User login

Recurrent head and neck cancer presenting as a large retroperitoneal mass

Worldwide, head and neck cancers account for more than half a million cases annually and nearly 400,000 deaths.1 Although the exact incidence of metastatic disease of these primarily squamous cell tumors is difficult to determine, the incidence is thought to be much lower than that of other solid tumors.2 When the different sites of metastatic disease of these tumors have been studied previously, the most common have been (in descending order of frequency) the lungs, bones, liver, skin, mediastinum, and bone marrow.2,3 It is extremely rare area for head and neck squamous cell cancers to metastasize to the retroperitoneum. To our knowledge, only 2 other such cases have been reported in the literature.4,5 In those two cases, the metastatic recurrence occurred at 6 and 13 months after definitive treatment of the primary cancer.

Case presentation and summary

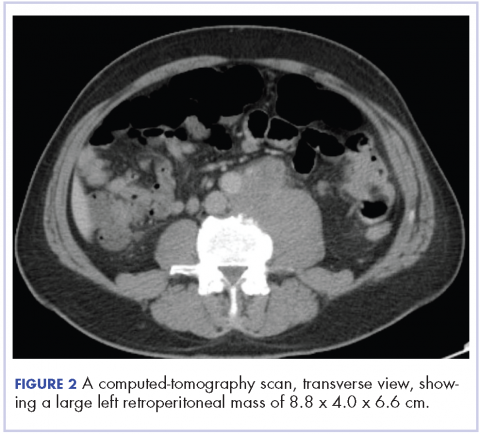

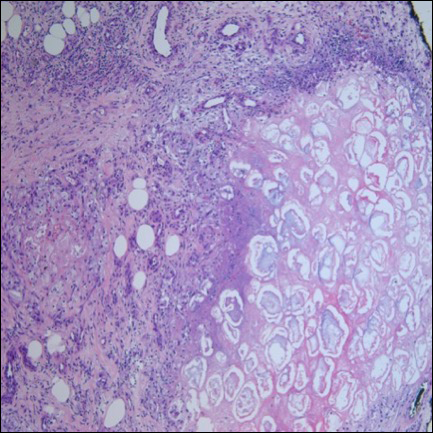

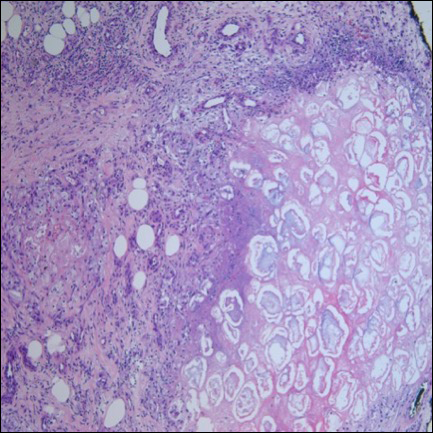

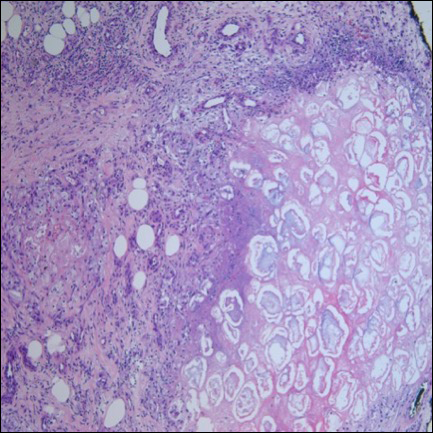

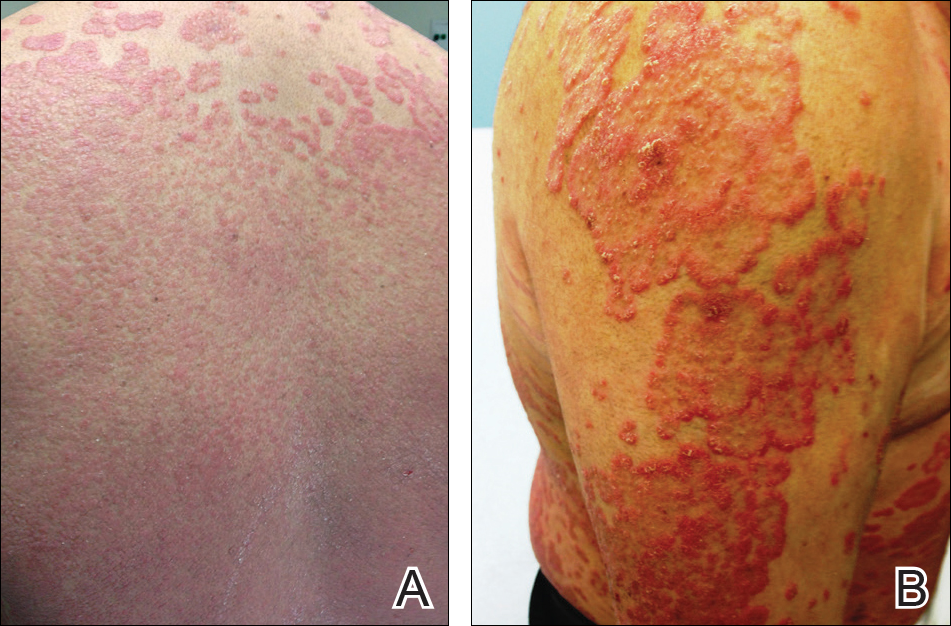

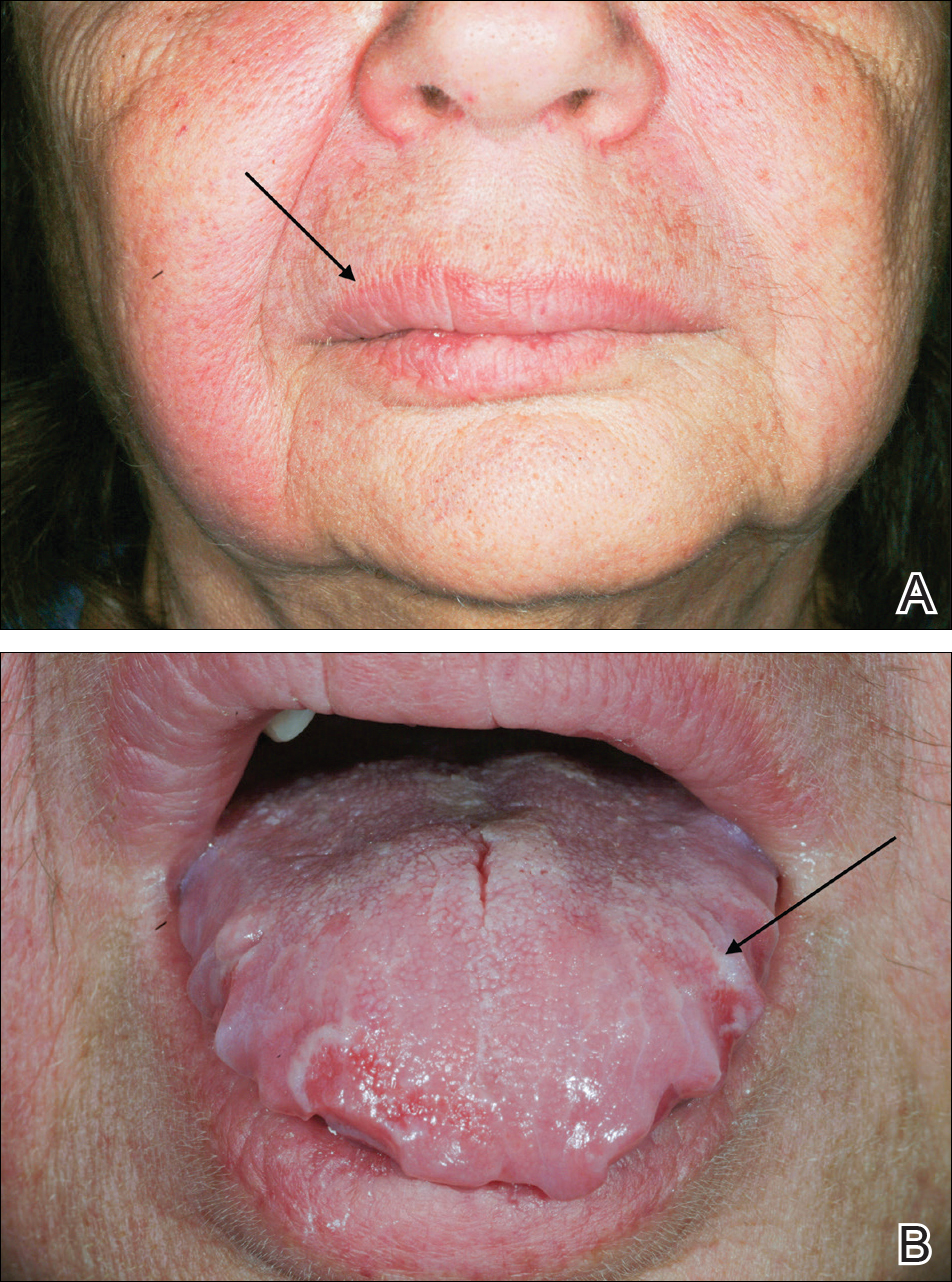

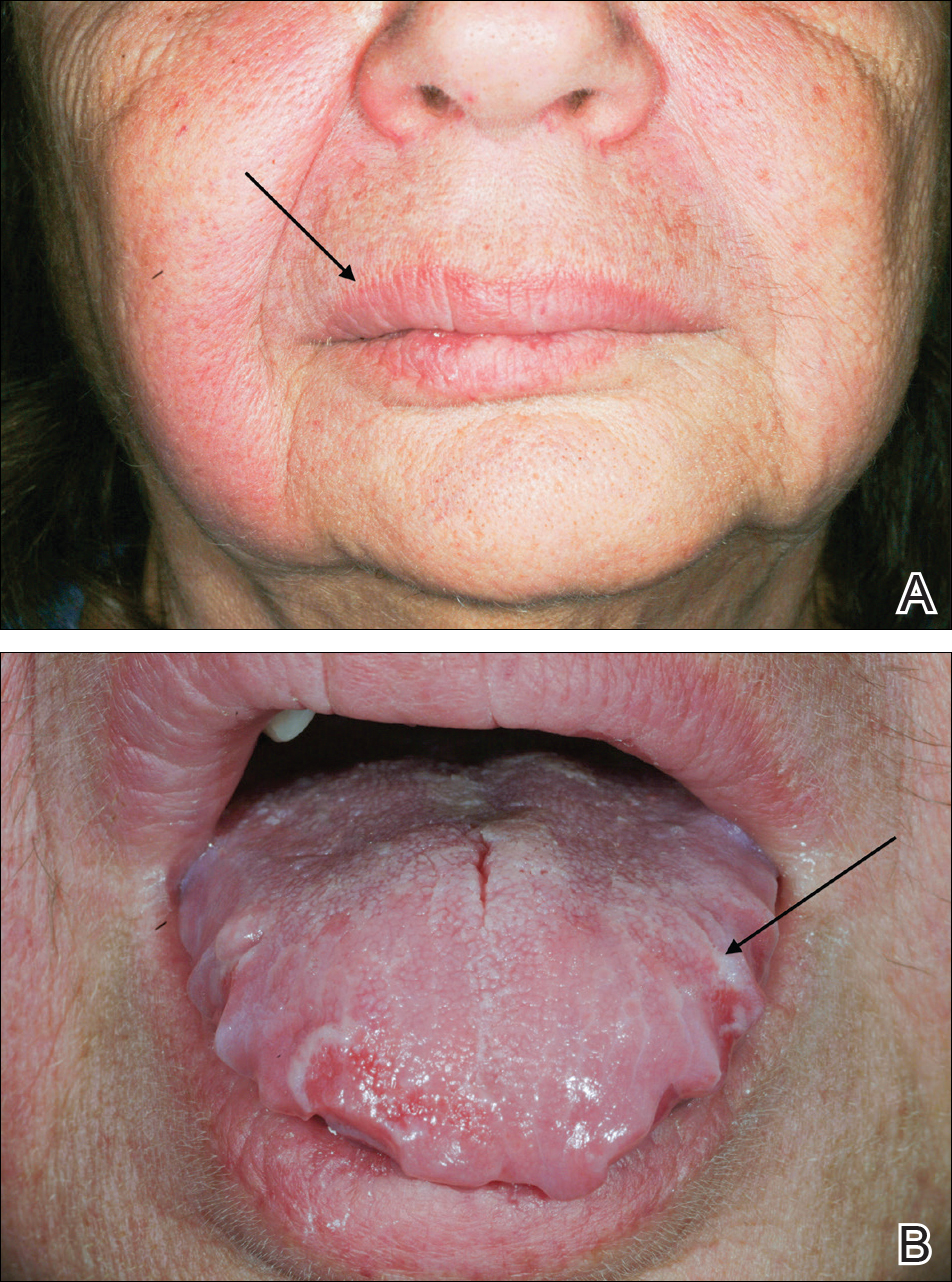

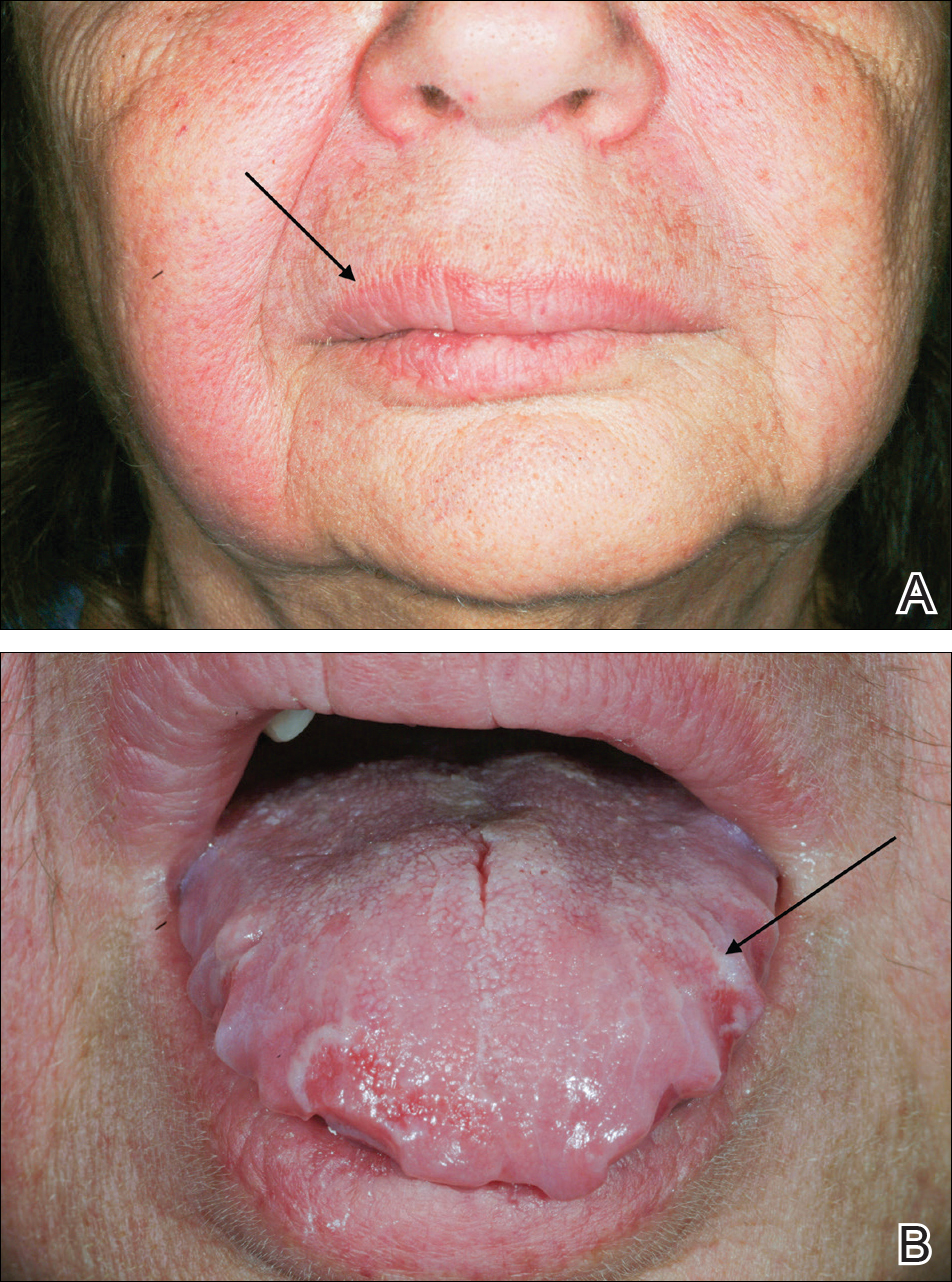

The patient in this case is a 60-year-old man with a history of stage IV moderately differentiated invasive squamous cell carcinoma (p16 negative, Bcl-2 negative, EGFR positive) of the hypopharynx that had been initially diagnosed in 2012. At that time, he underwent a total laryngectomy, partial pharyngectomy, and total thyroidectomy. A 2-centimeter mediastinal mass was also identified on a computed-tomography scan of the thorax and resected during the initial curative surgery. Final surgical pathology