User login

Telmisartan-Induced Lichen Planus Eruption Manifested on Vitiliginous Skin

To the Editor:

A 39-year-old man with a history of hypertension and vitiligo presented with a rapid-onset, generalized, pruritic rash covering the body of 4 weeks’ duration. He reported that the rash progressively worsened after developing mild sunburn. The patient stated that the rash was extremely pruritic with a burning sensation and was tender to touch. He was treated with betamethasone valerate cream 0.1% by an outside physician and an over-the-counter anti-itch lotion with no notable improvement. His only medication was telmisartan-hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) for hypertension. He denied any drug allergies.

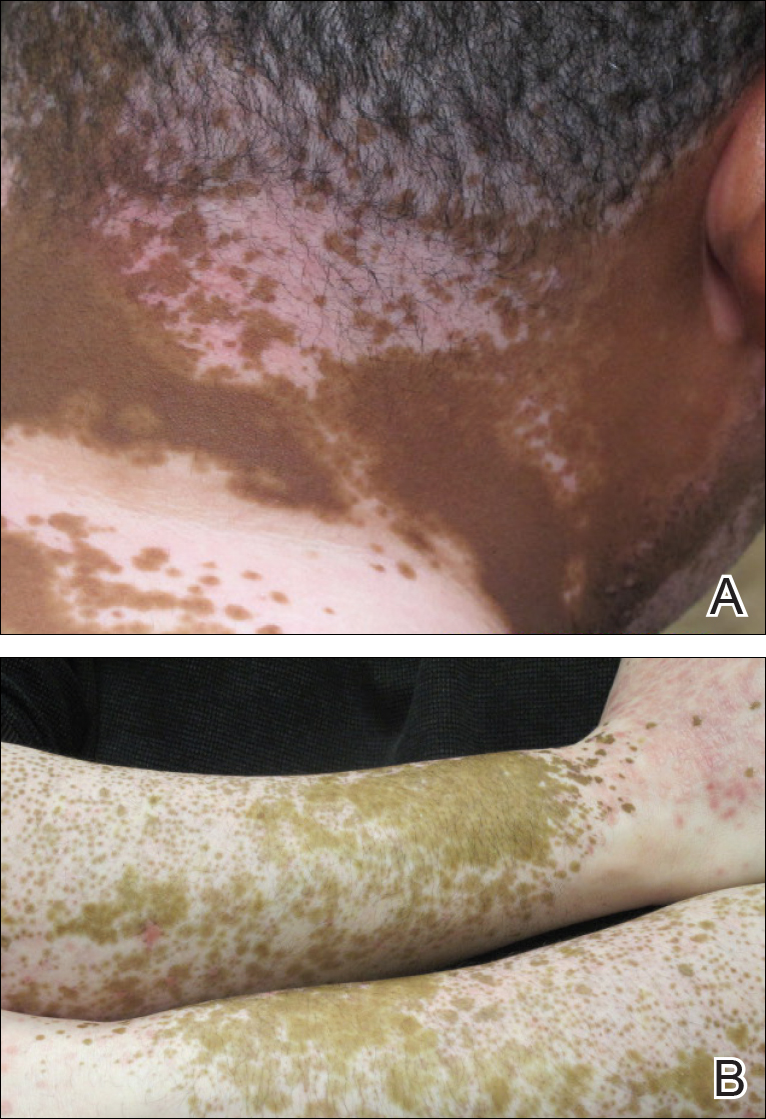

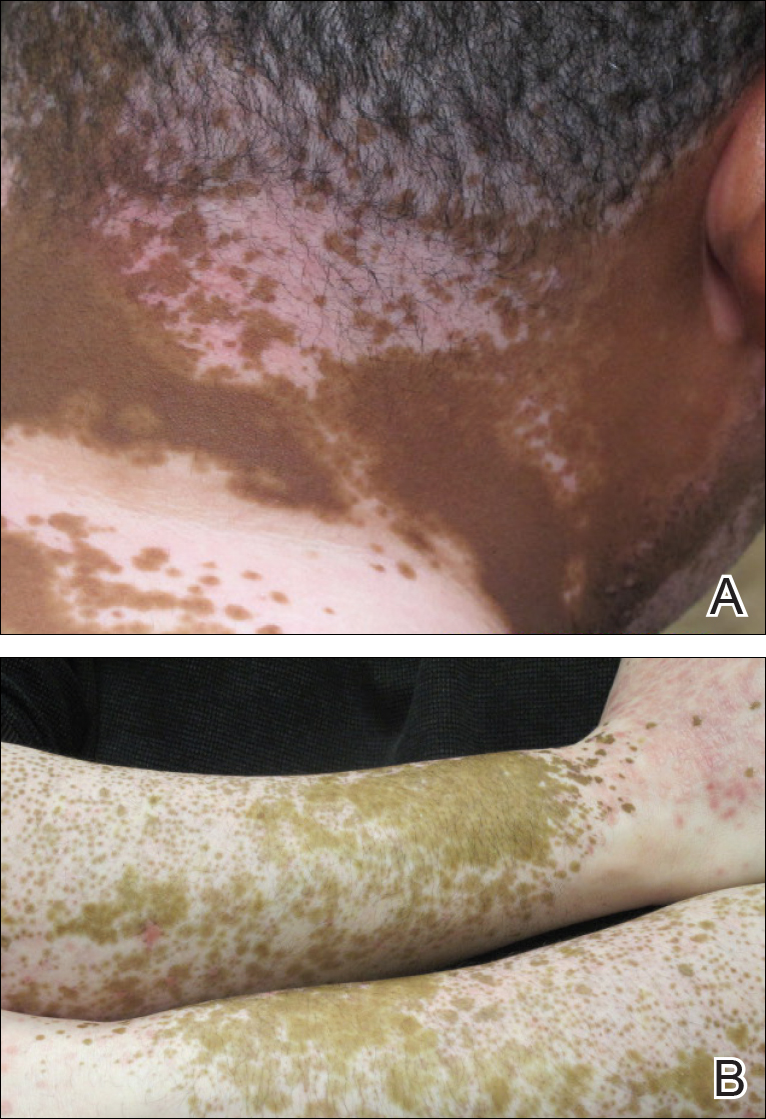

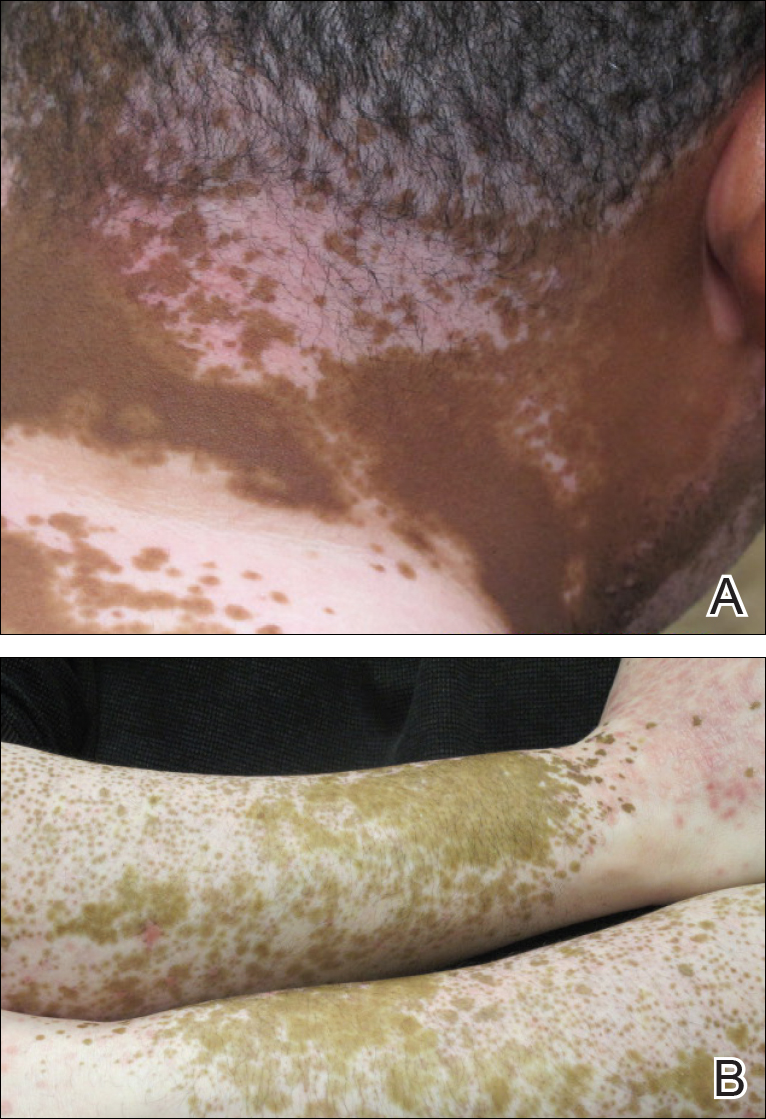

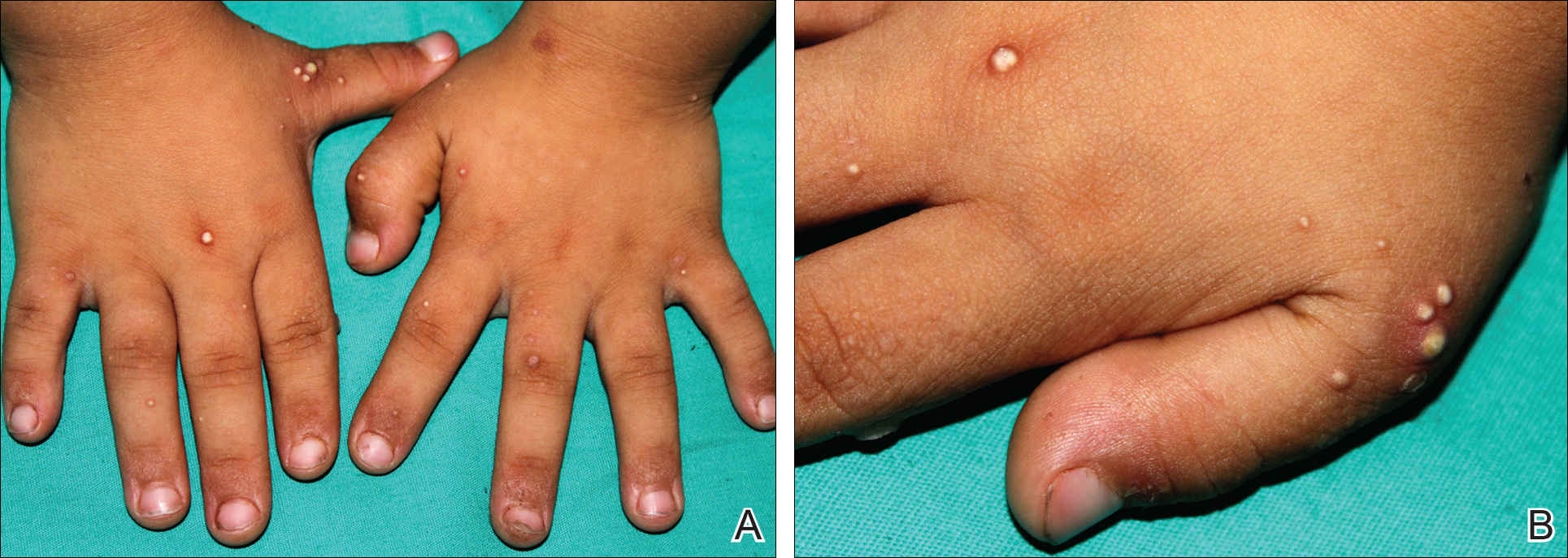

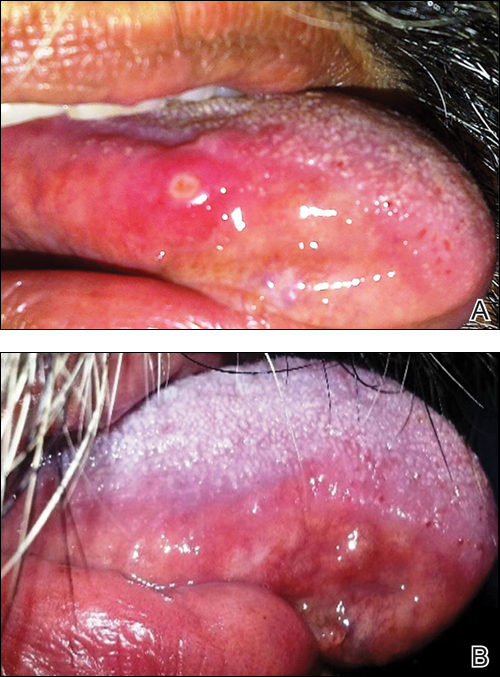

