User login

Everything We Say and Do: Digging deep brings empathy and sincere communication

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

What I say and do

I find a way to connect with my patients to express sincere appreciation.

A recent “Everything We Say and Do” column focused on an important element of high-impact physician-patient communication: closing the encounter by thanking the patient. Evidence suggests that patients feel more valued by their providers when expressions of gratitude are offered. However, it is not always easy to find a genuine and sincere way to incorporate a “thank you” at the end of a visit.

Why I do it

The physician-patient relationship is an inherently hierarchical one. Recognizing that the encounter represents a meeting of two people who equally stand to gain from the interaction goes a long way to strengthen trust, improve communication, and enhance the therapeutic effect.

How I do it

Many who don’t regularly experience serious illness firsthand take good health for granted. I appreciate my patients for reminding me to cherish my own good health. My patients offer me glimpses of hope as I watch them and their families rally through the trials that serious illness brings; in addition, they provide me inspiration and ideas for how I will handle these issues myself someday.

Some in other fields feel unfulfilled with their work as they contemplate their professional legacy. On the contrary, our patients validate our sense of purpose and strengthen our self-worth, as they allow us to participate in one of the noblest endeavors – caring for the sick. The unique insights physicians garner from patients via our intimate access to the private struggles and fears that all humans suffer, but rarely share, should strengthen our empathy for the greater human condition and enhance our own personal relationships.

Recalibrating my perspective makes it easier to harness and express sincere gratitude to patients, and enhances my ability to connect on a deeper level with those I serve.

Greg Seymann is clinical professor and vice chief for academic affairs, UCSD Division of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

What I say and do

I find a way to connect with my patients to express sincere appreciation.

A recent “Everything We Say and Do” column focused on an important element of high-impact physician-patient communication: closing the encounter by thanking the patient. Evidence suggests that patients feel more valued by their providers when expressions of gratitude are offered. However, it is not always easy to find a genuine and sincere way to incorporate a “thank you” at the end of a visit.

Why I do it

The physician-patient relationship is an inherently hierarchical one. Recognizing that the encounter represents a meeting of two people who equally stand to gain from the interaction goes a long way to strengthen trust, improve communication, and enhance the therapeutic effect.

How I do it

Many who don’t regularly experience serious illness firsthand take good health for granted. I appreciate my patients for reminding me to cherish my own good health. My patients offer me glimpses of hope as I watch them and their families rally through the trials that serious illness brings; in addition, they provide me inspiration and ideas for how I will handle these issues myself someday.

Some in other fields feel unfulfilled with their work as they contemplate their professional legacy. On the contrary, our patients validate our sense of purpose and strengthen our self-worth, as they allow us to participate in one of the noblest endeavors – caring for the sick. The unique insights physicians garner from patients via our intimate access to the private struggles and fears that all humans suffer, but rarely share, should strengthen our empathy for the greater human condition and enhance our own personal relationships.

Recalibrating my perspective makes it easier to harness and express sincere gratitude to patients, and enhances my ability to connect on a deeper level with those I serve.

Greg Seymann is clinical professor and vice chief for academic affairs, UCSD Division of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

What I say and do

I find a way to connect with my patients to express sincere appreciation.

A recent “Everything We Say and Do” column focused on an important element of high-impact physician-patient communication: closing the encounter by thanking the patient. Evidence suggests that patients feel more valued by their providers when expressions of gratitude are offered. However, it is not always easy to find a genuine and sincere way to incorporate a “thank you” at the end of a visit.

Why I do it

The physician-patient relationship is an inherently hierarchical one. Recognizing that the encounter represents a meeting of two people who equally stand to gain from the interaction goes a long way to strengthen trust, improve communication, and enhance the therapeutic effect.

How I do it

Many who don’t regularly experience serious illness firsthand take good health for granted. I appreciate my patients for reminding me to cherish my own good health. My patients offer me glimpses of hope as I watch them and their families rally through the trials that serious illness brings; in addition, they provide me inspiration and ideas for how I will handle these issues myself someday.

Some in other fields feel unfulfilled with their work as they contemplate their professional legacy. On the contrary, our patients validate our sense of purpose and strengthen our self-worth, as they allow us to participate in one of the noblest endeavors – caring for the sick. The unique insights physicians garner from patients via our intimate access to the private struggles and fears that all humans suffer, but rarely share, should strengthen our empathy for the greater human condition and enhance our own personal relationships.

Recalibrating my perspective makes it easier to harness and express sincere gratitude to patients, and enhances my ability to connect on a deeper level with those I serve.

Greg Seymann is clinical professor and vice chief for academic affairs, UCSD Division of Hospital Medicine.

How to make the move away from opioids for chronic noncancer pain

Standard care of chronic noncancer pain should start moving away from chronic opioid treatment, which can put patients in greater danger of developing a substance use disorder, according to evidence presented at a meeting held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education.

As the effects of the U.S. opioid epidemic continue to gain public attention – recently spurring a declaration of a state of emergency –

Use of opioid therapy for pain conditions such as osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, and migraine – once a common treatment approach – has been shown to be a dangerous breeding ground for opioid substance use disorders, and physicians would do well to re-evaluate their treatment methods, according to Edwin Salsitz, MD, assistant clinical professor at Mount Sinai Beth Israel Hospital, New York.

“Each prescriber is going to have to review this, digest it, reflect on it, and decide what they are going to do,” said Dr. Salsitz in an interview. “Base it on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s guideline as a good starting point, and then individualize it for yourself and your patients.”

One of the major steps toward lowering the rate of opioid addiction through prescription is avoiding opioids as a treatment for acute pain.

“The first recommendation [of the CDC guideline] is nonpharmaceutical therapy, including physical therapy, massage therapy, acupuncture, and cognitive-behavioral therapy – and there’s a whole lot of evidence for these types of therapy,” said Dr. Salsitz. “The second option is that if you’re going to use medications, use those that aren’t opioids, like Tylenol, Motrin, and antidepressants.”

If opioids are necessary, said Dr. Salsitz, immediate-release opioids in limited prescriptions are a good way to lower the risk of addiction.

“The extended-release opioids have many more milligrams than the immediate-release opioids,” according to Dr. Salsitz. “For example, in New York state, we have a law now that says for acute pain, you cannot prescribe for more than a 7-day amount.”

That 7-day limit helps keep excess opioids out of households, he noted, making it harder for patients to share their medication with friends and family, which has proven to be the most common source for opioids during the onset of substance use disorders. In the first 12 months of use, friends and family members accounted for 55% of reported sources of opioids, according to the U.S. 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

Providers may also want to consider screening pain patients for psychological disorders, Dr. Salsitz said, as many psychological conditions are associated with a high risk of developing a substance use disorder. Patients with major depression, dysthymia, or panic disorder were 3.43, 6.51, and 5.37 times more likely, respectively, than those without to initiate a prescription for and regularly use opioids, according to a study cited by Dr. Salsitz (Arch Intern Med. 2006 Oct 23;166[19]:2087-93).

One of the largest barriers preventing providers from implementing these methods, however, is a lack of resources, particularly in rural areas with increasing rates of opioid substance use disorders and limited provider options.

While these limitations do pose a problem, physicians should not feel they can’t provide proper care, according to Dr. Salsitz. “I think that each individual provider, wherever they are located, can do a reasonable job.”

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

Standard care of chronic noncancer pain should start moving away from chronic opioid treatment, which can put patients in greater danger of developing a substance use disorder, according to evidence presented at a meeting held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education.

As the effects of the U.S. opioid epidemic continue to gain public attention – recently spurring a declaration of a state of emergency –

Use of opioid therapy for pain conditions such as osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, and migraine – once a common treatment approach – has been shown to be a dangerous breeding ground for opioid substance use disorders, and physicians would do well to re-evaluate their treatment methods, according to Edwin Salsitz, MD, assistant clinical professor at Mount Sinai Beth Israel Hospital, New York.