on the primary hypopharygeal tumor revealed a 4.1-cm moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma with negative margins, but positive lymphovascular invasion (Figure 1). The 2-cm mediastinal mass also revealed the same squamous cell carcinoma as the hypopharyngeal primary. Final surgical margins were negative.

The patient went on to receive adjuvant treatment in the form of concurrent chemoradiation with cisplatin (100 mg/m2 every 21 days for 3 doses, with 70 Gy of radiation]. After his initial treatment, he was followed closely by a multidisciplinary team, including otolaryngology, radiation oncology, and medical oncology specialists. He underwent a positron-emission tomography–CT scan 1 year after the conclusion of adjuvant therapy that showed no evidence of local or distant disease. The patient underwent 12 fiberoptic pharyngoscopy procedures over the course of 4 years without any evidence of local disease recurrence. He underwent a CT scan of the neck in October of 2016 without any evidence of local disease recurrence.

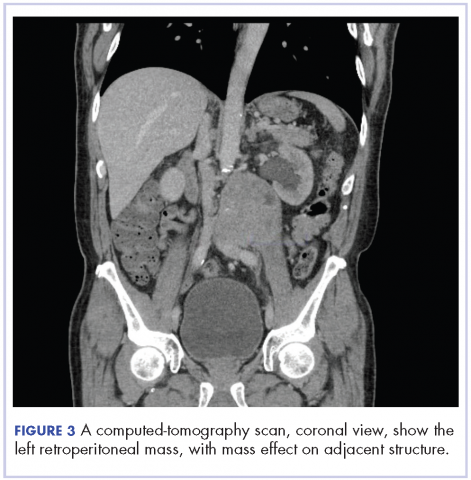

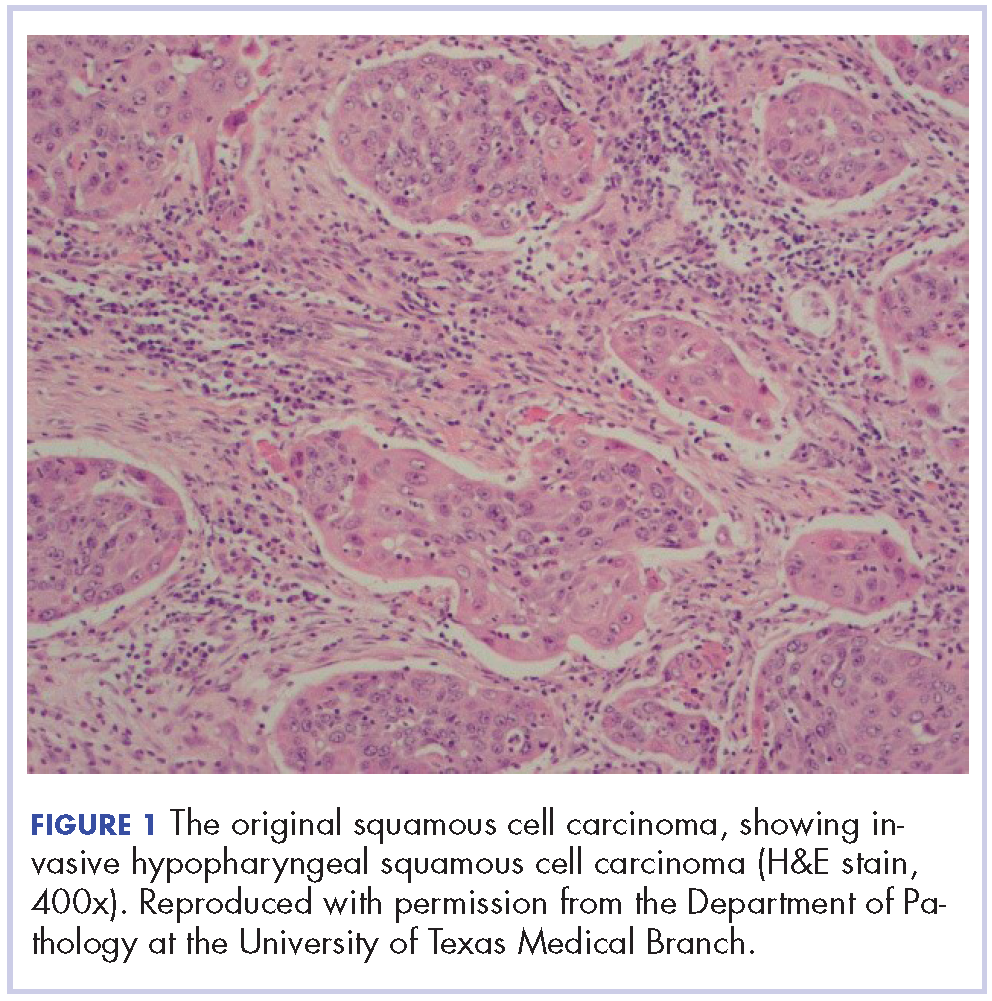

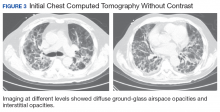

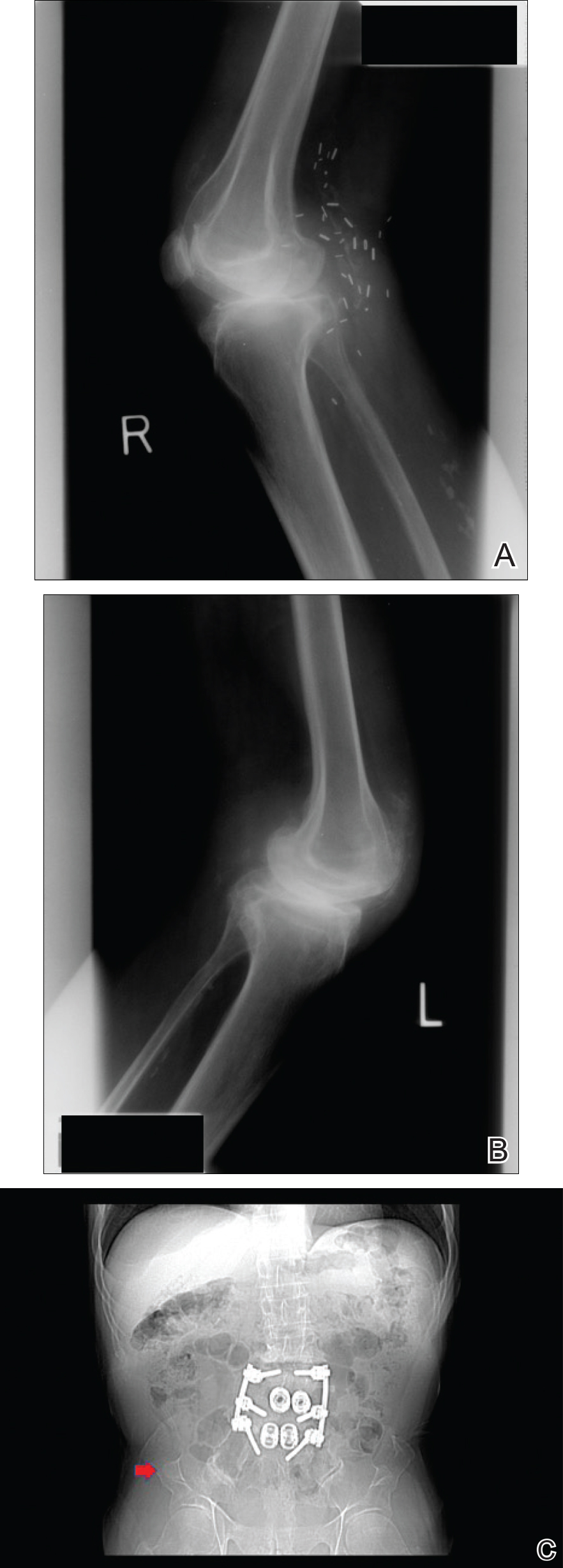

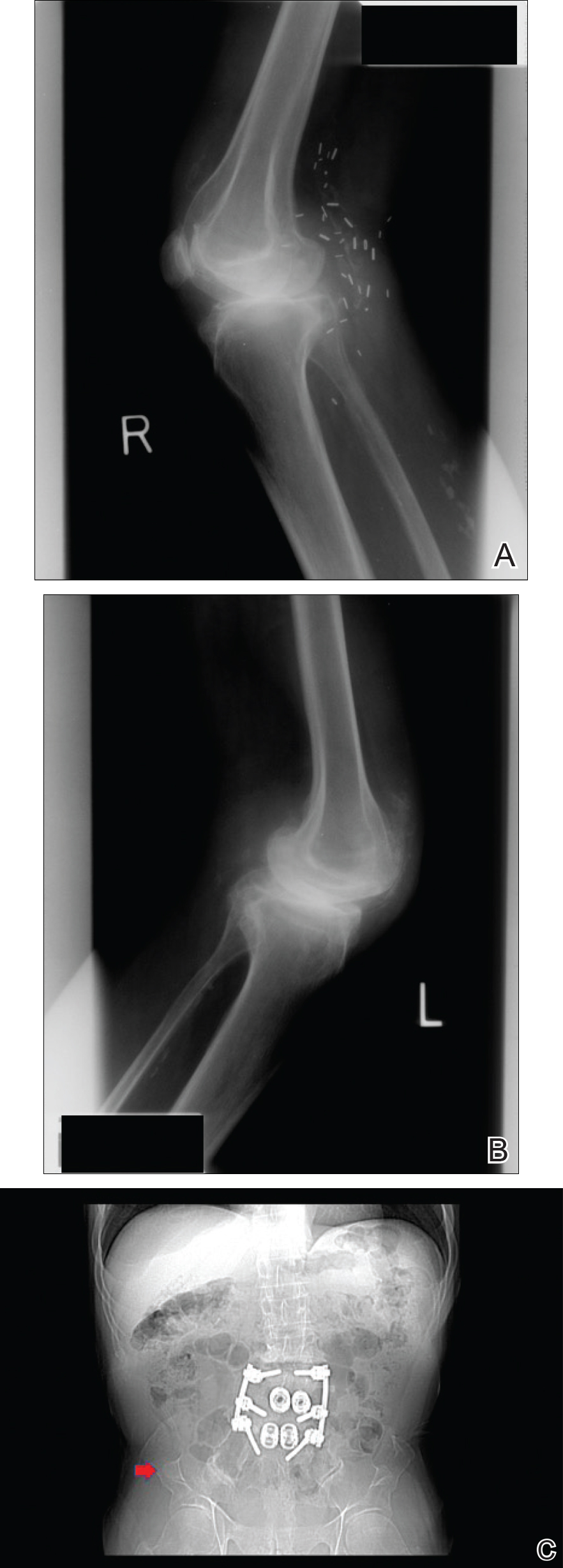

In early 2017, the patient presented with fatigue, abdominal pain, and back pain during the previous month. CT imaging revealed a left retroperitoneal mass of 8.8 x 4.0 x 6.6 cm, with bony destruction of L3-L4 causing left hydronephrosis (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Other staging work-up and imaging did not reveal any other distant disease or locoregional disease recurrence in the head and neck. Lab work was significant for an acute kidney injury that was likely secondary to mass effect from the tumor.

