User login

What are the risks of long-term PPI use for GERD symptoms in patients > 65 years?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2017 meta-analysis of 16 RCTs examined the risk of cardiovascular events in 7540 adult patients taking PPIs for GERD (mean ages 45-55 years).1 The primary outcome was cardiovascular events—including acute myocardial infarction, myocardial ischemia, angina pectoris, cardiac failure, and coronary artery stenosis—and cardiac disorders.

Analysis of pooled data found that PPI use was associated with a 70% increase in cardiovascular risk (relative risk [RR] = 1.7; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.13-2.56; number needed to harm [NNH] = 241) when compared with controls (placebo, H2 blocker, or surgery). A subgroup analysis found that PPI use for longer than 8 weeks was associated with an even higher risk of adverse cardiovascular events (6 trials, 2296 patients; RR = 2.33; 95% CI, 1.33-4.08; NNH = 67) when compared with controls. The meta-analysis wasn’t limited by heterogeneity (I2 = 0).

C difficile infection risk is higherfor PPI users

A 2016 meta-analysis of 23 observational studies (19 case-control, 4 retrospective cohort; 186,033 patients) examined the risk of hospital-acquired C difficile infections in adults prescribed PPI for any indication.2 PPI exposure varied from use at time of diagnosis or hospitalization to any use within 90 days. Of the 23 studies, 16 reported sufficient data to calculate the mean age for the patients which was 69.9 years.

The risk of C difficile infection was found to be higher with PPI use than no use (pooled odds ratio [OR] = 1.81; 95% CI, 1.52-2.14). Although a significant association was found across a large group, the results were limited by considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 82%).

Risk of community-acquired pneumonia also increases with PPI use

A 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis of 33 trials (18 case-control, 10 cohort, 4 RCTs, and 1 case-crossover study) examined the risk of CAP in adult patients prescribed PPI for any indication for durations ranging from less than 1 month to > 6 months.3 The systematic review was distilled to 26 studies because of overlapping study populations. These 26 studies included 226,769 cases of CAP among 6,351,656 patients. The primary outcome was development of CAP, the secondary outcome was hospitalization for CAP.

PPI use, compared with no use, was associated with an increased risk of developing CAP (pooled OR = 1.49; 95% CI, 1.16-1.92) and an increased risk of hospitalization for CAP (pooled OR = 1.61; 95% CI, 1.12-2.31).

In a subgroup analysis for age, patients older than 65 years were also found to have an increased risk of developing CAP with PPI use (11 trials, total number of patients not provided; OR = 1.33; 95% CI, 1.13-1.58). Despite the significant associations of PPI use with risk revealed in the primary, secondary, and subgroup analyses, the results were limited by marked heterogeneity, with an I2 > 99%.

Continue to: Hip and vertebral fracture risks associated with PPIs

Hip and vertebral fracture riskis associated with PPIs

A 2011 systematic review and meta-analysis investigated the risk of fracture in adult patients taking PPIs for any indication.4 The analysis included 10 observational studies (4 cohort, 6 case-control) with a total of 223,210 fracture cases. The authors examined the incidence of hip, vertebral, and wrist or forearm fractures.

No significant association was found between PPI use and wrist or forearm fracture (3 studies; pooled OR = 1.09; 95% CI, 0.95-1.24). A modest association was noted between PPI use and both hip fractures (9 trials; OR = 1.25; 95% CI, 1.14-1.37) and vertebral fractures (4 trials; OR = 1.5; 95% CI, 1.32-1.72).

Subgroup analysis didn’t reveal evidence of an effect of duration of PPI use on fracture. Investigators didn’t conduct subgroup analysis of different patient ages. Final results were limited by significant heterogeneity with an I2 of 86%.

RECOMMENDATIONS

A 2015 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria update recommends limiting PPI use because of increased risk of C difficile infections and fractures. It also recommends against using PPIs for longer than 8 weeks except for high-risk patients (such as patients taking oral corticosteroids or chronic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug users), patients with Barrett’s esophagitis, or patients who need maintenance after failure of a drug discontinuation trial or H2 blockers (quality of evidence, high; SOR, strong).5

Editor’s take

1. Sun S, Cui Z, Zhou M, et al. Proton pump inhibitor monotherapy and the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with gastro-esophageal reflux disease: a meta-analysis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;29:e12926.

2. Arriola V, Tischendorf J, Musuuza J, et al. Assessing the risk of hospital-acquired clostridium difficile infection with proton pump inhibitor use: a meta-analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37:1408-1417.

3. Lambert AA, Lam JO, Paik JJ, et al. Risk of community-acquired pneumonia with outpatient proton-pump inhibitor therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128004.

4. Ngamruengphong S, Leontiadis GI, Radhi S, et al. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of fracture: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1209-1218.

5. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:2227-2246.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2017 meta-analysis of 16 RCTs examined the risk of cardiovascular events in 7540 adult patients taking PPIs for GERD (mean ages 45-55 years).1 The primary outcome was cardiovascular events—including acute myocardial infarction, myocardial ischemia, angina pectoris, cardiac failure, and coronary artery stenosis—and cardiac disorders.

Analysis of pooled data found that PPI use was associated with a 70% increase in cardiovascular risk (relative risk [RR] = 1.7; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.13-2.56; number needed to harm [NNH] = 241) when compared with controls (placebo, H2 blocker, or surgery). A subgroup analysis found that PPI use for longer than 8 weeks was associated with an even higher risk of adverse cardiovascular events (6 trials, 2296 patients; RR = 2.33; 95% CI, 1.33-4.08; NNH = 67) when compared with controls. The meta-analysis wasn’t limited by heterogeneity (I2 = 0).

C difficile infection risk is higherfor PPI users

A 2016 meta-analysis of 23 observational studies (19 case-control, 4 retrospective cohort; 186,033 patients) examined the risk of hospital-acquired C difficile infections in adults prescribed PPI for any indication.2 PPI exposure varied from use at time of diagnosis or hospitalization to any use within 90 days. Of the 23 studies, 16 reported sufficient data to calculate the mean age for the patients which was 69.9 years.

The risk of C difficile infection was found to be higher with PPI use than no use (pooled odds ratio [OR] = 1.81; 95% CI, 1.52-2.14). Although a significant association was found across a large group, the results were limited by considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 82%).

Risk of community-acquired pneumonia also increases with PPI use

A 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis of 33 trials (18 case-control, 10 cohort, 4 RCTs, and 1 case-crossover study) examined the risk of CAP in adult patients prescribed PPI for any indication for durations ranging from less than 1 month to > 6 months.3 The systematic review was distilled to 26 studies because of overlapping study populations. These 26 studies included 226,769 cases of CAP among 6,351,656 patients. The primary outcome was development of CAP, the secondary outcome was hospitalization for CAP.

PPI use, compared with no use, was associated with an increased risk of developing CAP (pooled OR = 1.49; 95% CI, 1.16-1.92) and an increased risk of hospitalization for CAP (pooled OR = 1.61; 95% CI, 1.12-2.31).

In a subgroup analysis for age, patients older than 65 years were also found to have an increased risk of developing CAP with PPI use (11 trials, total number of patients not provided; OR = 1.33; 95% CI, 1.13-1.58). Despite the significant associations of PPI use with risk revealed in the primary, secondary, and subgroup analyses, the results were limited by marked heterogeneity, with an I2 > 99%.

Continue to: Hip and vertebral fracture risks associated with PPIs

Hip and vertebral fracture riskis associated with PPIs

A 2011 systematic review and meta-analysis investigated the risk of fracture in adult patients taking PPIs for any indication.4 The analysis included 10 observational studies (4 cohort, 6 case-control) with a total of 223,210 fracture cases. The authors examined the incidence of hip, vertebral, and wrist or forearm fractures.

No significant association was found between PPI use and wrist or forearm fracture (3 studies; pooled OR = 1.09; 95% CI, 0.95-1.24). A modest association was noted between PPI use and both hip fractures (9 trials; OR = 1.25; 95% CI, 1.14-1.37) and vertebral fractures (4 trials; OR = 1.5; 95% CI, 1.32-1.72).

Subgroup analysis didn’t reveal evidence of an effect of duration of PPI use on fracture. Investigators didn’t conduct subgroup analysis of different patient ages. Final results were limited by significant heterogeneity with an I2 of 86%.

RECOMMENDATIONS

A 2015 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria update recommends limiting PPI use because of increased risk of C difficile infections and fractures. It also recommends against using PPIs for longer than 8 weeks except for high-risk patients (such as patients taking oral corticosteroids or chronic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug users), patients with Barrett’s esophagitis, or patients who need maintenance after failure of a drug discontinuation trial or H2 blockers (quality of evidence, high; SOR, strong).5

Editor’s take

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2017 meta-analysis of 16 RCTs examined the risk of cardiovascular events in 7540 adult patients taking PPIs for GERD (mean ages 45-55 years).1 The primary outcome was cardiovascular events—including acute myocardial infarction, myocardial ischemia, angina pectoris, cardiac failure, and coronary artery stenosis—and cardiac disorders.

Analysis of pooled data found that PPI use was associated with a 70% increase in cardiovascular risk (relative risk [RR] = 1.7; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.13-2.56; number needed to harm [NNH] = 241) when compared with controls (placebo, H2 blocker, or surgery). A subgroup analysis found that PPI use for longer than 8 weeks was associated with an even higher risk of adverse cardiovascular events (6 trials, 2296 patients; RR = 2.33; 95% CI, 1.33-4.08; NNH = 67) when compared with controls. The meta-analysis wasn’t limited by heterogeneity (I2 = 0).

C difficile infection risk is higherfor PPI users

A 2016 meta-analysis of 23 observational studies (19 case-control, 4 retrospective cohort; 186,033 patients) examined the risk of hospital-acquired C difficile infections in adults prescribed PPI for any indication.2 PPI exposure varied from use at time of diagnosis or hospitalization to any use within 90 days. Of the 23 studies, 16 reported sufficient data to calculate the mean age for the patients which was 69.9 years.

The risk of C difficile infection was found to be higher with PPI use than no use (pooled odds ratio [OR] = 1.81; 95% CI, 1.52-2.14). Although a significant association was found across a large group, the results were limited by considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 82%).

Risk of community-acquired pneumonia also increases with PPI use

A 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis of 33 trials (18 case-control, 10 cohort, 4 RCTs, and 1 case-crossover study) examined the risk of CAP in adult patients prescribed PPI for any indication for durations ranging from less than 1 month to > 6 months.3 The systematic review was distilled to 26 studies because of overlapping study populations. These 26 studies included 226,769 cases of CAP among 6,351,656 patients. The primary outcome was development of CAP, the secondary outcome was hospitalization for CAP.

PPI use, compared with no use, was associated with an increased risk of developing CAP (pooled OR = 1.49; 95% CI, 1.16-1.92) and an increased risk of hospitalization for CAP (pooled OR = 1.61; 95% CI, 1.12-2.31).

In a subgroup analysis for age, patients older than 65 years were also found to have an increased risk of developing CAP with PPI use (11 trials, total number of patients not provided; OR = 1.33; 95% CI, 1.13-1.58). Despite the significant associations of PPI use with risk revealed in the primary, secondary, and subgroup analyses, the results were limited by marked heterogeneity, with an I2 > 99%.

Continue to: Hip and vertebral fracture risks associated with PPIs

Hip and vertebral fracture riskis associated with PPIs

A 2011 systematic review and meta-analysis investigated the risk of fracture in adult patients taking PPIs for any indication.4 The analysis included 10 observational studies (4 cohort, 6 case-control) with a total of 223,210 fracture cases. The authors examined the incidence of hip, vertebral, and wrist or forearm fractures.