“Each prescriber is going to have to review this, digest it, reflect on it, and decide what they are going to do,” said Dr. Salsitz in an interview. “Base it on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s guideline as a good starting point, and then individualize it for yourself and your patients.”

One of the major steps toward lowering the rate of opioid addiction through prescription is avoiding opioids as a treatment for acute pain.

“The first recommendation [of the CDC guideline] is nonpharmaceutical therapy, including physical therapy, massage therapy, acupuncture, and cognitive-behavioral therapy – and there’s a whole lot of evidence for these types of therapy,” said Dr. Salsitz. “The second option is that if you’re going to use medications, use those that aren’t opioids, like Tylenol, Motrin, and antidepressants.”

If opioids are necessary, said Dr. Salsitz, immediate-release opioids in limited prescriptions are a good way to lower the risk of addiction.

“The extended-release opioids have many more milligrams than the immediate-release opioids,” according to Dr. Salsitz. “For example, in New York state, we have a law now that says for acute pain, you cannot prescribe for more than a 7-day amount.”

That 7-day limit helps keep excess opioids out of households, he noted, making it harder for patients to share their medication with friends and family, which has proven to be the most common source for opioids during the onset of substance use disorders. In the first 12 months of use, friends and family members accounted for 55% of reported sources of opioids, according to the U.S. 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

Providers may also want to consider screening pain patients for psychological disorders, Dr. Salsitz said, as many psychological conditions are associated with a high risk of developing a substance use disorder. Patients with major depression, dysthymia, or panic disorder were 3.43, 6.51, and 5.37 times more likely, respectively, than those without to initiate a prescription for and regularly use opioids, according to a study cited by Dr. Salsitz (Arch Intern Med. 2006 Oct 23;166[19]:2087-93).

One of the largest barriers preventing providers from implementing these methods, however, is a lack of resources, particularly in rural areas with increasing rates of opioid substance use disorders and limited provider options.

While these limitations do pose a problem, physicians should not feel they can’t provide proper care, according to Dr. Salsitz. “I think that each individual provider, wherever they are located, can do a reasonable job.”

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

Standard care of chronic noncancer pain should start moving away from chronic opioid treatment, which can put patients in greater danger of developing a substance use disorder, according to evidence presented at a meeting held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education.

As the effects of the U.S. opioid epidemic continue to gain public attention – recently spurring a declaration of a state of emergency –

Use of opioid therapy for pain conditions such as osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, and migraine – once a common treatment approach – has been shown to be a dangerous breeding ground for opioid substance use disorders, and physicians would do well to re-evaluate their treatment methods, according to Edwin Salsitz, MD, assistant clinical professor at Mount Sinai Beth Israel Hospital, New York.

“Each prescriber is going to have to review this, digest it, reflect on it, and decide what they are going to do,” said Dr. Salsitz in an interview. “Base it on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s guideline as a good starting point, and then individualize it for yourself and your patients.”

One of the major steps toward lowering the rate of opioid addiction through prescription is avoiding opioids as a treatment for acute pain.

“The first recommendation [of the CDC guideline] is nonpharmaceutical therapy, including physical therapy, massage therapy, acupuncture, and cognitive-behavioral therapy – and there’s a whole lot of evidence for these types of therapy,” said Dr. Salsitz. “The second option is that if you’re going to use medications, use those that aren’t opioids, like Tylenol, Motrin, and antidepressants.”

If opioids are necessary, said Dr. Salsitz, immediate-release opioids in limited prescriptions are a good way to lower the risk of addiction.

“The extended-release opioids have many more milligrams than the immediate-release opioids,” according to Dr. Salsitz. “For example, in New York state, we have a law now that says for acute pain, you cannot prescribe for more than a 7-day amount.”

That 7-day limit helps keep excess opioids out of households, he noted, making it harder for patients to share their medication with friends and family, which has proven to be the most common source for opioids during the onset of substance use disorders. In the first 12 months of use, friends and family members accounted for 55% of reported sources of opioids, according to the U.S. 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

Providers may also want to consider screening pain patients for psychological disorders, Dr. Salsitz said, as many psychological conditions are associated with a high risk of developing a substance use disorder. Patients with major depression, dysthymia, or panic disorder were 3.43, 6.51, and 5.37 times more likely, respectively, than those without to initiate a prescription for and regularly use opioids, according to a study cited by Dr. Salsitz (Arch Intern Med. 2006 Oct 23;166[19]:2087-93).

One of the largest barriers preventing providers from implementing these methods, however, is a lack of resources, particularly in rural areas with increasing rates of opioid substance use disorders and limited provider options.

While these limitations do pose a problem, physicians should not feel they can’t provide proper care, according to Dr. Salsitz. “I think that each individual provider, wherever they are located, can do a reasonable job.”

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

FROM PAIN CARE FOR PRIMARY CARE

QI enthusiast to QI leader: Luci Leykum, MD

Editor’s Note: This ongoing series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Luci Leykum, MD, division chief, general and hospital medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio.

Luci Leykum, MD, MBA, MSc, FACP, SFHM, became familiar with inpatient medicine at age 9 years, when her grandfather contracted non-AB hepatitis from a postoperative blood transfusion. In the ensuing years, Dr. Leykum visited her grandfather during his frequent hospitalizations, keeping a close watch on the physicians charged with his care.

“It was when HIV and what we now think is hep C were just emerging, and there was a lot to figure out,” Dr. Leykum recalled of these formative experiences. Her interests in problem-solving, human relationships, and physiology led to enrollment years later as a medical student at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, where her keen observation skills led to a life-changing, “how did we get here?” moment.

Shortly before Dr. Leykum entered residency in 1999, New York Hospital and Columbia Presbyterian Hospital announced that they were merging. The timing was ideal for someone with Dr. Leykum’s acumen in business and medicine, and, as a resident, she began working with the chief medical officer for quality at the new, combined health system to identify quality improvement opportunities.

From there, the projects began pouring in: tracking phone hold times for residents; updating policies to reduce staff exposure to blood-borne pathogens and other infectious diseases; and monitoring flow through the hospitalization process. “In the progression of a few years, I was able to see important aspects of how the system came together,” said Dr. Leykum, “and how decisions were made around standards and metrics for the system as a whole and for its multiple individual hospital facilities.”

In 2004, two years out of residency, Dr. Leykum relocated to San Antonio to accept a clinician investigator position with the South Texas Veterans Health Care System/University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio (UTHSCSA). Research, she said, has allowed her to delve deeper into the underlying mechanisms that impact systems of health care. She sees the complementary sides of quality improvement and research.

“Through our quality improvement initiatives, we can evaluate and improve specific aspects of care, in specific contexts or systems,” Dr. Leykum explained. “In our research projects, we look for new insights that can be more broadly applied across contexts. With funding, you are able to look at things with a scope, depth, or time horizon beyond what you typically have with a QI project.”

Since joining the UTHSCSA/VA system, Dr. Leykum has participated in more than 15 externally funded studies, 6 as principal investigator. She joined SHM’s research committee in 2009, serving as chair for 6 years, and is currently working with the committee to implement the Improving Hospital Outcomes through Patient Engagement (i-HOPE) Study.

I-HOPE, funded through the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, is a project to develop a patient- and stakeholder-partnered research agenda to improve the care of hospitalized patients. Dr. Leykum is also involved in implementing a collaborative care model at University Health System, a patient-partnered, interprofessional model that “focuses on improving interconnections, relationships, and sense making,” in the hospital system, she explained. “It was motivated strongly by our desire to improve our partnerships with patients and other providers in the hospital as a strategy to improve care.”

