections in the field,” he said. “Because of this, I plan to continue to serve within SHM in multiple capacities throughout my career in hospital medicine.”

Are you a first- or second-year medical student interested in taking the next step in your hospital medicine career? Apply to SHM’s Student Hospitalist Scholar Grant program through late January 2020 at hospitalmedicine.org/scholargrant.

Ms. Cowan is a marketing communications specialist at the Society of Hospital Medicine.

When it comes to what future hospitalists should be doing to accelerate their careers, is there such a thing as a “no-brainer” opportunity? Aram Namavar, MD, MS, thinks so.

Dr. Namavar is a first-year internal medicine resident at UC San Diego pursuing a career as an academic hospitalist. He is passionate about building interdisciplinary platforms for patient care enhancement and serving disadvantaged and underserved communities.

Membership in the Society of Hospital Medicine is free for medical students and offers a diverse array of resources specifically curated for the ever-expanding needs of the specialty and its aspiring leaders. An active member of SHM since 2015, Dr. Namavar has looked to the organization for leading career-enhancing opportunities and resources in hospital medicine to help him achieve his altruistic career goals.

For Dr. Namavar, a few of these professional development–focused opportunities include becoming an active member of the Physicians-in-Training Committee, a founding member of the Resident and Student Special Interest Group, and a recipient of the Student Hospitalist Scholar Grant.

“I applied for the Student Hospitalist Scholar Grant to have a dedicated summer of learning quality improvement through being in meetings with hospital medicine leaders and leading my research initiatives alongside my team,” Dr. Namavar said. He described the experience as pivotal to his growth within hospital medicine and as a medical student.

The key component to SHM’s Student Hospitalist Scholar Grant opportunity is the ability for first- and second-year medical students to work alongside leading hospital medicine professionals in scholarly projects to help interested students gain perspective on working within the specialty.

“As a young, interested trainee in hospital medicine, working with a mentor who is established in the field allows one to learn what steps to take in the future to become a leader,” he said. “[It allowed me to] gain insight into leadership style and develop a strong network for the future.”

In addition to the program’s mentorship benefits, grant recipients also receive complimentary registration to SHM’s Annual Conference with the added perks of funding and research support, accommodation expenses, and acceptance into SHM’s RIV Poster Competition.

“I attended the SHM Annual Conference previously,” Dr. Namavar said. “However, as a grant recipient, you have the chance to connect with faculty who will come to your poster presentation and want to learn about your project. This platform allows you to meet individuals from across the nation and connect with those interested in helping trainees thrive within hospital medicine.”

With the grant funding, Dr. Namavar completed his project, “Evaluation of Decisional Conflict as a Simple Tool to Assess Risk of Readmission.” He described this endeavor as a multidimensional project that took on a holistic view of patient-centered readmissions. “We evaluated patient conflict in posthospitalization resources as a marker of readmission, social determinants of health, and health literacy as risk factors for hospital readmission.”

Described by Dr. Namavar as a “no-brainer” opportunity, SHM’s Student Hospitalist Scholar Grant “offers some of the best benefits overall – funding for your project, automatic acceptance at the Annual Conference, the chance to have your work highlighted in blog posts, networking opportunities with faculty across the nation, and travel reimbursement for the conference.”

Building your networks or establishing your professional career path does not stop at individual networking events or scholarship programs, Dr. Namavar said. It’s about piecing together the building blocks to set yourself up for success.

“My long-term involvement in SHM through working on a committee, leading a special interest group, attending annual meetings, and receiving the grant from SHM has helped me to build new, long-lasting connections in the field,” he said. “Because of this, I plan to continue to serve within SHM in multiple capacities throughout my career in hospital medicine.”

Are you a first- or second-year medical student interested in taking the next step in your hospital medicine career? Apply to SHM’s Student Hospitalist Scholar Grant program through late January 2020 at hospitalmedicine.org/scholargrant.

Ms. Cowan is a marketing communications specialist at the Society of Hospital Medicine.

PACT-HF: Transitional care derives no overall benefit

Women respond more to intervention

PHILADELPHIA – A clinical trial of a program that transitions heart failure patients after they’re discharged from the hospital didn’t result in any appreciable improvement in all-cause death, readmissions or emergency department visits after 6 months overall, but it did show that women responded more favorably than men.

