User login

Cutaneous Collagenous Vasculopathy

To the Editor:

Cutaneous microangiopathy describes pathology of the small blood vessels within the dermis.

We report a case of CCV in a 41-year-old woman who presented for evaluation of a rash on the bilateral lower extremities of 7 to 8 months’ duration. The eruption had started on the left ankle and spread over several weeks to the bilateral dorsal feet followed by the ankles and shins. The patient noted associated swelling and a pressure like dysesthesia of the lower legs. She was otherwise in good health, though she had started an oral contraceptive 1 year prior for heavy menstrual bleeding. A review of systems was negative for deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolus, and other thromboembolic phenomena, and the patient had no history of hepatic or renal dysfunction, cancer, or heart disease. Her family history was negative for clotting disorders or bleeding diatheses.

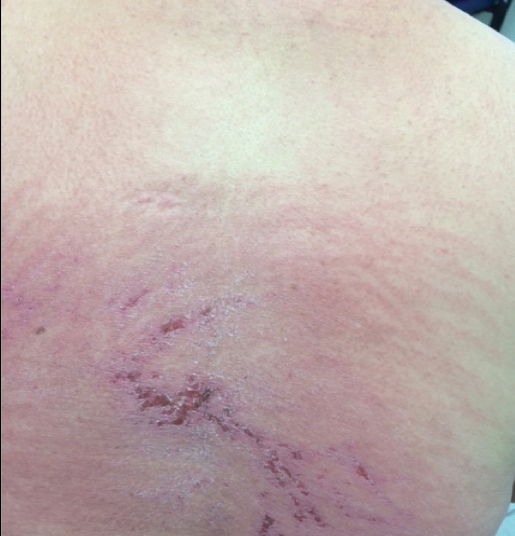

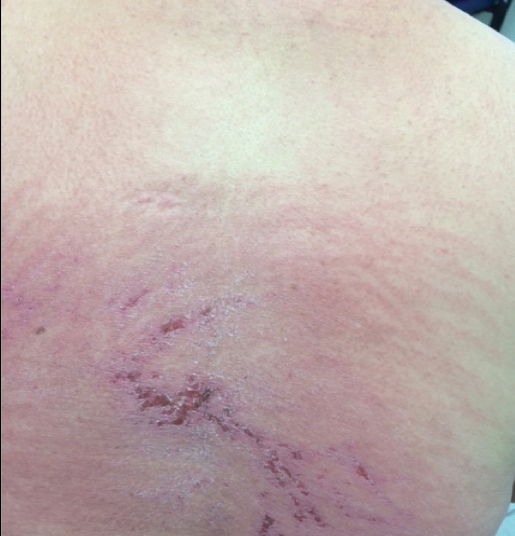

On physical examination, telangiectatic matting was present on the bilateral ankles and dorsal feet with an associated blanchable erythema (Figure 1). The matting extended into a fine, mottled, pretibial telangiectasia associated with Schamberg purpura. She had no pitting edema, and both dorsalis pedis and posterior popliteal pulses were intact and symmetric bilaterally. No popliteal lymphadenopathy or palpable cords were present.