In addition to the many professional responsibilities she manages as division chief of general and hospital medicine at UTHSCSA – a position she has held for hospital medicine since 2006 and for the combined division since 2016 – Dr. Leykum continues to play an integral role in multiple academic and research initiatives for SHM.

She encourages anyone considering a concentration in QI and research to seek opportunities to actively learn these skills and, more importantly, let other people know their interests.

“The value of talking with colleagues at other places is so high,” she said. “When you actively reach out, you find that most people are happy to share their knowledge. Networking is one of the best parts of the SHM annual meeting – there’s an energy and excitement in learning about what others are doing. Wander into the poster and special interest sessions and see what people are working on, get email addresses, and participate on committees.”

Editor’s Note: This ongoing series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Luci Leykum, MD, division chief, general and hospital medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio.

Luci Leykum, MD, MBA, MSc, FACP, SFHM, became familiar with inpatient medicine at age 9 years, when her grandfather contracted non-AB hepatitis from a postoperative blood transfusion. In the ensuing years, Dr. Leykum visited her grandfather during his frequent hospitalizations, keeping a close watch on the physicians charged with his care.

“It was when HIV and what we now think is hep C were just emerging, and there was a lot to figure out,” Dr. Leykum recalled of these formative experiences. Her interests in problem-solving, human relationships, and physiology led to enrollment years later as a medical student at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, where her keen observation skills led to a life-changing, “how did we get here?” moment.

Shortly before Dr. Leykum entered residency in 1999, New York Hospital and Columbia Presbyterian Hospital announced that they were merging. The timing was ideal for someone with Dr. Leykum’s acumen in business and medicine, and, as a resident, she began working with the chief medical officer for quality at the new, combined health system to identify quality improvement opportunities.

From there, the projects began pouring in: tracking phone hold times for residents; updating policies to reduce staff exposure to blood-borne pathogens and other infectious diseases; and monitoring flow through the hospitalization process. “In the progression of a few years, I was able to see important aspects of how the system came together,” said Dr. Leykum, “and how decisions were made around standards and metrics for the system as a whole and for its multiple individual hospital facilities.”

In 2004, two years out of residency, Dr. Leykum relocated to San Antonio to accept a clinician investigator position with the South Texas Veterans Health Care System/University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio (UTHSCSA). Research, she said, has allowed her to delve deeper into the underlying mechanisms that impact systems of health care. She sees the complementary sides of quality improvement and research.

“Through our quality improvement initiatives, we can evaluate and improve specific aspects of care, in specific contexts or systems,” Dr. Leykum explained. “In our research projects, we look for new insights that can be more broadly applied across contexts. With funding, you are able to look at things with a scope, depth, or time horizon beyond what you typically have with a QI project.”

Since joining the UTHSCSA/VA system, Dr. Leykum has participated in more than 15 externally funded studies, 6 as principal investigator. She joined SHM’s research committee in 2009, serving as chair for 6 years, and is currently working with the committee to implement the Improving Hospital Outcomes through Patient Engagement (i-HOPE) Study.

I-HOPE, funded through the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, is a project to develop a patient- and stakeholder-partnered research agenda to improve the care of hospitalized patients. Dr. Leykum is also involved in implementing a collaborative care model at University Health System, a patient-partnered, interprofessional model that “focuses on improving interconnections, relationships, and sense making,” in the hospital system, she explained. “It was motivated strongly by our desire to improve our partnerships with patients and other providers in the hospital as a strategy to improve care.”

In addition to the many professional responsibilities she manages as division chief of general and hospital medicine at UTHSCSA – a position she has held for hospital medicine since 2006 and for the combined division since 2016 – Dr. Leykum continues to play an integral role in multiple academic and research initiatives for SHM.

She encourages anyone considering a concentration in QI and research to seek opportunities to actively learn these skills and, more importantly, let other people know their interests.

“The value of talking with colleagues at other places is so high,” she said. “When you actively reach out, you find that most people are happy to share their knowledge. Networking is one of the best parts of the SHM annual meeting – there’s an energy and excitement in learning about what others are doing. Wander into the poster and special interest sessions and see what people are working on, get email addresses, and participate on committees.”

Editor’s Note: This ongoing series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Luci Leykum, MD, division chief, general and hospital medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio.

Luci Leykum, MD, MBA, MSc, FACP, SFHM, became familiar with inpatient medicine at age 9 years, when her grandfather contracted non-AB hepatitis from a postoperative blood transfusion. In the ensuing years, Dr. Leykum visited her grandfather during his frequent hospitalizations, keeping a close watch on the physicians charged with his care.

“It was when HIV and what we now think is hep C were just emerging, and there was a lot to figure out,” Dr. Leykum recalled of these formative experiences. Her interests in problem-solving, human relationships, and physiology led to enrollment years later as a medical student at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, where her keen observation skills led to a life-changing, “how did we get here?” moment.

Shortly before Dr. Leykum entered residency in 1999, New York Hospital and Columbia Presbyterian Hospital announced that they were merging. The timing was ideal for someone with Dr. Leykum’s acumen in business and medicine, and, as a resident, she began working with the chief medical officer for quality at the new, combined health system to identify quality improvement opportunities.

From there, the projects began pouring in: tracking phone hold times for residents; updating policies to reduce staff exposure to blood-borne pathogens and other infectious diseases; and monitoring flow through the hospitalization process. “In the progression of a few years, I was able to see important aspects of how the system came together,” said Dr. Leykum, “and how decisions were made around standards and metrics for the system as a whole and for its multiple individual hospital facilities.”

In 2004, two years out of residency, Dr. Leykum relocated to San Antonio to accept a clinician investigator position with the South Texas Veterans Health Care System/University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio (UTHSCSA). Research, she said, has allowed her to delve deeper into the underlying mechanisms that impact systems of health care. She sees the complementary sides of quality improvement and research.

“Through our quality improvement initiatives, we can evaluate and improve specific aspects of care, in specific contexts or systems,” Dr. Leykum explained. “In our research projects, we look for new insights that can be more broadly applied across contexts. With funding, you are able to look at things with a scope, depth, or time horizon beyond what you typically have with a QI project.”

Since joining the UTHSCSA/VA system, Dr. Leykum has participated in more than 15 externally funded studies, 6 as principal investigator. She joined SHM’s research committee in 2009, serving as chair for 6 years, and is currently working with the committee to implement the Improving Hospital Outcomes through Patient Engagement (i-HOPE) Study.

I-HOPE, funded through the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, is a project to develop a patient- and stakeholder-partnered research agenda to improve the care of hospitalized patients. Dr. Leykum is also involved in implementing a collaborative care model at University Health System, a patient-partnered, interprofessional model that “focuses on improving interconnections, relationships, and sense making,” in the hospital system, she explained. “It was motivated strongly by our desire to improve our partnerships with patients and other providers in the hospital as a strategy to improve care.”

In addition to the many professional responsibilities she manages as division chief of general and hospital medicine at UTHSCSA – a position she has held for hospital medicine since 2006 and for the combined division since 2016 – Dr. Leykum continues to play an integral role in multiple academic and research initiatives for SHM.

She encourages anyone considering a concentration in QI and research to seek opportunities to actively learn these skills and, more importantly, let other people know their interests.

“The value of talking with colleagues at other places is so high,” she said. “When you actively reach out, you find that most people are happy to share their knowledge. Networking is one of the best parts of the SHM annual meeting – there’s an energy and excitement in learning about what others are doing. Wander into the poster and special interest sessions and see what people are working on, get email addresses, and participate on committees.”

