User login

How safe and effective is ondansetron for nausea and vomiting in pregnancy?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Efficacy. A 2014 double-blind RCT compared ondansetron with pyridoxine plus doxylamine (standard care) for outpatient treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy.1 The 36 patients had an average gestational age of 8 weeks and received either 4 mg oral ondansetron plus placebo or 25 mg pyridoxine plus 12.5 mg doxylamine 3 times daily for 5 days. Nausea and vomiting severity was measured using 2 separate 10-cm visual analog scales (VAS) with scores ranging from 0 to 10 (worst nausea or vomiting imaginable). Researchers determined that a VAS score reduction of 2.5 cm was clinically significant.

Patients treated with ondansetron described greater improvements in nausea (mean VAS change −5.1 cm vs −2 cm; P = .019) and vomiting (mean VAS change −4.1 cm vs −1.7 cm; P = .049). No patient required hospitalization. The researchers didn’t report on adverse effects or birth outcomes. The study was limited by the small sample size and a high rate (17%) of patients with missing data or who were lost to follow-up.

IV ondansetron vs metoclopramide: Similar efficacy, fewer adverse effects

A 2014 double-blind RCT compared IV ondansetron with IV metoclopramide (standard care) for treating hyperemesis gravidarum.2 The 160 patients had an average gestational age of 9.5 weeks and intractable nausea and vomiting severe enough to cause dehydration, metabolic disturbance, and hospitalization. Patients received either 4 mg ondansetron or 10 mg metoclopramide IV every 8 hours for 24 hours. The primary outcomes were number of episodes of vomiting over 24 hours and self-reported sense of well-being rated on a 10-point scale.

No differences were found between the ondansetron- and metoclopramide-treated groups in terms of vomiting over 24 hours (median episodes 1 and 1; P = .38) or sense of well-being (mean scores 8.7 vs 8.3; P = .13). Patients treated with ondansetron were less likely to have persistent ketonuria at 24 hours (relative risk [RR] = 0.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.1-0.8; number needed to treat [NNT] = 6). They also were less likely to feel drowsy (RR = 0.3; 95% CI, 0.1–0.8; NNT = 6) or complain of dry mouth (RR = 0.4; 95% CI, 0.1-0.9; NNT = 8). The study didn’t report birth outcomes or adverse fetal effects.

Oral ondansetron outperforms oral metoclopramide in small study

A 2013 double-blind RCT compared ondansetron with metoclopramide (standard care) for controlling severe nausea and vomiting.3 The 83 patients, with an average gestational age of 8.7 weeks, had more than 3 vomiting episodes daily, weight loss, and ketonuria. They received either 4 mg oral ondansetron or 10 mg oral metoclopramide for 2 weeks as follows: 3 times daily for 1 week, then twice daily for 3 days, then once daily for 4 days. Patients rated nausea severity using a 10-cm VAS from 0 to 10 (severe nausea) and recorded the number of vomiting episodes.

Women treated with ondansetron had significantly lower VAS scores on Days 3 and 4 of treatment (5.4 vs 6, P = .024 on Day 3; 4.1 vs 5.7, P = .023 on Day 4). They also had fewer episodes of vomiting on Days 2, 3, and 4 (3.7 vs 6, P = .006 on Day 2; 3.2 vs 5.3, P = .006 on Day 3; and 3.3 vs 5, P = .013 on Day 4). The study was limited by the small sample size.

Safety. A 2016 systematic review examining the risk of birth defects associated with ondansetron exposure in pregnancy found 8 reports: 5 birth registries, 2 case-control studies, and 1 prospective cohort study.4 Investigators compared rates of major malformations—cleft lips, cleft palates, neural tube defects, cardiac defects, and hypospadias—in 5101 women exposed to ondansetron in the first trimester with birth defect rates in more than 3.1 million nonexposed women.

Continue to: No study demonstrated...

No study demonstrated an increased rate of major malformations associated with ondansetron exposure except for 2 disease registry studies with nearly 2.4 million patients that reported a slight increase in the risk of cardiac defects (odds ratio [OR] = 2; 95% CI, 1.3-3.1; OR = 1.6, 95% CI, 1-2.1). Comparisons of other birth defect rates associated with ondansetron exposure were inconsistent, with studies showing small increases, decreases, or no difference in rates between exposed and nonexposed women.

Exposure vs nonexposure: No difference in adverse outcomes

A 2013 retrospective cohort study looked at 608,385 pregnancies among women in Denmark, of whom 1970 (0.3%) had been exposed to ondansetron.5 The study found that exposure to ondansetron compared with nonexposure was associated with a lower risk for spontaneous abortion between 7 and 12 weeks’ gestation (1.1% vs 3.7%; hazard ratio [HR] = 0.5; 95% CI, 0.3-0.9).

No significant differences between ondansetron exposure and nonexposure were found for the following adverse outcomes: spontaneous abortion between 13 and 22 weeks’ gestation (1% vs 2.1%; HR = 0.6; 95% CI, 0.3-1.2); stillbirth (0.3% vs 0.4%; HR = 0.4; 95% CI, 0.1-1.7); any major birth defect (2.9% in both exposed and nonexposed women; OR = 1.12; 95% CI, 0.69-1.82); preterm delivery (6.2% vs 5.2%; OR = 0.9; 95% CI, 0.7-1.3), low birth weight infant (4.1% vs 3.7%; OR = 0.8; 95% CI, 0.5-1.1); and small-for-gestational-age infant (10.4% vs 9.2%; OR = 1.1; 95% CI, 0.9-1.4).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) states that insufficient data exist regarding the safety of ondansetron for the fetus.6 ACOG recommends individualizing the use of ondansetron before 10 weeks of pregnancy after weighing the risks and benefits. ACOG also recommends adding ondansetron as third-line treatment for nausea and vomiting unresponsive to first- and second-line treatments.

EDITOR'S TAKEAWAY

Higher-quality studies showed ondansetron to be an effective treatment for hyperemesis gravidarum. Lower-quality studies raised some concerns about adverse fetal effects. Although the adverse effects were rare and the quality of the evidence was lower, the cautionary principle suggests that ondansetron should be a second-line option.

1. Oliveira LG, Capp SM, You WB, et al. Ondansetron compared with doxylamine and pyridoxine for treatment of nausea in pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:735-742.

2. Abas MN, Tan PC, Azmi N, et al. Ondansetron compared with metoclopramide for hyperemesis gravidarum: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:1272-1279.

3. Kashifard M, Basirat Z, Kashifard M, et al. Ondansetrone or metoclopromide? Which is more effective in severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy? A randomized trial double-blind study. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2013;40:127-130.

4. Carstairs SD. Ondansetron use in pregnancy and birth defects: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:878-883.

5. Pasternak B, Svanström H, Hviid A. Ondansetron in pregnancy and risk of adverse fetal outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:814-823.

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 189: Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e15-e30.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Efficacy. A 2014 double-blind RCT compared ondansetron with pyridoxine plus doxylamine (standard care) for outpatient treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy.1 The 36 patients had an average gestational age of 8 weeks and received either 4 mg oral ondansetron plus placebo or 25 mg pyridoxine plus 12.5 mg doxylamine 3 times daily for 5 days. Nausea and vomiting severity was measured using 2 separate 10-cm visual analog scales (VAS) with scores ranging from 0 to 10 (worst nausea or vomiting imaginable). Researchers determined that a VAS score reduction of 2.5 cm was clinically significant.

Patients treated with ondansetron described greater improvements in nausea (mean VAS change −5.1 cm vs −2 cm; P = .019) and vomiting (mean VAS change −4.1 cm vs −1.7 cm; P = .049). No patient required hospitalization. The researchers didn’t report on adverse effects or birth outcomes. The study was limited by the small sample size and a high rate (17%) of patients with missing data or who were lost to follow-up.

IV ondansetron vs metoclopramide: Similar efficacy, fewer adverse effects

A 2014 double-blind RCT compared IV ondansetron with IV metoclopramide (standard care) for treating hyperemesis gravidarum.2 The 160 patients had an average gestational age of 9.5 weeks and intractable nausea and vomiting severe enough to cause dehydration, metabolic disturbance, and hospitalization. Patients received either 4 mg ondansetron or 10 mg metoclopramide IV every 8 hours for 24 hours. The primary outcomes were number of episodes of vomiting over 24 hours and self-reported sense of well-being rated on a 10-point scale.

No differences were found between the ondansetron- and metoclopramide-treated groups in terms of vomiting over 24 hours (median episodes 1 and 1; P = .38) or sense of well-being (mean scores 8.7 vs 8.3; P = .13). Patients treated with ondansetron were less likely to have persistent ketonuria at 24 hours (relative risk [RR] = 0.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.1-0.8; number needed to treat [NNT] = 6). They also were less likely to feel drowsy (RR = 0.3; 95% CI, 0.1–0.8; NNT = 6) or complain of dry mouth (RR = 0.4; 95% CI, 0.1-0.9; NNT = 8). The study didn’t report birth outcomes or adverse fetal effects.

Oral ondansetron outperforms oral metoclopramide in small study

A 2013 double-blind RCT compared ondansetron with metoclopramide (standard care) for controlling severe nausea and vomiting.3 The 83 patients, with an average gestational age of 8.7 weeks, had more than 3 vomiting episodes daily, weight loss, and ketonuria. They received either 4 mg oral ondansetron or 10 mg oral metoclopramide for 2 weeks as follows: 3 times daily for 1 week, then twice daily for 3 days, then once daily for 4 days. Patients rated nausea severity using a 10-cm VAS from 0 to 10 (severe nausea) and recorded the number of vomiting episodes.

Women treated with ondansetron had significantly lower VAS scores on Days 3 and 4 of treatment (5.4 vs 6, P = .024 on Day 3; 4.1 vs 5.7, P = .023 on Day 4). They also had fewer episodes of vomiting on Days 2, 3, and 4 (3.7 vs 6, P = .006 on Day 2; 3.2 vs 5.3, P = .006 on Day 3; and 3.3 vs 5, P = .013 on Day 4). The study was limited by the small sample size.

Safety. A 2016 systematic review examining the risk of birth defects associated with ondansetron exposure in pregnancy found 8 reports: 5 birth registries, 2 case-control studies, and 1 prospective cohort study.4 Investigators compared rates of major malformations—cleft lips, cleft palates, neural tube defects, cardiac defects, and hypospadias—in 5101 women exposed to ondansetron in the first trimester with birth defect rates in more than 3.1 million nonexposed women.

Continue to: No study demonstrated...