No significant association was found between PPI use and wrist or forearm fracture (3 studies; pooled OR = 1.09; 95% CI, 0.95-1.24). A modest association was noted between PPI use and both hip fractures (9 trials; OR = 1.25; 95% CI, 1.14-1.37) and vertebral fractures (4 trials; OR = 1.5; 95% CI, 1.32-1.72).

Subgroup analysis didn’t reveal evidence of an effect of duration of PPI use on fracture. Investigators didn’t conduct subgroup analysis of different patient ages. Final results were limited by significant heterogeneity with an I2 of 86%.

RECOMMENDATIONS

A 2015 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria update recommends limiting PPI use because of increased risk of C difficile infections and fractures. It also recommends against using PPIs for longer than 8 weeks except for high-risk patients (such as patients taking oral corticosteroids or chronic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug users), patients with Barrett’s esophagitis, or patients who need maintenance after failure of a drug discontinuation trial or H2 blockers (quality of evidence, high; SOR, strong).5

Editor’s take

1. Sun S, Cui Z, Zhou M, et al. Proton pump inhibitor monotherapy and the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with gastro-esophageal reflux disease: a meta-analysis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;29:e12926.

2. Arriola V, Tischendorf J, Musuuza J, et al. Assessing the risk of hospital-acquired clostridium difficile infection with proton pump inhibitor use: a meta-analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37:1408-1417.

3. Lambert AA, Lam JO, Paik JJ, et al. Risk of community-acquired pneumonia with outpatient proton-pump inhibitor therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128004.

4. Ngamruengphong S, Leontiadis GI, Radhi S, et al. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of fracture: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1209-1218.

5. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:2227-2246.

1. Sun S, Cui Z, Zhou M, et al. Proton pump inhibitor monotherapy and the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with gastro-esophageal reflux disease: a meta-analysis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;29:e12926.

2. Arriola V, Tischendorf J, Musuuza J, et al. Assessing the risk of hospital-acquired clostridium difficile infection with proton pump inhibitor use: a meta-analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37:1408-1417.

3. Lambert AA, Lam JO, Paik JJ, et al. Risk of community-acquired pneumonia with outpatient proton-pump inhibitor therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128004.

4. Ngamruengphong S, Leontiadis GI, Radhi S, et al. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of fracture: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1209-1218.

5. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:2227-2246.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

The use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) to control gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is significantly associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events such as acute myocardial infarction and myocardial ischemia, especially with treatment longer than 8 weeks (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review of randomized, controlled trials [RCTs]). This summary is based on data extrapolated from studies on all adults because there is limited evidence that specifically addresses patients older than 65 years.

Adults taking PPIs also appear to be at increased risk of Clostridium difficile infection, community-acquired pneumonia (CAP; with use for < 30 days), and fracture (SOR: B, systematic reviews of heterogeneous prospective and retrospective observational studies).

Is intra-articular platelet-rich plasma injection an effective treatment for knee OA?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