Immigration reforms: Repercussions for hospitalists and the health care industry

International medical graduates (IMGs) have been playing a crucial role in clinician staffing needs for U.S. hospitals, especially in hospital medicine and internal medicine. According to a study, IMGs comprise 25% of the total U.S. physician workforce and 36% of internists.1,2 According to data from the 2008 Today’s Hospitalist Compensation & Career Survey, 32% of practicing hospitalists are IMGs.3

Many IMGs come to work in the U.S. via one of three paths. Just like all roads lead to Rome, all visas lead to a permanent residency pathway, eventually based on the country of origin and number of years waiting. The first path is a green card – cases where IMGs were on a visa and within a certain amount of time they received a green card. The second path is J-1 visa waivers for physicians who trained in the U.S. under a J-1 Visa. Typically, physicians on J-1 Visa waivers need to provide their services for a minimum of 3 years working in underserved areas – where there’s a shortage of health professionals – before they can apply for permanent residency.

The third and most popular path is the H-1B visa, which hospitalists traditionally use as a springboard to apply for permanent residency. Studies have shown that IMGs are more likely to practice medicine in rural and underserved areas. In many instances, physicians end up working in these areas for long periods of time.4

The Department of Homeland Security has considered creating another visa pathway for the technology industry, whereby an alien graduating from a U.S. university with an advanced degree in a STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) course of study would receive a new visa and pathway to permanent residency. We believe hospitalists and other physicians should also have an expedited pathway to permanent residency. This step benefits both the U.S. health care system and hospitalists in many ways. It increases hospitalists’ portability and flexibility with schedules. With a traditional H-1B visa, hospitalists are bound to work with the one hospital/system that sponsors the H-1B, and would not be able to work at any other hospital without another extension/addendum to current visa status, even in cases where a physician had time off and would like to offer services at another facility. It is a well-known fact that hospitalist teams are understaffed and try to bring on per-diem staff to fill holes in schedules. The majority of hospitalists are working week-on/week-off schedules, and with an expedited pathway to a green card they would be able to work in different hospitals. They would also be able to move to remote places, or “doctor deserts,” and offer their services, helping to ensure the quality and safety of patient care to which all Americans are entitled.

In 2016 alone, around 1,500 H-1B visas were filed for hospitalist physicians.7 Each hospitalist has an average of 15 patient encounters per day, and for 1,500 physicians that amounts to about 4 million patient encounters annually.8 These data account for only new 2016 visa-holding physicians, and do not account for already approved or renewed visas. It would be very challenging to count the number of patient encounters by hospitalists who are on a visa, but 1 billion patient encounters is not overestimating. Recent studies show that quality of care provided by IMGs is not inferior to that of U.S. medical graduates. The study showed that patients cared for by IMGs have lesser mortality, compared with those cared by U.S. medical graduates.9

In this era of hospital medicine, hospitalists are focusing not only on clinical aspects of patient care but also on efficacy, quality of care, and patient safety and satisfaction, and they are working with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to develop cost-cutting programs to save billions of dollars in health care expenses. This is the primary reason a majority of hospitals are focused on developing a hospitalist track, and encouraging hospitalists to pursue leadership roles in managing hospitals effectively.

The U.S. health care system is starved for hospitalists and primary care physicians, and IMGs will continue to play a pivotal role. Yet IMGs must deal with shifting trends in immigration policy, and in some recent instances immigrant physicians have been asked to leave the U.S. because of immigration reforms.10,11 We would like the Society of Hospital Medicine to take a stand on behalf of IMG hospitalists and ask the U.S. Department of Labor and Homeland Security for an expedited permanent residency pathway for IMG hospitalists. We are certain that our request will get a fair hearing, as the former U.S. surgeon general was a hospitalist and, indeed, an immigrant.

Dr. Medarametla is medical director, Intermediate Care Unit, Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, Mass., and assistant professor of medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School. Dr. Pamerla is a hospitalist at Wilson Medical Center, Wilson, N.C.

References

1. Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates; ECFMG 2015 Annual Report. April 2016 http://www.ecfmg.org/resources/ECFMG-2015-annual-report.pdf.

2. Pinsky WW. The Importance of International Medical Graduates in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2017. doi: 10.7326/M17-0505.

3. Hart LG, Skillman SM, Fordyce M, et al. International medical graduate physicians in the United States: changes since 1981. Health Aff. 2007 July/August;26(4):1159-69.

4. Goodfellow A1, Ulloa JG, Dowling PT, et al. Predictors of Primary Care Physician Practice Location in Underserved Urban or Rural Areas in the United States: A Systematic Literature Review. Acad Med. 2016 Sep;91(9):1313-21.

5. https://www.uscis.gov/working-united-states/temporary-workers/h-1b-specialty-occupations-and-fashion-models/h-1b-fiscal-year-fy-2018-cap-season#count

6. https://www.graphiq.com/vlp/bCIqXCpVqF7

7. http://www.myvisajobs.com/Reports/2017-H1B-Visa-Category.aspx?T=JT&P=2

8. Steven M Harris: http://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/125455/appropriate-patient-census-hospital-medicines-holy-grail

9. Tsugawa Y, Jena AB, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Quality of care delivered by general internists in US hospitals who graduated from foreign versus US medical schools: observational study. BMJ. 2017;356:j273.

10. https://www.propublica.org/article/cleveland-clinic-doctor-forced-to-leave-country-after-trump-order

11. http://www.houstonchronicle.com/news/houston-texas/houston/article/Houston-immigrant-doctors-given-24-hours-to-leave-11040259.php

International medical graduates (IMGs) have been playing a crucial role in clinician staffing needs for U.S. hospitals, especially in hospital medicine and internal medicine. According to a study, IMGs comprise 25% of the total U.S. physician workforce and 36% of internists.1,2 According to data from the 2008 Today’s Hospitalist Compensation & Career Survey, 32% of practicing hospitalists are IMGs.3

Many IMGs come to work in the U.S. via one of three paths. Just like all roads lead to Rome, all visas lead to a permanent residency pathway, eventually based on the country of origin and number of years waiting. The first path is a green card – cases where IMGs were on a visa and within a certain amount of time they received a green card. The second path is J-1 visa waivers for physicians who trained in the U.S. under a J-1 Visa. Typically, physicians on J-1 Visa waivers need to provide their services for a minimum of 3 years working in underserved areas – where there’s a shortage of health professionals – before they can apply for permanent residency.

The third and most popular path is the H-1B visa, which hospitalists traditionally use as a springboard to apply for permanent residency. Studies have shown that IMGs are more likely to practice medicine in rural and underserved areas. In many instances, physicians end up working in these areas for long periods of time.4

The Department of Homeland Security has considered creating another visa pathway for the technology industry, whereby an alien graduating from a U.S. university with an advanced degree in a STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) course of study would receive a new visa and pathway to permanent residency. We believe hospitalists and other physicians should also have an expedited pathway to permanent residency. This step benefits both the U.S. health care system and hospitalists in many ways. It increases hospitalists’ portability and flexibility with schedules. With a traditional H-1B visa, hospitalists are bound to work with the one hospital/system that sponsors the H-1B, and would not be able to work at any other hospital without another extension/addendum to current visa status, even in cases where a physician had time off and would like to offer services at another facility. It is a well-known fact that hospitalist teams are understaffed and try to bring on per-diem staff to fill holes in schedules. The majority of hospitalists are working week-on/week-off schedules, and with an expedited pathway to a green card they would be able to work in different hospitals. They would also be able to move to remote places, or “doctor deserts,” and offer their services, helping to ensure the quality and safety of patient care to which all Americans are entitled.