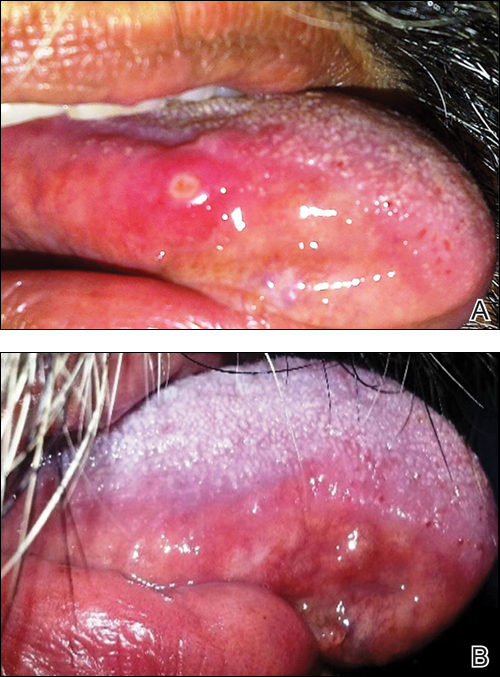

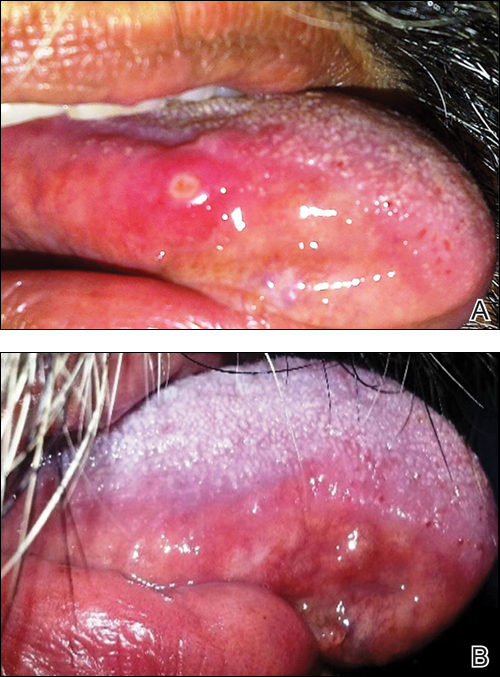

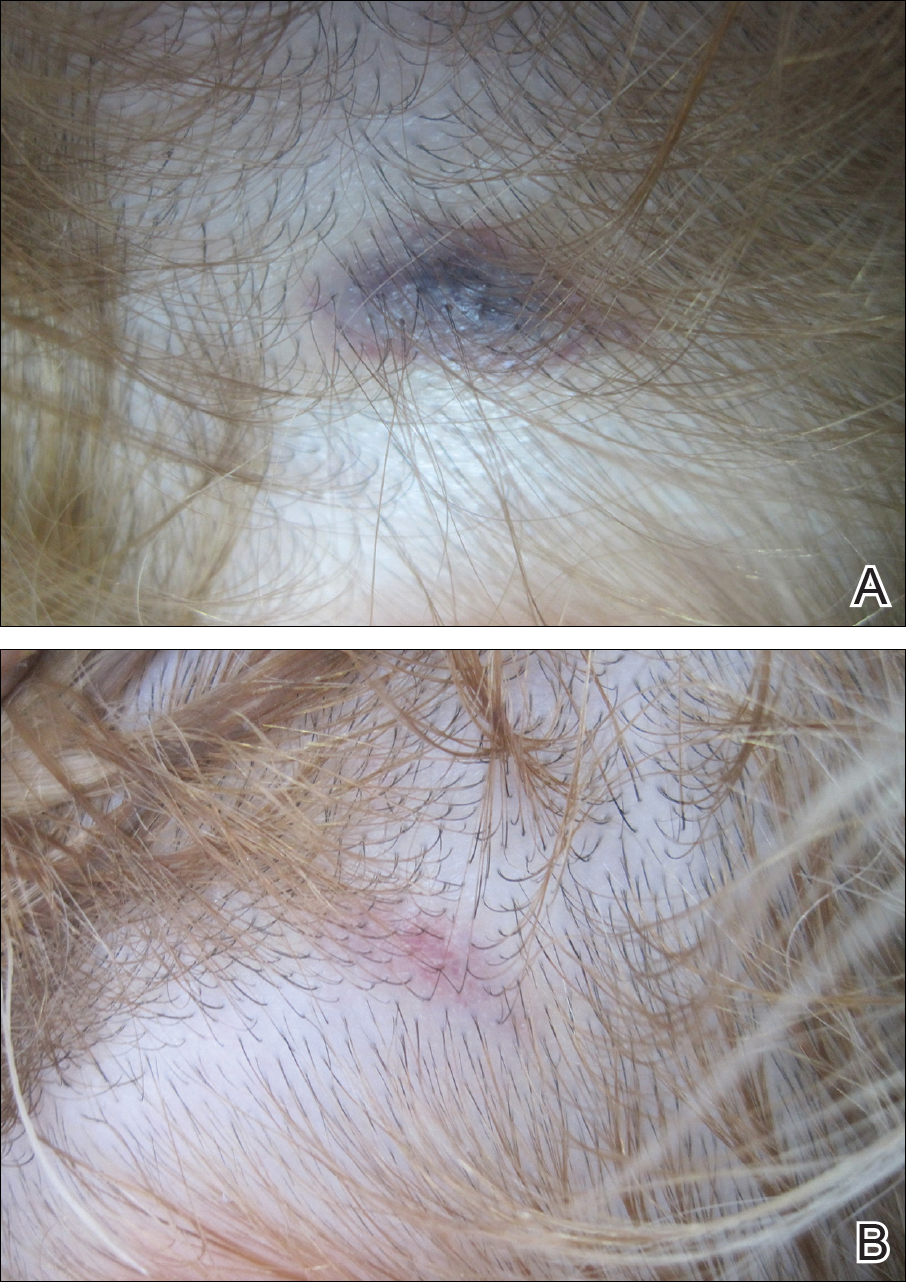

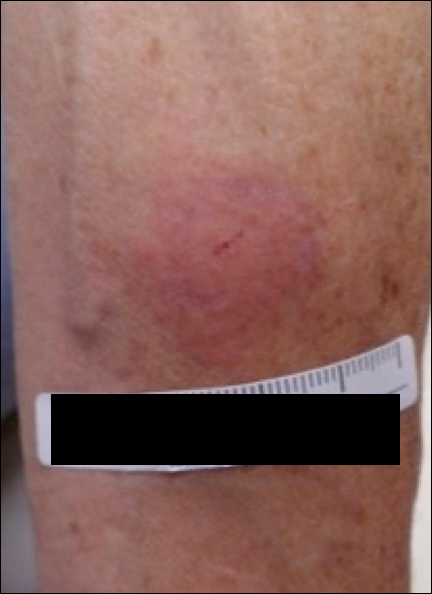

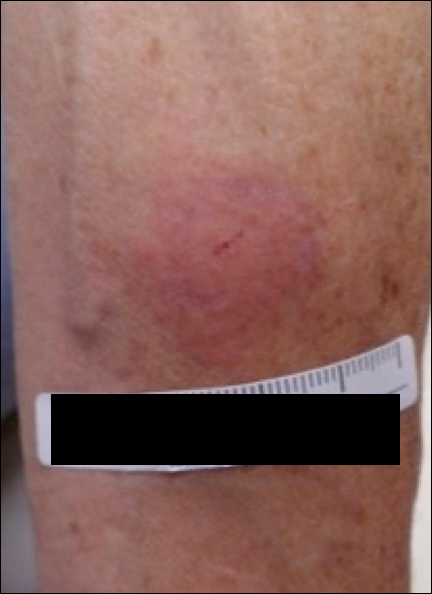

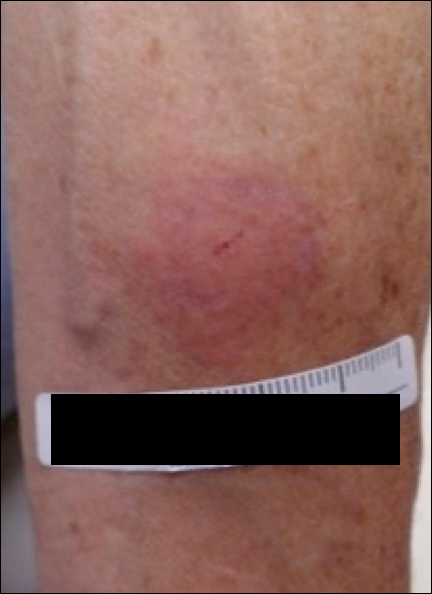

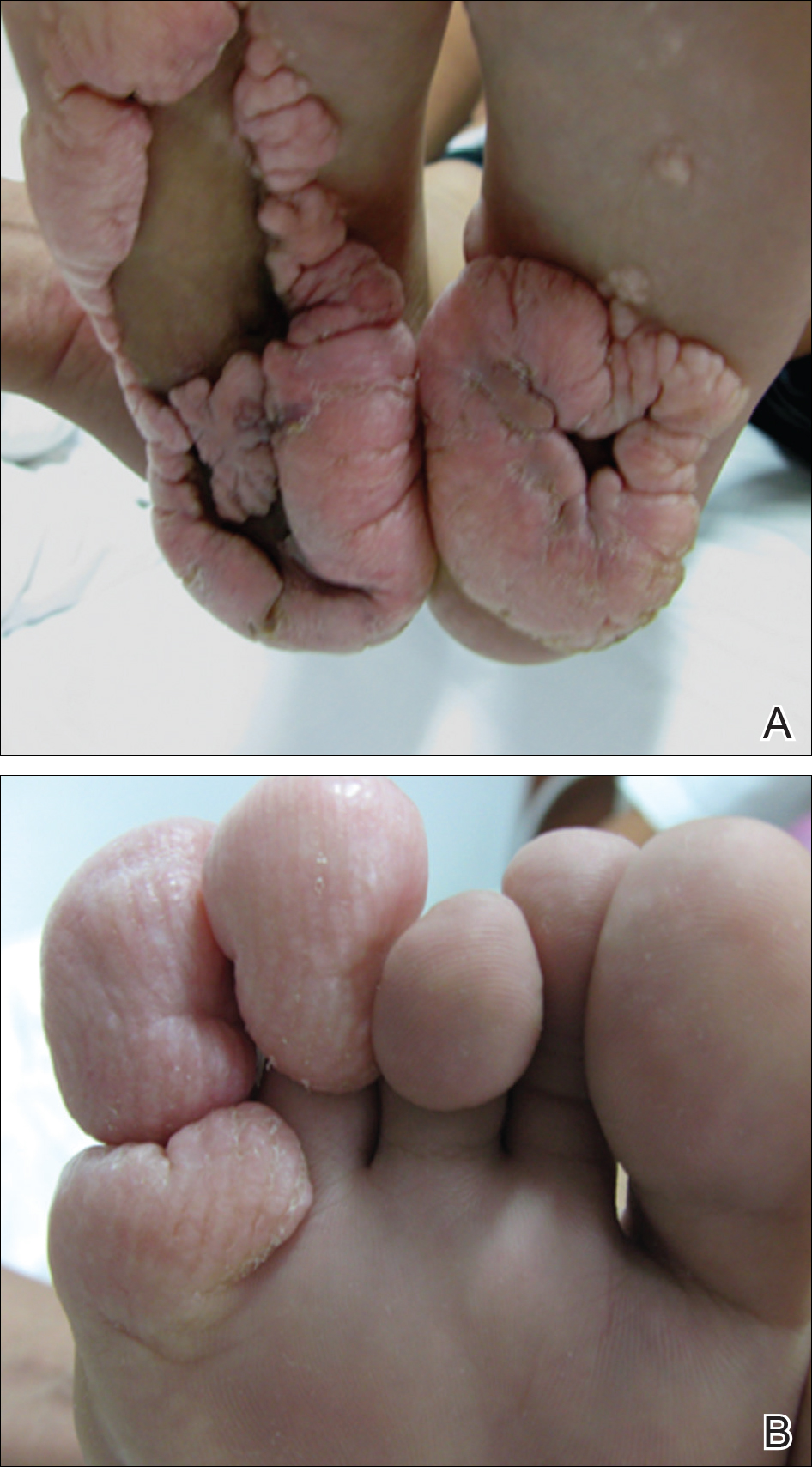

Physical examination revealed multiple discrete and coalescent planar erythematous papules and plaques involving only the depigmented vitiliginous skin of the forehead, eyelids, and nape of the neck (Figure 1A), and confluent on the lateral aspect of the bilateral forearms (Figure 1B), dorsal aspect of the right hand, and bilateral dorsi of the feet. Wickham striae were noted on the lips (Figure 1C). A clinical diagnosis of lichen planus (LP) was made. The patient initially was prescribed halobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily. He reported notable relief of pruritus with reduction of overall symptoms and new lesion formation.

