User login

Collagenous and Elastotic Marginal Plaques of the Hands

To the Editor:

Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands (CEMPHs) has several names including degenerative collagenous plaques of the hands, keratoelastoidosis marginalis, and digital papular calcific elastosis. This rare disorder is an acquired, slowly progressive, asymptomatic, dermal connective tissue abnormality that is underrecognized and underdiagnosed. Clinical presentation includes hyperkeratotic translucent papules arranged linearly on the radial aspect of the hands.

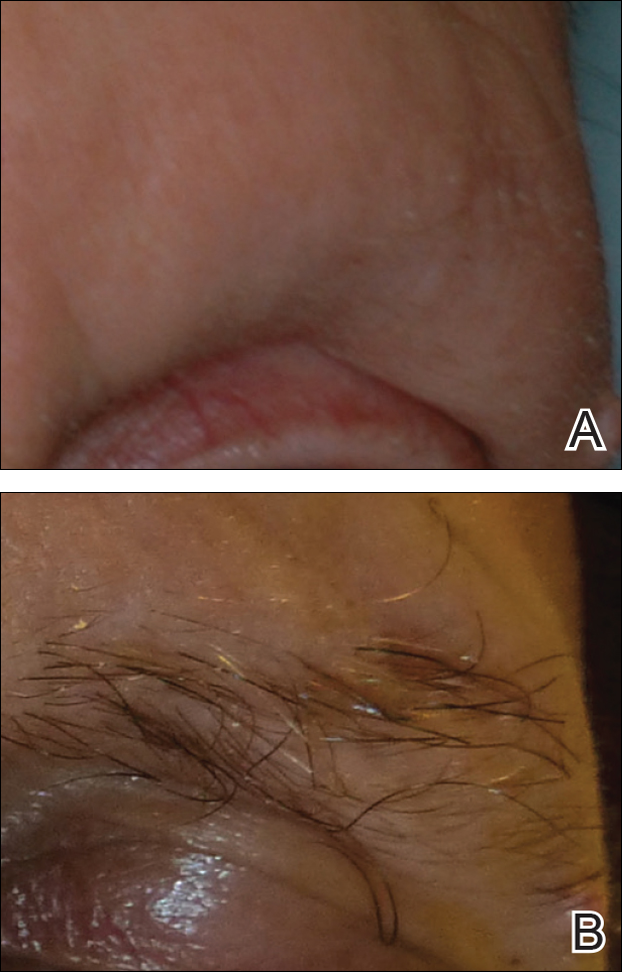

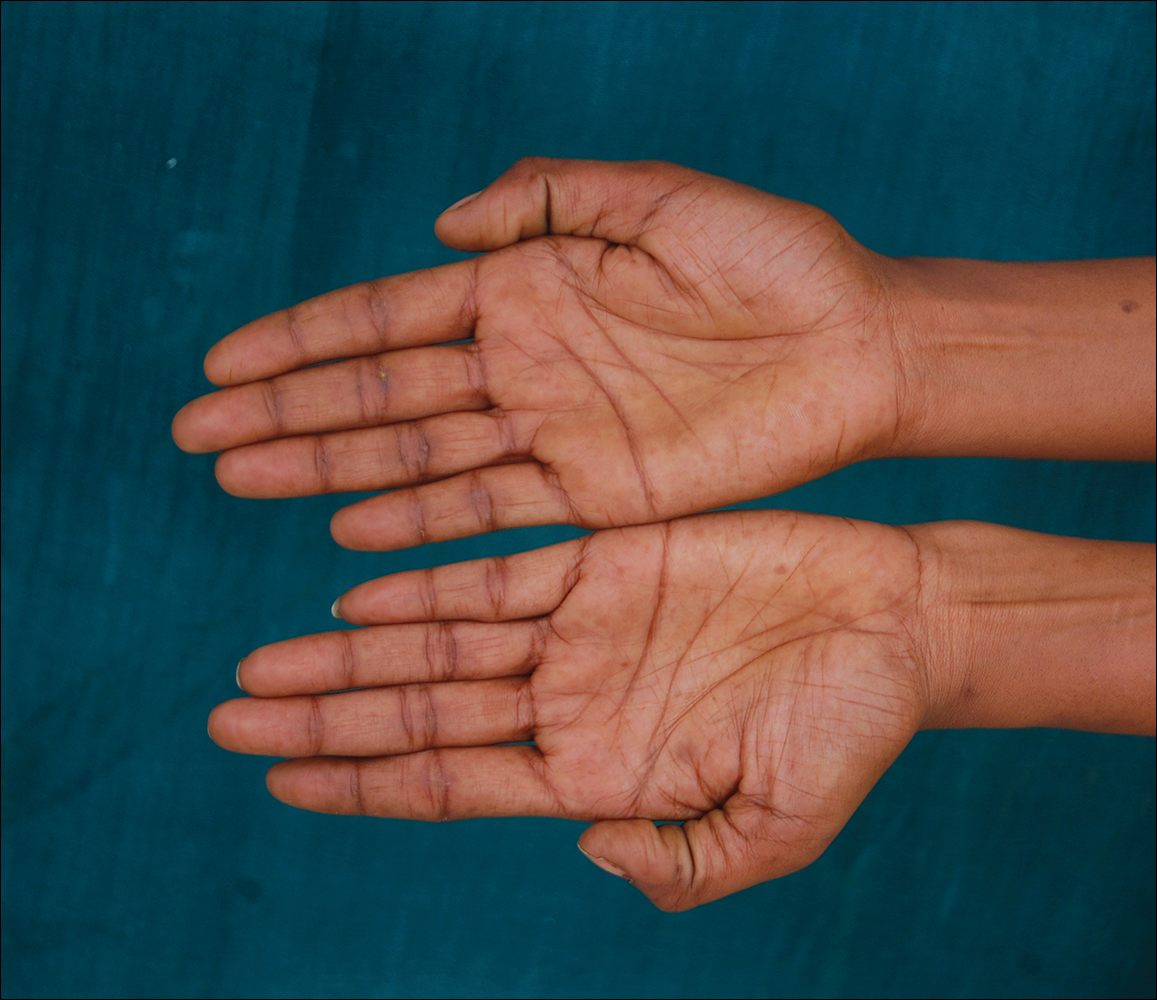

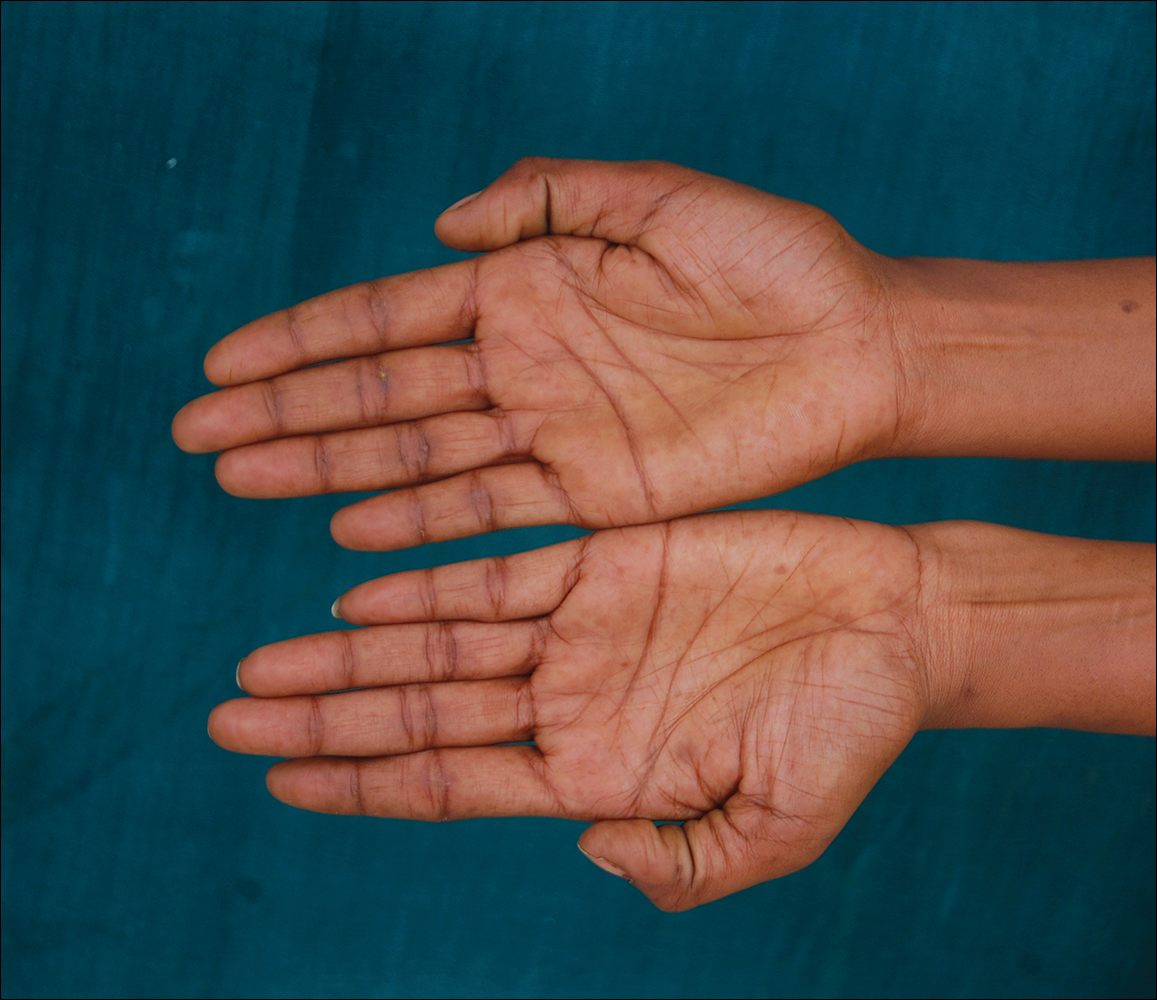

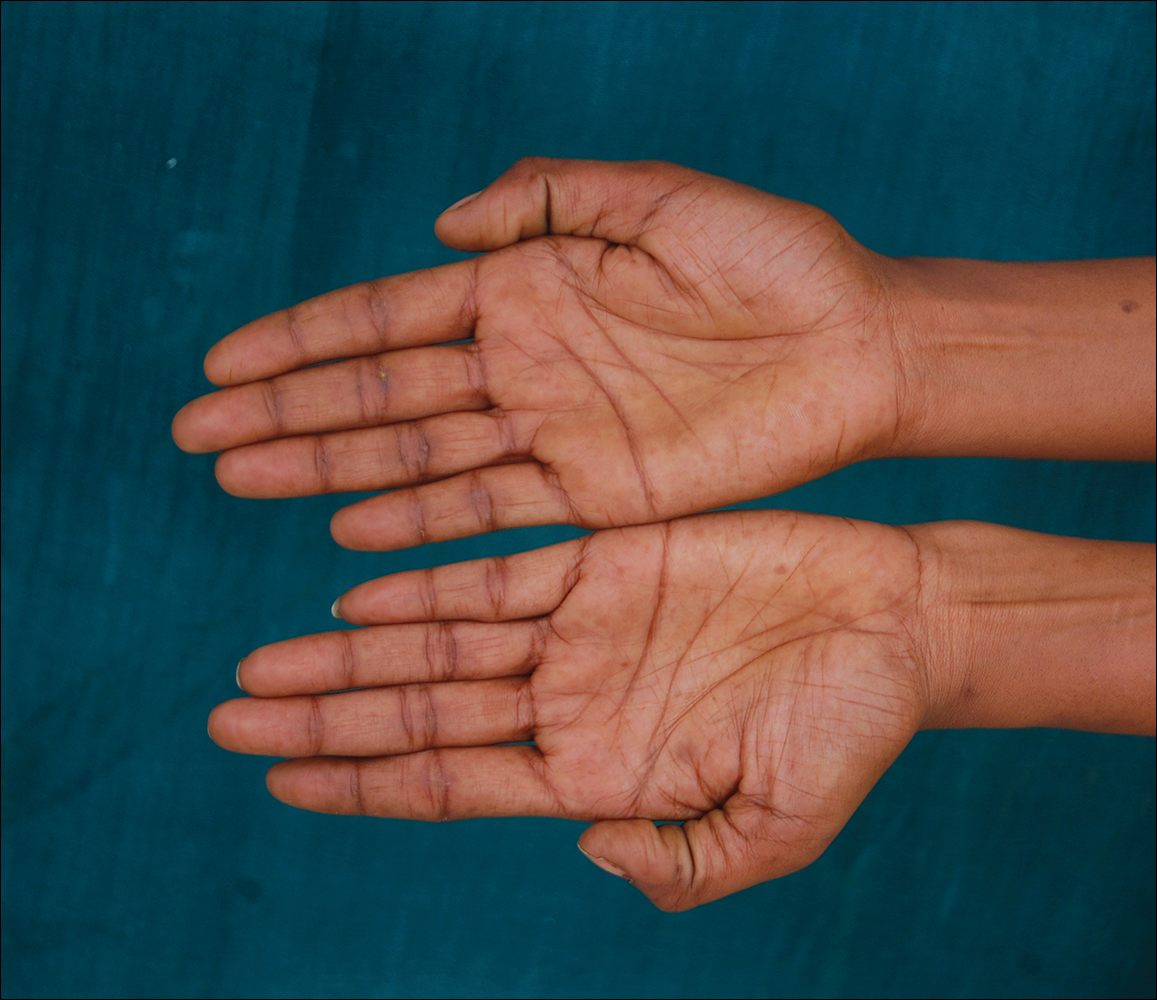

A 74-year-old woman described having "rough hands" of more than 20 years' duration. She presented with 4-cm wide longitudinal, erythematous, firm, depressed plaques along the lateral edge of the second finger and extending to the medial thumb in both hands (Figure 1). She had attempted multiple treatments by her primary care physician, including topical and oral medications unknown to the patient and light therapy, all without benefit over a period of several years. We have attempted salicylic acid 40%, clobetasol cream 0.05%, and emollient creams containing α-hydroxy acid. At best the condition fluctuated between a subtle raised scale at the edge to smooth and occasionally more red-pink, seemingly unrelated to any treatments.

The patient did not have plaques elsewhere on the body, and notably, the feet were clear. She did not have a history of repeated trauma to the hands and did not engage in manual labor. She denied excessive sun exposure, though she had Fitzpatrick skin type III and a history of multiple precancers and nonmelanoma skin cancers 7 years prior to presentation.