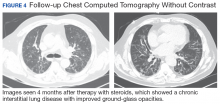

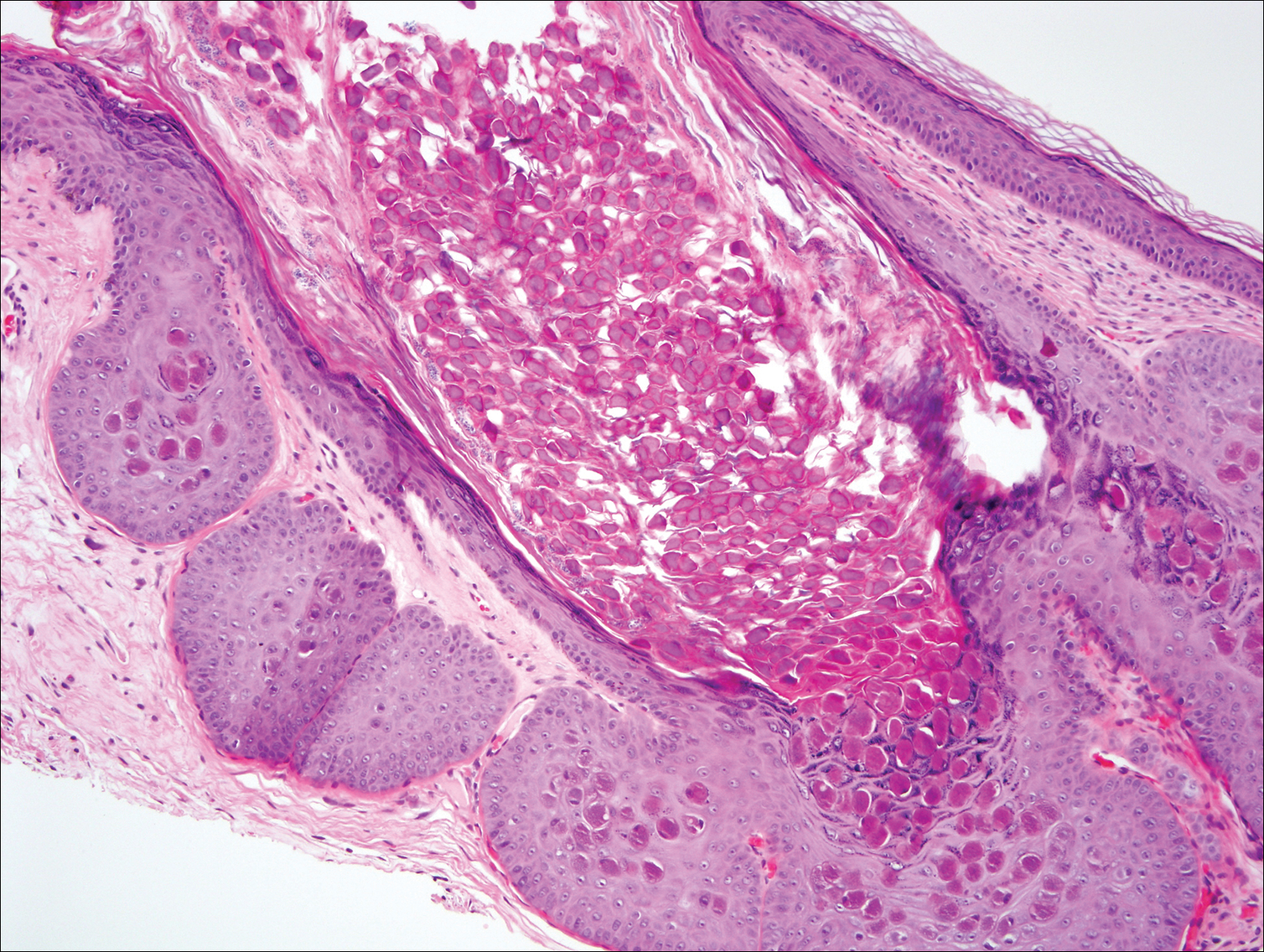

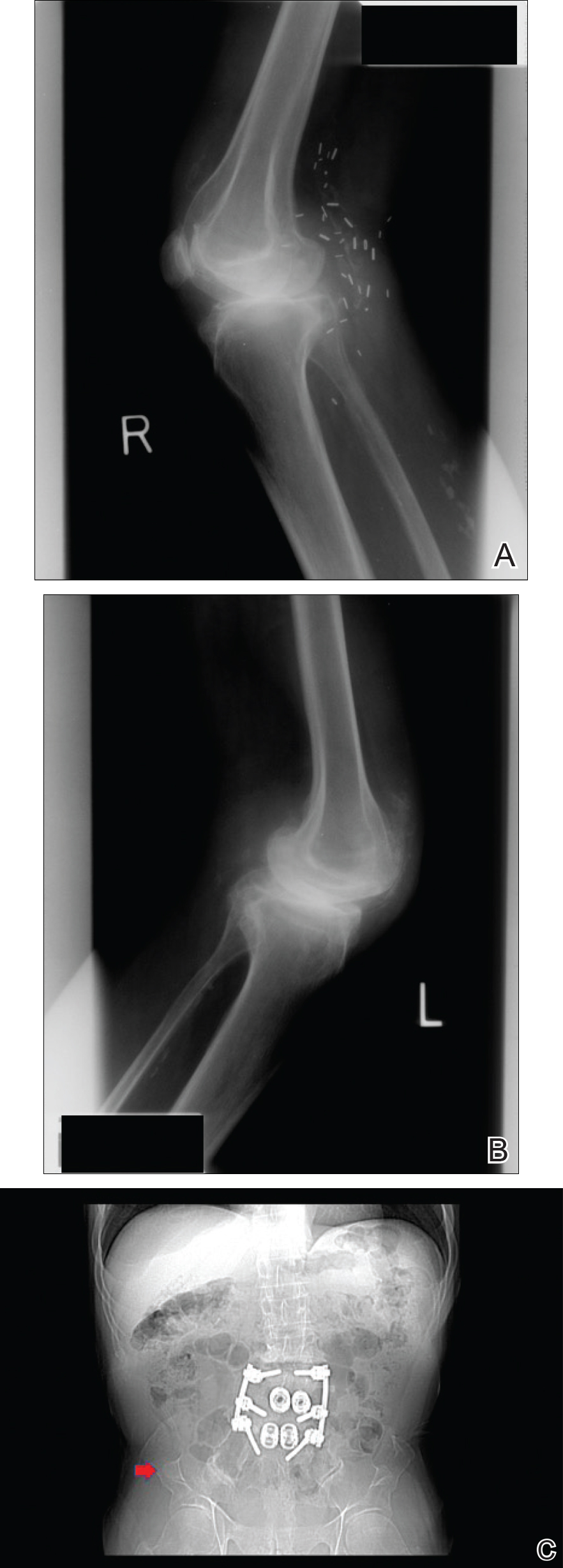

The mass was biopsied, with pathology revealing squamous cell carcinoma consistent with metastatic, recurrent disease from the previously known head and neck primary, and it was also p16 negative, Bcl-2 negative, and EGFR positive (Figure 4).

After a multidisciplinary discussion it was determined that the best front-line treatment option would be to treat with definitive concurrent chemoradiation. However, due to the size and location of the mass, it was not possible to deliver an effective therapeutic dose of radiation without unacceptable toxicity to the adjacent structures. Therefore, palliative systemic therapy was the only option. These treatment options, including systemic chemotherapy and immunotherapy, were discussed with the patient. However, he did not want to pursue any further cancer treatment and wanted instead to focus on palliation (pain control, antiemetics and nephrostomy to relieve obstruction) and hospice. He passed away 3 months later.

Discussion

Masses of the retroperitoneum have a wide differential diagnosis.6 Primary malignancies including lymphomas, sarcomas, neurogenic tumors, and germ cell tumors may all present primarily as retroperitoneal masses.6,7 Nonmalignant processes such as retroperitoneal fibrosis may also present in this manner.7 Certain tumors are known to metastasize to the retroperitoneum, namely carcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract and ovary as well as lung cancer or melanoma.5,8 Some primary retroperitoneal masses in women have been described in the literature as being HPV-associated squamous cell cancers of unknown primaries.9

When head and neck cancers metastasize they typically metastasize to the lungs, bone, liver, mediastinum, skin, and bone marrow. Most metastasis is pulmonary in origin, with the literature indicating it accounts for 52%-66% of head and neck cancer metastases, with bone metastases next in frequency at 12%-22%.2,3,10 In general, the incidence of distant metastatic disease in head and neck cancers is not as common as its other solid tumor counterparts, and even metastasis to other lymph node groups other than locoregional cervical nodes is rare.11 Furthermore, late metastasis occurring more than 2 years after definitive treatment is also an infrequent occurrence.12

When discussing distant metastatic disease in head and neck cancer, previous literature has described an increasing likelihood of distant metastases when there is locoregional disease recurrence.13 Moreover, the retroperitoneum is an exceedingly rare site of distant metastatic disease for head and neck cancer. There have been only 2 previous cases that have described this phenomenon, and in both cases the metastases occurred within or close to 1 year of definitive locoregional treatment.4,5

Conclusion

We present our case to present an exceedingly rare case of distant metastatic, recurrent disease from head and neck cancer to the retroperitoneum (without locoregional recurrence) that occurred 4 years after definitive treatment. We believe this to be the first case of its kind to be described when taking into consideration the site of metastases, when the metastatic recurrence occurred and that it happened without loco-regional disease recurrence. This case highlights the importance of keeping a wide differential diagnosis when encountering a retroperitoneal mass in a patient with even a remote history of head and neck cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following members of the Department of Pathology at the University of Texas Medical Branch: Asad Ahmad, MD; Eduardo Eyzaguirre, MD; Timothy C Allen, MD, JD, FACP; and Suimmin Qiu, MD, PHD.

1. Fitzmaurice C, Allen C, Barber RM, et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:524-548.

2. Ferlito A, Shaha AR, Silver CE, Rinaldo A, Mondin V. Incidence and sites of distant metastases from head and neck cancer. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2001;63:202-207.

3. Wiegand S, Zimmermann A, Wilhelm T, Werner JA. Survival after distant metastasis in head and neck cancer. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:5499-5502.

4. Hofmann U, O’Connor JP, Biyani CS, Harnden P, Selby P, Weston PM. Retroperitoneal metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the tonsil (with elevated beta human chorionic gonadotrophin): a misdiagnosis as extra-gonadal germ cell tumour. J Laryngol Otol. 2006;120:885-887.

5. Purkayastha A, Sharma N, Suhag V. Extremely rare and unusual case of retroperitoneal and pelvic metastasis from squamous cell carcinoma of vallecula. Int J Cancer Ther Oncol. 2016;4(2):1-4.

6. Rajiah P, Sinha R, Cuevas C, Dubinsky TJ, Bush WH, Kolokythas O. Imaging of uncommon retroperitoneal masses. Radiographics 2011;31:949-976.

7. Scali EP, Chandler TM, Heffernan EJ, Coyle J, Harris AC, Chang SD. Primary retroperitoneal masses: what is the differential diagnosis? Abdom Imaging. 2015;40:1887-1903.

8. Levy AD, Shaw JC, Sobin LH. Secondary tumors and tumorlike lesions of the peritoneal cavity: imaging features with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2009;29:347-373.

9. Isbell A, Fields EC. Three cases of women with HPV-related squamous cell carcinoma of unknown primary in the pelvis and retroperitoneum: a case series. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2016;16:5-8.

10. León X, Quer M, Orús C, del Prado Venegas M, López M. Distant metastases in head and neck cancer patients who achieved loco-regional control. Head Neck. 2000;22:680-686.

11. Alavi S, Namazie A, Sercarz JA, Wang MB, Blackwell KE. Distant lymphatic metastasis from head and neck cancer. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1999;108:860-863.

12. Krishnatry R, Gupta T, Murthy V, et al. Factors predicting ‘time to distant metastasis’ in radically treated head and neck cancer. Indian J Cancer. 2014;51:231-235.

13. Goodwin WJ. Distant metastases from oropharyngeal cancer. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2001;63:222-223.

Worldwide, head and neck cancers account for more than half a million cases annually and nearly 400,000 deaths.1 Although the exact incidence of metastatic disease of these primarily squamous cell tumors is difficult to determine, the incidence is thought to be much lower than that of other solid tumors.2 When the different sites of metastatic disease of these tumors have been studied previously, the most common have been (in descending order of frequency) the lungs, bones, liver, skin, mediastinum, and bone marrow.2,3 It is extremely rare area for head and neck squamous cell cancers to metastasize to the retroperitoneum. To our knowledge, only 2 other such cases have been reported in the literature.4,5 In those two cases, the metastatic recurrence occurred at 6 and 13 months after definitive treatment of the primary cancer.

