User login

Painful erections while being treated for OCD

CASE Prolonged, painful erections

Mr. G, age 27, who has a history of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), presents to his internist’s office with complaints of “masturbating several times a day” and having ejaculatory delay of up to 50 minutes with intercourse. The frequent masturbation was an attempt to “cure” the ejaculatory delay. In addition, Mr. G reports that for the past 5 nights, he has awoke every 3 hours with a painful erection that lasted 1.5 to 2.5 hours, after which he would fall asleep, only to wake once again to the same phenomenon.

Mr. G’s symptoms began 3 weeks ago after his psychiatrist adjusted the dose of his medication for OCD. Mr. G had been receiving fluoxetine, 10 mg/d, for the past 3 years to manage his OCD, without improvement. During a recent consultation, his psychiatrist increased the dose to 20 mg/d, with the expectation that further dose increases might be necessary to treat his OCD.

HISTORY Concurrent GAD

Mr. G is single and in a monogamous heterosexual relationship. Three weeks earlier, when he was examined by his psychiatrist, Mr. G’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale score was 28 and his Beck Anxiety Inventory score was 24. Based on these scores, the psychiatrist concluded Mr. G had concurrent generalized anxiety disorder (GAD).

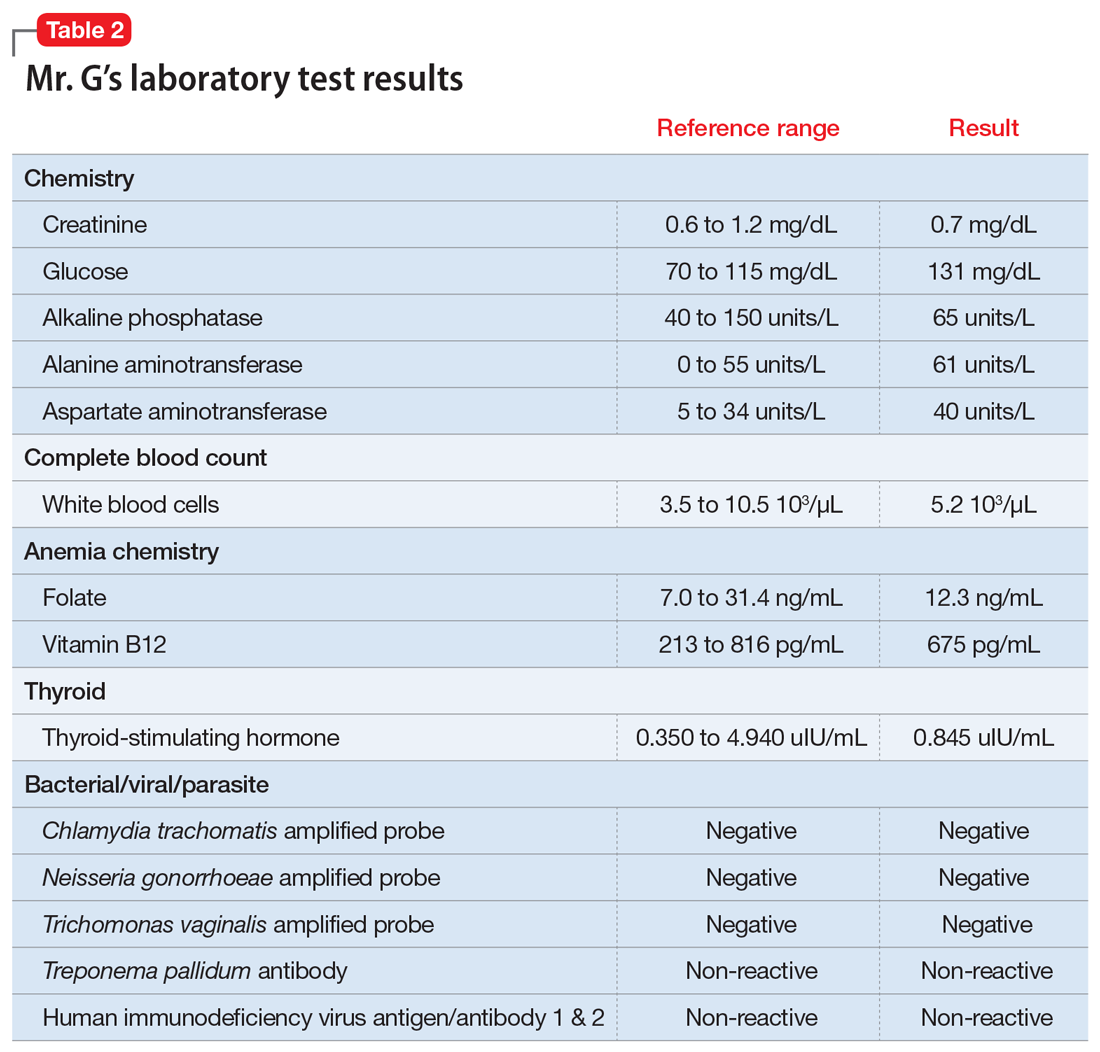

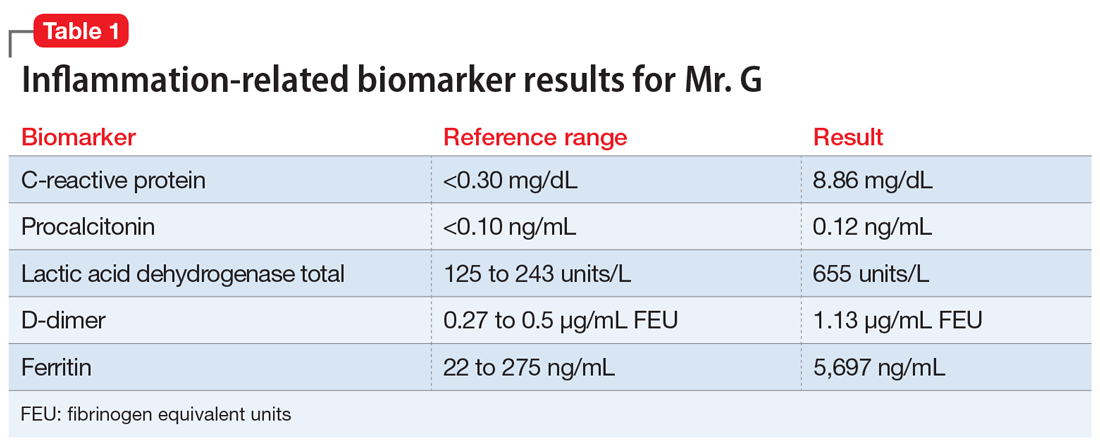

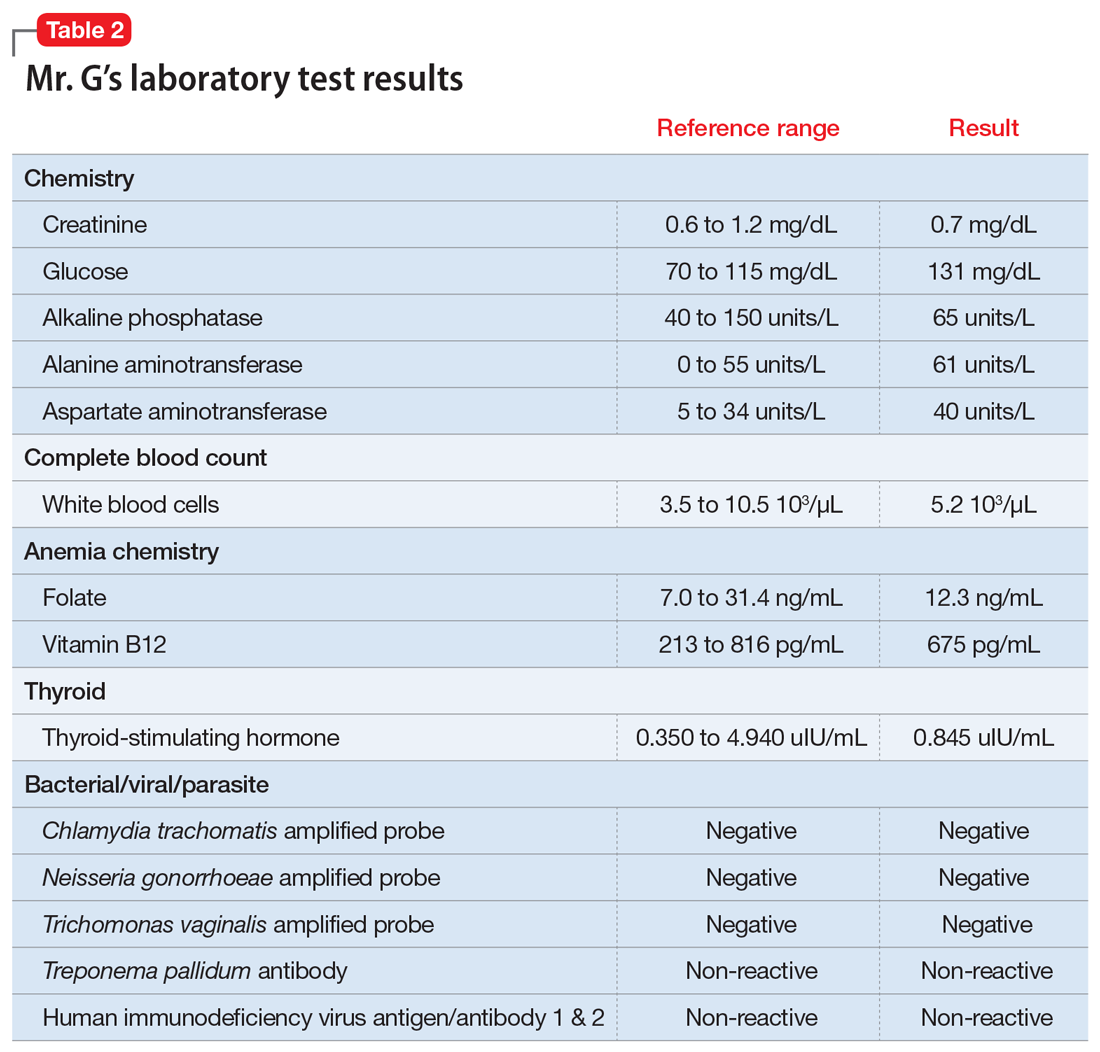

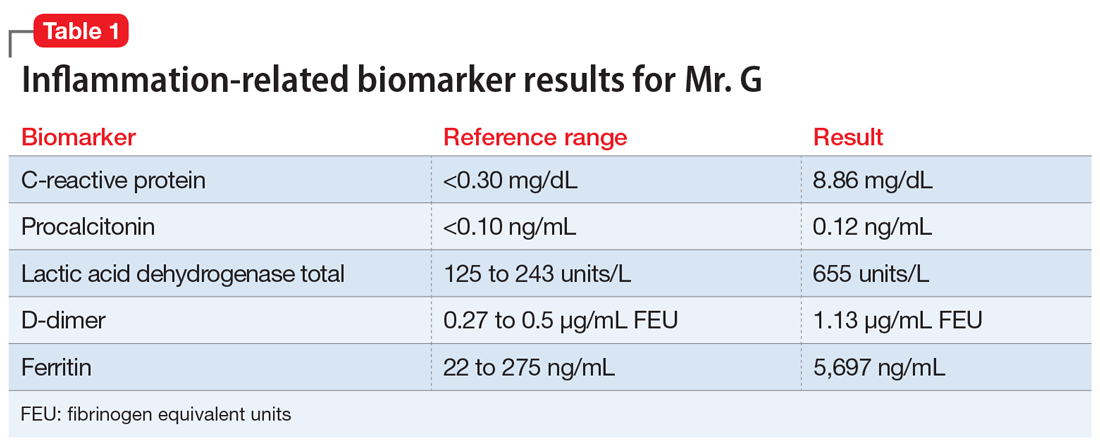

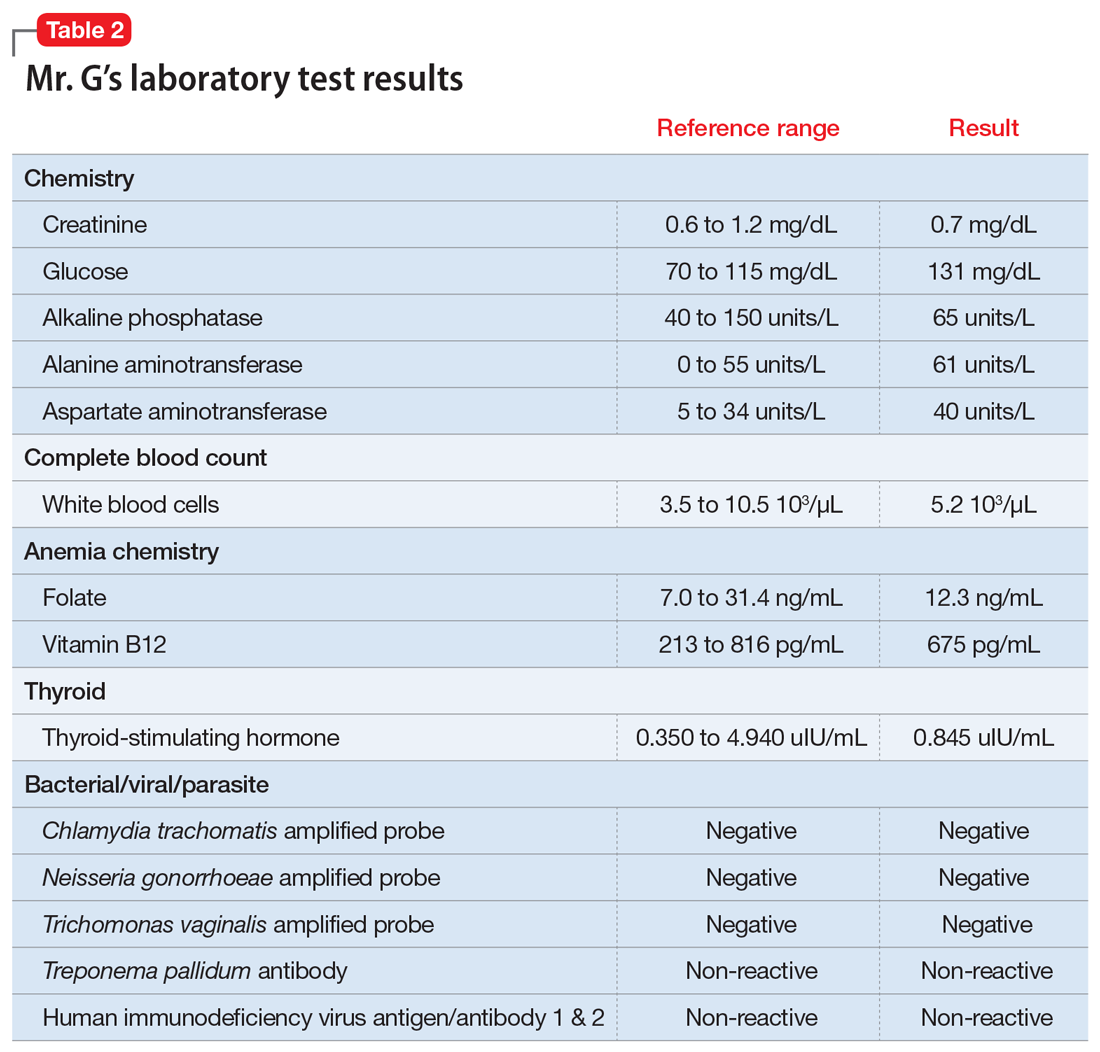

EVALUATION Workup is normal

On presentation to his internist’s office, Mr. G’s laboratory values are all within normal range, including a chemistry panel, complete blood count with differential, and electrocardiogram. A human immunodeficiency virus test is negative. His internist instructs Mr. G to return to his psychiatrist.

[polldaddy:10640161]

TREATMENT Dose adjustment

Based on Mr. G’s description of painful and persistent erections in the absence of sexual stimulation or arousal, and because these episodes have occurred 5 consecutive nights, the psychiatrist makes a provisional diagnosis of stuttering priapism and reduces the fluoxetine dose from 20 to 10 mg/d.

The author’s observations

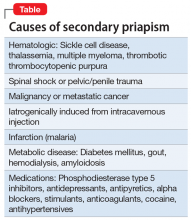

Priapism is classically defined as a persistent, unwanted penile or clitoral engorgement in the absence of sexual desire/arousal or stimulation. It can last for up to 4 to 6 hours1 orit can take a so-called “stuttering form” characterized by brief, recurrent, self-limited episodes. Priapism is a urologic emergency resulting in erectile dysfunction in 30% to 90% of patients. It is multifactorial and can be characterized as low-flow (occlusive) or high-flow (nonischemic). Most priapism is primary or idiopathic in nature; the incidence is 1.5 per 100,000 individuals (primarily men), with bimodal peaks, and it can occur in all age groups.2 Secondary priapism can occur from many causes (Table).

Mechanism is unclear

The molecular mechanism of priapism is not completely understood. Normally, nitrous oxide mediates penile erection. However, cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) acts at several levels to create smooth muscle reaction, leading to either penile tumescence or, in some cases, priapism. Stuttering or intermittent ischemic priapism is thought to be a downregulation of phosphodiesterase type 5, causing excess cGMP with subsequent smooth muscle relaxation in the penis.3

Continue to: Drug-induced priapism

Drug-induced priapism

Drug-induced priapism is commonly believed to be associated with alpha-1 adrenergic receptor blockade.4 This also results in dizziness and orthostatic hypotension.5 Trazodone is commonly associated with the development of secondary priapism; however, in the last 30 years, multiple case reports have demonstrated that a variety of psychoactive agents have been associated with low-flowpriapism.6 Most case reports have focused on new-onset priapism associated with the introduction of a new medication. Based on a recent informal search of Medline, since 1989, there have been >36 case reports of priapism associated with psychotropic use. Stuttering priapism is less frequently discussed in the literature.7

Ischemic priapism accounts for 95% of all reports. It can be associated with medication use or hematologic disorders, or it can be triggered by sexual activity. Often, patients who experience an episode will abstain from sexual contact.

The etiology of stuttering priapism is less clear. Episodes of stuttering priapism often occur during sleep and can resolve spontaneously.8 They are a form of ischemic priapism and are seen in patients with sickle cell anemia. It is not known how many patients with stuttering priapism will convert to the nonremitting form, which may require chemical or surgical intervention.9 Stuttering priapism may go unreported and perhaps may be overlooked by patients based on its frequency and intensity.

The activating selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine has a long half-life and is a potent inhibitor of the cytochrome P450 2D6 isoenzyme system. It inhibits serotonin transporter proteins. It is also a weak norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, an effect that increases with increasing doses of the medication. Its 5HT2C antagonism is proposed as the mechanism of its activating properties.10 In Mr. G’s case, it is possible that fluoxetine’s weak norepinephrine reuptake inhibition resulted in an intermittent priapism effect mediated through the pathways described above.