Harriette G.C. Van Spall, MD, MPH, reported 6-month results of the Patient-Centered Transitional Care Services in Heart Failure (PACT-HF) trial of 2,494 HF patients at 10 hospitals in Ontario during February 2015 to March 2016. They were randomized to the care-transition program or usual care. The findings, she said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions, “highlight the gap between efficacy that’s often demonstrated in mechanistic clinical trials and effectiveness when we aim to implement these results in real-world settings.” Three-month PACT-HF results were reported previously (JAMA. 2019 Feb 26;321:753-61).

The transitional-care model consisted of a comprehensive needs assessment by a nurse who also provided self-care education, a patient-centered discharge summary, and follow-up with a family physician within 7 days of discharge, which Dr. Van Spall noted “is not current practice in our health care system.”

Patients deemed high risk for readmission or death also received nurse home visits and scheduled visits to a multidisciplinary heart function clinic within 2-4 weeks of discharge and continuing as long as clinically suitable, said Dr. Van Spall, a principal investigator at the Population Health Research Institute, Hamilton, Ont., and assistant professor in cardiology at McMaster University in Hamilton.

The trial found no difference between the intervention and usual-care groups in the two composite endpoints at 6 months, Dr. Van Spall said: all-cause death, readmissions, or ED visits (63.1% and 64.5%, respectively; P = .50); or all-cause readmissions or ED visits (60.8% and 62.4%; P = .36).

“Despite the mutual overall clinical outcomes, we noted specific differences in response to treatment,” she said. With regard to the composite endpoint that included all-cause death, “Men had an attenuated response to the treatment with a hazard ratio of 1.05 (95% confidence interval, 0.87-1.26), whereas women had a hazard ratio of 0.85 (95% CI, 0.71-1.03), demonstrating that women have more of a treatment response to this health care service,” she said.

In men, rates for the first primary composite outcome were 66.3% and 64.1% in the intervention and usual-care groups, whereas in women those rates were 59.9% and 64.8% (P = .04 for sex interaction).

In the second composite endpoint, all-cause readmission or ED visit, “again, men had an attenuated response” with a HR of 1.03, whereas women had a HR of 0.83. Results were similar to those for the first primary composite outcome: 63.4% and 61.7% for intervention and usual care in men and 57.7% and 63% in women (P = .03 for sex interaction).

In putting the findings into context, Dr. Van Spall said tailoring services to risk in HF patients may be fraught with pitfalls. “We delivered intensive services to those patients at high risk of readmission or death, but it is quite possible they are the least likely to derive benefit by virtue of their advanced heart failure,” she said. “It may be that more benefit would have been derived had we chosen low- or moderate-risk patients to receive the intervention.”

She also said the sex-specific outcomes must be interpreted with caution. “But they do give us pause to consider that services could be titrated more effectively if delivered to patients who are more likely to derive benefit,” Dr. Van Spall said. The finding that women derived more of a benefit is in line with other prospective and observational studies that have found that women have a higher sense of self-care, self-efficacy, and confidence in managing their own health care needs than men.

Dr. Van Spall has no financial relationships to disclose.

Women respond more to intervention

Women respond more to intervention

PHILADELPHIA – A clinical trial of a program that transitions heart failure patients after they’re discharged from the hospital didn’t result in any appreciable improvement in all-cause death, readmissions or emergency department visits after 6 months overall, but it did show that women responded more favorably than men.

Harriette G.C. Van Spall, MD, MPH, reported 6-month results of the Patient-Centered Transitional Care Services in Heart Failure (PACT-HF) trial of 2,494 HF patients at 10 hospitals in Ontario during February 2015 to March 2016. They were randomized to the care-transition program or usual care. The findings, she said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions, “highlight the gap between efficacy that’s often demonstrated in mechanistic clinical trials and effectiveness when we aim to implement these results in real-world settings.” Three-month PACT-HF results were reported previously (JAMA. 2019 Feb 26;321:753-61).

