User login

Catheter ablation of AF in patients with heart failure decreases mortality and HF admissions

Background: Rhythm control with medical therapy has been shown to not be superior to rate control for patients with both heart failure and AF. Rhythm control by ablation has been associated with positive outcomes in this same population, but its effectiveness, compared with medical therapy for patient-centered outcomes, has not been demonstrated.

Study design: Multicenter, open-label, randomized, controlled superiority trial.

Setting: 33 hospitals from Europe, Australia, and the United States during 2008-2016.

Synopsis: A total of 363 patients with HF with LVEF less than 35%, New York Heart Association II-IV symptoms, and permanent or paroxysmal AF who had previously failed or declined antiarrhythmic medications were randomly assigned to undergo ablation by pulmonary vein isolation or to medical therapy. The primary outcome – a composite of death or hospitalization for heart failure – was significantly lower in the ablation group, compared with the medical therapy group (28.5% vs. 44.6%; P = .006) with a number needed to treat of 8.3. The secondary outcomes of all-cause mortality and heart failure admissions were also significantly lower in the ablation group (13.4% vs. 25%; P = .01 and 20.7% vs. 35.9%; P = .004 respectively). The burden of AF, as identified by patient implantable devices was significantly lower in the ablation group, suggesting the likely mechanism of ablation benefit. Limitations of this study include its small sample size and lack of physician or patient blinding to treatment assignment.

Bottom line: Compared with medical therapy, catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation for patients with symptomatic heart failure with LVEF less than 35% was associated with significantly decreased mortality and heart failure admissions.

Citation: Marrouche N et al. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation with heart failure. N Eng J Med. 2018 Feb 1; 378:417-27.

Dr. Salber is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor in medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Background: Rhythm control with medical therapy has been shown to not be superior to rate control for patients with both heart failure and AF. Rhythm control by ablation has been associated with positive outcomes in this same population, but its effectiveness, compared with medical therapy for patient-centered outcomes, has not been demonstrated.

Study design: Multicenter, open-label, randomized, controlled superiority trial.

Setting: 33 hospitals from Europe, Australia, and the United States during 2008-2016.

Synopsis: A total of 363 patients with HF with LVEF less than 35%, New York Heart Association II-IV symptoms, and permanent or paroxysmal AF who had previously failed or declined antiarrhythmic medications were randomly assigned to undergo ablation by pulmonary vein isolation or to medical therapy. The primary outcome – a composite of death or hospitalization for heart failure – was significantly lower in the ablation group, compared with the medical therapy group (28.5% vs. 44.6%; P = .006) with a number needed to treat of 8.3. The secondary outcomes of all-cause mortality and heart failure admissions were also significantly lower in the ablation group (13.4% vs. 25%; P = .01 and 20.7% vs. 35.9%; P = .004 respectively). The burden of AF, as identified by patient implantable devices was significantly lower in the ablation group, suggesting the likely mechanism of ablation benefit. Limitations of this study include its small sample size and lack of physician or patient blinding to treatment assignment.

Bottom line: Compared with medical therapy, catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation for patients with symptomatic heart failure with LVEF less than 35% was associated with significantly decreased mortality and heart failure admissions.

Citation: Marrouche N et al. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation with heart failure. N Eng J Med. 2018 Feb 1; 378:417-27.

Dr. Salber is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor in medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Background: Rhythm control with medical therapy has been shown to not be superior to rate control for patients with both heart failure and AF. Rhythm control by ablation has been associated with positive outcomes in this same population, but its effectiveness, compared with medical therapy for patient-centered outcomes, has not been demonstrated.

Study design: Multicenter, open-label, randomized, controlled superiority trial.

Setting: 33 hospitals from Europe, Australia, and the United States during 2008-2016.

Synopsis: A total of 363 patients with HF with LVEF less than 35%, New York Heart Association II-IV symptoms, and permanent or paroxysmal AF who had previously failed or declined antiarrhythmic medications were randomly assigned to undergo ablation by pulmonary vein isolation or to medical therapy. The primary outcome – a composite of death or hospitalization for heart failure – was significantly lower in the ablation group, compared with the medical therapy group (28.5% vs. 44.6%; P = .006) with a number needed to treat of 8.3. The secondary outcomes of all-cause mortality and heart failure admissions were also significantly lower in the ablation group (13.4% vs. 25%; P = .01 and 20.7% vs. 35.9%; P = .004 respectively). The burden of AF, as identified by patient implantable devices was significantly lower in the ablation group, suggesting the likely mechanism of ablation benefit. Limitations of this study include its small sample size and lack of physician or patient blinding to treatment assignment.

Bottom line: Compared with medical therapy, catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation for patients with symptomatic heart failure with LVEF less than 35% was associated with significantly decreased mortality and heart failure admissions.

Citation: Marrouche N et al. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation with heart failure. N Eng J Med. 2018 Feb 1; 378:417-27.

Dr. Salber is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor in medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Patent foramen ovale may be associated with increased risk of perioperative ischemic stroke

Clinical question: Are patients with patent foramen ovale (PFO) at increased risk of perioperative ischemic stroke?

Background: Prior research has identified an association between PFO and risk of stroke. However, little is known about the effect of a preoperatively diagnosed PFO on perioperative stroke risk.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Three Massachusetts hospitals, from January 2007 to December 2015.

Synopsis: The charts of 150,198 adult patients who underwent noncardiac surgery were reviewed for ICD codes for PFO. The primary outcome was perioperative ischemic stroke within 30 days of surgery, as identified via ICD code and subsequent chart review. After they adjusted for confounding variables, the study authors found that patients with PFO had an increased risk of perioperative ischemic stroke (odds ratio, 2.66; 95% confidence interval, 1.96-3.63; P less than .001) compared with patients without PFO. These findings were replicated in a propensity score–matched cohort to adjust for baseline differences between PFO and non-PFO groups. Patients with PFO also had a significantly increased risk of large-vessel territory ischemia and more severe neurologic deficits.

Given the observational design, this study could not establish a causal relationship between presence of a PFO and perioperative stroke. While the results support the consideration of PFO as a risk factor for perioperative stroke, research into whether this risk can be mitigated is needed.

Bottom line: Patients with PFO undergoing noncardiac surgery may be at increased risk of perioperative ischemic stroke.

Citation: Ng PY et al. Association of preoperatively diagnosed patent foramen ovale with perioperative ischemic stroke. JAMA. 2018 Feb 6;319(5):452-62.

Dr. Roy is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor in medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Clinical question: Are patients with patent foramen ovale (PFO) at increased risk of perioperative ischemic stroke?

Background: Prior research has identified an association between PFO and risk of stroke. However, little is known about the effect of a preoperatively diagnosed PFO on perioperative stroke risk.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Three Massachusetts hospitals, from January 2007 to December 2015.

Synopsis: The charts of 150,198 adult patients who underwent noncardiac surgery were reviewed for ICD codes for PFO. The primary outcome was perioperative ischemic stroke within 30 days of surgery, as identified via ICD code and subsequent chart review. After they adjusted for confounding variables, the study authors found that patients with PFO had an increased risk of perioperative ischemic stroke (odds ratio, 2.66; 95% confidence interval, 1.96-3.63; P less than .001) compared with patients without PFO. These findings were replicated in a propensity score–matched cohort to adjust for baseline differences between PFO and non-PFO groups. Patients with PFO also had a significantly increased risk of large-vessel territory ischemia and more severe neurologic deficits.

Given the observational design, this study could not establish a causal relationship between presence of a PFO and perioperative stroke. While the results support the consideration of PFO as a risk factor for perioperative stroke, research into whether this risk can be mitigated is needed.

Bottom line: Patients with PFO undergoing noncardiac surgery may be at increased risk of perioperative ischemic stroke.

Citation: Ng PY et al. Association of preoperatively diagnosed patent foramen ovale with perioperative ischemic stroke. JAMA. 2018 Feb 6;319(5):452-62.

Dr. Roy is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor in medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Clinical question: Are patients with patent foramen ovale (PFO) at increased risk of perioperative ischemic stroke?