OUTCOME Symptoms resolve

Approximately 1 week after Mr. G’s fluoxetine dose is reduced, his symptoms of priapism abated. The fluoxetine is discontinued and his ejaculatory delay resolves. Mr. G is started on fluvoxamine, 150 mg/d, which results in a significant decrease of both GAD and OCD symptoms with no notable ejaculatory delay, and no recurrence of priapism.

Continue to: The author's observations

The author’s observations

Mr. G’s case and other case reports suggest that psychiatrists should caution patients who are prescribed antidepressants or antipsychotics that stuttering priapism is a possible adverse effect.11 As seen in Mr. G’s case, fluoxetine (when used chronically) can moderate vascular responses at the pre- and post-synaptic adrenergic receptor.11 Priapism induced by a psychotropic medication will not necessarily lead to a longer-term, unremitting priapism, but it can be dramatic, frightening, and lead to noncompliance. Along with obtaining a standard history that includes asking patients about prior adverse medication events, psychiatrists also should ask their patients if they have experienced any instances of transient priapism that may require further evaluation.

Bottom Line

Any psychotropic medication that has the capacity to act on alpha adrenergic receptors can cause priapism. Ask patients if they have had any unusual erections/ clitoral engorgement while taking any psychotropic medications, because many patients will be hesitant to volunteer such information.

Related Resource

- Thippaiah SM, Nagaraja S, Birur B, et al. Successful management of psychotropics induced stuttering priapism with pseudoephedrine in a patient with schizophrenia. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2018;48(2):29-33.

Drug Brand Names

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Trazodone • Desyrel, Oleptro

1. Kadioglu A, Sanli O, Celtik M, et al. Practical management of patients with priapism. EAU-EBU Update Series. 2006;4(4):150-160.

2. Eland IA, van der Lei J, Stricker BHC. Incidence of priapism in the general population. Urology. 2001;57(5):970-972.

3. Halls JE, Patel DV, Walkden M, et al. Priapism: pathophysiology and the role of the radiologist. Br J Radiol. 2012;85(Spec Iss 1):S79-S85.

4. Wang CS, Kao WT, Chen CD, et al. Priapism associated with typical and atypical antipsychotic medications. Int Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2006;21(4):245-248.

5. Khan Q, Tucker P, Lokhande A. Priapism: what cause: mental illness, psychotropic medications or polysubstance abuse? J Okla State Med Assoc. 2016;109(11):515-517.

6. Dent LA, Brown WC, Murney JD. Citalopram-induced priapism. Pharmacotherapy. 2002;22(4):538-541.

7. Wilkening GL, Kucherer SA, Douaihy AB. Priapism and renal colic in a patient treated with duloxetine. Mental Health Clinician. 2016;6(4):197-200.

8. Morrison BF, Burnett AL. Stuttering priapism: insight into its pathogenesis and management. Curr Urol Rep. 2012;13(4):268-276.

9. Burnett AL, Bivalacqua TJ. Priapism: current principles and practice. Urol Clin North Am. 2007;34(4):631-642.

10. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: neuroscientific basis and practical applications. 4th ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

11. Pereira CA, Rodrigues FL, Ruginsk SG, et al. Chronic treatment with fluoxetine modulates vascular adrenergic responses by inhibition of pre- and post-synaptic mechanisms. Eu J Pharmacol. 2017;800:70-80.

CASE Prolonged, painful erections

Mr. G, age 27, who has a history of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), presents to his internist’s office with complaints of “masturbating several times a day” and having ejaculatory delay of up to 50 minutes with intercourse. The frequent masturbation was an attempt to “cure” the ejaculatory delay. In addition, Mr. G reports that for the past 5 nights, he has awoke every 3 hours with a painful erection that lasted 1.5 to 2.5 hours, after which he would fall asleep, only to wake once again to the same phenomenon.

Mr. G’s symptoms began 3 weeks ago after his psychiatrist adjusted the dose of his medication for OCD. Mr. G had been receiving fluoxetine, 10 mg/d, for the past 3 years to manage his OCD, without improvement. During a recent consultation, his psychiatrist increased the dose to 20 mg/d, with the expectation that further dose increases might be necessary to treat his OCD.

HISTORY Concurrent GAD

Mr. G is single and in a monogamous heterosexual relationship. Three weeks earlier, when he was examined by his psychiatrist, Mr. G’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale score was 28 and his Beck Anxiety Inventory score was 24. Based on these scores, the psychiatrist concluded Mr. G had concurrent generalized anxiety disorder (GAD).

EVALUATION Workup is normal

On presentation to his internist’s office, Mr. G’s laboratory values are all within normal range, including a chemistry panel, complete blood count with differential, and electrocardiogram. A human immunodeficiency virus test is negative. His internist instructs Mr. G to return to his psychiatrist.