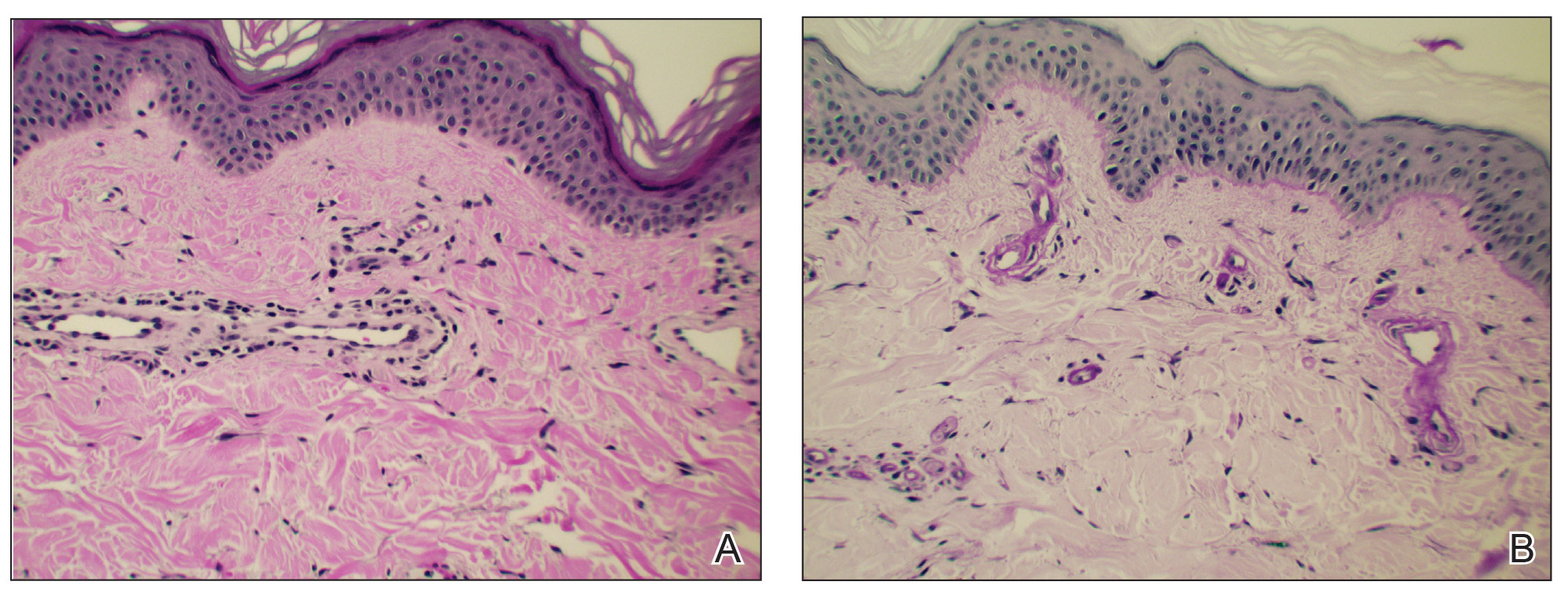

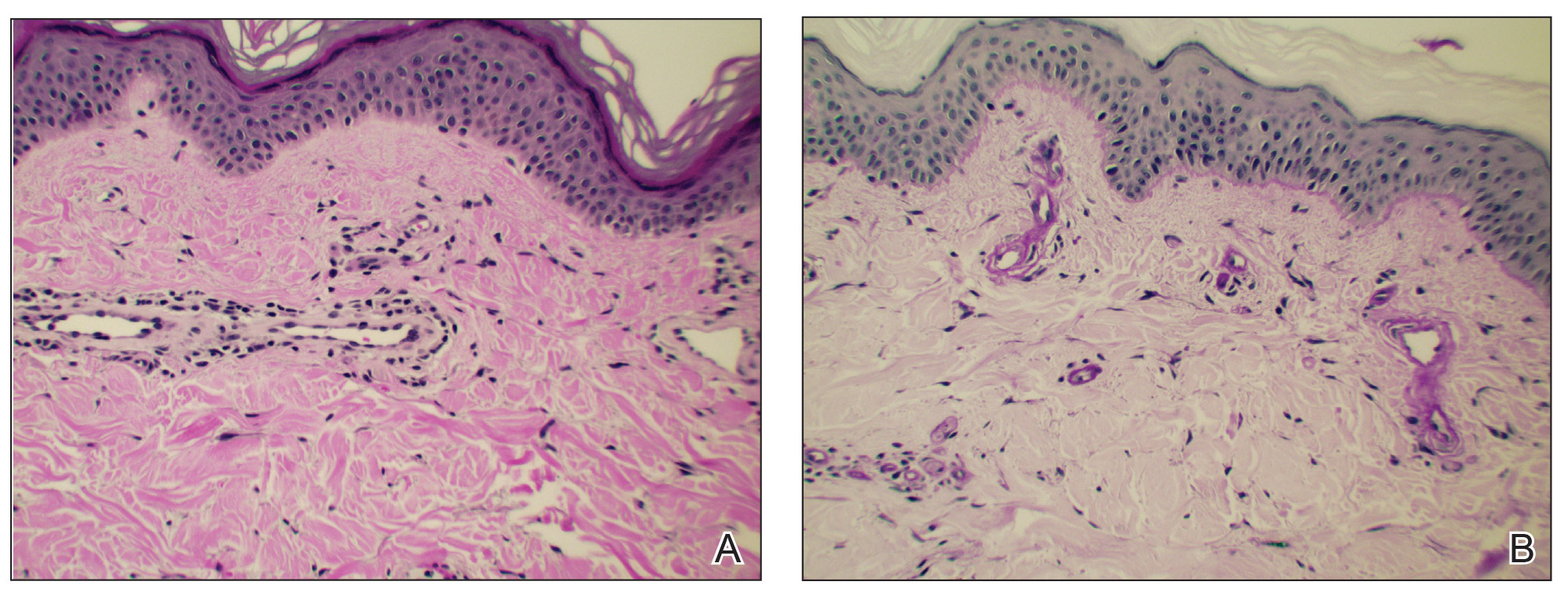

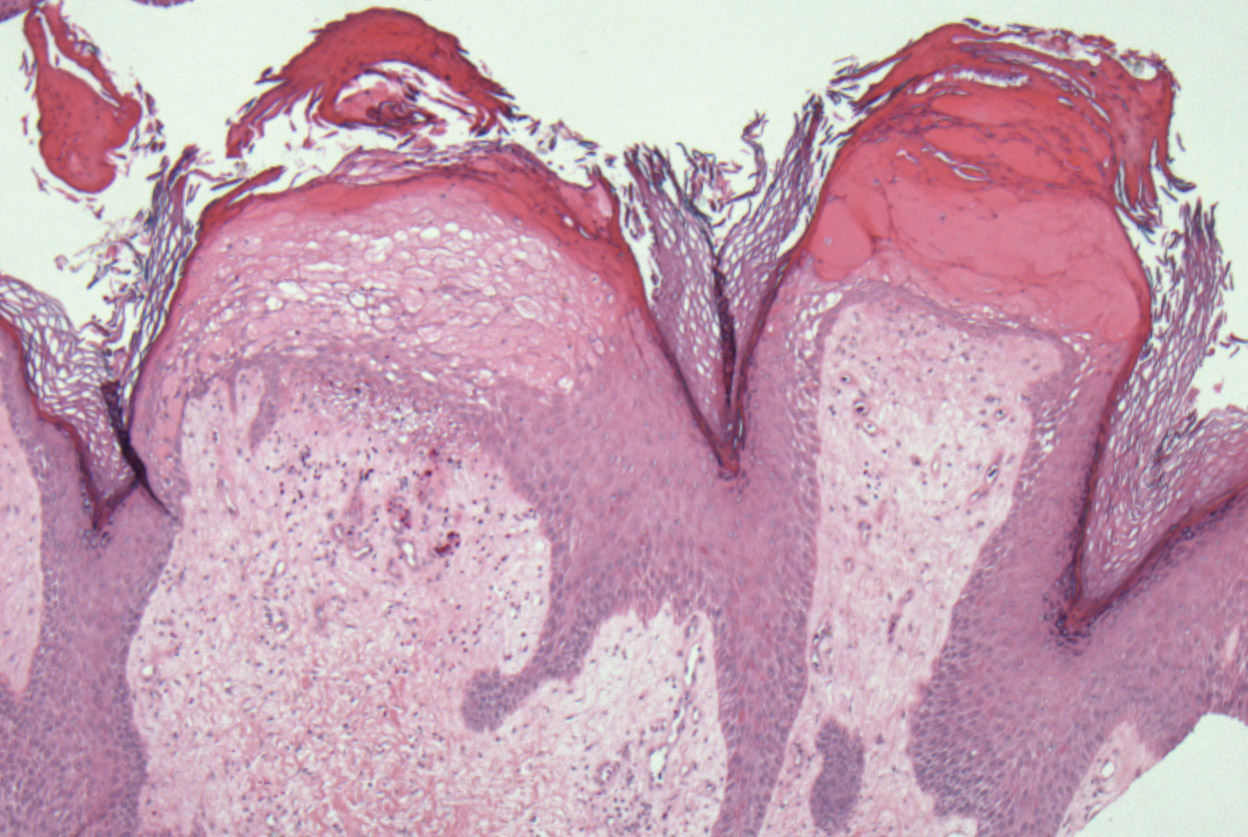

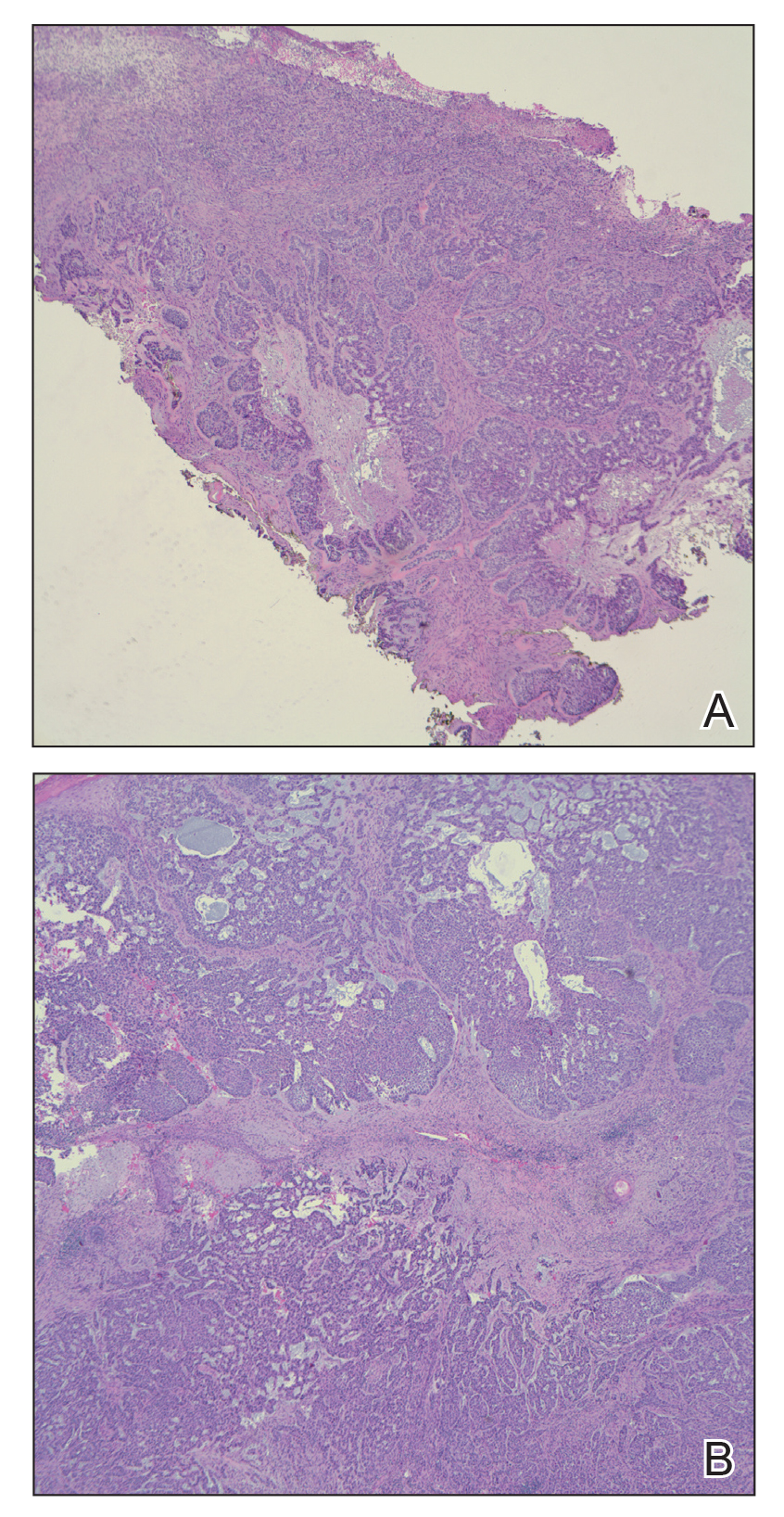

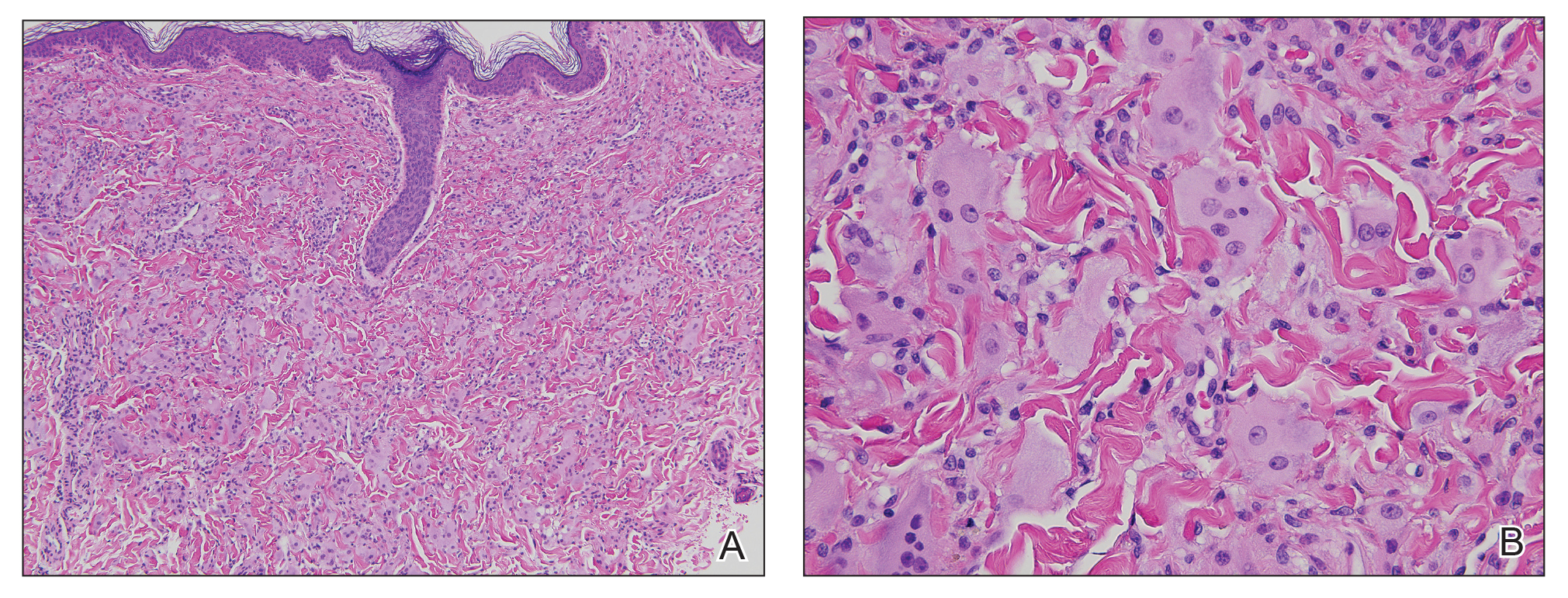

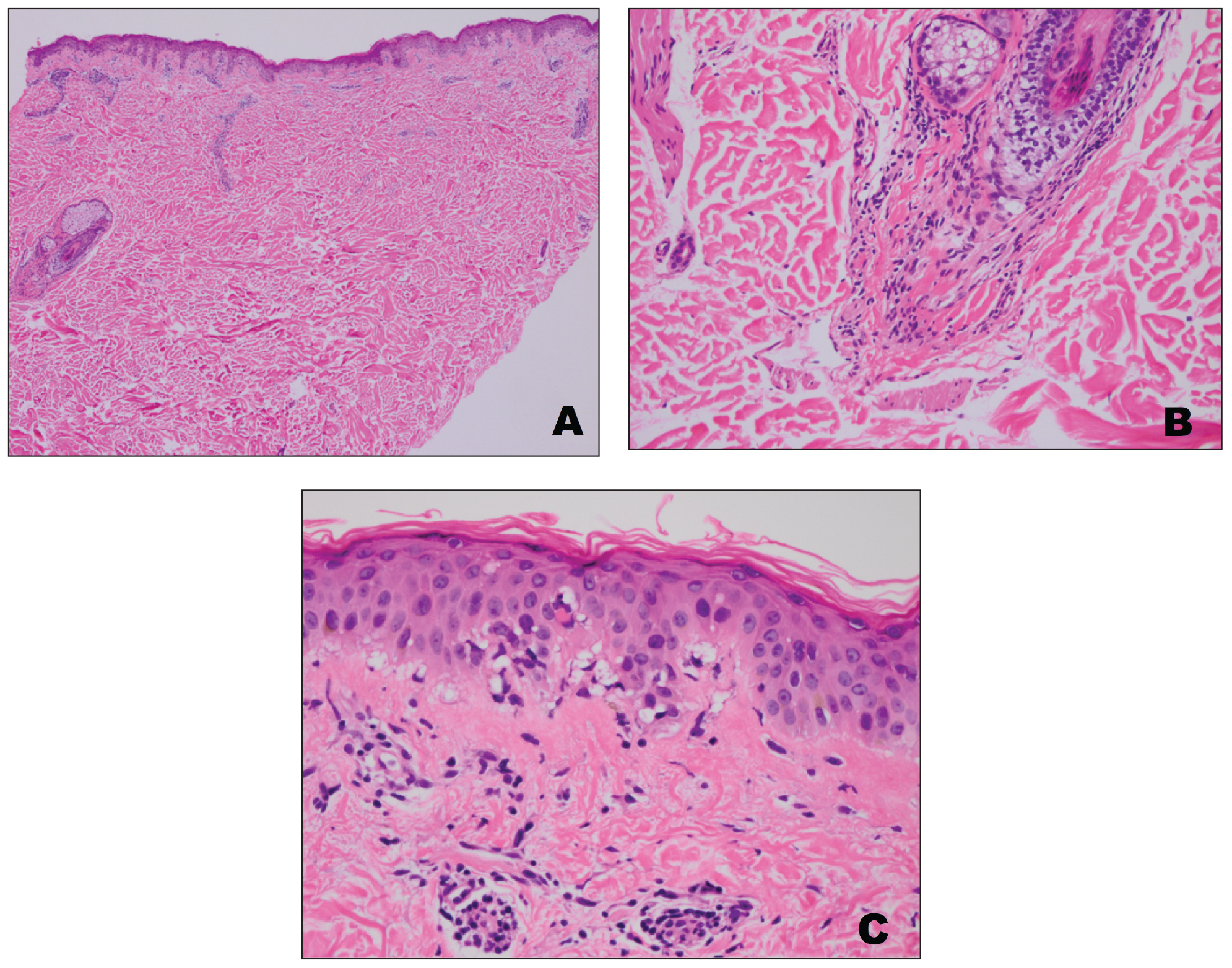

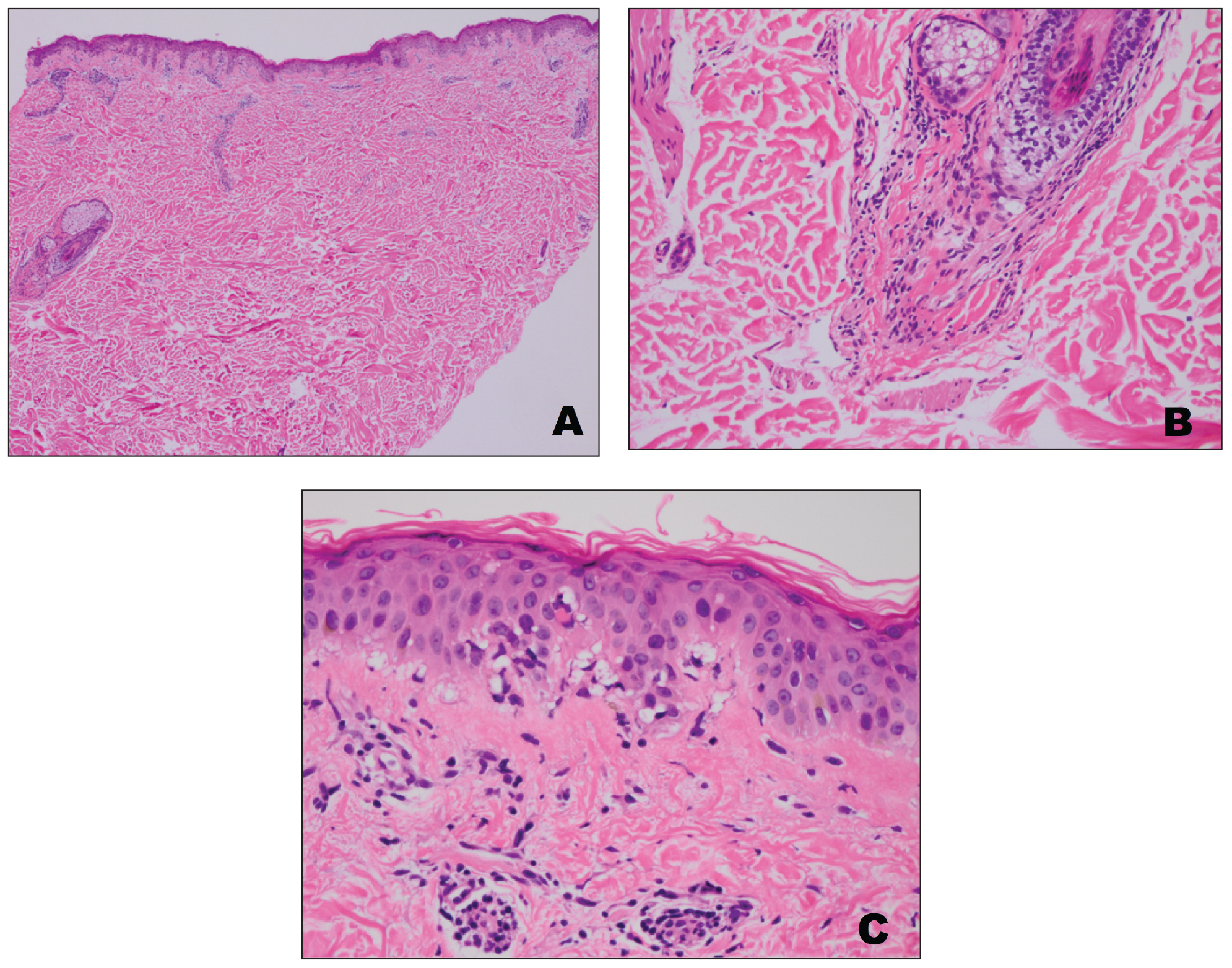

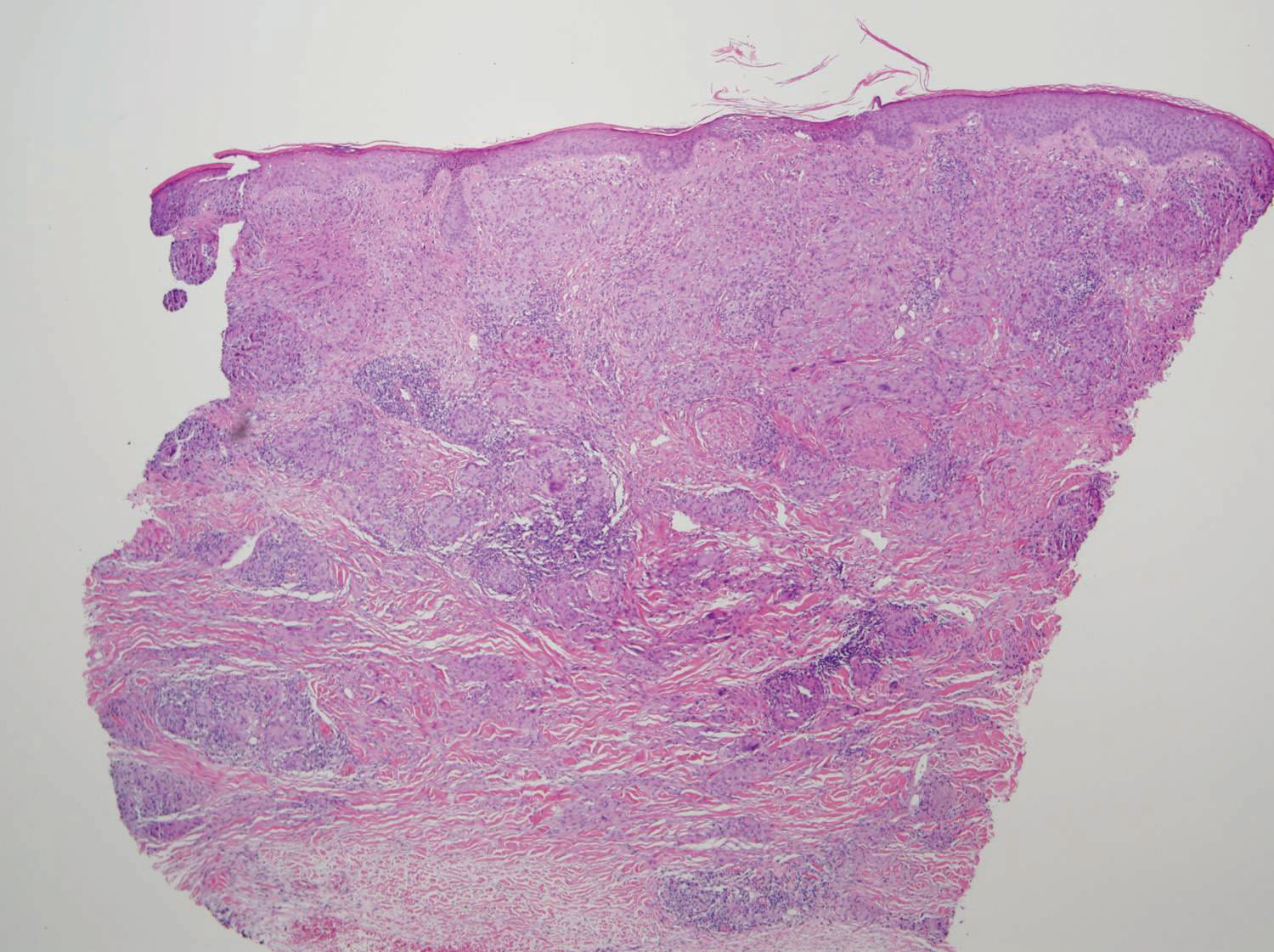

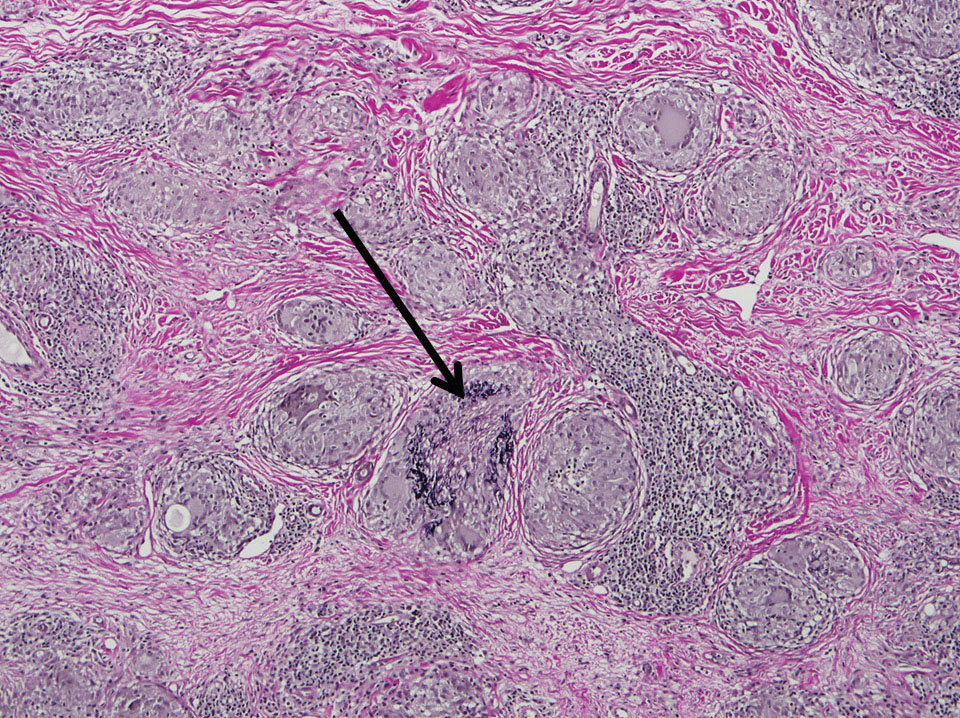

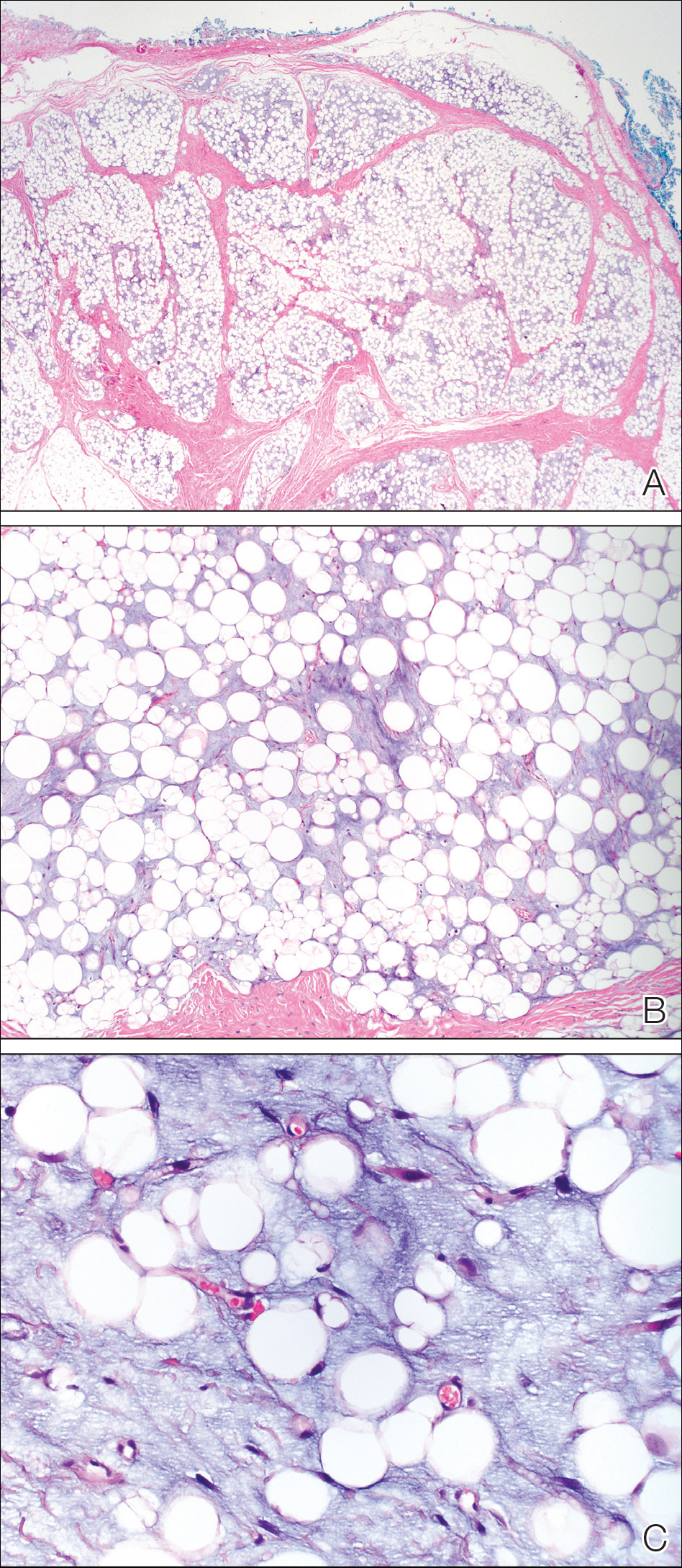

Two punch biopsies taken from the erythematous telangiectatic area on the left foot and metatarsal region demonstrated an unremarkable epidermis without interface change, thickening of the epidermal basement membrane, or single-cell dyskeratosis. There was mild dilatation of blood vessels within the superficial dermis with mild perivascular lymphocytic inflammation and rare extravasated erythrocytes. Leukocytoclastic debris, fibrinoid necrosis of vessel walls, and endothelial cell necrosis were not seen. As is classic in CCV, the vessel walls appeared thickened by eosinophilic hyaline material, which was periodic acid–Schiff positive and diastase resistant (Figure 2). Sclerotic thickening of collagen bundles or absence of periadnexal adipose tissue was not seen. CD34 immunohistochemical staining demonstrated normal retained CD34 interstitial dermal positivity, which excluded morphea. Additionally, direct immunofluorescence testing was negative for IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, fibrin, and C1q. Nodular reduplication of vessels or other changes of stasis were not seen. Fibrin thrombi or neoplastic cells were not identified. The clinical and histopathologic findings were suggestive of CCV.

Prior case reports of CCV have described a similar clinical manifestation with blanching macules that occur symmetrically on the lower extremities and spread cephalically.1-6 A distinction from hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia is the noninvolvement of mucous membranes and nails. The etiology of this rare microangiopathy has not been elucidated, though disease concurrence with local trauma, stressful events such as childbirth, and diabetes mellitus has been documented.6 As the body of literature continues to grow, more research regarding the etiology, mechanism, prognosis, and treatment options will enhance our understanding of CCV.

- Bondier L, Tardieu M, Leveque P, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of two cases presenting as disseminated telangiectasias and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:682-688.

- Salama S, Rosenthal D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:40-48.

- Lloyd BM, Pruden SJ, Lind AC, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of the first pediatric case. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:598-599.

- Salama S, Chorneyko K, Belovic B. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with intravascular occlusive fibrin thrombi. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:386-393.

- Perez A, Wain ME, Robson A, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia in two female patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:882-885.

- Burdick LM, Losher S, Somach SC, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare cutaneous microangiopathy. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:741-746.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous microangiopathy describes pathology of the small blood vessels within the dermis.

We report a case of CCV in a 41-year-old woman who presented for evaluation of a rash on the bilateral lower extremities of 7 to 8 months’ duration. The eruption had started on the left ankle and spread over several weeks to the bilateral dorsal feet followed by the ankles and shins. The patient noted associated swelling and a pressure like dysesthesia of the lower legs. She was otherwise in good health, though she had started an oral contraceptive 1 year prior for heavy menstrual bleeding. A review of systems was negative for deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolus, and other thromboembolic phenomena, and the patient had no history of hepatic or renal dysfunction, cancer, or heart disease. Her family history was negative for clotting disorders or bleeding diatheses.

On physical examination, telangiectatic matting was present on the bilateral ankles and dorsal feet with an associated blanchable erythema (Figure 1). The matting extended into a fine, mottled, pretibial telangiectasia associated with Schamberg purpura. She had no pitting edema, and both dorsalis pedis and posterior popliteal pulses were intact and symmetric bilaterally. No popliteal lymphadenopathy or palpable cords were present.

Two punch biopsies taken from the erythematous telangiectatic area on the left foot and metatarsal region demonstrated an unremarkable epidermis without interface change, thickening of the epidermal basement membrane, or single-cell dyskeratosis. There was mild dilatation of blood vessels within the superficial dermis with mild perivascular lymphocytic inflammation and rare extravasated erythrocytes. Leukocytoclastic debris, fibrinoid necrosis of vessel walls, and endothelial cell necrosis were not seen. As is classic in CCV, the vessel walls appeared thickened by eosinophilic hyaline material, which was periodic acid–Schiff positive and diastase resistant (Figure 2). Sclerotic thickening of collagen bundles or absence of periadnexal adipose tissue was not seen. CD34 immunohistochemical staining demonstrated normal retained CD34 interstitial dermal positivity, which excluded morphea. Additionally, direct immunofluorescence testing was negative for IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, fibrin, and C1q. Nodular reduplication of vessels or other changes of stasis were not seen. Fibrin thrombi or neoplastic cells were not identified. The clinical and histopathologic findings were suggestive of CCV.

Prior case reports of CCV have described a similar clinical manifestation with blanching macules that occur symmetrically on the lower extremities and spread cephalically.1-6 A distinction from hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia is the noninvolvement of mucous membranes and nails. The etiology of this rare microangiopathy has not been elucidated, though disease concurrence with local trauma, stressful events such as childbirth, and diabetes mellitus has been documented.6 As the body of literature continues to grow, more research regarding the etiology, mechanism, prognosis, and treatment options will enhance our understanding of CCV.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous microangiopathy describes pathology of the small blood vessels within the dermis.

We report a case of CCV in a 41-year-old woman who presented for evaluation of a rash on the bilateral lower extremities of 7 to 8 months’ duration. The eruption had started on the left ankle and spread over several weeks to the bilateral dorsal feet followed by the ankles and shins. The patient noted associated swelling and a pressure like dysesthesia of the lower legs. She was otherwise in good health, though she had started an oral contraceptive 1 year prior for heavy menstrual bleeding. A review of systems was negative for deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolus, and other thromboembolic phenomena, and the patient had no history of hepatic or renal dysfunction, cancer, or heart disease. Her family history was negative for clotting disorders or bleeding diatheses.

On physical examination, telangiectatic matting was present on the bilateral ankles and dorsal feet with an associated blanchable erythema (Figure 1). The matting extended into a fine, mottled, pretibial telangiectasia associated with Schamberg purpura. She had no pitting edema, and both dorsalis pedis and posterior popliteal pulses were intact and symmetric bilaterally. No popliteal lymphadenopathy or palpable cords were present.