Background: Prior research has identified an association between PFO and risk of stroke. However, little is known about the effect of a preoperatively diagnosed PFO on perioperative stroke risk.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Three Massachusetts hospitals, from January 2007 to December 2015.

Synopsis: The charts of 150,198 adult patients who underwent noncardiac surgery were reviewed for ICD codes for PFO. The primary outcome was perioperative ischemic stroke within 30 days of surgery, as identified via ICD code and subsequent chart review. After they adjusted for confounding variables, the study authors found that patients with PFO had an increased risk of perioperative ischemic stroke (odds ratio, 2.66; 95% confidence interval, 1.96-3.63; P less than .001) compared with patients without PFO. These findings were replicated in a propensity score–matched cohort to adjust for baseline differences between PFO and non-PFO groups. Patients with PFO also had a significantly increased risk of large-vessel territory ischemia and more severe neurologic deficits.

Given the observational design, this study could not establish a causal relationship between presence of a PFO and perioperative stroke. While the results support the consideration of PFO as a risk factor for perioperative stroke, research into whether this risk can be mitigated is needed.

Bottom line: Patients with PFO undergoing noncardiac surgery may be at increased risk of perioperative ischemic stroke.

Citation: Ng PY et al. Association of preoperatively diagnosed patent foramen ovale with perioperative ischemic stroke. JAMA. 2018 Feb 6;319(5):452-62.

Dr. Roy is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor in medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Documentation and billing: Tips for hospitalists

Is it AMS, Delirium, or Encephalopathy?

During residency, physicians are trained to care for patients and write notes that are clinically useful. However, physicians are often not taught about how documentation affects reimbursement and quality measures. Our purpose here, and in articles to follow, is to give readers tools to enable them to more accurately reflect the complexity and work that is done for accurate reimbursements.

If you were to get in a car accident, the body shop would document the damage done and submit it to the insurance company. It’s the body shop’s responsibility to record the damage, not the insurance company’s. So while documentation can seem onerous, the insurance company is not going to scour the chart to find diagnoses missed in the note. That would be like the body shop doing repair work without documenting the damage but then somehow expecting to get paid.

For the insurance company, “If you didn’t document it, it didn’t happen.” The body shop should not underdocument and say there were only a few scratches on the right rear panel if it was severely damaged. Likewise, it should not overbill and say the front bumper was damaged if it was not. The goal is not to bill as much as possible but rather to document appropriately.

Terminology

The expected length of stay (LOS) and the expected mortality for a particular patient is determined by how sick the patient appears to be based on the medical record documentation. So documenting all the appropriate diagnoses makes the LOS index (actual LOS divided by expected LOS) and mortality index more accurate as well. It is particularly important to document when a condition is (or is not) “present on admission”.

While physician payments can be based on evaluation and management coding, the hospital’s reimbursement is largely determined by physician documentation. Hospitals are paid by Medicare on a capitated basis according to the Acute Inpatient Prospective Payment System. The amount paid is determined by the base rate of the hospital multiplied by the relative weight (RW) of the Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Group (MS-DRG).

The base rate is adjusted by the wage index of the hospital location. Hospitals that serve a high proportion of low income patients receive a Disproportionate Share Hospital adjustment. The base rate is not something hospitalists have control over.

The RW, however, is determined by the primary diagnosis (reason for admission) and whether or not there are complications or comorbidities (CCs) or major complications or comorbidities (MCCs). The more CCs and MCCs a patient has, the higher the severity of illness and expected increased resources needed to care for that patient.

Diagnoses are currently coded using ICD-10 used by the World Health Organization. The ICD-10 of the primary diagnosis is mapped to an MS-DRG. Many, but not all, MS-DRGs have increasing reimbursements for CCs and MCCs. Coders map the ICD-10 of the principal diagnosis along with any associated CCs or MCCs to the MS-DRG code. The relative weights for different DRGs can found on table 5 of the Medicare website (see reference 1).

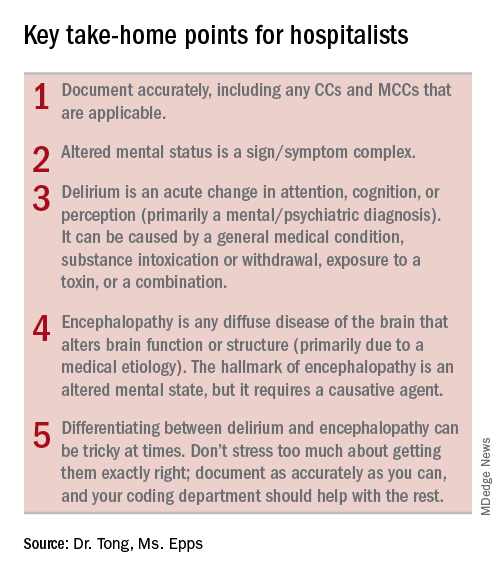

Altered mental status versus delirium versus encephalopathy

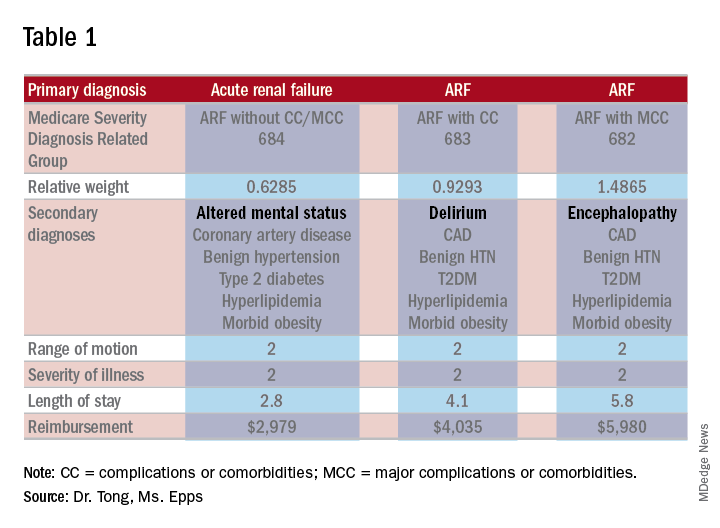

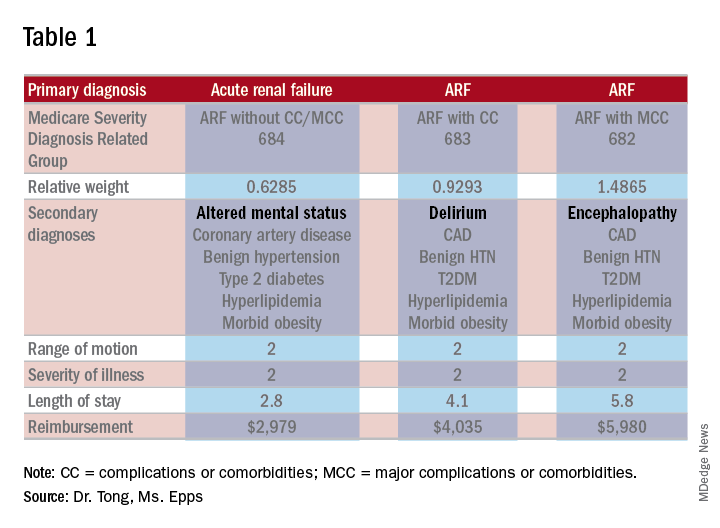

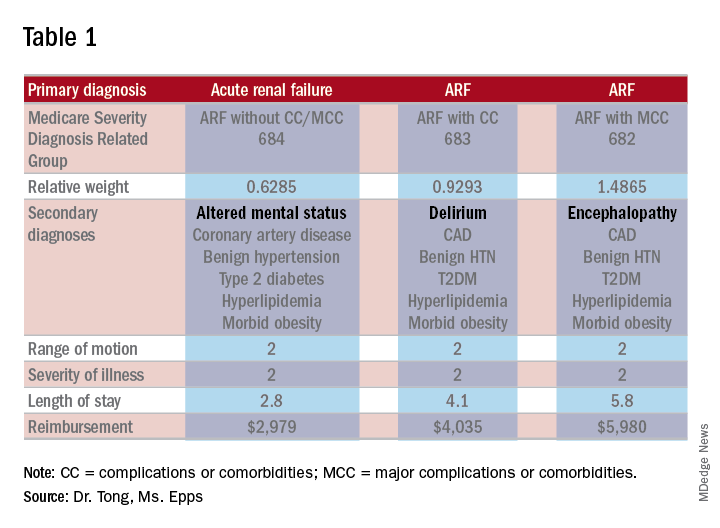

As an example, let’s look at the difference in RW, LOS, and reimbursement in an otherwise identical patient based on documenting altered mental status (AMS), delirium, or encephalopathy. (see Table 1)

As one can see, RW, estimated LOS, and reimbursement would significantly increase for the patient with delirium (CC) or encephalopathy (MCC) versus AMS (no CC/MCC). A list of which diagnoses are considered CC’s versus MCC’s are on tables 6J and 6I, respectively, on the same Medicare website as table 5.