[polldaddy:10640161]

TREATMENT Dose adjustment

Based on Mr. G’s description of painful and persistent erections in the absence of sexual stimulation or arousal, and because these episodes have occurred 5 consecutive nights, the psychiatrist makes a provisional diagnosis of stuttering priapism and reduces the fluoxetine dose from 20 to 10 mg/d.

The author’s observations

Priapism is classically defined as a persistent, unwanted penile or clitoral engorgement in the absence of sexual desire/arousal or stimulation. It can last for up to 4 to 6 hours1 orit can take a so-called “stuttering form” characterized by brief, recurrent, self-limited episodes. Priapism is a urologic emergency resulting in erectile dysfunction in 30% to 90% of patients. It is multifactorial and can be characterized as low-flow (occlusive) or high-flow (nonischemic). Most priapism is primary or idiopathic in nature; the incidence is 1.5 per 100,000 individuals (primarily men), with bimodal peaks, and it can occur in all age groups.2 Secondary priapism can occur from many causes (Table).

Mechanism is unclear

The molecular mechanism of priapism is not completely understood. Normally, nitrous oxide mediates penile erection. However, cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) acts at several levels to create smooth muscle reaction, leading to either penile tumescence or, in some cases, priapism. Stuttering or intermittent ischemic priapism is thought to be a downregulation of phosphodiesterase type 5, causing excess cGMP with subsequent smooth muscle relaxation in the penis.3

Continue to: Drug-induced priapism

Drug-induced priapism

Drug-induced priapism is commonly believed to be associated with alpha-1 adrenergic receptor blockade.4 This also results in dizziness and orthostatic hypotension.5 Trazodone is commonly associated with the development of secondary priapism; however, in the last 30 years, multiple case reports have demonstrated that a variety of psychoactive agents have been associated with low-flowpriapism.6 Most case reports have focused on new-onset priapism associated with the introduction of a new medication. Based on a recent informal search of Medline, since 1989, there have been >36 case reports of priapism associated with psychotropic use. Stuttering priapism is less frequently discussed in the literature.7

Ischemic priapism accounts for 95% of all reports. It can be associated with medication use or hematologic disorders, or it can be triggered by sexual activity. Often, patients who experience an episode will abstain from sexual contact.

The etiology of stuttering priapism is less clear. Episodes of stuttering priapism often occur during sleep and can resolve spontaneously.8 They are a form of ischemic priapism and are seen in patients with sickle cell anemia. It is not known how many patients with stuttering priapism will convert to the nonremitting form, which may require chemical or surgical intervention.9 Stuttering priapism may go unreported and perhaps may be overlooked by patients based on its frequency and intensity.

The activating selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine has a long half-life and is a potent inhibitor of the cytochrome P450 2D6 isoenzyme system. It inhibits serotonin transporter proteins. It is also a weak norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, an effect that increases with increasing doses of the medication. Its 5HT2C antagonism is proposed as the mechanism of its activating properties.10 In Mr. G’s case, it is possible that fluoxetine’s weak norepinephrine reuptake inhibition resulted in an intermittent priapism effect mediated through the pathways described above.

OUTCOME Symptoms resolve

Approximately 1 week after Mr. G’s fluoxetine dose is reduced, his symptoms of priapism abated. The fluoxetine is discontinued and his ejaculatory delay resolves. Mr. G is started on fluvoxamine, 150 mg/d, which results in a significant decrease of both GAD and OCD symptoms with no notable ejaculatory delay, and no recurrence of priapism.

Continue to: The author's observations

The author’s observations

Mr. G’s case and other case reports suggest that psychiatrists should caution patients who are prescribed antidepressants or antipsychotics that stuttering priapism is a possible adverse effect.11 As seen in Mr. G’s case, fluoxetine (when used chronically) can moderate vascular responses at the pre- and post-synaptic adrenergic receptor.11 Priapism induced by a psychotropic medication will not necessarily lead to a longer-term, unremitting priapism, but it can be dramatic, frightening, and lead to noncompliance. Along with obtaining a standard history that includes asking patients about prior adverse medication events, psychiatrists also should ask their patients if they have experienced any instances of transient priapism that may require further evaluation.

Bottom Line

Any psychotropic medication that has the capacity to act on alpha adrenergic receptors can cause priapism. Ask patients if they have had any unusual erections/ clitoral engorgement while taking any psychotropic medications, because many patients will be hesitant to volunteer such information.

Related Resource

- Thippaiah SM, Nagaraja S, Birur B, et al. Successful management of psychotropics induced stuttering priapism with pseudoephedrine in a patient with schizophrenia. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2018;48(2):29-33.

Drug Brand Names

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Trazodone • Desyrel, Oleptro

CASE Prolonged, painful erections

Mr. G, age 27, who has a history of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), presents to his internist’s office with complaints of “masturbating several times a day” and having ejaculatory delay of up to 50 minutes with intercourse. The frequent masturbation was an attempt to “cure” the ejaculatory delay. In addition, Mr. G reports that for the past 5 nights, he has awoke every 3 hours with a painful erection that lasted 1.5 to 2.5 hours, after which he would fall asleep, only to wake once again to the same phenomenon.

Mr. G’s symptoms began 3 weeks ago after his psychiatrist adjusted the dose of his medication for OCD. Mr. G had been receiving fluoxetine, 10 mg/d, for the past 3 years to manage his OCD, without improvement. During a recent consultation, his psychiatrist increased the dose to 20 mg/d, with the expectation that further dose increases might be necessary to treat his OCD.

HISTORY Concurrent GAD

Mr. G is single and in a monogamous heterosexual relationship. Three weeks earlier, when he was examined by his psychiatrist, Mr. G’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale score was 28 and his Beck Anxiety Inventory score was 24. Based on these scores, the psychiatrist concluded Mr. G had concurrent generalized anxiety disorder (GAD).

EVALUATION Workup is normal

On presentation to his internist’s office, Mr. G’s laboratory values are all within normal range, including a chemistry panel, complete blood count with differential, and electrocardiogram. A human immunodeficiency virus test is negative. His internist instructs Mr. G to return to his psychiatrist.

[polldaddy:10640161]

TREATMENT Dose adjustment

Based on Mr. G’s description of painful and persistent erections in the absence of sexual stimulation or arousal, and because these episodes have occurred 5 consecutive nights, the psychiatrist makes a provisional diagnosis of stuttering priapism and reduces the fluoxetine dose from 20 to 10 mg/d.

The author’s observations

Priapism is classically defined as a persistent, unwanted penile or clitoral engorgement in the absence of sexual desire/arousal or stimulation. It can last for up to 4 to 6 hours1 orit can take a so-called “stuttering form” characterized by brief, recurrent, self-limited episodes. Priapism is a urologic emergency resulting in erectile dysfunction in 30% to 90% of patients. It is multifactorial and can be characterized as low-flow (occlusive) or high-flow (nonischemic). Most priapism is primary or idiopathic in nature; the incidence is 1.5 per 100,000 individuals (primarily men), with bimodal peaks, and it can occur in all age groups.2 Secondary priapism can occur from many causes (Table).

Mechanism is unclear

The molecular mechanism of priapism is not completely understood. Normally, nitrous oxide mediates penile erection. However, cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) acts at several levels to create smooth muscle reaction, leading to either penile tumescence or, in some cases, priapism. Stuttering or intermittent ischemic priapism is thought to be a downregulation of phosphodiesterase type 5, causing excess cGMP with subsequent smooth muscle relaxation in the penis.3

Continue to: Drug-induced priapism

Drug-induced priapism

Drug-induced priapism is commonly believed to be associated with alpha-1 adrenergic receptor blockade.4 This also results in dizziness and orthostatic hypotension.5 Trazodone is commonly associated with the development of secondary priapism; however, in the last 30 years, multiple case reports have demonstrated that a variety of psychoactive agents have been associated with low-flowpriapism.6 Most case reports have focused on new-onset priapism associated with the introduction of a new medication. Based on a recent informal search of Medline, since 1989, there have been >36 case reports of priapism associated with psychotropic use. Stuttering priapism is less frequently discussed in the literature.7

Ischemic priapism accounts for 95% of all reports. It can be associated with medication use or hematologic disorders, or it can be triggered by sexual activity. Often, patients who experience an episode will abstain from sexual contact.

The etiology of stuttering priapism is less clear. Episodes of stuttering priapism often occur during sleep and can resolve spontaneously.8 They are a form of ischemic priapism and are seen in patients with sickle cell anemia. It is not known how many patients with stuttering priapism will convert to the nonremitting form, which may require chemical or surgical intervention.9 Stuttering priapism may go unreported and perhaps may be overlooked by patients based on its frequency and intensity.

The activating selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine has a long half-life and is a potent inhibitor of the cytochrome P450 2D6 isoenzyme system. It inhibits serotonin transporter proteins. It is also a weak norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, an effect that increases with increasing doses of the medication. Its 5HT2C antagonism is proposed as the mechanism of its activating properties.10 In Mr. G’s case, it is possible that fluoxetine’s weak norepinephrine reuptake inhibition resulted in an intermittent priapism effect mediated through the pathways described above.

OUTCOME Symptoms resolve

Approximately 1 week after Mr. G’s fluoxetine dose is reduced, his symptoms of priapism abated. The fluoxetine is discontinued and his ejaculatory delay resolves. Mr. G is started on fluvoxamine, 150 mg/d, which results in a significant decrease of both GAD and OCD symptoms with no notable ejaculatory delay, and no recurrence of priapism.

Continue to: The author's observations

The author’s observations

Mr. G’s case and other case reports suggest that psychiatrists should caution patients who are prescribed antidepressants or antipsychotics that stuttering priapism is a possible adverse effect.11 As seen in Mr. G’s case, fluoxetine (when used chronically) can moderate vascular responses at the pre- and post-synaptic adrenergic receptor.11 Priapism induced by a psychotropic medication will not necessarily lead to a longer-term, unremitting priapism, but it can be dramatic, frightening, and lead to noncompliance. Along with obtaining a standard history that includes asking patients about prior adverse medication events, psychiatrists also should ask their patients if they have experienced any instances of transient priapism that may require further evaluation.

Bottom Line

Any psychotropic medication that has the capacity to act on alpha adrenergic receptors can cause priapism. Ask patients if they have had any unusual erections/ clitoral engorgement while taking any psychotropic medications, because many patients will be hesitant to volunteer such information.

Related Resource

- Thippaiah SM, Nagaraja S, Birur B, et al. Successful management of psychotropics induced stuttering priapism with pseudoephedrine in a patient with schizophrenia. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2018;48(2):29-33.

Drug Brand Names

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Trazodone • Desyrel, Oleptro

1. Kadioglu A, Sanli O, Celtik M, et al. Practical management of patients with priapism. EAU-EBU Update Series. 2006;4(4):150-160.

2. Eland IA, van der Lei J, Stricker BHC. Incidence of priapism in the general population. Urology. 2001;57(5):970-972.

3. Halls JE, Patel DV, Walkden M, et al. Priapism: pathophysiology and the role of the radiologist. Br J Radiol. 2012;85(Spec Iss 1):S79-S85.

4. Wang CS, Kao WT, Chen CD, et al. Priapism associated with typical and atypical antipsychotic medications. Int Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2006;21(4):245-248.

5. Khan Q, Tucker P, Lokhande A. Priapism: what cause: mental illness, psychotropic medications or polysubstance abuse? J Okla State Med Assoc. 2016;109(11):515-517.

6. Dent LA, Brown WC, Murney JD. Citalopram-induced priapism. Pharmacotherapy. 2002;22(4):538-541.

7. Wilkening GL, Kucherer SA, Douaihy AB. Priapism and renal colic in a patient treated with duloxetine. Mental Health Clinician. 2016;6(4):197-200.

8. Morrison BF, Burnett AL. Stuttering priapism: insight into its pathogenesis and management. Curr Urol Rep. 2012;13(4):268-276.