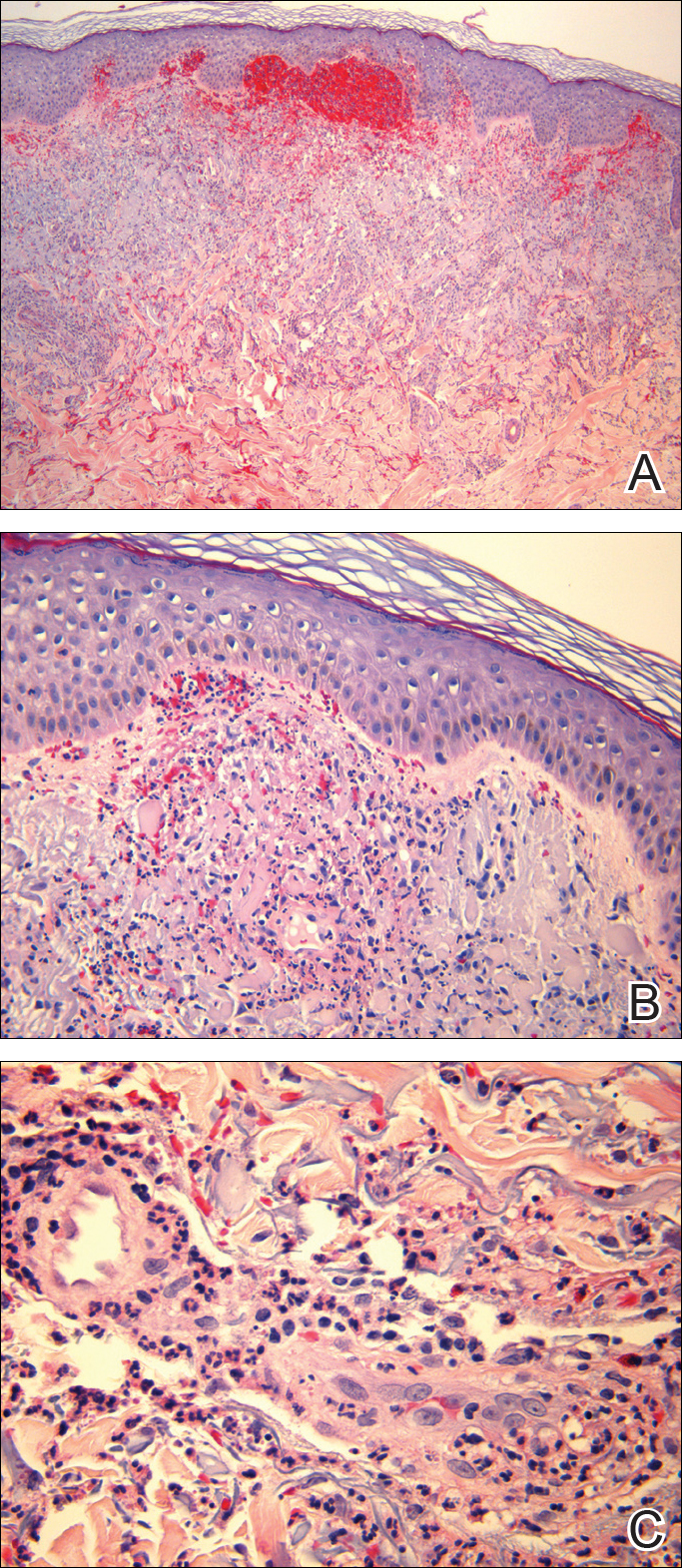

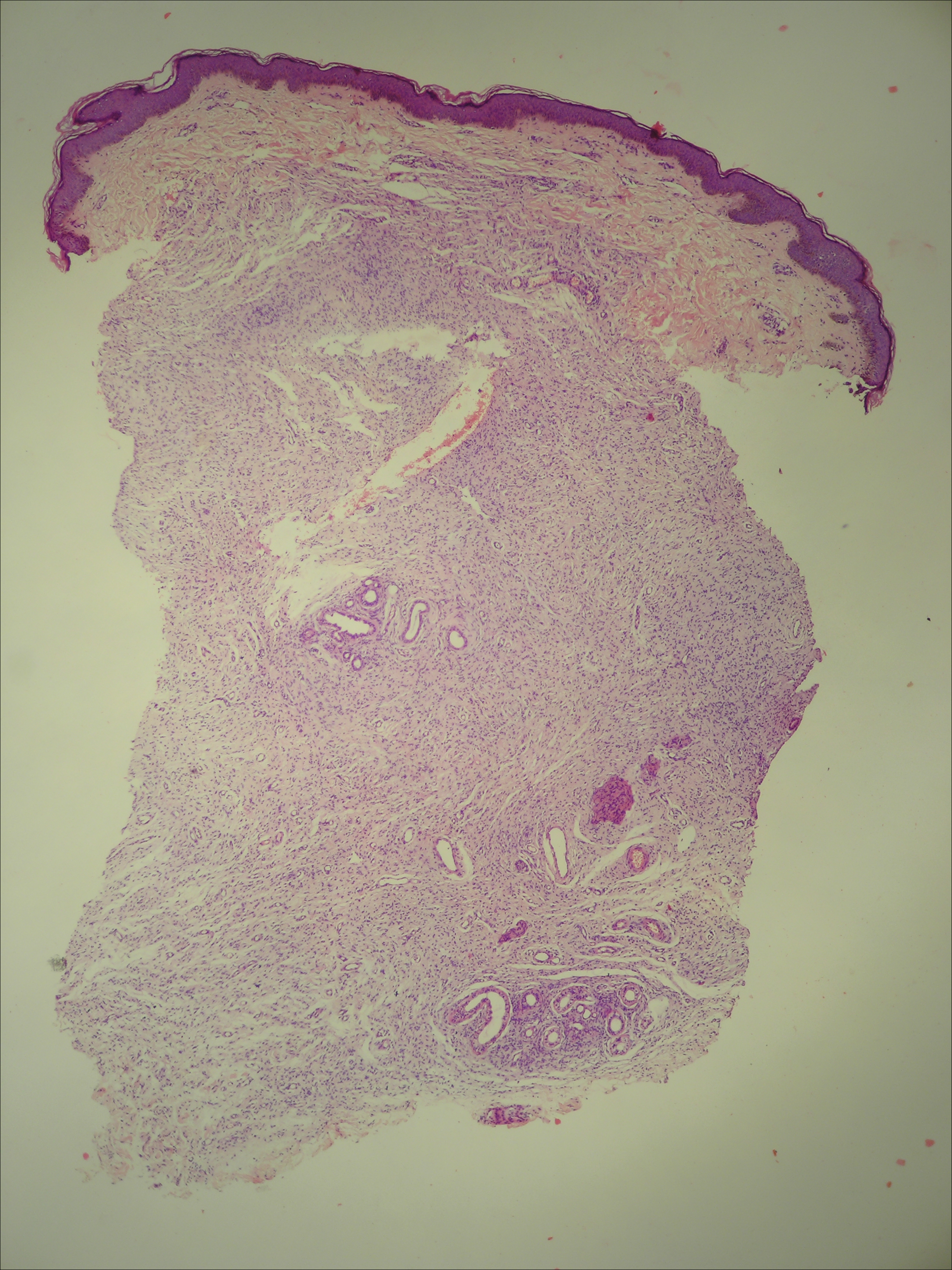

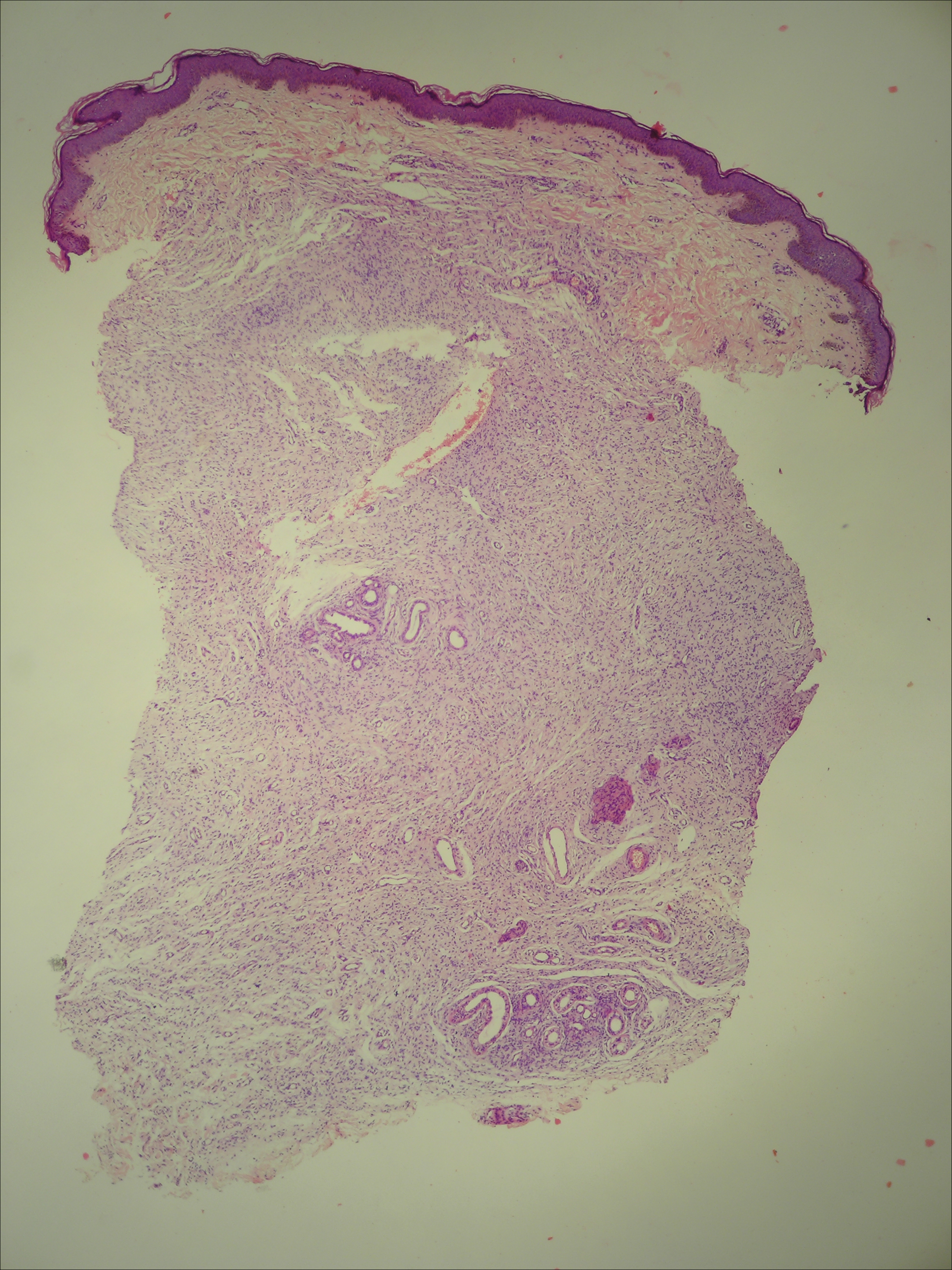

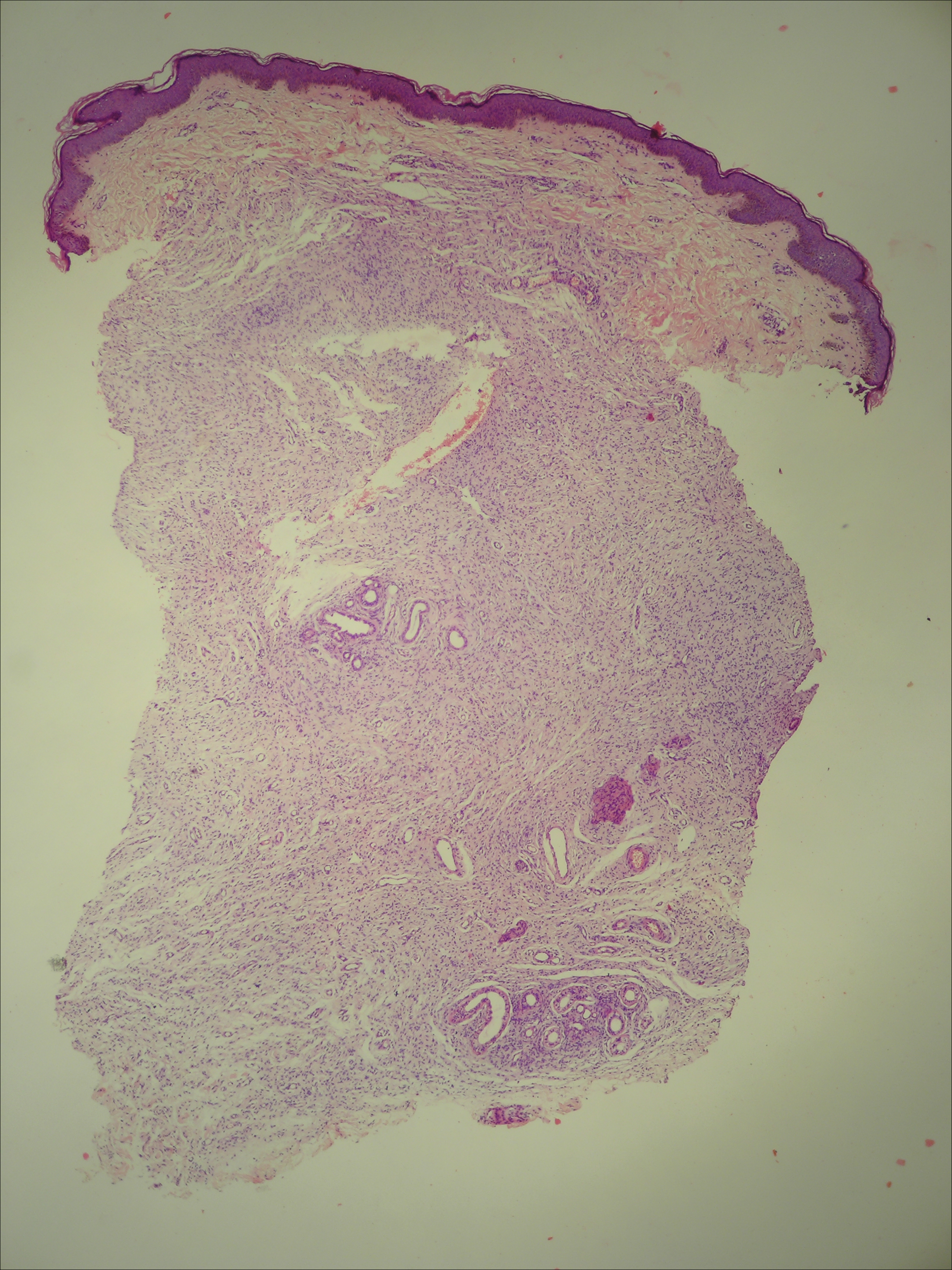

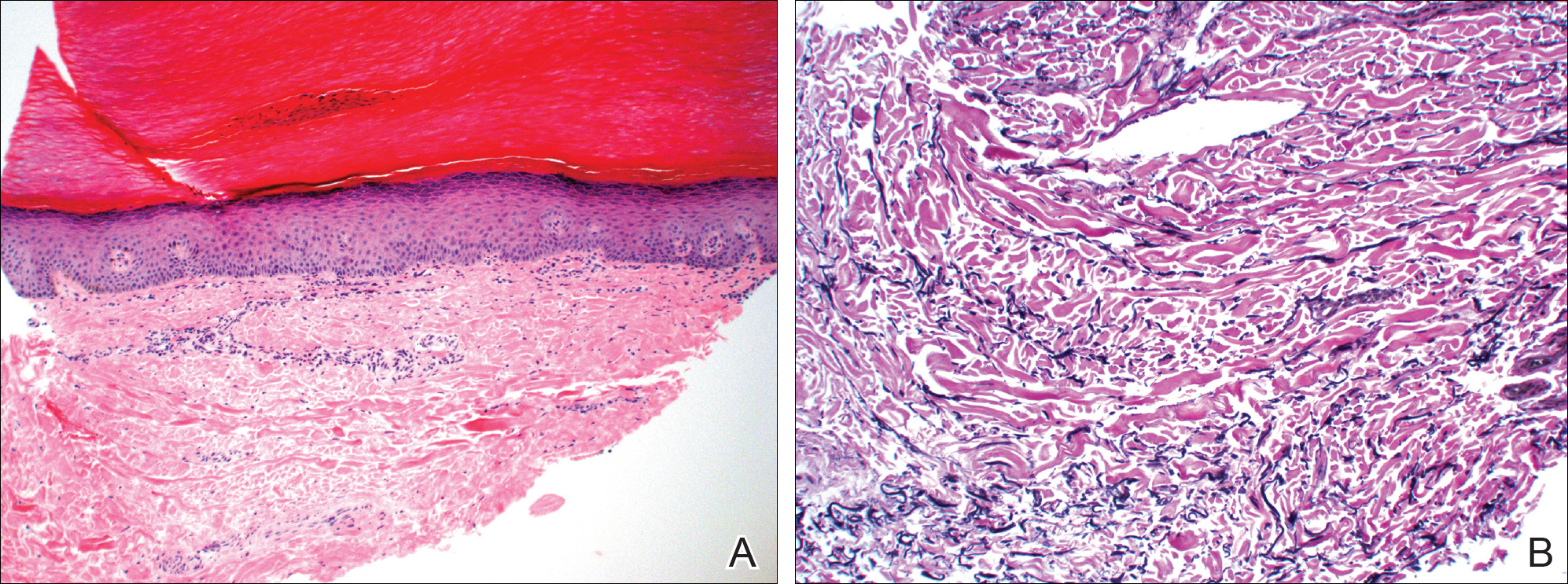

Histology of CEMPH reveals a hyperkeratotic epidermis with an avascular and acellular replacement of the superficial reticular dermis by haphazardly arranged, thickened collagen fibers (Figure 2A-2C). Collagen fibers were oriented perpendicularly to the epidermal surface. Intervening amorphous basophilic elastotic masses were present in the upper dermis with occasional calcification and degenerative elastic fibers (Figure 2D).

Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands is a chronic, asymptomatic, sclerotic skin disorder described in a 1960 case series of 5 patients reported by Burks et al.1 Although it has many names, the most common is CEMPH. Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands most often presents in white men aged 50 to 60 years.2 Patients typically are asymptomatic with plaques limited to the junction of the palmar and dorsal surfaces of the hands with only minimal intermittent stiffness around the flexor creases. Lesions begin as discrete yellow papules that coalesce to form hyperkeratotic linear plaques with occasional telangiectasia.3

The etiology of CEMPH is attributed to collagen and elastin degeneration by chronic actinic damage, pressure, or trauma.4,5 The 3 stages of degeneration include an initial linear padded stage, an intermediate padded plaque stage, and an advanced padded hyperkeratotic plaque stage.4 Vascular compromise is seen from the enlarged and fused thickened collagen and elastic fibers that in turn lead to ischemic changes, hyperkeratosis with epidermal atrophy, and papillary dermis telangiectasia. Absence or weak expression of keratins 14 and 10 and strong expression of keratin 16 have been reported in the epidermis of CEMPH patients.4

Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands do not have a specific treatment, as it is a benign, slowly progressive condition. Several treatments such as laser therapy, high-potency topical corticosteroids, topical tazarotene and tretinoin, oral isotretinoin, and cryotherapy have been tried with little long-term success.4 Moisturizing may help reduce fissuring, and patients are advised to avoid the sun and repeated trauma to the hands.