No study demonstrated an increased rate of major malformations associated with ondansetron exposure except for 2 disease registry studies with nearly 2.4 million patients that reported a slight increase in the risk of cardiac defects (odds ratio [OR] = 2; 95% CI, 1.3-3.1; OR = 1.6, 95% CI, 1-2.1). Comparisons of other birth defect rates associated with ondansetron exposure were inconsistent, with studies showing small increases, decreases, or no difference in rates between exposed and nonexposed women.

Exposure vs nonexposure: No difference in adverse outcomes

A 2013 retrospective cohort study looked at 608,385 pregnancies among women in Denmark, of whom 1970 (0.3%) had been exposed to ondansetron.5 The study found that exposure to ondansetron compared with nonexposure was associated with a lower risk for spontaneous abortion between 7 and 12 weeks’ gestation (1.1% vs 3.7%; hazard ratio [HR] = 0.5; 95% CI, 0.3-0.9).

No significant differences between ondansetron exposure and nonexposure were found for the following adverse outcomes: spontaneous abortion between 13 and 22 weeks’ gestation (1% vs 2.1%; HR = 0.6; 95% CI, 0.3-1.2); stillbirth (0.3% vs 0.4%; HR = 0.4; 95% CI, 0.1-1.7); any major birth defect (2.9% in both exposed and nonexposed women; OR = 1.12; 95% CI, 0.69-1.82); preterm delivery (6.2% vs 5.2%; OR = 0.9; 95% CI, 0.7-1.3), low birth weight infant (4.1% vs 3.7%; OR = 0.8; 95% CI, 0.5-1.1); and small-for-gestational-age infant (10.4% vs 9.2%; OR = 1.1; 95% CI, 0.9-1.4).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) states that insufficient data exist regarding the safety of ondansetron for the fetus.6 ACOG recommends individualizing the use of ondansetron before 10 weeks of pregnancy after weighing the risks and benefits. ACOG also recommends adding ondansetron as third-line treatment for nausea and vomiting unresponsive to first- and second-line treatments.

EDITOR'S TAKEAWAY

Higher-quality studies showed ondansetron to be an effective treatment for hyperemesis gravidarum. Lower-quality studies raised some concerns about adverse fetal effects. Although the adverse effects were rare and the quality of the evidence was lower, the cautionary principle suggests that ondansetron should be a second-line option.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Efficacy. A 2014 double-blind RCT compared ondansetron with pyridoxine plus doxylamine (standard care) for outpatient treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy.1 The 36 patients had an average gestational age of 8 weeks and received either 4 mg oral ondansetron plus placebo or 25 mg pyridoxine plus 12.5 mg doxylamine 3 times daily for 5 days. Nausea and vomiting severity was measured using 2 separate 10-cm visual analog scales (VAS) with scores ranging from 0 to 10 (worst nausea or vomiting imaginable). Researchers determined that a VAS score reduction of 2.5 cm was clinically significant.

Patients treated with ondansetron described greater improvements in nausea (mean VAS change −5.1 cm vs −2 cm; P = .019) and vomiting (mean VAS change −4.1 cm vs −1.7 cm; P = .049). No patient required hospitalization. The researchers didn’t report on adverse effects or birth outcomes. The study was limited by the small sample size and a high rate (17%) of patients with missing data or who were lost to follow-up.

IV ondansetron vs metoclopramide: Similar efficacy, fewer adverse effects

A 2014 double-blind RCT compared IV ondansetron with IV metoclopramide (standard care) for treating hyperemesis gravidarum.2 The 160 patients had an average gestational age of 9.5 weeks and intractable nausea and vomiting severe enough to cause dehydration, metabolic disturbance, and hospitalization. Patients received either 4 mg ondansetron or 10 mg metoclopramide IV every 8 hours for 24 hours. The primary outcomes were number of episodes of vomiting over 24 hours and self-reported sense of well-being rated on a 10-point scale.

No differences were found between the ondansetron- and metoclopramide-treated groups in terms of vomiting over 24 hours (median episodes 1 and 1; P = .38) or sense of well-being (mean scores 8.7 vs 8.3; P = .13). Patients treated with ondansetron were less likely to have persistent ketonuria at 24 hours (relative risk [RR] = 0.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.1-0.8; number needed to treat [NNT] = 6). They also were less likely to feel drowsy (RR = 0.3; 95% CI, 0.1–0.8; NNT = 6) or complain of dry mouth (RR = 0.4; 95% CI, 0.1-0.9; NNT = 8). The study didn’t report birth outcomes or adverse fetal effects.

Oral ondansetron outperforms oral metoclopramide in small study

A 2013 double-blind RCT compared ondansetron with metoclopramide (standard care) for controlling severe nausea and vomiting.3 The 83 patients, with an average gestational age of 8.7 weeks, had more than 3 vomiting episodes daily, weight loss, and ketonuria. They received either 4 mg oral ondansetron or 10 mg oral metoclopramide for 2 weeks as follows: 3 times daily for 1 week, then twice daily for 3 days, then once daily for 4 days. Patients rated nausea severity using a 10-cm VAS from 0 to 10 (severe nausea) and recorded the number of vomiting episodes.

Women treated with ondansetron had significantly lower VAS scores on Days 3 and 4 of treatment (5.4 vs 6, P = .024 on Day 3; 4.1 vs 5.7, P = .023 on Day 4). They also had fewer episodes of vomiting on Days 2, 3, and 4 (3.7 vs 6, P = .006 on Day 2; 3.2 vs 5.3, P = .006 on Day 3; and 3.3 vs 5, P = .013 on Day 4). The study was limited by the small sample size.

Safety. A 2016 systematic review examining the risk of birth defects associated with ondansetron exposure in pregnancy found 8 reports: 5 birth registries, 2 case-control studies, and 1 prospective cohort study.4 Investigators compared rates of major malformations—cleft lips, cleft palates, neural tube defects, cardiac defects, and hypospadias—in 5101 women exposed to ondansetron in the first trimester with birth defect rates in more than 3.1 million nonexposed women.

Continue to: No study demonstrated...

No study demonstrated an increased rate of major malformations associated with ondansetron exposure except for 2 disease registry studies with nearly 2.4 million patients that reported a slight increase in the risk of cardiac defects (odds ratio [OR] = 2; 95% CI, 1.3-3.1; OR = 1.6, 95% CI, 1-2.1). Comparisons of other birth defect rates associated with ondansetron exposure were inconsistent, with studies showing small increases, decreases, or no difference in rates between exposed and nonexposed women.

Exposure vs nonexposure: No difference in adverse outcomes

A 2013 retrospective cohort study looked at 608,385 pregnancies among women in Denmark, of whom 1970 (0.3%) had been exposed to ondansetron.5 The study found that exposure to ondansetron compared with nonexposure was associated with a lower risk for spontaneous abortion between 7 and 12 weeks’ gestation (1.1% vs 3.7%; hazard ratio [HR] = 0.5; 95% CI, 0.3-0.9).

No significant differences between ondansetron exposure and nonexposure were found for the following adverse outcomes: spontaneous abortion between 13 and 22 weeks’ gestation (1% vs 2.1%; HR = 0.6; 95% CI, 0.3-1.2); stillbirth (0.3% vs 0.4%; HR = 0.4; 95% CI, 0.1-1.7); any major birth defect (2.9% in both exposed and nonexposed women; OR = 1.12; 95% CI, 0.69-1.82); preterm delivery (6.2% vs 5.2%; OR = 0.9; 95% CI, 0.7-1.3), low birth weight infant (4.1% vs 3.7%; OR = 0.8; 95% CI, 0.5-1.1); and small-for-gestational-age infant (10.4% vs 9.2%; OR = 1.1; 95% CI, 0.9-1.4).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) states that insufficient data exist regarding the safety of ondansetron for the fetus.6 ACOG recommends individualizing the use of ondansetron before 10 weeks of pregnancy after weighing the risks and benefits. ACOG also recommends adding ondansetron as third-line treatment for nausea and vomiting unresponsive to first- and second-line treatments.

EDITOR'S TAKEAWAY

Higher-quality studies showed ondansetron to be an effective treatment for hyperemesis gravidarum. Lower-quality studies raised some concerns about adverse fetal effects. Although the adverse effects were rare and the quality of the evidence was lower, the cautionary principle suggests that ondansetron should be a second-line option.

1. Oliveira LG, Capp SM, You WB, et al. Ondansetron compared with doxylamine and pyridoxine for treatment of nausea in pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:735-742.

2. Abas MN, Tan PC, Azmi N, et al. Ondansetron compared with metoclopramide for hyperemesis gravidarum: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:1272-1279.

3. Kashifard M, Basirat Z, Kashifard M, et al. Ondansetrone or metoclopromide? Which is more effective in severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy? A randomized trial double-blind study. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2013;40:127-130.

4. Carstairs SD. Ondansetron use in pregnancy and birth defects: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:878-883.

5. Pasternak B, Svanström H, Hviid A. Ondansetron in pregnancy and risk of adverse fetal outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:814-823.

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 189: Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e15-e30.

1. Oliveira LG, Capp SM, You WB, et al. Ondansetron compared with doxylamine and pyridoxine for treatment of nausea in pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:735-742.

2. Abas MN, Tan PC, Azmi N, et al. Ondansetron compared with metoclopramide for hyperemesis gravidarum: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:1272-1279.

3. Kashifard M, Basirat Z, Kashifard M, et al. Ondansetrone or metoclopromide? Which is more effective in severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy? A randomized trial double-blind study. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2013;40:127-130.

4. Carstairs SD. Ondansetron use in pregnancy and birth defects: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:878-883.

5. Pasternak B, Svanström H, Hviid A. Ondansetron in pregnancy and risk of adverse fetal outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:814-823.

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 189: Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e15-e30.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Oral ondansetron is more effective than a combination of pyridoxine and doxylamine for outpatient treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, randomized controlled trial [RCT]).

For moderate to severe nausea and vomiting, intravenous (IV) ondansetron is at least as effective as IV metoclopramide and may cause fewer adverse reactions (SOR: B, RCTs).

Disease registry, case-control, and cohort studies report a slight increase in the risk of cardiac defects with ondansetron use in first-trimester pregnancies, but no major or other birth defects are associated with ondansetron exposure (SOR: B, a systematic review of observational trials and a single retrospective cohort study).

A specialty society guideline recommends weighing the risks and benefits of ondansetron use before 10 weeks’ gestational age and suggests reserving ondansetron for patients who have persistent nausea and vomiting unresponsive to first- and second-line treatments (SOR: C, expert opinion).

