User login

Postherpetic Isotopic Responses With 3 Simultaneously Occurring Reactions Following Herpes Zoster

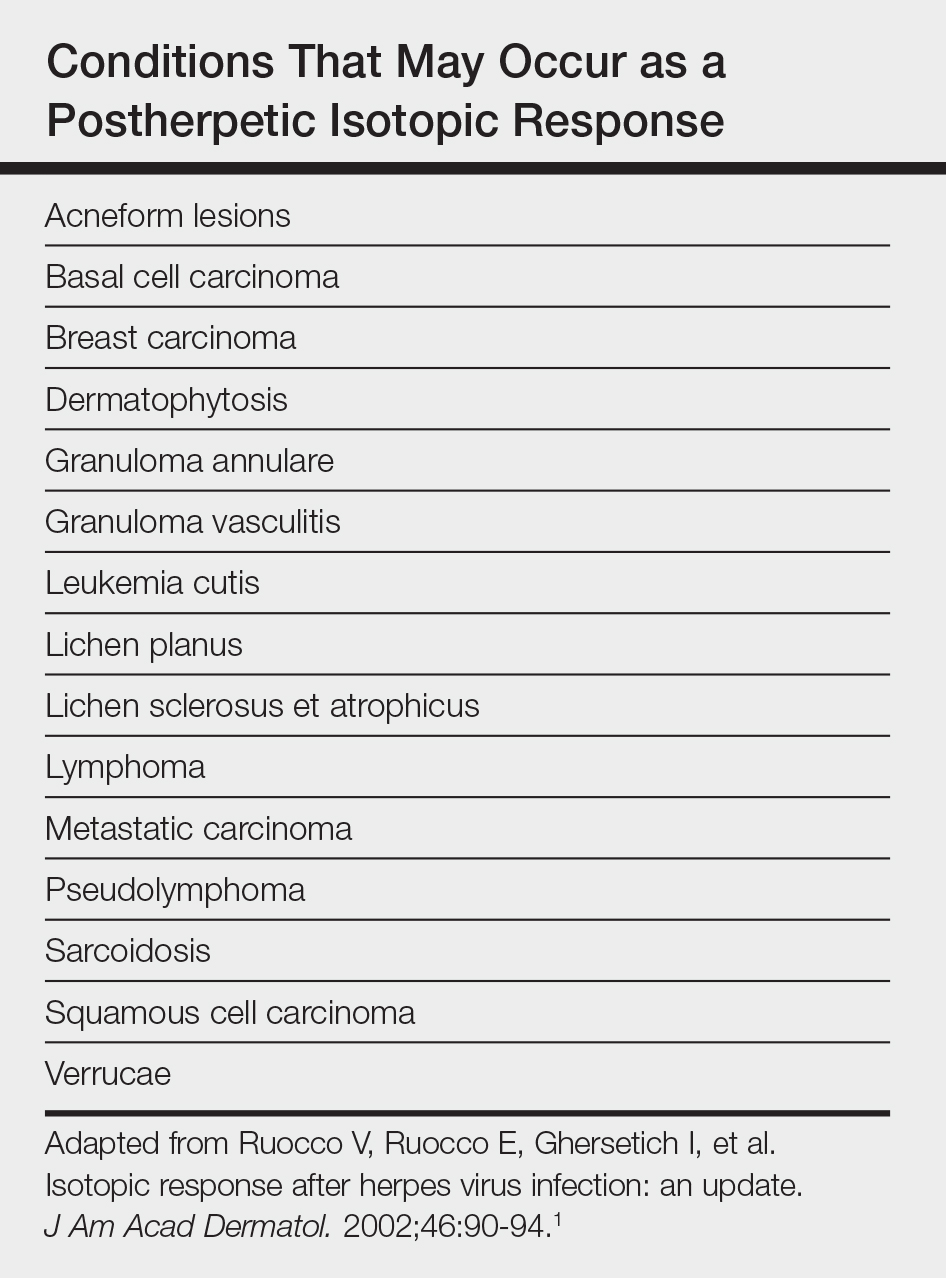

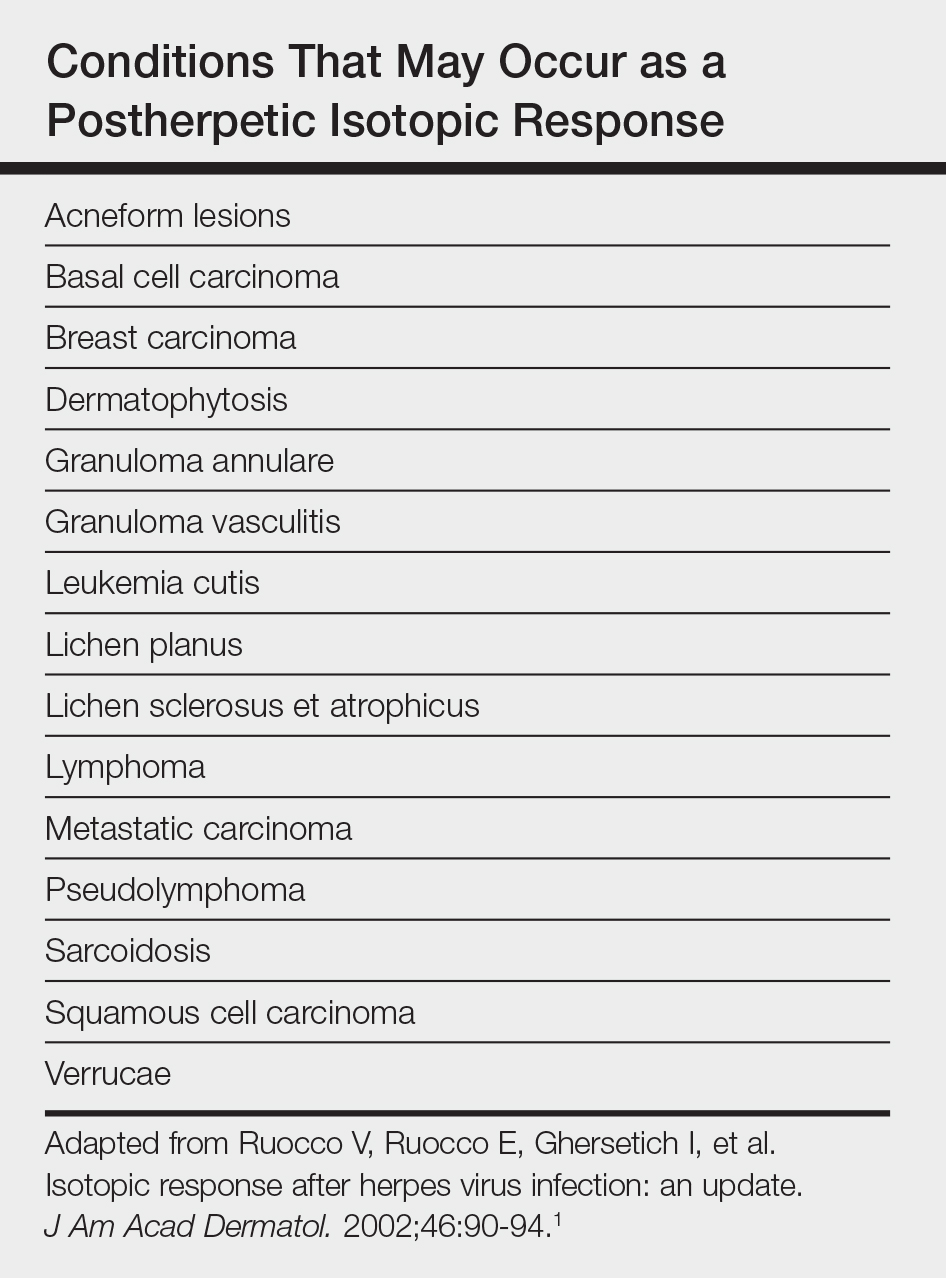

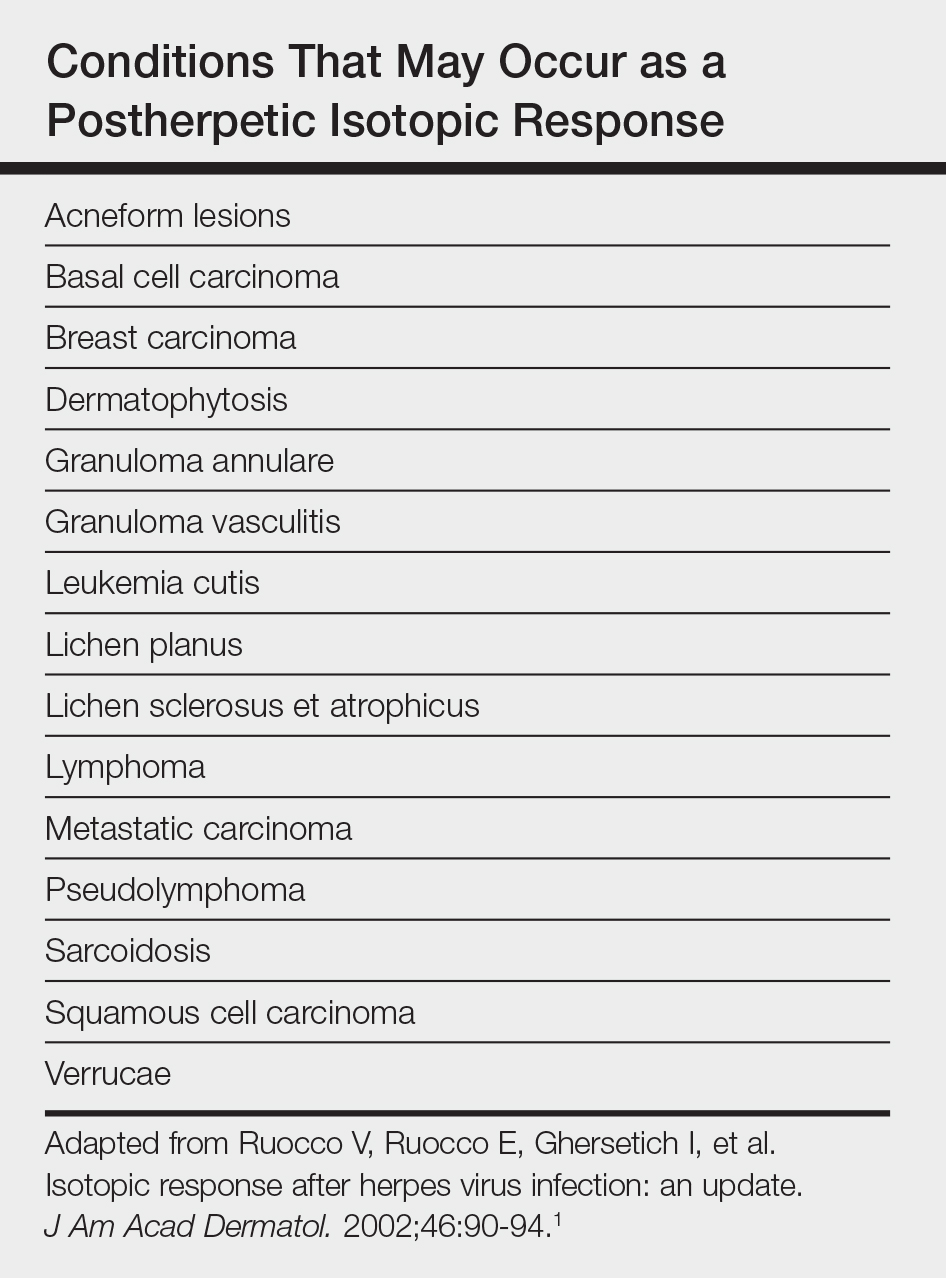

Postherpetic isotopic response (PHIR) refers to the occurrence of a second disease manifesting at the site of prior herpes infection. Many forms of PHIR have been described (Table), with postzoster granulomatous dermatitis (eg, granuloma annulare, sarcoidosis, granulomatous vasculitis) being the most common.1 Both primary and metastatic malignancies also can occur at the site of a prior herpes infection. Rarely, multiple types of PHIRs occur simultaneously. We report a case of 3 simultaneously occurring postzoster isotopic responses--granulomatous dermatitis, vasculitis, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)--and review the various types of PHIRs.