Two punch biopsies taken from the erythematous telangiectatic area on the left foot and metatarsal region demonstrated an unremarkable epidermis without interface change, thickening of the epidermal basement membrane, or single-cell dyskeratosis. There was mild dilatation of blood vessels within the superficial dermis with mild perivascular lymphocytic inflammation and rare extravasated erythrocytes. Leukocytoclastic debris, fibrinoid necrosis of vessel walls, and endothelial cell necrosis were not seen. As is classic in CCV, the vessel walls appeared thickened by eosinophilic hyaline material, which was periodic acid–Schiff positive and diastase resistant (Figure 2). Sclerotic thickening of collagen bundles or absence of periadnexal adipose tissue was not seen. CD34 immunohistochemical staining demonstrated normal retained CD34 interstitial dermal positivity, which excluded morphea. Additionally, direct immunofluorescence testing was negative for IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, fibrin, and C1q. Nodular reduplication of vessels or other changes of stasis were not seen. Fibrin thrombi or neoplastic cells were not identified. The clinical and histopathologic findings were suggestive of CCV.

Prior case reports of CCV have described a similar clinical manifestation with blanching macules that occur symmetrically on the lower extremities and spread cephalically.1-6 A distinction from hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia is the noninvolvement of mucous membranes and nails. The etiology of this rare microangiopathy has not been elucidated, though disease concurrence with local trauma, stressful events such as childbirth, and diabetes mellitus has been documented.6 As the body of literature continues to grow, more research regarding the etiology, mechanism, prognosis, and treatment options will enhance our understanding of CCV.

- Bondier L, Tardieu M, Leveque P, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of two cases presenting as disseminated telangiectasias and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:682-688.

- Salama S, Rosenthal D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:40-48.

- Lloyd BM, Pruden SJ, Lind AC, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of the first pediatric case. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:598-599.

- Salama S, Chorneyko K, Belovic B. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with intravascular occlusive fibrin thrombi. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:386-393.

- Perez A, Wain ME, Robson A, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia in two female patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:882-885.

- Burdick LM, Losher S, Somach SC, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare cutaneous microangiopathy. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:741-746.

- Bondier L, Tardieu M, Leveque P, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of two cases presenting as disseminated telangiectasias and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:682-688.

- Salama S, Rosenthal D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:40-48.

- Lloyd BM, Pruden SJ, Lind AC, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of the first pediatric case. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:598-599.

- Salama S, Chorneyko K, Belovic B. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with intravascular occlusive fibrin thrombi. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:386-393.

- Perez A, Wain ME, Robson A, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia in two female patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:882-885.

- Burdick LM, Losher S, Somach SC, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare cutaneous microangiopathy. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:741-746.

Practice Points

- In cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV), skin biopsy may demonstrate eosinophilic hyaline thickening of superficial dermal blood vessels with mild perivascular lymphocytic inflammation and rare extravasated erythrocytes.

- Lack of mucous membrane and nail involvement differentiates CCV from hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia.

Elephantiasis Nostras Verrucosa Secondary to Scleroderma

To the Editor:

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV) is a skin disorder caused by marked underlying lymphedema that leads to hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and verrucous growths on the epidermis.1 The pathophysiology of ENV relates to noninfectious lymphatic obstruction and lymphatic fibrosis secondary to venous stasis, malignancy, radiation therapy, or trauma.2 We present an unusual case of lymphedema and subsequent ENV limited to the arms and hands in a patient with scleroderma, an autoimmune fibrosing disorder.

A 54-year-old woman with a 5-year history of scleroderma presented to our dermatology clinic for treatment of progressive skin changes including pruritus, tightness, finger ulcerations, and pus exuding from papules on the dorsal arms and hands. She had been experiencing several systemic symptoms including dysphagia and lung involvement, necessitating oxygen therapy and a continuous positive airway pressure device for pulmonary arterial hypertension. A computed tomography scan of the lungs demonstrated an increase in ground-glass infiltrates in the right lower lobe and an air-fluid level in the esophagus. At the time of presentation, she was being treated with bosentan and sildenafil for pulmonary arterial hypertension, in addition to prednisone, venlafaxine, lansoprazole, metoclopramide, levothyroxine, temazepam, aspirin, and oxycodone. In the 2 years prior to presentation, she had been treated with intravenous cyclophosphamide once monthly for 6 months, adalimumab for 1 year, and 1 session of photodynamic therapy to the arms, all without benefit.

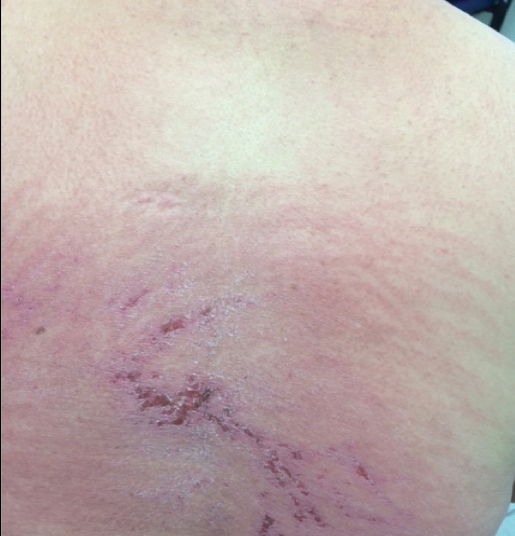

Physical examination showed cutaneous signs of scleroderma including marked sclerosis of the skin on the face, hands, V of the neck, proximal arms, and mid and proximal thighs. Excoriated papules with overlying crusting and pustulation were superimposed on the sclerotic skin of the arms (Figure 1).

A superinfection was diagnosed and treated with cephalexin 500 mg 4 times daily for 2 weeks; thereafter, mupirocin cream twice daily was used as needed. She was prescribed fexofenadine 180 mg twice daily and doxepin 20 mg at bedtime for pruritus.