The difference between AMS, delirium, and encephalopathy

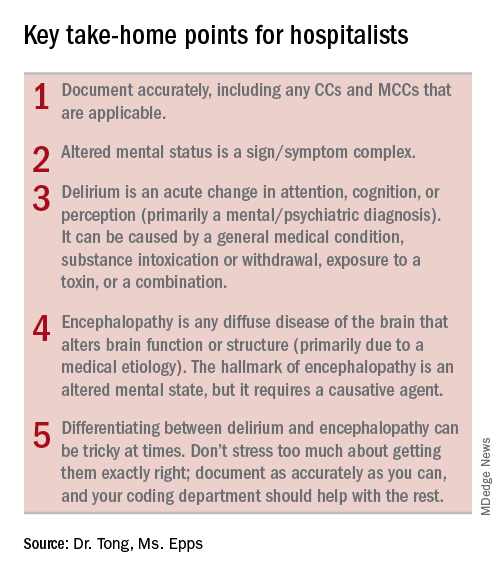

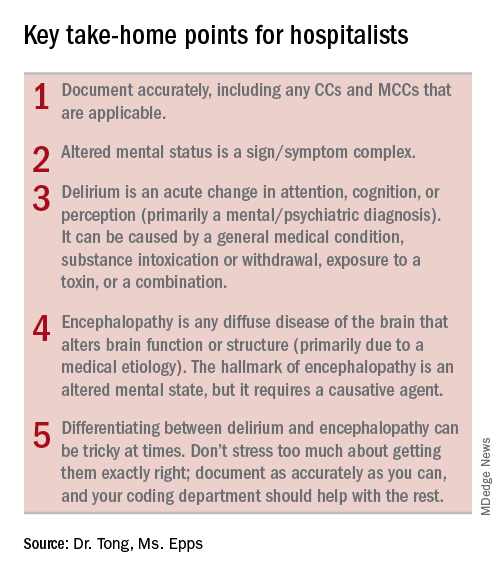

AMS is a sign/symptom complex similar to shortness of breath before an etiology is found. AMS can be the presenting symptom; when a specific etiology is found, however, a more specific diagnosis should be used such as delirium or encephalopathy.

Delirium, according to the DSM-5, is an acute change in the level of attention, cognition, or perception from baseline that developed over hours or days and tends to fluctuate during the course of a day. The change described is not better explained by a preexisting or evolving neurocognitive disorder and does not occur in the context of a severely reduced level of arousal, such as coma. There is evidence from the history, physical examination, or laboratory findings that the disturbance is a direct consequence of a general medical condition, substance intoxication or withdrawal, exposure to a toxin, or more than one cause.

The National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke defines encephalopathy as “any diffuse disease of the brain that alters brain function or structure. Encephalopathy may be caused by an infectious agent, metabolic or mitochondrial dysfunction, brain tumor or increased intracranial pressure, prolonged exposure to toxic elements, chronic progressive trauma, poor nutrition, or lack of oxygen or blood flow to the brain. The hallmark of encephalopathy is an altered mental state.”

It is confusing since there is a lot of overlap in the definitions of delirium and encephalopathy. One way to tease this out conceptually is noting that delirium is listed under mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders, while encephalopathy appears under disorders of the nervous system. One can think of delirium as more of a “mental/psychiatric” diagnosis, while encephalopathy is caused by more “medical” causes.

If a patient who is normally not altered presents with confusion because of an infection or metabolic derangement, one can diagnose and document the cause of an acute encephalopathy. However, let’s say a patient is admitted in the morning with an infection, is started on treatment, but is not initially confused. If he/she later becomes confused at night, one could err conservatively and document delirium caused by sundowning.

Differentiating delirium and encephalopathy can be especially difficult in patients who have dementia with episodic confusion when they present with an infection and confusion. If the confusion is within what family members/caretakers say is “normal,” then one shouldn’t document encephalopathy. As a provider, one shouldn’t focus on all the rules and exceptions, just document as specifically and accurately as possible and the coders should take care of the rest.

Dr. Tong is an assistant professor of hospital medicine and an assistant director of the clinical research program at Emory University, Atlanta. Ms. Epps is director of clinical documentation improvement at Emory Healthcare, Atlanta.

References

1. “Acute Inpatient PPS.” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed 2/17/18. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/index.html.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

3. “Details for title: FY 2018 Final Rule and Correction Notice Tables.” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Accessed 2/17/18. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/FY2018-IPPS-Final-Rule-Home-Page-Items/FY2018-IPPS-Final-Rule-Tables.html.

4. “Encephalopathy Information Page.” National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke. Accessed on 2/17/18. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Encephalopathy-Information-Page.

5. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992. http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37958.

Is it AMS, Delirium, or Encephalopathy?

Is it AMS, Delirium, or Encephalopathy?

During residency, physicians are trained to care for patients and write notes that are clinically useful. However, physicians are often not taught about how documentation affects reimbursement and quality measures. Our purpose here, and in articles to follow, is to give readers tools to enable them to more accurately reflect the complexity and work that is done for accurate reimbursements.

If you were to get in a car accident, the body shop would document the damage done and submit it to the insurance company. It’s the body shop’s responsibility to record the damage, not the insurance company’s. So while documentation can seem onerous, the insurance company is not going to scour the chart to find diagnoses missed in the note. That would be like the body shop doing repair work without documenting the damage but then somehow expecting to get paid.

For the insurance company, “If you didn’t document it, it didn’t happen.” The body shop should not underdocument and say there were only a few scratches on the right rear panel if it was severely damaged. Likewise, it should not overbill and say the front bumper was damaged if it was not. The goal is not to bill as much as possible but rather to document appropriately.

Terminology

The expected length of stay (LOS) and the expected mortality for a particular patient is determined by how sick the patient appears to be based on the medical record documentation. So documenting all the appropriate diagnoses makes the LOS index (actual LOS divided by expected LOS) and mortality index more accurate as well. It is particularly important to document when a condition is (or is not) “present on admission”.

While physician payments can be based on evaluation and management coding, the hospital’s reimbursement is largely determined by physician documentation. Hospitals are paid by Medicare on a capitated basis according to the Acute Inpatient Prospective Payment System. The amount paid is determined by the base rate of the hospital multiplied by the relative weight (RW) of the Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Group (MS-DRG).

The base rate is adjusted by the wage index of the hospital location. Hospitals that serve a high proportion of low income patients receive a Disproportionate Share Hospital adjustment. The base rate is not something hospitalists have control over.

The RW, however, is determined by the primary diagnosis (reason for admission) and whether or not there are complications or comorbidities (CCs) or major complications or comorbidities (MCCs). The more CCs and MCCs a patient has, the higher the severity of illness and expected increased resources needed to care for that patient.

Diagnoses are currently coded using ICD-10 used by the World Health Organization. The ICD-10 of the primary diagnosis is mapped to an MS-DRG. Many, but not all, MS-DRGs have increasing reimbursements for CCs and MCCs. Coders map the ICD-10 of the principal diagnosis along with any associated CCs or MCCs to the MS-DRG code. The relative weights for different DRGs can found on table 5 of the Medicare website (see reference 1).