Case Report

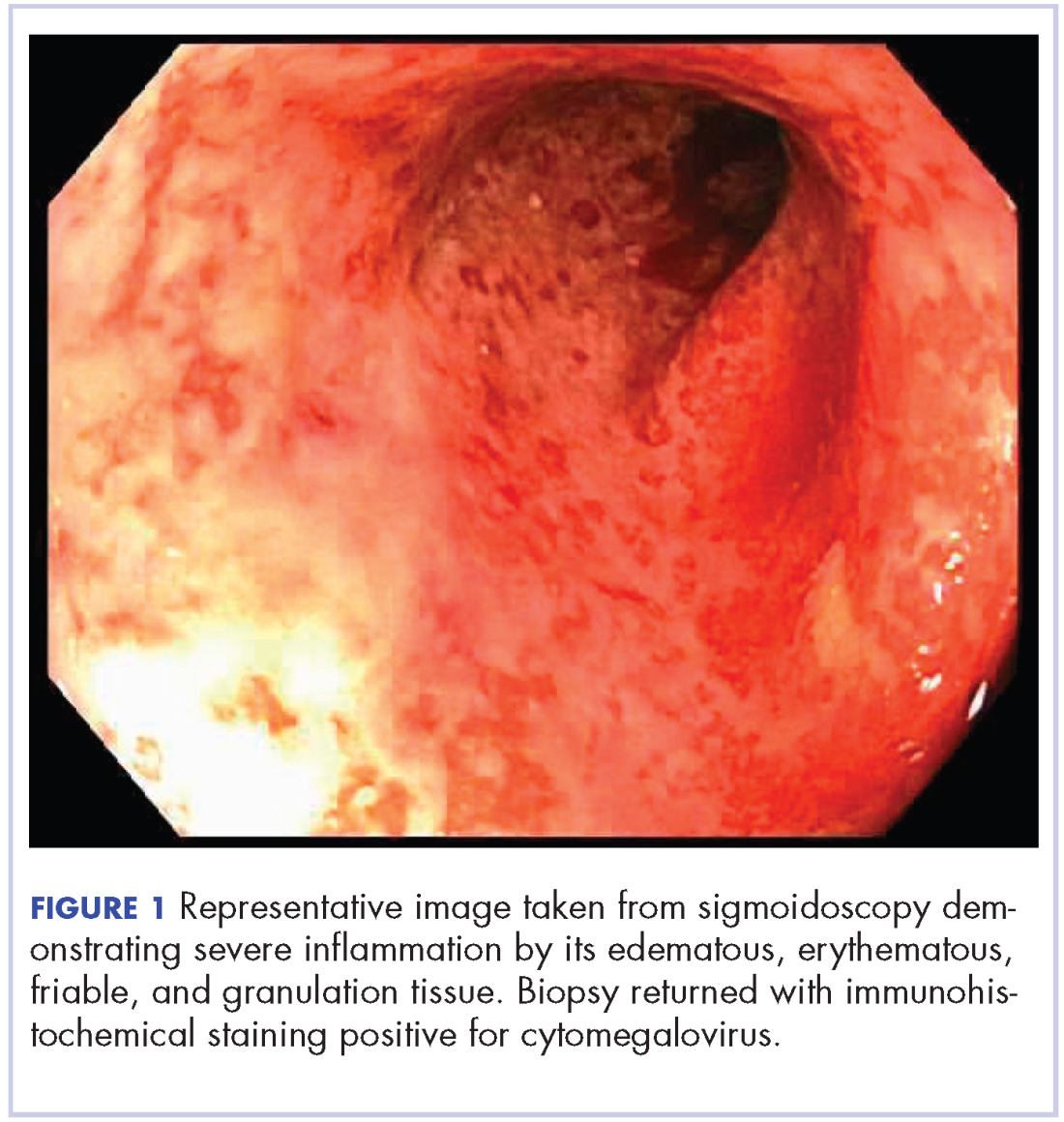

A 55-year-old man with a 4-year history of CLL was admitted to the hospital due to a painful rash on the left side of the face of 2 months' duration. Erythematous to violaceous plaques with surrounding papules and nodules were present on the left side of the forehead and frontal scalp with focal ulceration. Two months prior, the patient had unilateral vesicular lesions in the same distribution (Figure 1A). He initially received a 3-week course of acyclovir for a presumed herpes zoster infection and showed prompt improvement in the vesicular lesions. After resolution of the vesicles, papules and nodules began developing in the prior vesicular areas and he was treated with another course of acyclovir with the addition of clindamycin. When the lesions continued to progress and spread down the left side of the forehead and upper eyelid (Figure 1B), he was admitted to the hospital and assessed by the consultative dermatology team. No fevers, chills, or other systemic symptoms were reported.