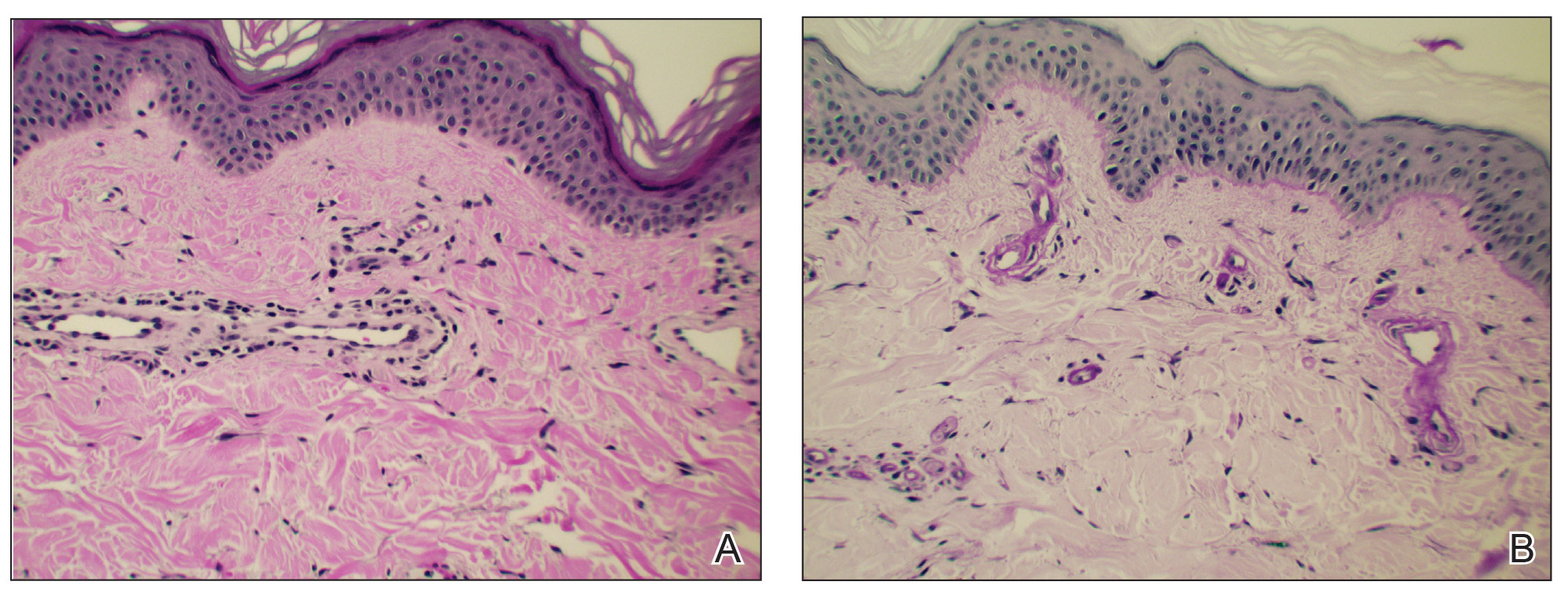

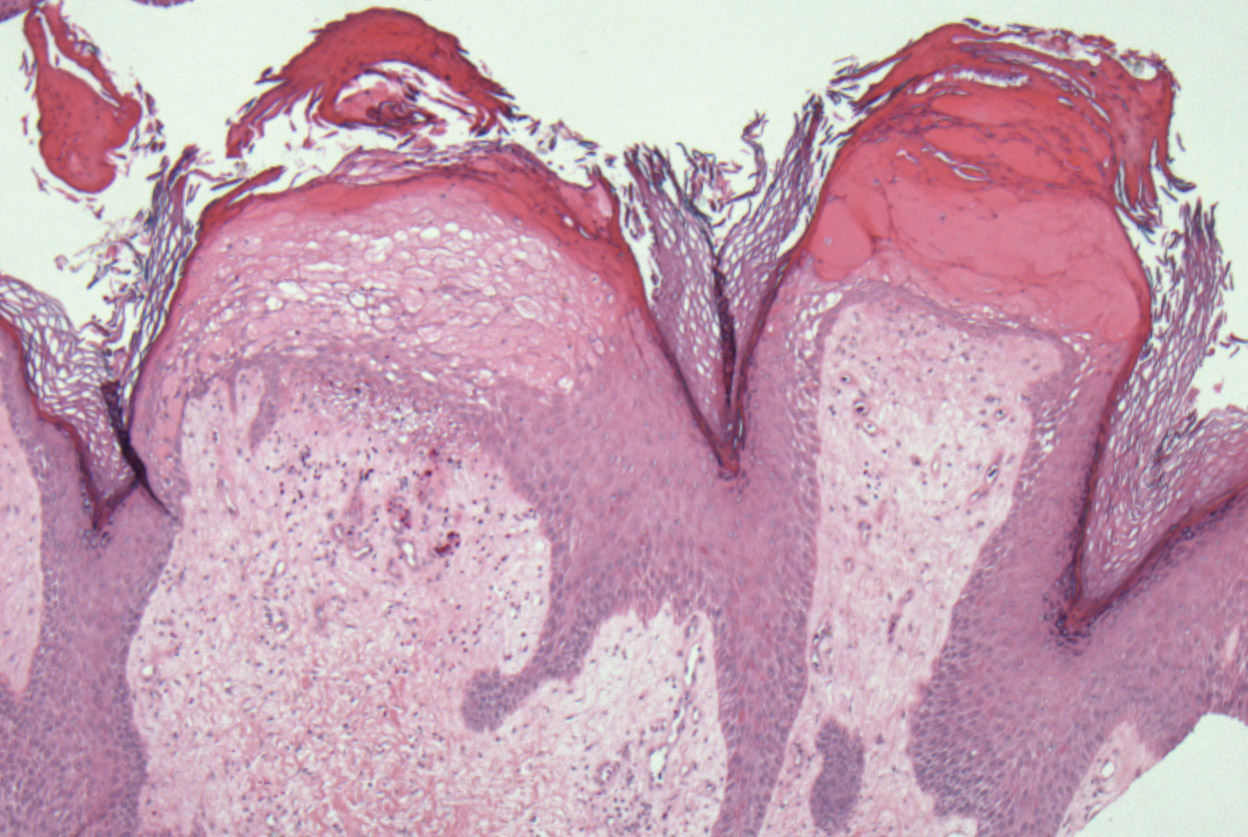

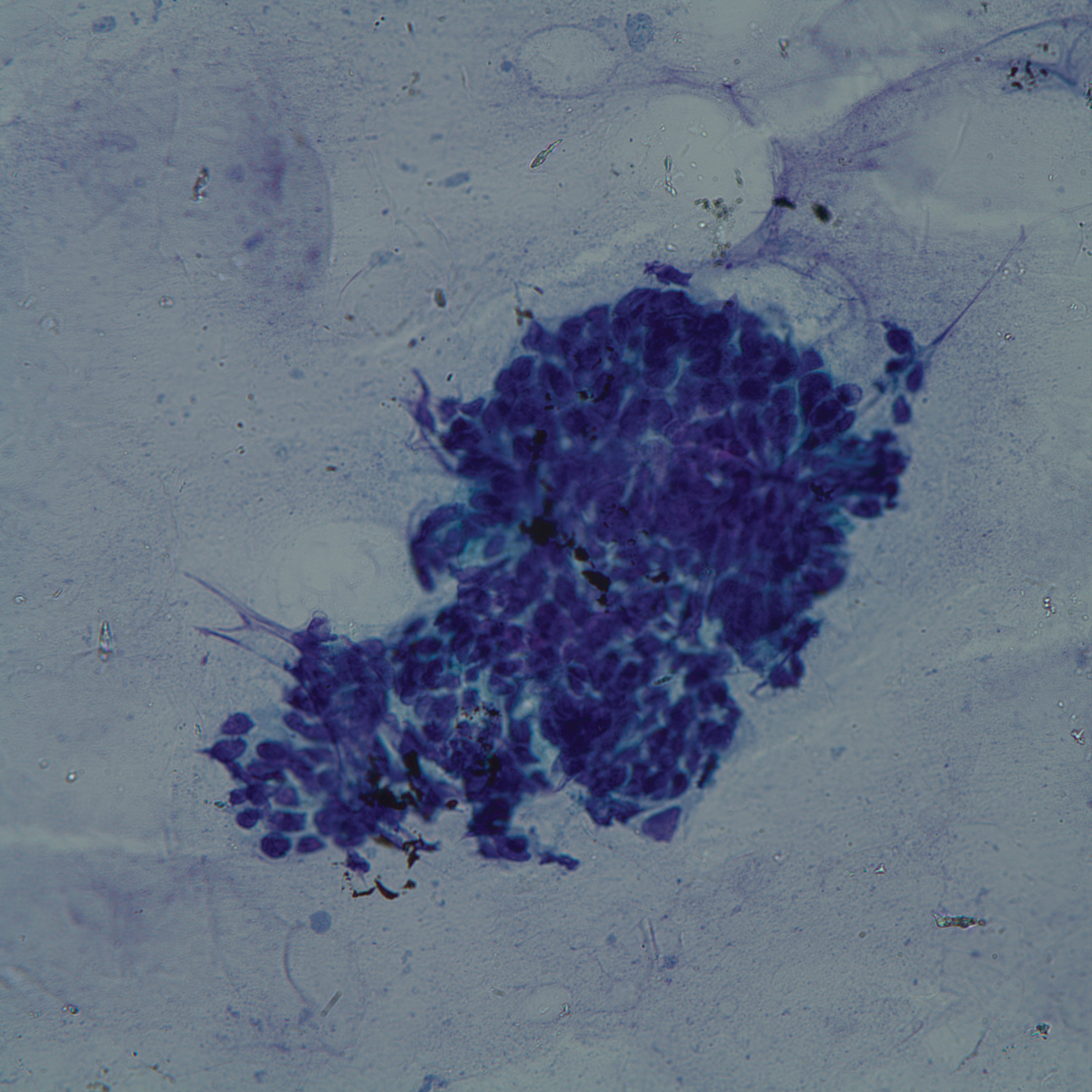

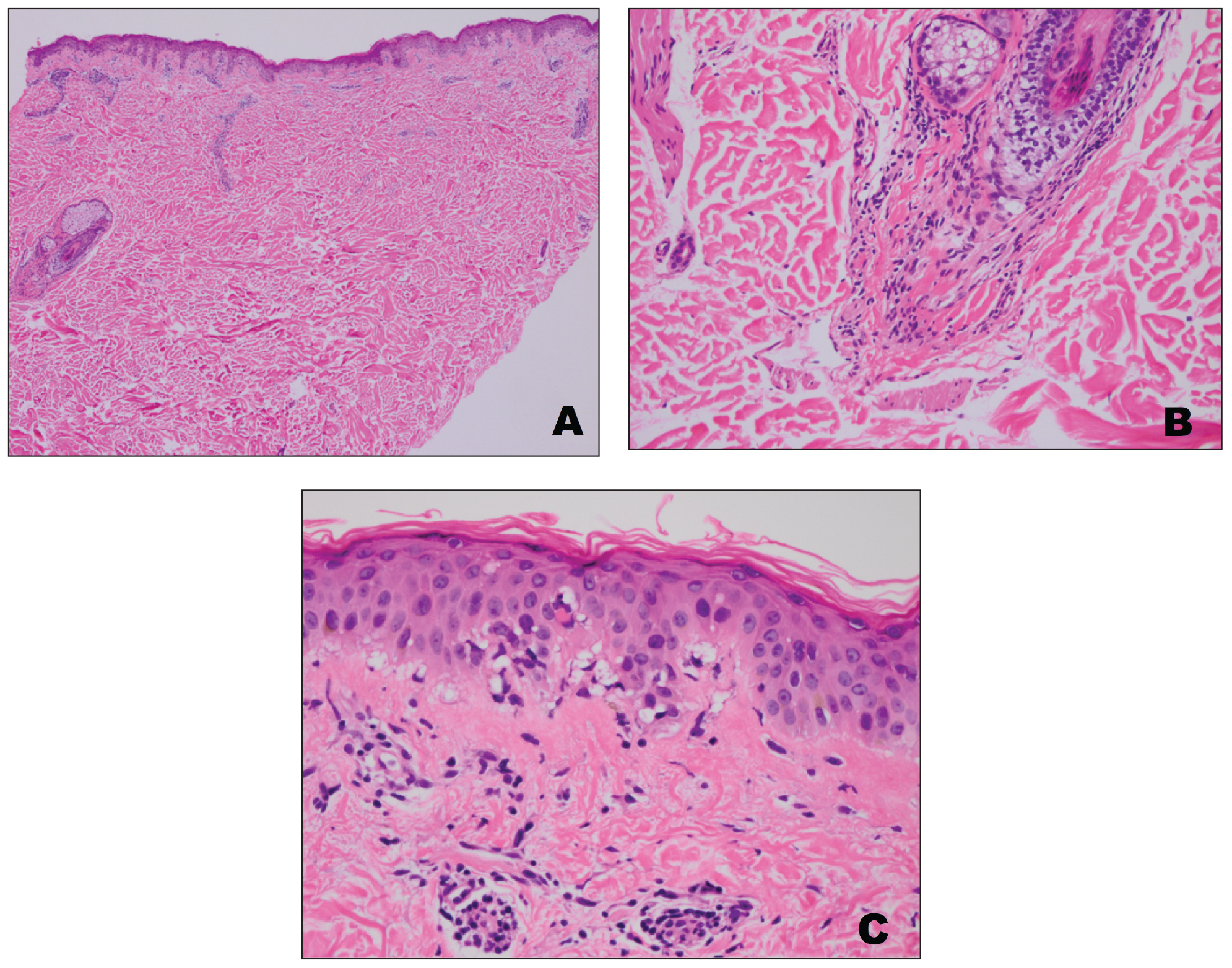

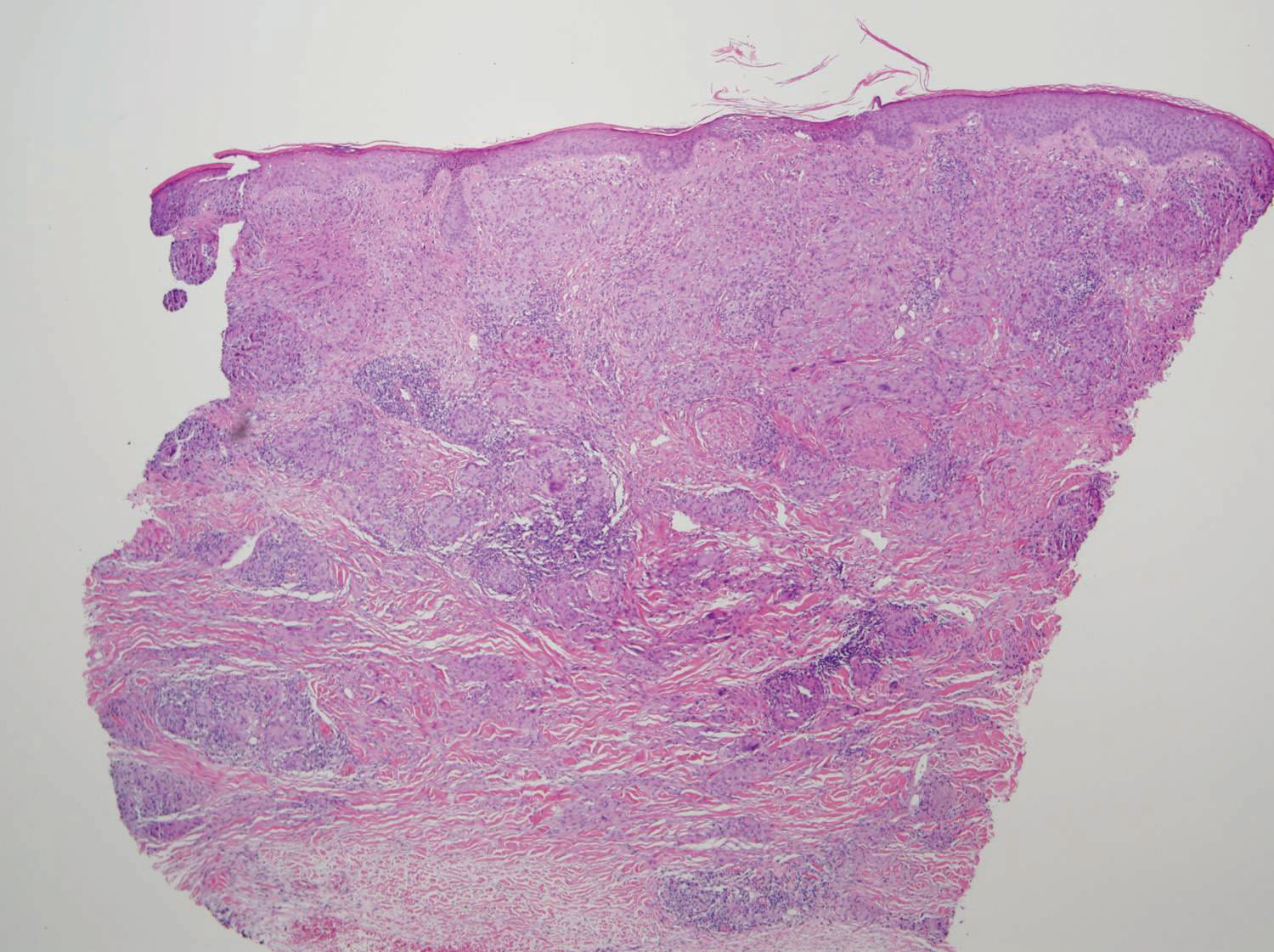

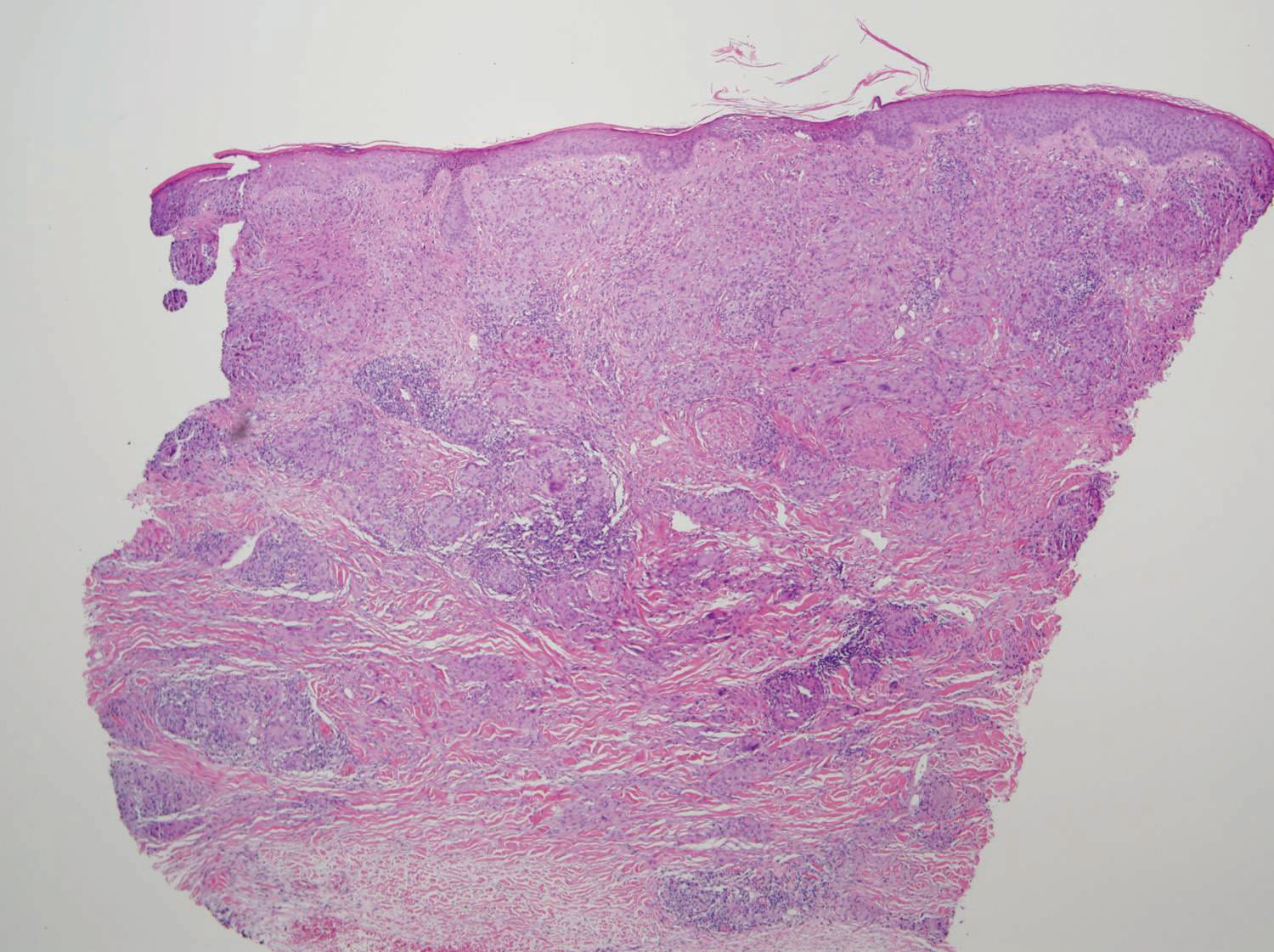

At 3-week follow-up, a trial of narrowband UVB therapy was recommended for control of pruritus. Two weeks later, a modified wet-wrap regimen using clobetasol ointment 0.5% twice daily covered with wet gauze followed by a self-adherent dressing was initiated only on the right arm for comparison purposes. This treatment was not successful. A biopsy taken from the left arm showed lymphedema with perivascular fibroplasia and epidermal hyperplasia consistent with ENV (Figure 2).

Two months after her initial presentation, we instituted treatment with tazarotene gel 0.1% twice daily to the arms as well as a water-based topical emulsion to the finger ulcerations and a healing ointment to the hands. A month later, the patient reported no benefit with tazarotene. She desired more flexibility in her arms and hands; therefore, after a discussion with her rheumatologist, biweekly psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) therapy was initiated. Five months after presentation, methotrexate (MTX) 15 mg once weekly with folic acid 1 mg once daily was added. The PUVA therapy and MTX were stopped 3 months later due to lack of treatment benefit.

The patient was referred to vascular medicine for possible compression therapy. It was determined that her vasculature was intact, but compression therapy was contraindicated due to underlying systemic sclerosis. She was subsequently prescribed mycophenolate mofetil 1000 mg twice daily by her rheumatologist. The options of serial excisions or laser resurfacing were presented, but she declined.

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa is differentiated from elephantiasis tropica, which is caused by a filarial infection of the lymphatic system. The chronic obstructive lymphedema characteristic of ENV can present as a result of various primary or secondary etiologies including trauma, malignancy, venous stasis, inflammation, or infection.3 In systemic sclerosis, extravascular fibrosis theoretically can lead to lymphatic obstruction and subsequent lymphatic stasis. In turn, the pathophysiology of dermal and subcutaneous fibrosis likely reflects autoantibodies (eg, anticardiolipin antibodies) that can damage lymphatic and nonlymphatic vessels.4,5

As the underlying mechanism of ENV, fibrosis of lymphatic vessels in systemic sclerosis is not well documented. Characteristic features of systemic sclerosis include extensive fibrosis, fibroproliferative vasculopathy, and inflammation, which are all possible mechanisms for the internal lymphatic obstruction resulting in the skin changes observed in ENV.6 It seemed unusual that the fibrotic changes of lymphatic vessels in our patient were extensive enough to cause ENV of the upper extremities; lower extremity involvement is the more common presentation because of the greater likelihood of lymphedema manifesting in the legs and feet. Lower extremity ENV has been reported in association with scleroderma.7,8

Regarding therapeutic options, Boyd et al9 reported a good response in a patient with ENV of the abdomen who was treated with topical tazarotene. Additionally, PUVA and MTX have been reported to be beneficial for the progressive skin changes of systemic sclerosis.10 Mycophenolate mofetil has been used in patients who fail MTX therapy because of its antifibrotic properties without the side-effect profiles of other immunosuppressives, such as imatinib.10,11 In our patient, skin lesions persisted following these varied approaches, and compression therapy was not advised due to the underlying sclerosis.

Because options for medical treatment of severe ENV are limited, surgical debridement of the affected limb often remains the only viable option in advanced cases.12 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms elephantiasis (MeSH terms) or elephantiasis (all fields) and scleroderma, systemic (MeSH terms) or scleroderma (all fields) and systemic (all fields) or systemic scleroderma (all fields) or scleroderma (all fields) or scleroderma, localized (MeSH terms) or scleroderma (all fields) and localized (all fields) or localized scleroderma (all fields) yielded only 1 other case report of lower extremity ENV in a patient with systemic sclerosis who ultimately required bilateral leg amputation.8 When possible, avoiding lymphostasis through compression and control of any underlying infections is important in the treatment and prevention of ENV.3

- Sisto K, Khachemoune A. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:141-146.

- Schissel DJ, Hivnor C, Elston DM. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa. Cutis. 1998;62:77-80.

- Duckworth A, Husain J, DeHeer P. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa or ‘mossy foot lesions’ in lymphedema praecox. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2008;98:66-69.

- Assous N, Allanore Y, Batteaux F, et al. Prevalence of antiphospholipid antibodies in systemic sclerosis and association with primitive pulmonary arterial hypertension and endothelial injury. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23:199-204.

- Derrett-Smith EC, Dooley A, Gilbane AJ, et al. Endothelial injury in a transforming growth-factor-dependent mouse model of scleroderma induces pulmonary arterial hypertension. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:2928-2939.

- Pattanaik M, Brown M, Postlethwaite A. Vascular involvement in systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). J Inflamm Res. 2011;4:105-125.

- Kerchner K, Fleischer A, Yosipovitch G. Lower extremity lymphedema update: pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment guidelines. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:324-331.

- Chatterjee S, Karai L. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa in a patient with systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e696-e698.

- Boyd J, Sloan S, Meffert J. Elephantiasis nostrum verrucosa of the abdomen: clinical results with tazarotene. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:446-448.

- Fett, N. Scleroderma: nomenclature, etiology, pathogenesis, prognosis, and treatments: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:432-437.

- Moinzadeh P, Krieg T, Hunzelmann N. Imatinib treatment of generalized localized scleroderma (morphea). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:e102-e104.

- Iwao F, Sato-Matsumura KC, Sawamura D, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa successfully treated by surgical debridement. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:939-941.

To the Editor:

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV) is a skin disorder caused by marked underlying lymphedema that leads to hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and verrucous growths on the epidermis.1 The pathophysiology of ENV relates to noninfectious lymphatic obstruction and lymphatic fibrosis secondary to venous stasis, malignancy, radiation therapy, or trauma.2 We present an unusual case of lymphedema and subsequent ENV limited to the arms and hands in a patient with scleroderma, an autoimmune fibrosing disorder.

A 54-year-old woman with a 5-year history of scleroderma presented to our dermatology clinic for treatment of progressive skin changes including pruritus, tightness, finger ulcerations, and pus exuding from papules on the dorsal arms and hands. She had been experiencing several systemic symptoms including dysphagia and lung involvement, necessitating oxygen therapy and a continuous positive airway pressure device for pulmonary arterial hypertension. A computed tomography scan of the lungs demonstrated an increase in ground-glass infiltrates in the right lower lobe and an air-fluid level in the esophagus. At the time of presentation, she was being treated with bosentan and sildenafil for pulmonary arterial hypertension, in addition to prednisone, venlafaxine, lansoprazole, metoclopramide, levothyroxine, temazepam, aspirin, and oxycodone. In the 2 years prior to presentation, she had been treated with intravenous cyclophosphamide once monthly for 6 months, adalimumab for 1 year, and 1 session of photodynamic therapy to the arms, all without benefit.

Physical examination showed cutaneous signs of scleroderma including marked sclerosis of the skin on the face, hands, V of the neck, proximal arms, and mid and proximal thighs. Excoriated papules with overlying crusting and pustulation were superimposed on the sclerotic skin of the arms (Figure 1).

A superinfection was diagnosed and treated with cephalexin 500 mg 4 times daily for 2 weeks; thereafter, mupirocin cream twice daily was used as needed. She was prescribed fexofenadine 180 mg twice daily and doxepin 20 mg at bedtime for pruritus.

At 3-week follow-up, a trial of narrowband UVB therapy was recommended for control of pruritus. Two weeks later, a modified wet-wrap regimen using clobetasol ointment 0.5% twice daily covered with wet gauze followed by a self-adherent dressing was initiated only on the right arm for comparison purposes. This treatment was not successful. A biopsy taken from the left arm showed lymphedema with perivascular fibroplasia and epidermal hyperplasia consistent with ENV (Figure 2).

Two months after her initial presentation, we instituted treatment with tazarotene gel 0.1% twice daily to the arms as well as a water-based topical emulsion to the finger ulcerations and a healing ointment to the hands. A month later, the patient reported no benefit with tazarotene. She desired more flexibility in her arms and hands; therefore, after a discussion with her rheumatologist, biweekly psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) therapy was initiated. Five months after presentation, methotrexate (MTX) 15 mg once weekly with folic acid 1 mg once daily was added. The PUVA therapy and MTX were stopped 3 months later due to lack of treatment benefit.

The patient was referred to vascular medicine for possible compression therapy. It was determined that her vasculature was intact, but compression therapy was contraindicated due to underlying systemic sclerosis. She was subsequently prescribed mycophenolate mofetil 1000 mg twice daily by her rheumatologist. The options of serial excisions or laser resurfacing were presented, but she declined.

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa is differentiated from elephantiasis tropica, which is caused by a filarial infection of the lymphatic system. The chronic obstructive lymphedema characteristic of ENV can present as a result of various primary or secondary etiologies including trauma, malignancy, venous stasis, inflammation, or infection.3 In systemic sclerosis, extravascular fibrosis theoretically can lead to lymphatic obstruction and subsequent lymphatic stasis. In turn, the pathophysiology of dermal and subcutaneous fibrosis likely reflects autoantibodies (eg, anticardiolipin antibodies) that can damage lymphatic and nonlymphatic vessels.4,5

As the underlying mechanism of ENV, fibrosis of lymphatic vessels in systemic sclerosis is not well documented. Characteristic features of systemic sclerosis include extensive fibrosis, fibroproliferative vasculopathy, and inflammation, which are all possible mechanisms for the internal lymphatic obstruction resulting in the skin changes observed in ENV.6 It seemed unusual that the fibrotic changes of lymphatic vessels in our patient were extensive enough to cause ENV of the upper extremities; lower extremity involvement is the more common presentation because of the greater likelihood of lymphedema manifesting in the legs and feet. Lower extremity ENV has been reported in association with scleroderma.7,8

Regarding therapeutic options, Boyd et al9 reported a good response in a patient with ENV of the abdomen who was treated with topical tazarotene. Additionally, PUVA and MTX have been reported to be beneficial for the progressive skin changes of systemic sclerosis.10 Mycophenolate mofetil has been used in patients who fail MTX therapy because of its antifibrotic properties without the side-effect profiles of other immunosuppressives, such as imatinib.10,11 In our patient, skin lesions persisted following these varied approaches, and compression therapy was not advised due to the underlying sclerosis.

Because options for medical treatment of severe ENV are limited, surgical debridement of the affected limb often remains the only viable option in advanced cases.12 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms elephantiasis (MeSH terms) or elephantiasis (all fields) and scleroderma, systemic (MeSH terms) or scleroderma (all fields) and systemic (all fields) or systemic scleroderma (all fields) or scleroderma (all fields) or scleroderma, localized (MeSH terms) or scleroderma (all fields) and localized (all fields) or localized scleroderma (all fields) yielded only 1 other case report of lower extremity ENV in a patient with systemic sclerosis who ultimately required bilateral leg amputation.8 When possible, avoiding lymphostasis through compression and control of any underlying infections is important in the treatment and prevention of ENV.3

To the Editor:

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV) is a skin disorder caused by marked underlying lymphedema that leads to hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and verrucous growths on the epidermis.1 The pathophysiology of ENV relates to noninfectious lymphatic obstruction and lymphatic fibrosis secondary to venous stasis, malignancy, radiation therapy, or trauma.2 We present an unusual case of lymphedema and subsequent ENV limited to the arms and hands in a patient with scleroderma, an autoimmune fibrosing disorder.

A 54-year-old woman with a 5-year history of scleroderma presented to our dermatology clinic for treatment of progressive skin changes including pruritus, tightness, finger ulcerations, and pus exuding from papules on the dorsal arms and hands. She had been experiencing several systemic symptoms including dysphagia and lung involvement, necessitating oxygen therapy and a continuous positive airway pressure device for pulmonary arterial hypertension. A computed tomography scan of the lungs demonstrated an increase in ground-glass infiltrates in the right lower lobe and an air-fluid level in the esophagus. At the time of presentation, she was being treated with bosentan and sildenafil for pulmonary arterial hypertension, in addition to prednisone, venlafaxine, lansoprazole, metoclopramide, levothyroxine, temazepam, aspirin, and oxycodone. In the 2 years prior to presentation, she had been treated with intravenous cyclophosphamide once monthly for 6 months, adalimumab for 1 year, and 1 session of photodynamic therapy to the arms, all without benefit.

Physical examination showed cutaneous signs of scleroderma including marked sclerosis of the skin on the face, hands, V of the neck, proximal arms, and mid and proximal thighs. Excoriated papules with overlying crusting and pustulation were superimposed on the sclerotic skin of the arms (Figure 1).

A superinfection was diagnosed and treated with cephalexin 500 mg 4 times daily for 2 weeks; thereafter, mupirocin cream twice daily was used as needed. She was prescribed fexofenadine 180 mg twice daily and doxepin 20 mg at bedtime for pruritus.

At 3-week follow-up, a trial of narrowband UVB therapy was recommended for control of pruritus. Two weeks later, a modified wet-wrap regimen using clobetasol ointment 0.5% twice daily covered with wet gauze followed by a self-adherent dressing was initiated only on the right arm for comparison purposes. This treatment was not successful. A biopsy taken from the left arm showed lymphedema with perivascular fibroplasia and epidermal hyperplasia consistent with ENV (Figure 2).

Two months after her initial presentation, we instituted treatment with tazarotene gel 0.1% twice daily to the arms as well as a water-based topical emulsion to the finger ulcerations and a healing ointment to the hands. A month later, the patient reported no benefit with tazarotene. She desired more flexibility in her arms and hands; therefore, after a discussion with her rheumatologist, biweekly psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) therapy was initiated. Five months after presentation, methotrexate (MTX) 15 mg once weekly with folic acid 1 mg once daily was added. The PUVA therapy and MTX were stopped 3 months later due to lack of treatment benefit.

The patient was referred to vascular medicine for possible compression therapy. It was determined that her vasculature was intact, but compression therapy was contraindicated due to underlying systemic sclerosis. She was subsequently prescribed mycophenolate mofetil 1000 mg twice daily by her rheumatologist. The options of serial excisions or laser resurfacing were presented, but she declined.

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa is differentiated from elephantiasis tropica, which is caused by a filarial infection of the lymphatic system. The chronic obstructive lymphedema characteristic of ENV can present as a result of various primary or secondary etiologies including trauma, malignancy, venous stasis, inflammation, or infection.3 In systemic sclerosis, extravascular fibrosis theoretically can lead to lymphatic obstruction and subsequent lymphatic stasis. In turn, the pathophysiology of dermal and subcutaneous fibrosis likely reflects autoantibodies (eg, anticardiolipin antibodies) that can damage lymphatic and nonlymphatic vessels.4,5

As the underlying mechanism of ENV, fibrosis of lymphatic vessels in systemic sclerosis is not well documented. Characteristic features of systemic sclerosis include extensive fibrosis, fibroproliferative vasculopathy, and inflammation, which are all possible mechanisms for the internal lymphatic obstruction resulting in the skin changes observed in ENV.6 It seemed unusual that the fibrotic changes of lymphatic vessels in our patient were extensive enough to cause ENV of the upper extremities; lower extremity involvement is the more common presentation because of the greater likelihood of lymphedema manifesting in the legs and feet. Lower extremity ENV has been reported in association with scleroderma.7,8

Regarding therapeutic options, Boyd et al9 reported a good response in a patient with ENV of the abdomen who was treated with topical tazarotene. Additionally, PUVA and MTX have been reported to be beneficial for the progressive skin changes of systemic sclerosis.10 Mycophenolate mofetil has been used in patients who fail MTX therapy because of its antifibrotic properties without the side-effect profiles of other immunosuppressives, such as imatinib.10,11 In our patient, skin lesions persisted following these varied approaches, and compression therapy was not advised due to the underlying sclerosis.