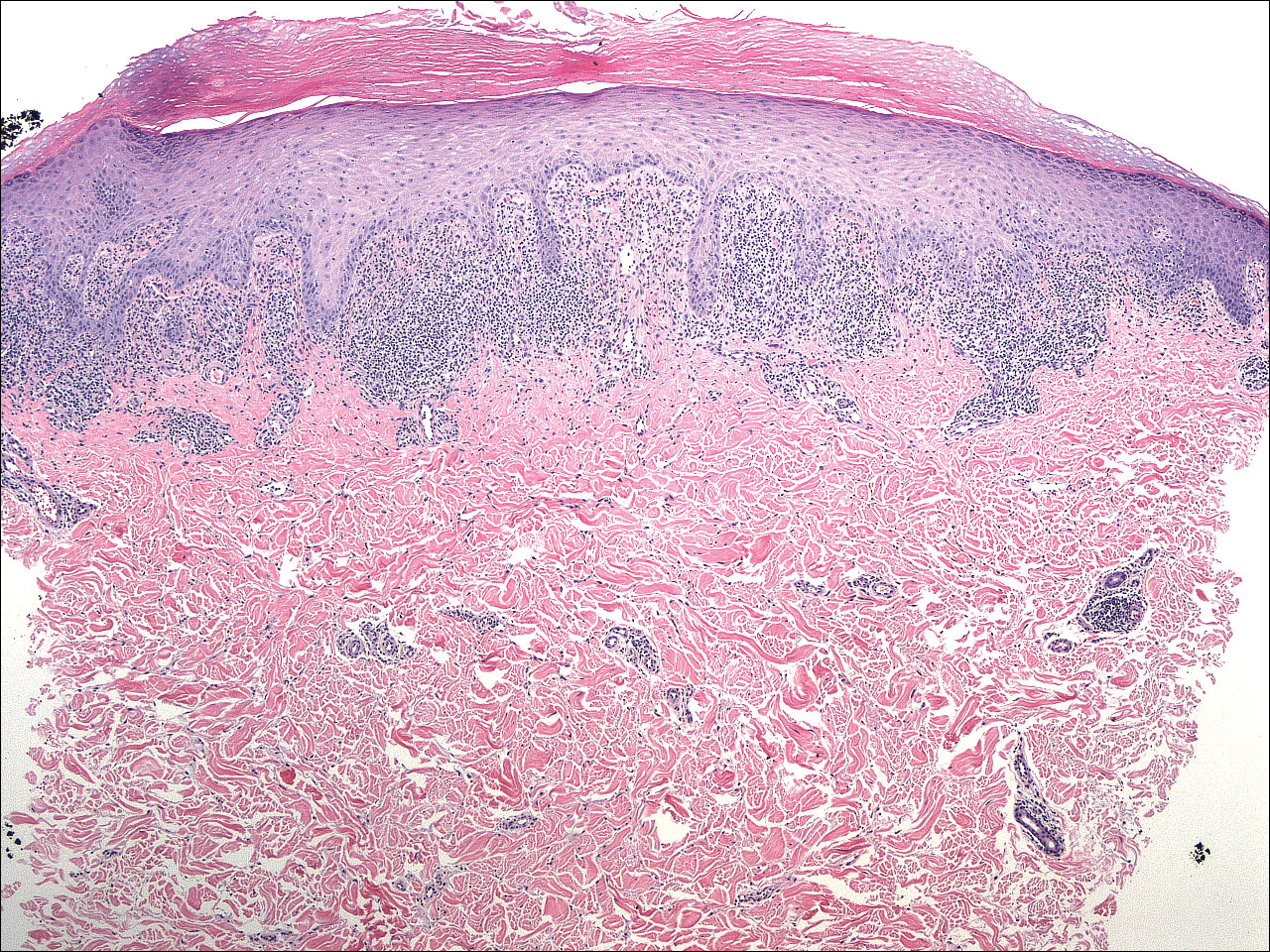

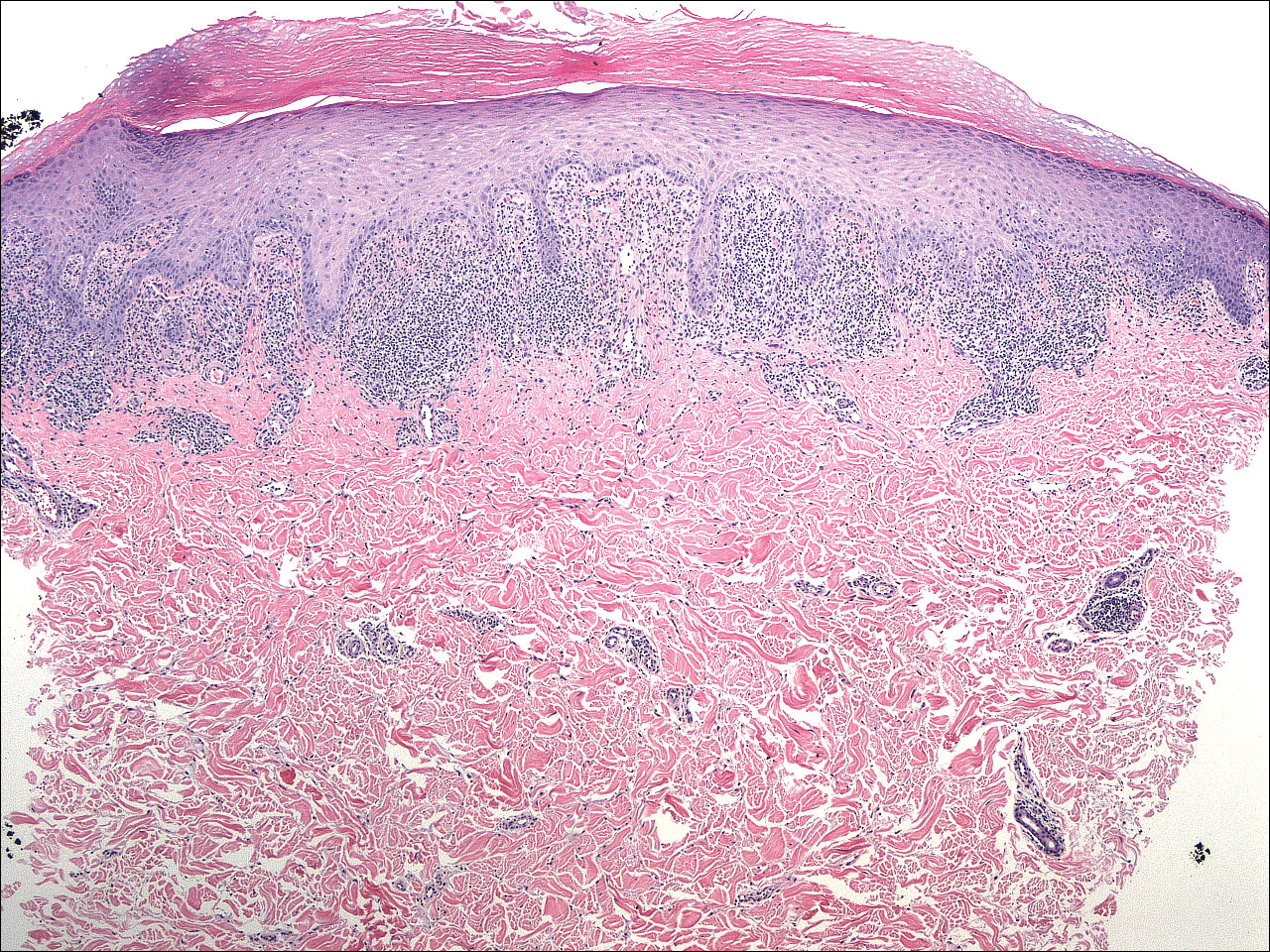

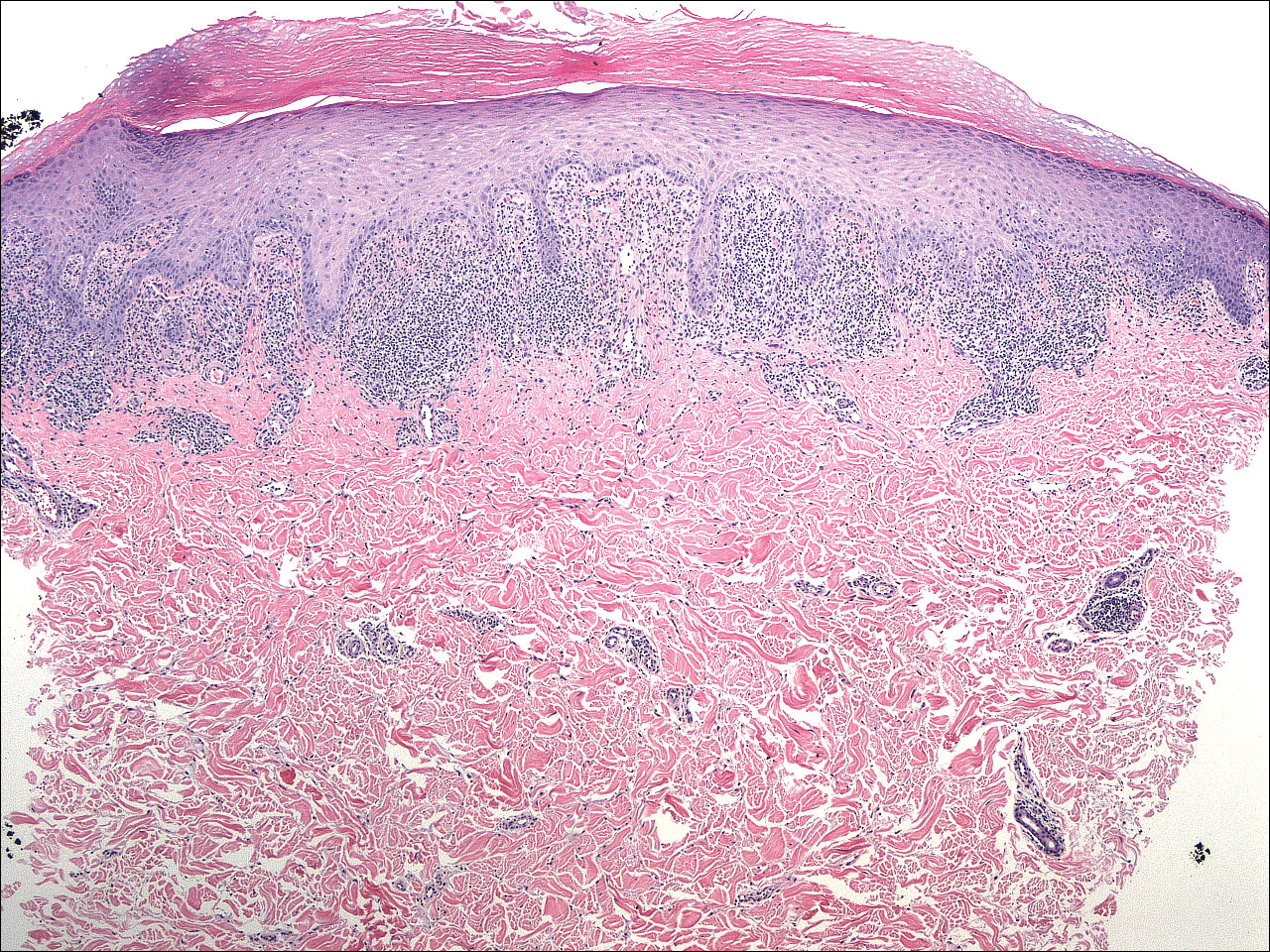

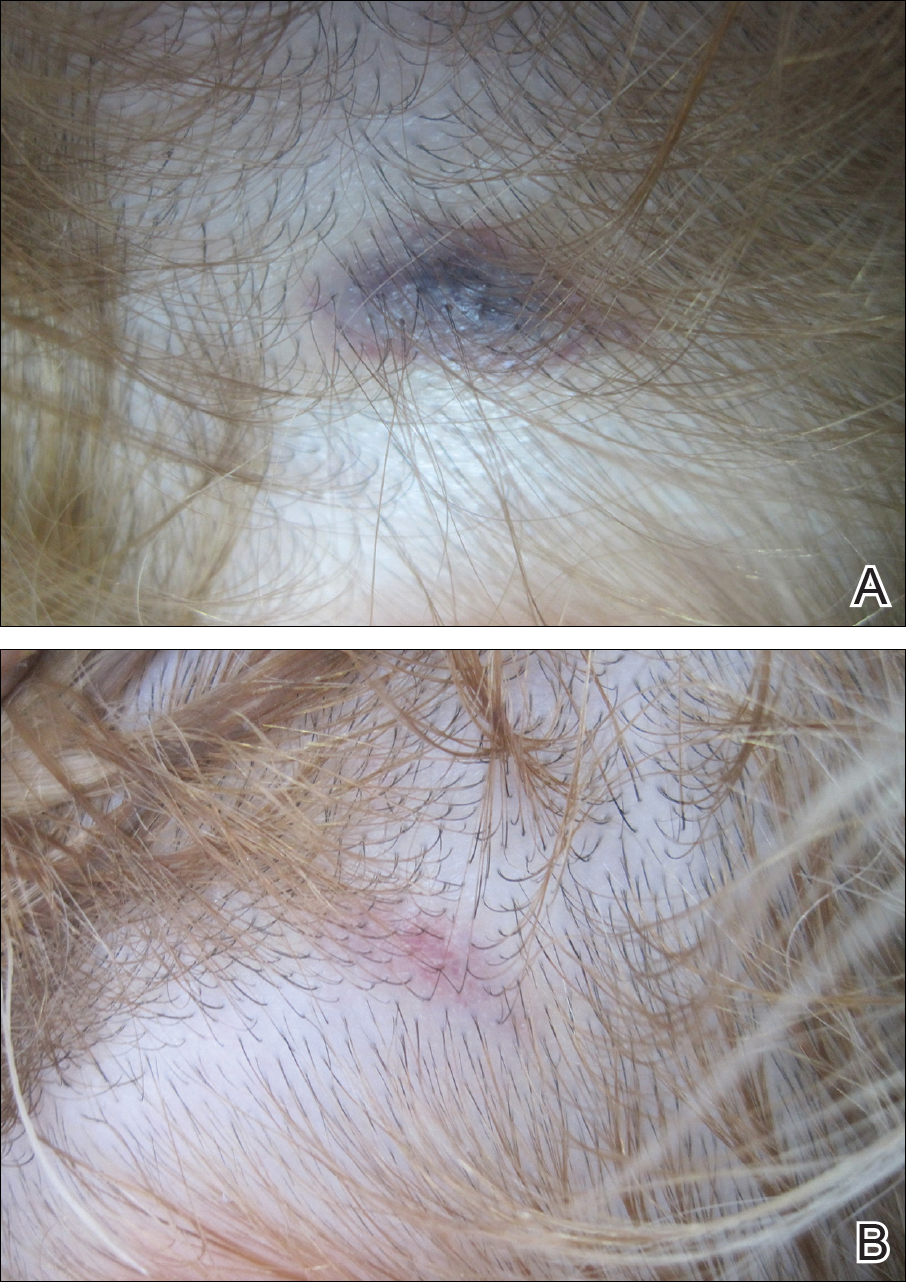

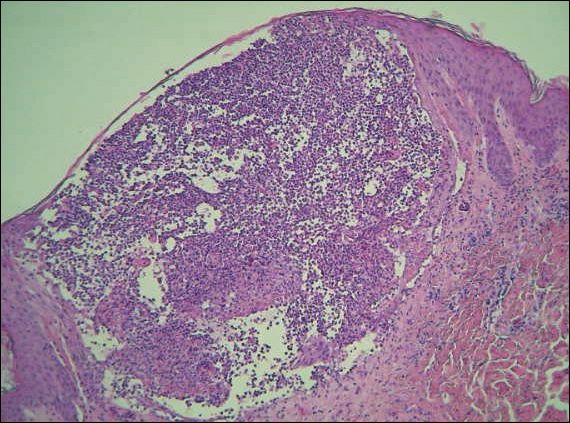

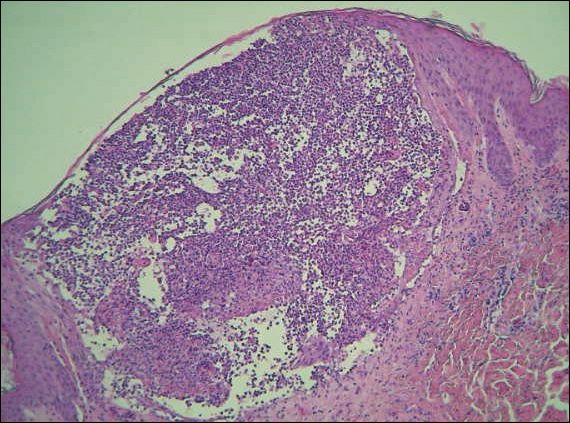

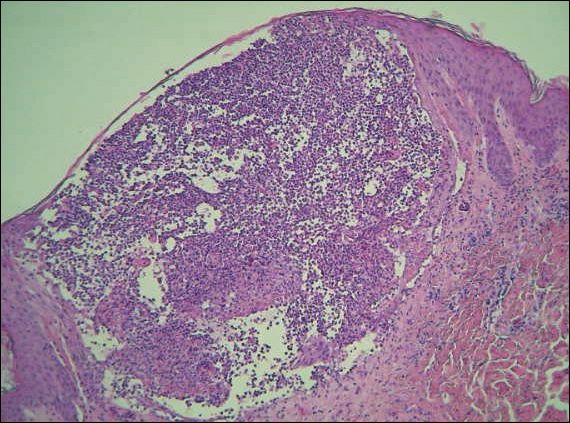

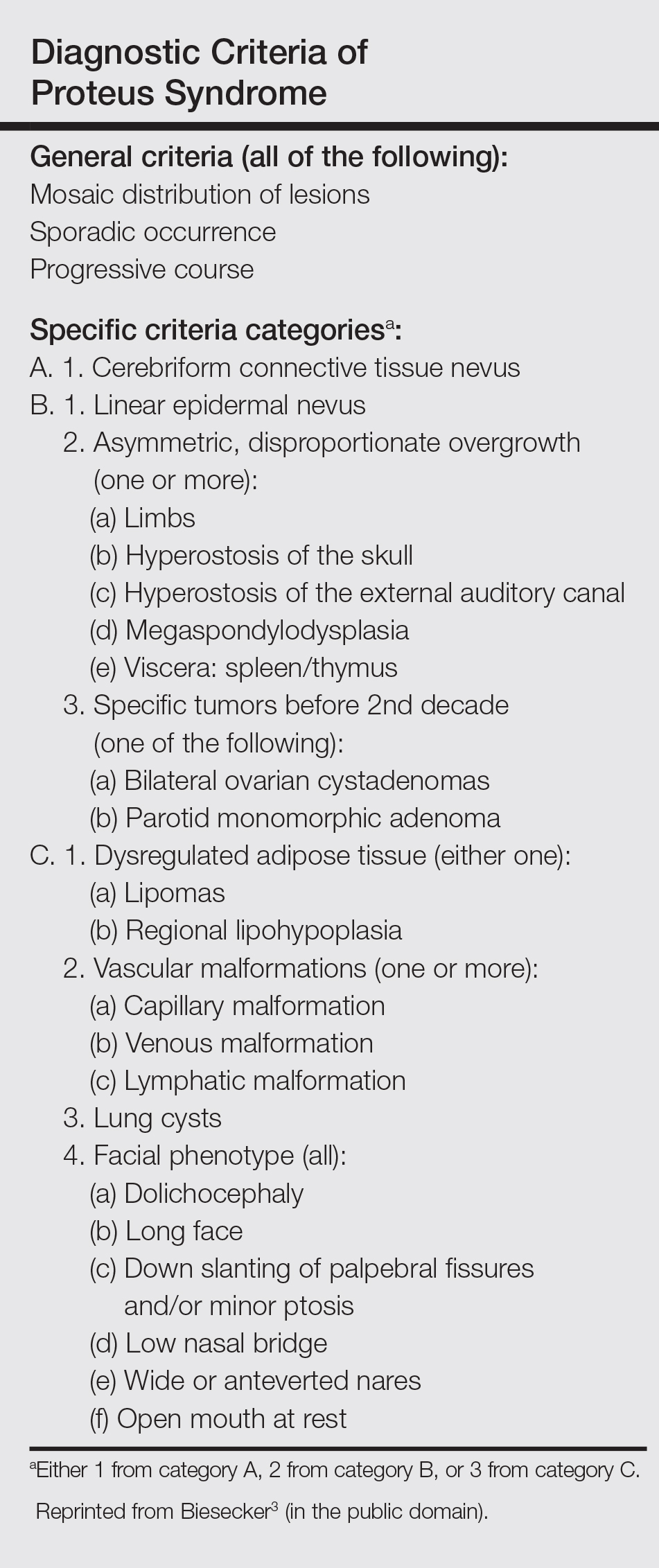

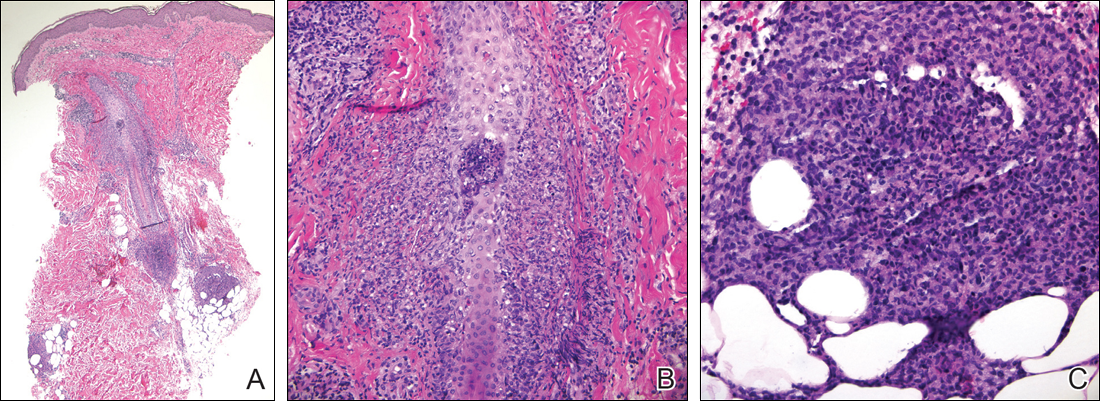

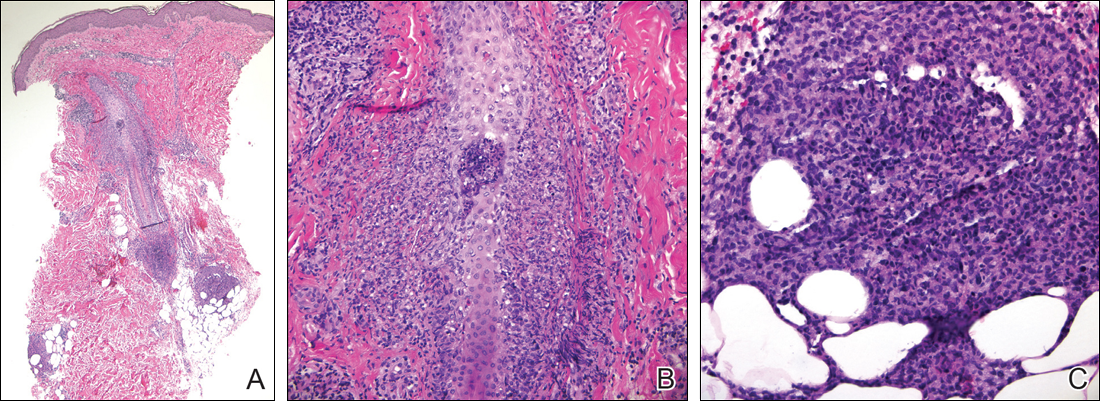

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed on the left forearm. Histopathology revealed LP. Microscopic examination of the hematoxylin and eosin–stained specimen revealed a bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate that extended across the papillary dermis, focally obscuring the dermoepidermal junction where there were vacuolar changes and colloid bodies. The epidermis showed sawtooth rete ridges, wedge-shaped foci of hypergranulosis, and compact hyperkeratosis (Figure 2).

