User login

Postpartum Psychosis in a Young VA Patient: Diagnosis, Implications, and Treatment Recommendations

Postpartum psychosis is a psychiatric emergency that can endanger the life of the mother and the newborn child if untreated. About 1 to 2 mothers in 1,000 experiences postpartum psychosis after delivery.1 This rate is much higher among women with an established diagnosis of bipolar disorder before pregnancy.1

Expedient recognition, diagnosis, and referral to a high-level psychiatric facility (usually a locked inpatient unit) are critical for ensuring the safety of mother and infant. A diligent medical workup followed by thorough education for the patient and family are important steps in caring for patients with postpartum psychosis. Close mental health follow-up, pharmacologic interventions, informed decision making regarding breastfeeding, and preserving the sleep-wake cycle are critical for stabilization.2

The authors present the case of a patient admitted to VA Central California Health Care System (VACCHCS) with postpartum psychosis and a discussion on existing research on the prevalence of postpartum psychosis, relevant risk factors, the association with bipolar disorder, and treatment strategies.

Case Presentation

A 31-year-old active-duty female with no history of mental illness was admitted to the psychiatric unit because new-onset disorganized behavior was preventing her from functioning at her workplace. Two weeks after giving birth to her second child, the patient began exhibiting an uncharacteristic, debilitating labile mood and disorganized behavior. Her supervisors required her to present for medical attention about 3 months after the birth of her child. She was transferred to VACCHCS for higher level medical care on military orders. The patient’s husband initially attributed these psychiatric symptoms to vocational stress and taking care of 2 young children. He observed the patient exhibiting tearfulness about her job, which quickly alternated with euphoric episodes of singing and dancing at inappropriate times, such as when the children had quieted down and were being prepared to go to bed.

At the initial psychiatric evaluation after transfer to VACCHCS, the patient appeared well-kept and slightly overweight. In general her appearance was unremarkable. Throughout the examination she sang both subtly and loudly and at times was confrontational and irritable.

She related oddly and often was guarded and difficult to engage; she sang and played with her blanket in a childlike way. She smiled and laughed inappropriately, mumbled incoherently to herself, scanned the room suspiciously, and often made intense eye contact. Her affect was labile, both tearful and euphoric at several points in the examination. Her thought process was tangential, illogical, grandiose, difficult to redirect, and with loose associations. Her thought content consisted of delusions (“I’ve got the devil on my back”) and grandiosity (“I am everyone, I am you…the president, the mayor”), and she often stated that she planned to become a singer or performer.

The patient claimed she was neither suicidal nor had thoughts of infanticide. She reported having no visual and auditory hallucinations but often seemed to be responding to internal stimuli: She mumbled to herself and looked intensely at parts of the room. Cognitively, the patient was fully intact to recent and remote events but displayed a poor attention span. She did not exhibit any motor abnormalities, such as tremor, rigidity, weakness, sensory loss, or abnormal gait.

The patient’s workup included full chemistry, complete blood count, thyroid-stimulating hormone, antithyroid antibodies, calcium, rapid plasma reagin to rule out syphilis, toxicology, folate, vitamin B12, and vitamin D. All laboratory results were negative or within normal limits, although the urine drug screen was positive for cannabis. The patient’s husband noted that his wife never used cannabis except the weekend before her admission, when she impulsively went dancing, which was out of character for her. Her psychotic symptoms had been present weeks before the cannabis use; therefore, the her symptoms could not be attributed to a substance-induced psychotic disorder. A test for synthetic cannabis derivatives was negative. Newer synthetic compounds can cause more severe substance-induced psychotic symptoms than those of cannabis.3

The patient was diagnosed with postpartum psychosis and was started on the oral antipsychotic olanzapine 10 mg at bedtime. Additional doses were administered to control ongoing symptoms, which included a disorganized thought process; loose associations; euphoria; grandiosity; delusional content, such as “You are just a tool in place to help me;” reports of feeling as though she were in “outer space, outside in the galaxy;” decreased need for sleep; and irritability. The patient spent an entire interview with her eyes closed, stating that she could “hear” better because she was overstimulated if her eyes were open. She also described olfactory hallucinations of “strong perfume,” which the 2 providers present could not detect.

Olanzapine was not well tolerated because of sedation and was discontinued in favor of risperidone, 2 mg twice daily. Risperidone was more effective and better tolerated. Lithium was initiated the next day with target dosing at 300 mg in the morning and 600 mg at night. The patient became capable of linear, organized discussion and planning but remained euphoric with high energy; she exhibited grandiosity with frequent singing and dancing throughout her hospital stay. She often described her mood as “good, excellent, exuberant, exciting,” perseverating on the way words sounded and giggling in a childlike manner. She continued to have intrusive dreams of “hell and the devil” and that she was killed by gunshot.

The patient was continued on lithium and risperidone and transferred to a larger military hospital for further inpatient management, respecting military orders. Before discharge, a family conference was held with the patient and her husband to educate them on the importance of continued treatment, close follow-up, regular sleep patterns, and not breastfeeding while taking the prescribed medications. Although she was not back to her baseline at the time of transfer, the patient had stabilized significantly and gained sufficient insight into her condition.

Discussion

Postpartum psychosis can present with a prodromal phase consisting of fatigue, insomnia, restlessness, tearfulness, and emotional lability, making early identification difficult. Later, florid psychotic symptoms can include suspiciousness, confusion, incoherence, irrational statements, obsessive concern about the infant’s health, and delusions, including a belief that the baby is dead or defective. Some women might deny that the birth occurred or feel that they are unmarried, virginal, or persecuted.1 More concerning symptoms include auditory hallucinations commanding the mother to harm or kill the infant and/or herself. Symptoms often begin within days to weeks of birth, usually 2 to 3 weeks after delivery but can occur as long as 8 weeks postpartum.1 Several cases of infanticide and suicide have been documented.1 The risk of experiencing another psychotic episode in subsequent pregnancies can be as high as 50%.4-6 Regardless of symptom severity at onset, postpartum psychosis is a psychiatric emergency and must be treated as such.

Bipolar Disorder and Postpartum Psychosis

A close relationship exists between postpartum psychosis and development of bipolar disorder. A postpartum psychotic episode often is the harbinger of bipolar illness.7 About two-thirds of women who have an episode of postpartum psychosis will experience an underlying affective disorder within a year of childbirth.1,8 It is unclear what triggers the psychotic episode, but it has been theorized that major systemic shifts in hormone levelsor trauma of delivery could instigate development of symptoms.1,9

Risk factors include obstetric complications; perinatal infant mortality; previous episodes of bipolar disorder, psychosis, or postpartum psychosis; family history of bipolar disorder or postpartum psychosis; sleep deprivation; increased environmental stress; and lack of partner support.10 The strongest risk factor for developing postpartum psychosis is a personal or family history of bipolar disorder or a related psychotic disorder.11 This risk factor is identified in about 40% to 50% cases of postpartum psychosis.11

Treatment

Standard treatment for postpartum psychosis includes an antipsychotic and often lithium and benzodiazepines.1,7,10,11 This treatment approach differs slightly from treating a patient with a nonpostpartum psychotic illness, who generally would not receive mood stabilizers, such as lithium. Including a mood stabilizer for postpartum psychosis is warranted because of the association between postpartum psychosis and bipolar disorder, which is treated with a mood stabilizer.

Prevalence

Postpartum psychosis is identified in 1 to 2 per 1,000 childbirths. In women who have had an earlier episode of postpartum psychosis or have a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, the rate is up to 100 times higher.1 Kendell and colleagues found that psychiatric admissions occurred at a rate 7 times higher in the 30 days after birth than in the prepregnancy period, suggesting that metabolic factors might be involved in triggering postpartum psychotic symptoms.12 An abrupt hormonal loss occurs at childbirth; hormones peak 200-fold during gestation and decline rapidly within a day after birth.9 Despite the severity of symptoms in postpartum psychosis, these patients tend to have a better prognosis than that of women with psychotic episodes not related to pregnancy.4

Brockington and colleagues found that patients with postpartum psychosis had more mood lability, distractibility, and confusion than those with psychosis unrelated to pregnancy.15 Patients with postpartum psychosis were more likely to have impaired sensorium, bizarre quality of delusions, and memory loss. Psychosis with onset after childbirth included high levels of thought disorganization, delusions of reference, delusions of persecution, and greater levels of homicidal ideation and behavior.16 This study also reported symptoms such as visual, tactile, and olfactory hallucinations and a presentation similar to that of delirium.

Chandra and colleagues found that 53% of women with postpartum psychosis had delusions about the infant, including beliefs that someone would harm or kill the baby or that the baby would be harmed by their breast milk.17 Compared with women with bipolar disorder, Oostheuizen and colleagues found that women with postpartum psychosis had delusions of control, such as feeling under the influence of an overpowering force that controlled their actions.18 Infanticidal thoughts are common among patients with postpartum psychosis, and about 4% of women committed infanticide.1

Rapid stabilization and treatment are important because postpartum psychosis is considered a psychiatric emergency.7 Potential consequences of delayed diagnosis and treatment include harm or death of the infant by infanticide and death of the mother by suicide. A thorough physical examination is important to rule out metabolic or neuroendocrine causes of psychosis other than postpartum hormonal shifts. These could include causes of altered mental status: stroke, pulmonary embolism, amniotic fluid emboli, Sheehan syndrome, thyroid disorders, electrolyte abnormalities, acute hemorrhage, sepsis, and substance toxicity or withdrawal.10 A complete blood count, full chemistry, thyroid function tests, antithyroid antibody tests, calcium, vitamin B12, and folate should be measured.7,10

Initial treatment should include antipsychotics and often mood stabilizers such as lithium. Managing insomnia aggressively is also necessary for initial stabilization and to prevent a repeat manic episode if the patient develops bipolar disorder.2 Many experts argue that sleep loss in combination with other risk factors might be the final common pathway for development of postpartum psychosis in women predisposed to this disorder.19,20

Treating insomnia in an outpatient setting includes teaching sleep hygiene practices and relaxation techniques. Although these methods to regulate sleep could be encouraged during the emergent inpatient stabilization of a patient with postpartum psychosis, pharmacologic approaches are necessary for acute mania and psychosis. Concern about possible dependence on benzodiazepines and other sedating sleep aids are valid; however, the benefit of acute stabilization of psychotic symptoms outweighs the potential risk of dependence.

Typically, first-line treatment is an antipsychotic, and second-generation antipsychotics generally are preferred over first-generation antipsychotics because of their more benign adverse effect profile.21,22 There are no controlled trials that compare antipsychotics with placebo or other interventions for postpartum psychosis. Therefore, use of atypical antipsychotics is based on randomized trials demonstrating efficacy in reducing psychosis in bipolar disorder, depression with psychotic features, and schizoaffective disorder.23,24 Once the patient is treated with an antipsychotic, further use of psychotropic medications, such as lithium or other mood stabilizers, should be based on the patient’s clinical presentation. For example, the patient in this case study primarily had manic symptoms consistent with bipolar disorder, making lithium or another mood stabilizer an appropriate choice.