Because options for medical treatment of severe ENV are limited, surgical debridement of the affected limb often remains the only viable option in advanced cases.12 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms elephantiasis (MeSH terms) or elephantiasis (all fields) and scleroderma, systemic (MeSH terms) or scleroderma (all fields) and systemic (all fields) or systemic scleroderma (all fields) or scleroderma (all fields) or scleroderma, localized (MeSH terms) or scleroderma (all fields) and localized (all fields) or localized scleroderma (all fields) yielded only 1 other case report of lower extremity ENV in a patient with systemic sclerosis who ultimately required bilateral leg amputation.8 When possible, avoiding lymphostasis through compression and control of any underlying infections is important in the treatment and prevention of ENV.3

- Sisto K, Khachemoune A. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:141-146.

- Schissel DJ, Hivnor C, Elston DM. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa. Cutis. 1998;62:77-80.

- Duckworth A, Husain J, DeHeer P. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa or ‘mossy foot lesions’ in lymphedema praecox. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2008;98:66-69.

- Assous N, Allanore Y, Batteaux F, et al. Prevalence of antiphospholipid antibodies in systemic sclerosis and association with primitive pulmonary arterial hypertension and endothelial injury. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23:199-204.

- Derrett-Smith EC, Dooley A, Gilbane AJ, et al. Endothelial injury in a transforming growth-factor-dependent mouse model of scleroderma induces pulmonary arterial hypertension. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:2928-2939.

- Pattanaik M, Brown M, Postlethwaite A. Vascular involvement in systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). J Inflamm Res. 2011;4:105-125.

- Kerchner K, Fleischer A, Yosipovitch G. Lower extremity lymphedema update: pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment guidelines. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:324-331.

- Chatterjee S, Karai L. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa in a patient with systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e696-e698.

- Boyd J, Sloan S, Meffert J. Elephantiasis nostrum verrucosa of the abdomen: clinical results with tazarotene. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:446-448.

- Fett, N. Scleroderma: nomenclature, etiology, pathogenesis, prognosis, and treatments: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:432-437.

- Moinzadeh P, Krieg T, Hunzelmann N. Imatinib treatment of generalized localized scleroderma (morphea). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:e102-e104.

- Iwao F, Sato-Matsumura KC, Sawamura D, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa successfully treated by surgical debridement. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:939-941.

- Sisto K, Khachemoune A. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:141-146.

- Schissel DJ, Hivnor C, Elston DM. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa. Cutis. 1998;62:77-80.

- Duckworth A, Husain J, DeHeer P. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa or ‘mossy foot lesions’ in lymphedema praecox. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2008;98:66-69.

- Assous N, Allanore Y, Batteaux F, et al. Prevalence of antiphospholipid antibodies in systemic sclerosis and association with primitive pulmonary arterial hypertension and endothelial injury. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23:199-204.

- Derrett-Smith EC, Dooley A, Gilbane AJ, et al. Endothelial injury in a transforming growth-factor-dependent mouse model of scleroderma induces pulmonary arterial hypertension. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:2928-2939.

- Pattanaik M, Brown M, Postlethwaite A. Vascular involvement in systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). J Inflamm Res. 2011;4:105-125.

- Kerchner K, Fleischer A, Yosipovitch G. Lower extremity lymphedema update: pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment guidelines. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:324-331.

- Chatterjee S, Karai L. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa in a patient with systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e696-e698.

- Boyd J, Sloan S, Meffert J. Elephantiasis nostrum verrucosa of the abdomen: clinical results with tazarotene. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:446-448.

- Fett, N. Scleroderma: nomenclature, etiology, pathogenesis, prognosis, and treatments: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:432-437.

- Moinzadeh P, Krieg T, Hunzelmann N. Imatinib treatment of generalized localized scleroderma (morphea). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:e102-e104.

- Iwao F, Sato-Matsumura KC, Sawamura D, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa successfully treated by surgical debridement. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:939-941.

Practice Points

- Scleroderma rarely may lead to elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV) of the upper extremities.

- Avoiding lymphostasis through compression and control of concomitant skin and soft tissue infections is important in the treatment and prevention of ENV.

Neurofibromatosis Type 1 in the Setting of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

To the Editor:

Patients with concurrent neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) rarely have been reported in the literature. Neurofibromatosis type 1 is one of the most common genetic disorders, with a worldwide birth incidence of 1 in 2500 individuals and prevalence of 1 in 4000 individuals.1 The incidence and prevalence of SLE varies widely depending on race and geographic location. Estimated incidence rates for SLE range from 1 to 25 per 100,000 individuals annually in North America, South America, Europe, and Asia.2,3 The reported worldwide prevalence is 20 to 150 cases per 100,000 individuals annually.2,4,5

Given the high prevalence of both conditions, the association between SLE and NF-1 likely is underrecognized; therefore, identifying more patients with concurrent SLE and NF-1 and describing the interplay between the 2 conditions may have important therapeutic implications. We present the case of a middle-aged woman with a history of SLE who had cutaneous lesions characteristic of NF-1 to further the understanding of these concurrent conditions.

A middle-aged woman presented to our academic dermatology clinic for evaluation and removal of dark spots that had been present diffusely on the trunk and extremities since birth. She reported a history of SLE with lupus nephritis, hypertension, and a nodular goiter following a partial thyroidectomy. She noted that she did not seek treatment for the skin findings sooner because she was more concerned about her other medical conditions; however, because she felt these conditions were now stable, she decided to seek treatment for the “rash.” Physical examination revealed hundreds of café au lait macules and numerous neurofibromas diffusely distributed on the trunk and extremities (Figure 1) as well as bilateral axillary freckling. A clinical diagnosis of NF-1 was made.

When questioned, the patient reported that she may have been diagnosed with NF-1 in the past by another physician, but she did not recall it specifically. The patient was advised that there were no treatments for the café au lait macules. We notified her other physicians of the NF-1 diagnosis so she could be monitored for systemic conditions related to NF-1, including optic gliomas, pheochromocytoma, renal artery stenosis, and internal neurofibromas. We also referred the patient for genetic counseling; of note, the patient reported she had 4 children without any evidence of similar skin lesions or chronic health problems.

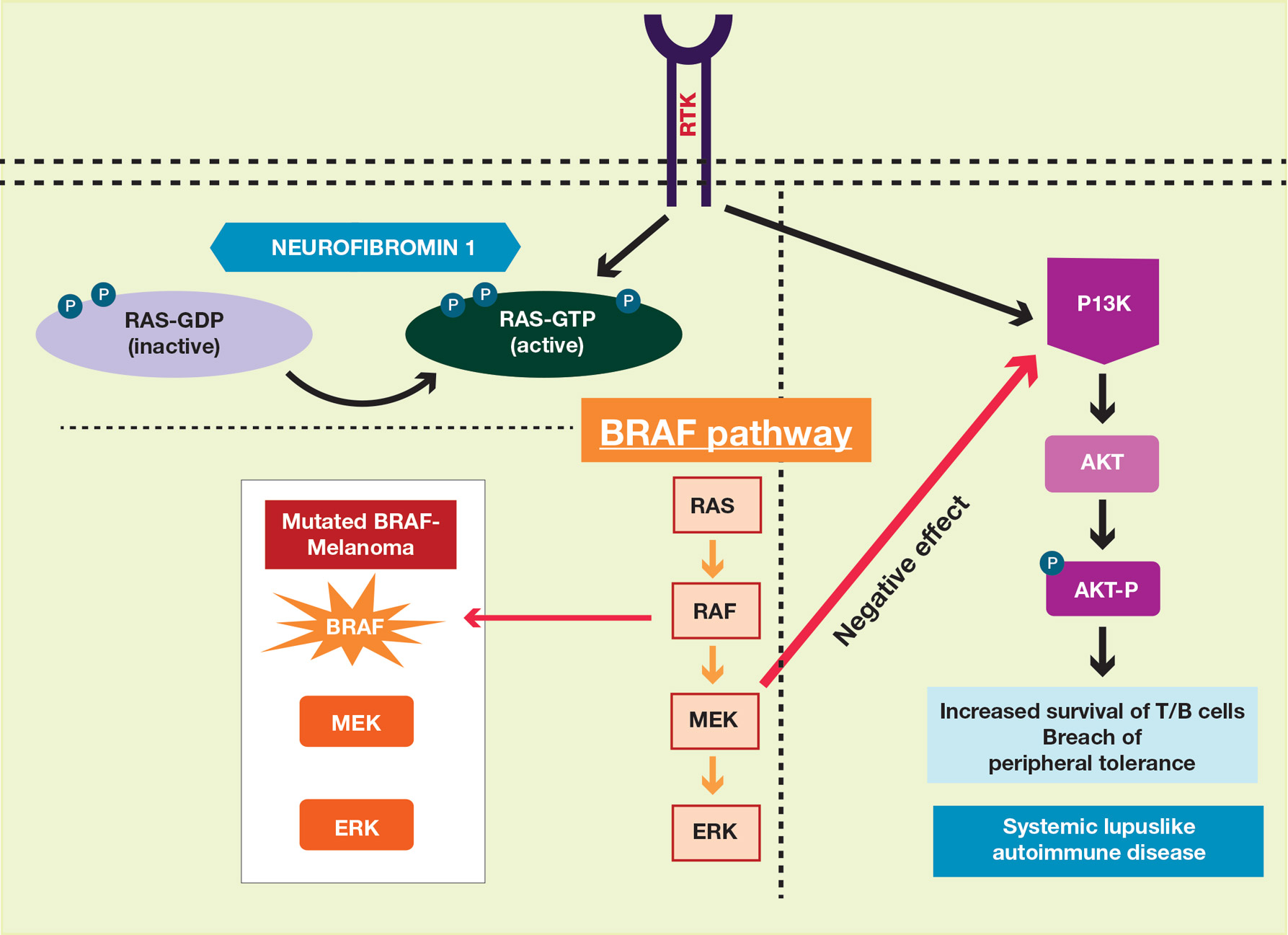

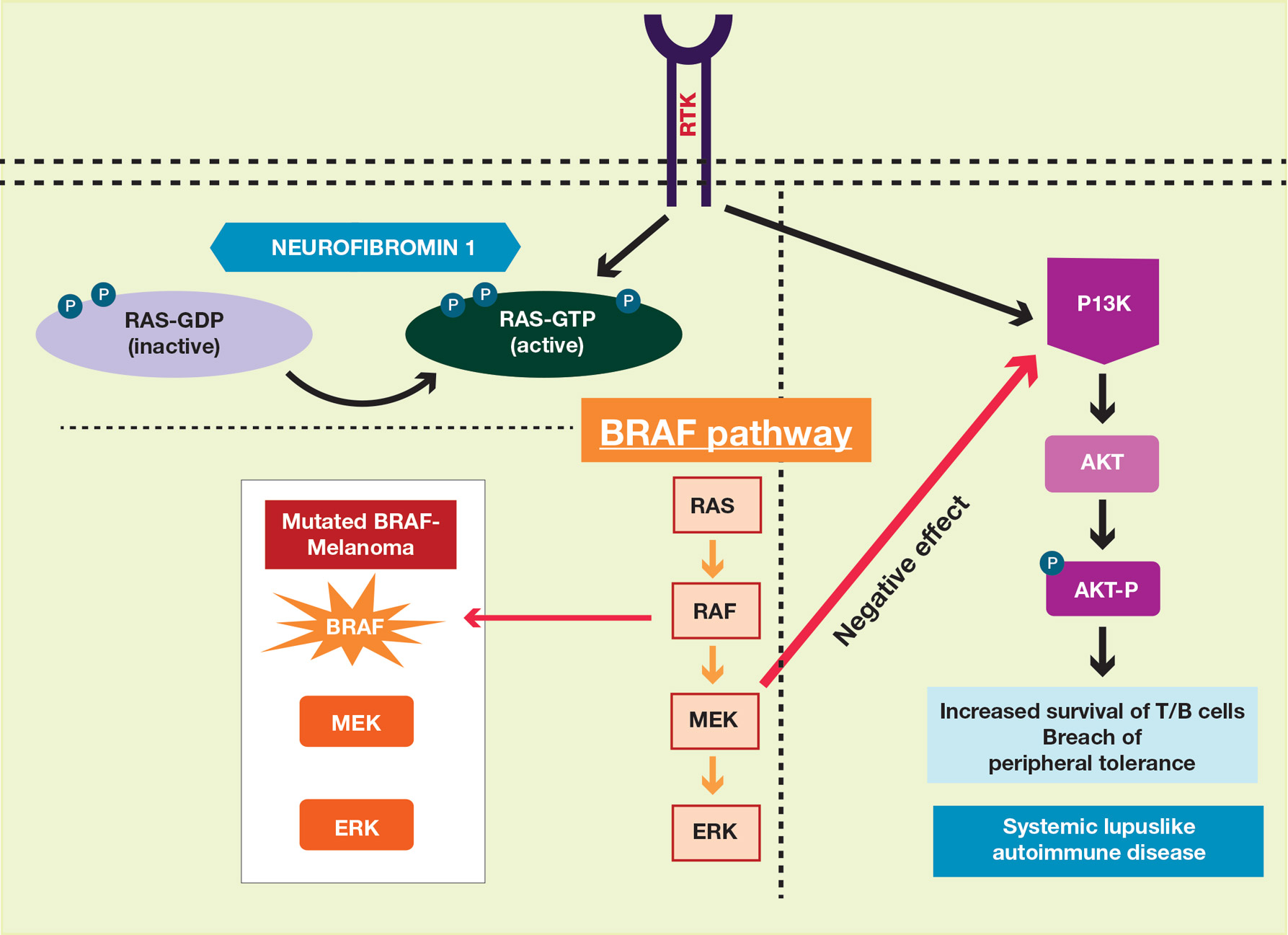

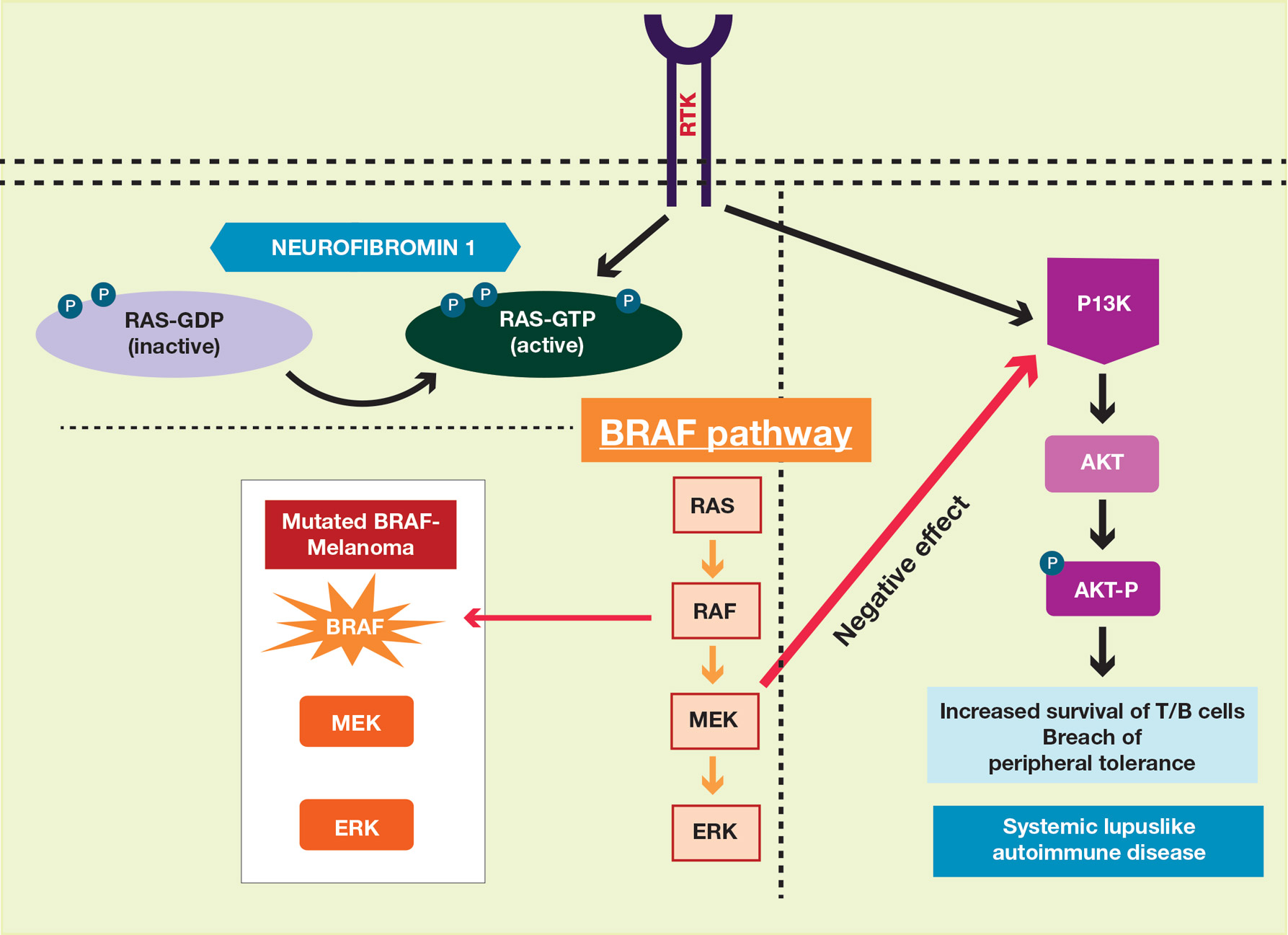

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms systemic lupus and neurofibromatosis yielded 8 cases of patients having both SLE and NF-1 (including our case).6-11 Our patient reported having multiple lesions since birth, decades before the onset and diagnosis of SLE. In 3 other cases, patients were diagnosed with SLE and then presented with neurofibromas, leading to NF-1 diagnosis.In the discussion of those 3 cases, it was proposed that immune system alterations caused by SLE leading to viral illness may have predisposed the patients to the development of tumors and other collagen diseases, or it could be coincidental.6,7 In another case, a patient with NF-1 developed SLE, which was thought to be coincidental.8 Akyuz et al9 described the case of a pediatric patient with NF-1 who subsequently was diagnosed with SLE. The authors suggested that the lack of neurofibromin contributed to the development of SLE, an autoimmune condition. Under normal circumstances, neurofibromin acts as a guanosine triphosphatase–activating protein for RAS in T cells.10 CD8+ T-cell function also is impaired in patients with SLE.9 Additionally, it has been reported that anti–double-stranded DNA antibodies and immune complexes were present in NF-1 patients, even though there were low titers.12 Thus, the authors proposed that the lack of neurofibromin led to dysregulation of the RAS pathway and impairment of T cells, creating an immune milieu that predisposed the patient to development of SLE. Our case gives additional credence to this theory, as our patient had a similar clinical course: the café au lait macules were present since birth and the symptoms of SLE surfaced much later in her late 20s and 30s. Another case by Makino and Tampo10 described a patient with a history of SLE who was later diagnosed with NF-1 based on choroidal findings highly specific for NF-1 but did not have other classic findings of NF-1. The authors mentioned that there might be a potential relationship between these two disorders but did not speculate any theory in particular for their case.10

The interplay between an autoimmune condition such as SLE and NF-1, a condition traditionally thought to be due to a genetic mutation, may have greater clinical and therapeutic implications beyond just these two disorders. Although it is well established that RAS pathway disruption causes NF-1, it has been uncovered that dysfunction in the RAS pathway also can contribute to melanoma oncogenesis.13,14 These insights have led to the development of and approval of targeted drugs designed to inhibit the RAS pathway (eg, vemurafenib, dabrafenib, trametinib).14-17 Melanoma also is considered a “model” tumor for studying the relationship between the immune system and cancer.18

Our case also is instructive in another point: our patient had never sought treatment for her skin lesions, as she said she had other more serious health conditions. Closer evaluation of her skin condition may have led to earlier diagnosis of NF-1, which has important health implications. The average lifespan of patients with NF-1 is 10 to 15 years lower than the general population, with cancer being the leading cause of death.20 Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors are the most common malignant tumors observed in such patients.21-23 Other cancers that are associated with NF-1 include rhabdomyosarcomas, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, neuroectodermal tumors, pheochromocytomas, and breast carcinomas.23