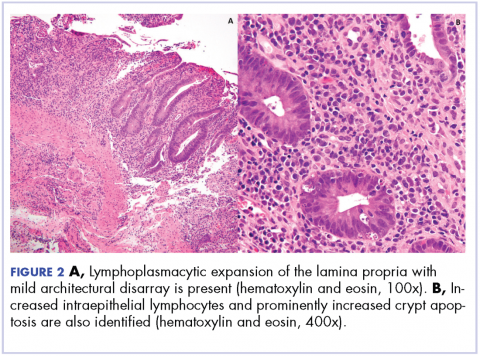

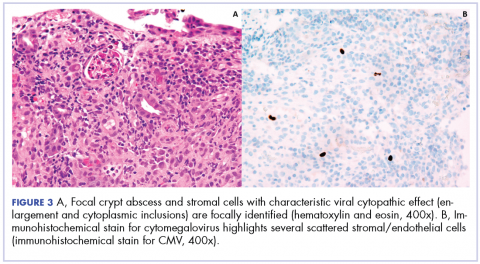

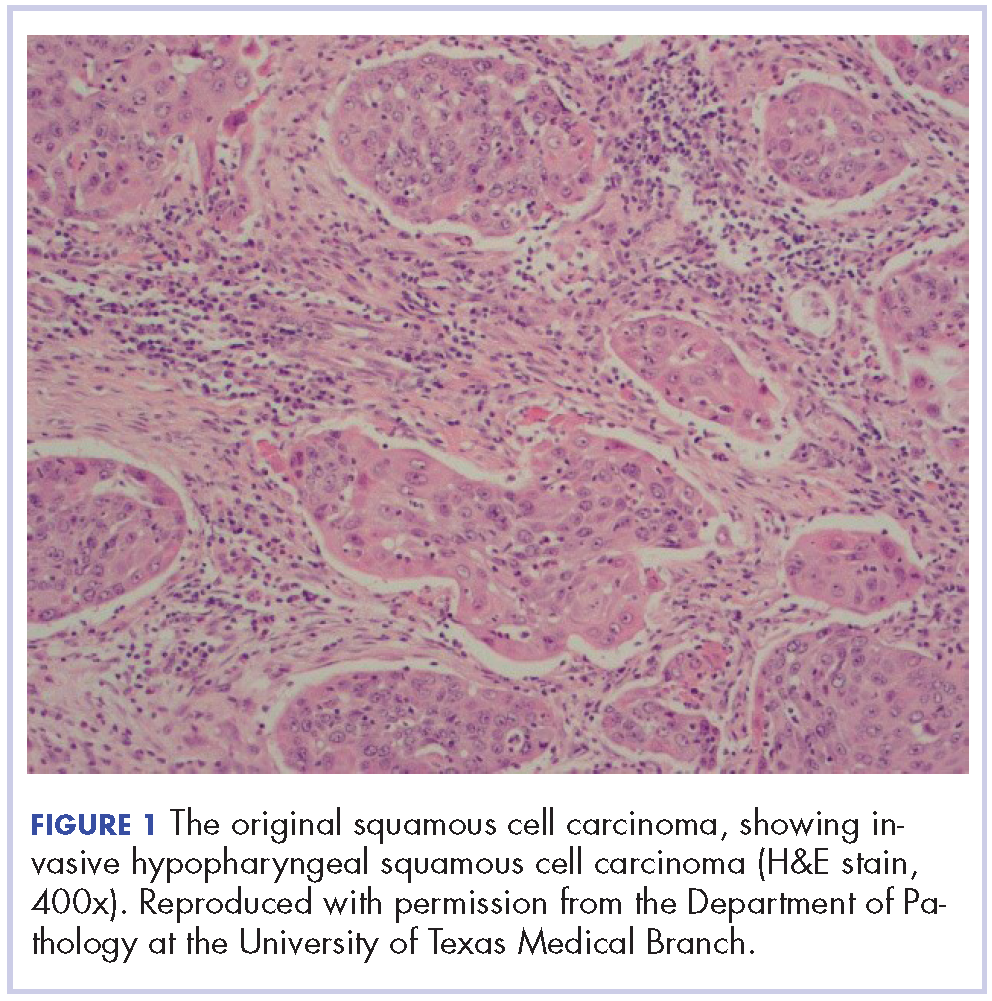

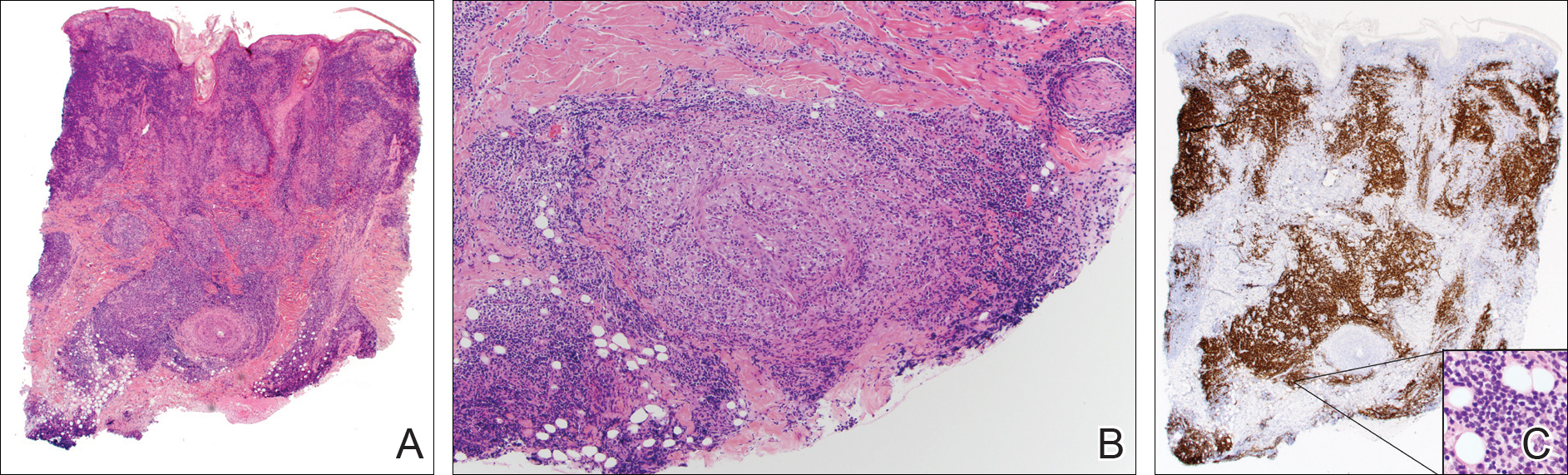

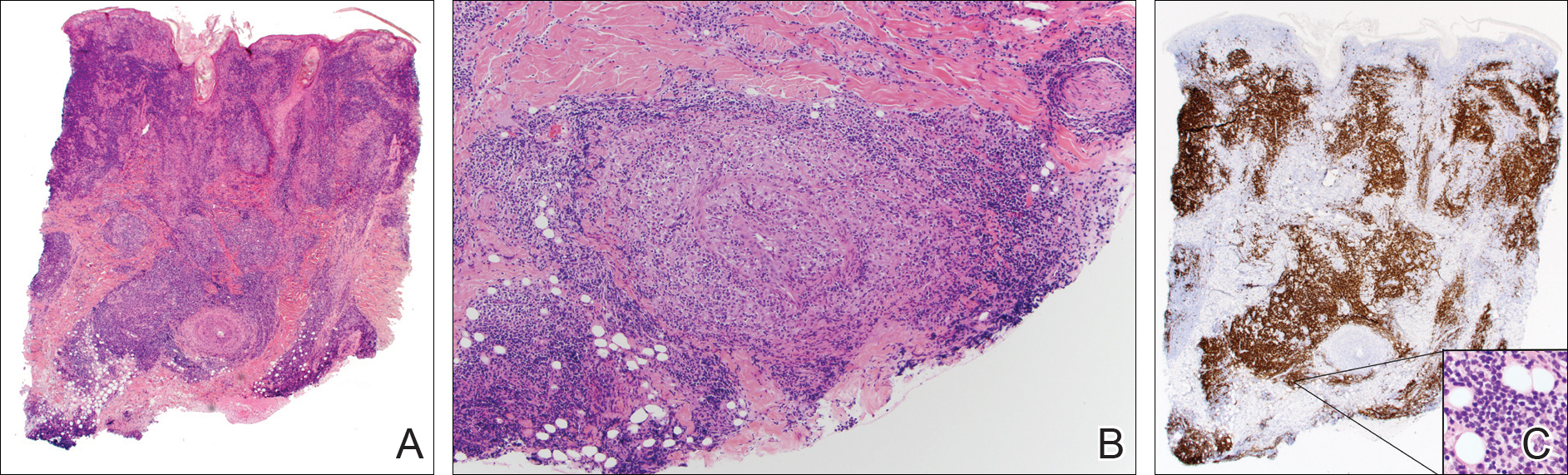

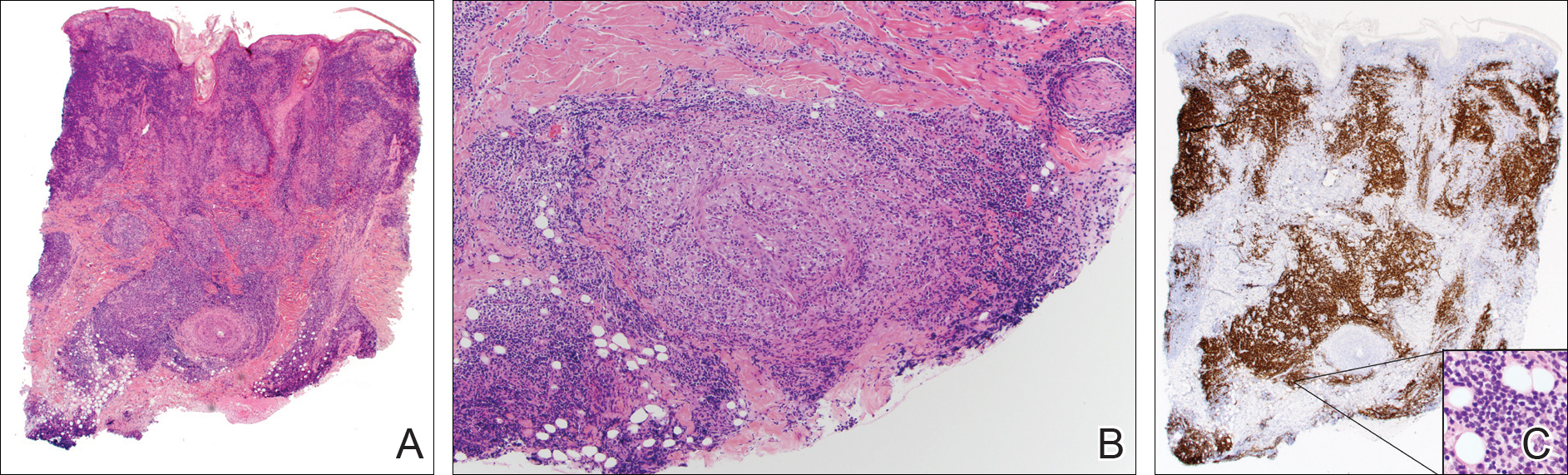

A punch biopsy showed a diffuse lymphocytic infiltrate filling the dermis and extending into the subcutis with nodular collections of histiocytes and some plasma cells scattered throughout (Figure 2A). A medium-vessel vasculitis was present with numerous histiocytes and lymphocytes infiltrating the muscular wall of a blood vessel in the subcutis (Figure 2B). CD3 and CD20 immunostaining showed an overwhelming majority of B cells, some with enlarged atypical nuclei and a smaller number of reactive T lymphocytes (Figure 2C). CD5 and CD43 were diffusely positive in the B cells, confirming the diagnosis of cutaneous CLL. CD23 staining was focally positive. Immunostaining for κ and λ light chains showed a marginal κ predominance. An additional biopsy for tissue culture was negative. A diagnosis of postzoster granulomatous dermatitis with vasculitis and cutaneous CLL was rendered.

Comment

Postherpetic Cutaneous Reactions

Various cutaneous reactions can occur at the site of prior herpes infection. The most frequently reported reactions are granulomatous dermatitides such as granuloma annulare, granulomatous vasculitis, granulomatous folliculitis, sarcoidosis, and nonspecific granulomatous dermatitis.1 Primary cutaneous malignancies and cutaneous metastases, including hematologic malignancies, have also been reported after herpetic infections. In a review of 127 patients with postherpetic cutaneous reactions, 47 had a granulomatous dermatitis, 32 had nonhematologic malignancies, 18 had leukemic or lymphomatous/pseudolymphomatous infiltrates, 10 had acneform lesions, 9 had nongranulomatous dermatitides such as lichen planus and allergic contact dermatitis, and 8 had nonherpetic skin infections; single cases of reactive perforating collagenosis, nodular solar degeneration, and a keloid also were reported.1

Pathogenesis of Cutaneous Reactions

Although postherpetic cutaneous reactions can develop in healthy individuals, they occur more often in immunocompromised patients. Postherpetic isotopic response has been used to describe the development of a nonherpetic disease at the site of prior herpes infection.2 Several different theories have been proposed to explain the pathogenesis of the PHIR, including an unusual delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to residual viral antigen or host-tissue antigen altered by the virus. This delayed-type hypersensitivity explanation is supported by the presence of helper T cells, activated T lymphocytes, macrophages, varicella major viral envelope glycoproteins, and viral DNA in postherpetic granulomatous lesions3; however, cases that lack detectable virus and viral DNA in these types of lesions also have been reported.4

A second hypothesis proposes that inflammatory or viral-induced alteration of the local microvasculature results in increased site-specific susceptibility to subsequent inflammatory responses and drives these isotopic reactions.2,3 Damage or alteration of local peripheral nerves leading to abnormal release of specific neuromediators involved in regulating cutaneous inflammatory responses also may play a role.5 Varicella-zoster virus utilizes the peripheral nervous system to establish latent infection and can cause destruction of alpha delta and C nerve fibers in the dermis.1 Destruction of nerve fibers may indirectly influence the local immune system by altering the release of neuromediators such as substance P (known to increase blood vessel permeability, increase fibrinolytic activity, and induce mast cell secretion), vasoactive intestinal peptide (enhances monocyte migration, increases histamine release from mast cells, and inhibits natural killer cell activity), calcitonin gene-related peptide (increases vascular permeability, endothelial cell proliferation, and the accumulation of neutrophils), and melanocyte-stimulating hormone (induces anti-inflammatory cytokines). Disruption of the nervous system resulting in an altered local immune response also has been observed in other settings (eg, amputees who develop inflammatory diseases, bacterial and fungal infections, and cutaneous neoplasms confined to stump skin).1

Malignancies in PHIR

The granulomatous inflammation in PHIRs is a nonneoplastic inflammatory reaction with a variable lymphocytic component. Granuloma formation can be seen in both reactive inflammatory infiltrates and in cutaneous involvement of leukemias and lymphomas. Leukemia cutis has been reported in 4% to 20% of patients with CLL/small lymphocytic leukemia.6 In one series of 42 patients with CLL, the malignant cells were confined to the site of postherpetic scars in 14% (6/42) of patients.5 Sixteen percent (7/42) of patients had no prior diagnosis of CLL at the time they developed leukemia cutis, including one patient with leukemia cutis in a postzoster scar. The mechanism involved in the accumulation of neoplastic lymphocytes within postzoster scars has not been fully characterized. The idea that postzoster sites represent a site of least resistance for cutaneous infiltration of CLL due to the changes from prior inflammatory responses has been proposed.7

Combined CLL and granulomatous dermatitis at prior sites of herpes zoster was first reported in 1990.8 In 1995, Cerroni et al9 reported a series of 5 patients with cutaneous CLL following herpes zoster or herpes simplex virus infection. Three of those patients also demonstrated granuloma formation.9 Establishing a new diagnosis of CLL from a biopsy of postzoster granulomatous dermatitis with an associated lymphoid infiltrate also has been reported.10 Cerroni et al9 postulated that cutaneous CLL in post-herpes zoster scars may occur more frequently than reported due to misdiagnoses of CLL as pseudolymphoma. Two additional cases of postherpetic cutaneous CLL and granulomatous dermatitis have been reported since 1995.7,10

Diagnosis of Multiple PHIRs

The presence of 3 concurrent PHIRs is rare. The patient in this report had postzoster cutaneous CLL with an associated granulomatous dermatitis and medium-vessel vasculitis. One other case with these 3 findings was reported by Elgoweini et al.7 Overlooking important diagnoses when multiple findings are present in a biopsy can lead to diagnostic delay and incorrect treatment; we highlighted the importance of careful examination of biopsies in PHIRs to ensure diagnostic accuracy. In cases of postzoster granulomatous dermatitis, assessment of the lymphocytic component should not be overlooked. The presence of a dense lymphocytic infiltrate should raise the possibility of a lymphoproliferative disorder such as CLL, even in patients with no prior history of lymphoma. If initial immunostaining discloses a predominantly B-cell infiltrate, additional immuno-stains (eg, CD5, CD23, CD43) and/or genetic testing for monoclonality should be pursued.

Conclusion

Clinicians and dermatopathologists should be aware of the multiplicity of postherpetic isotopic responses and consider immunohistochemical stains to differentiate between a genuine lymphoma such as CLL and pseudolymphoma in PHIRs with a lymphoid infiltrate.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Ghersetich I, et al. Isotopic response after herpes virus infection: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:90-94.

- Wolf R, Wolf D, Ruocco E, et al. Wolf's isotopic response. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:237-240.

- Nikkels AF, Debrus S, Delvenne P, et al. Viral glycoproteins in herpesviridae granulomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:588-592.

- Snow J, el-Azhary R, Gibson L, et al. Granulomatous vasculitis associated with herpes virus: a persistent, painful, postherpetic papular eruption. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72:851-853.

- Cerroni L, Zenahlik P, Hofler G, et al. Specific cutaneous infiltrates of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a clinicopathologic and prognostic study of 42 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1000-1010.

- Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130-142.

- Elgoweini M, Blessing K, Jackson R, et al. Coexistent granulomatous vasculitis and leukaemia cutis in a patient with resolving herpes zoster. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:749-751.

- Pujol RM, Matias-Guiu X, Planaguma M, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia and cutaneous granulomas at sites of herpes zoster scars. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:652-654.

- Cerroni L, Zenahlik P, Kerl H. Specific cutaneous infiltrates of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia arising at the site of herpes zoster and herpes simplex scars. Cancer. 1995;76:26-31.

- Trojjet S, Hammami H, Zaraa I, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia revealed by a granulomatous zosteriform eruption. Skinmed. 2012;10:50-52.

Postherpetic isotopic response (PHIR) refers to the occurrence of a second disease manifesting at the site of prior herpes infection. Many forms of PHIR have been described (Table), with postzoster granulomatous dermatitis (eg, granuloma annulare, sarcoidosis, granulomatous vasculitis) being the most common.1 Both primary and metastatic malignancies also can occur at the site of a prior herpes infection. Rarely, multiple types of PHIRs occur simultaneously. We report a case of 3 simultaneously occurring postzoster isotopic responses--granulomatous dermatitis, vasculitis, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)--and review the various types of PHIRs.

Case Report

A 55-year-old man with a 4-year history of CLL was admitted to the hospital due to a painful rash on the left side of the face of 2 months' duration. Erythematous to violaceous plaques with surrounding papules and nodules were present on the left side of the forehead and frontal scalp with focal ulceration. Two months prior, the patient had unilateral vesicular lesions in the same distribution (Figure 1A). He initially received a 3-week course of acyclovir for a presumed herpes zoster infection and showed prompt improvement in the vesicular lesions. After resolution of the vesicles, papules and nodules began developing in the prior vesicular areas and he was treated with another course of acyclovir with the addition of clindamycin. When the lesions continued to progress and spread down the left side of the forehead and upper eyelid (Figure 1B), he was admitted to the hospital and assessed by the consultative dermatology team. No fevers, chills, or other systemic symptoms were reported.