Case presentation and summary

The patient in this case is a 60-year-old man with a history of stage IV moderately differentiated invasive squamous cell carcinoma (p16 negative, Bcl-2 negative, EGFR positive) of the hypopharynx that had been initially diagnosed in 2012. At that time, he underwent a total laryngectomy, partial pharyngectomy, and total thyroidectomy. A 2-centimeter mediastinal mass was also identified on a computed-tomography scan of the thorax and resected during the initial curative surgery. Final surgical pathology on the primary hypopharygeal tumor revealed a 4.1-cm moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma with negative margins, but positive lymphovascular invasion (Figure 1). The 2-cm mediastinal mass also revealed the same squamous cell carcinoma as the hypopharyngeal primary. Final surgical margins were negative.

The patient went on to receive adjuvant treatment in the form of concurrent chemoradiation with cisplatin (100 mg/m2 every 21 days for 3 doses, with 70 Gy of radiation]. After his initial treatment, he was followed closely by a multidisciplinary team, including otolaryngology, radiation oncology, and medical oncology specialists. He underwent a positron-emission tomography–CT scan 1 year after the conclusion of adjuvant therapy that showed no evidence of local or distant disease. The patient underwent 12 fiberoptic pharyngoscopy procedures over the course of 4 years without any evidence of local disease recurrence. He underwent a CT scan of the neck in October of 2016 without any evidence of local disease recurrence.

In early 2017, the patient presented with fatigue, abdominal pain, and back pain during the previous month. CT imaging revealed a left retroperitoneal mass of 8.8 x 4.0 x 6.6 cm, with bony destruction of L3-L4 causing left hydronephrosis (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Other staging work-up and imaging did not reveal any other distant disease or locoregional disease recurrence in the head and neck. Lab work was significant for an acute kidney injury that was likely secondary to mass effect from the tumor.

The mass was biopsied, with pathology revealing squamous cell carcinoma consistent with metastatic, recurrent disease from the previously known head and neck primary, and it was also p16 negative, Bcl-2 negative, and EGFR positive (Figure 4).

After a multidisciplinary discussion it was determined that the best front-line treatment option would be to treat with definitive concurrent chemoradiation. However, due to the size and location of the mass, it was not possible to deliver an effective therapeutic dose of radiation without unacceptable toxicity to the adjacent structures. Therefore, palliative systemic therapy was the only option. These treatment options, including systemic chemotherapy and immunotherapy, were discussed with the patient. However, he did not want to pursue any further cancer treatment and wanted instead to focus on palliation (pain control, antiemetics and nephrostomy to relieve obstruction) and hospice. He passed away 3 months later.

Discussion

Masses of the retroperitoneum have a wide differential diagnosis.6 Primary malignancies including lymphomas, sarcomas, neurogenic tumors, and germ cell tumors may all present primarily as retroperitoneal masses.6,7 Nonmalignant processes such as retroperitoneal fibrosis may also present in this manner.7 Certain tumors are known to metastasize to the retroperitoneum, namely carcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract and ovary as well as lung cancer or melanoma.5,8 Some primary retroperitoneal masses in women have been described in the literature as being HPV-associated squamous cell cancers of unknown primaries.9

When head and neck cancers metastasize they typically metastasize to the lungs, bone, liver, mediastinum, skin, and bone marrow. Most metastasis is pulmonary in origin, with the literature indicating it accounts for 52%-66% of head and neck cancer metastases, with bone metastases next in frequency at 12%-22%.2,3,10 In general, the incidence of distant metastatic disease in head and neck cancers is not as common as its other solid tumor counterparts, and even metastasis to other lymph node groups other than locoregional cervical nodes is rare.11 Furthermore, late metastasis occurring more than 2 years after definitive treatment is also an infrequent occurrence.12

When discussing distant metastatic disease in head and neck cancer, previous literature has described an increasing likelihood of distant metastases when there is locoregional disease recurrence.13 Moreover, the retroperitoneum is an exceedingly rare site of distant metastatic disease for head and neck cancer. There have been only 2 previous cases that have described this phenomenon, and in both cases the metastases occurred within or close to 1 year of definitive locoregional treatment.4,5

Conclusion

We present our case to present an exceedingly rare case of distant metastatic, recurrent disease from head and neck cancer to the retroperitoneum (without locoregional recurrence) that occurred 4 years after definitive treatment. We believe this to be the first case of its kind to be described when taking into consideration the site of metastases, when the metastatic recurrence occurred and that it happened without loco-regional disease recurrence. This case highlights the importance of keeping a wide differential diagnosis when encountering a retroperitoneal mass in a patient with even a remote history of head and neck cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following members of the Department of Pathology at the University of Texas Medical Branch: Asad Ahmad, MD; Eduardo Eyzaguirre, MD; Timothy C Allen, MD, JD, FACP; and Suimmin Qiu, MD, PHD.

Worldwide, head and neck cancers account for more than half a million cases annually and nearly 400,000 deaths.1 Although the exact incidence of metastatic disease of these primarily squamous cell tumors is difficult to determine, the incidence is thought to be much lower than that of other solid tumors.2 When the different sites of metastatic disease of these tumors have been studied previously, the most common have been (in descending order of frequency) the lungs, bones, liver, skin, mediastinum, and bone marrow.2,3 It is extremely rare area for head and neck squamous cell cancers to metastasize to the retroperitoneum. To our knowledge, only 2 other such cases have been reported in the literature.4,5 In those two cases, the metastatic recurrence occurred at 6 and 13 months after definitive treatment of the primary cancer.

Case presentation and summary

The patient in this case is a 60-year-old man with a history of stage IV moderately differentiated invasive squamous cell carcinoma (p16 negative, Bcl-2 negative, EGFR positive) of the hypopharynx that had been initially diagnosed in 2012. At that time, he underwent a total laryngectomy, partial pharyngectomy, and total thyroidectomy. A 2-centimeter mediastinal mass was also identified on a computed-tomography scan of the thorax and resected during the initial curative surgery. Final surgical pathology on the primary hypopharygeal tumor revealed a 4.1-cm moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma with negative margins, but positive lymphovascular invasion (Figure 1). The 2-cm mediastinal mass also revealed the same squamous cell carcinoma as the hypopharyngeal primary. Final surgical margins were negative.

The patient went on to receive adjuvant treatment in the form of concurrent chemoradiation with cisplatin (100 mg/m2 every 21 days for 3 doses, with 70 Gy of radiation]. After his initial treatment, he was followed closely by a multidisciplinary team, including otolaryngology, radiation oncology, and medical oncology specialists. He underwent a positron-emission tomography–CT scan 1 year after the conclusion of adjuvant therapy that showed no evidence of local or distant disease. The patient underwent 12 fiberoptic pharyngoscopy procedures over the course of 4 years without any evidence of local disease recurrence. He underwent a CT scan of the neck in October of 2016 without any evidence of local disease recurrence.

In early 2017, the patient presented with fatigue, abdominal pain, and back pain during the previous month. CT imaging revealed a left retroperitoneal mass of 8.8 x 4.0 x 6.6 cm, with bony destruction of L3-L4 causing left hydronephrosis (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Other staging work-up and imaging did not reveal any other distant disease or locoregional disease recurrence in the head and neck. Lab work was significant for an acute kidney injury that was likely secondary to mass effect from the tumor.

The mass was biopsied, with pathology revealing squamous cell carcinoma consistent with metastatic, recurrent disease from the previously known head and neck primary, and it was also p16 negative, Bcl-2 negative, and EGFR positive (Figure 4).

After a multidisciplinary discussion it was determined that the best front-line treatment option would be to treat with definitive concurrent chemoradiation. However, due to the size and location of the mass, it was not possible to deliver an effective therapeutic dose of radiation without unacceptable toxicity to the adjacent structures. Therefore, palliative systemic therapy was the only option. These treatment options, including systemic chemotherapy and immunotherapy, were discussed with the patient. However, he did not want to pursue any further cancer treatment and wanted instead to focus on palliation (pain control, antiemetics and nephrostomy to relieve obstruction) and hospice. He passed away 3 months later.

Discussion

Masses of the retroperitoneum have a wide differential diagnosis.6 Primary malignancies including lymphomas, sarcomas, neurogenic tumors, and germ cell tumors may all present primarily as retroperitoneal masses.6,7 Nonmalignant processes such as retroperitoneal fibrosis may also present in this manner.7 Certain tumors are known to metastasize to the retroperitoneum, namely carcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract and ovary as well as lung cancer or melanoma.5,8 Some primary retroperitoneal masses in women have been described in the literature as being HPV-associated squamous cell cancers of unknown primaries.9

When head and neck cancers metastasize they typically metastasize to the lungs, bone, liver, mediastinum, skin, and bone marrow. Most metastasis is pulmonary in origin, with the literature indicating it accounts for 52%-66% of head and neck cancer metastases, with bone metastases next in frequency at 12%-22%.2,3,10 In general, the incidence of distant metastatic disease in head and neck cancers is not as common as its other solid tumor counterparts, and even metastasis to other lymph node groups other than locoregional cervical nodes is rare.11 Furthermore, late metastasis occurring more than 2 years after definitive treatment is also an infrequent occurrence.12

When discussing distant metastatic disease in head and neck cancer, previous literature has described an increasing likelihood of distant metastases when there is locoregional disease recurrence.13 Moreover, the retroperitoneum is an exceedingly rare site of distant metastatic disease for head and neck cancer. There have been only 2 previous cases that have described this phenomenon, and in both cases the metastases occurred within or close to 1 year of definitive locoregional treatment.4,5

Conclusion

We present our case to present an exceedingly rare case of distant metastatic, recurrent disease from head and neck cancer to the retroperitoneum (without locoregional recurrence) that occurred 4 years after definitive treatment. We believe this to be the first case of its kind to be described when taking into consideration the site of metastases, when the metastatic recurrence occurred and that it happened without loco-regional disease recurrence. This case highlights the importance of keeping a wide differential diagnosis when encountering a retroperitoneal mass in a patient with even a remote history of head and neck cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following members of the Department of Pathology at the University of Texas Medical Branch: Asad Ahmad, MD; Eduardo Eyzaguirre, MD; Timothy C Allen, MD, JD, FACP; and Suimmin Qiu, MD, PHD.

1. Fitzmaurice C, Allen C, Barber RM, et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:524-548.

2. Ferlito A, Shaha AR, Silver CE, Rinaldo A, Mondin V. Incidence and sites of distant metastases from head and neck cancer. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2001;63:202-207.

3. Wiegand S, Zimmermann A, Wilhelm T, Werner JA. Survival after distant metastasis in head and neck cancer. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:5499-5502.

4. Hofmann U, O’Connor JP, Biyani CS, Harnden P, Selby P, Weston PM. Retroperitoneal metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the tonsil (with elevated beta human chorionic gonadotrophin): a misdiagnosis as extra-gonadal germ cell tumour. J Laryngol Otol. 2006;120:885-887.

5. Purkayastha A, Sharma N, Suhag V. Extremely rare and unusual case of retroperitoneal and pelvic metastasis from squamous cell carcinoma of vallecula. Int J Cancer Ther Oncol. 2016;4(2):1-4.

6. Rajiah P, Sinha R, Cuevas C, Dubinsky TJ, Bush WH, Kolokythas O. Imaging of uncommon retroperitoneal masses. Radiographics 2011;31:949-976.

7. Scali EP, Chandler TM, Heffernan EJ, Coyle J, Harris AC, Chang SD. Primary retroperitoneal masses: what is the differential diagnosis? Abdom Imaging. 2015;40:1887-1903.

8. Levy AD, Shaw JC, Sobin LH. Secondary tumors and tumorlike lesions of the peritoneal cavity: imaging features with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2009;29:347-373.

9. Isbell A, Fields EC. Three cases of women with HPV-related squamous cell carcinoma of unknown primary in the pelvis and retroperitoneum: a case series. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2016;16:5-8.

10. León X, Quer M, Orús C, del Prado Venegas M, López M. Distant metastases in head and neck cancer patients who achieved loco-regional control. Head Neck. 2000;22:680-686.

11. Alavi S, Namazie A, Sercarz JA, Wang MB, Blackwell KE. Distant lymphatic metastasis from head and neck cancer. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1999;108:860-863.

12. Krishnatry R, Gupta T, Murthy V, et al. Factors predicting ‘time to distant metastasis’ in radically treated head and neck cancer. Indian J Cancer. 2014;51:231-235.

13. Goodwin WJ. Distant metastases from oropharyngeal cancer. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2001;63:222-223.

1. Fitzmaurice C, Allen C, Barber RM, et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:524-548.

2. Ferlito A, Shaha AR, Silver CE, Rinaldo A, Mondin V. Incidence and sites of distant metastases from head and neck cancer. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2001;63:202-207.

3. Wiegand S, Zimmermann A, Wilhelm T, Werner JA. Survival after distant metastasis in head and neck cancer. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:5499-5502.

4. Hofmann U, O’Connor JP, Biyani CS, Harnden P, Selby P, Weston PM. Retroperitoneal metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the tonsil (with elevated beta human chorionic gonadotrophin): a misdiagnosis as extra-gonadal germ cell tumour. J Laryngol Otol. 2006;120:885-887.

5. Purkayastha A, Sharma N, Suhag V. Extremely rare and unusual case of retroperitoneal and pelvic metastasis from squamous cell carcinoma of vallecula. Int J Cancer Ther Oncol. 2016;4(2):1-4.