Altered mental status versus delirium versus encephalopathy

As an example, let’s look at the difference in RW, LOS, and reimbursement in an otherwise identical patient based on documenting altered mental status (AMS), delirium, or encephalopathy. (see Table 1)

As one can see, RW, estimated LOS, and reimbursement would significantly increase for the patient with delirium (CC) or encephalopathy (MCC) versus AMS (no CC/MCC). A list of which diagnoses are considered CC’s versus MCC’s are on tables 6J and 6I, respectively, on the same Medicare website as table 5.

The difference between AMS, delirium, and encephalopathy

AMS is a sign/symptom complex similar to shortness of breath before an etiology is found. AMS can be the presenting symptom; when a specific etiology is found, however, a more specific diagnosis should be used such as delirium or encephalopathy.

Delirium, according to the DSM-5, is an acute change in the level of attention, cognition, or perception from baseline that developed over hours or days and tends to fluctuate during the course of a day. The change described is not better explained by a preexisting or evolving neurocognitive disorder and does not occur in the context of a severely reduced level of arousal, such as coma. There is evidence from the history, physical examination, or laboratory findings that the disturbance is a direct consequence of a general medical condition, substance intoxication or withdrawal, exposure to a toxin, or more than one cause.

The National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke defines encephalopathy as “any diffuse disease of the brain that alters brain function or structure. Encephalopathy may be caused by an infectious agent, metabolic or mitochondrial dysfunction, brain tumor or increased intracranial pressure, prolonged exposure to toxic elements, chronic progressive trauma, poor nutrition, or lack of oxygen or blood flow to the brain. The hallmark of encephalopathy is an altered mental state.”

It is confusing since there is a lot of overlap in the definitions of delirium and encephalopathy. One way to tease this out conceptually is noting that delirium is listed under mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders, while encephalopathy appears under disorders of the nervous system. One can think of delirium as more of a “mental/psychiatric” diagnosis, while encephalopathy is caused by more “medical” causes.

If a patient who is normally not altered presents with confusion because of an infection or metabolic derangement, one can diagnose and document the cause of an acute encephalopathy. However, let’s say a patient is admitted in the morning with an infection, is started on treatment, but is not initially confused. If he/she later becomes confused at night, one could err conservatively and document delirium caused by sundowning.

Differentiating delirium and encephalopathy can be especially difficult in patients who have dementia with episodic confusion when they present with an infection and confusion. If the confusion is within what family members/caretakers say is “normal,” then one shouldn’t document encephalopathy. As a provider, one shouldn’t focus on all the rules and exceptions, just document as specifically and accurately as possible and the coders should take care of the rest.

Dr. Tong is an assistant professor of hospital medicine and an assistant director of the clinical research program at Emory University, Atlanta. Ms. Epps is director of clinical documentation improvement at Emory Healthcare, Atlanta.

References

1. “Acute Inpatient PPS.” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed 2/17/18. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/index.html.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

3. “Details for title: FY 2018 Final Rule and Correction Notice Tables.” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Accessed 2/17/18. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/FY2018-IPPS-Final-Rule-Home-Page-Items/FY2018-IPPS-Final-Rule-Tables.html.

4. “Encephalopathy Information Page.” National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke. Accessed on 2/17/18. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Encephalopathy-Information-Page.

5. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992. http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37958.

During residency, physicians are trained to care for patients and write notes that are clinically useful. However, physicians are often not taught about how documentation affects reimbursement and quality measures. Our purpose here, and in articles to follow, is to give readers tools to enable them to more accurately reflect the complexity and work that is done for accurate reimbursements.

If you were to get in a car accident, the body shop would document the damage done and submit it to the insurance company. It’s the body shop’s responsibility to record the damage, not the insurance company’s. So while documentation can seem onerous, the insurance company is not going to scour the chart to find diagnoses missed in the note. That would be like the body shop doing repair work without documenting the damage but then somehow expecting to get paid.

For the insurance company, “If you didn’t document it, it didn’t happen.” The body shop should not underdocument and say there were only a few scratches on the right rear panel if it was severely damaged. Likewise, it should not overbill and say the front bumper was damaged if it was not. The goal is not to bill as much as possible but rather to document appropriately.

Terminology

The expected length of stay (LOS) and the expected mortality for a particular patient is determined by how sick the patient appears to be based on the medical record documentation. So documenting all the appropriate diagnoses makes the LOS index (actual LOS divided by expected LOS) and mortality index more accurate as well. It is particularly important to document when a condition is (or is not) “present on admission”.

While physician payments can be based on evaluation and management coding, the hospital’s reimbursement is largely determined by physician documentation. Hospitals are paid by Medicare on a capitated basis according to the Acute Inpatient Prospective Payment System. The amount paid is determined by the base rate of the hospital multiplied by the relative weight (RW) of the Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Group (MS-DRG).

The base rate is adjusted by the wage index of the hospital location. Hospitals that serve a high proportion of low income patients receive a Disproportionate Share Hospital adjustment. The base rate is not something hospitalists have control over.

The RW, however, is determined by the primary diagnosis (reason for admission) and whether or not there are complications or comorbidities (CCs) or major complications or comorbidities (MCCs). The more CCs and MCCs a patient has, the higher the severity of illness and expected increased resources needed to care for that patient.

Diagnoses are currently coded using ICD-10 used by the World Health Organization. The ICD-10 of the primary diagnosis is mapped to an MS-DRG. Many, but not all, MS-DRGs have increasing reimbursements for CCs and MCCs. Coders map the ICD-10 of the principal diagnosis along with any associated CCs or MCCs to the MS-DRG code. The relative weights for different DRGs can found on table 5 of the Medicare website (see reference 1).

Altered mental status versus delirium versus encephalopathy

As an example, let’s look at the difference in RW, LOS, and reimbursement in an otherwise identical patient based on documenting altered mental status (AMS), delirium, or encephalopathy. (see Table 1)

As one can see, RW, estimated LOS, and reimbursement would significantly increase for the patient with delirium (CC) or encephalopathy (MCC) versus AMS (no CC/MCC). A list of which diagnoses are considered CC’s versus MCC’s are on tables 6J and 6I, respectively, on the same Medicare website as table 5.

The difference between AMS, delirium, and encephalopathy

AMS is a sign/symptom complex similar to shortness of breath before an etiology is found. AMS can be the presenting symptom; when a specific etiology is found, however, a more specific diagnosis should be used such as delirium or encephalopathy.

Delirium, according to the DSM-5, is an acute change in the level of attention, cognition, or perception from baseline that developed over hours or days and tends to fluctuate during the course of a day. The change described is not better explained by a preexisting or evolving neurocognitive disorder and does not occur in the context of a severely reduced level of arousal, such as coma. There is evidence from the history, physical examination, or laboratory findings that the disturbance is a direct consequence of a general medical condition, substance intoxication or withdrawal, exposure to a toxin, or more than one cause.

The National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke defines encephalopathy as “any diffuse disease of the brain that alters brain function or structure. Encephalopathy may be caused by an infectious agent, metabolic or mitochondrial dysfunction, brain tumor or increased intracranial pressure, prolonged exposure to toxic elements, chronic progressive trauma, poor nutrition, or lack of oxygen or blood flow to the brain. The hallmark of encephalopathy is an altered mental state.”

It is confusing since there is a lot of overlap in the definitions of delirium and encephalopathy. One way to tease this out conceptually is noting that delirium is listed under mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders, while encephalopathy appears under disorders of the nervous system. One can think of delirium as more of a “mental/psychiatric” diagnosis, while encephalopathy is caused by more “medical” causes.

If a patient who is normally not altered presents with confusion because of an infection or metabolic derangement, one can diagnose and document the cause of an acute encephalopathy. However, let’s say a patient is admitted in the morning with an infection, is started on treatment, but is not initially confused. If he/she later becomes confused at night, one could err conservatively and document delirium caused by sundowning.

Differentiating delirium and encephalopathy can be especially difficult in patients who have dementia with episodic confusion when they present with an infection and confusion. If the confusion is within what family members/caretakers say is “normal,” then one shouldn’t document encephalopathy. As a provider, one shouldn’t focus on all the rules and exceptions, just document as specifically and accurately as possible and the coders should take care of the rest.

Dr. Tong is an assistant professor of hospital medicine and an assistant director of the clinical research program at Emory University, Atlanta. Ms. Epps is director of clinical documentation improvement at Emory Healthcare, Atlanta.