The transitional-care model consisted of a comprehensive needs assessment by a nurse who also provided self-care education, a patient-centered discharge summary, and follow-up with a family physician within 7 days of discharge, which Dr. Van Spall noted “is not current practice in our health care system.”

Patients deemed high risk for readmission or death also received nurse home visits and scheduled visits to a multidisciplinary heart function clinic within 2-4 weeks of discharge and continuing as long as clinically suitable, said Dr. Van Spall, a principal investigator at the Population Health Research Institute, Hamilton, Ont., and assistant professor in cardiology at McMaster University in Hamilton.

The trial found no difference between the intervention and usual-care groups in the two composite endpoints at 6 months, Dr. Van Spall said: all-cause death, readmissions, or ED visits (63.1% and 64.5%, respectively; P = .50); or all-cause readmissions or ED visits (60.8% and 62.4%; P = .36).

“Despite the mutual overall clinical outcomes, we noted specific differences in response to treatment,” she said. With regard to the composite endpoint that included all-cause death, “Men had an attenuated response to the treatment with a hazard ratio of 1.05 (95% confidence interval, 0.87-1.26), whereas women had a hazard ratio of 0.85 (95% CI, 0.71-1.03), demonstrating that women have more of a treatment response to this health care service,” she said.

In men, rates for the first primary composite outcome were 66.3% and 64.1% in the intervention and usual-care groups, whereas in women those rates were 59.9% and 64.8% (P = .04 for sex interaction).

In the second composite endpoint, all-cause readmission or ED visit, “again, men had an attenuated response” with a HR of 1.03, whereas women had a HR of 0.83. Results were similar to those for the first primary composite outcome: 63.4% and 61.7% for intervention and usual care in men and 57.7% and 63% in women (P = .03 for sex interaction).

In putting the findings into context, Dr. Van Spall said tailoring services to risk in HF patients may be fraught with pitfalls. “We delivered intensive services to those patients at high risk of readmission or death, but it is quite possible they are the least likely to derive benefit by virtue of their advanced heart failure,” she said. “It may be that more benefit would have been derived had we chosen low- or moderate-risk patients to receive the intervention.”

She also said the sex-specific outcomes must be interpreted with caution. “But they do give us pause to consider that services could be titrated more effectively if delivered to patients who are more likely to derive benefit,” Dr. Van Spall said. The finding that women derived more of a benefit is in line with other prospective and observational studies that have found that women have a higher sense of self-care, self-efficacy, and confidence in managing their own health care needs than men.

Dr. Van Spall has no financial relationships to disclose.

PHILADELPHIA – A clinical trial of a program that transitions heart failure patients after they’re discharged from the hospital didn’t result in any appreciable improvement in all-cause death, readmissions or emergency department visits after 6 months overall, but it did show that women responded more favorably than men.

Harriette G.C. Van Spall, MD, MPH, reported 6-month results of the Patient-Centered Transitional Care Services in Heart Failure (PACT-HF) trial of 2,494 HF patients at 10 hospitals in Ontario during February 2015 to March 2016. They were randomized to the care-transition program or usual care. The findings, she said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions, “highlight the gap between efficacy that’s often demonstrated in mechanistic clinical trials and effectiveness when we aim to implement these results in real-world settings.” Three-month PACT-HF results were reported previously (JAMA. 2019 Feb 26;321:753-61).

The transitional-care model consisted of a comprehensive needs assessment by a nurse who also provided self-care education, a patient-centered discharge summary, and follow-up with a family physician within 7 days of discharge, which Dr. Van Spall noted “is not current practice in our health care system.”

Patients deemed high risk for readmission or death also received nurse home visits and scheduled visits to a multidisciplinary heart function clinic within 2-4 weeks of discharge and continuing as long as clinically suitable, said Dr. Van Spall, a principal investigator at the Population Health Research Institute, Hamilton, Ont., and assistant professor in cardiology at McMaster University in Hamilton.

The trial found no difference between the intervention and usual-care groups in the two composite endpoints at 6 months, Dr. Van Spall said: all-cause death, readmissions, or ED visits (63.1% and 64.5%, respectively; P = .50); or all-cause readmissions or ED visits (60.8% and 62.4%; P = .36).