6. Rajiah P, Sinha R, Cuevas C, Dubinsky TJ, Bush WH, Kolokythas O. Imaging of uncommon retroperitoneal masses. Radiographics 2011;31:949-976.

7. Scali EP, Chandler TM, Heffernan EJ, Coyle J, Harris AC, Chang SD. Primary retroperitoneal masses: what is the differential diagnosis? Abdom Imaging. 2015;40:1887-1903.

8. Levy AD, Shaw JC, Sobin LH. Secondary tumors and tumorlike lesions of the peritoneal cavity: imaging features with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2009;29:347-373.

9. Isbell A, Fields EC. Three cases of women with HPV-related squamous cell carcinoma of unknown primary in the pelvis and retroperitoneum: a case series. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2016;16:5-8.

10. León X, Quer M, Orús C, del Prado Venegas M, López M. Distant metastases in head and neck cancer patients who achieved loco-regional control. Head Neck. 2000;22:680-686.

11. Alavi S, Namazie A, Sercarz JA, Wang MB, Blackwell KE. Distant lymphatic metastasis from head and neck cancer. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1999;108:860-863.

12. Krishnatry R, Gupta T, Murthy V, et al. Factors predicting ‘time to distant metastasis’ in radically treated head and neck cancer. Indian J Cancer. 2014;51:231-235.

13. Goodwin WJ. Distant metastases from oropharyngeal cancer. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2001;63:222-223.

Massive liver metastasis from colon adenocarcinoma causing cardiac tamponade

Colorectal cancer is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in the United States.1 About 5% of Americans will be diagnosed with colorectal cancer in their lifetime, of which 20% will present with distant metastasis.2 The most common sites of metastasis are regional lymph nodes, liver, lung and peritoneum, and patients may present with signs or symptoms related to disease burden at any of these organs.

Case presentation and summary

A 55-year-old man had presented to an outside hospital in August of 2014 with 6 months of hematochezia and a 40-lb weight loss. He was found to be severely anemic on admission (hemoglobin, 4.9 g/dL [normal, 13-17 g/dL], hematocrit, 16% [normal, 35%-45%]). A computed-tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast revealed a mass of 6.9 x 4.7 x 6.3 cm in the rectosigmoid colon and a mass of 10.0 x 12.0 x 10.7 cm in the right hepatic lobe consistent with metastatic disease. The patient was taken to the operating room where the rectosigmoid mass was resected completely. The liver mass was deemed unresectable because of its large size, and surgically directed therapy could not be performed. Pathology was consistent with a T3N1 moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma 11 cm from the anal verge. Further molecular tumor studies revealed wild type KRAS and NRAS, as well as a BRAF mutation.

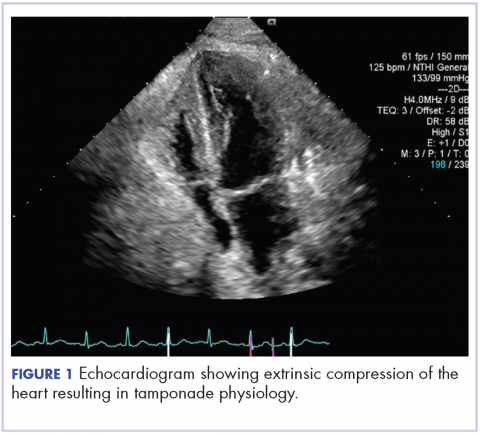

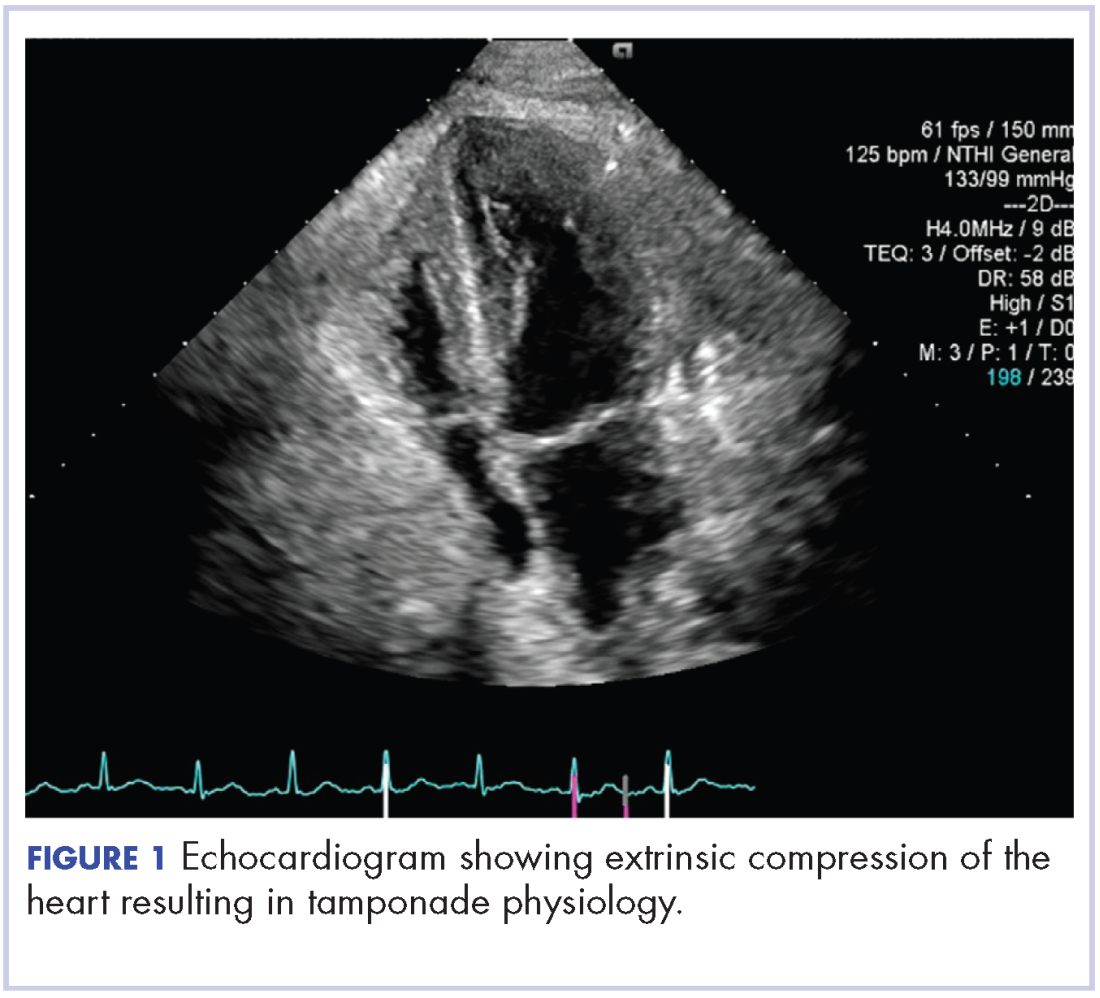

About 4 weeks after the surgery, the patient was seen at our institution for an initial consultation and was noted to have significant anasarca, including 4+ pitting lower extremity edema and scrotal edema. He complained of dyspnea on exertion, which he attributed to deconditioning. His resting heart rate was found to be 123 beats per minute (normal, 60-100 bpm). Jugular venous distention was present. The patient was sent for an urgent echocardiogram, which showed external compression of the right atrium and ventricle by his liver metastasis resulting in tamponade physiology without the presence of any pericardial effusion (Figure 1).

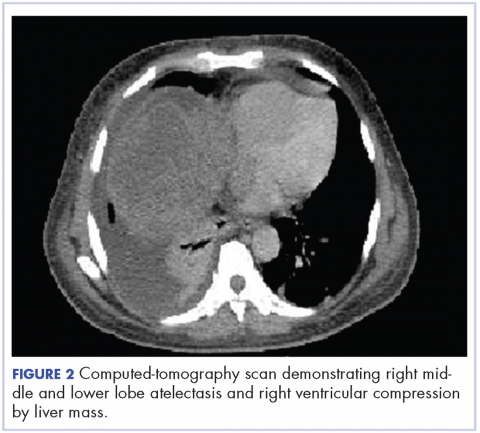

A CT of the abdomen and pelvis at that time showed that the liver mass had increased to 17.6 x 12.1 x 16.1 cm, exerting pressure on the heart and causing atelectasis of the right middle and lower lung lobes (Figure 2).

Treatment plan

The patient was evaluated by surgical oncology for resection, but his cardiovascular status placed him at high risk for perioperative complications, so such surgery was not pursued. Radioembolization was considered but not pursued because the process needed to evaluate, plan, and treat was not considered sufficiently timely. We consulted with our radiation oncology colleagues about external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) for rapid palliation. They evaluated the patient and recommended the EBRT, and the patient signed consent for treatment. We performed a CT-based simulation and generated an external beam, linear-accelerator–based treatment plan. The plan consisted of three 15-megavoltage photon fields delivering 3,000 cGy in 10 fractions to the whole liver, with appropriate multileaf collimation blocking to minimize dose to adjacent heart, right lung, and bilateral kidneys (Figure 3).

Before initiation of the EBRT, the patient received systemic chemotherapy with a dose-adjusted FOLFOX regimen (5-FU bolus 200 mg/m2, leucovorin 200 mg/m2, oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2, with infusional 5-FU 2,400 mg/m2 over 46 hours). After completing 1 dose of modified FOLFOX, he completed 10 fractions of whole liver radiotherapy with the aforementioned plan. He tolerated the initial treatment well and his subjective symptoms improved. The patient then proceeded to further systemic therapy. After recent data demonstrated improved median progression-free survival and response rates with FOLFOXIRI plus bevacizumab (infusional 5-FU 3200 mg/m2, leucovorin 200 mg/m2, irinotecan 165 mg/m2, and oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2, bevacizumab 5 mg/kg) versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab,3 we decided to modify his systemic therapy to FOLFOXIRI with bevacizumab to induce a better response.

Treatment response

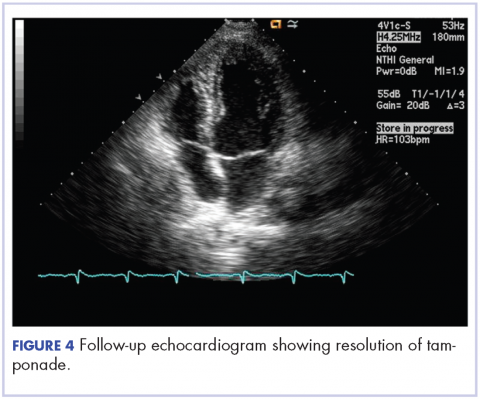

After 2 doses of chemotherapy and completion of radiotherapy, the edema and shortness of breath improved. A follow-up echocardiogram performed a month after completion of EBRT, 1 dose of FOLFOX, and 1 dose of FOLFOXIRI showed resolution of the cardiac compression (Figure 4).

A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis obtained after 3 cycles of FOLFOXIRI showed marked decrease in the size of the right lobe hepatic mass from 17.6 x 12.1 cm to 12.0 x 8.0 cm. Given the survival benefit of VEGF inhibition in colon cancer, bevacizumab (5 mg/kg) was added to the FOLFOXIRI regimen with cycle 4. Unfortunately, after the 5th cycle, a CT scan of the abdomen showed an increase in size of the hepatic lesions. At this time, FOLFOXIRI and bevacizumab were stopped, and given the tumor’s KRAS/NRAS wild type status, systemic therapy was changed to panitumumab (6 mg/kg). The patient initially tolerated treatment well, but after 9 cycles, the total bilirubin started to increase. CT abdomen at this point was consistent with progression of disease. The patient was not eligible for a clinical trial targeting BRAF mutation given the elevated bilirubin. Regorafanib (80 mg daily for 3 weeks on and 1 week off) was started. After the first cycle, the total bilirubin increased further and the regorafanib was dose reduced to 40 mg daily. Unfortunately, a repeat CT scan of the abdomen demonstrated progression of disease, and given that he developed a progressive transaminitis and hyperbilirubinemia, hospice care was recommended. The patient died shortly thereafter, about 15 months after his initial diagnosis.

Discussion

Massive liver metastasis in the setting of disseminated cancer is not an uncommon manifestation of advanced cancer that can have life-threatening consequences. In te present case, a bulky liver metastasis caused extrinsic compression of the right atrium, resulting in obvious clinical and echocardiogram-proven cardiac tamponade physiology. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of the treatment of a bulky hepatic metastasis causing cardiac tamponade. In this patient’s case, both radiotherapy and chemotherapy were given safely in rapid sequence resulting in quick resolution of the patient’s symptoms and echocardiogram findings. The presence of a BRAF mutation conferred a poor prognosis and poor response to systemic chemotherapy. Nevertheless, the patient showed good response to a FOLFOXIRI regimen, chosen in this emergent situation given its significantly higher response rates compared with the standard FOLFIRI regimen, which was tolerated well with minimal adverse effects.

Findings from randomized controlled trials examining the role of palliative radiotherapy for metastatic liver disease have suggested that dose escalation above 30 Gy to the whole liver may lead to unacceptably high rates of radiation-induced liver disease, which typically leads to mortality.4-8 Two prospective trials comparing twice daily with daily fractionation have shown no benefit to hyperfractionation, with possibly increased rates of acute toxicity in the setting of hepatocellular carcinoma.9,10 There is emerging evidence that partial liver irradiation, in the appropriate setting in the form of boost after whole-liver RT or stereotactic body radiotherapy, may allow for further dose escalation while avoiding clinical hepatitis.11 Although there is no clear consensus about optimal RT dose and fractionation, the aforementioned studies show that dose and fractionation schemes ranging between 21 Gy and 30 Gy in 1.5 Gy to 3 Gy daily fractions likely provide the best therapeutic ratio for whole-liver irradiation.