Which oral nonopioid agents are most effective for OA pain?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

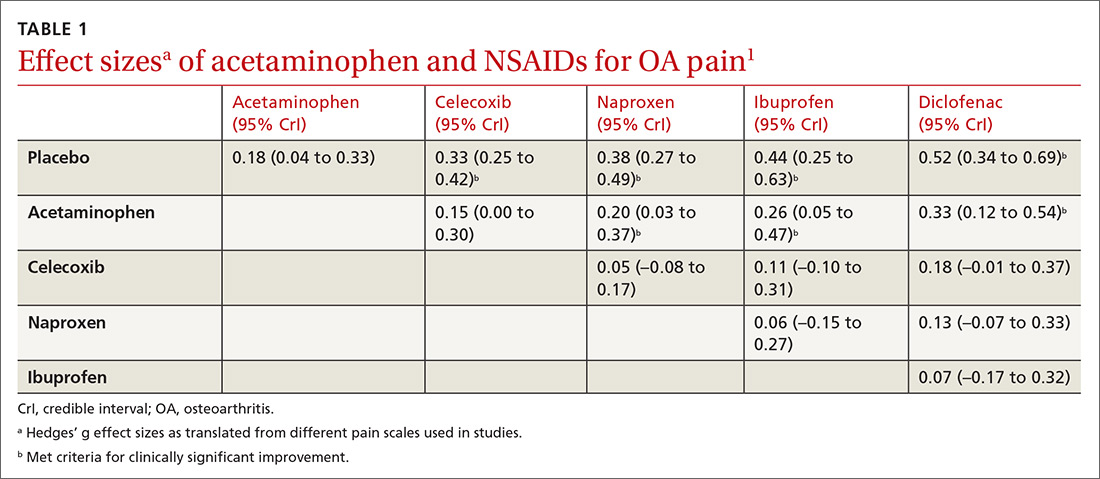

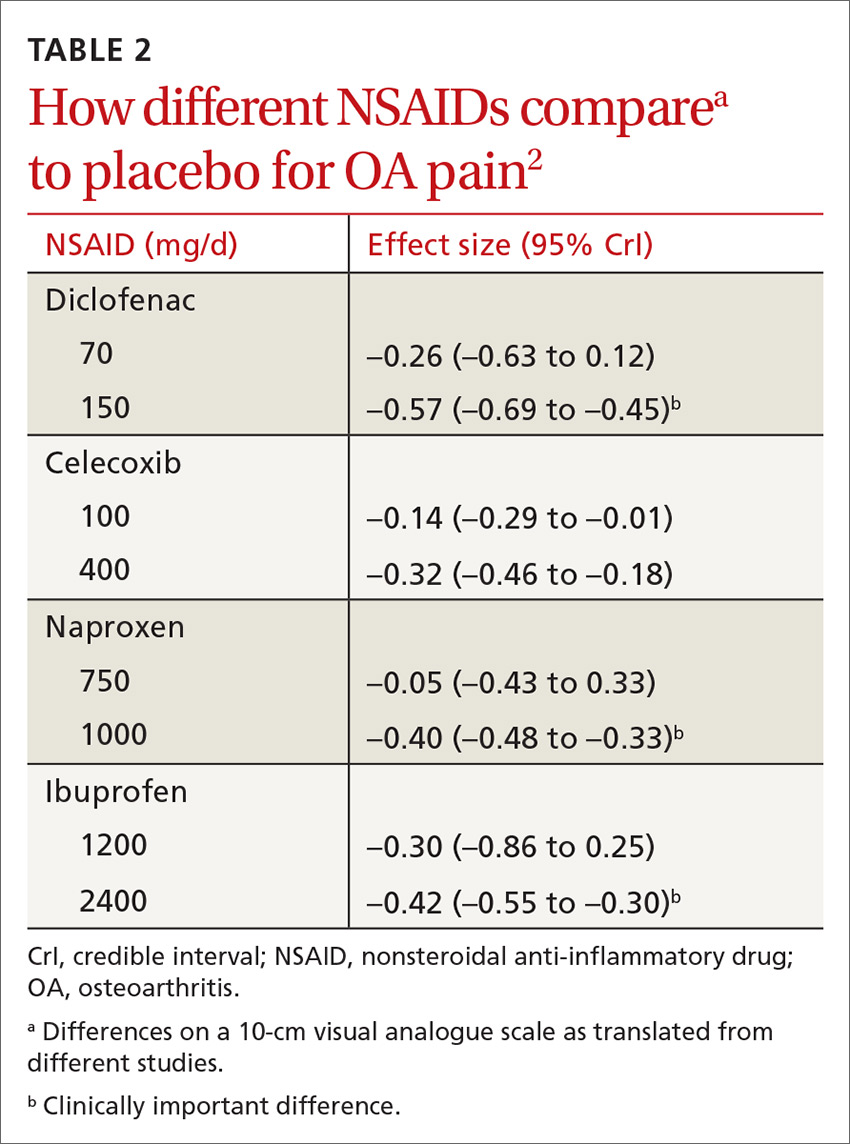

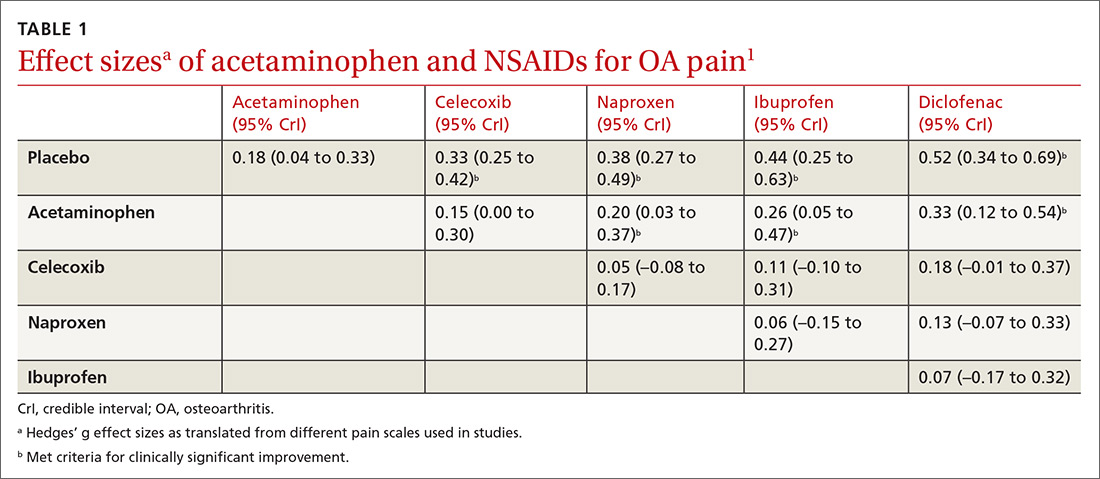

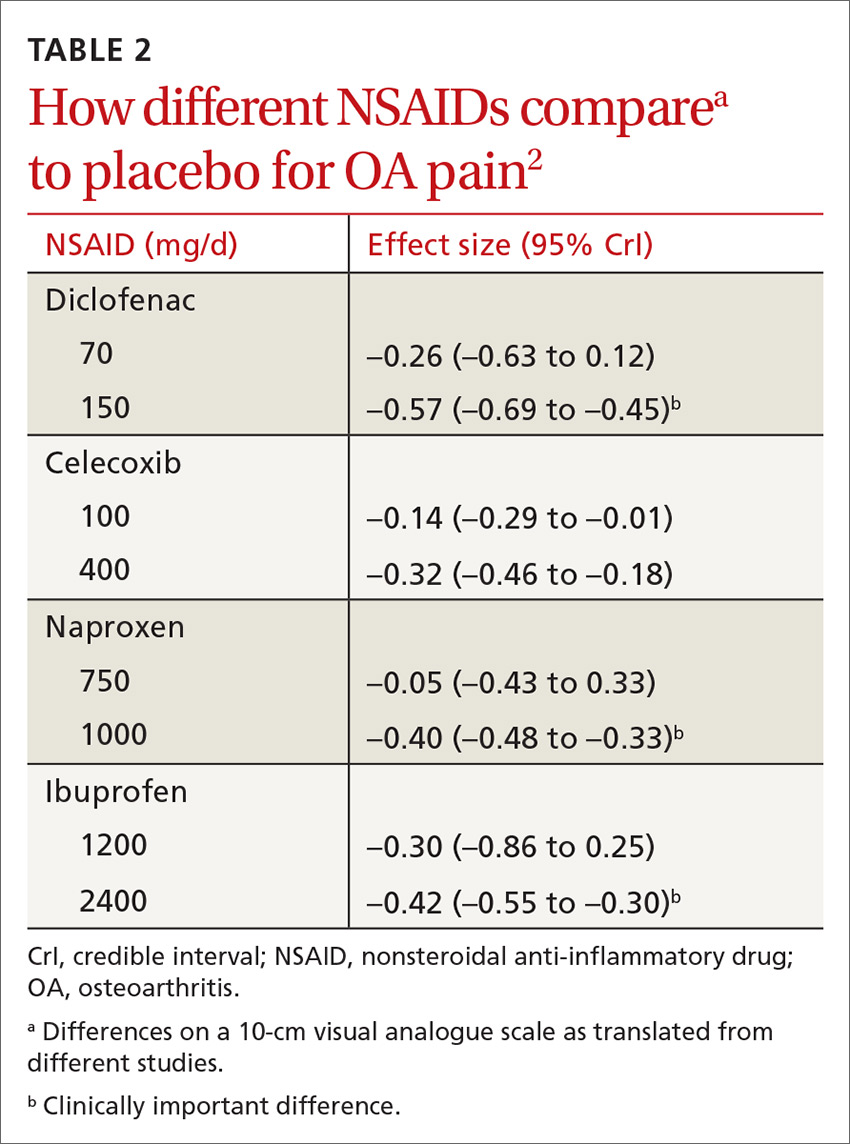

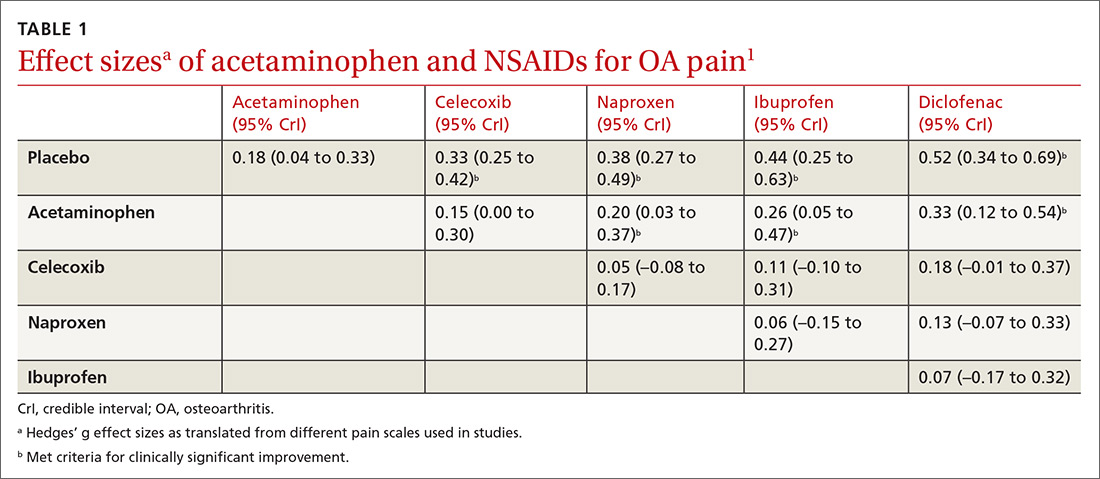

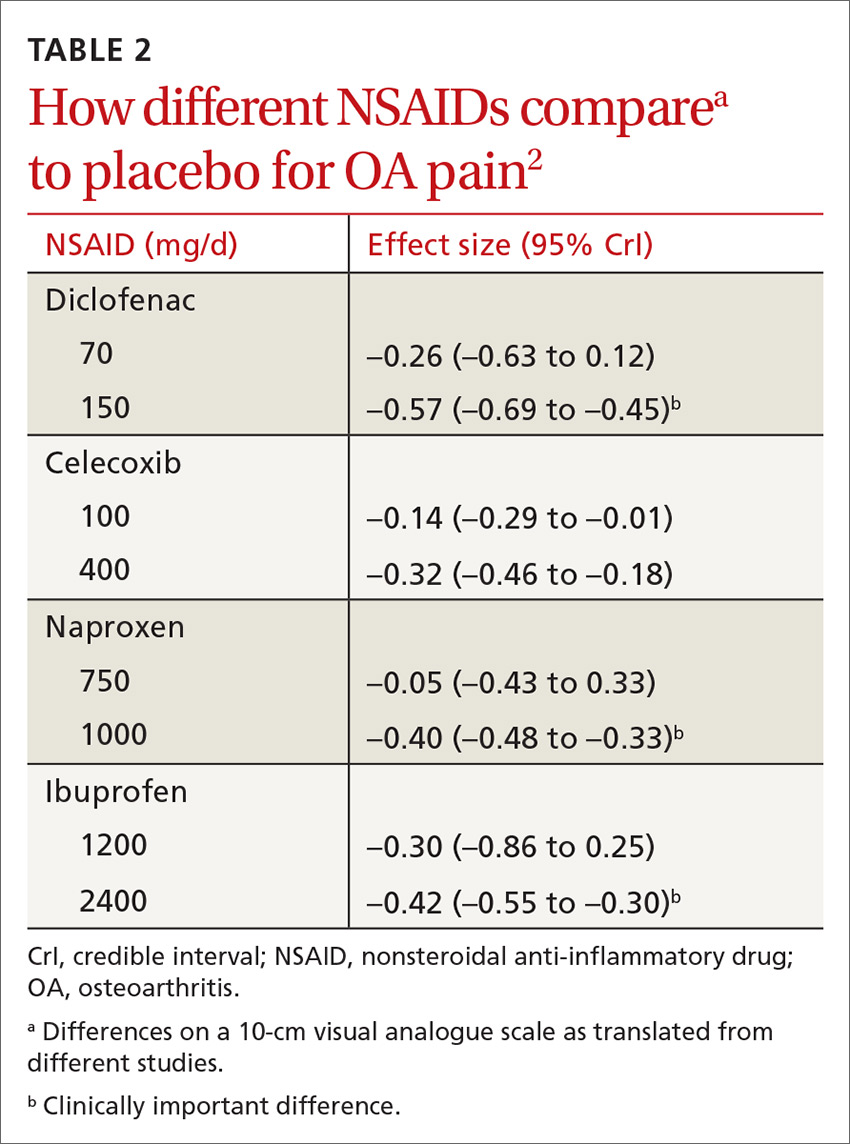

All NSAIDs at maximum clinical doses reduced large joint OA pain more effectively than placebo and acetaminophen based on data from a network meta-analysis of 129 RCTs with 32,129 patients (TABLE 1).1 When various doses of NSAIDs are ranked for efficacy based on their effect size compared to placebo, diclofenac 150 mg/d had the greatest treatment effect, followed by ibuprofen 2400 mg/d.2 Lower doses of NSAIDs—including diclofenac 70 mg/d, naproxen 750 mg/d, and ibuprofen 1200 mg/d—were not statistically superior to placebo (TABLE 2).2

Selective vs nonselective. There was no statistical difference in pain relief between the selective COX-2 inhibitor celecoxib and the nonselective NSAIDs naproxen, diclofenac, and ibuprofen (TABLE 1).1

Meloxicam. A systematic review of 16 RCTs and 22,886 patients found that meloxicam reduced pain more effectively than placebo (10-point visual analogue scale [VAS] score pain difference of –6.8; 95% CI, –9.3 to –4.2) but was marginally less effective than other NSAIDs (VAS score pain difference of 1.7; 95% CI, 0.8 to 2.7).3

Acetaminophen. Data from 6 RCTs involving 2083 adults with knee OA indicate acetaminophen did not achieve clinical significance compared to placebo (TABLE 1).1 Another meta-analysis of 5 RCTs involving 1741 patients with hip or knee OA also demonstrated that acetaminophen failed to achieve a clinically significant effect on pain, defined as a reduction of 9 mm on a 0 to 100 mm VAS (–3.7; 95% CI, –5.5 to –1.9).4 Another network meta-analysis of 6 RCTs including 58,556 patients with knee or hip OA, with the primary outcome of pain (using a hierarchy of pain scores, with global pain score taking precedence) also found no clinically significant difference between acetaminophen at the highest dose (4000 mg/d) and placebo (–0.17; 95% credible interval [CrI], –0.27 to –0.6).2

RECOMMENDATIONS

In a systematic review of mixed evidence-based and expert opinion recommendations and guidelines on the management of OA, 10 of the 11 guidelines that included pharmacologic management recommended acetaminophen as a first-line agent, followed by topical NSAIDs, and then oral NSAIDs. The exception is the most recent American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons guideline, which continues to recommend NSAIDs but is now unable to recommend for or against acetaminophen.5

1. Bannuru RR, Schmid CH, Kent DM, et al. Comparative effectiveness of pharmacologic interventions for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:46-54.

2. da Costa BR, Reichenbach S, Keller N, et al. Effectiveness of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the treatment of pain in knee and hip osteoarthritis: a network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2017;390:e23-e33.

3. Chen YF, Jobanputra P, Barton P, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (etodolac, meloxicam, celecoxib, rofecoxib, etoricoxib, valdecoxib and lumiracoxib) for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2008;12:1-278, iii.

4. Machado GC, Maher CG, Ferreira PH, et al. Efficacy and safety of paracetamol for spinal pain and osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo controlled trials. BMJ. 2015;350:h1225.

5. Nelson AE, Allen KD, Golightly YM, et al. A systematic review of recommendations and guidelines for the management of osteoarthritis: The Chronic Osteoarthritis Management Initiative of the U.S. Bone and Joint Initiative. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;43:701-712.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

All NSAIDs at maximum clinical doses reduced large joint OA pain more effectively than placebo and acetaminophen based on data from a network meta-analysis of 129 RCTs with 32,129 patients (TABLE 1).1 When various doses of NSAIDs are ranked for efficacy based on their effect size compared to placebo, diclofenac 150 mg/d had the greatest treatment effect, followed by ibuprofen 2400 mg/d.2 Lower doses of NSAIDs—including diclofenac 70 mg/d, naproxen 750 mg/d, and ibuprofen 1200 mg/d—were not statistically superior to placebo (TABLE 2).2