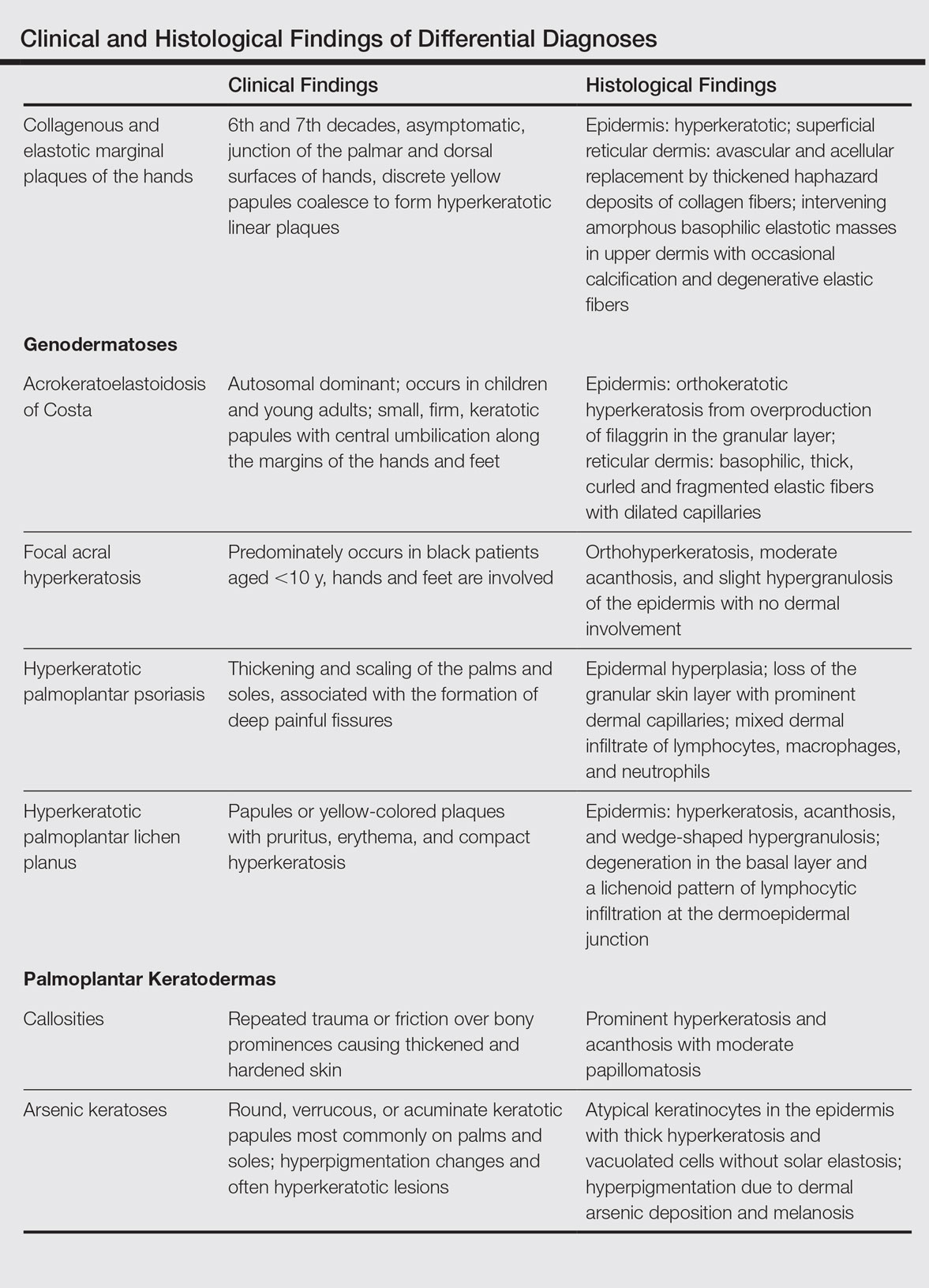

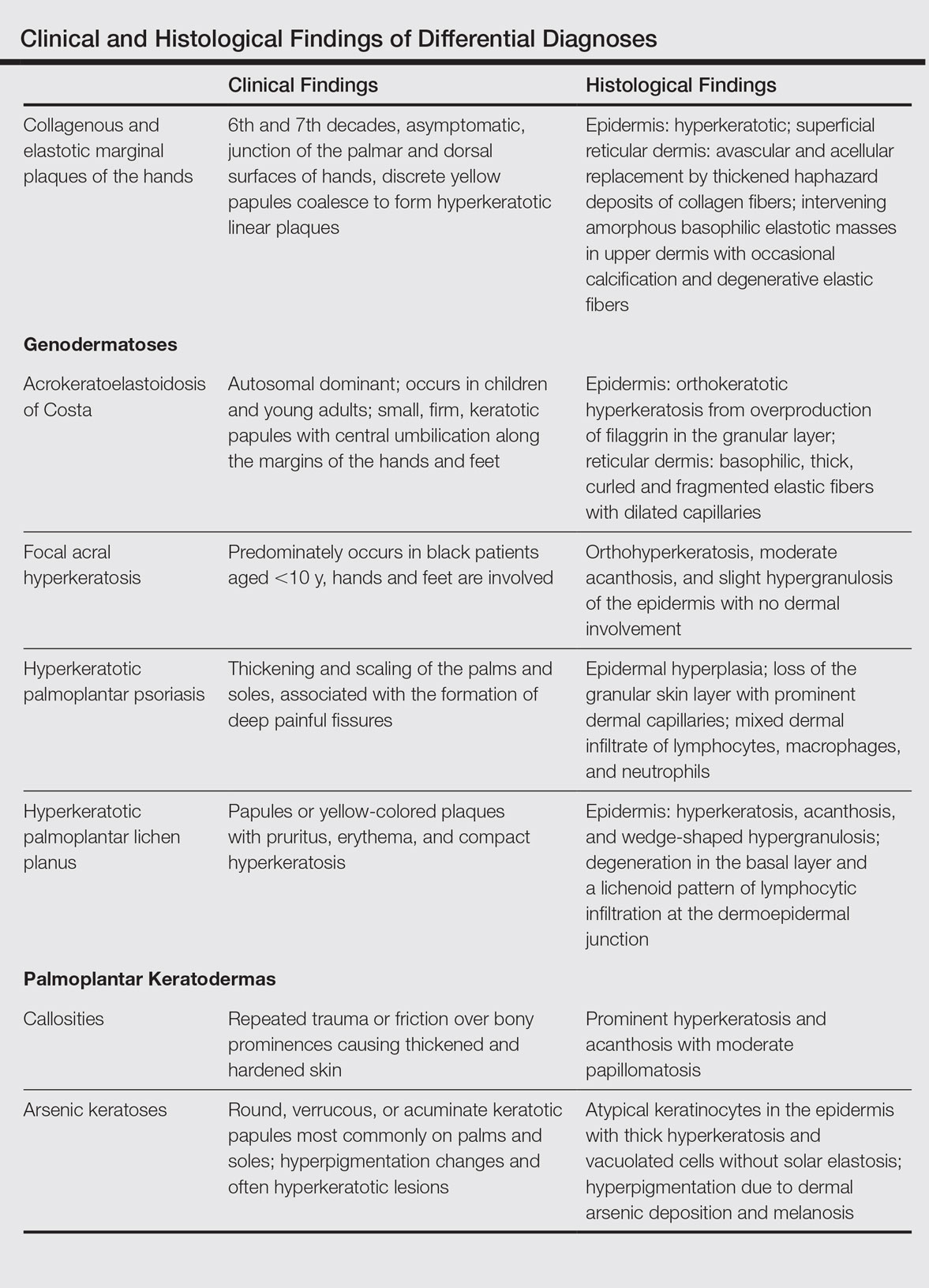

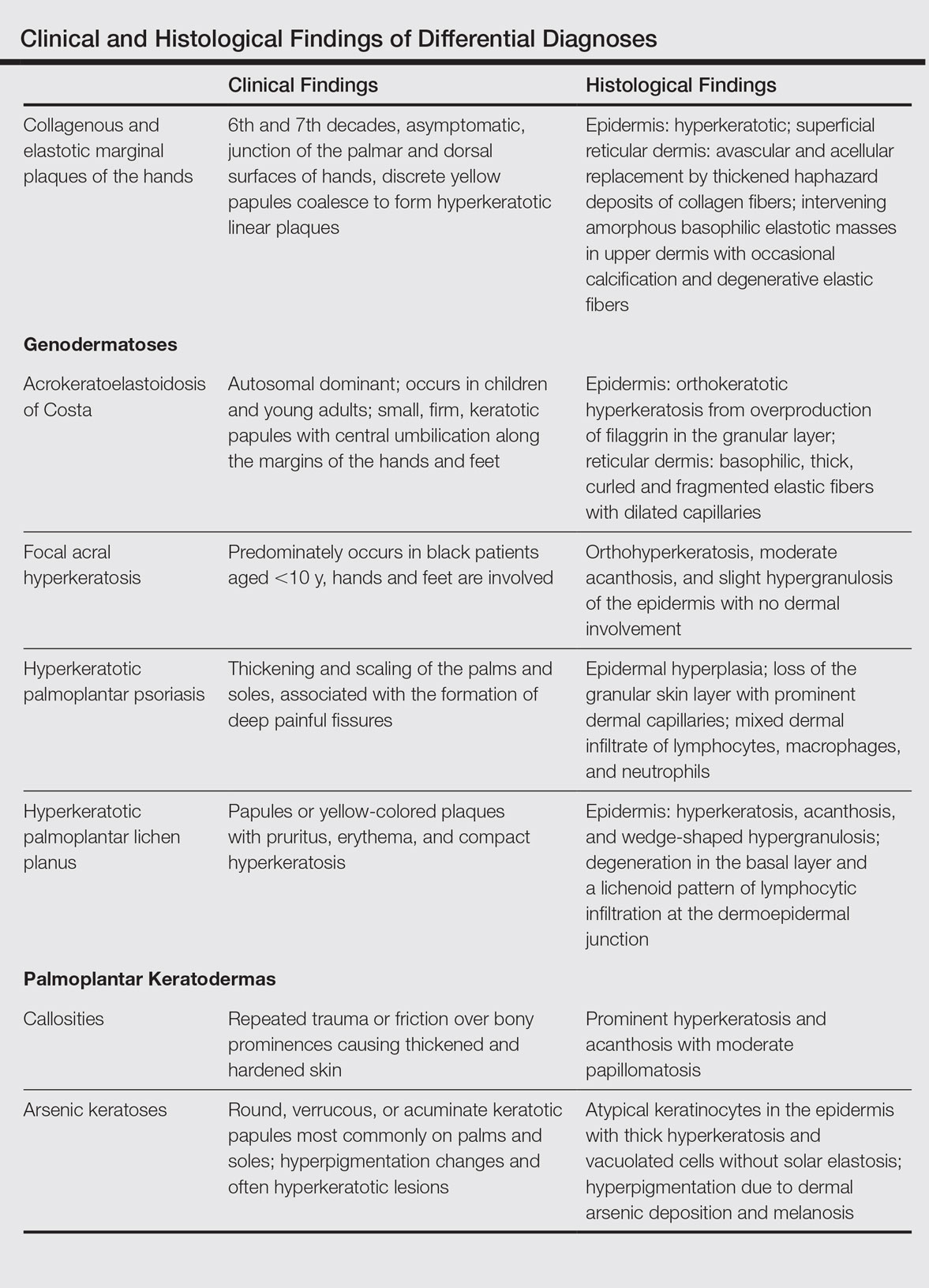

The differential diagnosis of CEMPH is summarized in the Table. Two genodermatoses—acrokeratoelastoidosis of Costa and focal acral hyperkeratosis—clinically resemble CEMPH. Acrokeratoelastoidosis of Costa is an autosomal-dominant condition that occurs without trauma in children and young adults. Histopathology shows orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis due to an overproduction of filaggrin in the granular layer of the epidermis. The reticular dermis shows basophilic, thick, curled and fragmented elastic fibers with dilated capillaries that can be seen with Weigert elastic, Verhoeff-van Gieson, or orcein stains. Focal acral hyperkeratosis occurs on the hands and feet, predominantly in black patients. On histology, the epidermis shows a characteristic orthohyperkeratosis, moderate acanthosis, and slight hypergranulosis with no dermal involvment.6

Chronic hyperkeratotic eczematous dermatitis is another common entity in the differential characterized by hyperkeratotic plaques that scale and fissure. Biopsy demonstrates a spongiotic acanthotic epidermis.7,8

Psoriasis of the hands, specifically hyperkeratotic palmoplantar psoriasis, is associated with manual labor, similar to CEMPH. Histology shows epidermal hyperplasia; regular acanthosis; loss of the granular skin layer with prominent dermal capillaries; and a mixed dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils.9 Hyperkeratotic palmoplantar lichen planus presents with pruritic papules in the third and fifth decades of life. Histologically, hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and wedge-shaped hypergranulosis with a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltration at the dermoepidermal junction is seen.10

Palmoplantar keratodermas due to inflammatory reactive dermatoses include callosities that develop in response to repeated trauma or friction on the skin. On histology, there is prominent hyperkeratosis and acanthosis with moderate papillomatosis.11 Drug-related palmoplantar keratodermas such as those from arsenic exposure can lead to multiple, irregular, verrucous, keratotic, and pigmented lesions on the palms and soles. Histologically, atypical keratinocytes are seen in the epidermis with thick hyperkeratosis and vacuolated cells without solar elastosis.12

In conclusion, CEMPH is an underdiagnosed and underrecognized condition characterized by asymptomatic hyperkeratotic linear plaques along the medial aspect of the thumb and radial aspect of the index finger. It is important to keep CEMPH in mind when dealing with occupational cases of repeated long-term trauma or pressure to the hands as well as excessive sun exposure. It also is imperative to separate it from other diseases and avoid misdiagnosing this degenerative collagenous and elastotic disease as a malignant lesion.

- Burks JW, Wise LJ, Clark WH. Degenerative collagenous plaques of the hands. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:362-366.

- Jordaan HF, Rossouw DJ. Digital papular calcific elastosis: a histopathological, histochemical and ultrastructural study of 20 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 1990;17:358-370.

- Mortimore RJ, Conrad RJ. Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:211-213.

- Tieu KD, Satter EK. Thickened plaques on the hands. Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands (CEMPH). Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:499-504.

- Todd D, Al-Aboosi M, Hameed O, et al. The role of UV light in the pathogenesis of digital papular calcific elastosis. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:379-381.

- Mengesha YM, Kayal JD, Swerlick RA. Keratoelastoidosis marginalis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2002;6:23-25.

- MacKee MG, Lewis MG. Keratolysis exfoliativa and the mosaic fungus. Arch Dermatol. 1931;23:445-447.

- Walling HW, Swick BL, Storrs FJ, et al. Frictional hyperkeratotic hand dermatitis responding to Grenz ray therapy. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;58:49-51.

- Farley E, Masrour S, McKey J, et al. Palmoplantar psoriasis: a phenotypical and clinical review with introduction of a new quality-of-life assessment tool. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:1024-1031.

- Rotunda AM, Craft N, Haley JC. Hyperkeratotic plaques on the palms and soles. palmoplantar lichen planus, hyperkeratotic variant. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1275-1280.

- Unal VS, Sevin A, Dayican A. Palmar callus formation as a result of mechanical trauma during sailing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:2161-2162.

- Cöl M, Cöl C, Soran A, et al. Arsenic-related Bowen's disease, palmar keratosis, and skin cancer. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107:687-689.

To the Editor:

Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands (CEMPHs) has several names including degenerative collagenous plaques of the hands, keratoelastoidosis marginalis, and digital papular calcific elastosis. This rare disorder is an acquired, slowly progressive, asymptomatic, dermal connective tissue abnormality that is underrecognized and underdiagnosed. Clinical presentation includes hyperkeratotic translucent papules arranged linearly on the radial aspect of the hands.

A 74-year-old woman described having "rough hands" of more than 20 years' duration. She presented with 4-cm wide longitudinal, erythematous, firm, depressed plaques along the lateral edge of the second finger and extending to the medial thumb in both hands (Figure 1). She had attempted multiple treatments by her primary care physician, including topical and oral medications unknown to the patient and light therapy, all without benefit over a period of several years. We have attempted salicylic acid 40%, clobetasol cream 0.05%, and emollient creams containing α-hydroxy acid. At best the condition fluctuated between a subtle raised scale at the edge to smooth and occasionally more red-pink, seemingly unrelated to any treatments.

The patient did not have plaques elsewhere on the body, and notably, the feet were clear. She did not have a history of repeated trauma to the hands and did not engage in manual labor. She denied excessive sun exposure, though she had Fitzpatrick skin type III and a history of multiple precancers and nonmelanoma skin cancers 7 years prior to presentation.

Histology of CEMPH reveals a hyperkeratotic epidermis with an avascular and acellular replacement of the superficial reticular dermis by haphazardly arranged, thickened collagen fibers (Figure 2A-2C). Collagen fibers were oriented perpendicularly to the epidermal surface. Intervening amorphous basophilic elastotic masses were present in the upper dermis with occasional calcification and degenerative elastic fibers (Figure 2D).

Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands is a chronic, asymptomatic, sclerotic skin disorder described in a 1960 case series of 5 patients reported by Burks et al.1 Although it has many names, the most common is CEMPH. Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands most often presents in white men aged 50 to 60 years.2 Patients typically are asymptomatic with plaques limited to the junction of the palmar and dorsal surfaces of the hands with only minimal intermittent stiffness around the flexor creases. Lesions begin as discrete yellow papules that coalesce to form hyperkeratotic linear plaques with occasional telangiectasia.3

The etiology of CEMPH is attributed to collagen and elastin degeneration by chronic actinic damage, pressure, or trauma.4,5 The 3 stages of degeneration include an initial linear padded stage, an intermediate padded plaque stage, and an advanced padded hyperkeratotic plaque stage.4 Vascular compromise is seen from the enlarged and fused thickened collagen and elastic fibers that in turn lead to ischemic changes, hyperkeratosis with epidermal atrophy, and papillary dermis telangiectasia. Absence or weak expression of keratins 14 and 10 and strong expression of keratin 16 have been reported in the epidermis of CEMPH patients.4

Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands do not have a specific treatment, as it is a benign, slowly progressive condition. Several treatments such as laser therapy, high-potency topical corticosteroids, topical tazarotene and tretinoin, oral isotretinoin, and cryotherapy have been tried with little long-term success.4 Moisturizing may help reduce fissuring, and patients are advised to avoid the sun and repeated trauma to the hands.

The differential diagnosis of CEMPH is summarized in the Table. Two genodermatoses—acrokeratoelastoidosis of Costa and focal acral hyperkeratosis—clinically resemble CEMPH. Acrokeratoelastoidosis of Costa is an autosomal-dominant condition that occurs without trauma in children and young adults. Histopathology shows orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis due to an overproduction of filaggrin in the granular layer of the epidermis. The reticular dermis shows basophilic, thick, curled and fragmented elastic fibers with dilated capillaries that can be seen with Weigert elastic, Verhoeff-van Gieson, or orcein stains. Focal acral hyperkeratosis occurs on the hands and feet, predominantly in black patients. On histology, the epidermis shows a characteristic orthohyperkeratosis, moderate acanthosis, and slight hypergranulosis with no dermal involvment.6

Chronic hyperkeratotic eczematous dermatitis is another common entity in the differential characterized by hyperkeratotic plaques that scale and fissure. Biopsy demonstrates a spongiotic acanthotic epidermis.7,8

Psoriasis of the hands, specifically hyperkeratotic palmoplantar psoriasis, is associated with manual labor, similar to CEMPH. Histology shows epidermal hyperplasia; regular acanthosis; loss of the granular skin layer with prominent dermal capillaries; and a mixed dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils.9 Hyperkeratotic palmoplantar lichen planus presents with pruritic papules in the third and fifth decades of life. Histologically, hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and wedge-shaped hypergranulosis with a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltration at the dermoepidermal junction is seen.10

Palmoplantar keratodermas due to inflammatory reactive dermatoses include callosities that develop in response to repeated trauma or friction on the skin. On histology, there is prominent hyperkeratosis and acanthosis with moderate papillomatosis.11 Drug-related palmoplantar keratodermas such as those from arsenic exposure can lead to multiple, irregular, verrucous, keratotic, and pigmented lesions on the palms and soles. Histologically, atypical keratinocytes are seen in the epidermis with thick hyperkeratosis and vacuolated cells without solar elastosis.12

In conclusion, CEMPH is an underdiagnosed and underrecognized condition characterized by asymptomatic hyperkeratotic linear plaques along the medial aspect of the thumb and radial aspect of the index finger. It is important to keep CEMPH in mind when dealing with occupational cases of repeated long-term trauma or pressure to the hands as well as excessive sun exposure. It also is imperative to separate it from other diseases and avoid misdiagnosing this degenerative collagenous and elastotic disease as a malignant lesion.