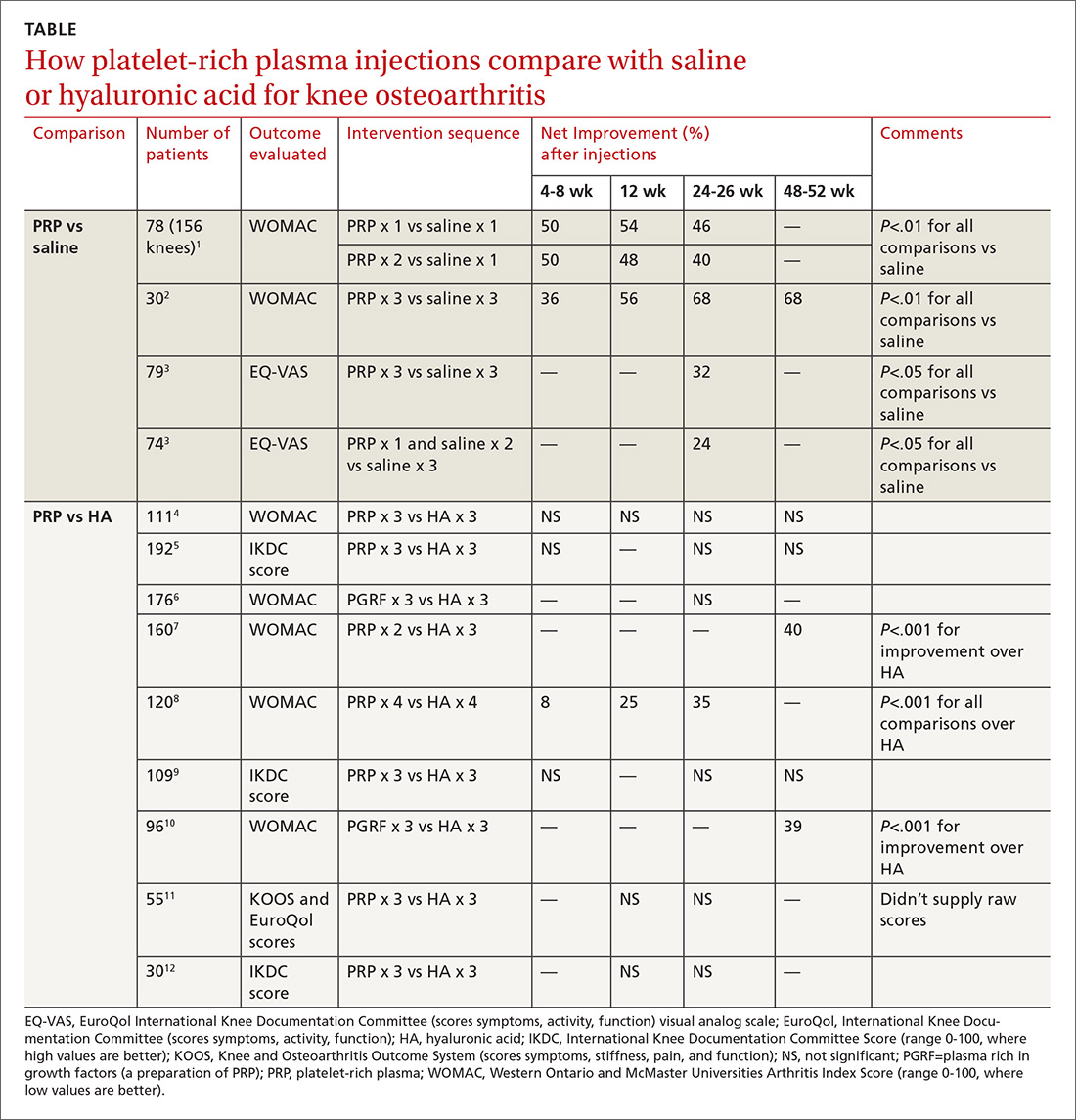

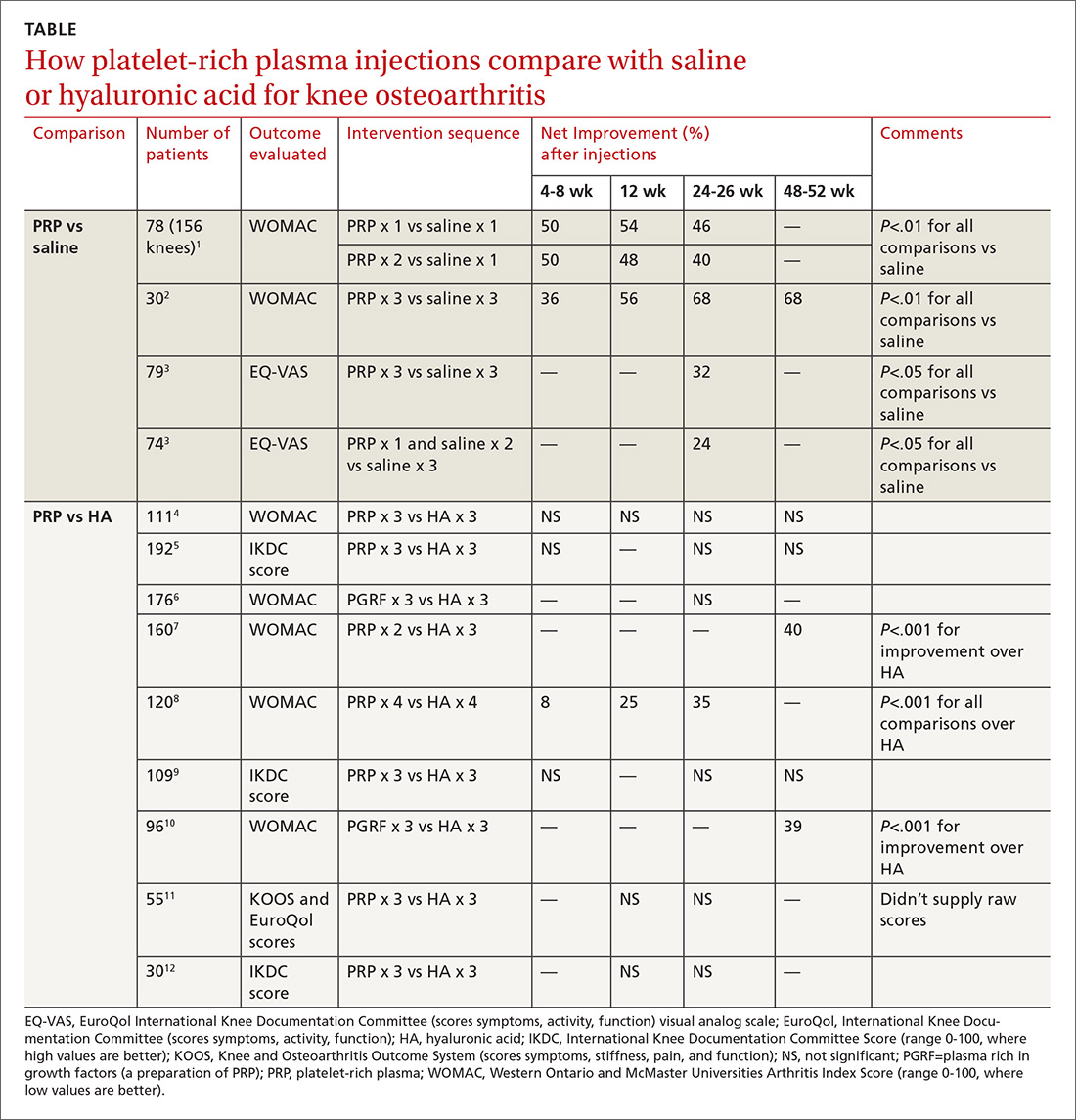

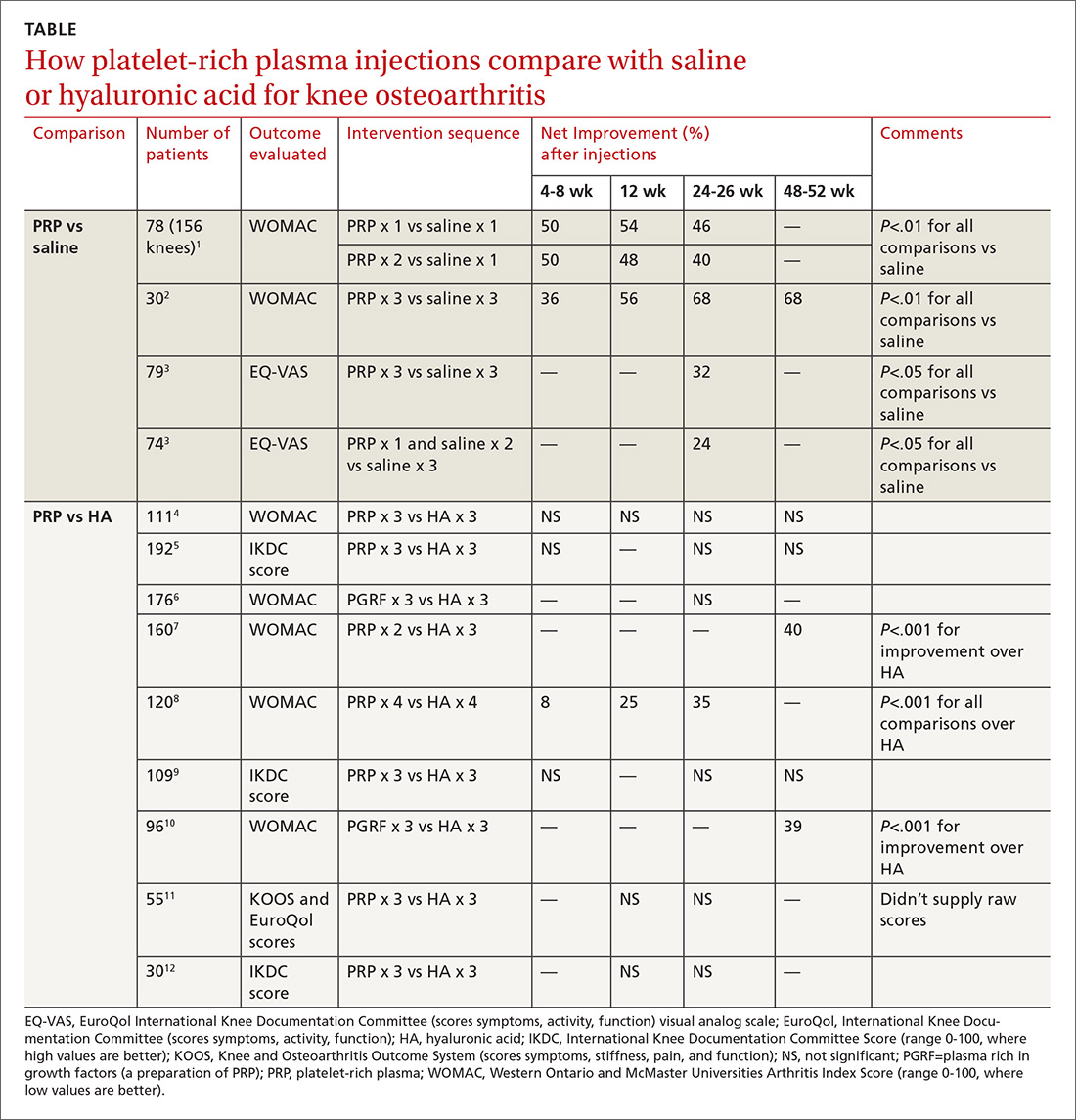

PRP vs placebo. Three RCTs compared PRP with saline placebo injections and 2 found that PRP improved the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC, a standardized scale assessing knee pain, function, and stiffness) by 40% to 70%; the third found 24% to 32% improvements in the EuroQol visual analog scale (EQ-VAS) scores at 6 months1-3 (TABLE1-12).

The first 2 studies enrolled patients (mean age early 60s, approximately 50% women) with clinically and radiographically evaluated knee OA of mostly moderate severity (baseline WOMAC scores about 50).1,2 Investigators in the first RCT injected PRP once in one subgroup and twice in another subgroup, compared with a single injection of saline in a third subgroup.1 They gave 3 weekly injections of PRP or saline in the second RCT.2

The third study enrolled mainly patients with early osteoarthritis (mean age early 50s, slightly more women). Investigators injected PRP 3 times in one subgroup and once (plus 2 saline injections) in another, compared with 3 saline injections, and evaluated patients at baseline and 6 months.3

PRP vs HA. Nine RCTs compared PRP with HA injections. Six studies (673 patients) found no significant difference; 3 studies (376 patients) found that PRP improved standardized knee assessment scores by 35% to 40% at 24-48 weeks.7,8,10 All studies enrolled patients (mean age early 60s, approximately 50% women) with clinically and radiographically evaluated knee OA of mostly moderate severity. In 7 RCTs, 4-6,9-12 investigators injected PRP or HA weekly for 3 weeks, in one RCT8 they gave 4 weekly injections, and in one7they gave 2 PRP injections separated by 4 weeks.

Three RCTs used the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) score, considered the most reliable standardized scoring system, which quantifies subjective symptoms (pain, stiffness, swelling, giving way), activity (climbing stairs, rising from a chair, squatting, jumping), and function pre- and postintervention.5,9,12 All 3 studies using the IKDC found no difference between PRP and HA injections. Most RCTs used the WOMAC standardized scale, scoring 5 items for pain, 2 for stiffness, and 17 for function.1,2,4,6-8.10

Risk for bias

A systematic review13 that evaluated methodologic quality of the 3 studies comparing PRP with placebo rated 21,3 at high risk of bias and one2 at moderate risk. Another meta-analysis14 performed a quality assessment including 4 of the 9 RCTs,8-10,12 comparing PRP with HA and concluded that 3 had a high risk of bias; the fourth RCT had a moderate risk. No independent quality assessments of the other RCTs were available.4-7,11

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons doesn’t recommend for or against PRP injections because of insufficient evidence and strongly recommends against HA injections based on multiple RCTs of moderate quality that found no difference between HA and placebo.15

1. Patel S, Dhillon MS, Aggarwal S, et al. Treatment with platelet-rich plasma is more effective than placebo for knee osteoarthritis: a prospective, double-blind, randomized trial. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:356-364.

2. Smith PA. Intra-articular autologous conditioned plasma injections provide safe and efficacious treatment for knee arthritis: an FDA-sanctioned, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:884-891.

3. Gorelli G, Gormelli CA, Ataoglu B, et al. Multiple PRP injections are more effective than single injections and hyaluronic acid in knees with early osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;25:958-965.

4. Cole BJ, Karas V, Hussey K, et al. Hyaluronic acid versus platelet-rich plasma: a prospective double-blind randomized controlled trial comparing clinical outcomes and effects on intra-articular biology for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2016;45:339-346.

5. Filardo G, Di Matteo B, Di Martino A, et al. Platelet-rich intra-articular knee injections show no superiority versus viscosupplementation: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:1575-1582.

6. Sanchez M, Fiz N, Azofra J, et al. A randomized clinical trial evaluating plasma rich in growth factors (PGRF-endoret) versus hyaluronic acid in the short-term treatment of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Arthroscopy: J Arth and Related Surg. 2012;28:1070-1078.

7. Raeissadat SA, Rayegani SM, Hassanabadi H, et al. Knee osteoarthritis injection choices: platelet-rich plasma (PRP) versus hyaluronic acid (a one-year randomized clinical trial). Clin Med Insights: Arth Musc Dis. 2015;8:1-8.

8. Cerza F, Carni S, Carcangiu A, et al. Comparison between hyaluronic acid and platelet-rich plasma, intra-articular infiltration in the treatment of gonarthrosis. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:2822-2827.

9. Filardo G, Kon E, Di Martino B, et al. Platelet-rich plasma vs hyaluronic acid to treat knee degenerative pathology: study design and preliminary results of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2012;13:229-236.

10. Vaquerizo V, Plasencia MA, Arribas I, et al. Comparison of intra-articular injections of plasma rich in growth factors (PGRF-endoret) versus durolane hyaluronic acid in the treatment of patients with symptomatic osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthroscopy: J Arth and Related Surg. 2013;29:1635-1643.

11. Montanez-Heredia E, Irizar S, Huertas PJ, et al. Intra-articular injections of platelet-rich plasma versus hyaluronic acid in the treatment of osteoarthritis knee pain: a randomized clinical trial in the context of the Spanish national health care system. Intl J Molec Sci. 2016;17:1064-1077.

12. Li M, Zhang C, Ai Z, et al. Therapeutic effectiveness of intra-knee articular injections of platelet-rich plasma on knee articular cartilage degeneration. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2011 25:1192-11966. (Article published in Chinese with abstract in English.)

13. Shen L, Yuan T, Chen S, et al. The temporal effect of platelet-rich plasma on pain and physical function in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Ortho Surg Res. 2017;12:16.

14. Laudy ABM, Bakker EWP, Rekers M, et al. Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma injections in osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:657-672.

15. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Clinical practice guideline on the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee, 2nd ed. www.aaos.org/cc_files/aaosorg/research/guidelines/treatmentofosteoarthritisofthekneeguideline.pdf. Published May 2013. Accessed February 22, 2019.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

PRP vs placebo. Three RCTs compared PRP with saline placebo injections and 2 found that PRP improved the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC, a standardized scale assessing knee pain, function, and stiffness) by 40% to 70%; the third found 24% to 32% improvements in the EuroQol visual analog scale (EQ-VAS) scores at 6 months1-3 (TABLE1-12).

The first 2 studies enrolled patients (mean age early 60s, approximately 50% women) with clinically and radiographically evaluated knee OA of mostly moderate severity (baseline WOMAC scores about 50).1,2 Investigators in the first RCT injected PRP once in one subgroup and twice in another subgroup, compared with a single injection of saline in a third subgroup.1 They gave 3 weekly injections of PRP or saline in the second RCT.2

The third study enrolled mainly patients with early osteoarthritis (mean age early 50s, slightly more women). Investigators injected PRP 3 times in one subgroup and once (plus 2 saline injections) in another, compared with 3 saline injections, and evaluated patients at baseline and 6 months.3

PRP vs HA. Nine RCTs compared PRP with HA injections. Six studies (673 patients) found no significant difference; 3 studies (376 patients) found that PRP improved standardized knee assessment scores by 35% to 40% at 24-48 weeks.7,8,10 All studies enrolled patients (mean age early 60s, approximately 50% women) with clinically and radiographically evaluated knee OA of mostly moderate severity. In 7 RCTs, 4-6,9-12 investigators injected PRP or HA weekly for 3 weeks, in one RCT8 they gave 4 weekly injections, and in one7they gave 2 PRP injections separated by 4 weeks.

Three RCTs used the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) score, considered the most reliable standardized scoring system, which quantifies subjective symptoms (pain, stiffness, swelling, giving way), activity (climbing stairs, rising from a chair, squatting, jumping), and function pre- and postintervention.5,9,12 All 3 studies using the IKDC found no difference between PRP and HA injections. Most RCTs used the WOMAC standardized scale, scoring 5 items for pain, 2 for stiffness, and 17 for function.1,2,4,6-8.10

Risk for bias

A systematic review13 that evaluated methodologic quality of the 3 studies comparing PRP with placebo rated 21,3 at high risk of bias and one2 at moderate risk. Another meta-analysis14 performed a quality assessment including 4 of the 9 RCTs,8-10,12 comparing PRP with HA and concluded that 3 had a high risk of bias; the fourth RCT had a moderate risk. No independent quality assessments of the other RCTs were available.4-7,11

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons doesn’t recommend for or against PRP injections because of insufficient evidence and strongly recommends against HA injections based on multiple RCTs of moderate quality that found no difference between HA and placebo.15

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

PRP vs placebo. Three RCTs compared PRP with saline placebo injections and 2 found that PRP improved the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC, a standardized scale assessing knee pain, function, and stiffness) by 40% to 70%; the third found 24% to 32% improvements in the EuroQol visual analog scale (EQ-VAS) scores at 6 months1-3 (TABLE1-12).