In conclusion, this case demonstrates the resolution of cardiac tamponade from a massive liver colorectal metastasis after chemoradiation and illustrates the potential utility of adding radiotherapy to chemotherapy in an urgent scenario where the former might not typically be considered.

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2015. https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/cancer-facts-figures-2015.html. Published 2015. Accessed October 10, 2017.

2. Siegel R, Desantis C, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(2):104-117.

3. Loupakis F, Cremolini C, Masi G, et al. Initial therapy with FOLFOXIRI and bevacizumab for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1609-1618.

4. Russell AH, Clyde C, Wasserman TH, Turner SS, Rotman M. Accelerated hyperfractionated hepatic irradiation in the management of patients with liver metastases: results of the RTOG dose escalating protocol. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;27(1):117-123.

5. Turek-Maischeider M, Kazem I. Palliative irradiation for liver metastases. JAMA. 1975;232(6):625-628.

6. Sherman DM, Weichselbaum R, Order SE, Cloud L, Trey C, Piro AJ. Palliation of hepatic metastasis. Cancer. 1978;41(5):2013-2017.

7. Prasad B, Lee MS, Hendrickson FR. Irradiation of hepatic metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1977;2:129-132.

8. Borgelt BB, Gelber R, Brady LW, Griffin T, Hendrickson FR. The palliation of hepatic metastases: results of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group pilot study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1981;7(5):587-591.

9. Raju PI, Maruyama Y, DeSimone P, MacDonald J. Treatment of liver metastases with a combination of chemotherapy and hyperfractionated external radiation therapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 1987;10(1):41-43.

10. Stillwagon GB, Order SE, Guse C, et al. 194 hepatocellular cancers treated by radiation and chemotherapy combinations: toxicity and response: a Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;17(6):1223-1229.

11. Mohiuddin M, Chen E, Ahmad N. Combined liver radiation and chemotherapy for palliation of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(3):722-728.

Colorectal cancer is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in the United States.1 About 5% of Americans will be diagnosed with colorectal cancer in their lifetime, of which 20% will present with distant metastasis.2 The most common sites of metastasis are regional lymph nodes, liver, lung and peritoneum, and patients may present with signs or symptoms related to disease burden at any of these organs.

Case presentation and summary

A 55-year-old man had presented to an outside hospital in August of 2014 with 6 months of hematochezia and a 40-lb weight loss. He was found to be severely anemic on admission (hemoglobin, 4.9 g/dL [normal, 13-17 g/dL], hematocrit, 16% [normal, 35%-45%]). A computed-tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast revealed a mass of 6.9 x 4.7 x 6.3 cm in the rectosigmoid colon and a mass of 10.0 x 12.0 x 10.7 cm in the right hepatic lobe consistent with metastatic disease. The patient was taken to the operating room where the rectosigmoid mass was resected completely. The liver mass was deemed unresectable because of its large size, and surgically directed therapy could not be performed. Pathology was consistent with a T3N1 moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma 11 cm from the anal verge. Further molecular tumor studies revealed wild type KRAS and NRAS, as well as a BRAF mutation.

About 4 weeks after the surgery, the patient was seen at our institution for an initial consultation and was noted to have significant anasarca, including 4+ pitting lower extremity edema and scrotal edema. He complained of dyspnea on exertion, which he attributed to deconditioning. His resting heart rate was found to be 123 beats per minute (normal, 60-100 bpm). Jugular venous distention was present. The patient was sent for an urgent echocardiogram, which showed external compression of the right atrium and ventricle by his liver metastasis resulting in tamponade physiology without the presence of any pericardial effusion (Figure 1).

A CT of the abdomen and pelvis at that time showed that the liver mass had increased to 17.6 x 12.1 x 16.1 cm, exerting pressure on the heart and causing atelectasis of the right middle and lower lung lobes (Figure 2).

Treatment plan

The patient was evaluated by surgical oncology for resection, but his cardiovascular status placed him at high risk for perioperative complications, so such surgery was not pursued. Radioembolization was considered but not pursued because the process needed to evaluate, plan, and treat was not considered sufficiently timely. We consulted with our radiation oncology colleagues about external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) for rapid palliation. They evaluated the patient and recommended the EBRT, and the patient signed consent for treatment. We performed a CT-based simulation and generated an external beam, linear-accelerator–based treatment plan. The plan consisted of three 15-megavoltage photon fields delivering 3,000 cGy in 10 fractions to the whole liver, with appropriate multileaf collimation blocking to minimize dose to adjacent heart, right lung, and bilateral kidneys (Figure 3).

Before initiation of the EBRT, the patient received systemic chemotherapy with a dose-adjusted FOLFOX regimen (5-FU bolus 200 mg/m2, leucovorin 200 mg/m2, oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2, with infusional 5-FU 2,400 mg/m2 over 46 hours). After completing 1 dose of modified FOLFOX, he completed 10 fractions of whole liver radiotherapy with the aforementioned plan. He tolerated the initial treatment well and his subjective symptoms improved. The patient then proceeded to further systemic therapy. After recent data demonstrated improved median progression-free survival and response rates with FOLFOXIRI plus bevacizumab (infusional 5-FU 3200 mg/m2, leucovorin 200 mg/m2, irinotecan 165 mg/m2, and oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2, bevacizumab 5 mg/kg) versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab,3 we decided to modify his systemic therapy to FOLFOXIRI with bevacizumab to induce a better response.

Treatment response

After 2 doses of chemotherapy and completion of radiotherapy, the edema and shortness of breath improved. A follow-up echocardiogram performed a month after completion of EBRT, 1 dose of FOLFOX, and 1 dose of FOLFOXIRI showed resolution of the cardiac compression (Figure 4).

A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis obtained after 3 cycles of FOLFOXIRI showed marked decrease in the size of the right lobe hepatic mass from 17.6 x 12.1 cm to 12.0 x 8.0 cm. Given the survival benefit of VEGF inhibition in colon cancer, bevacizumab (5 mg/kg) was added to the FOLFOXIRI regimen with cycle 4. Unfortunately, after the 5th cycle, a CT scan of the abdomen showed an increase in size of the hepatic lesions. At this time, FOLFOXIRI and bevacizumab were stopped, and given the tumor’s KRAS/NRAS wild type status, systemic therapy was changed to panitumumab (6 mg/kg). The patient initially tolerated treatment well, but after 9 cycles, the total bilirubin started to increase. CT abdomen at this point was consistent with progression of disease. The patient was not eligible for a clinical trial targeting BRAF mutation given the elevated bilirubin. Regorafanib (80 mg daily for 3 weeks on and 1 week off) was started. After the first cycle, the total bilirubin increased further and the regorafanib was dose reduced to 40 mg daily. Unfortunately, a repeat CT scan of the abdomen demonstrated progression of disease, and given that he developed a progressive transaminitis and hyperbilirubinemia, hospice care was recommended. The patient died shortly thereafter, about 15 months after his initial diagnosis.

Discussion

Massive liver metastasis in the setting of disseminated cancer is not an uncommon manifestation of advanced cancer that can have life-threatening consequences. In te present case, a bulky liver metastasis caused extrinsic compression of the right atrium, resulting in obvious clinical and echocardiogram-proven cardiac tamponade physiology. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of the treatment of a bulky hepatic metastasis causing cardiac tamponade. In this patient’s case, both radiotherapy and chemotherapy were given safely in rapid sequence resulting in quick resolution of the patient’s symptoms and echocardiogram findings. The presence of a BRAF mutation conferred a poor prognosis and poor response to systemic chemotherapy. Nevertheless, the patient showed good response to a FOLFOXIRI regimen, chosen in this emergent situation given its significantly higher response rates compared with the standard FOLFIRI regimen, which was tolerated well with minimal adverse effects.

Findings from randomized controlled trials examining the role of palliative radiotherapy for metastatic liver disease have suggested that dose escalation above 30 Gy to the whole liver may lead to unacceptably high rates of radiation-induced liver disease, which typically leads to mortality.4-8 Two prospective trials comparing twice daily with daily fractionation have shown no benefit to hyperfractionation, with possibly increased rates of acute toxicity in the setting of hepatocellular carcinoma.9,10 There is emerging evidence that partial liver irradiation, in the appropriate setting in the form of boost after whole-liver RT or stereotactic body radiotherapy, may allow for further dose escalation while avoiding clinical hepatitis.11 Although there is no clear consensus about optimal RT dose and fractionation, the aforementioned studies show that dose and fractionation schemes ranging between 21 Gy and 30 Gy in 1.5 Gy to 3 Gy daily fractions likely provide the best therapeutic ratio for whole-liver irradiation.

In conclusion, this case demonstrates the resolution of cardiac tamponade from a massive liver colorectal metastasis after chemoradiation and illustrates the potential utility of adding radiotherapy to chemotherapy in an urgent scenario where the former might not typically be considered.

Colorectal cancer is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in the United States.1 About 5% of Americans will be diagnosed with colorectal cancer in their lifetime, of which 20% will present with distant metastasis.2 The most common sites of metastasis are regional lymph nodes, liver, lung and peritoneum, and patients may present with signs or symptoms related to disease burden at any of these organs.

Case presentation and summary

A 55-year-old man had presented to an outside hospital in August of 2014 with 6 months of hematochezia and a 40-lb weight loss. He was found to be severely anemic on admission (hemoglobin, 4.9 g/dL [normal, 13-17 g/dL], hematocrit, 16% [normal, 35%-45%]). A computed-tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast revealed a mass of 6.9 x 4.7 x 6.3 cm in the rectosigmoid colon and a mass of 10.0 x 12.0 x 10.7 cm in the right hepatic lobe consistent with metastatic disease. The patient was taken to the operating room where the rectosigmoid mass was resected completely. The liver mass was deemed unresectable because of its large size, and surgically directed therapy could not be performed. Pathology was consistent with a T3N1 moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma 11 cm from the anal verge. Further molecular tumor studies revealed wild type KRAS and NRAS, as well as a BRAF mutation.

About 4 weeks after the surgery, the patient was seen at our institution for an initial consultation and was noted to have significant anasarca, including 4+ pitting lower extremity edema and scrotal edema. He complained of dyspnea on exertion, which he attributed to deconditioning. His resting heart rate was found to be 123 beats per minute (normal, 60-100 bpm). Jugular venous distention was present. The patient was sent for an urgent echocardiogram, which showed external compression of the right atrium and ventricle by his liver metastasis resulting in tamponade physiology without the presence of any pericardial effusion (Figure 1).

A CT of the abdomen and pelvis at that time showed that the liver mass had increased to 17.6 x 12.1 x 16.1 cm, exerting pressure on the heart and causing atelectasis of the right middle and lower lung lobes (Figure 2).

Treatment plan

The patient was evaluated by surgical oncology for resection, but his cardiovascular status placed him at high risk for perioperative complications, so such surgery was not pursued. Radioembolization was considered but not pursued because the process needed to evaluate, plan, and treat was not considered sufficiently timely. We consulted with our radiation oncology colleagues about external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) for rapid palliation. They evaluated the patient and recommended the EBRT, and the patient signed consent for treatment. We performed a CT-based simulation and generated an external beam, linear-accelerator–based treatment plan. The plan consisted of three 15-megavoltage photon fields delivering 3,000 cGy in 10 fractions to the whole liver, with appropriate multileaf collimation blocking to minimize dose to adjacent heart, right lung, and bilateral kidneys (Figure 3).

Before initiation of the EBRT, the patient received systemic chemotherapy with a dose-adjusted FOLFOX regimen (5-FU bolus 200 mg/m2, leucovorin 200 mg/m2, oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2, with infusional 5-FU 2,400 mg/m2 over 46 hours). After completing 1 dose of modified FOLFOX, he completed 10 fractions of whole liver radiotherapy with the aforementioned plan. He tolerated the initial treatment well and his subjective symptoms improved. The patient then proceeded to further systemic therapy. After recent data demonstrated improved median progression-free survival and response rates with FOLFOXIRI plus bevacizumab (infusional 5-FU 3200 mg/m2, leucovorin 200 mg/m2, irinotecan 165 mg/m2, and oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2, bevacizumab 5 mg/kg) versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab,3 we decided to modify his systemic therapy to FOLFOXIRI with bevacizumab to induce a better response.

Treatment response

After 2 doses of chemotherapy and completion of radiotherapy, the edema and shortness of breath improved. A follow-up echocardiogram performed a month after completion of EBRT, 1 dose of FOLFOX, and 1 dose of FOLFOXIRI showed resolution of the cardiac compression (Figure 4).

A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis obtained after 3 cycles of FOLFOXIRI showed marked decrease in the size of the right lobe hepatic mass from 17.6 x 12.1 cm to 12.0 x 8.0 cm. Given the survival benefit of VEGF inhibition in colon cancer, bevacizumab (5 mg/kg) was added to the FOLFOXIRI regimen with cycle 4. Unfortunately, after the 5th cycle, a CT scan of the abdomen showed an increase in size of the hepatic lesions. At this time, FOLFOXIRI and bevacizumab were stopped, and given the tumor’s KRAS/NRAS wild type status, systemic therapy was changed to panitumumab (6 mg/kg). The patient initially tolerated treatment well, but after 9 cycles, the total bilirubin started to increase. CT abdomen at this point was consistent with progression of disease. The patient was not eligible for a clinical trial targeting BRAF mutation given the elevated bilirubin. Regorafanib (80 mg daily for 3 weeks on and 1 week off) was started. After the first cycle, the total bilirubin increased further and the regorafanib was dose reduced to 40 mg daily. Unfortunately, a repeat CT scan of the abdomen demonstrated progression of disease, and given that he developed a progressive transaminitis and hyperbilirubinemia, hospice care was recommended. The patient died shortly thereafter, about 15 months after his initial diagnosis.