On further questioning during follow-up, the patient revealed that his hypertensive medication was changed from HCTZ, which he had been taking for the last 8 years, to the combination antihypertensive medication telmisartan-HCTZ before the onset of the skin eruption. Due to the temporal relationship between the new medication and onset of the eruption, the clinical impression was highly suspicious for drug-induced eruptive LP with Köbner phenomenon caused by the recent sunburn. Systemic workup for underlying causes of LP was negative. Laboratory tests revealed normal complete blood cell counts. The hepatitis panel included hepatitis A antibodies; hepatitis B surface, e antigen, and core antibodies; hepatitis B surface antigen and e antibodies; hepatitis C antibodies; and antinuclear antibodies, which were all negative.

The patient continued to develop new pruritic papules clinically consistent with LP. He was instructed to return to his primary care physician to change the telmisartan-HCTZ to a different class of antihypertensive medication. His medication was changed to atenolol. The patient also was instructed to continue the halobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily to the affected areas.

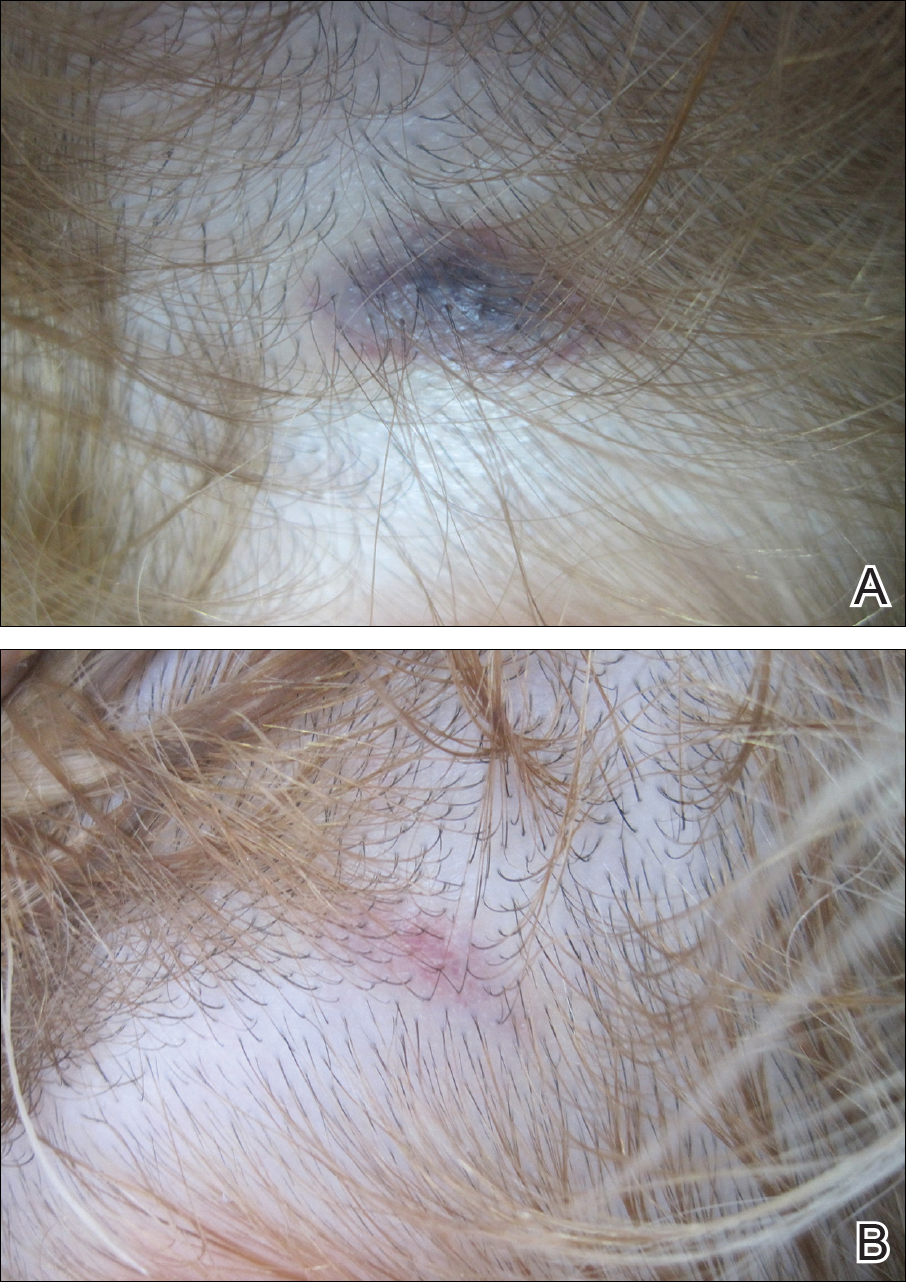

The patient returned for a follow-up visit 1 month later and reported notable improvement in pruritus and near-complete resolution of the LP after discontinuation of telmisartan-HCTZ. He also noted some degree of perifollicular repigmentation of the vitiliginous skin that had been unresponsive to prior therapy (Figure 3).

Lichen planus is a pruritic and inflammatory papulosquamous skin condition that presents as scaly, flat-topped, violaceous, polygonal-shaped papules commonly involving the flexor surface of the arms and legs, oral mucosa, scalp, nails, and genitalia. Clinically, LP can present in various forms including actinic, annular, atrophic, erosive, follicular, hypertrophic, linear, pigmented, and vesicular/bullous types. Koebnerization is common, especially in the linear form of LP. There are no specific laboratory findings or serologic markers seen in LP.

The exact cause of LP remains unknown. Clinical observations and anecdotal evidence have directed the cell-mediated immune response to insulting agents such as medications or contact allergy to metals triggering an abnormal cellular immune response. Various viral agents have been reported including hepatitis C virus, human herpesvirus, herpes simplex virus, and varicella-zoster virus.1-5 Other factors such as seasonal change and the environment may contribute to the development of LP and an increase in the incidence of LP eruption has been observed from January to July throughout the United States.6 Lichen planus also has been associated with other altered immune-related disease such as ulcerative colitis, alopecia areata, vitiligo, dermatomyositis, morphea, lichen sclerosis, and myasthenia gravis.7 Increased levels of emotional stress, particularly related to family members, often is related to the onset or aggravation of symptoms.8,9

Many drug-related LP-like and lichenoid eruptions have been reported with antihypertensive drugs, antimalarial drugs, diuretics, antidepressants, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antimicrobial drugs, and metals. In particular, medications such as captopril, enalapril, labetalol, propranolol, chlorothiazide, HCTZ, methyldopa, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, quinacrine, gold salts, penicillamine, and quinidine commonly are reported to induce lichenoid drug eruption.10

Several inflammatory papulosquamous skin conditions should be considered in the differential diagnosis before confirming the diagnosis of LP. It is important to rule out lupus erythematosus, especially if the oral mucosa and scalp are involved. In addition, erosive paraneoplastic pemphigus involving primarily the oral mucosa can resemble oral LP. Nail diseases such as psoriasis, onychomycosis, and alopecia areata should be considered as the differential diagnosis of nail disease. Genital involvement also can be seen in psoriasis and lichen sclerosus.

Treatment of LP is mainly symptomatic because of the benign nature of the disease and the high spontaneous remission rate with varying amount of time. If drugs, dental/metal implants, or underlying viral infections are the identifiable triggering factors of LP, the offending agents should be discontinued or removed. Additionally, topical or systemic treatments can be given depending on the severity of the disease, focusing mainly on symptomatic relief as well as the balance of risks and benefits associated with treatment.

Treatment options include topical and intralesional corticosteroids. Systemic medications such as oral corticosteroids and/or acitretin commonly are used in acute, severe, and disseminated cases, though treatment duration varies depending on the clinical response. Other systemic agents used to treat LP include griseofulvin, metronidazole, sulfasalazine, cyclosporine, and mycophenolate mofetil.

Phototherapy is considered an alternative therapy, especially for recalcitrant LP. UVA1 and narrowband UVB (wavelength, 311 nm) have been reported to effectively treat long-standing and therapy-resistant LP.11 In addition, a small study used the excimer laser (wavelength, 308 nm), which is well tolerated by patients, to treat focal recalcitrant oral lesions with excellent results.12 Photochemotherapy has been used with notable improvement, but the potential of carcinogenicity, especially in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types I and II, has limited its use.13

Our patient developed an unusual extensive LP eruption involving only vitiliginous skin shortly after initiation of the combined antihypertensive medication telmisartan-HCTZ, an angiotensin receptor blocker with a thiazide diuretic. Telmisartan and other angiotensin receptor blockers have not been reported to trigger LP; HCTZ is listed as one of the common drugs causing photosensitivity and LP.14,15 Although it is possible that our patient exhibited a delayed lichenoid drug eruption from the HCTZ, it is noteworthy that he did not experience a single episode of LP during his 8-year history of taking HCTZ. Instead, he developed the LP eruption shortly after the addition of telmisartan to his HCTZ antihypertensive regimen. The temporal relationship led us to direct the patient to the prescribing physician to discontinue telmisartan-HCTZ. After changing his antihypertensive medication to atenolol, the patient presented with improvement within the first month and near-complete resolution 2 months after the discontinuation of telmisartan-HCTZ.

Our patient’s LP lesions only manifested on the skin affected by vitiligo, sparing the normal-pigmented skin. Studies have demonstrated an increased ratio of CD8+ T cells to CD4+ T cells as well as increased intercellular adhesion molecule 1 at the dermal level.10,16 Both vitiligo and LP share some common histopathologic features including highly populated CD8+ T cells and intercellular adhesion molecule 1. In our case, LP was triggered on the vitiliginous skin by telmisartan. Vitiligo in combination with trauma induced by sunburn may represent the trigger that altered the cellular immune response and created the telmisartan-induced LP. As a result, the LP eruption was confined to the vitiliginous skin lesions.

Perifollicular repigmentation was observed in our patient after the LP lesions resolved; the patient’s vitiligo was unresponsive to prior treatment. The inflammatory process occurring in LP may exert and interfere in the underlying autoimmune cytotoxic effect toward the melanocytes and the melanin synthesis. It may be of interest to find out if the inflammatory response of LP has a positive influence on the effect of melanogenesis pathways or on the underlying autoimmune-related inflammatory process in vitiligo. Further studies are needed to investigate the role of immunotherapy targeting specific inflammatory pathways and the impact on the repigmentation in vitiligo.

Acknowledgment—Special thanks to Paul Chu, MD (Port Chester, New York).

- Pilli M, Zerbini A, Vescovi P, et al. Oral lichen planus pathogenesis: a role for the HCV-specific cellular immune response. Hepatology. 2002;36:1446-1452.

- De Vries HJ, van Marle J, Teunissen MB, et al. Lichen planus is associated with human herpesvirus type 7 replication and infiltration of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:361-364.

- De Vries HJ, Teunissen MB, Zorgdrager F, et al. Lichen planus remission is associated with a decrease of human herpes virus type 7 protein expression in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Arch Dermatol Res. 2007;299:213-219.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Escalonilla P, et al. Cutaneous reactions at sites of herpes zoster scars: an expanded spectrum. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:161-168.

- Al-Khenaizan S. Lichen planus occurring after hepatitis B vaccination: a new case. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:614-615.

- Boyd AS, Neldner KH. Lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:593-619.

- Sadr-Ashkevari S. Familial actinic lichen planus: case reports in two brothers. Arch Int Med. 2001;4:204-206.

- Manolache L, Seceleanu-Petrescu D, Benea V. Lichen planus patients and stressful events. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:437-441.

- Mahood JM. Familial lichen planus. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:292-294.

- Shimizu M, Higaki Y, Higaki M, et al. The role of granzyme B-expressing CD8-positive T cells in apoptosis of keratinocytes in lichen planus. Arch Dermatol Res. 1997;289:527-532.

- Bécherel PA, Bussel A, Chosidow O, et al. Extracorporeal photochemotherapy for chronic erosive lichen planus. Lancet. 1998;351:805.

- Trehan M, Taylar CR. Low-dose excimer 308-nm laser for the treatment of oral lichen planus. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:415-420.

- Wackernagel A, Legat FJ, Hofer A, et al. Psoralen plus UVA vs. UVB-311 nm for the treatment of lichen planus. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2007;23:15-19.

- Fellner MJ. Lichen planus. Int J Dermatol. 1980;19:71-75.

- Moore DE. Drug-induced cutaneous photosensitivity: incidence, mechanism, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 2002;25:345-372.

- Ongenae K, Van Geel N, Naeyaert JM. Evidence for an autoimmune pathogenesis of vitiligo. Pigment Cell Res. 2003;16:90-100.

To the Editor:

A 39-year-old man with a history of hypertension and vitiligo presented with a rapid-onset, generalized, pruritic rash covering the body of 4 weeks’ duration. He reported that the rash progressively worsened after developing mild sunburn. The patient stated that the rash was extremely pruritic with a burning sensation and was tender to touch. He was treated with betamethasone valerate cream 0.1% by an outside physician and an over-the-counter anti-itch lotion with no notable improvement. His only medication was telmisartan-hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) for hypertension. He denied any drug allergies.

Physical examination revealed multiple discrete and coalescent planar erythematous papules and plaques involving only the depigmented vitiliginous skin of the forehead, eyelids, and nape of the neck (Figure 1A), and confluent on the lateral aspect of the bilateral forearms (Figure 1B), dorsal aspect of the right hand, and bilateral dorsi of the feet. Wickham striae were noted on the lips (Figure 1C). A clinical diagnosis of lichen planus (LP) was made. The patient initially was prescribed halobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily. He reported notable relief of pruritus with reduction of overall symptoms and new lesion formation.

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed on the left forearm. Histopathology revealed LP. Microscopic examination of the hematoxylin and eosin–stained specimen revealed a bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate that extended across the papillary dermis, focally obscuring the dermoepidermal junction where there were vacuolar changes and colloid bodies. The epidermis showed sawtooth rete ridges, wedge-shaped foci of hypergranulosis, and compact hyperkeratosis (Figure 2).

On further questioning during follow-up, the patient revealed that his hypertensive medication was changed from HCTZ, which he had been taking for the last 8 years, to the combination antihypertensive medication telmisartan-HCTZ before the onset of the skin eruption. Due to the temporal relationship between the new medication and onset of the eruption, the clinical impression was highly suspicious for drug-induced eruptive LP with Köbner phenomenon caused by the recent sunburn. Systemic workup for underlying causes of LP was negative. Laboratory tests revealed normal complete blood cell counts. The hepatitis panel included hepatitis A antibodies; hepatitis B surface, e antigen, and core antibodies; hepatitis B surface antigen and e antibodies; hepatitis C antibodies; and antinuclear antibodies, which were all negative.

The patient continued to develop new pruritic papules clinically consistent with LP. He was instructed to return to his primary care physician to change the telmisartan-HCTZ to a different class of antihypertensive medication. His medication was changed to atenolol. The patient also was instructed to continue the halobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily to the affected areas.

The patient returned for a follow-up visit 1 month later and reported notable improvement in pruritus and near-complete resolution of the LP after discontinuation of telmisartan-HCTZ. He also noted some degree of perifollicular repigmentation of the vitiliginous skin that had been unresponsive to prior therapy (Figure 3).

Lichen planus is a pruritic and inflammatory papulosquamous skin condition that presents as scaly, flat-topped, violaceous, polygonal-shaped papules commonly involving the flexor surface of the arms and legs, oral mucosa, scalp, nails, and genitalia. Clinically, LP can present in various forms including actinic, annular, atrophic, erosive, follicular, hypertrophic, linear, pigmented, and vesicular/bullous types. Koebnerization is common, especially in the linear form of LP. There are no specific laboratory findings or serologic markers seen in LP.

The exact cause of LP remains unknown. Clinical observations and anecdotal evidence have directed the cell-mediated immune response to insulting agents such as medications or contact allergy to metals triggering an abnormal cellular immune response. Various viral agents have been reported including hepatitis C virus, human herpesvirus, herpes simplex virus, and varicella-zoster virus.1-5 Other factors such as seasonal change and the environment may contribute to the development of LP and an increase in the incidence of LP eruption has been observed from January to July throughout the United States.6 Lichen planus also has been associated with other altered immune-related disease such as ulcerative colitis, alopecia areata, vitiligo, dermatomyositis, morphea, lichen sclerosis, and myasthenia gravis.7 Increased levels of emotional stress, particularly related to family members, often is related to the onset or aggravation of symptoms.8,9

Many drug-related LP-like and lichenoid eruptions have been reported with antihypertensive drugs, antimalarial drugs, diuretics, antidepressants, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antimicrobial drugs, and metals. In particular, medications such as captopril, enalapril, labetalol, propranolol, chlorothiazide, HCTZ, methyldopa, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, quinacrine, gold salts, penicillamine, and quinidine commonly are reported to induce lichenoid drug eruption.10

Several inflammatory papulosquamous skin conditions should be considered in the differential diagnosis before confirming the diagnosis of LP. It is important to rule out lupus erythematosus, especially if the oral mucosa and scalp are involved. In addition, erosive paraneoplastic pemphigus involving primarily the oral mucosa can resemble oral LP. Nail diseases such as psoriasis, onychomycosis, and alopecia areata should be considered as the differential diagnosis of nail disease. Genital involvement also can be seen in psoriasis and lichen sclerosus.