To the Editor:

Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands (CEMPHs) has several names including degenerative collagenous plaques of the hands, keratoelastoidosis marginalis, and digital papular calcific elastosis. This rare disorder is an acquired, slowly progressive, asymptomatic, dermal connective tissue abnormality that is underrecognized and underdiagnosed. Clinical presentation includes hyperkeratotic translucent papules arranged linearly on the radial aspect of the hands.

A 74-year-old woman described having "rough hands" of more than 20 years' duration. She presented with 4-cm wide longitudinal, erythematous, firm, depressed plaques along the lateral edge of the second finger and extending to the medial thumb in both hands (Figure 1). She had attempted multiple treatments by her primary care physician, including topical and oral medications unknown to the patient and light therapy, all without benefit over a period of several years. We have attempted salicylic acid 40%, clobetasol cream 0.05%, and emollient creams containing α-hydroxy acid. At best the condition fluctuated between a subtle raised scale at the edge to smooth and occasionally more red-pink, seemingly unrelated to any treatments.

The patient did not have plaques elsewhere on the body, and notably, the feet were clear. She did not have a history of repeated trauma to the hands and did not engage in manual labor. She denied excessive sun exposure, though she had Fitzpatrick skin type III and a history of multiple precancers and nonmelanoma skin cancers 7 years prior to presentation.

Histology of CEMPH reveals a hyperkeratotic epidermis with an avascular and acellular replacement of the superficial reticular dermis by haphazardly arranged, thickened collagen fibers (Figure 2A-2C). Collagen fibers were oriented perpendicularly to the epidermal surface. Intervening amorphous basophilic elastotic masses were present in the upper dermis with occasional calcification and degenerative elastic fibers (Figure 2D).

Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands is a chronic, asymptomatic, sclerotic skin disorder described in a 1960 case series of 5 patients reported by Burks et al.1 Although it has many names, the most common is CEMPH. Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands most often presents in white men aged 50 to 60 years.2 Patients typically are asymptomatic with plaques limited to the junction of the palmar and dorsal surfaces of the hands with only minimal intermittent stiffness around the flexor creases. Lesions begin as discrete yellow papules that coalesce to form hyperkeratotic linear plaques with occasional telangiectasia.3

The etiology of CEMPH is attributed to collagen and elastin degeneration by chronic actinic damage, pressure, or trauma.4,5 The 3 stages of degeneration include an initial linear padded stage, an intermediate padded plaque stage, and an advanced padded hyperkeratotic plaque stage.4 Vascular compromise is seen from the enlarged and fused thickened collagen and elastic fibers that in turn lead to ischemic changes, hyperkeratosis with epidermal atrophy, and papillary dermis telangiectasia. Absence or weak expression of keratins 14 and 10 and strong expression of keratin 16 have been reported in the epidermis of CEMPH patients.4

Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands do not have a specific treatment, as it is a benign, slowly progressive condition. Several treatments such as laser therapy, high-potency topical corticosteroids, topical tazarotene and tretinoin, oral isotretinoin, and cryotherapy have been tried with little long-term success.4 Moisturizing may help reduce fissuring, and patients are advised to avoid the sun and repeated trauma to the hands.

The differential diagnosis of CEMPH is summarized in the Table. Two genodermatoses—acrokeratoelastoidosis of Costa and focal acral hyperkeratosis—clinically resemble CEMPH. Acrokeratoelastoidosis of Costa is an autosomal-dominant condition that occurs without trauma in children and young adults. Histopathology shows orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis due to an overproduction of filaggrin in the granular layer of the epidermis. The reticular dermis shows basophilic, thick, curled and fragmented elastic fibers with dilated capillaries that can be seen with Weigert elastic, Verhoeff-van Gieson, or orcein stains. Focal acral hyperkeratosis occurs on the hands and feet, predominantly in black patients. On histology, the epidermis shows a characteristic orthohyperkeratosis, moderate acanthosis, and slight hypergranulosis with no dermal involvment.6

Chronic hyperkeratotic eczematous dermatitis is another common entity in the differential characterized by hyperkeratotic plaques that scale and fissure. Biopsy demonstrates a spongiotic acanthotic epidermis.7,8

Psoriasis of the hands, specifically hyperkeratotic palmoplantar psoriasis, is associated with manual labor, similar to CEMPH. Histology shows epidermal hyperplasia; regular acanthosis; loss of the granular skin layer with prominent dermal capillaries; and a mixed dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils.9 Hyperkeratotic palmoplantar lichen planus presents with pruritic papules in the third and fifth decades of life. Histologically, hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and wedge-shaped hypergranulosis with a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltration at the dermoepidermal junction is seen.10

Palmoplantar keratodermas due to inflammatory reactive dermatoses include callosities that develop in response to repeated trauma or friction on the skin. On histology, there is prominent hyperkeratosis and acanthosis with moderate papillomatosis.11 Drug-related palmoplantar keratodermas such as those from arsenic exposure can lead to multiple, irregular, verrucous, keratotic, and pigmented lesions on the palms and soles. Histologically, atypical keratinocytes are seen in the epidermis with thick hyperkeratosis and vacuolated cells without solar elastosis.12

In conclusion, CEMPH is an underdiagnosed and underrecognized condition characterized by asymptomatic hyperkeratotic linear plaques along the medial aspect of the thumb and radial aspect of the index finger. It is important to keep CEMPH in mind when dealing with occupational cases of repeated long-term trauma or pressure to the hands as well as excessive sun exposure. It also is imperative to separate it from other diseases and avoid misdiagnosing this degenerative collagenous and elastotic disease as a malignant lesion.

- Burks JW, Wise LJ, Clark WH. Degenerative collagenous plaques of the hands. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:362-366.

- Jordaan HF, Rossouw DJ. Digital papular calcific elastosis: a histopathological, histochemical and ultrastructural study of 20 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 1990;17:358-370.

- Mortimore RJ, Conrad RJ. Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:211-213.

- Tieu KD, Satter EK. Thickened plaques on the hands. Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands (CEMPH). Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:499-504.

- Todd D, Al-Aboosi M, Hameed O, et al. The role of UV light in the pathogenesis of digital papular calcific elastosis. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:379-381.

- Mengesha YM, Kayal JD, Swerlick RA. Keratoelastoidosis marginalis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2002;6:23-25.

- MacKee MG, Lewis MG. Keratolysis exfoliativa and the mosaic fungus. Arch Dermatol. 1931;23:445-447.

- Walling HW, Swick BL, Storrs FJ, et al. Frictional hyperkeratotic hand dermatitis responding to Grenz ray therapy. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;58:49-51.

- Farley E, Masrour S, McKey J, et al. Palmoplantar psoriasis: a phenotypical and clinical review with introduction of a new quality-of-life assessment tool. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:1024-1031.

- Rotunda AM, Craft N, Haley JC. Hyperkeratotic plaques on the palms and soles. palmoplantar lichen planus, hyperkeratotic variant. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1275-1280.

- Unal VS, Sevin A, Dayican A. Palmar callus formation as a result of mechanical trauma during sailing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:2161-2162.

- Cöl M, Cöl C, Soran A, et al. Arsenic-related Bowen's disease, palmar keratosis, and skin cancer. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107:687-689.

- Burks JW, Wise LJ, Clark WH. Degenerative collagenous plaques of the hands. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:362-366.

- Jordaan HF, Rossouw DJ. Digital papular calcific elastosis: a histopathological, histochemical and ultrastructural study of 20 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 1990;17:358-370.

- Mortimore RJ, Conrad RJ. Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:211-213.

- Tieu KD, Satter EK. Thickened plaques on the hands. Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands (CEMPH). Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:499-504.

- Todd D, Al-Aboosi M, Hameed O, et al. The role of UV light in the pathogenesis of digital papular calcific elastosis. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:379-381.

- Mengesha YM, Kayal JD, Swerlick RA. Keratoelastoidosis marginalis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2002;6:23-25.

- MacKee MG, Lewis MG. Keratolysis exfoliativa and the mosaic fungus. Arch Dermatol. 1931;23:445-447.

- Walling HW, Swick BL, Storrs FJ, et al. Frictional hyperkeratotic hand dermatitis responding to Grenz ray therapy. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;58:49-51.

- Farley E, Masrour S, McKey J, et al. Palmoplantar psoriasis: a phenotypical and clinical review with introduction of a new quality-of-life assessment tool. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:1024-1031.

- Rotunda AM, Craft N, Haley JC. Hyperkeratotic plaques on the palms and soles. palmoplantar lichen planus, hyperkeratotic variant. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1275-1280.

- Unal VS, Sevin A, Dayican A. Palmar callus formation as a result of mechanical trauma during sailing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:2161-2162.

- Cöl M, Cöl C, Soran A, et al. Arsenic-related Bowen's disease, palmar keratosis, and skin cancer. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107:687-689.

Practice Points

- The etiology of collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands (CEMPHs) is attributed to collagen and elastin degeneration by chronic actinic damage, pressure, or trauma.

- It is important to keep CEMPH in mind when dealing with occupational cases of repeated long-term trauma or pressure to the hands as well as excessive sun exposure. It should be separated from other diseases and avoid being misdiagnosed as a malignant lesion.

Reversible Cutaneous Side Effects of Vismodegib Treatment

To the Editor:

Vismodegib, a first-in-class inhibitor of the hedgehog signaling pathway, is useful in the treatment of advanced basal cell carcinomas (BCCs).1 Common side effects of vismodegib include alopecia (58%), muscle spasms (71%), and dysgeusia (71%).2 Some of these side effects have been hypothesized to be mechanism related.3,4 Keratoacanthomas have been reported to occur after vismodegib treatment of BCC.5 We report 3 cases illustrating reversible cutaneous side effects of vismodegib: alopecia, follicular dermatitis, and drug hypersensitivity reaction.

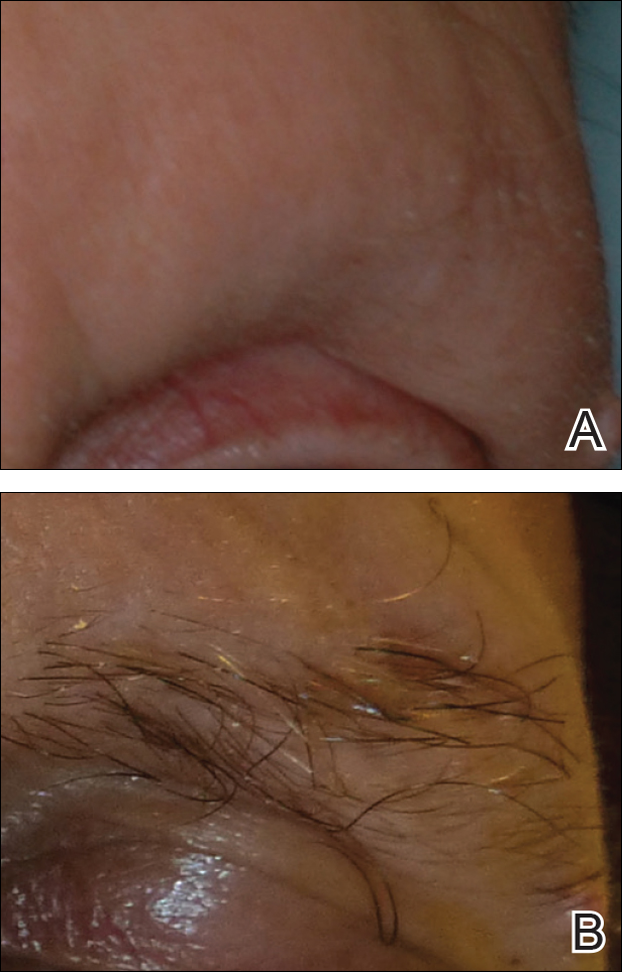

A 53-year-old man with a locally advanced BCC of the right medial canthus began experiencing progressive and diffuse hair loss on the beard area, parietal scalp, eyelashes, and eyebrows after 2 months of vismodegib treatment. At 12 months of treatment, he had complete loss of eyelashes and eyebrows (Figure, A). After vismodegib was discontinued due to disease progression, all of his hair began regrowing within several months, with complete hair regrowth observed at 20 months after the last dose (Figure, B).

A 55-year-old man with several locally advanced BCCs developed new-onset mildly pruritic, acneform lesions on the chest and back after 4 months of vismodegib treatment. Biopsy of the lesions showed a folliculocentric mixed dermal infiltrate. The patient did not have a history of follicular dermatitis. The dermatitis resolved several months after onset without treatment, despite continued vismodegib.

A 55-year-old man with locally advanced BCCs developed erythematous dermal plaques on the arms and chest after 2 months of vismodegib treatment. Lesions were asymptomatic. He was not using any other medications and did not have any contact allergen exposures. Punch biopsy showed superficial and deep perivascular dermatitis with occasional eosinophils, consistent with drug hypersensitivity. Although lesions spontaneously resolved without treatment after 1 month, he experienced a couple more bouts of these lesions over the next year. He continued vismodegib for 2 years without return of this eruption.

The average time frame for hair regrowth after vismodegib cessation has not been characterized and awaits future larger studies. The frequency of follicular dermatitis and drug eruption also has not been determined and may require careful observation by dermatologists in larger numbers of treated patients.

Because the hedgehog pathway is critical for normal hair follicle function, follicle-based toxicities of vismodegib including alopecia and folliculitis could be hypothesized to reflect effective blockade of the pathway.6 Currently, there are no data that these changes correlate with tumor response.

Although alopecia is a recognized side effect of vismodegib, regrowth has not been previously reported.1,2 Knowledge of the reversibility of alopecia as well as other toxicities has the potential to influence patient decision-making on drug initiation and adherence.

- Sekulic A, Migden MR, Oro AE, et al. Efficacy and safety of vismodegib in advanced basal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2171-2179.

- Chang AL, Solomon JA, Hainsworth JD, et al. Expanded access study of patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma treated with the Hedgehog pathway inhibitor, vismodegib. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:60-69.

- St-Jacques B, Dassule HR, Karavanova I, et al. Sonic hedgehog signaling is essential for hair development. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1058-1068.

- Hall JM, Bell ML, Finger TE. Disruption of sonic hedgehog signaling alters growth and patterning of lingual taste papillae. Dev Biol. 2003;255:263-277.

- Aasi S, Silkiss R, Tang JY, et al. New onset of keratoacanthomas after vismodegib treatment for locally advanced basal cell carcinomas: a report of 2 cases. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:242-243.

- Rittie L, Stoll SW, Kang S, et al. Hedgehog signaling maintains hair follicle stem cell phenotype in young and aged human skin. Aging Cell. 2009;8:738-751.

To the Editor:

Vismodegib, a first-in-class inhibitor of the hedgehog signaling pathway, is useful in the treatment of advanced basal cell carcinomas (BCCs).1 Common side effects of vismodegib include alopecia (58%), muscle spasms (71%), and dysgeusia (71%).2 Some of these side effects have been hypothesized to be mechanism related.3,4 Keratoacanthomas have been reported to occur after vismodegib treatment of BCC.5 We report 3 cases illustrating reversible cutaneous side effects of vismodegib: alopecia, follicular dermatitis, and drug hypersensitivity reaction.

A 53-year-old man with a locally advanced BCC of the right medial canthus began experiencing progressive and diffuse hair loss on the beard area, parietal scalp, eyelashes, and eyebrows after 2 months of vismodegib treatment. At 12 months of treatment, he had complete loss of eyelashes and eyebrows (Figure, A). After vismodegib was discontinued due to disease progression, all of his hair began regrowing within several months, with complete hair regrowth observed at 20 months after the last dose (Figure, B).

A 55-year-old man with several locally advanced BCCs developed new-onset mildly pruritic, acneform lesions on the chest and back after 4 months of vismodegib treatment. Biopsy of the lesions showed a folliculocentric mixed dermal infiltrate. The patient did not have a history of follicular dermatitis. The dermatitis resolved several months after onset without treatment, despite continued vismodegib.

A 55-year-old man with locally advanced BCCs developed erythematous dermal plaques on the arms and chest after 2 months of vismodegib treatment. Lesions were asymptomatic. He was not using any other medications and did not have any contact allergen exposures. Punch biopsy showed superficial and deep perivascular dermatitis with occasional eosinophils, consistent with drug hypersensitivity. Although lesions spontaneously resolved without treatment after 1 month, he experienced a couple more bouts of these lesions over the next year. He continued vismodegib for 2 years without return of this eruption.

The average time frame for hair regrowth after vismodegib cessation has not been characterized and awaits future larger studies. The frequency of follicular dermatitis and drug eruption also has not been determined and may require careful observation by dermatologists in larger numbers of treated patients.

Because the hedgehog pathway is critical for normal hair follicle function, follicle-based toxicities of vismodegib including alopecia and folliculitis could be hypothesized to reflect effective blockade of the pathway.6 Currently, there are no data that these changes correlate with tumor response.

Although alopecia is a recognized side effect of vismodegib, regrowth has not been previously reported.1,2 Knowledge of the reversibility of alopecia as well as other toxicities has the potential to influence patient decision-making on drug initiation and adherence.