Bergink and colleagues demonstrated positive outcomes with a treatment algorithm involving sequential use of benzodiazepines to improve sleep, an antipsychotic to decrease acute manic symptoms, lithium to stabilize mood based on symptoms, and electroconvulsive therapy if other treatments were not successful.25 Case studies document that administering estrogen led to recovery from postpartum psychosis, although patients often relapsed when estrogen was stopped.26 Electroconvulsive therapy has shown promising results, especially in patients who do not respond to antipsychotic medications or lithium.27,28

Antipsychotic and Other Psychotropic Medications

Choice of an antipsychotic and other psychotropic medications to treat postpartum psychosis is based on the patient’s breastfeeding status. The benefits of treatment should be weighed against the risks of a breastfeeding infant’s exposure to the medication. Because postpartum psychosis is a psychiatric emergency, the benefits of the medication are considered to outweigh any potential adverse effect to the breastfeeding infant exposed to the medication. Risks of untreated postpartum psychosis to the infant include rejection of the infant, poor parental relationships, suicide, infanticide, long-term failure to bond with the child, delayed infant development, and failure to thrive.29 Also, many mothers—including the patient in this presentation—decide that the benefits of treatment outweigh those of breastfeeding and choose to feed their infant with formula. Even if the patient chooses to bottle-feed her infant, consider administering medications that are considered safer for breastfeeding because the patient may need to continue the psychotropic during later pregnancies to prevent future psychotic episodes.30 All psychotropic medications pass into breast milk.29 Studies on the long-term effect of these medications on the infant are limited, but experts tend to recommend olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone over aripiprazole and ziprasidone.21,31-33

Lithium often is used to treat postpartum psychosis. Studies examining risk to the infant after long-term exposure to lithium through breast milk have not been conducted, but the American Academy of Pediatrics discourages its use during breastfeeding because of concerns about toxicity in the infant.34-36

Sleep regulation is important to treat bipolar disorder and to prevent future episodes.2,20,21 To ensure safety of the infant and mother before discharge, family education is imperative to establish close follow-up, adequate sleep, and reduction of stressors.7,10 Separation from the infant might be necessary after discharge, and someone should monitor the infant at all times until the outpatient mental health provider confirms that all psychotic symptoms have resolved.7,10 Successful treatment of postpartum psychosis requires close communication among the mental health provider, the pediatrician, and the obstetrician or women’s health provider.10 Because a close-knit team approach after discharge from the acute psychiatric unit is necessary, the care of such a patient and her child provides an educational opportunity for individuals working in integrated care clinics.

Conclusion

Postpartum psychosis is a psychiatric emergency requiring immediate treatment to prevent dire outcomes such as suicide or infanticide. Treatment considerations include the cost-benefit analysis of breastfeeding and the toxicity of psychotropic medications when ingested by the infant via breast milk. A close relationship has been demonstrated between postpartum psychosis and bipolar disorder.

Preferred treatment regimens include lithium and an antipsychotic. Educate the family as a unit about the diagnosis and treatment, the importance of adequate sleep for treatment and prophylaxis, and the decision on whether to discontinue breastfeeding despite its well-known benefits for mother and infant. Stabilization is a multifaceted process and needs to be reinforced with a solid plan for support and follow-up appointments. Because of the higher risk of relapse, educate patients about prophylactic treatment during subsequent pregnancies and monitor for development of bipolar disorder in the future.

1. Sadock B, Sadock V, Ruiz P. Kaplan & Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015.

2. Sharma V. Pharmacotherapy of postpartum psychosis. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2003;4(10):1651-1658.

3. Bassir Nia A, Medrano B, Perkel C, Galynker I, Hurd YL. Psychiatric comorbidity associated with synthetic cannabinoid use compared to cannabis. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1321-1330.

4. Rhohde A, Marneros A. Postpartum psychoses: onset and long-term course. Psychopathology. 1993;26(3-4):203-209.

5. Videbech P, Gouliaev G. First admission with puerperal psychosis: 7-14 years of follow-up. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1995;91(3):167-173.

6. Terp IM, Engholm G, Møller H, Mortensen PB. A follow-up study of postpartum psychoses: prognosis and risk factors for readmission. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1999;100(1):40-46.

7. Spinelli MG. Postpartum psychosis: detection of risk and management. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(4):405-408.

8. Blackmore ER, Rubinow DR, O’Connor TG, et al. Reproductive outcomes and risk of subsequent illness in women diagnosed with postpartum psychosis. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15(4):394-404.

9. Bloch M, Schmidt PJ, Danaceau M, Murphy J, Nieman L, Rubinow DR. Effects of gonadal steroids in women with a history of postpartum depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(6):924-930.

10. Monzon C, Lanza di Scalea T, Pearlstein T. Postpartum psychosis: updates and clinical issues. Psychiatric Times. 2014. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/special-reports/postpartum -psychosis-updates-and-clinical-issues. Published January 15, 2014. Accessed December 14, 2017.

11. Davies W. Understanding the pathophysiology of postpartum psychosis: challenges and new approaches. World J Psychiatry. 2017;7(2):77-88.

12. Kendell RE, Chalmers JC, Platz C. Epidemiology of puerperal psychoses. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:662-673.

13. Leibenluft E. Women with bipolar illness: clinical and research issues. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(2):163-173.

14. Chaudron LH, Pies R. The relationship between postpartum psychosis and bipolar disorder: a review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(11):1284-1292.

15. Brockington IF, Cernik KF, Schofield EM, Downing AR, Francis AF, Keelan C. Puerperal psychosis: phenomena and diagnosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38(7):829-833.

16. Wisner KL, Peindl K, Hanusa BH. Symptomatology of affective and psychotic illnesses related to childbearing. J Affect Disord. 1994;30(2):77-87.

17. Chandra PS, Bhargavaraman RP, Raghunandan VN, Shaligram D. Delusions related to infant and their association with mother-infant interactions in postpartum psychotic disorders. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2006;9(5):285-288.

18. Oosthuizen P, Russouw H, Roberts M. Is puerperal psychosis bipolar mood disorder? A phenomenological comparison. Compr Psychiatry. 1995;36(1):77-81.

19. Sharma V, Mazmanian D. Sleep loss and postpartum psychosis. Bipolar Disord. 2003;5(2):98-105.

20 Bilszta JL, Meyer D, Buist AE. Bipolar affective disorder in the postnatal period: investigating the role of sleep. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12(5):568-578.

21. Doucet S, Jones I, Letourneau N, Dennis CL, Blackmore ER. Interventions for the prevention and treatment of postpartum psychosis: a systematic review. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011;14(2):89-98.

22 Perlis RH, Welge JA, Vornik LA, Hirschfeld RM, Keck PE Jr. Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of mania: a meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(4):509-516.

23 Wijkstra J, Lijmer J, Balk FJ, Geddes JR, Nolen WA. Pharmacological treatment for unipolar psychotic depression: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:410-415.

24. Smith LA, Cornelius V, Warnock A, Tacchi MJ, Taylor D. Pharmacological interventions for acute bipolar mania: a systematic review of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9(6):551-560.

25. Bergink V, Burgerhout KM, Koorengevel KM, et al. Treatment of psychosis and mania in the postpartum period. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(2):115-123.

26. Ahokas A, Aito M, Rimón R. Positive treatment effect of estradiol in postpartum psychosis: a pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(3):166-169.

27. Reed P, Sermin N, Appleby L, Faragher B. A comparison of clinical response to electroconvulsive therapy in puerperal and non-puerperal psychoses. J Affect Disord. 1999;54(3):255-260.

28. Forray A, Ostroff RB. The use of electroconvulsive therapy in postpartum affective disorders. J ECT. 2007;23(3):188-193.

29. Robinson GE. Psychopharmacology in pregnancy and postpartum. Focus. 2012;10(1):3-14.

30. Wesseloo R, Kamperman AM, Munk-Olsen T, Pop VJ, Kushner SA, Bergink V. Risk of postpartum relapse in bipolar disorder and postpartum psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(2):117-127.

31. Sharma V, Smith A, Mazmanian D. Olanzapine in the prevention of postpartum psychosis and mood episodes in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(4):400-404.

32. Gobbi G. Quetiapine in postpartum psychosis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;34(6):744-745.

33. Uguz F. Second-generation antipsychotics during the lactation period: a comparative systematic review on infant safety. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;36(3):244-252.

34. Sachs HC; Committee on Drugs. The transfer of drugs and therapeutics into human breast milk: an update on selected topics. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):e796-e809.

35. Lithium [package insert]. Columbus, OH: Roxane Laboratories Inc; 2011.

36. Grandjean EM, Aubry JM. Lithium: updated human knowledge using an evidence-based approach: part III: clinical safety. CNS Drugs. 2009;23(5):397-418.

Postpartum psychosis is a psychiatric emergency that can endanger the life of the mother and the newborn child if untreated. About 1 to 2 mothers in 1,000 experiences postpartum psychosis after delivery.1 This rate is much higher among women with an established diagnosis of bipolar disorder before pregnancy.1

Expedient recognition, diagnosis, and referral to a high-level psychiatric facility (usually a locked inpatient unit) are critical for ensuring the safety of mother and infant. A diligent medical workup followed by thorough education for the patient and family are important steps in caring for patients with postpartum psychosis. Close mental health follow-up, pharmacologic interventions, informed decision making regarding breastfeeding, and preserving the sleep-wake cycle are critical for stabilization.2

The authors present the case of a patient admitted to VA Central California Health Care System (VACCHCS) with postpartum psychosis and a discussion on existing research on the prevalence of postpartum psychosis, relevant risk factors, the association with bipolar disorder, and treatment strategies.

Case Presentation

A 31-year-old active-duty female with no history of mental illness was admitted to the psychiatric unit because new-onset disorganized behavior was preventing her from functioning at her workplace. Two weeks after giving birth to her second child, the patient began exhibiting an uncharacteristic, debilitating labile mood and disorganized behavior. Her supervisors required her to present for medical attention about 3 months after the birth of her child. She was transferred to VACCHCS for higher level medical care on military orders. The patient’s husband initially attributed these psychiatric symptoms to vocational stress and taking care of 2 young children. He observed the patient exhibiting tearfulness about her job, which quickly alternated with euphoric episodes of singing and dancing at inappropriate times, such as when the children had quieted down and were being prepared to go to bed.

At the initial psychiatric evaluation after transfer to VACCHCS, the patient appeared well-kept and slightly overweight. In general her appearance was unremarkable. Throughout the examination she sang both subtly and loudly and at times was confrontational and irritable.

She related oddly and often was guarded and difficult to engage; she sang and played with her blanket in a childlike way. She smiled and laughed inappropriately, mumbled incoherently to herself, scanned the room suspiciously, and often made intense eye contact. Her affect was labile, both tearful and euphoric at several points in the examination. Her thought process was tangential, illogical, grandiose, difficult to redirect, and with loose associations. Her thought content consisted of delusions (“I’ve got the devil on my back”) and grandiosity (“I am everyone, I am you…the president, the mayor”), and she often stated that she planned to become a singer or performer.

The patient claimed she was neither suicidal nor had thoughts of infanticide. She reported having no visual and auditory hallucinations but often seemed to be responding to internal stimuli: She mumbled to herself and looked intensely at parts of the room. Cognitively, the patient was fully intact to recent and remote events but displayed a poor attention span. She did not exhibit any motor abnormalities, such as tremor, rigidity, weakness, sensory loss, or abnormal gait.

The patient’s workup included full chemistry, complete blood count, thyroid-stimulating hormone, antithyroid antibodies, calcium, rapid plasma reagin to rule out syphilis, toxicology, folate, vitamin B12, and vitamin D. All laboratory results were negative or within normal limits, although the urine drug screen was positive for cannabis. The patient’s husband noted that his wife never used cannabis except the weekend before her admission, when she impulsively went dancing, which was out of character for her. Her psychotic symptoms had been present weeks before the cannabis use; therefore, the her symptoms could not be attributed to a substance-induced psychotic disorder. A test for synthetic cannabis derivatives was negative. Newer synthetic compounds can cause more severe substance-induced psychotic symptoms than those of cannabis.3

The patient was diagnosed with postpartum psychosis and was started on the oral antipsychotic olanzapine 10 mg at bedtime. Additional doses were administered to control ongoing symptoms, which included a disorganized thought process; loose associations; euphoria; grandiosity; delusional content, such as “You are just a tool in place to help me;” reports of feeling as though she were in “outer space, outside in the galaxy;” decreased need for sleep; and irritability. The patient spent an entire interview with her eyes closed, stating that she could “hear” better because she was overstimulated if her eyes were open. She also described olfactory hallucinations of “strong perfume,” which the 2 providers present could not detect.

Olanzapine was not well tolerated because of sedation and was discontinued in favor of risperidone, 2 mg twice daily. Risperidone was more effective and better tolerated. Lithium was initiated the next day with target dosing at 300 mg in the morning and 600 mg at night. The patient became capable of linear, organized discussion and planning but remained euphoric with high energy; she exhibited grandiosity with frequent singing and dancing throughout her hospital stay. She often described her mood as “good, excellent, exuberant, exciting,” perseverating on the way words sounded and giggling in a childlike manner. She continued to have intrusive dreams of “hell and the devil” and that she was killed by gunshot.