9. Burnett AL, Bivalacqua TJ. Priapism: current principles and practice. Urol Clin North Am. 2007;34(4):631-642.

10. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: neuroscientific basis and practical applications. 4th ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

11. Pereira CA, Rodrigues FL, Ruginsk SG, et al. Chronic treatment with fluoxetine modulates vascular adrenergic responses by inhibition of pre- and post-synaptic mechanisms. Eu J Pharmacol. 2017;800:70-80.

1. Kadioglu A, Sanli O, Celtik M, et al. Practical management of patients with priapism. EAU-EBU Update Series. 2006;4(4):150-160.

2. Eland IA, van der Lei J, Stricker BHC. Incidence of priapism in the general population. Urology. 2001;57(5):970-972.

3. Halls JE, Patel DV, Walkden M, et al. Priapism: pathophysiology and the role of the radiologist. Br J Radiol. 2012;85(Spec Iss 1):S79-S85.

4. Wang CS, Kao WT, Chen CD, et al. Priapism associated with typical and atypical antipsychotic medications. Int Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2006;21(4):245-248.

5. Khan Q, Tucker P, Lokhande A. Priapism: what cause: mental illness, psychotropic medications or polysubstance abuse? J Okla State Med Assoc. 2016;109(11):515-517.

6. Dent LA, Brown WC, Murney JD. Citalopram-induced priapism. Pharmacotherapy. 2002;22(4):538-541.

7. Wilkening GL, Kucherer SA, Douaihy AB. Priapism and renal colic in a patient treated with duloxetine. Mental Health Clinician. 2016;6(4):197-200.

8. Morrison BF, Burnett AL. Stuttering priapism: insight into its pathogenesis and management. Curr Urol Rep. 2012;13(4):268-276.

9. Burnett AL, Bivalacqua TJ. Priapism: current principles and practice. Urol Clin North Am. 2007;34(4):631-642.

10. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: neuroscientific basis and practical applications. 4th ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

11. Pereira CA, Rodrigues FL, Ruginsk SG, et al. Chronic treatment with fluoxetine modulates vascular adrenergic responses by inhibition of pre- and post-synaptic mechanisms. Eu J Pharmacol. 2017;800:70-80.

The boy whose arm wouldn’t work

CASE Drooling, unsteady, and not himself

B, age 10, who is left handed and has autism spectrum disorder, is brought to the emergency department (ED) with a 1-day history of drooling, unsteady gait, and left wrist in sustained flexion. His parents report that for the past week, B has had cold symptoms, including rhinorrhea, a low-grade fever (100.0°F), and cough. Earlier in the day, he was seen at his pediatrician’s office, where he was diagnosed with an acute respiratory infection and started on amoxicillin, 500 mg twice daily for 7 days.

At baseline, B is nonverbal. He requires some assistance with his activities of daily living. He usually is able to walk without assistance and dress himself, but he is not toilet trained. His parents report that in the past day, he has had significant difficulties with tasks involving his left hand. Normally, B is able to feed himself “finger foods” but has been unable to do so today. His parents say that he has been unsteady on his feet, and has been “falling forward” when he tries to walk.

Two years ago, B was started on risperidone, 0.5 mg nightly, for behavioral aggression and self-mutilation. Over the next 12 months, the dosage was steadily increased to 1 mg twice daily, with good response. He has been taking his current dosage, 1 mg twice daily, for the past 12 months without adjustment. His parents report there have been no other medication changes, other than starting amoxicillin earlier that day.

As part of his initial ED evaluation, B is found to be mildly dehydrated, with an elevated sedimentation rate on urinalysis. His complete blood count (CBC) with differential is within normal limits. A comprehensive metabolic panel shows a slight increase in his creatinine level, indicating dehydration. B is administered IV fluid replacement because he is having difficulty drinking due to excessive drooling.

The ED physician is concerned that B may be experiencing an acute dystonic reaction from risperidone, so the team holds this medication, and gives B a one-time dose of IV diphenhydramine, 25 mg, for presumptive acute dystonic reaction. After several minutes, there is no improvement in the sustained flexion of his left wrist.

[polldaddy:10615848]

The authors’ observations

B presented with new-onset neurologic findings after a recently diagnosed upper respiratory viral illness. His symptoms appeared to be confined to his left upper extremity, specifically demonstrating left arm extension at the elbow with flexion of the left wrist. He also had new-onset unsteady gait with a stooped forward posture and required assistance with walking. Interestingly, despite B’s history of antipsychotic use, administering an anticholinergic agent did not lessen the dystonic posturing at his wrist and elbow.

EVALUATION Laboratory results reveal new clues

While in the ED, B undergoes MRI of the brain and spinal cord to rule out any mass lesions that could be impinging upon the motor pathways. Both brain and spinal cord imaging appear to be essentially normal, without evidence of impingement of the spinal nerves or lesions involving the brainstem or cerebellum.

Continue to: Due to concerns...

Due to concerns of possible airway obstruction, a CT scan of the neck is obtained to rule out any acute pathology, such as epiglottitis compromising his airway. The scan shows some inflammation and edema in the soft tissues that is thought to be secondary to his acute viral illness. B is able to maintain his airway and oxygenation, so intubation is not necessary.

A CPK test is ordered because there are concerns of sustained muscle contraction of B’s left wrist and elbow. The CPK level is 884 U/L (reference range 26 to 192 U/L). The elevation in CPK is consistent with prior laboratory findings of dehydration and indicating skeletal muscle breakdown from sustained muscle contraction. All other laboratory results, including a comprehensive metabolic panel, urine drug screen, and thyroid screening panel, are within normal limits.

[polldaddy:10615850]

EVALUATION No variation in facial expression

B is admitted to the general pediatrics service. Maintenance IV fluids are started due to concerns of dehydration and possible rhabdomyolysis due to his elevated CPK level. Risperidone is held throughout the hospital course due to concerns for an acute dystonic reaction. B is monitored for several days without clinical improvement and eventually discharged home with a diagnosis of inflammatory mononeuropathy due to viral infection. The patient is told to discontinue risperidone as part of discharge instructions.

Five days later, B returns to the hospital because there was no improvement in his left extremity or walking. His left elbow remains extended with left wrist in flexion. Psychiatry is consulted for further diagnostic clarity and evaluation.

On physical examination, B’s left arm remains unchanged. Despite discontinuing risperidone, there is evidence of cogwheel rigidity of the left wrist joint. Reflexes in the upper and lower extremities are 2+ and symmetrical bilaterally, suggesting intact upper and lower motor pathways. Babinski sign is absent bilaterally, which is a normal finding in B’s age group. B continues to have difficulty with ambulating and appears to “fall forward” while trying to walk with assistance. His parents also say that B is not laughing, smiling, or showing any variation in facial expression.

Continue to: Additional family history...

Additional family history is gathered from B’s parents for possible hereditary movement disorders such as Wilson’s disease. They report that no family members have developed involuntary movements or other neurologic syndromes. Additional considerations on the differential diagnosis for B include juvenile ALS or mononeuropathy involving the C5 and C6 nerve roots. B’s parents deny any recent shoulder trauma, and radiographic studies did not demonstrate any involvement of the nerve roots.

TREATMENT A trial of bromocriptine

At this point, B’s neurologic workup is essentially normal, and he is given a provisional diagnosis of antipsychotic-induced tardive dystonia vs tardive parkinsonism. Risperidone continues to be held, and B is monitored for clinical improvement. B is administered a one-time dose of diphenhydramine, 25 mg, for dystonia with no improvement in symptoms. He is then started on bromocriptine, 1.25 mg twice daily with meals, for parkinsonian symptoms secondary to antipsychotic medication use. After 1 day of treatment, B shows less sustained flexion of his left wrist. He is able to relax his left arm, shows improvements in ambulation, and requires less assistance. B continues to be observed closely and continues to improve toward his baseline.

At Day 4, he is discharged. B is able to walk mostly without assistance and demonstrates improvement in left wrist flexion. He is scheduled to see a movement disorders specialist a week after discharge. The initial diagnosis given by the movement disorder specialist is tardive dystonia.

The authors’ observations

Tardive dyskinesia is a well-known iatrogenic effect of antipsychotic medications that are commonly used to manage conditions such as schizophrenia or behavioral agitation associated with autism spectrum disorder. Symptoms of tardive dyskinesia typically emerge after 1 to 2 years of continuous exposure to dopamine receptor blocking agents (DRBAs). Tardive dyskinesia symptoms include involuntary, repetitive, purposeless movements of the tongue, jaw, lips, face, trunk, and upper and lower extremities, with significant functional impairment.1