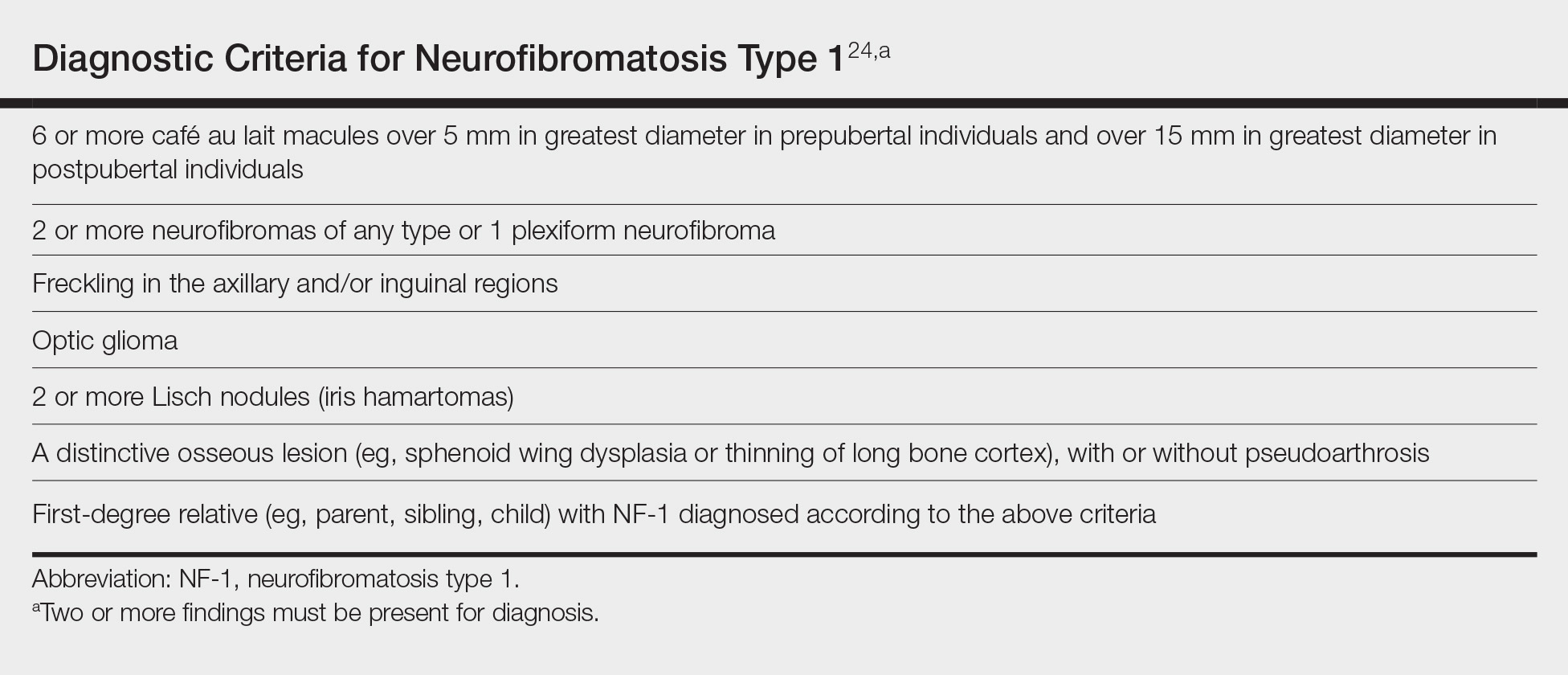

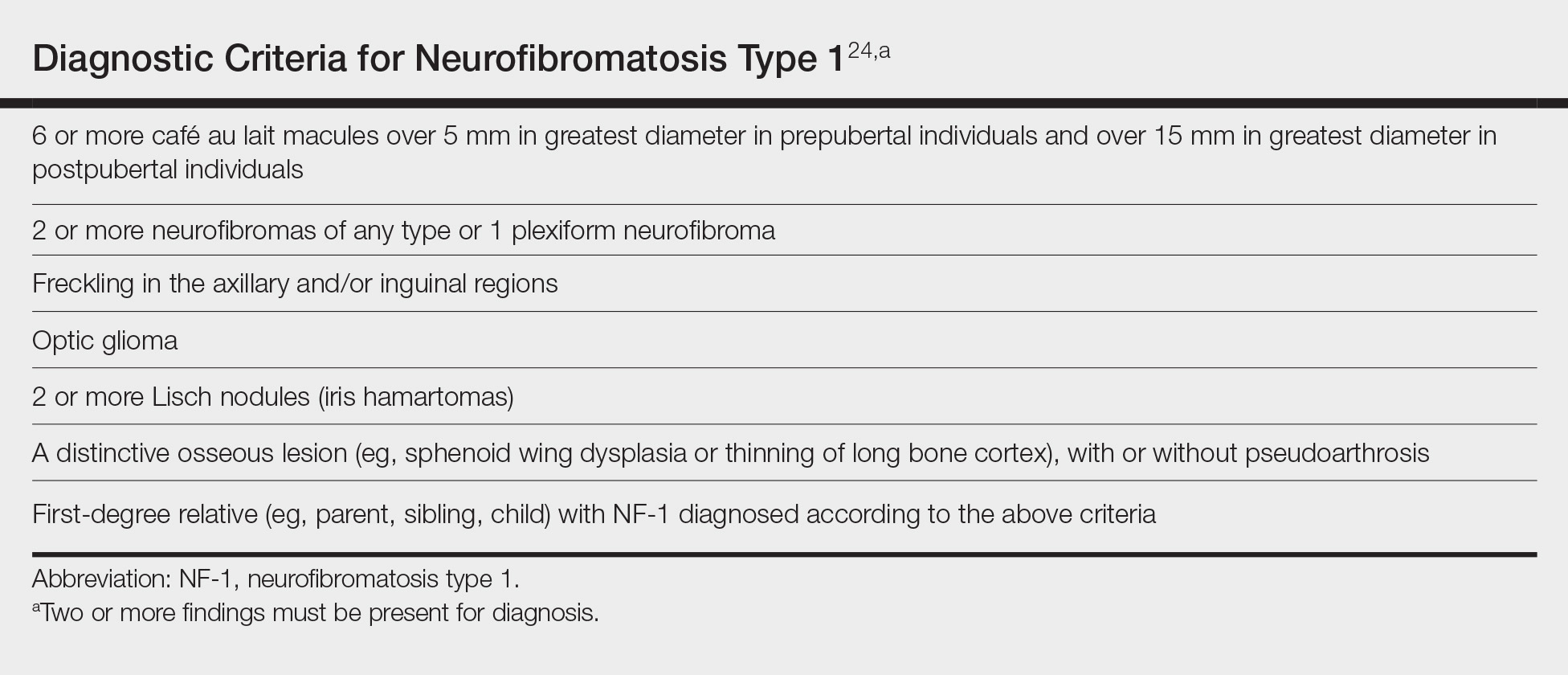

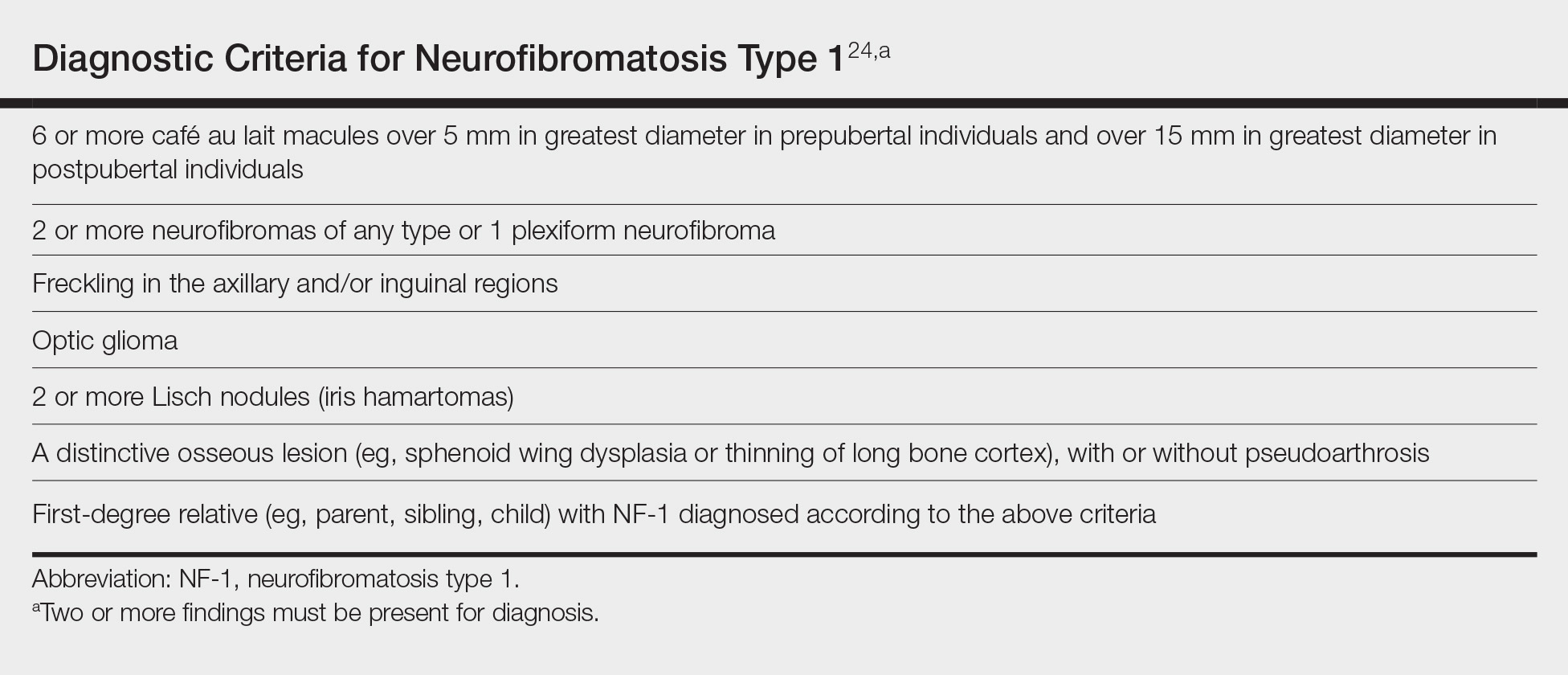

To make a clinical diagnosis of NF-1, a patient must have 2 of 7 cardinal clinical features as defined by the National Institutes of Health (Table).24 In our patient with hundreds of café au lait macules and dozens of neurofibromas, the diagnosis was clear; however, in other patients, the skin findings of NF-1 may not be as prominent. A patient could meet criteria for NF-1 diagnosis with the inconspicuous presentation of 6 café au lait macules and either 1 plexiform neurofibroma or 2 neurofibromas (of any type) on the entire body.

We recommend that patients with SLE undergo skin examinations to look for more subtle presentations of NF-1. Earlier diagnosis will help to initiate close monitoring of the disorder’s associated systemic health risks. In addition, the identification of more patients with both NF-1 and SLE may help shed light on the etiology of both conditions.

- Carey JC, Baty BJ, Johnson JP, et al. The genetic aspects of neurofibromatosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1986;486:45-56.

- Pons-Estel GJ, Alarcón GS, Scofield L, et al. Understanding the epidemiology and progression of systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010;39:257-268.

- Danchenko N, Satia JA, Anthony MS. Epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus: a comparison of worldwide disease burden. Lupus. 2006;15:308-318.

- Lawrence RC, Helmick CG, Arnett FC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:778-799.

- Chakravarty EF, Bush TM, Manzi S, et al. Prevalence of adult systemic lupus erythematosus in California and Pennsylvania in 2000: estimates obtained using hospitalization data. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2092-2094.

- Bitnun S, Bassan H. Letter: neurofibromatosis and SLE. N Engl J Med. 1975;292:429-430.

- Riccardi VM. Neurofibromatosis in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1983;26:574.

- Corominas H, Guardiola JM, Matas L, et al. Neurofibromatosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. a matter of coincidence? Clin Rhematol. 2003;22:496-497.

- Akyuz SG, Caltik A, Bulbul M, et al. An unusual pediatric case with neurofibromatosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:2345-47.

- Makino S, Tampo H. Rare and unusual choroidal abnormalities in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2013;4:81-86.

- Galvan JM, Hofkamp MP. Usefulness of intrapartum magnetic resonance imaging for a parturient with neurofibromatosis type I during induction of labor for preeclampsia. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2018;31:92-93.

- Gerosa PL, Vai C, Bizzozer L, et al. Immunological and clinical surveillance in Recklinghausen’s neurofibromatosis (NF1). Panminerva Med. 1993;35:80-85.

- Busca R, Abbe P, Mantoux F, et al. RAS mediates the cAMP-dependent activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs) in melanocytes. EMBO J. 2000;19:2900-2910.

- Sullivan RJ, Flaherty K. MAP kinase signaling and inhibition in melanoma. Oncogene. 2013;32:2373-2379.

- Hennessy BT, Smith DL, Ram PT, et al. Exploiting the PI3K/AKT pathway for cancer drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;12:988-1004.

- Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2507-2516.

- Hauschild A, Grob JJ, Demidov LV, et al. Dabrafenib in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:358-365.

- Maio M. Melanoma as a model tumour for immuno-oncology. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:(suppl 8):viii10-4.

- Zmajkovicova K, Jesenberger V, Catalanotti F, et al. MEK1 is required for PTEN membrane recruitment, AKT regulation, and the maintenance of peripheral tolerance. Mol Cell. 2013;50:43-55.

- Patil S, Chamberlain RS. Neoplasms associated with germline and somatic NF1 gene mutations. Oncologist. 2012;17:101-116.

- Carroll SL, Ratner N. How does the Schwann cell lineage form tumors in NF1? Glia. 2008;56:1590-1605.

- Rasmussen SA, Friedman JM. NF1 gene and neurofibromatosis 1. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:33-40.

- Yohay K. Neurofibromatosis type 1 and associated malignancies. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2009;9:247-253.

- Neurofibromatosis. conference statement. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:575-78.

To the Editor:

Patients with concurrent neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) rarely have been reported in the literature. Neurofibromatosis type 1 is one of the most common genetic disorders, with a worldwide birth incidence of 1 in 2500 individuals and prevalence of 1 in 4000 individuals.1 The incidence and prevalence of SLE varies widely depending on race and geographic location. Estimated incidence rates for SLE range from 1 to 25 per 100,000 individuals annually in North America, South America, Europe, and Asia.2,3 The reported worldwide prevalence is 20 to 150 cases per 100,000 individuals annually.2,4,5

Given the high prevalence of both conditions, the association between SLE and NF-1 likely is underrecognized; therefore, identifying more patients with concurrent SLE and NF-1 and describing the interplay between the 2 conditions may have important therapeutic implications. We present the case of a middle-aged woman with a history of SLE who had cutaneous lesions characteristic of NF-1 to further the understanding of these concurrent conditions.

A middle-aged woman presented to our academic dermatology clinic for evaluation and removal of dark spots that had been present diffusely on the trunk and extremities since birth. She reported a history of SLE with lupus nephritis, hypertension, and a nodular goiter following a partial thyroidectomy. She noted that she did not seek treatment for the skin findings sooner because she was more concerned about her other medical conditions; however, because she felt these conditions were now stable, she decided to seek treatment for the “rash.” Physical examination revealed hundreds of café au lait macules and numerous neurofibromas diffusely distributed on the trunk and extremities (Figure 1) as well as bilateral axillary freckling. A clinical diagnosis of NF-1 was made.

When questioned, the patient reported that she may have been diagnosed with NF-1 in the past by another physician, but she did not recall it specifically. The patient was advised that there were no treatments for the café au lait macules. We notified her other physicians of the NF-1 diagnosis so she could be monitored for systemic conditions related to NF-1, including optic gliomas, pheochromocytoma, renal artery stenosis, and internal neurofibromas. We also referred the patient for genetic counseling; of note, the patient reported she had 4 children without any evidence of similar skin lesions or chronic health problems.

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms systemic lupus and neurofibromatosis yielded 8 cases of patients having both SLE and NF-1 (including our case).6-11 Our patient reported having multiple lesions since birth, decades before the onset and diagnosis of SLE. In 3 other cases, patients were diagnosed with SLE and then presented with neurofibromas, leading to NF-1 diagnosis.In the discussion of those 3 cases, it was proposed that immune system alterations caused by SLE leading to viral illness may have predisposed the patients to the development of tumors and other collagen diseases, or it could be coincidental.6,7 In another case, a patient with NF-1 developed SLE, which was thought to be coincidental.8 Akyuz et al9 described the case of a pediatric patient with NF-1 who subsequently was diagnosed with SLE. The authors suggested that the lack of neurofibromin contributed to the development of SLE, an autoimmune condition. Under normal circumstances, neurofibromin acts as a guanosine triphosphatase–activating protein for RAS in T cells.10 CD8+ T-cell function also is impaired in patients with SLE.9 Additionally, it has been reported that anti–double-stranded DNA antibodies and immune complexes were present in NF-1 patients, even though there were low titers.12 Thus, the authors proposed that the lack of neurofibromin led to dysregulation of the RAS pathway and impairment of T cells, creating an immune milieu that predisposed the patient to development of SLE. Our case gives additional credence to this theory, as our patient had a similar clinical course: the café au lait macules were present since birth and the symptoms of SLE surfaced much later in her late 20s and 30s. Another case by Makino and Tampo10 described a patient with a history of SLE who was later diagnosed with NF-1 based on choroidal findings highly specific for NF-1 but did not have other classic findings of NF-1. The authors mentioned that there might be a potential relationship between these two disorders but did not speculate any theory in particular for their case.10

The interplay between an autoimmune condition such as SLE and NF-1, a condition traditionally thought to be due to a genetic mutation, may have greater clinical and therapeutic implications beyond just these two disorders. Although it is well established that RAS pathway disruption causes NF-1, it has been uncovered that dysfunction in the RAS pathway also can contribute to melanoma oncogenesis.13,14 These insights have led to the development of and approval of targeted drugs designed to inhibit the RAS pathway (eg, vemurafenib, dabrafenib, trametinib).14-17 Melanoma also is considered a “model” tumor for studying the relationship between the immune system and cancer.18

Our case also is instructive in another point: our patient had never sought treatment for her skin lesions, as she said she had other more serious health conditions. Closer evaluation of her skin condition may have led to earlier diagnosis of NF-1, which has important health implications. The average lifespan of patients with NF-1 is 10 to 15 years lower than the general population, with cancer being the leading cause of death.20 Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors are the most common malignant tumors observed in such patients.21-23 Other cancers that are associated with NF-1 include rhabdomyosarcomas, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, neuroectodermal tumors, pheochromocytomas, and breast carcinomas.23

To make a clinical diagnosis of NF-1, a patient must have 2 of 7 cardinal clinical features as defined by the National Institutes of Health (Table).24 In our patient with hundreds of café au lait macules and dozens of neurofibromas, the diagnosis was clear; however, in other patients, the skin findings of NF-1 may not be as prominent. A patient could meet criteria for NF-1 diagnosis with the inconspicuous presentation of 6 café au lait macules and either 1 plexiform neurofibroma or 2 neurofibromas (of any type) on the entire body.

We recommend that patients with SLE undergo skin examinations to look for more subtle presentations of NF-1. Earlier diagnosis will help to initiate close monitoring of the disorder’s associated systemic health risks. In addition, the identification of more patients with both NF-1 and SLE may help shed light on the etiology of both conditions.

To the Editor:

Patients with concurrent neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) rarely have been reported in the literature. Neurofibromatosis type 1 is one of the most common genetic disorders, with a worldwide birth incidence of 1 in 2500 individuals and prevalence of 1 in 4000 individuals.1 The incidence and prevalence of SLE varies widely depending on race and geographic location. Estimated incidence rates for SLE range from 1 to 25 per 100,000 individuals annually in North America, South America, Europe, and Asia.2,3 The reported worldwide prevalence is 20 to 150 cases per 100,000 individuals annually.2,4,5

Given the high prevalence of both conditions, the association between SLE and NF-1 likely is underrecognized; therefore, identifying more patients with concurrent SLE and NF-1 and describing the interplay between the 2 conditions may have important therapeutic implications. We present the case of a middle-aged woman with a history of SLE who had cutaneous lesions characteristic of NF-1 to further the understanding of these concurrent conditions.

A middle-aged woman presented to our academic dermatology clinic for evaluation and removal of dark spots that had been present diffusely on the trunk and extremities since birth. She reported a history of SLE with lupus nephritis, hypertension, and a nodular goiter following a partial thyroidectomy. She noted that she did not seek treatment for the skin findings sooner because she was more concerned about her other medical conditions; however, because she felt these conditions were now stable, she decided to seek treatment for the “rash.” Physical examination revealed hundreds of café au lait macules and numerous neurofibromas diffusely distributed on the trunk and extremities (Figure 1) as well as bilateral axillary freckling. A clinical diagnosis of NF-1 was made.