Discussion

Massive liver metastasis in the setting of disseminated cancer is not an uncommon manifestation of advanced cancer that can have life-threatening consequences. In te present case, a bulky liver metastasis caused extrinsic compression of the right atrium, resulting in obvious clinical and echocardiogram-proven cardiac tamponade physiology. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of the treatment of a bulky hepatic metastasis causing cardiac tamponade. In this patient’s case, both radiotherapy and chemotherapy were given safely in rapid sequence resulting in quick resolution of the patient’s symptoms and echocardiogram findings. The presence of a BRAF mutation conferred a poor prognosis and poor response to systemic chemotherapy. Nevertheless, the patient showed good response to a FOLFOXIRI regimen, chosen in this emergent situation given its significantly higher response rates compared with the standard FOLFIRI regimen, which was tolerated well with minimal adverse effects.

Findings from randomized controlled trials examining the role of palliative radiotherapy for metastatic liver disease have suggested that dose escalation above 30 Gy to the whole liver may lead to unacceptably high rates of radiation-induced liver disease, which typically leads to mortality.4-8 Two prospective trials comparing twice daily with daily fractionation have shown no benefit to hyperfractionation, with possibly increased rates of acute toxicity in the setting of hepatocellular carcinoma.9,10 There is emerging evidence that partial liver irradiation, in the appropriate setting in the form of boost after whole-liver RT or stereotactic body radiotherapy, may allow for further dose escalation while avoiding clinical hepatitis.11 Although there is no clear consensus about optimal RT dose and fractionation, the aforementioned studies show that dose and fractionation schemes ranging between 21 Gy and 30 Gy in 1.5 Gy to 3 Gy daily fractions likely provide the best therapeutic ratio for whole-liver irradiation.

In conclusion, this case demonstrates the resolution of cardiac tamponade from a massive liver colorectal metastasis after chemoradiation and illustrates the potential utility of adding radiotherapy to chemotherapy in an urgent scenario where the former might not typically be considered.

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2015. https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/cancer-facts-figures-2015.html. Published 2015. Accessed October 10, 2017.

2. Siegel R, Desantis C, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(2):104-117.

3. Loupakis F, Cremolini C, Masi G, et al. Initial therapy with FOLFOXIRI and bevacizumab for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1609-1618.

4. Russell AH, Clyde C, Wasserman TH, Turner SS, Rotman M. Accelerated hyperfractionated hepatic irradiation in the management of patients with liver metastases: results of the RTOG dose escalating protocol. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;27(1):117-123.

5. Turek-Maischeider M, Kazem I. Palliative irradiation for liver metastases. JAMA. 1975;232(6):625-628.

6. Sherman DM, Weichselbaum R, Order SE, Cloud L, Trey C, Piro AJ. Palliation of hepatic metastasis. Cancer. 1978;41(5):2013-2017.

7. Prasad B, Lee MS, Hendrickson FR. Irradiation of hepatic metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1977;2:129-132.

8. Borgelt BB, Gelber R, Brady LW, Griffin T, Hendrickson FR. The palliation of hepatic metastases: results of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group pilot study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1981;7(5):587-591.

9. Raju PI, Maruyama Y, DeSimone P, MacDonald J. Treatment of liver metastases with a combination of chemotherapy and hyperfractionated external radiation therapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 1987;10(1):41-43.

10. Stillwagon GB, Order SE, Guse C, et al. 194 hepatocellular cancers treated by radiation and chemotherapy combinations: toxicity and response: a Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;17(6):1223-1229.

11. Mohiuddin M, Chen E, Ahmad N. Combined liver radiation and chemotherapy for palliation of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(3):722-728.

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2015. https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/cancer-facts-figures-2015.html. Published 2015. Accessed October 10, 2017.

2. Siegel R, Desantis C, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(2):104-117.

3. Loupakis F, Cremolini C, Masi G, et al. Initial therapy with FOLFOXIRI and bevacizumab for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1609-1618.

4. Russell AH, Clyde C, Wasserman TH, Turner SS, Rotman M. Accelerated hyperfractionated hepatic irradiation in the management of patients with liver metastases: results of the RTOG dose escalating protocol. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;27(1):117-123.

5. Turek-Maischeider M, Kazem I. Palliative irradiation for liver metastases. JAMA. 1975;232(6):625-628.

6. Sherman DM, Weichselbaum R, Order SE, Cloud L, Trey C, Piro AJ. Palliation of hepatic metastasis. Cancer. 1978;41(5):2013-2017.

7. Prasad B, Lee MS, Hendrickson FR. Irradiation of hepatic metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1977;2:129-132.

8. Borgelt BB, Gelber R, Brady LW, Griffin T, Hendrickson FR. The palliation of hepatic metastases: results of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group pilot study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1981;7(5):587-591.

9. Raju PI, Maruyama Y, DeSimone P, MacDonald J. Treatment of liver metastases with a combination of chemotherapy and hyperfractionated external radiation therapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 1987;10(1):41-43.

10. Stillwagon GB, Order SE, Guse C, et al. 194 hepatocellular cancers treated by radiation and chemotherapy combinations: toxicity and response: a Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;17(6):1223-1229.

11. Mohiuddin M, Chen E, Ahmad N. Combined liver radiation and chemotherapy for palliation of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(3):722-728.

Cardiac pleomorphic sarcoma after placement of Dacron graft

Primary cardiac tumors, either benign or malignant, are very rare. The combined incidence is 0.002% on pooled autopsy series.1 The benign tumors account for 63% of primary cardiac tumors and include myxoma, the most common, and followed by papillary fibroelastoma, fibroma, and hemangioma. The remaining 37% are malignant tumors, essentially predominated by sarcomas.1

Although myxoma is the most common tumor arising in the left atrium, we present a case that shows that sarcoma can also arise from the same chamber. In fact, sarcomas could mimic cardiac myxoma.2 The cardiac sarcomas can have similar clinical presentation and more importantly can share similar histopathological features. Sarcomas may have myxoid features.2 Cases diagnosed as cardiac myxomas should be diligently worked up to rule out the presence of sarcomas with myxoid features. In addition, foreign bodies have been found to induce sarcomas in experimental animals.3,4 In particular, 2 case reports have described sarcomas arising in association with Dacron vascular prostheses in humans.5,6 We present here the case of a patient who was diagnosed with cardiac pleomorphic sarcoma 8 years after the placement of a Dacron graft.

Case presentation and summary

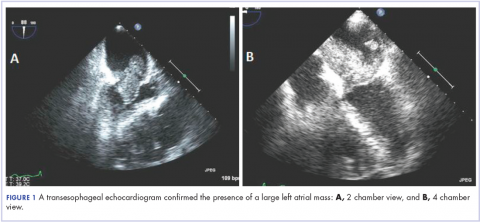

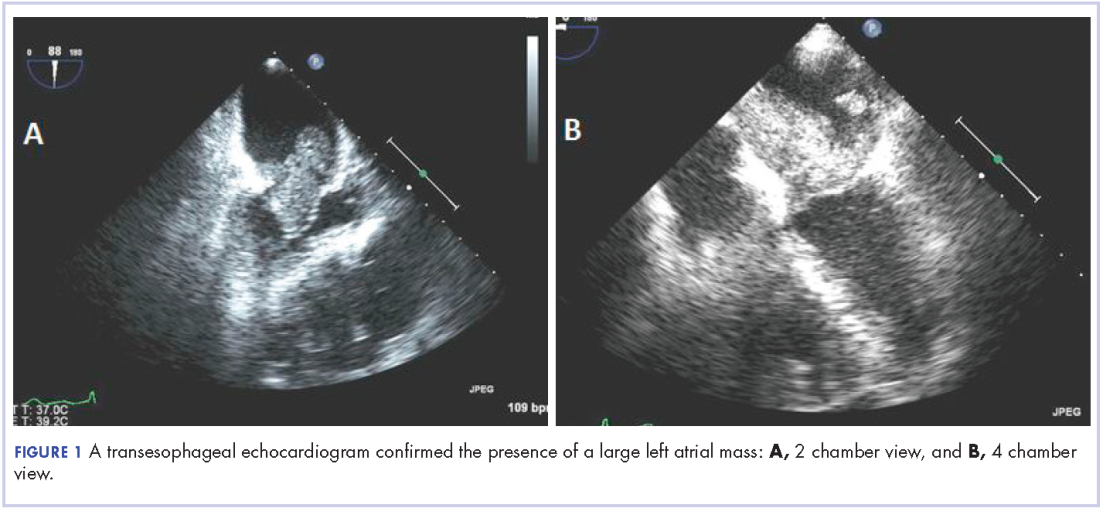

A 56-year-old woman with history of left atrial myxoma status after resection in 2005 and placement of a Dacron graft, morbid obesity, hypertension, and asthma presented to the emergency department with progressively worsening shortness of breath and blurry vision over period of 2 months. Acute coronary syndrome was ruled out by electrocardiogram and serial biomarkers. A computed-tomography angiogram was pursued because of her history of left atrial myxoma, and the results suggested the presence of a left atrial tumor. She underwent a transesophageal echocardiogram, which confirmed the presence of a large left atrial mass that likely was attached to the interatrial septum prolapsing across the mitral valve and was suggestive for recurrent left atrial myxoma (Figure 1). The results of a cardiac catheterization showed normal coronaries.

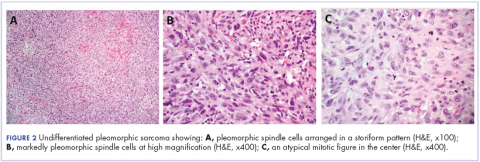

The patient subsequently underwent an excision of the left atrial tumor with profound internal and external myocardial cooling using antegrade blood cardioplegia under mildly hypothermic cardiopulmonary bypass. Frozen sections showed high-grade malignancy in favor of sarcoma. The hematoxylin and eosin stained permanent sections showed sheets of malignant pleomorphic spindle cells focally arranged in a storiform pattern. There were areas of necrosis and abundant mitotic activity. By immunohistochemical (IHC) stains, the tumor cells were diffusely positive for vimentin, and negative for pan-cytokeratin antibody (AE1/AE3), S-100 protein, Melan-A antibody, HMB45, CD34, CD31, myogenin, and MYOD1. IHC stains for CK-OSCAR, desmin, and smooth muscle actin were focally positive, and a ki-67 stain showed a proliferation index of about 80%. The histologic and IHC findings were consistent with a final diagnosis of high-grade undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (Figure 2).

A positron emission tomography scan performed November 2013 did not show any other activity. The patient was scheduled for chemotherapy with adriamycin and ifosfamide with a plan for total of 6 cycles. Before her admission for the chemotherapy, the patient was admitted to the hospital for atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response and had multiple complications requiring prolonged hospitalization and rehabilitation. Repeat imaging 2 months later showed diffuse metastatic disease. However, her performance status had declined and she was not eligible for chemotherapy. She was placed under hospice care.

Discussion

This case demonstrates development of a cardiac pleomorphic sarcoma, a rare tumor, after placement of a Dacron graft. Given that foreign bodies have been found to induce sarcomas in experimental animals,3,4 and a few case reports have described sarcomas arising in association with Dacron vascular prostheses, 5-10 it seems that an exuberant host response around the foreign body might represent an important intermediate step in the development of the sarcoma.

There is no clearly defined pathogenesis that explains the link between a Dacron graft and sarcomas. In 1950s, Oppenheimer and colleagues described the formation of malignant tumors by various types of plastics, including Dacron, that were embedded in rats. 3,4 Most of the tumors were some form of sarcomas. It was inferred that physical properties of the plastics may have some role in tumor development. Plastics in sheet form or film that remained in situ for more than 6 months induced significant number of tumors compared with other forms such as sponges, films with holes, or powders.3,4 The 3-dimensional polymeric structure of the Dacron graft seems to play a role in induction of sarcoma as well. A pore diameter of less than 0.4 mm may increase tumorigenicity.11 The removal of the material before the 6-months mark does not lead to malignant tumors, which further supports the link between Dacron graft and formation of tumor. A pocket is formed around the foreign material after a certain period, as has been shown in histologic studies as the site of tumor origin.9,10

At the molecular level, the MDM-2/p53 pathway has been cited as possible mechanism for pathogenesis of intimal sarcoma.12,13 It has been suggested that endothelial dysplasia occurs as a precursor lesion in these sarcomas.14 The Dacron graft may cause a dysplastic effect on the endothelium leading to this precursor lesion and in certain cases transforming into sarcoma. Further definitive studies are required.

The primary treatment for cardiac sarcoma is surgical removal, although it is not always feasible. Findings in a Mayo clinic study showed that the median survival was 17 months for patients who underwent complete surgical excision, compared with 6 months for those who complete resection was not possible.15 In addition, a 10% survival rate at 1 year has been reported in primary cardiac sarcomas that are treated without any type of surgery.16

There is no clear-cut evidence supporting or refuting adjuvant chemotherapy for cardiac sarcoma. Some have inferred a potential benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy although definitive conclusions cannot be drawn. The median survival was 16.5 months in a case series of patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy, compared with 9 months and 11 months in 2 other case series.17,18,19 Multiple chemotherapy regimens have been used in the past for treatment. A retrospective s

Radiation showed some benefit in progression-free survival in a French retrospective study.21 Radiation therapies have been tried in other cases, as well in addition to chemotherapy. However, there is not enough data to support or refute it at this time.15,17,20 Several sporadic cases reported show benefit of cardiac transplantation.21,22

Conclusion

In consideration of the placement of the Dacron graft 8 years before the tumor occurrence, the anatomic proximity of the tumor to the Dacron graft, and the association between sarcoma with Dacron in medical literature, it seems logical to infer that this unusual malignancy in our patient is associated with the Dacron prosthesis.