In 2016 alone, around 1,500 H-1B visas were filed for hospitalist physicians.7 Each hospitalist has an average of 15 patient encounters per day, and for 1,500 physicians that amounts to about 4 million patient encounters annually.8 These data account for only new 2016 visa-holding physicians, and do not account for already approved or renewed visas. It would be very challenging to count the number of patient encounters by hospitalists who are on a visa, but 1 billion patient encounters is not overestimating. Recent studies show that quality of care provided by IMGs is not inferior to that of U.S. medical graduates. The study showed that patients cared for by IMGs have lesser mortality, compared with those cared by U.S. medical graduates.9

In this era of hospital medicine, hospitalists are focusing not only on clinical aspects of patient care but also on efficacy, quality of care, and patient safety and satisfaction, and they are working with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to develop cost-cutting programs to save billions of dollars in health care expenses. This is the primary reason a majority of hospitals are focused on developing a hospitalist track, and encouraging hospitalists to pursue leadership roles in managing hospitals effectively.

The U.S. health care system is starved for hospitalists and primary care physicians, and IMGs will continue to play a pivotal role. Yet IMGs must deal with shifting trends in immigration policy, and in some recent instances immigrant physicians have been asked to leave the U.S. because of immigration reforms.10,11 We would like the Society of Hospital Medicine to take a stand on behalf of IMG hospitalists and ask the U.S. Department of Labor and Homeland Security for an expedited permanent residency pathway for IMG hospitalists. We are certain that our request will get a fair hearing, as the former U.S. surgeon general was a hospitalist and, indeed, an immigrant.

Dr. Medarametla is medical director, Intermediate Care Unit, Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, Mass., and assistant professor of medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School. Dr. Pamerla is a hospitalist at Wilson Medical Center, Wilson, N.C.

References

1. Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates; ECFMG 2015 Annual Report. April 2016 http://www.ecfmg.org/resources/ECFMG-2015-annual-report.pdf.

2. Pinsky WW. The Importance of International Medical Graduates in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2017. doi: 10.7326/M17-0505.

3. Hart LG, Skillman SM, Fordyce M, et al. International medical graduate physicians in the United States: changes since 1981. Health Aff. 2007 July/August;26(4):1159-69.

4. Goodfellow A1, Ulloa JG, Dowling PT, et al. Predictors of Primary Care Physician Practice Location in Underserved Urban or Rural Areas in the United States: A Systematic Literature Review. Acad Med. 2016 Sep;91(9):1313-21.

5. https://www.uscis.gov/working-united-states/temporary-workers/h-1b-specialty-occupations-and-fashion-models/h-1b-fiscal-year-fy-2018-cap-season#count

6. https://www.graphiq.com/vlp/bCIqXCpVqF7

7. http://www.myvisajobs.com/Reports/2017-H1B-Visa-Category.aspx?T=JT&P=2

8. Steven M Harris: http://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/125455/appropriate-patient-census-hospital-medicines-holy-grail

9. Tsugawa Y, Jena AB, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Quality of care delivered by general internists in US hospitals who graduated from foreign versus US medical schools: observational study. BMJ. 2017;356:j273.

10. https://www.propublica.org/article/cleveland-clinic-doctor-forced-to-leave-country-after-trump-order

11. http://www.houstonchronicle.com/news/houston-texas/houston/article/Houston-immigrant-doctors-given-24-hours-to-leave-11040259.php

International medical graduates (IMGs) have been playing a crucial role in clinician staffing needs for U.S. hospitals, especially in hospital medicine and internal medicine. According to a study, IMGs comprise 25% of the total U.S. physician workforce and 36% of internists.1,2 According to data from the 2008 Today’s Hospitalist Compensation & Career Survey, 32% of practicing hospitalists are IMGs.3

Many IMGs come to work in the U.S. via one of three paths. Just like all roads lead to Rome, all visas lead to a permanent residency pathway, eventually based on the country of origin and number of years waiting. The first path is a green card – cases where IMGs were on a visa and within a certain amount of time they received a green card. The second path is J-1 visa waivers for physicians who trained in the U.S. under a J-1 Visa. Typically, physicians on J-1 Visa waivers need to provide their services for a minimum of 3 years working in underserved areas – where there’s a shortage of health professionals – before they can apply for permanent residency.

The third and most popular path is the H-1B visa, which hospitalists traditionally use as a springboard to apply for permanent residency. Studies have shown that IMGs are more likely to practice medicine in rural and underserved areas. In many instances, physicians end up working in these areas for long periods of time.4

The Department of Homeland Security has considered creating another visa pathway for the technology industry, whereby an alien graduating from a U.S. university with an advanced degree in a STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) course of study would receive a new visa and pathway to permanent residency. We believe hospitalists and other physicians should also have an expedited pathway to permanent residency. This step benefits both the U.S. health care system and hospitalists in many ways. It increases hospitalists’ portability and flexibility with schedules. With a traditional H-1B visa, hospitalists are bound to work with the one hospital/system that sponsors the H-1B, and would not be able to work at any other hospital without another extension/addendum to current visa status, even in cases where a physician had time off and would like to offer services at another facility. It is a well-known fact that hospitalist teams are understaffed and try to bring on per-diem staff to fill holes in schedules. The majority of hospitalists are working week-on/week-off schedules, and with an expedited pathway to a green card they would be able to work in different hospitals. They would also be able to move to remote places, or “doctor deserts,” and offer their services, helping to ensure the quality and safety of patient care to which all Americans are entitled.

In 2016 alone, around 1,500 H-1B visas were filed for hospitalist physicians.7 Each hospitalist has an average of 15 patient encounters per day, and for 1,500 physicians that amounts to about 4 million patient encounters annually.8 These data account for only new 2016 visa-holding physicians, and do not account for already approved or renewed visas. It would be very challenging to count the number of patient encounters by hospitalists who are on a visa, but 1 billion patient encounters is not overestimating. Recent studies show that quality of care provided by IMGs is not inferior to that of U.S. medical graduates. The study showed that patients cared for by IMGs have lesser mortality, compared with those cared by U.S. medical graduates.9

In this era of hospital medicine, hospitalists are focusing not only on clinical aspects of patient care but also on efficacy, quality of care, and patient safety and satisfaction, and they are working with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to develop cost-cutting programs to save billions of dollars in health care expenses. This is the primary reason a majority of hospitals are focused on developing a hospitalist track, and encouraging hospitalists to pursue leadership roles in managing hospitals effectively.

The U.S. health care system is starved for hospitalists and primary care physicians, and IMGs will continue to play a pivotal role. Yet IMGs must deal with shifting trends in immigration policy, and in some recent instances immigrant physicians have been asked to leave the U.S. because of immigration reforms.10,11 We would like the Society of Hospital Medicine to take a stand on behalf of IMG hospitalists and ask the U.S. Department of Labor and Homeland Security for an expedited permanent residency pathway for IMG hospitalists. We are certain that our request will get a fair hearing, as the former U.S. surgeon general was a hospitalist and, indeed, an immigrant.

Dr. Medarametla is medical director, Intermediate Care Unit, Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, Mass., and assistant professor of medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School. Dr. Pamerla is a hospitalist at Wilson Medical Center, Wilson, N.C.

References

1. Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates; ECFMG 2015 Annual Report. April 2016 http://www.ecfmg.org/resources/ECFMG-2015-annual-report.pdf.

2. Pinsky WW. The Importance of International Medical Graduates in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2017. doi: 10.7326/M17-0505.

3. Hart LG, Skillman SM, Fordyce M, et al. International medical graduate physicians in the United States: changes since 1981. Health Aff. 2007 July/August;26(4):1159-69.

4. Goodfellow A1, Ulloa JG, Dowling PT, et al. Predictors of Primary Care Physician Practice Location in Underserved Urban or Rural Areas in the United States: A Systematic Literature Review. Acad Med. 2016 Sep;91(9):1313-21.