To the Editor:

Vismodegib, a first-in-class inhibitor of the hedgehog signaling pathway, is useful in the treatment of advanced basal cell carcinomas (BCCs).1 Common side effects of vismodegib include alopecia (58%), muscle spasms (71%), and dysgeusia (71%).2 Some of these side effects have been hypothesized to be mechanism related.3,4 Keratoacanthomas have been reported to occur after vismodegib treatment of BCC.5 We report 3 cases illustrating reversible cutaneous side effects of vismodegib: alopecia, follicular dermatitis, and drug hypersensitivity reaction.

A 53-year-old man with a locally advanced BCC of the right medial canthus began experiencing progressive and diffuse hair loss on the beard area, parietal scalp, eyelashes, and eyebrows after 2 months of vismodegib treatment. At 12 months of treatment, he had complete loss of eyelashes and eyebrows (Figure, A). After vismodegib was discontinued due to disease progression, all of his hair began regrowing within several months, with complete hair regrowth observed at 20 months after the last dose (Figure, B).

A 55-year-old man with several locally advanced BCCs developed new-onset mildly pruritic, acneform lesions on the chest and back after 4 months of vismodegib treatment. Biopsy of the lesions showed a folliculocentric mixed dermal infiltrate. The patient did not have a history of follicular dermatitis. The dermatitis resolved several months after onset without treatment, despite continued vismodegib.

A 55-year-old man with locally advanced BCCs developed erythematous dermal plaques on the arms and chest after 2 months of vismodegib treatment. Lesions were asymptomatic. He was not using any other medications and did not have any contact allergen exposures. Punch biopsy showed superficial and deep perivascular dermatitis with occasional eosinophils, consistent with drug hypersensitivity. Although lesions spontaneously resolved without treatment after 1 month, he experienced a couple more bouts of these lesions over the next year. He continued vismodegib for 2 years without return of this eruption.

The average time frame for hair regrowth after vismodegib cessation has not been characterized and awaits future larger studies. The frequency of follicular dermatitis and drug eruption also has not been determined and may require careful observation by dermatologists in larger numbers of treated patients.

Because the hedgehog pathway is critical for normal hair follicle function, follicle-based toxicities of vismodegib including alopecia and folliculitis could be hypothesized to reflect effective blockade of the pathway.6 Currently, there are no data that these changes correlate with tumor response.

Although alopecia is a recognized side effect of vismodegib, regrowth has not been previously reported.1,2 Knowledge of the reversibility of alopecia as well as other toxicities has the potential to influence patient decision-making on drug initiation and adherence.

- Sekulic A, Migden MR, Oro AE, et al. Efficacy and safety of vismodegib in advanced basal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2171-2179.

- Chang AL, Solomon JA, Hainsworth JD, et al. Expanded access study of patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma treated with the Hedgehog pathway inhibitor, vismodegib. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:60-69.

- St-Jacques B, Dassule HR, Karavanova I, et al. Sonic hedgehog signaling is essential for hair development. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1058-1068.

- Hall JM, Bell ML, Finger TE. Disruption of sonic hedgehog signaling alters growth and patterning of lingual taste papillae. Dev Biol. 2003;255:263-277.

- Aasi S, Silkiss R, Tang JY, et al. New onset of keratoacanthomas after vismodegib treatment for locally advanced basal cell carcinomas: a report of 2 cases. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:242-243.

- Rittie L, Stoll SW, Kang S, et al. Hedgehog signaling maintains hair follicle stem cell phenotype in young and aged human skin. Aging Cell. 2009;8:738-751.

- Sekulic A, Migden MR, Oro AE, et al. Efficacy and safety of vismodegib in advanced basal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2171-2179.

- Chang AL, Solomon JA, Hainsworth JD, et al. Expanded access study of patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma treated with the Hedgehog pathway inhibitor, vismodegib. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:60-69.

- St-Jacques B, Dassule HR, Karavanova I, et al. Sonic hedgehog signaling is essential for hair development. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1058-1068.

- Hall JM, Bell ML, Finger TE. Disruption of sonic hedgehog signaling alters growth and patterning of lingual taste papillae. Dev Biol. 2003;255:263-277.

- Aasi S, Silkiss R, Tang JY, et al. New onset of keratoacanthomas after vismodegib treatment for locally advanced basal cell carcinomas: a report of 2 cases. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:242-243.

- Rittie L, Stoll SW, Kang S, et al. Hedgehog signaling maintains hair follicle stem cell phenotype in young and aged human skin. Aging Cell. 2009;8:738-751.

Practice Points

- Hair loss is a common late side effect of vismodegib usage and is reversible, but regrowth takes many months.

- Mild folliculitis that resolves spontaneously has been observed in patients using vismodegib.

- Dermal hypersensitivity has been observed in patients on vismodegib, though the exact frequency of this type of dermatitis is not known.

Primary Cutaneous Cryptococcosis Presenting as an Extensive Eroded Plaque

To the Editor:

Primary cutaneous cryptococcal infection is rare. Cryptococcal skin infections, either primary or disseminated, can be highly pleomorphic and mimic entities such as basal cell carcinoma or even severe dermatitis, as in our case.

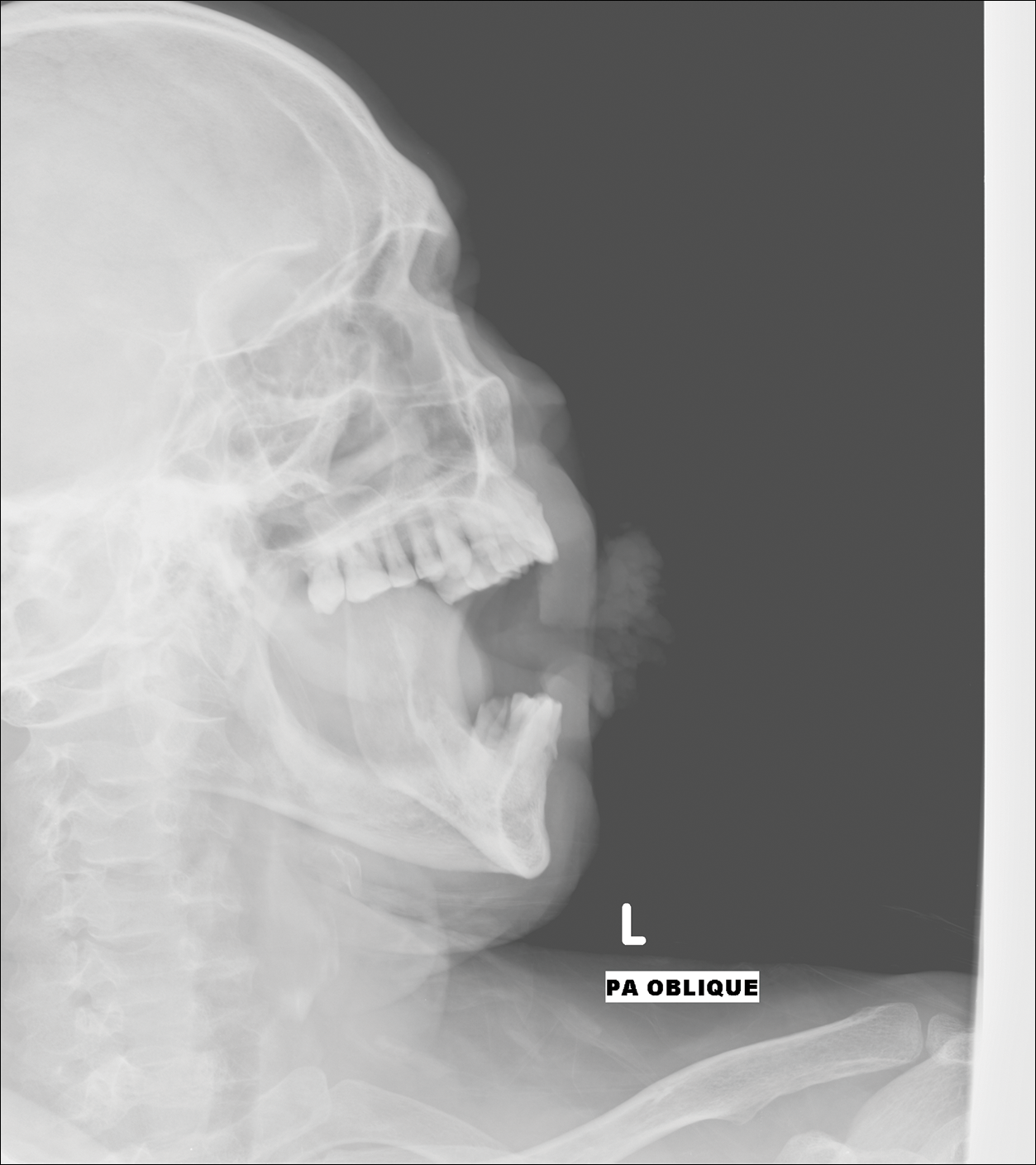

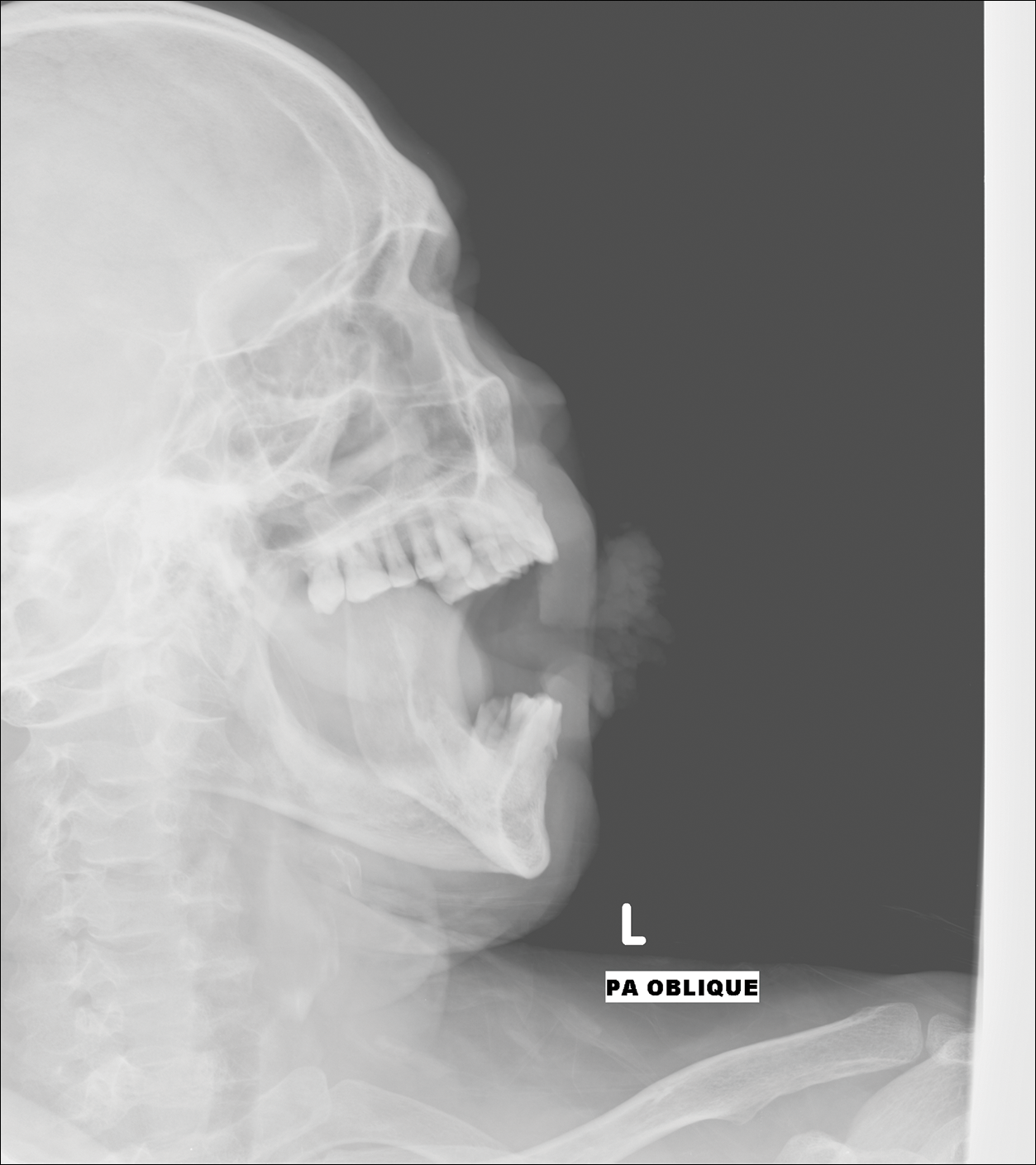

An 80-year-old woman who was residing in a nursing facility presented to the emergency department with an itchy nontender rash on the left arm of 2 to 3 weeks' duration that gradually spread. The patient had not started any new topical or oral medications and was otherwise healthy. A review of symptoms was negative for fever, weight loss, or new cough. Her medical history was notable for congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease requiring chronic low-dose prednisone, hypothyroidism, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, and dementia. On physical examination the patient had a large, well-demarcated, pink, scaly plaque with areas of ulceration extending from the dorsal aspect of the hand and fingers to the mid upper arm. There was minimal overlying yellow-brown crust (Figure 1). A potassium hydroxide preparation from a superficial scraping was negative. A punch biopsy specimen was obtained from the lesion and microscopic examination revealed histiocytes with innumerable intracytoplasmic yeast forms demonstrating small buds (Figure 2). The organisms were highlighted by periodic acid-Schiff and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains (Figure 3), while acid-fast bacillus and Fite stains were negative. The presumptive diagnosis of cutaneous cryptococcosis was made, and subsequent culture and latex agglutination test was positive for Cryptococcus neoformans. A chest radiograph showed no evidence of active disease. Infectious disease specialists were consulted and ordered additional laboratory studies, which were negative for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis, and fungemia. The patient had a low CD4 count of 119 cells/μL (reference range, 496-2186 cells/μL). Workup for systemic Cryptococcus, including head computed tomography, cerebral spinal fluid analysis, and bone marrow biopsy were all negative. Epstein-Barr virus and human T lymphotropic virus tests were both negative. The source of the patient's low CD4 count was never discovered. She gradually began to improve with diligent wound care and continued fluconazole 400 mg daily. The patient's history did reveal working on a chicken farm as an adult many years ago.

Cryptococcus is a yeast that causes infection primarily through airborne spores that lead to pulmonary infection. Cryptococcus neoformans is the most common pathogenic strain, though infection with other strains such as Cryptococcus albidus1 and Cryptococcus laurentii2 have been reported. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis is an exceedingly rare entity, with the majority of cases of cutaneous cryptococcosis originating from primary pulmonary infection with hematogenous dissemination to the skin. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis rarely can be caused by inoculation in nonimmunosuppressed hosts and infection of nonimmunosuppressed hosts is more common in men than in women.3 Manifestations of cutaneous cryptococcosis can be incredibly varied and diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion along with appropriate histological and serological confirmation. Cutaneous cryptococcosis can present in various clinical ways, including molluscumlike lesions, which are more common in patients with AIDS; acneform lesions; vesicles; dermal plaques or nodules; and rarely cellulitis with ulcerations, as in our patient. Cryptococcosis also can imitate basal cell carcinoma, nummular and follicular eczema, and Kaposi sarcoma.4

Histologic examination reveals either a gelatinous or granulomatous pattern based on the number of organisms present. The gelatinous pattern is characterized by little inflammation and a large number of phagocytosed organisms floating in mucin. The granulomatous pattern shows prominent inflammation with lymphocytes, histiocytes, and giant cells, as well as associated necrosis.

Treatment depends on the type of infection and host immunological status. Immunocompetent hosts with cutaneous infection may spontaneously heal. Treatment consists of surgical excision, if possible, followed by fluconazole or itraconazole. For disseminated cryptococcal infections in immunosuppressed hosts, the standard of care is amphotericin B with or without flucytosine.3

- Hoang JK, Burruss J. Localized cutaneous Cryptococcus albidus infection in a 14-year-old boy on etanercept therapy [published online June 5, 2007]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:285-288. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2007.00404.x.

- Vlchkova-Lashkoska M, Kamberova S, Starova A, et al. Cutaneous Cryptococcus laurentii infection in a human immunodeficiency virus-negative subject. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:99-100.

- Antony SA, Antony SJ. Primary cutaneous Cryptococcus in nonimmunocompromised patients. Cutis. 1995;56:96-98.

- Murakawa GJ, Kerschmann R, Berger T. Cutaneous Cryptococcus infection and AIDS. report of 12 cases and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:545-548.

To the Editor:

Primary cutaneous cryptococcal infection is rare. Cryptococcal skin infections, either primary or disseminated, can be highly pleomorphic and mimic entities such as basal cell carcinoma or even severe dermatitis, as in our case.

An 80-year-old woman who was residing in a nursing facility presented to the emergency department with an itchy nontender rash on the left arm of 2 to 3 weeks' duration that gradually spread. The patient had not started any new topical or oral medications and was otherwise healthy. A review of symptoms was negative for fever, weight loss, or new cough. Her medical history was notable for congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease requiring chronic low-dose prednisone, hypothyroidism, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, and dementia. On physical examination the patient had a large, well-demarcated, pink, scaly plaque with areas of ulceration extending from the dorsal aspect of the hand and fingers to the mid upper arm. There was minimal overlying yellow-brown crust (Figure 1). A potassium hydroxide preparation from a superficial scraping was negative. A punch biopsy specimen was obtained from the lesion and microscopic examination revealed histiocytes with innumerable intracytoplasmic yeast forms demonstrating small buds (Figure 2). The organisms were highlighted by periodic acid-Schiff and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains (Figure 3), while acid-fast bacillus and Fite stains were negative. The presumptive diagnosis of cutaneous cryptococcosis was made, and subsequent culture and latex agglutination test was positive for Cryptococcus neoformans. A chest radiograph showed no evidence of active disease. Infectious disease specialists were consulted and ordered additional laboratory studies, which were negative for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis, and fungemia. The patient had a low CD4 count of 119 cells/μL (reference range, 496-2186 cells/μL). Workup for systemic Cryptococcus, including head computed tomography, cerebral spinal fluid analysis, and bone marrow biopsy were all negative. Epstein-Barr virus and human T lymphotropic virus tests were both negative. The source of the patient's low CD4 count was never discovered. She gradually began to improve with diligent wound care and continued fluconazole 400 mg daily. The patient's history did reveal working on a chicken farm as an adult many years ago.