When questioned, the patient reported that she may have been diagnosed with NF-1 in the past by another physician, but she did not recall it specifically. The patient was advised that there were no treatments for the café au lait macules. We notified her other physicians of the NF-1 diagnosis so she could be monitored for systemic conditions related to NF-1, including optic gliomas, pheochromocytoma, renal artery stenosis, and internal neurofibromas. We also referred the patient for genetic counseling; of note, the patient reported she had 4 children without any evidence of similar skin lesions or chronic health problems.

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms systemic lupus and neurofibromatosis yielded 8 cases of patients having both SLE and NF-1 (including our case).6-11 Our patient reported having multiple lesions since birth, decades before the onset and diagnosis of SLE. In 3 other cases, patients were diagnosed with SLE and then presented with neurofibromas, leading to NF-1 diagnosis.In the discussion of those 3 cases, it was proposed that immune system alterations caused by SLE leading to viral illness may have predisposed the patients to the development of tumors and other collagen diseases, or it could be coincidental.6,7 In another case, a patient with NF-1 developed SLE, which was thought to be coincidental.8 Akyuz et al9 described the case of a pediatric patient with NF-1 who subsequently was diagnosed with SLE. The authors suggested that the lack of neurofibromin contributed to the development of SLE, an autoimmune condition. Under normal circumstances, neurofibromin acts as a guanosine triphosphatase–activating protein for RAS in T cells.10 CD8+ T-cell function also is impaired in patients with SLE.9 Additionally, it has been reported that anti–double-stranded DNA antibodies and immune complexes were present in NF-1 patients, even though there were low titers.12 Thus, the authors proposed that the lack of neurofibromin led to dysregulation of the RAS pathway and impairment of T cells, creating an immune milieu that predisposed the patient to development of SLE. Our case gives additional credence to this theory, as our patient had a similar clinical course: the café au lait macules were present since birth and the symptoms of SLE surfaced much later in her late 20s and 30s. Another case by Makino and Tampo10 described a patient with a history of SLE who was later diagnosed with NF-1 based on choroidal findings highly specific for NF-1 but did not have other classic findings of NF-1. The authors mentioned that there might be a potential relationship between these two disorders but did not speculate any theory in particular for their case.10

The interplay between an autoimmune condition such as SLE and NF-1, a condition traditionally thought to be due to a genetic mutation, may have greater clinical and therapeutic implications beyond just these two disorders. Although it is well established that RAS pathway disruption causes NF-1, it has been uncovered that dysfunction in the RAS pathway also can contribute to melanoma oncogenesis.13,14 These insights have led to the development of and approval of targeted drugs designed to inhibit the RAS pathway (eg, vemurafenib, dabrafenib, trametinib).14-17 Melanoma also is considered a “model” tumor for studying the relationship between the immune system and cancer.18

Our case also is instructive in another point: our patient had never sought treatment for her skin lesions, as she said she had other more serious health conditions. Closer evaluation of her skin condition may have led to earlier diagnosis of NF-1, which has important health implications. The average lifespan of patients with NF-1 is 10 to 15 years lower than the general population, with cancer being the leading cause of death.20 Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors are the most common malignant tumors observed in such patients.21-23 Other cancers that are associated with NF-1 include rhabdomyosarcomas, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, neuroectodermal tumors, pheochromocytomas, and breast carcinomas.23

To make a clinical diagnosis of NF-1, a patient must have 2 of 7 cardinal clinical features as defined by the National Institutes of Health (Table).24 In our patient with hundreds of café au lait macules and dozens of neurofibromas, the diagnosis was clear; however, in other patients, the skin findings of NF-1 may not be as prominent. A patient could meet criteria for NF-1 diagnosis with the inconspicuous presentation of 6 café au lait macules and either 1 plexiform neurofibroma or 2 neurofibromas (of any type) on the entire body.

We recommend that patients with SLE undergo skin examinations to look for more subtle presentations of NF-1. Earlier diagnosis will help to initiate close monitoring of the disorder’s associated systemic health risks. In addition, the identification of more patients with both NF-1 and SLE may help shed light on the etiology of both conditions.

- Carey JC, Baty BJ, Johnson JP, et al. The genetic aspects of neurofibromatosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1986;486:45-56.

- Pons-Estel GJ, Alarcón GS, Scofield L, et al. Understanding the epidemiology and progression of systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010;39:257-268.

- Danchenko N, Satia JA, Anthony MS. Epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus: a comparison of worldwide disease burden. Lupus. 2006;15:308-318.

- Lawrence RC, Helmick CG, Arnett FC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:778-799.

- Chakravarty EF, Bush TM, Manzi S, et al. Prevalence of adult systemic lupus erythematosus in California and Pennsylvania in 2000: estimates obtained using hospitalization data. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2092-2094.

- Bitnun S, Bassan H. Letter: neurofibromatosis and SLE. N Engl J Med. 1975;292:429-430.

- Riccardi VM. Neurofibromatosis in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1983;26:574.

- Corominas H, Guardiola JM, Matas L, et al. Neurofibromatosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. a matter of coincidence? Clin Rhematol. 2003;22:496-497.

- Akyuz SG, Caltik A, Bulbul M, et al. An unusual pediatric case with neurofibromatosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:2345-47.

- Makino S, Tampo H. Rare and unusual choroidal abnormalities in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2013;4:81-86.

- Galvan JM, Hofkamp MP. Usefulness of intrapartum magnetic resonance imaging for a parturient with neurofibromatosis type I during induction of labor for preeclampsia. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2018;31:92-93.

- Gerosa PL, Vai C, Bizzozer L, et al. Immunological and clinical surveillance in Recklinghausen’s neurofibromatosis (NF1). Panminerva Med. 1993;35:80-85.

- Busca R, Abbe P, Mantoux F, et al. RAS mediates the cAMP-dependent activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs) in melanocytes. EMBO J. 2000;19:2900-2910.

- Sullivan RJ, Flaherty K. MAP kinase signaling and inhibition in melanoma. Oncogene. 2013;32:2373-2379.

- Hennessy BT, Smith DL, Ram PT, et al. Exploiting the PI3K/AKT pathway for cancer drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;12:988-1004.

- Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2507-2516.

- Hauschild A, Grob JJ, Demidov LV, et al. Dabrafenib in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:358-365.

- Maio M. Melanoma as a model tumour for immuno-oncology. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:(suppl 8):viii10-4.

- Zmajkovicova K, Jesenberger V, Catalanotti F, et al. MEK1 is required for PTEN membrane recruitment, AKT regulation, and the maintenance of peripheral tolerance. Mol Cell. 2013;50:43-55.

- Patil S, Chamberlain RS. Neoplasms associated with germline and somatic NF1 gene mutations. Oncologist. 2012;17:101-116.

- Carroll SL, Ratner N. How does the Schwann cell lineage form tumors in NF1? Glia. 2008;56:1590-1605.

- Rasmussen SA, Friedman JM. NF1 gene and neurofibromatosis 1. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:33-40.

- Yohay K. Neurofibromatosis type 1 and associated malignancies. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2009;9:247-253.

- Neurofibromatosis. conference statement. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:575-78.

- Carey JC, Baty BJ, Johnson JP, et al. The genetic aspects of neurofibromatosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1986;486:45-56.

- Pons-Estel GJ, Alarcón GS, Scofield L, et al. Understanding the epidemiology and progression of systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010;39:257-268.

- Danchenko N, Satia JA, Anthony MS. Epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus: a comparison of worldwide disease burden. Lupus. 2006;15:308-318.

- Lawrence RC, Helmick CG, Arnett FC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:778-799.

- Chakravarty EF, Bush TM, Manzi S, et al. Prevalence of adult systemic lupus erythematosus in California and Pennsylvania in 2000: estimates obtained using hospitalization data. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2092-2094.

- Bitnun S, Bassan H. Letter: neurofibromatosis and SLE. N Engl J Med. 1975;292:429-430.

- Riccardi VM. Neurofibromatosis in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1983;26:574.

- Corominas H, Guardiola JM, Matas L, et al. Neurofibromatosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. a matter of coincidence? Clin Rhematol. 2003;22:496-497.

- Akyuz SG, Caltik A, Bulbul M, et al. An unusual pediatric case with neurofibromatosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:2345-47.

- Makino S, Tampo H. Rare and unusual choroidal abnormalities in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2013;4:81-86.

- Galvan JM, Hofkamp MP. Usefulness of intrapartum magnetic resonance imaging for a parturient with neurofibromatosis type I during induction of labor for preeclampsia. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2018;31:92-93.

- Gerosa PL, Vai C, Bizzozer L, et al. Immunological and clinical surveillance in Recklinghausen’s neurofibromatosis (NF1). Panminerva Med. 1993;35:80-85.

- Busca R, Abbe P, Mantoux F, et al. RAS mediates the cAMP-dependent activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs) in melanocytes. EMBO J. 2000;19:2900-2910.

- Sullivan RJ, Flaherty K. MAP kinase signaling and inhibition in melanoma. Oncogene. 2013;32:2373-2379.

- Hennessy BT, Smith DL, Ram PT, et al. Exploiting the PI3K/AKT pathway for cancer drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;12:988-1004.

- Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2507-2516.

- Hauschild A, Grob JJ, Demidov LV, et al. Dabrafenib in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:358-365.

- Maio M. Melanoma as a model tumour for immuno-oncology. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:(suppl 8):viii10-4.

- Zmajkovicova K, Jesenberger V, Catalanotti F, et al. MEK1 is required for PTEN membrane recruitment, AKT regulation, and the maintenance of peripheral tolerance. Mol Cell. 2013;50:43-55.

- Patil S, Chamberlain RS. Neoplasms associated with germline and somatic NF1 gene mutations. Oncologist. 2012;17:101-116.

- Carroll SL, Ratner N. How does the Schwann cell lineage form tumors in NF1? Glia. 2008;56:1590-1605.

- Rasmussen SA, Friedman JM. NF1 gene and neurofibromatosis 1. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:33-40.

- Yohay K. Neurofibromatosis type 1 and associated malignancies. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2009;9:247-253.

- Neurofibromatosis. conference statement. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:575-78.

Practice Points

- Patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1) benefit from early diagnosis and long-term follow-up.

- Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) may develop different malignancies given the immune dysregulation. We recommend that patients with SLE undergo detailed skin examinations to check for subtle clues for NF-1.

- Similarly, patients with NF-1 can develop SLE later in life.

Locally Destructive Metastatic Basal Cell Carcinoma

To the Editor:

A 60-year-old woman with a history of lymphoma presented to the emergency department for evaluation of intermittent diarrhea and vomiting of 2 weeks’ duration. On presentation, a rather large dressing covering the entire right half of the face was noted. Removal of the bandage revealed a necrotic, extensively destructive, right-sided facial lesion with a fully exposed ocular globe (Figure 1). The patient lived alone and was accompanied by a neighbor, who disclosed that the lesion had been neglected and enlarged over the last 15 years. Moreover, the neighbor reported that the patient had recently experienced several episodes of vertigo and frequent falls.