5. https://www.uscis.gov/working-united-states/temporary-workers/h-1b-specialty-occupations-and-fashion-models/h-1b-fiscal-year-fy-2018-cap-season#count

6. https://www.graphiq.com/vlp/bCIqXCpVqF7

7. http://www.myvisajobs.com/Reports/2017-H1B-Visa-Category.aspx?T=JT&P=2

8. Steven M Harris: http://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/125455/appropriate-patient-census-hospital-medicines-holy-grail

9. Tsugawa Y, Jena AB, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Quality of care delivered by general internists in US hospitals who graduated from foreign versus US medical schools: observational study. BMJ. 2017;356:j273.

10. https://www.propublica.org/article/cleveland-clinic-doctor-forced-to-leave-country-after-trump-order

11. http://www.houstonchronicle.com/news/houston-texas/houston/article/Houston-immigrant-doctors-given-24-hours-to-leave-11040259.php

New findings from first all-female TAVR registry

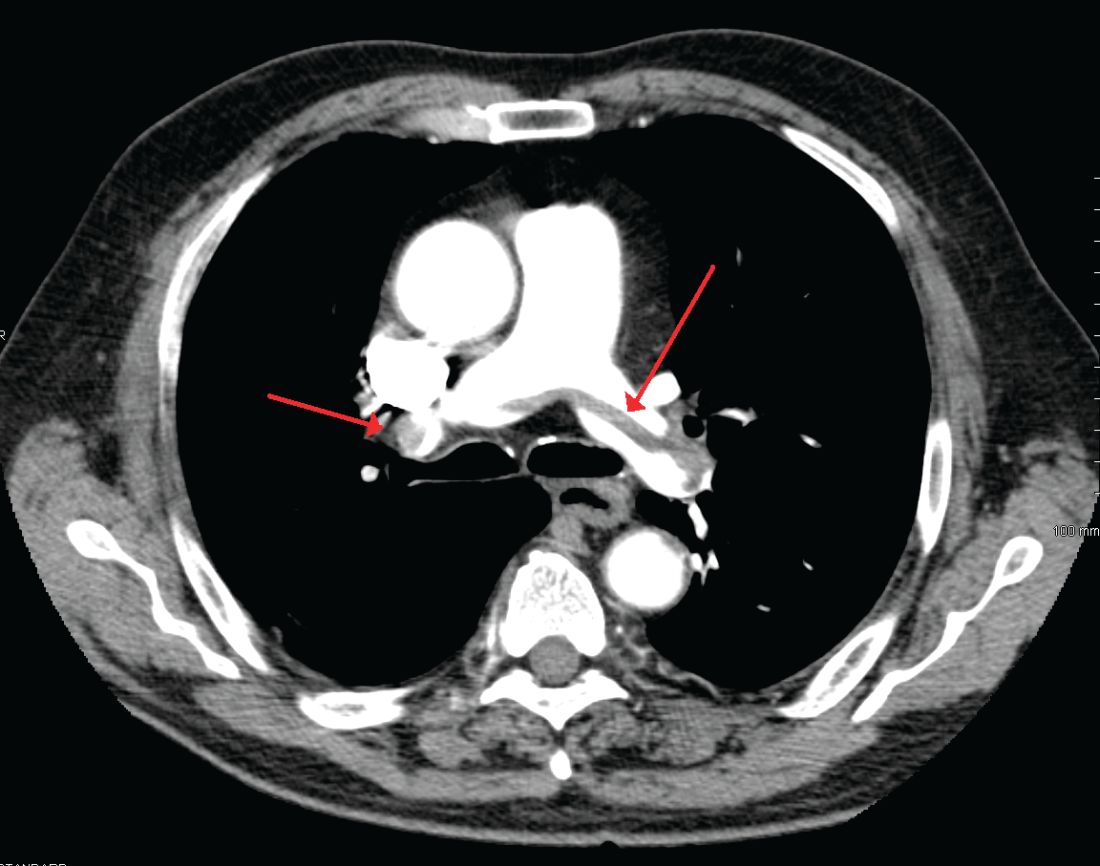

Paris – A history of pregnancy did not protect against adverse outcomes at 1 year in the Women’s International Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Registry (WIN-TAVI), even though it did within the first 30 days, Alaide Chieffo, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

One year ago, at EuroPCR 2016, she reported that in WIN-TAVI, a history of pregnancy – albeit typically more than half a century previously – was independently associated with a 43% reduction in the Valve Academic Research Consortium-2 (VARC-2) 30-day composite endpoint, including death, stroke, major vascular complications, life-threatening bleeding, stage 2 or 3 acute kidney injury, coronary artery obstruction, or repeat transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) done because of valve-related dysfunction. Those early findings, first reported in this publication, were later published (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016 Aug 8;9[15]:1589-600).

At 1 year of follow-up, however, the rate of the VARC-2 composite endpoint was no longer significantly different in women with or without a history of pregnancy. Nor was a history of pregnancy associated with a significantly reduced risk of the secondary endpoint of death or stroke: The 27% reduction in risk of this secondary endpoint in women with a history of pregnancy, compared with that of nulliparous women, didn’t achieve statistical significance in multivariate analysis, according to Dr. Chieffo of the San Raffaele Scientific Institute in Milan.

She speculated that pregnancy earlier in life provided strong protection against poor 30-day outcomes and a similar trend – albeit not statistically significant – at 1 year because women without children may have less family support.

“They are old women, left alone, without the family taking care of them. This is socially important, I think, because we are investing quite a lot of money in a procedure, and then maybe we’re adding adverse events because these patients are not properly taken care of when they are out of the hospital,” the interventional cardiologist said.

Neither of the other two female-specific characteristics evaluated in WIN-TAVI – having a history of osteoporosis or age at menopause – turned out to be related to the risk of bad outcomes at 1 year, she added.

WIN-TAVI is the first all-female registry of patients undergoing TAVR for severe aortic stenosis. The prospective, observational registry includes 1,019 women treated at 19 highly experienced European and North American TAVR centers. They averaged 82.5 years of age with a mean Society of Thoracic Surgeons score of 8.3%, putting them at intermediate or high surgical risk. A percutaneous transfemoral approach was used in 91% of cases. TAVR was performed under conscious sedation in 28% of the women and under local anesthesia in another 37%. Of the women in the registry, 42% received a newer-generation device.

In addition to the lack of significant impact of prior pregnancy on 1-year outcomes, another noteworthy finding at 1 year of follow-up was that preprocedural atrial fibrillation was independently associated with a 58% increase in the risk of death or stroke (P = .02). Prior percutaneous coronary intervention and EuroSCORE (European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation) were the only other independent predictors.

This observation suggests the need for a women-only randomized trial of TAVR versus surgical aortic valve replacement in women with intermediate surgical risk, Dr. Chieffo suggested. It will be important to learn whether the ability to surgically ablate preoperative atrial fibrillation in women during surgical valve replacement results in a lower 1-year risk of death or stroke than is achieved with TAVR.

Overall, the 1-year clinical outcomes seen in WIN-TAVI are “very good,” she noted. The VARC-2 composite endpoint occurred in 16.5% of women, all-cause mortality in 12.5%, cardiovascular mortality in 10.8%, and stroke in 2.2%. Only 3.2% of women were hospitalized for heart failure or valve-related symptoms. A new pacemaker was implanted in 12.7% of participants. At baseline 74% of women were New York Heart Association functional class III or IV; at 1 year, only 8.1% were. Moderate paravalvular aortic regurgitation was present in 6% of patients at 6 months and in 9.7% at 1 year

The WIN-TAVI registry is entirely self-funded. Dr. Chieffo reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

Paris – A history of pregnancy did not protect against adverse outcomes at 1 year in the Women’s International Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Registry (WIN-TAVI), even though it did within the first 30 days, Alaide Chieffo, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

One year ago, at EuroPCR 2016, she reported that in WIN-TAVI, a history of pregnancy – albeit typically more than half a century previously – was independently associated with a 43% reduction in the Valve Academic Research Consortium-2 (VARC-2) 30-day composite endpoint, including death, stroke, major vascular complications, life-threatening bleeding, stage 2 or 3 acute kidney injury, coronary artery obstruction, or repeat transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) done because of valve-related dysfunction. Those early findings, first reported in this publication, were later published (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016 Aug 8;9[15]:1589-600).