The first 2 studies enrolled patients (mean age early 60s, approximately 50% women) with clinically and radiographically evaluated knee OA of mostly moderate severity (baseline WOMAC scores about 50).1,2 Investigators in the first RCT injected PRP once in one subgroup and twice in another subgroup, compared with a single injection of saline in a third subgroup.1 They gave 3 weekly injections of PRP or saline in the second RCT.2

The third study enrolled mainly patients with early osteoarthritis (mean age early 50s, slightly more women). Investigators injected PRP 3 times in one subgroup and once (plus 2 saline injections) in another, compared with 3 saline injections, and evaluated patients at baseline and 6 months.3

PRP vs HA. Nine RCTs compared PRP with HA injections. Six studies (673 patients) found no significant difference; 3 studies (376 patients) found that PRP improved standardized knee assessment scores by 35% to 40% at 24-48 weeks.7,8,10 All studies enrolled patients (mean age early 60s, approximately 50% women) with clinically and radiographically evaluated knee OA of mostly moderate severity. In 7 RCTs, 4-6,9-12 investigators injected PRP or HA weekly for 3 weeks, in one RCT8 they gave 4 weekly injections, and in one7they gave 2 PRP injections separated by 4 weeks.

Three RCTs used the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) score, considered the most reliable standardized scoring system, which quantifies subjective symptoms (pain, stiffness, swelling, giving way), activity (climbing stairs, rising from a chair, squatting, jumping), and function pre- and postintervention.5,9,12 All 3 studies using the IKDC found no difference between PRP and HA injections. Most RCTs used the WOMAC standardized scale, scoring 5 items for pain, 2 for stiffness, and 17 for function.1,2,4,6-8.10

Risk for bias

A systematic review13 that evaluated methodologic quality of the 3 studies comparing PRP with placebo rated 21,3 at high risk of bias and one2 at moderate risk. Another meta-analysis14 performed a quality assessment including 4 of the 9 RCTs,8-10,12 comparing PRP with HA and concluded that 3 had a high risk of bias; the fourth RCT had a moderate risk. No independent quality assessments of the other RCTs were available.4-7,11

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons doesn’t recommend for or against PRP injections because of insufficient evidence and strongly recommends against HA injections based on multiple RCTs of moderate quality that found no difference between HA and placebo.15

1. Patel S, Dhillon MS, Aggarwal S, et al. Treatment with platelet-rich plasma is more effective than placebo for knee osteoarthritis: a prospective, double-blind, randomized trial. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:356-364.

2. Smith PA. Intra-articular autologous conditioned plasma injections provide safe and efficacious treatment for knee arthritis: an FDA-sanctioned, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:884-891.

3. Gorelli G, Gormelli CA, Ataoglu B, et al. Multiple PRP injections are more effective than single injections and hyaluronic acid in knees with early osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;25:958-965.

4. Cole BJ, Karas V, Hussey K, et al. Hyaluronic acid versus platelet-rich plasma: a prospective double-blind randomized controlled trial comparing clinical outcomes and effects on intra-articular biology for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2016;45:339-346.

5. Filardo G, Di Matteo B, Di Martino A, et al. Platelet-rich intra-articular knee injections show no superiority versus viscosupplementation: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:1575-1582.

6. Sanchez M, Fiz N, Azofra J, et al. A randomized clinical trial evaluating plasma rich in growth factors (PGRF-endoret) versus hyaluronic acid in the short-term treatment of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Arthroscopy: J Arth and Related Surg. 2012;28:1070-1078.

7. Raeissadat SA, Rayegani SM, Hassanabadi H, et al. Knee osteoarthritis injection choices: platelet-rich plasma (PRP) versus hyaluronic acid (a one-year randomized clinical trial). Clin Med Insights: Arth Musc Dis. 2015;8:1-8.

8. Cerza F, Carni S, Carcangiu A, et al. Comparison between hyaluronic acid and platelet-rich plasma, intra-articular infiltration in the treatment of gonarthrosis. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:2822-2827.

9. Filardo G, Kon E, Di Martino B, et al. Platelet-rich plasma vs hyaluronic acid to treat knee degenerative pathology: study design and preliminary results of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2012;13:229-236.

10. Vaquerizo V, Plasencia MA, Arribas I, et al. Comparison of intra-articular injections of plasma rich in growth factors (PGRF-endoret) versus durolane hyaluronic acid in the treatment of patients with symptomatic osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthroscopy: J Arth and Related Surg. 2013;29:1635-1643.

11. Montanez-Heredia E, Irizar S, Huertas PJ, et al. Intra-articular injections of platelet-rich plasma versus hyaluronic acid in the treatment of osteoarthritis knee pain: a randomized clinical trial in the context of the Spanish national health care system. Intl J Molec Sci. 2016;17:1064-1077.

12. Li M, Zhang C, Ai Z, et al. Therapeutic effectiveness of intra-knee articular injections of platelet-rich plasma on knee articular cartilage degeneration. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2011 25:1192-11966. (Article published in Chinese with abstract in English.)

13. Shen L, Yuan T, Chen S, et al. The temporal effect of platelet-rich plasma on pain and physical function in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Ortho Surg Res. 2017;12:16.

14. Laudy ABM, Bakker EWP, Rekers M, et al. Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma injections in osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:657-672.

15. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Clinical practice guideline on the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee, 2nd ed. www.aaos.org/cc_files/aaosorg/research/guidelines/treatmentofosteoarthritisofthekneeguideline.pdf. Published May 2013. Accessed February 22, 2019.

1. Patel S, Dhillon MS, Aggarwal S, et al. Treatment with platelet-rich plasma is more effective than placebo for knee osteoarthritis: a prospective, double-blind, randomized trial. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:356-364.

2. Smith PA. Intra-articular autologous conditioned plasma injections provide safe and efficacious treatment for knee arthritis: an FDA-sanctioned, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:884-891.

3. Gorelli G, Gormelli CA, Ataoglu B, et al. Multiple PRP injections are more effective than single injections and hyaluronic acid in knees with early osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;25:958-965.

4. Cole BJ, Karas V, Hussey K, et al. Hyaluronic acid versus platelet-rich plasma: a prospective double-blind randomized controlled trial comparing clinical outcomes and effects on intra-articular biology for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2016;45:339-346.

5. Filardo G, Di Matteo B, Di Martino A, et al. Platelet-rich intra-articular knee injections show no superiority versus viscosupplementation: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:1575-1582.

6. Sanchez M, Fiz N, Azofra J, et al. A randomized clinical trial evaluating plasma rich in growth factors (PGRF-endoret) versus hyaluronic acid in the short-term treatment of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Arthroscopy: J Arth and Related Surg. 2012;28:1070-1078.

7. Raeissadat SA, Rayegani SM, Hassanabadi H, et al. Knee osteoarthritis injection choices: platelet-rich plasma (PRP) versus hyaluronic acid (a one-year randomized clinical trial). Clin Med Insights: Arth Musc Dis. 2015;8:1-8.

8. Cerza F, Carni S, Carcangiu A, et al. Comparison between hyaluronic acid and platelet-rich plasma, intra-articular infiltration in the treatment of gonarthrosis. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:2822-2827.

9. Filardo G, Kon E, Di Martino B, et al. Platelet-rich plasma vs hyaluronic acid to treat knee degenerative pathology: study design and preliminary results of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2012;13:229-236.

10. Vaquerizo V, Plasencia MA, Arribas I, et al. Comparison of intra-articular injections of plasma rich in growth factors (PGRF-endoret) versus durolane hyaluronic acid in the treatment of patients with symptomatic osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthroscopy: J Arth and Related Surg. 2013;29:1635-1643.

11. Montanez-Heredia E, Irizar S, Huertas PJ, et al. Intra-articular injections of platelet-rich plasma versus hyaluronic acid in the treatment of osteoarthritis knee pain: a randomized clinical trial in the context of the Spanish national health care system. Intl J Molec Sci. 2016;17:1064-1077.

12. Li M, Zhang C, Ai Z, et al. Therapeutic effectiveness of intra-knee articular injections of platelet-rich plasma on knee articular cartilage degeneration. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2011 25:1192-11966. (Article published in Chinese with abstract in English.)

13. Shen L, Yuan T, Chen S, et al. The temporal effect of platelet-rich plasma on pain and physical function in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Ortho Surg Res. 2017;12:16.

14. Laudy ABM, Bakker EWP, Rekers M, et al. Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma injections in osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:657-672.

15. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Clinical practice guideline on the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee, 2nd ed. www.aaos.org/cc_files/aaosorg/research/guidelines/treatmentofosteoarthritisofthekneeguideline.pdf. Published May 2013. Accessed February 22, 2019.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Probably not, based on the balance of evidence. While low-quality evidence may suggest potential benefit, the balance of evidence suggests it is no better than placebo.

Compared with saline placebo, platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections may improve standardized scores for knee osteoarthritis (OA) pain, function, and stiffness by 24% to 70% for periods of 6 to 52 weeks in patients with early to moderate OA (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, small randomized controlled trials [RCTs] with methodologic flaws).

Compared with hyaluronic acid (HA), PRP probably improves scores by a similar amount for periods of 8 to 52 weeks (SOR: B, multiple RCTs with conflicting results favoring no difference). However, since HA alone likely doesn’t improve scores more than placebo (SOR: B, RCTs of moderate quality), if both HA and PRP are about the same, then both are not better than placebo.

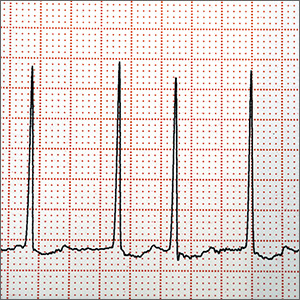

Does left atrial appendage closure reduce stroke rates as well as oral anticoagulants and antiplatelet meds in A-fib patients?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2017 network meta-analysis included 19 RCTs and 87,831 patients receiving anticoagulation, antiplatelet therapy, or LAAC for NVAF.1 LAAC was superior to antiplatelet therapy (hazard ratio [HR]=0.44; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.23-0.86; P<.05) and similar to NOACs (HR=1.01; 95% CI, 0.53-1.92; P=.969) for reducing risk of stroke.

LAAC and NOACs found “most effective”

A network meta-analysis of 21 RCTs, which included data from 96,017 patients, examined the effectiveness of 7 interventions to prevent stroke in patients with NVAF: 4 NOACs, VKA, aspirin, and LAAC; the analysis compared VKA with the other interventions.2 The 2 trials that investigated LAAC accounted for only 1114 patients.

When the 7 interventions were ranked simultaneously on 2 efficacy outcomes (stroke/systemic embolism and all-cause mortality), all 4 NOACs and LAAC clustered together as “the most effective and lifesaving.”

Fewer hemorrhagic strokes with LAAC than VKA

A 2016 meta-analysis of 6 RCTs compared risk of stroke for adults with NVAF who received LAAC, VKA, or NOACs.3 No significant differences were found between NOACs and VKA or LAAC and VKA. The LAAC group had a significantly smaller number of patients.

A 2015 meta-analysis of 2406 patients with NVAF found that patients who received LAAC had significantly fewer hemorrhagic strokes (HR=0.22; P<.05) than patients who received VKA.4 No differences in all-cause stroke were found between the 2 groups during an average follow-up of 2.69 years.