References

1. “Acute Inpatient PPS.” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed 2/17/18. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/index.html.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

3. “Details for title: FY 2018 Final Rule and Correction Notice Tables.” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Accessed 2/17/18. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/FY2018-IPPS-Final-Rule-Home-Page-Items/FY2018-IPPS-Final-Rule-Tables.html.

4. “Encephalopathy Information Page.” National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke. Accessed on 2/17/18. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Encephalopathy-Information-Page.

5. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992. http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37958.

Positive change through advocacy

SHM seen as an ‘honest broker’ on Capitol Hill

Editor’s note: The “Legacies of Hospital Medicine” is a recurring opinion column submitted by some of the best and brightest hospitalists in the field, who have helped shape our specialty into what it is today. It is a series of articles that reflect on Hospital Medicine and its evolution over time, from a variety of unique and innovative perspectives.

Medical professional societies have many goals and serve numerous functions. Some of these include education and training, professional development, and shaping the perception of their specialty both in the medical world and the public arena. Advocacy and governmental affairs are also on that list. SHM is no exception to that rule, although we have taken what is clearly an unorthodox approach to those efforts and our strategy has resulted in an unusual amount of success for a society of our size and age.

As my contribution to the “Legacies” series, I am calling upon my 20-year history of participation in SHM’s advocacy and policy efforts to describe that approach, recount some of the history of our efforts, and to talk a bit about our current activities, goals, and strategies.

In 1999 the leadership of SHM decided to create the Public Policy Committee and to provide resources for what was, at the time, a single dedicated staff position to support the work of the committee. As nascent as our efforts were, the strategy for entering into the Washington fray was clear. We decided our priorities were first and foremost to educate our “targets” on exactly what a hospitalist was and on the increasing role hospitalists were playing in the American health care system.

The target audience was (and has remained) Congress, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and the Medicare Payment Advisory Committee, which is the advisory board tasked to recommend to Congress how Medicare should spend its resources. The goal of this education was to establish our credibility and to advance the notion that we were the experts on care design for acutely ill patients in the inpatient setting. To this end, we decided that, when we met with folks on the Hill, we would ask for nothing for ourselves or our members, an approach that was virtually unheard of in the halls of Congress.

When responding to questions as to why we were not bringing “asks” to our Hill meetings, we would simply comment that we were only offering our services. And whenever they decided to try to make the health care system better and expertise was required regarding redesign of care in the hospital, they should think about us. Our stated goal: improve the delivery system and provide better and more cost-effective care for our patients.

We also exercised what I will call “issue discipline.” With very limited resources it was critical that we limit our issues to ones on which we could have significant impact, and had enough expertise to shape an effective argument. In addition, as we were going to be operating within a highly partisan system and representing members with varying political views, it was highly important that we did not approach issues in a way that resulted in our appearing politically motivated.

That approach took a lot of time and patience. But as a small and relatively under-resourced organization, we saw it as the only way that we could eventually have our message heard. So for many years the small contingent of SHM staff and the members of the Public Policy Committee (PPC) worked quietly to have our specialty and society recognized by policy makers in Washington and Baltimore (where CMS resides). But in the years just prior to and since the passage of the Affordable Care Act, when serious redesign of the American health care system began, our patience started to pay dividends and policy makers actually reached out for our input on issues related to the care of patients admitted to acute care hospitals. In addition, our advocacy efforts started to gain more traction.

Today, our specialty and society are well known by the key health care policymakers at CMS, MedPAC, and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), the latter of which was created by the ACA and whose role is to test the new alternative payment models (like accountable care organizations and bundled payments) to find out if they actually lead to better outcomes and lower costs. In the halls of Congress, especially with the health care staff for the committees of jurisdiction for federal health care legislation, our society is seen as an “honest broker” and as an organization committed not just to the issues that impact our members, but one that has the improvement of the entire health care system at the top of its priority list. We have been told that this perception gives us a voice that is much more influential than would be expected for a society of our age, size, and resources.

Along the way, the PPC has grown to a committee of 20 select members led by committee chair Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, SFHM. The committee is known to be among the most difficult committees to get on, and members commit to hours of work monthly to support our efforts. Our government relations staff in Philadelphia is still small at just three, but they are extremely bright and productive. Director Josh Boswell serves as their extremely capable leader. Josh Lapps and Ellen Boyer round out the incredibly strong team. Recently, my role evolved from being the long-term chairman of the PPC to one of volunteer staff, as the senior advisor for government relations. In this role I hope to support our full time staff, especially in our Washington-facing efforts.

The SHM staff has brought several systemic improvements to our advocacy work, including execution of several highly successful “Hill Days” and, more recently, the establishment of our “Grassroots Network” that allows a wider swath of our membership to get involved in the field. The Hill Days occur during years when the SHM Annual Conference is in Washington, and one of the days includes busing hundreds of hospitalists to Capitol Hill for meetings with their representatives to discuss our advocacy issues. Our next Hill Day will be at the 2019 annual conference, and we will be signing up volunteer members for this unique experience.

The success of our advocacy can be seen in several high-level “wins” over the last few years. Some of the more notable include:

- Successful application to CMS for a specialty code for Hospital Medicine (the C6 designation), so that performance data for hospitalists will be fairly compared with other hospitalists and not with our outpatient colleagues’ performance.

- Successful support of risk adjustment of readmission rates for safety net hospitals.

- Creation of a hardship exemption of Meaningful Use penalties for hospitalists, an initiative that saved our membership approximately $37 million of unfair penalties per year; this ensured a permanent exemption from these penalties within the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act.

- Implementation of Advanced Care Planning CPT codes to encourage appropriate use of “end of life” discussions.

- Establishment of a Hospitalist Measure set with CMS.

- Repeal of the Independent Advisory Board earlier this year.

- Creation of the “Facility Based Option” to replace Merit-Based Incentive Payment System reporting for hospital-based physicians including hospitalists. This voluntary method to replace MIPS reporting was first suggested to CMS by SHM, was developed in partnership with CMS, and will be available in 2019.

SHM continues to take the lead on issues that impact the U.S. health care system and our patients. For several years we have been explaining to CMS and Congress the complete dysfunction of observation status, and its negative impact on elderly patients and hospitals. We have taken advantage of the expertise of several members of the PPC, including research currently being done by member Ann Sheehy, MD, SFHM, to publish two iterations of a white paper on the subject, which was widely read by Hill staff and resulted in Dr. Sheehy testifying on the subject to Congress.

More recently, SHM released a consensus statement on the use of opioids in the inpatient setting, along with a policy statement on opioid abuse, both of which have been widely lauded after being distributed to key committees of both chambers of Congress. Our recommendations will undoubtedly be addressed in an opioid bill which, at the time of this writing, is moving to a vote on the Hill.

As the U.S. health care system undergoes a necessary transformation to one in which value creation is tantamount, hospitalists – by the nature of our work – are in a propitious position to guide the development of better federal policy. We still must be judicious in the use of our limited resources and circumspect in our selection of issues. And we must jealously guard the reputation we have cultivated as a medical society that is looking out for the entire health care system and its patients, while we also support our members and their work.

We want to continue to be an organization that, rather than resisting change, is focused on driving positive change through better ideas and intelligent advocacy.

Dr. Greeno is senior advisor for government affairs and past president of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

SHM seen as an ‘honest broker’ on Capitol Hill

SHM seen as an ‘honest broker’ on Capitol Hill

Editor’s note: The “Legacies of Hospital Medicine” is a recurring opinion column submitted by some of the best and brightest hospitalists in the field, who have helped shape our specialty into what it is today. It is a series of articles that reflect on Hospital Medicine and its evolution over time, from a variety of unique and innovative perspectives.

Medical professional societies have many goals and serve numerous functions. Some of these include education and training, professional development, and shaping the perception of their specialty both in the medical world and the public arena. Advocacy and governmental affairs are also on that list. SHM is no exception to that rule, although we have taken what is clearly an unorthodox approach to those efforts and our strategy has resulted in an unusual amount of success for a society of our size and age.