Cryptococcus is a yeast that causes infection primarily through airborne spores that lead to pulmonary infection. Cryptococcus neoformans is the most common pathogenic strain, though infection with other strains such as Cryptococcus albidus1 and Cryptococcus laurentii2 have been reported. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis is an exceedingly rare entity, with the majority of cases of cutaneous cryptococcosis originating from primary pulmonary infection with hematogenous dissemination to the skin. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis rarely can be caused by inoculation in nonimmunosuppressed hosts and infection of nonimmunosuppressed hosts is more common in men than in women.3 Manifestations of cutaneous cryptococcosis can be incredibly varied and diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion along with appropriate histological and serological confirmation. Cutaneous cryptococcosis can present in various clinical ways, including molluscumlike lesions, which are more common in patients with AIDS; acneform lesions; vesicles; dermal plaques or nodules; and rarely cellulitis with ulcerations, as in our patient. Cryptococcosis also can imitate basal cell carcinoma, nummular and follicular eczema, and Kaposi sarcoma.4

Histologic examination reveals either a gelatinous or granulomatous pattern based on the number of organisms present. The gelatinous pattern is characterized by little inflammation and a large number of phagocytosed organisms floating in mucin. The granulomatous pattern shows prominent inflammation with lymphocytes, histiocytes, and giant cells, as well as associated necrosis.

Treatment depends on the type of infection and host immunological status. Immunocompetent hosts with cutaneous infection may spontaneously heal. Treatment consists of surgical excision, if possible, followed by fluconazole or itraconazole. For disseminated cryptococcal infections in immunosuppressed hosts, the standard of care is amphotericin B with or without flucytosine.3

To the Editor:

Primary cutaneous cryptococcal infection is rare. Cryptococcal skin infections, either primary or disseminated, can be highly pleomorphic and mimic entities such as basal cell carcinoma or even severe dermatitis, as in our case.

An 80-year-old woman who was residing in a nursing facility presented to the emergency department with an itchy nontender rash on the left arm of 2 to 3 weeks' duration that gradually spread. The patient had not started any new topical or oral medications and was otherwise healthy. A review of symptoms was negative for fever, weight loss, or new cough. Her medical history was notable for congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease requiring chronic low-dose prednisone, hypothyroidism, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, and dementia. On physical examination the patient had a large, well-demarcated, pink, scaly plaque with areas of ulceration extending from the dorsal aspect of the hand and fingers to the mid upper arm. There was minimal overlying yellow-brown crust (Figure 1). A potassium hydroxide preparation from a superficial scraping was negative. A punch biopsy specimen was obtained from the lesion and microscopic examination revealed histiocytes with innumerable intracytoplasmic yeast forms demonstrating small buds (Figure 2). The organisms were highlighted by periodic acid-Schiff and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains (Figure 3), while acid-fast bacillus and Fite stains were negative. The presumptive diagnosis of cutaneous cryptococcosis was made, and subsequent culture and latex agglutination test was positive for Cryptococcus neoformans. A chest radiograph showed no evidence of active disease. Infectious disease specialists were consulted and ordered additional laboratory studies, which were negative for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis, and fungemia. The patient had a low CD4 count of 119 cells/μL (reference range, 496-2186 cells/μL). Workup for systemic Cryptococcus, including head computed tomography, cerebral spinal fluid analysis, and bone marrow biopsy were all negative. Epstein-Barr virus and human T lymphotropic virus tests were both negative. The source of the patient's low CD4 count was never discovered. She gradually began to improve with diligent wound care and continued fluconazole 400 mg daily. The patient's history did reveal working on a chicken farm as an adult many years ago.

Cryptococcus is a yeast that causes infection primarily through airborne spores that lead to pulmonary infection. Cryptococcus neoformans is the most common pathogenic strain, though infection with other strains such as Cryptococcus albidus1 and Cryptococcus laurentii2 have been reported. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis is an exceedingly rare entity, with the majority of cases of cutaneous cryptococcosis originating from primary pulmonary infection with hematogenous dissemination to the skin. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis rarely can be caused by inoculation in nonimmunosuppressed hosts and infection of nonimmunosuppressed hosts is more common in men than in women.3 Manifestations of cutaneous cryptococcosis can be incredibly varied and diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion along with appropriate histological and serological confirmation. Cutaneous cryptococcosis can present in various clinical ways, including molluscumlike lesions, which are more common in patients with AIDS; acneform lesions; vesicles; dermal plaques or nodules; and rarely cellulitis with ulcerations, as in our patient. Cryptococcosis also can imitate basal cell carcinoma, nummular and follicular eczema, and Kaposi sarcoma.4

Histologic examination reveals either a gelatinous or granulomatous pattern based on the number of organisms present. The gelatinous pattern is characterized by little inflammation and a large number of phagocytosed organisms floating in mucin. The granulomatous pattern shows prominent inflammation with lymphocytes, histiocytes, and giant cells, as well as associated necrosis.

Treatment depends on the type of infection and host immunological status. Immunocompetent hosts with cutaneous infection may spontaneously heal. Treatment consists of surgical excision, if possible, followed by fluconazole or itraconazole. For disseminated cryptococcal infections in immunosuppressed hosts, the standard of care is amphotericin B with or without flucytosine.3

- Hoang JK, Burruss J. Localized cutaneous Cryptococcus albidus infection in a 14-year-old boy on etanercept therapy [published online June 5, 2007]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:285-288. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2007.00404.x.

- Vlchkova-Lashkoska M, Kamberova S, Starova A, et al. Cutaneous Cryptococcus laurentii infection in a human immunodeficiency virus-negative subject. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:99-100.

- Antony SA, Antony SJ. Primary cutaneous Cryptococcus in nonimmunocompromised patients. Cutis. 1995;56:96-98.

- Murakawa GJ, Kerschmann R, Berger T. Cutaneous Cryptococcus infection and AIDS. report of 12 cases and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:545-548.

- Hoang JK, Burruss J. Localized cutaneous Cryptococcus albidus infection in a 14-year-old boy on etanercept therapy [published online June 5, 2007]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:285-288. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2007.00404.x.

- Vlchkova-Lashkoska M, Kamberova S, Starova A, et al. Cutaneous Cryptococcus laurentii infection in a human immunodeficiency virus-negative subject. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:99-100.

- Antony SA, Antony SJ. Primary cutaneous Cryptococcus in nonimmunocompromised patients. Cutis. 1995;56:96-98.

- Murakawa GJ, Kerschmann R, Berger T. Cutaneous Cryptococcus infection and AIDS. report of 12 cases and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:545-548.

Practice Points

- Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis is rare in nonimmunosuppressed patients.

- Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis secondary to inoculation can have a clinical presentation similar to more common conditions, such as molluscum, acne, and dermatitis.

Postoperative Henoch-Schönlein Purpura

To the Editor:

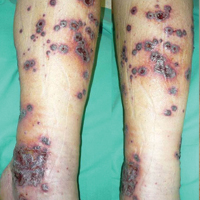

A 57-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension was hospitalized for heart disease resulting in an aortic valve replacement and multiple-vessel bypass grafting. He experienced a stormy septic postoperative course during which he developed numerous palpable purplish plaques (Figure 1). The lesions were bilateral and more heavily involved the lower legs and buttocks. The head and neck remained free of skin lesions. Additionally, the patient reported a bilateral burning sensation from the knees to the feet.