Treatment of LP is mainly symptomatic because of the benign nature of the disease and the high spontaneous remission rate with varying amount of time. If drugs, dental/metal implants, or underlying viral infections are the identifiable triggering factors of LP, the offending agents should be discontinued or removed. Additionally, topical or systemic treatments can be given depending on the severity of the disease, focusing mainly on symptomatic relief as well as the balance of risks and benefits associated with treatment.

Treatment options include topical and intralesional corticosteroids. Systemic medications such as oral corticosteroids and/or acitretin commonly are used in acute, severe, and disseminated cases, though treatment duration varies depending on the clinical response. Other systemic agents used to treat LP include griseofulvin, metronidazole, sulfasalazine, cyclosporine, and mycophenolate mofetil.

Phototherapy is considered an alternative therapy, especially for recalcitrant LP. UVA1 and narrowband UVB (wavelength, 311 nm) have been reported to effectively treat long-standing and therapy-resistant LP.11 In addition, a small study used the excimer laser (wavelength, 308 nm), which is well tolerated by patients, to treat focal recalcitrant oral lesions with excellent results.12 Photochemotherapy has been used with notable improvement, but the potential of carcinogenicity, especially in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types I and II, has limited its use.13

Our patient developed an unusual extensive LP eruption involving only vitiliginous skin shortly after initiation of the combined antihypertensive medication telmisartan-HCTZ, an angiotensin receptor blocker with a thiazide diuretic. Telmisartan and other angiotensin receptor blockers have not been reported to trigger LP; HCTZ is listed as one of the common drugs causing photosensitivity and LP.14,15 Although it is possible that our patient exhibited a delayed lichenoid drug eruption from the HCTZ, it is noteworthy that he did not experience a single episode of LP during his 8-year history of taking HCTZ. Instead, he developed the LP eruption shortly after the addition of telmisartan to his HCTZ antihypertensive regimen. The temporal relationship led us to direct the patient to the prescribing physician to discontinue telmisartan-HCTZ. After changing his antihypertensive medication to atenolol, the patient presented with improvement within the first month and near-complete resolution 2 months after the discontinuation of telmisartan-HCTZ.

Our patient’s LP lesions only manifested on the skin affected by vitiligo, sparing the normal-pigmented skin. Studies have demonstrated an increased ratio of CD8+ T cells to CD4+ T cells as well as increased intercellular adhesion molecule 1 at the dermal level.10,16 Both vitiligo and LP share some common histopathologic features including highly populated CD8+ T cells and intercellular adhesion molecule 1. In our case, LP was triggered on the vitiliginous skin by telmisartan. Vitiligo in combination with trauma induced by sunburn may represent the trigger that altered the cellular immune response and created the telmisartan-induced LP. As a result, the LP eruption was confined to the vitiliginous skin lesions.

Perifollicular repigmentation was observed in our patient after the LP lesions resolved; the patient’s vitiligo was unresponsive to prior treatment. The inflammatory process occurring in LP may exert and interfere in the underlying autoimmune cytotoxic effect toward the melanocytes and the melanin synthesis. It may be of interest to find out if the inflammatory response of LP has a positive influence on the effect of melanogenesis pathways or on the underlying autoimmune-related inflammatory process in vitiligo. Further studies are needed to investigate the role of immunotherapy targeting specific inflammatory pathways and the impact on the repigmentation in vitiligo.

Acknowledgment—Special thanks to Paul Chu, MD (Port Chester, New York).

To the Editor:

A 39-year-old man with a history of hypertension and vitiligo presented with a rapid-onset, generalized, pruritic rash covering the body of 4 weeks’ duration. He reported that the rash progressively worsened after developing mild sunburn. The patient stated that the rash was extremely pruritic with a burning sensation and was tender to touch. He was treated with betamethasone valerate cream 0.1% by an outside physician and an over-the-counter anti-itch lotion with no notable improvement. His only medication was telmisartan-hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) for hypertension. He denied any drug allergies.

Physical examination revealed multiple discrete and coalescent planar erythematous papules and plaques involving only the depigmented vitiliginous skin of the forehead, eyelids, and nape of the neck (Figure 1A), and confluent on the lateral aspect of the bilateral forearms (Figure 1B), dorsal aspect of the right hand, and bilateral dorsi of the feet. Wickham striae were noted on the lips (Figure 1C). A clinical diagnosis of lichen planus (LP) was made. The patient initially was prescribed halobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily. He reported notable relief of pruritus with reduction of overall symptoms and new lesion formation.

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed on the left forearm. Histopathology revealed LP. Microscopic examination of the hematoxylin and eosin–stained specimen revealed a bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate that extended across the papillary dermis, focally obscuring the dermoepidermal junction where there were vacuolar changes and colloid bodies. The epidermis showed sawtooth rete ridges, wedge-shaped foci of hypergranulosis, and compact hyperkeratosis (Figure 2).

On further questioning during follow-up, the patient revealed that his hypertensive medication was changed from HCTZ, which he had been taking for the last 8 years, to the combination antihypertensive medication telmisartan-HCTZ before the onset of the skin eruption. Due to the temporal relationship between the new medication and onset of the eruption, the clinical impression was highly suspicious for drug-induced eruptive LP with Köbner phenomenon caused by the recent sunburn. Systemic workup for underlying causes of LP was negative. Laboratory tests revealed normal complete blood cell counts. The hepatitis panel included hepatitis A antibodies; hepatitis B surface, e antigen, and core antibodies; hepatitis B surface antigen and e antibodies; hepatitis C antibodies; and antinuclear antibodies, which were all negative.

The patient continued to develop new pruritic papules clinically consistent with LP. He was instructed to return to his primary care physician to change the telmisartan-HCTZ to a different class of antihypertensive medication. His medication was changed to atenolol. The patient also was instructed to continue the halobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily to the affected areas.

The patient returned for a follow-up visit 1 month later and reported notable improvement in pruritus and near-complete resolution of the LP after discontinuation of telmisartan-HCTZ. He also noted some degree of perifollicular repigmentation of the vitiliginous skin that had been unresponsive to prior therapy (Figure 3).

Lichen planus is a pruritic and inflammatory papulosquamous skin condition that presents as scaly, flat-topped, violaceous, polygonal-shaped papules commonly involving the flexor surface of the arms and legs, oral mucosa, scalp, nails, and genitalia. Clinically, LP can present in various forms including actinic, annular, atrophic, erosive, follicular, hypertrophic, linear, pigmented, and vesicular/bullous types. Koebnerization is common, especially in the linear form of LP. There are no specific laboratory findings or serologic markers seen in LP.

The exact cause of LP remains unknown. Clinical observations and anecdotal evidence have directed the cell-mediated immune response to insulting agents such as medications or contact allergy to metals triggering an abnormal cellular immune response. Various viral agents have been reported including hepatitis C virus, human herpesvirus, herpes simplex virus, and varicella-zoster virus.1-5 Other factors such as seasonal change and the environment may contribute to the development of LP and an increase in the incidence of LP eruption has been observed from January to July throughout the United States.6 Lichen planus also has been associated with other altered immune-related disease such as ulcerative colitis, alopecia areata, vitiligo, dermatomyositis, morphea, lichen sclerosis, and myasthenia gravis.7 Increased levels of emotional stress, particularly related to family members, often is related to the onset or aggravation of symptoms.8,9

Many drug-related LP-like and lichenoid eruptions have been reported with antihypertensive drugs, antimalarial drugs, diuretics, antidepressants, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antimicrobial drugs, and metals. In particular, medications such as captopril, enalapril, labetalol, propranolol, chlorothiazide, HCTZ, methyldopa, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, quinacrine, gold salts, penicillamine, and quinidine commonly are reported to induce lichenoid drug eruption.10

Several inflammatory papulosquamous skin conditions should be considered in the differential diagnosis before confirming the diagnosis of LP. It is important to rule out lupus erythematosus, especially if the oral mucosa and scalp are involved. In addition, erosive paraneoplastic pemphigus involving primarily the oral mucosa can resemble oral LP. Nail diseases such as psoriasis, onychomycosis, and alopecia areata should be considered as the differential diagnosis of nail disease. Genital involvement also can be seen in psoriasis and lichen sclerosus.

Treatment of LP is mainly symptomatic because of the benign nature of the disease and the high spontaneous remission rate with varying amount of time. If drugs, dental/metal implants, or underlying viral infections are the identifiable triggering factors of LP, the offending agents should be discontinued or removed. Additionally, topical or systemic treatments can be given depending on the severity of the disease, focusing mainly on symptomatic relief as well as the balance of risks and benefits associated with treatment.

Treatment options include topical and intralesional corticosteroids. Systemic medications such as oral corticosteroids and/or acitretin commonly are used in acute, severe, and disseminated cases, though treatment duration varies depending on the clinical response. Other systemic agents used to treat LP include griseofulvin, metronidazole, sulfasalazine, cyclosporine, and mycophenolate mofetil.

Phototherapy is considered an alternative therapy, especially for recalcitrant LP. UVA1 and narrowband UVB (wavelength, 311 nm) have been reported to effectively treat long-standing and therapy-resistant LP.11 In addition, a small study used the excimer laser (wavelength, 308 nm), which is well tolerated by patients, to treat focal recalcitrant oral lesions with excellent results.12 Photochemotherapy has been used with notable improvement, but the potential of carcinogenicity, especially in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types I and II, has limited its use.13

Our patient developed an unusual extensive LP eruption involving only vitiliginous skin shortly after initiation of the combined antihypertensive medication telmisartan-HCTZ, an angiotensin receptor blocker with a thiazide diuretic. Telmisartan and other angiotensin receptor blockers have not been reported to trigger LP; HCTZ is listed as one of the common drugs causing photosensitivity and LP.14,15 Although it is possible that our patient exhibited a delayed lichenoid drug eruption from the HCTZ, it is noteworthy that he did not experience a single episode of LP during his 8-year history of taking HCTZ. Instead, he developed the LP eruption shortly after the addition of telmisartan to his HCTZ antihypertensive regimen. The temporal relationship led us to direct the patient to the prescribing physician to discontinue telmisartan-HCTZ. After changing his antihypertensive medication to atenolol, the patient presented with improvement within the first month and near-complete resolution 2 months after the discontinuation of telmisartan-HCTZ.

Our patient’s LP lesions only manifested on the skin affected by vitiligo, sparing the normal-pigmented skin. Studies have demonstrated an increased ratio of CD8+ T cells to CD4+ T cells as well as increased intercellular adhesion molecule 1 at the dermal level.10,16 Both vitiligo and LP share some common histopathologic features including highly populated CD8+ T cells and intercellular adhesion molecule 1. In our case, LP was triggered on the vitiliginous skin by telmisartan. Vitiligo in combination with trauma induced by sunburn may represent the trigger that altered the cellular immune response and created the telmisartan-induced LP. As a result, the LP eruption was confined to the vitiliginous skin lesions.

Perifollicular repigmentation was observed in our patient after the LP lesions resolved; the patient’s vitiligo was unresponsive to prior treatment. The inflammatory process occurring in LP may exert and interfere in the underlying autoimmune cytotoxic effect toward the melanocytes and the melanin synthesis. It may be of interest to find out if the inflammatory response of LP has a positive influence on the effect of melanogenesis pathways or on the underlying autoimmune-related inflammatory process in vitiligo. Further studies are needed to investigate the role of immunotherapy targeting specific inflammatory pathways and the impact on the repigmentation in vitiligo.

Acknowledgment—Special thanks to Paul Chu, MD (Port Chester, New York).

- Pilli M, Zerbini A, Vescovi P, et al. Oral lichen planus pathogenesis: a role for the HCV-specific cellular immune response. Hepatology. 2002;36:1446-1452.

- De Vries HJ, van Marle J, Teunissen MB, et al. Lichen planus is associated with human herpesvirus type 7 replication and infiltration of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:361-364.

- De Vries HJ, Teunissen MB, Zorgdrager F, et al. Lichen planus remission is associated with a decrease of human herpes virus type 7 protein expression in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Arch Dermatol Res. 2007;299:213-219.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Escalonilla P, et al. Cutaneous reactions at sites of herpes zoster scars: an expanded spectrum. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:161-168.

- Al-Khenaizan S. Lichen planus occurring after hepatitis B vaccination: a new case. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:614-615.

- Boyd AS, Neldner KH. Lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:593-619.

- Sadr-Ashkevari S. Familial actinic lichen planus: case reports in two brothers. Arch Int Med. 2001;4:204-206.

- Manolache L, Seceleanu-Petrescu D, Benea V. Lichen planus patients and stressful events. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:437-441.

- Mahood JM. Familial lichen planus. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:292-294.

- Shimizu M, Higaki Y, Higaki M, et al. The role of granzyme B-expressing CD8-positive T cells in apoptosis of keratinocytes in lichen planus. Arch Dermatol Res. 1997;289:527-532.

- Bécherel PA, Bussel A, Chosidow O, et al. Extracorporeal photochemotherapy for chronic erosive lichen planus. Lancet. 1998;351:805.

- Trehan M, Taylar CR. Low-dose excimer 308-nm laser for the treatment of oral lichen planus. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:415-420.

- Wackernagel A, Legat FJ, Hofer A, et al. Psoralen plus UVA vs. UVB-311 nm for the treatment of lichen planus. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2007;23:15-19.

- Fellner MJ. Lichen planus. Int J Dermatol. 1980;19:71-75.

- Moore DE. Drug-induced cutaneous photosensitivity: incidence, mechanism, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 2002;25:345-372.

- Ongenae K, Van Geel N, Naeyaert JM. Evidence for an autoimmune pathogenesis of vitiligo. Pigment Cell Res. 2003;16:90-100.

- Pilli M, Zerbini A, Vescovi P, et al. Oral lichen planus pathogenesis: a role for the HCV-specific cellular immune response. Hepatology. 2002;36:1446-1452.

- De Vries HJ, van Marle J, Teunissen MB, et al. Lichen planus is associated with human herpesvirus type 7 replication and infiltration of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:361-364.

- De Vries HJ, Teunissen MB, Zorgdrager F, et al. Lichen planus remission is associated with a decrease of human herpes virus type 7 protein expression in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Arch Dermatol Res. 2007;299:213-219.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Escalonilla P, et al. Cutaneous reactions at sites of herpes zoster scars: an expanded spectrum. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:161-168.

- Al-Khenaizan S. Lichen planus occurring after hepatitis B vaccination: a new case. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:614-615.

- Boyd AS, Neldner KH. Lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:593-619.

- Sadr-Ashkevari S. Familial actinic lichen planus: case reports in two brothers. Arch Int Med. 2001;4:204-206.

- Manolache L, Seceleanu-Petrescu D, Benea V. Lichen planus patients and stressful events. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:437-441.

- Mahood JM. Familial lichen planus. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:292-294.

- Shimizu M, Higaki Y, Higaki M, et al. The role of granzyme B-expressing CD8-positive T cells in apoptosis of keratinocytes in lichen planus. Arch Dermatol Res. 1997;289:527-532.

- Bécherel PA, Bussel A, Chosidow O, et al. Extracorporeal photochemotherapy for chronic erosive lichen planus. Lancet. 1998;351:805.

- Trehan M, Taylar CR. Low-dose excimer 308-nm laser for the treatment of oral lichen planus. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:415-420.

- Wackernagel A, Legat FJ, Hofer A, et al. Psoralen plus UVA vs. UVB-311 nm for the treatment of lichen planus. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2007;23:15-19.

- Fellner MJ. Lichen planus. Int J Dermatol. 1980;19:71-75.

- Moore DE. Drug-induced cutaneous photosensitivity: incidence, mechanism, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 2002;25:345-372.

- Ongenae K, Van Geel N, Naeyaert JM. Evidence for an autoimmune pathogenesis of vitiligo. Pigment Cell Res. 2003;16:90-100.

Practice Points

- Lichen planus (LP) is a T-cell–mediated autoimmune disease that affects the skin and often the mucosa, nails, and scalp.

- The etiology of LP is unknown. It can be induced by a variety of medications and may spread through the isomorphic phenomenon.

- Immune factors play a role in the development of LP, drug-induced LP, and vitiligo.