“Despite the mutual overall clinical outcomes, we noted specific differences in response to treatment,” she said. With regard to the composite endpoint that included all-cause death, “Men had an attenuated response to the treatment with a hazard ratio of 1.05 (95% confidence interval, 0.87-1.26), whereas women had a hazard ratio of 0.85 (95% CI, 0.71-1.03), demonstrating that women have more of a treatment response to this health care service,” she said.

In men, rates for the first primary composite outcome were 66.3% and 64.1% in the intervention and usual-care groups, whereas in women those rates were 59.9% and 64.8% (P = .04 for sex interaction).

In the second composite endpoint, all-cause readmission or ED visit, “again, men had an attenuated response” with a HR of 1.03, whereas women had a HR of 0.83. Results were similar to those for the first primary composite outcome: 63.4% and 61.7% for intervention and usual care in men and 57.7% and 63% in women (P = .03 for sex interaction).

In putting the findings into context, Dr. Van Spall said tailoring services to risk in HF patients may be fraught with pitfalls. “We delivered intensive services to those patients at high risk of readmission or death, but it is quite possible they are the least likely to derive benefit by virtue of their advanced heart failure,” she said. “It may be that more benefit would have been derived had we chosen low- or moderate-risk patients to receive the intervention.”

She also said the sex-specific outcomes must be interpreted with caution. “But they do give us pause to consider that services could be titrated more effectively if delivered to patients who are more likely to derive benefit,” Dr. Van Spall said. The finding that women derived more of a benefit is in line with other prospective and observational studies that have found that women have a higher sense of self-care, self-efficacy, and confidence in managing their own health care needs than men.

Dr. Van Spall has no financial relationships to disclose.

REPORTING FROM AHA 2019

State of Hospital Medicine Survey plays key role in operational decision making

Results help establish hospitalist benchmarks

The Hospitalist recently spoke with Brian Schroeder, MHA, FACHE, FHM, assistant vice president, Hospital & Emergency Medicine, at Atrium Health Medical Group in Charlotte, N.C., to discuss his participation in the State of Hospital Medicine Survey, which is distributed every other year, and how he uses the resulting report to guide important operational decisions.

Please describe your current role.

At Carolinas Hospitalist Group, we have approximately 250 providers at nearly 20 care locations across North Carolina. Along with my specialty medical director, I am responsible for the strategic growth, program development, and financial performance for our practice.

How did you first become involved with the Society of Hospital Medicine?

When I first entered the hospital medicine world in 2008, I was looking for an organization that supported our specialty. My physician leaders at the time pointed me to SHM. Since the beginning of my time as a member, I have attended the Annual Conference each year, the SHM Leadership Academy, served on an SHM committee, and participate in SHM’s multisite Leaders group. Additionally, I have served as faculty at SHM’s annual conference for 3 years – and will be presenting for the third time at HM20.

Why is it important that people participate in the State of Hospital Medicine Survey?

Participation in the survey is key for establishing benchmarks for our specialty. The more people participate (from various arenas like private groups, health system employees, and vendors), the more accurate the data. Over the past 4 years, SHM has improved the submission process of survey data – especially for practices with multiple locations.

How has the data in the report impacted important business decisions for your group?

We rely heavily on the investment/provider benchmark within the survey data. Over the years, as the investment/provider was decreasing nationally, our own investment/provider was increasing. Based on the survey, we were able to closely evaluate our staffing models at each location and determine the appropriate skill mix-to-volume ratio. Through turnover and growth, we have strategically hired advanced practice providers to align our investment more closely with the benchmark. Over the past 2 years, our investment/provider metric has decreased significantly. We were able to accomplish this while continuing to provide appropriate care to our patients. We also utilize the Report to monitor performance incentive metrics, staffing model trends, and encounter/provider ratios.

What would you tell people who are on the fence about participating in the survey – and ultimately, purchasing the finished product?

Do it! Our practice would never skip a submission year. The data produced from the survey helps us improve our clinical operations and maximize our financial affordability. The data also assists in defending staffing decisions and clinical operations change with senior leadership within the organization.