The patient was continued on lithium and risperidone and transferred to a larger military hospital for further inpatient management, respecting military orders. Before discharge, a family conference was held with the patient and her husband to educate them on the importance of continued treatment, close follow-up, regular sleep patterns, and not breastfeeding while taking the prescribed medications. Although she was not back to her baseline at the time of transfer, the patient had stabilized significantly and gained sufficient insight into her condition.

Discussion

Postpartum psychosis can present with a prodromal phase consisting of fatigue, insomnia, restlessness, tearfulness, and emotional lability, making early identification difficult. Later, florid psychotic symptoms can include suspiciousness, confusion, incoherence, irrational statements, obsessive concern about the infant’s health, and delusions, including a belief that the baby is dead or defective. Some women might deny that the birth occurred or feel that they are unmarried, virginal, or persecuted.1 More concerning symptoms include auditory hallucinations commanding the mother to harm or kill the infant and/or herself. Symptoms often begin within days to weeks of birth, usually 2 to 3 weeks after delivery but can occur as long as 8 weeks postpartum.1 Several cases of infanticide and suicide have been documented.1 The risk of experiencing another psychotic episode in subsequent pregnancies can be as high as 50%.4-6 Regardless of symptom severity at onset, postpartum psychosis is a psychiatric emergency and must be treated as such.

Bipolar Disorder and Postpartum Psychosis

A close relationship exists between postpartum psychosis and development of bipolar disorder. A postpartum psychotic episode often is the harbinger of bipolar illness.7 About two-thirds of women who have an episode of postpartum psychosis will experience an underlying affective disorder within a year of childbirth.1,8 It is unclear what triggers the psychotic episode, but it has been theorized that major systemic shifts in hormone levelsor trauma of delivery could instigate development of symptoms.1,9

Risk factors include obstetric complications; perinatal infant mortality; previous episodes of bipolar disorder, psychosis, or postpartum psychosis; family history of bipolar disorder or postpartum psychosis; sleep deprivation; increased environmental stress; and lack of partner support.10 The strongest risk factor for developing postpartum psychosis is a personal or family history of bipolar disorder or a related psychotic disorder.11 This risk factor is identified in about 40% to 50% cases of postpartum psychosis.11

Treatment

Standard treatment for postpartum psychosis includes an antipsychotic and often lithium and benzodiazepines.1,7,10,11 This treatment approach differs slightly from treating a patient with a nonpostpartum psychotic illness, who generally would not receive mood stabilizers, such as lithium. Including a mood stabilizer for postpartum psychosis is warranted because of the association between postpartum psychosis and bipolar disorder, which is treated with a mood stabilizer.

Prevalence

Postpartum psychosis is identified in 1 to 2 per 1,000 childbirths. In women who have had an earlier episode of postpartum psychosis or have a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, the rate is up to 100 times higher.1 Kendell and colleagues found that psychiatric admissions occurred at a rate 7 times higher in the 30 days after birth than in the prepregnancy period, suggesting that metabolic factors might be involved in triggering postpartum psychotic symptoms.12 An abrupt hormonal loss occurs at childbirth; hormones peak 200-fold during gestation and decline rapidly within a day after birth.9 Despite the severity of symptoms in postpartum psychosis, these patients tend to have a better prognosis than that of women with psychotic episodes not related to pregnancy.4

Brockington and colleagues found that patients with postpartum psychosis had more mood lability, distractibility, and confusion than those with psychosis unrelated to pregnancy.15 Patients with postpartum psychosis were more likely to have impaired sensorium, bizarre quality of delusions, and memory loss. Psychosis with onset after childbirth included high levels of thought disorganization, delusions of reference, delusions of persecution, and greater levels of homicidal ideation and behavior.16 This study also reported symptoms such as visual, tactile, and olfactory hallucinations and a presentation similar to that of delirium.

Chandra and colleagues found that 53% of women with postpartum psychosis had delusions about the infant, including beliefs that someone would harm or kill the baby or that the baby would be harmed by their breast milk.17 Compared with women with bipolar disorder, Oostheuizen and colleagues found that women with postpartum psychosis had delusions of control, such as feeling under the influence of an overpowering force that controlled their actions.18 Infanticidal thoughts are common among patients with postpartum psychosis, and about 4% of women committed infanticide.1

Rapid stabilization and treatment are important because postpartum psychosis is considered a psychiatric emergency.7 Potential consequences of delayed diagnosis and treatment include harm or death of the infant by infanticide and death of the mother by suicide. A thorough physical examination is important to rule out metabolic or neuroendocrine causes of psychosis other than postpartum hormonal shifts. These could include causes of altered mental status: stroke, pulmonary embolism, amniotic fluid emboli, Sheehan syndrome, thyroid disorders, electrolyte abnormalities, acute hemorrhage, sepsis, and substance toxicity or withdrawal.10 A complete blood count, full chemistry, thyroid function tests, antithyroid antibody tests, calcium, vitamin B12, and folate should be measured.7,10

Initial treatment should include antipsychotics and often mood stabilizers such as lithium. Managing insomnia aggressively is also necessary for initial stabilization and to prevent a repeat manic episode if the patient develops bipolar disorder.2 Many experts argue that sleep loss in combination with other risk factors might be the final common pathway for development of postpartum psychosis in women predisposed to this disorder.19,20

Treating insomnia in an outpatient setting includes teaching sleep hygiene practices and relaxation techniques. Although these methods to regulate sleep could be encouraged during the emergent inpatient stabilization of a patient with postpartum psychosis, pharmacologic approaches are necessary for acute mania and psychosis. Concern about possible dependence on benzodiazepines and other sedating sleep aids are valid; however, the benefit of acute stabilization of psychotic symptoms outweighs the potential risk of dependence.

Typically, first-line treatment is an antipsychotic, and second-generation antipsychotics generally are preferred over first-generation antipsychotics because of their more benign adverse effect profile.21,22 There are no controlled trials that compare antipsychotics with placebo or other interventions for postpartum psychosis. Therefore, use of atypical antipsychotics is based on randomized trials demonstrating efficacy in reducing psychosis in bipolar disorder, depression with psychotic features, and schizoaffective disorder.23,24 Once the patient is treated with an antipsychotic, further use of psychotropic medications, such as lithium or other mood stabilizers, should be based on the patient’s clinical presentation. For example, the patient in this case study primarily had manic symptoms consistent with bipolar disorder, making lithium or another mood stabilizer an appropriate choice.

Bergink and colleagues demonstrated positive outcomes with a treatment algorithm involving sequential use of benzodiazepines to improve sleep, an antipsychotic to decrease acute manic symptoms, lithium to stabilize mood based on symptoms, and electroconvulsive therapy if other treatments were not successful.25 Case studies document that administering estrogen led to recovery from postpartum psychosis, although patients often relapsed when estrogen was stopped.26 Electroconvulsive therapy has shown promising results, especially in patients who do not respond to antipsychotic medications or lithium.27,28

Antipsychotic and Other Psychotropic Medications

Choice of an antipsychotic and other psychotropic medications to treat postpartum psychosis is based on the patient’s breastfeeding status. The benefits of treatment should be weighed against the risks of a breastfeeding infant’s exposure to the medication. Because postpartum psychosis is a psychiatric emergency, the benefits of the medication are considered to outweigh any potential adverse effect to the breastfeeding infant exposed to the medication. Risks of untreated postpartum psychosis to the infant include rejection of the infant, poor parental relationships, suicide, infanticide, long-term failure to bond with the child, delayed infant development, and failure to thrive.29 Also, many mothers—including the patient in this presentation—decide that the benefits of treatment outweigh those of breastfeeding and choose to feed their infant with formula. Even if the patient chooses to bottle-feed her infant, consider administering medications that are considered safer for breastfeeding because the patient may need to continue the psychotropic during later pregnancies to prevent future psychotic episodes.30 All psychotropic medications pass into breast milk.29 Studies on the long-term effect of these medications on the infant are limited, but experts tend to recommend olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone over aripiprazole and ziprasidone.21,31-33

Lithium often is used to treat postpartum psychosis. Studies examining risk to the infant after long-term exposure to lithium through breast milk have not been conducted, but the American Academy of Pediatrics discourages its use during breastfeeding because of concerns about toxicity in the infant.34-36

Sleep regulation is important to treat bipolar disorder and to prevent future episodes.2,20,21 To ensure safety of the infant and mother before discharge, family education is imperative to establish close follow-up, adequate sleep, and reduction of stressors.7,10 Separation from the infant might be necessary after discharge, and someone should monitor the infant at all times until the outpatient mental health provider confirms that all psychotic symptoms have resolved.7,10 Successful treatment of postpartum psychosis requires close communication among the mental health provider, the pediatrician, and the obstetrician or women’s health provider.10 Because a close-knit team approach after discharge from the acute psychiatric unit is necessary, the care of such a patient and her child provides an educational opportunity for individuals working in integrated care clinics.

Conclusion

Postpartum psychosis is a psychiatric emergency requiring immediate treatment to prevent dire outcomes such as suicide or infanticide. Treatment considerations include the cost-benefit analysis of breastfeeding and the toxicity of psychotropic medications when ingested by the infant via breast milk. A close relationship has been demonstrated between postpartum psychosis and bipolar disorder.

Preferred treatment regimens include lithium and an antipsychotic. Educate the family as a unit about the diagnosis and treatment, the importance of adequate sleep for treatment and prophylaxis, and the decision on whether to discontinue breastfeeding despite its well-known benefits for mother and infant. Stabilization is a multifaceted process and needs to be reinforced with a solid plan for support and follow-up appointments. Because of the higher risk of relapse, educate patients about prophylactic treatment during subsequent pregnancies and monitor for development of bipolar disorder in the future.

Postpartum psychosis is a psychiatric emergency that can endanger the life of the mother and the newborn child if untreated. About 1 to 2 mothers in 1,000 experiences postpartum psychosis after delivery.1 This rate is much higher among women with an established diagnosis of bipolar disorder before pregnancy.1

Expedient recognition, diagnosis, and referral to a high-level psychiatric facility (usually a locked inpatient unit) are critical for ensuring the safety of mother and infant. A diligent medical workup followed by thorough education for the patient and family are important steps in caring for patients with postpartum psychosis. Close mental health follow-up, pharmacologic interventions, informed decision making regarding breastfeeding, and preserving the sleep-wake cycle are critical for stabilization.2

The authors present the case of a patient admitted to VA Central California Health Care System (VACCHCS) with postpartum psychosis and a discussion on existing research on the prevalence of postpartum psychosis, relevant risk factors, the association with bipolar disorder, and treatment strategies.

Case Presentation

A 31-year-old active-duty female with no history of mental illness was admitted to the psychiatric unit because new-onset disorganized behavior was preventing her from functioning at her workplace. Two weeks after giving birth to her second child, the patient began exhibiting an uncharacteristic, debilitating labile mood and disorganized behavior. Her supervisors required her to present for medical attention about 3 months after the birth of her child. She was transferred to VACCHCS for higher level medical care on military orders. The patient’s husband initially attributed these psychiatric symptoms to vocational stress and taking care of 2 young children. He observed the patient exhibiting tearfulness about her job, which quickly alternated with euphoric episodes of singing and dancing at inappropriate times, such as when the children had quieted down and were being prepared to go to bed.

At the initial psychiatric evaluation after transfer to VACCHCS, the patient appeared well-kept and slightly overweight. In general her appearance was unremarkable. Throughout the examination she sang both subtly and loudly and at times was confrontational and irritable.

She related oddly and often was guarded and difficult to engage; she sang and played with her blanket in a childlike way. She smiled and laughed inappropriately, mumbled incoherently to herself, scanned the room suspiciously, and often made intense eye contact. Her affect was labile, both tearful and euphoric at several points in the examination. Her thought process was tangential, illogical, grandiose, difficult to redirect, and with loose associations. Her thought content consisted of delusions (“I’ve got the devil on my back”) and grandiosity (“I am everyone, I am you…the president, the mayor”), and she often stated that she planned to become a singer or performer.