Healing of Leg Ulcers Associated With Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis (Wegener Granulomatosis) After Rituximab Therapy

To the Editor:

A 52-year-old woman with a history of arthralgia, rhinitis, sinusitis, and episodic epistaxis was admitted to the hospital with multiple nonhealing severe leg ulcerations. She noticed subcutaneous nodules on the legs 6 months prior to the development of ulcers. The lesions progressed from subcutaneous nodules to red-black skin discoloration, blister formation, and eventually ulceration. Over a period of months, the ulcers were treated with several courses of antibiotics and wound care including a single surgical debridement of one of the ulcers on the dorsum of the right foot. These interventions did not make a remarkable impact on ulcer healing.

On physical examination, the patient had scattered 4- to 5-mm palpable purpura on the knees, elbows, and feet bilaterally. She had multiple 1- to 8-cm indurated purple ulcerations with friable surfaces and raised irregular borders on the feet, toes, and lower legs bilaterally (Figure, A–C). One notably larger ulcer was found on the anterior aspect of the left thigh (Figure, A). Scattered 5- to 15-mm eschars were present on the legs bilaterally. She also had multiple large, firm, nonerythematous dermal plaques on the thighs bilaterally that measured several centimeters. There were no oral mucosal lesions and no ulcerations above the waist.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the foot showed some surrounding cellulitis but no osteomyelitis. Chest radiograph and computed tomography revealed bilateral apical nodules. Proteinase 3–antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (PR3-ANCA) testing was positive. Serum complement levels were normal. An antinuclear antibody test and rheumatoid factor were both negative. Skin biopsies were obtained from the thigh ulcer, foot ulcer, and purpuric lesions on the right knee. The results demonstrated leukocytoclastic vasculitis and neutrophilic small vessel vasculitis with necrotizing neutrophilic dermatitis and panniculitis. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) was diagnosed based on these findings.

Initial inpatient treatment included intravenous methylprednisolone (100 mg every 8 hours for 3 doses), followed by oral prednisone 60 mg daily. Two weeks later the ulcers were reevaluated and only mild improvement had occurred with the steroids. Therefore, rituximab (RTX) was initiated at 375 mg/m2 (700 mg) intravenously once weekly for 4 weeks. After 3 doses of RTX, the ulcerations were healing dramatically and the treatment was well tolerated. A rapid prednisone taper was started, and the patient received her fourth and final dose of RTX. Two months after the initial infusion, the thigh ulcer and most of the ulcerations on the feet and lower legs had almost completely resolved. Photographs were taken 5 months after initial RTX infusion (Figure, D–F). A chest radiograph 4 months after initial RTX infusion showed resolution of lung nodules. Two months after RTX induction therapy, azathioprine was added for maintenance but was stopped due to poor tolerance. Oral methotrexate 17.5 mg once weekly was added 5 months after RTX for maintenance and was well tolerated. At that time the prednisone dose was 10 mg daily and was successfully tapered to 5 mg by 9 months after RTX induction therapy.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis) is a granulomatous small- and medium-sized vessel vasculitis that traditionally affects the upper and lower respiratory tract and kidneys.1 Skin lesions also are quite common and include palpable purpura, ulcers, vesicles, papules, and subcutaneous nodules. Patients with active GPA also tend to have ANCAs directed against proteinase 3 (PR3-ANCA). Although GPA was once considered a fatal disease, treatment with cyclophosphamide combined with corticosteroids has been shown to substantially improve outcomes.1 Rituximab, a chimeric monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody, works by depleting B lymphocytes and has been used with success to treat diseases such as lymphoma and rheumatoid arthritis.2,3 The US Food and Drug Administration approved RTX for GPA and microscopic polyangiitis in 2011, with a number of trials supporting its efficacy.4

The success of RTX in treating GPA has been documented in case reports as well as several trials with extended follow-up. A single-center observational study of 53 patients showed that RTX was safe and effective for induction and maintenance of remission in patients with refractory GPA. This study also uncovered the potential for predicting relapse based on following B cell and ANCA levels and preventing relapse by initializing further treatment.5 Other small studies and case reports have shown similar success using RTX for refractory GPA.6-10 These studies included various combinations of concurrent therapies and various follow-up intervals. The Rituximab in ANCA-Associated Vasculitis (RAVE) trial compared RTX versus cyclophosphamide for ANCA-positive vasculitis.11 This multicenter, randomized, double-blind study found that RTX was as efficacious as cyclophosphamide for induction of remission in severe GPA.The data also suggested that RTX may be superior for relapsing disease.11 Another multicenter, open-label, randomized trial (RITUXVAS) compared RTX to cyclophosphamide in ANCA-associated renal vasculitis. This trial also found the 2 treatments to be similar in both efficacy in inducing remission and adverse events.12

Some conflicting reports have appeared on the effectiveness of using RTX for the granulomatous versus vasculitic manifestations of GPA. Aires et al13 showed failure of improvement in most patients with granulomatous manifestations of GPA in a study of 8 patients. A retrospective study including 59 patients who were treated with RTX also showed that complete remission was more common in patients with primarily vasculitic manifestations, not granulomatous manifestations.14 However, some case series that included patients with refractory ophthalmic GPA, a primarily granulomatous manifestation, have found success using RTX.15,16 More studies are needed to determine if there truly is a difference and whether this difference has an effect on when to use RTX. The skin lesions our patient demonstrated were due to the vasculitic component of the disease, and consequently, the rapid and complete response we observed would be consistent with the premise that the therapy works best for vasculitis.

Most of the trials assessing the efficacy of RTX utilize a tool such as the Wegener granulomatosis-specific Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score.17 This measure of treatment response does include a skin item, but it is part of the composite response score. Consequently, a specific statement regarding skin improvement cannot be made. Additionally, little is reported pertaining to the treatment of skin-related findings in GPA. One report did specifically address the treatment of dermatologic manifestations of GPA utilizing systemic tacrolimus with oral prednisone successfully in 1 patient with GPA and a history of recurrent lower extremity nodules and ulcers.18 The efficacy of RTX in limited GPA was good in a small study of 8 patients. However, the study had only 1 patient with purpura and 1 patient with a subcutaneous nodule.19 Several other case series and studies have included patients with various cutaneous findings associated with GPA.5-7,9,11 However, they did not comment specifically on skin response to treatment, and the focus appeared to be on other organ system involvement. One case series did report improvement of lower extremity gangrene with RTX therapy for ANCA-associated vasculitis.8 Our report demonstrates a case of severe skin disease that responded well to RTX. It is common to have various skin findings in GPA, and our patient presented with notable skin disease. Although skin findings may not be the more life-threatening manifestations of the disease, they can be quite debilitating, as shown in our case report.

Our patient with notable leg ulcerations required hospitalization due to GPA and received RTX in addition to corticosteroids for treatment. We observed a rapid and dramatic improvement in the skin findings, which seemed to exceed expectations from steroids alone. The other manifestations of the disease including lung nodules also improved. Although cyclophosphamide and corticosteroids have been quite successful in induction of remission, cyclophosphamide is not without serious adverse effects. There also are some patients who have contraindications to cyclophosphamide or do not see successful results. In our brief review of the literature, RTX, a B cell–depleting antibody, has shown to have success in treating refractory and severe GPA. There is little reported specifically about treating the skin manifestations of GPA. A few studies and case reports mention skin findings but do not comment on the success of RTX in treating them. Although the severity of other organ involvement in GPA may take precedence, the skin findings can be quite debilitating, as in our patient. Patients with GPA and notable skin findings may benefit from RTX, and it would be beneficial to include these results in future studies using RTX to treat GPA.

- Hoffman GS, Kerr GS, Leavitt RY, et al. Wegener granulomatosis: an analysis of 158 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:488-498.

- Plosker GL, Figgitt DP. Rituximab: a review of its use in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Drugs. 2003;63:803-843.

- Cohen SB, Emery P, Greenwald MW, et al. Rituximab for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial evaluating primary efficacy and safety at twenty-four weeks. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2793-2806.

- FDA approves Rituxan to treat two rare disorders [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; April 19, 2011. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm251946.htm. Accessed January 6, 2017.

- Cartin-Ceba R, Golbin JM, Keogh KA, et al. Rituximab for remission induction and maintenance in refractory granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s): ten-year experience at a single center. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:3770-3778.

- Keogh KA, Ytterberg SR, Fervenza FC, et al. Rituximab for refractory Wegener’s granulomatosis: report of a prospective, open-label pilot trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:180-187.

- Dalkilic E, Alkis N, Kamali S. Rituximab as a new therapeutic option in granulomatosis with polyangiitis: a report of two cases. Mod Rheumatol. 2012;22:463-466.

- Eriksson P. Nine patients with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-positive vasculitis successfully treated with rituximab. J Intern Med. 2005;257:540-548.

- Oristrell J, Bejarano G, Jordana R, et al. Effectiveness of rituximab in severe Wegener’s granulomatosis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Open Respir Med J. 2009;3:94-99.

- Martinez Del Pero M, Chaudhry A, Jones RB, et al. B-cell depletion with rituximab for refractory head and neck Wegener’s granulomatosis: a cohort study. Clin Otolaryngol. 2009;34:328-335.

- Stone JH, Merkel PA, Spiera R, et al. Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide for ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:221-232.

- Jones RB, Tervaert JW, Hauser T, et al. Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide in ANCA-associated renal vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:211-220.

- Aries PM, Hellmich B, Voswinkel J, et al. Lack of efficacy of rituximab in Wegener’s granulomatosis with refractory granulomatous manifestations. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:853-858.

- Holle JU, Dubrau C, Herlyn K, et al. Rituximab for refractory granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s granulomatosis): comparison of efficacy in granulomatous versus vasculitic manifestations. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:327-333.

- Taylor SR, Salama AD, Joshi L, et al. Rituximab is effective in the treatment of refractory ophthalmic Wegener’s granulomatosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:1540-1547.

- Joshi L, Lightman SL, Salama AD, et al. Rituximab in refractory ophthalmic Wegener’s granulomatosis: PR3 titers may predict relapse, but repeat treatment can be effective. Ophthalmol. 2011;118:2498-2503.

- Stone JH, Hoffman GS, Merkel PA, et al. A disease-specific activity index for Wegener’s granulomatosis: modification of the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score. International Network for the Study of the Systemic Vasculitides (INSSYS). Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:912-920.

- Wenzel J, Montag S, Wilsmann-Theis D, et al. Successful treatment of recalcitrant Wegener’s granulomatosis of the skin with tacrolimus (Prograf). Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:927-928.

- Seo P, Specks U, Keogh KA. Efficacy of rituximab in limited Wegener’s granulomatosis with refractory granulomatous manifestations. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:2017-2023.

To the Editor:

A 52-year-old woman with a history of arthralgia, rhinitis, sinusitis, and episodic epistaxis was admitted to the hospital with multiple nonhealing severe leg ulcerations. She noticed subcutaneous nodules on the legs 6 months prior to the development of ulcers. The lesions progressed from subcutaneous nodules to red-black skin discoloration, blister formation, and eventually ulceration. Over a period of months, the ulcers were treated with several courses of antibiotics and wound care including a single surgical debridement of one of the ulcers on the dorsum of the right foot. These interventions did not make a remarkable impact on ulcer healing.

On physical examination, the patient had scattered 4- to 5-mm palpable purpura on the knees, elbows, and feet bilaterally. She had multiple 1- to 8-cm indurated purple ulcerations with friable surfaces and raised irregular borders on the feet, toes, and lower legs bilaterally (Figure, A–C). One notably larger ulcer was found on the anterior aspect of the left thigh (Figure, A). Scattered 5- to 15-mm eschars were present on the legs bilaterally. She also had multiple large, firm, nonerythematous dermal plaques on the thighs bilaterally that measured several centimeters. There were no oral mucosal lesions and no ulcerations above the waist.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the foot showed some surrounding cellulitis but no osteomyelitis. Chest radiograph and computed tomography revealed bilateral apical nodules. Proteinase 3–antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (PR3-ANCA) testing was positive. Serum complement levels were normal. An antinuclear antibody test and rheumatoid factor were both negative. Skin biopsies were obtained from the thigh ulcer, foot ulcer, and purpuric lesions on the right knee. The results demonstrated leukocytoclastic vasculitis and neutrophilic small vessel vasculitis with necrotizing neutrophilic dermatitis and panniculitis. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) was diagnosed based on these findings.

Initial inpatient treatment included intravenous methylprednisolone (100 mg every 8 hours for 3 doses), followed by oral prednisone 60 mg daily. Two weeks later the ulcers were reevaluated and only mild improvement had occurred with the steroids. Therefore, rituximab (RTX) was initiated at 375 mg/m2 (700 mg) intravenously once weekly for 4 weeks. After 3 doses of RTX, the ulcerations were healing dramatically and the treatment was well tolerated. A rapid prednisone taper was started, and the patient received her fourth and final dose of RTX. Two months after the initial infusion, the thigh ulcer and most of the ulcerations on the feet and lower legs had almost completely resolved. Photographs were taken 5 months after initial RTX infusion (Figure, D–F). A chest radiograph 4 months after initial RTX infusion showed resolution of lung nodules. Two months after RTX induction therapy, azathioprine was added for maintenance but was stopped due to poor tolerance. Oral methotrexate 17.5 mg once weekly was added 5 months after RTX for maintenance and was well tolerated. At that time the prednisone dose was 10 mg daily and was successfully tapered to 5 mg by 9 months after RTX induction therapy.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis) is a granulomatous small- and medium-sized vessel vasculitis that traditionally affects the upper and lower respiratory tract and kidneys.1 Skin lesions also are quite common and include palpable purpura, ulcers, vesicles, papules, and subcutaneous nodules. Patients with active GPA also tend to have ANCAs directed against proteinase 3 (PR3-ANCA). Although GPA was once considered a fatal disease, treatment with cyclophosphamide combined with corticosteroids has been shown to substantially improve outcomes.1 Rituximab, a chimeric monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody, works by depleting B lymphocytes and has been used with success to treat diseases such as lymphoma and rheumatoid arthritis.2,3 The US Food and Drug Administration approved RTX for GPA and microscopic polyangiitis in 2011, with a number of trials supporting its efficacy.4

The success of RTX in treating GPA has been documented in case reports as well as several trials with extended follow-up. A single-center observational study of 53 patients showed that RTX was safe and effective for induction and maintenance of remission in patients with refractory GPA. This study also uncovered the potential for predicting relapse based on following B cell and ANCA levels and preventing relapse by initializing further treatment.5 Other small studies and case reports have shown similar success using RTX for refractory GPA.6-10 These studies included various combinations of concurrent therapies and various follow-up intervals. The Rituximab in ANCA-Associated Vasculitis (RAVE) trial compared RTX versus cyclophosphamide for ANCA-positive vasculitis.11 This multicenter, randomized, double-blind study found that RTX was as efficacious as cyclophosphamide for induction of remission in severe GPA.The data also suggested that RTX may be superior for relapsing disease.11 Another multicenter, open-label, randomized trial (RITUXVAS) compared RTX to cyclophosphamide in ANCA-associated renal vasculitis. This trial also found the 2 treatments to be similar in both efficacy in inducing remission and adverse events.12

Some conflicting reports have appeared on the effectiveness of using RTX for the granulomatous versus vasculitic manifestations of GPA. Aires et al13 showed failure of improvement in most patients with granulomatous manifestations of GPA in a study of 8 patients. A retrospective study including 59 patients who were treated with RTX also showed that complete remission was more common in patients with primarily vasculitic manifestations, not granulomatous manifestations.14 However, some case series that included patients with refractory ophthalmic GPA, a primarily granulomatous manifestation, have found success using RTX.15,16 More studies are needed to determine if there truly is a difference and whether this difference has an effect on when to use RTX. The skin lesions our patient demonstrated were due to the vasculitic component of the disease, and consequently, the rapid and complete response we observed would be consistent with the premise that the therapy works best for vasculitis.

Most of the trials assessing the efficacy of RTX utilize a tool such as the Wegener granulomatosis-specific Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score.17 This measure of treatment response does include a skin item, but it is part of the composite response score. Consequently, a specific statement regarding skin improvement cannot be made. Additionally, little is reported pertaining to the treatment of skin-related findings in GPA. One report did specifically address the treatment of dermatologic manifestations of GPA utilizing systemic tacrolimus with oral prednisone successfully in 1 patient with GPA and a history of recurrent lower extremity nodules and ulcers.18 The efficacy of RTX in limited GPA was good in a small study of 8 patients. However, the study had only 1 patient with purpura and 1 patient with a subcutaneous nodule.19 Several other case series and studies have included patients with various cutaneous findings associated with GPA.5-7,9,11 However, they did not comment specifically on skin response to treatment, and the focus appeared to be on other organ system involvement. One case series did report improvement of lower extremity gangrene with RTX therapy for ANCA-associated vasculitis.8 Our report demonstrates a case of severe skin disease that responded well to RTX. It is common to have various skin findings in GPA, and our patient presented with notable skin disease. Although skin findings may not be the more life-threatening manifestations of the disease, they can be quite debilitating, as shown in our case report.