As my contribution to the “Legacies” series, I am calling upon my 20-year history of participation in SHM’s advocacy and policy efforts to describe that approach, recount some of the history of our efforts, and to talk a bit about our current activities, goals, and strategies.

In 1999 the leadership of SHM decided to create the Public Policy Committee and to provide resources for what was, at the time, a single dedicated staff position to support the work of the committee. As nascent as our efforts were, the strategy for entering into the Washington fray was clear. We decided our priorities were first and foremost to educate our “targets” on exactly what a hospitalist was and on the increasing role hospitalists were playing in the American health care system.

The target audience was (and has remained) Congress, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and the Medicare Payment Advisory Committee, which is the advisory board tasked to recommend to Congress how Medicare should spend its resources. The goal of this education was to establish our credibility and to advance the notion that we were the experts on care design for acutely ill patients in the inpatient setting. To this end, we decided that, when we met with folks on the Hill, we would ask for nothing for ourselves or our members, an approach that was virtually unheard of in the halls of Congress.

When responding to questions as to why we were not bringing “asks” to our Hill meetings, we would simply comment that we were only offering our services. And whenever they decided to try to make the health care system better and expertise was required regarding redesign of care in the hospital, they should think about us. Our stated goal: improve the delivery system and provide better and more cost-effective care for our patients.

We also exercised what I will call “issue discipline.” With very limited resources it was critical that we limit our issues to ones on which we could have significant impact, and had enough expertise to shape an effective argument. In addition, as we were going to be operating within a highly partisan system and representing members with varying political views, it was highly important that we did not approach issues in a way that resulted in our appearing politically motivated.

That approach took a lot of time and patience. But as a small and relatively under-resourced organization, we saw it as the only way that we could eventually have our message heard. So for many years the small contingent of SHM staff and the members of the Public Policy Committee (PPC) worked quietly to have our specialty and society recognized by policy makers in Washington and Baltimore (where CMS resides). But in the years just prior to and since the passage of the Affordable Care Act, when serious redesign of the American health care system began, our patience started to pay dividends and policy makers actually reached out for our input on issues related to the care of patients admitted to acute care hospitals. In addition, our advocacy efforts started to gain more traction.

Today, our specialty and society are well known by the key health care policymakers at CMS, MedPAC, and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), the latter of which was created by the ACA and whose role is to test the new alternative payment models (like accountable care organizations and bundled payments) to find out if they actually lead to better outcomes and lower costs. In the halls of Congress, especially with the health care staff for the committees of jurisdiction for federal health care legislation, our society is seen as an “honest broker” and as an organization committed not just to the issues that impact our members, but one that has the improvement of the entire health care system at the top of its priority list. We have been told that this perception gives us a voice that is much more influential than would be expected for a society of our age, size, and resources.

Along the way, the PPC has grown to a committee of 20 select members led by committee chair Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, SFHM. The committee is known to be among the most difficult committees to get on, and members commit to hours of work monthly to support our efforts. Our government relations staff in Philadelphia is still small at just three, but they are extremely bright and productive. Director Josh Boswell serves as their extremely capable leader. Josh Lapps and Ellen Boyer round out the incredibly strong team. Recently, my role evolved from being the long-term chairman of the PPC to one of volunteer staff, as the senior advisor for government relations. In this role I hope to support our full time staff, especially in our Washington-facing efforts.

The SHM staff has brought several systemic improvements to our advocacy work, including execution of several highly successful “Hill Days” and, more recently, the establishment of our “Grassroots Network” that allows a wider swath of our membership to get involved in the field. The Hill Days occur during years when the SHM Annual Conference is in Washington, and one of the days includes busing hundreds of hospitalists to Capitol Hill for meetings with their representatives to discuss our advocacy issues. Our next Hill Day will be at the 2019 annual conference, and we will be signing up volunteer members for this unique experience.

The success of our advocacy can be seen in several high-level “wins” over the last few years. Some of the more notable include:

- Successful application to CMS for a specialty code for Hospital Medicine (the C6 designation), so that performance data for hospitalists will be fairly compared with other hospitalists and not with our outpatient colleagues’ performance.

- Successful support of risk adjustment of readmission rates for safety net hospitals.

- Creation of a hardship exemption of Meaningful Use penalties for hospitalists, an initiative that saved our membership approximately $37 million of unfair penalties per year; this ensured a permanent exemption from these penalties within the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act.

- Implementation of Advanced Care Planning CPT codes to encourage appropriate use of “end of life” discussions.

- Establishment of a Hospitalist Measure set with CMS.

- Repeal of the Independent Advisory Board earlier this year.

- Creation of the “Facility Based Option” to replace Merit-Based Incentive Payment System reporting for hospital-based physicians including hospitalists. This voluntary method to replace MIPS reporting was first suggested to CMS by SHM, was developed in partnership with CMS, and will be available in 2019.

SHM continues to take the lead on issues that impact the U.S. health care system and our patients. For several years we have been explaining to CMS and Congress the complete dysfunction of observation status, and its negative impact on elderly patients and hospitals. We have taken advantage of the expertise of several members of the PPC, including research currently being done by member Ann Sheehy, MD, SFHM, to publish two iterations of a white paper on the subject, which was widely read by Hill staff and resulted in Dr. Sheehy testifying on the subject to Congress.

More recently, SHM released a consensus statement on the use of opioids in the inpatient setting, along with a policy statement on opioid abuse, both of which have been widely lauded after being distributed to key committees of both chambers of Congress. Our recommendations will undoubtedly be addressed in an opioid bill which, at the time of this writing, is moving to a vote on the Hill.

As the U.S. health care system undergoes a necessary transformation to one in which value creation is tantamount, hospitalists – by the nature of our work – are in a propitious position to guide the development of better federal policy. We still must be judicious in the use of our limited resources and circumspect in our selection of issues. And we must jealously guard the reputation we have cultivated as a medical society that is looking out for the entire health care system and its patients, while we also support our members and their work.

We want to continue to be an organization that, rather than resisting change, is focused on driving positive change through better ideas and intelligent advocacy.

Dr. Greeno is senior advisor for government affairs and past president of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s note: The “Legacies of Hospital Medicine” is a recurring opinion column submitted by some of the best and brightest hospitalists in the field, who have helped shape our specialty into what it is today. It is a series of articles that reflect on Hospital Medicine and its evolution over time, from a variety of unique and innovative perspectives.

Medical professional societies have many goals and serve numerous functions. Some of these include education and training, professional development, and shaping the perception of their specialty both in the medical world and the public arena. Advocacy and governmental affairs are also on that list. SHM is no exception to that rule, although we have taken what is clearly an unorthodox approach to those efforts and our strategy has resulted in an unusual amount of success for a society of our size and age.

As my contribution to the “Legacies” series, I am calling upon my 20-year history of participation in SHM’s advocacy and policy efforts to describe that approach, recount some of the history of our efforts, and to talk a bit about our current activities, goals, and strategies.

In 1999 the leadership of SHM decided to create the Public Policy Committee and to provide resources for what was, at the time, a single dedicated staff position to support the work of the committee. As nascent as our efforts were, the strategy for entering into the Washington fray was clear. We decided our priorities were first and foremost to educate our “targets” on exactly what a hospitalist was and on the increasing role hospitalists were playing in the American health care system.

The target audience was (and has remained) Congress, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and the Medicare Payment Advisory Committee, which is the advisory board tasked to recommend to Congress how Medicare should spend its resources. The goal of this education was to establish our credibility and to advance the notion that we were the experts on care design for acutely ill patients in the inpatient setting. To this end, we decided that, when we met with folks on the Hill, we would ask for nothing for ourselves or our members, an approach that was virtually unheard of in the halls of Congress.

When responding to questions as to why we were not bringing “asks” to our Hill meetings, we would simply comment that we were only offering our services. And whenever they decided to try to make the health care system better and expertise was required regarding redesign of care in the hospital, they should think about us. Our stated goal: improve the delivery system and provide better and more cost-effective care for our patients.

We also exercised what I will call “issue discipline.” With very limited resources it was critical that we limit our issues to ones on which we could have significant impact, and had enough expertise to shape an effective argument. In addition, as we were going to be operating within a highly partisan system and representing members with varying political views, it was highly important that we did not approach issues in a way that resulted in our appearing politically motivated.