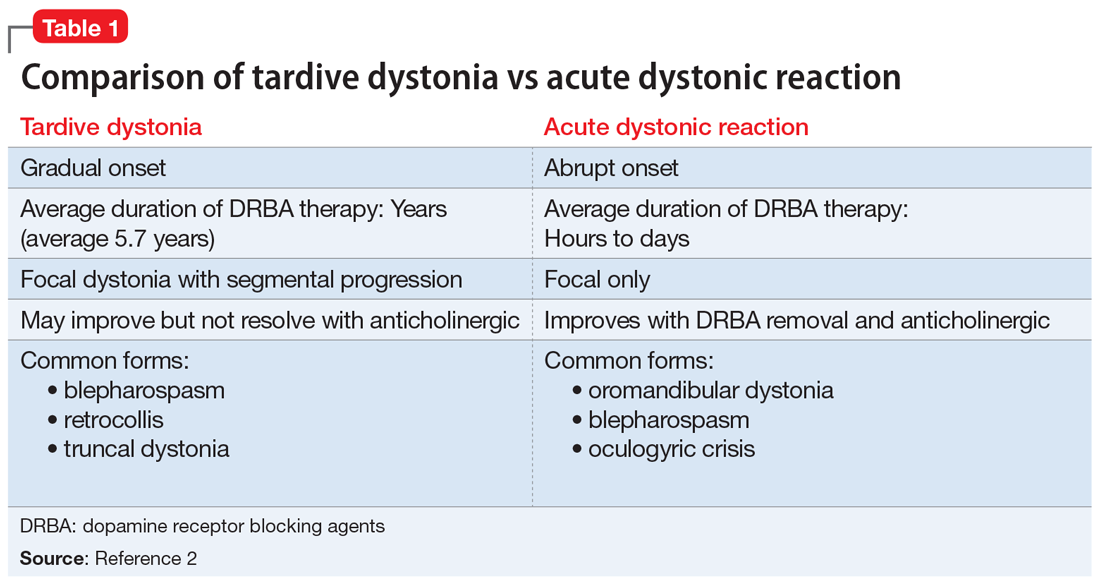

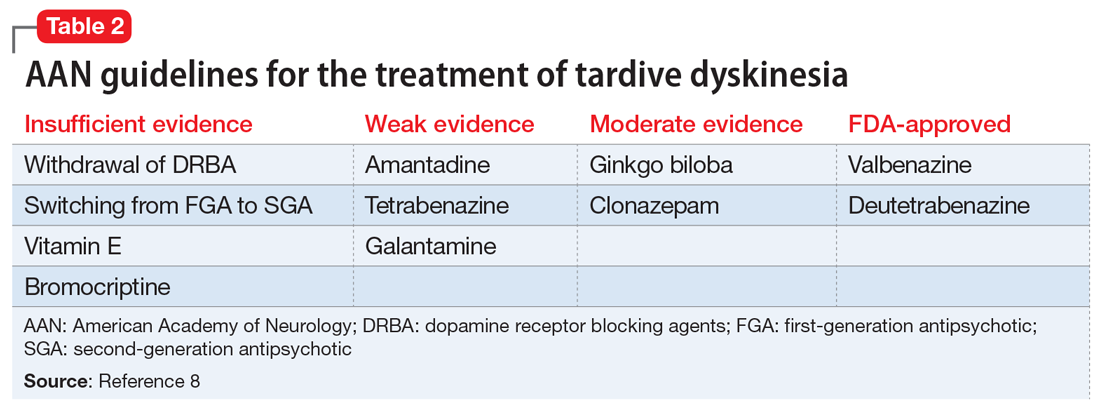

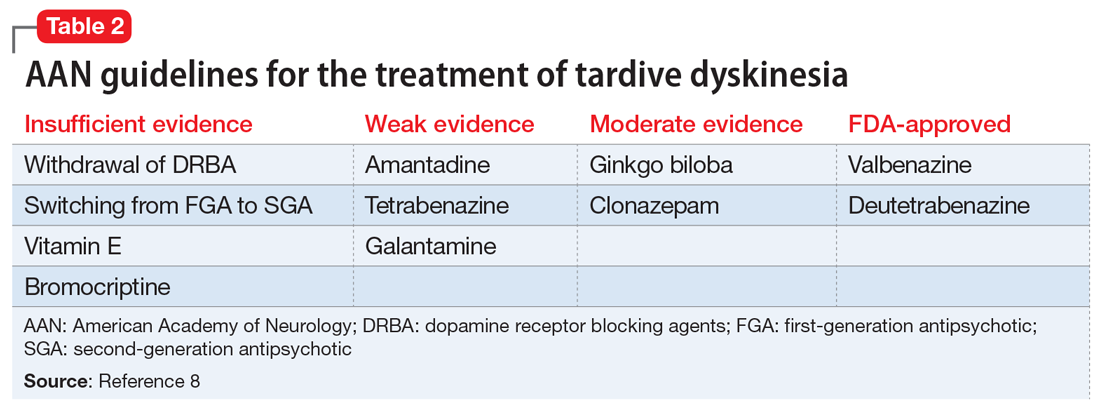

Tardive syndromes refer to a diverse array of hyperkinetic, hypokinetic, and sensory movement disorders resulting from at least 3 months of continuous DRBA therapy.2 Tardive dyskinesia is perhaps the most well-known of the tardive syndromes, but is not the only one to consider when assessing for antipsychotic-induced movement disorders. A key feature differentiating a tardive syndrome is the persistence of the movement disorder after the DRBA is discontinued. In this case, B had been receiving a stable dose of risperidone for >1 year. He developed dystonic posturing of his left wrist and elbow that was both unresponsive to anticholinergic medication and persisted after risperidone was discontinued. The term “tardive” emphasizes the delay in development of abnormal involuntary movement symptoms after initiating antipsychotic medications.3 Table 12 shows a comparison of tardive dystonia vs an acute dystonic reaction.

Continue to: Other tardive syndromes include...

Other tardive syndromes include:

- tardive tics

- tardive parkinsonism

- tardive pain

- tardive myoclonus

- tardive akathisia

- tardive tremors.

The incidence of tardive syndromes increases 5% annually for the first 5 years of treatment. At 10 years of treatment, the annual incidence is thought to be 49%, and at 25 years of treatment, 68%.4 The predominant theory of the pathophysiology of tardive syndromes is that the chronic use of DRBAs causes a gradual hypersensitization of dopamine receptors.4 The diagnosis of a tardive syndrome is based on history of exposure to a DRBA as well as clinical observation of symptoms.

Compared with classic tardive dyskinesia, tardive dystonia is more common among younger patients. The mean age of onset of tardive dystonia is 40, and it typically affects young males.5 Typical posturing observed in cases of tardive dystonia include extension of the arms and flexion at the wrists.6 In contrast to cases of primary dystonia, tardive dystonia is typically associated with stereotypies, akathisia, or other movement disorders. Anticholinergic agents, such as

The American Psychiatric Association has issued guidelines on screening for involuntary movement syndromes by using the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS).7 The current recommendations include assessment every 6 months for patients receiving first-generation antipsychotics, and every 12 months for those receiving second-generation antipsychotics.7 Prescribers should also carefully assess for any pre-existing involuntary movements before prescribing a DRBA.7

[polldaddy:10615855]

The authors’ observations

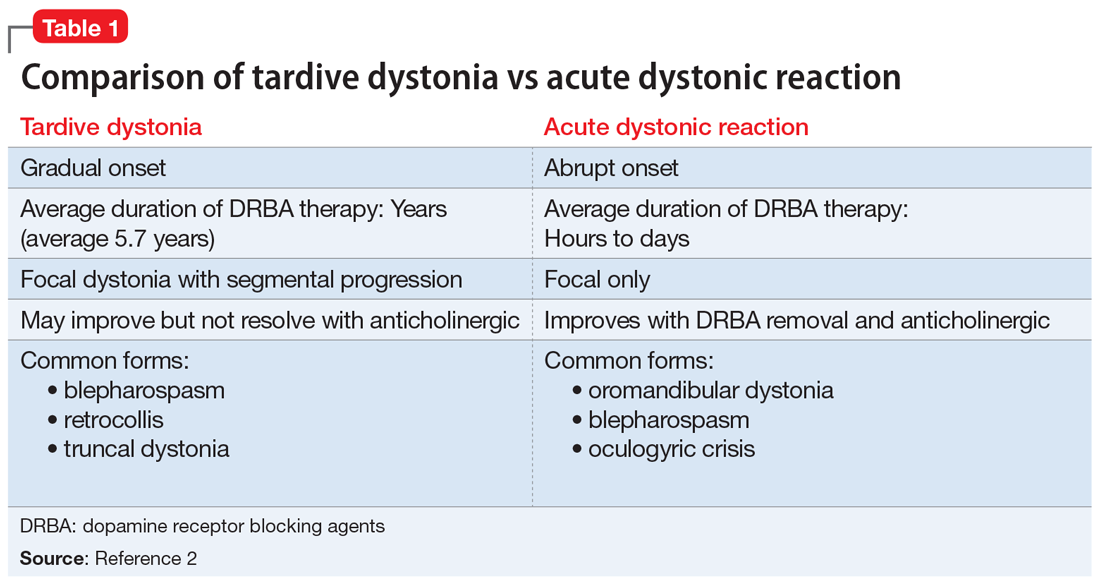

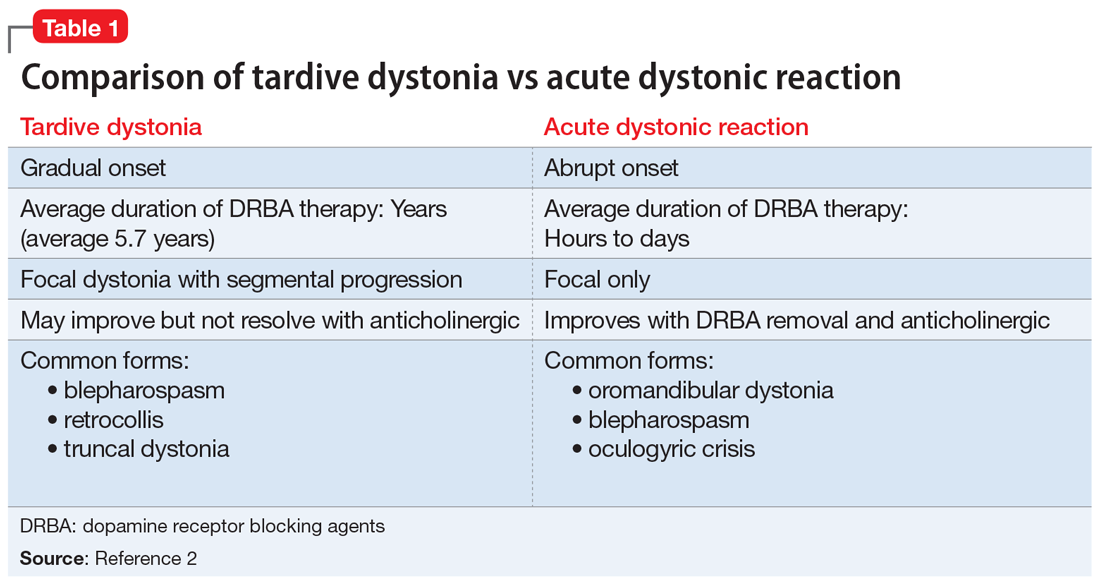

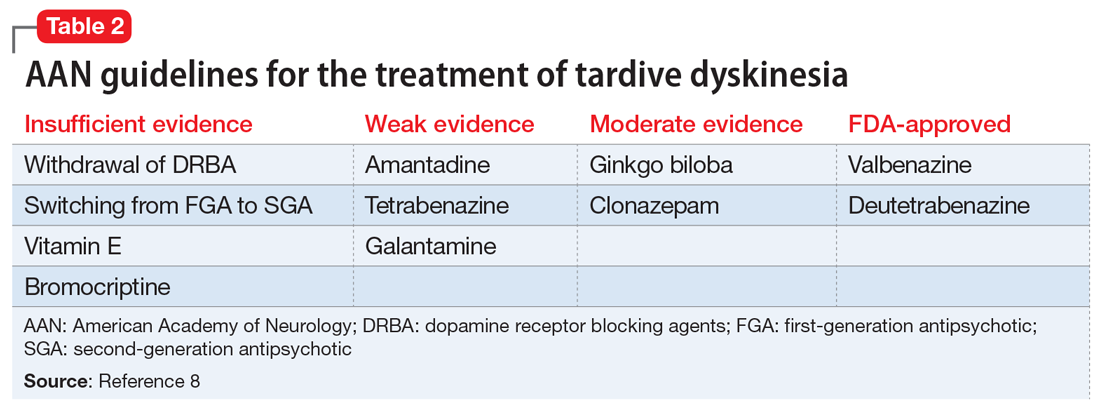

In 2013, the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) published guidelines on the treatment of tardive dyskinesia. According to these guidelines, at that time, the treatments with the most evidence supporting their use were clonazepam, ginkgo biloba,

Continue to: In 2017, valbenazine and deutetrabenazine...

In 2017, valbenazine and deutetrabenazine became the first FDA-approved treatments for tardive dyskinesia in adults. Both medications block the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) system, which results in decreased synaptic dopamine and dopamine receptor stimulation. Both VMAT2 inhibitor medications have a category level A supporting their use for treating tardive dyskinesia.8-10

Currently, there are no published treatment guidelines on pharmacologic management of tardive dystonia. In B’s case, bromocriptine, a dopamine agonist, was used to counter the dopamine-blocking effects of risperidone on the nigrostriatal pathway and improve parkinsonian features of B’s presentation, including bradykinesia, stooped forward posture, and masked facies. Bromocriptine was found to be effective in alleviating parkinsonian features; however, to date there is no evidence demonstrating its effectiveness in countering delayed dystonic effects of DRBAs.

OUTCOME Improvement of dystonia symptoms

One week after discharge, B is seen for a follow-up visit. He continues taking bromocriptine, 1.25 mg twice daily, with meals after discharge. On examination, he has some evidence of tardive dystonia, including flexion of left wrist and posturing while ambulating. B’s parkinsonian features, including stooped forward posture, masked facies, and cogwheel rigidity of the left wrist muscle, have resolved. B is now able to walk on his own without unsteadiness. Bromocriptine is discontinued after 1 month, and his symptoms of dystonia continue to improve.

Two months after hospitalization, B is started on quetiapine, 25 mg twice daily, for behavioral aggression. Quetiapine is chosen because it has a lower dopamine receptor affinity compared with risperidone, and theoretically, quetiapine is associated with a lower risk of developing tardive symptoms. During the next 6 months, B is monitored closely for recurrence of tardive symptoms. Quetiapine is slowly titrated to 25 mg in the morning, and 50 mg at bedtime. His behavioral agitation improves significantly and he does not have a recurrence of tardive symptoms.

Bottom Line

Tardive dystonia is a possible iatrogenic adverse effect for patients receiving long-term dopamine receptor blocking agent (DRBA) therapy. Tardive syndromes encompass delayed-onset movement disorders caused by long-term blockade of the dopamine receptor by antipsychotic agents. Tardive dystonia can be contrasted from acute dystonic reaction based on the time course of development as well as by the persistence of symptoms after DRBAs are withheld.