At 1 year of follow-up, however, the rate of the VARC-2 composite endpoint was no longer significantly different in women with or without a history of pregnancy. Nor was a history of pregnancy associated with a significantly reduced risk of the secondary endpoint of death or stroke: The 27% reduction in risk of this secondary endpoint in women with a history of pregnancy, compared with that of nulliparous women, didn’t achieve statistical significance in multivariate analysis, according to Dr. Chieffo of the San Raffaele Scientific Institute in Milan.

She speculated that pregnancy earlier in life provided strong protection against poor 30-day outcomes and a similar trend – albeit not statistically significant – at 1 year because women without children may have less family support.

“They are old women, left alone, without the family taking care of them. This is socially important, I think, because we are investing quite a lot of money in a procedure, and then maybe we’re adding adverse events because these patients are not properly taken care of when they are out of the hospital,” the interventional cardiologist said.

Neither of the other two female-specific characteristics evaluated in WIN-TAVI – having a history of osteoporosis or age at menopause – turned out to be related to the risk of bad outcomes at 1 year, she added.

WIN-TAVI is the first all-female registry of patients undergoing TAVR for severe aortic stenosis. The prospective, observational registry includes 1,019 women treated at 19 highly experienced European and North American TAVR centers. They averaged 82.5 years of age with a mean Society of Thoracic Surgeons score of 8.3%, putting them at intermediate or high surgical risk. A percutaneous transfemoral approach was used in 91% of cases. TAVR was performed under conscious sedation in 28% of the women and under local anesthesia in another 37%. Of the women in the registry, 42% received a newer-generation device.

In addition to the lack of significant impact of prior pregnancy on 1-year outcomes, another noteworthy finding at 1 year of follow-up was that preprocedural atrial fibrillation was independently associated with a 58% increase in the risk of death or stroke (P = .02). Prior percutaneous coronary intervention and EuroSCORE (European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation) were the only other independent predictors.

This observation suggests the need for a women-only randomized trial of TAVR versus surgical aortic valve replacement in women with intermediate surgical risk, Dr. Chieffo suggested. It will be important to learn whether the ability to surgically ablate preoperative atrial fibrillation in women during surgical valve replacement results in a lower 1-year risk of death or stroke than is achieved with TAVR.

Overall, the 1-year clinical outcomes seen in WIN-TAVI are “very good,” she noted. The VARC-2 composite endpoint occurred in 16.5% of women, all-cause mortality in 12.5%, cardiovascular mortality in 10.8%, and stroke in 2.2%. Only 3.2% of women were hospitalized for heart failure or valve-related symptoms. A new pacemaker was implanted in 12.7% of participants. At baseline 74% of women were New York Heart Association functional class III or IV; at 1 year, only 8.1% were. Moderate paravalvular aortic regurgitation was present in 6% of patients at 6 months and in 9.7% at 1 year

The WIN-TAVI registry is entirely self-funded. Dr. Chieffo reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

Paris – A history of pregnancy did not protect against adverse outcomes at 1 year in the Women’s International Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Registry (WIN-TAVI), even though it did within the first 30 days, Alaide Chieffo, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

One year ago, at EuroPCR 2016, she reported that in WIN-TAVI, a history of pregnancy – albeit typically more than half a century previously – was independently associated with a 43% reduction in the Valve Academic Research Consortium-2 (VARC-2) 30-day composite endpoint, including death, stroke, major vascular complications, life-threatening bleeding, stage 2 or 3 acute kidney injury, coronary artery obstruction, or repeat transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) done because of valve-related dysfunction. Those early findings, first reported in this publication, were later published (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016 Aug 8;9[15]:1589-600).

At 1 year of follow-up, however, the rate of the VARC-2 composite endpoint was no longer significantly different in women with or without a history of pregnancy. Nor was a history of pregnancy associated with a significantly reduced risk of the secondary endpoint of death or stroke: The 27% reduction in risk of this secondary endpoint in women with a history of pregnancy, compared with that of nulliparous women, didn’t achieve statistical significance in multivariate analysis, according to Dr. Chieffo of the San Raffaele Scientific Institute in Milan.

She speculated that pregnancy earlier in life provided strong protection against poor 30-day outcomes and a similar trend – albeit not statistically significant – at 1 year because women without children may have less family support.

“They are old women, left alone, without the family taking care of them. This is socially important, I think, because we are investing quite a lot of money in a procedure, and then maybe we’re adding adverse events because these patients are not properly taken care of when they are out of the hospital,” the interventional cardiologist said.

Neither of the other two female-specific characteristics evaluated in WIN-TAVI – having a history of osteoporosis or age at menopause – turned out to be related to the risk of bad outcomes at 1 year, she added.

WIN-TAVI is the first all-female registry of patients undergoing TAVR for severe aortic stenosis. The prospective, observational registry includes 1,019 women treated at 19 highly experienced European and North American TAVR centers. They averaged 82.5 years of age with a mean Society of Thoracic Surgeons score of 8.3%, putting them at intermediate or high surgical risk. A percutaneous transfemoral approach was used in 91% of cases. TAVR was performed under conscious sedation in 28% of the women and under local anesthesia in another 37%. Of the women in the registry, 42% received a newer-generation device.

In addition to the lack of significant impact of prior pregnancy on 1-year outcomes, another noteworthy finding at 1 year of follow-up was that preprocedural atrial fibrillation was independently associated with a 58% increase in the risk of death or stroke (P = .02). Prior percutaneous coronary intervention and EuroSCORE (European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation) were the only other independent predictors.

This observation suggests the need for a women-only randomized trial of TAVR versus surgical aortic valve replacement in women with intermediate surgical risk, Dr. Chieffo suggested. It will be important to learn whether the ability to surgically ablate preoperative atrial fibrillation in women during surgical valve replacement results in a lower 1-year risk of death or stroke than is achieved with TAVR.

Overall, the 1-year clinical outcomes seen in WIN-TAVI are “very good,” she noted. The VARC-2 composite endpoint occurred in 16.5% of women, all-cause mortality in 12.5%, cardiovascular mortality in 10.8%, and stroke in 2.2%. Only 3.2% of women were hospitalized for heart failure or valve-related symptoms. A new pacemaker was implanted in 12.7% of participants. At baseline 74% of women were New York Heart Association functional class III or IV; at 1 year, only 8.1% were. Moderate paravalvular aortic regurgitation was present in 6% of patients at 6 months and in 9.7% at 1 year

The WIN-TAVI registry is entirely self-funded. Dr. Chieffo reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

AT EuroPCR

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Prior pregnancy didn’t protect women against death or stroke at 1 year post TAVR.

Data source: WIN-TAVI, a prospective, multicenter, observational registry includes 1,019 women who underwent TAVR.

Disclosures: WIN-TAVI is entirely self-funded. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Student Hospitalist Scholars: First experiences with clinical research

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-2018 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second, and third years of medical school. As a part of the program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a biweekly basis.

The work on my summer project is moving along. Right now, I am collecting data from patients who had clinical deterioration events and unplanned transfers to the PICU in Cincinnati Children’s Hospital over the past year or so.