Selective vs nonselective. There was no statistical difference in pain relief between the selective COX-2 inhibitor celecoxib and the nonselective NSAIDs naproxen, diclofenac, and ibuprofen (TABLE 1).1

Meloxicam. A systematic review of 16 RCTs and 22,886 patients found that meloxicam reduced pain more effectively than placebo (10-point visual analogue scale [VAS] score pain difference of –6.8; 95% CI, –9.3 to –4.2) but was marginally less effective than other NSAIDs (VAS score pain difference of 1.7; 95% CI, 0.8 to 2.7).3

Acetaminophen. Data from 6 RCTs involving 2083 adults with knee OA indicate acetaminophen did not achieve clinical significance compared to placebo (TABLE 1).1 Another meta-analysis of 5 RCTs involving 1741 patients with hip or knee OA also demonstrated that acetaminophen failed to achieve a clinically significant effect on pain, defined as a reduction of 9 mm on a 0 to 100 mm VAS (–3.7; 95% CI, –5.5 to –1.9).4 Another network meta-analysis of 6 RCTs including 58,556 patients with knee or hip OA, with the primary outcome of pain (using a hierarchy of pain scores, with global pain score taking precedence) also found no clinically significant difference between acetaminophen at the highest dose (4000 mg/d) and placebo (–0.17; 95% credible interval [CrI], –0.27 to –0.6).2

RECOMMENDATIONS

In a systematic review of mixed evidence-based and expert opinion recommendations and guidelines on the management of OA, 10 of the 11 guidelines that included pharmacologic management recommended acetaminophen as a first-line agent, followed by topical NSAIDs, and then oral NSAIDs. The exception is the most recent American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons guideline, which continues to recommend NSAIDs but is now unable to recommend for or against acetaminophen.5

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

All NSAIDs at maximum clinical doses reduced large joint OA pain more effectively than placebo and acetaminophen based on data from a network meta-analysis of 129 RCTs with 32,129 patients (TABLE 1).1 When various doses of NSAIDs are ranked for efficacy based on their effect size compared to placebo, diclofenac 150 mg/d had the greatest treatment effect, followed by ibuprofen 2400 mg/d.2 Lower doses of NSAIDs—including diclofenac 70 mg/d, naproxen 750 mg/d, and ibuprofen 1200 mg/d—were not statistically superior to placebo (TABLE 2).2

Selective vs nonselective. There was no statistical difference in pain relief between the selective COX-2 inhibitor celecoxib and the nonselective NSAIDs naproxen, diclofenac, and ibuprofen (TABLE 1).1

Meloxicam. A systematic review of 16 RCTs and 22,886 patients found that meloxicam reduced pain more effectively than placebo (10-point visual analogue scale [VAS] score pain difference of –6.8; 95% CI, –9.3 to –4.2) but was marginally less effective than other NSAIDs (VAS score pain difference of 1.7; 95% CI, 0.8 to 2.7).3

Acetaminophen. Data from 6 RCTs involving 2083 adults with knee OA indicate acetaminophen did not achieve clinical significance compared to placebo (TABLE 1).1 Another meta-analysis of 5 RCTs involving 1741 patients with hip or knee OA also demonstrated that acetaminophen failed to achieve a clinically significant effect on pain, defined as a reduction of 9 mm on a 0 to 100 mm VAS (–3.7; 95% CI, –5.5 to –1.9).4 Another network meta-analysis of 6 RCTs including 58,556 patients with knee or hip OA, with the primary outcome of pain (using a hierarchy of pain scores, with global pain score taking precedence) also found no clinically significant difference between acetaminophen at the highest dose (4000 mg/d) and placebo (–0.17; 95% credible interval [CrI], –0.27 to –0.6).2

RECOMMENDATIONS

In a systematic review of mixed evidence-based and expert opinion recommendations and guidelines on the management of OA, 10 of the 11 guidelines that included pharmacologic management recommended acetaminophen as a first-line agent, followed by topical NSAIDs, and then oral NSAIDs. The exception is the most recent American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons guideline, which continues to recommend NSAIDs but is now unable to recommend for or against acetaminophen.5

1. Bannuru RR, Schmid CH, Kent DM, et al. Comparative effectiveness of pharmacologic interventions for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:46-54.