Our patient with notable leg ulcerations required hospitalization due to GPA and received RTX in addition to corticosteroids for treatment. We observed a rapid and dramatic improvement in the skin findings, which seemed to exceed expectations from steroids alone. The other manifestations of the disease including lung nodules also improved. Although cyclophosphamide and corticosteroids have been quite successful in induction of remission, cyclophosphamide is not without serious adverse effects. There also are some patients who have contraindications to cyclophosphamide or do not see successful results. In our brief review of the literature, RTX, a B cell–depleting antibody, has shown to have success in treating refractory and severe GPA. There is little reported specifically about treating the skin manifestations of GPA. A few studies and case reports mention skin findings but do not comment on the success of RTX in treating them. Although the severity of other organ involvement in GPA may take precedence, the skin findings can be quite debilitating, as in our patient. Patients with GPA and notable skin findings may benefit from RTX, and it would be beneficial to include these results in future studies using RTX to treat GPA.

To the Editor:

A 52-year-old woman with a history of arthralgia, rhinitis, sinusitis, and episodic epistaxis was admitted to the hospital with multiple nonhealing severe leg ulcerations. She noticed subcutaneous nodules on the legs 6 months prior to the development of ulcers. The lesions progressed from subcutaneous nodules to red-black skin discoloration, blister formation, and eventually ulceration. Over a period of months, the ulcers were treated with several courses of antibiotics and wound care including a single surgical debridement of one of the ulcers on the dorsum of the right foot. These interventions did not make a remarkable impact on ulcer healing.

On physical examination, the patient had scattered 4- to 5-mm palpable purpura on the knees, elbows, and feet bilaterally. She had multiple 1- to 8-cm indurated purple ulcerations with friable surfaces and raised irregular borders on the feet, toes, and lower legs bilaterally (Figure, A–C). One notably larger ulcer was found on the anterior aspect of the left thigh (Figure, A). Scattered 5- to 15-mm eschars were present on the legs bilaterally. She also had multiple large, firm, nonerythematous dermal plaques on the thighs bilaterally that measured several centimeters. There were no oral mucosal lesions and no ulcerations above the waist.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the foot showed some surrounding cellulitis but no osteomyelitis. Chest radiograph and computed tomography revealed bilateral apical nodules. Proteinase 3–antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (PR3-ANCA) testing was positive. Serum complement levels were normal. An antinuclear antibody test and rheumatoid factor were both negative. Skin biopsies were obtained from the thigh ulcer, foot ulcer, and purpuric lesions on the right knee. The results demonstrated leukocytoclastic vasculitis and neutrophilic small vessel vasculitis with necrotizing neutrophilic dermatitis and panniculitis. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) was diagnosed based on these findings.

Initial inpatient treatment included intravenous methylprednisolone (100 mg every 8 hours for 3 doses), followed by oral prednisone 60 mg daily. Two weeks later the ulcers were reevaluated and only mild improvement had occurred with the steroids. Therefore, rituximab (RTX) was initiated at 375 mg/m2 (700 mg) intravenously once weekly for 4 weeks. After 3 doses of RTX, the ulcerations were healing dramatically and the treatment was well tolerated. A rapid prednisone taper was started, and the patient received her fourth and final dose of RTX. Two months after the initial infusion, the thigh ulcer and most of the ulcerations on the feet and lower legs had almost completely resolved. Photographs were taken 5 months after initial RTX infusion (Figure, D–F). A chest radiograph 4 months after initial RTX infusion showed resolution of lung nodules. Two months after RTX induction therapy, azathioprine was added for maintenance but was stopped due to poor tolerance. Oral methotrexate 17.5 mg once weekly was added 5 months after RTX for maintenance and was well tolerated. At that time the prednisone dose was 10 mg daily and was successfully tapered to 5 mg by 9 months after RTX induction therapy.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis) is a granulomatous small- and medium-sized vessel vasculitis that traditionally affects the upper and lower respiratory tract and kidneys.1 Skin lesions also are quite common and include palpable purpura, ulcers, vesicles, papules, and subcutaneous nodules. Patients with active GPA also tend to have ANCAs directed against proteinase 3 (PR3-ANCA). Although GPA was once considered a fatal disease, treatment with cyclophosphamide combined with corticosteroids has been shown to substantially improve outcomes.1 Rituximab, a chimeric monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody, works by depleting B lymphocytes and has been used with success to treat diseases such as lymphoma and rheumatoid arthritis.2,3 The US Food and Drug Administration approved RTX for GPA and microscopic polyangiitis in 2011, with a number of trials supporting its efficacy.4

The success of RTX in treating GPA has been documented in case reports as well as several trials with extended follow-up. A single-center observational study of 53 patients showed that RTX was safe and effective for induction and maintenance of remission in patients with refractory GPA. This study also uncovered the potential for predicting relapse based on following B cell and ANCA levels and preventing relapse by initializing further treatment.5 Other small studies and case reports have shown similar success using RTX for refractory GPA.6-10 These studies included various combinations of concurrent therapies and various follow-up intervals. The Rituximab in ANCA-Associated Vasculitis (RAVE) trial compared RTX versus cyclophosphamide for ANCA-positive vasculitis.11 This multicenter, randomized, double-blind study found that RTX was as efficacious as cyclophosphamide for induction of remission in severe GPA.The data also suggested that RTX may be superior for relapsing disease.11 Another multicenter, open-label, randomized trial (RITUXVAS) compared RTX to cyclophosphamide in ANCA-associated renal vasculitis. This trial also found the 2 treatments to be similar in both efficacy in inducing remission and adverse events.12

Some conflicting reports have appeared on the effectiveness of using RTX for the granulomatous versus vasculitic manifestations of GPA. Aires et al13 showed failure of improvement in most patients with granulomatous manifestations of GPA in a study of 8 patients. A retrospective study including 59 patients who were treated with RTX also showed that complete remission was more common in patients with primarily vasculitic manifestations, not granulomatous manifestations.14 However, some case series that included patients with refractory ophthalmic GPA, a primarily granulomatous manifestation, have found success using RTX.15,16 More studies are needed to determine if there truly is a difference and whether this difference has an effect on when to use RTX. The skin lesions our patient demonstrated were due to the vasculitic component of the disease, and consequently, the rapid and complete response we observed would be consistent with the premise that the therapy works best for vasculitis.

Most of the trials assessing the efficacy of RTX utilize a tool such as the Wegener granulomatosis-specific Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score.17 This measure of treatment response does include a skin item, but it is part of the composite response score. Consequently, a specific statement regarding skin improvement cannot be made. Additionally, little is reported pertaining to the treatment of skin-related findings in GPA. One report did specifically address the treatment of dermatologic manifestations of GPA utilizing systemic tacrolimus with oral prednisone successfully in 1 patient with GPA and a history of recurrent lower extremity nodules and ulcers.18 The efficacy of RTX in limited GPA was good in a small study of 8 patients. However, the study had only 1 patient with purpura and 1 patient with a subcutaneous nodule.19 Several other case series and studies have included patients with various cutaneous findings associated with GPA.5-7,9,11 However, they did not comment specifically on skin response to treatment, and the focus appeared to be on other organ system involvement. One case series did report improvement of lower extremity gangrene with RTX therapy for ANCA-associated vasculitis.8 Our report demonstrates a case of severe skin disease that responded well to RTX. It is common to have various skin findings in GPA, and our patient presented with notable skin disease. Although skin findings may not be the more life-threatening manifestations of the disease, they can be quite debilitating, as shown in our case report.

Our patient with notable leg ulcerations required hospitalization due to GPA and received RTX in addition to corticosteroids for treatment. We observed a rapid and dramatic improvement in the skin findings, which seemed to exceed expectations from steroids alone. The other manifestations of the disease including lung nodules also improved. Although cyclophosphamide and corticosteroids have been quite successful in induction of remission, cyclophosphamide is not without serious adverse effects. There also are some patients who have contraindications to cyclophosphamide or do not see successful results. In our brief review of the literature, RTX, a B cell–depleting antibody, has shown to have success in treating refractory and severe GPA. There is little reported specifically about treating the skin manifestations of GPA. A few studies and case reports mention skin findings but do not comment on the success of RTX in treating them. Although the severity of other organ involvement in GPA may take precedence, the skin findings can be quite debilitating, as in our patient. Patients with GPA and notable skin findings may benefit from RTX, and it would be beneficial to include these results in future studies using RTX to treat GPA.

- Hoffman GS, Kerr GS, Leavitt RY, et al. Wegener granulomatosis: an analysis of 158 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:488-498.

- Plosker GL, Figgitt DP. Rituximab: a review of its use in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Drugs. 2003;63:803-843.

- Cohen SB, Emery P, Greenwald MW, et al. Rituximab for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial evaluating primary efficacy and safety at twenty-four weeks. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2793-2806.

- FDA approves Rituxan to treat two rare disorders [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; April 19, 2011. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm251946.htm. Accessed January 6, 2017.

- Cartin-Ceba R, Golbin JM, Keogh KA, et al. Rituximab for remission induction and maintenance in refractory granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s): ten-year experience at a single center. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:3770-3778.

- Keogh KA, Ytterberg SR, Fervenza FC, et al. Rituximab for refractory Wegener’s granulomatosis: report of a prospective, open-label pilot trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:180-187.

- Dalkilic E, Alkis N, Kamali S. Rituximab as a new therapeutic option in granulomatosis with polyangiitis: a report of two cases. Mod Rheumatol. 2012;22:463-466.

- Eriksson P. Nine patients with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-positive vasculitis successfully treated with rituximab. J Intern Med. 2005;257:540-548.

- Oristrell J, Bejarano G, Jordana R, et al. Effectiveness of rituximab in severe Wegener’s granulomatosis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Open Respir Med J. 2009;3:94-99.

- Martinez Del Pero M, Chaudhry A, Jones RB, et al. B-cell depletion with rituximab for refractory head and neck Wegener’s granulomatosis: a cohort study. Clin Otolaryngol. 2009;34:328-335.

- Stone JH, Merkel PA, Spiera R, et al. Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide for ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:221-232.

- Jones RB, Tervaert JW, Hauser T, et al. Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide in ANCA-associated renal vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:211-220.

- Aries PM, Hellmich B, Voswinkel J, et al. Lack of efficacy of rituximab in Wegener’s granulomatosis with refractory granulomatous manifestations. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:853-858.

- Holle JU, Dubrau C, Herlyn K, et al. Rituximab for refractory granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s granulomatosis): comparison of efficacy in granulomatous versus vasculitic manifestations. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:327-333.

- Taylor SR, Salama AD, Joshi L, et al. Rituximab is effective in the treatment of refractory ophthalmic Wegener’s granulomatosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:1540-1547.

- Joshi L, Lightman SL, Salama AD, et al. Rituximab in refractory ophthalmic Wegener’s granulomatosis: PR3 titers may predict relapse, but repeat treatment can be effective. Ophthalmol. 2011;118:2498-2503.

- Stone JH, Hoffman GS, Merkel PA, et al. A disease-specific activity index for Wegener’s granulomatosis: modification of the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score. International Network for the Study of the Systemic Vasculitides (INSSYS). Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:912-920.

- Wenzel J, Montag S, Wilsmann-Theis D, et al. Successful treatment of recalcitrant Wegener’s granulomatosis of the skin with tacrolimus (Prograf). Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:927-928.

- Seo P, Specks U, Keogh KA. Efficacy of rituximab in limited Wegener’s granulomatosis with refractory granulomatous manifestations. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:2017-2023.

- Hoffman GS, Kerr GS, Leavitt RY, et al. Wegener granulomatosis: an analysis of 158 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:488-498.

- Plosker GL, Figgitt DP. Rituximab: a review of its use in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Drugs. 2003;63:803-843.

- Cohen SB, Emery P, Greenwald MW, et al. Rituximab for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial evaluating primary efficacy and safety at twenty-four weeks. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2793-2806.

- FDA approves Rituxan to treat two rare disorders [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; April 19, 2011. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm251946.htm. Accessed January 6, 2017.

- Cartin-Ceba R, Golbin JM, Keogh KA, et al. Rituximab for remission induction and maintenance in refractory granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s): ten-year experience at a single center. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:3770-3778.

- Keogh KA, Ytterberg SR, Fervenza FC, et al. Rituximab for refractory Wegener’s granulomatosis: report of a prospective, open-label pilot trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:180-187.

- Dalkilic E, Alkis N, Kamali S. Rituximab as a new therapeutic option in granulomatosis with polyangiitis: a report of two cases. Mod Rheumatol. 2012;22:463-466.

- Eriksson P. Nine patients with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-positive vasculitis successfully treated with rituximab. J Intern Med. 2005;257:540-548.

- Oristrell J, Bejarano G, Jordana R, et al. Effectiveness of rituximab in severe Wegener’s granulomatosis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Open Respir Med J. 2009;3:94-99.

- Martinez Del Pero M, Chaudhry A, Jones RB, et al. B-cell depletion with rituximab for refractory head and neck Wegener’s granulomatosis: a cohort study. Clin Otolaryngol. 2009;34:328-335.

- Stone JH, Merkel PA, Spiera R, et al. Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide for ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:221-232.

- Jones RB, Tervaert JW, Hauser T, et al. Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide in ANCA-associated renal vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:211-220.

- Aries PM, Hellmich B, Voswinkel J, et al. Lack of efficacy of rituximab in Wegener’s granulomatosis with refractory granulomatous manifestations. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:853-858.

- Holle JU, Dubrau C, Herlyn K, et al. Rituximab for refractory granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s granulomatosis): comparison of efficacy in granulomatous versus vasculitic manifestations. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:327-333.

- Taylor SR, Salama AD, Joshi L, et al. Rituximab is effective in the treatment of refractory ophthalmic Wegener’s granulomatosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:1540-1547.

- Joshi L, Lightman SL, Salama AD, et al. Rituximab in refractory ophthalmic Wegener’s granulomatosis: PR3 titers may predict relapse, but repeat treatment can be effective. Ophthalmol. 2011;118:2498-2503.

- Stone JH, Hoffman GS, Merkel PA, et al. A disease-specific activity index for Wegener’s granulomatosis: modification of the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score. International Network for the Study of the Systemic Vasculitides (INSSYS). Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:912-920.

- Wenzel J, Montag S, Wilsmann-Theis D, et al. Successful treatment of recalcitrant Wegener’s granulomatosis of the skin with tacrolimus (Prograf). Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:927-928.

- Seo P, Specks U, Keogh KA. Efficacy of rituximab in limited Wegener’s granulomatosis with refractory granulomatous manifestations. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:2017-2023.

Practice Points

- Recognition of the dermatologic manifestations of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) may aid in an earlier diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

- Rituximab combined with corticosteroids may be a rapid and effective therapy for severe cutaneous ulcers related to GPA.

Cardiofaciocutaneous Syndrome and the Dermatologist’s Contribution to Diagnosis

To the Editor:

RASopathies, a class of developmental disorders, are caused by mutations in genes that encode protein components of the RAS/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. Each syndrome exhibits its phenotypic features; however, because all of them cause dysregulation of the RAS/MAPK pathway, there are numerous overlapping phenotypic features between the syndromes including cardiac defects, cutaneous abnormalities, characteristic facial features, neurocognitive impairment, and increased risk for developing some neoplastic disorders.

Cardiofaciocutaneous (CFC) syndrome is a RASopathy and is a genetic sporadic disease characterized by multiple congenital anomalies associated with mental retardation. It has a complex dermatological phenotype with many cutaneous features that can be helpful to differentiate CFC syndrome from Noonan and Costello syndromes, which also are classified as RASopathies.