The patient claimed she was neither suicidal nor had thoughts of infanticide. She reported having no visual and auditory hallucinations but often seemed to be responding to internal stimuli: She mumbled to herself and looked intensely at parts of the room. Cognitively, the patient was fully intact to recent and remote events but displayed a poor attention span. She did not exhibit any motor abnormalities, such as tremor, rigidity, weakness, sensory loss, or abnormal gait.

The patient’s workup included full chemistry, complete blood count, thyroid-stimulating hormone, antithyroid antibodies, calcium, rapid plasma reagin to rule out syphilis, toxicology, folate, vitamin B12, and vitamin D. All laboratory results were negative or within normal limits, although the urine drug screen was positive for cannabis. The patient’s husband noted that his wife never used cannabis except the weekend before her admission, when she impulsively went dancing, which was out of character for her. Her psychotic symptoms had been present weeks before the cannabis use; therefore, the her symptoms could not be attributed to a substance-induced psychotic disorder. A test for synthetic cannabis derivatives was negative. Newer synthetic compounds can cause more severe substance-induced psychotic symptoms than those of cannabis.3

The patient was diagnosed with postpartum psychosis and was started on the oral antipsychotic olanzapine 10 mg at bedtime. Additional doses were administered to control ongoing symptoms, which included a disorganized thought process; loose associations; euphoria; grandiosity; delusional content, such as “You are just a tool in place to help me;” reports of feeling as though she were in “outer space, outside in the galaxy;” decreased need for sleep; and irritability. The patient spent an entire interview with her eyes closed, stating that she could “hear” better because she was overstimulated if her eyes were open. She also described olfactory hallucinations of “strong perfume,” which the 2 providers present could not detect.

Olanzapine was not well tolerated because of sedation and was discontinued in favor of risperidone, 2 mg twice daily. Risperidone was more effective and better tolerated. Lithium was initiated the next day with target dosing at 300 mg in the morning and 600 mg at night. The patient became capable of linear, organized discussion and planning but remained euphoric with high energy; she exhibited grandiosity with frequent singing and dancing throughout her hospital stay. She often described her mood as “good, excellent, exuberant, exciting,” perseverating on the way words sounded and giggling in a childlike manner. She continued to have intrusive dreams of “hell and the devil” and that she was killed by gunshot.

The patient was continued on lithium and risperidone and transferred to a larger military hospital for further inpatient management, respecting military orders. Before discharge, a family conference was held with the patient and her husband to educate them on the importance of continued treatment, close follow-up, regular sleep patterns, and not breastfeeding while taking the prescribed medications. Although she was not back to her baseline at the time of transfer, the patient had stabilized significantly and gained sufficient insight into her condition.

Discussion

Postpartum psychosis can present with a prodromal phase consisting of fatigue, insomnia, restlessness, tearfulness, and emotional lability, making early identification difficult. Later, florid psychotic symptoms can include suspiciousness, confusion, incoherence, irrational statements, obsessive concern about the infant’s health, and delusions, including a belief that the baby is dead or defective. Some women might deny that the birth occurred or feel that they are unmarried, virginal, or persecuted.1 More concerning symptoms include auditory hallucinations commanding the mother to harm or kill the infant and/or herself. Symptoms often begin within days to weeks of birth, usually 2 to 3 weeks after delivery but can occur as long as 8 weeks postpartum.1 Several cases of infanticide and suicide have been documented.1 The risk of experiencing another psychotic episode in subsequent pregnancies can be as high as 50%.4-6 Regardless of symptom severity at onset, postpartum psychosis is a psychiatric emergency and must be treated as such.

Bipolar Disorder and Postpartum Psychosis

A close relationship exists between postpartum psychosis and development of bipolar disorder. A postpartum psychotic episode often is the harbinger of bipolar illness.7 About two-thirds of women who have an episode of postpartum psychosis will experience an underlying affective disorder within a year of childbirth.1,8 It is unclear what triggers the psychotic episode, but it has been theorized that major systemic shifts in hormone levelsor trauma of delivery could instigate development of symptoms.1,9

Risk factors include obstetric complications; perinatal infant mortality; previous episodes of bipolar disorder, psychosis, or postpartum psychosis; family history of bipolar disorder or postpartum psychosis; sleep deprivation; increased environmental stress; and lack of partner support.10 The strongest risk factor for developing postpartum psychosis is a personal or family history of bipolar disorder or a related psychotic disorder.11 This risk factor is identified in about 40% to 50% cases of postpartum psychosis.11

Treatment

Standard treatment for postpartum psychosis includes an antipsychotic and often lithium and benzodiazepines.1,7,10,11 This treatment approach differs slightly from treating a patient with a nonpostpartum psychotic illness, who generally would not receive mood stabilizers, such as lithium. Including a mood stabilizer for postpartum psychosis is warranted because of the association between postpartum psychosis and bipolar disorder, which is treated with a mood stabilizer.

Prevalence

Postpartum psychosis is identified in 1 to 2 per 1,000 childbirths. In women who have had an earlier episode of postpartum psychosis or have a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, the rate is up to 100 times higher.1 Kendell and colleagues found that psychiatric admissions occurred at a rate 7 times higher in the 30 days after birth than in the prepregnancy period, suggesting that metabolic factors might be involved in triggering postpartum psychotic symptoms.12 An abrupt hormonal loss occurs at childbirth; hormones peak 200-fold during gestation and decline rapidly within a day after birth.9 Despite the severity of symptoms in postpartum psychosis, these patients tend to have a better prognosis than that of women with psychotic episodes not related to pregnancy.4

Brockington and colleagues found that patients with postpartum psychosis had more mood lability, distractibility, and confusion than those with psychosis unrelated to pregnancy.15 Patients with postpartum psychosis were more likely to have impaired sensorium, bizarre quality of delusions, and memory loss. Psychosis with onset after childbirth included high levels of thought disorganization, delusions of reference, delusions of persecution, and greater levels of homicidal ideation and behavior.16 This study also reported symptoms such as visual, tactile, and olfactory hallucinations and a presentation similar to that of delirium.

Chandra and colleagues found that 53% of women with postpartum psychosis had delusions about the infant, including beliefs that someone would harm or kill the baby or that the baby would be harmed by their breast milk.17 Compared with women with bipolar disorder, Oostheuizen and colleagues found that women with postpartum psychosis had delusions of control, such as feeling under the influence of an overpowering force that controlled their actions.18 Infanticidal thoughts are common among patients with postpartum psychosis, and about 4% of women committed infanticide.1

Rapid stabilization and treatment are important because postpartum psychosis is considered a psychiatric emergency.7 Potential consequences of delayed diagnosis and treatment include harm or death of the infant by infanticide and death of the mother by suicide. A thorough physical examination is important to rule out metabolic or neuroendocrine causes of psychosis other than postpartum hormonal shifts. These could include causes of altered mental status: stroke, pulmonary embolism, amniotic fluid emboli, Sheehan syndrome, thyroid disorders, electrolyte abnormalities, acute hemorrhage, sepsis, and substance toxicity or withdrawal.10 A complete blood count, full chemistry, thyroid function tests, antithyroid antibody tests, calcium, vitamin B12, and folate should be measured.7,10

Initial treatment should include antipsychotics and often mood stabilizers such as lithium. Managing insomnia aggressively is also necessary for initial stabilization and to prevent a repeat manic episode if the patient develops bipolar disorder.2 Many experts argue that sleep loss in combination with other risk factors might be the final common pathway for development of postpartum psychosis in women predisposed to this disorder.19,20

Treating insomnia in an outpatient setting includes teaching sleep hygiene practices and relaxation techniques. Although these methods to regulate sleep could be encouraged during the emergent inpatient stabilization of a patient with postpartum psychosis, pharmacologic approaches are necessary for acute mania and psychosis. Concern about possible dependence on benzodiazepines and other sedating sleep aids are valid; however, the benefit of acute stabilization of psychotic symptoms outweighs the potential risk of dependence.

Typically, first-line treatment is an antipsychotic, and second-generation antipsychotics generally are preferred over first-generation antipsychotics because of their more benign adverse effect profile.21,22 There are no controlled trials that compare antipsychotics with placebo or other interventions for postpartum psychosis. Therefore, use of atypical antipsychotics is based on randomized trials demonstrating efficacy in reducing psychosis in bipolar disorder, depression with psychotic features, and schizoaffective disorder.23,24 Once the patient is treated with an antipsychotic, further use of psychotropic medications, such as lithium or other mood stabilizers, should be based on the patient’s clinical presentation. For example, the patient in this case study primarily had manic symptoms consistent with bipolar disorder, making lithium or another mood stabilizer an appropriate choice.

Bergink and colleagues demonstrated positive outcomes with a treatment algorithm involving sequential use of benzodiazepines to improve sleep, an antipsychotic to decrease acute manic symptoms, lithium to stabilize mood based on symptoms, and electroconvulsive therapy if other treatments were not successful.25 Case studies document that administering estrogen led to recovery from postpartum psychosis, although patients often relapsed when estrogen was stopped.26 Electroconvulsive therapy has shown promising results, especially in patients who do not respond to antipsychotic medications or lithium.27,28

Antipsychotic and Other Psychotropic Medications

Choice of an antipsychotic and other psychotropic medications to treat postpartum psychosis is based on the patient’s breastfeeding status. The benefits of treatment should be weighed against the risks of a breastfeeding infant’s exposure to the medication. Because postpartum psychosis is a psychiatric emergency, the benefits of the medication are considered to outweigh any potential adverse effect to the breastfeeding infant exposed to the medication. Risks of untreated postpartum psychosis to the infant include rejection of the infant, poor parental relationships, suicide, infanticide, long-term failure to bond with the child, delayed infant development, and failure to thrive.29 Also, many mothers—including the patient in this presentation—decide that the benefits of treatment outweigh those of breastfeeding and choose to feed their infant with formula. Even if the patient chooses to bottle-feed her infant, consider administering medications that are considered safer for breastfeeding because the patient may need to continue the psychotropic during later pregnancies to prevent future psychotic episodes.30 All psychotropic medications pass into breast milk.29 Studies on the long-term effect of these medications on the infant are limited, but experts tend to recommend olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone over aripiprazole and ziprasidone.21,31-33

Lithium often is used to treat postpartum psychosis. Studies examining risk to the infant after long-term exposure to lithium through breast milk have not been conducted, but the American Academy of Pediatrics discourages its use during breastfeeding because of concerns about toxicity in the infant.34-36

Sleep regulation is important to treat bipolar disorder and to prevent future episodes.2,20,21 To ensure safety of the infant and mother before discharge, family education is imperative to establish close follow-up, adequate sleep, and reduction of stressors.7,10 Separation from the infant might be necessary after discharge, and someone should monitor the infant at all times until the outpatient mental health provider confirms that all psychotic symptoms have resolved.7,10 Successful treatment of postpartum psychosis requires close communication among the mental health provider, the pediatrician, and the obstetrician or women’s health provider.10 Because a close-knit team approach after discharge from the acute psychiatric unit is necessary, the care of such a patient and her child provides an educational opportunity for individuals working in integrated care clinics.

Conclusion

Postpartum psychosis is a psychiatric emergency requiring immediate treatment to prevent dire outcomes such as suicide or infanticide. Treatment considerations include the cost-benefit analysis of breastfeeding and the toxicity of psychotropic medications when ingested by the infant via breast milk. A close relationship has been demonstrated between postpartum psychosis and bipolar disorder.

Preferred treatment regimens include lithium and an antipsychotic. Educate the family as a unit about the diagnosis and treatment, the importance of adequate sleep for treatment and prophylaxis, and the decision on whether to discontinue breastfeeding despite its well-known benefits for mother and infant. Stabilization is a multifaceted process and needs to be reinforced with a solid plan for support and follow-up appointments. Because of the higher risk of relapse, educate patients about prophylactic treatment during subsequent pregnancies and monitor for development of bipolar disorder in the future.