1. Patil HR, Singh D, Hajdu M. Cardiac sarcoma presenting as heart failure and diagnosed as recurrent myxoma by echocardiogram. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2010;11(4):E12.

2. Awamleh P, Alberca MT, Gamallo C, Enrech S, Sarraj A. Left atrium myxosarcoma: an exceptional cardiac malignant primary tumor. Clin Cardiol. 2007;30(6):306-308.

3. Oppenheimer BS, Oppenheimer ET, Stout AP, Danishefsky I. Malignant tumors resulting from embedding plastics in rodents. Science. 1953;118:305-306.

4. Oppenheimer BS, Oppenheimer ET, Stout AP, Willhite M, Danishefski, I. The latent period in carcinogenesis by plastics in rats and its relation to the presarcomatous stage. Cancer. 1958;11(1):204-213.

5. Almeida NJ, Hoang P, Biddle P, Arouni A, Esterbrooks D. Primary cardiac angiosarcoma: in a patient with a Dacron aortic prosthesis. Tex Heart Inst J. 2011;38(1):61-65; discussion 65.

6. Stewart B, Manglik N, Zhao B, et al. Aortic intimal sarcoma: report of two cases with immunohistochemical analysis for pathogenesis. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2013;22(5):351-356.

7. Umscheid TW, Rouhani G, Morlang T, et al. Hemangiosarcoma after endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. J Endovasc Ther. 2007;14(1):101-105.

8. Ben-Izhak O, Vlodavsky E, Ofer A, Engel A, Nitecky S, Hoffman A. Epithelioid angiosarcoma associated with a Dacron vascular graft. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23(11):1418-1422.

9. Fyfe BS, Quintana CS, Kaneko M, Griepp RB. Aortic sarcoma four years after Dacron graft insertion. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;58(6):1752-1754.

10. O’Connell TX, Fee HJ, Golding A. Sarcoma associated with Dacron prosthetic material: case report and review of the literature. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1976;72(1):94-96.

11. Karp RD, Johnson KH, Buoen LC, et al. Tumorogenesis by millipore filters in mice: histology and ultastructure of tissue reactions, as related to pore size. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1973;51:1275-1285.

12. Bode-Lesniewska B, Zhao J, Speel EJ, et al. Gains of 12q13-14 and overexpression of mdm2 are frequent findings in intimal sarcomas of the pulmonary artery. Virchows Arch. 2001;438:57-65.

13. Zeitz C, Rossle M, Haas C, et al. MDM-2 oncoprotein overexpression, p53 gene mutation, and VEGF up-regulation in angiosarcomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;153:1425-1433.

14. Haber LM, Truong L. Immunohistochemical demonstration of the endothelialnature of aortic intimal sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988 Oct;12(10):798-802. PubMed PMID: 3138923.

15. Simpson L, Kumar SK, Okuno SH, et al. Malignant primary cardiac tumors: review of a single institution experience. Cancer. 2008;112(11):2440-2446.

16. Leja MJ, Shah DJ, Reardon MJ. Primary cardiac tumors. Tex Heart Inst J. 2011;38(3):261-262.

17. Donsbeck AV, Ranchere D, Coindre JM, Le Gall F, Cordier JF, Loire R. Primary cardiac sarcomas: an immunohistochemical and grading study with long-term follow-up of 24 cases. Histopathology. 1999;34(4):295-304.

18. Putnam JB, Sweeney MS, Colon R, Lanza LA, Frazier OH, Cooley DC. Primary cardiac sarcomas. Ann Thorac Surg. 1990; 51; 906-910.

19. Murphy WR, Sweeney MS, Putnam JB et al. Surgical treatment of cardiac tumors: a 25-year experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 1990;49;612-618.

20. Llombart-Cussac A, Pivot X, Contesso G, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for primary cardiac sarcomas: the IGR experience. Br J Cancer. 1998;78(12):1624-1628.

21. Isambert N, Ray-Coquard I, Italiano A, et al. Primary cardiac sarcomas: a retrospective study of the French Sarcoma Group. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50(1):128-136.

22. Agaimy A, Rösch J, Weyand M, Strecker T. Primary and metastatic cardiac sarcomas: a 12-year experience at a German heart center. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2012;5(9):928-938.

Primary cardiac tumors, either benign or malignant, are very rare. The combined incidence is 0.002% on pooled autopsy series.1 The benign tumors account for 63% of primary cardiac tumors and include myxoma, the most common, and followed by papillary fibroelastoma, fibroma, and hemangioma. The remaining 37% are malignant tumors, essentially predominated by sarcomas.1

Although myxoma is the most common tumor arising in the left atrium, we present a case that shows that sarcoma can also arise from the same chamber. In fact, sarcomas could mimic cardiac myxoma.2 The cardiac sarcomas can have similar clinical presentation and more importantly can share similar histopathological features. Sarcomas may have myxoid features.2 Cases diagnosed as cardiac myxomas should be diligently worked up to rule out the presence of sarcomas with myxoid features. In addition, foreign bodies have been found to induce sarcomas in experimental animals.3,4 In particular, 2 case reports have described sarcomas arising in association with Dacron vascular prostheses in humans.5,6 We present here the case of a patient who was diagnosed with cardiac pleomorphic sarcoma 8 years after the placement of a Dacron graft.

Case presentation and summary

A 56-year-old woman with history of left atrial myxoma status after resection in 2005 and placement of a Dacron graft, morbid obesity, hypertension, and asthma presented to the emergency department with progressively worsening shortness of breath and blurry vision over period of 2 months. Acute coronary syndrome was ruled out by electrocardiogram and serial biomarkers. A computed-tomography angiogram was pursued because of her history of left atrial myxoma, and the results suggested the presence of a left atrial tumor. She underwent a transesophageal echocardiogram, which confirmed the presence of a large left atrial mass that likely was attached to the interatrial septum prolapsing across the mitral valve and was suggestive for recurrent left atrial myxoma (Figure 1). The results of a cardiac catheterization showed normal coronaries.

The patient subsequently underwent an excision of the left atrial tumor with profound internal and external myocardial cooling using antegrade blood cardioplegia under mildly hypothermic cardiopulmonary bypass. Frozen sections showed high-grade malignancy in favor of sarcoma. The hematoxylin and eosin stained permanent sections showed sheets of malignant pleomorphic spindle cells focally arranged in a storiform pattern. There were areas of necrosis and abundant mitotic activity. By immunohistochemical (IHC) stains, the tumor cells were diffusely positive for vimentin, and negative for pan-cytokeratin antibody (AE1/AE3), S-100 protein, Melan-A antibody, HMB45, CD34, CD31, myogenin, and MYOD1. IHC stains for CK-OSCAR, desmin, and smooth muscle actin were focally positive, and a ki-67 stain showed a proliferation index of about 80%. The histologic and IHC findings were consistent with a final diagnosis of high-grade undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (Figure 2).

A positron emission tomography scan performed November 2013 did not show any other activity. The patient was scheduled for chemotherapy with adriamycin and ifosfamide with a plan for total of 6 cycles. Before her admission for the chemotherapy, the patient was admitted to the hospital for atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response and had multiple complications requiring prolonged hospitalization and rehabilitation. Repeat imaging 2 months later showed diffuse metastatic disease. However, her performance status had declined and she was not eligible for chemotherapy. She was placed under hospice care.

Discussion

This case demonstrates development of a cardiac pleomorphic sarcoma, a rare tumor, after placement of a Dacron graft. Given that foreign bodies have been found to induce sarcomas in experimental animals,3,4 and a few case reports have described sarcomas arising in association with Dacron vascular prostheses, 5-10 it seems that an exuberant host response around the foreign body might represent an important intermediate step in the development of the sarcoma.

There is no clearly defined pathogenesis that explains the link between a Dacron graft and sarcomas. In 1950s, Oppenheimer and colleagues described the formation of malignant tumors by various types of plastics, including Dacron, that were embedded in rats. 3,4 Most of the tumors were some form of sarcomas. It was inferred that physical properties of the plastics may have some role in tumor development. Plastics in sheet form or film that remained in situ for more than 6 months induced significant number of tumors compared with other forms such as sponges, films with holes, or powders.3,4 The 3-dimensional polymeric structure of the Dacron graft seems to play a role in induction of sarcoma as well. A pore diameter of less than 0.4 mm may increase tumorigenicity.11 The removal of the material before the 6-months mark does not lead to malignant tumors, which further supports the link between Dacron graft and formation of tumor. A pocket is formed around the foreign material after a certain period, as has been shown in histologic studies as the site of tumor origin.9,10

At the molecular level, the MDM-2/p53 pathway has been cited as possible mechanism for pathogenesis of intimal sarcoma.12,13 It has been suggested that endothelial dysplasia occurs as a precursor lesion in these sarcomas.14 The Dacron graft may cause a dysplastic effect on the endothelium leading to this precursor lesion and in certain cases transforming into sarcoma. Further definitive studies are required.

The primary treatment for cardiac sarcoma is surgical removal, although it is not always feasible. Findings in a Mayo clinic study showed that the median survival was 17 months for patients who underwent complete surgical excision, compared with 6 months for those who complete resection was not possible.15 In addition, a 10% survival rate at 1 year has been reported in primary cardiac sarcomas that are treated without any type of surgery.16

There is no clear-cut evidence supporting or refuting adjuvant chemotherapy for cardiac sarcoma. Some have inferred a potential benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy although definitive conclusions cannot be drawn. The median survival was 16.5 months in a case series of patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy, compared with 9 months and 11 months in 2 other case series.17,18,19 Multiple chemotherapy regimens have been used in the past for treatment. A retrospective s

Radiation showed some benefit in progression-free survival in a French retrospective study.21 Radiation therapies have been tried in other cases, as well in addition to chemotherapy. However, there is not enough data to support or refute it at this time.15,17,20 Several sporadic cases reported show benefit of cardiac transplantation.21,22

Conclusion

In consideration of the placement of the Dacron graft 8 years before the tumor occurrence, the anatomic proximity of the tumor to the Dacron graft, and the association between sarcoma with Dacron in medical literature, it seems logical to infer that this unusual malignancy in our patient is associated with the Dacron prosthesis.

Primary cardiac tumors, either benign or malignant, are very rare. The combined incidence is 0.002% on pooled autopsy series.1 The benign tumors account for 63% of primary cardiac tumors and include myxoma, the most common, and followed by papillary fibroelastoma, fibroma, and hemangioma. The remaining 37% are malignant tumors, essentially predominated by sarcomas.1

Although myxoma is the most common tumor arising in the left atrium, we present a case that shows that sarcoma can also arise from the same chamber. In fact, sarcomas could mimic cardiac myxoma.2 The cardiac sarcomas can have similar clinical presentation and more importantly can share similar histopathological features. Sarcomas may have myxoid features.2 Cases diagnosed as cardiac myxomas should be diligently worked up to rule out the presence of sarcomas with myxoid features. In addition, foreign bodies have been found to induce sarcomas in experimental animals.3,4 In particular, 2 case reports have described sarcomas arising in association with Dacron vascular prostheses in humans.5,6 We present here the case of a patient who was diagnosed with cardiac pleomorphic sarcoma 8 years after the placement of a Dacron graft.

Case presentation and summary

A 56-year-old woman with history of left atrial myxoma status after resection in 2005 and placement of a Dacron graft, morbid obesity, hypertension, and asthma presented to the emergency department with progressively worsening shortness of breath and blurry vision over period of 2 months. Acute coronary syndrome was ruled out by electrocardiogram and serial biomarkers. A computed-tomography angiogram was pursued because of her history of left atrial myxoma, and the results suggested the presence of a left atrial tumor. She underwent a transesophageal echocardiogram, which confirmed the presence of a large left atrial mass that likely was attached to the interatrial septum prolapsing across the mitral valve and was suggestive for recurrent left atrial myxoma (Figure 1). The results of a cardiac catheterization showed normal coronaries.

The patient subsequently underwent an excision of the left atrial tumor with profound internal and external myocardial cooling using antegrade blood cardioplegia under mildly hypothermic cardiopulmonary bypass. Frozen sections showed high-grade malignancy in favor of sarcoma. The hematoxylin and eosin stained permanent sections showed sheets of malignant pleomorphic spindle cells focally arranged in a storiform pattern. There were areas of necrosis and abundant mitotic activity. By immunohistochemical (IHC) stains, the tumor cells were diffusely positive for vimentin, and negative for pan-cytokeratin antibody (AE1/AE3), S-100 protein, Melan-A antibody, HMB45, CD34, CD31, myogenin, and MYOD1. IHC stains for CK-OSCAR, desmin, and smooth muscle actin were focally positive, and a ki-67 stain showed a proliferation index of about 80%. The histologic and IHC findings were consistent with a final diagnosis of high-grade undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (Figure 2).

A positron emission tomography scan performed November 2013 did not show any other activity. The patient was scheduled for chemotherapy with adriamycin and ifosfamide with a plan for total of 6 cycles. Before her admission for the chemotherapy, the patient was admitted to the hospital for atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response and had multiple complications requiring prolonged hospitalization and rehabilitation. Repeat imaging 2 months later showed diffuse metastatic disease. However, her performance status had declined and she was not eligible for chemotherapy. She was placed under hospice care.

Discussion