LAAC found superior to warfarin for stroke prevention in one trial

A 2014 multicenter, randomized study (PROTECT-AF) of 707 patients with NVAF plus 1 additional stroke risk factor compared LAAC with VKA (warfarin).5 LAAC met criteria at 3.8 years for both noninferiority and superiority in preventing stroke, based on 2.3 events per 100 patient-years compared with 3.8 events per 100 patient-years for VKA. The number needed to treat with LAAC was 67 to result in 1 less event per patient-year.

A 2014 RCT (PREVAIL) evaluated patients with NVAF plus 1 additional stroke risk factor. LAAC was noninferior to warfarin for ischemic stroke prevention.6

Continue to: RECOMMENDATIONS

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Cardiology (ACC) recommends LAAC for patients with NVAF who are not candidates for long-term anticoagulation.7 Similarly, the 2016 European Society of Cardiology guidelines issued a Class IIb recommendation for LAAC for stroke prevention in those with contraindications for long-term anticoagulation.8 Lastly, in a 2014 guideline, the American Heart Association, ACC, and the Heart Rhythm Society issued a Class IIb recommendation for surgical excision of the left atrial appendage in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing cardiac surgery, but did not provide recommendations regarding LAAC.9

1. Sahay S, Nombela-Franco L, Rodes-Cabau J, et al. Efficacy and safety of left atrial appendage closure versus medical treatment in atrial fibrillation: a network meta-analysis from randomised trials. Heart. 2017;103:139-147.

2. Tereshchenko LG, Henrikson CA, Cigarroa, J, et al. Comparative effectiveness of interventions for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: a network meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016; 5:e003206.

3. Bajaj NS, Kalra R, Patel N, et al. Comparison of approaches for stroke prophylaxis in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation: network meta-analyses of randomized clinical trials. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0163608.

4. Holmes DR Jr, Doshi SK, Kar S, et al. Left atrial appendage closure as an alternative to warfarin for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: a patient-level meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:2614-2623.

5. Reddy VY, Sievert H, Halperin J, et al. Percutaneous left atrial appendage closure vs warfarin for atrial fibrillation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:1988-1998.

6. Holmes DR Jr, Kar S, Price MJ, et al. Prospective randomized evaluation of the Watchman Left Atrial Appendage Closure device in patients with atrial fibrillation versus long-term warfarin therapy: the PREVAIL trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:1-12.

7. Panaich S, Holmes DR. Left atrial appendage occlusion: Expert analysis. http://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2017/ 01/31/13/08/left-atrial-appendage-occlusion. Accessed April 5, 2018.

8. Kirchof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Europace. 2016;18:1609-1678.

9. January CT, Wann LS, Alpert LS, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary. JACC. 2014;64:2246-2280.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2017 network meta-analysis included 19 RCTs and 87,831 patients receiving anticoagulation, antiplatelet therapy, or LAAC for NVAF.1 LAAC was superior to antiplatelet therapy (hazard ratio [HR]=0.44; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.23-0.86; P<.05) and similar to NOACs (HR=1.01; 95% CI, 0.53-1.92; P=.969) for reducing risk of stroke.

LAAC and NOACs found “most effective”

A network meta-analysis of 21 RCTs, which included data from 96,017 patients, examined the effectiveness of 7 interventions to prevent stroke in patients with NVAF: 4 NOACs, VKA, aspirin, and LAAC; the analysis compared VKA with the other interventions.2 The 2 trials that investigated LAAC accounted for only 1114 patients.

When the 7 interventions were ranked simultaneously on 2 efficacy outcomes (stroke/systemic embolism and all-cause mortality), all 4 NOACs and LAAC clustered together as “the most effective and lifesaving.”

Fewer hemorrhagic strokes with LAAC than VKA

A 2016 meta-analysis of 6 RCTs compared risk of stroke for adults with NVAF who received LAAC, VKA, or NOACs.3 No significant differences were found between NOACs and VKA or LAAC and VKA. The LAAC group had a significantly smaller number of patients.

A 2015 meta-analysis of 2406 patients with NVAF found that patients who received LAAC had significantly fewer hemorrhagic strokes (HR=0.22; P<.05) than patients who received VKA.4 No differences in all-cause stroke were found between the 2 groups during an average follow-up of 2.69 years.

LAAC found superior to warfarin for stroke prevention in one trial

A 2014 multicenter, randomized study (PROTECT-AF) of 707 patients with NVAF plus 1 additional stroke risk factor compared LAAC with VKA (warfarin).5 LAAC met criteria at 3.8 years for both noninferiority and superiority in preventing stroke, based on 2.3 events per 100 patient-years compared with 3.8 events per 100 patient-years for VKA. The number needed to treat with LAAC was 67 to result in 1 less event per patient-year.

A 2014 RCT (PREVAIL) evaluated patients with NVAF plus 1 additional stroke risk factor. LAAC was noninferior to warfarin for ischemic stroke prevention.6

Continue to: RECOMMENDATIONS

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Cardiology (ACC) recommends LAAC for patients with NVAF who are not candidates for long-term anticoagulation.7 Similarly, the 2016 European Society of Cardiology guidelines issued a Class IIb recommendation for LAAC for stroke prevention in those with contraindications for long-term anticoagulation.8 Lastly, in a 2014 guideline, the American Heart Association, ACC, and the Heart Rhythm Society issued a Class IIb recommendation for surgical excision of the left atrial appendage in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing cardiac surgery, but did not provide recommendations regarding LAAC.9

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2017 network meta-analysis included 19 RCTs and 87,831 patients receiving anticoagulation, antiplatelet therapy, or LAAC for NVAF.1 LAAC was superior to antiplatelet therapy (hazard ratio [HR]=0.44; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.23-0.86; P<.05) and similar to NOACs (HR=1.01; 95% CI, 0.53-1.92; P=.969) for reducing risk of stroke.

LAAC and NOACs found “most effective”

A network meta-analysis of 21 RCTs, which included data from 96,017 patients, examined the effectiveness of 7 interventions to prevent stroke in patients with NVAF: 4 NOACs, VKA, aspirin, and LAAC; the analysis compared VKA with the other interventions.2 The 2 trials that investigated LAAC accounted for only 1114 patients.

When the 7 interventions were ranked simultaneously on 2 efficacy outcomes (stroke/systemic embolism and all-cause mortality), all 4 NOACs and LAAC clustered together as “the most effective and lifesaving.”

Fewer hemorrhagic strokes with LAAC than VKA

A 2016 meta-analysis of 6 RCTs compared risk of stroke for adults with NVAF who received LAAC, VKA, or NOACs.3 No significant differences were found between NOACs and VKA or LAAC and VKA. The LAAC group had a significantly smaller number of patients.

A 2015 meta-analysis of 2406 patients with NVAF found that patients who received LAAC had significantly fewer hemorrhagic strokes (HR=0.22; P<.05) than patients who received VKA.4 No differences in all-cause stroke were found between the 2 groups during an average follow-up of 2.69 years.

LAAC found superior to warfarin for stroke prevention in one trial

A 2014 multicenter, randomized study (PROTECT-AF) of 707 patients with NVAF plus 1 additional stroke risk factor compared LAAC with VKA (warfarin).5 LAAC met criteria at 3.8 years for both noninferiority and superiority in preventing stroke, based on 2.3 events per 100 patient-years compared with 3.8 events per 100 patient-years for VKA. The number needed to treat with LAAC was 67 to result in 1 less event per patient-year.

A 2014 RCT (PREVAIL) evaluated patients with NVAF plus 1 additional stroke risk factor. LAAC was noninferior to warfarin for ischemic stroke prevention.6

Continue to: RECOMMENDATIONS

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Cardiology (ACC) recommends LAAC for patients with NVAF who are not candidates for long-term anticoagulation.7 Similarly, the 2016 European Society of Cardiology guidelines issued a Class IIb recommendation for LAAC for stroke prevention in those with contraindications for long-term anticoagulation.8 Lastly, in a 2014 guideline, the American Heart Association, ACC, and the Heart Rhythm Society issued a Class IIb recommendation for surgical excision of the left atrial appendage in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing cardiac surgery, but did not provide recommendations regarding LAAC.9

1. Sahay S, Nombela-Franco L, Rodes-Cabau J, et al. Efficacy and safety of left atrial appendage closure versus medical treatment in atrial fibrillation: a network meta-analysis from randomised trials. Heart. 2017;103:139-147.

2. Tereshchenko LG, Henrikson CA, Cigarroa, J, et al. Comparative effectiveness of interventions for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: a network meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016; 5:e003206.

3. Bajaj NS, Kalra R, Patel N, et al. Comparison of approaches for stroke prophylaxis in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation: network meta-analyses of randomized clinical trials. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0163608.

4. Holmes DR Jr, Doshi SK, Kar S, et al. Left atrial appendage closure as an alternative to warfarin for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: a patient-level meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:2614-2623.

5. Reddy VY, Sievert H, Halperin J, et al. Percutaneous left atrial appendage closure vs warfarin for atrial fibrillation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:1988-1998.

6. Holmes DR Jr, Kar S, Price MJ, et al. Prospective randomized evaluation of the Watchman Left Atrial Appendage Closure device in patients with atrial fibrillation versus long-term warfarin therapy: the PREVAIL trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:1-12.

7. Panaich S, Holmes DR. Left atrial appendage occlusion: Expert analysis. http://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2017/ 01/31/13/08/left-atrial-appendage-occlusion. Accessed April 5, 2018.

8. Kirchof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Europace. 2016;18:1609-1678.

9. January CT, Wann LS, Alpert LS, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary. JACC. 2014;64:2246-2280.

1. Sahay S, Nombela-Franco L, Rodes-Cabau J, et al. Efficacy and safety of left atrial appendage closure versus medical treatment in atrial fibrillation: a network meta-analysis from randomised trials. Heart. 2017;103:139-147.

2. Tereshchenko LG, Henrikson CA, Cigarroa, J, et al. Comparative effectiveness of interventions for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: a network meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016; 5:e003206.

3. Bajaj NS, Kalra R, Patel N, et al. Comparison of approaches for stroke prophylaxis in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation: network meta-analyses of randomized clinical trials. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0163608.

4. Holmes DR Jr, Doshi SK, Kar S, et al. Left atrial appendage closure as an alternative to warfarin for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: a patient-level meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:2614-2623.

5. Reddy VY, Sievert H, Halperin J, et al. Percutaneous left atrial appendage closure vs warfarin for atrial fibrillation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:1988-1998.

6. Holmes DR Jr, Kar S, Price MJ, et al. Prospective randomized evaluation of the Watchman Left Atrial Appendage Closure device in patients with atrial fibrillation versus long-term warfarin therapy: the PREVAIL trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:1-12.

7. Panaich S, Holmes DR. Left atrial appendage occlusion: Expert analysis. http://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2017/ 01/31/13/08/left-atrial-appendage-occlusion. Accessed April 5, 2018.

8. Kirchof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Europace. 2016;18:1609-1678.

9. January CT, Wann LS, Alpert LS, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary. JACC. 2014;64:2246-2280.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Yes. Left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) with the Watchman device is noninferior to vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) and non-VKA oral anticoagulants (NOACs) for adults with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) and 1 additional stroke risk factor (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, multiple meta-analyses).

LAAC has consistently been shown to be superior to antiplatelet therapy (SOR: A, single meta-analysis). One randomized controlled trial (RCT) demonstrated superiority of LAAC to VKA (SOR: B, single RCT).