Continue to: Related Resources

Related Resources

- American Academy of Neurology. Summary of evidence-based guideline for clinicians: treatment of tardive syndromes. https://www.aan.com/Guidelines/Home/GetGuidelineContent/613. Published 2013.

- Dystonia Medical Research Foundation. https://dystonia-foundation.org/.

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Gocovri, Symmetrel

Amoxicillin • Amoxil

Baclofen • Kemstro, Liroesal

Benztropine • Cogentin

Bromocriptine • Parlodel

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Deutetrabenazine • Austedo

Galantamine • Razadyne

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Tetrabenazine • Xenazine

Trihexyphenidyl • Artane, Tremin

Valbenazine • Ingrezza

1. Margolese HC, Chouinard G, Kolivakis TT, et al. Tardive dyskinesia in the era of typical and atypical antipsychotics. Part 1: pathophysiology and mechanisms of induction. Can J Psychiatr. 2005;50(9):541-547.

2. Truong D, Frei K. Setting the record straight: the nosology of tardive syndromes. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2019;59:146-150.

3. Cornett EM, Novitch M, Kaye AD, et al. Medication-induced tardive dyskinesia: a review and update. Ochsner J. 2017;17(2):162-174.

4. Schooler NR, Kane JM. Research diagnoses for tardive dyskinesia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39(4):486-487.

5. Fahn S, Jankovic J, Hallett M. Principles and Practice of Movement Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2011:415-446.

6. Kang UJ, Burke RE, Fahn S. Natural history and treatment of tardive dystonia. Mov Disord. 1986;1(3):193-208.

7. Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(suppl 2):1-56.

8. Bhidayasiri R, Fahn S, Weiner WJ, et al, Evidence-based guideline: treatment of tardive syndromes: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2013;81(5):463-469.

9. Ingrezza [package insert]. San Diego, CA: Neurocrine Biosciences, Inc.; 2020.

10. Austedo [package insert]. North Wales, PA: Teva Pharmaceuticals; 2017.

CASE Drooling, unsteady, and not himself

B, age 10, who is left handed and has autism spectrum disorder, is brought to the emergency department (ED) with a 1-day history of drooling, unsteady gait, and left wrist in sustained flexion. His parents report that for the past week, B has had cold symptoms, including rhinorrhea, a low-grade fever (100.0°F), and cough. Earlier in the day, he was seen at his pediatrician’s office, where he was diagnosed with an acute respiratory infection and started on amoxicillin, 500 mg twice daily for 7 days.

At baseline, B is nonverbal. He requires some assistance with his activities of daily living. He usually is able to walk without assistance and dress himself, but he is not toilet trained. His parents report that in the past day, he has had significant difficulties with tasks involving his left hand. Normally, B is able to feed himself “finger foods” but has been unable to do so today. His parents say that he has been unsteady on his feet, and has been “falling forward” when he tries to walk.

Two years ago, B was started on risperidone, 0.5 mg nightly, for behavioral aggression and self-mutilation. Over the next 12 months, the dosage was steadily increased to 1 mg twice daily, with good response. He has been taking his current dosage, 1 mg twice daily, for the past 12 months without adjustment. His parents report there have been no other medication changes, other than starting amoxicillin earlier that day.

As part of his initial ED evaluation, B is found to be mildly dehydrated, with an elevated sedimentation rate on urinalysis. His complete blood count (CBC) with differential is within normal limits. A comprehensive metabolic panel shows a slight increase in his creatinine level, indicating dehydration. B is administered IV fluid replacement because he is having difficulty drinking due to excessive drooling.

The ED physician is concerned that B may be experiencing an acute dystonic reaction from risperidone, so the team holds this medication, and gives B a one-time dose of IV diphenhydramine, 25 mg, for presumptive acute dystonic reaction. After several minutes, there is no improvement in the sustained flexion of his left wrist.

[polldaddy:10615848]

The authors’ observations

B presented with new-onset neurologic findings after a recently diagnosed upper respiratory viral illness. His symptoms appeared to be confined to his left upper extremity, specifically demonstrating left arm extension at the elbow with flexion of the left wrist. He also had new-onset unsteady gait with a stooped forward posture and required assistance with walking. Interestingly, despite B’s history of antipsychotic use, administering an anticholinergic agent did not lessen the dystonic posturing at his wrist and elbow.

EVALUATION Laboratory results reveal new clues

While in the ED, B undergoes MRI of the brain and spinal cord to rule out any mass lesions that could be impinging upon the motor pathways. Both brain and spinal cord imaging appear to be essentially normal, without evidence of impingement of the spinal nerves or lesions involving the brainstem or cerebellum.

Continue to: Due to concerns...

Due to concerns of possible airway obstruction, a CT scan of the neck is obtained to rule out any acute pathology, such as epiglottitis compromising his airway. The scan shows some inflammation and edema in the soft tissues that is thought to be secondary to his acute viral illness. B is able to maintain his airway and oxygenation, so intubation is not necessary.

A CPK test is ordered because there are concerns of sustained muscle contraction of B’s left wrist and elbow. The CPK level is 884 U/L (reference range 26 to 192 U/L). The elevation in CPK is consistent with prior laboratory findings of dehydration and indicating skeletal muscle breakdown from sustained muscle contraction. All other laboratory results, including a comprehensive metabolic panel, urine drug screen, and thyroid screening panel, are within normal limits.

[polldaddy:10615850]

EVALUATION No variation in facial expression

B is admitted to the general pediatrics service. Maintenance IV fluids are started due to concerns of dehydration and possible rhabdomyolysis due to his elevated CPK level. Risperidone is held throughout the hospital course due to concerns for an acute dystonic reaction. B is monitored for several days without clinical improvement and eventually discharged home with a diagnosis of inflammatory mononeuropathy due to viral infection. The patient is told to discontinue risperidone as part of discharge instructions.

Five days later, B returns to the hospital because there was no improvement in his left extremity or walking. His left elbow remains extended with left wrist in flexion. Psychiatry is consulted for further diagnostic clarity and evaluation.

On physical examination, B’s left arm remains unchanged. Despite discontinuing risperidone, there is evidence of cogwheel rigidity of the left wrist joint. Reflexes in the upper and lower extremities are 2+ and symmetrical bilaterally, suggesting intact upper and lower motor pathways. Babinski sign is absent bilaterally, which is a normal finding in B’s age group. B continues to have difficulty with ambulating and appears to “fall forward” while trying to walk with assistance. His parents also say that B is not laughing, smiling, or showing any variation in facial expression.

Continue to: Additional family history...

Additional family history is gathered from B’s parents for possible hereditary movement disorders such as Wilson’s disease. They report that no family members have developed involuntary movements or other neurologic syndromes. Additional considerations on the differential diagnosis for B include juvenile ALS or mononeuropathy involving the C5 and C6 nerve roots. B’s parents deny any recent shoulder trauma, and radiographic studies did not demonstrate any involvement of the nerve roots.

TREATMENT A trial of bromocriptine

At this point, B’s neurologic workup is essentially normal, and he is given a provisional diagnosis of antipsychotic-induced tardive dystonia vs tardive parkinsonism. Risperidone continues to be held, and B is monitored for clinical improvement. B is administered a one-time dose of diphenhydramine, 25 mg, for dystonia with no improvement in symptoms. He is then started on bromocriptine, 1.25 mg twice daily with meals, for parkinsonian symptoms secondary to antipsychotic medication use. After 1 day of treatment, B shows less sustained flexion of his left wrist. He is able to relax his left arm, shows improvements in ambulation, and requires less assistance. B continues to be observed closely and continues to improve toward his baseline.

At Day 4, he is discharged. B is able to walk mostly without assistance and demonstrates improvement in left wrist flexion. He is scheduled to see a movement disorders specialist a week after discharge. The initial diagnosis given by the movement disorder specialist is tardive dystonia.

The authors’ observations

Tardive dyskinesia is a well-known iatrogenic effect of antipsychotic medications that are commonly used to manage conditions such as schizophrenia or behavioral agitation associated with autism spectrum disorder. Symptoms of tardive dyskinesia typically emerge after 1 to 2 years of continuous exposure to dopamine receptor blocking agents (DRBAs). Tardive dyskinesia symptoms include involuntary, repetitive, purposeless movements of the tongue, jaw, lips, face, trunk, and upper and lower extremities, with significant functional impairment.1

Tardive syndromes refer to a diverse array of hyperkinetic, hypokinetic, and sensory movement disorders resulting from at least 3 months of continuous DRBA therapy.2 Tardive dyskinesia is perhaps the most well-known of the tardive syndromes, but is not the only one to consider when assessing for antipsychotic-induced movement disorders. A key feature differentiating a tardive syndrome is the persistence of the movement disorder after the DRBA is discontinued. In this case, B had been receiving a stable dose of risperidone for >1 year. He developed dystonic posturing of his left wrist and elbow that was both unresponsive to anticholinergic medication and persisted after risperidone was discontinued. The term “tardive” emphasizes the delay in development of abnormal involuntary movement symptoms after initiating antipsychotic medications.3 Table 12 shows a comparison of tardive dystonia vs an acute dystonic reaction.

Continue to: Other tardive syndromes include...

Other tardive syndromes include:

- tardive tics

- tardive parkinsonism

- tardive pain

- tardive myoclonus

- tardive akathisia

- tardive tremors.

The incidence of tardive syndromes increases 5% annually for the first 5 years of treatment. At 10 years of treatment, the annual incidence is thought to be 49%, and at 25 years of treatment, 68%.4 The predominant theory of the pathophysiology of tardive syndromes is that the chronic use of DRBAs causes a gradual hypersensitization of dopamine receptors.4 The diagnosis of a tardive syndrome is based on history of exposure to a DRBA as well as clinical observation of symptoms.

Compared with classic tardive dyskinesia, tardive dystonia is more common among younger patients. The mean age of onset of tardive dystonia is 40, and it typically affects young males.5 Typical posturing observed in cases of tardive dystonia include extension of the arms and flexion at the wrists.6 In contrast to cases of primary dystonia, tardive dystonia is typically associated with stereotypies, akathisia, or other movement disorders. Anticholinergic agents, such as

The American Psychiatric Association has issued guidelines on screening for involuntary movement syndromes by using the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS).7 The current recommendations include assessment every 6 months for patients receiving first-generation antipsychotics, and every 12 months for those receiving second-generation antipsychotics.7 Prescribers should also carefully assess for any pre-existing involuntary movements before prescribing a DRBA.7

[polldaddy:10615855]

The authors’ observations

In 2013, the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) published guidelines on the treatment of tardive dyskinesia. According to these guidelines, at that time, the treatments with the most evidence supporting their use were clonazepam, ginkgo biloba,

Continue to: In 2017, valbenazine and deutetrabenazine...

In 2017, valbenazine and deutetrabenazine became the first FDA-approved treatments for tardive dyskinesia in adults. Both medications block the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) system, which results in decreased synaptic dopamine and dopamine receptor stimulation. Both VMAT2 inhibitor medications have a category level A supporting their use for treating tardive dyskinesia.8-10

Currently, there are no published treatment guidelines on pharmacologic management of tardive dystonia. In B’s case, bromocriptine, a dopamine agonist, was used to counter the dopamine-blocking effects of risperidone on the nigrostriatal pathway and improve parkinsonian features of B’s presentation, including bradykinesia, stooped forward posture, and masked facies. Bromocriptine was found to be effective in alleviating parkinsonian features; however, to date there is no evidence demonstrating its effectiveness in countering delayed dystonic effects of DRBAs.

OUTCOME Improvement of dystonia symptoms

One week after discharge, B is seen for a follow-up visit. He continues taking bromocriptine, 1.25 mg twice daily, with meals after discharge. On examination, he has some evidence of tardive dystonia, including flexion of left wrist and posturing while ambulating. B’s parkinsonian features, including stooped forward posture, masked facies, and cogwheel rigidity of the left wrist muscle, have resolved. B is now able to walk on his own without unsteadiness. Bromocriptine is discontinued after 1 month, and his symptoms of dystonia continue to improve.