2. da Costa BR, Reichenbach S, Keller N, et al. Effectiveness of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the treatment of pain in knee and hip osteoarthritis: a network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2017;390:e23-e33.

3. Chen YF, Jobanputra P, Barton P, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (etodolac, meloxicam, celecoxib, rofecoxib, etoricoxib, valdecoxib and lumiracoxib) for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2008;12:1-278, iii.

4. Machado GC, Maher CG, Ferreira PH, et al. Efficacy and safety of paracetamol for spinal pain and osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo controlled trials. BMJ. 2015;350:h1225.

5. Nelson AE, Allen KD, Golightly YM, et al. A systematic review of recommendations and guidelines for the management of osteoarthritis: The Chronic Osteoarthritis Management Initiative of the U.S. Bone and Joint Initiative. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;43:701-712.

1. Bannuru RR, Schmid CH, Kent DM, et al. Comparative effectiveness of pharmacologic interventions for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:46-54.

2. da Costa BR, Reichenbach S, Keller N, et al. Effectiveness of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the treatment of pain in knee and hip osteoarthritis: a network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2017;390:e23-e33.

3. Chen YF, Jobanputra P, Barton P, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (etodolac, meloxicam, celecoxib, rofecoxib, etoricoxib, valdecoxib and lumiracoxib) for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2008;12:1-278, iii.

4. Machado GC, Maher CG, Ferreira PH, et al. Efficacy and safety of paracetamol for spinal pain and osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo controlled trials. BMJ. 2015;350:h1225.

5. Nelson AE, Allen KD, Golightly YM, et al. A systematic review of recommendations and guidelines for the management of osteoarthritis: The Chronic Osteoarthritis Management Initiative of the U.S. Bone and Joint Initiative. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;43:701-712.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), when used at the maximum clinically effective dose, reduce osteoarthritis (OA) pain in large joints more effectively than either placebo or acetaminophen (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

When ranked for efficacy, diclofenac 150 mg/d was the most effective (SOR: A, network meta-analysis of RCTs). The selective COX-2 inhibitors, such as celecoxib, are not more effective at reducing pain than the nonselective NSAIDs (SOR: A, meta-analysis of RCTs). Meloxicam is superior to placebo but marginally inferior to other NSAIDs (SOR: A, systematic review of RCTs).

Acetaminophen is no more effective than placebo (SOR: A, meta-analysis of RCTs).

Can unintended pregnancies be reduced by dispensing a year’s worth of hormonal contraception?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2013 systematic review studied the effect of dispensing a larger amount of pills on pregnancy rate, abortion rate, and overall cost to the health care system.1 Three of the 4 studies analyzed found lower rates of pregnancy and abortion, as well as lower cost despite increased pill wastage, in the groups that received more medication. The 1 study that didn’t show a significant difference between groups compared only short durations (1 vs 4 months).

The systematic review included a large retrospective cohort study from 2011 that examined public insurance data from more than 84,000 patients to compare pregnancy rates in women who were given a 1-year supply of oral contraceptives (12 or 13 packs) vs those given 1 or 3 packs at a time.2 The study found pregnancy rates of 2.9%, 3.3%, and 1.2% for 1, 3, and 12 or 13 months, respectively (P < .05; absolute risk reduction [ARR] = 1.7%; number needed to treat [NNT] = 59; relative risk reduction = 41%).

More pills lead to longer use of contraception

The systematic review also included a 2011 trial of 700 women starting oral contraceptives.3 It randomized them to receive a 7- or 3-month supply at their initial visit, then evaluated use of oral contraception at 6 months. All women were invited back for a 3-month follow-up visit, at which time the 3-month supply group would receive additional medication.

Fifty-one percent of the 7-month group were still using oral contraceptives at 6 months compared with 35% of the 3-month group (P < .001; NNT = 7). The contrast was starker for women younger than 18 years (49% vs 12%; NNT = 3). Notably, of the women who stopped using contraception, more in the 3-month group stopped because they ran out of medication (P = .02). Subjects in the 7-month group were more likely to have given birth and more likely to have 2 or more children.

A 2017 case study examined proposed legislation in California that required health plans to cover a 12-month supply of combined hormonal contraceptives.4 The California Health Benefits Review Program surveyed health insurers and reviewed contraception usage patterns. They found that, if the legislation passed, the state could expect a 30% reduction in unintended pregnancy (ARR = 2%; NNT = 50), resulting in 6000 fewer live births and 7000 fewer abortions per year.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use recommend prescribing or providing as much as a 1-year supply of combined hormonal contraceptives at the initial visit and each return visit.5

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) supports over-the-counter access to oral contraceptives, effectively allowing an unlimited supply.6

EDITOR’S TAKEAWAY

Adequate evidence of benefits and strong support from the CDC and ACOG should encourage us to offer 1-year supplies of combined oral contraceptives. Even though the higher-quality studies reviewed also showed a cost savings, up-front patient expense may remain a challenge.

1. Steenland MW, Rodriguez MI, Marchbanks PA, et al. How does the number of oral contraceptive pill packs dispensed or prescribed affect continuation and other measures of consistent and correct use? A systematic review. Contraception. 2013;87:605-610.

2. Foster DG, Hulett D, Bradsberry M, et al. Number of oral contraceptive pill packages dispensed and subsequent unintended pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:566-572.

3. White KO, Westhoff C. The effect of pack supply on oral contraceptive pill continuation: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:615-622.

4. McMenamin SB, Charles SA, Tabatabaeepour N, et al. Implications of dispensing self-administered hormonal contraceptives in a 1-year supply: a California case study. Contraception. 2017;95:449-451.

5. Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-66.

6. Committee on Gynecologic Practice, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 544: Over-the-counter access to oral contraceptives. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1527-1531.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2013 systematic review studied the effect of dispensing a larger amount of pills on pregnancy rate, abortion rate, and overall cost to the health care system.1 Three of the 4 studies analyzed found lower rates of pregnancy and abortion, as well as lower cost despite increased pill wastage, in the groups that received more medication. The 1 study that didn’t show a significant difference between groups compared only short durations (1 vs 4 months).

The systematic review included a large retrospective cohort study from 2011 that examined public insurance data from more than 84,000 patients to compare pregnancy rates in women who were given a 1-year supply of oral contraceptives (12 or 13 packs) vs those given 1 or 3 packs at a time.2 The study found pregnancy rates of 2.9%, 3.3%, and 1.2% for 1, 3, and 12 or 13 months, respectively (P < .05; absolute risk reduction [ARR] = 1.7%; number needed to treat [NNT] = 59; relative risk reduction = 41%).

More pills lead to longer use of contraception

The systematic review also included a 2011 trial of 700 women starting oral contraceptives.3 It randomized them to receive a 7- or 3-month supply at their initial visit, then evaluated use of oral contraception at 6 months. All women were invited back for a 3-month follow-up visit, at which time the 3-month supply group would receive additional medication.

Fifty-one percent of the 7-month group were still using oral contraceptives at 6 months compared with 35% of the 3-month group (P < .001; NNT = 7). The contrast was starker for women younger than 18 years (49% vs 12%; NNT = 3). Notably, of the women who stopped using contraception, more in the 3-month group stopped because they ran out of medication (P = .02). Subjects in the 7-month group were more likely to have given birth and more likely to have 2 or more children.

A 2017 case study examined proposed legislation in California that required health plans to cover a 12-month supply of combined hormonal contraceptives.4 The California Health Benefits Review Program surveyed health insurers and reviewed contraception usage patterns. They found that, if the legislation passed, the state could expect a 30% reduction in unintended pregnancy (ARR = 2%; NNT = 50), resulting in 6000 fewer live births and 7000 fewer abortions per year.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use recommend prescribing or providing as much as a 1-year supply of combined hormonal contraceptives at the initial visit and each return visit.5

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) supports over-the-counter access to oral contraceptives, effectively allowing an unlimited supply.6

EDITOR’S TAKEAWAY

Adequate evidence of benefits and strong support from the CDC and ACOG should encourage us to offer 1-year supplies of combined oral contraceptives. Even though the higher-quality studies reviewed also showed a cost savings, up-front patient expense may remain a challenge.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2013 systematic review studied the effect of dispensing a larger amount of pills on pregnancy rate, abortion rate, and overall cost to the health care system.1 Three of the 4 studies analyzed found lower rates of pregnancy and abortion, as well as lower cost despite increased pill wastage, in the groups that received more medication. The 1 study that didn’t show a significant difference between groups compared only short durations (1 vs 4 months).

The systematic review included a large retrospective cohort study from 2011 that examined public insurance data from more than 84,000 patients to compare pregnancy rates in women who were given a 1-year supply of oral contraceptives (12 or 13 packs) vs those given 1 or 3 packs at a time.2 The study found pregnancy rates of 2.9%, 3.3%, and 1.2% for 1, 3, and 12 or 13 months, respectively (P < .05; absolute risk reduction [ARR] = 1.7%; number needed to treat [NNT] = 59; relative risk reduction = 41%).

More pills lead to longer use of contraception

The systematic review also included a 2011 trial of 700 women starting oral contraceptives.3 It randomized them to receive a 7- or 3-month supply at their initial visit, then evaluated use of oral contraception at 6 months. All women were invited back for a 3-month follow-up visit, at which time the 3-month supply group would receive additional medication.