1. Sadock B, Sadock V, Ruiz P. Kaplan & Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015.

2. Sharma V. Pharmacotherapy of postpartum psychosis. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2003;4(10):1651-1658.

3. Bassir Nia A, Medrano B, Perkel C, Galynker I, Hurd YL. Psychiatric comorbidity associated with synthetic cannabinoid use compared to cannabis. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1321-1330.

4. Rhohde A, Marneros A. Postpartum psychoses: onset and long-term course. Psychopathology. 1993;26(3-4):203-209.

5. Videbech P, Gouliaev G. First admission with puerperal psychosis: 7-14 years of follow-up. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1995;91(3):167-173.

6. Terp IM, Engholm G, Møller H, Mortensen PB. A follow-up study of postpartum psychoses: prognosis and risk factors for readmission. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1999;100(1):40-46.

7. Spinelli MG. Postpartum psychosis: detection of risk and management. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(4):405-408.

8. Blackmore ER, Rubinow DR, O’Connor TG, et al. Reproductive outcomes and risk of subsequent illness in women diagnosed with postpartum psychosis. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15(4):394-404.

9. Bloch M, Schmidt PJ, Danaceau M, Murphy J, Nieman L, Rubinow DR. Effects of gonadal steroids in women with a history of postpartum depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(6):924-930.

10. Monzon C, Lanza di Scalea T, Pearlstein T. Postpartum psychosis: updates and clinical issues. Psychiatric Times. 2014. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/special-reports/postpartum -psychosis-updates-and-clinical-issues. Published January 15, 2014. Accessed December 14, 2017.

11. Davies W. Understanding the pathophysiology of postpartum psychosis: challenges and new approaches. World J Psychiatry. 2017;7(2):77-88.

12. Kendell RE, Chalmers JC, Platz C. Epidemiology of puerperal psychoses. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:662-673.

13. Leibenluft E. Women with bipolar illness: clinical and research issues. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(2):163-173.

14. Chaudron LH, Pies R. The relationship between postpartum psychosis and bipolar disorder: a review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(11):1284-1292.

15. Brockington IF, Cernik KF, Schofield EM, Downing AR, Francis AF, Keelan C. Puerperal psychosis: phenomena and diagnosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38(7):829-833.

16. Wisner KL, Peindl K, Hanusa BH. Symptomatology of affective and psychotic illnesses related to childbearing. J Affect Disord. 1994;30(2):77-87.

17. Chandra PS, Bhargavaraman RP, Raghunandan VN, Shaligram D. Delusions related to infant and their association with mother-infant interactions in postpartum psychotic disorders. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2006;9(5):285-288.

18. Oosthuizen P, Russouw H, Roberts M. Is puerperal psychosis bipolar mood disorder? A phenomenological comparison. Compr Psychiatry. 1995;36(1):77-81.

19. Sharma V, Mazmanian D. Sleep loss and postpartum psychosis. Bipolar Disord. 2003;5(2):98-105.

20 Bilszta JL, Meyer D, Buist AE. Bipolar affective disorder in the postnatal period: investigating the role of sleep. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12(5):568-578.

21. Doucet S, Jones I, Letourneau N, Dennis CL, Blackmore ER. Interventions for the prevention and treatment of postpartum psychosis: a systematic review. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011;14(2):89-98.

22 Perlis RH, Welge JA, Vornik LA, Hirschfeld RM, Keck PE Jr. Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of mania: a meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(4):509-516.

23 Wijkstra J, Lijmer J, Balk FJ, Geddes JR, Nolen WA. Pharmacological treatment for unipolar psychotic depression: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:410-415.

24. Smith LA, Cornelius V, Warnock A, Tacchi MJ, Taylor D. Pharmacological interventions for acute bipolar mania: a systematic review of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9(6):551-560.

25. Bergink V, Burgerhout KM, Koorengevel KM, et al. Treatment of psychosis and mania in the postpartum period. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(2):115-123.

26. Ahokas A, Aito M, Rimón R. Positive treatment effect of estradiol in postpartum psychosis: a pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(3):166-169.

27. Reed P, Sermin N, Appleby L, Faragher B. A comparison of clinical response to electroconvulsive therapy in puerperal and non-puerperal psychoses. J Affect Disord. 1999;54(3):255-260.

28. Forray A, Ostroff RB. The use of electroconvulsive therapy in postpartum affective disorders. J ECT. 2007;23(3):188-193.

29. Robinson GE. Psychopharmacology in pregnancy and postpartum. Focus. 2012;10(1):3-14.

30. Wesseloo R, Kamperman AM, Munk-Olsen T, Pop VJ, Kushner SA, Bergink V. Risk of postpartum relapse in bipolar disorder and postpartum psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(2):117-127.

31. Sharma V, Smith A, Mazmanian D. Olanzapine in the prevention of postpartum psychosis and mood episodes in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(4):400-404.

32. Gobbi G. Quetiapine in postpartum psychosis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;34(6):744-745.

33. Uguz F. Second-generation antipsychotics during the lactation period: a comparative systematic review on infant safety. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;36(3):244-252.

34. Sachs HC; Committee on Drugs. The transfer of drugs and therapeutics into human breast milk: an update on selected topics. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):e796-e809.

35. Lithium [package insert]. Columbus, OH: Roxane Laboratories Inc; 2011.

36. Grandjean EM, Aubry JM. Lithium: updated human knowledge using an evidence-based approach: part III: clinical safety. CNS Drugs. 2009;23(5):397-418.

1. Sadock B, Sadock V, Ruiz P. Kaplan & Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015.

2. Sharma V. Pharmacotherapy of postpartum psychosis. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2003;4(10):1651-1658.

3. Bassir Nia A, Medrano B, Perkel C, Galynker I, Hurd YL. Psychiatric comorbidity associated with synthetic cannabinoid use compared to cannabis. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1321-1330.

4. Rhohde A, Marneros A. Postpartum psychoses: onset and long-term course. Psychopathology. 1993;26(3-4):203-209.

5. Videbech P, Gouliaev G. First admission with puerperal psychosis: 7-14 years of follow-up. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1995;91(3):167-173.

6. Terp IM, Engholm G, Møller H, Mortensen PB. A follow-up study of postpartum psychoses: prognosis and risk factors for readmission. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1999;100(1):40-46.

7. Spinelli MG. Postpartum psychosis: detection of risk and management. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(4):405-408.

8. Blackmore ER, Rubinow DR, O’Connor TG, et al. Reproductive outcomes and risk of subsequent illness in women diagnosed with postpartum psychosis. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15(4):394-404.

9. Bloch M, Schmidt PJ, Danaceau M, Murphy J, Nieman L, Rubinow DR. Effects of gonadal steroids in women with a history of postpartum depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(6):924-930.

10. Monzon C, Lanza di Scalea T, Pearlstein T. Postpartum psychosis: updates and clinical issues. Psychiatric Times. 2014. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/special-reports/postpartum -psychosis-updates-and-clinical-issues. Published January 15, 2014. Accessed December 14, 2017.

11. Davies W. Understanding the pathophysiology of postpartum psychosis: challenges and new approaches. World J Psychiatry. 2017;7(2):77-88.

12. Kendell RE, Chalmers JC, Platz C. Epidemiology of puerperal psychoses. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:662-673.

13. Leibenluft E. Women with bipolar illness: clinical and research issues. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(2):163-173.

14. Chaudron LH, Pies R. The relationship between postpartum psychosis and bipolar disorder: a review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(11):1284-1292.

15. Brockington IF, Cernik KF, Schofield EM, Downing AR, Francis AF, Keelan C. Puerperal psychosis: phenomena and diagnosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38(7):829-833.

16. Wisner KL, Peindl K, Hanusa BH. Symptomatology of affective and psychotic illnesses related to childbearing. J Affect Disord. 1994;30(2):77-87.

17. Chandra PS, Bhargavaraman RP, Raghunandan VN, Shaligram D. Delusions related to infant and their association with mother-infant interactions in postpartum psychotic disorders. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2006;9(5):285-288.

18. Oosthuizen P, Russouw H, Roberts M. Is puerperal psychosis bipolar mood disorder? A phenomenological comparison. Compr Psychiatry. 1995;36(1):77-81.

19. Sharma V, Mazmanian D. Sleep loss and postpartum psychosis. Bipolar Disord. 2003;5(2):98-105.

20 Bilszta JL, Meyer D, Buist AE. Bipolar affective disorder in the postnatal period: investigating the role of sleep. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12(5):568-578.

21. Doucet S, Jones I, Letourneau N, Dennis CL, Blackmore ER. Interventions for the prevention and treatment of postpartum psychosis: a systematic review. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011;14(2):89-98.

22 Perlis RH, Welge JA, Vornik LA, Hirschfeld RM, Keck PE Jr. Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of mania: a meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(4):509-516.

23 Wijkstra J, Lijmer J, Balk FJ, Geddes JR, Nolen WA. Pharmacological treatment for unipolar psychotic depression: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:410-415.

24. Smith LA, Cornelius V, Warnock A, Tacchi MJ, Taylor D. Pharmacological interventions for acute bipolar mania: a systematic review of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9(6):551-560.

25. Bergink V, Burgerhout KM, Koorengevel KM, et al. Treatment of psychosis and mania in the postpartum period. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(2):115-123.

26. Ahokas A, Aito M, Rimón R. Positive treatment effect of estradiol in postpartum psychosis: a pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(3):166-169.

27. Reed P, Sermin N, Appleby L, Faragher B. A comparison of clinical response to electroconvulsive therapy in puerperal and non-puerperal psychoses. J Affect Disord. 1999;54(3):255-260.

28. Forray A, Ostroff RB. The use of electroconvulsive therapy in postpartum affective disorders. J ECT. 2007;23(3):188-193.

29. Robinson GE. Psychopharmacology in pregnancy and postpartum. Focus. 2012;10(1):3-14.

30. Wesseloo R, Kamperman AM, Munk-Olsen T, Pop VJ, Kushner SA, Bergink V. Risk of postpartum relapse in bipolar disorder and postpartum psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(2):117-127.

31. Sharma V, Smith A, Mazmanian D. Olanzapine in the prevention of postpartum psychosis and mood episodes in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(4):400-404.

32. Gobbi G. Quetiapine in postpartum psychosis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;34(6):744-745.

33. Uguz F. Second-generation antipsychotics during the lactation period: a comparative systematic review on infant safety. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;36(3):244-252.

34. Sachs HC; Committee on Drugs. The transfer of drugs and therapeutics into human breast milk: an update on selected topics. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):e796-e809.

35. Lithium [package insert]. Columbus, OH: Roxane Laboratories Inc; 2011.

36. Grandjean EM, Aubry JM. Lithium: updated human knowledge using an evidence-based approach: part III: clinical safety. CNS Drugs. 2009;23(5):397-418.

Mild cough • wheezing • loud heart sounds • Dx?

THE CASE

A 25-year-old man, who was an active duty US Navy sailor, went to his ship’s medical department complaining of a mild cough that he’d had for 2 days. He denied having any fevers, chills, night sweats, angina, or dyspnea. He said he hadn’t experienced any exertional fatigue or difficulty completing the rigorous physical tasks of his occupation as an engineman on the ship. The patient had no medical or surgical history of significance, and he wasn’t taking any medications or supplements.

On exam, he was not in acute distress and his vital signs were within normal limits. Auscultation revealed mild wheezing throughout the upper lung fields and loud heart sounds throughout his chest that were audible even with gentle contact of the stethoscope diaphragm. He had no discernible murmurs, rubs, or gallops.