That approach took a lot of time and patience. But as a small and relatively under-resourced organization, we saw it as the only way that we could eventually have our message heard. So for many years the small contingent of SHM staff and the members of the Public Policy Committee (PPC) worked quietly to have our specialty and society recognized by policy makers in Washington and Baltimore (where CMS resides). But in the years just prior to and since the passage of the Affordable Care Act, when serious redesign of the American health care system began, our patience started to pay dividends and policy makers actually reached out for our input on issues related to the care of patients admitted to acute care hospitals. In addition, our advocacy efforts started to gain more traction.

Today, our specialty and society are well known by the key health care policymakers at CMS, MedPAC, and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), the latter of which was created by the ACA and whose role is to test the new alternative payment models (like accountable care organizations and bundled payments) to find out if they actually lead to better outcomes and lower costs. In the halls of Congress, especially with the health care staff for the committees of jurisdiction for federal health care legislation, our society is seen as an “honest broker” and as an organization committed not just to the issues that impact our members, but one that has the improvement of the entire health care system at the top of its priority list. We have been told that this perception gives us a voice that is much more influential than would be expected for a society of our age, size, and resources.

Along the way, the PPC has grown to a committee of 20 select members led by committee chair Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, SFHM. The committee is known to be among the most difficult committees to get on, and members commit to hours of work monthly to support our efforts. Our government relations staff in Philadelphia is still small at just three, but they are extremely bright and productive. Director Josh Boswell serves as their extremely capable leader. Josh Lapps and Ellen Boyer round out the incredibly strong team. Recently, my role evolved from being the long-term chairman of the PPC to one of volunteer staff, as the senior advisor for government relations. In this role I hope to support our full time staff, especially in our Washington-facing efforts.

The SHM staff has brought several systemic improvements to our advocacy work, including execution of several highly successful “Hill Days” and, more recently, the establishment of our “Grassroots Network” that allows a wider swath of our membership to get involved in the field. The Hill Days occur during years when the SHM Annual Conference is in Washington, and one of the days includes busing hundreds of hospitalists to Capitol Hill for meetings with their representatives to discuss our advocacy issues. Our next Hill Day will be at the 2019 annual conference, and we will be signing up volunteer members for this unique experience.

The success of our advocacy can be seen in several high-level “wins” over the last few years. Some of the more notable include:

- Successful application to CMS for a specialty code for Hospital Medicine (the C6 designation), so that performance data for hospitalists will be fairly compared with other hospitalists and not with our outpatient colleagues’ performance.

- Successful support of risk adjustment of readmission rates for safety net hospitals.

- Creation of a hardship exemption of Meaningful Use penalties for hospitalists, an initiative that saved our membership approximately $37 million of unfair penalties per year; this ensured a permanent exemption from these penalties within the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act.

- Implementation of Advanced Care Planning CPT codes to encourage appropriate use of “end of life” discussions.

- Establishment of a Hospitalist Measure set with CMS.

- Repeal of the Independent Advisory Board earlier this year.

- Creation of the “Facility Based Option” to replace Merit-Based Incentive Payment System reporting for hospital-based physicians including hospitalists. This voluntary method to replace MIPS reporting was first suggested to CMS by SHM, was developed in partnership with CMS, and will be available in 2019.

SHM continues to take the lead on issues that impact the U.S. health care system and our patients. For several years we have been explaining to CMS and Congress the complete dysfunction of observation status, and its negative impact on elderly patients and hospitals. We have taken advantage of the expertise of several members of the PPC, including research currently being done by member Ann Sheehy, MD, SFHM, to publish two iterations of a white paper on the subject, which was widely read by Hill staff and resulted in Dr. Sheehy testifying on the subject to Congress.

More recently, SHM released a consensus statement on the use of opioids in the inpatient setting, along with a policy statement on opioid abuse, both of which have been widely lauded after being distributed to key committees of both chambers of Congress. Our recommendations will undoubtedly be addressed in an opioid bill which, at the time of this writing, is moving to a vote on the Hill.

As the U.S. health care system undergoes a necessary transformation to one in which value creation is tantamount, hospitalists – by the nature of our work – are in a propitious position to guide the development of better federal policy. We still must be judicious in the use of our limited resources and circumspect in our selection of issues. And we must jealously guard the reputation we have cultivated as a medical society that is looking out for the entire health care system and its patients, while we also support our members and their work.

We want to continue to be an organization that, rather than resisting change, is focused on driving positive change through better ideas and intelligent advocacy.

Dr. Greeno is senior advisor for government affairs and past president of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

PE is rare in patients presenting to the ED with syncope

Clinical question: What is the prevalence of pulmonary embolism (PE) in patients presenting to the ED with syncope?

Study design: Retrospective, observational study.

Setting: Canada, Denmark, Italy, and the United States, from January 2010 to September 2016.

Synopsis: Longitudinal administrative databases were used to identify patients with ICD codes for syncope at discharge from the ED or hospital. Those with an ICD code for PE were included to calculate the prevalence of PE in this population (primary outcome).

The prevalence of PE in all patients ranged from 0.06% (95% confidence interval, 0.05%-0.06%) to 0.55% (95% CI, 0.50%-0.61%); and in hospitalized patients from 0.15% (95% CI, 0.14%-0.16%) to 2.10% (95% CI, 1.84%-2.39%). This is a much lower than the estimated 17.3% prevalence of PE in patients presenting with syncope estimated by the PESIT study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2016. Further definitive research is needed to better characterize prevalence rates.

Limitations of this study include the potential for information bias: The inclusion criteria of patients coded for syncope at discharge likely omits some patients who initially presented with syncope but were coded for a primary diagnosis that caused syncope.

Bottom line: PE in patients presenting to the ED with syncope may be rare.

Citation: Costantino G et al. Prevalence of pulmonary embolism in patients with syncope. JAMA. 2018;178(3):356-62.

Dr. Roy is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor in medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Clinical question: What is the prevalence of pulmonary embolism (PE) in patients presenting to the ED with syncope?

Study design: Retrospective, observational study.

Setting: Canada, Denmark, Italy, and the United States, from January 2010 to September 2016.

Synopsis: Longitudinal administrative databases were used to identify patients with ICD codes for syncope at discharge from the ED or hospital. Those with an ICD code for PE were included to calculate the prevalence of PE in this population (primary outcome).

The prevalence of PE in all patients ranged from 0.06% (95% confidence interval, 0.05%-0.06%) to 0.55% (95% CI, 0.50%-0.61%); and in hospitalized patients from 0.15% (95% CI, 0.14%-0.16%) to 2.10% (95% CI, 1.84%-2.39%). This is a much lower than the estimated 17.3% prevalence of PE in patients presenting with syncope estimated by the PESIT study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2016. Further definitive research is needed to better characterize prevalence rates.

Limitations of this study include the potential for information bias: The inclusion criteria of patients coded for syncope at discharge likely omits some patients who initially presented with syncope but were coded for a primary diagnosis that caused syncope.

Bottom line: PE in patients presenting to the ED with syncope may be rare.

Citation: Costantino G et al. Prevalence of pulmonary embolism in patients with syncope. JAMA. 2018;178(3):356-62.

Dr. Roy is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor in medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Clinical question: What is the prevalence of pulmonary embolism (PE) in patients presenting to the ED with syncope?

Study design: Retrospective, observational study.

Setting: Canada, Denmark, Italy, and the United States, from January 2010 to September 2016.

Synopsis: Longitudinal administrative databases were used to identify patients with ICD codes for syncope at discharge from the ED or hospital. Those with an ICD code for PE were included to calculate the prevalence of PE in this population (primary outcome).

The prevalence of PE in all patients ranged from 0.06% (95% confidence interval, 0.05%-0.06%) to 0.55% (95% CI, 0.50%-0.61%); and in hospitalized patients from 0.15% (95% CI, 0.14%-0.16%) to 2.10% (95% CI, 1.84%-2.39%). This is a much lower than the estimated 17.3% prevalence of PE in patients presenting with syncope estimated by the PESIT study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2016. Further definitive research is needed to better characterize prevalence rates.