Fifty-one percent of the 7-month group were still using oral contraceptives at 6 months compared with 35% of the 3-month group (P < .001; NNT = 7). The contrast was starker for women younger than 18 years (49% vs 12%; NNT = 3). Notably, of the women who stopped using contraception, more in the 3-month group stopped because they ran out of medication (P = .02). Subjects in the 7-month group were more likely to have given birth and more likely to have 2 or more children.

A 2017 case study examined proposed legislation in California that required health plans to cover a 12-month supply of combined hormonal contraceptives.4 The California Health Benefits Review Program surveyed health insurers and reviewed contraception usage patterns. They found that, if the legislation passed, the state could expect a 30% reduction in unintended pregnancy (ARR = 2%; NNT = 50), resulting in 6000 fewer live births and 7000 fewer abortions per year.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use recommend prescribing or providing as much as a 1-year supply of combined hormonal contraceptives at the initial visit and each return visit.5

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) supports over-the-counter access to oral contraceptives, effectively allowing an unlimited supply.6

EDITOR’S TAKEAWAY

Adequate evidence of benefits and strong support from the CDC and ACOG should encourage us to offer 1-year supplies of combined oral contraceptives. Even though the higher-quality studies reviewed also showed a cost savings, up-front patient expense may remain a challenge.

1. Steenland MW, Rodriguez MI, Marchbanks PA, et al. How does the number of oral contraceptive pill packs dispensed or prescribed affect continuation and other measures of consistent and correct use? A systematic review. Contraception. 2013;87:605-610.

2. Foster DG, Hulett D, Bradsberry M, et al. Number of oral contraceptive pill packages dispensed and subsequent unintended pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:566-572.

3. White KO, Westhoff C. The effect of pack supply on oral contraceptive pill continuation: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:615-622.

4. McMenamin SB, Charles SA, Tabatabaeepour N, et al. Implications of dispensing self-administered hormonal contraceptives in a 1-year supply: a California case study. Contraception. 2017;95:449-451.

5. Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-66.

6. Committee on Gynecologic Practice, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 544: Over-the-counter access to oral contraceptives. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1527-1531.

1. Steenland MW, Rodriguez MI, Marchbanks PA, et al. How does the number of oral contraceptive pill packs dispensed or prescribed affect continuation and other measures of consistent and correct use? A systematic review. Contraception. 2013;87:605-610.

2. Foster DG, Hulett D, Bradsberry M, et al. Number of oral contraceptive pill packages dispensed and subsequent unintended pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:566-572.

3. White KO, Westhoff C. The effect of pack supply on oral contraceptive pill continuation: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:615-622.

4. McMenamin SB, Charles SA, Tabatabaeepour N, et al. Implications of dispensing self-administered hormonal contraceptives in a 1-year supply: a California case study. Contraception. 2017;95:449-451.

5. Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-66.

6. Committee on Gynecologic Practice, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 544: Over-the-counter access to oral contraceptives. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1527-1531.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Probably, although studies that looked directly at this outcome are limited. A systematic review showed that women who received a larger number of pills at one time were more likely to continue using combined hormonal contraception 7 to 15 months later (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, consistent evidence from 2 cohort studies and 1 randomized, controlled trial), which might be extrapolated to indicate lower unintended pregnancy rates.

One of the large retrospective cohort studies included in the review demonstrated a significantly lower rate of pregnancy among women who received 12 or 13 packs of oral contraceptives at an office visit compared with 1 or 3 packs (SOR: B, large retrospective cohort study).

Do A-fib patients continue to benefit from vitamin K antagonists with advancing age?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A meta-analysis of 12 randomized trials of stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation (8932 patients, 63% male, mean age 72 years, 19.6% ≥ 80 years) examined outcomes of ischemic stroke, serious bleeding (systemic or intracranial hemorrhages requiring hospitalization, transfusion, or surgery) and cardiovascular events (ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, systemic emboli, and vascular death).1 Patients were randomized to oral anticoagulants (3430 patients), antiplatelet therapy (3531 patients), or no therapy (1971 patients).

Warfarin target international normalized ratios (INRs) ranged from 1.5 to 4.2. Previous stoke or transient ischemic attack varied across studies but averaged 22% (patient baseline characteristics were evenly distributed among all arms of all 12 studies, suggesting appropriate randomizations). Fifteen percent of patients had diabetes, 50% had hypertension, and 20% had congestive heart failure. They were followed for a mean of 2 years.

Overall, patients experienced 623 ischemic strokes, 289 serious bleeds, and 1210 cardiovascular events. After adjusting for treatment and covariates, age was independently associated with higher risk for each outcome. For every decade increase in age, the hazard ratio (HR) for ischemic stroke was 1.45 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.26-1.66); serious hemorrhage, 1.61 (95% CI, 1.47-1.77); and cardiovascular events, 1.43 (95% CI, 1.33-1.53).

Benefits of warfarin outweigh increased risk of hemorrhage

Treatment with vitamin K antagonists, compared with placebo, reduced ischemic strokes (HR = 0.36; 95% CI, 0.29-0.45) and cardiovascular events (HR = 0.59; 95% CI, 0.52-0.66) but increased the risk of serious hemorrhage (HR = 1.56; 95% CI, 1.03-2.37) in patients from 50 to 90 years of age. The benefits of decreased ischemic strokes and cardiovascular events consistently surpassed the increased risk of hemorrhage, however.

Across all age groups, the absolute risk reductions (ARRs) for ischemic stroke and cardiovascular events were 2% to 3% and 3% to 8%, respectively, whereas the absolute risk increase for serious hemorrhage was 0.5% to 1%. For those ages 70 to 75, for example, warfarin decreased the rate of ischemic stroke by 3% per year (number needed to treat [NNT] = 34; rates estimated from graphs) and the rate of cardiovascular events by 7% (NNT = 14) but increased the risk of serious hemorrhage by approximately 0.5% per year (number need to harm = 200).

Warfarin prevents major strokes more effectively than aspirin

A randomized open-label trial with blind assessment of endpoints, included in the meta-analysis, followed 973 patients older than 75 years (mean 81.5 years) with atrial fibrillation for 2 to 7 years.2 Researchers evaluated warfarin compared with aspirin for the outcomes of major stroke, arterial embolism, and intracranial hemorrhage. Major strokes comprised fatal or disabling strokes. Researchers excluded patients with minor strokes, rheumatic heart disease, a major nontraumatic hemorrhage within the previous 5 years, intracranial hemorrhage, peptic ulcer disease, esophageal varices, or a terminal illness.

Compared with aspirin, warfarin significantly reduced all primary events (ARR = 1.8% vs 3.8%; relative risk reduction [RRR] = 0.48; 95% CI, 0.28-0.80; NNT = 50). Warfarin decreased major strokes more than aspirin (21 vs 44 strokes; ARR = 1.8%; relative risk [RR] = 0.46; 95% CI, 0.26-0.79; NNT = 56) but didn’t alter the risk of hemorrhagic strokes (6 vs 5 absolute events, respectively; RRR = 1.15, 95% CI, 0.29-4.77) or other intracranial hemorrhages (2 vs 1 event, respectively; RR = 1.92; 95% CI, 0.10-113.3). Wide confidence intervals and the small number of hemorrhagic events suggest that the study wasn’t powered to detect a significant difference in hemorrhagic events.

Continue to: Large study finds net benefit for warfarin treatment

Large study finds net benefit for warfarin treatment

A retrospective cohort including all 182,678 Swedish Hospital Discharge Register patients with atrial fibrillation (260,000 patient-years) evaluated the net benefit of anticoagulation treatment decisions over an average of 1.5 years.3 The Swedish National Prescribed Drugs Registry, which includes all Swedish pharmacies, identified all patients who were prescribed warfarin during the study years of July 2005 through December 2008. The patients were divided into 2 groups, warfarin or no warfarin, and assigned risk scores using CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED.4,5

Researchers defined net benefit as the number of ischemic strokes avoided in patients taking warfarin, minus the number of excess intracranial bleeds. They assigned a weight of 1.5 to intracranial bleeds vs 1 for ischemic strokes to compensate for the generally more severe outcomes of intracranial bleeding.

Warfarin produced a net benefit at every CHA2DS2-VASc score greater than 0 (aggregate result of 3.9 fewer events per 100 patient-years; 95% CI, 3.8-4.1; NNT = 26). Kaplan-Meier composite plots of all-cause mortality, ischemic stroke, and intracranial bleeds showed a net benefit favoring warfarin use for all combinations of CHA2DS2-VASc greater than 0 (patients older than 65 years never have a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0 because they’re assigned 1 point at ages 65 to 74 years and 2 points at 75 years and older) and HAS-BLED scores (all curves P < .00001).

Hazard ratios (HRs) of every combination of scores favored warfarin use (HRs ranged from 0.26-0.72; 95% CIs, less than 1 for all HRs; aggregate benefit at all risk scores: HR = 0.51; 95% CI, 0.50-0.52,). The risk of intracranial bleed, or any bleed, on warfarin at all risk strata was less than the corresponding risk of ischemic stroke (or thromboembolic event) without warfarin except among the lowest risk patients (CHA2DS2-VASc = 0). The difference between thromboses and hemorrhages increased as the CHA2DS2-VASc score increased. Of note, a smaller percentage of the highest risk patients were on warfarin.

EDITOR’S TAKEAWAY

We have solid evidence that, although the risks of systemic and intracranial bleeding from warfarin therapy in older patients with atrial fibrillation increase steadily with advancing age, so do the benefits in reduced ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, thrombotic emboli, and overall cardiovascular death. Most important, the benefits continue to outweigh the risks by a factor of 2 to 4, even in the oldest age groups.

1. van Walraven C, Hart R, et al. Effect of age on stroke prevention therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. Stroke. 2009;40:1410-1416.

2. Mant J, Hobbs FD. Warfarin versus aspirin for stroke prevention in an elderly community population with atrial fibrillation (the Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of the Aged Study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370:493–503.

3. Friberg L, Rosenqvist M, Lip GY. Net clinical benefit of warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a report from the Swedish atrial fibrillation cohort study. Circulation. 2012;125:2298-2307.

4. Friberg L, Rosenqvist M, Lip G. Evaluation of risk stratification schemes for ischaemic stroke and bleeding in 182,678 patients with atrial fibrillation: the Swedish Atrial Fibrillation cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1500-1510.

5. Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, et al. A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: The Euro Heart Survey. Chest. 2010;138:1093-1100.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A meta-analysis of 12 randomized trials of stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation (8932 patients, 63% male, mean age 72 years, 19.6% ≥ 80 years) examined outcomes of ischemic stroke, serious bleeding (systemic or intracranial hemorrhages requiring hospitalization, transfusion, or surgery) and cardiovascular events (ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, systemic emboli, and vascular death).1 Patients were randomized to oral anticoagulants (3430 patients), antiplatelet therapy (3531 patients), or no therapy (1971 patients).