A punch biopsy showed a diffuse lymphocytic infiltrate filling the dermis and extending into the subcutis with nodular collections of histiocytes and some plasma cells scattered throughout (Figure 2A). A medium-vessel vasculitis was present with numerous histiocytes and lymphocytes infiltrating the muscular wall of a blood vessel in the subcutis (Figure 2B). CD3 and CD20 immunostaining showed an overwhelming majority of B cells, some with enlarged atypical nuclei and a smaller number of reactive T lymphocytes (Figure 2C). CD5 and CD43 were diffusely positive in the B cells, confirming the diagnosis of cutaneous CLL. CD23 staining was focally positive. Immunostaining for κ and λ light chains showed a marginal κ predominance. An additional biopsy for tissue culture was negative. A diagnosis of postzoster granulomatous dermatitis with vasculitis and cutaneous CLL was rendered.

Comment

Postherpetic Cutaneous Reactions

Various cutaneous reactions can occur at the site of prior herpes infection. The most frequently reported reactions are granulomatous dermatitides such as granuloma annulare, granulomatous vasculitis, granulomatous folliculitis, sarcoidosis, and nonspecific granulomatous dermatitis.1 Primary cutaneous malignancies and cutaneous metastases, including hematologic malignancies, have also been reported after herpetic infections. In a review of 127 patients with postherpetic cutaneous reactions, 47 had a granulomatous dermatitis, 32 had nonhematologic malignancies, 18 had leukemic or lymphomatous/pseudolymphomatous infiltrates, 10 had acneform lesions, 9 had nongranulomatous dermatitides such as lichen planus and allergic contact dermatitis, and 8 had nonherpetic skin infections; single cases of reactive perforating collagenosis, nodular solar degeneration, and a keloid also were reported.1

Pathogenesis of Cutaneous Reactions

Although postherpetic cutaneous reactions can develop in healthy individuals, they occur more often in immunocompromised patients. Postherpetic isotopic response has been used to describe the development of a nonherpetic disease at the site of prior herpes infection.2 Several different theories have been proposed to explain the pathogenesis of the PHIR, including an unusual delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to residual viral antigen or host-tissue antigen altered by the virus. This delayed-type hypersensitivity explanation is supported by the presence of helper T cells, activated T lymphocytes, macrophages, varicella major viral envelope glycoproteins, and viral DNA in postherpetic granulomatous lesions3; however, cases that lack detectable virus and viral DNA in these types of lesions also have been reported.4

A second hypothesis proposes that inflammatory or viral-induced alteration of the local microvasculature results in increased site-specific susceptibility to subsequent inflammatory responses and drives these isotopic reactions.2,3 Damage or alteration of local peripheral nerves leading to abnormal release of specific neuromediators involved in regulating cutaneous inflammatory responses also may play a role.5 Varicella-zoster virus utilizes the peripheral nervous system to establish latent infection and can cause destruction of alpha delta and C nerve fibers in the dermis.1 Destruction of nerve fibers may indirectly influence the local immune system by altering the release of neuromediators such as substance P (known to increase blood vessel permeability, increase fibrinolytic activity, and induce mast cell secretion), vasoactive intestinal peptide (enhances monocyte migration, increases histamine release from mast cells, and inhibits natural killer cell activity), calcitonin gene-related peptide (increases vascular permeability, endothelial cell proliferation, and the accumulation of neutrophils), and melanocyte-stimulating hormone (induces anti-inflammatory cytokines). Disruption of the nervous system resulting in an altered local immune response also has been observed in other settings (eg, amputees who develop inflammatory diseases, bacterial and fungal infections, and cutaneous neoplasms confined to stump skin).1

Malignancies in PHIR

The granulomatous inflammation in PHIRs is a nonneoplastic inflammatory reaction with a variable lymphocytic component. Granuloma formation can be seen in both reactive inflammatory infiltrates and in cutaneous involvement of leukemias and lymphomas. Leukemia cutis has been reported in 4% to 20% of patients with CLL/small lymphocytic leukemia.6 In one series of 42 patients with CLL, the malignant cells were confined to the site of postherpetic scars in 14% (6/42) of patients.5 Sixteen percent (7/42) of patients had no prior diagnosis of CLL at the time they developed leukemia cutis, including one patient with leukemia cutis in a postzoster scar. The mechanism involved in the accumulation of neoplastic lymphocytes within postzoster scars has not been fully characterized. The idea that postzoster sites represent a site of least resistance for cutaneous infiltration of CLL due to the changes from prior inflammatory responses has been proposed.7

Combined CLL and granulomatous dermatitis at prior sites of herpes zoster was first reported in 1990.8 In 1995, Cerroni et al9 reported a series of 5 patients with cutaneous CLL following herpes zoster or herpes simplex virus infection. Three of those patients also demonstrated granuloma formation.9 Establishing a new diagnosis of CLL from a biopsy of postzoster granulomatous dermatitis with an associated lymphoid infiltrate also has been reported.10 Cerroni et al9 postulated that cutaneous CLL in post-herpes zoster scars may occur more frequently than reported due to misdiagnoses of CLL as pseudolymphoma. Two additional cases of postherpetic cutaneous CLL and granulomatous dermatitis have been reported since 1995.7,10

Diagnosis of Multiple PHIRs

The presence of 3 concurrent PHIRs is rare. The patient in this report had postzoster cutaneous CLL with an associated granulomatous dermatitis and medium-vessel vasculitis. One other case with these 3 findings was reported by Elgoweini et al.7 Overlooking important diagnoses when multiple findings are present in a biopsy can lead to diagnostic delay and incorrect treatment; we highlighted the importance of careful examination of biopsies in PHIRs to ensure diagnostic accuracy. In cases of postzoster granulomatous dermatitis, assessment of the lymphocytic component should not be overlooked. The presence of a dense lymphocytic infiltrate should raise the possibility of a lymphoproliferative disorder such as CLL, even in patients with no prior history of lymphoma. If initial immunostaining discloses a predominantly B-cell infiltrate, additional immuno-stains (eg, CD5, CD23, CD43) and/or genetic testing for monoclonality should be pursued.

Conclusion

Clinicians and dermatopathologists should be aware of the multiplicity of postherpetic isotopic responses and consider immunohistochemical stains to differentiate between a genuine lymphoma such as CLL and pseudolymphoma in PHIRs with a lymphoid infiltrate.

Postherpetic isotopic response (PHIR) refers to the occurrence of a second disease manifesting at the site of prior herpes infection. Many forms of PHIR have been described (Table), with postzoster granulomatous dermatitis (eg, granuloma annulare, sarcoidosis, granulomatous vasculitis) being the most common.1 Both primary and metastatic malignancies also can occur at the site of a prior herpes infection. Rarely, multiple types of PHIRs occur simultaneously. We report a case of 3 simultaneously occurring postzoster isotopic responses--granulomatous dermatitis, vasculitis, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)--and review the various types of PHIRs.

Case Report

A 55-year-old man with a 4-year history of CLL was admitted to the hospital due to a painful rash on the left side of the face of 2 months' duration. Erythematous to violaceous plaques with surrounding papules and nodules were present on the left side of the forehead and frontal scalp with focal ulceration. Two months prior, the patient had unilateral vesicular lesions in the same distribution (Figure 1A). He initially received a 3-week course of acyclovir for a presumed herpes zoster infection and showed prompt improvement in the vesicular lesions. After resolution of the vesicles, papules and nodules began developing in the prior vesicular areas and he was treated with another course of acyclovir with the addition of clindamycin. When the lesions continued to progress and spread down the left side of the forehead and upper eyelid (Figure 1B), he was admitted to the hospital and assessed by the consultative dermatology team. No fevers, chills, or other systemic symptoms were reported.

A punch biopsy showed a diffuse lymphocytic infiltrate filling the dermis and extending into the subcutis with nodular collections of histiocytes and some plasma cells scattered throughout (Figure 2A). A medium-vessel vasculitis was present with numerous histiocytes and lymphocytes infiltrating the muscular wall of a blood vessel in the subcutis (Figure 2B). CD3 and CD20 immunostaining showed an overwhelming majority of B cells, some with enlarged atypical nuclei and a smaller number of reactive T lymphocytes (Figure 2C). CD5 and CD43 were diffusely positive in the B cells, confirming the diagnosis of cutaneous CLL. CD23 staining was focally positive. Immunostaining for κ and λ light chains showed a marginal κ predominance. An additional biopsy for tissue culture was negative. A diagnosis of postzoster granulomatous dermatitis with vasculitis and cutaneous CLL was rendered.

Comment

Postherpetic Cutaneous Reactions

Various cutaneous reactions can occur at the site of prior herpes infection. The most frequently reported reactions are granulomatous dermatitides such as granuloma annulare, granulomatous vasculitis, granulomatous folliculitis, sarcoidosis, and nonspecific granulomatous dermatitis.1 Primary cutaneous malignancies and cutaneous metastases, including hematologic malignancies, have also been reported after herpetic infections. In a review of 127 patients with postherpetic cutaneous reactions, 47 had a granulomatous dermatitis, 32 had nonhematologic malignancies, 18 had leukemic or lymphomatous/pseudolymphomatous infiltrates, 10 had acneform lesions, 9 had nongranulomatous dermatitides such as lichen planus and allergic contact dermatitis, and 8 had nonherpetic skin infections; single cases of reactive perforating collagenosis, nodular solar degeneration, and a keloid also were reported.1

Pathogenesis of Cutaneous Reactions

Although postherpetic cutaneous reactions can develop in healthy individuals, they occur more often in immunocompromised patients. Postherpetic isotopic response has been used to describe the development of a nonherpetic disease at the site of prior herpes infection.2 Several different theories have been proposed to explain the pathogenesis of the PHIR, including an unusual delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to residual viral antigen or host-tissue antigen altered by the virus. This delayed-type hypersensitivity explanation is supported by the presence of helper T cells, activated T lymphocytes, macrophages, varicella major viral envelope glycoproteins, and viral DNA in postherpetic granulomatous lesions3; however, cases that lack detectable virus and viral DNA in these types of lesions also have been reported.4

A second hypothesis proposes that inflammatory or viral-induced alteration of the local microvasculature results in increased site-specific susceptibility to subsequent inflammatory responses and drives these isotopic reactions.2,3 Damage or alteration of local peripheral nerves leading to abnormal release of specific neuromediators involved in regulating cutaneous inflammatory responses also may play a role.5 Varicella-zoster virus utilizes the peripheral nervous system to establish latent infection and can cause destruction of alpha delta and C nerve fibers in the dermis.1 Destruction of nerve fibers may indirectly influence the local immune system by altering the release of neuromediators such as substance P (known to increase blood vessel permeability, increase fibrinolytic activity, and induce mast cell secretion), vasoactive intestinal peptide (enhances monocyte migration, increases histamine release from mast cells, and inhibits natural killer cell activity), calcitonin gene-related peptide (increases vascular permeability, endothelial cell proliferation, and the accumulation of neutrophils), and melanocyte-stimulating hormone (induces anti-inflammatory cytokines). Disruption of the nervous system resulting in an altered local immune response also has been observed in other settings (eg, amputees who develop inflammatory diseases, bacterial and fungal infections, and cutaneous neoplasms confined to stump skin).1

Malignancies in PHIR

The granulomatous inflammation in PHIRs is a nonneoplastic inflammatory reaction with a variable lymphocytic component. Granuloma formation can be seen in both reactive inflammatory infiltrates and in cutaneous involvement of leukemias and lymphomas. Leukemia cutis has been reported in 4% to 20% of patients with CLL/small lymphocytic leukemia.6 In one series of 42 patients with CLL, the malignant cells were confined to the site of postherpetic scars in 14% (6/42) of patients.5 Sixteen percent (7/42) of patients had no prior diagnosis of CLL at the time they developed leukemia cutis, including one patient with leukemia cutis in a postzoster scar. The mechanism involved in the accumulation of neoplastic lymphocytes within postzoster scars has not been fully characterized. The idea that postzoster sites represent a site of least resistance for cutaneous infiltration of CLL due to the changes from prior inflammatory responses has been proposed.7

Combined CLL and granulomatous dermatitis at prior sites of herpes zoster was first reported in 1990.8 In 1995, Cerroni et al9 reported a series of 5 patients with cutaneous CLL following herpes zoster or herpes simplex virus infection. Three of those patients also demonstrated granuloma formation.9 Establishing a new diagnosis of CLL from a biopsy of postzoster granulomatous dermatitis with an associated lymphoid infiltrate also has been reported.10 Cerroni et al9 postulated that cutaneous CLL in post-herpes zoster scars may occur more frequently than reported due to misdiagnoses of CLL as pseudolymphoma. Two additional cases of postherpetic cutaneous CLL and granulomatous dermatitis have been reported since 1995.7,10

Diagnosis of Multiple PHIRs

The presence of 3 concurrent PHIRs is rare. The patient in this report had postzoster cutaneous CLL with an associated granulomatous dermatitis and medium-vessel vasculitis. One other case with these 3 findings was reported by Elgoweini et al.7 Overlooking important diagnoses when multiple findings are present in a biopsy can lead to diagnostic delay and incorrect treatment; we highlighted the importance of careful examination of biopsies in PHIRs to ensure diagnostic accuracy. In cases of postzoster granulomatous dermatitis, assessment of the lymphocytic component should not be overlooked. The presence of a dense lymphocytic infiltrate should raise the possibility of a lymphoproliferative disorder such as CLL, even in patients with no prior history of lymphoma. If initial immunostaining discloses a predominantly B-cell infiltrate, additional immuno-stains (eg, CD5, CD23, CD43) and/or genetic testing for monoclonality should be pursued.