Does amniotomy shorten spontaneous labor or improve outcomes?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A meta-analysis of 15 RCTs (5583 women) compared intentional artificial rupture of the amniotic membranes during labor (amniotomy) with intention to preserve the membranes (no amniotomy). The study found no differences in any of the measured primary outcomes: length of first stage of labor, cesarean section, maternal satisfaction with childbirth, or Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes.1

Investigators included 9 trials with both nulliparous and multiparous women and 6 trials with only nulliparous women. Thirteen trials compared amniotomy with intention to preserve the membranes, and 2 trials performed amniotomy in the control group if the membranes were intact at full cervical dilation.

Amniotomy doesn’t affect first-stage labor or cesarean risk

Five trials (1127 women) reported no difference in length of the first stage of labor between the amniotomy and no amniotomy groups (mean difference [MD]= −20 minutes; 95% confidence interval [CI], −96 to 55). Subgroups of primiparous and multiparous women showed no difference (MD= −58 minutes; 95% CI, −153 to 37 and MD= +23 minutes; 95% CI, −51 to 97, respectively).

Nine trials (5021 women) reported no significant difference in cesarean section risk overall or when compared by parity, multiparous vs primiparous (risk ratio [RR]= 1.27; 95% CI, 0.99-1.63). One trial (84 women) found no difference in maternal satisfaction scores with childbirth experience. Six trials (3598 women) that reported risk of low Apgar score (<4 at 1 minute or <7 at 5 minutes) found no difference overall (RR=0.53; 95% CI, 0.28-1.00), or when compared by parity (multiparous vs primiparous).

Investigators reported that the included trials varied in quality and described the following limitations: inconsistent or unspecified timing of amniotomy during labor, proportion of women in the control group undergoing amniotomy, and ≥30% of women not getting the allocated treatment in all but one of the trials.

Secondary outcomes: Amniotomy reduces oxytocin use

Eight trials (4264 women) evaluated oxytocin augmentation and found that amniotomy decreased its use in multiparous (RR=0.43; 95% CI, 0.30-0.60), but not primiparous, women.

Eight trials (1927 women) reported length of second stage of labor as a secondary outcome, with no difference overall (MD= −1.33 minutes; 95% CI, −2.92 to 0.26). Amniotomy produced a statistical but not clinically significant shortening in subanalysis of primiparous women (MD= −5.43 minutes; 95% CI, −9.98 to −0.89) but not multiparous women.

Continue to: Three trials...

Three trials (1695 women) evaluated dysfunctional labor, defined as no progress in cervical dilation in 2 hours or ineffective uterine contractions. Amniotomy reduced dysfunctional labor in both primiparous (RR=0.49; 95% CI, 0.33-0.73) and multiparous women (RR=0.44; 95% CI, 0.31-0.62).

No differences found in other maternal and fetal outcomes

Investigators reported no differences in other secondary maternal outcomes: instrumental vaginal birth (10 trials, 5121 women); pain relief (8 trials, 3475 women); postpartum hemorrhage (2 trials, 1822 women); serious maternal morbidity or death (3 trials, 1740 women); umbilical cord prolapse (2 trials, 1615 women); and cesarean section for fetal distress, prolonged labor, or antepartum hemorrhage (1 RCT, 690 women).

Investigators also found no differences in secondary fetal outcomes: serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death (8 trials, 3397 women); neonatal admission to neonatal intensive care (5 trials, 2686 women); abnormal fetal heart rate tracing in first stage of labor (4 trials, 1284 women); meconium aspiration (2 trials, 1615 women); and fetal acidosis (2 trials, 1014 women). Similarly, 1 RCT (39 women) that compared amniotomy with intent to preserve membranes in spontaneous labors that became prolonged found no difference in cesarean section, maternal satisfaction, or Apgar scores.

A few studies claim shorter labor with amniotomy

However, a later Iranian RCT (300 women) reported that early amniotomy shortened labor (labor duration: 7.5 ± 0.7 hours with amniotomy vs 9.9 ± 1.0 hours without amniotomy; P<.001) and reduced the risk of dystocia (RR=0.81; 95% CI, 0.59-0.90) and cesarean section (RR=0.82; 95% CI, 0.66-0.90).2

A similar Nigerian RCT (214 women) and an Indian RCT (144 women) both claimed that amniotomy also shortened labor (4.7 ± 0.9 hours vs 5.9 ± 1.3, and 3.9 ± 2 hours vs 6.1 ± 2.8 hours, respectively).3,4 In neither trial, however, did investigators explain how the difference was significant when the duration of labor times overlapped within the margin of error.

1. Smyth RMD, Markham C, Dowswell T. Amniotomy for shortening spontaneous labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(6):CD006167.

2. Ghafarzadeh M, Moeininasab S, Namdari M. Effect of early amniotomy on dystocia risk and cesarean delivery in nulliparous women: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;292:321-325.

3. Onah LN, Dim CC, Nwagha UI, et al. Effect of early amniotomy on the outcome of spontaneous labour: a randomized controlled trial of pregnant women in Enugu, South-east Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. 2015;15:1097-1103.

4. Vadivelu M, Rathore S, Benjamin SJ, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effect of amniotomy on the duration of spontaneous labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;138:152-157.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A meta-analysis of 15 RCTs (5583 women) compared intentional artificial rupture of the amniotic membranes during labor (amniotomy) with intention to preserve the membranes (no amniotomy). The study found no differences in any of the measured primary outcomes: length of first stage of labor, cesarean section, maternal satisfaction with childbirth, or Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes.1

Investigators included 9 trials with both nulliparous and multiparous women and 6 trials with only nulliparous women. Thirteen trials compared amniotomy with intention to preserve the membranes, and 2 trials performed amniotomy in the control group if the membranes were intact at full cervical dilation.

Amniotomy doesn’t affect first-stage labor or cesarean risk

Five trials (1127 women) reported no difference in length of the first stage of labor between the amniotomy and no amniotomy groups (mean difference [MD]= −20 minutes; 95% confidence interval [CI], −96 to 55). Subgroups of primiparous and multiparous women showed no difference (MD= −58 minutes; 95% CI, −153 to 37 and MD= +23 minutes; 95% CI, −51 to 97, respectively).

Nine trials (5021 women) reported no significant difference in cesarean section risk overall or when compared by parity, multiparous vs primiparous (risk ratio [RR]= 1.27; 95% CI, 0.99-1.63). One trial (84 women) found no difference in maternal satisfaction scores with childbirth experience. Six trials (3598 women) that reported risk of low Apgar score (<4 at 1 minute or <7 at 5 minutes) found no difference overall (RR=0.53; 95% CI, 0.28-1.00), or when compared by parity (multiparous vs primiparous).

Investigators reported that the included trials varied in quality and described the following limitations: inconsistent or unspecified timing of amniotomy during labor, proportion of women in the control group undergoing amniotomy, and ≥30% of women not getting the allocated treatment in all but one of the trials.

Secondary outcomes: Amniotomy reduces oxytocin use

Eight trials (4264 women) evaluated oxytocin augmentation and found that amniotomy decreased its use in multiparous (RR=0.43; 95% CI, 0.30-0.60), but not primiparous, women.

Eight trials (1927 women) reported length of second stage of labor as a secondary outcome, with no difference overall (MD= −1.33 minutes; 95% CI, −2.92 to 0.26). Amniotomy produced a statistical but not clinically significant shortening in subanalysis of primiparous women (MD= −5.43 minutes; 95% CI, −9.98 to −0.89) but not multiparous women.

Continue to: Three trials...

Three trials (1695 women) evaluated dysfunctional labor, defined as no progress in cervical dilation in 2 hours or ineffective uterine contractions. Amniotomy reduced dysfunctional labor in both primiparous (RR=0.49; 95% CI, 0.33-0.73) and multiparous women (RR=0.44; 95% CI, 0.31-0.62).

No differences found in other maternal and fetal outcomes

Investigators reported no differences in other secondary maternal outcomes: instrumental vaginal birth (10 trials, 5121 women); pain relief (8 trials, 3475 women); postpartum hemorrhage (2 trials, 1822 women); serious maternal morbidity or death (3 trials, 1740 women); umbilical cord prolapse (2 trials, 1615 women); and cesarean section for fetal distress, prolonged labor, or antepartum hemorrhage (1 RCT, 690 women).

Investigators also found no differences in secondary fetal outcomes: serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death (8 trials, 3397 women); neonatal admission to neonatal intensive care (5 trials, 2686 women); abnormal fetal heart rate tracing in first stage of labor (4 trials, 1284 women); meconium aspiration (2 trials, 1615 women); and fetal acidosis (2 trials, 1014 women). Similarly, 1 RCT (39 women) that compared amniotomy with intent to preserve membranes in spontaneous labors that became prolonged found no difference in cesarean section, maternal satisfaction, or Apgar scores.

A few studies claim shorter labor with amniotomy

However, a later Iranian RCT (300 women) reported that early amniotomy shortened labor (labor duration: 7.5 ± 0.7 hours with amniotomy vs 9.9 ± 1.0 hours without amniotomy; P<.001) and reduced the risk of dystocia (RR=0.81; 95% CI, 0.59-0.90) and cesarean section (RR=0.82; 95% CI, 0.66-0.90).2

A similar Nigerian RCT (214 women) and an Indian RCT (144 women) both claimed that amniotomy also shortened labor (4.7 ± 0.9 hours vs 5.9 ± 1.3, and 3.9 ± 2 hours vs 6.1 ± 2.8 hours, respectively).3,4 In neither trial, however, did investigators explain how the difference was significant when the duration of labor times overlapped within the margin of error.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A meta-analysis of 15 RCTs (5583 women) compared intentional artificial rupture of the amniotic membranes during labor (amniotomy) with intention to preserve the membranes (no amniotomy). The study found no differences in any of the measured primary outcomes: length of first stage of labor, cesarean section, maternal satisfaction with childbirth, or Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes.1

Investigators included 9 trials with both nulliparous and multiparous women and 6 trials with only nulliparous women. Thirteen trials compared amniotomy with intention to preserve the membranes, and 2 trials performed amniotomy in the control group if the membranes were intact at full cervical dilation.

Amniotomy doesn’t affect first-stage labor or cesarean risk

Five trials (1127 women) reported no difference in length of the first stage of labor between the amniotomy and no amniotomy groups (mean difference [MD]= −20 minutes; 95% confidence interval [CI], −96 to 55). Subgroups of primiparous and multiparous women showed no difference (MD= −58 minutes; 95% CI, −153 to 37 and MD= +23 minutes; 95% CI, −51 to 97, respectively).

Nine trials (5021 women) reported no significant difference in cesarean section risk overall or when compared by parity, multiparous vs primiparous (risk ratio [RR]= 1.27; 95% CI, 0.99-1.63). One trial (84 women) found no difference in maternal satisfaction scores with childbirth experience. Six trials (3598 women) that reported risk of low Apgar score (<4 at 1 minute or <7 at 5 minutes) found no difference overall (RR=0.53; 95% CI, 0.28-1.00), or when compared by parity (multiparous vs primiparous).

Investigators reported that the included trials varied in quality and described the following limitations: inconsistent or unspecified timing of amniotomy during labor, proportion of women in the control group undergoing amniotomy, and ≥30% of women not getting the allocated treatment in all but one of the trials.

Secondary outcomes: Amniotomy reduces oxytocin use

Eight trials (4264 women) evaluated oxytocin augmentation and found that amniotomy decreased its use in multiparous (RR=0.43; 95% CI, 0.30-0.60), but not primiparous, women.