Warfarin target international normalized ratios (INRs) ranged from 1.5 to 4.2. Previous stoke or transient ischemic attack varied across studies but averaged 22% (patient baseline characteristics were evenly distributed among all arms of all 12 studies, suggesting appropriate randomizations). Fifteen percent of patients had diabetes, 50% had hypertension, and 20% had congestive heart failure. They were followed for a mean of 2 years.

Overall, patients experienced 623 ischemic strokes, 289 serious bleeds, and 1210 cardiovascular events. After adjusting for treatment and covariates, age was independently associated with higher risk for each outcome. For every decade increase in age, the hazard ratio (HR) for ischemic stroke was 1.45 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.26-1.66); serious hemorrhage, 1.61 (95% CI, 1.47-1.77); and cardiovascular events, 1.43 (95% CI, 1.33-1.53).

Benefits of warfarin outweigh increased risk of hemorrhage

Treatment with vitamin K antagonists, compared with placebo, reduced ischemic strokes (HR = 0.36; 95% CI, 0.29-0.45) and cardiovascular events (HR = 0.59; 95% CI, 0.52-0.66) but increased the risk of serious hemorrhage (HR = 1.56; 95% CI, 1.03-2.37) in patients from 50 to 90 years of age. The benefits of decreased ischemic strokes and cardiovascular events consistently surpassed the increased risk of hemorrhage, however.

Across all age groups, the absolute risk reductions (ARRs) for ischemic stroke and cardiovascular events were 2% to 3% and 3% to 8%, respectively, whereas the absolute risk increase for serious hemorrhage was 0.5% to 1%. For those ages 70 to 75, for example, warfarin decreased the rate of ischemic stroke by 3% per year (number needed to treat [NNT] = 34; rates estimated from graphs) and the rate of cardiovascular events by 7% (NNT = 14) but increased the risk of serious hemorrhage by approximately 0.5% per year (number need to harm = 200).

Warfarin prevents major strokes more effectively than aspirin

A randomized open-label trial with blind assessment of endpoints, included in the meta-analysis, followed 973 patients older than 75 years (mean 81.5 years) with atrial fibrillation for 2 to 7 years.2 Researchers evaluated warfarin compared with aspirin for the outcomes of major stroke, arterial embolism, and intracranial hemorrhage. Major strokes comprised fatal or disabling strokes. Researchers excluded patients with minor strokes, rheumatic heart disease, a major nontraumatic hemorrhage within the previous 5 years, intracranial hemorrhage, peptic ulcer disease, esophageal varices, or a terminal illness.

Compared with aspirin, warfarin significantly reduced all primary events (ARR = 1.8% vs 3.8%; relative risk reduction [RRR] = 0.48; 95% CI, 0.28-0.80; NNT = 50). Warfarin decreased major strokes more than aspirin (21 vs 44 strokes; ARR = 1.8%; relative risk [RR] = 0.46; 95% CI, 0.26-0.79; NNT = 56) but didn’t alter the risk of hemorrhagic strokes (6 vs 5 absolute events, respectively; RRR = 1.15, 95% CI, 0.29-4.77) or other intracranial hemorrhages (2 vs 1 event, respectively; RR = 1.92; 95% CI, 0.10-113.3). Wide confidence intervals and the small number of hemorrhagic events suggest that the study wasn’t powered to detect a significant difference in hemorrhagic events.

Continue to: Large study finds net benefit for warfarin treatment

Large study finds net benefit for warfarin treatment

A retrospective cohort including all 182,678 Swedish Hospital Discharge Register patients with atrial fibrillation (260,000 patient-years) evaluated the net benefit of anticoagulation treatment decisions over an average of 1.5 years.3 The Swedish National Prescribed Drugs Registry, which includes all Swedish pharmacies, identified all patients who were prescribed warfarin during the study years of July 2005 through December 2008. The patients were divided into 2 groups, warfarin or no warfarin, and assigned risk scores using CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED.4,5

Researchers defined net benefit as the number of ischemic strokes avoided in patients taking warfarin, minus the number of excess intracranial bleeds. They assigned a weight of 1.5 to intracranial bleeds vs 1 for ischemic strokes to compensate for the generally more severe outcomes of intracranial bleeding.

Warfarin produced a net benefit at every CHA2DS2-VASc score greater than 0 (aggregate result of 3.9 fewer events per 100 patient-years; 95% CI, 3.8-4.1; NNT = 26). Kaplan-Meier composite plots of all-cause mortality, ischemic stroke, and intracranial bleeds showed a net benefit favoring warfarin use for all combinations of CHA2DS2-VASc greater than 0 (patients older than 65 years never have a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0 because they’re assigned 1 point at ages 65 to 74 years and 2 points at 75 years and older) and HAS-BLED scores (all curves P < .00001).

Hazard ratios (HRs) of every combination of scores favored warfarin use (HRs ranged from 0.26-0.72; 95% CIs, less than 1 for all HRs; aggregate benefit at all risk scores: HR = 0.51; 95% CI, 0.50-0.52,). The risk of intracranial bleed, or any bleed, on warfarin at all risk strata was less than the corresponding risk of ischemic stroke (or thromboembolic event) without warfarin except among the lowest risk patients (CHA2DS2-VASc = 0). The difference between thromboses and hemorrhages increased as the CHA2DS2-VASc score increased. Of note, a smaller percentage of the highest risk patients were on warfarin.

EDITOR’S TAKEAWAY

We have solid evidence that, although the risks of systemic and intracranial bleeding from warfarin therapy in older patients with atrial fibrillation increase steadily with advancing age, so do the benefits in reduced ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, thrombotic emboli, and overall cardiovascular death. Most important, the benefits continue to outweigh the risks by a factor of 2 to 4, even in the oldest age groups.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A meta-analysis of 12 randomized trials of stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation (8932 patients, 63% male, mean age 72 years, 19.6% ≥ 80 years) examined outcomes of ischemic stroke, serious bleeding (systemic or intracranial hemorrhages requiring hospitalization, transfusion, or surgery) and cardiovascular events (ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, systemic emboli, and vascular death).1 Patients were randomized to oral anticoagulants (3430 patients), antiplatelet therapy (3531 patients), or no therapy (1971 patients).

Warfarin target international normalized ratios (INRs) ranged from 1.5 to 4.2. Previous stoke or transient ischemic attack varied across studies but averaged 22% (patient baseline characteristics were evenly distributed among all arms of all 12 studies, suggesting appropriate randomizations). Fifteen percent of patients had diabetes, 50% had hypertension, and 20% had congestive heart failure. They were followed for a mean of 2 years.

Overall, patients experienced 623 ischemic strokes, 289 serious bleeds, and 1210 cardiovascular events. After adjusting for treatment and covariates, age was independently associated with higher risk for each outcome. For every decade increase in age, the hazard ratio (HR) for ischemic stroke was 1.45 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.26-1.66); serious hemorrhage, 1.61 (95% CI, 1.47-1.77); and cardiovascular events, 1.43 (95% CI, 1.33-1.53).

Benefits of warfarin outweigh increased risk of hemorrhage

Treatment with vitamin K antagonists, compared with placebo, reduced ischemic strokes (HR = 0.36; 95% CI, 0.29-0.45) and cardiovascular events (HR = 0.59; 95% CI, 0.52-0.66) but increased the risk of serious hemorrhage (HR = 1.56; 95% CI, 1.03-2.37) in patients from 50 to 90 years of age. The benefits of decreased ischemic strokes and cardiovascular events consistently surpassed the increased risk of hemorrhage, however.

Across all age groups, the absolute risk reductions (ARRs) for ischemic stroke and cardiovascular events were 2% to 3% and 3% to 8%, respectively, whereas the absolute risk increase for serious hemorrhage was 0.5% to 1%. For those ages 70 to 75, for example, warfarin decreased the rate of ischemic stroke by 3% per year (number needed to treat [NNT] = 34; rates estimated from graphs) and the rate of cardiovascular events by 7% (NNT = 14) but increased the risk of serious hemorrhage by approximately 0.5% per year (number need to harm = 200).

Warfarin prevents major strokes more effectively than aspirin

A randomized open-label trial with blind assessment of endpoints, included in the meta-analysis, followed 973 patients older than 75 years (mean 81.5 years) with atrial fibrillation for 2 to 7 years.2 Researchers evaluated warfarin compared with aspirin for the outcomes of major stroke, arterial embolism, and intracranial hemorrhage. Major strokes comprised fatal or disabling strokes. Researchers excluded patients with minor strokes, rheumatic heart disease, a major nontraumatic hemorrhage within the previous 5 years, intracranial hemorrhage, peptic ulcer disease, esophageal varices, or a terminal illness.

Compared with aspirin, warfarin significantly reduced all primary events (ARR = 1.8% vs 3.8%; relative risk reduction [RRR] = 0.48; 95% CI, 0.28-0.80; NNT = 50). Warfarin decreased major strokes more than aspirin (21 vs 44 strokes; ARR = 1.8%; relative risk [RR] = 0.46; 95% CI, 0.26-0.79; NNT = 56) but didn’t alter the risk of hemorrhagic strokes (6 vs 5 absolute events, respectively; RRR = 1.15, 95% CI, 0.29-4.77) or other intracranial hemorrhages (2 vs 1 event, respectively; RR = 1.92; 95% CI, 0.10-113.3). Wide confidence intervals and the small number of hemorrhagic events suggest that the study wasn’t powered to detect a significant difference in hemorrhagic events.

Continue to: Large study finds net benefit for warfarin treatment

Large study finds net benefit for warfarin treatment

A retrospective cohort including all 182,678 Swedish Hospital Discharge Register patients with atrial fibrillation (260,000 patient-years) evaluated the net benefit of anticoagulation treatment decisions over an average of 1.5 years.3 The Swedish National Prescribed Drugs Registry, which includes all Swedish pharmacies, identified all patients who were prescribed warfarin during the study years of July 2005 through December 2008. The patients were divided into 2 groups, warfarin or no warfarin, and assigned risk scores using CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED.4,5

Researchers defined net benefit as the number of ischemic strokes avoided in patients taking warfarin, minus the number of excess intracranial bleeds. They assigned a weight of 1.5 to intracranial bleeds vs 1 for ischemic strokes to compensate for the generally more severe outcomes of intracranial bleeding.