Conclusion

Clinicians and dermatopathologists should be aware of the multiplicity of postherpetic isotopic responses and consider immunohistochemical stains to differentiate between a genuine lymphoma such as CLL and pseudolymphoma in PHIRs with a lymphoid infiltrate.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Ghersetich I, et al. Isotopic response after herpes virus infection: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:90-94.

- Wolf R, Wolf D, Ruocco E, et al. Wolf's isotopic response. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:237-240.

- Nikkels AF, Debrus S, Delvenne P, et al. Viral glycoproteins in herpesviridae granulomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:588-592.

- Snow J, el-Azhary R, Gibson L, et al. Granulomatous vasculitis associated with herpes virus: a persistent, painful, postherpetic papular eruption. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72:851-853.

- Cerroni L, Zenahlik P, Hofler G, et al. Specific cutaneous infiltrates of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a clinicopathologic and prognostic study of 42 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1000-1010.

- Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130-142.

- Elgoweini M, Blessing K, Jackson R, et al. Coexistent granulomatous vasculitis and leukaemia cutis in a patient with resolving herpes zoster. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:749-751.

- Pujol RM, Matias-Guiu X, Planaguma M, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia and cutaneous granulomas at sites of herpes zoster scars. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:652-654.

- Cerroni L, Zenahlik P, Kerl H. Specific cutaneous infiltrates of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia arising at the site of herpes zoster and herpes simplex scars. Cancer. 1995;76:26-31.

- Trojjet S, Hammami H, Zaraa I, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia revealed by a granulomatous zosteriform eruption. Skinmed. 2012;10:50-52.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Ghersetich I, et al. Isotopic response after herpes virus infection: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:90-94.

- Wolf R, Wolf D, Ruocco E, et al. Wolf's isotopic response. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:237-240.

- Nikkels AF, Debrus S, Delvenne P, et al. Viral glycoproteins in herpesviridae granulomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:588-592.

- Snow J, el-Azhary R, Gibson L, et al. Granulomatous vasculitis associated with herpes virus: a persistent, painful, postherpetic papular eruption. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72:851-853.

- Cerroni L, Zenahlik P, Hofler G, et al. Specific cutaneous infiltrates of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a clinicopathologic and prognostic study of 42 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1000-1010.

- Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130-142.

- Elgoweini M, Blessing K, Jackson R, et al. Coexistent granulomatous vasculitis and leukaemia cutis in a patient with resolving herpes zoster. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:749-751.

- Pujol RM, Matias-Guiu X, Planaguma M, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia and cutaneous granulomas at sites of herpes zoster scars. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:652-654.

- Cerroni L, Zenahlik P, Kerl H. Specific cutaneous infiltrates of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia arising at the site of herpes zoster and herpes simplex scars. Cancer. 1995;76:26-31.

- Trojjet S, Hammami H, Zaraa I, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia revealed by a granulomatous zosteriform eruption. Skinmed. 2012;10:50-52.

Practice Points

- Multiple diseases may present in prior sites of herpes infection (postherpetic isotopic response).

- Granulomatous dermatitis is the most common postherpetic isotopic response, but other inflammatory, neoplastic, or infectious conditions also occur.

- Multiple conditions may present simultaneously at sites of herpes infection.

- Cutaneous involvement by chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) can be easily overlooked in this setting.

Anti-PD-1 therapy with nivolumab in the treatment of metastatic malignant PEComa

Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms (PEComas) are an uncommon class of tumors consisting on histology of perivascular epithelioid cells occurring in both localized and metastatic forms at various body sites. The approach to treatment of these tumors generally involves a combination of surgical resection, chemotherapy, and/or radiation therapy.1

Case presentation and summary

A 46-year-old man presented to our institution with a non-tender, slowly enlarging, 8.3 cm mass in his right popliteal fossa. Upon biopsy, the pathologic findings were consistent with an epithelioid malignancy with melanocytic differentiation most consistent with a PEComa. Discussion of the pathologic diagnosis of our patient has been reported by the pathology group at our institution in a separate case report.2

Our patient was initially offered and refused amputation. He was started on therapy with the mechanistic Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor everolimus, but was unable to tolerate the side effects after the first week of treatment. He then elected to monitor his symptoms clinically.

Approximately one year after his initial diagnosis, he presented to our facility with sepsis and bleeding from a now fungating tumor on his right knee. At this time, emergent above-knee amputation was performed. Re-staging images now showed the presence of multiple pulmonary nodules in his right lung as well as a lytic rib lesion, a concerning finding for metastatic disease. Video-Assisted Thorascopic Surgery (VATS) and right lower lobe wedge resection were performed and findings confirmed metastatic PEComa.

Given the patient’s intolerance to everolimus, he was started on the growth factor inhibitor, pazopanib. His disease did not progress on pazopanib, and improvement was noted in the dominant pulmonary nodule. Subsequently, however, he developed significant skin irritation and discontinued pazopanib. Repeat imaging approximately 2 months after stopping pazopanib showed significant disease progression.

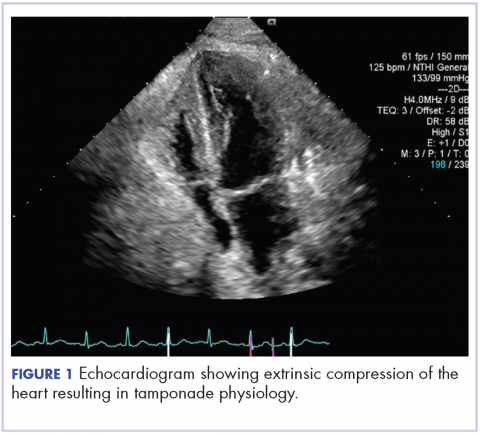

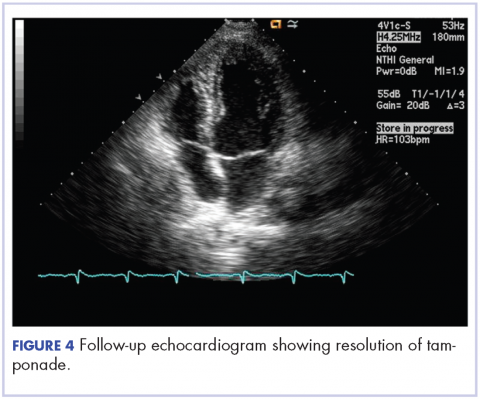

We elected to start the patient on a non-standard approach to therapy with nivolumab infusions once every 2 weeks and concurrent radiation therapy to the rib lesion. At 2 and 5 months after initiating this treatment approach, CT imaging showed improvement in disease. At 12 months, significant disease response was noted (Figure 1).

The patient is now at 12 months of nivolumab therapy with progression free survival and no new identifiable metastatic lesions. He has been tolerating the medication with minimal side effects and has had an overall improvement in his pain and functional status. He continues to work full time.

Discussion

Our patient’s response presents a unique opportunity to talk about the role of immunotherapy as a treatment modality in patients with PEComa. The efficacy of check-point blockade in soft tissue sarcoma is still unclear predominantly because it is difficult to assess the degree of expression of immunogenic cell surface markers such as programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1).1,3 Nivolumab has been tried in small cohorts for treatment of soft tissue sarcomas that express PD-1 and results showed some clinical benefit in about half of patients.4 Further, the expression of PD-1 has been assessed in soft tissue sarcomas and has been reported to suggest a negative prognostic role.5

To our knowledge, there has not yet been another reported case of PEComa that has been treated with immunotherapy and achieved a sustained response. Further clinical studies need to be done to assess response to agents such as nivolumab in the treatment of PEComa to bolster our observation that nivolumab is a viable treatment option that may lead to lasting remission. Our patient’s case also brings to light the need for further inquiry into assessing the immune tumor microenvironments, particularly looking at the expression of cell surface proteins such as PD-1, as it ultimately affects treatment options. TSJ

Correspondence

REFERENCES

1. Burgess, Melissa, et al. “Immunotherapy in Sarcoma: Future Horizons.” Current Oncology Reports, vol. 17, no. 11, 2015, doi:10.1007/s11912-015-0476-7.

2. Alnajar, Hussein, et al. “Metastatic Malignant PEComa of the Leg with Identification of ATRX Mutation by next-Generation Sequencing.” Virchows Archiv (2017). https://doi:10.1007/s004280172208-x.

3. Ghosn, Marwan, et al. “Immunotherapies in Sarcoma: Updates and Future Perspectives.” World Journal of Clinical Oncology, vol. 8, no. 2, 2017, p. 145., doi:10.5306/wjco.v8.i2.145.

4. Paoluzzi, L., et al. “Response to Anti-PD1 Therapy with Nivolumab in Metastatic Sarcomas.” Clinical Sarcoma Research, vol. 6, no. 1, 2016, doi:10.1186/s13569-016 0064-0.

5. Kim, Chan, et al. “Prognostic Implications of PD-L1 Expression in Patients with Soft Tissue Sarcoma.” BMC Cancer, BioMed Central 8 July 2016.

Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms (PEComas) are an uncommon class of tumors consisting on histology of perivascular epithelioid cells occurring in both localized and metastatic forms at various body sites. The approach to treatment of these tumors generally involves a combination of surgical resection, chemotherapy, and/or radiation therapy.1

Case presentation and summary

A 46-year-old man presented to our institution with a non-tender, slowly enlarging, 8.3 cm mass in his right popliteal fossa. Upon biopsy, the pathologic findings were consistent with an epithelioid malignancy with melanocytic differentiation most consistent with a PEComa. Discussion of the pathologic diagnosis of our patient has been reported by the pathology group at our institution in a separate case report.2

Our patient was initially offered and refused amputation. He was started on therapy with the mechanistic Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor everolimus, but was unable to tolerate the side effects after the first week of treatment. He then elected to monitor his symptoms clinically.

Approximately one year after his initial diagnosis, he presented to our facility with sepsis and bleeding from a now fungating tumor on his right knee. At this time, emergent above-knee amputation was performed. Re-staging images now showed the presence of multiple pulmonary nodules in his right lung as well as a lytic rib lesion, a concerning finding for metastatic disease. Video-Assisted Thorascopic Surgery (VATS) and right lower lobe wedge resection were performed and findings confirmed metastatic PEComa.

Given the patient’s intolerance to everolimus, he was started on the growth factor inhibitor, pazopanib. His disease did not progress on pazopanib, and improvement was noted in the dominant pulmonary nodule. Subsequently, however, he developed significant skin irritation and discontinued pazopanib. Repeat imaging approximately 2 months after stopping pazopanib showed significant disease progression.

We elected to start the patient on a non-standard approach to therapy with nivolumab infusions once every 2 weeks and concurrent radiation therapy to the rib lesion. At 2 and 5 months after initiating this treatment approach, CT imaging showed improvement in disease. At 12 months, significant disease response was noted (Figure 1).

The patient is now at 12 months of nivolumab therapy with progression free survival and no new identifiable metastatic lesions. He has been tolerating the medication with minimal side effects and has had an overall improvement in his pain and functional status. He continues to work full time.