Eight trials (1927 women) reported length of second stage of labor as a secondary outcome, with no difference overall (MD= −1.33 minutes; 95% CI, −2.92 to 0.26). Amniotomy produced a statistical but not clinically significant shortening in subanalysis of primiparous women (MD= −5.43 minutes; 95% CI, −9.98 to −0.89) but not multiparous women.

Continue to: Three trials...

Three trials (1695 women) evaluated dysfunctional labor, defined as no progress in cervical dilation in 2 hours or ineffective uterine contractions. Amniotomy reduced dysfunctional labor in both primiparous (RR=0.49; 95% CI, 0.33-0.73) and multiparous women (RR=0.44; 95% CI, 0.31-0.62).

No differences found in other maternal and fetal outcomes

Investigators reported no differences in other secondary maternal outcomes: instrumental vaginal birth (10 trials, 5121 women); pain relief (8 trials, 3475 women); postpartum hemorrhage (2 trials, 1822 women); serious maternal morbidity or death (3 trials, 1740 women); umbilical cord prolapse (2 trials, 1615 women); and cesarean section for fetal distress, prolonged labor, or antepartum hemorrhage (1 RCT, 690 women).

Investigators also found no differences in secondary fetal outcomes: serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death (8 trials, 3397 women); neonatal admission to neonatal intensive care (5 trials, 2686 women); abnormal fetal heart rate tracing in first stage of labor (4 trials, 1284 women); meconium aspiration (2 trials, 1615 women); and fetal acidosis (2 trials, 1014 women). Similarly, 1 RCT (39 women) that compared amniotomy with intent to preserve membranes in spontaneous labors that became prolonged found no difference in cesarean section, maternal satisfaction, or Apgar scores.

A few studies claim shorter labor with amniotomy

However, a later Iranian RCT (300 women) reported that early amniotomy shortened labor (labor duration: 7.5 ± 0.7 hours with amniotomy vs 9.9 ± 1.0 hours without amniotomy; P<.001) and reduced the risk of dystocia (RR=0.81; 95% CI, 0.59-0.90) and cesarean section (RR=0.82; 95% CI, 0.66-0.90).2

A similar Nigerian RCT (214 women) and an Indian RCT (144 women) both claimed that amniotomy also shortened labor (4.7 ± 0.9 hours vs 5.9 ± 1.3, and 3.9 ± 2 hours vs 6.1 ± 2.8 hours, respectively).3,4 In neither trial, however, did investigators explain how the difference was significant when the duration of labor times overlapped within the margin of error.

1. Smyth RMD, Markham C, Dowswell T. Amniotomy for shortening spontaneous labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(6):CD006167.

2. Ghafarzadeh M, Moeininasab S, Namdari M. Effect of early amniotomy on dystocia risk and cesarean delivery in nulliparous women: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;292:321-325.

3. Onah LN, Dim CC, Nwagha UI, et al. Effect of early amniotomy on the outcome of spontaneous labour: a randomized controlled trial of pregnant women in Enugu, South-east Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. 2015;15:1097-1103.

4. Vadivelu M, Rathore S, Benjamin SJ, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effect of amniotomy on the duration of spontaneous labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;138:152-157.

1. Smyth RMD, Markham C, Dowswell T. Amniotomy for shortening spontaneous labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(6):CD006167.

2. Ghafarzadeh M, Moeininasab S, Namdari M. Effect of early amniotomy on dystocia risk and cesarean delivery in nulliparous women: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;292:321-325.

3. Onah LN, Dim CC, Nwagha UI, et al. Effect of early amniotomy on the outcome of spontaneous labour: a randomized controlled trial of pregnant women in Enugu, South-east Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. 2015;15:1097-1103.

4. Vadivelu M, Rathore S, Benjamin SJ, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effect of amniotomy on the duration of spontaneous labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;138:152-157.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

No. Amniotomy neither shortens spontaneous labor nor improves any of the following outcomes: length of first stage of labor, cesarean section rate, maternal satisfaction with childbirth, or Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, large meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials [RCTs] and a single RCT with conflicting results).

Amniotomy does result in about a 55% reduction of pitocin use in multiparous women, a small (5 minutes) decrease in the duration of second-stage labor in primiparous women, and about a 50% overall reduction in dysfunctional labor—ie, no progress in cervical dilation in 2 hours or ineffective uterine contractions (SOR: A, large meta-analyses of RCTs and a single RCT with conflicting results).

Amniotomy doesn’t improve other maternal outcomes—instrumented vaginal birth; pain relief; postpartum hemorrhage; serious morbidity or death; umbilical cord prolapse; cesarean section for fetal distress, prolonged labor, antepartum hemorrhage—nor fetal outcomes—serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death; neonatal admission to intensive care; abnormal fetal heart rate tracing in first-stage labor; meconium aspiration; or fetal acidosis (SOR: A, large meta-analyses of RCTs and a single RCT with conflicting results).

What medical therapies work for gastroparesis?