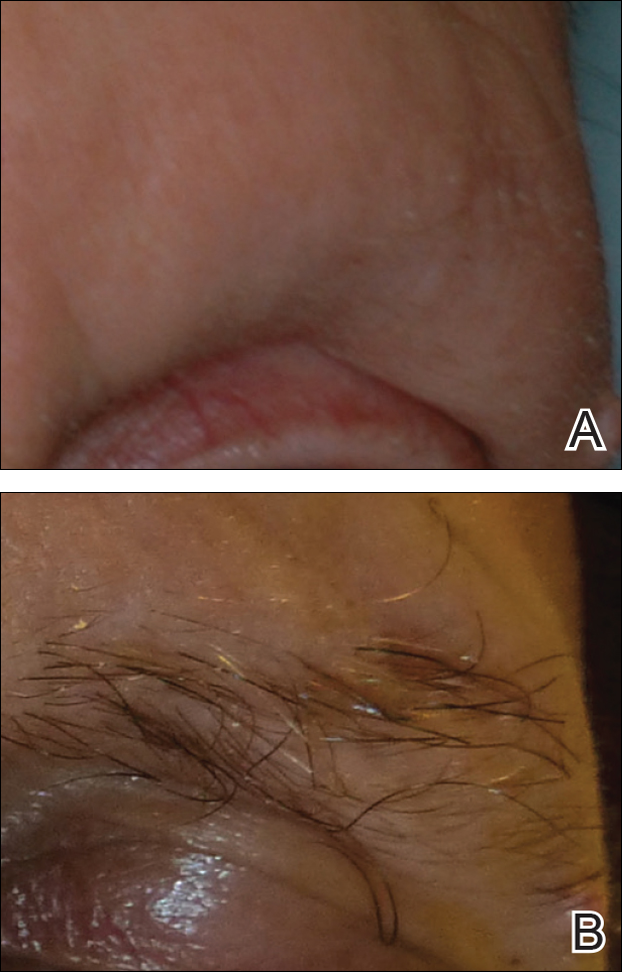

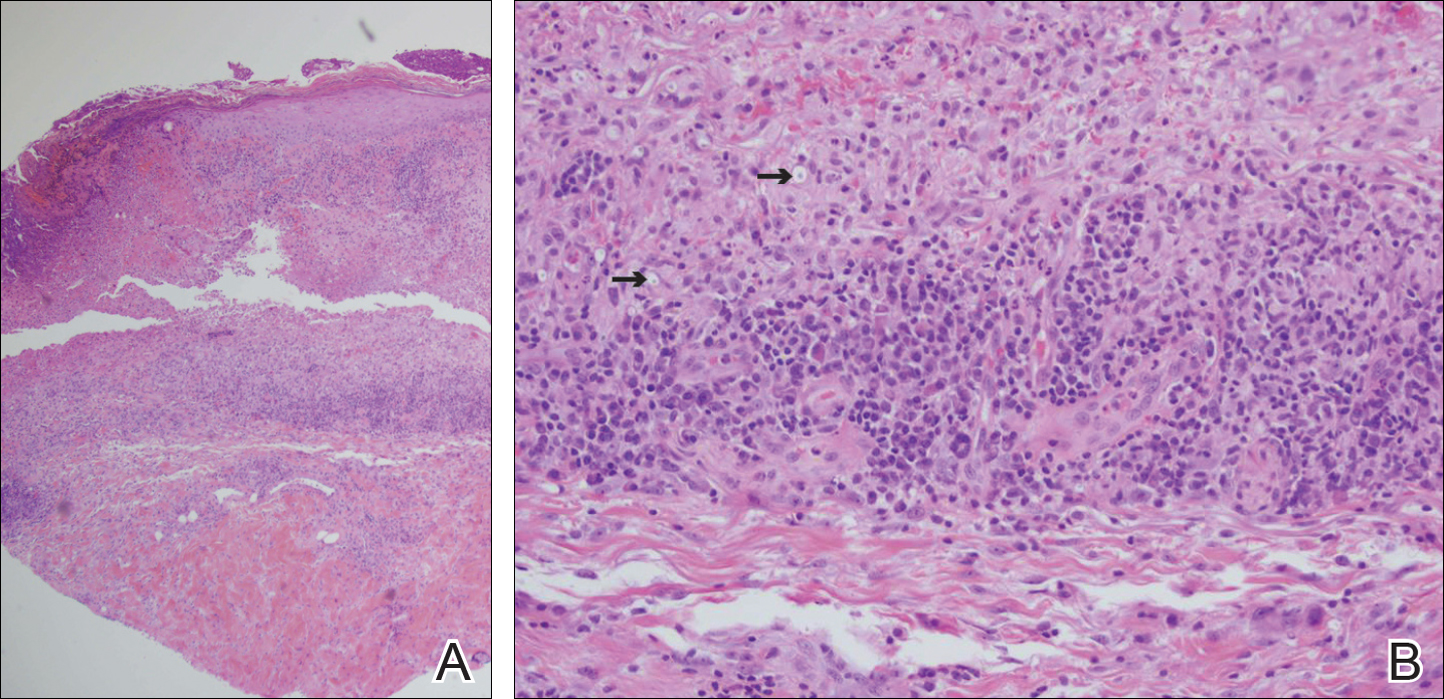

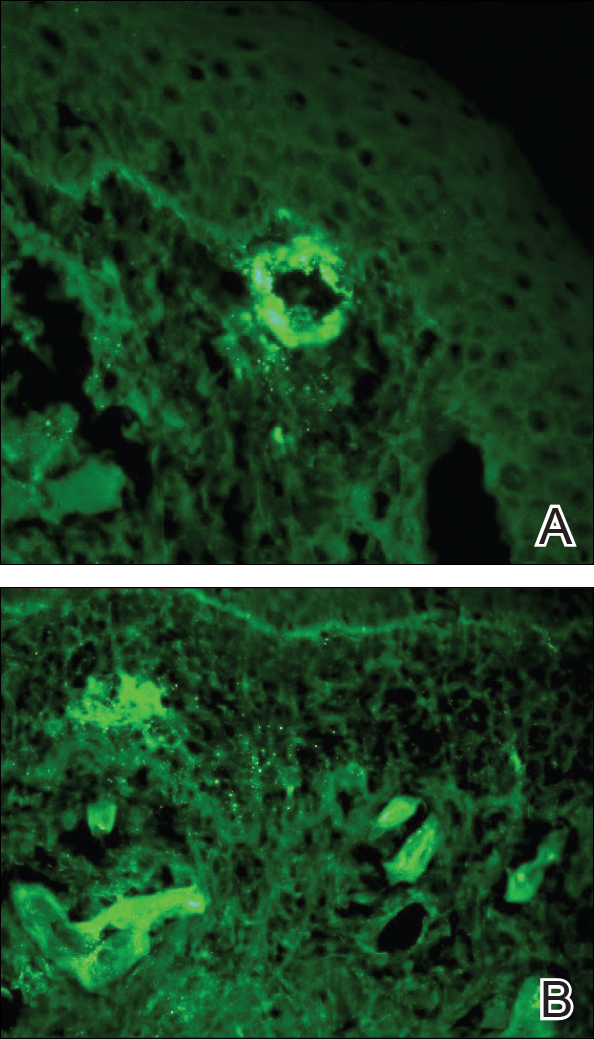

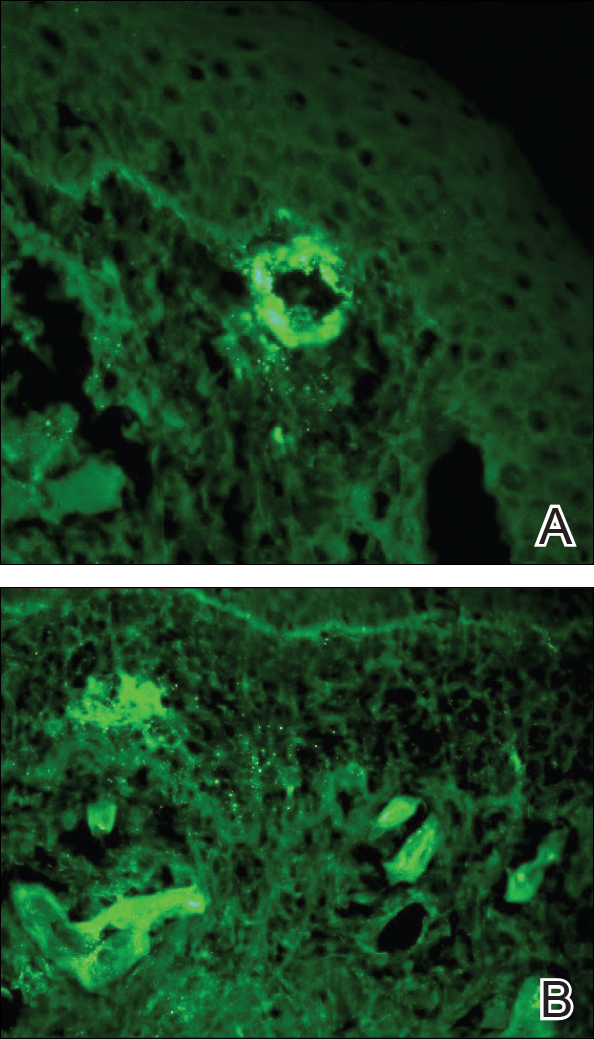

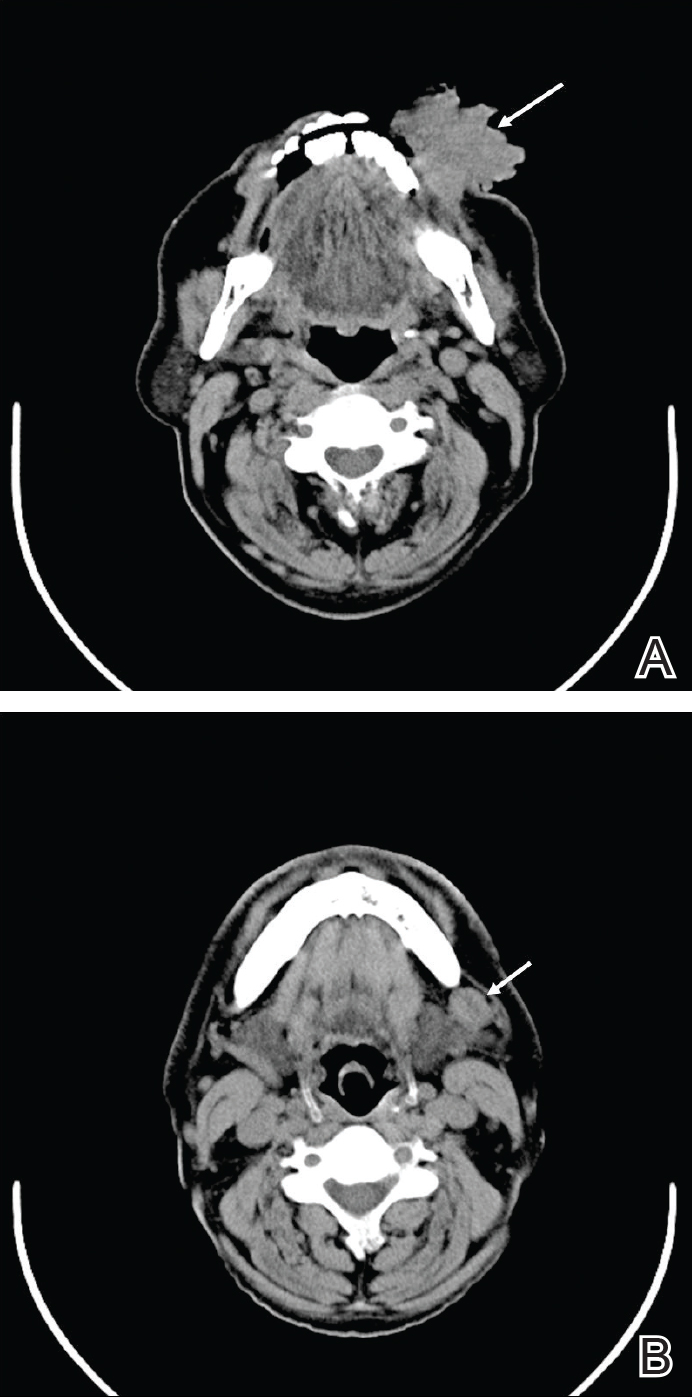

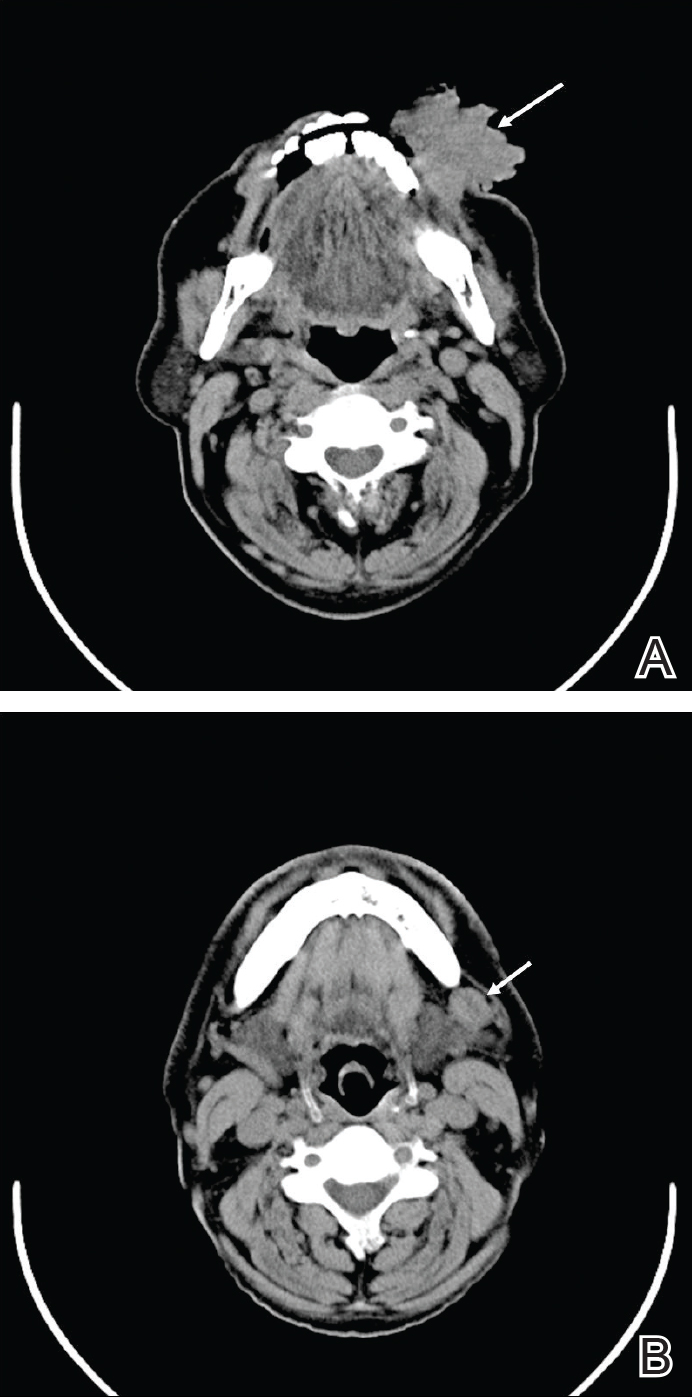

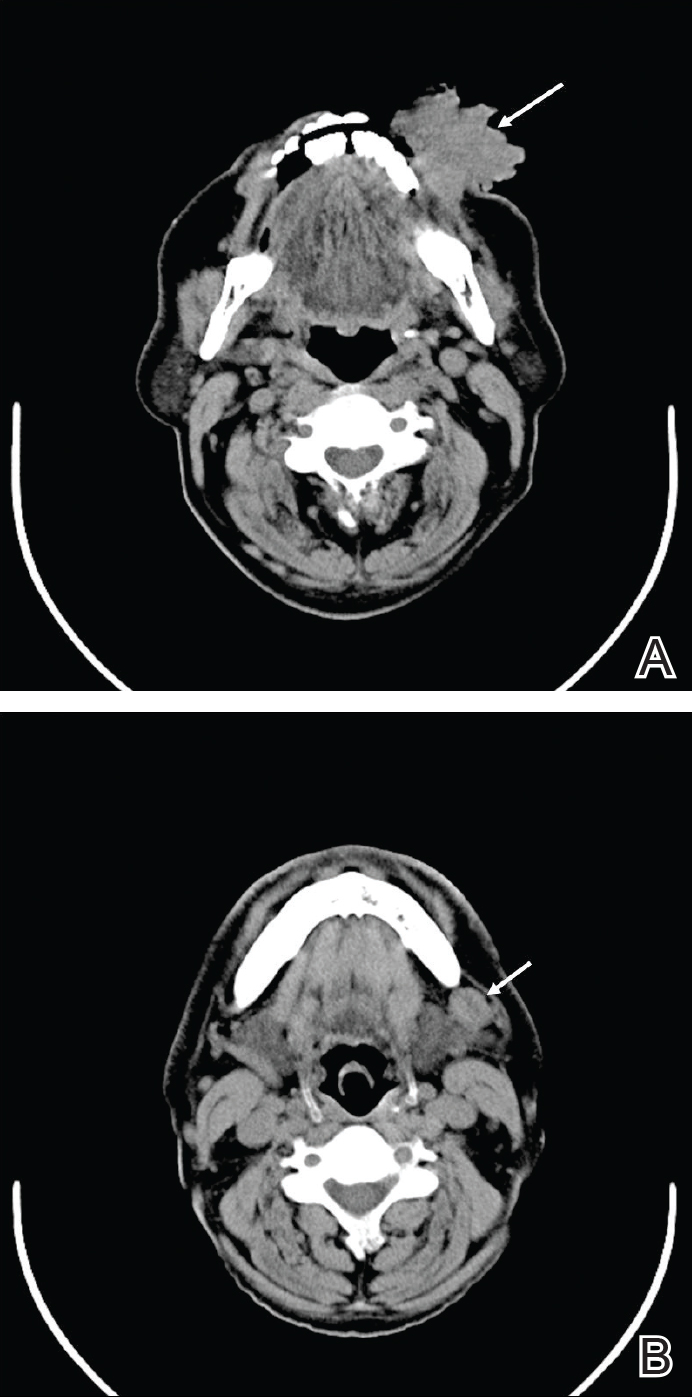

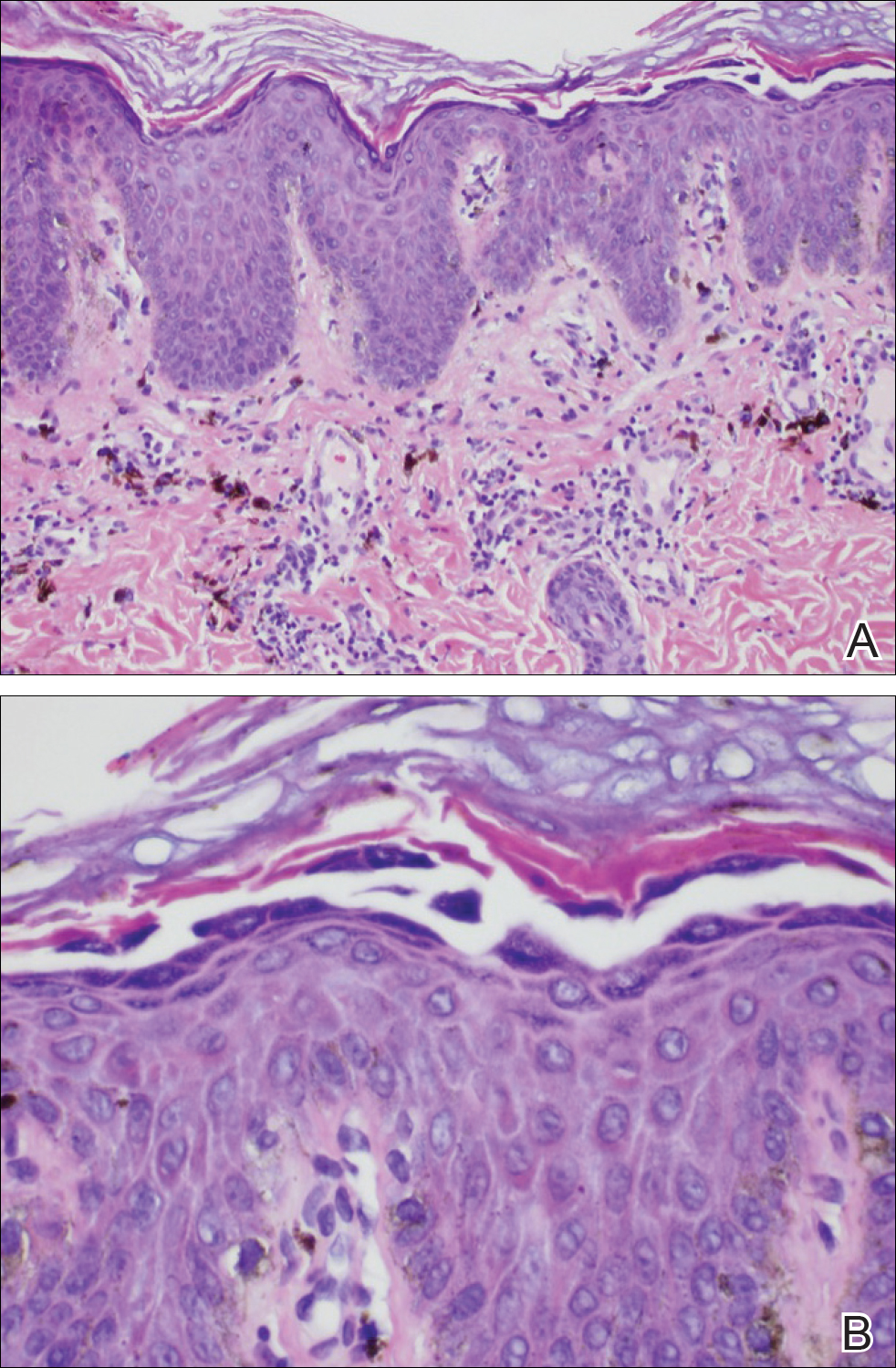

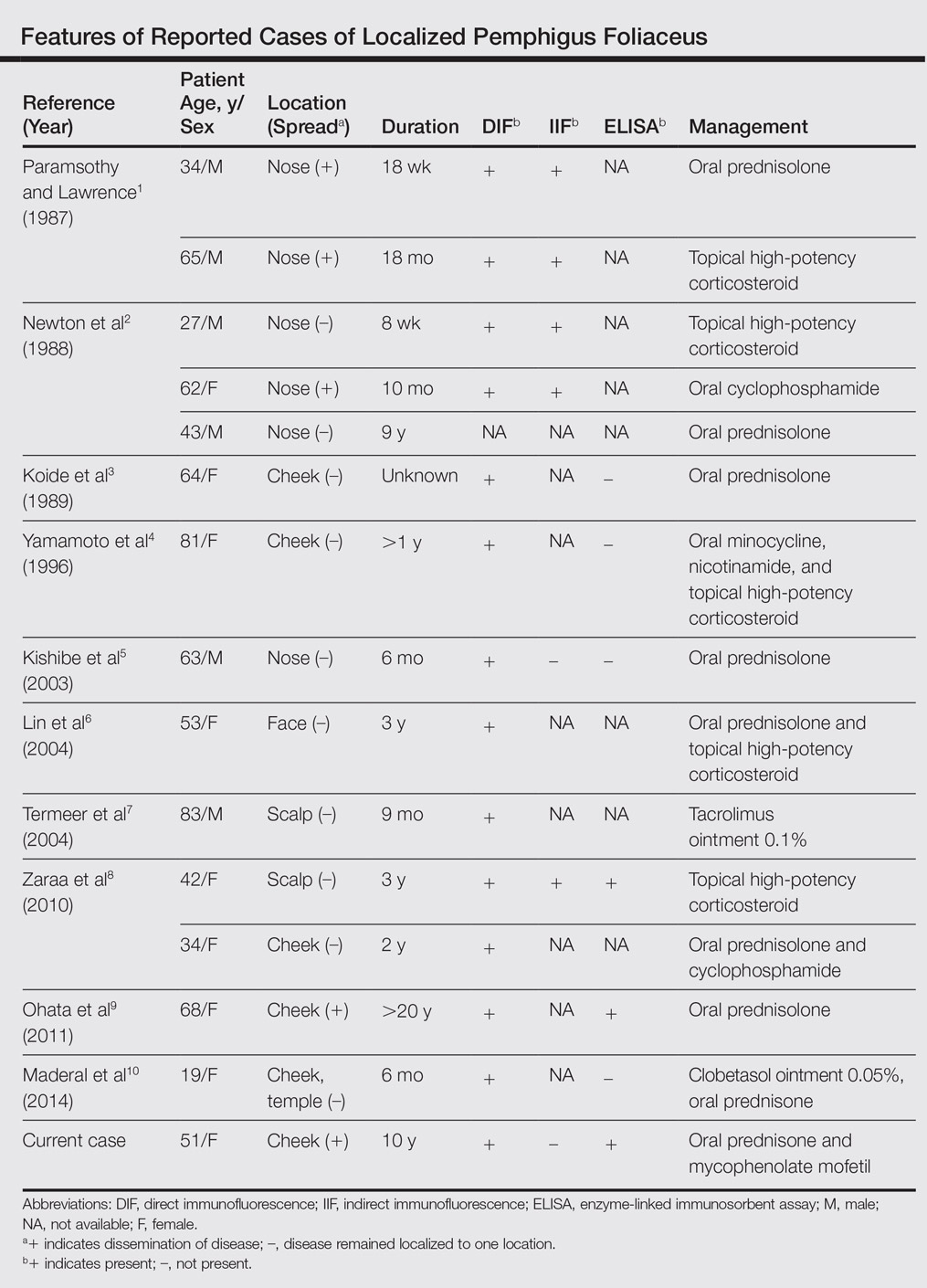

Punch biopsies of lesions from the right upper arm were obtained. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed neutrophilic-predominant small vessel vasculitis (Figure 2A) with the upper dermal location more heavily involved, as demonstrated by involvement of a superficial vascular plexus (Figures 2B and 2C) that was consistent with Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP). The diagnosis later was confirmed with immunofluorescence. Direct immunofluorescence revealed granular IgA deposition around the superficial vascular plexus (Figure 3). No IgG, IgM, C3, C5b-9 complement complex, or fibrinogen deposition was seen. Additionally, periodic acid-Schiff staining failed to show microorganisms, thrombi, or intravascular hyaline material.

At our initial consultation, we observed an ill-appearing afebrile man with purplish plaques. Our impression was that he had vasculitis and not warfarin necrosis, which had been suspected by the cardiovascular team. The burning sensation noted by the patient lent credence to our vasculitic diagnosis. Proteinuria and hematuria were present; however, the values for blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and glomerular filtration rate all remained within reference range. His signs and symptoms responded dramatically to prednisone. He remains on 1 mg of prednisone daily and a nephrologist continues to monitor renal function as an outpatient.

Henoch-Schönlein purpura is a systemic leukocytoclastic vasculitis involving small vessels. The small vessel vasculitis is associated with IgA antigen-antibody complex deposition in areas throughout the body. Palpable purpura typically is seen on the skin, which characteristically involves dependent areas such as the legs and the buttocks. Lesions normally are present bilaterally in a symmetric distribution. Initially, the lesions develop as erythematous macules that progress to purple, nonblanching, palpable, and purpuric plaques.1 Henoch-Schönlein purpura most commonly involves the skin; however, other locations for the immune complexes include the gastrointestinal tract, joints, and kidneys.2 The cause for the body's immunogenic deposition response is unknown in a majority of cases.