Discussion

Our patient’s response presents a unique opportunity to talk about the role of immunotherapy as a treatment modality in patients with PEComa. The efficacy of check-point blockade in soft tissue sarcoma is still unclear predominantly because it is difficult to assess the degree of expression of immunogenic cell surface markers such as programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1).1,3 Nivolumab has been tried in small cohorts for treatment of soft tissue sarcomas that express PD-1 and results showed some clinical benefit in about half of patients.4 Further, the expression of PD-1 has been assessed in soft tissue sarcomas and has been reported to suggest a negative prognostic role.5

To our knowledge, there has not yet been another reported case of PEComa that has been treated with immunotherapy and achieved a sustained response. Further clinical studies need to be done to assess response to agents such as nivolumab in the treatment of PEComa to bolster our observation that nivolumab is a viable treatment option that may lead to lasting remission. Our patient’s case also brings to light the need for further inquiry into assessing the immune tumor microenvironments, particularly looking at the expression of cell surface proteins such as PD-1, as it ultimately affects treatment options. TSJ

Correspondence

REFERENCES

1. Burgess, Melissa, et al. “Immunotherapy in Sarcoma: Future Horizons.” Current Oncology Reports, vol. 17, no. 11, 2015, doi:10.1007/s11912-015-0476-7.

2. Alnajar, Hussein, et al. “Metastatic Malignant PEComa of the Leg with Identification of ATRX Mutation by next-Generation Sequencing.” Virchows Archiv (2017). https://doi:10.1007/s004280172208-x.

3. Ghosn, Marwan, et al. “Immunotherapies in Sarcoma: Updates and Future Perspectives.” World Journal of Clinical Oncology, vol. 8, no. 2, 2017, p. 145., doi:10.5306/wjco.v8.i2.145.

4. Paoluzzi, L., et al. “Response to Anti-PD1 Therapy with Nivolumab in Metastatic Sarcomas.” Clinical Sarcoma Research, vol. 6, no. 1, 2016, doi:10.1186/s13569-016 0064-0.

5. Kim, Chan, et al. “Prognostic Implications of PD-L1 Expression in Patients with Soft Tissue Sarcoma.” BMC Cancer, BioMed Central 8 July 2016.

Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms (PEComas) are an uncommon class of tumors consisting on histology of perivascular epithelioid cells occurring in both localized and metastatic forms at various body sites. The approach to treatment of these tumors generally involves a combination of surgical resection, chemotherapy, and/or radiation therapy.1

Case presentation and summary

A 46-year-old man presented to our institution with a non-tender, slowly enlarging, 8.3 cm mass in his right popliteal fossa. Upon biopsy, the pathologic findings were consistent with an epithelioid malignancy with melanocytic differentiation most consistent with a PEComa. Discussion of the pathologic diagnosis of our patient has been reported by the pathology group at our institution in a separate case report.2

Our patient was initially offered and refused amputation. He was started on therapy with the mechanistic Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor everolimus, but was unable to tolerate the side effects after the first week of treatment. He then elected to monitor his symptoms clinically.

Approximately one year after his initial diagnosis, he presented to our facility with sepsis and bleeding from a now fungating tumor on his right knee. At this time, emergent above-knee amputation was performed. Re-staging images now showed the presence of multiple pulmonary nodules in his right lung as well as a lytic rib lesion, a concerning finding for metastatic disease. Video-Assisted Thorascopic Surgery (VATS) and right lower lobe wedge resection were performed and findings confirmed metastatic PEComa.

Given the patient’s intolerance to everolimus, he was started on the growth factor inhibitor, pazopanib. His disease did not progress on pazopanib, and improvement was noted in the dominant pulmonary nodule. Subsequently, however, he developed significant skin irritation and discontinued pazopanib. Repeat imaging approximately 2 months after stopping pazopanib showed significant disease progression.

We elected to start the patient on a non-standard approach to therapy with nivolumab infusions once every 2 weeks and concurrent radiation therapy to the rib lesion. At 2 and 5 months after initiating this treatment approach, CT imaging showed improvement in disease. At 12 months, significant disease response was noted (Figure 1).

The patient is now at 12 months of nivolumab therapy with progression free survival and no new identifiable metastatic lesions. He has been tolerating the medication with minimal side effects and has had an overall improvement in his pain and functional status. He continues to work full time.

Discussion

Our patient’s response presents a unique opportunity to talk about the role of immunotherapy as a treatment modality in patients with PEComa. The efficacy of check-point blockade in soft tissue sarcoma is still unclear predominantly because it is difficult to assess the degree of expression of immunogenic cell surface markers such as programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1).1,3 Nivolumab has been tried in small cohorts for treatment of soft tissue sarcomas that express PD-1 and results showed some clinical benefit in about half of patients.4 Further, the expression of PD-1 has been assessed in soft tissue sarcomas and has been reported to suggest a negative prognostic role.5

To our knowledge, there has not yet been another reported case of PEComa that has been treated with immunotherapy and achieved a sustained response. Further clinical studies need to be done to assess response to agents such as nivolumab in the treatment of PEComa to bolster our observation that nivolumab is a viable treatment option that may lead to lasting remission. Our patient’s case also brings to light the need for further inquiry into assessing the immune tumor microenvironments, particularly looking at the expression of cell surface proteins such as PD-1, as it ultimately affects treatment options. TSJ

Correspondence

REFERENCES

1. Burgess, Melissa, et al. “Immunotherapy in Sarcoma: Future Horizons.” Current Oncology Reports, vol. 17, no. 11, 2015, doi:10.1007/s11912-015-0476-7.

2. Alnajar, Hussein, et al. “Metastatic Malignant PEComa of the Leg with Identification of ATRX Mutation by next-Generation Sequencing.” Virchows Archiv (2017). https://doi:10.1007/s004280172208-x.

3. Ghosn, Marwan, et al. “Immunotherapies in Sarcoma: Updates and Future Perspectives.” World Journal of Clinical Oncology, vol. 8, no. 2, 2017, p. 145., doi:10.5306/wjco.v8.i2.145.

4. Paoluzzi, L., et al. “Response to Anti-PD1 Therapy with Nivolumab in Metastatic Sarcomas.” Clinical Sarcoma Research, vol. 6, no. 1, 2016, doi:10.1186/s13569-016 0064-0.

5. Kim, Chan, et al. “Prognostic Implications of PD-L1 Expression in Patients with Soft Tissue Sarcoma.” BMC Cancer, BioMed Central 8 July 2016.

Tumor lysis syndrome in an adolescent with recurrence of abdominal rhabdomyosarcoma: A case report and literature review

Introduction

Tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) is a life-threatening oncologic emergency that results when massive cell breakdown occurs either spontaneously or in response to cytotoxic chemotherapy. TLS is characterized by metabolic derangements, including hyperkalemia and hyperphosphatemia, secondary to the release of intracellular components into the systemic circulatory system. In addition, purine degradation can lead to hyperuricemia, and precipitation of calcium phosphate can result in hypocalcemia. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels are often elevated, especially in higher risk patients; however, this finding is not a specific marker for TLS.

TLS more commonly occurs in patients with rapidly proliferating hematological malignancies, such as acute leukemias with a high white blood cell count and Burkitt’s lymphoma, and is a relatively rare event in patients with solid malignancies.1-3 It is even more rare in patients with tumor recurrence.

There are few reported cases of TLS in children with solid malignancies. To our knowledge, only one case of TLS has previously been reported in a pediatric patient with abdominal rhabdomyosarcoma. We report the second such case, and what we believe to be the only reported case of TLS occurring in a pediatric patient with recurrence of a solid tumor.

Case Description

A 15-year-old male from Saudi Arabia presented to our hospital with confirmed stage IV abdominal rhabdomyosarcoma and lung metastases diagnosed in 2012. His initial treatment consisted of complete surgical resection, lung irradiation, and chemotherapy with intercalating cycles of ifosfamide/etoposide and vincristine/doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide, as per the COG-ARST0431 high-risk sarcoma protocol (NCT00354744). He completed treatment without any reported TLS in Saudi Arabia in June 2014. He had no residual tumor at the end of therapy, but six months later he was found to have an abdominal recurrence and started treatment with single-agent topotecan chemotherapy. He experienced worsening abdominal distention, pain, and difficulty voiding, prompting his family to seek further treatment options abroad.

The patient was admitted to our hospital in March 2015. Despite being severely malnourished, he was in stable condition. He was noted to have a markedly enlarged, firm, distended abdomen with dilated veins, abdominal and lower back pain, lower extremity pitting edema, and difficulty urinating.

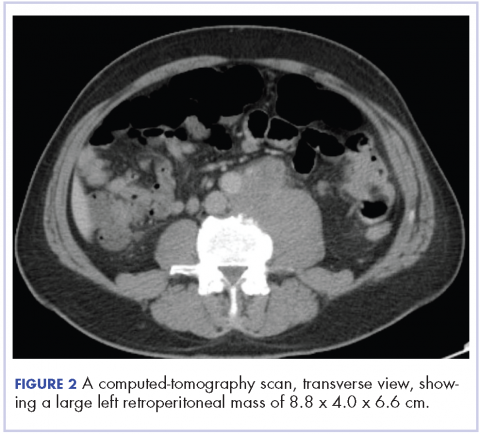

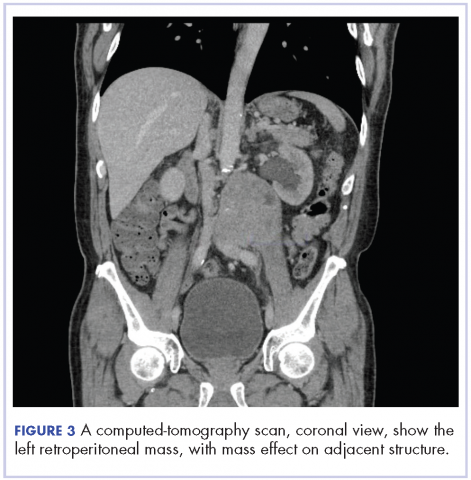

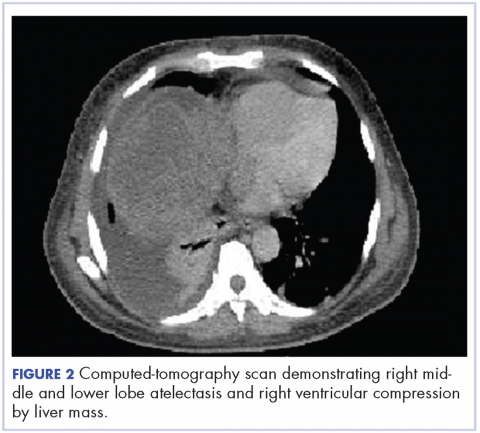

Initial laboratory findings were unremarkable except for elevated levels of BUN (29 mg/dL), creatinine (1.69 mg/dL), and phosphorus (5.6 mg/dL). MRI revealed a large pelvic mass measuring 15.3 x 15.2 x 21.3 centimeters in transverse, anterior-posterior, and craniocaudal dimensions, respectively; with concomitant severe bilateral hydroureternephrosis (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1. Sagittal (A) and Axial (B) T2-weighted MR images of the pelvis (prior to initiating therapy) demonstrating a large heterogeneous mass occupying the entire pelvis. There is evidence of edema involving the soft tissues of the perineum (long arrow) and a large associated hydrocele (short arrow).

Three days following admission, the patient’s urine output decreased and his creatinine level rose rapidly. His worsening abdominal distention was attributed to growing tumor bulk and obstructive nephropathy. He required emergency placement of bilateral nephrostomy tubes. Urine output subsequently improved; although, serum creatinine remained persistently elevated.

Given his worsening condition, chemotherapy was begun three days after nephrostomy tube placement with vinorelbine, cyclophosphamide, and temsirolimus, as per COG-ARST0921 (NCT01222715), at renal-adjusted doses. Laboratory studies approximately 24 hours after chemotherapy initiation demonstrated the presence of TLS (TABLE 1). Potassium level was at the upper end of normal at 4.9 mmol/L, calcium level was decreased to 7.1 mg/dL, phosphorus level elevated to 12 mg/dL, uric acid level was markedly elevated to 19.5 mg/dL, and LDH elevated to 662 unit/L. A dose of 0.15 mg/kg of rasburicase was immediately given with a second dose repeated 14 hours later, after which the uric acid level decreased to less than 0.5 mg/dL. Sevelamer, sodium polystyrene, calcium carbonate, and magnesium gluconate were also administered to treat other electrolyte imbalances. The patient remained at clinical baseline throughout, and the TLS laboratory derangements normalized by three days after the TLS diagnosis; LDH level normalized after one week. The patient continued with chemotherapy, per protocol, with no further TLS-related complications. Over subsequent weeks, his tumor continued to shrink dramatically. Pain related to intra-abdominal compression, lower extremity edema, and difficulty voiding resolved.