Two months after hospitalization, B is started on quetiapine, 25 mg twice daily, for behavioral aggression. Quetiapine is chosen because it has a lower dopamine receptor affinity compared with risperidone, and theoretically, quetiapine is associated with a lower risk of developing tardive symptoms. During the next 6 months, B is monitored closely for recurrence of tardive symptoms. Quetiapine is slowly titrated to 25 mg in the morning, and 50 mg at bedtime. His behavioral agitation improves significantly and he does not have a recurrence of tardive symptoms.

Bottom Line

Tardive dystonia is a possible iatrogenic adverse effect for patients receiving long-term dopamine receptor blocking agent (DRBA) therapy. Tardive syndromes encompass delayed-onset movement disorders caused by long-term blockade of the dopamine receptor by antipsychotic agents. Tardive dystonia can be contrasted from acute dystonic reaction based on the time course of development as well as by the persistence of symptoms after DRBAs are withheld.

Continue to: Related Resources

Related Resources

- American Academy of Neurology. Summary of evidence-based guideline for clinicians: treatment of tardive syndromes. https://www.aan.com/Guidelines/Home/GetGuidelineContent/613. Published 2013.

- Dystonia Medical Research Foundation. https://dystonia-foundation.org/.

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Gocovri, Symmetrel

Amoxicillin • Amoxil

Baclofen • Kemstro, Liroesal

Benztropine • Cogentin

Bromocriptine • Parlodel

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Deutetrabenazine • Austedo

Galantamine • Razadyne

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Tetrabenazine • Xenazine

Trihexyphenidyl • Artane, Tremin

Valbenazine • Ingrezza

CASE Drooling, unsteady, and not himself

B, age 10, who is left handed and has autism spectrum disorder, is brought to the emergency department (ED) with a 1-day history of drooling, unsteady gait, and left wrist in sustained flexion. His parents report that for the past week, B has had cold symptoms, including rhinorrhea, a low-grade fever (100.0°F), and cough. Earlier in the day, he was seen at his pediatrician’s office, where he was diagnosed with an acute respiratory infection and started on amoxicillin, 500 mg twice daily for 7 days.

At baseline, B is nonverbal. He requires some assistance with his activities of daily living. He usually is able to walk without assistance and dress himself, but he is not toilet trained. His parents report that in the past day, he has had significant difficulties with tasks involving his left hand. Normally, B is able to feed himself “finger foods” but has been unable to do so today. His parents say that he has been unsteady on his feet, and has been “falling forward” when he tries to walk.

Two years ago, B was started on risperidone, 0.5 mg nightly, for behavioral aggression and self-mutilation. Over the next 12 months, the dosage was steadily increased to 1 mg twice daily, with good response. He has been taking his current dosage, 1 mg twice daily, for the past 12 months without adjustment. His parents report there have been no other medication changes, other than starting amoxicillin earlier that day.

As part of his initial ED evaluation, B is found to be mildly dehydrated, with an elevated sedimentation rate on urinalysis. His complete blood count (CBC) with differential is within normal limits. A comprehensive metabolic panel shows a slight increase in his creatinine level, indicating dehydration. B is administered IV fluid replacement because he is having difficulty drinking due to excessive drooling.

The ED physician is concerned that B may be experiencing an acute dystonic reaction from risperidone, so the team holds this medication, and gives B a one-time dose of IV diphenhydramine, 25 mg, for presumptive acute dystonic reaction. After several minutes, there is no improvement in the sustained flexion of his left wrist.

[polldaddy:10615848]

The authors’ observations

B presented with new-onset neurologic findings after a recently diagnosed upper respiratory viral illness. His symptoms appeared to be confined to his left upper extremity, specifically demonstrating left arm extension at the elbow with flexion of the left wrist. He also had new-onset unsteady gait with a stooped forward posture and required assistance with walking. Interestingly, despite B’s history of antipsychotic use, administering an anticholinergic agent did not lessen the dystonic posturing at his wrist and elbow.

EVALUATION Laboratory results reveal new clues

While in the ED, B undergoes MRI of the brain and spinal cord to rule out any mass lesions that could be impinging upon the motor pathways. Both brain and spinal cord imaging appear to be essentially normal, without evidence of impingement of the spinal nerves or lesions involving the brainstem or cerebellum.

Continue to: Due to concerns...

Due to concerns of possible airway obstruction, a CT scan of the neck is obtained to rule out any acute pathology, such as epiglottitis compromising his airway. The scan shows some inflammation and edema in the soft tissues that is thought to be secondary to his acute viral illness. B is able to maintain his airway and oxygenation, so intubation is not necessary.

A CPK test is ordered because there are concerns of sustained muscle contraction of B’s left wrist and elbow. The CPK level is 884 U/L (reference range 26 to 192 U/L). The elevation in CPK is consistent with prior laboratory findings of dehydration and indicating skeletal muscle breakdown from sustained muscle contraction. All other laboratory results, including a comprehensive metabolic panel, urine drug screen, and thyroid screening panel, are within normal limits.

[polldaddy:10615850]

EVALUATION No variation in facial expression

B is admitted to the general pediatrics service. Maintenance IV fluids are started due to concerns of dehydration and possible rhabdomyolysis due to his elevated CPK level. Risperidone is held throughout the hospital course due to concerns for an acute dystonic reaction. B is monitored for several days without clinical improvement and eventually discharged home with a diagnosis of inflammatory mononeuropathy due to viral infection. The patient is told to discontinue risperidone as part of discharge instructions.

Five days later, B returns to the hospital because there was no improvement in his left extremity or walking. His left elbow remains extended with left wrist in flexion. Psychiatry is consulted for further diagnostic clarity and evaluation.

On physical examination, B’s left arm remains unchanged. Despite discontinuing risperidone, there is evidence of cogwheel rigidity of the left wrist joint. Reflexes in the upper and lower extremities are 2+ and symmetrical bilaterally, suggesting intact upper and lower motor pathways. Babinski sign is absent bilaterally, which is a normal finding in B’s age group. B continues to have difficulty with ambulating and appears to “fall forward” while trying to walk with assistance. His parents also say that B is not laughing, smiling, or showing any variation in facial expression.

Continue to: Additional family history...

Additional family history is gathered from B’s parents for possible hereditary movement disorders such as Wilson’s disease. They report that no family members have developed involuntary movements or other neurologic syndromes. Additional considerations on the differential diagnosis for B include juvenile ALS or mononeuropathy involving the C5 and C6 nerve roots. B’s parents deny any recent shoulder trauma, and radiographic studies did not demonstrate any involvement of the nerve roots.

TREATMENT A trial of bromocriptine

At this point, B’s neurologic workup is essentially normal, and he is given a provisional diagnosis of antipsychotic-induced tardive dystonia vs tardive parkinsonism. Risperidone continues to be held, and B is monitored for clinical improvement. B is administered a one-time dose of diphenhydramine, 25 mg, for dystonia with no improvement in symptoms. He is then started on bromocriptine, 1.25 mg twice daily with meals, for parkinsonian symptoms secondary to antipsychotic medication use. After 1 day of treatment, B shows less sustained flexion of his left wrist. He is able to relax his left arm, shows improvements in ambulation, and requires less assistance. B continues to be observed closely and continues to improve toward his baseline.

At Day 4, he is discharged. B is able to walk mostly without assistance and demonstrates improvement in left wrist flexion. He is scheduled to see a movement disorders specialist a week after discharge. The initial diagnosis given by the movement disorder specialist is tardive dystonia.

The authors’ observations

Tardive dyskinesia is a well-known iatrogenic effect of antipsychotic medications that are commonly used to manage conditions such as schizophrenia or behavioral agitation associated with autism spectrum disorder. Symptoms of tardive dyskinesia typically emerge after 1 to 2 years of continuous exposure to dopamine receptor blocking agents (DRBAs). Tardive dyskinesia symptoms include involuntary, repetitive, purposeless movements of the tongue, jaw, lips, face, trunk, and upper and lower extremities, with significant functional impairment.1

Tardive syndromes refer to a diverse array of hyperkinetic, hypokinetic, and sensory movement disorders resulting from at least 3 months of continuous DRBA therapy.2 Tardive dyskinesia is perhaps the most well-known of the tardive syndromes, but is not the only one to consider when assessing for antipsychotic-induced movement disorders. A key feature differentiating a tardive syndrome is the persistence of the movement disorder after the DRBA is discontinued. In this case, B had been receiving a stable dose of risperidone for >1 year. He developed dystonic posturing of his left wrist and elbow that was both unresponsive to anticholinergic medication and persisted after risperidone was discontinued. The term “tardive” emphasizes the delay in development of abnormal involuntary movement symptoms after initiating antipsychotic medications.3 Table 12 shows a comparison of tardive dystonia vs an acute dystonic reaction.

Continue to: Other tardive syndromes include...

Other tardive syndromes include:

- tardive tics

- tardive parkinsonism

- tardive pain

- tardive myoclonus

- tardive akathisia

- tardive tremors.

The incidence of tardive syndromes increases 5% annually for the first 5 years of treatment. At 10 years of treatment, the annual incidence is thought to be 49%, and at 25 years of treatment, 68%.4 The predominant theory of the pathophysiology of tardive syndromes is that the chronic use of DRBAs causes a gradual hypersensitization of dopamine receptors.4 The diagnosis of a tardive syndrome is based on history of exposure to a DRBA as well as clinical observation of symptoms.

Compared with classic tardive dyskinesia, tardive dystonia is more common among younger patients. The mean age of onset of tardive dystonia is 40, and it typically affects young males.5 Typical posturing observed in cases of tardive dystonia include extension of the arms and flexion at the wrists.6 In contrast to cases of primary dystonia, tardive dystonia is typically associated with stereotypies, akathisia, or other movement disorders. Anticholinergic agents, such as

The American Psychiatric Association has issued guidelines on screening for involuntary movement syndromes by using the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS).7 The current recommendations include assessment every 6 months for patients receiving first-generation antipsychotics, and every 12 months for those receiving second-generation antipsychotics.7 Prescribers should also carefully assess for any pre-existing involuntary movements before prescribing a DRBA.7

[polldaddy:10615855]

The authors’ observations

In 2013, the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) published guidelines on the treatment of tardive dyskinesia. According to these guidelines, at that time, the treatments with the most evidence supporting their use were clonazepam, ginkgo biloba,

Continue to: In 2017, valbenazine and deutetrabenazine...

In 2017, valbenazine and deutetrabenazine became the first FDA-approved treatments for tardive dyskinesia in adults. Both medications block the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) system, which results in decreased synaptic dopamine and dopamine receptor stimulation. Both VMAT2 inhibitor medications have a category level A supporting their use for treating tardive dyskinesia.8-10

Currently, there are no published treatment guidelines on pharmacologic management of tardive dystonia. In B’s case, bromocriptine, a dopamine agonist, was used to counter the dopamine-blocking effects of risperidone on the nigrostriatal pathway and improve parkinsonian features of B’s presentation, including bradykinesia, stooped forward posture, and masked facies. Bromocriptine was found to be effective in alleviating parkinsonian features; however, to date there is no evidence demonstrating its effectiveness in countering delayed dystonic effects of DRBAs.

OUTCOME Improvement of dystonia symptoms

One week after discharge, B is seen for a follow-up visit. He continues taking bromocriptine, 1.25 mg twice daily, with meals after discharge. On examination, he has some evidence of tardive dystonia, including flexion of left wrist and posturing while ambulating. B’s parkinsonian features, including stooped forward posture, masked facies, and cogwheel rigidity of the left wrist muscle, have resolved. B is now able to walk on his own without unsteadiness. Bromocriptine is discontinued after 1 month, and his symptoms of dystonia continue to improve.