Don’t miss your chance to submit data that will build the latest snapshot of the hospital medicine specialty. The State of Hospital Medicine Survey is open now and runs through February 16, 2020. Learn more and register to participate at hospitalmedicine.org/survey.

Results help establish hospitalist benchmarks

Results help establish hospitalist benchmarks

The Hospitalist recently spoke with Brian Schroeder, MHA, FACHE, FHM, assistant vice president, Hospital & Emergency Medicine, at Atrium Health Medical Group in Charlotte, N.C., to discuss his participation in the State of Hospital Medicine Survey, which is distributed every other year, and how he uses the resulting report to guide important operational decisions.

Please describe your current role.

At Carolinas Hospitalist Group, we have approximately 250 providers at nearly 20 care locations across North Carolina. Along with my specialty medical director, I am responsible for the strategic growth, program development, and financial performance for our practice.

How did you first become involved with the Society of Hospital Medicine?

When I first entered the hospital medicine world in 2008, I was looking for an organization that supported our specialty. My physician leaders at the time pointed me to SHM. Since the beginning of my time as a member, I have attended the Annual Conference each year, the SHM Leadership Academy, served on an SHM committee, and participate in SHM’s multisite Leaders group. Additionally, I have served as faculty at SHM’s annual conference for 3 years – and will be presenting for the third time at HM20.

Why is it important that people participate in the State of Hospital Medicine Survey?

Participation in the survey is key for establishing benchmarks for our specialty. The more people participate (from various arenas like private groups, health system employees, and vendors), the more accurate the data. Over the past 4 years, SHM has improved the submission process of survey data – especially for practices with multiple locations.

How has the data in the report impacted important business decisions for your group?

We rely heavily on the investment/provider benchmark within the survey data. Over the years, as the investment/provider was decreasing nationally, our own investment/provider was increasing. Based on the survey, we were able to closely evaluate our staffing models at each location and determine the appropriate skill mix-to-volume ratio. Through turnover and growth, we have strategically hired advanced practice providers to align our investment more closely with the benchmark. Over the past 2 years, our investment/provider metric has decreased significantly. We were able to accomplish this while continuing to provide appropriate care to our patients. We also utilize the Report to monitor performance incentive metrics, staffing model trends, and encounter/provider ratios.

What would you tell people who are on the fence about participating in the survey – and ultimately, purchasing the finished product?

Do it! Our practice would never skip a submission year. The data produced from the survey helps us improve our clinical operations and maximize our financial affordability. The data also assists in defending staffing decisions and clinical operations change with senior leadership within the organization.

Don’t miss your chance to submit data that will build the latest snapshot of the hospital medicine specialty. The State of Hospital Medicine Survey is open now and runs through February 16, 2020. Learn more and register to participate at hospitalmedicine.org/survey.

The Hospitalist recently spoke with Brian Schroeder, MHA, FACHE, FHM, assistant vice president, Hospital & Emergency Medicine, at Atrium Health Medical Group in Charlotte, N.C., to discuss his participation in the State of Hospital Medicine Survey, which is distributed every other year, and how he uses the resulting report to guide important operational decisions.

Please describe your current role.

At Carolinas Hospitalist Group, we have approximately 250 providers at nearly 20 care locations across North Carolina. Along with my specialty medical director, I am responsible for the strategic growth, program development, and financial performance for our practice.

How did you first become involved with the Society of Hospital Medicine?

When I first entered the hospital medicine world in 2008, I was looking for an organization that supported our specialty. My physician leaders at the time pointed me to SHM. Since the beginning of my time as a member, I have attended the Annual Conference each year, the SHM Leadership Academy, served on an SHM committee, and participate in SHM’s multisite Leaders group. Additionally, I have served as faculty at SHM’s annual conference for 3 years – and will be presenting for the third time at HM20.

Why is it important that people participate in the State of Hospital Medicine Survey?

Participation in the survey is key for establishing benchmarks for our specialty. The more people participate (from various arenas like private groups, health system employees, and vendors), the more accurate the data. Over the past 4 years, SHM has improved the submission process of survey data – especially for practices with multiple locations.

How has the data in the report impacted important business decisions for your group?