Discussion

A literature search was performed using Pubmed/Medline and Scopus from 1950 to July 2016 using key words “TLS,” “tumor lysis syndrome,” “pediatric tumor lysis syndrome,” “tumor lysis syndrome in solid malignancies,” “recurrence,” “solid tumor,” “sarcoma,” “rhabdomyosarcoma,” and their combinations. The references of relevant articles were reviewed. Baeksgaard and Sorensen,3 and Vodopivec, et al4 provide an organized review of reported cases of TLS in solid tumors until 2002 and 2011 respectively; their articles are supported by the 2014 literature review by Mirrakhimov, et al.1 Excluding our case, 13 cases of TLS have been described in pediatric patients with solid tumors, with only one occurring in patient with abdominal rhabdomyosarcoma5. Patients’ ages ranged from 2 days to 23 years; the cases are summarized in the following table (TABLE 2). To our knowledge, ours is the first case of TLS reported in association with a pediatric solid tumor recurrence.

It is important to note that the three reported cases of disseminated rhabdomyosarcoma6,7 were initially believed to be hematologic malignancies because of their presentation with lymphadenopathy, metastases to the bone marrow, and spontaneous onset of TLS. Rhabdomyosarcoma with bone marrow involvement without an obvious primary tumor is easily confused with acute leukemia, particularly of the lymphoblastic type.12 However, this disseminated-hematologic presentation of rhabdomyosarcoma differs from the solid abdominal-pelvic tumor, which we describe.

Cairo and Bishop13 categorize patients as either laboratory TLS, depicted by metabolic abnormalities alone, or clinical TLS, occurring when laboratory imbalances lead to significant, life-threatening clinical manifestations. Hyperkalemia may lead to cardiac arrhythmias such as torsades de pointes and cardiac arrest. Obstructive nephropathy can occur from the precipitation of calcium phosphate or uric acid crystals in the renal tubules. Hypocalcemia may cause neuromuscular irritability including tetany, convulsions, and altered mental status.13, 14The 2015 “Guidelines for the management of tumour lysis syndrome in adults and children with haematological malignancies on behalf of the British Committee for Standards in Haematology”4 state there are well-recognized risk factors for the development of TLS including, but not limited to, high tumor burden, tumors with rapid cell turnover, and pre-existing renal impairment. Cairo and Bishop, on behalf of the TLS expert panel consensus of 20102, classify patients as having low-risk disease (LRD), intermediate-risk disease (IRD), or high-risk disease (HRD) based on the risk factors and type of malignancy. All patients with solid tumors are classified into LRD, unless the tumors are bulky or sensitive to chemotherapy, mentioning specifically that neuroblastomas, germ-cell tumors and small cell lung cancers are classified as IRD. Cairo and Bishop take into account the risk factor of renal dysfunction/ involvement, which if present, increases the risk by one level. For example, if the patient has IRD and has renal dysfunction, risk increases to HRD2. However, these guidelines do not mention or address the significance of recurrence in any kind of malignancy with regards to assessing risk for TLS.

The British Committee’s 2015 Guidelines for management of TLS in hematologic malignancies14 provide recommendations for treatment based on the patient’s risk classification (TABLE 3). Children with HRD are recommended to be treated prophylactically with a single dose of 0.2 mg/kg of rasburicase. Patients with IRD are recommended to be offered up to 7 days of allopurinol prophylaxis with increased hydration post initiation of treatment or until risk of TLS has resolved. Patients with LRD are recommended to be managed essentially with close observation. Patients with established TLS should receive rasburicase 0.2 mg/kg/day - duration to depend on clinical response. If the patient is receiving rasburicase, the addition of allopurinol is not recommended, as it has the potential to reduce the effectiveness of rasburicase. Further, rasburicase is to be avoided in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency14.

Our patient likely developed TLS because of a fast growing tumor that caused significant tumor burden and renal involvement, indicated by an elevated phosphorus level. Despite these risk factors, TLS was not anticipated in the case presented; therefore, a uric acid level was not collected at the time of admission. Review of the literature indicates that the incidence of TLS in a solid tumor recurrence is either unheard of, or is likely under-reported and truly unknown. Further, the TLS expert panel consensus of 20102, which provides guidelines on risk assessment for TLS, does not address the risk of TLS in a malignancy recurrence. The British Committee’s 2015 guidelines14 also do not address hyperuricemia prophylaxis in a solid tumor recurrence.

Our case presents a question regarding the degree of risk for the development of TLS in a solid tumor recurrence. If the guidelines had existed at the time of the case presentation and had been applied, our patient would likely be classified as having IRD because of his renal involvement. This classification would have lead to a different course of management when initiating chemotherapy, likely prevented laboratory TLS, and provided more cost effective treatment, as rasburicase is known to be expensive.

On the other hand, it can also be argued that our patient classifies as LRD, considering the rarity of TLS in a solid tumor recurrence, that the patient had no TLS complication with his initial course of therapy, and also had a normal LDH on admission. LDH is sometimes used to assess risk in hematological malignancies, although it is not used to make the diagnosis of TLS2. However, with such an argument, it is assumed that the risk of TLS in a solid tumor malignancy recurrence, with no previous TLS complication, is less than the risk associated with a new-onset solid tumor malignancy when, truly, the actual risk is not known. Again, the question is raised of the degree of risk for the development of TLS in a case of a malignancy recurrence, and also in a pediatric patient with risk factors.

In our patient’s case, close observation allowed for prompt diagnosis, appropriate treatment of laboratory TLS, and prevented clinical symptoms from developing. However, a screening or baseline uric acid level may have lead to a more conservative approach towards hyperuricemia prophylaxis, similar to treating the patient as IRD. Therefore, we recommend that a screening or baseline uric acid level and LDH level be obtained when initiating chemotherapy, even in patients with LRD.

Our patient was never hyperkalemic, likely because of concomitant administration of furosemide in an attempt to improve his decreased urine output. Hyperuricemia dropped from 19.5 mg/dL to less than 0.5 mg/dL within 24 hours, following two doses of 0.15 mg/kg of rasburicase, confirming the efficacy of this therapy in cases of established TLS, as is recommended by the British Committee’s 2015 guidelines.14

Conclusion

TLS is a relatively rare event in patients with solid malignancies and even more rare in a tumor recurrence. While there is only one previously reported case of TLS occurring in a pediatric patient with abdominal rhabdomyosarcoma, there are not any reported cases to date of TLS occurring in pediatric solid tumor recurrence. This may be because the incidence is truly rare or because cases may be under-reported. Thus, a question is raised regarding the risk for TLS in a solid tumor recurrence, and moreover in a pediatric patient with pre-existing risk factors, such as renal involvement.

TLS remains a life-threatening emergency that can be prevented and reversed if a high index of suspicion is maintained. We recommend all patients with malignancies receiving chemotherapy, especially those with risk factors, have a baseline or screening uric acid and LDH level drawn, as part of the assessment and risk-stratification for TLS which should always be performed. TSJ

Correspondence

References

1. Mirrakhimov AE, Ali AM, Khan M, et al. Tumor lysis syndrome in solid tumors: an up to date review of the literature. Rare Tumors. 2014;6:68-74.

2. Cairo MS, Bertrand C, Reiter A, et al. Recommendation for the evaluation of risk and prophylaxis of tumour lysis syndrome (TLS) in adults and children with malignant diseases: an expert TLS panel consensus. Br J Haematol. 2010;149:578-586.

3. Baeksgaard L, Sorensen JB. Acute tumor lysis syndrome in solid tumors – a case report and review of the literature. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2003;51:187-192.

4. Vodopivec D, Rubio J, Fornoni A, et al. An unusual presentation of tumor lysis syndrome in a patient with advanced gastric adenocarcinoma: case report and literature review. Case Rep Med. 2012;2012:1-12.

5. Khan J, Broadbent VA. Tumor lysis syndrome complicating treatment of widespread metastatic abdominal rhabdomyosarcoma. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1993;10:151-155.

6. Bien E, Maciejka-Kapuscinka L, Niedzwiecki M, et al. Childhood rhabdomyosarcoma metastatic to bone marrow presenting with disseminated intravascular coagulation and acute tumour lysis syndrome: review of the literature apropos of two cases. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2010;27:399-407.

7. Patiroglu T, Isik B, Unal E, et al. Cranial metastatic alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma mimicking hematological malignancy in an adolescent boy. Childs Nerv Syst. 2014;30:1737-1741.

8. Hain RD, Rayner L, Weitzman S, et al. Acute tumour lysis syndrome complicating treatment of stage IVS neuroblastoma in infants under six months old. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1994;23:136-139.

9. Kushner BH, LaQuaglia MP, Modak S, et al. Tumor lysis syndrome, neuroblastoma, and correlation between serum lactate dehydrogenase levels and MYCN-amplification. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2003;41:80-82.

10. Bercovitz RS, Greffe BS, Hunger SP. Acute tumor lysis syndrome in a 7-month-old with hepatoblastoma. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22:113-116.

11. Lobe TE, Karkera MS, Custer MD, et al. Fatal refractory hyperkalemia due to tumor lysis during primary resection for hepatoblastoma. J Pediatr Surg. 1990;25:249-250.

12. Sandberg A, Stone J, Czarnecki L, et al. Hematologic Masquerade of Rhabdomyosarcoma. Am J Hematol. 2001;68:51-57

13. Cairo M, Bishop M. Tumour lysis syndrome: new therapeutic strategies and classification. Br J Haematol. 2004;127:3-11.

14. Jones G, Will A, Jackson GH, et al. Guidelines for the management of tumour lysis syndrome in adults and children with haematological malignancies on behalf of the British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Br J Haematol. 2015;169:661-671.

References

1. Mirrakhimov AE, Ali AM, Khan M, et al. Tumor lysis syndrome in solid tumors: an up to date review of the literature. Rare Tumors. 2014;6:68-74.

2. Cairo MS, Bertrand C, Reiter A, et al. Recommendation for the evaluation of risk and prophylaxis of tumour lysis syndrome (TLS) in adults and children with malignant diseases: an expert TLS panel consensus. Br J Haematol. 2010;149:578-586.

3. Baeksgaard L, Sorensen JB. Acute tumor lysis syndrome in solid tumors – a case report and review of the literature. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2003;51:187-192.

4. Vodopivec D, Rubio J, Fornoni A, et al. An unusual presentation of tumor lysis syndrome in a patient with advanced gastric adenocarcinoma: case report and literature review. Case Rep Med. 2012;2012:1-12.

5. Khan J, Broadbent VA. Tumor lysis syndrome complicating treatment of widespread metastatic abdominal rhabdomyosarcoma. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1993;10:151-155.

6. Bien E, Maciejka-Kapuscinka L, Niedzwiecki M, et al. Childhood rhabdomyosarcoma metastatic to bone marrow presenting with disseminated intravascular coagulation and acute tumour lysis syndrome: review of the literature apropos of two cases. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2010;27:399-407.

7. Patiroglu T, Isik B, Unal E, et al. Cranial metastatic alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma mimicking hematological malignancy in an adolescent boy. Childs Nerv Syst. 2014;30:1737-1741.

8. Hain RD, Rayner L, Weitzman S, et al. Acute tumour lysis syndrome complicating treatment of stage IVS neuroblastoma in infants under six months old. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1994;23:136-139.

9. Kushner BH, LaQuaglia MP, Modak S, et al. Tumor lysis syndrome, neuroblastoma, and correlation between serum lactate dehydrogenase levels and MYCN-amplification. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2003;41:80-82.

10. Bercovitz RS, Greffe BS, Hunger SP. Acute tumor lysis syndrome in a 7-month-old with hepatoblastoma. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22:113-116.

11. Lobe TE, Karkera MS, Custer MD, et al. Fatal refractory hyperkalemia due to tumor lysis during primary resection for hepatoblastoma. J Pediatr Surg. 1990;25:249-250.

12. Sandberg A, Stone J, Czarnecki L, et al. Hematologic Masquerade of Rhabdomyosarcoma. Am J Hematol. 2001;68:51-57

13. Cairo M, Bishop M. Tumour lysis syndrome: new therapeutic strategies and classification. Br J Haematol. 2004;127:3-11.

14. Jones G, Will A, Jackson GH, et al. Guidelines for the management of tumour lysis syndrome in adults and children with haematological malignancies on behalf of the British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Br J Haematol. 2015;169:661-671.