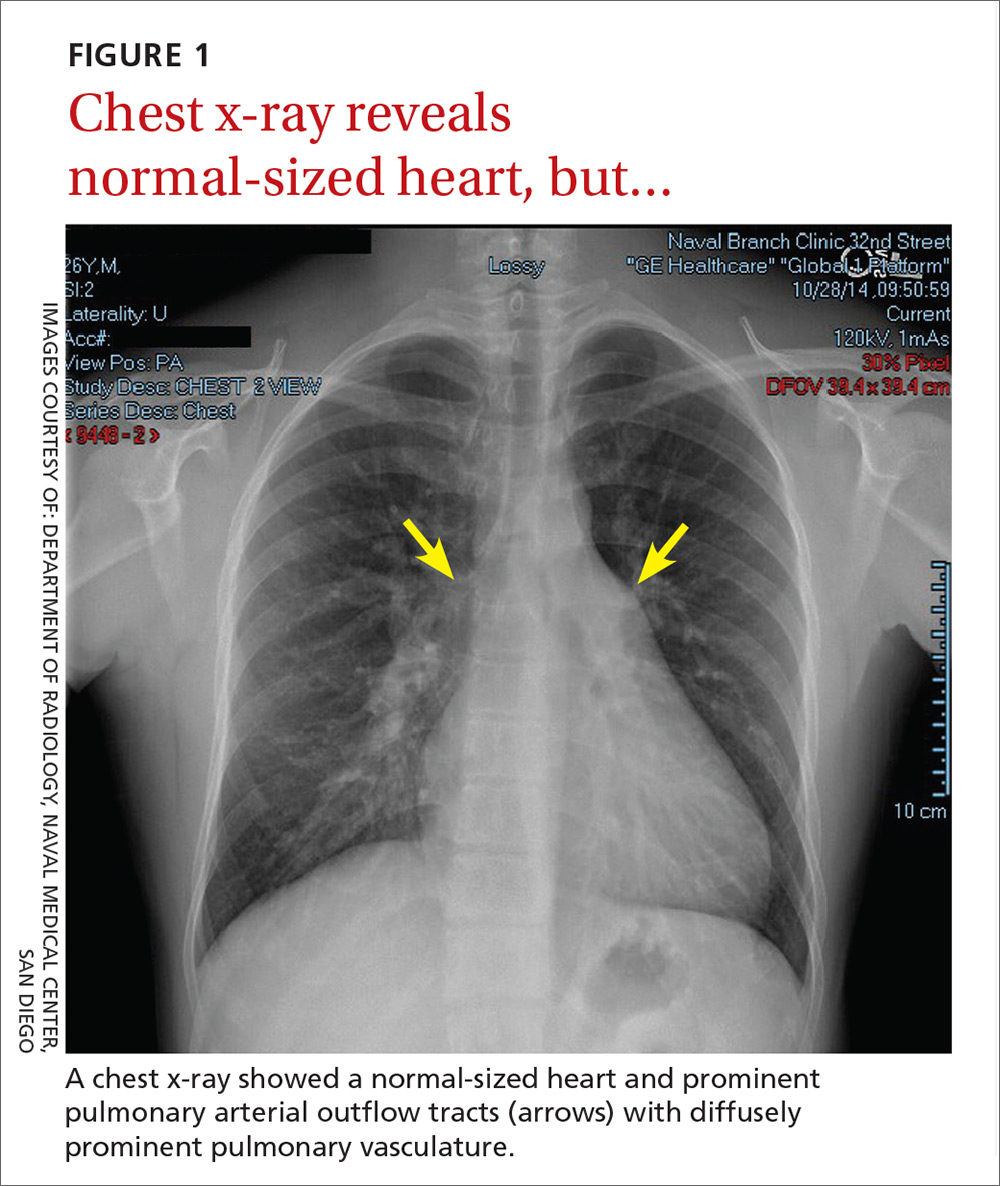

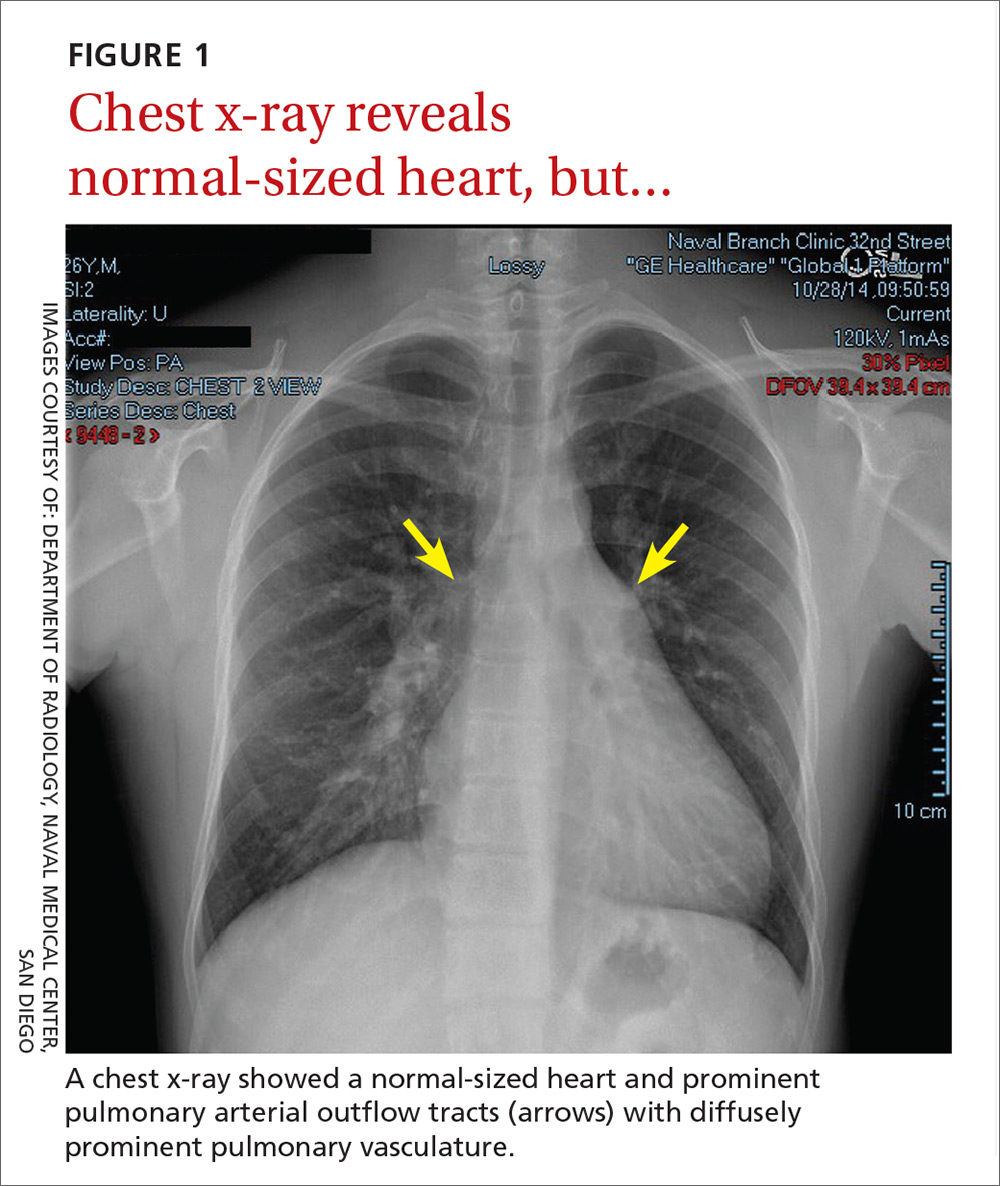

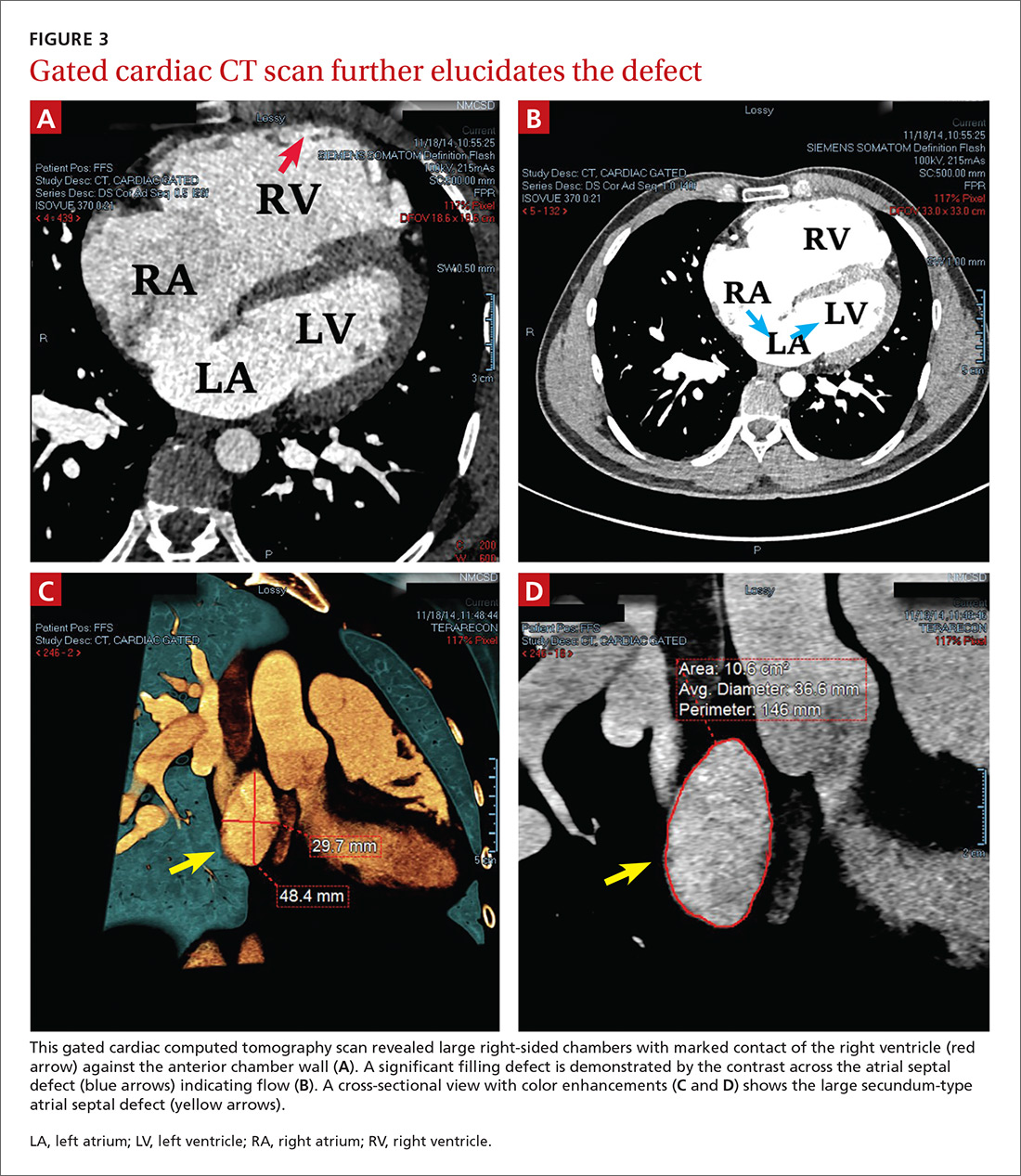

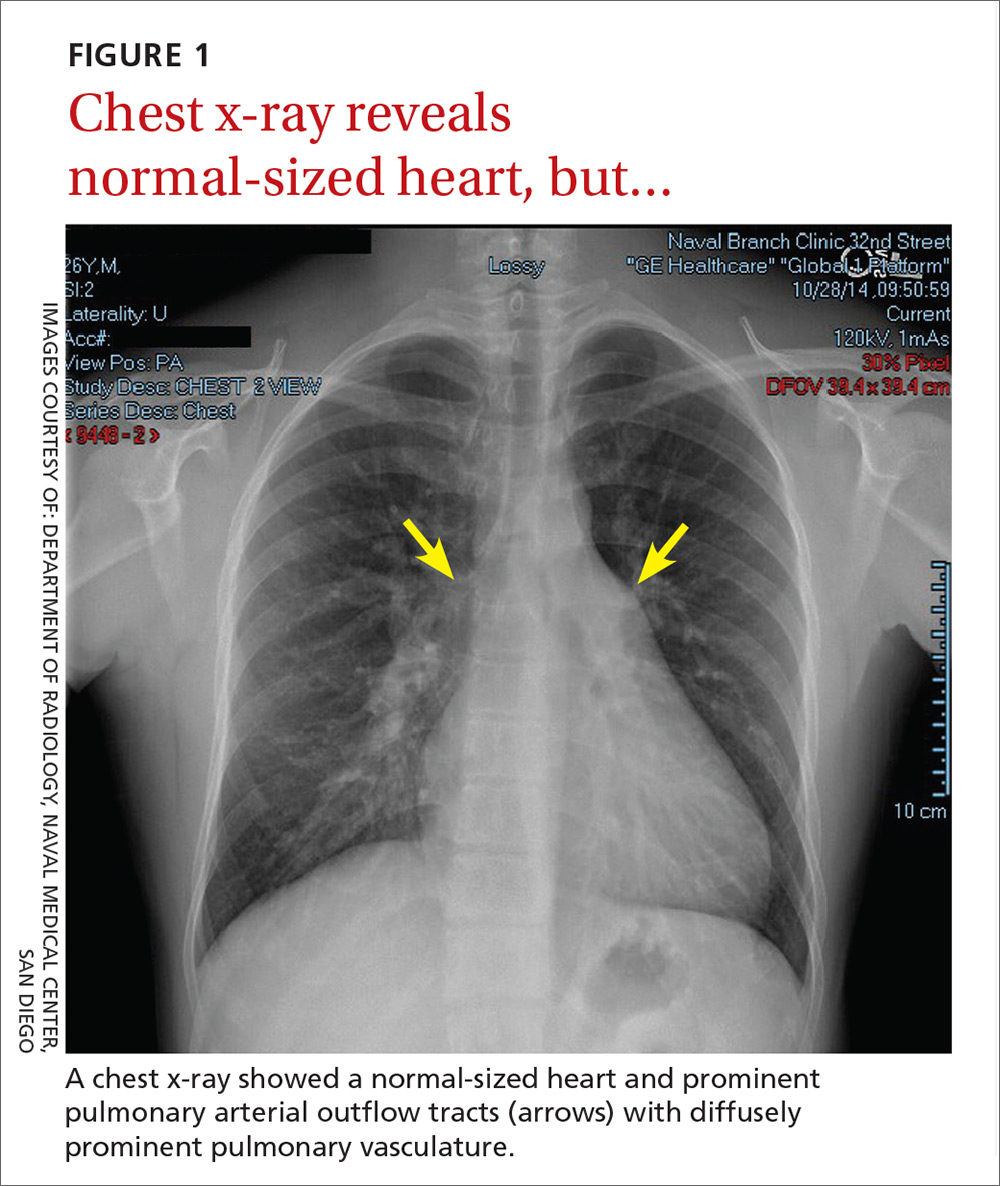

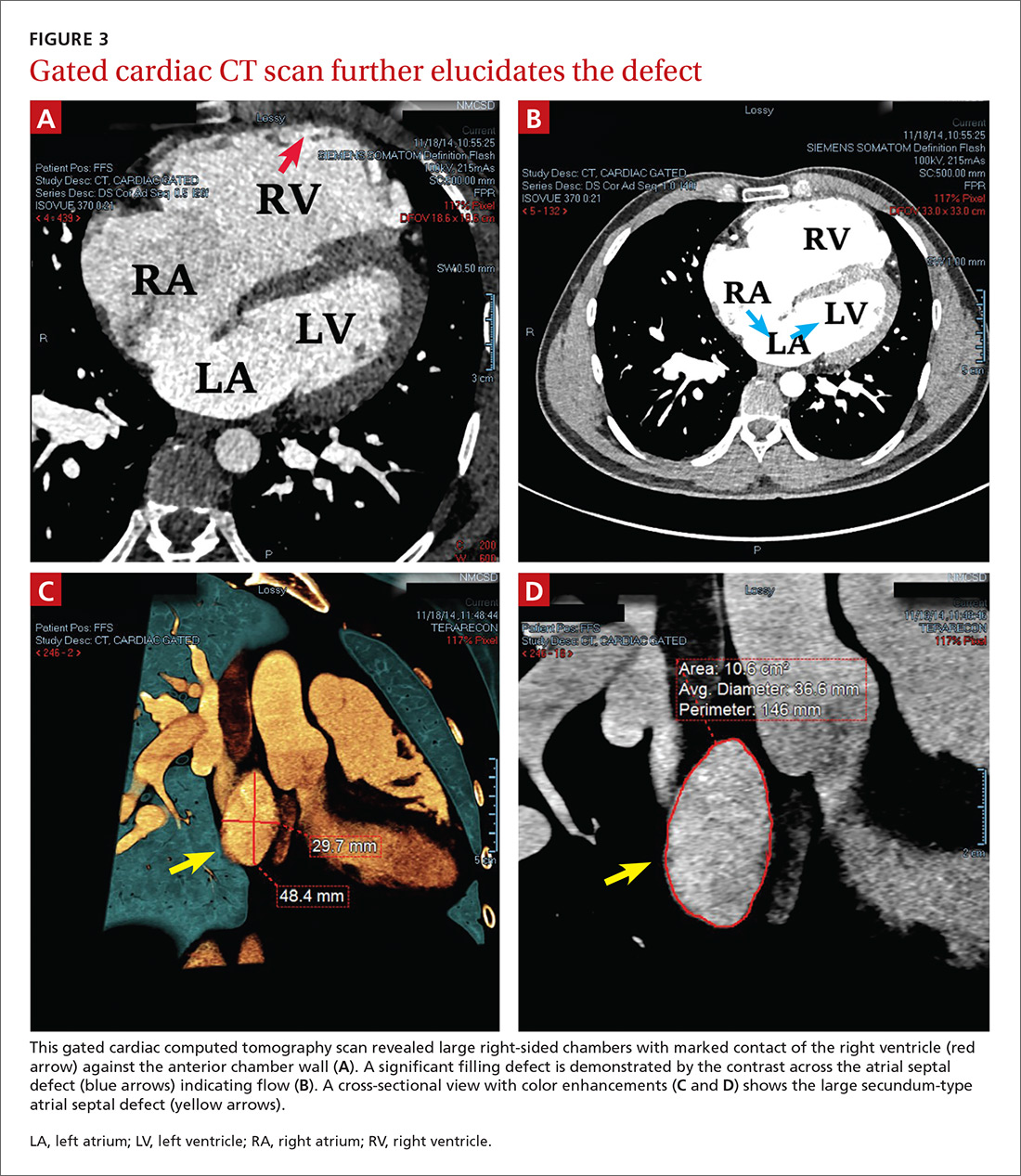

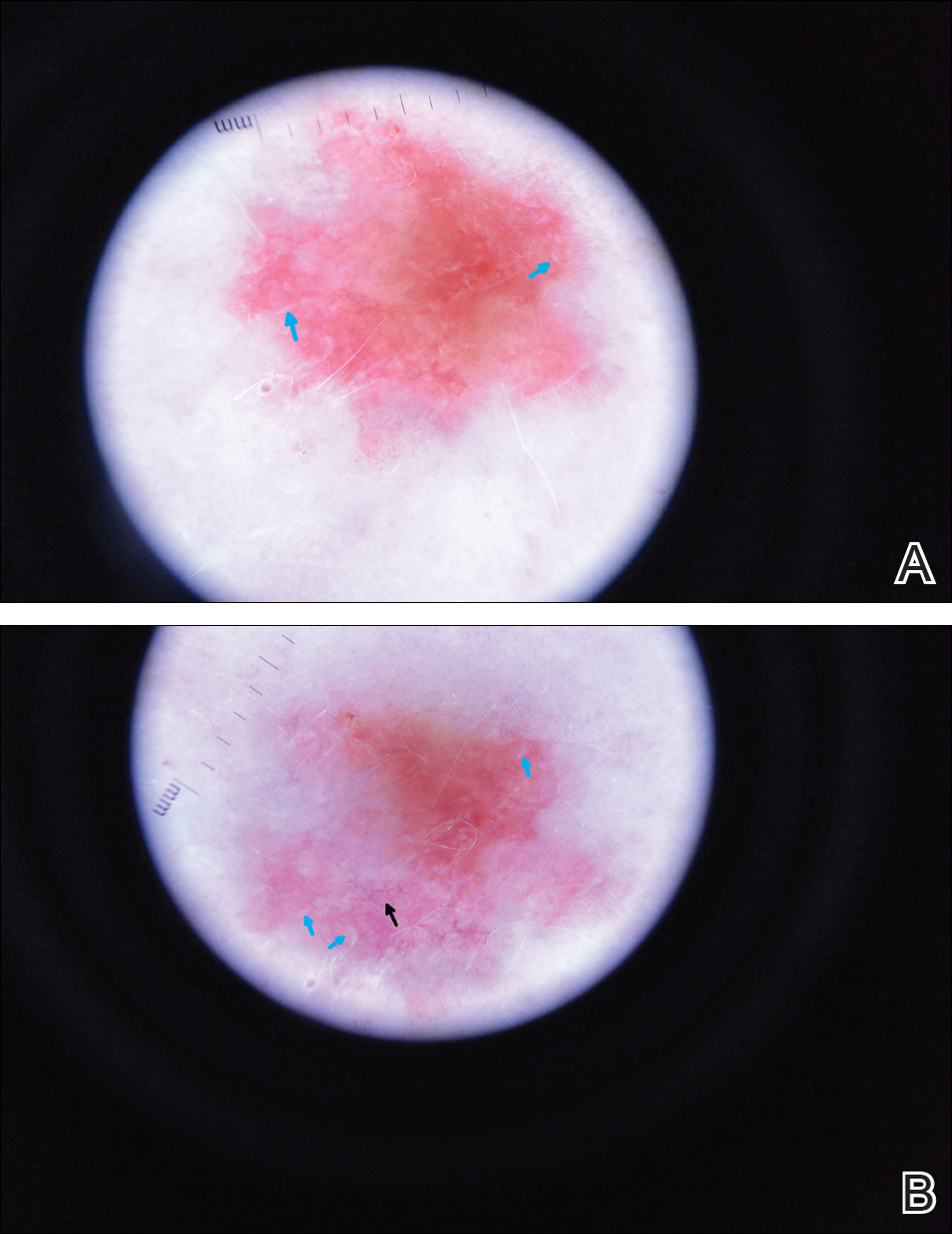

In light of the unusually loud heart sounds heard on exam, we performed an electrocardiogram. The EKG revealed a normal sinus rhythm, slight right axis deviation indicated by tall R-waves in V1 (also suggestive of right ventricular hypertrophy), an incomplete right bundle branch block, and a crochetage sign (a notch in the R-waves of the inferior leads).1 A chest x-ray (FIGURE 1) revealed a normal-sized heart and dilated pulmonary vasculature suggestive of pulmonary hypertension.