Warfarin produced a net benefit at every CHA2DS2-VASc score greater than 0 (aggregate result of 3.9 fewer events per 100 patient-years; 95% CI, 3.8-4.1; NNT = 26). Kaplan-Meier composite plots of all-cause mortality, ischemic stroke, and intracranial bleeds showed a net benefit favoring warfarin use for all combinations of CHA2DS2-VASc greater than 0 (patients older than 65 years never have a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0 because they’re assigned 1 point at ages 65 to 74 years and 2 points at 75 years and older) and HAS-BLED scores (all curves P < .00001).

Hazard ratios (HRs) of every combination of scores favored warfarin use (HRs ranged from 0.26-0.72; 95% CIs, less than 1 for all HRs; aggregate benefit at all risk scores: HR = 0.51; 95% CI, 0.50-0.52,). The risk of intracranial bleed, or any bleed, on warfarin at all risk strata was less than the corresponding risk of ischemic stroke (or thromboembolic event) without warfarin except among the lowest risk patients (CHA2DS2-VASc = 0). The difference between thromboses and hemorrhages increased as the CHA2DS2-VASc score increased. Of note, a smaller percentage of the highest risk patients were on warfarin.

EDITOR’S TAKEAWAY

We have solid evidence that, although the risks of systemic and intracranial bleeding from warfarin therapy in older patients with atrial fibrillation increase steadily with advancing age, so do the benefits in reduced ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, thrombotic emboli, and overall cardiovascular death. Most important, the benefits continue to outweigh the risks by a factor of 2 to 4, even in the oldest age groups.

1. van Walraven C, Hart R, et al. Effect of age on stroke prevention therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. Stroke. 2009;40:1410-1416.

2. Mant J, Hobbs FD. Warfarin versus aspirin for stroke prevention in an elderly community population with atrial fibrillation (the Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of the Aged Study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370:493–503.

3. Friberg L, Rosenqvist M, Lip GY. Net clinical benefit of warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a report from the Swedish atrial fibrillation cohort study. Circulation. 2012;125:2298-2307.

4. Friberg L, Rosenqvist M, Lip G. Evaluation of risk stratification schemes for ischaemic stroke and bleeding in 182,678 patients with atrial fibrillation: the Swedish Atrial Fibrillation cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1500-1510.

5. Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, et al. A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: The Euro Heart Survey. Chest. 2010;138:1093-1100.

1. van Walraven C, Hart R, et al. Effect of age on stroke prevention therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. Stroke. 2009;40:1410-1416.

2. Mant J, Hobbs FD. Warfarin versus aspirin for stroke prevention in an elderly community population with atrial fibrillation (the Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of the Aged Study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370:493–503.

3. Friberg L, Rosenqvist M, Lip GY. Net clinical benefit of warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a report from the Swedish atrial fibrillation cohort study. Circulation. 2012;125:2298-2307.

4. Friberg L, Rosenqvist M, Lip G. Evaluation of risk stratification schemes for ischaemic stroke and bleeding in 182,678 patients with atrial fibrillation: the Swedish Atrial Fibrillation cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1500-1510.

5. Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, et al. A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: The Euro Heart Survey. Chest. 2010;138:1093-1100.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Yes, patients with atrial fibrilla- tion who are between the ages of 50 and 90 years continue to benefit from vitamin K antagonist therapy (warfarin) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [RCTs] and large cohorts). Regardless of age, warfarin produces a reduction in risk of thrombotic events that is 2- to 4-fold greater than the risk of hemorrhagic events.

How effective is spironolactone for treating resistant hypertension?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2017 meta-analysis of 4 RCTs (869 patients) evaluated the effectiveness of prescribing spironolactone for patients with resistant hypertension, defined as above-goal blood pressure (BP) despite treatment with at least 3 BP-lowering drugs (at least 1 of which was a diuretic).1 All 4 trials compared spironolactone 25 to 50 mg/d with placebo. Follow-up periods ranged from 8 to 16 weeks. The primary outcomes were systolic and diastolic BPs, which were evaluated in the office, at home, or with an ambulatory monitor.

Spironolactone markedly lowers systolic and diastolic BP

A statistically significant reduction in SBP occurred in the spironolactone group compared with the placebo group (weighted mean difference [WMD] = −16.7 mm Hg; 95% confidence interval [CI], −27.5 to −5.8 mm Hg). DBP also decreased (WMD = −6.11 mm Hg; 95% CI, −9.34 to −2.88 mm Hg).

Because significant heterogeneity was found in the initial pooled results (I2 = 96% for SBP; I2 = 85% for DBP), investigators performed an analysis that excluded a single study with a small sample size. The re-analysis continued to show significant reductions in SBP and DBP for spironolactone compared with placebo (SBP: WMD = −10.8 mm Hg; 95% CI, −13.16 to −8.43 mm Hg; DBP: WMD = −4.62 mm Hg; 95% CI, −6.05 to −3.2 mm Hg; I2 = 35%), confirming that the excluded trial was the source of heterogeneity in the initial analysis and that spironolactone continued to significantly lower BP for the treatment group compared with controls.

Add-on treatment with spironolactone also reduces BP

A 2016 meta-analysis of 5 RCTs with a total of 553 patients examined the effectiveness of add-on treatment with spironolactone (25-50 mg/d) for patients with resistant hypertension, defined as failure to achieve BP < 140/90 mm Hg despite treatment with 3 or more BP-lowering drugs, including one diuretic.2 Spironolactone was compared with placebo in 4 trials and with ramipril in the remaining study. The follow-up periods were 8 to 16 weeks. Researchers separated BP outcomes into 24-hour ambulatory systolic/diastolic BPs and office systolic/diastolic BPs.

The 24-hour ambulatory BPs were significantly lower in the spironolactone group compared with the control group (24-hour SBP: WMD = −10.5 mm Hg; 95% CI, −12.3 to −8.71 mm Hg; 24-hour DBP: WMD = −4.09 mm Hg; 95% CI, −5.28 to −2.91 mm Hg). No significant heterogeneity was noted in these analyses.

Office-based BPs also were markedly reduced in spironolactone groups compared with controls (office SBP: WMD = −17 mm Hg; 95% CI, −25 to −8.95 mm Hg); office DBP: WMD = −6.18 mm Hg; 95% CI, −9.3 to −3.05 mm Hg). Because the office-based BP data showed significant heterogeneity (I2 = 94% for SBP and 84.2% for DBP), 2 studies determined to be of lower quality caused by lack of detailed methodology were excluded from analysis, yielding continued statistically significant reductions in SBP (WMD = −11.7 mm Hg; 95% CI, −14.4 to −8.95 mm Hg) and DBP (WMD = −4.07 mm Hg; 95% CI, −5.6 to −2.54 mm Hg) compared with controls. Heterogeneity also decreased when the 2 studies were excluded (I2 = 21% for SBP and I2 = 59% for DBP).

How spironolactone compares with alternative drugs

A 2017 meta-analysis of 5 RCTs with 662 patients evaluated the effectiveness of spironolactone (25-50 mg/d) on resistant hypertension in patients taking 3 medications compared with a control group—placebo in 3 trials, placebo or bisoprolol (5-10 mg) in 1 trial, and an alternative treatment (candesartan 8 mg, atenolol 100 mg, or alpha methyldopa 750 mg) in 1 trial.3 Follow-up periods ranged from 4 to 16 weeks. Researchers evaluated changes in office and 24-hour ambulatory or home BP and completed separate analyses of pooled data for spironolactone compared with placebo groups, and spironolactone compared with alternative treatment groups.

Continue to: Investigators found a statistically significant...

Investigators found a statistically significant reduction in office SBP and DBP among patients taking spironolactone compared with control groups (SBP: WMD = −15.7 mm Hg; 95% CI, −20.5 to −11 mm Hg; DBP: WMD = −6.21 mm Hg; 95% CI, −8.33 to −4.1 mm Hg). A significant decrease also occurred in 24-hour ambulatory home SBP and DBP (SBP: MD = −8.7 mm Hg; 95% CI, −8.79 to −8.62 mm Hg; DBP: WMD = −4.12 mm Hg; 95% CI, −4.48 to −3.75 mm Hg).

Patients treated with spironolactone showed a marked decrease in home SBP compared with alternative drug groups (WMD = −4.5 mm Hg; 95% CI, −4.63 to −4.37 mm Hg), but alternative drugs reduced home DBP significantly more than spironolactone (WMD = 0.6 mm Hg; 95% CI, 0.55-0.65 mm Hg). Marked heterogeneity was found in these analyses, and the authors also noted that reductions in SBP are more clinically relevant than decreases in DBP.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The 2017 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology evidence-based guideline recommends considering adding a mineralocorticoid receptor agonist to treatment regimens for resistant hypertension when: office BP remains ≥ 130/80 mm Hg; the patient is prescribed at least 3 antihypertensive agents at optimal doses including a diuretic; pseudoresistance (nonadherence, inaccurate measurements) is excluded; reversible lifestyle factors have been addressed; substances that interfere with BP treatment (such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and oral contraceptive pills) are excluded; and screening for secondary causes of hypertension is complete.4

The United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) evidence-based guideline recommends considering spironolactone 25 mg/d to treat resistant hypertension if the patient’s potassium level is 4.5 mmol/L or lower and BP is higher than 140/90 mm Hg despite treatment with an optimal or best-tolerated dose of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor blocker plus a calcium-channel blocker and diuretic.5

Editor’s takeaway

The evidence from multiple RCTs convincingly shows the effectiveness of spironolactone. Despite the SOR of C because of a disease-oriented outcome, we do treat to blood pressure goals, and therefore, spironolactone is a good option.

1. Zhao D, Liu H, Dong P, et al. A meta-analysis of add-on use of spironolactone in patients with resistant hypertension. Int J Cardiol. 2017;233:113-117.

2. Wang C, Xiong B, Huang J. Efficacy and safety of spironolactone in patients with resistant hypertension: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Heart Lung Circ. 2016;25:1021-1030.

3. Liu L, Xu B, Ju Y. Addition of spironolactone in patients with resistant hypertension: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2017;39:257-263.

4. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYP.0000000000000065. Accessed June 6, 2019.

5. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management. Clinical guideline [CG127]. August 2011. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg127/chapter/1-guidance#initiating-and-monitoring-antihypertensive-drug-treatment-including-blood-pressure-targets-2. Accessed June 6, 2019.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2017 meta-analysis of 4 RCTs (869 patients) evaluated the effectiveness of prescribing spironolactone for patients with resistant hypertension, defined as above-goal blood pressure (BP) despite treatment with at least 3 BP-lowering drugs (at least 1 of which was a diuretic).1 All 4 trials compared spironolactone 25 to 50 mg/d with placebo. Follow-up periods ranged from 8 to 16 weeks. The primary outcomes were systolic and diastolic BPs, which were evaluated in the office, at home, or with an ambulatory monitor.

Spironolactone markedly lowers systolic and diastolic BP