Two months after hospitalization, B is started on quetiapine, 25 mg twice daily, for behavioral aggression. Quetiapine is chosen because it has a lower dopamine receptor affinity compared with risperidone, and theoretically, quetiapine is associated with a lower risk of developing tardive symptoms. During the next 6 months, B is monitored closely for recurrence of tardive symptoms. Quetiapine is slowly titrated to 25 mg in the morning, and 50 mg at bedtime. His behavioral agitation improves significantly and he does not have a recurrence of tardive symptoms.

Bottom Line

Tardive dystonia is a possible iatrogenic adverse effect for patients receiving long-term dopamine receptor blocking agent (DRBA) therapy. Tardive syndromes encompass delayed-onset movement disorders caused by long-term blockade of the dopamine receptor by antipsychotic agents. Tardive dystonia can be contrasted from acute dystonic reaction based on the time course of development as well as by the persistence of symptoms after DRBAs are withheld.

Continue to: Related Resources

Related Resources

- American Academy of Neurology. Summary of evidence-based guideline for clinicians: treatment of tardive syndromes. https://www.aan.com/Guidelines/Home/GetGuidelineContent/613. Published 2013.

- Dystonia Medical Research Foundation. https://dystonia-foundation.org/.

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Gocovri, Symmetrel

Amoxicillin • Amoxil

Baclofen • Kemstro, Liroesal

Benztropine • Cogentin

Bromocriptine • Parlodel

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Deutetrabenazine • Austedo

Galantamine • Razadyne

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Tetrabenazine • Xenazine

Trihexyphenidyl • Artane, Tremin

Valbenazine • Ingrezza

1. Margolese HC, Chouinard G, Kolivakis TT, et al. Tardive dyskinesia in the era of typical and atypical antipsychotics. Part 1: pathophysiology and mechanisms of induction. Can J Psychiatr. 2005;50(9):541-547.

2. Truong D, Frei K. Setting the record straight: the nosology of tardive syndromes. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2019;59:146-150.

3. Cornett EM, Novitch M, Kaye AD, et al. Medication-induced tardive dyskinesia: a review and update. Ochsner J. 2017;17(2):162-174.

4. Schooler NR, Kane JM. Research diagnoses for tardive dyskinesia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39(4):486-487.

5. Fahn S, Jankovic J, Hallett M. Principles and Practice of Movement Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2011:415-446.

6. Kang UJ, Burke RE, Fahn S. Natural history and treatment of tardive dystonia. Mov Disord. 1986;1(3):193-208.

7. Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(suppl 2):1-56.

8. Bhidayasiri R, Fahn S, Weiner WJ, et al, Evidence-based guideline: treatment of tardive syndromes: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2013;81(5):463-469.

9. Ingrezza [package insert]. San Diego, CA: Neurocrine Biosciences, Inc.; 2020.

10. Austedo [package insert]. North Wales, PA: Teva Pharmaceuticals; 2017.

1. Margolese HC, Chouinard G, Kolivakis TT, et al. Tardive dyskinesia in the era of typical and atypical antipsychotics. Part 1: pathophysiology and mechanisms of induction. Can J Psychiatr. 2005;50(9):541-547.

2. Truong D, Frei K. Setting the record straight: the nosology of tardive syndromes. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2019;59:146-150.

3. Cornett EM, Novitch M, Kaye AD, et al. Medication-induced tardive dyskinesia: a review and update. Ochsner J. 2017;17(2):162-174.

4. Schooler NR, Kane JM. Research diagnoses for tardive dyskinesia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39(4):486-487.

5. Fahn S, Jankovic J, Hallett M. Principles and Practice of Movement Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2011:415-446.

6. Kang UJ, Burke RE, Fahn S. Natural history and treatment of tardive dystonia. Mov Disord. 1986;1(3):193-208.

7. Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(suppl 2):1-56.

8. Bhidayasiri R, Fahn S, Weiner WJ, et al, Evidence-based guideline: treatment of tardive syndromes: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2013;81(5):463-469.

9. Ingrezza [package insert]. San Diego, CA: Neurocrine Biosciences, Inc.; 2020.

10. Austedo [package insert]. North Wales, PA: Teva Pharmaceuticals; 2017.

Obsessions or psychosis?

CASE Perseverating on nonexistent sexual assaults

Mr. R, age 17, who has been diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), presents to the emergency department (ED) because he thinks that he is being sexually assaulted and is concerned that he is sexually assaulting other people. His family reports that Mr. R has perseverated over these thoughts for months, although there is no evidence to suggest these events have occurred. In order to ameliorate his distress, he performs rituals of looking upwards and repeatedly saying, “It didn’t happen.”

Mr. R is admitted to the inpatient psychiatry unit for further evaluation.

HISTORY Decompensation while attending a PHP

Mr. R had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder when he was 13. During that time, he was treated with divalproex sodium and dextroamphetamine. At age 15, Mr. R’s diagnosis was changed to OCD. Seven months before coming to the ED, his symptoms had been getting worse. On one occasion, Mr. R was talking in a nonsensical fashion at school, and the police were called. Mr. R became physically aggressive with the police and was subsequently hospitalized, after which he attended a partial hospitalization program (PHP). At the PHP, Mr. R received exposure and response prevention therapy for OCD, but did not improve, and his symptoms deteriorated until he was unable to brush his teeth or shower regularly. While attending the PHP, Mr. R also developed disorganized speech. The PHP clinicians became concerned that Mr. R’s symptoms may have been prodromal symptoms of schizophrenia because he did not respond to the OCD treatment and his symptoms had worsened over the 3 months he attended the PHP.

EVALUATION Normal laboratory results

Upon admission to the inpatient psychiatric unit, Mr. R is restarted on his home medications, which include

His laboratory workup, including a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, urine drug screen, and blood ethanol, are all within normal limits. Previous laboratory results, including a thyroid function panel, vitamin D level, and various autoimmune panels, were also within normal limits.

His family reports that Mr. R’s symptoms seem to worsen when he is under increased stress from school and prepping for standardized college admission examinations. The family also says that while he is playing tennis, Mr. R will posture himself in a crouched down position and at times will remain in this position for 30 minutes.

Mr. R says he eventually wants to go to college and have a professional career.

[polldaddy:10600530]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

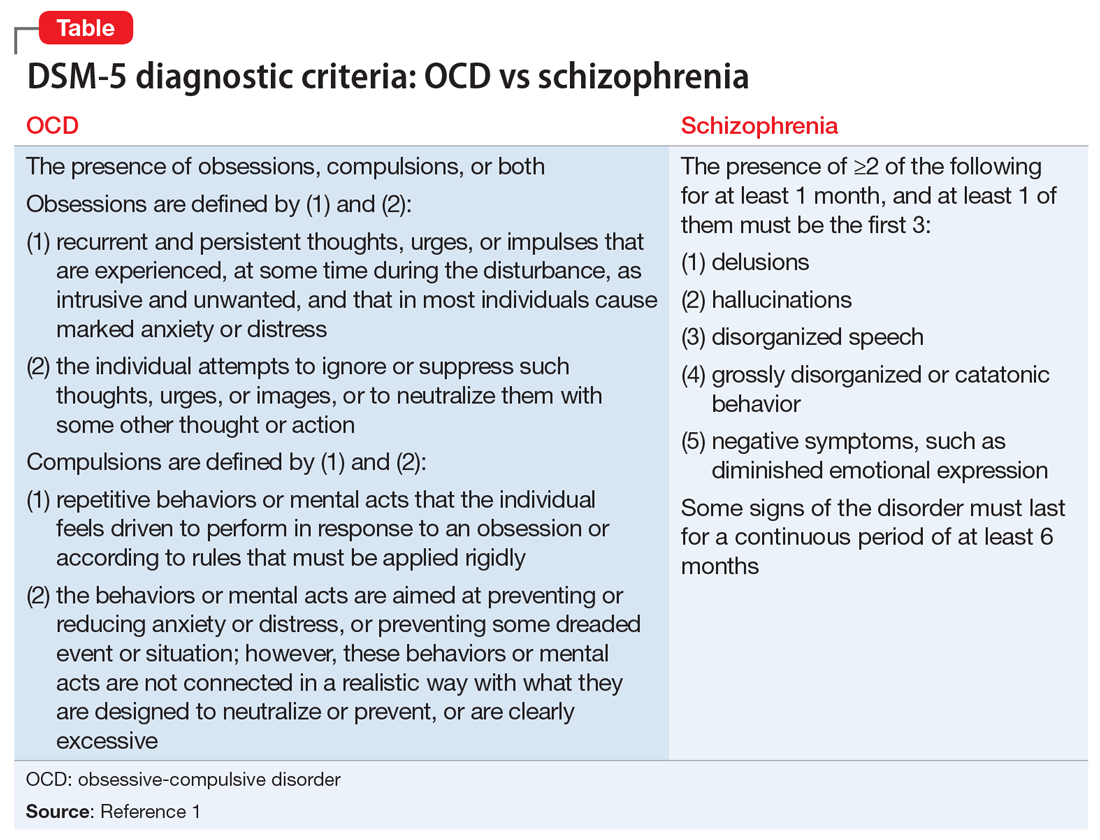

When considering Mr. R’s diagnosis, our treatment team considered the possibility of OCD with absent insight/delusional beliefs, OCD with comorbid schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and psychotic disorder due to another medical condition.

Overlap between OCD and schizophrenia

Much of the literature about OCD examines its functional impairment in adults, with findings extrapolated to pediatric patients. Children differ from adults in a variety of meaningful ways. Baytunca et al4 examined adolescents with early-onset schizophrenia, with and without comorbid OCD. Patients with comorbid OCD required higher doses of antipsychotic medication to treat acute psychotic symptoms and maintain a reduction in symptoms. The study controlled for the severity of schizophrenia, and its findings suggest that schizophrenia with comorbid OCD is more treatment-resistant than schizophrenia alone.4

Some researchers have theorized that in adolescents, OCD and psychosis are integrally related such that one disorder could represent a prodrome or a cause of the other disorder. Niendam et al5 studied OCS in the psychosis prodrome. They found that OCS can present as a part of the prodromal picture in youth at high risk for psychosis. However, because none of the patients experiencing OCS converted to full-blown psychosis, these results suggest that OCS may not represent a prodrome to psychosis per se. Instead, these individuals may represent a subset of false positives over the follow-up period.5 Another possible explanation for the increased emergence of pre-psychotic symptoms in adolescents with OCD could be a difference in their threshold of perception. OCS compels adolescents with OCD to self-analyze more critically and frequently. As a result, these patients may more often report depressive symptoms, distress, and exacerbations of pre-psychotic symptoms. These findings highlight that

[polldaddy:10600532]

Continue to: TREATMENT Improvement after switching to haloperidol

TREATMENT Improvement after switching to haloperidol

The treatment team decides to change Mr. R’s medications by cross-titrating risperidone to

The treatment team obtains a consultation on whether electroconvulsive therapy would be appropriate, but this treatment is not recommended. Instead, the team considers

Throughout admission, Mr. R focuses on his lack of improvement and how this episode is negatively impacting his grades and his dream of going to college and having a professional career.

OUTCOME Relief at last

Mr. R improves with the addition of sertraline and tolerates rapid titration well. He continues haloperidol without adverse effects, and is discharged home with close follow-up in a PHP and outpatient psychiatry.

However, after discharge, Mr. R’s symptoms get worse, and he is admitted to a different inpatient facility. At this facility, he continues sertraline, but haloperidol is cross-titrated to

Continue to: Currently...

Currently, Mr. R has greatly improved and is able to function in school. He takes sertraline, 100 mg twice a day, and olanzapine, 7.5 mg twice a day. Mr. R reports his rituals have reduced in frequency to less than 15 minutes each day. His thought processes are organized, and he is confident he will be able to achieve his goals.

The authors’ observations

Given Mr. R’s rapid improvement once an effective pharmacologic regimen was established, we concluded that he had a severe case of OCD with absent insight/delusional beliefs, and that he did not have schizophrenia. Mr. R’s case highlights how a psychiatric diagnosis can produce anxiety as a result of the psychosocial stressors and limitations associated with that diagnosis.