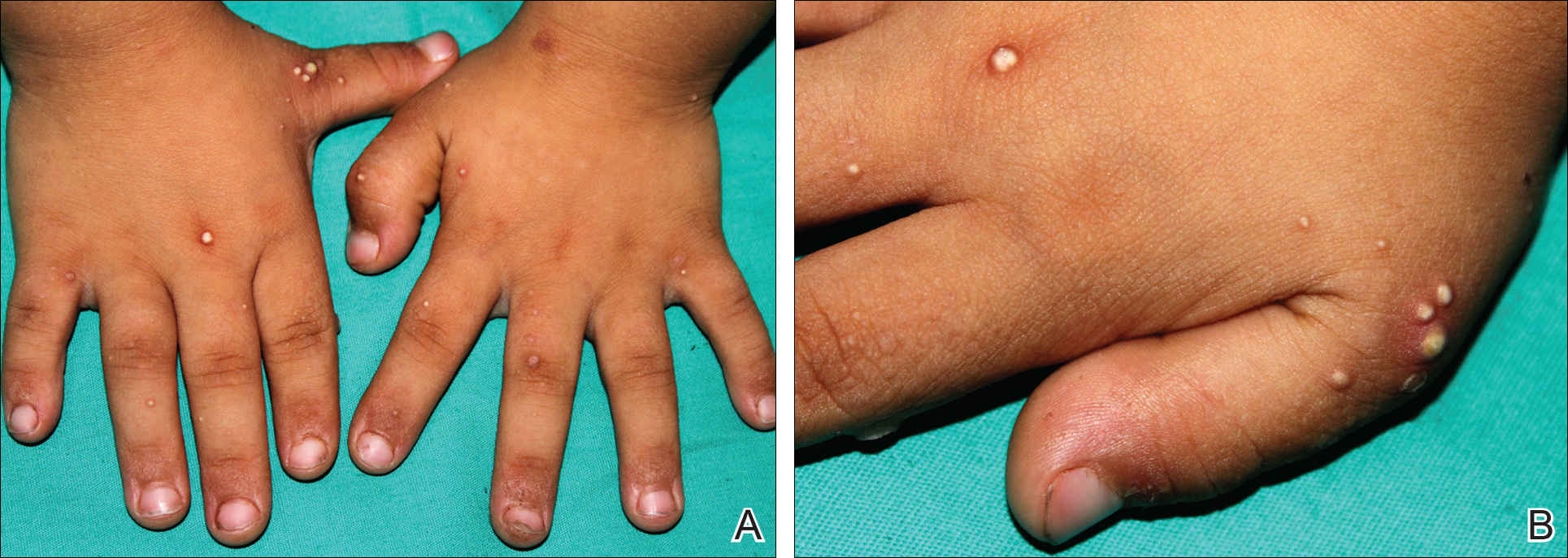

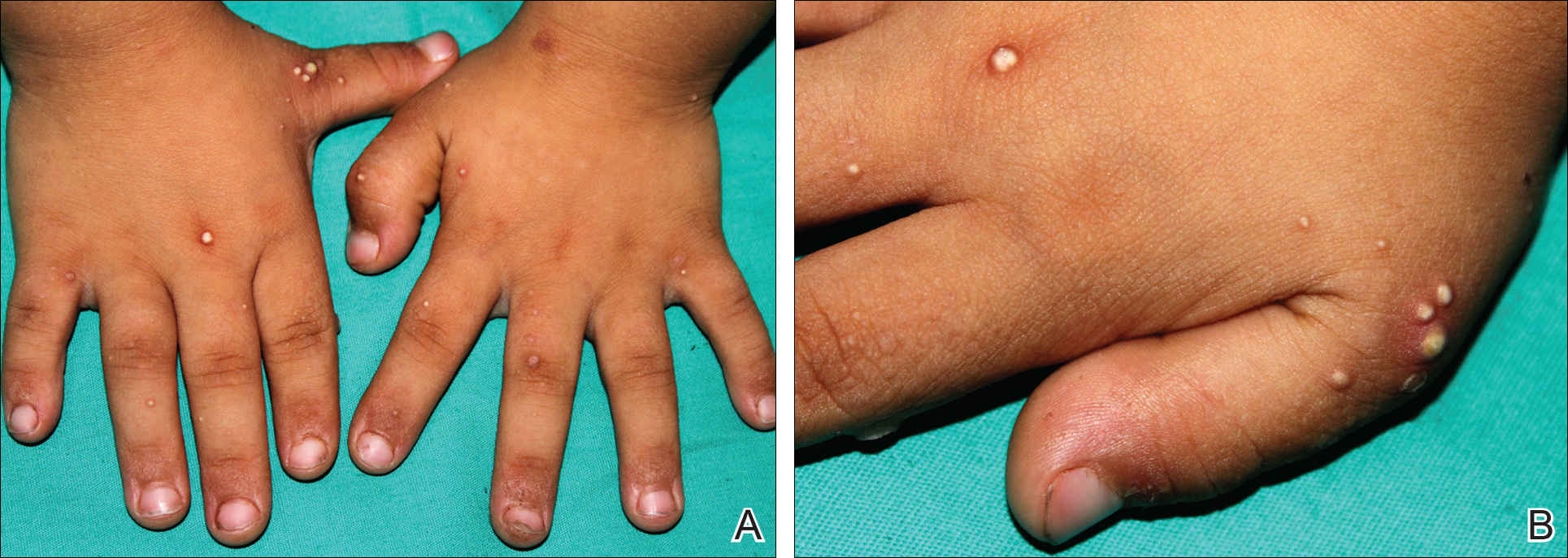

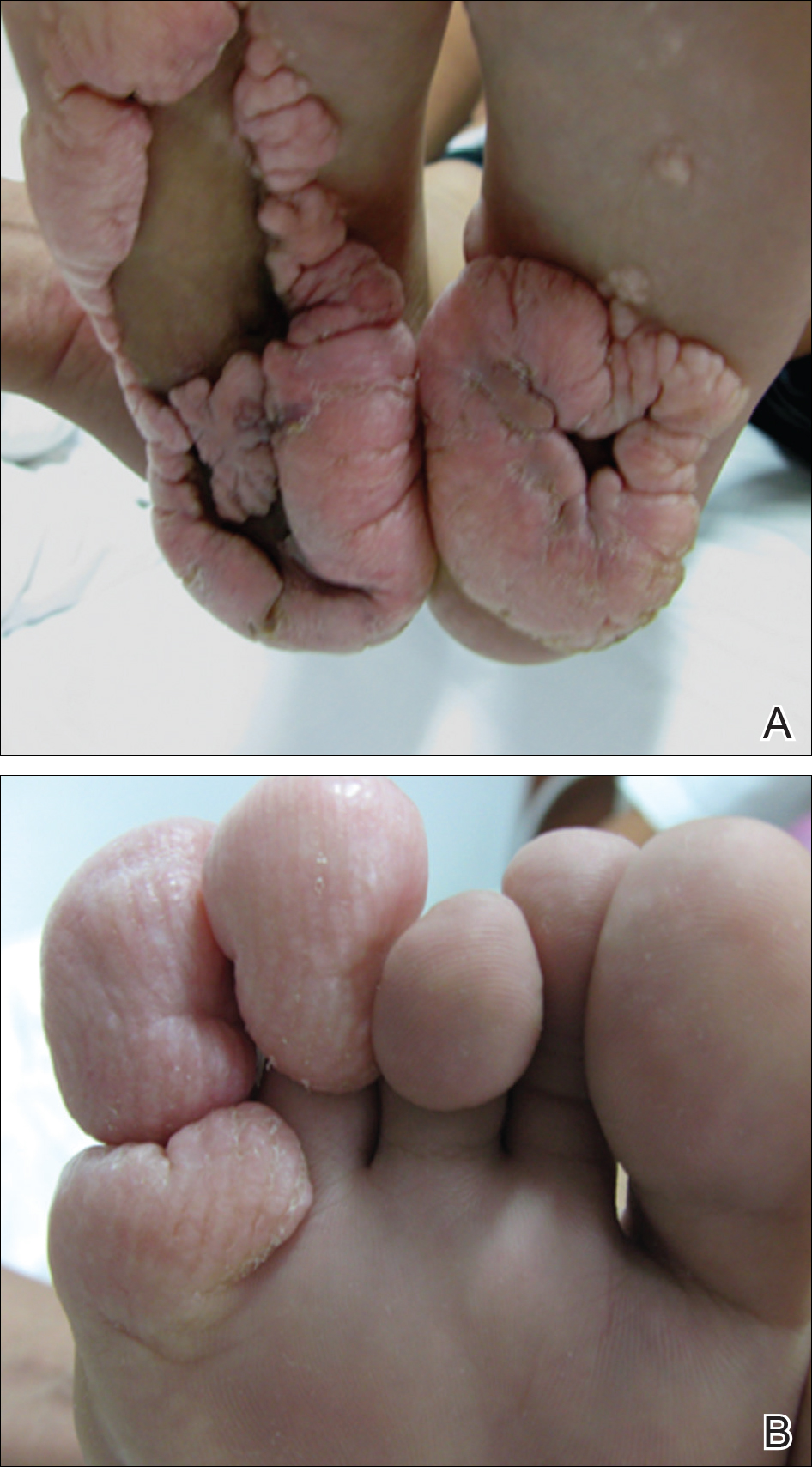

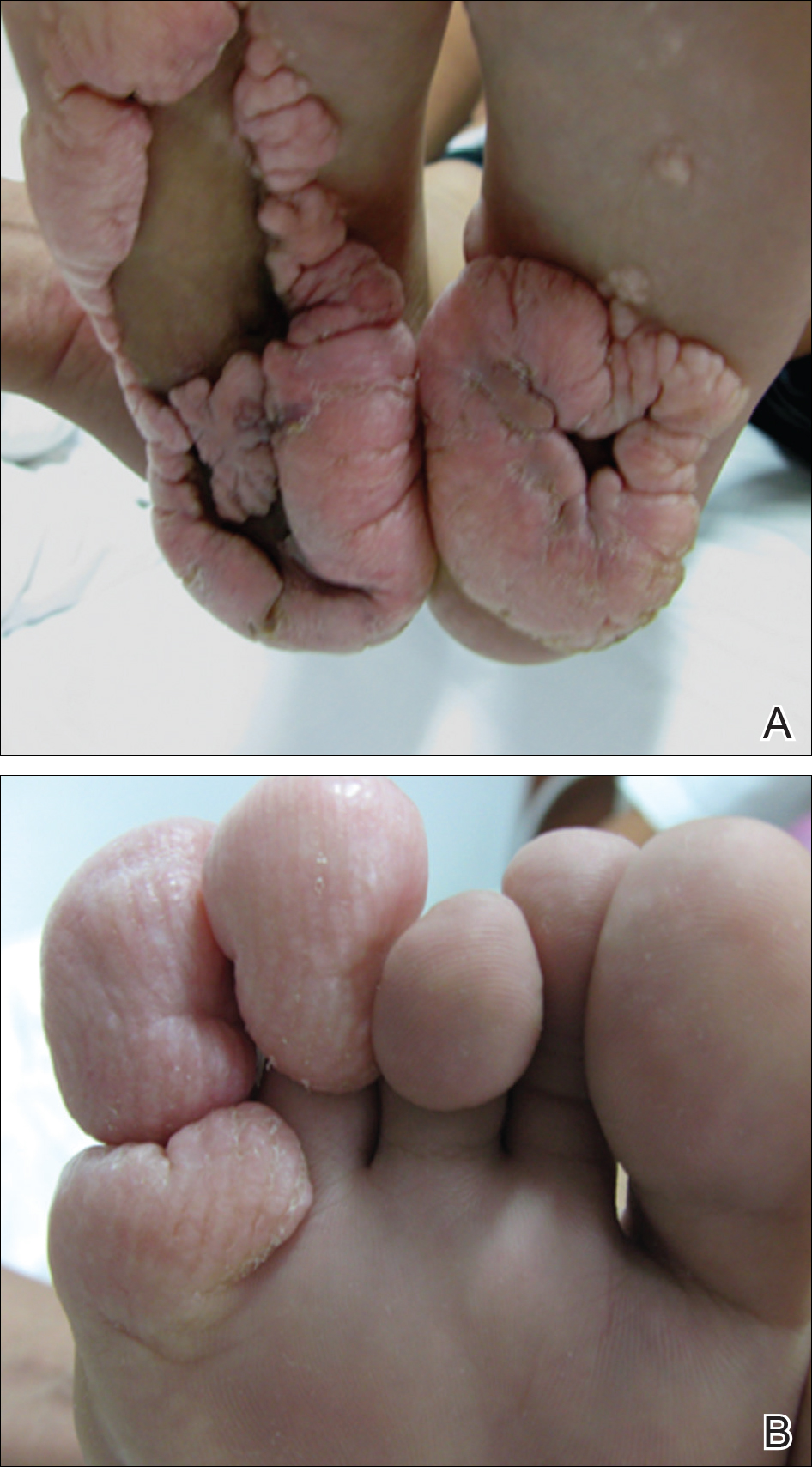

A 3-year-old girl presented with skin xerosis and follicular hyperkeratosis of the face, neck, trunk, and limbs (Figure 1). Facial follicular hyperkeratotic papules on an erythematous base were associated with alopecia of the eyebrows (ulerythema ophryogenes). Hair was sparse and curly (Figure 2A). Facial dysmorphic features included a prominent forehead with bitemporal constriction, bilateral ptosis, a broad nasal base, lip contour in a Cupid’s bow, low-set earlobes with creases (Figure 2B), and a short and webbed neck.

Congenital heart disease, hypothyroidism, bilateral hydronephrosis, delayed motor development, and seizures were noted for the first 2 years. Brain computed tomography detected a dilated ventricular system with hydrocephalus. There was no family history of consanguinity.

Pregnancy was complicated by polyhydramnios and preeclampsia. The neonate was delivered at full-term and was readmitted at 6 days of age due to respiratory failure secondary to congenital chylothorax. Cardiac malformation was diagnosed as the ostium secundum atrial septal defect and interventricular and atrioventricular septal defects. Up to this point she was being treated for Turner syndrome.

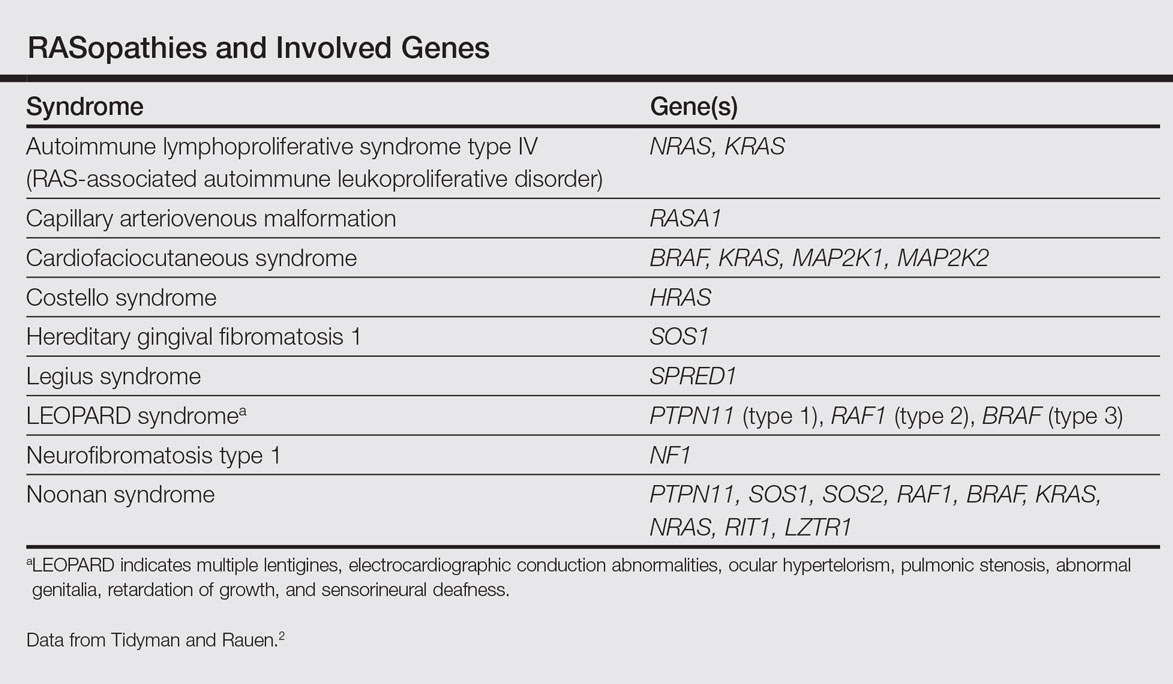

The RASopathies are a class of human genetic syndromes that are caused by germ line mutations in genes that encode components of the RAS/MAPK pathway.1 There are many syndromes classified as RASopathies (Table).2,3

Cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM] 115150) is a genetic disorder first described by Reynolds et al4 and is characterized by several cutaneous abnormalities, cardiac defects, dysmorphic craniofacial features, gastrointestinal dysmotility, and mental retardation. It occurs sporadically and is caused by functional activation of mutations in 4 different genes—BRAF, KRAS, MAP2K1, MAP2K2—of the RAS extracellular signal–regulated kinase molecular cascade that regulates cell differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis.1

As a RASopathy, CFC syndrome is a member of a family of syndromes with similar phenotypes, which includes mainly Noonan and Costello syndromes. Psychomotor retardation and physical anomalies, the common denominator of all syndromes, may be explained by the effects of the mutations during early development.5,6

In CFC, relative macrocephaly, prominent forehead, bitemporal constriction, absence of eyebrows, palpebral ptosis, broad nasal root, bulbous nasal tip, and small chin commonly are found. The eyes are widely spaced and the palpebral fissures are downward slanting with epicanthic folds.1,4,7