Limitations of this study include the potential for information bias: The inclusion criteria of patients coded for syncope at discharge likely omits some patients who initially presented with syncope but were coded for a primary diagnosis that caused syncope.

Bottom line: PE in patients presenting to the ED with syncope may be rare.

Citation: Costantino G et al. Prevalence of pulmonary embolism in patients with syncope. JAMA. 2018;178(3):356-62.

Dr. Roy is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor in medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Multifaceted pharmacist intervention may reduce postdischarge ED visits and readmissions

Clinical question: Can a multifaceted intervention by a clinical pharmacist reduce the rate of ED visits and readmission over the subsequent 180 days?

Background: The period following an inpatient admission contains many potential risks for patients, among them the risk for adverse drug events. Approximately 45% of readmissions from adverse drug reactions are thought to be avoidable.

Study design: Multicentered, single-blinded, randomized, control trial, from September 2013 to April 2015.

Setting: Four acute inpatient hospitals in Denmark.

Synopsis: 1,467 adult patients being admitted for an acute hospitalization on a minimum of five medications were randomized to receive usual care, a basic intervention (medication review by a clinical pharmacist), or an extended intervention (medication review, three motivational interviews, and follow-up with the primary care physician, pharmacy and, if appropriate, nursing home by a clinical pharmacist). The primary endpoints were readmission within 30 days or 180 days, ED visits within 180 days, and a composite endpoint of readmission or ED visit within 180 days post discharge. For these endpoints, the basic intervention group had no statistically significant difference from the usual-care group. The extended intervention group had significantly lower rates of readmission within 30 days and 180 days, as well as the primary composite endpoint compared to the usual-care group (P less than .05 for all comparisons). For the extended intervention, the number needed to treat for the main composite endpoint was 12.

Bottom line: For patients admitted to the hospital, an extended intervention by a clinical pharmacist resulted in a significant reduction in readmissions.

Citation: Ravn-Nielsen LV et al. Effect of an in-hospital multifaceted clinical pharmacist intervention on the risk of readmission. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(3):375-82.

Dr. Biddick is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor in medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Clinical question: Can a multifaceted intervention by a clinical pharmacist reduce the rate of ED visits and readmission over the subsequent 180 days?

Background: The period following an inpatient admission contains many potential risks for patients, among them the risk for adverse drug events. Approximately 45% of readmissions from adverse drug reactions are thought to be avoidable.

Study design: Multicentered, single-blinded, randomized, control trial, from September 2013 to April 2015.

Setting: Four acute inpatient hospitals in Denmark.

Synopsis: 1,467 adult patients being admitted for an acute hospitalization on a minimum of five medications were randomized to receive usual care, a basic intervention (medication review by a clinical pharmacist), or an extended intervention (medication review, three motivational interviews, and follow-up with the primary care physician, pharmacy and, if appropriate, nursing home by a clinical pharmacist). The primary endpoints were readmission within 30 days or 180 days, ED visits within 180 days, and a composite endpoint of readmission or ED visit within 180 days post discharge. For these endpoints, the basic intervention group had no statistically significant difference from the usual-care group. The extended intervention group had significantly lower rates of readmission within 30 days and 180 days, as well as the primary composite endpoint compared to the usual-care group (P less than .05 for all comparisons). For the extended intervention, the number needed to treat for the main composite endpoint was 12.

Bottom line: For patients admitted to the hospital, an extended intervention by a clinical pharmacist resulted in a significant reduction in readmissions.

Citation: Ravn-Nielsen LV et al. Effect of an in-hospital multifaceted clinical pharmacist intervention on the risk of readmission. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(3):375-82.

Dr. Biddick is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor in medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Clinical question: Can a multifaceted intervention by a clinical pharmacist reduce the rate of ED visits and readmission over the subsequent 180 days?

Background: The period following an inpatient admission contains many potential risks for patients, among them the risk for adverse drug events. Approximately 45% of readmissions from adverse drug reactions are thought to be avoidable.

Study design: Multicentered, single-blinded, randomized, control trial, from September 2013 to April 2015.

Setting: Four acute inpatient hospitals in Denmark.

Synopsis: 1,467 adult patients being admitted for an acute hospitalization on a minimum of five medications were randomized to receive usual care, a basic intervention (medication review by a clinical pharmacist), or an extended intervention (medication review, three motivational interviews, and follow-up with the primary care physician, pharmacy and, if appropriate, nursing home by a clinical pharmacist). The primary endpoints were readmission within 30 days or 180 days, ED visits within 180 days, and a composite endpoint of readmission or ED visit within 180 days post discharge. For these endpoints, the basic intervention group had no statistically significant difference from the usual-care group. The extended intervention group had significantly lower rates of readmission within 30 days and 180 days, as well as the primary composite endpoint compared to the usual-care group (P less than .05 for all comparisons). For the extended intervention, the number needed to treat for the main composite endpoint was 12.

Bottom line: For patients admitted to the hospital, an extended intervention by a clinical pharmacist resulted in a significant reduction in readmissions.

Citation: Ravn-Nielsen LV et al. Effect of an in-hospital multifaceted clinical pharmacist intervention on the risk of readmission. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(3):375-82.

Dr. Biddick is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor in medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Opioid use has not declined meaningfully

Opioid use has not significantly declined over the past 10 years despite efforts to educate prescribers about the risks of opioid abuse, with over half of disabled Medicare beneficiaries using opioids each year, according to a recent retrospective cohort study published in the BMJ.

“We found very high prevalence of opioid use and opioid doses in disabled Medicare beneficiaries, most likely reflecting the high burden of illness in this population,” Molly M. Jeffery, PhD, from the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and her associates wrote in their study.

The investigators evaluated pharmaceutical and medical claims data from 48 million individuals who were commercially insured or were Medicare Advantage recipients (both those eligible because they were older than 65 years and those under 65 years old who still were eligible because of disability). The researchers found that 52% of disabled Medicare patients, 26% of aged Medicare patients, and 14% of commercially insured patients used opioids annually within the study period.

In the commercially insured group, there was little fluctuation in patient opioid prevalence by quarter, with an average daily dose of 17 mg morphine equivalents (MME) during 2011-2016; 6% of patients used opioids quarterly at the beginning and end of the study. There was an increase of quarterly opioid prevalence in the aged Medicare group from 11% to 14% at the beginning and end of the study period. Average daily dose also increased during this period for the aged Medicare group from 18 MME in 2011 to 20 MME in 2016.

Researchers said commercial beneficiaries between 45 years and 54 years old had the highest prevalence of opioid use. The disabled Medicare group saw the greatest increase among groups in opioid prevalence and average daily dose, with a 26% prevalence in 2007 and 53 MME average daily dose, which increased to a prevalence of 39% and an average daily dose of 56 MME in 2016.

“Doctors and patients should consider whether long-term opioid use is improving the patient’s ability to function and, if not, should consider other treatments either as an addition or replacement to opioid use,” Dr. Jeffery and her colleagues wrote. “Evidence-based approaches are needed to improve both the safety of opioid use and patient outcomes including pain management and ability to function.”

The researchers noted limitations in the study, such as not including people with Medicaid, fee-for-service Medicare, or the uninsured. In addition, the data reviewed did not indicate the prevalence of chronic pain or pain duration in the patient population studied, they said.

The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Jeffery MM et al. BMJ. 2018 Aug 1. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k2833.

Opioid use has not significantly declined over the past 10 years despite efforts to educate prescribers about the risks of opioid abuse, with over half of disabled Medicare beneficiaries using opioids each year, according to a recent retrospective cohort study published in the BMJ.

“We found very high prevalence of opioid use and opioid doses in disabled Medicare beneficiaries, most likely reflecting the high burden of illness in this population,” Molly M. Jeffery, PhD, from the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and her associates wrote in their study.

The investigators evaluated pharmaceutical and medical claims data from 48 million individuals who were commercially insured or were Medicare Advantage recipients (both those eligible because they were older than 65 years and those under 65 years old who still were eligible because of disability). The researchers found that 52% of disabled Medicare patients, 26% of aged Medicare patients, and 14% of commercially insured patients used opioids annually within the study period.