My mentor has been very helpful in this process by setting up regular meetings with me and keeping communications open. He has provided me with some data from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital that identifies emergency transfer cases, as well as clinical deterioration cases. This saves me a significant amount of time and decreases the potential for errors in the data, because I don’t have to go back and decide which cases were emergency transfers on my own. We are discussing some of the exclusion criteria for the study at this point as well.

I’m enjoying this project, as it is one of my first experiences with clinical research. In addition to the research experience, I am also learning a good amount of medicine as I learn about the care given to these complex patients.

Farah Hussain is a 2nd-year medical student at University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and student researcher at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Her research interests involve bettering patient care to vulnerable populations.

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-2018 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second, and third years of medical school. As a part of the program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a biweekly basis.

The work on my summer project is moving along. Right now, I am collecting data from patients who had clinical deterioration events and unplanned transfers to the PICU in Cincinnati Children’s Hospital over the past year or so.

My mentor has been very helpful in this process by setting up regular meetings with me and keeping communications open. He has provided me with some data from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital that identifies emergency transfer cases, as well as clinical deterioration cases. This saves me a significant amount of time and decreases the potential for errors in the data, because I don’t have to go back and decide which cases were emergency transfers on my own. We are discussing some of the exclusion criteria for the study at this point as well.

I’m enjoying this project, as it is one of my first experiences with clinical research. In addition to the research experience, I am also learning a good amount of medicine as I learn about the care given to these complex patients.

Farah Hussain is a 2nd-year medical student at University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and student researcher at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Her research interests involve bettering patient care to vulnerable populations.

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-2018 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second, and third years of medical school. As a part of the program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a biweekly basis.

The work on my summer project is moving along. Right now, I am collecting data from patients who had clinical deterioration events and unplanned transfers to the PICU in Cincinnati Children’s Hospital over the past year or so.

My mentor has been very helpful in this process by setting up regular meetings with me and keeping communications open. He has provided me with some data from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital that identifies emergency transfer cases, as well as clinical deterioration cases. This saves me a significant amount of time and decreases the potential for errors in the data, because I don’t have to go back and decide which cases were emergency transfers on my own. We are discussing some of the exclusion criteria for the study at this point as well.

I’m enjoying this project, as it is one of my first experiences with clinical research. In addition to the research experience, I am also learning a good amount of medicine as I learn about the care given to these complex patients.

Farah Hussain is a 2nd-year medical student at University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and student researcher at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Her research interests involve bettering patient care to vulnerable populations.

A passion for education: Lonika Sood, MD

On top of her role as a hospitalist at the Aurora BayCare Medical Center in Green Bay, Wis., Lonika Sood, MD, FACP, is currently a candidate for a Masters in health professions education.

From her earliest training to the present day, she has maintained her passion for education, both as a student and an educator.

“I am a part of a community of practice, if you will, of other health professionals who do just this – medical education on a higher level.” Dr. Sood said. “Not only on the front lines of care, but also in designing curricula, undertaking medical education research, and holding leadership positions at medical schools and hospitals around the world.”

As one of the eight new members of The Hospitalist editorial advisory board, Dr. Sood is excited to use her role to help inform and to learn. She told us more about herself in a recent interview.

Q: How did you choose a career in medicine?

A: I grew up in India. I come from a family of doctors. When I was in high school, we found that we had close to 60 physicians in our family, and that number has grown quite a bit since then. At home, being around physicians, that was the language that I grew into. It was a big part of who I wanted to become when I grew up. The other part of it was that I’ve always wanted to help people and do something in one of the science fields, so this seemed like a natural choice for me.

Q: What made you choose hospital medicine?

A: I’ll be very honest – when I came to the United States for my residency, I wanted to become a subspecialist. I used to joke with my mentors in my residency program that every month I wanted to be a different subspecialist depending on which rotation I had or which physician really did a great job on the wards. After moving to Green Bay, Wis., I thought, “We’ll keep residency on hold for a couple of years.” Then I realized that I really liked medical education. I knew that I wanted to be a "specialist" in medical education, yet keep practicing internal medicine, which is something that I’ve always wanted to do. Being a hospitalist is like a marriage of those two passions.

Q: What about medical education draws you?

A: I think a large part of it was that my mother is a physician. My dad is in the merchant navy. In their midlife, they kind of fine-tuned their career paths by going into teaching, so both of them are educators, and very well accomplished in their own right. Growing up, that was a big part of what I saw myself becoming. I did not realize until later in my residency that it was my calling. Additionally, my experience of going into medicine and learning from good teachers is, in my mind, one of the things that really makes me comfortable, and happy being a doctor. I want to be able to leave that legacy for the coming generation.

Q: Tell us how your skills as a teacher help you when you’re working with your patients?

A: To give you an example, we have an adult internal medicine hospital, so we frequently have patients who come to the hospital for the first time. Some of our patients have not seen a physician in over 30 or 40 years. There may be many reasons for that, but they’re scared. They’re sick. They’re in a new environment. They are placing their trust in somebody else’s hands. As teachers and as doctors, it’s important for us to be compassionate, kind, and relatable to patients. We must also be able to explain to patients in their own words what is going on with their body, what might happen, and how can we help. We’re not telling patients what to do or forcing them to take our treatment recommendations, but we are helping them make informed choices. I think hospital medicine really is an incredibly powerful field that can help us relate to our patients.

Q: What is the best professional advice you have received in medicine?

A: I think the advice that I try to follow every day is to be humble. Try to be the best that you can be, yet stay humble, because there’s so much more that you can accomplish if you stay grounded. I think that has stuck with me. It’s come from my parents. It’s come from my mentors. And sometimes it comes from my patients, too.

Q: What is the worst advice you have received?

A: That’s a hard question, but an important one as well, I think. Sometimes there is a push – from society or your colleagues – to be as efficient as you can be, which is great, but we have to look at the downside of it. We sometimes don’t stop and think, or stop and be human. We’re kind of mechanical if data are all we follow.

Q: So where do you see yourself in the next 10 years?

A: That’s a question I try to answer daily, and I get a different answer each time. I think I do see myself continuing to provide clinical care for hospitalized patients. I see myself doing a little more in educational leadership, working with medical students and medical residents. I’m just completing my master’s in health professions education, so I’m excited to also start a career in medical education research.

Q: What’s the best book that you’ve read recently, and why was it the best?

A: Oh, well, it’s not a new book, and I’ve read this before, but I keep coming back to it. I don’t know if you’ve heard of Jim Corbett. He was a wildlife enthusiast in the early 20th century. He wrote a lot of books on man-eating tigers and leopards in India. My brother and I and my dad used to read these books growing up. That’s something that I’m going back to and rereading. There is a lot of rich description about Indian wildlife, and it’s something that brings back good memories.

On top of her role as a hospitalist at the Aurora BayCare Medical Center in Green Bay, Wis., Lonika Sood, MD, FACP, is currently a candidate for a Masters in health professions education.

From her earliest training to the present day, she has maintained her passion for education, both as a student and an educator.

“I am a part of a community of practice, if you will, of other health professionals who do just this – medical education on a higher level.” Dr. Sood said. “Not only on the front lines of care, but also in designing curricula, undertaking medical education research, and holding leadership positions at medical schools and hospitals around the world.”

As one of the eight new members of The Hospitalist editorial advisory board, Dr. Sood is excited to use her role to help inform and to learn. She told us more about herself in a recent interview.

Q: How did you choose a career in medicine?

A: I grew up in India. I come from a family of doctors. When I was in high school, we found that we had close to 60 physicians in our family, and that number has grown quite a bit since then. At home, being around physicians, that was the language that I grew into. It was a big part of who I wanted to become when I grew up. The other part of it was that I’ve always wanted to help people and do something in one of the science fields, so this seemed like a natural choice for me.

Q: What made you choose hospital medicine?