Introduction

Tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) is a life-threatening oncologic emergency that results when massive cell breakdown occurs either spontaneously or in response to cytotoxic chemotherapy. TLS is characterized by metabolic derangements, including hyperkalemia and hyperphosphatemia, secondary to the release of intracellular components into the systemic circulatory system. In addition, purine degradation can lead to hyperuricemia, and precipitation of calcium phosphate can result in hypocalcemia. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels are often elevated, especially in higher risk patients; however, this finding is not a specific marker for TLS.

TLS more commonly occurs in patients with rapidly proliferating hematological malignancies, such as acute leukemias with a high white blood cell count and Burkitt’s lymphoma, and is a relatively rare event in patients with solid malignancies.1-3 It is even more rare in patients with tumor recurrence.

There are few reported cases of TLS in children with solid malignancies. To our knowledge, only one case of TLS has previously been reported in a pediatric patient with abdominal rhabdomyosarcoma. We report the second such case, and what we believe to be the only reported case of TLS occurring in a pediatric patient with recurrence of a solid tumor.

Case Description

A 15-year-old male from Saudi Arabia presented to our hospital with confirmed stage IV abdominal rhabdomyosarcoma and lung metastases diagnosed in 2012. His initial treatment consisted of complete surgical resection, lung irradiation, and chemotherapy with intercalating cycles of ifosfamide/etoposide and vincristine/doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide, as per the COG-ARST0431 high-risk sarcoma protocol (NCT00354744). He completed treatment without any reported TLS in Saudi Arabia in June 2014. He had no residual tumor at the end of therapy, but six months later he was found to have an abdominal recurrence and started treatment with single-agent topotecan chemotherapy. He experienced worsening abdominal distention, pain, and difficulty voiding, prompting his family to seek further treatment options abroad.

The patient was admitted to our hospital in March 2015. Despite being severely malnourished, he was in stable condition. He was noted to have a markedly enlarged, firm, distended abdomen with dilated veins, abdominal and lower back pain, lower extremity pitting edema, and difficulty urinating.

Initial laboratory findings were unremarkable except for elevated levels of BUN (29 mg/dL), creatinine (1.69 mg/dL), and phosphorus (5.6 mg/dL). MRI revealed a large pelvic mass measuring 15.3 x 15.2 x 21.3 centimeters in transverse, anterior-posterior, and craniocaudal dimensions, respectively; with concomitant severe bilateral hydroureternephrosis (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1. Sagittal (A) and Axial (B) T2-weighted MR images of the pelvis (prior to initiating therapy) demonstrating a large heterogeneous mass occupying the entire pelvis. There is evidence of edema involving the soft tissues of the perineum (long arrow) and a large associated hydrocele (short arrow).

Three days following admission, the patient’s urine output decreased and his creatinine level rose rapidly. His worsening abdominal distention was attributed to growing tumor bulk and obstructive nephropathy. He required emergency placement of bilateral nephrostomy tubes. Urine output subsequently improved; although, serum creatinine remained persistently elevated.

Given his worsening condition, chemotherapy was begun three days after nephrostomy tube placement with vinorelbine, cyclophosphamide, and temsirolimus, as per COG-ARST0921 (NCT01222715), at renal-adjusted doses. Laboratory studies approximately 24 hours after chemotherapy initiation demonstrated the presence of TLS (TABLE 1). Potassium level was at the upper end of normal at 4.9 mmol/L, calcium level was decreased to 7.1 mg/dL, phosphorus level elevated to 12 mg/dL, uric acid level was markedly elevated to 19.5 mg/dL, and LDH elevated to 662 unit/L. A dose of 0.15 mg/kg of rasburicase was immediately given with a second dose repeated 14 hours later, after which the uric acid level decreased to less than 0.5 mg/dL. Sevelamer, sodium polystyrene, calcium carbonate, and magnesium gluconate were also administered to treat other electrolyte imbalances. The patient remained at clinical baseline throughout, and the TLS laboratory derangements normalized by three days after the TLS diagnosis; LDH level normalized after one week. The patient continued with chemotherapy, per protocol, with no further TLS-related complications. Over subsequent weeks, his tumor continued to shrink dramatically. Pain related to intra-abdominal compression, lower extremity edema, and difficulty voiding resolved.

Discussion

A literature search was performed using Pubmed/Medline and Scopus from 1950 to July 2016 using key words “TLS,” “tumor lysis syndrome,” “pediatric tumor lysis syndrome,” “tumor lysis syndrome in solid malignancies,” “recurrence,” “solid tumor,” “sarcoma,” “rhabdomyosarcoma,” and their combinations. The references of relevant articles were reviewed. Baeksgaard and Sorensen,3 and Vodopivec, et al4 provide an organized review of reported cases of TLS in solid tumors until 2002 and 2011 respectively; their articles are supported by the 2014 literature review by Mirrakhimov, et al.1 Excluding our case, 13 cases of TLS have been described in pediatric patients with solid tumors, with only one occurring in patient with abdominal rhabdomyosarcoma5. Patients’ ages ranged from 2 days to 23 years; the cases are summarized in the following table (TABLE 2). To our knowledge, ours is the first case of TLS reported in association with a pediatric solid tumor recurrence.

It is important to note that the three reported cases of disseminated rhabdomyosarcoma6,7 were initially believed to be hematologic malignancies because of their presentation with lymphadenopathy, metastases to the bone marrow, and spontaneous onset of TLS. Rhabdomyosarcoma with bone marrow involvement without an obvious primary tumor is easily confused with acute leukemia, particularly of the lymphoblastic type.12 However, this disseminated-hematologic presentation of rhabdomyosarcoma differs from the solid abdominal-pelvic tumor, which we describe.

Cairo and Bishop13 categorize patients as either laboratory TLS, depicted by metabolic abnormalities alone, or clinical TLS, occurring when laboratory imbalances lead to significant, life-threatening clinical manifestations. Hyperkalemia may lead to cardiac arrhythmias such as torsades de pointes and cardiac arrest. Obstructive nephropathy can occur from the precipitation of calcium phosphate or uric acid crystals in the renal tubules. Hypocalcemia may cause neuromuscular irritability including tetany, convulsions, and altered mental status.13, 14The 2015 “Guidelines for the management of tumour lysis syndrome in adults and children with haematological malignancies on behalf of the British Committee for Standards in Haematology”4 state there are well-recognized risk factors for the development of TLS including, but not limited to, high tumor burden, tumors with rapid cell turnover, and pre-existing renal impairment. Cairo and Bishop, on behalf of the TLS expert panel consensus of 20102, classify patients as having low-risk disease (LRD), intermediate-risk disease (IRD), or high-risk disease (HRD) based on the risk factors and type of malignancy. All patients with solid tumors are classified into LRD, unless the tumors are bulky or sensitive to chemotherapy, mentioning specifically that neuroblastomas, germ-cell tumors and small cell lung cancers are classified as IRD. Cairo and Bishop take into account the risk factor of renal dysfunction/ involvement, which if present, increases the risk by one level. For example, if the patient has IRD and has renal dysfunction, risk increases to HRD2. However, these guidelines do not mention or address the significance of recurrence in any kind of malignancy with regards to assessing risk for TLS.

The British Committee’s 2015 Guidelines for management of TLS in hematologic malignancies14 provide recommendations for treatment based on the patient’s risk classification (TABLE 3). Children with HRD are recommended to be treated prophylactically with a single dose of 0.2 mg/kg of rasburicase. Patients with IRD are recommended to be offered up to 7 days of allopurinol prophylaxis with increased hydration post initiation of treatment or until risk of TLS has resolved. Patients with LRD are recommended to be managed essentially with close observation. Patients with established TLS should receive rasburicase 0.2 mg/kg/day - duration to depend on clinical response. If the patient is receiving rasburicase, the addition of allopurinol is not recommended, as it has the potential to reduce the effectiveness of rasburicase. Further, rasburicase is to be avoided in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency14.

Our patient likely developed TLS because of a fast growing tumor that caused significant tumor burden and renal involvement, indicated by an elevated phosphorus level. Despite these risk factors, TLS was not anticipated in the case presented; therefore, a uric acid level was not collected at the time of admission. Review of the literature indicates that the incidence of TLS in a solid tumor recurrence is either unheard of, or is likely under-reported and truly unknown. Further, the TLS expert panel consensus of 20102, which provides guidelines on risk assessment for TLS, does not address the risk of TLS in a malignancy recurrence. The British Committee’s 2015 guidelines14 also do not address hyperuricemia prophylaxis in a solid tumor recurrence.

Our case presents a question regarding the degree of risk for the development of TLS in a solid tumor recurrence. If the guidelines had existed at the time of the case presentation and had been applied, our patient would likely be classified as having IRD because of his renal involvement. This classification would have lead to a different course of management when initiating chemotherapy, likely prevented laboratory TLS, and provided more cost effective treatment, as rasburicase is known to be expensive.

On the other hand, it can also be argued that our patient classifies as LRD, considering the rarity of TLS in a solid tumor recurrence, that the patient had no TLS complication with his initial course of therapy, and also had a normal LDH on admission. LDH is sometimes used to assess risk in hematological malignancies, although it is not used to make the diagnosis of TLS2. However, with such an argument, it is assumed that the risk of TLS in a solid tumor malignancy recurrence, with no previous TLS complication, is less than the risk associated with a new-onset solid tumor malignancy when, truly, the actual risk is not known. Again, the question is raised of the degree of risk for the development of TLS in a case of a malignancy recurrence, and also in a pediatric patient with risk factors.

In our patient’s case, close observation allowed for prompt diagnosis, appropriate treatment of laboratory TLS, and prevented clinical symptoms from developing. However, a screening or baseline uric acid level may have lead to a more conservative approach towards hyperuricemia prophylaxis, similar to treating the patient as IRD. Therefore, we recommend that a screening or baseline uric acid level and LDH level be obtained when initiating chemotherapy, even in patients with LRD.

Our patient was never hyperkalemic, likely because of concomitant administration of furosemide in an attempt to improve his decreased urine output. Hyperuricemia dropped from 19.5 mg/dL to less than 0.5 mg/dL within 24 hours, following two doses of 0.15 mg/kg of rasburicase, confirming the efficacy of this therapy in cases of established TLS, as is recommended by the British Committee’s 2015 guidelines.14

Conclusion

TLS is a relatively rare event in patients with solid malignancies and even more rare in a tumor recurrence. While there is only one previously reported case of TLS occurring in a pediatric patient with abdominal rhabdomyosarcoma, there are not any reported cases to date of TLS occurring in pediatric solid tumor recurrence. This may be because the incidence is truly rare or because cases may be under-reported. Thus, a question is raised regarding the risk for TLS in a solid tumor recurrence, and moreover in a pediatric patient with pre-existing risk factors, such as renal involvement.

TLS remains a life-threatening emergency that can be prevented and reversed if a high index of suspicion is maintained. We recommend all patients with malignancies receiving chemotherapy, especially those with risk factors, have a baseline or screening uric acid and LDH level drawn, as part of the assessment and risk-stratification for TLS which should always be performed. TSJ

Correspondence

References

1. Mirrakhimov AE, Ali AM, Khan M, et al. Tumor lysis syndrome in solid tumors: an up to date review of the literature. Rare Tumors. 2014;6:68-74.

2. Cairo MS, Bertrand C, Reiter A, et al. Recommendation for the evaluation of risk and prophylaxis of tumour lysis syndrome (TLS) in adults and children with malignant diseases: an expert TLS panel consensus. Br J Haematol. 2010;149:578-586.

3. Baeksgaard L, Sorensen JB. Acute tumor lysis syndrome in solid tumors – a case report and review of the literature. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2003;51:187-192.

4. Vodopivec D, Rubio J, Fornoni A, et al. An unusual presentation of tumor lysis syndrome in a patient with advanced gastric adenocarcinoma: case report and literature review. Case Rep Med. 2012;2012:1-12.

5. Khan J, Broadbent VA. Tumor lysis syndrome complicating treatment of widespread metastatic abdominal rhabdomyosarcoma. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1993;10:151-155.

6. Bien E, Maciejka-Kapuscinka L, Niedzwiecki M, et al. Childhood rhabdomyosarcoma metastatic to bone marrow presenting with disseminated intravascular coagulation and acute tumour lysis syndrome: review of the literature apropos of two cases. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2010;27:399-407.

7. Patiroglu T, Isik B, Unal E, et al. Cranial metastatic alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma mimicking hematological malignancy in an adolescent boy. Childs Nerv Syst. 2014;30:1737-1741.