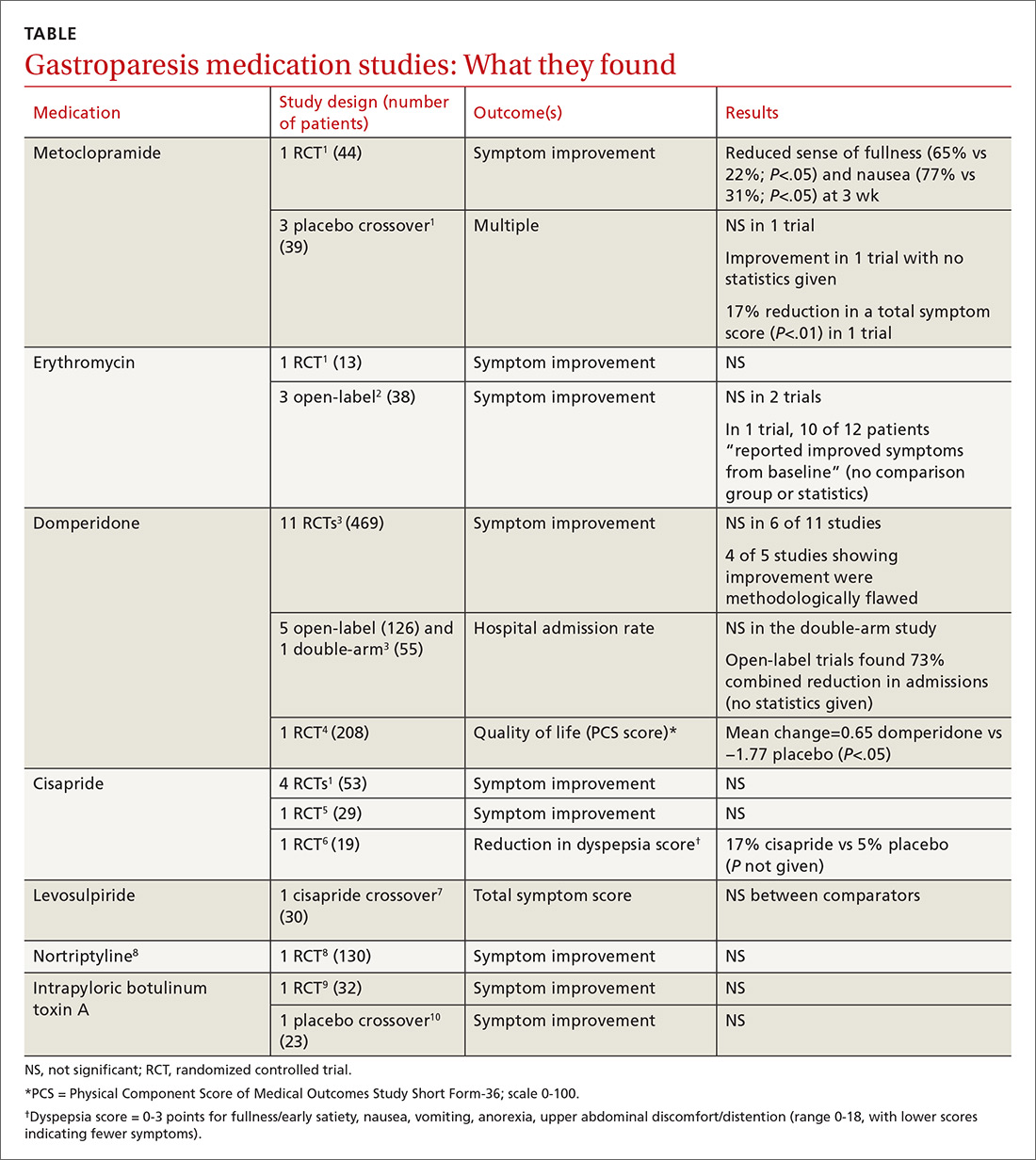

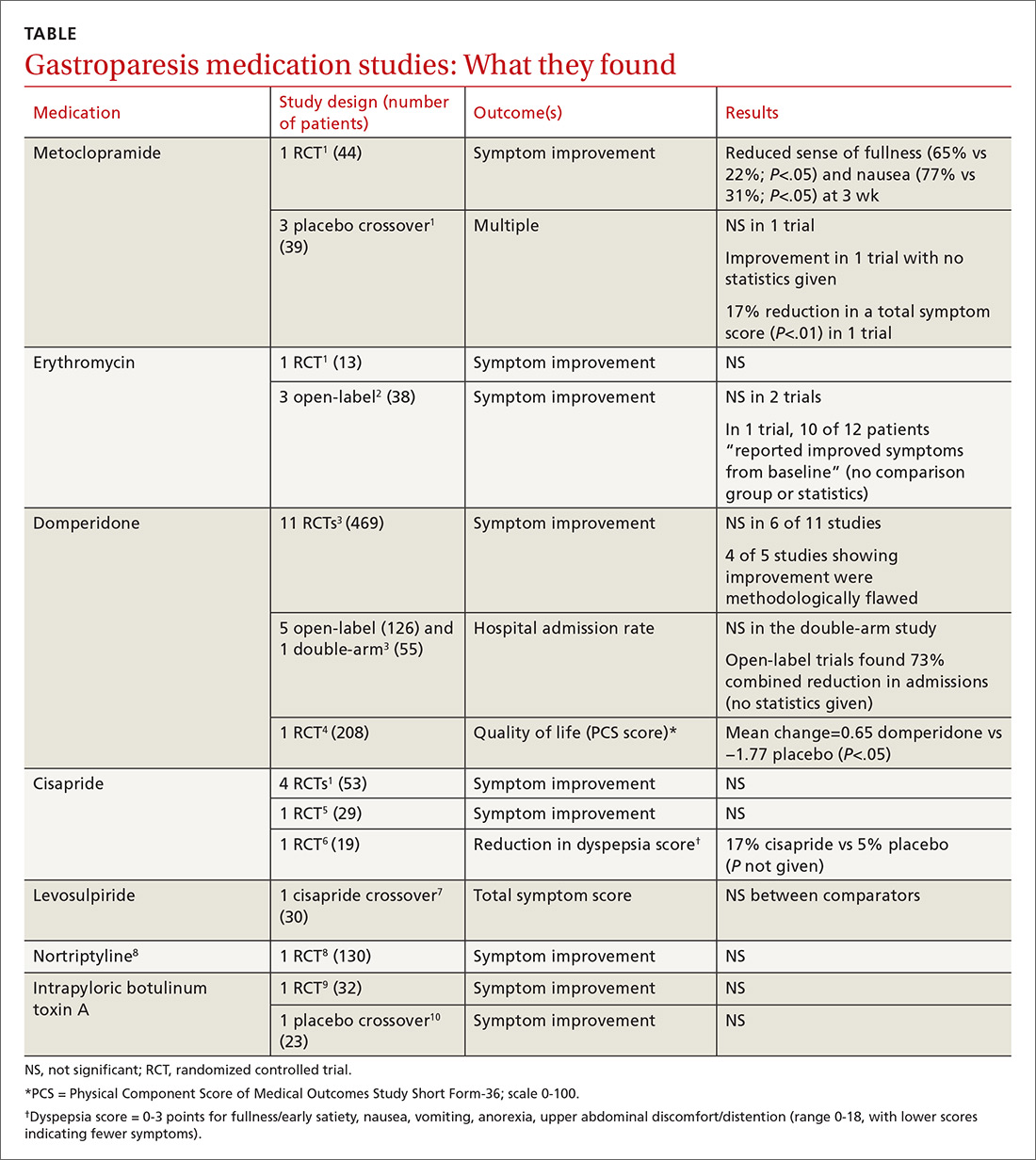

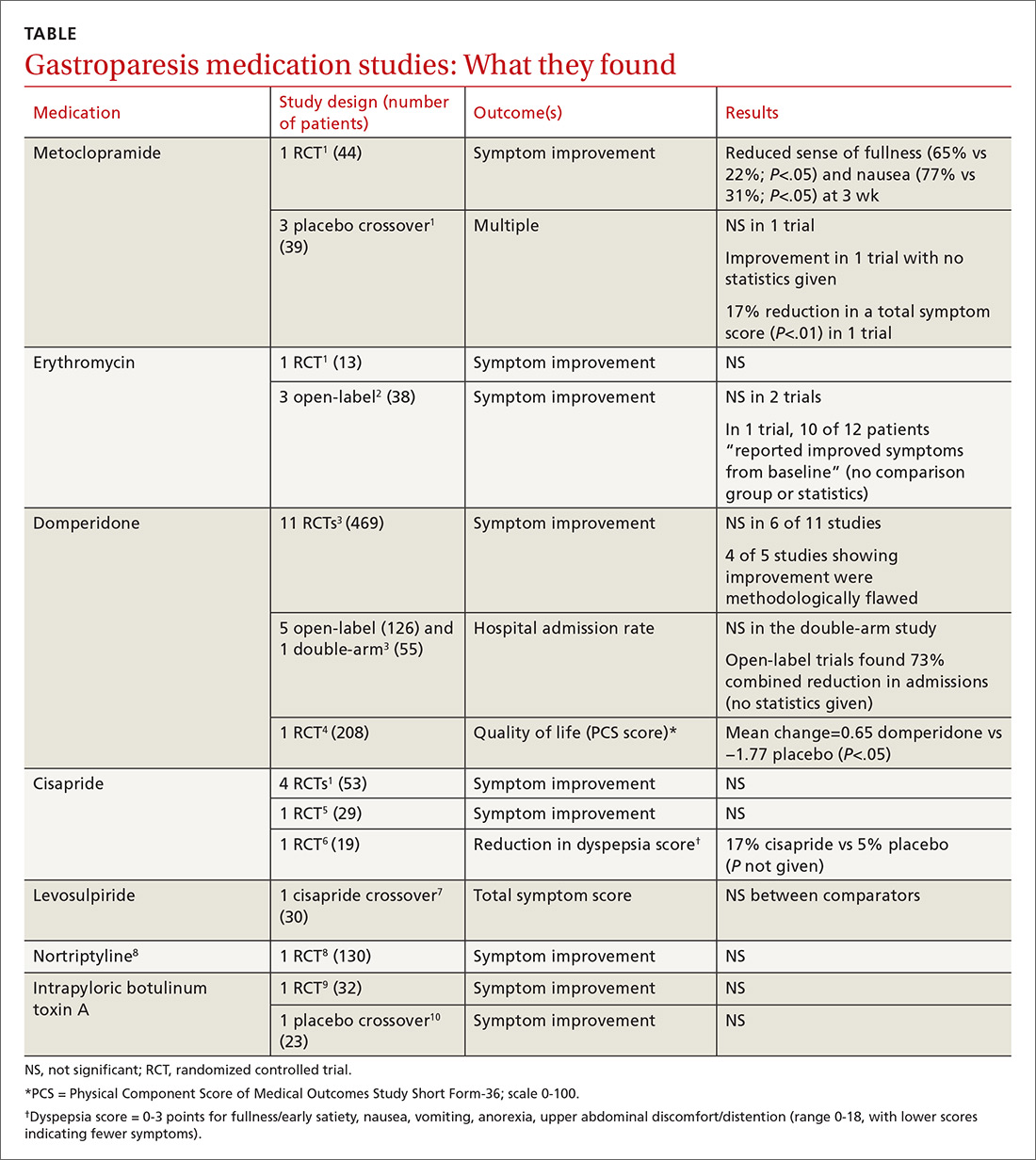

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Metoclopramide. One systematic review that looked at the efficacy of metoclopramide for gastroparesis identified one small RCT and 3 smaller placebo-controlled crossover trials.1 The RCT (using 10 mg of metoclopramide after meals and at bedtime) found consistent improvement in the sense of fullness over 3 weeks of therapy, with reduction of nausea at one and 3 weeks, but not at 2 weeks. Vomiting, anorexia, and early satiety didn’t improve. The crossover trials had inconsistent results. The largest one, with only 16 patients, didn’t find an improvement in symptoms.

Erythromycin. Two systematic reviews looked at the efficacy of erythromycin, primarily identifying studies 20- to 30-years old. The first systematic review identified only one small (single-blind) RCT in which erythromycin treatment didn’t change symptoms.1 A second review identified 3 trials described as “open label,” all with fewer than 14 subjects and all lasting a month or less.2 Erythromycin improved patient symptoms in only 1 of the 3, and this trial (like the others) had significant methodologic flaws. The authors of the second review concluded that “the true efficacy of erythromycin in relieving symptoms … remains to be determined.”

Domperidone. A systematic review and one subsequent RCT evaluated domperidone. The systematic review identified 11 randomized, placebo-controlled trials (469 patients).3 Six studies found no impact on patient symptoms, while 5 reported a positive effect. The review also identified 6 trials that evaluated domperidone treatment on hospitalization rates. Open-label (single-arm, unblinded) trials tended to find a reduction in hospitalizations with domperidone, an effect not seen in the one double-arm study that evaluated this outcome.

The review authors noted that given the small size and low methodologic quality of most studies “it is not surprising … that there continues to be controversy about the efficacy of this drug” for symptoms of gastroparesis.

One subsequent RCT, using domperidone 20 mg 4 times daily for 4 weeks, found a 2% improvement over placebo in the physical component of a multifaceted quality-of-life measure.4 The improvement was statistically significant, but of unclear clinical importance.

Cisapride. One systematic review and 2 subsequent RCTs evaluated the clinical effects of cisapride. The systematic review included 4 small RCTs (53 patients) that didn’t individually find changes in patient symptoms.

In one subsequent RCT, comparing 10 mg cisapride 3 times daily to placebo for 2 weeks, cisapride yielded no significant change in symptoms.5 The other RCT compared oral cisapride 10 mg 3 times daily to placebo for one year. Cisapride treatment produced a 17% reduction in symptoms (P<.002 vs baseline), and placebo produced a 5% reduction (P=NS vs baseline). The study didn’t state if the difference between the 2 outcomes was statistically significant.6

Continue to: Levosulpiride

Levosulpiride. One crossover study compared 25 mg levosulpiride with 10 mg cisapride (both given orally 3 times a day) on gastroparesis symptoms and gastric emptying. Each medication was given for one month (washout duration not given). The study found similar efficacy between levosulpiride and cisapride in terms of improvement in gastric emptying rates and total symptom scores.7 No studies compare levosulpiride to placebo.

Nortriptyline. A multicenter, parallel-group, double-blind RCT comparing 75 mg/d nortriptyline for 15 weeks with placebo in adult patients with moderate to severe symptoms of idiopathic gastroparesis for at least 6 months found that nortriptyline didn’t improve symptoms.8

Botulinum toxin A. An RCT comparing a single injection of 200 units intrapyloric botulinum toxin A with placebo in adult patients with severe gastroparesis symptoms found that botulinum toxin A didn’t result in symptomatic improvement.9 A crossover trial comparing 100 units monthly intrapyloric botulinum toxin A for 3 months with placebo in patients with gastroparesis found that neither symptoms nor rate of gastric emptying changed with the toxin.10

RECOMMENDATIONS

The 2013 guidelines from the American College of Gastroenterology list metoclopramide as the first-line agent for gastroparesis requiring medical therapy, followed by domperidone and then erythromycin (all based on “moderate quality evidence”). Antiemetic agents are also recommended for symptom control.11

1. Sturm A, Holtmann G, Goebell H, et al. Prokinetics in patients with gastroparesis: a systematic analysis. Digestion. 1999;60:422-427.

2. Maganti K, Onyemere K, Jones MP. Oral erythromycin and symptomatic relief of gastroparesis: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:259-263.

3. Sugumar A, Singh A, Pasricha PJ. A systematic review of the efficacy of domperidone for the treatment of diabetic gastroparesis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:726-733.

4. Farup CE, Leidy NK, Murray M, et al. Effect of domperidone on the health-related quality of life of patients with symptoms of diabetic gastroparesis. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1699-1706.

5. Dutta U, Padhy AK, Ahuja V, et al. Double blind controlled trial of effect of cisapride on gastric emptying in diabetics. Trop Gastroenterol. 1999;20:116-119.

6. Braden B, Enghofer M, Schaub M, et al. Long-term cisapride treatment improves diabetic gastroparesis but not glycaemic control. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1341-1346.

7. Mansi C, Borro P, Giacomini M, et al. Comparative effects of levosulpiride and cisapride on gastric emptying and symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia and gastroparesis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:561-569.

8. Parkman HP, Van Natta ML, Abell TL, et al. Effect of nortriptyline on symptoms of idiopathic gastroparesis: the NORIG randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310:2640-2649.

9. Friedenberg FK, Palit A, Parkman HP, et al. Botulinum toxin A for the treatment of delayed gastric emptying. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:416-423.

10. Arts J, Holvoet L, Caenepeel P, et al. Clinical trial: a randomized-controlled crossover study of intrapyloric injection of botulinum toxin in gastroparesis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1251-1258.

11. Camilleri M, Parkman HP, Shafi MA, et al. Clinical guideline: management of gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:18-38.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Metoclopramide. One systematic review that looked at the efficacy of metoclopramide for gastroparesis identified one small RCT and 3 smaller placebo-controlled crossover trials.1 The RCT (using 10 mg of metoclopramide after meals and at bedtime) found consistent improvement in the sense of fullness over 3 weeks of therapy, with reduction of nausea at one and 3 weeks, but not at 2 weeks. Vomiting, anorexia, and early satiety didn’t improve. The crossover trials had inconsistent results. The largest one, with only 16 patients, didn’t find an improvement in symptoms.

Erythromycin. Two systematic reviews looked at the efficacy of erythromycin, primarily identifying studies 20- to 30-years old. The first systematic review identified only one small (single-blind) RCT in which erythromycin treatment didn’t change symptoms.1 A second review identified 3 trials described as “open label,” all with fewer than 14 subjects and all lasting a month or less.2 Erythromycin improved patient symptoms in only 1 of the 3, and this trial (like the others) had significant methodologic flaws. The authors of the second review concluded that “the true efficacy of erythromycin in relieving symptoms … remains to be determined.”