THE DIAGNOSIS

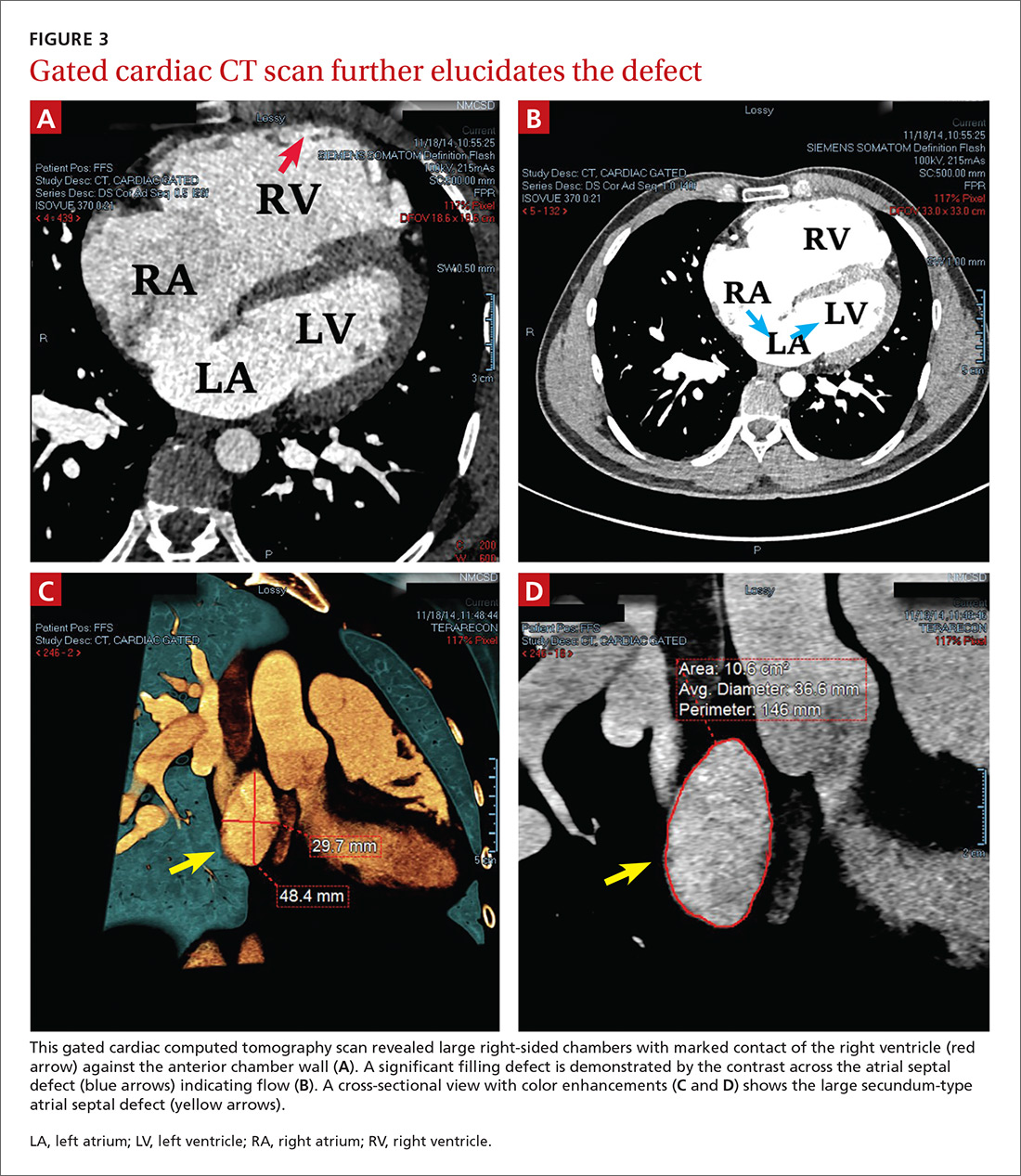

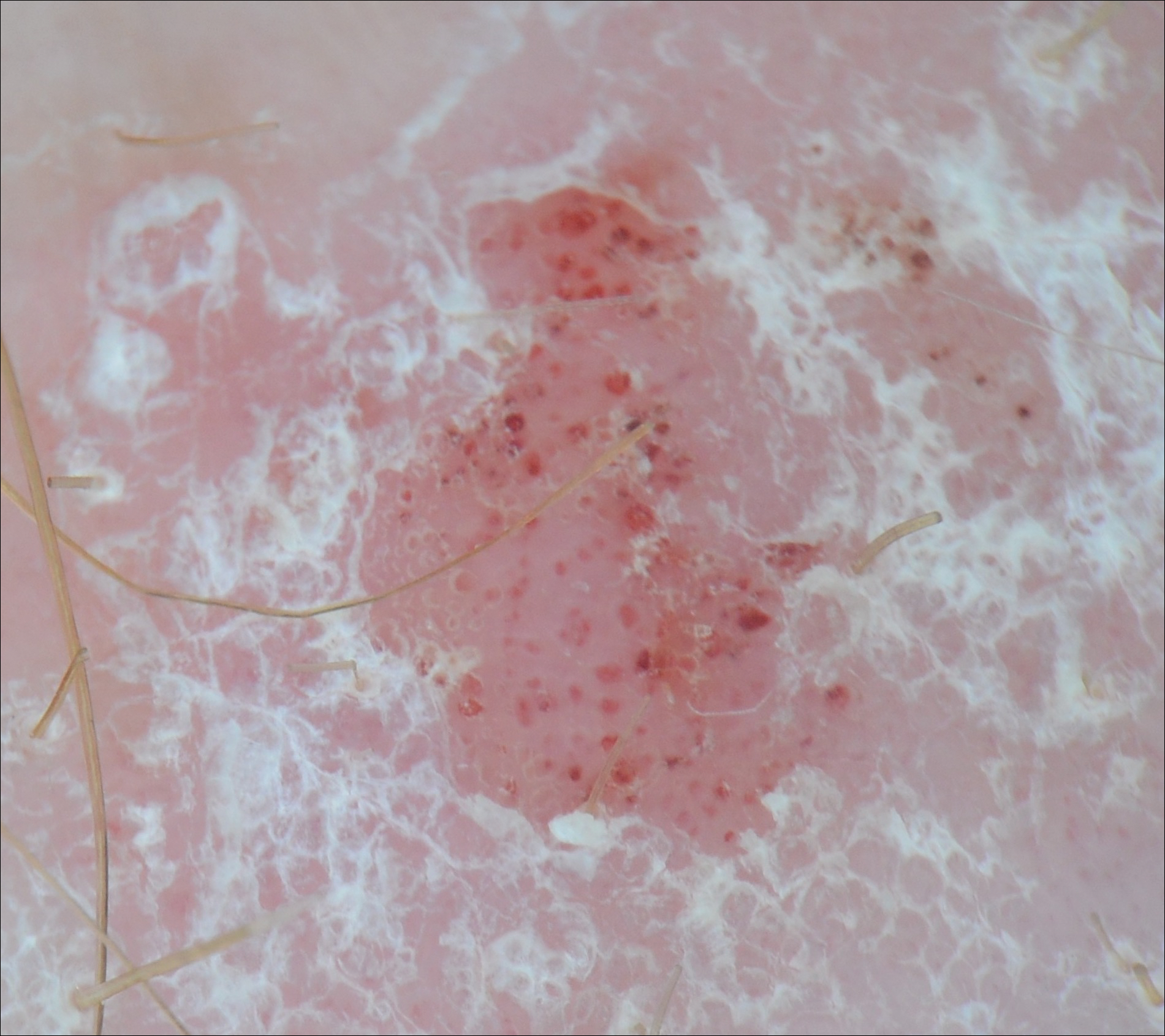

To further evaluate the cardiopulmonary findings, ultrasound studies (transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography) were performed. These demonstrated a very large secundum-type atrial septal defect (ASD), measuring at its largest point about 30 × 48 mm (FIGURE 2 and FIGURE 3C). Doppler flow analysis and a bubble study (VIDEOS 1 and 2) demonstrated significant shunting across the ASD. Gated cardiac computed tomography (CT) was also used to characterize the ASD (FIGURE 3). It revealed that the superior and posterior rims of the ASD were essentially absent and that the right atrium and ventricle were severely enlarged, while the left chambers were normal in size and function with an ejection fraction >55%. The notching of the R-waves of the inferior leads, seen in our patient’s EKG, is typically seen with large ASDs.1,2

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Transthoracic echocardiography with color Doppler flow (red) demonstrated significant shunting across a large atrial septal defect (white box). The largest white dot is positioned near the center of the defect.

LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Transthoracic echocardiography with a bubble study showed injected air bubbles traversing the atrial septal defect.

LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

DISCUSSION

ASDs are typically uncovered on exam via auscultation of heart sounds, which might reveal a split of the second heart sound (S2) and diastolic murmurs. ASDs are typically classified by size, and their management depends on this factor, along with the patient’s age and symptoms. In children with small defects (<6 mm), treatment usually consists of conservative observation, as more than half of these ASDs will spontaneously close.3 But, as children age, they are more likely to engage in exertional activity (work, recreational sports) and an unrepaired ASD may yield symptoms (angina, dyspnea, fatigue, other cardiopulmonary strain). With such symptoms and when closure is not spontaneously achieved by adolescence or adulthood, an invasive approach is often necessary to correct the defect.

ASD repair. Traditionally, repair has involved some form of open thoracotomy. More recently, several minimally invasive techniques have been developed. Catheter-based device closure, in which a catheter is percutaneously guided to the defect and a patch is deployed to seal the ASD, is a technique that has been shown to successfully correct large ASDs of up to 40 mm in size.4 Robotic procedures have also been developed to correct ASDs through much smaller incisions.5 Both of these techniques require a significant rim of residual septal tissue around the defect.

Individualized approach. Since our patient had a rather large ASD that did not have sufficient residual septal rim tissue, percutaneous and robotic approaches were not feasible. Instead, he required more invasive cardiothoracic surgery. In cases such as this, the exact technique and type of incision (sternotomy vs access through the lateral chest wall) depend on age, gender, and the presence of other comorbidities.6

Our patient. Because there was concern that any approach other than a median one might not afford enough space to fix an ASD of such considerable size, our patient underwent a median sternotomy by a pediatric cardiothoracic surgeon who specialized in these repairs (in children as well as young adults). During the procedure, the ASD was accessed and confirmed to be as large as predicted by diagnostic imaging. A surgical patch was sutured in place to correct the defect. There were no intra-operative or postop complications.

Four weeks later, the patient had a mild pericardial effusion that was managed medically with daily furosemide and aspirin. At his 8-week postop appointment, the fluid accumulation had resolved, and he was completely asymptomatic. The patient returned to full-time active duty in the US Navy.

Adults with rather large ASDs can present in a relatively asymptomatic manner and report none of the classic complaints (angina, dyspnea, fatigue). They may even engage in heavy exertional activity with no difficulty. The underlying defect may be discovered incidentally on exam by noting a split of the S2 on auscultation. If pulmonary hypertension exists, the clinician may also note a loud S2. An exam that raises suspicion for an ASD can then be followed by tests that solidify the diagnosis. Surgery is usually necessary to correct an ASD in an adult who is symptomatic or exhibits significant cardiopulmonary strain.

1. Heller J, Hagège AA, Besse B, et al. “Crochetage” (notch) on R wave in inferior limb leads: a new independent electrocardiographic sign of atrial septal defect. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:877-882.

2. Kuijpers JM, Mulder BJM, Bouma BJ. Secundum atrial septal defect in adults: a practical review and recent developments. Neth Heart J. 2015;23:205-211.

3. McMahon CJ, Feltes TF, Fraley JK, et al. Natural history of growth of secundum atrial septal defects and implications for transcatheter closure. Heart. 2002;87:256-259.

4. Lopez K, Dalvi BV, Balzer D, et al. Transcatheter closure of large secundum atrial septal defects using the 40 mm amplatzer septal occluder: results of an international registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2005;66:580-584.

5. Argenziano M, Oz MC, Kohmoto T, et al. Totally endoscopic atrial septal defect repair with robotic assistance. Circulation. 2003;108 Suppl 1:II191-II194.

6. Hopkins RA, Bert AA, Buchholz B, et al. Surgical patch closure of atrial septal defects. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:2144-2149.

THE CASE

A 25-year-old man, who was an active duty US Navy sailor, went to his ship’s medical department complaining of a mild cough that he’d had for 2 days. He denied having any fevers, chills, night sweats, angina, or dyspnea. He said he hadn’t experienced any exertional fatigue or difficulty completing the rigorous physical tasks of his occupation as an engineman on the ship. The patient had no medical or surgical history of significance, and he wasn’t taking any medications or supplements.

On exam, he was not in acute distress and his vital signs were within normal limits. Auscultation revealed mild wheezing throughout the upper lung fields and loud heart sounds throughout his chest that were audible even with gentle contact of the stethoscope diaphragm. He had no discernible murmurs, rubs, or gallops.