Henoch-Schönlein purpura most commonly is seen in the pediatric population with a predilection for males.3 The incidence in the pediatric population is 13.5 to 20 per 100,000 children per year; HSP is more rare in adults.4-6 Henoch-Schönlein purpura most often is a self-limiting disease that requires only supportive treatment. The signs and symptoms last 4 to 6 weeks in most patients and resolve completely in 94% of children and 89% of adults.7 Renal involvement carries a worse prognosis. Adult patients have a higher incidence of renal involvement, renal insufficiency, and subsequent progression to end-stage renal disease.3,8-10 In a study by Hung et al8 of 65 children and 22 adult HSP patients, 12 adults presented with renal involvement in which hematuria or proteinuria were present. Of them, 6 progressed to renal insufficiency (defined as having a plasma creatinine concentration>1.2 mg/dL).8 Fogazzi et al11 reported similar findings; 8 of 16 patients affected with HSP progressed to renal insufficiency with creatinine clearances ranging from 31 to 60 mL/min, and 3 patients required chronic dialysis. Pillebout et al9 evaluated 250 adults with HSP and 32% reached renal insufficiency with creatinine clearances of less than 50 mL/min, with 11% of patients developing end-stage renal disease. The degree of hematuria and/or proteinuria has been shown to be an effective prognostic indicator.9,10 Coppo et al10 found a similar prognosis among children and adults with HSP-related nephritis.

Our patient described the burning sensation as occurring bilaterally from the knees down to the feet, which provided an additional clue that small vessel vasculitis was involved, as occluded blood vessels can cause ischemia to nerves and perivascular involvement can affect nearby neural structures. Sais et al12 demonstrated that paresthesia in the setting of HSP was a risk factor for systemic involvement. Of note, our patient's paresthesia lasted only several days.

The cause of HSP is not always as evident in the adult population as in the pediatric population. Early diagnosis of HSP in adults may allow for the proper instatement of treatment to deter long-term renal complications. Follow-up with urinalysis is recommended because a small percentage of patients have a late progression to renal failure.13,14

Because the dermatologists involved in this case knew where and what types of biopsies to perform, a correct diagnosis was obtained quickly, allowing for the correct therapeutic intervention. After the diagnosis of HSP is made in an adult, nephrology should be consulted early in the treatment course.

- Rai A, Nast C, Adler S. Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:2637-2644.

- Helander SD, De Castro FR, Gibson LE. Henoch-Schönlein purpura: clinicopathologic correlation of cutaneous vascular IgA deposits and the relationship to leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:125-129.

- Garcia-Porrua C, Calvino MC, Llorca J, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children and adults: clinical differences in a defined population. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2002;32:149-156.

- Stewart M, Savage JM, Bell B, et al. Long term renal prognosis of Henoch-Schönlein purpura in an unselected childhood population. Eur J Pediatr. 1988;147:113-115.

- Watts RA, Scott DG. Epidemiology of the vasculitides. Semin Respir Crit Care. 2004;25:455-464.

- Gardner-Medwin JM, Dolezalova P, Cummins C, et al. Incidence of Henoch-Schönlein purpura, Kawasaki disease, and rare vasculitides in children of different ethnic origins. Lancet. 2002;360:1197-1202.

- Blanco R, Martínez-Taboada VM, Rodríguez-Valverde V, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in adulthood and childhood: two different expressions of the same syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:859-864.

- Hung SP, Yang YH, Lin YT, et al. Clinical manifestations and outcomes of Henoch-Schönlein purpura: comparison between adults and children. Pediatr Neonatol. 2009;50:162-168.

- Pillebout E, Thervet E, Hill G, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in adults: outcomes and prognostic factors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1271-1278.

- Coppo R, Mazzucco G, Cagnoli L, et al. Long-term prognosis of Henoch-Schönlein nephritis in adults and children. Italian Group of Renal Immunopathology collaborative study on Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:2277-2283.

- Fogazzi GB, Pasquali S, Moriggi M, et al. Long-term outcome of Schönlein-Henoch nephritis in the adult. Clin Nephrol. 1989;31:60-66.

- Sais G, Vidaller A, Jucgla A. Prognostic factors in leukocytoclastic vasculitis. a clinicopathologic study of 160 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:309-315.

- Kraft DM, McKee D, Scott C. Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a review. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58:405-408.

- Narchi H. Risk of long-term renal impairment and duration of follow up recommended for Henoch-Schönlein purpura with normal or minimal urinary findings: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:916-920.

To the Editor:

A 57-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension was hospitalized for heart disease resulting in an aortic valve replacement and multiple-vessel bypass grafting. He experienced a stormy septic postoperative course during which he developed numerous palpable purplish plaques (Figure 1). The lesions were bilateral and more heavily involved the lower legs and buttocks. The head and neck remained free of skin lesions. Additionally, the patient reported a bilateral burning sensation from the knees to the feet.

Punch biopsies of lesions from the right upper arm were obtained. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed neutrophilic-predominant small vessel vasculitis (Figure 2A) with the upper dermal location more heavily involved, as demonstrated by involvement of a superficial vascular plexus (Figures 2B and 2C) that was consistent with Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP). The diagnosis later was confirmed with immunofluorescence. Direct immunofluorescence revealed granular IgA deposition around the superficial vascular plexus (Figure 3). No IgG, IgM, C3, C5b-9 complement complex, or fibrinogen deposition was seen. Additionally, periodic acid-Schiff staining failed to show microorganisms, thrombi, or intravascular hyaline material.

At our initial consultation, we observed an ill-appearing afebrile man with purplish plaques. Our impression was that he had vasculitis and not warfarin necrosis, which had been suspected by the cardiovascular team. The burning sensation noted by the patient lent credence to our vasculitic diagnosis. Proteinuria and hematuria were present; however, the values for blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and glomerular filtration rate all remained within reference range. His signs and symptoms responded dramatically to prednisone. He remains on 1 mg of prednisone daily and a nephrologist continues to monitor renal function as an outpatient.

Henoch-Schönlein purpura is a systemic leukocytoclastic vasculitis involving small vessels. The small vessel vasculitis is associated with IgA antigen-antibody complex deposition in areas throughout the body. Palpable purpura typically is seen on the skin, which characteristically involves dependent areas such as the legs and the buttocks. Lesions normally are present bilaterally in a symmetric distribution. Initially, the lesions develop as erythematous macules that progress to purple, nonblanching, palpable, and purpuric plaques.1 Henoch-Schönlein purpura most commonly involves the skin; however, other locations for the immune complexes include the gastrointestinal tract, joints, and kidneys.2 The cause for the body's immunogenic deposition response is unknown in a majority of cases.

Henoch-Schönlein purpura most commonly is seen in the pediatric population with a predilection for males.3 The incidence in the pediatric population is 13.5 to 20 per 100,000 children per year; HSP is more rare in adults.4-6 Henoch-Schönlein purpura most often is a self-limiting disease that requires only supportive treatment. The signs and symptoms last 4 to 6 weeks in most patients and resolve completely in 94% of children and 89% of adults.7 Renal involvement carries a worse prognosis. Adult patients have a higher incidence of renal involvement, renal insufficiency, and subsequent progression to end-stage renal disease.3,8-10 In a study by Hung et al8 of 65 children and 22 adult HSP patients, 12 adults presented with renal involvement in which hematuria or proteinuria were present. Of them, 6 progressed to renal insufficiency (defined as having a plasma creatinine concentration>1.2 mg/dL).8 Fogazzi et al11 reported similar findings; 8 of 16 patients affected with HSP progressed to renal insufficiency with creatinine clearances ranging from 31 to 60 mL/min, and 3 patients required chronic dialysis. Pillebout et al9 evaluated 250 adults with HSP and 32% reached renal insufficiency with creatinine clearances of less than 50 mL/min, with 11% of patients developing end-stage renal disease. The degree of hematuria and/or proteinuria has been shown to be an effective prognostic indicator.9,10 Coppo et al10 found a similar prognosis among children and adults with HSP-related nephritis.

Our patient described the burning sensation as occurring bilaterally from the knees down to the feet, which provided an additional clue that small vessel vasculitis was involved, as occluded blood vessels can cause ischemia to nerves and perivascular involvement can affect nearby neural structures. Sais et al12 demonstrated that paresthesia in the setting of HSP was a risk factor for systemic involvement. Of note, our patient's paresthesia lasted only several days.

The cause of HSP is not always as evident in the adult population as in the pediatric population. Early diagnosis of HSP in adults may allow for the proper instatement of treatment to deter long-term renal complications. Follow-up with urinalysis is recommended because a small percentage of patients have a late progression to renal failure.13,14

Because the dermatologists involved in this case knew where and what types of biopsies to perform, a correct diagnosis was obtained quickly, allowing for the correct therapeutic intervention. After the diagnosis of HSP is made in an adult, nephrology should be consulted early in the treatment course.

To the Editor:

A 57-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension was hospitalized for heart disease resulting in an aortic valve replacement and multiple-vessel bypass grafting. He experienced a stormy septic postoperative course during which he developed numerous palpable purplish plaques (Figure 1). The lesions were bilateral and more heavily involved the lower legs and buttocks. The head and neck remained free of skin lesions. Additionally, the patient reported a bilateral burning sensation from the knees to the feet.

Punch biopsies of lesions from the right upper arm were obtained. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed neutrophilic-predominant small vessel vasculitis (Figure 2A) with the upper dermal location more heavily involved, as demonstrated by involvement of a superficial vascular plexus (Figures 2B and 2C) that was consistent with Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP). The diagnosis later was confirmed with immunofluorescence. Direct immunofluorescence revealed granular IgA deposition around the superficial vascular plexus (Figure 3). No IgG, IgM, C3, C5b-9 complement complex, or fibrinogen deposition was seen. Additionally, periodic acid-Schiff staining failed to show microorganisms, thrombi, or intravascular hyaline material.

At our initial consultation, we observed an ill-appearing afebrile man with purplish plaques. Our impression was that he had vasculitis and not warfarin necrosis, which had been suspected by the cardiovascular team. The burning sensation noted by the patient lent credence to our vasculitic diagnosis. Proteinuria and hematuria were present; however, the values for blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and glomerular filtration rate all remained within reference range. His signs and symptoms responded dramatically to prednisone. He remains on 1 mg of prednisone daily and a nephrologist continues to monitor renal function as an outpatient.

Henoch-Schönlein purpura is a systemic leukocytoclastic vasculitis involving small vessels. The small vessel vasculitis is associated with IgA antigen-antibody complex deposition in areas throughout the body. Palpable purpura typically is seen on the skin, which characteristically involves dependent areas such as the legs and the buttocks. Lesions normally are present bilaterally in a symmetric distribution. Initially, the lesions develop as erythematous macules that progress to purple, nonblanching, palpable, and purpuric plaques.1 Henoch-Schönlein purpura most commonly involves the skin; however, other locations for the immune complexes include the gastrointestinal tract, joints, and kidneys.2 The cause for the body's immunogenic deposition response is unknown in a majority of cases.

Henoch-Schönlein purpura most commonly is seen in the pediatric population with a predilection for males.3 The incidence in the pediatric population is 13.5 to 20 per 100,000 children per year; HSP is more rare in adults.4-6 Henoch-Schönlein purpura most often is a self-limiting disease that requires only supportive treatment. The signs and symptoms last 4 to 6 weeks in most patients and resolve completely in 94% of children and 89% of adults.7 Renal involvement carries a worse prognosis. Adult patients have a higher incidence of renal involvement, renal insufficiency, and subsequent progression to end-stage renal disease.3,8-10 In a study by Hung et al8 of 65 children and 22 adult HSP patients, 12 adults presented with renal involvement in which hematuria or proteinuria were present. Of them, 6 progressed to renal insufficiency (defined as having a plasma creatinine concentration>1.2 mg/dL).8 Fogazzi et al11 reported similar findings; 8 of 16 patients affected with HSP progressed to renal insufficiency with creatinine clearances ranging from 31 to 60 mL/min, and 3 patients required chronic dialysis. Pillebout et al9 evaluated 250 adults with HSP and 32% reached renal insufficiency with creatinine clearances of less than 50 mL/min, with 11% of patients developing end-stage renal disease. The degree of hematuria and/or proteinuria has been shown to be an effective prognostic indicator.9,10 Coppo et al10 found a similar prognosis among children and adults with HSP-related nephritis.

Our patient described the burning sensation as occurring bilaterally from the knees down to the feet, which provided an additional clue that small vessel vasculitis was involved, as occluded blood vessels can cause ischemia to nerves and perivascular involvement can affect nearby neural structures. Sais et al12 demonstrated that paresthesia in the setting of HSP was a risk factor for systemic involvement. Of note, our patient's paresthesia lasted only several days.

The cause of HSP is not always as evident in the adult population as in the pediatric population. Early diagnosis of HSP in adults may allow for the proper instatement of treatment to deter long-term renal complications. Follow-up with urinalysis is recommended because a small percentage of patients have a late progression to renal failure.13,14

Because the dermatologists involved in this case knew where and what types of biopsies to perform, a correct diagnosis was obtained quickly, allowing for the correct therapeutic intervention. After the diagnosis of HSP is made in an adult, nephrology should be consulted early in the treatment course.

- Rai A, Nast C, Adler S. Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:2637-2644.

- Helander SD, De Castro FR, Gibson LE. Henoch-Schönlein purpura: clinicopathologic correlation of cutaneous vascular IgA deposits and the relationship to leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:125-129.

- Garcia-Porrua C, Calvino MC, Llorca J, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children and adults: clinical differences in a defined population. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2002;32:149-156.

- Stewart M, Savage JM, Bell B, et al. Long term renal prognosis of Henoch-Schönlein purpura in an unselected childhood population. Eur J Pediatr. 1988;147:113-115.

- Watts RA, Scott DG. Epidemiology of the vasculitides. Semin Respir Crit Care. 2004;25:455-464.

- Gardner-Medwin JM, Dolezalova P, Cummins C, et al. Incidence of Henoch-Schönlein purpura, Kawasaki disease, and rare vasculitides in children of different ethnic origins. Lancet. 2002;360:1197-1202.

- Blanco R, Martínez-Taboada VM, Rodríguez-Valverde V, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in adulthood and childhood: two different expressions of the same syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:859-864.

- Hung SP, Yang YH, Lin YT, et al. Clinical manifestations and outcomes of Henoch-Schönlein purpura: comparison between adults and children. Pediatr Neonatol. 2009;50:162-168.

- Pillebout E, Thervet E, Hill G, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in adults: outcomes and prognostic factors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1271-1278.

- Coppo R, Mazzucco G, Cagnoli L, et al. Long-term prognosis of Henoch-Schönlein nephritis in adults and children. Italian Group of Renal Immunopathology collaborative study on Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:2277-2283.

- Fogazzi GB, Pasquali S, Moriggi M, et al. Long-term outcome of Schönlein-Henoch nephritis in the adult. Clin Nephrol. 1989;31:60-66.

- Sais G, Vidaller A, Jucgla A. Prognostic factors in leukocytoclastic vasculitis. a clinicopathologic study of 160 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:309-315.

- Kraft DM, McKee D, Scott C. Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a review. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58:405-408.

- Narchi H. Risk of long-term renal impairment and duration of follow up recommended for Henoch-Schönlein purpura with normal or minimal urinary findings: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:916-920.

- Rai A, Nast C, Adler S. Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:2637-2644.

- Helander SD, De Castro FR, Gibson LE. Henoch-Schönlein purpura: clinicopathologic correlation of cutaneous vascular IgA deposits and the relationship to leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:125-129.

- Garcia-Porrua C, Calvino MC, Llorca J, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children and adults: clinical differences in a defined population. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2002;32:149-156.

- Stewart M, Savage JM, Bell B, et al. Long term renal prognosis of Henoch-Schönlein purpura in an unselected childhood population. Eur J Pediatr. 1988;147:113-115.

- Watts RA, Scott DG. Epidemiology of the vasculitides. Semin Respir Crit Care. 2004;25:455-464.

- Gardner-Medwin JM, Dolezalova P, Cummins C, et al. Incidence of Henoch-Schönlein purpura, Kawasaki disease, and rare vasculitides in children of different ethnic origins. Lancet. 2002;360:1197-1202.

- Blanco R, Martínez-Taboada VM, Rodríguez-Valverde V, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in adulthood and childhood: two different expressions of the same syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:859-864.

- Hung SP, Yang YH, Lin YT, et al. Clinical manifestations and outcomes of Henoch-Schönlein purpura: comparison between adults and children. Pediatr Neonatol. 2009;50:162-168.

- Pillebout E, Thervet E, Hill G, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in adults: outcomes and prognostic factors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1271-1278.

- Coppo R, Mazzucco G, Cagnoli L, et al. Long-term prognosis of Henoch-Schönlein nephritis in adults and children. Italian Group of Renal Immunopathology collaborative study on Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:2277-2283.

- Fogazzi GB, Pasquali S, Moriggi M, et al. Long-term outcome of Schönlein-Henoch nephritis in the adult. Clin Nephrol. 1989;31:60-66.

- Sais G, Vidaller A, Jucgla A. Prognostic factors in leukocytoclastic vasculitis. a clinicopathologic study of 160 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:309-315.

- Kraft DM, McKee D, Scott C. Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a review. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58:405-408.

- Narchi H. Risk of long-term renal impairment and duration of follow up recommended for Henoch-Schönlein purpura with normal or minimal urinary findings: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:916-920.

Practice Points

- Henoch-Schönlein purpura is a multidisciplinary problem.

- Henoch-Schönlein purpura is an IgA-mediated disorder that is more common in children and has a more severe course in adults.

Phacomatosis Cesioflammea in Association With von Recklinghausen Disease (Neurofibromatosis Type I)

To the Editor:

Vascular lesions associated with melanocytic nevi were first described by Ota et al1 in 1947 and given the name phacomatosis pigmentovascularis. In 2005, Happle2 reclassified phacomatosis pigmentovascularis into 3 well-defined types: (1) phacomatosis cesioflammea: blue spots (caesius means bluish gray in Latin) and nevus flammeus; (2) phacomatosis spilorosea: nevus spilus coexisting with a pale pink telangiectatic nevus; and (3) phacomatosis cesiomarmorata: blue spots and cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita. In 2011 Joshi et al3 described a case of a 31-year-old woman who had a port-wine stain in association with neurofibromatosis type I (NF-1). We present a case of phacomatosis cesioflammea in association with NF-1.