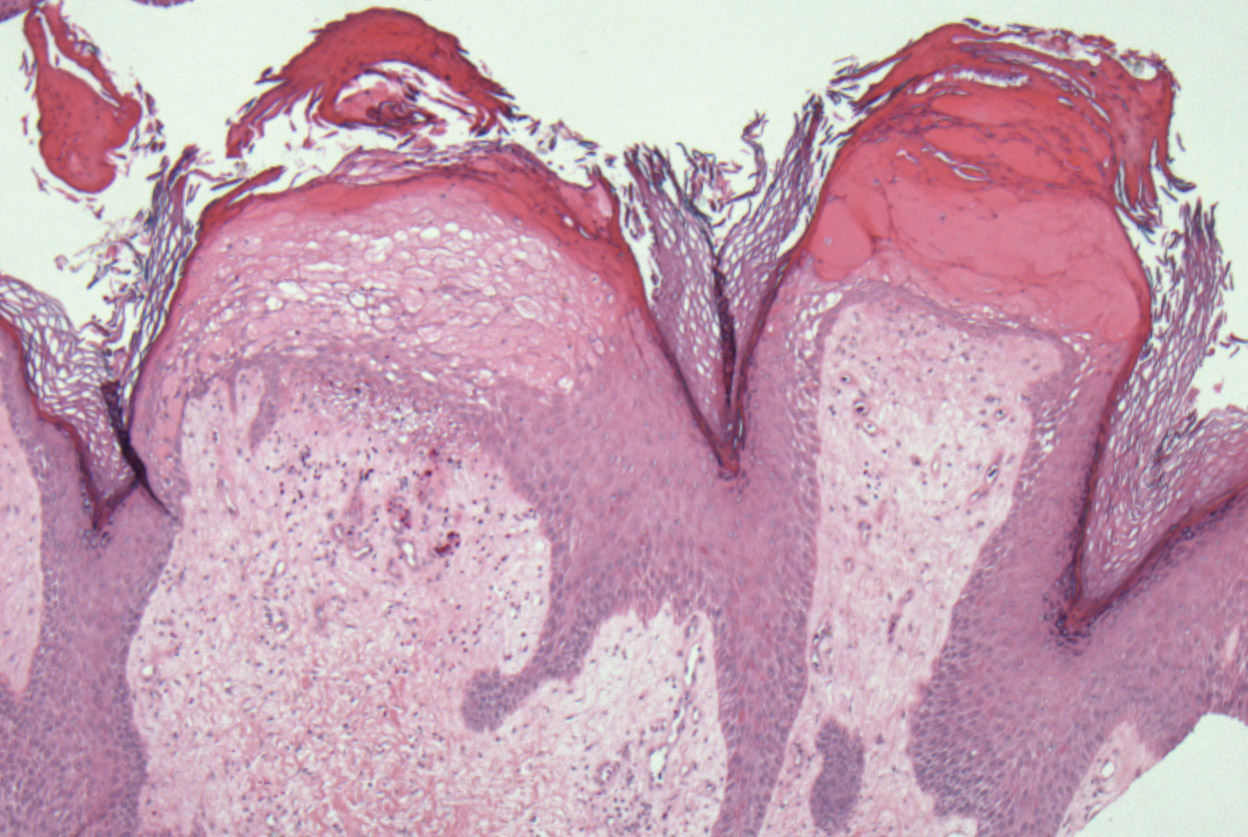

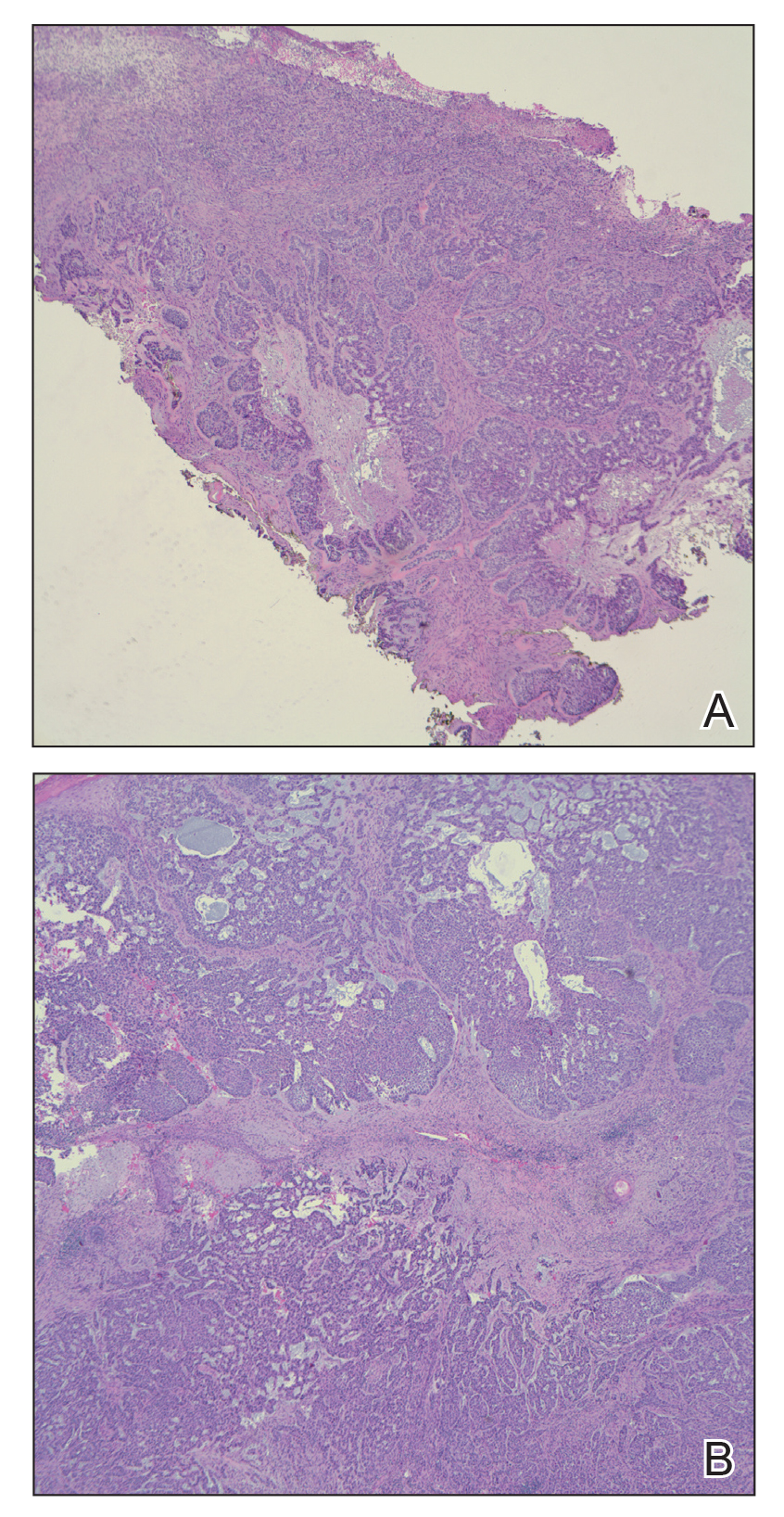

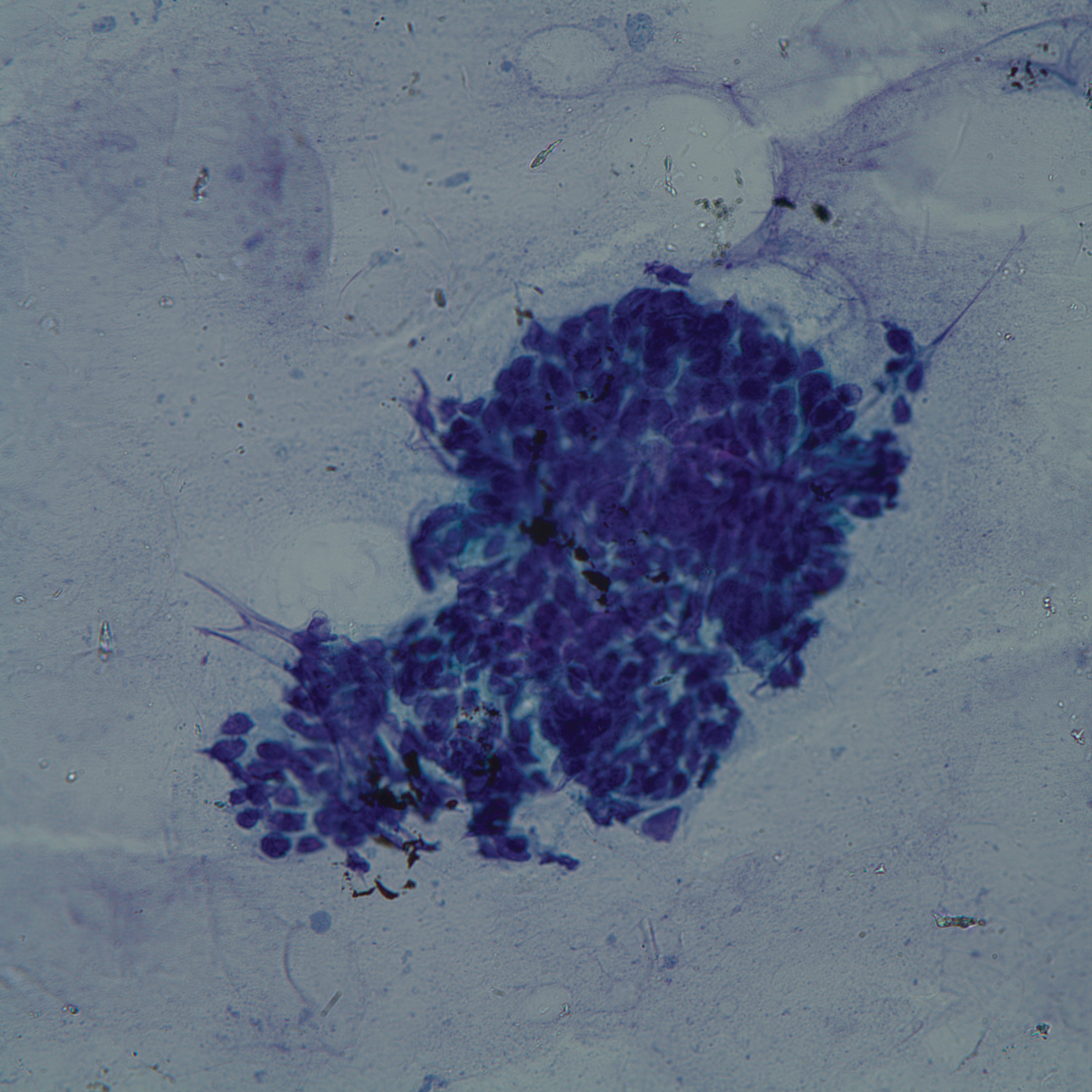

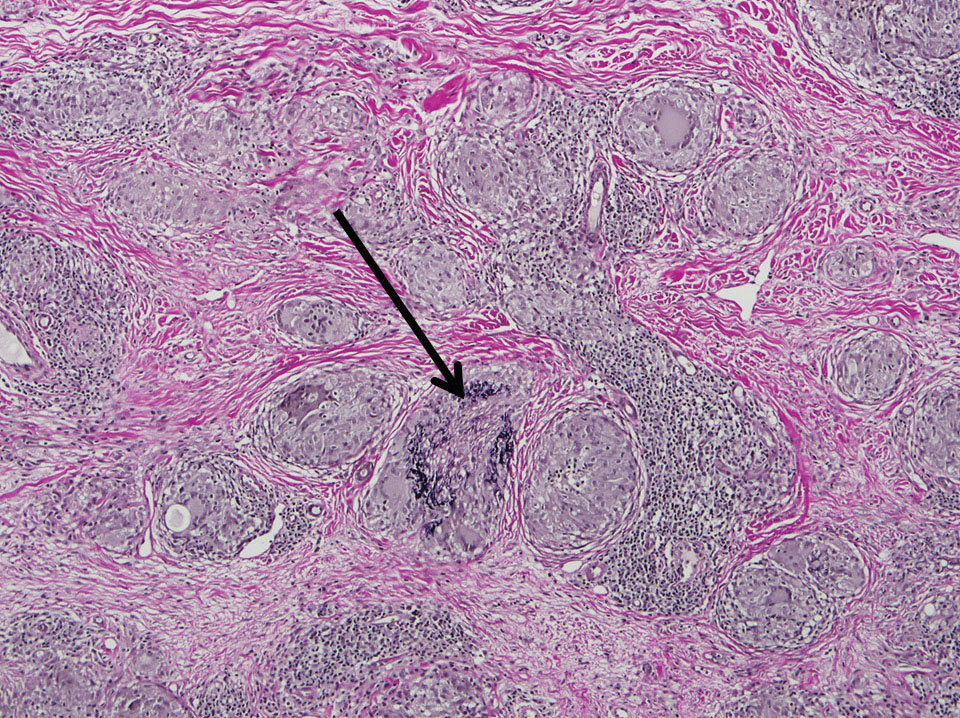

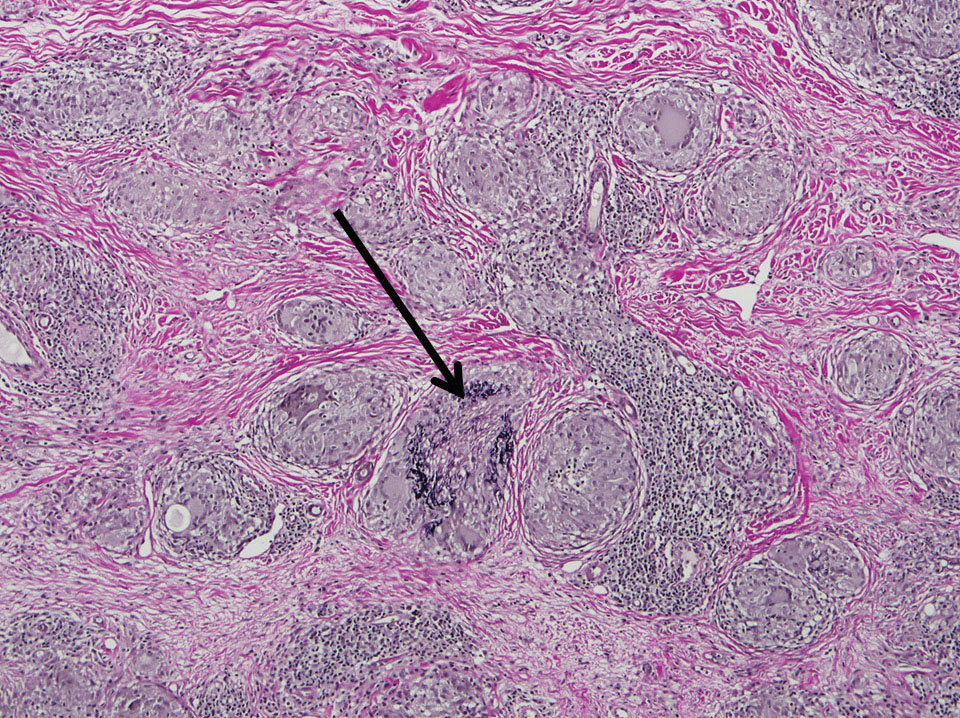

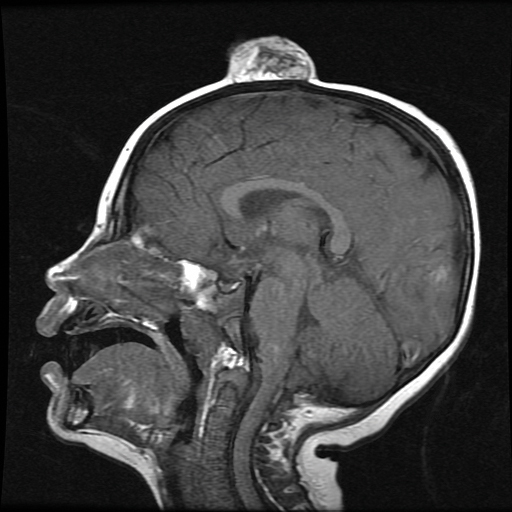

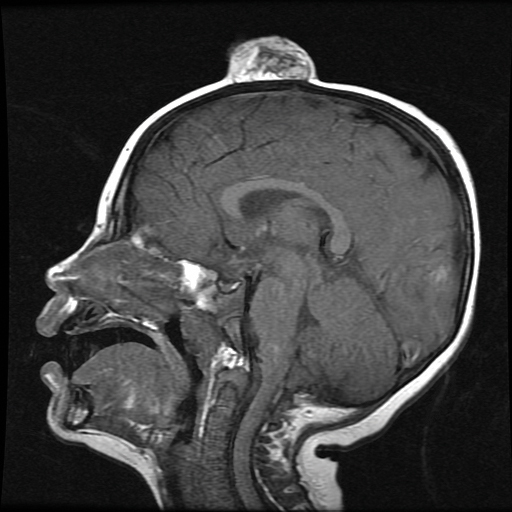

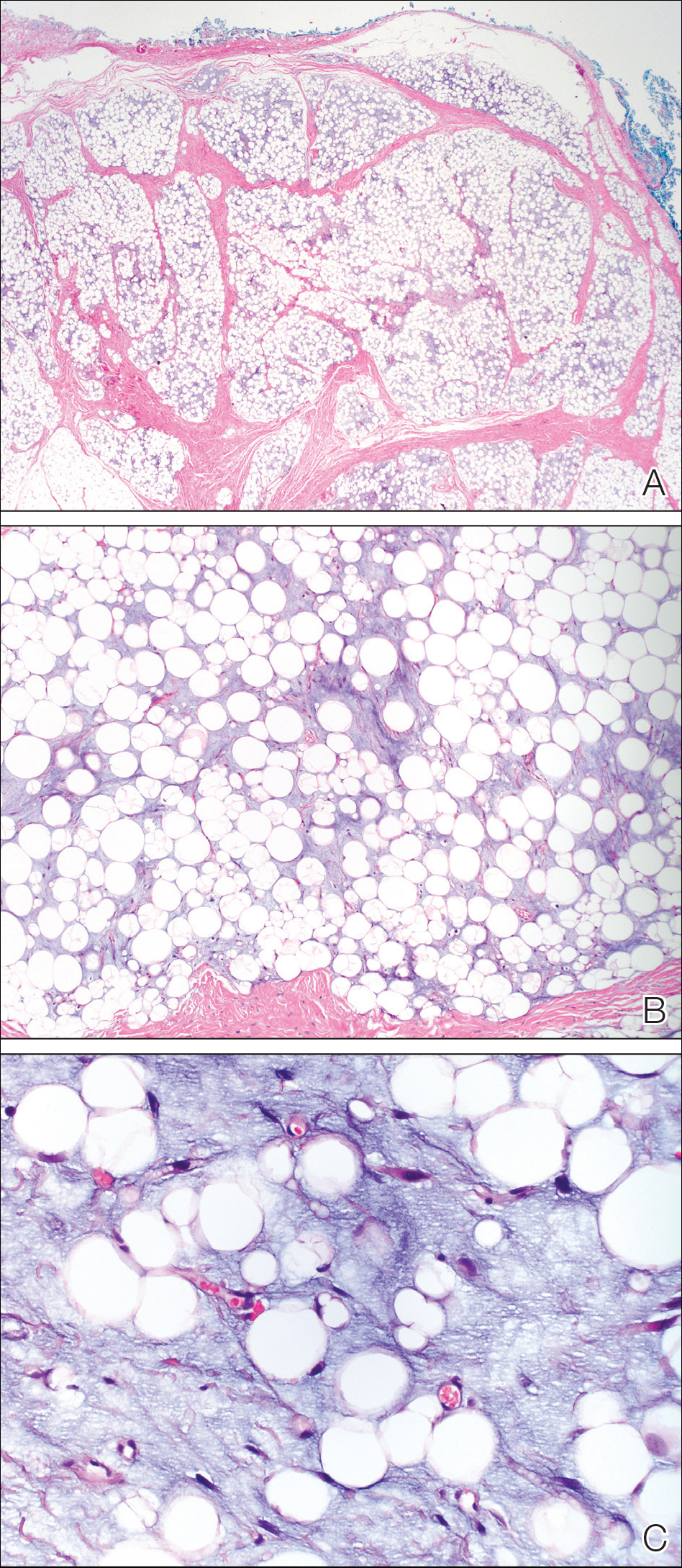

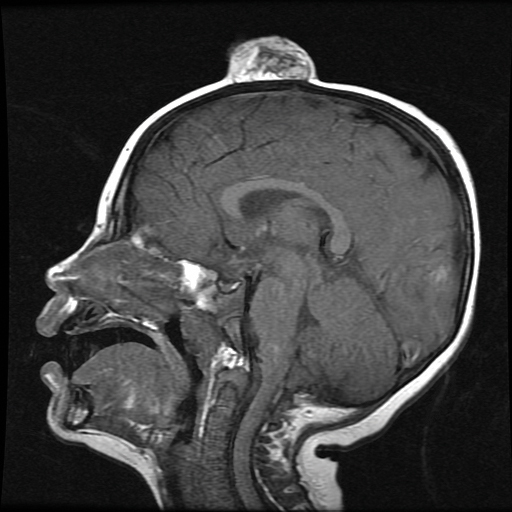

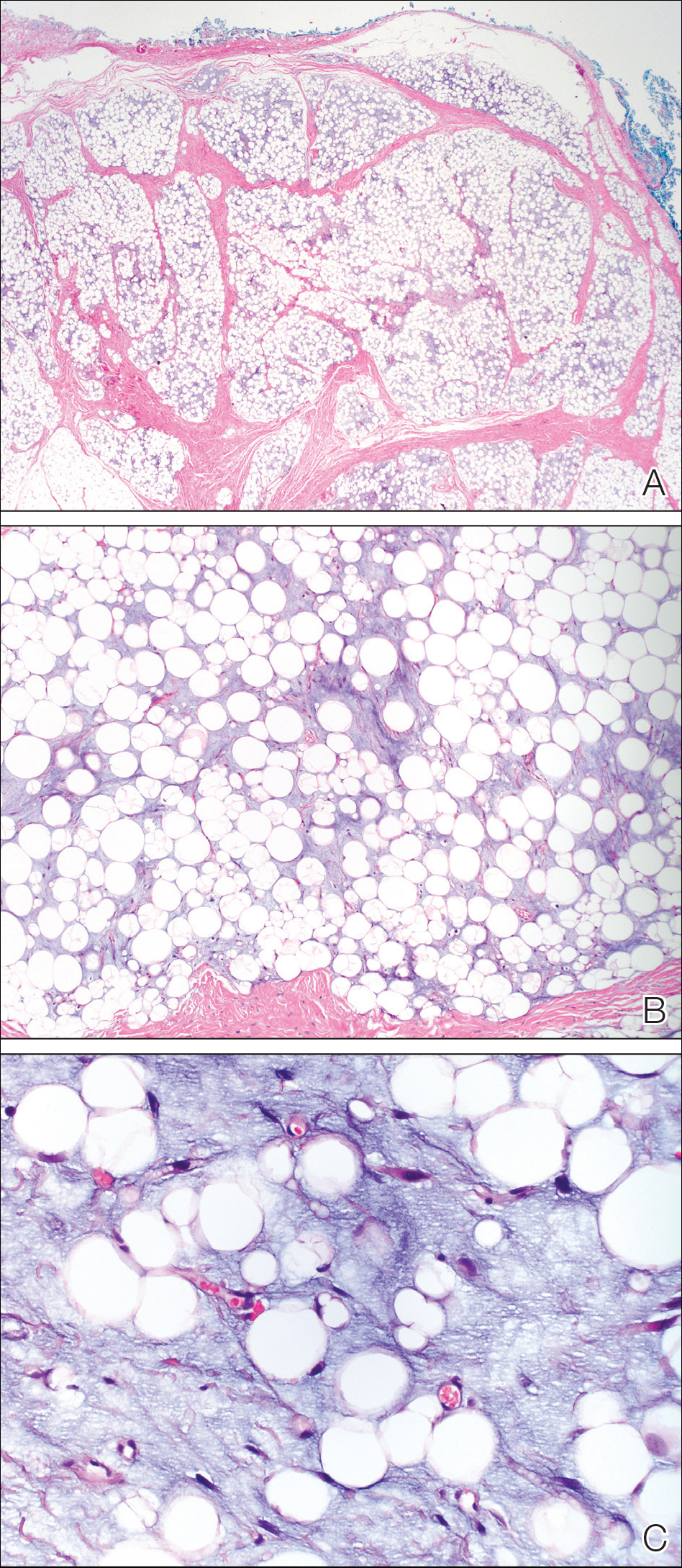

On admission to the hospital, dermatology was consulted and initial workup included computed tomography (CT) scan of the head and maxillofacial region, which showed a destructive process involving the right frontotemporal bone, maxillofacial region, sphenoid, and skull base with exposure of intracranial contents (Figure 2). An aggressive wound care regimen was instituted. Biopsy of the wound margin revealed nodular and focally infiltrative basal cell carcinoma (BCC) (Figure 3).

and focally infiltrative basal cell carcinoma (H&E, original magnifications×4 and ×10).

Several days into her hospitalization, the patient developed radicular pain in both arms and weakness in all 4 extremities. A CT scan of the neck revealed a pathologic fracture of the C7 vertebrae. Several medical and surgical services as well as psychiatry were consulted. Given the extensive nature of the disease involvement with limited treatment options, the patient sought to forego further interventions and was discharged to hospice care.

Basal cell carcinomas rarely metastasize, with a reported incidence of 0.0028% to 0.5%.1 The likelihood of metastasis is most closely related to tumor size and depth of invasion. Tumors greater than 3 cm in diameter have a 2% incidence of metastatic spread and/or death. The incidence of metastatic spread and/or death is estimated to be 25% for tumors with a diameter of 5 cm and 50% for tumors with a diameter of 10 cm or greater.2 Other risk factors for metastatic spread include long duration of disease, failure to respond to conventional treatment, and prior radiation treatment in the affected area.1 In one review, the median interval between onset of BCC and metastasis was 9 years.3 In our case, 15 years of neglect most likely led to the aggressiveness of the tumor. Although the workup in our patient was limited per her request, there was no evidence that her lymphoma had recurred or that she was in any other way immunocompromised. Unfortunately, in this patient’s case, the local destructiveness of the carcinoma with subsequent bony invasion and necrosis was complicated with secondary Rhizopus infection. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms basal cell carcinoma and mucormycosis revealed no other reported cases of BCC associated with mucormycosis; therefore, our case represents a rare presentation of this association. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis is the most common manifestation of mucormycosis and more commonly occurs in diabetics with ketoacidosis and in severely debilitated or immunosuppressed individuals.4 The extensive bony destruction, especially of the nasal region, of our patient’s tumor likely led to secondary infection with Rhizopus.

Approximately 85% of all metastatic BCCs originate in the head and neck region, with lymph nodes being the first site of metastasis and involved in approximately half of all cases.1,4 Metastases to the lungs, bone, liver, and other viscera can occur with advanced disease. Metastasis generally portends a poor prognosis, with survival rarely exceeding 1.5 years. Until recently, therapeutic options for metastatic disease were limited, with marginal response to chemotherapy with methotrexate, fluorouracil, bleomycin, and cisplatin.4 Vismodegib, a novel smoothened receptor inhibitor that blocks the sonic hedgehog pathway implicated in BCC carcinogenesis, offers a new promising treatment for management and control of advanced disease.5

- Junior W, Ribeiro SC, Vieira SC, et al. Metastatic basal cell carcinoma: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:18.

- Snow SN, Sahl WJ, Lo J, et al. Metastatic basal cell carcinoma: report of 5 cases. Cancer. 1994;73:328-335.

- Von Domarus H, Stevens PJ. Metastatic basal cell carcinoma: report of five cases and review of 170 cases in the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:1043-1060.

- Kolekar JS. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis: a retrospective study. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;67:93-96.

- Koehlblinger P, Lang R. New developments in the treatment of basal cell carcinoma: update on current and emerging treatment options with a focus on vismodegib. Onc Targets Ther. 2018;11:8327-8340.

To the Editor:

A 60-year-old woman with a history of lymphoma presented to the emergency department for evaluation of intermittent diarrhea and vomiting of 2 weeks’ duration. On presentation, a rather large dressing covering the entire right half of the face was noted. Removal of the bandage revealed a necrotic, extensively destructive, right-sided facial lesion with a fully exposed ocular globe (Figure 1). The patient lived alone and was accompanied by a neighbor, who disclosed that the lesion had been neglected and enlarged over the last 15 years. Moreover, the neighbor reported that the patient had recently experienced several episodes of vertigo and frequent falls.

On admission to the hospital, dermatology was consulted and initial workup included computed tomography (CT) scan of the head and maxillofacial region, which showed a destructive process involving the right frontotemporal bone, maxillofacial region, sphenoid, and skull base with exposure of intracranial contents (Figure 2). An aggressive wound care regimen was instituted. Biopsy of the wound margin revealed nodular and focally infiltrative basal cell carcinoma (BCC) (Figure 3).

and focally infiltrative basal cell carcinoma (H&E, original magnifications×4 and ×10).

Several days into her hospitalization, the patient developed radicular pain in both arms and weakness in all 4 extremities. A CT scan of the neck revealed a pathologic fracture of the C7 vertebrae. Several medical and surgical services as well as psychiatry were consulted. Given the extensive nature of the disease involvement with limited treatment options, the patient sought to forego further interventions and was discharged to hospice care.

Basal cell carcinomas rarely metastasize, with a reported incidence of 0.0028% to 0.5%.1 The likelihood of metastasis is most closely related to tumor size and depth of invasion. Tumors greater than 3 cm in diameter have a 2% incidence of metastatic spread and/or death. The incidence of metastatic spread and/or death is estimated to be 25% for tumors with a diameter of 5 cm and 50% for tumors with a diameter of 10 cm or greater.2 Other risk factors for metastatic spread include long duration of disease, failure to respond to conventional treatment, and prior radiation treatment in the affected area.1 In one review, the median interval between onset of BCC and metastasis was 9 years.3 In our case, 15 years of neglect most likely led to the aggressiveness of the tumor. Although the workup in our patient was limited per her request, there was no evidence that her lymphoma had recurred or that she was in any other way immunocompromised. Unfortunately, in this patient’s case, the local destructiveness of the carcinoma with subsequent bony invasion and necrosis was complicated with secondary Rhizopus infection. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms basal cell carcinoma and mucormycosis revealed no other reported cases of BCC associated with mucormycosis; therefore, our case represents a rare presentation of this association. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis is the most common manifestation of mucormycosis and more commonly occurs in diabetics with ketoacidosis and in severely debilitated or immunosuppressed individuals.4 The extensive bony destruction, especially of the nasal region, of our patient’s tumor likely led to secondary infection with Rhizopus.